The Documentarian / Le documentariste

Edward Burtynsky’s epoch-defining photography, plus the David Suzuki Foundation and a Calgary farm’s take on sustainable cities. / Les photos dans l’air du temps d’Edward Burtynsky et la collectivité durable vue par une ferme de Calgary et la Fondation David Suzuki.

Creativity has its place

Issue 26

La créativité a sa place

Numéro 26

expe rts a t b l end i n g c r a ft and s c i enc e make bet ter strategic decisions about your brand based on a fresh way of seeing the future human-centred research, innovation, and strategic growth for inquiries: 647.291.1459 | navATELIER@rsginc.net a n i dea a t RESE A R C H S T R AT E G Y G R O U P

KILLER CREATIVE TRGR.AGENCY

In this issue / Dans ce numéro

CONTRIBUTORS / NOS COLLABORATEURS 7

THE STARTING BLOCK / BLOCK DE DÉPART Block celebrates our creative community’s varying and inspired efforts towards greater sustainability. / Block célèbre les efforts divers et inspirés de notre communauté créative en faveur d’une plus grande durabilité 9

THE MOMENT / LE MOMENT On the cover: Photographer Edward Burtynsky pulls the veil off industrial sites. / En couverture : le photographe Edward Burtynsky lève le voile sur les sites industriels

MY SPACE / MON ESPACE Vegetable chef Matthew Ravenscroft’s home kitchen. / Le bureau de Matthew Ravenscroft, chef des légumes

10

15

THE BUSINESS / L’ENTREPRISE The David Suzuki Foundation’s Julius Lindsay on climate, crime and community. / Climat, crime et collectivité avec Julius Lindsay de la Fondation David Suzuki

ARTIST’S BLOCK / ART EN BLOCK Kelly Jazvac’s block is made with beer tabs and aluminum-cast seeds. / Les moules de Kelly Jazvac? Des languettes de canettes de bière

16

18

THE INTERIOR / L’INTÉRIEUR Architecture firm Lemay’s Toronto studio intrigues and welcomes. / Lemay, une agence d’architecture aussi intrigante qu’accueillante 20

THE CREATOR / LES CRÉATEURS Highfield Farm renews the former site of Calgary’s Blackfoot Farmers’ Market. / À Calgary, la ferme Highfield redonne vie à la terre du marché Blackfoot 26

WORK-IN-PROGRESS / LE CHANTIER Vancouver’s Unbuilders are reverseconstructing and reducing waste. / À Vancouver, Unbuilders déconstruit en minimisant les déchets

32

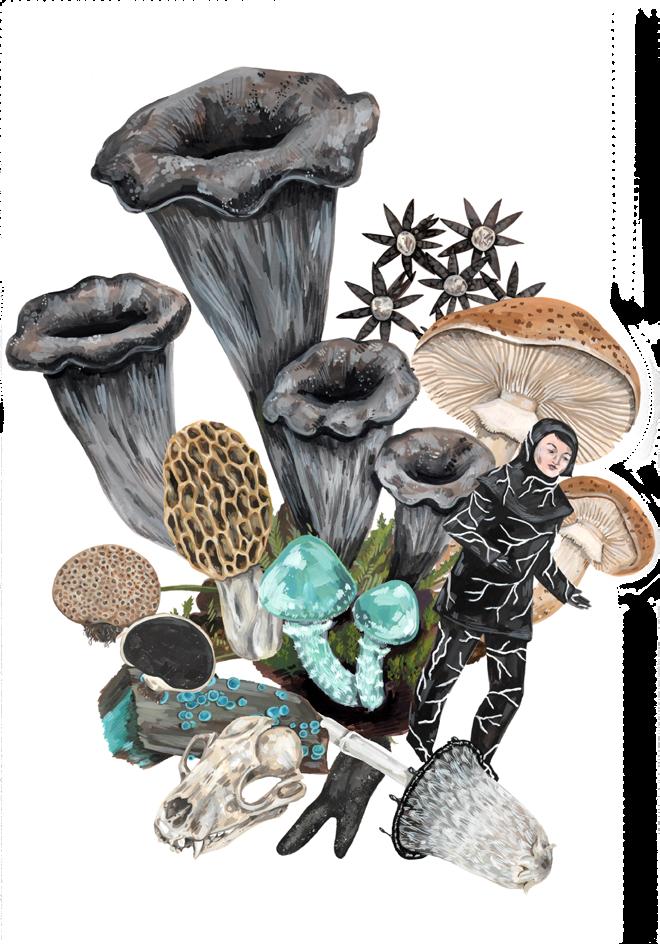

THE CONVERSATION / LA CONVERSATION On mushrooms, interdependence and artists’ role on the sustainability front. / On discute champignons et épanouissement mutuel avec deux écrivaines 38

MADE / FABRIQUÉ A credenza built from reclaimed skateboards by AdrianMartinus Design. / Le buffet en planches à roulettes recyclées d’AdrianMartinus Design 42

MAKE ROOM FOR THE ARTS / PLACE À L’ART Lisa Yang’s Rose, Ribbon, Glass at 60 Adelaide East. / Le triptyque de Lisa Yang au 60, rue Adelaide E. à Toronto

THE 1 KM GUIDE / 1 KM AUTOUR One Montréal neighbourhood’s best brunch, book and bouquet stops. / Brunch, livres, fleurs et café dans le Mile-End montréalais 46

NOW & THEN / D’HIER À AUJOURD’HUI The Wilson Building once housed Canada’s first postcard manufacturer. / L’édifice Wilson envoie une carte postale du passé 48

RETHINK / REPENSÉ Italian food culture and fruit tree-lined streets. / Arbres fruitiers urbains et écoalimentation italienne 49

THE BLUEPRINT / LE PLAN D’ACTION A DIY veg stock recipe that uses what you’ve got in your green bin. / Fait maison : un bouillon de légumes antigaspi 50

FILL IN THE BLANK / VEUILLEZ COMBLER L’ESPACE Kellen Hatanaka’s urban infill. / La dent creuse de Kellen Hatanaka 51

BLOCK / 5

16

38

45

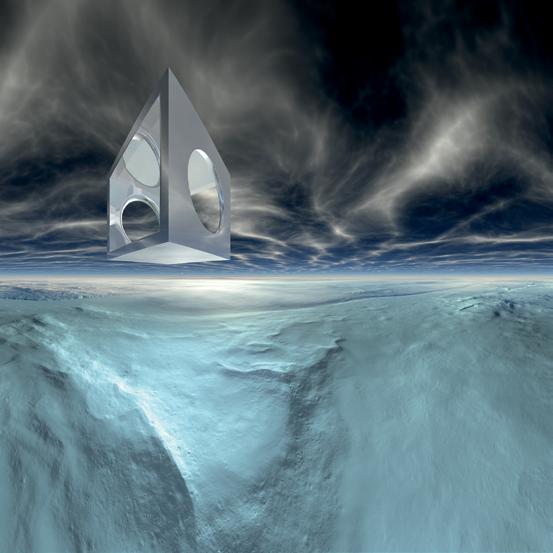

ON THE COVER / EN PAGE COUVERTURE EDWARD BURTYNSKY

PHOTO BY / PAR DEREK SHAPTON

Contents / Table des matières

Commercial - Éducationnel - Soins de santé

Commercial - Educational - Healthcare

SOLUTIONS EN MOBILIER l FURNITURE SOLUTIONS WWW.GROUPELACASSE.COM

Tour guide, photographer and writer Daniel Bromberg (The 1 KM Guide, p. 46, Now & Then, p. 48) is a proud Montréaler who shares his love for the city through storytelling. / Guide touristique, photographe et rédacteur, Daniel Bromberg partage son amour pour sa ville, Montréal, par tous les moyens (1 km autour, p. 46 et D’hier à aujourd’hui, p. 48).

Sara Baron-Goodman is a Montréal-born, Romebased writer, editor, social media specialist and cook who tells stories through food (Rethink, p. 49). / Sara Baron-Goodman est née à Montréal, mais c’est à Rome qu’elle écrit, cuisine et crée du contenu pour les réseaux sociaux, le tout en version pro (Repensé, p. 49).

Kelly Jazvac, a member of The Synthetic Collective, makes art from plastic recuperated from the advertising industry (Artist’s Block, p. 18). / Artiste et membre du collectif The Synthetic Collective, Kelly Jazvac surcycle le plastique publicitaire (Art en Block, p. 18).

Our Fill in the Blank (inside back cover) was contributed by Kellen Hatanaka, a Governor General’s Award-winning artist from Toronto whose work has been shown nationally and internationally. / Notre rubrique Veuillez combler l’espace, en troisième de couverture, est signée Kellen Hatanaka, un artiste torontois, lauréat du prix du Gouverneur général, dont les œuvres ont été exposées au Canada et à l’étranger.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF / RÉDACTRICE EN CHEF

Kristina Ljubanovic

CREATIVE DIRECTORS / DIRECTRICES ARTISTIQUES

Yasemin Emory, Whitney Geller, Jacqueline Lane

MANAGING EDITOR / DIRECTRICE DE LA RÉDACTION

Claire Reis

COMMISSIONING EDITOR / RESPONSABLE DES COMMANDES

Mélanie Ritchot

PHOTO & ILLUSTRATION EDITOR / ICONOGRAPHE

Catherine Dean

ASSISTANT PHOTO & ILLUSTRATION EDITOR / ASSISTANT ICONOGRAPHE

Michael Nyarkoh

DESIGNER / GRAPHISTE

Julie MacKinnon

TRANSLATOR / TRADUCTRICE

Catherine Connes

COPY EDITORS - PROOFREADERS / RÉVISEURES - CORRECTRICES

Suzanne Aubin, Jane Fielding, Lesley Fraser

ALLIED

134 Peter Street, Suite 1700

Toronto, Ontario

M5V 2H2 Canada

(416) 977-9002

info@alliedreit.com alliedreit.com

WHITMAN EMORSON

213 Sterling Road, Studio 200B

Toronto, Ontario

M6R 2B2 Canada

(416) 855-0550

inquiry@whitmanemorson.com whitmanemorson.com

BLOCK IS PUBLISHED TWICE A YEAR. / BLOCK EST PUBLIÉ DEUX FOIS PAR AN.

