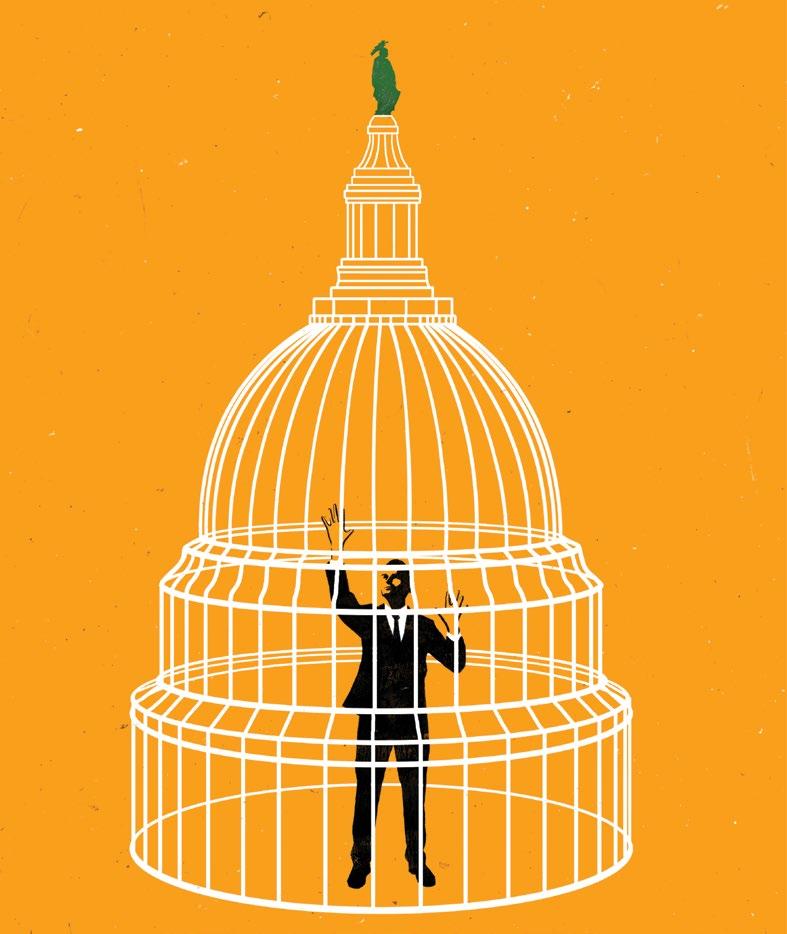

Washington ’s Secret Policy Engine

How economic models dominate and distort

How economic models dominate and distort

After decades of neglect, the United States is finally rebuilding its crumbling roads, bridges, water systems, railways, electrical grid, and more. And the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law requires that all this new infrastructure be Made in America, something 83% of registered voters support.

But special interest groups are aiming to weaken Buy America requirements and allow importers to nab taxpayer-funded contracts to build infrastructure! If they succeed, it would be a missed opportunity to make a once-in-ageneration investment while strengthening American manufacturing. Given the supply shortages of the past few years, the United States cannot afford to make this mistake!

The good news is that America’s factory workers stand ready to make everything from iron and steel to electric vehicle chargers and broadband fiberoptic cables – if given the opportunity that was promised to them in the infrastructure law.

Please join us in telling your state transportation officials to make sure our new infrastructure is Made in the USA!

04

The distorting power of macroeconomic policy models By Rakeen Mabud and David Dayen

Seemingly complex and sophisticated econometric modeling often fails to take into account common sense and observable reality. By Joseph E. Stiglitz

Reforms are needed to ensure that inaccurate budgetary math doesn’t take precedence over maximizing long-term prosperity. By Elizabeth Warren

The alleged science doesn’t match up to the real world. By Nick Hanauer

20

There are more economists doing useful real-world work. But the closer you get to the pinnacle of the profession, the less has changed. By Robert Kuttner

How Congress underwrites the models that trap American policymaking By Philip Rocco

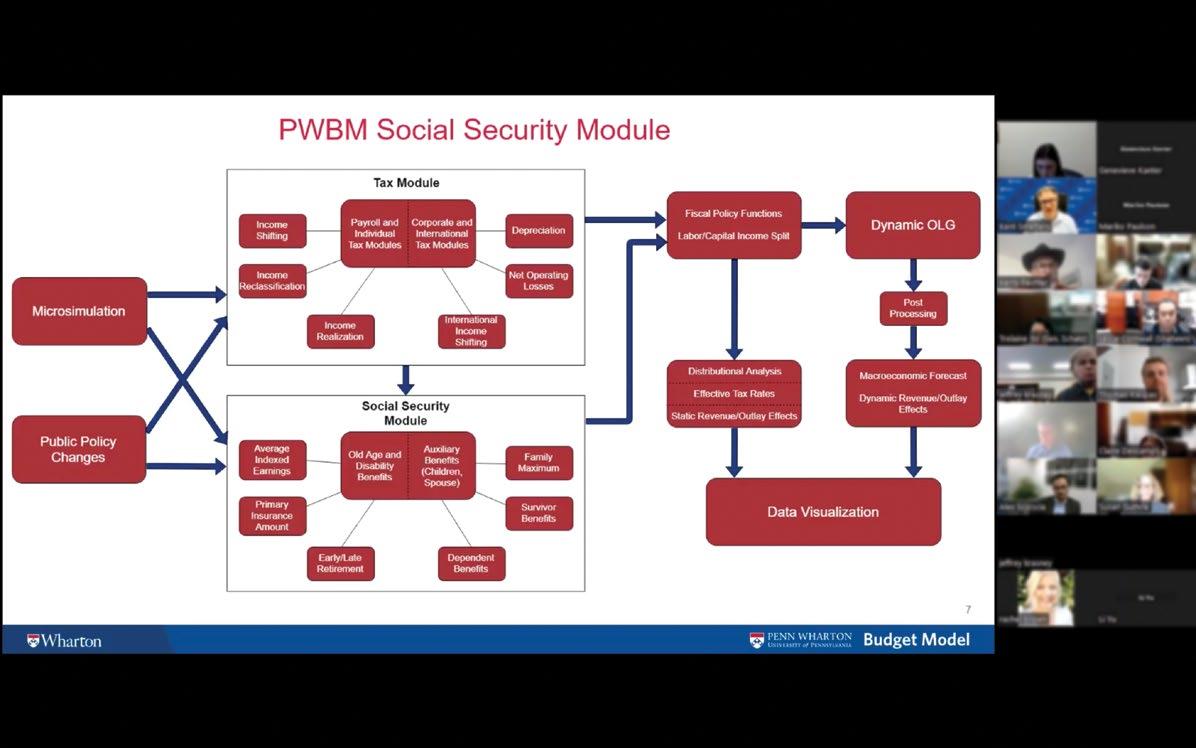

The Penn Wharton Budget Model, bankrolled by finance moguls, is out to grow its power in Washington. By Jarod Facundo

Despite decades of policies aimed at creating new generations of homeowners, many African Americans grapple with a hostile housing sector. Where did the assumptions go wrong? By Gabrielle Gurley

Government and the private sector rely increasingly on risk-modeling firms that claim they can zero in on exposure to climate change. By Lee Harris

In the Progressive and New Deal eras, there was a markedly different response to rising prices, and a different usage of economic theory. By Meg Jacobs

We need better economic models, but we also need Congress to free itself from the self-imposed constraints of modeling on the policymaking process. By Lindsay Owens

COVER AND ILLUSTRATIONS BY ROB DOBI

Visit prospect.org/ontheweb to read the following stories:

The latest newsletter from Prospect staff writers Lee Harris, Ramenda Cyrus, Jarod Facundo, and Luke Goldstein tracks positive, surprising, weird, and beautiful developments in politics, policy, and pop culture.

After the Silicon Valley Bank collapse and the extraordinary backstopping of the financial system, the Prospect has you covered on what you need to know about who’s responsible for the failure and how to fix it for the future.

From the tech giants to the old-school monopolies in railroads and telecom, the Prospect is all over how the biggest companies in the world are using their power.

