DUMMY CITY

NEIGHBORHOOD PLANNING IN LONDON

Authors: Guang Yang, Siqi Sun, Jiangcheng Sun, Hantang Li

This Booklet will focus on the context of London, using “Neighborhood Planning is a Dummy” as an argument, using the overall development of neighborhood planning in England, the particularity of London, interviews and report data as evidence to analyze and discuss the deep inequities faced by neighborhood planning.

Our goal is to be able to present and reflect on the story behind neighborhood planning, while summarizing, collecting and generating tools and strategies that can effectively help with different goals and problems. We present a community engagement proposal which focuses primarily on the need to inform people about the rules and regulations of the UK planning framework, with secondary attention to site-specificity and local context.

We developed tools, e.g. our game “Dummy City” and “Neighborhood Planning Encyclopedia”, that can help people to navigate the complexity of the legislation. These tools try to bridge the gap from layman language to complex legislative jargon in a series of layers, each one the more accessible and engaging.

Directors: Eduardo Rico José Alfredo Ramìrez

Studio Master: Clara Olòriz Seminar & Technical Staffs:

Shengyang(William) Huang Daniel Kiss Julian Besems Teresa Stoppani

Acknowledgement:

Angel Lara Moreira (AA DPL)

Alexander Krolak (AA DPL) Joel Newman (AA Audio Visual) Thomas Parkes (AA Audio Visual) Benjamin Ibbotson(AA Audio Visual)

CHAPTER 3

NEIGHBORHOOD PLANNING ENCYCLOPEDIA

p.7 p.8-9 p.10-21

CHAPTER 4 BOARD GAME “DUMMY CITY”

p.40 - 41 p.42 p.43 p.44 p.45 p.46 - 51

CHAPTER 5

ITERATION HISTORY AND FUTURE PLANS

p.52 - 53 p.54 - 55 p.56 - 57 p.58 - 59

CHAPTER 6 - APPDENDIX

1.1

BEFORE THE LOCALISM ACT 2011

Under the control of the planning system, the development process is as follows:

The LPA is the key decision-maker in the planning system. When a developer has an intention to develop, they need to submit a planning application to the LPA, and the LPA will only grant planning permission to developments that comply with the policies and regulations in the planning system.[3]

The main problems:

But even under this top-down constraint, there are still many developers who seek to circumvent them to obtain permits for short-term gain, to the detriment of local people and threatening local development.

On the other hand, the needs related to local housing, local economy, community facilities and infrastructure are still not being met.[4]

TOP-DOWN APPROACH

AFTER THE LOCALISM ACT 2011

Overview of the act:

The Act is lengthy, extending to over 240 sections, in excess of 20 Schedules and approaching 500 pages. Equally, the Act is broad in its scope. Part I introduces the ‘general power of competence’ under which local authorities are endowed with the ‘power to do anything that individuals generally may do’ provided it is not specifically prohibited.10 The essential idea is that under this novel power local authorities will be free to work with others in creative ways to reduce costs and, it is envisaged, meet local people’s needs more innovatively.

The Neighbourhood Planning:

NEIGHBORHOOD PLANNING IS A

TOP-DOWN APPROACH

DUMMY

DUMMY DUMMY

The central government has long hoarded and centralized power in the areas of planning and construction. Profit-oriented extractive development, in cooperation with external developers, a series of serious problems such as economic exploitation, racial inequality, gentrification, social cleansing and climate crisis affect people’s lives. The impact of social security cuts, housing market pressures and reduced local government funding has forced the state to throw more responsibility back to local governments, expecting people to solve problems through their own democratic cooperation and participation. Ideally, the Localism Act 2011 empowers residents to develop their communities’ future potential and meet their needs autonomously through Neighborhood Planning. On the one hand, it sets a new framework of policy restrictions for bad developers through the Neeighborhood Plan, and on the other hand, through the Neeighborhood Development Order, it gives the community the potential to be an internal developer and develops itself in a simpler and more efficient process.

However, on the one hand, differences in factors such as education, income, and social background lead to community planning that is not available to all, and a large number of people at the bottom are not yet involved, which may help exacerbate inequality. Studies have shown that the rise in homelessness in the UK after LA 2011 illustrates the disadvantage of localist policymaking to marginalized groups in society. [2] On the other hand, the state has delegated “services” to municipalities and regional groups, but it is usually only a cost diversion rather than a real decentralization of power and financial autonomy, that is, responsibility is decentralized, not money for the performance of its duties. In the absence of sufficiently sustainable financial and technical support, existing neighborhood planning organizations have too many responsibilities while volunteering; lengthy bureaucratic interactions with local planning departments have prevented community programs from getting really effective help; even the quality of the completed Neeighborhood Plan is so far from the same that without real financial resources and official support, all the content written in the Neeighborhood Plan can only be a beautiful fantasy of the people of the region Once back to the traditional development model, external developers can still use their wealth of experience to urgently extract benefits from within the community. Especially in the context of London’s huge, complex and unfair urban development, the big hands from all sides make neighborhood planning like a Dummy.

Therefore, we need to expose the unequal development of neighborhood planning in the context of power and resources and further exploration of neighborhood planning that can help shape a better democratic life for the future.

Neighbourhood planning is one of the community rights granted by the 2011 Localism Act.[5] Fundamental changes to the planning system are provded for under Part VI including the abolition of regional strategies, the introduction of neighbourhood plans and neighbourhood devel- opment orders, community right to build, the new homes bonus and reform of the community infrastructure levy.They can increase housing supply, improve the quality of developments and better cater to local needs – those of young families starting out, for example, or older people wanting to downsize.[6]

How Neighbourhood Planning can achive the community right:

Local people can exercise their right to participate in local development by producing their Neighbourhood Plans and Neighbourhood Development Orders.

Neighbourhood Plans and Neighbourhood Development Orders like the weapons for community. Neighbourhood plan for political framework to further constrain developers. Neighbourhood Development Orders can eliminate the process of development application, allowing for rapid development.

BOTTOM-UP APPROACH

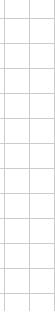

1.2 OVERALL TAKE-UP OF NEIGHBOURHOOD PLANNING IN NUMBERS

The Localism Act introduced ‘a new right for communities to draw up a neighbourhood plan.’ This means that communities in England are not legally required to produce a plan, but it gives them the choice whether to produce one or not. Given this voluntary nature of neighbourhood planning, without resourcing to ensure that all communities have the time and means to participate and create a plan, access to this right could be unequal, and reserved for only select communities with existing knowledge and funding to draw up their own plan.

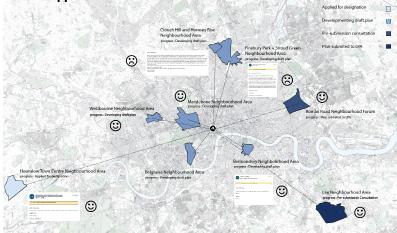

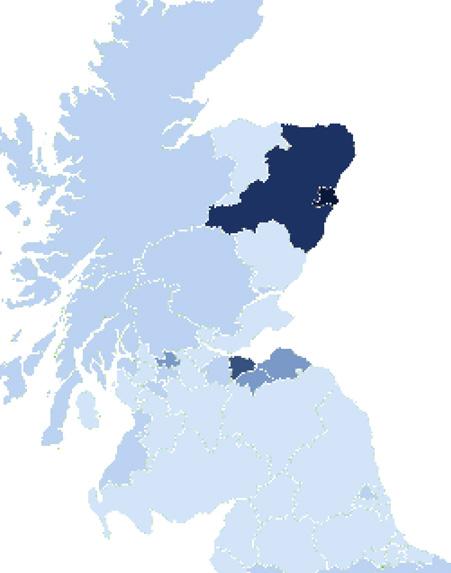

As in the studies of the overall development of take-up of NPing is biased towards parished, rural areas. There is activity in all region of England, although 18% of LPAs are completely without Neighbourhood Planning activity. There are higher levels of take-up in some areas, notably the South East and South West, and with correspondingly weaker take-up elsewhere, particularly in the North East and London.[8]

The vast majority are led by Parish / Town Councils[9]:

• 91.5% of area designations were led by Parish/Town Councils and 8.5% were Forum-led

• 94.3% of “made” Plans were led by a Parish/Town Council and 5.6% were Forum led.

• 58 LPAs have no neighbourhood planning activity (no designated areas) - 18%

• There are 22 business-led neighbourhood plans: 20 of which were Forum-led.

• Less than 10% of designated neighbourhood areas are Forum-led (i.e. unparished and predominantly urban) and the majority of the LPAs with no NP activity are located in urban areas.

