xcity.

For journalists. By journalists

xcity.

For journalists. By journalists

White lines and bylines: life at Loaded

Reporting on the run: stories from exile

Journalism isn’t as simple as it used to be. Supposedly, it is about truth telling: reporting the facts, holding institutions to account, giving people a voice. And yet, in 2023, it remains one of the country’s least-trusted professions. Some of that is understandable, some of it isn’t. Statistically speaking, it’s a fact.

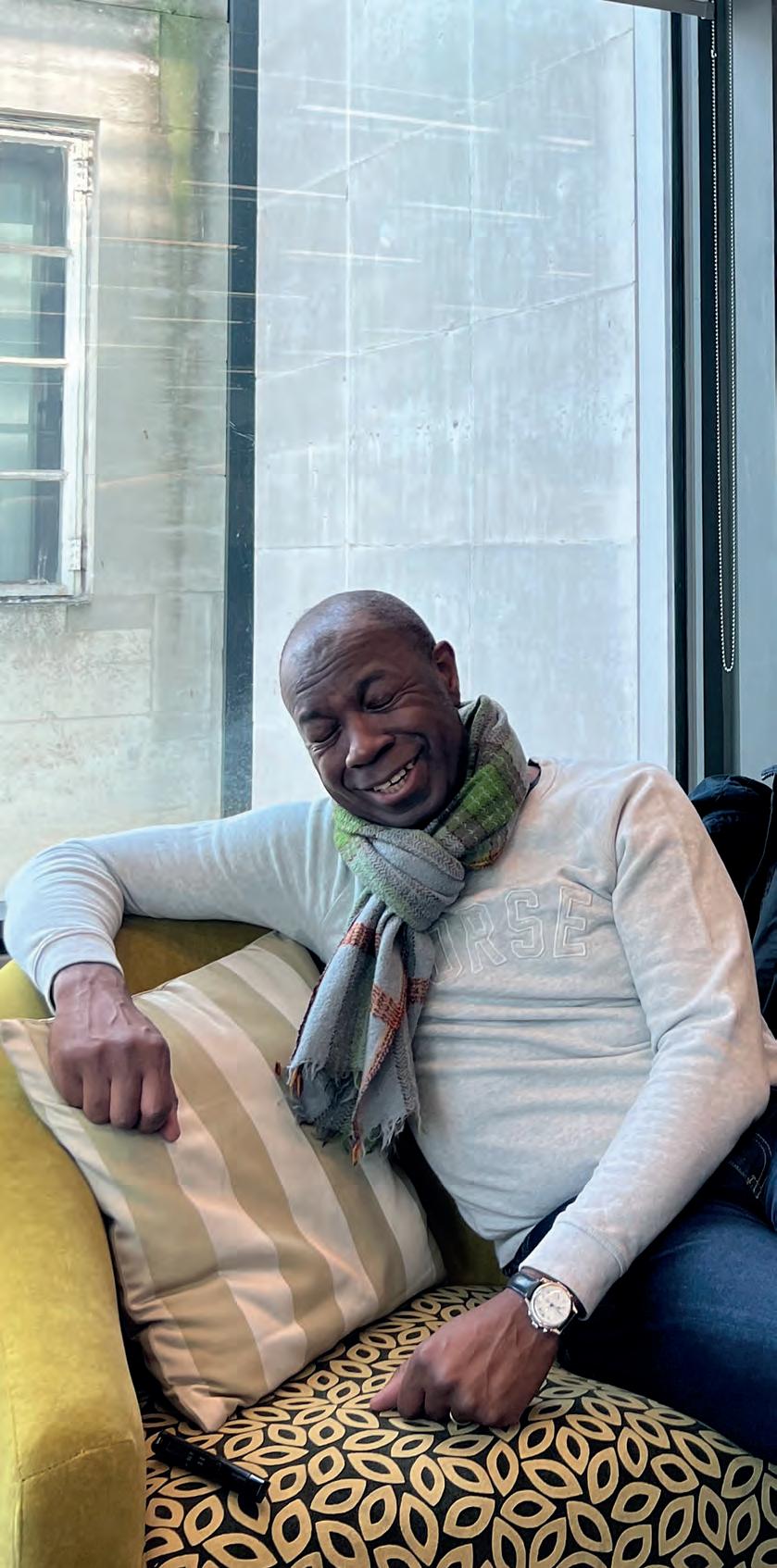

So what can we do about it? Well, in that greatest of writing traditions – endure. And by endure, that is to say, keep writing (or broadcasting). Our cover star Clive Myrie told us as much when he described journalism as a noble profession, which, when it delivers on its promise, is true. He is a prime example: a Black reporter who has risen to become one of the BBC’s most renowned correspondents before segueing into a role as a primetime TV host (p. 64). There are plenty more examples to admire: Ellie Flynn’s investigative talents (p. 93), Andrey Zakharov’s relentless reporting in exile (p. 83), and Victoria Derbyshire’s unwavering pursuit of the truth – now on TikTok (p. 46) – are snapshots of journalism not just done well, but right.

City, of course, believes in what journalism can be, too. Its investment in the UK’s frst podcasting MA (p. 4), frst archive dedicated to investigative journalism (p. 21), and AI technology in university (p. 5) are all examples of City’s faith in the power of reporting.

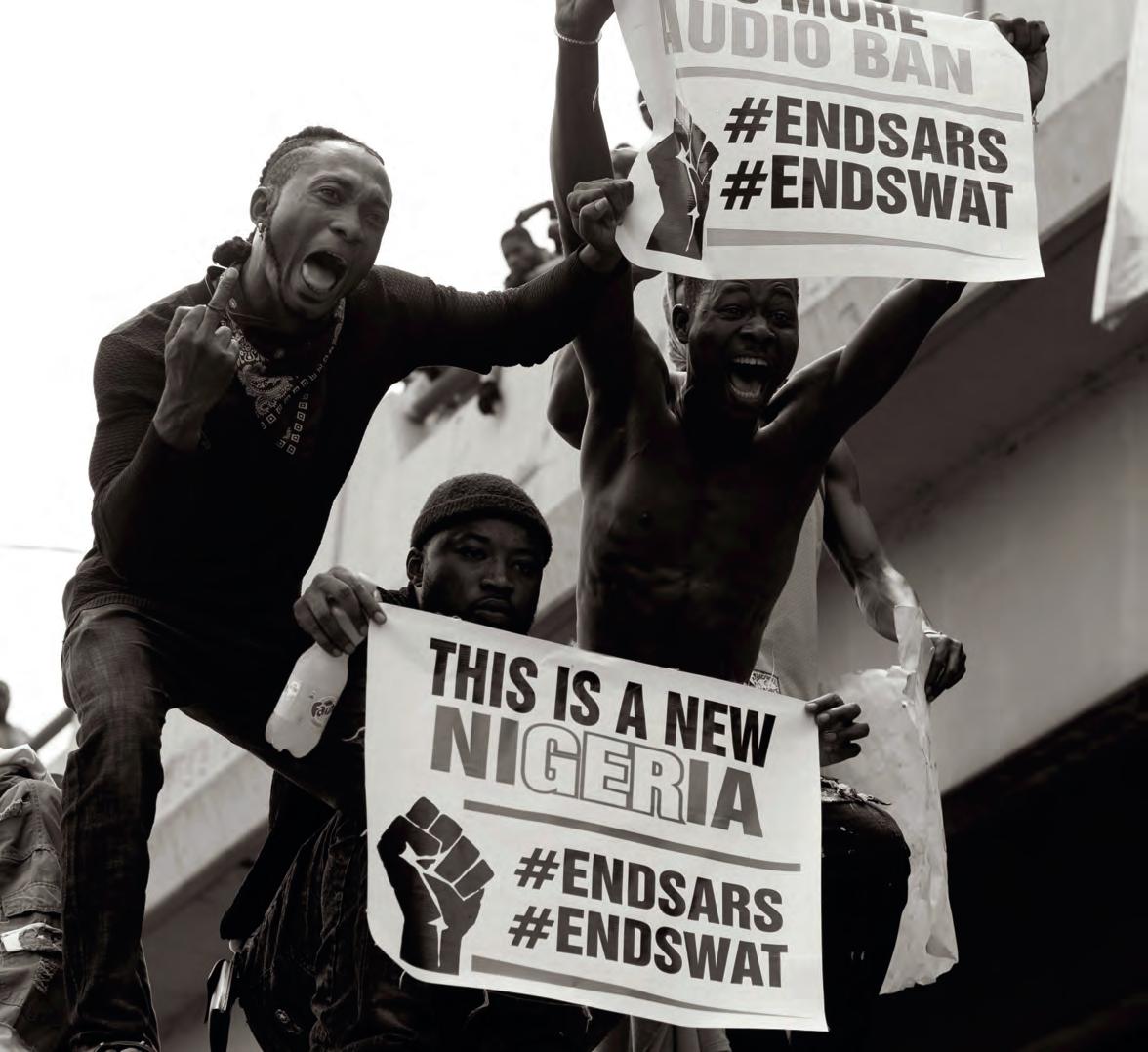

But to endure, journalism must also change. Why, in 2023, is it a profession that remains so inaccessible to those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds (p. 77) and less welcoming to those with learning differences (p. 110 )? Why are journalists from diverse backgrounds either targeted for their identities (p. 116) or pigeonholed into writing about them (p. 90)? These are just some of the obstacles journalism must tackle to regain the public’s trust.

And yet, journalism is always happening. There are always people with stories, even when the cameras aren’t on them. It exists where people endure – from

EDITOR

Tom Flanagan

DEPUTY EDITOR

Kiran Duggal

ART DIRECTOR

Shauna Brown

DEPUTY ART DIRECTOR

writing in rural India (p. 70) to the extremes of reporting in the Arctic (p. 50) – and even in places where people have otherwise been silenced, such as photojournalists in Ukraine (p. 56) and the reporters banned by Modi (p. 100).

