SEMI-SPLIT

Bulk Placement Technique

THE PREVENTIVE EFFECT of glass ionomer restorations on new caries formation

DENTSPLY SIRONA

Equips Qatar’s first dental school BIDM 2022

SEMI-SPLIT

Bulk Placement Technique

THE PREVENTIVE EFFECT of glass ionomer restorations on new caries formation

DENTSPLY SIRONA

Equips Qatar’s first dental school BIDM 2022

Based on the close and fruitful cooperation with dental institutes and practicing dentists since the 1940s, we have a uniquely broad portfolio of specially developed, innovative toothpastes, gels, sprays, mouthwashes and mouth baths. These products, which are marketed under the brands Tebodont®, Emofluor®, Emoform®, Depurdent® and Emofresh® are sold exclusively in pharmacies in Switzerland and in more than 40 other countries outside Switzerland, their various innovative formulations and compositions offer excellent solutions for daily dental care, addressing specific needs and problems (e.g. caries prevention, sensitive teeth, gum problems) and general oral health.

With the REDESIGN we have clarified the positioning of the oral care products: every toothpaste and every mouthwash now has a clear application area. At the same time, our new packaging is "digitalized": each product has a QR code that allows detailed information to be downloaded directly to the mobile phone. The redesign of the products should make the Wild brand tangible and perceptible.

• WILD will be used as umbrella brand on all products, which results in an easier promotion among the whole product range

• Same design for all brands leads to recognition and synergy effects across product range

• Clear unique main indication on the packaging avoids confusion among dental profession, pharmacists and end consumers due to overlapping benefits

• New design underscores clinical benefits and professionalism of the products which leads to cross-brand and cross-portfolio products awareness and helps to create trust among the dental profession, pharmacists and end consumers

• Unifying of the packaging system - all toothpastes in the same size and shape of tubes, all mouthwashes in the same size and packaging - leads to a uniform, eye-catching and space-saving shelf-impact

• Product portfolio becomes fresh, easy to recommend and attractive for the POS

Volume XXIX, Number IV, 2022

Volume XXIX, Number III, 2022

Alfred Naaman, Nada Naaman, Khalil Aleisa, Jihad Fakhoury, Dona Raad, Antoine Saadé, Lina Chamseddine, Tarek Kotob, Mohammed Rifai, Bilal Koleilat, Mohammad H. Al-Jammaz

Suha Nader

Marc Salloum

Micheline Assaf, Nariman Nehmeh

Josiane Younes

Albert Saykali

Gisèle Wakim

DIRECTOR ISSN

Tony Dib 1026-261X

DENTAL NEWS IS A QUARTERLY MAGAZINE DISTRIBUTED MAINLY IN THE MIDDLE EAST & NORTH AFRICA IN COLLABORATION WITH THE COUNCIL OF DENTAL SOCIETIES FOR THE GCC.

Statements and opinions expressed in the articles and communications herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Editor(s) or publisher. No part of this magazine may be reproduced in any form, either electronic or mechanical, without the express written permission of the publisher.

AIDC 2022

Alexandria

International Dental Conference

Kuwait Dental Association Conference

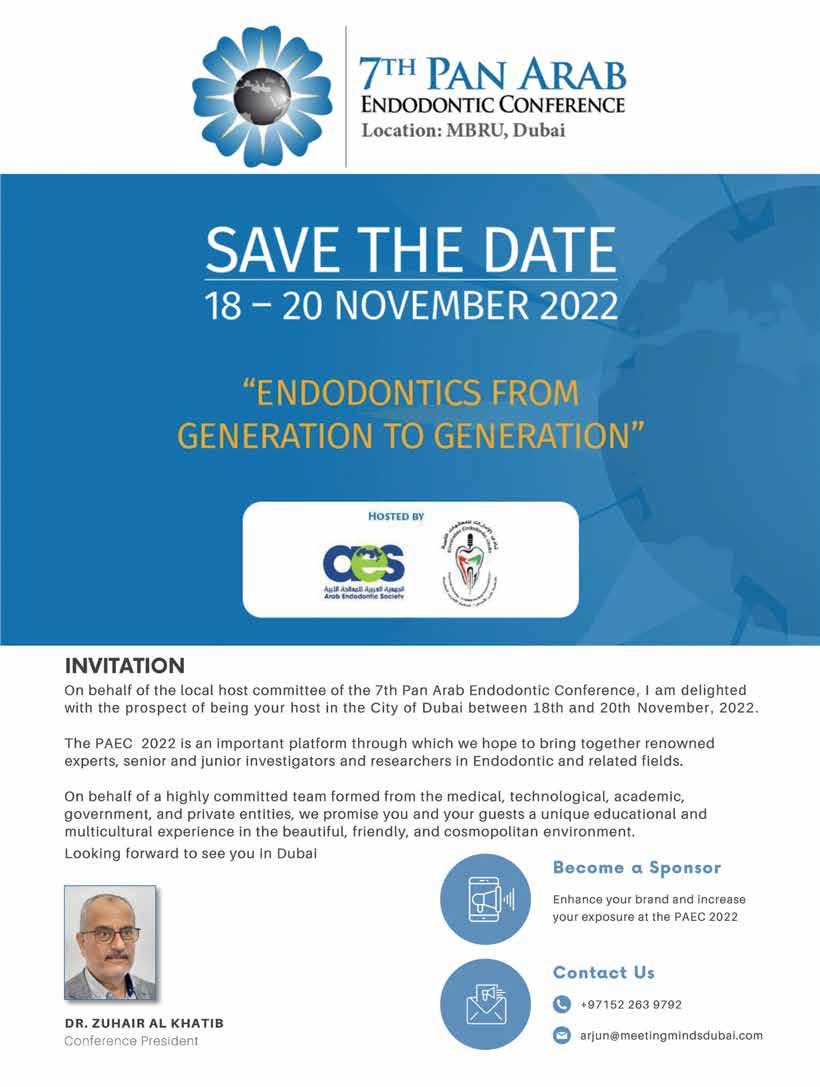

7th Pan Arab Endodontic Conference 2022

November 16-18 2022

Hilton Green Plaza, EGYPT www.aidconline.ney

November 17-19 2022 Jumeirah Hotel, KUWAIT and

DENTAL NEWS – Sami Solh Ave., G. Younis Bldg. POB: 116-5515 Beirut, Lebanon.

Tel: 961-3-30 30 48

Fax: 961-1-38 46 57

Email: info@dentalnews.com

Website: www.dentalnews.com www.instagram.com/dentalnews

ADF 2022

18 – 20 November, 2022 MBRU, Dubai, U.A.E. zzk321@gmail.com

November 22 _ 26, 2022 Palais des Congrès de Paris, FRANCE www.adfcongres.com

Greater NY Dental Meeting

27 – 30 November, 2022 Jacob Javits, New York, USA www.gnydm.com

This magazine is printed on FSC – certified paper. WWW.DENTALNEWS.COM

SIDC 2023

January 19 _ 21, 2023

The Saudi International Dental Conference Hilton Riyadh Hotel, KSA www.sds.org.sa

AEEDC 2023

February 7 _ 9, 2023

Dubai World Trade Center, UAE www.aeedc.com

IDS 2023

March 14 _ 18, 2023 Cologne, GERMANY www.english.ids-cologne.de

7TH PAN ARAB 63

A-DEC 25

AIDC 59

AEEDC 71

BIDM 64

BELMONT 9

DMP 1

DURR 23

Semi-Split Bulk Placement Technique For Overcoming The Loss of Adaptation At The Pulpal Floor of Large Occlusal Bulk-Fill Resin Composite Restorations

The preventive effect of glass ionomer restorations on new caries formation: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Dentsply Sirona equips Qatar’s first dental school with cutting-edge training tools to prepare the next generation of dental professionals

DIRECTA 27-29

DENTSPLY SIRONA 72

EDGE FILE 21

FKG 31

GNYDM 67

HS BA024 17

HENRY SCHEIN 33

ORTHO 15 PROMEDICA 39

ROLENCE 35

SHINING 3D 43

SDI 33

SIDC 55

ULTRADENT HALO 19

48 The Lebanese Orthodontic Society

JULY 15, 2022 - GEFINOR ROTANA, BEIRUT

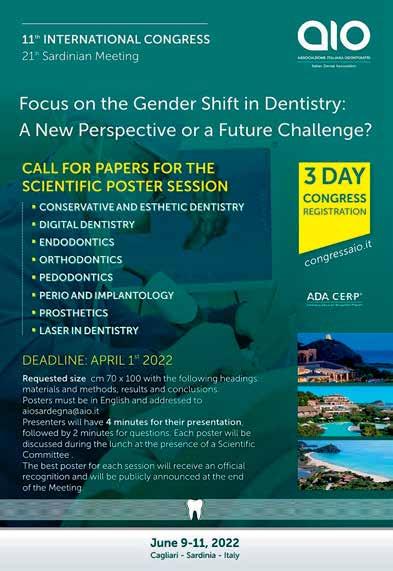

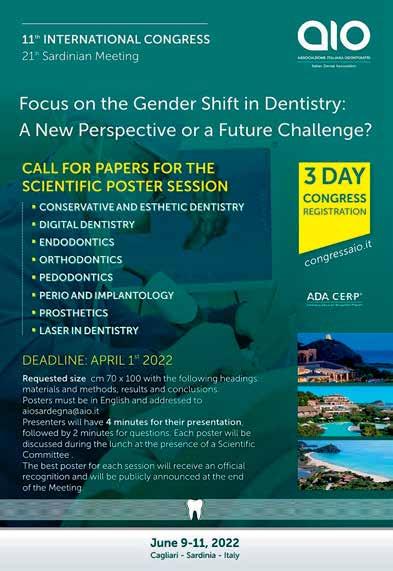

The Lebanese Dental Association congress AIO 56 68

OCTOBER 13-14, 2022

JUNE 9-11, 2022

CAGLIARI - SARDINIA - ITALY

MANI-JIZAI 37

IDS 71

MANI-JIZAI 37

VOCO 2, 13

WILD 3, 4, 5

Khamis A Hassan*, BDS, MSD, Doctorate, FADI *1, Professor of Operative Dentistry & Senior Clinical Consultant, Global Dental Centre, Vancouver, Canada

Salwa E Khier, BDS, MSD, MSc, PhD, FADM 2

Professor of Dental Biomaterials & Senior Research Consultant, Global Dental Centre, Vancouver, Canada

*Corresponding author

Dr. Khamis A Hassan, Professor of Operative Dentistry & Senior Clinical Consultant, Global Dental Centre, Vancouver, Canada. E-mail: globaldental@ shaw.ca

Keywords

Bulk placement, bulk-fill resin composite, debonding, diagonal gap, displacement, polymerization shrinkage, postoperative sensitivity, pulpal floor gap, semi-split bulk, stress reduction.