• 2612 areas are designated and can or have progressed Neighbourhood Plans; 9 were revising a “made” neighbourhood plan

• 865 of the total have been “made” and a further 16 have passed referendum (34%)

• 9 neighbourhood plans have failed examination, 6 failed referendum, 1 has been quashed in the High Court and a further 8 have formally withdrawn from the process.

“Neighbourhood Planning Progress & Proportion in England”[10]

1.3

LONDON IS DIFFERENT

Eleven years after the promulgation of the Localism Act in 2011, England has so far designated more than 2,600 Neighborhood Areas and nearly 1,000 neighbourhood plans, but London is seriously behind the country in implementing the Neighbourhood planning. We can see that although London accounts for 16% of the total population of England, it is only 3% of the plans that have been made.[11]

First, we can see that the vast majority of neighbourhood plans in the rest of England are set by established parish or town councils, while London has only one Queen’s Park Community Council. At the same time, London’s complex administrative structure and 3-level development plan system have also forced communities to implement the neighbourhood plan in the form of a forum. At the same time Neighbourhood Planning is a long term process, making it harder for people to participate in a plan that takes three to four years or more due to the frequent population changes in London.

It also seems to represent the potential for London to truly develop and be led by the people compared to other regions, but it’s still out of reach for London residents. We began to try to analyze and study existing community planning in London, to try to find deeper information on this kind of problem in London.

Charpter 1 - Neighborhood Planning in London

TYPE 1: GREEN AND INFRASTRUCTURE (GI)

In the Neighborhood Plan, Residents’ desire for infrastructure, including better transportation facilities, parking spaces, and more bicycle lanes. as well as specific needs for green space and the environment within the neighbourhood (often requiring more or protection of existing spaces, expectations to address noise and air pollution, and constraints on future developers, such as guarantees of green rates in future development areas and while participating). We combine the green and infrastructure requirements in the Neighborhood Plan based on the fact that both are requirements and defining frameworks for the development of physical space within the Neighborhood Area.

TYPE 3: SERVICES AND FACILITIES (SF)

TYPE 2: HERITAGE AND HOUSING (HH)

and social welfare housing or expect a unified architectural style (focusing definition of colors, windows, facades, etc.)

THE RANKING SYSTEM

In

How we score:

TYPE 4: BUSINESS AND EMPLOYMENT (BE)

Take the Beddington North Neighbourhood Area, for example, especially for Neighbourhood Planning in the draft stage, which includes ambitious green and infrastructure road remodeling plans for the community’s internal roads, including additional green belts and pedestrian-friendly bike paths.

1.3 The Struggles of Neighborhood Planning in London - Typical Solution of 4 Types of Demands -

TYPICAL

At the same time, we further analyzed and collated typical strategies and design approaches to the most important goals and problems in different types of community planning. In this way, we explore the potential relationship between the content of the plan and the universal needs.

1.3 The Struggles of Neighborhood Planning in London - K-Means Clustering Machine Learning Analysis with different factors of London -

Most Neighbourhood Forums do not have a strong ability to influence large scale businesses and the Neighbourhood Plan focuses more on local retail and small businesses to compensate for local employment. The design of the high street therefore tends to control the overall appearance in the document and to provide more commercial services: small street level gathering places, urban furniture etc.

MEASUREMENT

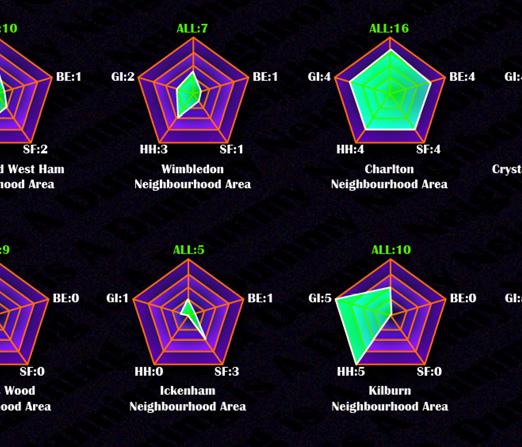

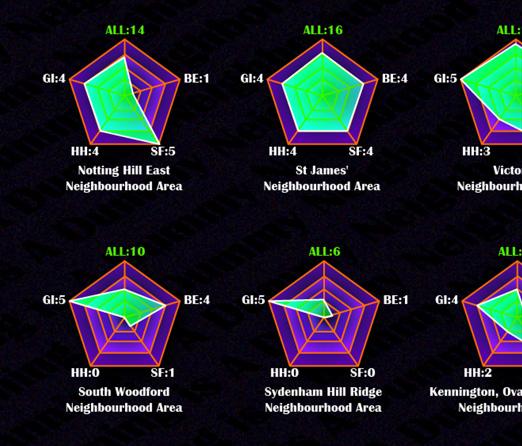

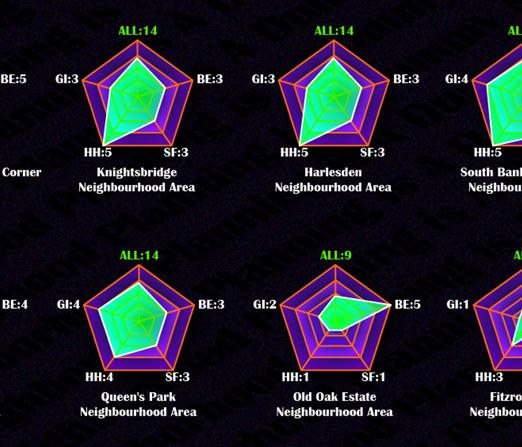

The score value (GI, HH, SF, BE) is presented as a positive integer from 1 to 5. In order to measure the propensity of each item in the corresponding Neighborhood Forum in a single Neighborhood Plan, the four items are scored. The value with the highest value is extracted separately to give 1 as the tendency direction of the main neighborhood plan of Neighborhood Forum, and the percentage of the remaining three values in the sum of the three items is the quantification of the tendency of the remaining three values in the neighborhood plan.

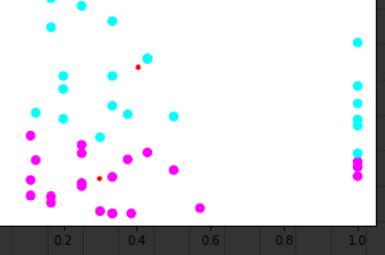

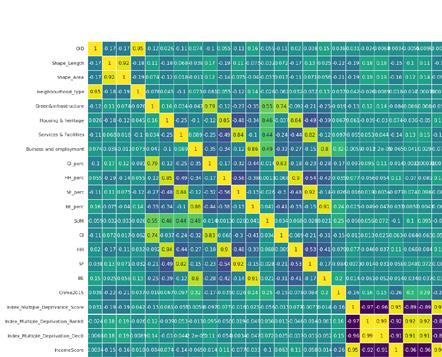

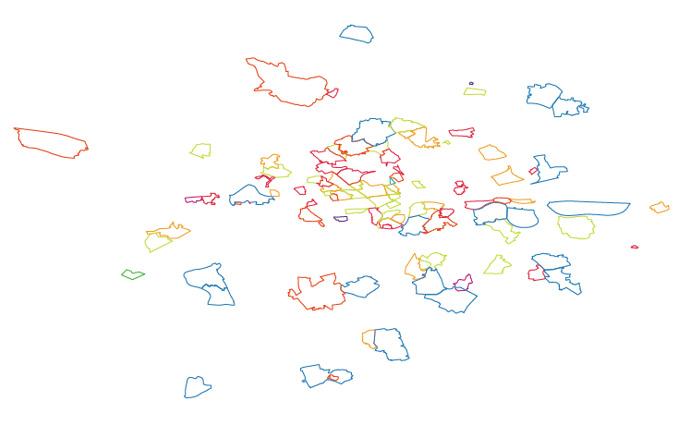

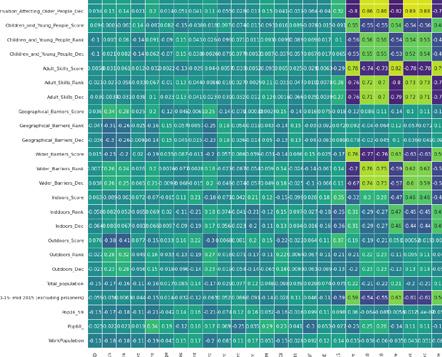

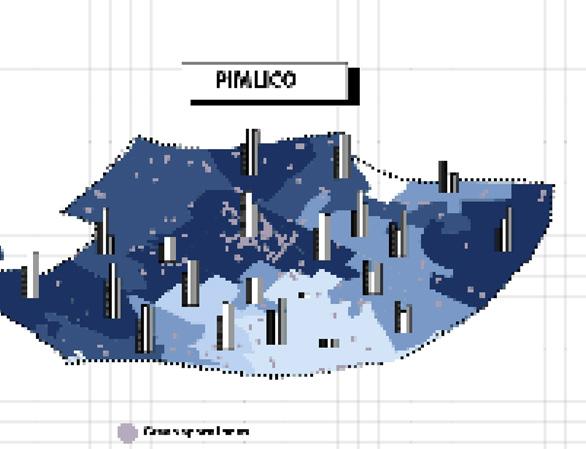

Using the kmeans algorithm to compare the four type of scores of each Neighborhood Area, Neighborhood Forum and Neighborhood Plan in the early stage with the corresponding area’s Income and Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD): determined by comprehensive indicators such as education, income, environment, etc. correspond. As the numerical output of the plane coordinate system, the two indices are expected to be found in the final output image. Whether the four scores we quantified and local conditions (education, environment, income, population, crime, etc. indices and rank) show a clear correlation (positive correlation and sub-correlation)

