APRIL 2024

122

CONTINUOUS POSITIVE AIRWAY PRESSURE: IS IT STILL THE GOLD STANDARD?

A THOUGHTFUL ANALYSIS WITH THE ADVENT OF ORAL APPLIANCE THERAPY

MARTIN DENBAR, DDS

Reprinted with permission from the American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine

128

TRENDING CULTURAL DRIVERS OF SMOKELESS TOBACCO FOR RECENT REFUGEE AND IMMIGRANTS AS KNOWLEDGE, ATTITUDES, AND BEHAVIOR DETERMINANTS:

A SOUTH TEXAS ORAL HEALTH NETWORK COLLABORATIVE STUDY

MOSHTAGH R. FAROKHI, DDS, MPH, MAGD, FICD, FPFA

JONATHAN A. GELFOND, PHD, MD

SAIMA KARIMI KHAN, DDS

MELANIE V. TAVERNA, MSDH, RDH, FADHA, MAADH FOZIA A. ALI MD

CAITLIN E. SANGDAHL

RAHMA MUNGIA, BDS, MSC, DDPHRCS

141

ASK THE POWERS CENTER

RADE PARAVINA, DDS, MS, PHD

142

ETHICS CORNER: UNDERSTANDING THE TRANSGENDER PATIENT

DONALD F. COHEN, DDS

Reprinted with permission from the American Dental Association

TDA Texas Dental Journal

2024 TDA MEETING

114 Texas Dental Journal | Vol 141 | No. 3

BOOTH 221

BOOTH 226

BOOTH 209

BOOTH 210

Anesthesia Education & Safety Foundation

Two ways to register: Call us at 214-384-0796 or e-mail us at sedationce@aol.com Visit us on the web: www.sedationce.com

NOW Available: In-Office ACLS & PALS renewals; In-Office Emergency Program Live Programs Available Throughout Texas

Two ways to Register for our Continuing Education Programs: e-mail us at sedationce@aol.com or call us at 214-384-0796

OUR GOAL: To teach safe and effective anesthesia techniques and management of medical emergencies in an understandable manner. WHO WE ARE: We are licensed and practicing dentists in Texas who understand your needs, having provided anesthesia continuing education courses for 34 years. The new anesthesia guidelines were recently approved by the Texas State Board of Dental Examiners. As practicing dental anesthesiologists and educators, we have established continuing education programs to meet these needs.

New TSBDE Requirement of Pain Management

Two programs available (satisfies rules 104.1 and 111.1)

Live Webcast (counts as in-class CE) or Online (at your convenience)

All programs can be taken individually or with a special discount pricing (ask Dr. Canfield) for a bundle of 2 programs:

Principles of Pain Management

Fulfills rule 104.1 for all practitioners

Use and Abuse of Prescription M edications and Provider Prescription Program Fulfills rules 104.1 and 111.1

SEDATION & EMERGENCY PROGRAMS:

Nitrous Oxide/Oxygen Conscious Sedation Course for Dentists:

Credit: 18 hours lecture/participation (you must complete the online portion prior to the clinical part)

Level 1 Initial Minimal Sedation Permit Courses:

*Hybrid program consisting of Live Lecture and online combination

Credit: 20 hours lecture with 20 clinical experiences

SEDATION REPERMIT PROGRAMS: LEVELS 1 and 2

(ONLINE, LIVE WEBCAST AND IN CLASS)

ONLINE LEVEL 3 AND 4 SEDATION REPERMIT AVAILABLE! (Parenteral Review) Level 3 or Level 4 Anesthesia Programs (In Class, Webcast and Online available): American Heart Association Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) and Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) Initial and Renewal Programs

NOTE: ACLS or PALS Renewal can be completed by itself at any combined program Combined ACLS-PALS-BLS and Level 2, 3 and 4

Program

WEBCASTING and ONLINE RENEWALS AVAILABLE! Live and archived webcasting to your computer in the comfort of your home. Here are the distinct advantages of the webcast (contact us at 214-384-0796 to see which courses are available for webcast):

1. You can receive continuing education credit for simultaneous live lecture CE hours.

2. There is no need to travel to the program location. You can stay at home or in your office to view and listen to the course.

3. There may be a post-test after the online course concludes, so you will receive immediate CE credit for attendance

4. With the webcast, you can enjoy real-time interaction with the course instructor, utilizing a question and answer format

OUR MISSION STATEMENT: To provide affordable, quality anesthesia education with knowledgeable and experienced instructors, both in a clinical and academic manner while being a valuable resource to the practitioner after the programs. Courses are designed to meet the needs of the dental profession at all levels.

Our continuing education programs fulfill the TSBDE Rule 110 practitioner requirement in the process to obtain selected Sedation permits. AGD Codes for all programs: 341 Anesthesia & Pain Control; 342 Conscious Sedation; 343 Oral Sedation This is only a partial listing of sedation courses. Please consult our www.sedationce.com for updates and new programs. Two ways to Register: e-mail us at sedationce@aol.com or call us at 214-384-0796

www.tda.org | April 2024 115

Approved PACE Program Provider FAGD/MAGD Credit. Approval does not imply acceptance by a state of provincial board of dentistry or AGD endorsement. 8/1/2018 to 7/31/2022. Provider ID# 217924

HIGHLIGHTS

A THOUGHTFUL ANALYSIS WITH THE ADVENT OF ORAL APPLIANCE THERAPY

Martin Denbar, DDS

Reprinted with permission from the American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine.

128 TRENDING CULTURAL DRIVERS OF SMOKELESS TOBACCO FOR RECENT REFUGEE AND

STUDY

Moshtagh R. Farokhi, DDS, MPH, MAGD, FICD, FPFA

Jonathan A. Gelfond, PhD, MD

Saima Karimi Khan, DDS

Melanie V. Taverna, MSDH, RDH, FADHA, MAADH

Fozia A. Ali MD

Caitlin E. Sangdahl

Rahma Mungia, BDS, MSc, DDPHRCS 141 ASK THE POWERS CENTER

Rade Paravina, DDS, MS, PHD 142 ETHICS CORNER: UNDERSTANDING

Donald F. Cohen, DDS

Reprinted with permission from the American Dental Association.

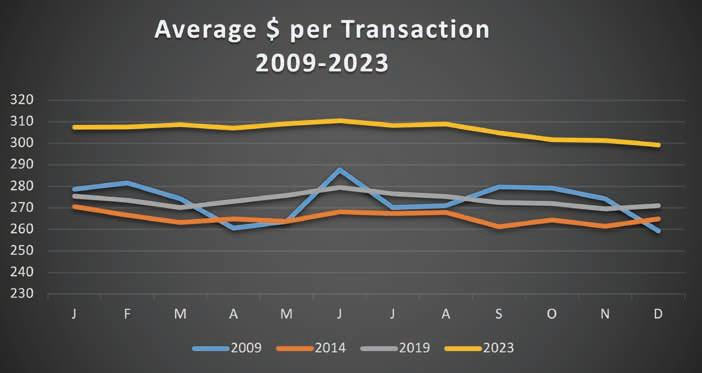

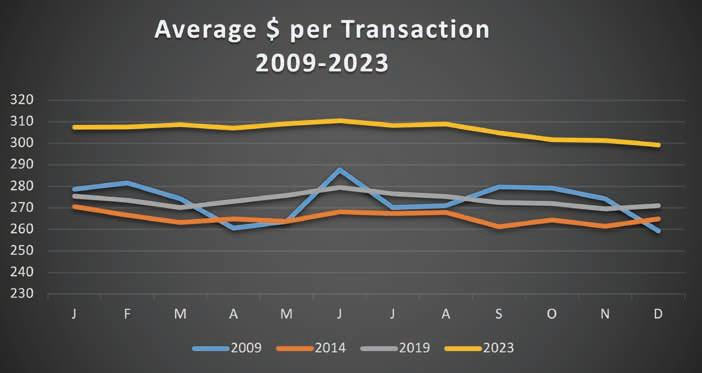

Value for Your Profession: Accepting Credit Card Payments is Getting Increasingly Expensive. Here’s What You Want to Know—and

It’s

about the cover

Many Texans were lucky enough to experience the total solar eclipse on April 8, 2024, which occurs when the Moon passes between the Sun and Earth, completely blocking the face of the Sun.1 The eclipse began in North America at Mazatlan, Mexico, and started darkening Texas at Eagle Pass. Weather across the state was spotty, but people near the middle of the path of the total solar eclipse enjoyed a duration of over 4 minutes.2 The next total eclipse across the United States will be on August 23, 2044, according to NASA.

