9 minute read

Il mistero dell’anguilla The mistery of the eel

Il mistero dell’anguilla

Le ricerche di un gruppo di studiosi spagnoli hanno recentemente confermato le conoscenze sul ciclo biologico di questo singolare pesce, che tuttavia presenta ancora aspetti ignoti ai ricercatori. Mentre a Cesenatico (Fc) hanno avuto successo le esperienze di riproduzione e di svezzamento delle larve in cattività The mystery of the eel Work by a group of Spanish scientists has recently confirmed much of what was already known about the biological cycle of this unique fish, but there are still blanks waiting to be filled in. Meanwhile in Cesenatico, on the Adriatic coast, researchers have managed to breed and raise larvae successfully in captivity by ALESSANDRO AMADEI

Advertisement

Un animale misterioso,

l’anguilla europea. Per lunghi secoli filosofi, zoologi e studiosi di varia estrazione si sono interrogati sulla sua natura, apparentemente ibrida tra quella di un organismo marino e quella di un rettile, e soprattutto in che modo e in quali luoghi si riproducesse questo singolare pesce. Tra i tanti nomi illustri ricordiamo Aristotele e Plinio il Vecchio, e in tempi più recenti anche un certo Sigmund Freud, che all’età di 19 anni fu inviato alla stazione Zoologica di Trieste alla ricerca degli organi riproduttivi di alcuni esemplari di genere maschile. Fu soltanto negli anni ’20 del secolo scorso che il naturalista danese Johannes Schmidt, dopo lunghe peregrinazioni con navi oceanografiche, diede un fondamentale contributo alla conoscenza del ciclo biologico dell’anguilla: gli esemplari adulti si riproducono nelle profondità del mare dei Sargassi, a nord est delle coste della Florida. Di qui inizia l’avventura: dalle uova si schiudono le larve, che lentamente assumono una forma appiattita, simile alla

Team vincente

Oliviero Mordenti, ricercatore del Dipartimento di Scienze Veterinarie dell’Università di Bologna e responsabile del Progetto anguilla

Winning team

Oliviero Mordenti, researcher at the Department of Veterinary Sciences of the University of Bologna, who heads the eel project

A mysterious creature,

the European eel. For centuries philosophers, zoologists and scholars of various extraction have pondered its nature, apparently a strange hybrid between a marine organism and a reptile. One of the main things they scratched their heads over was where and how eels bred. The pantheon of illustrious names investigating the issue includes such heavyweights as Aristotle and Pliny the Elder, and in more recent times a

Nelle serre ittiologiche di Cesenatico hanno avuto successo le esperienze di riproduzione in cattività dell’anguilla europea In the scientific fish tanks at Cesenatico the team has managed to successfully breed European eels in captivity

foglia dell’oleandro; i “leptocefali”, trascinati passivamente dalle correnti, attraversano l’Atlantico e una parte di essi entrano nel Mediterraneo, fino ad avvicinare le coste della Spagna e dell’Italia. Qui avviene la metamorfosi in ceche, che conferisce agli animali la struttura allungata che tutti conosciamo. Dal mare le ceche “vestite” (pigmentate) si trasferiscono nei fiumi e nelle lagune salmastre, dove inizia la lenta fase di crescita che li porta a diventare prima ragani, poi anguille gialle. Quando inizia la maturazione degli organi riproduttivi che dona a maschi e femmine una livrea dai riflessi argentati (anguilla “argentina”), gli animali sono stimolati a ritornare al mare e a compiere una lunga migrazione a ritroso, che attraverso lo stretto di Gibilterra li riporta negli abissi del mare dei Sargassi, dove si riproducono e muoiono. Dunque una lunga rotta transoceanica confermata solo in tempi recentissimi da un gruppo di ricercatori spagnoli, che hanno applicato delle marche satellitari a 8 anguille femmine: i capitoni hanno percorso il tragitto di 7.000 chi-

Occhio al pancione

Un ricercatore del Centro di Cesenatico mostra una femmina di anguilla europea con le uova In alto: una delle vasche partoincubatoio in cui i maschi hanno fecondato le uova emesse dalle femmine spontaneamente, senza bisogno della cosiddetta spremitura

Mummy tummy

A researcher from the Centre of Cesenatico with a European eel female with eggs Above: one of the incubator tanks where the males fertilised the eggs produced by the females spontaneously, without having to harvest their sperm artificially youthful Sigmund Freud, sent at the tender age of just 19 to the zoological station in Trieste in search of the reproductive organs of male specimens. It was only in the 1920s that the Danish naturalist Johannes Schmidt discovered, after a series of lengthily voyages on various research vessels, a fundamental clue to the eel’s biological cycle: the adult specimens reproduce in the depths of the Sargasso Sea, northeast of the coast of Florida. This is where it all starts for eels: the spawned eggs hatch into larvae, which then gradually morph into a flattened shape curiously similar to the leaf of an oleander. The

