KERUGOYA-KUTUS MUNICIPALITY URBAN ECONOMIC PLAN (UEP ) 1 Kerugoya-Kutus Municipality Urban Economic Plan (UEP) Sustainable Urban Economic Development Programme SUED October 2021

The development of the Kerugoya-Kutus Municipality Urban Economic Plan (UEP) has been made possible by funding from the UK government through UKaid’s Sustainable Urban Economic Development Programme (SUED) that is managed by Tetra Tech Company Coffey.

This report was developed by Atkins.

2

KERUGOYA-KUTUS MUNICIPALITY URBAN ECONOMIC PLAN (UEP ) 3 AD Anaerobic Digestion ASTGS Agriculture Sector Transformation and Growth Strategy CBD Central Business District CBO Community-based organisation CIDP Kirinyaga County Integrated Development Plan 2018 - 2022 CECM County Executive Committee Member CEREB Central Region Economic Bloc CoG Council of Governors CSP (Draft) County Spatial Plan 2015 - 2025 ECDE Early Childhood Development Education EIA Environmental Impact Assessment FA Focus Area FCDO Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office FGDs Focus Group Discussions FTE Full-Time Equivalent GBD Green Blue Development GBI Green Blue Infrastructure GBV Gender Based Violence GCP Gross County Product GDI Gender Development Index GEI Gender Equality Index GDP Gross Domestic Product GeSI Gender and Social Inclusion GVA Gross Value Added IDeP Kerugoya – Kutus Municipality Integrated Development Plan (2018 – 2022) IFI International Financing Institutions KC Kirinyaga County KES Kenya Shillings KeBS Kenya Bureau of Standards KeNHA Kenya National Highways Authority KeRRA Kenya Rural Roads Authority KIDA Kirinyaga Investment Development Authority KIHBS Kenya Integrated Household Budget Survey KII Key Informant Interview KKM Kerugoya – Kutus Municipality KOM Kick-off Meeting KIRIWASCO Kirinyaga Water and Sanitation Company KNBS Kenya National Bureau of Statistics KISIP Kenya Informal Settlement Improvement Programme KPLC Kenya Power and Lighting Company KURA Kenya Urban Roads Authority KUSP Kenya Urban Support Programme KRC Kenya Railways Corporation KyU Kirinyaga University LPLUDP Local Physical Land Use Development Plan MB Municipal Board MM Municipal Manager MSW Municipal Solid Waste Mt Mount NEMA National Environment Management Authority NIA National Irrigation Authority NCPWD National Council for Persons with Disability NGOs Non-Government Organisations NMT Non-motorised transport NSP National Spatial Plan PWD People Living with Disabilities PMT Tetra Tech Programme Management Team PSG Kerugoya – Kutus UEP Project Steering Group PSV Public Service Vehicle PV Photovoltaic SACCO Savings and Credit Cooperative Organizations SAPAD Strategies for Agro-Pastoralists Development SEZ Special Economic Zone SIG Special Interest Group SME Small and Medium Enterprises SWOT Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, And Threats SuDS Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems SUED Sustainable Urban Economic Development Programme TBP Technical Briefing Paper UN United Nations UNIDO United Nations Industrial Development Organisation USAID United States Agency for International Development UEP Urban Economic Plan VC Value Chain WSP Water Service Provider WASREB Water Services Regulatory Board Abbreviations and Acronyms

4 Table 2.1 SIGs and Exclusion Manifestation Table 31 Table 2.2 Business Identified Challenges to Growth 34 Table 4.1 Trade, Services and Eco-Tourism: SWOT 51 Table 4.2 Agriculture Action Plan 52 Table 4.3 Agri-Processing and Industry: SWOT 58 Table 4.4 Agri-Processing and Industry Action Plan 59 Table 4.5 Trade, Services and Eco-Tourism: SWOT 64 Table 4.6 Trade, Services and Eco-Tourism: Action Plan 64 Table 4.7 Process Volumes for Banana Flour 72 Table 4.8 Value Added 73 Table 4.9 Production Inputs and Volumes for Husk Lumber 81 Table 4.10 Production Inputs and Volumes for Husk Tableware 81 Table 4.11 Value Added 82 Table 5.1 GBI Proposals Overview for Each Focus Area 89 Table 5.2 Project 1 Summary Information 99 Table 5.3 Project 1 Basic Analysis and Timeline 99 Table 5.4 Project 2 Summary Information 101 Table 5.5 Project 2 Basic Analysis and Timeline 101 Table 5.6 Project 3 Summary Information 104 Table 5.7 Project 3 Basic Analysis and Timeline 104 Table 5.8 Project 4 Summary Information 107 Table 5.9 Project 4 Basic Analysis and Timeline 107 Table 5.10 Project 5 Summary Information 110 Table 5.11 Project 5 Basic Analysis and Timeline 110 Table 5.12 Project 6 Summary Information 116 Table 5.13 Project 6 Basic Analysis and Timeline 116 Table 5.14 Project 7 Summary Information 128 Table 5.15 Project 7 Basic Analysis and Timeline 128 Table 5.16 Project 8 Summary Information 138 Table 5.17 Project 8 Basic Analysis and Timeline 138 Table 5.18 Project 9 Summary Information 143 Table 5.19 Project 9 Basic Analysis and Timeline 143 Table 5.20 Project 10 Summary Information 154 Table 5.21 Project 10 Basic Analysis and Timeline 154 Tables

KERUGOYA-KUTUS MUNICIPALITY URBAN ECONOMIC PLAN (UEP ) 5 Table 5.22 Project 11 Summary Information 158 Table 5.23 Project 11 Basic Analysis and Timeline 158 Table 5.24 Project 12 Summary Information 163 Table 5.25 Project 12 Basic Analysis and Timeline 163 Table 5.26 Project 13 Summary Information 166 Table 5.27 Project 13 Basic Analysis and Timeline 166 Table 5.28 Comparison of Sanivation Briquettes to Wood and Charcoal 168 Table 5.29 Project 14 Summary Information 170 Table 5.30 Project 14 Basic Analysis and Timeline 170 Table 5.31 Project 15 Summary Information 174 Table 5.32 Project 15 Basic Analysis and Timeline 174 Table 5.33 Project 16 Summary Information 178 Table 5.34 Project 16 Basic Analysis and Timeline 178 Table 5.35 Project 17 Summary Information 182 Table 5.36 Project 17 Basic Analysis and Timeline 182 Table 5.37 Project 18 Summary Information 186 Table 5.38 Project 18 Basic Analysis and Timeline 186 Table 5.39 Project 19 Summary Information 190 Table 5.40 Project 19 Basic Analysis and Timeline 190 Table 5.41 Project 20 Summary Information 194 Table 5.42 Project 20 Basic Analysis and Timeline 194 Table 5.43 Project 21 Summary Information 198 Table 5.44 Project 20 Basic Analysis and Timeline 198 Table 5.45 Project 22 Summary Information 202 Table 5.46 Project 21 Basic Analysis and Timeline 202 Table 5.47 Project 23 Summary Information 209 Table 5.48 Project 23 Basic Analysis and Timeline 209 Table 6.1 Summary implementation costs estimates 216 Table 6.2 Implementation Costs and Delivery Mechanisms 217

6 Figure 1.1 Purpose of the Plan 15 Figure 1.2 Climate change and poverty interactions 16 Figure 1.3 SUED Principles 18 Figure 1.4 Climate change and poverty interactions 20 Figure 2.1 Map Illustrating the Municipality within CEREB and Kenya 27 Figure 2.2 Planning Context 28 Figure 2.3 Kerugoya Town Character 31 Figure 2.4 Kutus Town Character 33 Figure 2.5 The Three Dimension of Inclusion 35 Figure 2.6 Gross County Product per Capita, 2019 (in KES) 36 Figure 2.7 Kirinyaga GCP Breakdown 37 Figure 3.1 UEP Green Blue Development Framework 43 Figure 3.2 Multi-Benefits and Multi-Disciplinary Approach to GBD of KKM 47 Figure 4.1 Economic Development Plan 54 Figure 4.2 Banana Flour Processing 75 Figure 4.3 Operating Costs, 2026 77 Figure 4.4 Social inclusion recommendation for banana flour VC 80 Figure 4.5 Process Flow for Husk Lumber 84 Figure 4.6 Process Flow for Husk Tableware 84 Figure 4.7 Operating Costs, 2026 86 Figure 4.8 Social inclusion recommendations for husk products VC 89 Figure 5.1 Map Showing the Three Main Focus Areas 91 Figure 5.2 Map showing all GBI Proposals and Interventions 94 Figure 5.2a – Map with all projects in Sagana FA 95 Figure 5.3 Sagana Focus Area Overview 96 Figure 5.4 Phase 1 Sagana Green Industrial Hub 102 Figure 5.5 Map of Focus Area 2: Kutus 121