Resources

1. 2024 Total Solar Eclipse. [cited 2024 Apr 18]; Available from URL: https://science.nasa.gov/ eclipses/future-eclipses/eclipse-2024/ 2. Great Texan Eclipses! Annular eclipse of Oct 14 2023 and total eclipse of Apr 8 2024. [cited 2024 Apr 18]; Available from URL: https://www. greatamericaneclipse.com/eclipse-maps-andglobe/texas

Editorial Staff

Jacqueline M. Plemons, DDS, MS, Editor

Juliana Robledo, DDS, Associate Editor

Nicole Scott, Managing Editor

Barbara Donovan, Art Director

Lee Ann Johnson, CAE, Director of Member Services

Editorial Advisory Board

Ronald C. Auvenshine, DDS, PhD

Barry K. Bartee, DDS, MD

Patricia L. Blanton, DDS, PhD

William C. Bone, DDS

Phillip M. Campbell, DDS, MSD

Michaell A. Huber, DDS

Arthur H. Jeske, DMD, PhD

Larry D. Jones, DDS

Paul A. Kennedy, Jr., DDS, MS

Scott R. Makins, DDS, MS

Daniel Perez, DDS

William F. Wathen, DMD

Robert C. White, DDS

Leighton A. Wier, DDS

Douglas B. Willingham, DDS

The Texas Dental Journal is a peer-reviewed publication. Established February 1883 • Vol 141 | No. 3

Texas Dental Association

1946 S IH-35 Ste 400, Austin, TX 78704-3698

Phone: 512-443-3675 • FAX: 512-443-3031

Email: tda@tda.org • Website: www.tda.org

Texas Dental Journal (ISSN 0040-4284) is published monthly except January-February and August-September, which are combined issues, by the Texas Dental Association, 1946 S IH-35, Austin, TX, 78704-3698, 512-443-3675. PeriodicalsPostage Paid at Austin, Texas and at additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to TEXAS DENTAL JOURNAL, 1946 S IH 35 Ste 400, Austin, TX 78704. Copyright 2023 Texas Dental Association. All rights reserved. Annual subscriptions: Texas Dental Association members $17. Instate ADA Affiliated $49.50 + tax, Out-of-state ADA Affiliated $49.50. In-state Non-ADA Affiliated $82.50 + tax, Out-of-state Non-ADA Affiliated $82.50. Single issue price: $6 ADA Affiliated, $17 Non-ADA Affiliated. For in-state orders, add 8.25% sales tax.

Contributions: Manuscripts and news items of interest to the membership of the society are solicited. Electronic submissions are required. Manuscripts should be typewritten, double spaced, and the original copy should be submitted. For more information, please refer to the Instructions for Contributors statement included in the online September Annual Membership Directory or on the TDA website: tda.org. All statements of opinion and of supposed facts are published on authority of the writer under whose name they appear and are not to be regarded as the views of the Texas Dental Association, unless such statements have been adopted by the Association. Articles are accepted with the understanding that they have not been published previously. Authors must disclose any financial or other interests they may have in products or services described in their articles.

Advertisements: Publication of advertisements in this journal does not constitute a guarantee or endorsement by the Association of the quality of value of such product or of the claims made.

116 Texas Dental Journal | Vol 141 | No. 3

contents

FEATURES 122

POSITIVE AIRWAY PRESSURE: IS IT STILL

GOLD STANDARD?

CONTINUOUS

THE

IMMIGRANTS AS KNOWLEDGE, ATTITUDES,

BEHAVIOR DETERMINANTS:

HEALTH NETWORK COLLABORATIVE

AND

A SOUTH TEXAS ORAL

THE TRANSGENDER PATIENT

120

121

Notice 140 Official

TDA House

Delegates 148

160

164 Classifieds 170 Index to Advertisers

In Memoriam

2025 Proposed Budget

Call to the 2024

of

Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology: Case of the Month

How to Find Out What

Costing You.

THE 11 TH LINDA C. NIESSEN GERIATRIC DENTISTRY SYMPOSIUM SUCCESSFUL DENTAL MANAGEMENT OF GERIATRIC PATIENTS: TIPS & TOOLS

MAY 31, 2024 8:30 AM TO 4:30 PM (CST) Texas A&M School of Dentistry - Room 605 - Dallas, TX Linda C Niessen, DMD, MPH, MPP Professor and Dean Kansas City University College of Dental Medicine Vice Provost for Oral Health Affairs Event Organizer Helena Tapias Perdigon, DDS, MS Clinical Associate Professor Texas A&M School of Dentistry Comprehensive Dentistry Department REGISTER ONLINE: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/11th-annual-linda-niessen-geriatric-symposiumregistration-853674773227 for additional information and to register, please scan this QR code: Questions? Contact Dr. Helena Tapias: 214.828.8940 or htapias@tamu.edu Randy F. Huffines DDS, FRCSEd Director of Geriatric Dentistry Quillen Medical Center Johnson City, TN 7 Hours CE credits provided through Texas A&M University School of Dentistry Office of Continuing Education

FRIDAY,

JKJ Pathology

Oral Pathology Laboratory

John E Kacher, DDS

¥ Available for consultation by phone or email

¥ Color histology images on all reports

¥ Expedited specimen shipping with tracking numbers

¥ Reports available online through secure web interface Professional, reliable service with hightechnology solutions so that you can better serve your patients. Call or email for free kits or consultation. jkjpathology.com 281-292-7954 (T) 281-292-7372 (F) johnkacher@jkjpathology.com Protecting

Board of Directors Texas Dental Association

PRESIDENT Cody C. Graves, DDS 325-648-2251, drc@centex.net

PRESIDENT-ELECT Georganne P. McCandless, DDS 281-516-2700, gmccandl@yahoo.com

PAST PRESIDENT Duc “Duke” M. Ho, DDS • 281-395-2112, ducmho@sbcglobal.net

VICE PRESIDENT, SOUTHWEST Richard M. Potter, DDS 210-673-9051, rnpotter@att.net

VICE PRESIDENT, NORTHWEST Summer Ketron Roark, DDS 806-793-3556, summerketron@gmail.com

VICE PRESIDENT, NORTHEAST Jodi D. Danna, DDS 972-377-7800, jodidds1@gmail.com

VICE PRESIDENT, SOUTHEAST Shailee J. Gupta, DDS 512-879-6225, sgupta@stdavidsfoundation.org

SENIOR DIRECTOR, SOUTHWEST Krystelle Anaya, DDS 915-855-1000, krystelle.barrera@gmail.com

SENIOR DIRECTOR, NORTHWEST Stephen A. Sperry, DDS 806-794-8124, stephenasperry@gmail.com

SENIOR DIRECTOR, NORTHEAST Mark A. Camp, DDS 903-757-8890, macamp1970@yahoo.com

SENIOR DIRECTOR, SOUTHEAST Laji J. James, DDS 281-870-9270, lajijames@yahoo.com

DIRECTOR, SOUTHWEST Melissa Uriegas, DDS 956-369-9235, meluriegas@gmail.com

DIRECTOR, NORTHWEST Adam S. Awtrey, DDS 314-503-4457, awtrey.adam@gmail.com

DIRECTOR, NORTHEAST Drew M. Vanderbrook, DDS 214-821-5200, vanderbrookdds@gmail.com

DIRECTOR, SOUTHEAST Matthew J. Heck, DDS 210-393-6606, matthewjheckdds@gmail.com

SECRETARY-TREASURER* Carmen P. Smith, DDS 214-503-6776, drprincele@gmail.com

SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE* John W. Baucum III, DDS 361-855-3900, jbaucum3@gmail.com

PARLIAMENTARIAN** Glen D. Hall, DDS 325-698-7560, abdent78@gmail.com

EDITOR** Jacqueline M. Plemons, DDS, MS 214-369-8585, drplemons@yahoo.com

LEGAL COUNSEL Carl R. Galant

*Non-voting member • **Non-voting

118 Texas Dental Journal | Vol 141 | No. 3

patients, limiting your liability

your

www.tda.org | April 2024 119 DQ2676 (2.23) Scan the QR code to learn more about partnering with DentaQuest! PROMOTING DENTAL PROVIDER DIVERSITY TO IMPROVE THE ORAL HEALTH OF ALL WELCOME TO PREVENTISTRY ®

in memoriam

Those in the dental community who have recently passed

Joseph J Dusek

Houston

7/29/49–6/7/23

Good Fellow: 2002

Life: 2014

Harvey W Fodell

Houston

12/1/30–12/28/23

Good Fellow: 1983

Life: 1995

Fifty Year: 2008

Robert L Ellis

Houston

9/6/28–11/16/23

Good Fellow: 1983

Life: 1993

Fifty Year: 2008

Herbert E Eubanks Jr

Houston

9/14/30–8/5/23

Good Fellow: 1981

Life: 1995

Fifty Year: 2007

William H Greenlee

Dallas

6/19/32–2/20/24

Good Fellow: 1985

Life: 1997

Fifty Year: 2008

Jeran J Hooten

Austin

10/9/42–2/13/24

Good Fellow: 1996

Life: 2007

Fifty Year: 2016

James R Mellard

New Braunfels

9/20/52–2/29/24

Good Fellow: 2008

Life: 2017

Clarence E Musslewhite Jr

Houston

6/20/30–1/9/24

Good Fellow: 1980

Life: 1995

Fifty Year: 2005

Paul L Pearce

Llano

6/23/30–2/19/24

Good Fellow: 2010

Life: 2007

Charles B Schmidt Jr

Spring

11/4/29–2/20/24

Good Fellow: 1982

Life: 1994

Fifty Year: 2005

Harold L Smith

Tyler

2/13/23–10/13/23

Good Fellow: 1976

Life: 1988

Fifty Year: 2002

Harry G Wilson Jr

San Antonio

12/28/38–11/16/23

Good Fellow: 1991

Life: 2003

Fifty Year: 2016

James H Wooham

Ingram

11/10/45–2/17/24

Good Fellow: 1997 Life: 2010

120 Texas Dental Journal | Vol 141 | No.3

Notice

Texas Dental Association Delegates

Per the TDA Bylaws, “The proposed annual budget shall be submitted by the Board of Directors to the members of the House of Delegates at least thirty (30) days prior to the opening of the annual session of the House of Delegates.”

Thus, the 2025 Proposed Budget, including a financial report from TDA Secretary-Treasurer Dr Carmen Smith, will be available on tda.org no later than April 15, 2024.

We are pleased to announce...

Hulen Dental

Mark Malone, D.D.S. has acquired the practice of have acquired the practice of Houston, Texas Fort Worth, Texas We are pleased to have represented all parties in these transitions. & David C. Sun, D.D.S.

