$10.95 WINTER 2023 JACK KIRBY: ANIMATED JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR EIGHTY-FIVE

Captain America, H.E.R.B.I.E. TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. 1 8 2 6 5 8 0 0 4 8 0 4

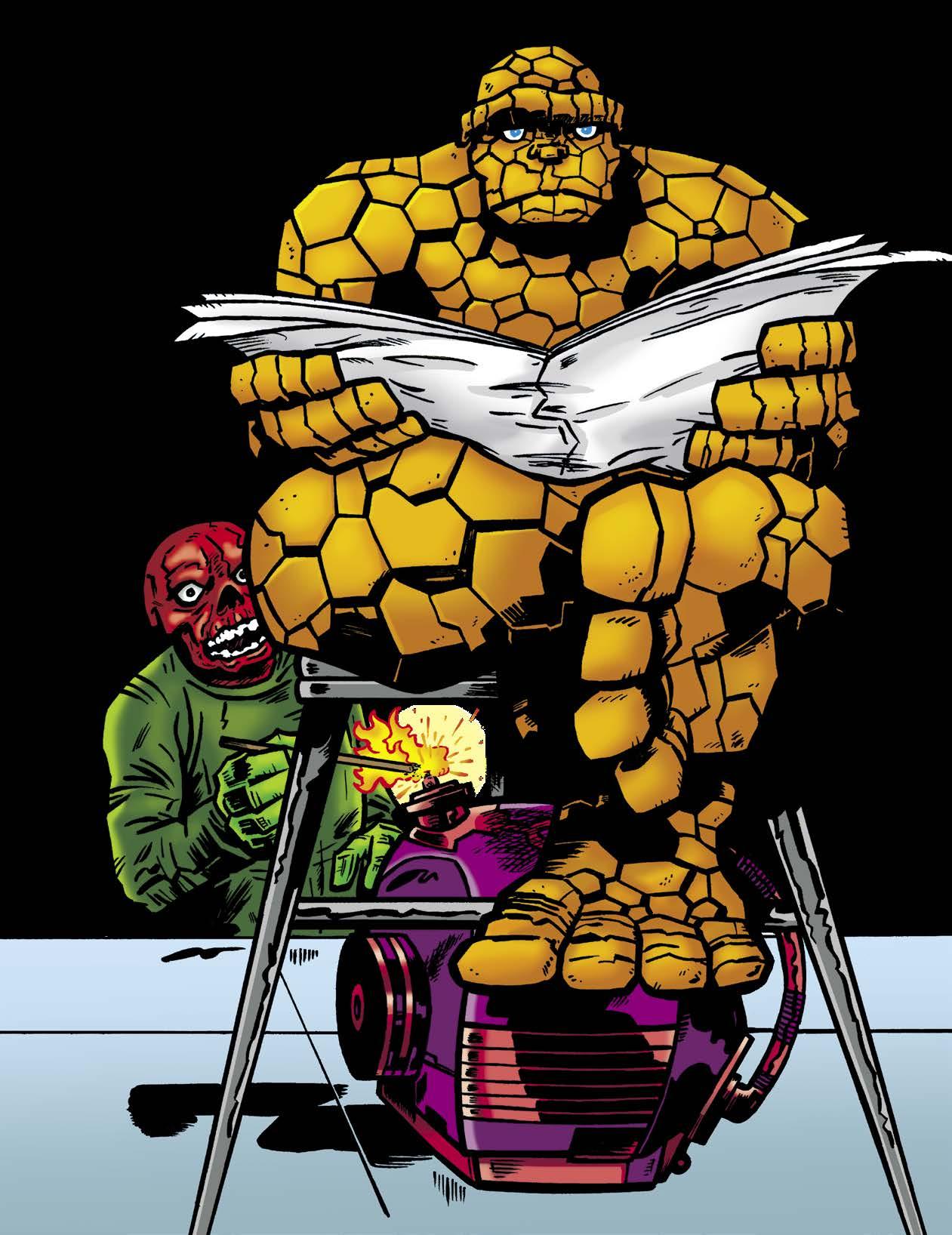

Thing, Red Skull,

JACK KIRBY: ANIMATED!

Front cover colors: TOM ZIUKO Special thanks to: JON B. COOKE

COPYRIGHTS: Captain America, Fantastic Four, Galactus, H.E.R.B.I.E. the Robot, Hulk, Journey into Mystery, Magneto, Rawhide Kid, Red Skull, Thing, Thor, Watcher TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. • Bat-Mite, Big Barda, Darkseid, Granny Goodness, Hawkman, Kalibak, Kamandi, Klik-Klak, Losers, Mr. Miracle, Mr. Mxyzptlk, Sandman, Sandy, Super Friends, Superman, Wonder Woman TM & © DC Comics • Herculoids, Mindbender, Scooby-Doo, Shaggy, Space Ghost, Space Stars, Teen Force TM & © Hanna-Barbera • Beavis and Butt-Head TM & © Viacom International Inc. • Tron TM & © Walt Disney Studios • Planet of the Apes TM & © 20th Century Fox • Popeye TM & © King Features Syndicate • The Soda Thief © Evan Dorkin

All other characters, concepts, and related properties shown here are TM & © Ruby-Spears Enterprises, Inc. (or successor in interest), including but not limited to: All American Hero, Animal Hospital, Captain Lightning, Centurions, CHimPS!, Col. Blimp, Cover Girls, Crusher, Dragonflies, Dragonspies, Eagle, Father Crime, Flash-Cat, Four Arms, Future Force, Gemini, Gloria Means, Glowfinger, Goldie Gold and Action Jack, Hassan the Assassin, Heartbreak High, Hidden Harry, Human Slitha, Human Tank, Jake, Lave Man, Little Big Foot, Lost Looee, Metallum, Micromites, Mighty Misfits, Monsteroids, Ookla the Mok, Pie-Eye, Power Planet, Rogue Force, Roxie’s Raiders, Sidney Backstreet, Skanner, Small Kahuna, Street Angels, The Bad Guys, The Outcast, Thundarr the Barbarian, Thunder Dragons, Tiger Shark, Time Angels, Turbo Team, Turbo Teen, Turbo Teens, Under sea Girl, Warriors of Illusion, Yogi Finogi.

[above] Kirby pencil drawing, done around the time he began his career in animation at DePatie-Freleng.

THE ISSUE #85, WINTER 2023

Published quarterly (he said animatedly) by and © TwoMorrows

John

Editor/Publisher. Single issues: $15 postpaid US ($19

Four-issue subscriptions:

Editorial package © TwoMorrows Publishing, a division of TwoMorrows Inc.

companies. All

is

Jack

unless otherwise noted. All editorial matter is

the respective authors. Views expressed

respective authors, and not necessarily those of

Publishing or the

1 Collector C’mon citizen, DO THE RIGHT THING! A Mom & Pop publisher like us needs every sale just to survive! DON’T DOWNLOAD OR READ ILLEGAL COPIES ONLINE! Buy affordable, legal downloads only at www.twomorrows.com or through our Apple and Google Apps! & DON’T SHARE THEM WITH FRIENDS OR POST THEM ONLINE. Help us keep producing great publications like this one! Don’t STEAL our Digital Editions! OPENING SHOT 2 JACK FAQs 8 Mark Evanier’s 1996 interview with Jon B. Cooke STONE AGES 19 The Thing’s rocky evolution INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY 24 how a fantastic “4” evolved FOUNDATIONS 26 another S&K Link Thorne story INNERVIEWS Steve Gerber 34 Joe Ruby ....................39 John Dorman 48 Jim Woodring 56 Tom Minton 58 Rick Hoberg 66 KIRBY OBSCURA 54 they loom large KIRBY KINETICS 63 one more trip to the cinema INFLUENCEES 72 Evan Dorkin speaks COLLECTOR COMMENTS 78 Front cover inks: EVAN DORKIN

The Jack Kirby Collector, Vol. 29, No. 85, Winter 2023.

Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614, USA. 919-449-0344.

Morrow,

elsewhere).

$53 Economy US, $78 International, $19 Digital.

All characters are trademarks of their respective

Kirby artwork

©

Kirby Estate

©

here are those of the

TwoMorrows

Jack Kirby Estate. First printing. PRINTED IN CHINA. ISSN 1932-6912

Contents

Mark Evanier

JACK F.A.Q.s

A column answering Frequently Asked Questions about Kirby

[below] Some DePatieFreleng New FF storyboards that were pieced together for Fantastic Four #236’s “new” Lee/Kirby story, without Jack’s knowl edge.

[next page, top] Jack’s design for H.E.R.B.I.E. the Robot.

Mark Evanier interview

Conducted by Jon B. Cooke on May 5, 1996

Transcribed and copyedited by John Morrow and Mark Evanier

JON B. COOKE: Did you get Jack involved with anima tion?

