KALEIDOSCOPE OF (HI)STORIES

MUSEUM DE FUNDATIE | WAANDERS PUBLISHERS, ZWOLLE | STAATLICHE KUNSTSAMMLUNGEN DRESDEN

Hilke Wagner Kaleidoscope of (Hi) stories is the first comprehensive exhibition of modern and contemporary Ukrainian art in Germany and the Netherlands. It is in many ways an extraordinary project. It was certainly not foreseeable that we would make a nation-focused exhibition, and for all of us - including curators Maria Isserlis and Tatiana Kochubinska and many of the participating artists - it was tragic in a way, because it reflects the state of emergency we have been in since the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Tatiana Kochubinska formulated this impressively at the opening in Dresden: “We see ourselves as Europeans, as citizens of the world - we hope for a future in which national borders are overcome, which previously played no role for us - especially in art.” Dana Kavelina’s science fiction film presented in the Dresden exhibition also ends in this spirit, looking ahead to a future without national borders and without difficulties and burdens.

Beatrice von Bormann It is extremely tragic that Russia’s attack on Ukraine has prompted this survey of art from Ukraine. At the same time, it is an important opportunity to get to know Ukraine’s great art and culture better, but unfortunately not under the circumstances one would wish: as a natural part of the international art scene. Many of the artists in the exhibition today live in diaspora in different countries or under very difficult conditions in Ukraine. It is all the more important to be able to show their art now, and to do so in an exhibition that also offers important historical retrospectives to show the development of art in this region at the same time. In this respect, the exhibition is also an outstretched hand towards the art world in Ukraine. These historical positions from 1912 to the 1980s are almost all on loan from museums in Ukraine, supplemented in Zwolle by some loans from the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo (NL). In addition, six artists have created new work for the Zwolle

exhibition, partly in dialogue with the collection, partly with the place itself. One of them, Anna Zvyagintseva, lives in the Netherlands; she did a residency at the Jan van Eyck Academy in Maastricht from 2021-2022.

Marion Ackermann Yes, the exhibition certainly came about under special circumstances. Due to the war situation, many archives, collections and libraries in Ukraine were inaccessible, which made research work difficult for our curators. Many works could only be brought out of the country with the greatest difficulty, especially by Ukrainian lenders and institutions, leaving Ukraine for the very first time. The preservation and sustainable protection of art and culture are fundamental museum tasks. It is therefore indispensable to support Ukrainian museums and provide them with a safe platform to present their artworks. But this is especially true for people. An essential aspect of the exhibition was therefore keeping spaces open for contemporary artists (and colleagues)

to develop new projects and exhibit existing works. In total, more than 50 artists can be seen in this exhibition, including new works created for the exhibition, such as the installations by Nikita Kadan and Lada Nakonechna, which were developed in dialogue with our collection and also remind us here in Dresden of our post-socialist heritage, or the impressive works by Masha Reva, Kateryna Lysovenko or Andrij Bojarov.

Discovering Ukrainian modernism and - thanks to the two curatorsespecially female modernism, was a revelation for me. Immersing myself in art and in Ukraine’s turbulent history, understanding the ongoing struggle for self-understanding in a multi-ethnic country, a country that is now so close to us, is an important experience for all of us. We look through a kaleidoscope at over 100 years of art - and depending on how we turn the kaleidoscope and where we focus it, different images, impressions and stories emerge, from which a complex picture emerges of the diversity and polyphony, continuities and fractures of Ukrainian art(hi) stories.

The exhibition shows how artists dealt with the political, social and cultural developments of their time - with all their ups and downs: from the spirit of optimism of the early 20th century to the new era.

HW During the many contacts with Ukrainian colleagues preparing the exhibition, it became clear how important culture is for Ukrainian society. The museum directors involved told us impressively that, even when the power went out, people still visited the museums in Ukraine and walked through the exhibitions with torches in their hands. Today, many originals have been moved to safety and are no longer displayed in the museums. We are grateful

that some of these works are now on display in Dresden and Zwolle. Many refugees from Ukraine, and there are almost 10,000 of them in Dresden alone, thus also find a piece of their culture and identity in our museums. Art and culture are important anchors of civilization - especially during war. With the Russian invasion, Ukrainian culture is experiencing a new decentralization and a new nomadism, as the curators put it. Many artists, like many other refugees, have been forced to live as migrants scattered around the world.

