Do challenges in daily commuting affect people’s livelihood?

Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course

Project Report, Autumn 2022

Urban Ecological Planning Master’s programme

Department of Architecture & Planning, Faculty of Architecture

Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway

AAR4525 - Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course

Executive Summary, Autumn 2022

Urban Ecological Planning Master’s Programme

Department of Architecture and Planning, Faculty of Architecture

Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim, Norway

Do challenges in daily commuting affect people’s livelihood?

An exploration into the links between urban accessibility & livelihood issues in the context of the Calvathy canal area, Fort Kochi

Kochi, Kerala, India

Course Coordinator: Supervision Team:

Gilbert Siame

Associate Professor, NTNU

Gilbert Siame

Associate Professor, NTNU

Rolee Aranya Professor, NTNU

Mrudhula Koshy

Assistant Professor, NTNU

Riny Sharma

Assistant Professor, NTNU

Booklet Layout:

Mrudhula Koshy

Assistant Professor, NTNU

Vija Viese

Research Associate, NTNU

Authors

Mohammed Mahdi Mahdi Zadeh Naeini

Naein, Iran

Atena Asadi Lamouki

Tehran Iran

Afif Muhammad Fatchurrahman

Jakarta, Indonesia

Co-Authors

Lateefah Joseph (UCT)

Cape Town, South Africa

Macdonald Galimoto (UCT)

Lilongwe, Malawi

Preface

After two years of pandemic-related restrictions which affected many aspects of the Urban Ecological Planning Programme (UEP), and especially its first semester obligatory fieldwork, the 2022 fieldwork under the Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course was conducted in Kochi, India. This was a planning studio project with emphasis on international mobility and knowledge exchange among students from India, South Africa, and Norway. The project forms a core component of the two-year International Master of Science Programme in Urban Ecological Planning under the Department of Architecture and Planning at the Faculty of Architecture and Design at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). The 2022 project activities rejuvenated the UEP passion and curiosity about challenges and opportunities being faced by cities of the Global South. Students spent eight weeks working in Kochi city in the Southern Indian state of Kerala. The project was structured and framed to contribute directly to the UTFORSK funded Norway-India-South Africa (UTFORSK-NISA) student and staff mobility project on localisation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Thus, the project involved NTNU, School of Planning and Architecture (SPA), New Delhi, India, All India Institute of Local Self Government (AIILSG) and the University of Cape Town (UCT) in South Africa. This report represents a major output from the integrated effort of communities, bureaucrats, and most importantly, the students from NTNU, SPA and UCT.

This project report is an outcome of studio work done by NTNU students. The report provides detailed information about students’ experiences, learning and context-informed recommendations for improving living conditions on study sites in Kochi city. Students’ learning and recommendations are based on UEP’s teaching philosophy of experiential learning. Students’ exposure to an unfamiliar context poses several challenges while working on an academic goal but it also provides the necessary ‘triggers’ for learning that is simply not possible in traditional planning studios that are of shorter duration and have less emphasis on being out in the field.

The project report is informed by methods that allow students to propose solutions to complex but interlinked urban problems based on area-based planning and participatory planning

approaches. This year’s report emphasises some of the most important UEP values and topics that include inclusive urban planning and development, ecological integrity in cities, and sustainable urban livelihoods and accessibility. By working with local communities, local and international stakeholders, students identified, analysed, articulated complex issues, and made realistic recommendations to improve living conditions on specific study sites.

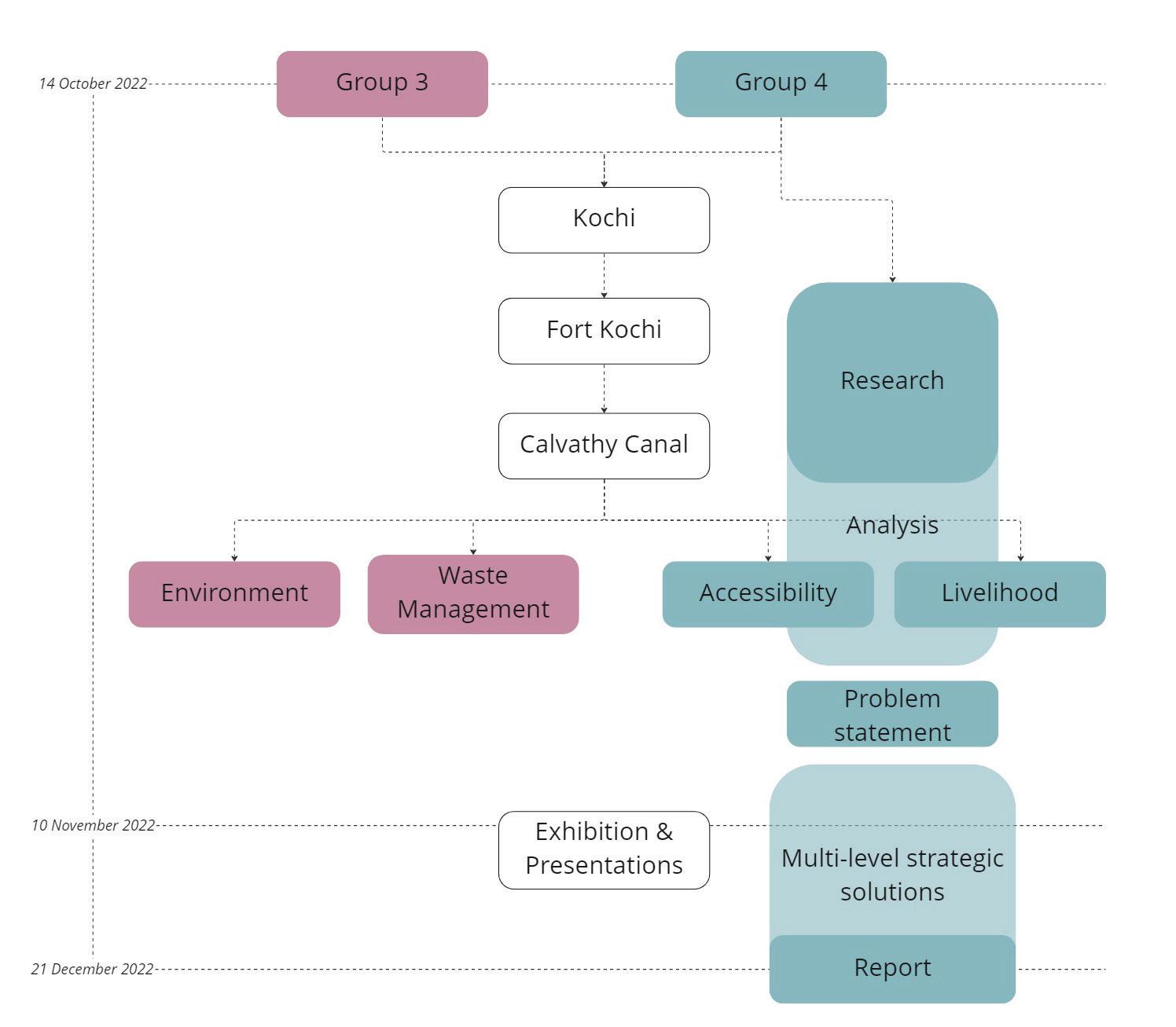

The students were divided in 4 groups and 2 of them worked in Fort Kochi while others in Ernakulam areas of Kochi city. Fort Kochi is a seaside historical area known for its Dutch, Portuguese, and British colonial architecture, and heritage and fishing. It is a significant tourist area for the Kerala State. On the other hand, Ernakulam is a sprawling residential and commercial hub well known for Marine Drive and a busy waterfront. Zeroing in on specific sites, the reports deeply reflect on the urban everyday life experiences, challenges, and opportunities for people in Kochi. While retaining the area-based planning approach, students’ work was based on the overarching theme of urban informality and guided by three themes: ecological vulnerability, urban markets, and urban mobility. As an outcome of their learning process, students prepared four reports to illustrate and reflect upon the participatory process through a situational analysis and reflection on methods and methodology that informed a problem statement which they tried to address in strategic proposals. This report summarizes the work of the group working with accessibility and livelihood theme in Fort Kochi.