Figure 5.10 Existing view looking north-east from the B25 showing the existing Livestock Market 134 Figure 5.11 Proposed view looking north-east from B25 showing the proposed urban park and community centre 134 Figure 5.12 Existing view looking east from River Thiba showing the existing Livestock Market 135 Figure 5.13 Proposed view looking east from River Thiba showing the proposed urban park and community centre 135 Figure 5.14 Existing high-level view looking west showing the existing Livestock Market 136 Figure 5.15 Proposed high-level view looking west showing the proposed urban park and community centre 136 Figure 5.16 Proposed ground level view looking south-east showing the proposed urban park and community centre 137 Figure 5.17 Proposed east-west section showing the various levels, terraces and the proposed community centre 138 Figure 5.18 Proposed aerial view showing the proposed urban park connections with the wider CBD area 139 Figure 5.19 Suggested road for improvement 144 Figure 5.20 GBI proposals in Focus Area 3 Kerugoya 148 Figure 5.21 High-level green space connectivity concept 150 Figures

Figure 5.6 Plan Showing Existing Land Uses, Primary Roads and Key Functions in the Pilot Area 123 Figure 5.7 Plan Showing Ongoing Interventions and Opportunities 125 Figure 5.8 Recommended Densities and Land Uses 127 Figure 5.9 Plan showing proposed layout and functions for the Urban Park and community centre 133

7

KERUGOYA-KUTUS MUNICIPALITY URBAN ECONOMIC PLAN (UEP )

Figure 5.22 Existing high level view of the central park looking south-east 151 Figure 5.23 Proposed high level view of the central park looking south-east 151 Figure 5.24 Existing high level view of the central park looking north-west 152 Figure 5.25 Proposed high level view of the central park looking north-west 152 Figure 5.26 Existing view of the central park looking south from the internal areas 153 Figure 5.27 Proposed view of the central park looking south from the internal areas 153 Figure 5.28 Proposed illustrative section of the central square showing various elements of the new park 154 Figure 5.29 Proposed thematic connectivity diagram showing the linkages between the bus park, the central park, and the urban forest 155 Figure 5.30 Proposed detailed connectivity diagram showing the linkages between the bus park, the central park, and the urban forest 155 Figure 5.31 Current parking arrangement (top) and access road to the park (bottom) 159 Figure 5.32 Map with GBI proposals beyond the Focus Areas 162 Figure 5.33 Household Water Access Challenges 163 Figure 5.34 Low-income areas in KKM 164 Figure 5.35 Small-scale treatment and reuse system comprising of treatment tank, mixer, roller press, drying beds and burning briquettes 169 Figure 5.36 Critical rural links in fair to poor condition requiring improvement 197 Figure 5.37 Priority routes to upgrade NMT facilities in Kutus (left) and Kerugoya (right) 201 Figure 6.1 UEP Development Framework Schedule 224

8

1. Introduction 12 1.1 Background 12 1.2 Purpose of the Plan 13 1.3 Approach 14 1.4 Key Principles 16 1.5 Climate Change, Social Exclusion and Poverty 18 1.6 Structure of this Report 23 2. Kerugoya-Kutus Urban Diagnostics 24 2.1 Study Area 25 2.2 Planning Context 26 2.3 State of Kerugoya-Kutus 27 2.4 Infrastructure Overview 35 2.5 Environment and Climate Change Risk Profile 36 2.6 Diagnostics Conclusion: Drivers and Barriers for Growth 37 3. Green Blue Development Concept 38 3.1 Introducing the Development Concept 38 3.2 UEP Vision 40 3.3 Economic Development – Sector Plans and VCs 41 3.4 Green Blue Development (GBD) Approach 42 4. Economic Development Plan 48 4.1 Economic Sector Action Plans 51 4.2 Value Chain Projects 69 5. Green Blue Infrastructure Development Framework 86 5.1 Introduction 86 5.2 Focus Area 1: Sagana Green Industrial Hub 91 5.3 Focus Area 2: Kutus 118 5.4 Focus Area 3: Kerugoya 145 5.5 KKM and KC-Level Proposals 160 6. Implementation Plan 212 6.1 Introduction 212 6.2 Stakeholders and institutional structures 214 6.3 Implementation Costs and Potential Funding Sources 216 6.4 Scheduling 226 6.5 Funding including Climate Funds 227 6.6 Recommendations for Capacity Building 230 6.7 Recommendations for Social Inclusion 231 6.8 Recommendations for Climate Change and Resilience 232 6.9 Next Steps 233 Contents KERUGOYA-KUTUS MUNICIPALITY URBAN ECONOMIC PLAN (UEP ) 9

The purpose of the plan is to:

Stakeholders’ interests and insights have been considered throughout the development of the UEP.

Chapter 2 sets out the diagnostic assessment of KKM, where the social, economic, planning, infrastructure, environmental and climate risk baseline has provided an understanding of the barriers and drivers to sustainable economic growth.

The UEP is an advisory document that builds on existing work and priorities identified under the County Integrated Development Plan (CIDP), the Mountain Cities Blueprint, the Draft County Spatial Plan (CSP), the Draft Local Physical and Land Use Development Plan (LPLUDP), and Integrated Development Plan (IDeP), as well as aligning and complementing work done by other donors. In doing so, it will provide a focused economic plan for the Municipal Board (MB) and Municipal Departments to enable them to deliver economic development within the Municipality and the County.

WS Atkins International Limited was commissioned to develop the Urban Economic Plan for Kerugoya – Kutus Municipality (KKM) as part of the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) Sustainable Urban Economic Development Programme (SUED). The aim of the programme is to support market-driven growth in emerging towns and cities in Kenya.

> Prioritise economic activities and Green Blue Infrastructure (GBI) that can maximise benefits and support the development of a sustainable economic future for KKM;

10 Executive Summary

> Identify and prepare value chain (VC) projects that can be considered further in terms of their feasibility and bankability before SUED seed financing is committed.

The Municipality comprises the two main towns of Kerugoya and Kutus, which are 10 km apart and linked by the B27 road and Rutui River. KKM is the Kirinyaga County (KC) headquarters and administrative centre together, as well as the health, financial, commercial, retail and wholesale market hub. Lack of proper planning, poor implementation of plans and poor enforcement of regulations have led to uncontrolled urban growth and informal settlements with inadequate access to basic services, as well as poor road conditions with limited accessibility and environmental degradation.

> Bring together stakeholders on deciding the economic future of KKM and implementing it; and

The Municipality and the County are relatively small in size and population but have a sound economy and are leading producers of rice and other agricultural produce such as tea, coffee and tomatoes. KKM is mostly rural in character, with land use predominantly agricultural.

The Gender and Social Inclusion Study (GeSI) was a key part of the diagnostic, providing recommendations for meeting the aims of the SUED Programme to advance inclusion of people with disabilities (PWD) and youth. The Wezesha Development Programme has been a key driver to inclusive growth in KC which has empowered smallholder farmers, and particularly women, youth, and other vulnerable groups.

> Provide an inclusive economic strategy that can guide future development towards increasing prosperity in KKM;

of the economy, through these key sectors, will be the improvement of infrastructure particularly in areas affecting production potential such as roads and transport accessibility, insufficient water supply to support growing population and businesses, poor solid waste management, sanitation and drainage. The cost of electricity is very high, and most people use firewood and charcoal for cooking.

> Trade, services and eco-tourism, reflecting the existing commercial activity in KKM and its strategic location, as well as the future growth opportunities presented by Criticaleco-tourism.forthedevelopment

The bespoken approach recognises the multi-functional, multi-benefits and multi-disciplinary inputs to GBD in order to achieve KKM’s UEP economic vision, which has been developed with key stakeholders: “A well-planned, integrated, vibrant and greenwhilstopportunitiesindustrialMunicipalitysustainablewithagreenhub,thatprovidesforallitscitizensenhancingitsuniqueblueresources.”

> Industry and agri-processing, driven by Kirinyaga Investment Development Agency (KIDA) and Kenya’s Agricultural Sector Transformation Growth Strategy (ASTGS).