Abstract

When composite resin hardens by light curing, it shrinks and undergoes deformation which occurs in one region more than other regions within the composite bulk. This behavior is mainly related to variations in bonding to enamel and dentin of surrounding cavity walls. Bonding to surrounding cavity walls creates restrained shrinkage which develops tensile stresses within the composite bulk. The developed tensile stresses act against the tensile strength of the composite resin, and may cause cracks in enamel or composite, as well as residual strain at the adhesive interface, forming marginal and internal gaps.

Using the bulk filling technique, a bulk of 4mm increment of bulk-fill resin composite is placed in a deep Class I cavity. Within the composite bulk, shrinkage displacement occurs axially in the top region more than in the bottom region, resulting in debonding and gap formation at the pulpal floor. This gap is associated with persistent postoperative

sensitivity and consequent pain. The semi-split bulk filling technique is a modification of the bulk filling technique used for placing bulk-fill resin composites in large occlusal cavities. It aims at diminishing the shrinkage stresses within the composite bulk and minimizing the incidence of pulpal floor gap formation and the consequent postoperative sensitivity and pain.

Introduction

In the past decade, bulk-fill resin composites have been introduced in the dental market as a new concept for restoring posterior teeth. 1-3 They became popular among dentists who prefer simpler clinical procedures with reduced working time. 4,5

Bulk-fill resin composites were claimed by manufacturers to have a depth of cure of up to 4- 5mm. The increased depth of cure is achieved by using more efficient photoinitiators 6 , or by using fillers and monomers with similar refractive index. 7

Another group of bulk-fill resin composite was claimed by manufacturers to have a reduced shrinkage stress, as compared to that of the conventional composites placed incrementally. The stress reduction is achieved by additions in the organic matrix of low-shrink monomers, higher molecular weight monomers, or stress-relieving additives. 1

Polymerization shrinkage is an undesired property of dental composites which causes a discrepancy in dimensions when the restoration hardens. This affects the interface and results in residual strains at the adhesive interface, or marginal/internal gap formation. 5,6

The polymerization shrinkage stress is a complex phenomenon as it depends on several factors. Among which are the boundary conditions, the amount of material, and the polymerization reaction. They all play essential roles in stress development and/or transmission to tooth structures. 8,9

Within a large occlusal composite restoration placed as in bulk of 4mm increment using the bulk filling technique, a greater shrinkage strain or displacement takes place in the top composite region, where it undergoes more axial displacement than the bottom composite. 7,10 Additionally, the top composite displacement exerts an upward pull on the bottom composite region resulting in its debonding from the pulpal floor, and formation of pulpal floor gap beneath the composite restoration. 5,6,11

Several studies found that bulk-fill resin insertion technique resulted in higher rates of postoperative sensitivity compared to conventional resins. This sensitivity was attributed to the formation of pulpal floor gap in bulk-fill resin composite occlusal restorations. The dentinal fluid in the gap undergoes contraction or expansion with cold or hot stimuli, resulting in sudden movement of the fluid in dentinal tubules and causes pain. 1,12-14

The objective of this paper is to present the semisplit bulk filling technique, as a modification of the bulk filling technique which is used for placing bulk-fill resin composites in large occlusal cavities. This technique aims to reduce the shrinkage stresses generated due to the polymerization of bulk-fill resin composites, as well as to minimize the incidence of gap formation at pulpal floor, and consequent postoperative sensitivity and pain.

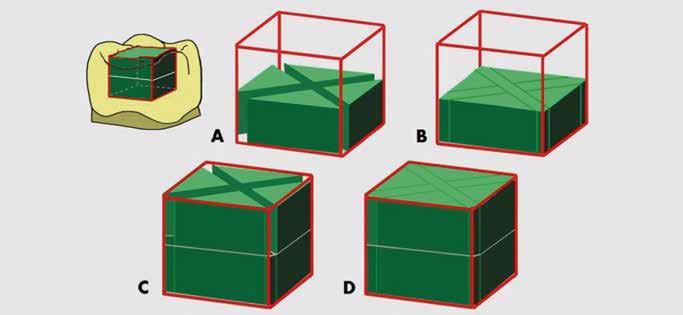

In the semi-split bulk filling technique, a diagonal gap (1.5mm wide) is created vertically into the 4mm composite bulk inserted in a large occlusal bonded cavity. This gap extends for a depth of 2mm, prior to light polymerization, using a Tefloncoated plastic filling instrument in push stroke.

This gap splits the top composite 2mm region into two equal segments. The segmented composite bulk is then light cured. The diagonal gap is then filled with the same bulk-fill resin composite and light cured.

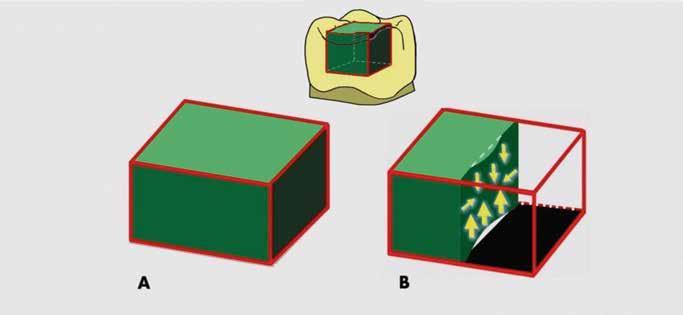

The shrinkage stresses generated in bulk-fill resin composites exert tension on the bonding adhesive and surrounding tooth structure during the polymerization process. If this tension exceeds the adhesive bond, or the strength of either the composite or tooth, it can cause interfacial debonding, resulting in internal/marginal gaps. Comparing the incremental vs. the bulk filling techniques, the bulk filling technique was reported to produce more interfacial debonding. 15-17 In the bulk filling technique, the shrinkage stress occurs during light polymerization within a bulk of 4mm increment of bulk-fill resin composite inserted into a large occlusal cavity. (Fig. 1- A) The magnitude and direction of shrinkage stress varies between the top and bottom composite regions. 7,10 The polymerizing bulk-fill resin composites undergo shrinkage displacement in both axial and lateral dimensions, with less displacement occurring laterally than axially. The axial displacement in the top 2mm composite region occurs in downward direction, whereas it takes place in upward direction in the bottom 2mm composite region. 18,19 Additionally, the top composite displacement exerts an upward pull on the bottom composite region strong enough to result in its debonding from the pulpal floor, and formation of pulpal floor gap beneath the composite restoration. 2022 (Fig. 1-B) The strength of the upward pulling is augmented by bonding the composite in the top region to enamel and dentin of surrounding cavity walls, as compared to bonding to dentin only in the bottom region. Moreover, the upward pull is boosted by the position of the light tip closer to the occlusal outer area of the cavity, leading to its faster polymerization than that at the cavity floor, 22,23 and subsequently resulting in immobilization of the resin matrix in the top composite sooner than in the bottom composite. 24-26 It is noteworthy to mention that scattered areas of bonding and gaps could coexist within the same restoration. 27

It is well understood that bulk-fill resin composites

were introduced in the dental market for their easy placement in cavity preparations as one piece using the bulk filling technique which saves much of the chairside time. However, this technique is reported to cause more axial than lateral shrinkage displacement in the top composite region and to generate more axial stresses which result in debonding at the pulpal floor and gap formation, leading to persistent postoperative sensitivity and pain. 1,5-7,10-14

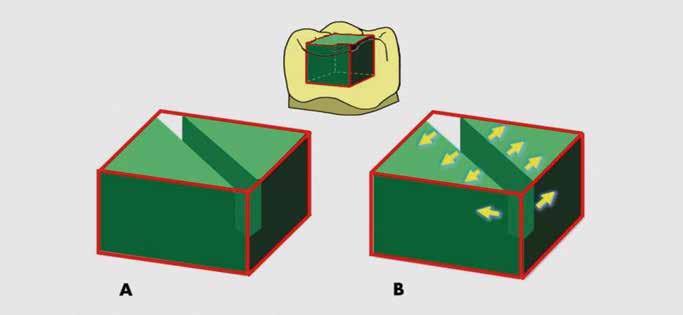

As a solution, the semi-split bulk filling technique is presented for modifying the bulk filling technique by using an additional step which needs a little extra chairside time. This technique is based on creating a diagonal gap into a bulk of 4mm increment of bulk-fill resin composite, prior to light curing. This gap is 1.5mm wide and extends for a depth of 2mm in the top composite region splitting it into two equal segments. (Fig.2-A) The rationale for the presented technique is that the created diagonal gap would enable, through its adhesion-free surfaces, each composite segment to undergo more lateral than axial shrinkage displacement, in contrast to the more axial than lateral shrinkage displacement which occurs in composite bulk when using bulk fill technique. The outward displacement is expected to exert a lateral pull on each composite segment in opposite direction away from the gap center and towards the bonded cavity walls. The outward displacement of each segment in opposite direction is anticipated to greatly relieve the polymerization shrinkage stress and preserve the marginal and internal gap formation in cavity walls, resulting in volume reduction of each segment and diagonal gap widening. (Fig.2-B) Furthermore, the created diagonal gap is expected to disable the less occurring axial displacement from gaining strength through bonding to enamel and dentin in the top composite region and exerting upward pull on the bottom composite region, preventing/ minimizing its debonding away from the pulpal wall and forming a pulpal gap, in contrast to that which occurs in composite bulk when using bulk fill technique. (Fig.3-A)

Following the light curing of the segmented composite bulk, the diagonal gap is filled with the same bulk-fill resin composite and light cured, (Fig. 3-B). Considering the small composite volume used for filling the diagonal gap, the generating shrinkage stress is judged to be unable to cause

deleterious effects on tooth enamel, composite resin, and/or adhesive interfaces.