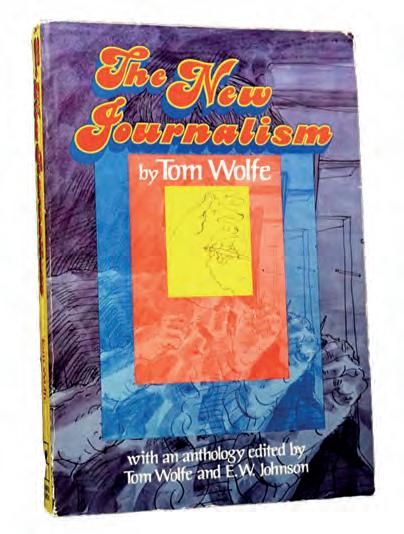

So where do we go from here? This issue of XCity touches on the future of the profession: Chat GPT (p. 33), journalism infuencers (p. 102), New Journalism (p. 73), and writing that doesn’t always ft the mould.

As the next generation of journalists, we’ve spent the year learning about what makes a good journalist: writers as sensitive to the law as they are to their sources, creative as they are comprehensive. And looking through this year’s XCity issue, that’s all there. But beyond simply good journalism, what do we want a journalist to bring to every story?

There’s no one answer, but if this issue is anything to go by, I’d say it would be a little fearlessness. We want the truth, but we want humanity, too. It takes a lot to be vulnerable when you write. You’re leaving behind a piece of yourself. Forever. And yet these stories do just that.

Poet Nayyirah Waheed once wrote, “The thing you are most afraid to write, write that.” Flicking through these pages, I’m glad we did.

Sharnya Rajesh

FEATURES EDITOR

Killian Faith-Kelly

DEPUTY FEATURES EDITORS

Poppy Burton

Alex Berry

NEWS EDITOR

Ella Kipling

DEPUTY NEWS EDITOR

Eoghan O’Donnell

LISTINGS EDITOR

Maira Butt

DEPUTY LISTINGS EDITOR

Megan Geall

PRODUCTION EDITOR

Lucy Sarret

DEPUTY PRODUCTION EDITOR

Ciéra Cree

PICTURES EDITOR

Gaelle Biguenet

DEPUTY PICTURES EDITOR

Amy McArdle

CHIEF SUB-EDITOR

Samantha Fink

DEPUTY SUB-EDITORS

Megan Warren-Lister

Caroline Whiteley

XCity magazine writers: Amiya Baratan, Ruby Borg, Dani Clarke, Gabby Colvin, Ella Gauci, Seraphina Kyprios, Tiffany Lai, Nicole Panteloucos, Alex Rigotti, Katie Ross, Nandni Sharma, Dimple Shiv, Caroline Tonks, Daniela Toporek, Alice Wade, Honey Jane Wyatt

Illustrators: Rachel Berman www.rachel-b-art.com, Chloe Dootson-Graube www.chloedootsongraube.com, Maddy Thorp @mads_artsngraphics, Poppy Burton, Gabby Colvin

With special thanks to Malvin Van Gelderen www.idesigntraining.co.uk

If you have any concerns about XCity, please email the Course Leader Ben Falk at: ben.falk@city.ac.uk or write to Ben Falk, Journalism Department, City University, Northampton Square, London EC1V 0HB

MANAGING EDITOR AND ADVERTISING MANAGER

Katie Daly

SOCIAL MEDIA EDITOR

Chloé Williamson

DEPUTY SOCIAL MEDIA EDITORS

Henrietta Taylor

Emily Smith

PUBLISHERS

Jason Bennetto

Ben Falk

The UK’s frst MA in Podcasting is to launch at City in September along with a Centre of Podcasting Excellence.

Pioneered by Sandy Warr, a multi award-winning broadcaster and fellow of the Radio Academy, the MA will train a new generation of podcasters. Ms Warr is currently in active discussions with a variety of podcast frms about the creation of bursaries and sponsorships that will run parallel to the course.

The MA will also be taught by Emmy awardwinning journalist and City lecturer Fernando Pizarro and podcast producer Mark Sandell from 6Foot6

Productions. Taking on the role of Director of the Centre of Podcasting Excellence will be former BBC and Bauer Media executive, Brett Spencer. The programme aims to tap into a market which lacks trained podcasters.

Ms Warr said: “As much as City Journalism School has this brand-leading reputation, one reason for that is because we keep reinventing ourselves. We keep going: ‘What’s happening in the world?’. We need to be ahead of it as much as possible”

The LBC News presenter recognised the demand for podcasting education within the university three years ago when 140 students signed up for the podcasting elective

the department offered. It became apparent that there was a real desire from students to learn beyond what the elective could teach them.

While this new MA will contain traditional City journalistic skills such as media law and ethics, Ms Warr is committed to changing the standard mould. “What will be unique about it is that it won’t just be journalism. We want to create a much more creative space for people to be more imaginative.”

The programme will include topics ranging from the history of storytelling to media management and even guided meditation to learn about immersive audio experiences. There will be

a heavy focus on branding and audience engagement, something Ms Warr believes is vital in the podcasting industry.

With a predicted 28 million podcast listeners in the UK alone by 2026, the new MA refect’s City’s adaptation to the changing face of journalism more broadly.

The Centre for Podcasting Excellence will run alongside the programme, hosting monthly events, speakers, and short courses about podcasting.

City already has a vast alumni network of podcasters from Dino Sofos to the Atlantic’s Ben Green, but this specialised course hopes to train the next wave of industry experts.

Unlike other MA courses, the Podcasting programme will also be available for students to take part-time. Ms Warr said this will help bring in a more diverse cohort of students.

She said: “It’s partly a refection of the fact that the podcast industry tends to be demographically a bit different from linear broadcasting, newspapers, and magazines. It’s more entrepreneurial, and we’re seeing voices that are not being heard anywhere else fnding a platform because of the very nature of the medium.”

The frst cohort of Podcasting MA students will start in September 2023.

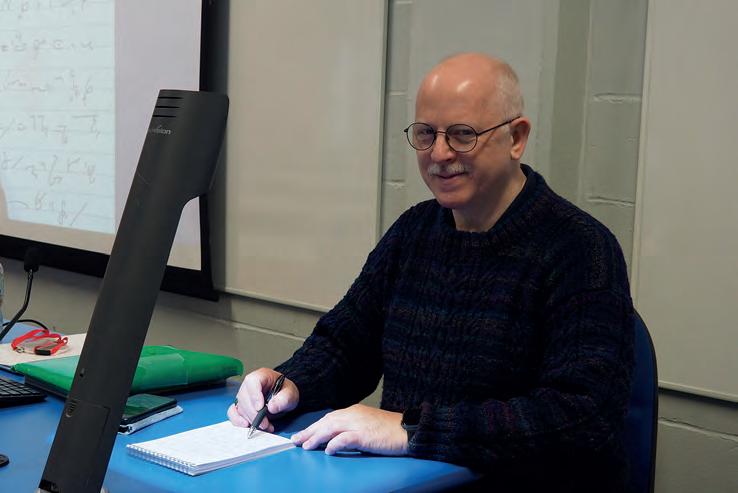

Ella Gauci Sandy Warr in one of the department’s new podcasting boothsEssays written by ChatGPT have produced some “terrifying” results that could lead to changes to City’s assessments, the head of the journalism department said.

Professor Mel Bunce called AI a “huge game changer”. After becoming aware

of the new technology, she ran some of City’s frst year essay prompts through ChatGPT and got some “very, very good responses”.

Professor Bunce explained that the department has been having “urgent conversations about whether we should change frst-year assessments”.

While AI can be helpful for trawling through large datasets in hospitals, there are “immediate implications” for universities, Professor Bunce said. Lecturers have begun to worry that ChatGPT could be used to write assignments.

“I see it as a tool that massively changes your ability to gather information and present it in an accessible form instantaneously,” she said.

ChatGPT has over one million users and was even put to use in Westminster when Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt used it to write about the economy in January.

For journalists, Professor

Bunce can see AI being helpful for doing “quick background research and getting it into a palatable shape”.

Its ability to pull information together could also be an advantage, as much of a journalist’s work cannot be done by AI.

“So much of what we teach and what’s important to us about adding value to public discourse is about going beyond anything that this could do,” she said.

Discovering new information and insight is at the core of journalism, which is why Professor Bunce feels the department is more prepared for the rise of ChatGPT than other departments..

The debate around the use of the technology in journalism has been ongoing. Sky News put ChatGPT to the test in December when it assisted a reporter in writing an article on itself. Meanwhile, BuzzFeed announced that it would be using AI for quizzes to “enhance” and “personalise” its content.

With Microsoft’s ten billion dollar investment into OpenAI, AI is set to be at the heart of journalism in the future.

Professor Mel Bunce, head of the journalism department, wants to introduce more entrepreneurial modules to prepare students for careers as freelancers, entrepreneurs and business owners.

The journalism department hopes to partner with Bayes Business School to launch a new “freelance” module.

Professor Bunce said: “The big picture is that we want to teach multimedia modules across pathways, so if a student is interested in something that Financial Journalism or Broadcast does, then they can do that.”

Students will be able to develop their business skills with this new approach, according to Professor Bunce, who wants to introduce innovative concepts like developing news and media products.

Professor Bunce said: “Having the business skills and knowledge to set up as entrepreneurs is crucial in journalism.”

She added: “Alongside traditional skills, we have trained our students for big organisations. Now, many of them are self-employed. They’re becoming transformative thinkers and we want to encourage that.”

Visiting lecturer, Julian Linley, also believes that modules such as the Business of Media, (taught on the Magazine MA), are what gives students the chance to develop their entrepreneurial skills.

Mr Linley works with students while they research, create and develop business ideas for the modern media.

Examples this year include Spark, a dating magazine, and The Changing Room, a platform covering women’s sports. Both were presented to industry experts, allowing students to network while developing their presenting skills.

Mr Linley also encourages students to develop their knowledge of social media such as TikTok and Instagram.”

He said: “Modern media is more of a democracy nowadays. It gives journalists the tools they need to build their brands, outside of traditional publishing.

“It’s important to teach the fundamentals of building a media business to anyone interested in becoming a journalist or creator.”

Chloé Williamson Ella KiplingIt used to be the home of toned swimmers thrashing up and down a 30 metre pool, training for the 1908 Olympics. Fast forward 115 years and room AG19 in the College building has become a new social space for journalism students.

Cutting the ribbon at the pool’s opening event on 9 February was City journalism alumna and founding editor of gal-dem Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff, who

was “happy to be back at City”.

“When I was here in 2015, we used to congregate in the corridor because there was no common room,” Brinkhurst-Cuff said. “You didn’t really meet other people from different parts of the building.”