K-MEANS CLUSTERING

SPATIAL VISUALIZATION

Moreover, the dataset files of the original running system are combined to establish the range of values under each heading. Through Grasshopper K-Means, the existing neighbourhoods in London are visually distributed in the clustering. Mapping and classification of clustering in the coordinate system for each Neighborhood Area. The diagram shows the clustering and classification of Neighborhood Area in the coordinate system for each list with similar values But we found that the classification relationship of the computer-calculated neighborhood plan’s clustering was far from the four different categories of clustering we preset.

EXPLORE RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN DIFFERENT FACTORS AND TYPES

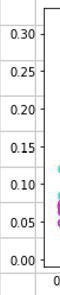

In order to be more able to confirm the correlation between the neighborhood planning tendency of each community and the various values in the IMD multiple deprivation index, we used Matrix to visualize the gis export csv table. It can be found from the figure that the correlation between the overall neighborhood plan score and the various values in the IMD is weak, and the value fluctuates between 0.25 and -0.25.

This further proves that the content of neighborhood plans is not entirely related to the ability of the community to be rich or poor. In addition to the obvious positive correlation between the community with environmental problems and the plan preferrence of “Green & Infrastructure”, other influencing factors cannot completely determine the plan content and degree of the neighborhood planning.

INTERVIEW PROGRESS

Purpose: We contacted Neighborhood Forums at different stages and with different basic community conditions to conduct interviews to collect the most pressing and real needs of people in different neighborhoods and different neighborhood planning stages (focusing on the part where people participate).

Scope: Fortunately, most of the communities we contacted were very interested in our proposal, and they also wanted a better engagement tool for residents. However, different demands lead to different demand for tools in each neighborhood forum, including the expectation of better translation of text to lower the threshold for dissemination of draft neighborhood plans (Roman Road Forum), and public consultation on specific upcoming projects. Vote & Suggest (Lee Forum) etc.

CHAOTIC DEVELOPMENT

Ideally, neighbourhood planning should provide self-protection for local residents within the framework of policies. Within the framework of democratized decision-making, through neighborhood programs, people shape the future of their communities according to their own will. However, in the previous analysis and research, we found that the basic attributes and outcomes of urban development are not directly equivalent to the results of “excellent” neighborhood planning, and there is a huge gap in the content of the neighborhood plan development process between communities, which can be seen in the four scoring criteria of the neighborhood plan (green infrastructure, housing heritage, services and facilities, and commercial employment). At the same time, in the process of communication between the members of the various neighborhood forum organizations, the relevant personnel further showed us the inequalities and difficulties of neighborhood planning and development.

London’s Neighborhood Planning has been manipulated as a “Dummy” for a long time. On the one hand, the Government has delegated “services” to local authorities and regional communities, but it is often just a cost shift rather than a real dispersion of power and fiscal autonomy. On the other hand, due to differences in education, income, social background and other factors, neighborhood planning is not available to everyone. And a large number of people at the bottom have not yet participated. Even if someone were able to get involved, the consequence would be far from the same.

However, the true effectiveness of neighborhood planning cannot be simply defined by a single factor of wealth or poverty, education, or other factors, and inequality can be exacerbated or reduced by subtle interrelationships. Therefore, we have tried to summarize the factors and influencing factors that can play a role in neighborhood planning and proposed a dynamic input model. And by showing the problems and situations in different neighborhood planning stages to assist in demonstrating this dynamic model and understanding the development of inequalities in neighborhood planning.

Basic attributes (fixed attributes) influence to some extent the quantity and quality of the type of costs that can be invested. The quality and variety of the costs invested will influence the conversion rate of each action (dynamic input, consisting of three aspects: the amount of money the community invests in the project, the time it is willing to spend and the level of public participation). A forum with good basic attributes can afford to invest quality costs to achieve the desired results. A forum with poor basic attributes, on the other hand, has a limited quality and variety of costs to invest, and therefore the end result is a poorly protected and developed community. This ultimately determines the different development-preservation forms of the forum. Bridging the financial and technical gaps, saving time and increasing the level of community engagement is a potential way forward to bridge the existing Neighbourhood Planning without changing the basic attributes inherent in the community.

However, the inequality of neighborhood planning is more prominent due to the large disparities in the underlying attributes of different communities, and we will further demonstrate this issue based on interviews and reports at each neighborhood planning stage.

2.3 DIFFERENT ATTITUDES OF THE

OFFICIAL AND RECORDS

Building a strong relationship with the local council could be an opportunity. The third of neighborhood plans are in the borough, confirms Roger Winfield, chair of the Kentish Town Neighborhood Forum, who has been very helpful from his borhood planning’.[27]

THE BEGINNING OF THE DIFFICULTY

Support from the councils varied. Most members were negative about their relationship with the local council. This was mentioned by the chair of the LEE community when we spoke to her, and the Grove Park Forum fought against Lewisham Council for a considerable period of time. Stephen Kenny, Chair of the Grove Park Forum, said that Lewisham Council had prevented the Grove Park Forum from receiving an extra £50,000 to become a ‘front runner’ (A small number of forums received additional funding to be ‘frontrunners’ to encourage early designation) to encourage the designation of neighborhood forums and developments.[28]

The last type is the ‘Desert Area’, where the local council issues little or no information and advice on the neighborhood plan.

In the course of our interviews we further confirmed that the help given by different councils and local planning authorities is completely different. Even in a generally bureaucratic and lengthy process, the feedback from the Westminster area was most positive, whereas a Forum such as LEE, which spans two different Boroughs, Levisham and Greenwich, is quite difficult to receive active and prompt help from government departments.

if they are less enthusiastic about neighborhood planning. “The third type of municipality is the ‘Conforming Authorities’. The third type of municipality is the ‘Interventionist & resistant authorities’, which place additional hurdles and criteria on top of the normal application criteria for resident community groups, requiring them to provide information that goes well beyond the legally specified criteria.

As we mentioned in the previous chapters, we can see that the vast majority of Neighborhood Planning in the rest of England is made by established parish or town councils, whereas London has only one Queen’s Park Coummunity Council. small towns and villages have distinct boundaries, usually determined by the boundaries of the parish councils in the area. The designation of neighborhood planning areas is therefore relatively straightforward. In contrast, London is a large and complex urban area where ‘relevant bodies’ with common needs may simultaneously cross local authority boundaries in a dispersed and fluid manner, making neighborhood planning areas more difficult to form.

This difference can also be partly attributed to London’s local government structure, with the Borough nestled between the Neighborhood Forum and the Greater London Authority. This can create new challenges when forming neighborhood forums and boroughs, and in ongoing planned developments. The complexity of London’s communities means that in London, each borough will contain several different communities, and communities can often cross borough boundaries.[31]

In addition, the Neighborhood Area designation shows that in two areas, Marylebone and Pimlico, there are phenomena worthy of consideration. In these two areas we can clearly see a clear boundary created by the superimposition of different conditions. Marylebone and Pimlico, which should have been designated as a neighborhood as a whole, have been divided into the Marylebone neighborhood Area and the Church Street neighborhood Area, and the Pimlico neighborhood Area and the These less favourable areas were excluded from the “good” plan at the outset.

