“BEING

“BEING

“One’s personal portmanteau should be selected, both upon purchase and for each day’s tasks, with as much care and attention as one’s suit of clothes.”

Gustav Temple, CHAP Spring 22

thechap@barrowhepburngale.com | barrowhepburngale.com | @barrowhepburngale

Editor: Gustav Temple Art Director: Rachel Barker

Picture Editor: Theo Salter

Circulation Manager: Andy Perry

The editor of The Chap for the last 20 years is also the author of The Chap Manifesto, The Chap Almanac, Around the World in 80 Martinis (Fourth Estate), Cooking For Chaps and Drinking For Chaps (Kyle Books) and How To Be Chap (Gestalten). He is currently working on a book without ‘Chap’ in the title.

Actuarius is an artist, essayist, photographer and journalist. A selfconfessed petrolhead, he mainly produces works based around his twin passions of Art Deco and mechanised transport, making the shortlist for the highly prestigious Guild of Motoring Writers Feature Writer of the Year in 2021.

Chris Sullivan is The Chap’s Contributing Editor. He founded and ran Soho’s Wag Club for two decades and is a former GQ style editor who has written for Italian Vogue, The Times, Independent and The FT. He is now Associate Lecturer at Central St Martins School of Art on ‘youth’ style cults. @cjp_sullivan

By day Sam Knowles is a data storyteller; on summer Sundays he combines his passion for narrative and numbers on the cricket pitch. He is the co-refounder, scorer and match reporter for the Gentlemen of Lewes Cricket Club, whose exploits can be followed on Twitter @GoLCC_Lewes

The Chap Ltd 69 Winterbourne Close Lewes, East Sussex BN7 1JZ

Sub-Editor: Romilly Clark

Subscriptions Manager: Jen Rainnie

Contributing Editors: Chris Sullivan, Actuarius, Ed Needham Subscriptions 01442 820 580 contact@webscribe.co.uk

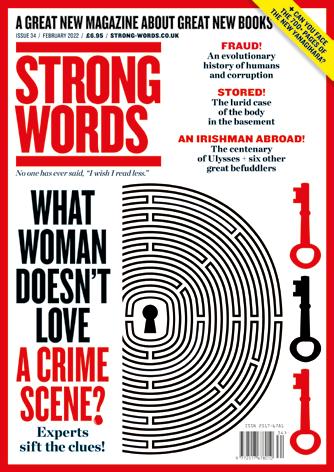

Ed Needham is the editor and publisher of Strong Words magazine, launched in 2018 to give book enthusiasts a fighting chance of keeping up with the blizzard of new titles, with reviews that don’t feel like homework. He was previously editor of FHM in its million-selling nineties heyday and managing editor of Rolling Stone in New York.

OLIVIER WOODESFARQUHARSON

Olivier Woodes-Farquharson is an adventurer, diplomat, voice actor and writer, although not always in that order. When not travelling to obscure places that may or may not exist, he is most likely to be found at Cheltenham Races – the best place to blood his latest tweed – or furiously foraging in the English countryside.

Advertising Paul Williams paul@thechap.co.uk +353(0)83 1956 999

Printing: Micropress, Fountain Way, Reydon Business Park, Reydon, Suffolk, IP18 6SZ

David Evans is a former lawyer and teacher who founded popular sartorial blog Grey Fox Blog nine years ago. The blog has become very widely read by chaps all over the world, who seek advice on dressing properly and retaining an eye for style when entering the autumn of their lives.

@greyfoxblog

John Minns has been a collector, buyer and seller of antiques and collectables from the age of nine, when he first immersed himself in the antique world by foraging London antique markets in the morning before school, then selling his finds to his eager school pals. His passion is still as strong today.

Raised by circus performers in Cairo, Torquil Arbuthnot learned card sharping and knive throwing as a child, skills that got him a place at Balliol College, Oxford, from where he was expelled for reciting Dada poetry through a megaphone in the Bodlean Library.

Nicole is a self-taught home cook who has been working as a freelance recipe developer and food stylist for the past 10 years. She will be sharing recipes culled from her grandmother’s recipe notebooks. She is also a member of a ladies’ cricket team and is learning to play the double bass. One day she hopes to have a pet ferret which she will call Mrs Washington. @nicolethechap

Email chap@thechap.co.uk

Website www.thechap.co.uk

Twitter @TheChapMag Instagram @TheChapMag Facebook/TheChapMagazine

1 THOU SHALT ALWAYS WEAR TWEED. No other fabric says so defiantly: I am a man of panache, savoir-faire and devil-may-care, and I will not be served Continental lager beer under any circumstances.

2 THOU SHALT NEVER NOT SMOKE. Health and Safety “executives” and jobsworth medical practitioners keep trying to convince us that smoking is bad for the lungs/heart/skin/eyebrows, but we all know that smoking a bent apple billiard full of rich Cavendish tobacco raises one’s general sense of well-being to levels unimaginable by the aforementioned spoilsports.

3 THOU SHALT ALWAYS BE COURTEOUS TO THE LADIES. A gentleman is never truly seated on an omnibus or railway carriage: he is merely keeping the seat warm for when a lady might need it. Those who take offence at being offered a seat are not really Ladies.

4 THOU SHALT NEVER, EVER, WEAR PANTALOONS DE NIMES. When you have progressed beyond fondling girls in the back seats of cinemas, you can stop wearing jeans.

5 THOU SHALT ALWAYS DOFF ONE’S HAT. Alright, so you own a couple of trilbies. Good for you - but it’s hardly going to change the world. Once you start actually lifting them off your head when greeting passers-by, then the revolution will really begin.

6 THOU SHALT NEVER FASTEN THE LOWEST BUTTON ON THY WAISTCOAT. Look, we don’t make the rules, we simply try to keep them going. This one dates back to Edward VII, sufficient reason in itself to observe it.

7 THOU SHALT ALWAYS SPEAK PROPERLY. It’s really quite simple: instead of saying “Yo, wassup?”, say “How do you do?”

8 THOU SHALT NEVER WEAR PLIMSOLLS WHEN NOT DOING SPORT. Nor even when doing sport. Which you shouldn’t be doing anyway. Except cricket.

9 THOU SHALT ALWAYS WORSHIP AT THE TROUSER PRESS. At the end of each day, your trousers should be placed in one of Mr. Corby’s magical contraptions, and by the next morning your creases will be so sharp that they will start a riot on the high street.

10 THOU SHALT CULTIVATE INTERESTING FACIAL HAIR. By interesting we mean moustaches, or beards with a moustache attached.

42 BELFAST DANDY

Paul Stafford takes us on a walking tour of the city he has shocked with his peacockery for several decades

56 STANLEY BIGGS

Sophie Bainbridge announces the thrilling opening of a bricks and mortar store for the vintage-style menswear brand

59 FRENCH ELEGANCE

Jean-Emmanuel Deluxe on how Parisian chic evolved from the Zazous in the 1940s to Vanessa Seward and Bertrand Burgalat in the present

68 PRATT & PRASAD

Gustav Temple reveals the finished suit made for him by off-Savile Row tailor Haddon Pratt

70 GREY FOX COLUMN

David Evans celebrates Shantung ties, collar studs, British watches and introduces his new Masters of Style series

CHAP LIFE

76 THE SECOND GRAND FLANEUR WALK

A photographic chronicle of this sensational saunter without destination

84 JAMES BROOKE

Chris Sullivan on the swashbuckling adventures of the 19th century Rajah of Sarawak

94 HIGHCLERE CASTLE GIN

The superb new gin that connects the Queen, Downton Abbey and the Vintage Egyptologists

100 COOKING FOR CHAPS

Nicole Drysdale celebrates the arrival of summer with six delicious tarts

106 MOTORING

Actuarius pays a visit to the Morgan factory in the Malvern Hills to road test their revived three-wheeler

114 ECO CLASSICS

Keeping a 60-year-old petrol car on the road might be better for the planet than driving a Tesla, argues Actuarius

121 TRAVEL: BORNEO

Chris Sullivan treads gingerly in the footsteps of James Brooke, trying to avoid stepping on monkeys and wild boar

130 AUTHOR INTERVIEW

Ed Needham meets Simon Kuper, author of a new book about the Oxford chums who ended up running the country

136 BOOK REVIEWS

New books about Randolph Churchill, waiters in Paris and eccentric mitteleuropa hotels

140 GET CARTER

Robert Chilcott reviews the re-release of the 1971 cult noir classic starring Michael Caine

