There is a serenity that surrounds Lynda Day George, the 77-year-old actress who is hopeful of a return to performing after a long hiatus. Best known as Casey on Mission: Impossible, the attractive actress has a long résumé of television and film credits, but her beginnings were far more modest ones.

Born Linda Louise Day on December 11, 1944, she was raised in San Marcos, Texas, by her mother Betty and father Claude, an Air Force officer. Soon after her brother Richard was born, Claude was transferred to Joplin, Missouri, bringing the family with him. At one point, her mother remarried Del Whitehead, and in 1957 the entire family relocated to Phoenix, Arizona. There, she found herself amidst budding talents who would intersect with her later career.

Her mother, Betty Louise Avey Day-Whitehead, taught poise and charm at a modeling school, which proved influential on the young child. Initially, Lynda was thinking about becoming a surgeon, but her good looks and mother’s influence had her thinking in new directions. When she was 12, Lynda began entering beauty contests, and was handing out flyers for the modeling school where she also met Lynda Carter (yes, that Lynda Carter). One day, as they handed out flyers, Wayne Newton and his brother Jerry came across the street from a guitar store and introduced

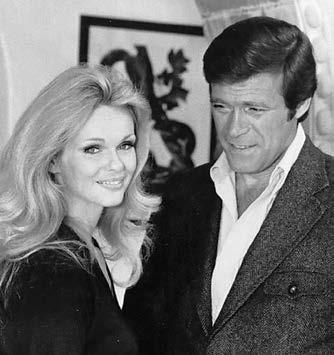

Your mission, RetroFan reader, should you choose to accept it—and who wouldn’t??—is to enjoy this profile of the fabulous Lynda Day George. (ABOVE) One of our favorites of her roles is as Casey, from television’s coolest, smartest espionage show, Mission: Impossible. Her castmates were Peter Graves, Greg Morris, and Peter Lupus. © Paramount Pictures Television.

themselves. Wayne eventually asked her to an eighth-grade dance. She attended West High School, while Wayne and Jerry were across town at North High School; they kept up their friendship and she was present when Wayne debuted in Las Vegas, becoming an iconic mainstay.

While in high school, she represented her school in the Maid of Cotton competition, the first of many such accolades. From a friend’s ranch in Montana, George wistfully looked back on those days. She explained that her mother’s influence got her to model, and it was not long after, at 15, that she was scouted to work for the famous Eileen Ford Modeling Agency in New York City. A former Ford model had opened her own agency in Phoenix and spotted

Her track record suggests she was well regarded given the steadiness of her career along with her versatility, allowing her to excel in sitcoms and dramas. In The Complete Mission: Impossible Dossier, director Gerald Mayer recounted an incident when he was helming an episode of The Fugitive. “At the last moment an actress who was to play a very strong emotional part bowed out, and they replaced her with Lynda Day, whom I’d never heard of. She was just marvelous in a very dramatic part, absolutely terrific.”

Apparently, watching series star David Janssen was influential on her, as he made a point to know the name of every member of the cast and crew, including personal details. He was also good

Among those roles, she did four episodes of The FBI, including one just after she and George married. They began frequently working together on series, films, and even game shows. It helped that they shared an agent who knew they liked working with one another so they often got cast on the same episode of a series together.

She recalls seeing FBI star Efrem Zimbalist, Jr. frequently on the set whether he was needed or not and despite not sharing a lot of screen time with him, they had several fruitful conversations.

Across the years, she worked with some of the greatest names in Hollywood. Asked to name which ones stood out, she demurs, saying, “Oh, you know, I was so blessed to be working with all these actors.

friends with Christopher George, and she recalls seeing them having many deep conversations.

She was popular enough to consistently be cast for pilots, only one of which went to series. For Universal in 1969, she shot Fear No Evil, a movie-of-the-week/pilot, opposite Louis Jourdan, who was a psychiatrist with a healthy skepticism over the supernatural, but whose cases often had him questioning that belief. It performed well enough to commission a second telefilm, this one sans Lynda, and it never went to series. She had tremendous respect for Jourdan, who she saw as unique, very sophisticated in bearing. “I was blown away” by working in television, which was rapidly evolving from mere entertainment to stories with more dramatic themes.

Many of her guest appearances were on Quinn Martin Produc tions, followed by many Aaron Spelling series. She notes how both men had “strong visions for what could be done on television” and she was happy to be working with both legendary producers.

There would be a very long list of the best I worked with. There were so many great productions.”

She said that being the visiting cast member was thrilling since every show had its own vibe. “Everyone on the crew couldn’t have made me feel more welcome,” she says.

In 1969, she thought a lucky break came when she was cast in Chisum, a feature film mounted by John Wayne at Warner Bros. Her part was a small one, but it brought a feature film salary and a chance to be seen on the big screen. The movie, adapted by Andrew J. Fenady from his short story “Chisum and the Lincoln County Cattle War,” was directed by Andrew V. McLaglen. Shot in Durango,

(LEFT) Promotional photo for the short-lived, M:I-like The Silent Force (1970–1971). (FRONT) Lynda Day as Amelia Cole. (BACK, LEFT TO RIGHT) Ed Nelson as Ward Fuller and Percy Rodriguez as Jason Hart. © CBS Studios, Inc.

Mexico, it had a large cast including Wayne, Forrest Tucker (coming off F-Troop), Ben Johnson, and Christopher George. Day was reunited with her friend and this time their romance heated up.

As 1970 dawned, Lynda Day divorced Pantano, who she has little to say about, and on May 15, married Christopher George. Their film opened to rave reviews just a month later. Later, they petitioned the courts to have Nicky recognized as his natural son.

Over the course of her career, she shot a total of nine pilots, starting with the only one to go to series, The Silent Force. Others of note included Cannon and The Barbary Coast. She laughs at the notion she was either a good luck charm for studios or a curse given her one-for-nine record.

Still, the half-season Silent Force proved providential on several fronts. First, it was shot on the Paramount lot in 1970, where Christopher was shooting his ABC series The Immortal. This allowed them to travel together and visit whenever they weren’t needed on set.

(RIGHT) Lynda Day George as part of the Mission: Impossible cast, on the January 22–28, 1972 cover of TV Guide. Mission: Impossible © Paramount Pictures Television. TV Guide © TV Guide. (INSET) What a handsome couple! Lynda Day George and Christopher George.

The series was about three U.S. Government agents who went undercover to fight organized crime. Lynda was partnered with Percy Rodriguez and Ed Nelson. If the premise sounds familiar, it should; it was clearly patterned after the success of CBS’ juggernaut, Mission: Impossible Silent Force was created by Luther Davis, a prolific award-winning playwright and screenwriter; this was his sole foray into television. An Aaron Spelling production, it was critically panned and was cancelled in January 1971, airing a mere 15 episodes. The half-hour drama could never match the draw of NBC’s Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In or CBS’s Here’s Lucy. George is dismissive of it, given its short running time, and feels, to her, it was filler prior to Monday Night Football Still, Lynda loved having a regular role at long last. She grew to bond with her costars and really enjoyed getting to know the crew. She didn’t have much to say about her character, Amelia Cole, who wasn’t given much personality or background.

BY w ILL MURRAY

BY w ILL MURRAY

I still remember the first time I laid eyes on the Man of Steel. I was very, very young. I don’t remember where I lived, but I remember that the scenes came from the Adventures of Superman starring George Reeves. “The Clown Who Cried” was the name of the episode.