BLOCK / 7 Contributors / Nos collaborateurs

ILLUSTRATIONS BY / PAR KAGAN MCLEOD

NEW SPRING ARRIVALS BLOKES

803 1st Street SW T2P 7N2

Calgary Alberta Canada

MENSWEAR.CA

This year marks the 10th anniversary of Block. From the onset, the magazine has been a celebration of creativity and community—all the diverse people and industries that rub up against one another in chaotic-yet-harmonious fashion in our cities (and in Allied’s buildings). Ten years later, this is still Block’s mandate, and it’s worth maintaining—along with something else. Sustaining our planet—our ways of living and thriving—may be the biggest project of our collective lifetime. While tactics like installing solar panels and recycling plastics are still vitally important, sustainability has permeated our rituals and routines and has found expression in new and entirely creative ways—beyond what we could have previously imagined. That’s why this issue of Block focuses on the many ways sustainability is being tackled by creatives and creative enterprises today—for the benefit of the next decade and beyond.

Take our cover subject, Ed Burtynsky (The Moment, p. 10), whose career spent photographing landscapes manipulated by human industry has culminated in a reframing of our current epoch—the Anthropocene. Then there’s Julius Lindsay of the David Suzuki Foundation (The Business, p. 16) and the team behind Calgary’s Highfield Farm (The Creator, p. 26), who are enacting climate action in our cities, impacting the very soil underfoot and involving multiple levels of government. And, finally, in a brand-new section in the magazine that encourages readers to do-it-yourself, vegetable chef Matthew Ravenscroft (The Blueprint, p. 50) teaches us how to, simply, in our everyday lives, give second life to so-called “organic waste.”

Allied was built on the idea that knowledge-based industries, “new ideas,” as Jane Jacobs said, “must use old buildings.” Sustainability is core to Allied’s purpose, and it’s expressed not just through natural lighting, high-performance building systems, roof gardens and apiaries but in the very fabric of the enterprise, because, invariably, the most sustainable building is the one that’s already built.

Cette année, Block fête son dixième anniversaire. Depuis ses débuts, le magazine met à l’honneur la créativité et la collectivité : toutes ces personnes et entreprises qui se côtoient dans le chaos et l’harmonie de nos villes, et des immeubles d’Allied. En 2023, sa mission est toujours d’actualité et s’enrichit d’une nouvelle composante.

La préservation de notre planète, de nos modes de vie et de notre épanouissement pourrait bien être le plus grand projet collectif qui soit. Bien que l’installation de panneaux solaires ou le recyclage des plastiques soient toujours d’une importance vitale, l’écoresponsabilité s’est introduite dans nos routines et a trouvé de nouveaux moyens d’expression hautement créatifs. C’est pourquoi ce numéro de Block s’intéresse aux diverses manières dont les entreprises créatives, petites ou grandes, s’attaquent aujourd’hui à la question de la durabilité.

On rencontre Edward Burtynsky (en couverture et dans Le moment p. 10) qui consacre son temps à photographier des paysages dénaturés par l’activité humaine pour recadrer notre nouvelle ère, l’anthropocène. Puis Julius Lindsay de la Fondation David Suzuki (L’entreprise, p. 16) et le trio calgarien de la ferme Highfield (Les créateurs, p. 26) qui se mobilisent en faveur du climat en englobant différents niveaux de gouvernement ou en revitalisant le sol urbain. Enfin, dans une toute nouvelle rubrique invitant nos lecteurs et lectrices à passer à l’action (Le plan d’action, p. 50), le chef Matthew Ravenscroft nous montre comment donner une seconde vie à nos soidisant déchets de cuisine, et ce, le plus simplement du monde.

Allied a fait sienne cette phrase de Jane Jacob qui disait que « les nouvelles idées doivent utiliser les vieux bâtiments ». La durabilité est au cœur des objectifs d’Allied et s’exprime non seulement par l’éclairage naturel, les équipements à haute performance, les jardins et ruches sur les toits, mais aussi par le fondement même de l’entreprise, car, sans contredit, le plus durable des bâtiments est celui déjà construit.

BLOCK / 9

The Starting Block / Block de départ

Photo by / par Dylan Leeder

Sustainability has permeated our rituals and routines and has found expression in new and entirely creative ways. / L’écoresponsabilité s’est introduite dans nos routines et a trouvé de nouveaux moyens d’expression hautement créatifs.

The team at Calgary’s Highfield Farm implement regenerative agriculture strategies. The project is a model for other urban brownfield sites. / La ferme Highfield implante un modèle d’agriculture régénératrice à Calgary. Un projet pilote qui pourrait intéresser d’autres friches industrielles.

A self-described “nomad” in his early career, Burtynsky settled at 80 Spadina in 2002, in part to house his growing archive. / Nomade à ses débuts, Edward Burtynsky a fini par s’installer au 80, avenue Spadina à Toronto, notamment pour y stocker ses archives.

10 The Moment / Le moment

2023-03-15 13:27 EST/HNE

BY / PAR EMILY WAUGH

PHOTOS BY / PAR DEREK SHAPTON

Edward Burtynsky sees the world differently—not just as an artist but because he spends up to three months of the year looking at it from hundreds of feet in the air. Using a helicopter, airplane or drone, he flies over restricted industrial sites and resource-extraction landscapes shooting photographs that, as he puts it, “pull the veil” off how these processes affect the earth.

“Even with a helicopter or fixed-wing [aircraft], it’s a bit of an art to getting what you want because you can never get back to that place,” he says, noting that he once tried a weather balloon, but it was a “full fail” because the balloon followed the wind instead of Burtynsky’s intuition.

When he’s back in the Toronto studio, his home base since 2002, he can most often be found at the almost floor-to-ceiling magnetic pinup board where he marks up large-format prints, fine-tuning them for optimal viewing conditions, whether they’ll hang in a corporate office or private home or on a gallery wall.

Today, Burtynsky hovers over a different type of landscape—a sea of copies of his most recent book, African Studies , waiting to be signed. The collection is Burtynsky’s first look at the reach of globalism on the African continent and features photos of the otherworldly industrial landscapes we have come to associate with his work: inky black tailings from a diamond mine in South Africa and pink salt pans in Namibia.

It also highlights his more recent focus on the world’s remaining natural landscapes, including a mountain-like sand dune in the Namib desert and a “flamboyance” of flamingos on the shore of Kenya’s Lake Bogoria.

After what Burtynsky calls his “40-year lament on the loss of the natural world,” he now depicts these intact natural systems as a reminder that they are still worth fighting for.

“The problem is so big and so frightening that there is a danger of paralysis,” he says. “It’s incumbent on us to make sure that it doesn’t feel hopeless.” With his camera, Burtynsky opens that window of hope. “It’s still here. We haven’t shredded all of the DNA to extinction.”

Edward Burtynsky voit le monde autrement. De beaucoup plus haut. Ses yeux d’artiste passent près de trois mois par an à le regarder depuis les airs. Hélicoptère, avion, drone, tous les moyens sont bons pour survoler sites industriels et autres lieux d’extraction de ressources afin de les photographier. La raison? « Lever le voile », comme il le dit, sur ces activités humaines qui mutilent la terre.

« Même avec un hélicoptère ou un aéroplane, c’est tout un art d’arriver à mes fins car on ne peut jamais revenir à l’instant T », explique-t-il, se rappelant notamment la fois où il s’est servi d’un ballon-sonde : un « échec total », car le ballon avait préféré suivre le vent plutôt que l’intuition du photographe.

De retour à son studio torontois, son pied-à-terre depuis 2002, il passe le plus clair de son temps devant un immense tableau magnétique sur lequel il peaufine ses tirages grand format, qui s’envoleront à leur tour vers les murs d’une entreprise, d’un particulier ou d’une galerie.

Ce mercredi, Edward Burtynsky contemple un tout autre panorama : une montagne d’African Studies, son dernier livre photos, qu’il s’apprête à dédicacer. Marais salants roses en Namibie ou résidus noir d’encre d’une mine de diamants en Afrique du Sud, cette série de paysages industriels surnaturels, dans la veine de l’artiste, est son premier regard sur les effets du mondialisme sur le continent africain.

Il y souligne aussi son récent intérêt pour les beautés naturelles qui existent encore sur notre planète, comme cette gigantesque dune dans le désert du Namib ou cette « flamboyance » de flamants roses sur les rives du lac Bogoria au Kenya.

Après avoir dépeint ce qu’il appelle ses « 40 ans de lamentations sur la perte de la nature », Edward Burtynsky caresse du regard l’intact, ce pour quoi il vaut encore la peine de se battre.

« Le problème est si vaste et si effrayant qu’il y a un risque de paralysie, conclut-il. Il nous incombe d’entretenir l’espoir. » C’est ce qu’il tâche de faire à travers son objectif : « L’espoir est toujours là. On n’a pas conduit tout l’ADN à l’extinction. »

BLOCK / 11 The Moment / Le moment

ABOVE: Burtynsky reviews an image of a tailings pond at a diamond mine in South Africa under two different lighting systems: a daylight balance unit and a 3000K colour temperature LED to mimic traditional gallery settings. /

CI-DESSUS : Edward Burtynsky compare le rendu d’une image de bassins de résidus miniers en Afrique du Sud sous deux éclairages : un effet lumière naturelle et une DEL de 3000 K simulant l’éclairage muséal classique.

PREVIOUS PAGE (detail): The artist uses a black Sharpie to mark up a print of a salt pond near Fatick, Senegal. Each photo is taken in what he says is “a fraction of a second.” The rest of the work is post-production. / PHOTO PAGE 11 : le photographe annote au marqueur noir le tirage d’un marais salant près de Fatick, au Sénégal. Les photos sont prises en une fraction de seconde explique-t-il, tout le reste se fait en postproduction.

