SAO TOME . FONTAINHAS . MALA Panaji, INDIA Urban Ecological Planning AAR4525 – Urban Informality: Project Norwegian University of Science and Technology

SAO TOME, FONTAINHAS, AND MALA

Goa, India Fieldwork 2019

AAR4525 Urban Informality: Project Urban Ecological Planning

Department of Architecture and Planning Faculty of Architecture and Design Norwegian University of Science and Technology

Group 5

Sao Tome and Fontainhas

Annalise Winter Robin Surya Shayesteh Shahand

Group 6 Fontainhas and Mala

Fabian Wildner Nora Sønstlien Ursula Sokolaj

As a yearly tradition, the master students of Urban Ecological Planning (UEP) at the Faculty of Architecture and Design at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) embark on an immersive fieldwork during their first semester. This report is the outcome of a one-semester fieldwork in Panaji, India, conducted by the students in collaboration with the School of Planning and Architecture (SPA) Delhi. The fieldwork was part of a research project “Smart Sustainable City Regions in India” (SSCRI), financed by the Norwegian Centre for International Cooperation in Education (SIU), which included fieldwork in Bhopal in 2018 and Pune in 2017.

The diverse backgrounds and nationalities of students participating in the UEP fieldwork ensures a multi-perspective view. This year’s 19 fieldwork participants are architects, food sociologist, engineers, landscape architects and planners, coming from Albania, Australia, Austria, Ecuador, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Iran, Nepal, New Zealand, Norway, the UK and the USA.

PREFACE

The immersion of the fieldwork gives students a real-life practice of the ‘UEP approach’, which focuses on addressing urban complexities from an area-based and participatory point of view, leading to contextual, inclusive and humandriven development processes. Through daily interactions with local communities and relevant stakeholders, students become acquainted with residents and discover the complex realities of these areas, with their specific assets and challenges. By using a variety of participatory (design) methods, the students work on co-designing strategic proposals with the community and other stakeholders.

Students worked in the colonial Fontainhas area, the central business district and along the St Inez Creek. While the main topic of the course is urban informality in all its forms, this year’s students addressed topics such as public space, heritage, livability and environmental challenges. Warmly hosted by Imagine Panaji Smart City Development Limited, IPSCDL, students were asked to put their areas and proposals in the perspective of the Smart

Cities Mission, the large urban development fund and initiative currently implemented by the Government of India.

As an outcome of their learning process, students prepared three reports to illustrate and reflect upon the participatory process through a situational analysis and reflection on methods and methodology that informed a problem statement which they tried to address in strategic proposals. This report sums up the work done by group 5 and 6 in Sao Tome, Fontainhas, and Mala.

Hanne Vrebos, Rolee Aranya, Brita Fladvad Nielsen and Peter Andreas Gotsch, fieldwork supervisors, NTNU, Department of Architecture and Planning

3

PREFACE TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS INTRODUCTION HISTORY SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS GROUP 5 : SAO TOME AND FONTAINHAS 1: METHODS AND FINDINGS Preliminary Phase Secondary Phase Concluding Phase 2: STAKEHOLDERS 3: SUMMARY AND PROBLEM 4: PROPOSALS Conclusion 2 4 6 8 13 21 46 53 73 79 83 92

TABLE OF CONTENTS GROUP 6 : FONTAINHAS AND MALA 1. TIMELINE 2. METHODS Empathizing Defining Ideating Testing & Prototyping 3. STAKEHOLDERS 4. FINDINGS 5. PROPOSALS Community, Pride and Ownership Achieve Change in Regulations Building Awareness REFLECTION ETHICS STATEMENT LIST OF FIGURES REFERENCES 96 100 102 122 130 138 154 156 158 162

Dedicated to everyone who was involved throughout the process of making the following research and report feasible. Whom without, this work would not have been possible.

Firstly, we want to thank our professors from NTNU, Dr. Rolee Aranya, Dr. Peter Gotsh and Dr. Britta Fladvad Nielsen for their feedback and input they provided throughout the duration of the fieldwork. Special regards to our research assistant Hanne Vrebos, who organized insightful stakeholder presentations and meetings for us and who was always there for us during the entire three month fieldwork!

Having a beautiful workspace in the Old Secretariat, Adil Shah Palace, would not have been possible without the support from Imagine Panaji Smart City Development Limited. We enjoyed the wonderful facilities and the possibility to cooperate and collaborate with their team. They assisted generously in guiding us through understanding the structure, systems, and culture of India, Goa, and Panaji.

6

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We want to thank our wonderful host university, the School of Planning and ArchitectureDelhi, for inviting us to collaborate with their professors and students. Special thanks to Arunava Das Gupta, Sanjay Kanvinde, and Shveta Mathur who gave knowledge and guidance. And to Aditya Kushwaha, Arunima Saha, Hari Krishnan, Ranjit Singh, Rudra Sharma and Tarang Matia, we gained many skills and knowledge through your presence during the workshop week. It was a joy to work with you.

Last but not least, we want to thank all the residents and stakeholders who accepted us and embraced cooperation. We felt very welcome in our study area and were lucky to meet so many openhearted people, many of whom invited us into their homes and shared their stories with us. Special acknowledgement to the Bookworm Library for offering their facilities, making our workshop possible. And to Raghuvir Mahale for giving us constructive feedback countless times and consistently being open to discuss our ideas and proposals.

And finally, we would not have survived these 12 weeks without the strong cohesion amongst our cohort. Thank you for solving issues together, having a shoulder to lean on, and of course, having lots of fun and sharing laughter. It was probably the most extreme team-building experience ever and we are looking forward to the next semesters to come! To all the wonderful exchange students, you have been a crucial asset to our projects and your diverse backgrounds have made for a challenging and insightful collaboration. We will miss you and wish you luck in your future studies!

7

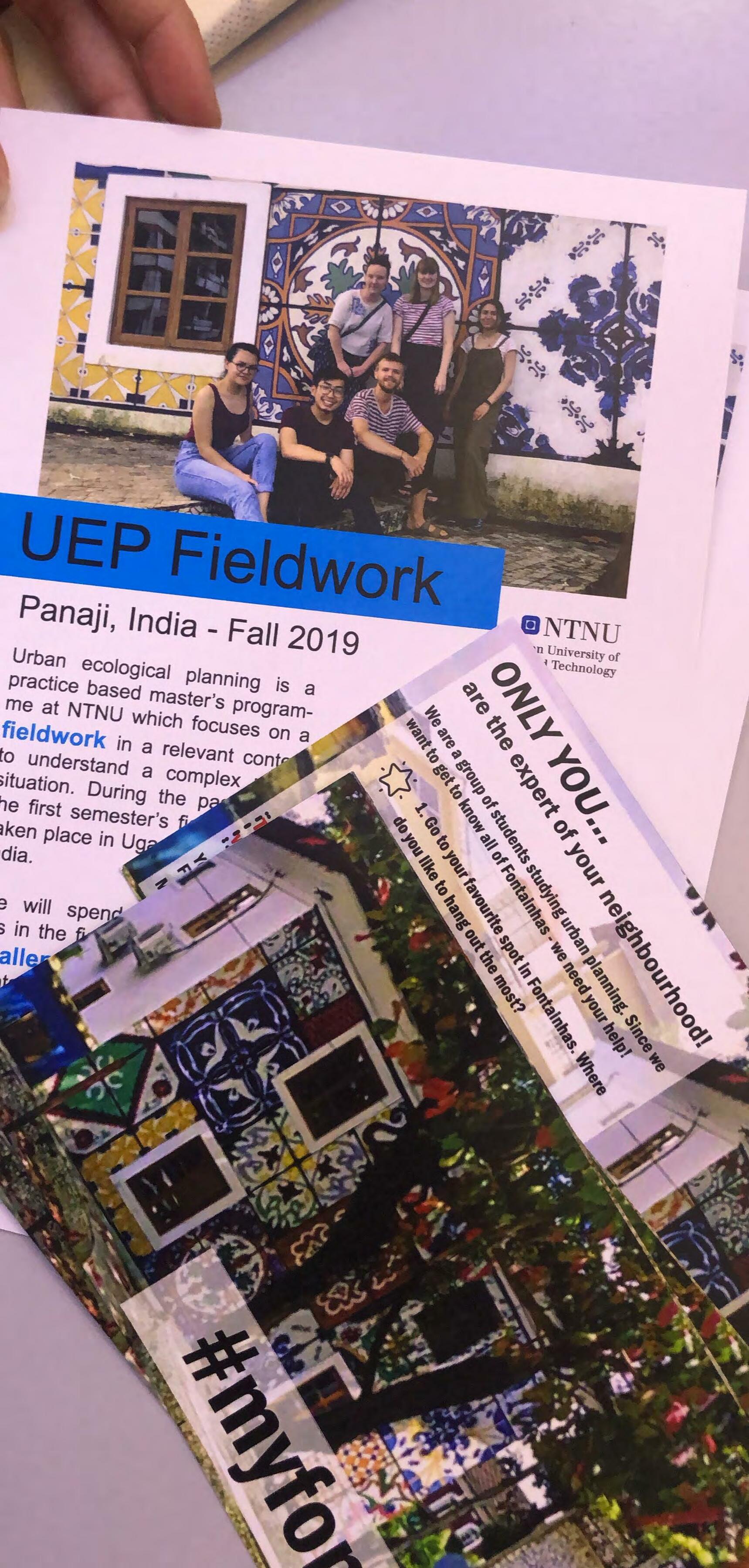

Figure 1.1. Students and Faculty of NTNU and SPA

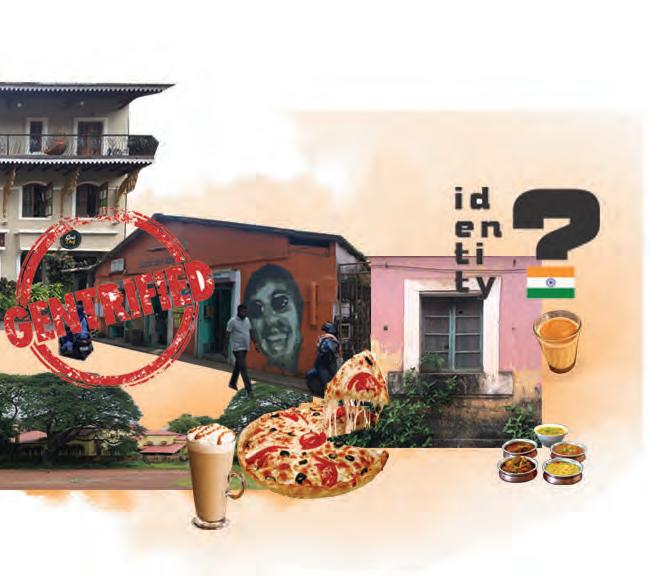

Entering Fontainhas is like taking a step back in time. Unlike anywhere else in India, the remnant of the Portuguese era is ever present in Panjim, but specifically in the neighborhoods of Sao Tome, Fontainhas, and Mala, some of the first areas of colonialism in Goa. Entering from the north, colorful heritage homes line the narrow and winding streets with their beautiful façades painted to perfection. There are restaurants, cafés, galleries and guest homes scattered throughout this historical area. But as the streets progress, the atmosphere and exterior begin to shift. Colors begin to fade, unkept buildings have fallen to ruins, and evidence of economic struggles emerge.

In the mornings, you will find locals outside their homes, noise picks up during the afternoons when the school children emerge, and in the evenings, you can spot tourists dining in the restaurants. While inside the neighborhood is fairly quiet and little traffic, the east boundary on Rua De Ourém street is a commercial hub, mainly catering to tourists, with heavy traffic,

8

INTRODUCTION

both vehicle and pedestrian. In the evenings, the smell of the river Rio De Ourém fills the air, making late night strolls less than pleasant. While often referred to as solely as Fontainhas, the area is actually comprised of three neighborhoods, Sao Tome, Fontainhas, and Mala. Each carries a unique identity, but with overlapping values and blurred boundaries.

For 10 weeks, our group of six masters students from the Urban Ecological Planning (UEP) program from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), conducted fieldwork in this area, attempting to grasp the complexities and challenges this historic area presents. The goal was to not only understand this place and the people in it, but also to uplift the residents and address their most pressing challenges. We collaborated with the stakeholders in this area to support their needs and bring them together as best as we could.

The following report provides a brief history of Panaji and Fontainhas and what the current

Smart Cities office, Imagine Panaji Smart City Development Limited, is addressing in the city. Following comes a situational analysis, pieced together through research, interviews, and lectures. After, the report splits into two sections as while there were six students in the field, after several weeks, we divided the area and worked three and three. Each section dives deep into the participatory methods used to gather data, an overview of stakeholders in these areas and proposals for strategic interventions. These proposals are meant to represent a bottom up approach and exemplify the needs of the community through their own voices. We did our best to act as facilitators of knowledge and not let our personal biases impose on the people we aim to serve.

9

Figure 2.2. Heritage house in FontainhasFigure

Figure 2.2. Heritage house in FontainhasFigure

2.1.

31st January Roadc

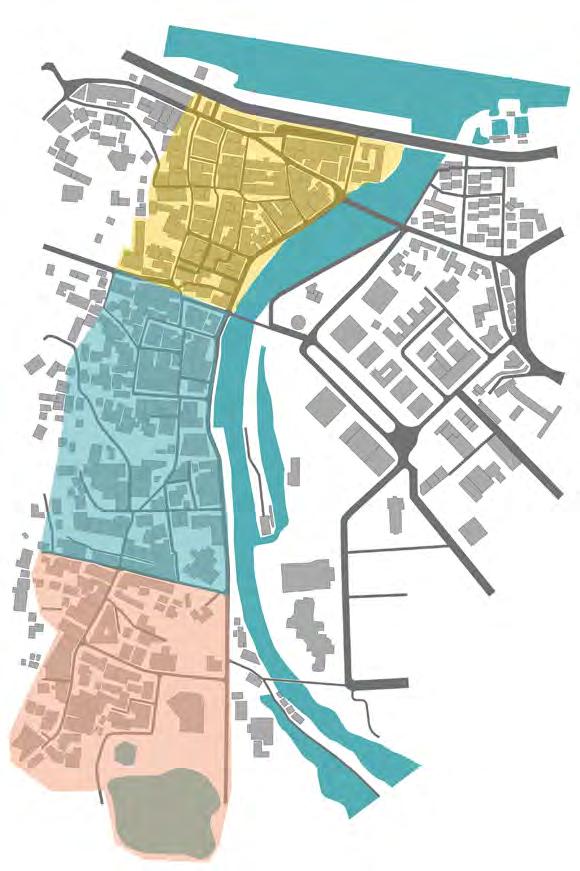

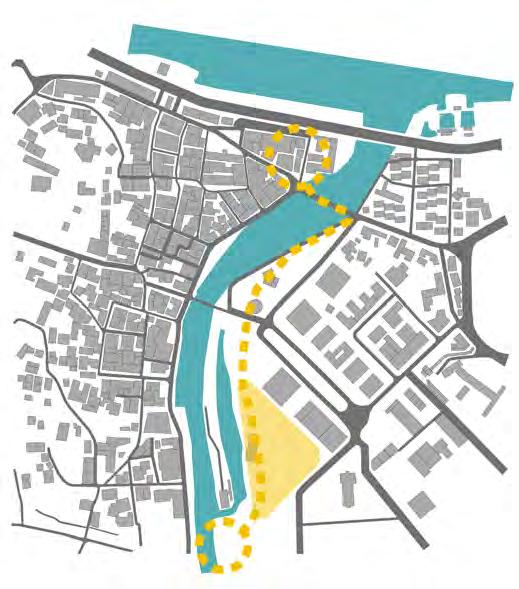

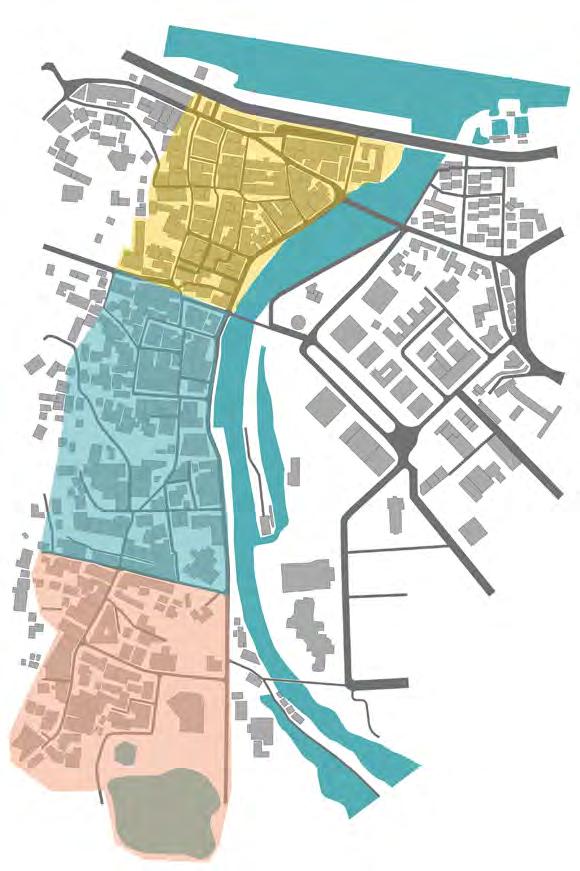

11 SAO TOME FONTAINHAS MALA City Center Patto Figure 2.4. Fieldwork SiteFigure 2.3. House in Mala

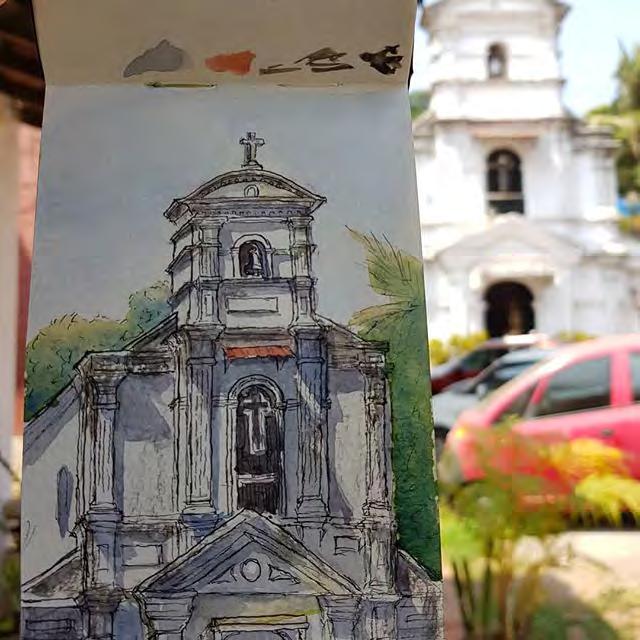

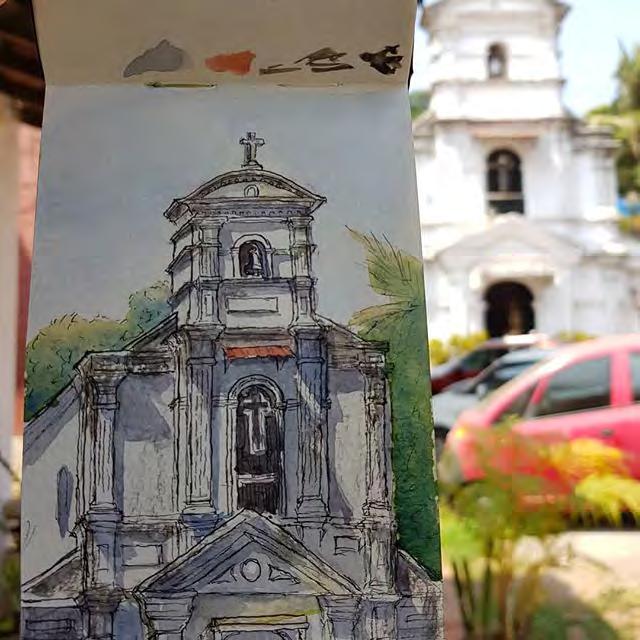

Figure 3.1. A sketch of Saint Sebastian Chapel in Fontainhas

Figure 3.1. A sketch of Saint Sebastian Chapel in Fontainhas

HISTORY

Panaji, also known as Panjim, is the capital city of the state of Goa in southern India and is known for its Portuguese architecture, seafood specialties, culture, and more recently, casinos. While Old Goa used to serve as the capital city, in 1843, Panjim was declared as the new capital by the royal decree, but was named Nova Goa at the time, under Portugeuse rule (Ahmed & Shankar 2012b). After liberation in 1961, Panjim was still the acting capital for the territories of Goa, Daman, and Diu and in 1987, the government officially reconfirmed Panjim as the capital once Goa gained its statehood (GHAG 2017, pg.34 ). But before becoming the capital city, Panaji served as a coconut grove surrounded by rivers, creeks, canals, and saltwater rice paddies that was ruled by Portuguese colonizers for more than 450 years. Goans gained their freedom over 50 years ago, but the lasting effects of this history can be seen throughout the entire city through language, religion, and perhaps most

discernible, architecture. Panjim’s borders include the Mandovi river to the north and Rio De Ourém creek to the east. This created plenty of opportunities for trade and fishing along the waterways, making it an ideal location for settlement.

