IMPLEMENTATION: POLICY MADE CONCRETE

FEBRUARY 2023 PROSPECT.ORG IDEAS, POLITICS & POWER

KRISTA BROWN & MOE TKACIK THE TICKETMASTER SAGA

HAROLD MEYERSON WORKER FREEDOM

David Dayen | Robert Kuttner | Jarod Facundo | Lee Harris

Made in America is a Progressive Value

Over the past two years, progressives have helped build new economic policy centered on American workers, U.S. factories, and a clean energy future. In 2023, it’s time to make it real by:

• Building upon industrial policy like the CHIPS and Science Act and Inflation Reduction Act

• Making good on clean energy investments like domestic solar production and electric vehicles

• Fully implementing infrastructure investment

• Enforcing Buy America laws to ensure our future in Made in America

• Making sure the jobs created are good-paying, familysupporting jobs

Let’s keep the work going.

americanmanufacturing.org

Features

14 A Pitched Battle on Corporate Power

Biden’s expansive executive order seeks to restore competition in the economy. It’s been a long, slow road to get the whole government on board—but there are some formidable gains. By David Dayen

24

Reclaiming U.S. Industry

Biden’s industrial policies represent a stunning ideological reversal. The harder part will be making them work.

By Robert Kuttner

34 Reanimating the Taxman

The impossible task ahead for the newly flush Internal Revenue Service By Jarod Facundo

42 Wall Street’s Big Bet on Rewiring America

Ithaca has put its Green New Deal in the hands of a green private equity fund, a private foundation, and a Goldman Sachs–backed software company. By Lee Harris

48

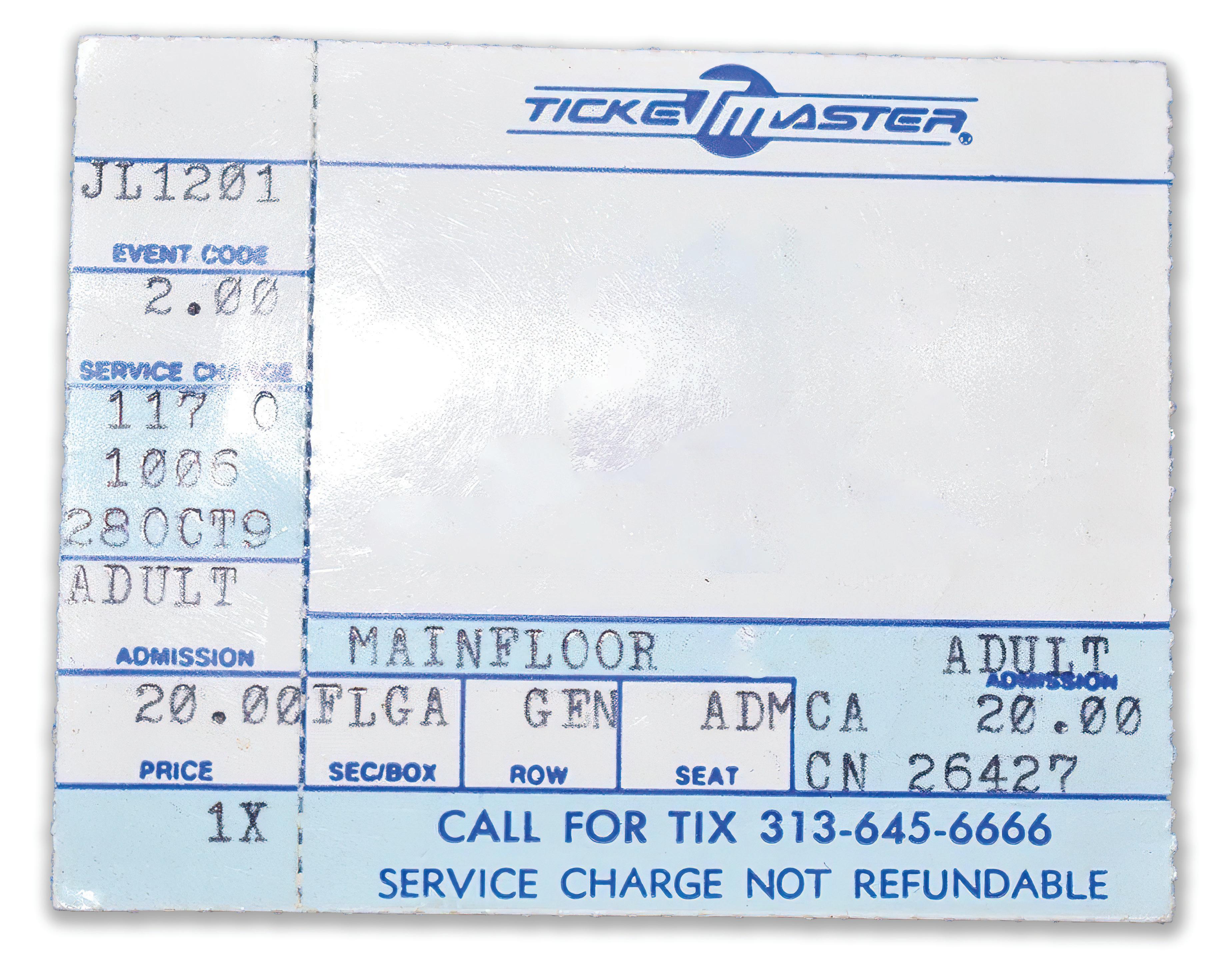

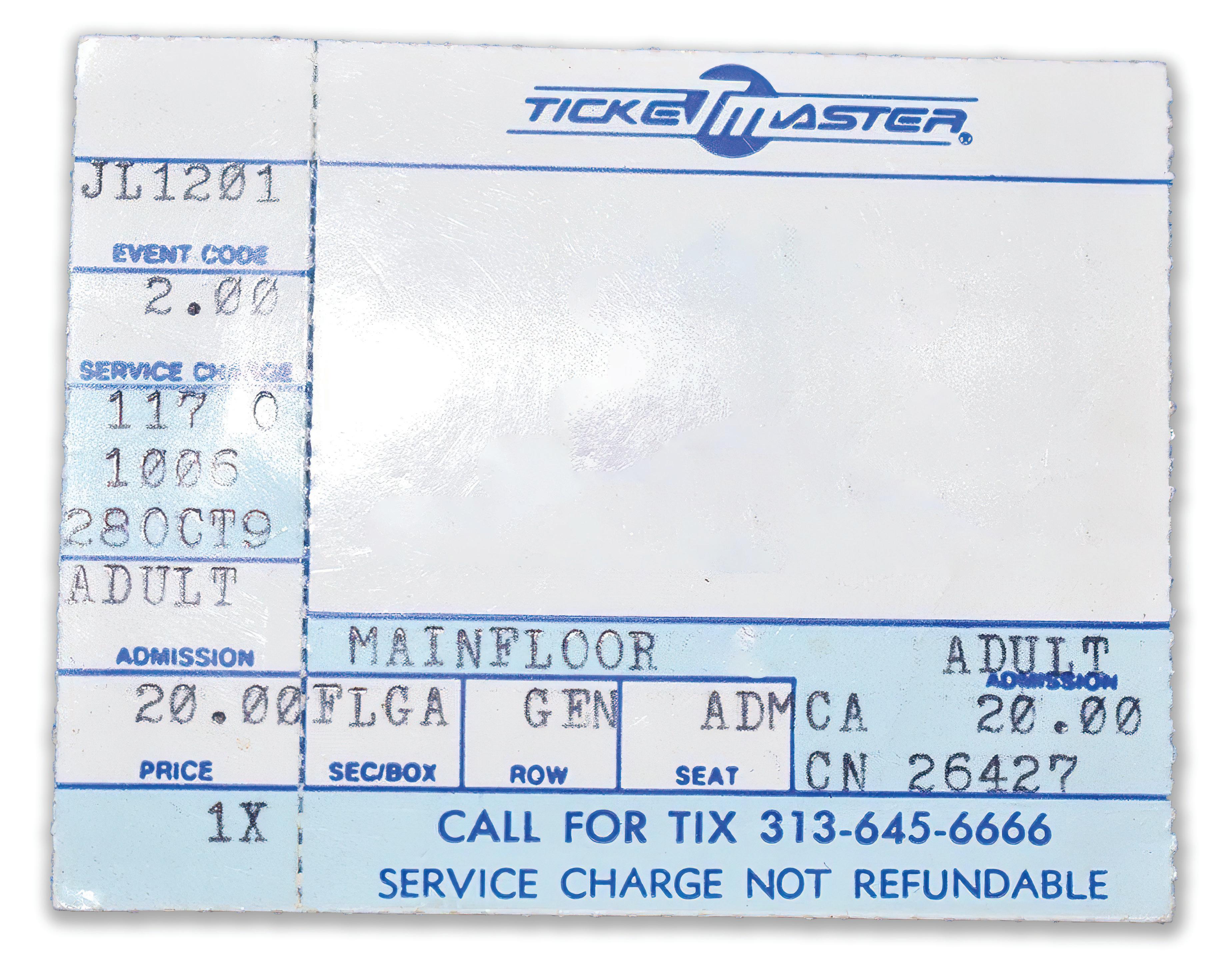

Ticketmaster’s Dark History

A 40-year saga of kickbacks, threats, political maneuvering, and the humiliation of Pearl Jam

By Maureen Tkacik and Krista Brown

By

By Joan Fitzgerald 10

Green Public Power By Ryan Cooper 12 The Slow Extraction of Lead Water Pipes By Ramenda Cyrus

Culture

57 Gabrielle Gurley on The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration 60 Blaise Malley on Pacific Power Paradox: American Statecraft and the Fate of the Asian Peace 64 Parting Shot: Human Intelligence By Francesca Fiorentini

Cover art by Alex Eben

48 7

Supercharging

Prospects 04 Restoring Workers’ Freedoms

Harold Meyerson Notebook 07 What Could Chill Heat Pumps

February 2023 VOL 34 #1 14

Visit prospect.org/ontheweb to read the following stories:

The Great Inflation Myths

This Prospect series challenges the dominant orthodoxies mainstream economists and the Federal Reserve have been espousing about inflation and the need for interest rate hikes to tame it.

