(Re) gaining Ecological Futures Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India

Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course Project Report, Autumn 2022

(Re) gaining Ecological Futures Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India

Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course Project Report, Autumn 2022

AAR4525 - Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course

Executive Summary, Autumn 2022

Urban Ecological Planning Master’s Programme

Department of Architecture and Planning, Faculty of Architecture Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim, Norway

Course Coordinator: Supervision Team:

Gilbert Siame Associate Professor, NTNU

Gilbert Siame Associate Professor, NTNU

Rolee Aranya Professor, NTNU

Mrudhula Koshy Assistant Professor, NTNU

Riny Sharma Assistant Professor, NTNU

Booklet Layout:

Mrudhula Koshy Assistant Professor, NTNU

Vija Viese Research Associate, NTNU

2 |

Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

(Re) - Gaining

Ecological Futures

Urban Ecosocial interrelations Kunnumpuram, Fort Kochi, India

Authors Maria Magdalena Mühleisen Stavanger, Norway Eloïse Redon Bordeaux, France Nahida Yeasmin Tonni Rajshahi, Banglaesh

Mohammadreza Movahedi Tehran, Iran

(RE) - GAINING ECOLOGICAL FUTURES - KUNNUMPURAM -YOUTUBE

| Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

3

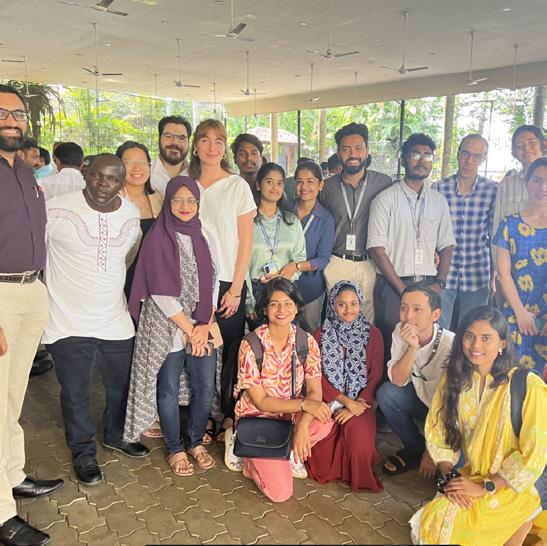

Preface

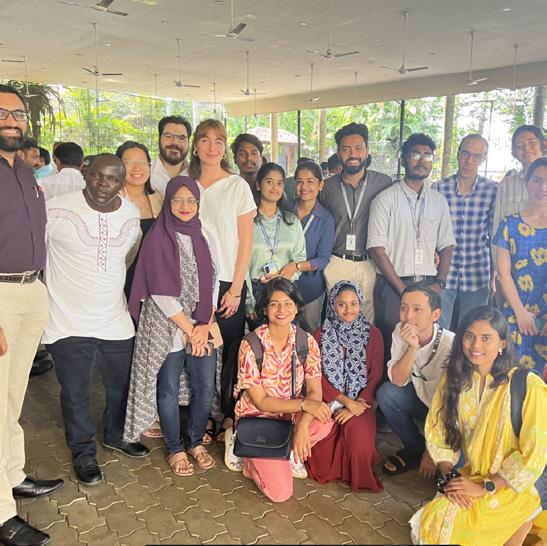

After two years of pandemic-related restrictions which affected many aspects of the Urban Ecological Planning Programme (UEP), and especially its first semester obligatory fieldwork, the 2022 fieldwork under the Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course was conducted in Kochi, India. This was a planning studio project with emphasis on international mobility and knowledge exchange among students from India, South Africa, and Norway. The project forms a core component of the two-year International Master of Science Programme in Urban Ecological Planning under the Department of Architecture and Planning at the Faculty of Architecture and Design at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). The 2022 project activities rejuvenated the UEP passion and curiosity about challenges and opportunities being faced by cities of the Global South. Students spent eight weeks working in Kochi city in the Southern Indian state of Kerala. The project was structured and framed to contribute directly to the UTFORSK funded Norway-India-South Africa (UTFORSK-NISA) student and staff mobility project on localisation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Thus, the project involved NTNU, School of Planning and Architecture (SPA), New Delhi, India, All India Institute of Local Self Government (AIILSG) and the University of Cape Town (UCT) in South Africa. This report represents a major output from the integrated effort of communities, bureaucrats, and most importantly, the students from NTNU, SPA and UCT.

This project report is an outcome of studio work done by NTNU students. The report provides detailed information about students’ experiences, learning and context-informed recommendations for improving living conditions on study sites in Kochi city.

4 | Kunnumpuram,

| (Re) -

Kochi, India

Gaining Ecological Futures

Students’ learning and recommendations are based on UEP’s teaching philosophy of experiential learning. Students’ exposure to an unfamiliar context poses several challenges while working on an academic goal but it also provides the necessary ‘triggers’ for learning that is simply not possible in traditional planning studios that are of shorter duration and have less emphasis on being out in the field.

The project report is informed by methods that allow students to propose solutions to complex but interlinked urban problems based on area-based planning and participatory planning approaches. This year’s report emphasises some of the most important UEP values and topics that include inclusive urban planning and development, ecological integrity in cities, and sustainable urban livelihoods and accessibility. By working with local communities, local and international stakeholders, students identified, analysed, articulated complex issues, and made realistic recommendations to improve living conditions on specific study sites.

The students were divided in 4 groups and 2 of them worked in Fort Kochi while others in Ernakulam areas of Kochi city. Fort Kochi is a seaside historical area known for its Dutch, Portuguese, and British colonial architecture, and heritage and fishing. It is a significant tourist area for the Kerala State. On the other hand, Ernakulam is a sprawling residential and commercial hub well known for Marine Drive and a busy waterfront. Zeroing in on specific sites, the reports deeply reflect on the urban everyday life experiences, challenges, and opportunities for people in Kochi. While retaining the area-based planning approach, students’ work was based on the overarching theme of urban informality and guided by three themes: ecological vulnerability, urban markets, and urban mobility. As an outcome of their learning process, students prepared four reports to illustrate and reflect upon the participatory process through a situational analysis and reflection on methods and methodology that informed a problem statement which they tried to address in strategic proposals. This report summarizes the work of the group working with Re - Gaining Ecological futures, Nature - Culture interralations and inclusive Public space in Fort Kochi.

5 | Kunnumpuram,

India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Kochi,

Acknowledgements

As an introduction we first of all want to start with thanking the Faculty of Architecture and Design at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) in Trondheim, Norway for creating this knowledge sharing platform of a program, helping the world moving towards taking action for the SDGs and creating a bridge between the global south and global north, working towards creating unity and peace. We would like to thank Vija Viese, research assistant, and Riny Sharma, assistant professor, for their help and support over the semester. As well as our supervisor, Professor Gilbert Siame, Assistant Professor Mrudhula Koshy and Hanne Vrebos for guiding us through their insightful and interesting courses and informing our work with the “Urban Ecological Planning’’ approach and participatory action research, and teaching us the integrated area based situation analysis and proposal making with strategic planning methods, together with theories from major scholars like Henri Lefvebre.

We want to give a huge thanks to our translators Faeiz, Abdul Kalam and Nora, who gave us the unique opportunity to get even more connected to the local community with their language and local knowledge skills, from the School of Technology and Applied Science (STAS). The project is based on the local community and all the people we met there, and all the relevant stakeholders. We want to bring a huge thanks to the former mayor Mr. Sohan, and the ward counselor of Kochi Mr. Ashraf for taking their time to help us understand the broader context of the city, and get insightful local knowledge that helped inform our project.

This is the final project report conducted by us, four students from around the world, in collaboration creating our project (Re-Gaining Ecological futures) in Kunnumpuran, Fort Kochi, India. We would like to take this opportunity to express our gratitude to all those who have helped us to bring this project together, and informed our process during the fieldwork process and back at NTNU, and all the substantial support for which we are incredibly grateful. The project would never come together without the residents of Kunnumpuram, and all the warm and inspiring people we met there. We want to give a special thanks to the people we got close to, in the family of Aïsha, and all the help they gave us.

We want to bring a huge thanks to the students from University of Cape Town, South Africa, for joining us in Kochi, bringing in new valuable and interesting perspectives, reflections and changing the process and project outcome to the new and better. Also a huge thanks to their professor Mercy Brown-Luthango for all the guidance and knowledge she gave and shared with us. We were inspired by the constructive comments and suggestions UCT gave us through the process in Kochi, and this study would not have been done without them. And we are very thankful for the help of Mrudhula and Gilbert, going out in the field with us, and helping offering valuable thoughts and supporting us in the process of discovering strengths and weaknesses and identifying opportunities and challenges in the area, together with connecting with people through games and highly interesting conversations.

6 | Project location | Project Title

Acronyms and Abbreviations

PNA KSWMP ULB GIZ KSWMP E.U. SDG PLA CSML C-HED NTNU SPA UCT UEP WRI

Participatory Needs Assessment

Kerala Solid Waste Management Project

Urban Local Bodies

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit

Kerala Solid Waste Management Project European Union Sustainable Development Goals

Participatory Learning and Action Cochi Smart City Limited Center for Heritage, Environment and Development Norwegian University of Science and Technology

UNDRR

School of Planning and Architecture University of Cape Town Urban Ecological Planning World Resources Institute Blue Green Infrastructure

United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction BGI

7 | Kunnumpuram,

India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Kochi,

8 | Kunnumpuram,

|

(Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures Kunnumpuram, Fort Kochi, India

Kochi, India

(Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

9

|

Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India |

(Re)

- Gaining Ecological Futures

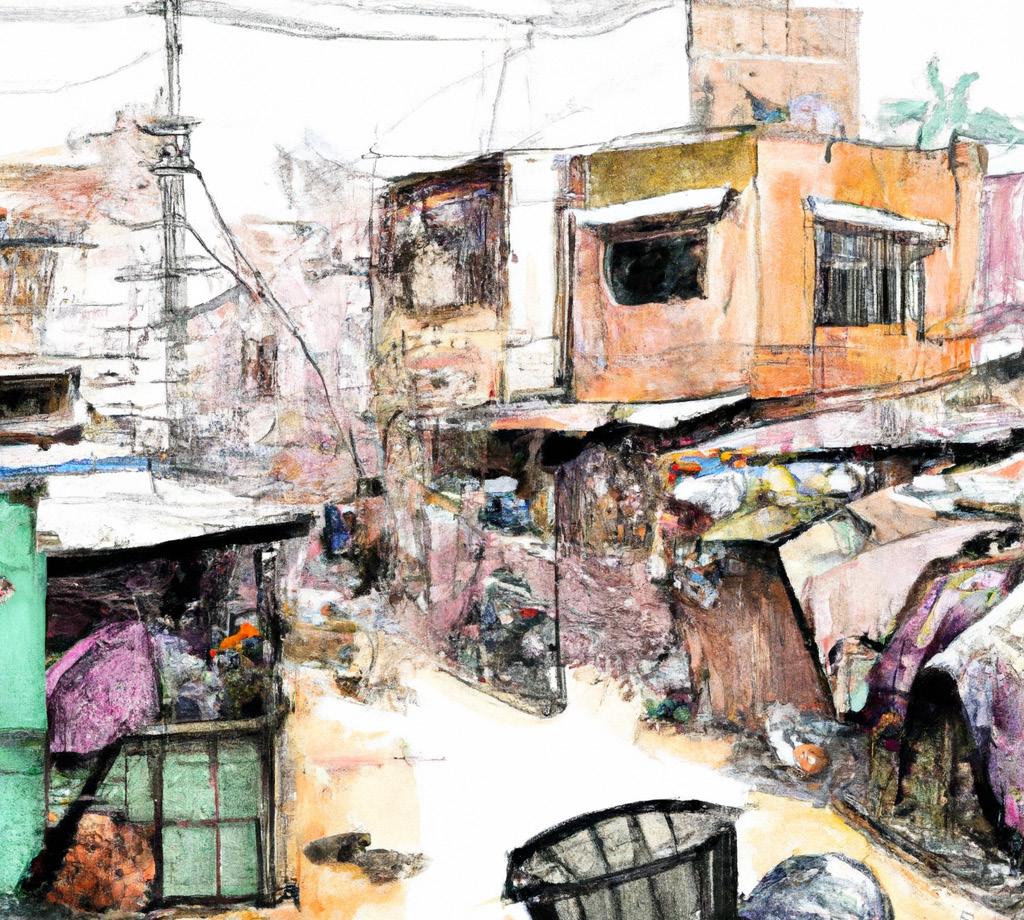

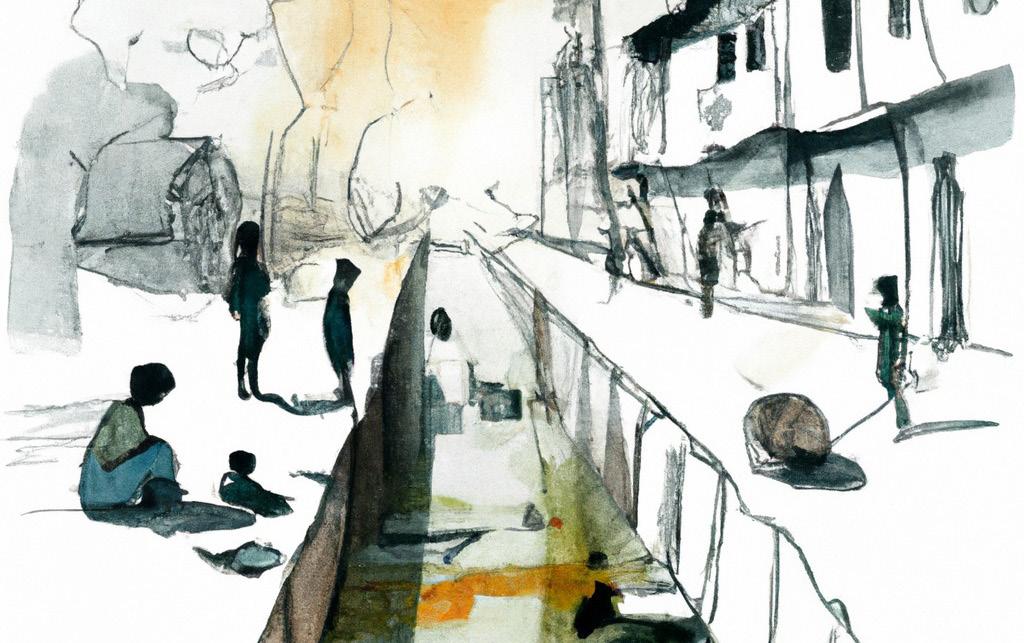

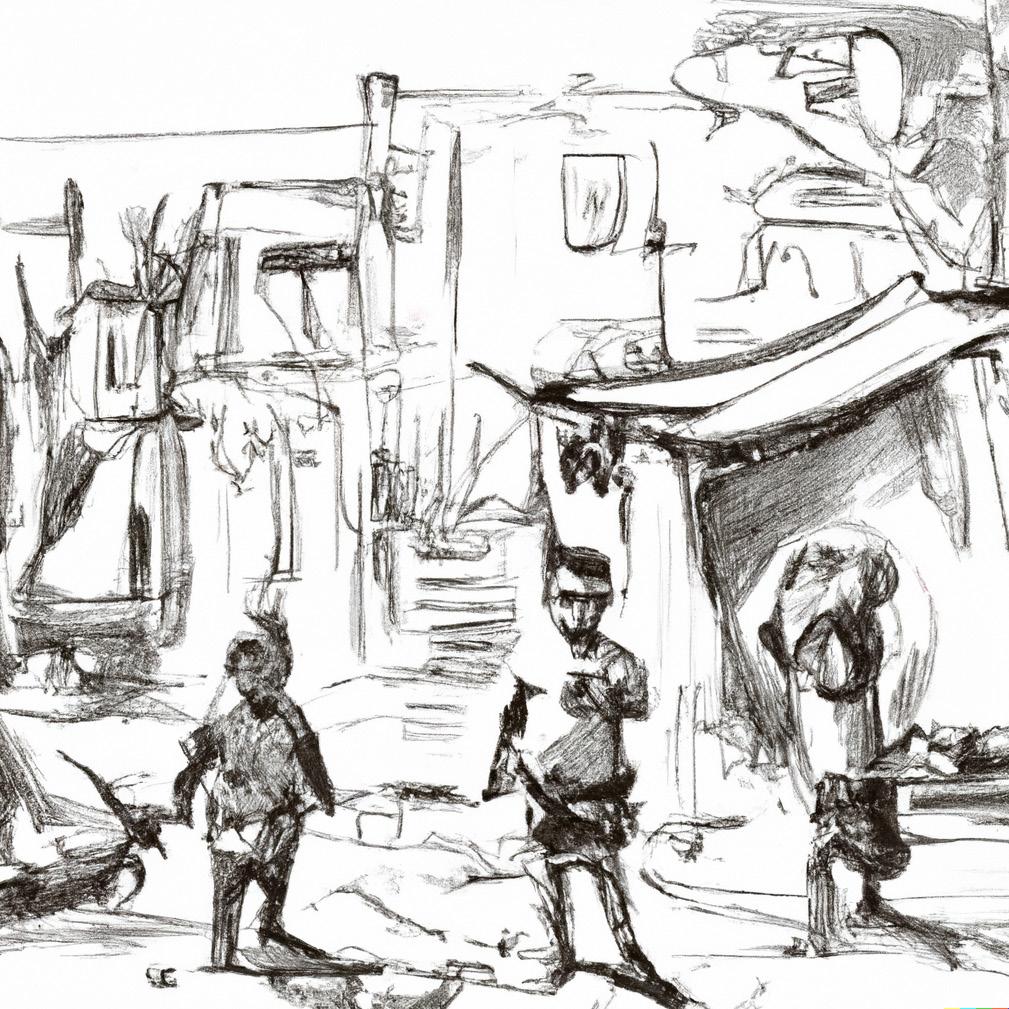

Figure 1. 1 The dense streetscape of Kunnumpuram

Contents

Preface

1. Introduction

1.1 Kochi, Kerala, India 1.2 History 1.3 City context 1.4 Site presentation 2. Methods 2.1 Introduction to methods 2.2 Process 2.3 Local knowledge and site research 2.4 Data collection 2.5 The tangible experiences linked with theory 2.6 Challenges located at site 2.7 Participatory workshop 2.8 Stakeholder-issues interrelationship 2.9 Stakeholder meetings 2.10 Chapter endnote

3. Situation analysis 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Public spaces 3.3 Pathways’ walkability issues 3.4 Gender inequalities 3.5 Waste management 3.6 Environmental degradation and canals 3.7 Chapter end note

15 17 18 20 23 26 28 32 34 36 38 40 42 44 46 52 55 56 58 62 36 66 70 72

10 | Kunnumpuram,

| (Re)