Veronica Y. Chen, D.D.S.

Jini P. Kuruvilla, D.D.S.

Practices For Sale

MULTI-MILLION DOLLAR PRACTICE OPPORTUNITY: Large GP located north of Houston is available with real estate. The office is in a stand-alone building with 8 ops and is in excellent condition, with digital x-rays, Pano, and paperless charts. The office operates 45 hours per week with 3 clinicians. There is over 6,500+ active patients, 70% Medicaid & 30% PPO/FFS, with an average of 96 new patients per month. Opportunity ID: TX-01979

FANTASTIC GROWTH POTENTIAL: Cypress GP in a busy retail center with great visibility and foot traffic. This 3,000 sq. ft. office has 8 ops, 6 of which are equipped with 2 additional plumbed and ready for expansion. The office is all digital with paperless patient files and Open Dental operating software. With over 1,200 active FFS/PPO patients, this practice has the location and potential to be a huge collecting office with the right motivated purchaser. Opportunity ID: TX-01929

ROOM FOR GROWTH WITH POSSIBLE IMMEDIATE MERGER OPTION: Fort Worth GP located in the retail level of a live/work/play community. The office has 3 ops fully equipped with digital x-ray, Pan and paperless patient files; 2 additional ops are available. The office is in excellent condition with newer equipment. The practice currently operates on 4 doctor days and one hygiene day per week. This practice has over 2,000 active patients that are a blend of 20% FFS, 65% PPO, & 15% Medicaid. Opportunity ID: TX-01913

FANTASTIC RETAIL LOCATION: Plano GP in a highly visible retail center. This practice operates with the owner and 1 PT associate, is open 7 days a week and provides regular dental care as well as emergency services. The practice has over 1,750 active patients who are ~20% FFS, ~70% PPO, and less than 10% Medicaid. The office has 4 fully equipped ops and is in excellent condition. This is a great opportunity for growth by capitalizing on the existing patient base and expanding services. Opportunity ID: TX-01829

www.tda.org | April 2024 121 Since 1968

Go to our website or call to request information on other available practice opportunities! 800.232.3826 Practice Sales & Purchases Over $3.2 Billion www.AFTCO.net

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure: Is It Still the Gold Standard?

A Thoughtful Analysis With the Advent of Oral Appliance Therapy

Martin Denbar, DDS

Austin Apnea & Snoring Therapy; Diplomate, American Board of Dental Sleep Medicine; Assistant Clinical Professor (non-principled) Texas A&M School of Medicine

Adapted and printed with permission from the American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine. Available from: www.jdsm.org. The views presented in this paper do not necessarily reflect those of the JDSM/AADSM.

It can be said that the term ‘gold standard’ is assumed to mean near perfection.

But what is the definition of this term and how should it be applied to the field of airway management? Segen’s Medical Dictionary defines gold standard as “a method or procedure that is widely recognized as the best available.” McGraw-Hill Concise Dictionary of Modern Medicine defines it as “the best or most successful diagnostic or therapeutic modality for a condition against which new tests or results and protocols are compared.” An excellent conceptual analysis article in the Frontiers of Psychology stated that “the phrase “gold standard” is often used to characterize an object or procedure described as unequivocally the best in its genre, against which all others should be compared”.1 Analysis of the use of this term should be updated when describing continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and its role in treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) when compared with the use of an oral appliance.2

From a practical viewpoint, for any therapy to be successful it should be affordable, have a high patient compliance rate, easy to use, have minimal or comparable adverse effects, and customizable to meet the unique needs of each patient. Any product, test, or procedure that is considered the gold standard should score above all competing therapies, in this instance oral appliance therapy (OAT), for each of the aforementioned criteria. Let’s review the comparisons.

122 Texas Dental Journal | Vol 141 | No. 3

LETTER TO THE EDITOR reprint

How does CPAP compare to OAT when considering affordability? There have been few real comparisons because of the infancy of the field of OAT. One recent analysis stated, “A cost analysis of these two OSA treatment options presented at the 2021 Virtual Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine attempts a true head-to-head cost comparison. This analysis, based on Medicare fee schedules, suggests that CPAP may be cheaper initially, but that OAT comes with fewer costs over time.”3,4 Of course, there are fees being charged that are significantly higher than the Medicare rate at this time, but as more dental providers enter this field and insurance carriers begin to allow for in-network medical credentialling for dentists with reasonable contracted reimbursement schedules, costs will become more standardized, validating the aforementioned quote even more so.

How does CPAP compare with OAT as far as patient compliance is concerned? Significant numbers of studies have shown that OAT is much more accepted than CPAP by the patient. No matter how good a therapy is, it has to be used if treatment outcomes are to be successful.5-15 Also, research has shown that if the oral appliance is not as effective as CPAP for a given patient but worn every night versus sporadically as can be the case with CPAP, the resulting

treatment outcome between the two therapies is comparable.16-38

When considering ease of use of a particular therapy, the simplest answer is how comfortable and therefore compliant a patient is. In most studies to date, OAT has a much higher patient compliance and preferability rating than CPAP.15-20

The next issue is the adverse effects of using oral appliances versus CPAP. Almost every form of therapy has some degree of adverse effects. The real question is what the risk versus benefits are for the patient. One of the major adverse effects of wearing an oral appliance is the effect on a patient’s bite.21,27 There are very few major lifealtering or life-threatening issues when dealing with an occlusion that would justify nontreatment because sleep apnea is a life-threatening condition for the patient and potentially others (for example, falling asleep at the wheel and causing a car accident).22 Most dental issues can be managed with conservative titration techniques.21 CPAP-induced adverse effects are also a major issue when dealing with patient compliance. If patient compliance is affected by the presence of adverse effects, it would appear that CPAPinduced adverse effects have a greater effect than those caused by an oral appliance because OAT has a much higher acceptance and compliance rate.23-26

When reviewing the issue of customization for CPAP versus OAT to fit the patient’s needs, there can be a significant difference between the two therapies. Positive airway pressure devices come in different models depending on the needs of the patient, but they still involve headgear and/or a chin strap of some type and potentially

high air pressures, which can result in diminished compliance.29 Also, few if any patients have ever experienced wearing any form of face mask, whether while sleeping or awake, during their lifetime.

However, there are more than 100 different types of oral appliances to choose from, and some appliances can be easily modified to fit the patient’s unique dental needs.28 Most patients have either worn braces with or without a retainer, an athletic mouthguard, or an appliance for bruxism. Having an oral appliance is very familiar to patients’ past experiences with the aforementioned dental appliances.

Wearing a conventional CPAP device over an oral appliance (type 1 therapy) does improve the therapeutic result, but many patients still have to deal with the CPAP headgear/chin strap issue.31,32,37 With the advent of the Airway Management, TAP-PAP Interface, a customized chairside attachment connecting a CPAP device to the oral appliance without any headgear and chin strap (type 2 therapy), patients can experience even more comfort and freedom of movement even in the most severe cases of OSA.33-36 However, there are significant numbers of patients with severe OSA who have had success with type 1 therapy.39 Experienced dentists using either type 1 or type 2 therapy have with consistency successfully treated patients with an apnea-hypopnea index from 20 to 144 events/hour and nadirs down to 45%, having a full complement of teeth, and a partially edentulous or fully edentulous situation. Therefore, type 1 and type 2 combination therapy could really be considered the new gold standard.30-31,37,39 Oral appliances allow for more treatment flexibility and thereby enhance the efficacy of CPAP by creating the best of both worlds,

www.tda.org | April 2024 123

Oral appliance therapy (OAT)

reduced therapeutic pressures and minimal mandibular advancement. Also, this treatment modality reduces most adverse effects created by either individual therapy, resulting in a higher compliance rate.

It can be said that there have been no high-level studies using combination therapy with or without a TAP-PAP Interface. Almost all higher level studies are performed through dental or medical schools or other professional organizations, but there will continue to be a lack of studies until these entities decide to perform the needed research.39 Hundreds if not thousands of patients have already been successfully treated with either type 1 or type 2 therapy and studies have been performed, mostly at a lower level or with limited numbers of patients. Although few in number, some private practices have a wealth of well-documented information with more than 10 to 20 years of follow-up treatment data. It would be a significant loss to let this existing information go to waste.

In conclusion, the term ‘gold standard’ can be reconsidered when referring to CPAP therapy with the advent of OAT. Although new to most physicians and dentists, combination therapy has been available and used for more than 20 years and is really the new gold standard when considering all the issues discussed. Both therapies are needed, can coexist, and should be used to derive the most therapeutic and least invasive treatment for the patient.

CITATION

Denbar M. Continuous positive airway pressure: Is it still the gold standard? A thoughtful analysis with the advent of oral appliance therapy. J Dent Sleep Med. 2023;10(4).

REFERENCES

1. Brodsky SL, Lichtenstein B. The gold standard and the Pyrite Principle: Toward a supplemental frame of reference. Front Psychol. 31 March 2020.

2. Duggna PF. Time to abolish “gold standard”. BMJ.1992;304 (6841):1568-1569.

3. Rapaport L. Which costs more: CPAP or oral appliance therapy? Sleep Review. Jan 18, 2022. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://sleepreviewmag.com/ sleep-treatments/therapy-devices/ oral-appliances/costs-cpap-oralappliance-therapy/

4. de Vries GE, Hoekema A, Vermeulen KM, et al. Clinicaland cost-effectiveness of a mandibular advancement device versus continuous positive airway pressure in moderate obstructive sleep apnea, J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(10):1477-1485.

