I consider myself to have been a very lucky kid for many reasons, most of which are the subjects of my RetroFan columns. One of them was an animated series I grew up with during the birth of made-for-television cartoons. With The Flintstones, Yogi Bear, Quick Draw McGraw, and a fleet of others that were mostly funny-animal characters, Hanna-Barbera Productions was the powerhouse of the new “limited animation” industry that rapidly replaced all of the cartoons from the Twenties into the Fifties that kids like me had already memorized. Jay Ward Productions’ Rocky and His Friends and The Bullwinkle Show were very successful as well.

But by the early Sixties, two more studios received significant public attention and licensees for their new series. One was Format Films’ The Alvin Show! Created by singer, songwriter, and ArmenianAmerican actor Ross (Rear Window, Stalag 17) Bagdasarian, Alvin

was based on novelty records and singing chipmunk puppets, with an insider’s look at show biz and a nutty, fourth-wall-breaking inventor named Clyde Crashcup. [Editor’s note: Oddball World will spotlight The Alvin Show! in RetroFan #31.]

The other newcomer was Snowball Studios’ animated revival of a well-received TV puppet show from the previous decade, owned and created by the truly legendary animation director Bob Clampett. It was Beany and Cecil (B&C), presented by its sponsor, Mattel Toys, under the umbrella title Matty’s Funday Funnies (ABC, 1962).

I was ten, the right age to add both The Alvin Show! and Beany and Cecil to my ever-expanding list of cartoon favorites. Their contemporary scheduling is where both shows’ similarities ended. Alvin was set in the music industry and therefore as hip as kids’ cartoons got in 1962. B&C, crawling with puns, was both hip and corny, with parodies and references to current events. Plus, one of the central cast of Beany and Cecil was a “dirty guy” who dressed all in black, a theatrical fink named Dishonest John. His signature catchphrase was simply a sneering, snarky, self-satisfied laugh that slithered down the tongue: “Nyah-ha-ha!” He became the breakout villain most of the kids I knew liked to imitate. I particularly leaned into the addiction once I realized that “Nyah-ha-ha!” was the perfect reply to deflect any of my parents’ observations, questions,

on CBS radio, which replaced Jack Benny’s show in 1957. These assignments directly led to on-screen roles in feature films such as Callaway Went Thataway (1951), Geraldine (1954), and It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963).

Stan gained more attention for his comedy 45s and albums for Capitol Records. Some of his most famous 45s were “John and Marsha” (1951), “St. George and the Dragonet” (1953), “The Great Pretender” (1956), “Banana Boat (Day-O)” (1957), and “Green Chri$tma$” (1958). Among Stan’s most popular LPs were Stan Freberg Presents the United States of America, Volume One: The Early Years (1961), Freberg Underground (1966), and Stan Freberg Presents the United States of America, Volume Two: The Middle Years (1996). Stan was also seen on television, including The Ed Sullivan Show, The Monkees, The Girl from U.N.C.L.E., Roseanne, and The Weird Al Show. He also had his own special on ABC in 1962: Stan Freberg Presents the Chun King Chow Mein Hour: Salute to the Chinese New Year.

Stan revolutionized the advertising industry by creating ad campaigns for radio and television that caught on with the public due their clever satirical content. After founding the Los Angeles–based ad agency, Freberg Limited, his clients included Butternut coffee, General Motors, Contadina tomato paste, Jeno’s pizza rolls, Sunsweet pitted prunes, Heinz Great American Soups, Encyclopedia Britannica, Kaiser Aluminum, and Chun King Chinese food, among many others.

Charles Dawson, a.k.a. “Daws” Butler (November 16, 1916–May 18, 1988), was born in Toledo, Ohio. As a young man, he had a fascination with imitating his friends, his teachers, and various celebrities. In 1935, he became a professional impressionist, performing in vaudeville theaters.

Daws’ first animation voiceover job was for Screen Gems in 1948, but he was soon working on Tex Avery’s shorts for MGM, beginning with Little Rural Riding Hood (1949). He became a favorite of Tex’s, contributing to MGM’s Out-Foxed, The Cuckoo Clock, The Peachy Cobbler, Droopy’s Double-Trouble, Magical Maestro, One Cab’s Family, Little Johnny Jet, Three Little Pups, Sheep Wrecked, Billy Boy, and Walter Lantz’s The Legend of Rockabye Point.

After Daws Butler began writing and voicing TV commercials, Stan Freberg asked him to collaborate on writing material for Stan’s records for Capitol. The result was “St. George and the Dragonet.” The duo continued to work together on Stan’s songs, especially co-writing dialogue routines. Daws also was part of the Stan Freberg Show on CBS radio.

Daws expanded his list of animation studios that were casting him. For UPA, he provided the voice of Waldo, the nephew of Mr. Magoo. For Walter Lantz Productions’ theatrical shorts, he put words in the mouths of Chilly Willy; his laid-back canine co-star, Smedley; Gabby Gator; and Ali Gator.

But in 1957, the newly formed Hanna-Barbera Productions, run by MGM’s Tom and Jerry creators/ producers/directors William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, would soon occupy a major percentage of Daws’ career. Starting with the voice of Reddy on The Ruff and Reddy Show, the studio’s first series, Daws quickly became one of H-B’s most relied-upon voice talents. Among many others, here are some of Daws’ most recognizable voices for the studio’s cast of characters: Augie Doggie; Barney Rubble (subbing for Mel Blanc); Quick Draw McGraw and Baba Looey; The Jetsons ’ Elroy,

(ABOVE) Surrounding the Beany doll are (LEFT TO RIGHT): Daws Butler, Stan Freberg, Bob Clampett, and Jack Benny. (LEFT) A TV Guide (Aug. 8, 1954) spread about Time for Beany. © Bob Clampett Productions. TV Guide © TV Guide Magazine, LLC. Courtesy of the Prelinger Archives via the Internet Archive.

Cogswell, and Henry Orbit; Lippy the Lion; Huckleberry Hound; Dixie Mouse and Mr. Jinx; Bingo; Hokey Wolf; Peter Perfect; Hair Bear; Super Snooper and Blabber Mouse; Yogi Bear; Wally Gator; Snagglepuss; Peter Potamus; the Funky Phantom, and many others. He not only worked on H-B’s TV shows but also the studio’s TV commercials and kids’ records.