The Portuguese came to Panjim in the 16th century and are responsible for constructing all the now designated heritage buildings of Panjim, with the exception of the Adil Shah Palace, which was constructed by Muslim king Adil Shahi in the 15th century prior to Portuguese conquer. After this time, the construction of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception Church finished in the beginning of the 17th century and still stands as the centerpiece landmark of the city (Government of Goa 2019). In the 18th and 19th centuries, Portuguese settlers began constructing the first residential neighborhoods in Sao Tome, Fontainhas, Mala, and Portais, on the west

13

side of Rio De Ourém, while government and official buildings were constructed on the hill of Altinho. Due to the natural water boundaries, as the city expanded, construction took place west of existing neighborhoods, creating what we now know today as the central business district.

The neighborhoods of Sao Tome, Fontainhas and Mala sit on land that was formerly occupied by coconut plantations, village huts, rice paddies and mangroves (Ahmed & Shankar 2012, pg.546). But as wealth in the area increased, residential development by wealthy Catholic Portuguese descendants cleared the area and created the vibrant neighborhoods that remain on the east side of Panjim. The homes are unique in every way due to the clash between the European Portuguese style, Goan influence, and building materials available in the region. Characteristics include brightly colored exteriors, Mangalore tiled roofs and Solomonic columns, all of which can be seen today. Construction of these homes in these wards began in the early 1800’s and continued until liberation in the 1960’s.

Panjim experienced a rapid economic growth towards the end of the second millennium, due to thriving tourist economies and mining in the state, creating new opportunities for Goans (Ahmed & Shankar 2012a). The rapid expansion and development in the 1990’s can be looked at as positive for the city, but it came at the cost of demolishing old structures to manufacture new and modern buildings. This happened throughout the city, even in

the neighborhoods of Sao Tome, Fontainhas, Mala, and Portais, as it became more valuable for the land and property owner to rebuild then to add onto or fix existing property. While economic gain for the owner is an important value of land ownership, history, heritage and significance of the uniqueness of historic homes became apparent when many were lost, thus creating need for preservation. Therefore, the neighborhoods were declared a heritage conservation zone in 1974 and were reaffirmed in the 2011 Panaji development plan (Sukhij 2019). The Charles Correa Foundation and Goa Heritage Action group have documented each heritage home in their book The Mapped Heritage of Panaji Goa.

Panjim Today

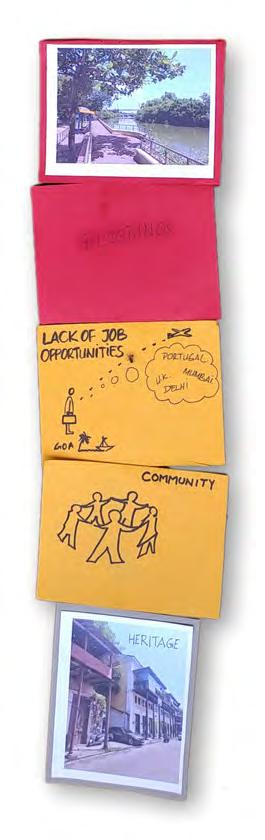

Panjim today is a thriving capital, full of life and culture, and is one of the few places in India where Christians, Hindus, and Muslims live harmoniously as neighbors. But things have been changing rapidly over the past decade. Goa is unique for several reasons, one of those being the legality of gambling in this state. That has brought 15 live gambling casinos to the state since 1999, five of those being boats on the Mandovi river (BBC 2013). While the taxes from the casinos have brought a huge amount of revenue to the state and local governments, locals are less excited about how this recent industry has changed and shaped the city. Previously, tourism in Panjim was focused on heritage and Portuguese architecture, but the introduction of gambling into the city, and state, has brought an influx of domestic

14

Figure 3.3. Mandovi River and Adil Shah Palace from 1950s (Nadkarni 2003, pg. 23)

Figure 3.2. A Historic Photo of Ourém Creek from 1950s (Nadkarni 2003, pg. 26)

Figure 3.4. Fontainhas and Mala Seen from Altinho Hill

Figure 3.3. Mandovi River and Adil Shah Palace from 1950s (Nadkarni 2003, pg. 23)

Figure 3.2. A Historic Photo of Ourém Creek from 1950s (Nadkarni 2003, pg. 26)

Figure 3.4. Fontainhas and Mala Seen from Altinho Hill

tourists. Ask any local and they will blame the casinos and gambling for misfortunes of the city. While not responsible for all the troubles in Panjim, the river boat casinos do have major implications for residents including parking and traffic congestion, river pollution and increased tourism to Panjim.

Smart City Mission Panjim

Imagine Panaji is one of the 98 branches of Smart Cities in India, initiated by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA). The goal of a Smart City is to provide life enhancing alterations to a city through infrastructure or societal changes. Smart City works on new or existing development projects with an emphasis on inclusion, sustainability and technology. Projects should improve lives, economic opportunities and prioritize citizens as well as display replicability for other cities going through the same challenges (Imagine Panaji 2019).

Panjim’s Smart City development and projects are being designed and implemented by Imagine Panaji Smart City Development Limited (IPSCDL), a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) of the state government (Imagine Panaji 2019). This government company is led by Managing Director and CEO Swayandipta Chaudhuri and a team of urban planners, architects, and public policy leaders. The purpose of this SPV is to fast-track development projects that enhance the quality of the city. IPSCDL has the freedom to mobilize resources, fund and execute projects in a way that traditional planning departments

16

Figure

3.6.

Beautification on Stairscase in Mala

Figure 3.5. Casinos on Mandovi River

lack. They claim to focus on citizen well-being, pedestrian friendly initiatives, sustainability, livability, biodiversity, and multi-modal transit systems. Existing projects for Panaji include a redesign of parking policy for the city, emphasis on beautification and public space around Panaji, and cleanup of waterways in the city as well as many others.

Fontainhas Today

Sao Tome, Fontainhas, and Mala sit at the base of Altinho hill, with Sao Tome being the northern most neighborhood of the area, Fontainhas in the middle, and Mala to the south. Collectively, this area can be referred to as Fontainhas but there are notable differences in the land-use and religious influences between the neighborhoods, as Sao Tome is more commercial and Catholic, Fontainhas is residential and Catholic, and Mala is a residential neighborhood but predominantly Hindu. And though today, these areas may look very similar to the colorful neighborhoods built by the Portuguese Catholics, many things have changed in the area as a result of the long history. Fontainhas was named after the spring at the southern end of the neighborhood that historically supplied the area with water (Panjim and Its History 2019). It is commonly referred to today as the Latin Quarter of Panjim for the style of housing and chapels, specifically the Chapel of St. Sebastian and St. Thomas Chapel in Sao Tome. Due to its history and beauty, the neighborhoods of Sao Tome and Fontainhas have become a hub for tourism. The buildings painted in bright reds, yellows,

17

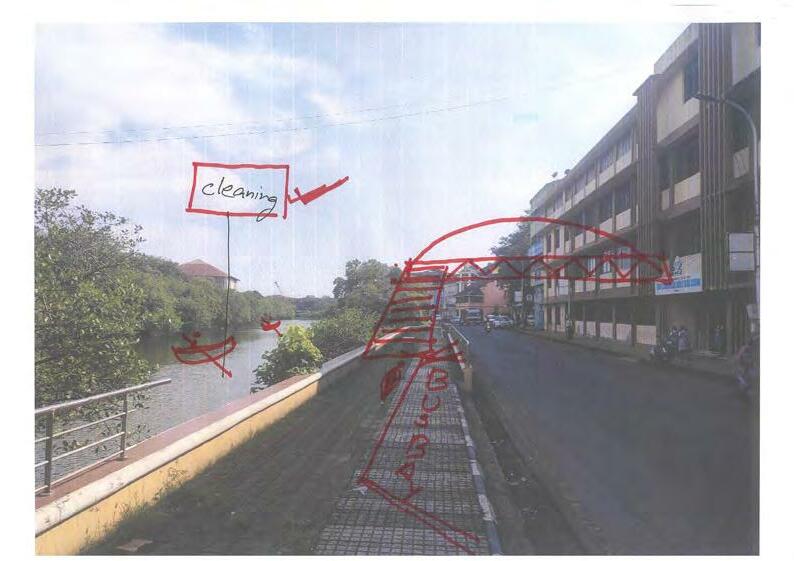

Figure 3.7. Beautification on Pedestrian Bridge over Rio De Ourém Creek

Figure 3.8. Marquito’s Guest House Fontainhas

and blues attract both domestic and foreign tourists and walking through the streets, one can see the influx of passersby’s observing the structures and taking photos.

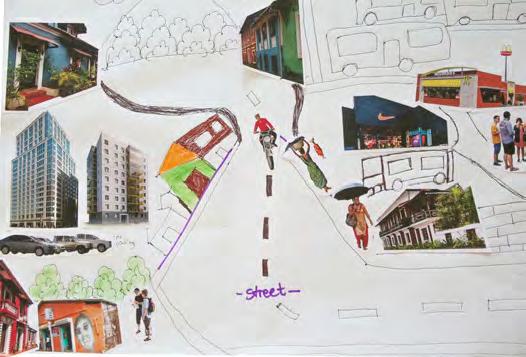

The beauty that has attracted tourists and the heritage conservation designation has created an interesting and complicated dynamic for residents of Sao Tome and Fontainhas. The regulations on heritage conservation of the homes has created an undue financial burden on the residents, yet the preservation brings in tourism. This has created economic opportunity for residents and through the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, we can see a transition in many of the homes from residential space to commercial space in the form of guest homes, restaurants, cafés, galleries, and boutiques. This type of transition still happens today, but the residents struggle with this double-edged sword. On one hand, tourism brings money and jobs to Fontainhas, yet on the other, tourism brings noise, disruption, and rubbish as well as puts a strain on infrastructure and resources.

Smart City Mission Fontainhas

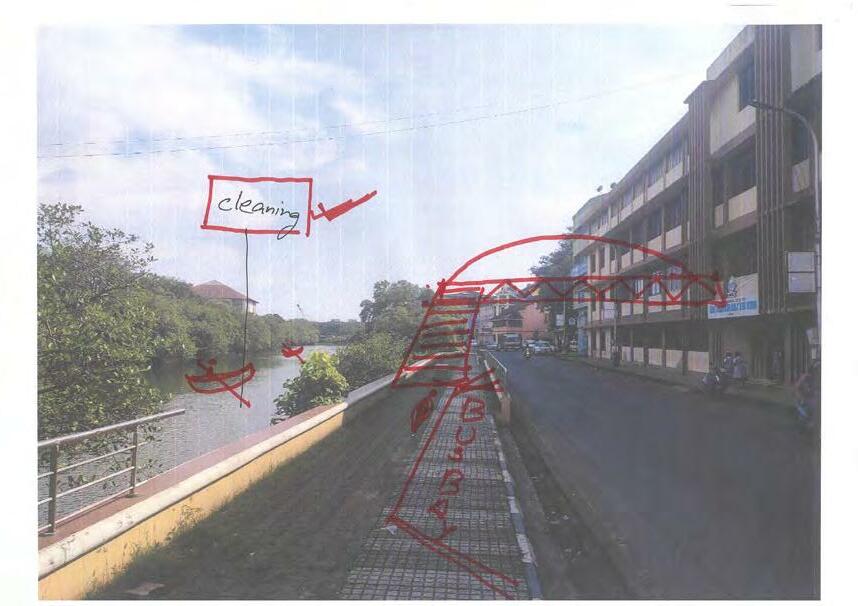

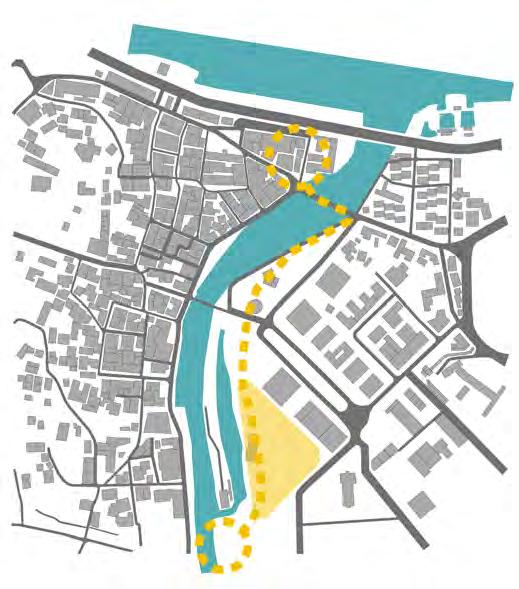

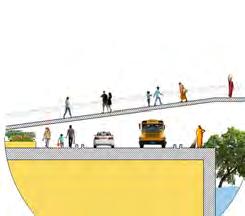

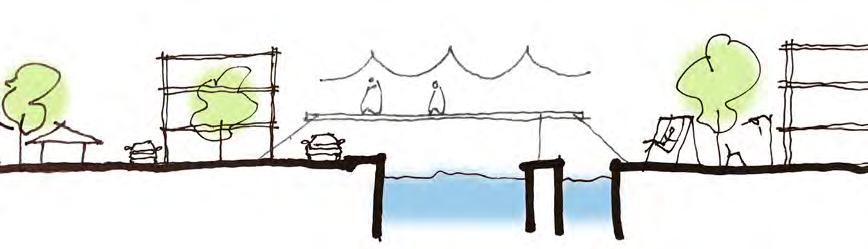

IPSCDL has already completed several projects in the Sao Tome, Fontainhas, and Mala neighborhoods, as well as pertinent projects nearby, that while technically not inside the boundaries of Fontainhas, have implications for the residents of these neighborhoods. Beautification projects have taken place on a large staircase in Mala and on the footbridge connecting Fontainhas neighborhood to Patto, the new business district. If one crossed the

footbridge and headed south towards the public library, they would find another Imagine Panaji project behind the public institution, the Mangrove Boardwalk. While technically in Patto, the boardwalk is accessible by foot to the residents of Sao Tome, Fontainhas, and Mala.

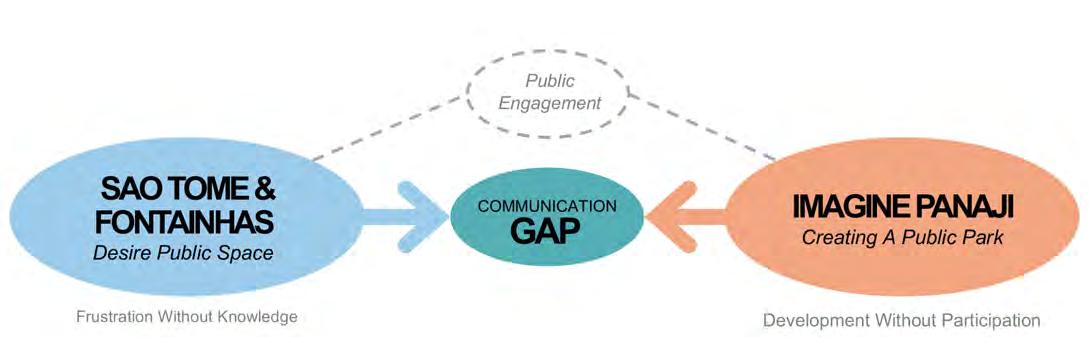

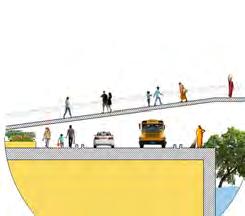

Future projects that are being considered for the area are a redesign of Rua De Ourém street to reduce traffic congestion and hazards and a redesign of the junction at the north end of the same street in an effort to increase traffic ease and efficiency. The last major project for the area is on the east side of Rio De Ourém in Patto and is an addition to the completed Mangrove Boardwalk. Using existing infrastructure in combination with new development, Imagine Panaji plans to connect the Mangrove Boardwalk to the Mandovi river, allowing one to walk the entire stretch of the east side of the river. There are also plans for a public park that connects to this boardwalk.

18

Figure

Figure

3.9. Heritage

Buildings in Fontainhas

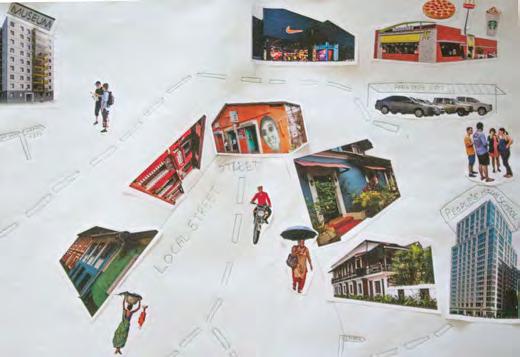

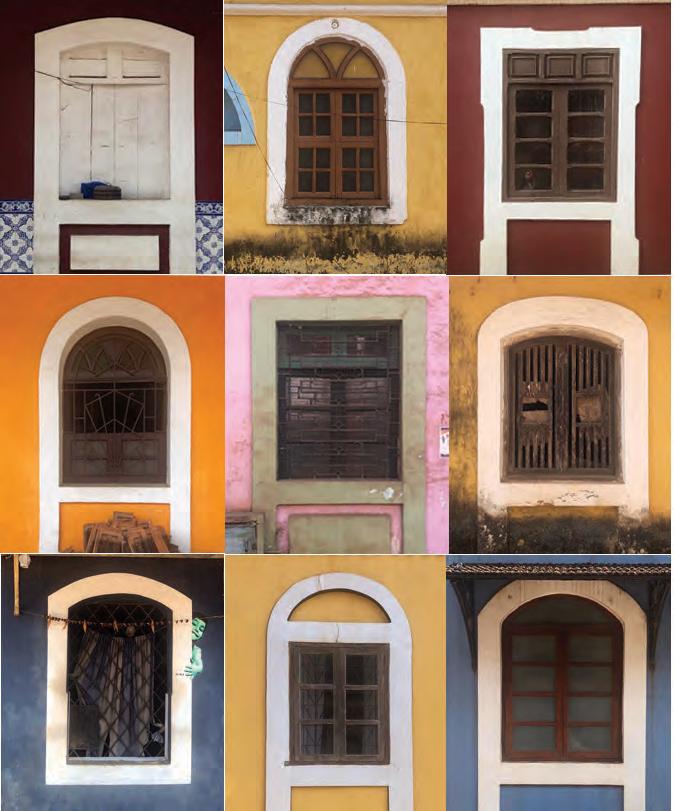

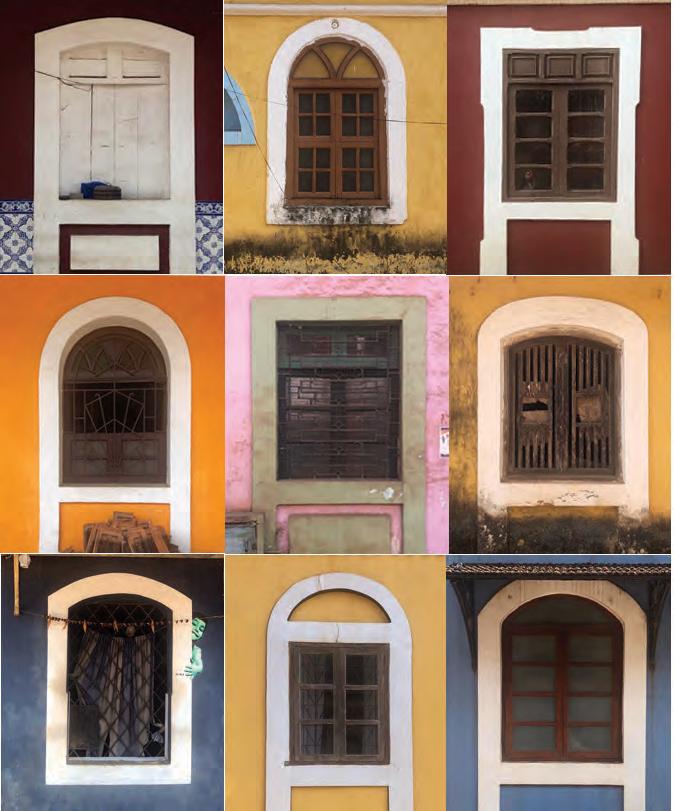

Figure 4.1. Collage of

Windows

in

Fontainhas

SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS

Analysis of the current situation in Fontainhas has been assessed using the livelihoods framework proposed by Carole Rakodi. Trying to understand and capture the complexities of a new area can be overwhelming and there are a multitude of ways to approach it. We chose to use this framework for our analysis to provide a comprehensive overview of the current situation in Sao Tome, Fontainhas, and Mala. The framework defines five types of assets: human capital, social capital, natural capital, physical capital and financial capital, each of which is explored and applied to the research field. This approach not only tries to grasp the vast range of resources and activities in which people depend for their livelihoods but also attempts to achieve an exhaustive view of the structure, strengths and essentials within a community. The livelihoods framework is a useful tool to capture crucial components and build a foundation for identifying potential leverage points for interventions (Rakodi 2002).