12 The Moment / Le moment

“We haven’t shredded all of the DNA to extinction.” / « On n’a pas conduit tout l’ADN à l’extinction. »

As one of Canada’s leading insurance brokerages, Mitch Insurance has coverages that fit businesses of any size. From affordable out-of-the-box packages to custom solutions, we’ve got your company covered. Start saving today. Call us at 1-888-574-4685. Business insurance that works for you mitchinsurance.com

14

Well Seasoned À sa sauce

After working in some of Toronto’s most notable restaurants and leading veg-forward visions at Rosalinda and Gia, Matthew Ravenscroft now works out of his home kitchen, creating menus for private clients and meals for his family. He calls himself a vegetable chef and is excited about the growing interest in vegetarian cooking. “Even if they’re omnivores, people are seeing the versatility and possibility of plant-focused eating.” / Après avoir travaillé dans de grands restaurants torontois et mis le végétal en valeur chez Rosalinda et Gia, Matthew Ravenscroft imagine des menus pour ses clients et sa famille chez lui, derrière ses fourneaux. Ce chef des légumes, comme il aime à se nommer, se réjouit de l’intérêt pour la cuisine végétarienne : « Même quand on est omnivore, on se rend compte des multiples possibilités d’une alimentation à base de plantes. »

1. Rancilio Espresso Machine / Une machine à espresso Rancilio

“This was purchased secondhand off Facebook Marketplace as a gift to ourselves for the birth of our child. We wanted to [buy] less coffee out, use fewer [disposable] coffee cups and be able to explore the world of coffee a little bit deeper. I have between two and five espressos a day.” / « On l’a trouvée d’occasion sur le marché Facebook. On se l’est offerte pour la naissance de notre fils. On voulait [acheter] moins de cafés à emporter, utiliser moins de tasses [jetables] et explorer plus en profondeur cet univers. Je bois deux à cinq espressos par jour. »

2. Son Logan’s Framed Painting / Les peintures de Logan

“If things go the way people are predicting in terms of climate change and what that means for food scarcity and food security, the reality is I probably won’t have to endure a lot of that, but our kids will, and their kids definitely will. That’s what I want to be reminded of every day, and we hang up Logan’s little paintings that are so silly and cute for that very reason.” / « Si les changements climatiques, et leurs conséquences sur la pénurie et la sécurité alimentaires, se réalisent dans les délais prévus, je n’en souffrirai probablement que peu. Par contre, nos enfants en souffriront, ainsi que leurs enfants. C’est pour y penser tous les jours que j’accroche les petites peintures de mon fils, Logan, si ridicules et si mignonnes à la fois. »

3. Oigen 24-Centimetre Cast-Iron Pan / Une poêle en fonte Oigen de 24 cm

“This was a gift from my father, purchased from the first place I ever bought a knife. I wanted to learn how to season it and maintain it and to move away from the non-stick world. It’s something that we can keep for an extremely long time and could eventually hand down to Logan if I take care of it properly.” / « C’est un cadeau de mon père, qui vient du même endroit où j’ai acheté mon premier couteau. Je voulais sortir des revêtements antiadhésifs, apprendre à la graisser, à l’entretenir. Si j’en prends bien soin, je vais pouvoir la garder longtemps et la transmettre à Logan. »

4. Cookbook Collection / Des livres de recettes

“There isn’t really any parameter for what cookbook enters the collection. It’s more like, ‘Wow, I love this person as a creator, as a chef, and their world.’ To me, their food is a lens into their mind. It’s a reflection of them.” / « Il n’y a pas de critères particuliers pour entrer dans ma collection. Il suffit que j’aime la personne, ses créations culinaires, son univers. Avec ses plats, je vois dans son esprit. Ils sont son propre reflet. »

5. Monstera Plant / Un Monstera

“It’s a trimming from a much larger plant that I have, called Wanda. This plant is significant because it was the shifting point into [my] really wanting to get inquisitive about nature.” / « C’est une bouture d’une plante bien plus grosse, que j’ai prénommée Wanda. Elle est importante, car elle a été le point de départ de ma curiosité pour la nature. »

BY / PAR MARYAM SIDDIQI PHOTO BY / PAR ASHLEY VAN DER LAAN

BLOCK / 15 My Space / Mon espace

1 2 3 4 5

Climate Intersects Croisements climatiques

I live in Toronto, and if you look at the data for our average summer temperature and violent crimes like homicides, there’s a pretty close connection: The hotter the summer, the more gun violence and homicides there are in our city.

This is one example of the focus of a lot of my work at the David Suzuki Foundation during the past year, which has been centred around the intersections of climate action and other social challenges.

We did some polling at the end of last year during the municipal elections and we got feedback about how the environment-and-climateonly message is not resonating with people. So we’re really interested to know how that message can be connected to other priorities that people have.

At the end of the day, I’ve found there are a lot of different issues that become climate-action questions when we look at them through that lens of heating or flooding, or ice as well. Yet the big challenges [facing] everybody surround the social and financial issues the pandemic raised, and those are impacting climate action in cities across the country.

I believe climate action needs to be intersectional for this reason, encompassing all levels of government and all members of our communities—people with diverse lived experiences, challenges and solutions—in order to make our cities more sustainable.

I also believe that for climate adaptation to be successful, it will be important for climate-action organizations to collaborate and partner across other movements, including, for example, housing, labour and finance.

Je vis à Toronto. Quand on compare les données de la température moyenne estivale à celles des crimes violents, on s’aperçoit qu’il existe un lien : plus l’été est chaud, plus il y a de violence par arme à feu et d’homicides dans notre ville.

C’est un exemple de mon travail à la Fondation David Suzuki. Ces derniers mois, je me suis intéressé aux croisements entre l’action climatique et les autres défis sociaux.

Fin 2022, pendant les élections municipales, on a fait un sondage. On a constaté qu’un message unique, qui ne porte que sur l’environnement, ne trouvait pas d’écho auprès de la population. On s’est alors demandé comment relier ce message aux autres priorités des citoyens.

Après réflexion, je remarque qu’en étudiant diverses questions sous l’angle de la chaleur ou des inondations, elles deviennent des questions environnementales. Cela dit, les difficultés sociales et financières soulevées par la pandémie représentent le grand défi à surmonter, et elles ont un impact sur l’action climatique dans les villes partout au pays.

C’est pourquoi je crois que toute mobilisation pour le climat doit être intersectionnelle, englober tous les niveaux de gouvernement et tous les membres de la collectivité — des personnes ayant un vécu différent, avec leurs problèmes et leurs solutions — afin de rendre nos villes plus durables.

Je crois également que l’adaptation au climat ne réussira que si les organismes de lutte contre le changement climatique collaborent et s’associent à d’autres mouvements, notamment dans les domaines du logement, du travail et de la finance.

16 The Business / L’entreprise

We spoke to Julius Lindsay, the director of sustainable communities at the David Suzuki Foundation, about how the environment affects social wellness and why climate action must be an inclusive, collaborative effort.

On parle du lien entre environnement et bien-être social et de l’effort collectif nécessaire à l’action climatique avec Julius Lindsay, directeur des collectivités durables à la Fondation David Suzuki.

AS TOLD TO / PROPOS RECUEILLIS PAR MERAL JAMAL ILLUSTRATION BY / PAR RICHARD CANE

BLOCK / 17 The Business / L’entreprise

Green Placed by/de Kelly Jazvac

Kelly Jazvac’s block is made from cob (clay, straw and sand) and covered with pumpkin seeds cast from aluminum pull tabs from cans of beer the artist drank during the pandemic. The background is a found vinyl billboard featuring a coniferous forest. / Le bloc en torchis (argile, paille et sable) est recouvert de graines de citrouille moulées dans des languettes en aluminium provenant des canettes de bière que l’artiste a bues pendant la pandémie. En fond, une forêt de conifères se déploie sur un panneau en vinyle récupéré.

18 Artist’s Block / Art en Block

Photo by/par Kyle Tryhorn

EACH ISSUE, WE ASK AN ARTIST TO CREATE A BLOCK USING THE MEDIUM AND APPROACH OF THEIR CHOICE. / DANS CHAQUE NUMÉRO, NOUS DEMANDONS À UN ARTISTE DE CRÉER EN TOUTE LIBERTÉ UNE ŒUVRE D’ART FAÇON BLOC.

BLOCK / 19

Artist’s Block / Art en Block

A view into the space created by the raw-birch “ribbon,” which Fiorino calls an “homage to Canadian culture.” The material has acoustic muffling properties for some privacy but is ultimately open-ended—like the studio, with its flat hierarchy. / Coup d’œil dans l’espace créé par « le ruban » en bouleau brut, « un hommage à la culture canadienne » selon Robert Fiorino. Isolant acoustique naturel, il garantit une certaine intimité tout en formant un ensemble ouvert, à l’image de la gestion transversale de l’agence.

20 The Interior / L’interieur

An Open Invitation Une invitation permanente

BY / PAR KRISTINA LJUBANOVIC PHOTOS BY / PAR NAOMI FINLAY COURTESY OF / OFFERTES PAR LEMAY

Architecture firm Lemay’s Toronto space welcomes new ideas, flexible working styles and a Net Positive approach.

There’s an “air of intrigue” when the elevator doors open on the fourth floor of Allied’s 60 Adelaide Street East to a glowing wall casting a signature Pantone red onto a doorway and entry sign. A transom window affords a peek inside.

“I’ll often overhear someone ask, ‘What is Lemay?’” says Alena Crowne, a senior marketing and media specialist for the mystery company.

“It’s the biggest firm you don’t know,” answers CMO Robert Fiorino. This, despite its status as one of the largest privately held architectural practices in Canada, with offices in Montréal, Calgary, Toronto and New York (plus plans for further expansion).

