VAN GOGH CÉZANNE LE FAUCONNIER

& THE BERGEN SCHOOL

& THE BERGEN SCHOOL

& THE BERGEN SCHOOL

& THE BERGEN SCHOOL

Compilation and editing

Marjan van Heteren & Chris Stolwijk

Authors

Marjan van Heteren

Anita Hopmans

Maaike Rikhof

Chris Stolwijk

STEDELIJK MUSEUM ALKMAAR

WAANDERS PUBLISHERS, ZWOLLE

Vincent van Gogh, Almond Blossom , 1890 (detail fig. 170)

Vincent van Gogh, Almond Blossom , 1890 (detail fig. 170)

‘Like Birds, they Alighted in Bergen’

‘Fame from North to South’

The Reception of Vincent van Gogh, 1888-1920

Symbolist, Post-Impressionist, Cubist, Traditionalist The Reception of Paul Cézanne in the Netherlands, 1890-1930

Henri Le Fauconnier, ‘Trait d’Union’

Van Gogh, Cézanne, Le Fauconnier & the Bergen School

Paul Cézanne, The Flowered Vase , 1896-1898 (detail fig. 136)

Paul Cézanne, The Flowered Vase , 1896-1898 (detail fig. 136)

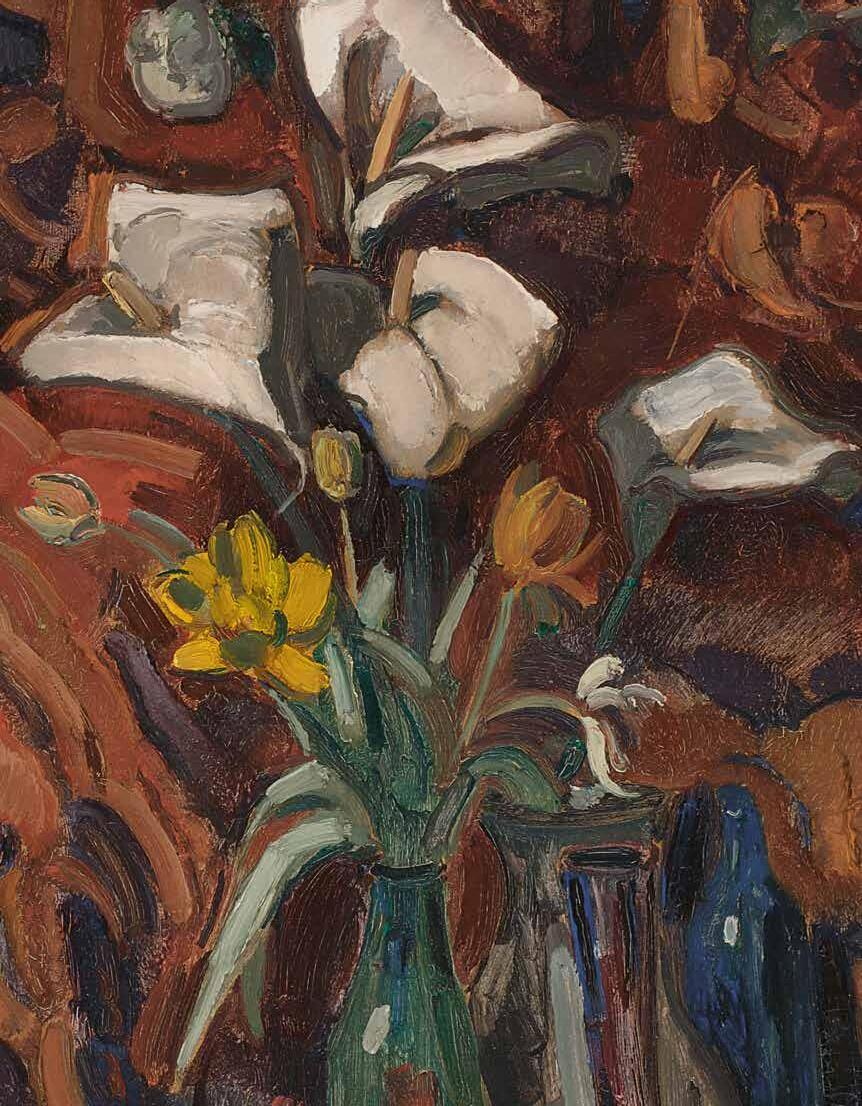

Dirk Filarski, Still Life with Calla Lilies (detail fig. 137)

Patrick van Mil

Dirk Filarski, Still Life with Calla Lilies (detail fig. 137)

Patrick van Mil

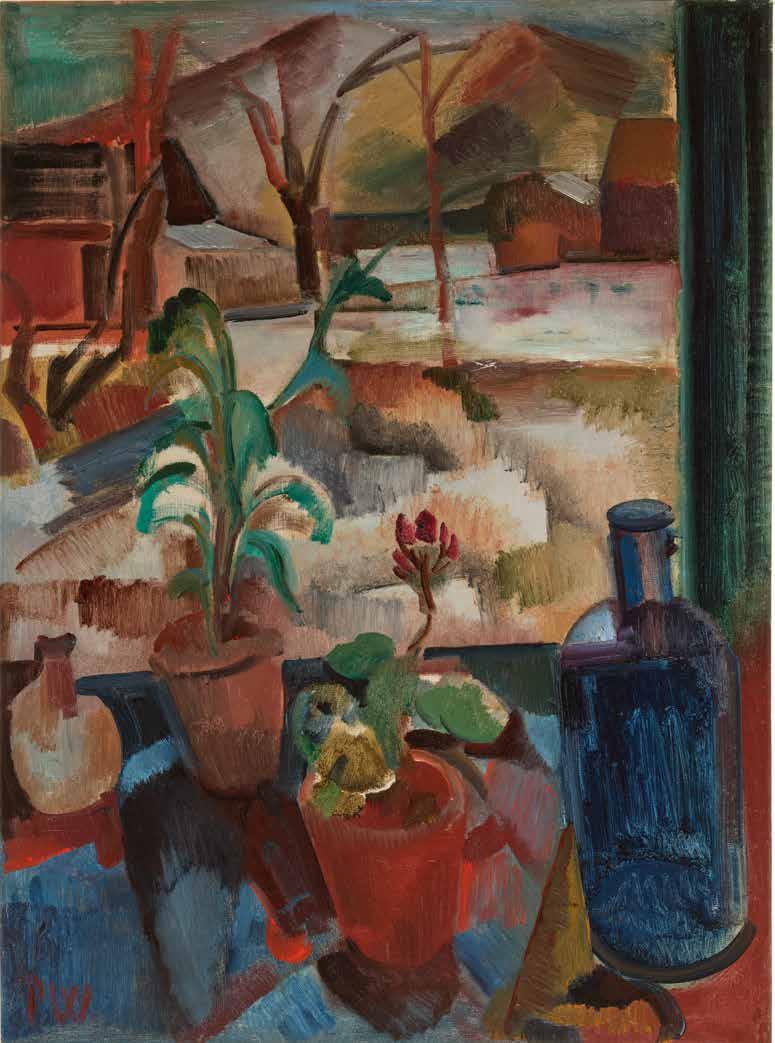

Leo Gestel 1932 1

Whether it was the punk movement in London in the late 1970s, the Nouvelle Vague in French cinema in the 1960s or the Vijftigers who revitalised the Dutch poetry scene after the Second World War, every new artistic movement is inspired by individuals who exert decisive influence on its emergence. This was also the case with the Bergen School artists, who settled in the coastal village in the province of Noord-Holland in the 1910s and went on to form the first Expressionist movement in the Netherlands. For them, the work of Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) and later that of the French Cubist Henri Le Fauconnier (18811945) were a seminal, guiding light. Less well known, but equally important, was the impact of Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) on the development of the Bergen School, not only through his style and use of colour, but also his individual expression. After a period during which the Dutch art world was dominated by Hague School painters, these three artists offered wonder, fresh ideas and boundless new pathways to the questing young artists.

Although the names of those who inspired new artistic movements are generally known, we are often in the dark regarding how exactly their influence unfolded, when the seeds were sown and how they germinated in the young artists. And this is simply because information is often lacking. The same holds true for the Bergen School, which is all the more reason for trying to gain a greater understanding of it.

A few years ago, Marjan van Heteren, curator at the Stedelijk Museum Alkmaar, in collaboration with the

RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, started an extensive (source) study into the origins of the Bergen School. This research yielded surprising results and new insights. The fruits of this labour are presented in this richly illustrated publication Van Gogh, Cézanne, Le Fauconnier & the Bergen School, which accompanies the exhibition of the same name in the Stedelijk Museum Alkmaar.

Both the exhibition and this publication showcase telling combinations of works by Bergen School artists such as Leo Gestel (1881-1941), Gerrit Willem van Blaaderen (1873-1935) and Else Berg (1877-1942) with ones by Van Gogh, Cézanne and Le Fauconnier, which served as examples for them and which they were able to see with their own eyes at the time – the years 19051915. How inspiration plays out is rarely demonstrated so strikingly and vividly as here. The archival and literature research also provided compelling accounts of this turbulent time in the history of Dutch art. For instance, how the first presentations in the 1890s and the retrospective of Vincent van Gogh’s work in 1905 hit the Netherlands like a bombshell. How the then completely unknown Van Gogh was initially received by the public as an outgrowth of modern, French painting and as a ‘sickly’ artist, and increasingly embraced after 1900 because of his Dutch roots. What a sublime collection of modern art the Netherlands boasted at that time thanks to the progressive collector Cornelis Hoogendijk: it comprised some 400 works of modern art by Gauguin (1848-1903), Monet (1840-1926), Signac (1863-1935) and others, and he also owned no fewer than

‘Art suggests, hints, makes one dream, sings, is boundless, makes one marvel, not admire.’

31 paintings by Cézanne. Parts of this impressive collection were on display at the Rijksmuseum from 1909 onwards, only to be sold abroad a decade later due to some extent to the Dutch state’s disinterest. This was condemned in 1950 by Willem Sandberg, then director of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, as ‘the gravest disaster that has befallen our art property in recent decades.’2

You will find all of these and many other fascinating stories in this publication. The focus is on the genesis of the Bergen School and the influence Van Gogh, Cézanne and Le Fauconnier exerted on it successively and sometimes simultaneously. Incidentally, the essays afford fascinating insight into the Dutch art world in the period 1905-1925 and sketch the many international contacts that artists maintained in that period. They include Picasso (1881-1973), who visited Alkmaar and Schoorl in 1905, and Henri Le Fauconnier, who travelled from Paris to Munich to meet Kandinsky (1866-1944) and Der Blaue Reiter, before settling in Amsterdam and Bergen.

Thorough research is indispensable for these kinds of exhibitions and publications. In medium-sized museum organisations, such as the Stedelijk Museum Alkmaar, however, there is relatively little time for such a study. Accordingly, we are particularly grateful for the Prince Bernard Culture Fund’s curatorial grant, which enabled our curator Marjan van Heteren to spend a year researching this project. I would like to thank the authors of this publication for their contribution, especially Chris Stolwijk (General Director RKD –Netherlands Institute for Art History) who, together with Marjan van Heteren, was charged with the final editing. Special thanks go to Arnold Ligthart and Kees

van der Geer for generously sharing their research data. Also on behalf of the authors, I would like to thank numerous people for their advice, information and support. For their indispensable contribution to the project, special mention must be made of Lisette Almering-Strik, Ineke Aronds, Joanna Baker (Kreeger Museum), Nienke Bakker (Van Gogh Museum), Beatrice von Bormann (Museum De Fundatie), Christian Briend and Ariane Coulondre (Centre Pompidou), Barbara Buckley and Cindy Kang (Barnes Foundation), Sarah de Clerq and Evelien Jansen (Sotheby’s), Renske Cohen Tervaert (Kröller-Müller Museum), Pierre-Marie Deparis, Maite van Dijk (Museum More), Rudi Ekkart, Gladys Fabre, Marianne van Gils, Lily Goldberg (Museum of Modern Art), Doede Hardeman (Kunstmuseum), Linda Horn, Margot Jongedijk (Noord-Veluws Museum), Sandra Kisters (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen), Lisa Kloosterman, Olga Kruisbrink, Anne van Lienden (Singer Laren), Jan Louter, Nicole Myers (Dallas Museum of Art), Daphne Nieuwenhuijse (Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands), Maureen C. O’Brien (Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design), Dolf D. van Omme, Anna Pravdová (Národí Galerie), Jenny Reynaerts (Rijksmuseum), Belle de Rode, Caroline Roodenburg-Schadd, Manja Rottink and Christine Ryall (Christie’s) and last but not least Renée Smithuis.