148 CRICKET

The Chap’s cricket correspondent on the legendary Gentlemen V Players fixtures

154 CAPTAIN FAWCETT’S A-Z OF EXERCISE

A fitness regime for those who prefer not to set foot in a gymnasium

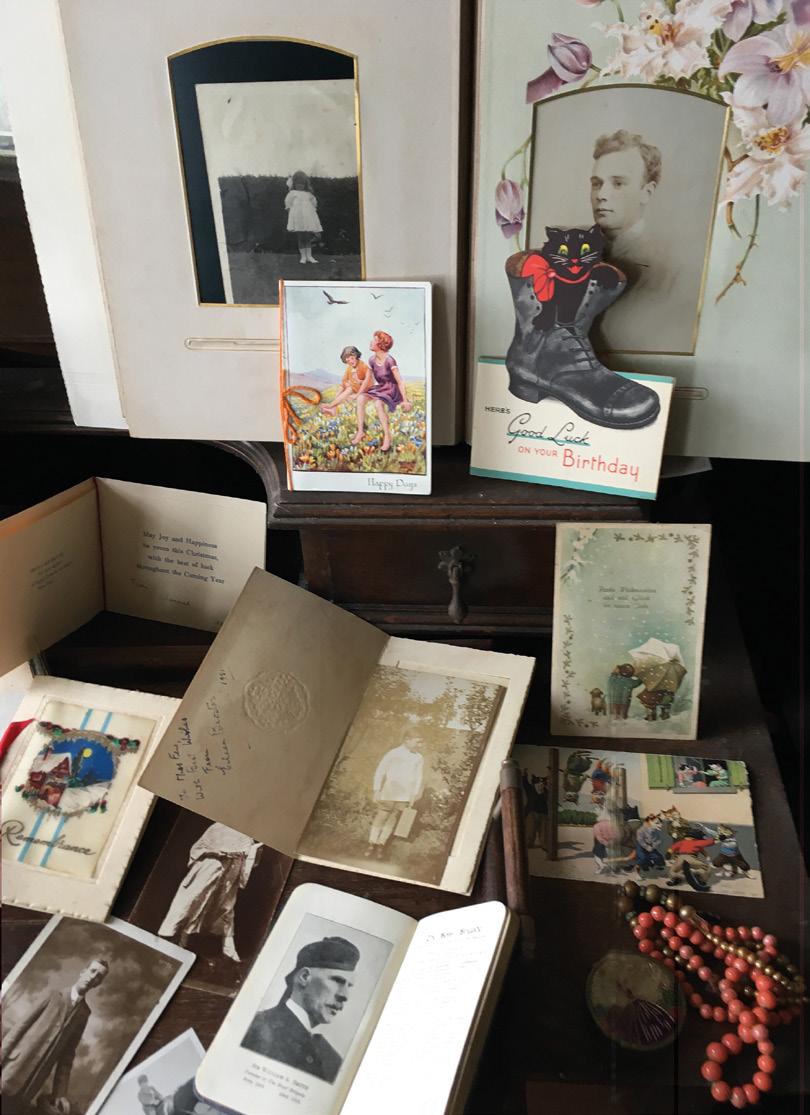

157 ANTIQUES

John Minns visits a perfectly-preserved Edwardian time capsule full of antique treasures

162 CROSSWORD

SEND PHOTOS OF YOURSELF AND OTHER BUDDING CHAPS AND CHAPETTES TO CHAP@THECHAP.CO.UK FOR INCLUSION IN THE NEXT ISSUE

Alexey Ostudin hails from the currently unfashionable country of Russia, but that didn’t stop him out-Chapping all other entrants for the coveted title of Star Chap, with his choice of attire while boarding the Trans-Siberian Express.

“Please peruse this little snapette of myself,” writes Matt Stannard. “I’m wearing my usual attire, all vintage clothes apart from the cords. The tie is of course a Handlebar Club tie and the moustaches are styled with Debonair Moustache wax, the excellent collaboration between The Chap and Captain Fawcett.”

The use of newspaper as a pocket square is highly original, sir, and is very ‘on trend’ with environmental concerns.

Russell and Sara Nash found it too inconvenient to field the constant barrage of questions about their splendid outfits, so they hopped on the Queen Mary to get away from it all. The other passengers observed strict cruise liner etiquette of never mentioning any Agatha Christie novel set on a ship.

“I had to send you a postcard photo from my renewed wanderings after a two-year pause,” writes Simon ‘What’s wrong with denim?’ Doughty. “I was accosted by a vintage gendarme in the antique market of old town Nice.”

If the dummy could speak, he would be echoing our own sentiments, sir; to wit, “I see you are hatless today, monsieur?”

“Although duelling is long forbidden,” writes Max Knoth, “some unsavoury elements still challenge you on the open streets, accompanied by their gutless henchmen.”

Sir, the pen may be mightier than the sword, but the umbrella is clearly mightier than the Strawberry flavoured Mr. Freeze Ice Pop.

Among this group of ladies is one decent tweed outfit. If only they could agree upon whose turn it is to wear it today.

“My name is Shehla Choudhry and I would like to share some pictures of my boyfriend Neil. Since the first time I met Neil, I have always been impressed with his great sense of dressing and they way he carries himself. However, he strongly disagrees with me on this subject, so he challenged me to contact you and send his photos to see if you feel the same as me. Of course I’m keeping this a surprise until I get a response back.”

Madam, I think we are with Neil on this one.

Whereas this couple both have some sort of sartorial dyslexia, which causes them to put on some of the right clothes, but in the wrong order. The so-called Tweed Run has a lot to answer for, it seems.

IN RESPONSE TO A FEATURE ABOUT THE IMPORTANCE OF PAYING AS MUCH ATTENTION TO ONE’S PORTMANTEAU AS TO ONE’S CLOTHING, WE ASKED READERS TO SEND US PHOTOS OF THEIR FAVOURED CARRYING VESSEL. WITH ONE EXCEPTION (WILLIAM WALKER, PROBABLY A SPY), THE ASTOUNDING CONCLUSION IS THAT EACH OF THEM IS USING MORE OR LESS THE SAME CASE.

Jason Frost uses a charmingly weathered leather satchel to carry around his large collection of ultra-violent video games.

Sturdy, brown, handsome, patriotic: the Julio Iglesias of leather portmanteaux favoured by Grant Jukes

Mr. Walker’s valise is of a more modest girth, but nevertheless is equipped with a sturdy metal bar, presumably because the contents are protected by the Official Secrets Act.

This unnamed correspondent’s portmanteau is designed for a much heavier load, and comes with an additional shoulder strap for the extra weight, undoubtedly of a literary nature.

Not to be left out, Alexey Ostudin carries a slim leather briefcase during an assignment to investigate Lord knows what nefarious activity in the Urals.

Torquil Arbuthnot, having retired from the secret service, spills the beans on how he was originally recruited and trained as a spy

Although this manuscript has been cleared by MI5, MI6 and GCHQ, they have insisted that certain words are redacted for reasons of national security, and to keep the KGB guessing. was first approached to be a spy by the usual method, the ‘tap on the shoulder’. My tutor at Oxbridge suggested I might like to dine with the Master of [redacted] College, as there was some frightfully good egg from the Foreign Office he thought I might it find amusing to meet. I duly toddled along and was seated next to Colonel [redacted], a lean, scarred man with a pronounced limp who proceeded to quiz me on my views on the

“The more louche and unhinged recruits went to Flashman’s, where they were let loose on the dressing-up box. Their training included how to ride a camel, opium smoking, sword fighting and escaping without one’s trousers”

Matabeleland question, whether I could field-strip a Webley Mk 5 revolver blindfolded and how long it took me to do The Times crossword. He must have liked what he saw and heard because, the next month, I was asked to lunch at the Travellers’, and by the time the port and stilton arrived I’d agreed to be trained as a secret agent.

I was given a railway chitty and duly travelled down to a large manor house in secluded grounds just outside Chipping [redacted]. The first week was spent being interviewed by a variety of experts to determine one’s aptitude and talents (or lack thereof). One’s level of sanity was also assessed by the resident psychiatrist. “In some situations,” the trick-cyclist explained, in between swatting at imaginary flies, “the barmier you are, the better.” I was asked what foreign languages I spoke and admitted to fluency in French and German (due to my time at the Sorbonne and Heidelberg), passable Spanish (from matador school) and a smattering of various Nilo-Saharan dialects (my gap year as a Barbary pirate). My interviewer looked a bit askance

at this, explaining that speaking foreign languages was often accompanied by other disagreeable proclivities. “All very well being glib in frou-frou languages like French if you’re a dancing instructor.”

After the initial interviews and tests, we were assigned our training. Rather like at prep school, we were allocated boarding houses based on our evaluations. For example, those grammar school types with a chip on their shoulder were sent to Deighton’s, while those who had a C-grade or above in O-level Maths went to Bletchley’s. The training differed between houses. Those in Le Carré’s were taught to speak in elliptical sentences and encouraged to use baffling vocabulary, so that even a pencil was known as a ‘bowstring’ and a bus ticket was a ‘nightingale’. They were intensively trained to be barely-functioning alcoholics.

