Service Design with the Planet in Mind

34 COMBINING SERVICE DESIGN, ECO-DESIGN AND CIRCULAR DESIGN Florie BugeaudRemond 50 WHAT’S CUSTOMER CENTRICITY GOT TO DO WITH THE CLIMATE CRISIS? Ben Reason, Anne van Lieren 53 PAVING THE WAY FOR SUSTAINABLE CHANGE Joost van Leeuwen 70 “WHAT NOW?” Joan Ball

vol 12 no 3 | october 2021 | 18 €

Touchpoint

Volume 12 No. 3

October 2021

The Journal of Service Design

ISSN 1868-6052

Published by Service Design Network

Publisher

Birgit Mager

Editor-in-Chief

Jesse Grimes

Project Management

Axia Zucchi

Cristine Lanzoni

Art Direction

Miriam Becker

www.studio-mint.de

Cover

Miriam Becker

Cover Image

© rawpixel

Pictures

Unless otherwise stated, the copyrights of all images used for illustration lie with the author(s) of the respective article

Printing

Hundt Druck GmbH

Fonts

Mercury G2 Apercu

Service Design Network gGmbH Mülheimer Freiheit 56 D-51063 Köln Germany

www.service-design-network.org

Contact & Advertising Sales Axia Zucchi journal@service-design-network.org

For ordering Touchpoint, please visit www.service-design-network.org/ touchpoint

Service Design with the Planet in Mind

As this issue of Touchpoint goes to press, COP26 is just a few weeks away. This will be the 26th edition of the UN’s climate change summit, and it comes with an urgent burden: It is seen as “… the world’s best last chance to get runaway climate change under control.” No pressure then, as they say.

If the thoughts of thousands of suited delegates meeting in Glasgow does not provide you confidence that our climate emergency will be adequately addressed –and the history of past emission reduction pledges and even announcements from China in the run-up to COP26 don’t inspire confidence – then what are you to do?

What you’re about to read might be a beacon of hope, and offer you the chance to direct your impact as a service designer towards addressing the climate crisis and sustainability concerns in general. As the authors of this issue share from their different perspectives, we can learn to not only take sustainability concerns into account in our work, but our tools and methods can be adapted and expanded to ensure we make positive steps towards addressing them.

Whether it’s applying strategic foresight to develop resilient and sustainable solutions (see Rebello and Black, page 18), adding the concepts of eco-design and circular design to our repertoire (see Bugeaud-Remond, page 34), or getting organisations focussed on their future customers (see Reason and van Lieren, page 50), there is plenty of inspiration as well as actionable insights waiting for you in the upcoming pages. Only time will tell if COP26 achieved its supremely ambitious goal. And looking at the success of past international efforts, it can seem that achieving meaningful progress and a real course reversal would be an incredible breakthrough. However I hold out hope for another reason: More and more service designers from our dispersed, global community are finding themselves in positions of influence in both government and the largest organisations. If – through our roles – we can apply the mindset and techniques shared here, we can surely make a collective impact.

As Al Gore, Nobel Laureate and former US Vice President, said, “Solving the climate crisis is within our grasp, but we need people like you to stand up and act.” Let’s hope this issue (further) inspires you to act, using the unique position you hold as a service designer.

Jesse Grimes is Editor-in-Chief of Touchpoint and has fourteen years of experience as a service designer and consultant. He is an independent practitioner, trainer and coach (kolmiot.com), based in Amsterdam and working internationally. Jesse is also Senior Vice President of the Service Design Network and Head of Training for the SDN Academy.

Beata Bienkowska, Deputy Research and Project Lead, Transition Pathway Initiative, London School of Economics. Prior to this Programme Manager at CISL Accelerator at Cambridge University and officer in the EU institutions and national administration.

Agusta Callaway is a Senior Consultant at Cambria Solutions. Previously she has been an organic farmer, beekeeper, entomological cataloger for Dr. E.O. Wilson, and community wellness initiative leader.

Emiliano Carbone is a Senior Business Designer at Tangity (part of NTT DATA Design Network). He worked both in industry and academia. In today’s service economies, he is engaged in research and strategy for large corporates.

Erik Roscam Abbing is a service designer and innovator with over 25 years of professional experience as consultant, public speaker, author, teacher, coach, entrepreneur and director. He is the global director of innovation at Livework, and teaches at the TU Delft.

Birgit Mager, publisher of Touchpoint, is professor for service design at Köln International School of Design (KISD), Cologne, Germany. She is founder and director of sedes research at KISD and is co-founder and President of the Service Design Network.

Touchpoint 12-3 3 from the editors

Jesse Grimes

34

40

46

Kirsikka

50

LAB LAB UX LAB UX UX 01 02 03 04 types of design structure company A company B & C company D company E Touchpoint 12-3 4 2 IMPRINT 3 FROM THE EDITORS 6 NEWS 8 KERRY'S TAKE 8 Service Design for the Planet Kerry Bodine 10 CROSS-DISCIPLINE 10 Service Design Perspectives: Innovation Labs and UX teams Clarissa Biolchini, Filipe Campelo

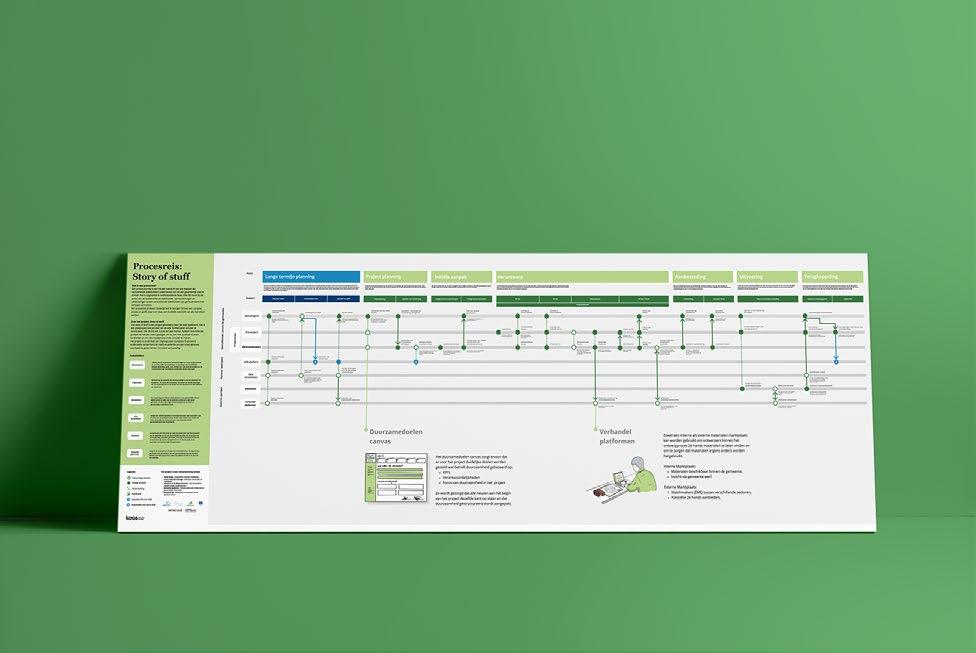

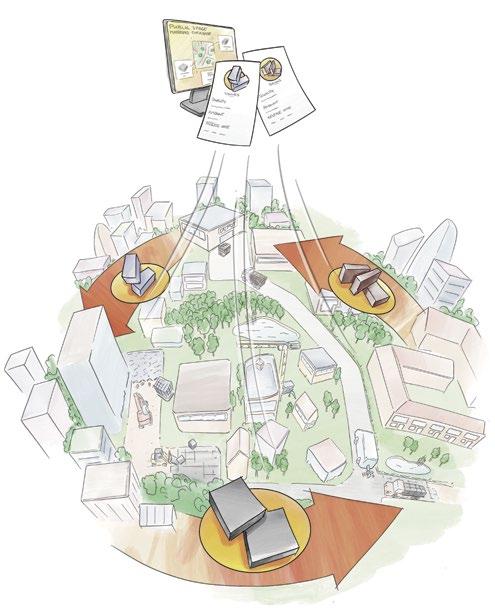

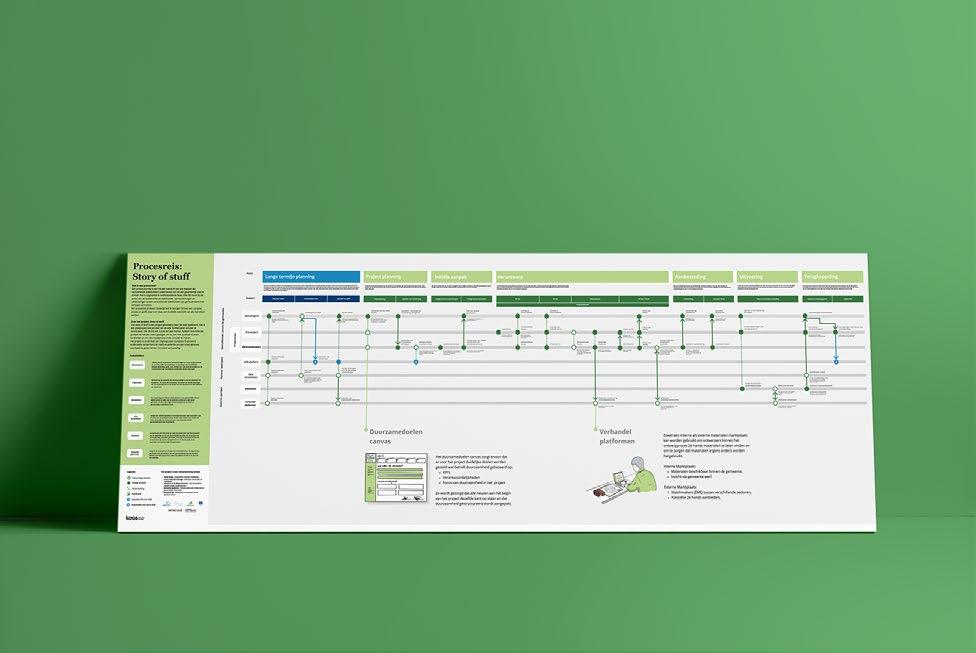

FEATURE: SERVICE DESIGN WITH THE PLANET IN MIND 18 Designing the Future We Need Stephanie Rebello, Rebecca Black 24 Emulating Natural Ecosystems in Service Design Sharina Khan 30 Service Design Tools for Sustainable Behaviour Change Mirja Kälviäinen

