Director

Director

Yves Besançon Prats

Comité editorial

Editorial committee

Pablo Altikes

Javiera Benavides

Yves Besançon

Gabriela de la Piedra

Francisca Pulido

Pablo Riquelme

Lucía Ríos

Sebastián Rozas

José Rosas

Alberto Texidó

Edición

Editor

Sofía Arnaboldi

Dirección de arte y diseño

Art direction & graphic design

DRAFT Diseño

Traducción

Translation

WordsforWords

Correción de textos

Proofreading

Roberto Gómez

Representante legal

Legal representative

Mónica Álvarez de Oro

Pablo Jordán F.

Marisol Rojas Sch.

Gerente General

General manager

Lucía Ríos O’Ryan

Jefe de proyecto

Project manager

Valentina Pérez

Coordinación administrativa

Administrative coordination

Marcela Catalán

Presidente AOA

President of AOA

Pablo Jordán Fuchs

Impresión

Printing Ograma Impresores

Juan de Dios Vial Correa 1351, 1˚ piso

Providencia, Santiago, Chile

(+56 2) 2263 4117

www.aoa.cl / revista@aoa.cl

ISBN: 9770718318001

Para la composición de textos de esta publicación se utilizarón fuentes diseñadas por chilenos y comercializadas en Latinotype:

Majora & Majora Stencil

Por: Luis Bandovas

as ciudades son el mejor lugar para vivir”, dice Edward Glaeser en su libro El triunfo de las ciudades. Desde sus comienzos, las ciudades han sido espacios de la civilidad donde socializamos, nos educamos y cultivamos, trabajamos y crecemos como comunidades, familias, profesionales y servidores públicos. A medida que las ciudades crecen, con el paso del tiempo, van dejando atrás sus planes originales, lo cual puede resultar en la pérdida de parte de su esencia y sus raíces históricas si no se realiza una adecuada planificación. Expertos y urbanistas han dedicado rigurosos estudios a la planificación urbana, buscando la recuperación y cambios positivos en pequeños núcleos urbanos o ciudades específicas. Esto se analiza en el reportaje central que destaca a Salamanca, Coyhaique y Antofagasta como ejemplos de estas transformaciones planificadas.

Nuestras ciudades necesitan desafiar los paradigmas que han sido dominantes en la planificación urbana hasta ahora. Es fundamental reconsiderar la relación entre los asentamientos humanos y el entorno natural, así como enfocarse en la planificación de ciudades saludables y abordar las realidades que conduzcan a comunidades urbanas equitativas y justas. Estas parecen ser las claves para lograr una verdadera cohesión social y relaciones humanas respetuosas y éticamente coherentes.

Las necesidades sociales para una vida placentera y digna, así como el cuidado de la salud mental de los habitantes, son aspectos urgentes que deben ser considerados. A través de ejercicios desarrollados por diversas universidades y profesionales de diferentes disciplinas, se ha demostrado que es posible cambiar el rumbo y mejorar significativamente la calidad de vida en barrios, pueblos y ciudades. Esto requiere de voluntad política tanto a nivel local como central, para implementar acciones concretas que impulsen dicho cambio y mejorar sustancialmente la calidad de vida de barrios, pueblos y ciudades.

Otro factor determinante en las nuevas ciudades es lograr espacios públicos más seguros y accesibles para todos, teniendo en cuenta los aspectos necesarios para proporcionar condiciones equitativas para hombres, mujeres y niños. Los arquitectos, como constructores de las ciudades del futuro, también comparten la preocupación por estos procesos de rehabilitación urbana, en los cuales tanto el sector privado como el Estado deben acercarse de manera urgente para enfrentar y resolver este desafío, que no es otro que el rescate de nuestras ciudades. La recuperación y renovación de nuestros barrios, pueblos y centros urbanos dependerá de acciones concretas que promuevan un cambio de paradigma, evitando repetir las mismas prácticas en beneficio de todos y para lograr un hábitat y una calidad de vida mejores.