Deighton types would spend much of their training being taught how to submit expenses claims in triplicate, how to cheek their betters and being sent on Cordon Bleu cookery courses. They received a clothing allowance for off-the-peg suits and

beige raincoats. (Once the beige raincoats become threadbare they are handed down to the spies in Le Carré’s.) The more louche and unhinged recruits went to Flashman’s, where they were let loose on the dressing-up box. Their training included how to ride a camel, opium smoking, sword fighting and escaping without one’s trousers. They would also spend many months at the School of Oriental and African Studies, learning exotic languages and picking up exotic diseases.

I was allocated to Fleming’s, where my first exercise was to memorise the 1930 edition of The Savoy Cocktail Book. I was then sent on placement to a French casino to master the roulette wheel, and spent some time with a card-sharp in Las Vegas, learning the tricks of the trade. We were sent on exercises; attaching a limpet mine to the Woolwich ferry, for example, or stealing the hubcaps from the Russian Ambassador’s car.

We all received general lectures on the threats facing Britain, both internal and external: the Russian Bear, North Korea, Johnny Afghan,

alumni of the London School of Economics and megalomaniacs with their own private store of nuclear bombs. We were informed that MI5 no longer infiltrates left-wing groups, since these are comprised of undercover policemen looking for girlfriends. Finally it was drummed into us fledgling spies that, although the Boche are never to be trusted, the real enemy is always the French.

On successfully completing spy probation we were given a badge, a cyanide pill, a box of false moustaches, a bottle of invisible ink, a set of monogrammed [redacted] and an account at Majestic Wine. On my last day at ‘spy school’ I asked the HR-wallah about job security. He said it was hard to guarantee, as I might end up riddled with machine-gun bullets while shinning over the Berlin Wall, or my parachute might fail over the Gobi Desert. But if I made it through unscathed then I would, at the end of my years of loyal service to my grateful country, be able to retire with an OBE and a decent pension, or the Order of Lenin and a dacha outside Moscow. n

By Wisbeach

An advice column in which readers are invited to pose pertinent questions on sartorial and etiquette matters, and even those of a romantic nature. Send your questions to wisbeach@thechap.co.uk

Barrington Gardner: I have recently been given a set of gold cufflinks. Should they be considered too ostentatious and discreetly put aside? If not, is it acceptable to wear these with day wear or should they be reserved for formal dress occasions? Your guidance would be much appreciated.

Wisbeach: Sir, it depends entirely on the style of cufflink. If they are anything like those pictured left,

then you may wear them day or night, formal or informal; if they are more like those pictured right, then you should lock them in a drawer and never speak of them again.

Montague ‘Chaps’ Gristle: I have been invited to the Royal Garden Party at Buckingham Palace next June. In the event of Her Majesty passing a witticism about my choice of tie, should I snicker, snigger, or titter?

Wisbeach: At time of writing, sir, Her Majesty has taken a temporary respite from activities that require excessive mobility, and in her stead will be HRH The Prince of Wales. He is unlikely to pass any witticisms about your tie, although if he does, you might wish to retort with a suitable

quote from Sir Pelham Grenville Wodehouse such as “Red hair, sir, in my opinion, is dangerous.” That should silence him.

...

Alan Peters: I was speaking to a Chap today and he mentioned an item of clothing called a ‘manthorpe’. He said that they are all the rage in the city. Have you heard of them and can you advise of a gentleman’s outfitters who may stock them?

Wisbeach: I can find no record of this singular item in the Cordings catalogue, sir, which leads me to believe that your chap in the city was attempting to hoodwink you. City boys tend towards this ribald type of humour, sir, and there may be huge guffaws emanating from hostelries around Broadgate at the notion of your making enquiries in gentlemen’s clothing emporia. I hope that my reply has at least saved you this ignominy.

Montague ‘Chaps’ Gristle: My 14-year-old nephew, Pelham is showing thespian tendencies. He is spending his pocket money on DVDs featuring the actor Benedict Cummerbund. Pelham insists that I have got the name wrong and it is ‘Cumberbatch’, not ‘Cummerbund’. I have looked in my dictionaries and encyclopedias for any entry on ‘Cumberbatch’ and found none. I have, of course found entries for ‘Cummerbund’, which I think conclusively settles the argument. Pelham will have none of it and has invited Mr. C to dinner, to settle our dispute.

Mr. C’s RSVP read ‘Delighted to attend dinner, although please note that, a) I am allergic to potted shrimps, and b) I am currently filming Lady of the Lamp and am in character as Florence Nightingale. For verisimilitude please can dinner table topics be restricted to nursing practices in Victorian Britain and my place as a feminist icon, rather than the etymology of my name’.

Should I suggest to Pelham that the dinner invitation be postponed until the film is in post production, or talk blood and bandages over the crème brulee?

Wisbeach: Sir, I think you should invite Mr. Cumberbatch to afternoon tea instead, as I hear he is rather partial to a scone, which will also lead to a debate on pronunciation and provenance of said baked items that should take up the entire afternoon. ...

Montague ‘Chaps’ Gristle: My lady ‘who does’ wishes to retire. Mrs Quince has been doing for me for the past 20 years, but now feels that at the age of 90 she has flicked her last duster. I feel some sort of gift is in order to thank her for her help in cleaning my dusty passages. Would a £5 book token be too generous?

Wisbeach: I believe a gift of such magnitude would only confuse dear Mrs Quince, and she may come to the conclusion that you are in love with her. A more suitable gift, to aid her comfort after retirement, would be a Reduc-O-Matic Portable Steam Bath (above). You can present this gift with a comment about it being her turn to be pampered. n

Gustav Temple meets the former Formula 1 world champion racing driver, to discuss his late father Graham Hill, playboy racers, handlebar moustaches, The Beatles, rivalry between racing drivers and enlightenment behind the wheel

You sent me a wonderful clip of your father Graham Hill from 1964, where he’s discussing gear ratios before a race at Brands Hatch, dressed in a sharp suit. I thought that would appeal to you! I always thought my dad was a cross between Leslie Philips, David Niven and Terry-Thomas.

Well that’s TheChap summed up in three people, actually. I’ve never seen so much Brylcreem on one man’s head! He did have an amazing head of hair. There was this German cosmetics company who wanted to do a male range, and they called it Graham Hill. He definitely fitted that impeccable Savile Row look.

Perhaps more so than others. He’s wearing a mohair suit in that clip, with cufflinks and a

“Being dastardly and just winning at all costs, that doesn’t sit comfortably with me, and I don’t think it did with my dad. He drummed into me when I was growing up that cheating is only cheating yourself”

pocket square, for a quick meeting with his –what do you call that chap he’s talking to?

That’s Tony Rudd, head of engineering at BRM (Formula 1 team British Racing Motors) and he went on to Lotus, but during the War he’d designed

air intakes for Spitfires, stuff like that. He and my dad worked together very closely. That’s how my father became the first British racer to drive an entirely British-made car and go on to become world champion in 1962 – sixty years ago this year.

So would you have had a similar meeting to that one in the clip with your engineer, or was that something of the past? They only seem to have a couple of bits of paper and a pen in front of them.

Sort of, yes, but in those days they had so much less data to go on. They’d get the feedback from the engine people and they’d say things like, ‘the power band is here, you need to be in these revs for that part of the circuit’, then they’d use their empirical understanding of these things to come up with a tactic. What’s most interesting is that they’re getting feedback from the driver. Now that all comes from computers and sensors in the car and the engineers

work it out, then they tell the driver that this is what the data says. Whereas in those days, the data was the driver. In that clip, they were preparing for a race at Brand’s Hatch.

And at Brand’s Hatch there’s a Graham Hill Bend now, isn’t there?

There is now, but back then it was called ‘Bottom Bend’! My dad would have been delighted that he got the bottom!

You wrote that your father grew what he described as ‘an RAF fighter pilot moustache’ when he was in the Navy, knowing full well that they didn’t approve of moustaches.

Yes, there is a photo him from much earlier than the clip we spoke about, from after he left the Navy, in a sheepskin coat with a great big handlebar moustache. He’d come out of the Navy but he had

to keep going back for refresher courses every six months, and he knew it would wind up the officers.

It was a very subtle snub, because only people in the services would know that the Navy don’t approve of moustaches and that they only belong in the RAF. You compared Hill Sr. to Terry-Thomas in School for Scoundrels. Was there overall something of the bounder in your father, which perhaps

helped him gain a reputation as a bit of a playboy racer?

I think there was, yes. In those days words like ‘sauciness’ were more acceptable, in other words you could refer to the fairer sex in a way that might not be approved of today. He was definitely a funloving person, which offset the very serious job he was doing. I honestly think that the Navy taught him how to drink! In his own autobiography, he says that because he was a petty officer, he got double

the amount of rum that the ratings got. And so every day he’d get smashed on this quart of rum he was given. So the Navy left its mark on him. He wasn’t a huge drinker but he liked to party. If that race in the clip was the British Grand Prix at Brands Hatch, which it may well have been, on the Saturday night after the race they’d all go back to his cottage for a massive party.