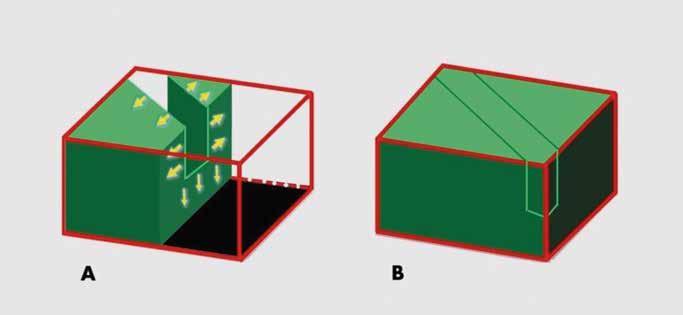

There are variations in the number of diagonal gaps and depth between the presented technique and the original split-increment technique. In the presented technique, the gap extends halfway for a depth of 2mm into the 4mm thick composite bulk, whereas in the original split-increment technique 28, it extends into the full thickness of each of the 2mm increments.

(Fig. 4) In the presented technique, the reason for not extending the gap into the full depth of 4mm thick increment is that the diagonal splitting created in the top composite minimizes its axial displacement and greatly decreases the likelihood of exerting an upward pull on the bottom composite. As for the number of diagonal gaps, only one diagonal gap is created into the single composite bulk in the presented technique, whereas two gaps are created in the original technique (Fig. 4). The creation of two diagonal gaps in the presented technique is considered unnecessary because of the generation of lower polymerization shrinkage stress in most bulkfill composites, according to manufacturers, as compared to that developed in the conventional resin composites used in the original technique. Several studies 15,29,30 reported that bulkfill resin composites resulted in higher rates of postoperative sensitivity as compared to conventional composite resins and was attributed to pulpal gap formation beneath the composite restoration. The pulpal gap formation is attributed to postoperative sensitivity which fills with dentinal fluid. This fluid undergoes contraction or expansion by cold or hot stimuli, resulting in its sudden movement in the dentinal tubules which makes postoperative sensitivity persistent and causes pain. 29 It has also been reported that bulk-fill flowable composites also resulted in gap formation over the internal walls of the restored cavities. 30

The restorative techniques, along with some other factors were reported to affect the shrinkage stress generation, debonding, and postoperative tooth sensitivity, as well as microleakage, and secondary caries. 1 The original split-increment technique, as compared to the oblique layering technique, significantly minimized microleakage in Class V silorane-based resin composite restorations. 31 Also, it had the least microleakage

• Excellent adhesion

• Precise marginal fit

• Secure and quick bonding (self-adhesive)

• Almost

Source: Prof. Dr. Jürgen Manhart, Munich / Germany

Figure 1: The bulk filling technique for placing a single composite bulk. (a) A large occlusal bulk fill resin composite restoration. (b) A sectional view, illustrating more axial than lateral shrinkage displacement and more upward axial displacement along with gap formation at pulpal floor.

Figure 2: The semi-split bulk filling technique using a single composite bulk; (a) Prior to light curing, a 2 mm deep diagonal gap created in composite bulk; (b) Upon light curing, each composite segment undergoes lateral shrinkage displacement from the gap center outwards, resulting in volume reduction of each segment and diagonal gap widening.

Standardize and simplify your SLX® Clear Aligner cases, reducing total treatment time and the number of aligners required

The Carriere® Motion 3D™ Appliance is used at the beginning of treatment for rapid A/P correction prior to braces or aligners when there are no competing forces operating, and patient compliance is at its highest. By resolving the most difficult part of treatment first, you can achieve an ideal Class I platform in 3 to 6 months, which can then shorten overall treatment time by up to 6 months with SL X 3D Brackets or SLX Clear Aligners.

Employing SAGITTAL FIRST ™ also means many fewer trays and simple, ��-minute bonding is perfect for same-day starts. 3 — 6 MONTHS*

Figure 3: The semi-split bulk filling technique; (a) A sectional view, illustrating more lateral than axial shrinkage displacement of the top composite, resulting in no gap formation at pulpal floor; (b) Diagonal gap filled with the same composite, and light cured.

Figure 4: The original split-increment technique using two increments of conventional composite resin; (a) Prior to light curing, two diagonal gaps are created in first composite increment, and light cured; (b) Diagonal gaps filled using the same composite resin, and light cured; (c and d) Diagonal gaps in the second increment created and filled, as in the first increment.

• Plug and play micromotor, easy to install

• Connects to your chair’s air supply

• Cost-efficient conversion to electric

• Perfect for speed increasing handpieces

• Internal spray and LED

• Brushless endo motor with inbuilt apex locator

• 6:1, 360° rotatable contra-angle head.

• Presets for many file types incl. EdgeEndo.

• Small head diameter (8mm) and height (9.7mm): more visibility during operation

• Speed range: 100-2500rpm

• Torque range: 0.4Ncm-5.0Ncm

• 1:5 red band contra-angle

• Anti-retraction valve

• Less aerosol generation

• Ceramic bearings

• Fibre-optics and quadruple spray

• Titanium body with PVD coating

at occlusal and gingival margins in Class II composite restorations, followed by centripetal and oblique techniques. 32 Moreover, the original technique exhibited lower degrees of microleakage at the occlusal and gingival margins of Class V, as compared to the oblique and occlusogingival incremental techniques. 33 Furthermore, the split-increment technique and the group with fiber inserts in gingival increment technique showed significantly lower microleakage at gingival margins in Class II restored with a nanocomposite resin when compared to bulk insertion, oblique, centripetal, and flowable composite techniques. 34

Based on the results of the research studies conducted on the original split-increment technique, it is expected that the presented semi-split bulk filling technique would be able to minimize the shrinkage stress and decrease the incidence of pulpal gap formation beneath the large occlusal bulk-fill resin composite restorations.

A research study is currently underway to investigate the effect the presented technique on reducing shrinkage stresses and pulpal gap formation in large occlusal bulk-fill resin composite restorations.

Summary

The use of the presented semi-split bulk filling technique for restoring large occlusal bulk-fill resin composite restorations can minimize shrinkage stress and prevent or decrease the incidence of pulpal gap formation beneath the restoration. This would consequently result in less occurrence of persistent postoperative sensitivity and pain.

References

1. Al Sunbul H, Silikas N, Watts DC. (2016) Polymerization shrinkage kinetics and shrinkagestress in dental resin-composites. Dent Mater. 32(8): 998-1006.

2. Engelhardt F, Hahnel S, Preis V, et al. (2016) Comparison of flowable bulk-fill and flowable resin-based composites: an in vitro analysis. Clin Oral Invest. 20(8): 2123–2130.

3. Ilie N, Schoner C, Bucher K, et al. (2014)

An in-vitro assessment of the shear bond strength of bulk-fill resin composites to permanent and deciduous teeth. J Dent.

42(7): 850–855.

4. Tauböck TT, Jäger F, Attin T. (2019) Polymerization shrinkage and shrinkage force kinetics of high- and low-viscosity dimethacrylate- and ormocer based bulk-fill resin composites. Odontology. 107(1): 103-110

5. Gonçalves F, Campos LM, RodriguesJúnior EC, et al. (2018) A comparative study of bulk- fill composites: degree of conversion, post-gel shrinkage and cytotoxicity. Braz Oral Res. 32: e17-e26.

6. Menees TS, Lin CP, Kojic DD, et al. (2015) Depth of cure of bulk fill composites with monowave and polywave curing lights. Am J Dent. 28(6): 357-361.

7. Boaro LCC, Lopes DP, de Souza ASC, et al. (2019) Clinical performance and chemicalphysical properties of bulk fill composites resin —a systematic review and metaanalysis. Dent Mater. 35(10): e249–e264.

8. Stansbury JW, Trujillo-Lemon M, Lu H, Ding X, et al. (2005) Conversion-dependent shrinkage stress and strain in dental resins and composites. Dent Mater. 21(1): 56–67.

9. Watts DC. (2005) Reaction kinetics and mechanics in photo-polymerised networks. Dent Mater. 21(1): 27–35

10. Kim HJ, Park SH. (2014) Measurement of the internal adaptation of resin composites using micro-CT and its correlation with polymerization shrinkage. Oper Dent. 39(2): e57– e70.

11. Souza-Junior EJ, de Souza-Regis MR, Alonso RC, et al. (2011) Effect of the curing method and composite volume on marginal and internal adaptation of composite restoratives. Oper Dent. 36: 231–238.

12. Manhart J., Chen H.-Y., Hickel R. (2010) Clinical evaluation of the posterior composite Quixfil in class I and II cavities: 4-year followup of a randomized controlled trial. J Adhes Dent. 12(3):237-243.

13. Correia A., Jurema A., Andrade M.R., et al. (2020) Clinical evaluation of noncarious cervical lesions of different extensions restored with bulk-fill or conventional resin composite: preliminary results of a randomized clinical

The easy-to-use HALO sectional matrix system allows you to create beautiful, anatomically contoured composite restorations in less time.

trial. Oper Dent. 45(1): E11–20.

14. Canali G.D., Ignácio S.A., Rached R.N., et al. (2019) One-year clinical evaluation of bulk- fill flowable vs. regular nanofilled composite in non-carious cervical lesions. Clin Oral Investig. 23(2):889–897.

15. Park J, Chang J, Ferracane J, et al. (2008) How should composite be layered to reduce shrinkage stress: Incremental or bulk filling? Dent Mater. 24(11):1501–1505.

16. AbbasG, Fleming G, Harrington E, et al. (2003) Cuspal movement and microleakage in premolar teeth restored with a packable composite cured in bulk or in increments. J Dent Res. 31(6): 437-444.

17. Li H, Li J, Yun X, Liu X, et al. (2011) Non-destructive examination of interfacial debonding using acoustic emission. Dent Mater. 27(10):964-971.

18. Novaes JB Jr, Talma E, Las Casas EB, et al. (2018) Can pulpal floor debonding be detected from occlusal surface displacement in composite restorations? Dent Mater. 34(1): 161- 169.

19. Sun J, Eidelman N, Lin-Gibson S. (2009) 3D mapping of polymerization shrinkage using X- ray micro-computed tomography to predict microleakage. Dent Mater. 25(3): 314-320.

20. Chiang YC, Rosch P, Dabanoglu A, et al. (2010) Polymerization composite shrinkage evaluation with 3D deformation analysis from microCT images. Dent Mater. 26(3): 223-c231.

