Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course

Executive summary, Autumn 2022

Urban Ecological Planning Master’s programme

Department of Architecture & Planning, Faculty of Architecture

Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway

AAR4525 - Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course

Executive Summary, Autumn 2022

Urban Ecological Planning Master’s Programme

Department of Architecture and Planning, Faculty of Architecture

Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim, Norway

Course Coordinator: Supervision Team:

Gilbert Siame

Associate Professor, NTNU

Gilbert Siame

Associate Professor, NTNU

Rolee Aranya Professor, NTNU

Mrudhula Koshy

Assistant Professor, NTNU

Riny Sharma

Assistant Professor, NTNU

Booklet Layout:

Mrudhula Koshy

Assistant Professor, NTNU

Vija Viese

Research Associate, NTNU

2 | Executive Summary | Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course

4 | Executive Summary | Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course 5 | Executive Summary | Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course Place of origin of authors Group 1 Group 2 Group 3 Group 4

Preface

After two years of pandemic-related restrictions which affected many aspects of the Urban Ecological Planning Programme (UEP), and especially its first semester obligatory fieldwork, the 2022 fieldwork under the Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course was conducted in Kochi, India. This was a planning studio project with emphasis on international mobility and knowledge exchange among students from India, South Africa, and Norway. The project forms a core component of the two-year International Master of Science Programme in Urban Ecological Planning under the Department of Architecture and Planning at the Faculty of Architecture and Design at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). The 2022 project activities rejuvenated the UEP passion and curiosity about challenges and opportunities being faced by cities of the Global South. Students spent eight weeks working in Kochi city in the Southern Indian state of Kerala. The project was structured and framed to contribute directly to the UTFORSK funded Norway-India-South Africa (UTFORSK-NISA) student and staff mobility project on localisation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Thus, the project involved NTNU, School of Planning and Architecture (SPA), New Delhi, India, All India Institute of Local Self Government (AIILSG) and the University of Cape Town (UCT) in South Africa. This report represents a major output from the integrated effort of communities, bureaucrats, and most importantly, the students from NTNU, SPA and UCT.

This project report is an outcome of studio work done by NTNU students. The report provides detailed information about students’ experiences, learning and context-informed recommendations for improving living conditions on study sites in Kochi city. Students’ learning and recommendations are based on UEP’s teaching philosophy of experiential learning. Students’ exposure to an unfamiliar context poses several challenges while working on an academic goal but it also provides the necessary ‘triggers’ for learning that is simply not possible in traditional planning studios that are of shorter duration and have less emphasis on being out in the field.

The project report is informed by methods that allow students to propose solutions to complex but interlinked urban problems based on area-based planning and participatory planning

approaches. This year’s report emphasises some of the most important UEP values and topics that include inclusive urban planning and development, ecological integrity in cities, and sustainable urban livelihoods and accessibility. By working with local communities, local and international stakeholders, students identified, analysed, articulated complex issues, and made realistic recommendations to improve living conditions on specific study sites.

The students were divided in 4 groups and 2 of them worked in Fort Kochi while others in Ernakulam areas of Kochi city. Fort Kochi is a seaside historical area known for its Dutch, Portuguese, and British colonial architecture, and heritage and fishing. It is a significant tourist area for the Kerala State. On the other hand, Ernakulam is a sprawling residential and commercial hub well known for Marine Drive and a busy waterfront. Zeroing in on specific sites, the reports deeply reflect on the urban everyday life experiences, challenges, and opportunities for people in Kochi. While retaining the area-based planning approach, students’ work was based on the overarching theme of urban informality and guided by three themes: ecological vulnerability, urban markets, and urban mobility. As an outcome of their learning process, students prepared four reports to illustrate and reflect upon the participatory process through a situational analysis and reflection on methods and methodology that informed a problem statement which they tried to address in strategic proposals. This report summarizes the work of the group working with accessibility and livelihood theme in Fort Kochi.

We would like to give a special mention for Centre for Heritage, Environment and Development (C-HED) and World Resources Institute (WRI) India for their constant support to our students in terms of giving them insights on local context and different themes that students worked on and for connecting them further with relevant stakeholders and documents.

6 Executive Summary | Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course 7 Executive Summary Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course

Gilbert Siame, Rolee Aranya, Riny Sharma, Mrudhula Koshy, Vija Viese

Fieldwork supervisors, NTNU, Department of Architecture and Planning.

4. Do challenges in daily commuting affect people’s livelihood?

Policies in play: Reclaiming livelihoods and heritage in the Ernakulam market 8 Executive Summary | Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course Preface 1. Introduction 2. Group 1 2.1 Introduction and Context 2.2 Methodologies 2.3 Situation Analysis 2.4 Spatial Solution 3. Group 2 3.1 Introduction and context 3.2 Methodology 3.3 Situation analysis 3.4 Spatial solutions 3.5 Conclusion 4. Group 3 4.1 Introduction and Methodology 4.2 Situation Analysis 4.3 Goals, Strategies and Spatial solutions 4.4 Urban Governance 4.5 Reflection and Conclusion 5. Group 4 5.1 Site context and Methodology 5.2 Situation Analysis: Findings, Challenges, and Limitations 5.3 Strategic Spatial Solutions 5.4 Conclusion and Reflection 6. References and List of figures

2 Reviving the social and ecological vibrancy of Sandakhulam

3. (Re) gaining Ecological Futures Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India

10 12 14 17 19 22 24 26 27 30 32 35 36 38 40 42 45 47 48 50 53 56 61 62

Contents

1. Policies in Play - reclaiming livelihoods and heritage in the Ernakulam Market, Kochi

This executive summary is part of the group’s UEP fieldwork report from Kochi in 2022. The group was divided into 4 groups in 2 two focal area of the city. Group 1 and 2 were focused on The Ernakulam market around the market canal area on mainland Ernakulam. Group 3 and 4 were focused on the Calvathy canal area in Fort Kochi. Different themes was selected by each groups to cater to diverse theme that could be analyzed in the city’s urban context.

Group 1 analyses the redevelopment of the Ernakulam Market through a critical lens. It looks at the case in a contextual setting, discussing how this will affect the urban dynamics on the multiplicity of scales in which the market operates. Furthermore, it discusses the market redevelopment as a part of global tendencies in urban development. Lastly, it discusses alternative planning pathways that can include multi-level governance structures and most importantly, that can respond to the networks, relations, logics, as well as the history, heritage, and stories that make up the daily life of the city.

For group 2, ecological vulnerability has become a global issue as the ecology of the planet is being disrupted day after day. The absence of wise environmental management, inadequate use of resources, poor urban policy and design that disregards contextual and environmental aspects have contributed to the ecological vulnerability of the urban site. Ecological Vulnerability is the sensitivity of people, places, ecosystems, and species to stress or perturbation. This also includes the resilience of the exposed people, places, ecosystems, and species in terms of their capacity to absorb shocks and perturbations while maintaining function

Group 3 focuses on a neighborhood in Fort-Kochi called Kunnumpuram, and located between two canals, the Calvathi canal and the Eraveli canal Both canals were originally built during the British colonization and served the dual purpose of dividing areas and as a route for the transportation of goods. This area has a rich historical context and and is referred to as « Mini India » as it is rich of cultures and religions, embodying the different faces of India.

The neighborhood is low-income area affected by a serie of environmental, social, economic and governance issues that have been negatively affecting the residents’ livelihoods in the area. However, we saw a lot of potential and were convinced Kunnumpuram has the capacity to become a thriving, resilient, and inclusive community.

Finally, a bit similar to the previous group, the chosen site of group 4 is on the larger scale of the Calvathy canal area, Fort Kochi. Having analyzed the situation in the area, the group concluded that the pressing issues are the current public transportation system quality, walkability struggle, and safety and inclusivity issues. Hence, the group decided to focus on those issues, which covers transport and mobility, and critically analyze how thos aspects affect the local’s livelihood condition. Based on that frame, the group proposed a set of multilevel, strategic, holistic, and comprehensive urban planning spatial solutions. In focusing the efforts to cater to the needs of the local context, with an area-based approach - direct hands-on observation and interactions, participatory workshops, and community engagement are crucial in the development and implementation of the proposed solutions.

10 Executive Summary | Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course 11 | Executive Summary | Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course 1. Introduction

Figure 1.1: The student groups during some of the activities in the fieldwork

Policies in Play - Reclaiming livelihoods and heritage in the Ernakulam Market

Policies in Play - Reclaiming livelihoods and heritage in the Ernakulam Market

Ami Joshi

Stine Kronsted Pedersen

Aditi Patil

Karl Schulz

Ill. 2.1 - Ernakulam Market

Policies in Play: Reclaiming livelihoods and heritage in the Ernakulam Market

Introduction Context

This is a proposal for a revised urban planning scheme for the Ernakulam Market in Kochi, India.