Councils are limited by funds and planning officers may not have the necessary knowledge.[29] Brian O’Donnell emphasized the importance of maintaining a strong relationship with forums in Camden. He explained that one reason for limited support from some Councils is that they often have limited resources themselves, with small planning policy teams, and that support they provide to neighbourhood planning draws resources away from other areas. Councils receive no dedicated funding for Neighbourhood Planning yet are liable for the costs of running referendums and examinations of the plans. In addition to limited funding, Stephen Kenny said, ‘planning committees do not have the knowledge. There needs to be an evidence based education for them so that they can make informed decisions especially after a general election when a planning committee member with absolutely no knowledge whatsoever about planning, is being led by an offi

The second type of municipality is known as ‘Conforming Authorities’, which provide ‘Conforming’ information about neighborhood planning on their websites, even officer whose mandate is about compensation…’

DIFFICULT TO BUILD THE COLLECTIVE

In the second phase of Neighborhood Planning, people also face different problems. London’s cultural and demographic diversity also provides significant challenges for Neighborhood Planning. Overall, London has a higher proportion of renters than the rest of the UK, which tends to result in a more transient population, making it more difficult for people to engage in plan-making that takes four or more years.[34]

However, it is worth noting that Neighborhood Forums have been designated and community plans completed in many different locations, both geographically and economically.

The difficulty of establishing NFs is also linked to the aforementioned level of support from the LPA, whose rejection of local NF proposals has led to the aspirations of an emerging forum being crushed at the first step, and these communities without established NFs are referred to as ‘orphan communities’. Orphan area designations are often the result of disputes between the forum and the designating body, or between local groups. A great deal of time and effort is wasted. In most of the above cases, it seems clear that the local authorities would like to see the designation rejected and that no neighbourhood plan should be implemented.[35]

Yet another complication is the reaction of an area to the creation of a forum in a neighborhood: “There are other forums in my ward, so we have to have one, don’t we?” It is therefore argued that the threat posed by neighbouring communities developing policies that may affect other districts has led to reactive action by neighbouring districts. Each designated community area can only generate one community plan and forum. The ability of the forum to cross the fi hampered by the fact that local authorities are placed in a difficult and time-consuming mediation role due to competing applications from different groups with overlapping geographical boundaries.[36]

It is reported that those interested in holding a neighborhood forum under the new system were clustered in the city centre, with 46% of people in the boroughs of Westminster and Camden expressing interest in setting up a community forum to date. Many reasons can explain this concentration of interest and activity. Boroughs that have historically had a large number of civic and amenity societies, and those with established experience of supporting these groups, may be better placed to respond to neighborhood planning applications.[37]

Evidence & Discussion

- Stage of Designation of Neighborhood Forum -

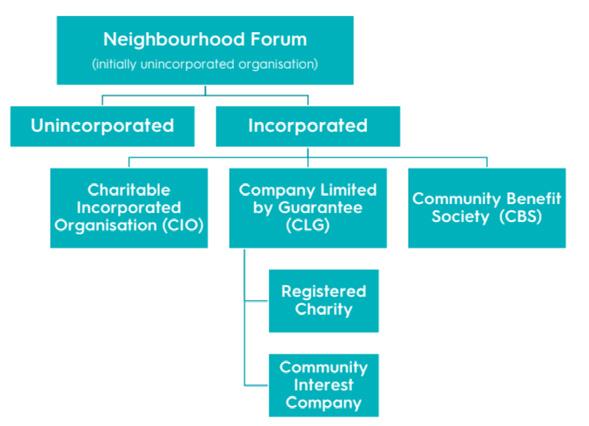

At the same time, it is important to have a clear and visionary constitution for the future maintenance of the forum at the time of the neighborhood forum designation. Choosing the right type of legal structure for the forum will also play an important role in the future use of community funds, the application of grants and the operation of the membership.

However, while the ‘average’ neighborhoods are still struggling to meet the basic requirements for a neighborhood forum, the ‘good’ neighborhoods have already made a fantastic start to the future of their neighborhoods. As we can see, in Belgravia, the committee members of the forum are the elite from all walks of life, whose work and place of residence undoubtedly places them at the very centre of power in the area, and who make the most of the potential diversity and capability of the neighborhood forum. In contrast, in the Crouch Hill and Hornsey Rise neighborhood Forum, the instability brought about by the initial membership and the constitution, along with the death of many of the area’s leading members after the epidemic, led to the complete stagnation of the entire forum and its dissolution

“Comparison of Neighborhood Forum Member and Basic Attributes”

ENGAGEMENT) ARE AFFECTED

In the early days of Neighborhood Planning, for the average neighborhood community. Lengthy and bureaucratic interactions with local planning authorities, occasional humanitarian help from technical members of local professional bodies and forums, allow site information to be professionally collected and fed back in years. For example, the Westbourne Neighborhood Forum, they are about to start a evidence-based review, but the information used is still a resident survey collected 5 years ago. In contrast, the “successful” Marylebone community hired professionals from different fields to identify problems in the region through the perfect use of Community Infrastructure Levy(CIL), efficiently and quickly achieving the desired results.

Only communities that are “trusted” by local agencies can get CIL amounts that can really help at any stage. The truth is, when you’re still being rejected or reducing the amount of CIL for a community meeting, other forums are already getting a large amount of CIL for

CONTROL OF RESOURCES AND POWER

Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) is a levy developed for new infrastructure to help address this need In most parts of England, local parishes can decide how they spend their money, and if they have a neighborhood plan they can get 25% up to 15%. If they don’t, they encourage parishes to develop a scheme levy part of which must be spent on the communities they collect.[39]

At the same time, however, the Community Infrastructure Levy arrangement remains a controversial issue locally, in some areas. As many local conservation areas do not have a CIL schedule, it does not benefit or act as an incentive for many community planning areas. Instead, in one case ‘too much’ money went to a community (by their own admission), even though the area was not obliged to accept it. Although there are some cases where CIL has provided significant amounts of money to communities, the vast majority of community questionnaire respondents (84%) indicated that CIL was either not an incentive or did not apply to their situation because they had not allocated land for development to generate CIL income.[40]

Planning Aid for London (PLA) said that some of the [Neighborhood Planning Applications] being undertaken in Camden could take up to three years and that it would cost between £80,000 and £100,000 to produce them.[41] At the end of the process, a referendum would be held - a Queen’s Park Parish Council referendum, the size of a community, at a cost of £23,000 Cost implications are significant. If all the community forums were to reach the final stage, plus the cost of salaries for “at least a small number of planners” over the next few years, Westminster alone would face a referendum bill of £500,000. So funding is very limited.[42]

Funding conditions are too rigid, and availability of additional funding is variable. Jane Briginshaw said the new criteria made it harder to secure grant funding, ‘Because of this new business about what you can spend it on, we have to contort ourselves.[43] Some forums also successfully secured funding beyond the government grants (between £9,000 and £17,000). For example, the Greater Carpenters forum secured grants from Trust for London, Loretta Lees, London Tenants Federation and UCL’s Engineering Exchange.[44] However, availability of additional funding can vary, and the process of seeking it can be time consuming. Jane Briginshaw had ten meetings with Wandsworth Council to seek the 2,000 shortfall that her forum needed but had no success.[45]

SIMILAR CONTENT DOES NOT REPRESENT THE SAME FUTURE

The Neighborhood Plans of the different forums reflect different levels of protection and self-development.

1. Lee’s plan is more idealistic in that it identifies the specific roadways and locations that it wants to enhance and provides solutions, which is more targeted and has a more realistic and effective protection; and it has already started the design of the first development project.

2. In contrast, the Highgate plan only specifies a general area and sets out development restrictions, without specific proposals for specific sites and areas.

3. Roman road has a specific development policy and project plan, but no funding to bring it to fruition.

DISCUSS POTENTIAL AND THE FUTURE

Through a longitudinal study of the entire process of neighborhood planning, as well as a horizontal comparison of the basic attributes and dynamic inputs between neighborhood forums at the same stage. We have a deeper understanding and appreciation of how neighborhood planning, so-called “new power of the people,” continues to exacerbate inequalities in urban development. As mentioned earlier in this section, in the process of developing neighborhood planning, the key factors that determine the ultimate quality of neighborhood planning are the basic properties of the place and the dynamic input. Communities with high social status, more power and resources, and highly educated residents have easy access to financial and technical support from governments and institutions. Conversely, marginalized community groups with few resources and incomes struggle to exercise what is known as the “right to bottom-up development”.

In a situation where innate local fundamentals cannot be easily changed, the time cost spent, the level of community engagement, and the amount of funding and technical support obtained are the only potential research directions that can reduce the obstacles that disadvantaged communities encounter in exercising power and chasing their dreams.

In the following chapters, we will give our views and suggestions on how to improve the results of neighborhood planning.

2.4 THE DESIRED OBJECTIVES

The goal is to focus on the future of communities that can help the weak and small with different underlying attributes and to continue to develop indigenous bottom-up communities efficiently and freely. Time, funding technology and community engagement related issues are the most direct and effective help. We have gradually summarized the following main tasks:

Objective 1. How to convert professional and complex planning information into a simple and easy-to-understand form for non-professional auditors in NF through a certain platform or facility, so that they can be more autonomous without the frequent help of LPA officials review these data.

Objective 2. How to convert the simple results of discussions between NF and the masses into professional and complex planning information through a certain platform or facility to LPA’s technical support staff, so that they can have more confidence that the community can produce effective and correct planning solutions.

Objective 3. How to use a certain platform so that the final generated NP can be converted into a version that is easier to understand, so that people who participate in voting can truly understand the future of the community, and at the same time allow more people to participate.

Objective 4. How to reduce the information gap between community residents with different majors, different sources, different education levels and other factors by some means, so that more people can fully and suggestively understand the power they have, and at the same time obtain Wanted information about NP.

Objective 5. How to attract those special groups that are important in the community but generally difficult to cooperate with through a certain software or platform to better communicate with NF

Objective 6, How to let more people understand and participate in neighborhood planning, further expose and expose the inequalities in the development of existing planning, so that people can consciously understand the gaps between small and weak individuals and regions.

Objective 7, How to modify and strengthen the existing neighborhood planning organizational structure from the institutional framework and find a new sustainable development structure.

Therefore, to alleviate these situations, we defined the most important objectives, which is “How to enable people from different backgrounds to fully understand individual rights and the forms of their application within the complex professional legal and planning framework, to be able to identify and assemble groups with the same needs and interests, to master the framework of neighborhood planning the and ability to realize the collective vision within. “

After summarizing the documents and framework of neighborhood planning, we made a roadmap that detailed the process of neighborhood planning so that people can clearly find the corresponding steps and structures.

3.2

SECOND LAYER FOR SIMPLIFYING COMPLEX LEGISLATION

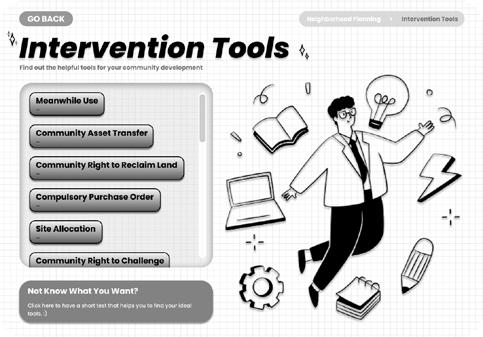

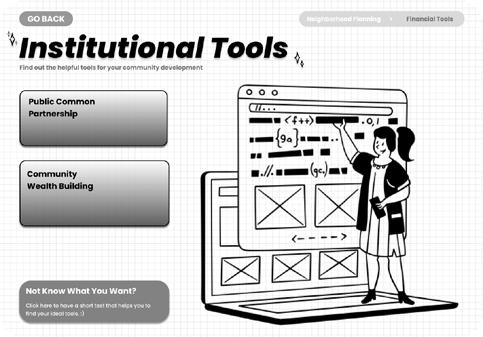

Based on the roadmap and other research, we use the Figma platform first developed a “Neighborhood Planning Encyclopedia” to categorize, organize, generalize and recompile all the complex information about neighborhood planning. Through a more convenient and repeatable interactive interface, residents can clearly understand the detailed process within the neighborhood planning framework, the corresponding application forms and technical support, laws and legislation and other effective tools.

At the same time, for minority groups, finding legislation and tools to address demands may be far more effective than engaging in lengthy neighborhood plans. Therefore, they can be quickly located on the page of tools that may be applicable through a simple questionnaire.

For different types of users, we roughly divide the home page into three sections.

The first is “non-professionals,” which primarily serve residents who may know a part of neighborhood planning and have been involved. Those with an understanding of the basics of neighborhood planning can learn more details about NF and NA on the left side of the home page.

The second is “professionals”. In this section, members of the neighborhood forum or relatively professional community members who are very familiar with the internal planning process of the community can easily find information about any stage of neighborhood planning, and get effective and fast help without having to read and search repeatedly tedious planning details.

Finally, there is the “rookies” section, located at the bottom right of the homepage, for residents who are completely ignorant of neighborhood planning and community development. As long as they have community-related needs, they can simply go through a few questionnaires to locate the tools they might need without having to go through the whole tedious details of neighborhood planning.

PROFESSIONALS

In the “Professionals” section, you can first view the details of each step of the neighborhood planning, such as the “Evidence Base” shown on the right. The encyclopedia will explain to you why you need to build an evidence base and its main content constitute. Each subdivision icon can be entered to explore more details. It is important to establish a complete and comprehensive “Evidence Base” in the early stages of neighborhood planning.

At the same time, according to the categories of tools and regulations, we have divided them into four major categories: “Intervention, Protection, Institutional & Financial Tools”, and you can find tools that can help you according to your needs.

NONPROFESSIONALS

For people who are “Non-professionals” but have a certain understanding of neighborhood planning, the establishment of Neighborhood Areas and the formation of Forum Constitution are very important.

Building a long-term, sustainable and diverse forum structure is quite beneficial to the maintenance and community development of the later forum. From here, they can learn how to become or discover a “contributing” community member.

ROOKIES

For those “Rookies”, being able to quickly and easily locate or understand the tools that can solve the problem is most important, and learning the overall content of neighborhood planning and other tedious knowledge is secondary to them. Therefore, they can use this “Magic Quick Questionare” to enter the target tool page by analyzing and classifying their initial intention, ownership and usage status of the target item.

For example, the process on the right shows a scenario:

After the epidemic, many shops in the community are vacant. There is a minority group who have always wanted a venue where they can showcase their community’s cultural and ethnic art, but they didn’t know how to meet this need, so they targeted “Meanwhile Use” by using our “Magic Quick Questionnaire”, that tool might meet their needs.

“Meanwhile Space” the use of temporary contracts that allow community groups, small businesses or individuals to move into these vacant spaces and set up shop, on the understanding that they will leave within an allotted time.

In 2009, the first central government programme on meanwhile use. It describes a process of “intelligent use of unproductive empty buildings and underused land”; a process which bolsters local liveability by fostering business innovation and experimentation. “Meanwhile Space” approach is distinct in its ethos, in that it encourages low-cost community investment by providing access to cheap floorspace for local small businesses, community care projects and start-ups.

You can start “Meanwhile Use” when you find any of the following elements within the community:

1. Underused Spaces within your community;

2. Certain demands from collective or even individual.

“Meanwhile Use” unlocks underused space for the benefit of community cohesion, placemaking and enterprise. This is typified by finding wasted space, transforming unloved visible, interesting, dilapidated, difficult buildings, into something useful. Beneficiaries include seed and startup development stage businesses that require affordable space with flexible terms and support to thrive (or fail).

Ebury Edge is a temporary work and community space at the heart of Westminster designed in collaboration with Jan Kattein Architects, combining affordable workspace and retail units with a café, a community hall and a public courtyard.

As part of the Ebury Bridge Estate redevelopment, which will see 781 new homes created and existing housing blocks retrofitted just south of London Victoria, Westminster City Council (WCC) was keen to provide the local community with an immediate sign of regeneration.

The project sets a precedent by embracing the creative potential of the regeneration process. By bringing community amenities to the Estate in advance of long-term redevelopment, the scheme provides residents with valuable social spaces to meet and the infrastructure to facilitate local business. The design and consultation approach has resulted in a striking appearance, reflecting residents’ wishes to invite communities old and new into the renewed Estate.

3.3 DETAILED

INTERFACE

For example, they may find that “Meanwhile Use”, a tool for shortterm use of the underutilized space of the community, can meet their needs very well. Through the Neighborhood Planning Encyclopedia, users can quickly understand the specific concepts and legal support of the tool, when it can be used, the ways and experiences of different groups of people, find relevant technical guidance and financial help, and at the same time can access similar legislation and tools to understand and tell the difference.

4.1 THE ULTIMATE FORM OF

Educational Techniqual

Among all the knowledge collected and organized on “local development planning,” we have selected three types of knowledge that “ordinary” community residents need to frame in the introductory stage:

Recreational

To add interest, we have selected and combined various systems from different games, including:

Considering the difficulty of getting started with the game and the player’s ability to play, we have selected appropriate technologies to assist in helping players

understand the gameplay and develop relevant knowledge faster. Techniques include.

Finger Tracking

1. Basic urban knowledge; 2. Developmentrelated knowledge; 3. Planning policies and tools.

This knowledge is simplified and integrated into our game board, skill cards, and game rules.