21. Cho E, Sadr A, Inai N, et al. (2011) Evaluation of resin composite polymerization by three- dimensional micro-CT imaging and nanoindentation. Dent Mater. 27(11): 10701078.

22. Papadogiannis D, Kakaboura A, Palaghias G, et al (2009). Setting characteristics and cavity adaptation of low-shrinking resin composites. Dent Mater. 25(12): 1509-1516.

23. Sato T, Miyazaki M, Rikuta A, et al. (2004) Application of the laser speckle-correlation method for determining the shrinkage vector of a light-cured resin. Dent Mater J. 23(3): 284-290.

24. Shortall AC, Palin WM, Burtscher P. (2008) Refractive index mismatch and monomer

reactivity influence composite curing depth. J Dent Res. 87(1): 84-88.

25. Van Ende A, Van de Casteele E, Depypere M, et al. (2015) 3D volumetric displacement and strain analysis of composite polymerization. Dent Mater. 31(4): 453-461.

26. Van Meerbeek B, Peumans M, Poitevin A, et al. (2010) Relationship between bondstrength tests and clinical outcomes. Dent Mater. 26(2): e100-e121.

27. Bortolotto T, Bahillo J, Olivier Richoz O, et al. (2015) Failure analysis of adhesive restorations with SEM and OCT: from marginal gaps to restoration loss. Clin Oral Invest. 19(8):1881-1890.

28. Hassan K, Khier S. (2005) Splitincrement horizontal layering: A simplified placement technique for direct posterior resin restorations. Gen Dent. 53(6): 406409.

29. Brännström M. (1984) Communication between the oral cavity and the dental pulp associated with restorative treatment. Oper Dent. 9(2): 57-68.

30. Furness A, Tadros MY, Looney SW, et al. (2014) Effect of bulk/incremental fill on internal gap formation of bulk-fill composites. J Dent. 42(4): 439-449.

31. Usha HL, Kumari A, Mehta D, et al. (2011) Comparing microleakage and layering methods of silorane-based resin composite in Class V cavities using confocal microscopy: An in vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 14(2): 164168.

32. Nadig RR, Bugalia A, Usha G, et al. (2011) Effect of four different placement techniques on marginal microleakage in class ii restorations: an in vitro study. World J Dent. 2(2): 111-116.

33. Khier S, Hassan K. (2011) Efficacy of composite restorative techniques in marginal sealing of extended class v cavities. International Scholarly Research Network. (ISRN) Dentistry. 2011:80197.

34. Bugalia A, Yujvender, Bramta N, et al. (2015) Effect of placement techniques, flowable composite, liner and fibre inserts on marginal microleakage of Class II composite restorations. J Evidence Based Med & Healthcare. 2(11): 4779-4787.

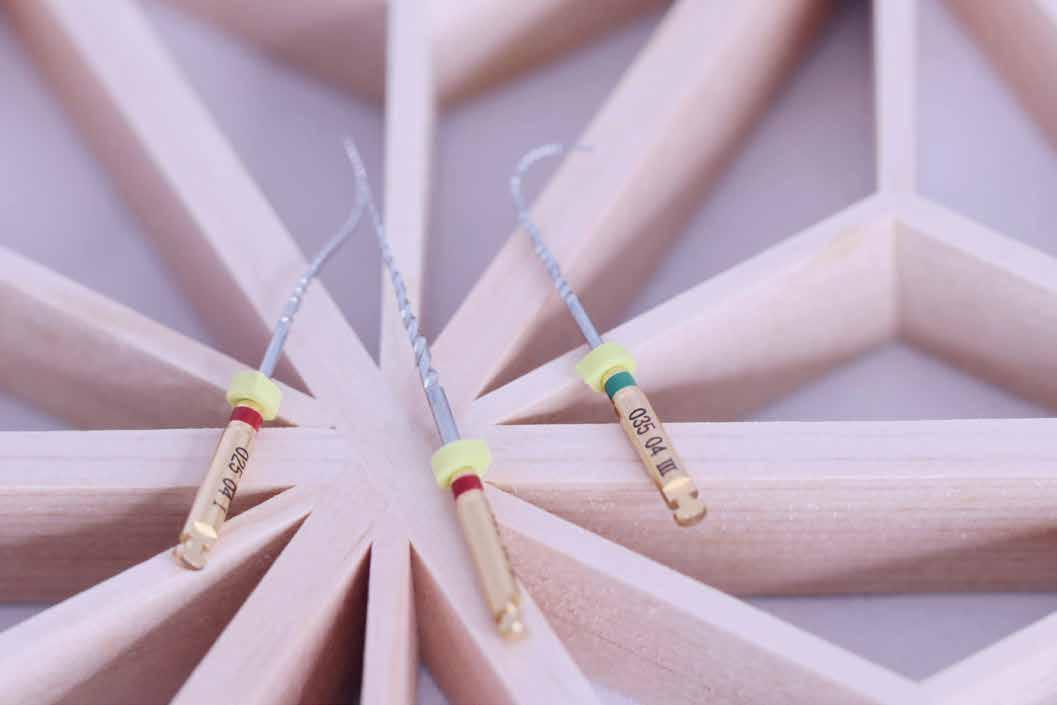

• EdgeEndo®’s #1 selling file system - globally

• Leading file used by Endodontists

• Proprietary heat treatment process

- FireWire™ NiTi Alloy improves strength and flexibility

• Available in .04 and .06 Constant Taper

- Variable Pitch

• Maximum flute diameter 1mm allows for minimally invasive preparation

• Parabolic Cross Section non-cutting tip

- Maximizes file cutting efficiency

• Reduced handle length for increased posterior access

• ISO tip size 17-45

• Available lengths: 21, 25 & 29 mm

The preventive effect of glass ionomer restorations on new caries formation: A systematic review and meta-analysis

PrevalenceandRiskofDentalErosioninPatientswith ,SvetlanaV.Lyamina , MoscowStateUniversityofMedicineandDentistryNamedafterA.I.Evdokimov,127473Moscow,Russia; mail@msmsu.ru(O.O.Y.);igormaev@rambler.ru(I.V.M.);nataly0088@mail.ru(N.I.K.);svlvs@mail.ru(S.V.L.); phlppsokolov@gmail.com(F.S.S.);estetstom.fpdo@gmail.com(M.N.B.);p.bely@ncpharm.ru(P.A.B.); Aim:Thepresentpaperaimstosystematizedataconcerningtheprevalenceandriskof dentalerosion(DE)inadultpatientswithgastroesophagealrefluxdisease(GERD)comparedto controls.Materialsandmethods:Coreelectronicdatabases,i.e.,MEDLINE/PubMed,EMBASE, Cochrane,GoogleScholar,andtheRussianScienceCitationIndex(RSCI),weresearchedforstudies assessingtheprevalenceandriskofDEinadultGERDpatientswithpublicationdatesrangingfrom 1January1985to20January2022.Publicationswithdetaileddescriptivestatistics(thetotalsample sizeofpatientswithGERD,thetotalsamplesizeofcontrols(ifavailable),thenumberofpatients withDEinthesampleofGERDpatients,thenumberofpatientswithDEinthecontrols(ifavailable)) wereselectedforthefinalanalysis.Results:Thefinalanalysisincluded28studiesinvolving4379 people(2309GERDpatientsand2070controlsubjects).ThepooledprevalenceofDEwas51.524% (95CI:39.742–63.221)inGERDpatientsand21.351%(95CI:9.234–36.807)incontrols.Anassociation wasfoundbetweenthepresenceofDEandGERDusingtherandom-effectsmodel(OR5.000,95%CI: =79.78%)comparedwithcontrols.Whenanalyzingstudiesthatonlyusedvalidated instrumentalmethodsfordiagnosingGERD,alongsidevalidatedDEcriteria(studiesthatdidnot specifythemethodologiesusedwereexcluded),asignificantassociationbetweenthepresenceofDE =85.14%).Conclusion:Themeta-analysis demonstratedthatDEisquiteoftenassociatedwithGERDandisobservedinabouthalfofpatients

Kelsey XingyunGe,

Faculty of Dentistry, The University of Hong Kong, 34 Hospital Road, Hong Kong SAR, China

RyanQuock,

,SvetlanaV.Lyamina , MoscowStateUniversityofMedicineandDentistryNamedafterA.I.Evdokimov,127473Moscow,Russia; mail@msmsu.ru(O.O.Y.);igormaev@rambler.ru(I.V.M.);nataly0088@mail.ru(N.I.K.);svlvs@mail.ru(S.V.L.); phlppsokolov@gmail.com(F.S.S.);estetstom.fpdo@gmail.com(M.N.B.);p.bely@ncpharm.ru(P.A.B.); Aim:Thepresentpaperaimstosystematizedataconcerningtheprevalenceandriskof dentalerosion(DE)inadultpatientswithgastroesophagealrefluxdisease(GERD)comparedto controls.Materialsandmethods:Coreelectronicdatabases,i.e.,MEDLINE/PubMed,EMBASE, Cochrane,GoogleScholar,andtheRussianScienceCitationIndex(RSCI),weresearchedforstudies assessingtheprevalenceandriskofDEinadultGERDpatientswithpublicationdatesrangingfrom 1January1985to20January2022.Publicationswithdetaileddescriptivestatistics(thetotalsample sizeofpatientswithGERD,thetotalsamplesizeofcontrols(ifavailable),thenumberofpatients withDEinthesampleofGERDpatients,thenumberofpatientswithDEinthecontrols(ifavailable)) wereselectedforthefinalanalysis.Results:Thefinalanalysisincluded28studiesinvolving4379 people(2309GERDpatientsand2070controlsubjects).ThepooledprevalenceofDEwas51.524% (95CI:39.742–63.221)inGERDpatientsand21.351%(95CI:9.234–36.807)incontrols.Anassociation wasfoundbetweenthepresenceofDEandGERDusingtherandom-effectsmodel(OR5.000,95%CI: =79.78%)comparedwithcontrols.Whenanalyzingstudiesthatonlyusedvalidated instrumentalmethodsfordiagnosingGERD,alongsidevalidatedDEcriteria(studiesthatdidnot specifythemethodologiesusedwereexcluded),asignificantassociationbetweenthepresenceofDE =85.14%).Conclusion:Themeta-analysis demonstratedthatDEisquiteoftenassociatedwithGERDandisobservedinabouthalfofpatients

- Faculty of Dentistry, The University of Hong Kong, 34 Hospital Road, Hong Kong SAR, China

- Department of Restorative Dentistry and Prosthodontics, School of Dentistry, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, TX, United States

Chun-HungChu, Faculty of Dentistry, The University of Hong Kong, 34 Hospital Road, Hong Kong SAR, China

Ollie YiruYu

Faculty of Dentistry, The University of Hong Kong, 34 Hospital Road, Hong Kong SAR, China

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the effectiveness of glass ionomer cement (GIC) restorations on preventing new caries in primary or permanent dentitions compared with other types of restorations.