Yves Besançon Prats / Director

“Cities are the best place to live”, says Edward Glaeser in his book The Triumph of Cities. Since their inception, cities have been civic spaces where we socialize, educate and cultivate, work, and grow as communities, families, professionals, and public servants. As cities grow, over time, they leave behind their original plans, which can result in the partial loss of their essence and historical roots if proper planning is not implemented. Experts and urban planners have dedicated rigorous studies to urban planning, searching for recovery and positive changes in small urban centers or specific cities. This is analyzed in the central report, which highlights Salamanca, Coyhaique, and Antofagasta as examples of these planned transformations.

Our cities need to challenge the paradigms that have been dominant in urban planning until now. It is essential to reconsider the relationship between human settlements and the natural environment, as well as to focus on planning healthy cities and addressing the realities that lead to equitable and just urban communities. This seems to be the key to achieving true social cohesion and respectful and ethically coherent human relationships.

The social needs for a pleasant and dignified life, as well as the inhabitants' mental health care, are urgent

aspects that must be considered. Through exercises developed by various universities and professionals from different disciplines, it has been shown that it is possible to change the course and significantly improve the quality of life in neighborhoods, towns, and cities. This requires political will at both the local and central levels to implement concrete actions to promote this change and substantially improve the quality of life in neighborhoods, towns, and cities.

Another determining factor for new cities is to achieve safer and more accessible public spaces for all, taking into account the necessary aspects to provide equitable conditions for men, women, and children. Architects, as builders of the cities of the future, also share the concern for these urban rehabilitation processes, in which both the private sector and the State must urgently come together to face and resolve this challenge, which is none other than to rescue our cities. The recovery and renovation of our neighborhoods, towns, and urban centers will depend on concrete actions that promote a paradigm shift, avoiding the repetition of the same practices to benefit everyone and achieve a better habitat and quality of life.