KERUGOYA-KUTUS MUNICIPALITY URBAN ECONOMIC PLAN (UEP ) 11

1. Polycentric development means to develop multiple towns / urban centres with a specialised urban function instead of a single town The County is greatly influenced by Mt Kenya, determining three main ecological zones: the highlands in the north, the midlands, and lowlands or plains in the south. Climatic conditions range from cool and higher rainfall in the highlands to drier and warmer conditions in the plains. KC is well-endowed with water resources thanks to rivers emanating from the mountain system. Key climate risks are drought and rainfall variability (including onset and duration of rainfall), localised flooding, particularly for informal settlements, and increased temperatures accelerating reduction in snow and glacier cover at Mt Kenya, which has in turn decreased the reliability of river flows into KKM and KC. Chapter 3 presents the Green Blue Development (GBD) concept, overarching the economic sector plans, VC opportunities and the implementation of the Development Framework of Green Blue Infrastructure (GBI) projects and initiatives. This GBD concept is also a response to the polycentric1 development suggested in the main planning documents. The GBD approach is a significant opportunity for both KKM and KC to drive sustainable economic development, protect its unique water and natural resources and enhanced environmental resilience, whilst also improving the health and wellbeing of its citizens.

The diagnostic stage identified three key economic sectors that KKM should prioritise for development, as: > Agriculture, the local population largely rely on this sector as the main economic subsistence activity.

> Focus Area 2: Kutus town, the wholesale trading centre and well-known university town as it hosts the Kirinyaga University (KyU). The proposed interventions aim at supporting the development of the trade and services sectors, particularly the existing student population.

12

To realise the vision and KKM’s role, the development framework proposals are organised around three main Focus Areas: > Focus Area 1: Sagana green industrial hub, a site identified by KC and KIDA with benefits of good accessibility and connectivity by both road and railway with the wider regional area. The site presents an opportunity to cluster at the same location the two priority VCs, all potential VCs and other industrial businesses, to allow for economies of scale, and to share facilities and infrastructure. The industrial site will be developed as a green industrial park in line with the GBD approach to avoid inefficient use of resources, and to limit pollution and damage to the natural environment.

> Banana flour would also capitalise on the growing international niche market for banana flour and KC being one of the leading producers of banana in Kenya.

>

Chapter 4 sets out the Economic Development Plan in response to the economic vision and the sectoral SWOT assessment undertaken at diagnostic stage and aims to strengthen synergies between the different areas of the County by creating complementarities rather than competition between them. Action Plans include economic ambitions and a list of interventions for each of the key sectors. The plans are aligned and support the GBD through developing a resilient agriculture system; growing the agri-processing and industrial sector; establishing a developed service economy and improve the eco-tourism offer. The plans will complement and provide an enabling environment for the prioritised value chain (VC) opportunities.

Chapter 5 sets out the GBI development framework, which structures, prioritises and phases urban development in the most suitable locations in a coherent and coordinated manner considering the limited availability of developable land across the Municipality.

> Capacity building specialists to enhance the local capacity to implement the projects and ensure revenue generation;

> Husk products: lumber and tableware would capitalise on the high production of rice in the County, which currently generates about 24,000 tonnes of rice husk each year, and the increasing volume of husk from coffee and macadamia nuts providing about 4,000 tonnes of husk per year.

> Investment climate experts to address policy and regulatory constraints; and

The UEP is an advisory document owned and administered by the Municipality and the main responsible authority for its future implementation. Similarly, the Municipality is responsible to agree appropriate funding from the County budget as well as seeking any additional funding from IFIs, donors, and/or private sector to support the implementation of the VC and GBI projects.

Following the completion of the UEP, during the next phase of the SUED programme, the identified projects will be developed further by:

Chapter 6 provides the Implementation Plan, which presents relevant considerations across partnerships, funding and scheduling for the proposed VC and climate-resilient and inclusive infrastructure projects, including estimated delivery costs. This section also presents recommendations for capacity building, social inclusion and climate resilience, as crucial elements for implementing the UEP.

These VCs are:

Kutus could become a knowledge cluster with a better urban environment, offering a range of accommodation opportunities and supporting local employment.

Eight potential VC projects were shortlisted and further assessed for inclusion to the UEP. Their assessment included consideration of target market, costs and revenues, competitiveness, land and infrastructure requirements, and climate vulnerability and social inclusion assessment. All of these opportunities would be suitable for development in Kerugoya-Kutus. However, two priority VC opportunities have been selected to maximise benefits with their ability to catalyse the industrial sector, utilising synergies to existing assets and the opportunity to implement a circular economy.

Focus Area 3: Kerugoya town, the second largest town within KC and main provider of health, financial and retail services. The proposed interventions aim to support the fast-growing population and consolidate its role as service provider by improving green open spaces, public realm and enabling infrastructure.

> Investment experts to develop feasibility studies, business cases and investment promotion strategies for the projects.

Other GBI interventions have been proposed outside these Focus Areas to address issues that benefit KKM and its economic role, however, the County or the location is not defined yet due to limitations on land availability including utilities projects, upgrading of critical roads, improvement to the livelihoods of farmers and conservation of key natural assets such as Mt Kenya.

KERUGOYA-KUTUS MUNICIPALITY URBAN ECONOMIC PLAN (UEP ) 13 LandfillsKKM19 AND KIRINYAGA COUNTY GENERAL INTERVENTIONS Kerugoya and Kutus Water Supply12 Kerugoya and Kutus Sanita�on Provision2213 NMT and Urban Street Improvements Cri�cal Rural Feeder Roads21 Micro-Hydro Projects14 Solar Refrigera�on (Cold Stores)15 Solar Irriga�on16 Streetligh�ng17 Waste Collec�on18 Catchment Management in Mt. Kenya20 Donkey Management23 21 21 21 21 21 21 21 21 21 21 21 21 12221319 12221319 19 FOCUS AREA: SAGANA GREEN INDUSTRIAL HUB1 FOCUS AREA: KUTUS BUILT-UP AREA2 FOCUS AREA: BUILT-UPKERUGOYAAREA 3 FOCUS AREA 2: KUTUS BUILT-UP AREA Kutus Pilot Area Urban Regenera�on7 Kutus Urban Park and Community Centre8 Improved Access to Kutus Markets9 87 9 FOCUS AREA 1: SAGANA GREEN INDUSTRIAL HUB Sagana Green Indutrial Park1 Water, Wastewater and Drainage Service Provision for Phase 1 Sagana2 Energy Solu�ons for Phase 1 Sagana4 Organic Waste Processing for Phase 1 Sagana3 Access Road to Phase 1 Sagana5 Sagana Railway Sta�on Upgrade6 1 2 4 3 5 6 FOCUS AREA 3: KERUGOYA BUILT-UP AREA Kerugoya Central Park10 Kerugoya Bus Park Improvements11 10 11 KerugoyaKutus Kagio Sagana MunicipalityTowns Boundary Key toCriticalFocusFocusFocusCountyRailwayThibaRiversRoadsDamBoundaryArea1Area2Area3FeederRoadsbeimproved

14 1. Introduction

1.1 Background WS Atkins International Limited was commissioned to develop the Urban Economic Plan (UEP) for Kerugoya - Kutus Municipality (KKM) as part of the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) Sustainable Urban Economic Development Programme (SUED). The aim of the programme is to support market-driven growth in emerging towns and cities in Kenya. Supporting these smaller centres provides an environment to create economic opportunities and job creation in a way that balances growth across the country, develops economic sectors that can contribute towards increasing the national output, and provides an incentive for minimising uncontrolled migration.

KERUGOYA-KUTUS MUNICIPALITY URBAN ECONOMIC PLAN (UEP ) 15

Combining local knowledge and international expertise, the Kerugoya-Kutus Urban Economic Plan: Figure 1.1 Purpose of the Plan Provides an inclusive economic strategy that can guide future development towards increasing prosperity in KKM; Prioritises economic activities and climate resilient infrastructure that can maximise benefits and support the development of a sustainable economic future of KKM and introduce international best practice and Bringsinnovation;together stakeholders on deciding the economic future of KKM and implementing it; and Identifies and prepares value chain projects that can be considered further in terms of their feasibility and bankability before SUED seed financing is committed.

The UEP is an advisory document that builds on existing work and priorities identified under the County Integrated Development Plans (CIDP), Municipality Integrated Development Plans (IDeP), the Mountain Cities Blueprint 2032, Draft Local Physical and Land Use Development Plan (LPLUD) and the Draft County Spatial Plan (CSP) as well as aligning and complementing work done by other donors. In doing so, it will provide a focused economic strategy for the Municipal Board and Municipal Departments to enable them to deliver economic development within the Municipality.