Data

Randomized controlled clinical trials evaluating caries experience increment or caries incidence in patients with GIC restorations, including conventional GIC (CGIC) and resin-modified GIC (RMGIC) restorations, were included.

Sources

A systematic search of publications in English was conducted in PubMed/ Medline, Web of Science, Cochrane, and Scopus databases.

Study selection/results

This review included 10 studies reporting caries preventive effect of GIC restorations and selected 5 studies for meta-analysis. Patients with GIC restorations showed lower caries incidence compared with other restorations in primary and permanent dentition [RR=0.67, 95% CI:0.55–0.82, p < 0.0001]. Patients with CGIC restorations showed lower caries incidence compared with amalgam restorations [RR=0.57, 95% CI:0.43–0.76, p = 0.0001] and RMGIC restorations [RR=0.70, 95% CI:0.56–

0.87, p = 0.002], but no statistical difference with composite resin restorations [RR=0.73, 95% CI:0.51–1.04, p = 0.08] in primary dentition. Patients with RMGIC restorations showed no statistical differences of caries incidence compared with composite resin restorations in primary and permanent dentition [RR=0.83, 95% CI:0.56–1.22, p = 0.33].

GIC restorations presented a better preventive effect on new caries than other restorations did in primary and permanent dentitions. CGIC restorations presented a better caries preventive effect on new caries than RMGIC and amalgam restorations in primary dentitions did. RMGIC restorations showed similar preventing effect on new caries with composite resin restorations in primary and permanent dentitions.

This review affirmed the potential of GIC in preventing new caries development in the dentition.

Glass ionomer cement, Resinmodified glass ionomer cement, Caries prevention, Fluoride, Systematic review

Dental caries, or tooth decay, is one of the most common chronic diseases worldwide [1] . According to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) report, dental caries affects 60–90% of schoolchildren globally and almost all adults [2]. Dental caries can occur throughout life in both primary and permanent dentitions. It can damage the tooth crown and expose the root surfaces in a later lifetime [3]. Untreated caries can cause pain, develop into apical periodontitis, form abscesses and even infection [4]. A survey reported that pain and discomfort due to untreated dental caries were found in 18% of 5–6-year-olds and 64% in older adults [5] Different types of direct restorative materials are used to restore teeth affected by dental caries. Glass ionomer cement (GIC), including conventional glass ionomer cement (CGIC) and resin-modified glass ionomer cement (RMGIC), are commonly used as dental restorative materials [6]. The Government Chemist Laboratory (London, UK) developed CGIC in 1969. They are used as restorative materials, liners and bases, fissure sealants and bonding agents [7]. CGIC has several advantages, including adhesion to tooth structures, biocompatibility, long-lasting fluoride release and simple clinical operation [6,8]. However, CGIC also has disadvantages, such as moisture sensitivity, low mechanical strength and compromised aesthetics [9]. To overcome the problems traditionally associated with the CGIC materials [10], Mitra introduced RMGIC as evolution of CGIC in 1989 [11]. RMGIC are used for numerous specific applications in clinical dentistry, notably as liners/bases, luting agents and restorative materials [12]. The RMGIC maintain the clinical advantages of the CGIC, such as the fluoride release and simplicity in clinical operation. They are more aesthetic than CGIC [13]

Based on laboratory data regarding sustained fluoride release, CGIC and RMGIC have been associated with caries prevention. An in vitro study showed that CGIC or RMGIC restorations increased the fluoride uptake in adjacent tooth structure [14]. Previous in vitro studies also showed that interproximal caries-like lesions adjacent to CGIC restorations presented a higher degree of remineralisation compared with those

of resin-based restorations [15]. Because the fluoride can diffuse through the saliva in the oral cavity, CGIC or RMGIC restorations may promote the remineralisation in the other teeth in the dentition [16]. Therefore, CGIC and RMGIC may prevent new caries formation in the dentition.

Although in vitro studies have demonstrated the potential effect of GIC restorations on caries prevention, clinical evidence of the effect of GIC restorations, including CGIC or RMGIC restorations, in preventing new caries formation is limited. A systematic quantitative evaluation of the available evidence on the preventive effect of GIC restorations, including CGIC or RMGIC, on new caries formation has never been undertaken. Therefore, this review aimed to evaluate the preventive effect of GIC restorations, including CGIC or RMGIC restorations, on new caries compared with other types of dental restorations.

2.1.

This review answered the research question of, ‘What is the effectiveness of glass ionomer cement (GIC), including conventional glass ionomer cement (CGIC) restorations and resin-modified glass ionomer cement (RMGIC) restorations, on preventing new caries formation in permanent and primary dentitions compared with other types of dental restorations?’. This systematic review was written following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) Statement [17]. This systematic review and meta-analysis was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO Registration ID: 302,578).

2.2.

A comprehensive literature search was conducted on May 15, 2022, to identify the available studies evaluating the prevention of caries lesions in GIC restorations, with no limits of publication year. The literature search was conducted in four databases, including PubMed/ Medline, Web of Science, Cochrane and Scopus. The search strategy was developed as follows. 1 “demineralization” OR “tooth demineralization” “teeth demineralization” OR “caries” “carious”

OR “tooth decay” OR “teeth decay” OR “dental caries” OR “caries susceptibility”

2 “glass ionomer cement” OR “glass ionomer” OR “GIC” “glass polyalkenoate cement” OR “glass-ionomer cement” OR “ART” OR “atraumatic restorative procedure”.

3 “#1″ AND “#2″

Two independent reviewers (KXG & OYY) conducted the study selection. Both authors independently screened titles, compared findings and included full texts after deduplication. The third author (CHC) was consulted when there was disagreement. Studies with consensus being reached through discussion were included.

This review used participants, intervention, comparison, outcome and type of study (PICOT) to formulate questions in evidencebased practice. The inclusion criteria were developed based on PICOT strategy. The PICOT strategy for the inclusion criteria is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. The PICOT (participants, intervention, comparison, outcome and type of study) strategy used for selection of publications in the review.

The inclusion criteria of the studies were:

Participants Studies with participants of all ages were included

Intervention GIC restorations including CGIC or RMGIC restorations for caries treatment

Comparison CGIC restorations compared with other types of dental restorations

RMGIC restorations compared with other types of dental restorations

Outcome

Type of study

1 To be the randomized controlled clinical trials.

2 To investigate GIC for restorations application in patients.

3 To evaluate the caries incidence or caries experience increment. Caries incidence refers to the rate of new caries development in the adjacent teeth after the restoration. The development of secondary caries was not

Caries incidence Caries experience increment

Randomized controlled clinical trial (RCT)

included. Caries experience increment refers to DMFT/DMFS (decayed, missing, and filled teeth/surfaces in permanent teeth) increment or dmft/dmfs (decayed, missing, and filled teeth/surfaces in primary teeth) increment.

The exclusion criteria of the studies were:

1 To be the in vitro studies, animal studies, reviews, letters to the editor, case report/series and observational studies.

No need for forceps.

The foil is pre-mounted in a sturdy plastic frame.

No ink on your fingers. The foil is covered on both sides at the grip.

Super thin foil.

The foil is only 8 micron thick and inked on both sides. Available in blue or red.

Protective strip Easily removed before use.

TrollFoil takes the guesswork out of occlusal adjustments.

The only articulating foil you will ever need!

TrollFoil can be used under a wide variety of clinical situations including wet or dry teeth, limited opening, limited vestibular space, gaggers, and metal and non-metalic restorations. You are able to verify occlusal contacts for both arches from one tooth to an entire quadrant using the mini or the original quadrant size. The double-sided foil is only 8 microns thick, and it has no problem marking wet surfaces, dry surfaces or highly polished surfaces such as cast gold or BruxZir.

For further information please contact your local dealer or Annelie Johansson, Area Sales Manager – Product specialist TrollDental x-ray, Finland, Baltic, East Europe, Greece, Turkey, MENA annelie.johansson@directadental.com www.directadental.com

2 To investigate other types of restorations but did not include the GIC.

3 To investigate GIC for nonrestorative application in clinic (i.e., fissure and sealant, liners/bases or cement).

4 To output data that did not contain the caries incidence or caries experience increment.

The reviewers collected the required information of the eligible studies. For each included study, the following data were systematically extracted from each paper:

• Publication details: authors name, publication year and duration

•Tooth characteristics: type of dentition and number of restorations for each material

•Outcome information: assessment, outcome measure, and main findings

All the data obtained from patients with GIC restorations were extracted to Group CGIC or RMGIC in this review, regardless of the original study design.

The assessment of risk of bias to longitudinal trials assessment was performed according to bias assessment forms (Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.4.1).

The Cochrane ‘risk of bias’ instrument was used to assess the risk of bias. Three independent reviewers performed this evaluation. Disagreements between estimators were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached. The risk of bias was classified into three categories:

(a) Low risk of bias: all domains were marked as ‘low risk’.

(b) Moderate risk of bias: no domain was marked as ‘high risk’; one or more domains were coded as ‘unclear risk’.

(c) High risk of bias: one or more domains were marked as ‘high risk’.

The participants’ caries experience increment in DMFT/DMFS and dmft/dmfs was based only on the first and last measurements. The DMFT/DMFS and dmft/dmfs increments were calculated by subtracting the results at baseline from the results at follow-up.

Meta-analysis of the caries incidence after GIC restorations, including CGIC or RMGIC restorations, was carried out. The Review Manager 5.4.1 was used for conducting the meta-analysis. Heterogeneity was assessed via the I2 statistic on the level of α=0.10. If there was considerable or substantial heterogeneity (I2>50%), a random-effects mode was adopted; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used. The results of the intervention effect were presented as risk ratio (RR) utilizing 95% confidence intervals (CI). All tests were 2-tailed, and p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 5456 studies was retrieved from the four databases. After subtracting 2486 duplicated studies, 2970 potential studies were identified and screened for inclusion. After screening the titles and abstracts, 2616 studies were excluded. 354 studies were considered potentially relevant and were read for the full text. With the reviewers’ consensus, 10 studies that reported the new caries preventive effect of the GIC restorations were included for this review. Seven of the studies were on CGIC restorations while three were on RMGIC restorations. The details of search procedure are presented in a flowchart (Fig. 1).