BvB In the Netherlands, the Ukrainian diaspora has grown from 20,000 to more than 110,000 people since the Russian invasion in February 2022. Of these, 91,000 are refugees. Many Ukrainians also live in Zwolle; for them, the exhibition offers a rare opportunity to experience an important part of their culture, especially as the works of these artists have never been shown in this constellation before. For Museum de Fundatie, this project is also an opportunity to break new ground. In previous years, the museum regularly focused on the East, initially meaning mainly Germany. Now our orientation reaches further, making its way to the borders of Europe and beyond, with the museum’s location and collection always being the starting point.

That is why, for example, Oleksandr Archypenko’s sculpture Standing Nude (1921) from our collection is included in the exhibition as an important testimony to the region’s early avant-garde. Another artist, Lada Nakonechna, treats works from the respective collections in Dresden and Zwolle and creates a new work from them. The same goes for Nikita Kadan, who interweaves postcolonial aspects of the collection in Zwolle with the history of Ukraine. Thus, different histories are naturally intertwined

and offer a different perspective on part of our own collections. Despite all the difficulties and the limited freedom of movement, a number of artists visited Zwolle in the run-up to the exhibition to get to know the museum and, together with curator Aude Christel Mgba, explore options for presenting their work.

MA The art collections of Dresden state also see themselves as a gateway to the East because of their location. We have dedicated ourselves to telling the micro-histories of Central and Eastern European art history that have so far received too little attention. With the resources of our large museum association and our international reach, we want to help shake up the one-sided canon and make it more accessible. We can only do this by defining ourselves as a network museum. And especially from Dresden, with its own “Eastern” identity within Germany and centuries of cultural exchange with some Central and Eastern European countries, it is particularly important to investigate why there has been hardly any knowledge transfer with other countries.

HW This bridging role brings with it a special responsibility and we need to learn the right lessons. For too long, we have paid too little attention to Ukraine from a Western European perspective. Against this background, I was particularly moved by the works of Boris Mikhailov and Lesia Khomenko, which depict the faces of the Maidan demonstrations in 2014. They show the people’s aspirations for democracy, independence and Enlightenment values. They also represent Ukrainian civil society’s struggle against electoral fraud, corruption and Russian influence. I was very impressed by this process of social rapprochement and empowerment. Today we see similar

images from Georgia and the Republic of Moldova - and I would very much like us to look more closely this time. Especially as interest in a post-Soviet perspective is slowly starting to penetrate the art world. Basically, the themes of the exhibition are universal; after all, most of the works were made before the war. The four main themes of the exhibition, Practices of Resistance, Culture of Memory, Spaces of Freedom and Thoughts about the Future concern us all, and many of the participating artists were seen less as Ukrainian than as internationally active contemporary artists before the war.

BvB Yes, but the historical positions in this exhibition also show how international the Ukrainian art world was already at the beginning of the 20th century - Archypenko, for example, born in Kyiv, moved to Paris after his training in Kyiv, Odesa and Moscow and then to the US in 1923. After the official establishment of Ukraine in 1991, artists started travelling again, working in different places and exhibiting internationally. This exhibition offers a rare opportunity to see many of these artists together, grouped in the four themes you mentioned. Many of them relate their art to current or historical events, which is not surprising given Ukraine’s turbulent history. So their art also provides an opportunity to rethink history, to reflect on what it means to live in a country whose borders have been and continue to be questioned, and what connections there are between cultural memory(s) and places in Ukraine. An artist such as Sasha Kurmaz directly reflects on these two questions by marking a fictional space in the museum with a red line and thus a border. This is reminiscent of the destroyed buildings of Ukraine, but also raises the question: who stands where, what is ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ in this case?

MA Sasha Kurmaz’s work also deals with fields of tension between citizens and the state, power structures and the occupation of spaces. In Mykola Ridnyi’s impressive film Dima, a police officer, disillusioned by corruption and abuse of power, resorts to sculpture. Both works were made before the war and also show domestic grievances. The exhibition as a whole makes it clear how important art is as a medium for dialogue. It shows us how art can help overcome borders and create understanding between people.

BvB Some works were given additional meaning by war, such as Zhanna Kadyrova’s Shots and Fractures series, originally created between 2009 and 2014 as a shape experiment by literally shelling round and square ceramic plates, but now defined by the artist herself as a “commentary on the destruction of buildings and infrastructure due to military activity”. Other works, such as the huge painting by Masha Reva, refer to the historical avant-garde and show similar motifs enlarged and in a new context.

HW At the same time, we should not forget that Ukraine has been in a permanent crisis for many years: first the massive state, social and economic upheaval after the breakup of the Soviet Union and then the Russian war in Crimea and the Donbas. Ukraine, its people and its culture seemed very distant from a Western European perspective. Especially the war against Ukraine from 2014 onwards - although on European soil - received far too little and only selective attention in the West, for instance after the shooting down of the passenger plane MH 17. Nikita Kadan described it very aptly in an interview: ‘The Donbas could not compete with other conflicts in terms of attention economy’. The

situation became a ‘dull catastrophe’ for Western Europe.

MA At the same time, Masha Reva’s work, which Beatrice talks about, is also an image of hope. Just as the exhibition gives us insight not only into the past and present, but also into the future of Ukraine, which I think is particularly important.

So we thank all involved and hope for many interested visitors and readers, who will hopefully be touched by the art from Ukraine!

Neither the exhibition nor this book would have been possible without the huge efforts of the many participating artists. We would like to thank them most sincerely for collaborating on this project, in what were sometimes very difficult circumstances.

We are also very grateful to all the lenders who have loaned work for the exhibition, but above all to the Ukrainian institutions that have done so: The National Art Museum of Ukraine (NAMU) in Kyiv, the Odessa Art Museum, the National Museum of Ukrainian Decorative Folk Art in Kyiv, the Stedley Art Foundation, the Prymachenko Family Foundation, the Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Center, the MOCA NGO, the Artsvit Gallery, the Pavlo Gudimov Ya Gallery Art Center, the BIRUCHIY CONTEMPORARY ART PROJECT, the Fedir Tetianych Archive and the Asortymentna Kimnata. It has been possible to bring these artworks from Ukraine during a war thanks to these Ukrainian museums which, at this difficult time, did everything in their power to ensure the exhibition could go ahead. It would not have been possible without the support of the German Federal Foreign Office and the huge efforts of the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture.

We cannot thank curators Maria Isserlis and Tatiana Kochubinska

enough for developing this exhibition, which has been both cleverly and lovingly curated, right down to the smallest detail. It was thanks to the Ukraine funding provided by the Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung that it has been possible to engage Tatiana Kochubinska, one of the most expert art historians in Ukraine, as co-curator at Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (SKD) for a year. Curator Maria Isserlis of SKD worked hard to bring this about, and to forge contacts between many other German institutions and Ukrainian curators, as well as with Francesca Thyssen-Bornemisza and her “Museums for Ukraine” initiative, and with the Ukrainian Institute, which organised an outstanding public programme to accompany the exhibition in Dresden.

Aude Christel Mgba was able to achieve a huge amount in a short time, shortly after joining the De Fundatie in Zwolle as a curator, contacting all artists and institutions, and overseeing the planning of the exhibition at our museum. This applies in particular to her support for the six artists who have made new work for this second venue. We would therefore like to express our great appreciation for the hard work she has put into this exhibition. The same is true of Sanne van de Kraats, who advised on the exhibition in Zwolle, oversaw the production of this publication in a highly professional manner and, as head of marketing, was responsible for communication on the exhibition. Thanks to Harald Slaterus for the graphic design of the book, and Aliona Solomadina, who conceived the visual identity of both exhibition and book. Thanks to Marloes Waanders of Waanders Publishers for making this book possible. Docus van der Made, who recently joined us as head of

Education and Interpretation in Zwolle, swiftly put together and oversaw an inspiring public programme, and we would like to express our gratitude to him, too.

It is incredible what has been achieved in a relatively short period of preparation!

Last but not least, we would like to thank the sponsors who made this exhibition possible: for the SKD, the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung and the European Cultural Foundation; it is also great that some of the works could be bought by the SKD with the help of our Friends of MSU. Museum de Fundatie warmly thanks the Municipality of Zwolle, especially also for their extra support for this project, the Province of Overijssel, the Ministry of OCW, the VriendenLoterij and the Founders and Friends of the museum. A warm thanks to the V-Fonds that made the public program of this exhibition possible.

We would also like to give a mention to the fantastic teams at both institutions, responsible for everything from exhibition management, marketing, education, collections to technical installations, floor managers and stewards. In particular, however, we are grateful for the pleasant collaboration between our two institutions, at all levels. It has been a great pleasure!

Marion Ackermann is general director of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Beatrice von Bormann is director of Museum de Fundatie, Zwolle and Heino / Wijhe.

Hilke Wagner is director of the Albertinum, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden.

We do not seek, we look. This became the motto for our exhibition. It came about as we were making preparations and gathering material, in discussions with artists, while searching archives, collections and libraries that were not accessible because of occupation, destruction and the general war situation in Ukraine. Kaleidoscope of (Hi) stories is an attempt to approach and describe Ukraine through its art.

Historically, Ukraine emerged under the influence of the different states to which its territory belonged. A range of artistic, cultural and ethnic influences produced a colourful fabric that is reflected in the country’s complex, layered identity. But what exactly is that identity? It is a concept that constantly changes, especially in the case of Ukraine. We cannot pinpoint any generally applicable universal paradigm for the manifestations of Ukrainian identity, the development of the country and its art. The identity of Ukraine continues to change. To this day, Ukraine has many faces. We regard the exhibition as an environment in which we are able to think about our own cultural heritage in all its cultural and geographical multiplicity, and to understand it – for the development of art and culture in the various regions of Ukraine is related to a range of historical paradigms and connotations.

Kyiv, a city with a long history, the home of St. Sophia’s Cathedral with its unique examples of Byzantine art, is where Mykhailo Boychuk’s (1882 – 1937) original school of monumental art was located. The modernist and, to some extent, constructivist art of the 1920s is particularly significant to Kharkiv, and and to Odesa is the myth of the unique, multicultural, “Mediterranean”

city. The situation is entirely different in Lviv, which only became part of the Soviet Union in 1939, and where there was sporadic military resistance until the mid-1950s. The regions in the east and southeast of Ukraine, like Zaporizhzhia and Dnipro, with their industrial economy, were the cradle of Ukrainian anarchism in the 1920s, and the major miners’ strikes in Donetsk in 1989-1990 can be seen as the beginnings or the awakening of Ukrainians’ current political awareness – the start of their struggle for civil rights and a civil society. This has become especially clear in recent years, since the Revolution of Dignity in 2013–2014.

All these internal disputes and conflicts highlight the kaleidoscopic aspect that is reflected in the title of the exhibition. The kaleidoscope is a natural metaphor; every time the angles change, new images emerge. These changes of perspective are also important in the exhibition, the perspective in respect of history, experience and artistic practice. The four main themes of the exhibition – Practices of Resistance, Culture of Memory, Spaces of Freedom and Thoughts about the Future – flow seamlessly, inviting visitors to take a journey through a complex collection of different experiences and histories that bear witness to the multifaceted but shared history of the country.

Ukraine is now developing a new character despite – or because of – the war, but at any rate in connection with it. As we are confronted with that which has remained unsaid, which is uncomfortable and complex, it is art that enables us to recognise new paths, and to take our first steps upon them.

Kaleidoscope of (Hi)stories: Art from Ukraine brings together works by key historical figures in the art history of Ukraine with those of a selected number of contemporary artists. Encompassing painting, drawing, video, installation art, performance, sculpture, sound, photography, and textile art, the exhibition provides a glimpse into the vast richness and diversity of over a century of Ukrainian art history. From naïve and folk art, socialist realism, and constructivism to futurism, abstraction, and conceptualism, this snapshot describes the complex connection between the avant-garde, modernism, and contemporary art that is unique to the history of art in Ukraine.

For this iteration in Zwolle we have kept majority of the works that were shown in the Albertinum Museum in Dresden, additionally with a different selection of existing works from a few number of same participant artists like Yevgenia Belorusets, Dana Kavelina, Katya Buchatska, Sergey Bratkov and Andrij Bojarov. In Museum de Fundatie Zwolle Kaleidoscope of (Hi)stories is spread around three floors spanning non chronologically the period from 1910 to 2023, fluidly organized around the four initial themes sometimes intersecting one another: Practices of Resistance, Culture of Memory, Spaces of Freedom, and Thoughts about the Future

The works in this exhibition translate how Ukrainian contemporary artists have always been and are still in dialogue with their modernist and avant-garde predecessors, adopting and drawing inspiration from their aesthetics while engaging with the current global discourses. Ukraine’s position at the crossroads of multiple cultural, artistic, and religious influences has given birth to a rich heritage. Its encounters with Byzantine, Eastern Slavic, Western European, and Central Asian cultures have produced a wide range of artistic styles and techniques (including embroidery, ceramics, woodcarving, pysanky, and tapestry) that Ukrainian artists have appropriated and contemporized. Some of the rooms translate that idea like the one putting together Kateryna Bilokur’s painting next to Maria Kulikovska, soap figure with flowers which series intentionally uses folk Ukrainian art as an inspiration.

Kateryna Lysovenko, Alevtina Kakhidze, Nikolay Karabinovych, Lesia Khomenko , Kateryna Snizhko, and Anna Zvyagintseva have been invited for a new commission. Kateryna Lysovenko, who is presenting an installation of banners/flags outside at the main entrance of the museum addressing the impossibility of making a homogeneous world. Alevtina Kakhidze addresses hope

by inviting us to learn from plants and children through an installation in one of the rooms of the first floor composed of a drawing of kids made during a workshop where they discussed borders, states, war and peace, a film and a series of drawings of hers. With a multimedia sonic installation Nikolay Karabinovych looks into the idea of resilience tools in times of despair through humour and language. Lesia Khomenko is producing an adaptation of Max in the Army, a series of works tackling the challenge of image making during war that started as a depiction from photographs taken by her husband of him and his military comrades. Among many other motivations, the multiples tumultuous moments Ukraine has gone through historically have prompted the displacement of many people outside of the country. Ukrainian diasporic communities have formed themselves around the West playing an important role in preserving and spreading Ukrainian culture, language and traditions and like in many other fields, many Ukrainian artists have contributed to the art scene in the Netherlands. Among many of them we invited Kateryna Snizhko, who is based in Amsterdam since 2012, as a local Ukrainian voice. In this exhibition she presents an installation/sculpture made of ceramics through which she addresses questions of fragmentation of territory. Anna Zvyagintseva who was participating in a residency in Maastricht when the war in Ukraine started, creates a 1:1 scale of an example of a “2 walls” rule using as paper and textile to talk about the fragility of safety.

Next to the new commissions, Lada Nakonechna and Nikita Kadan are producing adaptations of existing works contextualizing their presentation in Dresden to the Netherlands, looking and engaging specifically with the collection of Museum de Fundatie. They separately stretch the framework of current debates about war and history in Ukraine to the one of the Netherlands, Europe through a postcolonial lens.

This exhibition further shows how the art scene in Ukraine has also been shaped by artist collectives, which a large number of the artists shown have been and are part of. In the exhibition two collectives Open Group (Yuriy Biley, Pavlo Kovach, Anton Varga) and the duo Roman Khimei and Yarema Malashchuk present recent video works that engage with the current political and social situation of the country.

Even though the war has prompted this project, we can recognise that it plays a crucial role for ongoing conversations around what we still designate as global

History of Art which has excluded, appropriated and contributed to the invisibilization of many geographies, histories, cultures, bodies, races, genders and sexualities. If Kaleidoscope of (Hi)stories. Art from Ukraine could also be considered as an invitation to look back into our collections and rethink historical boundaries and ways some artists have been framed. We started by doing so selecting works of Oleksandr Archypenko, Oleksandr Bohomazov from our collection and from the Kröller Müller Museum for this exhibition.

Considering the very sensitive circumstances under which this exhibition had to be done, it is with real pleasure and gratitude that we would like to thank Sergey Anufriev, Yevgenia Belorusets, Andrij Bojarov, Sergey Bratkov, Katya Buchatska, Davyd Chychkan, Danylo Halkin, Nikita Kadan, Zhanna Kadyrova, Alevtina Kakhidze, Nikolay Karabinovych, Roman Khimei & Yarema Malashchuk, Dana Kavelina, Lesia Khomenko, Maria Kulikovska, Sasha Kurmaz, Yuri Leiderman, Kateryna Lysovenko, Larion Lozovyi, Pavlo Makov, Boris Mikhailov, Lada Nakonechna, Open Group (Yuriy Biley, Pavlo Kovach and Anton Varga), Vlada Ralko, Masha Reva, Mykola Ridnyi, Andriy Sahaidakovskyi, Kateryna Snizhko, Anna Zvyagintseva,the institutions and museums in Ukraine, and the curators Tatiana Kochubinska and Maria Isserlis for their trust and for holding space for us the team of the museum. This process has been enriching and quite important for our introduction to the art scene and the History of Art in Ukraine.

Oksana Pavlenko

Long Live March 8! | 1930-1931 | oil on canvas | 150 x 115 cm

National Art Museum of Ukraine

Resistance. It means first and foremost disagreeing, adopting a position at odds with prevailing conventions and abandoning clichés enshrined in ‘public opinion’. Resistance arises from the need to defend the right to life, work and creativity, to withstand violence, injustice and oppression – political, psychological and social. Acts of resistance occur when a stable system is threatened, prompted by disruptive life events, war and other mechanisms that subvert the normal order of things.

Art as resistance takes various forms, and encompasses a range of methods, from agitation and propaganda, to the occupation of the public space and protest against established norms that curtail the freedom to think, live and act.

In Ukraine art bears witness to tumultuous revolutions and gives a good insight into the politicised reality and the controversial events associated with it,1 resulting from the struggle for self-determination. Ukraine has repeatedly faced hostilities within its borders.

‘... in January 1918, when Kyiv was under heavy artillery fire, we were painting from life. One of the most dedicated female models came to pose for us regularly, and the bravest students worked every day. An artillery grenade hit the bottom floor of the building which was housing a hospital at the time. The heavy explosion threw the students and models, and their easels and palettes, to the ground…’,2 artist Oksana Pavlenko (1896 – 1991) recalled of this event.

In his screenplay Ukraine in Flames, Oleksandr Dovzhenko (1884 – 1956) described the tragic destruction of Ukrainian land during the Second World War: ‘They (Nazi forces, ed.) lined up whole families and shot them, as they set their homes on fire. They hanged people, laughing like idiots, pursued women, took their children from them and threw them in the flames. […] The hanging bodies on their

terrible gallows still swung, casting unforgettably hideous shadows on the ground. The entire village was on fire. Everyone and everything that could not flee in time to the forest, to the reed beds, to the secret hiding places under the ground – everything perished.’3

A reality such as this, so it seems, should be preserved in the darkness of history, passed from generation to generation in the form of someone’s narrative, a personal recollection, bringing with it a trail of cruelty in order to prevent any renewed instances of dehumanisation. But this is now a hard reality again. Today’s Ukrainian cities are once more the scene of hostilities.

Violence, blood and conflict define the familiar backdrop against which art in Ukraine has developed, and continues to develop, in the 20th and 21st centuries. This seems to be an oft-repeated pattern anywhere in the world where art faces totalitarianism, civil war, oppression and political imprisonment.

In the post-revolutionary 1920s the work of artists like Leonila Hrytsenko (1909 – 1992), Viktor Palmov (1888 – 1929) and Oksana Pavlenko was about opposition to global historical injustice and the Tsarist regime of the Russian Empire. Their art was imbued with a belief in global revolution.

Oksana Pavlenko was not understood by the farming community she came from, where art was held to be something exclusively for the elite. She first had to assert her right to be an artist. Later, when she was studying in Mykhailo Boychuk’s (1882 – 1937) monumental painting studio, the future artist was once again confronted with inequality: ‘Boychuk very reluctantly accepted girls to the studio and resolutely refused to accept me at first. His motivation was that girls were inherently unreliable. He would spend time and effort on them, and then they would marry and abandon art… But I was patient and

sought his consent for a long time, so he eventually accepted me.’4

Pavlenko’s early work contemplates the new role of women in society after the revolution.5 Her most famous piece is probably Long Live March 8!, which depicts a group of women all wearing the same clothes and shoes against the background of a farming landscape. They are holding a red banner which reads ‘Long Live March 8!’, symbolising women’s quest for emancipation and struggle for their rights and freedoms. As art historian Tetiana Zhmurko has remarked: ‘Women are acting as a united front here; Pavlenko does not show an individual, but a social group fighting for their rights’. Zhmurko sees in this ‘the embodiment of Mykhailo Boychuk’s artistic method, in which the typical and the general prevail over the individual’.6