1.2 Purpose of the Plan

Source: Atkins

Source: Atkins (note: KOM – Kick-off Meeting)

/=, /-, IdentificationK of

1.3 Approach

Diagnostics Phase UEP BriefingTechnicalPhase UEP Phase International/NationalFrameworktrends Analysis of Strengths, ThreatsOpportunitiesWeaknesses,andofkeyeconomicsectors

The Kerugoya-Kutus UEP has been developed utilising primary and secondary research and analysis, ranging from the review of local and national strategies and international studies to statistical analyses, to focus group discussions with stakeholders and surveys. A key component has been consultation with local stakeholders.

the

ValueresilientFrameworkDevelopmentactions&ClimateinfrastructureAnchorprojects:chainopportunities

> Phase 4 – Development of the Final UEP which sets out in detail economic opportunities and actions and prioritises climate-resilient infrastructure projects for implementation.

Interest

The approach and methodology have been developed in response to the FCDO terms of reference and in consultation with the SUED Team and FCDO and have been tailored to consider local conditions in Kerugoya-Kutus. The aim was to enable a collaborative approach between different local stakeholders and the consultant team to assess Kerugoya-Kutus’ economy in a systematic way, develop an agreed economic vision and prioritise actions that will have maximum impact and are ready to attract donor co-financing.

The preparation of the UEP comprised four main phases:

> Phase 1 – Inception Phase which focused on the Kick-off Meeting. The aim was to present the approach of the UEP and capture key opportunities and challenges affecting economic growth in KKM as defined by local stakeholders

EvaluatingUEPandprioritisingVCopportunities

16

Evaluatingopportunitiesclimateresilientgreeninfrastructureopportunities short listed VC opportunities and climate resilient infrastructure with Municipal Board, Municipality & County officers, Businesses, Special Groups

Consultation

> Phase 2 – The Diagnostics Phase was developed to provide a comprehensive and wide-ranging assessment of Kerugoya-Kutus’ economy, demographics, infrastructure, environment and climate change risk profile against national and international context.

throughcommentsinitialstakeholderengagement-KOMInceptionPhase

Economic EnvironmentalInfrastructureDemographicandandTransportationprovision&Climatechangeriskprofile

Assessing requirements &

Setting Vision & key economic sector

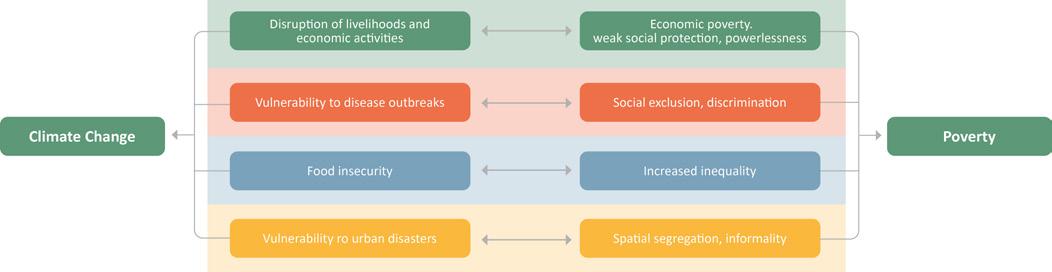

Figure 1.2 Climate change and poverty interactions Gather

impact of shortlisted VC

> Phase 3 – The Technical Briefing Paper set out a development framework for Kerugoya-Kutus and identified, assessed and prioritised economic growth opportunities and their requirements.

Setting the principles for the development of

Policy

The aim is to ensure the PSG is representative of the needs and challenges associated with the Municipality whilst being aligned and familiar with existing County and Municipal policies and regulations.

> To ensure that the development of the Urban Economic Plan is inclusive and is undertaken in a manner that fits with Kerugoya-Kutus’ business and community culture; > To ensure that all stakeholders are clear on the purpose, scope, recommendations and outcomes of the Urban Economic Plan as well as meeting key stakeholders’ aspirations and gain buy-in from them; > To understand better the interests of specific groups and how the Urban Economic Plan can benefit them, and

> To provide a regular flow of information to and from key stakeholders.

A business consultation was also undertaken to understand how businesses operate in KKM and their views on future growth opportunities and constraints. This consultation was composed of 1:1 interviews with 57 businesses, reflecting KKM’s main sectoral activities. Many of these were small businesses or independent workers – given the nature of the local economy. Each interview was supported with a detailed questionnaire.

The KKM stakeholders include:

KERUGOYA-KUTUS MUNICIPALITY URBAN ECONOMIC PLAN (UEP ) 17

A Project Steering Group (PSG) was formed to enable the exchange of ideas and information between the Municipal Board and the SUED technical team. The PSG was formed of the following members: > Municipal Manager; > County Governor’s Office Representative; > County Physical Planner; > County Engineer; > County Economist; > Special Interest Groups Representative; > Chamber of Commerce Representative; > Climate Change Champion; > Municipal Board Representatives.

The PSG, under an elected representative, also facilitated the dissemination of information on the various components and progress of the UEP and the broader SUED Programme, including liaison with the County Government, the Municipality, and the Municipal Board. It includes champions on SUED’s key themes of climate change and social inclusion.

The PSG was also tasked with arranging meetings and workshops as and when required by the SUED team, as part of the overall Programme roll out. The PSG was updated on a weekly basis on progress in the UEP process and the following meetings between the PSG and the SUED team took place.

The Gender and Social Inclusion study (GeSI) involved a related literature review and primary research, covering interviews with key project informants and four focus group discussions. This resulted in the identification of socially-excluded groups, of how their exclusion manifests, and processes that perpetuate the exclusion and development of the inclusion interventions as proposed in this UEP.

The purpose of stakeholder engagement was to ensure that stakeholders’ interests are taken into consideration throughout development and reflected in the Kerugoya-Kutus Urban Economic Plan. More specifically, the aims were:

Stakeholder Engagement

> County Government including the County Director; CECM Lands and Physical Planning; Chief Officers, County Administration and County Assembly members, KIDA; > Municipal Board including Chairperson, Vice-Chair, Municipal Manager and Board Members; > Business Representatives including Chamber of Commerce (KNCCI), organised business groups, traders and Jua Kali, SACCOs, banks and finance organisations, Industrial and Commercial Development Cooperation (ICDC), farmers and coffee millers; > Utilities and Service Providers including the Water Resource Authority (WRA), KIRIWASCO and the matatu owner’s and boda boda associations; KURA, KENHA, KPLC, and > Special Interest Groups (SIGs) including representatives for youth and people living with disability (PWD), representative Wezesha Kirinyaga Project. A critical process in developing the UEP report has been stakeholder management including: > Project Steering Group meetings; > Stakeholder workshops; > Formal social inclusion consultations; and > Business consultations.

The second virtual workshop with the PSG and MB in February 2021 included discussions on the sectoral SWOTs and identification of emerging economic opportunities. Following the submission of the Diagnostics Report, another virtual workshop was conducted in April 2021 to focus on gathering feedback from the PSG and wider stakeholders on the findings of the diagnostics assessment. A wider stakeholder workshop in May 2021 comprised a visioning exercise for the UEP, emerging development concept and development framework, and reaching consensus with the PSG, Municipality and key stakeholders.

Virtual and physical stakeholder workshops were undertaken depending on the Covid-19 restrictions in place at the time, including the Kick-off Meeting (KOM) to gather feedback from stakeholders throughout the project. The first workshop (KOM), in December 2020, presented the project and process and collated information from 45 stakeholders in terms of key characteristics, strengths and challenges (captured within the Inception Report). Stakeholders included the Municipal Board, Municipality and County officers, private sector, civil society groups and non-government organisations and representatives from Special Interest Groups (SIGs).

18 1.4

The development of the UEP and identification and prioritisation of proposed projects are grounded on key principles that support the Programme’s aim to create market-driven growth and build resilience. The Atkins SUED Team has defined these principles as: Figure 1.3 SUED Principles Source: Atkins

Key Principles

All proposed projects (VCs and infrastructure projects) contained within the UEP have been screened and refined for their contribution to improving livelihoods by considering: availability; accessibility; affordability; acceptability; and adaptability, across special interest groups as well as low-income groups, the urban poor and informal sector. The aim is to minimize inequalities and improve access to job opportunities for optimum benefits to the community. Social exclusion makes it difficult to achieve social objectives, such as reducing poverty, due to often hidden barriers in reaching those who are socially marginalised. Exclusion also causes conflict, and it is almost impossible to achieve economic gains in conflict environments.

KERUGOYA-KUTUS MUNICIPALITY URBAN ECONOMIC PLAN (UEP ) 19

Socially Inclusive – The UEP will be socially inclusive building on the thorough analysis of the status of social inclusion within KKM through stakeholder meetings and focus group discussions. Especially, the identified excluded groups of PWD and youths are included in the UEP development process, the VCs and infrastructure projects to ensure that their impacts will equitably benefit all members of the community.