Ultimate Interproximal Solution - ContacEZ dental strips for restorative, orthodontic, and laboratory needs. The innovative, single-handed design of ContacEZ Dental Strips offers optimal tactile control and grants easy access to tight anterior and posterior spaces. Flexible strips curve and conform to the natural contours of the teeth, while the central opening offers better visual perception and access for tools. This user and patient-friendly design eliminates gagging and prevents soft tissue irritation.

ContacEZ Restorative Strips System are designed to achieve ideal proximal contacts and complete marginal sealing as well as removing subgingival overhangs and more.

The ContacEZ IPR strips makes it easy to perform safe and stress-free interproximal reduction in connection with orthodontic treatment.

5 Reasons – to switch to ContacEZ Strips

• Optimal tactile control – prevent cutting lips and gums

• Built-in flexibility conforms to natural contours

• Ergonomic design eliminates hand fatigue

• Better visibility with central opening

• Autoclavable

5,456 studies were retrieved in four databases

• PubMed (Medline): 1,745

• Scopus: 1,599

• Cochrane: 994

• Web of Science: 1,118

2,486 duplicate studies were excluded

2,970 potential studies identi ed and screened for inclusion

Step 1 - Titles and abstracts were reviewed

2,616 studies were excluded, including

• studies not relevant (n=2,118)

• reviews, case report or laboratory studies (n=273)

• studies did not investigate GIC restorations (n=225)

354 studies were retrieved for full text evaluation

Step 2 - Full-lenght articles were retrieved

344 studies were excluded, including

• studies did not investigate caries preventinve effect (n=58)

• studies on GIC sealants, liner, base or cement (n=62)

• studies on preventive effect on secondary caries (n=224)

10 studies reported the new curies preventive e ect of the GIC restorations

7 studies reported the new caries preventive e ect of the CGIC restorations

3 studies reported the new caries preventive e ect of the RMGIC restorations

3 studies were eligible for CGIC meta-analysis

2 studies were eligible for RMGIC meta-analysis

4 studies in GIC were eligible for meta-analysis

Fig. 1. Flow diagram of the systematic review. GIC: glass ionomer cement (including CGIC and RMGIC); CGIC: conventional glass ionomer cement; RMGIC: resin-modified glass ionomer cement.

3.2.1.

Seven included studies published between 1997 and 2020 investigated the preventive effect of the CGIC restorations on new caries. The included studies involved 2655 CGIC restorations, 2182 participants, aged from 2 to 74 years old. The average follow-up period of the included studies was 3.3 years. One study was performed in permanent dentition, published in 2003. The study involved 417 CGIC restorations in 81 participants [18]. Six studies were performed in primary dentition, published between 1997 and 2020. These studies involved 2238 CGIC restorations in 2101 participants, aged from 2 to 13 years [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24].

3.2.2.

Three studies were included for the RMGIC restorations, published between 2000 and 2004 [25], [26], [27]. These studies investigated 328 RMGIC restorations in 271 participants, aged from 4 to 53 years. The average follow-up period of the included studies was 1.7 years. One study, published in 2000, had the outcome assessment in permanent dentition [27]. This study involved 114 RMGIC restorations and 106 composite resin restorations in 118 participants, aged from 4 to 53 years. Two studies, published in 2004, had the outcome assessment in primary dentition [25,26]. These studies investigated on 214 RMGIC restorations and 41 composite resin

et al. 2000 (Meta-analysis)

Kotsanos et al. 2004 (Meta-analysis)

Qvist et al. 1997

ysis)

Foley et al. 2004

(Meta-analysis)

Qvist et al. 2004 (Meta-analysis)

restorations on 153 participants, aged from 4 to 15 years. The main characteristics of the studies included in the study are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Characteristics of included randomized controlled clinical trials studies. CGIC: conventional glass ionomer cement; RMGIC: resin-modified glass ionomer cement. Main findings showed the results of the outcome measure for each study.

Among the 10 included RCTs, 7 studies had one or more ‘high’ ratings due to the method about the blinding of participants and outcome

Faley et al.(2004)

Kotsanos et al.(2004)

Moura et al.(2020)

Arrow et al.(2015)

Bolgul et al.(2004)

Qvist et al.(2004)

Arrow et al.(2016)

Qvist et al.(1997)

Vilkinis et al.(2000)

Zanata et al.(2003) Random sequence generation (selection bias) Allocation concealment (selection bias) Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Selective reporting (reporting bias) Other bias

Fig. 2. Risk of bias summary: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

assessment. The statement of the method of allocation concealment was not reported in 4 studies. Four studies had ‘unclear’ ratings due to lack of information. The risk of bias assessment ratings for each study are shown in Fig. 2, Fig. 3 .

(Random sequence generation (selection bias (Allocation concealment (seleciton bias (Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias (Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias (Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias (Selective reporting (reporting bias Other bias

Fig. 3. Risk of bias graph: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Zanata et al. assessed the caries experience increment by analysing DMFS score in the dentition with CGIC restorations compared with that of zinc oxide-eugenol (ZOE) and composite resin restorations. The results showed that permanent dentitions with CGIC restorations showed a lower increase of the DMFS compared with dentitions with ZOE or composite resin restorations [18]

Three studies assessed the caries incidence by bitewing radiographs in the primary dentition with CGIC restorations and compared with dentitions with amalgam [24], RMGIC [22] or composite resin restorations [23]. These studies showed that primary dentitions with CGIC restorations showed a lower caries incidence compared with amalgam, RMGIC and composite resin restorations.

Three separate studies investigated the caries experience increment by analysing dmft/ dmfs score in the primary dentitions with CGIC restorations. No other types of restoration were included. These studies investigated the dmft/ dmfs increment after CGIC restorations with different clinical protocols, such as the atraumatic

restorative treatment (ART), standard care approach and minimum intervention dentistry (MID-ART) [19], [20], [21]. The results suggested the use of the CGIC by ART technical may be an effective option for managing caries in preschool-aged children.

Vilkinis et al. investigated the caries incidence in the permanent dentitions with RMGIC restorations compared with composite resin restorations. Main findings showed that RMGIC and composite resin had a 15.9% and 10.0% caries incidence respectively. The results showed that no statistical significant differences between the RMGIC restorations and composite resin restorations were observed with respect to the caries incidence [27].

Bolgul et al. investigated caries experience increment by dmft score in the primary dentition with RMGIC restorations and reported the dmft differences between different controlled levels of the insulin-dependant diabetes mellitus (IDDM) patients [26]. The results showed that the dmft

Study or Subgroup

1.1.1 Amalgam

Qvist et al. (1997)

Subtotal (95% CI)

Heterogeneity: Not applicable

Test for overall effect: Z= 3.83 (P= 0.0001)

1.1.2 Composite resin

Foley et al. (2004)

Kotsanos et al. (2004)

Vilkinis et al. (2000)

Subtotal (95% CI)

score decreased in all the IDDM patients’ primary dentition with RMGIC restorations. Kotsanos and Arizos evaluated the caries incidence by radiographs in the primary dentitions with RMGIC restorations compared with composite resin restorations. The results showed no statistically significant differences between the RMGIC and composite resin restorations with respect to the caries incidence [25].

Five studies were included for the meta-analysis. Three studies were on CGIC restorations and two were on RMGIC restorations. We also pooled the data of CGIC and RMGIC restorations to analyse the caries preventive effect of GIC restorations. Four out of the five studies were included the meta-analysis on GIC restorations. One study was not included in the meta-analysis of GIC restorations, because this study compared the caries preventive effect of CGIC restorations with that of RMGIC restorations, not with other types of restorations [22]. The main results of the metaanalysis are presented in Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9.

[0.43,

[0.43, 0.76]

-0.3198 0.1833 29.0% 0.73 [0.51, 1,04]

0.2114

0.87 [0.57, 1.32]

0.5539 3.2% 0.58 [0.20, 1.72] 53.9% 0.77 [0.59, 1.00]

Heterogeneity: Chi2 - 0.69, df - 2 (P = 0.71): 12 - 0%

Test for overall effect: Z = 1.94 (P = 0.05)

Total (95% CI)

Heterogeneity: Chi2 - 2.93, df - 3 (P = 0.40): 12 - 0%

Test for overall effect: Z = 4.02 (P < 0.0001)

Test for subgroup differences: Chi2 - 2.24, df - 1 (P = 0.13): 12 - 55.3% 100.0% 0.67 [0.55, 0.82]

Fig. 4. Meta-analysis of caries incidence in all dentitions with all GIC restorations vs amalgam or composite restorations. GIC: glass ionomer cement.

The preventive effect of glass ionomer restorations on new caries formation: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Study or Subgroup

2.1.1 2 years

Kotsanos et al. (2004)

Vilkinis et al. (2000)

Subtotal (95% CI)

-0.1398 0.2114 40.4% 0.87 [0.57, 1.32] -0.5428 0.5539 5.9% 0.58 [0.20, 1.72] 46.3% 0.83 [0.56, 1.22]

Heterogeneity Chi2 = 0.46, df = 1 (P = 0.50); I2 = 0%

Test for overall effect: Z = 1.97 (P = 0.33)

2.1.2 7 years

Foley et al. (2004)

Subtotal (95% CI) -0.3198 0.1833 53.7% 0.73 [0.51, 1,04] 53.7% 0.73 [0.51, 1.04]

Heterogeneity: Not applicable

Test for overall effect: Z = 1.74 (P = 0.08)

Total (95% CI)

Heterogeneity: Chi2 - 0.69, df = 2 (P = 0.71): I2 = 0%

Test for overall effect: Z = 1.94 (P = 0.05)

Test for subgroup differences: Chi2 = 0.23, df = 1 (P = 0.63), I2 = 0% 100.0% 0.77 [0.59, 1.00]

Fig. 5. Meta-analysis of caries incidence in all dentitions with GIC restorations vs composite resin restorations, with defined follow up period. GIC: glass ionomer cement.