16

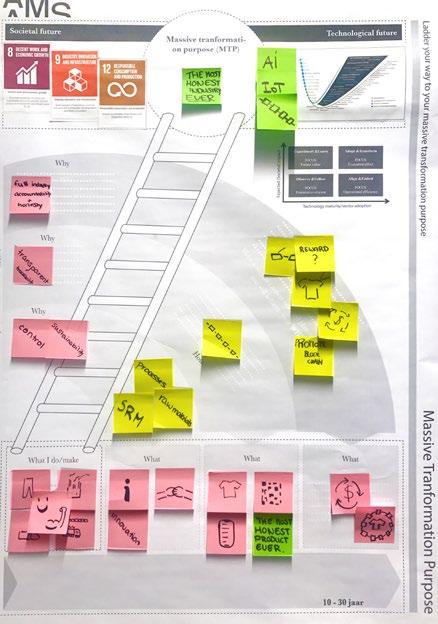

Combining Service Design, Eco-Design and Circular Design

Bugeaud-Remond

Florie

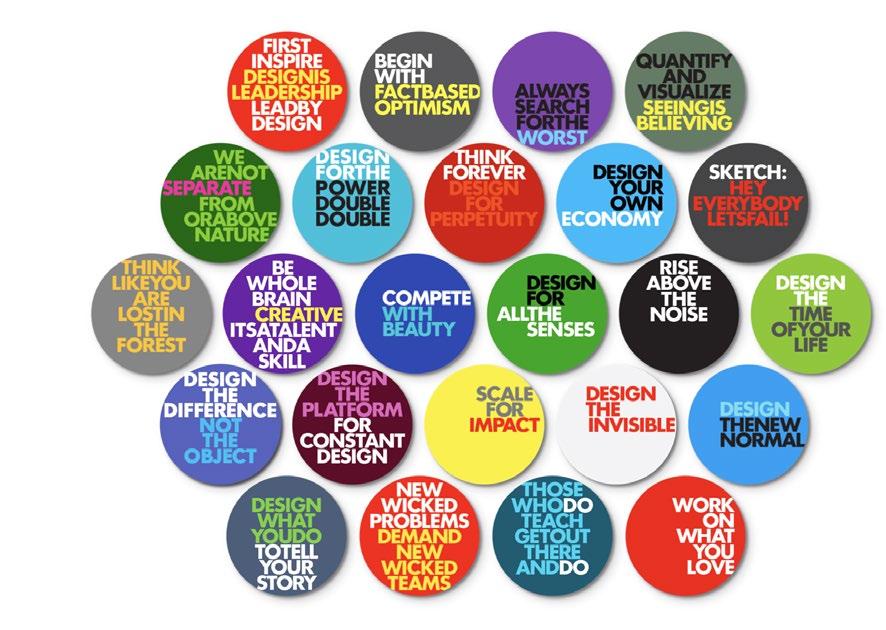

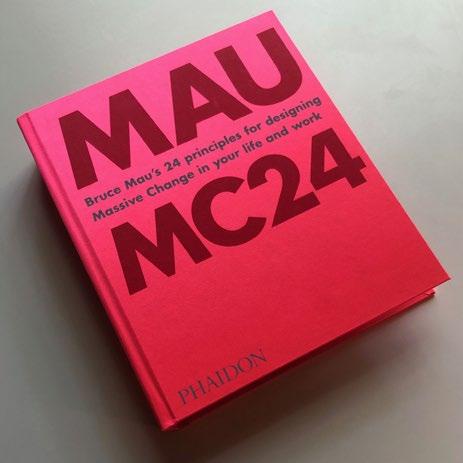

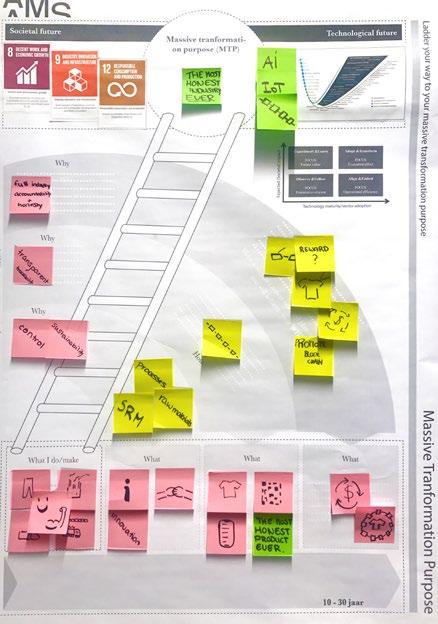

Massive Change –Life-Centred Design

Mager in conversation with Bruce Mau

Birgit

Envisioning Desirable Futures

Vaajakallio, Zeynep Falay

Flitter, Sonja Nielsen, Anna Pyyluoma

Von

What’s Customer Centricity Got to Do with the Climate Crisis?

Reason, 10 40 53

Ben

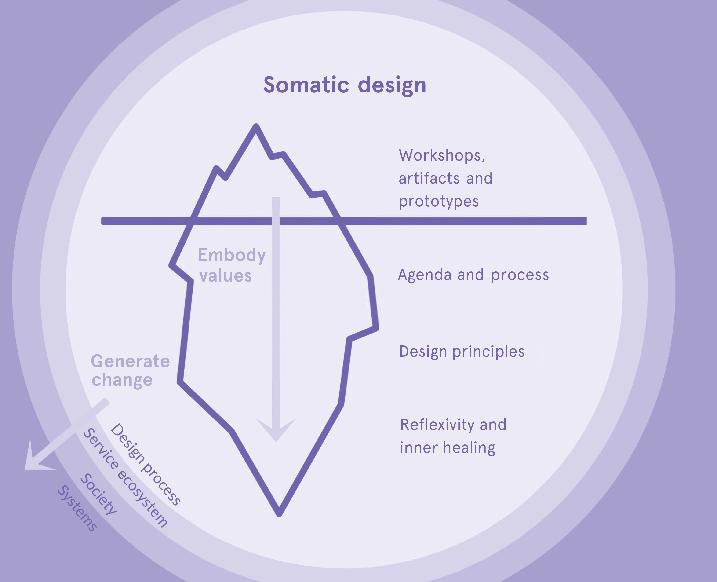

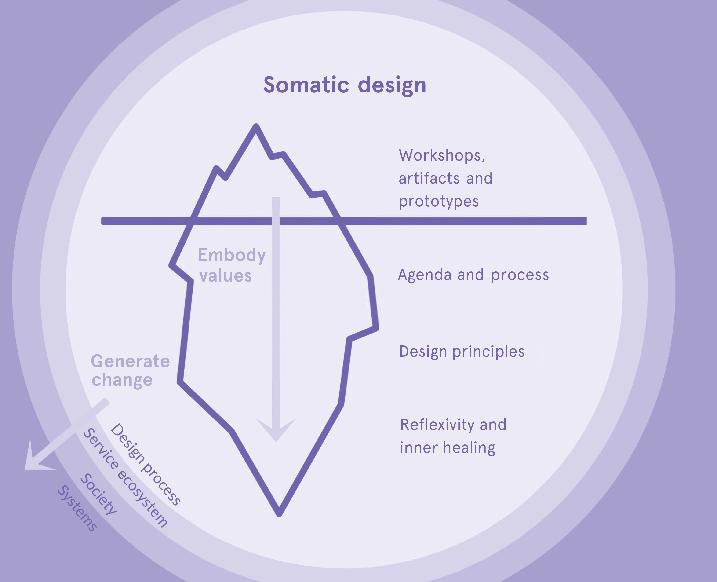

Touchpoint 12-3 5 contents Anne van Lieren 53 Paving the Way for Sustainable Change Joost van Leeuwen 56 ‘Somatic Design’: Engaging the Body for Climate Healing Emily Wright 62 The Thoughts You Allow Determine Your Actions Remco Lenstra 66 Introducing ‘Planetary’ to Design Yulya Besplemennova 70 “What Now?” Joan Ball 76 TOOLS AND METHODS 76 Applying a Service Design Approach to Understand Household Consumption and Disposal of Medicines in India Urmi Shah, Padma Rele, Shamit Shrivastav 80 Zoom-in on Customer Value Ulla Jones 83 INSIDE SDN 83 Service Design Day 2021 –Thank you for your participation! 84 Financial Inclusion at the Forefront 66 Economic value Hedonic value Altruistic value Emotional value Functional value Directly experienced value Indirectly experienced value Directly and indirectrly experienced value 80

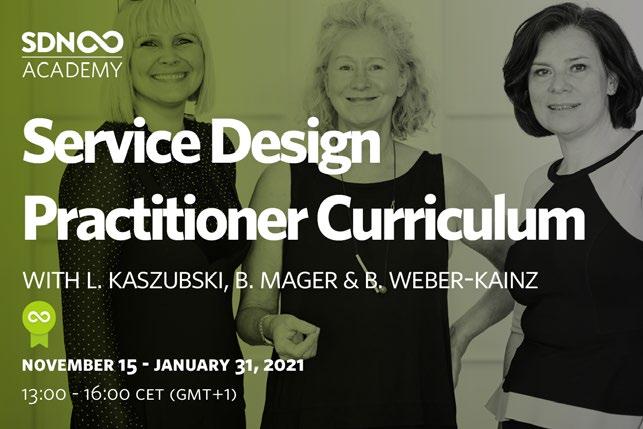

SERVICE DESIGN PRACTITIONER CURRICULUM (TRAINING AND ACCREDITATION)

The SDN Academy is proud to introduce to you our newest initiative: The Service Design Practitioner Curriculum Program starting on November 15, 2021. This unique training program is designed for those who want to build a solid foundation of service design practice and gather theoretical foundations, methodological skills and practical experience. In short, this training is for anyone who wants to learn the basics of service design.

