MACMAG 48 {1}

48

MACKINTOSH SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

EDITORS:

EWAN BROWN

FELICITY PIKE

LUCY FAIRBROTHER

YAN PRZYBYSZEWSKI

MACKINTOSH SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

GLASGOW SCHOOL OF ART 167 RENFREW STREET GLASGOW G3 6RQ

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ISSN 1363-3155

MACMAG 48

48

MACMAG

DEDICATED TO EMMA BURKE NEWMAN

MACMAG 48

This year the Mackintosh School of Architecture has fully opened its studio doors once again. We arrived to our new desks, unpacked and there was a very clear sense of excitement and new energy about the year that was about to start. With the enforced separation of the last few years, this has given time for reflection and provided new perspectives. We were, once again, back in place not only surrounded by aspiring architects, but other creatives too.

This idea forms the focus of the 48th edition of MACMAG. Titled Creative Allies, through a collection of interviews, articles and work produced by the school, we have explored both within and outside of the school, how architecture sits amongst the creative fields and this manifests itself in practice.

As with every year, MACMAG48 relied heavily on the support of the students and staff of the school, as well as the generous support of our sponsors. We would particularly like to highlight some individuals, without whom this edition would not have been possible.

Thank you especially to Sally, Craig, Jack, Vivian, Sam, Pauline, Clem and Johnny.

We really hope you enjoy reading this edition and looking through all the wonderful work produced by the school, as much as we have enjoyed making it.

MACMAG48 EDITORS

EWAN BROWN

FELICITY PIKE

LUCY FAIRBROTHER

YAN PRZYBYSZEWSKI

MACMAG 48

FOREWORD

All images by Vivian Carvalho unless stated otherwise.

Creative Allies: So what difference does it make?

The MACMAG 48 team have chosen to explore creative allies, a subject both appropriate to the here and now but one that will probably have re-occurring resonance with anyone involved in creative practice.

Thinking about now, we find ourselves post-covid in a contact both familiar but different. We have got used to looking at work, structuring our time and dealing with each other in different ways, some productive and enjoyable, others limiting and obtrusive - awkward even.

Over this year we have moved closer to understanding how to work beside each other once again, and to understand how we see the potential in the connections co-operating, collaborating and finding our creative partners can have, and what is missing when these are not there.

For me as a Head of School, this has meant meeting, yes actually meeting, colleagues I have known again, and recognising very quickly the gaps that opened up when talking and sharing ideas and problems with these supportive partners was not possible, and when these allies were not part of my regular head space and practice space. But then I know I’m fortunate, to have what I can consider to be creative allies forged over time. For many students who have had their education disrupted during covid, these allies are only just beginning to form.

So looking ahead and into the pages of MACMAG 48, there are some simple obvious things worth saying. There is no single model for a creative partnership, (as the articles and interviews you will read show). They involve all sorts, operating in many different ways and contributing different things to the creative process. Architecture is seldom realised by a lone person, so the sooner you find the people that compliment your thinking and skill set the better. Not necessarily your tribe only, but a wider ecosystem. Allies work both ways as do supportive communities, we learn from each other even when we are in competition.

The context and circumstances we operate in now and in the future will need us to imagine and bring to life, forms of allies we haven’t thought of before, to answer problems we don’t yet understand.

Enjoy seeking out those partnerships, alliances and allies. Make new friends, but keep the old.

Sally Stewart

MACMAG 48 LETTER FROM HEAD OF SCHOOL

MACMAG 48 23 13 32 45 56 66 93 79 74 TABLE OF CONTENTS 08

MACMAG 48 INTRODUCTION STAGE ONE A MATTER OF NATIONAL TRUST MATERIAL CHOICES FRIDAY LECTURE SERIES STAGE TWO BACK TO THE DRAWING BOARD BOURDON TO BIENNALE ARCH AND CRAFTS STAGE THREE CONFORMING TO UNCONFORM NEW PRACTICE EMMA BURKE NEWMAN

FOUR IN SEARCH OF CONNECTION

OF THE OBSCURE

TO THE INTERIOR

FIVE ARCHITECTURAL STUDIES EQUALLY GENEROUS: EPILOGUE 08 13 23 32 38 45 56 66 74 79 93 98 106 111 126 129 134 145 163 170 TABLE OF CONTENTS 98 111 126 129 134 145 TABLE OF CONTENTS

STAGE

AESTHETICS

EXTERIOR

STAGE

INTRODUCTION

Creative Allies

This year’s edition of MACMAG seeks to explore the relationship between the arts and architecture. Through a range of conversations and articles we explore the interdisciplinary nature of contemporary practice, showcasing a celebration of diversity in our architectural education and industry.

The Mackintosh School of Architecture sits within a unique context both geographically and socially; the art school’ s presence poses as an intrenchment on the architecture school’s values. This enrichment for the school comes from a reliance on the arts, both academically and in an informal social relationship. MSA prides itself on it' s contextual relationship with the art school. Our building, the Bourdon, sits with other studios filled with artists,

photographers and fashion designers across the street. As students, it is inevitable to be immersed in a diverse array of creative disciplines, whether consciously or subconsciously. This exposure has a profound impact on students' perspectives, their creative output, and the trajectory of their professional journey beyond academia. Our interviews with Will Knight, former MSA student turned artist, and Andy Summers, an architect, educator and curator, explore this idea further.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh, who our school is named after, is a prime example of where this collaboration between the arts can be seen working at its best. Charles, and fellow architecture student James Herbert MacNair, formed a creative alliance with sisters Margaret and Frances Macdonald, day

students at GSA, to produce an innovative and distinctive design style which came to be known as the ‘Glasgow style’. We are reminded of Mackintosh’s legacy every time we pass by the Mackintosh Building. We delved into his work and his approach to the arts and architecture in our conversation with Liz Davidson

The school’s ability for dawning professional and social relationships with the arts is clear. Though can we assume this is carried through to practice?

As students of the Glasgow School of Art we pose the question: what is the interdisciplinary nature of contemporary practice? How do the arts manifest in this? We ask, where is the line between arts and architecture and is this line continuously moving?

MACMAG 48 {8}

MACMAG 48 {9}

In a period of post pandemic global uncertainty the urgent concerns of climate change were again on our minds, so in Stage 1 for 2021-22 we continued our preoccupation with the future inhabitation of the planet. Our core ethos, taken from RIAS’ Sustainability Policy 2016 ‘Maximum Architectural Value - Minimum Architectural Harm’ was our guide as we explored architecture under a series of historical and contemporary lenses.

‘Architecture & HUMANS’ was a 5 week critical enquiry into ethical and equitable design for people of ‘difference’. We investigated aspects of space, light, comfort and wellbeing to redesign a familiar space for people of physical and neurological divergencies.

‘Architecture & VALUES’ moved us to an urban scale to undertake a 3 week investigation of Olympia House in the East End of Glasgow. Through drawing this existing building, inside and out, at a variety of scales we probed what can be ‘valued’ in architecture. This project developed into ‘architecture & PLANET’, a design proposal for the adaptive re-use of Olympia House with an emphasis on low

STAGE ONE

energy, loose fit and ambitions of architectural atmospheres.

‘Architecture & ME’ was an innovation for Stage 1. We introduced for the first time a long span, self- directed research project, which introduced themes given in the RIBA’ s 'The Way Ahead'. Our students were given freedom to follow their individual interests within these parameters.

In our cross school CoLab courses, we speculated in Semester 1 about ‘Being an Architect in The Anthropocene’ as COP26 was held in Glasgow. Starting from a study of global vernacular architectures our students speculated with manifestos and designs for a better future. In Semester 2 our students worked in interdisciplinary teams, drawn from across the whole of GSA first year, to continue to probe and evolve projects around the Anthropocene.

These investigations were an opportunity for our students to explore, experiment and communicate their ideas, learn to embrace mistakes, be challenged by uncertainty, and enjoy their first foray into architecture.

MACMAG 48 {13} STAGE ONE

Stage Leader

Kathy Li

Co-Pilot

James Tait

Tutors

Chris Platt

Sam Brown

India Czulowski

Iain Monteith

Student works featured in this segment are from 2021/ 2022

MACMAG 48 {14} STAGE ONE

Olympia House OWEN HOURSTOUN

This project focuses on adapting the existing building of Olympia House in Bridgeton, Glasgow. Through close analysis of the local context, I tried to create an elegant, fitting design whilst creating a loose-fit interior which utilises a playful use of light. The proposal' s development was achieved through hand drawing and sketch models to gain a thorough understanding of daylight features.

MACMAG 48 {15} STAGE ONE

House Within A House

AILSA HUTTON

In a period of post pandemic global uncertainty the urgent concerns of climate change were again on our minds, so in Stage 1 for 2021-22 we continued our preoccupation with the future inhabitation of the planet. Our core ethos, taken from RIAS’ Sustainability Policy 2016 ‘Maximum Architectural Value - Minimum Architectural Harm’ was our guide as we explored architecture under a series of historical and contemporary lenses.

‘architecture & HUMANS’ was a 5 week critical enquiry into ethical and equitable design for people of ‘difference’. We investigated aspects of space, light, comfort and wellbeing to redesign a familiar space for people of physical and neurological divergencies.