Risk Ratio Risk Ratio

Study or Subgroup

log(Risk Ratio)

3.1.1 Amalgam - primary dentition

Qvist et al. (1997)

Subtotal (95% CI)

Heterogeneity : Not applicable

Test for overall effect: Z = 3.83 (P= 0.0001)

3.1.1 Amalgam - permanent dentition

Subtotal (95% CI)

Heterogeneity : Not applicable

Test for overall effect: Not applicable

3.1.3 Composite resin - primary dentition

Foley et al. (2004)

Kotsanos et al. (2004)

Subtotal (95% CI)

SE Weigh IV, Fixed, 95 % CI IV, Fixed, 95 % CI

0.1453

0.57 [0.43, 0.76]

0.57 [0.43, 0.76]

Heterogeneity Chi2 = 0.41, df = 1 (P = 0.52); I2 = 0%

Test for overall effect: Z = 1.75 (P = 0.08)

3.1.3 Composite resin - permanent dentition

Vilkinis et al. (2000)

Subtotal (95% CI)

Heterogeneity : Not applicable Test for overall effect: Z = 0.98 (P = 0.33)

Total (95% CI)

Heterogeneity: Chi2 = 2.93, df = 3 (P = 0.40): I2 = 0%

Test for overall effect: Z = 4.02 (P < 0.0001)

0.67 [0.55, 0.82]

Test for subgroup differences: Chi2 = 2.51, df = 2 (P = 0.28), I2 = 20.4%

Fig. 6. Meta-analysis of caries incidence in dentitions with GIC restorations. Not estimable: no studies were eligible for meta-analysis. CGIC: conventional glass ionomer cement; RMGIC: resinmodified glass ionomer cement; GIC: glass ionomer cement (including CGIC and RMGIC).

• Excellent working time and the setting time is individually adjustable by light-curing

• Immediately packable after placement in the cavity

• No varnish required- fill, polymerise and finish

• No need to condition the dental hard tissue

• Does not stick to the instrument and is easy to model

• Suitable for large cavities

Are you interested in our entire product range and detailed product information? Visit our website or contact us directly!

Material GmbH

Study or Subgroup

4.1.1 RMGIC

Qvist et al. (2004)

Subtotal (95% CI)

Heterogeneity : Not applicable

Test for overall effect: Z = 3.15 (P= 0.002)

4.1.2 Amalgam

Qvist et al. (1997)

Subtotal (95% CI)

Heterogeneity : Not applicable

Test for overall effect: Z = 3.83 (P= 0.0001)

4.1.3 Composite resin

Foley et al. (2004)

Subtotal (95% CI)

Heterogeneity : Not applicable

Test for overall effect: Z = 1.74 (P= 0.08) -0.3542 0.1123 50.7% 0.70 [0.56, 0.87] 50.7% 0.70 [0.56, 0.87] -0.5561 0.1453 30.3%

(95% CI)

Heterogeneity: Chi2 = 1.50, df = 2 (P = 0.47): I2 = 0%

Test for overall effect: Z = 5.11 (P < 0.00001)

1.04]

0.66 [0.57, 0.78]

Test for subgroup differences: Chi2 = 1.50, df = 2 (P = 0.478), I2 = 0%

Fig. 7. Meta-analysis of caries incidence in primary and permanent dentitions with CGIC restorations vs RMGIC, amalgam or composite resin restorations. CGIC: conventional glass ionomer cement; RMGIC: resin-modified glass ionomer cement.

5.1.1 RMGIC - primary dentition

Qvist et al. (2004)

Subtotal (95% CI)

Heterogeneity : Not applicable

Test for overall effect: Z = 3.15 (P= 0.002)

5.1.2 RMGIC - permanent dentition

Subtotal (95% CI)

Heterogeneity : Not applicable

Test for overall effect: Not applicable

5.1.3 RMGIC - primary dentition

Qvist et al. (1997)

Subtotal (95% CI)

Heterogeneity : Not applicable Test for overall effect: Z = 3.83 (P= 0.0001)

5.1.4 RMGIC - permanent dentition

Subtotal (95% CI)

Heterogeneity : Not applicable

Test for overall effect: Not applicable

5.1.5 Composite resin - primary dentition

Foley et al. (2004)

Subtotal (95% CI)

Heterogeneity : Not applicable

Test for overall effect: Z = 1.74 (P= 0.08)

5.1.6 Composite resin - permanent dentition

Subtotal (95% CI)

Heterogeneity : Not applicable

Test for overall effect: Not applicable

0.66 [0.57, 0.78] Total (95% CI)

Heterogeneity: Chi2 = 1.50, df = 2 (P = 0.47): I2 = 0%

Test for overall effect: Z = 5.11 (P < 0.00001)

Test for subgroup differences: Chi2 = 1.50, df = 2 (P = 0.47), I2 = 0%

Fig. 8. Meta-analysis of caries incidence in primary or permanent dentitions with CGIC restorations vs RMGIC, amalgam or composite resin restorations. Not estimable: no studies were eligible for meta-analysis. CGIC: conventional glass ionomer cement; RMGIC: resinmodified glass ionomer cement.

6.1.1 Composite resin-primary dentition

Kotsanos et al. (2004

Substotal (95% CI)

Heterogeneity: Not applicable

-0.1398 0.2114 87.3% 0.87 [0.57, 1.32] 87.3% 0.87 [0.57, 0.32]

Test for overall effect: Z= 0.66 (P= 0.51)

6.1.2 Composite resin-primary dentition

Vilkinis et al. (2000)

Substotal (95% CI)

Heterogeneity: Not applicable

-0.1398 0.2114 12.7% 0.58 [0.20, 1.72] 12.7% 0.58 [0.20, 1.72]

Test for overall effect: Z= 0.98 (P= 0.33)

Heterogeneity: Chi2 - 0.46, df = 1 (P = 0.50): 12 - 0%

Test for overall effect: Z = 0.97 (P = 0.33)

Test for subgroup differences: Chi2 - 0.46, df - 1 (P = 0.50): 12 - 0% 100.0% 0.87 [0.56, 1.22] Total (95% CI)

Fig. 9. Meta-analysis of caries incidence in primary or permanent dentitions with RMGIC restorations vs composite resin restorations. RMGIC: resin-modified glass ionomer cement.

Meta-analysis showed that patients with GIC restorations showed a lower caries incidence compared with other restoration types [RR=0.67, 95% CI: 0.55–0.82, p<0.00001] (Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6). The heterogeneity of this meta-analysis was 2.93 (I2=0%). Patients with CGIC restorations showed a lower caries incidence compared with other restoration types [RR=0.66, 95% CI: 0.57–0.78, p < 0.00001] (Figs. 7 and 8). The heterogeneity of this meta-analysis was 1.50 (I2=0%). Patients with RMGIC restorations showed no significant differences in the caries incidence compared with composite resin restorations [RR=0.83, 95% CII:0.56–1.22, p = 0.33] (Fig. 9). The heterogeneity of this metaanalysis was 0.46 (I2=0%).

3.5.1. Preventive effect of GIC on new caries in primary and permanent dentition

The results of meta-analysis showed that patients with GIC restorations (either CGIC or RMGIC restorations) exhibited a lower caries incidence compared with amalgam restorations [RR=0.57, 95% CI:0.43–0.76, p = 0.0001]. Patients with GIC restorations exhibited a lower caries incidence compared with composite resin restorations [RR=0.77, 95% CI:0.59–1.00, p = 0.05] (Fig. 4).

Data from the studies with different follow-up periods showed that patients with GIC restorations

exhibited no significant differences in the caries incidence compared with composite resin restorations in 2 years [RR=0.83, 95% CI:0.56–1.22, p = 0.33] and 7 years [RR=0.73, 95% CI:0.51–1.04, p = 0.08] (Fig. 5).

Preventive effect of GIC on new caries in primary dentition

The results of meta-analysis showed that primary dentition with GIC restorations exhibited a lower caries incidence compared with amalgam restorations [RR=0.57, 95% CI:0.43–0.76, p = 0.0001]. Patients with GIC restorations showed no significant differences in the caries incidence compared with composite resin restorations in primary dentition [RR=0.78, 95% CI:0.60–1.03, p = 0.08] (Fig. 6).

Preventive effect of GIC on new caries in permanent dentition

Patients with GIC restorations showed no significant differences in the caries incidence compared with composite resin restorations in permanent dentition [RR=0.58, 95% CI:0.20–1.72, p = 0.33] (Fig. 6).

3.5.2. Preventive effect of CGIC on new caries in primary and permanent dentition

The results of meta-analysis showed that patients with CGIC restorations exhibited a lower caries

incidence compared with RMGIC restorations [RR=0.70, 95% CI:0.56–0.87, p = 0.002] and amalgam restorations [RR=0.57, 95% CI:0.43–0.76, p = 0.0001], but no statistical difference with composite resin restorations [RR=0.73, 95% CI:0.51–1.04, p = 0.08] (Fig. 7).

Preventive effect of CGIC on new caries in primary dentition

The results of meta-analysis showed that primary dentition with CGIC restorations exhibited a lower caries incidence compared with amalgam restorations [RR=0.57, 95% CI:0.43–0.76, p = 0.0001] and RMGIC restorations [RR=0.70, 95% CI:0.56–0.87, p = 0.002]. Primary dentition with CGIC restorations exhibited a lower caries incidence compared with composite resin restorations, but the difference had no statistical significance [RR=0.73, 95% CI:0.51–1.04, p = 0.08] (Fig. 8).

Preventive effect of CGIC on new caries in permanent dentition

No study that investigated the preventive effect of CGIC on new caries in permanent dentition was eligible for meta-analysis. The results of the preventive effect of CGIC on new caries in permanent dentition are listed as ‘not estimable’ in Fig. 8.

3.5.3. Preventive effect of RMGIC on new caries in primary and permanent dentition

Patients with RMGIC restorations showed no significant differences in the caries incidence compared with composite resin restorations [RR=0.83, 95% CI:0.56–1.22, p = 0.33] (Fig. 9).

Preventive effect of RMGIC on new caries in primary dentition

Primary dentition with RMGIC restorations showed no significant differences in the caries incidence compared with composite resin restorations [RR=0.87, 95% CI:0.57–1.32, p = 0.51] (Fig. 9).

Preventive effect of RMGIC on new caries in permanent dentition

Permanent dentition with RMGIC restorations showed no significant differences in the caries incidence compared with composite resin restorations [RR=0.58, 95% CI:0.20–1.72, p = 0.33] (Fig. 9).