Kochi, India

- Gaining Ecological Futures

Contents

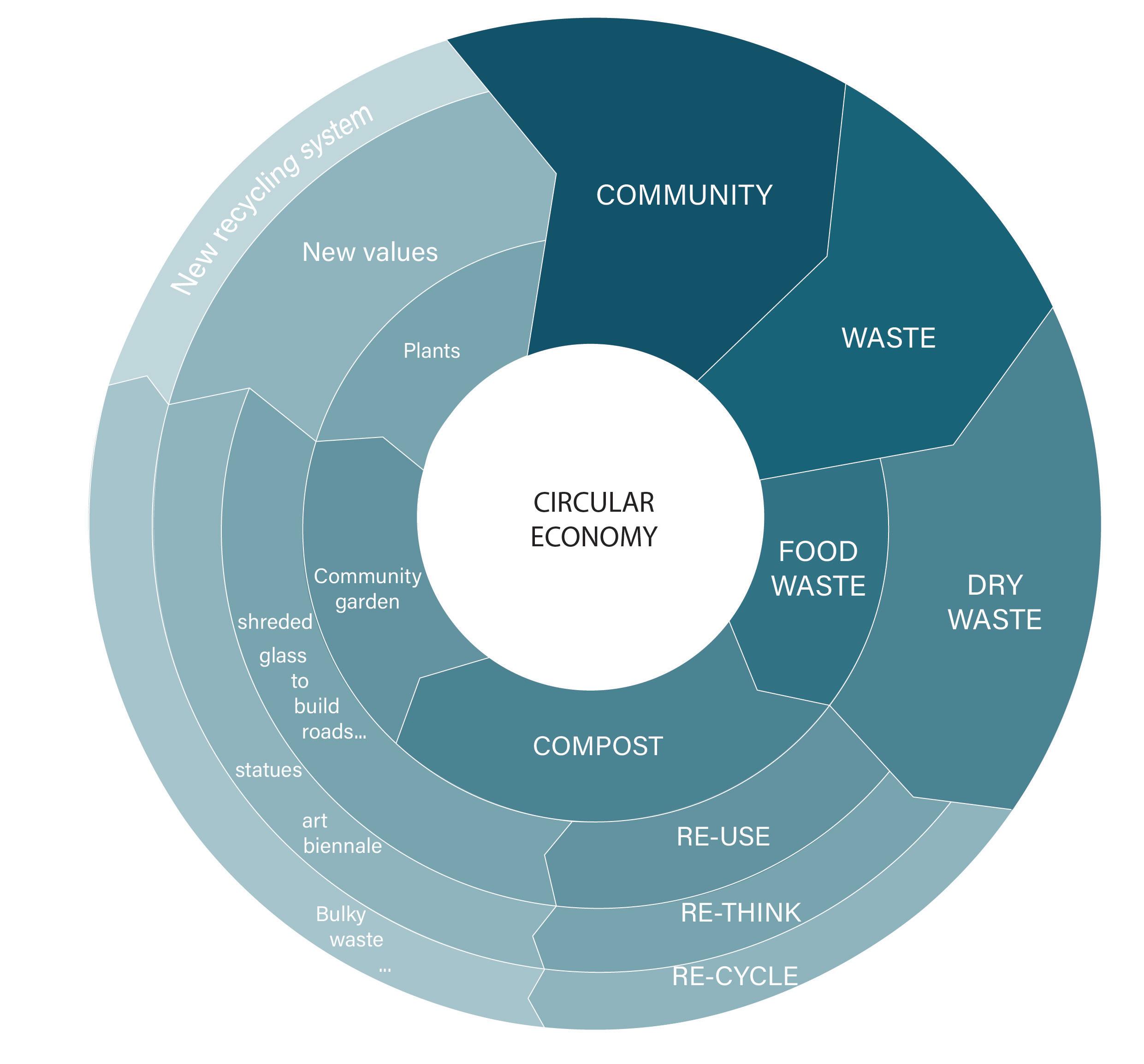

4. Spatial Solution

4.1 Vision statement

4.2 Reaching goals and strategies

4.3 Inclusive vibrant public space

4.3.1 Making the pathways more walkable project 4.3.2 Placemaking Project : An inclusive green place for the community 4.3.3 Communal water 4.3.4 Urban community garden 4.4 A segregative waste management system 4.5 Ecological regeneration 4.6 Chapter Endnote

5. Governance

5.1 Urban Governance 5.2 Strategies of governance towards inclusive public space 5.3 Strategies of governance towards cleaning the canal 5.4 Strategies of governance towards sustainable waste management

Reflection Conclusion References and Bibliography List of Figures

76 78 80 82 84 86 88 91 94 96 100 102 104 108 110 112 114 116 118 120

11 | Kunnumpuram,

| (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Kochi, India

Eloïse Redon

I am an exchange student coming from the Architecture School of Bordeaux (ENSAP Bx), in France, and have a bachelor in Architecture. Over the years I became more and more aware of the ecological challenges we are facing. Through architecture and now the UEP program, my hope is to learn and experiment with new approaches and find alternatives that will help me, as a future planner or architect, to act and create projects that have meaning and participate in the creation of a brighter future. I sincerely believe that gathering people and working with the communities around common goals will help us find solutions to go toward social and ecological transition.

Mohammadreza Movahedi

I have a bachelor’s degree in Architecture and a master’s degree in urban design from the National University of Iran, Tehran. After graduation, I worked as a freelance architect for a year; then, I worked as an architect in an architectural firm in Tehran for three years. My delightedness in thinking and reading about city challenges and issues made me decide to come back to university and pursue my interest in urban studies. Urban Ecological Planning (UEP) fitted my interests best since it equipped me with the knowledge to see urban planning worldwide sustainability issues from a different perspective and from a different scale.

12 | Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Maria Magdalena Mühleisen

I have a bachelor’s in Architecture from Bergen School of Architecture. I worked one year as an intern at Helen & Hard architects in Stavanger, then one year at their office in Oslo as an architect. I am now doing my master in Architecture at NTNU, and am joining the Urban Ecological Planning program for this semester. My interest is in how to find new ways of planning and drawing for the future. Urban Ecological planning is catching my attention in the way it is contributing to the future, with its sensitive holistic understanding of the world, and the apectsof how to deal with real issues on ground where it is needed, and finding relevant solutions.

Nahida Yeasmin

Tonni

I have done my bachelor in Urban and Regional Planning from Rajshahi University of Engineering & Technology, Bangladesh. My thesis was related to “Economic Valuation of Environmental Change of A Natural Wetland” and during my thesis I grew my interest to work further in ecological aspects of planning. That is why I decided to do my Master’s in Urban Ecological Planning in NTNU. I am looking forward to researching more on how planning can improve the living standard of people and make the world livable for future generations.

Figure 1. 2 World map 13 | Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

14 | Project location | Project Title

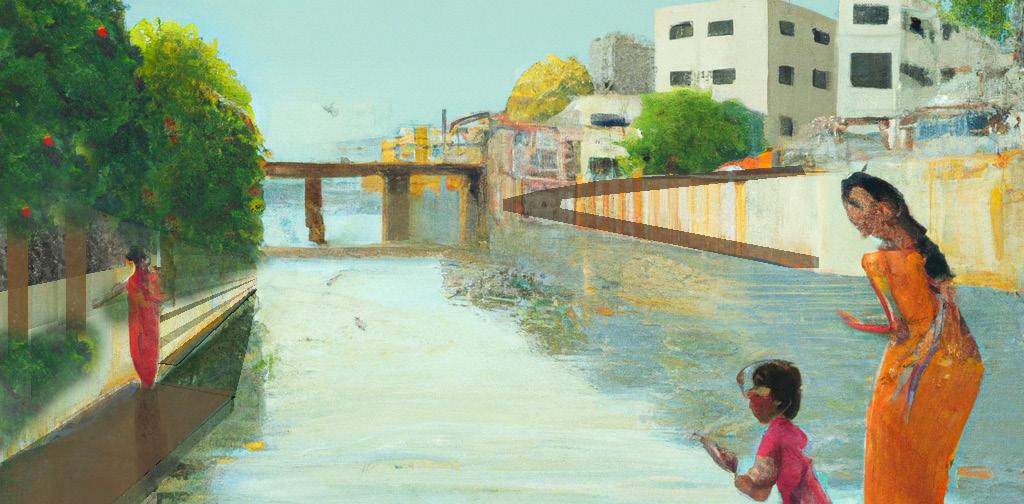

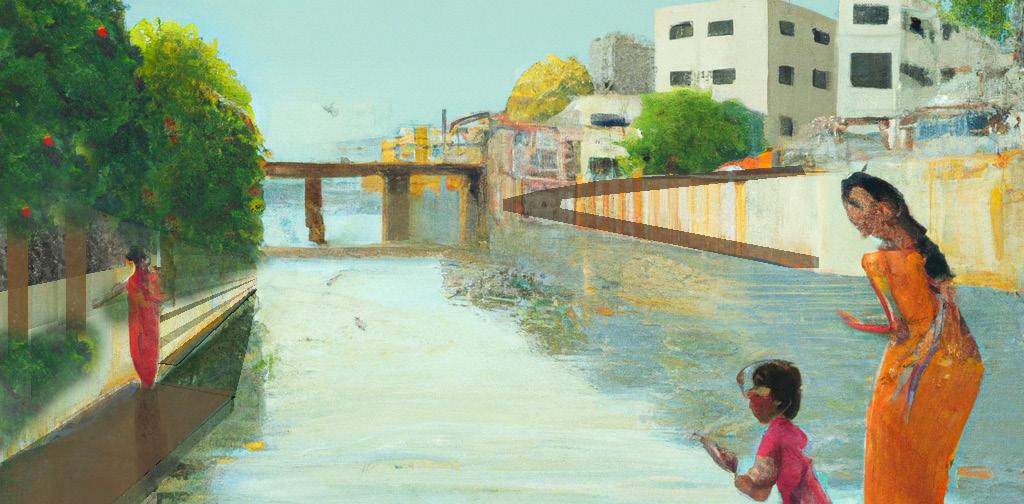

Figure 1. 3 The Calvathy canal, Kunnumpuram, Fort Kochi

1. Introduction

The city of Kochi and our chosen site Kunnampuram

Figure 1.4 Goats in the street, Kunnumpuram, Fort Kochi

15 |

| (Re) -

Futures

Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India

Gaining Ecological

Kerala in India, state on the Malabar coast Inaugurated 1st november 1956

It is the 21st largest state in India Main language: Malayalam Population: 34.63 million Economy: 9th largest in India Povert in Kerala: 64,006 extremely poor families

Figure 1.5 State of Kerala in India

16 |

Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

1.1 Kochi, Kerala, India

The city

Koch city is a part of the district of Ernakulam, located in the Southeast of India in the state of Kerala. Historically referred to as “Queen of the Arabian Sea” situated between a mountain range the Western Ghats to the east, and the Arabian Sea to the west. Upon the Western Ghats there are wild lands covered with dense forest and deep cut valleys.

Other regions are cultivated as coffee and tea plantations. The coastal belt of Kerala is relatively flat with interconnected canals and rivers running through, crisscrossing the beaches, together with groves of coconut trees. The coastal city has a wet humidmarine tropical climate, influenced by heavy rain seasons brought up by monsoons.

It is the largest city in Kerala with approximately 3.3 million people, while entire Kerala has a population of over 34.6 million people.

The economy of the Kerala district is the 9th largest in India. The states capita per income is in general 60% higher than average, and contributes with 4% to the national GDP. The main industries are shipping, IT, tea, manufacturing, tourism, fishing and retail. The city has a diverse rapid evolving culture with a cosmopolitan outlook, and is a highly educated part of South India, with many famous universities such as Kochi University of Technology. (Roman, Et Al, 2022)

17

|

|

Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India

(Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Figure 1. 6 Image from

Kunnumpuram

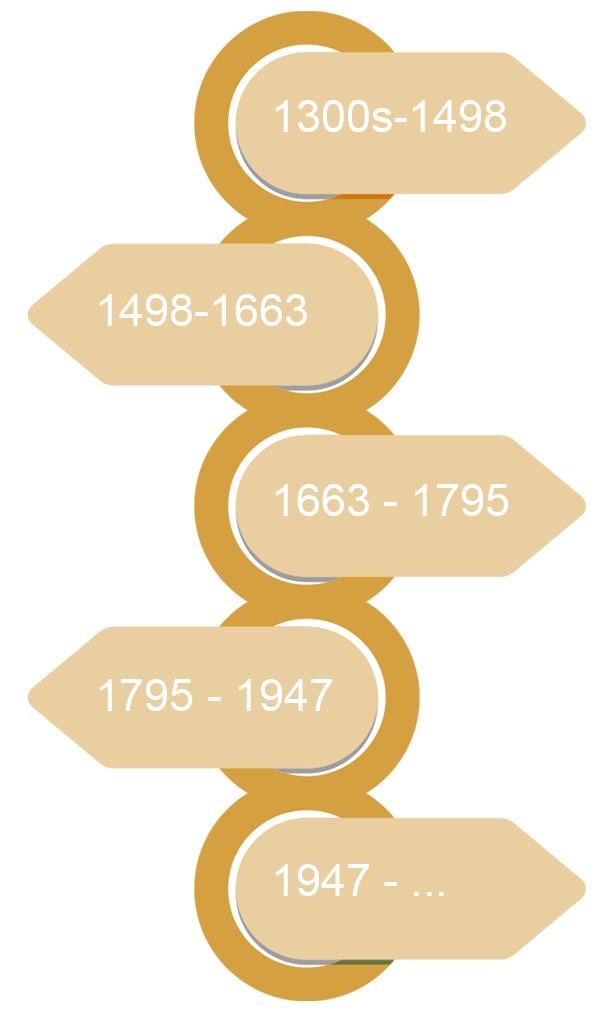

1.2 History of Kochi

Historically, Kochi was a trading center for centuries. It is strategically located with a close connection to the Arabian Sea. Kochi was an insignificant fishing village until, in the 14th century, the backwaters of the Arabian Sea caused the separation of the village from the mainland, turning it into one of the safest ports on India’s southwestern coast. Arabs and Chinese are believed to have been the firsts to migrate to Kochi trading with spices in the 14th century. ( Britannica encyclopedia)

The year 1498 proved to be a pivotal year in the history of Kochi and India. It was during this year that Vasco du Gama and other Portuguese explorers found their ways to Kochi. Trade and colonization underwent rapid changes as a result. From this point, Kochi experienced numerous rounds of colonization, becoming India’s first European settlement around 1500 and an entry point for further colonial encounters. As it is shown in the historical timeline, Portuguese, Dutch, and British took control of Kochi until India gained its independence in 1947.

When British East India Company defeated the Dutch in 1795 as the last colonizer of Kochi, the city became part of the British Empire. Port city developed rapidly under their rule. For instance, some canals were created in Fort Kochi to separate areas and transportation goods.

In the canals running through the site we have been doing our case study, were built during this time. According to our interviews with the local stakeholders, and community these canals were deeper than they are today. And they were cleaner in previous decades. However, they gradually have gotten polluted, and they lost their functionalities.

For centuries, Kochi has remained an important destination and trading center in Southern India.

As an important port of Kerala, diverse groups of people migrated to Fort Kochi in different times throughout the history. So, Fort Kochi, that the study area is located, is a multicultural zone that includes many communities and religions living together peacefully.

After the Indian Independence, the Government of India’s 1 November 1956 States Reorganisation Act inaugurated a new state: Kerala. On 9 July 1960, the Mattancherry council passed a resolution that was forwarded to the government, requesting the formation of a “Municipal Corporation” by combining the existing municipalities of Fort Kochi, Mattancherry and Ernakulam. Thus, on 1 November 1967, exactly 11 years since the conception of the state of Kerala, the corporation of Cochin came into existence, by the merger of the municipalities of Ernakulam, Mattancherry and Fort Kochi, along with that of the Willingdon Island and four panchayats viz.

18 | Kunnumpuram,

| (Re) -

Kochi, India

Gaining Ecological Futures

Portuguese Rule

Vasco da Gama discoverer of the sea route to India (1498), established the first Portuguese factory (trading station) there in 1502

British Rule

Kochi became part of the British Empire in 1814. Fort Kochi became British Kochi, and in 1866, it became a municipality.

Port city became more developed with the British and the canals were created for the trade purposes and seperate the areas from each other.

Pre-Portuguese era

Arabs were believed to be the firsts to migrate to Kochi for spice trade. Followed by the Chinese. It is believed that Chinese fishing nets were introduced in Kochi by Chinese in this era.

Dutch Rule

Kochi prospered under their rule by shipping spices and copper. It was also ok for native ethnic-religious groups. Under their reign the Jewish identity

Independent India

As one of the main tourist destinations in South India, Kochi remained an influential trading center after India’s independence. it is a multi-cultural city that includes many communities and religions living in harmony and peace. Despite this, the city has a number of issues including environmental degradation.

19 | Kunnumpuram,

India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Kochi,

Figure 1.7 The historical timeline of Kochi

1.3 City context

Culture

Kochi is a multicultural city as many people from different parts of the world and from different cultural backgrounds have migrated to Kochi (Kochi Culture, 2013). The city has influenced by all cultures, in each part of the city represents a culture. Kochi has a colonial effect due to rule by the Portuguese, Dutch and British (Raheem, 2013). In the Indian context, the Hindu caste system still exists which divides them into social hierarchical four groups named Brahmins (priests, teachers), Kshatriyas (rulers, warriors), Vaishyas (landowners, merchants), and Sudras (servants), based on their karma (work) and dharma (duty) according to their ancient belief (Tóth, 2019). According to Zsuzsa Tóth, caste discrimination affects people’s daily lives in a terrible way, reducing their access to employment, education, and social standing.

Kochi is a city with a diverse population, including Muslims, Christians, Hindus, and others. Despite the caste system and the religious divisions that exist in India, in Kochi city, a unique communal harmony can be noticed. According to sociologist Ashis Nandy, communal harmony is based on their mutual understanding of differences, not because of secularism (A unique communal harmony in Kochi - The Hindu, 2014).

Politics, governance and corruption

According to the Corruption Perceptions Index, 2021 reported by Transparency International, India is in the 85th position out of 180 countries which indicates the high level of corruption in India. According to the president of V4 Kochi, Pavizham Biju political parties only want to lure people rather than solve their problems which indicates the opacity of the political parties (New fronts in Kochi to battle corruption, inefficiency - The Hindu, 2020).

According to the community politicians are giving the impression that they are truly speaking for the people.

India’s most pressing problem is corruption, which has become pervasive and endemic. Although certain Indian regions are working to increase transparency and community-based efforts, there is not much proof that these measures would actually reduce corruption (Sukhtankar, Vaishnav, and others, 2015).

Economic disparity is a major problem in India since the privileged have managed to seize a large portion of the country’s wealth. Corruption has a significant impact on all developmental projects, which worsens the situation for the underprivileged. While politicians and bureaucrats profit from the corruption in India, low income groups are its primary victims (Murthy, 2010).