MARK EVANIER: More or less. The first thing Jack did in animation that didn’t date back to working for the Fleischers, was the Fantastic Four cartoon show DePatieFreleng did in 1978. I was working at Hanna-Barbera at the time, and they developed the show initially. Iwao Takamoto was the art director there, and I heard they

were having artists imitate Kirby’s stuff. I went to Iwao’s office and asked him about it, and I said, “Why don’t you get Jack Kirby to do this artwork?” Iwao said, “Oh, we’d love it, but he works in New York, doesn’t he?” I said, “Jack’s out here in Thousand Oaks,” and I don’t remember if I gave him Jack’s number, or called Roz and gave her the number, but the next day Roz drove Jack down to the studio and Hanna-Barbera hired Jack to do presentation art for this Fantastic Four show which they were pitching to NBC. NBC accepted the show, and at that point Marvel decided they wanted to do the show with DePatie-Freleng instead of HannaBarbera. There was no contract, just a sort of handshake understanding. What ultimately happened was that a deal was made. DePatie-Freleng had developed a Godzilla show for NBC, and Hanna-Barbera had this Fantastic Four show, so they swapped. Doug Wildey had devel oped the Godzilla show, and he had the choice of staying at DePatie-Freleng and doing Fantastic Four, or going to Hanna-Barbera and doing Godzilla, at the same time that both studios put in an offer for Jack’s services. So Doug chose to stay with Godzilla and he wound up with an office at Hanna-Barbera right next to mine

JON: Was Jack involved in concepts on it? Was H.E.R.B.I.E. the Robot his idea?

MARK: The name H.E.R.B.I.E. was not his, he had another name for the robot. I don’t know who came up with the idea of putting in a robot. At that point, the Human Torch had been optioned to Universal; every

8

body thinks they took him out because they didn’t want to have a character on fire, but actually it was a legal problem. Universal was developing a TV movie. But basically, they tried an experiment. Usually in animation, you write a script and then a sto ryboard artist turns it into a series of panels. What they tried was having Jack storyboard first and then they’d add the dialogue at a later time, and it didn’t really work. There are a couple of reasons. One of them was that Jack did not have the experience with story boards to do that job well. The second prob lem was that because it would have limited animation, you have to have the right amount of dialogue during a speech, to make up for the fact that they aren’t moving very much. So you can’t really storyboard it and then figure out later how long the dialogue is going to be. It has to be done the other way around. And also, Stan Lee dialogued most of them, and he was not at that point that proficient at writing for animation. So the method really didn’t work. The people on the production staff, mostly a man named Lew Marshall, had to re-storyboard the thing and try to turn this into a real storyboard by animation standards. There was a lot of wasted effort.

JON: Did Jack come up with the stories himself?

MARK: Most of the stories were adapted from old [comics stories] My understanding is, they gave him a little synopsis, and he would sketch out the storyboard before any dialogue was written.

JON: Did Jack work with Stan at all on the Fantastic Four show?

MARK: Oh yeah, absolutely. They probably had a number of meet ings, and on the phone. DePatie-Freleng had an office on Van Nuys Boulevard, and Jack probably came in once or twice a week and met with them for an hour or two.

JON: How long did he work at DePatie-Freleng?

MARK: Well, the show lasted one season.

JON: Had he left Marvel by that time?

MARK: I think what happened was, they gave him a leave of absence. He was ready to leave. Prior to this thing coming into his life, Jack had told me that when his contract was up, he was going to leave Marvel and not go back. They suspended his contract, or otherwise let him out of it, so he could work on that show. That may have been one of the reasons that he chose to go with DePatie-Freleng as opposed to Godzilla at Hanna-Barbera, because he could fulfill his Marvel contract.

JON: Was he giving up on comics at that time, or just giving up on Marvel?

MARK: Well, at that point it was kind of the same thing. His options were DC or Marvel; there were no other publishers out there that could pay him enough; there were really no other publishers out there at that point. He didn’t want to go back to DC. I think he was pretty much giving up on comics.

JON: Do you know the circumstances behind his storyboards being published in Fantastic Four #236 [left]?

MARK: The circumstances were that it was the anniversary issue, and they called Jack and asked him for a brand new story for that issue. He declined. At that point, he wanted nothing to do with Marvel, and for some reason they decided to

9

create a fake Jack Kirby story. They took his storyboards and traced them, without his knowledge or permission.

JON: And what was his response?

MARK: He was quite upset. He did not feel it was his work, but it was being billed as his. They were not paying him for the work. They had created a Jack Kirby story out of nothing by using his work. His name was being utilized without his permission. On the John Byrne cover, if you look, Stan Lee is in the scene, but there’s a blank spot where Jack had been in there, and Marvel at the last minute decided they didn’t have the right to do that, and they erased him. It was not a very nice thing to do. I think it was done more out of ignorance than malice. I think they just thought, “Hey, we own this material, why can’t we create a Jack Kirby story?”

JON: Before you found that opportunity for Jack at Hanna-Barbera, had you discussed the possibility of him working in animation?

MARK: Not really. It actually didn’t even dawn on me, nor was I really sure what Jack could do in animation. Most animation jobs are done in the studio. You report to work every day, and Jack was not equipped to do that. He couldn’t drive, and he really wasn’t the kind of guy to go to a studio every day. It really didn’t dawn on me. We had a dinner meeting, which I vaguely recall was just before or after Christmas of 1977. Some things were going on with Jack and his Marvel relationship. He was having a lot of problems with the office back there. He wasn’t getting along with them, and they

weren’t getting along with him. I had been asked by Marvel to inter vene, to work with Jack on his stuff for Marvel, and I felt that was not their place to be asking me. If Jack wanted to ask me, that would be fine.

JON: The relationship was just breaking down.

MARK: Well, yes. He just wasn’t getting along with them. One of the problems was, there were a lot of guys in the office who were just dying to write stories for Jack to draw. But anyway, he didn’t feel he had much of a future at Marvel. He felt he’d kind of gone backwards in his career, and his eyes were starting to bother him a bit at that point. He worried he wasn’t going to be able to keep up the same amount of pages at that rate that he was expected to draw. At dinner, I didn’t discuss animation. I wasn’t involved that much in animation myself. I was working at Hanna-Barbera doing their comic book line. I had met Iwao because he was my official superior over the artwork I bought; that’s how I knew him.

JON: Was that a real anxious time for Jack?

MARK: I would think it was. Jack was always very concerned with making a living, and doing his best work. I think he felt after so many years working in the comic book industry, there was no place for him to go. That’s not a happy thing.

JON: Did you introduce Jack to Joe Ruby?

MARK: I think I did. Steve Gerber thinks he did. As far as I know, I did. I was working for Ruby-Spears on a show called Thundarr the

villains for Roxie’s Raiders.