1v1 matchmaking mode in Risk; each plot uses a numerical size comparison to make it easier for players to calculate. ②

Numeral Calculating Project Mapping

Random card selection mode in Auto Chess to reduce players’ over-decision in card selection.

DUMMY CITY

Two players meet in a grid of urban plots of different uses. The objective is to re-develop as many plots as possible for your camp.

A single development is successful if you arrive at the end of the process having accumulated enough “effort points”. You can take actions by spending your budget consolidating your developments, investing in new areas or undermining your opponent’s strategy by “buying away” their “effort points”.

Spread too thinly and you risk systemic failure….. Focus too much and you will be surrounded….

The Economy and Employment typology represents the community’s solid aspirations for retail, commercial centers, entertainment and recreation, economic transformation, and employment. The Services and Amenities type includes, but is not limited to, providing in the community issues such as health care facilities, senior-friendly services, children’s play spaces, education, and community safety controls

The Housing and Heritage type represents residents’ aspirations for goals such as affordable housing, community benefit housing, community cultural heritage, and architectural style

INTERFERENCE

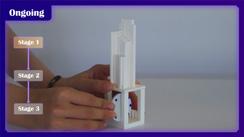

In reality, there is a process for both developers and community to obtain “ownership” of a “New” building. The game will be simplified as follows: stage1: application; stage2: complementary documents; stage3: settlement. Stage1

SIMPLIFY

SKILL CARDS CLASSIFICATION

Real people in real communities need help with money and time: to save time in the application process or to have more money to move forward with development. So our skills work around the elements of “money” and “time,” matching real-world policies and tools into the game.

SKILL CARDS CLASSIFICATION BY REALITY

COMMUNITY

The effects of developer skills all correspond to realistic development (behaviors) consequences that developers may have and the impact that behaviors have on communities. Players can learn from them which actions of real developers affect the community and make more rational community development decisions

When the game skill cards correspond to realistic policies and tools, they are divided by the type of help provided. impact.

When the game skill card corresponds to the impact real developers bring to the community, it is divided by the type of

be less exploited and plundered by foreign developers, it can also allow more residents to realize their common aspirations, and it can also build a better living land for the next generation.

Community Infrastructure Levy, which has been largely unknown to the general public, is one of the biggest sources of income for residents to fight against bad developers. In richer areas, the CIL brought by development projects is correspondingly higher, and residents in ordinary or poor areas should learn and understand the mechanism of CIL more so that they can change this situation with collective power, allowing developers to The compensation mechanism can also give back to these regions.

Local Green Space designation is for use in Local Plans or Neighbourhood Plans. These plans can identify on a map (‘designate’) green areas for special protection. Anyone who wants an area to be designated as Local Green Space should contact the local planning authority about the contents of its local plan or get involved in neighbourhood planning. With it, developers can’t easily destroy the natural environment of the community

With it, developers can’t easily destroy the natural environment of the community

The Community Infrastructure Levy (the ‘levy’) is a charge which can be levied by local authorities on new development in their area. It is an important tool for local authorities to use to help them deliver the infrastructure needed to support development in their area.

Most new development which creates net additional floor space of 100 square metres or more, or creates a new dwelling, is potentially liable for the levy.

Site Allocation can be an important tool in neighborhood planning to determine the future of your community, you can use it to change the land use type of a lot of land, and you can also use it to fend off developers and prevent the spread of bad development projects.

After you have established various “anchor institutions” using public land in the community, by implementing plural ownership of the economy, progressive procurement of goods and services, etc., the community funds and interests are completely retained and circulated within the community. This sound financial cycle can help the community build better development through cooperation with CIL.

Community Asset Transfer (CAT) is a process that allows community organizations to take over publicly owned land or buildings in a way that recognizes the public benefit the transfer will bring. The Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act defines the legal process for the transfer of assets, empowers communities with new rights and gives public bodies responsibilities.

CAT can be implemented in a number of different ways depending on the community’s requirements - a transfer of ownership of full ownership, the use of long-term leases, or a de facto management agreement.

MEETING,

SCAN

Council tenants are being forced out of their homes due to estate renewal, welfare reforms, poverty, and the precarity of low-income work. Social cleansing can be understood as a geographical project made up of processes, practices, and policies designed to remove council estate residents from space and place, what we call a ‘new accumulative form of (state-led) gentrification’. Local governments are their accomplices.

be fooled by designers.

The gentrification process is typically the result of increasing attraction to an area by people with higher incomes spilling over from neighboring cities, towns, or neighborhoods.

Further steps are increased investments in a community and the related infrastructure by real estate development businesses, local government, or community activists and resulting in economic development, the increased attraction of business, and lower crime rates. In addition to these potential benefits, gentrification can lead to population migration and displacement.

If you can’t afford it, you have to move.

5.1 ITERATIONS

RESPONDING TO SOCIAL

ISSUES

wanted to expose the fact that neighborhood planning is unequal to the public. The effects of Gentrification in poor neighborhoods, such as rising house prices and prices, are driving people away from their homes. But in affluent eager for land appreciation and increased commercialization to bring more wealth accumulation. After in-depth communication with the Marylebone Neighborhood Forum, we found that wealthy people have completely difthan ordinary communities, so we came up with a bold cation in the region, revealing these inequalities through this irony.

Edgware road.During the epidemic period, a large number of shops were vacant. We want to use “Meanwhile such as fashion pop-up stores, artist exhibition halls, etc., to awaken the vitality of the community and enhance the commercial value of Marylebone.

In talking to Marylebone we found that one of the big problems they had was that the community was so large and each person had their own opinion, which was difficult to unify and record, so we started with an interactive map where people could enter their postcode to get their location and comment on the existing environment in the community and upload photos. This helps the community to better collect people’s opinions and allows people to see what others have to say about the community.

We then analysed the site factors of the community and expressed what we thought were the problems in this site and the corresponding solutions in the form of façade materials, allowing people to design the façade by simply dragging their fingers through the materials to the different components of the façade. At the same time, the top left corner provides real-time feedback on how people have mitigated various environmental problems in the com-munity, such as noise and air pollution, by combining different materials.

Through our design, people can design any façade they want and post it to the forum for a referendum, with the highest number of votes participating in the actual construction. It will also meet the needs of the Marylebone community for a vibrant and unused space through wall painting.

If we are obsessed with improving the aesthetics and sustainability of the façade, the design of the façade will drive up the value of the building and cause the price of the building to skyrocket, in which case the owner or developer will inevitably charge more for the occupants/tenants and the scheme will become a capital tool, which is not our intention.

But in the process of thinking about this may cause gentrification, we found that for wealthy classes and regions, rising house prices and a more gorgeous and glorious atmosphere are acceptable and even pursued, which has to let us go further through this idea. Satire and exposé of neighborhood planning look completely different in the hands of different groups.

In the end, we still wanted to choose a positive entry point to help London’s neighbourhood planning, so we dropped this option.

5.2 ITERATIONS

A POSITIVE RESPONSE TO SOCIAL ISSUES

When the study was repeated in May 2021, the vacancy rate had risen by 16%, although some of

9% in January 2021 to 17% in May 2021.

So we started by designing an interactive map

the community to better gather people’s opinions and allows people to see what others have to say more about the community, such as building owners, developers, realtors, etc. After submitting their opinions about the community, we provided an interface for people to enter their needs and sort them, which allowed us to keep a good record of what people wanted and to further process and visualise the data. After people initially enter their postcode, they are shown their location on the interface and we process the data to show the nearest 1-2 simultaneously used spaces that their needs correspond to. After processing the data, we match the different demands for simultaneous space use, and the demands near the simultaneous space use are ranked according to the number of people providing those demands to prioritise the demands.

At the same time, we analyse the data of this community space in the backend of the system and express what we consider to be the problems of this space and the corresponding solutions in a game-like way. If people choose these needs, the character they control is rewarded with an attack, indicating that their need is exactly the solution to the community’s current problem. Along with the visualisation of the data, we matched the number of demands people had, and the more people with the same demand, the stronger the weapon durability of the game character, indicating more demand.

Different numbers of needs correspond to different weapon durability levels.

Once you have completed the attack power and weapon durability of the game character, it is time for the ene-mies. The enemies of people’s demands are undoubtedly the site factors that prevent people from fulfilling their needs, such as the developer’s plans, the history of the building, etc... These are translated into the life points (HP) of the monstersOnce people have chosen their needs and got their weapons, then the battle begins. Every time the charac-ter attacks, the weapon’s durability is reduced and the monster’s life is reduced. When the character’s weapon durability is 0, if the monster has not been defeated, then one’s needs may not be a good solution to these block-ing conditions, indicating that one’s needs are not well adapted to the field. At this point people can try another demand and start fighting again.When the monster is dead and the character’s durability is not yet 0, this indicates that people’s needs far out-weigh the organisational factors, suggesting that people’s needs are very well adapted to the field, which can give landlords and developers a better idea of the opportunities to make money - after all, a lot of demand means a lot of revenue.And when the monster dies and the character’s weapon durability approaches 0, it shows that people’s demand can be adapted to the field, but it is not necessarily the best choice, and people can try again with other weapons to learn the most suitable demand conditions that are really adapted to the field.