20 | Kunnumpuram,

| (Re)

Kochi, India

- Gaining Ecological Futures

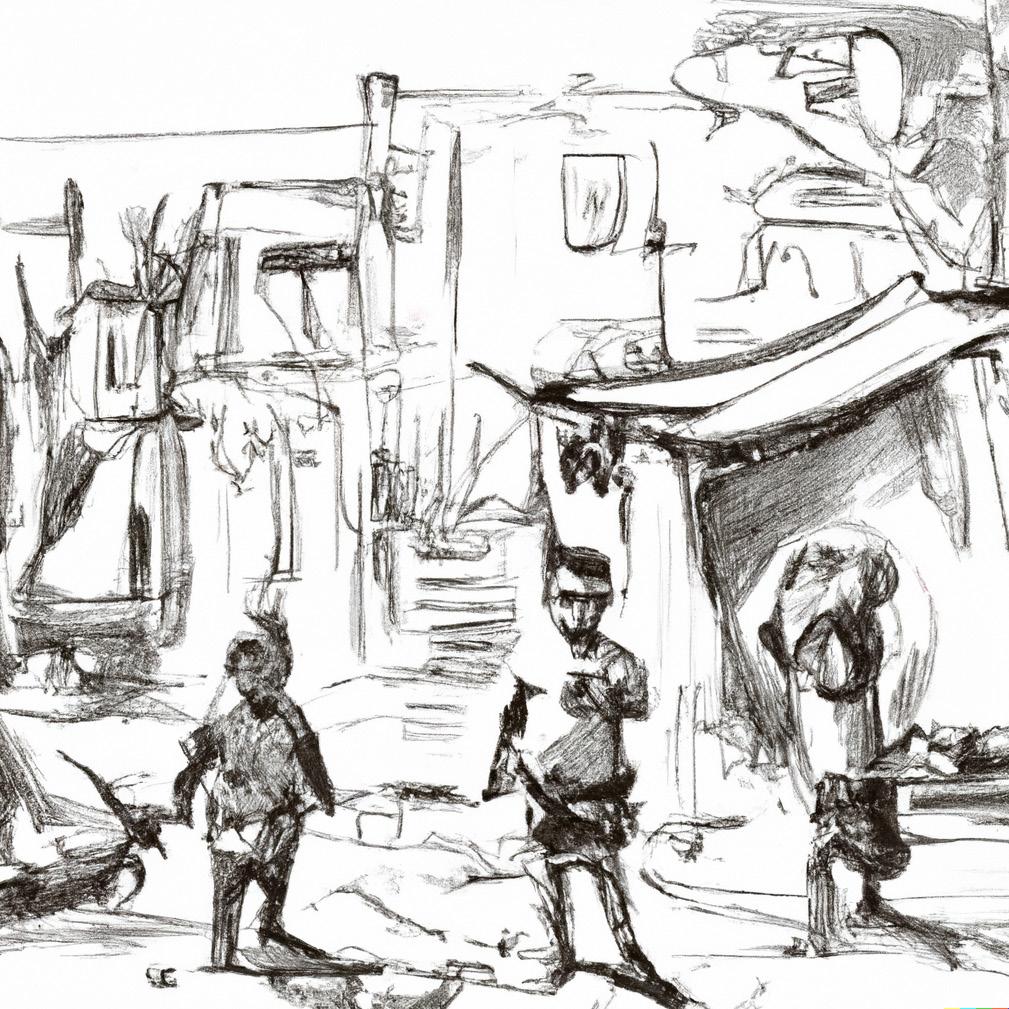

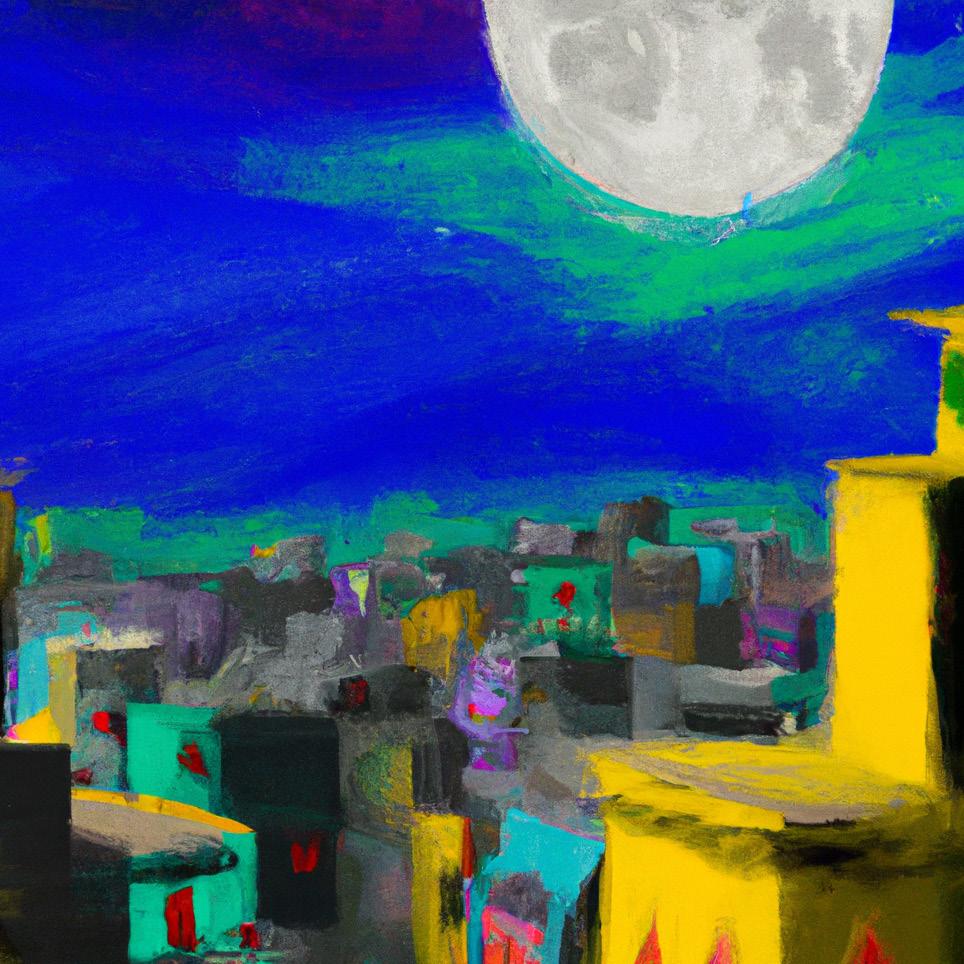

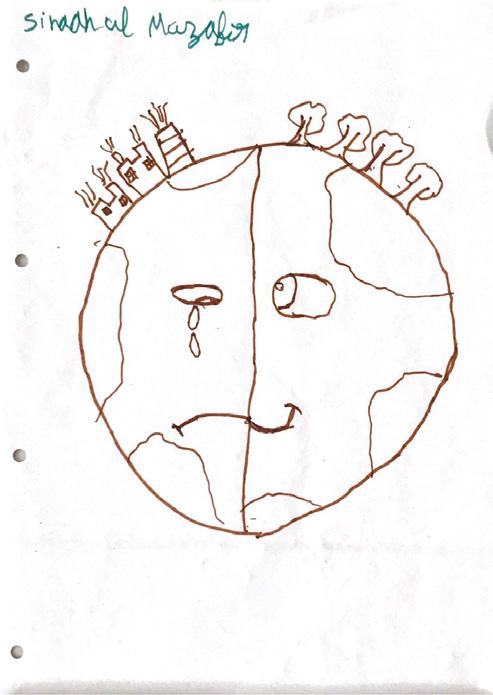

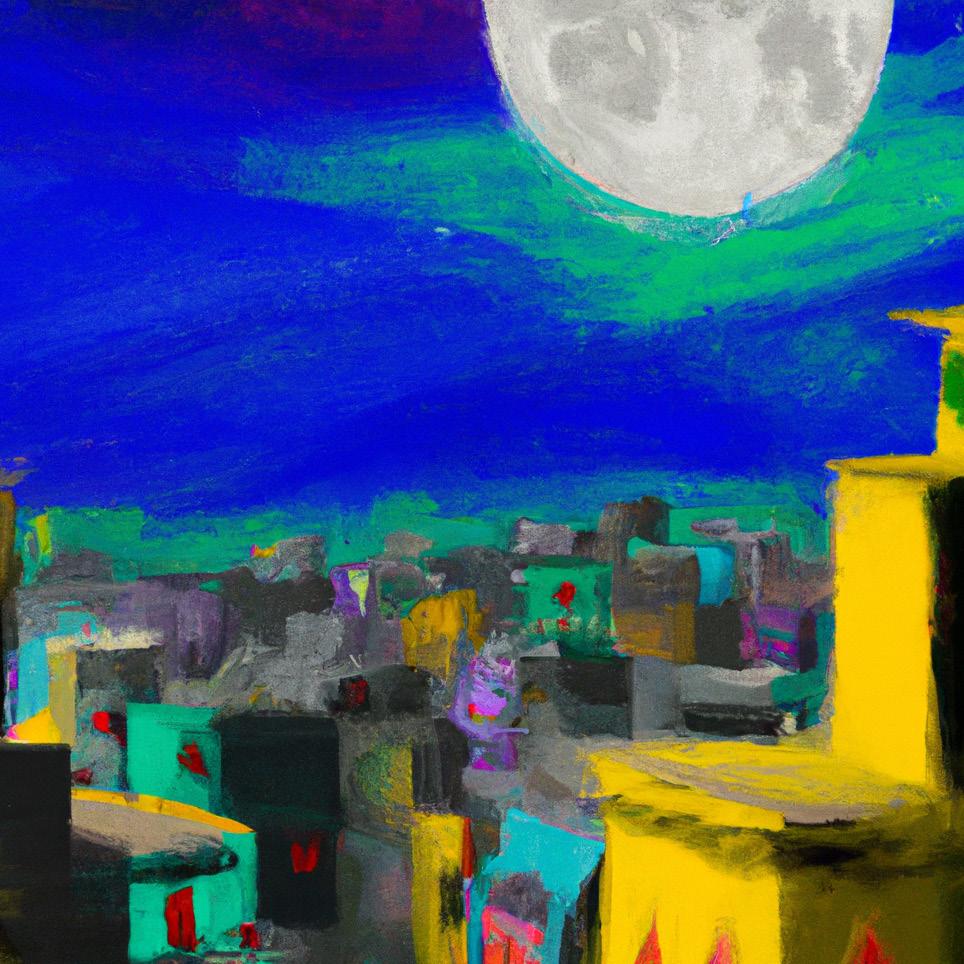

Climate and climate change

The climate of Kochi is topical. Due to its geographic location, Kochi experiences some slight temperature variations as well as moderate to high levels of humidity. During the monsoon season, there is significant rainfall in Kochi (Thomas et al., 2014).

Kochi is considered Kerala’s most polluted city and the average PM 10 (particulate matter 10 micrometers or less in diameter) is touching the permissible limit (Nambudiri, 2020). According to pulmonologist Dr. Ramesh Nair, the cases of respiratory disease are getting higher over the years due to the pollution from construction sites, road works effects, etc. The canals of Kochi are facing a high level of e-coli contamination which is beyond the permissible limits (Narayanan, 2021). The presence of chemical contamination is also found in the canal water as well which is directly going to the sea.

In 2018, Kerala experienced the worst flood due to climate change and high pollution in the canals and low-lying wetlands. The network of the canal has been destroyed over the years by improper construction and planning and the pollution has hindered the natural flow of the water toward the sea (Vohra, 2022).

Global warming is affecting Kochi in various ways in the upcoming years including sea level rising, intense tidal flooding, extreme rainfall (Jacob, 2022). The land that is referred to as God’s Own Country will change into a location where people will be terrified to reside due to the rising sea level, heavy rainfall, and high levels of pollution.

21 | Kunnumpuram,

| (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Kochi, India

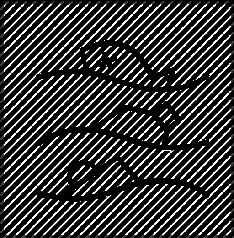

Figure 1.8 Sketch representing issues regarding climate change in Kunnumpuram, Kochi

Kunnumpuram Fort Kochi, India

22

|

Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

1.4 Site presentation

Selecting site

Kochi is a dense complex city, an example of one of the Global South cities. The metropolitan area’s population is increasing by over 3% every year (Indiaonlinepage, 2020). Due to the extremely rapid urbanization, it is facing multiple challenges regarding the economy, social aspects, politics, and sustainability.

To choose a site to work within this context, we started by exploring and walking around the city.

We found many interesting places, and after some discussions and research we ended up choosing a livelihood area in Fort Kochi. We knew that we wanted to work on ecological vulnerability, and this site appeared to have both many challenges but also a lot of opportunities regarding those subjects.

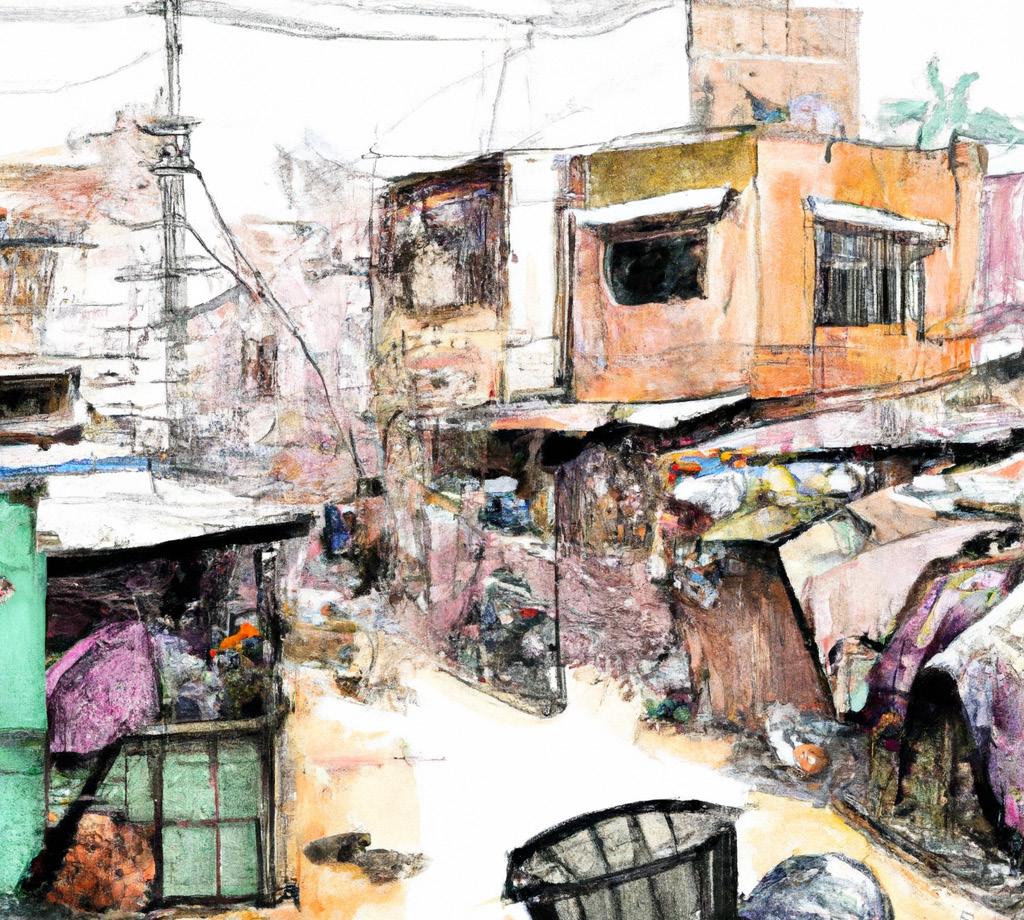

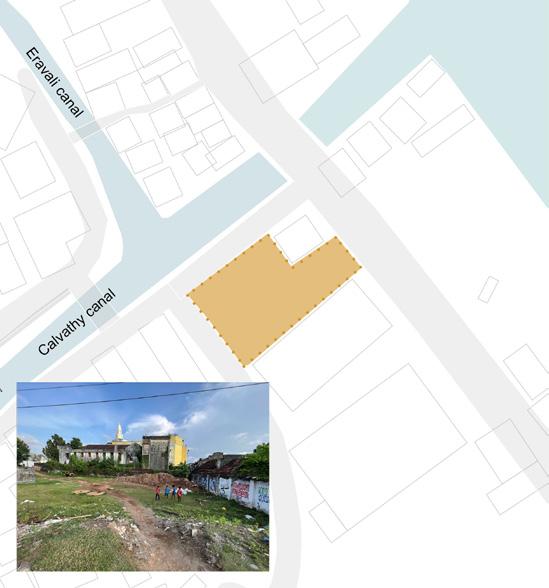

Kunnumpuram

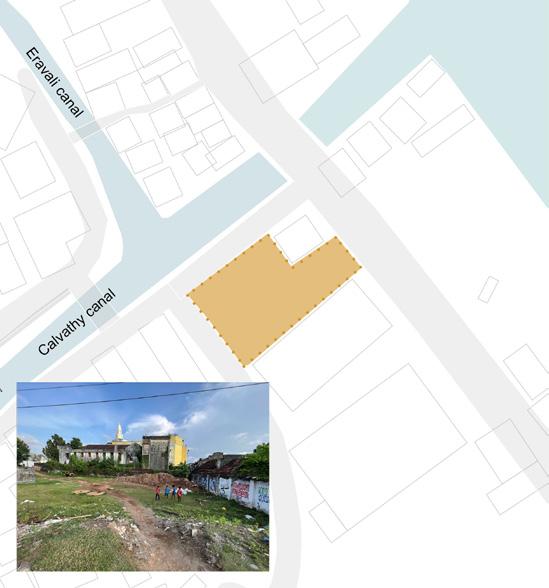

Our site is located in Fort Kochi, in a neighborhood called Kunnumpuram, considered as a “slum area” by the city.

As a low-income area, the rate of poverty is high. It is one of the more dense areas of Fort-Kochi, with small and precarious houses that can shelter up to three families. The shifting of the previous market to Ernakulam, in the mainland, resulted in a loss of economic opportunities in the neighborhood. (Raman et al. 2022).

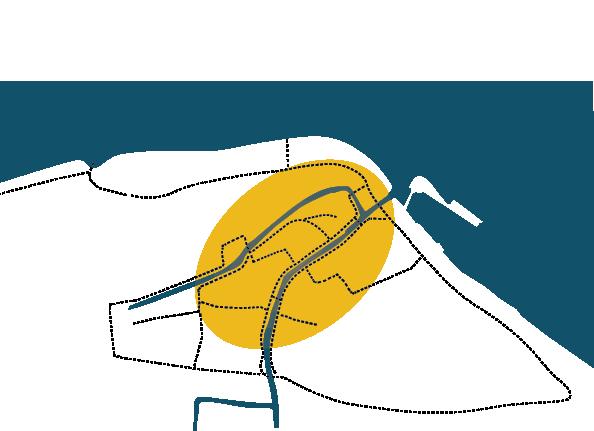

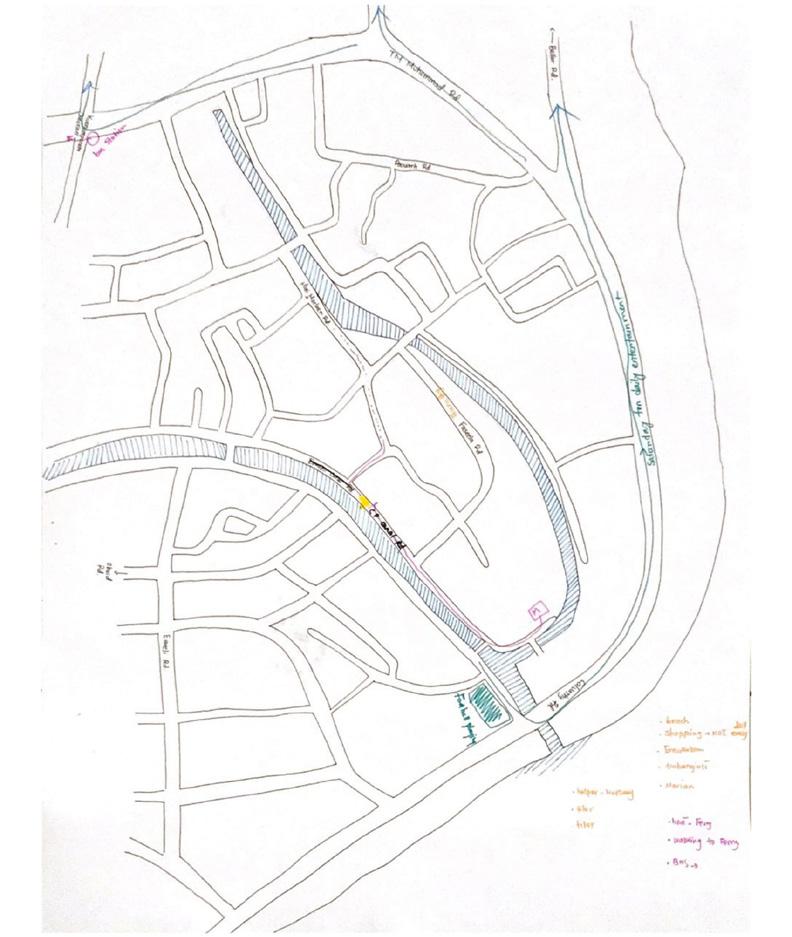

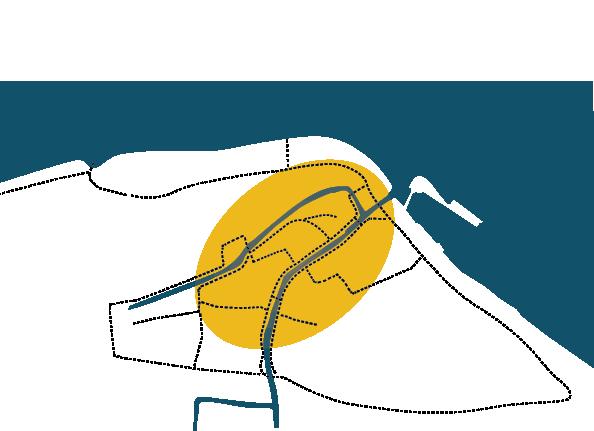

Located in the South-west of India, in Kerala, Kochi (formely known as Cochin) is one of the major cities of the state and is rich of culture and history. During our month of fieldwork, we selected a site to work on and discovered more in depth what the city had to reveal. Figure 1.9 Site area

It is surrounded by two canals : the Kalvathy canal

23 | Kunnumpuram,

| (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Kochi, India

and the Eraveli canal. Both canals were originally built during British colonization and served the dual purpose of dividing areas and as a route for the transportation of goods. The history of the neighborhood still has an impact on the structure of the city, and nowadays, the canals are isolating the area from the rest of the city.

