Preface

After two years of pandemic-related restrictions which affected many aspects of the Urban Ecological Planning Programme (UEP), and especially its first semester obligatory fieldwork, the 2022 fieldwork under the Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course was conducted in Kochi, India. This was a planning studio project with emphasis on international mobility and knowledge exchange among students from India, South Africa, and Norway. The project forms a core component of the two-year International Master of Science Programme in Urban Ecological Planning under the Department of Architecture and Planning at the Faculty of Architecture and Design at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). The 2022 project activities rejuvenated the UEP passion and curiosity about challenges and opportunities being faced by cities of the Global South. Students spent eight weeks working in Kochi city in the Southern Indian state of Kerala. The project was structured and framed to contribute directly to the UTFORSK funded Norway-India-South Africa (UTFORSK-NISA) student and staff mobility project on localization of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Thus, the project involved NTNU, School of Planning and Architecture (SPA), New Delhi, India, All India Institute of Local Self Government (AIILSG) and the University of Cape Town (UCT) in South Africa. This report represents a major output from the integrated effort of communities, bureaucrats, and most importantly, the students from NTNU, SPA and UCT.

This project report is an outcome of studio work done by NTNU students. The report provides detailed information about students’ experiences, learning and context-informed recommendations for improving living conditions on study sites in Kochi city. Students’ learning and recommendations are based on UEP’s teaching philosophy of experiential learning. Students’ exposure to an unfamiliar context poses several challenges while working on an academic goal but it also provides the necessary ‘triggers’ for learning that is simply not possible in traditional planning studios that are of shorter duration and have less emphasis on being out in the field.

The project report is informed by methods that allow students to propose solutions to complex but interlinked urban problems based on area-based planning and participatory planning

approaches. This year’s report emphasises some of the most important UEP values and topics that include inclusive urban planning and development, ecological integrity in cities, and sustainable urban livelihoods and accessibility. By working with local communities, local and international stakeholders, students identified, analysed, articulated complex issues, and made realistic recommendations to improve living conditions on specific study sites.

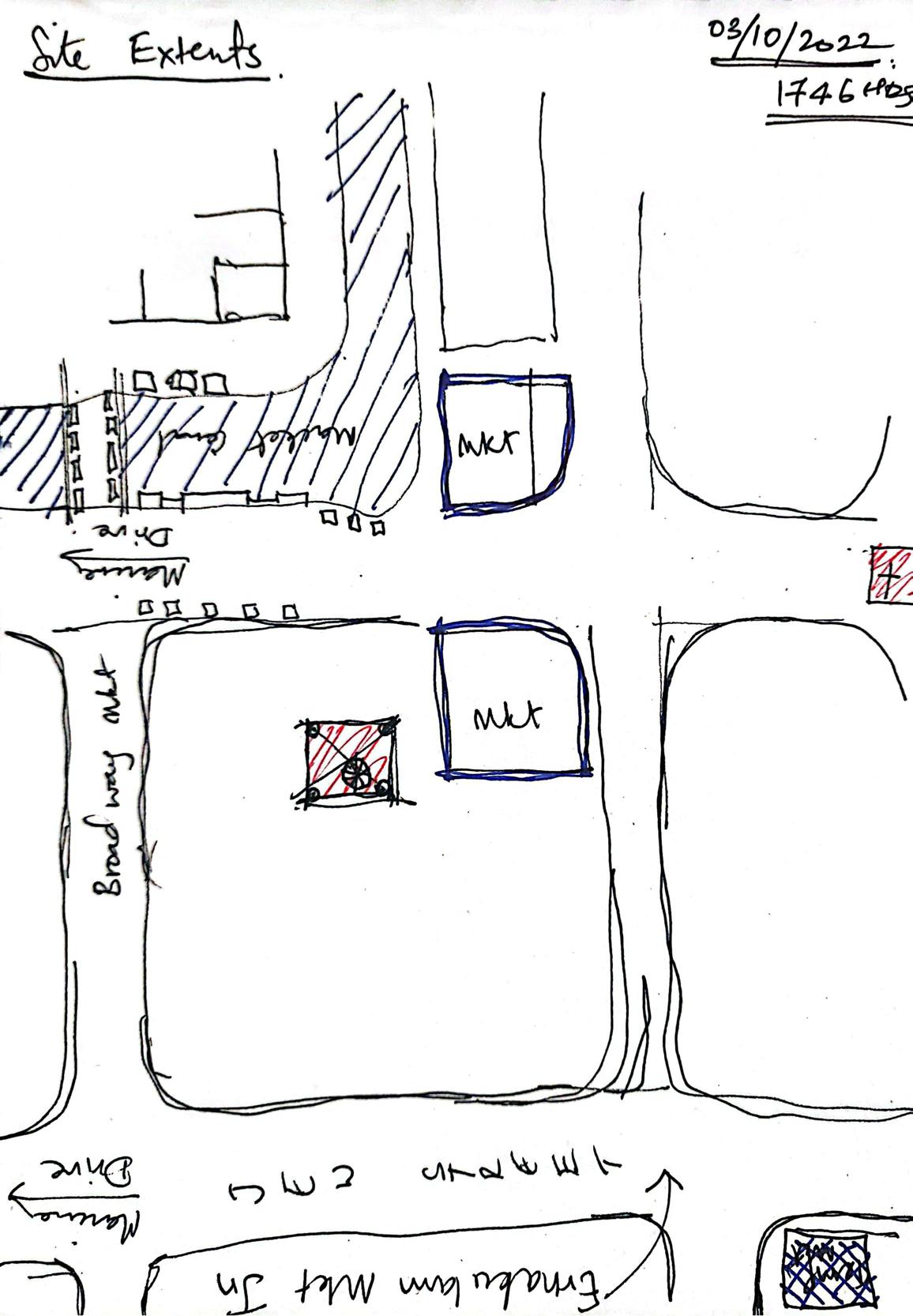

The students were divided in 4 groups and 2 of them worked in Fort Kochi while others in Ernakulam areas of Kochi city. Fort Kochi is a seaside historical area known for its Dutch, Portuguese, and British colonial architecture, and heritage and fishing. It is a significant tourist area for the Kerala State. On the other hand, Ernakulam is a sprawling residential and commercial hub well known for Marine Drive and a busy waterfront. Zeroing in on specific sites, the reports deeply reflect on the urban everyday life experiences, challenges, and opportunities for people in Kochi. While retaining the area-based planning approach, students’ work was based on the overarching theme of urban informality and guided by three themes: ecological vulnerability, urban markets, and urban mobility. As an outcome of their learning process, students prepared four reports to illustrate and reflect upon the participatory process through a situational analysis and reflection on methods and methodology that informed a problem statement which they tried to address in strategic proposals. This report summarizes the work of the group working with market redevelopment in Ernakulam.

We would like to give a special mention for Centre for Heritage, Environment and Development (C-HED) and World Resources Institute (WRI) India for their constant support to our students in terms of giving them insights on local context and different themes that students worked on and for connecting them further with relevant stakeholders and documents.

5 | Group 1 Fall 2022

Gilbert Siame, Rolee Aranya, Riny Sharma, Mrudhula Koshy, Vija Viese

Fieldwork supervisors, NTNU, Department of Architecture and Planning.

Acknowledgements List of Abbreviations

We would like to thank the University, our professors and colleagues who were a large part of the process and its successful completion.

To the people of Kochi, thank you for allowing us to come to your city and learn about the relationships, culture and social aspects of the historic city. The people of the market who constantly remained forthcoming for us whenever we visited and engaged with you all. For all the inputs we got from the people of the market, we hope our project does justice to the time you took out to engage with us.

ATP C-HED CPI (M) CSES CSML DAPP IC4 KMC KMCC

To institutions like Center for Heritage, Environment and Development (C-HED) and CSES, thank you for allowing us to learn from your expertise and engaging with us at all opportunities.

To CSML for hosting us and giving us an incite into the world of Smart City and its potential.

Adaptive Tipping Points

Center for Heritage, Environment and Development

Communist Party of India (Marxist)

Center for Socio- Economic and Environment Studies

Cochin Smart Mission Limited

Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways

Integrated Command, Control and Communication Center

Kochi Municipal Corporation

Kerala Merchants Chamber of Commerce

7 Group 1 | Fall 2022 6 Kochi Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in

Market

Ernakulam

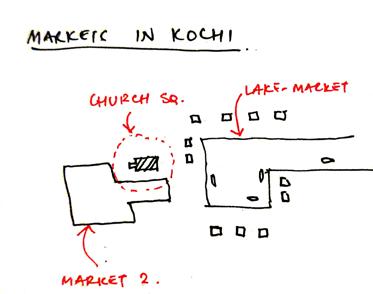

Ill.

1 - Ernakulam Market

Policies in Play - Reclaiming livelihoods and heritage in the Ernakulam Market Kochi 2022

Contents

Preface Group introduction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Setting the context

2.1 Locating Kochi

2.2 Transitions over time

2.3 Problem statement 3. Methodologies

3.1 Process timeline

3.2 Desktop research and literature studies 3.3 Spatial Mapping 3.4 Transect walks

3.5 Interviews 3.6 Co-production 3.7 Risk assessment and the area-based approach

3.8 Iterative sketching - the diagram as a tool 3.9 Reflection on methods

4. Situation Analysis

4.1 The market across multiple scales 4.2 The market and the food-supply chain

4.3 Stakeholder analysis

Page number 12 13 14 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 32 34 36 38 42 48 50 52 54 56 60

4.4 Stakeholder issue-interrelationships

4.5 Stakeholder mapping

4.6 The formal-informal continuum 4.7 Shop typologies 4.8 Tabula rasa urbanism 4.9 Reflection

5.

Policies in play

5.1 Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways

5.2 “Adaptive Tipping Points” emerging from the site

5.3 Proposal for a reviewed governance structure

5.4 Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways - Impact of Objectives and Actions on site

5.5 DAPP responding to actions - alternative trajectories of development

5.6 Revised stakeholder power-interest analysis

5.7 Policies in play - market site 5.8 Shop typologies to fit the everyday needs 5.9 Possible spatial outcomes

Reflection

Discussion Conclusion References List of Figures

62 64 66 68 70 72 74 76 77 78 80 82 84 86 88 90 98 100 102 104 105

11 | Group 1 | Fall 2022 10 Kochi Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

Abstract

We are group 1 in the first semester at the Master of Science in Urban Ecological Planning programme at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

We are four group members, Aditi Patil, Ami Joshi, Stine Kronsted and Karl Schulz. In the group we have a broad range of expertise that we have made use of during the process of developing this project. Ami and Aditi are from India and have backgrounds in Architecture, having studied their bachelor’s degrees at, respectively, the School of Environment and Architecture and Pillais HOC College of Architecture in Mumbai, India. Stine is Danish and has a background in Urban Design, with a bachelor’s degree from Aalborg University. Karl is Latvian and has a background in Public Planning and Administration, with a bachelor’s degree from Volda University College. These various backgrounds have provided us with an interdisciplinary base of knowledge that has informed the project. In the process we have learned from each other’s expertises and capacities, as well as variations in geographical backgrounds and cultures.

Aditi Patil Ami Joshi Stine Kronsted Karl Schulz

This booklet is an urban planning project that has been developed as part of the 1st semester of the Master of Science in Urban Ecological Planning at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. It is a proposal for a revised urban planning scheme for the Ernakulam Market in Kochi, India.

First, it sets the context of the market. The market is located in a historical part of Kochi and has a distinct heritage value. Then it describes the current situation, where the market is undergoing a transformation undertaken by the Cochin Smart Mission Limited (CSML). The empirical findings indicate the new market proposal was based on a top-down approach to planning, resulting in the loss of livelihoods of the people who depend on the market activities. The problem is stated: How does a top-down approach to planning a living, growing public space like the market affect the livelihoods, and the socio-spatial relationships within the community? What kind of insecurities does this approach bring in the minds of the different stakeholders?

To answer this question, primary and secondary research methodologies have been used; spatial mapping, transect walks, desktop research, community interviews, co-production of knowledge and design, and more. Based on engagement with the market community, and with a theoretical grounding in current theories and practices related to planning, informality, gender, and governance, an alternative governance structure of the market is proposed. The planning scheme is derived from the theory of “Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways” (DAPP) (Haasnoot et al., 2019) and approaches planning as a dynamic process, where decisions and policies are made over time, responding to actions that take place in the urban reality.

It is concluded that a top-down, westernised approach to planning has the tendency to accelerate gentrification, resulting in pushing out the people who can not afford to be a part of this development. As an example of a South Asian city experiencing rapid development, Kochi is at risk of undergoing this process. Looking at the effects of this planning scheme proposed by CSML, an alternative planning pathway for Kochi is proposed. The DAPP is one alternative. However, the most important aspect of planning is to ensure that the people whose voices are not usually heard, are included in planning, and that policies and governance responds to their urban reality.

13 | Group 1 Fall 2022 12 | Kochi Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

Ill. 2 - Group picture

Group introduction

1. Introduction

In the process of urban development lies a conflict between retaining what is, and responding to what should be. The question is, do we handle heritage by freezing it in time? Or do we start over, tabula rasa*, to build the city responding to our future fantasies? Is there a middle way?

The Ernakulam Market in Kochi, where the research has been made for this report, is in this process where the city has to find a balance between the past, the present and the future. The market, a historical site reflecting the development of Kochi as a city of trade, is a “sublime example of ‘living heritage’” (C-HED, 2019: 27). However, the market has been deemed insufficient in meeting the needs of the contemporary Kochi, and is currently undergoing reconstruction. Centre for Heritage, Environment and Development (C-HED) reflects on this process as being “constantly faced with the conflict of conserving and protecting heritage on the one hand, and addressing the living and economic needs of our huge population on the other” (C-HED, 2019: 27).

The market has a historical position in the development of the city of Kochi. When the British invaded the region in the early 19th century, the local population was relocated from the administrative centre of Fort Kochi to the mainland, Ernakulam. In this process, the market was the first public amenity to be established. Since then the market has been the trade link between the mainland of Kerala, to the Arabian sea, shipping spices, tea and other goods from India to the rest of the world. Changes in societal frameworks have informed the development of the market, which has proved resilient and adaptive to changes in patterns of supply and demand over time. Today, the market is the centre of a supply chain exchanging goods from across the region of India to city-wide retail buyers across Kochi.

While the trading activities have evolved and adapted, the maintenance of the market has not been following the same trajectory of modernisation. A thorough market redevelopment was requested by a broad representation of stakeholders, including the Kochi Municipal Corporation (KMC) and the Market Association. While a new market is currently being built, the market activities have been moved to a nearby, temporary site provided by the KMC. This process has resulted in increase in rent for the shop owners, reduction of space in the shops, less space for trucks resulting in less products being sold, which consequently results in loss of livelihoods for The everyday users of the market. The old market has been demolished, and the new proposal has been designed by the Cochin Smart Mission Limited (CSML) to, in their own words, “be like the Lulu Mall” (one of India’s biggest luxury shopping malls. CSML, 2022).

