ExEcutivE Summary

Fieldwork in Panaji, India - Fall 2019

Urban Ecological Planning

AAR4525 - Urban Informality Project Department of Architecture and Planning Faculty of Archtecture and Design

Fieldwork Advisers:

Brita Fladvad Nielsen, Ph.D. Hanne Vrebos, M.S. Peter Gotsh, Ph.D. Rolee Aranya, Ph.D.

Cover Photo by Rudra Sharma

Cover Photo by Rudra Sharma

As a yearly tradition, the master students of Urban Ecological Planning (UEP) at the Faculty of Architecture and Design at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) embark on an immersive fieldwork during their first semester. This report is the outcome of a one-semester fieldwork in Panaji, India, conducted by the students in collaboration with the School of Planning and Architecture (SPA) Delhi. The fieldwork was part of a research project “Smart Sustainable City Regions in India” (SSCRI) financed by the Norwegian Centre for International Cooperation in Education (SIU), which included fieldwork in Bhopal in 2018 and Pune in 2017.

The diverse backgrounds and nationalities of students participating in the UEP fieldwork ensures a multiperspective view. This year’s 19 fieldwork participants are architects, food scientists, engineers, landscape architects and planners, coming from Albania, Australia, Austria, Ecuador, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Iran, Nepal, New Zealand, Norway, the UK and the USA.

The immersion of the fieldwork gives students a reallife practice of the ‘UEP approach’, which focuses on addressing urban complexities from an area-based and participatory point of view, leading to contextual, inclusive and human-driven development processes. Through daily interactions with local communities and relevant stakeholders, students become acquainted with residents and discover the complex realities of these areas, with their specific assets and challenges. By using a variety of participatory (design) methods, the students work on co-designing strategic proposals with the community and other stakeholders.

Students worked in the colonial Fontainhas area, the central business district and along the St Inez Creek. While the main topic of the course is urban informality in all its forms, this year students addressed topics such as public space, heritage, livability and environmental challenges. Warmly hosted by Imagine Panaji Smart City Development Limited, IPSCDL, students were asked to put their areas and proposals in the perspective of the Smart Cities Mission, the large urban development fund and initiative currently implemented by the Government of India.

As an outcome of their learning process, students prepared three reports to illustrate and reflect upon the participatory process through a situational analysis and reflection on methods and methodology that informed a problem statement which they tried to address in strategic proposals. This report sums up the work done by groups by all six groups.

Central Business

Sao Tome, Fontainhas and Mala

India is a truly unique, vast country and the world’s largest democracy - with a population of over 1.3 billion people spread across 29 states and seven union territories. (The World Factbook, 2019). The population is also incredibly diverse in terms of religion, culture and language. It’s people speak around 122 major languages and 1,599 other languages (Census 2011). In addition, it holds the impressive accolade of being one of the fastest growing economies in the world (Asian Development Bank, 2019).

The State of Goa is located in the Southwestern region of India. With a population of just 1.4 million, it is tiny by Indian standards and yet boasts the highest GDP per capita among all Indian States. It is world renowned for its natural beauty, historical sites, and pristine coastlines that attract over 31 million tourists per annum, which are a major contributor to its economic prosperity (Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India, 2015, p.17).

Goa’s population has experienced rapid growth after the end of Portugese occupation in 1961. During the period from 1960 to 1981, the population increased by 70.8% from 589,997 to 1,007,749 persons. The distribution of population within rural and urban areas has changed distinctively since 1961, when 85% of the population of the state lived in rural areas compared to 2011 where 62% of the population occupied urban areas.

Panaji is the capital of the State of Goa and is home to around 40,000 people, plus an average floating population of 5,000 - 15,000 on a daily basis. The city serves as the administrative centre for the state and as a major tourist hub for the area. Panaji is designated as a City Corporation (CCP) (Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India, 2015, p.28).

The city is special in India in part due to its unique heritage. As a result of Portuguese colonisation up until 1961, the city is characterised by Portuguese-inspired architecture and a planned grid system that defines the city centre. An enormous 98% of the city’s population is engaged in the tertiary sector, and the population is expected to grow to 60,000 by 2041. The average household size is 3.9 persons per household and therefore lower than the State average. Most recently, Panaji was selected as one of many Indian cities to be transformed into a “Smart City” under the Smart Cities Mission (Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India, 2015, p.19,28-30).

The CCP area has an approximately 50-50 split between residential and commercial land use. Although the city does not have any officially recognized slums, few areas have been identified with characteristics similar to a slum-like conditions such as a poor quality of infrastructure and other essential services.

Panaji city is a very well-educated area with a literacy rate of 87% and has numerous educational facilities such as pre-primary, primary, secondary, higher secondary schools and degree colleges (Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India, 2015, p. 30).

This fieldwork was built upon the desire to “build critical self-awareness of the role of the urban practitioner in challenging environments” (NTNU, 2019). The process followed in pursuit of this objective was far from linear but instead, mostly cyclical, a rotation from divergent and messy phases to structured and convergent phases. Multiple frameworks and theories were utilized throughout the fieldwork to ensure the data collection, situational analysis and ideation phases were grounded in theory related to more human-centered, bottom-up planning approaches.

“Our apprOach tO the fieldwOrk

was far remOved frOm that Of a traditiOnal planning exercise, which has failed Our cOmmunities in the past. we wanted nOt tO plan fOr peOple, but tO be facilitatOrs Of cOmmunicatiOn and the resOurces

which are needed tO imprOve peOple’s lives.” -student

Due to the complexities involved in working with the communities over a short period of time, a structured and rational approach was applied to the fieldwork. The fieldwork methodology followed the framework of the Principles of Design Thinking (Miller, Benjamin, 2017), where five different phases were used to shape data collection, situational analysis and ideation and how interactions with the communities.

To ensure the fieldwork was directed under a humancentered approach, the core of the research was conducted under participatory research methods. These methods were informed from a broad review of literature and Urban Ecological Planning practises discussed in lectures. These participatory research methods aim to be more inclusive by including marginalized communities and other stakeholders that aren’t typically represented in traditional planning processes. Students had to be creative in the development of these methods to overcome certain barriers such as language.

Some of the participatory research methods utilized in this report include, but are not limited to:

Throughout this cyclical process, one method would inform the other while issues and solutions were reassessed continuously. Drawing upon numerous different methods from IDEO’s The Fieldwork Guide to Human-Centered Design (2015) and university lectures, we took an explorative and participatory approach to data collection. Feedback from the community along this process was also crucial to the participatory approach for maximum community engagement.

• Semi-Structured and Interviews: Used as a way for students to learn more about their areas and as a means of sensitizing stakeholders to the presence of the students in their respective areas. This method also served as a way for the student teams to build up “social capital” in their respective areas.

