Maureen Tkacik on health care Ponzi schemes

David Dayen on the new industrial policy

Ramenda Cyrus on predatory lending

IDEAS, POLITICS & POWER

Maureen Tkacik on health care Ponzi schemes

David Dayen on the new industrial policy

Ramenda Cyrus on predatory lending

IDEAS, POLITICS & POWER

BY LUKE GOLDSTEIN

BY LUKE GOLDSTEIN

Over the past two years, progressives have helped build new economic policy centered on American workers, U.S. factories, and a clean energy future. In 2023, it’s time to make it real by:

• Building upon industrial policy like the CHIPS and Science Act and Inflation Reduction Act

• Making good on clean energy investments like domestic solar production and electric vehicles

• Fully implementing infrastructure investment

• Enforcing Buy America laws to ensure our future in Made in America

• Making sure the jobs created are good-paying, familysupporting jobs

Let’s keep the work going.

americanmanufacturing.org

12 How Washington Bargained Away Rural America

Every five years, the farm bill brings together Democrats and Republicans who are normally at each other’s throats. The result is the continued corporatization of agriculture. By Luke

Goldstein20 Quackonomics

Medical Properties Trust spent billions buying community hospitals in bewildering deals that made private equity rich and working-class towns reel. By Maureen

Tkacik28 A Liberalism That Builds Power

The goals of domestic supply chains, good jobs, carbon reduction, and public input are inseparable. By David

Dayen38 An Unemployment System Frozen in Amber

Pandemic-era benefit boosts worked for jobless recipients and the economy. Why did they go away? By Bryce

Covert46 Getting Across Baltimore

Gov. Wes Moore’s credibility in the largest city in Maryland rides on building a light-rail line long blocked by racist fears.

By Gabrielle Gurley52 Predatory Lending’s Prey of Color

Black and Latino borrowers are more likely to get trapped in cycles of debt, because they have few other options for dealing with structural poverty. By Ramenda Cyrus

04 A China Reset? By Robert Kuttner

07 What’s the Refugee Endgame for Latin America? By Jarod Facundo

10 How Big Pharma Rigged the Patent System By Ryan Cooper

57 Lee Harris on Crack-Up Capitalism

61 Rhoda Feng on Who Cares: The Hidden Crisis of Caregiving, and How We Solve It

64 Parting Shot: Why Gun Jokes No Longer Work

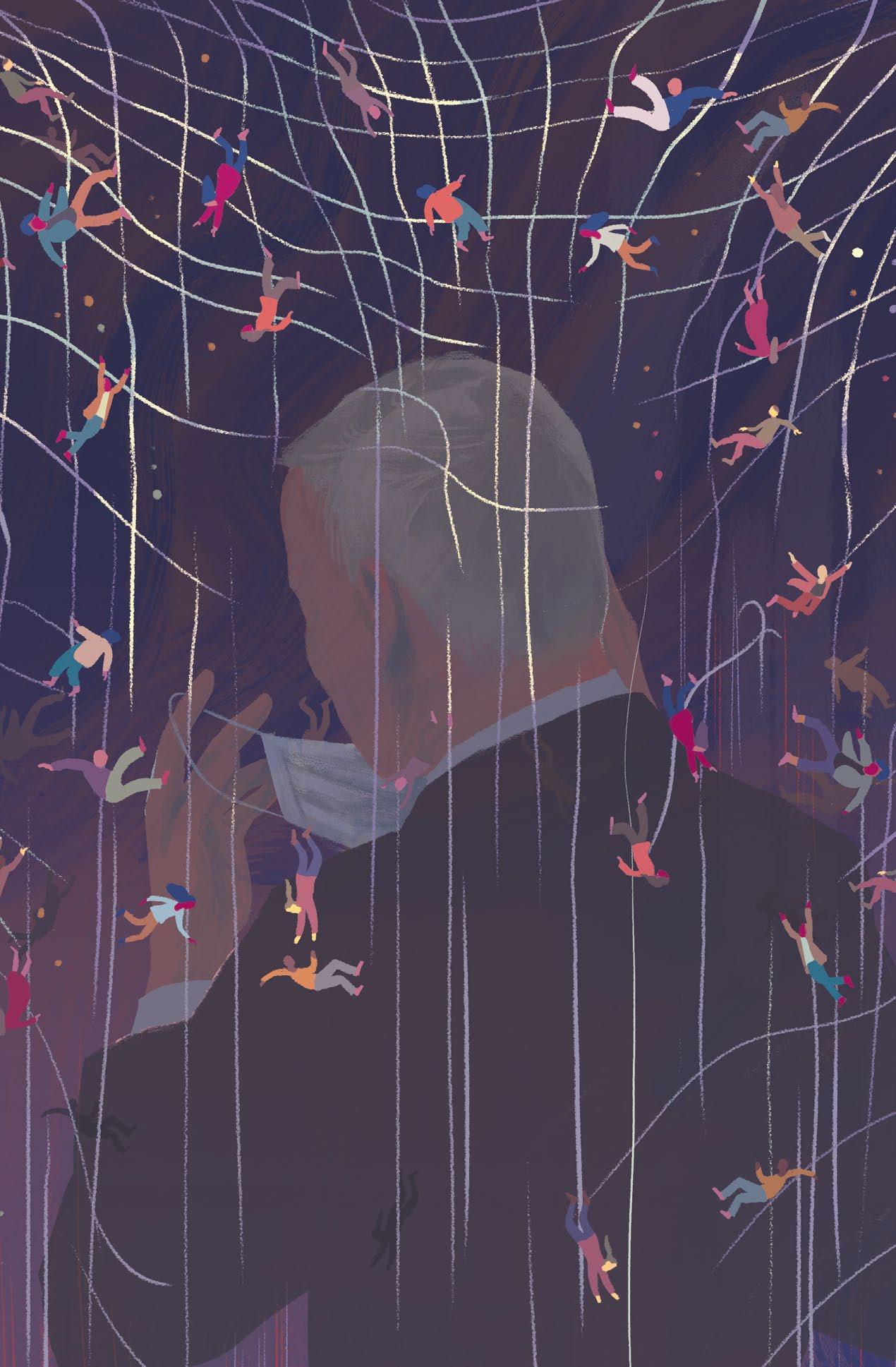

By Francesca FiorentiniCover art by Peter and Maria

HoeyVisit prospect.org/ontheweb to read the following stories:

Donations by Big Pharma to Republican senators during the 2018, 2020, and 2022 election cycles. But with FDA approvals under attack by a judge Republicans confirmed, David Dayen asks if it was money well spent.

“Americans are taught in high school civics classes that our laws are legitimate because they apply to everyone equally. If we even want to pretend that we believe in this ideal, then Congress must immediately investigate Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas.”

to contrast the country over which he hopes to preside with the country where Republicans are busy stripping basic rights from women... and to make his case for freedom so forcefully that he dispels some of the doubts raised by his age—which he can only do by subjecting himself to the media and the public more than he has.”

—From Meyerson On Tap

“While the company was obviously cratering, it still managed to sell a lot of stock. But the dumb money that bought the shares must have taken the serious loss. Shares, which were trading at almost $6 as recently as February, are [in April] trading at 12 cents.”

—From Kuttner On Tap

“GOP lawyer Cleta Mitchell declared that polling places close to dorms, a previously unknown threat to the republic, somehow made it easier for packs of college sloths ‘to roll out of bed, vote, and go back to bed.’ ”

100 PEOPLE ARE KILLED AT WORK EVERY WEEK

in the U.S., according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Terri Gerstein examines the dire state of workplace safety.

“Prisoners

—Max Moran on judicial corruption

Gabrielle Gurley looks at the Republican war on youth voting

and their families are an easy mark—a captive audience in the most literal terms—for telecom corporations. But telecoms are a utility. And states—and the federal government—regulate utilities.” Kalena Thomhave writes about how public utility commissions can reduce the cost of prison communications.