Sustainable –The UEP will promote Green Blue Infrastructure that supports the development of KKM while minimising the environmental impacts of increased population and economic activity in the future, as well as protecting the abundant water resources within the County.

Resilience – The prioritised projects will have to be resilient against shifts in the economy, both for domestic and international markets, to remain competitive. They will also need to be adaptive to the climate change impacts specific to the area, such as lesser rainfalls and higher temperatures, while ensuring that technological advancement through smart solutions can be introduced where possible.

Resource Efficiency –To preserve the environmental assets and agricultural land, the UEP will be directing economic growth towards resource efficiency, by integrating the VCs to establish a circular economy, promoting minimisation of waste and optimising water and energy use, whilst aiming to promote rural-urban linkages. While these principles are closely linked and overlap in their definition, each one of them emphasises a different aspect that is not fully captured by the others. Thus, it is important that all four principles are embedded and balanced in the UEP and its implementation. In addition to these principles, it is critical to ensure the UEP develops the competitiveness of the town. At its core the UEP seeks to create employment opportunities accessible to all, and set out economic measures and supporting actions and projects that can help directly or indirectly lift the local population out of poverty whilst supporting crucial livelihoods such as the informal sector.

Persons with Disability (PWD) and youth in KKM face challenges that are either caused by, or lead to, exclusion, and recommendations for their inclusion are fully integrated in the UEP. People who are excluded are not ‘just like’ the rest of the poor, only poorer. They are also disadvantaged by who they are or where they live, and as a result are locked out of the benefits of development.

Climate Change, Social Exclusion and Poverty

Source:

Figure 1.4 Climate change and poverty interactions

20 1.5

At the time of preparing this UEP, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to disrupt societies and economies around the globe. The impacts, both health and economic, have been felt across different geographies and locally in Kerugoya-Kutus. While governments are trying to address current challenges, this pandemic has brought to the fore the need to understand better the connection between vulnerable groups, livelihoods, and shocks from critical events such as climate change. Climate change poses a serious risk to livelihoods and poverty reduction efforts. Climate hazards and the depletion of natural resources disproportionally affect women, PWD, the elderly, and people with chronic illnesses. Low-income households that rely on weather-sensitive subsistence livelihoods such as agriculture are especially vulnerable. Harmful social norms pose additional challenges, by limiting the participation of these groups in formal risk reduction and climate adaptation programmes. Atkins

In KKM, youth and PWD are often excluded from socio-economic activities; they lack access to information, assets, and finance; and they do not participate in decision-making processes. This makes them more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and other shocks such as the COVID-19 Statistically,pandemic.PWDare more likely to have lower levels of education, be illiterate or unemployed. Due to discrimination, they usually have less access to support networks and social capital than their able-bodied counterparts. These social networks are recognised as a key factor that enables groups to prepare for, respond to, and recover from, climate variability and shocks, and this lack of access increases the vulnerability of PWD to climate change. In KKM, PWD often operate small businesses, yet they lack access to finance and adequate spaces to develop their economic activities and to invest in measures that would better prepare their businesses for extreme events and climate hazards. This makes them more exposed to climate change and extreme events. PWD also face limitations in their access to infrastructure and mobility and climate events such as flooding can severely affect their livelihoods and daily routines. Young people lack access to capital or assets to manage the impacts of climate change and other similar shocks. While young men and women are heavily engaged in agricultural livelihoods, their work is often not well regarded. Limited access to credit and financial resources and reduced social safety nets critically affect their ability to recover from disasters such as floods or droughts. Those who engage in transportation services also see their access to markets and their sales or income disrupted when there are extreme weather events. Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic severely affected youth-owned businesses. People who live on informal settlements are also identified as a vulnerable group within this context in KKM. Rapid, unplanned urbanisation increases the vulnerability to climate hazards for the urban poor. Informal settlements are often located in hazard-prone areas and are excluded from formal risk reduction and climate adaptation programmes. They are often settled on marginal land and have limited drainage and sanitation infrastructure. Flooding is a significant issue, in particular regarding contamination of water sources, and associated health impacts. Their livelihoods, most often in the informal sector, are reliant on being able to trade every day and are more vulnerable to disruption, be it a pandemic, or an environmental disaster. In addition, they face similar problems with access to credit and financial resources as youth and PWD, which limits their ability to proactively adapt to climate variability and change.

Increasing the resilience of current and future livelihoods and infrastructure is key to poverty reduction and has been addressed systematically throughout the UEP to avoid creating polarisation and further exclusion. Similarly, ensuring that infrastructure projects, VC opportunities and development policies are climate-resilient will not only help the built environment to better respond to future climate risk but also communities and excluded groups to be less affected by climate change events.

KERUGOYA-KUTUS MUNICIPALITY URBAN ECONOMIC PLAN (UEP ) 21

Consequently, it is imperative to understand exposure, and vulnerabilities, to build resilience into future projects through appropriate adaptation measures including green blue infrastructure. In particular it is important to ensure that adaptation measures do not act to reinforce or deepen existing inequalities, but need to be accessible to groups that are already marginalised. For example, climate-resilient technologies need to be affordable, accessible to all, and culturally appropriate. Their implementation needs to be accompanied by capacity building and technical support. As well as considering inclusion and poverty elements of all adaptation and climate risk management measures, excluded groups may require targeted interventions designed to help build their resilience to climate change.

> Increased awareness of hygiene signifies increased demand for limited resources like water, as well as increased demand for disinfectant used for hand cleaning and sanitization, with additional costs to society, particularly where access is not straightforward.

22

> Road freight and logistics have been interrupted as long-distance truck drivers are suspected to be a major source of imported infections and transmission. This has had implications for trade and cross-border activities. Goods take longer to reach destinations. For perishable agricultural commodities, post-harvest loses become rampant.

1.5.1 COVID-19 Impacts in Kenya In Kenya, the impact of COVID-19 has been real and devastating. The pandemic has significantly impacted all aspects of life such as health, institutional revenues and livelihoods. COVID-19 has hit the most vulnerable the hardest, particularly the densely populated informal settlements, as well as other people lacking access to adequate housing and basic services. The informal economy employing about 70% of Kenyans has been drastically affected as lockdowns and curfews were introduced to curb the transmission of the virus. Low wage earners have been hit the hardest because they rely on the informal sector and daily wages. Mostly they lack the option to work from home as they are mostly in the service industries and more exposed to the virus. Despite the low wages, some have also received pay cuts, and some have lost their jobs all together. There has also been loss of revenue due to reduced activities in other sectors like industry, commerce and hospitality with the effects felt throughout their supply chains.

The COVID 19 outbreak has affected people differently based on their age, gender, ability or disability, sexual orientation, health status, migrant status, and ethnicity among other aspects. Crises exacerbate existing gender inequalities, exclusion, and discriminative practices, and vulnerable groups are highly likely to be more adversely affected by the outbreak and the consequences of the response.

Travel restrictions have led to a sharp and substantial fall in demand for movement and subsequent impacts on supply chains:

> Kenya is the world’s number 2 exporter of tea and the world’s number 4 exporter in flowers, and both these critical industries have experienced a negative impact from COVID related restrictions. For instance, tea prices declined by 18% year-over-year in May, reaching the lowest point since 2014 and fresh cut flower sales declined by about 40% in March versus the previous month.

> Disruptions in global supply chains have also led to shortages or delays for critical inputs for agriculture ultimately disrupting production and food supply and manufacturing, leading to price increases.

COVID-19 Impacts in KKM

Emerging evidence on the impact of COVID-19 suggests that women’s economic and productive lives have been affected disproportionately in comparison with men. This is because women earn less, save less, and are more likely to be employed in the informal sector. Their capacity to absorb economic shocks is therefore less than that of men. Women are also the majority of front-line health workforce and caregivers and therefore at higher risk. Cultural factors may restrict women’s access to information and services, and some women may be particularly affected, e.g. Older women living alone, and isolation may lead to an increased risk of violence in the are already among the most affected by the socio-economic impacts of COVID-19. In addition to losing employment, the closure of businesses, and the need to keep away from schools and universities, the youth are also at high risk of increased anxiety and mental health problems. Additionally, the youth make up more than 30% of the migrants and refugees’ population who are likely disproportionately affected due to limited movement and fewer employment opportunities caused by the pandemic. Young women and girls are also at high risk of many forms of domestic and gender-based violence during the pandemic.