• Image Exercises: Used to capture feelings about certain areas. Included the use of diagrams, images, and emojis as a way to overcome the language barrier.

• Drawing Exercises: Used as a way to include children and to capture their insights. This also helped to build trust and a deeper relationship with the students as researchers.

• Transact Walks: Self-guided or community guided walks through sites to observe as a participant.

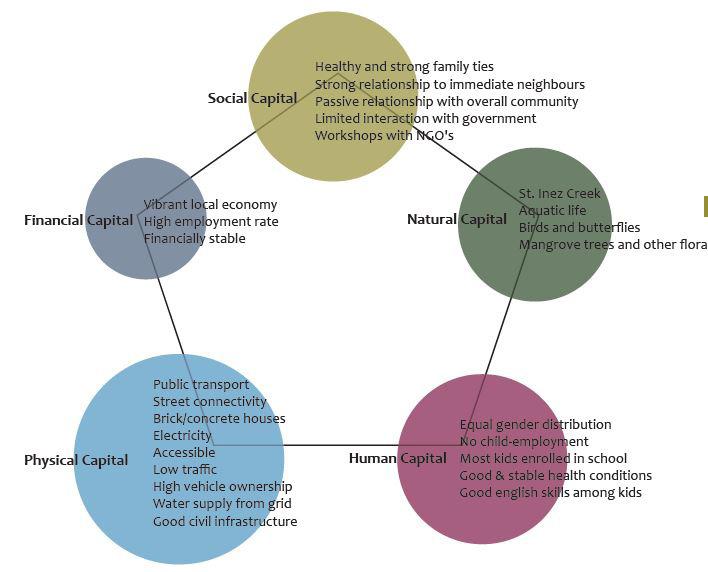

The Livelihoods Framework, outlined by Caroline Moses and developed by the DFID, was used to identify and define the assets of the selected communities. This provided an understanding of how individuals exploited their assets to support their livelihoods and how the absence of certain assets could increase the vulnerability of communities. Assets were outlined under 5 capitals (Adapted from Radoki, Carole, 2002):

• Human capital: Quantity and quality of labour resources, and the ability of the community to access them.

• Social capital: Social structures, rules, trust and norms in a society.

• Physical capital: Basic infrastructure and productive equipment.

• Financial capital: The financial resources available for the community.

• Natural capital: The natural resources or services provided by nature which support peoples livelihoods.

• Political capital: Access to political and decisionmaking processes

The result of these data collection and analysis methods are a series of community-driven planning interventions to strengthen the ability of residents and households to acquire and retain assets, by strengthening social, environmental, physical and political systems.

“the purpOse Of the fieldwOrk was tO gain an understanding Of the livelihOOds and assets Of a range Of cOmmunities thrOughOut wider panaji, including sOme Of the mOst marginalized cOmmunities within the city. thrOugh the use Of mOre humancentered planning principles, the factOrs restricting the cOmmunity’s ability tO participate in the cOntext Of wider, cOmplex systems were identified and pOtential cOmmunityspecific planning sOlutiOns were prOpOsed tO alleviate this.” -student

Groups one and two were studying the complexities of the Camrabhat and St. Inez Bandh areas, both socially isolated and marginalised communities located adjacent to the St. Inez Creek. Camrabhat is a community that is located on the outskirts of the municipal area of Pana ji at the southern end of the St Inez Creek. The area is characterized by its slum-like conditions and disconnect from the immediate community. The St. Inez Bandh is a dense row of compact homes spanning the length of about 260 metres that contrasts greatly with the vast development of multi-storey apartment complexes and businesses that surround it.

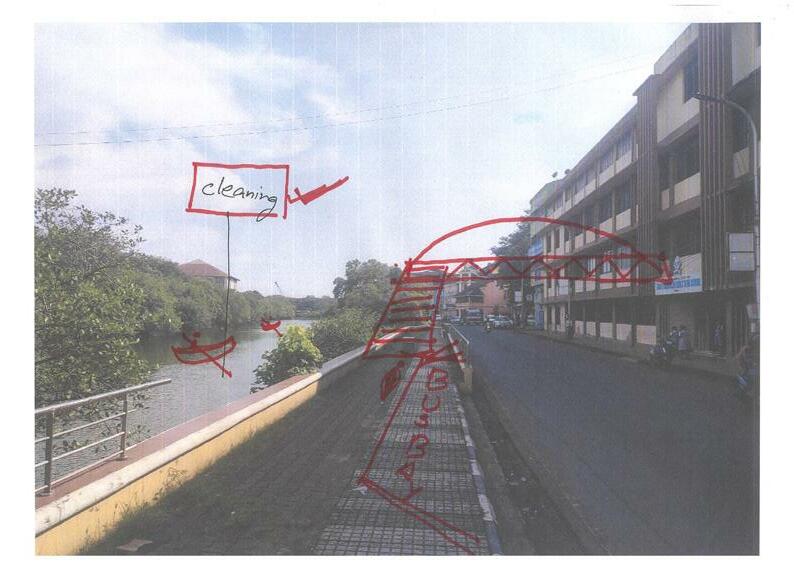

The St Inez Creek is an important natural asset in Panaji, but has seen mass degradation along its length over the last 15 - 20 years. As the groups discovered through their fieldwork, complex social, political, and environmental changes in just 20 years have transformed the Creek from a community asset into a liability for the city. Throughout the fieldwork, the groups worked in close proximity with local communities and a diverse range of stakeholders to understand the role of the Creek in people’s lives and why it has seen such drastic change.

Build-up of sandbank in the mouth of the Creek

Hardening of the banks of the Creek

Illegal dumping of solid waste

Inappropriate bridge construction

Hard-edged development directly adjacent to Creek

Informal sewage discharge

Loss of creekside flora

Breeding of mosquitos

Loss of community livelihoods

Loss of navigability

Seasonal flooding

Loss of ecosystems

A summary of the primary causes for environmental and social degradation of the St Inez Creek.

Whilst neglect by those in power is clearly a primary driver, the reasons for the degradation of the Creek are complex, multifaceted and often opaque. There is a clear lack of governance and accountability among government agencies for managing the Creek and enforcing environmental regulations.

Through analysis of the community and their assets under the Livelihoods Framework, it became clear there was a range of complex attributes contributing to the economic, social, and physical security of households in Camrabhat. As the community lives in varying degrees of poverty, they have varying levels of asset accumulation therefore contributing to different levels of vulnerability within households. This contributes to their stance as Panaji’s “only slum” and “the most marginalised community in Panaji”.