The area has a rich historical context, and is referred to as “Mini India”. Indeed, many cultures and religions are living here among each other, embodying the different faces of India. With the majority of the residents being Muslims, a mosque is located near the canal. Additionally, among the few existing facilities, we can find a community center, a school, and a small meat market.

The area is beautiful, with canals running through it to the ocean. Despite the noticeable challenges, particularly regarding pollution and the need of rehabilitation, we were able to see how much potential the site has to offer. We were convinced from the beginning that some improvements could help to create a very pleasant area with a strong community bond.

24 |

Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Figure 1.10 Eravali Canal

Figure 1. 11 Typologies at site

25

| Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

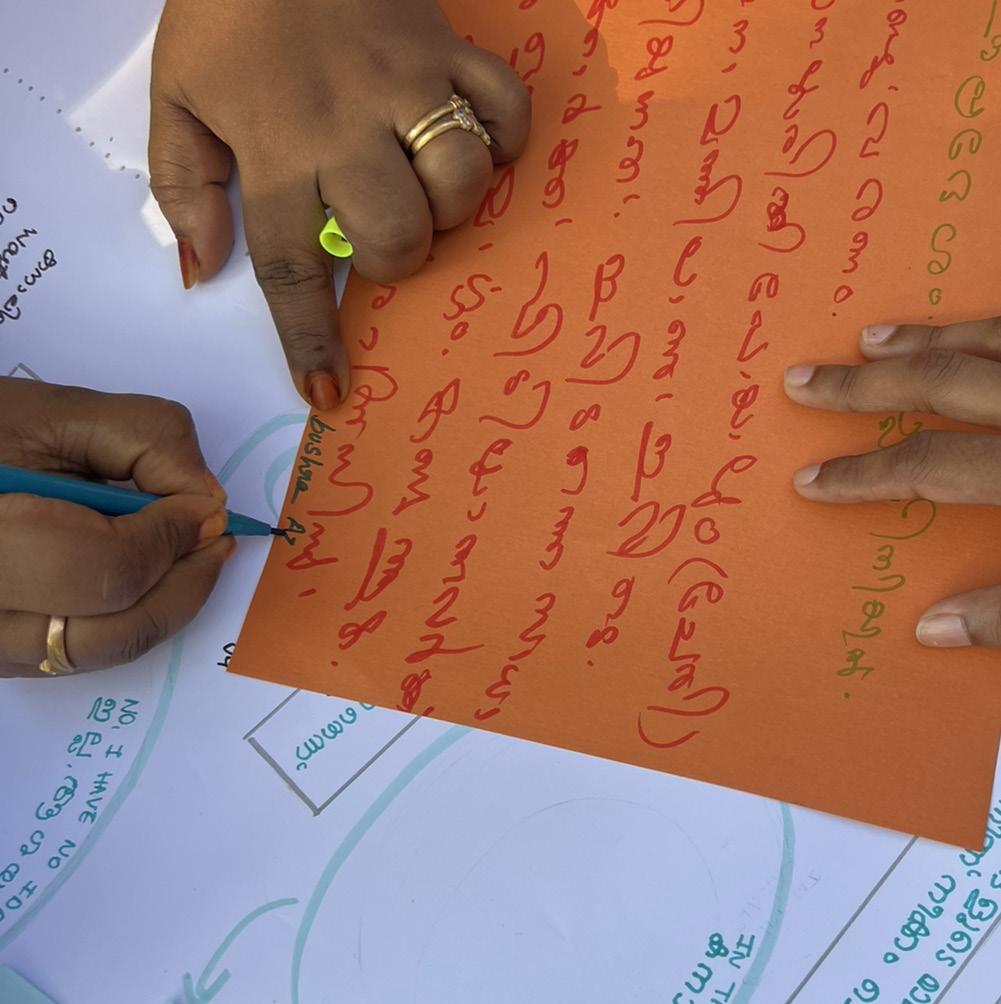

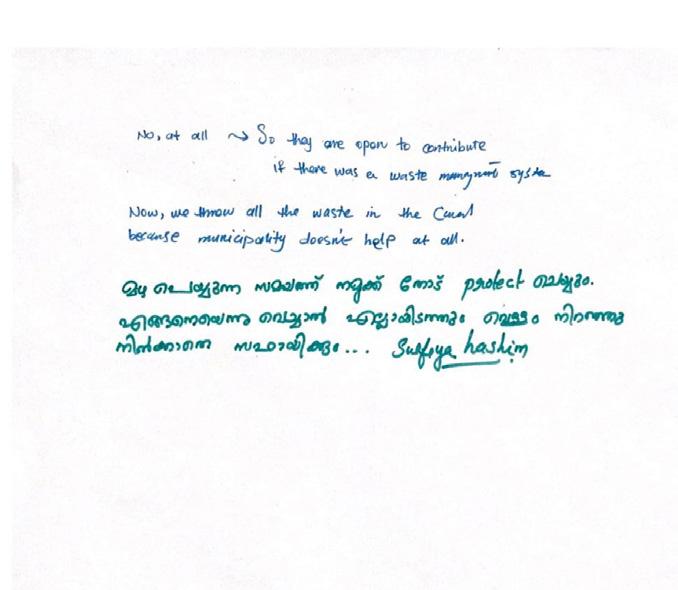

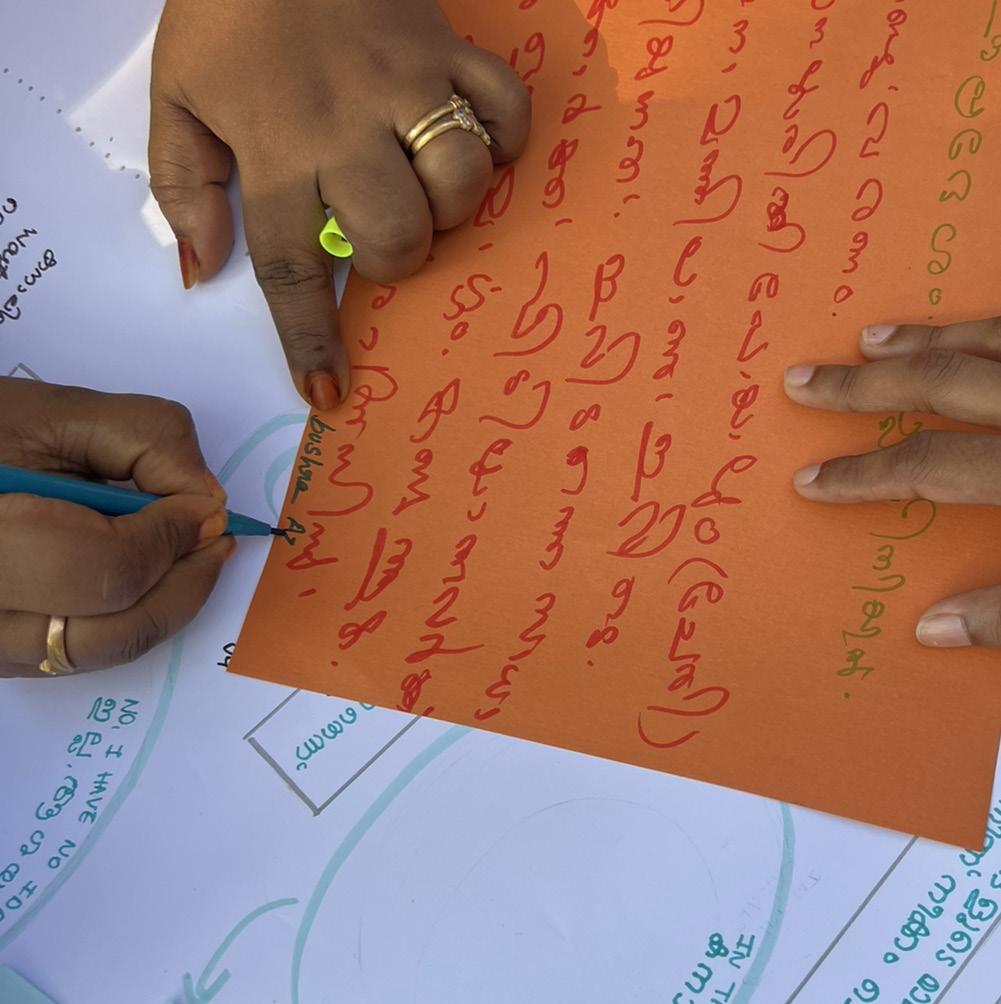

Figure 2.1 Participatory workshop, letters from women

26

| Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

2. Methods & Issues adressed Participatory action research in Kunnampuram

During our Fieldtrip we conducted action research in the local community. This method is based on democratic participation in the process of solving problems located at the site. It follows the logic of Plan - Do - Study - Act. In our project we aimed to be at the highest level of Arnsteins ladder of participation, defined as the degree of citizen power. Local stakeholders together with the community got involved in the project. And new understandings of the area, was turned into local problem-solving and action - research. This chapter goes through our process and methods used when we were conducting our fieldwork.

Figure 2. 2 Participatory workshop

27

| (Re)

|

Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India

- Gaining Ecological Futures

2.1 Introduction to methods

The 21st century is facing increasingly more “wicked problems” propounded by climate change (Vogel, Scott, Culwick & Sutherland, 2016).

As an example of a Global South country, India has been facing plentiful environmental issues, as well as social, economic, and governance ones routed in this country’s improper planning and development issues. Roy (2009) explored this issue, and states that the fast-paced growth in India, particularly in urban areas and cities, has resulted in an urban crisis. The unsuccessful planning strategies of Indian cities have led to inadequate infrastructure and a sharp social division between citizens.

In our project, we want to reflect and act on how we contribute to shaping and nurturing ecological inter-relations with the social spatial environment. We want to critically engage with human-centered planning approaches toward radical transformative planning, discovering new ways of entering the future. This necessitates the use of transdisciplinary and co-production of knowledge approaches to environmental and urban problem-solving (Ibid. 2016).

This research is based on primary, secondary data and the qualitative analysis of direct observation, in-depth interviews and participatory activities with the residents of Kunnumpuram, carried out during October and November 2022. This area-based approach allowed us to record different viewpoints about the ongoing challenges of the neighborhood.

“Participatory Needs Assessment gives the right to speak, to the people living in local communities and, moreover, it attempts to place the problems and solutions submitted by citizens on the working agendas of the public authorities, which acts as decision-makers.” (Sandru, 2014. p.2)

28 | Kunnumpuram,

| (Re) -

Kochi, India

Gaining Ecological Futures

Figure 2.3 Diagram of methods

To conduct our project, we used different methods along the way to assess the needs of the community, understand their challenges and opportunities, and formulate our goals and strategies.

Our overall aim was to develop a bottom-up approach that puts the community at the center of our research.

By using participatory needs assessment methods at the beginning of our project we allowed the community to reflect on their issues. (PNA) gives the opportunity for people to reflect and gain a sense of empowerment (Sandru, 2014). “PNA is truly the most certain way to find the perception of the community members on their collective needs.” and therefore find adapted solutions, stands the author. Step by step we gathered qualitative information and met a lot of people with different visions

29 | Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

for the area. We built our method from the lectures we got, the theories we studied, and by experimenting and adjusting on-site. The guide written by UN-Habitat (UN-Habitat, 2020) gave us a frame of work and inspired us to set up some participatory activities.

We started with an area-based approach and street interviews to understand the view of the community. By coming multiple times, explaining the purpose of our work and being present and willing to listen, we built some level of trust with the community. And as we collected more data, we developed other methods to take our project one step forward.

Like a gear, our method process is a mechanism where the first action activates the next one and everything works together (Figure 2.3). It is not a linear process but a big system that turns simultaneously. Therefore, from an area-based approach with a lot of observation and street interviews, we moved to meetings with stakeholders, conducted semi-structured interviews, organized a participatory workshop, created visuals, brainstormed on the socio and spatial solutions that can be implemented, and asked for reviews from the community. Through the process, we went back and forth between interviewing stakeholders, interacting with the community and reflecting as a group (Figure 2.4).

Overall, we involved the community every step of the way to give them a sense of ownership and conduct a project that is local-specific and rational.

30 | Kunnumpuram,

Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Figure 2.4 Organization of project work in Kochi - reflectivity and adaptation

31

|

Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Figure 2.5 Fieldwork overview of the process

2.2 Process

Walking and observing

As one of the first steps of our work we walked around in the neighborhood and observed to get a better understanding of the area

Meeting with K.J. Sohan

Semi-conducted interview with the former mayor of Kochi who helped us understand the current situation and challenges in the city

Picture with Aïsha’s family that helped us a lot. Walk to present the neighborhood, the challenges and getting insights from Gilbert

Participatory workshop

Street interviews around the area

Conference about urban sustainability

Discussing with the women of the neighborhood and drawing with children to understand their views

Exchanging with different groups of people. We got invited to play Carom with some men and discussed about the neighborhood

A conference organized by the city of Kochi in partnership with the E.U. to understand the decision-makers’ points of views. And met students from Kochi

32 | Project location | Project Title

Transect walk with Gilbert

Introducing the SPA students to Kunnumpuram

Presenting our work and the neighborhood to Seth and Aidan that joined our group and gave us a lot of insights during 10 days

Dinner with the translators

Discussing and getting to know the Kochi students that helped us to translate our interviews

Brainstorming about the spatial solutions

Through our process of reflections we used a lot of sticky-notes to write down and organize our ideas

Reflections

between groups

Issues analysis and opportunities identification with group 4 who is working in the same area as us

Final exhibition in Kochi

A fulfilling day where we got the opportunity to expose all the work done and get fruitful insights and reviews

Final presentation poster printing

Seeing the result of our work and preparing for the final presentation before finishing the report

Figure 2.6 Picture collage of process 33 | Project location | Project Title

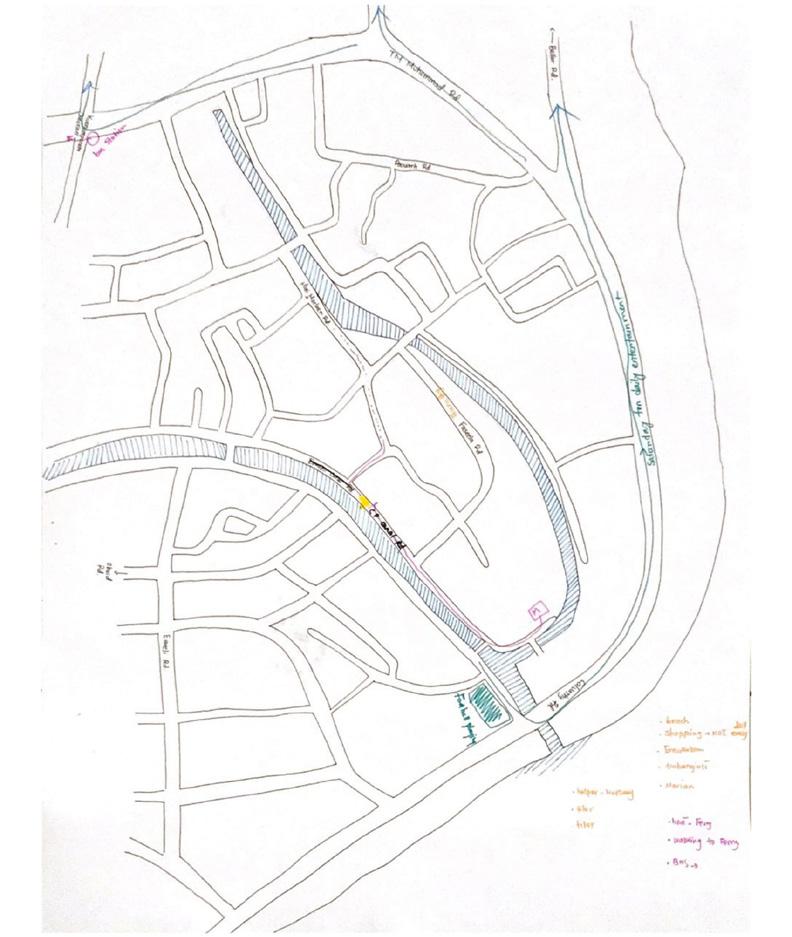

2.3 Local knowledge and site research

We were doing transect walks and participatory mapping in Kunnumpuram Fort Kochi where we chose to locate our site. We were going together as a group, walking around in the community, and we tried to identify environmental and social resources in the area.

We did interviews with by-passers and got an understanding of the social issues, resources, and conditions. The characteristics of the place were very clear to us, with extremely polluted canals running through the area, together with a lot of trash laying around. Very dense streets, and lack of public space.

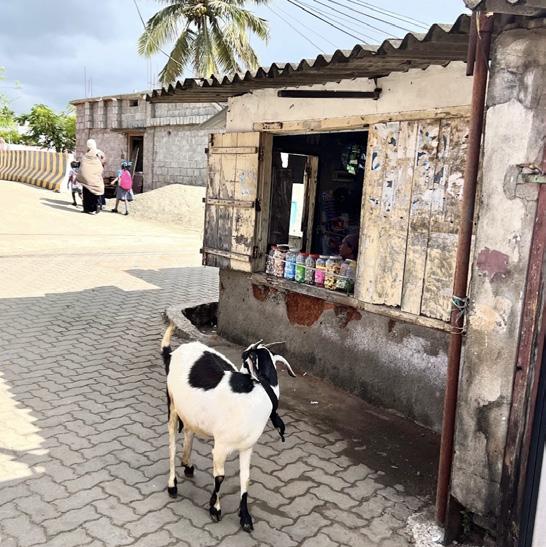

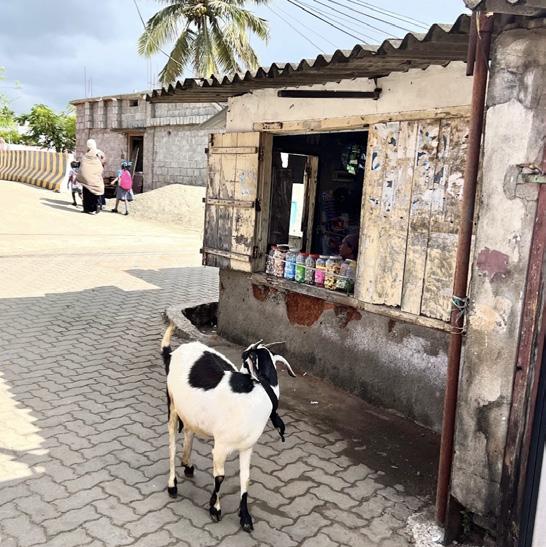

The place had its beauty, with lush old rainwater trees, coconut trees, and other lush greenery, there were and many different birds, insects and even turtles in the canals. The streets were filled with goats, and chicken.