Daws was also heard in many of Jay Ward Studios’ TV shows and commercials, such as Aesop’s Son, Cap’n Crunch, and Quisp. He did voices for all three of Kellogg’s Rice Krispies’ Snap, Crackle, and Pop. The roles of a penguin and a turtle in Mary Poppins were his only work for Walt Disney. In 1975, Daws Butler started to host acting workshops in the guesthouse in his Beverly Hills backyard. It spawned a number of very successful voice-over artists.

Fortunately, both men lived in Los Angeles. Bob Clampett asked Stan to do the voices of Cecil and the bad guy, Dishonest John, and asked Daws to be the voices of Beany and Cap’n Huffenpuff— if the show was bought. They had no idea that their vocal performances would be only one of the tasks that were expected of them.

By 1949, the relatively new medium of television was becoming affordable and desirable to the American public. At the end of 1946, only 44,000 homes owned a television set; by the end of 1949, there were 4.2 million sets in homes; and by 1952, 50% of American homes owned a TV set. At the time, no one yet knew how to cheaply produce animated cartoons for television, but a puppet show was an absolutely feasible concept. But it was a concept that none of Bob’s potential clients understood at all. After all, the television industry was still in its infancy.

In an interview with Jim Korkis in 1978, Bob said, “When I first went out to sell my puppet show in the early days of television, people would say, ‘You are known for your cartoons, so give us cartoons. Don’t give us puppets.’ And no matter how I tried to enthuse them about puppets, they kept stressing animation.”

After getting rejected by the networks, Bob decided to pitch his puppet show to local stations. At the time, Los Angeles County had a population of approximately four million people, a healthy amount of potential viewers. All Bob needed was for someone to say “yes.”

Someone finally did. On February 28, 1949, Paramount’s KTLA-TV studio aired the first episode of Bob Clampett’s was broadcast live. Bob and his crew did a 15-minute black-and-white show five days a week, 52 weeks a year, for six years.

As Bob planned, the show’s voice actors were Daws Butler as Beany and Cap’n Huffenpuff and Stan Freberg as Cecil and Dishonest John. Fortunately for Bob, both men were also very competent puppeteers. When Stan wasn’t available, Daws would do all the voices and vice versa, with the help of multiple puppeteers.

“We managed to become the number one children’s show, while appealing to adults as well,” claimed Freberg in his autobiography. “Whole families would gather before their TV sets each evening to watch Time for Beany. A 70 share of the audience was not unusual. With mikes on our chests and both arms holding various puppets in the air, Butler and I literally had our hands full.”

Indeed, Time for Beany frequently contained topical references, usually of a satirical nature. Children could laugh at the silliness,

and adults could laugh at the political and social satire, something for everyone.

With only Freberg and Butler doing puppets, the scenarios were limited to only four characters at a time (one puppet for each hand), and Clampett had grander designs than that restriction. Walker Edmiston was doing voices for Walter Lantz cartoons but also designed and built ventriloquist dummies. “I told Clampett my hobby was designing and building puppets,” said Edmiston. “That combined with the voice imitations did the trick. I was hired, and my career was launched as Daws and Stan’s other pair of arms. Now there could be six characters in a scene.” The writers were Charles Shows, Lloyd Turner, Bill Scott, Chris Allen, Adam Bracci, and of course Freberg, and Butler supplied a lot of ad-libbed material. The puppets, created by Maurice Seiderman, were presented against simple sets or crude background drawings.

In 1950, KTLA-TV’s Time for Beany was distributed nationwide via kinescope by the Paramount Television Network. With a much bigger audience, the puppet show attracted a lot of viewers. Time for Beany received three Emmys for Best Children’s Program in 1949, 1950, and 1952. It was nominated for the Emmy in 1954, but it did receive the Peabody Award that year. Stan Freberg was nominated for the Best Actor Emmy in 1950.

After Butler and Freberg quit the show during 1952 or 1953—after all, it was an incredibly grueling job in many ways—Jim

In the Sixties, Saturday morning television was for children. That’s how I, a Baby Boom tot, came across reruns of The Roy Rogers Show My siblings and I woke up as early as we could on Saturday, careful not to wake our parents so they wouldn’t tell us to turn off the TV and go do something useful. We poured bowls of Cap’n Crunch or Cocoa Krispies, settled onto the family room floor, and tuned in to the cartoons that dominated the era: Beany and Cecil, Tennessee Tuxedo, Mighty Mouse, and Underdog

But sometimes I convinced my siblings to watch The Roy Rogers Show instead. I was fascinated by the Dale Evans character, owner of the Eureka Café in Mineral City, California. A cook worked for her, a man named Pat Brady, who split his time with the Double R Bar ranch where he served as foreman. There, the boss was Roy Rogers, who spent a lot of his time tracking down the bad guys in pursuit of justice in the entire Paradise Valley. Brady was the “comical sidekick” always doing goofy things. Dale Evans, though, saddled up with Roy Rogers—she on Buttermilk, he on Trigger, often energetically followed by Roy’s “wonder dog,” the German Shepherd, Bullet—to fight crime.

I didn’t give a second thought to the incongruities of life in Paradise Valley. Dale and Roy, along with nearly all the supporting characters, rode horses and/or used horse-drawn wagons, the streets in Mineral City looked unpaved and were bordered by wooden sidewalks, with buildings made of stucco or wood, all imitating life in a mythical Old West. Yet modern technology existed as well: Pat Brady’s jeep called Nellybelle, indoor electricity, telephones, kitchen appliances. Dale’s clothes also gave a nod to the Old West, from the sensible skirt that swished along the tops of the sturdy, well-worn boots to the turned-up brimmed hat

kept anchored on her head by a leather chin strap. She also wore a holster as casually as a belt.

And there was Dale’s voice—strong and assertive, with a slight Texas twang. Throughout the episodes, she spoke with confidence, often tinged with kindness, but sometimes with sternness if she was talking to someone who’d done something wrong. Then, at the end of each episode, Dale sang. Sitting astride Buttermilk, next to Roy Rogers on Trigger, they warbled the soothing and hopeful “Happy Trails.”

Despite my childhood fascination with Dale Evans and The Roy Rogers Show, I didn’t grow up to be a cowgirl. I went to graduate school and studied American history, became a university professor, and wrote books on women’s history. The more I understood about the changing lives of women through the 20th Century, the more I remembered those Saturday mornings and the café-owning Dale Evans. I wondered about the story behind the real-life Dale Evans. How did she become a television star? To find out, I wrote a biography.

Dale Evans’ involvement with television pre-dated The Roy Rogers Show by about 20 years. In the very early Thirties, before she took the stage name Dale Evans, she was Frances Johns (nee Smith), a native-born Texan trying to establish herself as a singer in Chicago.

The single inroad she made in the Windy City’s entertainment milieu was a brief, part-time job at WIBO, a radio station that

provided audio for Chicago’s first television station, WCFL. Frances probably sang and/or played the piano to augment the images projected for television.

Frances Johns moved on, changing her name to Dale Evans, finally finding success as a radio and nightclub singer in Memphis, Dallas, and then, to her great satisfaction, in Chicago. After securing a year-long contract at 20th Century-Fox in 1941, she moved to Hollywood. The movie studio gave Dale a few bit parts then declined to renew the agreement, so in 1943 she signed on with Republic Pictures, known for its B-movies. She acted in a string of low-budget musical comedies, starting with Swing Your Partner, but set her sights on starring roles in Republic’s “prestige” feature films.

Republic Pictures was where Dale Evans met the studio’s most bankable singing cowboy, Roy Rogers. In early 1944, they began filming The Cowboy and the Senorita, which became a hit with Roy’s legions of fans and expanded Dale’s burgeoning fan base. The two became good friends while working on this production and the next three: The Yellow Rose of Texas, Song of Nevada, and San Fernando Valley The movies did well at the box office, but Dale worried she’d never become a true movie star by appearing in “horse operas.”

She tried to break away from the studio but couldn’t. Dale, who divorced in 1945, and Roy Rogers, who became a widower (with three young children) the following year, became more than friends. As they spent more time together working on movies, Roy’s radio show, and personal appearances, their feelings for each other deepened into love. They married on New Year’s Eve 1947.

Herbert Yates, head of Republic, claimed that movie-goers wouldn’t accept a real-life husband-and-wife team as movie costars, so he fired Dale. Outraged fans inundated the studio with letters demanding her reinstatement. Yates held firm, and Dale, always hard-working and ambitious, didn’t wait around for him to change his mind. Understanding her supporters preferred her in Westerns, she concluded a verbal agreement in 1948 with independent producer Louis Lewyn to star in a series of Annie Oakley–style movies, beginning with Two Girls on a Horse. But by early 1949, before the plan went any further, Yates rehired Dale at Republic, putting her opposite Roy in Susanna Pass and Down Dakota Way

An unexpected development then slowed down the 37-year-old cowgirl. As Dale headed into her second year of marriage with Roy, she learned she was pregnant. She bowed out of filming Westerns near the beginning of 1950 because her obstetrician advised against the strenuous physical activity they required. But studio

executives wouldn’t have cast Dale anyway. By the standards of the time, it wasn’t acceptable for a female actor to be on set after she announced a pregnancy.

Television, still in its early years of post–World War II broadcasting, proved more flexible. In April, Dale appeared on Rancho Tela Vista, a new, live Western musical variety show that broadcast weekly at 8:00 on Thursday nights over KECA-TV in Los Angeles. She intended to continue “almost up to the birth of the baby.” Still, Dale took care not to flaunt her pregnancy. On set, she stood behind a fence that concealed most of her expanding midsection as she sang and chatted with the audience.

Despite Dale’s plan, health issues forced her to quit after about a month. She curtailed her public appearances, increased her bed rest, and spent more time with family until the birth of her daughter, Robin, in August. The baby was frail at birth, diagnosed with a heart murmur and Down syndrome. Dale spent much of her time at home that first month, tending to the baby with the help of a trained baby nurse, then she returned to the radio on The Roy Rogers Show and resumed filming movies.

Dale later claimed that Robin inspired her to write what would become her most popular and enduring song (she was an accomplished songwriter as well as singer): “Happy Trails.” Dale thought about the challenges ahead for her baby, and she

This hat worn on screen by the Queen of the West netted $836.50 at an April 2007 Heritage auction. Courtesy of Heritage.

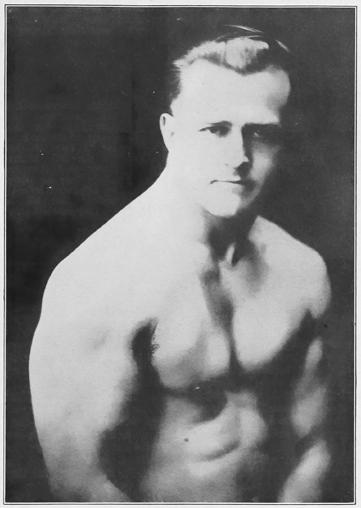

If you read comic books in the Seventies, you likely saw Charles Atlas ads, including the most familiar of the bunch, “The Insult That Made a Man out of Mac.” The centerpiece of the ad was a comic strip that showed a slender 97-pound weakling with a young woman at the beach getting sand kicked in his face by a larger, more muscular bully. Humiliated, he kicks a chair and vows to improve himself. He does so with the help of Charles Atlas’ mail-order course. Atlas would claim that this story was true and happened while on a date to Coney Island when he was 16. The chair being kicked in frustration has never been verified and, sadly, the part of the ad where the now-muscular Mac re-encounters the bully and punches him hard in the face did not happen in real life. This classic Charles Atlas ad appeared in the first comic book to feature all-new material, New Fun #1 (Feb. 1935).

Charles Atlas was too perfect a name to be true, and it wasn’t. He was born Angelo Siciliano near Acri, Cosenza, Italy, on October 30, 1892. To those who knew him before his fame, he was Angelino or Angie or Charley. Angelo immigrated to America with his mother in 1904. His father appears to have either returned to or stayed in Italy and was not an active part of Angelo’s life. Young Angelo’s time in Brooklyn, New York, was rough. Among those who beat up on the slight young man (apart from the bully at the beach) was a local street punk and an uncle.

Angelo was determined to improve his physique. Unable to pay for membership to the local YMCA (a.k.a. the Young Men’s Christian Association or more simply “the Y”), he studiously watched exercises in action and then repeated them at home. He would watch strongmen perform at

Coney Island and ask questions about their muscle-making methods and diet. He read an early bodybuilding magazine, Physical Culture. Part of his legend is a trip to the Prospect Park Zoo in Brooklyn, New York, where he saw a muscular lion. How did the lion (which Atlas referred to as “this old gentleman”) develop his body without weights or other gadgets? Angelo surmised, incorrectly it turns out, that the King of Beasts had developed his muscles by pitting one muscle against the other. This false epiphany would form the basis of his personal exercise regime and his later mail-order courses.

Angelo dropped out of school after the eighth grade and learned leatherworking so he could help support his family.

His muscular transformation stunned his friends, who compared him to a statue of Atlas. It wasn’t long before Angelo, now a bodybuilder at a time when that was not only rare but also a distinct oddity, began to call himself Charles Atlas.

So, the question for Atlas now was, What’s a bodybuilder to do?

It was not uncommon in the days of sideshows and circuses to have muscle men perform feats of strength. Young Atlas spent time bending railroad spikes and tearing phone books in half in sideshows.

He earned five dollars a week for his effort but also had to sweep up after himself. A sculptor discovered Atlas after seeing him perform around 1915, and soon other artists used him as a model as well. For one particular statue, “The Dawn of Glory” (1924) by Pietro Montana located in Highland Park, Brooklyn, Atlas’ body is quite identifiable.

Concurrently with his modeling, Atlas was one half of a vaude ville act with another bodybuilder. Back in his YMCA days, Atlas met a fellow physical-culture enthusiast, Earle E. Liederman, who was just a few years older. Like Atlas he was a former scrawny kid, but was a bit ahead of Atlas in body improvement. Liederman was also a physique model for artists and previously was a wrestler and a boxer. Together, Liederman and Atlas traveled to

eventually perform as a Coney Island sideshow act, the very place where Atlas first tasted sand. Very briefly, the two opened a shop selling fitness equipment. The vaudeville act was apparently less than memorable. So the young men went their separate ways.

The modeling work paid well, the vaudeville act didn’t. The Twenties were a real heyday

themselves and their body improvement systems though cheap magazine advertising. Liederman and Atlas would both get into the mail-order business. One of these men would become the “King of mail-order muscle” while the other’s business would be on the brink of collapse as the clouds of the Great Depression loomed.

While the Twenties were a busy time for the muscle-by-mail business, it wasn’t a new concept. The first attempts date to the late 19th Century. Eugen Sandow, a German bodybuilder usually referred to by only his last name, was a major success in promoting physical culture (what we now basically just call fitness) via advertising in the early years of the 20th Century. Liederman admired Sandow, and while Liederman was unable to capture the same amount of fame of his idol, he did establish himself as the “King of Mail Order Muscle.”

Liederman’s success with his business was quite notable given the sheer number of competing hustlers. And it was a hustle. There was virtually zero oversight of the many claims made in these muscular-improvement ads. Photos of successful students along

advertising for Atlas’ mail-order course. Instead of promising big muscles, he focused on how the Atlas course could make you more of a man, someone who could be in charge of his own destiny. It was Roman who gave a proper name to the resistance musclebuilding technique that Atlas developed. He called it Dynamic Tension. That it required no equipment only added to the appeal of the Atlas method, especially during the Great Depression.

And it was Charles Roman who created the comic-strip-style “the Insult that made a man out of Mac” ad campaign.

The success of the new advertising approach was quick. The course, in its entirety, cost $29.95 then (close to $160 today) and remained at that price for decades. Still, it was a lot of money to spend on a quest to become more of a He-Man or, in the words of

(ABOVE AND OPPOSITE) Even though the “Insult That Made a Man out of Mac” was an instant classic, ad writer Charles Roman continued to try variations that might be more effective. (INSET) Atlas was always ready to show his physique. © Charles Atlas, Ltd.

Atlas’ most famous ad, “Hero of the Beach!” during such a bad financial downturn. Adding to his success, competitors started to fall away, opening up the field thereby allowing Atlas to dominate.

Strength magazine folded in 1930 (though Physical Cultur e hung on for years longer), but Atlas found plenty of other magazines directed to boys and men with cheap advertising in which to push his positive message. But it was when comic books emerged in the Thirties that Roman soon saw them as a perfect location for Atlas ads, where they became iconic mainstays.

Charles Atlas, Ltd. was a huge success. So what does a bodybuilder with lots of money do? He gets into a fight.

Without having heard of the term “thought provoking,” seven-year-old me was thinkin’ up a storm while watching a rerun of The Twilight Zone. Rod Serling’s 1959–1964 anthology series often presented deep-dive reflections on the human condition disguised as fantasy and sci-fi. The episode I beheld was the one with Inger Stevens, the one with the robots. You know the one.

In 1960’s “The Lateness of the Hour,” Jana (Stevens) feels isolated and generally creeped out while cooped up in a wellappointed mansion with her elderly parents, as uniformed servants dish out cocktails and massages. Jana’s mom (Irene Tedrow) really digs the massages—her incessant moaning makes this clear. Jana can’t take another minute of this. She insists that her father (John Hoyt), a wealthy inventor, dismiss the staff. She has her reasons. Though the servants easily pass as regular humans, they are... robots.

When Dad orders the servants to “go downstairs and wait for me,” they know exactly what this means: dismantlement. They all protest. Says the butler: “But I’ve been an excellent butler, sir.” Says the maid: “There isn’t a more efficient maid in the entire country.”

This moment punched me in the stomach. I felt so sorry for the robots! One minute, they’re serving martinis, the next, they’re headed for the scrap pile.