From the groups observations in the community and information gathered on their livelihood assets, the students identified three key issues affecting the community and the sustainability of their livelihoods, which contributes to the community's high levels of vulnerability. These issues were identified as limited access to water, damage due to annual flooding and the degradation of the St Inez Creek and the communities surrounding natural environment.

They also identified strengths in the community, particularly the involvement of key community activists in working to create stronger social cohesion within the community and reestablish the communities’ relationship with the Creek.

“Many of the basic needs of the residents of Camrabhat are not met. The community experiences an unreliable and restricted water supply to all properties, the wider environment is degraded and regular flooding ruins the livelihoods of many. A failure of governance, a lack of coordination between responsible agencies, weak inter nal cohesion and poor external connectivity has created a sense of abandonment, a loss of pride and emergent and sustained vulnerability to shocks and stresses.”

There are a multitude of internal and external factors that can make up and influence a household’s quality of life. There are several models and theories that attempt to break down and organize these factors so that they can be better understood and responded to accordingly. In an effort to obtain a more holistic understanding of the St. Inez Bandh, group 2 applied aspects of the Livelihoods Framework, specifically, identifying and measuring five distinct assets and capitals - physical, natural, human, social, and financial.

It was recognised that the concepts of informality and formality also played a role in shaping the lives of the residents within this area. Within group 2, there was a basic understanding of informality as “life finding a way in response to various challenges and barriers.” Recognising how informality manifested itself in the St. Inez Bandh was essential towards gaining a better understanding of the complexities in this community. Subsequently, as the students acted as planners, they could be mindful of this as they drafted solutions that addressed the root causes of these “informalities” and how they themselves could also be a part of the planning process.

Based on the methods implemented in the field, their observations, and the feedback that was gathered from members of the community, group 2 were able to identify three major issues for the St Inez Bandh area. These are environmental degradation of the creek, lack of communal spaces, and degraded relationships between the St. Inez Bandh and the greater community.

Group 2 formulated the following problem statement to serve as a guiding point for their work:

“Through observations, exercises, and interviews carried out with stakeholders within the St. Inez Bandh, it has been demonstrated that this area is struggling with degraded environmental conditions, a lack of communal spaces, and degraded relationships with the greater community. Residents need to feel empowered and have a strong sense of belonging in their community so that these issues can be addressed and the quality of life can be enhanced.”

Interactions with internal and external stakeholders as part of the fieldwork have made it clear that groups often are competing due to differing interests in the Creek, and this is a significant driver behind its degradation. The Panaji 24/7 Report recognises that multiple agencies are responsible for the Creek, and that “One organisation should accept overall ownership and responsibility” (Royal Haskoning DHV, 2019). A lack of information, distrust and split or unclear responsibilities are emergent features of the system of governance on the Creek.

Drawing on inspiration from similar projects in Bengalu ru and Delhi, the teams jointly proposed a Resident Wel fare Association (RWA) to be formed to democratise and devolute decision-making around the Creek. This RWA would be tasked with the rejuvenation and maintenance of the Creek. It would comprise of an association and an elected board with voting rights for decisions concerning the creek. The long-term intention with this project is to establish this association as the care-taker of the creek with the responsibility for decision making delegated to it as well.

The Cambrabhat community has access to running water, albeit at limited quantities and times. A water header tank has been proposed for the Cambrabhat community as a means of bringing 24 hour water service to this area, along with a run-off water garden to filter the water into the Creek. This tank would be situated in a co-designed community space consisting of a public seating and play area and a centralised waste collection area. This project would aim to greatly improve the quality of life for the residents in this area.

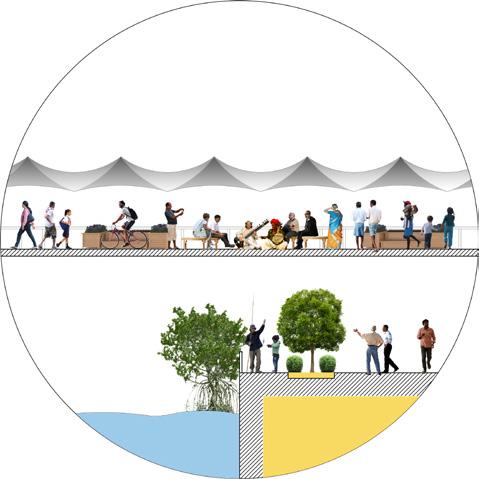

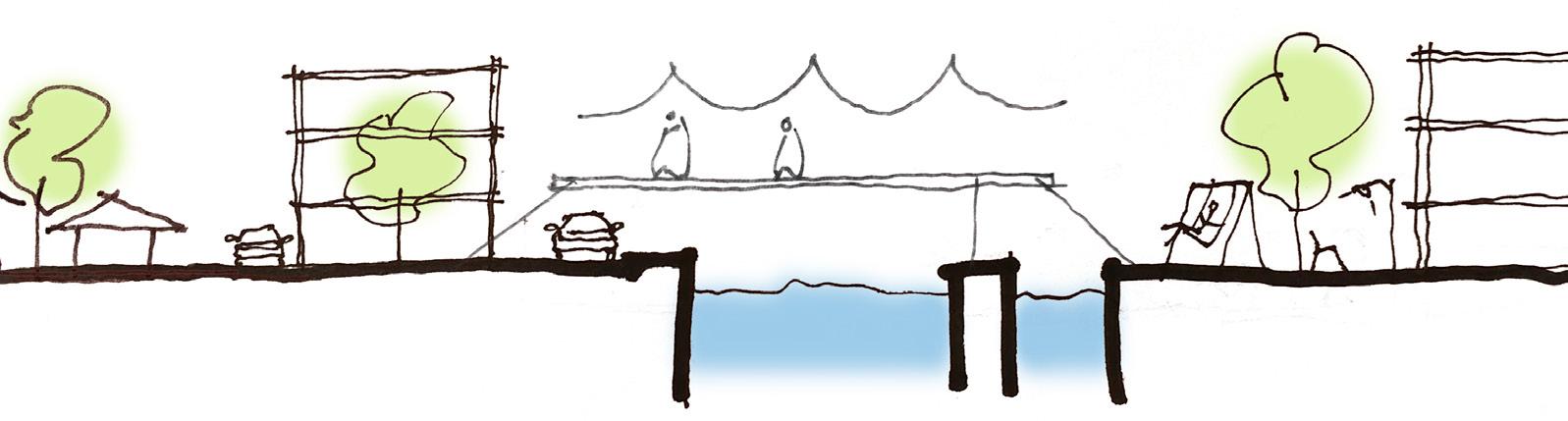

Flooding is a major issue that affects communities located alongside the creek, especially in the Camrabhat area. Attenuation Ponds are proposed as a means of mitigating flooding in this area, with the ponds serving as catchment areas for excess water during periods of extreme rainfall. Alongside this, the ponds can support aquatic vegetation along their shoreline and support the growth or freshwater fish within the ponds. To further integrate the proposal into the community, a boardwalk area was proposed alongside the attenuation ponds to connect Camrabhat to the neighbouring wetlands and provide a place for social interaction with the wider community. If maintained properly, these Attenuation Ponds could transform the landscape of the surrounding area and bring about numerous cultural and economic benefits.