* an absence of preconceived ideas or predetermined goals; a clean slate

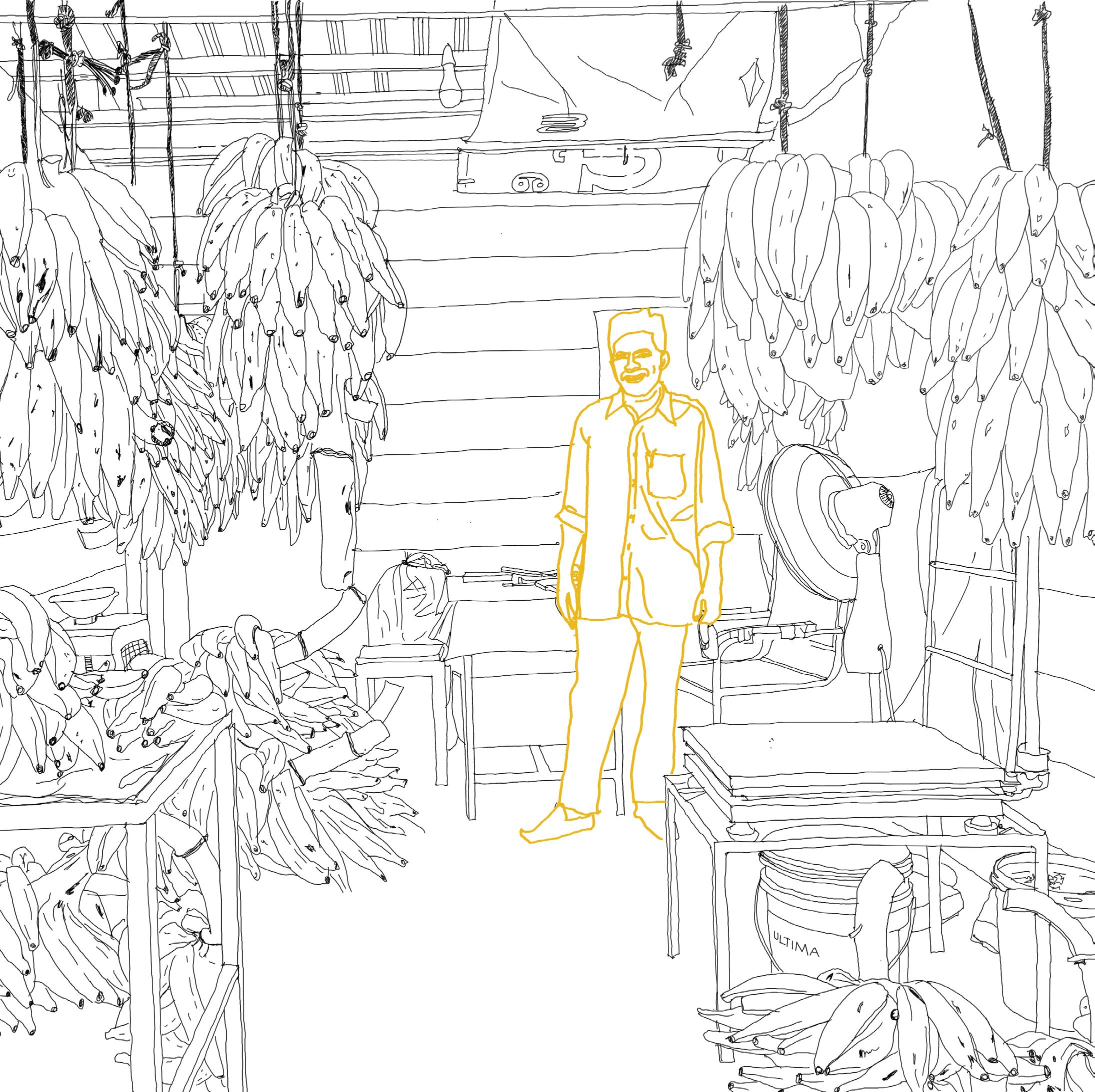

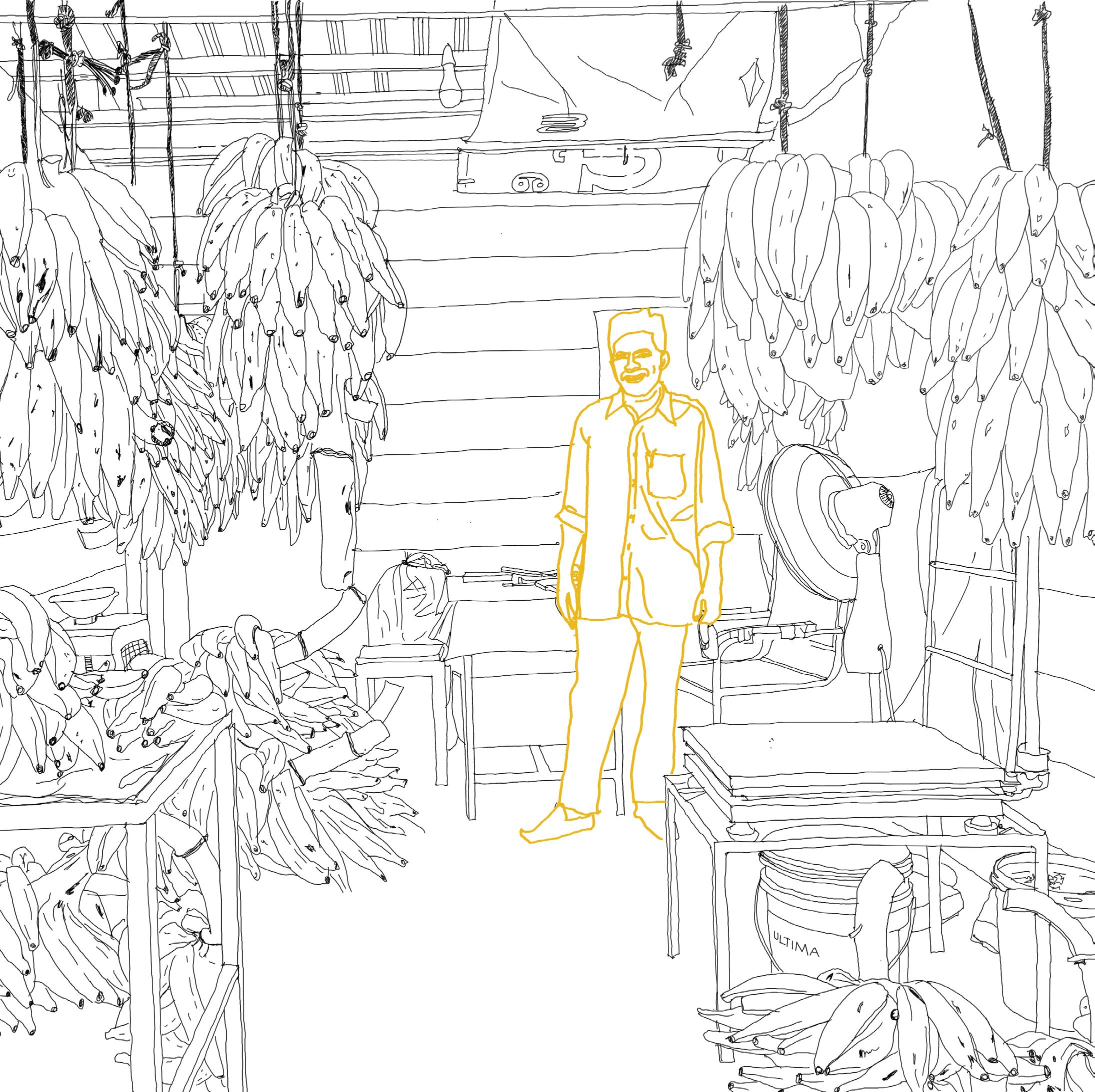

Ill. 3 - Drawing of bananna shop >

Continues next page

15 | Group 1 Fall 2022 14 | Kochi Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

Introduction continued

The process of moving the market has implied moving vendors who have built and modified their shops through generations, into a formal structure that does not take into account the individual needs of each specific shop. As a response to this, the shop owners have broken down walls, claimed the sidewalks, subdivided and combined shops according to their needs. Practices that in the former markets were an integral part of space-making, are in the new market ‘informal interactions’, a response to the formal structure failing to cater for the needs of the everyday users of the market.

The market redevelopment can be seen as a part of a global tendency of cities in the South Asian context undertaking urban development schemes influenced by westernised modernist city ideals (Watson, 2009). These are ideals of functionality, efficiency, technology and order, stemming from early 20th century visions of urban development in Europe and North America. Behind these ideals lies the belief that modernisation and building the city of tomorrow means ordering the disordered city(CIAM, 1933). The CSML reflects tendencies of this planning vision as they state their ambition of “redeveloping the existing wholesale and retail market into an organized, highly accessible and best in class shopping destination” (Csml.co.in, 2021) How this ‘’organized’’ space corresponds to day-to-day activities in the vegetable market is questionable. One can ask if this process will be able to cater for the needs of the everyday users of the market, or if this is a pretext for displacing disordered processes and systems that do not fit into the vision of the city of tomorrow?

This report analyses the redevelopment of the Ernakulam Market through a critical lens. It looks at the case in a contextual setting, discussing how this will affect the urban dynamics on the multiplicity of scales in which the market operates. Furthermore, it discusses the market redevelopment as a part of global tendencies in urban development. Lastly, it discusses alternative planning pathways that can include multi-level governance structures and most importantly, that can respond to the networks, relations, logics, as well as the history, heritage, and stories that make up the daily life of the city.

Ill. 4 - Drawing of egg shop >

17 Group 1 | Fall 2022 16 Kochi Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

2. Setting the context

Understanding a site means understanding how it is situated in its context.

Ernakulam Market is located in a commercial area in the Ernakulam district of Kochi. This area has a particular geography being situated adjacent to the mouth of a complex network of backwaters, streams and canals. This specific geographical position is related to the history of the site - there is a reason why the market evolved exactly in that place. In the process of understanding the context, studying these aspects give insights into why the site is as it is today.

The context can be understood as the local, nearby area, but it can also be understood as the context of Kerala, the context of India, or the global context. It is a multiscalar concept and understanding the Ernakulam Market means understanding how it is related to the world, from the day-to-day activities on the site, to the relation to historical global and trade networks of the past, present and future.

This chapter first locates Kochi geographically, then it moves on to understanding how the site has changed over time, to finally arrive at a research question.

Ill. 5 - Picture from Jew Street intersection >

livelihoods

Ernakulam Market

19 Group 1 Fall 2022 18 | Kochi Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and

in

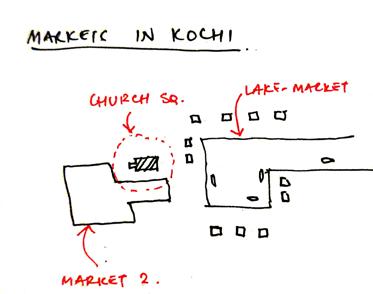

2.1 Locating Kochi

Understanding a place means understanding how it is related to the world. Looking at Ernakulam through different scales: from the world, the country, the state and the region, opens up for an understanding of the implications of the geography of the site.

The biggest country in South Asia

Kerala and the world

Large Coastline

Ill. 6 - 9 - Locating Kochi across geographical scales

Locating Ernakulam

Kerala State

Arabian Sea

Bay of Benghal

Western Ghats

India is one of the world’s largest growing economies. With more than 1 billion people, it is the second-most populated country. It is situated in South Asia, neighbouring Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh and Burma.

Kochi, formerly known as Cochin, is situated in the southern tip of India. It is a major city in the state of Kerala. Kerala goes under the name of ‘‘God’s own country’’ due to its lush, green mountains, forests and coastal landscapes.

Kochi region

Arabian Sea

Ernakulam Vypin Island Arabian Sea

Kochi is located on the coastline of the Arabian Sea. It is connected to the mainland via backwaters. The waters have served as tradelines from the mountain range of the Western Ghats to the rest of the world.

Kochi is a water-city interweaved by an intricate network of canals and backwaters. The different areas of the city are of remarkably different characters, with Ernakulam being the everyday-city and the centre of commercial activity.

21 | Group 1 Fall 2022 20 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in

Market

Ernakulam

Fort Kochi Willingdon Island

2.2 Transitions over time

The market as a node for development

Kochi has a strategic position on the coastline of the Arabian Sea, which has attracted traders from all over the world since its founding in the late 14th century. Arab spice traders, Jewish merchants, followed by the invasion of Portuguese, Dutch and British, respectively, have resided in Fort Kochi, giving form to the way it looks today. When the British arrived in the late 18th century, the local population was moved out of Fort Kochi, and the first public amenity to be constructed was the Ernakulam Market. The market was a water-based market(picture above), where goods from the mainland were sold and packed for shipping beyond India. The market was an important node for development of the city (Menon, 2022).

Erasing heritage

The intensity of activity in the market increased and the neighbourhood around the market evolved into a commercial district. The market itself was poorly maintained, and a renovation was agreed upon among multiple stakeholders. A renewal plan was developed by C-HED and other associate consultants in 2019. The plan was contextual and reflected the heritage of the old Ernakulam Market. A spatial plan was proposed as well as an incremental process of governing the space. In the end, however, the proposal was cancelled, in favour of a design proposed by the CSML in late 2021. Under the market redevelopment project the old market has been demolished (picture above).

Informality in formal structures

During the construction process, the market has been moved to a temporary location appointed by CSML. The temporary market offers the same system of stalls as the previous market. However, each stall has less space, the rent has increased and due to lack of space, less trucks are arriving with goods. These factors all affect the livelihoods of the people related to the market, resulting in some shops moving out of the area. The temporary market offers a framework based on the same unit, however, each vendor has modified the shop to fit their needs and maximise their livelihoods; walls are being built or broken down, shops are combined, divided, or extended to the surrounding space beyond the shop.

The smart city

The ambition of the new market is “... to revive the high commercial value of the decaying traditional market in the heart of the city by redeveloping the existing wholesale and retail market into an organised, highly accessible and best in class shopping destination.” (Csml.co.in. (2021)) (picture above: proposed Ernakulam Market)

The market will be on the ground floor, with retail shops on upper floors, including a skywalk and multi-story parking. The contrast between the existing market dynamics and this ‘organised, best class shopping destination’ is stark.

23 | Group 1 Fall 2022 22 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

Ill. 7 - 13 - Past, present future Ernakulam Market

How will the market development affect the dayto-day activities of the market, the livelihoods, and the already ongoing gentrification of the community of Ernakulam?

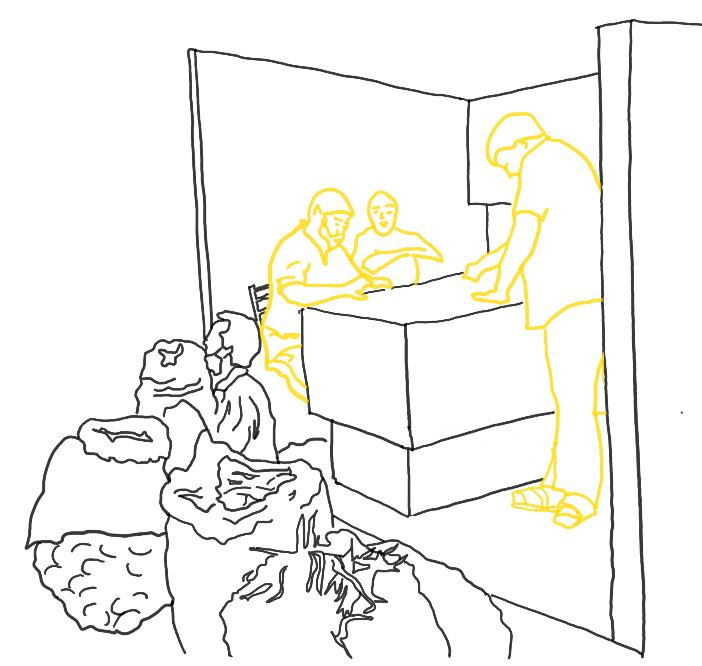

Ill. 11 - Staff and customers in a vegetable shop >

25 Group 1 Fall 2022 24 | Kochi Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and

in

Market 2.3

livelihoods

Ernakulam

Problem statement

3. Methodologies

There are multiple ways of analysing a site. The tools you use for approaching fieldwork shapes the outcome of the project.

Throughout the project we have been navigating between different methods for each stage of the process: from the research, to the site analysis, to participation and finally, to communicating the project. Some were familiar, some were new to us and had a more experimental character.

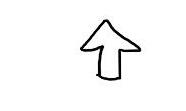

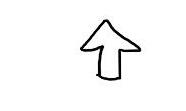

Throughout the process we have been moving between observations and understanding We have become aware of that in the process of deepening our comprehension of the context, we become increasingly aware of the complexity.

The process has been a hermeneutic fluctuation between seeing the market as a whole, while at the same time trying to understand separate interactions and processes that take place within this whole (Uxbooth.com, 2015).

Overall, we have been moving from observations to understanding - an inductive approach to knowledge has given us an understanding of general tendencies from the complex whole. However, it is clear that a process is never truly inductive. We arrive at the site with bias and preunderstandings of the context that has shaped our way of approaching the site (Raimo Streefkerk, 2022).

We have been walking, observing, talking, taking pictures, filming, facilitating, and asking questions for two months in Kochi.

This chapter is about the different methods that we have used, and how they have, or have not, been helping us in developing our project.

Deduction

Testing the validity of a theory in reality

A hermeneutic process

A non-linear process of understanding individual parts in themselves, and as a part of a whole.

Ill. 15 - How we were introduced to the context

Induction

Drawing conclusions based on empirical observations

Ill. 16 - How the actual process of analysis went

Ill. 17 - Decoding complexity

27 | Group 1 | Fall 2022 26 Kochi Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

Unstructured

Semi-structured

Project start August 2022

Departure for Kochi September 2022 SPA Students October 2022

Deskop research

Spatial mapping

Interviews on site

The process was not a linear process. It was a constant overlapping of different phases in the project development.

Ill. 18 - timeline

Stakeholder identification

Problem statement

Stakeholder mapping

Spatial strategies Co-design

Return to Trondheim November 2022 Finalisation and post-production End of project December 2022 UCT Students November 2022

29 Group 1 | Fall 2022 28 Kochi Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in

Market

Ernakulam

3.1 Process timeline

What it is

Desktop research, or secondary research, is a process of studying data that is already available. Where primary research is dealing with collecting empirical data first-hand, the secondary research studies other people’s primary research.(Research.com, 2021)

What we did

To familiarise ourselves with the context of Kochi, we studied existing urban plans and literature related to the city and its development. These were plans developed by the municipality, or architecture and urban design projects made by other institutions or student’s work in Kochi. In the process of building our theoretical framework for the project, we studied academic literature related themes of conceptualisation of informality (Altrock, 2018: Recio et al., 2016: Roy, 2009), of insurgent and radical planning(Beard, 2003: Miftarab, 2009), of urban planning (Watson, 2009) and governance structures (Galuszka, 2019).

What we thought

The combination of primary and secondary data in the process of building our understanding of the site and the context was essential, and the two methods of gathering information complemented each other in the process. The local communities are most likely not aware of the planning framework that they live as a part of in their daily life in the city. On the other hand, there are aspects of the everyday interactions that take place in the city, which no report or planning proposal will be able to account for.

Ill. 19 - Collage of literature studies

31 | Group 1 Fall 2022 30 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

3.2 Desktop research and literature studies

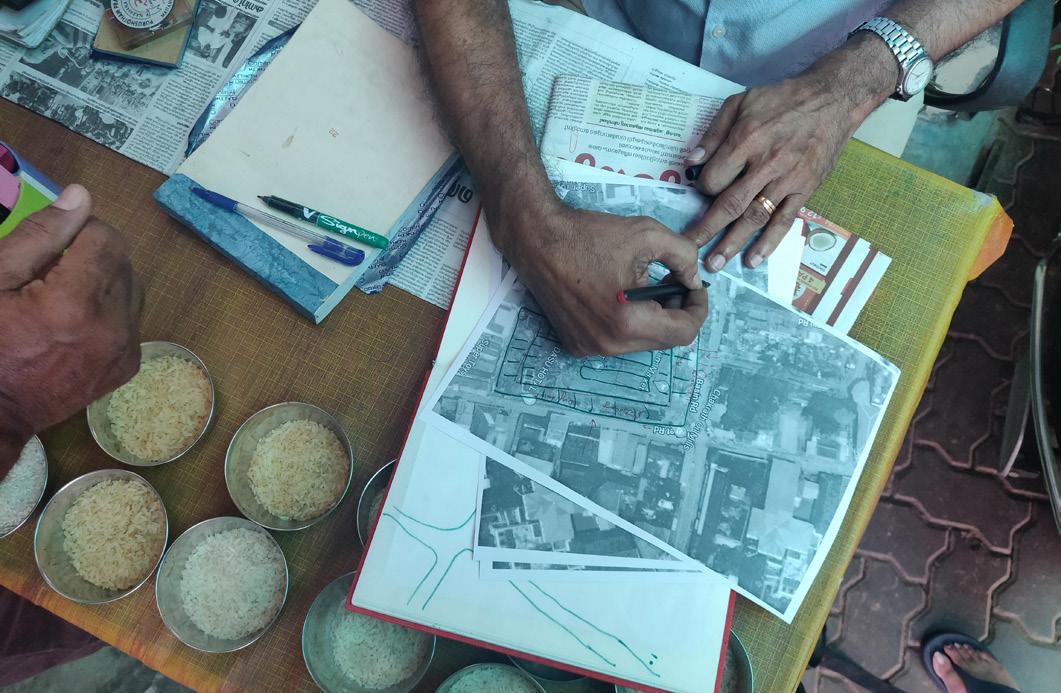

What it is

Spatial mapping is a tool for understanding how spatial entities are related to each other in a geographical area It is a process that can consist of both desktop research, by studying maps of the site, in combination with field visits for mapping distinct features and functions on the site. Mapping in itself can be both a part of a process as well as an outcome in itself, depending on what it is needed for. In our case, mapping was used as a processual tool for understanding the context.

What we did

Spatial mapping of the area showed how the market is embedded in a complex network of places and connections. It showed the important relation to the canal and how the canal is both connected to the mainland of Kerala, as well as the Arabian Sea. Furthermore, it gave an overview of important functions in the area, major roads and access points, religious institutions and land-use.

What we thought

The spatial mapping process was interesting for understanding the distinct spatial logic of the site. The combination of studying maps as well as seeing these spatial relations in the field gave an understanding of how the site is situated in the neighbourhood and in the larger urban region. However, the spatial mapping process should ideally have been done in collaboration with the community. In this way, the important features of the area would be highlighted based on the input of people living and working there, rather than based on our interpretation from the outside. As architects and planners we are trained to think and see in a specific way, and this affects how we undertake mappings. Maybe the shop owner would highlight aspects that we would never have thought of?

Ill. 20 - 21 - Spatial mapping

33 Group 1 Fall 2022 32 Kochi Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

3.3 Spatial

mapping

What it is

A transect walk is a tool for gathering information along a defined trajectory. It is based on “observable” features along a chosen path, for example natural features, landuse, signposting, housing typologies, etc. As you proceed along the path, the feature of analysis is mapped out, according to the location on the path. This allows for studying patterns, tendencies or cause/effect relationships. (Sswm.info, 2019)

What we did

The transect walk was the first mapping exercise we conducted in the field. As a point of entry to understand the logic of the area, we wanted to map the commercial activities along the most central street in the area, Jew Street. The centrality and the busyness of the street was the reason for selecting this street. We walked from the start to the end of the street and mapped the shop typologies. This analysis revealed a pattern of multiple shops with the same products being situated next to each other. Furthermore we recognised a pattern of retail shops being towards the waterfront, and the further away from this area, the more wholesale shops dominated the cityscape.

What we thought

The transect walk was a useful tool as an entry point to the area, and it allowed us to get to know the commercial pattern along Jew Street. However, we only ended up conducting one transect walk, since we wanted to get more in-depth with the socio-spatial structure of the area, rather than doing mapping based on observations. We could have spent more time on the transect walks, however, we were more eager to get in touch with people in the market. This method could be particularly interesting to use in collaboration with the local community.

Ill. 21 - Transect walks

35 Group 1 Fall 2022 34 Kochi Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

3.4 Transect walks

What it is

Interviews are an efficient tool if you want to understand people’s point of view. In this way, you can get different opinions, perspectives and views of the world explained. The unstructured interview is conducted without a specific interview guide, and is useful to get people talking in an informal setting. The semi-structured interview follows an interview guide, where certain questions have to be answered, but where there is space for follow-up questions or talking beyond the questions. The focus-group interviews include multiple respondents at the same time, and seeks to cover the norms and construction of opinions in a group (122509@au.dk, 2019).

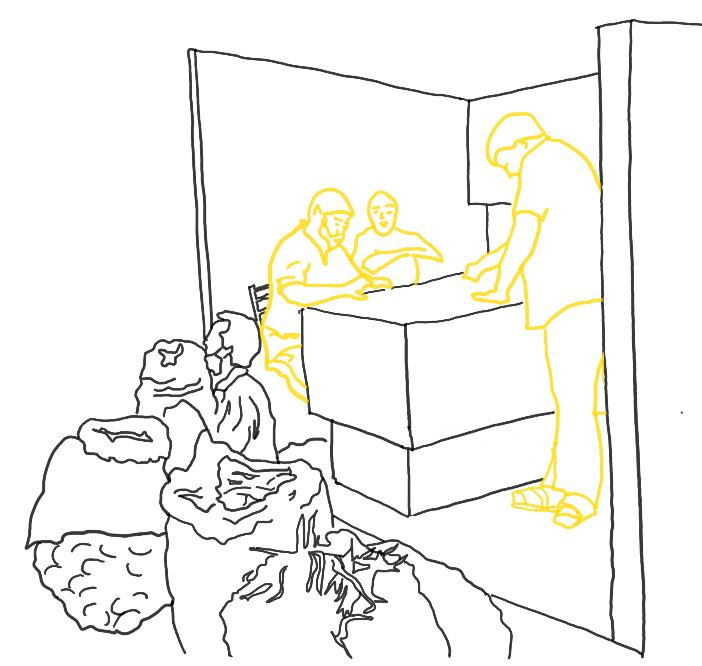

What we did

Most of the information that forms the base of our proposal comes from the interviews we did on site. We heard about the history of the market from individuals, we heard about how it has affected their lives, their livelihoods, how they were not included in the process, etc. What we also experienced from the interviews was a general belief among the vendors and workers that their opinion did not matter. They often tried to point us to more knowledgeable or powerful people, not because they did not want to talk to us, but because they felt unimportant. This experience has informed our proposal.

What we thought

The unstructured interview was a good tool for getting involved with the people on site, and was particularly useful as we could get back to the same people multiple times. However, the openness of the interview often resulted in less informative conversations. We introduced the semi-structured interviews to be more specific with regards to the information that we needed. This was helpful, but required a lot of guidance from the interviewer, so the conversation did not also end somewhere beyond the topic. The focus-group interview was conveyed with the union workers, and was useful for us to get an understanding of their perspectives as a group. This form of interview could have been conducted with more of the stakeholder groups, as it would have been useful to have their opinions as a group, rather than drawing conclusions based on individual perspectives.

Ill. 23 - Unstructured interviews

Ill. 24 - Semi-structured interviews

Ill. 25 - Focus-group interviews

37 | Group 1 | Fall 2022 36 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market 3.5 Interviews

Co-production

What it is

Co-production is a collaborative research methodology, where stakeholders are included in the process of forming the agenda, the design, and interpret and integrate the findings. It has the potential to improve the relevance of the research, and include voices that are not usually heard in urban planning processes (Redman et al., 2021).

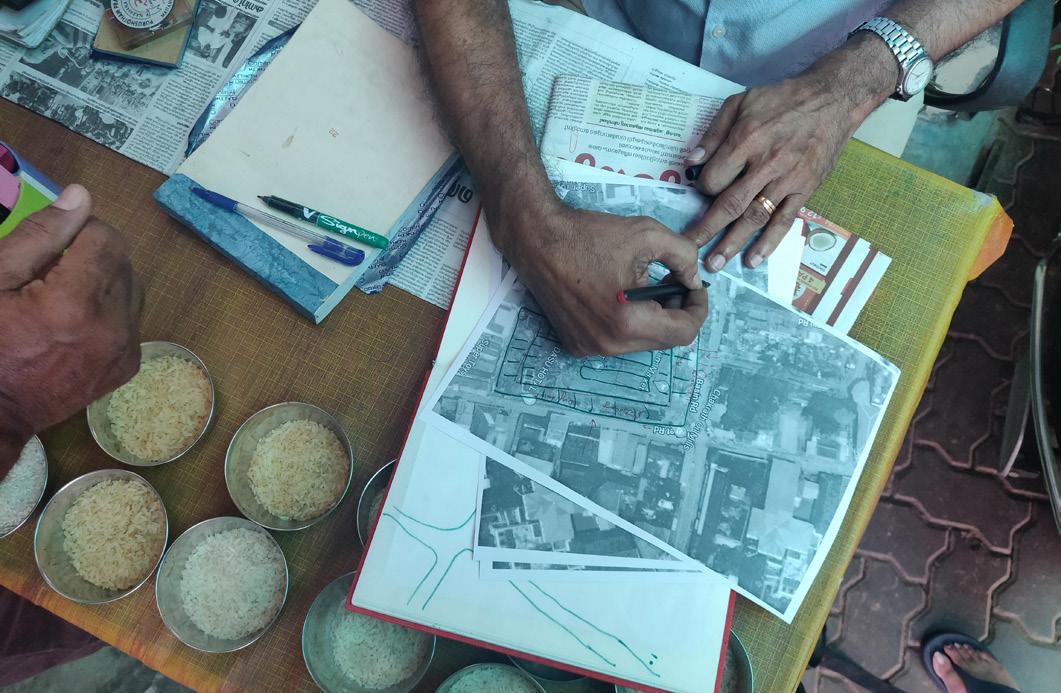

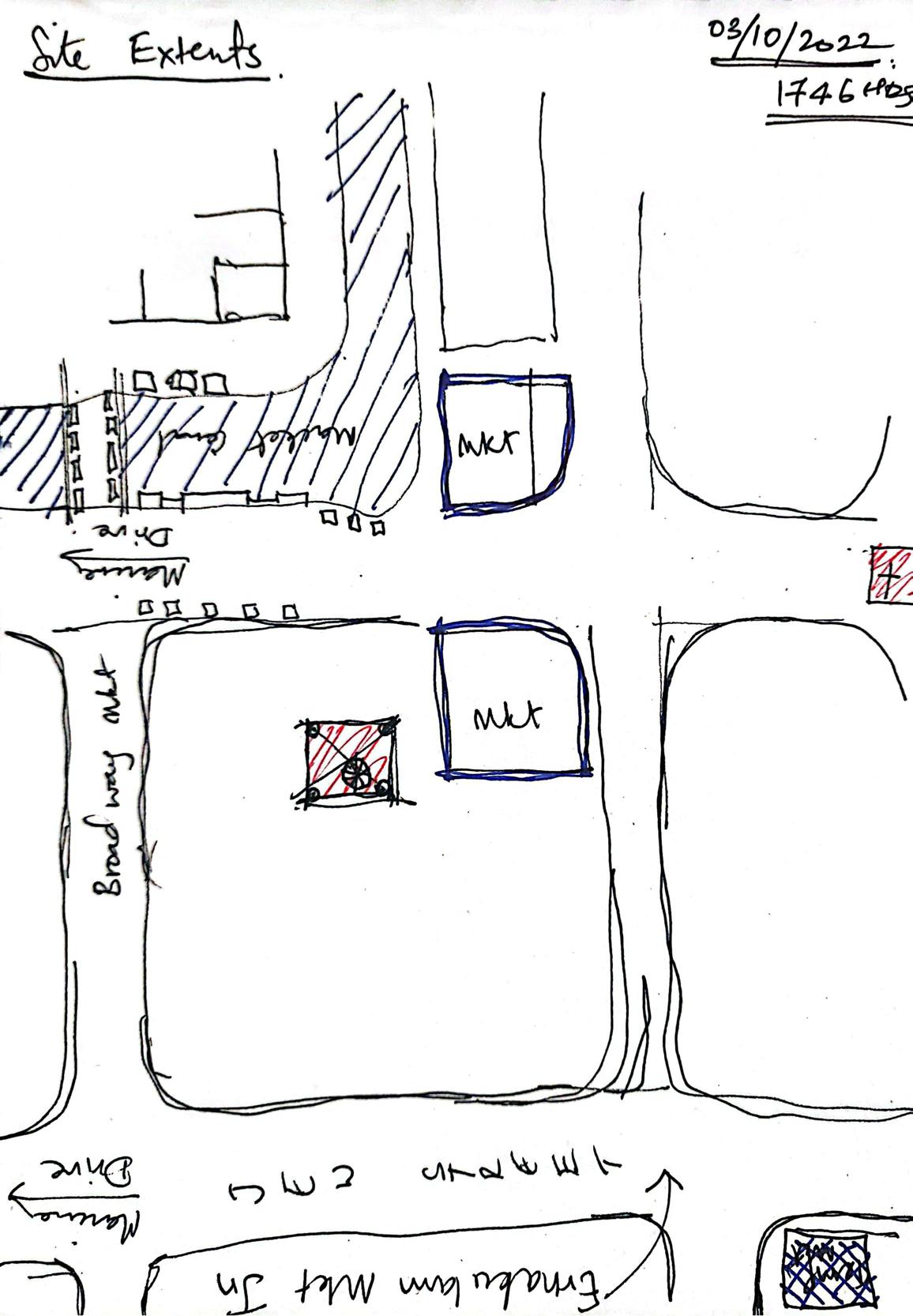

What we did

In the project we did co-production of maps and co-production of spatial designs. We drew maps in collaboration with the market stakeholders, which allowed us to gain knowledge that would not otherwise be available for us. They based their mapping on stories and memories, and we transferred these stories into spatial entities. The co-production of spatial designs was a process where we developed a series of drafts for shop typologies based on their input, and they gave recurring feedback on these drafts, redrew, and changed them according to their opinion. The idea was that shopowners and workers should be the ones designing their own shops, based on their own needs.

researchers citizens policy-makers

Ill. 26 - Co production is “the triangle that moves the mountain” (Adapted from Tangchareoensathien, 2021)

Ill. 28 - Flyer to hand out in the market

UEP STUDENTS IN ERNAKULAM MARKET

We are Master’s students in Urban Ecological Planning from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. For our fall semester, we are conducting field work in Kochi, and we are studying the Ernakulam Market as a case.

Urban Ecological Planning is a program that studies cities, communities and how to develop a sustainable future of urban areas.

Ill. 27 - Co production of knowledge (maps)

We are interested in the historical area of Ernakulam and Broadway, in how the current market has changed compared to the former market, and how the new market will respond to the needs of the community.

YOU are the day - to day user of the market and YOU are the expert of your community. That is why we are here. We would like to hear your opinions and your stories.

For questions, please refer via whatsapp or email to:

(Student) Stine: +91 9037586103 email: stinkron@stud.ntnu.no or Prof. Gilbert Siame: +260979457414 email: gilbert.siame@ntnu.no

What we thought

A major takeaway from co-producing knowledge and co-designing with stakeholders on the site, is that trustbuilding is a process that takes time We entered the market with no connection to the people in the site, and thus we had to spend a lot of time explaining ourselves. We experienced a high degree of mistrust from the stakeholders, especially the ones with a low degree of power. This resistance could have been reduced with a local gatekeeper with high integrity in the community, who could have shown the people on the site that you are on their side. Based on this, we developed a flyer explaining who we were, and where we came from. In this way we showed integrity and we could, most often, skip a step of explaining ourselves when interacting with people on the site.

Over time, we ended up going back to the people who had been willing to interact with us previously. This resulted in a high reliance on their perspective. This would have been a point of attention if the process was to continue further.

September We are Norwegian we are Ernakulam

Urban and how We are how the and how YOU are and YOU are That is stories. For questions, (Student) or Prof.

Ill. 29 - Co production of spatial designs (below)

39 Group 1 | Fall 2022 38 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in

Market 3.6

Ernakulam

September 15 November 10 2022

UEP

3.7 Risk assessment and the area-based approach

What it is

A risk assessment is a tool for understanding the vulnerability and the risk in an area, as well as the capacities and assets in the area to respond to the risks. It is useful to conduct as a part of an area-based planning process. The area-based approach is multi-sectoral support in a defined graphical area, including multiple stakeholders, thróugh a participatory process (USWG, 2019).

The area-based approach has the potential to create a platform for collaboration around crosssectoral issues, by bringing together a multitude of actors, building on existing structures and mechanisms, and facilitating a flexible planning process to accommodate for the needs of a diverse range of people (Smith, 2020).

What we did

The risk assessment mapped out and clarified the risk, vulnerabilities, capacities and assets in the market area. It revealed that the area has a strong existing social structure that could be built upon in the planning proposal. The area based approach looked at the market in relation to the surrounding area. To understand the risks that the market is facing this is a crucial approach. Furthermore, the multi-stakeholder approach to the market redevelopment is crucial since the area is highly politicised with a lot of interests across sectors. The area-based approach is in this case useful to avoid conflicts between stakeholders with varying opinions

What we thought

Ideally, the risk assessment should have been done in a more collaborative manner. The information we used for the assessment came from interviews with multiple stakeholders on site, but it could have been interesting to make the assessment as a collaborative process, where multiple stakeholders, in their own words, had to work together around the assessment. We found the area-based approach crucial to integrate as a part of the market redevelopment. In comparison, our evidence shows that the current process facilitated by CSML is looking at the market site detached from the surroundings, which then risks overlooking crucial aspects of the everyday dynamics of the area.

41 | Group 1 Fall 2022 40 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

Ill. 30

- Risk assessment

Ill. 31 - Processual sketches reflecting the area-based approach

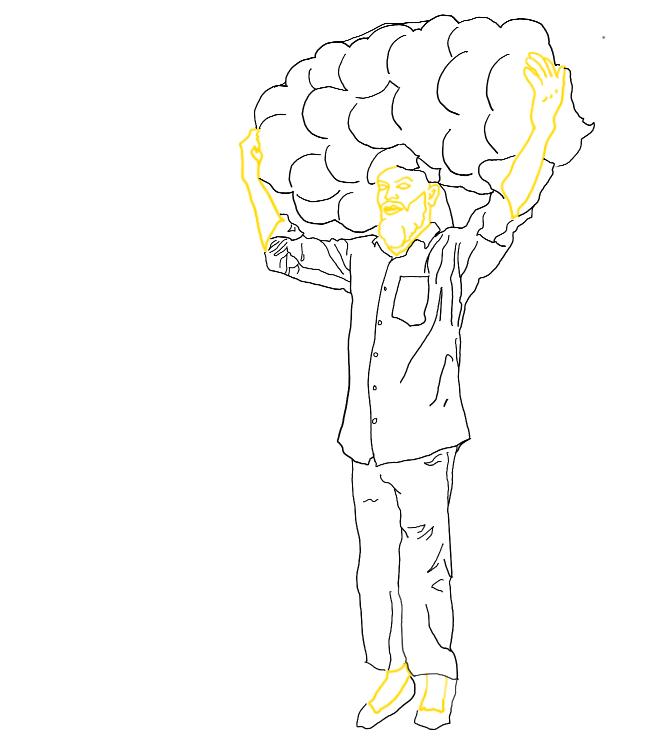

Ill. 32 - Drawing of the shopowner in a bananna leaf stall

43 Group 1 Fall 2022 42 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and

in Ernakulam Market

livelihoods

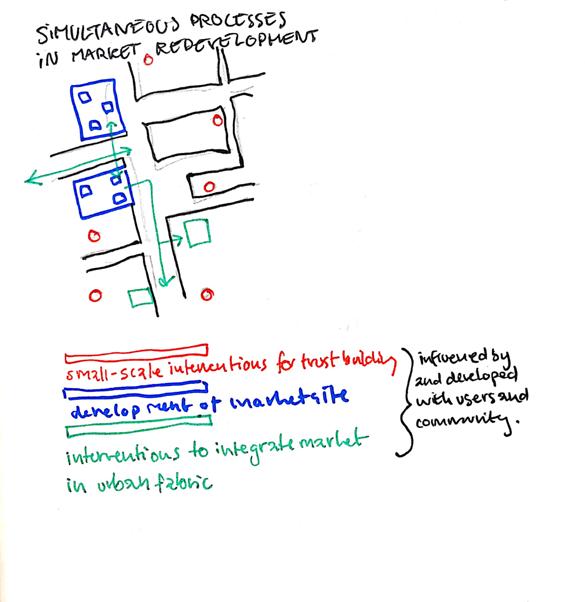

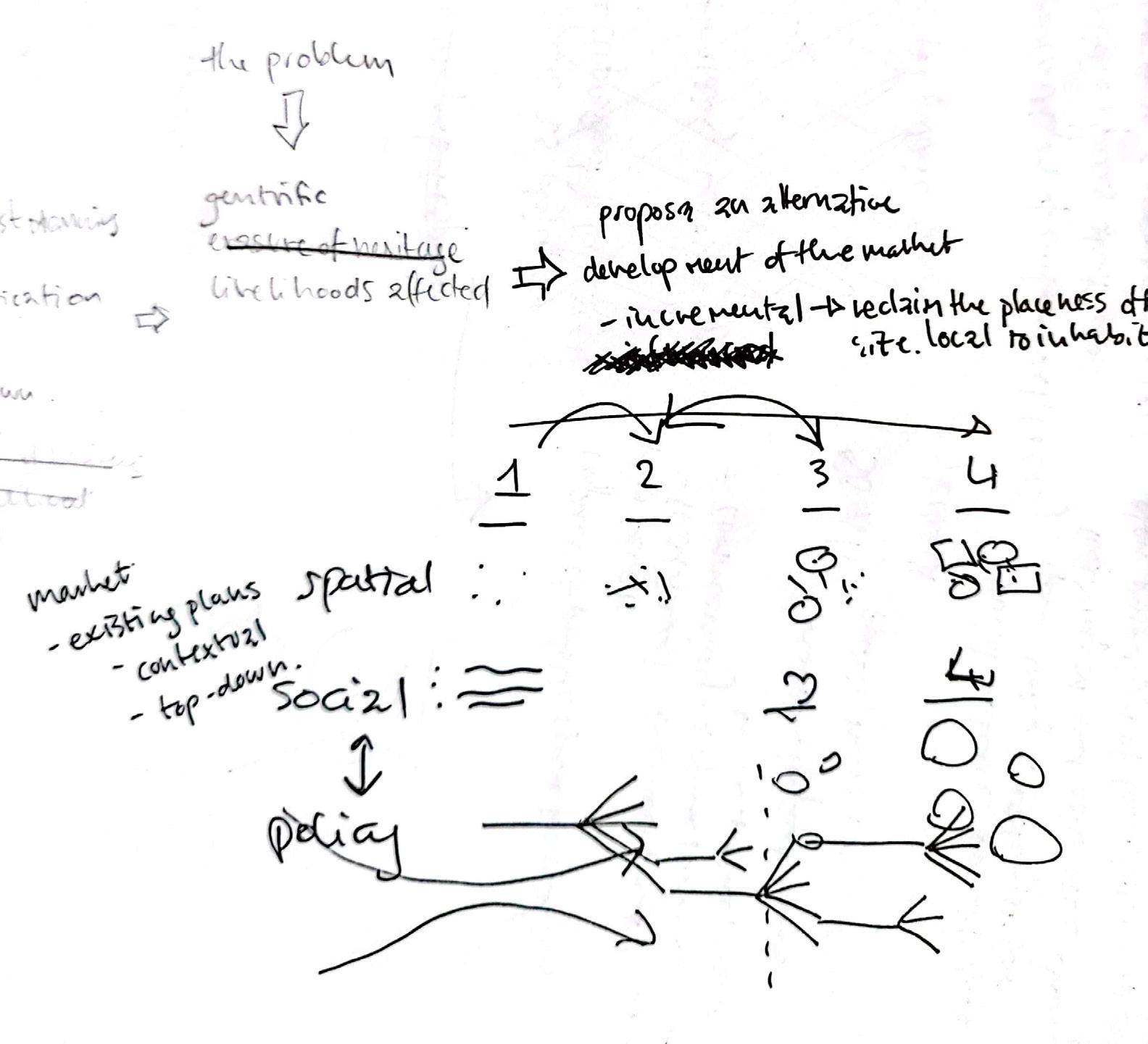

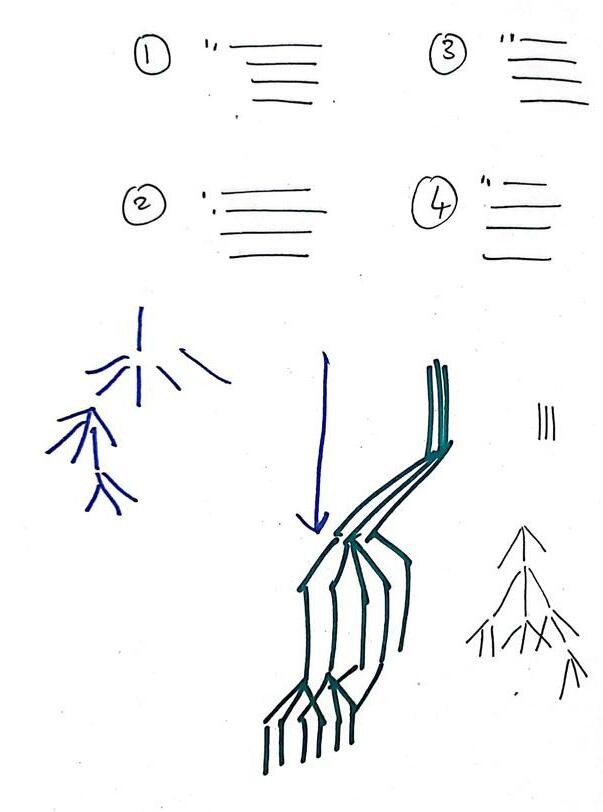

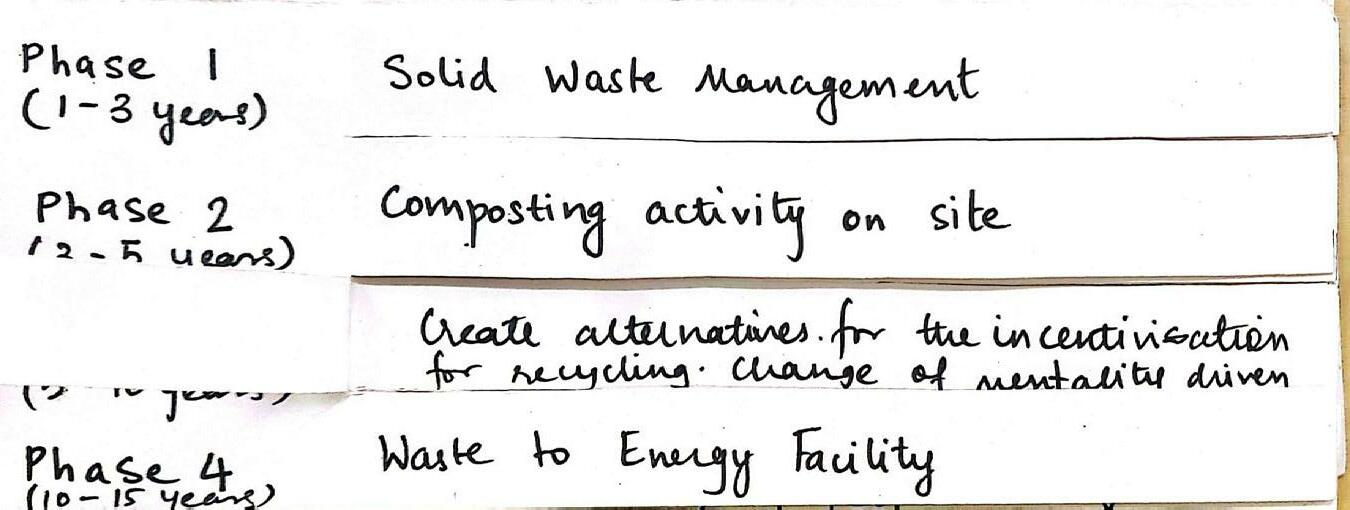

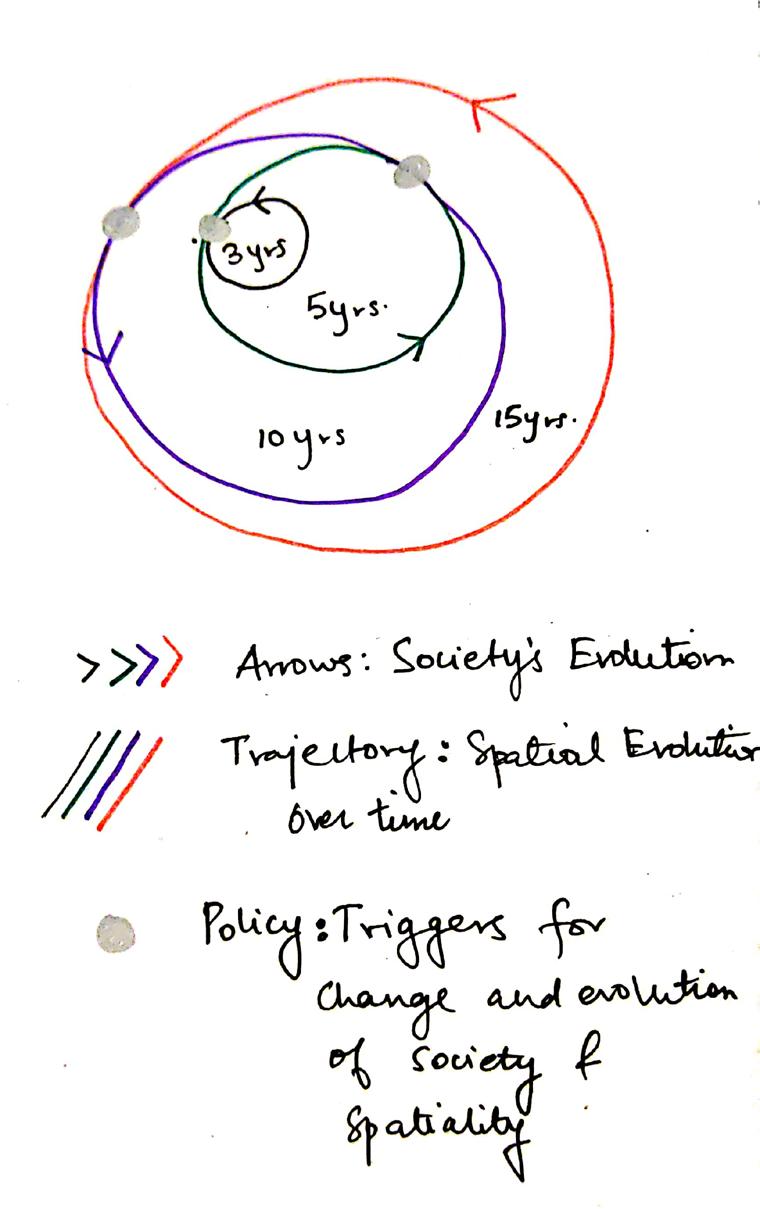

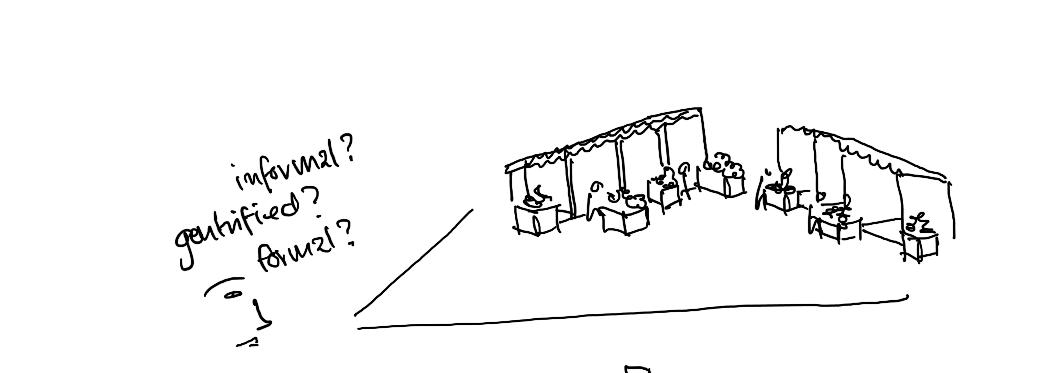

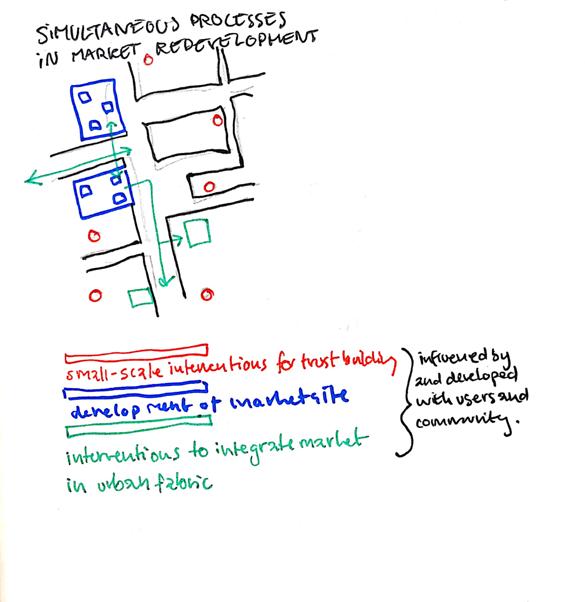

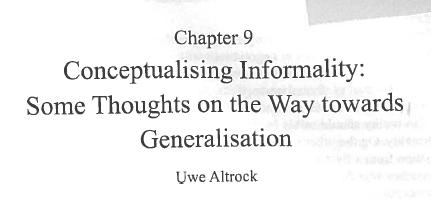

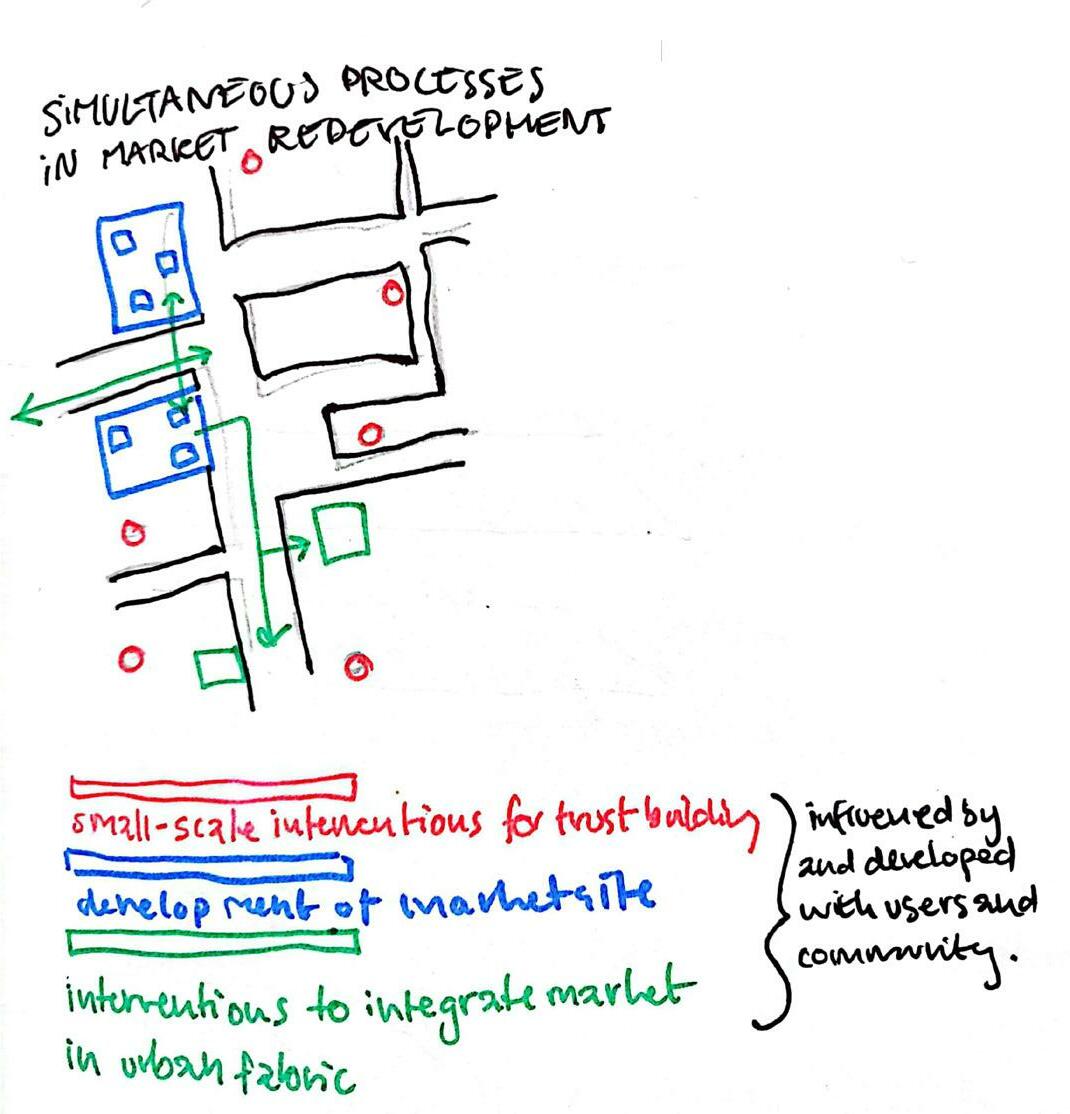

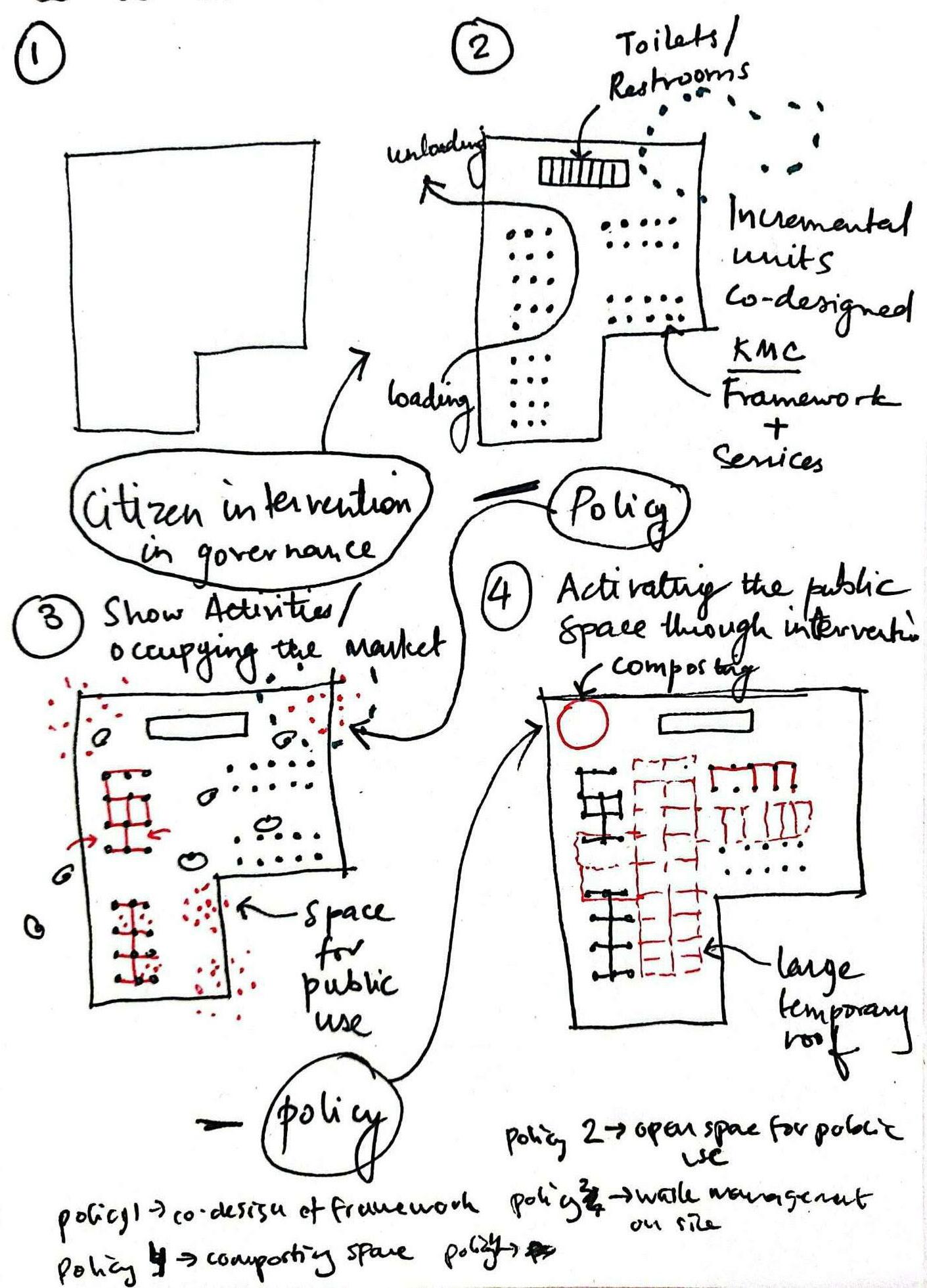

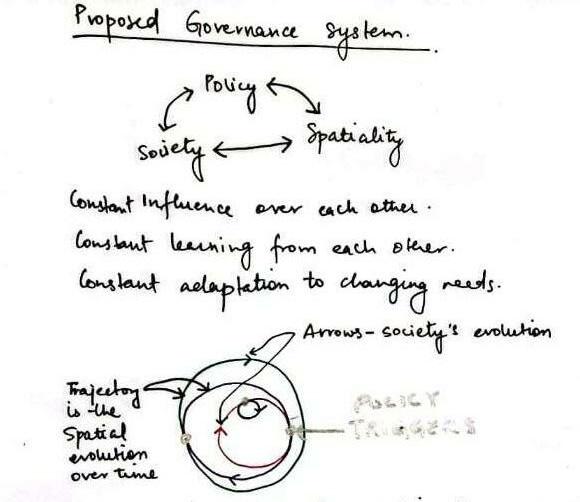

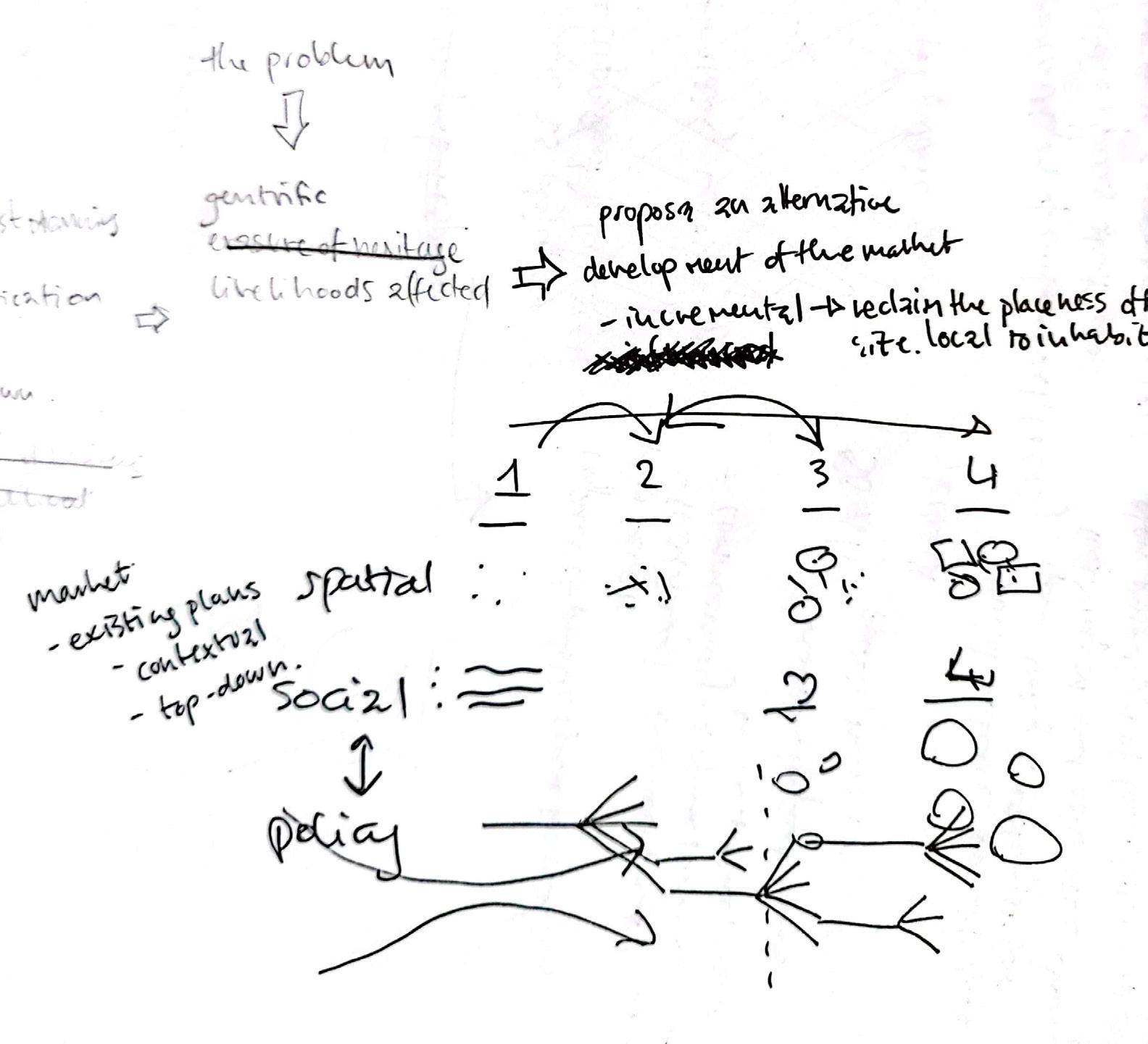

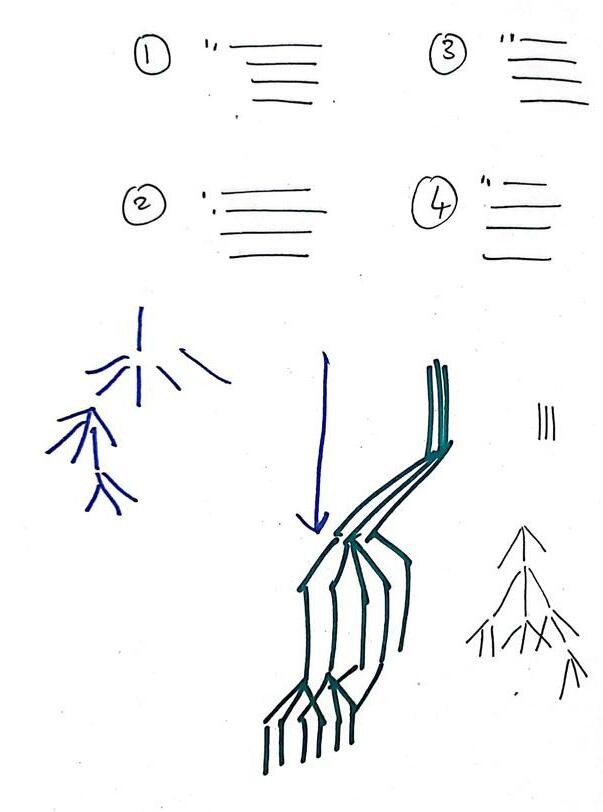

3.8 Iterative sketching - the diagram as a tool

Ill. 34 - Process sketch from understanding the spatial constraints and possibilities >

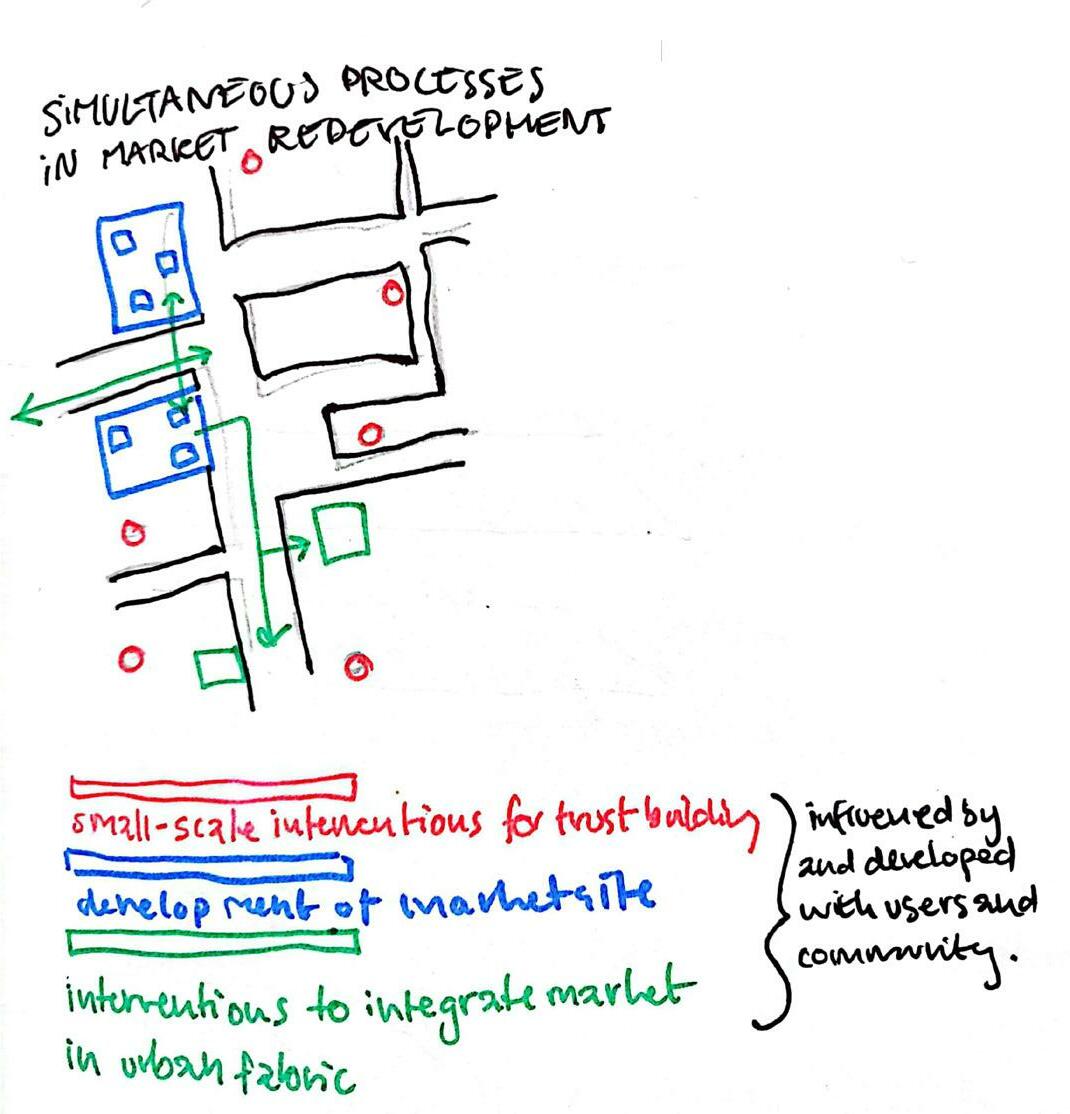

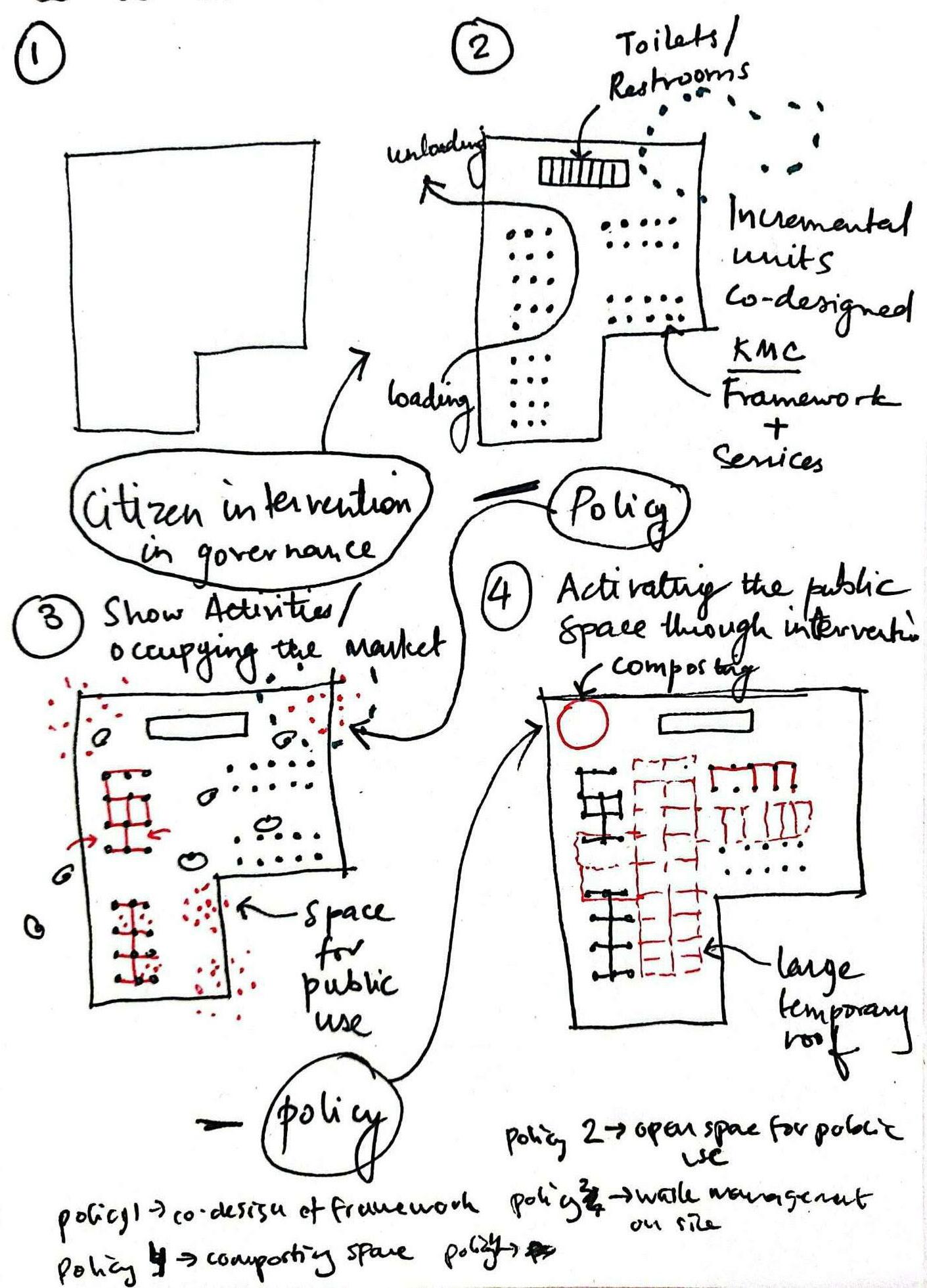

An important part of our process has been to develop the proposal through diagrams and sketches. The diagramming and sketching has been iterative, going back and forth between analysis, ideas and synthesis. Looking at our process through the sketches that we have made as we have proceeded, there is a clear trajectory of iterations that has brought us closer to an appropriate proposal for a planning strategy.

The diagramming has allowed us to visualise the processes that we have imagined. It has helped us to think spatially, converting words into form. It has allowed us to communicate within the group, making sure that we were on the same page when discussing ideas and concepts.

This methodology has reflected an essential idea that has formed our process - that policies related to space can not just be words. There an inherent spatiality and tactility in urban planning that has to be reflected through the process, or as James Corner (2006: 32) says: “A good designer must be able to weave the diagram and the strategy in relationship to the tactile and the poetic.”

Policies can not just be words. Diagrams can illustrate policies related to space.

Ill. 33 - The iterative process where we move back and forth between stages. The final proposal is a point in time but the process could continue through more iterations. Adapted from Hansen and Knudstrup (2005).

44 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

Ill. 35 - Process sketch to understand scales of interventions, interrelationships between policy and space

Ill. 36 - Process sketch to gauge the spatial outcomes and their phases

47 | Group 1 Fall 2022 46 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

Ill. 37 -Above and Right: Process sketch from conceptualising the governance structure

49 Group 1 | Fall 2022 48 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

Reflection on methods

Participation?

A core aspect of the project that had been stressed from the beginning of the semester, was that we should facilitate participatory processes. The project should be developed with the participation of the stakeholders who are related to the site.

We were introduced to literature that was critically assessing the term “participation”, e.g. White (1996), Arnstein (1969), Galuszka (2019). In the literature, the authors call for a nuancing of the term, to look at what actually takes place in the process, rather than seeing participation as a box that has to be ticked. However, we experienced that this critical assessment of the substance of the participatory practices were missing in the class discussions. It felt like the most important part was to engage with people on the site, but the manner in which we interacted with people was of less importance. Consequently, a large part of the interaction with stakeholders on site was merely extraction of knowledge, and not participation. This is related to what Galuszka (2019: 144) describes as:

“The classic model in which external stakeholders consult the local population has proven to be susceptible to misuse by a wide array of urban actors, starting with public administrations and ending with the community members themselves”.

In the last two weeks in Kochi, we managed to undertake participatory processes, where we co-produced knowledge and co-designed spaces. With more time, this process of actual coproduction would have been more extensive.

There may be many reasons for the limited amount of actual participation. This was the first time in the field for a large part of the class, we spent a lot of time on understanding the context, and

we did not have any gatekeepers to form a bridge between us and the communities. However, we think it is important to be reflective about the processes we are conducting, and the implications of this. Rather than insisting that it was participation, we should call it what it is, because only thus we can critically discuss our processes in order to improve our practices.

Who are the stakeholders?

In our analysis of the stakeholders on the site, we fell into the trap of merely including the people that were present on the site, as well as the powerful institutions that were located somewhere else. This, we have learned, only renders a superficial picture of reality. Since there were only few women on the site, and there were language barriers with the ones that were there, we have not included a single perspective from a woman related to the market. However, this does not mean that women are not affected by the changes related to the market. We left out the entire discussion of gender-related issues because they were “not there”. A major learning from this is that it is simply not enough to include the people who are present on site.

We learned a lot from reading Broto (2021), who writes that queer issues are thought of in isolation from other issues, and are limited to specific topics that heteronormative planning practices expect that they are affected by. This is also applicable to questions of gender in planning. We have to ask: who is not present on the site? And why are they not there? This relates to gender, but also to aspects of intersectionality like age, accessibility, race, religion, etc. If we are to have a truly participatory process, we have to include a broad representation of people in the process.

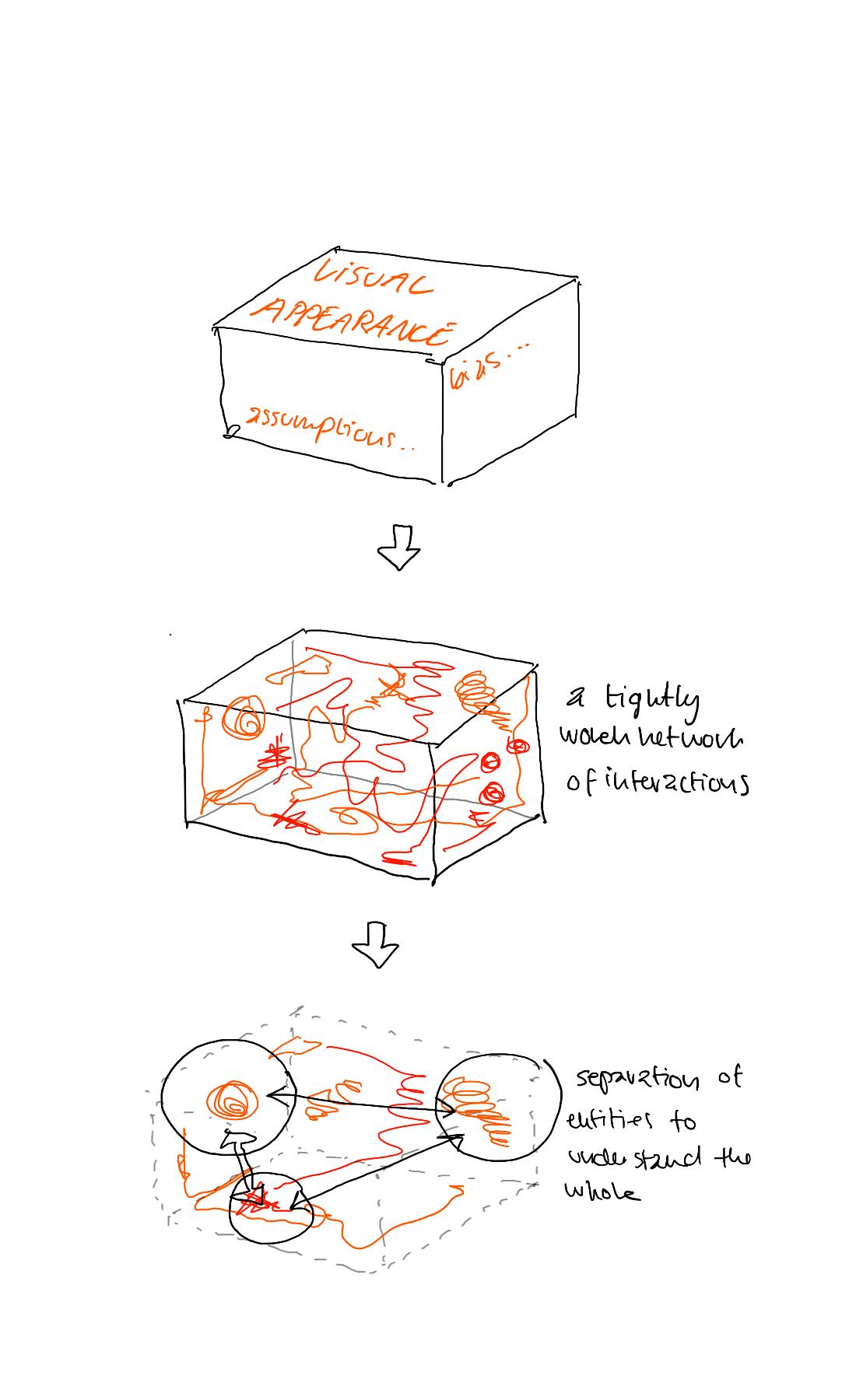

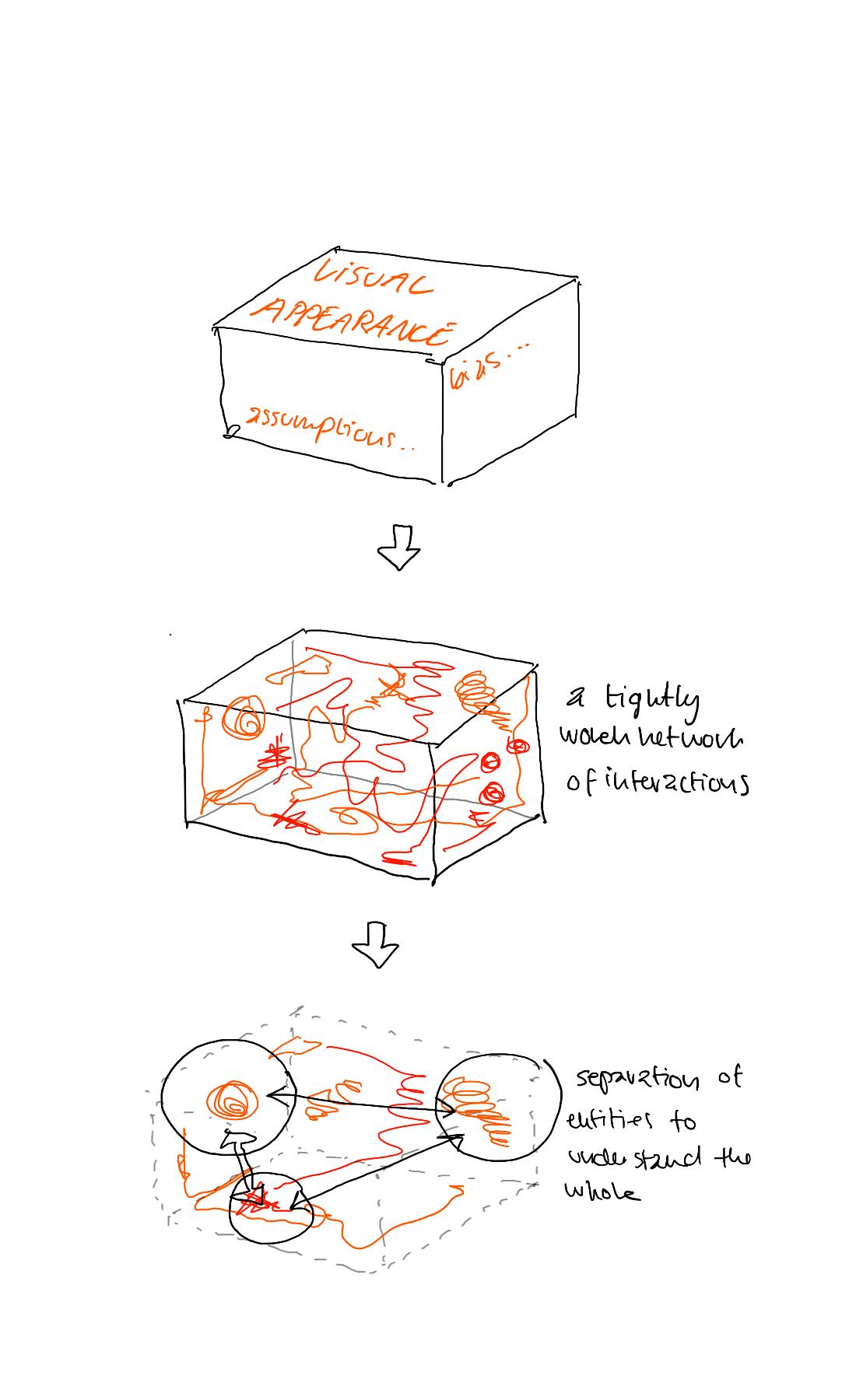

Ways of seeing – deductive versus inductive analysis

The first point of reflection is concerned with the way in which we approach the analysis of urban situations. Arriving in Kochi with a set of theoretical concepts imprinted in our minds, based on lectures in Trondheim, we were eager to see the city through these lenses. We were advised to look for relevant sites based on concepts of ‘informality’ and ‘gentrification’. However, we were struggling with applying these concepts directly to our observations It felt forced, and this approach gave us a feeling of restricting our way of seeing to look for ‘indicators of informality’ and ‘signs of gentrification’, not being open to observations that fell outside of these categories.

This experience has given rise to a reflection about the methodological approach to analysing urban situations. Do we have a preconstructed understanding that we are seeking proof of (deduction), or will we build our understanding on empirical observations and induce meaning from this (induction)?

As of now, we believe that with a deductive approach there is a risk of applying assumptions and simplifying reality to fit into known concepts. While having a framework for understanding the world may be a useful approach in some situations, we think it is important to be aware of when you look for patterns to fit into your inherent understanding of the world, and to know when to move beyond this way of seeing.

51 | Group 1 Fall 2022 50 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

3.9

4. Situation analysis

The situation analysis looks at the context, but goes one step further, and tries to understand the issues and relations between people that are not necessarily visible, but requires an interactive dimension in the analysis. It is about networks, relations, and understanding the dynamics of these and how it affects the day-to-day activities on the site.

The data we present is stemming from interviews and interactions with people on the site. First, we talk about the different scales of interactions in the market network, the people that are related to this, and the multi-scalar implications of distorting the market system. Then we show our analysis of how the market is embedded in a network that spans across the country of India. We go in-depth with the stakeholder analysis, and finally, we reflect on the market situation through theoretical frameworks of the formal-informal continuum, and top-down vs bottom-up urban governance.

Ill. 38 - Neighbourhood map of Ernakulam

53 Group 1 Fall 2022 52 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

4.1 The market across multiple scales

The market is related to activities across multiple scales, ranging from the workers and vendors that are present in the market space, to regions far away from the market space in Ernakulam. People’s livelihoods depend on the day-to-day activities of the market from

the exchange of cash for an apple in the shop, to the nurturing of crops in the agricultural regions where vegetables are grown. Altering the market activities means distorting a complex supplychain system that has evolved through generations.

Ill. 39 - 44 (drawings) Illustrating the different scales of interactions Ill. 45 - 50 (Images) People related to the different scales in which the market operates Ill. 44 - 48

The individual The shop The market

Most of the shops in the market are family businesses that have been inherited through generations. The owners are proud of their shops and are decorated with personal pictures of gods or the grandfathers who founded the shop.

Each shop has one or more employees. Some workers are from Kochi, while others have migrated from distances as far as Northern India. The migrant workers often come in small groups from the same area to seek employment opportunities.

Several strong institutions govern the market. The Market Association links the market to the municipal corporation. The workers who load and unload the trucks belong to a union, and they are visible on site by wearing similar blue shirts.

The neighbourhood

The market is embedded in all neighbourhood activities. The vendors and workers take breaks at the surrounding chai stalls. They drink chai and eat snacks. In the picture you see a chai vendor that circulates the market during the day.

The city The region

Retail buyers from across the city come to the market to buy their vegetables. Tuctucs are loaded with everything from banana leaves to carrots and cucumbers before they head off to hotels, restaurants or smaller retail shops across town.

Spices, vegetables and fruits are being transported from all over the country to Ernakulam with large trucks. The trucks come in multiple times per week. Livelihoods in states as far as Assam and West Bengal depend on the market activities.

55 Group 1 Fall 2022 54 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage

Market

and livelihoods in Ernakulam

4.2 The market and the food-supply chain

The Ernakulam market is a part of a regional food supply-chain. Fruits and vegetables are being transported from a large number of Indian states, to Kochi. Several times per week, trucks arrive with goods from far distances.

Kochi. The market space can not be understood in isolation from the food-supply chain that it is a part of.

This food network implies that changes in the market space, whether that is relocation of the site, less turnover in the day-today activities, or change of the social structure, will affect levels in the supply-chain that are geographically located far away from

In addition to that, the market is also a destination for workers migrating from regions far away from Kerala. Most of the shops have workers that are either hired on a daily basis, depending on what tasks that are needed, or they are permanently employed in the same shop. These workers are from different regions of India, but have come to Kochi for livelihood opportunities. Primarily, the migrant workers are from Northern India.