MACMAG 48 {16} STAGE ONE

MACMAG 48 {17} STAGE ONE

The Public in the Urban Aspect

DANIIL SOLOMOU

Exploring the idea of a genuinely public space in the urban aspect through various Nolli-styled maps.

A Nolli map is a type of ichnographic map focusing on open civic spaces. Showing the plans of public spaces and blacking out other privately owned buildings.

Studying three vastly different cities across Europe (Nicosia, Amsterdam, Glasgow) and exploring what the public means. Through this exploration, you can identify a city's values and socioeconomic history and how it morphed into what it is now.

MACMAG 48 {18} STAGE ONE

MACMAG 48 {19} STAGE ONE

Floating House On The Clyde CHARIS RITCHIE

For this project I decided to tackle the imposing local threat of flooding to Glasgow and discovered there was a danger zone determined across the area of the River Clyde, estimating which landmasses will be underwater in the next 3 decades. Through physical experimentation, I came up with a ‘floating’ modular structure inspired by pontoons used in the ‘Floating House’ design in Canada. My design would adapt to the changing water levels over time and spark a change to adapt larger scaled structures using the same method. The modular structure would exist to educate the local community on gradual flooding.

MACMAG 48 {20} STAGE ONE

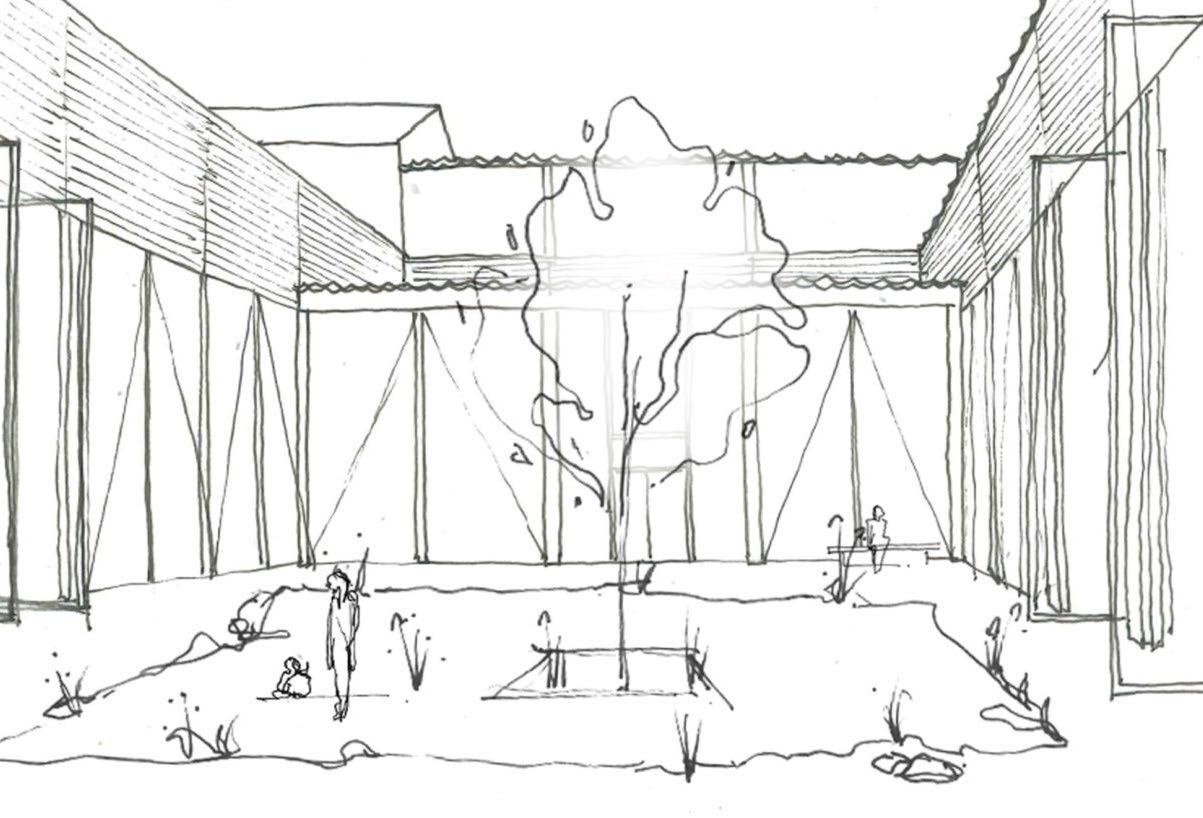

The name of the project is the “Wellbeing Garden”. Reflecting upon my experience with nature and its impact on me as I came to Glasgow as a student led me to studies on the impact of nature to the mind. Namely, the Stress Reduction Theory, the Biophilia Hypothesis and the Attention Restoration Theory. This prompted me to consider how making a nature space available to students at the Glasgow School of Art in the city centre would contribute to their wellbeing.

After suffering two devastating fires, the shell of the beloved Mac posed itself as a perfect host for the garden. It offers plenty of light as it has no roof, it creates an opportunity for the garden to have multiple levels, and it allows garden users privacy, as its walls act as a barrier from the outside world. The garden features meandering paths, an abundance of vegetation, calming water features, a greenhouse and a view over the city from the top floor.

MACMAG 48 {21} STAGE ONE

EMILY EARSMEN

Wellbeing Garden

A MATTER OF NATIONAL TRUST

In

conversation with Liz Davidson

Liz Davidson graduated from Edinburgh College of Art as a post graduate in Architectural Conservation. Since then Liz has held a number of senior posts including leading the Heritage Lottery funded Townscape Heritage programme to regenerate the Merchant City; as director of Glasgow Building Preservation Trust, a charitable property developer rescuing and bringing back to life numerous historic buildings and head of Heritage and Design at Glasgow City Council with an active statutory role in maintaining the highest standards of historic building repair and maintenance.

Liz was senior project manager on the Glasgow School of Art Regeneration project from 2014 through to 2022 and has more recently been involved with the Hill House Project

MACMAG spoke to Liz in April 2023 to discuss her work on the Mackintosh regeneration project and on the Hill House, working alongside Sarah MacKinnon on both projects. Sarah is currently Head of Conservation of Properties for the National Trust for Scotland.

MM: To begin with, could you tell us a little bit about yourselves and how you came to be involved with the Mackintosh restoration?

LD: Prior to my work on the Mackintosh Building, I had been the Director of the Building Preservation Trust in Glasgow and in 2014, when the fire occurred, I was Head of the Conservation Department and Head of City Design. Sarah was the Director of a different trust in the West of

Scotland so we both came from a building preservation trust background. Following the fire, Glasgow School of Art advertised for people to work on the restoration, repair and conservation of the building and I was appointed. I was lucky enough to get involved at the tail end of 2014 and my first job was to advertise for an assistant. Sarah came and was easily the best person to come on board. Very quickly there were two people whose background was

MACMAG 48 {23} A MATTER OF NATIONAL TRUST

coordinating building projects, pulling together all the briefs, procurement, with the skill set for running a building project. I must say the school was an absolutely fantastic place to work at that point. The Reid had opened in 2014. It had a great Estates Department that knew how to get exhibitions put up and move students around.

Working on the Mackintosh was the best privilege of both our lives, we would both say that no matter what job we have done previously or have gone on to do, the Mackintosh was something out of the ordinary as a project to work on, with fantastic consensus, support, energy, and creativity throughout all

levels of the school. It was a real delight as a project, until sadly the 2018 fire and everything came to a juddering halt

MM: What led you into this field of work?

LD: I did History and English as my background, but I did a postgrad in Edinburgh in Architectural Conservation because my interest was in the hands-on aspect of history, rather than just teaching or reading about it. It was about the architecture, but also about the place. When I was at the Building Preservation Trust (BPT), we launched something called Doors Open Day. It was the first one in the

UK at that point and it is still running in Glasgow. It was all about engaging people in their neighbourhoods and in the quality of the built environment. The BPT was very much about taking on buildings at risk, but only if you had a good reason to restore them and put them into use, in terms of the social capital of putting a building back into use in a community and society. It was that mixture of the fact that every city in Scotland, or town or countryside, has got extraordinary wealth from the past, both in terms of the embodied energy that you have got in existing buildings but also the craftsmanship and what they mean to a place. There was never a project that did not have

MACMAG 48 {24} A MATTER OF NATIONAL TRUST

somebody that felt really dear about a building or that meant a lot to a local community to have that building back in use. Bringing a building back into use has so much repercussion in terms of how people feel about a place, especially if you can get it into public and social usage as well. I think it is just an amazing profession to be in because you learn about a building, how it has been put together in the past and then you combine it with the fact that this country has amazing skills in terms of design and that there is more sustainable and ecological technology that is coming forward. That all coming together and fusing creates brilliant moments of drama in architecture and places, and that is what interests me the most. I can never be an architect but I do love historic buildings.

The Mackintosh is probably the best case I have ever come across. There was not a day in the four years, before that second fire, that Sarah and I would not have been walking in that building and spotted something we had not seen before. You just thought, oh, how clever was that to think about doing it like that. The way that the building, uniquely in my experience, used light; how cleverly it bounced light around and used light to create mood and atmosphere. It really did affect your soul. Which is why the second fire was such an extraordinary tragedy. I hope that is what the Mackintosh School of Architecture and School of Design still retains – it is that transformative power of great design from the past and how it inspires the future. It all came

together for us in that place.