The original pool was the only local public swimming pool between WW1 and WW2. In the 1920s, the roof began to slowly collapse above the swimmers, due to high condensation and rising

chlorine gases.

Once an open air swimming pool, it was subsequently used as an ammunition storage facility - surviving a German bomb in the second world war..

It was eventually forced to close in 1998, when fallen roof glazing led to its demise. Though the university considered investing £500,000 into remedial works, a fre in the building in 2001 dissuaded them.

A swimmer preparing to dive into the Olympic pool in 1898.By the early 2000s, the pool had become a study area for arts students and temporary home to an overfowing law library.

“We had to be very careful about where we put the bookshelves since there was still a massive hole in the ground,” said Emily Allbon, Associate Professor and former librarian at City.

Most recently, with the “massive hole” buried under the foorboards, the area has been used as a research space for PhD students. And now, rows of compartmentalised desks, booths, and couches offer a quiet working and conferencing space for journalism

students. The old changing rooms for swimmers, however, have been retained and now function as small study spaces.

Like City faculty, Ms Brinkhurst-Cuff sees immense value in a common space for journalism students spending any time in the College Building.

“The people I met on my course have been amazing people to know throughout my time in the industry and extending that to a wider pool of people is really important,” she said.

“The thing about journalism is that you have to learn to pull yourself out of your comfort zone and have uncomfortable conversations with people you don’t

know and starting at university is really good.”

According to City’s Executive Dean, Professor Anna Whitelock, the space will allow students and visiting creatives to “meet, think, and create”.

“We are a community and an inclusive and supportive place for ideas to spark, and connections to be made,” said Professor Whitelock. “We look forward to spoken-word performances, comedy, music as well as even more opportunities to stretch and relax with movement activities such as yoga.”

Samantha FinkSlicked-back buns, stage makeup, and glittery costumes have become commonplace among City students after a prestigious performing arts school joined the university this academic year.

The Urdang Academy specialises in musical theatre and is recognised as one of the UK’s best performing arts colleges. It has a strong international reputation thanks to the impressive number of alumni landing roles in leading West End shows like Hamilton, The Lion King, and Wicked

The acquisition is part of an ambitious new strategy to enhance and develop City’s reputation for music and its engagement with the creative industries. As part of the

department of performing arts, Urdang has joined the newly established umbrella school of communication and creativity.

Commenting on the development, City’s President, Professor Sir Anthony Finkelstein, said: “This is an exciting development for City, and we are delighted to welcome Urdang staff and degree students to our family. Our shared ethos and ambition make City and Urdang a powerful combination and provide a strong foundation for the development of the academy.”

Following the initial announcement in Spring 2022, the CEO of Urdang, Solange Urdang said: “The time is right for the Urdang Academy to take the next step

to blossom and grow.”

Students attending Urdang will continue to study from its current base at the Grade II listed building, the Old Finsbury Town Hall, which is home to six spacious dance studios, whilst also benefting from support and facilities in City’s department of music.

Speaking about the transition, student Robynne Evans said that using City’s facilities was “overwhelming” to begin with as a result of having access to so many more practice rooms and additional study space.

“The frst term was a bit chaotic,” said Ms Evans. “[City] was so big and we were all getting lost. Now we’ve settled in, it’s much smoother sailing. Using the practice studios has been very useful.”

As well as the additional facilities, Ms Evans said that joining the University has increased her social circle, and created new opportunities to join other societies and activities.

Merging with the music department will allow Urdang to maintain its founding ethos, whilst beneftting from City’s focus on practice and professionalism.

“I am delighted that City will take on this challenge, especially given the close alignment of our beliefs and values, and the support and development opportunities that City can offer,” said Ms Urdang. “I look forward to seeing Urdang fourish under the City umbrella.”

Megan Geall Image credit: Seamus Ryan Directed by Rob Archibald. Choreographed by Christopher Tendai, Musical Direction from Ian Brandon, Set Design by Emily Bestow, Costume Design by Rebuen Speed, Lighting by Devante Benjamin.Professor Jane Singer, who has taught in City’s journalism department since 2013 and served as director of research, has retired.

Before joining City as Professor of Entrepreneurial Journalism, later changed to Professor of Journalism Innovation, she held teaching positions at the University of Central Lancashire, the University of Iowa, and Colorado State University.

Her impressive career is being recognised this year with the Paul J. Deutschmann Award for Excellence in Research, which honours a body of signifcant research over the course of an individual’s career. The award is given by the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication.

Professor Singer has written and co-written 57 journal articles and two books.

“I am honoured and happy that my explorations of journalistic adaptation to change have proved useful to

other researchers,” she said.

Professor Singer began her career as a print journalist on the East Coast of the US in the 1970s. She then went to work for CBS, which was exploring “this wild, crazy idea of delivering information electronically”.

“When I was in graduate school in the mid-90s, no one else was paying any attention to digital at all,” she said.

This meant that she was in demand as a teacher and researcher when publications such as the BBC and The New York Times were going online.

Professor Singer was the founding news manager of Prodigy, one of the frst national online news services in America. Her friends who worked at newspapers continued to ask her why she left journalism.

“I would say ‘I haven’t left journalism. I’m still in journalism, it’s just a different format,” Professor Singer said. “There would be a pause, and then they would say, ‘But do you miss journalism?’”

This reaction to digital journalism ultimately led to her decision to pursue teaching. She explained: “I thought it might be good to try and get into a university and teach people because younger people would get it.”

After teaching for 17 years in small towns in the US and the UK, it didn’t take “too much convincing” for her to move to City, a university “in the middle of a media capital in a wonderful cosmopolitan city”.

Journalism is one of the best things at City, Professor Singer said, and “it has been for a long time”.

Throughout her tenure, the department has continued to evolve.

“We’re continually innovating in the way that we teach and fnding better ways to connect to students,” she said.

Research also plays a part in the evolution, she added.

The expert in journalism innovation is always thinking about what is coming next in the feld and said that virtual reality is something she is keen to keep an eye on. While museums are using the technology, it’s yet to get a lot

of pickup in news.

“It would be interesting, not necessarily positive. There is potential for an immersive experience to be an unpleasant experience. There are opportunities for journalism to engage people’s senses in different ways, which has led to ethical issues.”

What comes next, Professor Singer explained, could be something “completely different that we haven’t envisioned yet”.

Ella KiplingThe head of fnancial journalism at City has expressed her concern for how the worsening economic climate will impact female reporters.

Jane Martinson, the Marjorie Deane Professor of Financial Journalism, a columnist for The Guardian, and an honorary committee member of the Women in Journalism network, fears that the cost-of-living crisis will force female journalists

to turn to extra freelance work or leave the profession altogether.

“It’s always worrying when there is an economic downturn as it’s often women who leave the workforce frst, something we’re conscious of,” she said, speaking about the WiJ network.

“More women leave fulltime employment, not just due to caring responsibilities. It is a lack of confdence, feeling like they need the fexibility or

freedom to be freelance. But then are more likely to be in vulnerable jobs,” Professor Martinson added.

Professor Martinson has stressed that more needs to be done to protect the livelihoods of women in media. According to research by the World Economic Forum, women are more likely to have insecure jobs. Refecting on the success of editors in the past year, she said: “The editors of the Financial Times,

The Wall Street Journal and The Guardian are women, which is great. It’s not been a bad year but we have to be careful that women don’t suffer disproportionately from the economic downturn.”

Professor Martinson has been working on her upcoming book, How to Buy an Island, on the power and fortune of the Barclay brothers.

Katie DalyThe media has a responsibility to be more critical of the monarchy, a royal expert at City has claimed.

Anna Whitelock, Professor of the History of Monarchy at City, and the Executive Dean of the School of Communication and Creativity, highlighted the difference between reporting on the monarchy, and on politicians and political parties.

Professor Whitelock said this reporting needs to be more impartial. “So much of the reporting of the monarchy is partial, uncritical and not very well informed.”

The author and broadcaster continued: “This isn’t just about a family. It’s a monarchy that has power and infuence.”

Given the control that the monarchy has, including sovereign power which places the monarch above the law, Professor Whitelock explained that critical reporting “does matter”.

The royals have been the centre of attention this past year, with the death of Queen Elizabeth II, the ascension of King Charles to the throne., the release of Prince Harry’s memoir, Spare, and his Netfix show: Harry & Meghan.

Professor Whitelock said the media’s relationship with the family can be traced to the 1950s when the BBC broadcasted the Coronation of the Queen.

“There was this sense of that relationship with the television companies and, in the sense the BBC, to be one of respect and reverence.”

Speaking about media outlets today, she added: “They want access to the monarchy. They want do the royal broadcast, so they accept the royals’ terms.”

However, Professor Whitelock said that it is vital for journalists to be “informative, questioning, and critical” in their reporting of the royal family in the same way they are with politics.

Professor Whitelock added that events such as royal weddings, appearances, and births are “in a sense, a distraction”.

The general perception of being a royal reporter is that you go on royal tours and attend events, Professor Whitelock explained. But you can also be a “real investigative journalist”.

“I would like to think future journalists see this as an institution that plays a role in our national life, in terms of diplomacy, politics and society,” she said.

Ella KiplingThe journalist and former City lecturer Melanie McFadyean has died of cancer aged 72. A campaigner who wrote for a range of magazines and newspapers, she was known for her fearlessness and sense of humour.

She taught at City from 2001 to 2015, running the Investigative MA and later taught on the Magazine MA.

Sebastian Payne, a columnist at The Times, tweeted: “I was fortunate enough to be taught by Melanie at City University. She was the most wonderful teacher and inspiration a budding journalist could ask for – I’ll never forget her withering look at my

silly errors and inability to know what a story is.”

Adrian Monck, former head of the journalism department, described Melanie as “a devoted and much-loved teacher”.

Matters of social justice, and the plight of refugees and asylum seekers, were burning issues for her. The publications she wrote for included the Sunday Times, the Daily Telegraph, the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, Cosmopolitan, and Marie Claire. She was an agony aunt, with a column ‘Dear Melanie’ in Just Seventeen magazine from its launch in 1983 until 1986.

Strikes by lecturers and staff at City and 149 other universities are set to run into the summer after a stalemate over negotiations. The long-running dispute continues for multiple reasons including pensions, pay, and workload.

Members of the University And College Union (UCU) are being reballoted, which could lead to more disruption in the coming months, unless a deal can be reached.