He was friends with people like Prince Rainier and Princess Grace of Monaco, and he would often

“I think that John Lennon got to a point where he rejected what was on offer, which was just to carry on being a Beatle. He seemed to be saying, there’s got to be more to life than that. To step back and see if he could work it out before his next move, that’s more or less what I did when I finished with my racing career”

be invited to come and sup champagne with them. He went on to win the Monaco Grand Prix 50 per cent of the time in the 60s, five times from 62-69.

When you embarked on your own career in motor racing in the late eighties, was the age of the playboy racing driver long gone?

James Hunt was probably the last of the big playboy racers, then you had Nelson Piquet, Alan Jones, Keke Rosberg, but they were petering out by the time I got there. People like Ayrton Senna were very serious, while Nigel Mansell is a teetotaller, I think. Eddie Irvine liked to party and David Coulthard has a similar reputation. But it was done in a different way, in the sense that there wasn’t the media problem that they have now. You could go to a bar with a journalist and it would all be off the record.

From your anecdotes of team ribaldry on the racetrack and in the pits, one gets the impression that your rivals displayed much more aggressive macho swagger than you did. Were you ever described as a ‘gentleman racer’ and would you have been happy with this sobriquet?

Yes, I used to hear that ‘nice guys don’t win’ thing a lot, and I just thought, I don’t believe that. I don’t believe it isn’t possible to be successful and be sporting. Being dastardly and just winning at all costs, that doesn’t sit comfortably with me, and I don’t think it did with my dad. He drummed into

me when I was growing up that cheating is only cheating yourself; if you don’t like something, you don’t go bleating to all and sundry about what isn’t fair. Although he was fun and did all those wacky things every now and then to ham it up a bit, underneath it all he was a grown-up. And he had a lot of respect for the other drivers. They all appreciated the other drivers’ skills.

It’s come back a bit to that today and they get on much better. But when I was racing at the tail end of the eighties, it was bitter. The Mansell era, and the Rosberg and Arnoux eras, and Didier Peroni – they all hated each other! My dad would not have liked that at all.

There always seems to have to be a duel between two drivers in Formula 1. Lauda/ Hunt, Senna/Prost etc. They all have one man to battle against. Yours was Michael Schumacher, wasn’t it?

In our sport, two into one doesn’t go; you can’t have two people win a race. It invariably comes down to

two of them, and only one of those can win it. The focus of each competition becomes almost like a boxing match. The press want to build it up, and they will take something that you said and they’ll keep asking about the other guy. Sooner or later something comes out that sounds a little bit challenging and you end up with these rivalries, blown out of all proportion. There’s not really anything you can do about it. I made the mistake of playing up to it a few times, and it nearly always bit me back.

There was a point during the Prost/Senna rivalry where Senna wouldn’t even use Prost’s name; he would just refer to him as ‘him’. And before that they’d been the best of friends. On the few occasions when people felt that my dad had been robbed because of some dastardly driving, he never rose to that sort of behaviour. He just wasn’t the kind of person to complain at all.

The term ‘sportsmanlike’ used to have a gentlemanly connotation towards your fellow competitors.

I think that now it means something else. There are a lot more challenging things in life than being beaten in a motor race. You’re lucky to be in the race in the first place.

Given the unusual circumstances of your career, after losing your father in an aeroplane crash when you were aged only 15, do you wonder whether things may have turned out very differently if he hadn’t died, and whether you would have become a racing driver at all?

I think that’s definitely possible, the idea of pushing it to him. First of all, I don’t know if I’d have had the courage to tell him I wanted to go and race motorbikes, because I think I would have known the answer. I’d have to have wanted to do it really badly in order to convince him. My dad had enough support from his parents in what he wanted to do, but a lot of drivers didn’t. There was a guy called Dick Seaman who was told in no uncertain terms that he wouldn’t be going racing, but he went anyway. Sadly he was killed.

Then there were people like Jackie Stewart, whose mum said to him that if he went racing she would never speak to him again, so he raced under a pseudonym. James Hunt and Niki Lauda’s fathers both fought against them becoming racing drivers. So racing against the will of their parents set off quite a strong tension there. When my father was once asked, when I was a young boy, if he’d like me to become a racing driver, he replied that he thought I was too intelligent. So I rather let him down!

Many of the references in your 2016 autobiography Watching the Wheels are not those one would expect from a racing driver. You quote Shakespeare and Greek tragedians, among others. You took a degree in English literature after retiring from racing? Well, I hadn’t gone to university because I was racing. My kids were growing up and I thought, I can’t really expect them to knuckle down and do all the hard work of a degree if I haven’t done it myself, plus I was curious to see what it involved. And I liked the subject; I liked what I was learning. And then of course I got competitive about it and

had to get the best score I could! I got a first, but I’ve no idea how; maybe a bit of compliance on my part. Had I written what I really wanted to write I might not have got a first.

Did you see a parallel during those ten years after you retired, when you hardly left the house, and John Lennon’s years in New York when his second son was born? You chose the title of your book from a song he wrote about that period, Watching the Wheels. Philosophically, the Beatles had such a huge influence on culture and generations, the message was very strongly towards how we can live more peacefully and be nicer towards each other, and I think that John Lennon got to a point where he rejected what was on offer, which was just to carry on being a Beatle. He seemed to be saying, there’s got to be more to life than that. To step back and see if he could work it out before his next move, that’s more or less what I did when I finished with my racing career. I had an opportunity which not many people get in their life, which is to have a bit of money in the bank and a bit of time to think about things and decide what to do next. I think there’s too much emphasis on keeping busy just for the sake of keeping busy. Or trying to stay in the limelight in case people forget you. That didn’t make sense to me. Otherwise you’re just chasing some shadow of yourself. I certainly was asking myself the question, what might I have done had I not become a racing driver?

And did you find the answer? No, I didn’t!

You describe an out-of-body experience during the Japanese Grand Prix in 1996 at Suzuka, in the Williams-Renault FW18 that led to you beating Michael Schumacher, where you had a feeling of being physically removed from the action yet completely focused on the task. Do you think that feeling can be achieved by any other means than while driving a car at 200 miles an hour? You hear it quite a lot when people are in extremely stressful situations; there’s a point where they become

detached from what’s going on around them. I’m sure it’s some sort of survival mechanism in us. We’re so often prevented from fulfilling ourselves because we think about it too much, whereas if you remove the thinking and replace it with just the will to either win the race, or get the hell out of there, or whatever, then what we call consciousness becomes irrelevant. There is no longer any need to rationalise anything; your inner instincts are quite capable of doing better without you.

It sounds like the sort of thing that would help you if you were in a Buddhist monastery at the top of a mountain, but when you’re driving in a Formula 1 race, don’t you need your consciousness more than ever?

I remember thinking to myself, I’ve tried my best, and I made this little appeal for what you might call ‘outside assistance’, and at that point there’s a kind of letting go, which is what a Buddhist monk might try and teach you. By holding on to things, you are interfering with the natural process. You’re holding on to some concept of yourself, and maybe there isn’t actually a self. What if you were just to be?

I’m sure a neuroscientist would have a much more plausible explanation. It would be easy to become too spiritual about it; I don’t believe that the hand of God came and lifted me along, or something like that. I think it is simply a phenomenon of our consciousness that we can experience these states, and they are out of the

ordinary. Which rather suggests that we muddle along in a kind of fog of ordinariness the rest of the time, occupying ourselves with stuff that isn’t really important, but we’re happy enough.

In a book about Eastern philosophy, the writer was saying that most of us get two sunsets in our lives, in other words, only two of those experiences where we feel completely outside of ourselves.

I’d say that’s right, because the other one I had was when I was sitting on a beach with my son, staring into the infinite horizon. Something else happened then, at the opposite end of the spectrum, as I was totally unstressed. The only similarity was that I must have completely let go of the idea of who I am or what I was supposed to be doing. And bingo, this extraordinary feeling. Either that or I’ve got brain damage or something!

But you may not have had that moment with your son, had you not gone through all the ups and downs of your childhood grief and your racing career? Can anyone expect to just go and sit on a mountain, without all the difficulties beforehand, and experience a feeling like that?

Maybe it is one that one begets the other. If you talk to people who’ve had really rough experiences in life, they appreciate a peaceful moment much more than people who’ve had more plain sailing. n

With such a wealth of wonderful actors gracing ours screens and stages, Olivier Woodes-Farquharson plummets to the other end of the spectrum to explore the life and work of Robert Coates – very possibly the worst actor who ever lived

“His dress was like nothing ever worn. In a cloak of sky-blue silk, profusely spangled, red pantaloons, a waistcoat of white muslin surmounted by an enormous cravat, a wig in the style of Charles II capped with a plumed opera hat, he presented one of the most grotesque spectacles ever witnessed upon the stage”

Self-awareness is a gift that some of us could display a bit more. Our politicians, our entertainers, and so many other figures in public life contain among their tribes some who understand the impression that they give off to others with their words and deeds, and, by the same token, many who fundamentally do not. Robert Coates, an actor during the age of the

great dandies two centuries ago, believed himself to be a transcendental genius when pounding the theatrical stages of London, interpreting Shakespeare in a way never before attempted and (thankfully) never replicated since.