Bioswales involve the use of green infrastructure to in tegrate and facilitate natural filtration in the creek as a means of restoration and maintenance. Bioswales are essentially vegetated patches that capture stormwater run-off and filter the water through a series of natural layers. The end result is cleaner water that is flowing into the creek. Besides rejuvenating a body of water, the stu dents’ bioswale proposal aims to build environmental literacy and awareness in the community through an educational campaign and an “Adopt a Bioswale” scheme that would give organisations the opportunity to provide resources, labour, or capital to maintain the Bioswale ini tiative.

When group 2 were working in the St. Inez Bandh area, they observed the children of the neighbourhood playing in a parking lot and heard from residents that they didn’t really interact with members outside of their community, a park was proposed for this parking lot. The park was proposed in a way that the space would be divided equally with one have being dedicated for play/ gathering and the other half being dedicated for the residents that use the lot to park their vehicles. The park would serve as an important facilitator in bringing together the residents from the different housing complexes and it would also provide children with a safe

The dynamics of the Central Business District (CBD) represent many diverse community aspects and informs the relationship between people and place. As in Murphy’s and Vance’s (1954) opinion, the CBD has been “the heart of the city.” With an array of users from full-time residents to business travelers, the CBD is challenged with meeting many diverse needs.

The CBD is characterized by an accumulation of large commercial areas, government offices, and complex tourist-related activities which form the economy of the community. The dominant businesses in this area are typically small businesses that have been within the family for multiple generations. Of Panaji, 75% of commercial activity occurs within the CBD, which has been growing rapidly in the past two decades due to mass urban densification (Haravi 2010). This has given rise to an increase in the number of residents leaving the CBD. With the conversion of residential and single-story dwellings into commercial and high-rise buildings, there is evidence of the CBD failing to meet the needs of its residents.

The morphology of CBD is not static but continuously changing in character. While some areas of the CBD reflect the past in their original site conditions, others show evidence of changes over time. The central areas, and in particular of the historical centers, contain an economic potential that is not sufficiently supported. The architectural heritage and the traditional character of the urban fabric can become productive factors, attractive for the installation of tourist, cultural, commercial activities, and even financial linked to globalization.

With so many stories to listen to, the original team of six narrowed down the scope to two sites where they could conduct area-based initiatives. After several weeks

of semi-structured interviews and expert interviews, they conducted a mind-mapping exercise on the street. From this, they identified two more distinct zones/ neighborhood from which to spur more in-depth fieldwork: the Market, and East CBD.

These teams approach the work of Urban Ecological Planning and this fieldwork with humility and compassion. When traveling to Panaji, they did not do so as subject experts but rather as practitioners of the built environment who listen carefully to those who live, work, and play in the area. It is the locals who are the experts of the city, and the students are simply the facilitators with the skills to show them what is possible and how to achieve it.

To frame the fieldwork, they developed two objective statements to guide the work:

1) Use human-centered design thinking to get a holistic understanding of the study area and the many communities within it

2) Co-design strategic actions that would move the community towards their expressed desires, either in whole or through incremental steps

As international students with three months in the area, they faced many limitations. Many of these were logistical challenges such as the language barrier, understanding local history, and detailing the complex civic structure. The more significant challenges were gaining trust within the community, finding the hidden processes, and anchoring the project.

Panaji Municipal market is located on the west side of the Central Business District. The central location makes it suitable for catering to the daily needs of the inhabitants around the city.

We have focused our study on the relationship between social structures and physical space in the fish market. The association running the fish market has a reputation of doing this well, however, they have less to share regarding future visions. Communication between the old market vendors and vendors inside the fish market was minimal. This is a major reason why the spaces in the middle like the plaza are becoming neglected as no one is taking responsibility. The plaza is getting highlighted for criminal and prostitution activities after the market shuts down.

We feel like the social spaces inside the market do not have sufficient quality. There is a lack of space to rest in the afternoon when there is less activity. They use the space on the road and pull their plastic chairs outside on the road during their break. Some use window sills to rest their heads while others sleep on their platform.

There is no suitable space which can facilitate for everybody to be included in meetings. Discussions regarding requirements and issues are therefore done in smaller groups. If we take an example from the implementation of Phase 1 & 2 in the main market, we see that lack of discussions amongst the sellers led to a few unsatisfactory designs. The clerk of the official association stated:

“Although the government did a good job but only if there was a discussion with the sellers before it was designed, there wouldn’t have been small design issues that now create problems for the sellers.”

Looking at learnings from the last phases of development proves that discussing with the sellers would be beneficial for creating their space. Changing the design process this way would create long term benefits for the users.

There is a lack of communication between the vendors of the market. We believe triggering a discussion would lead to tapping unexplored potentials. If people feel inclusive in a discussion of their space, they would take responsibility and sense of ownership to the space. This would be an added value for the market and the municipality as well.

This would be beneficial as the new phase is underway and discussions amongst the users led by the strong leaders could help them design their own space hand in hand with the municipality.

“The involvement of an entire group at this scale is understandably challenging. We believe that facing this challenge has the potential of creating an influential movement with stronger social bonds.”

“Areas in the market are left to decay, we work under the hypothesis that these areas could be improved if awareness and empowerment was brought to more people. “

“Any organization consisting of 100 people face social challenges.”

“The association is mentioned by both representatives from the government and the market doing a critical job for the functionality of the market”

Our action proposal is Empowering an inclusive urban movement. We wanted to give them some tools that would strengthen the market community and make it more inclusive using the resources at their disposal.

One of the tools proposed was to initiate a get together where everyone could come and socialize and reflect on topics relevant to their lives. The idea was to bring people with different resources and ideas together. We also wanted to see the social connections between the leaders and the rest of the market.

This proposal was building a prototype meeting, with the topic discussing the history of the market in a social way.

We started this initiative together with the leading members of the market to hear if they had any thoughts or want for such an event. Their influence was important to us for making this event happen so we wanted them on our side early in the process. The proposal took flight initially and people took on responsibilities to suggest space for the meeting and suggested practical arrangements such as chairs. We proposed using the plaza as we looked for new purposes for this space. After discussing this with them we agreed that the chapel would be more suitable as this is the only common area with a certain standard. All of these discussions were still limited to the leaders. One of our visions from a public discussion with everyone was bringing up more ideas and awareness. We wanted to arrange an interactive activity inviting everybody involved in these spaces. This would lead to discussions and exchanging ideas.

The challenge with this idea was the influence of the municipality. The municipality owns the land and seems to have a stronghold on the things happening in the market. The association wanted to confirm with the government before deciding on doing the event. We were told that the municipality turned down our proposal. This forced us back to the ideation stage. We ended up doing a simple game with the people in the market. This was both fun and an interesting way for us to observe different relationships and inclusiveness.

By analyzing three levels (CBD, East CBD, and Jardim Garcia D’Orta) the team gained an understanding of the macro and micro-processes that affect various individuals. They observed the landscape, regime, and niche (Macagno 2019) systwems at work. They better understood the stakeholders and team players, which includes becoming familiar with the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats to the area and the people.

East CBD is centrally located between tourist hotspots, civil institutions, and local commerce, with sparse residential sprinkled throughout the area. The area is framed by casinos in the north, religious institutions in the East and South, high commercial activity on the West, and Jardim Garcia D’Orta (City Garden) at its core.

Perhaps the largest consensus among children is the negative sense of safety. During interviews and the Observe walk, the children consistently raised the issue of safety in parks and on the streets. This is reflected in how schools and parents limit childrens’ time outside safe walls. Children cite a multitude of factors that influence their decision from perceived dangerous strangers, to heavy traffic, and poor walkability,

Through the team’s observation, it is clear that children are not considered in the planning and designing of public spaces within the city. Each of the parks within

the East CBD area are designed primarily, if not solely, for the leisurely pace of resting adults and gossiping elderly. Children are only seldomly welcomed into the parks when they are activated with events for families. The other 360 days of the year, they are met with signs that deter children from using the space.

In large part, children of all ages are overlooked when it comes to the planning and design of the CBD. What little facilities there are for children, is left to deteriorate. Small children are unable to cross gutters, teens cannot play sports in the park, and parents must hold their children’s hand tight when crossing the street in fear their child may become another statistic in the second deadliest state for traffic accidents (Gururaj, 2008).

Create a sense of ownership and empowerment amongst the local schools and residents while engaging CCP to create high-quality public space for children. When cities are built to include children, they are better for everyone in terms of accessibility, safety, and utility.

Create a community council under the Imagine Panaji umbrella with representatives of Imagine Panaji, local residents, school officials, and religious institutions, with at least 30% voting representation by children. The pilot project of this council is to address the vacant lot south of Jardim Garcia D’Orta.

Replicate and adapt the prior mentioned school workshop with other schools in the area and any interested institution such as the Immaculate Conception Church and the Head Mosque.

Based on this participation, implement the design using the resources of Imagine Panaji. From the previously mentioned methods, here is one potential scenario:

The park includes prefabricated and atypical play equipment suitable for many ages, a mini-library, a reading spot, and a community garden. Each organization represented on the community council would assist Imagine Panaji in building the park. Contactors do the excavation, parents build the planter boxes from wood, and children plant the garden. By having a hand in the execution, the community develops a sense of ownership of the project and the results. The maintenance of the lot will be handed over to CCP. The schools or religious institutions will manage the garden and the mini library. Schools can coordinate recess times throughout the week to improve children’s growth and development. Time spent playing outside and interacting with the natural environment is proven to have a positive impact on motor development in children as well as preventive health effects (Fjørtoft & Sageie, 2000).

The utility of the park will be examined by the council after project completion every three months. At the end of the first year, the council will reconvene to examine any adaptations to the design. Potential future adaptations could range from expanding upon successful elements, reassessing the viability of less successful elements, and proposing new uses.

This framework of the community council focusing on public space will be utilized as a replicable precedent for all public space projects pursued by Imagine Panaji. While this proposal focuses on one lot, every public space must be designed with children in mind for the city to be inviting.

It is undeniable that Panaji has car issues. Within a state that has the highest vehicle ownership (Comprehensive Mobility Plan for Goa 2019), Panaji has steadily deregulated two and four-wheel vehicles. For a city of just over 40,000 people, Panaji suffers excessive mobility issues from parking, pedestrian accessibility, and efficiency. The consequences are not limited to the frustration of drivers but extended to poor air quality for children going to school, a higher opportunity cost for businesses, and an overall decrease of livability for those in the area.

The lack of regulation has led to the streets being underutilized. Casino goers leave their vehicles in front of businesses for many hours without showing a rupee to the stores as they enter the economic island of the casino. Valuable parking spots are taken up by idle tourist vehicles whose drivers are hoping to make a day’s pay in one or two rides. Curbside parking is perhaps one of the most valued pieces of land, yet it is left to be consumed without any checks.

While mobility is a comprehensive topic spanning walking, bicycling, driving, and public transport, it is not treated as such in Panaji. Imagine Panaji started addressing mobility by publishing the Comprehensive Mobility Plan for Goa. Granted this plan takes critical first steps to understand the current situation and moving the conversation forward; it lacks tangible action points. There lacks a detailed plan that takes into account every mode of transportation and how the streets are managed for Panaji. Residents even report inter-agency fighting over whose responsibility it was to resurface a road after utility work.

Given Imagine Panaji’s commitment to mobility, the goal is to provide tangible steps to inform the public and work collaboratively to achieve better streets for everyone, especially those who are marginalized and rely on walking and public transportation.

Initiate an information campaign to inform local property and business owners of the benefits of enhancing the walkability of streets. While those in built environment professions know that pedestrianized streets help residents lead healthier lives and boost retail sales, this is often not understood by shop owners who have sharply opposed traffic and parking regulations in the past.

In partnership with businesses, CCP will place metal barricades that prevent vehicles from blocking the pedestrian pathway at intersections, thus enhancing the walkability for everyone, especially those most in need. By creating less hostile streets for disabled persons, Panaji reinforces the equal access rights solidified in the Constitution of India (i.e. Articles 15, 17, and 23) as the street serves as the means by which individuals access job opportunities, places of worship, their property, etc.

Once trust and cooperation has been built, regulations can be reimplemented, such as instituting a 2-hour parking limit from 08:00 to 19:00. For residents and property owners, exemption permits may be granted for their respective street. The Traffic Police would be the primary enforcement agency. Imagine Panaji would contribute license plate scanners to assist the enforcement.

Sao Tome, Fontainhas, and Mala sit at the base of Altinho hill, with Sao Tome being the northern most neighborhood of the area, Fontainhas in the middle, and Mala to the south. Fontainhas was named after the spring at the southern end of the neighborhood that historically supplied the area with water (Panjim and Its History 2019).