The market is located in a historical part of Kochi and has a distinct heritage value. Currently, the market is undergoing a transformation undertaken by the Cochin Smart Mission Limited (CSML). The empirical findings indicate the new market proposal was based on a top-down approach to planning, resulting in the loss of livelihoods of the people who depend on the market.

How does a top-down approach to planning a living, growing public space like the market affect the livelihoods, and the socio-spatial relationships within the community? What kind of insecurities does this approach bring in the minds of the different stakeholders?

Understanding a site means understanding how it is situated in its context. Ernakulam Market is located in a commercial area in the Ernakulam district of Kochi. This area has a particular geography being situated adjacent to the mouth of a complex network of backwaters, streams and canals. This specific geographical position is related to the history of the site.

The context can be understood as the local, nearby area, but it can also be understood as the context of Kerala, the context of India, or the global context. It is a multiscalar concept and understanding the Ernakulam Market means understanding how it is related to the world, from the day-to-day activities on the site, to the relation to historical global and trade networks of the past, present and future.

Kochi has a strategic position on the coastline of the Arabian Sea, which has attracted traders from all over the world since its founding in the late 14th century. When the British arrived in the late 18th century, the local population was moved out of Fort Kochi, and the first public amenity to be constructed was the Ernakulam Market. The market was a water-based market (picture above), where goods from the mainland were sold for exporting.

The intensity of activity in the market increased and the neighbourhood around the market evolved into a commercial district. The market itself was poorly maintained, and a renovation was agreed upon among multiple stakeholders. A renewal plan was developed by C-HED and other associate consultants in 2019. The plan was contextual and reflected the heritage of the old Ernakulam Market. The project did not go forward.

Informality in formal structures

During the construction process, the market has been moved to a temporary location appointed by CSML. The temporary market offers the same system of stalls as the previous market. However, each stall has less space, the rent has increased and due to lack of space, less trucks are arriving with goods.

The smart city

The ambition of the new market is “... to revive the high commercial value of the decaying traditional market in the heart of the city by redeveloping the existing wholesale and retail market into an organised, highly accessible and best in class shopping destination.” (Csml.co.in. (2021)) (picture: proposed Ernakulam Market).

14 | Kochi, India | Policies in play: Reclaiming livelihoods and heritage in the Ernakulam market 15 | Kochi, India | Policies in play: Reclaiming livelihoods and heritage in the Ernakulam market

Erasing heritage

The market as a node for development

Ill. 2.2 - Drawing of the shopowner in a bananna leaf stall

Ill. 2.4 - 7- Past, present future Ernakulam Market

Ill. 2.3 - Drawing of bananna shop >

How will the market development affect the day-to-day activities of the market, the livelihoods, and the already ongoing gentrification of the community of Ernakulam?

Methodologies

There are multiple ways of analysing a site. The tools you use for approaching fieldwork shapes the outcome of the project. Throughout the project we have been navigating between different methods for each stage of the process: from the research, to the site analysis, to participation and finally, to communicating the project. Some were familiar, some were new to us and had a more experimental character.

Research: To familiarise ourselves with the context of Kochi, we studied existing urban plans and literature related to the city and its development. These were plans developed by the municipality, or architecture and urban design projects made by other institutions or student’s work in Kochi.

Spatial Mapping and Transect Walks: Spatial mapping of the area showed how the market is embedded in a complex network of places and connections. It showed the important relation to the canal and how the canal is both connected to the mainland of Kerala, as well as the Arabian Sea. Furthermore, it gave an overview of important functions in the area, major roads and access points, religious institutions and land-use.

Interviews: Most of the information that forms the base of our proposal comes from the interviews we did on site. We experienced from the interviews was a general belief among the vendors and workers that their opinion did not matter. This experience has informed our proposal.

Co-production: In the project we did co-production of maps and co-production of spatial designs. We drew maps in collaboration with the market stakeholders, which allowed us to gain knowledge that would not otherwise be available for us. They based their mapping on stories and memories, and we transferred these stories into spatial entities.

Thinking through Diagrams: The diagramming and sketching has been iterative, going back and forth between analysis, ideas and synthesis. Looking at our process through the sketches that we have made as we have proceeded, there is a clear trajectory of iterations that has brought us closer to an appropriate proposal for a planning strategy.

We are interested in the historical area of Ernakulam and Broadway, in how the current market has changed compared to the former market, and how the new market will respond to the needs of the community.

YOU are the day to day user of the market and YOU are the expert of your community.

That is why we are here. We would like to hear your opinions and your stories.

For questions, please refer via whatsapp or email to:

(Student) Stine: +91 9037586103 email: stinkron@stud.ntnu.no or Prof. Gilbert Siame: +260979457414 email: gilbert.siame@ntnu.no

UEP STUDENTS IN ERNAKULAM MARKET

September 15 November 10 2022 We are Master’s students in Urban Ecological Planning from Norwegian University of Science and Technology. For our fall we are conducting field work in Kochi, and we are studying the Urban Ecological Planning is a program that studies cities, communities We are interested in the historical area of Ernakulam and Broadway, how the current market has changed compared to the former and how the new market will respond to the needs of the community. opinions

(Student) Stine: +91 9037586103 email: stinkron@stud.ntnu.no or Prof. Gilbert Siame: +260979457414 email: gilbert.siame@ntnu.no

16 Kochi, India | Policies in play: Reclaiming livelihoods and heritage in the Ernakulam market 17 | Kochi, India Policies in play: Reclaiming livelihoods and heritage in the Ernakulam market

UEP STUDENTS IN ERNAKULAM MARKET September 15 November 10 2022 We are Master’s students in Urban Ecological Planning from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. For our fall semester, we are conducting field work in Kochi, and we are studying the Ernakulam Market as case. Urban Ecological Planning is program that studies cities, communities and how to develop sustainable future of urban areas.

Ill. 2.9 - The iterative process where we move back and forth between stages.

Ill. 2.8 - Staff and customers in a vegetable shop >

The market across multiple scales

Most of the shops in the market are family businesses that have been inherited through generations. The owners are proud of their shops and are decorated with personal pictures of gods or the grandfathers who founded the shop.

Each shop has one or more employees. Some workers are from Kochi, while others have migrated from distances as far as Northern India. The migrant workers often come in small groups from the same area to seek employment opportunities.

Several strong institutions govern the market. The Market Association links the market to the municipal corporation. The workers who load and unload the trucks belong to a union, and they are visible on site by wearing similar blue shirts.

Who are the stakeholders?

Ill. 2.13 - 18 (drawings) Illustrating the different scales of interactions

The market is embedded in all neighbourhood activities. The vendors and workers take breaks at the surrounding chai stalls. They drink chai and eat snacks. In the picture you see a chai vendor that circulates the market during the day.

Retail buyers from across the city come to the market to buy their vegetables. Tuctucs are loaded with everything from banana leaves to carrots and cucumbers before they head off to hotels, restaurants or smaller retail shops across town.

Spices, vegetables and fruits are being transported from all over the country to Ernakulam with large trucks. The trucks come in multiple times per week. Livelihoods in states as far as Assam and West Bengal depend on the market activities.

20 Kochi, India | Policies in play: Reclaiming livelihoods and heritage in the Ernakulam market 21 | | Kochi, India | Policies in play: Reclaiming livelihoods and heritage in the Ernakulam market

KMC

Shopowner

Shopworkers (market) Shopowners (market) Union workersWorker’s union CPI (M)

Hawkers Daily-wage workers Retail buyers

Truck driver Local residentsVendors (canal)

Local councillor

(lanes) Market Association

Customers

The individual The shop The market

city The region The neighbourhood

The

Ill. 2.12 - Stakeholder drawing

Spatial Solution: Reviewed Governance system Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways

Governance and governance systems operate on a mechanism of trust, adaptability and accountability. What the study points out in the case of Ernakulam Market, however, is that there is a lack of trust in the minds of the stakeholders of the market (vendors, workers and shop owners) when it comes to government, administration and the representatives. At the same time those working in the bureaucratic and administrative offices hold the people responsible for a lack of desired outcomes when it comes to implementing policies. This indicates that there are gaps existing in the system that need to be addressed before real change and

progress can be made.

The project seeks to relook at the governance system to address these concerns. It looks at rebuilding relationships between the people and the representatives of people to collectively address, monitor and improve situations on ground. This requires a new set of skills in the representatives so that they can listen, learn and cooperate with the people. The project assesses a need for both groups to come forward and acknowledge the shortcomings on their end to co-produce a more cooperative system of mutual accountability.

Previous market site Open, unplanned space | Tabula rasa KMC framework and services | Spaces left open | Loading+unloading

The proposal focuses on an approach that looks at long-term objectives and that is realised through short term actions. The approach is derived from the “Dynamic Adaptive Policy Framework”(DAPP) (Haasnoot et al, 2019). The aim is to ensure that the governance system adapts itself to a dynamic urban reality

and to the needs of the people of the city changing over time. It recognises the need to learn from the way people respond to policy implementation, and assesses the progress it makes to the everyday lives of people. The approach is capable of self-analysing and responding to changing circumstances in an efficient manner.