Persons with disability have been left without vital support and advocacy due to social distancing. The majority of PWD in SUED Municipalities operate small businesses in market centres, which have been adversely affected therefore they have experienced loss of livelihood. For PWD that rely on their hands for walking and are sole breadwinners, the question of not touching surfaces is not applicable and they therefore are at high risk of being infected with COVID-19. Street families are also highly exposed to the danger of the virus because they lack shelter. Many of them rely on market centres where they ferry goods for a wage, and with the closure of markets they have lost livelihoods.

A business survey and engagement with local stakeholders has revealed that COVID-19 has had an impact on the entire economy. Trade on the markets have been reported to have significantly declined. One trader indicated a 90% drop in revenues, and a restock every 1 or 2 months instead of every 3 weeks before the pandemic. Another trader said they went from selling 8 to 10 bags of cereals per day to just 1 to 2 on market days. The closure of schools and universities has led many young people to try to work on the market, despite the lack of demand. Lack of demand for agricultural products has created an overproduction of most products, leading to price drops and considerable wastage. Farmers and traders have had difficulties repaying loans, leading to financial instability at the macroeconomic level.

KERUGOYA-KUTUS MUNICIPALITY URBAN ECONOMIC PLAN (UEP ) 23

Younghome.people

> Prioritising policies to confront spatial, social and economic exclusion with the aim of cushioning the vulnerable in the face of another shock.

24

> Redefining green spaces and the way town centres are designed for business.

> Ensuring resilient supply chains for agricultural and manufacturing sectors focusing on local inputs to ensure food security, and safeguard export-oriented products.

1.5.2 Lessons from COVID-19 Drawing upon the lessons learned from the current COVID-19 crisis, these have informed the proposed GBI projects (in Chapter 5) and Sector Action Plans (section 4.1) to ensure long-term planning, green recovery and resilience is embedded in the UEP. This is an opportunity to get insights into a future fully-fledged climate change crisis and KKM has a critical role to play in addressing these challenges. Some initial key lessons include:

> Through the Wezesha Programme, continue mobilising and empowering women, youth, and other vulnerable groups by creating new employment opportunities and engaging them in economic activities through technical support and financing.

> Emphasising the need for adaptive, urban integrated plans to ensure sustainable urban development and infrastructure provision, including appropriate housing for all that can help minimise impact from high risks.

> Strengthening preparedness and emergency response capacity is critical. This means better preparedness in terms of financing, service delivery and business continuity, including budgeting for future crises, emergency operations centres, capacity building, drills, and human resources redeployment plans.

> Leveraging information technology (IT) systems to better match the required transport demand with excess supply in real time and provide travel pattern visibility, helping passenger and logistics operations become nimbler considering a quickly evolving context.

> Making sure public awareness campaigns are consistently available to all in a format and language understandable to all.

> Improving marketing efficiency through adoption of innovative processes that connect buyers and sellers. This may include adoption of technology to promote marketing and information sharing, formalizing product delivery services etc.

> Chapter 4 set outs the Economic Development Plan. Each of the key sectors is presented with a summary of its SWOT analysis and a Sector Action Plan. The priority Value Chain (VC) projects are then set out in detail.

This has been undertaken to outline the climate vulnerability context for the selected infrastructure projects to be developed in Kerugoya-Kutus. The Climate Vulnerability Assessment will complement associated pre-feasibility and feasibility study.

Appendix C – KKM Gender and Social Inclusion Study

KERUGOYA-KUTUS MUNICIPALITY URBAN ECONOMIC PLAN (UEP ) 25

This captures the process followed from identification to assessment of growth opportunities for Kerugoya-Kutus and provides recommendations on those with the greatest potential to maximise benefits and to be developed further.

This study was a key part of the diagnostic process and engaged with special interest groups through interviews and focus group discussions. The study identified the groups that are excluded in socio-economic activities in Kerugoya-Kutus and explored how and why they are excluded. The Study made a series of recommendations for the SUED programme to ensure inclusion and to address the multiple barriers (communication, physical, attitudinal and organisational) that these groups face.

1.6 Structure of this Report

Appendix D – Climate Vulnerability Assessment

The report is supported by a series of appendices, in which:

Appendix A – KKM Diagnostic Report

Appendix B – Technical Briefing Paper

> Chapter 2 provides a summary of key findings from the Diagnostics Report, which forms the basis for the development of the UEP. Summaries of the planning context, the demographic and economic profiles and the infrastructure and environmental assessments are presented. The section details the key challenges and drivers for growth, identifying Kerugoya-Kutus’ key sectors.

Following this introduction, the report is structured as follows:

> Chapter 5 outlines the Development Framework of the Green Blue Infrastructure projects and interventions that have been identified for enabling urban and economic growth within Kerugoya-Kutus.

> Chapter 3 introduces the Kerugoya-Kutus’ development concept introducing the Green Blue approach and how it aligns to economic actions and infrastructure proposals. It is supported by the economic vision developed by local stakeholders.

> Chapter 6 presents a range of implementation considerations to support the next stages of the SUED Programme.

The purpose of the report is to assess the current position of the economy and state of infrastructure, alongside the regional, national and international context, before the consideration of emerging economic growth opportunities and infrastructure needs.

The contents of this report will form the backbone of the UEP.

DiagnosticsKutusKerugoya-Urban Before any proposed interventions are developed it is important to understand the local development context and potential opportunities and barriers to growth. The Municipality’s assessment has been undertaken in the UEP diagnostic process, as presented in Appendix A. The diagnostics phase was a critical process to establish a solid foundation for identifying solutions that can deliver economic, social and environmental benefits. This section provides a summary of the diagnostic report’s assessment of: KKM’s planning and regional context, its socio-economic profile, with urban and economic conditions and trends; The state of existing infrastructure; and climate risks.

26 2.

>

> Environmental

>

22. Draft LPLUPD (2030) 23. Draft CSP Figure 2.1 Map Illustrating the Municipality within CEREB and Kenya Source: Atkins

The geographical focus of the UEP is KKM, comprising the towns of Kerugoya and Kutus, and covering approximately 70.5km222. KKM is geographically located in the centre of Kenya, approximately 100km north of Nairobi and about 30km west of Embu. KKM is situated within the Central Region Economic Bloc (CEREB) that aims to enhance trade and investment opportunities through collaboration. KKM is the headquarters and administrative centre of Kirinyaga County (KC). Kirinyaga is one of the smallest counties in Kenya, covering approximately 1,482km223. As shown in Figure 2.1, the County borders Nyeri to the north and west, Muranga to the south, Embu to the east and south and Mount Kenya to the north. Mount Kenya National Park covers about 20% of land within KC. It is a protected area, where development is not permitted, which makes it a potential asset to further explore ecotourism opportunities.

2.1 Study Area

KERUGOYA-KUTUS MUNICIPALITY URBAN ECONOMIC PLAN (UEP ) 27

The Kirinyaga County Integrated Development Plan 2018 –2022 aims to coordinate development and allocate budgets at a County level. The strategic goals of the CIDP are: 1. Job creation through new industries and diversification; 2. Affordable and accessible health care; 3. Increased income through competitive and efficient productivity and market accessibility, 4. Improved urban planning and infrastructure, 5. Enhanced knowledge and skills to create a talented and unique work force.

Figure 2.2 Planning Context trendsInternational

RecoveryGreenRevolution4thImpactsClimateresourcesDepletiontrendsUrbanisationofchangeoftheIndustrialpost-Covid

Kerugoya –PrioritiesMunicipalityKutuschange KIDA support to industrial development to add value to abundant agriculture produce Continue to be the main rice producer in Kenya and improve value Adequateadditionprovision of infrastructure to fulfil needs of local population and Protectionvisitors,and conservation of unique water and natural resources such as Mt Kenya and Mt Kenya BenefitsNational from its central location and good connection with the rest of the ImproveCountrylivelihood of residents through creation of green jobs National Polices and Strategies Kenya Constitution 2010 (Chapters 5 & 12) County Governments Act No. 17 of 2012 (revised Urban2017) Areas and Cities Act of 2011 (revised 2019) The Physical and Land Use Planning Act (2019) Kenya Vision 2030 National Spatial Plan Kenya(NSP) Green Growth MediumStrategy Term Plan (MTP III) and the Big Four Agenda Source: Atkins

County (LPLUDP)PlanLandDraftPlanDevelopmentMunicipalityBlueprintMountainPlanDraft2018DevelopmentIntegratedPlan–2022,CountySpatial2015–2025(CSP)Cities2032Integrated2018–2022(IDeP)LocalPhysicalandUseDevelopment2020–2030

The IDeP is the guiding instrument for the Municipal Board to achieve the vision “to enhance a vibrant, innovative and sustainable Municipality, characterised by holistic growth and equitable opportunities for all” through proper management of the environment and natural resources. The plan is anchored by the main programmes of solid waste management, natural resource management and mainstreaming climate change into development plans.