EXECUTIVE EDITOR David Dayen

FOUNDING CO-EDITORS Robert Kuttner, Paul Starr

CO-FOUNDER Robert B. Reich

EDITOR AT LARGE Harold Meyerson

SENIOR EDITOR Gabrielle Gurley

MANAGING EDITOR Ryan Cooper

ART DIRECTOR Jandos Rothstein

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Susanna Beiser

STAFF WRITER Lee Harris

JOHN LEWIS WRITING FELLOW Ramenda Cyrus

WRITING FELLOWS Jarod Facundo, Luke Goldstein

INTERNS Hannah Crosby, Luca GoldMansour, Andrea L. Pastor, Imani Sumbi

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Austin Ahlman, Marcia Angell, Gabriel Arana, David Bacon, Jamelle Bouie, Jonathan Cohn, Ann Crittenden, Garrett Epps, Jeff Faux, Francesca Fiorentini, Michelle Goldberg, Gershom Gorenberg, E.J. Graff, Bob Herbert, Arlie Hochschild, Christopher Jencks, John B. Judis, Randall Kennedy, Bob Moser, Karen Paget, Sarah Posner, Jedediah Purdy, Robert D. Putnam, Richard Rothstein, Adele M. Stan, Deborah A. Stone, Maureen Tkacik, Michael Tomasky, Paul Waldman, Sam Wang, William Julius Wilson, Matthew Yglesias, Julian Zelizer

PUBLISHER Ellen J. Meany

PUBLIC RELATIONS SPECIALIST Tisya Mavuram

ADMINISTRATIVE COORDINATOR Lauren Pfeil

BOARD OF DIRECTORS Daaiyah Bilal-Threats, Chuck Collins, David Dayen, Rebecca Dixon, Shanti Fry, Stanley B. Greenberg, Jacob

S. Hacker, Amy Hanauer, Jonathan Hart, Derrick Jackson, Randall Kennedy, Robert Kuttner, Ellen J. Meany, Javier Morillo, Miles Rapoport, Janet Shenk, Adele Simmons, Ganesh Sitaraman, William Spriggs, Paul Starr, Michael Stern, Valerie Wilson

PRINT SUBSCRIPTION RATES $60 (U.S. ONLY)

$72 (CANADA AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL)

CUSTOMER SERVICE 202-776-0730, ext 4000 OR info@prospect.org

MEMBERSHIPS prospect.org/membership

REPRINTS prospect.org/permissions

Vol. 34, No. 3. The American Prospect (ISSN 1049 -7285) Published bimonthly by American Prospect, Inc., 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, D.C., and additional mailing offices. Copyright ©2023 by American Prospect, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this periodical may be reproduced without consent. The American Prospect ® is a registered trademark of American Prospect, Inc. POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to American Prospect, 1225 Eye St. NW, Ste. 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

Every membership level includes the option to receive our print magazine by mail, or a renewal of your current print subscription. Plus, you’ll have your choice of newsletters, discounts on Prospect merchandise, access to Prospect events, and much more. Find

You may log in to your account to renew, or for a change of address, to give a gift or purchase back issues, or to manage your payments. You will need your account number and zip-code from the label:

To renew your subscription by mail, please send your mailing address along with a check or money order for $60 (U.S. only) or $72 (Canada and other international) to: The American Prospect 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005 info@prospect.org | 1-202-776-0730 ext 4000

are sour, with President Xi Jinping escalating military threats against Taiwan, walling off basic economic data on the Chinese economy, and doubling down on predatory development strategies. China views U.S. export controls as a deliberate scheme to maintain U.S. “technological hegemony.”

The Xi-Biden summit in Bali last November was quickly overtaken by the spy balloon fiasco, which led to a cancellation of a longplanned fence-mending visit by Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

Innumerable commentators have called for a reset, to break the cycle of escalation and counter-escalation, reduce military tensions, and achieve an economic truce. As Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen put it in a somewhat wishful speech April 20, “We believe that the world is big enough for both of us.” That, of course, is axiomatic. The difficult question is who defines the terms.

A reset is the plea of the U.S. business and financial elite that profits from trading with China, outsourcing production to China, and investing in China. That sanguine view is shared by free-market economists who are appalled by the Biden administration’s turn to industrial policy, yet think that China’s state-led capitalism is somehow consistent with free trade.

But given the fundamental differences in national interests and strategies, is a symmetrical reset even possible? Under Xi’s increasingly authoritarian regime, China’s determination to displace the U.S. has only intensified. Would gestures to reduce conflict and seek a peaceful economic coexistence be reciprocated—or just treated as a sign of weakness?

While Biden is going full speed ahead with

domestic industrial policy, the U.S. has already pulled back on policies to contain China. In many ways, the get-tough approach to China’s predatory mercantilism peaked last year.

Two emblematic cases are China’s access to U.S. capital markets, and the long-pending revision of strategic export controls. In 2020, Congress passed by voice vote the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act. The law required Chinese companies to comply with SEC disclosure and audit requirements, or they would be delisted from U.S. exchanges. The bipartisan lead sponsors included Republican John Kennedy of Louisiana in the Senate and Democrat Brad Sherman of California in the House.

Biden’s SEC , under Gary Gensler, was strongly supportive. In 2021, Gensler went after shell companies of China-based corporations, incorporated in offshore regulatory havens such as the Cayman Islands. Their affiliates are listed on U.S. stock exchanges with little if any accurate financial information.

Gensler directed SEC staff to “take a pause” from listing Chinese shell companies and warned investors about the risks. “I’ve asked the SEC staff to ensure that the companies provide full and fair disclosure that what [shareholders are] investing in is actually a shell company in the Caymans,” Gensler said in a video posted at the SEC YouTube channel.

In August 2022, the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, a self-governing nonprofit created by Congress to oversee accounting standards, made a deal with Chinese financial authorities that gives PCAOB access to the audits of Chinese companies performed by Chinese accounting

firms. In return, a China-based company can use a Chinese accountant to satisfy the requirements of U.S. law. In December 2022, based on field work in China and Hong Kong reviewing audits by two large accounting firms, the PCAOB retracted its earlier finding that Chinese authorities were blocking audits. This then freed Chinese companies to list on U.S. stock exchanges.

Gensler noted that PCAOB inspectors had found “numerous deficiencies at audit firms in China and Hong Kong,” and warned that if the Chinese do not deliver full access, the SEC would prohibit trading in these companies’ securities. But as Gensler also pointed out, the law gives China three years (recently reduced to two) to comply before sanctions can be imposed.

In February 2023, the Chinese government began a pressure campaign on Chinese companies to drop Western auditors in favor of Chinese accounting firms that are themselves subject to pressure from the Chinese regime. The PCAOB acknowledges that its review of audits has found multiple and serious deficiencies. It does have the power to bring enforcement actions against auditors, including fines, publicizing the deficiencies, and even barring auditors from practice. But no matter how many deficiencies it finds, the ultimate sanction—delisting from U.S. exchanges—cannot take effect for two more years.

A few Chinese companies have preemptively delisted from U.S. stock exchanges and relisted in Hong Kong or Shanghai, where they can still get U.S. capital investment. But according to the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, as of January 2023 there were 252 Chinese companies listed on U.S. exchanges, with a total market capitalization of $1.03 trillion, up from a market value of $775.6 billion in the third quarter of 2022.

In addition, there is nothing in the law to prevent U.S. investors from putting money into exchange-traded funds or other mutual funds that invest in China. These are huge moneymakers for U.S. financial companies, which in turn lobby for little or no limits on U.S. capital flows to China. So, despite the burst of hawkishness on capital flows late in the Trump administration and early in Biden’s, China’s state-led capitalism can get all the U.S. capital it wants.

The Biden administration also seems to be tempering a more confrontational stance in

its long-awaited revised executive order on strategic export controls. In October 2022, the administration stunned Beijing with a dramatic increase in prohibited exports. These rules ban the export of advanced semiconductors, software for chip design, as well as chip manufacturing equipment. They also apply to any foreign-owned company that relies on U.S. technology.

The White House reportedly plans revisions of the export control order, to further restrict China’s access to advanced technology, AI, and quantum computing. But the order has been delayed for several months.

Advocates of a tougher policy have called for a “reverse CFIUS.” The existing Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, based in the Treasury Department, screens proposed foreign investments in U.S. companies or technologies, and vetoes investments or corporate takeovers deemed inconsistent with the national security. A reverse CFIUS would screen proposed outgoing investments in China by American individuals and firms, and veto ones that could help either the Chinese military or its acquisition of advanced technology. But my sources tell me that the pending order will stop far short of comprehensive screening.

In the meantime, China keeps finding ways to circumvent existing export controls. The Financial Times reported that Chinese AI surveillance groups targeted by U.S. sanctions have obtained restricted technology by using cloud providers and rental arrangements with third parties, as well as purchasing chips through subsidiary companies in China. iFLYTEK , a U.S.-blacklisted, state-backed voice recognition company, has been renting access to Nvidia’s A100 chips, which are subject to sanctions.