The program consists of 32 hours, structured in six modules of online sessions, five modules of assignments and on-demand content. The participants of this curriculum will get free access to the Accreditation Test to become an official SDN Accredited Practitioner, which includes a two-year SDN membership with all its benefits. This training will be facilitated

by our very own SDN President and SDN Accredited Master, Prof. Birgit Mager, our SDN Accredited Master Barbara WeberKainz, Linda Kaszubski and other exclusive international guests.

Please note: SDN Members enjoy a discounted course fee. We at the SDN support financial inclusion

as part of our DEI mission (Diversity, Equity and Inclusion), based on the world bank clusters. If you think you are eligible for a reduction in the course fee due to the country you live in, please get in touch with us at info@sdn-academy.org!

You can register for the course at https://bit.ly/SDNA_SDPC21 .

SERVICE DESIGN AWARD 2020/21 AT SDGC21

The SDN is incredibly pleased to invite you to join the Service Design Award Ceremony, where we will celebrate our finalists and announce the winners, on 21 October during the Service Design Global Conference (SDGC21). Our host will be Kerry Bodine, Head of Jury 2020/21.

We cannot wait to honour ten extraordinary finalist projects and give them a spotlight they deserve. We encourage you to take a look at their excellent project work! The complete list of shortlisted projects and finalist case studies is available at https://www.service-design-network. org/service-design-award-finalists.

All attendees of SDGC21 will have a unique opportunity to hear from our winners and find out more about their incredible work, as part of the conference programme. Each winning project will be presented in a 20-minute session followed by Q&A.

Once again, congratulations to our finalists on their work and for being recognised as a benchmark for a world-class service design.

We hope you will join us to see our nominees and discover the winners!

Special thanks to the 2020/21

Jury: Kerry Bodine, Taina Mäkijärvi, Kate Okrasinski, Luis Alt, Damian Kernahan, J. Margus Klaar and Florian Vollmer.

Written by Sonja Jazic –Project Manager at the SDN

Service Design Award Finalists

Touchpoint 12-3 7 news

S E R V I C E D E S IG N AWAR D 2 021

GLOBAL BENCHMARK FOR WORLD-CLASS SERVICE DESIGN

THE

#SDAWARD

Photo by Kvalifik on Unsplash

Service Design for the Planet

Driving along the U.S Route 27 north of Cincinnati, Ohio, you can catch sight of a mountain. It’s not majestically jagged like the European Alps — nor endlessly undulating like the much older Appalachians, which sweep from Canada through the southern United States. In fact, you might not understand the true nature of Mt. Rumpke until you get closer… and smell it.

Named for the Rumpke Waste & Recycling company, this ‘mountain’ stands 328 meters above sea level, towering above all other landforms in Hamilton County, and counts as the sixth largest landfill in the U.S.

Whenever I throw something into our kitchen wastebin, which I’ve labelled ‘landfill’ to subtly encourage my family and me to make more environmentally friendly purchases, I think of Mt. Rumpke — and the continually growing landfills around the world. A disturbing statistic sticks in my mind: In my home county of Sonoma, California, the landfills will reach capacity in 28 years if we don’t change how we manage our waste. And our lives.

The online shopping dilemma One of the biggest changes to my personal behaviour over the past

decade has been how often I opt to shop online. Like many people, I struggle to pack in all of my mustdo’s and want-to-do’s into each day’s schedule. There are a million online retailers that make online shopping easy and offer nearly everything I could ever want. Most often free shipping and returns. And to be completely honest, I hate trying on clothes in a dressing room. In short: Online shopping works for me. And it works for millions of others, too.

But with every click of the ‘add to cart’ button, I stress about the environmental impact of my purchases. Rather than taking advantage of optimised bulk product shipments to retail stores, my online purchases prompt companies to pack up individual items in plastic and Styrofoam and use fossil fuels to deliver them right to my door. And

more often than I’d like, I see terrible inefficiencies in the packaging. A recent purchase of three small cork boxes from retailer Design Within Reach — which we purposely selected over plastic alternatives — arrived in three separate packages, each filled to the brim with a ridiculous amount of packing paper.

Even worse is the returns process. I recently purchased a bunch of inexpensive summer dresses from discount retailer Target. Given the current supply chain delays, I didn’t think much when they arrived in separate packages over the course of a couple weeks — I just dutifully waited for all of the items in my order to arrive so that I could return my unwanted items all in one go. But when I started the returns process, Target instructed me to return the items from each individual shipment in a separate package.

This process was an inconvenience from my perspective as a customer — it would have been so much easier to just put everything into one bag or box. But Target’s requirement also necessitated additional packaging and tons of non-biodegradable tape. Sigh. I thought of Mt. Rumpke and made a mental note not to order online from Target again.

Touchpoint 12-3 8

Designing the backstage

Online shopping is not going away. Nor are many other modern services that we’ve come to rely on — services that often fulfill our immediate needs at the expense of our long-term human objectives. I don’t believe these two things need to be at odds with one another. And I know that service designers are uniquely positioned to marry these two seemingly competing forces.

Service designers can create backend processes for sourcing environmentally friendly packing materials and for ensuring items are packed as efficiently as possible. Service designers can define warehouse procedures that accept return packages with items from multiple shipments and multiple shipping locations.

All it takes is a desire on the part of service designers to truly embrace the nitty, gritty (and sometimes complex and ugly) backstage people, processes and technology behind the services we’ve all grown to rely on.

Staffing for the planet

As our business landscape has changed over the past several decades, organisations have responded by creating new roles

to support both business mechanics and customers. I’ve personally seen the introduction of corporate responsibility specialists, diversity and inclusion managers, customer experience professionals, customer success managers and journey managers. It’s time to expand this list to include professionals focused on reducing the carbon footprint of their employers.

Recology — a waste, recycling and composting company headquartered in San Francisco — has Waste Zero Specialists who are responsible for helping residential, commercial and industrial customers throw away less — and recycle and compost more. Such roles shouldn’t be limited to waste management companies. And service designers are in a unique position to champion the creation of these positions with their clients or employers.

Driving change through demand

At the end of the day, organisations respond to the demands of their customers or constituents. And so, the most effective way for all of us to impact the future of our planet may be for us to become better ‘consumers.’ I typically avoid this

word, as I feel it reduces humans to resource-gobbling automatons.

But in this case, it feels appropriate. We all need to think about how we can consume less. How we can reduce and reuse more. And when organisations realise that their bottom lines depend on meeting our collective needs to support our planet, change will come.

Kerry Bodine is a customer experience expert and the co-author of Outside In Her research, analysis and opinions appear frequently on sites such as Harvard Business Review, Forbes, and Fast Company.

Follow Kerry on Twitter at @kerrybodine

Touchpoint 12-3 9 kerry ' s take

Service Design Perspectives: Innovation Labs and UX teams

A study of service providers in Brazil

Clarissa Biolchini, CEO of Archipelago, adjunct professor at PUC-Rio and guest lecturer at Berlin School of Creative Leadership. One of the co-authors of the book This is Service Design Doing from Stickdorn et al

Filipe Campelo, professor and researcher at Design Graduate Program Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos (UNISINOS). His research interests are related to user experience, design management and food design.

In the 21st century, design’s scope has been amplified in the business context. Due to the digital revolution and the emergence of new technologies, in order to foster innovation and adapt to market changes and to new consumer needs, the majority of organisations have increased their investments in design.

As mentioned by Mager and Moussavian1 , service design and Design Thinking have been applied in large companies to deal with the great complexity of companies and markets. This article presents the results of research about in-house innovation labs in large Brazilian organisations, represented by five service providers in the insurance, finance, payment methods and media industries, all of which are non-digital native companies that were established around fifty years ago. The focus of our research was on in-house, design-driven innovation labs – which are mainly service design labs. However, due to the digital transformation processes identified during the interviews, the User Experience (UX) areas appeared as an

essential element, since they represent the major design areas in organisations

Innovation labs can be understood as vehicles to disseminate the service design process and enable non-designers to experiment 2 . One of their missions is to increase organisational cultural transformation towards a more designoriented mindset. They can enable knowledge diffusion amongst different organisational silos as well as promote space for collaboration and innovation3 .

Non-digital-native companies versus digital-native companies

For better understanding design’s increasing relevance in corporate practices, it is important to take into

2 Magadeley, W. & Birdi, K. (2009). Innovation labs: an examination into the use of physical spaces to enhance organisational creativity. Creativity and innovation management, 18, 4, 315-325.

