SUMMER EXHIBITION 2022

A selection of projects from semester two, 2022 at The University of Western Australia, School of Design.

The University of Western Australia acknowledges that its campus is situated on Noongar land, and that Noongar people remain the spiritual and cultural custodians of their land, and continue to practice their values, languages, beliefs and knowledge.

Designed and edited by Lara Camilla Pinho, Andy Quilty and Samantha Dye. Marketing Officer: Natasha Briggs.

Image: UWA School of Design, Summer Exhibition 2022 opening night, 16 November 2022. Photography by Samantha Dye.

Image: UWA School of Design, Summer Exhibition 2022 opening night, 16 November 2022. Photography by Samantha Dye.

INTRODUCTION BY DR KATE HISLOP

The School of Design marked several important milestones in 2022. Architecture and Landscape Architecture courses underwent professional accreditation, both being awarded the maximum five year terms. As well, Landscape Architecture and Fine Arts each celebrated thirty years since the courses were introduced at UWA, and we look forward to the events to mark these occasions that will be held in 2023. Together, accreditations and anniversaries have provided us with opportunities to reflect on the evolution and future imperatives of these courses in particular, and on the direction of the School more broadly. We are excited to take this momentum forward.

It is a privilege once again to enjoy the fruits of our students’ efforts captured in this catalogue of work from the second semester of 2022. First introduced three years ago as an alternative when physical exhibitions were not possible, this series of digital records of student work from across the School’s many disciplines has been one of the positive outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic. While only a relatively small number of individuals have work featured within the pages, it is nonetheless a comprehensive account of the depth of ideas, range of approaches, and array of techniques explored and mastered by those in the Architecture, Fine Arts, History of Art, Landscape Architecture, and Urban Design courses. Projects engage with Country, culture, context and critique. They are bold, sensitive, clever, provocative. Quite clearly and most reassuringly, in what can only be described as a time of global uncertainty, there is an abundance of energy, passion, care, curiosity and talent on show. We are all beneficiaries of the dedication and investment that students make in their and our collective futures.

Congratulations to all who were selected for inclusion in this catalogue: we look forward to seeing what you do next! And thank you to the inspiring group of School of Design staff who led units, mentored projects and supported students. Finally, my sincere thanks once again to the team of Lara Camilla Pinho, Andy Quilty and Samantha Dye, who have collected, compiled and cajoled to ensure the production of this catalogue. It is wonderful to have this edition added to the collection.

Dr Kate Hislop, Dean/Head of School, UWA School of Design

FOREWORD BY PROFESSOR MARIA IGNATIEVA

2022 is the jubilee year for the Landscape Architecture Programme at UWA. Thirty years ago, landscape architecture had been established in the School of Design. This is the only accredited program by the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects (AILA) in Western Australia.

Landscape Architecture is based on three ‘pillars’ - design, planning, and management, and works with natural and built landscapes to improve the quality and our experience of the environment and community. In a collaborative environment and by using real-world scenarios of varying scales, landscape architecture students gain the knowledge, critical thinking, and skills to respond to, complex issues such as climate change, biodiversity loss, urban ecology, ecological sustainability, quality and health of landscapes, heritage conservation and restoration and water sensitive design by applying systems thinking and creative practice to develop longterm, multi-scale solutions.

Landscape Architecture is primarily a design discipline concerned with the quality of the environment however it has a unique interdisciplinary nature that applies scientific as well as aesthetic principles. In 30 years the UWA Landscape Architecture programme educated a cohort of practitioners and academics who contributed to the development of landscape architecture in WA and Australia. Many of our alumni work for government agencies and local governments, nature conservation agencies, heritage conservation, planning consultancies, horticulture and landscape industry.

Landscape Architecture at UWA addresses the unique opportunities of the west coast of Australia and regional positioning in one of the 35 biodiversity hotspots. Landscape architecture studio and research work at UWA clearly highlight the leading role of landscape architects in dealing with the interactions between natural and cultural ecosystems.

The Landscape Architecture program at UWA offers a research pathway – Master’s dissertation by design and PhD dissertations. There was a wide range of research themes from sustainable landscape design and green-blue infrastructure to nostalgia and memory, water-sensitive design, planning and management practices, biodiversity-friendly botanical gardens and spontaneous urban plants and natures that are an authentic part of urban landscapes.

This catalogue documents the works of landscape architecture students at different stages of their education in landscape architecture at UWA alongside the work of their peers in the disciplines of Fine Arts, Architecture, History of Art and Urban Design.The range of presented examples celebrates the unique interdisciplinary nature of landscape architecture. Examples from the studio and theoretical units allowed us to see that landscape architecture students are broad thinkers who thrive on seeing the big picture. They address important issues of our challenging time: creating a resilient urban environment, nature protection and restoration, addressing cultural awareness, creating liveable spaces for sustainable communities, and saving water.

FINE ARTS & HISTORY OF ART

Art is not effortless, there is no artist nor designer that creates with ultimate ease and clarity, and the university is just one stage in this journey. Entering the world of academia as an artist can be difficult, it transforms and tests prior understandings of practice and the work we make. University is not without conflict, but the conflicts and evolutions we face as artists and designers, ultimately culminate into refined practices and the wonderful and challenging work which we see in this exhibition.

I started out my studies with no intention to major in Fine Arts, yet I remember distinctly taking a class in Biological Art unit led by Dr. Ionat Zurr through the ever-inspiring SymbioticA, and was immediately challenged. There was a feeling that I could really create something amazing in this environment that fostered critique and hard work, challenging me to push myself, my art and my writing. Studying art and design is gruelling, it tests one’s love for art and art making. Honing your craft in an academic institution is not without disagreements and frustrations and the hurdles faced often cause disillusion and feel unfair, especially when your studies and art are so tied to the self and experiences, but despite this, these frustrations can be transformed to create a stronger practice and a stronger artist.

Perhaps a well-trodden discourse but creating work in this present time is not easy, art often feels powerless, and it is difficult to gather the energy and creativity required to make work. The more art I create and the more study I do, there is a sense of urgency and need to create important and impactful work that continues to intensify. I often question my decision to study art and sometimes find myself looking to different careers and pathways that are more ‘important’, but this urgency that I feel for change is born out of my practice, my art and those who have supported and inspired me throughout my studies. Great art is hard to come by without work, critique and questioning, and this reflection that art provokes is so important to the self and to the community. It is wonderful to see the work produced this year filled with the energy and urgency needed to provoke the thought and feelings we all need.

The works you see in this exhibition are the imprints of immensely hard work performed by artists, designers and creatives. They represent hours of work, physical labour and research, a journey embedded with urgency and importance, as important as the artwork itself. It is a joy to see the works produced by these emerging artists and creatives who have pushed through the past year and pieced together their practices and experiences to create works that feels urgent, that feels important and extremely powerful.

Cedar Rankin-Cheek, Fine Arts (Honours), 2022

FINE ARTS

Master of Fine Arts by Research

Supervisor: Dr Ionat Zurr

ANNIE HUANG

‘The Outlines of Our World Are Not So Hard After All’

The Outlines of Our World Are Not So Hard After All is an exhibition created as part of a Master of Fine Arts by Research project. It seeks to create an intersectional space where the viewer navigates a narrative that is both inviting yet alien and strange. Here, the audience is subject to a spectrum of experiences that are reflective of the insider-outsider narrative that informs the second-generation migrant subjective where understanding and non-understanding are simultaneously at play with one another. There are three works within this project, including Ephemeral Translations, My mum says I must not leave a single grain, and In Between. Each installation combines multiple forms of narrative telling mediums including animations both hand-drawn and three-dimensionally rendered. Ephemeral Translations is a graphite-pencil animation that references the fluidity of language and comprehension, projection mapped onto a scroll-like, translucent fabric that drapes from the ceiling. My mum says I must not leave a single grain depicts six bowls that were thrown on a potter’s wheel in stoneware clay. Projection mapped on the inside of each bowl are hand-drawn animations based on old photographs of the artists’ parents and grandparents in China. This work explores the displacing feelings that are a result of navigating extended relationships across generations and cultures. The final work, In Between, depicts a fragmented, puzzle like screen. Mapped onto each individual shape, is an animation that combines the handdrawn with the digital 3D rendering of strange and abstract landscapes and maps. What is highlighted, are the intersections between what we know and what is unfamiliar - an awareness of the empty spaces and the gaps that inform our perspectives. What we are familiar with, can all at once become imbued with a narrative that is unfamiliar and alien.