We would like to give a special mention for Centre for Heritage, Environment and Development (C-HED) and World Resources Institute (WRI) India for their constant support to our students in terms of giving them insights on local context and different themes that students worked on and for connecting them further with relevant stakeholders and documents.

Acknowledgements

“None of us, including me, ever do great things. But we can all do small things, with great love, and together we can do something wonderful.” – Mother Teresa Collaboration is a keypoint in the research and production process of this report. Thus, we would like to express our heartfelt gratitude in this section to acknowledge all the precious and wonderful individuals, groups, and organizations who make it possible for us to deliver this report.

In Kochi, we were majorly helped by people from several important local and international organizations. Special thanks to C-HED (Center for Heritage, Environment, and Development), especially Dr. Rajan Chedambath, for providing us with a working and lecture space and guidance throughout our whole stay in Kochi. Secondly, many thanks to WRI India, especially Achu Ee Rajasekharan, Shabna Seemamu, Visakha KA, Amy Rachel Joseph, who has given us a guided tour in Fort Kochi, and further dialogue with us for directions, guidance, and insights. Furthermore, thanks to AIILSG (All Indian Institute of Local Self-Government) who helped us with the fieldwork’s administration and practical assistance. Another special thanks to CSML (Cochin Smart Mission Limited) who has shown us the latest smart city technologies, and Shubash Bose Park for letting us enact our exhibition in the area.

We also received collaboration opportunities from two wonderful local schools and one international university, SPA (School of Planning and Architecture) Delhi and University of CUSAT (Cochin University of Science and Technology). Special thanks are presented to two students from CUSAT; Faeiz Ahammed and Abdul Kalam, who accompanied us during our site visits and act as our translators and guide. Honorable mention also to Matthew A Varghese from MG (Mahatma Gandhi) University. Lastly, many thanks to students from UCT (University of Cape Town), Mercy Brown-Luthango, who joined us in our last couple of weeks of work and helped our group work effort, especially Lateefah Joseph and Macdonald Galimoto.

As our main approach is to be heavily connected with the local community, we also received help from several important actors on our site. Special thanks to KJ Sohan: Cochin former mayor, TK Ashraf: Calvathy Ward Councilor, Nisa: UPAD (Urban Poverty Alleviation Department), Central Calvathy School, Salafi Jum’ah Masjid, and Aisha’s family.

Last but not least, our own university, NTNU (Norwegian University of Science and Technology), who has provided us with the opportunity to conduct the fieldwork. Especially the UEP (Urban Ecological Planning) faculty staff, coordinators, & professors: Rolee Aranya, Mrudhula Koshy, Gilbert Siame, Riny Sharma, Vija Viese, and Peter Andreas Gotsch. Finally, a very special and heartfelt thanks also to our colleagues, members of group 3: Maria Magdalena Von Muhleisen, Mohammadreza Movahedi, Eloise Veronique Marie Redon, and Nahida Yeasmin Tonni, who did the initial phase of the research and fieldwork together with us.

Sincerely,

Group 4 of the 2024 batch UEP students:

Afif Muhammad Fatchurrahman

Atena Asadi Lamouki

Mohammed Mahdi Mahdi Zadeh Naeni

Acronyms and Abbreviations

All Indian Institute of Local Self-Government

Center for Heritage, Environment, and Development

Centre of Indian Trade Unions

Cochin Smart Mission Limited

Cochin University of Science and Technology

Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission

Kochi Municipal Corporation

Kochi Metro Rail Limited

Karnataka State Road Transport Corporation

Low Income Groups

Middle Income Groups

Mahatma Gandhi University

Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelige universitet

School of Planning and Architecture Delhi

State Water Transport Department

University of Cape Town

Urban Ecological Planning

Urban Poverty Alleviation Department

World Resource Institute India

Contents

5. Strategic spatial solutions

5.1 Main concept for proposed solutions

5.2 Ideas & precedence

5.3 Auto-Rickshaw (tuk-tuk) as micro-feeder transport system

5.4 Safe & inclusive corridor transformation

5.5 Public space provisions in strategic urban pockets

5.6 Implementation Plans

Do challenges in daily commuting affect people’s livelihood?

Calvathy canal, Fort Kochi - Kochi, Kerala, India

Afif Muhammad Fatchurrahman

Atena Asadi Lamouki

Mohammed Mahdi Mahdi Zadeh Naeni

Our group had the opportunity to spend 1 month in the city of Kochi, India, to do a fieldwork project. We tried mainly to dedicate our time there to preparing a situational analysis, gathering data, familiarizing ourselves with the area and situation, and meeting different organizations and stakeholders to talk to them and enrich our information as much as possible to eventually be able to propose strategic changes with the participation of people and different stakeholders which can lead to the development of the community.

During our stay in Kochi city, we visited the area several times and within our visits, we focused on engaging with locals and different stakeholders to have a better comprehension of the study area and understand the issues and also the strength of the area from their points of view. To achieve this goal, we adopted various methods like observation and transect walks, photography, and other methods which mainly were focused on the local community like participatory workshops, interviews, and meetings. Identifying the stakeholders in the area, their level of interests and influences, how they influence each other, and the relationship among them has supported our work significantly.

In forming the problem statement for our research, we found several pressing issues from the engagements that we had in the community which ultimately lead to the theme of accessibility and livelihood, and how they are interwoven with each other. Eventually, we have taken it forward and assembled our proposed strategic solutions to ensure a comprehensive mobility and transport system for the neighborhood, which also ensures the developments in the area include safety and inclusivity as the main focus.

2. Site Context

2.1 The city of Kochi

Kochi is a city located in the southwest of India in Kerala state. The city is in the Ernakulam district and is known as the Kochi corporation which was established by merging the nearby towns of Ernakulam, Mattanchery, and Fort Kochi. The city is, by all accounts, the commercial and industrial capital of Kerala Blessed with natural beauty and a good climate. It also boasts good road, rail, and air connectivity with other Indian metropolises such as Mumbai, Chennai, and Bengalooru (Joseph, 2009). Kochi has a tropical climate. The annual variation of temperature is between 26°C and 33°C. The humidity is high all year round because of its proximity to the sea and large inland water bodies, or backwaters. The city, like other parts of Kerala, experiences two major seasons (Kerala Sustainable Urban Development Project, 2005).

The History of the City of Kochi starts with the natural phenomenon in 1341 AD when the great flood in Periyar washed away a sizable piece of land creating the sea mouth and natural harbor of Kochi. The first settlements of Kochi have been recorded around Mattanchery facing the protected lagoons in the east, which provided safe anchorage to country crafts in all seasons. Mattanchery was linked to the entire coastal stretch of Kerala through these inland waters (Kochi City Development Plan, 2006).

Kochi Port was formed in 1341 when the heavy floods of that year silted up the mouths of the Musiris harbor and the surging waters forced a channel past the present inlet into the sea. The old merchants of Musiris shifted to Kochi as soon as the new outlet became more or less stable. As the harbor gained prominence, then the ruler of the region shifted his capital also to Kochi, giving impetus to the growth of the town. (Kochi City Development Plan, 2006)

The city has always been the main harbor center in this part of India because of its accessibility to the Arabian sea. Therefore, so many traders from different parts of the world such as Arab traders, Jewish merchants, Portuguese,

Dutches, and British explored Kochi city and affected the city situation in different ways.

From the 16th Century, Kochi witnessed rapid changes through the trading and colonizing attempts of European powers (Kochi City Development Plan). Portuguese were the first to arrive in Kochi. They founded Fort Kochi, established factories and warehouses, schools and hospitals, and extended their domain on the political and religious fronts. (Kochi City Development Plan, 2006)

The Dutch’s rule over Kochi started from mid of 17th century. Cochin prospered under Dutch rule by shipping pepper, cardamom, and other spices, coir, coconut, and copper. The native ethnic religious groups in the city like the Hindus, Muslims, Syrian, Christians, and Jewish minorities too raked profits of the prosperity (https://www.cochin.org.uk/).