5. Rotenberg BW, Murariu D, Pang KP. Trends in CPAP adherence over twenty years of data collection: A flattened curve. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016; 45: 43.

6. Weaver TE, Sawyer AM. Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure treatment for obstructive sleep apnoea: implications for future interventions. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:245–258.

7. Aarab G, Lobbezoo F, Heymans MW, Hamburger HL, Naeije M. Longterm follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of oral appliance therapy in obstructive sleep apnea. Respiration. 2011;82(2):162-168.

8. Ferguson KA, Ono T, Lowe A, Keenan SP, Fleetham JA. A randomized crossover study of an oral appliance vs nasal-continuous positive airway pressure in the treatment of mild-moderate obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1996; 109(5):1269-1275.

9. Randerath WJ, Heise M, Hinz R, Ruehle K-H. An individually adjustable oral appliance vs continuous positive airway pressure in mild-to-moderate obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 2002; 122(2):569-575.

10. Tan YK, L’Estrange PR, Luo YM, et al. Mandibular advancement splints and continuous positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea: A randomized cross-over trial, Eur J Orthod. 2002;24(3):239-249.

11. Salepci B, Caglayan B, Kiral N, et al. CPAP adherence of patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Respir Care. 2013;58(9):1467-1473

12. Summer J, Singh A. Oral appliances for sleep apnea. Sleep Foundation. September 30, 2022. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www. sleepfoundation.org/sleep-apnea/ oral-appliance-for-sleep-apnea

13. Radmand R, Chiang H, Di Giosia M, et al. Defining and measuring compliance with oral appliance therapy. J Dent Sleep Med 2021;8(3).

14. Obstructive sleep apnea: Study finds excellent agreement between subjective and objective compliance with oral appliance therapy. Science News. American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine, June 13, 2011.

15. Basyuni S, Barabas M, Quinnell T. An update on mandibular advancement devices for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea hypopnoea syndrome. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(Suppl 1):S48-S56.

16. Phillips CL, Grunstein RR, Darendeliler MA, et al. Health outcomes of continuous positive airway pressure versus oral appliance treatment for obstructive

124 Texas Dental Journal | Vol 141 | No. 3

sleep apnea: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013; 187(8):879-887.

17. Sutherland K, Phillips CL, Cistulli PA. Efficacy versus effectiveness in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: CPAP and oral appliances. J Dent Sleep Med. 2015;2(4):175–181.

18. Sutherland K, Cistulli PA. Oral appliance therapy for obstructive sleep apnoea: State of the art. J Clin Med. 2019;8(12):2121.

19. Li W, Xiao L, Hu J. The comparison of CPAP and oral appliances in treatment of patients with OSA: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Care. 2013;58(7):1184-1195.

20. Kalonia N, Raghav P, Amit K, Sharma P. Effect of mandibular advancement through oral appliance therapy on quality of life in obstructive sleep apnea: A scoping review. Indian J Sleep Med. 2021;16(4):125–130.

21. Sheats RD, Schell TG, Blanton AO, Braga PM. Management of side effects of oral appliance therapy for sleep-disordered breathing. J Dent Sleep Med. 2017;4(4):111-125.

22. Jean-Louis G, Zizi F, Clark LT, Brown CD, McFarlane SI. Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: Role of the metabolic syndrome and its components. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4(3):261–272.

23. Ghadiri M, Grunstein RR. Clinical side effects of continuous positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea. Respirology. 2020;25(6):593-602.

24. Koutsourelakis E, Vagiakis E, Perraki M, et al. Nasal inflammation in sleep apnoea patients using CPAP and effect of heated humidification. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(3):587-594.

25. Brown LK. Up, down, or no change: Weight gain as an unwanted side

effect of CPAP for obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16(suppl_1):21S–22S.

26. Rotty M-C, Suehs CM, Mallet J-P, Martinez C, Borel J-C. Mask sideeffects in long-term CPAP-patients impact adherence and sleepiness: the InterfaceVent real-life study. Respir Res. 2021;22(1):17.

27. Fritsch KM, Iseli A, Russi EW, Bloch KE. Side effects of mandibular advancement devices for sleep apnea treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(5):813-818.

28. Burhenne M. Sleep apnea oral appliances: Types, uses, and how they work. August 7, 2023. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://askthedentist.com/sleepapnea-oral-appliance/

29. Summer J, Singh A. What are the different types of CPAP machines? Sleep Foundation. August 31, 2023. Accessed September 13, 2023

30. Custom TAP-PAP. Airway Management. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://tapintosleep.com/ products/tap-pap-cs/

31. El-Solh AA, Moitheennazima B, Akinnusi ME, Churder PM, Lafornara AM. Combined oral appliance and positive airway pressure therapy for obstructive sleep apnea: A pilot study. Sleep Breath. 2011;15(2):203-208.

32. Upadhyay R, Dubey A, Kant S, Singh BP. Management of severe obstructive sleep apnea using mandibular advancement devices with auto continuous positive airway pressures. Lung India. 2015;32(2):158–161.

33. Prehn RS, Swick T. A descriptive report of combination therapy (custom face mask for CPAP integrated with a mandibular advancement splint) for longterm treatment of OSA with literature review. J Dent Sleep Med.

2017;4(2):29–36.

34. Denbar MA. A case study involving the combination treatment of an oral appliance and an auto-titrating CPAP unit. Sleep Breath. 2002 Sep;6(3):125-128.

35 Denbar MA, Essick GK, Schram P. Hybrid Therapy, A case study using hybrid therapy Sleep to treat a soon to be deployed soldier with obstructive and central sleep apnea. Sleep Review. June 2012.

36. Sanders AE, Denbar MA, White J, et al. Dental clinicians observations of combination therapy in PAP intolerant patients. Sleep Review. March 9, 2015,

37. Liu H-W, Chen Y-J, Lai Y-C, et al. Combining MAD and CPAP as an effective strategy for treating patients with severe sleep apnea intolerant to high-pressure PAP and unresponsive to MAD. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0187032.

38. Uniken Venema JAM, Doff MHJ, Sokolova D, Wijkstra PJ, van der Hoeven, JH, Stegenga B, Hoekema A. LONG-TERM OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA THERAPY; A 10-YEAR FOLLOW-UP OF MANDIBULAR ADVANCEMENT DEVICE AND CONTINUOUS POSITIVE AIRWAY PRESSURE, JDSM. Abstracts, Issue 6.3

39. Tanaka Y, Adame JM, Kaplan A, Almeida FR. The simultaneous use of positive airway pressure and oral appliance therapy with and without connector: A preliminary study. J Dent Sleep Med. 2022;9(1).

SUBMISSION AND CORRESPONDENCE

INFORMATION: Submitted for publication June 7, 2023; Accepted for publication August 21, 2023.

Correspondence: Martin Denbar, DDS; Email: drmdenbar@tx-dss.com

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The author has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

www.tda.org | April 2024 125

126 Texas Dental Journal | Vol 141 | No. 3 1. Do you have or have you considered an exit strategy? 2. How long do you plan on being a practice owner? If your health allows, would you like to continue practicing after that point? 3. Do you know what your practice is worth today? How do you know? When was your last Practice Valuation done? 4. Have you met with a financial planner and have a documented plan? Have you established a liquid financial resources target that will enable you to retire with your desired lifestyle/level of income? Henry Schein Dental Practice Transitions has your best interests has your best in mind throughout your career. Schedule a complime a complimentary consultation with your local Transition Sales Consultant today! If you answered no or do not know to any of these questions, let’s have a conversation! As a Practice Owner, You Should be Able to Answer the Following Questions: C ll: 866-335-2947 © 2024 Henry Schein, Inc. No copying without permission. Not responsible for typographical errors. 23PT2801 www.henryscheinDPT.com 866-335-2947 n C C n n B Y

www.tda.org | April 2024 127 Content on the Texas Health Steps Online Provider Education website has been accredited by the UTHSCSA Dental School Office of Continuing Dental Education, the Texas Medical Association, American Nurses Credentialing Center, National Commission for Health Education Credentialing, Texas State Board of Social Worker Examiners, and Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Continuing Education for multiple disciplines will be provided for some online content. Join 250,000+ professionals who get free Continuing Education (CE) with Texas Health Steps Online Provider Education. Choose from a wide range of courses developed by trusted Texas experts, for dental experts like you. Courses such as caries risk assessment and dental quality measures are available 24/7. Texas Health Steps is health care for children from birth through age 20 who have Medicaid. Learn more at TXHealthSteps.com Practical dental CE, at your pace.