PHYSICAL CAPITAL

Physical capital is the basic infrastructure (transport, water, shelter, energy, communications) and the production equipment which enables people to pursue their livelihoods (Rakodi 2002, pg.11). It is one of the most dominant assets of Fontainhas, based on its value as a heritage area. In this analysis, it has been categorized into four main topics: land use, building typology, infrastructure and mobility.

LAND USE

While residential is the dominating land use category in Fontainhas overall, its density differs between the three wards composing the area. Mala has remained a more quiet neighborhood consisting mostly of residences. However, in Sao Tome and Fontainhas, many of the houses have been converted through the years, partially (ground floor) or fully, into commercial functions such as shops, cafés, restaurants, hotels and guesthouses, thus resulting in a mixed use character.

21

Public Building Commercial Residential Figure 4.2.

Land Use Map of Sao Tome, Fontainhas and Mala

Housing and Heritage

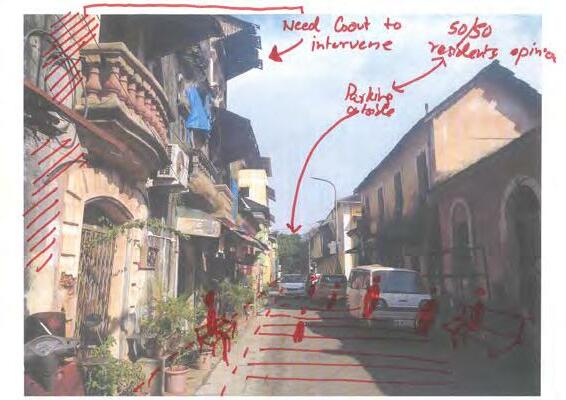

The Portuguese influence is strongly manifested in the area in the Indo-Portuguese style of architecture. With the narrow colorful streets and the facades decorated with pilasters, cornices and moldings, Fontainhas has been considered and protected by law as a Heritage Conservation area since 1974 (Mohta 2011, pg. 34).

The basic material used in the construction of the houses was taipa (wetted mud), reinforced with bamboo netting and coconut husk, while the walls were plastered with a lime and cane jaggery mixture (Ahmed & Shanker 2011). The houses date back to the early 19th century, meaning they are nearly 200 years old. While the materials then were in abundance, today these construction techniques require a lot of effort. Furthermore, consistent maintenance for these buildings demands financial resources that the residents do not possess. Today, many of them face physical deterioration due to lack of funds. Some of the owners have chosen to disregard the regulations and demolish the heritage houses to build modern buildings in their place. This has been done with no consideration to the historical context, by both disrupting the height proportions and the architectural style.

Ownership

Another important factor contributing to the current problematic condition of the houses is

the issue of ownership. Having been inherited from one generation to the other over a long period of time, the houses now have split ownership between many people within the same family. This brings disagreements, long procedures and even lack of responsibility, making it difficult to take any kind of action.

INFRASTRUCTURE

Streets

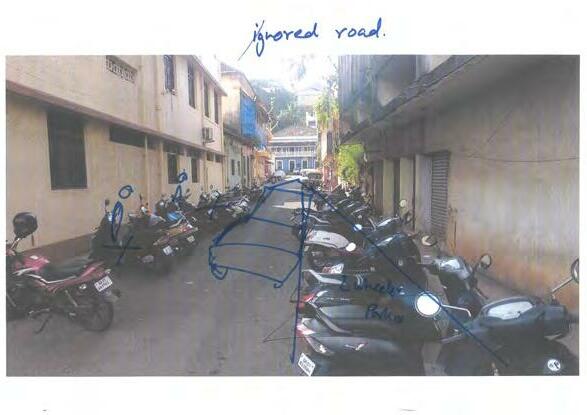

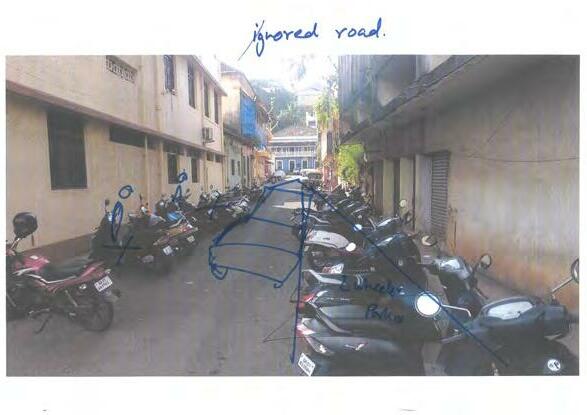

Fontainhas is organized in a linear profile, along a main spine of Rua 31 de Janeiro. The spine stretches and narrows organically, adding an element of surprise to the experience of walking through it. Houses on both sides open directly onto it. The spine was initially created as a pedestrian pathway, but nowadays it suffers from vehicular congestion disturbing the street life.

23 BUILDING TYPOLOGY

Figure

4.3.

Rua 31 de Janeiro

Narrow Alleys

The smaller streets on the sides of the spine have less vehicular movement. Because of this, the residents take their function beyond just transportation, turning them into extended living areas, especially for smaller households.

Main Open Spaces

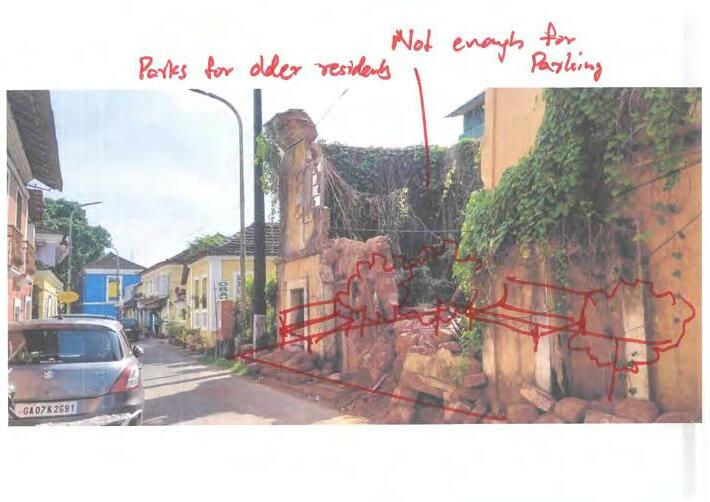

The Marble Plaza, the Hedgewar school playground and the Mala lakefront are the main open spaces in the area. The Marble plaza is the most active one, used by different groups of people at different times of the day. In the morning hours you will see loud primary school kids brought by their teachers for their playtime. In the afternoon, high school students will come during their break for a chat or a badminton game. And at all times of day, commuters, tourists and residents will be hanging out and relaxing under the shade. The Hedgewar school playground, located in Mala, is used mostly for games and tournaments, however, with the relocation of some of the schools from the area, it has become vacant more often than not. This is especially true during the rainy season when because of the mud, its usage is inconvenient. The Mala lakefront is another space with high potential, however because of the poor conditions of the lake, it has turned into a forgotten area.

Several proposals for revitalization of the lake have been created, but all were dismissed before they sought funding.

Figure 4.4.

Narrow Alleys as Extended Living Areas

Mobility

Location and Connectivity

Fontainhas is a linear narrow settlement which is bounded on the east by Rio De Ourém creek and on the west by Altinho hill. It stretches from Mandovi river on the north until Fonte Phoenix, marking its southern limit. Fonte Phoenix at the foot of the hill is where the settlement initially started growing.

Fontainhas can be accessed by public transport only along its edges, Avenida Dom Joao de Castro Street and Rua de Ourém

along the creek, while the interior roads of the neighborhood can only be entered by private vehicles.

In comparison to the rest of the city, the area does not suffer from as severe traffic congestion, with the exception of the school ending hours, when the parents picking up their kids overcrowd the streets with their vehicles.

Parking however is an issue in the area. With no designated car parks, people have no choice but to park their cars and motorbikes on the sides of the roads, making them even narrower than before and disturbing the historical character of the area.

25

Figure 4.6. Public Transport and Traffic Congestion Points

Figure 4.5. Marble Plaza

Figure

Figure

4.7.

Students from Mary Immaculate High School

HUMAN CAPITAL

Human capital is defined in the livelihoods framework as the quantity and quality of labor resources available to a household. The ability of households to manage their labor assets and take advantage of opportunities for economic activity is constricted and facilitated by the levels of education, skills and health status of the household members (Rakodi 2002, pg. 11). In Fontainhas, the people have decent opportunities to get an education, learn skills and take care of their health.

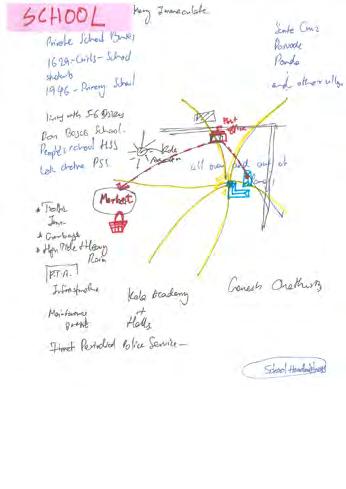

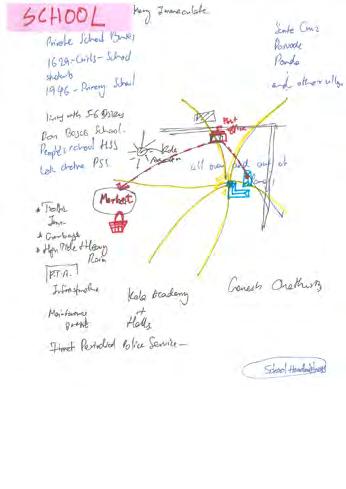

EDUCATION

Within the Fontainhas area there are many options for education, both for children and adults. There are four schools, one public and three private, ranging from pre-primary to high school level. The People’s Higher Secondary School, founded in 1936, is the only public school in the area. This is a highly regarded institution, and pupils come from far outside the community to study there.

Two of the private schools are run by religious organizations, Mary Immaculate Girls High School, opened in 1971, and the Seventh Day Adventist English School, opened in 1974. Lastly, there is a private pre-primary school started in 2001, Lok Chetana. All the schools have good rankings and many extracurricular activities.

In addition to the schools in the area, there are several places that offer private tutoring for

children after school. This is usually in private apartment or houses.

In terms of skill building and adult education, there are various opportunities for the residents. First one is Stenodac, an institute for career training and professional education for adults. It was established in 1971 and has courses within a broad range of fields and subjects such as journalism, computers, office training, etc.

Secondly, the Bookworm library is a library and non-profit organization which hosts a variety of free workshops for children and adults. They have reading and writing workshops, a needle craft group, a preschool program and an adult arts program.

The last one is the women’s association where women come together to cook and sell their food in the Panjim main market. This promotes skills such as cooking and business management.

HEALTH

The residents of Fontainhas have a few options regarding health services. The first one is a private hospital located in the southern part of Fontainhas. This is part of a chain of private hospitals and is not a viable option for a lot of the residents as it is quite expensive. The other option is a public hospital in Bambolim, which is 5-6 km away, so it’s necessary to travel by vehicle to get there.

There is also a small pharmacy in the area where the residents can get medicine and medical aid for small injuries

27

SOCIAL CAPITAL

HIGH - INCOME TOURISTS

Staying for 2-3 days, mostly in heritage-hotels

Heritage-Walks, Fine-dining, organized trips

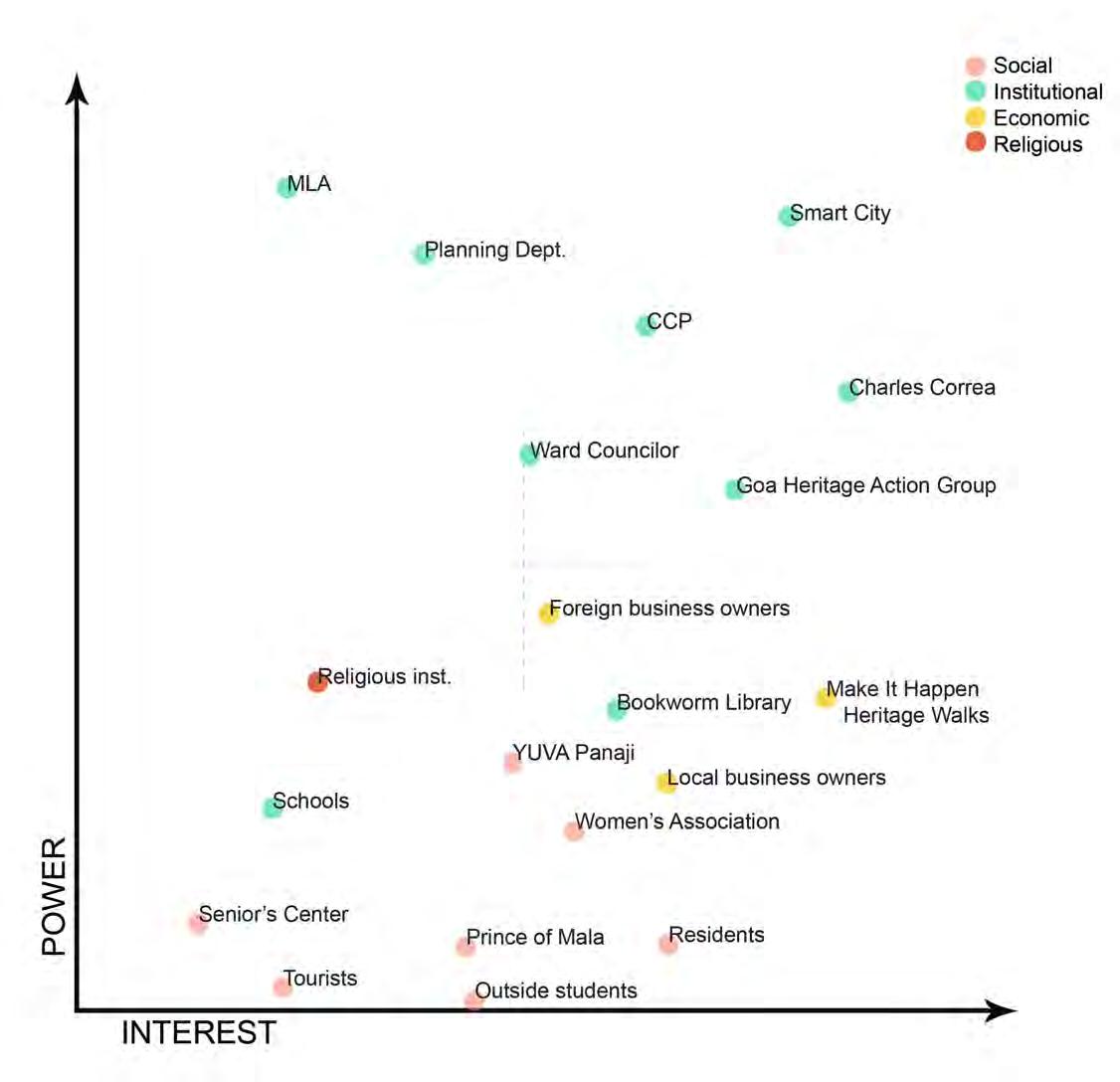

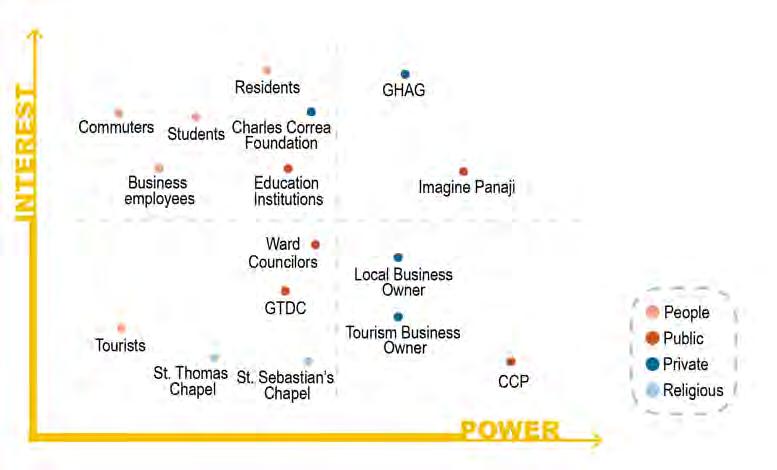

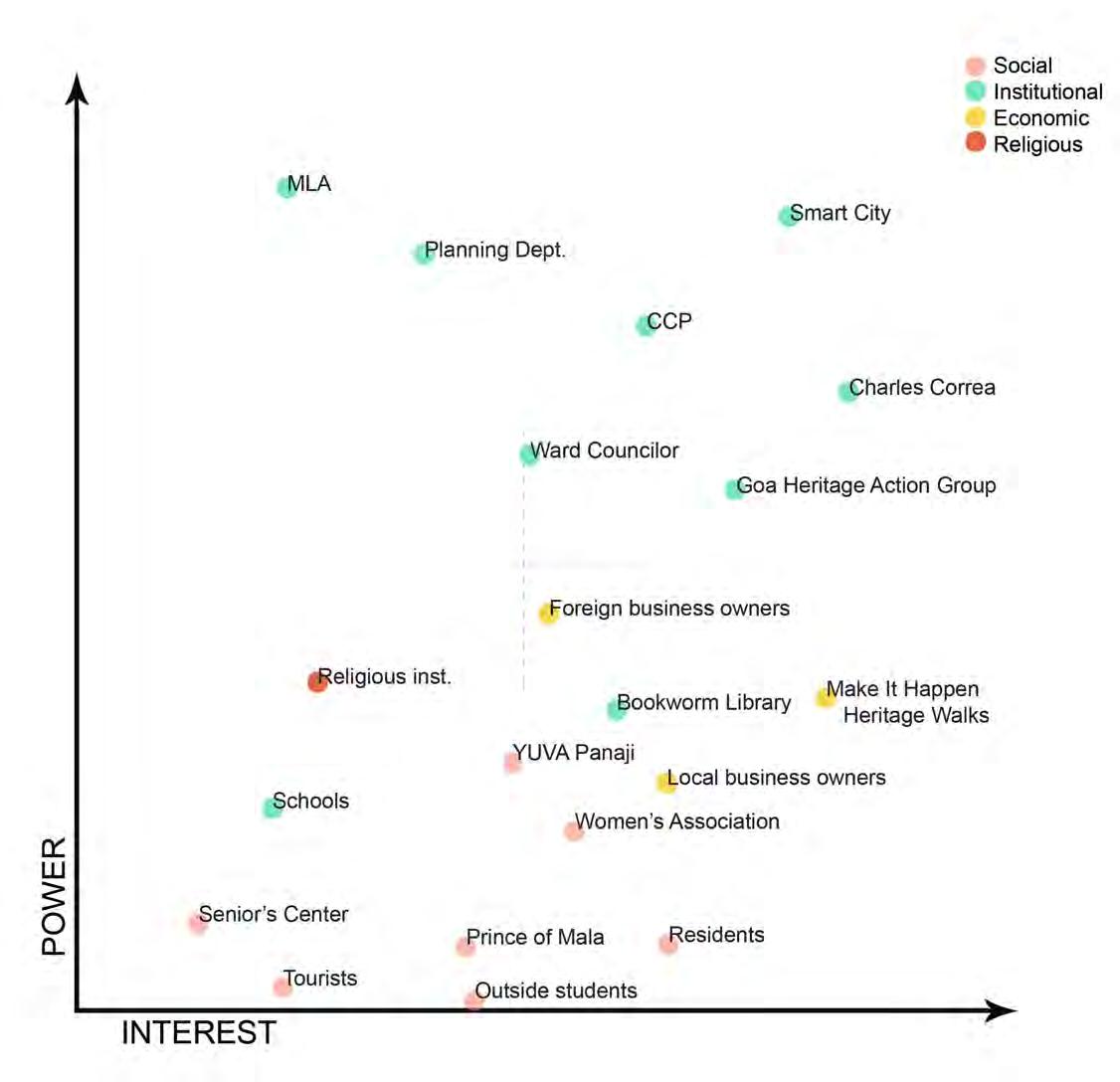

Social capital is one characteristic of a neighborhood and one of the components of the sustainable livelihood framework. Regarding to the Department of International Development social capital is defined as “social resources upon which people draw in pursuit of their livelihood objectives.” (Department for International Development, 1999) These resources contain networks (vertical or horizontal, bonding or bridging), memberships and relationships. In our study area we focused on showing and analyzing the different user-groups as well as to highlight the existing civic engagements like associations, foundations or even institutions.