This review’s results showed that patients with GIC restorations, had a lower caries incidence compared with other types of restorations, demonstrating that GIC restorations obtain a better caries preventive effect. Since the RMGIC restorations did not present a better preventive effects than other restorations, this result may be due to the effect of CGIC in the pool of the collected data. This result is consistent with previous studies that claimed that GIC restorations can be used as a tool in caries prevention28 This may be due to the fluoride-releasing and recharging ability of GIC. Fluoride delivered by dentifrices or topical fluoride treatments can be taken up into GIC and released again [29]. In addition, fluoride can inhibit biofilm formation by S. mutans and other bacterial species. Caries treatment of GIC may offer enhanced protection for the surrounding tooth structure [30]

We found that GIC restorations were more effective in preventing new caries compared to amalgam restorations. Amalgam contains silver compounds, which have antimicrobial effects on the Streptococcus mutans and Actinomyces viscosus [31]. GIC obtains the cariostatic effect, which is partially due the antibacterial effect of GIC. Meanwhile, the fluoride release of GIC might contribute to the inhibition of bacterial acid production [32]. The hypothesis that the preventive effect of GIC restorations on new caries was related to the sustained fluoridereleasing property instead of the antibacterial property was supported with the result [33] .

This review’s results suggested that GIC restorations might result in a lower caries incidence effect compared to composite resin with a statistical significance (p = 0.05), though CGIC (p = 0.08) and RMGIC (p = 0.33) had no significant differences in the reducing the caries incidence compared with composite resin restorations. The composite resin system has a hydrophobic medium, and the ion exchange from the fluoride component is reduced [34]. A previous study reported that GIC materials showed better cariostatic effects compared to composite resin [35], which is consistent with our results. Note that the CGIC meta-analysis only included one study. Further high-quality randomized control trials are needed to support the results.

The study included in our review showed that CGIC restorations presented a better cariostatic effect of than RMGIC restorations did [22]. We analysed

the caries preventive effect of CGIC and RMGIC separately. The differences of the cariostatic effect between CGIC and RMGIC could be due to replacing part of the water in the GIC by the resin, which might affect the fluoride release kinetics of RMGIC [36]. In addition, the fluoride content of restorative resins is limited by the need for the restorative cements’ translucency. The enhanced translucency of the RMGIC had improved aesthetic effects but was accompanied by a reduction in fluoride content [37,38]. Meanwhile, the resin matrix might firmly encapsulate the fluoride ions in RMGIC. Consequently, the fluoride release rate of RMGIC into an aqueous environment might be smaller and slower compared to that of CGIC [39]. The lower fluoride release of RMGIC might attribute to the reduced preventive effect of RMGIC on new caries than CGIC.

This study’s results showed that no statistically significant differences were observed with respect to the caries incidence between RMGIC and composite resin restorations in permanent dentition. Similarly, Yengopal et al. compared the preventive effect of RMGIC on recurrent caries to the composite resin and found no evidence to indicate that RMGIC had a superior cariostatic preventive effect in primary dentition [40]. The possible explanations might be that the high level of fluoride ions released initially from RMGIC might plateau within the first weeks of setting and that its composition behaves similarly to the composite resin thus leading to a lower fluoride release rate than CGIC [38,41]

Only 1 out of 7 studies investigating the preventive effect of CGIC on new caries were performed on permanent dentition. None of these studies were eligible for the meta-analysis, and thus were listed as not estimable in the results of metaanalysis (Fig. 8). The limited investigation on CGIC in permanent dentition might be due to its poor mechanical strength [42]. Further randomized control trials about CGIC on permanent dentition are needed.

In the results of meta-analysis on the preventive effect of RMGIC on new caries, we only obtained the RR of RMGIC restorations compared to composite resin restorations (Fig. 9). The data from one study assessing the caries incidence in primary dentition with RMGIC vs CGIC restorations were pooled and presented in the meta-analysis of caries progression of CGIC [43]. One of the included studies assessing the caries incidence in primary dentition contained data of both CGIC and RMGIC restorations. The

data from this study were pooled and presented in the meta-analysis of caries incidence in dentitions with CGIC restorations with RMGIC restorations as comparison [22]. Therefore, it was not appropriate to present the data again in the results of meta-analysis of caries incidence of dentition with RMGIC restoration. In this case, the caries incidence in dentitions with RMGIC restorations were not compared with CGIC again in Fig. 9. Other studies on RMGIC included for meta-analysis only compared the caries incidence between RMGIC and composite resin restorations. Therefore, this review only presented the results of the comparison between RMGIC and composite resin restorations regarding the caries preventive effect of RMGIC.

The follow-up periods of the included studies ranged from 1 year to 8 years. The average followup period of the included studies with CGIC restorations was 3.3 years, while on the RMGIC restorations, it was 1.7 years. Seven studies had the follow-up period of less than 3 years. The included studies had relatively short follow-up periods, which could be another limitation of the study. The follow-up periods were relatively short. This may be because most of the GIC were used in the primary dentition, which have a limit on follow up time due to natural exfoliation. In addition, CGIC is brittle and easily to fracture. Previous studies showed a CGIC restoration fracture rate of 10% after two years, which prevented follow up6. Studies also reported that GIC restorations showed an overall 18% cumulative loss rate during the 6-year follow-up [44]. This may be the reason why the most included GIC studies had shorter follow-up years.

The follow-up periods of the included studies in the meta-analysis varied. To minimize the effect of the follow-up period on the review’s results, we compared the new caries preventive effect of GIC with composite resin in 2 years and 7 years, respectively (Fig. 5). Regarding the meta-analysis of the new caries preventive effect of RMGIC compared with other restorations, we did not separate them into different follow-up groups because they had similar follow-up periods.

We included three studies on CGIC and two studies on RMGIC reporting the caries incidence for the meta-analysis. The other included studies with the outcome measure of caries experience increment were not eligible for the meta-analysis and were included only in qualitative analysis. The reason was because three studies assessed the caries experience increment in the dentition

after CGIC restorations without a negative control group [19], [20], [21],[45]. Meanwhile, some included studies did not perform the blinding of participants or examiners due to the obvious visual differences of CGIC and other types of restoration [46]. The failure of blinding might cause detection/performance bias, which led to the ‘high’ ratings for risk of bias. The results of the included studies might have been affected [47]. Further high-quality randomized control trials are needed to verify the results.

The number of the included studies were limited due to the insufficiency of previous publications on clinical studies, which was a limitation of this review. Since the included studies did not provide enough data (Fig. 6), comparing the caries preventive effect of GIC restorations on permanent dentition with primary dentition was not achievable in this review. Meanwhile, the number and size of restorations received by the patients, caries risk of the patients and the fluoridated factors might have influences on the caries incidence. Due to the limited data and information collection, these factors were not considered in the current review.

The preventive effect of GIC restorations on secondary caries, i.e., caries developed beneath the restoration, was not the aim of the review. Previous studies on secondary caries were always evaluated by United States Public Health Service (USPHS) criteria [48]. The outcome measures of these study were very different from the studies on new caries. Therefore, it was not appropriate to pool the data and perform the meta-analysis.

GIC is a favourable restorative material class with unique and advantageous properties, especially with a better preventive effect on new caries compared to other restorative materials. However, brittleness may limit their use in the load-bearing posterior regions. Several attempts to improve their mechanical strength and caries preventive effect might expand their clinical application.

Based on the limited evidence, GIC restorations have a better preventive effect on new caries compared to other restoration types in primary and permanent dentition. CGIC present a better preventive effect on new caries compared to RMGIC and amalgam restorations, but no statistical differences with composite resin restorations in primary dentition. RMGIC restorations showed no statistical differences in

preventive effect on new caries compared with composite resin restorations in both primary and permanent dentitions.

1- R.H. Selwitz, A.I. Ismail, N.B. Pitts

Dental caries

Lancet, 369 (2007), pp. 51-59, 10.1016/S01406736(07)60031-2

2-P.E. Petersen, D. Bourgeois, H. Ogawa, S. Estupinan-Day, C. Ndiaye

The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health

Bull. World Health Organ., 83 (2005), pp. 661-669

3- R.A. Bagramian, F. Garcia-Godoy, A.R. Volpe

The global increase in dental caries. A pending public health crisis

Am. J. Dent., 22 (2009), pp. 3-8

View Record in ScopusGoogle Scholar

4- C.H. Chu, S.S.S. Wong, R.P.C. Suen, E.C.M. Lo

Oral health and dental care in Hong Kong

Surgeon, 11 (2013), pp. 153-157, 10.1016/j. surge.2012.12.010

5- L. Prasai Dixit, A. Shakya, M. Shrestha, A. Shrestha

Dental caries prevalence, oral health knowledge and practice among indigenous Chepang school children of Nepal BMC. Oral. Health, 13 (2013), 10.1186/1472-6831-13-2020-20

6- U. Lohbauer

Dental glass ionomer cements as permanent filling materials? – Properties, limitations future trends

Mater, 3 (2009), pp. 76-96, 10.3390/ma3010076

-7 S.K. Sidhu, J.W. Nicholson

A review of glass-ionomer cements for clinical dentistry

J. Funct. Biomater., 7 (2016), pp. 16-31, 10.3390/ jfb7030016

8- S. Hoshika, S. Ting, Z. Ahmed, F. Chen, Y. Toida, N. Sakaguchi, B. Van Meerbeek, H. Sano, S.K. Sidhu

Effect of conditioning and 1 year aging on the bond strength and interfacial morphology of glass-ionomer cement bonded to dentin

Dent. Mater., 37 (2021), pp. 106-112, 10.1016/j. dental.2020.10.016

9- R. Nantanee, B. Santiwong, C. Trairatvorakul, H. Hamba, J. Tagami

Silver diamine fluoride and glass ionomer differentially remineralize early caries lesions, in situ Clin. Oral Investig., 20 (2016), pp. 1151-1157, 10.1007/s00784-015-1603-4

10- J. Zhao, D. Xie

A novel hyperbranched poly (acrylic acid) for improved resin-modified glass-ionomer

restoratives

Dent. Mater., 27 (2011), pp. 478-486, 10.1016/j. dental.2011.02.005

11- A. Agha, S. Parker, M.P. Patel

Development of experimental resin modified glass ionomer cements (RMGICs) with reduced water uptake and dimensional change