Founded in 1957 as Lemay Leclerc Architectes in Verdun, Quebec, the firm was “rebaptized” as Lemay three decades later. Founder Georges Lemay’s son Louis took the helm in 1998 and expanded the enterprise, envisioning a “pan-Canadian practice,” says Fiorino, and opening new locations and acquiring complementary businesses to grow the skill set and offerings.

Today, Lemay is a transdisciplinary firm that offers architecture, urban planning, branding and digital solutions—all with a focus on and commitment to sustainability. Its Net Positive approach ensures healthy environments and carbon-emission reductions as well as significant operating- and capital-cost savings for clients.

Il y a du mystère dans l’air quand s’ouvre l’ascenseur au quatrième étage du 60, rue Adelaide Est, un immeuble torontois d’Allied. Un mur rutilant projette un rouge Pantone signature sur une porte d’entrée arborant une découpe vitrée en clin d’œil aux curieux.

« J’entends souvent les gens se demander ce qu’est Lemay », confie Alena Crowne, spécialiste du marketing et des communications pour l’énigmatique entreprise.

« C’est la grande inconnue », répond le directeur du marketing Robert Fiorino. Et ce, bien qu’elle soit l’une des plus grandes agences d’architecture privées canadiennes avec des bureaux à Montréal, Toronto, Calgary et New York (et des projets d’expansion).

Fondé en 1957 sous le nom de Lemay Leclerc Architectes à Verdun, le cabinet québécois est « rebaptisé » Lemay 30 ans plus tard. Louis Lemay, fils du fondateur, reprend la barre en 1998. Animé d’une « ambition pancanadienne », il ouvre de nouvelles agences et rachète des entreprises complémentaires afin de diversifier compétences et services.

Aujourd’hui, Lemay est une agence transdisciplinaire qui offre des solutions en architecture, urbanisme, stratégie de marque et numérique avec un seul mot d’ordre : le Net positif, une démarche qui crée des milieux de vie sains tout en réduisant les émissions de carbone ainsi que les coûts d’exploitation et d’investissement côté clients.

BLOCK / 21

L’annexe torontoise de l’agence d’architecture Lemay rime avec nouvelles idées, flexibilité et une écodémarche nommée Net positif.

The Interior / L’interieur

ABOVE: At the beginning of each project, the team hosts what they call an “opportunity meeting,” gathering the brightest minds from various disciplines—and Lemay locations— to enrich potential solutions for their clients. / CI-DESSUS : Au début de tout projet, l’équipe tient une « réunion de perspectives » qui rassemble les plus brillants esprits de chaque discipline, et des diverses agences, pour enrichir les solutions à proposer au client en question.

RIGHT: Workstations are unassigned, and lockers in the kitchen (where some elect to work) offer space for belongings. Unlike his teammates, Carter-Wingrove keeps a fixed desk. He says his “Post-its are everywhere.” / À DROITE : Aucun espace de travail n’est assigné, des casiers dans la cuisine accueillant les effets personnels de chacun. Contrairement à ses collègues, Ross Carter-Wingrove a son bureau « et des Post-its partout », confie-t-il.

NEXT SPREAD (left): The space is “a catalyst for people to come in,” says Crowne. While the Toronto office is an extension of Montréal, “micro-created, it’s also our space.” /

PHOTO PAGE 24 : Le bureau est « un catalyseur pour quiconque y entre » selon Alena Crowne. L’annexe torontoise a beau être un prolongement de celle de Montréal, « c’est notre micro-espace. »

22 The Interior / L’interieur

“There’s a generosity here” and a sense of hospitality inherited from the firm’s Québécois DNA. / « Il y a une vraie générosité ici » et un sens de l’hospitalité hérité de l’ADN québécois.

While the Montréal headquarters, called The Phenix, is Lemay’s experimental lab for innovation, model shop and a demonstration of the firm’s sustainability in practice, the Toronto outpost is “a proper studio,” says regional director and resident “dad” Ross Carter-Wingrove.

Carter-Wingrove takes it upon himself to ensure that the 20-odd architects, landscape and interior designers and other key staff members in his employ are well kept with fresh tunes (on his stilloperational iPod), fresh-cut veggies—and fresh ways of collaborating through a flexible office arrangement.

Workspaces are unassigned, so people can plug and play depending on their mood or need—from a sit/stand workstation, the slate-grey kitchen or a soft seating area (furnished with classic Steelcase and Herman Miller pieces sourced from local vintage store Guff) next to 33 south-facing windows that provide great light and city-street views.

However, it’s the “ribbon,” a Baltic-birch curvilinear wall that articulates zones within and around it, which provides multitudinous

Appelé Le phénix, le siège social montréalais est un laboratoire expérimental et un modèle en matière de développement durable et de conception d’espace de travail. L’antenne torontoise est plus « un atelier au sens propre », explique Ross Carter-Wingrove, directeur régional et « papa » attitré.

En effet, ce dernier s’est donné pour mission de prendre soin de la vingtaine d’architectes, paysagistes et designers d’intérieur sous sa houlette : musique à la mode (sortie tout droit de son iPod vintage), légumes frais et flexibilité dans l’air du temps.

Aucun espace de travail n’est assigné, ce qui permet à chacun, selon son envie ou ses besoins, de se brancher où bon lui semble, que ce soit à un bureau assis-debout, dans la cuisine gris ardoise ou dans un des fauteuils signés Steelcase ou Herman Miller, achetés chez Guff, une boutique locale, et installés devant les 33 fenêtres plein sud, offrant bain de lumière et panorama urbain.

Celui qui articule les diverses zones de travail, c’est « le ruban », un

BLOCK / 23 The Interior / L’interieur

options for working: Here, it creates an area for meeting with clients, where a roll of tracing paper can be unfurled for spontaneous collaboration; there, it can be used as a surface for mounting sketches or presentation drawings (and maybe even bicycles in the warmer months).

Handmade in the Montréal shop and shipped to Toronto, the ribbon resembles a scaled-up architectural model, but in no way is it merely decorative or demonstrative. “It actually works—it’s not [just] an object,” says Fiorino. Further delineation is provided by corrugated-paper partitions that are adjustable and mobile. Together, these devices create space without excluding or precluding collaboration.

Crowne calls it “an open invitation,” which tracks with the firm’s modus operandi.

“There’s a generosity here,” says Fiorino, and a sense of hospitality inherited from the firm’s Québécois DNA. Even so, the team prides itself on standing a bit apart from “big almighty Lemay.”

“I think the notion for Toronto is being this small, nimble, creative hub,” says Crowne. “I kind of feel like the cool younger sibling.”

mur curviligne en bouleau aux multiples options. Ici, il délimite un coin rencontre, où l’on peut déployer de grandes feuilles de papier calque pour croquer sur le vif en compagnie d’un client. Là, il se fait support à dessin, à présentation et même à vélo quand arrive les beaux jours.

Fabriqué à la main dans le labo montréalais et expédié à Toronto, le ruban a beau ressembler à une maquette à grande échelle, il n’est ni décoratif ni démonstratif. « Il fonctionne vraiment, ce n’est pas un objet déco », explique Robert Fiorino. Des cloisons en papier ondulé, réglables et mobiles, le rendent encore plus pratique : elles balisent l’espace sans entraver la collaboration.

Pour Alena Crowne, c’est une « invitation permanente » dans le sillage du modus operandi de l’entreprise.

« Il y a une vraie générosité ici », seconde Robert Fiorino, et un sens de l’hospitalité hérité de l’ADN québécois. Pourtant, l’équipe tient à se démarquer quelque peu du « tout-puissant Lemay ».

« Je crois que l’agence de Toronto se veut petite, agile, créative, conclut Alena Crowne. On est la petite sœur cool en quelque sorte. »

24 The Interior / L’interieur

Find out what a chiropractor can do for you at chiropractic.ca.

26

The Creator / Les créateurs

Farming the Post-industrial Culture sur friche industrielle

In a province infamous for resource extraction, three Calgarians are finding new ways to give back to the land and to the community. / Dans une province tristement célèbre pour l’extraction de ressources, trois Calgariens trouvent le moyen de donner en retour, tant à la terre qu’à la collectivité.

BY / PAR XIMENA GONZÁLEZ PHOTOS BY / PAR DYLAN LEEDER

a collective background working in composting, living soils, edible landscapes and permaculture, in 2019, long-time friends Mike Dorion, Jay Fish and Jeremy Zoller joined forces with the City of Calgary to launch a state-of-the-art project: a regenerative farm on a post-industrial site called a brownfield.

“We wanted to excite our community and bring that land back to life,” says Fish, reminiscing about the site’s former glory as the Blackfoot Farmers’ Market, a farmer-led market that operated from 1983 to 2008.

In operation since 2020, Highfield Farm originated as a city-led initiative to reactivate a vacant lot in Calgary’s inner city. But when Dorion, Fish and Zoller took over the program’s first (and, so far, only) site, their passion for self-sufficient agricultural ecosystems transformed the underused 15,000-square-foot land parcel into something more than just an urban farm.

Active participants in Calgary’s permaculture and composting scenes, the trio have succeeded in creating a community hub where members of groups such as the Calgary Horticultural Society and the Permaculture Calgary Guild converge. “We set out to join these groups,” says Fish. “[To] have a space for them all to operate and stay passionate about their work.”

Prior to launching Highfield Farm, Zoller and Fish grew heirloom tomatoes together. Currently, Zoller runs Sunshine Earth Works,

2019, Mike Dorion, Jay Fish et Jeremy Zoller, trois amis de longue date spécialisés en permaculture, aménagement paysager comestible, sol vivant et compostage, s’associent à la municipalité de Calgary pour lancer un projet dans l’air du temps : une ferme régénératrice installée sur une friche industrielle.

« On voulait que cette terre reprenne vie pour le plus grand plaisir des citoyens », explique Jay Fish, se rappelant la beauté passée du lieu, occupé de 1983 à 2008 par le marché fermier Blackfoot.