Yves Besançon Prats / Director

“L

Índice Contents

PATRIMONIO

Heritage

Arquitectura y República

Architecture & Republique

R Brunet de Baines en Santiago de Chile, 1848-1855

R Brunet de Baines in Santiago Chile, 1848-1855

R Teatro Municipal o el ideario del patrimonio propio del centro de Santiago

R Municipal Theateror the Proper Heritage

Ideology of Downtown Santiago

ENTREVISTA

Interview

Fernando Pérez Oyarzún

ARQUITECTO INVITADO

Guest Architect

Marcial Jesús

REPORTAJE

Feature Article

Planes y proyectos de recuperación urbana. Parte 1

Urban Recovery Plans & Projects. Part 1

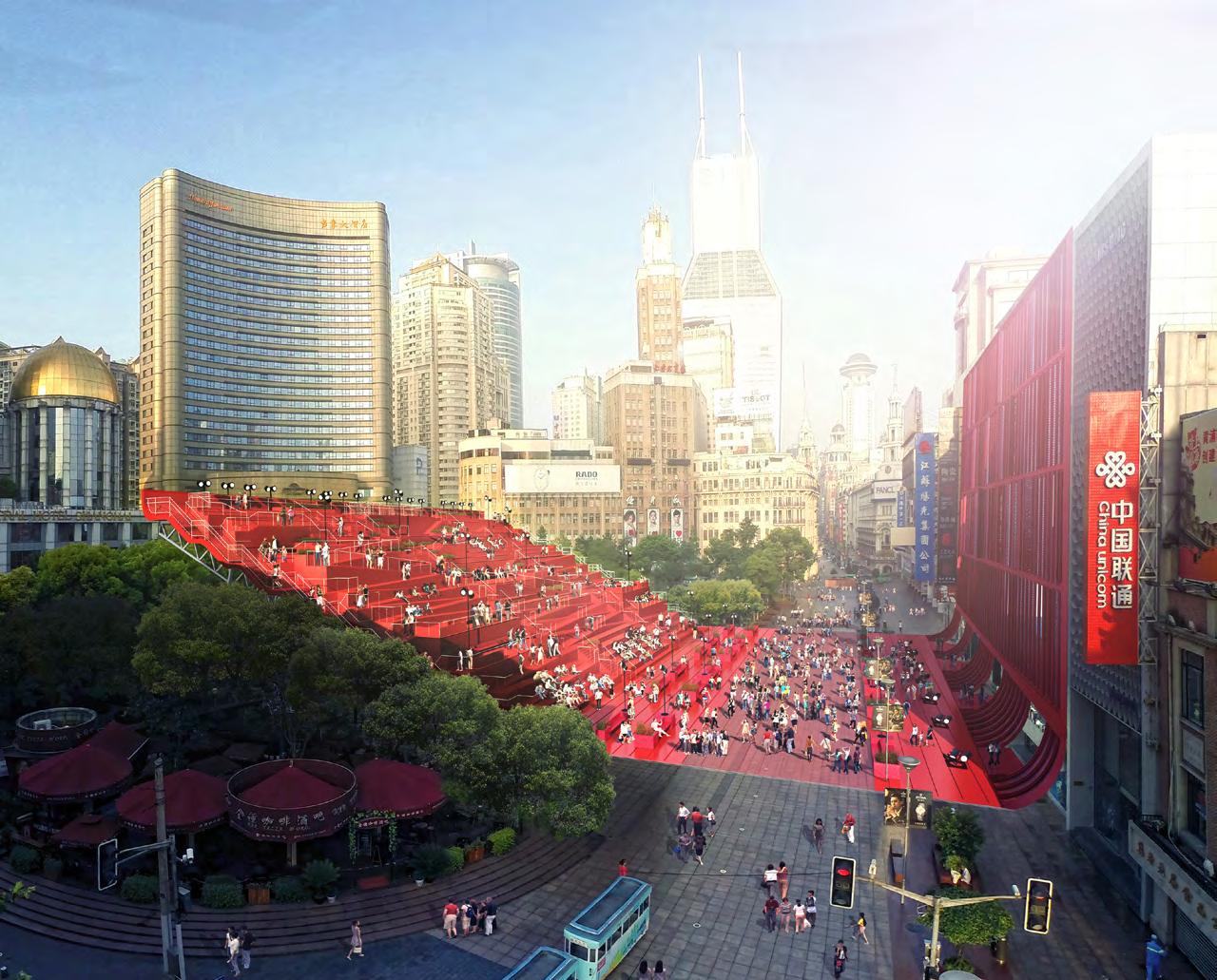

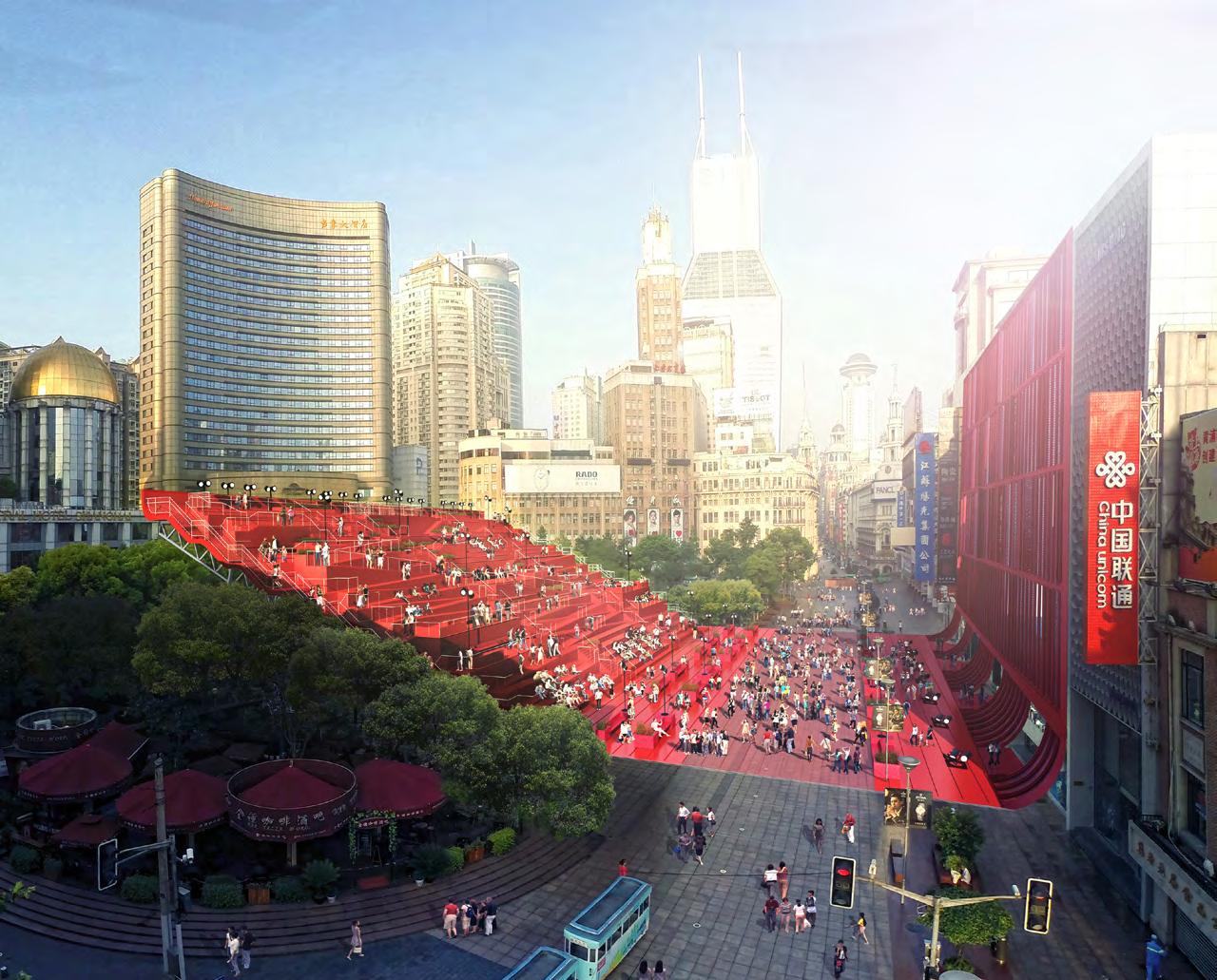

R CREO Antofagasta

R CREO Antofagasta

R Obras en Salamanca

R Works in Salamanca

OBRAS

Works

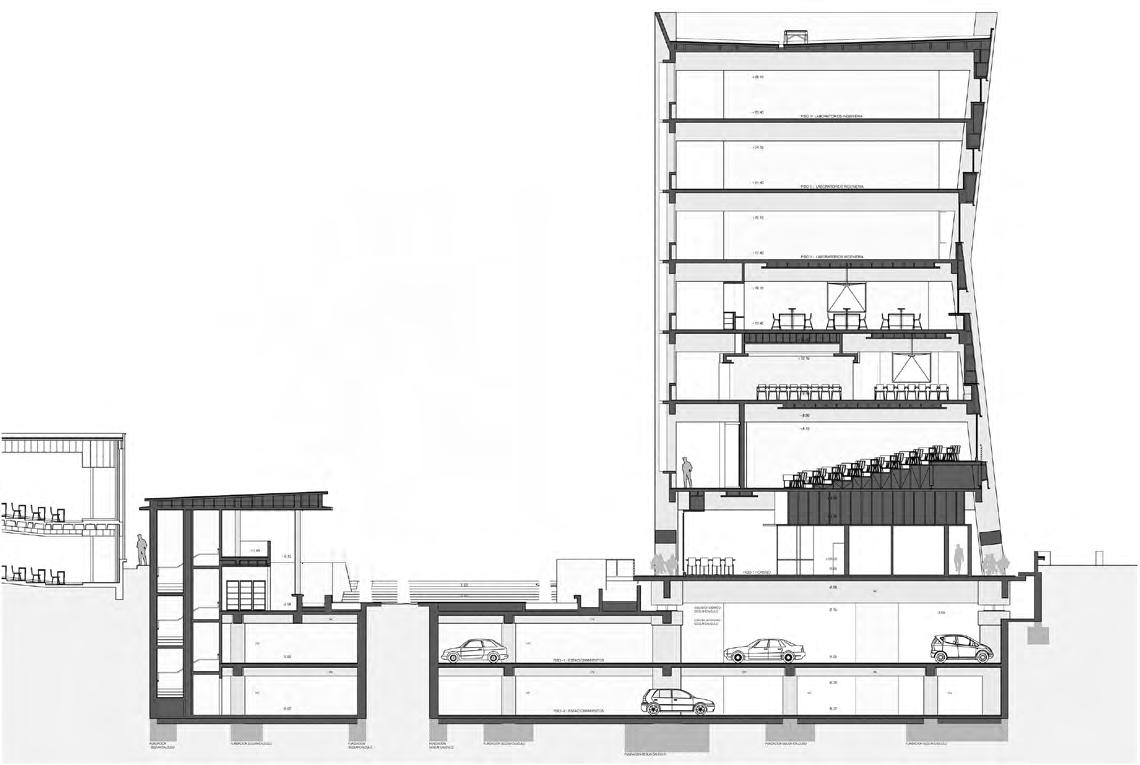

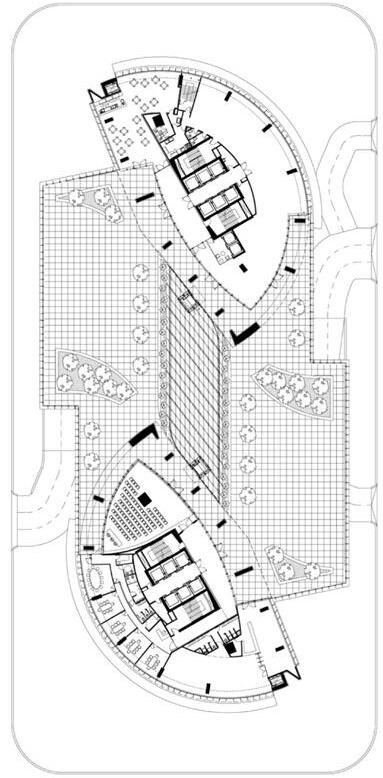

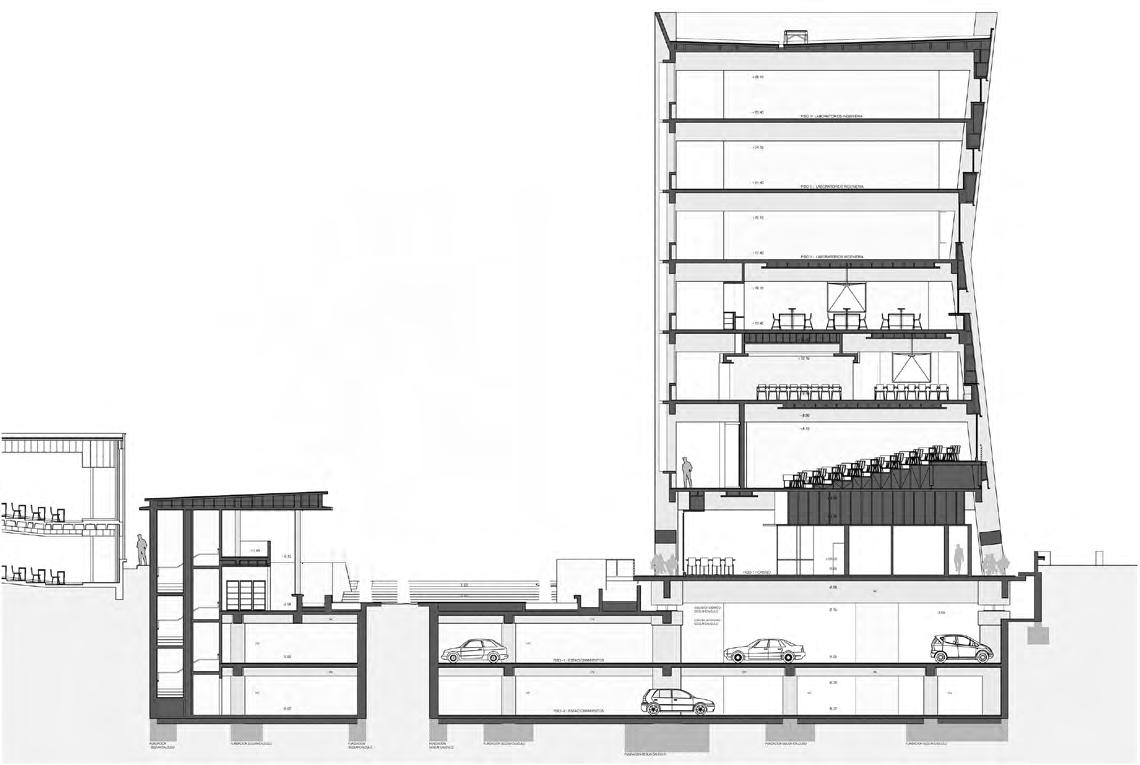

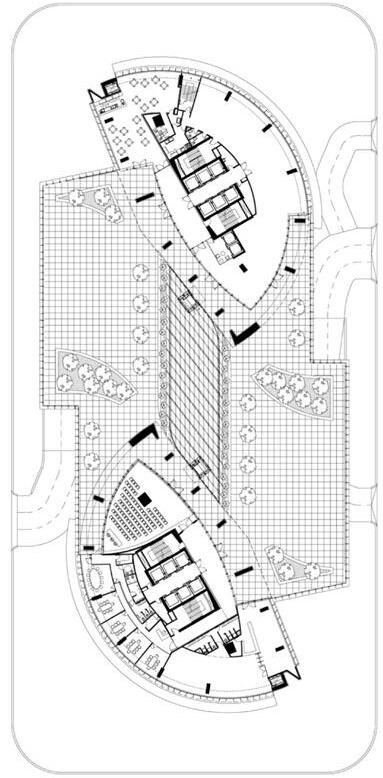

R Edificio Ciencia y Tecnología PUC

R PUC Science & Technology Building