After designing the game, we reflected on it and found it to be immature and lacking in many areas.

1 Adults are not always willing to play the game to achieve the effect we want, which might be possible if it were children.

2 People should be decisive in their needs and trying to change them through play is not the best way to do it.

3 Not well thought out for developers and owners of meanwhile use space. It is risky. Once the leased site is irreplaceable in the community, it will change from short-term to long-term use, which is not in the interests of developers and landlords

But we gradually started to focus our research on user needs, and we started to explore an interesting way to document the real needs of users.

Subsequently, we tried to start from a more general point of view, without explicitly restricting Local Context and Site-Specific. Attempt to bring into the game the developers who are causing many problems in urban development as a confrontational target. At the same time, the four types of neighborhood planning plans analyzed in Chapter 1 & 2 are also integrated into the game. By recombining the real land use, the urban development projects corresponding to these four types are mixed and dispersed into the four types of land use. Looking forward to getting the “real needs” of players after the game, at the same time through various “intervention” and “protection” skills to let players know more about the tools and regulations of neighborhood planning.

GAME PLAY

This is a strategy game similar to The Plague Company. Developers will wantonly construct within your community. When the development comes, the prices are likely go up, therefore, the happiness index for those who living there will go down. Developers will continue to infect and multiply until all community benefits are fully exploited.

But at the same time, in a certain type of land, they will bring funds proportionate to increase land value, this will add up a small amount of money into your community wallet.

So you have to expect them to randomly come to areas with higher yields and less diffusion effects. The game is a balance between those happiness indexes and money till you die.

Some of the process behind the game will be linked to effective planning items. for instance, obtaining money from development can be associated with Section 106 or Community Infrastructure Levy.

We pixelate and remap the landuse of different Neighborhood Areas into several 15*15 city grids, these forums represent different game difficulties, land type proportions, corresponding initial funds, and residents’ happiness index.

You need to survive from the erosion of developers within the five-year period of a neighborhood plan, by using protective tools to buffer and reduce immediate gentrification from developers. At the same time, the ongoing impact from developers is cleaned up and mitigated with intervention tools.

For example, spend a small amount of community funds to use the “Meanwhile Use” tool to perform activities that meet the community’s expectations, so as to get a small amount of happiness index, and briefly pause the continuous impact of the area for a few rounds to get a chance to breathe.

We found that the game was unbalanced in terms of fairness, that the developer first would greatly reduce the community win rate, that users would need to keep track of predicting future developments while knowing the rules of the space, and that it would also take a lot of mental effort to learn the card skills. This, combined with the number of dynamic variables on the field (spread, turns, blood, money), makes it very difficult and time-consuming to play, taking around an hour to play a game. Finally, the test results tell us that the playability is not very high either.

But it built the basic game framework for our follow-up “dummy city”. After two or three small game mechanics adjustments and modifications, our final “Dummy City” was born.

First of all, in our previous presentation and the

game, the developers have always been relatively evil characters in the process of Neighborhood Planning. Because we hope that through this game experience, players and audiences can more deeply understand the social impact and tragedies hidden behind the development, and learn how to deal with them.

However, in real life, there are also great developers who work for the benefit of the community. Therefore, we consider adding third-party players in subsequent game versions that can help the community fight against evil developers, so that players can understand and learn the various abilities and potentials of developers from multiple dimensions.

5.4

FUTURE PLANS

After the final presentation, we can still continue to develop and upgrade our “Dummy City” to further explore the possibilities in terms of game mechanics, social impact, customization, randomness, rationality, entertainment and education. Improve existing rules, further reduce game time, and allow residents of more age groups to participate. At the same time, making physical games more portable can expand more users.

Secondly the next iteration of the game is able to be customised by different local contexts.

For example, in Lee or Roman Road Bow Neighborhood Area, each unique landuse type and spatial form will greatly change the player’s decision-making.

At the same time, the rule Section 1o6 will be significantly different from those in wealthy Neighborhood Areas like Marylebone.

And the initial ‘Effort Points’ for developers and communities will vary accordingly, etc.

In addition, from a long-term perspective, we are also developing an online version of the game, hoping it will be able to function as a wider range of specific “Decision Making” data collection and user analysis for different local contexts.

The last one, in order to further improve user engagement and randomness of immersive gaming experience, as well as alerting the public to the climate crisis and various social issues.

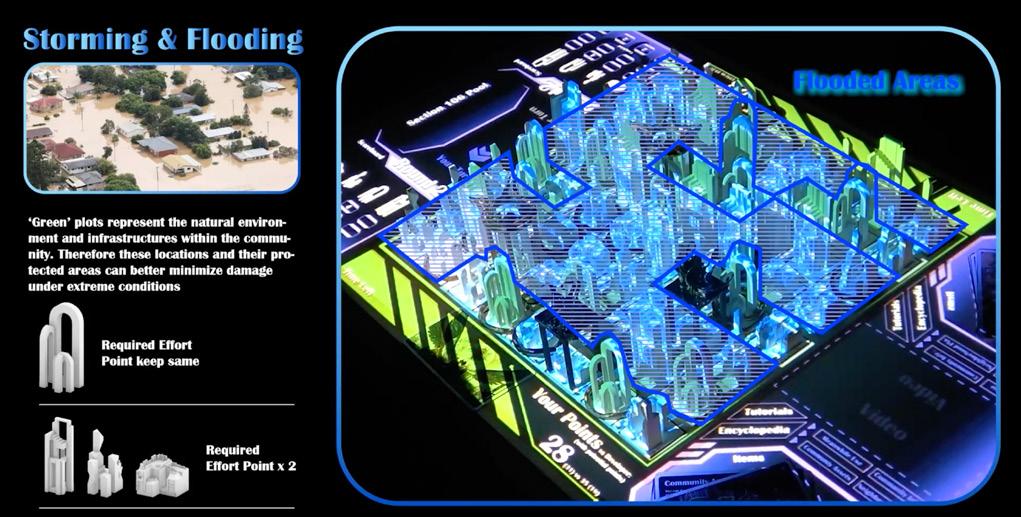

We will randomly project emergencies such as floods, droughts, wars, etc. on the chessboard. The corresponding area will then change the rules of the game, and the game results and player experience will be further complicated and entertaining.

Finally, we will randomly trigger extreme climate and social events in each Game Round. For example, in extreme weather such as storming and floods, the rules of only Green Plots and its surrounding area will not be affected, and the difficulty of developing the remaining areas on the game board will be doubled. We aim to raise public awareness of the climate crisis and various social issues by those different random events in a more immersive engagement experience.

That’s all of our team’s research on unequal so-called bottom-up Neighborhood Planning as “Dummy” at this stage. In an ideal world, people are truly empowered to build their homes in more democratic and creative ways that will bring a better future to their communities. But by analysing the differences in the political power structure between London and the rest of the UK, and comparing and analyzing horizontal data from existing forums in London, it is clear that the “better future” originally envisioned by neighbourhood planning has not been realized, or not for all. It is still unable to shake off the social shackles of social hierarchy, education level, income between rich and poor, and nd a fulcrum that can lift these heavy shackles, and try to explore feasible solutions that can increase community participation awake the awareness of effort(time, technology and capital costs) and educate the public through the combined use of our board game “Dummy City”

and “Neighborhood Planning Encyclopedia”.

In the final part of this Booklet, we have also listed a few more ideas for Neighborhood Planning. And at the same time, we have produced, edited, and collated the text content of the “Neighborhood Planning Encyclopedia” for non-professionals and people who want to have a deeper understanding of Neighborhood Planning, aiming to help everyone.