Thirty years later Alla Horska (1929 – 1970) wrote: ‘Monumental art is the art of the collective. It is like the sea, which is formed by rivers that are all called ‘I’. If one of those rivers turns and spreads, it loses its power and the sea becomes shallow. There are no performers in our

monumental art. Every performer is an artist.’7 The revival of Ukrainian monumentalism – the school that had been lost in the 1930s – occurred mainly in the 1960s. The monumental work of Horska, murdered because of her political beliefs, nevertheless suited the general artistic ideology of the Soviet era. Her famous mosaic Victory Banner which is dedicated to the Young Guard8 – a partisan movement during the Second World War – pays tribute with the typical pathos of the time to the heroic acts of young people who gave their lives in the fight against Nazism. Horska’s own generation – the generation of the 1960s, often referred to as the ‘children of the war’ – were now a new ‘Young Guard’. This generation was destined to become part of the post-war reconstruction of the country, to contemplate the burden of Stalinist oppression and to protest against the withdrawal of civil freedoms in the late 1960s. ‘Over the past year political trials have taken place in the Soviet Union against young people from the creative and academic intelligentsia. [...] Above all, we cannot but be concerned at the fact that many of these trials have violated the laws of our country. For example, all trials

in Kyiv, Lviv and Ivano-Frankivsk in 1965-1966 were held behind closed doors, in contravention of what is directly and unequivocally guaranteed under the constitution of the USSR. All these and many other facts demonstrate that the political trials of recent years are becoming a form of oppression of dissidents. [...] In Ukraine, where violations of democracy increased and exacerbated by perversions of the national issue, the symptoms of Stalinism are manifested in an even clearer and coarser manner.’9 This letter blazes with the idealistic pathos of the 1960s. The signatories cited the constitution of the USSR, the rights of Soviet citizens, in their attempt to peacefully claim the right to a dissenting opinion.

In a letter to Alla Horska the artist Opanas Zalyvakha (1925 – 2007) wrote that ‘...a philosopher once said that if we had given children weapons humanity would have ceased to exist long ago. Let us grow up, so that it need not end so tragically.’10 But humanity has not grown up.

In October 2013, just a month before the start of the Revolution of Dignity, Mykola Ridnyi (born 1985) showed his Water Wears Away the Stone for the first time. One key element of the work is the video Dima, in which a former police officer talks about how corruption and arbitrariness have destroyed the ideals of police work.11 Writer and activist Gregory Sholette (1956) wrote that it is possible to understand social dilemmas if art manifests

itself as a specific work carried out intellectually and creatively in collaboration with another.12 This is the case in Dima

After his career in the police, the main character in the film retrained as a stonemason. Ridnyi interrupts Dima’s daily routine by asking him to carve some huge police boots in granite. The work was made during the regime of the former Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych, a period dominated by coercive force. The work is now regarded as a manifesto against police violence around the world, wherever public demonstrations are brutally repressed, resulting in deaths.