At the end of the 18th century, the British came and took the control of Kochi. The port city of Cochin had become highly developed during the time of British rule in India (https://www.cochin. org.uk/). After India’s independence, this city became the first princely state to join the Indian Union willingly after India achieved Independence from British rule (https://www.cochin.org.uk/).

2.2 Urbanization and its influences

One thing constant about the city is that its strategic location has always made it stand out as a significant commercial and industrial hub of Kerala (https://www.cochin.org.uk/).

Industrialization in turn resulted in population increase and consequent urban growth. Kochi thus witnessed unprecedented trends of urbanization during the past four decades (Kochi City Development Plan). Nowadays, the population of the city is around 600,000, and due to its rapid development, people are facing many issues that have influenced their livelihood severely.

The three municipalities of Fort Kochi, Mattanchery, and Ernakulam were not able to address urban issues of the area separately and they could observe that there must be a significant

collaboration between them to tackle the problems properly. In order to streamline the municipal administration, the Kochi Corporation was formed in 1967, incorporating the three Municipalities (Kochi City Development Plan).

2.3 Economically dense city

Kochi city is a major destination for tourists in India. The tourism sector plays an important role in economic development and contributes a significant share of the State’s economy. The tourism sector is identified as an alternative economic growth source for the State. Kochi, however, functions mostly as a transit point for domestic and foreign tourists (Kerala Sustainable Urban Development Project, 2005).

The growth in economic factors has made Kochi the economic capital of Kerala.

The literacy rate of the state and city is high and the young generation is highly educated. They are enthusiastic about finding employment opportunities that are related to their educational background. There are not so many available opportunities in the city of Kochi which has made them migrate to other states of India. Meanwhile, due to growth in the industrial and tourist

sectors of the state and city, there are so many manual job opportunities. But there are not enough workers for this economic sector of the state and city. In Kerala, there is a lack of native workers responding to Economic expansion and industrial development. Therefore, the state attracts migrants from northeastern Indian states, and many end up living in slums within the city (Kuriakose& Philip,2021). This issue has made the corporation of Kochi densely populated.

In Kochi City Region, The population is not spread uniformly across the various constituent units but is concentrated in a few pockets (Joseph, 2009). The reason is that people want to live in areas with more and better infrastructure and more job opportunities.

While the area under the Corporation is only around 25.2 percent of the total area under the Kochi City Region, it holds over 51.2 percent of the total population (Joseph, 2009).

2.4 Development Plans

In the past two decades, there have been two major development plans which have had major impacts on Indian cities.

The first is Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM). It was initiated by the Indian government in December 2005. In the mission statement of this plan, it has been indicated that “The aim is to encourage reforms and fast track planned development of identified cities. Focus is to be on efficiency in urban infrastructure and service delivery mechanisms, community participation, and accountability of urban local bodies/ Parastatal agencies towards citizens.” The duration of program was extended until March 2014. The program had considerable improvements on different aspects of urban issues in Indian metropolises. This can be seen in the increase of quality housing for citizens who were previously living in slums or substandard dwellings and an overall improvement to transportation systems and other public spaces within Indian metropolises (https://www.nnvns.org/author/admin/, 2021).

The second significant development plan in India is the smart city mission that was launched by the government in June 2015. The objective of this program is “to promote cities that provide core infrastructure, clean and sustainable environment and give a decent quality of life to their citizens through the application of ‘smart solutions’ (https://csml.co.in/ smart-cities-mission/).” This plan has been conducted in 20 cities of India. In Kochi, Cochin Smart Mission Limited (CSML) is the special urban body that has been implementing the projects in the city. They have described their purpose as “CSML aims at a planned and integrated development of the Central Business District and Fort Kochi-Mattancherry area by improving the civic infrastructure with the application of smart solutions thereby improving access to city amenities, clean and sustainable environment and livelihood promotion (https://csml.co.in/mission-vision/).”

2.5 Specific site area: Fort Kochi

Located right at the sea mouth, Fort Kochi has experienced immense trade-related activities and has developed a rich pluralistic culture and tradition unique to this heritage zone (Kochi City Development Plan, 2006).

This unique characteristic of this area is the reason that despite the fact that there is a very low level of investment and development in this area compared to the Ernakulam area, the neighborhood is still alive and it can be said that the economy of the neighborhood is dependent on tourism.

Another important outcome of this rich pluralistic culture is the presence of various religious groups in Kochi and especially Fort Kochi. The majority of religious groups are Hinduism, Christianity, and Islam. Within the neighborhoods in Fort Kochi, we can observe the differences between these groups living in this area but the crucial point is that the level of conflict between them is very low and actually, the cohesion of the communities is one of the strong points that inhabitants have benefited from.

Fort Kochi accommodates a large population but is short on land thanks to its unique geographical circumstances. Furthermore, this area is where most of the poorer sections of Kochi city region urban areas live. They depend on the mainland mostly for their employment needs and make use of the ferry system and bus services to commute to the

mainland in the morning and evening (Joseph, 2009). It can be observed that in these hours of the day these modes of transport are busy and even though people used them as their main means of transport, their level of availability is not adequate. On the mainland, there are metro railways that people use for transportation. But there is not this possibility for people in the Fort Kochi area.

As Fort Kochi was mainly used to be a place for different nations to trade, the canal was built for connecting the sea and the mainland fort Kochi area. Thus, in the past, the canal was totally usable and active, especially for smaller boats. However, based on the information gathered from the interview with the former mayor of Kochi city, the expansion of roads and settlements in the area has resulted in the encroachment of the canal width and the canal cannot be used significantly as a means of transportation. Therefore, the canal lost its usage and has been turned into an infamous feature of the area, mainly used merely as sewage and wastedumping.

The ferry is the preferred mode of transportation for people in this area mostly because of two main reasons. First is the price for every ferry trip and It is only six rupees per trip. And the second reason is the time that would be spent in comparison to other modes of transportation. But The important factor in this regard is that there are no specific safe paths for pedestrians and have made so many difficulties for inhabitants.

In this specific situation, it can be observed how much the accessibility condition in a neighborhood can influence people’s livelihood. In this case, the road situation and transport modes have had significant impacts on inhabitants’ economic situation and safety. Based on these preliminary observations and analysis, group 4 of UEP 2022 fieldwork has focused on the issues related to accessibility and livelihood, the relation between them, and their impacts on people’s lives in Fort Kochi, specifically in the Calvathy canal neighborhood.

Kochi is a dense urban area faced with rapid urbanization and development. These in turn caused various pressing issues such as ecological, cultural, and historically sensitive situations. The issues are evident in both the tangible and intangible aspects of the city.

3. Methods

We, as a research group, benefit from various forms and tools for gathering information and different viewpoints which are needed for conducting the project in our fieldwork. These tools can be varied from simple observation and photography to interacting with locals for acquiring a more comprehensive viewpoint about the study area. In the case of this fieldwork, the crucial point is to conduct these methods in a participatory manner. The priority has been to use these tools as means for giving local people a voice and professionals a clear idea of local people’s needs in order to bring about an improvement to their own neighborhood or community.”(Neighborhood Initiatives Foundation (1995) cited in Hamdi & Goethert (1997)).

3.1 Observation and transect walks

“Observation is a technique that involves systematically selecting, watching, listening, reading, touching, and recording the behavior and characteristics of living beings, objects, or phenomena.“ (Iedunote)

The first step toward achieving an overall view of a study area is observation. The advantage of this method is the direct and tangible data gathered within first experiences encountering the area. Within this step, the process is observing the different locations, especially what can be considered a landmark, locals’ daily activities, the overall situation of people’s accessibility to various kinds of infrastructures, and witnessing how they cope with various situations.