10

Jack’s

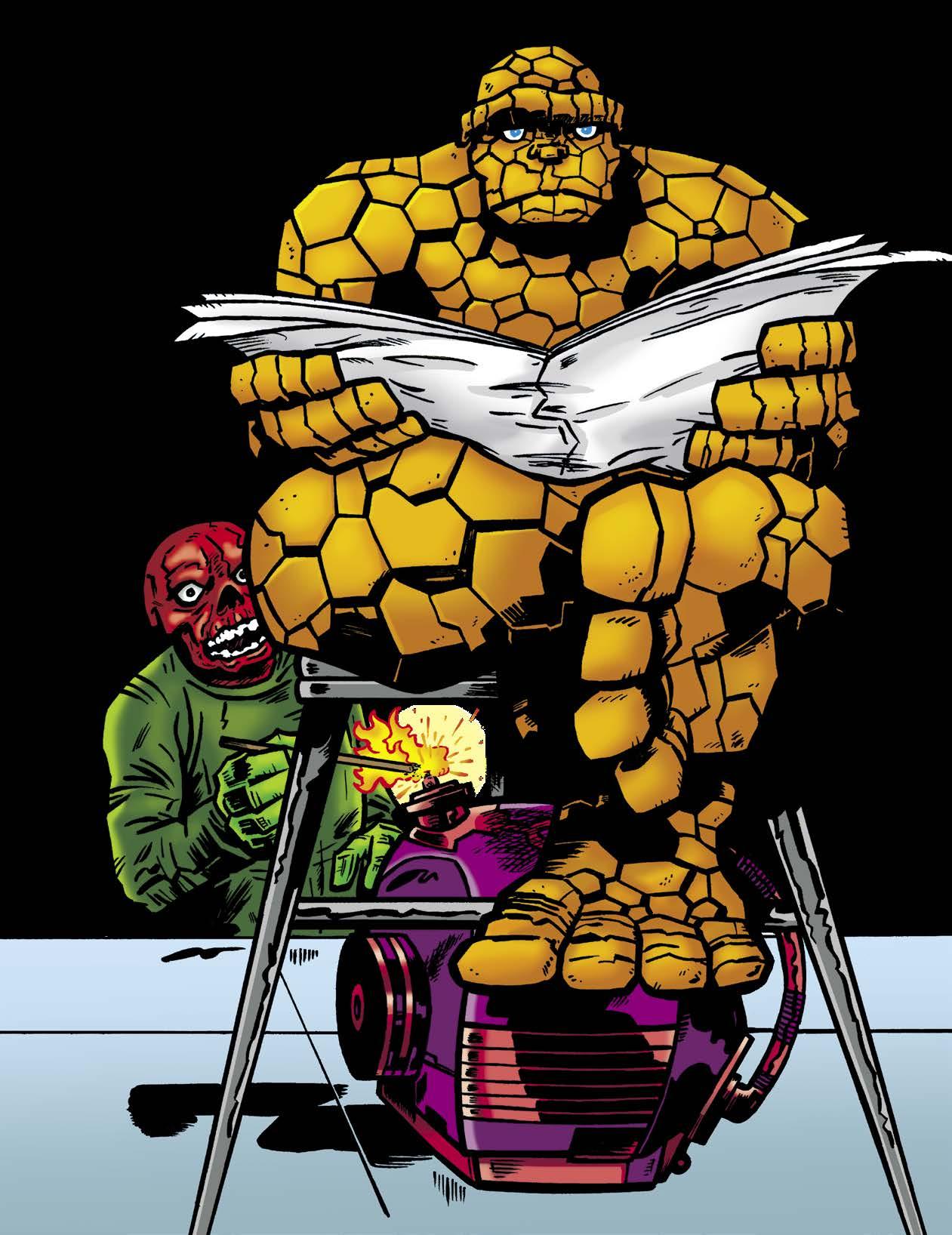

Stone AgeS

[above] A sketch done for

[below] There was no shortage of Things at Marvel/Atlas prior to Benjamin J. Grimm’s debut in Fantastic Four #1 [top].

[right] The Thing’s first pin-up, from Fantastic Four #2. Very dino saur-like!

Sample Headline

The Rocky Evolution of the Thing!

ne of the most memorable and enduring characters to emerge out of the early Marvel Universe was Benjamin J. Grimm, better known as the Thing. But he was not a character who was created, so much as discovered—one who rapidly evolved over the course of the first few years of The Fantastic Four.

“In my plot synopsis,” said co-creator Stan Lee, “I asked Jack to draw a big, burly, grotesque creature that I called the Thing. I had no idea how Jack would draw him. I just said, ‘Let’s get a real monster in there.’ But, like so many characters, the Thing just kind of took over.”

In his earliest appearances, the Thing was a brutish man-monster cursed with a sour and sulky personality. Over time, Lee and Kirby pushed away from that original portrayal, in part perhaps because once the Incredible Hulk appeared on the scene less than a year after the FF’s 1961 debut, many readers decried the Hulk as a mere carbon copy of the Thing.

Certainly, the two Marvel monsters displayed similar personalities and speech patterns, including a fondness for the exclamation, “Bah!” Both were ordinary men mutated by radiation into becoming inhuman monsters with superhuman strength.

A ROCK-SOLID DESIGN (EVENTUALLY)

While the Hulk retained an outward semblance of his human form, the Thing became a walking lump of misshapen muscle, whose appearance often changed from issue to issue––sometimes panel to panel! His hair and ears disappeared beneath his ugly reptilian hide. The Thing also lost some digits on his hands and feet after being transformed. The Hulk did not.

“I thought I should do something new with Ben Grimm,” revealed Kirby. “If you’ll notice, the begin nings of Ben Grimm was, he was kind of lumpy. I felt he had the power of a dinosaur and I began to think along those lines. I wanted his skin to look like dinosaur hide. He kind of looks like your outside patio, or a close-up of dinosaur hide.”

The chief difference distinguishing Marvel’s first heroic monsters is that the Hulk could transform back into Bruce Banner through various means, while Ben Grimm was stuck being the Thing except for the occasional spontaneous reversion, which gave him hope of an eventual cure for his mutated condition. Grimm hated being the Thing, while the Hulk’s irradi ated brain lost all memory of his human identity and at times despised “puny” Bruce Banner as if he were another person entirely.

by Will Murray

Almost from the beginning, Jack Kirby tinkered with the Thing’s outward form. Originally, he resem bled a great number of Kirby monsters that had stormed through the pages of Strange Tales and Tales of Suspense. Colorist Stan Goldberg painted the Thing the same brownish-orange tones as many of those lumber ing creatures.

Over the course of the first year of The Fantastic Four, the Thing evolved from an animated lump of brownish-orange clay into that of a figure who appeared to have the thick skin of an alligator.

“It takes about four issues to get a superhero’s looks the way he will end up,” explained Kirby. “I took

19

Lucasfilm historian Jonathan Rinzler.

the liberty of changing him. At first he looked a little pimply and I felt that was kind of ugly. What I did was give him the skin of a dinosaur. I felt that would add to his power. Dinosaurs had thick plated hides, and of course, that’s what the Thing had.”

Here, Kirby is referring to the group of prehistoric crea tures known as Thyreophora, meaning “shield bearers.” Think Stegosaurus or Ankylosaurus, the so-called “armored” dinosaurs which are covered in horny plates called scutes. Modern animals such as turtles and armadillos are also protected by shells which are covered by clusters of scutes, as are alligators and crocodiles, whose scutes are embedded in their thick skin. So when the artist used the term “plate,” he meant scutes. Kirby assistant Steve Sherman once called the Thing’s scutes “scales,” which implies that Kirby also used that term as well. And Mark Evanier recalled FF inker Frank Giacoia’s opinion that the Thing’s outer form suggested a “reptile.”

Stan Lee had the identical understanding. The first time Dick Ayers drew the Thing was for the Human Touch story in Strange Tales #106 (March 1963), “The Threat of the Torrid Twosome.” Under a panel featuring the Thing, Lee scribbled a note to Ayers which said: “scales like reptile—not lines” [above]. Evidently, the artist’s pencil version of the character was not in keeping with the look Kirby had established at that time.

Clearly, the cosmic rays that transformed Ben into the Thing did not turn him into living rock. Presumably, if one could pry off the assorted scutes, some version of the human Ben Grimm would be uncovered.

Ironically, the first foe the Thing ever battled was a giant rock creature on Monster Isle in Fantastic Four #1. The difference between the two brutes is clear and distinct. One is defi nitely rocky, and it ain’t the Thing!

A procession of inkers, ranging from George Klein in the

beginning to Sol Brodsky, Dick Ayers, Joe Sinnott, and others, all interpreted Kirby’s pencils through the filter of their own artistic sensibilities. Because pencilers and inkers did not typically commu nicate with one another, they were on their own trying to figure out the Thing’s actual structure.

Because of this, it’s difficult to trace the evolution of the Thing from issue to issue, especially after Ayers took over inking with issue #6. Ayers liked to render the Thing as if he was covered in lumpy hide.

But that was not how Jack Kirby penciled the character over the years 1962 and 1963.

INK VS. PENCIL

A glimpse of the unadulterated Kirby Thing first appeared on the cover of Fantastic Four #7, which Kirby himself inked. There, the character takes on the beginning of his ultimate form. Only his head is depicted, but it is clearly encased in thick, bony plates of differing shapes.

I once asked Ayers why he didn’t follow Kirby’s pencils faith fully on that character, and this was his response:

“Stan put the Thing in there—much to my chagrin. I didn’t like drawing him. When I first started inking the Thing, I had him looking like he was made of mud. Then somebody made him look like he was chiseled little bricks. I could never figure out what he was. To this day, when I draw the Thing, I have these damn squares to contend with.”

Ayers’ solution was to simplify and homogenize the figure, keeping the Thing in line with Kirby’s earliest depictions.

“When I saw it for the first time,” Ayers said in another inter view, “it looked like a rug of blocks or something, not even like an alligator, so I made it nice and soft.”

A panel from Fantastic Four #15 survives in pencil form [see next page], showing the so-called “rocky” Thing before Ayers sanded down his hard edges in that issue. The difference is dramatic.

It should be noted that the Steve Ditko-inked Thing of the pre vious issue differs from the Ayers interpretation. Although it is more impressionistic, the skin pattern shows greater complexity in some panels. This makes it difficult to determine when the more complicated Thing design was introduced by Kirby. But the cover to FF #13, which was supposedly inked by Don Heck (but looks to me more like Vince Colletta) is definitely the angular version. I’m inclined toward the belief that Kirby introduced his new version of Ben Grimm with issue #12, where he first faces off against the Hulk. But it might have been earlier. The Thing figure apparently inked by Kirby himself on the cover of #11 is more sharply rendered than the Ayers’ version inside. It’s possible that after the brief reversion to Ben Grimm in FF #11, the new version of the Thing manifested on page 10 of “A Visit with the Fantastic Four.” However, the art is ambiguous, thanks to Dick Ayers’ inking. It may be that Kirby tinkered with the character’s looks until he arrived at a final construction he thought worked. This process probably commenced with FF #7, the first monthly issue. Going monthly may have motivated Kirby to treat the series as one that might last.