MM:That leads perfectly on to the next question, could you tell us a little bit about your specific role pre 2018 and what that would involve?

LD: My role title was Senior Project Manager, but I was really more a project director or co-ordinator, pulling together the other streams. Sarah came on to work with me as the project manager. She is, arguably, one of the best project managers in Scotland and she has now gone on to something much higher and much more important in the National Trust for Scotland, handling one and a half thousand buildings. My initial job was to write the brief for the restoration and in that triangle of any job, when you have got cost, quality and time, it was all about time. Get it back for the students as soon as you can. Quality was not really even in the triangle, that was non-negotiable. Quality had to be at the level that Mackintosh had built it, and more, because we wanted to do extra in terms of digital enabling and sustainability. Quality was not a factor, programme was, so I was on a fairly fast track to write the brief, get it through procurement, appoint the team and then assemble the contractor, put it out for tender and get the works underway. We were pretty well on target, which would have been Easter 2019 for a soft opening and then a full opening to the students in September 2019. But then the fire occurred in June 2018.

At that stage the work was pretty far advanced because we had been on site for the best part of

three years. It was coming out of the ground looking absolutely extraordinary. What was really thrilling was the knowledge that the craftsmanship had not been lost. Sometimes it was just one or two guys, they might been plasterers, joiners or carpenters, but the work was absolutely extraordinary and as good as of its day. That was the really rewarding part, working with that level of craftsperson. The job was obviously the building and to get it going there was a bit of fundraising involved. We personally did not have huge amounts to do in terms of the main funding, which would have been from the insurance, but we were at all the meetings with the insurers, assuring them that this is how it was going to be done. Then there was a huge amount of public speaking and just making sure that people were engaged.

Something that we actually got criticised for at the time by the press, was the sheer amount of people that we took through the building, including students. We felt it was really important to make sure as many of the GSA students, in particular, saw the building. We did not want it to be something that you put the shutters up for four years and then opened it and had a ta-da moment. We wanted people to see the works in progress at all stages because the majority of the building after the 2014 fire was not damaged. The loss was about 17% of the building. The library was the main tragic loss and then a lot of it was smoke damage or water damage on the West side. But over 2/3 of the building really was not affected at all. So you could still take people

MACMAG 48 {25} A MATTER OF NATIONAL TRUST

in and talk about the building and just see the beauty of it.

We took one elderly married couple in their mid 90s, Tom and Audrey Gardner, wonderful Fine Arts students who had studied there before the Second World War, and had remained students during the war, and who had been on the roof of the building during the Clydebank Blitz, where their romance had possibly kindled. They came back and walked right way up to the top, which is a lot of staircases. After their visit they wrote in the visitor’ s book something like ‘We are glad we have seen the building and she is being healed’. I think most people who knew the Mackintosh before the fire and had studied there or been part of it, really felt it was a kind of living organism – it had soul. It is as if it were alive and had been badly hurt by the fire but it was being beautifully hospitalised and was coming out of it looking absolutely magnificent. The other joy that would have happened if it had got through to completion was that we were discovering so much. The building over the years had had masses of well meaning janitorial coats of paint and varnish. A lot of the building was very black and white before the first fire; all the woodwork was very, very dark, if not black. When you look back at the original photographs, early drawings or images of the building, all the wood was much lighter and you can always see the grain of the wood. We took down a moulded architrave that was damaged and we found the original colours of something that had been there previously. Mackintosh was a

great believer in not hiding the material he used. The building would have come back in a much lighter form, through the woodwork in particular and the wood he used was just beautiful. It would have just been outstanding as a space to be in.

MM: You worked on the building both before and after the second fire – how did it differ the second time around?

LD: The fire in June 2018, was a massive trauma for everyone - the school and the local community were absolutely stunned and horrified because it affected everybody so badly. The first thing that we had to do as a team was, overnight, become not a building restoration team, but a school recommissioning team because for two and a half months all the buildings in the immediate vicinity were evacuated. The next thing we had to do was to make the building safe as quickly as possible to allow people into the streets around the area, hence the mass of scaffolding on the building which was the quickest way to stop the Council from saying ‘this is dangerous, we are going to demolish it’. This meant we did not have the luxury of doing something like we did with The Hill House where you have a very beautifully framed steel box over the building protecting it.

The engineers and the contractors had to come in and were immediately faced by the building control department, saying this is dangerous we are bringing it down if you cannot prove to us this is not going to fall into the street and destroy other properties. We had to use

drone flights and cherry pickers and monitor the situation. Here, again, the school was very helpful. We had them on board from day one, taking point cloud imagery to compare with the point cloud imagery we already had, to show if there had been any movement and where it had occurred. We were able to take a scientific case back to the Council to say there have only been areas of movement in the library and in the northeast corner at top of Dalhousie Street and in those areas we are going to throw scaffolding on right now to stop any further movement. Eventually we had to go around the whole building and just prop it up and brace it from the inside. That took up all the next three or four months, and in the meantime, what we were doing was coordinating all the visits into The Reid and The Bourdon to ensure that we could get the building decontaminated because the smoke would have got into ventilation systems or water systems. We were managing a huge amount of decontamination work and safety checks. In The Reid the glass was cracked so we were having to monitor that and put safety barriers behind it, just so we could get the buildings back in use. The returning students had to do work off site for the first week and then we did get the students all back in by a hairs breath, pretty well, for the start of term. Having said that, you know it was a disruptive experience for any student to come back into, whatever stage they were at.

We were immediately no longer in charge of the project, the project stopped that night. The

MACMAG 48 {26} A MATTER OF NATIONAL TRUST

contractor KEIR could no longer do a job that was a restoration job, so the next thing we had to face was getting involved at every level, with dealing with the insurance, the fire service, the investigation. There were all the contractual legalistic issues that have to be dealt with to stop a contract that has still got a year to go. We had to work solidly alongside what was the Scottish Fire and Rescue Service, painstakingly looking at the archaeological salvaging of what was in the building. The fire service wanted to do a forensic examination of the building to find out how the fire started and they never actually did find the root cause, but it took them three years to painstakingly sift through the building. Every time we moved into a corridor or into a studio, you first of all had to send the engineers in and the contractors in to say, is this safe? That was finished in June 2021. More or less every working moment was to do with making sure that we could keep the building safe and constantly try and put more strength back into it, while the school was running a business case for a feasibility study to look at what was the right thing to do on the site: Is it to keep the building? Is it to restore it? Luckily that was the end decision, so doing that painstaking work was correct because if the conclusion at the end had been to demolish it, then that would have been quite a lot of wasted effort in the way that it was gone about. At the moment the school is looking to start the process of appointing a team to look at the restoration again. That will be a long haul job, which is why in the summer of last year, I figured that it was the right time to leave the project – Sarah having left already - because it will be another length of time before the restoration building

MACMAG 48 {27} A MATTER OF NATIONAL TRUST

works can start properly.

MM: Could you give. us a bit of background on The Hill House Project, how you got involved and what your roles were?

Sarah left GSA around December 2021 and went to a big job in the National Trust. She is now Head of Conservation of Properties for the entirety of the National Trust for Scotland. I left in the summer of 2022. Sarah has oversight of all the buildings and their repair maintenance needs. The Hill House is a specific project. It has been in the trust ownership since 1982, and it is a phenomenal building. It is Mackintosh at his finest, a most mature, domestic work, comparable to Windy Hill which was an earlier work of his. What the client here was really saying to Mackintosh was we want an iconic Mackintosh building. We want you to design a building for us at one of the prime sites in Helensburgh, which in itself was a smart, Victorian Glaswegian suburb. The building was in one family's ownership, the Blackie’ s (as in the publishers) for something like 60 years, and then they passed it to a like-minded architect and their family. It would have been at a good price at the time because even then, there were known issues with the fabric of the building. They owned the building for another 20 years or so, and at that point it passed to the Royal Corporation of Architects, who looked after the property for the next 10 years.

In 1982 the National Trust for Scotland took it into their guardianship and have had it for just over 40 years now

and I think there has not been a quinquennial survey that has not thrown up the issues that it has always had, which is to do with the Portland cement material that wraps around in the building.

The building was built between 1902 and 1904, about the same time that the second phase of the Mackintosh Building was getting built and the material that Mackintosh uses here, and the detailing is very similar to what he ended up using in the second-half of the Mackintosh Building. For Mackintosh one of his great stylistic drivers was the whole issue of the sculptural form of the building. He was a great innovator and very early adopter of modern technology, modern materials and the new developments that were coming forward, and Portland cement at the time was the absolute wonder material and it did do a lot of what it said on the tin. So the issue we have got with combining his stylistic forms at The Hill House and this wonder material was the fact that he, unlike other arts and crafts architects of the day, was one of the first to really do away with all the traditional detailing that you need on a building, particularly in the West of Scotland, to shed water. If you were in the South of France, this might be fine. You could have a flat roof and hardly any drip mouldings and overhangs and gutters, but we are in the West of Scotland and that has got worse rather than better with climate change.