Hence, during our analysis, alongside finding concrete information through scientific resources and interacting with powerholders, we have had the aim to hear locals’ stories about their neighborhoods through various approaches. It is believed that participatory planning increases the effectiveness and adaptivity of the planning process and contributes adaptivity and stability to the societal system (Smith, R.1973).

In this manner, one of the main tools is the transect walk which is a type of mapping activity, but it involves actually walking across an area with a community member or a group, observing, asking questions, and listening as you go (Thomas, 2004). The information collected in this way can illustrate the neighborhood condition in a way that a researcher can see the area from the locals’ eyes. Generally, the comprehension that is obtained through the early observations is the basis of future analysis and addressing the issues.

For instance, locals’ walkability struggles and its significant influences could be observed through the first walks in the neighborhoods of Fort Kochi and this issue has had a great impact on our whole project.

3.2 Photography & Videography

An important visual tool in the documentation and analysis process is taking photographs and videos through site visits. It is one of the essential and preliminary steps that we took to gather the information that is needed to create the primary analysis upon it and use them in supplementary analysis later. In this manner, we try to capture the scenes of the locals’ lives that are not usually portrayed. “This focus on the sensoriality of everyday life experiences and their affective dimensions might always have figured in applied research that attempts to understand other people’s perspectives” (Pink, 2009). The important point about photography is that it has

a very decisive impact on the viewers that other tools are not able to indicate. “visuals allow the ‘oppressed’ to make statements that are not possible by words” (Singhal, 2003). Besides the analysis, in the design phase, the pictures are useful to show the practicality and the visions of proposals by utilizing them.

3.3 Interviews

An interview is another influential step toward acquiring a better understanding of different factors that are affecting people’s livelihood. For instance, within a session with an influential person in a community, we could achieve some crucial quantitative and qualitative data about the study area that can help to conduct the project more realistically.

As mentioned about the importance of inhabitants’ opinions in previous sections, interviews with locals are a critical tool to observe a neighborhood from their perspective and realize important points that are normally hidden or not considered. Therefore, we attempted to engage in some friendly conversations with different groups of people such as fishermen, teenagers, shop owners, tuk-tuk drivers, etc. in our study neighborhoods. Through these interviews, we understand some key points regarding the significant problem in the study area and how inhabitants have tried to respond to these issues.

The engagements with locals were alongside some meetings with stakeholders who have a significant impact on planning programs and development implementation such as the former mayor, councilor and some influential organizations like CSML and GIZ.

3.4 Participatory Workshop

In this manner, One of the main methods employed during our analysis was a participatory workshop which played a very significant role in the identification of different aspects of locals’ lives such as their daily activities, the main issues they face throughout the day, how current infrastructures respond to their needs, the differences that multiple development projects have made in their livelihood, etc. We considered this opportunity as a valuable session in which we could learn more and more about locals’ ways of living. Hence, In this participatory workshop, we had this important point in our mind that users” are treated not as passive recipients, but as active and creative contributors—as ‘experts of their experience.” (Steen, M. 2013).

In the participatory workshop in the Calavthy canal area, the focus of our group was mostly on understanding the problems that people face regarding the current road situation and public transport infrastructures and how these influence their livelihood. As the workshop was a part of the initial research on the site, we conducted the workshop together with our colleagues from group 3, who are focused on the issue of the environment and the canal condition.

It is argued that citizen participation is an essential element in making the planning process a learning system. This leads to a strengthening of the definition and role of communities in the urban system, and to an unexpected requirement of planners who would adopt a participatory planning process (Smith, R.1973).

We tried to conduct a community mapping in the first participatory planning workshop with the locals. The quest was to better understand the local’s livelihood conditions and pattern of daily activities. Considering this, we adapted various tools such as papers, base maps, some color pens and markers, tons of color pencils and stickers for the children.

During this workshop we faced two challenges the first one was the language barrier which could make the results not as comprehensive as it could be. Another one was our timing for holding this workshop. The workshop was held at 2 in the afternoon, this reduced our chance to talk with men and our main audience and participants were women and children. In Spite of these challenges the outcome of this session as the first attempt was very valuable.

The whole process was about engaging them to help us find the issues and problems they have. To show us what their needs are and try to find the first rationale behind that need or the people who are responsible to solve them. Since we had maps, they could show the nodes which they take the most, the roads and streets and shops that they use more or they could easily draw to express themselves. Some of them answered orally which were recorded and some wrote their answers and the rest drew or painted.

Based on the experience that we have got from the first workshop, the next site visit was even more productive, since we had the chance to be accompanied by translators from CUSAT university. He was fluent in Malayalam and English so that helped us significantly to get more information. During this session which was more like an ask and answer session, we talked to people and asked their opinion about the situation. This time we had the chance to meet more people and engage both genders and people in different ages.

3.5 Exhibition

On the 8th of November, our whole class enacts an exhibition in one of the largest local parks in Kochi, the Shubash Bose park. This exhibition was enacted to showcase the result of our research, findings, and proposed solutions. By showcasing our works to the locals, both from our site and the city, we could gather even more feedback and input from the perspective of the local citizens, expanding our work to even more possibilities, while staying true to the local context of our site.

We prepared some materials and stationery for the audience to leave their feedback, comments, and suggestions on our work. Furthermore, we also did some live presentations to explain our work in more detail to several groups of people. We also have the chance to sit and discuss intensely with one of the employees from the smart city. In these manners, the effort is done so that our work could create interactions and discussions with the local community.

Our group strives to collect as much input from the local stakeholders in our site, so that our understanding is contextual, accurate, and appropriate based on the local community. In applying these methods, we learn that even though our approach is quite a time-consuming process, the experience and value that we got while interacting with the locals are priceless.

4. Situation Analysis: Findings, challenges, and limitations

4.1 Existing conditions & Stakeholders

Our study area is governed under 2 wards, Calvathy and Eravelli. Wards in the context of Kochi, are predefined locations/districts set within the municipality of Kochi. The governance of wards is led by a single councilor, who oversees and manages his/her ward area, and falls directly under the Kochi Municipal Corporation and the Mayor. Several of these councilors could organize themselves together to form a committee that handles specific themes in the city.

Our site has several different stakeholders, which mainly include governmental/municipal actors, who hold the highest power and resources to make changes, local’s public & non-governmental organizations, and the local residents themselves who have high interest but do not really have the power & resource to create substantial changes. Even more so when the area is considered as a slum due to the general perceptions of unpleasant living conditions by the people outside the community.

The lack of local workers in the state of Kerala has attracted a large number of workers from other states of India to Kerala. A considerable number of this group of people are living in the Fort Kochi and Mattancherry areas. This issue has made these areas very congested neighborhoods and their infrastructures cannot respond properly to the inhabitants’ needs. The other important point about the significant number of people living in these areas is that they are considered in the low-income group (LIG) or middle-income group (MIG). LIG is identified in terms of the economic

basis, as households with a monthly income of less than Rs.5,000. MIG is also identified in terms of the economic basis and are households with a monthly income greater than Rs.5,000 but below Rs.10,000 (Kerala Sustainable Urban Development Project, 2005).

There are two main public transport services that pass through the site’s peripheral area. One is the ferries that take passengers to mainland Ernakulam and Vypin island area. The other is the public bus service which has a bus stop in front of the Fort Kochi Govt. Hospital. Within the neighborhood, a lot of auto-rickshaw drivers live. This point creates the possibility for the locals to directly get an auto-rickshaw for reaching places that are

too difficult to reach with public transport alone. Other than that, for those who have adequate monthly income to own a private vehicle, consisting of either four-wheels or two-wheels, it becomes their main mean of mobility in their daily use.

4.2 Challenges & Problems

Based on the methods that we used throughout our fieldwork, we identified some predominant problems in the neighborhood which formed the main framework that we have worked on during the research project.