THE REAL DEAL

The authentic Thing next surfaces on the cover of FF #18 [left] Though the interior was finished by Ayers, George Roussos inked the cover and the Thing is again revealed in all his angular glory. This was also the case with the next two issues. Roussos was the inker whom Ayers complained had made the character resemble bricks.

20

Incidental Iconography

cartoon from 1978 is largely only remembered from intro ducing H.E.R.B.I.E. the Robot as a replacement for the Human Torch. There were only thirteen episodes in total, and the show has never gotten a proper full release on home video (there were only a few episodes released on VHS, and a Region 2-only DVD of the series was briefly available in 2008), nor has it been made available on any legal streaming platform yet.

The show should be considered more significant, though, because it got Jack Kirby back into the field of animation (which provided him more financial stability and security than comics ever had) after four decades since leaving the Fleischer Studios.

This time, DePatieFreleng was putting together a cartoon based off the Fantastic and Mark Evanier told them that the man who designed the characters in the first place lived only about 30 miles away from their Burbank studios. Thus, Jack was hired to create storyboards for the cartoon, loosely based on the comics he had himself worked on in the early 1960s.

“4”.

So let’s take a look at how Jack drew the Fantastic Four’s uni form for these cartoons, and compare that against what he had done for the comics. (For the focus of this piece, I’ll be setting aside the initial design considerations like masks that Jack changed before the comics were even published, as shown above for the Thing.)

The first thing I should point out is that the animators were not relying on Jack’s artwork for the specific character designs, only the basic shot compositions. Jack was still largely drawing as if he were working on a comic book, and the animators needed character designs that were easier to animate, so a number of details from the boards didn’t make it onto the animation cels. Brad Case is credited as the animation director, but I can’t seem to find if he was actually the one who worked up character model sheets for the animators. Regardless, if you do get access to the cartoons themselves and wonder why they look nothing like Jack’s work, that’s why.

While the Fantastic Four’s basic jumpsuit design is pretty straightforward, there were a few details I thought to key in on. The two I had previously noticed that had changed just within the comics were the “4” chest emblem and the width of the black collar. Except the collar width changed with issue #6,

...The FOur?

An ongoing analysis of Kirby’s visual shorthand, and how he inadvertently used it to develop his characters, by Sean Kleefeld

24

The Thing in his short-lived costume (with helmet!), from Fantastic Four #3 (March 1962). Note the whited-out and redrawn shadowed

