VIRGINIA LITERARY REVIEW

The Virginia Literary Review

www.virginialiteraryreview.com vlreditor@gmail.com

A message from Tom Pollard, VLR Editor-in-Chief:

Welcome to the latest issue of The Virginia Literary Review! Over the past few years, the magazine went dormant during a period of leadership transition. I’m happy to announce that with this issue, the oldest undergraduate magazine at the University of Virginia is back!

Founded in 1979, the VLR is published twice a year in the fall and spring semesters. The review staff considers literary and photography submissions from individuals in the University community during the first three-quarters of each term. For more information about submis sion guidelines, please visit: www.virginialiteraryreview.com/submit

Copyright 2021. No material may be recorded or quoted, other than for review purposes, without the permission of the artists.

Although this organization has members who are University of Virginia students and may have University employees associated or engaged in its activities and affairs, the organization is not a part of or an agency of the University. It is a separate and independent organization which is respon sible for and manages its own activities and affairs. The University does not direct, supervise or control the organization and is not responsible for the organization’s contracts, acts or omissions.

Contents / Spring 2021

Poetry

7 / My Serpentine 10 / Self Portrait as Caravaggio as the Head of Goliath 15 / Teresa 29 / Hawk 39 / The Boys 40 / Old Dominion 53 / The Existence of God Confirmed! 63 / My Brother, After a Snakebite

Prose

12 / Self: Cataloged 16 / I Will Always Be Ten Years Old 22 / Darling 28 / A Dilemma 31 / Excerpt from Klondike, Texas 37 / Self-Portrait at the Center of the Universe 41 / Thank You Five 48 / What I Know About Love 49 / Here 55 / The Ant 57 / Excerpt from Winter Solstice 62 / The Infestation

Visual Art

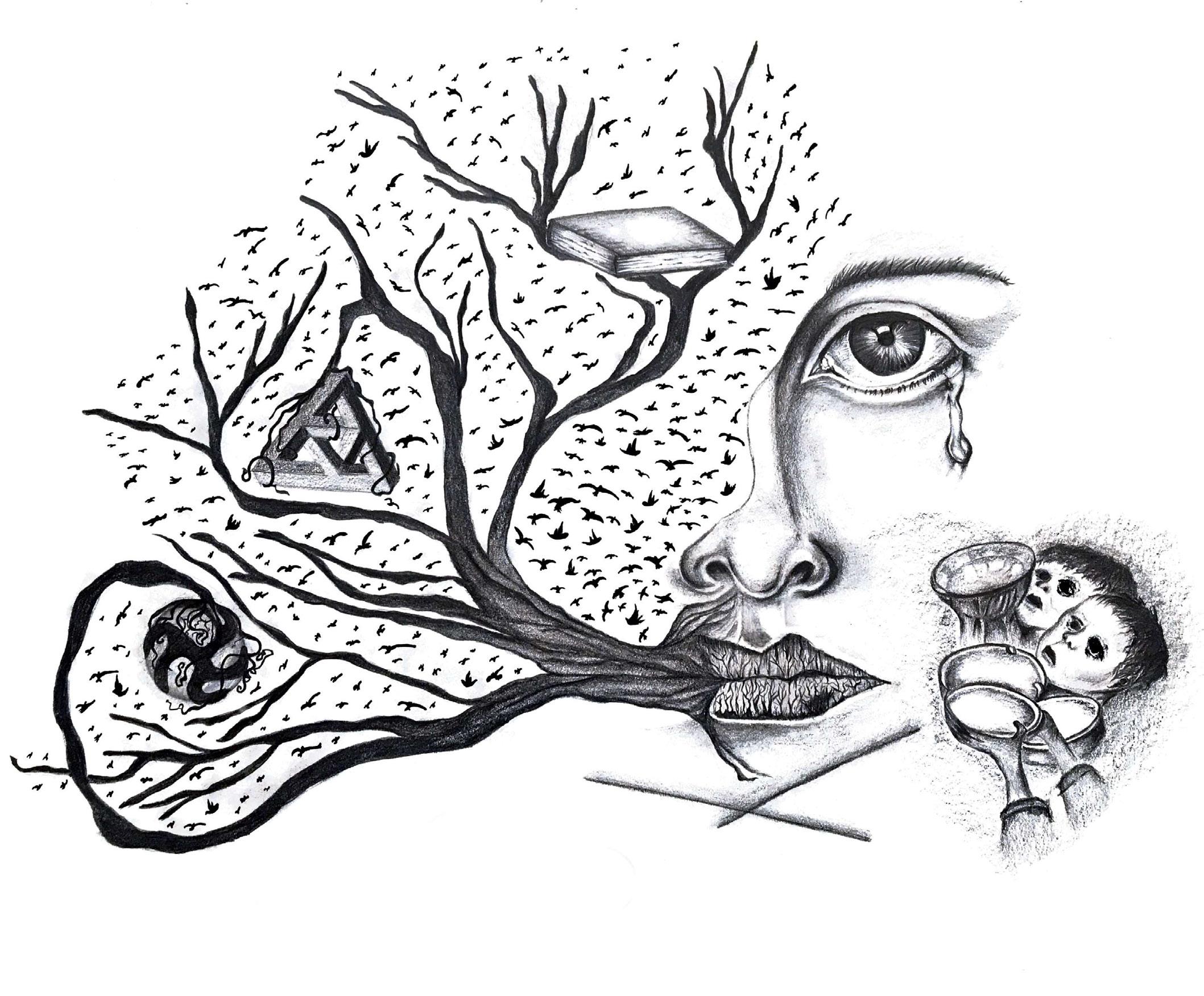

Cover & 14 / Assembly of Concepts

20 / i’ve [lost all concept of time] 30 / My Reflection 38 / *escapism* 45 / The Unjust World 61 / girl../ it’s a panoramic

Jayla Hart Lyla Ward

Annie Parnell

Gabriella Chellis Annie Parnell Gabriella Chellis Ryan Winegardner Annie Parnell

Anouck Dussaud Elizabeth Smith Isabelle Aldridge Annie Parnell Austin Rhea Elizabeth Smith Eva Petersen Anouck Dussaud

Rachel Hapanowicz Catherine Orescan Neal Dhar Anouck Dussaud

Baheshta Azizi

Val Deshler

Baheshta Azizi Val Deshler

Baheshta Azizi Val Deshler

My Serpentine

You are the garden snake that slithers through my freshly plowed Lawn Wraps itself around my swollen ankles and calls me: “Boy” Curve its way up my spine until I have no choice but to kneel

My serpentine

You see the way my aching hands bleed Cracked skin faithfully stacking cracked brick Under a sweltering southern sun

My serpentine Tonight, I scrub the crinkled stone walls clean Wipe off the venom before it stains my skin Let my tears water the trees that loan me shade

When did time become cemented between / these bricks?

My serpentine

Forgive me for overstepping unmarked boundaries For stepping all over these bountiful gardens Pavilions that leave you perched above me In a sickening silence that swells in my ear

Hear the names of my brothers and sisters Echoing down from pristine balconies The crack of your whip meets the click of our tongues Our languages remain foreign to one another

My serpentine

You changed your colors with the seasons Turned your Confederate cardinal red to orange and blue Kept your hatred tucked inside corks and curls Now you see some secrets simply must unfurl

And topple, the way Kitty Foster’s home did Left in the shadows while your Rotunda was rebuilt Such recklessness reigning from those called rational The consequences of your actions are far from fractional

My serpentine

Must Swanson sue you to gain your attention

Use your laws, your language, until you bite your own tongue Crouch between your colonnades quoting Jefferson Until the contradictions catch you off guard

Catch you idle as my humanity is threatened Catch you silent as my community is displaced Catch you indifferent as my story is erased Watch how quickly you craft the next excuse

When did hate become cemented between these bricks?

My serpentine

Your fang marks stay swollen on my chest

Trying to suck the life out of our families Trying to suck the soul out of our names Trying to suck the truth out of our histories

When I shout for justice, you cry for understanding Your hot breath fogs up windows until I am invisible When I demand change, you question my legitimacy Pretend I speak of myths, Boy, check your white fragility

My serpentine

I see you Fierce eyes, scales, and all You cannot shed yourself of me My body My being

My serpentine

I built you Winding curves, cracks, and all You cannot see yourself without me My body My being

My serpentine

I write you down and capture myself

I tear you down and free myself

Read on April 11th, 2021 at the dedication for the UVA Memorial to Enslaved Laborers Jayla Hart

Self Portrait as Caravaggio as the Head of Goliath

The earth was without form, & void; & darkness was on the face of the deep. & you said, let there be light: & there was light & shadow & you said, let there be Mary; & there was your woman Fillide.

& you said, let Fillide be Mary then; & you painted her for the Carmelites. & the Carmelites said, send us a better one, because Fillide was a prostitute, because her legs were bare, because she was dying belly up on a table like a prostitute woman.

& you said, let this Mary be mine only then; & then there was her pimp. & you said, let this man have no manhood; & you took his penis. & you said, whoops; & you took his life.