Throughout the first observations that we had in the study area, we could notice that people have many struggles walking through the neighborhood. There are many paths without any separation between pedestrians and vehicles and this issue has increased the possibility of accidents in the area. Furthermore, despite of hot and humid weather, there are no public or shaded places in the neighborhood for people who are walking to rest for some moment.

despite the existing problems, people mostly walk toward their destination. There is no public transportation in the inner areas of the neighborhoods and The auto rikshaws play the main role in transportation for those who consider their trip not walkable.

There is a large number of workers living in the area who have jobs on the mainland, mostly in Ernakulam. They are dependent on the ferry boat jetty station for transportation to this area of Kochi city. The other options for them are public buses and auto-rickshaws which are time-consuming and financially not suitable. The important point is that they mostly walk toward the station and are also facing the aforementioned problems.

Figure 11: Illustration on the site uneven roads condition & public transport’s limited reach within the site area (next page)

Figure 11: Illustration on the site uneven roads condition & public transport’s limited reach within the site area (next page)

Public bus tickets are around Rs.10 and ferry tickets are Rs.6. These two options are financially reasonable for the local people but As mentioned above, people usually do not use public buses because it takes too much time and they are dependent on the ferry for reaching the mainland. A trip from the ferry station to Ernakulam takes about half an hour and with the bus about 70 minutes.

If people want to get auto-rikshaws to the ferry boat jetty station, based on their distance from the station, they will spend around Rs.50-100. Hence, if someone just walks towards the ferry station, without considering the trip from the Ernakulam station to their work area, the person must spend Rs.12 for a ferry boat ticket, and if he/she takes an auto-rikshaws to and from the station, the cost will be around Rs.112-212 per trip.

For a low to mid-income worker group, who is at least working 5 days a week, taking auto-rickshaws everyday with the current price is not financially sustainable.

Based on A Study on Inland Water Transportation in Kochi City Region by Yogi Joseph, 2012, about 20 percent of users of the ferry station have an average income of less than Rs.5000, and about 50 percent of them have an average income between than Rs.5000-10000. These statics show that a high percentage of ferry station users are in LIG and MIG.

Additionally, the sanitation condition of the neighborhood is in very poor condition. There is no sewage system in the area and also the waste collection system is not responding to the current demand of inhabitants. As a result, most of the residents throw their garbage into the canal, and also the domestic sewage is ended up there. Therefore, the canal which can be a potential strong point of the area and utilized for different purposes in the future has turned into a significant environmental problem.

4.3 Problem & Opportunity Statements

With all the data and findings, we have identified the main influential problems in our study area in regard to accessibility problems and their impacts on livelihood:

Current public transportation system is not at a good level of accessibility for people.

On one hand, residents in the inner neighborhood of Fort Kochi do not have proper access to bus stops which are located on main roads. On the other hand, Walking toward the other possible option of public transportation, ferry jetty boats, is not really safe because there is a lack of designated sidewalks for pedestrians throughout the neighborhood which has made so many struggles for the local people.

Some people use their own private vehicles or auto rikshaws for not walkable trips in the neighborhoods or to the ferry jetty station. But financial limitations are the main barriers to using this mode of transportation all the time.

In spite of those, we also see some strengths and opportunities as depicted in the diagrams on page 39, that could be used to enhance the current situation in the area. It is important to consider these points when we are moving forward in our spatial solution and involve the existing community qualities.

4.4 Thematical Approach

Our findings and contextual understanding of the site indicate that several frameworks have been worked on and focused on including environmental and sustainability issues. However, we observed that in the area’s developmental trend, there are themes that are not discussed considerably, such as accessibility. Hence, we decided to focus on that issue, which covers transport and mobility, and how it affects the local’s livelihood. Accessibility, as defined by the Oxford English language dictionary, is the quality of being able to be reached or entered. Furthermore, Adhvaryu, S. Mudol (2021) defined accessibility in the context of human settlements to be generally perceived as the ease of access to goods and services across various destinations. Also, livelihood is perceived as the means and capabilities of how people fulfill their daily basic

““A livelihood comprises the capabilities, assets (both natural and social) and activities required for a means of living” Chambers, Conway (1992)

needs, which comprise various goods and services. These qualities are evident in our site where several conditions regarding the public transport scheme and the area’s physical infrastructure affect the local’s access and mean to procure goods and utilize public services.

Furthermore, it is important to distinguish between mobility and transport modes in the city context. Here we refer to mobility as the ease with which city dwellers can access different modes of transport. Mobility is the means by which a person gets from A to B (britannica.com) - private vehicles, trains, buses, taxis, scooters, tuk-tuks, boats, bicycles, and walking. Modes of transport are the infrastructure on which various mobility actions take place (britannica.com)roads, railway lines, dedicated bicycle or pedestrian lanes, avenues, and pavements. From here, an important point arises: unobstructed access to a mode of transport does not necessarily mean that an individual will be easily mobile in that mode. For example, a person can easily access a road but because of damage, tuk-tuks do not come along that way; or a person can access a canal but because of high levels of pollution, no boats operate in that area.

These types of problems may compel people to find alternative ways to get to their destination which can increase costs caused by being forced to take longer (alternative) routes; adding to this are tuk-tuks, taxis, boat operators, and others losing out on potential customers, all of which affects people’s livelihoods.

Accessibility, especially in terms of mobility and transport, impacted the livelihood level in the community, which then produce a living condition which is fragmented from the whole city system with much more limited opportunities to improve their livelihood

5. Strategic Spatial Solutions

5.1 Main concept for proposed solutions

With the city of Kochi focusing its future efforts and developments on “smart city” initiatives, there is an observable rise in disparities between what is actually implemented on the field and what the people need, especially those in a poorer state of livelihood and living in an area of heritage with rich historical context.

Thus we try to ask the question; what is our imagination of the smart city?

Is it a utopian world free from crime, pollution, and poverty in which all physical and human processes are cared for by technology? What informs us about what a smart city should look like and is there set criteria of what is entailed in order to qualify as a smart city?

For all its grand ambitions, in most practices, the smart city vision lacks inclusivity. We cannot deny the convenience, comfort, and overall human benefits that technology brings us, and in today’s intricately connected world and economy, there’s no room but to embrace it. So it is not so much about what smart cities can bring to an area, but more about the conversations, research, and pre-planning of the process. There is a “pre-packaged” idea of what a smart city should look like and aspire towards based largely on a technocratic obsession and influence on Eurocentric models (Aurigi & Odendaal 2020; Datta 2015).

This doesn’t work because local contexts have to be considered especially in the Global South – as Aurigi and Odendaal (2015:2) state, “This pre-packaged city concept vastly contrasts with the messy textures of real cities.” Secondly, the proposed planning of smart cities is not inclusive of local knowledge and opinions which is an act that pines the way forward to include local communities as co-researchers. So how is it that the ‘need’ to build smart cities is projected as sustainable when the areas in which the smart city is to be built, do not even consult with the communities who reside there?

We hope to fill in the gap here- to be the urban planners concerning the city of Fort Kochi by recognizing its unique ‘city-ness’ (Datta 2015) whilst including different spheres of the public and private sectors in all aspects of planning and research in the hope of building an efficient transport system that was created in an integrated manner.

The hope is to not implement a city that is preconceived as ‘right’ based on Western ideologies or imaginaries but to be smart about how we tackle urban problems based on the local context and with the assistance of local residents.

5.2 Ideas & Precedences

In focusing our efforts to work on different scales and systems for tackling the problems, we look at the existing example of how solutions for similar situations and context.

There are already several existing first and last-mile connection modes of transport in Asia. In Indonesia, for example, “bemo” which is a kind of a larger auto-rickshaw that could fit several people together, and “angkot” a minivan whose purpose is practically the same as autorickshaw, has been the major transportation providers for decades.

Secondly, the study and practice of inclusivity and accessibility, especially for the disabled, has resulted in the universal design standard code, which consists of additional markings and physical alteration in the space for those in need. Cyclist lane is also not a foreign concept anymore that has been tried to be implemented in Asian cities, although its success still needs to be questioned.

Finally, stands for auto-rickshaw to park and wait for customers has been existing in Kochi. Managed by the CITU (The Centre of Indian Trade Unions), these stands, sometimes formalized with a physical pole with signs, sometimes not, act as the place for drivers to gather and for passengers to seek auto-rickshaw service. What is lacking though is an open public space for resting and shading. Thus, we move forward with our proposed strategic solutions.

5.3 Auto-rickshaw (tuk-tuk) as micro-feeder transport system

Auto-rickshaws have played a major and important role in transportation and mobility mostly in south and southeast Asia and in some parts of Africa throughout the past century.

It has become a significant cultural and heritage aspect of the urban context in India. However, in the current flow of modernization & development in the country, the management & systems of auto-rickshaw have somewhat been perceived not as a priority, and even face considerable criticism from policy-makers. Even to the point where some cities have abandoned the use of it entirely. This argument is even highlighted by Hasan, Md. Musleh

Uddin and Davila, Julio D. (2018) in their study of the auto-rickshaw ban in Dhaka. They stated that the argument against auto-rickshaw is a result of a ‘glocal’ (global-local) coalition of political maneuvers to be a part of the auto-oriented and anti-NMTs (non-motorized transport) development trend. Additionally, it also helps to secure a place for national and international capital in costly transport infrastructure.

When analyzing and comparing various modes of transport, there is a great deal of use and advantages of auto-rickshaws in general, especially in the Indian urban context.

Harding, Simon E. et al (2016) describes the typical use of auto-rickshaws is when other transport modes are either unavailable or when walking or taking the bus may be more time-consuming and impractical.

They are most useful when used as first-mile and last-mile connectivity. They are often used for shopping, social trips, accessing health care, and as a popular means of carrying children to and from school. Furthermore, the elderly often prefer to hire them even for short-distance trips especially when a car is unavailable, and because negotiating busy roads on foot, or taking the bus, may be inconvenient or hazardous. Additionally, auto-rickshaws are also useful for carrying

goods to the market. They are also used by a wide range of income groups from the highest to the lowest due to their ease and availability.

In comparison, taxis, albeit more convenient and comfortable, are nearly twice as expensive to use per kilometer. Furthermore, unlike buses, they offer door-to-door, on-demand service. Even when hired on the street, auto-rickshaw trips involve considerably lower walking and waiting times than bus trips. Auto-rickshaws are mostly available at off-peak times, and away from public transit routes; these features are particularly important in the urban periphery, where public transit service may be lacking.

In terms of the auto-rickshaws management system, based on explanations from Hasan, Md. Musleh Uddin and Davila, Julio D. (2018), The rickshaw industry and its related service in India is almost entirely regulated by rickshaw (garage) owners. They may form some associations but these associations are patronized by political parties and deemed to have little success in putting forward the interest of the drivers. This kind of system is mostly a one-sided system where the owner is the one who decides the conditions and fares. Furthermore, depending on the local government, there is mostly no arrangement of auto-rickshaw basic fares from the government. This kind of scheme is not sustainable in the long run for auto–rickshaw drivers, especially when their daily income, as opposed to that of daily wage earners, is determined by their daily revenues and costs, which are complex and dynamic.

In the case of the calvathy canal neighborhood in Fort Kochi, as mentioned earlier, public transport is not a widely available option for the locals. They would rather walk or use their private vehicles which is not an available option for many poor families. Also, the dense inner neighborhoods do not have the capacity for a major transport system like public buses on the main roads. Autorickshaws are the type of vehicles that can go through these neighborhoods.

Furthermore, observation from the site reveals that most of the auto-rickshaw vehicles in the area park near where the driver lives when they are not roaming around the city, and there are a lot of drivers living there. After we got the chance to interview some of them, the conclusion we get is that:

“They love being auto-rickshaw drivers in the area because the area provides a lot of opportunities and income for them, both inside the neighborhood and the tourist area outside the neighborhood.”

“The drivers are organized under the CITU (The Centre of Indian Trade Unions), for their management and operations.”

“Main concern for them is mostly regarding the condition of the road, especially in the rainy season where gutters would be covered by a puddle of water.”

We are aware of the fact that autorickshaws are working under the supervision and support of some organizations like CITU and Fort Cochin Co-operative Society. This was the initial potential that we observed and thought that we can improve what has been functioning in the community more comprehensively. In this manner, we aim to enhance the availability of this type of transport by forming a comprehensive management system that includes the integration of formal and informal actors in a collaborative manner. This integration is crucial since acknowledging the complex reality of the existing diverse organizational bodies, they need to form a way to work together in a more effective way while ensuring socio-economical justice for the drivers.

The national and local government, down to Kochi’s municipality, together with the major transportation and infrastructure development agencies, acts as the formal body of this management system. This body could serve as the main legislator and resource provider, that could protect the auto-rickshaw vehicle and drivers’ legal framework, while also providing them with the opportunity to technically develop further.

On the other hand, the local governance which consists of wards, committees, and several existing organizations in the area act as the informal part of the management system. Informality here is not in the aspect of its organization, but rather in the aspects of its interaction and collaboration, where actions outside the formal sphere could happen easier in a more organic manner. This is done in hope that the interests of the local community and especially the drivers could be prioritized and advocated more.

As an example, formal stakeholders like urban governmental bodies can help in providing financial and technical resources that must be provided for the implementation and later evaluating the success of the project. Some other stakeholders like CITU can help in organizing the drivers and explain to them the goals of the project and how they can benefit from it.

At some point, even acknowledging the important role of women in the area, with the help of the Kudumbashree organization initiatives, could provide an initial discourse and potential for the cultural aspect of why almost all of the auto-rickshaw drivers are men. Furthermore, by managing the wages, fares, and availability of the auto-rickshaw modes of transport, on where and how they could gather and park based on the other proposals, this solution has the potential to improve their economic condition by providing more stable income, while also providing more opportunity for both the local residents and traveler from outside the area to have larger options to access the area.

5.4 Safe & inclusive corridor transformation

Based on our findings, the current situation of the paths in our study area’s neighborhoods is considered unsafe. There are no designated sidewalks for pedestrians in most parts of the neighborhoods. Therefore, no separation between car and pedestrian paths has made walkability struggles for inhabitants. Even though some paths have sidewalks for pedestrians to reduce the usual threats, the widths of these routes are not enough to ensure locals’ safety when they are walking through the neighborhoods. Furthermore, locals mainly walk toward their everyday destinations and these hazardous paths are a significant issue for the people living in this area. In this regard, we have considered some modifications that can be made to improve the current condition of the paths and modify them to corridors that are safe to walk and are not dominated by vehicles.

In this manner, first, we have presumed that the modification can be operated at a level that is not affecting inhabitants’ lives instantly and just illustrate how safe the roads can be.

Therefore, the first level of transformation to safe paths can be conducted by marking the paths to separate people and vehicle movements. The designated areas for pedestrians can be shown with some simple colors on the ground. In this way, residents in the neighborhoods can experience roads with less dominance of cars. After creating these markings, people’s opinions about this change must be gathered to see how much these designated paths have improved their lives.

The second level of changes can be implemented by creating physical alterations in the current paths. We could observe that the primary roads, the main road around the neighborhoods, and secondary roads, around the canal areas, have about 9 meters widths. There could be 1.8 meters of paths for pedestrians and 2.7 meters for cars. For local paths in inner areas of the neighborhoods, the widths are around 3.6 meters. The important difference between this kind of path with primary and secondary paths is that the cars’ movements are not so intense in the local ones. Hence, there could be half of the path designated for pedestrian movement. In this way, people have the possibility to walk on sidewalks that have acceptable widths which people are actually able to use and have a safer movement in the area.

The next phase of alteration cannot be implemented in the current condition of the roads. There must be an increase in the width of the streets to accommodate this change. In this phase, there could be a specific path for bicycles on primary and secondary roads to propose a new mode of transportation to people living in these neighborhoods. Hence, people can have more safe possible options for their transportation modes. In the local roads, in the case of any enlargements in the widths of streets, the priority can be considered for adding another pedestrian sidewalk. Meanwhile, the crucial point is that local people should express their opinion about this priority and within the reviews of the different phases of the proposed solutions, this priority can be understood.