The Universities & Colleges Employers Association (UCEA) is offering a pay rise of at least fve per cent and a review of the pension scheme. The UCU’s decisionmaking committee, however, voted not to put the offer to members and continue the industrial action.

An evaluation in March 2020 of the Universities Superannuation Scheme Limited (USS) resulted in a series of pension cuts for academics, due to market crash during the Covid-19 pandemic. These cuts meant that the average member would lose 35 per cent from their guaranteed future retirement income. However, it was reported in November 2022 that USS had a surplus of £5.6bn, sparking further outrage.

Staff pay has fallen by over 25 per cent over the last 10 years, with many academics on short-term or zero-hours contracts. Additionally, University employees have not had a pay increase that matches infation for 13 years.

Another complaint from strikers is over pay inequality. Women, people of colour, and those with disabilities are being paid signifcantly less than their white, male counterparts.

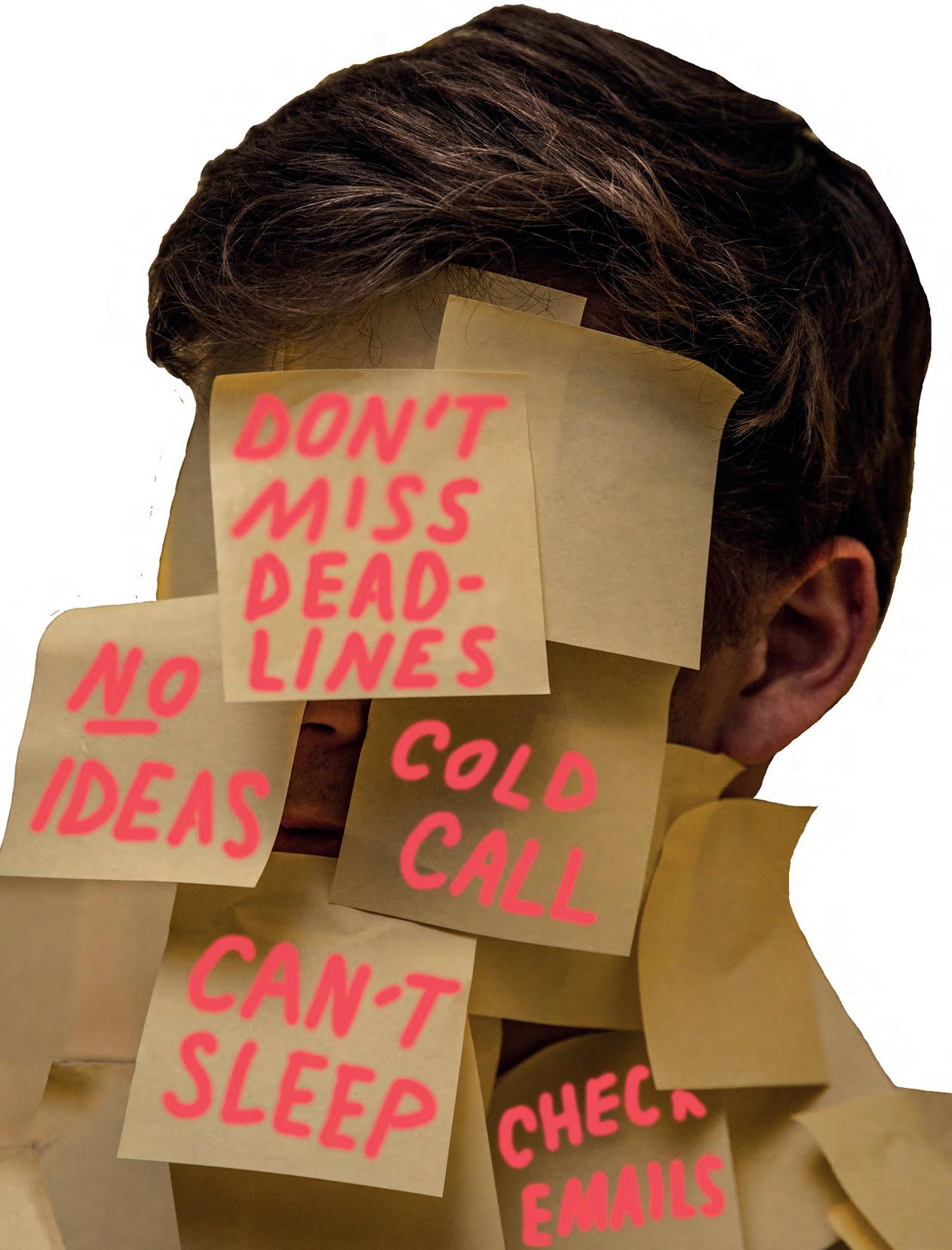

They also claim that the staff workload has been overwhelming due to increased student enrolment. Keith Simpson, president of City’s UCU, said: “I have seen our workload increase year after year after year.”

Mr Simpson said due to this increasing pressure, many have taken leave for stress-related illnesses or have been forced to go part-time to cope with mounting workloads.

Dr Lauren McCarthy, Bayes Business School lecturer, added: “I’m striking because I believe we have a fantastic university system in the UK and I’m worried if it continues this way, it’ll become a privatised and privileged industry. Higher education should be accessible for as many people as possible.”

MA Journalism student Katie Ross said: “I support the strikes as it is important that lecturers have pension security and a wage that refects their work. However,

it is frustrating when students are missing the education they’ve paid so much for.”

Mr Simpson urged students who want to show their support to complain to the university over their loss of education. He claimed that staff conditions have worsened since he joined the university in 1997, impacting staff ability to offer pastoral support to students.

Anthony Finkelstein, the president of City, said: “Staff investment is by far the largest area of our spending. On top of pay, City contributes the equivalent of 21.6 per cent of each employee’s salary to their pension pot each month.

“It is reasonable to ask why we are unable to meet the demands of the unions,” he added. “Put simply, we do not have the ability to do so because tuition fees set by the Government have been frozen for several years. Meanwhile, our costs are rapidly increasing.”

Alice Wade and Lucy Sarret

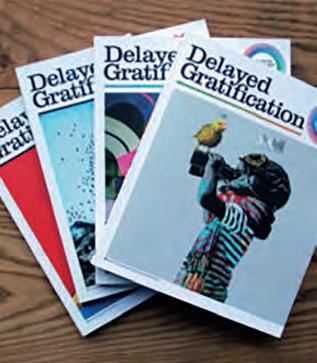

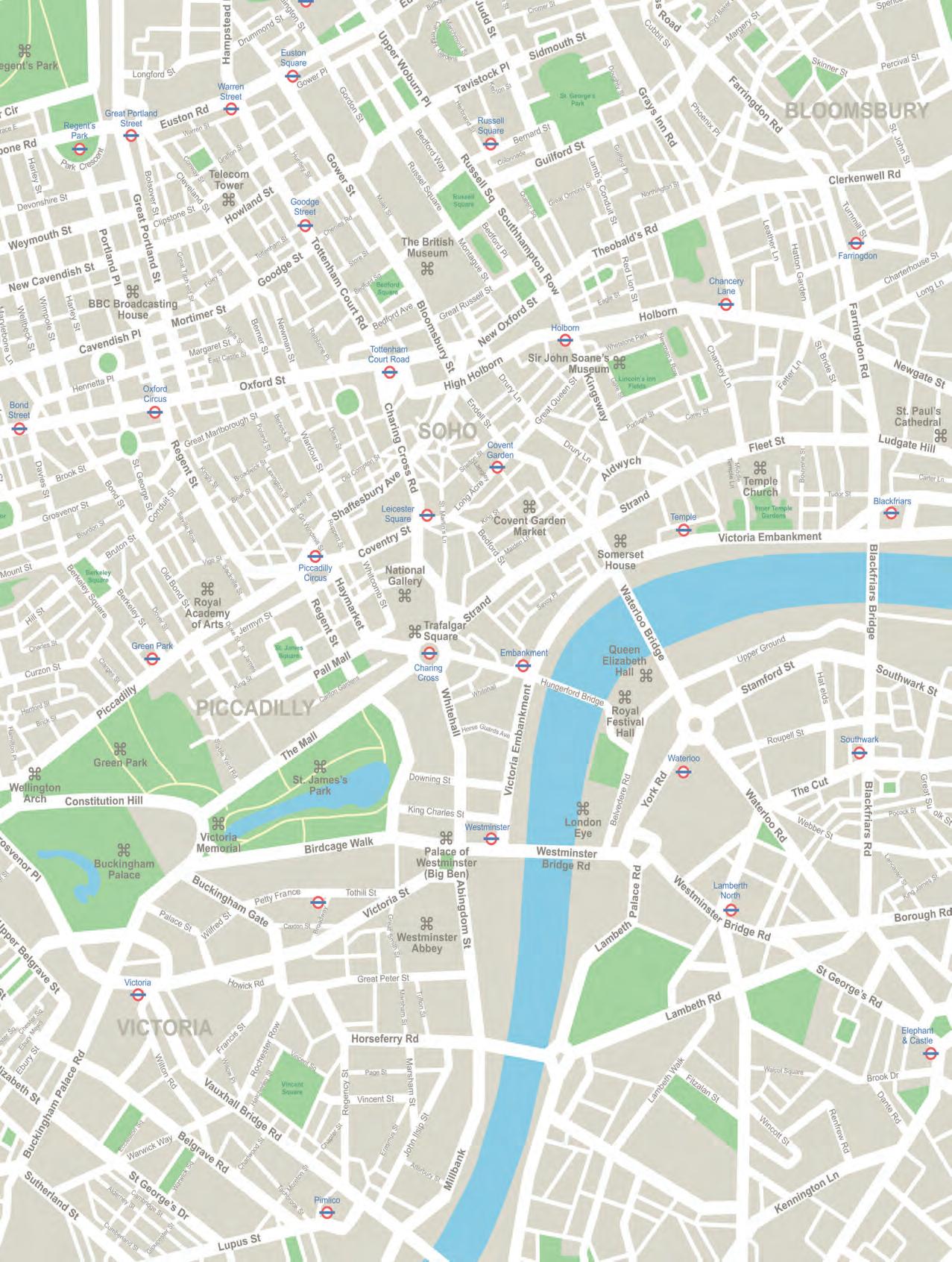

Kate Samuelson (MA Magazine, 2015), won the Georgina Henry Award that rewards storytelling and innovation for her company Cheapskate, a free newsletter informing subscribers of the free London-based events each week.