1 Mager, B. & Moussavian, R. (2017). Design thinking inhouse – design-driven innovation labs. Service Design Network.

3 Fecher, F; Winding, J.; Hutter, K. & Füller, J. (2020). Innovation labs from a participant’ perspective. Journal of Business Research, 110, 567-576.

Touchpoint 12-3 10

consideration two different types of organisations. Over the past two decades, a great number of companies such as Uber and Airbnb have emerged in the consumer market, presenting new business models and ecosystems, and offering new value propositions and experiences for their customers. Most of these digital-native companies adopt design principles as a regular practice, combining them with technology, as a natural way to achieve better results. These companies are structured based on an agile mindset and place user experience (UX) and user centricity as the main pillars of their organisational culture and structures. On the other hand, the largest 20th century service providers such as those in the banking and insurance industries turned out suddenly to be laggards compared to these ‘new kids on the block’.

Driven by increasingly complex challenges, these ‘non-digital-native’ companies were forced to focus on digital transformation. Among other strategies, they created in-house, design-driven innovation labs, adopting Design Thinking and service design as core engines for their innovation processes.

Innovation labs versus UX teams

The results of this research lead to several findings described further in this article. The study points out the main connections between service design and UX teams with regard to organisational aspects, such as the company’s design maturity level, the industry’s market innovation level and the organisational culture. Finally, it presents a perspective of service designers’ roles in these companies and offers a future vision of how service design will evolve in future years in organisational terms.

According to our study, non-digital-native companies created their in-house innovation labs to foster product or service innovation and to amplify design and innovation culture within their corporate contexts. These companies typically created their labs around 2012. Due to the lack of organisational know-how in design culture, they hired external innovation consultancies in order to assist them to structure their labs’ work in the initial phases of the design process. In addition, they also created their first UX structures. One of the biggest companies we researched created five service design squads and a UX team by then, all under the IT department. Initially, four of these service design teams were working for specific business units, such as the “UX team for credit cards”, and one of them functioned more like an innovation lab under the label of “Innovation and UX area”. The function of these teams was to deliver research reports focused on the integration of technology, digital products and users. Even though these first five design teams were not named as ‘labs’, they functioned as such, developing new ideas and services for the business units. They were seen as in-house suppliers to their own business units. “Our company was very focused on products, and the design and IT teams were seen as internal suppliers”, said a service design manager.

Innovation labs versus UX teams: Roles, scope and team structures

While innovation labs work more according to a consultancy model, focusing on specific projects and creating deliverables such as a service blueprints, the UX teams work according to an ongoing operation

Touchpoint 12-3 11

cross - discipline

model, in order to continuously deliver and improve the digital experience for the end customer.

Considering the working models of these design teams in non-digital native companies, the labs have two types of clients: internal clients (within the company) and external clients (the company’s own clients as well as business partners with which they co-create new products or business models for partnership). They also tackle in-house demands, such as organisational design projects or employee experience projects. On the other hand, the UX teams focus on end consumers, aiming to provide a better digital experience for end customers – a common goal for both digital and non-digital-native companies.

As such, in non-digital-native companies, design expansion has occurred by combining innovation labs with the work of UX teams. In these companies, while innovation labs generally focus on innovation for services and business models, the UX teams focus on digital user experiences.

Concerning roles and organisational structure, our study revealed that all the companies studied have different design structures, either innovation labs or UX teams, according to their sizes, industries and business models. The different structures and roles might vary according to their organisational contexts. In the non-digital-native companies, depending on their structure, innovation labs might belong to different areas, such as product development, marketing or business development or Customer Experience (CX), whereas the UX teams are generally connected to the IT department. In contrast, in the digital company, UX is a core area, and UX teams are directly connected to business units.

Team structures

In terms of team members, UX teams typically feature a wide range of design expertise, from design researchers to UI designers, all of whom are focused on digital products, without a defined scope for service design. In digital companies, UX teams follow this same model, however, UX teams’ heads take on

more strategic roles, since they are connected to the business units and report to the corporate level.

Concerning the total number of designers in the company, due to the growth of digital areas in 21st-century companies, UX areas typically have many more designers, compared to the number present in innovation labs. While team sizes in innovation labs can go up to 10 or 11 designers, UX teams have many more, ranging from 60 to 280 people. In total, in Company A, there are around 150 designers (internationally), including the 13 global innovation labs’ teams and the UX team in the US, which has approximately 80 people. Company B has about 65 designers, Company C around 300 designers, Company D around 180 designers, and Company E around 170 designers in total. The 170 designers of Company E (digital company) are part of the UX team that has 336 professionals – including design, research and content specialists. The table with the description of the cases studied is shown in Figure 1.

The merger of innovation labs and UX teams

In non-digital-native companies, as design has become more and more integrated into their corporate cultures, and digital transformation has taken over organisational strategy, the original labs have eventually merged into other areas. Some of them have been incorporated into UX areas and others have been integrated into new design areas, in marketing or business units. As a senior manager said, “Over the years, the labs finally got diluted. It didn’t make sense to have innovation labs anymore.”

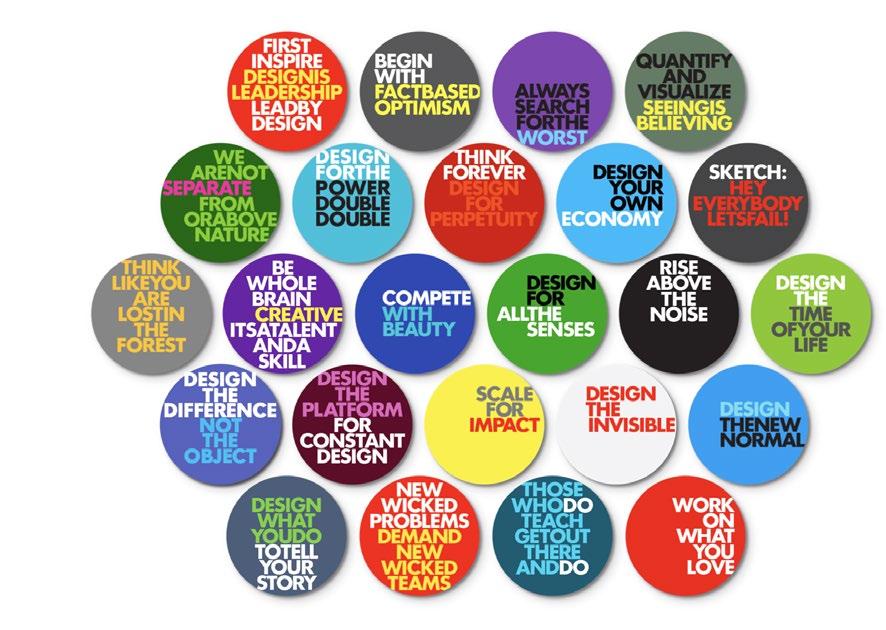

According to the four types of design structures presented in Figure 2, in companies A to D, the design structures have evolved from being only innovation labs, towards having independent labs and UX teams, towards a merged team. Finally, the digital company (E) does not have a lab and possesses the largest UX department among the five companies reviewed, composed of a 336-employee team in the Latin American region. “Since innovation is spread over the areas of UX, products, IT areas and some business units, there is no need for an innovation lab”, said a UX leader.

Touchpoint 12-3 12

Company

Industry

A

Financial services

Design area’s name Company area

“Innovation Studio” Solutions & innovation

Design structure

LAB

Team structure

Scope of areas

Type of client

LAB + UX

LAB 3 people

Total

~ 150 designers*

LAB: Service and business model innovation**

External Type 1 Insurance

“Innovation Labs”

C

Life insurance (product area)

Type 3 Type 4 B

LAB + UX

Media Communication “Strategic Design & Innovation” Innovation

Banking

E-commerce

“CX” “UX”

Channels & experience IT

LAB + UX area

LAB 5 people

Total

~ 65 designers

LAB: Service/ produt innovation (starting on business model innovation)

UX: digital channels

Internal (end consumer) and external Type 2

LAB + UX

LAB + UX areas

LAB 11 people

Total

~ 300 designers

CX (Design + UX) + other labs and service design (marketing)

UX + Design + SD

Total ~ 170 designers

UX

UX

Total

~ 170 designers

LAB: service design focused on business design

UX: digital experience

Internal and external Type 2

Service/product design and user experience

Service/product design and user experience

Internal (end consumer) and external

Internal (end consumer)

D

Touchpoint 12-3 13 cross - discipline

E

Fig. 1: Company characteristics

The innovation lab role and a future vision of service design Innovation labs play a fundamental role in digital transformation processes in non-digital native companies, since they foster innovation by creating better services for their customers –whether digital or not – and they also nurture the organisation’s innovation culture. For all non-digital native companies, labs have taken on the role of building up innovation culture, based on design principles, such as user-centricity, problem-solving, creativity, empathy and divergent thinking.

Our research points to a future scenario in which Labs might no longer exist in the nondigital-native companies, at least not with their initial role and structure. Depending on the type of industry and design maturity level of the company, labs teams might evolve into in-house service design areas, or merge into UX teams. On the other hand, in digital companies, UX teams will likely focus on digital products, with UX heads frequently taking over the role of strategists, as business designers and service designers.

According to the 12 executives interviewed in these companies, the leaders of UX teams must have a more strategic vision, guided by service design and business expertise. According to them, over the next decade, service design will play a more strategic role in all kinds of organisations.

Furthermore, service design skills will be needed in strategic positions, connected to business areas in order to support service innovation from a strategic point of view. Therefore, the future of service design is likely to become more strategic and fundamental to business.