Trending

Cultural Drivers of Smokeless Tobacco

Attitudes, and Behavior Determinants: A South Texas Oral Health Network Collaborative Study

128 Texas Dental Journal | Vol 141 | No. 3

Knowledge,

for Recent Refugee and Immigrants as

AUTHORS

Moshtagh R. Farokhi, DDS, MPH, MAGD, FICD, FPFA

Corresponding Author, Professor/Clinical, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, School of Dentistry, San Antonio, Texas; Department of Comprehensive Dentistry, Dental Director, The San Antonio Refugee Health Clinic, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, Texas; Office: 210.567.4589; Email: farokhi@ uthscsa.edu

Jonathan A. Gelfond, PhD, MD

Professor, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Joe and Teresa Long School of Medicine, Department of Population Health Sciences, San Antonio, Texas

Saima Karimi Khan, DDS

Dentist, Lucent Dental Group, Private Practice Dentistry, Duncanville, Texas

Melanie V. Taverna, MSDH, RDH, FADHA, MAADH

Assistant Professor, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, School of Dentistry, Department of Periodontics, Division of Dental Hygiene, San Antonio, Texas

Fozia A. Ali, MD

Professor/Clinical, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Joe and Teresa Long School of Medicine, Department of Family and Community Medicine, San Antonio, Texas

Caitlin E. Sangdahl

Practice-Based Research Network Coordinator, Supporting Older Adults through Research Network (SOARNet), South Texas Oral Health Network (STOHN). Institute for Integration of Medicine and Science, Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas

Rahma Mungia, BDS, MSc, DDPHRCS

Associate Professor, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, School of Dentistry, Department of Periodontics, San Antonio, Texas

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: This study was conducted by the South Texas Oral Health Network (STOHN), supported by the National Center for Advancing Translation Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1TR002645. This study was approved by the University of Texas Health San Antonio Institutional Review Board as an Exempt Study. All participants gave written or verbal consent to participate. The content is solely the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. All authors affirm that they have no financial affiliation (employment, direct payment, stock holdings, retainers, consultantships, patent-licensing arrangements, or honoraria) or involvement with any commercial organization with a direct financial interest in the subject or materials discussed in this manuscript, nor have any such arrangements existed in the past three years. The authors deny any conflicts of interest related to this study. We also acknowledge the work of Ms Anusha Kuchibhotla and Ms Kayla Hernandez, interns from the South Texas Oral Health Network. We want to acknowledge Ms Marissa Mexquitic, who was instrumental in this study’s IRB acquisition and all related administrative tasks.

FUNDING STATEMENT: The study described was supported by the Institute for Integration of Medicine & Science Community Engagement Small Projects Grant, UT Health San Antonio.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the South Texas Oral Health Network (STOHN) website: https://iims. uthscsa.edu/ce/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2023/08/SmokelessTobaccoCEGr_DATA_ LABELS_2023-08-02_0932.xlsx

ABSTRACT

Objectives: Smokeless tobacco (SLT) use is a phenomenon that is detrimental to the health of adults worldwide and dramatically impacts the health of resettled populations. The prevalence of SLT has exponentially grown as a public health threat for the refugee and immigrant populations and is worthy of addressing. This research study examined the SLT cultural drivers of the Texas immigrant and refugee community, which led to their knowledge, perception, awareness, and cessation practices.

Methods: A convenience sample of refugee and immigrant community members resettled in San Antonio was recruited from the local Health Clinic and Center. Ninety-four consented participants completed a 29item survey that gathered participants’ demographics, SLT history, beliefs, knowledge, perceptions of the risk, awareness, availability of SLT, and cessation practices influenced by their culture.

Results: Of the 94 participants, 87.2% identified as Asian or natives of Afghanistan, Myanmar, and Pakistan. 70% reported SLT as a ‘feel good’ or recreational use, while 33% used it to relieve stress. Thirty-five percent stated they continuously use or have the desire to use SLT first thing in the morning. 86.2% perceived SLT products as unsafe for their health, 83% believed that it caused oral cancer and periodontal disease, and 76.6% were aware that SLT contains nicotine. 63.8% wished to stop using them, and 36.2% attempted to quit unsuccessfully but were unsuccessful. 54% sought cessation assistance from a family member, 32% from a friend, and only 12% from a healthcare provider.

Conclusion: SLT use is culturally prevalent within the immigrant and refugee populations. Participants’ quit attempts likely failed due to a lack of professional cessation support that was taxing due to language, interpretation, and literacy barriers. Healthcare providers are well-positioned to offer cessation interventions and reduce SLT use to achieve community well-being pathways.

Keywords

Culture, Oral Health, Health Belief Model, Refugees, Tobacco Use Cessation, Smokeless Tobacco Use

www.tda.org | April 2024 129

INTRODUCTION

Smokeless tobacco (SLT) use is a health determinant for millions of adults globally, especially those from Southeast Asian ethnic backgrounds.1 Evidence-based tobacco interventions are established pathways to prevent tobacco-related cancer.2,3 Of the 5.7 million adults (2.3%) who consume SLT products in the U.S., individuals of Asian ethnicity have the highest percentage (6.8%) of use.5,6 The 2016 U.S. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System reports males (7.4%) are more likely to use SLT products than females (1.3%) in Texas.7

SLT use varies from inhaling to chewing products, where moist tobacco is placed between cheeks, lips, gums, and nasal cavities.8 Dry snuff powder originates from cured or fermented tobacco leaves.9 Dipping tobacco is shredded leaves that are easily pinched and placed inside the mouth. Snus is the moist tobacco placed behind the upper lip as loose or portioned sachets resembling miniature tea bags.10

Betel quid (Gutka) combines powdered tobacco, areca nut, slaked lime, and catechu.11 Mawa is areca nut, tobacco, and slaked lime, khaini is used with slaked lime, and Chimo is a syrup or paste from Venezuela.12,13 Naswar (Nass) is a dip used by Afghans made from sun-dried, powdered tobacco (N. rustica), ash, oil, flavoring agents (e.g., cardamom, menthol), coloring agents (indigo), and, in some areas, slaked lime placed in the oral cavity to achieve a euphoric sensation.14

Health consequences of SLT use, like cigarette smoking, include impairments in brain neurology that change cognitive and neurobehavioral functions.15 Tobacco-specific nitrosamines are tobacco alkaloids from curing,

fermentation, and aging as the most abundant carcinogens in chewing tobacco and snuff SLT products.16

Oral health consequences of SLT use include oral carcinomas and malignant disorders presenting as leukoplakia and erythroplakia.17 Snuff and betel leaf are risk factors for oral cavity cancer.18 SLT use is a predisposing risk factor for tooth decay, tooth loss, and periodontal disease.19,20

Resettlement depends on individuals choosing to move from their native land to live permanently in a foreign country (immigrants) or if they are forced to move (refugees).21 As the resettlements increase due to global conflicts, refugee patients seeking care present with a higher incidence of SLT-related oral lesions.22

Cultural implications of SLT use include activities between family and friends, where traditions, spiritual values, and religious beliefs are formed, SLT use is influenced by accessibility and affordability, except for lower socioeconomic South Asian populations that use SLT products to suppress hunger and boredom.14,23-26 In Saudi Arabia, the use of Shammah (SLT) is culturally and socially bonding family and friends, and in Venezuela, chimó (SLT) is a traditional practice from the pre-Columbian Indian era.27,28 Religion either prohibits SLT use or condones it as a stress-coping mechanism.29

Healthcare providers should be aware of cultural drivers leading to family and peers as primary SLT cessation support. We hypothesized that SLT cessation interventions are feasible when the providers 1) understand their refugee and immigrant patients’ cultural drivers and perspectives promoting SLT use and 2) recognize patient barriers deterring the cessation process.

METHODS

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this study as HSC20220274EX for this study. The study was funded by a small grant from the Institute for Integration of Medicine and Science (IIMS) Community Engagement Small Project. Verbal and written consent for the study was obtained from all participants.

Participants

Participants were members of San Antonio’s local refugee and immigrant populations, such as any refugee or immigrant community member 18 years and older who used SLT as a lifetime or current practice and consented to participate. Participants were compensated with a $20 gift card for their time.

Ninety-four (n=94) participants were recruited from the San Antonio Refugee Health Clinic and El-Bari Community Health Center, where providers delivered healthcare to this local refugee and immigrant population. The study coordinators visited site-specific Health Fairs to recruit participants with assistance from certified interpreters to address language and health literacy barriers. Random participants were approached and asked about SLT product use. Participants who currently or had previously used SLT and consented were informed about the IRB protocol and surveyed.

Survey Design

The quantitative survey design included a 29-question multiple-choice, dichotomous, validated survey (Table 1).23 The survey design was a deliberate act to tackle participants’ reading and comprehension since they either spoke English as a second language or used an interpreter to complete

130 Texas Dental Journal | Vol 141 | No. 3

Table 1: THE VALIDATED SURVEY

Risk and Prevalence of Oral Cancer and Oral Leucoplakia of Smokeless Tobacco Use in Bangladesh

About You:

A1. Are you? Male Female

A2. How old are you? __________Years old

A3. What is your father’s job if he is working?

A4. What is your mother’s job if she is working? Smokeless Tobacco Habits:

B1. Have you ever used smokeless tobacco, such as Pan with Jarda, Gul, Pan Masala etc., even just a small amount?

Yes (If yes, then what brand or type of smokeless tobacco you used

No

[If you tried smokeless tobacco, then answer the next questions. Otherwise, go to B15.]

B2. How old were you when you first tried using smokeless tobacco?

I have never tried using smokeless tobacco

7 years old or younger

8 or 9 years old

10 or 11 years old

12 or 13 years old

14 or 15 years old

B3. During the past 30 days, how many days did you use smokeless tobacco?

0 days

1 or 2 days

3 to 5 days

6 to 9 days

10 to 19 days

20 to 29 days

All 30 days.

B4. How many times did you usually use smokeless tobacco per day, in the past 30 days?

I did not use smokeless tobacco during the past 30 days

Less than once per day

Once per day

2 to 5 times per day

6 to 10 times per day

11 to 20 times per day

More than 20 times per day.

B5. Do you ever use smokeless tobacco or feel like using smokeless tobacco first thing in the morning?

No, I don’t use or feel like using smokeless tobacco first thing in the morning

Yes, I sometimes use or feel like using smokeless tobacco first thing in the morning

Yes, I always use or feel like using smokeless tobacco first thing in the morning.

B6. How soon after you use smokeless tobacco, do you start to feel a strong desire to use it again that is hard to ignore?