The award by the Women in Journalism organisation highlights the achievements of women in a male-centric industry. With a cash prize of £4,000, Cheapskate plans on expanding its subscriber base through

Ms Samuelson, who has recently been made Editor in Chief at slow journalism newsletter The Know, said: “It was amazing to win. We’ve been doing this for three years with full-time jobs, and it’s incredibly rewarding. There are thousands more Londoners who would beneft from us, we just want to put the word out there.”

Lucy Sarret

Lauren McCarthyACity visiting lecturer was part of the reception at Buckingham Palace to celebrate and recognise British East and Southeast Asian (ESEA) communities.

Helena Lee (MA Magazine, 2011), Features Director at Harper’s Bazaar and editor of East Side Voices, met King Charles and Queen Consort Camilla, and later commented that media representation of ESEA communities is “massively important” .

The inaugural reception, which fell during the Lunar New Year in February, welcomed guests in the community from all industries including healthcare, business, government, and fashion. Other attendees included Chinese-Irish designers John and Simone Rocha, Chinese-English model Alexa Chung, and Japanese-British actor Will Sharpe (The White Lotus). May Parsons, the Filipino nurse who helped administer the frst Pfzer coronavirus vaccine in the UK, was also present.

Ms Lee said: “It was a meaningful event for many communities who feel overlooked. It was also an important recognition for those from these communities who have worked hard to get where they are.”

Last year, King Charles (then Prince Charles) and Camilla walked around Chinatown in London to boost the morale of the ESEA community, who suffered increased racial abuse during the pandemic. The prince also attended a roundtable meeting about the impact of

hate crimes on the community.

According to recent National Hate Crime statistics released by the Home Offce, hate crimes increased by 26 per cent in the year ending in March 2022. Of 156, 000 hate crimes recorded, 47,000 targeted Asian communities.

“I spoke directly with Charles at Buckingham Palace. He’s a good listener and is interested. I reminded him that we had met exactly a year before at the roundtable for hate crime, and he was surprised that it had been a full year,” Ms Lee said.

“When I was growing up, I never saw anyone who was British-Asian, or British South or Southeast Asian,” Ms Lee added. “Being an object of mockery is historically how Asians and Southeast Asians have been represented in media and culture.”

In the UK, 50 per cent of South Asian women report that they rarely, or never, see people from their ethnic group in advertisements, according to research from UM media agency.

“The work and experiences of ESEA communities in the UK are as valid as anyone else’s,” Ms Lee said. “Representation is massively important.

“Change in attitudes towards communities can be a slow process. However, if a change is getting on people’s radars and people are being heard, then it’s all the better for it.”

Ms Lee created East Side Voices in early 2020, a literary salon that “aims to increase the number of voices in the

media, flm, in the arts, and literature by bringing to the fore stories that illuminate what it is to be ESEA”. The salon’s mission is to dispel clichés, change cultural narratives around ESEA, and unite the community. Ms Lee edited an anthology of essays and poetry under the same name, published in January 2022. Speaking on the representation of ESEA communities in the media, Ms Lee said: “It’s hugely important that there is an understanding of the issues of the nuances and textures of different communities that make up our society.”

Eoghan O’DonnellMagazine alumna Sarah Green won the 2022 PPA Student Journalist of the Year award, the 14th time out of the last 15 years a student from the City course has triumphed. Ms Green’s winning portfolio included an investigation into US adoption fraud. The 5,000-word piece – which started as Ms Green’s fnal project –was published by ELLE

The judges described Ms Green as a “true editorial talent” and somebody who “tackles serious topics with tenacity, maturity, confdence and real heart”. Ms Green said: “I moved across the world to pursue my MA at City. Being recognised reminded me of how far I’ve come and how far I have yet to go.”

Ian Jones

A£6,000 bursary will be available in September 2023 for a young foreign reporter studying on MA International Journalism (MAIJ) at City.

The bursary is launched in memory of foreign correspondent and foreign editor of The Times, Richard Beeston.

The Richard Beeston Bursary Trust was established in 2014 after the journalist’s untimely death from cancer. With the help of James Harding among others, Beeston’s widow, Natasha Fairweather, founded the bursary in an effort to assist talented young journalists pursuing careers in foreign news. The recipient may also have the opportunity to do work experience at The Times.

Ms Fairweather said: “I am happy that we are partnering with City University to provide this award in memory of my husband. The Richard Beeston Bursary Trust has provided a springboard for a number of young journalists who have gone on to work for the Financial Times, The Guardian and The Washington Post

“We are looking for a candidate who strives for journalistic excellence and can also demonstrate fnancial need,” Ms Fairweather added.

As well as its an annual award for the MAIJ programme, the Richard Beeston Trust will also award a £6,000 bursary

to young foreign correspondents at a later stage of their career. This additional bursary will offer the chance to spend six weeks abroad reporting on a foreign news story in collaboration with The Times. Applicants must have two years of journalism experience and be under 30 at the time of the closing date. Recent City alumni would be ideal candidates for this opportunity to pursue an international story of their choice.

“There are two main benefts to the MAIJ bursary,” Ms Fairweather reiterated. “It will allow the winning students time to develop their skills within an established institution, as well as providing work experience opportunities at The Times.”

Suzanne Franks, professor and funding

organiser at City, expressed gratitude towards Mr Beeston’s family for providing City students with the opportunity. “I am delighted that the Richard Beeston Trust is offering this generous support, intended to help a young upcoming journalist at City. We are very grateful to all the trustees,” she said.

The bursary is open to any international student accepted onto the MAIJ course for the coming academic year.

The deadline is 1 May 2023 and applications should be submitted to richardbeestonbursary@gmail.com. Candidates can visit richardbeestonbursary.com for more details.

At the Broadcast Journalism Training Council (BJTC) Awards in November 2022, MA Broadcast and Television Journalism students were nominated in six categories and won in each one.

Of the 14 listed categories, there were: Best TV News Report, Best TV Documentary, Best Social Short Video, Best Podcast, Best Radio Newsday, and the Derek Dowsett Award.

The latter, one of the highest honours of the night, recognises stories focusing on social inclusion within television journalism. It was won by students Olivia Andrews and Hanna Schnitzer for their report “Rotherhithe residents march to save ‘local hero’ from deportation”. This

came with a £1000 prize and a week of work experience with ITV News. The other projects nominated for this award were also created by City students.

“I was so incredibly proud of the students, and it was so lovely for so many of them to get the recognition that the work they’re producing is of such a high standard,” said Sally Webb, head of the MA Broadcast and Television courses. “I always tell the students that were shortlisted but didn’t win: ‘You’re all winners because even to get short-listed is such a prestigious honour.’ For those who do win, it’s just the icing on the cake.”

The BJTC Awards showcases works produced by graduates from

distinguished journalism courses around the UK. These works are in TV, radio, digital, podcast, and social media content.

“I always get tearful with pride because I am so passionate about my students,” Professor Webb added. “I couldn’t be more proud of what they go on to achieve, not only on the course and the work that they produce, but also when they go into the industry.”

The BJTC is a stepping stone for winners, displaying their work to leading media companies across the UK and the world for potential job opportunities in the industry.

Caroline Tonks Seraphina Kyprios and Ciéra Cree Richard Beeston in Kabul

Belinda Goldsmith, global media director of Save the Children, has joined the journalism department as a visiting lecturer this year.

The former Editor-in-Chief of the Thomson Reuters Foundation is teaching the Humanitarian Specialism, which covers topics including reporting on international aid, the protection of children and vulnerable adults, and disaster reporting.

Ms Goldsmith said: “With a record number of people globally in need of humanitarian assistance, there has never been a more important time to train journalists on how to get the stories of vulnerable communities into the headlines.

“It is great to see City recognising this need and providing a course for people interested in humanitarian journalism or working in the aid sector.”

An experienced freelance writer and author joined the journalism department this year to teach the Arts and Culture Specialism.

Kat Lister writes for multiple publications including The Guardian, The Independent and Vogue. She studied English at university before starting a job in PR that she did ‘very badly’ for a year and a half before deciding to pursue her dream of writing.

She specialised frst in music journalism, spending much of her 20s writing for NME. Since then, Ms Lister has published her memoir The Elements which explores grief and widowhood.

Alongside teaching at City, Ms Lister now writes for arts and culture sections. She said: “I was a little nervous before I started the module but I couldn’t have asked for a more passionate and engaged group of students. Not only have I enjoyed teaching these classes, they’ve reminded me of all the reasons why I got into this profession in the frst place. It’s been an absolute joy.”

Anna Batchelor

A BBC flm critic and podcast host is the new tutor for City’s Film, TV, Video and Radio Specialism course.

Rhianna Dhillon, flm critic on BBC Radio5Live and host of The PodPod podcast, said: “I have enjoyed the challenge of making the course interactive. Teaching at City has given me the frsthand opportunity to see young women want to come up and talk about flms, which is awesome.”

Determined to make her class participative and the closest real life experience to being a flm critic, Ms Dhillon has gone to great lengths to bring in diverse guest lecturers, including a BAFTA-winning flm director and a podcast commissioner.

Ms Dhillon joked that her career “peaked at its very beginning” when she became the in-house flm critic for Radio 1 before she graduated from the University of Reading.

Fourteen years after graduating, City alumna Lara Whyte has returned to the journalism department as a lecturer. Lara Whyte joined City this year to teach TV and production to broadcast journalism students.

She graduated from City’s broadcast journalism course in 2008 and has worked across a range of television, broadcast, and print journalism since, including as a producer at ITN Productions. Her book, Freedom Fighter, written alongside Joanna Palani, focuses on the story of Ms Palani’s personal war against ISIS on the frontlines in Syria.

Ms Whyte advised young journalists, “Be respectful and empathetic and treat people like they’re real people. Experiment with your own technical capacity. Technical skills can be learned, so don’t be intimidated by other mediums.”

Investigative journalist Jenna Corderoy had success at this year’s prestigious British Journalism Awards, bringing home the prize for Campaign of the Year.

The City alumnus and visiting lecturer was honoured in recognition of her work for openDemocracy, an independent media platform reporting on British public life, with the aim of holding power to account. The outlet described the achievement as “the biggest

prize of [their] 21 year history.”