Master of Fine Arts by Research Supervisor: Dr Ionat Zurr

NAZILA JAHANGIR ‘Forget-Me-Not’

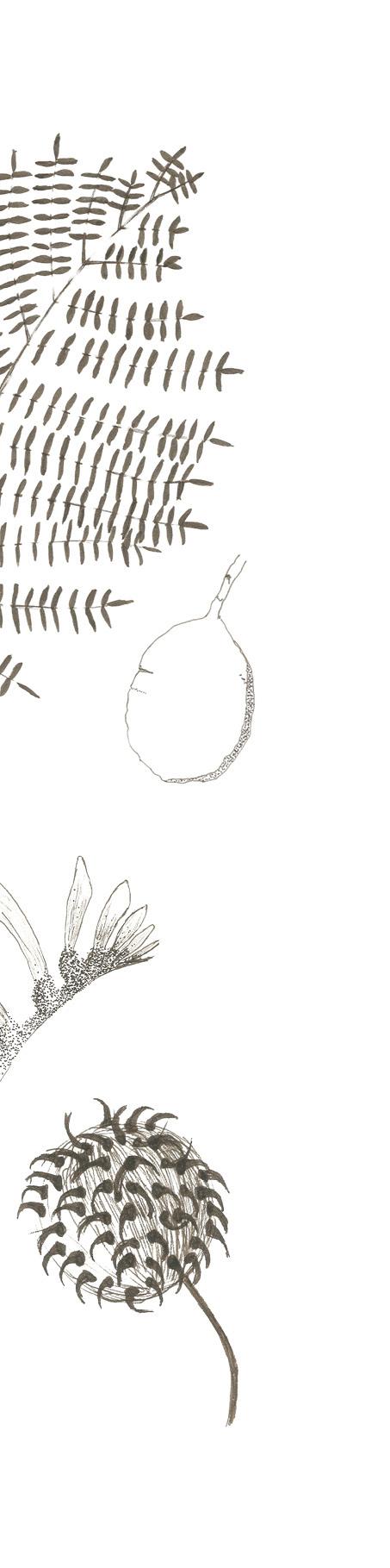

Inspired by pioneer women botanical artists, Nazila Jahangir explores interconnections among feminist art, botanical illustration and environmentalism. Her creative practice is an extended form of botanical art. Besides focusing on an accurate presentation of plants’ anatomy, she also experiments with planting her flowers or seed pods in different contexts and various narratives, playfully troubling the human/non-human divide. The diversity in subject matters and painting styles, as well as the grotesque imagination, are the axils of Nazila’s work. She deploys these elements to make an intriguing and whimsical form of story-based art making.

Nazila’s recent collection, “Forget-Me-Not”, celebrates Western Australian flora intending to contest “plant blindness” and enhance empathy and care for the local flora.

https://nazilajahangir.com/

Master of Fine Arts by Research Supervisors: Dr Ionat Zurr and Dr Vladimir Todorovic

SAMUEL BEILBY

‘Workwelt Logistics’

Workwelt Logistics explores the volatile relationship between neoliberalism, automation technologies and the natural labour systems that they appropriate. The project seeks to amplify the fundamental qualities of swarming (biological and machinic) and showcase how it manifests through material voicings, mechanical agency, and historical legacies within the contemporary e-commerce fulfilment centre workplace. Through using the motif of the industrious ant swarm, robotics, insect field recordings, various AV components, construction materials and media-archaeological aesthetics this site magnifies an archaic labour spectacle that has been revived through artificial and machinic form to extract and embellish its presence and worldliness.

The exhibition intends to incite speculation of a fictional fulfilment centre that utilises swarm technologies and automation mechanics but engages in labour that is not at all directed towards generating capital. The project reconsiders the utilitarian function of automation technologies by scheming an abstract story, a fabricated history, about the cathartic emancipation of an authorial swarmic voice from a neoliberal worksite.

For this fictional fulfilment centre, human consumers and human industrialists have been removed from the equation. We are left with their residual presence, the Workwelt Logistics corporation however, this corporation is no longer concerned with fiscal revenue. The exhibition envisions swarmic labourers that have taken it upon themselves to blast through the ceiling of noise parameters that were established in the company’s formative years when human CEO figures sat in the director’s chair. Instead of shifting tangible inventory, shelves or crates, they shift their own body (individual and collective). Hooked up to contact microphones that amplify their mechanical functioning, this stethoscopic set-up operates to project the “anatomy” of swarming to a jarring scale.

CEDAR RANKIN CHEEK

‘Beige-ness’

Cedar Rankin-Cheek’s work explores the parallels between the organising of domestic spaces and the organising of bodies and the history of cleanliness as a tool to organise and control. Beige-ness is a soft sculpture installation that explores notions of cleanliness as classiness and how capitalism has harnessed the oppressiveness of neatness to sell furniture, positing that you can purchase and organise your way into a better life. The monochromality of the work is satisfying yet overwhelming, the oppressive ‘beigeness’ a reference to the ‘covering’ of culture with Western ideals of cleanliness and valuableness. The uncanny ambiguity and indecipherable functionality of Beige-ness offers a representation of the exclusion of communities through carefully coded symbols of wealth and class.

Fine Arts Honours

Unit Coordinator: Dr Ionat Zurr

CATHERINE BRINDLEY

‘The reunion of forgotten things’

What will your objects think of you, after all this time?

In The reunion of forgotten things, objects come together to reimagine childhood memories in a new light.

The reunion invites us to remember the treasured objects of our childhood; the things we could not part with, and asks where are they now? Using a process of personal reflection and analysis, the work examines childhood attachment through a series of experiments to understand and communicate the complexities of our relationship with objects, while honouring their vitality and separateness.

Fine Arts Honours

Unit Coordinator: Dr Ionat Zurr

JUDITH BODGER

‘Cloak of curiosities’

Cloak of Curiosities explores the fascinating world of microbes, using the cloak as a metaphorical reference to the pervasiveness of their miniscule forms. We simultaneously love and loath them; for adding culture to our beer and cheese, and for infecting our throats and blocking our nares. Exploring essential relationships such as the usually invisible microbe through their magnification provides endless imaging opportunities for the artist, and a constant challenge for creative imagination.

ARTF3050 Advanced Major Project

Unit Coordinator: Sarah Douglas

ANNIE ZHUANG

‘From above and Surrounded’

As a first-generation Chinese-Australian, the natural landscape has always helped the artist build their cross-cultural identity. Informed by their Chinese culture, traditional philosophical beliefs about the environment and the idea of “Oneness with nature” shared with the Western ideals about nature and garden design. These objects are representations of imagined nature biomes informed by known surroundings and unique features of Australian flora to capture the sense of place. Explored through textiles and informed by landscape architecture, memories, sense of place and materiality. The contemplative, intricate process invites the audience to move in, to contemplate the work and to derive an understanding of the artists underlying message and arrive at their own conclusions about their sense of place within the natural environment.

and wood.

ARTF3050 Advanced Major Project

Unit Coordinator: Sarah Douglas

AIDAN BOWDEN

‘M.E.T.A (Modal Environmental Therapy Aid)’

With an ever-growing effort in the pursuit of perfecting a simulated reality, monolithic tech corporations are driving humanity towards a dark future devoid of any real connection with the natural biomes we sacrificed in the name of progress. M.E.T.A is an imagining of the ersatz solution that technology offers to sate our longing for a connection to place and nature, and challenging the effectiveness of our simulated realities in that pursuit.

ARTF3050 Advanced Major Project

Unit Coordinator: Sarah Douglas

AGATHA OKON

‘Outside of truth and Self-portrait with fruit’

Entities can be described in terms of pure information, yet we are unable to comprehend this information. In the obsession with data, we have forgotten that information is not the same as reality. Informatic residues of real objects have been created by processes such as photogrammetry, inscription of information onto paper, and extraction of DNA, with the mangled conversions placed into a constructed world mimicking reality. Is it reasonable to treat this extracted knowledge in the same way as the originating object? Are my DNA, scans, and writing the same as me? Obviously not. Yet, highly personal intimate information, like DNA and demographic characteristics, are regarded as being equivalent to, and even superior to, an individual.

ARTF2054 Drawing, Painting & Print Studio

Unit Coordinator: Andy Quilty

Teaching Staff: Andy Quilty, Bina Butcher and Mark Tweedie

DANIEL GLOVER

‘to use and to possess’

In our consumption and collection of objects, we often remain unaware of the relationships we create around them. This body of works explores and sheds light on the relationships between objects in my life and the value systems I assign them; some holding nostalgic memories and others having little to no value. For example, the cookbook that serves as the base for my arrangements was given to me by my mother when I first moved to Perth, whom I would often bake with as a kid. Moreover, my aunt who passed away from cancer lives on in memory through the little red clock that sits by my bed; one of the few objects I own to remind me of her. She had the most contagious laugh and even though we spent very little time together I can still hear it echo in the back of my mind. My grandmother, who suffers from dementia, holds very few memories of me now, but I can look at the striped bowl and sugar container, and remember her visits, and when she’d stay the night and forget her false teeth in the morning and give us all a big toothless smile. Investing these in the composition juxtaposes these objects saturated with sentimentality against prints of food objects that I pay no attention to. I had to throw out the bunch of bananas last week before I could use them and I have three opened bags of spaghetti in my pantry, but I’ll probably buy another one because I keep forgetting about the ones at home. It is this repetitive consumption of these food objects in my everyday life that blurs them to the point that I no longer remain conscious of my possession of them but I would never forgive myself if I broke grandma’s striped bowl.