I never feel a strong desire to use it again after

using smokeless tobacco

Within 60 minutes

1 to 2 hours

More than 2 hours to 4 hours

More than 4 hours but less than one full day 1 to 3 days 4 days or more.

B7. Why do you use smokeless tobacco? (You can have more than one answer for this question)

Taste

Smell

Pleasure

To feel better/good/Happy Because my friend is using it

Don’t Know.

Other reason (Please Specify)

B8. Do you want to stop using smokeless tobacco now?

I don’t use smokeless tobacco now Yes No

B9. During the past 12 months, did you ever try to stop using smokeless tobacco?

I did not use smokeless tobacco during the past 12 months

I tried, but not successful

Yes No

B10. If you have tried to stop, but are not successful, why?

B11. Have you ever received help or advice to help you stop using smokeless tobacco? (If necessary, you can give more than one answer)

Yes, from a program or professional Yes, from a friend

Yes, from a family member

No

B12. The last time you used smokeless tobacco during the past 30 days, how did you get it? (If necessary, you can give more than one answer)

I did not use smokeless tobacco during the past 30 days

I bought it in a store or shop in the school canteen

I bought it from a street vendor outside the school gate

I got it from someone else

I bought it from a store near to my house

I bought it from a store on the way to school I got it some other way. If you are willing to state how, please do

B13. During the past 30 days, did anyone refuse to sell you smokeless tobacco because of your age?

I did not try to buy smokeless tobacco during the past 30 days

Yes, someone refused to sell me smokeless tobacco because of my age

No, my age did not keep me from buying smokeless tobacco.

B14. During the past 30 days, did you see any health warnings on smokeless tobacco packages?

Yes, but I didn’t think much of them. Yes, and they led me to think about quitting smokeless tobacco or not starting smokeless tobacco.

No.

B15. If one of your best friends offered you smokeless tobacco, would you use it?

Definitely not

Probably not

Probably yes

Definitely yes

B16. Once someone has started using smokeless tobacco, do you think it would be difficult for them to quit?

Definitely not

Probably not

Probably yes

Definitely yes

Health Effects of Smokeless Tobacco Use:

C1. Do you think smokeless tobacco use is: Good for your health

Neither good nor bad for your health

Not good for your health

Don’t Know

C2. Are there benefits of smokeless tobacco to your body and health?

Yes, please name them

No

C3. Does smokeless tobacco cause less harm to your health compared to smoking tobacco?

Yes No

Don’t Know.

C4. Does smokeless tobacco cause white patches in the mouth?

Yes No

Don’t Know.

C5. Can smokeless tobacco cause oral cancer?

Yes No

Don’t Know

C6. Does smokeless tobacco cause gum disease (Gum disease is an infection of the gum that surrounds and supports your teeth)?

Yes No

Don’t Know

C7. Does smokeless tobacco cause heart disease?

Yes No

Don’t Know.

C8. Does smokeless tobacco contain nicotine? (Nicotine is a chemical that is present in cigarettes that makes people addicted)?

Yes No

Don’t Know.

www.tda.org | April 2024 131

survey questions. The survey was also planned with the cultural and linguistic assistance of refugee and immigrant community interpreters as an online REDCap30 web-based link. The design generated a culturally appropriate health-literate and plain language survey with illustrative aptitude.31 The survey gathered participants’ sociodemographic data, history of SLT use, types of SLT products, beliefs, knowledge, perceptions about SLT use, awareness, availability, and SLT cessation practices. The survey blended the cultural and behavioral attitudes, intentions, or motivational factors influencing behavior toward SLT use, adapted from the worldview of Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) and the Health Belief Model (HBM).32,33

The SCT model emphasizes internal and external influences by which individuals acquire and maintain behavior.32 SCT considers whether behavioral action will occur with expectations that shape whether an individual will engage in a specific behavior and why they engage in that behavior.

For this study, SCT questions related to the effect of social environment on the individual’s health behavior, such as using SLT products, enabled researchers to understand cultural and external factors that affect someone’s decision to use SLT.23 Environmental influences were trended as questions about cultural and religious appeals, social norms, peer pressure, recreational use, and stress. Environmental determinants of health indicated the availability and accessibility of SLT products and exposure to SLT advertisements.

The HBM model construction includes the perceived quitting benefits from a health or social perspective, perceived barriers or potential obstacles to

quitting, and perceived self-efficacy as the self-ability to stop smoking.33 HBM derives components of healthrelated behavior that influence strategies promoting healthy behaviors by preventing and treating health conditions.33 The HBM model also includes the decision-making process of accepting a recommended health action as internal (e.g., wheezing, difficulty swallowing) or external factors (e.g., culturally influenced advice from friends). Finally, this model braces an individual’s confidence in their ability to succeed.

For this study, HBM survey questions were related to understanding motives to partake in SLT use, and reasons for unsuccessful SLT quit attempts.23 Questions about the harmful effects of SLT measured participants’ perceived susceptibility, and items asking about

barriers determined reasoning for SLT use. Questions about attitude refer to the degree to which a person has a favorable or unfavorable evaluation of the behavior of interest.

Analysis

The study’s primary goal was to identify the perspectives of recently resettled refugee and immigrant SLT users. Percentages summarized categorical variables, and continuous outcomes defined the medians and interquartile ranges (25th and 75th percentiles). The hypothesis tested was that the characteristics of SLT users would vary by ethnicity. This was assessed using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric tests for continuous outcomes. All testing was two-sided at a significance level of p=.05.

132 Texas Dental Journal | Vol 141 | No. 3

Areca Nut 23.4% n=22 Chewing Tobacco 12.8% n=12 Dissolvable Tobacco 1.1% n=1 Snuff Tobacco 28.7% n=27 Dip Tobacco 27.7% n=26

Paan/Betel Quid/

Table 2. PARTICIPANT SOCIODEMOGRAPHICS

Characteristic

Smokeless Use Yes

Education

No education at all Less than a high school diploma

High school diploma or GED

Some college Associate degree

Bachelor’s degree Graduate degree

Household Size

Income

Up-to (> or = to) $25,000

$25,001-$50,000

$50,001-$100,000

Over $100,000

Prefer not to answer

1n (%): Median (IQR)

2Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test: Pearson’s Chi-squared test

RESULTS

Sociodemographic data for the 94 participants trended an age range of 1978 years, where the majority (87%,n=82) were males compared to 13% (n=12) females. 87.2% self-identified as Asian or natives of Afghanistan, Myanmar,

and Pakistan. Participant’s highest level of education obtained varied by their ethnicity (p=.002). 31% (n=29, 36% Asians vs. 0% Latino and 0% Non-Latino White) had completed less than a high school education. Considering higher education, they received associate’s (2.1%, n=2), bachelor’s (15%, n=14), and

graduate degrees (11%, n=10). Most had annual incomes less than or equal to $25,000 (57%, n=54). Asian participants reported the lowest income level (64%, n=51) compared to 25% for Latinos, mainly from Venezuela, and 0% for nonLatino whites (p=.014, Table 2).

www.tda.org | April 2024 133

Age Unknown

Gender Female Male

Overall N = 941 94 (100%) 36 (31, 44) 1 12 (13%) 82 (87%) 17

29

18

4

2

14

10

5.00

54

17

8

7

8

Asian N = 801 80 (100%) 36 (31, 44) 0 6 (7.5%) 74 (92%) 17 (21%) 29 (36%) 15 (19%) 2

1

10

6

5.00

51

14

5

6

4

Latinos N = 121 12 (100%) 38 (34, 48) 1 6 (50%) 6 (50%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 3

1 (8.3%) 1

3 (25%) 4

5.00

3

3

2

1

3

Non-Latino/ White N = 21 2 (100%) 34 (32, 37) 0 0 (0%) 2 (100%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 4.00 (3.50,

0 (0%) 0 (0%) 1 (50%) 0 (0%) 1 (50%) p-value2 0.8 <0.001 0.002 0.8 0.014

(18%)

(31%)

(19%)

(4.3%)

(2.1%)

(15%)

(11%)

(3.00, 6.00)

(57%)

(18%)

(8.5%)

(7.4%)

(8.5%)

(2.5%)

(1.3%)

(12%)

(7.5%)

(3.00, 7.00)

(64%)

(18%)

(6.2%)

(7.5%)

(5.0%)

(25%)

(8.3%)

(33%)

(5.00, 5.25)

(25%)

(25%)

(17%)

(8.3%)

(25%)

4.50)

Table 3. PARTICIPANT REPORTED DRIVERS OF SLT USE

Characteristic/

Recreational

Cultural Drivers

Socialization

1n (%)

2Pearson’s Chi-squared test

Smokeless Tobacco (SLT) Use and Beliefs According to the Survey

The frequency of SLT use was highest among the Asian refugee population, or 100% of the participants reported using SLT at some point. More than half (52%, n=49) used SLT every day monthly. SLT use during the past 30 days before the survey ranged from 2-5 times daily (30%, n=28) to 6-10 times a day (16%, n=15), and 29.8% (n=28) had not used any SLT products in the past 30 days.