Our first original podcast puts younger and older Prospect staffers into conversation with one another to talk about culture, politics, history, and more. You can find Prospect: Generations wherever you get your podcasts.

Every day, senior editors Harold Meyerson and Robert Kuttner bring you the latest in news and analysis of the biggest stories.

EXECUTIVE EDITOR David Dayen

FOUNDING CO-EDITORS Robert Kuttner, Paul Starr

CO-FOUNDER Robert B. Reich

EDITOR AT LARGE Harold Meyerson

SENIOR EDITOR Gabrielle Gurley

MANAGING EDITOR Ryan Cooper

ART DIRECTOR Jandos Rothstein

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Susanna Beiser

STAFF WRITER Lee Harris

JOHN LEWIS WRITING FELLOW Ramenda Cyrus

WRITING FELLOWS Jarod Facundo, Luke Goldstein

INTERNS Hannah Crosby, Luca GoldMansour, Andrea L. Pastor, Imani Sumbi

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Austin Ahlman, Marcia Angell, Gabriel Arana, David Bacon, Jamelle Bouie, Jonathan Cohn, Ann Crittenden, Garrett Epps, Jeff Faux, Francesca Fiorentini, Michelle Goldberg, Gershom Gorenberg, E.J. Graff, Bob Herbert, Arlie Hochschild, Christopher Jencks, John B. Judis, Randall Kennedy, Bob Moser, Karen Paget, Sarah Posner, Jedediah Purdy, Robert D. Putnam, Richard Rothstein, Adele M. Stan, Deborah A. Stone, Maureen Tkacik, Michael Tomasky, Paul Waldman, Sam Wang, William Julius Wilson, Matthew Yglesias, Julian Zelizer

PUBLISHER Ellen J. Meany

PUBLIC RELATIONS SPECIALIST Tisya Mavuram

ADMINISTRATIVE COORDINATOR Lauren Pfeil

BOARD OF DIRECTORS Daaiyah Bilal-Threats, Chuck Collins, David Dayen, Rebecca Dixon, Shanti Fry, Stanley B. Greenberg, Jacob

S. Hacker, Amy Hanauer, Jonathan Hart, Derrick Jackson, Randall Kennedy, Robert Kuttner, Ellen J. Meany, Javier Morillo, Miles Rapoport, Janet Shenk, Adele Simmons, Ganesh Sitaraman, William Spriggs, Paul Starr, Michael Stern, Valerie Wilson

PRINT SUBSCRIPTION RATES $60 (U.S. ONLY)

$72 (CANADA AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL)

CUSTOMER SERVICE 202-776-0730, ext 4000 OR info@prospect.org

MEMBERSHIPS prospect.org/membership

REPRINTS prospect.org/permissions

Vol. 34, No. 2. The American Prospect (ISSN 1049 -7285) Published bimonthly by American Prospect, Inc., 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, D.C., and additional mailing offices. Copyright ©2023 by American Prospect, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this periodical may be reproduced without consent. The American Prospect ® is a registered trademark of American Prospect, Inc. POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to American Prospect, 1225 Eye St. NW, Ste. 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

Every membership level includes the option to receive our print magazine by mail, or a renewal of your current print subscription. Plus, you’ll have your choice of newsletters, discounts on Prospect merchandise, access to Prospect events, and much more. Find

You may log in to your account to renew, or for a change of address, to give a gift or purchase back issues, or to manage your payments. You will need your account number and zip-code from the label:

To renew your subscription by mail, please send your mailing address along with a check or money order for $60 (U.S. only) or $72 (Canada and other international) to:

In 2019, as a part of her presidential bid, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) released a bold policy proposal: a wealth tax on the richest Americans. The 2 percent annual tax on total assets above $50 million, rising to 6 percent above $1 billion, would have hit plutocrats hard, from Jeff Bezos to Warren Buffett. According to the Warren campaign, the wealth tax was estimated to raise $3.75 trillion over ten years, and perhaps even more critically, decrease the political power of wealthy individuals.

With similar proposals on the table from Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT), it seemed like there was a real acknowledgment of the way that tax policy could be leveraged to reshape the power dynamics of the U.S. economy. But with one report, the momentum behind these proposals ground to a halt.

An institution called the Penn Wharton Budget Model (PWBM) conducted an analysis of Sen. Warren’s proposed tax and found that it would raise $1 trillion less than what her campaign had argued. More importantly, according to the model used by Penn Wharton, wealthy individuals would reduce their investment to avoid taxes, which would depress long-run economic growth and even lower wages across the economy.

The PWBM failed to factor in many aspects of Sen. Warren’s proposal, including a heightened tax enforcement regime

and especially the economic benefits of programs that she proposed funding with the tax revenue (universal child care, increased education funding, and student loan forgiveness), which would expand the economy on their own. But the widespread news coverage of the findings, blaring headlines linking the policy to recession, ultimately provided important ammunition for conservatives to push back against the proposed tax and paint it as bad policy. In the fight over Build Back Better, while a minimum tax on corporations did make it into law, wealth taxes were largely sidelined.

Because of the high profile of Warren’s plan and the presidential race, we know about this particular policy, and the pushback that ultimately doomed it. But there are dozens of other ideas that are more quietly shoved aside, or not even contemplated, thanks to a series of obscure gatekeepers who have come to dominate the way we deal with America’s most pressing challenges. They use the language of math and the presumption of certainty to dismiss innovative solutions before they can build a coalition of popular support. They claim to be neutral arbiters reflecting rigid realities about how the world works. But their methods are uncertain, their biases barely concealed, and their ideological goals apparent—if you know where to shine the light.

The key mechanism used to assert this

dominance is the macroeconomic policy model. It’s important to be very precise here. Models can be constructive tools that process the best available evidence and incorporate, to the extent possible, the desires of policymakers and elected representatives. The Environmental Protection Agency’s air quality model that formed the basis for how to fight acid rain was a sterling example of the best approximation of the real-world effects of policy driving to a positive result.

As an economist and a journalist who rely on data and evidence, we are in no way reflexively skeptical of the use of numbers. We would not condemn models per se, any more than we would condemn a calculator or a slide rule. But we also know the old adage that predictions are hard, especially about the future. The bigger the system being modeled, the harder it is for those predictions to represent the truth. That’s particularly true when you’re talking about enormous sectors like health care or the environment, or in the case of macro models, the entire national economy over a span of years or even decades.

We believe there should be more humility about the results of macro policy models when they are used in policy debates, especially given how they frequently serve as political weapons. While they produce potentially useful metrics for assessing policy, models are only as good as the assumptions built into them and the information that gets inputted.

The specific modelers most listened to in Washington today are a particular set of economists, think tanks, and government agencies. Budgetary scorekeepers at the Congressional Budget Office and the Federal Reserve, and outside practitioners like the Penn Wharton Budget Model , the State Tax Analysis Modeling Program (STAMP), REMI , and the Tax Foundation’s Taxes and Growth Model, hold immense power over what gets considered. They help ingrain narratives into the public consciousness, dictating how policymakers, journalists, and other players understand what is good or bad for the economy. This creates invisible shackles on policymakers, guardrails that cannot be touched, problems that cannot be solved, no matter how ingenious the prescription.

The modelers and the models they use are rarely scrutinized deeply, even by those most closely attuned to the world of policymaking. Yet for all the claims of neutrality and rigor, these modelers are neither dispassionate, comprehensive, or even accurate much of the time.

In this special issue, we shine a bright light on these gatekeepers to try to understand what the models they use are, where they

get their power, and how they acquired so much influence. We will dig into the history of macro models, and try to understand why fixating on the macroeconomy can often lead us down the wrong path. We will better understand the ways that macro models constrain our scope of imagination about what is possible in the policy landscape, and what needs to change in order to make these tools useful.

As Elizabeth Popp Berman detailed in her book Thinking Like an Economist , over the past several decades an economic style of thinking has taken hold over policy debates in Washington. Prior to this era, major legislation about societal problems could target power dynamics, or uphold universal rights. But starting in the 1960s, this gave way to an approach that sees policy questions through the lens of market dynamics. The best policy, under this framework, is that which finds the most efficient path to solving the problem.