So the issues we faced at The Hill House are that for decades that building has managed to let in moisture and water, trapped it into the stone substrate of

the building, and because of the concrete it is not very easy to get the water to evaporate out and the water over the years has been tracking into the building to come out through the plasterwork and through Margaret McDonnell stencils, the painted finishes, the panelling and the plasterwork generally. It has had a history of just flaking paint and plaster and rot in some places and ceiling collapses. The moisture readings of the building over the last decade have been taken very scientifically, using all kinds of gizmos - thermography and microwave readings, and many other forms of scanning of the building to record just where the moisture is and it is still very much in the core of the building, in the chimneys and everywhere basically.

What Mackintosh did was do away with sills, with any drip mouldings, any hoods over the windows. When he had a Gable head, he did not put lead on it; he did not put stone on it - he just wrapped the material up and over so it went vertical, wrapped into the reveals of the windows, wrapped over the parapets, over the wall heads, over the chimney heads, and in all those areas that water may get in. When it is coming onto a flat surface, it is finding its way in. The Portland cement itself has developed shrinkage over the years. It has not had enough flexibility to avoid the kind of hairline cracking that you get and that of course has a wonderful effect - capillary action of taking water in very slowly, quite deep into the core of the building and then, moving around but not finding its way back out.

MACMAG 48 {28} A MATTER OF NATIONAL TRUST

Our job at the Hill House is to find a material that will create this unifying effect that Mackintosh was seeking to do.

I think if you look at the survey work on the building, about 80% of the Portland cement has been at least changed over the last 120 years of its existence. People have systematically and regularly found areas too damp and they have taken it off. Different approaches have been used over the years. There is been waterproofing to stop water getting in but that has only served to trap water in rather than to stop it getting in. It has had treatments where it has actually taken off the render and put brick behind it instead of stone because the stone is quite porous. A lot of it is face bedded as well, which is

a problem. The stone has lost compressive value because it has been put on end and not laid in the correct bedding strata for how it should work in a sandstone building and it has had other experimental things done to it, such as carbon rods behind the render to actually pin it back and then grouted and things like this to try and keep the render on. The big decision that has been taken over the last decade was to decide that it is not about material, it is about the design. That is a big relief for the trust to know that it has not got to work through something like the Venice Charter, which would say materiality is everything. It is not all about keeping that piece of wood or that piece of glass. We have now got beyond that philosophical debate and

decided it is the appearance and it is the style and it is the modelling of the building that is important. It is all about Mackintosh's vision for the design not that particular piece of portland cement. We will have findings here at The Hill House that will have implications, hopefully beneficial, for the Mackintosh because it is exactly the same material, albeit on brick rather than stone, and we can share any findings with the school on that which we would really hope to do.

At the moment we have got a plan that looks at about four years work. Mackintosh has got 2 anniversaries in 2028, one is the 160th anniversary of his birth in June of 2028, and the other one, sadly, is the 100th anniversary of his death

MACMAG 48 {29} A MATTER OF NATIONAL TRUST

in December. We are going to hit 2028 as our date for the opening. If earlier that would be great. I do not really like long programmes because it only costs more and the building stands around getting damper. In 2019, Carmody Groarke, a London architect, erected the box over The Hill House. It is a fairly extraordinary structure, and at the time, probably drew a lot of criticism from some quarters, who felt that spending the 4 million or whatever it cost in the end, could have been used on the building, but I think it was, with hindsight, a great decision because it has dried out the building, so it has now got a relative humidity that is quite stable. It stands off the building by about 3 metres, 4 metres in some areas and it allows a natural ventilation, so there is no forcing of moisture. It is all naturally just airing and drying out. With COVID and everything running slow for the best part of two years the building has had time to recover. We would have hit more problems if we had fired in and there has been more research and the buildings is now sound. It has a protective big cloak

over it, which means we can work within that box to do the restoration. This protective shield over the building can remain while we are doing the work on the building and opening it up. Unlike the poor old Mack, which is covered in scaffolding, although I think they are going to get a roof over the Mack which is great.

The Trust is good at getting visitors through and what has been wonderful about the project is over the last 10 years they have really gone to town in terms of the research about the building and the materials and the technology used. We have a massive foundation that will form the basis of the tender that will go out this year to a design team to come on board to take this on because the new design aspect of this is going to be that there will be a visitor centre. We want to make sure that it is a striking, stunning piece of architecture, of the same quality but of a modern design, as Mackintosh's vision for The Hill House. It will be a two headed project with the garden wrapping in as part of it. I am hoping we can move

the project really fast because again, it is one of those buildings that is a real victim of climate change, particularly in that part of Scotland. How do you deal with water and how do you deal with an ecological solution that is net carbon as far as we can and a net zero carbon building in the longer term?

MM: Can we ask you a little bit about your team?. The projects that you work on must require specialist knowledge. What skills or experience do you look for when assembling your wider team?

LD: There is an incumbent team at the moment that has done the work to date which is LDN architects in Edinburgh and Narro who are the engineers. Narro are the engineers on the Mack so there is a link there immediately between both buildings, which is nice because they really know their Mackintosh structures and his idiosyncrasies. We would always look for architects or engineers that had a conservation accreditation through the RIBA, the RIAS or through consulting engineers institutes.

MACMAG 48 {30} A MATTER OF NATIONAL TRUST

Narro are one of the few that have that. It is wonderful to have a really strong design ethos and it's important to be abreast of all the developments in technology, particularly in sustainability but we also are looking for a company that has that kind of youth coming through and that knowledge and that adventurousness and being right at the forefront and cutting edge of innovation. Having said that we also want to know that the architects know about traditional building and how older materials work and function and perform and the idiosyncrasies of how a building like this will have been put together. So they need to have both sides of that knowledge base really within the practice. That is what we are looking for. We do not want a practice that can only do conservation. They can happily re-render the building for us but that is not enough because we need to know that we can make it much more environmentally efficient and we are going to put this building back so how can we accommodate

insulation? What about low VOC paint? Somebody that has a very strong ecological bent will be essential for any job in the trust and we would be looking for somebody who has a desire to utilise the latest technology in terms of energy saving measures and things like that, so that is important.

We will also be looking for a team that can handle the new visitor centre and have a really holistic approach to something that works. Some bids might come in with two halves.. You could have two architects, with one main architect for design and another architect for conservation. I think it would be wonderful for the scale of this building to think about a practice that had all of that in house and had the sensitivity to do a really brilliant job with really skilled craftspeople and know how to detail that instruction to those people, but also to come up with something that really reflects The Hill House but is a is a strikingly modern building because that is exactly what Mackintosh would do if he were

still alive. He would not design in an older style, he would design in the style that he had grown into. We will be looking to find the best we can and we may have to go out of Scotland, in terms of the craftspeople we may need and that's a shame because, for instance, for paint analysis there are no companies now really up in Scotland. Most of it is South of the border. I am not being overly nationalistic about this, but it is just nice to know that there are people, in terms of the economy, who are setting up in Scotland and doing this work. I will obviously make it an open competition and we will see who comes through on it, but the practices we have had working on it so far have really done superb work on the research of the building and in their knowledge of it. We know we have got the depth of experience and ability in a Scottish sense, which is reassuring.

MACMAG 48 {31} A MATTER OF NATIONAL TRUST

MATERIAL CHOICES

A Whole-life design approach at Hawkins\ Brown

Louisa Bowles was a student at the Mackintosh School of Architecture from 2002-2004. She is now a Partner and Sustainability Lead at Hawkins\Brown. Since joining Hawkins\ Brown in 2004, she has led several complex architectural projects from concept to completion in a range of sectors including education, science, research, commercial and civic. She led the co-funded research with a UCL EngD that resulted in the concept for H\B:ERT, the in-house Whole Life Carbon design tool and subsequently led the launch and ongoing development of the tool. She has worked full time in her sustainability focused role since 2019 and was the AJ 2022 Sustainability Champion and is a Mayor’s Design Advocate.

Hawkins\Brown is an internationally renowned practice of architects, designers and researchers, based in London, Manchester, Edinburgh, Dublin and LA. We work across a range of different sectors and at a variety of different scales from school pavilions to large city-wide infrastructure projects and masterplans. This has meant our approach to sustainable design needs to respond to a range of different clients, context and scales.

However, what unites our range of projects can be filtered down into a simple concept that is flexible enough to apply to all sectors, scales and easy for people with little specific training to explain. Reducing carbon, improving society. This is an evidence-based design approach to ensure our

buildings enhance the lives of the future generation.

To embed these principles across the practice Hawkins\ Brown created the Specialist Design Studio to spread best practice expertise from people with all kinds of specialist skills including digital design, BIM, visualisation, technical and delivery skills. Sustainability sits within this group and the power of this is the ability to spread the knowledge, approaches and milestone checkpoints among a greater number of people, so having more impact.

One of the questions we are regularly asked is how did the HB Sustainability team and effort start or evolve. Formal staffing started late 2017 and the size of the team and the range of in-house skills has

MACMAG 48 {32} MATERIAL CHOICES

"flexible enough to apply to all sectors, scales and easy for people with little specific training to explain."

Louisa Bowles

been gradually increasing. This has been as a result of a number of external stimuli including various industry initiatives, regulation and an awareness that the situation is getting more complex with increasing client, media and planning demands. We believe Architects have a real place in leading this as we are often the Lead Consultant or Designer, so the more we can do in-house the smoother our processes will be.