The starting point of the process of a new market space is the blank site of the previous market. There are no physical remnants of the market, however, in shared memories in the community the market space remains. A new proposal builds on this memory.

A spatial framework is co-developed by the market community and the KMC. In this way, the space can reflect the needs of the people who use the space on a daily basis. Services and public facilities are provided, and space is left open to accomodate public life.

Incremental construction and placemaking Policies manifested spatially Open spaces being inhabited spatially

Feedback on policies affecting socio-spatial dynamics | Continuous incremental construction of marketplace and placemaking

The framework allows for the people of the market to inhabit, organise, modify and construct the space on their own terms. The process is incremental and reflects the occuring needs of the people who use the space.

As policies manifest themselves socio-spatially, recurring feedback and evaluation mechanisms ensure that the governance of the space adapt to realities of the people using the space. Construction of space is a process rather than a product.

22 Kochi, India | Policies in play: Reclaiming livelihoods and heritage in the Ernakulam market 23 | Kochi, India | Policies in play: Reclaiming livelihoods and heritage in the Ernakulam market

Ill. 2.19 - 22 - Diagrams illustrating the how policies come into play in the spatia evolution of the Ernakulam Market

Reviving the Social and Ecological vibrancy of Sandhakulam

Kochi, Kerala, India

Chowdhury Ferdoushi, Hossain Suhi

Miguel Angel, Rosas Jimenez

My An, Dinh

Sharanya, Hoskote Bhavani Shankar

Sandakhulam

Source: Sandhakulam group

The absence of wise environmental management, inadequate use of resources, poor urban policy and design that disregards contextual and environmental aspects have contributed to the ecological vulnerability of the urban site. Ecological Vulnerability is the sensitivity of people, places, ecosystems, and species to stress or perturbation and includes the resilience of the exposed people, places, ecosystems, and species in terms of their capacity to absorb shocks and perturbations while maintaining function. This part focuses on the ecological vulnerable aspects of Ernakulam market canal area in Kochi, a coastal city in the Kerala state of Southwest India and tries building a feeling of attachment between the people and the canal that helps revive its lost heritage and importance while also ensuring its ecological viability.

Ernakulam is still the center of Kochi, it is the most dynamic area of the city, and Ernakulam market remains the most important market of the biggest city of Kerala and one of the most important markets of the state, even if some changes occurred, especially with the development and industrialization. The Ernakulam market canal played an essential role in the economic development of the city. In fact, this market acted like a wholesale provider for the whole city but for the whole state as well. That is why the district have a strong historical heritage and history.

3.2. Methodology

Phase 1: site analysis

After conducting literature research, attending conferences and meetings, and visiting the city, we had to proceed to the site selection, regarding the features that were interesting for us. In our case we were focused on ecological vulnerability. After our several site visits, all of us were really attracted by the Ernakulam market area and especially the canal. In order to come to the problem statement, we first had to proceed to the stakeholders mapping after having defined them first. After having defined the stakeholders, we aimed at understanding the needs assessment of the site. We conducted on-site interviews with the different stakeholders to have their point of view and understand their personal needs and interests and we incorporated them into our observations and issues we noticed on site. We worked with semi structured questionnaires with open questions that we verbally submitted to the locals, and listened to their answers, feedback and history. Understanding the needs goes with understanding the governance of the site: who has the most influence? What are their interests? What are the relations between the stakeholders? Is there any tension between them? By answering these questions, we got to know better who it is better to reach for each of our purposes.