NETWORK STRUCTURE AND INFLUX

Fontainhas is the most multicultural area of Panaji city, due to its historical context which leads to a mix of religious groups. The numerous institutions such as schools, care-centres, public and private institutions and others, make Fontainhas an important location on a local and regional level.

Tourists

The influx of tourism in Fontainhas has been rising over the last 15 years when the beauty and uniqueness of the old heritage, and its importance for tourists, was rediscovered. Since tourism in the state of Goa is still mainly focussed on beach and leisure activities and less on culture, Panaji is often used as a stopover for tourists who arrive via Goa

€

More pro t for non-local operators

BUDGET TOURISTS

Staying for 1-2 days, prefering hostels/homestays

Self-exploring, local experience

€

More pro t for community

DAY TOURISTS

Staying for less then 24h

Heritage-Walks, Fine-dining, organized trips

Less value for the neighbourhood

Figure 4.8. Types of Tourists in Fontainhas

International Airport. Additionally, there are often daily excursions for tourists from cruise ships that stop at the nearby Mormugao port or from hotels and resorts north or south of Panaji that offer organized trips to Fontainhas. The tourism due to the casinos that are anchored in Mandovi river, just across the study area, affect the influx of tourists, especially during evenings. There are a few casino guests who use guesthouses close to the boats and stay only for a short period. Culture and heritage of the neighborhood are not their main focus, but bars and restaurants in the area can profit from them.

The local-added-value and the profit from

28

DURATION INTERESTS ADDED VALUE

DURATION INTERESTS

tourism for the community varies depending on the type of tourist. Tourist activities are limited to the Fontainhas and Sao Tome areas whereas in Mala, with the exception of only a few tourists who get lost when they want to visit the Maruti Temple or the Phoenix Spring, despite similar heritage architecture, there is little to no infrastructure which would attract tourists to stay.

Students

The study site has a high density of educational institutions. Those are mainly focused in Fontainhas whereas schools from Mala have been shifted to other parts of state in nearby cities, such as Bambolin, over the past years due to emerging traffic issues.

Schools in Fontainhas are attracting students from all over the city as well as suburban areas because of its advantageous location close to the main axis to Old Goa and to the Porvorim. The way of transport to and from the school, and the resulting influx of traffic within the neighborhood, is dependent on the student’s age and place of residence.

As observed, students are using local facilities during their breaks or to skip a class during lunchtime or in the afternoon. Established local restaurants or cafés around schools function often as third places for both local and commuting students. Public spaces, like the Marble Plaza, are used for sports activities like playing badminton or football. This specific ground is even used by teachers who want

to spend the sports class with their students outside since some schools lack sufficient outdoor facilities.

Workers

The described user groups in the study area, students and especially tourists, have an influence on needed labour forces. Lodging establishments transformed in the past years from mostly local influenced homestays to more professional hotels or hostels, where additional affordable labour is needed. Here we can only rely on informal sources since no statistics about labour influx are available. Resulting from our investigation, we have heard that many workers are coming from suburbs like Taleigao or Porverim. In the more established commercial area of Sao Tome, most shops are run by local workers who live in the house of their shop or in suburbs of Panjim, such as Dona Paula and Nagalli Hills.

Institutional “Special Influx”

Besides the broadest influx group, there is also some local influx due to the existing institutions or associations in the study area, which underlines the importance of the Fontainhas neighborhood on a local level. For example, the recently opened BNM Senior Citizens Recreation Centre attracts residents from all over Panaji and the surrounding suburbs. The North Goa Planning Department, the responsible authority for the northern part of the state of Goa, has an even broader importance. Similar to the Charles Correa Foundation, they organize exhibitions and have national

29

CIVIC ENGAGEMENT

Associations

Charles Correa Foundation

The foundation is a declared non-profit organization and is situated right in the heritage area of Fontainhas, near St. Sebastian chapel, in a building designed by Charles Correa himself. Some of the foundation’s past and present projects have worked with the cultural heritage of the Fontainhas area. An important one was the mapping, cataloguing and evaluation of the heritage buildings, which serves as a base for the categorizing of the buildings by level of protection. Doors are always open to serve, with information for people interested in their work.

Bookworm Library

Situated in the facilities of a former primary school, the Bookworm library offers a wide variety of

children’s books which can be lent by members for a small annual membership fee and focuses on educational activities like reading or cooking workshops. Another target is on organizing events for the community, not just for Mala or Fontainhas, but for all members of this area, regardless of religion or income. “Usually children from Mala come to the free-events and children from Fontainhas to the events where you have to pay” (Employee of Bookworm Library). After opening the library in 2018 in its new location, they tried to involve the surrounding neighborhoods in their activities. People were sceptical in the beginning, but in the end, they gained one new employee who comes from Mala, helping bridge the gap between communities. Due to the library’s spacious facilities and also to support community activities, Bookworm Library makes it possible to rent the event room on the upper floor, free of charge, if the event serves community purposes.

Basantrai Nihalchand Melvani Senior Citizens Recreation Centre

Located in an old heritage building in Fontainhas, it was always the dream of the deceased homeowner to “do something against the lonely plight of seniors as age caught up with them” – as one employee explained to us. It was only one year ago that the already ruined building was renovated and reopened as a senior’s centre. To become a member, a one time payment of INR 500 is taken. Members get offered a daily schedule of activities like lectures from doctors or gym classes. Members can also gather for playing

30 importance and impact.

Figure 4.9. Bookworm Library in Fontainhas

games during which we see a clear separation between men and women. During our visit, the former were playing Carrom, the latter were coloring Mandalas. As we found out, only few people come from Sao Tome, Fontainhas and Mala, most members come from the whole area of Panaji city because there is a lack of similar centres in the city.

Mala Women’s Association (Shri Vitthal Rakhumai Mahila Sanghatna)

The Mala Women’s Association consists of about 40 women and is a cooperative oriented towards economical collaboration of women in the neighborhood. Founded in 2010, the idea was to empower women and give them the chance to cooperate and generate their own income. The association is mainly focused on making food products, selling them at the main market of Panaji as well as offering catering for events. The food gets produced at the women’s private residences since a bigger, community kitchen is not available. Also handcrafted products like diaries get sold at the market. The primary school close to Mala lake serves as a meeting place, where the women meet once a month to discuss their activities.

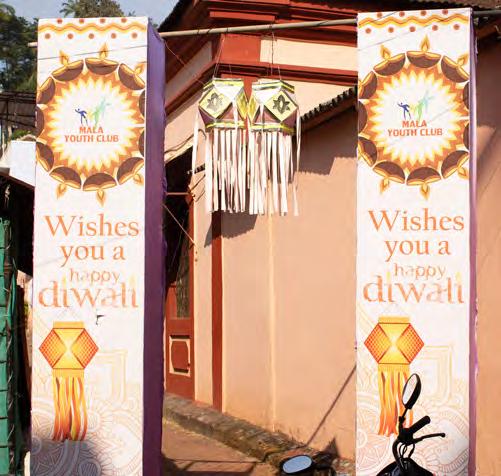

Prince of Mala

This association is mainly focused around the Diwali festival. Around a week before the start of the festival, its members, male only, start to prepare the Narkasur demon, a 5m tall metal skeleton covered with paper mâché, which is ceremoniously burned on beginning of the

31

Figure 4.11. Narkasur Prepared by the Prince of Mala Association

Figure 4.10. Senior Citizens Recreation Centre

Diwali festival. During the year, activities are mainly focusing on informal meetings of the members.

Role of Religious Institutions

There are two religions mainly dominating the study area. Where as Sao Tome and Fontainhas are largely catholic, the area of Mala was always considered Hindu. South of Rua Armade Portuguesa, you can recognize pots of basil plants before the house entrances, signifying a Hindu household.

Catholic Religion

The St. Sebastian chapel is the main meeting point for the catholic community in Fontainhas where the holy mass happens every Sunday morning. Due to its bad condition, the chapel was refurbished in the past years and the work was finished in November 2019 when a big opening ceremony was held. The money for the renovation was raised from members of the community. A committee consisting of residents of Fontainhas and the priest were in charge of collecting the money. There is also a small chapel, Saint Thomas, in Sao Tome.

Hindu Religion

Two temples are situated in Mala, the Shri Vithal Rakhumai Mandir temple on the border to Fontainhas and the Maruti temple on the slope to Altinho.

32

Figure 4.12. Maruti Temple

Figure 4.13. St. Sebastian Chapel

What is Your Neighborhood Called?

Basil plants in front of the house entry symbolize if a household is Hindu, but nowadays, it can be seen as an indicator for receiving financial support from the municipality. The current ruling nationalist BJP party prefers, as we heard from stories, to give funds to associations that are Hindu orientated. So it happens that festivities get funded but not the important ongoing maintenance issues of many heritage houses.

People also say that today’s political situation in the country leads to a bigger division among the neighborhoods then it was before.

Name Differences in Fontainhas

Less shaped social networks can also be seen through the different interpretation of the neighborhood’s naming. While officially the area is divided into Sao Tome, Fontainhas and Mala, different terms are used by residents. If you ask people of Mala about the differences between Fontainhas and Mala they would respond that they also belong to Fontainhas since the origin of the name, the Phoenix spring (Fontainhas means in Portuguese “spring on the bottom of the hill”), is situated in Mala neighborhood. On the other hand, people of Fontainhas see a clear border between the neighborhoods south of Rua Armada Portuguesa.

33

Figure 4.14. Different Terms Used by the Residents to Call Their Area

Political dimension

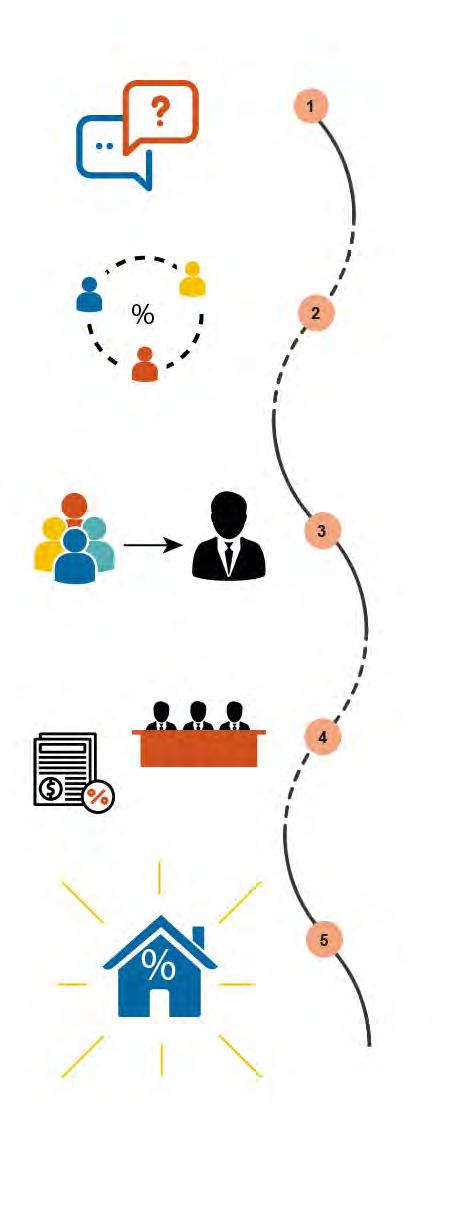

The City Corporation of Panaji is made up of a ward committee (37 territorial constituencies in the area of Panaji, the study area comprises three wards – Sao Tome, Fontainhas and Mala). Each ward has one seat in the ward committee which gets elected for a period of five years. These members are also known as ward councillors. This elected councillor serves as a representative on a local level for the residents and can be asked for mainly infrastructural matters such as waste distribution, road issues or anything regarding the infrastructure or livelihoods of the area.

While for municipal services like wastemanagement, the City corporation of Panaji is the main responsible authority and the political and legal situation do not differ from other parts of the city. The legislation for receiving permissions for building or modifications varies because of the heritage conservation law.

Listed buildings in the heritage conservation zone, are amenable to several restrictions which should protect and keep the original shape of the buildings that remained from the Portoguese time. Responsible authorities are the North Goa Planning Department and the Town and Country Planning department.

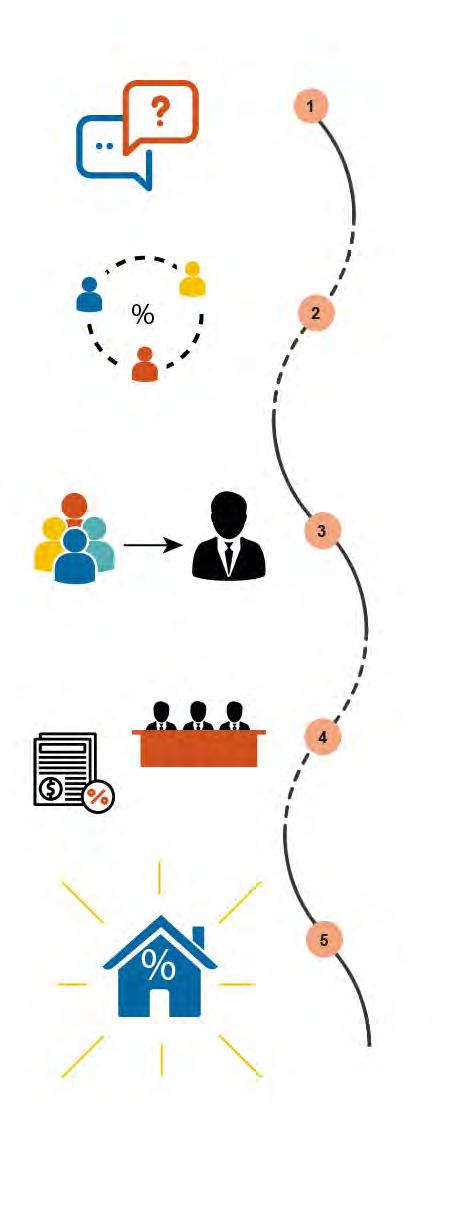

We demonstrate the process of receiving a building permit with and without heritage conservation laws in Figure 4.15.

Social Neighborhood Cohesion

“People were asking me, how I could open up a hotel in this kind of neighborhood,’’ said a guest home owner, one of the oldest hotel in Fontainhas. One reason for that was the Fontainhas Arts Festival that was a yearly festival starting in 2003. Organized by the Goa Heritage Action Group, it had the aim to bring the, until then, rather shabby neighborhood into a new spotlight. Concerts and exhibitions were organized, not only in the public space of the area but heritage house owners opened their doors and invited guests to listen to concerts or visit art exhibitions inside the houses. The profits of the event were equally split between organizers, artists and house owners. Even the houses were repainted for this particular event (following the old Portuguese tradition where the houses had to be painted by law annually). Due to some issues inside the community, the organization of the event was not continued after several years, but community members are working to revive the festival in the near future.

34

FINANCIAL CAPITAL

Financial capital is the monetary resource for people to have different options for livelihoods. This can take the form of income, savings, credit, remittances, and pensions (Rakodi 2002, pg.11 ). The state of Goa may be the physically smallest state in India, however, Goa has the highest GDP per capita of any state in the country (Kumar Jha 2019). This high income is derived from the previous mining industry and, past and presently, Goa’s expansive tourism industry.

Here in the area of Fontainhas, financial capital is mainly generated from the salaries of residents in the ares, businesses in Fontainhas, and commercialization in the tourism sector.

OCCUPATION

Looking at the occupations in the area enable us to see the monetary income of the people working and living in the area. Many residents of Fontainhas are business owners, government employees, lawyers, doctors, and dentists, or retired from said professions. There are few young adults living in the area compared to retired individuals. This has developed due to lack of job opportunities for educated young people. They see their best chance for a sustainable livelihoods as getting government jobs, but openings can be rare and applicants are extremely competitive. Those who have studied arts degrees over the sciences, are faced with the options to work in tourism related jobs, try to work in the casinos

Process of receiving a building permit (simplified)

Transmitting Plans to CCP, North Goa Planning Department, Town & Country Planning Department

Development/re-development/repairs/ change of colour/demolition falls in Conservation Zone?

YES NO

Plans have to be referred to Conservation Committee

Committee examines building plans and reject them if they don’t accord to the law.

Approval from CCP, North Goa Planning Department, Town & Country Planning Department

35

Figure 4.15. The diagram shows the process of applying building permit

Figure 4.16. Shop Owner in Mala

or to migrate to larger Indian cities or abroad. These factors have led to an aging population in Fontainhas and makes retired individuals the dominant population group in the area, whom rely on their pensions and savings to acquire daily needs and unexpected expenses. Those who struggle financially to maintain their homes, often commercialize their house into income generating businesses, such as guest homes, small convenience stores, and boutiques.

BUSINESS

Sao Tome and Fontainhas are still residential areas, but they also have a lot of commercial activities, with more and more permeating the neighborhoods as the years progress. The number of businesses have increased there over the past few decades, though there is a difference with the business in these neighborhoods. Sao Tome area contains more businesses related to daily activity for locals while businesses in Fontainhas are more tourism related. In Mala, the neighborhood has not commercialized and only has a couple businesses for the local residents including a pharmacy and some corner stores.

Some of the businesses in Sao Tome are operated by the owner of the house. For example, Welfit Tailors, a gents specialist tailor, is owned and managed by a 53 year old man who lives on the premises. He is the second generation that runs the business and also has the tenure rights of the house. There are also businesses that rent space from the owner of

36

Figure 4.17. Tourism Related Business

Figure 4.18. Local Business in Sao Tome

the house, like Pereira Pimenta, a showroom of building products such as bricks and cement works. Other businesses in this area include barbers and salons, clothing, notary, architects, electronics, dentist, and art galleries and shops.

An activist and architect, who has been working in Panjim for most of her professional career, explained to us that around 15 years ago, as mentioned in the previous section, the Goa Heritage Action Group was hosting an annual art festival. The purpose was to raise funds for residents and homeowners in Fontainhas to preserve and upkeep their homes. Furthermore, the owner of a hotel said the annual art festivals helped to increase awareness of the value of Fontainhas. Since then, tourism related businesses have grown. Eventually the annual event stopped running due to internal conflict, but this did not stop the tourism activity in Fontainhas. Restaurants, guest houses, and shops keep popping up in many corners of the neighborhood, and the numbers are growing rapidly.

Figure 4.19. Map Shows Business and Commercial Activity

Figure 4.19. Map Shows Business and Commercial Activity

The residents in Fontainhas also have to maintain the façade according to certain standards due to the heritage laws, but without any help or funds from the government. A resident told us these regulations outprice some people from their homes and they have had to move out of the neighborhood since they could not afford the house maintenance. Another consequence is an increase in abandoned properties in the area. Some of these fall into disrepair and regulations make it

hard to redevelop the properties.

Figure 4.20. Mangrove Trees by Rio De Ourem Creek

Figure 4.20. Mangrove Trees by Rio De Ourem Creek

NATURAL CAPITAL

Natural capital refers to the natural resource stocks including land, water and other environmental resources, that people can draw on for their livelihoods (Rakodi 2002). Natural resources and their contribution to livelihoods receive relatively little attention in urban context compared to rural areas as they are typically limited in urban spaces yet remain an important asset to analyze . In the research area, natural capital consists of three main categories: Mandovi river, Ourém creek and green spaces.

Both the north and east of Fontainhas and Mala are surrounded by a river and a creek. Located to the north of Fontainhas, Mandovi river, is one of the major rivers of the state of Goa. For Goans, the Mandovi is very important as it provides recreation and opportunities for fishing. Moreover, it waters the rice crops and serves as a means of transport. Cargo ranging from iron ore to coconuts are carried down the river on boats of varying sizes. The river also hosts offshore casinos, cruises and music boats.

Rio De Ourém creek goes along east side of Fontainhas and Mala and used to provide a beautiful space for boating, fishing and recreation. Although nowadays, the creek is suffering from pollution, lack of freshwater and dumping of untreated sewage. While the quality

39

Figure 4.21. Transport Ferry and Casinos on Mandovi River

Figure 4.22. Mala Lake

of the river has declined over the years, it still has many opportunities and potential. In the evenings, you can still see some people fishing in the creek or canoeing. It also offers a fertile ground for mangrove vegetation. Mangroves in the bank of the creek provide a slew of benefits for coastal human communities. In addition to storing carbon, they reduce flooding and erosion, act as nurseries for fish, and filter pollutants from water (Erickson-Davis 2018). These mangroves are also home to a host of biodiversity such as birds, insects, crustaceans, fish, etc. In recent years the lack of proper protection of them leads to many problems such as increasing probability of flooding, especially in Mala.

Green spaces such as parks and sports fields play a significant role in urban areas. Green spaces are important for both physical and mental health. They help filter out harmful air pollution and facilitate physical activities, relaxation, social interaction and recreation. They can reduce health inequalities and improve well-being. In Sao Tome, Fontainhas and Mala, there are not many green spaces. Buildings form a dense neighborhood and due to the heritage conservation regulations, they have not changed significantly during the last decades, limiting the availability of public and green space. However, people and residents try to bring some greenery by using flower pots in front of their buildings.

40

Figure 4.23. Green Spaces, East of Rio De Ourém Creek

Green spaces in the research area are as follows:

● Small park in front of the post office in Sao Tome area but it is fenced, preventing use by people.

● Riverbank is seen as a green space but because of the lack of environmental protection, pollution and unpleasant smell has limited its availability of use as public space.

● Marble Plaza, next to a Bombay café, is sometimes used by students to gather and play badminton.

● Vacant lot in Mala and Hedgewar school playground, despite the poor conditions, provide a place for children to play and enjoy their time.

● Mala lake is an artificial lake which, based on our findings from people, was initially established for recreation purposes. However, it has been neglected for years after plans for its beautification by North Goa Planning and Development Authority fell through. Redevelopment was halted due to financial disputes.

Figure 4.24. Open Spaces in Fontainhas

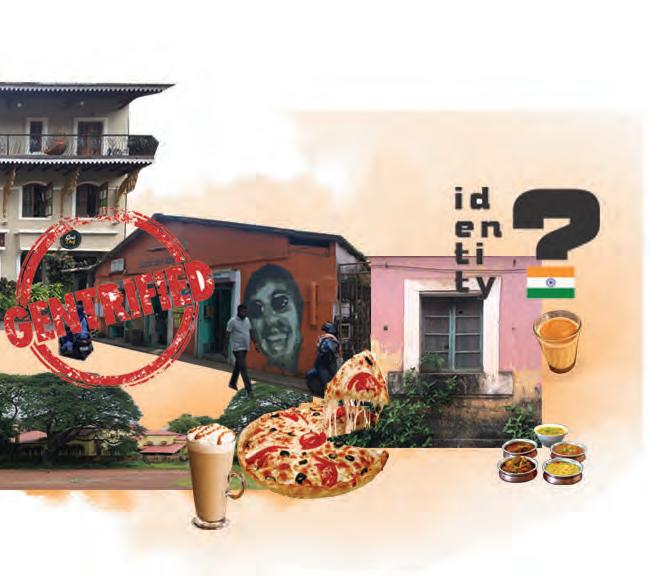

INFORMALITY

Informality can present itself in many ways and is dependent upon the context of a place (Altrock 2012, pg. 172). Informality can be defined in relation to legality, commerce, housing, land tenure, and more, and is not always performed by people, but can include government bodies as well (Meijer & Ernste 2019, pg. 3). When discussing India and informality, it is often in the context of informal housing, sometimes referred to as slums, a category that other NTNU students worked with this semester.

But Fontainhas is different, and informality takes place in other ways around the area. With the heritage conservation regulations, anyone who makes alterations to their property that go against these laws without written permission from the government, is practicing informality as they are operating outside the law.

In Sao Tome, we heard a story surrounding a building that was a hotel with a restaurant underneath that caught fire and burned the building down. Some people said it was an accident, others speculated that it was intentional to avoid preserving the building. If the latter is true, while unverifiable, this is a form of informality. Throughout the area, one can also see rental buildings in disrepair. The tenants often pay low rents if they have lived there for a certain number of years. Because landlords want a higher return, they will not

repair damages in hopes of having tenants leave, renovate the space, and charge higher rent. While technically legal, this borders informality.

We also see informality in small ways such as a woman who became frustrated that cars kept parking in front of her home, blocking the pathway to enter. She decided to put large, heavy planters in the street to physically block cars from parking there. While she knows it is possible that the government could come ticket her or confiscate the planters, she does not care, as she needed to take back her space.

Throughout Fontainhas, there are many street art installations and graffiti, this is informality.

We can spot informality throughout the field site in a multitude of manners. While neither group 5 or 6 tackled informality head on, the effects of these factors had an impact on our analysis, methods, and proposals in subtle ways.

42

Figure 4.25.

Abandoned unmaitaned building

CONCLUSION

Our analysis of the area gave us a comprehensive overview of the current situation in Sao Tome, Fontainhas, and Mala. We identified the different types of inhabitants that reside in these neighborhoods, found struggles in the municipal systems, listened to concerns over parking and traffic, learned about the existing institutions and associations, and observed the tension between different parties in the area. These, and many other factors, gave us a general understanding of the field and aided in dividing the areas into two seperate field work sections, each examined further by group 5 and group 6.

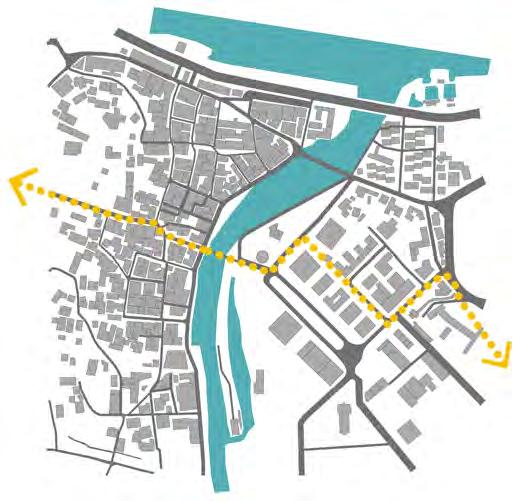

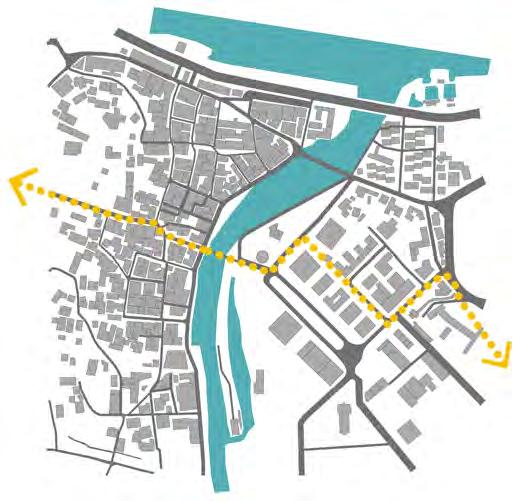

Group 5 chose Sao Tome and Fontainhas as their research field, splitting Fontainhas in half at St. Sebastian chapel on Rua De Natal. While the two areas have differences, there are many similarities among identity, residential structure, and commercial activities.

Group 6 chose the lower half of Fontainhas, south of Rua De Natal, and Mala as their research area. These two areas have very different identities and a harsh dividing line, the largest separator being religion. Fontainhas is predominantly Catholic while Mala is nearly unanimously Hindu.

The separation of the field in this manner allowed researchers to focus on different challenges in the area and target interventions to address concerns applicable to people in those neighborhoods.

44

45 Sao Tome and Fontainhas Fontainhas and Mala Figure 4.26. Division of Fieldwork Areas

group5 Sao Tome & Fontainhas

48

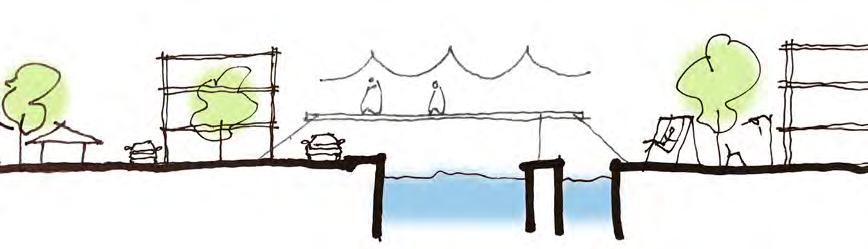

49 Figure 5.1. Current

Situational

Sketch of

Fontainhas

INTRODUCTION

After conducting the situational analysis, the entire area was divided into two sections, the north consisting of Sao Tome and the upper half of Fontainhas and the south consisting of the lower half of Fontainhas and Mala, with the dividing line near St. Sebastian chapel on Rua De Natal street. Through analysis, a divide in identity presented itself with Sao Tome and Fontainhas consisting of mainly Catholic residents whereas further south you see more Hindu and Muslim families present. While upon first glance, the neighborhoods could be viewed as more formalized, preserved, and maintained compared to other parts of the city, residents and stakeholders in this area combat many difficulties in their daily lives.

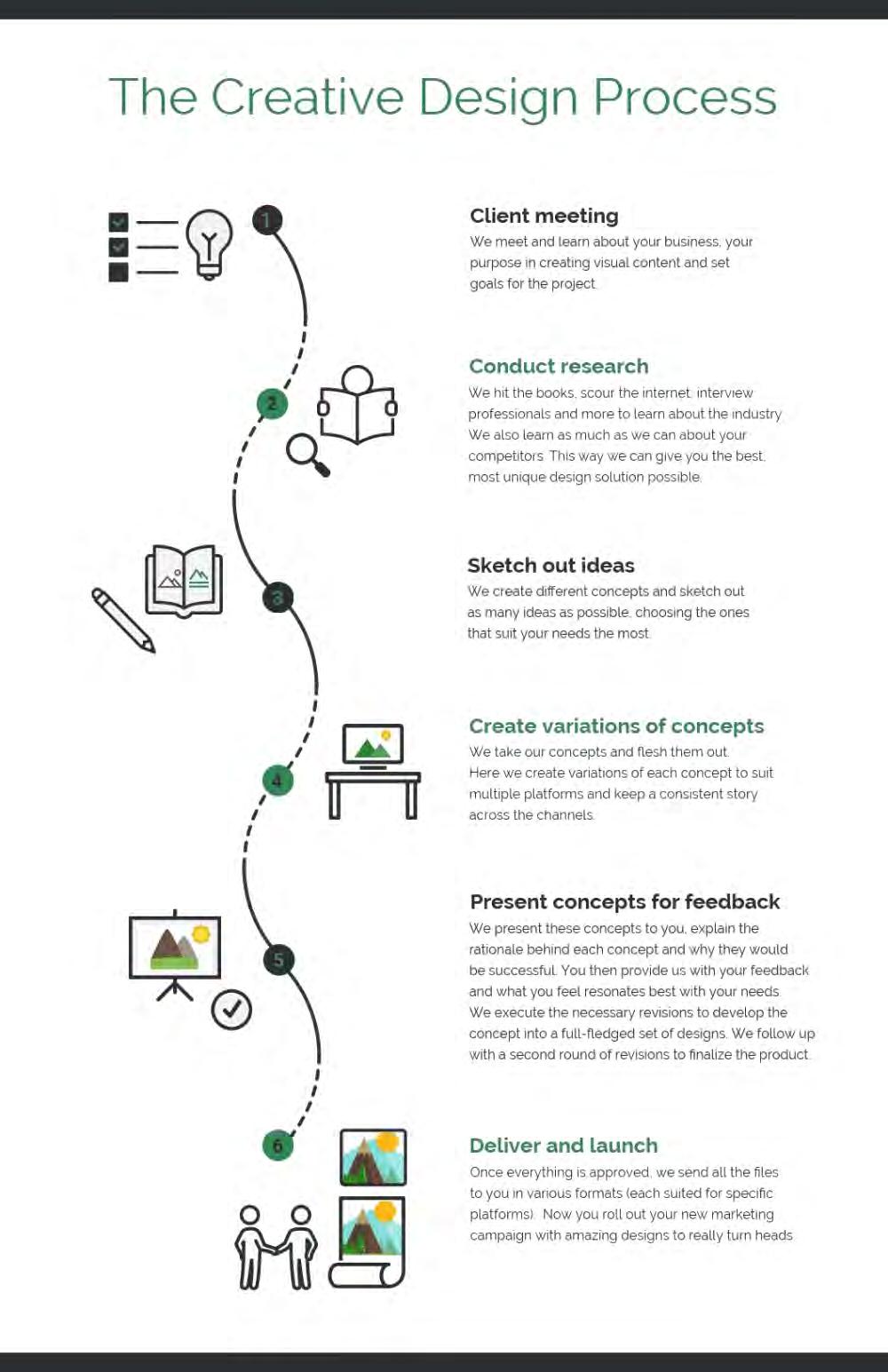

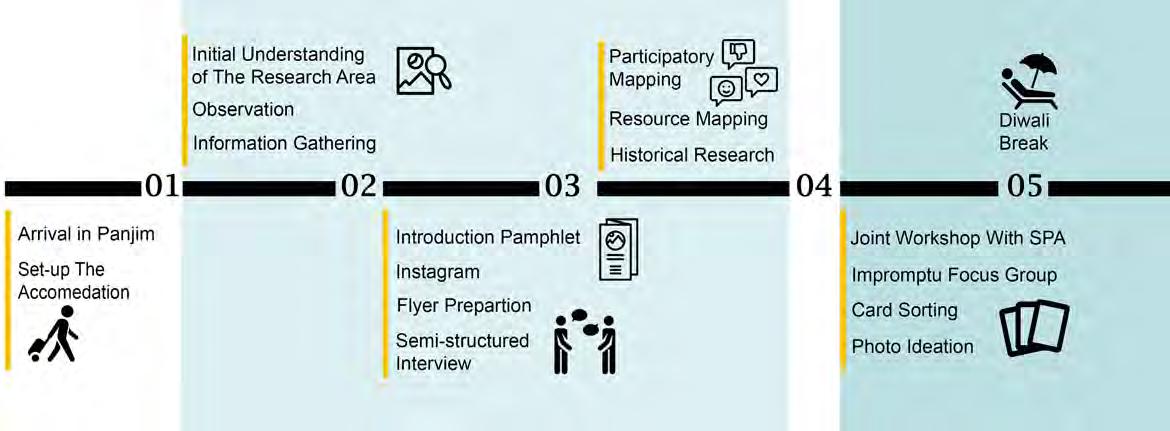

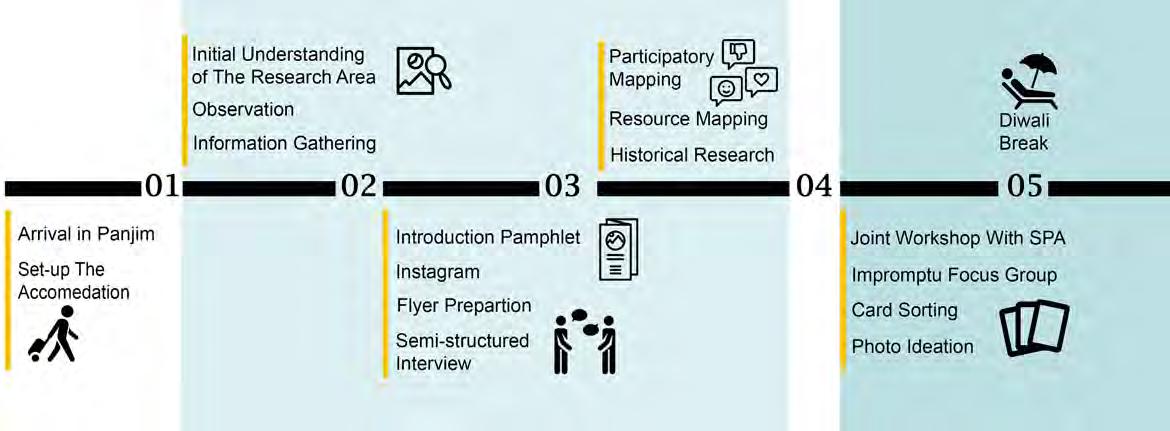

Our process began upon arrival to Panjim, just after the monsoon season. We spent time exploring the city before we were assigned our research and fieldwork area. The next few weeks were spent analyzing the area, practicing many methods and talking to as many people as possible. Leading up to the halfway mark, we had a crash course collaboration with second year masters students from the School of Planning and Architecture-Delhi where we dove deeper into our site and learned new participatory methods. After a much needed break, we began discussing our problem statement and proposals before bringing them back to our community for input. We concluded our fieldwork by constructing our report and

50

Preliminary Phase Secondary Phase

proposals while simultaneously continuing to collect input and feedback from stakeholders and looking at ways to anchor our ideas.

The following methods, findings, and proposals are applicable to Sao Tome and Fontainhas, where our group conducted fieldwork for 10 weeks, analyzing the area, listening to stories and struggles, and codesigning solutions with the community.

ToCityCenter

51

Mandovi River

OurémCreek Main Street

Panjim Bus Stand

Sao

Tome

Fontainhas

Concluding Phase

Figure

5.2. Map of Focused Area Figure 5.3. Timeline

Figure

Figure

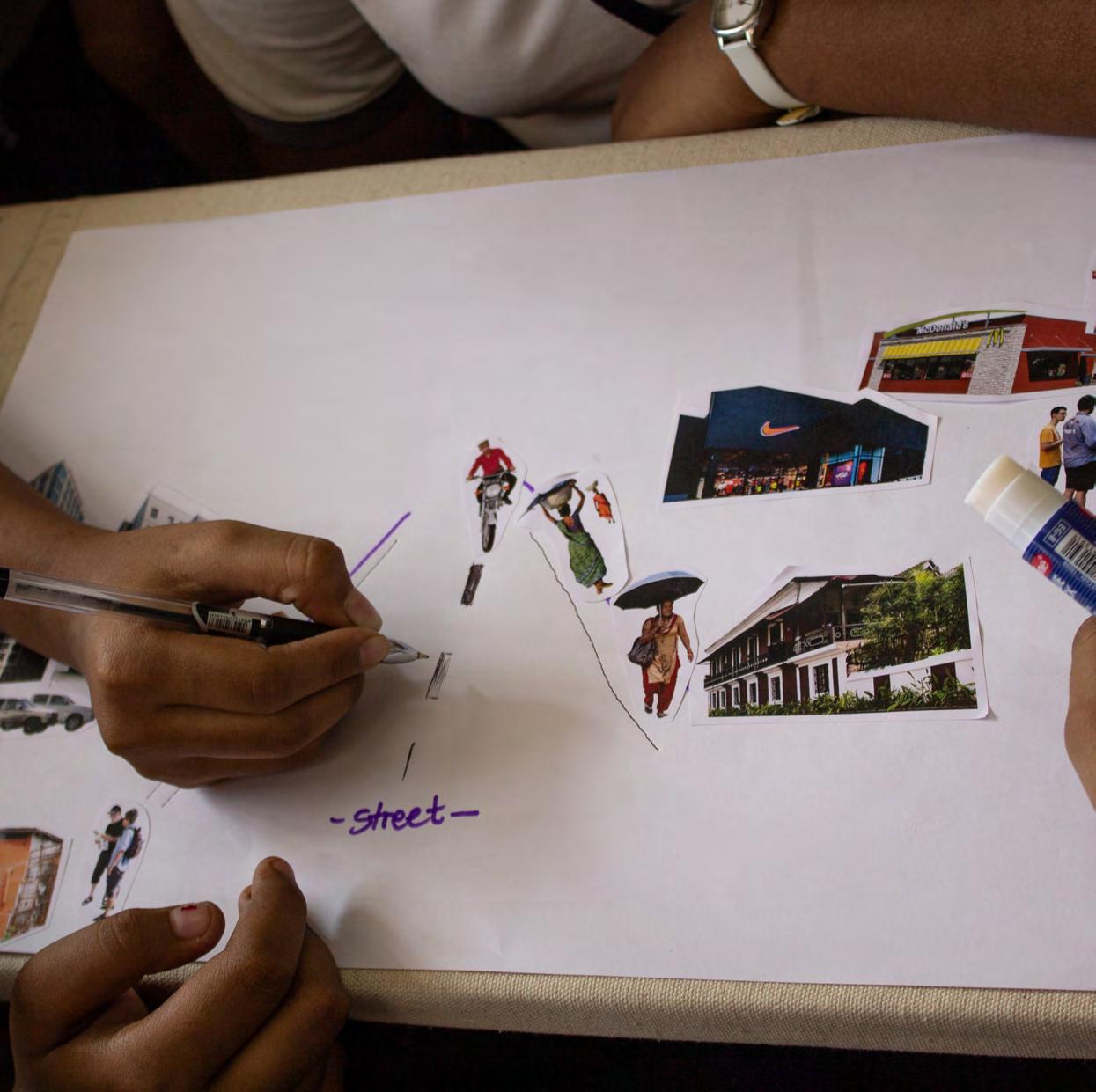

5.4.

Participatory Mapping Method

1: METHODS AND FINDINGS

Throughout the fieldwork, our goal was to realize and address some of urban challenges of Sao Tome and Fontainhas by working directly with the community and stakeholders in the area. We wanted to hear about the area through their voices and acknowledge some of the challenges living here presents. As a main focus point for the Urban Ecological Planning program, we explored many different participatory methods and tailored each with the intent of collecting certain types of information throughout our fieldwork. We have categorized our process into three phases, as we experienced a natural progression throughout our research.

Preliminary – Our first phase was focused on gathering as much information from as many people as possible. We wanted to understand the area, people, and challenges living and working in Sao Tome and Fontainhas bring.

Secondary – After gathering preliminary data, we wanted to focus on what people feel were the most important issues to tackle in the area. We used this phase to allow citizens to voice their concerns and solutions to those concerns.

Methods focused on stakeholder solutions.

Concluding – Our last phase was focused on co-design. We used methods to allow citizen creation as well as feedback on our interpretation of their needs. The intent was to address important issues as well as create viable and desired solutions.

PRELIMINARY PHASE

Observations

Our research started with observations and getting familiar with the research area. First, the colorful facades of houses and Portuguese’s architecture caught our attention immediately, as it drastically stood out from the rest of Panjim. It became obvious that Sao Tome and Fontainhas were special and we understood the need for conservation of this beautiful heritage site. In the first days, we walked along the narrow streets, spending time in context at cafés, restaurants and galleries, trying to get to know more about the current situation and

53

st PHASE1

AIM

To gain awareness of the area, meet community members, educate residents on our intent in the neighborhood, and begin mapping the space and people’s movement within it.

METHODS

Observations

Semi-Structured Interviews

Flyers & Social Media

nd PHASE2

AIM

Participatory Mapping

Resource Mapping

Historical Research

people interactions with the physical space and each other. We recorded things we saw and heard and used this preliminary information to help us develop and shape our next methods.

Semi-Structured Interviews

To deepen our understanding of Sao Tome and Fontainhas, empathize with the struggles residents face, identify areas of concern, and begin gathering community solutions to community issues.

METHODS

Impromptu Focus Group Card Sorting

Photo Ideation / Participatory Design

rd PHASE3

AIM

To allow stakeholders to dictate and design proposals, provide feedback and criticism to the proposals, and to create something of meaning for the people of Sao Tome and Fontainhas.

METHODS

Movement Mapping Stakeholder Co-Designing Community Feedback on Proposals

Figure 5.5. Methods Used in Different Phases

After observations, we began conducting semistructured interviews. We conducted informal and open-ended interviews with people working in local shops, libraries and galleries. We also targeted residents within Sao Tome and Fontainhas. When trying to approach people on the street, we quickly realized many of the people in this area were not residents but tourists and commuters, thus we began going door to door to gather information from the residents. Our intentions were to understand the space and the community better and to develop an understanding of how the community functions. We practiced guiding the interviewee into the direction we wanted through trial and error with our questions, which sometimes worked and sometimes did not. They were sharing information about themselves, positive and negative aspects of the surroundings as well as their challenges and concerns regarding the neighborhood. Most of them were so eager to respond and spend time to talk with us when they found out we were students. While we focused on this method in the beginning phase, we continued to use it throughout the entire fieldwork as it helped us to get basic information and an impression of the area as a whole.

54

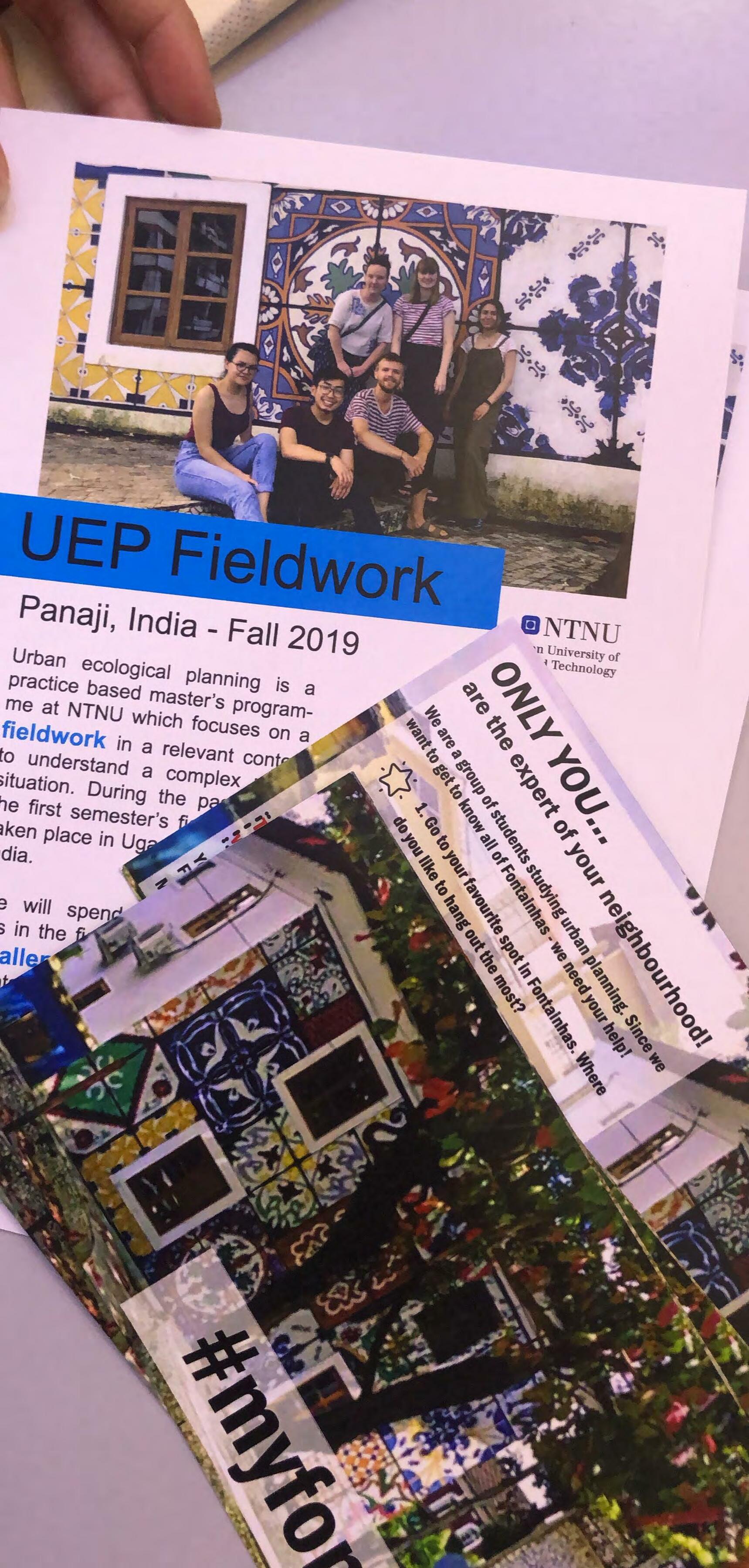

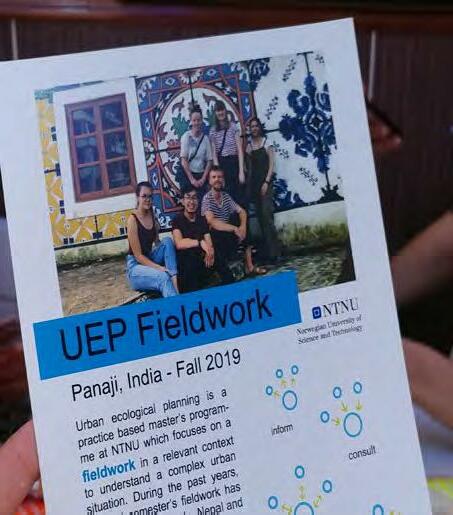

Flyers and Social Media

After we began conducting semi-structured interviews, we realized that people were very curious about us and our purpose in their neighborhood, especially coming in as foreigners to this country. Thus, we prepared printed flyers to inform people of our purpose and intent as well as use them as conversation starters and a way to attract attention to our work. We tried to design a simple eyecatching flyer, with suitable context and colors. Moreover, the contact information helped for further communication as well as to create an atmosphere of trust and professionalism.

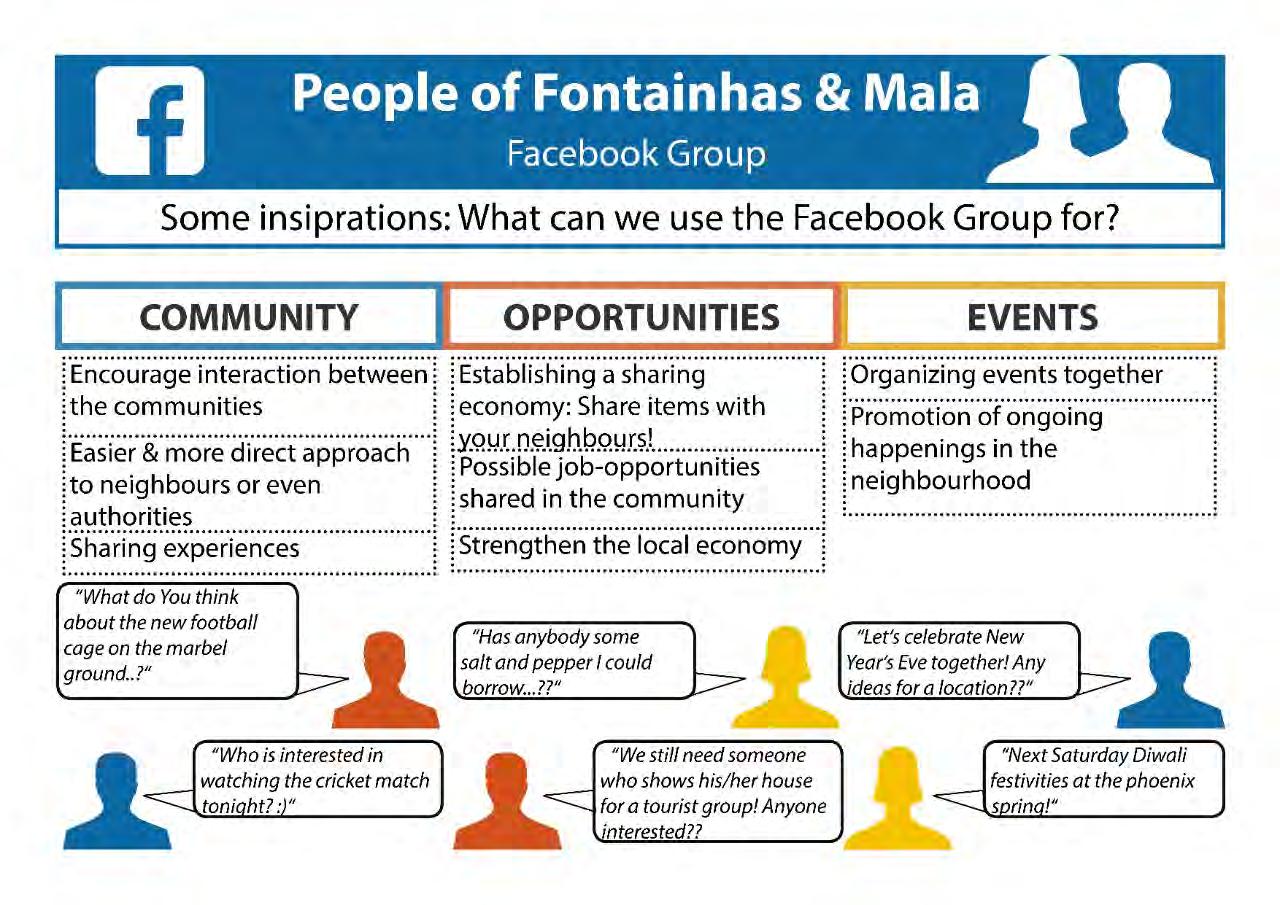

As UEP students, seeing the area from the community’s perspective is significant to our work. We want to be able to lift up people’s voices and perspectives, not only report our perception of what was said. Social media gave us opportunity to ask people to share their favorite views or spots in Fontainhas. In collaboration with group 6, we created a social media campaign with flyers that contained brief instructions and asked people to post photos on Instagram using the hashtag #myfontainhas. We created this campaign spontaneously and thought it would be an interesting way to try to continuously gain information throughout the entire research period. Only after spending more time on the site did we realize that many of the residents in Fontainhas are older and less active on social media. While still an interesting and potentially useful method, it was not the right tool for this population and we have received limited data from it.

55

Figure 5.7. Participatory Mapping Poster

Figure 5.6. Distributed Flyer

Participatory Mapping

Since the focus area is touristy and often foreigners are present in Sao Tome and Fontainhas, we needed some tools to attract people’s attention to us specifically and try to start conversations with residents and strollers. Therefore, we prepared a simplified map of the neighborhood that included the mains roads and footpaths as well as landmarks in the area and printed a large poster. While we are used to reading maps, many people we engaged were not. They had a hard time understanding the image in relation to their neighborhood and the places they frequented. By highlighting landmarks in Panjim, we were able to orientate them better to the map. We asked three simple and easy to understand questions, in English and Hindi, associating each with a different colored sticker. We requested people to place the stickers on the map, indicating if they liked a certain place, disliked a certain place, or wished some place was changed. This allowed them to tell us a briefly about their neighborhood and showed us the most liked and used places in the area as well as the places of concern which we investigated further later on. The poster was a one tool used to facilitate communication with different groups of stakeholders including residents, workers, students and tourists in Fontainhas. While at first, we were feeling discouraged, patterns and trends of feedback became apparent and we quickly identified the most loved places and least favored spots.

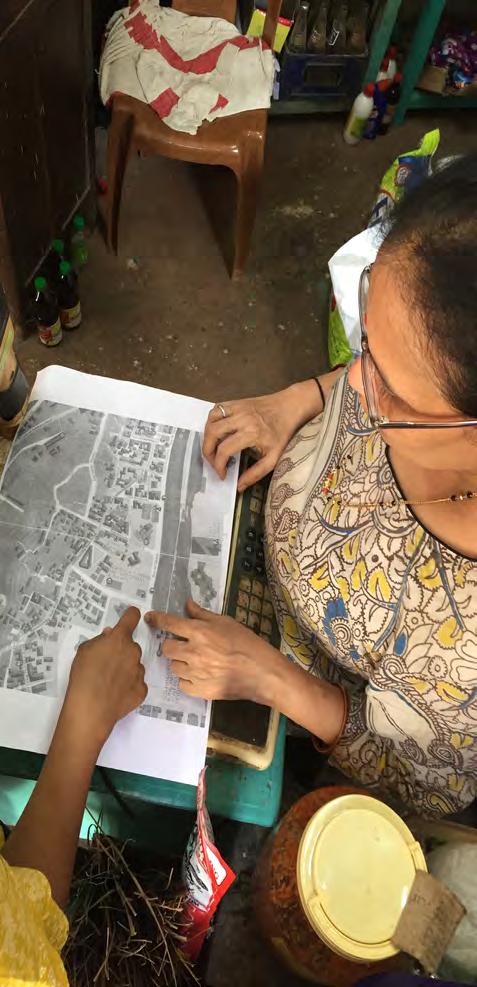

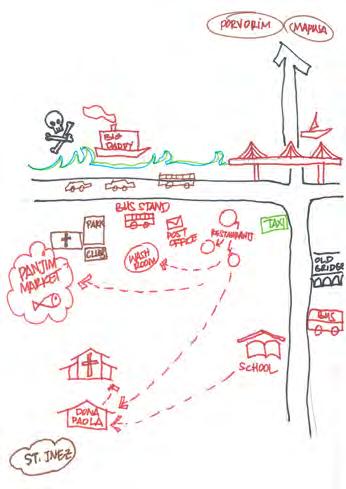

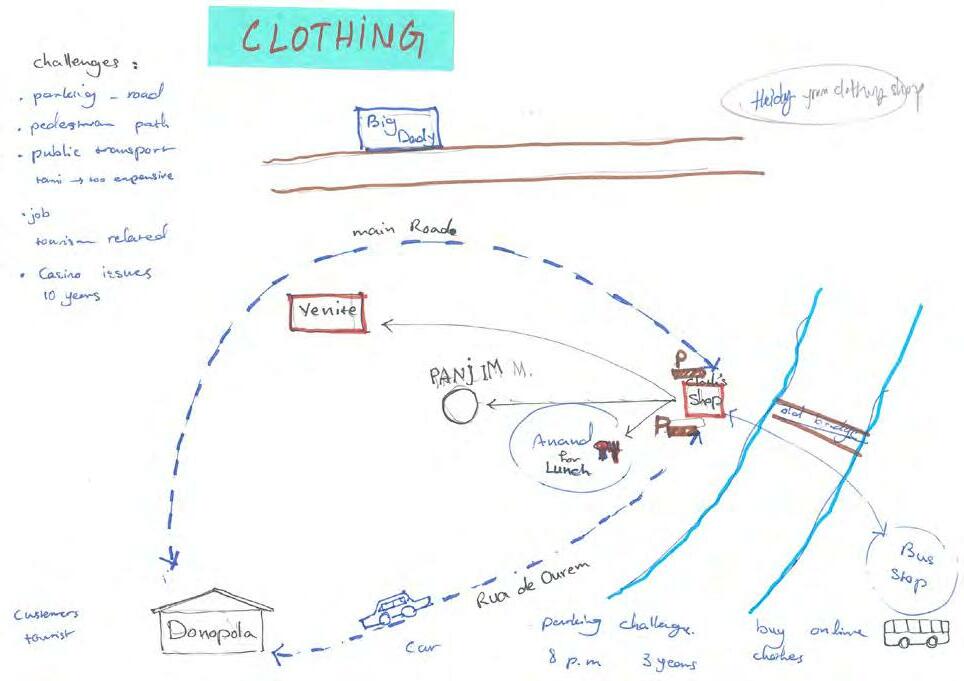

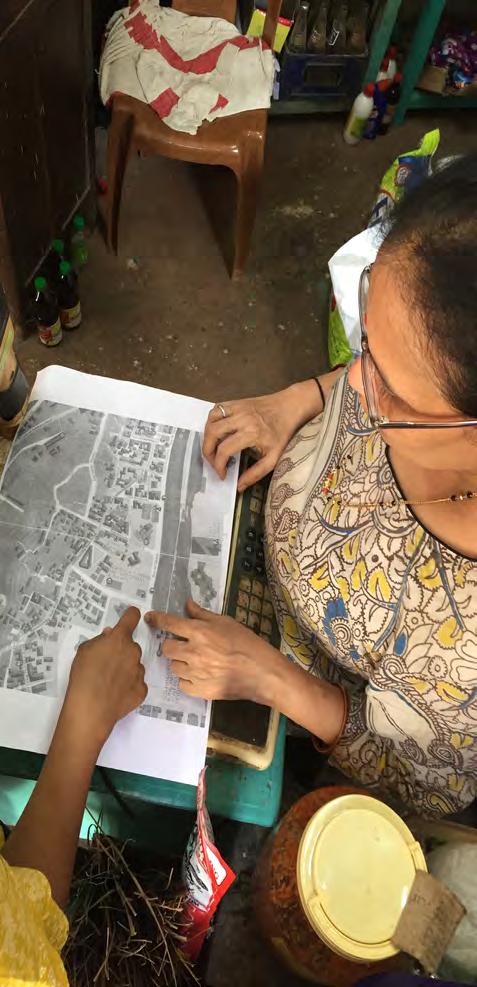

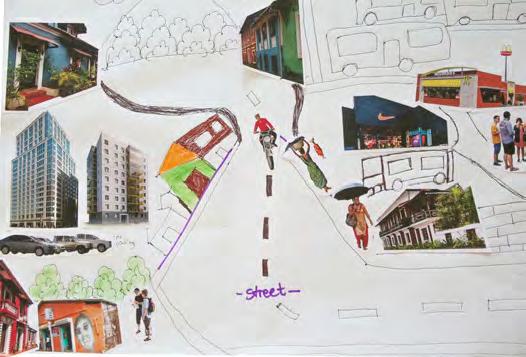

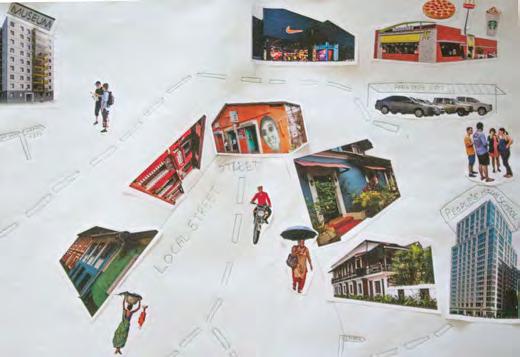

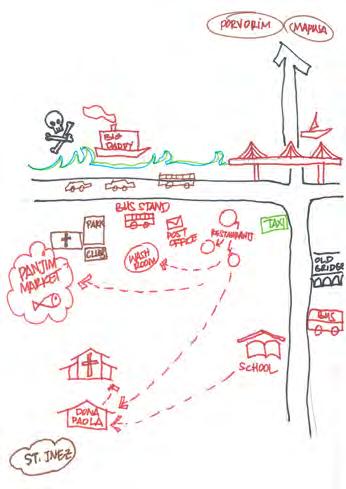

The last method of this preliminary phase was, resource mapping, a method taught to us by the SPA Delhi students with whom we collaborated with for one week. Resource mapping not only gave us the opportunity to understand how people live, work and meet their daily needs in Sao Tome and Fontainhas but also allowed us to see the connections between our area and the rest of Panjim. The method starts with one or two participants and a blank piece of paper. We then asked the person to draw a map based on their daily activities such as buying groceries, commuting from home to work, or which restaurants they liked to eat at. We found people were often hesitant at first, in this case, one of us would draw a landmark and a street, allowing the participant to visually understand what we were trying to accomplish. Then the participant would add in other things, usually outside Fontainhas and into the city center or away from the city if they lived or worked outside the area. We asked them to include daily needs, special occasions such as

Resource Mapping

56

Figure 5.8. Restaurant Owner in Sao Tome

Figure 5.9.

Practicing Resource Mapping

Resource Mapping

festivals, and typical places they usually use in leisure time.

Sometimes a participant wanted to dictate and not draw themselves, we found if a researcher put a landmark in the wrong place, every time the participant took the pen and began drawing themselves. This was an interesting way to encourage the participant to take control. Saying that someone is an expert of their city and space is easy, but they might not believe you or feel insecure about the knowledge they hold. By us making one small, but intentional mistake, it showed them how much they actually know and encouraged them to share and demonstrate that knowledge. This approach provided the general overview of easily accessible resources and also the lack of available resources in Fontainhas and Panjim. We tried to let people become the experts of their area and show what it is really like to live in Fontainhas and how they must travel to live their lives.

Historical Research

In addition to the participatory methods conducted during this phase, we also dug into historical research on Sao Tome and Fontainhas. As a heritage conservation zone, several academics have written about the area and challenges in planning and developing in such an area. We also found that many architecture students use the area for projects and theses, so we looked into past masters thesis work to gain an understanding of how

58

Figure 5.10. Results of

the area was in recent history. Lastly, we visited the Goa College of Architecture and looked into student coursework that has been conducted in Fontainhas in the past. The reports from the university gave us similar information to what we had been gathering ourselves, but the masters thesis work we discovered elaborated on architecture, which when paired with the articles published by the planning department, gave a preliminary understanding of the challenges of building within this conservation zone.

Findings of Preliminary Phase

This phase was dedicated to hearing the voices and understanding the lives of the people we are designing with as well as gain an understanding of the physical space and how people interact with it. Information was gathered from many people with different ages, genders and social position to collect various perspectives. What we observed and heard during these methods was recorded in the form of writings, drawings and photos. When entering the field, we usually started with broad questions about people’s lives and gradually steered the conversation towards the challenges in the area. At the end of this stage researchers achieved the broad vision of the strengths and challenges in the area. We then used this information to divide the boundaries of our research area and develop the next methods.

Residents told us good things about the area, such as how quiet the neighborhood is, the

accessibility of buses, and the proximity to Panjim market for fresh foods. A woman who runs a restaurant in Sao tome told us she looked very favorably on the development in Patto as she was hoping it could bring more business to her restaurant. This is where we began to see conflicting information based on which group we were talking to. As she liked the development, many older residents told us that recent developments were leading to flooding on their streets. The development removed Mangroves in the area, a tree that helps hold rainwater and redistribute it to the ground, causing displacement of rainwater. In a city where monsoon rains come several months out of the year, it can have drastic effects on residents.

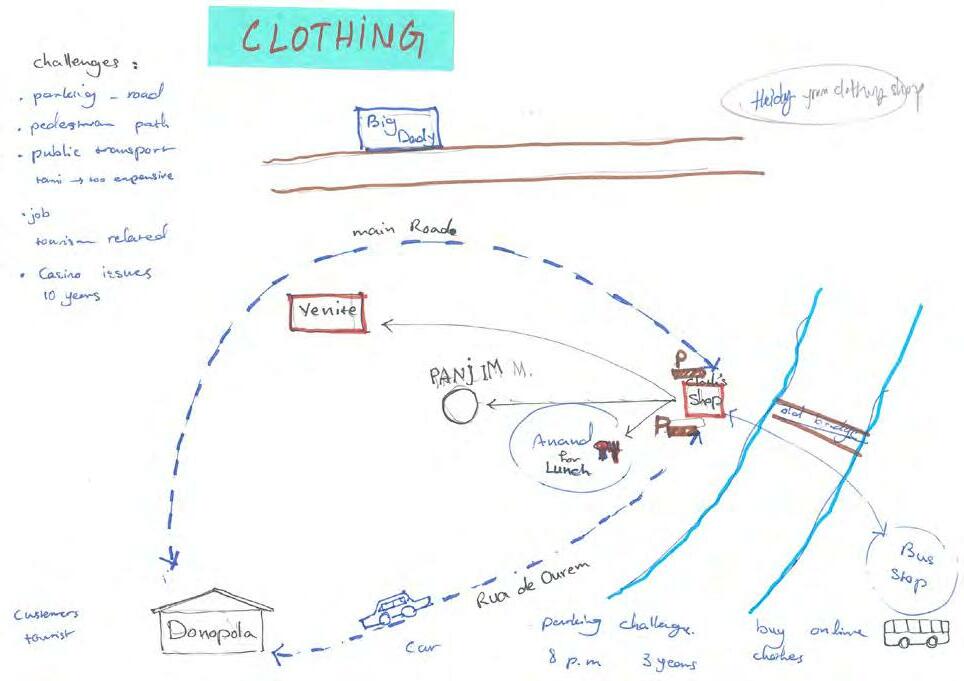

Other concerns voiced by the residents were contaminated well-water, lack of parking for residents and customers of businesses, sidewalks and walkways were poorly maintained, tourism is bringing too many people into the neighborhood, traffic is dangerous and congested, casinos are bringing nuisance, streets are littered with rubbish, young people are migrating out of Goa due to a lack of job opportunities in sectors outside of tourism, heritage laws are restricting desired alterations on homes, rental buildings are poorly maintained, lack of community cohesion, rivers are polluted from casinos and hotels dumping sewage into them, and development can happen illegally with enough money. We also heard concerns in regard to Imagine Panaji. One woman told us she could not understand

59

why they were painting stairs when people did not have drinking water, that does not make a smart city.

We used this information to try to think about what issues could we potentially address in this neighborhood and what could we eliminate based on resources available. We then tried to develop our next methods with these things in mind.

SECONDARY PHASE

Impromptu Focus Group

Although group interviews and discussions can offer a quick understanding of community’s life and challenges, they can sometimes lack deep information compared to individual interviews

or more focused discussions. In the process of research, group discussions and resource mapping were conducted with taxi drivers, as many do not live in Fontainhas but work there every day. They were using the northeast of Sao Tome as an informal taxi stand as they waited to be called. While not a formal focus group, the congregation of one type of stakeholder allowed us to gather information quickly about their needs and the comfort of having their peers around allowed them to open up to us. Through resource mapping as a starting point, we were able to ask questions about home and work life, good and bad things about Panjim, find out their needs and desires, and gain an understanding of the struggles of being a young man in this area. While diverse groups can spark discussion and debate, homogeneous groups can provide ease and

60

Figure 5.11. Group Interview With Taxi Drivers

understanding in sensitive situations. The purpose of formal focus groups is to create a welcoming atmosphere for participants, a place where they can speak freely without judgement. We were able to achieve this same atmosphere on the street at the taxi stand and gather meaningful data.

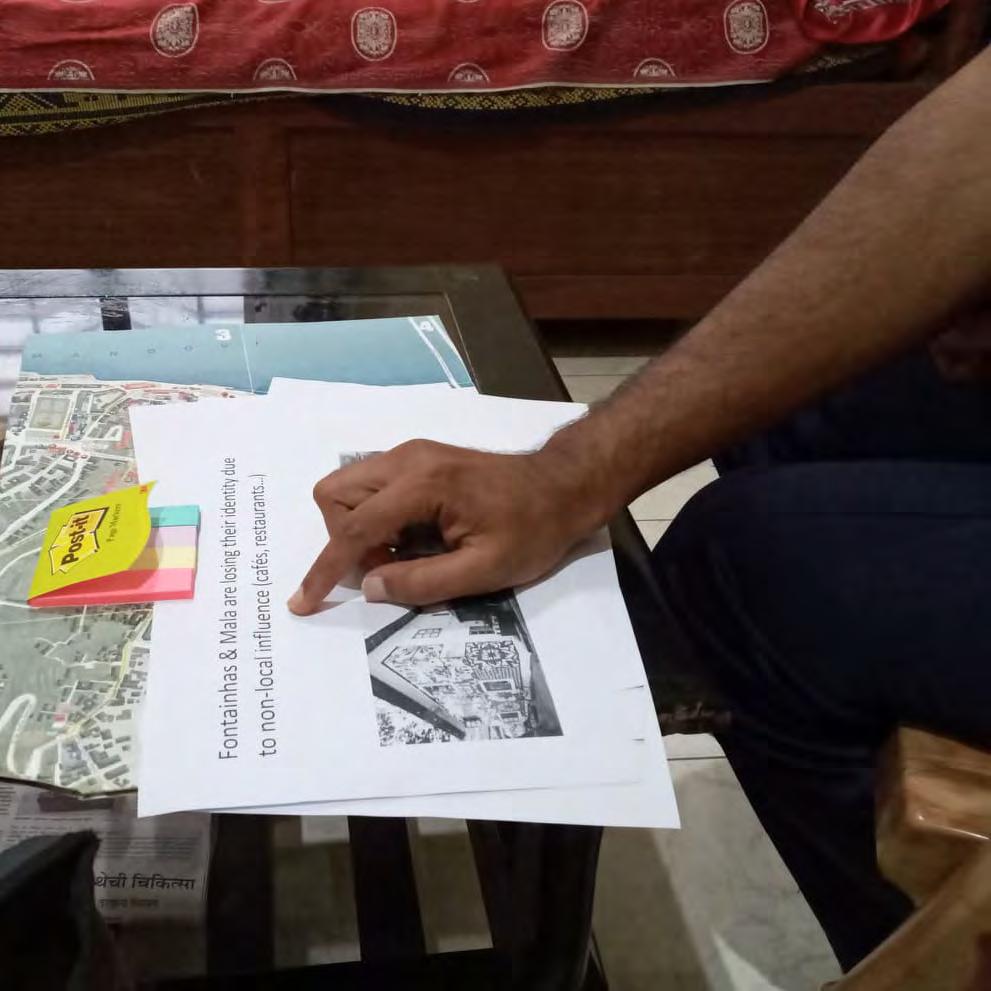

Card Sorting

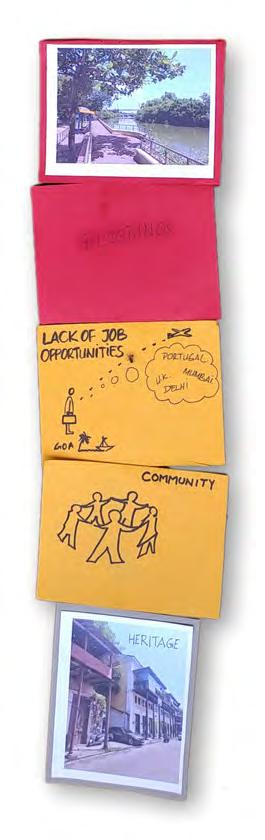

Card sorting is a simple exercise that gives the chance to spark the conversation about the most important issues of the people we are designing with and let them prioritize their concerns (IDEO 2015, pg. 57). Based on the previously gathered information from our preliminary phase, we identified key issues and concerns for residents and stakeholders. We prepared cards with simple images, sketches, words and phrases to represent each of these key issues

as well as blank cards for them to write new topics. For this method, we targeted residents as the stakeholder of interest since they have the greatest knowledge and understanding of the fieldwork area. Additionally, they have the biggest stake in the neighborhood as they face these topics and challenges on a daily basis. People were asked to prioritize the issues based on their biggest concerns or areas of interest. The first few participants we interacted with became fixated on the casino card and could not discuss any issues beyond that. Because casino related issues are a city-wide problem and not specific to the people in Sao Tome and Fontainhas, we experimented with removing that card for the remaining participants and acquired much more interesting results. We noted the most pressing concerns for people and continuously referred back to them in later stages and when beginning to develop our

61

Figure

5.12. (Left)

Cards for Card Sorting Method (Right) Card Sorting Method Participant

Figure

Figure

5.13.

Card Sorting Method with Participants

proposal. This exercise not only allowed us to rank people’s concerns, it also helped us to have deeper conversations with residents and understand their values.