Precarious Geopolitics

The Prospect ’s international coverage focuses on global tensions from America’s economic nationalism and confrontation with China, as well as integrations in the developing world.

Building America

2023 will be a year of executive action to implement the Biden agenda, and the Prospect has all the details.

On TAP

Every day, senior editors Harold Meyerson and Robert Kuttner bring you the latest in news and analysis of the biggest stories.

On the Web

2 PROSPECT.ORG FEBRUARY 2023

Left Anchor Prospect managing editor Ryan Cooper and Alexi the Greek host an in-depth podcast covering politics, power, and progressive policy.

EXECUTIVE EDITOR David Dayen

FOUNDING CO-EDITORS Robert Kuttner, Paul Starr

CO-FOUNDER Robert B. Reich

EDITOR AT LARGE Harold Meyerson

SENIOR EDITOR Gabrielle Gurley

MANAGING EDITOR Ryan Cooper

ART DIRECTOR Jandos Rothstein

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Susanna Beiser

STAFF WRITER Lee Harris

JOHN LEWIS WRITING FELLOW Ramenda Cyrus

WRITING FELLOWS Jarod Facundo, Luke Goldstein

INTERNS Sunni Bean, Stephen Borrelli, Julia Merola

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Austin Ahlman, Marcia Angell, Gabriel Arana, David Bacon, Jamelle Bouie, Jonathan Cohn, Ann Crittenden, Garrett Epps, Jeff Faux, Francesca Fiorentini, Michelle Goldberg, Gershom Gorenberg, E.J. Graff, Bob Herbert, Arlie Hochschild, Christopher Jencks, John B. Judis, Randall Kennedy, Bob Moser, Karen Paget, Sarah Posner, Jedediah Purdy, Robert

D. Putnam, Richard Rothstein, Adele M. Stan, Deborah A. Stone, Michael Tomasky, Paul Waldman, Sam Wang, William Julius Wilson, Matthew Yglesias, Julian Zelizer

PUBLISHER Ellen J. Meany

PUBLIC RELATIONS SPECIALIST Tisya Mavuram

ADMINISTRATIVE COORDINATOR Lauren Pfeil

BOARD OF DIRECTORS Daaiyah Bilal-Threats, Chuck Collins, David Dayen, Rebecca Dixon, Shanti Fry, Stanley B. Greenberg, Jacob S. Hacker, Amy Hanauer, Jonathan Hart, Derrick Jackson, Randall Kennedy, Robert Kuttner, Ellen J. Meany, Javier Morillo, Miles Rapoport, Janet Shenk, Adele Simmons, Ganesh Sitaraman, William Spriggs, Paul Starr, Michael Stern, Valerie Wilson

PRINT SUBSCRIPTION RATES $60 (U.S. ONLY)

$72 (CANADA AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL)

CUSTOMER SERVICE 202-776-0730, ext 4000 OR info@prospect.org

MEMBERSHIPS prospect.org/membership

REPRINTS prospect.org/permissions

Vol. 34, No. 1. The American Prospect ( ISSN 1049 -7285) Published bimonthly by American Prospect, Inc., 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, D.C., and additional mailing offices. Copyright ©2023 by American Prospect, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this periodical may be reproduced without consent. The American Prospect ® is a registered trademark of American Prospect, Inc. POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to American Prospect, 1225 Eye St. NW, Ste. 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

Thank You, Reader, for Your Support!

Convert Your Print Subscription to a Full Prospect Membership

Every membership level includes the option to receive our print magazine by mail, or a renewal of your current print subscription. Plus, you’ll have your choice of newsletters, discounts on Prospect merchandise, access to Prospect events, and much more.

Find out more at prospect.org/membership

Update Your Current Print Subscription

prospect.org/my-TAP

You may log in to your account to renew, or for a change of address, to give a gift or purchase back issues, or to manage your payments. You will need your account number and zip-code from the label:

ACCOUNT NUMBER ZIP-CODE

EXPIRATION DATE & MEMBER LEVEL, IF APPLICABLE

To renew your subscription by mail, please send your mailing address along with a check or money order for $60 (U.S. only) or $72 (Canada and other international) to:

The American Prospect 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005

info@prospect.org | 1-202-776-0730 ext 4000

FEBRUARY 2023 THE AMERICAN PROSPECT 3

Restoring Workers’ Freedoms

Left

es, capitalism invariably demands a reversion to the mean—and by “mean,” I mean cruel, abusive, proprietary treatment of its workers.

Time was when American capitalism wasn’t left entirely to its own devices. During the three decades when the New Deal social contract was in place and fully a third of the nation’s workforce was unionized, the power that owners and employers wielded over those who did their work was partially reined in. By the mid-1970s, those constraints began to give way to the forces of business and finance; and with the coming of Reagan Republicanism to American governance a few years later, the modest countervailing power that workers had once exercised, with the government’s backing, to control aspects of their work lives was radically diminished.

The workers’ loss was threefold. They lost power, provision, and freedom.

The loss in power was chiefly the result of deunionization. In the half-century since corporate America ended its semi-toleration of unions, the share of private-sector workers who could bargain collectively for wages and benefits has declined from a quarter of the workforce to a bare 6 percent. Years of anti-labor court decisions hollowed out the National Labor Relations Act, whose threadbare remnants no lon-

ger offered any protections to workers who sought to unionize.

The loss of power was accompanied by a loss of provision. The federal minimum wage lagged further and further behind the cost of even penurious living. Save for brief intervals when the economy was close to full employment, workers’ wages stagnated in the absence of any way for workers to effectively bargain with management and in the presence of increasing low-wage competition from the low-wage employees and contract workers of multinational corporations—many of them American—in the developing world. Workers’ incomes also stagnated as companies labeled them independent contractors and gig workers rather than employees, not subject to minimumwage laws or employer provisions for Social Security, nor the other social contracts of the New Deal.

And third, beginning in the 1990s, came the loss even of economic freedoms. Emboldened by relentlessly anti-worker court decisions, and by even more antiworker Republicans and by too many complaisant Democrats, employers clamped down on two sets of freedoms that most American workers had assumed were theirs simply by dint of their rights as citizens.

Previously, if they had a grievance at work or had suffered damages in the work-

place, assuming they had no union, they could always take their employer to court. But after a 1991 court decision effectively stripped them of that right by giving employers the right to subject those workers to a mandatory arbitration process—most often, as a condition of employment—workers lost their right to have their day in court. According to a 2018 study for the Economic Policy Institute by Alexander J.S. Colvin, just 2 percent of workers were contractually subjected to forced arbitration in 1992. By 2018, however, that number had risen to 56.2 percent of private-sector non-union workers, or roughly 60 million.

The other freedom workers have lost is even more elemental, and fundamental: the right to leave one job to take another. A large number of American workers are compelled to sign noncompete agreements, with which their employers forbid them from taking a job at a rival firm or leaving their job to start a business of their own in the same field. In recent decades, emboldened by the courts’ attitude—ranging from indifference to hostility to worker rights—employers have expanded this practice from the relatively small number of professional workers privy to proprietary trade secrets to any workers who may at some point want to move from the burger joint they’re working at to the burger joint across the street.

Which is one reason why the Bidenappointed majority on the Federal Trade Commission announced in January that it was beginning a process to abolish noncompete agreements. “Economic liberty, not just political liberty, is at the heart of the American experiment,” FTC Chair Lina Khan wrote in a New York Times op-ed , explaining the proposal. “You’re not really free if you don’t have the right to switch jobs or choose what to do with your labor. But millions of American workers can’t fully exercise that choice because of a provision that bosses put into their contracts: a noncompete clause.”

The two means of dealing with an institution that’s not meeting your needs, the economist Albert O. Hirschman wrote, are voice and exit. For millions, perhaps a majority, of American workers, the extirpation of unions and the rise of forced arbitration have eliminated the possibility of voice, while the spread of noncompetes has blocked the possibility of exit.

It’s these erosions of worker power and freedom that Biden-age Democrats in Con-

4 PROSPECT.ORG FEBRUARY 2023

to its own devic-

PROSPEC TS

Harold Meyerson

gress (when they have the votes), in blue states, and at federal agencies have been working to reverse.

Biden himself is no Johnny-come-lately to the fight against noncompetes. In a 2018 talk at the Brookings Institution, he called them a significant cause of wage stagnation. (Indeed, the FTC ’s fact sheet on its proposed rule change estimates that it could increase workers’ yearly earnings by between $250 billion and $296 billion.) Once in the White House, Biden cited the need to scrap noncompetes as a centerpiece of his administration’s policy to create a more competitive economy.

In appointing Khan to head the FTC , Biden was entrusting what has often been a somnolent agency to one of the most intellectually and legally adept critics of the monopolies and monopsonies that dominate our economy. Khan’s proposal to strike down noncompetes provided ample testimony to her chops. Rather than continuing to document individual cases of employers’ use of noncompetes that ran afoul of restraint-of-trade laws, and ordering those employers to cease and desist, Khan argued instead that the FTC could proactively ban the practice under the longneglected, often-forgotten Section 5 of the act that created the FTC, which empowers the Commission to curtail “unfair methods of competition.” For the past half-century, court decisions have largely limited the FTC to dealing with individual cases, but Section 5 is still on the books.

When the FTC passes such a rule (it is now just beginning the lengthy rulemaking process), it will doubtless be challenged by various business organizations in the courts. By choosing noncompetes as the battlefield on which she’ll fight, Khan has selected the one kind of restraint of trade on which the trustbusters can gain the most public support. The episodes in which employers have wielded noncompetes outrageously are legion. In announcing its proposed rule-setting, the FTC cited one recently settled case in which a Michigan security guard company used a noncompete clause to forbid its employees, who were working at or near the minimum wage, from going to work for any other guard companies within 100 miles of their employer, and when some did, charging them the $100,000 that the fine print of their employment agreement said would be the penalty.

How many low-paid workers with no proprietary knowledge are covered by these agreements? One study, headed by University of Maryland economist Evan Starr, that’s based on a 2014 survey of 11,505 workers found that roughly 18 percent of workers are bound by noncompetes, and while the rate was higher among higher-paid employees, it was still considerable among those who did more routine work. Among those making more than $40,000 annually, the rate was 25 percent; among those making less, the rate was 13 percent.

Another study, this from the Economic Policy Institute, of 634 businesses found that 49 percent said that some of their employees had been required to work under noncompetes and about 32 percent said that all their employees were. Based on that methodology, the EPI survey concluded that anywhere between a little over one-quarter and a little less than one-half of American workers had noncompete requirement in their contracts. The EPI authors believed that large numbers of employees didn’t know that they fell under noncompete restrictions, while all the employers in their survey knew perfectly well when they did. Starr’s survey bears out EPI’s assumption that many workers may not even know that they’re covered. Only 10 percent of the workers he surveyed had actually negotiated with their employer over a noncompete; for the remaining 90 percent, their coverage was a fait accompli, usually buried in the fine print, upon their hiring. Only three states ban noncompete agreements, all of them with laws passed in the 19th century: California, North Dakota, and Oklahoma. In recent years, as awareness of noncompetes has spread, a number of blue states (and one purple state: New Hampshire) have banned them for low-paid or low-skilled workers, while some red states (Georgia most particularly) have passed laws making noncompetes more enforceable. One of the blue states that came late to limiting the scope and enforceability of noncompetes was Massachusetts. Some economic analysts have

attributed the rise of California’s Silicon Valley and the decline of Massachusetts Route 128 as the hubs of tech innovation to the fact that California’s ban on noncompetes led to the proliferation of startups by young techies who left their previous employers, while Massachusetts’s ban on such job-switching, which wasn’t repealed until 2010, prevented a similar dynamic.

As with noncompetes, so with forced arbitration. In 2019, California became the only state to ban the practice outright, but California’s law is on hold awaiting a likely hostile ruling in the federal courts.

It’s not just culture-war issues like abortion rights, then, that are completely at variance from state to state. In the absence of federal lawmaking, it’s also issues of workers’ power (public employees can unionize in blue states and can’t in the red ones) and workers’ provision (minimum wages are higher in blue states than red) and workers’ freedoms.

An FTC ban on noncompetes would at least end this one crazy-quilt approach to what most Americans surely believe to be one of their most basic rights.

With Congress gridlocked, it falls to Biden’s appointees in various regulatory agencies to assert—in some cases, bring back from the dead— the legal basis for restoring some of the power and freedoms that American workers once had. Khan’s resurrection of Section 5 is of a piece with National Labor Relations Board General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo’s resurrection of long-forgotten Board rulings , like the one in the Joy Silk Mills decision, that once gave workers the legal assurance that they could unionize.

At a time when more than 70 percent of Americans have a favorable opinion of unions, a government structured to reflect the public will would legislate changes to empower the nation’s workers. That path is currently blocked by the divided Congress, but our government has latent executive power that it has not used—until lately. So keep an eye on the Biden agencies and the blue states. For now, at least, that’s where the changes will come. n

FEBRUARY 2023 THE AMERICAN PROSPECT 5

TAP NEEDS CHAMPIONS

Join the Prospect Legacy Society

The American Prospect needs champions who believe in an optimistic future for America and the world, and in TAP’s mission to connect progressive policy with viable majority politics. You can provide enduring financial support in the form of bequests, stock donations, retirement account distributions and other instruments, many with immediate tax benefits.

Is this right for you? To learn more about ways to share your wealth with The American Prospect, check out Prospect.org/LegacySociety

Your support will help us make a difference long into the future

6 PROSPECT.ORG FEBRUARY 2023

What Could Chill Heat Pumps

The obstacles to installing a transformative technology

By Joan Fitzgerald

Many cities and states are banning or restricting fossil fuel hookups in new buildings as part of a broader strategy to reduce carbon emissions from buildings. Electrification of buildings is a key climate strategy because space heating, cooling, and water heating comprise 46 percent of residential and commercial building emissions and more than 40 percent of the primary energy used. In addition, getting fossil fuels out of buildings has health and equity benefits.

Heat pumps could accelerate electrification. The story of why heat pump adoption is going so slowly reveals what a complex policy environment surrounds a simple technology.

Heat pumps take heat from outside and move it into your home in the winter and take heat from inside in hot weather and move it outside. Some systems use ducts like hot-air furnaces and some are ductless— you’ve probably seen these on a restaurant wall. Heat pumps offer considerable energy savings because the quantity of heat and cooling brought into your home is considerably greater than the quantity of electricity used to power the system. Households that go all-electric by installing heat pumps for space and water heating, adding rooftop solar, and using an electric car will save an average of $1,800 annually.

A recent study by University of Texas at Austin professor Thomas A. Deetjen estimated that 32 percent of U.S. houses would benefit economically from installing a heat pump, and 70 percent of U.S. houses could reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Added to the 8.7 million homes that have heat pumps already, these new installations would create an economic benefit of about $7.1 billion annually and an 8.3 percent drop in carbon emissions annually, which would avoid $1.7 billion in climate damages annually.

Some 15 states and almost 100 cities and counties have policies to promote heat pump adoption. Only four of them—Cali-

fornia, Massachusetts, Maine, and New York—have set targets for the number of heat pumps to be installed, and meeting the targets will be difficult.

Regulatory and Permitting Obstacles. Local regulations and the permitting process are often confusing and difficult to navigate for both installers and customers. Heat pumps can violate local noise ordinances, particularly in cities with small lots. If the heat pump makes noise beyond the legal level, the contractor usually is responsible for rectifying it.

In most states, each city and town has specific regulations that contractors have to take the time to master before starting a job. One contractor told me of a recent job he completed that required multiple permits. After the assessment of the home’s heating and cooling needs (referred to as a Manual J) specific to town inspector’s requirements, the permitting required sign-off from the home insurance company and a certified plot plan (cost of $2,000) for placement of the condensing units. If the requirements are not adhered to, there are fines and costs to reconfiguring and changing equipment.

FEBRUARY 2023 THE AMERICAN PROSPECT 7

NOTEBOOK

Heat pumps pull hot air into homes in the winter, and push out hot air in the summer.

NOTEBOOK

He decided not to work in that town again.

Confusing Rebate Programs. In addition to local regulations, the requirements of rebate and subsidy programs are often confusing and contradictory to state climate goals. Some rebates require that homes be weatherized first—an expensive undertaking even with rebates.

Most states offer rebates that require the customer to pay for the system up front. A lot of people can’t afford the up-front payment and for many the rebate isn’t enough incentive. The Inflation Reduction Act’s heat pump incentive program will help by offering point-of-sale rebates of up to $8,000 for purchasing a heat pump. The amount of subsidy depends on household income.

Supply Chain Delays. It is not uncommon for the ideal unit for a particular home to be unavailable. The chip shortage is partly responsible for limiting production, but there is almost no manufacturing of heat pumps in the U.S. Most heat pumps are made by Japanese or German producers. The Department of Energy investment of $250 million to promote domestic heat pump manufacturing is much needed.

Inadequate Workforce. In many states, there are not enough contractors with the skills to install heat pumps. We need to build more green-technology career ladder programs in our high schools, community colleges, and universities. At the federal level, the DOE is exploring additional investment in workforce development for heat pump manufacturing and installation. The Massachusetts Clean Energy Center is investing in training programs to bring underrepresented populations into the clean-energy trades, including heat pump installation. New York City’s Precision Employment Initiative seeks racial and climate justice through job training in the green economy for youth in areas of poverty and high levels of gun violence.

As Goes Maine. The national leader in promoting wide installation of heat pumps is Maine. With 62 percent of its households heated by highly polluting fuel oil in 2019, Maine offi-

cials knew that heat pumps would have to be a big part of reaching the state’s goal of cutting greenhouse gas emissions 45 percent by 2030. And they’re not a hard sell—every heat pump installed saves consumers $300 to $600 in heating costs annually. The Efficiency Maine Trust, the administrative unit charged with overseeing funds for energy efficiency improvement and greenhouse gas reduction, coordinates all the policy supports needed to ensure widespread heat pump adoption: offering information, advice, and rebate and loan programs. Most importantly, the Maine legislature has taken action to require utilities to do the grid improvement planning needed for a more electrified future.

Efficiency Maine started offering rebates for air-source heat pumps in 2013 and accelerated the program in 2019 when Gov. Janet Mills set a goal, and the legislature then passed a bill to install 100,000 heat pumps in residences and commercial buildings by 2025. An online dashboard shows that 82,326 heat pumps have been installed since 2019, with roughly 7 percent of these in low-income homes.

Easy Rebates. Several factors drive this success. Easy-to-apply-for rebates are part of the story. The first hurdle to be overcome

was creating consumer confidence in the product. Maine has long, cold winters that first-generation heat pumps couldn’t handle. Efficiency Maine examined the capabilities of heat pumps on the market and chose to offer higher rebates for those with a minimum Heating System Performance Factor (HSPF) of 12.0, which is greater than the standard needed for achieving the federal government’s Energy Star certification. Units at this level can provide heat at temperatures as low as negative 15 degrees Fahrenheit.

It costs between $3,500 and $5,000 to install a single “mini split” heat pump in Maine. Rebates are between $400 and $800 for the first heat pump installed and $200 and $400 for the second, depending on the efficiency level installed. Staff at Efficiency Maine are considering different tiers of rebates to accelerate adoption even more. As Michael Stoddard, executive director of Efficiency Maine, told me, “When we started, our goal was to give as many residents as possible a taste of what it is like to heat with at least one heat pump. Now we want everyone to heat completely with heat pumps.”

Two programs help low- and moderateincome residents secure heat pumps. For residents who document their eligibility through the federal Low-Income Home

8 PROSPECT.ORG FEBRUARY 2023

Maine has been a national leader in promoting wide installation of heat pumps.

Energy Assistance Program, or several income-dependent state programs, to receive rebates, the Maine State Housing Authority has dedicated some of its funds to pay for 100 percent of heat pump installation costs for the neediest households. Those customers, as well as anyone owning a home where the town’s tax-assessed property value for the home is in the bottom quartile in the county, can receive a $2,000 rebate from Efficiency Maine for the first heat pump and another $400 for a second.

About 40,000 eligible households in Maine have installed at least one heat pump. In April 2022, the Maine legislature passed a bill mandating that new affordable-housing projects funded by the Maine State Housing Authority use all-electric heating and cooling systems and must meet a recognized standard of high energy efficiency, such as Passive House.

The bulk of the funding for the rebates comes from Efficiency Maine’s participation in the ISO New England (the regional grid operator) Forward Capacity Market. Efficiency Maine receives between $5 million and $10 million annually for the reduced usage it can deliver, all of which is dedicated to heat pump rebates.

Getting Rates Right. Maine has taken action to ensure that the Maine Public Utilities Commission (PUC) is aligning its pricing and planning for grid upgrades that support state policy. The Governor’s Energy Office, Efficiency Maine, the Maine Office of the Public Advocate, and several industry and environmental groups negotiated with the utilities to establish rate discounts to encourage residents to electrify and adopt renewable energy. As a result, in December 2022, the Maine PUC ordered the state’s two largest utilities (Versant and Central Maine Power) to pilot reduced electric rates for customers adding solar panels with energy storage, switching to heat pumps, or purchasing electric-vehicle chargers.

Another rate strategy seeks to reduce peak demand. The Seasonal Heat Pump

rate has lower rates in cold-weather months and higher rates in summer. For households that have electric usage, the Electric Technology rate offers a higher fixed charge yearround, but a lower charge per kilowatt to encourage adoption of electric appliances. The time-of-use rate is being adapted to promote off-peak electric use (e.g., for charging cars, running dishwashers, etc.).

Stoddard comments that by switching to the new Electric Technology rate, consumers who are using more than 1,000 kWh per month should see savings of between $100 and $200 a year in electricity costs. These voluntary rates are being piloted for two years to assess how they influence demand. While critics point out that the rates should be lower and go into effect sooner, there is widespread agreement that these rates will motivate more electrification while spreading demand to help defer and reduce the need for expensive new grid additions.

Growing a Green Grid. In April 2022, the legislature passed a new law that requires the state’s utilities to engage in a transparent and integrated process to ensure the future readiness of the grid to support the increased electrification and renewable-energy adoption called for in the state’s climate plan. Dan Burgess, director of the Maine Governor’s Energy Office, explains that the Maine Climate Council estimated that the grid will need to at least double its current capacity by 2050 to meet this growth.

Further, the shape of the distribution peak will change over the course of the day and time of year. For example, the current summer peak will change to winter as more buildings are heated with electric systems. Managing and planning for changes such as these, as well as the integration of other distributed energy resources and loads like home battery storage, EV charging, and rooftop solar, is central to the legislation’s requirements. Thus, the key factors to be considered are the upgrades that need to happen in the distribution grid and how much of that can be avoided through rate design, and by leveraging other clean-energy technologies.

The for-profit utility model is to make capital expenditures on grid capacity and infrastructure and pass those costs along to ratepayers. An integrated planning process forces those investment decisions in the open, with improved transparency and public input. Jack Shapiro, the clean-

energy director at the Natural Resources Council of Maine, presents the example of a neighborhood served by a substation with a few thousand homes. The utility will present a scenario that every system is running at the same time and assume solar capacity is offline. Such a scenario would suggest a need to, say, triple the capacity of substation transformers to serve the neighborhood. Integrated grid planning challenges those assumptions.

If the sun is shining and there is rooftop or distributed solar in that area, it lowers demand from the broader grid. Smart devices can be programmed to respond to grid needs and avoid the highest annual or daily peaks. Contracts with battery operators can incentivize off-peak charging. All of these interventions can reduce the need for expanded grid capacity and could significantly lower the costs of the overall energy transition.

Creating a

New Skilled Trade. Efficiency

Maine has also acted to increase the supply of qualified installers. The number of companies has doubled since 2015, with more than 700 qualified installers listed on the website—more per capita than any other state, according to Burgess. This growth can be attributed to the Maine Clean Energy Partnership, which has released two reports that target the clean-energy industry, which includes energy efficiency contractors.

Kennebec Valley Community College opened a new heat pump training lab to support degree and certificate programs in plumbing; heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC); and sustainable-energy systems. Students can also take shorter-term heat pump installation and maintenance training courses. Efficiency Maine worked with the college in developing the programs.

In December 2022, Gov. Mills announced $2.5 million in new workforce grants to be awarded to nine organizations for training residents in weatherization, electric-vehicle repair, solar installation, and related careers.

Ideally, there will be a rendezvous between the new federal subsidies for clean energy and state-level policies to make maximum use of them. Maine’s success shows both the complexity and the possibility. n

FEBRUARY 2023 THE AMERICAN PROSPECT 9

Joan Fitzgerald is a professor of public policy and urban affairs at Northeastern University and the author of Greenovation: Urban Leadership on Climate Change.

In many states, there are not enough contractors with the skills to install heat pumps.

Supercharging Green Public Power

The president’s signature climate bill is a huge deal for publicly owned electricity. But it will take work to unlock its potential.

By Ryan Cooper

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA ) will certainly be remembered as a major accomplishment of the Biden administration and the Democratic Congress. One of its most significant parts is an innocuous-sounding provision called “direct pay.” This refers to a change in how renewable-energy tax credits are administered. Before the IRA , publicly owned utilities or nonprofit power cooperatives were not directly eligible for these credits, because they had no tax liability. The only way to get some of the benefit was to contract with private developers, which is both cumbersome and inefficient, since much of the value of the credits is then taken up by the developer. But now, public agen-

cies and nonprofits can get the credits essentially as grants—which makes new green investment and the resulting power considerably less expensive for those entities.

Public agencies and nonprofits generate about a quarter of American electricity, so this is a major upgrade to U.S. climate policy. But it’s also a major change in the policy landscape for these institutions, which will have to drastically change the way they operate. It’s an urgent priority to get direct pay flowing as fast as possible, so I spoke to several experts to investigate the state of the policy landscape—if anyone in this space is ready to start moving, what any obstacles might be, and how they might be removed.

The first thing that needs to happen is for the Treasury Department and the IRS

to release guidance on how exactly direct pay will work. Back in October, the IRS submitted a request for comment, and experts expect that the full guidance will probably come out around March this year.

The fact that the guidance is not out yet is probably why I could only find two institutions that are definitely planning to take advantage of the direct pay credits. The first is the Salt River Project, a nonprofit utility cooperative owned by the state of Arizona. SRP is in the process of building 55 megawatts of utility-scale solar owned by itself for the first time. “The recent passage of the Inflation Reduction Act allows notfor-profit public power utilities like SRP to directly receive federal incentive payments for renewable projects,” the agency said in a

10 PROSPECT.ORG FEBRUARY 2023 SRP PHOTO NOTEBOOK

Public utilities generate about a quarter of American electricity.

press release. The second is East Bay Community Energy, a public agency launched in 2018 by Alameda County, California, and several of its cities. CEO Nick Chaset posted a thread on Twitter about how the IRA will allow his agency to provide renewable power more cheaply “by allowing public sector and not for profit electricity suppliers to directly monetize these tax credits instead of relying on contracting with a privately owned company to realize the value of the tax credits.”

Everyone I spoke with agreed that the most obvious move here is for the administration to publish the guidance as quickly as possible. The sooner the rules are available, the sooner institutions can start investment, and once a few have demonstrated viable procedures, others will likely start to copy them. “Utilities by their nature are slow-moving companies,” Mike O’Boyle, a director at Energy Innovation, told the Prospect. “It takes utilities a while to fully digest any bigstep changes in technology costs, integrate into their plans, and then change course.”

“There is no time to waste,” said Uday Varadarajan, a principal at the Rocky Mountain Institute, in an interview.

The administration would also be well advised to make the application procedure simple. “Make it as easy as possible,” Desmarie Waterhouse, senior vice president at the American Public Power Association, told the Prospect. Many public utilities and rural co-ops are quite small, and so don’t have much staff available to start spinning up new projects. Even a lot of the big ones don’t have much experience with renewable-energy projects. If you’ve been running, say, a handful of gas and coal plants for 40 years, solar and wind are both more distributed and more erratic in their production—requiring new investment and different grid management to compensate for the changes.

By the same token, it would be wise for the administration, together with outside groups, to provide technical, contracting, and legal assistance for firms that might need it, especially rural cooperatives. If small institutions have to hire an accountant and a tax lawyer to get their direct pay, they might decide it’s not worth the headache.

The administration could also help by funding transmission upgrades. Renewables are more useful if the power can be transmitted over longer distances—for instance, from areas where the sun is shining or wind is blowing to dark or calm ones. “There are a lot of transmission upgrades

that need to be made in the system to enable the higher penetration of renewables,” said Varadarajan. “The federal government also has some authorities in the [Department of Energy] loan program that can be used for new interregional transmission lines,” as well as reducing the cost of upgrading existing lines. Doing so “could be a real important piece of that puzzle,” he added.

The Tennessee Valley Authority deserves special attention. This federal agency is the largest public utility in the country, serving all of Tennessee and parts of six other states (mainly with nuclear and natural gas), and also contracts with over 100 other utilities in the region. It would be an ideal choice to set an example for the rest of the country—indeed, it is specifically mentioned in the IRA as being eligible for direct pay credits. But a TVA representative told me that the agency doesn’t have anything in the works yet: “It is still too early to speculate on exactly how TVA would participate,” he said via e-mail.

The TVA is, however, rushing to replace much of its coal power capacity with even more gas. On December 2, it completed the environmental review of a planned decommissioning of the Cumberland Fossil Plant and its switch to the preferred alternative of a gas replacement. “Natural gas provides the flexibility needed to reliably integrate renewables,” Jacinda Woodward, a TVA senior vice president, said in a statement.

This is a bizarre argument. For one thing, the TVA already gets about 28 percent of its power from gas. For another, the intermittency problem that comes with solar and wind is well understood by now, and grid operators have largely figured out how to compensate. That, plus the fact that wind and solar are extremely cheap (and getting cheaper), is why private utilities are now stampeding into renewables—in 2021, solar

and wind made up about 83 percent of all new utility-scale power investment.

What’s more, while intermittency issues can become quite challenging when renewables make up a big share of total power, the TVA’s power mix includes just 3 percent from wind and solar. And even if it were a problem, unlike almost all utilities the TVA has significant hydropower assets—which are excellent backup for renewables because they are very easy to turn on and off. “TVA could absolutely manage its hydro system in such a way as to balance and complement resources like wind and solar,” Zachary Fabish, a senior attorney at the Sierra Club, told the Prospect. “That’s a huge advantage that TVA has that most other utilities in this country don’t have.”

More gas investment also carries a significant price risk. Thanks to Putin’s war in Ukraine, Europe is frantically trying to wean itself off Russian gas—and is filling that gap with liquefied natural gas exports from the United States. Multiple LNG terminals have been constructed in recent years on both sides of the Atlantic, and more are coming. It’s a safe bet that the dirt-cheap gas of the mid2010s is not ever coming back, and anyone reliant on gas power will be paying the price.

In short, the TVA’s decisions here don’t pass the smell test. Fortunately, in late December the Senate finally confirmed all six of Biden’s nominees to the nine-member agency board, where they now constitute the majority. The board has ultimate control over the agency, and they can and should replace CEO Jeff Lyash (a former private utility executive) with someone more favorable to renewables.

To end on a note of optimism, there’s one final aspect of direct pay that could help improve America’s electric grid. Previous renewable tax credits incentivized private utilities to invest in zero-carbon power, but only on the basis of whether each individual project made financial sense. Accordingly, few of those utilities have been paying attention to other crucial factors when taking on new projects, such as planning and “grid topology”—that is, where renewables, transmission upgrades, and so on would make the most sense in terms of regional needs or even the whole national grid. “Direct pay creates an opportunity for public agencies … to be project developers themselves,” Paul Williams, executive director of the Center for Public Enterprise, told the Prospect. It will “help move the energy transition forward in a more coordinated and thoughtful way.” n

FEBRUARY 2023 THE AMERICAN PROSPECT 11

Renewables are more useful if the power can be transmitted from areas where the sun is shining or wind is blowing to dark or calm ones.

The Slow Extraction of Lead Water Pipes

By Ramenda Cyrus

By Ramenda Cyrus

Denver Water had a problem. A water utility since 1918, the company provides water to the greater Denver area that is lead-free. In 1994, the utility adjusted its pH and alkalinity levels to meet standards set by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment’s Lead and Copper Rule.

Still, in 2012, Denver Water surpassed the lead action level, a threshold set federally by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The problem was simple, in a way: Water delivered through service lines that contained lead would likely always have some level of lead in it. Lead exposure has numerous negative health outcomes associated, and it was important to manage and eliminate its levels in water.

But Denver Water didn’t own any water lead service lines. Those are laid by developers when a property is built, pumping water from the main that Denver Water owns.

“Those lead service lines are really the biggest source of lead entering drinking water to our community,” said Travis Thompson, spokesperson for Denver Water.

Lead service lines have been a major public-health concern, one that became especially salient during the Flint, Michigan, water crisis. President Biden has repeatedly promised to replace all lead service lines in the country, a promise that became part of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which was passed in 2021. The IIJA designated $15 billion toward replacing lead service lines. Another $11.7 billion was granted to improve drinking water systems, some of which could go to lead pipe removal. In all, the bill earmarks $50 billion to water programs.

A year after the IIJA’s passage, the situation remains largely unchanged. The amount allocated is the largest investment in the removal of lead pipe in the history of the country, and the total water investment

package has been hailed as historic by the Biden administration. But $15 billion is not enough money to replace every lead service line in the country—estimates lie anywhere between $28 billion and $60 billion.

Moreover, the work of replacing these lines falls to water agencies like Denver Water, which face a fundamental challenge. Water agencies can only replace the lines they own; the rest of the responsibility falls on private owners, many of whom are less than keen given the logistics. To fulfill their mission, water agencies must persuade owners of the benefits of lead removal, and manage the costs. And that’s if the agencies can find all the lead service lines in the first place.

The majority of water funding in the IIJA is distributed through the Clean Water and Drinking Water State Revolving Funds (CWSRF and DWSRF), which have been addressing lead abatement in water since the late 1980s. Funds are to be distributed over a five-year period; the first $3 billion was announced in December 2021.

Any amount of lead exposure is dangerous, and its prevalence in everything from paint to gasoline means that millions of children have been exposed. Lead has been linked to learning problems and slowed growth in children, according to the EPA . Children exposed during pregnancy may underdevelop and even risk miscarriage. An article published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences estimated that over half of adults had elevated levels of lead exposure in early childhood.

The Flint water crisis revealed racial and economic disparities of lead exposure. The IIJA attempted to address this by earmarking at least $5 billion of the grants for disadvantaged communities. The IIJA also requires that almost half the funding distributed through the DWSRF go toward disadvantaged communities.

Before the IIJA passed, Denver Water proposed a solution for lead abatement. After receiving an exemption from the EPA , the utility instituted a five-point initiative to replace every lead water service line. This has led to the replacement of 15,000 lines as of December 2022. The plan includes replacing the lead pipes, mapping the lines, and installing lead removal filters, all at no cost to homeowners. It is funded through bonds, water rates, cash reserves, and hydropower generation, Thompson said.

The IIJA funding was a welcome addition that Denver Water was able to immediately put to use. It applied to access the first year of funding through Colorado’s state revolving fund and was granted a low-interest

12 PROSPECT.ORG FEBRUARY 2023

NOTEBOOK

President Biden has promised to replace all of the lead service lines in the country, but there’s not enough money and not enough time.

loan of $76 million. Denver Water estimates that the money will shave off more than a year from a 15-year plan.

While Denver Water could be seen as a model for lead pipe removal, it’s not a simple solution. The agency still has to coordinate with homeowners and obtain their permission to act. And not every utility is as far along as Denver Water to immediately utilize IIJA funds effectively.

Elin Betanzo of Safe Water Engineering points out how there is a spectrum among municipal water agencies’ willingness to replace lead service lines. Some agencies are reluctant to even acknowledge the issue.

“Most water systems don’t have a program already,” Betanzo said. And the money does not just appear one day for agencies to use: To be approved for IIJA funding, a utility must propose a plan “directly connected to the identification, planning, design, and replacement of lead service lines,” according to an EPA memorandum.

For some agencies, this means starting from scratch, while others like Denver Water are ready to jump into action. The Lead Service Line Replacement Collaborative, a coalition of organizations, works to “accelerate voluntary lead service line replacement in communities across the United States,” by closing the gap in preparedness. The organization provides resources for water agencies to create an action plan for service line replacement, and apply for federal funds.

“States are moving forward with putting the funds to use based on their assessment of the needs and their understanding of how many lead pipes they may have, where they are located, and whether some utilities are prepared to accelerate lead pipe replacement,” Tom Neltner, senior director of the Environmental Defense Fund’s Safer Chemicals initiative, said over email.

Agencies need to know where the lines are before meaningful action can be taken.

The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) estimates between 9.7 million and 12.8 million lead service lines nationwide, but that’s not a precise figure and doesn’t identify the whereabouts of lead pipes in every community.

While some utilities operate mains that contain lead and are working to replace those, other utilities only know that their water flows through lead service lines, not where they are. Agencies need to map the lines to take action, adding time to the process.

“There’s certainly a benefit to being careful and using the data you have available [and] identifying where the lead lines are,” said Dan Hartnett of the Association of Metropolitan Water Agencies.

Usually, in order to receive money from the DWSRF, the state must provide a 20 percent match. The IIJA does not require a state match to access the $15 billion to replace service lines. For the nearly $12 billion that goes through the revolving fund, the IIJA

reduced the state match to 10 percent for the first two years.

Betanzo found that in the first allotment, states with the most lead lines received the least amount of money. Ohio, which has approximately 650,000 lead lines, received just about $100 per line. This is compared to Hawaii, which received $10,000 per line, despite only having about 3,000 lines. While there is time for this to be corrected within the five years, it’s another hurdle.

In response, the EPA points out that the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) requires that funds from the DWSRF get distributed based on the Drinking Water Infrastructure Needs Survey and Assessment. The EPA expects to release the seventh assessment in 2023, and it will be the first to include information on lead service lines, which will be used for the next allotment.

The EPA also points out that the SDWA allows for funds to be reapportioned. “Under this reallotment process, EPA expects more lead service line funds to flow to states with more lead service line projects over time,” EPA spokesperson Robert Daguillard said over email.

As Denver Water’s story illustrates, replacing part of a water line that contains lead continues the contamination. The IIJA combats this by only allowing states to access the $15 billion if they have a plan to replace the entire lead pipe, unless a portion has already been replaced, or the utility is planning to replace it through other funding.

However, Neltner said that the EPA does not seem to be enforcing this requirement on the additional $12 million allocated for the state revolving funds, which are usually used to replace water mains. There is a concern that “some states are allowing utilities to conduct harmful partial lead service line replacements where the resident is unable to pay to replace the portion on their property,” Neltner said.

Bureaucracy moves slow, and change moves slower. Neltner sees the IIJA investment “as a critical down payment toward President Biden’s goal of eliminating lead service lines.”

It is not easy to appreciate the full suite of actions a utility has to take in order to replace a lead service line. From planning and mapping to replacing the lines, agencies and communities are being asked to take on a momentous task, one that will surely take more than five years. And if the money is not used efficiently, the progress that could be made may still fall short. n

FEBRUARY 2023 THE AMERICAN PROSPECT 13

Some utilities only know that their water flows through lead service lines, not where they are.

Biden’s expansive executive order seeks to restore competition in the economy. It’s been a long, slow road to get the whole government on board—but there are some formidable gains.

BY DAVID DAYEN

A PITCHED BATTLE ON CORPORATE POWER

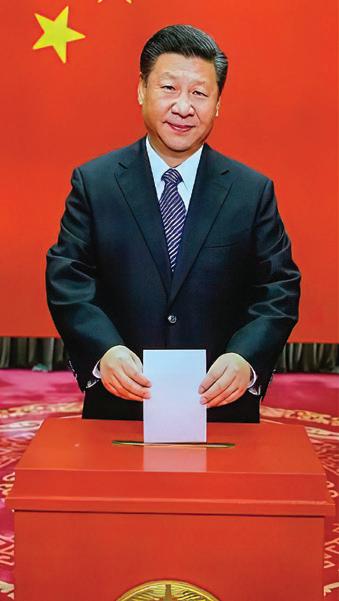

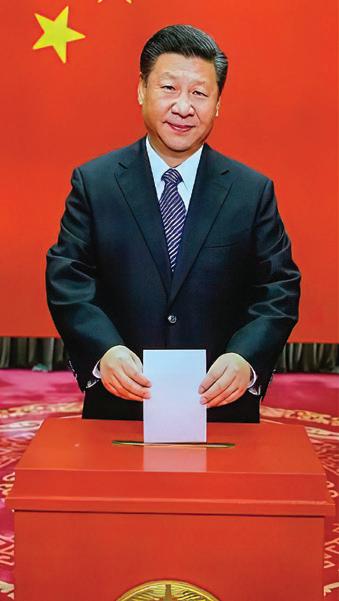

On July 9, 2021, President Joe Biden signed one of the most sweeping changes to domestic policy since FDR . It was not legislation: His signature climate and health law would take another year to gestate. This was a request that the government get into the business of fostering competition in the U.S. economy again.

Flanked by Cabinet officials and agency heads, Biden condemned Robert Bork’s pro-corporate legal revolution in the 1980s, which destroyed antitrust, leading to concentrated markets, raised prices, suppressed wages, stifled innovation, weak-

14 PROSPECT.ORG FEBRUARY 2023

ened growth, and robbing citizens of the liberty to pursue their talents. Competition policy, Biden said, “is how we ensure that our economy isn’t about people working for capitalism; it’s about capitalism working for people.”

The executive order outlines a whopping 72 different actions, but with a coherent objective. It seeks to revert government’s role back to that of the Progressive and New Deal eras. Breaking up monopolies was a priority then, complemented by numerous other initiatives—smarter military procurement, common-carrier requirements, banking regulations, public options—that centered competition as a counterweight to the industrial leviathan.

It’s been a year and a half since Biden signed the executive order; its architect, Tim Wu, has since rotated out of government. Not all of the 72 actions have been completed, though many have. Some were instituted rapidly; others have been agonizing. Some agencies have taken the president’s urging to heart; others haven’t. But the new mindset is apparent.

Seventeen federal agencies are named specifically, tasked with writing rules, tightening guidelines, and ramping up enforce -

ment. I wrote to each agency, asking how they have complied with the order; all of them answered but one (the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, whose role is admittedly tangential). Even Cabinet departments that weren’t mentioned wrote in to explain their approach to competition. Clearly, agencies are aware of the emphasis being put on reorienting their mission.

Bringing change to large bureaucracies is often likened to turning around a battleship. One way to get things moving is to have the captain inform every crew member of the intention to turn the battleship around,

FEBRUARY 2023 THE AMERICAN PROSPECT 15

counseling them to take every action from now on with that battleship-turning goal in mind. The small team that envisioned and executed the competition order put the weight of the presidency behind it, delivering a loud message to return to the fight against concentrations of power. It’s alarming and maybe a little disconcerting that you have to use a high-level form of peer pressure to flip the ship of state. But that battleship is starting to change course.

Tim Wu was the first of the triumvirate of Wu, Khan, and Kanter (a motto emblazoned on mugs by advocates) to actually get appointed in the Biden administration, joining the National Economic Council (NEC) to work on competition policy in early March 2021. Hiring the author of The Curse of Bigness signaled the administration’s strong anti-monopoly thrust. Khan (Lina, chair of the Federal Trade Commission) and Kanter (Jonathan, heading the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division) would arrive later.

The competition order was released four months after Wu’s appointment, but in reality, it was laid out over the previous five years. In that time, a collection of policymakers, journalists, lawyers, politicians, and experts, sometimes known as the New Brandeis movement , warned of the dangers of economic concentration. Wu, Khan, and Kanter were part of this crusade, and prior to the 2020 election, they and others strategized about how to reinvigorate competition policy if Democrats took the presidency.

In this magazine, Sandeep Vaheesan of the Open Markets Institute outlined an anti-monopoly framework for our Day One Agenda series. It included revitalizing rulemaking authority at the FTC, rewriting merger guidelines to reverse laissez-faire bias at the antitrust agencies, restoring consumer rights to repair their own electronic equipment, and completing rules that protect farmers and ranchers from agribusiness exploitation. But even Vaheesan was surprised that the Biden administration embraced all of his recommendations and much more. “I wasn’t really thinking of an executive order when I wrote the piece,” he told me.

Vaheesan mildly questioned the wisdom of including so many action items. “It tries to do everything and maybe ends up doing nothing,” he said. But in its breadth as much as its particulars, the order informed offi-

cials across agencies that the White House was supremely attentive on this issue, and would have their backs on the tough decisions. “When we were going around and talking to agency staff, I would say, ‘Why don’t you do this,’” Wu told me. “They’d say, ‘That’s a land mine.’ Our idea was, let’s step on all the land mines at once. We will take your land mines, we will stand on them for you. And if industry complains, we would say, ‘Get in line.’”

When Wu entered the White House, he had a basket of low-hanging fruit, which he supplemented by asking federal agencies what they could do on competition. One constraint was that some of the agencies named in the order are independent commissions outside the Cabinet. So the language had to downshift from ordering agencies to take action to terms like “con-

sider” or “encourage.” Still, the message was clear.

A new White House competition council, led by the NEC, was established to monitor implementation of the 72 actions, as well as legislative and administrative efforts outside the order. There are nine core agencies on the council, each with a senior-level designee on competition policy. The order requires regular council meetings for members and other invited agencies.

That created a kind of show-and-tell dynamic: Agencies needed to display some forward motion on competition at consistent intervals. Wu and his small team—mainly deputy NEC director Bharat Ramamurti, senior policy official Hannah Garden-Monheit (who will take over for Wu as he returns to teaching at Columbia), and a couple of others—created a workshop for designees

16 PROSPECT.ORG FEBRUARY 2023

DOJ successfully blocked the Penguin Random House/Simon & Schuster merger on the grounds that authors would get smaller advances.

on how to best work together. There are regular check-ins and happy hours. A “happy news” email group has bred a kind of competition within the competition council, as designees fight to highlight their victories to the White House.

Perhaps most important, Biden has shown up to two of the three council meetings. Nobody wants to come to the chief executive empty-handed. “We wanted the president personally involved,” Wu said. “If you have an agency that feels all alone, their friends become industry. It’s about getting into the heads of agencies and making them feel supported to do things they might not like.”

The executive order’s preamble validates Khan and Kanter’s aggressive perspective on competition policy, hinting at the practices of previous reform eras. For example, antitrust enforcement since the Bork revolution of the 1980s has relied solely on one criterion: Does an anti-competitive action

explicitly harm consumer welfare, defined as higher prices. But the preamble to Biden’s order stresses the plight of workers in a concentrated economy, which impedes the ability “to bargain for higher wages and better work conditions.” Though the consequences of too few buyers in an economy (monopsony) had been the subject of numerous studies in recent years, presidential-level discussion of monopsony and monopoly in the same breath was novel.

The Justice Department centered worker harms in its biggest legal victory to date, a successful challenge to the merger between publishers Simon & Schuster and Penguin Random House. The deal would have narrowed major publishers in the U.S. from five to four, and the Antitrust Division argued that authors would suffer from fewer bidders and smaller advances for their work. The judge ruled in DOJ ’s favor, saying that the deal would “substantially lessen competition to acquire the publishing rights to

anticipated top-selling books.” For a judiciary that has focused primarily on consumers as defined by Bork in antitrust cases, it was a sea change and a model for the future.

Labor harms were also highlighted in a DOJ Antitrust lawsuit against three poultry processors who colluded to deny workers $84.8 million in wages and benefits. It followed an interagency report on labor market competition , showing that concentration can lower wages by as much as 20 percent. “I do think that the focus on competition is getting people to dig into the topic in a policy-relevant way,” said Joelle Gamble, chief economist at the Department of Labor.

For years, Biden has been emphasizing one vividly abusive aspect of monopsony: noncompete agreements, which prevent workers from switching jobs to competitors in the same industry. At least 1 in 3 businesses require noncompetes, including professions like fast-food preparation, dog grooming, and custodial work . At the executive order signing, Biden spent a long time condemning noncompetes and vowing to end them: “Let workers chose who they want to work for.”

An FTC proposed ban on noncompetes was finally issued in January. Getting the FTC to write rules at all was another priority of the competition order. Under Section 5 of the FTC Act, the agency has broad authority to make rules preventing “unfair methods of competition.” But this authority has languished for decades, and a 2015 policy statement constricted its use further. A new policy statement released in November verified that Section 5 rulemaking is allowable, citing voluminous case law in an attempt to fend off inevitable court challenges

The order actually called for a number of Section 5 rules, including on unfair competition in prescription drug patents, internet marketplaces, occupational licensing, and real estate listings. But FTC spokesperson Doug Farrar told me there’s nothing imminent in those areas. “If you asked me a year ago, I would have thought FTC would have done more by now,” Vaheesan said. One problem was that, having abandoned rulemaking long ago, the FTC had no staff with expertise. When commissioner Rebecca Kelly Slaughter was acting FTC chair before Khan’s appointment, she set up a rulemaking group in the general counsel’s office. But administrative procedure for new rules takes an eternity, especially if starting from scratch.

One rule the FTC has begun work on

FEBRUARY 2023 THE AMERICAN PROSPECT 17

FTC proposed a ban on noncompete agreements that prevent worker freedom of movement.

concerns personal data collection and surveillance , a sleeper competition issue highlighted in the order’s preamble. The preamble also included discussion of “serial mergers” of “nascent competitors,” which monopolists use to strangle competition before it starts. The FTC followed up on this when it sued Meta (formerly Facebook) for its acquisition of virtual reality startup Within, on the grounds that potential future competition may be harmed. That case went to trial in December, putting a little-used idea from anti-monopoly reformers to a real-world test.

Perhaps the most quietly radical passage of the preamble states that “the United States retains the authority to challenge transactions whose previous consummation was in violation” of the antitrust laws, citing the Standard Oil breakup of 1911 as an example. Retroactive merger review had essentially been abandoned since the Microsoft case in the late 1990s. “We wanted to bring it back to the mainstream of conversation,” Wu said. The FTC’s late-2020 lawsuit against Facebook , specifically over its acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp, is a recent example of retroactive review; DOJ Antitrust’s current investigation of the ruinous deal between Live Nation and Ticketmaster shows that breakups are being reestablished as a policy tool.

The culmination of these efforts are the new merger guidelines, co-authored by the FTC and DOJ’s Antitrust Division. The guidelines lay out the conditions by which the agencies will intervene to block mergers, and while they place no mandates on how judges follow the law, they do shape legal opinion. “These are layman judges, they can rely on precedent and case law or they can rely on expertise from the agencies,” said Ron Knox of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. “And if the agencies say these are the kind of mergers that harm competition, judges will take it into account.” Knox added that the guidelines will create deterrents for companies that don’t want to be tied up in years of lawsuits.

The guidelines are expected in the first quarter of this year. In remarks at a Federalist Society event in December, challenging legal conservatives to acknowledge that efficient capitalism depends on genuine competition, Kanter said that “the first principles of antitrust shouldn’t be a book written by a professor, it should be the words of the statute,” which suggests a return to laws

that focus on threats to competition over consumer welfare. He added that the entire DOJ Antitrust staff has been consulted on the guidelines, which must incorporate the perspective of the FTC, as well as over 5,000 public comments.

The merger guidelines seek to change the entire focus of competition policy. Despite laying the groundwork for years, that’s ultimately a long-term struggle. “Eighteen months seems like a long time in terms of horse-race politics,” Knox said. “Eighteen months to turn around the philosophy of large federal agencies? That’s not a huge amount of time.”

While the FTC and DOJ Antitrust are America’s lead competition authorities, numerous other agencies have license to tame monopoly power. The executive order outlines a whole-of-government approach, targeting specific industries—tech, agriculture, pre -

scription drugs, hospitals, telecom, financial services, container shipping. “If you’re worried about the plight of farmers, the Department of Agriculture will have to take the lead,” said Spencer Weber Waller, a professor at Loyola University Chicago who served as a senior adviser to FTC chair Khan for one year. He added that the order “allows agencies to figure out what they’re trying to achieve in the real world and see which superheroes can do it.”

Of the 72 actions, 12 required reports to the competition council, on everything from concentration in retail food markets to procurement agreements on military equipment. Reports are traditionally a pretend accomplishment that get filed away, mostly unread. But the dynamic of reporting to a dedicated White House policy group has spawned a rare Washington sight: postreport action.

18 PROSPECT.ORG FEBRUARY 2023

FDA finalized rules that allow hearing aids to be sold without a prescription, breaking up a cartel that artificially raised prices.

Last February, Lockheed Martin abandoned its proposed merger with Aerojet Rocketdyne, after an FTC lawsuit in consultation with the Pentagon. Strengthened merger oversight came directly out of a recommendation from the Defense Department’s review on competition in the military industrial base. The Treasury Department’s Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) led a report on market access in alcohol markets , showing that, despite the flourishing of small craft producers, consolidation in beer production remained (two brewers control 65 percent of the market by revenue, and own many “craft” beer makers themselves). Concentrated distributors often use market power to lock up independent producers and deny them retail space held for larger brands, a process known as “shelving.” In November, TTB issued an advance notice of proposed rulemaking (ANPR) to address this exclusionary conduct.

Other actions wouldn’t have to be articulated if government functioned properly. In 2017, bipartisan legislation from Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Chuck Grassley (R-IA) allowed patients to buy certified hearing aids without a prescription. That requirement created barriers for new market entrants, and allowed a small cartel to artificially raise prices so much ($4,700 in 2013) that only one-fifth of Americans with hearing loss managed to purchase auditory devices. But despite a statutory mandate to complete rules for the new market by 2020, Donald Trump’s Food and Drug Administration (FDA) simply didn’t follow through, amid cartel lobbying and an inattention to competition issues. Biden’s executive order set a 120-day deadline for establishing the market, spurring the FDA to propose new rules before the deadline. The final rule was issued in August; millions of hearingimpaired Americans now have access to affordable assistance. “If you talk about

revitalizing antitrust enforcement, that won’t get people’s attention,” said Waller. “If you can say, ‘I just saved $3,000 on hearing aids,’ that gets people’s attention.”

One problem in the hearing aid market is so-called “patent pooling,” where oligopolistic firms share essential patents and exclude rivals. There’s been a long-standing fight between patent holders and manufacturers over the key components they need to make products, which Wu described to me as “impossible to talk about without people shouting at each other.” The Trump administration had taken the side of patent holders in an interagency letter, effectively saying that violating commitments to license patents under fair, reasonable, and nondiscriminatory (F/RAND) commitments would never be an antitrust violation. Per the competition order’s urging, that letter was withdrawn in June , but the agencies replaced it with nothing, trashing a draft policy statement that was more neutral. “It ended in a tie,” Wu said.

The F/RAND battle reveals the occasional difficulties of reconciling administrative intentions with agency drift. The order urged cross-agency partnerships with the FTC and DOJ Antitrust on merger oversight, investigations, and remedies, and Khan and Kanter clearly wish to restore antimonopoly traditions. But not every agency agrees. On the F/RAND issue, the Commerce Department subagencies that regulate in this area have traditionally given more leeway to patent holders.

Another example is bank mergers. The Federal Reserve approved over 3,500 bank mergers from 2006 to 2021, with zero denials; the day of the executive order, the Fed approved another one. The controlling statute, the Bank Merger Act of 1960, actually created a higher merger standard than other industries, and DOJ Antitrust has been leading a review. But it must be coordinated with financial regulators. While Fed vice chair for financial supervision Michael Barr and FDIC chair Martin Gruenberg have called merger policy a priority, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency has planned a symposium for February, no changes have been announced, to the chagrin of advocates. (The Fed did finally deny one merger in 2022.)

DOJ Antitrust has signed memorandums of understanding (MOU s) with multiple agencies , lending investigators and legal analysis. But this doesn’t automatically con-

FEBRUARY 2023 THE AMERICAN PROSPECT 19

Treasury proposed rules to address exclusionary conduct among beer distributors.

fer a good working relationship. Take for example the MOU with the Federal Maritime Commission (FMC). In 2017, DOJ investigators raided a meeting of the largest ocean carriers, issuing subpoenas over alleged price-fixing involving shipping “alliances” that the FMC had previously approved. This generated lingering hostility, and while the FMC, alarmed by skyrocketing shipping rates after the pandemic, has diligently addressed high fees and implemented a new shipping reform law, nothing has emerged yet from the MOU. The FMC said that ongoing investigations “cannot be discussed publicly.”

Perhaps the most schizophrenic interagency relationship has been between DOJ Antitrust and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). On the positive side, the agencies created a joint portal to solve a simple problem: When farmers and ranchers faced unfair practices from agribusiness, they didn’t know where to file a complaint. FarmerFairness.gov became a one-stop shop, with over 80 submissions according to a USDA official. DOJ’s lawsuit on poultry processor collusion came out of this process.

Tom Vilsack, who ran USDA under Barack Obama, returned as secretary of agriculture. The Obama administration promised action to protect small farmers from Big Ag and failed to deliver. This time, Vilsack hired Andy Green, who is respected in anti-monopoly circles, to handle competition policy. USDA has made concerted efforts to fund new competitors, making $1 billion in grants to small meatpackers and putting $500 million into fertilizer capacity, along with supporting state and local government procurement of homegrown food. USDA is also enhancing greater transparency in cattle markets, where nearly all sales are spot sales, making it hard for ranchers to know the going rate.

But when DOJ Antitrust sued to block the merger of sugar giants U.S. Sugar and Imperial, USDA chief economist Barbara Fesco testified for the sugar industry in the case, stating that the merger would benefit consumers despite admitting to having no data confirming that. “Knowing these people as long as I have, ‘I had high faith that [the deal] was good,’” Fesco said at the trial. The judge ruled against DOJ last September, explicitly stating that Fesco was a credible witness.

The testimony seemed to violate USDA and DOJ’s shared commitment to promoting competition, even though Fesco stated that

she was operating in her “personal capacity.” USDA took no official position on the merger, and in a statement, a spokesperson said, “USDA remains committed to the vigorous application of the antitrust laws in every sector of agriculture, including sugar.” The agency also noted that Fesco was compelled to testify by a subpoena. Still, Fesco’s appearance angered lawmakers who saw an administration at odds with itself, and an agency bureaucratic structure still in thrall to big business.

Frustration has also arisen in USDA’s hesitations on rulemaking. One of Lina Khan’s first votes as FTC chair finalized a rule targeting imitation “Made in the USA” labeling on products made outside the country. But though the competition order called for a companion rule on food items with “Product of USA” labeling, a USDA official would only say it was engaged in a “comprehensive review,” seeking information on whether consumers are confused. Joe Maxwell of Family Farm Action, an anti-monopoly organization, said that officials have told him something I heard too, that USDA wants to tread carefully and make “legally durable” rules. “But FTC just did it,” Maxwell said. “We feel it’s delay, delay, delay.”

Delays have similarly plagued a desperately needed rewrite of Packers and Stockyards Act regulations, which outline anti-competitive violations. Under Obama, Vilsack failed to get the rules finalized after eight years; Trump’s USDA then threw them out. But instead of just picking up what was already written, Biden’s USDA is moving deliberately. Two rules have been proposed, one on discrimination, deception, and retaliation, and another to increase transparency in poultry contracting. The key rule would clarify that USDA doesn’t need to demonstrate harm to the entire industry to establish a violation, a hurdle for many Packers and Stockyards cases. That rule, though asked for in the executive order, has yet to be released.

The rule on poultry contracting is instructive. The notorious tournament system pits chicken farmers against one another, forcing them to work exclusively for and abide by the precise instructions of large processors. Farmers who grow the biggest chickens win, but their bonuses come out of the pay of their neighbors. The USDA rule only affords transparency to poultry farmers who already know they’re getting screwed. By contrast, the Justice Department paired approval of a merger between

20 PROSPECT.ORG FEBRUARY 2023

chicken processor Cargill and Sanderson Farms with a consent decree that essentially banned the tournament system, by calling it a deceptive practice under the Packers and Stockyards Act.

The Cargill ban covers 15 percent of the poultry market, but USDA could apply similar treatment elsewhere. USDA issued a notice on fairness issues in poultry, which is under review. But Maxwell, whose organization has asked USDA to follow DOJ, believes the sense of urgency is not there. “As we say on the farm,” Maxwell said, “I’m not sure about their want-to.”

When partnerships among different agencies are successful, they can be powerful. The Surface Transportation Board (STB) is the chief regulator for freight rail, an industry that has narrowed from 40 Class I competitors to seven, which split up the country and don’t compete much. (A proposed merger would cut this to six.) “There certainly is a concentration problem,” STB chair Martin Oberman told the Prospect “As bad as services get or as bad as prices may rise, customers do not have an option.”