“Leptocephals “ - as they are technically known - then float passively on the prevailing currents across the Atlantic, and part of them end up in the Mediterranean, all the way up to the coasts of Spain and Italy. Here they develop into glass eels, with that familiar elongated shape we all associate with their kind. From the sea the “pigmented” glass eels head inland into rivers and the brackish waters of the salt marshes, where they begin the slow process of growing into first elvers, and then adult yellow eels. When their reproductive organs develop both males and females sport silver dapples, which is why they are known as silver eels at this stage. This is when they feel the urge to 40 return to the sea and start 41 the long return journey through the columns of Hercules, across the Atlantic again and back to their spawning grounds in the Sargasso Sea, where they reproduce and die. This epic Atlantic journey was what the group of Spanish scientists

lometri nell’arco di un anno, nuotando a una profondità di 800 metri di giorno e 400 metri di notte. “In realtà – osserva Oliviero Mordenti, ricercatore del Dipartimento di Scienze Veterinarie dell’Università di Bologna in forza alla sede di Cesenatico – nel mare dei Sargassi non è ancora mai stata pescata alcuna femmina con le uova. E la conoscenza della biologia riproduttiva di questo pesce è migliorata soltanto negli ultimi 5-6 anni, da quando, cioè, hanno avuto successo le esperienze di riproduzione in cattività. Qui a Cesenatico siamo stati tra i primi al mondo a riprodurre artificialmente l’anguilla europea con numeri consistenti di embrioni, e tra i primi a ottenerne la riproduzione spontanea”. In effetti nelle serre ittiologiche di Cesenatico i ricercatori dell’Università di Bologna hanno centrato due primati assoluti, che hanno avuto una certa eco a livello mondiale: nel 2015 il team di Mordenti è riuscito a mettere a punto una vasca parto-incubatoio nella quale un gruppo di adulti, tenuti a particolari condizioni di luce, temperatura e salinità e stimolati per via ormonale, si sono riprodotti. I maschi hanno infatti fecondato le uova emesse dalle femmine spontaneamente, senza bisogno della cosiddetta spremitura. Gli embrioni generati sono stati separati e accuditi negli incubatoi, e si sono infine schiuse un numero consistente di larve. “Oggi – sottolinea il nostro interlocutore – da una femmina di anguilla riusciamo a produrre dai 2-300mila fino a un milione di individui”. Di qui le prime esperienze di allevamento di questi microscopici, delicatissimi organismi, culminate in un nuovo successo datato giugno 2019: i preleptocefali hanno consumato un particolare preparato alimentare offerto dai ricercatori italiani. Un risultato che, qualora venisse confermato e consolidato fino alla conoscenza delle condizioni necessarie per garantire la sopravvivenza delle larve fino almeno ai 50-60 giorni di vita (“sono convinto che dopo sarebbe tutto più facile”, sottolinea Mordenti), comporterebbe due importanti ricadute applicative. Da un lato il ripopolamento dei nostri fiumi e dei nostri bacini salmastri, attualmente depauperati (non a caso l’anguilla europea è nella lista rossa delle “specie in pericolo critico”); dall’altro lato l’approvvigionamento degli allevamenti europei, oggi in crisi per la difficoltà nel reperimento di ceche selvatiche a prezzi abbordabili. Per i gourmet di casa nostra, ma anche per quelli olandesi e danesi che da sempre consumano e apprezzano le gustose carni di anguilla, sarebbe un’ottima notizia.

Prime forme di vita

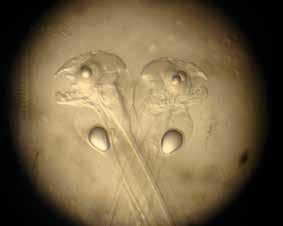

Dalle uova embrionate (a sinistra) si schiudono le larve (a destra)

Early development

The larvae (right) hatch from the fertilised eggs (left)

Attenzione ai dettagli

Occhio sviluppato e pinna pettorale allungata: ecco alcuni dei caratteri che evidenziano la fertilità di un’anguilla argentata

Significant details

A fully-developed eye and pectoral fin: two of the characteristics which show that a silver eel is fertilet

recently confirmed by applying satellite geolocators to eight female eels. They found that the tracked eels logged an impressive 7000 km in a year, swimming at a depth of 800 metres by day and 400 metres by night. “As a matter of actual fact” observes Oliviero Mordenti, a researcher from the Department of Veterinary Sciences at the University of Bologna who works at their Cesenatico headquarters, “We have never managed to capture a female with eggs in the Sargasso Sea. And we’ve only really been able to study the reproductive biology of eels closely over the last 5-6 years, since our attempts to breed them in captivity have been successful. Here in Cesenatico, we were one of the first teams in the world to artificially reproduce a consistent number of European eel embryos and again among the first to get them to spontaneously breed in captivity.” In fact, in the scientific fish tanks at Cesenatico the University of Bologna researchers have achieved two absolute records, which have caused a fair stir in their field worldwide. In 2015 Mordenti’s team developed a birthing tank where a group of adults, kept under particular conditions of light, temperature and salinity, and hormonally stimulated, managed to reproduced - with the males fertilizing the eggs produced by the females spontaneously, without needing to harvest the sperm artificially. The fertilised eggs were then separated and housed in the hatcheries until finally a consistent number of larvae hatched. Mordenti emphasised that this meant “we are now able to produce between twothree hundred thousand and one million individuals from a single female eel.” The first successful breeding of these microscopic and incredibly delicate organisms led to a new breakthrough in June 2019. The Italian researchers managed to feed the larvae using a particular preparation. If this result is confirmed and they can consolidate a process and all the conditions necessary to ensure the survival of the larvae to up to at least 50-60 days of life, Mordenti is convinced it would be mostly downhill from there on and would have a huge environmental and economic impact. On the one hand it would mean successfully managing to repopulate our rivers and salt marshes - European eels are currently on a red light on the endangered species list - on the other it would be manna from heaven for fish farmers, who currently struggle to find wild glass eels at a competitive price. It would also be exceptionally good news for Italian gourmets, not to mention their fellow connoisseurs in Holland and Denmark, where delicious eel dishes are a national tradition.