ARTF2054 Drawing, Painting & Print Studio

Unit Coordinator: Andy Quilty

Teaching Staff: Andy Quilty, Bina Butcher and Mark Tweedie

DIXIE BARTLE

‘Kimberley Landscapes’

Exploring the energy, diversity, textures and colours of the Kimberley landscape with monotype printmaking, these works were achieved using a hand pressed reductive ink technique on a smooth film surface. Found objects were utilised to enrich mark making in both the plate preparation and pressing stages. The marks represent the landscape as referenced from an abundance of perspectives, interweaving micro rock textures, wildlife tracks in beach sand, sweeping pindan cliff views and aerial images of waterways and landforms.

ARTF2054 Drawing, Painting & Print Studio

Unit Coordinator: Andy Quilty

Teaching Staff: Andy Quilty, Bina Butcher and Mark Tweedie

BRINDY DONOVAN

‘la petite misère (ordinary suffering)’

The phrase la petite misère (ordinary suffering), coined by the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, describes our everyday experiences of discontentment that arise from social class stratification. The phrase speaks too to the Buddhist concept of dukkha (suffering) whereby our discontentment is attributed to our continual desire for things we don’t have and our aversion to what we do have.

In this project, I reflect on how ordinary suffering manifests in my experience of social class mobility. Being of low socioeconomic status brings with it the stress of material precarity, and yet there is also a freedom in having idle time and no desire to “keep up with the Jones”. Moving into full-time work after graduation, I will have a level of income I’ve not experienced before, but this is in return for the free time I’ve enjoyed so far and the stress of additional responsibilities. In both instances, one form of ordinary suffering is traded for another and this tension is expressed in the use of juxtaposing elements within each work and between the painting and sculpture.

Clear polypropylene ceiling allow for greater observation while working and is able to be sterilized with alcohol

Clean work area

Polypropylene sheets line the working area so they can be sanitized with alchol

catches particles

ARTF2031 Living Art

Unit Coordinator: Dr Ionat Zurr

With thanks to the support of Dr. Donna Franklin

KEALI PYVIS

‘Collaboration Station: The Quest for Do-It-Yourself Sterility’

room air and plenum

My artwork Collaboration Station was born out of the difficulties in the relationship that I grew to have with mycelium and fungi, namely, contamination. As I attempted to culture fungi, contamination from “invaders” of unknown bacteria and fungi thwarted my attempts. No matter how I tried to control the contamination it was a failure.

At the basic level, to prevent microbiological contamination of specimens, a sterile work environment is needed, and this is created with filtered air and laminar flow. I set out to design a DIY clean bench to do so, room air is pulled through a pre-filter (filters up to 0.5 microns) by a blower fan. The fan then feeds this air into another chamber (called a plenum) which builds up pressure, allowing air to pass evenly through a HEPA filter (which filters up to 0.3 microns). This even passage of air through the HEPA filter means the air particles move parallel to each other without turbulence resulting in a sterile environment where specimens can be kept free from contamination.

From an anthropomorphic view the clean bench can be seen as an artificial womb. A controlled and manufactured environment that allows humans and specimens to participate and work together. Although fungi survive without any human intervention in many different and shifting environments, to “work” with these living organisms we desire to control them and their environment. In the working relationship between humans and fungi, we force them to rely on us for their optimal survival.

capable of filtering up

The clean bench is not only for collaboration with living specimens, but also conception requires the community of UWA for support in its construction. In that way the clean bench is a utilitarian object and a metaphoric statement for community and collaboration.

onstructed

,

The filtered laminar flow air creates a workspace free of contaminants

ARTF2031 Living Art

Unit Coordinator: Dr Ionat Zurr

ROSHEN CHARLES WILLIAM WARD ‘PLAYTIME’

PLAYTIME looks at the idea of ‘play’ in the lifecycle of humans and non-human organisms. The work engages with the early stages of fungi growth, known as mycelium. It explores the similar traits shared between mycelium and children; traits such as curiosity, resilience, and resourcefulness.

The use of a train set symbolises the concept of time and child play. The train illustrates the duration of growth and the journey for development and the aesthetics of a wooden toy train set reminders us of child play and our younger self.

The work also looks at the idea of imagination and creativity. The intentional lack of bridges, tunnels and stations activates the need to imagine the environment and to create a story. It is an interactive installation that requires the touch and the action of play to experience the nostalgic connection to childhood.

ARTF1053 Digital Art and Object Making

Unit Coordinator: Dr Vladimir Todorovic

Teaching Staff: Dr Vladimir Todorovic, Samuel Beilby, Paul Boyé and Annie Huang

BELLA RICHMOND

‘Lifeline’

The story follows a genetically engineered baby which turns into an adult growing in an artificial womb. Quickly, this character is getting used to its own body. From the needle connoting a medical intervention to the swimming sperm and finally the blinking of a confused person, this animation ends with them waking up from this nightmarish dream. It speculates on how these new humans will be shaped based on the desires and intentions of their creators.

ARTF1053 Digital Art and Object Making

Unit Coordinator: Dr Vladimir Todorovic

Teaching Staff: Dr Vladimir Todorovic, Samuel Beilby, Paul Boyé and Annie Huang

GERMAINE CHAN

‘Visions from the Future’

Rapid technological advancements are unceasing and we are constantly having to adapt to our changing environments. Under the broad theme of ‘X from the Future’, this piece documents my vision of the possibilities in our surroundings that the future holds. Conceptually and visually experimental, I wanted to paint different scenes that could exist beyond our comprehension of the real. Seemingly bright and colourful, these environments are bleak and desolate. Each of the four panels laid out on the screen plays a different scene simultaneously, mimicking the concept of surveillance cameras that we are familiar with. These cameras follow the journey of a futuristic train moving from one station to the other, a depiction of the daily commute in this fictional world. With a palpable absence of humans, some may believe that it actually depicts the rapture. Despite the environment’s transformation, I wanted to use the emptiness of the atmosphere to create a subtle feeling of unease. One may even consider the view of a mind repository of memories, where technology has become infused with our brains, and even the most natural of our human processes are distorted.

ARTF1053 Digital Art and Object Making

Unit Coordinator: Dr Vladimir Todorovic

Teaching Staff: Dr Vladimir Todorovic, Samuel Beilby, Paul Boyé and Annie Huang

MICHAEL DAY ‘HoneyBeest’

It has been known for some time that bee populations have been declining, affecting their ability to sustain their role as natural pollinators, which the ecosystem relies on them for. The Honeybeest is a prototype of a self-sufficient mobile beehive, a concept with the goal of enabling populations of bees to continue their natural pollination over a wider area with less struggle on their part. I have incorporated Theo Jansen’s Strandbeest leg design, which allows the foot to travel in a smooth stepping motion, minimising disruption to the hive caused by unnecessary movement. The base of the hive module is hexagonal and rotates depending on the direction of the wind as bees are known to build their hives out of reach of the wind, for example a hollowed-out tree trunk. The rotating hive and leaning blades provide similar protection in whichever direction the Honeybeest leg structure faces.

HISTORY OF ART

HART3330 Art Theory

Unit Coordinator: Arvi Wattel

Teaching Staff: Arvi Wattel and Daniel Dolin

BRINDY DONOVAN

‘Artwork and/or Artifact?

Gell’s Anthropological Answer’

Introduction

In 1988 anthropologist Susan Vogel curated an exhibition titled ART/artifact at the Center for African Art, New York. Various African artifacts and artworks were exhibited in a white-washed and dramatically lit gallery space without identification or contextual information1. Of note was the centrepiece Zande hunting net that had been rolled and bound. The ambiguity of this object, whether it was an artwork or only an artifact, became a central point of contestation for the authors to be discussed.

The 1980s saw several notable exhibitions that sought to question the division between Western and non-Western works, including Primitivism (1984) and Magicians of the Earth (1989). Within art and academia more broadly, shifts were made towards embracing postcolonial and critical theory. In the field of anthropology, the seminal book Writing Culture2 brought to attention methodological limitations, particularly around textual representations of other cultures. The influence of these ideas is noticeable in Vogel’s curatorship.