La ferme Highfield, en activité depuis 2020, est née d’une initiative municipale visant à revitaliser un terrain vacant du centre-ville. Grâce à leur vif intérêt pour les écosystèmes autosuffisants et l’autonomie alimentaire, les trois hommes ont fait de cette parcelle de 1 400 m2 bien plus qu’une simple ferme urbaine.

Impliqués localement dans le compostage et la permaculture, ils ont réussi à créer un véritable carrefour communautaire où se côtoient tant la Société horticole de Calgary que la Guilde de la permaculture de Calgary. « On a fait en sorte de réunir ces différentes entités en leur offrant un espace commun pour y exercer leur activité et continuer à cultiver leur passion », ajoute-t-il.

Avant ce projet, lui-même cultivait des variétés de tomates anciennes avec Jeremy Zoller. Aujourd’hui,

Earth

ce dernier dirige Sunshine

Works, une entreprise d’aménagement paysager comestible.

BLOCK / 27

EN WITH The Creator / Les créateurs

The Creator / Les créateurs

PREVIOUS SPREAD: To help revitalize Highfield Farm’s depleted soil, more than 100 native plant plugs were installed last year. The farm’s regenerative practices helped divert roughly 7,050 cubic yards of landscaping waste from the landfill and produced 25 cubic yards of compost. / DOUBLE PAGE PRÉCÉDENTE : Pour revitaliser le sol, la ferme Highfield a commencé par y planter une centaine d’espèces indigènes l’année dernière. Écoresponsable, elle a détourné 5 400 m3 de déchets paysagers de la décharge et produit une vingtaine de mètres de compost.

THIS PAGE: Even in the quieter winter months, there’s still work to do. Building and repairing growing beds and seeding racks keeps the volunteer team busy before spring. / CI-CONTRE : Même en hiver, il y a du travail. L’équipe de bénévoles en profitent pour fabriquer, ou réparer, bacs de culture et étagères à semis pour le printemps.

an edible-landscape construction enterprise, while Dorion has been working with compost for nearly a decade at his company Living Soil Solutions.

As the skills and interests of the trio blend seamlessly, their vision of an urban agriculture model that can be replicated in brownfield sites across the city is slowly materializing.

“We’re trying to create a system that [makes] things better and improves them as we continue through our process,” Dorion says about their agricultural practices.

Because of the site’s past uses, the soil hasn’t yet been deemed suitable to grow produce for consumption. So the implementation of regenerative agriculture practices is expected to transform the dirt into soil. To infuse nutrients into the tightly compacted earth and remove any traces of pollutants, native grasses and cover species such as mushrooms and willows will be planted on the site.

“After being used as the farmers’ market, [the site] was used as a parking lot,” Fish says, “so it got a lot of soil compaction, not a lot of organic matter.”

In the meantime, nutrient-dense produce—including lettuce, carrots and green beans—grows in 44 raised beds that occupy an area of roughly 11,000 square feet. Dorion explains that growing these staples in Calgary ensures that they retain the nutrients that, otherwise, would be lost after travelling a long distance from a warmer place.

Despite the benefits of urban agriculture, two of the main obstacles to the long-term sustainability of this practice in Calgary are the long winters and the high cost of labour. At Highfield Farm, the group is addressing the former by adapting planting plans to the local climate and the latter by encouraging the community to lend a hand.

Quant à Mike Dorion, il parfait son art du compostage depuis presque 10 ans par le biais de sa société Living Soil Solutions.

Partageant compétences et centres d’intérêt, le trio souhaite reproduire son modèle d’agriculture urbaine dans les friches industrielles alentour. Une idée qui prend lentement racine.

« On essaie de créer un système qui ne va qu’en s’améliorant », explique Mike Dorion à propos de leurs pratiques agricoles.

La première étape? Prendre soin du sol. Dégradé en raison de ses utilisations antérieures, il n’est pas prêt à la culture de produits destinés à la consommation. Il va falloir le régénérer pour retrouver un terreau sain et fertile. Pour ce faire, ils vont commencer par y planter des espèces indigènes, comme des graminées, couvre-sols, champignons et saules, qui vont décompacter et dépolluer la terre tout en la nourrissant.

« Après avoir accueilli le marché fermier pendant des années, l’endroit est devenu un stationnement, ce qui a compacté la terre et ne lui a pas apporté beaucoup de matière organique », constate Jay Fish.

En attendant, des produits riches en nutriments, dont de la laitue, des carottes et des haricots verts, s’épanouissent sur 44 buttes potagères s’étirant sur près de 1 000 m2. D’après Mike Dorion, cultiver ces légumes de base sur place a un avantage majeur : sans voyage ni transplantation, ils conservent tous leurs oligoéléments.

La durabilité de cette agriculture en milieu urbain se heurte à deux obstacles : les longs hivers calgariens et le coût élevé de la maind’œuvre. À la ferme Highfield, on contourne le premier en acclimatant les plants et le second en invitant les citoyens à prêter main forte.

Actuellement, la ferme emploie une responsable d’exploitation à temps plein, Heather Ramshaw, et un ou deux stagiaires durant l’été.

28

Each season, more than a hundred volunteers help weed, water and seed. / Plus d’une centaine de bénévoles participent aux semis, à l’arrosage et au désherbage.

BLOCK / 29 The Creator / Les créateurs

The Creator / Les créateurs

30

Dorion (left) and Fish have known each other for 35 years. Their shared interest in permaculture brought them together as co-conspirators, leading to the creation of Highfield Farm in 2020. / Mike Dorion (à gauche) et Jay Fish se connaissent depuis 35 ans. Leur intérêt commun pour la permaculture les a tout naturellement conduits à créer la ferme régénératrice Highfield en 2020.

Currently, the farm hires one full-time operations manager, Heather Ramshaw, and an intern or two in the summer. And during Calgary’s short growing season, between late May and September, more than a hundred volunteers help weed, water and seed, which made the production of roughly 2,000 pounds of fresh produce possible in 2022.

But returning the land to a productive state isn’t the only goal of Highfield Farm: For Dorion, Fish and Zoller, fostering social connection during a challenging time is also essential. For this reason, the group created a number of programs that allow Calgarians to learn about our food system and the important role people play in it.

“We wanted to inspire people to come and take a class and learn how to grow a few things,” Fish says, “and maybe get the idea that they could take a more active role in that. [Here,] there’s a place to learn and there’s a community of people to support you.”

After the installation of a greenhouse last year, the growing capacity of the farm is expected to double in 2023. This expansion will allow Highfield Farm to increase the amount of fresh produce it donates to the Calgary Food Bank and The Mustard Seed, two of the city’s most prominent not-for-profit organizations.

“It’s part of that generative model,” says Dorion. “If you’re going to grow a certain amount of food, then some of that abundance gets shared. If we can share it with these food-security groups, then that’s a win for everyone.”

While Highfield Farm is still a pilot project, the seeds the Calgary trio plant today will continue to reap fruit in the years to come. “It’s a labour of love,” says Fish. “It’s an investment into the future for us.”

PREVIOUS SPREAD (right): With the help of 144 volunteers, Highfield Farm produced over 2,000 pounds of fresh produce last year, a third of which was donated to Calgary food charities. / PHOTO PAGE 29 : Aidée de 144 bénévoles, la ferme Highfield a produit 900 kg de légumes frais en 2022, dont un tiers a été donné aux banques alimentaires de Calgary.

LEFT: Before planting, seeds are placed on a seeding rack for up to eight weeks until they sprout. In Calgary, the growing season starts in late May and ends in September. / CI-CONTRE : Avant d’être plantées, les semences sont placées en germination pendant quelques semaines. À Calgary, la saison est courte, de fin mai à septembre.

En haute (et courte) saison, de fin mai à septembre, plus d’une centaine de bénévoles participent aux semis, à l’arrosage et au désherbage. Résultat? Une production d’environ 900 kg de légumes frais en 2022.

Mais redonner vie à cette terre n’est pas le seul objectif de la ferme Highfield : Mike Dorion, Jay Fish et Jeremy Zoller cherchent également à tisser un lien social en ces temps malmenés. Ils proposent donc plusieurs ateliers qui permettent à la population d’en savoir davantage sur notre système alimentaire et sur l’importance d’y participer en tant qu’être humain.

« On veut être une source d’inspiration, inciter les gens à venir et à apprendre à faire pousser deux ou trois choses, confirme Jay Fish. Et peut-être leur donner envie de jouer un rôle dans tout ça. Ici, on partage nos connaissances et on s’entraide. »

Grâce à l’ajout d’une serre en 2022, la capacité de production devrait doubler cette année. La ferme Highfield pourra alors augmenter ses dons de légumes frais à la banque alimentaire de Calgary et à The Mustard Seed, deux grands OSBL locaux.

« Cela fait partie de ce modèle générateur, poursuit Mike Dorion. Quand on cultive une bonne quantité de légumes, il est logique de partager. Et si ce partage se fait avec des organismes de sécurité alimentaire, tout le monde y gagne. »

Même si la ferme Highfield n’est encore qu’un projet pilote, les semences plantées par les trois hommes continueront de porter leurs fruits dans les années à venir. « C’est une vraie passion, conclut Jay Fish. Et un investissement pour notre avenir à tous et à toutes. »

BLOCK / 31

The Creator / Les créateurs

Layer by layer, over the course of six months, the Unbuilders crew deconstructed three buildings in downtown Victoria. Non-structural elements were removed and disposed of, while wood flooring and windows were salvaged. / Couche par couche, pendant six mois, l’équipe d’Unbuilders a déconstruit trois bâtiments au centre-ville de Victoria. Elle a récupéré le bois d’œuvre, les planches et les fenêtres. Les éléments non structurels ont été éliminés.