LAB LAB UX LAB UX UX 01 02 03 04 types of design structure company A company B & C company D company E Touchpoint 12-3 14

Fig. 2: Types of design structures

Touchpoint 12-3 15 Want to Dive Deeper? Have a Look at Our Publications! Service Design Award Annual Softback 168 pages 190 x 255 mm 4-colour litho Designed by the SDN with love Design Thinking Inhouse Digital Publication (PDF) 107 pages 210 x 150 mm Published in English and German You can order these and many more publications on our website: www.service-design-network.org/ books-and-reports. 25 % Discount for SDN Members

Service Design with the Planet in Mind

feature

Designing the Future We Need

How design and foresight can support community sustainability strategies and spur transformative change

Stephanie Rebello is a design researcher and strategist specialising in sustainability and purpose-driven programming, Steph is focused on building equitable and inclusive communities, products and services at leading Canadian organisations, Steph holds a BA in Sociology from Western University and a Master of Design in Strategic Foresight and Innovation at OCADU.

Rebecca Black works with a range of international clients seeking low-carbon solutions and behaviours to address the climate crisis at her design consultancy Black Current. Rebecca holds a Master of Environmental Studies specialising in Business & Sustainability from York University, and a Master of Design program in Strategic Foresight & Innovation at OCADU.

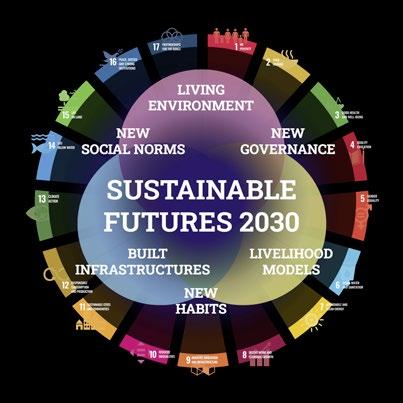

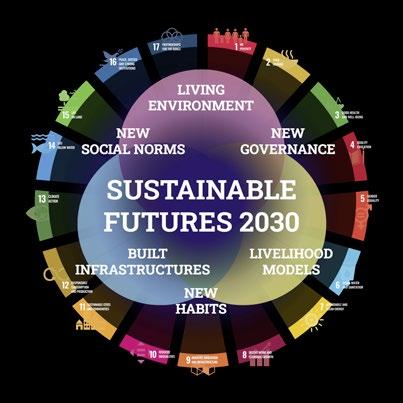

The concept of sustainability embraces a wide range of opportunity areas, as the diversity of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) demonstrates1. What role might service design play to address the SDGs and help steer the transformation to sustainable and resilient solutions? We explore how organisations might respond strategically to these challenges and opportunities through the practice of strategic foresight and design.

As catastrophic climate events spur disastrous human and planetary impacts, it’s clear that current sustainability strategies aren’t meeting international sustainability targets2 . Decades of minimal responsiveness and incremental action have failed.

As sustainability practitioners alarmed by the slow pace of change, we set out to gain a deeper understanding of why we are stuck in an incremental change process when bigger action is urgently needed. We started by exploring the interconnected nature of the sustainability challenge and what’s holding transformative change back (see Fig. 1).

We also sought out new and emerging approaches and tools for defining and designing for sustainability. Of particular inspiration was Ezio Manzini, Professor of Industrial Design at Milan Polytechnic and a leading expert on sustainable design. His focus is on scenario building toward improved environmental and

social outcomes. At Barcelona’s ElisavaDesign School and Engineering, his work draws inspiration from the practice of collaborative food networks, describing sustainability at its core as ‘new ways of living and producing’. His work informs an emerging definition of sustainability which is rooted in “a multiplicity of initiatives performed by a variety of people, associations, enterprises, and local governments who, from different starting points, move towards similar ideas of wellbeing and production”4 . Our resultant understanding of the macro-systems and current trends that are shaping the sustainability

1 https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/

2 Hrvatin, V. (2016, May 31). A brief history of Canada’s climate change agreements. [article]. Canadian Geographic. Retrieved July 14, 2021, at canadiangeographic.ca/article/brief-historycanadas-climate-change-agreements

18 Touchpoint 12-3

Barriers to transformative sustainability

Economy built on natural resource

A linear supply chain with poorly resourced and incentivised recycling system

Culture of convenience

A consumer base focused on immediate gratification

Legac y of in stitutionalised racis m

Historical ignorance to indigenous sustainability principles

Political frag mentation

Conflicting priorities and tensions amongst federal and provincial levels of government

Green-washing

Precarious corporate philanthropy and profit-driven cause marketing

Ambiguous definition of sustainability

Practitioners approach sustainability differently, this misalignment causes silos, and feeds competition

Sustainability as a premium product

Sustainability remains largely reserved for Canada's elite as a status indicator

landscape, and emerging models of design for community resilience, provided the foundation for the design case study explored in the article.

Towards Sustainable Futures: The FutureTREC Case Study

TREC (Toronto Renewable Energy Co-op) is a nonprofit leader in community-scale renewable energy and social finance in Toronto, Canada. TREC believes in a democratic, community-scaled vision of sustainability.

3 Black, R. & Rebello, S. (2021). Towards Sustainable Futures –Using strategic foresight in the design of transformative sustainability [Masters Thesis].

4 See Manzini (2013), Resilient Systems & Sustainable Qualities. Small, local, open, connected: An emerging scenario [report]

In the past 15 years they have incubated communityfinanced solar and wind power cooperatives and a social finance service that helps organisations leverage community capital to support iconic local projects. Their approach is highly aligned with Manzini’s communitybased solutions.

In early 2020, TREC intended to conduct a strategic planning process to determine their next direction to propel the clean energy and sustainability sector. They were keen to try something new and different, despite the global pandemic, which introduced a new layer of complexity to planning.

We jumped at the invitation to design a process for TREC that would inspire creativity and spur participants to make some big but relevant bets on what a sustainable future and strategic

Touchpoint 12-3 19 service design with the planet in mind

Fig. 1: A summary of key barriers towards transformative sustainability revealed through an evaluation of Canada’s history with sustainable practice and policy3

direction might look like. Designing a participatory and collaborative creative design process, dubbed FutureTREC, allowed our case-partner to engage its robust community, clients and stakeholders.

Over a five-month timeline, we leveraged strategic foresight to explore the use of future scenarios to help spur transformative change. The process involved using persona mapping and prototyping to situate emergent strategies and ideas, and mapping insights across an innovation matrix to support TREC in resourcing the transformation. The process evolved at each phase, as we iterated based on emerging knowledge from our research and, more importantly, with the insights and feedback from TREC participants.

Defining Sustainability for the FutureTREC Project

The concept of sustainability embraces a wide range of opportunity areas, as the diverse list of the SDGs demonstrates. In the FutureTREC project, we worked with management to pinpoint what types of projects and opportunity areas embraced the SDGs and aligned with the organisation's core values. We landed on five opportunity areas that were then tested through a TREC community survey:

1. Driving the Circular Economy: Educate, advocate and incubate inspirational projects that help decouple local economic growth from the consumption of finite world resources;

2. Improving Lives in our Cities: Create breakthrough urban experiences by leveraging democratic, collaborative, community-building financing, tools and systems;

3. Promoting Local Energy Independence: Accelerate our transition to a zero-carbon future through locally owned, community-scaled energy projects;

4. Facilitating Inclusive Communities: Amplify and prioritise projects led by members of underserved communities including youth;

5. Community Economic Resilience: Help our communities thrive in the face of unprecedented challenges, through local investments in projects that promote sustainability and foster local job growth.

The survey results saw Community Economic Resilience selected as the most viable, desirable and feasible opportunity area for FutureTREC.

The TREC Board collaborated on a definition that reflected their collective insights. The ‘working definition’ that the group landed upon was this:

Resilient local economies are those that can provide fulfilling livelihoods and create emotional cohesion within a community of people, who are using their fair share of resources to generate a range of community assets and transaction types – personal, economic and governmental – that build the capacity to move forward sustainably in response to short term shocks and long-term changes, whether they be ecological, social and/or economic.

And with that milestone accomplished, the strategic foresight planning process for TREC was underway.

Five Phases of the Strategic Foresight & Design Process

Below we breakdown each phase, showcasing the tools used, outcomes gained and the practitioner learnings gained along the way.

Phase One was rooted in one of three emerging pathways identified by Manzini, building a new set of boundaries around the value and role of connected places and local economies. Local food networks are an example: they offer an alternative to an already precarious globalised supply chain by building a collaborative network based on bottom-up initiatives and an openness to grassroots social innovation.

Phase Two pushed participants into a creative space, challenging them to imagine potential futures within the guardrails of two critical uncertainties facing TREC as an organisation. This phase inspired four distinct future scenarios which would serve TREC in designing multiple opportunity spaces based on their organisational strengths. Our approach aligned to a second pathway highlighted through Manzini’s work, the need for feasible, flexible and attractive visions of sustainable and reimagined futures, allowing people to see themselves in a range of better environments.

Phases Three and Four shepherded earlier creative activities into a focused strategic plan and set of

20 Touchpoint 12-3

5–7 Black, R. & Rebello, S. (2021). Towards Sustainable Futures –Using strategic foresight in the design of transformative sustainability [Masters Thesis].

Goal Tools

Focused an community participation and the co-creation of new visions for sustainability

• Literature review and environmental scan: Building knowledge to better understand and assess opportunities and context

• Community survey: Reaching out to key stakeholders to garner their perceptions, ask their input, and gain insights to inform decision-making

Diversity starts here

Practitioner learnings

Goal Tools

Goal Tools

Practitioner learnings

Practitioner learnings

Building a diverse participant list requires early intention and consultation

Participants are the designers

Striking the right balance between leading a process, and allowing participants to lead the design

Scoping sustainability is a on-going process

Revisit definitions and be critical of who is involved and impacted by decisionmaking 1

Challenging participants to think beyond their organisation

Challenging participants to think beyond their organisation

Horizon Scanning: The horizon scanning process involves sourcing information about external forces of change that are affecting the opportunity area

Goal Tools

Practitioner learnings

Horizon Scanning: The horizon scanning process involves sourcing information about external forces of change that are affecting the opportunity area

Participatory workshop – 2 x 2 matrix: Using a 10-year timeframe, our collected trends were plotted against two critical uncertainties

Empathy for the end-user

Participatory workshop – 2 x 2 matrix: Using a 10-year timeframe, our collected trends were plotted against two critical uncertainties

Explaining the 'why' and the 'so what' was critical for buy-in

Empathy for the end-user

Explaining the 'why' and the 'so what' was critical for buy-in

World-building in the time of Covid-19

World-building in the time of Covid-19

In a time of increased uncertainty and volatility, asking participants to reach into the future was impacted 2

In a time of increased uncertainty and volatility, asking participants to reach into the future was impacted

2

Personas: Creating reli able and reali sti c representations of key acto rs involved in the o ppo rtuni ty area

Customer journey mapping: Used to understand what pro blems end-users mi ght be trying to solve

Expert interviews: So urcing di verse perspecti ves and insights from experts in communi ty-b uilding

Preconceived destinations

lt is challenging to let go, to disconnect from current sustainability practices and embrace an unknown future

Pivot back to people

Connecting back to user-research was a constant practice that rooted participants back into the "why"

The power of the group

Leveraged group co-design and ideation to spark an iterative solution cycle 3

Fig. 2: Phase One: Understand Today5

Fig. 3: Phase Two: Imagine the Future6

Fig. 4: Phase Three: Design the Possible7

Touchpoint 12-3 21 service design with the planet in mind

Ap pl ying a h um an- c entred l ens to g enerating solu t i ons

Goal Tools

Practitioner learnings

Transition planning and resourcing transformation

Innovation Ambition Matrix: Helps organise solutions and draw connections between them, while measuring their novelty against current company offering and customer markets

Rethinking orthodoxies

What are the systems of power and privilege that exist in our tools?

Structure matters

How might this process need to change for other types of organisations?

Foresight accessibility

For a sector that is resource-constrained, foresight must be accessible and sustainable?

Scoping transformation

Transformation is only measurable once strategies are acted upon 4

actions. Phase Three helped participants build out community-centered solutions using Manzini’s final pathway, with a greater emphasis on designing product-service innovations to provide new ways of doing things and to re-organise supply systems to avoid the incremental eco-efficiency trap.

Phase Four of the project brought the focus back to TREC: Which of the ideas and strategies put together by project participants aligned best with their innovation ambition? Which best helped to accelerate TREC towards their vision of a sustainable and resilient future? The goal for this phase was to support TREC in articulating their innovation ambition and creating a sustainable and manageable portfolio of innovative ideas.

Project outcomes

Today, TREC is exploring innovative community economic resilience ideas and strategic opportunities, which emerged through this foresight and design

8 Black, R. & Rebello, S. (2021). Towards Sustainable Futures – Using strategic foresight in the design of transformative sustainability [Masters Thesis].

9 Nagji, B. and Tuff, G. (2012). Managing Your Innovation Portfolio. Harvard Business Review.

https://hbr.org/2012/05/managing-your-innovation-portfolio

project. The FutureTREC innovation portfolio consists of core, adjacent and transformational initiatives 9 and includes a range of ideas that span from building on core competencies, to those that require entry into new areas, to transformational opportunities that require exploring by leaps. The common denominator is they all have the potential to accelerate TREC's vision of community economic resilience.

Feedback on the foresight and design process from participants highlighted their appreciation of: Context-driven future scenarios that were hyper- local, with people at the forefront; The systems design approach, which mapped the complexity and interrelationships of possible innovation strategies, helping participants to better understand the dynamics of change – including unintended outcomes – and create insights allowing for solutions that better support authentically SDGs; The emphasis on enabling knowledge generation and skill-building by participants throughout the process. By developing an understanding, appreciation, and comfort for the uncertain nature of futuring work and the ambiguity of possibility, participants felt they were better equipped to continue to iterate and build upon their visions of sustainability.

22 Touchpoint 12-3

Fig. 5: Phase Four: Select and Undertake8

What we learned as designers

As researchers, designers and practitioners of strategic foresight for sustainability, our impact will arguably only be as strong as our ability to engage organisations that want to discover transformative innovations, and to provide meaningful experiences that generate exciting and actionable results.

The TREC project put this premise to the test. Execution matters. As we reflected on our strategic foresight experience from the perspective of process designers, we explored what aspects not only broke down barriers towards transformative change but were core to the service design approach. Here we share the values that supported our research and sense-making process. They act as guideposts when designing and executing strategic foresight processes for transformative sustainability.

1. The process is collaborative: While collaboration is so deeply embedded in service design work as to be assumed, our experience highlighted how designing in pervasive collaboration for sustainability solutions opens space for participants to co-create new positive visions for the future while reframing individualistic or competitive approaches to solution-making. The collaborative space and process also supports moving beyond incremental change mindset to leverage collective creativity. The process encouraged participants to re-think current systems of doing and making at a time when large-scale transition and alternative sustainability solutions are pressingly needed. The collaborative approach may also address the growing incidence of climate anxiety at the individual level through enabling, collective solutioning.

2. The process empowers intersectionality: It’s often the most vulnerable people who are excluded from the decision-making table. As designers, we grounded this experience in the needs of the community by opening space for a diversity of participants, perspectives and voices, and extended the inclusive and equitable approach when developing future actors, scenarios and solutions. Actively and consistently practicing Design Thinking helped unearth unmet needs, driving creative and unexpected solutions that authentically solve real problems at the human and community level.

3. The process helps to rewire systems: Focusing on product-service innovation restores individual and collective agency and moves away from an over-reliance on breakthrough technology to solve social and ecological challenges. By focusing on new ways of doing and making, we can accelerate the shift to a circular economic model that helps refocus local economic growth from the consumption of finite world resources.

All (designer) hands on deck

The conversation and action around sustainability is evolving quickly. In the summer of 2021, the United Nations’ IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) landmark report by the world’s top climate scientists showed that Earth’s climate is warming at a faster rate than previously thought, forecasting greater and more widespread consequences for society and the planet10 . The new urgency spurs individuals and organisations to rethink their existing models and incrementalism overall. As designers, the FutureTREC project gave us confidence that inclusive, agile models of research coupled with collaborative foresight tools can deliver valuable, actionable and authentic insights into ways in which organisations might strategically steer the transition to more sustainable solutions. We encourage other designers to explore service design and strategic foresight as frameworks for building disruptive and transformative approaches to sustainability, to build the future you desire and the future we need.

Touchpoint 12-3 23 service design with the planet in mind

10 IPCC (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis [report] accessed at https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/ report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Full_Report.pdf

Sharina Khan is a Senior Experience Design Consultant at Thoughtworks. Sharina is currently working with multiple stakeholders and agencies from the public sector in Singapore on a highly complex case management system to get a clearer picture of pain points, stream line business processes and deliver maximum value to both clients and end users.

Emulating Natural Ecosystems in Service Design

Introducing the Macro Service Mapping method

What relationship do UX, CX, service design and systems design share? Like our natural ecosystem, they all exist from the microscopic levels of an individual to the complex ecosystems we interact with.

The omnichannel1 service complexities of today can be addressed by understanding the interactions that occur between the layers they share, from the individual to the larger systems that impact their experiences in the end. Starbucks, Nike and Disney are examples of companies that have mastered this. Taking Starbucks as an example, a customer may visit one of their coffee shops after seeing, hearing or reading about it through a physical or digital medium. That customer then orders in store, pays, and gets the full Starbucks experience, including the associated aromas and personalised greeting. Afterward, they may be tempted to sign up for a Starbucks newsletter for in-store discounts, and once they have used a few of these, they will be invited to join Starbucks Rewards for even more savings and easier payments, thereby becoming a digitally registered customer (Wallace, T. 2020).

“We have to think of [digitally registered customers] as the top of the funnel; an enabler of the relationships that we can create that lead people eventually into the Starbucks Rewards Program.”

Matthew Ryan, Executive Vice President & Global Chief Strategy Officer, Starbucks

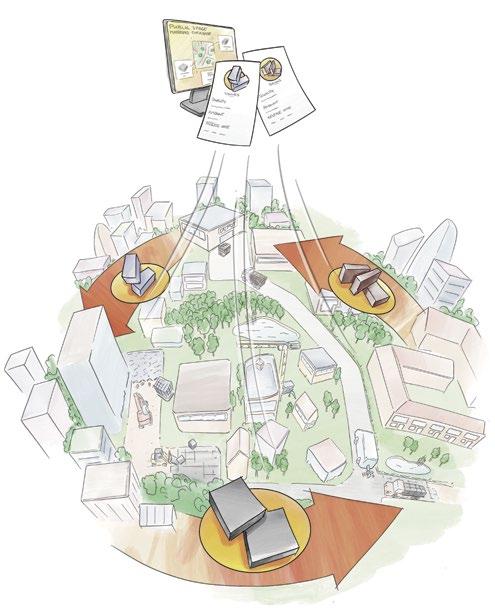

Macro Service Mapping method

This article will discuss the symbiotic relationship between UX, CX, service design and systems design, with the aim of providing a systematic framework for designers and non-designers using the ‘Macro Service Mapping’ method. In this method, customers are guided through interactive workshops to reduce the complexities and interdependencies between various omnichannel services into easily digestible tasks and processes. Mapping

24 Touchpoint 12-3

1 Omnichannel is an approach to providing a consistent and connected customer experience across multiple touchpoints.

this process visually gives stakeholders a better understanding of the people and the props involved in a specific process. By examining these maps in concert, stakeholders can focus on possible intervention areas.

This method helps to determine: (1) How to approach problems in a customer-centric manner, (2) Map any micro-interactions such as physical and digital that occur between the groups to identify their dependencies, and (3) Prioritise ideas based on the value to the user, business and environment. The case study will elaborate on this method in more detail.

The three key components of service design processes, props and people will be examined here. The intent is to demonstrate the resemblance of these three components across UX, CX and systems design.

Processes – Reviewing and streamlining processes to eliminate unnecessary steps and actions and potentially automating mundane tasks

Props – Reducing clutter, data management and optimisation

People – Identify all across the actions to explore how we could improve their experience

Relationship between natural ecosystems and service design

We can draw parallels between service design and a natural ecosystem, where living and non-living organisms interact in communities, including through chemical, physical, and biological interactions, in harmony.

There are four major components in natural ecosystems: biotic components, abiotic components, energy flow and cycling nutrients. Likewise, in service design, these elements can also be expressed as process, props and people. Biotic components are any organisms living in a community such as plants, animals or microorganisms, which can be viewed as the people involved in the whole omnichannel service process. The abiotic components of an ecosystem include the non-living things that are essential to living organisms, such as soil, air, water, rocks, temperature, and sunlight, which are also viewed as the props that people interact

with throughout a service. The process in a service is analogous to the flow of energy and cycling of nutrients in a natural ecosystem, which describes the steps and interdependencies of abiotic and biotic elements.

Deconstructing, UX, CX, service design and systems design

The way natural ecosystems coexist in harmony illustrates the importance of analysing each layer of customer experience, user experience, service design and systems design and understanding how they all work together in order to create exceptional omnichannel experiences.

Apart from service design, props, process and people are also evident in CX, UX and systems design. As you can see in the adjacent diagram, we start with the underlying level, which is a collection of individual and grouped user actions, which we map to reveal the props and people they interact with and the emotions they manifest. Here is where UX comes into play. User experience encompasses all aspects of the end user’s interaction with the company, its services and its products.”2

1 Norman and Nielsen, 2011 CX

Relationship between CX, service design, systems design and UX Touchpoint 12-3 25 service design with the planet in mind

Brand actions

Support process actions

Employee actions

User actions

Systems

Services

UX

Define task here

Positive emotions

Emotions

Negative emotions

Task: People Props

Process

On the second layer, there's service, which consists of physical and digital touchpoints that exist both on-stage and behind the scenes, mainly relating to employee actions.

Thirdly, there is the system layer, which includes all support processes within an organisation, including internal systems and external ones, as well as how people interact with these systems, which are also known as props.

The top of the stack is customer experience, which is the sum of all interactions and experiences customers have with a company, ensuring a seamless, engaging relationship with the brand as a whole. Furthermore, the props people and processes in this layer are evident across the multitude of channels over which the brand is engaged, and thus, they all need to be consistent to provide a high quality customer experience.

The case study outlined below will provide a preliminary translation of this theory into practice.

Service design workshop case study

This half-day workshop was conducted with eight participants (non-designers) as part of the ‘Making Ideas Tangible’ module at the Singapore Institute of Technology (SIT). For this activity, participants were

Physical touchpoint

Digital touchpoint

Internal systems

External systems

Macro Service Mapping method

divided into groups of three to experience a McDonald's meal in a different way. Three tasks were assigned to the students to provide an array of different touchpoints based on the experience they had with the service.

The three tasks assigned were:

1. Pick up food at McDonald's using an external food delivery app

2. Dine at McDonald’s by ordering food from the kiosk

3. Take away food from McDonald's by ordering from the counter

The Macro Service Mapping Method was then introduced in five steps to participants.

1. Choose the task (each group is given a specific task here)

2. Make use of Lego blocks and figurines to map out the actual journey

3. Use high and low curves to convey emotions

4. Identify digital and physical touchpoints and artefacts

5. Identify the internal and external systems in the journey

26 Touchpoint 12-3

Their initial step was to outline the journey for their given scenarios using the Lego blocks and figurines provided, as illustrated in Figure 2. This helped to ease their mapping process by enabling them to visualise relationships and identify micro-interactions that exist between the various components of their service providers, the props, people and process. In addition, they had to specify the type of touchpoint: either digital or physical. When it comes to digital touchpoints, they need to identify whether it is an internal or external system. The term ‘external system’ would imply one which is not produced by McDonalds, for example, by a company who supports McDonalds’ services.

They also had to include the lows and highs of the entire journey, from positive to negative experiences. Utilising the ‘five whys’ method, the groups explored the pain points associated with the lowest point of their journey, allowing them to further understand the root cause of the issue. The same method was used to examine the peak of their journey in order to understand what contributed to their happiness. This initial mapping is illustrated in the associated figure.

For the first group, they identified McDonald's pickup as the most frustrating part of the process because the distance displayed on the map does not adequately represent how certain routes can be taken, such as walking, taking the bus, or cycling, which tended to be their preferred means of transportation for pick-up orders.

The distance from their home to the pick-up location was the only information provided. It would be more useful to know how long it will take them to get to their destination by different means of transportation. Having this information could have helped them decide which shops to purchase food at. Because of the lack of clarity in this information, they might be discouraged from picking up future food orders on their own, which could reduce the need for motorbikes or cars for deliveries and thus reduce carbon emissions.

This led them to craft their opportunity statement: “How can order pick-ups be made more transparent in terms of the quickest and greenest routes?”

The second group evaluated ordering via kiosks and identified their biggest pain point as having too many choices on the menu, and therefore taking a long time to decide what to order. Thus, they slowed-down the queue and delayed orders for other customers. That group formulated their opportunity statement as follows: “How can we speed up the ordering process in-store?”

In the final group, the spatial configuration was examined, because they needed to place orders in-store and take their food home. During the investigation, they found too many people within the interior space, affecting the safe distancing measures put into place due to Covid-19. Their opportunity statement was as follows: “To ensure compliance with the Covid-19 regulations, how can the store's interior and exterior space be optimised?”

Outcomes from three groups Touchpoint 12-3 27 service design with the planet in mind

Benefits of Macro Service Mapping method

By providing participants with a tangible representation of the services, they were better able to understand how the process, people and props interconnect, leading them to look at services they interact with from a macro perspective.

The mapping of micro-interactions also enabled them to grasp the dependencies between physical and digital touchpoints. From this perspective, they got an understanding of how macro interactions exist between internal and external systems.

The Macro Service Mapping method allows different users along the journey, together with service providers and stakeholders, to collectively map out the micro-interactions quickly and see connections between them clearly.

From the feedback shared by participants during the workshop, they found this method to be more effective for helping them understand the concept of service blueprinting.

Additionally, this method was later applied through a remote workshop with design students to enhance the understanding of the interconnectedness of processes, props and people in a service (see associated diagram).

Visually mapping out a journey, either in person or in a remote workshop session, can serve as a macro blueprint for aligning and communicating between all parties in the service journey. As a result of breaking down processes into manageable functions and associating them with various people and objects, businesses can analyse specific processes in greater depth without losing sight of the overall picture.

This method is particularly useful for early stages of the review of an omnichannel service. It can be employed in an open workshop setting where endusers are able to participate and map out a preliminary framework overview so that other stakeholders can comprehend what is actually happening on the

Macro Service Mapping method (remote session) 28 Touchpoint 12-3

Digital prop Physical prop Process People 3 People 2 People 1 Step Step Step Step Step List Step List Step List Step List Define Task Before Time Time Emotions Time Time Time Time Time Time Time Time During After

ground. This light-hearted and digestible method will also be easier for end users to engage in.

In an ecosystem, every factor impacts the other factors either directly or indirectly. For example, a temperature change in an ecosystem will affect the plant species that will grow there. Plant-dependent animals will have to adapt to the changes, move to another ecosystem, or perish. Similarly, how a consumer interacts with any touchpoint throughout his or her journey impacts their decision to continue utilising the service or move on to another. Because of this, it is essential to illustrate these interactions, just as we understand natural ecosystems through graphs and visual representations, such as photosynthesis. In a similar way to how natural ecosystems coexist in harmony, omnichannel services can be visualised with the same approach to identify micro interactions that need fixing, to ensure they can work properly in harmony.

Designing a brighter future.

We’re strategists, designers, and advisors focused on people, above all else.

Slalom’s global experience strategy and design teams are driven to help organizations realize their vision. We leave clients stronger after every engagement, foster trust for the next big challenge, and build a brighter future together.

Touchpoint 12-3 29

Step 1 Step 3 Step 5 Step 7 Step 8 + List down digital prop Step 6 + List down digital prop Step 4 + List down digital prop Step 2 + List down digital prop Time strategy | technology | business transformation Learn more at slalom.com

Mirja Kälviäinen is a Principal Lecturer of MA studies in Design Thinking at the Institute of Design, LAB University of Applied Sciences, Finland. Her recent research and development interests have focused on Design Thinking, user-driven innovation and service design applied especially to environmentally and socially sustainable solutions.

Service Design Tools for Sustainable Behaviour Change

Many tools for sustainable behaviour change exist to help design services in the transition towards sustainable lifestyles. These tools provide guidance on how to create support for the drivers to motivate change, for customers to understand and learn what to do, and how to sustain new consumption habits.