It’s always good to remind ourselves why we are concerned with sustainable design and specifically carbon emissions and material specifications. Globally, we need to limit the average increase of temperatures to 1.5deg. Nationally we have legal commitments to be Net Zero Carbon by 2050 with a 78% reduction by 2035. If we keep spending our carbon budget to 2050 at the current rate we will run out many years before this. The UKGBC roadmap to Net Zero project indicated the work required and policies required to maintain the reduction trajectory required to meet the 2050 target.

To support, we have standard resources, support networks and data collection processes to track performance. These have evolved and been updated and expanded on numerous occasions to improve them and as new people enter the team. The more we learn on one project the more we can transfer to another within tight programmes.

We advocate for Whole Life Carbon to be integrated into

MACMAG 48 {33} MATERIAL CHOICES

the design process where possible. Starting with benchmarking, a rough idea of the aspirations, outline material palette and project abnormals will usually indicate whether it will be possible to meet the most onerous performance or not. We can then optioneer to prove this and track through whole building analysis at key milestones.

We recognize that there are always more drivers than carbon so we often group information on material choices into matrices so carbon, cost, aesthetic, buildability and other factors can be weighted. It is rare there is one perfect answer. And we know from our own analysis and industry benchmarking etc that the structure and facade are often the key indicators of meeting one target over another in regards embodied carbon.

So in regards to structure there are three key material options, concrete, steel and timber or a hybrid of the two. A decision will most likely be made based on function, clear span, material efficiency and hence cost, speed of construction and potentially embodied carbon. However, as you can see here many of our projects expose the chosen material where we can, for joint aesthetic and efficiency reasons. The IStructE guidance has had a huge influence over the recent years and we are seeing more attention to optimization before specification changes, but this is still a key lever to reducing.

In regards facades the situation is more complex as a

case study later will show. We have almost infinite finishes and window configurations but also need to adhere to noncombustibility and thermal performance requirements. Broadly there are some rules of thumb we propose to our teams early on as much of the embodied carbon is still in the sub-framing on most buildings at scale. So, reduce the cladding weight, reduce the use of metals. Where you can use recycled products. And in regards the finish itself, review the replacement cycle and really consider how that will be done.

Case Study 1: TEDI CAMPUS

Our first case study looks at re-use, modular construction and design for deconstruction. TEDI-London, is an HE engineering enterprise, cofounded by three global universities: King’s College London, Arizona State University and UNSW Sydney. Phase 1 is now complete at British Land’s Canada Water development, constructed from volumetric modules and is designed to be deconstructed at the end of life for further re-use. Phase 2 has used preloved modular frames.

The deconstruction is a planned for event as the campus will only be here for up to 7 years but effort was also spent ensuring an overall enhancement of the site and student experience. All materials can be stripped off and separated for use elsewhere. Built in the UK, the building itself took just six weeks to construct once the modular components had

MACMAG 48 {34} MATERIAL CHOICES

"

A decision will most likely be made based on function, clear span, material efficiency and hence cost, speed of construction and potentially embodied carbon. "

arrived on the site, minimising disruption to the local area. Each module uses lightweight steel frame boxes clad with insulation and requires no deep piles or concrete.

Case study 2: 55 Great Suffolk Street

This project was featured in the recent RIBA Exhibition; Long Life, Low Energy: Designing for a Circular Economy. The original brief from Fabrix for the refurbishment of 55 Great Suffolk Street included the need for steel re-use and circular economy strategies.

What struck the whole team was how beautiful and raw the original building was so that design concept was always to retain as much material as possible but the means of access was tricky to provide without damaging the existing integrity. What transpired was a weather-protected circulation core that sat outside of the main building volume.

The inspiration for the materilaty of this key addition was the refence to the original warehouse as storage for paper and resulting exploration of pattern generated from

corrugations.

However, it is the steel reuse that has been of primary interest so far on the project due to the current rarity, but increasing interest and need, of this occurring. We have just undergone RIBA Stage 4 including a lot of detailed collaborative work together with Fabrix, Cleveland Steel and our structural engineers Symmetrys. Part of the building has been designed to work with existing steels from another site. This required some reciprocal work up front. Instead of choosing sections from a

MACMAG 48 {35}

MATERIAL CHOICES

catalogue, an inspection was taken of what was available. The spec of the steel was generated, a testing regime for the sections deemed most suitable was devised and then the results compared to the spec. Adjustments made where required or alternates found.

Case study 3: Two science and research buildings compared

A few quick observations about how all can sometimes not be what it seems with embodied carbon and material choices. We compared two of our recently completed life sciences buildings; IBRB at the University of Warwick and the Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin Building for the University of Oxford. The material choices were carefully considered based on the scientific requirements, long term flexibility, construction methodology and health and wellbeing but not in regards embodied carbon per se at the time. Both of these were designed around 2015.

Our thought was that the timber structure used for 50% of the IBRB should have resulted in a figure that reflected a reduction. But in fact the DCHB came out lower. We have attributed this to a few factors including the steeply sloping IBRB site requiring far more piles than in Oxford where the ground conditions enabled a hybrid raft and piled solution. Both concrete structures were pre-fabricated and designed to similar loadings and spans but a higher % of cement

replacement used in the DCHB. And the form factor on the DHBC was more efficient as the building is deeper plan with a central toplit atrium. So often factors other than pure material choice massively affect the carbon emissions.

Case study 4: St Mary’ s Catholic Academy

And finally an example of a project that has focused on both embodied and operational carbon from the start. St Mary’s Catholic Academy in Derby is an example of a very low energy, low carbon proposal which we’ve been working on for the Department of Education based on their GenZero principles. The scale has enabled the use of primarily natural materials and modular SIPS panels. Biophilic design is really important here so every wing of the school looks out onto carefully crafted external spaces that create distinct characters through the seasons. Some are functional or productive or educational and some of them are obviously for play.

So the natural materials obviously help as you can see from the embodied carbon figures at around 440kgco2e/ sqm. This principle has been used for the majority of building elements except for the polished concrete floor aimed at ensuring thermal mass while reducing the embodied carbon of sheet floor finishes and short replacement cycles. But the timber is doing more than contributing to a nice number. It is embedded in the principle of providing supportive, calm, healthy learning environments

MACMAG 48 {36} MATERIAL CHOICES

with good air quality, acoustics and connections to external spaces.

So our conclusion - there is no right answer, we must think through our choices at each design stage and life cycle stage through a number of lenses. And we can advocate for Architects as Lead Consultants to take control of each design. Drive through passive design, fabric first and energy efficiency measures. And lead the conversation on materials. While the sub and super-structure is the largest proportion of embodied carbon in a building the Architect is still the curator of the design and has the widest influence over a holistic decision, balancing all factors. It also has to be recognised that there is no perfect answer – the lowest carbon option is not to build at all, but that is unlikely the full answer. So we build less by retrofitting and re-using and we are efficient with material by using the right thing for the right job. One of the focusses of the Environmental Audit Committee which resulted in the recommendation for a national policy on Whole Life Carbon reporting is that there is not much to be gained through demonising specific materials but that all materials need to be used efficiently and decarbonised versions made more available.

MACMAG 48 {37} MATERIAL CHOICES

FRIDAY LECTURE SERIES

“Re-establishing Identities” Mackintosh School of Architecture's Lecture Series

Why do we need to re-establish Identities in Architecture? Identity expression has been illustrated physically by many art forms throughout generations, for instance artists like Diane Arbus in the 1960’s, whose compassionate photographic lens included those otherwise excluded from mainstream physical and economic norms, and more recently Lubaina Himid whose work foregrounds black people and black identities within the context of white history or in contrast to cultural stereotyping. This same expression is not often found in Architecture, and in this Lecture series we wanted to focus on people who have been denied the opportunity to articulate their needs, voices, feelings in the spaces they reside in.

Architects, urban designers and city planners are starting to realise that our cities have been, and continue to be, built largely for a single identity, White men. Feminist geographer Kim England notes that ideas men have about the city are “fossilised into the concrete appearance of space. Hence the location of residential areas, work-places, transportation networks, and

the overall layout of cities in general reflect a patriarchal capitalist society’s expectations of what types of activities take place where, when and by whom.” This approach has caused architecture and urban environments to be exclusionary and representative of a very singular way of thinking and being. There is an understanding that the lack of diversity in our built environment professions is partly to blame, researchers quoting that ''architecture is the creative industry where it' s least likely to find working-class people as well as having only 9% people of colour involved'' . Academics are making headway in articulating inequalities in lived experiences within built environment, Leslie Kern chews over many of these issues in her book Feminist City in 2020, but cities are hugely diverse, with shifting needs and populations, as well as, different degrees of privilege, barriers, and social assets, so there is still a considerable task ahead. A good way to combat this is broadening out the profession, but if we are going to address these imbalances in the city, our Friday lecture series highlighted that to truly re-establish

MACMAG 48 {38} FRIDAY LECTURE SERIES

Ollie Simpson & Gilda Plati

Identities in architecture and urbanism we need to go one step further, we need citizen participation.

Contemporary academics are illustrating the need for listening to a much broader range of people, In the book, Complaint! Sarah Ahmed introduces us to a term that she calls a ‘feminist ear ’, she describes this as “to hear with a feminist ear is to hear who is not heard, how we are not heard.” It is the process of retraining our ears to pay attention to people or experiences we haven't listened to before, and unpacking how they have been previously silenced. In the built environment, How do we ‘hear who is not heard’?