The exhibition catalogue included an essay titled “Artifact and Art”3 by the philosopher of art Arthur Danto where he argues that the Zande hunting net was not an artwork. It is this conclusion that the anthropologist Alfred Gell critiques in his article “Vogel’s Net”4 written some years after the exhibition. Gell argues instead for the philosopher of art George Dickie’s “institutional theory” of art, along with a more ethnographically grounded understanding of African artifacts.

In this essay, I argue that this discourse marked an important turning point within the discipline towards a more anthropologically aware and sociologically grounded understanding of art. I begin my discussion by outlining both Danto and Dickie’s theories. I then discuss Gell’s critique of Danto and the alternative answer he provides. I conclude with a discussion of its ongoing relevance.

Artwork and/or Artifact?

In “Artifact and Art”, Danto draws an absolute line between artworks and artifacts. He locates the distinction not in the object’s appearance — Warhol’s Brillo Boxes (1964) looks identical to real Brillo boxes, but only the former is an artwork — but rather in its nonexhibited properties. For Danto, the necessary condition is that the artifact must embody meaning or idea(s), or what Hegel terms Absolute Spirit, of the culture from which it was produced5. Danto pushes back on the idea that anything and everything can be art, including the Zande net because only a subset of artifacts can embody ideas or meaning. Instrumental artifacts like nets, he claims, have meaning that is “exhausted in their utility” and do not “express universal content” that could push them into the category of artwork6.

He argues for his case using his “Pot People and Basket Folk”7 thought experiment. Although pots and baskets have identical appearances and uses in both groups, only to the Pot People do pots possess meaning and symbolic significance but not baskets, and vice versa for the Basket Folk. Thus, according to his criterion, only the pots of the Pot People could be categorised as artworks, but not the baskets; the opposite case is true for the Basket Folk. Because of the identical appearances of pots/baskets from both groups, the line between artwork and artifact is unclear for those outside the cultures. To make the distinction, Danto says that we would need to

defer to the opinion of the “Wise Persons”8 of these cultures who could describe the meaning (or lack thereof) of each object. Thus, to Danto the Zande net could not be art because it does not embody any higher meaning other than its instrumental function. In comparison, Dickie proposes an “institutional theory” that outlines two conditions for something to be an artwork: (1) artifactuality; (2) conferred status as being art9. Conferrence implies someone with the authority to do so. Dickie, drawing on Danto’s earlier work10, locates this authority amongst members of the “artworld” comprised at its core of artists, presenters (e.g., curators, galleries), and gallerygoers; but also, art critics, theorists, art historians, and the media amongst others11. One has the legitimacy to confer the status of art onto an object as a function of being a member of the artworld. Analogously, a judge can confer legal status to a person as a function of occupying the role in the state’s judicial system. Thus, in the case of the Zande net, it satisfies both conditions Dickie has laid out. It is an artifact in virtue of being made, and it has been conferred the status of art by the curator Vogel and received as such by gallery-goers as members of the artworld.

Vo[Gell]’s Net

Gell, being an anthropologist, brings a different set of analytical tools, theoretical concepts, and assumptions to the debate. In his article, he highlights the errors made in Danto’s reasoning and provides an alternative answer for consideration.

Noticeably lacking from Danto’s essay is an awareness of the ethnographic literature. One example is Danto’s liberal use of the term “primitive” which had decades earlier been rejected within anthropology12. Without proper familiarity with the ethnographic record, Danto also makes sweeping, unsubstantiated claims about African cultures (e.g.,

“I do not believe Africans have this metaphysics of Reason”13)14. His analysis can thus be described as ethnocentric, in that he privileges his own cultural perspective and assumptions and projects them onto an imaginary homogenous “African culture.” Consequently, in not being reflective of real ethnography, the “Wise Persons” of which his thought experiment relies on is reducible to caricatures of authority figures15.

Moreover, it is apparent that Danto’s theory is subsumed by Dickie’s. Danto reserves the power of conferrence only to “Wise Persons”, whilst curators, gallery-goers, and art theorists are disenfranchised from exercising this function; not only members of the artworld, but also the artisans, traders, and other members of the culture from which the object was made. In his overly narrow focus, he fails to see how art theorists like himself analogously assume the function of “Wise Persons” in the Western artworld16; and yet, the final say on what is or is not an artwork does not in practice always rest with them.

Gell concludes that the Zande net is art for two reasons. First, it has been conferred the status of art by Vogel the curator. Through a process of “complex intentionalities”17, Vogel has intended it to be artwork through placing it in a gallery and engaging with it in art theorical terms. This is true even if the netmaker did not intend it to be art. Second, the net is latent with meaning in virtue of its form: it is a trapped net. It embodies the Absolute Spirit, if not that of its origins, at the very least that of our age. It is, in Danto’s own words, “a work of art, [as] a function of what other works of art show it to be.”18

Conclusion: Implications for Art Theory and Art History

The exhibition and surrounding discourse have continuing relevance for understanding artworks and artifacts of non-Western cultures, but also the

heterogeneity of contemporary art. Furthermore, it brought attention to the institution and functioning of the artworld. Whilst Danto was too limited in his scope of who could confer the status of art, his account does unwittingly reveal how in practice legitimacy is not equally distributed. Whilst it could be the case that in some cultures the claims of “Wise Persons” have greater weight than ordinary people, it is the case that at present the opinions of artists, curators, and art critics have greater weight than those of ordinary gallery-goers. This often plays out negatively to the exclusion of marginalised groups (who less frequently occupy these positions of authority within the artworld) from partaking in the dominant discourse.

Gell’s anthropological approach to the debate also reflected the broader concerns of his discipline, particularly regarding the attempt to shift away from “speaking for” other cultures to finding ways to let other cultures speak on their own terms. The anthropologist Faris notes, however, that the Zande net had been in the possession of the American Museum of Natural History since pre-World War I19 and its original ownership is unknown. Moreover, ART/artifact “had little to say about how and why African materials exist outside their context and is silent on issues of repatriation.”20 How then can members of the artworld best engage with and understand artifacts that are completely decontextualised because of past colonialism? Rather than Danto’s naïve deference to unreachable “Wise Persons”, Faris calls instead for “an aesthetic that admittedly dissolves the content/form union ensured by context and uses the emancipated products as it will” because this is “the only defensible position (and that only because it is honest)”21; just as Vogel had done in ART/artifact

Endnotes

1. James C. Faris, ““Art/artifact”: On the Museum and Anthropology,” Current Anthropology 29, no. 5 (1988), 775.

2. James Clifford and George E. Marcus, Writing Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986).

3. Arthur Danto, “Artifact and Art,” in ART/artifact: African Art in Anthropology Collections, ed. Susan Vogel (New York: The Centre for African Art and Prestel Verlag, 1988).

4. Alfred Gell, “Vogel’s Net: Traps as Artworks and Artworks as Traps,” Journal of Material Culture 1, no. 1 (1996).

5. Danto, “Artifact and Art,” 23.

6. Ibid, 31.

7. Ibid, 23.

8. Ibid, 24.

9. George Dickie, Art and the Aesthetic: An Institutional Analysis (New York: Cornell University Press, 1974), 34.

10. Arthur Danto, “The Artworld,” The Journal of Philosophy 61, no. 19 (1964).

11. Dickie, Art and the Aesthetic: An Insitutional Analysis, 35–6.

12. Francis L. K. Hsu, “Rethinking the Concept “Primitive”,” Current Anthropology 5, no. 3 (1964).

13. Danto, “Artifact and Art,” 31.

14. An example that disproves Danto’s claim is the notable 17th century Ethiopian philosopher Zera Yacob, whose works predates similar works by Enlightenment philosophers like René Descartes. See: Claude Summer, “The Significance of Zera Yacob’s Philosophy,” Ultimate Reality and Meaning 22, no. 3 (1999).

15. Gell, “Vogel’s Net: Traps as Artworks and Artworks as Traps,” 22.

16. David Davies, “The Anthropology of Art,” in A Companion to Arthur C. Danto, ed. Jonathan Gilmore and Lydia Goehr, Blackwell Companions to Philosophy (Wiley, 2022), 110.

17. Gell, “Vogel’s Net: Traps as Artworks and Artworks as Traps,” 37.

18. Danto, “Artifact and Art,” 18.

19. Faris, ““ART/artifact”: On the Museum and Anthropology,” 776.

20. Ibid, 777.

21. Ibid, 779.

HART2275 Italian Renaissance Art Now

Unit Coordinator: Arvi Wattel

Teaching Staff: Arvi Wattel and Amias Neville

SOPHIE JEFFCOTE

‘The Divine (Feminine) and the Place of Religion: Examining Botticelli in Picabia’

Write a referenced essay in which you compare and contrast a modern or contemporary artwork with a Renaissance artwork and discuss how the modern work derives meaning from its Renaissance reference.

Introduction

The Renaissance was an era characterised by a reignition of development for humanity. With fervent innovations in arts and sciences, Europe burst out of the Middle Ages with a taste for the classical, the beautiful, and the divine; perhaps nowhere more than Italy. With schools of humanistic thought entwining into the ruling minds of Milan, Rome, and Florence, Italian art underwent a veritable explosion. In 16thcentury Florence, Sandro Botticelli flourished under the Medici family, intertwining the religious and the mythological to create paintings that floundered until the pre-Raphaelites of the 19th century revived his legacy and made them some of the most famous artworks in history. His work has been referenced again and again since then, with contemporary artists often drawing on his images in modern contexts to create new meanings – for example, how Francis Picabia referenced his painting Christ the Redeemer (c. 1495-1505) in Salomé (1930). Though the two paintings were created in entirely different contexts and styles, they both tie into similar religious themes, and the use of the Renaissance reference in Picabia’s work creates new meanings about femininity and religion.

Christ the Redeemer

Christ the Redeemer, was completed by Botticelli between 1495 and 1505. It depicts Christ on a black background, dressed in ornate robes, blessing the viewer. The work is an unquestionably devotional image, created to celebrate Christ and his holy presence. As a half-length portrait, his facial expression and pose are detailed and expressive, casting no doubt about the subject of the painting. As typical of religious Renaissance work, Christ is portrayed as a Caucasian man with soft and benevolent features. His facial expression is serene; drooping eyelids are almost absent, broken only by the single tear visible underneath his left eye. This is at odds with the drops of blood leaking from his forehead and dark maroon gashes in his face and chest – creating a sinister moment in an otherwise peaceful image. Christ’s hands are positioned with one blessing the audience and the other measuring his chest wound, a popular object of worship at the turn of the 16th century.

In terms of composition, the focal point of the painting is Christ’s face – the human eye is naturally drawn to the face, and leading lines from his cape edges create a triangle arrowing towards it. The juxtaposition between the black background, his radiant halo, and the golden tones of his skin also draws the eye through a moment of contrast. The background is entirely black – almost chiaroscuro – creating completely negative space around Christ to make him the unmistakable focus. The painting, therefore, uses composition to celebrate Christ and acts as a devotional image in the Catholic tradition. The colouring of the painting is classic of religious Renaissance paintings. Christ’s skin, halo, and the elaborate detailing of his robes are gold. His robes themselves are a deep scarlet underneath a rich peacock-blue cape, patterned with tiny gold crosses. Shiny, tawny hair falls symmetrically onto his shoulders,

broken only by the dark crown of thorns. Golden light haloes his head and radiates from his wounds, painted in thin, regular lines. This almost robotic use of line work differs from the rest of the painting, which draws on humanism and naturalism in its fluidity and realistic curvature. The general atmosphere of the painting is one of warmth, richness, and holiness; celebrating Christ; and fitting into the canon of religious Renaissance painting smoothly.

Salomé

Salomé was painted by Picabia in 1930. Drawing on contemporary influences of surrealism and abstractionism, it portrays a nude female dancer and figures amidst classical architecture, with the outline of Botticelli’s Christ superimposed in line work. The title is visible in the top-left corner, a reference to the biblical story of Salomé and John the Baptist. The painting’s perspective can be broken down into three layers: first, a full-length dancer and severed head, foregrounded in a Hellenistic building, while two supporting figures in the background point towards the doorway. Second: the outline of Botticelli’s Christ as a bust-view portrait, entirely transparent. Third, the flowers and leaves trailing across the whole painting, also transparent, following the lines of Christ’s hair and the dancer’s upper body. With these multiple transparent layers atop the base image, the number of lines is very distracting, almost overwhelming – arguably leading to no focal point. Form is simultaneously rigid and fluid; firm, gridlike lines mark the tiled floor and columns, but these are frequently intercut by Christ’s wavy hair or the curve of the dancer’s body. Audiences are therefore forced to decipher each layer, compelling their active participation in the artistic process.1 But amidst this chaos, the subject of the painting is the dancer – she is painted in the most detail, with purposeful black shadows around her silhouette creating contrast and

drawing the eye without disturbing the background. Careful attention is shown to the shading of her muscle and the curves of her hands and feet – she is empowered in the gentle sensual, confident curves of her body without being overtly sexualised.

Colour is used much more minimalistically in Picabia’s work, present in dull, desaturated swatches to highlight key moments such as Christ’s lips and the blood of the severed head. Otherwise, the painting is washed in a murky golden hue, largely without differences to separate the layers. The only point of contrast is the silvery-blue glimmer of the doorway in the background, which the supporting figures are pointing to. The atmosphere of the painting seems to enmesh the religious and the classical – Christ’s huge face imparts an unmistakably religious flavour, but the clothing of supporting figures, swooping drapes, and amphorae suggest a Greek tragedy.

Comparison

The major similarity between these two paintings is, of course, the same image of Christ featured in both. The posing of his face is identical, both wear twin downcast expressions, the same rays of light halo each. But where Botticelli’s Christ is a traditional image in the religious Renaissance canon, Picabia’s is decidedly not. His depiction of Christ is feminised with long eyelashes, clean jaw and highlighted red lips.2 The face and neck are also thinner and flimsier – an effect augmented by the use of simple line work rather than the intricately detailed oils of Botticelli. Picabia’s Christ is also framed in a much closer perspective than Botticelli’s, showing in greater detail the drooping eyelids and thinly arched brows reminiscent of 1920-30s glamour. Through these differences, Picabia takes Botticelli’s devotional image celebrating Christ and deconstructs it, reverses its gender, and places a woman in the divine position instead. This idea of the divine feminine is echoed

in the symbolism of Picabia’s painting: when tying in the title - Salomé, named for the dancer who brought about John the Baptist’s death by decapitation – it becomes apparent that the severed head on the floor is John, and the confidently-posed woman is Salomé. Thus, Picabia deconstructs Botticelli’s original meaning: the celebration of Christ is replaced by an exaltation of the feminine.

The paintings are also similar in colouring. The same golden tones dominate both images, and the paintings are completed predominantly in a primary colour palette. Botticelli’s red robes are echoed in the clothes of Picabia’s background figures; the blue of Christ’s cape is present in the faded hues of Picabia’s floral imagery. The difference is the saturation of each of the paintings; while Botticelli’s rich colours emit warmth, radiance, and a sense of holiness, Picabia’s painting seems dull and murky - indeed, Christ has lost all colour but for his lips and is completely transparent. This perhaps makes a comment on the diminishing relevance of Botticelli’s original religious meanings in contemporary times, a sentiment echoed in the subject and composition of the paintings. While Christ was unquestionably Botticelli’s subject and focal point, this meaning is lost in Picabia’s contemporary recreation – instead, the subject is the woman, and Christ is reduced to a literally transparent idea. The black negative space of Botticelli’s painting, which brought all focus to Christ, has been replaced by the chaotic, distractingly busy deep space of a classically Greek background; multiple figures; and focus on the body of the female dancer. There is literally more to look at than Christ – while he is still present, the background holds much more interest than him. The differing styles of the paintings continue to reinforce this – where Boticelli’s image depicts Christ in the humanistic style associated with devotional images, Picabia portrays him as lost in the contemporary surrealist style. Where Christ is the

absolute focus, the only image, of Botticelli’s work; here, he is one layer of transparent lines atop an image populated with people surrounded by another mythological time; they do not see him or need him. Hence, Picabia’s Salomé derives its meaning from its Botticelli reference: the divine Christ is replaced by the divine feminine; and the importance of Christ is reduced to a transparent echo.

Conclusion

Christ the Redeemer and Salomé are thus signs of their time: Botticelli’s work is an exemplar of the traditional Renaissance devotional painting in its exaltation of Christ; and Picabia’s deconstruction of this idea in a contemporary age. Though they share similarities in composition and religious themes, their differences define their separate meanings but the meaning of Picabia’s work is lost without its reference to Botticelli: without the image of Christ, it might simply be a recreation of the biblical story of Salomé. By drawing on Botticelli’s work, Picabia creates meaning as multi-layered as his painting itself.

Montua, Gabriel. “Giving an Edge to the Beautiful Line: Botticelli Referenced in the Works of Comtemporary Artists to Address Issues of Gender and Global Politics.” In Botticelli Past and Present, edited by Ana Debenedetti and Caroline Elam, 290306. UCL Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv550cgj.23

Picabia, Francis. Salomé. 1930. Oil and lacquer on canvas. 195 x 139cm. Private collection.

Snow-Smith, Joanne. “Sandro Botticelli: A Study of his major allegorical paintings” (M.A., University of Arizona, 1968), 21. https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/347627

Endnotes

1. Carrie N. Edlund, “Picabia’s Ply over Ply.” Paideuma: Modern and Contemporary Poetry and Poetics, 16, no. 3 (1987): 99–109. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24724816.

2. Gabriel Montua. “Giving an Edge to the Beautiful Line: Botticelli Referenced in the Works of Comtemporary Artists to Address Issues of Gender and Global Politics.” In Botticelli Past and Present, edited by Ana Debenedetti and Caroline Elam, 290306. UCL Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv550cgj.23.

Bibliography

Botticelli, Sandro. Christ the Redeemer. c. 1495-1505. Tempera and gold on panel. 47.6 x 32.3cm. Accademia Carrara, Bergamo. Edlund, Carrie N. “Picabia’s Ply over Ply.” Paideuma: Modern and Contemporary Poetry and Poetics, 16, no. 3 (1987): 99–109. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24724816.

Lugli, Emanuele. The Hair is Full of Snares: Botticelli’s and Boccaccio’s Wayward Erotic Gaze.” Mitteilungen Des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 61, no. 2 (2019): 203–33. https://www.jstor.org/ stable/26922482

HART2223 Modernism and the Visual Arts

Unit

Coordinator: Dr Darren JorgensenJESS VAN HEERDEN

‘Dismantling Art Historical Frameworks from Within: Ser-Gil establishes new dialectical visual relationships to portray India’s dynamic post-colonial modern context’

Considered by many art historians the ‘Frida Kahlo’ of India, Amrita Sher-Gil’s innovative union of aesthetic conventions from East and West allowed her to convey the hybrid quality of modernity and the reality of living in India during this turbulent time. Sher Gil’s Self Portrait as a Tahitian (1934) is a monumental masterpiece that tackles multiple concerns including the status of women, the genre of the female nude, racial stereotypes and colonial power discrepancies. This essay will argue that across Sher-Gil’s oeuvre she creates a discourse between East and West, in which ideologies and aesthetic practices enter an exchange. Sher-Gil opposes the misleading narrative of universalism, maintaining distinctly Indian qualities in her work, whilst dismantling colonial frameworks and assumptions (such as the ‘exotic other’).

The myth of universalism in modernism actively excluded non-European art practices via the equating of Western norms with different, specialised modern contexts (the assumption that the Western norms forged at cosmopolitan centres are global norms)1.

Considering and assigning value to modernist art practices from a universal framework creates a comparison of purely temporal positions, where geography is not considered. This decontextualising effect of a universal framework devalues and discredits modernist art from the outskirts of cosmopolitan centres and from the colonies2, where in reality artists are responding to different versions of modernity and promoting different agendas, so

that formal and aesthetic choices have different significances and outcomes.

Modernism [or the avant-garde, or modernism -consider best phrasing], is a response to the dominant ideologies and values of a specific context, where the avant-garde seeks to push against and upturn them, consequently, all meaning is lost in a process of decontextualization. The principal implication of a universal consideration of modernism is that it permits art history to be viewed as linear, allowing for a hierarchy to form as, from this perspective, all modern art can be read within a single criterion – a criterion that actively promotes and maintains a Western colonial position. Aside from the issue of decontextualization, approaching art history with a single, Eurocentric, criterion also has the limiting consequence of creating skewed hierarchical relationships, where art of the periphery is assigned lesser value or even excluded altogether. Partha Mitter aptly describes the limiting effect of a singular approach, “The purely formalist aspects in abstract paintings are considered to be part of the art historical continuum, while ‘exotic’ eastern spiritual elements are essentially inimical to and incompatible with artistic progress . . .3

Whilst there were certainly other Indian modernist artists whose work represented a synthesis of Western and Eastern pictorial traditions and influences, and who articulated scenes of modern India, their work was typically discredited and excluded from high art categories due to a phenomenon that Mitter describes as ‘Picasso Manaque Syndrome.’4 He coins this term to explain the systematic marginalisation of artists engaging with Cubism from outside of a European cosmopolitan centre. As Cubism was a product of the dominant West and India was a colonised nation, Indian artists were locked into a dependant, inferior relationship in the eyes of European critics, resulting in a situation

where adhering too much to Cubism was mindless imitation and where branching further from it was a failure of learning and lack of understanding.

. . . Where Sher-Gil’s work is different, however, is in her active dismantling of Western conventions from within her work. Instead of falling victim to hyperbolic criticisms, like the ‘Picasso Manaque Syndrome,’ Sher-Gil forces us to re-examine the engrained practices and assumptions that silently maintain colonially skewed power imbalances. This is evident in Self Portrait as a Tahitian, where Sher-Gil’s dialectical approach – an amalgamation of visual language and influences from East and West – portrays the dynamism of modernity, and her creation of a sombre mood portrays the harsh reality of everyday life in modern, colonial India, shattering the illusion of the ‘exotic other’ in the process. In this union of influences and formal choices, Sher-Gil dismantles art historic frameworks, creating a work that speaks to the dynamism and displacement implicit in modernity, yet is grounded in its geography (distinctly Indian).

Sher-Gil’s Self Portrait as a Tahitian is a tribute to Gaugin, as it depicts the artist in the guise of one of Gauguin’s Tahitian women (a visual trope the artists established throughout his oeuvre). While there is evidence to suggest that Sher-Gil admired Gaugin’s use of form5, this work presents a scathing critique of colonialism in Sher-Gil’s upturning of the ‘exotic other’ narrative through her construction of the figure’s subjectivity. This is achieved in Sher-Gil’s purposeful deviation from the conventions Gaugin uses to depict his utopistic Tahitian subjects, and in the figure’s gaze. Gaugin’s depictions of Tahitian women, for example in Two Tahitian Women with Mango Blossoms (1899), are typically set against a natural backdrop giving the impression that they are decorative and wild themselves, the oriental stereotype given a physical form. Gaugin’s women

are passive in their gaze, carefree objects upon which to project his supressed desires as a European man6. Sher-Gil’s unselfconscious Self Portrait as a Tahitian is definitely not intended for the male gaze as although she does not meet our eye, there is a fiery determination and self-assuredness in her distant stare, giving the former ‘subject’ a subjectivity and presence. The figure’s sexuality is not accessible to us, the viewer, as she is positioned on a three-quarter angle, and as her crossed hands deny us access to her body. Saloni Mathur explains that this selfcontained quality and a lack of access subverts the modernist conventions of the female nude and the exotic other.7

Aside from creating agency and dismantling colonial art historical assumptions, Sher-Gil’s construction of the gaze is also significant in Self Portrait as a Tahitian as it conveys the “…the painful paradoxes of colonial modernity…”8. Across Sher-Gil’s oeuvre there is a common thread of an inwardness and deep sadness conveyed through the gaze of the figures depicted. Despite not meeting the viewers eye, the figure’s gaze in Self Portrait as a Tahitian is no exception: a look of deep contemplation and melancholia. Mitter explains that this characteristic construction of the gaze is a depiction of the reality of living in modern, colonial India, as Sher-Gil finds beauty in the every day yet must also acknowledge the suffering and struggle of existence for many during this time; an aesthetic tied to experiences of hunger, genocide and the fragmentation of political and cultural solidarities.9

Sher-Gil’s Self Portrait as a Tahitian is an amalgamation of East and West in both content and form. The artist’s nuanced understanding of traditional Indian culture and aesthetics, and of Western art historical frameworks and contemporary practices, allowed her to depict India’s contemporary context but also the dynamism of modernity (a hybrid state

of being). What truly made Sher-Gril an avant-garde artist, however, was her criticism and dismantling of repressive colonial art historic frameworks (such as the exotic other). In her art practice, Sher-Gil constructed new relationships between the East and West that emphasised juxtapositions (maintaining and celebrating Indian history and neglecting misleading narratives of universalism), but were void of the skewed Eurocentric hierarchies previously implicit in art history.

Endnotes

1. Partha Mitter, “Modern Global Art and Its Discontents,” in Decentring the Avant-Garde (New York: Brill, 2014): 36.

2. Laura Winkiel, “Postcolonial Avant-Gardes and the World System of Modernity/Coloniality,” in Decentring the Avant-Garde (New York: Brill, 2014): 97-98.

3. Partha Mitter, “Modern Global Art and Its Discontents,” 40.

4. Partha Mitter, “Modern Global Art and Its Discontents,” 39.

5. Saloni Mathur, “A Retake of Sher-Gil’s Self-Portrait as Tahitian,” Critical Inquiry 37, no. 3 (2011): 521.

6. Géza Bethenfalvy, “Amrita Sher-Gil: A Painter of Two Continents,” Hungarian Quarterly 52, no. 3 (2011): 94.

7. Saloni Mathur, “A Retake of Sher-Gil’s Self-Portrait as Tahitian,” 524.

8. Subir Rana, “Framing the Political, Rebellious, and ‘Desiring’ Body: Amrita Sher-Gil and the ‘Modern’ in Painting,” India International Quarterly 44, no. 2 (2017): 36.

9. Sanjuka Sunderason, “Toward an Aesthetic of Decolonisation,” Partisan Aesthetics: Modern Art and India’s Long Decolonization, (Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2020), 261.

ARCHITECTURE, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE & URBAN DESIGN

ARCHITECTURE

FOREWORD BY AMY STEWART

I enrolled in the Master of Landscape Architecture program as a conversion student in early 2020, during the height of the Black Summer fires in the Eastern States. Fresh from finishing my undergraduate studies in Conservation Biology, I was attracted to the program by a desire to make an actionable change in the face of environmental catastrophe. As I reflect now on the last three years, it is impossible to separate my experiences from the broader context of rapid global change occurring in real time- from fires to floods, and the ongoing pandemic that continues to impact our communities and landscapes. The students at the School of Design today are graduating into a distinctly different world, one where the consequences of climate change, once thought of as an abstract future, are unfolding in front of our very eyes.

And yet I can’t help but feel so spoilt. To have spent the last six years of my life studying full time, immersed in the complexities of landscape. To have gained a deeper understanding of place on the banks of the Derbarl Yerrigan, in the heart of one of the most unique, rich, and vulnerable ecological systems on the planet. To have had the opportunity to learn from the wonderful teaching staff who continue to share their wealth of knowledge and experience in the profession, and who continue to foster a passion for design and landscape in their students every semester despite the ever-amounting challenges. It has been a privilege to learn alongside the plethora of creatively minded and passionate students throughout my postgraduate studies, some of whose work is documented in this catalogue. I am very excited to start my career with them and to see how they use their talents, developed, and refined here, to contribute to and shape the profession of Landscape Architectureboth in WA and across the world.

Amy Stewart, Master

ARCHITECTURE

ARCT5511 Independent Design Research Part 2

Unit Coordinator: Dr Kate Hislop

Supervisor: Craig McCormack DEXTER WONG

‘Queer Spaces: Invisible Queer Spaces in Perth, Western Australia’

Homosexuality was widely unlawful across the globe and still is in many countries. Western Australia only recently abolished a law legalising assault on homosexuals as a defence in 2008. Historically queer individuals were persecuted, resulting in their queer history not being valued due to the ramifications of being queer.

The research examined and uncovered historical queer spaces in Northbridge, Western Australia because there were gaps in queer scholarship within architecture and wider Australia. Due to the historical perception of the LGBTQIA+ community, there are gaps in queer architecture research. However, the historical queer spaces do exist and are significant to the LGBTQIA+ community and Northbridge community. Queer methodologies were used including carrying out informal discussions about queer history, archival research on historical periodicals, and the act of mapping and plotting these queer spaces on a map. Planometric-type drawings were used to reconstruct eight of these historical queer spaces.

The main findings were that these queer spaces do exist and have historically been clandestine, with any physical evidence destroyed due to the illegality of homosexuality. Furthermore, a lot of these spaces were hospitality venues such as hotels, pubs and bars concentrated primarily around the fringes of the Perth CBD, Northbridge. This research contributes to a larger scholarship on queer spaces globally but also contributes to the local history of Northbridge. This queer history of Northbridge is validated through planometric drawings and queer maps. Both the drawing and maps contribute to wider queer space research.

Lastly, this research in queer history contributes to the ongoing efforts of collecting queer history at the historic centre of the City of Vincent. This queer research further instils the significance and importance of historical LGBTQIA+ spaces in Northbridge, Perth in educating both the queer community and the general public.

ARCT5511 Independent Design Research Part 2

Unit Coordinator: Dr Kate Hislop Supervisor: Lara Camilla PinhoKATHY CHAPMAN

‘Improving Captive Numbat Welfare Through Design’

This dissertation discussed captive animal welfare, namely the welfare of captive numbats (Myrmecobius Fasciatus), also known by First Nations people as the Walpurti. 1 Welfare was assessed and speculated upon through the critical analysis of past and current enclosure designs, interviews with relevant professionals, and contemplation regarding the future of exhibit design.

The four pillars that uphold the contemporary zoo are recreation, education, research, and conservation,2 allowing urban zoos to operate with the best intentions. The earth has entered a new epoch, the Anthropocene, an era where mankind as a hyper-keystone species has had an unparalleled effect on the environment.3 Due to this, zoos are becoming havens of conservation for many endangered species whilst educating zoogoers about environmental degradation and the necessity of environmentally friendly lifestyles. However, the process of designing animal enclosures for metropolitan zoos is complex. When designing for other animals, designers must translate speciesspecific lifestyles into environments that tackle the dichotomy between encouraging the animals’ natural behaviour, such as hiding and creating engaging displays for the public. The design must navigate these opposing factors delicately, otherwise at least one of the four pillars upholding the urban zoo will be compromised. Designers also must consider and interpret the current social and scientific zeitgeists surrounding animal welfare, utilising policy frameworks, historical records, husbandry guides,

and other publications to define these outlooks. Improving enclosures while also providing engaging educational opportunities for the general public is a difficult task; not all designs will be beneficial for zoogoers and responding to difficulties with compassion is important. Additionally, the concept that metropolitan zoos can act as prominent green spaces within an increasingly urban environment was explored within this project. In 2050, two-thirds of the global population is estimated to be living in metropolitan areas,4 highlighting the importance of urban biodiversity and its’ essential role in preventing further species extinction. Scientists have discovered that due to rapid urbanisation, a significant portion of native vegetation has been replaced by a small number of invasive species through a process called biotic homogenisation.5 Cities and zoos have a symbiotic relationship with one another, as zoos are becoming key places of refuge for wild fauna that have been displaced from their habitat as a result of urbanisation. Local flora can be planted in both the public realm of the zoo and in private enclosures where appropriate, further encouraging local animals such as birds and insects to reside in the zoo. These animals can then germinate the surrounding urban areas with native flora seeds and pollen,6 highlighting the interdependence of plants and animals to zoogoers, and reinforcing the urban zoo’s value of education. This dissertation took this information into account to discuss previous and current enclosure designs for the numbat, particularly focusing on the design of the enclosure in context with the scientific knowledge available at that time. The numbat was selected for this project due to its extremely small population size, the species only being found naturally in Western Australia, and Perth Zoo is the only zoo globally to breed the species. This provided a unique