Ms Corderoy spent months on a team investigating Freedom of Information (FOI) censorship, involving journalists, researchers and members of the public being denied their right to information by public bodies; shining a light on the corrupt machinations of government secrecy.

Asurprise appearance by former prime minister David Cameron put City journalism students’ interviewing skills to the test. After a visit shrouded in secrecy, the politician admitted that the questions he faced were “quite challenging”.

Mr Cameron spoke to the students about the nature of the relationship between politicians and the media on the same day that Isabel Oakeshott leaked Matt Hancock’s ministerial WhatsApp messages.

Professor Barney Jones, lecturer at City and former Editor of the Andrew Marr Show, organised the event. Right until the last minute, the political guest remained anonymous as a security precaution. Audience members were shocked to uncover his identity upon their arrival at the free event.

Professor Jones said: “David Cameron speaks publicly rarely nowadays and he was very generous in giving up an evening to come to City’s journalism department.”

When Professor Jones previously

organised political interviews at the BBC, he met Mr Cameron many times. At a social event before Christmas, the lecturer asked the former prime minister if he would join the long list of politicians who have come to City and spoken to its journalism students.

Professor Jones said: “I was a bit surprised when he readily agreed. And even more surprised when his offce swiftly fxed a date!”

Students took the opportunity to question him on major points of presentday politics and Mr Cameron’s time in offce. Students also asked considered questions about his economic record and

the decisions made during his premiership, covering topics such as climate change, Putin, the UK’s relationship with China, and of course, Brexit.

Mr Cameron answered every tricky question that came his way, providing students with a great opportunity to practice their interview techniques against a high-profle politician.

Before he left City’s campus, he said: “I enjoyed speaking to the journalism students. They’re a bright group - really engaged and quite challenging in their questions.”

According to House of Commons records, Boris Johnson was paid £250,000 for speaking to bankers last November and Theresa May was paid £100,000 for speaking to fnanciers in Switzerland. While Mr Cameron is likely capable of commanding similar sums, his only request during his visit to City was a bottle of still water.

The former Prime Minister is currently fulflling a role at New York University Abu Dhabi, teaching a course entitled Practicing Politics and Government in the Age of Disruption.

Amy McArdle Ciéra Cree

David Cameron with Barney Jones

Jenna Corderoy and Ramzy Alwakeel at the British Journalism Awards 2022

ASV Photography Ltd for Press

Adam Tinworth

Ciéra Cree

David Cameron with Barney Jones

Jenna Corderoy and Ramzy Alwakeel at the British Journalism Awards 2022

ASV Photography Ltd for Press

Adam Tinworth

Anetworking group for journalism alumni and former staff is being set up to help disadvantaged students become journalists.

The Friends of the Journalism Department will connect former students and staff and help raise funds Professor Lis Howell

The co-founders of the new group are City teaching legends Dr Barbara Rowlands and Professor Lis Howell.

Dr Rowlands, MA magazine journalism course director from 1999-2018 said: “It’s a fantastic networking opportunity for journalists who normally wouldn’t meet.”

Professor Howell, the Director of Broadcasting from 2009 to 2018 and Head of Postgraduate Studies from 2016 to 2018 added: “We are also looking for former contacts of the department to provide support for potential students who may not be the obvious candidates in the school.”

Dr Rowlands said: “We’re well aware journalism and newsrooms need more diversity. Whether ethnic, minority, BAME, LGBTQ+. We want to help people who might not have the money to come to City otherwise.”

In a 2021 report from nongovernmental lobbying organisation The World Economic Forum reported that “a diverse newsroom is essential for media institutions that pride themselves on providing well-researched, complex stories that explore different perspectives and voices”.

Both said the Friends of Journalism Department would be an “enormous

The UK Press Awards was a successful night for City, with alumni collecting fve awards and three high commendations.

resource, particularly for former staff”. It will reconnect people who once taught at the university or were students.

“It would be great to get former staff back in touch and involved with the department,” Professor Howell said.

The frst move is getting in touch with former staff members stretching back “as far as we can go”, who are a repository of information about journalism alumni, said Dr Rowlands.

They will be invited to City in the autumn for a celebratory lunch and a guided tour of the department. “We believe there is enthusiasm for a project like this among our former colleagues,” Dr Rowlands said.

City has a powerful alumni spread across print, digital and broadcast media in the UK and overseas. At a meeting with the head of the department, Professor Mel Bunce, it was agreed that a similar tour and event for student alumni in 2024 to network and raise money for bursaries would be arranged.

“They are loyal to the department and understand that journalism needs more diversity in the newsroom,” Dr Rowlands said. “City has helped many people in their careers, and we hope people will want to give back.”

Recent graduate Shayma Bakht (MA Broadcast, 2020) won Young Journalist of the Year, while Isaan Khan (MA Investigative, 2019) took home the award for Sports Journalist of the Year.

Other winners included Megan Agnew (MA Magazine, 2018) who won News Feature Writer of the Year, Ian Birell (PG Diploma, 1986) who won Feature Writer of the Year, and Joremo Starkey (PG Diploma, 2004) who won News Editor of the Year

Adding to her winning streak, Pippa Crerar (MA Newspaper, 2000) picked up the prize for Political Journalist of the Year.

Ella KiplingThe same report showed that “journalists are more likely to come from households where a parent works/ worked in a higher-level occupation”, one of the key determinants of social class in the UK. Additionally, 80 per cent of journalists had a parent in one of the three highest occupational groups, compared to 42 per cent of all UK workers.

Junior journalists in the UK also appear to be less diverse than their more senior editors, according to NCTJ fndings. There is also an increase in the proportion of people in journalism coming from the highest social classes, with 75 per cent in 2020 to 80 per cent in 2021.

“This combination results in a narrow viewpoint of the world, and we need to widen it out to give different stories in different ways,” Dr Rowlands said.

Eoghan O’DonnellCity has come top for journalism in The Guardian’s 2023 UK university rankings.

The university scored 100/100 in The Guardian’s rating of excellence – an aggregate score across nine factors that include student satisfaction and postgraduate employment – beating other journalism heavyweights like Cardiff, Oxford Brookes, and Sheffeld.

Professor Mel Bunce, head of journalism at City, said: “It was wonderful for so many reasons. I think we have always been well-known for and successful at producing

journalists that go on to run the industry.

“People that work in journalism know how superb City journalism is, but it hasn’t always broken beyond that to those outside of the industry.”

It is the frst time City has been ranked number one for undergraduate journalism in The Guardian’s league table. City has risen 26 places on last year’s ranking which previously grouped subjects such as publishing and PR alongside journalism.

The Guardian ranking differs from other major league tables by prioritising factors like student satisfaction and

job prospects over traditional metrics like academic research.

Professor Bunce said the employment factor is one reason she is so happy to see City at the top of the league table in particular.

“A lot of our students are the frst in their family to go to university and come from a variety of ethnic and religious backgrounds,” she said. “It’s really special with that type of cohort in particular when you help them secure jobs that they may not have otherwise been able to.”

The Guardian accolade follows recognition by other major university guides, such

as The Sunday Times University Guide 2022 and The Complete University Guide 2023, which ranked City’s communications and media department as number one in the country.

Tom FlanaganA series of investigations into UK public fgures with ancestral links to the slave trade have been headed up by City lecturer Dr Paul Lashmar alongside journalist Jonathan Smith.

In an article published 4 February 2023 in The Observer, Dr Lashmar and Mr Smith spoke with members of the Trevelyan family. The family discussed their journey to the Caribbean, where they publicly apologised on behalf of their ancestors for owning over 1000 African slaves in the mid-1700s.

The Trevelyans are not the frst well-known name Dr Lashmar and Mr Smith have reported on regarding ancestral involvement in the slave trade.

In November 2022, the duo wrote a piece on Conservative MP Richard Drax, who they discovered was still legally the owner of a plantation in Barbados.

When speaking about the impact of publishing the Drax exposé, Dr Lashmar, the former head of City’s journalism department, said: “What’s been most interesting

is that when I’m talking to people who perhaps are not aware of what I do, when the name Drax comes up they go, ‘Oh is that the man who owns the slave plantation?’ And you think, actually I’ve had an impact.”

Dr Lashmar said the story has garnered a number of responses from both sides of the political spectrum.

He explained: “You’ve got the liberal tendency, people who are trying to work out the families who have had a history in slavery, those who feel they should do something.

“On the other side are those who, perhaps represented by Richard Drax, have been very reluctant to even talk about it, let alone commit to any action that would be considered to be reconciliation or reparation.”

Dr Lashmar said his investigative work into the slave trade is far from over. He is in the process of publishing a book on the Drax family.

Emily Smith Image: Dr Paul LashmarAcourse covering health, science, and environmental reporting was suspended this year after less than two per cent of students chose the module.

This is the frst time the Health and Science specialism has not run due to lack of interest, provoking disappointment among staff and students.

Dr Mark Honigsbaum, a senior lecturer who leads the course, was surprised: “We’ve just lived through a pandemic and everyone’s talking about climate change. There couldn’t be more of a moment for understanding science.”

He added: “It could be that we didn’t do a good enough job of explaining what you study, and maybe we need to do a better job of selling it to postgraduates.”

Dr Honigsbaum said there were also

perceptions of science as being too diffcult: “Students think it will be harder than some of the other specialisms.”

City offers 13 short courses as part of its specialisms offering, including popular modules such as Lifestyle, Arts and Culture, and Investigative. The Health and Science specialism has run for seven years. The department intends to run it next year, providing enough students choose it.

Jason Bennetto, director of specialisms, said: “It was very disappointing not to be able to run the Health and Science module this year, but with only three MA journalism students out of 160 putting it as their frst choice, it was not tenable.

“I’m surprised so few students wanted to study the topics of health and the environment, given that climate change

Musicians, actors and spoken word poets are among the artists that will join forces with City’s journalism department this year as part of a new Creatives in Residence scheme aimed at championing different creative felds.

Pioneered by Professor Anna Whitelock, Dean of the School of Communication and Creativity, the scheme will provide a space for early career creatives to explore their craft whilst working alongside City students. The scheme will involve a six-month residency programme in which creative practitioners will work on their own projects, hold masterclasses for students, and provide mentoring.

The frst creatives chosen for this project include singer-songwriter Joseph Bell, multidisciplinarian Darcy Dixon, and spoken word artist Chloe Carterr.