Furthermore, the canal was an important means of transportation in the past, but the encroachments during the time, which reduced the width of the canal, made the utilization of it as a mode of transportation impossible.

There is not enough space for boats to move in two directions in the canal. Also, a specific place must be created as stations for this mode of transportation in some points of the neighborhoods around the canal which even make the proposal more like a long-term project that seems impossible for the people. It must be considered that changes in the width of the canal can result in possible flood threats. Therefore, these kinds of modifications need a deep analysis of the possible danger in this respect.

The other issue in regard to the present condition of the canal is sanitation problems. Nowadays, Domestic sewage is ended up in the canal and also people are dumping their waste in it. These issues have made any use of the canal impossible and for conducting any new projects for utilizing the potential use of the canal, first, these issues must be addressed. Proposing suggestions for how the canal could be used is impractical and does not seem rational to local people and other stakeholders. Therefore, it would not attract their support for these kinds of proposals.

Thus, this solution mainly focuses on improving the existing road conditions. We illustrate this improvement by identifying three types of roads in the area which consist outside (main road) and within the neighborhood; Primary, secondary, and local roads.

The hope with this solution is so that we could raise the local inhabitant’s awareness about road safety, and show the other uses of path to the vehicle owners through visual markings, while also still giving the user, especially locals, and other people the opportunity to discuss and review the result of the implementation.

5.5 Public space provisions in strategic urban pockets

Improving the current condition of corridors by creating physical alterations in the neighborhoods of Fort Kochi cannot reduce the concerns for pedestrian movements by itself in regard to walkability struggles. One of the important factors in Fort Kochi is the weather conditions in the area. The weather is always hot and humid and after walking for 150-200 meters, walking would not be easy in the area.

Based on primary observations in our transect walks, we could truly feel what locals are experiencing through their walkings in the area. Besides, there are no specific public spaces for inhabitants in Fort Kochi neighborhoods, paths do not have shaded areas to improve the walkability condition of roads for local residents.

In this manner, we have identified some abandoned areas without any specific land uses through the neighborhoods which can provide the public areas that are needed in the current situation of the area. Without an appropriate use for these spaces, it will contribute to a higher rate of safety and inclusivity issues. As this is the kind of situation that the area is facing right now, with some of these spaces are being used for drug-dealing and gathering for the alcoholic, thus making it very dangerous especially for women and children to access or go through these spaces.

The primary aim is to engender these places in walkable distances like 150-200 meters. These places varied from shaded places on the side of the roads to some public areas in the inner neighborhoods within which families can benefit. The provision of adequate lighting and open instead of fenced area is crucial to give these spaces easy community surveillance possibilities so that there are no dark pockets that could potentially be used for crime.

Some of these spaces should also be utilized as auto stands for the proposed autorickshaw system in the previous solution to give a more walkable and reachable place where people could board the auto-rickshaw. Based on our observations, the auto-rickshaw drivers tend to gather in the areas where there is more presence of people and it is normal. Because there are better possibilities for them to have more passengers.

However, there is a potential threat for public spaces which are utilized as auto stands to lose their inclusivity and be transformed into spaces that would not attract every group of people.

For instance, women mainly expressed that they do not feel comfortable around places where autorickshaw drivers gathered and they will not use them as public spaces where they can spend their free time with their children. Also, cultural issues regarding gender roles are also influencing this issue significantly. Therefore, the differentiation between these public spaces must also be considered.

5.6 Implementation Plan

To strategically implement all of the solutions mentioned above, we need to think of a strategic plan and timeline for how to realize them. This is especially true for us since the solutions provided are not individual separate solutions that are different from each other, but rather they are solutions that tackle the local challenges through a multi-level and multi-faceted approach.

Similar to our fieldwork and research approach, community focus is an integral part of our work, this translates to the need for these solutions to have multiple stages of workshops, reviews, and feedback sessions to test its relevance over time. Especially when there are a lot of stakeholders involved, and to prevent these solutions from being handled merely in a top-down manner and entangled in political chaos.

For the auto-rickshaw management system, the formation of this organization and management system involving every stakeholder is the initial and most important part of the process, to ensure that it’s effective and every part of the organization could contribute to the system. After that, it is also crucial to socialize this system to the executor themselves, the

drivers. Drivers need to be protected and prioritized in this system, so a robust database and information system regarding them needs to be built. This encompasses the holistic aspect of their occupation, from legal status and work contracts, to technical and intangible job-improving needs.

Another part of the implementation is the identification of the urban pockets and types of roads, so planners and constructors, collaborating with the local community, could appropriately choose which kind of intervention that is contextually accurate based on their analysis. This effort then needs to be monitored and reviewed through the second stage of the workshop, reviews, and feedback session since at this stage, there would have been interventions from the initial phase that are already happening.

By conducting the implementation of these solutions in this manner, if successful, we could then imagine the future possibility of these solutions being more sustainable and could even shift their priority to adhere to the green agenda even more. Focusing not only on the social aspect of these solutions, but also on their environmental aspect such as creating a more eco-friendly auto-rickshaw technology.

Strategic multi-level approach solutions are needed to address the accessibility and livelihood issues in the area. These solutions then need to be ensured so that they will cater to the local community’s needs. By creating a comprehensive implementation plan, hopefully, the solutions proposed could act as a bridge between the implementor and the people.

6. Conclusion

6.1 A Retrospective on Accessibility & Livelihood

After reaching the last stage of our project, we realized that both accessibility and livelihood, as aspects that are most prominent in an urban context, play an important role both in themselves and in relation to each other.

Based on our own experience on going through the site, the challenges of going around the area are clear and we could imagine how it is for the locals, especially for those who need to go to another place to fulfill their daily needs and economic income. Although the condition is somewhat perceived as normal by the local residents, and they don’t have many complaints, even regarding the canal’s conditions, we as scholars have the moral obligation to criticize how the condition is normalized and has become the norm for them.

Our argument emphasizes the livelihood aspect, especially for the breadwinner and the vulnerable groups such as women, children, and the elderly. Without effective modes of commuting, and the insurance of safety and inclusive development in the area, it will be a constant struggle for them to have an ideal liveability condition for their daily life or even for their future possibilities. That is where accessibility then becomes crucial, not only in the aspect of the ability to access destinations but also in the aspect of how to access them: mobility and transport. In a complex and dense urban context that is, but not limited to, our fieldwork site, a strategic, holistic, and comprehensive urban planning solution is needed. In focusing the efforts to cater to the needs of the local context, with an area-based approach, direct hands-on observation and interactions, participatory workshops, and community engagement become crucial in developing our proposed solutions. We hoped that by addressing these issues, among others, with our approach, we could provide an example of how appropriate and contextual urban planning intervention ideas could be done in the area.

Furthermore, we also emphasize that sometimes, the most obvious solution is not always the most appropriate. This is the case for the canal situation in the area and is the reason why we don’t prioritize our solutions on that aspect. While it is true that it was historically used as access for small boats, and could potentially be restored so that it could be used again as a means of transport, years and decades of degradation and encroachment of the canal have left it in a very bad shape. In order for the canal to be even considered, tremendous and complex efforts need to be done, especially in terms of waste management, canal revitalization, and pollution. Which are not realistic enough to be handled when our focus is not on those aspects.

6.2 Group reflection

We acknowledge that in order to have a truly comprehensive results in our project, we would need more resources and most importantly, time.

Due to being the second batch of students who arrived in Kochi, with the least number of group members, we are presented with a much more limited time and manpower to work in the field until our departure date back to Trondheim.

This report is by no means to give some condescending argument to any particular party, but rather, we tried to analyze the local context and try our best to develop ideas on what could be a solution for the local issues. Enriched and nuanced by our methods and process that are guided by our faculty and course coordinator, we hoped that we have approached this matter as inclusive as we could, and should.