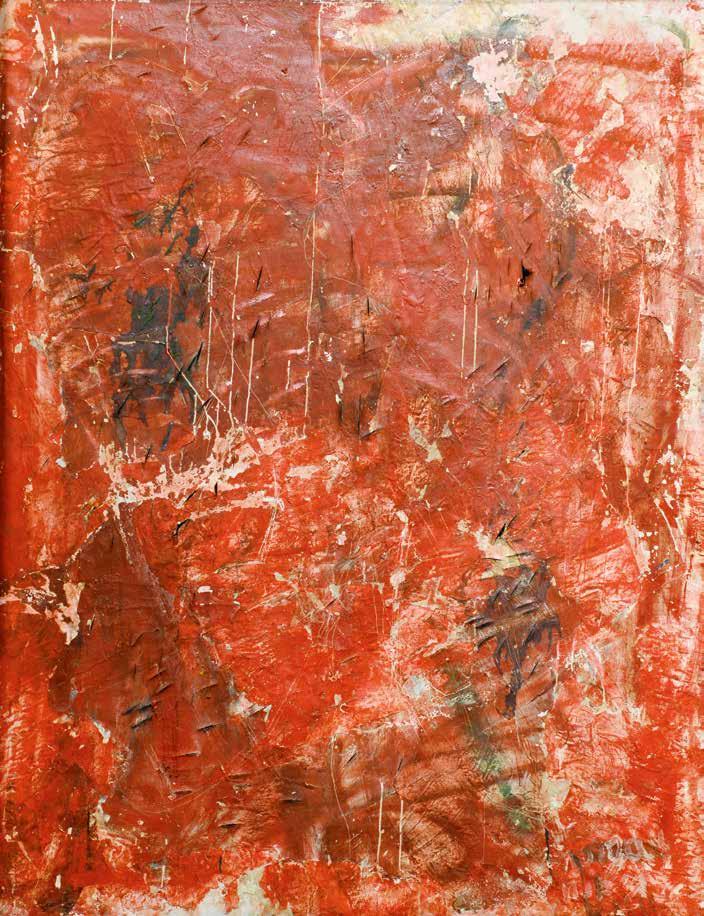

Over time, artistic practice has attempted to reinvent an artistic language that is able to describe the new challenges of the changing resistance paradigm. Given the tragic political history of Ukraine, it is not often that art directly reflects resistance in its very fabric, on the surface of the art itself, art that resists, denies and challenges itself. In his 1989 work Untitled Andriy Sahaidakovskyi (1957) manages to express a premonition of a collapse of the existing order. The artist rejects didactic narrative language and lets the painting speak for itself, by presenting it as an independent fluid material, showing a different kind of resistance.

1 The February and October Revolutions of 1917; the proclamation of the Ukrainian National Republic (UNR) and the West Ukrainian People’s Republic (ZUNR) in 1918; the Great Famine/Holodomor of 1932-1933; the Second World War and the German-Soviet War of 1941-1945; the Chornobyl disaster in 1986; the collapse of the USSR in 1991; the Orange Revolution of 2004; the Revolution of Dignity in 2013-2014; the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation on 24 February 2022.

2 Zhmurko, Tetiana: PORTRAIT: OKSANA PAVLENKO. ON BOICHUKISM, FEMINISM AND BUILDING A NEW FUTURE; YourArt, 30 December 2019; online source: https:// supportyourart.com/stories/ oksana-pavlenko/

3 Dovzhenko O. P. Ukraine in Flames: Screenplay, Diary at the Front by author O.M. Pidsukha.—edited K. Rad, author, 1990.— 416 p.

4 Iakovlenko, Kateryna: Why There Are Great Women Artists in Ukrainian Art. Kyiv 2019, p. 21.

5 Tetiana Zhmurko sees in Pavlenko a tragic personal story, in which the socialist revolution opened the way for a professional life, but she lost her nearest and dearest, her fellow artists and friends, including her mentor Mikhail Boichuk, verloor, who was shot in 1937.

6 Zhmurko, Tetiana: PORTRAIT: OKSANA PAVLENKO. ABOUT BOICHUKISM, FEMINISM AND CONSTRUCTING A NEW FUTURE; YourArt, December 30, 2019; online resource: https:// supportyourart.com/stories/ oksana-pavlenko/

7 Alla Horska : Chervona tin kalini: listi, spogadi, statti / ed. and orde. O. Zaretsky, M. Marichevsky. – Kyiv: Spalakh LTD, 1996. – 240 p.

8 An underground antifascist Soviet organisation of young girls and boys, active mainly in the Voroshilovgrad region (now the Luhansk region in Ukraine, since April 2014 partly under the control of the so-called ‘People’s Republic of Luhansk’).

9 Excerpt from an open letter of protest against political persecution in Ukraine, also known as the “Letter of one hundred and thirty nine”, addressed to the SecretaryGeneral of the Central Committee of the CPSU Leonid Brezhnev, the chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR A.N. Kosygin, and the chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR M.V. Podgorny.

10 Alla Horska : Chervona tin kalini: listi, spogadi, statti / ed. and orde. O. Zaretsky, M. Marichevsky. – Kyiv: Spalakh LTD, 1996. – 240 p.

11 The National Police emerged as a central executive body in Ukraine in 2015.

12 Sholette, Gregory: The Art of Activism and the Activism of Art (New Directions in Contemporary Art), 2022.