Sherry Arnstein in her journal ‘A Ladder of Citizen Participation’ suggests that participatory decision making could be this answer. She provides a ‘ladder’ that is a guide to levels of citizen involvement, rating it from ‘ nonparticipation’ (no involvement at all) all the way to ‘citizen control’ (full power to the community) This can be related to the development of a built project, with degrees of community and user involvement from no consultation at all, to tokenistic informing, to co-design and vetoing powers given to communities.

Identity expression in architecture has been very limited. In Feminist City, Leslie Kern writes ‘All forms of urban planning draw on a cluster of assumptions about the ‘typical’ urban citizen: their daily travel plans, needs, desires, and values. Shockingly, this citizen is a man. ’ This assumption created a lot of inappropriate housing, infrastructure and public

MACMAG 48 {39} FRIDAY LECTURE SERIES

spaces. Expressing Identities in Architecture is slowly improving, but not drastically. Laws like the Equalities act in 2010, do set out 9 protected characteristics, but its impact on de facto equality within the architecture profession and the wider built environment has been limited. New construction in urban or suburban areas in the UK also continues to be poor, with the majority of suburban new build housing has been described as “soulless” by Richard Vize in 2019. Large quantities of bland boxes that developers have assumed people want to live in, often based on old-fashioned attitudes to the nuclear family, which are at least 50 years out of date. The lack of reflection or appreciation of the local and diverse lived experience is what makes so much speculative development feel cold and alienating. The bland, identikit tower blocks filling up central London and Manchester seem to be designed with only one customer in mind - affluent young professionals. The new development at Battersea Power Station in London is a particularly potent example, Olly Wainwright called the new starchitect housing a “characterless playground for the super rich”

Some developers are starting to recognise the importance of engaging with communities to create a more appropriate and valid identity, developers websites claiming they are consulting with ‘key community stakeholders’, but many just treat it as a tick box exercise, organising tokenistic events. A recent survey found that only a shocking 2 percent of the population in the UK

said they trusted developers. The overall state of a plural expression of Identities in our built environment is generally poor. There is a definite need for more genuine participation to inject life into future projects.

There is a growing number of practitioners who are making headway in this area, however. We invited Dr Joshua Mardell, Resolve Collective, Austris Mailitis, Dr Adele Patrick, In The Making and Nick Newman to speak as part of the 2023 Mackintosh School of Architecture Friday Lecture Series. They Illustrated how they’ve better established Identities and brought a much broader diversity of voices forward through participatory architecture.

Joshua Mardell spoke to his experience of writing “Queer Spaces” published in 2022, a book co-edited by Adam Nathanial Furman, which attempted to reconcile the absence of queer Identities in architecture across the globe. Joshua’s work focuses on historiographical reflection. Reflecting on the way architectural history has been written, what has been chosen and by who, critiquing authors, and finding the missing sections in order to reconcile specifically queer and feminist absences. Specifically in this case, rediscovering undocumented queer identities. To find these absences, it's a key part of Mardell’s process to turn to collaborators to co-author missing histories. In his lecture he quotes Brown and Nash, who describe the research of queerness as “fluid, unstable, and perpetually becoming”

Queer identities are constantly evolving, so having a single person ’s definition will miss a whole host of voices. In turn suggesting that if you want to get a truer, more holistic picture of these Identities, there is a need for multiple authors from multiple viewpoints to capture the truest sense of this evolving narrative.

Instead of curating the book with queer spaces they knew about, and writing from their own personal experiences, Joshua and Adam reached out to collaborators from across the globe. Joshua told us they “Left it to the authors, there are 55 of them, to decide what constitutes a queer space, we ’ve honoured their definitions. Thus we hope to be sensitive to a whole host of cultural traditions.” By writing the entries in this way, commissioning ‘experts’ (people who lived, worked, visited, heavily researched) to write the extracts, they gave the atlas even more truth and identity. This resulted in a variety of voices and short pieces of over 90 ‘ queer ’ spaces.

A Participatory process can also be applied to more traditional architecture projects, another one of our invited guests, Resolve Collective, Illustrate this, who practice what they call ‘Community Mining’. They were invited by Southwark council to take on an engagement role alongside DSDHA who were creating options for the masterplan for Tustin Estate in South London. Their approach manifested in both general engagement events, to ‘mine’ community knowledge, feelings and opinions, as well as series

MACMAG 48 {40} FRIDAY LECTURE SERIES

of more tailored events. The general engagement consisted of pulling up in front of the school on the estate with coffee and food, giving information about the redevelopment process, when and where important meetings were, and starting the conversation. The second approach which was to expand the ‘community mining’ beyond the set brief, they began to work on projects that used the newly tapped resource to create projects that were unrelated to the redevelopment, but enabled the residents to have more autonomy over their space. These events included a Youth workshop which was a knowledge exchange; the kids that attended were taught the basics of a design process, and then tasked with designing a small light hearted intervention they felt their neighbourhood needed. They also collaborated with residents on the estate to design and deliver a community Garden that any resident could use, once completed

the organisation of the garden would be handed over to a resident steering group, which would give them full autonomy.

This project illustrates how Resolve took a deep dive into helping residents have their identities heard. It's interesting how they acted in two ways, one by plugging people into the decision-making process, but also by taking the funding they had to create third spaces for residents that they would have more autonomy over. Unfortunately, the project was halted by the outbreak of Covid19, so its had to discuss the long term impact, but after presenting a lecture for the Architecture Foundation, residents and a senior councillor from Southwark praised the project because the architect and council team had consistently shown that they’d taken on resident' s feedback and adjusted the scheme accordingly. This is an important part of the process,

as without this the engagement would not have instilled the project with any more of an identity, the cross collaboration and listening with a ‘feminist ear ’ is key.

These are just two examples of how beneficial citizen participation can be to establish Identities. Our speakers and many more practitioners like Glasgow’s own New Practice and Green party’s Holly Bruce are paving the way to a much more collective expression of architecture and urbanism. All of this term's Lectures are accessible to students on GSA’s planet E Stream.

MACMAG 48 {41} FRIDAY LECTURE SERIES

Stage Leader

Luca Brunelli

Co-Pilot

Neil Mochrie

Tutors

Graeme Armet

Jonny Fisher

Colin Glover

Alan Hooper

STAGE TWO

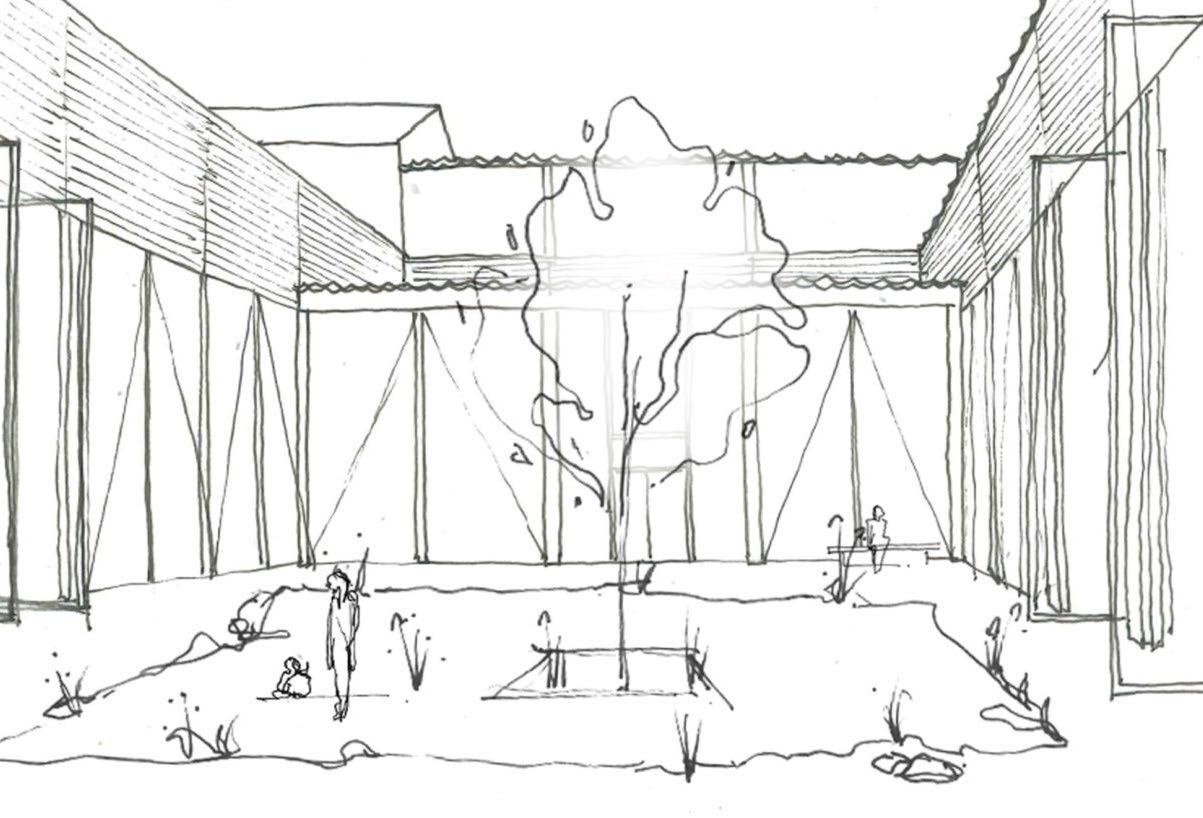

Stage 2 Studio Work continues to ask students to explore the convivial potential of architecture to foster a community’s freedom to interact and to contribute creatively to the environment in which they live, outside the dominant forms of production and consumerism. The entire year’s work is set in Bo’ness, a small commuter town on the shore of the Firth of Forth.