CHANGE - ‘NEW NEIGHBOURHOOD PLANNING +’

Central government has been hoarding and centralizing power in the areas of planning and construction for a long time. A range of economic exploitation, racial inequality, gentrification, social cleansing and the climate crisis have affected people’s lives through profit-oriented extractive development in partnership with external developers. The impact of social security cuts, housing market pressures and reduced funding for local government has forced the state to throw more responsibility back on local government, expecting people to solve problems through their own democratic cooperation and participation. On an ideal level, the Localism Act 2011, through Neighborhood Planning, empowers residents to develop the future potential of their own communities from the bottom up and to take ownership of their own needs. On the one hand, it sets a new policy framework for unscrupulous developers through the Neighborhood Plan, and on the other hand, through the Neighborhood Development Order, it empowers the community

However, from another point of view, differences in factors such as education, income, and social background lead to community planning that is not available to all, and a large number of people at the bottom are not yet involved, which may help exacerbate inequality. Studies have shown that the rise in homelessness in the UK after Localism Act 2011 illustrates the disadvantage of localist policymaking to marginalized groups in society.[46] On the other hand, the state has delegated “services” to municipalities and nancial autonomy, that is, responsibility is decentralized, not money for the performance of its duties.[47] In the absence of sufficiently sustainable financial and technical support, existing neighborhood planning organizations have too many responsibilities while volunteering; long bureaucratic interactions with local planning departments make it impossible to get really effective help for Neighborhood Plans; even nancial resources and official support, all the content written in community plans can only be the beautiful fantasies of the people of the region, once returning to the traditional Public Private Partnership development model, External developers can still use their wealth of experience to squeeze benefits from within the community. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the potential tools for autonomous development within community planning, and this essay will discuss a more radical combination of development models, New NP+ formed by Neighborhood Planning, Community Wealth Building and Public

Common Partnership, to create the ideology and local development of true democratic autonomy that follows.

The Community Wealth Building(CWB) model has excellent potential in terms of the scale of development of a local region and the structural and systemic support for the economic aspects of neighborhood planning. Emergencies such as the covid-19 epidemic and climate crisis have, in different ways, exposed the fundamental dysfunction of the UK national and local economy and the failure of the existing economic system to deliver economic, environmental and social justice for the planet, people and places.[48] In recent years power and responsibility for economic development in the UK has been shifting from local authorities to local enterprise partnerships, with speculative development further exacerbating regional gentrification and locally entrenched systemic poverty and deprivation. CWB is an effective tool for changing this situation at the local level and achieving social and economic justice. Rather than pursuing “Growth at all costs,” it seeks to adjust the makeup of the local economy itself so that wealth is widely held, shared, and democratized. The CWB attempts to shift the direction of local economies from “wealth extraction” to “community common wealth building”; from “environmental extraction” to “environmental management”; from “financialized and high-growth sectors” to “real economy and everyday economy”; from “productivity” to “satisfactory employ-

Advice & Ideas Other Than Tools Introduced Above

On the other hand, Public Common Partnership (PCP) helps neighborhood planning opening up new possibilities in terms of how infrastructure and public service projects can be developed. A popular tool that is now used worldwide for infrastructure and public services such as transport, water and sewerage, energy, environmental protection and public health is the Public-Private Partnership (PPP) (Fig.1).[53] However, the controversy surrounding the privatization of community project assets by private developers is also ongoing, and the accumulation of wealth by a few does not change the inequality within communities. At the same time, PPPs require collaboration to work, but the most important goal of PPP projects is often to achieve coordination, coherence and co-production, rather than consensus on decision-making.[35] Collective decision-making is secondary in PPPs, which further exacerbates the conflict between community infrastructure projects developed by large companies and local interests and demands. For example, the Haringey Development Vehicle programme, which has been cancelled, involves £2 billion worth of social assets to be transferred. The proposed redevelopment plan by private developer Lendlease would demolish 1,400 council houses from 7 estates and replace them with luxury developments and so-called ‘affordable’ houses. There is no doubt that once this PPP project is implemented, a new round of social cleansing and gentrification will hurt the people of Haringey.

From a fair and justice perspective, the UK’s economic transformation and local economic green recovery focus around ownership, control, democracy, participation and green transformation.[55] Thus, the Public Common Partnership offers a new possibility. PCP offers an alternative institutional design that frees us from the simple market-state dualism. Instead, they involve shared ownership between local authorities and civilian organizations, as well as shared governance with specific stakeholders in the project.[56] As one of the core elements of the socialist change project, PCP not only affected the direct redistribution of wealth and power, but also had a positive impact on the development of collective autonomy and the decommodification of daily life. By developing distributed forms of governance, people at the bottom can be fundamentally closer to the decisions that concern them. The ability of national governments to shape the social and collective environment is no longer too strong and centralized, and this power is decentralized and distributed outward to more ordinary people. Through this new form, urban dwellers can become collective decision-makers, moving away from simply being coerced by oligarchs and politicians as consumers or voters.[57] In a way, this is very similar to Localism Act 2011 and the ideal of neighborhood planning to empower people.

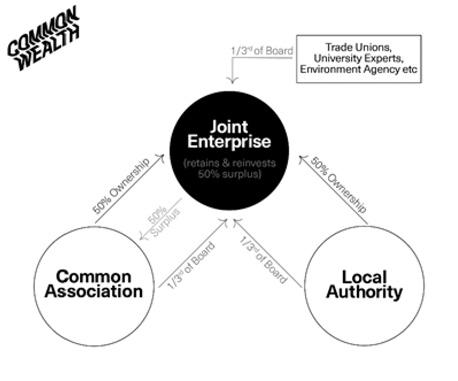

The first principle is the Joint Enterprise (Fig.2), in which the state agent (e.g. local councils) and the common associations (e.g. mixed cooperatives or community interest companies) are the principal members. They support, collaborate, co-manage and own a community asset with the organizations (e.g. trade unions, environmental agencies, tenant groups and specialist groups) that run the PCP project. At the same time, each shareholder member has only a single vote, regardless of the number of shares they own and the background they come from. The second principle is ‘distributed democratic control of surplus value’, whereby when a PCP project is formally operational, the profits accumulated through earnings are retained by the Joint Enterprise and are under the collective control of the board of directors. It can then go on to develop the next self-expanding circuit of democratic governance based on new community assets, achieving a virtuous circle of communalisation and democratic ownership. (Fig.3) Most importantly, the primary use of any surplus managed by the Joint Enterprise is to capitalise other PCP projects without expectation of financial return. Projects with clear profit potential, such as energy, water, housing and transport infrastructure, are excellent starting points for PCPs, and thus continue to drive new PCP circuits.

Most importantly, the primary use of any surplus managed by the Joint Enterprise is to capitalise other PCP projects without expectation of financial return. Projects with clear profit potential, such as energy, water, housing and transport infrastructure, are excellent starting points for PCPs, and thus continue to drive new PCP circuits.[58]

With the designation of the Neighborhood Forum, it inherently has the ability to become an agent of the state (as a legitimate owner of public assets) and a common association as mentioned above. We can see that the con-

uential institutions and groups. Local organizations such as schools, t of this spending to the local economy is limited.[50] They can have a huge positive impact on the region by commissioning and buying goods and services within the community, through their workforce and employability and

ment”; from “supporting private enterprises” to “supporting democratic economies”, and so on. [49] The key is the ‘anchor’ institution, for running the CWB by identifying and bringing together local influential hospitals, local authorities, clubs, etc. spend millions of pounds each year on goods and services, but the additional benefit through creative use of local facilities and land assets.[51]

From the outset, the ‘anchor’ led approach has provided utility to justice movements. For example, a central aspect of the Cleveland Model in the US is the use of procurement and spending of an anchor institution to provide financial support for the green cooperative movement. A large worker-owned and community-gain enterprise model, worker ts localized for mutual benefit.[52] By creating multiple ownership of the economy, local employee ownership results in decisions being made for the benefit of the local community rather than going ts being reinvested in the community, local employment or distributed as dividends to each ordinary member. CWB is going to influence key sectors such as local planning, capital investment, energy, transport and housing, and within this, planning and capital investment, as common ve core principles of ‘Progressive Procurement of Goods and Services’, ‘Making Financial Power Work for Local Places’ and ‘Fair Employment and Just Labor Markets’. A better solution to one of the most significant problems faced by community forums when undertaking community planning, the lack of sufficient funding for the development and maintenance of the actual projects in the community plan. The progressive procurement of contracts for community planning projects into smaller bids has facilitated the participation of local small and ts within the community. At the same time, by Making Financial Power Work for Local Places ‘, certain neighborhood planning projects with public investment value allow local authorities and competent anchor institutions to establish cooperative investment funds or local banks, for example using regional pension funds to invest in local public services and

cooperatives, supply local institutions, such as hospitals, councils and universities, that are jointly owned and operated by their members to keep profits into the pockets of external shareholders and investors, with profits areas of community planning, allow CWB to play a considerable role in helping Neighborhood Planning to thrive. Through the CWB’s three of five medium-sized engineering enterprises, the third sector, cooperatives and social enterprises, both to minimize construction costs and to keep development profits infrastructure.