Inclusivity and diversity are at the forefront of the project, and Professor Whitelock hopes that the calibre of these creatives will refect City’s enduring mission to amplify a vast range of voices within the arts.

“The Creatives in Residence scheme

is part of the school’s evolving strategy to engage with creative practitioners and create an inclusive community within and beyond the school,” she explained.

Interdisciplinary projects run by the creatives themselves will be instrumental in achieving these goals. Students will partake in songwriting classes, mentoring on freelancing, and clowning workshops.

Projects like these offer a unique opportunity for students to explore new creative felds.

“I hope the students learn creativity beyond that which we currently offer in the School and that the scheme allows students to learn from those already in the world of work,” said Professor Whitelock.

The scheme will offer the creatives access to performance spaces and studios on campus as well as the opportunity to hold events or exhibitions at Finsbury Town Hall. Professor Whitelock hopes the scheme will become a permanent fxture in the department if this cohort of creatives does well.

Ella Gauciand Covid are the two biggest stories on the planet.”

Dr Honigsbaum felt that burnout may also have played a part: “For students whose whole education was disrupted [by the Covid-19 pandemic], it was probably too overwhelming, and it was maybe a case of, ‘The last thing I want to do is study it even more.’” Yasmeen Eltahan, a Broadcast student who was one of the three to choose the module, said: “I was excited to start the Health and Science specialism and felt really gutted when told that it was cancelled.”

She continued: “I really wanted to do more health, particularly mental health journalism but will now have to do that outside of the university.”

Maira Butt

Darcy Dixon [top], Joseph Bell [bottom]

Maira Butt

Darcy Dixon [top], Joseph Bell [bottom]

Evidence that two in fve female journalists in Africa face harassment at work is “too often dismissed by bosses”, according to a senior journalism lecturer at City.

A recent study by by WAN-IFRA Women in News found that 40 per cent of women worldwide face verbal or physical sexual harassment in the media workplace. A workshop was held by the African Women in Media association at its annual event in Fes, Morocco in December, based on research conducted by City’s Dr Lindsey Blumell and Dinfn Mulupi. They investigated the prevalence of sexual harassment in the media industry over the last fve years, and suggested measures for companies to help eradicate harassment.

“What we found is most times organisations will either dismiss the report or they will just give a warning,” said Dr Blumell.

Sexual harrassment policies currently in place in African countries have proved to be ineffective.

“The point of this workshop is to enable newsrooms to implement better policies, and actually act on them,”

Dr Blumell explained. The report also found that one in two female media professionals in Africa face sexual harassment in the workplace and under a third of sexual harassment cases are reported to management.

The workshop focused on best practice guidelines for defning sexual harassment, the procedures of the complaint process, and the handling. The fnal part is monitoring and adjusting the policy based on needs.

As part of her ongoing research, Dr Blumell will follow up with the organisations to see whether new policies or changes have been implemented.

“They basically have to change the hierarchies of newsrooms and change how things work to hold people accountable,” said Dr Blumell. “It’s a slow process, but if it were easy then we would have been able to eradicate sexual harassment overnight. #MeToo would have addressed it.

“We’re challenging the core ideas of gender and society, shifting the culture, and attitudes. That takes a lot of education, training and time.”

Kiran DuggalA special journalism version of the BBC’s famous Question Time was held at City and called on some distinguished political journalists and reporters.

City alumni Pippa Crerar (political editor at The Guardian and MA Newspaper graduate), Faisal Islam (economics editor at BBC News and MA Newspaper graduate), and Katy Balls (political editor at The Spectator and MA Magazine Journalism graduate) returned to the department.

Chris Mason, another former City student, was posed to dash from BBC Studios to host the panel but was unable to make it to the event. Fortunately, Professor Barney Jones, who leads the Political Headlines module and previously worked as the editor of The Andrew Marr Show, stepped in.

Speaking about her experience returning to City, Ms Balls said: “It’s always nice to come back and see the next year of students.”

John Nicolson MP, a journalist-turned-politician who previously worked for the BBC and ITV as a political broadcast journalist, served as the fourth guest on the panel.

Journalism head, Professor Mel Bunce said: “One of the biggest privileges of teaching at City is knowing that your students will go on to make a difference in the world, and that could not be better illustrated than our panel for this inaugural Question Time event.

“The work that Pippa, Faisal, and Katy do holds politicians to account,” she said. “It has helped topple governments, and informs and infuences how audiences think about the world.”

Ella Kipling

Students with Pippa Crerar [centre]

(1) Speaker at the event (2) Dr Lindsey Blumell (3) Fes, Morocco

Ella Kipling

Students with Pippa Crerar [centre]

(1) Speaker at the event (2) Dr Lindsey Blumell (3) Fes, Morocco

David Bawden from the information science department. Working with them is Emma Markiewicz, director of the LMA, and Laurence Ward, head of digital services.

The Journalist Archive Project (JAP) will work closely with the LMA to establish the best practices for creating and maintaining an archive of journalists’ materials, and making them readily available to the public.

Dr Glenda Cooper, the deputy head of City’s journalism department, has spent signifcant time researching and accessing archives in the US. She said: “Archiving journalists personal papers is taken seriously in the US – we would like City to take the lead doing something similar in this country.” Dr Cooper added that she would like any alumni who have a potential archive to get in touch for this project.

Anew project between City and the London Metropolitan Archives (LMA) attempts to create a repository of archives collected by journalists during their careers and make them publicly available.

City’s Higher Education and Innovation Fund (HEIF) is funding a pilot study looking at the archiving practices of investigative journalists. In the UK, some journalists’ personal archives are contained in various libraries and archives, but there is no central repository. The few personal archives that do exist are spread across libraries and archives, making the information diffcult to fnd.

The archive of Dr Paul Lashmar, a City lecturer and investigative journalist who has worked for The Observer, World in Action, The Independent, and Channel 4’s Dispatches, will participate in the pilot. He said: “Archives of investigative journalists often have rich material – they contain documents of historical value not available elsewhere in the public domain.

“Such a repository would be of great value to historians, political scientists, media academics, lawyers, and those looking into miscarriages of justice.”

The City team consists of Dr Lashmar and Dr Glenda Cooper from the journalism department and Professor

The JAP is an important step towards preserving the history of journalism and making it accessible for generations to come. As the project moves forward, the team will continue to encourage more journalists to contribute to this resource.

Ruby BorgNewspaper pathway graduate, Esme Wren, is under Hollywood’s spotlight for a Netfix flm following her crucial role in uncovering the scandalous friendship between Prince Andrew and convicted felon Jeffrey Epstein.

Wren will be played by Romola Garai (Becoming Elizabeth). Fran Unsworth, who was the Director of News and Current Affairs at the BBC at the time, will be played by fellow BAFTA nominee Lia Williams.

SCOOP will delve into the events leading up to the 2019 exposé which also centred around Prince Andrew’s alleged assault of a minor. An adaptation of Sam McAlister’s book Scoops: Behind the Scenes of the BBC’s Most Shocking Interviews, this flm features a star cast with Sex Education fan favourites Gillian Anderson and Connor Swindells, as well as Billie Piper as McAlister and Rufus Sewell as the prince.

Wren moved from the BBC to Channel 4 News shortly after the shocking interview aired and has been with them ever since.

The flm currently has no offcial release date. Tudum!

Amiya Baratan and Dimple Shiv

I was a YouTuber and I wanted to do something that made my voice more legitimate. I enjoyed that I was able to expose things, champion causes, and stand up for human rights. But I felt like people weren’t taking me very seriously. The vibe was always to do something within LGBTQ+ or human rights journalism and I just wanted to continue that on YouTube, but for a bigger audience. So, I decided to start looking at options for getting into journalism.

I think I’ve achieved it to be honest. I have hit the peak of what I set out to do. It’s quite weird to say but I challenge governments, I’ve held people to account, I’ve made people feel good about their sexualities and their gender identities, and I’ve travelled the world. I left the BBC because I wanted to expose more and investigate more, and Vice gave me the opportunity to do that.

I’ve defnitely been caught off guard by how toxic and scary, and at times, unrewarding journalism can be. Within the human rights space, I’ve spoken to other journalists who agree that there are certain things that we weren’t prepared for. There’s a lot of jealousy within journalism. Journalism is incredibly competitive and there are only a few entry routes into certain newsrooms every year and it means some of the people who you start with (who are your closest friends), almost become your enemies – because you all want the same opportunities.

It can be quite a learning experience, because you want to speak to people about how tired you are, how stressed you are, how scared you are, but you have to do it with the knowledge that you got an opportunity that other people

wanted, and that can be very diffcult. All these years later, I know that a lot of my friends in journalism do fnd it quite lonely. It can be challenging because you’re expected to be really grateful for very diffcult, lowpaid, and challenging shifts. Sometimes it’s diffcult to be grateful because you can’t pay your rent and you can’t afford lunch, and you’ve pulled an all-nighter working for a newsroom where people don’t even remember your name.

“Exclusive: this terrible thing has happened,” and someone will respond to me saying: “Hi! I just saw you in CostCo!” I think: ‘What!?’

Have you ever experienced racism, microaggressions or homophobia in your career?

All of the above! During my frst few months as a journalist, I interned for a lot of newsrooms and in that time I probably closed my eyes to a lot more negativity than I should have done. I would hope that if I went back into those situations now, I’d be able to call it out.

I do think there’s been a change in certain UK newsrooms – or I hope that there has been – but I’ve encountered homophobia, racism, and ageism. I was told that I wasn’t old enough to be a reporter; to be a correspondent; to be on BBC News at Ten Classism is an issue too. They told me I didn’t sound good enough to be on the Radio 4 Today programme, and I’d get emails from people telling me they didn’t like my accent.

What is the funniest (or rudest) piece of feedback you’ve had on your work?

When people slide into my DMs and tell me I’m sexy – I fnd it funny because usually it’s around the most inappropriate, deep, and dark stories. I also fnd it funny when people see me out and about and then message me, or take a sly photo of me. There have been occasions when people have done it and I’ve just released a story and I’ll go on Twitter like

One thing that I will say is that I’ve not changed myself when it comes to my principles since becoming a correspondent. I’ve worked with incredible people who have helped me to stay true to myself, which is amazing. I’m so grateful to my mentors for supporting me in that, because I know that some people don’t have the same opportunities that I do - to investigate what they want to, or travel to the countries that they want to, or to hold governments to account in the way that I have.