But be under no illusions: Genius he was not. He was – and this really cannot be overstated –utterly dreadful.

“Coates’ crest, planted boldly at the front, took the form of a lifesize silver cockerel, wings outstretched, and surrounded by the words ‘While I live, I’ll crow’. If passers-by somehow missed seeing this unique sight, they would surely have heard it, as he was usually to be seen being followed by street urchins screaming Cock a Doodle Doo!”

Yet the origin of this delusion lay not in the West End but in the West Indies, for Coates was

born in 1772 in Antigua to plantation owners who were perhaps never fully aware either of Coates’ suffocating devotion to the theatre, or of his stultifying take on the art form of acting. He had popped over to England as a teenager, developed a taste – if not an aptitude – for acting, and bided his time until his father dutifully passed away, passing on his estate and a huge £40,000 inheritance to his only surviving child. Coates hotfooted it straight back to England in 1808, armed with plenty of cash, a determination to make it as an actor and a unique taste in clothing.

These assets together made Coates glaringly stand out. He explored the London scene first, but was then quickly drawn to the handsome town of Bath, still a hub of fashion long after the glory days of uber-dandy Beau Nash. Breakfasting and lunching daily at George Street’s chic York House, he inevitably stumbled across theatre manager William Dimond and offered his services to play his favourite character, Romeo, at the Theatre Royal. An unsure Dimond saw a huge risk but also a man of considerable wealth who was basically offering to

bribe him to stage the play. Thus, in February 1809, Bath was privy to one of the most memorable performances ever of Romeo and Juliet, albeit for terrible reasons.

Coates’ Romeo – the actor’s favourite character – was nearly three times older than the 16-year-old that Shakespeare envisaged. But even putting aside this inconvenience, it was his attire that first forced jaws to drop. A member of the audience wrote the following day: ‘His dress was like nothing ever worn. In a cloak of sky-blue silk, profusely spangled, red pantaloons, a waistcoat of white muslin surmounted by an enormous cravat, a wig in the style of Charles II, capped with a plumed opera hat, he presented one of the most grotesque spectacles ever witnessed upon the stage.’ Speckled liberally throughout this monstrosity of an outfit were Coates’ favourite jewels: Diamonds. For good measure, the whole outfit was a size too small, perhaps to highlight its wearer’s masculinity in a Regency take of deliberate male ‘cameltoe’. This was a mistake. Deep into one speech, Coates bent over, bursting the seams of his breeches, displaying

to all a “quantity of white linen sufficient to make a Bourbon flag.” Unlike Coates’ breeches, the audience was in stitches, not least as Coates himself remained oblivious throughout.

But Robert was only getting started. He loved Shakespeare, but to him the great playwright’s actual words were merely an indication of feeling rather than something to be recited verbatim. He often forgot his lines but cared little, for he preferred to improvise. On more than one occasion in rehearsals he was heard to misquote his lines, only to retort, on this being pointed out, “Aye, that is the reading I know . . . but I think I have improved upon it.” During the famed balcony scene, Coates thought nothing of pausing proceedings to get out his snuffbox and take a hearty pinch, even offering it to some of the more nonplussed members of the audience.

Mistaking the crowd’s roaring laughter for the desire for an encore, he proceeded to act out the entire death scene twice again. As baffled theatregoers started heckling ‘Why don’t you just die?’, his long-suffering Juliet miraculously came

back to life and hustled him off the stage, as Dimond quickly brought down the curtain. At that moment, Coates – never a man to be kept awake at night weighed down by the burden of self-doubt –was heard to utter ‘Haven’t I done it well?’

The gossip around Bath went into overdrive,

“To confirm both Coates’ high profile and his utter lack of selfconsciousness, several pastiches of his legendary performances were now being performed across London – although Coates viewed them more as flattering homages”

for here was an actor who simply demanded to be seen, and whose accidental talents dwarfed those of the true comedians. He performed several more times in Bath to bulging crowds, before touring across England, including Brighton and Stratfordupon-Avon. His deep pockets satisfied not just the theatre managers but also his fellow actors, all of whom he had to pay handsomely to share a stage with him. Ever confident, Coates felt by 1811 that he was ready to grace the London stage with his stupefying talents. But was London ready for him? Perhaps his Caribbean upbringing had made him sensitive to the cold, as he pranced about the city always wearing thick luxurious furs, even in midsummer, forever drenched in his beloved diamonds.

And while others used more standard modes of transport, unsurprisingly Coates chose a different path. He made his way around the city in a small carriage known as a curricle, and there

“The comics of the day, perhaps in one of their darker moments, believed he would have secretly enjoyed such a dramatic and drawn-out death scene. Sadly, he would perform it only once”

was never any mistaking it for someone else’s. With a luxurious seat in the shape of a scallop shell, the carriage was bright vermillion, with the wheel spokes painted the colours of the rainbow, drawn by two white horses. With such splendour, thought Coates, it was only right that he should magic up a heraldic symbol and motto. His crest, planted boldly at the front, took the form of a life-size silver cockerel, wings outstretched, and surrounded by the words ‘While I live, I’ll crow’. If passers-by somehow missed seeing this unique sight, they would surely have heard it, as he was usually to be seen being followed by street urchins screaming ‘Cock a Doodle Doo!’

Yet this didn’t seem to put the ladies off, for Coates was meticulously polite, and his stand-out swarthy complexion seemed popular with ladies of higher breeding, who calculated – rightly – that there was absolutely no chance that they would be missed as he squired them through Hyde Park. Coates was a hit, too, with many of the dandies of the day, who all enjoyed his company, including the fabulously named Scrope Davies and Lumley Skeffington.

Later that year, Coates was itching to perform Romeo again, and the Theatre Royal in Richmond acceded, hoping perhaps that his ghastly attempts at acting would be more than outweighed by fat revenues coming from full houses of punters seeking a jolly good laugh. For some it was too funny, and several theatregoers laughed themselves so ill that they had to be escorted outside and treated by a doctor.

Nevertheless, this ‘success’ allowed the prestigious Haymarket Theatre to open up the possibility, in December 1811, of Coates playing his second favourite character: Lothario in Nicholas Rowe’s The Fair Penitent. To distinguish him from his incomparable Romeo, Coates chose to wear white satin breeches peppered with diamonds, a bright

red waistcoat and cloak, and a patently absurd hat almost resembling a sombrero, again with the obligatory ostrich feathers belching out of it. He truly believed himself to be God’s gift to greasepaint.

Over 1000 people were turned away on the first night, with the black market charging an enormous £5 a ticket for the honour and pleasure of seeing this terrifically appalling actor delude himself on stage – the Prince Regent himself being one of them. But the crowds loved it and the newspapers gleefully reported it. The Haymarket invited him back a few weeks later to play his beloved Romeo, which he proudly accepted, ensuring this time that, while his costume would be a size bigger, he would make up for it by lacing it with even more diamonds. Too many, perhaps, for on one night, as a scene ended with Coates needing to exit stage right, he instead got onto his knees and shuffled energetically around the stage like a bloodhound, for he had lost a diamond shoe buckle. Once the buckle was eventually found, a composed Coates turned to his guffawing audience to deliver his final line which was – and you couldn’t make it up – ‘O let me hence. I stand on sudden haste’.

To confirm both Coates’ high profile and his utter lack of self-consciousness, several pastiches of his legendary performances were now being performed across London – although Coates viewed them more as flattering homages. He attended one of these, with comic actor Charles Matthews playing ‘Romeo Rantall’, and the audience roared at all the right cues, including the farcical clothing, the meticulous preparation for the death scene and the ostentatious display of diamond shoe buckles, even when playing dead. When Matthews spotted Coates in the audience, he invited him on stage for a warm handshake, Coates enjoying it thoroughly, oblivious to the fact that the joke was squarely on him.

Although he carried on playing his two favourite characters, by 1815 audiences were gradually wearying of his dreadfulness, and theatre managers had to hire policemen at some performances to keep order. By the following year, they gave up supporting him altogether; Coates’ shooting-star acting career was effectively over. This downturn on the stage was mirrored by difficult circumstances at his Antigua plantation which, when coupled with his gentlemanly generosity of giving or lending money to all and sundry, left him on hard times. He moved to Boulogne in northern France to regroup his

finances, along the way meeting the charming and fragrant Emma Anne Robinson, daughter of a British Naval officer. They returned to London in 1823, married and settled, this time with Coates, still a hugely popular member of society, attending many plays from the stalls rather than on the stage.