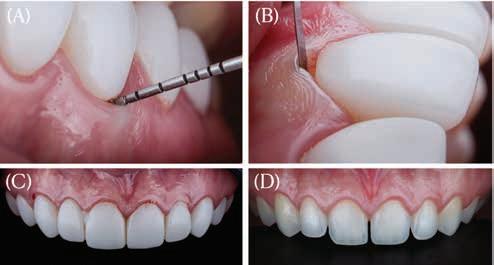

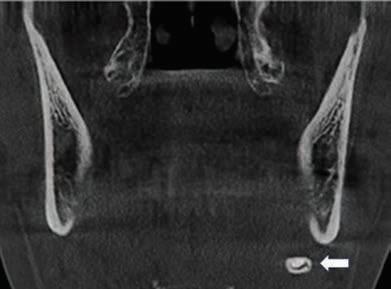

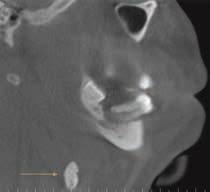

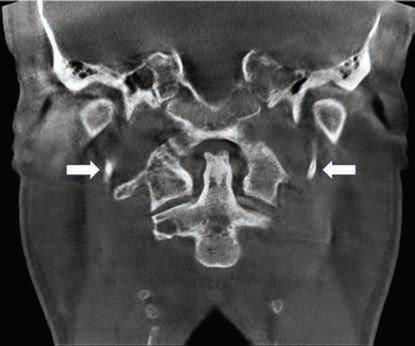

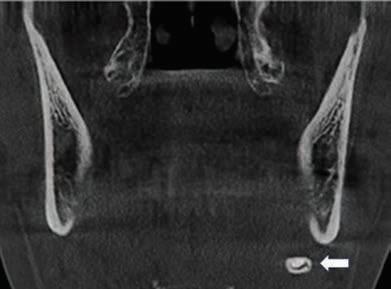

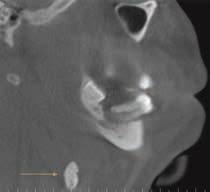

SLT Types of product use and dependence indicated that snuff tobacco (28.7%, n=27), dip tobacco (27.7%, n=26), Paan/betel quid/areca nut (23.4%, n=22), and chewing tobacco (12.8%, n=13), were most frequently forms used (Figure 1). SLT dependence rates were limited to 20.2% (n=19) of participants who reported a strong desire to use SLT within a 60-minute window of waking up. Many participants (76.6%, n=72) started using SLT at 15 years or older, and 3.2% (n=3) reported first-time use at 7 years or younger.

Drivers of SLT use reported by the participants were to 1) to feel good or happy (34%, n=32), 2) use it as recreation (35%, n=33), 3) cope with stress (33%, n=31), 4) taste (18%, n=17), and because of peer pressure (12% n=Table 3 ). Participants reported that cultural drivers, including family (8.5%, n=8), social purposes (17%, n=16), and overall culture (7.4%, n=7, p=0.001), influenced their decision to use. Meanwhile, 9.6% (n=9) of the participants used SLT for the smell, and 11% (n=10) used it for curiosity (Table 3).

134 Texas Dental Journal | Vol 141 | No. 3

Drivers Taste Smell Feel Happy

Family Use

Other including loneliness

No Unknown Overall N = 941 17 (18%) 9 (9.6%) 32 (34%) 33 (35%) 8 (8.5%) 16 (17%) 11 (12%) 7 (7.4%) 31 (33%) 10 (11%) 4 (4.3%) 8 (8.5%) 8 (100%) 86 Asian N = 801 14 (18%) 8 (10%) 31 (39%) 30 (38%) 5 (6.2%) 15 (19%) 8 (10%) 3 (3.8%) 25 (31%) 7 (8.8%) 3 (3.8%) 4 (5.0%) 4 (100%) 76 Latinos N = 121 2 (17%) 1 (8.3%) 1 (8.3%) 2 (17%) 3 (25%) 1 (8.3%) 2 (17%) 4 (33%) 4 (33%) 3 (25%) 1 (8.3%) 4 (33%) 4 (100%) 8 Non-Latino/ White N = 21 1 (50%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 1 (50%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 1 (50%) 0 (0%) 2 (100%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (NA%) 2 p-value2 0.5 0.9 0.069 0.3 0.086 0.5 0.2 0.001 0.12 0.2 0.7 0.004

Friends/peer Cultural Reason Stress Curious Don’t Know

Other Reason

Knowledge, risks, and perception for most participants (86.2%, n=81) was that SLT products were unsafe for their health, caused changes in their mouth (87.2%, n=82)), and caused oral cancer and gum disease (83%, n=78). When comparing SLT to smoking other tobacco use, 60.2% (n=56) perceived it to be less harmful, and a vast majority (76.6%, n=72) understood that the SLT products contained nicotine. The immigrants and refugees of Asian ethnicity were most likely to use SLT products despite an increased awareness (89%, n=71) of their harmful effects and because of cultural norms.

Awareness, availability, and warning statements indicated that participants purchased SLT products within the past 30 days at a convenience store or gas station (48%, n=45) or at a supermarket (22.3%, n=22). 46.8% (n=44) were aware of positive advertising to promote tobacco products at the point of sale, and 43.6% (n=41) did not recall any advertisements or promotions at the point of purchase. More than half (59.6%, n=56) did not notice any health warning statement on SLT packages, and 21% (n=17) reported having seen warning labels but did not think much of them.

STL cessation practices indicated that 63.8% (n=60) desired to stop using SLT, and 22.3% 9n=21) no longer used SLT. 36.2% (n=34) attempted to quit using SLT on their own unsuccessfully, 26.6% (n=25) did not quit at all, and 19% (n=18) stopped using SLT products within the past 12 months of the survey.

Reasons for unsuccessful cessation practices included increased levels of stress, anxiety, loneliness, addiction, and peer pressure as family or friends’ cultural offers. Most who attempted to quit SLT use received support from

their family (54%) and friends (32%). Only 12% received an intervention from a healthcare provider, and 1.1% from a health program. 45% percent believed that once someone started using SLT, quitting attempts would be difficult. 50% of non-Latino White (50%) and 51% of Asian participants reported that SLT was hard to quit, relative to the 0% of Latino participants (p<.001).

DISCUSSION

This study found that the most significant SLT use was among South Asians and presented as a cultural norm for predominantly male participants (100%), supported by research, even though some females prefer the SLT form of tobacco, as did the immigrant Venezuelan females for this study.34,35

We found that the prevalence of SLT use by participants was rooted in easy access to the products at nearby ethnic convenience stores, gas stations, or supermarkets catering to their purchasing needs, also reported by research.26 However, participant SLT use escalated due to their desire to feel happy or cope with stress and loneliness as determinants of health as supported by similar research highlighting immigrants’ cultural beliefs about using tobacco products (e.g., aiding digestion or sleep effectiveness).26

Our study found that participants’ dependence on SLT products, culturally acceptable SLT use, and stressors were risk factors inhibiting quitting. The dependent nature of SLT products explained why participants continued using them even though they understood the adverse health effects. Finally, culture and religion as recreation and social interactions influenced the profound use of SLT as supported by research from Pakistan, indicating

family, friends, and peer pressure significantly impacted SLT use.28-29,36

The limitations of this study include the self-reported survey and the proportion of Afghan participants as the dominant Asians, even though this composition is scaled to the current resettled population in Texas. Participants included individuals who considered Venezuela (Latinos), Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Myanmar (Asians) as their native lands and resettled in San Antonio. Considering the results may not precisely scale to other cities, the resettled population represents the global community using SLT products. Finally, our study trended frequent forms of Naswar (Afghans), Paan (Burmese), and Betel Quid (Pakistanis) for the current refugee and immigrant population served in San Antonio.

Clinical relevance connects oral to overall health outcomes as tobacco cessation intervention is prioritized by professional associations, including the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American Dental Education Association, where providers are called to intervene.37,38 Healthcare providers should connect their vulnerable patients’ social, cultural, and addictive nature of SLT use with tailored interventions.

Providers should examine their refugee/immigrant patient SLT use by considering their limited access to care due to oral health literacy, financial, transportation, and interpretation challenges upon resettlement in the U.S.39 It was discouraging to realize that practitioners and community intervention programs played an insignificant role for this population’s SLT quit attempts.

www.tda.org | April 2024 135

Based on this study and supportive current research, future interventions should focus on tailored, culturally sensitive intervention approaches endorsed by the WHO.40 SLT interventions should focus on 1) resettlement-induced stressors and cultural norms combating SLT cessation, 2) the role that underlying trauma, loneliness, stress, and anxiety play in SLT quitting attempts and relapse challenges, 3) assessing the patient’s level of health literacy preinterventions, and 4) addressing patient barriers to quitting realizing that SLT tobacco cessation protocols are further complicated for refugee patients requiring time and interpretation services for cessation interventions.

CONCLUSION

This effort aims to empower providers to enhance their vulnerable resettled patient SLT cessation practices as participants either did not have access to professional support or were not offered tailored cessations.

Practitioners must aim for more upstream early cessation interventions in contrast to the traditional downstream late-stage cancer detection approach.29 The critical role of friends and family in supporting the use and the quitting process of SLT should not be underestimated. Cultural norms and easy access to SLT products intertwined with literacy and language barriers are trials providers encounter engaging with their newly resettled patients.

REFERENCES

1. Singh PK. Smokeless tobacco use and public health in countries of South-East Asia region. Indian J Cancer. 2014 Dec;51 Suppl 1: S1-2.

2. National Cancer Institute and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smokeless Tobacco and Public Health: A Global Perspective. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. 2014; NIH Publication No. 14-7983.

3. Hecht SS, Hatsukami DK. Smokeless tobacco and cigarette smoking: chemical mechanisms and cancer prevention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022 Mar;22(3):143-155.

4. Hatsukami D, Zeller M, Gupta P, et al. Smokeless Tobacco, and Public Health: A Global Perspective. 2014. The National Institute of Health Publication No. 14-7983.

5. Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Wang TW, et al. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults - United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022 Mar 18;71(11):397-405.