The people were very warm and interesting to share thoughts with us, their life and reality. And we are so thankful for what they have contributed and shared with us, to make us able to do this project together with them.

Figure 2. 7 Our site in Fort Kochi

-Maria

-Maria

“We repeatedly did transect walks during our stay, this brought us very close to the community and its reality”

34 | Project location | Project Title

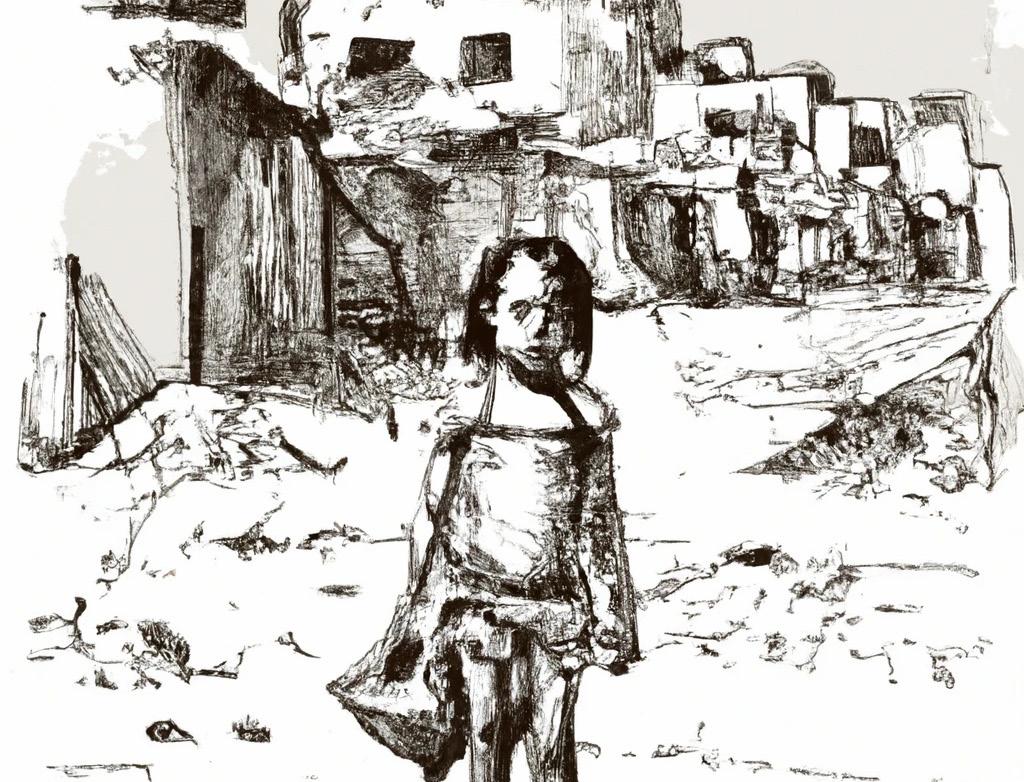

Woman in front of her home

Urban reality in Kunnumpuram Fort Kochi, woman sitting outside her door. With the lack of public space, the entrance serves as a multifunctional space for resting, and participating in the outdoor streetscape.

Goat

Local people are informally managing goats as livestock in the streets. A local resource for food.

Narrow Streets

The only sense of Urban Public space that exists in Kunnumpuram is the narrow streets, without pederstrianfriendly pathwats. No transition between road and doorsteps.

Small scale interaction

Informal sitting arrangement in the street providing small scale interactions.

Vendors

Street vendors sell small fish affordable to the locals in the area.

Fruit shop Local fruit shop, not directly located at site.

Figure 2.8 Images of situations at site

35

| Project location | Project Title

2.

36

| Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

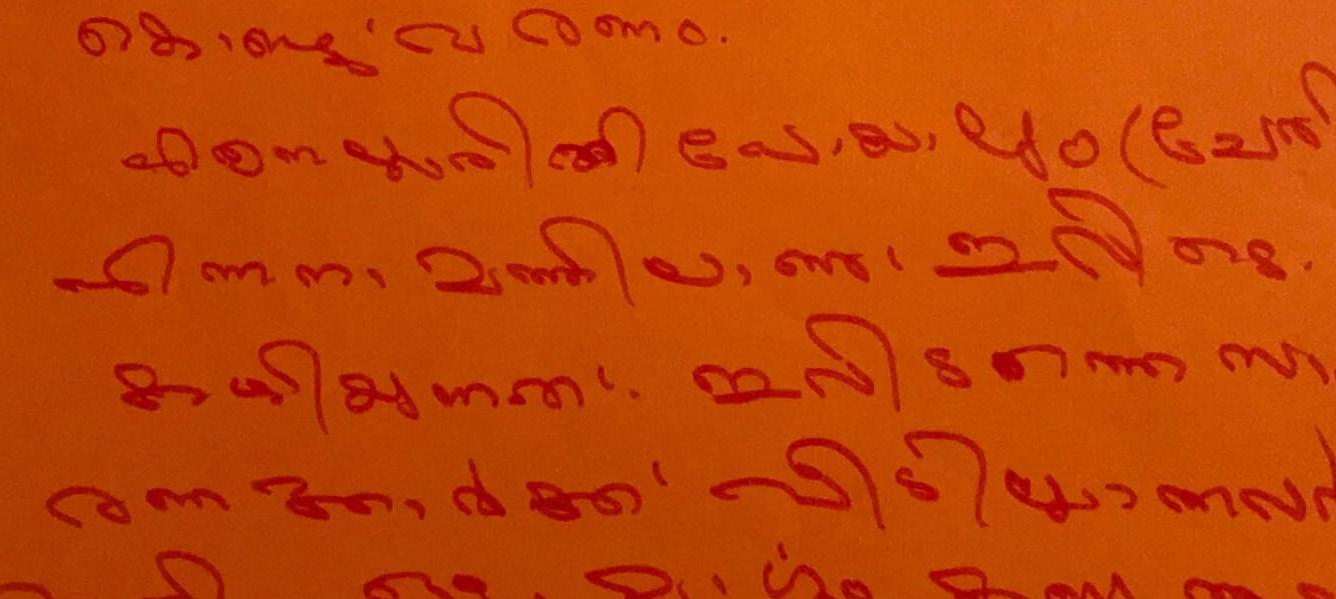

Figure

9 Indian woman and the letter she wrote during the participatory workshop.

2.4 Data Collection

In our participatory processes doing interviews was a way of collecting data where our overall goal was to identify the desire for change in the community. In order to make a planning project, with relevance for opportunities and solutions benefitting the area, we were seeing it as an important aspect to understand the true issues on the ground. As mentioned we had initial collaborations with community members we met, and started to build trust with them. Together we collaborated on researching their interests, and issues. This was a cyclic way of working, where our first participatory sessions informed us about how the next sessions would be making more sense to us, the project, and the community.

Participatory processes made a unique insight into how life in the community was structured. It showed how women were responsible for the house, starting the day by collecting water for the family”

The tangible experience of public space linked to theory

As it has been shown before, in our Anthropocene epoch, nature is seen as a ‘resource’ to serve the human species. Therefore, the degradation of the environment has a direct impact on the construction of public spaces. And those public spaces, mostly shaped by male planners and designers, “created urban spaces that catered to their needs, while reflecting and perpetuating the patriarchal gender norms of their society.” stands Terraza (Terraza et al. 2020, p.26) and became the spatial product and representation of the patriarchal society. Hence, the women and minority groups are “left feeling that they do not belong in the public realm : that the space is not theirs” (Ibid, p.26). These gender gaps are directly visible and suggest a differentiated perception of the environment. First of all, women are more threatened by climate change than men. Through economic pressure and social norms, they struggle to make their voices heard and don’t have the same rights as men. “Women, girls, and sexual and gender minorities are more susceptible to climate risk due to poverty and lower socioeconomic status, especially in informal areas.” (Ibid, p.43) Public places have been developing as notably masculine terrain. In the Indian context, women have a fear of crime; this has been identified as one of the primary drivers behind the masculinization of public space, which manifests as real, tangible, and physical environments to which women have less access. One other primary factor contributing to Indian women’s absence from public spaces is their common experience of sexual intimidation and their fear of being viewed negatively (Paul, 2011). Ecofeminists has profoundly expounded that the root of ecological crisis is closely related to patriarchal culture (Rao, 2012).

37 | Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

38

| Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Figure 2. I0 A view of a street at site

2.5 The tangible experiences linked with theory

More than half of the world’s population is urbanized, and the major part is living in the global south. Urbanization, rapid population growth, lack of infrastructure, climate change, and resource depletion are some of the issues leading many cities into crisis.

Public space is defined as open places that are owned by the public and fosters to create communal bonds and cultural richness in a society. Public space provides freedom of expression and conveys the image of the city.

UN-Habitat among others views urban planning as a part of the problem. The faulty planning systems of many cities in the world are creating spatial and social exclusion. Many urban plans are antipoor, without any level of engagement towards climate change and social, economic, and environmental sustainability. Leaving people in poverty, even more, fragile and unsupported. (Watson, 2009)

The pathways, streets, gardens, parks, open spaces, public buildings, and other areas can all be considered public space, but it needs to be made accessible to everyone. Due to rapid urbanization the there is a lack of open public space in the Global South. Here spaces are vulnerable due to urban heat, flooding, and other climate change related issues. (Hatuka and Saaroni, 2013).

39 | Kunnumpuram,

Kochi, India

| (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures Figure 2. 11 Fish vendor

2.6 Challenges located at site

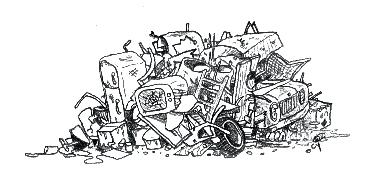

Public Space

During the participatory workshops the main issue the community focused on was public space. All the issues address in our project are linked to the use and experience of the public sphere. The degradation of the canal is affecting the entire area with its bad smell flooding, and polluted appearance. Waste is lying everywhere, creating unpleasant environments, and endangering nature and humans. High pollution of ear soil and water creates a health risk to humans, animals, and insects. The disturbed natural environment is out of balance because of high density, and no greenery. Native species are threatened or extinct. Due to a patriarchal society women feel excluded from public spaces, and they face higher levels of danger related to climate, abuse, and violence when participating in the public landscape. The high density in the streets is a threat to the community, there are not many open sightlines, and there is a lack of eyes on the street to ensure safety. The infrastructure and lack of streetlights are also creating a threat. Climate change with more extreme weather effects the conditions of the neighborhood, and the unpredictable future also makes it difficult for people living here to plan for their life. Accessibility and inclusive pathways for women, children, men, elders, and people with disabilities are nonexistent.

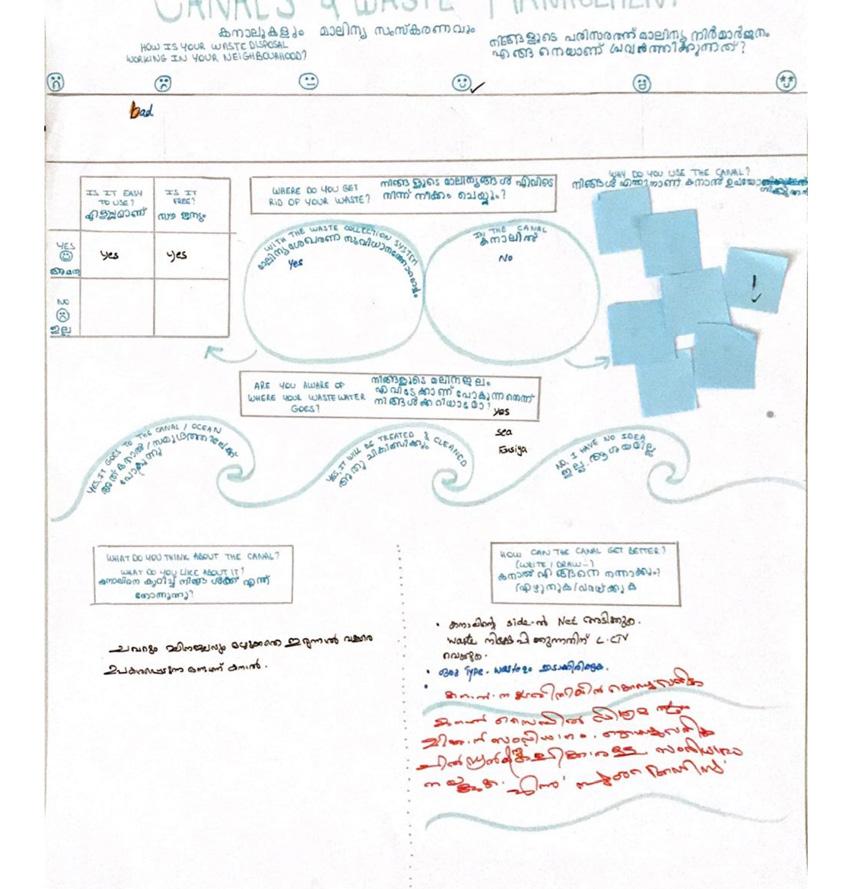

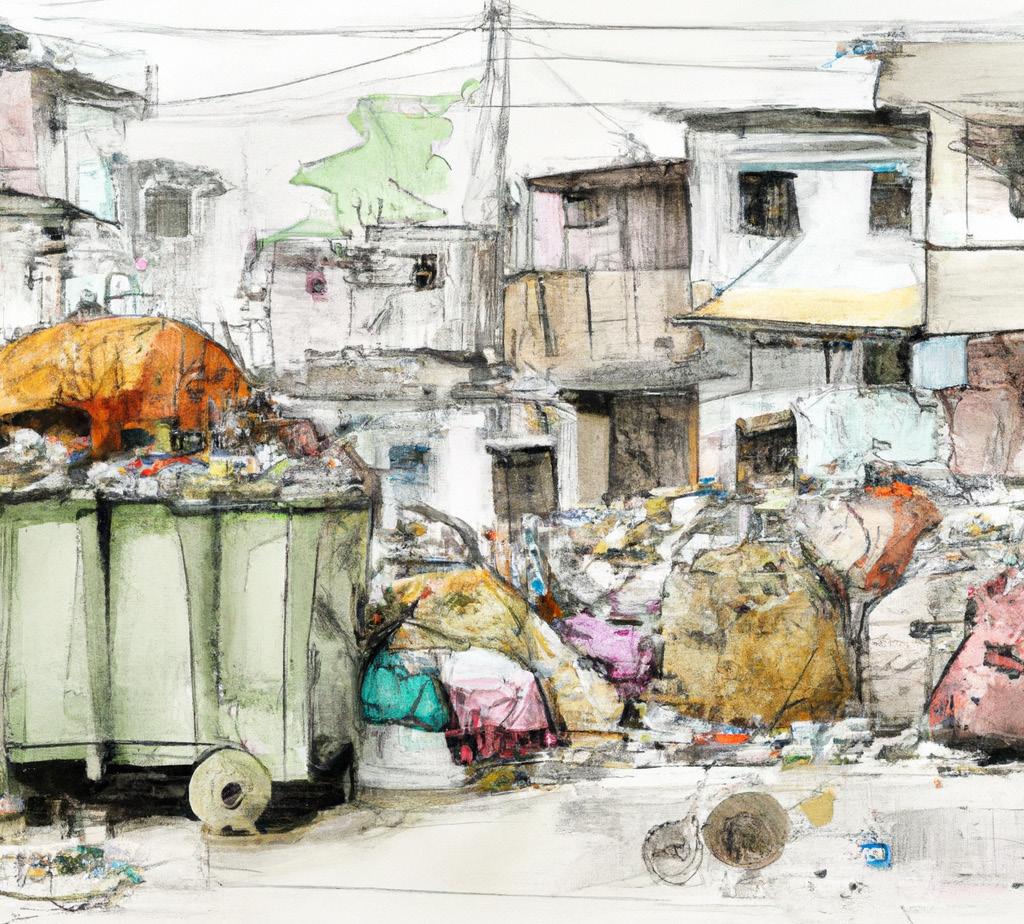

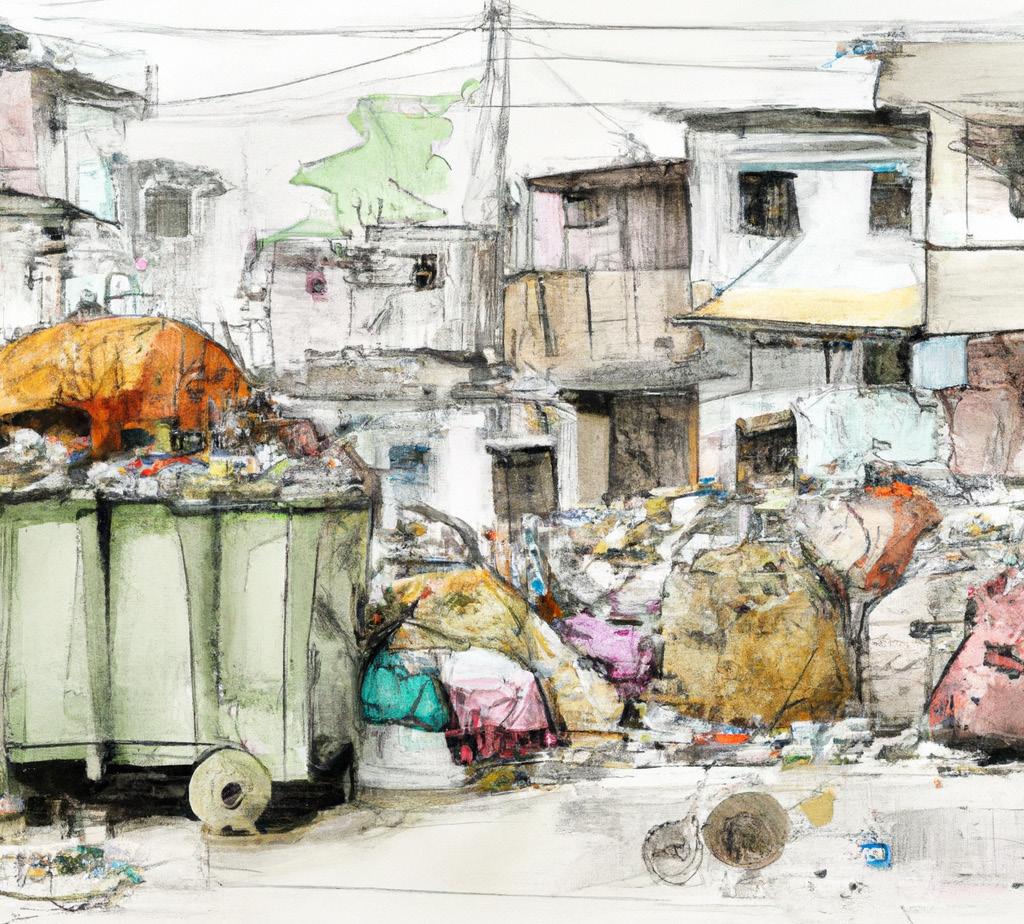

Canals, an important natural asset of the area, due to pollution they have degraded and put the lives of citizens at risk. Sadly, they act as a drainage systems for sewage and waste. Due to the large amount of trash they are stagnant and suffer from an extreme odor.

Gender

Because of cultural norms and a patriarchal society, women were suffering the most. With no appropriate public space in the area, making even stronger gender inequality. In this area men are were routinely being prioritised over women and children.

40 | Project location | Project Title

1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - 7 2 1 5 Canal

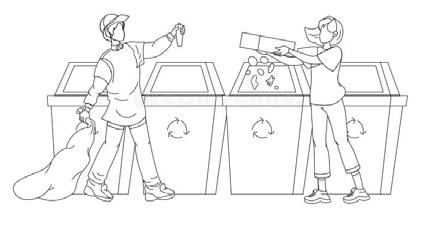

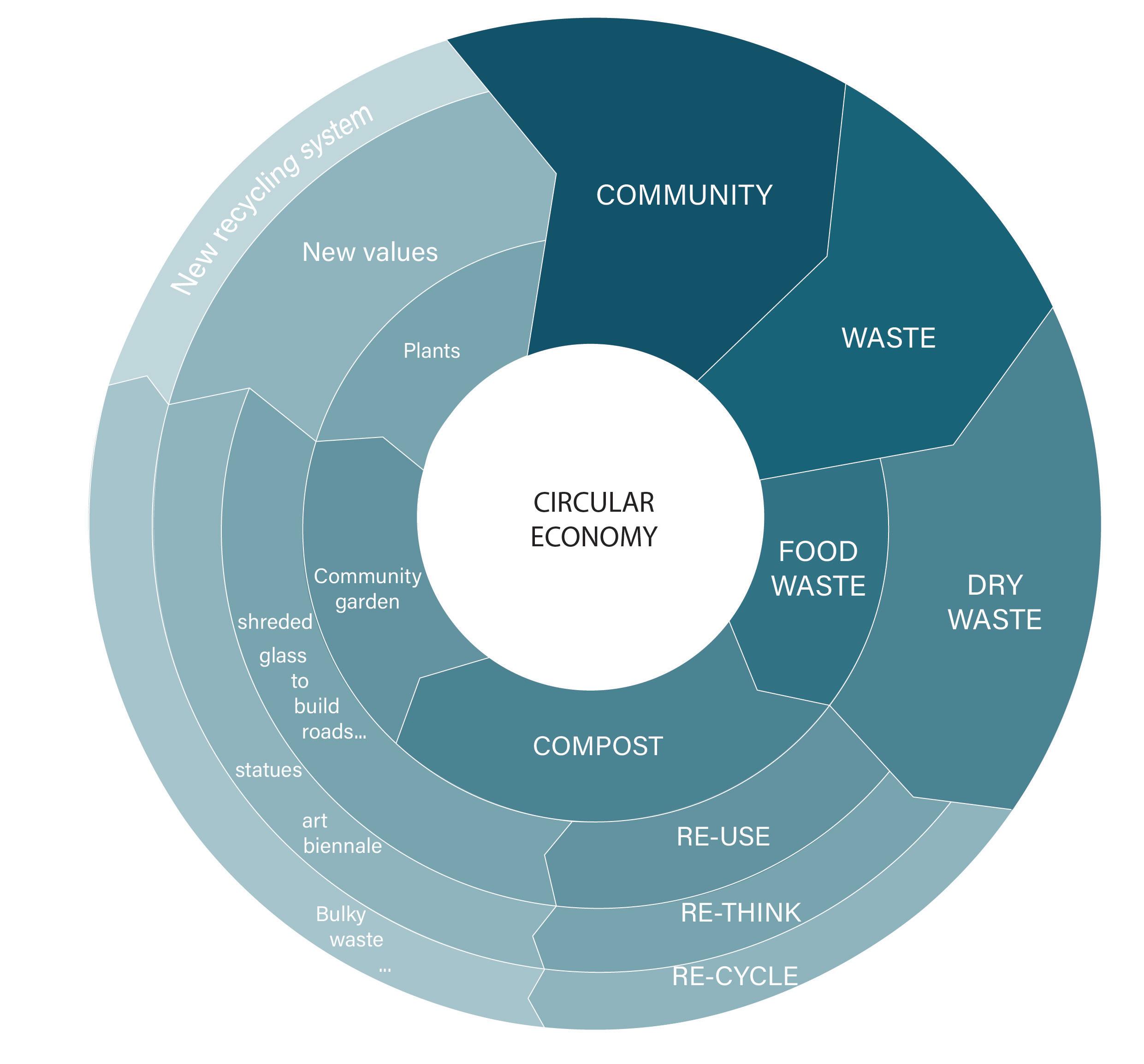

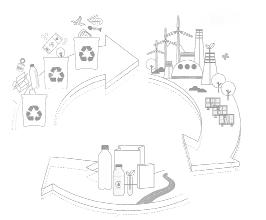

The area has a dysfunctional waste management system which results in a lot of issues, the segregation of waste is not sufficient and only separates solid and biodegradable waste. Due to this people are practicing opening burning and waste goes into the canals and the ocean. Waste is also lying around everywhere in the streets.

4

Ecology

Waste Safety Pathways

The high level of pollution and the very dense streets together with climate change is threatening the local biodiversity and the native species. The degraded green ecology in the area makes the social-ecological aspects suffer.

According to people living in Kunnumupuram, drug addicts were a threat. Children and women did not feel safe outside at night. Many women expressed how they were afraid of rumors when being outside. They did not feel like the public ground was an area where they could participate equally with men. The lack of street lights and dense streets with traffic made a huge threat to people, especially children.

This area is characterized by high density and few resources, resulting in narrow streets, unsafe conditions, and limited security. The lack of pedestrian-friendly pathways makes it especially dangerous for children and women.

41 | Project location | Project Title Figure 2. 12 Kunnumpuram

6 7

3

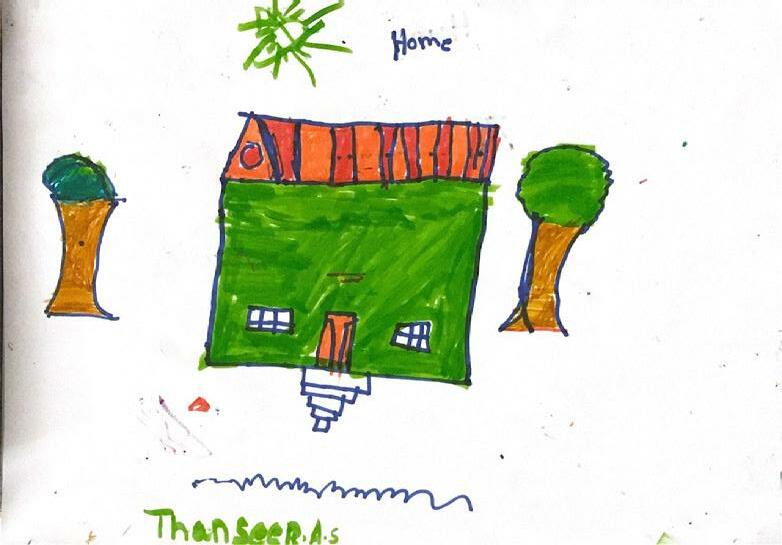

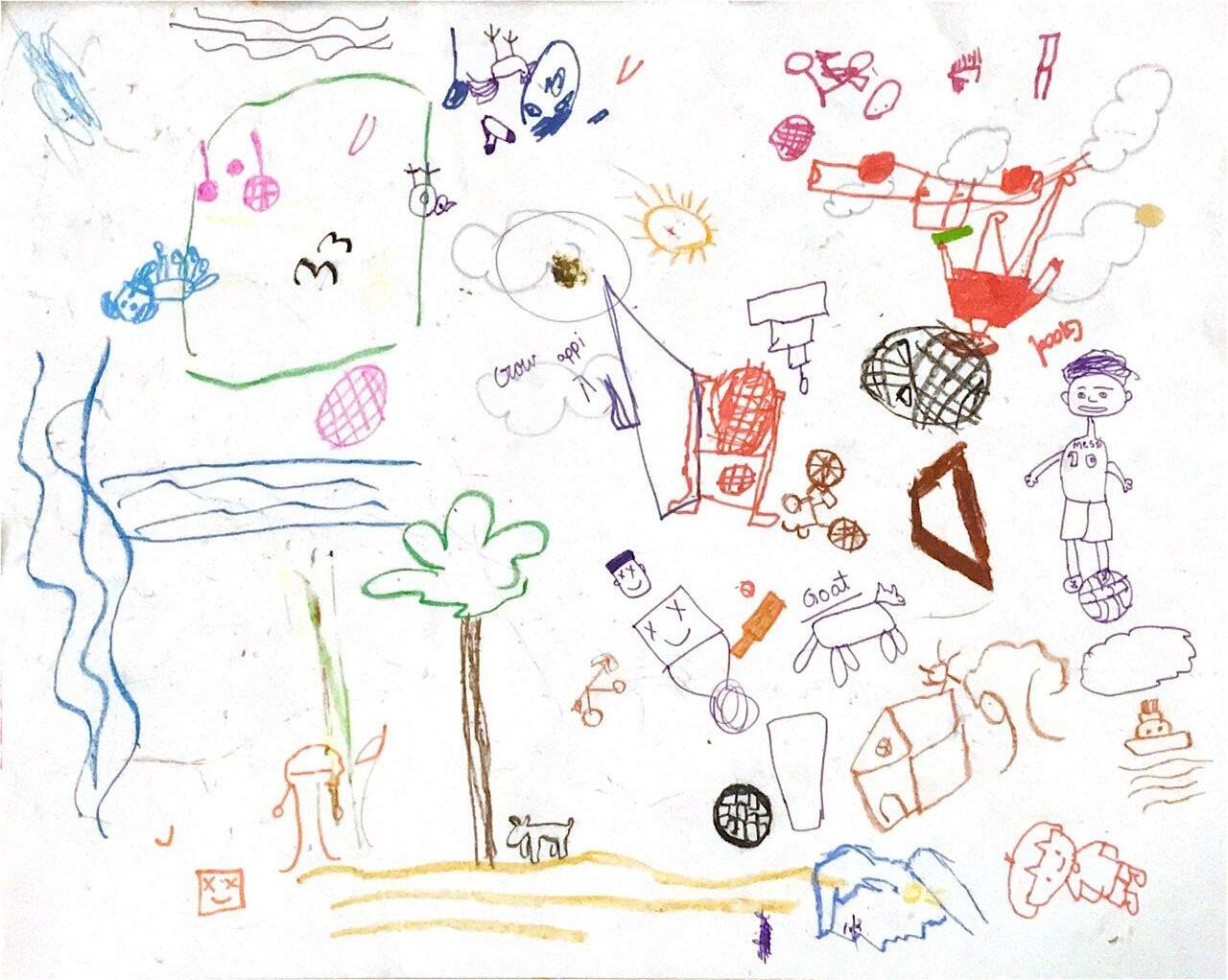

2.7 Participatory workshop - Young people’s views

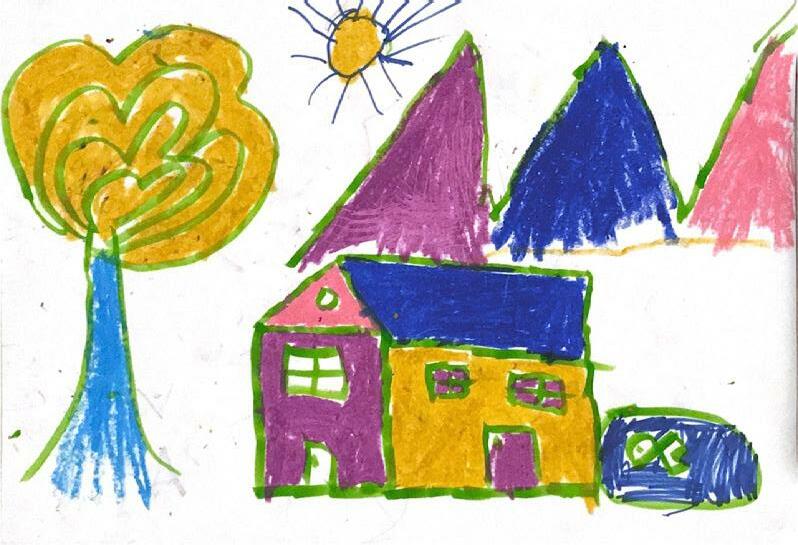

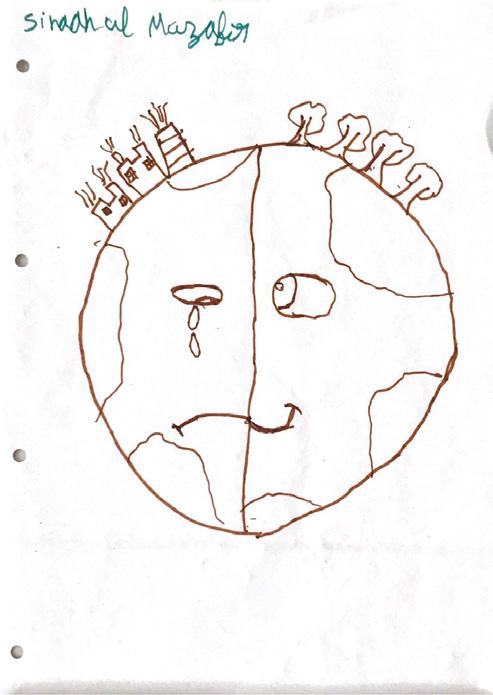

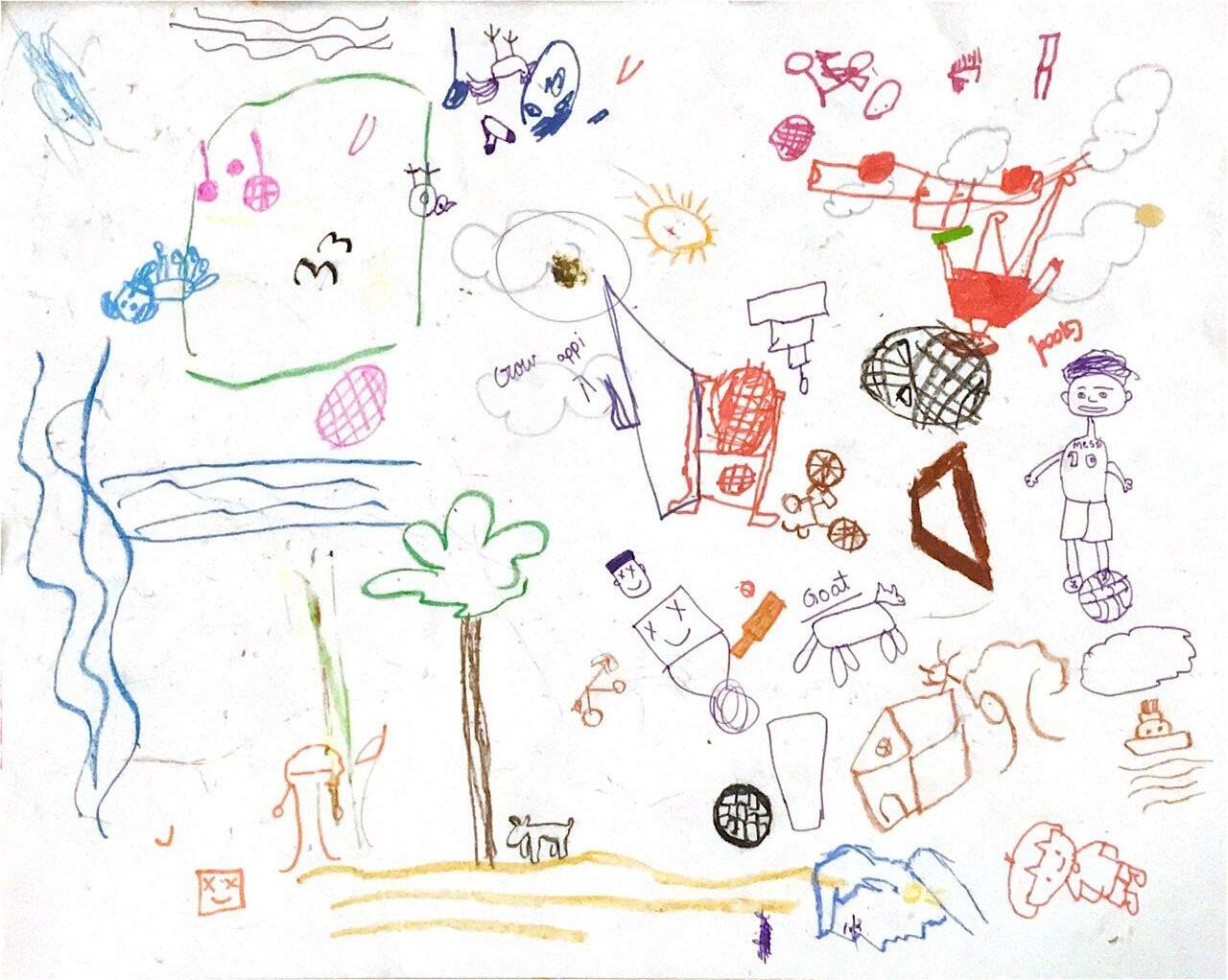

During the participatory workshop, our focus was on the views and perceptions of the women and children of the neighborhood. While women were discussing specific topics with the help of pens and posters we prepared, we also brought some large sheets of paper, pastels, and colored markers for the young people to express themselves . As we were expecting the language barrier to be more apparent with them, our strategy was to use visuals as a means of communication. Luckily some of them knew some English and helped us a little. The young people, from 4 to 14 years-old, were free to draw whatever they wanted. However, we tried to encourage them to draw what they like, their neighborhood, and how they see the future.

It resulted in many colorful drawings of their houses, the canal, nature, and even the earth, showing that they are aware of climate change. For them, the main issues were the pollution and the lack of space to play outside. We learned that boys are authorized to play outside but girls are mainly staying inside, gathering in groups in a house, under the responsibility of one parent. Showing that gender inequalities are visible from a very young age. Some kids also expressed their concerns about their futures and were already picturing themselves studying abroad later, in countries with more opportunities for them. It was a very fulfilling workshop. We learned a lot from the children and were impressed by their liveliness at such a young age.

42

|

Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Figure 2. 14 Youth with their drawings

Figure 2. 13 Picture with the youth from the workshop

Figure 2.15 Drawings from the youth

43 |

| (Re)

Futures

Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India

- Gaining Ecological

2.8 Stakeholder-issues interrelationship

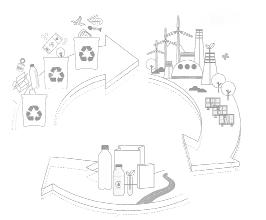

Any group or person that has the potential to have an impact on or is impacted by a policy, project, or organization is referred to as a stakeholder (Friedman and Miles, 2006). In the Kunnumpuram area, the waste management, public space and environmental degradation are the main issues which is impacting the inhabitants directly. The several government and private organization shown in figure Figure 2. 16 are the stakeholders managing the Kunnumpuram area.

The GIZ- German development agency and Municipality are the key stakeholders involved in putting policies into place and running the waste collection system. The GIZ and the municipality both have control over the waste collectors because they are an integral part of the municipality. Improper waste collection and open sewage pipelines that lead directly to the canal is a large issue.

CSML-Cochin Smart Mission Limited is in response of taking care of the public space in the area. People have only religious institutions as their meeting places. Those who suffer from inadequate public space are mostly the women and children. They occasionally meet at Kudumbashree office (Poverty eradication and women empowerment program), and the lack of effective planning from the municipality and CSML directly affects the people. The locals don’t feel like they belong there or are connected to other regions of the city.

The area is highly polluted, and none of the stakeholders are at all concerned about the ecology there. The degraded biodiversity and the polluted canal have a significant impact on the neighborhood. Stakeholders like C-HED (Centre for Heritage, Environment and Development) and WRI (World Resources Institute) are not actively involved in the modifications being implemented there.

44 | Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Figure 2. 16 Stakeholder diagram

45 | Kunnumpuram,

| (Re) -

Futures

Kochi, India

Gaining Ecological

2.9 Stakeholder meetings

The study team meets with various stakeholders to discuss the problems and future action planning. The most important project milestones are the meetings with stakeholders since they aid in understanding the project’s organizational components and gaps.

The former mayor- K.J. Sohan

K.J. Sohan is a former city Mayor and Fort Kochi Veli councilor. He gave crucial details regarding the Kunnumpuram region. According to K.J. Sohan, “The only open space in the Kunnumpuram region is now occupied by the Rajiv Awas Yojana project, and under the pretense of slum rehabilitation the area is becoming extremely densified. In the long run, the initiative won’t either improve people’s quality of life or offer a remedy to environmental damage. Relocating individuals to the outskirts of the city is preferable to moving them to a densely populated building. Additionally, it takes up the only open public space in the area, further suffocating the neighborhood.” (Figure 2.9)

The ward councilor, T.K. Ashraf

According to the councilor for the Kunnumpuram neighborhood, by eliminating the direct pipelines from the canal and attempting to create a functional sewerage system, CSML will expand its pilot project to the area in 2023. The funding will come from the central government, and it will be connected to the sea-based treatment plant. The councilor regarded the Slum Rehabilitation as a project that was successful in giving the homeless people a place to call home. Additionally, he added that CSML was working on a project to install fencing along the canal to stop people from tossing trash into it. (Figure 2.10)

GIZ, Representative

The GIZ representative and the research team met to discuss the waste management system. There was no doubt about the organization’s prejudice and lack of accountability. They accuse the populace of failing to maintain an effective trash disposal system. It is obvious how far apart the organization is from the local community. The GIZ struggles with adequate planning and tries to implement policies that will not benefit society. One startling claim was that they believed building a barrier along the canal would prevent people from dumping trash into it and that the garbage would automatically be cleaned by the ocean’s turbulence.

46 | Kunnumpuram,

Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures Meeting with GIZ, Representatives

Figure 2. 18 Meeting with the ward councilor, T.K. Ashraf

Figure 2. 17 Meeting with the former Mayor- K.J. Sohan

Figure 2. 18 Meeting with the ward councilor, T.K. Ashraf

Figure 2. 17 Meeting with the former Mayor- K.J. Sohan

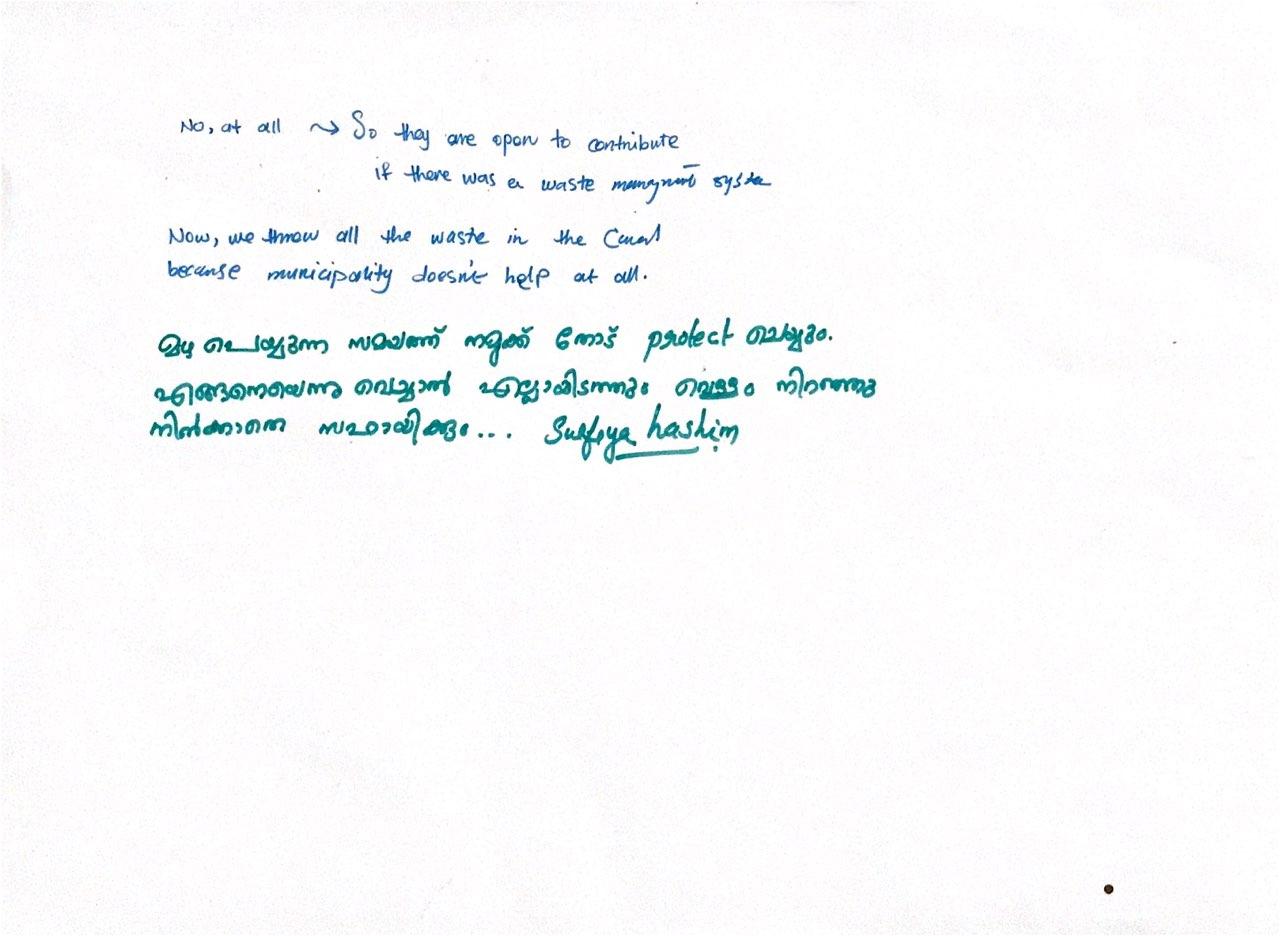

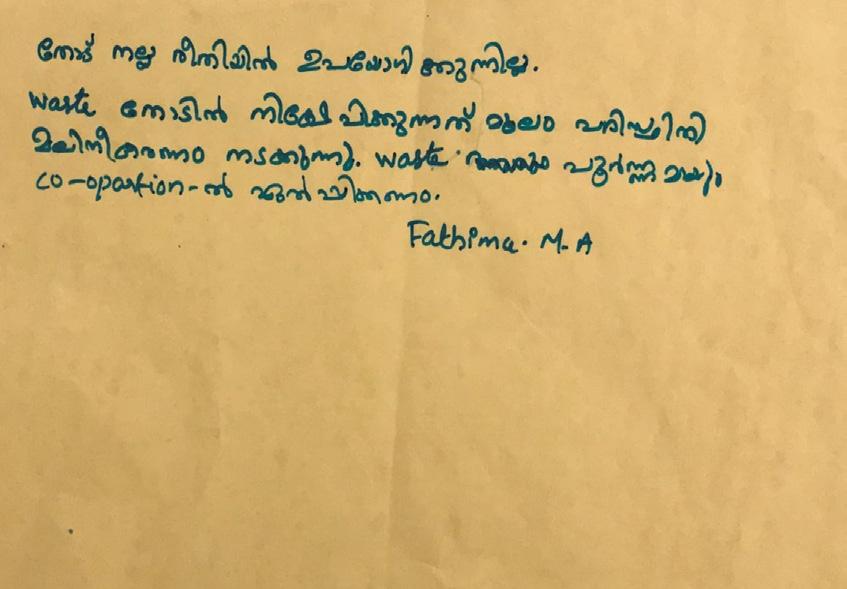

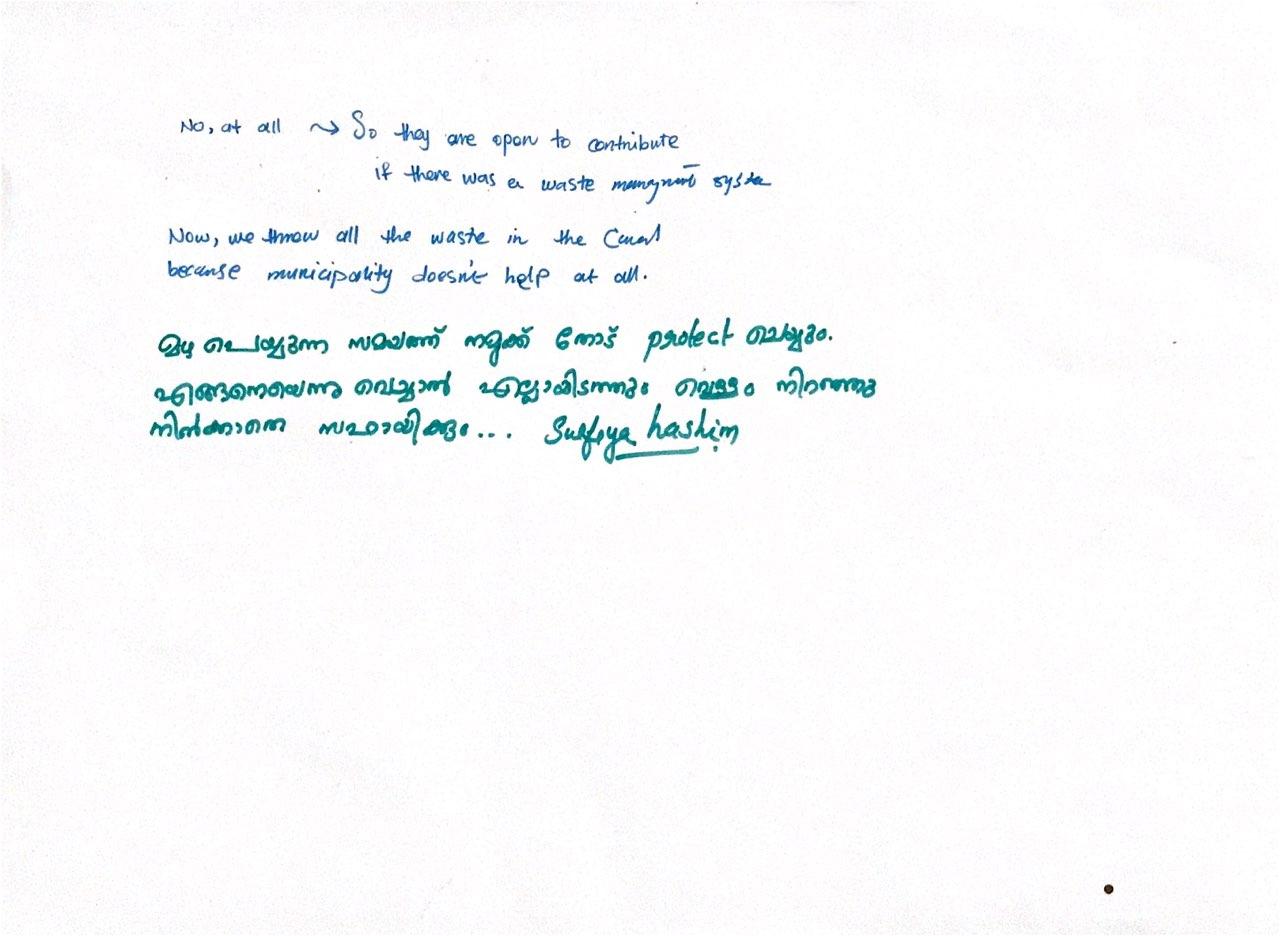

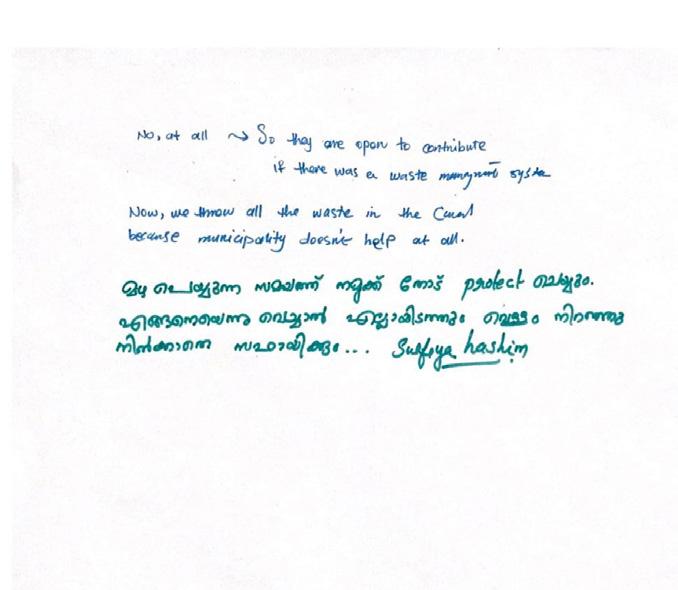

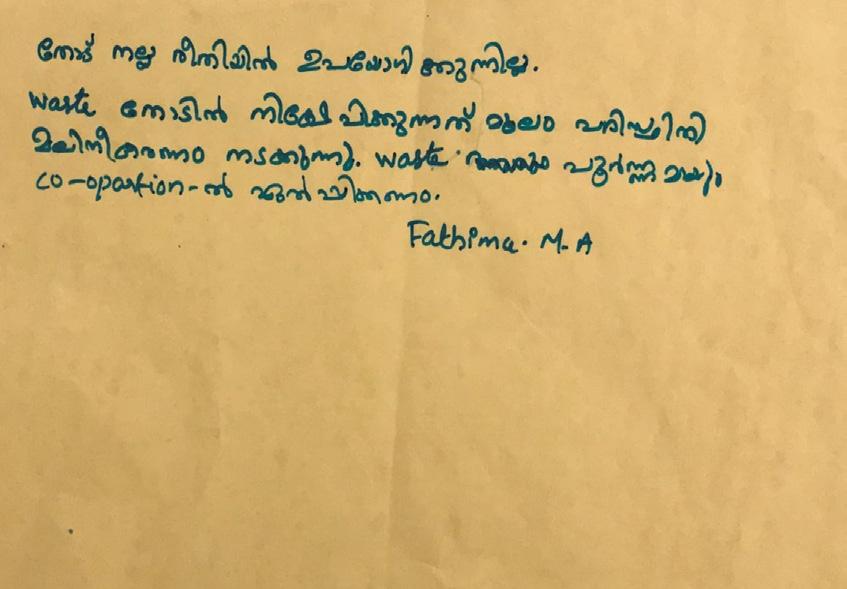

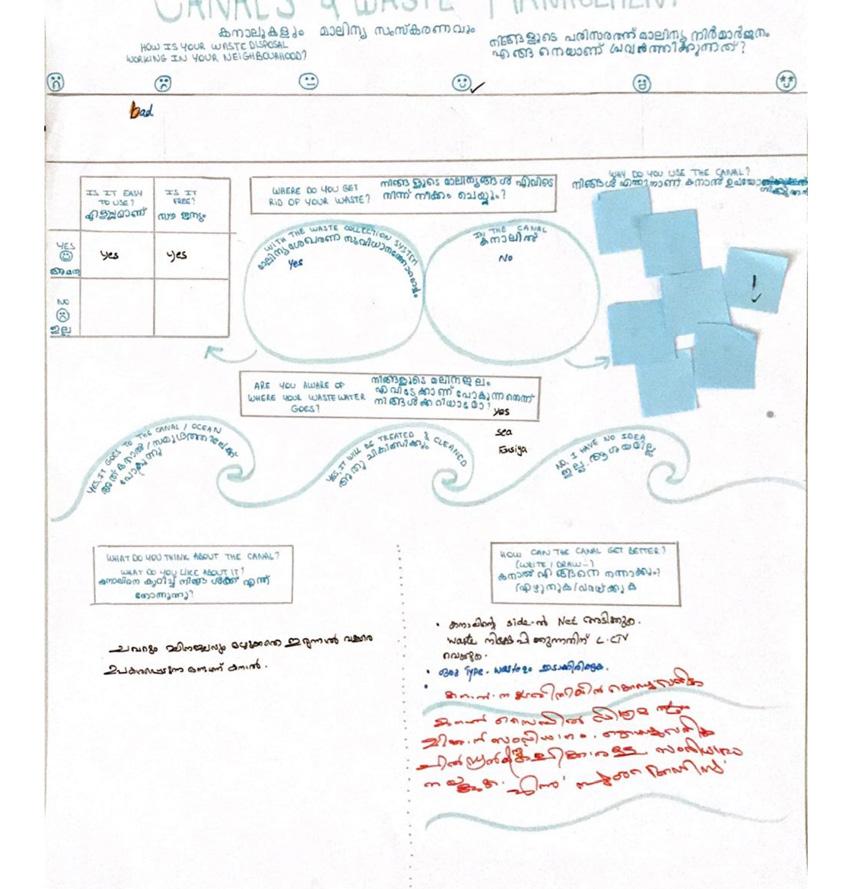

The images shown in Figure 2.19 are from one of our Participatory Sessions, where our main focus was to include women and youth, two vulnerable groups in the Indian context. Beforehand we made different maps both social and geographical kinds. We also made questionnaires in Malayalam language and papers with symbols combined with text.

We brought a lot of different papers and colors to the workshop for people to feel free to visually express themselves and their thoughts.

We had a very free and radical approach where everyone was encouraged to write letters to us, talk or draw on the premade documents. We organized two groups, one with youths. They freely drew all the things they felt like. The other group was women and mothers, both old and young.

They gave us incredibly valuable knowledge about their experiences with the polluted canal, the insufficient water infrastructure, and the lack of resources in the neighborhood.

They told us about gender-related issues regarding public space, and how only boys played outside. We got to know that they spent most of the day inside, and how they were in response of all household activities. They told us about their life, and how they experiences their community. At

Figure 2.19: Images of participatory workshop

48 | Kunnumpuram,

| (Re) -

Kochi, India

Gaining Ecological Futures

The former mayor- K.J. Sohan

49 | Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

49 | Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

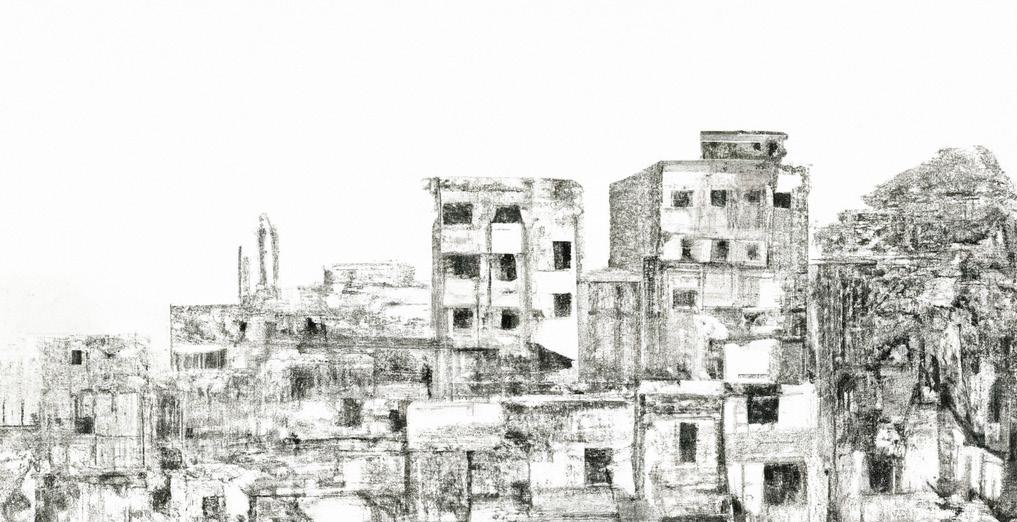

Due to the interplay between the social, political, ecological, and economic aspects of everyday urban life and anthropogenic climate change, Kunnumpuram faces numerous challenges. There are a number of environmental issues and high health risks in the area as a result of extreme levels of water, soil, and air pollution combined with flooding, extreme heat, heavy rain.

Environmentally related challenges

Canals, an important natural asset of the area, have degraded and put the lives of the citizens at risk. Sadly, they act as drainage systems for sewage and waste. Due to the large amount of trash and being stagnant, they suffer from an extreme odor, and serve as a serve as a breading habitat for mosquitos.