In the view of the China hawks, we need the opposite sort of reset, with much more aggressive limits on U.S. investment in China and more stringent export controls. The hawks include many in Congress, most commissioners of the U.S.-China Commission, scholars such as Clyde Prestowitz and James Mann (who also serves as a commissioner), and critics such as Michael Stumo of the bipartisan Coalition for a Prosperous America. “The only thing that slows China down is concrete leverage and obstacles,” says Prestowitz. “We have all the leverage, access to our export market and financial markets,” adds Stumo. “Their domestic consumption is too weak and their export

surplus keeps rising. We are the biggest absorber of all that surplus.”

On May 3, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer proposed an omnibus China bill that toughens both export and capital controls and creates a U.S.-led rival to the Belt and Road project, whereby China partners on infrastructure projects in emerging markets around the world. The bill, which restores some measures that were dumped from what became the CHIPS and Science Act, has the support of key Democratic committee chairs. This would represent a substantial decoupling of the sort that Secretary Yellen explicitly disavowed.

A broad analogy is the containment policy that defined U.S. strategy toward Soviet Rus-

in early May. “Our view is that we need to play in that market.”

Prestowitz has called this outrageous. “Having just been gifted $50 billion or more by the U.S. government to help them stay technologically ahead of China,” he writes, “are these rich darlings of Silicon Valley truly saying they won’t cooperate with U.S. government China policy?”

In fairness to Biden, he has resisted pressure to cut tariffs on Chinese exports first imposed by Donald Trump. He has appointed several people who understand how China plays the game, most notably U.S. trade representative Katherine Tai and China expert Rush Doshi.

Biden also needs to keep China from giving any more support to Putin’s war on Ukraine. Biden is further hobbled by the lack of support of U.S. allies in Europe. French President Macron and German Chancellor Scholz have sought to increase their countries’ economic ties with China, and Macron has spoken of a China policy independent of the United States.

sia during the Cold War. But China is a much tougher adversary than the USSR ever was. The Soviet Union suffered from deep internal rot. Its system was an economic failure. China’s is mostly an economic success. And while Soviet Russia had an extensive spy network, China has a much more potent Trojan horse: U.S. business. Domestically speaking, the China lobby is corporate America.

The U.S. solar industry, which depends on Chinese components, functions as part of that lobby. Last June, the Solar Energy Industries Association succeeded in getting the White House to block a Commerce Department investigation of illegal transshipments of Chinese solar products.

The U.S. semiconductor industry is lobbying against any restrictions on its ability to do business in or with China. “It’s our biggest market and we’re not the only industry that lays claim to that,” John Neuffer, president and chief executive officer of the Semiconductor Industry Association, said

Even as national-security adviser Jake Sullivan has embraced a salutary economic nationalism, the China hawks are less influential inside the administration. John Kerry, Biden’s special climate ambassador and a leading advocate of rapprochement with China, reports directly to Biden, going around Secretary of State Blinken. Tai is an outlier among senior Biden officials. Doshi, author of the pathbreaking book The Long Game: China’s Grand Strategy to Displace American Order, has the title of Director for China of the National Security Council. But it’s not clear how much influence he has on policymaking.

If his colleagues have read Doshi’s book, they would know that the Chinese Communist Party is unlikely to change its goals or tactics. The Biden administration has been pursuing modest confidence-building measures, such as ending restrictions on flights to and from China. But there is no sign that China is reciprocating.

“I’m skeptical of the possibility of a fundamental reset,” says James Mann. “The strategic differences are too great, unless the reset would be overwhelmingly on China’s terms.” Unless Biden stops splitting the difference, U.S. policy could be just strong enough to annoy the Chinese leadership and lead to more political and military countermoves, but not strong enough to make much difference in China’s geopolitical behavior or its economic grand strategy.

TAP and FreeWill make DAF giving easy

Donor Advised Funds are an increasingly popular way that readers like you are supporting The American Prospect — and there’s a good reason! DAFs offer immediate tax benefits from charitable contributions you then pass along at opportune moments later on.

Today is an opportune moment!

When you recommend a grant from your DAF to the Prospect, your donation goes directly to our editorial mission. We really can’t do it without you.

This secure online tool from our partner, FreeWill, lets you accomplish your contribution in as little as ten minutes. Try it now!

FreeWill.com/daf/tap

Your support will sustain us long into the future!

“We saw a lot of human desperation and hardship,” Maureen Meyer, vice president for programs of the Washington Office on Latin America, a research and advocacy organization, told me over the phone. Meyer had arrived back in the United States after a trip to Honduras just days before. She described encountering 1,300 migrants at a camp who were awaiting proper documentation from the Honduran government, namely an “exit visa” that would allow them

to legally leave the country and continue their journey northward.

To even reach Honduras, a migrant must first cross the Darién Gap, one of the most dangerous migration routes on the planet. It’s a roadless 60-mile-long jungle that connects South America to Central America— Colombia to Panama. Migrants can either pay syndicate networks that offer a loosely guided passage through the dangerous, bandit-infested jungle, or they can pay to be smuggled via boat, which is somewhat safer, but also much more expensive and

has a higher chance of being detected by law enforcement. After the Darién Gap, they must move through Costa Rica and Nicaragua before entering Honduras.

Across presidencies, despite tweaks in immigration policy, the general thrust of U.S. immigration priorities has been to opt for punitive deterrence measures. President Biden has been no exception in this matter. Looking weak on the border is seen as an electoral liability. In Biden’s case, three decades of incongruous policy have come to roost as migration patterns continue unabated.

It isn’t working.A smuggler ferries migrants across the Rio Grande.

According to Meyer, Honduras is a relative reprieve from the rest of the journey. “They’ve been through hell. You talk to enough [migrants] and they would say I would never do that again.” And that’s not just in reference to the violence and dangerous conditions of the migration. Meyer added that many migrants described a persistent dehumanization and exploitation. “They feel taken advantage of and mistreated by authorities throughout the region. Everything has a price. Everybody charges. And it’s extra because they’re migrants,” referring to the stream of payments for passage.

“What awaits them in Guatemala and Mexico can be just as bad if not worse,” Meyer said. “Mexico is a lot of abuse at the hands of corrupt Mexican agents and criminal groups that kidnap or rape.”

That’s not including instances like the fire at a migrant center in late March, just across the border from El Paso in Juarez, which left 40 dead. Mexican authorities said that among the dead and injured were migrants from Guatemala, Honduras, Venezuela, El Salvador, Colombia, and Ecuador. VICE reported that, according to survivors of the fire and security guards at the facility, the migrant center operated more as an extortion center where only migrants who could pay at least $200 were released.

Presumably, many of the migrants at the Juarez facility intended to eventually enter the U.S., further emphasizing how the Juarez center is a micro-example of the kinds of black markets entirely sustained by human desperation and suffering—a downstream effect of the Biden administration’s preference for deterrence as a strategy over easing restriction.

The Biden administration’s posture toward the border and enforcement activities has been based upon an “addressing the root causes of migration in Central America” approach, to quote a July 2021 report whose foreword was written by Vice President Harris just after the White House announced that Harris was in charge of spearheading a private economic development effort throughout the Northern Triangle. The idea is that because so many migrants move because of terrible problems in their home countries, American policy should try to fix those problems.

The idea isn’t wrong. When migrant justice advocates talk about root causes, Khury Petersen-Smith, a researcher from the Institute for Policy Studies, told me, “we’re talking

about economic policies that have devastated economies such that people can’t make a living in [their native countries].” But concrete effects have been scarce. Other advocates who spoke to the Prospect characterized administration language and policy as sounding nice, but in practice amounting to very little.

Perhaps the most glaring embarrassment for the U.S. has been that Central America’s “success story” is El Salvador’s immensely popular president Nayib Bukele. Under Bukele, his autocratic government has exterminated gang life from the former homicide capital of the world. Outside Western groups have criticized Bukele’s action against gangs as coming at the cost of unlawful killings, disappearances, arbitrary arrests, detention, and more. Even as that may be true, Bukele still touts an approval rating between 60 and 90 percent, depending on the polling you look at.