It was on one such occasion that tragedy truck. On 15th February 1848, the 76-year old Coates left Drury Lane Theatre, needing to retrieve his opera glasses in his curricle. A hansom cab came carelessly round the corner and crushed him between the two carriages. Six agonising days later he finally expired at his home in Montague Square. The comics of the day, perhaps in one of their darker moments, believed he would have secretly enjoyed such a dramatic and drawn out death scene. Sadly, he would perform it only once. n

Readers who browse the fields of Instagram may be familiar with Paul Stafford, who regularly posts images of his vast wardrobe while roaming the streets of Belfast. We asked Paul what it’s like being the dandiest cat in the city

@paulstafford1

PHOTOGRAPHS BY LEE MITCHELL WWW.LEEMITCHELLPHOTOGRAPHY.COM

@LEEMITCHELLPHOTOGRAPHY

“I didn’t want to just ponce around in a beautifully cut Mark Powell suit, I wanted to use the city as a backdrop to who am and what these areas or people are to me. I try to convey the underlying stories of what Belfast was, its great inventors, architects, poets and writers, but also its rebels, villains and victims”

Are you Belfast born and bred?

I was born and bred in Belfast, growing up on the Falls Road in the west of the city. Carnaby Street it was not, but in spite of the ongoing political and social issues, the area – and in fact the city – was rich with music and fashion, and I’m led to believe that there was a smattering of Bowie clones and glam rockers hiding behind barricades. But it was Punk that really set the city alight; okay, maybe a bad analogy when talking about Belfast, but in this case appropriate.

The famous line attributed to Terry Hooley, the Belfast godfather of punk, is ‘New York had the haircuts, London had the trousers but Belfast had the reason’. My parents moved to the south of Ireland in the late 70s, just as the mod revival and then two-tone were kicking off, and when I returned to Belfast at weekends all my friends had suddenly become fully fledged mods and rude boys. Living in a small border town, I felt like I’d missed out on this really exciting movement, so I set about reinventing my own image, first by copying the dress sense of my friends but gradually

being more drawn to the emerging new romantic scene.

When did your interest in vintage clothes and style begin?

Weirdly my first encounter with vintage clothes or style was through my mum’s family. Her brothers arrived back to Derry from London in the mid 1950s dressed head to toe in teddy boy drapes, brothel creepers, bootlace ties and drainpipes, and of course the ubiquitous DA Haircuts. By the time of the rock ‘n’ roll revival of the 1970s, my uncles still had that look and started to travel to the festivals to see their 50s heroes. I remember the dandy aspect of it all and, combined with a love for Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly and Little Richard, I was completely invested in the look and style of the Teddy Boy movement, inheriting some items from my uncles, as well as having a drape coat tailored for my 12th birthday.

“Belfast is a tough city; you need to be thick skinned, resilient and driven to make a success of your life here, and there are the wounds and battle scars, as well as the fresh shoots of hope that make the city the juxtaposition it really is”

Does Belfast boast many emporia of gentlemanly raiment, whether new or vintage?

The mecca of menswear in Belfast is undoubtedly The Bureau. As you can imagine by the name, it takes its roots from a modernist background and has been at the forefront of menswear in Ireland for over three decades. Their styling has moved considerably over the years from its original focus towards a more Japanese workwear and utilitarian streetwear look, but still has that modernist Ivy League sensibility. My go-to tailor in Belfast is Patricia Grogan at The Cut, a trained tailor with

impeccable taste and a great idea for detail. Her signature styles are modern takes on Great Gatsby 1920s three-piece suits, with beautiful features and luxury cloths at about a third of the cost of a Savile Row suit.

What proportion of your clothing do you have to look further afield than the UK for?

Recently I’ve started to buy more things from Japan, because the quality, cost and fit are better overall. I love Dry Bones, and I’ve found Kazuki Kodaka at Adjustable Costume very reliable at getting things to you quickly. Claudio at DNA is another reliable source of great value and new ideas, and has a brilliant eye for detail; Lorenzo at Capirari is another who always surprises me by the quality he can provide at very affordable prices.

What is your favourite spot in Belfast for a well-dressed passegiatta?

My instagram account is more of a diary than a platform for dressing up; a record of my love affair with Belfast. It’s a very one-sided relationship in some ways. Belfast is a tough city, you need to be thick skinned, resilient and driven to make a success of your life here, and there are the wounds and battle scars, as well as the fresh shoots of hope that make the city the juxtaposition it really is. When we shoot the City Streets series, I didn’t want to just ponce around in a beautifully cut Mark Powell suit (though I certainly do that regularly); I wanted to use the city as a backdrop to who I am and what these areas or people are to me. I try to convey the different aspects of the city that make it truly unique, or the things that people wouldn’t expect, the underlying stories of what Belfast was; its great inventors, architects, poets and writers, but also its rebels, villains and victims. There are ugly scorched waste grounds where there was once industry and people, and there are soulless grey concrete boxes where there was once breathtaking architecture. But then there is that Belfast attitude that it will all be okay in the end.

What is the general reaction from the good people of Belfast to you in your vast array of fabulous outfits?

I suppose dressing up is the same for everyone: if you wear a pair of spectator shoes or a hat you are sort of asking for trouble, especially if you are just wandering around Tesco at 10 am. By and large, people are pretty complimentary, but then Belfast is small and I know most people, as we’ve been in the hair industry for nearly 40 years. Of course I often get the Peaky Blinders comments, or ‘is the circus in town’ from the lads outside the pub, but it isn’t as bad as the 1980s, when you’d get chased by a bunch of skinheads or football thugs for wearing a bit of eyeliner. The weirdest moment recently was a bunch of goth kids sitting outside the city hall, with the usual green hair, black lips and piercings, sitting exactly where we used to sit many years ago as young mods or rockabillies. I suddenly heard one of them say “Weirdo!” out loud to me! You never lose it!

“My favourite city in the world is New York, undoubtedly; the energy, the streets, the history and of course the New Yorkers, I love them! From the very first moment I set foot in Manhattan I knew it was my spiritual home. I hung around outside the Chelsea Hotel and snuck in when the desk clerk was away, and we ran around the corridors trying to get to the upstairs garden or Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe’s old room”

Which is your most treasured city outside of Belfast, for general sauntering, style and shopping for clothes?

My favourite city in the world is New York,

undoubtedly; the energy, the streets, the history and of course the New Yorkers, I love them! From the very first moment I set foot in Manhattan I knew it was my spiritual home. I hung around outside the Chelsea Hotel and snuck in when the desk clerk was away, and we ran around the corridors trying to find Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe’s old room. I went to CBGBS when it was still a dive bar before it became an All Saints for would-be rock stars, and I walked the Brooklyn bridge the night I got married and thought we would never leave. We did, but returned many, many times and it never disappoints.

Which is the city in the world with the largest quantity of stylish men, in your view? London is the best-dressed city in the world. The street culture, the music, that English eccentric aesthetic, the multicultural influence and of course just far too many cool people doing wonderful things. My trips to London always include a visit to the king of Soho, Mark Powell, an original if ever there was one. I also love to have a mooch around Hunky Dory, Levinsons and Blackout Vintage. I love Thomas Farthing – vintage styling that does not look like costume, and a visit to Lock & Co in St James’s is always dangerous.

Who are the historical personages who have most inspired you sartorially?

My first real style hero was Elvis Presley. That period of 1954-1962 was without a doubt his most sartorially influential period, though his 1960s wardrobe was not without its merits; even as he veered towards the 1970s full-blown Vegas look, his off-stage gear was still pretty cool. Then Bowie’s Young Americans period, almost kitsch but so ahead of its time: glam 1950s-inspired suiting or sports jackets with wide open-collared shirts and balloon pegs, and then that haircut: prototype wedge, blow-dried to perfection and almost breathing… it lives! Then of course there are Cary Grant, Montgomery Clift and Errol Flynn, stylish men all but effortlessly cool. Kevin Rowland is a true stylist, who is not only cool but also truly fearless, as was Ian Dury, whose pre-punk pub rocker look inspired so many. True Dandies one and all! n

Sophie Bainbridge showcases the brand-new Stanley Biggs store, housed in what was once also a clothiers and outfitters 90 years ago

You may already know of Stanley Biggs, which has been creating gorgeous garments, style campaigns and gaining momentum since 2019. In fact, if you have recently watched Hugh Laurie’s directorial debut, Why Didn’t They Ask Evans?, you will recognise many items from The Biggs Collection. Stanley Biggs was chosen as the clothier of choice for the hero of the story, played by Will Poulter.

The Stanley Biggs team has breathed new life into a mock-Tudor building in Jacksdale, Notts, exactly 99 years after the shop first opened in 1923. This history, combined with the traditional service you’d expect from an early 20th century outfitters, adds to your overall experience. Be prepared to step back in time the moment you see the shop front.

The shop itself has its own unique history that the brand has showcased. For as far back as many can remember, the building housed the County Library (the Biggs Team even found a document dated 1941 hidden away!). Closing as the library in 2019, the store has been affectionately named

‘The Old Library’ to remember this part of its heritage.Keen to find out as much history as possible, the Biggs Team began scraping away at the stubborn layers of paint that covered the long glass sign; and, after nearly 90 years, the beautiful sign of the original shop was revealed. Confirming the name of the shop owner, one George Hardwick, the sign also confirmed that the shop was originally built as… a Clothiers and Outfitters!