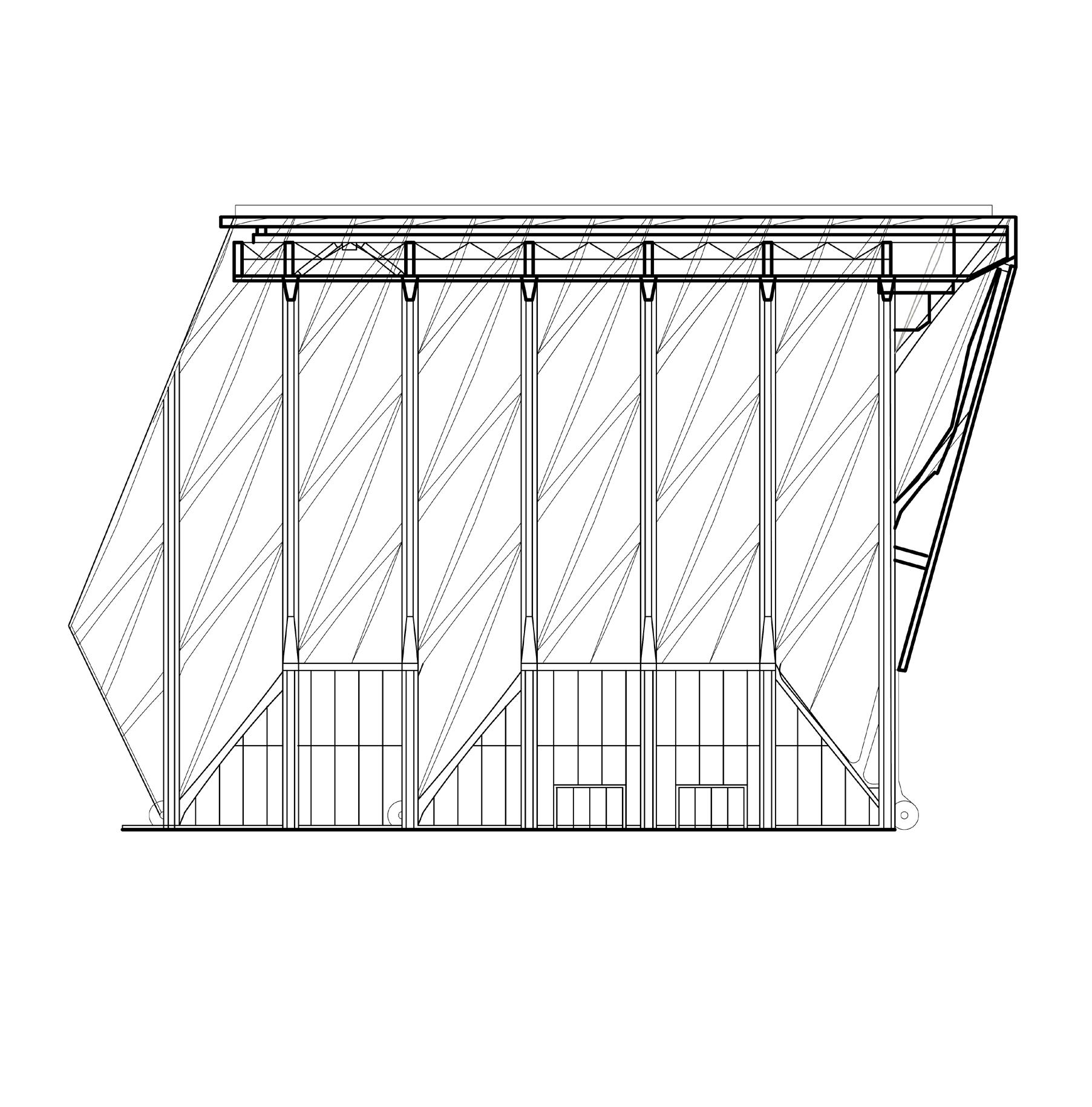

Image: An example of a modular system that could be utilised in the 2030 Perth Zoo Masterplan. The height of the modules allows for natural numbat digging behaviours to occur whilst also preventing the intrusion of other animals and numbat predation. Vegetation and distance are combined to limit the noise and visual impact of people, and sustainable materials such as wood and mycelium are recommended for a variety of implementations throughout this project.

opportunity to collaborate with relevant professionals in person, whilst also having a significant impact on the understanding of the species. As the design of zoo enclosures is inherently multidisciplinary, this research was necessary prior to exploring potential implementations for future numbat enclosures. A series of interviews with professionals in the fields of architecture, landscape architecture, numbat research, veterinary science, and zoology provided invaluable insight into assorted topics such as animal welfare and local biodiversity. These discussions created an informed dialogue that was applied when analysing both past and present enclosure design, while also specifying various opportunities and limitations to be considered when designing subsequent implementations.

This dissertation subsequently investigated alternative materials and aspects of the enclosure, culminating in a series of speculative implementations. By undertaking this study, this thesis aimed to provide innovative approaches to numbat housing facilities, with the goal of improving animal welfare. As Perth Zoo is currently undergoing a massive transformation with the design of the 2030 Perth Zoo Masterplan, this is a crucial time for progress. While it should be noted that although we can learn from previous decisions made for captive numbat enclosures, implementations and decisions made now could still influence the upcoming design of the numbat enclosures in the new ‘Conservation Precinct’ at Perth Zoo, and future numbat enclosure designs at other locations. Examples of successful design implementations can also be viewed in the enclosure design of other animal species with similar characteristics. A notable example of this is the implementation of non-climbable walls in meerkat enclosures7 as an alternative to wire mesh recommended for numbat exhibits, which has caused physical injuries such as broken bones and torn nails.8 Furthermore, a discussion with Perth Zoo

researchers highlighted specific architectural implementations that could be investigated in this project. Some ideas that could potentially be explored were the potential for a modular facility to be constructed within the next few years and then transported to a permanent site when the Conservation Precinct is built, with sustainably sourced materials. These materials and design for an enclosure wall allows a viewing window into the numbat area while minimising visual and auditory impacts of zoogoers on the numbat. The roofing options provide protection from other species while allowing light in winter and shade in summer, and the consideration of substrate options allows for adequate drainage and burrow construction with the possibility of regular replacement.9

As this was a year-long dissertation, time and other resources were limited, and therefore not all of these research options were explored. The modular system was the most prominent potential implementation explored, and within the bounds of this system, sustainably sourced materials and the human-animal connection have been investigated. Through the addition of endangered, endemic vegetation, the modular system has the potential to aid local biodiversity efforts. The implementations proposed within this dissertation have been informed through previous design experience and additional research previously undertaken throughout this project. However, for these theoretic implementations to become a reality, the collaboration between a variety of professionals is required before this concept is fully realised. The success of this system will require the close observation of the animals in their enclosure, and for changes to be made if the absence or presence of certain behaviours is displayed by the numbats. An additional indicator that this modular system is effective would be a comparative study of the captive colony’s breeding

season over an extended time period, noting how many young were born each year.

As zoologists and researchers gain a better understanding of the numbat and its’ captive husbandry necessities, the modular system can evolve to conform and better suit these requirements. As there is a comparative lack of information on both the numbat and its enclosure, it would be shortsighted to not consider the current research being undertaken when designing. For example, researcher Sian Thorn’s doctoral thesis on the subpopulation of numbats in the Upper Warren region may illustrate that climbing is an important characteristic of the numbat, this behaviour was simply not noted in Dryandra field studies. This would result in the modular system evolving through collaboration with other professionals and further research would need to be undertaken to deem the enclosures appropriate.

Success is influenced by time and the design of animal enclosures does not have the immediacy of other buildings. If an intervention can benefit its’ users, this design is deemed successful. As many of these implementations involve the use of biobased materials, such as mycelium as an alternative to polycarbonate, intense observation of the captive numbats and any subsequent behavioural changes must be noted prior to deeming these materials appropriate. If the material is no longer deemed suitable for a captive numbat environment, the biobased materials can be easily composted and only certain recommendations are exclusive to the numbat. Therefore, this modular system can be altered to suit the needs of an animal species similar in size and behaviour to the numbat, with the caveat that additional research and studies will need to be undertaken to ensure that this system is appropriate.

Endnotes

1. A. A. Burbidge, et al., “Aboriginal Knowledge of the Mammals of the Central Deserts of Australia,” Wildlife Research (East Melbourne) 15, no. 1 (1988): 17. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1071/ WR9880009.

2. Jackie Ogden and Joe E Heimlich, “Why Focus on Zoo and Aquarium Education,” Zoo Biology 28, no. 5 (2009): 357. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.20271

3. Boris Worm and Robert T. Paine, “Humans as a Hyperkeystone Species,” Trends in Ecology & Evolution (Amsterdam) 31, no. 8 (2016): 600. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.05.008

4. N. Müller and P. Werner, “Urban Biodiversity and the Case for Implementing the Convention on Biological Diversity in Towns and Cities,” in Urban Biodiversity and Design, 3 (Oxford, UK: Wiley‐Blackwell, 2010).

5. Janet E. Kohlhase, “The New Urban World 2050: Perspectives, Prospects and Problems: The New Urban World 2050,” Regional Science Policy & Practice 5, no. 2 (2013), 153, DOI: https://doi. org/10.1111/rsp3.12001

6. Kathy Chapman, “Zootopia? An analysis of the past, present, and future of urban zoo design in the context of animal welfare,” Research Proposal, (The University of Western Australia, 2022), 14.

7. AZA Carnivore Taxon Advisory Group, Mongoose, Meerkat, & Fossa (Herpestidae/Eupleridae) Care Manual (Maryland, USA: Association of Zoos and Aquariums, 2011), 17.

8. Vicki-Louise Power and Cree Monaghan, “CH04 – Numbats” (Unpublished Book Chapter, September 15, 2020), typescript, 34.

9. Dr Harriet Mills, Emily Polla, and Kathryn Cadwell (Perth Zoo employees), personal communication with author. August 2022.

ARCT5502 Independent Design Research

Unit Coordinator: Dr Kate Hislop

Supervisor: Dr Fernando Jerez SARAH

WONG

‘Is cyberspace a ‘place’?’

Cities of antiquity were full of ‘place’ – spaces of interaction and social vitality. Over time, cities have grown to unprecedented scales and complexities. To manage this, designers and city planners have developed the metropolis of super modernity into a high-functioning, well-oiled machine, wherein efficiency, connectivity and speed are king. A caveat is a population plagued by solitude, individualism and boredom (or lack thereof); the modern city has become overrun by non-place. Prior to the introduction of high-speed internet in the 1980s, ‘non-places’ consisted of railways, airports, supermarkets and high-speed roads. Now, they are everywhere. More specifically, we carry non-place-inducing devices with us everywhere, in the form of the ubiquitous smartphone. With such devices, humans disconnect themselves from the mundane world. As such, what were once places are reduced to mere transitory space. With the rise of social media platforms and virtual reality, it seems that the complete obsoletion of the city is inevitable.