6. Han BH, Wyatt LC, Sherman SE, et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Cultural Smokeless Tobacco Products among South Asian Americans in New York City. J Community Health. 2019 Jun;44(3):479-486.

7. Hu SS, Wang TW, Homa DM, et al. Cigarettes, Smokeless Tobacco, and E-Cigarettes: State-Specific Use Patterns Among U.S. Adults, 2017-2018. Am J Prev Med. 2022 Jun;62(6):930-942.

8. Chagué F, Guenancia C, Gudjoncik A, et al. Smokeless tobacco, sport and the heart. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2015 Jan;108(1):75-83.

9. Titova, OE., Baron JA, Michaëlsson, K, et al. Swedish snuff (snus) and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality: a prospective cohort study of middle-aged and older individuals. BMC Med. 2021:19, 111.

10. Clarke E, Thompson K, Weaver S, et al. Snus: a compelling harm reduction alternative to cigarettes. Harm Reduct J. 2019; 16: 62.

11. Patidar KA, Parwani R, Wanjari SP, et al. Various terminologies associated with areca nut and tobacco chewing: A review. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2015 JanApr;19(1):69-76.

12. Chadda R, Sengupta S. Tobacco use by Indian adolescents. Tob Induc Dis. 2002 Jun 15;1(2):111-119.

13. Gonzalez-Rivas JP, Santiago RJG, Mechanick JI, et al. Chimo, a Smokeless Tobacco Preparation, is Associated with a Lower Frequency of Hypertension in Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Cardiovas. Sci. 2017;30(5): 373-379.

14. Nakhaei Moghaddam T, Mobaraki F, Darvish Moghaddam MR, et al. A review on the addictive materials paan masala (Paan Parag) and Nass (Naswar). SciMedicine Journal. 2019; 1(2): p. 64-73.

15. Nadar MS, Hasan AM, Alsaleh M. The negative impact of chronic tobacco smoking on adult neuropsychological function: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21, 1278.

16. Richter P, Hodge K, Stanfill S, et al. Surveillance of moist snuff: total nicotine, moisture, pH, un-ionized nicotine, and tobacco-specific nitrosamines. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008 Nov;10(11):1645-52.

17. Muthukrishnan A, Warnakulasuriya S. Oral health consequences of smokeless tobacco use. Indian J Med Res. 2018 Jul;148(1):35-40.

136 Texas Dental Journal | Vol 141 | No. 3

18. Khan SZ, Farooq A, Masood M, et al. Smokeless tobacco use and risk of oral cavity cancer. Turk J Med Sci. 2020 Apr 9;50(1):291-297.

19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Factsheet: Smokeless Tobacco: Health Effects. December 2016. Available from: https://www. cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/ fact_sheets/smokeless/health_ effects/index.htm.

20. Kamath KP, Mishra S, Anand PS. Smokeless tobacco use as a risk factor for periodontal disease. Front Public Health. 2014; Oct 20;2:195.

21. The United Nations Commission of Refugees. Available from: https:// www.unhcr.org/what-refugee.

22. Dreher A, Langlotz S, Matzat J, Parsons C. Immigration, Political Ideologies and the Polarization of American Politics. CESifo WP 8789. Munich 2020.

23. Ullah MZ, Lim JN, Ha MA, et al. Smokeless tobacco use: pattern of use, knowledge, and perceptions among rural Bangladeshi adolescents. PeerJ. 2018 Aug 21;6:e5463.

24. Rollins K, Lewis C, Edward Smith T, et al. Development of a Culturally Appropriate Smokeless Tobacco Cessation Program for American Indians. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2018 Spring;11(1):45-55.

25. Auluck A, Hislop G, Poh C, et al. Areca nut and betel quid chewing among South Asian immigrants to Western countries and its implications for oral cancer screening. Rural Remote Health. 2009 Apr-Jun;9(2):1118.

26. Blank M, Deshpande L, Balster RL. Availability and characteristics of betel products in the U.S. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2008 Sep;40(3):309-313.

27. Moafa I, Crutzen R, van den Borne B, et al. Towards a better understanding of the psychosocial determinants associated with adults’ use of smokeless tobacco in the Jazan Region of Saudi Arabia: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2022 Apr 13;22(1):732.

28. Kamen-Kaye D. Chimó: an unusual form of tobacco in Venezuela. Bot Mus Lealf Harv Univ. 1971 Jan 20; 23:1-59.

29. Farhadmollashahi L. Sociocultural reasons for smokeless tobacco use behavior. Int J High Risk Behav Addict. 2014; Jun 1;3(2): e20002.

30. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009 Apr;42(2):377-381.

31. Shohet L, Renaud L. Critical analysis on best practices in health literacy. Can J Public Health. 2006 MayJun;97 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S10-3.

32. Bandura A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychol. Health. 1998;13(4):623–649.

33. Pribadi ET, Devy SR. Application of the Health Belief Model on the intention to stop smoking behavior among young adult women. J Public Health Res. 2020 Jul 2;9(2):1817.

34. Hussain A, Zaheer S, and Shafique K. Individual, social and environmental determinants of smokeless tobacco and betel quid use amongst adolescents of Karachi: a school-based crosssectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2017; 17(1): 913.

35. Pampel F, Khlat M, Bricard D, et. al. Smoking Among Immigrant Groups in the United States: Prevalence, Education Gradients, and Male-toFemale Ratios. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020 Apr 17;22(4):532-538.

36. Mukherjea A, Morgan PA, Snowden LR, et al. Social and cultural influences on tobacco-related health disparities among South Asians in the USA. Tob Control. 2012 Jul;21(4):422-428.

37. American Association of Family Physicians. Ask and Act Tobacco Cessation Program. Available from: https://www.aafp.org/ family-physician/patient-care/careresources/tobacco-and-nicotine/ ask-act.html.

38. American Dental Association Position on Tobacco Cessation. Available from: https://www.ada. org/about/governance/currentpolicies#tobacco.

39. Farokhi MR, Muck A, Lozano-Pineda J, et al. Using Interprofessional Education to Promote Oral Health Literacy in a Faculty-Student Collaborative Practice. J Dent Educ. 2018 Oct;82(10):1091-1097.

40. World Health Organization (WHO) monograph on tobacco cessation and oral health integration. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available from: https://www. who.int/publications/i/item/whomonograph-on-tobacco-cessationand-oral-health-integration.

www.tda.org | April 2024 137

OFFICIAL CALL TO THE 2024 TEXAS

DENTAL ASSOCIATION HOUSE OF DELEGATES

HOUSE OF DELEGATES:

In accordance with Chapter IV, Section 70, paragraph A-1 of the Texas Dental Association (TDA) Bylaws, this is the official call for the 154th Annual Session of the Texas Dental Association House of Delegates. All sessions of the House will be in the Hemisfair C-3 Ballroom of the Henry B. Gonzalez Convention Center, 900 E. Market Street, San Antonio, Texas. The opening session of the House will convene at 8:00 AM on Thursday, May 16, 2024. The second meeting of the House will be at 1:30 PM on Friday, May 17, 2024. The third meeting of the House will be at 8:00 AM on Saturday, May 18, 2024, followed by the fourth meeting at 10:00 AM until close of business.

Please see the TDA Meeting website for details and additional information (www.tdameeting.com).

Component Societies are urged to certify an accurate list of Delegates and Alternates to fill each of their seats on the floor of the TDA House of Delegates.

FINANCIAL FORUM:

The TDA Secretary-Treasurer will facilitate a question-and-answer financial forum at 10:00 AM, or 15 minutes after adjournment of the first meeting of the House of Delegates, on Thursday, May 16, 2024, open to all members who are present in the Hemisfair C-3 Ballroom of the Henry B. Gonzalez Convention Center, 900 E. Market Street, San Antonio, Texas (same room as the House of Delegates meetings).

Reference Committee hearings will follow the financial forum.

REFERENCE COMMITTEE

HEARINGS: Reference Committee hearings will be combined and facilitated to follow the financial forum at approximately 10:30 AM on Thursday, May 16, 2024, and open to all members who are present in the Hemisfair C-3 Ballroom of the Henry B. Gonzalez Convention Center, 900 E. Market Street, San Antonio, Texas (same room as the House of Delegates meetings). Hearings will conclude when no further testimony is presented.

Combined Topics:

• Administration, Budget, Building, House of Delegates, Membership Processing

• President’s Address, Miscellaneous Matters, Component Societies, Subsidiaries, Strategic Planning, Annual Session

• Dental Education, Dental Economics, Health and Dental Care Programs

• Legislative, Legal and Governmental Affairs

• Constitution, Bylaws, Ethics & Peer Review

The agenda for the Reference Committee hearings will be included in the Reference Committee section of the House Documents.

REFERENCE COMMITTEE

REPORTS: Reference Committee Reports will be made available in PDF format to the members of the House of Delegates (reports may be downloaded from any location with Internet access). Printed copies will not be provided.

TDA CANDIDATES FORUM:

The TDA “Meet the Candidates Forum” will be held on Friday, May 17, 2024, from 10:30 AM to 11:30 AM in the in the

Hemisfair C-3 Ballroom of the Henry B. Gonzalez Convention Center, 900 E. Market Street, San Antonio, Texas (same room as the House of Delegates meetings). There will not be an ADA candidates forum this year due to scheduling conflicts.

DIVISIONAL CAUCUSES:

Divisional Caucuses (Northwest, Northeast, Southwest, Southeast) will be facilitated at 5:30 PM on Friday, May 17, 2024, in the Convention Center and open to all current members— please see the TDA website for details and additional information. (Room assignments: SE-303C; SW-304A; NE304B; NW-304C).

DELEGATE MATERIALS: