1 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course Project Report, Autumn 2021 Urban Ecological Planning Master’s programme Department of Architecture & Planning, Faculty of Architecture Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway Public Space Network Ila, Trondheim

AAR4525 - Urban Ecological Planning: Project Course

Project Report, Autumn 2021 Urban Ecological Planning Master’s Programme

Department of Architecture and Planning, Faculty of Architecture

Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim, Norway

Course Coordinator: Marcin Sliwa Assistant Professor (NTNU) Doctoral Researcher (University of Oslo)

Main Supervisor: Peter Gotsch Professor, NTNU

Supervision Team: Marcin Sliwa Assistant Professor (NTNU), Doctoral researcher (University of Oslo)

Mrudhula Koshy Assistant Professor

Riny Sharma Research Associate, NTNU

Booklet Layout: Mrudhula Koshy Assistant Professor, NTNU

2 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Public Space Network

Ila, Trondheim

Authors

Angela Subedi

Architecture Nepal Anne Klenge

Environmental Engineering Germany

Azam Mirjalali

Architecture Iran

Bhuvana Nanaiah Architecture India

Marcela Moraga Architecture and Urbanism Chile

Michael Dyblie Global Studies USA Nathaniel Gallishaw

Transportation Engineering USA

Olawale Olugbade

Real Estate Management Nigeria

Rupak Bhattarai

Civil Engineering Nepal

3 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Preface

This project report consolidates the results of the 2021 Autumn semester conducted by students of the 2-year International Master of Science Program in Urban Ecological Planning (UEP) at the Faculty of Architecture and Design at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) in Trondheim, Norway.

For the second consecutive year, the COVID-19 pandemic made it impossible to conduct the usual fieldwork we have been undertaking traditionally. Before 2020, most UEP student groups have been traveling to Nepal, India and Uganda to study urban informality and practice areabased and participatory approaches to planning. However, mobility restrictions caused by the pandemic forced us to modify the fieldwork logistics and our pedagogical approaches to adjust to the uncertain situation, and at the same time work towards the similar learning objectives as before.

As opposed to last year, where most students performed individual fieldwork in their home cities, in 2021 all the UEP students worked in Trondheim, Norway, which is the home city of our university. For the first time in the UEP program, the entire class has been working together in a Global North context. The students were divided into 6 groups and were assigned three different cases. This report summarizes work of the group working in the neighbourhood of Ila. In their project work, students practiced the “Urban Ecological Planning” approach, which places emphasis on integrated area-based (as opposed to sectorial) situational analysis and proposal making using participatory and strategic planning methods. Our approach was inspired by the Chicago school, which proposed ethnography as a way to study urban spaces and social ecology as a framework to understand them. This approach is not new to UEP, but this year we had to make pedagogical changes to adjust the fieldwork courses to a Global North context. This included revising our compendiums to make it more relevant to urban planning in Norway, distributing students in groups in a way that helps them with language barriers and using our existing research network to kick start three parallel student projects in Trondheim.

4 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

By spending a large amount of time in the assigned areas and engaging with local communities as well as other relevant stakeholders, students gained an in-depth understanding of the local context. This allowed them to discover strengths and weaknesses and identify opportunities and challenges in each of their assigned areas, something that would be impossible to achieve by applying traditional technocratic and purely quantitative planning methods. The rich evidence and data collected in the field was used by the student groups as a basis for proposals for spatial and policy interventions in their corresponding areas.

We hope that you enjoy reading this document as much as we enjoyed supervising students in their work!

Marcin Sliwa, Riny Sharma, Mrudhula Koshy and Peter Gotsch

Fieldwork Supervisors, NTNU, Department of Architecture and Planning

5 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Acknowledgements

During the process of this fieldwork, our project team has received substantial support for which we are incredibly grateful. First, we would like to thank our supervisor, Professor Peter Andreas Gotsch. Throughout the process, his expertise and assistance have been invaluable. We thank him for the time he invested and constructive feedback he provided.

Furthermore, we would like to thank all our other advisors for their insightful feedback that advanced our work. We thank Marcin Sliwa, Mrudhula Koshy, and Riny Sharma for sharing their knowledge and offering valuable guidance. Additionally, we received helpful suggestions from Rolee Aranya, Hans Christian Bjørne, and Per Gunnar Røe for which we are also thankful.

Without Ila’s residents, volunteers, community leaders, business owners, interviewees, participants in our workshops, and everyone else involved in our various methodologies, it would have been impossible to complete this project. We thank everyone who got involved and made this participatory approach possible. We would especially like to thank Annette Taraldsen, April Maja Almaas, Bjørn Fjeldvær, Bjørn Inge Melås, Grete Kristin Hennissen, Merete Støvring, Nabin Thakur, Sigrid Gilleberg, Stian Wannebo, and Øystein Aarlott Digre.

Finally, we are sincerely grateful to our families and friends for their moral support throughout the project.

6 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Acronyms and Abbreviations

ArcGIS Generic term for Geographic information system software products of the company ESRI

ATM Automated Teller Machine

COVID-19 Coronavirus disease 2019

Friviligsentral Eng. Volunteer Centre

GIS Geographic Information System

Iling/Ilinger demonym for resident(s) of Ila (singular/plural)

Kommune Eng. Municipality

NTNU Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelige universitet

SWOT Strengths, Weakness, Opprtunities and Threats

UEP Urban Ecological Planning

UN United Nations

7 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

8 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network Public Space Network Ila, Trondheim

9 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

10 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network Contents 1. Introduction to the Project 12 2. Project Timeline 14 3. Introduction to case study area and its context 16 4. History of Ila 18 5. Main Methodological Approaches 20 5.1. Situational Analysis 22 5.2. Reaching an Opportunity Statement 28 5.3. Conceptualizing a Strategic Implementation Plan 30 5.4. Generating Spatial Solutions 33 6. Findings of the Situational Analysis 35 6.1. Social and Cultural Dimension 36 6.2. Spatial and Physical Dimension 47 6.3. Reaching an Outcome 59 7. Opportunity Statement 64 8. Conceptualizing a Strategic Implementation Plan 66 8.1. Strategic Implementation Plan 66 8.2. Spatial Interventions 68

11 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network 8.3. Engaging the Community 72 9. Spatial Solutions Public Space Network Ila 74 9.1. Group 5 Solutions 79 9.2. Group 6 Solutions 91 9.3. Future Outlooks 108 10. Reflection 110 11. Conclusion and Recommendations 114 12. References 115 12.1. Literature 115 12.2. Images 117 13. List of Figures 118 14. Appendix 120

1. INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT

It is projected that 68% of the world population will live in cities by 2050 (United Nations, 2018). The population of Trondheim has been growing by about 3,000 residents annually in recent years, with much of the growth occurring in areas such as Ranheim, Ila, and Kattem (Trondheim Municipality, 2019). To accommodate this growth, it is important to create and enhance facilities that make neighborhoods more livable and give the residents a sense of belonging to the urban network.

While in many cases professionals dictate these changes, such top-down approaches often fail to incorporate the perspectives of its end users. The resultant ‘solutions’ neither cater to the real needs of the residents, nor utilize the community’s

potential. The Urban Ecological Planning (UEP) approach instead focuses on using participatory methods to develop humancentered solutions. These solutions provide frameworks for addressing complex urban issues and creating more sustainable communities. The UEP approach formed the foundation of this semester-long fieldwork undertaken by the project team in Ila.

The team endeavored to achieve promising yet flexible outcomes that, through an iterative implementation process, can stand the test of time.

Ila’s diversity of built environments, proximity to natural beauty, and evidence of contested land use make this neighborhood located west of Trondheim’s city center unique. The colossal

12 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Figure 1.1: Ilevollen (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

corn silos form the backdrop to a quaint row of vibrantly colored, historic houses inhibited by warm and friendly faces. The ambience makes one feel as though they traveled back in time to an old Norwegian village, all while being in the heart of the country’s third-largest city. Located a few blocks to the west is the newer, denser development known as Ilsvika. The buildings in this section of Ila look like many of the other concrete residential complexes in Trondheim. The spaces between the buildings feel private, secluded, and disconnected from the welcoming aura of the original housing settlement. Despite the higher population density, Ilsvika’s residents are visibly absent from its many public spaces. The cause of this problem is not just the architecture of the area, but also the influence of its spaces on social dynamics. Nevertheless, the consensus is that the entire neighborhood of Ila is an attractive place to live.

The initial exposure to Ila and UEP sparked questions that acted as guidelines for the fieldwork. What are the problems in Ila?

How can the UEP approach be tailored to suit the designated project context? What do the residents of Ila want? How can the project team make use of existing resources for the benefit of Ila?

What external factors should be accounted for when facilitating development? And finally, what can other neighborhoods in Trondheim learn from Ila? This report details how the project team used the UEP approach to guide its exploration and experimentation in Ila. It explains how opportunities in the neighborhood were identified through citizen participation and how a framework was developed to enhance community cohesion by magnifying existing strengths.

13 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Figure 1.2: Juxtaposition of the old residential buildings with the corn silos (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

14 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network 2. PROJECT TIMELINE August 16, 2021 Start of Semester November Spatial October 29, 2021 Presentation of Opportunity Statement October 1, 2021 Situational Analysis (Authorship of Team Ila, UEP 2021) (Authorship of Team Ila, UEP 2021) (Authorship of Team Ila, UEP 2021) (Authorship of TeamFigure 2.1: Project Timeline (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

15 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network November 2021 Solutions November 19, 2021 Presentation of Draft Spatial Solutions December 3, 2021 Final Group Presentation December 10, 2021 Submission of Final Report (Authorship of Team Ila, UEP 2021) (Authorship of Team Ila, UEP 2021) eam Ila, UEP 2021) (Authorship of Team Ila, UEP 2021)

3. INTRODUCTION TO CASE STUDY AREA AND ITS CONTEXT

When asked what comes to mind when thinking of Norway, one might mention the high standard of living, equality and flat hierarchies, a strong bond to nature, and an exemplary urban development framework. However, the country is located at the far northern periphery of the European continent, and is therefore exposed to harsh weather conditions. Icy winters and darkness leave their mark on the Norwegian mindset. Kuvac and Schwai describe the Norwegian identity by saying that “in an inaccessible and sparsely populated country, rich in vast natural beauty, a ‘small nation’ lives characterized by modesty and patience, but also by loneliness, depression, and cold” (2017).

Located in the middle part of this country, on the shore of Trondheim Fjord, one can find Norway’s third-largest city, Trondheim. Norway’s so-called innovation capital is home to Ila, a neighborhood and district located west of the Midtbyen, the city center. Ila is connected to its surroundings by numerous modes of transit, such as Trondheim’s only tram line, bus routes, a nearby train station, and a motorway. With a rich history, Ila has taken quite a different development path than the Municipality had intended back in the mid-20th century. As a result, the area is mostly residential nowadays. The steel and agricultural industries that remain in the neighborhood are confined to a section of land north of the residential areas (Trondheim Municipality, 2021).

Of note are the three physical divisions of the residential area into what can be considered ‘Core Ila’ 1 to the east, Ilsvika to the west, and Ilsvikøra in between. One will notice changes in the built environment when moving through these areas. In Core Ila, many residents living here today have a strong connection with Ila’s industries, both past and present. Also, several retirement homes were built in Core Ila in the 1960s, on land that had previously been hotels. This is just one example of the continual

evolution of land use in this area (Kjenstad, 2004; Rosvold, 2020; Trondheim Municipality, n.d.). Ilsvika, meanwhile, was formerly the site of metal works factories. There is a heritage preservation site at Ilsviken gård, formerly a terraced garden laid out between the main building and the fjord. Ilsvika today primarily consists of new residential developments constructed in the early 2000s. These were constructed over the span of about a decade, with the same developers overseeing the project (Kjenstad, 2004; Rosvold, n.d.; Trondheim Municipality, n.d.). The area is noticeably newer than the rest of Ila, with taller buildings overall, and less diversity of building typology. Ilsvikøra became the first urban renewal area (specially regulated for conservation) in the city of Trondheim after residents won the battle for conservation in the 1960s. The former fishing village was and is a place of strong family ties and local pride. This is part of the reason that the area was preserved after intense debate over the area’s future in the 1960s and 1970s (Kjenstad, 2004; Kuvac and Schwai, 2017; Rosvold, 2020; Trondheim Municipality, n.d.).

Regarding the historical and cultural value of the area, it is evident that the construction of (social) identities in Ila is a continuous, never-ending process. Dynamic and independent, but still linked to the visible physical framework, identity is the invisible association with a particular place (Kuvac and Schwai, 2017). Space is changeable, which shows that identification with it is more of an evolution than a constant. In Ila, three parts, different in their external appearances, become neighbors. Older and newer built environments in Ila, Ilsvika, and Ilsvikøra house various societal groups within the same larger spatial context. The question of how to shape common identity within a neighborhood may be considered. One important finding is that identification happens in exchange. That is why public space is considered to play a special role in identity creation. Public space

16 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

enables interaction, communication, and a common sharing of values within the same spatial context (Murphy, 2011). The strengthened identification in a spatial context ultimately leads to public participation, which in turn promotes identity within this space (Haeberle, 1987). Finally, this neighborhood identity loop effect can be perceived beyond the boundaries of the neighborhood itself (Sadeque, et al., 2020).

1 For the sake of consistency, the project team decided to refer to the oldest residential area, located in the eastern part of the neighborhood, by the unofficial name of Core Ila.

17 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Figure 3.2: Ilsvika (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

Figure 3.1: Ila (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

18th century

First school, Ilens Friskole,

The first buildings

built in Ila

18th century

19th Century

first Norwe gian Constitution

developed as an industrial area

developed as an entertainment center of Trond

Elisabeth’s Hospital was established

six years of construction, Ilen Church was consecrated

18 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network 4. HISTORY OF ILA Early

18891826Late

Early

1880

were

St.

Ila

Ila

heim

was established After

The

Day parade was organized in Ila 1 1 1 2 1 2 1 (Olsen, 1900-1908) (Schrøder, 1939) (Næss, Unknown) 6 5 7 8 9 10(Unknown, 1915) (Unknown, 1945) * The photographs are representation of the area from the past, but they were taken at different times than the dates mentioned in the timeline. (Unknown, Unknown) Figure 4.1: History of Ila (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021) References: 1. Rosvold, 2009 2. Hapnes, 2003 3. Kjenstad, 2004 4. Trondheim Kommune, 2008 * The photographs are representation of the area from the past but they were taken at different times than the dates mentioned in the timeline.

Ilaparken was created

Ila Line (carts pulled by horses)

established

Ila and Midtbyen

Late 19th Century

substantial amount of dense, working-class housing for indus trial laborers was built in Ila

Ila Line,

A municipal propos al to demolish Ilsvikøra to make way for additional industry was not implemented due to strong community opposition

estate developers began construct ing contemporary buildings in Ilsvika

19 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network 1893 1891 1901

1970 2003

A

The

was

between

Tracks were built for the

with trams replacing horses Real

1 3 1 3 1 (Authorship of Team Ila, UEP 2021) (Authorship of Team Ila, UEP 2021) 4 11 12 13 (Unknown, 1870s) (Authorship of Team Ila, UEP 2021) (Unknown, Unknown) (Unknown, Unknown)

5. MAIN METHODOLOGICAL APPROACHES

To better identify and address the needs of the community, the project team used participatory approaches at every stage of the project. The initial stage of the project involved deciding which methods to use in order to implement this approach as successfully as possible. This chapter will present the methodological path that was taken in examining the fieldwork area and analyzing the needs of the residents of Ila. The chapter is subdivided based on the phases of the project.

20 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

GIS Traffic Modelling Mappingof existing/potentia Situational Analysis Opportunit y Statement C o n c e p t s f o r S t r a t e g i c P l a n laitapStfarDnoituloS laniF noituloS TransectWalkDesign thinking andbrainstorming OnlinTraffic Count Opportunity PrioritizationBoard Co-designing Storytellin GROUP METHODOLOGY Figure 5.1: Group Methodology (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

of Ideas

Stakeholder Validation

The methodology used in each stage was collectively decided by the team based on our past expeiriences, learnings from the theory and methods course, case studies, and suggestions by the course coordinator. The process was not linear and involved alot of back and forth. Regular group and self reflection of project and team dynamics helped us learn through experience, and streamline the process better.

21 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network Sketching Exhibition

Spatial Plan PrioritizationBoard

Case

Studyofalvalues

Realistic

Renders

e

Survey Co

ff

ee Stand Interview Attend Public Meetings

Internal

Prioritization

Secondary Research SWOTMapping

Tree

Sketching Case

Studies Useof ToolkitsDesign thinking andbrainstorming

ng

5.1 Situational analysis

5.1.1. Quantitative methods

5.1.1.1. Census data analysis

From the earliest stage of the project, it was important to understand the Ilinger. To this end, demographic data from Statistics Norway were analyzed. Because these data were presented by rectangular census tract (250 m by 250 m), the project area did not fit neatly into a set of these tracts. Therefore, the population data of those tracts that contained part of Ila and part of an adjacent neighborhood were apportioned based on each neighborhood’s proportion of land area within that tract. Those tracts that contained only populated areas within Ila were analyzed normally. While apportioning the population data introduced a potential source of error, more granular data were unfortunately not available. The data analyzed were population, gender distribution, and age distribution.

5.1.1.2. Traffic count

Two major intersections within Ila were chosen for traffic counts. At each intersection, the number of buses, bicycles, cars, motorcycles, trucks, and pedestrians during a 15-minute period was observed. These samples were taken at specific times throughout the day in accordance with general traffic counting procedures: weekday AM peak, weekday midday off-peak, weekday PM peak, weekday evening off-peak, Saturday off-peak, and Sunday off-peak. Using this data, the proportion of people using each mode of transportation and the total traffic volumes were calculated.

Figure 5.2: Census Tracts Containing Parts of Project Ila (Statistics Norway, 2021)

Figure 5.3: Traffic Count (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

22 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

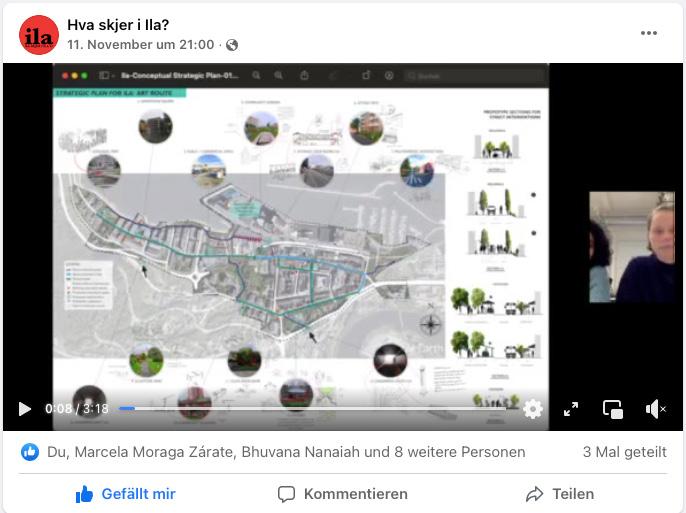

5.1.1.3. Online survey

An online survey consisting of 22 questions was created for the purpose of gathering feedback from the community. The first several questions were demographic (age, gender, occupation, and housing situation); these were followed by questions about appreciation of the neighborhood, identity and community dynamics, mobility, and public space. Residents were also invited to provide additional comments. The questionnaire was posted on a Facebook page popular in the community: Hva skjer i Ila? (“What is going on in Ila?”) and hard-copy posters were put up at Frivilligsentral, the community volunteer center. Norwegian and English versions of the document were created to maximize the reach of the survey in the community, facilitating communication with both native-born Norwegians and immigrants.

Figure 5.4: Social Media Post for the Online Survey (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

5.1.2. Qualitative methods

5.1.2.1. Design thinking and brainstorming: Sticky notes

Starting a project course with a multidisciplinary and multicultural team posed challenges and opportunities. Different views and ideas were discussed during a brainstorming session using sticky notes, with team members endeavoring to answer 3 central questions: What? How? and Who?

• “What?” refers to the information that was considered relevant to understanding Ila and its community.

• “How?” refers to the methods to apply in order to obtain and organize the relevant information; this included techniques and representation tools.

• “Who?” refers to the person(s) responsible for working on each defined method, for which interest and ability, according to team members’ diverse professional backgrounds, were prioritized.

Figure 5.5: Brainstorming with Sticky Notes (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

23 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

5.1.2.2. Secondary research and online research

With respect to history and demographics, existing literature and various Internet webpages were reviewed for information applicable to the project area. In addition, available data from Trondheim Municipality was used. This proved to be particularly useful when researching future projects planned in Ila.

5.1.2.3. Interviews

The project team scheduled nine interviews for the purpose of collecting qualitative data about Ila. These semi-structured conversations with stakeholders and residents allowed a deeper insight into the neighborhood and its existing social structures

and dynamics. The team hoped to learn about problems or positive elements in the community. The interviewees provided the basis for expanding the team’s social network within Ila and reaching new relevant contacts. This created a snowball effect by which the project team was able to obtain even more valuable information.

24 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Figure 5.6: Online Research (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

Figure 5.8: Interview with a Stakeholder (Source: Authorship of Team IlaUEP 2021)

Figure 5.7: Group Interview at Ila Frivilligsentral (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

5.1.2.4. Transects

Each visit to Ila revealed new spatial and social phenomena that the project team observed through transect walks. For visual representations of these walks, elevation views of some of the most interesting paths through the neighborhood were developed and notes and pictures of the team’s observations were included. Conducting the transects individually, as a group, and with community members supported a better understanding of the needs and wants of Ilinger, especially as it pertained to the spatial dimension. The four main axes for the walks were

Mellomila, Ilevollen, Ilsvikøra to Iladalen, and Koefoedgeilan.

While walking, the following questions were reflected upon:

• What does a particular space do well?

• What could be improved upon?

• How does this space relate to other spaces within the project area?

• What feelings and thoughts do the residents have when they walk in these areas?

25 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Figure 5.9: Transects (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

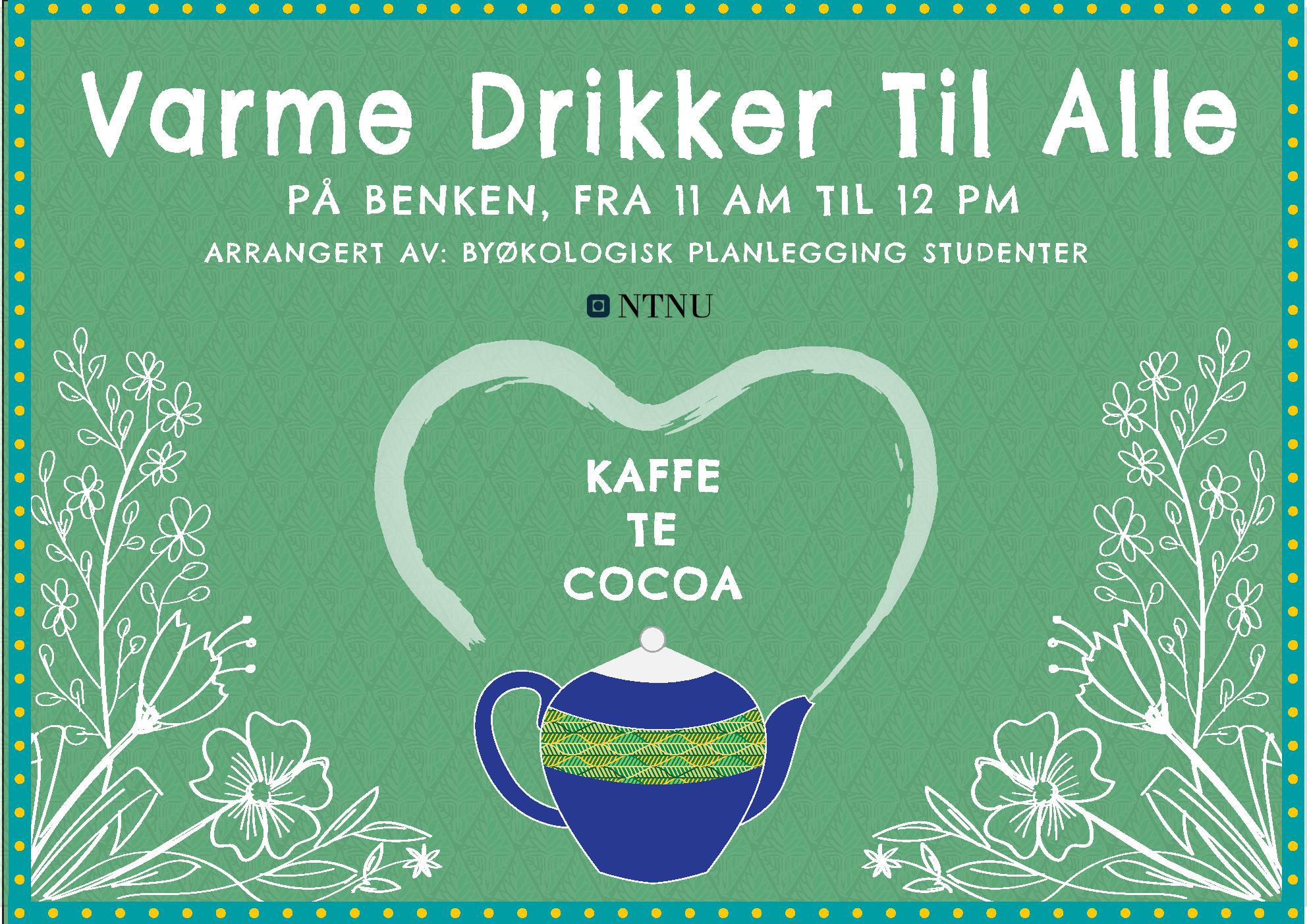

5.1.2.5. Coffee stand

After publishing the online survey, the project team organized a free coffee stand to raise awareness about the project and to encourage residents to complete the survey. At midday on a Sunday and with a pleasant weather forecast, coffee, tea, cocoa, and snacks were offered next to the Ila Free Fridge, a well-known point in the neighborhood. The event was advertised beforehand on Facebook so that residents could visit either deliberately or spontaneously. According to Nabeel Hamdi, a concept such as this tends to attract invisible stakeholders, “those community members unidentified as part of any stakeholder group” (Hamdi, 2010).

26 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Figure 5.10: Coffee Stand next to the Free Fridge (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

Figure 5.11: Coffee Stand Poster (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

5.1.2.6. Attend public meetings

Existing institutions in the neighborhood, such as Ilen Kirke (the local church), Frivilligsentral, or Ila Brainnstasjon (a local bar) offer space for community interaction. In order to experience the spirit of the community, the project team participated in several community events in Ila. These included Waffle Tuesday at the Frivilligsentral, a Bible study at Ilen Kirke, and an evening at Brainnstasjon. The team had the chance to talk to several residents about their experiences and perspectives. Volunteers were able to share their experiences of serving various members of the community. Through these conversations, the team gained the sense that Ila was an artistic and creative place.

5.1.2.7. Mapping: Event/Cultural/Stakeholders/Land-use

Mapping was used to visually depict the observations collected through the various ‘walks and talks’ in Ila. With a base map of the project area as a backdrop, culturally relevant locations in Ila and different land uses were able to be visualized. Stakeholder mapping was used to create a graphical depiction of the stakeholders involved in the project and their relationships both to one another and to specific issues.

questions were addressed: How does Ila fare when compared to other parts of Trondheim? What can other parts of Trondheim learn from Ila?

5.1.2.8. Studying Other Neighborhoods: Lademoen, Svartlamon

Since the Norwegian context was relatively new to the entire project team, it was decided that comparing Ila to other popular neighborhoods of Trondheim, such as Lademoen and Svartlamon, would provide a better understanding of the city’s urban dynamics. These neighborhoods would be compared to Ila both quantitatively and qualitatively. Through secondary research, direct observation, and conversations with peers, the following

5.1.2.9. SWOT analysis

A SWOT Analysis enabled the team to identify the neighborhood’s existing Strengths and Weaknesses, and its potential Opportunities and Threats. Numerous factors were included, including COVID-19 and climate change. The factors deemed most important would be given special consideration in the subsequent definition of the problem (or, in this case, opportunity) statement (Leigh, 2009).

27 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Figure 5.12: Public Meetings (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

5.1.3. Mixed methods

5.1.3.1. Internal prioritization

In the final stage of the situational analysis phase, all topics were examined, including identity, events and community activities, public space, traffic and mobility, demographics, and vision for the future. This step led to a prioritization of opportunities. In a team brainstorming session, the issues raised by the community were formulated into seven ideas for community interventions. These ideas would then be visualized using an opportunity prioritization board.

5.2. Reaching an opportunity statement

5.2.1. Mixed methods

5.2.1.1. Opportunity prioritization board

Once the internal prioritization from the previous phase was completed, a participatory activity was held in which these seven alternatives were presented to the community. Participants were given the chance to choose which issues they believed were most relevant. Each person was given three votes (in the form of stickers) that they could distribute to one, two, or three different projects. Most residents distributed one sticker each to three projects; however, a few chose to put all their stickers on just one of the alternatives. The activity happened on a weekend in Ilaparken, a popular outdoor space for the community.

28 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Figure 5.13: Internal Prioritization (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

Figure 5.14: Opportunity Prioritization Board with Stickers (Source: Author ship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

5.2.2. Qualitative methods

5.2.2.1. Tree of ideas

After completing the prioritization exercise, participants could then contribute their proposals for potential solutions to the ‘tree of ideas.’ It consisted of a box with hanging slips of paper, on which people could write their ideas. This enabled the gathering of additional feedback from the community and the collection of numerous ideas to be considered for the solution phase of the project. The tree of ideas is an artifact that facilitates urban participation and allows planners to gather thoughts, concerns, and ideas from the community in a qualitative manner (Ciudad Emergente, 2013).

Figure 5.15: Tree of Ideas (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

5.2.2.2. Design thinking and brainstorming

The first step towards developing an opportunity statement was assessing the needs of the community. Input from interviews, the opportunity prioritization board, and the tree of ideas were considered by the project team. These ideas provided a foundation for the team’s collaborative work, which took the form of a mural using the platform Miro. Later, a template from the Field Guide for Human-Centered Design, specifically the “Frame Your Design Challenge” (Ideo, 2015) was used. It started with a tentative statement that was then modified, using the questions included in the template as a guide.

Figure 5.16: Brainstorming to Reach an Opportunity Statement (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

29 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

5.3. Conceptualizing a Strategic Implementation Plan

5.3.1. Quantitative methods

5.3.1.1. Traffic modelling using GIS

In order to improve pedestrian and bicycle access, the team considered proposing the closure of a portion of Mellomila to vehicular traffic. To this end, ArcGIS network analysis tools were used to model the impact of detouring traffic. In addition, traffic signal times of the roads that would be utilized by the detour were measured, modeled, and added to the network analysis results. The data gathered was later used to model pedestrian and bike friendly measures in Mellomila.

Figure 5.17: Traffic Modelling of Proposed Situation (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

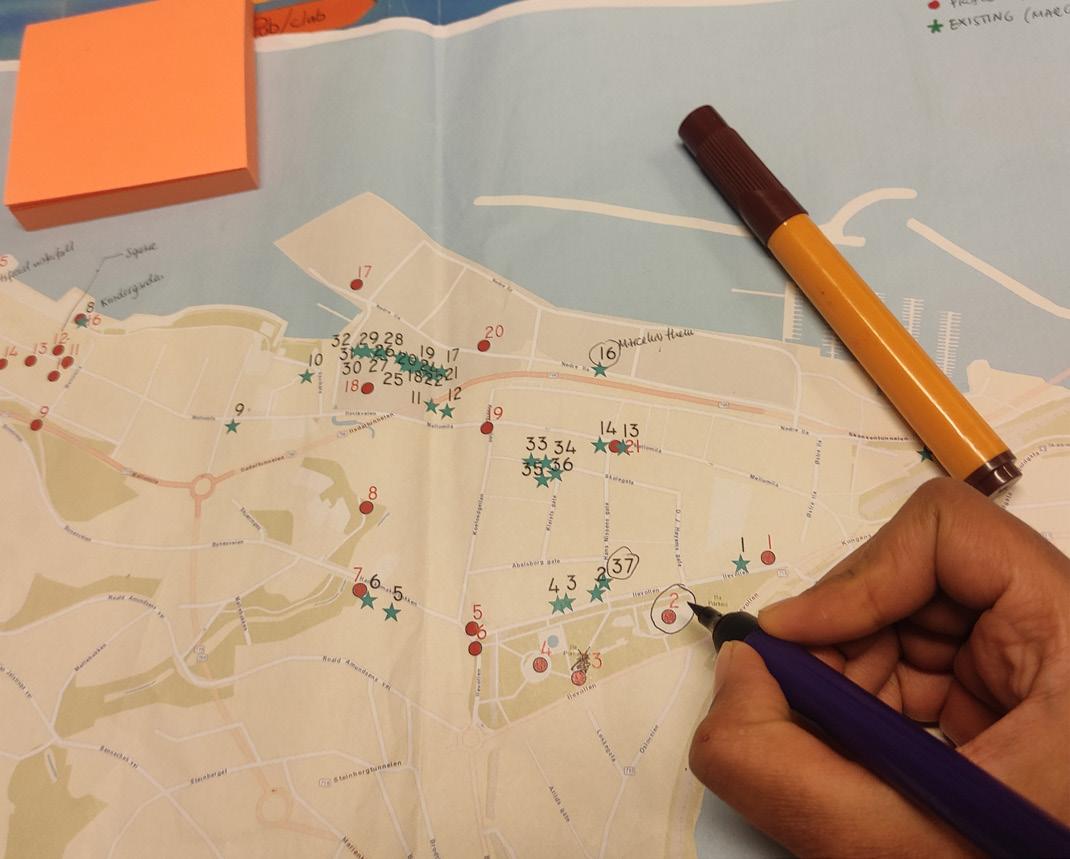

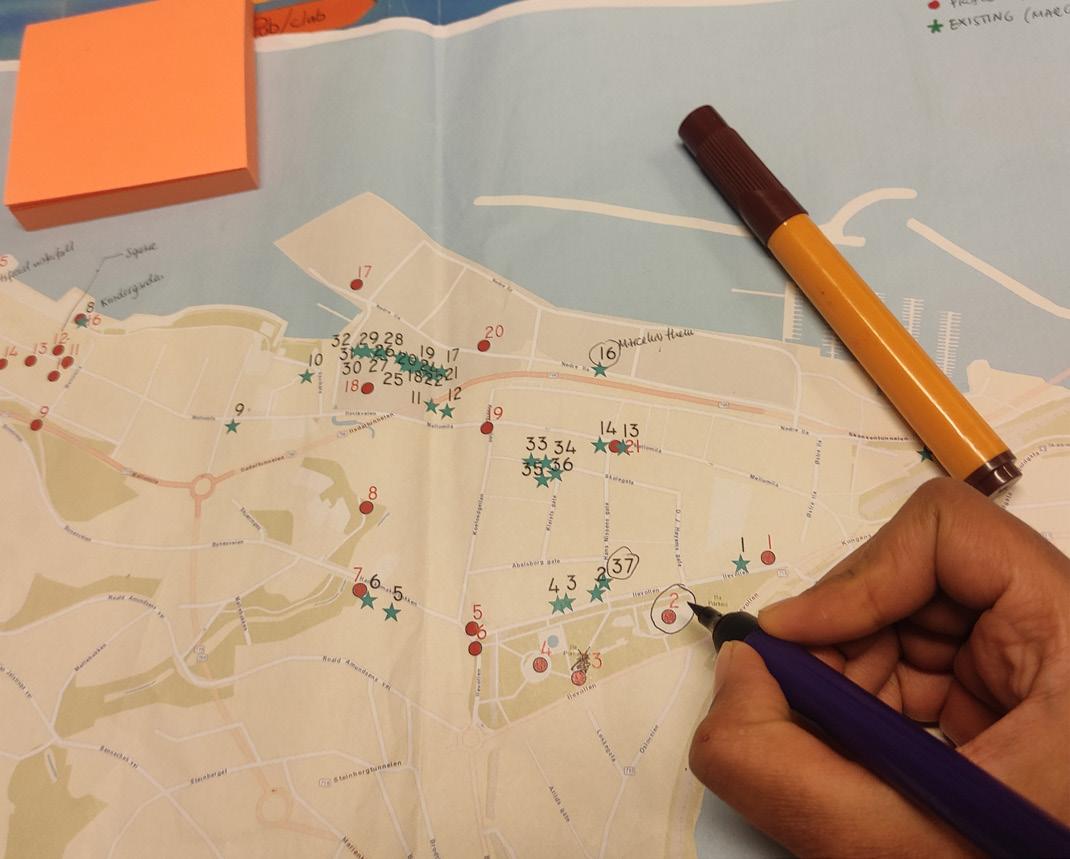

5.3.1.2. Mapping of Existing Values / Mapping of Potential Values

To make the project team’s proposal cohesive and utilize the available resources of the neighborhood, the existing points of interest in Ila, as well as places with the potential to be integrated into the proposal, were identified. The project team again walked through the area to get a better spatial understanding of these two types of places. Using the application Input, these points were mapped and compiled into an ArcGIS file, and a map showing these points was created. This allowed for the recognition of areas with higher concentrations of points of interest, which contributed to detailing the art path as part of the Strategic Implementation Plan.

Figure 5.18: Mapping of Existing/Potential Values (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

30 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

5.3.2. Qualitative methods

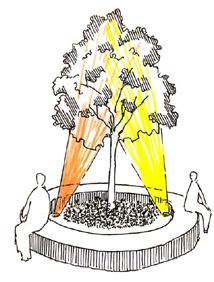

5.3.2.1. Case Studies: Urban Art all over the World

Formulating an opportunity statement necessitated another brainstorming process. This time, the process was more focused than the initial brainstorming session as many previously unknown data were now known. After a consensus on the concept was reached, to encourage the creative process, each team member presented one or more examples of urban art that inspired them. These examples from around the world were visualized using a mind map. In addition, secondary research of Johannesburg was also conducted in order to better understand how art can be used as a medium of cohesion and urban upliftment.

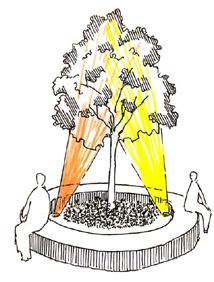

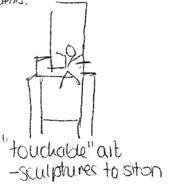

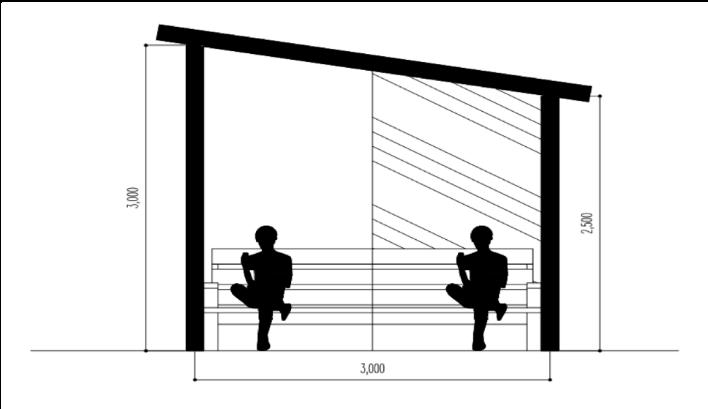

5.3.2.2. Sketches for Strategic Implementation Plan

Once the areas of potential intervention were spatialized on a map, the actual interventions were formulated, adhering to the interests of the participating residents and stakeholders. Handmade sketches were created to portray ideas for uses of the various spaces. Showing these sketches to residents would spark conversations about additional potential interventions at a later stage of the project. Abstract representations were used so that changes could be easily adapted.

Figure 5.20: Sketches for Strategic Implementation Plan (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

31 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Inspiration from all around the world

Valparaiso, Chile Boston, USANagpur, India

India India

STREET GAMES AND ACTIVITY Iran

India

SCULPTURES Iran Iran

TEMPORARY Germany

USA IranUSA

ChileNigeria LIGHTS

GRAFFITI Spain

Iran Iran

Figure 5.19: Urban Art References (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

5.3.3. Mixed methods

5.3.3.1. Strategic Implementation Plan Prioritization Board

After the Strategic Implementation Plan was developed, neighborhood participation provided new momentum for the project. In another participatory activity in Ila, passersby living in Ila were asked to prioritize three of the 13 detailed interventions presented to them. In addition to the specific interventions, they were also asked to cast a vote for which one of four designated sections of the neighborhood they believed was most in need of intervention. Conducted on a Wednesday afternoon in cold, sunny weather conditions, nearly 20 residents participated in the survey in just under two hours.

Figure 5.21: Prioritization of Strategic Implementation Plan (Source: Author ship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

5.3.3.2. Feedback Collection for Strategic Implementation Plan

After conducting the street survey, the project team sought more qualitative data, which was obtained through targeted feedback solicitation. Four specific stakeholders were invited to the UEP Studio, where the project team provided a detailed explanation of the Strategic Implementation Plan. These stakeholders then provided valuable feedback on the proposed concepts. This process was also used by the team to obtain inter-disciplinary insights from practitioners of fields such as geography, sustainable architecture and industrial economics .The step proved to be valuable for the further progress of the project.

Figure 5.22: Feedback for Strategic Implementation Plan (Source: Author ship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

32 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

5.4. Generating spatial solutions

5.4.1. Qualitative methods

5.4.1.1. Co-designing Workshops with Community Members

To continue with the team’s participatory approach to the project work, co-designing was used in this phase of the project. This method seeks to obtain creative input from residents. Due to the situation regarding the COVID-19 pandemic at this time, the workshop was conducted online using social media. Ilinger were asked to contribute to the design using their own creativity and imagination. The co-design focused on the spatial solutions that the project team, relying heavily on the community’s input, had chosen. The format of the contribution was left open-ended in order to allow as much innovation as possible.

Figure 5.23: Co-designing Workshops with Community Members (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

5.4.1.2. Sketches / Drawings for Spatial Solutions

To convey the role of visuals in this project and to evoke creativity and imagination, hand-drawn sketches and drawings were used in the process of generating the spatial solutions. They were supplemented by detailed renderings that were created in Photoshop.

5.4.1.3. Video Editing

A montage video complements the Photoshop renderings by presenting moving images. Drone footage was also used in the video to reinforce spatial classifications.

Figure 5.24: Video Editing (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

33 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

34 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

6. FINDINGS OF THE SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS

In order to define the geographical boundaries of Ila for the purposes of this project, Trondheim Municipality’s official neighborhood delimitation was consulted. However, the distrct identified as Ila by the Municipality covered one square kilometer and was deemed too extensive for the scope of the project. Therefore, it was decided to consult numerous residents, including community leaders, about their understanding of Ila’s boundaries. Synthesizing the various answers received, the

project team defined the limits of Project Ila. With a total area of 40.2 hectares, Project Ila consists of three distinctive residential areas: Core Ila, Ilsvikøra, and Ilsvika. The parklands of Ilaparken, Iladalen, and the western portion of Skansenparken are included within the limits, as is the industrial area along Trondheim Fjord dominated by Felleskjøpet’s towering corn silos.

35 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Figure 6.1: Map with

Definition

of

Boundaries

of

Ila Neighborhood

(Source:

Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

6.1. Social and Cultural Dimension

Ila is a well-known neighborhood within Trondheim, with particular social dynamics that are highly valued by its residents. It has a prominent cultural scene that is attractive not only to the local community but also to other neighborhoods of the city. In this section, these aspects will be examined in accordance with the diverse methods applied during the situational analysis phase.

6.1.1. Demographics and Characterization of Ilinger

Based on official estimates, Project Ila is populated by 2,551 people, distributed over an area of 40.2 hectares (Statistics Norway, 2021). Excluding the industrial area for the purpose of comparing Ila’s population density with other parts of Trondheim, Ila has a net area of 29.4 hectares. The resulting density is 87 inhabitants/ ha, which is significantly higher than that of Midtbyen, the central business district of Trondheim, which has 51 inhabitants/ha. Ila’s gender distribution is equal to that of Trondheim Municipality, with the female-to-male ratio in both entities being 49% to 51% (Trondheim Municipality, 2021).

Residents of Ila describe their neighborhood as “a very nice and diverse district,” which can be explained at least in part by the presence of immigrants and by the varied age distribution (Ila Survey, 2021). Immigrants account for 15.9% of the neighborhood population, which is higher than the proportion for the city of Trondheim, where 12.0% of residents are foreign-born (Trondheim Municipality, 2021). With respect to age, Ila is, on average, slightly older than Trondheim Municipality. The median age in Ila is 39.7 years. Dividing Ila into age brackets of 20 years, the 20-39 age bracket contains a plurality (47%) of residents. Only 6% of the population is under the age of 20. The 40-59 and 60-79 age brackets contain 18% and 22% of the population, respectively, with an additional 7% of residents over the age of 80. Something

quite distinctive about Ilsvika, according to an interview with local senior citizens, is that this area houses a higher concentration of elders, most of whom own their apartments. One resident characterized it as “a comfortable place to live.”

Figure 6.2: Chart with Age Distribution within Ila, in Brackets of 20 years, in Percentages (Source: Trondheim Population Statistics 2021)

During the initial stage of the project, residents were asked to answer an online survey created by the project team. The survey received an encouragingly high 97 responses. The age of the respondents ranged from 16 to 82 years old, with a mean of 45 and a standard deviation of 16, indicating that many participants were well into adulthood. Regarding the gender distribution of the respondents, women (71%) were overrepresented relative to their census population in Ila (49%). Most of the participants were of Norwegian origin (89%), with 10% of respondents having been born elsewhere in Europe and the remaining 1% coming from Oceania. Those who answered the survey work in a diverse range of occupations, including schoolteachers, advisors and

36 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

consultants, kindergarten teachers, health care professionals, artists, musicians, and academic staff at NTNU. Pensioners and students made up 15% and 6% of respondents, respectively.

When asked about their housing situation, 80% of the respondents indicated that they are owners and 18% indicated that they are renters. The rest of the respondents (2%) stated that they were staying with friends or relatives.

An interesting result from the survey data was the length of time that residents had lived in Ila. The plurality of residents had lived in Ila for less than 5 years (31%); this was followed in magnitude by those who had lived there for 11 to 20 years (25%) and those who had lived there for 6 to 10 years (21%). These data show that many residents are new to the area, which is consistent with Statistics Norway data from 2018 showing that 25.5% of Ila residents had just moved into the community during that year. This is much higher than the proportion for the entire city (15.3%).

However, a substantial number of respondents had lived in the area for over 20 years (15%). One of these residents is “Mama Ila,” a senior citizen who was interviewed during the fieldwork. She is

well known in the community, and several residents interviewed referred to her by her ‘matriarchal’ name. She was born in Ila and had lived in the neighborhood all her life. She and several other senior women from Ila explained that many residents who leave the neighborhood during their twenties tend to come back later in life, especially when they decide to settle down and start families. These women perceive there to be many creative people in Ila; they find that this contributes positively to community dynamics.

31, female

41, female

Figure 6.3: Response to Survey about Years Living in Ila (n=97). (Source: Survey carried out by Team Ila - UEP program, 2021 in September)

Figure 6.4: Response to Survey about Satisfaction with the Neighborhood (n=97) (Source: Survey carried out by Team Ila - UEP 2021 in September)

37 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

“Very good. Charming and safe district with proximity to most things.”

“Great place to stay. It has everything I love about a neighborhood.”

During the interview, this group of senior women also mentioned that they saw Ila as “the jewel of Trondheim,” and used the following phrases to describe their neighborhood: “inclusiveness,” “people who take care of each other,” “very safe place,” “nice buildings,” and “active community.” Their glowing reviews of Ila were mirrored in the survey data, where 93% of respondents were either satisfied or highly satisfied with their neighborhood.

During an interview with the project team, representatives of Trondheim Municipality’s City Planning Office stated that most people in Ila were highly content with their neighborhood. Nevertheless, the representatives pointed out that there are some small units in Ila where low-income residents live. Some of these residents live in Ila not by choice but by necessity, as it is more affordable than other neighborhoods located near the center of Trondheim.

6.1.2. Community Dynamics

When asked to evaluate their relationships with neighbors and other community members, residents had slightly lower levels of satisfaction. In this case, 84% of residents were either satisfied or highly satisfied, with an additional 7% expressing low levels of satisfaction. According to the data, there is no correlation between years of residency in the neighborhood and satisfaction with the community dynamics. However, during the interview with the senior group of women, all of them expressed great satisfaction with the neighborhood and highlighted that “people in Ila are great at supporting each other, especially in hard moments, such as grief for the loss of a loved one.”

In terms of residents’ affiliation to community initiatives and organizations, the survey revealed that most respondents take part in community activities in Ila (51%), while a substantial number of people participate in other types of initiatives (28%). The volunteer center involves 21% of Ila residents from a variety of

42, female

age groups. However, it is possible that the residents who do not take part in its activities would still like to have more community spaces within the neighborhood.

Figure 6.5: Response to Survey about Satisfaction in terms of the Relation ship with Other Members of the Community (n=97) (Source: Survey carried out by Team Ila - UEP 2021 in September)

38 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

“Suitable mix of known and unknown faces. Belonging and unity.”

“Beautiful, historical with a rich cultural life and inclusive community.” 29, male

“Would be nice with more common activities that connect the neighborhood, flea markets, etc. [...]” 34, female

The group of elders also mentioned that Ila now offers more social activities than it did in the past. They explained that people meet up more often, and they believe that social media has made it easier for them to participate in activities and stay informed.

As Annette, the chief coordinator of Frivilligsentral, confirms, the elders of Ila use Facebook often, having done so especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. On this topic, the survey shows that most respondents (67%) believe that COVID-19 has not had a significant effect on their community dynamics. Some think that the pandemic changed these dynamics for the better (10%) and others, for the worse (21%).

During the fieldwork, it was identified that there are many activities and initiatives occurring throughout the year, with many seasonal types of events. The community is quite active in comparison to other parts of Trondheim, as some of the residents pointed out. Ilinger organize and participate in various activities, shown on the map below, such as:

• Urban Gardening takes place on a plot of land behind Mellomila 52 and above Ilsviktunnelen; 33 families participate, with about 50% of them being native-born Norwegians and 50% being immigrants (Melås, 2021).

• Benken, or “bench” in English, consists of informal community meetings where residents gather to share waffles and discuss issues of interest. It is limited to the warm months of the year.

• Bålet på Skansen, or “bonfire at Skansen” in English, consists of informal meetings that the attendees normally organize through a Facebook group. It takes place in Skansenparken, where people light bonfires using pallets from the corn silos. Improvised jams and parties take place in an area with no neighbors other than the boats in the marina. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this outdoor gathering attracted many people due to the restrictions on indoor events in Trondheim.

Figure 6.6: Response to Survey about Participation in Neighborhood Organizations (n=97) (Source: Survey carried out by Team Ila - UEP 2021 in September)

• The Free Fridge is an initiative that takes place throughout the year and provides the opportunity for food sharing, which many residents enjoy.

• Ila Dagen is a one-week festival that takes place during the warmer months and includes several activities that take place in various parts of Ila. Residents and visitors take part in the music performances, children’s activities focused, community gatherings, and flea markets.

Other institutions and organizations that gather people both from inside and outside the neighborhood are:

• Ila Brainnstasjon, a local cafe and pub, is a common meeting place for Ila residents. There is a stage inside the building where musicians perform regularly. Sometimes there are larger events, such as visiting international artists.

• Home/restaurant Visit Bjørn is a unique place in Trondheim since it is the only place in the entire city with a permit to operate as a restaurant within someone’s home. The place

39 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

is solely run by homeowner Bjørn, who prepares the meals and plays music for the paying guests. He also performs at the local pub sometimes.

• Ilen Kirke is a 19th-century church that hosts services every week along with several different activities throughout the year. Some of the events are done in collaboration with Ila Frivilligsentral. The church hosts several religious activities for a wide range of age groups and hosts a non-religious event during October where a group of residents gathers for a jam session that is open to all.

• Galleri Dropsfabriken is an art gallery that opened its doors in 2018 and presents Norwegian contemporary art. It has a permanent exposition but also organizes several temporary exhibitions each year. It is a place that attracts both residents of Ila and other inhabitants of Trondheim.

• Galleri Ismene AS is one of Norway’s leading private art galleries, that focuses on visual art. In parallel with continuous exhibition activities, the gallery operates eight graphics clubs and the exhibition business of graphic circulation. (Galleri Ismene, n.d.)

• Ila Frivilligsentral is the volunteer center in the neighborhood, and it provides a vast number of activities and events which are mostly catered to Ila residents, but also attract people from other areas. They have daily activities at their community building such as community walks, Zumba and yoga classes, knitting days, Waffle Tuesday, bingo night, children’s activities, and a Christmas market. They also offer the possibility to rent their hall for events such as christenings, birthdays, and lectures.( Taraldsen, 2021)

40 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Figure

6.7:

Sociocultural Mapping of Ila Activities, Institutions, and Organizations

(Source:

Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP 2021)

Another part of analyzing the social dynamics of the community was identifying major stakeholders in the project. This was an inexhaustive process, where new stakeholders were continually discovered during every interaction with the community.

During the course of the project, a substantial number of stakeholders were identified. Individual persons or institutions either show interest, have reasonable amounts of power, are affected, or influence the process and outcome of the project. In a stakeholder-issue interrelationship diagram (Figure 6.9), the most relevant stakeholders are placed in their proper contexts among the opportunities identified as priorities by the community. This manner of representation conveys the dynamics of who supports, might support, or might oppose the interventions that this project proposes for addressing specific issues in Ila. As can be seen in the diagram, the majority of stakeholders support the idea of

having a space for community interaction and for creativity and business. This is especially true for institutions whose mission is to provide a social framework, such as Ila Frivilligsentral and Ilen Kirke. Trondheim Municipality is a powerful stakeholder and is considered to be a supporter of the interventions, notwithstanding applicable legal restrictions and alternate urban development strategies. Following the participatory approach, residents were always given a role in shaping the process. While not very influential at the individual level, residents as a group are to be valued and not underestimated. Two potential conflicts arise around an outspoken community leader. His visions of two specific interventions might conflict with the Ila nursing home in one case and a private property owner in the other. It is also important to consider the role of restaurants in Ila; some of the proposed interventions would be beneficial to this type of business.

41 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Figure 6.8: Stakeholders Power Interest Diagram and Influence between them (Source: Authorship of Team Ila – UEP 2021)

Trondheim

Kommune

Support

Support Support

DIAGRAM

Support Visitors

Might oppose

Need

SupportMightsupport/oppose

Residents Norwegians

Port (Skansen)

Businesses Café, Salon, Bar

Support

Might oppose

Health care

Potential conflict

Support Support Support Support

Enhancement of sidewalks and bicycle lanes Integration between Corn silos and Ila Integration between Ila and Ilsvika

Ila Sykejhem

Space for creativity and business

Potential conflict Support

A Property owner

Trondheim city Residents Immigrants

A Community Leader

Space for interaction

Support

Support

A Researcher

Might support

Might support Residents Immigrants

Figure 6.9: Stakeholder-Issue Interrelationship DIagram (Source: Authorship of Team Ila – UEP 2021)

Ila Frivillig Sentral

Might support

Ila Kirke Community activities and festivals

Need Industries Might oppose Real estate developers Might oppose Need

Student Dormitory

Educational institutions

42 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

STAKEHOLDER-ISSUE INTERRELATIONSHIP

INTERVIEWS

Chief coordinator of Frivilligsentral, and two senior ladies

Overall, the chief of the volunteer center and the elderly ladies communicated a very positive image of Ila. They stated that they do not like the newer housing developments in the area and identified some services missing in Ila, such as pharmacies and ATMs.

Regarding the role of the volunteer center in the neighborhood, the chief coordinator explained that “people from all over Trondheim come here, not just residents from Ila.” She pointed out that the building is quite old and has had several uses through the years, but it has always been an important meeting place for the community. Even though the activities are open to all, they are mostly attended by Norwegian-speaking residents. According to the interviewees, immigrants usually attend the language café, where they have the chance to practice Norwegian. The group highlighted the role of this chief coordinator in Frivilligsentral and indicated that since she started working there, the center had become much more active than it was before, something they greatly appreciate.

She indicated that “most people come to the volunteer center in the wintertime” because the center offers indoor activities, but she said that there are still many activities throughout the year.

Priest of Ilen Kirke

The priest of Ila parish, states that Ilen Kirke is the home church of not only all Ilinger, but also of the people of many surrounding neighborhoods. She was the person who first introduced the project team to the fact that Ila had historically been a haven for people who were outcasts from society. She explained that the medieval city of Trondheim was located entirely on the peninsula known today as Midtbyen, strategically surrounded by the fjord and the Nidelva river, with only the isthmus of Skansen requiring military defense. Thus, the city wall was built at Skansen, and the community of Ila was founded just outside the wall. As a result, Ila welcomed those who Trondheim rejected, including prostitutes and outcasts. This shaped Ila’s identity as a home for people who were a little rebellious or outside the societal norm. She also shared her experiences in Trondheim as an immigrant and a member of a minority race. She has found that while those who attend her church are almost exclusively native-born Norwegians, she has had only positive experiences with respect to her race and immigrant status in Ila. Whereas in other areas of Trondheim she has experienced overt racism, she has found Ila to be a very accepting community.

43 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Business owner of the restaurant Visit Bjørn

Visit Bjørn has a special permit unique not only to Ila but to all of Trondheim. Its owner is the only person in the municipality who holds a license allowing his kitchen to be used both for commercial and private use. He continuously emphasized how lucky and thankful he was to the Municipality for granting him such an opportunity. He noted that if the Municipality were to grant similar licenses to others in Ila and around Trondheim it could help foster the creation of various new and unique local businesses that would have the potential to add more life and character to their neighborhoods. He also highlighted that if asked in the right manner and consistently, the Municipality is willing to entertain such ideas as they have done in his case.

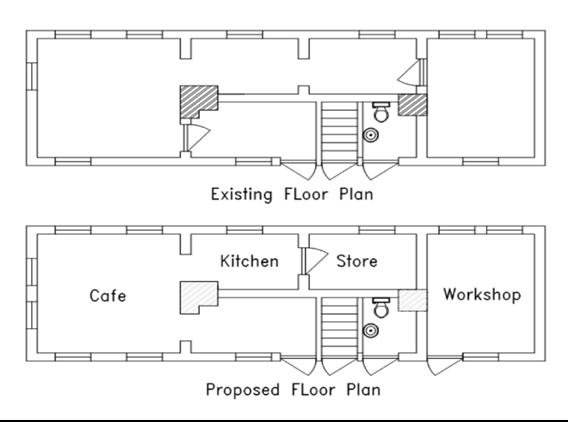

Merete Støvring, owner of the Red Building

The current use of the Red Building is residential, with housing on the upper floor. The ground floor is currently under construction. Merete does not want to create any expectations, but she envisions the place to serve as a modest, family-friendly cafe that underlines the natural atmosphere of the park. As the owner of an ecological store in the city center, she believes that there is an existing demand to buy local products in the area. Merete does not want the future use of the Red Building to be dominated by any one group, but rather to be open for everyone.

NTNU researcher writing on Urban Farming in Ila

Urban Farming in Ila involves 33 urban agricultural plots. About 50% of those participating are not native-born Norwegians. The researcher interviewed stated that there could be more agricultural gardens and that it is practiced more as a social activity than as a source of food, with workshops and activities throughout the year. In addition, he said that Ila needs indoor spaces with activities in winter. A lot of things have potential in Ila; for example, it would be nice to reuse a currently unused space as a (bookable) community space (in Norwegian, a grendehus). As space is valuable, he agreed that it could be beneficial to move parking in the area underground.

Business owner of Indian Curry and Nepali Restaurant

Nabin explained that Ila is a beautiful place where people both from Norway and from abroad live. He mentioned that Ilaparken and the nearby fjord were the most popular spots in Ila. During the interview, he stated that he had opened the restaurant recently and did not live in Ila. Nabin further explained that even though there were community activities in the nearby community center, he did not take part in such activities due to lack of language skills. When asked how Ila could be better, he stated that frequent community gatherings would help strengthen community bonds. He also expressed his concern about drug abuse in the younger generations. Nabin identified issues with traffic congestion in the area during peak hours. He explained that there were no environmental and commercial conflicts in the community of which he was aware.

44 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

A ‘community leader’ in Ila, as stated by several residents

This community leader came to Ila after having grown up in the Bakklandet neighborhood. As a child in such a popular and well-known neighborhood of Trondheim, he felt that he was always being photographed, as if his life were part of a tourist attraction. In Ila he found community and life away from the tourist spotlight. Over his 15 years in Ila, he has become a prominent community figure in the area, with his house serving as a common place for community gatherings. Outside of his home sits the Ila Free Fridge, for which he provides the space and electricity. He highlighted the need and desire for more businesses, cafes, and places to meet within Ila, and pointed to the past to highlight how Ila used to be a neighborhood full of commercial activity. He pointed out the site of Ilevollen helse- og velferdssenter (a local elderly home) as a potential location for more shops and businesses in the future. Ilevollen is, in his view, the prime street in Ila for such activities. He felt that this building’s purpose should, at some point in the future, evolve to fill that niche.

Trondheim Municipality, represented by Grete Kristin Hennissen and Sigrid Gilleberg

Trondheim Municipality is currently not heavily focused on Ila, as there exist other areas in the city that require more attention. It was explained that at present there are no densification plans for the Ila area. This is informed by the fact that Ila’s schools are already at capacity and that the neighborhood receives an unfavorably low amount of sunlight. There are no specific plans for redevelopment of the corn silos or the rest of the industrial area as they are an important part of Norway’s agricultural industry. Also, the Municipality explained that in the city center there exists a renting system for temporary market stands; this is something that could potentially be implemented in Ila. It was also noted that the narrow sidewalks on Mellomila are not optimal for traffic flow and accessibility.

45 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Geographer and resident of Ila

Stian is a particularly insightful resident of Ila who is interested in this project’s subject matter and, generally speaking, to the development patterns of Norway in general. Stian highlighted the concept of ‘Ma,’ or empty space, especially as it pertains to public space. In the context of Ila, Ma would be the space between the buildings. The way users of a space perceive this Ma is quite dependent on the buildings and other amenities themselves. Stian pointed out that humans tend to feel more comfortable in spaces with a lot of variety in shapes and sizes. For example, spaces with large squares that turn into narrow alleys have this tendency. Spaces with open first floors appeal to human instinct as they provide opportunities to escape potential dangers or discomforts. Furthermore, spaces with mixed typologies of buildings (buildings of a variety of shapes, sizes, numbers of floors, and architectural styles) tend to be more favorable when compared to spaces of a monotone nature. Such a monotone style might include buildings or spaces that are copies of a basic template. These spaces tend to make people uncomfortable as there is not enough variety for the human brain to subconsciously contemplate. They are, in a sense, “too perfect,” giving the brain an eerie feeling as it struggles to look for imperfections, blemishes, and character in the space. In the context of this project, Core Ila represents to Stian a more favorable kind of Ma, with the older mix of buildings from a variety of eras and former uses helping to create a space that is more inviting. It is no surprise, then, that more people are found frequenting the outdoor spaces of this area. Ilsvika, however, represents a less favorable kind of Ma. As a development that was built entirely around the same time and with little to no thought given to much of the first-floor space, the area is rarely frequented by those who do not live in the area. Streets are quiet, as there are hardly any cafes, businesses, or inviting meeting spaces in the area, and the monotony and height of the buildings creates spaces that are not at a human scale. Stian suggested that one way to better connect both sections of Ila would be to encourage the development of more first floor activities, such as shops, cafes, restaurants, or bars. These types of places would give more life to spaces, giving people a reason to be there in the first place.

46 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

6.2. Spatial and Physical Dimension

6.2.1. Diversity in Land Use and Residential Typologies

Several methods of analysis were conducted in order to better understand the spatial/physical dimension of Ila. To this end, residents were asked in the survey to identify the characteristics they valued the most in their neighborhood. Five such characteristics were frequently recognized and are listed here from most to least common: accessibility/mobility, proximity to services, landscape, members of the community, and history/ architecture. These results match the observations of Kuvac and Schwai in their analysis of Ila; they state that “despite this high level of urbanity, the residents pointed to proximity to nature as the main characteristic of the neighborhood, including its position in relation to the center of the city and its excellent transport connections” (2017).

In terms of land use, mapping tools revealed that residential buildings comprise most of the buildings in Ila. While Core Ila and Ilsvikøra are mostly composed of single- and doublestoried residential buildings, the rest of Ila has multi-storied apartment buildings with commercial- or business-related activities happening on their first floors. However, some of these activities do not generate significant levels of interaction on the first floor because much of the space on the western side of the neighborhood is used primarily by offices. Neither is attention given to the public, nor are services offered to the community.

In addition to this, the industrial sector in the northern part of the neighborhood occupies a major portion of Ila’s built-up area. The road network here is disconnected from the rest of Ila and lacks the orderliness evident in the rest of the neighborhood.

Other prominent land use includes kindergartens, commercial spaces, business areas, green spaces, and healthcare facilities.

Open spaces, both private and public, are plentiful. Also, one notable space within Ila is the school, located on the western side of the neighborhood. According to senior residents, this is the oldest school in Norway still in use. The priest of Ilen Kirke stated that this school receives foreign children who arrive in Trondheim and must learn the Norwegian language; as a result, it is a highly diverse institution. In terms of the services that the neighborhood does not offer, senior residents expressed their desire for having pharmacies, ATMs, and more cafes.

In Ilsvika, most residential developments have courtyard-style open spaces surrounded by built structures on at least three sides. Most importantly, Ila’s location amid an abundance of natural settings, such as the fjord to the north and Bymarka to the west, and its proximity to the city center enhance its desirability as a place.

Given that the most prominent function in the neighborhood is residential, it is important to emphasize that the residential buildings were built in different years and thus comprise various typologies.

In the 18th century, the area comprised some farmhouses for wealthy families in the region; nevertheless, there are very few of this type of building left in the Ilsvika area. Ilsviken gård is one such building. The most dominant type of housing is semidetached or row housing both in traditional and modern style. Towards the western side of Ila, newer developments in Ilsvika area are mixed-use houses which have commercial ground floors and residences above. Newer developments also feature multi-family medium and large houses, reflecting the housing densification trend in Trondheim. When senior residents were asked how they felt about changes in the neighborhood, they were generally fine with them. A resident known as ‘Mama Ila’ said that “the world moves forward and there are things we like and do not like, but they will still happen.” However, they

47 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

stated that they did not like the newer housing developments in the area. Additionally, as residents of the Ilsvika area, they expressed their desire for “buildings to stay with a lot of space in between them.” This is reflected in the relatively small difference in population density between Ilsvika and Core Ila; the first one has an estimated 96 inhabitants/ha, slightly higher than the 83 inhabitants/ha of the second one.

Something interesting to observe about Ilsvika is that it corresponds to a relatively new residential development from the early 2000s (Trondheim Municipality, 2008). Unlike the rest of Ila, it was populated all at once by a diverse group of people. Most people living in Ilsvika own their homes instead of renting.

Therefore, this part of the neighborhood was shaped by diverse societal groups (with different identities) that abruptly became neighbors and did not know how to dialogue in the public spaces that they share (Marcus, 2011; Kuvac and Schwai, 2017).

The elders also expressed their impressions of the rest of the neighborhood. They see Ilsvikøra as a great place in Ila and feel that it raises the standard of the neighborhood. Regarding the corn silos, they maintain that they were never consulted when they were built (around the 1960s to 1970s); however, they do not have a problem with their presence now. This was not the case a couple of decades ago when there was an issue with dust pollution, which was later solved. Talking about some of

48 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Figure 6.10: High Level of Mixed Uses Identified in Land-Use Mapping in Ila (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP program, 2021)

the historical milestones of Ila, they remember when residents fought to keep the area residential and think back to when they won that battle. They remember when in the 1980s some of the old industrial buildings were turned into housing units.

49 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Figure

6.11: Matrix with Housing

Typologies Identified,

Including

Single Family and Multi-family Units (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP program,

2021) Figure 6.12: Diverse Housing Typologies were also Identified in Ila (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP program, 2021)

6.2.2. Public and common use spaces

Public spaces and common infrastructure were a fundamental part of the analysis of Ila. Both observations from the project team during the fieldwork and inputs from the residents were extremely valuable. Some of the main findings were that even though there is a great number of public (or publicly used) spaces in the neighborhood, many of them are underutilized by residents. This is also reflected in the survey results; most respondents only make regular use of parks and squares, mainly Ilaparken according to several resident testimonies. The rest of the spaces, however, were found to have few respondents ever making use of them.

One of the factors that could explain this observation is the evaluation of public spaces and infrastructures by respondents to the survey. Their highest evaluations were of those spaces they use the most, such as parks and squares, streets and sidewalks, and on-street vegetation. The built environment, meaning urban facades and the exterior condition of housing in general, as well as illumination also have positive evaluations. However, for urban amenities, sports infrastructure, and public buildings, the survey reveals less satisfied or indifferent views from the majority of respondents.

50 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Figure 6.13: Unused

Public Space near the Waterfront

(Source:

Authorship

of

Team

Ila - UEP 2021)

Figure 6.14: Response to survey about use of public/common spaces within the last 30 days (n=97) (Source: Survey carried out by Team Ila - UEP program, 2021 in September)

Figure 6.15: Response to survey about evaluation of public places and infrastructure in Ila (n=97) (Source: Survey carried out by Team Ila - UEP program, 2021 in September.

51 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

MELLOMILA: It was also observed that Mellomila serves a fundamental purpose for the neighborhood, as it has both diverse uses and building typologies, and it serves as a connection between Skansen and Ilsvika. However, its condition differs greatly when comparing the east side of the street (Core Ila) to the west side (Ilsvika). In the resident survey, a great number of residents identified the Ilsvika area as one of their favorite places within Ila, highlighting the waterfront area. Nevertheless, several other residents identify Ilsvika as one of the places they least like in Ila, and they emphasize that the building typology is one reason for this. As observed by the project team, streets

and public spaces are generally less inviting on this side of the neighborhood, and the dimensions of the sidewalk are not wider despite the increased housing density in this area. As stated by the municipal representatives interviewed during the fieldwork, this is an issue that the Municipality plans to address in the coming years. Another interesting observation about Mellomila is the differently colored building facades in Ila, but a lack of such diversity in Ilsvika, as well as the variety of vegetation. Diversity creates a better walking environment and makes an area more attractive, which could explain the high level of walkability and cyclability within Ila.

52 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

Figure 6.16: Transects analyzed during the fieldwork in Ila: Mellomila (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP program, 2021)

Figure 6.17: Transects analyzed during the fieldwork in Ila: Ilevollen (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP program, 2021)

Figure 6.18: Transects analyzed during the fieldwork in Ila: Ilsvikøra – Iladalen park. (Source: Authorship of Team Ila - UEP program, 2021)

ILEVOLLEN: As previously noted, it was possible to observe a lack of indoor-outdoor connectivity on the first floor, which is especially lacking in the western part of Ila. However, this does not only occur on Mellomila, but also on Ilevollen and Hanskermakerbakken (important road axes in the neighborhood) in terms of cultural and commercial activities. However, despite these streets’ central role in mobility as transport corridors, there is not much human interaction. The only exceptions are the bus stops where commuters concentrate during peak hours. One of the reasons for this is the land use in the area, with a nursing home and a medical center occupying a large proportion of the

northern side of Ilevollen. These buildings have mostly closed facades that do not allow for interaction

HANSKEMAKERBAKKEN: With regards to Hanskemakerbakken at its intersection with Koefoedgeilan, the situation is similar to that of Ilevollen. This is an area where vehicles and people mostly pass by and do not stay. However, Hanskemakerbakken has potential for more social interaction due to existing commercial uses, including small shops, cafes, and a restaurant. This is also the site of Ila Frivilligsentral, the community building. As one of the residents commented in the survey, “The buildings on one side

53 | Ila, Trondheim | Public Space Network

of Hanskemakerbakken pull down the neighborhood. Quawah [cafe] lifts it up a lot, but the remaining buildings on the same side .... pull down the neighborhood” (Ila Survey, 2021). Another situation observed here is the large footprint of car parking on the south side of the street, especially notable considering that the parking lot behind the volunteer center is rarely occupied.