I don’t know why I retained fragmentary memories of that episode. It’s the only Superman experience I could remember having before I purchased my first Superman comic book late in

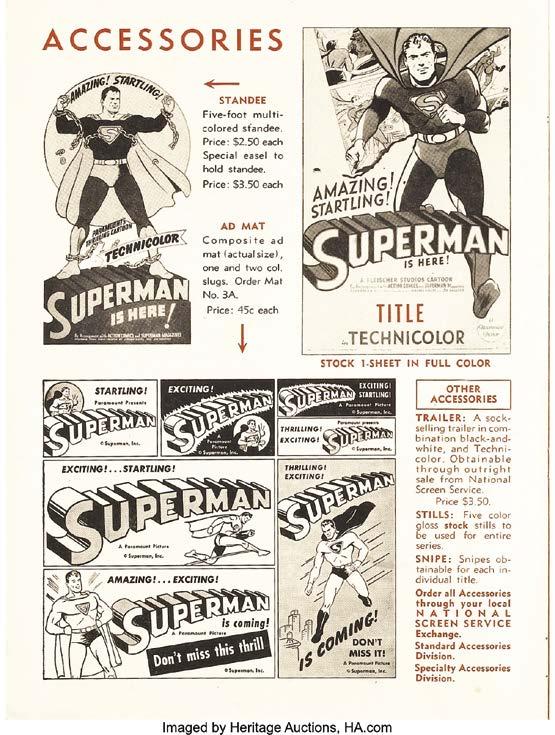

It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s… a cartoon series! Title and sample images from the Fleischer Studios Superman animated shorts from the Forties. Superman TM & © DC Comics. Courtesy of Heritage.

TV again. This wasn’t George Reeves in the flesh, but an even older, animated incarnation.

One Saturday morning cartoon show—probably the local Bozo the Clown —in the very early Sixties included in the line-up a wartime episode of the Forties Max Fleischer Technicolor Superman cartoons. Destruction, Inc. was the title. It involved the Man of Steel battling saboteurs at the defense plant.

I don’t think we had a color TV set then, although we might have. My family was the first in our neighborhood to purchase one. But that episode was mesmerizing. I was especially enthralled because this version of Superman had to work at being the Man of Steel. He could shrug off bullets like his DC Comics descendent, all right. But in one memorable scene where he’s buried in a massive pile of steel girders, he had to struggle. It didn’t take him long to shrug them off. But just those few moments of suspense really grabbed me.

I don’t think I saw another episode until the Seventies, when the larger comic-book conventions began showing them in 16-milli meter projection. They were as much a thrill then as they are now, a half a century later.

Eventually, the Fleischer Superman cartoons were released on video and then posted on YouTube, so anyone could watch them, at any time. If you’ve never seen one, they are an absolute joy.

So I thought for this column I would look into the circumstances behind which Superman first appeared on the silver screen, way back in 1940.

The Man of Steel took America by storm in 1938–1939. A newspaper comic strip and radio program appeared before the character was much more than a year old.

Hollywood noticed.

Republic Pictures envisioned producing a 15-chapter Superman live-action serial in 1939, and acquired an option to do so. But the project was slow to get off the ground.

According to DC Comics publisher Harry Donenfeld, a Republic contract arrived on a Monday. Donenfeld was superstitious about signing contracts on the first day of the business week. So he put it aside.

The next day, a better offer came from Paramount Pictures, for a series of Superman animated cartoons. Donenfeld made that deal, leaving Republic to make do with Captain Marvel.

At the time, Donenfeld boasted, “Because I always thought Superman was too fantastic a character to be played by a real man, I jumped at the chance. We expect to gross about ten times as much money on the cartoons.”

(TOP) This pressbook was presented to movie theaters in 1941 to help promote the Fleischer Studios’ new Superman cartoon shorts. Superman TM & © DC Comics. Courtesy of Heritage. (LEFT) Move over, Jor-El and Pa Kent! Superman’s real fathers were his co-creators, writer Jerry Siegel (STANDING) and artist Joe Shuster.

That was the story Harry Donenfeld told the press in 1940. However, as Ray Pointer revealed in his book, The Art and Inventions of Max Fleischer, that was a publicity yarn. The truth was that Fleischer Studios made the cartoon offer, not Paramount, which was only the distributor. Republic later unsuccessfully sued Donen feld for breach of contract.

The Fleischer Studios’ plan called for a series of Superman cartoons, which would be released by Paramount. For a hero who could vault skyscrapers and outrace locomotives, animation made perfect sense. Fleischer was a self-contained operation located in Miami, Florida, owned by two brothers, Max and Dave.

Max, the older brother, was the driving force. He had long wanted to produce more realistic cartoons, and the science fiction

premise of Superman especially appealed to him. Dave was more comfortable with traditional cartoony subjects. Fearing the technical complications of animating realistic characters, he was against the project.

“I didn’t want to make Superman,” Dave Fleischer confessed. “Paramount wanted it. They called me over and asked why I didn’t want to make it. I told them because it was too expensive, they wouldn’t make any money back on it. The average short cost nine or $10,000, some ran up to 15: they varied. I couldn’t figure how to make Superman look right without spending a lot of money. I told them they’d have to spend $90,000 on each one… They spent the $90,000. But they were great.”

Actually, the cost was $50,000 for the first episode, and $30,000 after that, but it was still tremendously expensive. When the deal was announced in the summer of 1940, Paramount promised a Christmas release. But they were overconfident. Technical issues stalled the project, pushing the release deep into the following year.

The first entry took seven months to produce—twice as long as the usual cartoon short. Approximately 90 artists—most uncredited and many of them women—produced an estimated 1,000,000 illustrations in order to bring the acclaimed character to life.

“Superman,” promised Dave Fleischer in 1941, “will be the first animated short to tell a straight dramatic story, using humor only

where it would normally occur; the first cartoon short employing quick emotional close-ups of the human head, and the first cartoon short to utilize ‘quick cut-backs,’ which are flash shots of extreme brevity used for their cumulative affect to show the reaction of groups of people to a single decisive event.”

Superman pitted the Man of Steel against the depredations of a mad scientist and his destructive Electrothanasia-ray. It premiered in September 1941 and set the tone for most of what followed, with only necessary variations in the formula. Typically, Lois Lane would follow a news story into peril, which required Clark Kent to dramatically doff his blue business suit for his trademark blue tights, rescue Lois, and defeat the cartoon’s menace.

Superman’s cartoon debut was nominated for an Academy Award, and is today considered one of the greatest examples of theatrical animation ever produced.

Much of the modern Superman mythos was pioneered in the Fleischer Studio. In the comics, the Man of Steel could only leap long distances, but the Fleischer animators realized this made him look like a blue grasshopper, so they gave him the power of true flight. The comics adopted this innovation in 1943. The trope of Clark Kent ducking into a phone booth in order to change into the Man of Steel originated with these cartoons.

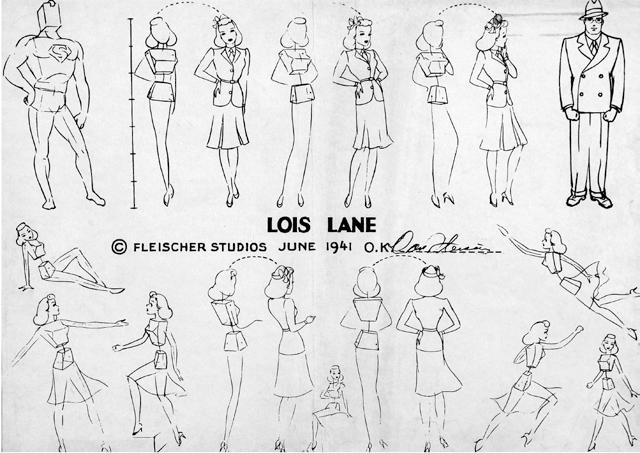

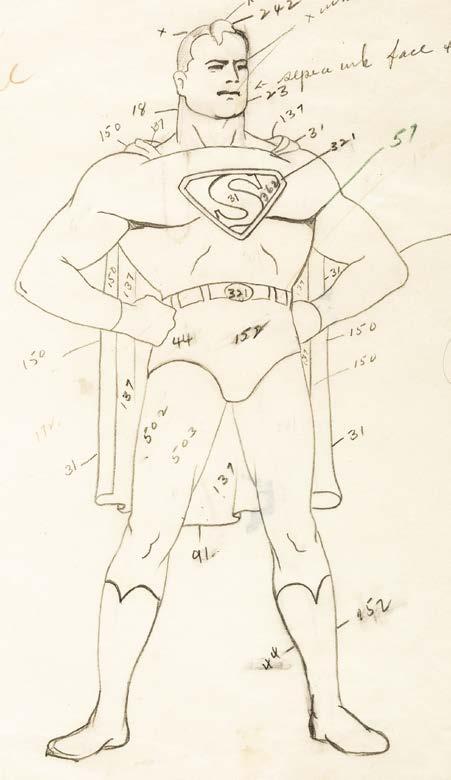

Fleischer Studios’ interpretation of the Man of Steel streamlined the hypermuscular comic-book version rendered by Superman co-creator Joe Shuster. Shown here are a Superman color model sheet and head model sheet, plus a Lois Lane model sheet. Superman TM &© DC Comics. Courtesy of Heritage.

BY ANDY MANGELS

BY ANDY MANGELS

(RIGHT) Superman faces off against “The Force Phantom” in the first The New Adventures of Superman show. (INSET) Clark Kent from a Filmation model sheet used to aid animators. TM

Look, up in the sky! It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s Andy Mangels’ Retro Saturday Morning, your constant guide to the shows that thrilled us from yesteryear, exciting our imaginations and capturing our memories. This issue, you get a double-dip into two parts of the Man of Steel’s animated history: look elsewhere for the spotlight on the tremendous Fleischer theatrical shorts, but stay tuned for a look at TV’s exciting The New Adventures of Superman!

Following his debut in Action Comics #1 (June 1938), the Kryptonian super-hero shone brighter than all other comic characters, and media of the time soon followed. A Superman newspaper strip came first, in January 1939, and actor Ray Middleton portrayed Superman at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Beyond the printed page, the first adaptation of Superman was a radio show titled The Adventures of Superman. The syndicated show began on February 12, 1940 as a 15-minute serialized story, airing from three to five times per week. The series was sponsored by Kellogg’s Pep cereal.

Announcer and narrator Jackson Beck gave the opening of the series, which thrilled young viewers: Up in the sky, look! It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s Superman! Yes, it’s Superman— strange visitor from the planet Krypton who came to Earth with powers and

abilities far beyond those of mortal men. Superman, who can leap tall buildings in a single bound, race a speeding bullet to its target, bend steel in his bare hands, and who, disguised as Clark Kent, mild-mannered reporter for a great Metropolitan newspaper, fights a never-ending battle for truth and justice!

Although uncredited initially to maintain secret-identity mystique, Bud Collyer played both Clark Kent and Superman (except for some final-year shows that featured Michael Fitz maurice), while Rolly Bester, Helen Choate, and Joan Alexander portrayed Lois Lane. The series introduced not only the concept of kryptonite to the mythos, but also the characters of Daily Planet editor Perry White (voiced by Julian Noa), copyboy Jimmy Olsen (voiced by Jackie Kelk and Jack Grimes), and Police Inspector Bill Henderson (voiced by Matt Crowley and Earl George). All of these characters quickly transitioned into the comics as well.

With no repeats aired, The Adventures of Superman lasted for an amazing 2,088 original episodes, finally ending its 11-year run on March 1, 1951. By that time,

The Adventures of Superman radio show voice actors: (LEFT TO RIGHT) announcer and narrator Jackson Beck, Lois Lane Joan Alexander, and Superman Bud Collyer.

producer Robert Maxwell was already working on a new format for Superman to conquer… television!

The new Adventures of Superman series was a syndicated half-hour live-action show debuting around September 19, 1952 (actual airdates are contested due to the syndicated nature of the program). As with the radio series, Kellogg’s sponsored the TV show, which starred George Reeves as Clark Kent/Superman, Phyllis Coates and Noel Neill as Lois Lane, Jack Larson as Jimmy Olsen, John Hamilton as Perry White, and Robert Shayne as Inspector Henderson. The series was originally filmed in black-and-white for the first two seasons of 26 episodes each, but filming switched to color for seasons three through six, which added an additional 13 episodes for each year. [Editor’s note: See RetroFan #11—still available at www.twomorrows. com —for our lavishly illustrated look back at Adventures of Superman.] In all, 104 episodes were produced, plus a short-form episode made for the U.S. Treasury Department titled “Stamp Day for Superman.”

Voiced by Bill Kennedy, the show’s opening narration was a variation on the radio show: Faster than a speeding bullet! More powerful than a locomotive! Able to leap tall buildings at a single bound! Look! Up in the sky! It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s Superman! Yes, it’s Superman… strange visitor from another planet, who came to Earth with powers and abilities far beyond those of mortal men! Superman... who can change the course of mighty rivers, bend steel in his bare hands, and who, disguised as Clark Kent, mild-mannered reporter for a great metropolitan newspaper, fights a never-ending battle for truth, justice, and the American way!

The final episode of Adventures of Superman aired around April 28, 1958, although pilot episodes for both a Superboy and Superpup spin-off series were shot later. The producers made plans to make two more years of episodes, but the 1958 death of John Hamilton threw one monkey wrench into the gears. Plans were completely shut down after the unexpected and mysterious death of star George Reeves on June 16, 1959.

Because it was already in syndication, Adventures of Superman basically never left the air for several decades after its cancellation. But in 1965, plans were put into place for a new media incarnation for the Man of Steel…

In the early Sixties, having worked for animation houses including Kling Studios, Walter Lantz, Ray Patton Productions, Warner Bros., and others, animator Lou Scheimer founded Filmation Associates with fellow animator Hal Sutherland and disc-jockey-turned-pro ducer Norm Prescott. Filmation was a scrappy young company that brokered outside animation jobs and commercials, but they really needed some way to make their mark, or they would disappear.

“It was 1965, and after only a few years in business it looked like Filmation Associates was going to have to close its doors,” said Scheimer in my interviews with him for the 2012 TwoMorrows book, Lou Scheimer: Creating the Filmation Generation. “The studio was now down to two employees—myself and Hal—and a shutdown was imminent. Norm was doing his best to try to raise money from someone, somewhere, somehow… We had 24 empty desks and some equipment gathering dust. We didn’t have a Moviola to sell, or it would have probably been gone already.” Filmation’s offices

(TOP) Early Filmation studio location. (BOTTOM) Filmation’s top brass circa the Sixties: (LEFT TO RIGHT) Norm Prescott, Hal Sutherland, and Lou Scheimer. (INSET) Legendary Superman comics editor, Mort Weisinger.

did have one other “person” in the office, but she didn’t say much; at the front desk was a mannequin wearing glasses and a dress from Lou’s wife. Visitors would sometimes talk to the “receptionist” before realizing she wasn’t real. It was a sign of things to come…

“One day the phone rang, and Hal answered it,” Scheimer continued. “A moment or so later his eyes got wide, and he said, ‘Louie, maybe you’d better talk to them!’… He had a peculiar look on his face, ‘He says his name is Superman Weisinger calling from DC. He’s looking for Prescott! … I got on the phone and said, ‘Hello, Mr. Superman, are you calling from a phone booth?’ I figured it was a prank call. The voice on the other end said, ‘Mort Weisinger here. I’m the story editor on Superman, and I’d like to talk to Norm Prescott.’ I said, ‘Well, Norm’s not here right now. Is there anything I can do to help?’ He said, ‘No, I’ve got to talk to Prescott!’ I explained to him that Prescott was in a hotel on Sunset Boulevard and was going to leave for New York the next day and told him to call him shortly. I hung up and quickly called Norm and said, ‘There’s some

How does one become a comic-book hero? Offhand, I can think of at least three ways: be born on Krypton; get bitten by a radioactive spider; or become a funnyman in the movies.

At least, that’s how it was in the olden days.

When you’re a little squirt, you just accept things. Like, if you were a kid in the Sixties who bought DC comic books at the corner drugstore, you didn’t question your options: Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, The Flash, Green Lantern, The Adventures of Bob Hope The Adventures of Jerry Lewis Wait, what?

Can you imagine a child in the Sixties who’d want to read a comic book about Bob Hope? The movie comedian’s onscreen persona was the opposite of kid-friendly: a balding flimflammer in a suit who broke the fourth wall referencing show-biz pals—Hope’s constant name-dropping of Bing Crosby could be a drinking game—and who, when in the presence of pretty ladies, acted all flustered. (Cant’cha just hear Hope doing his trademark guttural snarl?)

Jerry Lewis, at least, did slapstick—always a hit with the kiddies—and his movie persona had a six-year-old mentality. But as the Sixties got their groove on, Lewis’ onscreen antics began to sour (in lackluster films like Hook, Line & Sinker and Don’t Raise the Bridge, Lower the River). Meanwhile, his comic-book counterpart was still making like the vital, Brylcreemed Jerry of the early days. Time warp!

Still, we urchins bought, read, and dug the Hope and Lewis books. The creative teams’ secret sauce for holding our interest? Cram the books with lots of hip, or at least faux hip, supporting characters. This distracted us from the woeful un-hipness of the titular comedians.

What we pre-teen punks didn’t realize was that in the previous decade, Hope and Lewis were “hired” by DC to help sustain the comics industry at a time when super-heroes were out of fashion—temporarily, it turned out.

I once broached the subject of the Hope and Lewis books being an odd cultural fit with writer Arnold Drake, who scripted many issues of both titles for DC. The urbane, introspective Drake (1924–2007) told me something I’d never heard before—not in comics history books, the comics press, or anecdotally: that in the middle-Sixties, there had been a plan afoot, a slow-moving coup,

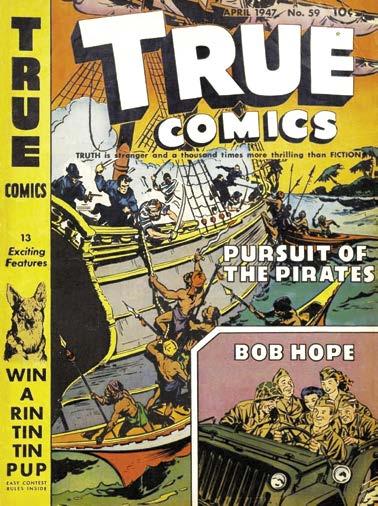

It remains a mystery from the olden days of the medium how DC Comics published books “starring” movie comedians Bob Hope (LEFT) and Jerry Lewis (RIGHT), that were bought and read by children. Both the Hope and the Lewis books exceeded 100 issues, something that will never happen again.

© DC Comics.

against Hope. (Cue needle-scratch on 33-RPM record.) DC was plotting to remove Bob Hope from his own comic book. Et tu, DC? But before we get into the “Bag Bob” conspiracy, as I’ll call it, a bit of contextualization is in order.

Screen comedians were depicted in comics from the early days of both the “moving pictures” and the “funny papers.” It seems safe to say that the first such instance was Charlie Chaplin’s Comic Capers, a syndicated strip that debuted in 1915 from the Chicago-based J. Keeley Syndicate. Chaplin was depicted as the “Little Tramp” character—bowler, cane, Hitler mustache—from his Essanay films of the era, such as The Champion, His New Job, and In the Park (all from 1915).

But many early depictions of movie comedians in the comics were largely unseen in America. Amalgamated Press of London published Film Fun between 1920 and 1962. Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton, Laurel and Hardy, Abbott and Costello, and an upstart comedy team called Martin and Lewis (more on them later) were graphically depicted alongside British comedians virtually unknown here.

From the Thirties through the Fifties, the so-called “Tijuana bibles”—unauthorized pornographic comics illustrated by pros, but not publicly sold—depicted W. C. Fields, Laurel and Hardy, the Marx Brothers, Jimmy Durante, and Joe E. Brown in compromising situations. (Trust me on this: It’s even skeevier than it sounds.)

In 1945, Rural House brought Red Skelton to the comics in their teen-genre title Patches, in issue #11. (A cartoon Skelton is seen uttering his catchphrase “I dood it!” on the cover.)

In 1947, Fiction House featured Skelton in Movie Comics #4, with their adaptation of “Merton of the Movies.” Film Fun ran Skelton comics in its 1957 annual. (For the following, I leaned heavily on Robert M. Overstreet’s Official Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide, as any fellow comic-book freak should have no trouble recognizing.)

In the late Forties, St. John rolled the dice on comic books featuring three comedy teams. In 1948, St. John launched its Abbott and Costello series, which ran for 40 issues through 1956, often with artwork by MAD caricaturist Mort Drucker. (The publisher also depicted A&C in Comics Edition #16 in 1950.) St. John brought out its and Hardy series in 1949, which ran for six issues through 1956, albeit with an erratic publishing schedule. That same year, St. John’s Jubilee imprint kicked off its

six-issue series The Three Stooges, illustrated by Norman Maurer and Joe Kubert.

We should also note appearances by movie comedians in K.K. Publications’ long-running March of Comics (1946–1982). These weren’t comic books per se, but commercially sponsored giveaways. Characters depicted include Our Gang, Laurel and Hardy, and the Stooges.

Owing to the TV popularity of the Our Gang shorts, Dell’s long-running anthology title Four Color brought Spanky, Alfalfa, and friends to the funnybooks with 12 issues of The Little Rascals beginning with Four Color #674 in 1956. A TV resurgence was also behind Dell/Gold Key’s later 55-issue revival of The Three Stooges (1959–1966); Charlton’s 22-issue revival of Abbott and Costello (1968–1971); and Dell/Gold Key’s six-issue revival of Laurel and Hardy (1962–1967).

No one was safe. Woody Allen met the fictional rockers the Maniaks in DC’s Showcase #71 (1967), illustrated by Mike Sekowsky. For the life of me, I can’t determine whether this was an authorized use of Allen’s name and likeness. Somehow, I doubt it.

If being a movie comedian is a way to become a comic-book hero, how does one become a movie comedian?

Bob Hope was born Leslie Townes Hope in London in 1903, and lived to be 100. Well, he was an inveterate golfer, a ladies man (to put it politely), and a proponent of the health benefits of daily massage.

Hope made his film debut in the 1934 short Going Spanish, and finished his career in a 1997 K-Mart commercial that also featured Martha Stewart and Big Bird.

Anyone over 70 can tell you four things about Hope: His theme song was “Thanks for

©

©

the Memories.” He entertained U.S. troops through six wars. He hosted the Oscars 19 times. And he made seven “Road” pictures with Bing Crosby and Dorothy Lamour.

Hope’s appeal is undeniably dated, so it takes a nostalgic person (like myself) to get through movies like I’ll Take Sweden; Boy, Did I Get a Wrong Number!; and How to Commit Marriage

Jerry Lewis was born Jerome Levitch in 1926 in Newark, New Jersey, and entered the show-biz field by pantomiming records. (You can see Lewis recreate the bit to Count Basie’s bouncy jazz instrumental “Cute” in his 1960 film Cinderfella.)

He initially won fame as the dimwitted sidekick of suave singer Dean Martin. The duo made their debut in Atlantic City on July 25, 1946. (The exact date is often noted because they broke up ten years later, to the day.) Their first film appearance was in My Friend Irma (1949)

starring Marie Wilson. For those ten years, Martin and Lewis were kings of the entertainment world in broadcasting, movies, and on the nightclub stage. They dissolved the union, not amicably, in 1956 (though Frank Sinatra brokered a live TV reunion 20 years later). Lewis hosted marathons on behalf of the Muscular Dystrophy Association from 1966 through 2010, and died at age 91.

Not everyone loved Lewis’ onscreen persona. Depending on your viewpoint, the comedian portrayed a hilarious and endearing, or unfunny and obnoxious, buffoon in dozens of films. Me? I’d call Lewis a comic genius that sometimes needed to be reeled in. That rarely happened, and his films would suffer. But when he was funny—boy, was this guy funny.

When DC launched The Adventures of Bob Hope and The Adventures of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis (as the Lewis book was titled for its first 40 issues), the comics industry was going through an anxious time.

By the late Forties, super-hero characters waned in popularity, as Western, war, crime, horror, romance, teen, and “funny animal” comic books dominated newsstands. Increasingly, publishers turned to movies

(LEFT) Rascally Bob is smothered in kisses in a panel from Bob Hope #26 (1954). © DC Comics. (RIGHT) Prior to their DC run, Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis appeared in Movie Love #12 (1951). © Famous Funnies.

Oh, I wish I were an Oscar Mayer wiener That is what I’d truly like to be ’Cause if I were an Oscar Mayer wiener Everyone would be in love with me.

Richard Trentlage is likely the first person to write a tune I couldn’t get out of my head. Most people don’t know his name, but when he died in 2016 at the age of 87, his obituary appeared in places as diverse as the New York Times, National Public Radio, AdWeek, the Hollywood Reporter, and Rolling Stone magazine. Trentlage wrote commercial jingles professionally and the big one, the one most of us Retronauts can still recall word for word, is “The Oscar Mayer Wiener Song.”

Popular culture origin stories often have multiple versions in the historical record, but the creation of this particular little ditty is pretty consistent. The Wiener Song came about thanks to a jingle contest organized by Oscar Mayer’s ad agency, J. Walter Thompson, and open only to advertising professionals. At the time Oscar Mayer & Co. was a family-owned business and not yet national. It was the final day of the contest when Trentlage heard about it and decided to take a shot. He wrote the jingle in an hour after coming up with the “Oh, I wish…” line (based on a wistful statement from his son who wanted to be a “dirt-bike hot dog”). Recording his son and daughter (she had a cold and it was felt that this would appeal to the moms) singing the tune took about 20 minutes. He composed the music on a ukulele and banjo. His wife played the standup bass. And then… it took a year before the public heard—and then was unable to forget—“The Oscar Mayer Wiener Song,” which debuted

in an animated commercial. Once more, Trentlage’s son and daughter (with a cold again) recorded the song in a studio presum ably more advanced than the one in the family’s living room.

Former Oscar Mayer V.P. of Marketing Jerry Ringlien was quoted in Rolling Stone as admitting, “It was the commercial that carried Oscar Mayer to national distribution.” The Wiener Song was finally retired in 2010. Jerry Ringlien would himself create the “My Bologna Has a First Name” campaign. The commercial with little four-year-old Andy Lambros fishing and eating a bologna sandwich appeared in 1974 and was also a hit for the company.

My bologna has a first name It’s O-S-C-A-R

My bologna has a second name It’s M-A-Y-E-R

Oh, I love to eat it every day And if you ask me why I’ll say ’Cause Oscar Mayer has a way with B-O-L-O-G-N-A!!!!

Ringlien would admit that selling bologna was a lot harder than selling hot dogs, but at least the tune pushed the brand name.

Adorable actor Andy Lambros fishin’ and eatin’ his bologna sandwich (1974). © Kraft Foods. All Rights Reserved.

BY SHAQUI LE v ESCONTE

BY SHAQUI LE v ESCONTE

September thirteenth, nineteen ninety-nine. A massive nuclear explosion… cause—human error! The Moon is torn out of Earth orbit and hurled into outer space—doomed to travel forever through hostile galaxies. And for the beings on Moonbase Alpha, one over-riding purpose—survival.

– Original Space: 1999 opening narration, from early Year Two scripts

In hindsight, Space: 1999 seems like an exercise in how not to create a series, let alone a science-fiction one. Star Trek was several years in its gestation, which Space: 1999 was and still is compared to. Gene Roddenberry’s vision was a future where space travel was commonplace, on a realistically sized starship akin to modern navy vessels. A large crew, headed by a smaller cast of regulars in command, gave rise to numerous spin-offs set in that same universe.

The genesis of Space: 1999 goes back with its producers, husband-and-wife team Gerry and Sylvia Anderson. They were behind the popular Supermarionation puppet series such as Fireball XL5, Stingray, Thunderbirds [see RetroFan #4 —ed.], and Captain Scarlet, which dominated the British airwaves through the Sixties. Each had an easy-to-understand format and, backed and distributed by Lew Grade’s ITC (Incorporated

they spearheaded a wave of marketing and merchandise the likes of which had never been achieved in the U.K. before.

By the end of the Sixties, the Andersons had effectively shot themselves in the foot by saturating the British television market with their series, with local channels opting out of latter productions Joe 90 and The Secret Service. They had made a break into live-action with the feature film Doppelgänger (a.k.a. Journey to the Far Side of the Sun) in 1968, which laid the foundations for doing so with a television series. The result was UFO, first airing in the U.K. in 1970, and following suit stateside

The show was a ratings hit in New York, and interest in a second season was shown. Pre-production art and documents were commissioned. With the original cast and crew disbanded with the closure of the Andersons’ Century 21 Productions the previous year, ITC’s American president Abe Mandell mooted updating the format to 1999. New characters would operate from an expanded “Moon City,” as those episodes of UFO not set on Earth had been more popular with viewers. But fate can be fickle, and as surprising as the high ratings had been, they

Television Company), (ABOVE) The cover and cast introduction from the 1975 pressbook touting the release of Space: 1999. © Incorporated Television Company (ITC). Courtesy of Heritage. (INSET) Sci-fi hardware was also a “star” of Space: 1999. Noted model builder Martin Bower constructed this hand-painted miniature replica of the series’ transport vehicle, the Eagle. Space: 1999 © ITC. Courtesy of Heritage. Moon photo: NASA.suddenly plummeted and American backing was withdrawn, leaving the Andersons with a massive outlay for no purpose.

All was not lost, and the art and format were used to pitch a new show. UFO was about aliens harvesting humans to sustain their own dying race, and perhaps other nefarious purposes. “UFO 1999” proposed the aliens neutralizing the Moon’s gravity and hurling it out of orbit, taking Moon City’s fight into deep space. For the new series, the separation of Earth and Moon would be retained but eliminating alien involvement. The accidental deto nation of nuclear waste would be responsible for this odyssey into the unknown, and for the 311 occupants of the renamed Moonbase Alpha.

Space: 1999 was introduced to the press in the summer of 1973. Grade gave the go-head with a budget of $6.5 million—$275,000 per episode—making it the most expensive television series at the time. A verbal agreement was given by CBS to purchase the series if the stars were American, in what would be the Andersons’ first network sale since Fireball XL5

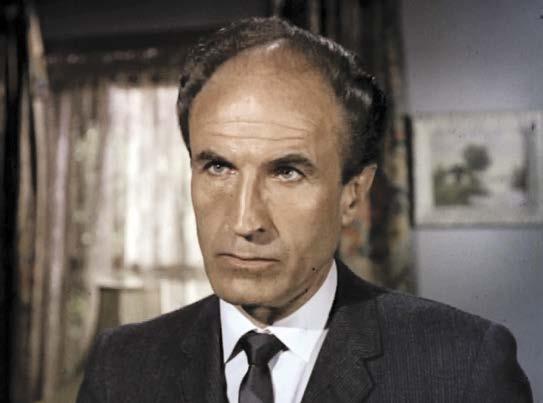

Another husband-and-wife team, Martin Landau and Barbara Bain, were cast as Commander John Koenig and Doctor Helena Russell. Stars of the early seasons of Mission: Impossible, they were faces known to the all-important American market. British-Cana dian actor Barry Morse, equally famous from his role as Lt. Gerard in The Fugitive and more recently in ITC’s The Adventurer, took the role of Professor Victor Bergman.

Filling out the cast were Australian Nick Tate as pilot Captain Alan Carter, Prentis Hancock as Koenig’s second-in-command Controller Paul Morrow, and Burmese-born actress Zienia Merton as data analyst Sandra Benes. Anton Phillips was Doctor Russell’s deputy medical officer Bob Mathias, with Clifton Jones as computer expert David Kano, replacing Lon Satton’s Ben Ouma after the opening episode.

It was planned that Space: 1999 would air for the 1974–1975 season, but fate dealt a blow. The threatened closure of MGM Elstree Studios meant the entire production was illicitly moved to those at Pinewood, resulting in union blacklisting. England was in the midst of economic turmoil, with strikes and power cuts which slowed down filming. CBS had purchased the Planet of the Apes television series for the 1974–1975 season instead, and cancelled its order for Space: 1999, now well into production. Neither of the other two networks wanted a series they had had no input to. Like the Moon in Space: 1999, the production was adrift in the mercurial television sales market.

International sales, helped by ITC’s marketing, were healthy enough, but America still counted for a major percentage of it. Grade and Mandell started a drive to sell Space: 1999 to the States’ many local stations for the 1975–1976 season. By the time it made

Familiar faces: (TOP LEFT) Martin Landau and (TOP RIGHT) Barbara Bain in publicity photos from TV’s Mission: Impossible. © Paramount Pictures Television. Courtesy of Heritage. (ABOVE) Screen capture of Barry Morse from TV’s The Fugitive. © Quinn Martin Productions/United Artists Television.

its debut in the U.S.A., over 150 such stations had bought the series, with 90% of them being network affiliates. A brand new highbudget show gave them the opportunity to pre-empt the usual network offerings.

But what of the series itself?

When in a situation of retro-fitting a format to suit invariables imposed on you—that the Moon had to be separated from Earth was the main immutable factor—there were going to be compromises to scientific accuracy. One major flaw was the Moon being perceived as a solid whole which could be blasted out of orbit. Critics commented that an explosion big enough to shift the Moon would more likely fragmentize it.

In the year 1999, at least in the establishing episode “Breakaway,” mankind had probably only got as far as Mars. Subsequent

BY SCOTT SHAw !

BY SCOTT SHAw !

WKRP in Cincinnati was promoted as “America’s Favorite Radio Station”… and in many ways, it was and still is. It’s certainly my favorite primetime sitcom, primarily because of one of its breakout characters.

Every once in a while, a new character pops up in a television series that makes you think, “I’ve known people exactly like this character, but it’s the first time I’ve seen her/him in entertainment.” And that’s how some of TV’s most unique and oddly appealing characters—such as Leave It to Beaver ’s insincere wiseass Eddie Haskell, The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis ’ devotedly unem ployed beatnik Maynard G. Krebs, The Andy Griffith Show ’s incompetent authoritarian Deputy Barney Fife, Taxi ’s spaced-out burnout Reverend Jim Ignatowski, Happy Days ’ tough-little-guy-with-a-lot-of-heart Arthur “Fonzie” Fonzarelli, The A-Team’s outrageous adventurer B. A. Baracus, and The Big Bang Theory ’s obsessive self-absorbed genius Sheldon Cooper—have all become timeless icons of the tube. Here’s another...

I’ve often thought of myself as “the Dr. Johnny Fever of cartoonists” (and not just because we’re both survivors of Sixties/Seventies counterculture). He was the seasoned (by time, place, and substances) morning deejay of multiple air-names on WKRP in Cincinnati, as well as the character who attracted me—and many viewers—to the series. Johnny Caravella/Johnny Duke/Johnny Style/Johnny Cool/ Johnny Sunshine/Heavy Early/Rip Tide/Dr. Johnny Fever worked for all types of radio stations around the country… for a lo-o-ong time. I worked for all types of comic-book publishers around the country and animation studios around Hollywood… for a lo-o-ong time. Also, deejays and cartoonists have similar professions: We sit in a room by ourselves, making something entertaining out of almost nothing. I also understand how a career that makes you resilient, crafty, and thick-skinned is hard to leave. Why? Because we cartoonists love our job—and we’re mostly suckers to let the money-people know how to control us. But I digress…

A number of similarly unique characters were core cast members of WKRP in Cincinnati, a sitcom that subtly changed sitcoms forever. Among those were two standouts, Howard Hesseman’s seasoned-and-stoned deejay Dr. Johnny Fever, and Loni Anderson’s stunning-and-smart receptionist Jennifer Marlowe.

But they weren’t the only ones—the show’s cast represented a number of characters with that “I’ve known people exactly like this character” vibe. Although the creatively progressive mindset of WKRP in Cincinnati wasn’t obvious, it had a huge influence on a

The cast of WKRP in Cincinnati —“America’s Favorite Radio Station.” (FRONT ROW) Loni Anderson as Jennifer Marlowe, Howard Hesseman as Dr. Johnny Fever, and Jan Smithers as Bailey Quarters. (CENTER ROW) Frank Bonner as Herb Tartek and Gary Sandy as Andy Travis. (BACK ROW) Richard Sanders as Les Nessman, Gordon Jump as Arthur Carlson, and Tim Reid as Venus Flytrap. WKRP in Cincinnati © MTM Enterprises.

number of classic TV series that followed. But let’s look at the land scape of network-aired, primetime, live-action situation comedies that preceded WKRP in Cincinnati

In the mid-to-late Sixties, standard TV sitcoms primarily featured hillbillies and rural communities (The Beverly Hillbillies, Green Acres), fantasy (The Addams Family, Bewitched, I Dream of Jeannie, Get Smart, etc.), and domestic family shows that had flogged the same old plots for years. Their ratings were based on the total number of people who were watching a specific show. In the late Sixties and early Seventies, the ratings system changed, evaluating shows by using demographics. Ratings were broken down into age, gender, and social groupings, so that advertisers could learn what sort of people were watching what sort of shows. Bob Wood, who became the president of CBS in 1970, advocated

that his network needed to reach the more upscale, purchase-oriented group to attract potential advertisers by airing more sophisticated material. [Editor’s note: See RetroFan #15 for columnist Scott Saavedra’s look back at this “Rural Sitcom Purge.”] The early Seventies brought on a wave of the new style of comedies, trig gered by MTM Enterprises’ The Mary Tyler Moore Show (1970) and Norman Lear’s All in the Family (1971), which both aired on CBS. Although Lear’s show got higher ratings and more attention due to its controver sial themes, MTM’s storylines were much more subtle with its progressive messaging and therefore, more palatable to a wider range of viewers. [You did catch our interview with Norman Lear in RetroFan #22, didn’t you? —ye buttinski ed.]

But after a few years, the era of “social issue comedies” seemed to wane, with lightweight sitcoms such as Gary Marshall’s Happy Days, Laverne & Shirley, and Mork & Mindy, all with the occasional moral for the young, but rarely with a social issue. Even Norman Lear’s output changed, with similar series like Diff’rent Strokes and The Facts of Life. MTM launched more dramas such as Lou Grant, The White Shadow, Hill Street Blues, and St. Elsewhere, series where “issue” storylines were a standard theme.

Then a TV series came along that was really different, thanks to an office copier salesman. Hugh Wilson (August 21, 1943–January 14, 2018) was born in Miami, Florida. He graduated from the University of Florida in 1964 with a degree in journalism. After working as an office copier salesman, Wilson was a staff writer for a cork company’s trade magazine. There, he met Jay Tarses and Tom Patchett, who both would one day be major forces in TV situation comedies. They all moonlighted as stand-up comics in Miami, but Tarses and Patchett decided to move to Los Angeles to enter Hollywood’s entertainment industry. Wilson relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to enter the world of advertising in 1966 as a copywriter for the Burton-Campbell Agency. By 1970, he was the company’s creative director and in 1973, he became its president. But Wilson retained his interest in creating entertainment, keeping in touch with Tarses and Patchett. In 1975, Jay and Tom set up an interview between their old friend Hugh and Grant Tinker, the then-current head of MTM Enterprises. It led to Hugh Wilson writing for The Bob Newhart Show, and all three of them, along with Gary David Goldberg, writing for The Tony Randall Show

In 1977, Tinker asked Wilson and Goldberg to each pitch show concepts for the upcoming fall season. Wilson delved into his past and pitched a workplace sitcom set at a radio station based on stories from his friend at Atlanta’s WQXI. (Goldberg’s was rejected, but he went on to create such shows as Family Ties and Spin City.) Clark Brown was the advertising salesman for WQXI who spent a lot of time at Harrison’s, a watering hole for the locals in advertising and media. There, Hugh Wilson met a number of people who worked for WQXI and other Atlanta stations. Their stories and

(INSET) What’s in a name? Dr. Johnny Fever’s coffee mug. Courtesy of Scott Shaw! (LEFT) WKRP creator Hugh Wilson. Legacy.com. (RIGHT) WKRP in Cincinnati ’s breakout characters, Dr. Johnny Fever (Hesseman) and Jennifer Marlowe (Anderson), in a behindthe-scenes photo from the personal collection of Loni Anderson. © MTM Enterprises. Courtesy of Heritage.

attitude about their profession provided lots of legitimate valuable input for what would become Wilson’s first and best-known television series.

Interested in the show’s potential, a week later, Tinker took Wilson to meet with Andrew Siegel, CBS’ Vice President for Comedy Development. Impressed by the concept, Siegel gave the okay for Wilson to write a pilot script for the still-nameless project.

Before developing the pilot’s cast of characters, Wilson returned to Atlanta to hang out at WQXI for a day with his pal Clark Brown. This was very fruitful for Hugh, whose concept began to jell. One aspect that paid off was that Clark dressed in loud polyester clothes that were typical of many salesmen in those days. That provided a unique visual label that inspired the fashion sense of WKRP ’s Exec utive Sales Manager Herbert R. Tarlek. One of WQXI’s deejays was a sleepy guy who’d seen it all and done it all, sometimes even while sober, named “Skinny” Bobby Parker. Hugh has claimed that he was the inspiration for Dr. Johnny Fever, but Howard Hesseman never agreed with that. According to actor Gordon Jump, WKRP ’s Arthur Carlson, Jr. was also based on an employee of WQXI, a radio executive who concocted the all-too-real “turkey drop” while working at a Texas station. He not only inspired the creation of Mr. Carlson, his disastrous stunt also became the basis for WKRP in Cincinnati ’s bestknown episode, considered one of the funniest tales in the history of televised comedy. Wilson also drew from personal sources while filling out the cast of his evolving concept. Andy Travis, WKRP ’s new station manager, was based on Hugh’s cousin, who was a Colorado

f Tim Reid was born on December 19, 1944 in Norfolk, Virginia, and was raised in Chesapeake, Baltimore, and Nashville. While in high school, he was on the track team, the student council, and the yearbook, which he edited. Tim attended Norfolk State College and received a Bachelor of Business Administration de gree in 1968. It led to him getting hired by the Dupont Corporation, where he worked for three years. That same year, while at a Junior Chamber of Commerce meeting, he befriended Tom Dre esen. While working together on their humorous an ti-drug program created for local grade schools, they decided to form the first bira cial comedy team, “Tim and Tom.” Within six months, Tim and Tom started getting gigs on TV shows hosted by Merv Griffin, David Frost, and others. Eventually, while Tom remained in standup comedy, Tim struck out for Hollywood, soon appearing on Rhoda, Lou Grant, Maude, Fernwood 2-Night, What’s Happening!!, and a recurring role on The Richard Pryor Show. When he audi tioned for the role of WKRP ’s hip and colorful Venus Flytrap, he wasn’t the only one who showed up, but he may have been the only actor who wasn’t eager to portray “another stereotypical black character.” In fact, he told Hugh Wilson exactly that, who appreciated and valued Tim’s honest input. “I wanted to have a black DJ, and he hardly appears in the pilot, he just comes in at the end… I use him really as a stage device to scare the hell out of [Momma] Carlson,” said Hugh. “Then Timmy and I sat down and really talked the thing over, and he decided that he would rather play away from the street black. I immediately agreed with him on that. So his character—he shows up in a wild outfit—began to change quite rapidly.”

f Jan Smithers, born on July 3, 1949, and grew up in Woodland Hills in Los Angeles’ San Fernando Valley, not far from the movie and television studios a few miles east. While attending William Howard Taft High School, she was photographed for the cover of the March 2, 1966 issue of Newsweek magazine; its theme was “The Teenagers: A Newsweek Survey of What They’re Really Like.” As Jan remembered, “One had long hair and cameras around his neck. They walked right up to me and said, ‘We’re doing an article on teens across the country, and we’re looking for a girl from California. We’re wondering if you’d be interested in doing the article.” One of the photographers, Julian Wasser, recalled seeing young Ms. Smithers for the first time. “How can I forget? I was walking on the beach looking for someone and there was this incredibly beautiful girl. She was nobody then, just a high school kid. She thought [the article] was a big fake. She was a typical California raving beauty who didn’t know it.” Two weeks before the Newsweek issue hit the racks,

(LEFT) A young Jan Smithers represented the American teenager on the March 21, 1966 cover of Newsweek. © Newsweek.

(RIGHT) A Smithers publicity photo during her WKRP stardom.

her parents got divorced. Racing home to show the magazine to her mom, Jan had a traffic accident that sent her to the hospital with a broken jaw. Then, not long after its publication, both her brother and her mother died unexpectedly, understandably leaving Jan feeling adrift and alone. To counter those feelings, she decided to accept some of the TV commercials she’d been offered as a result of the recent Newsweek cover. She also began studying at the California Institute of the Arts. At 19, Jan chose to become a professional actor. She achieved small roles in the films Where the Lilies Bloom, When the North Wind Blows, and Our Winning Season, as well as in the Love Story and Starsky and Hutch TV series. When Jan auditioned for the part of WKRP ’s shy and smart advertisement scheduler Bailey Quarters, she matched many of the aspects of Hugh Wilson’s wife, the original inspira tion of the character, who he felt was “very shy, but very smart— the sort of person people tend to dismiss as a jerk until they find out she’s got so much to offer.” Touched by her personality, he immediately gave Jan the role. “Other actresses read better for the part, but they were playing shy. Jan was shy.”

f Richard Sanders was born on August 23, 1940 in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and grew up in Leavenworth, Kansas, where he dreamed about becoming an actor. Richard was always the class

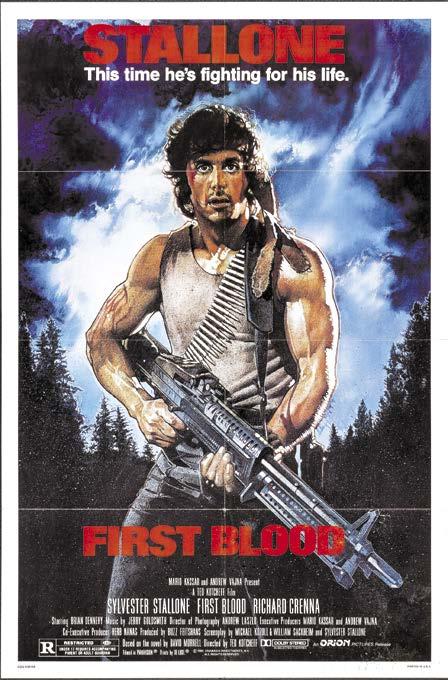

“His name was Rambo, and he was just some nothing kid for all anybody knew, standing by the pump of a gas station at the outskirts of Madison, Kentucky.”

So begins First Blood, David Morrell’s 1972 debut novel. Morrell’s story of troubled Vietnam veteran John Rambo and his bloody, violent battle with hippiehating police chief (and Korean War vet) Wilfred Teasle would go on to become one of the most influential novels of the latter 20th Century, literally reinventing the action story and introducing a character destined to become as recognizable as Tarzan, Superman, or Sherlock Holmes.

It didn’t take long for popular culture to make Rambo an iconic figure. Since his introduction, Rambo has appeared in an eclectic array of forms, media, and formats, including motion pictures, novelizations, action figures, toys, comic books, an animated television series, trading cards, and much, much more. Five decades out, Rambo remains as popular as ever.

Morrell was a graduate student at Penn State from 1966 to 1970 as the Vietnam War escalated. The events of that period struck the Canadian transplant, causing him to fear that the United States was headed for a civil war.

“What I thought I would do was bring the Vietnam War to the United States and show the polar opposites that were happening in the country with all the riots and the police reaction, someone representing the establishment and someone representing the disaffected,” Morrell explained to this writer in a 2015 interview for Videoscope Magazine. “In this case, it would be someone who had been in the war and came back hating what it had done to him. So that was basically the concept of the novel. It took me three years to write the book because I was still learning how to write a novel, and because it took me a little while to figure out that the chapters would bounce back and

(LEFT) Author David Morrell introduced the world to Vietnam vet/ ultimate survivalist John Rambo in this 1972 novel, First Blood. © David Morrell.

Courtesy of Heritage. (BELOW) David Morrell. © Jennifer Esperanza.

forth between Rambo and the police chief. Their alternating viewpoints represent the way the country was alternating back and forth, the contrast of the two points of view.”

Morrell attended Penn State to study with Hemingway scholar Philip Young, and wrote his Master’s thesis on Hemingway’s style. “What I noticed was the way Hemingway wrote about action as if no one had ever written about it before,” Morrell continued. “My goal in writing First Blood was two-fold. One was to dramatize the polar opposites that were dividing the country in the late Sixties, and also to write an action book that didn’t feel like a genre book. To try to write it so it felt like a real novel and not something out of the pulp pages. My agent and I felt that because I was writing action in a different way, we might have some resistance from publishers who might think it was too realistic. But the novel was sold to a publisher within six weeks of being submitted to various places.”

The story of how First Blood became a motion picture is a long tale of false starts, sudden stops,

fetched $60,000 at a December 18, 2015 Heritage auction. First Blood © Anabasis Investments, N.V. Movie poster and props courtesy of Heritage.

and a lot of frustration. According to Morrell, Hollywood expressed interest before the novel was even released, with director Stanley Kramer snagging the first option. Or so it was announced. “We waited and waited, but the contract never showed up, and it turned out he was lying to us,” Morrell revealed. “There were even print ads that talked about Stanley Kramer making the movie, or that it had been optioned to him at least, and the publisher was very upset.”

The book went through a lot of hands over the ensuing years, including Lawrence Turman, one of the producers for The Graduate Turman and director Richard Brooks went to Columbia Pictures, which purchased the book outright. Brooks worked on the script for a year, Morrell reported, only to have Columbia sell the book to Warner Bros.

“There was talk of Paul Newman playing the police chief with Martin Ritt directing, because they had worked together many times and Ritt had just finished a Southern picture called Sounder,” Morrell explained. “That did not work out. Then Steve McQueen was signed to play Rambo with Sidney Pollack directing. I talked with Sidney years later and he told me how they were all very excited until someone realized that the picture was going to be made in 1975. Steve McQueen was in his 40s and there were no 40-year-old Vietnam veterans in 1975. It was a young person’s war. So they realized the picture couldn’t be made believably and they stopped production.”

All told, 26 scripts were produced for First Blood. The film finally became a reality with the involvement of Carolco, a production company owned by film distributors Mario Kassar and Andrew Vajna. “They’d struck up a relationship with director Ted Kotcheff,” Morrell told Videoscope. “They said, we want you to make a movie for us, you can do whatever you want. And he said, I worked for a while on a movie called First Blood when I was at Warner Bros. and I’d like to make that movie.”

William Sackheim and Michael Kozoll pounded out yet another script, and the search was on for an actor with international appeal. Someone recommended Sylvester Stallone, who had a hit with Rocky, but whose subsequent films weren’t as successful. “So there was a certain risk,” Morrell said. Stallone ran the script through his own typewriter, added some elements such as Rambo’s survival knife, and the film moved forward with a $17 million budget, funded by one of Kassar’s wealthy relatives.

The 97-minute film is a fairly faithful adaptation of Morrell’s novel, with one very important exception—Rambo survives at the end. In the novel, both Rambo and Teasle die as a result of their mutual violence, and in Sackheim and Kozoll’s initial shooting script, Rambo takes his own life with Col. Trautman’s gun. Test audiences hated that ending, so it was quickly reshot with Rambo going to prison instead. “They had no intention of making a sequel,” according to Morrell. “And then the movie scored so well with Rambo alive. So for [the producers], it was a blessing.”

Rambo: First Blood Part II, a Vietnam rescue mission, and Rambo , set in Soviet-occupied Afghanistan, followed three years apart, with Morrell agreeing to write the novelizations. James Cameron had written a script for Rambo: First Blood Part II (much of which was rewritten by Stallone), and Morrell incorporated numerous elements from Cameron’s contribution. “The shooting script was just 80 pages, and it was literally, ‘Rambo shoots this guy. Rambo shoots that guy,’” Morrell revealed. “I asked what else they had, and they said, well, we have this James