& you were to be beheaded; an eye for an eye, a head for a penis, & accidentally a head.

You did not want to die; you were hiding in Naples. You said, let there be David; & there was David. You said, let there be Goliath; & there was your head.

Your head spoke. It said not look, I’ll do it myself, but: look what they’ll do, please help me, please stop them.

If ever you did want to die, it was not like yearning for the darkness on the face of the deep,

but only like saying, look how beautiful David looks, sorrow-gazing on what he’s done.

Lyla WardShe often wishes that she was sexless and that there was nothing pink between her legs. She tends to sleep deeply unless a streetlight or the moonlight comes in through her windows. She keeps herself secret by speaking over herself. She hides herself from others by announcing herself loudly, insisting on visibility, making sweeping claims, interrupting her friends.

She looks like this: brown hair, mostly brown eyes, a dignified nose—she thinks there is nobility in its size and aquiline shape, the bony crest at the bridge, its handsome, unapologetic presence—and a face that is half long and half short due to an arthritic joint in her left jaw that grinds against itself (even her body is compulsive, turning on itself, growing so many layers of extra skin that white plaques form at her elbows and behind her ears, and her joints mash into each other like mortar and pestles made of bone. She is coming apart at her hinges!), a long torso, nicely arched feet, white spots on all her fingernails, small breasts, and a tilted smile that shows more gum and tooth on the right side than the left.

She has recently taken up flossing. Her gums are raw and red, forming lifted flaps between each tooth, lifted away from the teeth by vigorous flossing. She crouches on the bathroom floor for her nightly inspection of the white thread. She feels de light when she sees pieces of food on the floss, and disappointment when it comes back clean and red. She shaves her legs from every which way. First, with the grain of her hair. Then, against it. And then, she comes across the leg in slight diagonal strokes until her legs are perfectly bald and as slippery as eels when she rubs her calves together under the bathwater.

She is afraid of organs and hates to notice the rise and collapse of her lungs as they inflate and deflate like a leather bellow. If she notices her eyeballs they begin to ache so much from the awareness that she cannot sleep. They press and strain against the wet underside of her eyelids. She often thinks about all the organs in her body, and what color they are. The color of cow tongue, of mold, of black currents? Spleen, pancreas, lungs, heart, stomach, intestines, kidneys, liver, blad der, brain, ovaries, uterus, appendix, all fitted inside her like clothes in a suitcase. If she thinks about her insides she feels reduced to a bagful of squishy wet things that throb. The cavity of her torso does not seem big enough to contain it all. She thinks it’s strange that there are parts of herself she can never touch. She thinks it’s strange that there are purple things inside her that might be weighed on a silver scale and wrapped in brown butcher paper, or sliced diagonally and splayed across a serving dish.

She is also afraid of permanence, carbon monoxide gas leaks, natural gas leaks, impermanence, car crashes, blow jobs, tumors, multiple sclerosis, aneurysms, imper manence, unforgiving people, stalkers, deathbeds, touching herself, zebra mussels, exposure, the afterlife, shark mouths, decomposition, reincarnation, outer space, physics, pornography, fault lines, fires, ash, subtropical climate zones, rising sea levels, talking too loud, talking too fast, sudden infant death syndrome, the smell of refrigerated leftovers, irritable bowel syndrome, disemboweling, gods, roaches, spiders, spider crickets, intubation, feeding tubes, urinary catheters, barbiturates, and children.

She was not so afraid of death when she did not love her life.

Teresaafter Bernini’s The Ecstasy of St. Teresa

Consider his eyes –longlocked angel gazing unto skin, his soft smile, how a finger tugs the robe away, how her chest might heave. Seraphim burn and cry out –holy, holy, holy. She, exposed, ready for fire, rapture in his hands. She tilts, agape, awaiting. Need he whisper, now, to her –be not afraid?

ParnellI Will Always Be Ten Years Old

10

Sweet tea and cigarettes. That’s what I smell. The green smell of tea leaves mixed over the stove with too much sugar. The smoke and nicotine that carries itself into the house from the garage. That’s what I’ll smell at the end of all ends. That smell is the perfume on my neck. It’s in the hair on my arms. I can conjure it in a second –just a thought!

I am bending down, picking up the ice cubes that fell out of the dispenser, and dropping them into the dogs’ water bowl. Corgis, always corgis. I can hear them running around the house now – their nails on the wooden floor. Five corgis, all running around the house, nipping at kids’ ankles, and I am dropping the ice cubes into the water bowl.

There is mud soup getting stirred into the hollow knot of a tree in the backyard. There are fairy houses being built out of sticks and moss by the creek. There are pine needles falling onto the trampoline, waiting to stab my feet when I come back down out of the air.

A thunderstorm is rolling in right now. The sky is dark gray, and the thunder is a little way off. Cicadas are in the trees, invisible and humming and omnipresent. The pool is 87 degrees. Like bathwater. I float, and I don’t stop floating. The thunder is always rolling.

Irene is eating Watergate salad. Irene eats dessert first on Thanksgiving before everyone else sits down at the table for dinner. It is green, and her hair is orange. People are always telling Irene to stop dying her hair orange. Irene is 84 years old and doesn’t care. She keeps dying her hair orange, and she keeps eating her Watergate salad before dinner.

Anne is rolling her eyes. When Anne rolls her eyes, she doesn’t stop. She looks up at God as she yells. God, give me the strength to deal with this man. She is yelling and rolling her eyes and looking up at God.

Bridget has long, long hair. Brown and straight. I comb it and braid it. Matt has no hair. He is bald, bald. I look at Matt’s bald head while I braid Bridget’s hair.

I reach over the chain link fence to pet Angus. The fence is just a little too tall for me, and the top is pressing into my armpit painfully. Angus stands on his back legs. Even then, I can only scratch the very top of his head with my fingertips. I am always reaching for Angus.

It’s the fourth of July. There are melting popsicles and sparklers and cousins all dressed in matching shirts from Old Navy. The sun has set, but it is still hot. I am catching fireflies. I cup one in my hands gently, and it crawls around my fingers. This is the moment right before it takes off again. Its butt glows.

Three bodies, and their feet are buried in the South. They are always walking around the house. Always smoking. Always making sweet tea and potato salad with mustard. My feet are in the South. Let me walk around the house.

16

I am driving Katie and Colleen to school. The music is too loud. It shakes the windows of the Corolla. I am on the bridge. The sun is rising. Blinding. Melting the leftover frost on the windshield. I put down the visor, but I am too short, and the sun is still too low. I am driving straight into the sun, with my foot on the brake just in case.

Two mothers, two now, walk around the neighborhood in the purple evening with their children. On the leash is the last corgi. The last corgi waddles when he walks. He is getting old in his bones. They walk past an elementary school and laugh at the name. They laugh at Weems Elementary School and the last corgi waddles as he walks.

Four sisters sleep together on two twin mattresses pushed together on the floor. Sydney falls into the crack between them at night. Her eyes open in her sleep. Sydney is always falling in the crack between the mattresses. She is always asleep, watching.

Jen is decorating a birthday cake. She scoops chocolate frosting out of the container with the spatula. She writes a message with candy letters. There aren’t enough N’s to spell Nona. Jen writes Noma instead. Jen is laughing at Noma.

Michael steals vodka from the freezer. Michael drinks the vodka with soda and sits in my new bed at night. Michael wonders. He questions. He thinks something is wrong with him. I listen. I do not know. I never know.

I pass bedroom doors and wince when the wooden stairs creak. I am sneaking out now. My hand is on the doorknob. I listen for my father’s snoring. I can hear him snore from anywhere. My hand is always on the doorknob.

There’s a blue and white beach ball floating in the pool. There are bathing suits drying on lounge chairs in the sun. There are naps being taken on couches in the sunroom. There are boxes, old and dusty and precious, sitting in the shed.

The minivan drives south to Savannah. There is residue from stickers on the win dows. There is goo in the door handles. There are cardboard signs promising boiled peanuts and billboards promising eternities in Hell. The minivan is shaking with the cracks in the road.

In the backyard, Mom asks the four sisters to sing again. We look at the fire pit and brush marshmallow on our jeans. The four sisters are always singing.

Mom drinks vodka and cranberry juice out of a plastic tumbler. It is just me and her in the living room, and the electric fireplace hums out a weak heat. She cries. She apologizes. She misses her mother. I cry too. I am scared. I am looking at myself.

It is dark, and everything is dim and quiet and covered. I’m in the ditch with snow up to my shins, soaking through my boots and jeans. I can hear kids on the hill in the distance, but I cannot see them. They laugh and shriek and it echoes in the ditch. I am standing there alone.

22

I am breathing in the smoke of the first cigarette at Dell Pond. It is midnight. It is Easter. Sarah is coughing. Sarah is saying Oh My God as she coughs. I look at the little circle of ash on the stone wall. I am still breathing in the smoke.