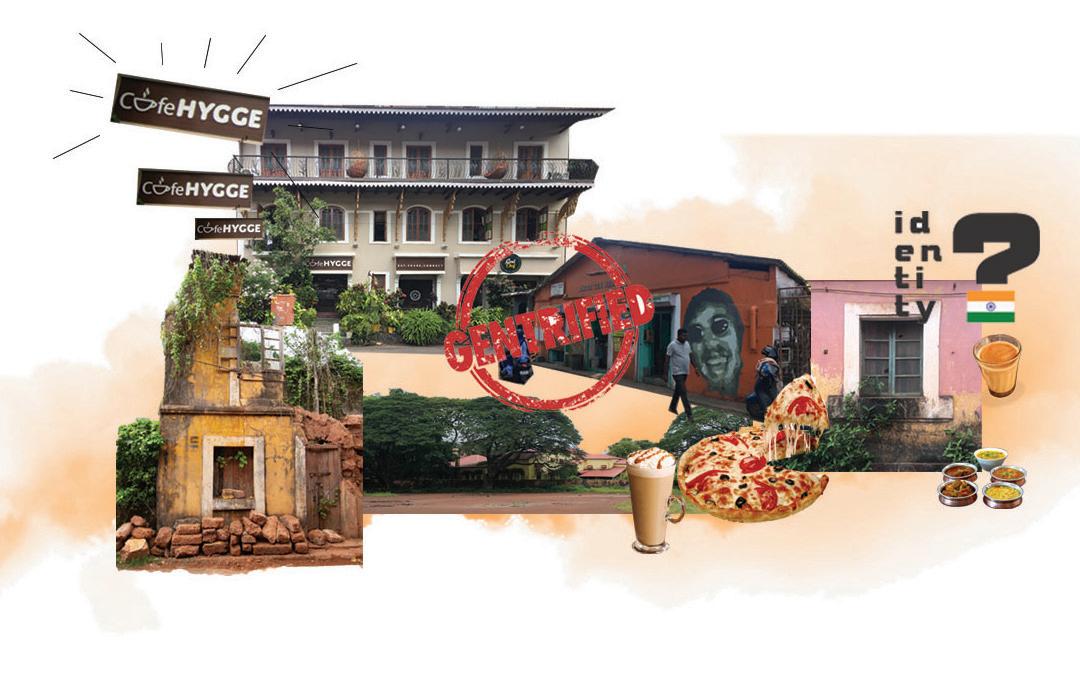

Fontainhas has been considered and protected by law as a Heritage Conservation area since 1974 (Mohta 2011, pg. 34). It is commonly referred to today as the Latin Quarter of Panjim. The buildings painted in bright reds, yellows, and blues attract both domestic and foreign tourists. This has created an interesting and complicated dynamic for the residents of the area.

The Portuguese influence is strongly manifested in the area in the Indo-Portuguese style of architecture. However, today many of the buildings face physical deterioration due to high cost, lack of funding and shared ownership.

The settlement is organized along a main spine, which narrows and stretches organically. It was initially created as a pedestrian pathway, but nowadays it suffers from vehicular congestion.

Within the area there are many options for education, both for children and adults. There are four schools, ranging from pre-primary to high school level, attended by students from all over Goa. An important institution for the area is the Bookworm library, which hosts a variety of free workshops for children and adults.

There is a clear divide between the wards, especially between Fontainhas, and Mala. This originates in the historical division based on religious affiliations. Where as Sao Tome and Fontainhas are largely catholic, the area of Mala was always considered Hindu. This division is then reflected in other aspects as well. Social cohesion within the Hindu community is stronger than the Catholic one. However the community is generally not very interactive and most importantly there’s a lack of civic engagement.

The financial capital in the area is mainly generated from the salaries of the residents, businesses in Fontainhas, and commercialization in the tourism sector. Those who struggle financially to maintain their buildings, often commercialize their house into income generating businesses, such as guest homes, small convenience stores, and boutiques.

In Sao Tome, Fontainhas and Mala, there are not many green spaces. Buildings form a dense neighborhood and limit the availability of public and green spaces. The main open spaces are the Marble Plaza, Hedgewar school playground and Mala lakefront. The Marble Plaza is the most active and is used at different times of the day by different user groups.

After identifying the different types of inhabitants that reside in these neighborhoods, finding the struggles in the municipal systems, learning about the existing institutions and associations and observing the tension between different parties in the area, the students were able to divide the zone into two seperate field work sections, each examined further by group 5 and group 6.

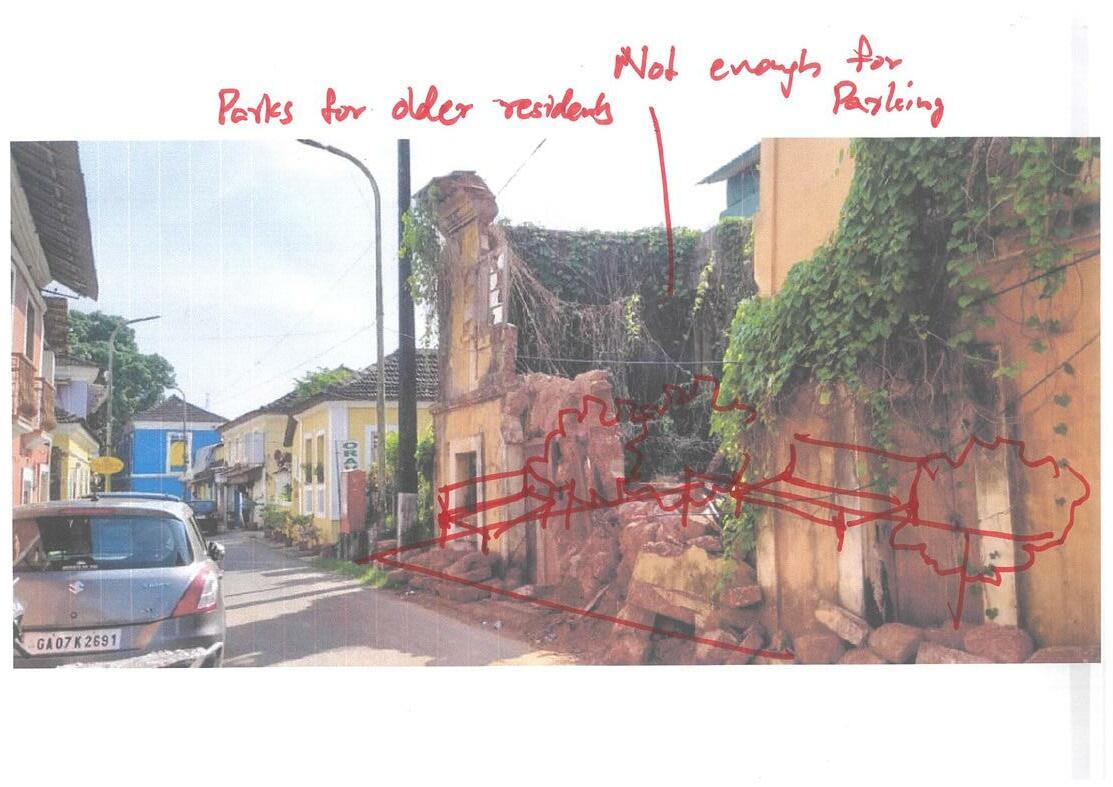

Methods and fieldwork selected were designed to hear the voices of Sao Tome and Fontainhas and to begin to understand the lives of the people we are designing for. Information gathered was to better understand physical constructs in the area as well as social. The students found much satisfaction with the neighborhood such as how quiet the neighborhood is, the accessibility of buses, and the proximity to Panjim market for fresh foods. But there are issues as well. Concerns were heard over flooding, contaminated well-water, lack of parking for residents and customers of businesses, sidewalks and walkways were poorly maintained, tourism is bringing too many people into the neighborhood, traffic is dangerous and congested, there is little green and public space, casinos are bringing nuisance, streets are littered with rubbish, young people are migrating out of Goa due to a lack of job opportunities in sectors outside of tourism, heritage laws are restricting desired alterations on homes, rental buildings are poorly maintained, lack of community cohesion, rivers are polluted from casinos and hotels dumping sewage into them, frustration with lack of communication from government development and bribes allowing some developers to bypass laws. There were also concerns in regard to Imagine Panaji as people distrust some of the choices they are making. The students used all this informations to try to think about what issues could potentially address in this neighborhood and what could be eliminated based on resources available. Then the students began to asses how an intervention could address multiple concerns at once. While tackling certain infrastructure issues felt impossible, traffic, safety, and public space felt approachable as well as potentially incorporating new economic opportunities for young residents in the area.

Historical construction in the area, paired with the heritage preservation laws in Sao Tome and Fontainhas, has created limited access to public space in the neighborhoods as well as congested streets and heavy traffic. Considering regulations in the area, how can we create access to high quality public space, alleviate traffic congestion, and potentially create economic opportunities?

Integrate community participation into Imagine Panaji and Smart City protocol. Stakeholders in Sao Tome and Fontainhas have demonstrated they want more participatory methods and collaborative decision making

in regard to development and changes in their areas. One method of implementation is to have an internship or fellowship program for students or recent graduates in disciplines such as planning, architecture, urban development, or public policy. This team could focus on research and participation alongside existing Imagine Panaji projects and proposals.

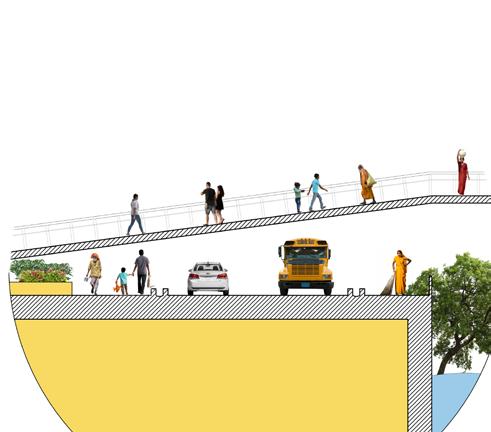

Transformation and improvements to community space. There is an opportunity to create a small park in Sao Tome where the ruins of a vacant building remain. The park would be tailored to the older residents of Sao Tome who may have trouble walking to the new public park. The proposal also suggests pedestrianization of half of Rua de Natal in replacement of one side of parking and repairs be made to the light fixtures on the current footbridge that crosses Rio de Ourem, as it becomes dangerous after dark.

Additional pedestrian bridge. Our design includes a pedestrian bridge from Rua de Natal that begins on the west side of Rua de Ourém and ends at the new public park. This bridge will act to reduce the dangers for pedestrians crossing the road and increase foot traffic through the area. Furthermore, it can create a space for community interactions, through the inclusion of bike paths for children and adults and designated stalls for food and commercial street vendors who can receive free vendor permits in exchange for keeping their section of the bridge clean and tidy. The proposal was envisioned to be more than just a footbridge to a park, but a socializing destination on its own.

The colorful streets and the characteristic architecture style make Fontainhas a loved destination for a lot of tourists. However, the residents look at the area with a different perspective. The maintenance of the houses comprises an issue because of several reasons, the main one being the high cost. Moreover, there is no funding or incentive from the government to assist with this. Shared ownership between members of joint families is another factor contributing to the poor conditions of the houses. This not only brings disagreements and long procedures when it comes to making decisions regarding the buildings, but it also lowers the wish to invest in the house, when not all members share the expenses. Faced with these issues, a lot of residents have sold their houses to outsiders to start businesses, or have moved away leaving their houses abandoned and prone to complete deterioration.

While the high tourist influx should be an opportunity for economic benefits for the residents, it is becoming, on the contrary, a detriment for them. Commercialization is contributing to the gentrification of the area, with the new businesses being opened by outsiders more often than by residents themselves. Furthermore, their target being the tourists, they become places the residents cannot use because of the inability to afford them. Led by financial interests, in an attempt to conform to the preferences of the ongoing wave of tourists, the newly opened businesses promote anything but the local culture. While the authentic characteristics and unique elements of the area could be utilized to differentiate this destination and enhance its attractive values, the cultural identity is not being preserved.

Although interviews with residents and users of the area initially lead the students to believe there was a strong sense of community and social networking, further activities and observations made it evident that was not the case. There is a clear division between Fontainhas and Mala, originating in the different religious affiliations but reflected in other areas as well. The community is not very interactive and there’s a lack of civic engagement. Lack of maintenance of open public spaces further hinders social gatherings. Enhanced by the loss of trust in the governmental authorities and their belief that they are powerless in bringing a change, the residents demonstrate no willingness to engage in and initiate action for their area.

Problematic heritage conservation laws and regulations result in incapability of maintaing the houses, loss of identity, and gentrification of the area.

To make the maintenance expenses more affordable, the students propose introducing a catalogue of small measures that effect in a financial discharge of the households. This is expected to motivate the owners to improve the current conditions of their houses. Three different measures were ideated:

1. Cutting house tax for heritage buildings

2. Cutting utility costs

3. Repair loans without interest

The residents would not be the only ones benefiting from this tax package. The state of Goa would benefit from the rising willingness of the owners to invest in the future of their houses to keep the value of the heritage buildings. This corresponds with the long-term plans of the tourism-strategy of Goa where the focus is set on cultural tourism. Investing indirectly through tax incentives into the heritage helps to preserve its value and the importance of this unique area.

The target of the students in this topic is to raise the pride and create awareness for heritage among the youth. Since youngsters are the future decision makers of the area, it’s important that they grow up knowing the values of heritage, so that they take conscious actions in the future. A well informed youth will affect the parents and wider community. Moreover, good understanding can increase the feeling of belonging and impact the youth to stay when they grow up, instead of moving away as a lot of the young people are doing today.

To do this, the students propose reviving the heritage club at People’s Higher Secondary School, within the HECS network. Heritage Education and Communication Service (HECS) is dedicated to spreading awareness to all, especially young people, about India’s natural, built, and cultural heritage. Though currently the school already has a heritage club in collaboration with HECS, its activities are only limited to participating in a film festival. Therefore, the students suggest reviving it, by introducing more activities which will encourage more children to join. Examples of these activities are heritage walks, drawing competitions and “adopt a house” project, which consists of children being responsible to learn about the history of a house and monitor it. Later involvement of experts in the project would enable the kids to learn practical skills on the maintenance of the heritage buildings.

Under this topic the students hope to strengthen the feeling of belonging and responsibility for the area among the residents, strengthen the community bond and give the power back to the people. In order to do this they looked at two main strategic interventions that could be done.

The current situation of the social capital in the study area calls for a tool to unify the community and especially integrate the two wards – Fontainhas and Mala - with each other. Initially, the idea was to encourage the residents to create an association, however considering the current situation of the social capital, it was understod that this would be quite difficult to achieve. With smart phones and social media being omnipresent in our daily lives, an online platform would be a quicker and more practical space for residents to come together and interact. Furthermore, it would make it possible

to encompass a wider scope of participants and stakeholders. A Facebook group would be a catalyst to facilitate exchange of information within the community. Posts about common interests can become niches for people to meet up in real life, so the online group will gradually lead to integration of the community in reality. This will enhance the feeling of belonging. Additionally, people united as a whole will have the power to approach authorities and hold them accountable for their actions.

Throughout the interviews and other methods organized with the community, the memories of the festival that revived the area are of the most outstanding ones. It was then that Fontainhas regained its beauty and pride, by becoming an attraction point of visitors and investments in the area. It is evident that in the organization of a big event lies a great potential of rebuilding social network and capital. The students proposal therefore is to activate the public space for community building and to organize different events like festivals, street parties, etc. Not only will the event foster a sense of civic pride and create new links between members of the community, but it will also generate revenue which can be used to invest in the maintenance of the houses. Especially during the planning phase, the bonds between the residents themselves and the different organizations are forged. The Facebook group created ahead can be the niche to initiate the event and encourage the two neighborhoods for engagement and collaboration.

“Make it Happen” heritage walk tour guides showed motivation to not only assist but even initiate big scale events spreading through the length of the settlement. The students served as a bridge to link them to resource people from the two wards, Fontainhas and Mala, so as to create an initiating team, and helped ideate activities for an initial event. New Year’s was chosen as a neutral festivity, not associated with any religion.

.

The three months of fieldwork proved fruitful as all six groups engaged with their communities, analyzed the built environment and its systems, and constructed strategic proposals. From working with informal communities to the busy streets at the center, the students employed participation methods that highlighted the voices of residents.

Before coming to Panjim, the students were told how lucky they were that the fieldwork was taking place in Goa. They heard stories about pristine beaches, raging parties, and advanced infrastructure and municipal services compared to other parts of India. But when they arrived at Dabolim Airport (Goa International) it was quite a culture shock. They quickly realized that although the state of Goa is known as a resort destination, Panjim was much more.

As the weeks progressed, they found the beauty in the city and its people. Things began falling into place as they learned about the history, culture and individuality of Goa, a place like no other. As foreigners, they were glared at yet tolerated, with only the occasional person trying to take photos of them. They stood out, yet in a place known for tourism, they also weirdly blended in. They developed new routines but each time they thought they had a grasp on the complexities, India would throw new challenges their way.

Working on the sites confronted their preconceived ideas about what fieldwork really means. For many of them, stepping into someone else’s neighborhood and homes felt intrusive, especially when it was obvious by their skin color and accents that they did not belong. But more times than not, they were welcomed in unexpected ways. Being offered beverages in people’s homes, having children want to show the students around the areas

they are most proud of, and sparking an interest in collaboration between the community and government bodies. When working with certain stakeholders, the students also got to feel the appreciation for their work approach and the stakeholders were genuinely interested in the community-based methods, which were very different from the hierarchical way projects are traditionally organized in Panaji. The students also had the pleasure of getting to know a variety of people who actually believe in possible change, want to improve their communities, and do not let themselves get frustrated by the slow bureaucratic process.

But it was still hard. Being an intruder and knowing that they cannot make any promises to the people they felt drawn to helping , because at the end of the project, they had to go home. It is hard not to feel disheartened by this fact and the dichotomy between academic agenda and meaningful impact will always remain in this kind of project. Nevertheless, the analysis and proposals outlined above represent the passionate collaboration between the students and the residents.

Group 1

Aleisha Martal

Hamish Hay

Vårin Lyngstadaas

Group 2

Alvira Shrestha Ellen Margethe Romsaas Michaela Schmidt Moses Viveros

Group 3

Anders Schive Hoel Jayati Grover Occitane Mestre

Group 4

Isabella Moran Karla Cristina Flores Nick A. Kiahtipes

Group 5

Annalise Winter Robin Surya Shayestah Shahand

Group 6 Fabian Wildner Nora Sønstlien Ursula Sokolaj

Pictured: Students and Faculty from NTNU and SPA Delhi

“Asian Development Bank, 2019, ADB’s Work in India. [online] Available at: https://www.adb.org/countries/ india/overview [Accessed 30 Oct. 2019].

Fjørtoft, I., & Sageie, J. (2000). The natural environment as a playground for children: Landscape description and analyses of a natural playscape. Landscape and Ur ban Planning, 48(1), 83–97. https://doi.org/https://doi. org/10.1016/S0169-2046(00)00045-1

Gururaj, G. (2008). Road traffic deaths, injuries and disabilities in India: current scenario. National Medical Journal of India, 21(1), 14–20.

Imagine Panaji Smart City Development Limited. (2019a). Comprehensive Mobility Plan for Goa [Strategic Report].

Ministry of Urban Development, 2015, Revised City De velopment Plan - Panaji 2041, Panaji Royal Haskoning DHV, 2019, Panaji 24/7 Water Supply and Saint Inez Creek Rejuvenation Project

The World Factbook., 2019, South Asia: India. [online] Available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/ the-world-factbook/geos/in.html [Accessed 30 Oct. 2019].