Meanwhile, by allowing El Salvador to accept Bitcoin as legal tender, Bukele has hitched his economy to the volatile cryptocurrency, and the results have been tumultuous. Bitcoin is trading at less than half the value it had in 2021 when Bukele made it a legal currency, and Salvadorans who rely on it for payments could end up losing a fortune. Bukele has earned positive notices for authoritarian crackdowns, but with economics often being the biggest driver of Central American migration, he has not addressed the root causes and maybe even exacerbated them.

The story is somewhat different in Mexico. When it and the U.S. signed free-trade deals in the 1990s, economists promised rapid growth would follow. One mining magnate even promised it would save Mexican politics, in a New York Times op-ed from 2000: “Because of NAFTA , Mexico can now afford the luxury of democracy.”

For a period, those new jobs in Mexico offered new opportunities, Princeton University professor Filiz Garip told me. But since these new jobs were concentrated along border towns, it meant that people had to move from rural areas to cities where these jobs were located. “This was a lot of assembly work,” Garip said. “After one year, [the new workers] would be totally exhausted and replaced by a new group of people … then they would be in the border region where they couldn’t find any other work and then they had to migrate.”

A 2003 Times article on NAFTA’s impact in Mexico alludes to these economic distortions

and worker burnout: “Real wages in Mexico are lower now than they were when the agreement was adopted despite higher productivity, income inequality is greater there and immigration has continued to soar.” As a result, thousands of Mexicans continued to cross the border into the U.S. during these years.

Garip noted that the degradation of economic opportunities came as the United States militarized its border. Taken together, those factors created a dynamic that undermined efforts to tighten the border, becoming a flashpoint for the sorts of immigration policy battles seen today. “Employers still needed the same workers, their [labor] demands did not diminish, and they knew they could hire [migrants],” she said. Without a legal framework for managing labor mobility between countries, Garip said, the result was unpredictability.

“You know that you can go back [to your native country],” Garip said, referring to migrants on temporary visas. But when those avenues are restricted, and migrants thus cross illegally, the calculation changes. With steep penalties for attempting to cross back to one’s home country, it makes more sense from a migrant’s perspective to stay in the U.S., even if it’s unlawful.

Today, economic conditions in Mexico itself have improved somewhat, despite an ongoing crime crisis. This generation of migrants from Latin America are coming from Honduras, Guatemala, or even Venezuela. And they are not fleeing their countries for the exact reasons as the wave of Mexican migrants from the immediate post-NAFTA years, though the broad strokes are similar. However, they are hitting the same administrative hurdles in the U.S. immigration system that were set up in the early 21st century.

On May 11, the administration phased out its use of Title 42. Technically, Title 42 comes from the 1944 Public Health Service Act. In theory, the law is intended to allow

Advocates characterized administration language and policy in the Northern Triangle as sounding nice, but in practice amounting to very little.

federal agencies to control the spread of disease. It was the basis for the Centers for Disease Control’s authority throughout the worst bouts of the pandemic. Applied to immigration, Title 42 became an easy tool for border control, allowing federal officials to expel migrants from the United States without a formal asylum process.

Anticipating chaos after the end of Title 42, the Biden administration announced that it would be sending 1,500 active-duty troops from the Army and Marine Corps to the U.S.-Mexico border. According to an internal Department of Homeland Security memo obtained by the Washington Free Beacon, authorities anticipate that up to 15,000 migrants a day will try illegally entering the United States. In a follow-up report from the Free Beacon, internal communications said that those troops would be assisting with “data entry” and not border enforcement.

In a post–Title 42 world, immigration

officials will revert to using Title 8, the immigration laws in place before the pandemic—but this is cold comfort. Under Title 8, for example, being caught for unauthorized immigration results in removal for 5 to 20 years, depending on how many times a migrant has attempted to enter the country. The idea is that steep penalties will incentivize migrants to apply for asylum before arriving at the border.

But it hasn’t worked. The United States’ refusal to process asylum claims has backlogged the Mexican government’s asylum system, a result of the continued “Remain in Mexico” policy first put forward under former President Trump. Though Biden has tried to end the program, a U.S. judge paused Biden’s move, and so the system remains clogged. As I reported earlier this year, the U.S. had 1.6 million pending asylum hearings.

The end of Title 42 is expected to create

additional dysfunction. In early May, in El Paso, Texas, the city’s mayor announced it would be entering a state of emergency ahead of the end of Title 42, in addition to opening up two temporary shelters.

Any plan for dealing with immigration policy is likely to stoke outrage from all sides. On the one hand, Republican attorneys general across the country have asked Biden and Secretary of State Antony Blinken to designate Mexican drug cartels as “foreign terrorist organizations” (FTOs). That pressure increased as Rep. Chip Roy (R-TX) reintroduced legislation with the same effect.

Rebekah Wolf from the American Immigration Council said in an interview that this was merely a symbolic gesture, but it seems to have had an effect. When Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) recently asked U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland if he would object to Congress designating cartels as FTO s, Garland responded: “I wouldn’t be opposed.” If cartels were designated as FTOs, Wolf said, it would further complicate the ability for migrants to claim asylum, because it’s nearly impossible for a migrant to make it to the southern border without paying cartels and other crime syndicates for passage.

On the other hand, harsh Trump-style immigration policy infuriates immigrant rights activists who feel betrayed by Biden’s moves.

Meyer summarized the Biden administration’s predicament like this: On the one hand, it is increasing access to legal pathways for migrants from Venezuela, Cuba, Honduras, and Nicaragua, so long as they can provide valid passports and they have sponsors in the U.S. That’s a legal pathway for entry into the U.S. for up to 360,000 people a year. In addition, the administration plans to boost resources for migrant processing centers, thereby setting migrants on a path to filing family-based petitions for refugee status.

On paper, those changes should increase legal pathways. But in practice, Meyer said that based upon migrants she and her colleagues encountered in Honduras, they don’t have the documents or meet eligibility requirements, yet still plan on making the journey northward. Desperate people are like that. She recalled frequently being asked by migrants questions such as “What should I do?” or “What are my options?” The most likely scenario is migrants stuck in Mexican border towns hoping for a change in U.S. policy that may never even come. n

Back in March, the Patent Office of India denied an application from Janssen Pharmaceuticals (a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson) to extend to 2027 its patent on its drug bedaquiline, which is the best lastditch treatment for drug-resistant tuberculosis. The decision came thanks to the work of two activists, Nandita Venkatesan from India and Phumeza Tisle from South Africa, who filed a petition with the office with the backing of Médecins Sans Frontières and other nonprofits.

From the perspective of the Indian government, this decision was a no-brainer. Not only was the patent extension an obvious attempt by J&J to secure a few more years of monopoly profits due to tiny, inconsequential changes they’d made to the drug, but India has the worst tuberculosis burden in the world. Some 40 percent of its population is TB-positive, and it has the largest population of drug-resistant TB cases of any country—a problem that got much worse during the COVID -19 pandemic, which badly disrupted efforts to test and treat new infections. Refusing the patent extension is estimated to cut the cost of bedaquiline treatment in India from $46 per month to $8—a huge benefit for a country that is still quite poor.

The United States doesn’t have anything like such a problem with tuberculosis. But we have a much worse infestation of patent abuse from pharmaceutical companies. Instead of swatting down companies like Johnson & Johnson, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has more often than not bent over backwards to enable maximum corporate profit extraction.

One legal strategy Big Pharma uses is filing dozens or even hundreds of patents on the same drug. An Initiative for Medicines, Access, and Knowledge (I-MAK) report from September last year investigated these “patent thickets” on America’s ten best-selling drugs, and the revelations were staggering. The companies have obtained an average of 74 patents apiece on each of those drugs. More tellingly still, of the 140 patent applications on these drugs (on average), twothirds of them happened after the drug was approved by the FDA

The point is to create a huge legal deterrent to any generic or biosimilar competitors who might attempt to enter the market when the original patent expires. Even when a competitor might have a legal right to produce the original formulation of a drug, cutting through the patent thicket would require millions of dollars in litigation and take years.

For example, AbbVie managed to extend patent protection on its arthritis drug Humira for an additional seven years. It filed 312 patents on the drug, 94 percent of which after it had already received FDA approval, and secured 166 of those patents. Its original patent expired in 2016, but the rest of the patents extended its complete control of the medication through the first quarter of 2023. As a result, Humira was the top-selling drug in the U.S. market in 2021, with $17.3 billion in sales—almost twice as much as secondplace Revlimid (a cancer drug). Of all the money AbbVie has made on Humira, about two-thirds (or nearly $100 billion) came after its primary patent expired.