This is a brand in love with history. Every item is named after a pioneer, adventurer or a grand hall, many from their local area. Championing British manufacturing, textiles and designs, Stanley Biggs is the up and coming brand incredibly proud of its Midland roots. Adventurous and dashing tones have been united with timeless designs to create iconic pieces that will stand the test of time. Alongside the authentic ‘Biggs Look’, you can also enjoy the same quality and attention to detail in their contemporary collection of Rugby Shirts, T-Shirts, Sweaters and Hoodies. Stanley Biggs really has something for everyone. n

Jean-Emmanuel Deluxe gallops through seven decades of French elegance, from the Zazous to Vanessa Seward

Not unlike in the UK, the French pop revolution injected new energy and shaped a new paradigm for local youth to emulate. As yéyé pop reinvented anglo-saxon sounds along with swinging London, there was also a ‘swinging Paris’. It had similarities with what was happening in the English capital but also had its uniqueness; a French flavour which still fascinates today, well beyond the Seine and the Channel. A sophisticated style that honours Parisian women and elegant gallic people of all shapes and sizes.

IN THE BEGINNING: THE ZAZOUS

There’s zazous in my neighborhood. I’m already halfway like ‘em. André Jaubert

In 1938, French singer Johnny Hess, inspired by Cab Calloway’s song Zah Zuh Zaz, shouted frantically in his song I Am Swing the following chorus: ‘I am swing, I am swing, zazou, zazou, zazou zazou dé’. The song became the 1939 hit song and was featured in the 1942 film Mademoiselle Swing about a young swing fanatic who is bored to death by her provincial life and seeks some adventure.

Along with their love for American jazz, Zazous became known during the occupation for their Anglophile and Americanophile attitudes, which were not to the liking of German occupiers. Boris Vian (French writer, poet, musician, singer, translator, critic, actor, inventor and engineer) wrote, “The male got a curly and scruffy hairdo and wore a sky blue suit whose jacket fell down to his calves [...] the female also wore a jacket which protruded by at least one millimeter from a loose pleated skirt in Mauritius tarlatane fabric”.

Flash forward to the post-war years, from the taboo club cave up to Saint Germain’s cafés.

Boris Vian looked like a proto Mod and Juliette Greco like a beatnik girl worthy of the girl on the cover of Rod McKuen’s Beatsville LP. Anglophilia really started in Paris during the sixties. While English mods came from the lower classes, their French cousins originated mostly from the capital’s upper crust. A well-groomed crew who chose for their HQ Le Publicis Drugstore on the Champs Élysées. Ironically, Jacques Dutronc used to call them the ‘Minets’, “who eat their purr at the drugstore”. But it would be wrong to dismiss these young Anglophile and Parisian dandies, such as Boris Bergman, a great Russian-Jewish-Anglophile

“Minets: pseudo beatniks and dandies hating everything French –that drugstore gang is above all anti-yéyé. These few young people were

offbeat aesthetes who were into clothes and pop culture.

They

were

a strange kind of mix between Barbey d’Aurevilly and Pete Townsend”

lyricist, who grew up in London and then expatriated himself to Paris. He wrote the English adaptations of Serge Gainsbourg’s songs and was a lyricist for Sophia Loren, Anthony Quinn, Marcelo Mastroniani and Juliette Greco. “I was already part of a Saint-Michel band,” Bergman recalls, “then all the various gangs merged at the Drugstore. There were a lot of ‘our betters’ kinda kids. I was quite apart as I sort of came up from the gutters.”

“I was in the same class as Michel Taittinger

(co-director of Godard’s Rolling Stones film, 5+1 and heir of the Taittinger Champagne brand). It was an ‘Absolute Beginners’ gang. Some of them rose up to greater things; there was the future press photographer Serge Kornilov, future producer of Vanessa Paradis Marc Lumbroso, as well as famous rock critics François Jouffa and Jean Bernard Hebey. Marc Kalinowski, who would became a great sinologist, was there too. If only I knew back them what we all would become!”

The Drugstore youth wore Maurice Renoma’s ‘English blazers’ outfits. Boris Bergman adds, “At the time I was importing Penny Loafers to make end meet.” Jean Monot, in his Les Barjots book, wrote, “Minets: pseudo beatniks and dandies hating everything French – that drugstore gang is above all anti-yéyé”. These few young people were offbeat aesthetes who were into clothes and pop culture. They were a strange kind of mix between Barbey d’Aurevilly and Pete Townsend.

Sixties girls like Brigitte Bardot (right), Jane Birkin

and Françoise Hardy loved to wear Paco Rabanne, Courège and, a little later, Jean Bouquin (Saint Tropez hippy chic) garments. Aged 23 in 1963, Maurice Renoma opened his first store at Rue de la Pompe in Paris. Before that he had already dressed the Drugstore’s hipsters, for whom he had imposed the curved cut: “Curved clothes give a chic allure to men and women. When curved, young people feel good about themselves.” Among Renoma’s famous customers who became his ambassadors you could spot: Jacques Dutronc, Serge Gainsbourg, the Beatles, Andy Warhol, Salvador Dali, Catherine Deneuve, Elton John, Jim Morrison, Françoise Hardy, Bob Dylan, Pelé, Keith Richards, Yves Saint Laurent, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing and François Mitterrand. Renoma made a mark on his era and, if his work is still relevant today, it’s because he always preferred real avant guard to hype.

In the early seventies, as everyone was stuck in hippy antics, a fringe of trendy young people reacted. These beautiful people lived way beyond

their means. They made Gustave Flaubert’s “The superfluous is the greatest of needs” their motto. In England, the Glam Rock scene affected both sophisticated artists and teenyboppers. In contrast, French ‘decadents’ were much less numerous, very elitist and mostly based in Paris.

Yves Adrien is a mythical author and an unlikely rock critic fascinated by Sainte Thérèse de Lisieux. Yves Adrien wrote about the French post-May ‘68 hippie youth, “Teenagers prefer bubblegum pop to Marxism, it’s more fun ... Imagery of the experience goes beyond any logic based on reasoning. This is the teenage force. The leftist adventure is not, in the musical/electric concept that concerns us, more important than the twist dance craze fashion or platform boots.”

For those who liked it camp, there was the Gazolines (above), a dissident group of the FHAR (Homosexual Front of Revolutionary Action) who challenged with glitter and joie-de-vivre the greyish leftist demos of the day. Among them were the sublime Marie France, but also Maud Molyneux, Helene Hazera Jenny Bel’Air and Paquita Paquin. Their tongue in cheek slogans were “Make-up is a

“These beautiful people lived way beyond their means. They made Gustave Flaubert’s “The superfluous is the greatest of needs” their motto.

In England, the Glam Rock scene affected both sophisticated artists and teenyboppers. In contrast, French decadents were less numerous, very elitist and mostly based in Paris”

way of life, proletarians of all countries, caress yourselves!” and “Nationalise glitter factories!” The Gazolines disbanded themselves around 1974 and Jenny Bel’Air became a physionomist at the Palace, and Maud Molyneux a feared critic at the Libération newspaper. At the Palace, under Fabrice Emaer’s direction, old faces of ex-Gazolines

mixed with new figures such as Edwige (ex Punk queen and Jean-Paul Gauthier muse), Jérome Braque (an electro-pop artist and tongue-in-cheek dandy), Djemila Khelfa (who makes Kate Moss seem like an altar boy), Alain Pacadis (the ‘teddy bear who smelled bad’, according to Lio), the great photographer Philippe Morillon, Jacno, Elli Medeiros, Fifi Chachnil, Pierre et Gilles, JeanCharles de Castelbajac (who designed many artists’ clothes at that time) and so many other creatures of the night. The brilliant composer Jérome Braque recalls, “We were spoiled children. Daring to say no to golden opportunities and dressing up in clothes from St Cloud Flea market. I even had a tuxedo I got recut to my size”.

“Teenagers prefer bubblegum pop to Marxism, it’s more fun ... This is the teenage force. The leftist adventure is not, in the musical/electric concept that concerns us, more important than the twist dance craze fashion or platform boots”

To evoke French elegance, both modern and resulting from the sartorial revolutions mentioned above, we should conclude with the mythical modern couple formed by stylist Vanessa Seward and über cool composer and producer Bertrand Burgalat. In her book The Gentlewoman’s Guide, Madame Seward-Burgalat offers us a breviary of feminine elegance.

In a alphabetical form, there’s mention of Lubeck (a Young Catholic Girls institute from where many of the pupils would go on to work for Dior, Chanel and Vogue); of anti show-off attitudes; of neo-bourgeoisie. As a Parisian born in Argentina and raised in London, Vanessa Seward is the essence of style when she writes about silk pyjamas, Marine sweaters, lack of fortune and sensitive luxury. Way beyond the fabric, the essence of French elegance is an art of living and therefore of dying. Boris Vian sang, “And when I would be dead I want a Dior shroud”. n www.vanessaseward.com www.tricatel.com

FRANÇOISE HARDY – As she never cared about clothes and has always been unaware of her beauty and her charm.