I am particularly indebted to the fellow museums and private lenders, both at home and abroad, who entrusted their valuable possessions to us for this exhibition.

Finally, I would like to thank the municipality of Alkmaar and all the funds that have supported this project. Without these contributions, the exhibition and this publication would never have seen the light of day. The readers of this book will undoubtedly share my gratitude.

Henri Le Fauconnier, Abundance , 1911 (detail fig. 108)

Henri Le Fauconnier, Abundance , 1911 (detail fig. 108)

Marjan van Heteren

Marjan van Heteren

The Bergen School arose in the years preceding the First World War and reached its apex between 1915 and 1925. The artists involved in no way set out to unite and consciously create a ‘school’; nor did any of them stand at the centre and draw followers. Looking back, Matthieu Wiegman (18861971), one of the Bergen artists, said: ‘There never was a “school.” A school with a teacher and pupils. The artists were like birds, who alighted in Bergen. They wanted to see Space, because Space was their domain.’1 Nevertheless, in art history one speaks of a school if there are similarities in ideology or some stylistic affinity. And this was acknowledged by the same

Matthieu Wiegman: ‘The painters of the Bergen School have in common that they wanted to simplify form. There are great differences between them, but … each and every one of them are personalities. They are artists, wanderers, who know only one resting point, one reality, the rhythmic purpose, which is revealed to them as a mystery in all things.’2

The term ‘Bergenschen Gruppe’ was coined by Friedrich Markus Huebner (1886-1964) in November 1921.3 This German art historian, who lived in the Netherlands for several years, discerned stylistic similarities among the group of young artists who had gathered in the coastal town of Bergen in the province of North Holland. The appellation ‘Bergen School’ became steadily more common in the years that followed. In 1925, curator Gerardus Knuttel Wzn (1889-1968) spoke of the ‘Amsterdamsch-Bergensche’ group, which included Jan Sluijters (1881-1957), Leo Gestel (1881-1941) and the Wiegman brothers and in which Piet Boendermaker (1877-1947) played an important role as benefactor.4

Indeed, the individual artists visited the coastal town for shorter or longer periods of time before settling there for the long haul [fig. 1].5 Dirk Filarski (1885-1946) arrived in Bergen to paint in the summer of 1907, followed shortly thereafter by Arnout Colnot (1887-1983) and Jaap Weijand (1886-1960).6 Matthieu Wiegman lived in Schoorl and Bergen from 1910 onwards. Leo Gestel alternated between his studios in Amsterdam and Bergen from 1911, until moving permanently to the village in 1921. Else Berg (1877-1942) and Mommie

Schwarz (1876-1942) first came to Bergen in 1913, while Piet Wiegman (1885-1963) moved into a small house in Groet, near Bergen, in the same year. Frans Huysmans (1885-1954) arrived in May 1913 and Gerrit Willem van Blaaderen (1873-1935) was one of the last to settle in Bergen in 1918.

Hence, by 1915 the main members of the Bergen School were communing in Bergen and in the nearby villages of Schoorl and Groet.7 Only Piet van Wijngaerdt (1873-1964) would never leave his beloved Amsterdam behind.8 The most important reason for sojourning in Bergen was the landscape: the polders, the dunes and the tranquillity. ‘We have a miserable climate here,’ wrote Van Blaaderen, who often spent time in sunnier France, ‘that is for sure, and I often grumble about it and want to leave. Go away from here; but, I know that I will then miss the polder. There is a peace and quiet in this region not found anywhere else. When you walk on the dike, it is a delight to be able to gaze all around.’9 Gestel, too, had lost his heart forever: ‘Enchanting countryside with high, broad skies and immeasurable polders. Old Bergenland with its woods, its extensive dune ridges and the infinite sea beyond.’10

In addition to the varied unspoilt landscape, an important binding factor was the Amsterdam-born patron of the arts Piet Boendermaker, who settled in Bergen in 1918 and who was considered the social and economic linchpin of the group.11 The collector bought their works of art by the dozens and paid in monthly instalments, thus ensuring them a basic income.