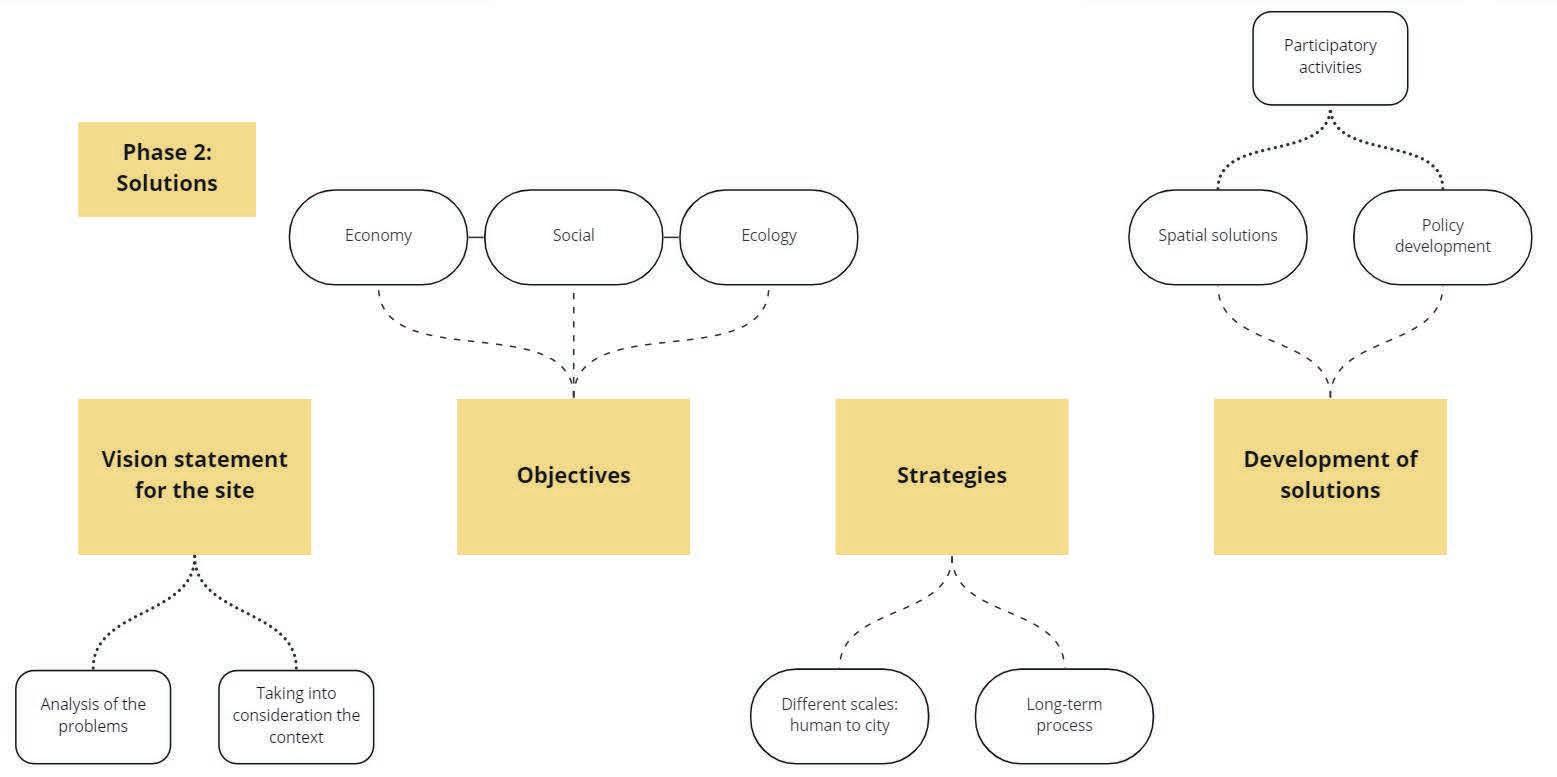

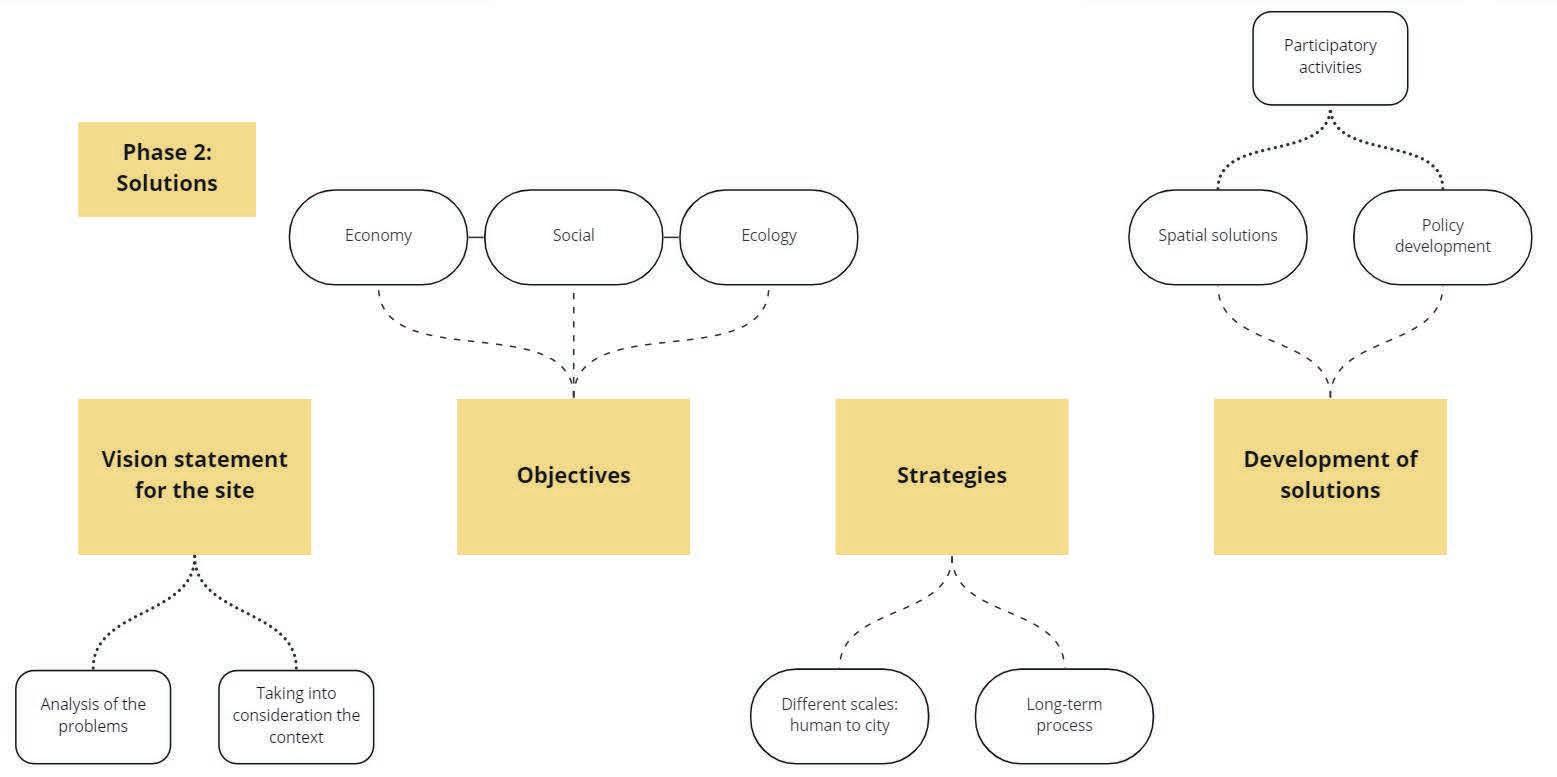

Phase 2: development of solutions

We came up with a vision for the site, what we imagined the space thanks to all the information we gathered and especially the information from the different people we talked to during the site analysis. Our vision is not only personal, it considers the community’s voice by trying to tackle the challenges of our theme, ecological vulnerability. We set certain objectives that we want to reach, objectives that would answer ecological issues but social and economic ones as well. Our strategy is targeting a long-term purpose on a big scale by tackling smaller scale issues in a shorter term. The strategy includes different domains, such as physical implementations but proposals of some policies to a broader scale as well. The last step is the development of the solutions, spatial solutions, policies but above all, keeping the community at the core of the design and creation of the solution. Co-designing the site. We used participatory activity by showing our vision to the different stakeholders, we gathered inputs from them, see what they were attracted or reluctant to. With the input that we received from the locals, we proceeded to make changes in order to come to the most efficient and relevant proposal possible. But we had to keep in mind the theme of our work and find a balance between the different stakeholder’s interests and the ecological situation. Finding a solution that would fit everyone’s interest was the most difficult part of the development of the solutions.

26 Ernakulam market area | Reviving the social and ecological vibrancy of Sandhakulam 27 | Ernakulam market area Reviving the social and ecological vibrancy of Sandhakulam

Figure 3.1.3. India, map of Kochi, Ernakulam market canal

Figure 3 .1.1 : Ernakulam market area

Source: Sandhakulam group

Source: Google Earth

Figure 3.1.2: Pictures of the time: Ernakulam market Source Shop owner in Ernakulam market area

3. 1 Introduction and context

Figure 3.2.1: Pictures of participatory acitivities

Source: Sandhakulam group

Plase 2 : Opinions of the locals based on our analysis Existing

“Already in the Marine area. This won’t work here”

“Boats are cheaper transportation for goods”

“Those stalls on the canal should be removed and given to another place”

“After cleaning!”

“Like this idea of boats trasnporting goods”

“If this works, tourists will come”

Source: Sandhakulam group

“Garbarge should be cleaned daily. It should be another place to dump trash”

Source: Sandhakulam group

We have noticed that people’s lack of interesting the canal was the main issue to tackle. We tried to create a socially inclusive, ecological friendly, economical efficient, and pleasant area. So, in the 2nd phase of the interview we tried to propose few interventions based on the understanding of the existing situation. It was a much easier to understand “what could be changed” for the localities and the community to pictorictally imagine and give their feedback.

28 Ernakulam market area | Reviving the social and ecological vibrancy of Sandhakulam 29 Ernakulam market area Reviving the social and ecological vibrancy of Sandhakulam

condition

Our vision

Figure 3.2.2: Diagram of the process followed the throughout the fieldwork

3.3 Situation analysis and Problem statement

The first impression that we had during our first visit, was the disorganisation of space and movement. People, car, two wheels, trucks,are evolving in the same area. Everything is happening at the same place. Our group also noticed a loss of heritage in this strong historical area. There is nothing left from this important water trade period, except some stairs connecting to the water. The water and ground are polluted . It has degraded the biodiversity of the canal ecosystem and had impacted the fauna and flora of the site.

Nowadays the canal has no economical activity anymore. Because of this loss of activity, people lost interest in the canal over time. While before the canal was central in their economical and daily life and activity. It became part of the environment and people don’t see any potential anymore.

Problem statement

STRENGTH WEAKNESSES OPPORTUNITIES THREATS

Economical activity (potential strength in uplifting economy)

Dynamism

Location

Major landmarks

Existing vegetation in some part of the street

Infrastructures (narrow streets/ public facilities)

Improper public transport facility / connectivity

No parking facility

No trash bins

Congestion of roads

High traffic volume

Lack of vegetation

Absence of continuity of green space/ vegetation

Canal (future oriented development)

Lost spaces --> public spaces

Multi-model transport

Increasing activity to the canal

Over density of buildings

Dirty/littered streets

Irregular planning

No signage’s

Congestion of traffic lane

Traffic accidents

Pollution

Increase of noise

Climate ( heat waves / humidity )

Increase of co2 emission

Densely populated

Source: Sandhakulam group

30 Ernakulam market area Reviving the social and ecological vibrancy of Sandhakulam 31 | Ernakulam market area | Reviving the social and ecological vibrancy of Sandhakulam

Figure 3.3.1: Table of the SWOT analysis

“ How can we create a feeling of attachment between the people and the canal that helps revive its lost heritage and importance while also ensuring its ecological viability ? “

Figure 3.3.2: Situation analysis diagram Source: Sandhakulam group

Restoring the use of canal as mean of water transport system for goods

3.4 Spatial solutions

Vision statement

“ An ecologically sustainable and socially vibrant Sandhakulam community. “

Permeable drain cover.

Replacing solid concrete drain covers with permeable ones will prevent the solid waste from entering the drainage while allowing unobstructed flow into and in the drainage. During heavy monsoon, the water can smoothly be soaked in, filtering the solid out.

Using the canal for good transportation directly impacts the economic livelihood of the stakeholders. The shop owners suggested this implementation.will make good transportation cheaper and efficient. This creates a vital link between the canal and the locals, especially the younger generation and migrants who don’t have past memorable nostalgia about the canal to feel a connection with it. This strategy will also help to prevent water stagnation.

Pocket spaces for public use

Bio-waste to Compost

The biodegradable waste can be used as a raw material for a compost factory that produces fertilizers used for vegetation. This strategy involves the concept of circular economy where the waste produced after consumption can be reused and upcycled and recycled over and over. Managing the bio-waste will also help in solid-waste management as it will reduce the amount of waste that needs to be collected and it will be easier to segregate.

Small pocket space, with sitting modules and provision for plantation, can be designed around the canal.The canal passes through the market with different zones. Sitting space around the docking zone can be placed for merchants to wait for goods.Small pockets along the canal and nearby shops will allow the shop owners to take tea breaks and interact without losing sight of their business. A much quieter zone of the canal can be used differently as public space with more greens and less commercial activity that will welcome more visitors including children and women.