I would turn up to lectures. I probably had the worst attendance on record and looking back now I feel like I missed out on the opportunity to network more with the people on the course, and get advice from lecturers.

“I’ve encountered homophobia, racism, and ageism”

Henrietta Taylor speaks to the Vice World News LGBTQ correspondent about telling human rights stories, and the “toxic and scary” side of the profession

the good, the bad and the downright weird

With looming deadlines, we often turn to that fated Twitter hashtag: #journorequest. Sometimes, the questions are purely functional; other times, they’re self-serving, niche, and downright odd. Katie Daly compiles some of our favourites

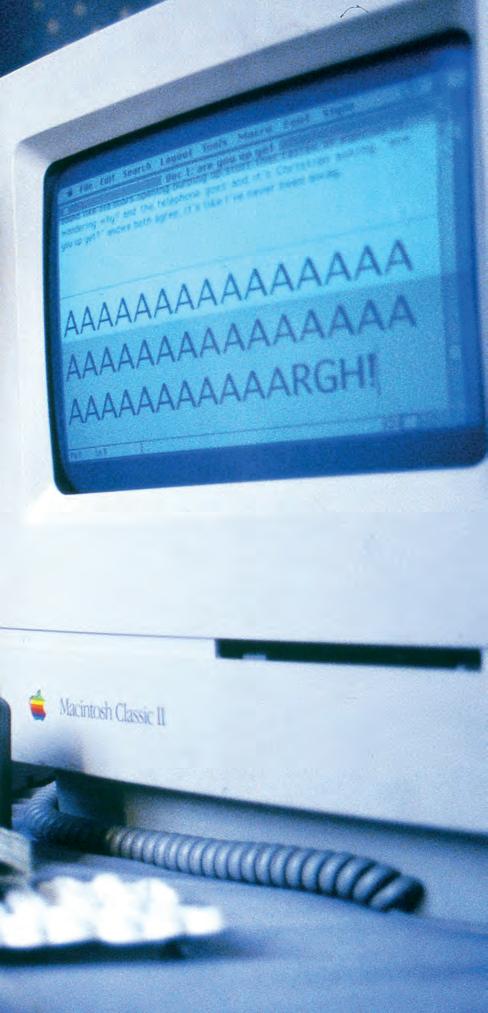

“The only time the police came into the offce was to buy the magazine,” insists former Loaded editor James Brown. “I remember two offcers walking in and saying: ‘Hide your dope! We’ve come to buy a copy.’”

It was the mid-Nineties and the Loaded offces “stank of skunk”. The magazine’s young and controversial editor had deliberately created a subculture in which prep for an editorial meeting meant racking up lines of cocaine or rolling a blunt. But the illicit habits of Loaded’s staff weren’t just fodder for the gossip columns – they were the secret behind their success. The publication’s outrageous, gonzo-style journalism allowed readers to vicariously experience their

debauched lifestyle. It proved so wildly popular that even the local coppers were willing to turn a blind eye.

showed young men as they really were –even when “they should know better,” as the magazine’s strapline once claimed. “It was showing men as they hadn’t been represented in a publication before,” says Brown. Drinking, clubbing, smoking – and occasionally snorting.

“The reason we were able to get away with it was because we were hugely successful,” says Brown. The frst issue sold nearly 60,000 copies, and by the third, the publication was already turning a proft.

Brown attributes Loaded’s popularity to its honest and authentic representation of male youth culture. While other magazines suggested a squeaky clean image, Loaded

“People of my generation looked at life like something to be grabbed and messed around with. You didn’t take the safe road,” adds Piers Hernu, former editor of rival publication Front magazine. “We were more concerned with having fun and being hedonistic and doing what we liked rather than what was legal.” This is not surprising from a man once arrested for smuggling gold into Nepal, in an incident so infamous it was later documented in an episode of Banged up

It’s been 30 years since the launch of iconic men’s magazine, Loaded. Shauna Brown and Nicole Panteloucos look back on E’s, wizz, and the mag biz with former editor James Brown

wanna have a

“My era of Loaded was like being in the Mondays or the Stones”

James Brown

Abroad

Of course, Loaded was not the only magazine where illicit behaviour was rife. In his early days as a staff writer at NME, Brown recalls that amphetamines were quite prevalent (he was once “so f***ed on speed” that he was forced to dictate an article to a colleague, who then wrote it for him).

they shamelessly documented their drugfueled escapades for entertainment. Thinlyveiled attempts to code these anecdotes with street slang were mediocre at best, and gossip columns were rampant with rumours of staff moving drugs around the city via bike service.

which had a knock-on effect for the music, nightlife, and magazines of the era. Modern day youth culture publications like VICE and Dazed are still trying to replicate the provocative personality of publications like Loaded and Front through frst person anecdotes of sex, drugs, and club toilet encounters . But it was a zeitgeist that cannot be recreated – and perhaps for the best.

“They were [dealing],” he says. “Though I had no knowledge or interest in whether they were using the bike service – it certainly wasn’t allowed.” However, it was one story in particular about Brown and another writer “chopping up cocaine” in the middle of a river that prompted intervention from their publisher. “That’s when they panicked,” he says. “The next day we removed all the drugs from the offce.”

Publications such as The Guardian have criticised Loaded’s editorial practices, and while the magazine’s overt sexism would be called out today, Brown’s tenure represented a different time – where ladism was a winning formula. “My era of Loaded was like being in the Mondays or the Stones,” he says. “The only difference is we weren’t going on stage and playing music. We were going into an offce and creating a magazine.”

After making his start in the industry as a music writer, Brown sought to emulate the excessive lifestyle of Nineties bands, many of whom were as glorifed for their misbehaviour as their sound. “I felt that if we had a lot of drugs around us too, it would be good fun,” he says. “So I deliberately appointed somebody to the staff who I knew was a small-time drug dealer. We just had coke in the offce every day.”

But while their antics were entertaining for the masses (and proftable for their publisher), it was simply not sustainable. It was in 1997, when Brown left Loaded to become editor of GQ, that the severity of his substance abuse became impossible to conceal. “There were incidents that happened that made it clear that I had a big problem,” he admits. One such moment was when Brown placed a bucket of his own vomit in the writers’ room.

“Younger people of today’s generation are less likely to be embracing hedonism and more likely to be cautious about ‘well what happens if I wake up with a hangover’ and ‘am I going to die if we take this pill?’” says Hernu. Brown – who documented his editorial escapades in his 2022 memoir, Animal House – agrees that the moment has passed, claiming he would not be able to launch a magazine like Loaded today. But even after years of sobriety, he still takes pride in its chaotic legacy.

“We were just having fun, we weren’t hurting anybody,” he says. “It was a f***ing great rock and roll time.” Still, when the party’s over, no one wants to be the last one out the door.

While music journalists in the Nineties rode the wave of MDMA, the party culture associated with the fashion industry was also a hotbed for addiction.

“There was sort of an offce speed dealer, who also dealt to people like The Fall and The Pogues,” he says. Within a year of him joining the magazine, the arrival of ecstasy had an unprecedented impact on the British music scene, including NME. “Ecstasy changed how many people were using drugs, and it almost replaced alcohol as what you wanted for a night out,” says Brown. “It f***ed a couple of people up.”

While substance abuse was a part of the wider culture at NME and many other magazines, Brown intentionally introduced it into the writer’s room at Loaded, where

“A responsible person or someone who didn’t have a drink or drug addiction wouldn’t have been throwing up in the afternoon,” he says. What had become normalised behaviour for Brown within the confnes of Loaded – where even company lawyers cracked jokes about employees’ coke habits – was concerning enough for Condé Nast to refer Brown to therapy.

“My mum had died of an overdose and I was self-medicating with alcohol and drugs. I do regret how I spoke to staff at times. I was really young and mercurial,” he says, refecting on his tenure as editor.

Against the backdrop of the British rave scene, it’s really no wonder Brown was able to disguise his addiction for as long as he did. The cultural shift of the early Nineties was fueled by the emergence of new drugs,

“You can hide in plain sight if you’ve got a problem,” says Melanie Rickey, current digital editor of Sphere Magazine and founding editor of Grazia. “I worked in fashion media in the late Nineties. I was in quite a glamorous, hedonistic world of parties, events, and shows. There’s often free bars and you’re given more alcohol than food. I can’t blame the industry, but at the end of the day, it enabled a lot of people.”

One of the things about addiction is it’s a progressive illness,” she says. “So what was once fun when you’re in your twenties, and a little bit naughty in your thirties, by the time you get to your early forties, it’s not a good look. I really knew I had to do something about it when it was no longer fun and it just felt embarrassing.”

“We just had coke in the ofce, every day”

“It was a f***ing great rock and roll time”Image credit: Martyn Goodacre

Prince Harry’s infamous memoir Spare reminds us of something many publishing houses would like us to forget: just because you have a story doesn’t mean you’re the best person to tell it. With ghostwriter J.R. Moehringer’s million-dollar commission for Spare splashed across headlines, what was once the publishing industry’s “dirty little secret” is now frmly in the spotlight.

Matt Whyman, who has published twenty novels of his own, was frst inspired to pursue ghostwriting after reading an athlete’s memoir to his young son. “I gave it to him for his birthday and while reading it, I realised it was just terrible,” he says. “I thought, ‘I can do better than that.’ I felt like I’d given my son a poor, totally uninspiring book.”

Now as a seasoned ghostwriter, Whyman takes on somewhat of a public relations role with his ghost clients. He cites reporters chasing the woman to whom Prince Harry lost his virginity. After celebrity memoirs come out, journalists often dig around, hoping to reveal more than the book does. As such, Whyman encourages his clients to be as transparent as possible to avoid pushback from the press. “There’s always going to be a consequence,” Whyman says.

“When it’s my project, I have a responsibility to [my client] to say, ‘This is how it’s going to be perceived.’ I have to know where the bodies are buried.”

Well-known ghostwriter Andrew Crofts

reveals that he frst got into the profession after writing several books for a wealthy businessman. “I was interviewing him for a magazine and he told me he had been commissioned to write a series of books but didn’t have time,” says Crofts. “He asked me to write them for him, which I did.” Since then, Crofts has ghostwritten a dozen Sunday Times number one bestsellers, some of them for victims of forced marriages, sex workers, orphans, and survivors of war.