Consumption change is required

The question of environmental sustainability has been linked for decades to the consequences of – and necessary changes in – production systems. In developed societies, the reality and the main cause of environmental damage lies in excess consumption. The sustainability challenge is not only to redesign production systems, but to push people to change their behaviour to new consumption activities alongside those changes. With all the various innovations in technology and envisioned transformations in economic system solutions such as circular, doughnut or regenerative economies, and even de-growth models, there exists the interconnected question of how to transform consumption behaviour accordingly. This is a vital task for service designers to support through co-designing, because typically few other experts within the sustainable economy are tackling the socially- and culturallybound solution-people interactions.

The decrease in the environmental impact of daily consumption should be as much as 70% to even 90% of current figures in Western societies, and this could influence the emerging consumption habits in developing countries as well. Despite research which uncovered positive consumer attitudes towards environmentally conscious lifestyles, actual behaviour typically does not represent these attitudes. Instead, one typically finds an attitude-behaviour gap, which includes everyday barriers and a lack of drivers for sustainable behaviour.

Barriers and drivers for sustainable consumption

Barriers for sustainable consumption include pressures related to lack of time, knowledge, various non-green, everyday-related criteria, and expensive prices. The media offer complex and contradictory information, the search for solutions is complex, and it all triggers feelings of doubt. Because society tends to support unsustainable

30 Touchpoint 12-3

The motivational, opportunity and capability factors (COM-B) for behaviour change should be integrated in the sustainable behaviour change customer journey

consumption, green consumption is associated with significant efforts being made by truly devoted, fanatical people. For typical consumers, sustainable living seems difficult and dull.

Everyday habits are hard to break. The rational choice model does not explain or promote social, cultural and psychological motives. Everyday consumer drivers follow strong self-interests: Health, wellbeing, identity, capabilities, freedom, safety, trust, family bonds and pressure from established socialcultural norms from network values are typically stronger than altruistic, ‘save the world’ motives.

As Lucy Shea from Futerra explained in the Brands for Good webinar in September 2020, the ‘Pioneers, Big World’ people with a ‘change the world’ perspective are few. ‘Energisers and Prospects, Me’ people who appreciate health and status, or realistic ‘Settlers or Fixers’ with a small-world perspective who appreciate home and family are more common. For all those who are not enthusiastic to ‘save the world’, things should be made easy. Close relationships with others and identity-building through social acceptance is important. Consumers need quick feedback and ways of making the negative environmental impact and the results of doing visible, concrete and local.

Comprehensive models for behaviour change

User research in Finland for what would impress and help people in environmentally-positive behaviour showed a necessity to provide them with supportive processes. Service design offers a process-based framework that can be co-designed by necessary sustainability and behavioural expertise to integrate with consumers’ everyday interests and activities, so that sustainable behaviour is smoothly embedded into their daily lives, which contain multiple demands and activities.1

Service design also includes contextual research techniques which take different user groups and local circumstances into consideration. The psychologybased explanations of behaviour change similarly point to the necessity of a process for change in which awareness and interest is triggered, and new habits are learned and eventually maintained.

The customer journey can be made to match the required psychological factors in behaviour change. The COM-B model is based on a wide meta-analysis and depicts simultaneous effects of user capabilities, contextual opportunities and motivation in the change

Kälviäinen,

COM-B factors need to be findable in the process Capabilities Motivation Opportunity Personal interests Understandable transparent information Social interaction and norms support Easy to find information Personal interests FINDING CHOICES LOW IMPACT USE AND SHARING REUSE Findability Accessibility Positive image support Easy or familiar use Positive feedback, visible results Findability Accessibility BEFORE DURING AFTER

Touchpoint 12-3 31 service design with the planet in mind

1

M. (2019). Green Design as Service Design. In: Miettinen, S. & Sarantou, M. (Eds,). Managing Complexity and Creating Innovation through Design, Routledge, 100-113.

required. 2 For service design purposes, it is useful to change the order of these factors and make sure that the motivational drivers and information understanding come first, and then provide contextual opportunities and ensure ease of use or learning support along the process.

The SHIFT framework for successful sustainable change factors, acquired through another meta-analysis, describes the factors of social influence, habit formation, identity matching, feelings, cognition and tangibility that have proved useful in succesful solutions for sustainable change. 3 These factors cover the difficult question of social-cultural influence. It is important to consider social norms and influencers or to strive for building desirable identities when designing and personalising the service style and service moments to different consumer segments. Breaking and learning new habits can be supported with consideration for positive feelings, guidance and ease of use, and by making information, behaviour cues and results concrete and understandable.

Behaviour change interventions

The practical guidance for a further specification of the customer journey as service moments and touchpoints with guidance, nudges and prompts exists also in the form of several behaviour design tools such as persuasive and change-promoting ideation cards. 4 These kinds of ideation tools are based on psychological findings about how we as human beings tend to use quick and easy heuristics from the past with emotionally or otherwise biased thinking when we make quick and intuitive decisions and behave unconsciously in everyday life.

2 Michie, S., Atkins, L., & West, R. (2014). The Behaviour Change Wheel. A Guide to Designing Interventions. Silverback Publishing.

3 White, K. & Habib, R., (2018). SHIFT - A review and framework for encouraging ecologically sustainable consumer behaviour. Sitra Studies 132. Sitra. [Online] Retrieved April 4, 2021, from https://www.sitra.fi/julkaisut/shift/

4 E.g. Bridgeable. 2018. Designing for Behaviour Change Toolkit. [Online] Retrieved June 20, 2021, from https://toolkit.bridgeable. com/.; Lockton, D. (2018). Design, behaviour change and the Design with Intent toolkit. In: Niedderer, K., Clune, S. & Ludden G. (Eds.). Design for Behaviour Change. Theories and Practices of Designing for Change, Routledge, 58-73.

Behavioural and cognitive psychology takes this biased quick thinking into consideration and provides mechanisms and patterns that help to direct our behaviour with behaviour change interventions. Psychology talks about interventions when it points to psychological, pattern-based interactions that persuade users towards behaviour change. In service design, these interventions can be embedded in service moments or in smaller touchpoints.

For the use of the interventions, it is worthwhile to notice that some of the behaviour patterns are suitable for the initial drivers, awareness and motivation phases of the process, while others are relevant for the adapting and learning-to-use phases. Some point to commitments and sustaining the habit for a longer period. Examples of first-hand drivers can be framing and anchoring the deeds to customer interests or offering small, tasty bites to try.

It is also advisable to ask to make changes alongside other major changes. In adaptation, consumers should be able to follow the impact of their actions and see and understand the results as something familiar. Information should be simply grouped and sharing it provides social support. Sustaining can be supported by constant feedback and rewards from the system. It could be visible how other people are doing the same. The results can be shown off socially, or others can provide feedback. There can be competitions with your own skill level or against others. New features can provide rewards and the joy of learning or competing. Personification possibilities will support commitment.

Behaviour change design in practice

Consumer lifestyle change requirements for low environmental impact use and management relate to housing solutions, energy and water use, low impact mobility, food and products, and services and their use. A practical business example comes from the consumer waste management field. When asking the question of how to help residents in efficient waste sorting, it is important to note that a realistic journey requires several public-private stakeholders to collaborate in providing the necessary process. The journey of supporting waste

32 Touchpoint 12-3

sorting in apartment buildings includes major homebased activities and is connected to purchasing decisions. It includes sorting and storing the waste with adequate understanding and know-how, carrying it to the joint collection points and depositing it correctly.

Try it yourself

Required sustainable change should not only happen in production systems, but also on an individual level. Many actions, such as waste management, need to be carried out locally and by individual consumers for the new sustainable economies to work. For their implementation and execution, the

abstract scenarios, calculations and technologies of these economies require service designers to create situated, citizen-driven behaviour change solutions.

Together with contextual user understanding, the mechanisms of social-cultural and psychological behaviour interventions provide powerful tools to accelerate solution creation for the necessary change towards more sustainable lifestyles. My research, observations and analysis comparing and applying behaviour change factors and patterns to sustainable behaviour change cases confirm that at least the tools presented here are practical and efficient in change creation. I hope you will try them too.

The following suggestions exemplify how the different phases of waste management in apartment buildings can be supported with ideas deriving from the design tools described in this article

Learning gradually what and how to purchase to avoid waste and to produce only sensibly recyclable waste

Shopping

House Internet channel as part of the city channel: Famous influences showing examples of waste reduction, composting and basic sorting. Harm to health info of untreated waste.

Social idea sharing and commenting possibility how to avoid food waste, how to re-use waste materials at home.

Social sharing of waste food and other usable stu locally

Sorting bins and bags are o e red for di e rent waste on behalf of the house: Size and form point to specifi c waste and restrict the amount, can be used as benches or other furniture since space is scarce, smell decreasing function, bins work also as bags.

Basic information shared in the house channel and as paper versions every half a year: How sorted waste is cheaper for the residents as expense, how waste is used for new products (x = y) and how much and what it saves as fresh raw-materials, energy and water . Basic sorting rules easy to find on the channel and on paper leaflets, special guidance and personal guide for new residents and info campaigns for all when there are changes in waste management system of the house.

Guidance boards for basic sorting to attach beside home sorting area, tags with concrete symbols to attach to sorting bins and same symbols at the joint house containers to minimise cognitive load.

Quick emptying when containers are full, waste sorting competitions and prizes for the residents and for your own development, weight measured at the collection point, special deliveries of waste sorting of dangerous and exceptional waste, possibility to o e r usable items to other residents, joint cleaning days. Concrete simulation information at the house channel about the city waste management system and how the waste is treated and re-used.