For some, that counts as a smashing success. President Trump’s choice to head the USPTO, Andrei Iancu, was a partner at IP law firm Irell & Manella both before and

after running the agency. In a recent op-ed for Bloomberg Law, he argued that AbbVie’s use of patents “should be celebrated.”

Another strategy is to “make slight modifications to the drug,” Robin Feldman, a professor at UC College of the Law, San Francisco, who studies patent abuses, told the Prospect in an interview. By making small changes to dosages, formulation, method of administration, and so forth, drug companies can then apply for a new patent or a patent extension and extend their monopoly. According to her research, “more than 78 percent of new patents are not new drugs,” she said. One common tactic is to strategically produce an extendedrelease form of the drug right before the original patent is about to expire, because the companies can then receive an additional three-year exclusivity right under “new clinical investigation” rules.

A lot of these patents are probably bunk even by the lax standards of U.S. law. On the rare occasion when generics manufacturers have taken Big Pharma to court to contest patent validity, they have won about three-quarters of the time, Feldman said. But again, that costs time and money—something the major drug companies are counting on.

Yet another strategy is to obtain nonpatent exclusivities. The government grants companies that do certain kinds of research, like treatments for pediatric or tropical diseases, or develop “orphan” drugs to treat rare conditions, additional time-limited rights, like keeping their data private or a monopoly on marketing. (Congress wanted more attention paid to these particular disease areas, but it may have succeeded too well, as companies have piled on resources to develop treatments for relatively uncommon conditions that are often not very effective.)

Finally, there is the “pay for delay” tactic. When patents or other legal protections are about to expire, drug companies commonly take their enormous profits and offer generics manufacturers hefty bribes to stay out of the market, thus preventing competition. The Federal Trade Commission, which has filed some lawsuits against this practice, estimates that this tactic alone costs the country $3.5 billion in higher drug costs every year.

As usual in health care matters, the U.S. is a huge outlier on drug patents compared to peer nations. Returning to Humira, AbbVie obtained 6.4 times more Ameri -

Drug patents are supposed to expire in 20 years. Thanks to legal trickery, though, it usually takes a lot longer than that.

can patents than it did in the European Union, and its patents ran out in October 2018 on the continent. Another more than four years of patent protection in the U.S. market secured an additional $68 billion in monopoly profits.

All this outrageous price-gouging is a major reason why American health care is so expensive. A 2018 study found that drug spending makes up about 15 percent of U.S. health care spending—the highest fraction of any rich country and much higher in absolute terms because our health care is so expensive. In dollar terms, we spend about half again as

much as Switzerland per person, more than twice as much as France, and more than three times as much as the Netherlands. That is largely due to hyper-expensive patented drugs. Just 8 percent of American prescriptions are for brand-name drugs, but thanks to extreme prices—Gilead originally priced its hepatitis C cure at $84,000, though it was later reduced somewhat—they make up 84 percent of total drug spending.

Finally, the broken patent system also provides a toxic incentive for pharmaceutical companies. The ability to extract year after year of hyper-profits from a handful of blockbuster drugs pushes companies to spend heavily on drug modification and lawyers who’ll protect their patent monopoly instead of investing in genuinely new drug research. In 2021, Keytruda alone made up 48 percent of Merck’s profits; Eylea 48 percent of Regeneron/Bayer’s; and Humira 40 percent of AbbVie’s. Feldman’s research found that once a drug company starts down the patent abuse road, it tends to rely on it more and more as time passes.

In the longer term, however, going down

this road might prove to be a risky strategy. Even in the U.S., patents run out eventually, and drug development is expensive, slow, and prone to failure. Relying on one drug for such a huge share of revenue could easily leave such companies twisting in the wind—particularly if Congress were to pass intellectual-property reform.

What should be done about this? Feldman suggests that one simple step would be to clarify the meaning of “non-obviousness” in U.S. patent law. To obtain a patent, one must demonstrate that the invention is something that required skill and effort to produce. There is a lot of legislation in this area, as well as a large body of case law, the details of which are beyond the scope of this article. But clearly it is far too easy to get a drug patent in this country, as shown by how many fewer patents are awarded in the European Union. In the U.S., companies can get patents on stone obvious ideas like “an extended-release formula” that have been well known for decades. The USPTO could also be better funded; its small staff is frequently overwhelmed by drug companies’ blizzard of highly technical filings. The FDA , which has many more medical specialists, might also be assigned to help in this area.

Another more radical idea is a “one and done” patent system. This would outright forbid companies from obtaining more than one patent on the same drug. They would be able to choose between a normal patent, or one of the other exclusivities mentioned above, but not more than one. That would solve the problem at a stroke.

There are at least moderately encouraging signs on the horizon. Both the American Rescue Plan passed back in March 2021 and the Inflation Reduction Act passed last year contain a number of drug price reforms. The former allowed Medicaid to penalize companies that raise their prices above the rate of inflation, prompting Eli Lilly to lower its list price of insulin; the latter allows Medicare to negotiate the price of a limited number of prescription drugs, with new prices starting to take effect in 2026.

Now, these are pretty small-bore and slow reforms. But they are still the biggest defeats Big Pharma has suffered in decades. Drug prices (like the rest of the health care system) are simply so outrageous that even the rickety American government is starting to do something about them. Patent reform is the obvious next step. n

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office has more often than not bent over backwards to enable maximum corporate profit extraction.The pharmaceutical industry routinely avoids U.S. taxes by assigning its drug patents to subsidiaries in low-tax jurisdictions.

A classic premise in American cinema is the buddy comedy, epitomized by films like Tommy Boy or Midnight Run . Two characters who can’t stand each other are thrown together by circumstance, forced to make a screwball pilgrimage across the country to finish a job. Hilarity ensues.

This same storyline infects our politics every five years when the farm bill comes up for reauthorization. Two parties at the brink of civil war are pressured to cooperate in order to deliver for their respective constituents. Congress’s version of this tumultuous road trip runs through both rural and urban America, uniting liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans. But the ultimate winner of this madcap romp is one of the country’s most infamous heels: Big Agriculture.

Despite its title, the farm bill, which is due for reauthorization this September, impacts more than just farmers. Over 80 percent of the allocated funds supports the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

(SNAP), formerly known as food stamps, one of the largest welfare programs and arguably the United States’ closest imitation of a Scandinavian social safety net. The fate of SNAP’s 42 million impoverished recipients is shackled to a baroque patchwork of agriculture subsidies that could rival any late-Soviet central-planning efforts.

The real function of the modern farm bill is to deliver windfalls to industry by subsidizing cheap commodity grains, mostly corn and soybeans used for animal feed, that sell below the cost of production to agribusiness, fast-food chains, and global exports. Oil and gas companies are also major beneficiaries of subsidized corn production, used in ethanol and biofuel. And the structure of the subsidies tilts the playing field in favor of the biggest factory farms and middlemen monopolists.

Low commodity prices drive down incomes for family farmers who actually put in the labor to produce the nation’s food. The government steps in to keep farmers on

just enough life support so that they can continue serving their overlords in agribusiness. Subsidy payments are primarily available for grain commodities like corn, soybeans, and wheat, which drives farmers toward a monocrop culture. Those who raise animals for meat products, though, don’t get covered by the payments, and instead are left to fend for themselves against dominant middlemen.

This economic arrangement, which many of today’s farmers call a new form of serfdom, not only devastates farmers but incentivizes a food system that is causing rising obesity rates, limited access to fresh foods in inner-city areas, and nearly one-third of greenhouse gas emissions globally.

“There’s just no intention or goal anymore … we essentially do ag policy like it’s one large casino run by agribusiness, giving farmers just enough chips so they can play and keep betting but never win,” said Ferd Hoefner, a policy consultant who’s worked and advised lawmakers on farm bills since the 1970s.

Liberal Democrats may be hesitant about

Every five years, the farm bill brings together Democrats and Republicans who are normally at each other’s throats. The result is the continued corporatization of agriculture.

lavishing subsidies on powerful corporations, but their main priority is to make sure poor people can afford food. Conservative Republicans have often fulminated against so-called welfare queens, but they want to keep farm interests happy. And so a corrupt bargain is struck every half-decade, where neither side does much to really challenge the other’s prized possession. The bundling of rural and urban interests ensures the farm bill’s passage, but it comes at a steep cost: a status quo bill full of endless logrolling and backroom deals, which stacks the deck against family farmers.

This leaves only a narrow window for progress. A reform movement, composed of independent farmers and ranchers, environmental advocates, and anti-monopolists from both parties, may be more organized than it’s been since the 1980s farm crisis. But it will square up against the might of Big Ag, which spends more on lobbying in Washington than the defense industry. Ag lobbyists are so enmeshed in congressional dealings that in 2014 one of the largest trade groups, the North American Meat Association, held a barbecue with House Agriculture Committee lawmakers inside the very hearing room where the lobbyists’ clients testified the next day.

“David and Goliath might not fully capture what we’re up against,” said Rhonda Perry, the executive director at the Missouri Rural Crisis Center and a founder of the historic Campaign for Family Farms and the Environment, who has experienced the coercive industry efforts firsthand.

Farm policy in America has become such an empty ritual that members of Congress have yet to fully reckon with the damage the bill is inflicting on what’s left of farm country, not to mention the public health of the citizenry. Step one in undoing the myopic farm bill consensus lies in telling the story of how a radical New Deal program became an appendage of industrial agriculture.

In rural pockets of the country, the ongoing crisis in farming today has echoes of the poverty during the Great Depression, when agriculture markets collapsed and farmers couldn’t find enough demand for the crops they’d harvested the previous year. On the brink of ruin and without government support, farmers held mass protests that were so widespread that government officials worried it would turn into outright rebellion if action wasn’t taken. (That wouldn’t be

an incident without precedent in American history: President Washington had to send in federal troops to put down the Whiskey Rebellion, whipped up by farmers and distillers in opposition to alcohol taxes.)

Agriculture has always required a greater degree of government involvement because of the unconventional nature of the market, prone to periodic booms and busts, weather disasters, price swings, and fluctuations in supply and demand. Unlike a widget factory, production cannot just be quickly ramped up and down to respond to market conditions, which exposes farmers to volatility. As the Depression raged, policymakers finally recognized this core need for government regulation and oversight.

Soon after FDR took office, Congress passed the first radical intervention into agricultural markets. The 1933 farm bill set up the parity system, guaranteeing farmers a base level of income when market prices dropped below the cost of production. It also set up a supply management system to balance supply and demand for most commodity goods, by establishing governmentheld reserves and paying farmers to keep surplus crops off the market, in the hopes of stabilizing prices.

The drastic measures largely succeeded, boosting farmer net income from $2.285 billion in 1932 to $7.723 billion by 1941. However, farming didn’t fully stabilize until World War II, when exports soared as the U.S. became the food provider for allied nations. This geopolitical chip would define the postwar era of food policy and trade.

Roosevelt also signed the first food stamp program, both to feed the hungry and bump demand for surplus crops in the market. Structured as an emergency program, it eventually phased out, but would re-emerge as a political fight during the 1960s.

Agribusiness and corporate leaders abhorred the parity system from the beginning, decrying it as “socialism.” Government production controls, for example, made it harder for would-be monopolists to dislodge farmers who were granted more personal security, and also limited the amount of fertilizers that farmers needed to purchase from agrochemical corporations. But the continual reauthorization of the farm bill every five years gave corporate forces the ability to refashion it as a vehicle for mass industrial production.

The locus for this revolt was the Committee for Economic Development, a research

organization that became the policy engine for turning the political class against New Deal policies. With ties to the Chamber of Commerce and the American Bankers Association, the CED explicitly advocated for liquidating family farmers from the commercial landscape, to make way for industrialized mega-farms that could produce cheaper goods at scale. They christened their plan “the farm problem,” which they went about executing with such methodical precision that it would put a smile on the face of any dekulakization proponent from across the Iron Curtain.

Just as the Chicago school revolution began dismantling antitrust laws, the CED’s influence also came to a head during the 1970s. Nixon’s secretary of agriculture Earl Butz famously declared that farmers would have to “get big or get out,” urging them to plant “fencerow to fencerow,” a monoculture farming model that favors large single-crop operations over diversified family farms. Monoculture farming entails far greater use of nitrogen fertilizer to boost yields and counteract rapid soil erosion—a major cause of greenhouse gas emissions by releasing carbon from the soil.

The “get big or get out” era became the defining doctrine of U.S. ag policy for decades to come. Agribusiness succeeded at using farm bills to chip away at the supply management system. The parity payments were stripped of any requirements for conservation land set-asides, acreage restrictions, or other production controls. Payments to farmers were triggered by target prices when the market price for select commodity crops dropped below a certain level set by Congress.

This set up a vicious boom-and-bust cycle. Overproduction led to lower commodity prices and farm incomes, which in turn required greater taxpayer assistance to make up the difference. Between 1950 and

The bundling of rural and urban interests ensures the farm bill’s passage, but it stacks the deck against family farmers.

1990, over two million farmers were pushed out of the industry. But the changes lowered costs for agribusiness, and allowed them to dominate.

In the 1980s, farm markets crashed under the weight of this burden, a Soviet grain embargo, and the interest rate spike engineered by Federal Reserve chair Paul Volcker to fight inflation. Farm debt exploded, and income dropped from $92.1 billion in 1973 to just $8.2 billion a decade later. Exits, bankruptcies, and foreclosures spiked, which culminated in a greater consolidation of land by corporations and financiers.

Amid relative neglect from President Reagan, a reform effort known as Farm Aid (marked by a concert featuring Willie Nelson, Kris Kristofferson, and Neil Young) sprung up during the 1985 farm bill, not only to raise money for family farms but to try to reverse course on the corporate takeover of farming. It succeeded in pressuring Congress to pass several conservation programs, but was largely unsuccessful in reviving a new supply management system, as it had hoped.

The 1996 farm bill, signed by President Bill Clinton, completed the full deregulation of the agricultural system that farmers face

today. The Freedom to Farm Act (known as “Freedom to Fail” by farmers) entirely dismantled the remaining price parity and supply management controls, promising that the magic of the free market would fix farming. Prices crashed by as much as 32 percent in the next two years as overproduction surged, and the government had to intervene to institute direct payments just to keep farmers afloat.

“The Freedom to Farm Act was a massive giveaway to the rising giants in agriculture we know today,” said Patty Lovera, the policy director for the Organic Farmers Association and a longtime advocate for family farmers.

By revoking supply management, government subsidies to farmers have grown exponentially. A University of Tennessee/National Farmers Union study found that supply management would have saved taxpayers $96 billion between 1998 and 2010, while keeping food prices more stable for consumers.

While farmers struggled, Freedom to Farm delivered the greatest gift the rising meatpacker monopolists could have asked for. It dropped the cost of animal feed below the cost of production, allowing Tyson, for example, to scale up its operations and cap -

ture a dominant position in chicken processing. The company saved nearly $300 million per year on chicken feed in the decade after the 1996 farm bill. These savings were not passed on to consumers as promised, with meat processors—who also owned many of the mega-farms—cross-subsidizing their own operations.

The 1990s saw another transformation. Trade agreements like NAFTA and the WTO required that member nations not directly subsidize their own national producers’ goods to artificially lower prices and prevent global competition. This posed a challenge to congressional farm supports, but their work-around ultimately delivered another boon to Big Ag. The U.S. decoupled farmer payments from production to avoid WTO penalties, and shifted its model to base acreage. It wasn’t about how many bushels of corn a farmer produced, but instead how large the farming operation was. This further incentivized factory farming operations and the buy-up of land to qualify for larger subsidies.

Base acreage still defines farm bill subsidies, even after the 2014 bill ended direct payments and shifted the entire structure to a crop insurance model. Now, the government

pays for private insurance premiums on up to 85 percent of a farm’s acreage, costing billions of dollars. Only the major commodity crops—mainly corn, wheat, and soybeans— can access these funds, and not so-called specialty crops like fruits and vegetables.

The shift in farm bill policy set the stage for the monopolization of agriculture. Decades of lax antitrust enforcement led to a merger boom and an industry rollup, which has turned the market from an open to a closed one, dominated by powerful middlemen on both the buyer and supplier side. Farm bill policy also played a role by rewarding larger operations and subsidizing cheap commodity grains, which are as vital to industrial agriculture as semiconductor chips are to the tech economy. As monopolies grew in size, they wielded their market power and lobbying dollars to turn the farm bill into a corporate handout.

At harvest time, most grain farmers today are forced to sell to just four processing firms that make up 90 percent of grain trading. Much of that grain ends up as feed

for livestock. Hog, chicken, and beef farmers are either under contract by just four meatpackers—Cargill, Tyson Foods, JBS SA, and National Beef Packing—or independently forced to sell to them as the only buyers. Recent mergers between Dow and DuPont, as well as Bayer and Monsanto, have narrowed the Big Six seed and agrochemical manufacturers to just four. The top four producers of nitrogen fertilizer rake in two-thirds of all sales.

This cabal of Big Ag monopolies squeezes farmers for all they’re worth, controlling every aspect of production, shortchanging them on the fruits of their labor and ratcheting up costs for necessary inputs like equipment, seeds, and fertilizers. Farmers pay three times higher on inputs today than in the 1990s.

Small- and even medium-sized farming has become a losing enterprise. Incomes continue to plummet, forcing many to supplement annual crop sales with off-farm work just to make ends meet. For most of the past decade, the majority of farm households in the U.S. have lost more money than they made from farming. Debt, bankruptcies,

and even suicide rates are rising, and regional rural economies that depend on agriculture to support grocery stores, schools, and hospitals are verging on collapse.

These financial conditions push farmers to exit the business entirely. More often than not, their land gets flipped into concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), which pack thousands of animals into cramped facilities to produce at the scale demanded by the meatpackers. While CAFOs are convenient for Big Ag, they’re detrimental to animal health and lead to environmental damages from the feces pooling into toxic manure lagoons.

“Both by design and corporate hijacking, government policies have turned our farmlands into a paradise for big business and a wasteland for the rest of us,” said Rebecca Wolf, a policy analyst at Food and Water Watch.

Democrats and Republicans, with rare exceptions, have gone along with the corporate annexation of the farm bill because of an agreement brokered in the 1960s. The deal broadened the stakeholders for the bill

and increased the degree of difficulty for anyone wanting to break the special-interest obstacles to a more fair and humane farm policy.

While the highest-profile conflicts over the bill today fall along partisan lines, feuds between regional coalitions historically played a greater role. In the 1960s, Midwestern corn, wheat, and soybean interests clashed with the South’s coalition for cotton, a domestic good waning in power due to global competition. Southern Democrats controlled the Agriculture Committee in both the House and Senate, and dutifully doled out subsidies to fit their own agricultural needs.

In 1964, farm bill negotiations reached an impasse, with the cotton coalition unable to find enough partners for passage. Desperate Southern Democrats turned to the urban legislators who caucused with them. Since the expiration of FDR’s emergency food benefits in the 1940s, advocates for low-income communities and their representatives in the inner cities had fought to restore the food stamp program. Southern Democrats, who opposed handouts to the racially coded underclass in the cities, blocked them time and again. It was a familiar dynamic dating back to the original farm bill, when segregationist Democrats ensured that Black sharecroppers wouldn’t be able to receive parity payments, despite bearing the brunt of the acreage restrictions imposed on farmers to slash production.

Food stamp legislation all but certainly had enough support to pass on a floor vote if the Ag Committee would have allowed it; President Johnson was even able to get a pilot “surplus commodities” program instituted administratively in 1962. Finally, to save the farm bill, the Southerners struck an agreement to build on the surplus commodities demonstration and include food stamps in the package. This arrangement

was permanently enshrined in the 1977 farm bill.

“That historical contingency forever changed the politics of the farm and thus the direction of our country’s ag policy,” said Jonathan Coppess, the author of The Fault Lines of Farm Policy and the former administrator of the Farm Service Agency at the Department of Agriculture under President Barack Obama.

Republicans dominate rural America today, and Democrats the urban core. This polarization set up a recurrent political dynamic, which began after Republicans took the House in 1994. Republicans wage war on the poor by threatening cuts to SNAP in order to gain political leverage, even though rural areas are increasingly signing up for SNAP as poverty rises. This allows the GOP to extract as many pounds of flesh as they can for their Big Ag benefactors. In recent years, that’s meant loopholes for a cap on payments that a single farm can receive and also allowing the extended family of farmers to acquire subsidies even if they don’t actually work on the farm.

For their part, Democrats expend their political capital to protect SNAP, and cede most decision-making about agricultural programs to Republicans. To the extent that Democrats push for changes to the agriculture titles, they often broker compromises to expand programs that suit the parochial interests of the states they represent. For example, Michigan Sen. Debbie Stabenow, the current Democratic chair of the Senate Agriculture Committee, championed the Local Agriculture Market Program (LAMP) in the 2018 farm bill, which delivers grants to help farmers markets.

“It’s a lot like a hostage negotiation between both parties to jam their priorities through,” said policy adviser Ferd Hoefner.

By the end of the bipartisan back-scratching, hardly any lawmakers understand the full scope of the bill they’re voting for. Usually checking in at nearly 1,000 pages, the legislative boondoggle is so long and convoluted that you’d have better odds finding lawmakers who’d read the entirety of a Thomas Pynchon novel than the full text.

Most of the programs Republicans fight for in the farm bill would not be able to pass in their current form on a straight floor vote. SNAP, on the other hand, carries much higher popularity among voters in polling. The welfare side of the bill is what makes the package politically possible. But the ag

subsidies are what keeps rural America in a perpetual state of crisis.

The usual buddy comedy that is the farm bill unites liberals and conservatives to protect the basic framework of the program. This year, however, the script may be flipping.

The defining odd couple is shaping up to be Cory Booker, the cheery New Jersey senator prone to impassioned, long-winded speeches about hope and the power of love, and Republican Chuck Grassley, the octogenarian curmudgeon of the Senate better known for his so-bad-they’re-good tweets than his long-held enmity against the meatpackers. Despite their ideological differences, they are working in concert with a chorus of anti-monopoly and conservation advocates in trying to subvert the usual dynamic and redirect the course of U.S. agriculture policy to suit the needs of independent farmers rather than Big Ag.

Though Grassley is a mostly down-theline conservative from Iowa corn country—a major driver of farm bill subsidies—he has been an outspoken adversary to ag consolidation for decades, often diverging from Republican leadership. During his six terms, he consistently championed legislation that would curb the meatpackers’ power to throttle independent cattle ranchers.

This year, he’s pushing for changes alongside Sen. Booker, who is just as quixotically determined to curb concentration in agriculture. Despite being nicknamed the Garden State, New Jersey does not carry a particularly large agricultural economy, representing only 1.3 percent of state GDP. But Booker, as the Senate’s resident vegan, has the perfect credentials to wage a personal crusade against animal cruelty at factory farms.

Dating back to his time as mayor of Newark, Booker has also fought against food deserts, a scourge afflicting urban areas across the country without access to grocery stores carrying fresh foods like fruits and vegetables.

It wasn’t until a meeting Booker took in 2018 with the former Democratic lieutenant governor of Missouri, Joe Maxwell, that he made the connection between limited innercity access to grocery stores and the monopoly crisis that farmers face in the heartland.

“He had a strong foundation of knowledge about concentrated power in retail, so I just had to add some limbs on the tree and get the wind going in another direction to

Democrats expend their political capital to protect SNAP, and cede most decision-making about agricultural programs to Republicans.

show him that the same power is impacting family farmers too,” said Maxwell, a softspoken fourth-generation hog farmer who speaks more with a preacher’s charm than a politician’s salesmanship.

After their meeting, Maxwell invited Booker to visit his home state on a kind of disaster tourism trip through rural America. The two traveled together from the Bootheel and up along the Mississippi River through Southern Illinois. Along the route, they spoke with a broad cross section of independent farmers, from cattle ranchers to medium-sized corn and soybean growers, who bear the scars of decades of failed farm bill policies that greased the skids for corporate concentration.

The trip made a lasting impression on Booker, who returned to Washington and began evangelizing for breaking up Big Ag and other market reforms. Though some suspected that Booker staked out the issue as a 2020 presidential play for the Iowa caucuses, he has continued to champion the cause even after his campaign ended. Many of the competition policy initiatives both Booker and Grassley are aiming to include in this year’s farm bill tie back one way or another to the New Jersey senator’s caravan through Missouri with Maxwell.

Reflecting back on the trip today, Maxwell noted that to any outside observer, it would be a strange sight to behold: a Democratic senator who grew up just outside Newark sitting on hay bales across from farmers who mostly vote Republican, despite feeling that the party’s leadership class sold them out to industry.

At a farm bill conference earlier this year, hosted by Maxwell’s organization Farm Action, Sen. Booker delivered the keynote address, detailing his takeaway from the trip: “I heard wrenching stories from farmers who had deeds on their walls from the Homestead Act but now after generations have to sell the farms … because our food system is broken.”

This year, industry groups are strong-arming legislators to revert back to the direct emergency payment structure phased out in the 2014 farm bill. This would supplement the existing commodity-favored crop insurance model that the government has in place. In addition to crop insurance, commodity farmers also get subsidized coverage, known as Price Loss Coverage, that

pays back for lost revenues in the case of market slumps, which happens frequently. With the help of Republicans, interest groups representing mega-farms are working to get a higher reference point for insurance coverage in order to guarantee larger payouts to farmers.

In addition, the Republican majority in the House will surely push for more strenuous work requirements on the SNAP program, which could leave over 700,000 current recipients ineligible, according to the Food Research and Action Center. The House GOP already included SNAP work requirements in their wish-list bill to extend the debt limit in April.

The cross-partisan pressures that make up the farm bill leave little room for the Grassley-Booker coalition to gain a foothold. For years, the graveyard for amendments has always been the conference committee, after the House and Senate pass their versions and the logrolling takes place behind closed doors to decide what will be included in the final bill. Legislation to curb Big Ag concentration or cap subsidy payments historically gets left on the cutting-room floor.

In 2002, it took near-herculean efforts for Minnesota Sen. Paul Wellstone, one of the last populist Democrats from a rural state at the time, to get a vote on a bill that would have banned meatpackers from owning their own livestock. The bill passed handily on the floor with bipartisan support, but was stripped from the final bill in conference committee.

Another amendment that successfully passed in the 2008 farm bill directed the U.S. Department of Agriculture to update the Packers and Stockyards Act, a major piece of antitrust legislation that grants the USDA authority to prohibit unfair and deceptive practices by meatpackers but has gone unenforced for years. Under massive pressure from Big Ag, USDA Secretary Tom Vilsack dragged his feet on following Congress’s mandate. Then, Republicans passed riders in subsequent bills that neutered the amendment entirely. Vilsack, now agriculture secretary again under President Biden, is still trying to complete Packers and Stockyards rules.

This year’s coalition of family farm advocates and environmentalists aren’t under any illusions about the challenges ahead. But so far, many of their key proposals are picking up traction with

members of both parties, spearheaded by Booker and Grassley.

“Our forces are stronger together when we can get support from across the aisle,” said Adam Zipkin, who serves as counsel to Sen. Booker on food and agriculture policy.

The odd-couple senators are each supporting a collection of complementary competition titles to deconcentrate agriculture and promote an open market for independent farmers to sell into. Both senators are proposing a rule that would force meatpackers to purchase at least 50 percent of their animals in the open spot market instead of through contract, which would give independent ranchers a chance to compete. The measure is also supported by Sen. Jon Tester (D-MT), a self-described “dirt farmer ” and a frequent partner with Booker on the Democratic side. Booker has also called for placing a moratorium on CAFOs

“We [anti-monopolists] used to be greeted on the Hill like we were wearing tinfoil hats for saying we had a consolidation problem, and now everyone is like ‘of course we do,’” said Lovera, who’s worked on farm bills since the early 2000s.

The USDA’s checkoff program is also in the crosshairs of reformers. The program effectively acts as a government-run slush fund, bankrolled by a tax on all farmers, that agribusiness can tap for both industry marketing and lobbying. In essence, small farmers pay for Big Ag to destroy them. Booker introduced a bill earlier this year that would prohibit checkoff dollars going to any lobbying organization. Another primary concern for the farm bill is to reinstate country-of-origin labels, a long-sought priority for independent farmers to distinguish their goods from large meatpackers’ foreign sourcing of products.

In addition to competition policy, there’s a major push this year to make the farm bill resemble something more like a climate bill,

In addition to competition policy, there’s a major push this year to make the farm bill resemble something more like a climate bill.

in order to fulfill President Biden and Secretary Vilsack’s pledges to curb greenhouse gas emissions. Environmental groups and family farm advocates are aligning their priorities to deliver more funding to practices like rotational grazing and crop-covering, rather than using those dollars to retrofit the mega-farms driving the highest emissions.

“In its current form, many conservation programs at the USDA aren’t accessible to small farmers, whose applications get denied at higher rates but could help cover the costs of sustainable farming,” said Antonio Tovar, senior policy associate at the National Family Farm Coalition.

Much of the current funding for climaterelated farm bill policies has turned into a money pit for factory farms. A good example of how this works is the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), one of the largest USDA conservation funds.

A provision in the 2002 farm bill, written by lobbyists, required that over a third of the EQIP funds used in Iowa go to livestock operations, which are dominated by factory farm CAFOs. As the Environmental Working Group has documented, over a third of EQIP

funds, totaling around $62 million, finance animal waste cleanups and containment at corporate farms, like manure lagoons and toxic runoffs. Taxpayer dollars help backstop rather than penalize environmental harms by factory farms, when those funds could instead support family farms using sustainable practices that keep carbon in the soil. Booker and Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT) plan to fight for an amendment in the farm bill that would amend the livestock requirement and direct funding to small farmers.

The Inflation Reduction Act also included a pot of almost $20 billion for climate-smart agriculture at the USDA . It didn’t include an EQIP livestock requirement, which was seen as a victory for progressive advocates. They are now pushing to protect that IRA funding, which faces opposition from Republican lawmakers, in the farm bill.

Along with distributing access to conservation funding, Maxwell’s group Farm Action is leading the charge to restructure the bill’s prioritization of payments to fencerow commodity crop production, which promotes monoculture. The core subsidy payments exclude specialty crops like fruits and vegetables, and also dissuade

diversified crop farming, which is primarily used by small family farms. Diversified farming is shown to be far better for soil health and doesn’t require the same amount of nitrogen fertilizers and other agrochemicals to replenish eroded soil.

Several members of the Congressional Progressive Caucus have spoken favorably about incentivizing specialty crop farming, including Rep. Katie Porter (D-CA), who grew up on a family farm in Iowa.

“The fact that only 4 percent of the subsidies go to fruits and vegetables is not because politicians don’t know that fruits and vegetables are good for you … it’s the corporatization of agriculture,” said Rep. Porter in an interview with the Prospect

Another conversation among lawmakers on the Hill is to cut down on wasteful farm payments. Mega-farms collect the largest subsidies because of the base acreage model instituted after the WTO agreements. However, merely revoking subsidies across the board would harm medium-sized and small farms, which rely on government payments more than ever because agriculture markets are fundamentally broken. A bipartisan bill introduced by Sen. Grassley would shift to a subsidy model that caps payments for wealthy mega-farms, to ensure the bulk of the program goes to farmers who actually need government assistance.

These reform efforts are ambitious. It will likely take more than one farm bill in order to turn around years of failed policies. Joe Maxwell’s Farm Action has laid out a decade-long strategy to accomplish reform goals. It begins with getting lawmakers to understand what exactly the stakes are in the legislation, how it works, and how to fix it. In other words, it begins with breaking the bargain at the heart of the farm bill, which has led to a corporatized, consolidated agriculture policy.

“It’s not just about one farm bill, our coalition’s goal is to shift the entire conversation in Congress for years to come to make the family farm the center of our government’s policies, not industry,” said Maxwell. n

No one in the coastal farming town of Watsonville, California, was much impressed when the cash-strapped owner of their struggling hospital, Quorum Health, announced in June 2019 that it was selling them out to something called Halsen Healthcare.

Halsen was a limited liability vehicle incorporated by a guy named Dan Brothman literally the day before the press release went out. Brothman’s last hospital job had involved orchestrating a diabolical whistleblower retaliation campaign against a doctor who’d written an email to other doctors about the hospital’s precarious finances; it had later emerged in court that the hospital had paid a strip club bouncer to plant a gun in the

doctor’s car and get him arrested in a phony “road rage” incident as a means of “humbling” him. It was hard to believe Brothman was allowed to work in a hospital in California, much less own one.

What worried the nurses most was the financing mechanism by which Brothman was proposing to “buy” the Watsonville Community Hospital. First, Halsen would purchase the hospital for $39 million, or $46 million, or $30 million; the figure fluctuated depending on who was reporting it. Then , Brothman would immediately sell the hospital’s underlying real estate to an Alabama real estate investment trust named Medical Properties Trust (MPT), for $55 million, and lease it back for millions of dollars a year in rent and interest

payments. The hospital had always been profitable, employees say, but not profitable enough to cough up $5 million a year in rent.