JEAN D’ORMESSON – A very mediocre and pontificating writer, but very well fashioned (his wife was rich).

STÉPHANE AUDRAN – Because she was witty and intelligent, that’s what made her so attractive.

HÉLÈNE ROCHAS – “One of the most beautiful women I’ve ever seen”, John Fairchild.

VALÉRY GISCARD D’ESTAING – He made a lot of mistakes, but he was always perfectly dressed.

HUBERT DE GIVENCHY – A rare specimen of fashion designer who doesn’t look pathetic.

...AND BURGALAT’S REPLY TO THE SIMPLE QUESTION: WHAT IS FRENCH ELEGANCE? French elegance is like French music; it’s ok when it is not calculated. If there is a French spirit, it cannot be codified or claimed, otherwise it becomes folklore. I don’t think Alain Delon, Jean Gabin or Lino Ventura cared that much about clothes, but they wanted to be well dressed out of respect for the public.

Gustav Temple finally collects the bespoke suit for which he has waited eight long weeks and made four visits to his tailor

In the previous edition, we chronicled the lengthy process of having a bespoke suit made by Pratt & Prasad. In fact, so lengthy that the suit wasn’t finished until the subsequent issue

My fourth stroll along the windswept boulevards of Clapham was repetitive in more ways than one: on each visit to Pratt & Prasad, I felt obliged to don the same black vintage suit I had worn to the first consultation so the comparison could be made. I knew this would be the last time I would wear this ensemble of mismatched blacks and weights of fabric. Goodbye, old friend, I said to it, brushing yet more lint off the lapels; you have served me well but now the Platonic shadow in the cave is to be replaced by the Real Thing.

Haddon was nearly as excited as I was, forgetting to offer me the usual cup of tea in his haste to show me his creation. I saw it immediately; a lone black figure nestled among the bright violets and pastel blues of Haddon’s more adventurous clients. A plain black wool suit like this only really comes to life when it’s put on. And it wasn’t only the suit that sprang into life. The trousers slid on like a pair of silk pyjamas, and when I put on the coat, my carriage was instantly more erect, almost as if some form of orthopaedic back brace had been applied.

Haddon proudly pointed out some of the key features, such as the luxurious roll on the lapel (compared to the flat, lifeless lapels on the vintage coat); the generous armholes, entirely concealed from the outside; the tightly jetted pocket flaps; the vampiric sweep of the scarlet lining. If I were a different type of person I would have given this

“Haddon

proudly pointed out some of the key features, such as the luxurious roll on the lapel, the generous armholes, the vampiric sweep of the scarlet lining.

If I were a different type of person I would have given this talented

tailor a high-five”

talented tailor a high-five. Instead I merely nodded, knowing as well as Haddon did that this suit would alter my bearing in the world.

The street welcomed a different man when I left Pratt & Prasad. A slightly taller, more elegant man with a more confident step. Every movement in a bespoke suit is a pleasure; every gesture rewarded with a gentle yielding of the cloth. It is as if the suit is asking its wearer: what do you want to do next, sir, and how can we assist you? No matter how fabulous a vintage garment one may have acquired and how well it seems to fit, there is nothing quite so harmonious and satisfying as wearing a suit that no other man will ever inhabit so precisely. n

www.prattandprasad.co.uk

David Evans gallops through detachable collars, British watches, shantung ties, travel luggage and Bond headwear www.greyfoxblog.com

What a relief at last to be able to attend events where we can dress up properly and shed the lockdown grunge that has eclipsed style over the last two years or more! My son and daughterin-law, married in late 2020 with a total of 14 people during the restrictions of lockdown, had the chance to celebrate properly earlier this year. The day was superb: blue skies, a magical venue, an honour guard from The Welsh Guards and a large room full of stylishly dressed guests.

I dusted off my morning dress, unworn since my daughter’s wedding and a visit to the Derby some years ago. I wore a shirt from Budd Shirtmakers with a stiff collar to add to the formality of the occasion (I hadn’t worn a detachable collar since schooldays over 50 years ago). I probably felt almost as uncomfortable as the Guardsmen in their thick red woollen tunics and highly polished heavy boots, but it felt wonderful. The pleasure of making an effort is nothing to do with vanity. Looking good equates with feeling

“I wanted a Shantung silk tie to wear at the marriage celebration. Shantung is a gorgeously slubby silk that adds interest to a tie. I tend to avoid striped ties, as they look too school or regimental for my taste, but when made out of this highly textured silk they are unlikely to be mistaken for such”

good, respect for others and indeed for ourselves. The psychological benefits of dressing well have scientific support, although those of us who enjoy dressing up don’t need science to tell us what we experience when we don our glad rags. Sometimes we forget that it’s small things like this that bring us pleasure – so needed in a world gone increasingly mad, with politicians and world leaders at the forefront of making life miserable for everyone.

This year saw the coincidence, almost in the same week, of collaborations between four British watchmaking brands. England was, many years ago, the centre of the watchmaking industry in Europe. British watchmakers have been responsible for much of the technology that now powers our watches – think of Harrison, who designed the first successful marine chronometer, for example. The industry is slowly being restored by brands such as those mentioned below.

The watch from Fears Watches and Garrick is 42mm in diameter, made at Garrick’s workshop in the UK and only available through Fears. It uses the Garrick UT-G04 movement with power reserve indicator: It’s hand wound and regulated to within 5 seconds a day. The hands are the usual Fears skeleton design and the watch marries the key elements of both watch brands very well. I’ve seen and worn timepieces from both Fears and Garrick and they are made to the highest specifications and quality.

The watch from Bremont and Bamford is a different animal; very contemporary in appearance with its black DLC-treated case. The S500 sports

bright blue indices that jump out against the dark layered dial, making this a practical yet stylish timepiece. The watch is chronometer rated, with enhanced shock proofing and water resistant to 500m. On the wrist it’s comfortable with not too much bulk. This is a timepiece that likes to be noticed.

Incidentally, Bremont have produced a handsome chronometer that I would love to have on my wrist if budget allowed. The Bremont WR22 is designed in collaboration with Williams Racing, made in their workshops in Henley and with a distinctly handsome, racy appearance. It comes on a bracelet, but I think looks best on the black Alcantara strap. It also comes with a Williams Racing car wheel nut!

I wanted a Shantung silk tie to wear at the marriage celebration mentioned above. Shantung is a gorgeously slubby silk that adds interest to a tie. I tend to avoid striped ties, as they look too school or regimental for my taste, but when made out of this highly textured silk they are unlikely to be mistaken for such. I found mine at Rampley & Co, who also supply gorgeous pocket squares and have recently branched out into clothing.

If you’re travelling this summer, there are a couple of pieces of British-made luggage that I’d like to recommend. Globetrotter makes wonderfully stylish cases with a strong hint of nostalgia. Their Dr No collection has a gorgeous dark blue wheeled carry-on case that will make you the envy of the other passengers. From Bennett Winch comes a suit carrier holdall that combines a soft bag and suit carrier – the ultimate travel companion for the sartorial traveller. Finally, the Hatbag (left) provides a solution to the age-old problem of how to transport headwear across continents without one’s fedora or trilby reaching the destination a mis-shapen mess.

Finally, continuing the James Bond theme, Lock Hatters’ new collection celebrates 60 years since the first Bond film, Dr No. Throughout this year they are releasing hats based on those worn in the films. Among the first is the Auric cap (pictured below), handmade from russet Escorial wool to match the rust-coloured tweed golfing suit, with baggy plus fours and oversize soft yellow cardigan, worn by arch-villain Auric Goldfinger.

As Matt Spaiser observes on bondsuits.com, Goldfinger’s suit closely follows Fleming’s description in the 1958 book: “Everything matched in a blaze of rust-coloured tweed, from the buttoned ‘golfer’s cap’ centred on the huge, flaming red hair, to the brilliantly polished, almost orange shoes. The plus-four suit was too well cut and the plus-fours themselves had been pressed down the sides…” Clearly Goldfinger’s style was by no means comme il faut, but then one would expect such lapses of taste from a villain.

Links: lockhatters.com bremont.com bamfordwatchdepartment.com fearswatches.com garrick.co.uk rampleyandco.com buddshirts.co.uk hatbag.com

Over the next few columns I want to introduce you to some Masters of Style, whose taste and sartorial skills offer inspiration to those of us less confident. These first appeared in a slightly different format on greyfoxblog.com. I’ll start with Shaun Gordon, one of the most naturally stylish men I know.

GREY FOX: Please introduce yourself. Where are you based and what do you do?

SHAUN GORDON: My name is Shaun Gordon, I am a London based multi-product menswear designer. Until recently I handcrafted neckties and fine accessories but am now moving on to other things.

GF: Please describe the main style influences in your life, past and present.