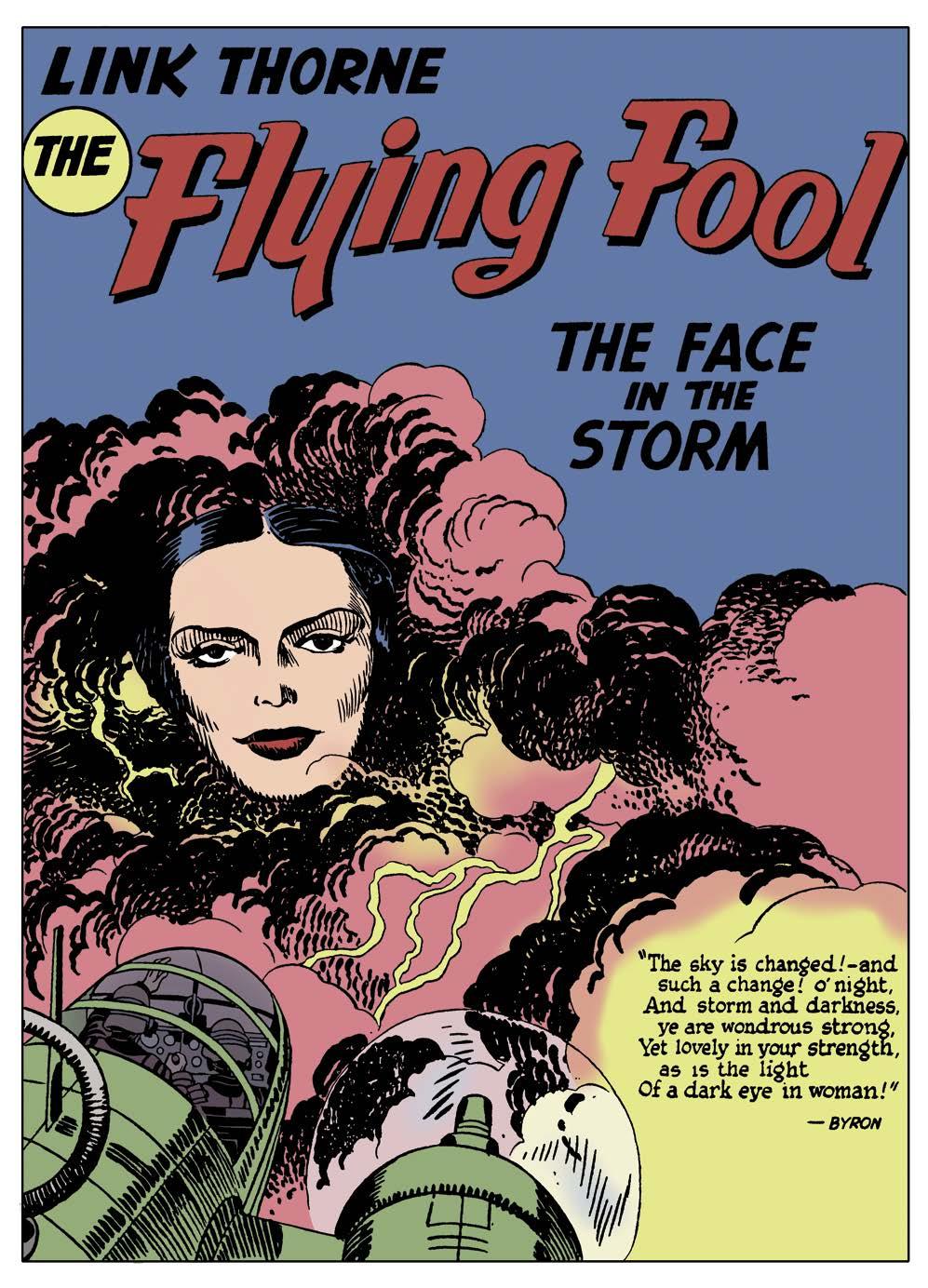

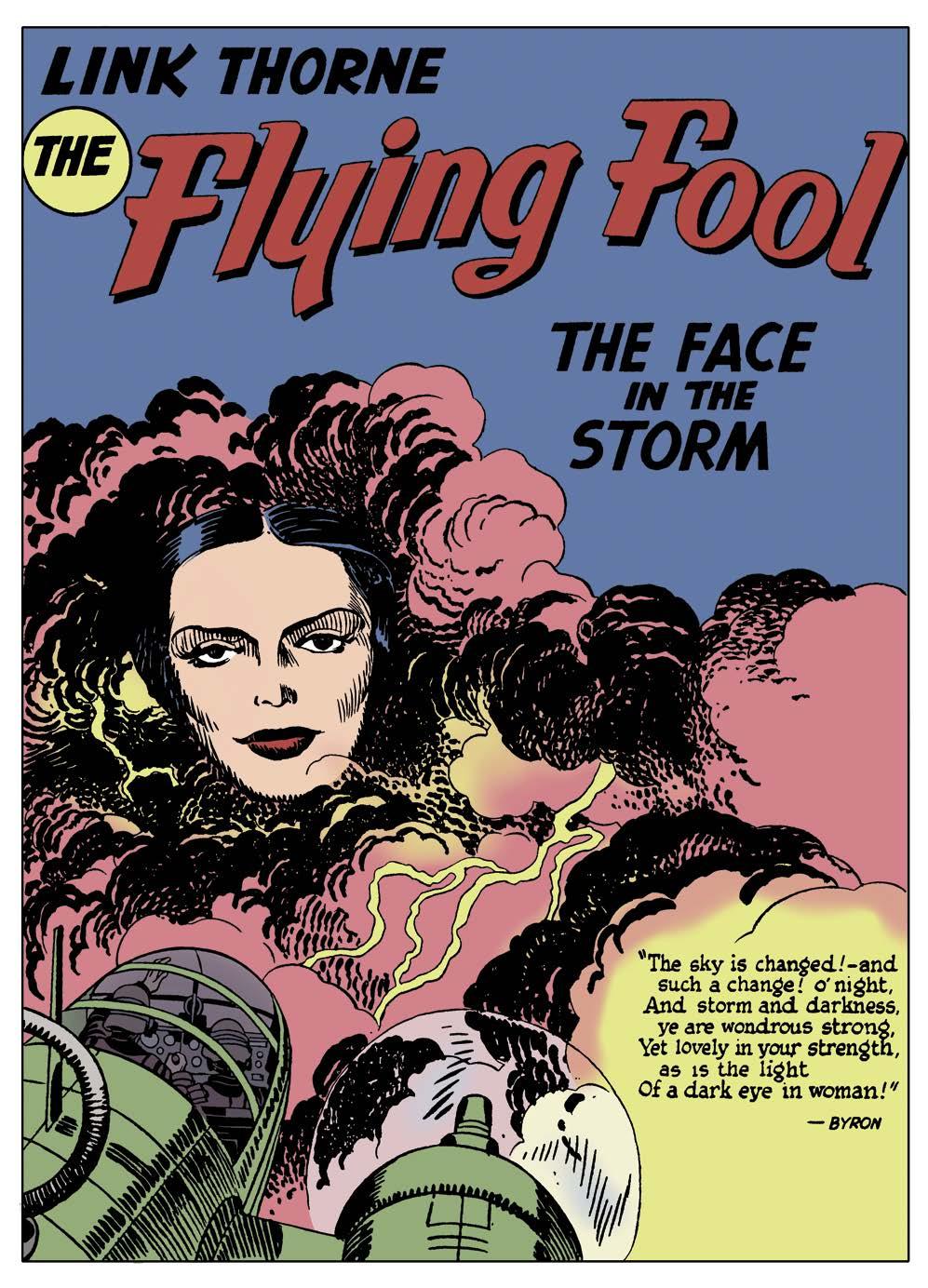

Foundations

Here’s still more of Simon & Kirby’s “Flying Fool” work, “Face In A Storm” from Airboy Comics V4, #10 (Nov. 1947), with art reconstruction and coloring by Chris Fama. Look for the final installment of the complete Link Thorne stories next issue!

Here’s still more of Simon & Kirby’s “Flying Fool” work, “Face In A Storm” from Airboy Comics V4, #10 (Nov. 1947), with art reconstruction and coloring by Chris Fama. Look for the final installment of the complete Link Thorne stories next issue!

26

A Chat with Steve Gerber

[Steve Gerber (September 20, 1947–February 10, 2008) is probably best known within comics as the creator of Howard the Duck, but his work for Marvel also included Man-Thing, Omega the Unknown (created with Mary Skrenes), and many other properties. While engaged in a legal battle with Marvel over ownership of Howard the Duck (which made him a vanguard in the fight for creator’s rights), he approached Jack Kirby and several others to donate their services producing the benefit comic Destroyer Duck. This interview took place after Gerber had settled that dispute, wherein he reflects on his experiences with Jack Kirby at the Ruby-Spears animation studio.]

JON B. COOKE: What was your earliest exposure to Kirby’s work?

STEVE GERBER: I really had associated Jack with the few issues of The Fly and Private Strong he did—the revival of The Shield. The Shield stuff I liked quite a bit, actually.

JON: Do you still agree with your Fantastic Four #19 Fan Page letter (October 1963), that you’ve never seen a worse artist combination than Kirby and Ditko?

STEVE: [laughs] Yes. [laughs] They were wonderful separately, and

absolutely awful together. Ditko is one of Kirby’s worst inkers of all time. For two artists who were so wonderful separately, I never thought the combination worked at all.

JON: Did you get a chance to work with Jack at Marvel, when he came back?

STEVE: No, not at Marvel.

JON: You left Marvel in 1978?

STEVE: Yeah, I left a little after he came back. All the stuff he was doing at that time, he was doing alone: Black Panther, Machine Man and all those things.

JON: So you first met Jack when?

STEVE: I think 1979, when he came to Ruby-Spears to work on the Thundarr series.

JON: His job was replacing Alex Toth?

STEVE: Probably not replacing. Alex did the initial designs for the series. I don’t know if Alex was ever contracted to do more than that. It doesn’t work the same way in televi sion that it does in comics. Somebody’ll be brought in to do a particular presentation piece for the network, and that’s the begin ning and the end of their job. They may have nothing whatsoever to do with the series after that. I suspect Alex was brought in on a basis like that, so that when he left, he may have gone on to something else altogether.

JON: Did you work closely with Alex?

STEVE: No. I never met Alex.

JON: In your initial concept, what did Alex have to work from for Ookla?

STEVE: Well, I don’t remember exactly the words I used, but I gave a description of the character. He’s about eight feet tall, big and hairy, a little bit like an ape, a little bit like a bear—doesn’t talk, afraid of water, whatev er. And I just tried to give an impression of the character, the same way I would describe a character for a comic book artist to draw.

JON: And Alex came back with a really classic Toth-like, quintessential design. How would you characterize your experience working in animation?

STEVE: Oh brother. When I first went to work for Ruby-Spears, a friend of mine named Gordon Kent worked there. He came up to me and said, “Don’t expect it all to be like this.” [laughs] What had happened was, I’d come in and sold the first series I’d ever proposed to anybody. The producers saw it about 85% the same way I did. The network saw it about 85% the way he did, and while we certainly had conflicts with Standards & Practices—anytime you do an action show, that happens—the show basically went very

INNERVIEW

34

Conducted by Jon B. Cooke on April 30, 1996 • Transcribed and copyedited by John Morrow

smoothly and turned out a lot like what I had in mind. It never happened again.

[laughter]

JON: What other shows did you work on?

STEVE: Oh, no! For that very reason, I will never tell you! [laughs] It was five or six years before the next satisfying expe rience in animation came along, and that was story-editing G.I. Joe.

JON: Was Larry Hama involved in the animation side of that?

STEVE: Not really. He worked very closely with the toy company on the East Coast, but had almost nothing to do with the animation end of it.

JON: What was so gratifying about working on G.I. Joe?

STEVE: It was two things. It was a syndicated series, not a network series, so we didn’t have Standards & Practices to deal with. We had an incredibly intelli gent producer by the name of Jay Bacal; he was a Harvard graduate, and younger than I was. If anything, he was pushing me to kick at the seams of the envelope a little more. It was some of the best stuff I’d ever

[previous page] Thundarr concept work.

[right] Since Steve enjoyed Jack’s 1959 revival of The Shield, he must’ve really loved this Alfredo Alcalainked concept drawing for Ruby-Spears.

35

Joe Ruby: A Real Gem

[Joe Ruby (March 30, 1933–August 26, 2020) wore many hats in the animation industry, including writer, producer, and even music editor. He is best known as a co-creator of the animated Scooby-Doo franchise, together with partner Ken Spears. In 1977, they co-founded RubySpears Productions to create animated series for network television and syndica tion, and made R-S the most successful TV animation company for a period in the 1980s. His hiring of Jack Kirby marked a major turning point in Jack’s life and career.]

So on Thundarr, he did the design work of all the other characters for the series, and then continued to work with us.

JON: Were you aware of Jack Kirby’s reputation before hand?

JOE: I was very familiar with all of the characters that he had created, but I can’t really remember if I was familiar with him. I probably was, yes.

JON: When he was working for you, was he answering directly to you, or John Dorman, or...?

JOE: He basically answered to me, but John was in the middle. John was the art director on the show, so he would go to John as well. But whatever happened had to come through me at the end, obviously.

[top] Upon first see ing Jack’s “Hidden Harry” concept in the Unpublished Archives card set, this mag’s editor thought The King must’ve been slipping when he came up with it. Aahhh, but I didn’t realize Jack was also pitching toy ideas, which makes a lot more sense for HH!

JON B. COOKE: When did you first meet Jack?

JOE RUBY: It was in the early 1980s. He did some work for us, and we liked him so much, that we continued to do a lot of work, and we put him on staff for six years.

He was great!

JON: Do you remember how he came to work for you?

JOE: We were doing a show called Thundarr the Barbarian, and we needed someone to design—because in those days, we took a kind of comic book, older-type skew on the show. We wanted someone who really could design great characters. Jack was brought in. I don’t remember exactly, but that’s how it happened.

JON: Did you give Jack specific assignments, or did he just go off and create concepts?

JOE: I gave him specific assignments, and he also did other things that he brought me. He was very prolific, as you know. He was uncanny; he would just bring in stuff all the time.

JON: I’ve been speaking to other people who worked at Ruby-Spears, and they say you and Jack spoke the same language. Were you personal friends?

JOE: We weren’t close personal friends, but we were friends, yeah. When someone works for you for six years, and you see them all the time, you become

39

Conducted by Jon B. Cooke on May 9, 1996 Transcribed and copyedited by John Morrow

friends with that person, and his wife Roz, who was very nice. They lived out in Thousand Oaks. But Jack generally would work at home, and come in maybe once or twice a week. We did work very closely, and we did speak the same language. It was just very easy, you know? When I’d say something, he’d know exactly what I wanted, and he’d deliver it. He was terrific.

JON: In the early 1980s, was that the Golden Age of Ruby-Spears?

JOE: Yeah. I think for us it was from the 1980s into the early 1990s. We had so many shows, I can’t even begin to tell you. We had a huge staff of people, and we did quite a bit of artwork. We would develop toys as well as shows. We were venturing into a lot of things. We sold several toys and other things as well. We had some of the top people in the industry working for us at the time—very creative people.

JON: What were your personal favorites, of the cartoons Ruby-Spears produced?

JOE: Well, I thought Thundarr the Barbarian was one of the best ones we’ve done. We also did Alvin and the Chipmunks, which was a huge success. We did Mr. T…

JON: Goldie Gold and Action Jack. JOE: Yes, those were the originals. The others were

based off known personalities, and there were also the established characters. We did Brewster; Rubik, the Amazing Cube; all the video games at the time, like Dragon’s Lair. We had an hour video game series on, which featured five or six video games we turned into shows. We did Rambo, that was syndication. We did Centurions, which was a toy show. Sectaurs We did Police Academy, Superman, Heathcliff.

41

JON: Do you know where the concept of Turbo Teen came from?

JOE: Yeah, that’s was mine. A boy turns into a car. It was kind of a wild one. In those days, they thought I was nuts, but ABC bought it. [laughs] It was a good show. It could be even wilder today.

JON: Can you give me a brief background of Ruby-Spears? How did it begin?

JOE: Well, my partner Ken Spears and I were working for ABC at the time, for Fred Silverman. We go way back; we were writers at Hanna-Barbera, and we also did live-action things. For animation we were writers, and we were at Hanna-Barbera for many years. We got Scooby-Doo off the ground, and then we came to work for CBS, and ABC for Fred Silverman. We created a lot of shows: Captain Caveman, Blue Falcon and Dyno-Mutt. Then Filmways was looking for a studio, and Peter Roth, who we worked with at ABC, recom mended us and put us in business. So we went into business, and Fred gave us a commitment. Fangface was our first show. That’s how we got started, in the very late 1970s.

We were at Filmways a few years, and then we were sold to the Taft Broadcasting Company. We were there through the switch to Great American Broadcasting, for a total of ten years. And then when Turner Broadcasting bought them, they only kept HannaBarbera. They had several other companies, and they dissolved them, us included. And we’ve been independent since then.

JON: And you’re still making presentations and making pitches?

JOE: Yeah. The business has changed quite a bit. In the heyday, the major studios weren’t involved. Warner Brothers and Disney weren’t putting out the shows. The competition has completely gone around. It’s much, much tougher. There’s not as many spots open, and the availability of certain properties, and the monies involved in getting properties—and now you have to try to get partners, and things have changed from a business point of view.

JON: People have said it was an event when Jack would come into the offices. Did you witness that in the art department, when he would come in on Mondays with his arms full of art boards? Was it an event for you?

JOE: Oh yeah, I always was anxious to see what Jack had. When he’d come into the office, yeah, he had a whole bunch of stuff with him. A lot of artwork, and he would spread out, and we’d have a good time. Everything was terrific. I always wanted to do a pure Jack Kirby show, where we wouldn’t change things like proportions for anima tion, and just do his stuff “pure.” But we never were able to.

JON: Do you remember any specific stories about Jack?

JOE: Not off the top of my head. There was just a lot of stuff we were working on. I’d have to go back and check into the artwork.

JON: Would you characterize any of the unproduced work, or the produced work, as being quintessentially Jack’s ideas? I know the concepts were all worked on by lots of people, but is there anything that comes to mind?

JOE: There’s a few things in the unproduced stuff, that were his stuff, but I’d have to go back and look at it.

JON: The Gargoids? Power Planet? Roxie’s Raiders? Street Angels?

JOE: No. A lot of that stuff was mine. I used to feed him a lot of proj ects. These were all ideas that we handed out.

JON: What was Animal Hospital based on?

JOE: We were just trying to make a soap opera.

JON: Jack produced an enormous amount of work at Ruby-Spears, but not much of it got produced. Is that the nature of the business?

JOE: Yes, it’s the business. Obviously, there’s only so many series or shows you can sell, and we were also doing different types of shows. Some were action, some were comedy which had more cartoony

42

John Dorman Interview INNERVIEW

[Animation veteran Tom Minton summed up John Dorman (June 29, 1952–January 29, 2011) thusly, following Dorman’s passing: “In addition to being a prolific and experienced creative talent, John Dorman was a near-mythic character with an epic sense of the absurd. He was much more than a storyboard artist or art director, as anyone who worked for him in the early to mid-1980s can attest... John defined ‘intense’ and could be tough to please, but ultimately took the people he believed in more seriously than he did himself.” From storyboard artist to art director, his influence in anima tion cannot be overstated. Here, he discusses what he did to make Ruby-Spears such a remarkable place to work, and his own experiences with Jack Kirby.]

JON B. COOKE: When did you first encounter Jack and his work?

JOHN DORMAN: The first time I saw Jack in the industry, was when I worked at DePatie-Freleng. I was hired to draw layouts, and I was supposed to draw storyboards on the Fantastic Four. They said, “You can draw boards, because we only have one board artist, and that’s Jack Kirby.” Now, storyboards are the hardest, most labor-intensive, anonymous, difficult, techni cally rife portion of animation. It’s a really hard job, so if you can do a half-hour show in five–six weeks, you’re really fast. That’s a very fast artist.

I didn’t even meet Jack there; my first encoun ter with him was that he would turn in a finished half-hour storyboard every week—that he wrote while he was drawing it. He wrote it and drew it.

Normally, you had careful scripts, like at DC Comics, where the animation and every scene is fig ured out. The character is going left to right, with close-up directions. You can almost just follow the directions and do it. Even the visuals are taken care of in the writing. A lot of that is because they had so much product they needed quickly, and there’s not enough storyboard artists, and they had to get other artists that don’t know how to make film, but know how to draw heads, and they know how to draw a close-up. Artists were almost never invited into creative meetings, except to graft a look onto a show, after it had been created.

Jack brought a whole different mentality. He came in and his worked just punched its way right through the wall by saying, “I invent this stuff. I write it. I draw it. I do that all faster than any team has ever done, all by myself.” And by the way, Jack was also producing two finished comics a month at the time: Devil Dinosaur and Machine Man, and a storyboard a week for a half-hour episode, and he would design all the incidental char acters too. This normally takes a huge body of people, and he’d do everything all by himself. That’s the thing that was really alarming

Conducted by Jon B. Cooke on May 10, 1996 • Transcribed and copyedited by John Morrow

48

John Dorman at Filmation studios in 1979. Photo by Tom Minton.

inker in the business. He gave this industry a big shot in the arm. Joe was an honest, conscientious, fair, and generous guy.

Anytime a minor success came in, Joe and Ken gave the max imum of recognition to us. They put us in really great big offices; anything we wanted, we got. Any art equipment we wanted, we got, and we ordered lots! [laughs] At Hanna-Barbera, they had a relative of one of the owners, who sat in a closet in a suit and hand ed out pencils, and took down who was taking the pencils. [laughs] He asked me what I had in mind to do with this pencil, and I said, “You’re kidding.” [laughs] I’d say, “I’m planning on drawing lay outs,” and he’d say, “Well, why do you need two pencils?” [laughs] We stole all the best artists; all the other companies’ artists wanted to work with us, cause we’d pay them more, they got more liberties, and they were around people that truly loved what they were doing. And Steve bred that type of thing among the writers. It was easy to work with them, cause they weren’t trying to seize authorship over something. It really was special, and Joe and Ken were dispersing money like it was being printed someplace close.

Ken Spears [below], even though he was in charge of production at that company, never acted like he was an expert. He was always excited about doing something new and better. He was always trying to rearrange budgets and work things out, and he always suc ceeded. Ken was a really fair guy, and he was always kind, and listening, and saw everyone’s side. He’s just one of those guys that, within minutes of meeting him, you really liked him.

We first had a floor with just artists, and then we had a separate building. As the artists got more liberties, we felt we

had to be better than everybody else, and work harder, and then we could do anything we wanted. That last part bugged everybody who wasn’t part of our group, but they were only there from 9-5 anyway, and we were there overnight, often. The artists were so happy about what was happening, and there was just such a general good vibe, that people put in more personal time and energy to see to it that the whole thing kept going.

COOKE: Did you consciously foster that?

DORMAN: Of course! Because we had so many shows, and we were adding artists from the comic book industry. Comic artists were all about instant gratification; they liked first-round knockouts. They didn’t worry that their stuff wouldn’t animate, or their drawing was only good for one pose.

We kept moving to different buildings, different annexes. We had one completely wood house which Cheech and Chong owned. We worked in there awhile, and then Jack started reporting to me, and getting assignments from me. But you have to understand something about the dynamic of Jack. If Jack comes in, and you go, “Jack, here’s what we need. We’re gonna do a deal with a toy company, and we’re going to do a thing about a guy with a boat that’s the fin of a living iceberg” or something real peculiar for him to draw, you don’t know how he’d handle it. Well, he’d handle it by coming back with a show about another planet. [laughs] He competed with you; he tried to blow you out of the water. And I realized, that’s just how he is. With Jack, what we tried to do was find out what he liked, and accommodate him. You could ask Jack to do one kind of show, and he’d come back with another, and you’d save it and go, “Let’s try to make a show out of this” or you’d use it in another show. Jack thought such big ideas, that he was treated different than I’ve seen any other artist treated. He basically got to come in and do anything he wanted at all times, and he was loved for it.

52

Jim Woodring Interview

They did a TV show called Thundarr the Barbarian, and he did some of the character design and some of the show design for that. Right after he did that, I started working there, and they tried to find other things for him to do. They gave him a stab at storyboards, without really telling him how to do storyboards, and he just tried to wing it. He did some really innovative things, like he had a close-up of somebody’s face, to the extent that all you could see was their eyes, and the shot called for the camera panning from the left eye to the right eye while about two minutes of dialogue were spoken. [laughs] He just made up his own rules.

JON: Did he come up with the concept for the stories he was story boarding?

[Jim Woodring is best known in comics for his self-published magazine Jim, and as the creator of his character Frank, who has appeared in a number of short comics and graphic novels, but he’s also an accomplished fine artist and animator. Jon B. Cooke considers him one of “the top five greatest cartoonists alive,” and here he quizzes Woodring about his tenure under friend and art director John Dorman at Ruby-Spears Productions.]

JON B. COOKE: When did you first meet Jack Kirby?

JIM WOODRING: I first met him in 1981, when I started working at Ruby-Spears. He already had been hired when I came aboard.

Based on the eye on her palm, this unnamed female may’ve been a character for—or which morphed into—the unproduced Warriors of Illusion project [next page, bottom].

JIM: No, he was given a script, like all the storyboard artists were. He looked at some other boards, and from his own take on how it was done, he did his. But it was completely unusable. It couldn’t have been done the way he called for it. He didn’t really understand how to do it.

JON: So what was he primarily doing at Ruby-Spears?

JIM: Character design and show ideas. When I started working there, his job was to come up with ideas that might be turned into TV shows. So he would come in every Monday morning with a big thick stack of Crescent board under his arm, on which he had drawn characters and settings and show ideas, and he’d given names to all the shows and all the vehicles and all the characters. They were all really, really imaginative. In fact, there’s a set of Jack Kirby cards

Conducted by Jon B. Cooke on May 6, 1996 • Transcribed and copyedited by John Morrow

iNNerview

56

out, and that stuff is a lot of the pitch artwork he did for RubySpears. They were quarter sheets of Crescent board, so they were 20" x 30".

JON: Did you color and ink a lot of these?

JIM: Yeah, I did. I inked most of them, and colored a lot of them.

JON: Some of this stuff is outstanding. Like the Warriors of Illusion; did you do the coloring on that?

JIM: I did some of the coloring on that. Most of that was done by a guy named James Gallego.

JON: You were unfamiliar with Jack’s work prior to that?

JIM: Yeah. I was aware of his name, and aware that he was a comic artist, and well regarded. But I couldn’t have told you what he drew, or how he drew.

JON: So you weren’t even aware of his reputation as one of the Marvel guys?

JIM: Not until I’d been working there a couple of weeks. I’d tell people that I ran into, that I was work ing with him…

JON: Were they floored?

JIM: A lot of them, yeah.

JON: Were they surprised to find out he was working in animation?

JIM: Yeah.

JON: What was your impression of him when you first met him?

JIM: Well, that he was unusual in a good way. How shall I put it? He didn’t seem to have the kind of adult, pragmatic, hard, dull edge that most other grown-ups did. I think it comes from hav ing such a rich inner life, and putting such value on drawing and imagination, and comics and cartoon ing. That was his business, that was his life. He just wasn’t a cold-edged prag matist. He lived for more and better works of fancy.

JON: How did he react to the world of Hollywood?

JIM: Well, I only saw him at work. I was never up to his house. He had a professional demeanor; a way of being nice that was genuine, but you also knew it was his work face. So I don’t really have much of an idea of what went on in his mind, or how he felt about any thing really, because he was pretty superficial when he was in the office. I know that at Ruby-Spears, at a certain point after he’d done all these drawings and none of them had been made into TV shows, he began to be a little frustrated by that. Because he was doing all this work and coming up with really good ideas, and none of them ever went anywhere.

JON: Did you ever talk to him about the business?

JIM: Well, I listened to him talk about the business. There was abso lutely nothing I had to tell him. His take on the business was pretty personal and idiosyncratic. He didn’t seem to have much awareness about what other people were doing; he was just clued into his work, and some times are better than others. He had that Old World habit of maintaining respect for the office of Editor. He was loathe to say bad things about editors or the people he worked for. When I met him, it was at the very height of that “God Save The King” and “Give Jack Back His Artwork” and all that, and even in the thick of all that, when he had plenty of encouragement to, he never said anything bad about Stan Lee.

JON: Was it just Mondays when he’d come in?

JIM: Well, he’d come in Mondays with a big stack of Crescent boards under his arm, and we’d all come in and look at them. We’d all stand around and laugh, and point at the various things, and try to make him stay and talk and tell us stories.

JON: Did you go back and look at Jack’s earlier work after meeting him?

JIM: Yeah, I did.

JON: I seem to perceive an increasingly bizarre sense of humor coming out of him at that point. Did that permeate his work that you saw?

JIM: Oh yeah, especially toward the end of his ten ure there. His work got sort of recklessly crazy. The one that I really wish I could find is, he did a drawing of a character named Heidi Hogan, which was a bearded lumberjack in a pinafore dress, jumping off a cliff with a propeller beanie. [laughs] It just looked like pure automatic pilot. He must’ve been thinking of something else entirely, and automatically drew this nonchalantly insane picture. [laughs]

There was another kind of ill-fated project the studio had going called Animal Hospital. I don’t know if he was asked to do it; I sup pose he was. He suddenly started coming in with newspaper daily strips. Penciled but not inked, but he had written it, and someone else had lettered it, and it featured all the characters he’d invented for Animal Hospital. It was like five or six days’ worth.

JON: Did he come up with the Animal Hospital concept?

JIM: No, that was by Joe Ruby, I believe.

JON: What was the genesis for that?

JIM: The desire to create a sophisticated post-primetime TV show

57

[below] A nice exam ple of Gil Kane’s presentation art, for an unknown character.

[next page, top] Rick Hoberg retold Thor’s origin in What If? #10. [next page, bottom] Unrealized R-S pitch The Outcast, set in 1990, featuring Jack’s “Slitha”, an “organic engine of destruction.”

Rick Hoberg Interview

[Rick Hoberg (born 1952) has had a highly successful career as both comic book artist and animator. He began in the mid-1970s working on Tarzan comics for Russ Manning, and later assisted him on the Star Wars comic strip from 1979–1980. Other comics work includes The Invaders, Conan, and What If...? for Marvel Comics, plus All-Star Squadron, Batman, The Brave and the Bold, and others for DC Comics. He’s been active since 1978 as a storyboard artist and model designer for all the major animation studios, and had the privilege of working at Ruby-Spears while Jack Kirby was in their employ.]

JON B. COOKE: When did you first meet Jack?

RICK HOBERG: Oh, I met Jack years before I ever worked with him in the animation industry. I’m pretty sure the San Diego Con was the first time. Jack was always the most congenial of people. He was always willing to tell stories and sit with the fans and talk with them.

JON: Your art took some inspiration from Jack?

RICK: Of course. I’m one of those people who in the 1970s subscribed to the three Ks of comics: Kirby, Kubert, and Kane. Jack Kirby is to me the essence of storytelling excellence. His figures literally move on the page.

JON: How did you get involved in animation?

RICK: I was pulled into it literally by Mark Evanier. He gave my name to Doug Wildey, the creator of Jonny Quest, and Doug was producing a show over at HannaBarbera at the time. I went over to see him and got a job from him right off the bat. Doug ended up hon ing my skills better than any other person I’ve worked with. He was marvelous. Just a wonderful human being. One of the most giving teachers I’ve ever worked with. The guy literally had no qualms about sitting down and teaching you something. That relationship continued until he passed away. We were good friends right up to the end. I saw Doug as a cross

between Clint Eastwood and Bugs Bunny. [laughs] He had this New York/Brooklynese accent and he looked like Eastwood in a lot of ways. And he was always willing to pull a joke, but at the same time was always willing to be serious. He was just a wonderful guy. He inspired a lot of people, including Dave Stevens with his Rocketeer work. Many guys you’ll talk to who had any contact with Doug just loved the guy—a great fella.

JON: What year did you get involved in animation?

RICK: 1976. Shortly after I started working with Doug, after nine months or so, I ran off and started working on Star Wars stuff for Marvel, and then came back to work for him. We were working on a show called Godzilla, that’s shown even now on Cartoon Network. It was partnered with a show called Jana of the Jungle Neither one of them were groundbreaking material, but they were a lot of fun to work on, and I know a lot of them won’t admit to it: Will Meugniot worked on it, Dave Stevens worked on it, Bill Wray worked on it. A lot of people in comics ended up working on that show.

JON: Were you at Ruby-Spears before Thundarr started? Did John Dorman bring you on?

RICK: I came in just after it started. Actually, Jerry Eisenberg and Larry Huber brought me over, and I began working for John Dorman. John was the story board supervisor over there.

JON: What were your duties there?

RICK: Layout department, basically. I did charac ter design and layout on Thundarr and Plastic Man. Thundarr was a lot of fun to work on. It was a ground breaking kind of show. Nothing like it had actually ever been done for Saturday morning, in that it was a real straight adventure show, with no funny animals in it per se. We didn’t have any dog sidekicks or anything like that; the nearest thing you had to it was Ookla the Mok, the big Wookie character. It did pretty well; it ran two seasons. At that time, that was good for an adventure show. At that point, they were looked at as almost kind of a break from the comedy shows. Kids were watching Thundarr.

The real groundbreaker I was involved in over at Marvel was G.I. Joe. It was tremendously successful. Even though it was syndicated, it was a huge hit, with marvelous ratings. I believe the G.I. Joe show was on for eight or nine years.

JON: Steve Gerber mentioned being story editor of G.I. Joe as the highlight of his career in animation, along with Thundarr

RICK: It actually had some very good stories. You had a lot of good writers involved in that: Buzz Dixon and Steve Gerber, Roger Slifer was there. It was the first time comic book people were pulled in big time on the writing end. It didn’t rely on any formula of the time. It didn’t rely on having to deal with comedy. You could do a comedy episode, but you didn’t have to have a funny animal or comedy relief sidekick. It just relied on the straight character of the heroes involved, and the

66

Conducted by Jon B. Cooke on May 20, 1996 • Transcribed and copyedited by John Morrow

INNERVIEW

remember, he was the guy who designed the original Turbo Teen, which when you think about it, seems like a real Jack Kirby con cept—a kid turns into a car. Even though I hated working on the show, it was fascinating to see his ideas were still being put forth in animation, and they actually were used in those shows back then.

JON: What do you see as the most “Kirby” of those shows?

RICK: Oh, Thundarr. He did quite a few shows. He did an unproduced knockoff of that She-Ra, Princess of Power thing that they did over at Filmation. He was always coming up with, especially, villain designs. He did some design work on The Pirates of Dark Water when it was initially put for ward. There’s a lot of stuff he worked on. Jack would do things like design concepts. Sometimes they’d get painted up, sometimes we’d just ink them. In the end, they’d quite

villains; and the villains were total bad guys, which is something that hadn’t been done a lot. It was quite a good show, and I was happy to be involved. I only stuck around for the first season because there were other shows we were working on, like the Incredible Hulk, and the first Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends show. This led us along to breaking ground for further shows, cause at the time, most of the adventure shows being done were still done in these old vaudevillian-style staging methods, with characters were brought on Stage Left, and exited Stage Right, as opposed to cutting it like Hitchcock or Ford. We were approaching the cutting with a more melodramatic flair.

Jack actually was doing a lot of real fun designs over at Ruby-Spears. Even though some of the shows themselves weren’t particularly designed in that vein, he was always coming up with real energetic and interesting things. As I

often get Gil Kane to do a real nice comp, and they’d get painted from that. Some of those paintings are quite lovely.

JON: Have you seen the trading card set? It’s called Jack Kirby: The Unpublished Archives, but a good fourth of it is Gil’s work. It’s not factually correct, but it’s still fasci nating and beautiful.

RICK: No, I haven’t at this point. But I think this is why that’s in there. Jack did a lot of the actual designs you’ll see, and Gil Kane ended up doing the compositions they used to help sell the ideas. Jack would be a conceptual artist, but he’s not the one whose art they would use to sell it. Technically,

67

Influencees

Evan Dorkin Interview

[below] A page from Superman and Batman: World’s Funnest, wherein Evan did a masterful job of channeling Kirby in his dialogue. The very Kirbyesque art is by David Mazzucchelli.

[next page, top] Kirby’s version of Space Ghost from Space Stars Finale for the 1981 Space Stars show

[next page, bottom] For TwoMorrows’ Kirbyinspired book Streetwise (2000), Even drew his autobiographical story “The Soda Thief!”. Our thanks to Evan for again helping us out, by inking this issue’s cover!

[next two pages] Kamandi sketches by Evan (includ ing Klik-Klak!), and a couple of simian-based presentations by Jack.

[Cartoonist Evan Dorkin (born 1965) is best known for his comic books Milk and Cheese and Dork, but his experience runs much further than the printed page. With wife Sarah Dyer, he’s written for such animated series as Space Ghost Coast to Coast, Superman: The Animated Series, and many others. His most celebrated work within mainstream comics is arguably his 2000 one-shot DC comic Superman and Batman: World’s Funnest, which he wrote for a who’s who of comics’ best artists to illustrate. He’s received widespread acclaim for his Eisner Award-winning Beasts of Burden books, and he recently returned to the comics of Bill & Ted with Bill and Ted Are Doomed (2021). He’s currently heavily involved in animation, and Kirby is a never-ending influence on his work, as you’ll see here.]

ERIC NOLEN-WEATHINGTON: What was your first encounter with Kirby’s work?

EVAN DORKIN: I can’t pinpoint my first exposure to Kirby’s work, but the first Kirby comic I remember buying for myself was Marvel’s Greatest Comics #55, which reprinted the story where the FF fought Thor, Spider-Man, and Daredevil. This was in 1975, and I was ten years old.

ERIC: Were you old enough to be aware of Kirby’s move from Marvel to DC?

EVAN: No, it would have been a few years too early for me. At that time I would have been mostly reading newspaper comics and Tintin, which was running in Children’s Digest magazine.

ERIC: Did you read any of his DC work regularly?

EVAN: I did not. I didn’t like DC when I was a kid, I only collected Marvel. I would read my friend Clifford’s Atlas comics, my sister’s Harvey and Archie comics, but for some rea son I just didn’t take to DC at all. I didn’t start reading DC comics until the ’80s. I came to Kirby’s ’70s DC work even later.

ERIC: As you were starting out drawing, did you ever try to copy his stuff?

EVAN: Oh, of course. Mostly the Fantastic Four, inked by Joe Sinnott—with absolutely terrible results. [Eric laughs]

ERIC: What elements did you take away from Kirby and incorporate into your own work?

EVAN: Intensity. Energy. Bombast. Mayhem. Action. Crowds. Costuming. Detail. Huge, wide-open scream ing mouths. Monstrously large screaming mouths. That’s where Milk & Cheese’s mouths came from.

ERIC: Did you ever meet Kirby in your early days of attending comic conventions? Did you ever show him your comics?

EVAN: I met him when I was a teenager, on line at a con, getting a comic signed. Like most people, I gushed and stammered at him while he signed my copy of The Fantastic Four. I never had an opportunity to show Kirby my work; I wouldn’t have done so even if I had the chance. I did meet Kirby briefly at the San Diego Comic Con after I broke into comics. Bob Schreck introduced me to him in 1992 during his 75th birthday event. I shook hands with him and gushed and stam mered just like when I was a kid. [Eric laughs]

ERIC: What were some of your favorite cartoons growing up?

EVAN: The old studio cartoon shorts, any Disney car toons that got shown on The Wonderful World of Disney, Scooby-Doo and all the Saturday Morning junk, the Peanuts and Rankin-Bass specials. Living in Brooklyn meant having access to a lot of TV stations, so I was also a fan of things like Kimba the White Lion, Speed Racer, and The International Animation Festival show on PBS. When I got older, I loved the early syndicated Nelvana specials, Battle of the Planets, and Star Blazers I saw Yellow Submarine, The Phantom Tollbooth, and Wizards in the theater. I was into animation as much as comics and monster movies.

ERIC: Did you watch Thundarr the Barbarian? And, like I did, did you watch the credits just to see the names of the comic creators who worked on that show? Were you paying attention to that kind of thing by that point?

72

Conducted by Eric Nolen-Weathington in September 2022

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK TO ORDER THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DIGITAL FORMAT!

COLLECTOR #85 KIRBY: ANIMATED! How JACK KIRBY and his

leaped

celluloid, to paper, and

and

KIRBY

concepts

from

back again! From his 1930s start on Popeye

Betty Boop and his work being used on the 1960s Marvel Super-Heroes show, to Fantastic Four (1967 and 1978), Super Friends/Super Powers, Scooby-Doo, Thundarr the Barbarian, and Ruby-Spears. Plus EVAN DORKIN on his aban doned Kamandi cartoon series, and more! (84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95 (Digital Edition) $4.99 https://twomorrows.com/index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=98_57&products_id=1667

Here’s still more of Simon & Kirby’s “Flying Fool” work, “Face In A Storm” from Airboy Comics V4, #10 (Nov. 1947), with art reconstruction and coloring by Chris Fama. Look for the final installment of the complete Link Thorne stories next issue!

Here’s still more of Simon & Kirby’s “Flying Fool” work, “Face In A Storm” from Airboy Comics V4, #10 (Nov. 1947), with art reconstruction and coloring by Chris Fama. Look for the final installment of the complete Link Thorne stories next issue!