At a local level, the planning policy and development framework in KKM is mainly guided by the Municipality Integrated Development Plan 2018 – 2022 (IDeP) and the Draft Local Physical and Land Use Development Plan 2020 – 2030 (LPLUDP). The Draft LPLUDP seeks to guide future growth, providing an integrated physical development by setting out the zoning and proposed land uses and development control regulations, prioritising infrastructure projects and budget.

The Mountain Cities Blueprint 2032 is the conceptual model for polycentric development of KC, with a vision and guiding principles. The plan proposes to brand and differentiate each constituency with an economic function grounded on existing activities and future opportunities. The suggested function for each constituency were identified through public participation forums.

The Draft County Spatial Plan 2015 – 2025 (CSP) is the long-term land use and spatial planning framework that aims to guide the allocation and distribution of resources to promote sustainable growth. The Draft Plan identifies the towns of Sagana, Wang’uru, Kerugoya, Kutus and Kagio as the main urban centres, earmarking the vision for KC to “be an agriculturally viable, industrialised and economically prosperous County with reliable infrastructure, utility and social service provision’’.

Local Plans

28 2.2 Planning Context

The Planning Context sets the basis for the development of the UEP. The Diagnostic Report in Appendix A covers key international and national trends likely to influence the sustainable growth trajectory of KKM; national strategies and policies, and; KKM’s own priorities and ambitions.

2.1 State of Kerugoya-Kutus

2.1.1 Municipality Character KKM is mostly rural in character, with agricultural land use predominantly occurring through the Municipality, which is similar to KC. The Municipality contains two main towns: Kerugoya in the north and Kutus in the south, which are about 10 km apart and linked by the B27 road and Rutui river. There are other smaller built-up areas such as Kibingo, Mukinduri, Kiamwenja, Ithareini, Karia and Kiamirici spread across the TheMunicipality.Municipality widely benefits from its strategic location, due to its close proximity to Nairobi, located within the Central region and Mt Kenya climatic zones, the existing railway station at Sagana and its rich agricultural land and resources. The Municipality and the County are relatively small, but have a sound economy and are leading producers of rice and other agricultural produce such as tea, coffee and tomatoes. Given its predominant land use across KC and KKM, agriculture has been identified as the main economic activity, with 87% of the population relying on agriculture for their livelihoods and 72% of household income.

KERUGOYA-KUTUS MUNICIPALITY URBAN ECONOMIC PLAN (UEP ) 29

Lack of proper planning, poor implementation of plans and poor enforcement of regulations have led to uncontrolled growth and informal settlements. These settlements across KKM and KC are characterised by higher residential and population densities, inadequate housing, land tenure insecurity, poor roads and accessibility, inadequate access to basic services and environmental degradation. These neighbourhoods also suffer from social deprivation, including high levels of unemployment, lack of schooling, security issues and drug and alcohol abuse.

> Financial hub, where many banks, financial institutions and insurance companies are settled; and > Retail, commercial enterprises and markets, Kerugoya market has recently been upgraded and is the largest in the SimilarCounty.totheother urban centres in KC, Kerugoya is reliant on agricultural-related activities due to its rich agricultural hinterland. Agri-processing or light industries such as milling, the slaughterhouse and coffee factories (Rutui and others) are located in the town.

Kerugoya Town Character Kerugoya is located in the north of the Municipality and is the second largest town in KC, with a population of 30,045. The town has mainly been developed as a district headquarters and administrative centre, including the provision of key urban services such as:

30

> Health centre, hosting private and public hospitals such as ACK Mt Kenya, Kerugoya Referral Hospital and the on-going construction of Kerugoya Multipurpose Medical Complex;

KERUGOYA-KUTUS MUNICIPALITY URBAN ECONOMIC PLAN (UEP ) 31 Figure 2.3 Kerugoya Town Character Source: Atkins

32 Kutus Town Character Kutus has a population of 9,143. The town is the wholesale trading centre and also serves as an administrative centre, owing to the relocation of the KC headquarters, which was enabled when gaining Municipality status in 2018. Kutus is growing rapidly due to the establishment of Kirinyaga University (KyU), which has influenced its development as a university town. There are more than 2,500 students at the university and the number is expected to grow, which means increasing pressure from students seeking accommodation, employment opportunities, entertainment, and other social Theactivities.town is centrally located and easily accessible from all parts of KC. It is a transit town and a regular stop for many when travelling from Nairobi to Meru. A high proportion of the urban area is comprised of educational and public land, largely land owned by the KyU and other public institutions.

KERUGOYA-KUTUS MUNICIPALITY URBAN ECONOMIC PLAN (UEP ) 33 Figure 2.4 Kutus Town Character Source: Atkins

34 2.1.2 Socio-Economic and Demographic Profile Population inhabitants39,188in KKM in 2019 –including 30,045 in Kerugoya and 9,143 in Kutus.

KC urban population has been growing fast, but less in KKM than in other urban areas. KKM is projected to have nearly 44,000 inhabitants by 2030 if current growth rates continue 26% of those living in KC were below the poverty line (135,000 Comparedinhabitants)with45%nationally

Despite this rapid urbanisation, Kirinyaga represents the 6th smallest County in Kenya and the smallest of the CEREB in terms of land area, and the 13th least populated County in TheSocialKenya.InclusionvisionoftheKKM IDeP is to enhance a vibrant, innovative and sustainable Municipality, characterised by holistic growth and equitable opportunities for all. Leaving no one behind is a central theme that underlines both this vision and the UN Sustainable Development Goals adopted in 2015.

The population of KKM is estimated to be 39,188, which accounts for 6% of the County’s population. This comprises 30,045 in Kerugoya and 9,143 in Kutus. Within the County’s population, 22% of the population was classified as urban, which is less than the CEREB average of 34%. Most of the urban population in Kirinyaga live in eight urban centres: Kerugoya, Kutus, Wanguru, Kagio, Sagana, Kimbimbi, Kagumo and Kianyaga. The population density of the County is 413 inhabitants per km2, making it the 6th most densely populated County in Kenya. The County has experienced one of the fastest urbanisation rates in Kenya in recent years, with the urban population increasing by 40% between 2009 and 2019. However, this growth was not evenly spread across the County, as KKM absorbed just 5% of population growth – increasing at a very slow rate of 1% per annum between 2009 and 2019.

KKM:63% Nationally:48% Lower levels of poverty: growth:Population

KKM:1.0%Urban5.2%population: Nationally:35%KKM:42%

The approach to gender and social inclusion (GeSI) was guided by the SUED Programme’s need for age, gender, persons with disability (PWD) and refugees’ inclusion, and the Consultant’s use of a three-dimensional approach covering social, economic and spatial dimensions of inclusion as illustrated in Figure 2.5 The Three Dimension of Inclusion.

Demographic Profile

Annual population growth: Secondary andhigher education: population:Working KC:1.5% KC:38%

Source: Atkins

In addition, PWD and youth from the informal settlements of KKM face more challenges such as poor water and sanitation services, insecurity, limited access to power in most settlements, and land ownership issues. All these exacerbate youth and PWD challenges as they generally operate from poor non-inclusive infrastructure, businesses and living environments.

> Lack of involvement in decision-making: Often youth and PWD are hardly involved in planning for projects. They are even left out decision-making on matters that concern them. This creates a gap between the SIGs and the government and projects because the SIGs do not get opportunities to express their views about projects or matters that concern them.

> Lack of implementation of disability laws: Lack of governments, projects and programmes’ goodwill to implement disability-related laws that lead to PWD being left out in job and procurement opportunities allocation, cash transfers and use of demeaning language against PWD.

Youth Lack of Youth involvement in vital decision making, even regarding matters that directly concern them.

Youth in business and farming find it difficult to do large scale trade or farming due to limited access to capital. Underpayment of youth in employment because they are desperate for jobs. High unemployment rates amongst Youth, often leaving them idle and predisposed to substance abuse. Source: Atkins

The Three Dimension of Inclusion

KERUGOYA-KUTUS MUNICIPALITY URBAN ECONOMIC PLAN (UEP ) 35

Lack of inclusive infrastructure that limits their mobility and access to vital socioeconomic spaces and services.