This Twilight Zone episode went through a twist or two before reaching its climax, none of which I wish to spoil here despite its being more than 60 years old. (That’s what the internet is for.)

But it illustrates shifting attitudes about robots that were emerging in popular culture by the Sixties. Heretofore, when robots were presented in a story, the fact itself was a source of marvel. A robot?! But by the Sixties, their presence was so commonplace—in movies and television, I mean—that comedy, irony, “thinky” stuff and even glamour crept in. Robots infiltrated prime-time TV series (My Living Doll, Lost in Space); movies (Creation of the Humanoids, Dr. Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine); animation (Rosie in The Jetsons, Gigantor); comic books (Metal Men, Magnus: Robot Fighter); and toys (Rock ’Em Sock ’Em Robots). It was kind of a golden age. Or at least a transistor age.

Three generations later, robots are all around us in real life, here on Earth-Prime. But none of them look like the metallic one from Lost in Space, and especially not the sexy one from My Living Doll. Alexa and Siri answer trivia questions, give us weather reports, and remind us to check the roast. “Autonomous” vacuum cleaners patrol our carpets like Bop-a-Bears.

Drones take spectacular vacation videos… and kill people. (Talk about a wide range of usage.) We used to drive cars. Now cars drive us.

Real-life phenoms such as the Industrial Revolution in America (beginning in the 1870s) and Henry Ford’s implementation of the “assembly line” (beginning in 1913) found humans using machinery to do the heavy lifting, both actual and metaphorical. Perhaps a few less bodies would be required, but it was all for the greater good, right? Eh, eh, eh...

The classic humanoid robot, as initially envisioned, was popularized in science fiction on the stage, in print, and on film. The word “robot” is said to be a derivative of “robota,” a Slavonic term translated as “forced labor.” The word was introduced in the 1920 dystopian play R.U.R. by Czech writer Karel Čapek. These earliest ’bots were living beings made with synthetic flesh and blood who could pass as humans.

Robots of every stripe were described in stories published in the sci-fi “pulps”—that is, pulp-fiction digests which sold for a dime in the pre-everything age. (Without sophisticated portable devices with which to entertain themselves, people used to read.) Artists like Earle K. Bergey, Frank R. Paul, and Frank Kelly Freas delineated robots on the covers of such pulp-fiction magazines as Weird Tales, Amazing Stories, Astonishing Stories, Astounding Stories, Astounding Science Fiction, Thrilling Wonder Stories, and Fantastic Adventures.

One of the earliest robots on film was the shiny, sleek female Maschinemensch in Fritz Lang’s masterpiece of German Expressionism, Metropolis (1927). “She” was played by Brigitte Helm, also seen in human form as Maria. In these prescient dual roles, Helm struck a blow for womankind and machinekind— and did some far-out dancing.

Maschinemensch was an Art Deco marvel of design and execution, but robots in the movies would not always be so exquisitely rendered. Crank-’em-out movie serials depicted robots as plodding, boxy automatons that were destructive but easily outrun. Movie cowboy Gene Autry fought an army of such

(ABOVE) Brigitte Helm as the Maschinemensch in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927). © Universum Film. (INSET) Exciting art by Earle K. Bergey on the cover of the sci-fi pulp Startling Stories (1950). © Thrilling.

machines in the 1935 serial The Phantom Empire. Bela Lugosi was clearly between major film roles as a goateed mad scientist who commanded an eight-foot robot (Ed Wolff) in another serial, The Phantom Creeps (1939).

Robots continued to be refined into the Forties and Fifties. In his sci-fi short story “Runaround” (1942), Isaac Asimov conceived the “Three Laws of Robotics,” a sort of declaration of principles. It wouldn’t be long before the first such law was disregarded by robots in subsequent fiction: “A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.”

When Klaatu (Michael Rennie) emerged from his flying saucer to wag his finger at we destructive humans in Robert Wise’s The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), his traveling companion was Gort, a mysterious giant robot with a tank-melting ray. Robby the Robot in Fred M. Wilcox’s Forbidden Planet (1956) couldn’t provide meaningful companionship for wild child Altaira Morbius (Anne Francis), which may explain why she canoodled with Earthling interlopers.

Many times over the past century, science fiction has become science fact. During the post–World War II boom, crude robots

(LEFT) Gort demonstrates his tank-melting ray in The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951). © Twentieth Century Fox. (RIGHT) Anne Francis gets a hug from Robby the Robot—um, OK—in Forbidden Planet (1956). © Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Alan Young (1919–2016) was a man of many talents. Born in England, as a teenager in Canada he began working in radio broadcasting. This led him into a long and successful career as an actor, writer, and voice actor in films and television. His comedy-variety program The Alan Young Show was aired on radio and later on television in the Forties and Fifties, earning him a pair of Emmy Awards in 1951. RetroFans may recall him in films such as George Pal’s The Time Machine, or as the voice of Walt Disney’s Uncle Scrooge McDuck, but his most famous role was as the straight man to a talking horse in the popular Sixties sitcom Mister Ed

This interview was conducted with Mr. Young on September 26, 2013, roughly three years before his passing. The interview was transcribed by Randy Clawson and has been edited for presentation in RetroFan

RetroFan: Do you mind telling me a little bit about the beginnings of your career? And how you got into radio?

Look who’s talking now—TV’s favorite talking horse razzes Wilbur Post, played by our interview subject, Alan Young. Detail from the cover of Gold Key Comics’ Mister Ed #5 (Nov. 1963).

Alan Young: I entered the business in Vancouver, Canada. I did a little entertainment for some group and in the group was a girl who was a singer on a radio station and she said, “How’d you like to be on radio?” And I said, “Sure!” I was only about 14 or 15, I guess. So they took me to a station called CJOR in Vancouver… and I did my little act. From then on I was in Vancouver and did a few variety shows. Then I became a jack-of-all-trades, answering the phones and things of that nature…. stooge, and so on… and that was the beginning of my career.

RF: Were you a Canadian citizen?

AY: No, I was British. I was born in Northern England.

RF: The radio show you did do in Canada, what was its name?

AY: The Bathhouse Review was the Saturday night show I did.

RF: Was it a comedy show?

AY: Yes, it was a variety show, and I did a lot of imitations of English performers that people liked because many of them [the audience] were probably from England. I wrote little sketches and it started my writing career.

RF: How did you learn to do imitations so well?

AY: They had a program I’ll never forget called The British Empire Program, and there were recordings of Gracie Fields, and all different British performers, and I began to imitate them. And that’s how I did my dialects.

(ABOVE) David Stern’s 1946 novel Francis, the Talking Mule inspired more books, a film franchise of seven movies with Donald O’Connor as Francis’ human co-star, a syndicated comic strip, comic books, and more. © Universal Pictures. (RIGHT) Carol and Wilbur Post— actors Connie Hines and Alan Young—and their stable resident on the cover of Gold Key Comics’ Mister Ed #1 (Nov. 1962). © Waterman Entertainment.

Heritage.

AY: Yes. I participated in the rewrites. We would do a preview of some sort. Then we would get together in the office and rewrite it. We’d then do a read-over, and after the read-over I would go in with the writers. We had a head writer who was so good! They asked me to go in and do it with them.

George Burns was in the rewrites, and that was fun!

RF: How long did it take to film each episode?

AY: We would work about three days shooting them. We had a single camera. We shot it like a movie. You couldn’t shoot it with an audience because with the horse, he would get too nervous with all the people.

After the show went off the air, I used to ride him every morning. He was living with the trainer in back of the trainer’s house. I’d go over every morning and knock on the trainer’s door, and he’d say, “He’s in the back, Alan.” So I’d walk back and say, “Hey, Ed!” And he’d stick his head out of the barn and we’d go for a ride in Griffith Park.

RF: Wow! How old was the horse when he died?

AY: He was about nine. Actually, he should have lived longer, but we were all away, and Lester Hinton, who was the trainer of the horse—and he was a wonderful trainer—was away, and they had a horse sitter come in. Ed had a very heavy body and very slender legs. And when he rolled around—rolled himself, you know, like on the grass—he had a little trouble getting up, but he’d get up. The horse sitter saw him fumbling around and thought he was having a fit, so he gave him a pill. Ed had never taken pills or anything. This was a tranquilizer, and he just slept away, which was a big disappointment to everybody.

RF: Had you ever ridden a horse before the Mister Ed show?

AY: Never.

RF: Did you continue riding after Ed’s passing?

AY: I didn’t at all. I had taken dressage lessons, which were the hardest lessons you could take, because they wanted me to learn to ride properly for Ed, but I never was a good rider.

I would never have to use the reins with Ed. I would nudge him, and I’d just say, “Let’s go, Ed!” And he would start in. And I’d say, “Let’s stop here!” And he’d stop. I’d say, “Turn right!” And he would turn, I would lean right and he would turn, and so I never had to use the reins with him at all.

RF: Was Mister Ed the first real Hollywood performance for the horse?

AY: No, no. The trainer was sent up to northern California, where they have a lot of ranches to pick the handsomest horse they could get, and so he came back with Mister Ed. Ed came from a very fine line of horses.

RF: Was the horse owned by the studio?

AY: Yes.

RF: What about your wife on the show?

AY: Oh, Connie Hines. A beautiful girl! We were going to audition [actresses] for my wife, and Connie Hines walked in. One

Where can you find hardback books dedicated to the favorite television shows of your youth? Where can you find previously unseen adventures of the likes of Starsky and Hutch or Magnum P.I. or, even, Inch High Private Eye? Where are there articles about Max, the Bionic Dog, or puzzles and games about Wagon Train? Or, how about Huckleberry Hound playing cricket? All these, and more, were to be found in the hardcover annuals produced in vast quantities by British publishers from the Fifties to the Eighties (and beyond, albeit in diminishing numbers). Retro Brit once more steps into the place where British and American pop culture meet to explore this phenomenon.

The annual publication is a long-established tradition and RetroFan readers will probably be aware, for example, that Sherlock Holmes first appeared in Beeton’s Christmas Annual in 1887. The British children’s annuals were a distinct sub-category of this publishing phenomenon. Unlike the annuals produced by U.S. comic publishers, which have typically been in the form of a higher-page-count version of an ongoing comic book, British annuals were made to look like books rather than magazines. They were anywhere from 60 to 160 pages and usually contained a mix of comic-form stories, text stories with

(ABOVE) The Starship Enterprise ’s voyagers, as seen on the front and wacky back covers of the 1976 Star Trek Annual. (RIGHT) The Bionic Dog, from the pages of The Bionic Woman Annual #2 from 1978. Star Trek

illustrations, features, puzzles, coloring pages, photo features, and anything else the editors thought the readers would like. They were magazine sized in dimensions, rather than comic-book sized and bound between hardcovers rendering an artifact that was made to last. While many of the annuals produced were based on British properties, RetroFan readers may be interested to know how many of these books were based on U.S. TV shows.

Kids cared little about the point of origin of TV shows. They just knew what they liked, and if they liked it, then publishers were only too happy to step in to supply spin-off books, if there was a profit to be made. So, how did this work? The annuals were usually published in August or September each year with a cover date for the following year. So, for example, Star Trek Annual 1977 would be in the shops around September 1976. This gave a long lead time for the Christmas market to which they were marketed. Because they were priced as the hardback books they were, the main purchasers were parents and grandparents who bought them as Christmas gifts. One aspect of this was that the adults buying the books liked to think they were buying something like a “proper book” for the kids so the publishers made sure to include a fair proportion of text stories and features. Enough, at least, that once unwrapped on Christmas morning they would keep the recipient busy for the next few days and buy the adults some peace and quiet. Once the holiday season was done the booksellers quickly remaindered the leftover stock. Kids wise to this tactic could take Christmas gift money and buy themselves another few annuals for less than half price, as often as not. One risk of this business model was that the lead time meant the annuals has to be started

I clearly recall the first time I saw a promo for an upcoming NBC TV show. I thought to myself, “Who would watch something called Miami Vice?”

As it turned out, I would!

I didn’t tune in right away. In those days, I wasn’t watching much TV. Months later, I caught a teaser for an upcoming episode so compelling I decided to check it out.

It was a nail-biting hostagerescue piece called “The Maze.” I was hooked.

Miami Vice had its origins in a movie script called Gold Coast written by Anthony Yerkovich of Hill Street Blues fame. The title had to be changed for copyright reasons. But it survived as the name of the Organized Crime Bureau’s cover operation, Gold Coast Shipping Company.

About this time, NBC president Brandon Tartikoff penned his now-famous “napkin” memo: “MTV cops.” The video music cable channel MTV was only three years old.

“I do think you have to be cognizant that there is a whole generation of younger viewers who are not only watching these videos, but who may have been spoiled by the production values,” Tartikoff explained. “So we’re trying to incorporate these devices wherever possible, without destroying the integrity of the show.”

Enter producer-director Michael Mann, whose credits ran from Starsky & Hutch to Thief

“What they were looking to me to bring to the show was a very contemporary, highly stylized look,” he explained.

Yerkovich was fascinated by South Florida’s changing face. The Mariel boatlift brought an influx of Cuban refugees and the drug trade was booming.

“I read a statistic that said one-third of the illegal revenues in the United States came out of South Florida,” he noted. “I wanted to explore the changes in a city that used to be a middle-class vacationland. Today Miami is like an American Casablanca, and it’s never really been on television.”

Learning of asset seizure forfeiture, where the police confiscated ill-gotten gains and used them for undercover work, Yerkovich realized that justified his stars driving high-end cars and wearing high-fashion clothes and Rolex watches.

The show was designed to explore the lives of a small undercover Miami anti-vice unit, but the star would be James “Sonny” Crockett, a detective who lived on a sailboat with a pet alligator in his double life as a hard-partying ocean guide of questionable means. His partner would be Ricardo Tubbs, a black New York cop who comes to Miami on a personal vendetta.

Casting was critical to the show’s success. Scores of potential Crocketts and Tubbses were auditioned. NBC wanted Nick Nolte or Jeff Bridges. For a time, Larry Wilcox of CHiPs was under serious consideration, as was Mickey Rourke. Countless Black actors were auditioned for the part of Tubbs, Denzel Washington among them; Washington’s career had yet to take off.

Surprisingly, Saundra Santiago was the first actor cast for the series, in the role of Gina Calabrese. Originally, she was Sonny’s steady love interest.

“I was given third billing as the leading lady,” Santiago recalled. “It was supposed to be a part like Veronica Hamel’s on Hill Street Blues.”

Casting Crockett and Tubbs proved tough. A roulette wheel of actors was tested until one pair clicked.

The season ended with “Lombard,” in which former Chicago detective Dennis Farina played the titular mob boss, who had previously appeared. The episode ended with a strong hint that Al Lombard, who was forced to testify against another crime boss, was about to be hit.

Early ratings were lackluster. But Miami Vice took off during the summer rerun season, which is where I came in.

Nor was I alone. Not only in becoming a fan but also in being slow off the mark. For a show that became a tremendous hit and a landmark cultural icon, Miami Vice didn’t start catching on until the end of its first season.

During that first year, a balance was struck between Crockett and Tubbs, the latter of whom Michael Mann once called “nobody’s Tonto.”

Mann later acknowledged, “The equivalency lasted most of the first season, but for reasons that had to do with the two actors and one thing or the other, that eroded a little bit.”

The Sonny-Gina relationship soon fell by the wayside under the inevitable necessity of propelling the lead into new romantic entanglements.

“I decided to approach Gina in a kind of offbeat way,” Santiago observed. “I mean, here she slept with Crockett and feels kind of guilty about it because they work together. She likes him, she’s attracted to him, but knows she shouldn’t be involved with him.”

By the time Miami Vice returned on September 27, 1985, everyone, it seemed, was watching it.

“By the beginning of the second season,” recalled Don Johnson, “it had become phenomenally successful. But I didn’t really pay much attention to it. I just sort of kept my head down and kept working. I was the last one to know it was a hit.”

Jan Hammer, who composed the synthesized score and incidental music, became hot in his own right, winning a Grammy for his score. The Miami Vice Soundtrack hit #1 on the Billboard Top Pop album chart. It eventually sold four million copies, going quadruple platinum.

“It was very intense,” he reminisced. “The thing that made it work is that I was given complete artistic freedom. I was not locked into a ‘Miami Vice’ sound. There were weeks when the music was Afro-Cuban, jazz, then experimental electronic, even flat-out rocking. There was no need to worry about consistency. Every week

Eagle-eyed RetroFans will recognize rocker Glenn Frey with Detectives Tubbs and Crockett in this promo photo from “Smuggler’s Blues,” Miami Vice ’s 16th episode, first seen on February 1, 1985. (INSET) Frey’s “Smuggler’s Blues” record. IMDb. Miami Vice © NBCUniversal.

was different. I could respond to the songs that were placed in the show. When the score came out of the song, sometimes they almost blended together.”

The producers credited Hammer with saving plot-murky episode 13 with his artful use of incidental music.

From 1973 to 1983 on ABC-TV Saturday mornings, the Super Friends series had gone through numerous title changes, two cancellations, and tonal changes that seemed multiversal—not to mention having an entire season animated but never aired in the United States! DC’s pantheon of Justice League members—Superman, Batman and Robin, Wonder Woman, and Aquaman, aided by the Wonder Twins, Zan and Jayna, with their space monkey, Gleek— seemed as if retirement might be coming for them as they exited the air in Fall 1983.

But DC Comics and Hanna-Barbera Productions weren’t quite ready to let their super-heroic cash cow go, and with the help of a toy company, 1984 looked promising for a fresh new look at the venerable series…

In the previous three issues, we examined the first decade of Super Friends (SuperFriends in some incarnations), ABC’s 13-year Saturday morning hit. And now read on as Andy Mangels’ Retro Saturday Morning wraps up your guide to the longest-running animated super-hero series ever!

In 1982, toy company Mattel introduced a line of musclebound action heroes that combined barbarian action with sciencefiction and magic. The Masters of the Universe line saw the adventures of He-Man and his fellow heroes fighting against Skeletor and his evil cronies, for control of Eternia. The toy line was a massive hit, jolted into the stratosphere with Filmation’s He-Man and the

Masters of the Universe animated series, which debuted in the fall of 1983 with a five-day-a-week schedule. [Editor’s note: See RetroFan #22 for a Masters of the Universe history.]

Suddenly, every toy company was looking for its own franchise that could turn kids into piggy banks, leading to toy lines and syndicated series for Inspector Gadget, G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero, Transformers, and eventually Thundercats, She-Ra: Princess of Power, Care Bears, My Little Pony, Jem, and dozens of others.

Kenner Products was still producing the popular Star Wars line of action figures, but with no new movies on the horizon, that line was dying. In 1982, they approached DC with a pitch to get the master toy license. Mego Corporation had been producing DC character eight-inch dolls for most of the Seventies, but they closed their offices and declared bankruptcy in 1982. Kenner competed against Mattel for the DC master license—except for DC’s barbarian figures Warlord, Arak, and Hercules, concurrently being produced by Remco—but Kenner did a massive presentation, utilizing DC Style Guide art by José Luis García-López and pitching at least three years’ of figures, as well as playsets and action vehicles.

Cover to Kenner’s pitch for a DC character master toy license (competing against Mattel) which was ultimately successful. TM & © DC Comics.

Kenner repainted a Star Wars figure as Captain Marvel (Shazam!) and attached him to a rod device to simulate flying, repainted some of their Glamour Gals dolls to resemble Wonder Woman and Supergirl, and added a wheel in a Mego Pocket Heroes Batman that allowed him to punch. This latter was crucial to Kenner’s presentation as they wanted the emphasis on the line to be that each hero had a “Super Powers Feature” that would enhance kids’ play. A line of girls’ 12-inch fashion dolls was also planned, as well as a line of “Super Jrs.” baby toys and a “Micro Collection” with die-cast features, as Kenner had done with Star Wars

Kenner was awarded the license, but the new line—titled “Super Powers Collection”—wouldn’t be ready until Spring 1984. This gave DC time to go to Hanna-Barbera with the news, and for the animation company to pitch their old pals at ABC. In quick succession, a new SuperFriends series was ordered to tie in with the toys.

For this season of SuperFriends, a secondary title was added, to tie in to the toy line. Thus was born SuperFriends: The Legendary Super Powers Show. The opening titles featured new music by Hoyt Curtin, with an announcer only repeating the title at the end. The sequence featured an animated short of the various DC heroes fighting a giant robot and the evils of Darkseid, Brainiac, Luthor, DeSaad, and Kalibak. The sequence also featured the introduction of new hero character Firestorm (who had appeared in the comics since 1978), as well as showcasing Wonder Woman’s new bodice, emblazoned with a WW symbol (which she had adopted in 1982). Oddly, although both were featured in the opening, Aquaman and the Flash never appeared in this season at all, and the opening featured old designs for Lex Luthor and Brainiac that didn’t correspond to their new toy looks (based on new comic designs by George Pérez and Ed Hannigan).

SuperFriends: The Legendary Super Powers Show debuted on September 8, 1984, with a two-part story called “The Bride of Darkseid.” In it, Jack Kirby’s Fourth World villain and his grotesque son Kalibak used their “Star Gates” (known in comics as Boom Tubes) to teleport from Apokolips to Earth to capture Wonder Woman, upon whom Darkseid developed a crush. The Justice Leaguers, meanwhile, met Firestorm, a young hero who could transmute matter, and who was really a teen boy named Ronnie Raymond, fused with the mind of Professor Raymond Stein.

“Darkseid was a difficult character to get past Broadcast Standards at that time,” said writer Alan Burnett. “When they saw

(ABOVE) Title card to Hanna-Barbera’s SuperFriends: The Legendary Super Powers Show. (BELOW) The fearsome and power-mad Darkseid (LEFT) and his cruel, brutish son Kalibak stand before a “Star Gate” encircled by sparkly lights. TM & © DC Comics.

Transmuted from the comics page to television, Firestorm could change the components of any inorganic matter. He was secretly student Ronnie Raymond, with the mind of Professor Martin Stein linked in! TM & © DC Comics.

Darkseid (LEFT) encounters the more fearsomelooking new style Brainiac. (INSET) Animation model sheet of the old style Brainiac. TM & © DC Comics.

the initial drawings of him they were, ‘Oh, this is much too scary for our audience’... The biggest fight we had was getting his name accepted… Darkseid, with the spelling being S-E-I-D… they thought it was going to offend their German viewers! So they refused to allow us to use the name… I am told that that question about the spelling of his name actually went to the President of ABC to decide!”

Fellow writer John Semper stressed the frustration with Standards. “From the moment you had an idea for a cartoon, the entire process in a way was just a giant beatdown. It was, ‘Let’s see how many ways we can find to take the life out of what it is you’re writing and trying to bring to the screen.’”

Viewers of the season saw changes all throughout: Although the episode title cards still featured Wonder Woman’s eagle bodice, they also now featured writer’s credits; the Wonder Twins, Zan and Jayna—with Gleek—were in only a trio of stories; and the so-called “ethnic” heroes of color—Apache Chief, Black Vulcan, Samurai, and El Dorado—featured far more regularly. Green Lantern got one cameo appearance, but previous teammates such as Atom,

(INSET) Writer John

Batman, Superman, and Firestorm with two heroes of color: El Dorado and Black Vulcan. TM & © DC Comics.

Hawkman and Hawkgirl, and Rima the Jungle Girl were nowhere to be seen.

Semper talked about the ethnic characters on the DVD set. “Everything the network did was very ham-fisted. There was nothing subtle about anything they did. So consequently, just as you got ham-fisted plots and kind of ham-fisted handling of super-heroes, you got this sort of brute force injection of ethnic characters into SuperFriends… Are the characters sort of ludicrous and ridiculous? Yes. Are they at a disadvantage because we don’t know their backstory, they don’t have backstories? Of course. Really all that they were, were cartoon character versions of ethnicities.”

More DC villains did appear, including Flash villain Mirror Master and Superman foe Mr. Mxyzptlk, and clear stand-ins for

Semper. (RIGHT) (LEFT TO RIGHT)