Semester 1 focuses on housing typology and terraced housing in particular, as a generative tool to explore spatial organisations that can support new forms of living and working together, those which

promote sustainable lifestyles, reduced transport needs, lower energy use and the sharing of resources.

Semester 2 is informed by the material harvesting approach developed in the urban mining exercise examined in the collaborative Studio Practices exercise with Product Design Engineering students. The final project of the year asks students to become acquainted with the contemporary debate on adaptive reuse through intervening on the existing local library building, carefully crafting a tectonic strategy to reimagine the nature of this public institution for the future.

MACMAG 48 {45} STAGE TWO

Student works featured in this segment are from 2021/ 2022

MACMAG 48 {46} STAGE TWO

A Warehouse and a Social Condenser

STEFANS PAVLOVSKIS

In the place of Bo’ness library stands a pool of shared knowledge and resources.

The existing library premises are reduced in size and, by the creation of a new spatial order, turned into a warehouse fit for anything, open to anyone. The library as a repository is liberated from its social duties; those are greatly exaggerated and moved elsewhere - to the High Street, where their presence contributes towards a social condenser - the centre of exchange, work and leisure.

The vacant High Street retail premises are taken as found, fitted with simple interventions ensuring spatial and programmatic affordances and enabled with active objects- risographs, hearths and extremely long tables dismantled and reused due to minimal adhesives and mechanical fixings.

MACMAG 48 {47} STAGE TWO

ADAM WALSH

The aim of this project was to create a new extension for the library in Bo’ ness, accommodating a pair of old industrial buildings that make up a portion of the existing library’ s footprint.

My design tried to connect Bo’ ness ’ old industrial harbour and shipbreaking history to the town that it is today. The new extension, reminiscent of a ship’s skeletal keel and clad in pre-rusted Corten steel, protrudes out towards the old quay and the Firth of Forth beyond that. The spaces created inside and around the new build aim to draw in visitors, turning the waterfront into a hub of activity once again.

MACMAG 48 {48} STAGE TWO Library

A Modular Manifestation

JAKE STEWART

JAKE STEWART

Bo’ness library, a hidden public space. The missing element to the existing building is its very existence, The clarity of public is not made as the library is lost in its inability to architecturally communicate itself as such. Conviviality within the library space thus needs a welcoming architectural language promoting a collectiveness within Bo’ness. Working within the briefs specification of sustainable adaptability, modular elements developed as a solution in creating a needed expansion of the existing buildings footprint and circulation but importantly to project outwards the ongoings within the building. This being phase 4 of Bo’ ness libraries historical development, the modular block network proposal seeks to adapt with time and not remain stagnant, providing a future development strategy/blueprint.

MACMAG 48 {49} STAGE TWO

Bo' ness

MILES WILTSHIRE

The proposed structural columns are designed as a latticework with the walls serving as bookshelves to create the library function. The library is mostly secluded with little glazing which creates privacy and tranquillity. The restaurant draws people into the building encouraging them to engage with the facilities. The restaurant straddles between the existing tavern and the new canopy which hangs within the double-height library space. The book-filled walls provide acoustic attenuation for the sound permeating from the busy restaurant.

MACMAG 48 {50} STAGE TWO

MACMAG 48 {51} STAGE TWO

Re-Assembling The Library Of Bo'Ness

JULIETTE DE METZ

JULIETTE DE METZ

The new library retains three elements of the old library independents, as historic prints: the tobacco warehouse, the tavern and the staircase, part of the extension built in the 1980’s. The intervention consists of linking these parts together with an open space that contrasts with the existing. The existing is characterised by defined and closed spaces, whereas the extension is a polyvalent open space allowed by the curtains. The landscape influences the project: the extension seems to expand towards the open view, the entrance interacts with the street and creates a feeling of enclosure that welcomes people in the library.

MACMAG 48 {52} STAGE TWO

MACMAG 48 {53} STAGE TWO

Re-assembling the library of Bo' ness

RONNELL CALIWAG

The project is to analyse and understand the presence and quality of Bo’ness library’s materials and develop a strategy of alteration, addition and occupation. Develop the existing library with the design proposal of reuse and expansion, and the physical presence of the existing building and its part should be carefully considered. The final design combines traditional stone structure and modern structure style. The new proposed extension building was inspired by a sailing ship because Bo’ness has been known for ports since the 18th century. There is a space for informal assembly or exhibition on the ground floor, and on the first floor is a space for meeting other activities. There is a large window between the old and new buildings so that people can see the connection between the two buildings. On the second floor, there is quiet reading and research with an extended Lozenge or stairs to access the new building. There is a skylight on the single storey of the building and a glass wall that can provide natural light and minimise the number of artificial lights.