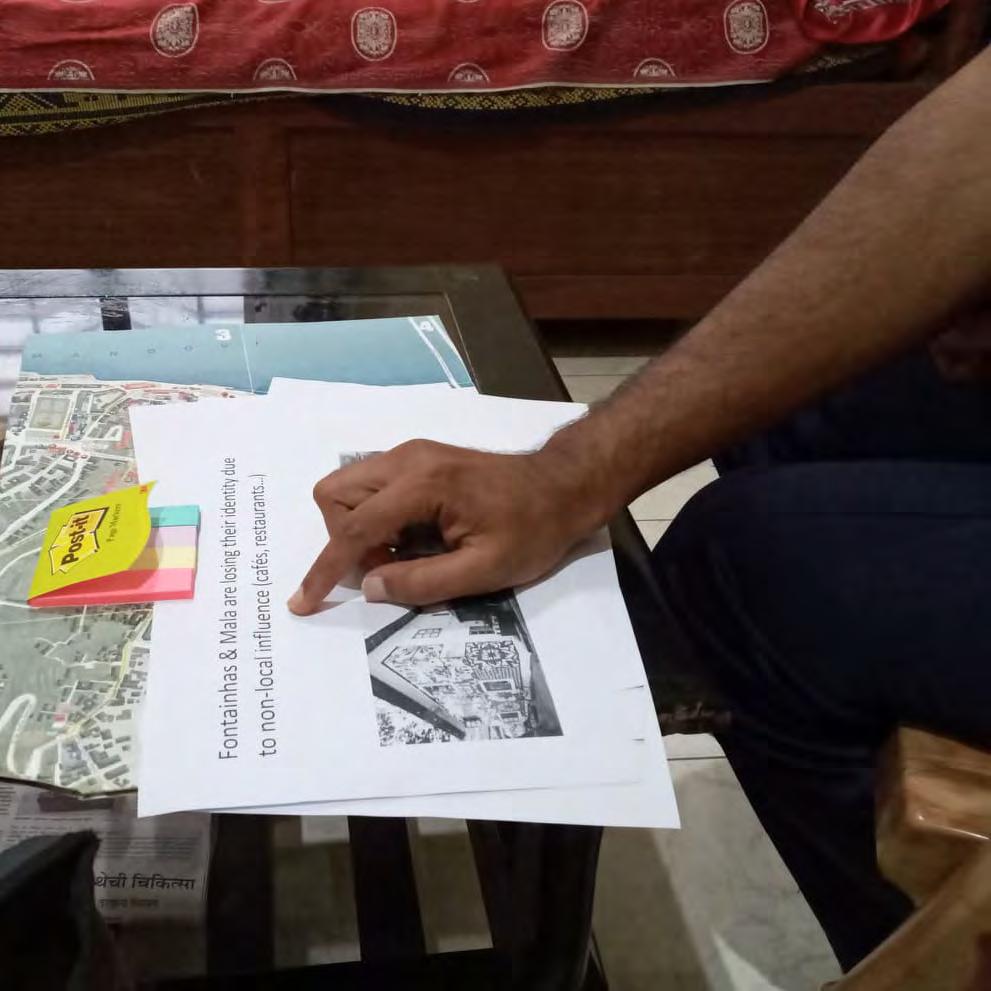

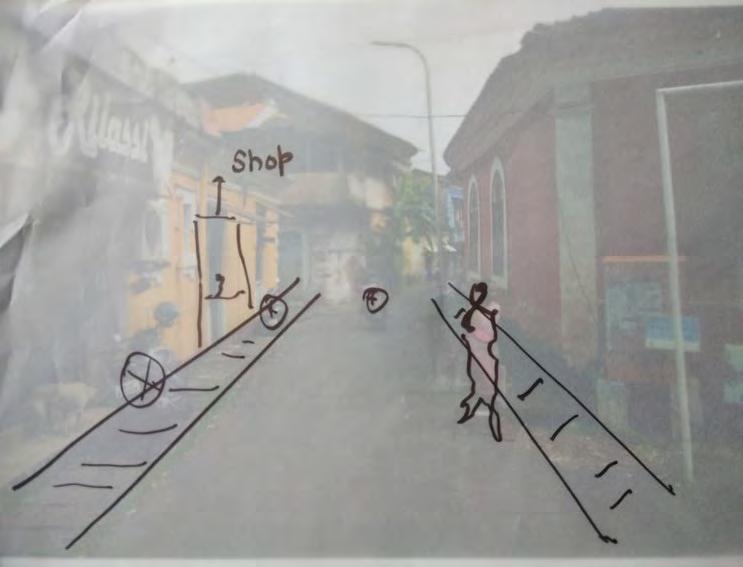

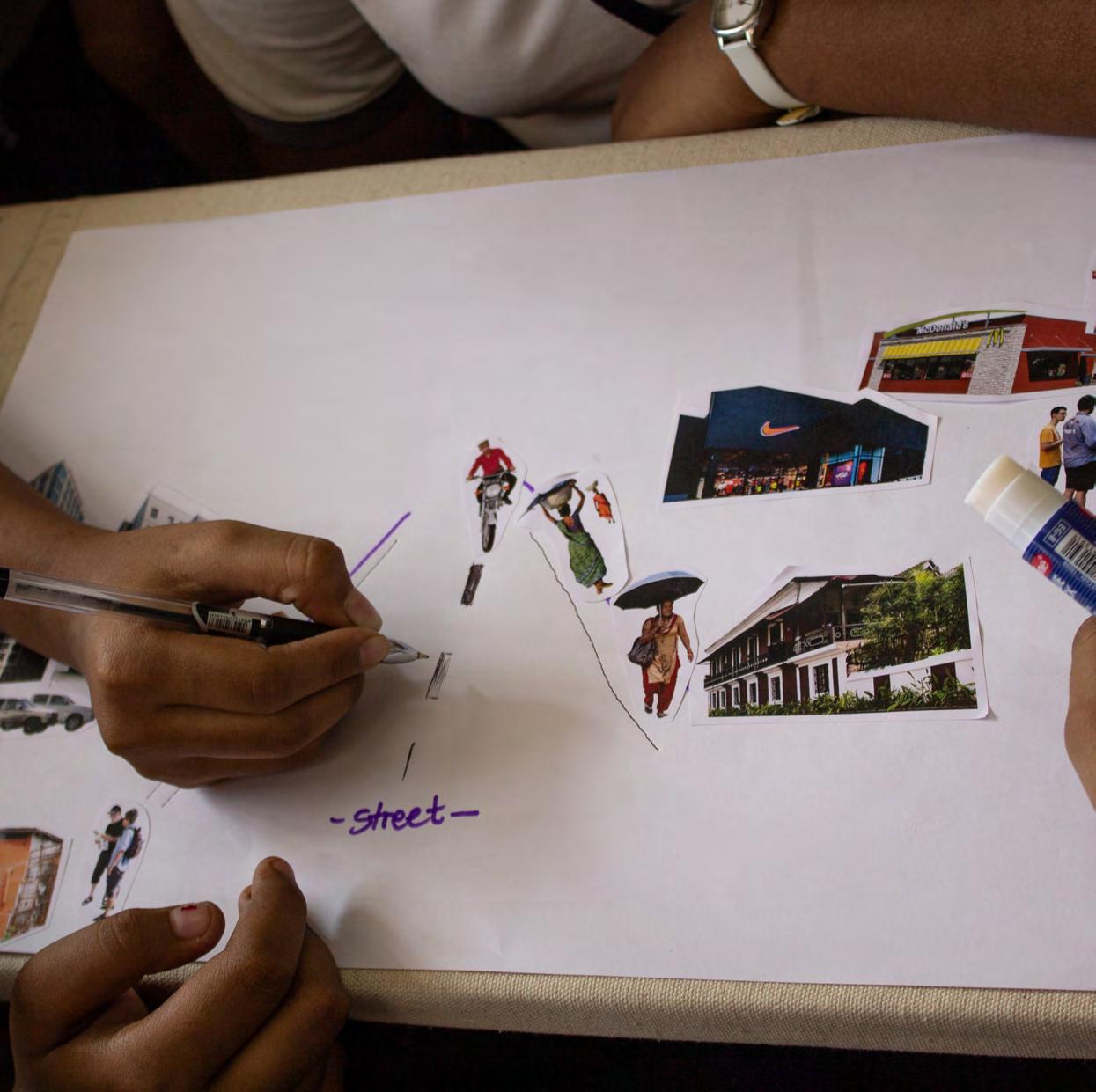

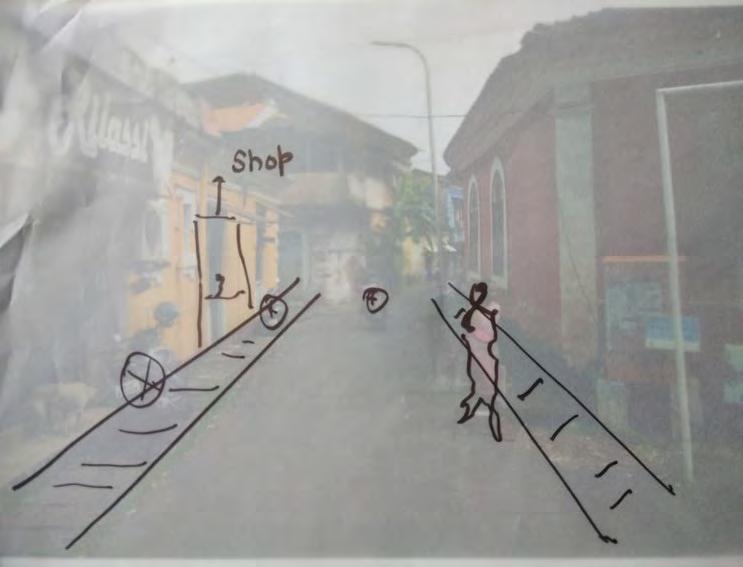

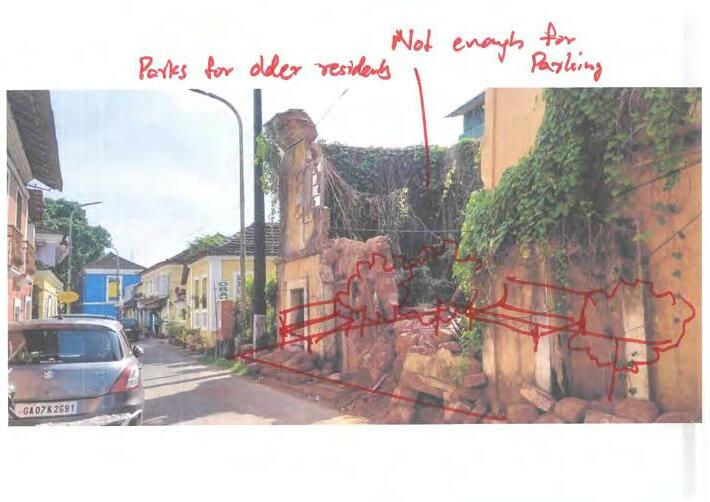

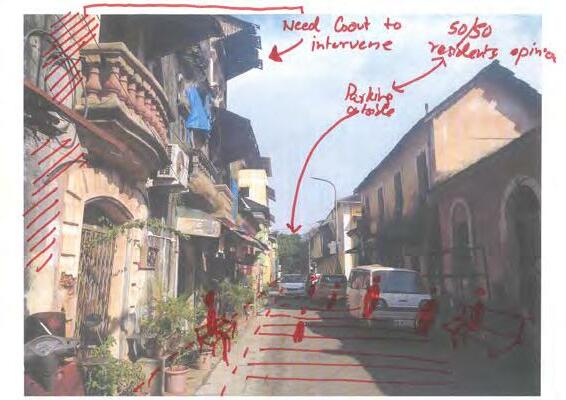

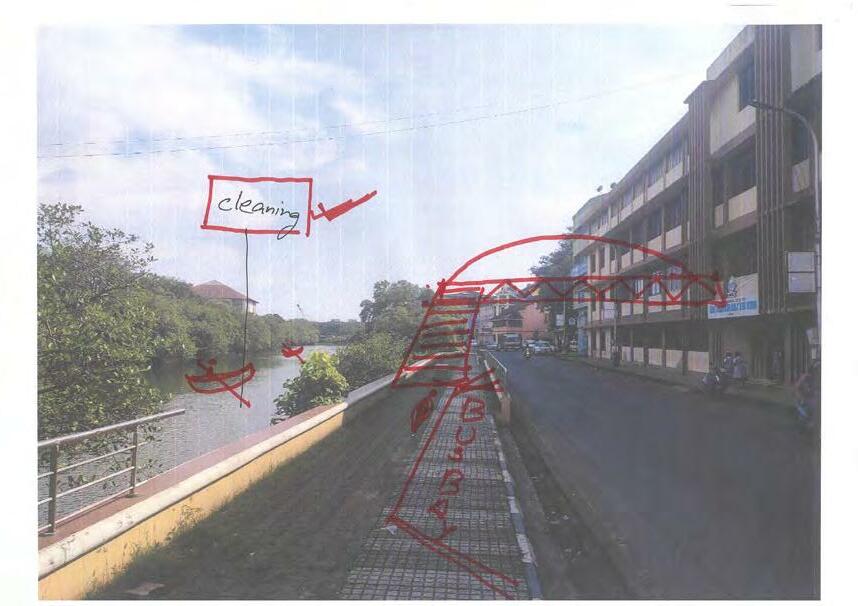

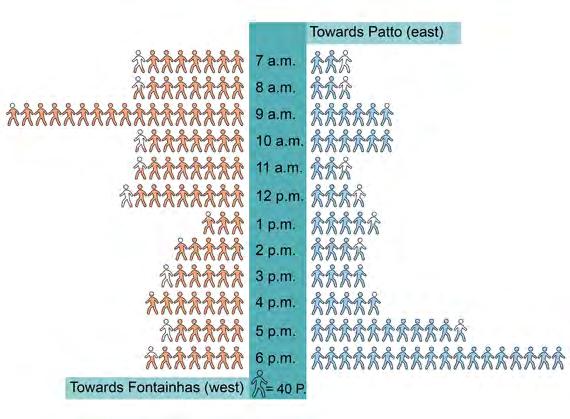

Photo Ideation/Participatory Design

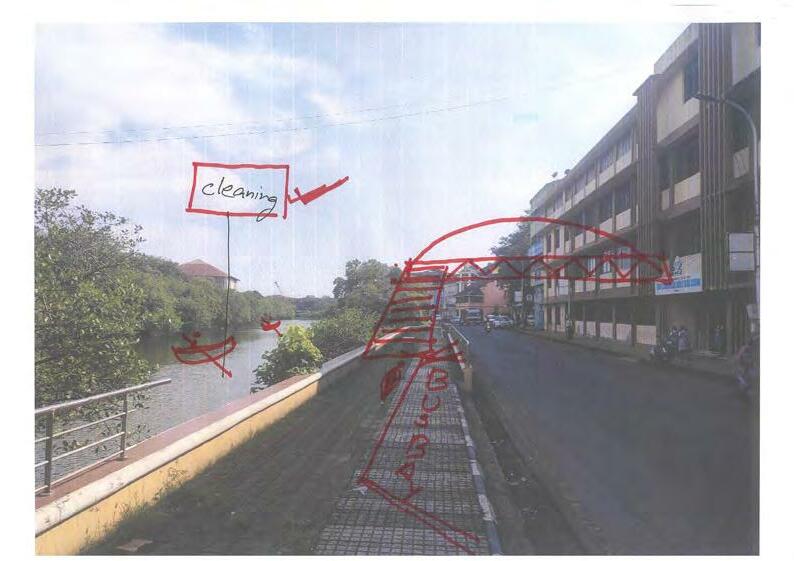

Photo Ideation was one of the methods we conducted that gave us impressive results and useful insights. We began this method by taking photos of different areas in the neighborhood, then worked with participants to allow them to draw on the photos and visually create changes they would want to see in the area. This method was not useful for every participant, as some were too shy or busy to sit with us for a considerable period of time, but

the respondents we did get to participate made some incredible images. We experienced hesitation at first, but similar to the resource mapping, if one person helped them get started, they would take over from there. By demonstrating one or two things on the photo, it allowed the participant to then take control and complete their own vision. One young college age man drew images of taking back parking space and converting it into a play area for children in the neighborhood. A woman drew an image of a footbridge that goes over Rua De Ourém street so people can cross more easily. Many of the themes people presented to us revolved around traffic safety and public space. We took these ideas, compiled them, and used the people’s ideas and desires to create proposals.

63

Figure

5.14.

(Left) Results of Photo Ideation (Right) Photo Ideation Participants

Figure 5.15. Photo Ideation

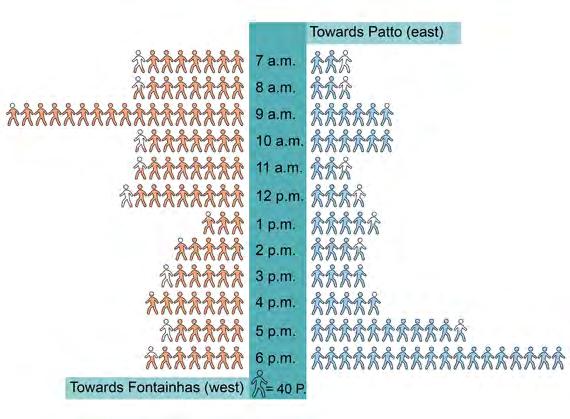

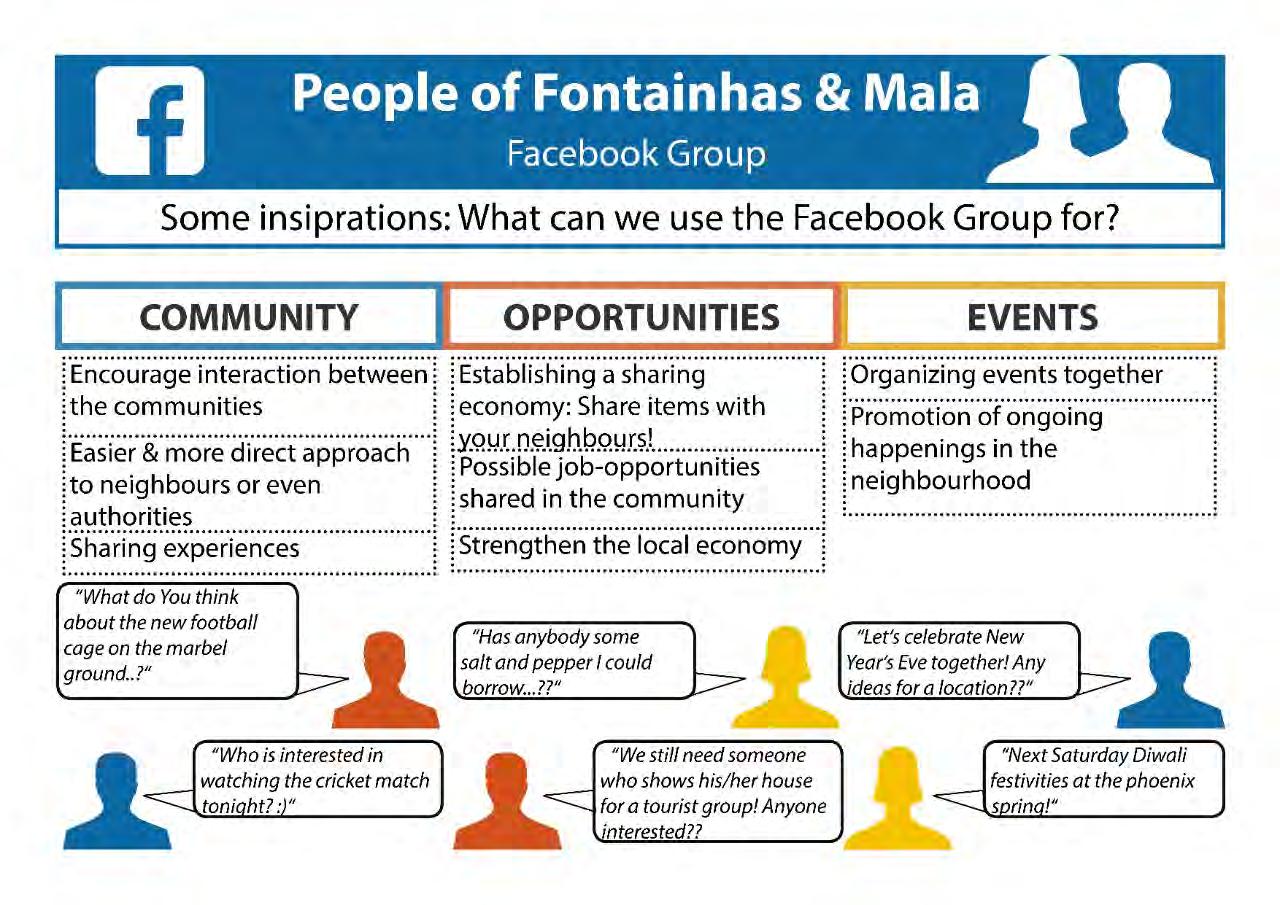

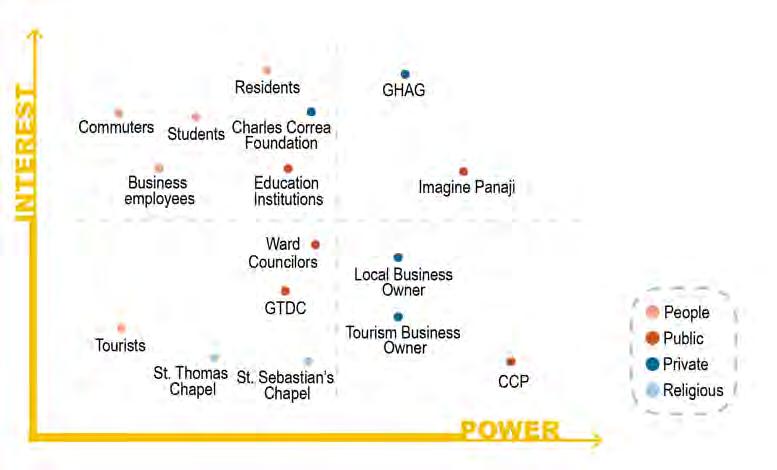

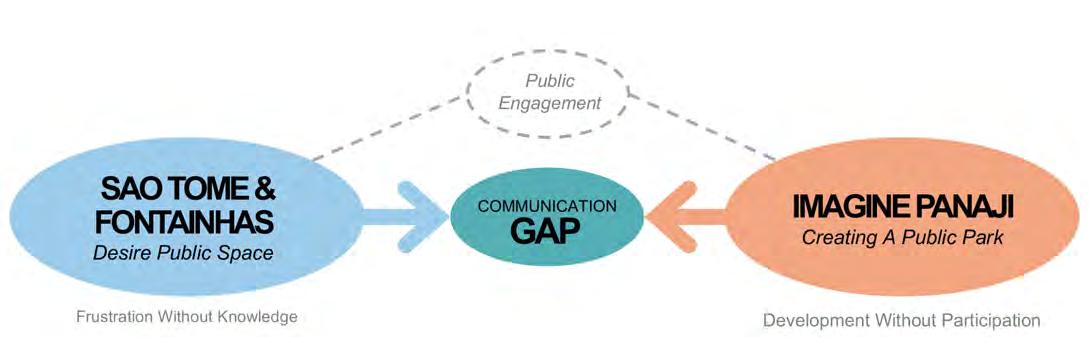

Findings of Secondary phase