32 Work-in-Progress / Le chantier

Mass Salvage Planches de salut

Unbuilders deconstructs three Victoria buildings, saving materials typically lost to the demolition process. / À Victoria, Unbuilders déconstruit trois bâtiments en récupérant les matériaux habituellement perdus lors d’une démolition.

BY / PAR XIMENA GONZÁLEZ PHOTOS COURTESY OF / OFFERTES PAR UNBUILDERS

In the summer of 2022, three heritage buildings in downtown Victoria were decommissioned in an unusual fashion. Using a reverse construction system, Adam Corneil and his crew at Unbuilders diverted more than 300,000 board feet of lumber from the landfill, making room for a development while offsetting a portion of the carbon footprint that a brand-new building represents.

Based in Vancouver, Corneil’s company has been deconstructing buildings across British Columbia to sell or donate materials that would otherwise be destined for the landfill since 2018 as his vision for a more sustainable future comes to fruition. “The entire point of [deconstructing] is maximizing salvage value and minimizing waste,” he says. “and doing so in a time-effective and cost-effective manner.”

In Canada, demolition accounts for 12 percent of all solid waste generated. But not everything that ends up in the landfill should. “There’s not a single project that has no salvage value,” Corneil says, noting that sinks, cabinets, windows and flooring can often get a second life.

Usually, demolition companies salvage big timber from commercial jobs, but given the fast-paced nature of their work, Corneil explains, they only scratch the surface. “If we take the same building and our crew [demolishes] it … they’re getting 5 to 10 percent of what our crew gets.”

When the Salient Group, an award-winning developer, proposed the idea of “unbuilding” three heritage structures on Fort Street, Corneil jumped at the opportunity. “All three buildings were built very differently,” he says. “It was interesting for our team.”

After an initial evaluation of each building’s components, the crew identified areas that had toxic materials, like asbestos and lead, in need of removal. “There were some really odd things in these buildings,”

À l’été 2022, trois bâtiments patrimoniaux du centre-ville de Victoria se sont vu déclasser de manière inhabituelle. Adam Corneil, fondateur de Unbuilders, et son équipe les ont déconstruits, et non démolis. En détournant plus de 300 000 pieds-planches de bois du centre d’enfouissement, ils ont libéré l’espace pour un projet immobilier flambant neuf tout en compensant une partie de son empreinte carbone à venir.

Déconstruire pour bâtir un avenir plus durable, telle est la mission que s’est donnée Unbuilders. Basée à Vancouver depuis 2018, elle vend ou donne les matériaux des immeubles qu’elle démantèle en Colombie-Britannique. « Notre but est de maximiser la valeur de récupération et de minimiser les déchets. Et ce, de manière efficace et rentable », explique Adam Corneil.

Au Canada, le secteur de la démolition représente 12 % des déchets solides produits. Pourtant tout ne devrait pas finir à la décharge. « Il n’existe pas un chantier sans récupération », ajoute-t-il, notant qu’éviers, armoires, fenêtres et revêtements de sol sont bien souvent partants pour une seconde vie.

Généralement, les entreprises de démolition récupèrent les grosses poutres mais, soumises à des contraintes de temps, elles ne font qu’effleurer la surface, poursuit-il. « Elles ne prennent que 5 à 10 % de ce que nous pourrions retirer du même immeuble. »

Quand Salient Group, un promoteur primé, lui a proposé de déconstruire trois immeubles patrimoniaux dans la rue Fort, Adam Corneil a sauté sur l’occasion. « C’était intéressant, car ils étaient tous de construction très différente. »

Une première évaluation des composantes de chaque bâtiment a permis de repérer les matières dangereuses, tels l’amiante ou le plomb. « Il y avait des choses vraiment bizarres : l’immeuble du milieu,

BLOCK / 33 Work-in-Progress / Le chantier

says Corneil. “The middle building was four storeys with concrete walls on the sides and brick on the front and back, and they’d used some sort of asbestos tar that had dripped down the concrete for four storeys.”

This unlikely discovery led to some initial “hiccups” that Unbuilders quickly addressed, but a month later, the workers were back on track and ready to begin the initially planned salvage.

Deconstructed in two stages, the buildings were first stripped of drywall, utilities and flooring. Afterward, crews dismantled structural elements such as roofing, columns and beams. But this was not a simple process.

“It was extremely complex. Engineering was involved,” says Corneil. “The side buildings, built in 1908, were wood-floor structures with brick all around, so a lot of the brick [had to be] taken down by hand.”

haut de quatre étages, avait des murs en béton sur les côtés et en brique à l’avant et à l’arrière. Et on avait utilisé une espèce de goudron d’amiante, qui avait coulé le long du béton sur tous les étages. »

Un mois plus tard, après avoir géré ce fâcheux contretemps, l’équipe d’Unbuilders était prête à attaquer la déconstruction.

Elle a commencé par retirer les cloisons sèches, les installations électriques, la plomberie et les revêtements de sol. Puis tous les éléments structurels, comme la toiture, les colonnes et les poutres. Plus vite dit que fait.

« C’était extrêmement complexe, très technique, poursuit Adam Corneil. Les immeubles latéraux, datant de 1908, étaient des structures à plancher de bois avec des briques tout autour, qu’on a dû enlever en grande partie à la main. »

BELOW: The advantages of salvaging old-growth lumber go beyond environmental factors as it is stronger and denser than standard lumber. / CI-DESSOUS : Écoresponsable, la récupération du vieux bois de charpente a un autre avantage : il est plus solide et plus dense que les poutres standard.

34

Work-in-Progress / Le chantier

Furthermore, because the Edwardian facades of two of the buildings had to be preserved and the salvage process would take place in tandem with the demolition of structural concrete walls, Corneil and his crew had to find a way to maintain the building’s structural integrity while dismantling it.

“We braced the entire building, almost like [when] you’re pouring concrete,” Corneil describes. Once the exterior structure was secured, a mini-excavator was lifted onto the top storey, where it began its descent to the ground floor, carefully pulling down the lumber on each of the four levels along the way.

Sans compter que leurs façades à architecture édouardienne devaient être préservées. La récupération des matériaux se faisant en tandem avec la démolition des murs de béton, il fallait trouver un moyen de maintenir l’intégrité structurelle du bâtiment central tout en le démantelant.

« On a consolidé l’ensemble de l’immeuble, un peu comme si on allait couler du béton », raconte-t-il. Une fois la structure extérieure sécurisée, une mini-excavatrice a été hissée au dernier étage, d’où elle a entamé sa descente jusqu’au rez-de-chaussée, retirant avec précaution la charpente de bois de chaque étage sur son passage.

ABOVE: The most complex part of the demolition project was deconstructing the middle building because the side walls had to be remediated prior to demolition and the historical facade of an adjacent building preserved. / CI-DESSUS : L’immeuble du milieu a été le plus complexe à démanteler : il fallait soutenir ses murs latéraux avant la récupération tout en préservant la façade historique du bâtiment adjacent.

BLOCK / 35

Work-in-Progress / Le chantier

RIGHT:

walls were deconstructed by hand using a process that ensured that the integrity of the bricks would be maintained so they could be reused. Damaged bricks were recycled. / CICONTRE : Afin de pouvoir les réutiliser, les briques des murs ont été enlevées une par une à la main. Les plus abîmées ont été recyclées.

36

Work-in-Progress / Le chantier

Brick

LEFT: Unbuilders salvages dimensional lumber, shiplap, large posts and beams as well as plank flooring and sells these materials locally. In this project alone, 300,000 board feet of lumber were diverted from the landfill. / CI-CONTRE : Unbuilders récupère les poutres et colonnes de soutien ainsi que les revêtements en bois, qu’elle revend localement. Ce seul projet a permis de détourner plus de 300 000 piedsplanches du centre d’enfouissement.

While the bricks removed were sent for recycling, other salvaged materials were either sold or locally donated. The precious old-growth lumber was sold and shipped to a reclaimed-wood manufacturer in Montana.

But deconstructing a building to ensure that its components can be reused is only half the challenge. The other half, Corneil explains, is generating consumer interest in the salvaged materials.

Building owners tend to favour new materials because these are perceived to be more durable and cost-effective. But as consumers become more mindful of the pressures this mindset poses for a planet with finite resources, Corneil hopes the interest in reclaimed materials will expand.

“It’s cheaper to throw away and build new,” he says. “But that time is coming to an end, and we’re realizing that the circular economy is the economy of the future. We need to start rethinking how all of our processes and society work.”

Tous les matériaux récupérés ont été soit vendus, soit donnés localement. Les briques ont été envoyées au recyclage, le précieux bois d’œuvre expédié à un fabricant d’objets en écobois au Montana.

Mais déconstruire un bâtiment en veillant à ce que ses divers éléments soient réutilisables ne représente que la moitié du défi. Il faut également susciter l’intérêt du consommateur pour ces matériaux de récupération.

Et ce n’est pas une mince affaire. Les propriétaires ont tendance à préférer le neuf, perçu comme plus durable et plus rentable. Pourtant, de plus en plus de gens prennent aujourd’hui conscience des ressources limitées de notre planète, ce qui donne de l’espoir à Adam Corneil.

« Jeter et reconstruire du neuf, c’est simplement meilleur marché. Mais cette époque tire à sa fin. On réalise que l’économie circulaire, c’est l’économie de demain. On doit repenser l’ensemble de notre fonctionnement en tant que société. »

BLOCK / 37

Work-in-Progress / Le chantier

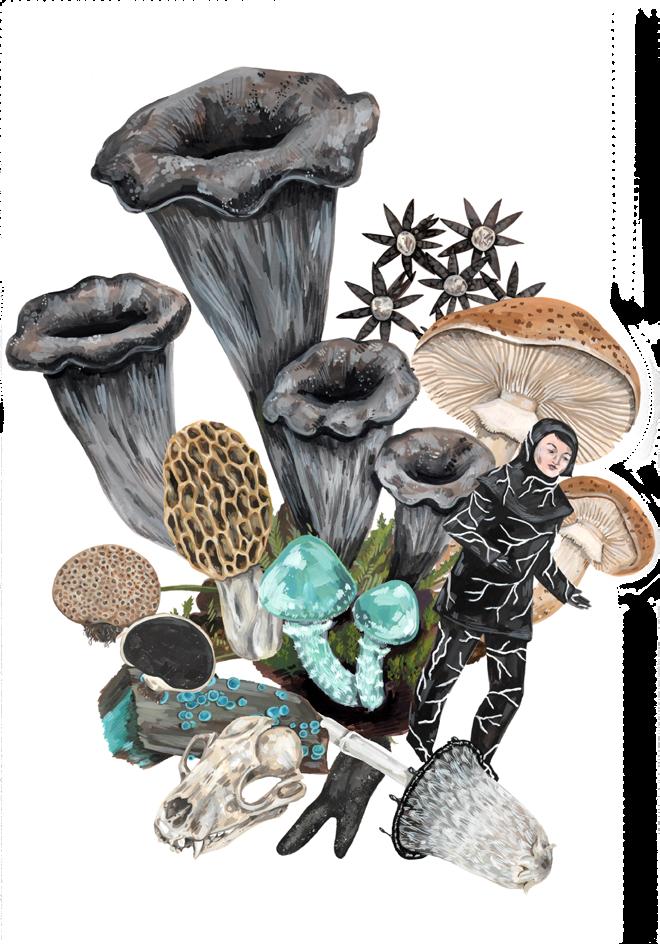

38 The Conversation / La conversation

Collage by Diane Borsato with illustrations by Kelsey Oseid (2022) from Mushrooming: The Joy of the Quiet Hunt, by Diane Borsato and illustrated by Kelsey Oseid. / Collage de Diane Borsato (2022) à partir des illustrations de Kelsey Oseid, tirées du livre Mushrooming: The Joy of the Quiet Hunt

Hidden Kingdom Un monde caché

BY / PAR DIANE BORSATO AND / ET JANALYN GUO

Mushrooms were The New York Times ’ food of the year in 2022, and in January, the Mushroom Council—a very real council composed of fungi producers—said the trend is continuing. Diane Borsato, an artist and the writer of Mushrooming: The Joy of the Quiet Hunt , and Janalyn Guo, author of Our Colony Beyond the City of Ruins , spoke with Block about the “loathed and lusted after” kingdom Fungi, and how these organisms can help us pay closer attention to our environment.

JANALYN GUO: Diane, your book Mushrooming is a forager’s guide in a sense, but it also describes a way of looking at and being in the world. How would you describe it?

DIANE BORSATO: Mushrooming is essentially an uncommon field guide. It was written by an artist rather than a scientist, and it’s grounded in cultural conversations and contemporary art about mushrooms, nature, land and many other themes that fungi invoke, like death and decay, fairies and demons, aphrodisiacs and beauty. It is a work of love, really. I have learned a lot while walking slowly in the woods observing fungi. The “quiet hunt,” as it is sometimes called, has been a way to practise looking and seeing things closely.

Et si on parlait champignons? Élus aliments de l’année 2022 par le New York Times, ils sont toujours tendance en 2023 d’après le Mushroom Council, une organisation américaine de producteurs de champignons. Diane Borsato, artiste et autrice de Mushrooming: The Joy of the Quiet Hunt, et Janalyn Guo, autrice de Our Colony Beyond the City of Ruins, discutent de l’amourhaine qu’on porte à ces fongus et du regard réflexif qu’ils nous invitent à porter sur la nature.

JANALYN GUO : Diane, votre livre est un guide illustré des champignons, mais c’est aussi une manière de regarder le monde. Diriez-vous la même chose?

DIANE BORSATO : En fait, c’est un guide pratique qui sort des sentiers battus. Écrit par une artiste et non une botaniste, il prend racine dans la culture populaire et l’art contemporain. On y parle champignons, nature, sol, mais aussi mort et décomposition, fées et démons, aphrodisiaques et beauté. C’est une histoire d’amour avec les champignons. J’ai beaucoup appris en me promenant dans la forêt pour les observer. Cette « quiet hunt », ou chasse en silence, m’a permis de regarder la vie de plus près.

BLOCK / 39 The Conversation / La conversation

JG: How cool to catalogue all the varied colourful fungi that greet you on your walks. They have their way of creeping into my work as well, maybe because they resonate with what I’m often thinking about: adaptation and resilience in the face of great environmental change, communication, connectivity and decay.

DB: A theme that seems to recur in your writing is an invasive nature— mushrooms or trees growing on or out of bodies calling us back to a natural environment.

JG: In my story “The Cave Solution,” a woman who volunteers to grow a tree inside her body finds herself able to communicate directly with the Humongous Fungus (a fungal mass in Oregon that once claimed the title of largest single organism on Earth). I am drawn to weird and mysterious things; since we know the least about fungi (compared to plants and animals), they’re very evocative to me.

DB: I love that she volunteers to grow a tree inside her body . It’s a beautiful image, though violent too—the most extreme imaginable level of a cross-species union. But why are mushrooms so villainous in your work? Are you fundamentally afraid of fungi?

JG: I think because there’s so much we don’t know about fungi, they haunt us. We fill in the blanks. They get tangled in our collective hopes and fears and anxieties. Some people proclaim that mushrooms are going to cure cancer and save the world. Then there are these works of weird horror, like The Beauty by Aliya Whiteley and Paradise Rot by Jenny Hval and the movie Matango , that all feature fungi and explore the notion of being overtaken, subsumed or changed in ways we can’t imagine that are beyond our control.

I mean, I wouldn’t mind being subsumed into a mushroom entity if it was helping us!

DB: It’s a striking image, though I think I prefer subsuming them , as in roasting and using them to garnish pasta. But you’re right about the mysteriousness of mushrooms and how they grow and reproduce. Imagine these beings that appear suddenly and grow in the dark. They don’t contain chlorophyll or act like plants at all. And they can cause frightening hallucinations, poisonings and a painful death. Fungi are a source of terror and fascination, feared and prized, loathed and lusted after—sometimes for the same reasons.

JG: For sure. I think mushrooms should have a spot in fancy tasting rooms, alongside coffee beans and wine and chocolate, where we talk about their terroir and mouth feels.

DB: I love that idea! So often, wild fungi are described vaguely as “earthy,” though there is as much diversity among mushrooms as there is among cheeses. Some are flowery or taste like apricots or cinnamon.

JG: I’m curious about how seeing things closely became important to your work. Was there a time when it wasn’t?

DB: As a visual artist, it is my main work to look at things closely. I noticed that walking in the woods looking for mushrooms was a great way to practise this. Identifying them also requires great sensory literacy, including touch and smell and taste —but especially seeing . You have to spot them, camouflaged in the leaf litter, and then attune your vision to see the subtlest shifts in colour, striation, luminosity… I bring my studio art students into the woods too and tell them it’s a practice of seeing a hidden kingdom.

JG: I recently started rockhounding in the desert, and I relate to this. I feel like it takes forever to zero in on that first rock, but after that initial discovery—once your eyes are attuned to that certain sparkle it gives off—you suddenly see them winking at you from everywhere all at once.

DB: This kind of attention to our immediate environment informs all of our thinking as artists. It contributes to our understanding of some of the most critical ideas of our time—that Indigenous scientists like Robin Wall Kimmerer of Potawatomi Nation describe as the urgency of expressing gratitude, living reciprocally with other beings and understanding how all our flourishing is mutual.

JG: Our human health and collective well-being are deeply connected to the health of the environment. When I write about trees and plants growing out of bodies, I just want to emphasize how much we’re connected.

DB: Mushrooming together with others in the forest brings a collective experience of this. If we are paying close attention, we might be present to ways in which land and weather are affected by colonial and environmental violence, to the wild diversity and wondrousness of living things and to our complex interdependence. To make contemporary environmental art, this experience and knowledge are essential.

Do you think writers and artists can have an effect on how we make decisions about the future of our environment?

JG: Scientists and activists are doing very hard and often unappreciated work on this front. I can’t claim to understand the truly complicated dynamics of an ecosystem, and I’m not directly interacting with and organizing people, but I do think that we as artists bring something of our own to the conversation. I think artists are evocative and perhaps a little bit sneaky. We can really surprise people into recognizing something true about themselves and their world when they least expect it. There’s something distinctive about that.

40

The Conversation / La conversation

You can find Borsato’s Mushroomingin most major Canadian book retailers and online. Guo’s “Night Fragrance” appears in the anthology Mooncalves, published by NO Press.

“[Fungi] resonate with what I’m often thinking about: adaptation and resilience in the face of great environmental change.”

J. G. : C’est génial de répertorier toutes les variétés colorées qu’on croise en chemin. Les champignons se faufilent aussi dans mon travail à leur façon, peut-être parce qu’ils font écho à mes réflexions sur l’adaptation et la résilience face aux changements environnementaux, sur la communication, la connectivité, le déclin.

D. B. : Un thème semble récurrent dans vos écrits : une nature invasive avec des champignons, ou des arbres, qui poussent à l’intérieur ou à l’extérieur de nous.

J. G. : Dans une de mes nouvelles, une femme qui se porte volontaire pour faire pousser un arbre dans son corps peut alors entrer en communication directe avec le Mégafongus, une masse fongique qui revendique le titre de plus grosse espèce unicellulaire de la Terre. L’étrange et le mystérieux m’attirent. On en sait si peu sur les champignons, par rapport aux plantes ou aux animaux, qu’ils me fascinent.

D. B. : Elle se porte volontaire pour faire pousser un arbre dans son corps… J’aime l’image : elle est à la fois belle et violente, une union interespèces à la limite de l’imaginable. Mais pourquoi les champignons jouent-ils les infâmes? Les redoutez-vous à ce point?

J. G. : Je crois qu’ils nous hantent. On en sait si peu qu’on cherche à combler les vides. Ils s’enchevêtrent dans nos espoirs, nos craintes, nos angoisses collectives. Certains disent que les champignons vont éradiquer le cancer et sauver le monde. D’autres, comme ces livres et films d’horreur, tels que The Beauty d’Aliya Whiteley, Paradise Rot de Jenny Hval ou Matango, mettent en scène des champignons qui nous subsument, nous changent de façon inimaginable et hors de tout contrôle.

En fait, ça ne me dérangerait pas d’être subsumée dans une entité fongique si cela était d’une quelconque utilité!

D. B. : L’image est frappante! Pour ma part, je crois que je préfèrerais les subsumer, en les faisant sauter un poêlon par exemple. Mais vous avez raison, les champignons restent une énigme : ils apparaissent comme par magie, poussent dans l’obscurité, ne contiennent pas de chlorophylle, ne se comportent pas comme les plantes. Ils peuvent provoquer des hallucinations, des empoisonnements et une mort douloureuse. Ils sont source de terreur et de fascination, on les craint et on les apprécie, on les aime et on les déteste, parfois pour les mêmes raisons.

J. G. : Tout à fait. Il devrait y avoir des dégustations de champignons, comme pour le vin, le café ou le chocolat. On y parlerait de leur terroir et de leur longueur en bouche.

D. B. : Quelle bonne idée! Ils sont trop souvent décrits comme « terreux », alors que, à l’instar des fromages, les champignons ont toute une palette de saveurs. Certains ont des notes florales, d’autres d’abricot ou de cannelle.

J. G. : Je me demande si le fait de regarder les choses de plus près a eu une influence sur votre travail… Ou l’avez-vous toujours fait?

D. B. : En tant qu’artiste visuelle, j’ai l’habitude de regarder les choses de près. Chercher des champignons dans le bois était un excellent exercice. Leur identification fait appel à tous les sens : le toucher, l’odorat, le goût, mais surtout la vue. Il faut d’abord les repérer, camouflés entre les feuilles, puis ajuster son œil pour discerner les subtiles variations de couleur, de stries, de luminosité… J’amène d’ailleurs mes étudiants en art dans la forêt, à la découverte de ce monde caché.

J. G. : Je comprends, je me suis lancée dans la chasse aux minéraux dans le désert. Ça prend une éternité pour trouver la première pierre, mais après, une fois que l’œil sait ce qu’il cherche, qu’il a mémorisé l’éclat si particulier des cristaux, il en voit partout.

D. B. : Ce type d’attention portée à notre environnement immédiat nourrit notre réflexion d’artiste. Il nous permet de comprendre certaines idées fondamentales de notre époque, ce que la biologiste Robin Wall Kimmerer de la nation des Potéouatamis décrit comme l’urgence d’exprimer de la gratitude, de vivre en réciprocité avec les autres êtres vivants car notre épanouissement est mutuel.

J. G. : La santé humaine et notre bien-être collectif sont étroitement liés à la santé de la nature. Je raconte des histoires d’arbres qui poussent à l’intérieur de nous pour souligner à quel point nous sommes liés justement.

D. B. : Partir à plusieurs en forêt à la cueillette de champignons en fait une expérience collective. Si on est attentifs, on peut être témoins des effets de la violence coloniale et environnementale sur le sol et le climat, de l’incroyable diversité des êtres vivants, de leur extraordinaire et de la complexité de notre interdépendance. Ce vécu et ce savoir sont indispensables à l’écoart contemporain.

Pensez-vous que les écrivains et artistes peuvent peser sur les décisions concernant l’avenir de l’environnement?

J. G. : Les scientifiques et les militants y travaillent fort. Ce qu’ils font est difficile et souvent peu apprécié. Je ne prétends pas comprendre la dynamique complexe d’un écosystème, je n’interagis pas avec les gens ni ne les mobilise, mais je crois que nous, les artistes, participons au débat à notre manière. Je pense que nous sommes inspirants et peut-être un peu dissimulateurs. Nous pouvons réellement surprendre notre monde en lui faisant admettre une vérité à son sujet quand il s’y attend le moins. C’est cela qui nous distingue.

BLOCK / 41

The Conversation / La conversation

Mushroomingde Diane Borsato est en vente dans les grandes librairies canadiennes et en ligne. Night Fragrancede Janalyn Guo fait partie du recueil de nouvelles Mooncalves, publié par NO Press.

«

[Les champignons] font écho à mes réflexions sur l’adaptation et la résilience aux changements environnementaux. »

The Stackton by/signé AdrianMartinus Design

BY / PAR MÉLANIE RITCHOT PHOTO BY / PAR JEREMY FOKKENS

Adrian and Martinus were inspired by Japanese artist Haroshi’s work recycling skateboards into sculptures. The team turns hundreds of used skateboards collected from shops in western Canada into veneers, in a two-week process that happens twice a year, to be used in furniture builds. / La source d’inspiration d’Adrian et Martinus? Haroshi, un artiste japonais qui surcycle les planches à roulettes en sculptures. Le duo récupère des centaines de planches à roulettes usagées ici, dans les magasins alentour, pour en faire du placage : une opération de deux semaines qui a lieu deux fois par an.

The credenza has tambour doors with narrow strips made from the recycled skateboards and backed with canvas, which allows the doors to slide along a curved track. / Stackton est doté de portes coulissantes à l’horizontale : composées de fines bandes de planches à roulettes recyclées et doublées de toile, elles glissent le long d’un rail incurvé.

42 Made / Fabriqué

After working in carpentry and salvaging discarded materials from construction sites for years, two Alberta brothers, Adrian and Martinus Pool, started a design company rooted in sustainable practice and quality woodwork. (They were joined later by Adrian’s wife, Anne Tranholm.) AdrianMartinus Design turns used skateboards into mid-century modern and Japanese-inspired furniture—like the Stackton credenza—and decor pieces. / Après avoir travaillé des années dans la menuiserie et la récupération de matériaux sur les chantiers, deux frères albertains, Adrian et Martinus Pool, ouvrent leur atelier d’écoébénisterie (ils seront rejoints plus tard par l’épouse d’Adrian, Anne Tranholm). AdrianMartinus Design transforme des planches à roulettes usagées en meubles et objets déco mi-japonisants mi-modernistes. Le buffet Stackton en est un bel exemple.

The Stackton originally had more angular pieces and covered sides, resulting in nearly a foot of lost space. Now, in its second iteration, offcuts from the ash, oak or walnut used for the tops of the credenzas are made into smaller furniture and decor pieces, like record shelves, to minimize waste. / Le tout premier modèle, plus anguleux, était aussi moins spacieux. Le deuxième gagne presque 30 cm et gaspille encore moins, puisque ses chutes de bois de frêne, de chêne ou de noyer servent à fabriquer des cimaises à disques vinyle et autres objets déco.

The AdrianMartinus team won the Etsy Design Award in 2020 for the Stackton and have since shipped out more than 40 of the credenzas across North America, with more in the works in their homebased workshops. / En 2020, Stackton remporte le prix Etsy Design. Depuis, le carnet de commandes ne désemplit pas. L’atelier AdrianMartinus en a livré plus d’une quarantaine en Amérique du Nord et d’autres sont en cours de fabrication.

BLOCK / 43 Made / Fabriqué

COURTESY OF / OFFERTE PAR ADRIANMARTINUS DESIGN

Garden Room Jardin intérieur

BY / PAR KRISTINA LJUBANOVIC

VOUS STEPPING

into the lobby of Allied’s 60 Adelaide East—on an especially blustery Toronto morning—one is struck by an unexpected sight: a moss wall, just beyond the elevator bank, with improbable tufts of emerald and chartreuse green so vibrant you must touch to believe. (I did, and it’s real.)

Adjacent to the moss display—perhaps in conversation with it—hangs Montréal-based photographer Lisa Yang’s tripartite photographic series Rose, Ribbon, Glass , curated and installed by a team at MASSIVart. In each of the images, a single rose is manipulated, enrobed in ribbon and pressed between glass and diffuser film, rendering it ghostly, X-ray-like and strangely romantic.

Moss and roses? Is this a commercial building lobby or the set of a Charlotte Brontë novel?

“It’s like having a little garden in the building,” says Yang, who often uses natural materials in her personal and commercial work. (The largely self-taught artist doubles as a set designer and prop stylist. In fact, Rose, Ribbon, Glass was created while she was shooting a commercial project.)

“When I first started, I focused on fruits and then naturally progressed to florals,” she says. Indeed, Yang’s online portfolio reveals a profusion of nature-infused images: beauty-product packaging set on dried grass or perched between tree limbs and eyewear hanging from budding branches or propped on a pile of artichoke, beet and rutabaga.

“I like working with objects,” says Yang, “especially when they’re not man-made. It’s up to you to create something new out of them.” When she was first starting out, the decision to use fruits and flowers was a simple matter of accessibility; they were items she had in her house already.

While Yang finds aesthetic inspiration on Instagram and, these days, is even dabbling in AI-generated art, ultimately, you can’t beat Mother Nature as a muse. “When there’s good sunlight, I’m inspired.”

pourriez être surpris·e en entrant au 60, rue Adelaide Est à Toronto. Dans cet immeuble appartenant à Allied, c’est un mur de mousse qui vous accueille. Des touffes d’un vert chartreuse et d’un vert émeraude si éclatants qu’il faut les toucher pour y croire (je l’ai fait, et c’est du vrai).

À côté de ce tableau végétal, et peut-être en conversation avec lui, se déploie Rose, Ribbon, Glass, le triptyque de la photographe montréalaise Lisa Yang, installé par l’équipe de MASSIVart. Dans chaque panneau, roses et rubans sont pressés contre une plaque de verre et un film diffuseur de lumière pour un effet étrangement romantique, mi-fantomatique mi-radiographique. De la mousse, des roses… Se trouve-t-on dans le hall d’un immeuble ou dans un roman de Charlotte Brontë?