I am leaving home for the last time, but I don’t know that yet. The car is cresting the top of a hill somewhere in Keswick. The trees are casting patchy shadows over the road. The sun is casting patchy light. I am speeding up at the top of the hill. I am speeding up in anticipation of the drop.

Under the covers, I am taking off my socks. I am scratching the tops of my feet. I cannot sleep at night because all of my nerves are in the skin of my feet. My fingers are in the bands of my socks, itching.

I am sitting at the breakfast table my father built. The whole world is early morning blue gray. There are bare feet on cold linoleum. There are baby bowls with suction bottoms. There is the bus outside, missed for the third time this week. I am always a child in this chair.

I am sitting on a rock on the bank of the Rappahannock. Somewhere out in the water, something new is floating on its back. We are watching the heat lightening above the trees. We are looking across the water for just a glimpse. In the last light of the day, we are calling his name.

There are felt cowboy hats being worn during a debate. There is the echo of ten nis balls hitting rackets on the courts across the street. There is the forgotten oven, heating up the kitchen.

A stick floats in the still waters of a canal, dropped from the bridge above. In the ugly yellow light of a streetlamp, I see the algae creeping back toward the stick. Like flesh, like a mouth, it is healing, it is consuming. I feel the algae entomb the stick.

Two daughters are hiding in the basement. Two daughters are remembering the house as it used to be. For just a second, I can smell it again.

Three graves, and I kneel over them. The heat of the sun is in my hair and on my back. I clean the headstones. I wipe away the dirt. I burn my fingers on the granite. I stand where I have always stood, where I watch them lower her into the ground. I watch for ten years. I clean the graves.

Darling

I had this dream once. It was of Jasper, and his cigarettes, and the smell of lem on cupcakes with melting icing. He was reaching for me as I sunk away, grasping for something that got me higher than he did. I was in the bathtub of Maggie and Jon’s house when I woke up, there were smells of baking chicken wafting in from the kitchen, I could hear the plastic of toy cars crunching together as Parker played on the floor outside of the bathroom door, his elbow softly tapping the wood every once and a while like a little angel asking me to come alive. I sunk lower in the chilling water, my fingers grasping onto porcelain edges letting me draw myself deeper. Everyone always thought I would die from an overdose, but I always thought death by suicide was more likely. I startled at a knock on the door. Maggie peaked her head in, auburn hair wisping around her face, eyes wide and brown like the lord made her to stare into the soul of Bambi. I looked down at my sagging breasts, the fading tattoo of mountains on my wrist.

Maggie rolled up her sleeves and cut carefully through the water as she pulled the rubber plug, the drain gulping water like a mouth swallowing its tongue. My toes curled. Parker rolled over a Hot Wheels car and screeched like I wish I could. Maggie whispered over my head that dinner is almost ready darling, and that I will catch a cold if I stay in any longer. She cracked the door. I remembered when I ran a half marathon. When the fat hanging off my hips didn’t indent when I pressed, when I wasn’t so malleable. There was this one in April, I could feel hot urine run down my leg as I hit mile 11, my heart thumping straight into the sky as I dripped down onto the pavement below me, leaving a little bit behind with every drop. Jasper wasn’t waiting for me at the finish line, I knew he wouldn’t. I never told him I was running again, that detail seemed to get lodged in my throat every time we lay sweaty. I didn’t know how to tell him that the dripping of hot salty liquid down my thighs only counted if it was mine. It was just Maggie, belly full of Parker who was waiting for his name, water bottle in hand as if she could give me back what I had lost. There was something loose in the way she held me when I crossed under the banner, as if she thought I would crumble in like the fat on my hips if she pressed too hard. I sunk lower in the dying water, wondering if I could drown myself in only a few inches. I heard more screeching in the kitchen. All cries are proof of pursuit, some primal consequence of wanting more than cigarettes or cold water or chicken in the oven. I knew when Maggie picked up parker just like I knew when she called me on the phone, or reached between my shaking knees to pull the plug on the bathtub. The crying stopped.

Their dinner table was red, I always thought that was strange but Maggie found it at a Consignment shop when Parker was little enough to be strapped to her back, and sweet-talked the manager into delivering it for free. Jon placed a plate of chicken and butter beans in front of me, setting the gravy boat at the center of the

table. I watched Maggie strap Parker into his high chair, placing small bits of food in front of him to play with. We all knew he was picky, Maggie would spend half an hour after dinner enticing him with pieces of chicken and a sippy cup of milk, but it was fun to pretend. Maybe one of these days he will start eating on his own, but I wasn’t holding my breath. Why would he? Maggie was always there. I rest ed my chin on my palms as my brother talked about his buddies at the accounting firm, about how one of their wives was asking for Maggie’s recipe for the cherry pie she brought to the last pot luck. I took a sip of water, wishing it was something stronger. I had lived here three months and still have yet to see anyone touch a drop of liquor, or see lips stained red with wine. I heard Maggie poured it down the drain while I was away, fingers clenching in determination that hulked over my own weakness, the overdose that sent me to a place where no one has anything left, where we were all asked to give up the only thing we really had. I only wished for more hardened elixirs on nights like these. The nights with accounting buddies and cherry pie and soft lights casting a shadow on the food Parker was smearing around. I checked my phone under the table, wishing to have a piece of something for myself, wishing for Jasper.

I met Jasper at a bar. He let me lean on him as we shouldered our weight onto the sticky wood in front of me. I asked him to order me a shot of whisky, my mouth watering in all the wrong ways. I had never liked Whisky much. Brown liquor seemed dirty to me, like if I let it slide down my throat it would turn my insides dark and I would rot from the inside out. I slammed back the shot. Mike, the burley old bartender leaned over to look me in the eye. He asked if I wanted another, I stared. He poured me a double, and that too was gone within minutes. Getting drunk like that had never held any sort of secret pleasure for me, it had no hidden talents of lure or false promises. Whiskey was the liquor for a girl wanting to curdle her insides until they sour.

And Jasper was there to witness my undoing, my reckless abandon of all security, all semblance of personal safety. I had just met him, and yet his willingness to cover my tab, to hold my hips lightly instead of the harsh press I was used to warmed me slightly, enough to take him home and let him use my body in the way only a Christian, Arizona boy would. As if I meant something to him and the broken promises he made to a God that never loved me anyway held a vow of something more. It was only until after that first time, as I lay there sweating and he rolled a joint of something that smelled unfamiliar, new, sweet, that I realized this would be my un doing. And so I let him come back, time after time, to let my body belong to him for a few minutes every weekend, if only to gain some amount of relief from the cold, and the lonely. If only to taste that sweet more that came after sex, the joints that turned to needles, running flowering heady heat through my veins. Longing festers

and sits at the base of your skull and makes your head hang heavy, and when mine was pressed into a pillow as my hips were grasped from behind I let the tension in my neck go. Part of me wished I would be smothered, at least I wouldn’t die alone. And after the sweet smoke, the heated veins, I would run the ten miles home, letting myself feel the night love me like no one else could. Letting my chest tingle with feel ings I thought were imagined, with feelings of being my own whole entire world.

There was always a part of me that wanted him gone. His sandy hair, tall thick stature, I knew I should want him but I never could. He was always warm which only made me seem more... so when he would finish, one of his hands pressed into the pillow and the other pushing my hips back into him I would pull away and ask for what I really wanted. My sex was growing cold by the second and his desire to touch me with hands that had been warmed by a mother’s homemade cookies made my skin crawl. He would hand me a black plastic bag as I wrapped myself in a blanket and run out the door. He knew that was what I came for. I told Maggie and Jon I was training for a half-marathon, that it was cooler at night, when every thing seemed still and I seemed even faster.

The night before my final overdose, I ran to Maggie and Jon’s house instead of my own. Sweat traced the edges of my scalp as I tapped on the door, asking to see parker, asking to hold something sweet in my arms, something that I could touch, even though I could feel everything. I remember her trying to wrestle the black bag from my fingertips, my skin pink from the hot summer air, fingers with a forgetfully tight grip. Their red table seem to ask me to lie on it, a colored warmth that was more comforting than what Jasper had provided. I remember hearing Jon’s whis pered tones as I lay my cheek against the table, Maggie’s soft hand resting on the back of my neck. I thought it would be nice to die here, nicer than underneath Jasper. Maybe they would let Parker climb over my body, finally giving it a use for someone other than myself.

I came out of my fog to Jon tapping his fingers impatiently on the table. I turned to him and smiled tightly, taking a careful bite of my chicken. He sighed, and asked me about that friend of yours from Rehab, you know, the one with the blue on the side of her head. He was talking about Cheryl, a recovering Heroin addict. He kept talking, something about how she had mentioned painting a picture of Maggie and Parker for him when they all came to pick me up in the maroon minivan with dog stickers on the back. I looked down at my plate, wishing for a cigarette, thinking of sitting on the back steps of the sterile building next to Cheryl, listening to her talk about all of her children, some whose names she couldn’t remember. Whenever she talked about heroin she always talked about Lucy, estimated to be around six years old by now. How she would pull baby Lucy into her arms, sweetness running

through her veins, and dance around the kitchen. It felt like flying. She said the baby made her high, I always thought she was drug high because of the baby. Cheryl was with me the first day I was allowed to go outside. When my face hit the air I gave in to the urge to kneel down and smell every flower I could reach. There is something delicious about never running out; of those buds, the soft petals flirting over your fingertips. They beg at you to come close, just once more, to breath in until your lungs are full of a smell that reminds you of something you can’t place. I was sick of rehab, or sick from rehab, I wasn’t sure. There was this girl who remind ed me of Maggie. I watched her hold her baby on family day, let small hands play with her sunflower-shaped stress ball. She had these sunken eyes that would halt and catch at every bright light. When she was high she would pretend the world was faerie land, would hoist her daughter onto her boney shoulders, feel the air like I felt the night, like love was finally within her grasp. She had other stories too, ones without coke, ones where she heated bottles of formula and shopped online for a baby carrier with better safety-features. I never thought drug addicts could be mothers like that. I thought that was only for people like Maggie, people who didn’t want so much.

When my brother married Maggie, I felt relieved that at least one of us had done something right. She wore peach roses around her face and glimmered like the plastic cheeks of a played-with barbie doll. I was a drunken bridesmaid, texting Jasper behind my bouquet—all dirty things. Thinks that never passed the lips of a sparkly doll. Things that Maggie would be taught by my brother, who grew up with a mind like mine, as she lay on cotton sheets somewhere beautiful. Somewhere she pasted a picture of on her wall in fourth grade, dreaming of the white horses and peach roses and pin-up dolls cloaked in white. There were no shots or dirty allies coated in the smell of sweetened white powder and exhaust fumes. I was with her when she bought her dress, still high but not sure from what. Her mother tried to stuff her full of tulle but she was beautiful on her own, simple in a white satin dress that skimmed her shoulders and made her look like a faerie, the ones the rest of us could only imagine. Her mother gave her a china teapot patterned with roses as a wedding present, the kind that you would see in Alice in Wonderland. I stood in the corner waiting for Jasper to sneak between the bushes of the outdoor reception. I bet she would use it for real life tea parties with her real-life friends, tea parties with actual tea, maybe Jasmine. She would invite me for sure, as she was raised right, and I would sneak a flask in my sleeve, twirling a spoon in my liquored tea until all I taste is ruin. I felt Jasper’s hands on my waist and I turn around, breath ing in the smell of smoke. He had swiped a lemon cupcake from the dessert table on his way in, and he presented it to me as if it were a vice, like the contents of the black bag, whisking a dollop of icing onto my nose. I let the tang of lemon drip

down over my lips and onto my tongue, the sweetness rolling around my molars. This is what I was supposed to want, this sugared decadence. Jaspers pupils dilated as he asked me if I wanted to get out of here. I looked back at Maggie, at her satin dress, at the tea pot and lemon cupcakes, the scent floating after me as I followed Jasper out, sticking my hand in his back pocket, searching for some reprieve from the cold fingers of want that clawed at my hipbones and painted the world a jeal ous shade of green.

Jon stood to start clearing the table. I gazed blurrily around me, the food on my plate practically untouched, Maggie giving me a concerned smile from across the table. Parker gurgled happily when I turned to him, gravy smeared all over his mouth as little flecks of chicken dotted his shirt. Maggie reached for the bottom of her apron to clean him up. I wished she had left him, his eyes full of joy and a smug sort of control over his body. Us messy ones are never allowed to wear it on the outside. It made me think of the first day I was brought to stay at Maggie and Jon’s after rehab. Maggie was hosting the moms from Mommy and Me over for brunch, each of them coming with kitten heels and sweetheart necklines, toddlers settled easily over their hips. I watched from the cracked door of my bedroom as they drank mimosa’s and chewed quartered strawberries, the kids running around the living room in their own land of perfection, each with a belt or bow carefully tucking them in so they could run far and fast but not away from the momma that made them. I tried to pick out parker among the crowed. I watched as Maggie dressed him this morning. Watched as she ran a comb through his hair, tucked in a little yellow polo into khaki shorts, cinching the belt just tight enough below his toddler belly. I stood behind her, arms wrapped around my torso, not sure if I was craving a drugged high or the high you get from being someone’s whole entire world. And suddenly, I found Parker. He sat on the top of the couch, reaching for Maggie as she lifted him in her arms and nuzzled his nose. I crept silently to the bathroom, standing in front of the mirror and reaching for my hairbrush. I looked at myself crudely, at the wrinkles forming around my eyes, my sallow skin, cracked lips, and I shut my lids tightly, running the brush through my hair as slow as I could muster. And in the darkness, the clawing teeth at my scalp, I could almost pretend it was Maggie. That it was her hand touching the side of my head lightly, running the brush through the tangles until I was made brand new.

Maggie finished wiping Parker’s mouth and left to the kitchen to start on the dishes. I remained motionless in my chair, Jon reaching around me to collect my plate and utensils. We hadn’t spent any time alone since I came back from rehab, my chest ached as I drew my knees up and buried my face in my thighs. There was this one night when Jon came over without Maggie. I answered the door in underwear and broken leather boots, unlit cigarette resting in my fingers. It was before I got clean,

before the bathtubs and chicken dinners and Parker. I sat on my porch swing next to my brother as he inhaled my smoke. This was when Jasper kept a toothbrush next to my Kitchen sink, when Jon and Maggie were seven months in and nine dates from a ring. When the sky still glowed when I looked at it, when all the world seemed to play around me like dancing toy cars and picked roses and tea pots hov ering in the sky. When faerie land seemed not so far away, when I could run ten thousand miles and be fucked into oblivion and as if my body had never existed in the first place. When all the world was a single sensation. Jon looked at me as he spoke about Maggie, about how her mother kept bringing by casserole dishes of mashed potatoes. How he hates potato’s, how Maggie will place sprigs of parsley on them every night for dinner, at a table set with the candles I used to burn my fingertips as a child. About how every night he ate every bite, one after the other, until the plate was clean and Maggie smiled and promised to have her mother bring more tomorrow. About how he can’t anymore. The mashed potatoes, the candles, Maggie with her Bambi eyes and ruffled apron. He told me, as he took a drag of my cigarette, how he can’t. Not one more time. He can’t, he can’t, he can’t.

A Dilemma

Her new phone has a setting that allows her to designate certain contacts as emergency-bypassing. When she mutes her notifications at night, a setting she uses to make sleep easier, these numbers’ messages can still alert her anyway, ping ping ping, just in case. She has compiled a cursory list, and adds their names. They are best friends brother sister parents roommates, the people who she believes are most likely to need her in the middle of the night, whose needs she is most likely to be able to fill.

She doesn’t tell them about this, the upper echelon, the ones who can wake her up at will. Mostly, she thinks that they would be taken aback at this level of preoccupa tion. It could be intimidating to know that they have the power to disturb.

There is also the issue of determining when someone has gotten close enough to her to be included. She has friends who have known her for years who aren’t on the list, and one who is she has only known for a few months. If she were to men tion it, people might begin to ask if they made the cut. Those who didn’t might be offended. Conversely, a friend who could bypass the nightly muting setting might accuse her of thinking that they were prone to emergencies, or particularly fragile. These aren’t things she wants the people she loves to think she believes about them.

Often, the emergency-bypass contacts do text her after hours, but rarely is it due to an emergency. She startled awake from a deep sleep one night because of a message from her brother saying that she owed him five dollars. Once, too, a new love woke her up by sending her the lyrics to a song that she already knew. When she turned her cheek against the pillow to fall asleep again, she dreamt that it was stuck in her head; later, in the morning, she found herself mouthing the words to the chorus while she brushed her teeth.

Hawk

Set me as a seal upon your heart, as a seal upon your arm; for love is strong as death, passion fierce as the grave. Its flashes are flashes of fire, a raging flame. -Song of Songs 8:6

I deign to descend for feeding and thirst. This burnished blue bubble of sky is my home And I rule all beneath my dome My talons are my crown.

Chasing prey, day up, day down, Spying where sharp-fanged rodents lurk, While sailing whiplash winds is... work, Or play? You may decide.

Nothing from my longing gaze can long hide. Not the tiniest trembling heart For I am always, in my art, Relentless as the grave.

More terrible than a tidal wave My eyes are darker than an ocean trench But filled with fire that none can quench. Crueler than winter, warmer than sun,

Beyond the clouds, I wait, hidden, but run! Divine falconry is at royal play. I’m breath o’er storm. You? Clay. Stare at me, behold your king. So stare, behold your king.

I will not for your pleasure sing I am not your goldfinch, sir. Hunt me on the mountains, sure That I will find you first.

Excerpt from Klondike, Texas

Walker swatted another mosquito and looked at the tiny prick of blood on his palm. Too slow.

Many old folks and more than a few of the men in camp said smoke kept the bugs at bay. He’d heard that about bees; his mama was wild about them, planted five apiaries across their land just so she could spend all day scraping honey off comb and fix up each queen like it was another one of her many daughters. Some times Walker had joined her, when he wasn’t out with the Tallmadges or by him self, wandering through limestone canyons with nothing but a map and a pen and a loaded gun in a holster. It helped how he was used to the miniscule motions of drawing maps, how fragile even the tiniest movement could be, and was better than any of his sisters at getting as much honey as he could out without doing damage to the hive. A simple task, much simpler than trekking through more trees and brush than he ever thought existed.

All in all, smoking didn’t do damn all about mosquitos, not really. But most of the men that were here in the employ of Mr. Roderick Staytz, Esquire, traipsed around with something lit between their lips anyway. The acrid scent of tobacco smoke or the sweeter smell of pipe ash constituted their excuses, as did the ease that settled into their limbs when they took a deep enough drag. For his part, Walk er tried to limit himself to one pack a month, if any. It was a bad habit, but a persistent one.

Sun set a couple of hours ago. Nice night. Nicer than the ones they’d had lately, anyway. When Walker wiped his forehead with the back of his hand it took almost twice as long as it usually did for it to become saturated again, which con sidering all things seemed optimistic. And there was a breeze, even if it was as musty and damp as the regular air, enough to feel something close to cool against all the sweat pooling in every crevice and cranny of his skin. Close to two months into the job and it wasn’t getting any cooler—August was a veritable demon in Tex as, worse than June or July, and it wouldn’t get any more bearable until well into September at least.

“Evenin, Mr. Walker.”

The man Walker’d noticed the first day in camp stood at the bottom of the stairs, looking up with wide, open eyes that reflected the lantern light as brightly as a mirror, tiny dots of white and yellow dancing off darkness. Walker had gotten to know him a little more over the weeks: he knew that his name was Daniel, and he was a good cook and a better shot. Walker’d been the one to teach him how to smear wax on his lips to keep them from chapping so much that they bled at night, but Daniel was the one who’d been able to fix Walker’s best shirt when that moun tain lion had surprised them all a couple of weeks ago after dinner.

“Don’t have to call me Mr. Walker right now, Danny,” Walker informed him. “It’s late.”

He would’ve been happy if someone dropped the “Mr.”; it was isolating, alienating, even if he made it a habit to keep people from using his first name. He knew it was strange, how every time someone used it he pictured another time, another pairs of lips speaking, a vigor and harshness he couldn’t stamp out from his memory. But Daniel seemed as good a candidate as any to assume that lesser type of familiarity.

Daniel smiled. Walker noticed something in his hands, something wrapped in a small, pale cloth, probably one of his handkerchiefs. When Daniel saw Walk er looking he lifted it, and explained, “They were throwin out the last of the pan bread. Someone used too much butter this morning, and it won’t hold until tomor row, so I asked if I could take it.”

His smile seemed hesitant, something like pride or embarrassment or nervousness playing on his lips. “You want some, sir? I already put some syrup on it, cause it’s been a while since we’ve had a proper dessert, you know, but other than that it’s just like the others make it.”

It really was late, and tomorrow, just as they’d done every other day in sight, they were getting up early. Walker was already wincing at the sound of the bell that would sound an hour before sunrise, and how heavy sleep would feel as it lingered in his eyes, heavy as lead. He was leading another extended scouting par ty, which would mean up to a week away from main camp, just him and Nathaniel Johnson and one of the other cartographers and some other men, and much less sleep than he was used to. It was important for him to get enough sleep tonight, more important than usual.

But he said, “Sure, why not.” And then, “Gotta take what we can when we can, right?”

“Right.” Daniel smiled with his teeth this time, very neat teeth, and climbed up the stairs. It was a bit of a strange sight—since they’d arrived, Walker’d only had people over to go over maps, or discuss scouting. He’d never had anyone over before in such a casual setting. Certainly not Daniel.

True enough, Daniel held out one piece of pan bread for Walker, keeping one for himself, and when he handed it over Walker could feel the tackiness of the syrup on his hand. Walker lifted his slice in a kind of cheers, and Daniel reciprocated the gesture.

It was sweet on the tongue, sweet and grainy from being soaked in butter all day. There was salt and a savoriness from the cornmeal, but the taste of the syrup Daniel had used was present above it all. It tasted like luxury, not some day-old mushy bread that had only just been saved from being thrown in the mud, or to the horses. Walker knew he himself wouldn’t have been that thoughtful. It reminded him of his mother’s cooking, filling and rich and comforting. That’s pretty good,” he admitted, chewing slowly. “Thank you for thinkin of me.”

“No problem, sir.” Daniel tore off a small piece of his own bread and put it in his mouth. His mouth was smooth, shiny from the wax, almost full as a girl’s. “You think tomorrow’s gonna be rough?” he continued. He still had that note in his voice, the one that was hopeful and light despite everything life had surely thrown at him. Walker knew that would fade; he himself still had the scar on his jaw from when he smacked into the cobblestones after Jonathan Tallmadge threw him there. But Walker would feel bad when Daniel suffered anything close to that fate. Wasn’t easy being out here, in land that wasn’t your own and never would be, and a lot harder if you’d lost that feeling. Was it naivety? Hope? Innocence? It had been so long he couldn’t tell.

“Aint every day been hard?” Walker replied, and Daniel didn’t say anything to that. He just kept looking at Walker, really looking, and took another bite of his bread, exposing his light pink tongue behind his lips and teeth. There was a mosquito on his cheek, but Walker didn’t move to slap it away. Too easy to administer a slap when you were trying to be kind. And just as he thought about reaching out slowly to brush it off Daniel’s face, the bug flew away.

Daniel reached under his shirt and made a face as he pulled at the bind ings underneath. Every one of the people on this trip was running from something, Walker’d learned, and he knew Daniel was one of the men that was running from something other people had subscribed to him. Walker felt bad for him sometimes, if only for how he and the other men avoiding past names got chafing on their chests and backs much faster than anyone else, so bad that they needed more boiling kettles and bandages than most amputees. He’d seen one of them when he’d been hauled up after the mountain lion attack, dizzy with fever from an infected blister, and quietly hoped Daniel had never had to experience anything so harsh.

“Can I get you anything?” Walker asked, wiping his hands on his pants. His fingers still felt the slightest bit sticky, and when he pulled them away from his pant leg little bits of lint and hair stuck to his palms.

“Oh, no, sir, I’m fine.” Daniel rolled his shoulder; his eyes scrunched in pain and a sharp intake of breath whistled between his teeth before he resumed his normal, placid face. “Been a long day, that’s all.”

“I’ve got some medicine inside,” Walker pressed. He rolled up his left sleeve, exposing the still-red scabs of where that damn cougar had gotten him those weeks ago. Coyotes were more common, but less dangerous, and Walker was still kicking himself for getting caught before managing to shoot the bastard once and for all. “It’s antiseptic, real stuff. I’m sure whatever you’ve been usin is fine, but I did spend good money on it.”

Daniel’s brow furrowed for a moment. Walker knew that face, offers that could be traps, used against you in the next breath. “You sure, sir?”

“Dead certain.” Walker stood and ducked inside. His cabin was small, but at least it was his own—men like Daniel, in lower positions, walk-ons, were lucky to get their own tent, and more often than not they were sharing two or three to a tent. The small pot of salve he’d bought when he got the chance to go into the nearest town was in the top drawer of his chest, and he grabbed it and a clean washcloth and strode back to the porch.

Daniel was pressing his fingers to his shoulders, the white edge of the bind ings exposed. Walker could see that they were stained with sweat just like everyone else’s shirts were, the skin around it shining with the familiar sheen of perspiration. “Don’t know if I can reach the back,” Daniel admitted. He wouldn’t meet Walker’s eyes, looking out into the line of trees as if he was hoping to find some other answer there. Walker didn’t want to give him the wrong kind of reassurance, the kind that only solidified the strangeness and otherness that he knew Daniel was trying to run away from. He didn’t want earnestness to come off as something nas ty.

“I don’t mind,” he assured Daniel. There would have been silence between them if not for the cicadas, and the bugs chirped and screamed as neither man said a word. Somewhere else in camp a man shouted, and the dim wail of a harmonica echoed out to them. Walker felt more than one bead of sweat slide down the individual vertebrae of his spine. The same deep, grating fear that had plagued his bones when Mr. Staytz asked if he was a convict returned in his stomach—he had to fight the urge to qualify, to retract.

Daniel pulled his shirt over his head and held it in his lap. His shoulders were narrow, bony, his collarbone drawn stark against his pale skin. The bindings were grimy, streaked with dirt and blood and charcoal and candle wax that Walker could tell was the residue left after many, many washings. He could see the culprit of Daniel’s discomfort, half-covered as it was: skin peeled back, burst blisters glis tening with the clear liquid that was not sweat. Walker’s own skin ached in sympa thy.

“Christ, Danny, you’ve really done a number here,” he murmured, unscrewing the top of the medicine.

“Can’t help it,” Daniel replied, and closed his eyes as Walker scooped out some of the whitish paste. “No other way to get it done.”

Walker didn’t know what to say to that. It wasn’t his struggle; commenting wouldn’t do any good. So he just took his clean hand and pulled the bindings back enough to expose all the blistered skin, and felt Daniel wince when the medicine touched him.

“It’s alright, it’s alright,” Walker heard himself say. “If its stingin, it’s workin. Least that’s what they told me, and I’m doin just fine.”

Daniel’s chest rose and fell; his jaw was clenched so tight to keep any kind of groan or cry inside that Walker worried he was going to burst a blood vessel. “Relax,” he urged again, sitting, and drew his eyes level with Daniel’s. He held the bindings off the medicated shoulder and moved to expose the other one, but stopped when Daniel’s hand clapped down onto Walker’s knee, a movement that lacked even the courteous warning of a rattlesnake. All his ease was gone, his fin gers shook, and the tendons in his shoulders stiffened under Walker’s hands.

“That’s just fine, Mr. Walker,” Daniel said. His voice was much quieter now, and seemed half stuck in his throat. “Very kind of you. I appreciate it.”

His fingers were long compared to his palms, longer than Walker’s and thinner, and his knuckles seemed stained with something dark and dirt-like (coal? Gunpowder?) that made him look as if he’d clawed his way out of the earth instead of walking over from the mess tent. Walker wondered if they were at all soft despite that, despite the work they’d been shackling themselves to for these weeks. He wondered if that softness in his eyes and voice was held anywhere in Daniel’s body. He hoped it was.

Walker laid the bindings back over his shoulder wounds delicately, hoping it wouldn’t stick and that he’d put enough on to keep a protective layer against the dirt and sweat. He wished he’d bought more gauze when he’d got the medicine, for Daniel’s sake, not his own. Wiping his own hands clean with the cloth, Walker’s fingers felt soft, softer than they’d been earlier in the day.

“Try to keep weight off it tomorrow,” he advised. “Don’t want this to get any worse, or else you’ll have to go to someone above me.”

“Not exactly sure how I’m supposed to avoid that.”

He had a point, and Walker knew that. He knew that Daniel’s job was a physical one, that he helped build more houses in the time where he wasn’t keeping inventory on the camp’s firearms. An important job, one that didn’t pair well with a day off. An idea formed in Walker’s mind, and he let it turn over a couple of times, thinking before he said anything too rash.

Daniel’s hand still rested on Walker’s knee. They both seemed to realize this at the same time, and when Daniel withdrew it, Walker felt as though something had gone missing. He knew the gesture had been one of hesitance, a boundary, but its absence was something else entirely.

He took Daniel’s shirt from where it rested in Daniel’s lap and bunched it up. Nodding to the still-fresh wounds he instructed, “Lift your arms. Carefully, now.”

Walker stood again, chair scraping against the porch as he slid the thin cot ton over Daniel’s arms, resting it on his slim shoulders, a gesture more delicate than even the minute markings on his maps. Had to be careful, really. Every man was needed out here.

“Listen,” Walker said, a feeling that wasn’t pity but something close to it burning in his chest, heat index well over 100. He couldn’t keep it in any longer; there was no way he could let Daniel go to his work like this, no way in his good conscience. “Come with me to scout tomorrow. You won’t have to carry a thing once your pack is strapped to a horse, and your eyesight’s miles better than mine even without a glass. You’d be a welcome addition.”

Daniel cleared his throat and scratched his palm, lacing his fingers together in a tight fist. “You sure, Mr. Walker?”

“As long as your leg can take it.” Daniel was a good man, a dependable one, and the way his flesh had felt so flayed and raw under Walker’s fingertips was a worry.

“It can.” Daniel smiled again, teeth perfectly even. “Should I meet you here tomorrow?”

“No, I’ll come find you once I’m packed, after breakfast. Just bring some pens, and somethin to write on, and some clothes. We’ll take it from there.”

“Alright.”

The piece of cloth Daniel had used to wrap up the bread had fallen to the floor between them, and Daniel bent to pick it up. His curls brushed against Walk er’s hand, and when he straightened he stood and said, “Thank you again, Mr. Walker. It was nice sittin with you.”

“Nice of you to come by, Danny.”

Walker watched him walk down the stairs, glad to see how freely Daniel’s shirt hung on his shoulders. The rhythm of his steps — thump-THUMP-thump-THUMPthump-THUMP — resonated in the wood, and as Daniel walked away Walker caught himself breathing in time with the other man’s gait. The next light was far off, with the group of tents, and before long Daniel was part of the night, unseen.

Walker raised his hands to his nose. One smelled of syrup, sweet, cloying, nostalgic; the other of mint, something sharp and antiseptic. The slightest hint of blood from when Walker got bit and the remnants of his own wound mixed up in the medicine lingered, foreign and wholly human. How likely was it that some small part of him was in Daniel now, a bit of skin or hair or something else lodged in his exposedness?

A firefly and a mosquito landed on Walker’s bare elbow. The firefly lit up, went dark, lit up, went dark. The mosquito drank deep from the dark vein in the crook of his arm, and Walker didn’t swat it away.

Self-Portrait at the Center of the Universe

The desert bends over backwards, snaps in the heat of the sun, and there is Alice in all her red glory, halfway between Darwin and Adelaide. Short mountains that made her impossible to find for a century, and a river that never runs, and a liquor store where a man shoves wine bottles down his pants. Red dirt that cakes into school shoes, and white ghost trees, and the living hum of millions of cicadas. Everything shimmers as if it were gold.

The trampoline is a viewing deck for UFOs. At night, the golf course is the home of delinquent children and kangaroos and the security guards who chase them both. And the Queen of England owns that playground next door.

The embarrassing slap of puberty, of Christian private school, of refinement, of wilderness. Slap. The white chalk on my palms billowing as they meet the uneven bars. The smell of sweat soaked into the mats. Green leotards, and nerves, and Imogen’s music on the loudspeaker as she dances through her floor routine.

Slap. The rain on the tin roof, the first rain in seven years. The Todd floods, runs again, murky with silt and debris. No one goes out to feed the wallabies behind that motel, and they are starving for those tasteless pellets (like zoo food), snap ping and biting at hands, grabbing and holding fingers with their own, alarmingly human.

Slap. The grasshoppers stir up, explode, hit legs as they walk past. The little troop treks through the bush, junior-rangering, searching for scat. Or visits a graveyard outside of town to see one monument, a red stone man panning, lost and dead searching for gold.

The Boys

They are careless with their boy-bodies. One stretches out his boy-legs whenever he sits down and forgets where he has put them. Another has a habit of running into doorframes. This one’s arms swing out when he walks; often, they apologize for accidentally grazing each other’s hands.

All of them are amazed at how small she is. They say things like coxswain, second baseman, running back. One says “I always forget how short you are until the next time I see you.” On her shoes, he adds: “look at them! Tiny Timberlands!”

One night, some of them are going to a vampire-themed party. She offers up an old stick of eyeliner and makes them nervous. They have never done this before. They close their eyes, trusting, tilt their chins upward slightly when she tells them to. She asks them not to twitch if they can help it.

This one’s eyelids are covered in freckles. Another’s eyes are bigger, and deeper-set. One says he thinks he looks better when his are open wide and a fourth one’s close tightly when he laughs. Still another has a stye that has not healed yet. He keeps rubbing at it. She has told him to press lukewarm tea bags against it before bed, but he is afraid of using one that is too hot accidentally and burning himself.

She has just said a particularly formal word in casual conversation with one of them. He repeats it back, softly: cos-mo-po-li-tan.

Old Dominion

Skies of gray and seas of greenEmeralds on a silver chainMixed as in a tempest-dream

Marble clouds that threaten rain Swathe the railways,twists and turns Silver wrapping round the train

I have one thought and it burns, Like a fevered forehead does Yet soft-stirs my mind, like ferns

Rustled in the woods because Low slow humid airs float by -One sole dew-drop thought now: Twas

That you were mine, and not, and I Could walk your seas forever, tread Your jade cool carpet silent, shy.

Lore-led, then, and wonder-fed Infinite her mossy floor I would seek the end and, led

By memories and honest lore I’d find the path the fairies tread If fairies lived here anymore.

Thank You Five

Five minutes to curtain. Thank you five! Five minutes to transformation, reinvention, reinterpretation. Five minutes to costume, five minutes to hair. Thank you five! Don’t touch props that aren’t yours. The food, the plates, everything on the props table, do! Not! Touch! Thank you, thank you five. Where are my jazz shoes? Thank you five. To sit in solemn silence/On a dull dark dock/In a pestilential prison/with a lifelong lock. Thank you five. Where is the stage manager? The director? The head of costumes? I need to ask them something. Thank you five! Oh God what is that smell what is that smell what is that smell? I must have some. So what if I’m in cos tume? It’s just a French fry/it’s just a granola bar/it’s just a low-budget production of Guys and Dolls. I know, I know. Thank you five! She is so beautiful; I hate her guts. Thank you five! Five minutes to makeup. Thank you five! Five minutes to toner, moisturizer, primer, foundation, concealer, bronzer, highlight, eyeshadow, eyeliner, false eyelashes, eyelash glue, mascara, lipstick, do it in twenty when you really needed an hour; oh do you need help? Here, let me do it for you. Oh shoot, I’m sorry. Here; have a makeup wipe. Have a Q-tip. Beautiful, good as new. Thank you five! The shirt fits but the pants don’t. Did you look at the notes? Five minutes to notes! Oh shoot. Thank you five! Anyone got hair gel? I’m all out. I look horrible, absolutely horrible. (No you don’t). Hmm. Five minutes ‘til stunt call! Thank you five. You see here, It’s like Chekhov’s gun but with a banana. Get it? It’s a whole concept. I think the audience is gonna dig it. Thank you five! What’s playing at the Roxy? (thank you five) I’ll tell you what’s playing at the—sorry, your tag’s stick ing out. Thank you! Thank you five! Does anyone have a bobby pin? Hairspray? Hair gel? (sorry, I’m all out.) A condom? Rubber gloves? Duct tape? Gaffers tape? (thank you five!) A hairdryer? A steamer? Geez, you really would think--thank you five! Where are my street clothes? I put them down here a second ago. Thank you five! OhfuckI’mbleedingI’mbleedingI’mbleedingHELP oh thank GOD what would I do without you??? Thank you five. I’m sorry, but I have a paper due in an hour and I’m only on page two. How many? Ten. I have a ten page paper due in an hour and I’m only on page two. Thank you five! Oh that’s awful, how did that hap pen—never mind, I don’t want to know. Only tell me if you’re comfortable sharing. Thank you five! Look at it, isn’t it huge? oh it’s not that bad.) I’m gonna pop it, I’m gonna pop it. (not now we’re about to go onstage) Too late! It’s popped. Ohfuc kI’mbleeding. What should I do, what should I do? Thank you five! A cigarette, just one cigarette. Just something to calm me down before I go on. Oh we’re starting in five? Why didn’t you tell me earlier? Christ almighty. Thank you five! Oh they won’t

miss me. Just one more cigarette. What are they gonna do, start without me? I’m the lead for chrissakes, they can’t start without me. Is Tommy gay? No reason, just asking for a friend. How about Sawyer? How about about Amir? Lawrence? James? Bill? No… really? Geez, that’s shocking. Actually now that I really think about it… What? Oh, sorry! Thank you five! Oh fuck I still need to fill in my brows. What’s that sound? Can you hear it? From the left stall. Who’s crying? Is it Sarah? Not again. Geez Louise, you would really think she’d’ve learned by now. Doesn’t she know we’re going on in five? Someone tell her. Not me, I don’t know her well enough. You should go in and go talk to her, tell her we’re going on in five. Yes, yes I know. No, no I don’t. Thank you five! Do you think we could—no no, it’s too risky. But no one will see us! How about the costume loft? Or the doghouse? Thank you five! Why is she in our dressing room? Hers is down the hall. Doesn’t she know that? Honestly, the audacity. What? Yeah, I know. Thank you five. What do you mean you don’t know your lines? Christ almighty Sarah, it’s opening night! What is she still doing in there, my God, doesn’t she know it’s opening night? Doesn’t she know who’s in the audience? The principal, the district superintendent, the mayor and his husband? Oh shut up shut up shut UP! (thank you five.) Is she okay? I hope she’s okay. Did it happen at the football game? Under the bleachers? In her car? In his car? In the woods behind the softball field? In the dressing room? Oh God, not the dressing room. When did they have time to—oh shit! Thank you five! Is she okay, someone should really talk to—sorry ladies, I hate to be the bad guy (oh no! you’re not the bad guy.) but there’s a lot of people out there, could you keep it down? We go on in five. Yes yes, of course! Thank you five! I’m worried, oh I’m so worried. We are not ready. Did you see them trying to run through Bushel and a Peck on Saturday? Christ almighty, we’re screwed. Yeah, I know. Thank you five! Did you see them kissing? Did you see them kiss? Jaden said it was in the costume loft. The costume loft! Can you believe it? I mean she’s a whole head taller than him and way too pretty but (thank you five) I guess if it—no I don’t have hair gel—if it works for them then it works for them I guess. Did you see them kissing? Yeah we know, we know. They kissed in the—yeah we know, we know. Has anyone seen Sarah? We go on in five. Yes, thank you five! I don’t know man. Should we check on her? No it’s fine. I’m sure it’s fine. Thank you five. I don’t know man, I’m kind of worried (thank you five). I think she was crying. Yeah, Maddie’s with her right now. She’ll know what to do. Thank you five. Do you have a cigarette? Oh thank GOD. You know, I could really go for some chicken nuggets right about now. What’s that

smell? Does someone have food? Who has food? DOES ANYONE HAVE FOOD?

Oh shit, I’m so sorry. Thank you five! Has anyone seen the assistant director? Tell her her mother is here. Thank you five! Oh my gosh is that—shh!—oh my gosh you’re not actually going to—shut up!—that’s awful you’re awful what if someone sees you what if they find out—thank you five!—oh my gosh I can’t believe you’re doing this—honestly Amy shut UP—but—I said shut UP—places in five!--oh shit oh shit oh shit—what are you going to do?—pour it down the sink I guess—oh gosh—places in five!—yes we know we know. Thank you five! Oh God, I’m so worried. Have you seen Bushel and a Peck? Christ, it looks awful. And last I checked, Lucy was still smoking outside. Five minutes to curtain ladies! Thank you five! I think she’s still in the bathroom, crying. Has someone checked on her? Christ almighty. We go on in five! Thank you five. I mean, if I were her I’d be crying too. He’s a dick. A real, bona-fide dick. Like literally the worst person in the whole entire world. And like he’s not even that cute. I think Maddie’s in there talking to her right now; everything should be fine. Thank you five. Stupid stupid STUPID how could I be so STUPID??? (you’re not stupid.) And he’s not even that cute! (mmhmm, not even that cute.) And he TRICKED ME yes he TRICKED ME (mmhmm mmhmm) and now it’s opening night and the fucking MAYOR and his STUPID HUSBAND are in the audience and I DON’T EVEN KNOW MY LINES! (mmhmm mmhmm)(I’m sure it will all be fine)(hi ladies sorry to interrupt but I just wanted to let you all know that we’re on in five) (ok thank you five) AND I JUST WANT TO (also could you keep it down? Sorry sorry it’s just that we have a full house tonight--)(we have a full house tonight?)(holy shit)(yeah I know it’s crazy literally my mom is working the box office rn and she just texted me saying we sold out)(oh my gosh)(yeah it’s kinda crazy)(does anyone have hair gel)(no we don’t)(omg I didn’t know there was a whole thing happening here I’m so sorry)(no no you’re fine)(carry on) So like… I don’t know. I really don’t know. I just… unghhh… (oh my gosh oh my gosh)(hold her hair back)(holy shit) (oh my gosh)(Christ on a BIKE where is the assistant director)(should we tell Kayla? She’s the understudy.) No no I’m fine I just… unghhh… (forget Kayla, can someone call her mom?) Please don’t call my mom. (I’m calling your mom)(hi guys)(omg Henry what are you doing in here this is the GIRLS BATHROOM) (holy shit are you fucking dense)(sorry sorry but I just came in to say that we go on in five)(yeah we know Henry)(ok bye). How is everything in there? I don’t know, they kicked me out. Ok. Whatever. You did your part and that’s what matters. Yeah. So, the may or’s here tonight. That’s cool. Yeah. And he brought his boyfriend. Yeah, I heard.

That’s wild. Is he actually running for president? I don’t know man. Who would vote for him? Gay people I guess. Yo dude, don’t say that. That’s racist. Dude, are you stupid? That’s not racism. What? That’s homophobia. So what? What’s the difference? Christ almighty Stephen. Hey guys we go on in five, can you please take your places? Places, places! Everyone take your places! Places places! Five minutes to curtain people! Five minutes to curtain! Thank you five (thank you five) thank you five! Whatever, I don’t care anymore. I don’t care. He’s a dick (yep he’s a dick) and I don’t care. Awaiting the sensation/of a short sharp shock. 30 people in this cast and no one has hair gel. So what if he runs for president? I don’t care. I don’t like politics. Five minutes to curtain! Thank you five! You smell like cigarettes. So? And what about it? Christ almighty. Where is she? Where is he? Where are they? In the costume loft. Oh for chrissakes. Five minutes to curtain! And they what? Christ almighty. Where the fuck is the mic tape? Where is the banana? We’re scrapping the banana. What? Places, places. Where was the five minute warning? Did we ever get one? No, I don’t think we did. The incompetence of the people in this theatre department I swear to God. Shh! My mom just texted me and—oh! Places, places. Five minutes to curtain! Take your places! I love you/A bushel and a peck. OhGodI’mBleeding. Has anyone seen Sarah? Henry? Amy? Jaden? Lucy? Bill? Amir? Oh thank God you’re here. Chekhov’s banana? Oh it was a stupid idea anyway. Ok shut up shup the show’s starting. Places!

What I Know About Love

People have been falling in love for a very, very long time. It was not always so regulated, and in the very beginning, it wasn’t studied or even said out loud, only felt. Two (or three, or four!) hairy, smelly bodies rolling around on the cool floor of a cave, or necking in the orange light of Man’s very first campfire. It only grew from there. Ancient Greeks fed each other olives and danced under the moonlight. Bathsheba and David got it on. Men with vitamin C deficiencies aboard the HMS Endeavour fell in love on the high seas, and King Henry VIII of England fell in and out of love six whole times. Madame Bovary was bad at love and Eliza beth Bennet was good at it. Love was quantified in fat juicy emeralds and gaggles of geese and babies and fidelity. People fell in love and then got married. People got married and then fell in love. People fell in love and didn’t get married. People didn’t fall in love and got married anyway. People fell in love with the same person again and again and again. People loved one-sided and two-sided and many-sided. Lots of us pulled our hair out trying to sniff out the best ways to love or to figure out where it all went wrong. We stood on rocky outcroppings and gazed at the sea, or wrote sonnets by candlelight, or lay on sofas with our eyes closed and tried to explain it to strangers.

My grandmother could never love a man properly because she was really in love with her brother. Not pathological, incestuous love, but love all the same. Maybe the same could be said for him because he spent his life eating women like one eats pink frosted petit fours or finger sandwiches—he gobbled them up whole. He died in a head-on collision with a Ford GT. Five months later my grandmother married a man who tried to kill her with a can of whipped cream. My mother was in love with my father but he struggled to in-love her back. As much as I want to think there was a high-minded reason for this, I have the feeling he just woke up one day and found her repellent. He never did anything about it—the not in-loving— and I’m not sure my mother ever knew but I have to imagine she had a sneaking suspicion. I fell in love with a boy from school and we slept together in the back of his car with the seats folded down, parked in a lovers’ lane. He was very nervous but I wasn’t scared at all until afterward when I remembered the Zodiac Killer and the Texarkana Moonlight Murders and possible charges for public indecency and thought about how foolish we were. I think I fell in love with a girl-friend of mine in college but it could never be confirmed because I didn’t know what to measure it against and nobody offered me a ruler.

I met Harry in the summertime in Virginia. He was wearing a red bandana around his neck, no shirt, dirty jeans, and boots with the silver spurs that look like something from the inside of a watch face. I was taking my charge—an elderly woman with Down Syndrome—for a walk in the woods. Her name was Jane and she was always very irritable, wringing her hands and complaining, pinching and

pulling the soft skin on my upper arms. He was standing in the trail, the red triangle at his throat, lots of black hair on his chest, and going in a line down his belly. Jane was wagging her finger at him as if to say nonono or I don’t think so mister or don’t you dare. I waved and Harry nodded. I went for a walk every day (without Jane) until I met him again.

We got engaged. I told my parents over the telephone that he lived on a farm and I would be living there, too. We were married by a large animal vet erinarian who moonlighted as a minister. Harry ran a stable and I worked with Jane and the other people at the community across the big green field. I loved that he rode horses and could corral a stampede of huffing puffing cows with a yeeeeeeeeeaw sound. I loved that he loved his dogs and smelled like yellow hay and slept butt naked and did not cry and moved deliberately and spoke the same way. I’m not sure what he loved about me because he was never one to say things outright and maybe not even to think them outright. I do know the parts of my body that he loved because he paid them special attention. The obvious parts but others, too. The arch of my foot and the hard bottom of my heel. The knobby bone be tween my breasts where the rib cage joins. The inside of my wrists.

Harry was as silent as a stone and he would not budge. I spent my days alone or with Jane, spoon-feeding her yogurt. Harry was with the horses, with the cows, with a beer, with Joe at the fence, operating loud machinery, squatting by creeks, yanking out ticks, listening to owls hoot-hoot and hawks whistle and not listening to me. I talked myself in circles. We ate without speaking or I spoke by myself. I read books that I asked Harry to read but he didn’t. His father died and then my mother died. He got quieter and I got louder to make up for it. We made a latein-life baby so I would have someone to talk to and play with because Jane died. I didn’t have anything to do with myself but talk in circles or yell at his quiet face that made me so angry because it was so smooth, unhurried, not busy, not longing. The baby was a little girl we both loved. Harry actually talked to her and it made me so angry I could scream. So, I was jealous of my own baby girl because she got what I wanted and she couldn’t even speak English yet.

Then, Lucy was in school and things were as usual, only we were even older. I longed for less because I was tired even of longing. Harry was as usual only he was leaving the gate open and the cows were tramping into the road. He was opening beers, having two sips and leaving them on the armrest of the deck chair and going to the fridge and getting himself another. He would sit down only to find the one he’d already opened sweating in the sun, leaving ring marks. I knew some thing was not right when I found him asleep on the toilet even though he said oh well, it happens to the best of us.

Harry and I were sitting on the deck chairs and I had my feet in his lap. At this point, we already knew what was happening, although he remembered what

it was that was happening less and less. He was holding the hard bottom of my foot in his hand. The dog was panting and taking big sighs that wobbled his jowls, snapping at fat carpenter bees. The air was thick with bees and leftover heat from the sun that was now behind the blue hills. Even I couldn’t remember the last time Harry held my feet like this, with the heel fitted into the palm and the flat of his thumb pressed up against my ankle. A big black fly was crawling up my leg, stop ping here and there to rub its hands like some kind of sneak up to no good. I want ed to shoo it away but I didn’t because I had a feeling about the moment we were in. Something was going to happen and I didn’t want to scare away whatever shy thing was making its way towards us in the evening air. Harry started squeezing the heel of my foot very hard. He opened his mouth, closed it, and then opened it again. I looked in his eyes and they were working and reaching. He was squeezing my heel so hard it was turning white where he wasn’t pressing with his fingers. He was making noises with his mouth and throat like he wanted to speak but he couldn’t make the words come out, only a lolling sound like his tongue was swelled up, and he looked so angry.

This is what I know about love: There is that honeyed time when nothing is real and you are in love—this passes. Then, there is the time when you realize this is “real,” which is a new, different, and dignified delight. And then comes the time for expectations of how you should each behave and what you each need and what is not given and what is given too much. And this is a long, long time with lots of feelings of betrayal and anger and running up against each other’s walls. And then there comes the time, a long time later, when you stop expecting anything from them at all and find that’s what you’ve been working towards all along.

Here

The bark of the tree I’m leaning against bites into my back as I stand on the outskirts of what was once the Eloines’ family land. The fifty acres are now county property. I take a puff of the cigarette and observe the festivities of the thirtieth annual Duck Tape Festival. This place is, after all, where the headquarters once resided. The carnival trucks still pull up here, funded by the supercorp Duck Tape in dustry, even though its headquarters is probably now in some thriving urban center. There’s a burn that hits the back of my throat as I take another drag from the cigarette. I blow out the smoke and tilt my head to watch it dissipate into the clouds. I want to follow it.

Closing my eyes, I feel this heaviness deep in my chest. Then it’s rising, past my shoulders, above my head, and I find myself going all numb and light, until I’m not really me anymore. I’m floating up, up, out of myself, watching the bodies below. I keep climbing towards the sky until I can look down and see blobs instead of the people. The blobs are probably weaving their way through thin tents now, showing off elaborate Duck Tape outfits and crafts, holding outstretched arms to partners to dance to the live band, and chattering in lines for sketchy food trucks. It’s their obliviousness—their contentment, their settlement—that should anger me, but I’m Above and can’t feel a thing.

The first time I went Above was when everything turned to shit in Iraq. I was there, and then suddenly I was flying up, so far up until I found myself drifting in the quietness of blue sky. Above.

There wasn’t any pain there. There wasn’t anything. I come back down.

Shifting my weight onto the hip without scar tissue, I take in another long draw and hold the cigarette out to my youngest brother Sammy. I let the smoke es cape my lips and float up to the graying sky. He shakes his head and kicks a stray chunk of gravel from who-knows-which carnival station set up. He’s always twitch ing, and he does it now, his shoulder jerking up and down.

“This shit’ll help you relax,” I say as I bring it back to my lips.

“Nah, Marisol will kill me,” he says, and I nod, knowing she would flip out if he started out on Camels at fifteen. Even though Bibi used to go through a pack a day.

I watch the Witch’s Wheel ride start up again, its lights blinking and turning into one circular blur as it picks up its pace. I take another drag. It’s all the same, as if I never left. Sammy eyes me, his shaggy hair falling down past his forehead. “You good?” he asks, one of his eyebrows raised in concern, and I see the kid like he was at three, running around in diapers making that same face when Bibi was having one of her episodes.