32 Ernakulam market area | Reviving the social and ecological vibrancy of Sandhakulam 33 Ernakulam market area | Reviving the social and ecological vibrancy of Sandhakulam

Figure 3.4.2: Waste filtration Source: Sandhakulam group

Figure 3.4.1: Vision for the public space along the greener part of the canal

Figure 3.4.4: Vision for the public space and activity related to the canal Source: Sandhakulam group

Figure 3.4.3: Compost economy Source: Sandhakulam group

Figure 3.4.3: Compost economy

Figure 3.4.5: Pocket spaces Figure 3.4.6: Vision for pockets spaces

Source: Sandhakulam group Source: Sandhakulam group

Strategy: Project developement in terms of scales

Site

3. 5 Conclusion

The group learned to turn the issues on site to potential opportunities and approached with focus on participatory, inclusive and developmental planning practice. With the concept of the eleventh SDG to make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable, the group was aware of the context at stake. Moreover, they interacted with the community and shared their ideas as well. The exchange of ideas facilitated in developing the proposed solution with a bottom-up approach.

more and were eager in giving feedback and suggestions for further development. This participatory approach was helpful in both ends. On the one hand the students got valuable inputs and were able to involve the stakeholders in the planning process. The interactive sessions not only helped to assess the needs but also helped to gain trust and cooperation from the stakeholders, which in turn helped to generate empathy and understanding between the group and the locals. On the other hand, the stakeholders opened their perspective on the resources and the potential of their own site.

Human Community City

Even though the project proposals are based on the concept of participatory approach, it was very challenging for the group to actually go through it and involve participation. As foreigners on site,with language and cultural differences, it was difficult to interact with the community and comprehend the context. The local stakeholders were very friendly but they were also confused as to what the group was actually doing. The group had to develop ideas of engaging the public in the process when they were still not comfortable with even talking with the foreign students and were doubtful about the validation of the work. Time limitation was also a factor where the group was unable to go deeper in some of the aspects of site analysis and public participation.

In conclusion, the program helped the group to develop as urban planners but also as individuals. The group learned the value of the local context and its resources and to work outside the structured box. They also had the advantageous experience of participation in planning. The cooperation from local authorities and stakeholders helped to generate proposals that are relevant with the context.The project, accompanied with practical experience and teamwork, broadened the perspective in understanding the dynamism in urban planning.

Being foreign to the context of the site selected, it was hard to communicate and relate with the context initially. That is why the group used visuals to interact with the stakeholders to overcome the language barrier. With such interactions the locals opened up

34 Ernakulam market area | Reviving the social and ecological vibrancy of Sandhakulam 35 Ernakulam market area | Reviving the social and ecological vibrancy of Sandhakulam

and waste management

the use of the canal Global water trade route in the city

the canal

Flood

Re-enact

Cleaning

(Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Kunnumpuram, Fort Kochi, India

Mohammadreza Movahedi

Maria Magdalena Mühleisen

Eloïse Redon

Nahida Yeasmin Tonni

A short presentation video of our fieldwork study

4.1. Introduction and Methodology

Located in the South-West of India, in the state of Kerala, Kochi (formerly known as Cochin) is one of the major cities of the state which is rich in culture and History. Due to the extreme rapid urbanization, the city is facing multiple challenges regarding economy, social aspects, politics, and sustainability. Our site is located in Fort Kochi, in an environmentally sensitive neighborhood called Kunnumpuram It is situated between two canals: the Calvathy canal and the Eraveli canal. Both canals were originally built during British colonization and served the dual purpose of dividing areas and as a route for the transportation of goods. The area is often referred to as “Mini India”, as many cultures and religions are living here among each other, embodying the different faces of the country. This neighborhood is comprised of small narrow streets and low-rise housing in a variety of colors and typologies. The canals are extremely polluted, emitting a harsh smell, and creating an unpleasant environment for the people who are living alongside them. In the area, the residents lack public spaces for all, as part of their rights to their city. Additionally, the ongoing global environmental crisis and their neighborhood’s environmental degradation have been affecting their livelihoods.

1 Canal

Canals are an important natural asset of the area. Due to pollution they have degraded and put the lives of citizens and nature at risk.

4.2 Methods

2 Waste

During our Fieldwork, we based our work on democratic participation in the process of solving problems located on the site. We aimed to be at the highest level of Arnstein’s ladder of participation, defined as the degree of citizen power Local stakeholders together with the community got involved in the project, and a new understanding of the area was turned into local problem-solving and action - research

3 Ecology

The high levels of pollution, climate change and the very dense streets are threatening the comunity and the local biodiversity.

4 Gender

Women are suffering from this patriarchal society. Public spaces are the spatial representation of the gender inequalities happening in the neighborhood.

This research is based on primary, secondary data and the qualitative analysis of direct observation, in-depth interviews, and participatory activities with the residents of Kunnumpuram, carried out during October and November 2022. This area-based approach allowed us to record different viewpoints about the ongoing challenges of the neighborhood. Like a gear, our method process (Figure 4.2) was like a mechanism where the first action activated the next one and everything worked together. The interviews with different stakeholders and the participatory workshops we conducted gave us incredibly valuable knowledge.

Overall, we involved the community every step of the way to give them a sense of ownership and conduct a project that is local-specific and rational.

38 Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures 39 Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

The area has a dysfunctional waste management system which results in a lot of issues like open burning and waste dumping.

Figure 4.2 : Diagram of methods

Figure 4.3 : Picture of the participatory workshop

4.2. Situation Analysis

In a community facing many issues and opportunities, we were engaging with the local community and stakeholders to understand the context, and its potential for the future. We clearly saw how polluted streets, sea and canals were impacting the life of the inhabitants and their use of public space, especially women who already were vulnerable and in lack of resources . Indeed, with almost no open public space in the area, women were oppressed by the patriarchic society (Figure 4.8).

Public Space

Previously the area used to have one open public space, where they played sports and gathered. The municipality took over this green public place and is now developing the area to serve as a site for a new highrise building. This results in even more social exclusion in the area, where the most vulnerable grups, like LGBTQ, women and children, elders and disabled are the ones having to deal with the worst consequences. Now they have nowhere to go, and spent their time inside their small houses, viewing the streets as a threath and obstacle (Figure 4.4).

Gender inequalities

Gender differentiation is predominant in India. In the market, in the streets, in public transport etc. Every public space is mainly populated by men. After work, they gather around street shops to drink tea and socialize while women are staying in their households. Women seem absent from the public space across the city (Figure 4.5).

Waste Management

The waste management system is insufficient and too expensive for the poorest people in the community. Pollution is prominent in the neighborhood. People do not have space to keep the waste in their small houses that often are shared by multiple families. In addition, the sewage system run open with wastewater directly into the canals, a small meat market nearby is using the canals as a dumping area to clear the waste of their slaughterhouse (Figure 4.6).

Environmental degradation and canal

The environment is highly degraded due to pollution, climate change and high density. The canal biodiversity is in a severe danger as the water is highly polluted. In the monsoon season, flooding is a high risk. Mosquito breeding is another issue which also affects the health of the inhabitants. The native species has been declining drastically over the years (Figure 4.7).

The lack of involvement from the broader society is leading to a sense of abandonment among the citizens. Water supply restrictions and improper waste management are putting many lives at risk. Many of the resident’s basic needs aren’t being met. Misgovernance and environmental degradation have resulted in the lack of public space and dangerous streets, threatening women, children, and the elderly.

40 Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Figure 4.6 Waste management diagram

Figure 4.5 Gender inequality diagram

Figure 4.4 Public space diagram

Figure 4.7 Environmental degradation diagram

GSEducationalVersion

Figure 4.8 Issues at site

41 | Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Problem statement

Vision statement

In the heart of the area, alongside the canals, rewilding and regeneration of natural greenery is happening, providing a habitat for native species to coexist with humans in this dense urban context. These green and open spaces will serve as socially inclusive places, programmed with activities for all groups in society, children, women, youth, men, elderly, disabled, both the local community and visitors will be visually invited to enjoy and socialize, regardless of ethnicity or religion. Various responsive governance strategies using social resources from the local community, and actions by the public and private sectors, we hope will unlock Kunnumpuram’s ecological and social potential.

4.3. Goals, Strategies, and Spatial solutions

Inclusive Vibrant Public Spaces

The main strategy to reach this goal is to make environmentally sustainable public spaces that are safe and gender-inclusive to ensure that the need of all groups in society, both humans and non-humans are met.

A. Making the Pathways more walkable project: This proposal’s aim is to make the pathways more inclusive, safe and vibrant. We have used the term walkable, which is a more general term that covers inclusivity and vibrancy (figure 4.10, 4.11). Kunnumpuram could potentially be a walkable zone that provides a variety of safe options for the residents’ movement and accessibility to the other areas. To make the neighborhood safer, we need a new participatory approach toward street design that addresses different people’s needs. So, our proposal is an inclusive one that considers different street design-related needs and ideas. For this matter, we think of distinguishing the sidewalks and car lanes with giving the priority to the pedestrians. The connectivity of the sidewalks to create a network in the whole area and the surroundings is the key in our proposal. Since there are not enough traffic signages on the streets, we also recommend to integrate proper street signs.

B. Placemaking Project, An inclusive green place for the community: In this proposal, our goal is to create a vibrant public place in the vacant area near the canal. The vacant area works as a connection between our own case study and Mattanchery neighborhood (figure 4.12). In this regard, our main solution is to use the idea of “placemaking” as the lead. Based on our literature review, we’ve used the term “place”. Here, our aim as a spatial solution is to make an inclusive comfortable public place that addresses the needs of different genders and ages groups, including biodiversity. In this proposal, we’ve concerned the connections between various people and the place in the form of place identity, access and movement discipline of the area, the ecological aspect with native species, rewilding and regeneration, and the built form of the place.

SPATIAL SOLUTIONS

In this chapter, we firstly present our main vision for kunnumpuram’s future. To reach out the vision, we propose three main goals. For each of the goals, we have strategies, and we’ve proposed solutions and actions to reach out the goals.

C. Communal water: Shared communal water will contribute to our goal which is to make vibrant and inclusive public spaces by providing fresh and clean water to the public (figure 4.13). It will also be a program with a special focus on inclusiveness and gender equity. Because women do not move freely around in the area, collecting water will serve as a legit reason to be outside in the public. The main long-term goal is for the community to be connected to the city’s water-infrastructure. This will also be a way of providing them with proper urban citizenship and a feeling of belonging. Shared water taps will be placed in open public areas where we aim to create a foundation for an inclusive, safe, and democratic society. Here, people will be invited, through holistic, spatially sensitive planning, to collect water during the entire day and night.

D. Urban community garden: In this proposal our goal is to provide means for the inhabitants of Kunnumpuram to make their public spaces as a daily part of their lives. In this regard, we will try to engage the locals in the urban community garden project. The goal is to provide inclusive public space and regenerate the ecology for the inhabitants of Kunnumpuram (figure 4.14). Urban gardens can act as public space, because as a part of the public realm, the garden has benefits for both humans and non-humans. Urban gardens offer the neighborhood the “spirit of place” which connects people with nature (Francis, 1989).

As a means of achieving this, we intend to carry out two different strategies. The first one would be to create a socially and environmentally sustainable segregating waste system, and the second strategy would be to ensure that waste management policies are being put into action through local community groups in the long run.

42 Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures 43 Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures 01

Figure 4.10 Making the Pathways more walkable (1)

02 A segregative waste management system

Figure 4.11 Making the Pathways more walkable (2)

Figure 4.12 Placemaking Project

Figure 4.13 Communal water for the people

Figure

4.14

Communal water for the people

Figure 4.9 Perspective of the future

A social and environmentally sustainable segregating waste system: Through a circular economy approach and by involving the community in different stages, our actions will have different steps, with the aim of inspiring change.

In the short term, the goal would be to improve the collection of waste and segregate it. In order to do so, the idea is to implement shared waste bins accessible for the community across the neighborhood, especially close to the canals where a lot of trash is being thrown away. This circular economic approach focuses on the environmental and social aspects (Figure 4.15). By developing new ways to treat the waste, the aim is to repurpose and revalorize as much as possible to create new values for these materials.

Ecological Regeneration

The Green revitalization and urban rewilding, in respect of the local context and its natural identity is our main strategy for this goal. Secondly, it’s important for us that the natural assets of the neighborhood, like the two main canals, remain clean and lively in a long perspective.

Canal Revitalization Project: Our proposal’s most essential point is to ensure that residents are informed enough to understand the repercussions of canal pollution on their livelihoods (Figure 4.16). This “resident awareness” proposal involves various groups of citizens, including women, youth, and the elderly. First, the canals will be cleaned, and residue will be removed, then the transition between the canals and their surroundings will be changed. The transition should be soft and inclusive enough to allow the local community and visitors to interact actively with the canals. By fostering close relationships between people and the canals, this proposal aims to improve the liveliness and vibrancy of the context, and make people regain their historical relation with the canal as a blue public space.

We have set goals, strategies, and proposals (Figure 4.17) for the interventions based on the SDGs. The role of the local community in our proposals is essential. They have strong social bonds, and they are helping each other. This is an important social resource, we are planning for the community groups to co-create and co-produce with NGOs and local stakeholders, and be the drivers for the change when working towards achieving the spatial solutions.

4.4 Urban Governance

Urban governance policies will manage the roles-responsibilities and financial aspects of the project. Spatial solutions require the involvement of different stakeholders for a better governance system.

Significant Stakeholders

There are various stakeholders with diverse power interests and visions for the neighborhood. Spatial solutions will need the help and support of a good governance structure, involving decision-makers as well as the community. Therefore, we selected a range of stakeholders who have the most power and/or interest to actively contribute to the implementation of these solutions with specific responsibilities (Figure 4.18). The main focus is the community, which has low power but high interest.

We created some community groups, who, with the help of local NGOs, will act and finally regain ownership of their neighborhood.

Municipality is the main governing authoriy and they will collaborate with all other stakeholders to implement the spatial solution. For future solutions, the collaboration will expand with E.U. GIZ is a German Development Agency that works in collaboration with the municipality on waste management. The collaboration will extend further for upgraded waste mangement.

CSML (Cochin Smart Mission Limited) will collaborate with municipality to create inclusive public space and to clean the canal.

Ecology Youth Group

This group will be responsible to make people aware about the canals and their outer space. They will help the governing stakeholders to ensure the maintenance of the strategies at a community level.

Waste Management Youth Group

This group will help to create awareness among the community about their space. The unheard young voices will be turned into actions towards clean inclusive public space.

Community Garden Group

The community group will be responsible for maintaining the gardens and make sure biodegradable waste from the community is turned into soil. Resilient green gardens will make a new food supply, and provide biodiversity.

44 Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures 45 Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Figure 4.15 Diagram of our circular economic approach

Figure 4.16 Canal and the people

03

Figure 4.17 Map of the spatial solutions

New public spaces Community gardens Shared

taps

Segregated waste bins

water

Figure 4.18 Diagram regarding involvement of stakeholders in proposals

Strategies of governance

The main strategy of governance is to involve various stakeholders specifically in different stages of the creation of inclusive public spaces, canal cleaning and sustainable waste management.

Inclusive public space

In the first step, in 2023, the municipality and CSML will work together to provide a social inclusive public space. Further, in 2024, soft transition between canal and pathways will be executed to develop connection between nature and the built environment. The Ecology Youth Group will arrange public awareness programs regarding green and sustainable public space. The long-term strategy is to upgrade roads and waste management system to create an inclusive area. By 2030, we will progress towards SDG Goal 11.7 Universal access to safe and inclusive green public spaces particularly for women, children and disabled (4.19).

Cleaning the canal

First step will be to remove waste and clean the canal. In the long term, sewage lines will be connected to the main infrastructure of the city. Municipality with CSML will clean and dig up waste from the canal in 2023. Further, the Youth Group and a local NGO will be in charge of the long term strategy to make sure the canal is kept clean. The process will help to achieve the SDG goal 6.6 -Protect and Restore Water-Related Ecosystems.

Sustainable waste management

GIZ and the municipality will provide separated bins for bio and non-bio degradable waste. And turn bio waste into soil for the community gardens. Further, recycling and reusing of plastic bottles will be executed in collaboration with the youth group. Awareness programs will be arranged in the community to improve the whole system. In long term, the entire waste system management will be upgraded with full segregation and connected to a wider system for the entire city.

Existing situation:

4.5 Reflection and Conclusion

The urban environment in Kunnumpuram has rapidly changed over the last decades due to extreme urbanization in Kochi, and unplanned random development. After one month of intense fieldwork, the learning process has been long and insightful. After some time, we started to build contacts and did various participatory events with the community. They invited us into their homes and lives with kindness and openness beyond what can be described. We had a huge language difficulty at the beginning of the project, but later, with the help of translators from India, we broke this cultural bridge, making it easier to approach the community, and got the opportunity to really understand the needs and wishes of the people.

Overall, the main issues we noticed on site were concerning the waste management system, the lack of public space, gender inequalities, and the threat to the environment. Those four challenges are closely linked together and finding answers for one would help the improvement of the others as well, and the public spaces would become the support of our spatial solutions.

To tackle those challenges, we set up three goals: the first one is to create inclusive vibrant public spaces, that are safe and encourage gender equity, The second goal is to have a segregative waste management system that creates a social and environmentally sustainable neighborhood, and the third goal is the ecological regeneration of the area.

First step in 2023: Municipality + CSML

Providing social-inclusive space with facilities like shading, shared water taps, solar lights, shared waste bins, native plants, urban furnitures

Creating pedestrian and disabled friendly pathways

Upgrading local road infrastructure

Long-term solution in 2030: Municipality + CSML + Ecology Youth Group + NGO-Navajeevan Community Development And Innovations Network

Upgrading infrustructure regarding roads and sanitation system and waste management

Returing water transport system for heritage purpose and tourist attraction

Regaining the relation between the community and the canal by providing a wide bridge

No public space

The area is filled with trash

No lights and security

Presence of drug addicts

Highly polluted canal and dangerous roads

Further steps in 2024: Municipality + CSML

Soft transition from pedestrian pathways to the canal

Use of permeable and natural stones to make it more nature friendly

Use of art and sculptures to give some aesthetic look

Use of signage to provide user friendly space

Focus on Public Space in 2025: Municipality +CSLM + NGO-Navajeevan Community Development And Innovations Network

Pedestrian friendly and Inclusive design Safe and secure Knowledge sharing Open public space with community engaging programs Proving biodiversity

We got to see Kunnumpuram through many individuals’ eyes, and their perceptions. The conflicting interests and values in the area revealed themselves through these interactions. The fieldwork and research we conducted in Kunnumpuram’s neighborhood helped us understand the larger challenges and structures that affect the entire city and the Global South as a whole.

The usual method used to conduct urban projects in Kochi is a top-down approach that makes the community feel powerless and neglected, creating a lack of trust and communication with the decision-makers. For this fieldwork, we used a bottom-up approach to give a voice to the community and imagined a project that would reach the highest level of Arnstein’s ladder of participation (Arnstein, 1969), or what Sarah White (1996) describes as “transformative participation” with the aim of giving back power to the citizens and restore trust. We based our solutions on the rationality of this area-based planning, with an inclusive and holistic approach, and identify what could be the drivers of change in the community.

The spatial solutions are all together working towards creating a shared context of meaning for the community, creating purpose, equality and justice. The improvements in the area will be closely linked to the improvement of the city in general, as many of the challenges on a small scale are related to a broader system. Those spatial solutions couldn’t be implemented without a great governance structure that helps with the creation and maintenance of the solutions. We identified relevant stakeholders that would be the most relevant to contribute and created some community groups to give ownership and a voice to the locals of the neighborhood. The work that we have done here is just a preview of what could be done in a neighborhood, as an example of a Global South city.

46 Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures 47 | Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Today Further Process Aware Long Term

Tomorrow

Figure 4.19 Diagram regarding strategies of governance towards inclusive public space

Kunnumpuram has a lot of challenges but also the capacity to become a thriving, resilient, and inclusive community.

Do challenges in daily commuting affect people’s livelihood?

Calvathy canal, Fort Kochi - Kochi, Kerala, India

Afif Muhammad Fatchurrahman

Atena Asadi Lamouki

Mohammed Mahdi Mahdi Zadeh Naeni

5.1. Site context and methodology

1.1 Calvathy canal area, Fort Kochi

Located right at the sea mouth, Fort Kochi has experienced immense trade-related activities and has developed a rich pluralistic culture and tradition unique to this heritage zone (Kochi City Development Plan, 2006).

This unique characteristic of this area has kept the neighborhood still alive and it can be said that the economy of the neighborhood is dependent on tourism. Another important outcome of this rich pluralistic culture is the presence of various religious groups such as Hinduism, Christianity, Islam, etc. in Kochi and especially Fort Kochi. we can observe the differences between these groups living in this area but the crucial point is that the level of conflict between them is very low and actually, the cohesion of the communities is one of the strong points that inhabitants have benefited from.

mainland mostly for their employment needs and make use of the ferry system and bus services to commute to the mainland in the morning and evening (Joseph, 2009).

The ferry is the preferred mode of transportation for people in this area mostly because of two main reasons. First is the price for every ferry trip and It is only six rupees per trip. And the second reason is the time that would be spent in comparison to other modes of transportation. But The important factor in this regard is that there are no specific safe paths for pedestrians and have made so many difficulties for inhabitants.

A development plan for the city is already in place in the form of Cochin Smart Mission Limited (CSML). CSML is the special urban body that has been implementing smart city projects in the city. They have described their purpose as “CSML aims at a planned and integrated development of the Central Business District and Fort Kochi-Mattancherry area by improving the civic infrastructure with the application of smart solutions thereby improving access to city amenities, clean and sustainable environment and livelihood promotion (https://csml.co.in/ mission-vision/).”

However, In this specific situation, our analysis shows how much the accessibility condition in a neighborhood can influence people’s livelihood.

Even though the civic infrastructures in some part of the area has been improved, it could still be observed that the road situations and transport modes issues that have significant impacts on the inhabitants’ economic situation and safety still persist.

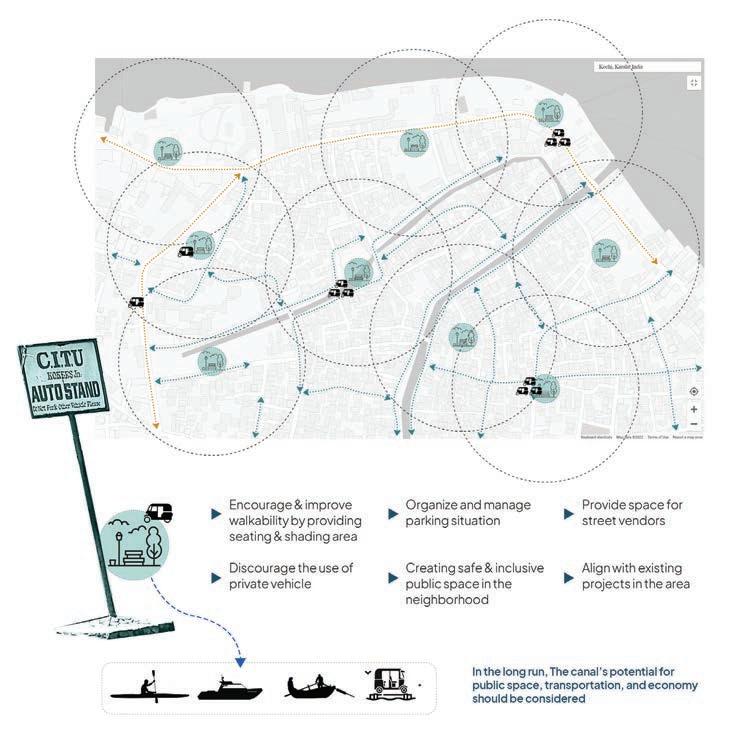

Based on these preliminary observations and analysis, group 4 of UEP 2022 fieldwork has focused on the issues related to accessibility and livelihood, the relation between them, and their impacts on people’s lives in Fort Kochi, specifically in the Calvathy canal neighborhood.

1.2 Methodology

We, as a research group, benefit from various forms and tools for gathering information and different viewpoints which are needed for conducting the project in our fieldwork. These tools can be varied from simple observation and photography to interacting with locals for acquiring a more comprehensive viewpoint about the study area. In the case of this fieldwork, the crucial point is to conduct these methods in a participatory manner.

As Fort Kochi was mainly used to be a place for different nations to trade, the canal was built for connecting the sea and the mainland fort Kochi area. Thus, in the past, the canal was totally usable and active, especially for smaller boats. The expansion of roads and settlements in the area has resulted in the encroachment of the canal width and the canal cannot be used significantly as a means of transportation. Therefore, the canal lost its usage and has been turned into an infamous feature of the area, mainly used merely as sewage and waste-dumping. Furthermore, this area is where most of the poorer sections of Koch city region urban areas live. They depend on the Figure 5.1: Northern Fort Kochi area, where the site is located, which mainly consists of area with significant historical and heritage contexts

The priority has been to use these tools as means for giving local people a voice and professionals a clear idea of local people’s needs in order to bring about an improvement to their own neighborhood or community. (Neighborhood Initiatives Foundation (1995) cited in Hamdi & Goethert (1997)).

For instance, through the observations, transect walks, and photography, we were able to understand locals’ walkability struggles and their significant influences could be observed through the first walks in the neighborhoods of Fort Kochi and this issue has had a great impact on our whole project. Figure 5.3: Methods used in the project

50 Calvathy, Fort Kochi, Kochi | Do challenges in daily commuting affect people’s livelihood? 51 | Calvathy, Fort Kochi, Kochi | Do challenges in daily commuting affect people’s livelihood?

Figure 5.2: Participatory workshop with families and childrens living near the Calvathy canal

5.2. Situation Analysis: Findings, challenges, and limitations

2.1 Existing condition

Our study area is governed under 2 wards, Calvathy and Eravelli. Wards in the context of Kochi, are predefined locations/ districts set within the municipality of Kochi. The governance of wards is led by a single councilor, who oversees and manages his/her ward area, and falls directly under the Kochi Municipal Corporation and the Mayor. Several of these councilors could organize themselves together to form a committee that handles specific themes in the city.

Our site has several different stakeholders, which mainly include governmental/municipal actors, who hold the highest power and resources to make changes, local’s public & non-governmental organizations, and the local residents themselves who have high interest but do not really have the power & resource to create substantial changes.

A considerable number of workers from outside of Kerala state are living in the Fort Kochi and Mattancherry areas. Therefore, the neighborhoods are very congested and their infrastructures cannot respond properly to the inhabitants’ needs. The other important point about a significant number of people living in these areas is that they are considered in the low-income group (LIG) or middle-income group (MIG). LIG is identified in terms of the economic basis, as households with a monthly income of less than Rs.5,000. MIG is also identified in terms of the economic basis and are households with a monthly income greater than Rs.5,000 but below Rs.10,000 (Kerala Sustainable Urban Development

Project, 2005). These workers, that live in the area, have jobs on the mainland, mostly in Ernakulam. They are dependent on the ferry boat jetty station for transportation to this area of Kochi city.

2.2 Challenges/Problems

Throughout the first observations that we had in the study area, we could notice that people have many struggles walking through the neighborhood. There are many paths without any separation between pedestrians and vehicles and this has made paths unsafe. Furthermore, despite of hot and humid weather, there are no public or shaded places in the neighborhood for people who are walking toward their daily destinations.

despite the existing problems, people mostly walk toward their destination. There is no public transportation in the inner areas of the neighborhoods and The auto rikshaws play the main role in transportation for those who consider their trip not walkable.

Public bus tickets are around Rs.10 and ferry tickets are Rs.6. These two options are financially reasonable for the local people but As mentioned above, people usually do not use public buses because it takes too much time and they are dependent on the ferry for reaching the mainland. A trip from the ferry station to Ernakulam takes about half an hour and with the bus about 70 minutes.

If people want to get auto-rikshaws to and from the ferry boat jetty station, based on their distance from the station, they will spend around Rs.112-212 per trip. For a worker, who is at least working 5 days a week, taking auto-rikshaws with the current price is not financially sustainable. About 20 percent of users of the ferry are considered in LIG and 50 percent are in MIG.

53 Calvathy, Fort Kochi, Kochi | Do challenges in daily commuting affect people’s livelihood?

Figure 5.4: Project’s site area, with places of interest highlighted (left)

2.3 Problem statement & Opportunities

With all the data and findings, we have identified the main influential problems in our study area in regard to accessibility problems and their impacts on livelihood: Current public transportation system is not at a good level of accessibility for people. Also, Walking toward the other possible option of public transportation, ferry jetty boats, is not really safe because there is a lack of designated sidewalks for pedestrians throughout the neighborhood.

Some people use their own private vehicles or auto rikshaws for not walkable trips in the neighborhoods or to the ferry jetty station. But financial limitations are the main barriers to using this mode of transportation all the time.

On the other hand, we also see some strengths and opportunities that could be used to enhance the current situation in the area. It is important to consider these points when we are moving forward in our spatial solution and involve the existing community qualities.

2.4 Themes

Our findings and contextual understanding of the site indicate that several frameworks have been worked and focused on including environmental and sustainability issues. Hence, we decided to focus on issues which covers transport and mobility, and how it affects the local’s livelihood. These qualities are evident in our site where several conditions regarding the public transport scheme and the area’s physical infrastructure affect the local’s access and mean to procure goods and utilize public services.

These types of problems may compel people to find alternative ways to get to their destination which can increase costs caused by being forced to take longer (alternative) routes; adding to this are tuk-tuks, taxis, boat operators, and others losing out on potential customers, all of which affects people’s livelihoods.

54 Calvathy, Fort Kochi, Kochi | Do challenges in daily commuting affect people’s livelihood? 55 Calvathy, Fort Kochi, Kochi | Do challenges in daily commuting affect people’s livelihood?

Figure 5.6: Diagram map depicting the issue of the public transport’s reachability within the neighborhood.

Figure 5.5: Comparison diagram & map depicting distances, route, travel time, and fares from the site area to the mainland Ernakulam area

5.3. Strategic Spatial Solutions

3.1 Vision Statement, objectives, and strategies

With the city of Kochi focusing its future efforts and developments on “smart city” initiatives. For all its grand ambitions, in most practices, the smart city vision lacks inclusivity. There is a “pre-packaged” idea of what a smart city should look like and aspire towards based largely on a technocratic obsession and influence on Eurocentric models (Aurigi & Odendaal 2020; Datta 2015). This doesn’t work because local contexts have to be considered especially in the Global South –as Aurigi and Odendaal (2015:2) state, “This pre-packaged city concept vastly contrasts with the messy textures of real cities.”

We hope to fill in the gap here- to be the urban planners concerning the city of Fort Kochi by recognizing its unique ‘city-ness’ (Datta 2015). The hope is to not implement a city that is preconceived as ‘right’ but to be smart about how we tackle urban problems based on the local context and with the assistance of local residents.

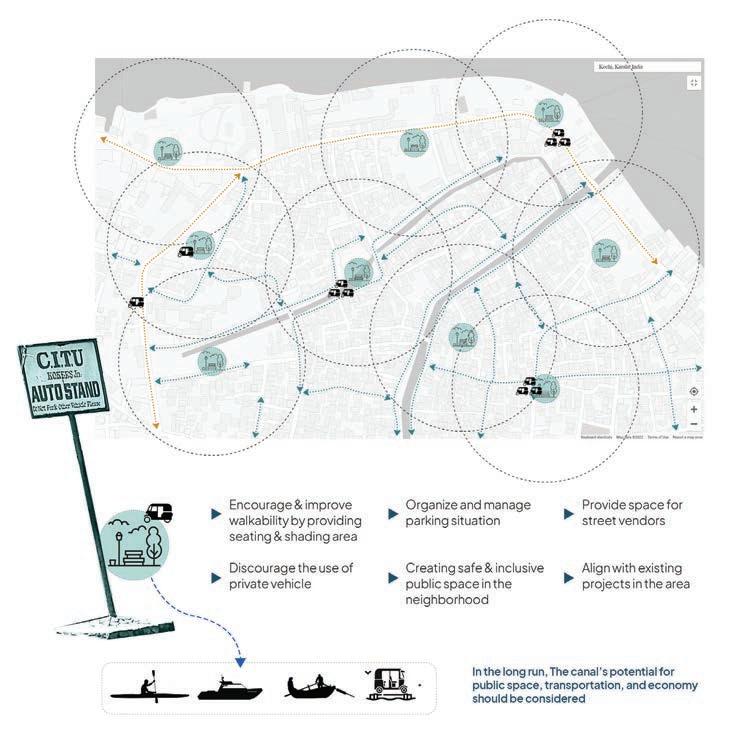

In trying to fill the gap, we derived our strategic solutions into three main objectives, which focus on the aspect of the auto-rickshaw governance and management model, safe and inclusive road transformation, and public space providence.

3.2 Auto-Rickshaw (tuk-tuk) as feeder transport system

Auto-rickshaws have played a major and important role in transportation and mobility mostly in south and south-east Asia. It has become a significant cultural and heritage aspect of the urban context in India. There are some criticism toward this mode of transport. Even to the point where some cities have abandoned the use of it entirely.

In the case of the calvathy canal neighborhood in Fort Kochi, the dense inner neighborhoods do not have the capacity for a major transport system like public buses on the main roads. Autorickshaws are the type of vehicles that can go through these neighborhoods.We are aware of the fact that autorickshaws are working under the supervision and support of some organizations like CITU and Fort Cochin Co-operative Society. This was the initial potential that we observed and thought that we can improve what has been functioning in the community more comprehensively. In this manner, we aim to enhance the availability of this

type of transport by forming a comprehensive management system that includes the integration of formal and informal actors in a collaborative manner. This integration is crucial to form a way to work together in a more effective way while ensuring socio-economical justice for the drivers.

The national and local government, down to Kochi’s municipality, together with other related stajeholders, acts as the formal body of this management system. They can act as the main legislator and resource provider, legal framework of the proposal, while also providing them with the opportunity to technically develop further.

Informality here would be an important factor in a way of this system’s interaction and collaboration. In this manner, outside the formal sphere, the process could happen easier in a more organic way. This is done in hope that the interests of the local community and especially the drivers could be prioritized and advocated more.

56 Calvathy, Fort Kochi, Kochi | Do challenges in daily commuting affect people’s livelihood? 57 | Calvathy, Fort Kochi, Kochi Do challenges in daily commuting affect people’s livelihood?

Figure 5.7: Description fo the project proposals’ vision statement, objectives, and strategies

Figure 5.8: Proposed management system and organization structure

3.2 Safe & inclusive corridor transformation

Based on our findings, the current situation of the paths in our study area’s neighborhoods is considered unsafe. In this regard, we have considered some modifications that can improve the current condition of the paths and modify them to corridors that are safe to walk and are not dominated by vehicles.

In this manner, first, we have presumed that the modification can be operated at a level that is not affecting inhabitants’ lives instantly and just illustrate how safe the roads can be. Therefore, the first level of transformation is marking the paths to separate people and vehicle movements. After creating these markings, people’s opinions about this change must be gathered to see how much these designated paths have improved their lives.

The second level of changes can be implemented by creating physical alterations. We could observe that the primary roads, the main road around the neighborhoods, and secondary roads, around the canal areas, have about 9 meters widths. There could be 1.8 meters of paths for pedestrians and 2.7 meters for cars. For local paths in inner areas of the neighborhoods, the widths are around 3.6 meters. There could be half of the path designated for pedestrian movement because of the low level of movement. In this way, people