R Manzana 40

R Manzana 40

R Edificio Puerta Costanera

R Puerta Costanera Building

R Edificio Vitacura

R Vitacura Building

R Pabellón YR

R YR Pavillion

R Guatero

R Guatero

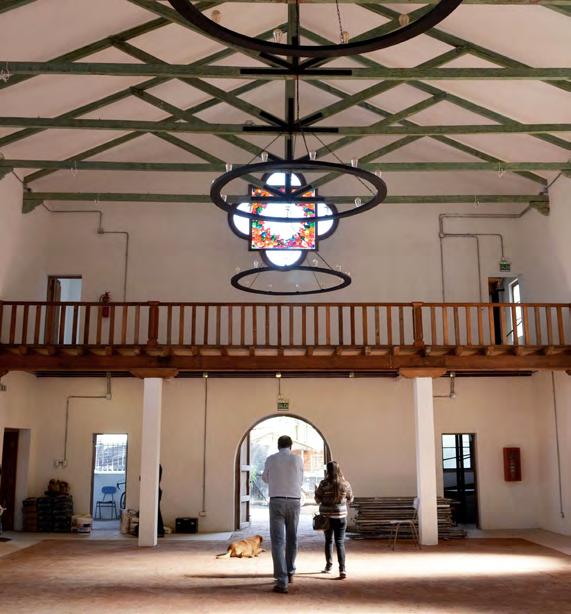

R Restauración Iglesia Santa Bernardita y rehabilitación Sede Social Ocoa

R Restoration of Santa Bernardita Church

Rehabilitation Of Ocoa Social Headquarters

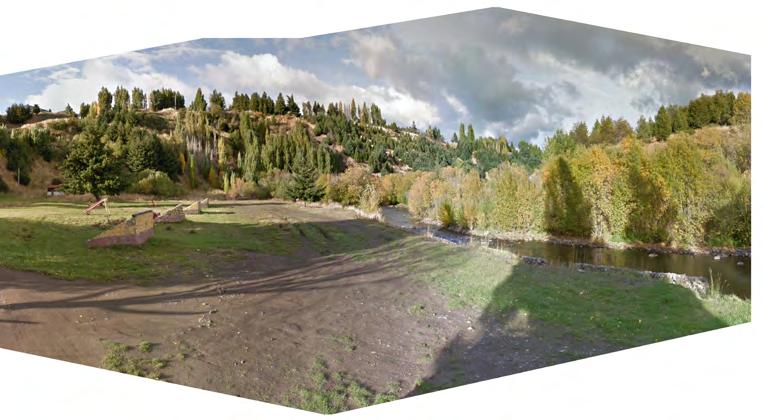

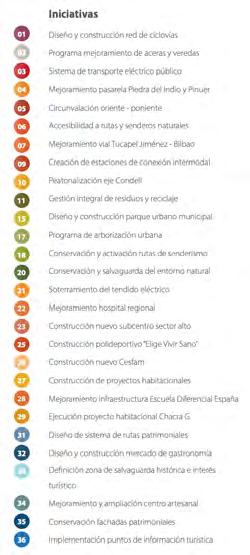

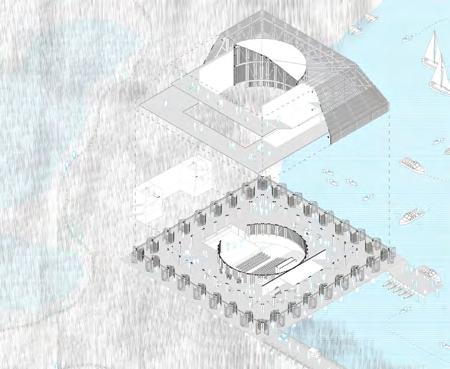

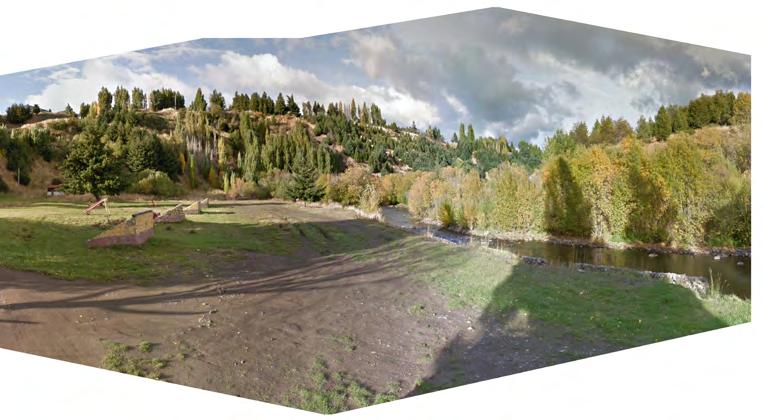

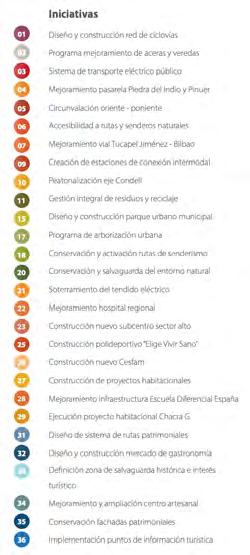

R “Coyhaique: La ciudad que queremos”

R “Coyhaique: The city we want"