It is thus evident, that the challenge of accessibility in our site area posed quite a number of potential issues that will in turn affect the people’s livelihood quality.

References and Bibliography

Adhvaryu, B. and Mudhol, S.S., 2022. Visualising public transport accessibility to inform urban planning policy in Hubli-Dharwad, India. GeoJournal, 87(4), pp.485-509.

Anon., 2005. Kerala Sustainable Urban, Kochi: Government of Kerala.

Anon., n.d. Kochi Guide. [Online] Available at: https://www.cochin.org.uk/

Anon., 2021. NNVNC. [Online] Available at: https://www.nnvns.org/jawaharlal-nehru-national-urban-renewalmission/

Anon., n.d. Cochin Smart Mission Limited. [Online] Available at: https://csml.co.in/smart-cities-mission/

Chambers, R. and Conway, G., 1992. Sustainable rural livelihoods: practical concepts for the 21st century. Institute of Development Studies (UK).

Corporation of Cochin (2006) “City Development Plan for Kochi City”

Datta, A., 2015. New urban utopias of postcolonial India: ‘Entrepreneurial urbanization’in Dholera smart city, Gujarat. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(1), pp.3-22.

Gachassin, M., Najman, B. and Raballand, G., 2010. The impact of roads on poverty reduction: a case study of Cameroon World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (5209).

Hamdi, N. & Goethert, R., 1997. Tools in operation. In: Action Planning for Cities: A Guide to Community Practice. s.l.:Academy Press, pp. 81-108.

Harding, S.E., Badami, M.G., Reynolds, C.C. and Kandlikar, M., 2016. Auto-rickshaws in Indian cities: Public perceptions and operational realities. Transport policy, 52, pp.143-152.

Hasan, M. and Dávila, J.D., 2018. The politics of (im) mobility: Rickshaw bans in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Journal of transport geography, 70, pp.246-255.

References and Bibliography List of Figures

Joseph, Y., 2012. A study on inland water transportation in Kochi City Region. Centre for Public Policy Research (CPPR) Working Paper Series.

Kuriakose, P.N. and Philip, S., 2021. City profile: Kochi, city region-Planning measures to make Kochi smart and creative. Cities, 118, p.103307.

Odendaal, N. and Aurigi, A., 2020. Towards an agenda of place, local agency-based and inclusive smart urbanism. In The Routledge Companion to Smart Cities (pp. 93-108). Routledge.

Pink, S., 2011. Images, Senses and Applications: Engaging Visual Anthropology. Visual Anthropology, Taylor & Francis Group, LLC, Volume 24, pp. 437-454.

Singhal, A. & Devi, K., 2003. Visual Voices in Participatory communication. 38(2).

Thomas, A. and Trost, J., 2017. A study on implementing autonomous intra city public transport system in developing countries-India. Procedia computer science, 115, pp.375-382.

Witten, K., Exeter, D. and Field, A., 2003. The quality of urban environments: mapping variation in access to community resources. Urban studies, 40(1), pp.161-177.

Figure 1: The group during participatory workshop in the Calvathy canal banks with local families. Source: Author

Figure 2: History and location of the project area: Kochi, Kerala, India. Source: Author’s modification from Livable urbanism research booklet by Cardiff University and Welsh School of Architecture (2021)

Figure 3: Evolution of Kochi over time from a trading outpost to a market centre. Source: Prageeja, K (2011)

Figure 4: A very dense market road in Ernakulam. Source: https://irisholidays.com/keralatourism/wp-content/ uploads/2011/04/broadway-shopping-kochi.jpg

Figure 5: Northern Fort Kochi area, where the site is located, which mainly consists of area with significant historical and heritage contexts. Source: Author’s modification from https://www.architecturaldigest.in/content/ essential-guide-kochi/ and Livable urbanism research booklet by Cardiff University and Welsh School of Architecture (2021)

Figure 6: list of methods used in the project. Source: Author

Figure 7: Diagrams of the 1st and 2nd initial site visits. Source: Author

Figure 8: Diagrams of the 1st and 2nd initial site visits. Source: Author

Figure 9: Diagram of the preliminary chosen site area. Source: Author

Figure 10: Interview session with Calvathy ward councillor, T.K. Ashraf. Source: Author

Figure 11: Impromptu interview session with one of the local elder in one of the community gathering space, conducted when students from NTNU and UCT visit Fort Kochi site together. Source: Author

Figure 12: Some of the results from the participatory workshop, mostly written by the local participants (Housewives, teens, and children) in Malayalam language. Source: Author

Figure 13: Participatory workshop with families and childrens living near the Calvathy canal. Source: Author

Figure 14: Presenting our work to the audience during the exhibition session. Source: Author

Figure 15: Wards allocation map in Fort Kochi. Source: Author’s modification from https://oneworld.website/keralapanchayatelection2020

Figure 16: Project’s site area, with places of interest highlighted. Source: Author

Figure 17: Stakeholders diagram & Government structure of Kochi Municipal Corporation’s (KMC) city area. Source: Author

List of Figures

Figure 18: Stakeholders diagram & Government structure of Kochi Municipal Corporation’s (KMC) city area.

Source: Author

Figure 19: Diagram of the average income of Kochi citizens. Source: Joseph, Yogi (2012)

Figure 20: Diagram map depicting the issue of the public transport’s reachability within the neighborhood..

Source: Author

Figure 21: Section diagram depicting the road condition on the selected area based on the previous map.

Source: Author

Figure 22: Images of some area in the site, depicting the existing road and canal conditions. Source: Author

Figure 23: Comparison diagram & map depicting distances, route, travel time, and fares from the site area to the mainland Ernakulam area. Source: Author

Figure 24: Image of the Fort Kochi Govt. Hospital where the bus station is located, and image of the inside of the Fort Kochi ferry jetty.

Source: Author

Figure 25: Image of the Fort Kochi Govt. Hospital where the bus station is located, and image of the inside of the Fort Kochi ferry jetty.

Source: Author

Figure 26: Excerpts from the interviews with local communities. Source: Author

Figure 27: Main problem statement and problem tree diagram. Source: Author

Figure 28: Opportunity and possible objective diagram.

Source: Author

Figure 29: Systems thinking diagram dissecting and connecting the theme of accessibility and livelihood. Source: Author

Figure 30: Description fo the project proposals’ vision statement, objectives, and strategies. Source: Author

Figure 31: Images of ideas & references for each proposed strategy & solution. Source: shutterstock.com, kookynet.net

Figure 32: Images of ideas & references for each proposed strategy & solution. Source: csml.co.in, Manuturi, V., & Asterina, N. (2022)

Figure 33: Images of ideas & references for each proposed strategy & solution. Source: Author, https://www. openplans.org/opsm

Figure 34: Diagram showing modal share of trips for different household (HH) income (inc.) Groups, 2009.

Source: Md. M.U. Hasan, J.D. Dávila (2018)

List of Figures

Figure 35: Conceptual framework of the 1st solution. Source: Author

Figure 36: Proposed management system and organization structure. Source: Author

Figure 37: Conceptual framework of the road’s transformation solution. Source: Author

Figure 38: Example of proposal’s implementation on the site. Source: Author

Figure 39: Conceptual framework of the public space solution. Source: Author

Figure 40: Render/collage showing the example of the possible public spaces. Source: Author

Figure 41: Render/collage showing the example of the possible public spaces. Source: Author

Figure 42: Implementation plan timeline. Source: Author

Figure 43: Timeline of the whole fieldwork process for our group in parallel with the other group. Source: Author

Figure 44: Photos of group 4 from the 2024 batch of UEP’s program conducting the fieldwork. Source: Author

Figure 45: Photos of group 4 from the 2024 batch of UEP’s program conducting the fieldwork. Source: Author

Figure 46: Photos of group 4 from the 2024 batch of UEP’s program conducting the fieldwork. Source: Author