The other issue in the area is about the waste management. This system is insufficient, as well as being too costly to be afforded by the poorest people within the community. The area also faces climate change-related problems. In particular, sea level rise, extreme rainfall events and intense tidal flooding are among them.

Globally, sea levels have been rising at an increasing rate because of accelerated ocean warming and the thawing of Arctic glaciers. In the coming decades, large swathes of low-lying areas will be submerged by sea level rise due to the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC]. As a result of global climate change, IPCC predicts that tropical tidal flooding will become more severe. Kochi-Vembanadu could be experiencing such a phenomenon already, aggravated by changing rainfall patterns because of the climate change.

Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Public spaces related challenges

Kunnumpuram is characterized by high density and few resources, resulting in narrow streets ( see figure 2.6) , unsafe conditions, and limited security. The lack of pedestrian-friendly pathways makes it particularly dangerous for children and women. Because of cultural norms and a patriarchal society, there is no appropriate public space in the area, resulting in gender inequality, especially for women. The area of the case study is regularly dominated by men over women and children.

Governance related challenges

There has been a lack of proper governance in the community. People, power holders, and responsible agencies rarely collaborate. As a result, citizens feel abandoned and the official sector fails to communicate effectively with them. Lack of political will and limited resources make it difficult for the community to solve its own problems.

Residents of Kunnumpuram are often unable to meet their basic needs. There is a limited water supply in the community, as water is only provided twice a day. It is an unclean and insecure source of water.

Interviews indicate that citizens need to be more involved in decision-making processes. It is their belief that the government does not adequately address their needs, nor does it act to turn city plans into action in order to address their problems. There is a lack of trust between citizens and government on both sides, as the mayor and municipality view the people as “sensitive” and unwilling to accept change. People see the government as careless and incapable of helping. Having to wait for top-down decisions is a big challenge for them.

50 |

Figure 2.20 Issues at site

There are various issues associated with the Kunnumpuram. The canals smell, and they are highly polluted because of the improper waste management system. There is a lack of sanitation. The streets are narrow with little greeneries, and the neighborhood suffers from a lack of inclusive public space.

51 | Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures GSEd ca ona Ve s on

2.10 Chapter Endnote

During a month of research. We were walking, observing, talking, doing participatory action research events and engaging with people on the ground. We were invited into people’s homes many times. We played games with the locals, trying to understand their everyday lives. So, we achieved to make a close relationship with the community.

We were engaging with a various range of stakeholders, like the former mayor, the word counselor, the main governing structure of public space CSML, and others. We met many different views and opinions, and through the eyes of the people on the ground we have tried to build a project, serving their interests and their needs.

On a small scale our project is the image of a future we hope for in Kunnumpuram.

we used a variety of different methods in order to understand the character and the identity of the area from the viewpoint of the different disciplines. By using each method, a new range of data unraveled for us. Although time-consuming, participatory methods that we were using were interesting for us, and they let different groups of people including women and children engage more in our data collection process. Based on our data collected, we tried to plan the future with respect to nature-culture interactions, and human non-human space collaborations promoting people’s well being. Besides, the public inclusive space that fulfills the needs of different groups of people was a crucial goal for us. In our view, these spaces should be open and multifunctional that entails different programs to co-exist. They are inviting users from different groups, including women, children, men, elderly, disabled to share experiences, express themselves and be empowered to fully live in equity and equality.

52 | Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Figure 2.21 Workshop at site

53

| Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Figure 3. 1 The Calvathy canal in Kunnumpuram

3. Situation analysis

Conducted research in Kunnumpuram

Introduction to our conducted research in Kunnumpuram, Fort Kochi, India. In a community facing many issues and opportunities, we were engaging with the local community and stakeholders to understand the context, and its potential for the future. We clearly saw how polluted streets, sea and canals were impacting the life of people and their use of public space, especially women who already were vulnerable and in lack of resources. There were almost no open public space in the area. Women were oppressed by the patriarchic society, in their use of public space and the neighborhood differed from men, who could move around freely. The high levels of pollution and lack of open inclusive public space were also affecting women, children, the elders and people with disabilities. The community had a strong social bond between them, which was an important resourse. Stakeholders and the community have informed our project. This chapter goes through a situation analysis based on our findings.

55 |

| (Re) -

Futures

Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India

Gaining Ecological

3.1 Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to analyze the current situation based on our findings from our participatory approach. Kunnumpuram is getting affected by a series of environmental, social, economic, and governance issues that have been negatively affecting residents’ livelihoods in the area. The lives of citizens have been subjected to several risks that were illustrated in one diagram. The Figure 3.2 provided us with an overview of the site’s possible risks. And here, by using the term “risk”, we mean “disaster risk” based on UNDRR terminology definition: “The potential loss of life, injury, or destroyed or damaged assets which could occur to a system, society or community in a specific period of time, determined probabilistically as a function of hazard, exposure, vulnerability and capacity.”

After clustering the risks that our site is suffering from, we explained these issues in our content which is organized in three different sections: public space issues, canal and environmental issues, and waste management issues.

As the role of the canals as a risk the health of the residents is bold, we believe that understanding the ecological features of the site is the key in our situational analysis. From the environmental point of view, the area has been suffering from degradations based on its ecological vulnerability from one hand, and the climate change-related issues from the other. Flooding, improper waste management, and biodiversity-loss due to the extreme water and soil pollution are some of the examples of this ongoing environmental degradation.

From the social point of view, people are also struggling with many different challenges because the basic needs of the residents of Kunnumpuram are not met. Poor infrastructure, insecure access to clean water, and improper waste management are some of them.

56 | Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Figure 3.2 Risk diagram

57 | Kunnumpuram,

| (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Kochi, India

3.2 Public spaces

Poor urban conditions

Based on our community mapping, participatory workshops, transect walks and engagement with various stakeholders, we got to understand how Kunnumpuram is facing a lack of resources on many levels, and how public space is such an important aspect of their marginalized conditions.

Urban public space has become much denser and more polluted in the last decades. The streets are very narrow, and no planned public space is left open. The community has a large population growth and no place to physically expand. As we got to know, in some places up to four families are living together in one house. Many can not afford to buy their own place therefore rent their entire life. This makes a feeling of less responsibility among the citizens to maintain their houses. Many also completely lack the resources to do so. The landowners do not seem to care much about keeping the houses to a certain standard.

In the area, people do not feel very connected to the streetscape, and lack of ownership together with overburdened lives, makes it seem like they ignore their streets.

As we got to understand, on an individual level, the residents do not see any benefit from using resources on the public environment, which makes a lot of sense because here people are working hard to meet their basic needs of survival.

Previously the area used to have one open public space, where they played sports, and gathered. The municipality took over this green public place and is now developing the area to serve as a site for a new highrise building. This real estate development has not just limited the communitys access to public space but removed the only place they had. This results in even more social exclusion in the area, where the most vulnerable grups, women and children, elders and dissabled are the ones having to deal with the worst consequences. Now they have nowhere to go, and spent their time inside their small houses, viewing the streets as a threath and obstacle.

58 | Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

59 | Kunnumpuram,

| (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures Figure 3.3 Sketch of site

Kochi, India

Low urban spatial conditions

There is a lack of public investment in the area, resulting in very low urban spatial qualities. Poor urbanism is almost serving as a tool for social exclusion from public space. The patriarchic religious society with its norms and culture, combined with the dense dangerous streetscape is resulting in exclusion and gender inequality.

Kochi has had fast economic growth in the last decades, and the city has become very modernized because of this. Kunnumpuram is suffering from this economical contrast, where the surrounding areas are in fast growth and development, and the differences are just getting bigger. This has made members of the community so poor they cannot manage life. The municipality is planning to put all the poorest members of the area into the new Highrise they are building on the last public spot that was left for the community. Even if this was done with the best intentions, we see it as an isolating and dehumanizing act.

Suffering Blue and green public space

Climate change, ecological degradation, and high pollution is resulting in green and blue public spaces that are suffering. According to the European Environment Agency both physical and mental health, and social well-being is depending on green and blue spaces in public. High-quality green space can play an important role in reducing inequalities. (Agency, 2022)

60 | Kunnumpuram,

| (Re)

Kochi, India

- Gaining Ecological Futures

Globalization

“Globalization and Colonialism has influenced the planning system of the global south with planning solutions and ideas borrowed from the global north. Especially from the USA and Western Europe during the last century. In the Global South, many of these old planning ideas are stuck in slow stagnant planning systems. The systems are not changing in pace with the extremely fast-evolving society and its urgent needs. There is no complete solution to all the complex problems that cities are facing. (Watson, 2009)”

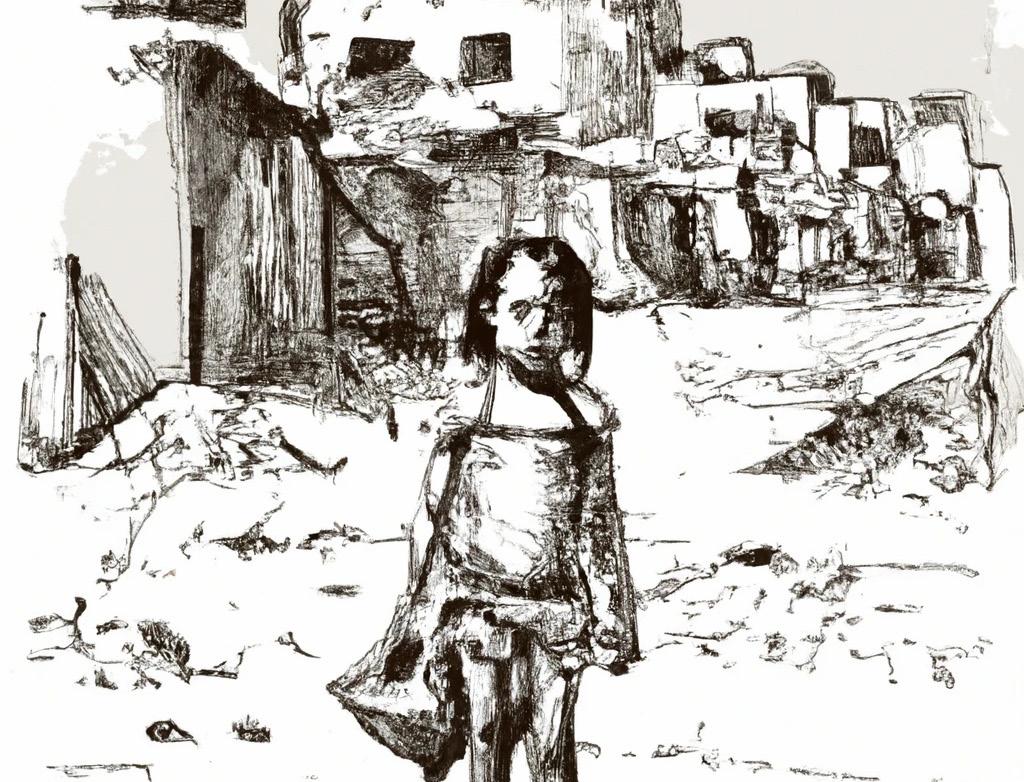

Figure 3.4 Girl at the street in Kunnumpuram

Trends

These trends are defining the issues in Kunnumpuram. Where climate change, social issues and ecological vulnerability are overseen, poor urban planning and lack of governance are leading the area into crisis. With no open public green spaces left. The government is suffering from being stuck with old planning ideas and a modernist approach to the crisis they are facing.

61 | Kunnumpuram,

India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Kochi,

Figure 3.5 Roofscape in Kunnumpuram

3.3 Pathways’ walkability issues

The research team considered the walkability-related issues of the pathways in Kunnumpuram. Forsyth (2015) grouped walkability definitions into two categories: some discussions focus on environmental features or “means” of making walkable environments, such as traversability, compactness, physical enticing and safety. Others deal with outcomes potentially fostered by such environments, such as making places lively, enhancing sustainable transportation options, and inducing exercise. Based on our topic, we focus on the environmental definition of walkability in Kunnumpuram.

Compact

The compact place with a high density or proximity of destinations and people is an ideal walkable place. According to the interviews, people have access to their daily needs by walking to the public market in Mattancherry. Despite this, they lack proper access to public transportation. Therefore, transportation planning needs to be revised.

Physically enticing

It refers to environments that have full pedestrian facilities. The area is dominated by cars and traffic, and pedestrians are not provided with proper signage or separation from the car area. So, we cannot consider the area as “pedestrian-friendly”. There is not distinguishing between the pedestrian areas and sidewalks, and the car traffic side. And, as there is no appropriate lighting system, nights are pretty much dangerous for the residents to walk freely outside.

A lack of proper urban furniture and facilities for different age groups also plagues the site. In Kunnampuram, there aren’t enough safe inclusive sidewalks to meet the needs of the disabled, such as blinds and handicapped citizens. For people who want to get around and get some exercise, there aren’t enough services available. Furthermore, there are no bike lanes, nor are the sidewalks connected to be considered a “network”. Finally, there is no vista point that would give visual access to the area’s architectural attractions. Safe

Two general features of safety are important to assess: Firstly, the Street design: Sidewalks and safe crossings are essential to walkability. The sidewalks in Kunnumpuram are inadequate, and car areas and walking paths are not clearly separated. The second aspect of safety is aboutcrime and crashes. Although this area is potentially a valuable tourist destination, Kunnumpuram lacks efficient street lighting that illuminates the canals’ surrounding environment at night. Because of this, lack of street lighting is one of the factors preventing the area from having a night life culture which is helpful not only for nights’ safety, but also for the neighborhood’s economy.

Furthermore, based on our interviews, women report a feeling of exclusion from being active in their neighborhood environments because of a sense of insecurity. As the streets could be potentially dangerous for them and their children, they usually do not let their children play outside. Due to safety measures, they even mention that their children must be accompanied to school.

62 |

Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

Traversable

To be traversable, Kunnumpuram paths should have the basic physical conditions to allow people to get from one place to another without major impediments. However, the connection between the two sides of the canals does not accommodate the needs of different groups. Two bridges cross the canal in the research area. One of them was built without considering disabled residents who cannot use the bridge’s stairs. Due to this, disabled people, elderly people, and people who have difficulty using the stairs have to use another bridge that is relatively far away.

Figure 3.6 Bridge

Figure 3.7 Site at night

63

| Kunnumpuram,

Kochi, India

| (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

3.4 Gender inequalities

Gender inequalities in India

Gender differentiation is predominant in India. In the market, in the streets, in public transport. Every public space is mainly populated by men. After work, they gather around street shops to drink tea and socialize while the women are staying in their households. The women seem absent from the public space across the city. The only times we can see them accompanied by kids, as a group, or with men.

The perspective and impression of the city as a woman is a different experience (Figure 3.8). By feeling the gaze upon themselves, the women often don’t feel safe walking alone. According to Paul (2011), a gendered sense of place,

resulting in physical and emotional responses, is induced by the social and cultural processes that exist in society. For him “Women’s restricted access to public space is a manifestation of socially produced fear that is constituted by the way space is perceived and imagined.” (Ibid, p.3). Therefore, public spaces become a “spatial expression of patriarchy” (Ibid, 2011).

Gender inequalities on site

Those observations were made similarly at a smaller scale (Figure 3.9). Walking around Kunnumpuram’s streets, we realized how the lack of public space affected women and their safety, enhanced by the cultural norms and patriarchal tendencies observed in Indian society, where women are often expected to take care of the household and to be the “caregivers” while men are the “breadwinners” (Terraza et al. 2020). With nowhere to go and no professions, most of the women are staying inside their houses and very few of them are visible outside. Since their younger age, they are facing gender exclusion in public space, encouraged to play inside when boys can go outside, leading to a

“feeling that they do not belong in the public realm : that the space is not theirs.” (Terraza, 2020).

During our participatory workshop, the aim was specifically to give women a voice. We had the opportunity to speak about their challenges encountered as women in India. In addition to the lack of public space in the area and the cultural traditions, women are not going outside above all because they don’t feel safe. The lights on the streets are not sufficient and the pathways are dangerous.

64 | Kunnumpuram,

| (Re)

Kochi, India

- Gaining Ecological Futures

Women Children No Sitting Arrangements

Drug Addicts Cultural Barrier

Lack of Public Space

Not Enough Lights Polluted Streets

No Pedestrian Friendly Pathways

Figure 3.8 Diagram of the women and youth’s challenges

Connection to theories

According to Paul (2011), women have a different cognitive understanding of public spaces, where the fear of crime is playing a key constraining factor. Moreover, they also fear shame and dishonor. Outside, they are really precautionary. As a self-protection mechanism, they usually restrict their mobility to the places they already know and are familiar with. But those constraints reinforce gendered constructions and the public spaces are constituted through power relations and everyday practices to become the spatial representation of social relations (Ibid. 2011).

“Cities have historically been planned and designed for men and by men. They tend to reflect traditional gender roles and gendered division of labor. In general, cities work better for heterosexual, able-bodied, cisgender men than they do for women, girls, sexual and gender minorities, and people with disabilities.” (Terraza et, al, 2020)

The cities are often the support of gender inequalities . In the World Bank’s handbook for Gender-inclusive Urban planning design, Terraza (2020) explains that in general, urban planning activities have been gender-blind in terms of key aspects of the city/built environment which include access, mobility, freedom from violence, health and hygiene, climate security, housing, and land tenure. Moreover, women are under-considered in many countries. However, as UN-Habitat reminds (1995), women play multiple roles in the Human settlements development process as economic producers, managers of households, producers of services, caretakers, and raising children. They are essential for the community and society and deserve equal rights.

Therefore, efforts must be put into planning to promote equity among all citizens. Paul (2011) encourages women to reclaim space for themselves and Kern (2020) stands that “by first recognizing

these unequal systems and social dynamics, we can then imagine new ways of inhabiting urban spaces.” (Kern, 2020).

Overall, gender inequalities are stringent in many societies and through urban planning, we have the possibility to make a difference in a community to make every group feel safe, included, and integrated.

Figure 3.9 Gender inequality diagram

65 | Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India | (Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

3.5 Waste management

Waste management challenges

The pollution generated by waste disposal is a threat to the environment but also to health. Urban growth in India is continuously rising and impacts the ecosystem, as it has been noticed on site. “The growth in urban settlements had doubled the generation of solid waste within a decade.” enlightens Mishra (Mishra et al., 2018, p.3).

In the Kunnumpuram’s neighborhood, the waste management system is insufficient and too expensive for the poorest people in the community. Pollution is prominent in the neighborhood, due to several issues (Figure 3.12). Among them, the lack of storing space for the inhabitants to keep the waste in their small houses shared by multiple families. The sewage system releases the wastewater directly into the canal a small meat market nearby is using the canal to clear the waste of their slaughterhouse. Combined with the waste dumping, it results in a strong smell coming from the canal in the whole neighborhood. A man living nearby explained to us that the canal used to be 10 feet deep and is now only reaching his knees because of the accumulation of waste at the bottom of the canal.

The lack of a proper waste management system results in a lot of issues in Kunnumpuram and in India in general. “Uncollected waste often lies outside the designated bins in most of the urban areas due to inappropriate design, capacity, location and poor attitude of the community towards using bins” explains Mani (2015, p.3), and the segregation of waste is almost inexistent in most cities, even though the door-to-door collection is improving.

With a lack of recycling centers, open burning and waste dumps are still the main methods of disposal in India. “These methods are continuous sources of harmful gases and highly toxic

Figure 3.10: Drawing of a polluted street illustrating the situation in Kochi

liquid leachate.” (Mani et al., 2015. p.4) and lead to environmental and health degradation. “The contaminated water affects people’s health and biodiversity. Dumps and exposure increase the risk of negative impacts like the growth of invasive species, pathogens, infections disease and toxicity.” (Mishra et al. 2018)

66 |

|

Kunnumpuram, Kochi, India

(Re) - Gaining Ecological Futures

The waste management system in Kochi