Fish,

Ill. 53 - Map of states where vegetables are coming from

57 | Group 1 | Fall 2022 56 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in

Market

Ernakulam

Ill. 51 - 52 - Trucks arriving with goods from far distances to Ernakulam Market

Apples from Kashmir

Various vegetables from West Bengal

Various vegetables from Andhra Pradesh

Dried fish from Odisha

Various vegetables from Tamil Nadu

eggs, pineapples and chickens from Kerala

Onions from Karnataka

Onions from Gujarat

4.3 Stakeholder analysis

The state of Kerala has a distinct political identity. There is a strong history of self-organisation throughout the state. This culture of self-organisation translates to the Ernakulam Market, where several interest groups make up the day-to-day management of the market. The market is a site with a complex network of multiple stakeholders, each with their own agenda. The stakeholders impact each other, however, there is a clear hierarchy when it comes to site-level decision-making. The daily users of the market: the shopowners and the workers, have a low degree of power in decision-making. However, with their livelihoods depending on the market, they have a high interest in the development of the space.

This system of interactions represented in the market site can be understood as a local-scale example of how a top-down governance system works. Interviews on the site have revealed that there is a gap in communication between the different stakeholder groups. The day-to-day users of the space are not being heard in decision-making processes, which results in a lack of representation of what people working in the market on a daily basis actually need.

Stakeholder power-interest analysis

Stakeholders on site

Ill. 54 - The stakeholder power-interest matrix visualises the power each stakeholder has in decision-making, in relation to the interest they have in the development. It is based on Eden and Ackerman (1998: 122). Adapted from Bryson (2004: 30) >

1 - Shopowners (Market)

2 - Retail Buyers

3 - Shopworkers (Market)

4 - Daily-wage Workers

5 - Union Workers

6 - Labour Union

7 - Shopowners (Lanes)

8 - Customers 9 - Market Association 10 - Political Party (CPIM) 11 - KMCC 12 - Local Counsellors 13 - CSML 14 - Local residents

15 - Vendors (Canal) 16 - Truck Drivers 17 - Hawkers 18 - Architects/Planners 19 - Media 20 - KMC

59 Group 1 | Fall 2022 58 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

Who are the stakeholders?

KMC Local councillor Shopowner (lanes)

Truck driver CSML Local residents Vendors (canal) KMCC

Customers Hawkers Daily-wage workers Retail buyers

61 Group 1 Fall 2022 60 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

Architects/planners Media Market Association Shopworkers (market) Shopowners (market) Union workers Worker’s union CPI (M) Ill. 55 - Stakeholder drawing

4.4 Stakeholder issue-interrelationships

Through interviews with people present on site, several issues that they were concerned with came up. These are issues such as waste management, congestion of traffic, and increased rent. The issue-interrelations analysis looks at how each stakeholder group is affected by the issues present on site. What is clear is that shopowners and the workers are affected by a multitude of issues. These are also stakeholder groups with a low degree of power in decision-making processes. The organisations with a high degree of power in decision making are not directly affected by the issues present on the site.

Ill. 56 - The issue-interrelations diagram visualises how different stakeholders relate to issues on the site. Based on Bryson 2004, p. 38

63 Group 1 Fall 2022 62 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

Mapping the stakeholders according to where they are physically based, reveals that most stakeholder groups are present on the market site itself. However, the high-level decision makers, the CSML and the KMC are based in other parts of the city. This de-links decisions from the everyday dynamics of the site. This is symptomatic of the tendency described in the above sections: that there is little connection between decisions made on a high level, and the day-to-day activities in the market.

65 Group 1 | Fall 2022 64 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

4.5 Stakeholder mapping

Ill. 57 -Based on Marklund-Nagy (2020)

4.6 The formal-informal continuum

Informality was first conceptualised in scholarly work by Keith Hart in 1973, who defined the informal as low-income urban citizens who took part in petty capitalism, substituting wage employment, in order to gain income (Hart, 1973; Recio et al., 2016). Other definitions have related informality to the ability to survive without a job officially recognised by the state (Cooper, 1987), through economic activities that cannot be defined as modern (CoqueryVidrovitch, 1991), and thus relies on small-scale activities existing outside the formal system, in unregulated markets (ILO, 1972). These early conceptions represent a dualistic understanding of the relation between ‘the informal’ and ‘the formal’. In the late 20th century, definitions building on the dichotomous perception of the formal-informal interactions emerged. These were concepts such as “bazaar economies (Geertz, 1963), upper and lower circuits of urban economy (Santos, 1979) and unenumerated sectors (Sethuraman, 1981)” (Recio et al. 2018). However, Jenkins (2001) argues that there is a high degree of acceptance of informal practices in contexts of developing countries and that “the bases of mental models and informal institutions are embedded in the socio-economic and political conditions and are coping with the global North-oriented formal rule of law” (Recio et al. 2018: p. 137). Thus, the structural foundation of the north-south dichotomy is a “subtle expression of a complex web of structural relations” (Recio et al, 2018: 137).

The notion of informality in contrast to formality has not emerged due to the increase of informal practices. What is commonly defined as informal were common practices before the rise of the formal sector, meaning for example institutionalisation of labour in industrialised countries (Portes, 1983). This points to an understanding of informality through the lens of structures and agency (Giddens, 1984), and “how social structures (e.g. economic policies) and human actions (e.g. resistance) shape the causes,

consequences, practices and benefits of informal economic transactions” (Recio et al. 2018: 137)

Through this lens, informality is not a sector that operates in contrast to formal practices. Rather, formal and informal interactions form a continuum where economies, spaces and relations interweave (Roy, 2005; Donovan, 2008; Dovey, 2012). Hence, “the perceived difference between the formal and informal economy is, in reality, artificial in nature. There exists only one national economy with formal and informal livelihood approaches.

The perceived difference lies in the fact that there is a lack of awareness and/or understanding of the mutual dependency of these two aspects of the economy” (ESCR-Asia, 2002). This points to a post-dualistic understanding of informal-formal interactions, where organisational or individual agents respond to what is structurally given (Recio et al., 2018).

In relation to this, Altrock (2018) differentiates between interactions happening in a setting where there are no formal rules, or interactions replacing formal frameworks where they do not work properly. Respectively, these forms of informal practices are conceptualised as complementary and supplementary to formal practices. However, most importantly, Altrock states that “one ought not to speak about a formal-informal divide but rather a hybrid formal-informal arrangement” (Altrock, 2018: 171)

Informal processes within the formal structure of the Ernakulam Market

The study of the Ernakulam Market in Kochi reflects exactly this process of hybrid arrangements of interactions between formal and informal practices.

The market redevelopment is undertaken by KMC, in collaboration with the CSML. These are the formal institutions responsible for the provision of a temporary structure to ensure that the market can retain its commercial activities. The temporary structure that has been provided for the shop owners constitute stalls similar in size and features, a one-size-fits-all solution that does not take into account the required spatiality of each shop for them to retain their livelihoods. What can be observed on the site is that, within the short amount of time that the temporary market has existed, the vendors have modified their shops to accommodate their needs for their shop space. They have broken down walls, built new walls, built attics, installed racks in the ceiling, subdivided or combined stalls, and encroached the surrounding floorspace. The everyday users of the space, the shop owners, have reclaimed agency over their space by modifying their shops outside of the formal structure.

The motive of this behaviour is explained by an owner of a store selling dried fish:

“In the new market, we do not have enough space. It is smaller than what we had before. So we have moved our products out on the street. The space is actually a parking lot, and it is illegal to place anything here, but I don’t care, it makes me sell more. And we are all in the same position, so no one will report this to anyone”

Looking at this through the lens of the structure-agency theory (Giddens, 1984), the framework provided by the KMC is the structure, and the agency is how people respond to this structure. Within this framework, the actions of the shop owners are informal and illegal. However, the state of the shop modifications being ‘informal’ and ‘illegal’ arise only due to the introduction of the formal, ready-made structure of the temporary market space. The process of the shop owners modifying their spaces can further be analysed as a response to the inadequacy of the formal structure to provide sufficient livelihood opportunities for the users. This is what Altrock (2018) referred to as supplementary informality, namely “informal institutions replacing formal ones where they do not work properly” (Altrock, 2018: 171), with the “institutions” understood here as “practices’’.

This process of the shop owners reclaiming agency over their livelihoods by altering their spaces constitute the everyday functionality of the market. The formal and informal practices of the everyday life of the market co-exist and interweave to form a continuum, where the one cannot exist without the other.

67 | Group 1 Fall 2022 66 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

4.7 Shop typologies

The process of moving the market into a temporary space has implied moving from a spatial logic that has evolved through generations, to a formal structure consisting of units with a uniform spatiality - an 8 m2 (85 ft2), rectangular box.

The temporary market space opened in early 2022, less than a year ago. In this short amount of time, each vendor has modified the spatiality to fit the specific needs of the shop. The vendors make efforts to maximise their livelihoods to make up for the fact that they have less space than previously. The vendors have made informal alterations of the formal physical structure; walls have been broken down, walls have been built, complex vertical storage

Ill. 58 - 63 - The shopowners have modified their shops according to their needs.

systems have been installed and horizontal space beyond the shop area is permanently encroached.

This is a process of the vendors reclaiming agency within the space provided from a top-down process, and due to the temporal character of the current market space, illegal and informal practices are largely overlooked by the governing structures of the space. It is questionable to what degree this practice can take place in the ‘organised, best class shopping destination’ of the future ‘smart-city’ market.

How will this affect the livelihoods of the people of the market?

Some of the shops rent off parts of their space to other vendors, since they have been allocated more space than needed to maintain their business.

The banana shops require a dark storage room and racks from which they can hang bananas. The vendors have built storage space behind their shop and installed racks in the ceiling.

Some shops require only a small space for their counter but a large space to store their goods. These are particularly dryfoods stores where their goods require a lot of space.

Some shops need permanent walls to showcase products and build altars, while others need the option to combine two adjacent shops by having flexible wall structures.

Many shops have built vertical storage space in the form of shelves or small attics. Each shop has different requirements for the accessibility of the goods stored vertically.

Many of the outermost shops extend their commercial space by encroaching space that goes beyond their shop. This is space that is otherwise designated for on-site parking.

69 Group 1 | Fall 2022 68 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

4.8 Tabula rasa urbanism

As stated by the CSML, the market redevelopment “...intends to redefine the concept of wholesale market with sophisticated infrastructure and amenities” that is an “organised, highly accessible and best in class shopping destination” (CSML, 2021). The market redevelopment can be seen as a part of a larger process of modernising the city through the narrative of formalising the ‘unsophisticated’ and ‘disorganised’. This is a tendency that can be observed across several cities of the Global South. (Watson, 2009) This narrative is based on westernised ideals of the organised city, stemming from the early 20th century modernist ideals; a narrative that influences southern urban development “through complex processes of colonialism and globalisation” (Watson, 2009: 151). The persistence of planning ideals derived from Western countries suppresses the contextual conceptualisation of cities and planning, resulting in marginalisation of people living lives that do not correspond to the Western assumptions (Watson, 2009).

Within the framework of this critique, urban planning is in itself the root cause of exclusion of certain groups of people. Thus, “urban planning... needs a fundamental review if it is to play any meaningful role in current urban issues” (Watson, 2009: 151)

The neocolonial narrative presents the formal city as the ideal city (Watson, 2009). However, as Roy(2009) states: “the formal and the legal are perhaps better understood as fictions, as moments of fixture in otherwise volatile, ambiguous, and uncertain systems of planning. In other words, informality exists at the very heart of the state and is an integral part of the territorial practices of state power.”

When formalisation sweeps the people away - development for whom?

The process of the redevelopment of the Ernakulam Market reflects

this tendency that ‘the formal city is the ideal city’. A tendency that results in urban planning causing marginalisation of people.

Through the top-down process of moving the market activities from the original site to the temporary site, effects of the gradual process of formalisation can already be observed. As explained earlier, vendors and workers have reported that their livelihoods have been affected by this transition. The formalisation and ‘cleaning up’ the market, transforming it into a ‘modern, orderly’ space and not leaving space for the vendors to inhabit the space on their own terms results in loss of livelihoods of people who did not fit into the ‘box’ of the formal market structure. (insert diagram). The one-size-fits-all does not fit the everyday users of the space.

The market is an example of the issue with formalisation being an end goal in itself. With the effects of formalisation of the market space already affecting the livelihoods of the users in temporary market space, it can be expected that this effect will further increase with the transformation to the new market space that will be “like the Lulu mall” (CSML interview, 2022). One can thus ask:

Who is the new market actually for? Who is the modern city for?

Contextual urban planning means decolonising planners’ imagination by questioning the assumption that every plan and policy must insist on modernisation through formalisation. This mental decolonisation requires recognising how the ideal of the Western city has been deployed historically in the colonial era, and is now deployed in the neoliberal era to advance a certain paradigm of development and capital accumulation. A collective of developers, planners, architects and politicians and a powerful industry of marketing and imagemaking have promoted the Western city as an object of desire (Perera, 1999), or as Watson (2009) puts it: “More of a challenge will be shifting towns and cities away from urban goals and visions that have to do with aesthetics,

global positioning, and ambitions of local elites to replicate American or European lifestyles, to the far more demanding objectives of achieving inclusive, equitable and sustainable cities”(p. 190).

In the interest of retaining existing socio- spatial relationships, livelihoods and characteristics of historic spaces, learning from these contexts along with localising global ideas may be useful and a more appropriate way to upgrade contexts like the urban market. What is evident is that there are “no ready-made solutions for Southern urban contexts” (Watson, 2009: 151) Urban spaces have networks that “transcend municipal boundaries” (Benz, et

Ill. 59 - The temporary market made by KMC Ill. 61 - The market redevelopment is expected to accelerate development in the surrounding neighbourhood.

Ill. 60 - The new market proposed by CSML

al., 2015) and this needs to be acknowledged in decision making processes. Governance structures that overlook planning to be more inclusive, spatially and socially, may help with bringing relevant concerns from the everyday users of the space to the forefront. They often lack a synchronisation of thoughts, common understanding at multiple levels and parameters to measure its trajectories of success and failures over time (Fenton and Gustaffson, 2017). This needs to happen in two ways: inclusive and adaptive policy making and mutual accountability between the communities and the governance structures, both local and state level.

71 | Group 1 | Fall 2022 70 | Kochi Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

The gentrified city

Gentrification has been and continues to be a cause of concern for various Indian cities today. With the introduction of schemes like the Smart City Mission, technology and results are favoured over people and process, with the aim of making cities ‘smart’. However, is this ‘smart’ city also a city for people? And what are the consequences of a ‘smart city’ relying on technology, when part of the population does not have access to this technology?

The Smart City Mission, conceived by the central government as a way to bring development to Indian cities, adopts the idea to give a makeover to the city by upgrading heritage and culturally important landmarks to ‘global standards’. These changes in the urban fabric, especially in important cultural nodes like the Ernakulam Market, can lead to increasing rents in the overall area, resulting in pushing out the people who can not afford to take part in the urban development

One of the greatest challenges of Indian cities is combating gentrification and protecting the rights of the local communities to their city (Lefebvre, 1968). Protecting and safeguarding communities from gentrification is a difficult but important role of urban planners. However, it is important to note that improvement and upgradation is necessary. Planners have the knowledge and can facilitate positive gentrification of areas. A gentrification without the displacement of the local communities, one that leads to improvement within community infrastructure, aimed at bringing development to the very roots of cities. Afterall, ‘Gentrification without displacement is possible through socially conscious development that honors and recognizes all races, colors, and creeds as a necessary component to revitalization’ (SAA| EVI, BLOG, 2017)

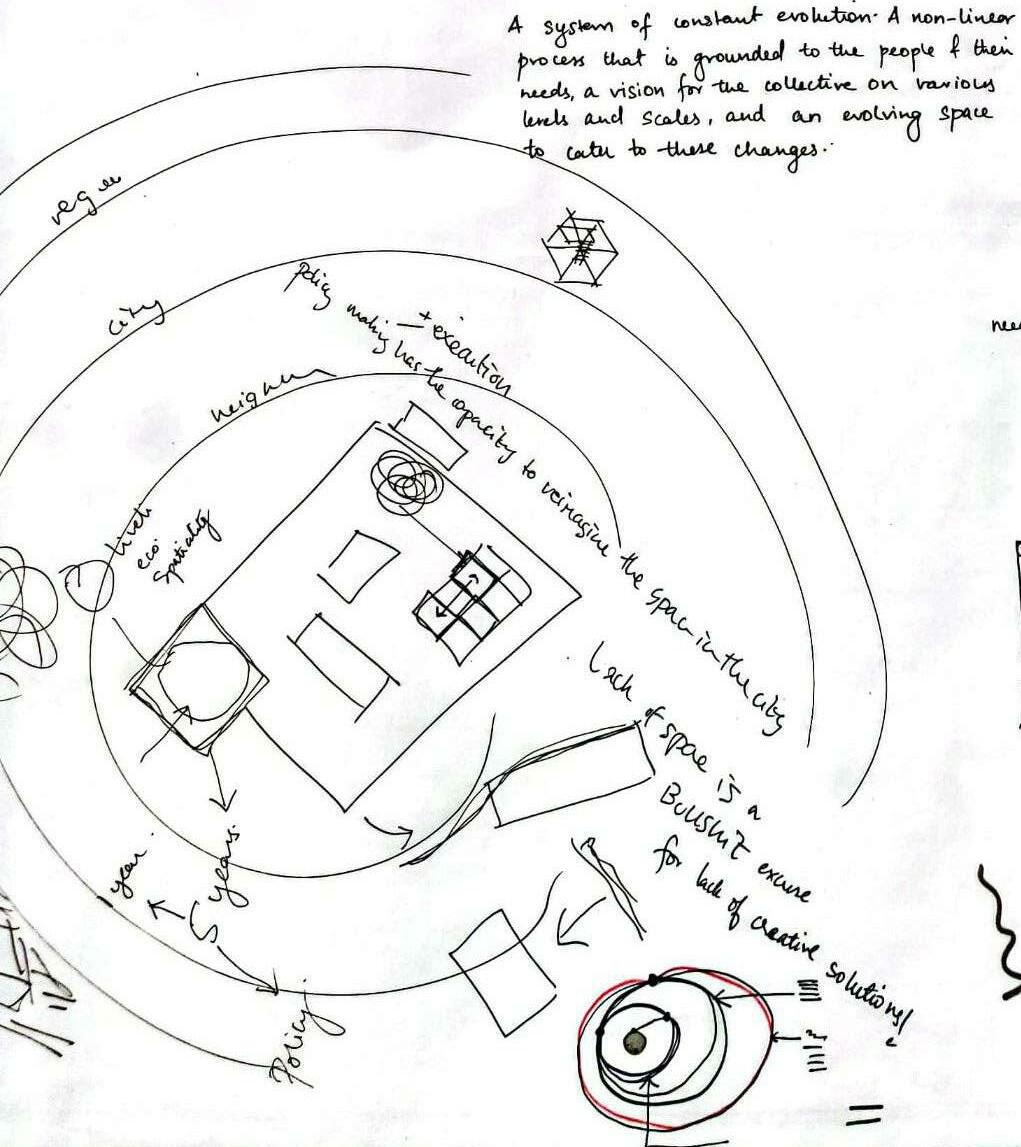

A governance structure capable of including the multiple

layers that make up a city

One of the major challenges in Indian cities today is the correlation between aspirations of an urbanity as perceived by the people in positions of power, namely the government, and the ability to achieve these objectives through contextually relevant policy and urban design initiatives. The study of the Ernakulam Market brings out some key factors that affect the ability to achieve these goals in the Indian context.

Urban challenges are complex to address due to the layering and interrelationships between social and cultural aspects of the context. These aspects coexist and influence each other. To address the complexity of the urban reality a holistic approach to urban planning is necessary, which includes the understanding of the interweaving of formal and informal processes.

The Smart City Mission operates with a one-size-fits-all model, applying the same planning principles to contexts with high variation among them. The Smart City Missions, in the case of Kochi, has a majority of engineers in the team, while there are no urban planners or architects. This leads to a focus on realising the smart city by means of technology through, for example, surveillance and tracking strategies. While these aspects may be important and improve the efficiency of urban systems, this smart city must be embedded in the complex dynamics of the everyday city.

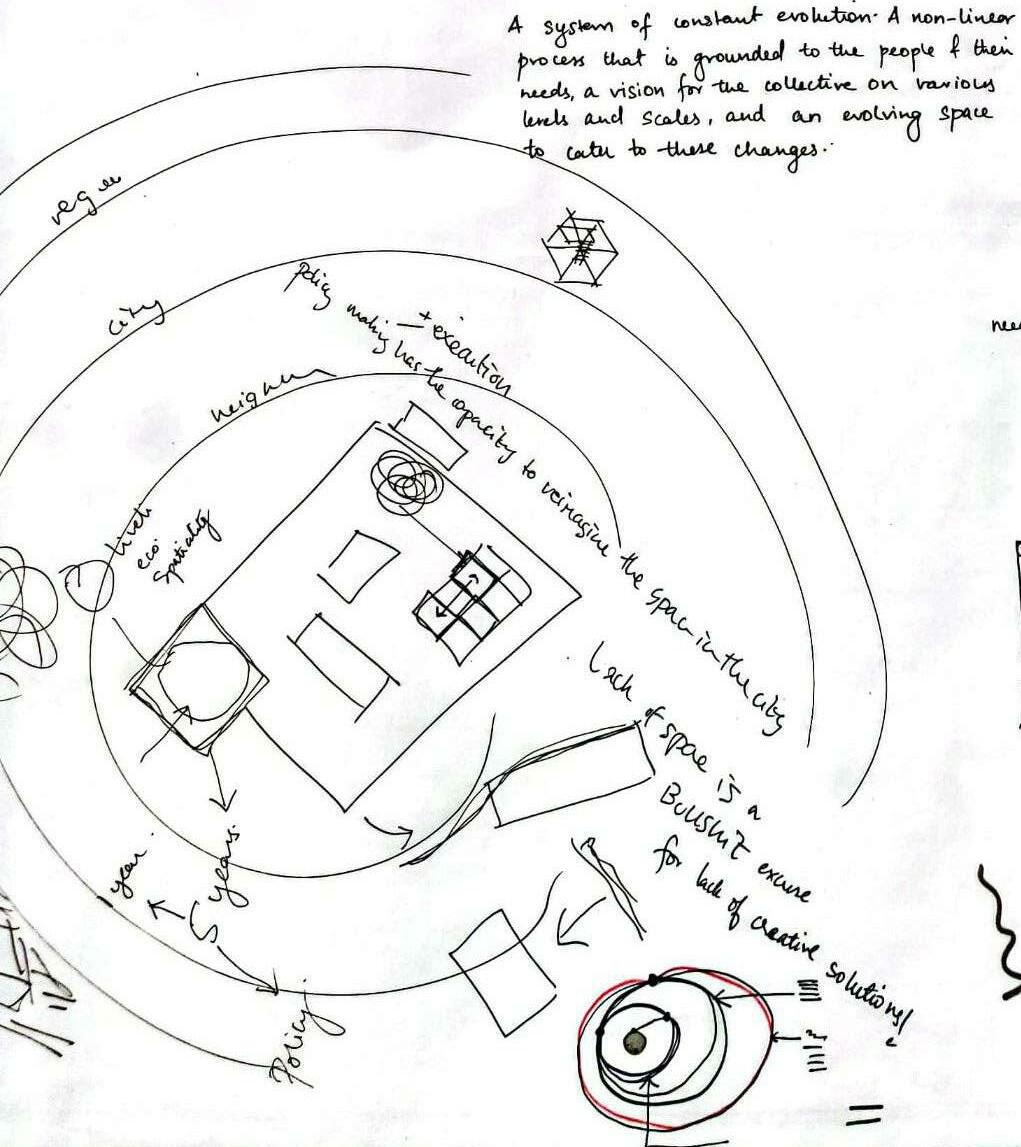

In contrast, this project attempts to look at the layering of issues in society to develop a framework that is capable of taking multiple realities into account when forming urban policies. The images show the early attempts of engaging in this multi-layered understanding of urban issues by layering them. The project argues for the need to look at these issues not in isolation but as a relationship of cause and effect.

Ill. 67 -Development of a governance structure that can include multiple layers and pathways that overlap and intersect (below)

73 | Group 1 | Fall 2022 72 | Kochi Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

4.9 Reflection

5. Policies in play

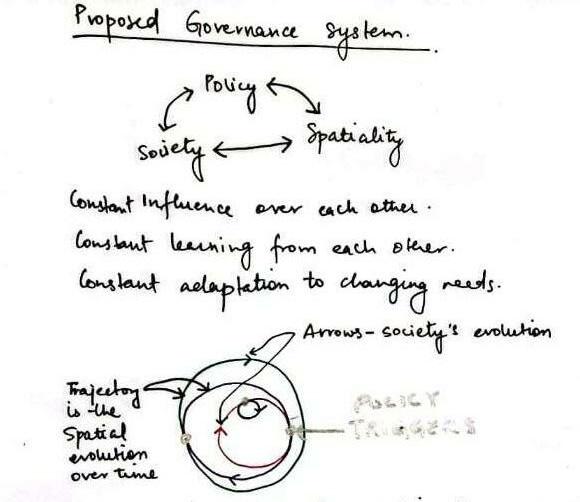

Governance and governance systems operate on a mechanism of trust, adaptability and accountability. What the study points out in the case of Ernakulam Market, however, is that there is a lack of trust in the minds of the stakeholders of the market (vendors, workers and shop owners) when it comes to government, administration and the representatives. At the same time those working in the bureaucratic and administrative offices hold the people responsible for a lack of desired outcomes when it comes to implementing policies. This indicates that there are gaps existing in the system that need to be addressed before real change and progress can be made.

The project seeks to relook at the governance system to address these concerns. It looks at rebuilding relationships between the people and the representatives of people to collectively address, monitor and improve situations on ground. This requires a new set of skills in the representatives so that they can listen, learn and cooperate with the people. It needs the people to take responsibility and participate in representing their interests, while at the same time taking responsibility to ensure that they participate and act towards their collective wellbeing. The project assesses a need for both groups to come forward and acknowledge the shortcomings on their end to co-produce a more cooperative system of mutual accountability. This is a system that brings forward positive change in improving governance responses to long standing contextual challenges, what Galuszka (2019) describes as “co-production of governance”.

The proposal focuses on an approach that looks at long-term objectives and that is realised through short term actions. The approach is derived from the “Dynamic Adaptive Policy Framework”(DAPP) (Haasnoot et al, 2019). The aim is to ensure that the governance system adapts itself to a dynamic urban reality and to the needs of the people of the city changing over time. It recognises the need to learn from the way people respond to policy implementation, and assesses the progress it makes to the everyday lives of people. The approach is capable of self-analysing and responding to changing circumstances in an efficient and transparent manner.

In order to do this, it is important to strengthen ties of the administration with the local people, local representatives, citizen groups, associations and corporations. Mobilising a Public Private Partnership can go a long way in achieving a responsive and mutually accountable system of governance.

Ill. 68 - Drawing of the shopowner and the shopworker in a vegetable stall >

75 | Group 1 Fall 2022 74 Kochi | Policies in play - Reclaiming heritage and livelihoods in Ernakulam Market

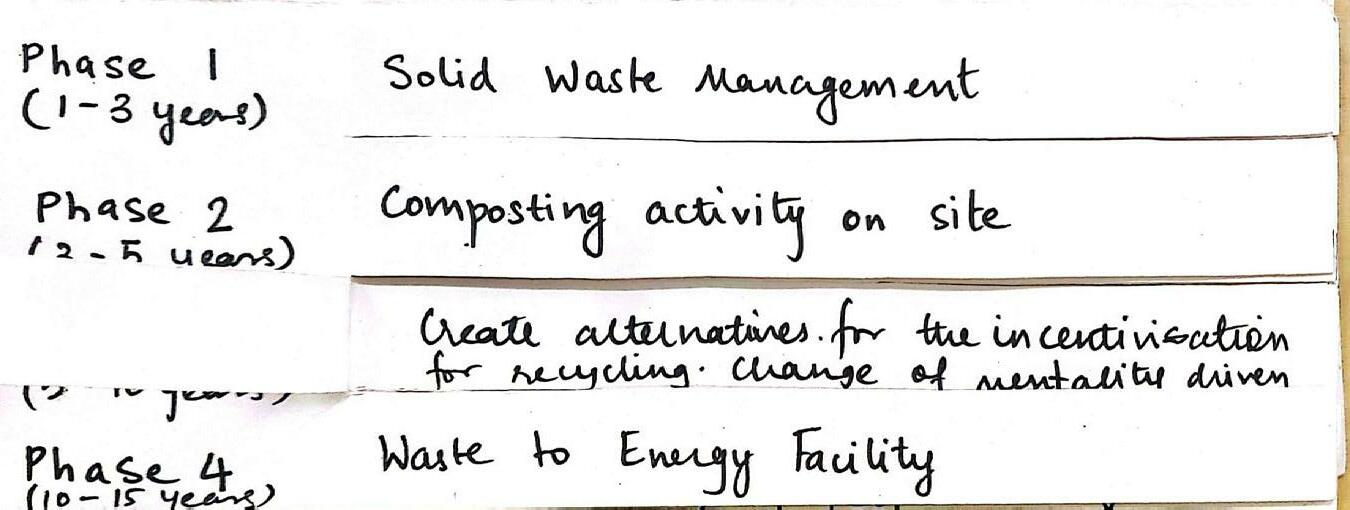

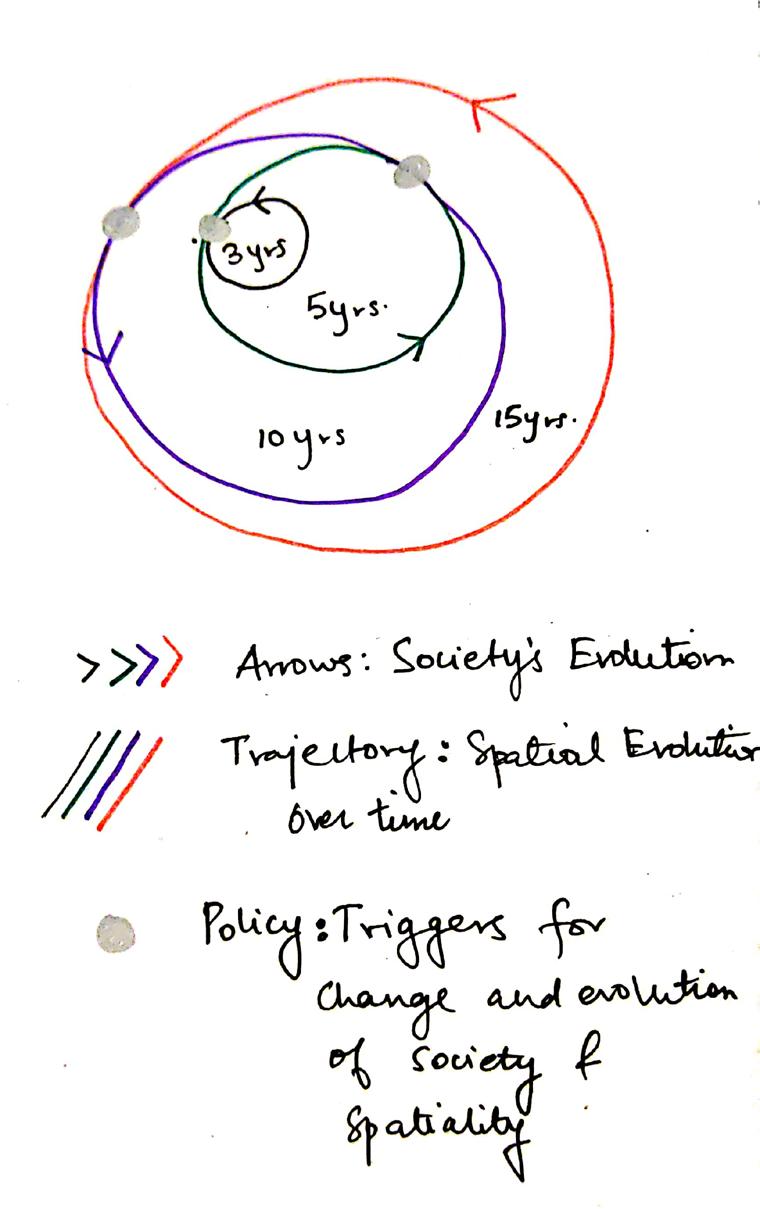

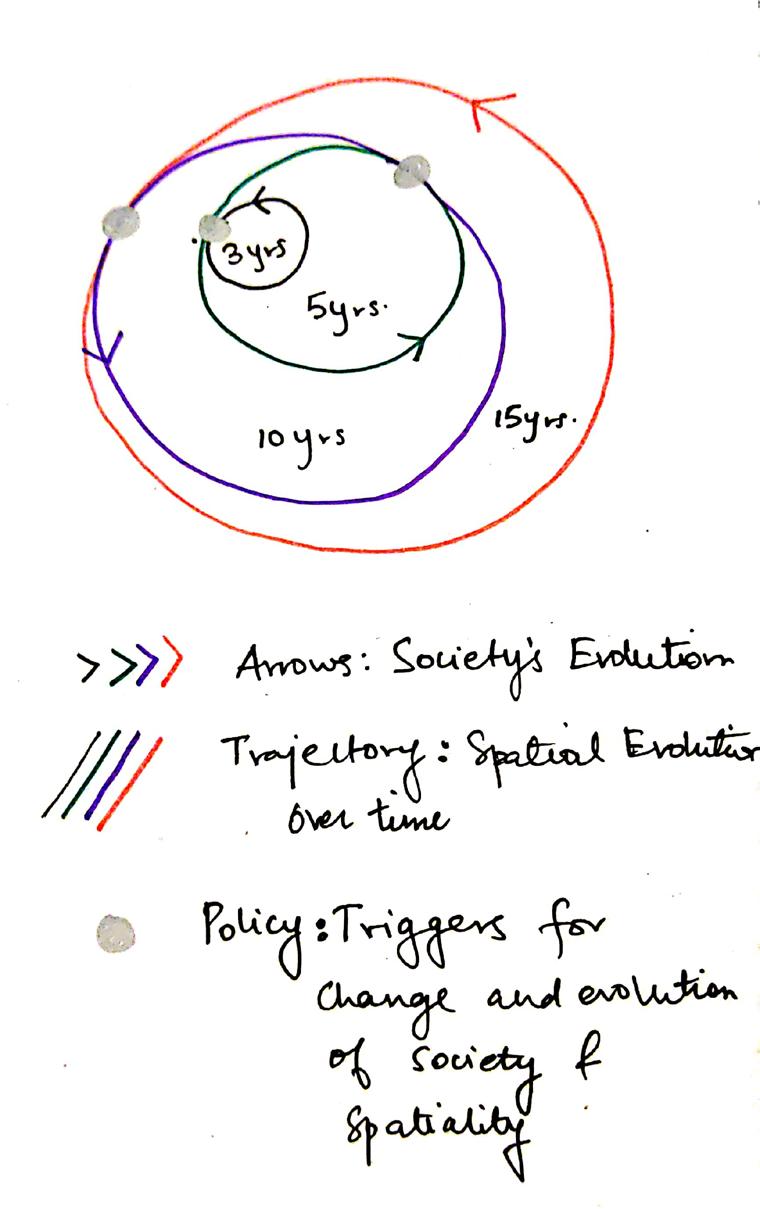

5.1 Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways

Ernakulam Market is an example of how informal practices take place in a formal structure. The users of the market have organised their spaces and social structures according to what is needed for them in their everyday practices. However, the proposal for the market redevelopment seeks to ‘formalise’ and ‘order’ the ‘disorderlyness’ of the original market. This has implied demolishing the original market, wiping the slate clean, which has resulted in disconnecting the relationships between the built space of the market and the people who have been a part of forming it through generations.