MACMAG 48 {54} STAGE TWO

MACMAG 48 {55} STAGE TWO

BACK TO THE DRAWING BOARD

In conversation with Will Knight

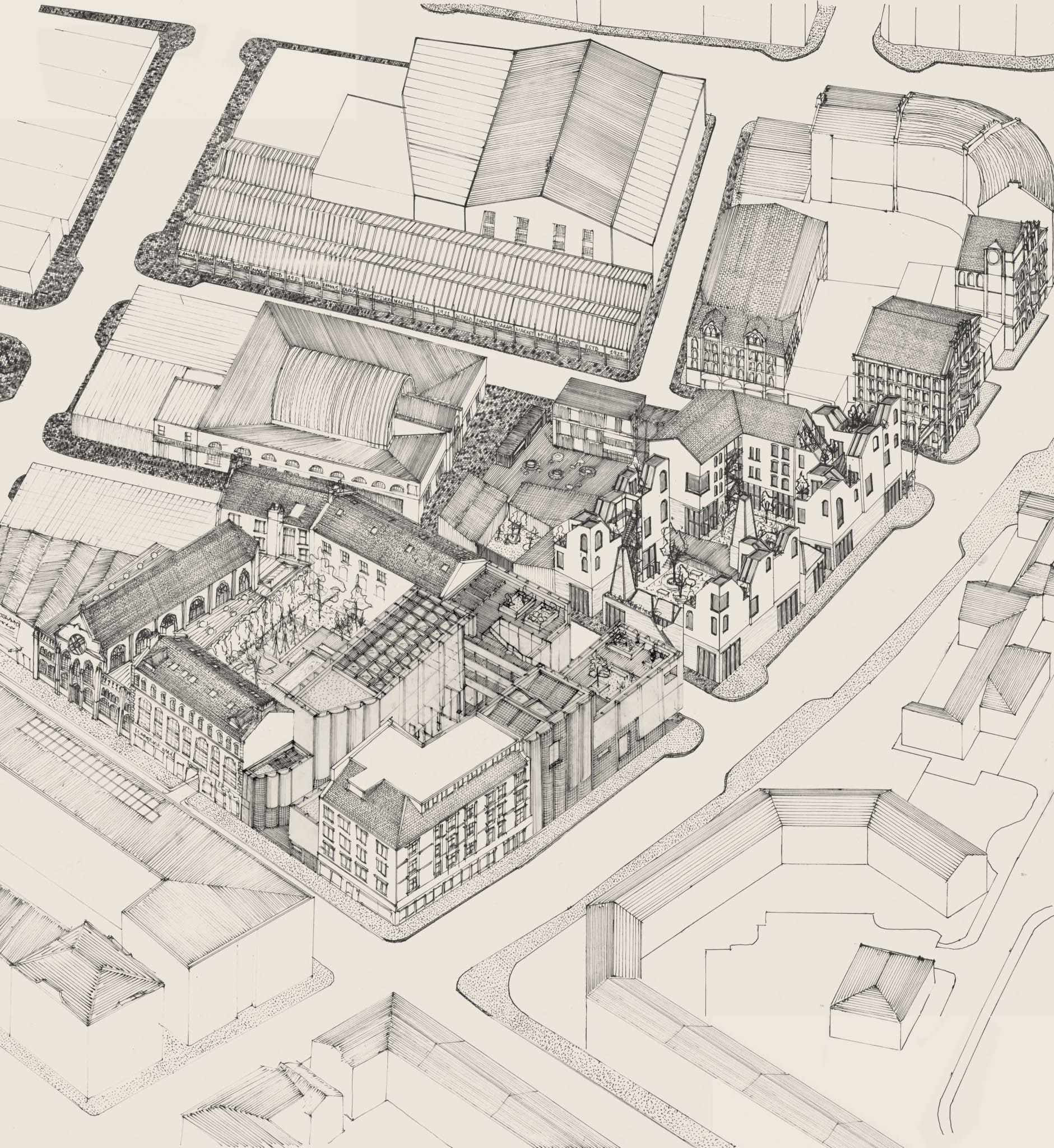

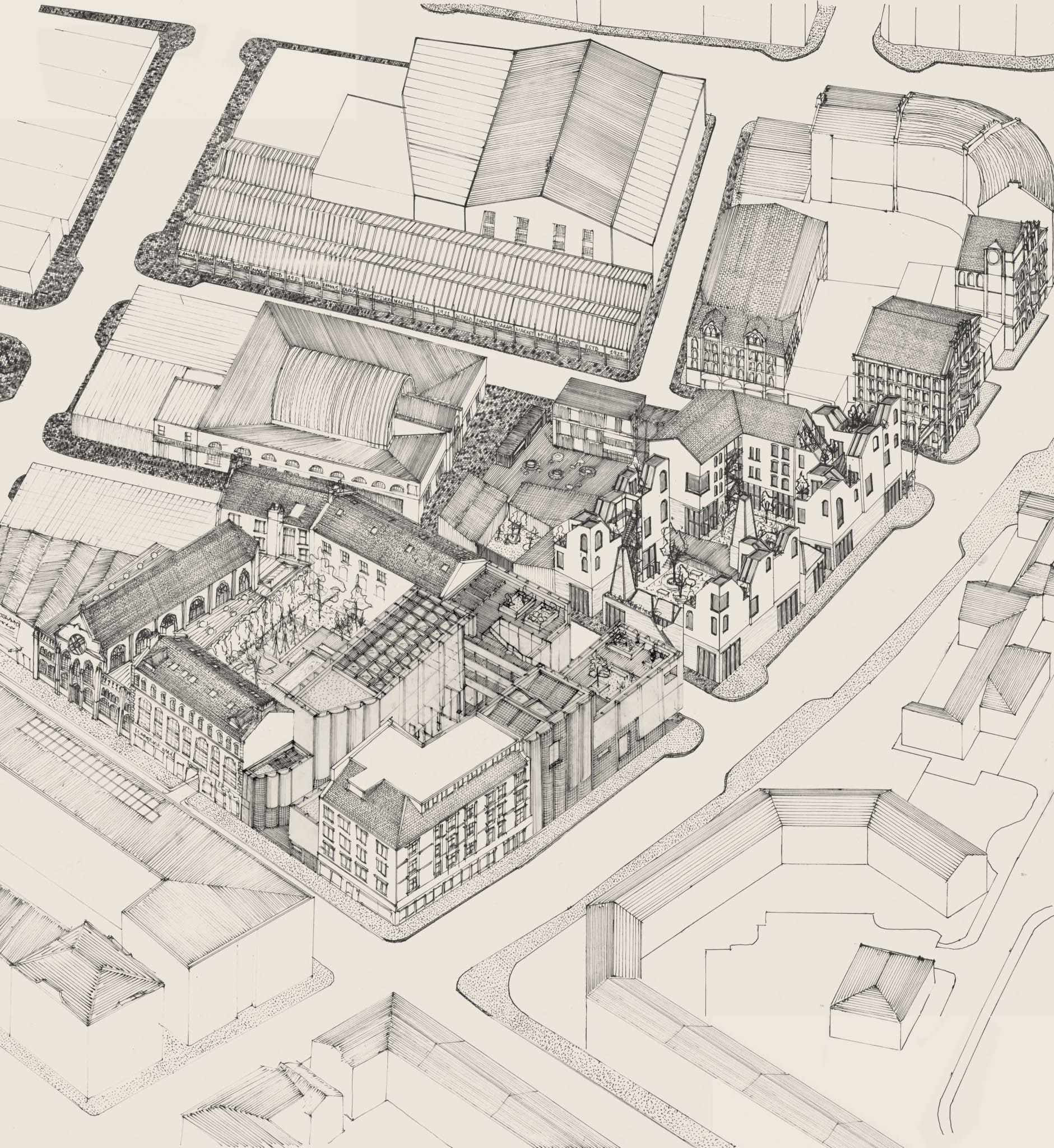

Will Knight is a freelance artist who studied at the Mackintosh School of Architecture between 2007 and 2014 before working for Carson & Partners and StudioKAP. He is known for his drawings of domestic, industrial and commercial buildings which he investigates through recording, measurement and drawing by hand. In 2022 he was commissioned by the Glasgow City Heritage Trust to draw a contemporary bird’ s eye view of Glasgow as part of the Gallus Glasgow project.

MacMag interviewed him at his flat in March 2023 to talk to him about how he developed his individual style, how training as an architect influenced that style and about how he approached his recent work.

MACMAG: To begin with, could you give us in your own words an overview of what your work entails?

Will Knight: My studies in architecture definitely informed my approach to drawing and my approach to looking at the world around me. It was my Masters by Conversion that led me to begin to draw in this way of accurately representing the world in scale and through plan, section, and elevation. It is a way of interpreting existing architecture through drawing and then helping us, through the drawing, to look again at what is around us.

MM: If you had not decided to

study architecture do you think you would have still considered being an artist and would you have been as interested in the arts?

WK: I have always had a love of drawing. It started as a child and then in school which probably led me into architecture. I have always liked the idea of working in the realms of reality. As a kid I forensically drew pirate ships and then football stadiums, and then obviously played with Lego where you're being creative but within a sort of programme or within a boundary and a certain limitation. The way I draw buildings and the way I interpret the world has been massively informed by

MACMAG 48 {56} WILL KNIGHT

studying architecture. I think that the education taught me to think about buildings in a way that I would not have before. Although there is a shift, a lot of the education is about designing, whereas I am now recording. Though even in the way that I am looking at things would be the same way that a designer would look at things, rooms or spaces that inspire me or qualities of a space or a certain aesthetic, so I think, certainly, I would not be creating these drawings were it not for studying architecture. Absolutely not.

MM: And following on from this, how would you say that your time in practice working as an architect informed your perspective?

WK: In terms of the drawing, I have not really considered it. I think I often saw the two as so different. My time in practice gave me a greater appreciation of any architecture that does get built in terms of how complex buildings are and how the journey from paper to a building is an exercise in collaboration. I think it maybe gave me a sort of greater zeal to enjoy drawing and to enjoy the freedom of creativity and it maybe gives me more confidence in a sort of professional sense as well. As I was once in the world of work you have an experience and I think perhaps having had that experience, that benefits me in terms of ‘I've worked in architecture and now I do these drawings’. I think in terms of the sort of aesthetic of the drawing it’s probably quite different to what is produced in CAD in practice. Certainly

MACMAG 48 {57} WILL KNIGHT

some of the qualities are there. I worked at Studio KAP and their survey drawings were always pretty detailed. Certainly in terms of practically doing surveys, that has helped going into drawing. I suppose in the way that an architect wants to ideally cover everything, I think there was maybe that obsession with recording and covering everything too, but there is definitely a difference in the, perhaps to my detriment, idea of when an architect produces a drawing in the office there is time and a cost of that drawing, and sometimes I approach these drawings as if there is limitless time and the hourly rate would not necessarily be what you would get as a Part I. There is a great essay by Helen Thomas about the idea of non-productive expenditure. The idea that you can produce something beautiful that you cannot measure in monetary terms but there is something about the practice of drawing that is not necessarily about getting it in for planning, getting it printed and getting it sent off to the client.

MM: How did the transition from drawing as an architect to drawing as an artist come about

and was it a gradual process?

WK: I think it was a gradual process. I started doing these sorts of drawings in my Master’s project. I was drawing bakeries in Glasgow. I think they are still in the Bourdon, at the Mack, and they were quite well received by tutors. And I enjoyed the process of making them, and I enjoyed the idea of a research project where I am effectively an architect and these bakeries were the clients, and you are bringing people with you. So I think it is far more collaborative than I thought it would be in terms of you are not just producing something for yourself, you are taking someone on the journey and showing them, and they are welcoming you into their world, for you to record though drawing.

MM: Would you say there is a particular drawing that you ’ve done that you would say encompasses what your practice represents?

WK: I do not think I could say that because they are all real spaces; they all have their own qualities that I appreciate. I think it comes back to enjoying

the whole process and I think each of them do that which sounds highfalutin, but I think it is down to the fact that you are drawing everything and you are spending time in the place to survey it. One of the key things about drawing is I never make a drawing without the stakeholder’ s permission. I never just turn up and start walking around bars, cafes, shops or people’ s houses. Each of the drawings has a person behind it, which maybe sometimes is lacking in exhibitions where people want to know who owns this place, who lives there and what is the story of this place. I guess each of the drawings has that so I think it is very difficult to say one particular one. It is probably drawings that I enjoy the aesthetic of, but whether that is about it encapsulating my whole practice, probably not, but more about enjoying the interior; somewhere like the Laurieston Bar, for example, which I am working on at the moment and I am really enjoying recording that through drawing. There is a brilliant tea and coffee shop in Dundee called J.A Braithewaites and it has been in the same family since 1924 and I drew that. It has all

MACMAG 48 {58} WILL KNIGHT

these tea caddies and I guess it is places that are beautiful and full of life, but not necessarily in the way that we would design as architects - places that have layers of history. But I could not pick one.

MM: What are the steps that go into your drawing process? Could you run through how you would begin a piece?

WK: Absolutely. I would start with going to the place and then doing some quick sketches in my sketchbook of what the client or what I would see if I got the section in a certain way or a plan or elevation. Then from that, we would make a decision and then use that drawing to then make a survey. I am only ever surveying to make a drawing, which is probably quite different to how an architect would survey where they are having to make a whole suite of drawings. That survey drawing is then translated usually at 1: 20 scale, which I find is a scale that is manageable in terms of paper size but also enables