Processes that perpetuate exclusion in KKM were identified as:

The Study sought to understand KKM’s special interest groups (SIGs) through GeSI – a related literature review, key informant interviews, focus group discussions and observation. Further, SIGs’ representatives have attended all the UEP development workshops and participated in the business survey; and youth and PWD now have a representative (Inclusion Champion) in the PSG. KC recorded the highest Gender Equality Index at 56%, out of 10 counties that were assessed by the Council of Governors in collaboration with UN Women in 2019. This finding was validated by the primary data collection exercise where key informant interviews established that women in KC have the same opportunities as men and can participate in both the economy and decision-making processes. The “Wezesha” programme has been key to KC’s gender inclusion efforts, enabling women and other vulnerable groups to achieve their best in different economic activities. Nevertheless, the study established that PWD and youth are often excluded in socio-economic activities in KKM. The two groups face challenges that are either caused by, or lead to, exclusion, as indicated in Table 2.1 below.

barriers for the hearing and visually impaired, meetings do not have sign language interpreters or Braille material, health officers and medics are not trained on sign language.

Table 2.1 SIGs and Exclusion Manifestation Table SIG Exclusion Manifestation Persons Disabilitywith Partial to complete lack of implementation of disability laws. Lack of PWDs involvement in vital decision making, even regarding matters that directly concern them. Discriminated against for employment Communicationopportunities.

> Discriminatory design processes: Lack of inclusive infrastructure accessible by everyone, this has limited PWD’ mobility and access to vital socio-economic spaces and services. Such spaces include public transport, government offices and markets. In public transport, wheelchair users are also charged more than the rest of the passengers.

> Information barriers: Both the County and national governments do not develop communication plans with PWD in mind e.g. communication barriers for people who are deaf are rampant as most meetings do not have sign Opportunitieslanguage.for inclusion in the SUED Programme include involvement of all in decision-making and in the development of safe, inclusive and climate-resilient infrastructure. This will enable better access to capacity building initiatives, seed capital and employment opportunities – especially through participation in the VC projects. Special attention will need to be given to the informal settlements within the Municipality.

Figure 2.5

Spatial Inclusion Improving access to infrastructure, affordable land & housing Economic Inclusion Ensuring opportunities for all and sharing of benefits Multi-Dimensional Approach to Inclusive Cities Social Inclusion Improving the terms for individuals and groups to take part in society /=, /-, K

Figure 2.6 Gross County Product per Capita, 2019 (in KES)

Nyandarua MarakwetElgeyo Nairobi Mombasa Nakuru Lamu Kiambu Nyeri Machakos Embu Bomet NithiTharaka Kisumu Kirinyaga Narok Muranga 100,000150,000200,000250,000300,000350,000400,00050,0000

As36 raised in Section 1.5, there are interlinkages between climate change and poverty, as climate change will have an impact on income security and quality of life. It is important to understand where the burden of climate change impacts may fall and how societal groups can be included in proposed mitigation measures. Social inclusion is cognisant of this relationship. The UEP has adopted climate adaptation approaches, as well as inclusivity in all forms, to avoid exclusion of certain groups and to reduce inequality. Similarly, it has sought to address how infrastructure and VCs can be made more resilient to climate shocks, with the understanding that climate impacts hit vulnerable groups the hardest. Economic Profile The CEREB region contributes towards 28% of national output, with a combined GDP of KES 2,115,565. Half of CEREB’s economic activity is driven by three counties: Nakuru, Kiambu and Meru. In contrast, Kirinyaga represents one of the smallest economies in CEREB. In 2017, it accounted for just 5% of the Bloc’s GCP, with only Laikipia and Tharaka Nithi accounting for Kirinyaga’sless.

Laikipia Busia Meru Nyamira Kericho TavetaTaita Uasin-Gishu Baringo Nandi Kajiado Kisii NzoiaTrans RiverTana Marsabit Makueni Kwale Isiolo BayHoma Bungoma Kakamega Siaya Vihiga Kitui Samburu Garissa Migori Kilifi Wajir Turkana PokotWest Mandera

GCP per capita (2017) Kenya average Source: Atkins

GCP per capita was slightly higher than the national average in 2019, at KES 162,666 – compared to Kes 161,499 nationally. Figure 2.7 demonstrates that most of the counties in CEREB, including KC, also had a higher GCP per capita than the national average. While Kirinyaga remains a small economy in absolute terms, its GCP relative to its size, per capita, is on par with the Kenyan average.

KERUGOYA-KUTUS MUNICIPALITY URBAN ECONOMIC PLAN (UEP ) 37

Figure 2.7 Kirinyaga GCP Breakdown Source:

The CEREB region is heavily reliant on agriculture, which accounts for 52% of GCP. This is followed by technical services – such as ICT, finance and real estate (15%), and construction and logistics (11%). Focusing on Kirinyaga’s internal economy, GCP analysis indicates some individual differences with these CEREB sector specialisations, as highlighted in Figure 2.7. While agriculture is the largest sector of KC’s economy (40% of GCP), this is lower than the Bloc’s average (52%), with only Embu and Kiambu being less reliant on agriculture. Nevertheless, a significant proportion of Kirinyaga’s residents are employed in agriculture, especially in rice-related businesses, and the sector remains the backbone of the County’s economy. In 2009, about a third of the Kenyan workforce (32%) worked in family agricultural holdings, while this was significantly higher in Kirinyaga County (45.7%) and Kirinyaga Central (41.2%). This could suggest that the agriculture sector is less productive in KC, and therefore would account for a smaller share of the County’s output compared to some other counties. Mining activities, as well as utilities, account for 9% of the County GCP, which is higher than the CEREB average (4%). However, those two sectors remain very small in absolute terms. Technical services (ICT, finance and real estate) are well represented in Kirinyaga (16%), on par with the CEREB average (15%). Importantly, the vast majority of employment in KC and KKM is likely to be in the informal sector. In 2019, almost 83% of employment in Kenya was in the informal sector. While no statistics are directly available at smaller geographies, employment composition and GCP specialisation in agriculture suggests a similar pattern in KC and KKM. Atkins

and agri-processing businesses that buy from local farmers are sometimes unable to guarantee a price to farmers. Access to finance

Table 2.2 Business Identified Challenges to Growth Main Challenge

Hotels and jua kali workers referred to the high cost of taxes and various licences. A business selling in another County might also be required to get certain licenses or permits, resulting in a double charge.

Both markets at Kerugoya and Kutus towns were described as being too congested, and lacking facilities including shelter, shade, toilets and water.

Hotels indicated that they were facing regular water and electricity disruptions.

Several farmers mentioned the high cost of input such as fertilisers, seeds and other sourcing products, which ultimately lead to high production costs.

Lack of storage

Fluctuation in market prices was mentioned as a constraint across various industries. The COVID-19 pandemic has created uncertainty among buyers and consumers, which has disrupted the supply chain and affected prices. For instance, one trader said the value of restock (cereals) went down from Kes 50,000 to Kes Cooperatives20,000.

Many products experience significant variations of supply across the year. November to February is the high season where many crops are being harvested. However, many traders mentioned the lack of storage that resulted in considerable waste and uneven revenues.

One trader mentioned that they would benefit in having access to short-term loans to buy non-perishable products at harvesting season when supply is high and price is low, such as cereals, and sell throughout the year, but this was seen as risky by the bank.

Source: Atkins

Description Cost of input, taxes and licences

Fifty-seven businesses, reflecting KKM main sectoral activities, were consulted with in-depth interviews to inform the understanding of the business environment and socio-economic inclusion. Many of these were small businesses or independent workers – given the nature of the local economy – but large employers were also consulted, including banks, health and education facilities, and processing plants. Businesses in KKM are usually small and with markets centred within the County. There are typically few linkages with other businesses, upstream or downstream. Of the business linkages reported, most were with local suppliers or distributors, though rice production presents a longer value chain. As KC produces more than 60% of Kenyan rice, rice grains from KC are sold everywhere in the country.

Some products could however be easily stored, such as rice, where supply is high and costs lower in TheftsDecember.were also mentioned, in particular in the coffee industry. Market price fluctuations

The38 State of Business in Kerugoya-Kutus

Many respondents indicated they had access to finance through banks and loans. However, some farmers and traders were mentioning more difficulties – mostly because they have little collateral.

More generally, some respondents mentioned the poor state of the roads, in particular rural roads.

Many farmers get their supply locally and sell on local markets in KKM, or sell to local traders who then operate on the market. A large proportion of trade in Kutus market also seems to be for wholesale rather than retail. The proximity to Nairobi, the diverse variety of produce and the availability of rice is likely to explain why many brokers travel to the market. Services tend to be more local in KKM, using local suppliers and catering for local customers, such as banks, administration, etc. Most businesses consulted indicated that they were expected to grow in the next couple of years. However, COVID-19 was mentioned at various occasions as a hindrance to growth, alongside several common identified barriers to growth. A consensus on the key challenges to growth for business was identified: