Years before he died, Robert “Bob” Keeshan said he would like to be remembered this way: “Oh, just that I made children feel a little better about themselves, in general. I certainly didn’t do it with every child, but that was my intent.”

There’s little doubt Keeshan made the world a better place for children. The veteran entertainer, who died in 2004 at age 76, provided a lifetime of memories during the 29 years he spent as television’s Captain Kangaroo.

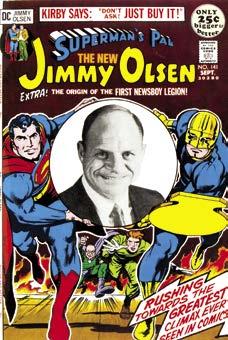

Upon Keeshan’s passing, the New York Times noted the “roundfaced, pleasant, mustachioed man possessed of an unshakable calm” who served as “one of the most enduring characters television ever produced.”

Captain Kangaroo debuted on CBS in October 1955. Make-up and a gray wig transformed a 28-year-old Keeshan into the grandfatherly Captain. Over the next several decades, Keeshan would age into the role. For nearly 10,000 episodes, the program educated and

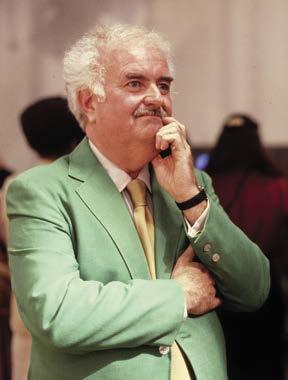

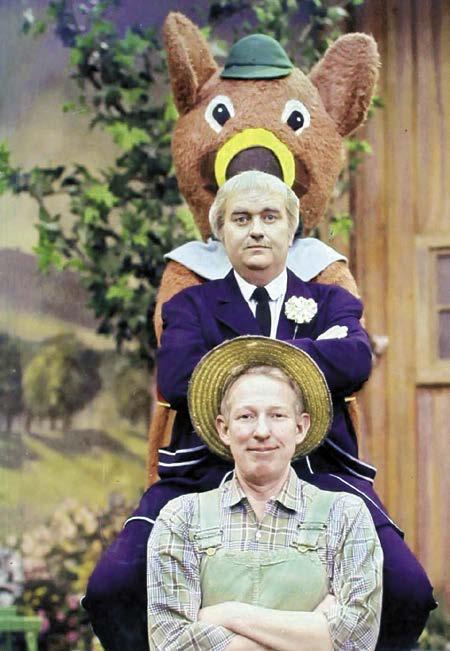

(ABOVE) Children’s television host Bob Keeshan originally donned make-up to become the grandfatherly Captain Kangaroo, but over the decades matured into the role. Captain Kangaroo ’s colorful cast, including Mr. Green Jeans, Dancing Bear, Mr. Moose, and Grandfather Clock, became as beloved as the Captain himself. © Creative Artists Agency. Photos courtesy of the Captain Kangaroo Facebook page.

series of interviews I conducted with him in the late Nineties. “You’ve got to entertain.”

For his success in doing just that, Keeshan collected a shelf full of accolades, including Emmy Awards, Peabody Awards, and honorary degrees, as well as the adoration of millions of children. He worked without a studio audience and instead spoke directly to the child watching at home.

Keeshan grew up in Queens, New York, in an era when broadcast entertainment came from a bulky radio. During his senior year in high school, he made the trip to Manhattan each afternoon where he worked as a page at NBC Studios, pulling down $13.50 a week. The job wasn’t complicated; he showed members of the audience for the network’s radio shows to their seats. Upon graduating, he followed his brothers into the military and enlisted in the Marines to fight World War II. Despite persistent rumors about Keeshan’s combat service, he never left the United States.

“They dropped the bomb when I was in boot camp, so that ended any threat to me,” he said. “I then spent my life running around closing schools, literally. They would send me to Japanese language school, and I’d be there for six weeks, and it occurred to somebody they no longer needed

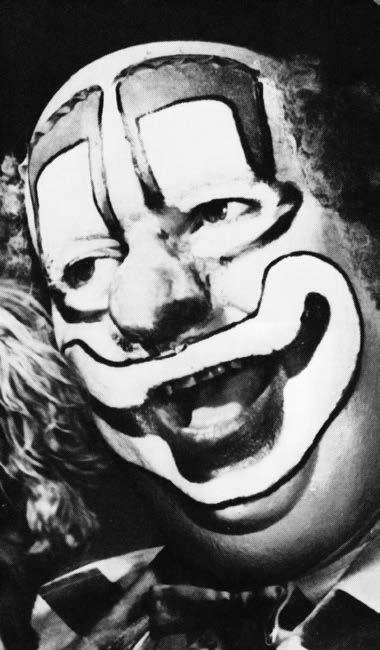

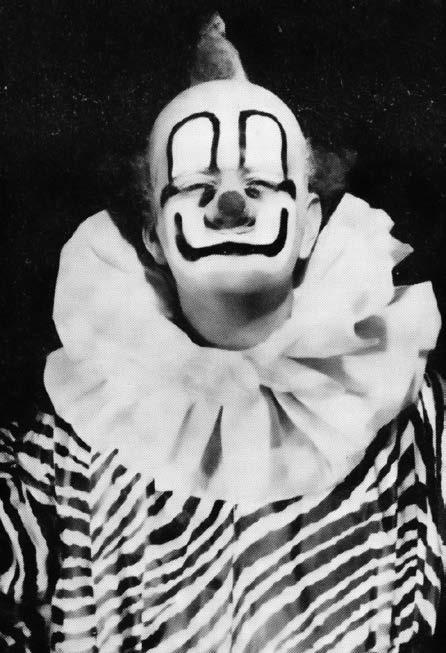

(LEFT) Keeshan as Howdy Doody ’s Clarabell the Clown in a publicity photo.

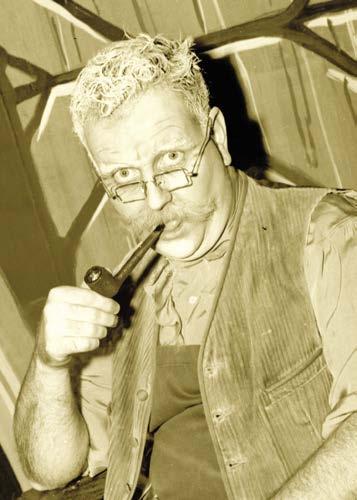

(RIGHT) From the Time for Fun program, Keeshan as Corny the Clown. (BELOW) Keeshan, the young broadcaster. All courtesy of L. Wayne Hicks.

interpreters because that was all over with. They sent me to signal school, and they decided they didn’t need that anymore. I spent a year or so after boot camp closing down schools that had been very active.”

Discharged, Keeshan returned to New York and his old job at NBC. He studied at Fordham University at night with the goal of becoming a lawyer. Gradually, though, the pull of broadcasting became too strong to ignore. Keeshan was asked to research and supply historical factoids to a writer working for a radio personality known as Buffalo Bob Smith. Keeshan would provide these random facts for a twice-weekly feature, such as how much a loaf of bread cost in 1918 or what a men’s suit would go for then. From there, he helped Buffalo Bob hand out prizes on a Saturday morning radio quiz show for children. When NBC offered Buffalo Bob a TV show in 1947, he brought Keeshan along to help with what became Howdy Doody. [Editor’s note: Say, kids, it’ll be Howdy Doody time in our pages next year in RetroFan #31!]

At first, Keeshan merely wore a sports coat. Buffalo Bob dressed as a ringmaster to go along with the circus setting. To fit in, Keeshan became a clown named Clarabell. He didn’t have any lines, but was armed with a horn to honk and a seltzer bottle to squirt. Keeshan spent five years in the make-up and costume.

Keeshan said he learned “almost everything I know” about television from Buffalo Bob. “Now, don’t confuse the live television and the technical aspects of it—all of which

As it actually turned out, it was probably less than a tenth of the program material. But it gave us physical relief in doing the show.”

Technological advancements changed the show tremendously. The advent of videotape eliminated the need to perform the same program twice each morning. Captain Kangaroo was able to be produced using taped segments, and Keeshan could get back to clowning around. He suited up as the Town Clown.

“It literally was almost an hour of make-up and costume and of course that couldn’t be done on live television,” he said. “But once we started to tape the program, then we were able to take an afternoon of production and get me into make-up and costume and do maybe five or six two-, three-, four-minute sequences, which were then edited into the program.”

No longer tethered to the demands of live television, Captain Kangaroo saw an increase in its production values. “Ultimately we were doing the show more like they do motion pictures and television because we would do three minutes here and a minute and a half there, and we could always do a 20-second segue. All of this came together in the editing suite. We could mix and match shows. For example, we could do a story—a fairy tale of some kind, or our interpretation of a fairy tale—which would require large sets maybe and guests and so on, expenditures which we could never have afforded it when it was done just for the one live show. But now, because we were able to tape it and edit it and perfect it, it went into the library. That might then be amortized over 12 runs over three years or something of that sort.”

(TOP LEFT) The big stuffed pockets of Captain Kangaroo. (CENTER) Bob Keeshan on set circa 1970.

(RIGHT) The Captain and Mr. Green Jeans with Bunny Rabbit and Mr. Moose (noted ping-pong ball dropper).

(LEFT) Captain Kangaroo and an unidentified rabbit.

© Creative Artists Agency.

Captain Kangaroo waiting to go live in the early days of the show. The word “yawn” is spelled out in small blocks on the shelf.

(TOP TO BOTTOM) The Dancing Bear, Captain Kangaroo, and Mr. Green Jeans.

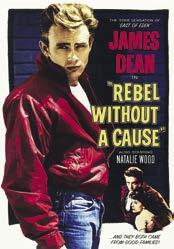

One recent evening, the trailer for Rebel Without a Cause (1955) came on. There was James Dean, his face scrunched into an expression of emotional anguish, bellowing at his parents, “You’re tearing me apart!” Dean looked like a human powder keg ready to blow.

I thought: That’s just like Michael Landon in I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957).

Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause was a big-studio Hollywood motion picture in CinemaScope and WarnerColor. Gene Fowler, Jr.’s I Was a Teenage Werewolf (IWATW ) was a non-widescreen, black-and-white cheapie that nonetheless raked in a surprising $2 million at the box office.

Rebel preceded IWATW by two years. The earlier film spawned many imitators. Landon’s earnest, intense performance in IWATW is as much about teen angst as, you know, fangs ’n’ fur. The two films have significant plot parallels. Both protagonists are high school outcasts with anger issues. Both are counseled by understanding cops (Edward Platt in Rebel, Barney Phillips in IWATW ). Both have ineffectual father figures (Jim Backus in Rebel, Malcolm Atterby in IWATW ).

And, not for nuthin’, both protagonists rocked iconic outerwear. Dean wore that cool, red nylon windbreaker which became “the” look of the middle Fifties. And Landon was the first werewolf in horror movie history to wear a letter jacket.

When horror met hepcats

and hot-rodders

Dawn Richard isn’t in the movie much, but she’s in a lot of the photos and posters. What’s that about?

© American International PicturesOkay, I’ve tortured the comparison enough. Let’s talk about the fun, frightful—albeit, fleeting—teenage monster genre. Aw-woooo!

There’s a consensus that the term “teenager” wasn’t really in popular use prior to World War II. When the term entered the vernacular, it was initially used as an advertising demographic. (Yay, capitalism!)

A film series like MGM’s Andy Hardy movies of the Thirties and Forties, which starred Mickey Rooney as a pint-sized Casanova, are teen movies, kind of, with an important caveat: they are pre-rock ’n’ roll teen movies. Many cliches about teens in Fifties movies were inherited from Andy: the malt shop, the jalopies, the Jughead hats, the girl-craziness. (Well, girl-craziness goes back to Adam and Eve.)

The only thing missing was rock ’n’ roll… and rebellion. Andy would never dream of sassing his sage papa, Judge Hardy (Lewis Stone), during one of the old man’s many lectures on proper behavior in that stuffy, book-lined study of his.

The Dead End Kids, later the East Side Kids, later the Bowery Boys, came close to teen film status. And the ensemble—often led by Leo Gorcey (bossy) and Huntz Hall (goofy)—certainly oozed rebellion. In the course of their many permutations between 1937 and 1958, these films began as dramatic thrillers (Angels With Dirty Faces, Crime School ) and ended as cookie-cutter comedies (Dig That Uranium, Crashing Las Vegas).

But some of the films qualify as early harbingers of the teenage monster genre, especially if you (like me) stretch the definition to include movies about teen protagonists who encounter monsters, whether or not they become monsters themselves. Still with me?

In the running are the East Side Kids films Spooks Run Wild (1941) and Ghosts on the Loose (1943), both starring Bela Lugosi, no less, and the Bowery Boys films Spook Busters (1946), Master Minds (1949, with three-time Frankenstein monster Glenn Strange as a werewolf), Ghost Chasers (1951), and The Bowery Boys Meet the Monsters (1954). Of course, by the Fifties, the “boys” were all pushing 40, still milking the juvenile delinquent thing.

Three years later, the surprise hit I Was a Teenage Werewolf kicked off the teenage monster genre proper, as it altered the fortunes of the indie machine American International Pictures (AIP). Produced and co-written by Herman Cohen, IWATW provided future Bonanza star Landon his first starring role as Tony Rivers, a Rockdale High student who is obstinate, violent, and somehow likable. Maybe it’s his fantastic hair?

Tony plays dirty during a fistfight, swinging a shovel and throwing dirt in his opponent’s eyes. After tough-but-fair Detective Donovan (Phillips) breaks up the fight, he recommends that Tony see Dr. Alfred Bradford (Whit Bissell, an actor born to play roles like this). “He’s modern. He uses hypnosis,” Donovan says of the doc.

“No headshrinker for me, thank you,” Tony shoots back. “You keep the man in the white coat for the goofs.”

Which narration opened the third incarnation of ABC’s gathering of DC comic-book heroes, titled Challenge of the SuperFriends? Was it William Woodson announcing, “Gathered together from the cosmic reaches of the universe, here in this great Hall of Justice are the most powerful forces of good ever assembled: Superman… Batman and Robin… Wonder Woman… Aquaman… and the Wonder Twins, Zan and Jayna, with their space monkey, Gleek. Dedicated to truth, justice, and peace for all mankind!”

Or was it Stanley Jones intoning, “Banded together from remote galaxies are 13 of the most sinister villains of all-time. The Legion of Doom! Dedicated to a single objective… the conquest of the

universe! Only one group dares to challenge this intergalactic threat… the SuperFriends! The Justice League of America versus the Legion of Doom! This is the Challenge of the SuperFriends!”

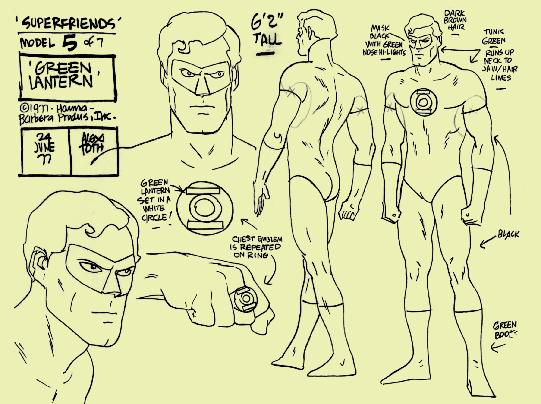

(CLOCKWISE) Super Friends (or SuperFriends, in this incarnation) Superman, Hawkman, Wonder Woman, Robin, Batman, the Flash, Green Lantern, and the King of the Seas, Aquaman, who has somehow gained the power of flight (maybe he just leapt like a flying fish out of the Hall of Justice’s fountain in the background…). TM & © DC Comics.

Wonder Twins were in these stories, but no other outside guestheroes were. The stories were a bit more “cosmic” than their predecessors, with episodes that included the Wonder Twins’ planet of Exxor, a subterranean world beneath the Earth’s crust, UFOs, Dracula, space pirates, and a space circus, and visits to Aquaman’s Atlantis and Mount Olympus, home of Wonder Woman’s Greek goddesses and gods. In the final episode, Superman villain Mr. Mxyzptlk appeared, while in another one, three Kryptonian villains escaped from the Phantom Zone. This latter was likely timed to coincide with Superman: The Movie, which was about to debut in theaters in December 1978, and which featured the Phantom Zone.

It wasn’t the only bit of tie-ins that Super Friends was making. Mego action dolls of most of the TV characters were on the shelves, desired by children everywhere, and some of the Mego boxes even used Super Friends art. Additionally, there were Super Friends

themed school supplies and sheets and clothing, although most of them did not use the specific name. Ironically, while one set did feature the Super Friends name and logo and characters (including Wendy, Marvin, and Wonder Dog), it also

featured a pack of super-villains—Mirror Master, Poison Ivy, Penguin, Captain Boomerang, Trickster, Reverse Flash, Pied Piper, Heat Wave, Catwoman, Joker, and Captain Cold—with a similar logo. One catch, though: none of those villains had ever appeared on the show!

Featuring several Batman villains there—and in the Mego line—was not so odd as the fact that Batman and his villains had been appearing on two different networks since early 1977. Due to a deal Filmation had with DC Comics following their 1968 The Batman/ Superman Hour, Filmation had been able to continue developing projects for Gotham’s Caped Crusader, even while he and Robin were appearing on ABC’s Super Friends shows! CBS debuted a halfhour animated series, The New Adventures of Batman, on February 12th, 1977, from Filmation, and the series utilized live-action actors Adam West and Burt Ward to reprise their roles vocally (plans to have them introduce the shows live, in character, were scrapped). Why didn’t Filmation use Olan Soule and Casey Kasem for voices, as they had in 1968? Because they were on ABC, voicing the same characters for Hanna-Barbera’s Super Friends!

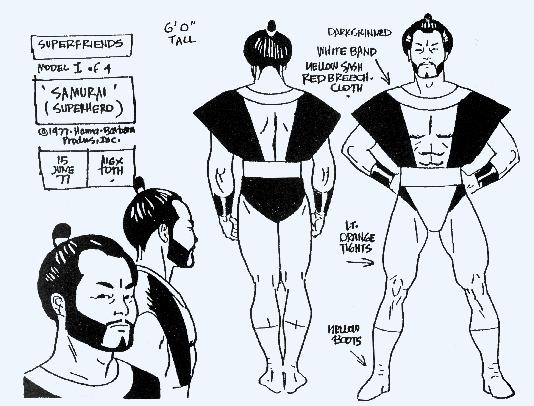

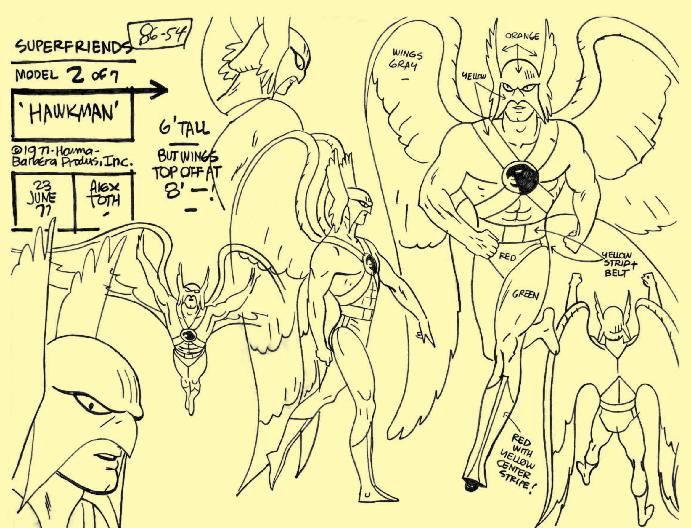

(TOP LEFT) Model sheet for Green Lantern. (TOP RIGHT) The Super Friend known as Samurai. (LEFT) Classic hero Hawkman in awesome hero poses. (BELOW) Superman, Wonder Woman, and (somehow) Aquaman fly into action. TM & © DC Comics.

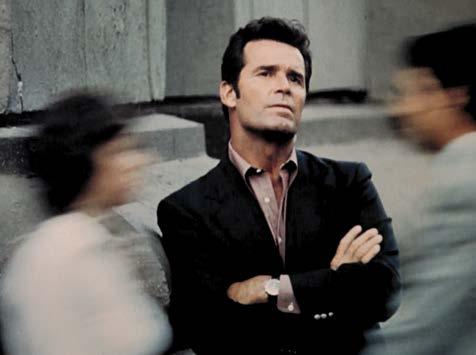

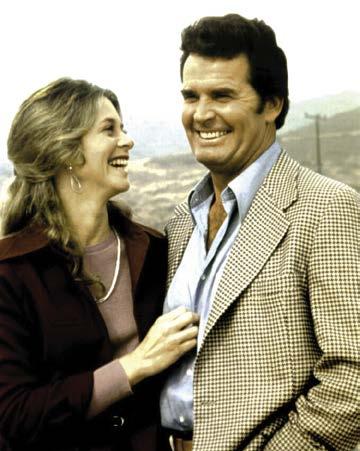

In college, I had a girlfriend who one night turned on The Rockford Files starring James Garner. She was a big fan. And after watching “The No-Cut Contract,” in which private detective Jim Rockford becomes embroiled in the unscrupulous machinations of semi-pro quarterback King Sturtevant (played by Rob Reiner), I became a bigger fan.

This was a third season episode, so I came in late. And while the girlfriend and I eventually parted company, I’ve been watching The Rockford Files ever since. True, the series went off the air in 1980, but it’s endlessly re-watchable. Over the decades, I managed to catch them all, most several times. It was that kind of a show.

The Rockford Files came along when TV private eyes were dull, square-jawed bunch. Mannix was the top of the heap.

After watching so many Rockford episodes, I started digging into the origins of the series.

Before Rockford came along, I liked a one-season wonder called The Outsider. Forgotten now, it starred Darren McGavin before starring as Carl Kolchak in The Night Stalker series. [Editor’s note: See RetroFan #11 for our Night Stalker coverage.]

McGavin played David Ross, an ex-con turned private eye. Perpetually down on his luck, he stumbled through a seedy Los Angeles. The show wasn’t quite satire, but McGavin portrayed a rumpled and sometimes pathetic loser of a character. He was the anti-Mannix.

Sound familiar? Like a precursor to Jim Rockford? That’s because he was. Producer-writer Roy Huggins created Ross and later co-created Rockford. But not all the credit can go to him.

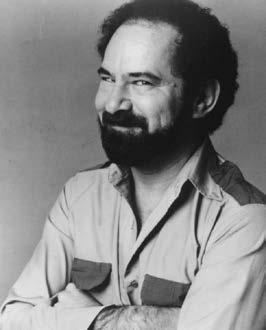

Enter Stephen J. Cannell. He was a young TV writer, a fan of Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. After catching a few episodes of The Outsider, he decided to script an episode.

Cannell was impressed that the lead was not your typical hero. “That was a terrific hardboiled private eye kind of anti-hero guy,” he later said. “I wrote a spec script for The Outsider, and I could not get it to Roy Huggins. I tried every connection I knew. I thought it was a pretty good script. And it ended up coming back to me, and I threw it in my drawer.”

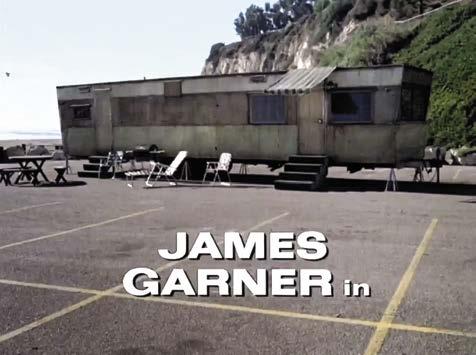

(LEFT) Screen captures from The Rockford Files ’ introduction, including glimpses of Rockford’s dilapidated trailer and Noah Beery, Jr. as his dad, Rocky. © NBCUniversal.

BY WILL MURRAY

BY WILL MURRAY

until executives told him point-blank not to use Angel Martin again. Then Margolin got an Emmy nomination. End of argument.

Margolin based Angel on a golf hustler he knew. “In my mind, Angel is a descendent of him. He’s a hustler, a street character. Angel’s a snitch. He’s like the characters Elisha Cook played. He’s out of O’Henry and Damon Runyon.”

No one sandbagged poor Rockford as much or more often than Angel. Yet he kept getting ensnared in Angel’s schemes.

“Rockford is his scapegoat,” revealed Margolin. “He’s the most available guy to point the finger at. I think he trusts Rockford the most, and Rockford trusts Angel to do certain things. He knows he will sell him out. He’s consistent.”

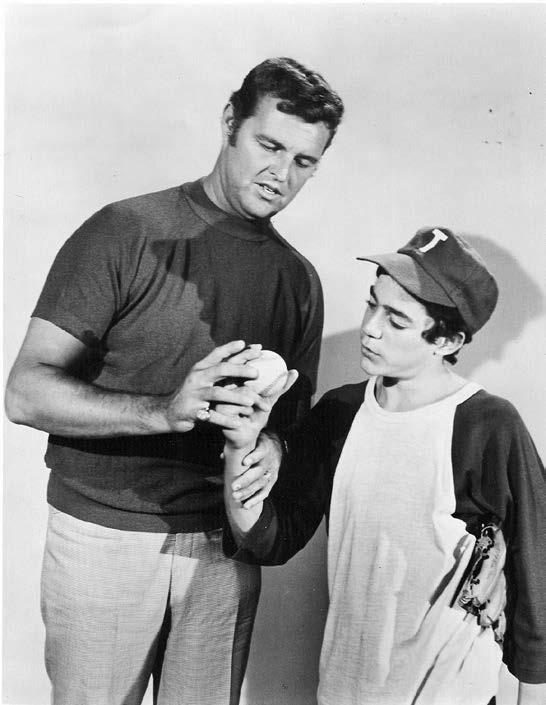

Robert Donat played Joseph “Rocky” Rockford in the pilot, but Noah Beery, Jr. took over the role for the series. He had been the original choice, but was unavailable for the pilot.

Cannell modeled the crusty truck-driving character after his own father. “He could not understand why I didn’t stay in the furniture business. Rocky Rockford could not understand why Jim Rockford would risk his life as a private detective when he could get a solid job as a trucker.”

Beery was nonchalant about his role. “I don’t know that I really fit into any category on the show,” he once said. “Sometimes Jim and I switch places and he takes care of his stupid father. I guess it’s more of an association. They could easily do without me, but they keep me around.”

Jim Garner saw it differently. “I think Rockford’s relationship with his father is the emotional backbone of the show. Sometimes they get on each other’s nerves, but the affection is there through it all.”

BY MICHAEL EURY

BY MICHAEL EURY

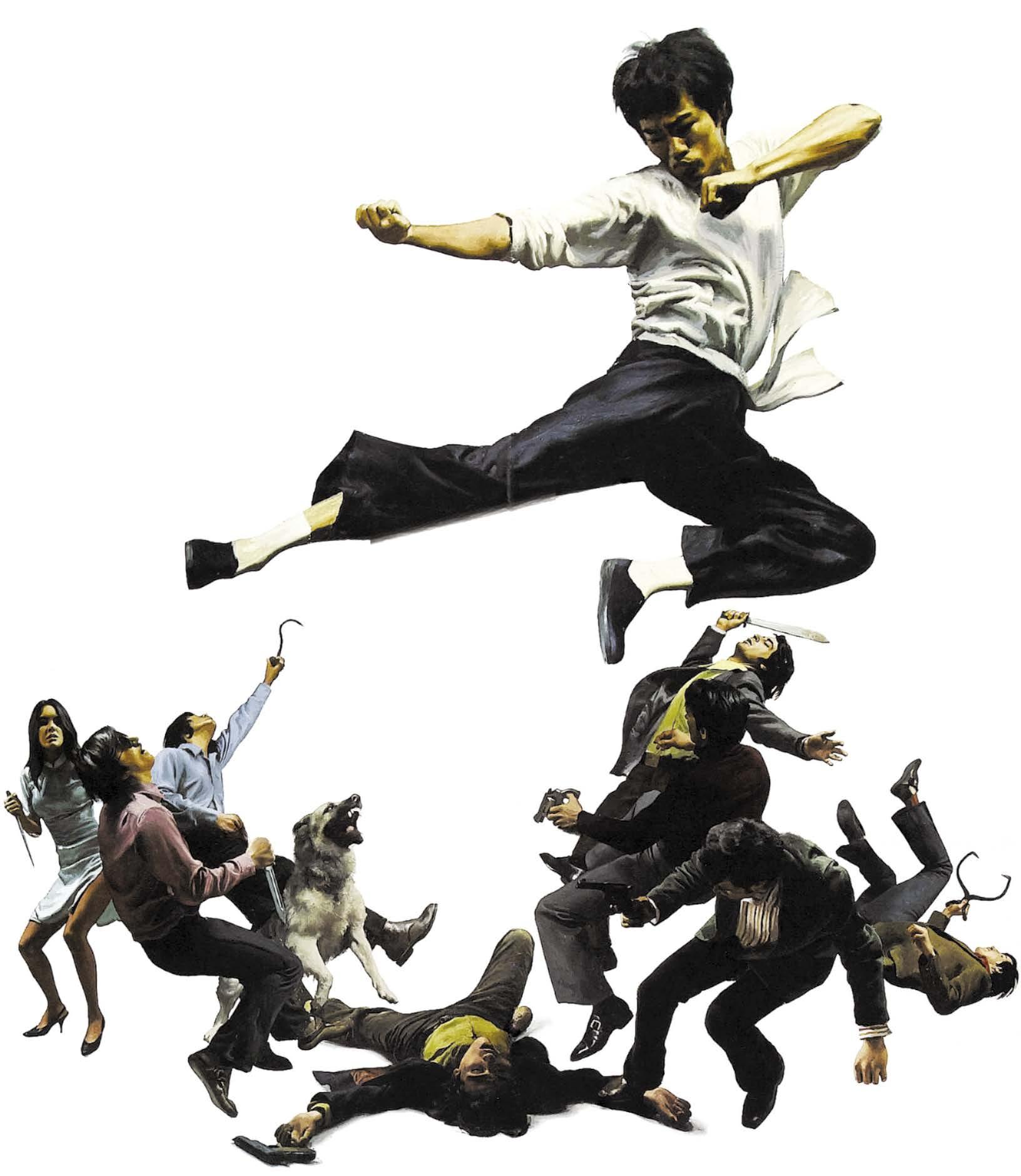

The kung-fu craze of the Seventies nearly cost me a toe. I was in my teens in 1973 when I thought it was a good idea to “test” my martial-arts prowess, “honed” from my fascination with the movie Billy Jack and the rattler-fast moves of its guardian of a progressive school for indigenous and with-it teens. My “opponent” was unwisely picked: my uncle Hershel, a giant of a man who was a decorated combat veteran of the Korean and Vietnam Wars. As I poised to strike, I imitated my new screen hero by quoting a line the woefully outnumbered Billy Jack quipped to an antagonist: “I’m

(ABOVE) Detail from the poster of the 1973 film Fists of Fury. © National General Pictures Corp.

gonna take this right foot, and I’m gonna whop you on that side of your face… and you wanna know something? There’s not a damn thing you’re gonna be able to do about it.” Uncle Hershel dismissively blocked my kick with his mammoth arm. I assume his arm was as flesh and blood as mine, but it sure felt like I was kicking an anvil with my bare foot. My throbbing little piggy turned a horrid shade of purple that you’d never find in a box of Crayolas.

Martial arts were certainly nothing new by the time kids like me flipped over kung fu. These ancient fighting and self-defense

sports comprise a range of East Asian cultures’ unarmed and armed competitions. Many, if not most, of us do not understand the differences between such disciplines as kung fu, aikido, budo, taekwondo, karate, kendo, and savate, tossing them all into a lingual blender and labeling the whole lot “kung fu.” RetroFan respectfully bows to those who are serious students and practitioners of the martial arts, but in the spirit of the lighthearted tone of our “RetroFad” column we are anchoring this martial-arts discussion upon the cultural contagion that occurred in the early Seventies. But first, a little history…

According to journalist and blogger Terence Towles Canote, wushu (martial arts) date back to the third or second century BC, and in later centuries were chronicled in Chinese literature in a subgenre called wuxia. Other East Asian nations, including Japan and Korea, had their own forms of physical warfare and selfdefense that permeated their lore.

In the early 20th Century, these disciplines began their stretch onto a larger global stage. The nascent Chinese film industry released 1919’s Robbery on a Train, which Canote suspects is the earliest kung-fu movie. Karate, judo, and jujutsu (jiu-jitsu) made their way into the U.S.A., and many American soldiers in World War II were exposed to martial arts during their Far Eastern journeys. Once a karate dojo (studio) opened in the States in 1945, more followed. Canote writes, “By the Fifties and Sixties, karate dojos were scattered across the country.” As part of this burgeoning trend, athletes and wannabes alike attempted to smash through wooden planks and bricks using barehanded karate chops. Judo even became an Olympic sport beginning in 1964.

According to Canote, one of the earliest examples of a martial art appearing in an American television series was “Karate,” a Gene Roddenberry–penned episode of The Detectives originally aired on January 8, 1960; following on March 19, 1960 was “Black Belt,” an episode of Wanted Dead or Alive, the TV Western starring Steve McQueen.

Then the success of the first theatrical James Bond movie, 1962’s Dr. No, triggered the spy craze (see RetroFan #6). Television and movie secret agents including 007, The Avengers ’ Cathy Gale and Emma Peel, Honey West, our man Derek Flint, and the wild, wild James West fought foes using some type of martial arts—usually judo flips and karate chops. Deputy Barney Fife, the shakiest gun in Mayberry, and Jethro Bodine, as a would-be “double-naught spy,” tried their hand at it, too.

Martial arts were also seen in Sixties animated cartoons. Bob Kuwahara, a native of Japan, created for America’s Terrytoons the animated character Hashimoto-San, a mouse that was a Japanese judo instructor. Joe Jitsu (Dick Tracy), Karate (Batfink), and Mr. Muto the Karate Ant (Atom Ant) were among other cartoon characters

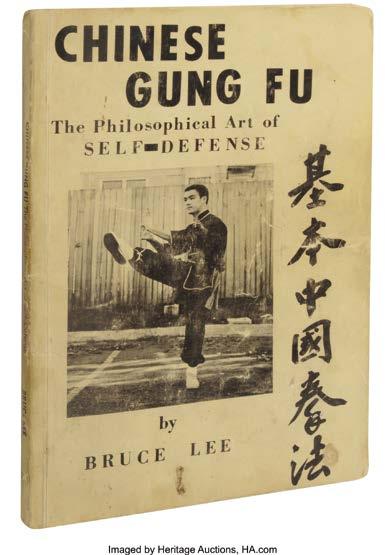

(LEFT) This mid-Sixties release was one of several martial-arts books by Bruce Lee, who would soon rocket to international superstardom. Courtesy of Heritage.

with Asian and martial-arts backgrounds; their exaggerated ethnic affectations are considered offensive to modern audiences.

These flashy new (to Americans) forms of combat were tailor made for comic books. Artist Frank McLaughlin’s Judomaster was one of Charlton Comics’ “Action Heroes” line of the mid-Sixties. Marvel’s karate-chopping Karnak premiered with his allies the Inhumans in Fantastic Four #45 in 1965. At DC Comics, teenaged writer Jim Shooter introduced Karate Kid as a member of the Legion of Super-Heroes in 1966’s

Sixties TV icons Barney Fife (of The Andy Griffith Show) and Emma Peel (of The Avengers) practiced martial arts, as did CBS’ cartoon star HashimotoSan, who was also seen in various Gold Key comic books. The Andy Griffith Show © CBS. Emma Peel © Studiocanal S.A. Hashimoto-San and Deputy Dawg © CBS.

Adventure Comics #346. Two years later, Diana Prince, the erstwhile, now-powerless Wonder Woman, became DC’s alternative to the martial artist Emma Peel, with a blind sensei embarrassingly named I Ching as her mentor and companion. (Historically, comic books had previously flirted with martial arts, from the judo skills of Harvey Comics’ Black Cat in the Forties to the Jay-Jay Corp.’s Judo Joe comic in the Fifties.)

But no one in live action, animation, or illustration could out-kick, out-block, or out-move Bruce Lee, who electrified TV audiences in his star-making turn as the living weapon Kato on The Green Hornet (1966–1967). Born in San Francisco in 1940 but reared in British Hong Kong, Lee opened martial-arts schools in the Sixties in Washington State and California, teaching his hybrid brand of self-defense called Jeet Kune Do. The handsome, likable warrior was soon guest starring on television episodes, bringing his

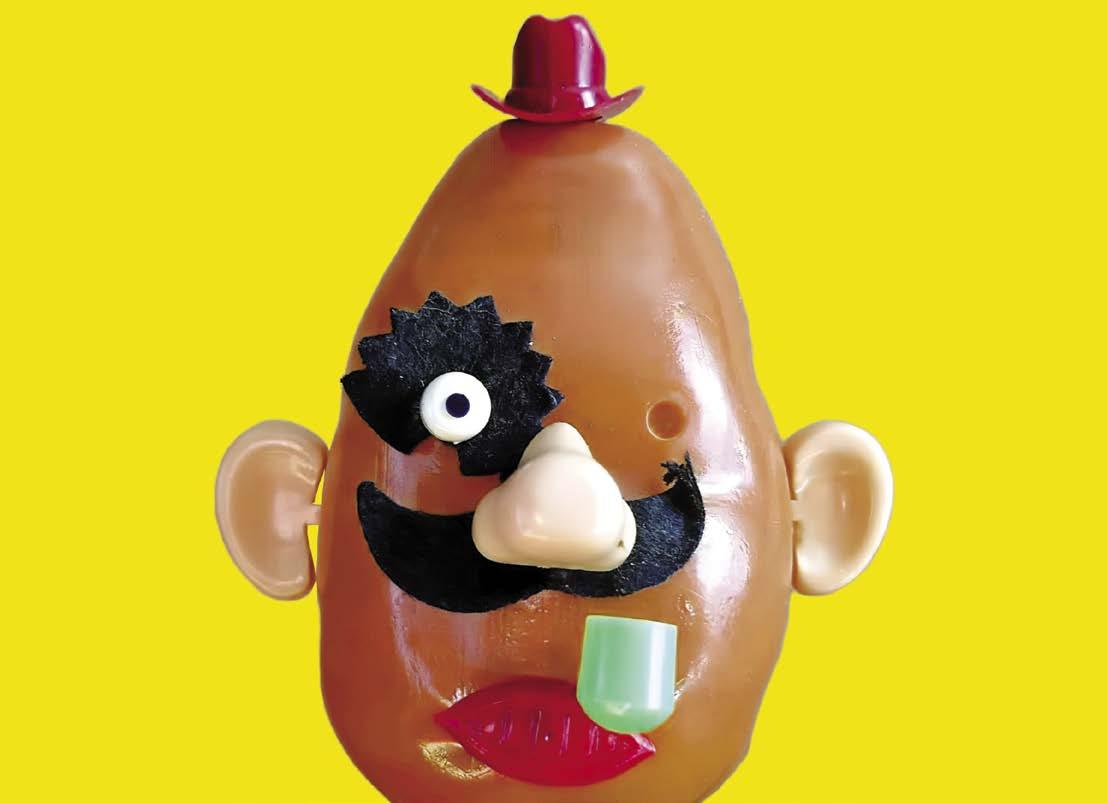

Beloved toy favorite Mr. Potato Head was, in its early days, made with hard plastic pieces strong enough to plunge into actual fruit and vegetables. Mr.

BY SCO tt SAAv EDRA

BY SCO tt SAAv EDRA

“We’d like to show you another one of Mr. Mainway’s products… it’s called Bag O’ Glass. Mr. Mainway, this is simply a bag of jagged, dangerous, glass bits.”

– Consumer Reporter“Yeah, well, look—you know, the average kid, he picks up, you know, broken glass anywhere, you know? We’re just packaging what the kids want! I mean, it’s a creative toy, you know? If you hold this up, you know, you see colors, every color of the rainbow!”

– Irwin MainwayMr. Irwin Mainway, maker of General Tron’s Secret Police Confession Kit, Johnny Switchblade: Adventure Punk, and the above-referenced Bag O’ Glass, is not, of course, a real toymaker, but rather a character played by Dan Aykroyd. Mainway made his first appearance in an NBC’s Saturday Night skit (Season 2, Episode 10, in 1977, before it became Saturday Night Live or just SNL). Mainway returned in a few later episodes selling Halloween costumes (a plastic bag with a rubber band was a space helmet) and as a school lunch provider serving “dog’s milk” to schoolchildren (obtaining such milk was apparently “a very interesting process”). The morally outraged reporter was played by the show’s host for the week, Candice Bergen, and later by Aykroyd’s fellow Not Ready for Primetime Player, Jane Curtain.

Few toymakers have been as predatory as the fictional Irwin Mainway (is what I hope). That’s not to say that there haven’t

been poorly made or poorly thought-out playthings for kids sent into the marketplace. Absolutely, there have been. And some have been completely bonkers. But even relatively well-designed toys can have unintended consequences as anyone who has ever stepped—barefooted—on a sturdy, brilliantly designed Lego piece in the dark can confirm.

Weirdly, I became worried about potential hazards of toys as a kid. At first, it was just Mr. Potato Head parts with pointy shafts made to plunge into a plastic (or real) potato that worried me. Distinctly I recall wondering why a toy company, in this case Hasbro, would make something so obviously able to inflict pain and injury. And I say this as someone who really, deeply wanted to have a Mr. Potato Head (which I did eventually get from the local Dime Store). Still, the little potato eyeballs with plastic shivs coming out the back particularly unnerved young me.

If that was all we had to worry about in terms of unsafe toys during the Retro Years, then we could end the story here, but we all know that is not the case. Not then and not in the years before then. In fact, we Retronauts had it pretty safe compared to our forefathers (or actual fathers). So before we look at how dangerous our playtime could be for us, let’s take a quick look at how completely hazardous it was before many of us were born.

The A. C. Gilbert Company was once one of the largest toy companies in the known world. It was founded by a part-time magician

and Olympic Gold Medalist in Pole Vaulting, Alfred Carlton Gilbert, who originally made magic sets. Gilbert was best known for his steel construction toy, Gilbert Erector sets, which appeared in 1913 following a 1911 version known by the catchy name Mysto Erector Structural Steel Builder, and as “the man who saved Christmas.” The later was the result of convincing the Council of National Defense to drop its plans for an end to toy production as America was entering World War I.

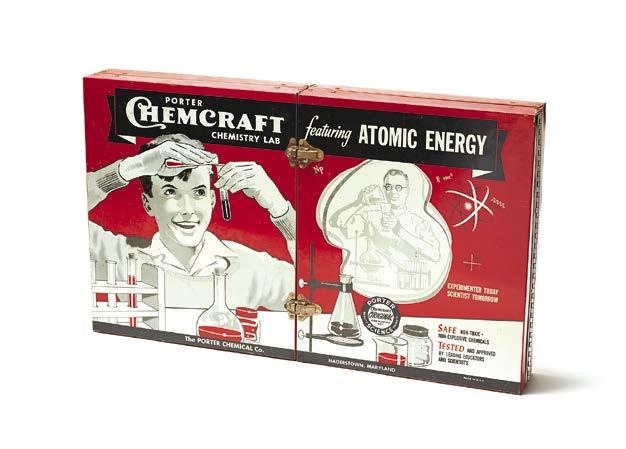

Gilbert thought that inventing was vital for America and wanted to promote the benefits of science. Despite noble intentions, he produced some notorious non-Erector kits. The classic example is the No. U-238 Atomic Energy Lab (1951) with actual radioactive uranium ores. The rumor is that the U.S. government quietly suggested the need for such a kit to Gilbert; while interesting, this has yet to be proved. But I do want to press the point: this child’s plaything was radioactive And it wasn’t the only one. Gilbert included radioactive uranium in some of its chemistry sets during the Fifties.

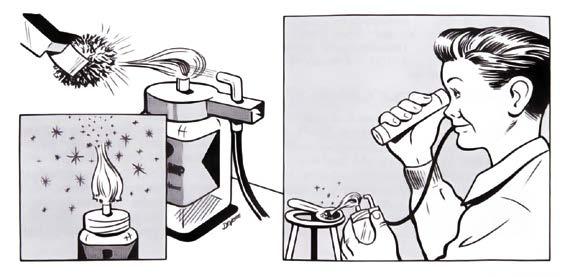

Experimental Glass Blowing (for Boys) was another Gilbert kit (M512-C) to provide a sense of wonder, experimentation, and possible injury. Glass blowing is very cool. But as a home activity for kids, the combination of glass and open flame from an alcohol burner is a problematic mix. It’s notable that none of the illustrations in the kit’s instruction booklet show just how close the child’s face needs to get to the heat source to do the various experiments.

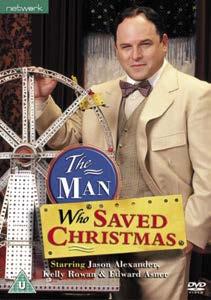

The Man Who Saved Christmas (2002) was the fictionalized story of the real effort by A. C. Gilbert to keep toy production active during the First World War. Seinfeld ’s Jason Alexander played Gilbert. © Alliance Atlantis Communications/Orly Adelson Productions.

One of the experiments contains instructions on how to make a blowgun. Using a dangerous toy to create another dangerous toy out of glass is certainly a bold move.

Speaking of blowguns: Zulu Blowguns were offered up to young boys in the Twenties. The sets came with eight arrows and some paper targets for use indoors (yep), but we can safely guess that it was pets and little brothers that were most in danger. The narrow arrows had blunt tips, but any kid with a pocketknife could sharpen things up right quick. Fun Fact: Zulu warriors did not use blowguns.

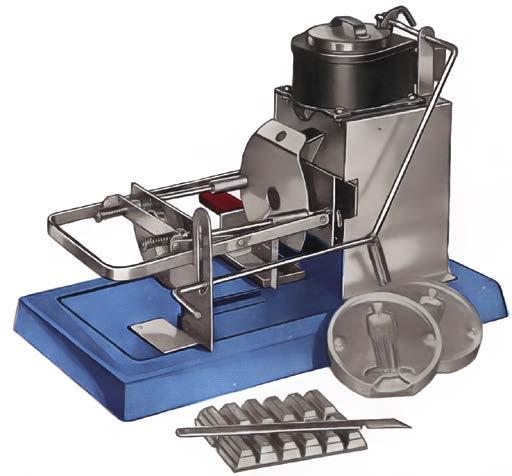

Lead. The dangers of this metal have been known since before the 20th Century. It is toxic. Children, the future of our species, are extremely vulnerable. Lead used to be a component of paint, which was often used to make toys more colorful and exciting and poisonous (not on purpose, but still). Toy soldiers were made of lead, and with a casting set you could make your own. There were other manufacturers of lead-casting sets, but I’m picking on the A. C. Gilbert Company right now. They had a number of casting

(LEFT) A well-dressed lad and his blow gun in this detail from a 1928 ad. (BELOW LEFT) The Dutch Boy’s Lead Party booklet (1923). Booklet courtesy of Worthpoint. (BELOW) A Gilbert Kaster Kit from a 1941 Gilbert catalog. From the collection of the author.

(ABOVE) Radioactive uranium ore and an asbestos heat shield, and (BELOW) an easy-to-make flame-thrower, you know, for kids.

a bit too industrial and not home-friendly at all. Oh, and two more things: Molten. Metal.

Surprisingly, lead-casting sets were around at least into the Sixties, a lot longer than its glass-blowing and atomic-energy toy store buddies lasted.

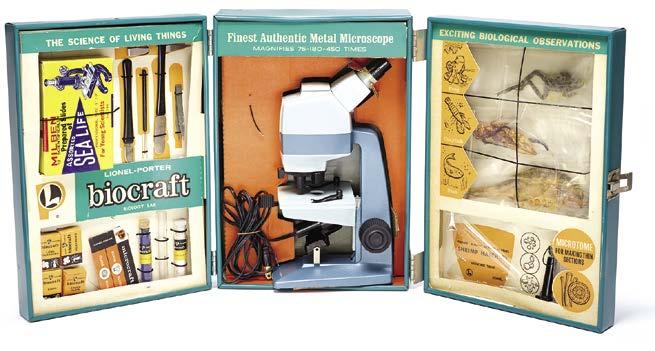

Chemistry sets may conjure images of mad science experiments, but they weren’t really designed for mayhem, but education. I very much wanted a chemistry set way back when, but it was a no-go with the folks since I had very young brothers at the time, and it was deemed unsafe. I was very interested in science, the space program, and inventing during the late Sixties (I wanted to be the Wright Brothers). I did get a very nice microscope, perhaps as a consolation prize, which I really liked. It came with dozens of glass slides full of bug parts and stuff. Stupidly, I kept bringing the lens in too close to each slide and eventually broke every single one of them. Kids and glass, right?

The Fifties were an especially ripe time for chemistry sets as the Cold War and Space Race brought out a need for scientists and educated people to bolster Our Side. It was common for chemistry sets to try to assure parents that it was all safe and harmless and the patriotic thing to have: “Prepares Young America for World Leadership.” That said, chemistry sets have included elements that have raised concerns; mainly about caustic, explosive, and poisonous materials.

The earliest chemistry sets included tools and chemicals contained in simple wooden boxes with scientists and students as the intended market. In 1914, the Porter brothers, John and Harold, created and produced Chemcraft Kits. These toy chemistry sets were inspired by the earlier English versions and A. C. Gilbert’s Erector Set, which had been introduced the year before.

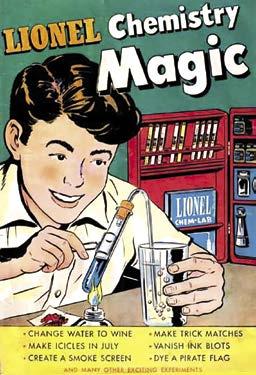

The easiest elements to worry about in these sets were the chemicals. Some sets contained potassium nitrate, a component of gunpowder that can be used to make smoke bombs (or just buy a pre-made one via a Johnson Smith catalog); iodine solution, poisonous if ingested; and calcium hypochlorite, which can be used to make chlorine gas (see World War I). Chemistry sets also had lots of glass parts: pipettes, beakers, thermometers, test tubes, and more (like the previously mentioned: uranium). Not to mention alcohol burners that, with the right adapter, could be turned into a simple blowtorch (not making this up).

The biggest problem for chemistry set manufacturers moving into the Sixties was the customers. Parents had concerns about

(LEFT) Porter Chemcraft got into the Atomic Energy game also in the Fifties. (RIGHT) The Lionel Corporation, best known for its trains, teamed with Porter to produce this biocraft Biology Lab (1961) about the “science of living things.” It comes with dead things and sharp objects. Courtesy of the Science History Institute.

chemistry sets and soon, limited by the Federal Hazardous Substances Labeling Act of 1960 and the Toxic Substances Control Act of 1976 among other legislation, began to lose their luster and some of their most interesting chemicals. Lest you think that the government is always about being a buzz-kill, a 1939 press release from the United States Department of Agriculture about dangerous toys is fascinating. It warned parents that they were responsible for making sure that chemistry sets with chemicals labeled “poison” could be used by their child “with safety.” (Yes, but still, what?)

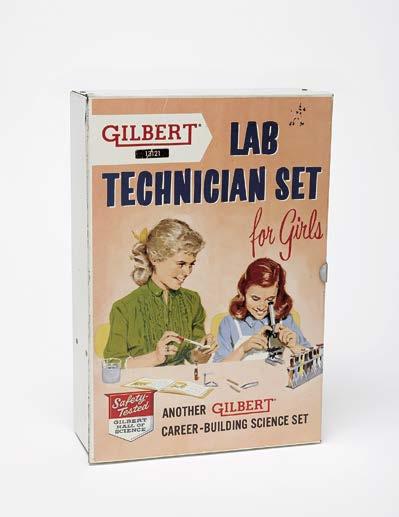

Chemistry sets had been marketed to boys, but sets for girls emerged. One encouraged young ladies to become lab assistants (seriously, had none of these guys ever heard of physicist and chemist Marie Curie, who died due to, ahem, long-term exposure

(LEFT) The Lionel Chemistry Magic comic book (1946) offers instructions to change water to wine (sure), make a lot of smoke, make trick matches, and—this is absolutely true— make a hydrogen explosion. (RIGHT) Meanwhile, girls get to watch and make notes with the Gilbert Lab Technician Set for Girls (1958). Courtesy of the Science History Institute.

BY DAv ID KRELL

BY DAv ID KRELL

Don Drysdale had a right arm that batters feared and an on-camera presence that Hollywood producers sought.

On August 11, 1969, the three-time Major League Baseball strikeout leader announced what Los Angeles Dodgers fans dreaded but knew was inevitable. Retirement. His right shoulder no longer had the elasticity necessary to play at an optimum level. Plus, the risk of injuries was increasingly apparent.

The Dodgers were in third place in the newly formed National League West, one game behind the Atlanta Braves and threeand-a-half games behind the Cincinnati Reds. “This team has a chance to go all the way,” said the 33-year-old Van Nuys, California, native to the San Pedro News-Pilot. “I don’t want to jeopardize their chances.” Drysdale had pitched in 62 innings across 12 games in his final season when he stepped away. His record was 5-4.

Then in their 12th year in Los Angeles after moving from Brooklyn, the Dodgers had added three World Series titles to their roster of achievements—1959, 1963, and 1965—since settling in Southern California. Sandy Koufax retired after the Baltimore Orioles swept the Dodgers in the 1966 World Series. The southpaw’s phenomenal power resulted in winning three Cy Young Awards; leading Major League Baseball in strikeouts four times; and throwing four no-hitters—including a perfect game.

With Drysdale now gone, the void on L.A.’s pitching staff was even starker. “I have immensely enjoyed my relationship with the Dodgers,” said the righthander to the Hollywood Citizen-News. “I owe quite a bit to baseball—just about everything. It’s been great. I wouldn’t trade it for anything.”

Drysdale’s first major-league appearance ended with nine strikeouts in a complete game, 6-1 victory against the Philadelphia Phillies at Connie Mack Stadium on April 23, 1956. It was the beginning of a formidable career: a 209-166 win-loss record, two-time

leader in innings pitched, a Cy Young Award, and nearly 2,500 strikeouts.

He also led MLB four times—and the NL five times—in hitting batters with pitches.

“I was called ‘intimidating,’ and I wasn’t about to dispute that,” wrote Drysdale in his 1990 autobiography (written with Bob Verdi), Once a Bum, Always a Dodger: My Life in Baseball from Brooklyn to Los Angeles (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990). “I never talked about my reputation, but I was very much at peace having others talk about it. Baseball then was a game of intimidation, and if opposing batters figured you were going to throw the ball inside at 94 miles an hour on a day when you didn’t feel like you could break a pane of glass, fine. Let ’em think that way. Perfect.”

Fearsomeness was a sharp arrow in Drysdale’s quiver. Endurance, another. He led both leagues in games started from 1962 to 1965.

Moreover, Drysdale had dominated the opposition just one year before retiring, when he broke the record for consecutive scoreless innings. Carl Hubbell had held the National League record with 45 in 1933; Walter Johnson’s 56 in 1913 topped the majors. Drysdale blanked the opposition for 58. In the midst of Drysdale’s streak, Robert F. Kennedy won the 1968 California Democratic Presidential Primary and used his victory speech to praise the pitcher: “I want to first express my high regard to Don Drysdale, who pitched his sixth

BY SCO tt SHAW!

BY SCO tt SHAW!

The first time I met Jack Kirby was when he was a special guest at the first official San Diego Comic-Con (at the time a.k.a. Golden State Comic Con) on August 1–3 in 1970, and I was so excited I could barely speak.

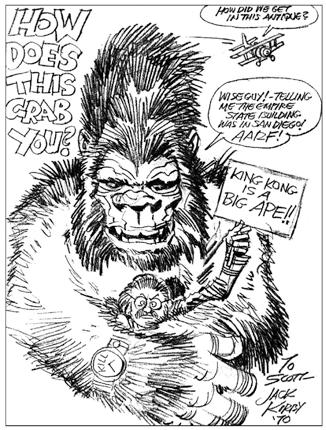

The second time I met Jack was at his home in SoCal’s Thousand Oaks, along with my other teenage San Diego Comic-Con co-originator pals in 1971. I blurted out, “Jack Kirby!?! You’re my favorite cartoonist!” Surprisingly, Jack seemed quite pleased to be described by that simple term, usually applied to those of us who write and draw nothing but the funny stuff. After all, comics aficionados have dubbed him “King” Kirby (a title he wore with some discomfort), and have compared his work to that of Da Vinci, Rembrandt, and Rockwell, among other artistic greats. I suppose that’s because Jack probably saw himself as a cartoonist, partially because he wrote the stories he drew. A few weeks later, he sent me a penciled caricature of myself getting strangled by King Kong (see inset).

If you are a loyal reader of RetroFan’s non-comics-related material, it’s very

possible that you have no idea who Jack Kirby was. From the Forties into the Eighties, Jack was comics’ most prolific creator. Whether he was working with Joe Simon, Stan Lee, or by himself, Jack’s concepts and characters were exciting, unique, and popular. He worked in every comic-book genre, but is best known for co-creating such super-heroes as Captain America, the X-Men, the Avengers, and the Fantastic Four. If it wasn’t for Jack, there would be no Marvel Universe in comics or films. But Jack’s work went far beyond Marvel. Not only did he do work for almost every publisher of comics, but his style of storytelling and character designs educated the entire funnybook industry in how to make comics that people will eagerly purchase.

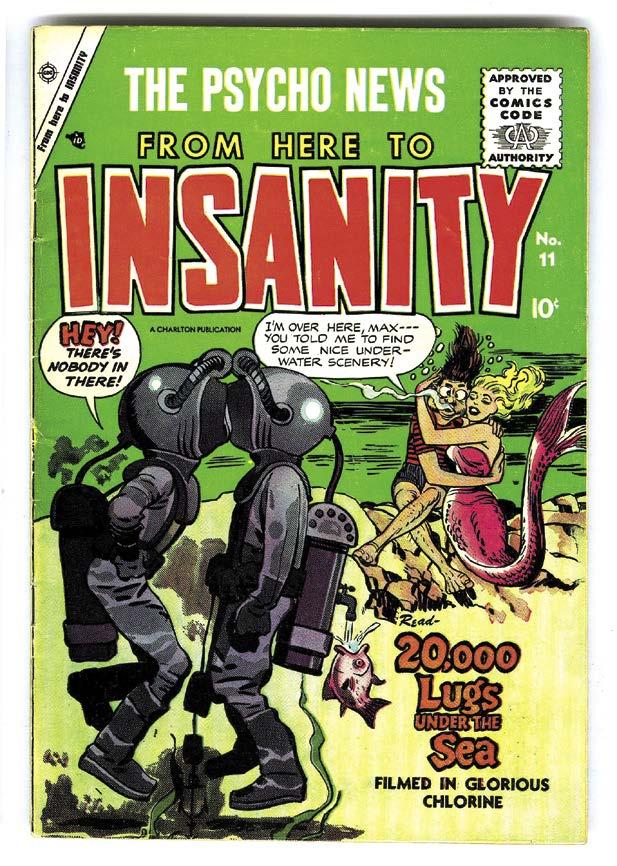

(ABOVE) You may know Jack Kirby for his work on Captain America, Fantastic Four, The Mighty Thor, and so many other super-hero series, but the King of Comics was no stranger to humor and other oddball work, such as cartooning for Charlton’s MAD knock-off From Here to Insanity #11 (Aug. 1955). Courtesy of Heritage.

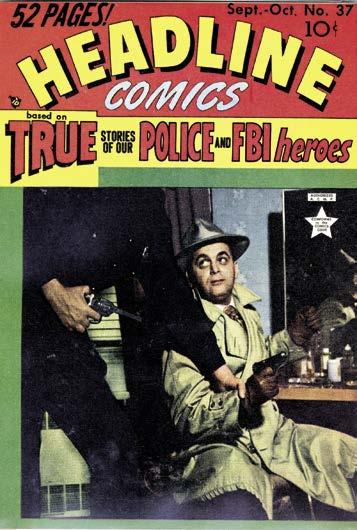

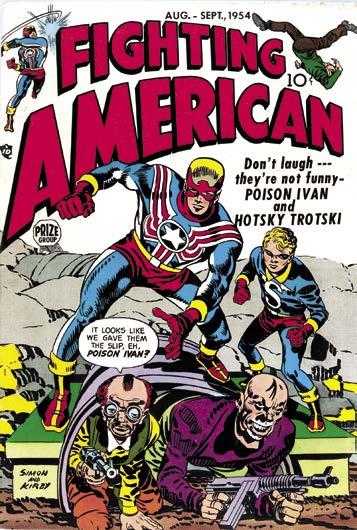

(LEFT) Yes, that’s Kirby himself, on the wrong side of the law, on the photo cover of Prize Publications’ Headline Comics #37 (Aug.–Sept. 1949). © 1949 Prize Publications. (CENTER) Poison Ivan and Hotsky Trotski don’t stand a chance against Simon & Kirby’s patriotic, Commie-crushing hero. Fighting American #3 (Aug.–Sept. 1954). (RIGHT)

American and his sidekick Speedboy got this one-shot from Harvey Comics in the campy year of 1966.

Myrtle, the toast of a Sultan’s harem. Based on the strip’s surviving artwork, Jacob’s work was starting to look more exaggerated, an important aspect of his later style.

Of all the projects that Jacob created for Lincoln Features Syndicate, The Romance of Money was a series that wasn’t syndicated. Instead, it was published as a giveaway sequential panel story booklet for savings banks. Some consider it to be Jack Kirby’s very first comic book.

By the advent of super-heroes in what we now call the Golden Age of Comics, Jacob Kurtzberg had become Jack Kirby and had partnered with Joe Simon, another cartoonist with similar abilities, goals, and ethics. After co-creating Timely/Marvel’s Captain America, Simon & Kirby noticed that many readers identified with Cap’s teenage sidekick, Bucky Barnes. It led to teaming the young super-hero with an urban-raised boy, a matrix sparked by the creation of the Golden Age “kid gang” by Simon & Kirby. And no matter if the team was Timely/Marvel’s Sentinels of Liberty or Young Allies, DC’s Newsboy Legion or Boy Commandos, or even Harvey’s non-super-hero-genre Boys’ Ranch or Boy Explorers, it had its own comedy relief character.

Both Joe and Jack would return to the genre in the Seventies, each with his own outlandish Oddball concept.

After WWII, most super-hero comics disappeared from the stands, leaving very few survivors. Established and new genres took the place of the costumed characters that were associated with that just-concluded war. Funny-animal comics were big sellers, as were the new themes of teenage comics, WWII comics, humor comics, horror comics, and romance comics—the latter

genre having been created by Simon & Kirby. Fortunately, they had no problem adjusting to new styles and genres.

Hillman Periodicals published Punch and Judy Comics, a long-running (1944–1951) funnybook aimed at a readership that was still learning how to read: little kids. The series featured lots of puppets, talking animals, and fairies. Never fazed by a new challenge, Jack leapt into Punch and Judy ’s world of funny animals with gusto in the mid-Forties with “Earl the Rich Rabbit” and “Lockjaw the Alligator.” As a cartoonist who’s done more than a few funny animals myself, I feel I must emphasize that Jack truly excelled at this type of material, and that it’s a real shame he rarely ever revisited the genre. Although lightweight in story, these are some of the most dynamic and powerful pages I’ve ever seen! It’s also noteworthy that “Earl” predated Carl Barks’ Uncle $crooge McDuck, who made his first appearance in 1948! The series also featured Jack’s Toby—a teenage boy in the “Archie” mode—in one of the later issues of Punch and Judy

Simon & Kirby also worked on all four issues of Hillman’s My Date (1947–1948), a pleasantly cartoony series that was intended to exploit the popularity of Archie Comics’ line of humorous comics.

Around the same time, Jack and Joe also drew a teen humor strip in Archie Comics Publications, Inc.’s Laugh Comics #24 (Dec. 1947) called “Pipsy.”

Although neither Joe Simon nor Jack Kirby had any of their material in Prize/Headline Publications’ Headline Comics vol. 5, #1/#37 (Sept.–Oct. 1949), it’s still a major collectable for Jack Kirby fans. Why? This issue’s photo-cover depicts a policeman busting a burglar mid-heist... with Joe Simon as the cop and Jack Kirby as the crook.

Strange World of Your Dreams (Prize, 1952–1953) was created to appeal to the same readership that was reading Simon & Kirby’s

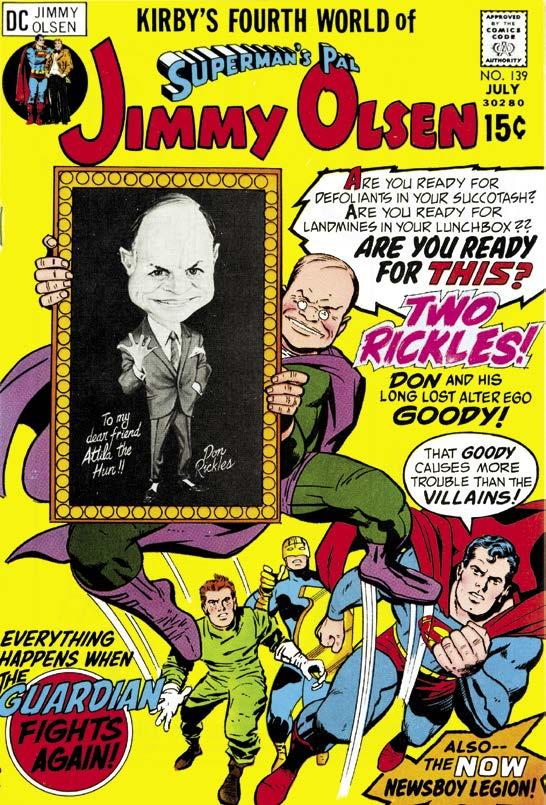

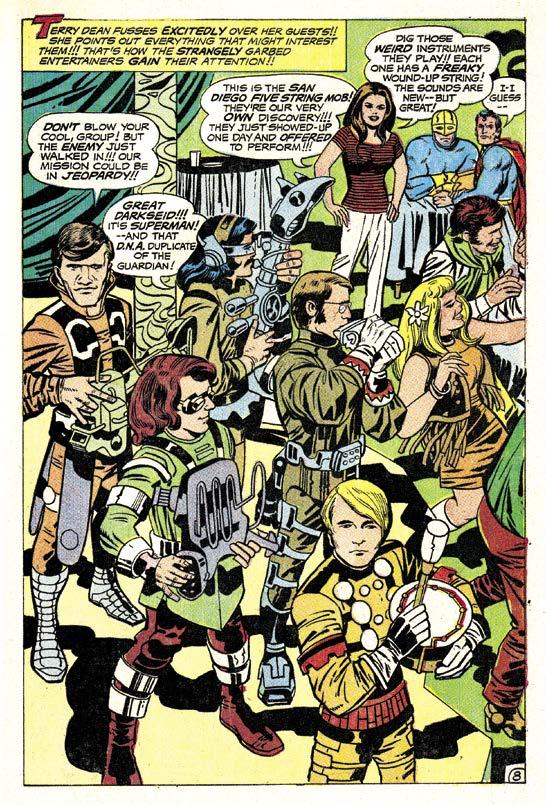

(LEFT) If you thought the Giant Turtle Olsen was the weirdest thing you’d seen in a Jimmy Olsen comic book… behold, Don Rickles—and Goody Rickels! Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen #139 (July 1971). (ABOVE) From Mister Miracle #6 (Jan.–Feb. 1972), the self-aggrandizing Funky Flashman and sycophantic Houseroy. (BELOW) Can you identify the members of the San Diego Five String Mob from this page from Jimmy Olsen #144? TM & © DC Comics. Scan courtesy of Scott Shaw!

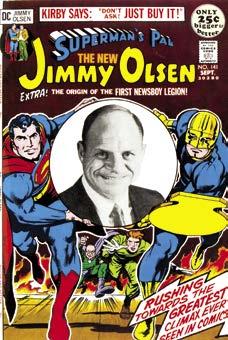

When Jack relocated to DC Comics in the early Seventies, he brought his sense of humor with him. Comedian Don Rickles’ lookalike “Goody Rickels” first appeared in Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen (hereafter JO) #139 (July 1971), and the second and final installment of the Goody Rickels saga, JO #141 (Sept. 1971), bore what possibly remains the greatest comic-book cover blurb of all time: “Kirby Says: Don’t ask! Just buy it!” [Editor’s note: Issue #140, published between the Rickels’ story’s two parts, was a giant issue with Jimmy Olsen reprints.]

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK TO ORDER THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DIGITAL FORMAT!

JO #144 (Dec. 1971) introduced the San Diego Five String Mob, a rock band from the planet Apokolips sent to the Earth by Darkseid to kill Superman. JO #145 (Jan. 1972) was the last time the San Diego Five String Mob was sighted. Who were anyway?

Here’s who... the secret origin of the San Diego Five String Mob! In 1971, many of us from the original San Diego Comic-Con committee visited Jack and his wife Roz in their home on a steep street in Thousand Oaks, California. At one point, we were sitting around Jack when he said, “I could turn anyone into a comic-book character—even you guys!” As we immediately responded in unison, “Okay, let’s do it!,” I noticed an “Oy vey, why did I promise that?” expression quickly passing across Jack’s face. But many months later, Mike Towry, Roger Freedman, John Pound, Will

Lund, Yours Truly, and Barry Alfonso as “Barri-Boy” appeared as the maniacal musicians from Apokolips in Jimmy Olsen. (That’s Jack Kirby-style arithmetic, folks.)

(84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95 (Digital Edition) $4.99

Sometime in the mid-Seventies, the San Diego Comic-Con decided to create a “Friend of Fandom” award and asked Jack

https://twomorrows.com/index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=98_152&products_id=1701