This is how we got housing vouchers over

public housing, cap-and-trade over mandated reductions in pollution, “bending the cost curve” over Medicare for All. The economic style tended to downplay regulation in favor of behavioral nudges. It tended to prefer market forces over public forces. “Economists, and the economic style, are not the primary reason that Democratic policy positions moved away from the high liberalism associated with the KennedyJohnson era and the Great Society,” Berman writes. “But … economists, and the economic style, were the channel through which this change took place in the Democratic Party.”

Modeling became the further channel for economists to adopt this policy approach, as the primary way to quantify gains and weigh them against costs. And structures rose to account for this.

The Congressional Budget Office was established in 1974, with the goal of wrestling expertise out of the executive branch and back toward Congress. In the hands of its first director, Alice Rivlin, CBO became a

go-to forecaster, beyond just presenting the budgetary outlook for particular bills. Its long-term estimates of deficits, interest rates, demographic shifts, expected economic and employment growth, and other economic indicators became one way that the public heard about the state of the nation.

CBO has a point of view, described in the Prospect in 2020 as short-run Keynesian and long-run classical. As Nick Hanauer explains in this issue, CBO deliberately minimizes the long-term economic benefits of public investments, building into the model the assumption that over time, public spending crowds out private spending. And the entire project of CBO, to assess policy solely in terms of its budgetary cost rather than its total effects on national income and quality of life, stresses the politics of deficits and debt over equality and prosperity. That perspective is broadly in line with other practitioners of macro models, both inside and outside of government.

These models reinforce, justify, and calcify a particular theory of change, backed

by the same players that have been trying to embed a conservative, neoliberal ideology in Washington politics for decades. And it’s clear why this has been so successful: In the hands of a politician, an estimate that makes your policy look good or an opponent look bad can be extremely powerful. Even if the modeler makes caveats about ranges of estimates, having one number to use as a cudgel can be seductive. And that number can launch a thousand headlines, without the context or uncertainty that underlies it.

Every time a politician or media figure ties budgetary numbers to a particular policy, it reinforces the macro model’s importance. But when that evidence is rooted in assumptions and ideologies that ultimately damn progressive ideas to the dumpster, these models are only useful for those who agree with them.

The economy, of course, is not a simple set of equations that can be neatly resolved

with some elegant number-crunching. The economy is a complicated, messy system, featuring hundreds of millions of individual actors pushing and pulling in different directions. Boiling progressive policy proposals down to one number belies the complexity of systemic, long-standing crises, and gives policymakers a pass from actually grappling with that complexity and the inevitable trade-offs. Many have tried to map the economy scientifically with precision; many have failed, as you will see in this issue.

Though economists may not want you to believe it, the assumptions they build into their models to make the math work are actually embedding a perspective about the economy. Some of these assumptions can belie common sense. There’s the idea that investments in children or the climate that pay off over the long term are too costly in the short term to justify; or that distributional outcomes by race, gender, wealth, and other salient characteristics are irrelevant to policy considerations. Other assumptions fail to incorporate the last several decades of economic research, such as the idea that public investment and private investment are substitutes rather than complements, or the idea that concentration in goods production or labor markets doesn’t matter for long-run economic outcomes.

That these assumptions are divorced from reality is not just a technical matter. The lack of grounding in reality also means that these models are wrong. The Trump tax

cuts were rolled out with the imprimatur from both CBO and Penn Wharton that they would expand the economy over the next ten years—CBO’s model predicted an increase in GDP of 0.7 percent, while Penn Wharton provided a range from 0.6 to 1.1 percent. Notwithstanding the point that the models couldn’t have foreseen the pandemic and the emergency economic measures taken to counteract it, if you control for that it remains clear that this did not bear out. Despite the macro religion, the tax cuts were simply not expansionary.

The fact that these assumptions are hidden under tangles of math has enormous implications. The lack of transparency means that massive decisions that affect the lives of millions are being justified using a set of equations that only a few people fully understand and control. And yet, when we look under the hood, it becomes clear that the same money and power that governs influence all over Washington has its hand in these technical gatekeepers as well. Ideologies should be challenged in the marketplace of ideas, not buried under a mountain of numbers.

Those who publicize the work of the macro modelers, whether in politics or the press, are only interested in the results, and have no interest in the way the sausage was made. They trust the figures as the product of impartial observers who simply apply the math. They don’t question the methods, or the biases. That’s what gives the models their power; it’s the way they are used, or

abused, by the modern political system that gives them outsized sway over the policies that govern our lives.

In this issue, we dig inside two of the biggest modelers, the CBO and the Penn Wharton Budget Model, exposing their blind spots and in some cases their hidden ideologies. We detail the questionable assumptions built into macro models, and the ways in which economists have come to rely on a process that excuses them from looking at the real world. We give space to progressive economists and policymakers who have had to work under the world that the macro modelers built, constrained by the hidden handcuffs on their ambitions and the illogic that faulty models predict. And we try to sketch out another world, mindful of the boldness of the past but also the necessary perspective of the future, that can give economic analysis its proper place in the policymaking process: as an aid to problem solving, not a roadblock to overcome.

Leon Keyserling, President Harry Truman’s chair of the Council of Economic Advisers who was a major figure in constructing the Fair Deal, once wrote to his immediate predecessor, Edwin Nourse, complaining about the flaccid state of the economic profession. “While we economists have long talked in the refined atmosphere of theoretical underpinnings,” Keyserling said, “we live in a world where prices and wages and profits are being made.” That real world is where policy must emanate from, not through retreating to perfect dioramas of a model economy.

Our economic challenges continue to grow ever larger in scale and scope, in ways that crude algorithms of dubious quality cannot reach. Combating existential threats like climate change and racial injustice will require analyses that account for the benefits that come from shifting our economy fundamentally over the long run, even if they come with significant up-front costs. The models of the future will have to recognize that not everything can be boiled down into a simple cost-benefit analysis.

In other words, if tackling the challenges of the future requires us to rethink the trickle-down, neoliberal approach to policymaking, the models must follow. n

Though economists may not want you to believe it, the assumptions they build into their models are actually embedding a perspective about the economy.

Economics is commonly described as the science of scarcity.

We have limited resources, and we have to use them wisely. So there are trade-offs. In the old textbook example, if we want to spend more on guns, we have to spend less on butter. And so, not surprisingly, the question of how much we have to spend, now and in the future, is critical.

There are many things wrong with this seemingly impeccable and simple logic.

The first is that if we are not using our resources fully, then we can have more guns and more butter at the same time. Sometimes, we have people who would like to work but we don’t have jobs to give to them;

other times, as the former head of the Federal Reserve Ben Bernanke once claimed, we have a “saving glut,” with firms and households saving so much the money has nowhere productive to go. In those instances, we don’t have to make any trade-offs. The country, and the world, has frequently been in such a situation. In the Great Depression, 1 out of 4 workers were unemployed; in the Great Recession, more than 1 out of 10. At the height of the pandemic, 1 out of 7.

The second problem with the guns-orbutter logic is that the market economy is often inefficient. Resources are wasted when they are not used as productively or as wisely as they could be. Of course, ensuring that resources are used well is supposed to be a core virtue of the market economy,

as ruthless competition ensures that firms produce what consumers want at the lowest cost possible. But no one living in 21stcentury America should believe that such a myth describes the economy today, marked as it is by mega-monopolies and oligopolies.

Can it possibly be the case that the most efficient use of our limited research resources should be directed toward making an ever-better advertising machine (the business model underlying Facebook and Google) aimed at better exploiting consumers through discriminatory pricing and targeted and often misleading advertising? Would an efficient 21st-century “market machine” be unable to deliver safe baby formula? That’s a simple enough product to get right, and yet last year, the country

Seemingly complex and sophisticated econometric modeling often fails to take into account common sense and observable reality.

faced a massive shortage. And why did the market creep so slowly toward cost-saving renewable energy?

When there are inefficiencies of this kind, the economy can produce more guns and more butter by reducing these distortions. The economy is rife with such “market failures.” Public policy needs to be directed at reducing their magnitude.

Another major weakness in today’s economy results from lack of sufficient public investments. The obvious example is infrastructure: If we don’t invest enough in roads, harbors, and airports, it will cost private firms much more than it should to get their goods to market. Because there has been such severe underfunding in these areas, the returns on these public investments today are far higher than those on the average private investment.

And what matters for economic performance is social returns. When there are market distortions, such as when firms spend money to enhance their market power, they can create large private returns but low or even negative social returns. Arguably, investments in building a better advertising machine to target consumers more precisely may have a negative social return, even if Google and Facebook wind up being among the wealthiest firms on the planet.

Public policies redirecting overall investment toward more socially productive uses increases the size of the economic pie. But the economic returns from public investments in health and education and basic research and technology are even higher than in hard infrastructure, so the scope for increasing the size of the pie is even larger.

There is a third problem in the simplistic

trade-off analysis, which centers on how those trade-offs are calculated. To do this, economists use models. Models are simplifications of reality. They attempt to capture statistically what will happen if we spend more on infrastructure or raise taxes. Underneath the arcane mathematics, though, there are always simplifying assumptions. There is nothing wrong with simplification. The problem is that if the models make the wrong simplification, they will give the wrong answer. And often, the simplification determines the answer. If one assumes that the economy is efficient, then of course one can’t get more guns without giving up butter. But why would one make that assumption in the first place, one might well ask, when

it is obviously wrong? It’s hard to answer that question without impugning motives.

Most of the models that economists currently use ignore the role of market power in today’s economy. And in the gizzards of the models are a variety of other assumptions that affect how the consequences of any policy are calculated, including the macroeconomic consequences that determine the size of the pie and the nature of the tradeoffs. The estimated responses to any policy change are claimed to be the most reliable estimates of what will happen, based on past data, using the “best” models and best statistical techniques. Typically, these estimates are not robust—with large variations in the estimates depending on how they are

done and the sample period over which they are done. The sample period is in fact critical: The current situation may be markedly different from the one in which the studies were conducted. Applying those results to today leads to faulty conclusions.

For instance, if most of the time, in the historical sample, the economy was near full employment, as it was during the late 1990s and the beginning of this century, an increase in government spending would not lead to an increase in GDP. How could it? But both in 2008 and in 2020, government spending had a big effect, with GDP increasing a multiple of the amount of government spending, as standard Keynesian economics had predicted. During these periods, there were underutilized resources, and the underutilization would have been far worse in the absence of government action. The increased aggregate demand resulting from government spending led to a better utilization of resources.

Often, simple reasoning can beat out seemingly complex and sophisticated econometric modeling. In 2017, then-President Donald Trump proposed, and Congress adopted, a massive cut in the corporate income tax. The claim was made, supposedly based on models, that it would massively stimulate investment. It did not. It simply stimulated increases in share buybacks and dividends, funneling money to investors. It was, in effect, a big gift to rich corporations and their shareholders.

I had predicted that investment would not increase by much. Why? The corporate profits tax is a tax on pure profits, on the excess of returns over all the costs of production: labor, the goods that go into production, and capital. Firms make such pure profits, for instance, when they have market power. Some firms have a little market power. But in our economy marked by ever-increasing market power, many have a lot of market power—and thus large profits. The 2017 tax bill allowed firms not only to deduct the cost of their plants and equipment, but even to deduct some of the interest they paid. A basic result of standard economics is that a tax on pure profits does not discourage either investment or employment—and, by the same token, a lowering of such a tax doesn’t encourage investment or employment.

The standard models used by corporate interests to sell the tax cut assumed that the tax was equivalent to a tax on capital,

simply forgetting the fact that expenditures on capital were tax-deductible. (It was, I suspect, not an innocent mistake.) If it were a tax on capital, it would have discouraged capital expenditures. One can easily calculate by how much a tax on capital might discourage investment, and voilà, one has an estimate of how much lowering the corporate income tax will encourage investment. The magic is in the assumptions, which are hard to discover.

A coherent model of the entire economy recognizes that such a corporate tax will lower the value of firms’ equity—and lowering the tax will correspondingly increase the value of equity. If there is a pool of savings to be allocated between holding equity (reflecting the value of after-tax pure profits) and productive capital, then an increase in the value of equity will crowd out real capital accumulation. At least in the medium term, lowering the corporate income tax may actually result in less investment, and reduced GDP

Another critical assumption that goes into the standard modern macro econometric model concerns full employment. This is usually taken to be the level of unemployment below which inflation starts to increase, a number that is referred to as the natural unemployment rate, or NAIRU (non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment). The idea is simple: If labor markets get too tight, wages start to increase, increasing the rate of inflation.

The problem is that the NAIRU cannot be reliably estimated, as the debate in the aftermath of the pandemic illustrates. Before the pandemic, we had very low levels of unemployment with very little inflation. Some thought that the pandemic had induced a permanent change in the labor market; for example, Larry Summers

believed that undoing the inflation (which he wrongly attributed to excess aggregate demand, but was clearly the result of a series of pandemic-induced supply-side shortages and demand shifts) would require a high level of unemployment for a long period of time. Others thought the pandemic, with its unprecedented levels of job separations (particularly stark in the U.S.), had temporarily shifted the relevant curves, but that eventually matters would normalize. It might take a while; we know, for instance, that quit rates are much higher in the early years of a new job. With a much larger fraction of workers getting new jobs, aggregate quit rates would be expected to be higher. In fact, there is mounting evidence of a normalization of labor markets in just a few years as the pandemic winds down.

A third example of a macro model assumption involves estimating the impact of public investments. I’ve already pointed out that public investments yield very high returns, and even if taxing corporations resulted in less private investment (which it does not), diverting resources from private to public investment would increase the size of the national pie. But because public investment may actually increase the returns to private investment, such investments may crowd in private investment. Typically, such longer-term effects are not included in the budgetary analyses. While there may be uncertainty about the value of these effects, we can say, with some certainty, that they are significant. Assuming them away, as much of the budgetary modeling does, is wrong, and prejudices the policy analysis.

There are a host of other examples. Models build in our views of how the economy and society function. We know that there are

There is a remarkable record of poor forecasts in critical moments, like the 2oo8 financial crisis.

differences in these views, and that predominant views change over time, so we shouldn’t be surprised that models incorporating different views would yield different results. Tragically for our country, the models that have been prevalent for the last quarter-century embed a particular set of views that are increasingly out of touch with the realities of today’s economy.

I’ve mentioned one aspect—the assumption of a competitive economy. More broadly, the “neoclassical economy” presumes profit-maximizing firms interacting with utilitymaximizing individuals in perfectly competitive and efficient markets. But we know that neither firms nor households behave according to that model, and that markets are far from perfect.

These deviations can be of first-order importance. To take but one example: In the perfectmarket model, there is what Arthur Okun called “ The Big Tradeoff .” One can only have more equality at the cost of poorer economic performance. But increasingly, experts recognize that in our economy marked by high levels of imperfections, including rent-seeking from firms with market power, equality and economic performance can be complementary. We pay not only a high price for inequality in terms of social and political divides, but even more narrowly in terms of economic performance. Even establishment institutions like the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the International Monetary Fund view it this way. Yet, this perspective is still not incorporated into standard macro budget models.

To be fair, the models used in the U.S. are not as bad as they could be. A standard model of the right—dating back to Herbert Hoover and before—entails “expansionary austerity.” This view says that cutting spending, even in a recession, is expan -

sionary, not contractionary! The magic is worked by what Paul Krugman has called the “confidence fairy.” Somehow, the cutbacks inspire such confidence that investors rush in and, in a self-fulfilling prophecy, this not only undoes the effect of the cutbacks but propels growth.

A main problem with this “theory” is that it runs counter to virtually all experience. Hoover’s cutbacks didn’t propel the economy into a new boom, but into an ever-deeper Depression. As did the IMF ’s cutbacks in East Asia, Greece, Spain, Portugal, and Ireland. Investors understood the underlying economics better than the “modelers.” They understood that contractionary policies, like raising interest rates and budget cuts, are … well … contractionary. They understood that when the economy goes into a downturn, sales decrease and bankruptcies increase—and returns to capital decrease. Austerity leads to less investment. Households, worried about the future, husband their resources, so it can even lead to curbing consumption. The knock-on effects of

austerity deepen the downturn. Common sense, once again, triumphs over the model.

There is a remarkable record of poor forecasts in critical moments, like the 2008 financial crisis and the euro crisis, by central banks and the international financial institutions. All of them were based on bad modeling. If the flawed modeling were just an academic exercise, that would be one thing. But policies are based on these models. Educations were interrupted and lives were broken by austerity. Millions lost jobs, homes, and livelihoods.

Flawed models have made us face false choices. It’s time to formulate new ones that accurately reflect the world in which we live. Only then can we make informed decisions that will lead to a healthy and robust economy for all citizens. n

If you’re wondering why the U.S. has failed so miserably in developing a workable child care and early-childhood education system, consider the role of economic modeling.

In 2021, when the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released its much-anticipated score for the cost of the child care provisions in the Build Back Better Act, it produced one headline number: $381.5 billion. This was what CBO estimated as the amount of money the government would lay out for child care.

But that budget score badly missed the mark on the net cost of the program. It did not account for any of the savings predicted by reams of academic research on the long-term economic benefits of child care. Nothing about how kids with high-quality early care do better in school, stay out of trouble, and have higher lifetime earnings. Nothing about the increased tax revenues generated by mamas and daddies who could now work full-time. Nothing about the mountains of data that show that when mothers are held out of the workforce in their early years, their lifetime earnings and even their security in retirement are seriously undercut—something universal child care could reverse. And nothing about the impact of higher wages for child care workers—wages that would mean many of those workers would be paying more taxes and wouldn’t need SNAP, Medicaid, housing supplements, and other help offered to the lowest-paid people in the country. In other words, according to CBO, investing in our children and filling a wheelbarrow with $381.5 billion in cash (a big wheelbarrow) and setting it on fire would have exactly the same impact on our national budget and our nation.

To every CEO of a Fortune 500 company or owner of a small neighborhood restaurant, budget scoring like this must sound like a crazy way of doing business. After all, investments don’t just have costs—they also have benefits. That’s why companies invest in things like building factories, converting to green energy, or offering employee benefits, even if they have to book a big cost up front. Those corporate executives don’t take on big-ticket projects out of the goodness of their hearts; they take them on because they want to boost profits, retain workers, and improve the company’s long-term outlook.

Budget rules, by contrast, tilt against investing in people. And there’s a reason for that. Decades ago, Congress decided that CBO cannot account for the indirect or secondary effects a policy change may have on other parts of the budget. Research shows, for example, that federal spending on things like safe housing and nutrition assistance for babies makes people healthier and reduces total health costs. But because of the rules Congress set, CBO cost estimates for these programs cannot assume taxpayers would save any money on health insurance costs or that taxpayers would spend less on Medicaid. Meals on Wheels helps seniors stay out of much more costly nursing homes and saves Medicare and Medicaid billions of dollars, but the federal government says it is nothing but an expense.

These and other self-imposed rules structurally bias the policymaking process away from making commonsense investments that meet families’ needs.

Bad budget modeling, and how members of Congress respond to it, also distorts the way we design policies. Consider again our country’s need for child care. The U.S. is 33rd out of the 37 richest nations in terms of what we

spend on child care, and millions of parents— mostly mamas—are kept out of the workforce because they can’t find safe, affordable child care. The pandemic drove this crisis into the open, fueling a national outcry over the sorry state of care for our youngest children.

When I was invited to deliver one of the keynote speeches at the all-remote 2020 Democratic convention, I spoke from a closed child care center in Springfield, Massachusetts—standing amid the blocks, tiny chairs, and individual cubbies in the room for threeyear-olds. As more people rallied behind the need for universal child care, and as Democrats won both the White House and Congress, I believed this was our moment.

But as I assembled a new, comprehensive bill, the first question I got was the dreaded “How does it score?” The answer hobbled the process from the start. Instead of fighting for good policy, Democrats arbitrarily decided that the child care provisions in the bill would need to cost less than $400 billion. Universal care costs a lot more than that.

So the bill that ultimately moved forward was not based on how much money it would take to make certain every child had access to care. Instead, it was loaded with ways to game the policy design so the CBO score would meet the $400 billion threshold. The bill cut out millions of families that needed care, delayed implementation for years, and let states opt out. Bad budget modeling meant that these decisions weren’t driven by what would maximize our children’s well-being or our nation’s long-term growth. Instead, decisions were driven by the political imperative to produce a smaller score, regardless of what it meant for the workability of the proposed program.

The only number used to evaluate a child

Reforms are needed to ensure that inaccurate budgetary math doesn’t take precedence over maximizing long-term prosperity.

care program was the direct outlay for care. The compromises made to hit a politically palatable CBO number raised questions about who would and wouldn’t benefit from a compromise program, draining away support. As one bill after another passed the 2021-2022 Congress, child care was left behind.

Our current budget models don’t create random errors. They don’t sometimes overstate and sometimes understate costs. They create systematic errors, making many investments look far more expensive than they are. They lead to the routine underfunding of critical programs and enforcement activities, and they distort the policymaking process from start to finish.

For those who want to shrink the government to a size that can be drowned in a bathtub, the current budget-scoring model works great. But for those who live in the

real world and want a country in which all our people have a chance to thrive, bad budget models are choking us.

Reforming these economic models would not be easy. CBO cost estimates generally exclude the potential macroeconomic effects of a proposed policy precisely because, as they explain it, they have too few analysts to crunch the numbers. Worse, say former CBO scorers, the “estimates of macroeconomic effects are highly uncertain.” Translation: It’s hard.

Yes, estimating the costs and benefits of major investments decades out is hard— really hard. Figuring out the right model and the right assumptions is tricky and uncertain, and real life can prove our best estimates wrong. Politics can weave its way into judgment calls. Data are imperfect. But “hard” is no excuse for not trying.

Congress has a responsibility to maximize our people’s long-term prosperity, and

we need economic models that stand a better chance of doing that.

We should start by changing the rules on modeling so that both costs and benefits are accounted for. And because this is hard, we should ensure that the agencies we rely on for modeling have the resources they need to provide a solid understanding of both the likely costs and the likely benefits of any given policy.

We should also ensure that our modelers, who make countless judgment calls in doing their work, reflect a real diversity of perspectives. Consider CBO’s Panel of Economic Advisers. CBO relies on these experts, “selected to represent a variety of perspectives,” to help calibrate their models and gut-check their assumptions. But look at the team: Of the 22 people on last year’s panel, 20 had doctorates in economics; 11 of those 20 went to the same three Ph.D. programs. Recognizing that economic modeling is highly uncertain and highly dependent upon assumptions means that we should strive for diversity among our modelers and be open to different kinds of models when making decisions. CBO shouldn’t be the only game in town. We should also build accountability into the modeling system. Instead of scoring, voting, and moving on, we should assign independent outside teams to collect data on programs that have been adopted to see how far wide of the mark past modeling turned out to be. That information would arm us to improve modeling over time.

Finally, policymakers need to remember that modeling the costs and benefits of major public policies isn’t just about numbers—it’s also about our values. Yes, we need better data and better models, but we also can’t be afraid to make the case for bold investments, even when the (accurate) price tag is high. I believe that with accurate modeling, high-quality child care pretty much pays for itself. But even if not, such care helps us create an America in which everyone has opportunities—and “everyone” includes mamas. An investment in care is also an investment in care workers, treating them with respect for the hard work they do. In other words, just as a CEO would make the case to her board for taking a bet on a big new project, Congress shouldn’t shy away from making the investments the American people and our economy need. n

Americans have been hammered for decades with an economic message that amounts to this: When wealthy people like me gain even more wealth through tax cuts, deregulation, and policies that keep wages low, that leads to economic growth and benefits for everyone else in the economy. And equally, that investing in you, raising your wages, forgiving your debt, or helping your family would be bad—for you! This is the trickle-down way of thinking about economic cause and effect, and there can be no doubt that it has substantially contributed to the greatest upward transfer of wealth in the history of the world.

You would think that trying to sell such a disastrous outcome for the broad mass of citizens would be incredibly unpopular. No politician would outright say they want to shrink the middle class, make it harder to get by, or reward hard work less. No politician would outright say that rich people should get richer, while everyone else struggles to make a decent life.

But this message has been hidden under the confusing, technical-sounding, and often impenetrable language of economics. Many academic economists do important work trying to understand and improve the

world. But most citizens’ experience of economics comes from hearing a story—a narrative that rationalizes who gets what and why. The people who benefit from trickledown policy the most have deployed economists to work their magic to tell this story, and explain why there is no alternative to its scientific certitude.

One of the trickle-down economists’ main persuasive tools is the economic model, used to predict and assess the outcome of economic policies and other major economic developments. These existing models exert such great force on the political debate in large part because their predictions are treated by politicians and reporters as neutral, technocratic reality—simple economic facts, produced by experts, that reflect our best understanding of economic cause and effect.

What few understand is that these economic models do not, and never can, fully reflect the extraordinary complexity of human markets. Rather, the point is to create useful abstractions to provide decision-makers with a sense of the budgetary and economic impacts of a given policy proposal. More disturbingly, the assumptions baked into these models completely define what the models predict. If the assumptions are wrong, the models will be wrong too.

And these models are deeply and consistently wrong.

But “wrong” doesn’t capture the true problem. The deeper problem is that these models are all wrong in the very same way, and in the same direction. They are wrong in a way that massively benefits the rich, and massively disadvantages everyone and everything else.

The headlines derived from these models consistently reflect this bias: “Raising Minimum Wage to $15 Would Cost 1.4 Million Jobs, CBO Says,” or “Biden Corporate Tax Hike Could Shrink Economy, Slash U.S. Jobs, Study Shows.”

Models serve less as scientific analysis and more as incantations from the cult of neoliberalism, and if politicians and journalists continue to accept them with the same naïve credulity that they always have, they will hamper the astounding middle-out economic progress that the Biden administration has made toward rebuilding a more equitable, prosperous economy for all.

The problem is that few people take the time to explain what these faulty assumptions are, why they all promote the worldview of the rich and powerful, and why they shouldn’t be treated as science but as a trickle-down fantasyland.

Here are six of the assumptions built into most economic models that are among the most pernicious:

1. Models assume that public investments will “crowd out” private investment, and are by definition less productive than private investments.

What happens to the economy if the federal government spends $1 billion? The normal person would say that it depends what they spend it on, and how the policy is designed.

Not so in most economic models. They assume that any government spending will have less of a return than whatever private businesses spend their money on. Always.

But that’s not all. They say that government spending even comes with a penalty: It automatically causes businesses to spend less, leading to lower overall investment. Always.

Essentially, models assume that every increase in public investment is canceled out by the combination of lower returns and reduction in private investment. Taking this assumption to its logical extreme, there’s almost nothing government should ever invest in. It’s a good thing Eisenhower took office before the neoliberal style of thinking came to dominate Washington, or instead of interstate highways we’d still have dirt roads.

These assumptions aren’t even well hid-

den in models but baked directly into the math. As economist Mark Paul has noted , the Congressional Budget Office model assumes that all public investments are exactly half as productive as private investments. Public investments return 5 percent annually, while the same amount of private investment returns 10 percent.

The first indication that something is amiss here can be sensed in all these round numbers—a flat declaration that public spending is 50 percent less good than private spending. Precisely 50 percent. Every time. Obviously, this is not the result of rigorous data analysis. It’s simply recapitulating the old trickle-down myth that government is by definition wasteful, while private invest-

ment is always maximized for the greatest efficiency and return.

And it’s not even a little bit true. Think about health care. The U.S. government invests billions in basic research each year and is responsible for funding an incredible range of innovations, from m RNA vaccine technology to new antibiotics. Everyone benefits from this publicly funded research, sparking further innovations and benefits— much of it carried out by the private sector.

Then consider how Big Pharma invests its profits: with huge marketing budgets, predatory patent enforcement, $577 billion in stock buybacks over five years (more than was spent on research and development), and a 14 percent increase in executive compensation. It’s a bonanza for those corporations, but it’s the opposite of efficiency—except in the make-believe world constructed by economic models.

The point isn’t that government spending always returns more than private spending, just that the flat assumption that it is always worse by 50 percent simply doesn’t map to reality. We should assess policy by what it proposes to do, not who proposes to do it.

The other idea, that public investment leads to lower private investment, is usually expressed with a fancy term: “crowd out.” It is a bedrock principle of neoliberal economics, and most models simply assume it’s true. The Penn Wharton Budget Model, for example, explicitly holds that government investments reduce the amount of private capital investment. Because the model also assumes that private investment is “productive” and public spending is “unproductive,” this automatically results in any large-scale government investment causing lower growth and lower returns. That informs their budget model’s analyses that the bipartisan infrastructure law will somehow lead to a 0.2 percent decline in productive private capital, that the $2 trillion Build Back Better proposal would reduce GDP by 0.2 percent, and that the COVID relief package would also reduce GDP by a similar amount.

The State Tax Analysis Modeling Program (STAMP) from the Beacon Hill Institute makes an even stranger decision, modeling government simply as a pass-through entity that causes “no indirect or induced effects” whatsoever.

Thankfully, President Biden rejects this nonsense. A central plank of Biden’s middleout approach is to attract private investment in key industries through the strategic use

of public dollars. As Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo explained about the implementation of the CHIPS and Science Act, “If we do our job right, the $50 billion of public investment will crowd in $500 billion or more of private investment of additional funding for manufacturing, for research and development, for startups” (emphasis added).

This strategy is already working. According to the Semiconductor Industry Association, the CHIPS and Science Act has already sparked $200 billion in private investment. The Climate Smart Buildings Initiative— created by the Inflation Reduction Act—is expected to attract over $8 billion of private-sector investment for modernizing federal buildings. The Biden administration has allocated $2.8 billion in public funds for investments in battery manufacturing for electric vehicles, which has already leveraged $9 billion in additional private investments. The story is much the same across the Biden administration’s constellation of strategic middle-out investments—public dollars are attracting private dollars, not displacing them, wholly disproving model assumptions in the court of reality.

2. Models assume workers’ wages are a direct reflection of their productivity.

Does Jamie Dimon produce 917 times what the average JPMorgan Chase worker produces? Does the CEO of McDonald’s produce 2,251 times the average cook or cashier? The answer is obviously no.

People are not paid what they are worth. They are paid what they have the power to negotiate. You don’t ask for a raise when the company just laid off an entire division and unemployment is high. If the company just posted a bunch of job openings? That’s a good time. We’d like to think that our hard work and worth to the company determines our salary, but just look around the office.

Most of the time, bargaining power, not the value that worker provides, tells the story.

But the Econ 101 assumptions embedded in these budget models claim that wages are a direct and perfect reflection of a worker’s economic contributions—that every worker is paid exactly what they’re worth.

There’s no discrimination in the alternate universe created by models, so structurally lower pay for women, immigrants, and people of color must necessarily reflect their lower productivity. Separately, Wall Street speculators—who produce pretty much nothing of value for anyone but themselves—are of the highest economic value because they get paid the most. Does anyone really believe that private equity barons are more productive in society than teachers? The models do, because they assume wages perfectly reflect productivity.

If the models correctly understood that power plays the primary role in wages, they would see raising the minimum wage as correcting for the power imbalance of a loose labor market or an exploitative industry. But since the models connect wages with productivity, raising the minimum wage, by definition, lifts a worker’s income above their economic value, and thus should cause substantial job losses. That’s just what the REMI model and the synthetic University of Washington model and the Employment Policies Institute model and the CBO model said. The Baker Institute’s DiamondZodrow model even reached the ludicrous conclusion that a higher minimum wage negatively impacts children’s health, modeling that a 1 percent increase in minimum wage caused a 0.1 percent decrease in their height-for-age, in spite of empirical evidence to the contrary

These predictions occurred throughout the Fight for $15 as minimum wages rose across the country. And if the models were

Models serve less as scientific analysis and more as incantations from the cult of neoliberalism.

right, Seattle and California and New York and Florida would have seen substantial job losses. But guess what? It never happened. On the contrary, businesses, particularly those affected by the minimum wage, like restaurants, boomed. Not once did these increases cause predicted job losses in the real world.

That reflects a simple fact about the economy. When more workers have more money, they will spend at more businesses. And that broad-based consumer demand sparks growth and innovation, which in turn drives productivity. In other words, higher wages are a cause of productivity, not a reflection of it.

3. Models assume that higher taxes on corporations and high-income people reduce growth and investment.

While corporate lobby groups and the zillionaires they represent regularly complain that taxes kill jobs and slow overall economic activity, no such relationship is detectable in the historical record. If anything, the opposite is closer to the truth: When the top marginal tax rate was above 90 percent in the 1950s, overall economic growth was

remarkably strong and broad-based. When the top rate was slashed to 28 percent in Reagan’s trickle-down revolution, inequality exploded, and growth sagged for decades as money was redistributed upward.

But the economic models that control the D.C. policy debate take as absolute truth the trickle-down assumption that people will work less if they are taxed more, and that this effect is very large. Any increase in tax rates on the rich therefore reduces the amount of work performed by the very richest people—and since rich people are in the world of these models the most productive people around, that means a sharp reduction in economic output.

In reality, of course, rich people don’t organize their lives as a tax-avoidance strategy, much less work less if they earn less. The model assumes away any factor that drives people to make a lot of money; ego, to use one example.

A corollary assumption is that high incomes arise in a world of perfect competition, where new products are able to beat out incumbents by force of their genius alone, supply and demand are always in

perfect equilibrium, and monopoly is just the name of a board game. In this world, all taxes and regulations must simply reduce productive corporate spending, and thus reduce economic growth.

The Tax Foundation’s Taxes and Growth model, for example, arbitrarily assumes that all payroll taxes are fully borne by workers, and corporate income taxes are assumed borne 50 percent by capital and 50 percent by workers. Therefore, corporate tax cuts will always “increase the capital stock and expand the whole economy, including wages and employment,” while a payroll tax cut will do nothing for investment and economic expansion. By contrast, a corporate tax increase would harm investment and growth.

It’s no accident that this is entirely untethered from actual human behavior or productivity measures—it’s the point of the model. In the real world, dominant market players regularly take advantage of their position to extract excessive rents and stifle innovation. Anyone who has flown on a commercial jet or tried to buy concert tickets has experienced the wildly imperfect competition that exists in the American economy.

Well-designed public policy can get at these problems by aiming taxes specifically at those places where rents are extracted, making the entire economy more productive. And antitrust enforcement can similarly spark meaningful competition where it may have been eroded by predatory market actors. The only place where this doesn’t make sense is in the middle of an economic model.

4. Models assume that investing in poor people reduces economic activity, and that immigrants are less productive than domestic American workers.

What happens if the government gives people in need financial help?

If you get $50 for food, will you eat more food? If you get $100 for health care, will you go to the doctor more? If you get $100 for rent, will you be able to afford an apartment? And will any of these benefits enhance your personal well-being?

In the world of models, all of that is irrelevant. No matter what the money is for, the result of any federal assistance is that you will work fewer hours. Always.

While the models insist that rich people must be offered higher wages or lower taxes to incentivize them to work more, they hold that more economic support to lower-income people leads to them working less. In other words, rich people require the

promise of even more wealth to motivate them to be productive, but the poor must be threatened with destitution in order to motivate them.

The Baker Institute’s Diamond-Zodrow model makes the explicit assumption that “any increases in government transfers … reduce labor supply as individuals choose to ‘consume’ more leisure because household income level has increased.” The Tax Foundation’s model makes a similar assumption: that people choose between leisure and work, and that such choices are sharply impacted by taxes and transfers. These kinds of assumptions are how the Penn Wharton Budget Model’s analysis of Biden’s Build Back Better proposal could find that “lowering the Medicare age to 60 and making the ACA subsidies more generous lower households’ financial risk, so they save and work less,” and that reducing Medicare drug prices similarly reduces hours worked (and, oddly, reduces household savings as well).

This is nefarious stuff. These models assume negative consequences from the government investing in affordable housing or food security—basic necessities that make it possible for people to participate in society. It’s an Ebenezer Scrooge understanding of the economy: People are poor due to their own laziness, so any dime you flick in their direction just encourages them to do even less.

Most experiments with basic income, child tax credits, and other transfers finds that basic investments enable people to participate more fully in the economy and in their communities. Plus, providing a basic standard of living can also spur future economic gains. Only a sociopath could unequivocally conclude that giving people food always makes them work less. The models are even more direct when it comes to immigrant workers. The Penn Wharton model incorporates a baseline assumption that, as a natural law of economics, immigrants produce less than American-born workers do.

This is stupid and wrong, not to mention racist. While immigrant workers do tend to get paid less than other workers, there is no data whatsoever showing that they produce less. In fact, research even suggests the opposite: that increased immigration is tied to higher employment, higher incomes, and higher productivity.

5. Models work on ten-year budget horizons that force short-term thinking.

By the rules of Congress, the country’s best-known model, the CBO model, is required to estimate budget impacts of policy proposals over a ten-year window. For this reason, Penn Wharton, the Tax Foundation, and others follow suit. That

decade-long window creates the jaw-dropping multitrillion-dollar numbers that make headlines when Congress debates economic policy.

This arbitrary time frame is the worst of both worlds. It’s long enough that the accuracy of the estimates becomes highly questionable, and it’s also far too short to even begin to assess the economic impact of interventions on generational issues like climate change or early-childhood education.

For example, essentially everyone agrees that universal pre-K produces extraordinary benefits to children’s education, and essentially everyone agrees that these investments will create better outcomes for the entirety of a child’s life.

But over ten years, that investment won’t be realized. Children enrolled in pre-K at three years old are still in middle school ten years later—not really time to see much (if any) economic impact, now that child labor is (generally) frowned upon. So universal pre-K is basically worthless to these models, no matter how much economic growth it may create over the next six or seven decades. Investments in children are mostly thought to pay for themselves, except in the case of a budget model.

Some policies have a short enough scope that the impact is realized in the budget window. But the arbitrary ten-year cutoff cannot possibly be appropriate for all policy interventions. It literally shortchanges longterm planning, which is about as wrongheaded as you can get.

Models measure GDP and revenue rather than well-being.

Economic growth is generally a good thing. It brings more people into the econ-

omy, and creates more resources to produce solutions to human problems. This is fundamental to how markets work.

But not every positive human outcome can be measured in terms of growing GDP or increased revenue. As Bobby Kennedy so eloquently pointed out in his March 1968 remarks at the University of Kansas, an exclusive focus on these strictly numerical measures of the economy counts napalm and nuclear weapons as positives, ignores the value of health, education, and community, and “measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.”

This measurement gap stubbornly persists in today’s budget models, which have no way to interpret things that generate economic activity but that we might want less of—for example, carbon emissions or water pollution. Viewed as a model input, reduced carbon emissions and pollution could tend to reflect less economic activity—a net negative.

It’s certainly true that the economic value of these reductions is hard to measure solely in terms of dollars. And it might not even be desirable for economic models to attempt to calculate a literal price on mass shootings or the net present value of a climate apocalypse. But to the extent that we continue to let the numerical results of these flawed models drive our economic decision-making, we preclude even the possibility of reducing the factors we want less of in order to build a better society for generations to come.

When we clarify the extent to which the dominant economic models we use to judge policy are rigged against working families and the broader economy, the cause of the extraordinary upward transfer of wealth in

the past four decades becomes much easier to understand. Policymakers in Washington have based their decisions on models that are consistently biased toward the status quo, the rich, and private capital. They often amount to little more than a Mad Libs version of trickle-down economics, their exalted status in media and politics notwithstanding.

The basic structure of these models always remains fixed. Government is too inefficient and public investments are too expensive to make a difference; competition is perfect, market concentration is imaginary, and corporate power should be left alone; discrimination does not exist, all markets are at equilibrium, and wages perfectly correspond to productivity. The adjectives, policies, and numbers may vary a bit, but the story is always the same. Any policy benefiting capital, industry, or the rich is an unalloyed good. Any policy that benefits people directly is inefficient, kills incentives, and will harm the overall economy.

By tilting the playing field to restrict investment, undermine regulation, push down taxes, and lower wages, these economic models are doing their best to kill the economy. They may produce dense economic jargon and elegant mathematics that sounds super-impressive and scientific when it’s quoted on the front page of The New York Times. But on closer inspection, it looks a lot more like a protection racket for the rich and powerful than a social science.

Until we build models that reflect how the economy really grows, our leaders and the media should eye models from mainstream economists with skepticism. Models trying to convey the effects of policy should reflect the basic understanding that when more people have more money, that’s good for business. We need models that understand the basic principle that when the economy grows from the middle out, that’s good for everyone, and when more people participate in the economy, their consumer demand drives job creation and sparks innovation. In other words, our economic models must reflect the world as it really is—not as it was portrayed in the trickle-down Econ 101 classrooms of the 20th century. n

Models have no way to interpret things that generate economic activity but that we might want less of—for example, carbon emissions or water pollution.

You can tell two stories about what has happened to the economics profession in this century. In the first story, academic economics has changed, significantly and for the better. Economists are less imprisoned by the unreal assumptions of models and more committed to real-world inquiry. Those with once-heretical views have been welcomed into the profession.

In the second story, change has come mainly around the edges. The heterodox thinkers doing important work are for the most part not in elite economics departments or top economics journals. Economics is still substantially captive to the use of abstruse models and ever more elaborate equations. And the teaching of economics, especially to undergraduates and first-year grad students, is depressingly familiar.

There is an ideological dimension to this conflict. Standard economics is a handy commercial for political conservatism. If markets are efficient by definition, then any state intervention must make things worse. So the market paradigm becomes a one-size-fits-all

cudgel against regulation, progressive taxation, wage regulation, public investment, and the rest of the arsenal to produce a more just society. And if the math is impenetrable to the laity, so much the better. Best to leave these questions to the experts.

Milton Friedman added the claim that market freedom is the essence of liberty. By contrast, job security, the ability to get good health care and education irrespective of private means, or freedom from hidden toxic substances, workplace hazards, and ruined environments, are not really freedoms.

A little autobiography is in order. As a 21-year-old, I explored getting a doctorate in economics. It turned out that the kind of economics I wanted to study was something called political economy—the interplay of power, institution, history, and the question of who gets what. Once, this was the core of economic inquiry, taught at elite schools.

My professors advised me that I was born too late. So I went off to UC Berkeley, to study international political economy as a political scientist. I never did get my doctorate and became an economics journalist.

I’ve been a critic of academic economics

ever since. If the profession is changing, that’s long overdue.

According to the hopeful view, the unreal assumptions of the Chicago school model, which colonized not only mainstream economics but law and political science as well, have been embarrassed by reality and now have far less influence. They included the ideas that markets are invariably efficient; that prices accurately reflect supply and demand, not manipulation or asymmetric information or market power; that labor markets efficiently pay workers what they deserve based on their marginal productivity; that people behave rationally; that all transactions by definition are voluntary and thus power doesn’t matter; that policy makes no constructive difference because economic actors rationally anticipate the impact and alter their behavior accordingly; and that economic concentration doesn’t matter because if prices get too far out of line, new competitors will enter the market.

Events have blown away such assumptions. Even some key Chicagoans such as Michael Jensen, author of the influential

There are more economists doing useful real-world work. But the closer you get to the pinnacle of the profession, the less has changed.

theory that the only duty of a corporation is to “maximize shareholder value,” have recanted in the face of evidence of pervasive share-price manipulation.

After the discrediting of the Chicago model, there has been a profusion of more venturesome theoretical and applied work. Computers have allowed the tabulation of massive amounts of data, which has allowed economists to return to empirical inquiry and be less captive to prior assumptions. The Nobel Prize, and the prestigious John Bates Clark Medal for the best economist under 40, keep being awarded to those with views and research techniques that once might have been shunned. Presidential addresses to the American Economic Association regularly criticize the profession and raise policy questions that defy simplistic modeling.

Two years ago in the Prospect , Harold Meyerson profiled the economics department at Berkeley, which had recruited Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, two younger mainstream economists doing pioneering empirical work on income inequality. The economics department worked in

close collaboration with other schools, such as the public-policy school where Robert Reich was based. Berkeley became a national center of eclectic applied work, without sacrificing academic rigor.

One key figure in the makeover of Berkeley economics was David Card, who had been recruited from Princeton in 1997, where he and his colleague, the late Alan Krueger, wrote one of the seminal works that overthrew bad theory with ingenious use of data. In standard economics, raising the minimum wage results in increased unemployment. But in 1992, the adjoining states of New Jersey and Pennsylvania offered Card and Krueger something that rarely occurs in economics, a natural experiment.

New Jersey raised the minimum wage; Pennsylvania did not. Closely tracking 410 fast-food places in the adjoining areas of the states, they found no impact on unemployment. Good data had refuted bad theory. The article was published in the ultra-mainstream American Economic Review (AER) and expanded into a book, Myth and Measurement. Card later won the Nobel.

I asked Card if he thought his experi-

ence was emblematic of a shift in the profession. “You can find a lot more papers in the AER and the QJE [Quarterly Journal of Economics] that are highly empirical,” he told me. Some subfields of economics, especially Card’s area of labor economics and development economics, are far more data-driven today, but others are still “cultish and formalistic.”

Another fine example is David Autor at MIT, a mainstream and empirical economist venturing far afield into realms that would have been unthinkable a generation ago. Autor is also curious about real-world institutions and political feedback loops, a sensibility that was all but driven out of the mainstream profession in the heyday of Chicago.

In 2020, Autor and three co-authors published a pathbreaking research article in the flagship American Economic Review with the startling title “Importing Political Polarization?: The Electoral Consequences of Rising Trade Exposure.” The researchers, using an extensive data set, concluded that areas heavily impacted by free trade and outsourcing populated by the white working class “saw an increasing market

share for the Fox News channel (a rightward shift), stronger ideological polarization in campaign contributions (a polarized shift), and a relative rise in the likelihood of electing a Republican to Congress (a rightward shift).” They also became more likely to elect Republican representatives. Majorityminority areas with these characteristics, by contrast, were more likely to elect liberal instead of moderate Democrats.

In addition to the unorthodox subject matter and research questions, it contained a respectful shout-out to “an emerging political economy literature that connects adverse economic shocks to sharp ideological realignments that cleave along racial and ethnic lines.” Political economy is ordinarily disdained by mainstream economists as something less than real economics. The piece also rebukes standard trade theory, which holds that if trade increases economic efficiency (which it does by definition), then the political consequences are of little interest. In any case, we can always decide to compensate the losers with a formulation splendidly oblivious to the political feedback effects.

Several others whom I interviewed pointed to a new openness. In a 2019 essay on the state of post-neoliberal economics in the Boston Review, three of the leading heterodox economists— Dani Rodrik of Harvard’s Kennedy School, Suresh Naidu of Columbia, and Zucman of Berkeley—wrote, “Economists also often get overly enamored with models that focus on a narrow set of issues and identify first-best solutions … Many policy failures—the excesses of deregulation, hyper-globalization, tax cuts, fiscal austerity—reflect such first-best reasoning.”

But they see significant and hopeful change. “The typical course in microeconomics spends more time on market failures and how to fix them than on the magic of competitive markets. The typical macroeconomics course focuses on how governments can solve problems of unemployment, inflation, and instability rather than on the ‘classical’ model where the economy is self-adjusting.”

As good empiricists, they added, “The share of academic publications that use data and carry out empirical analysis has increased substantially in all subfields and currently exceeds 60 percent in labor economics, development economics, international economics, public finance, and macroeconomics.”

I was beginning to be persuaded. Then I got in touch with Luigi Zingales.