MOVIMIENTO MODERNO

Modern Movement

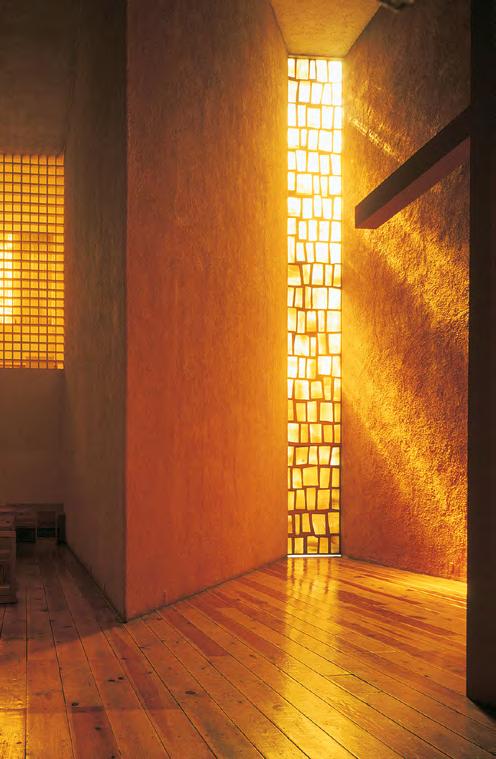

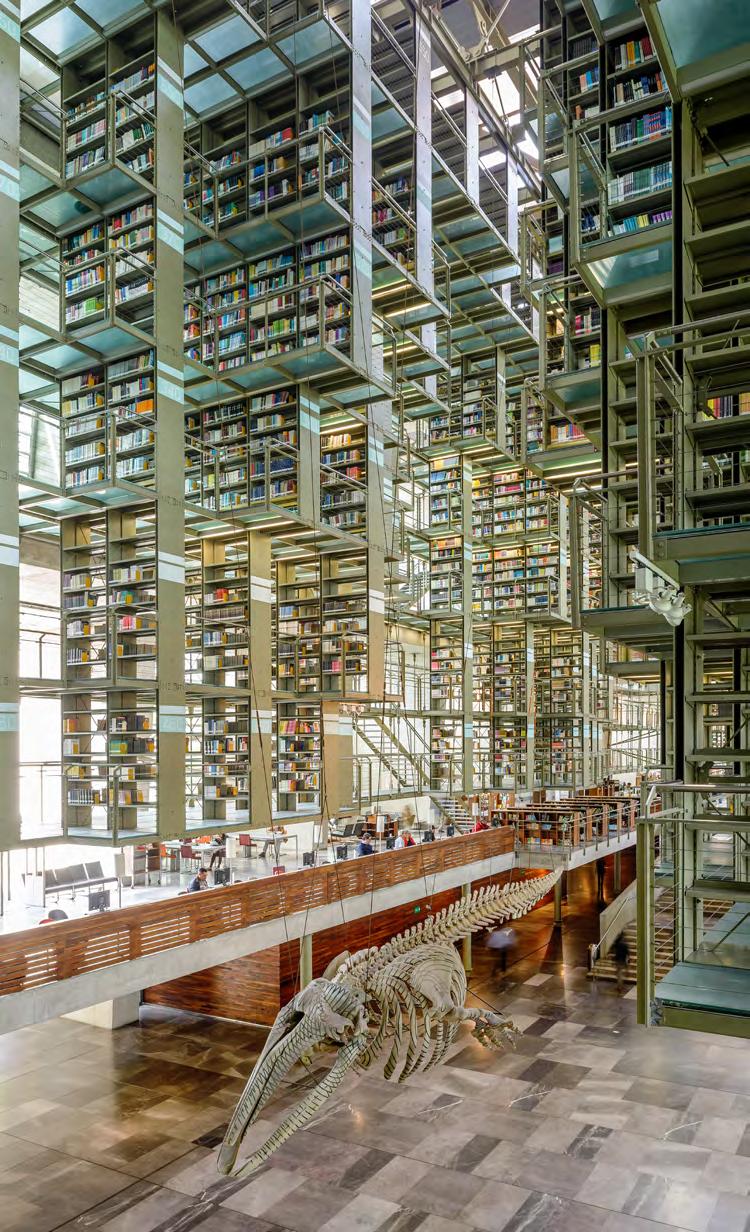

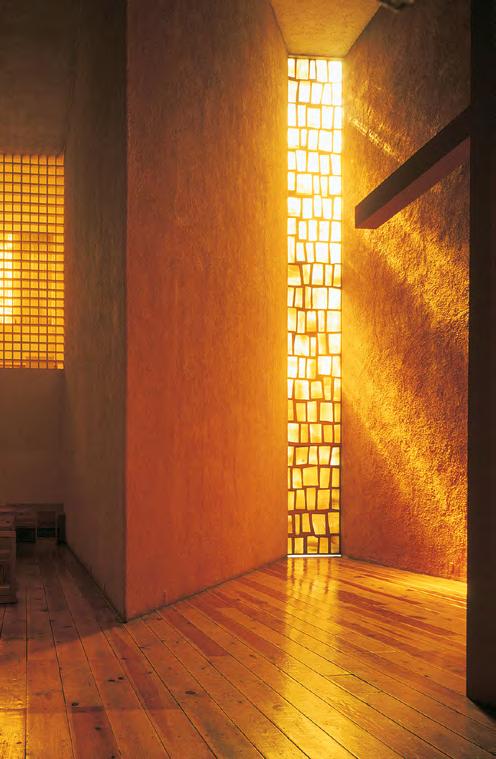

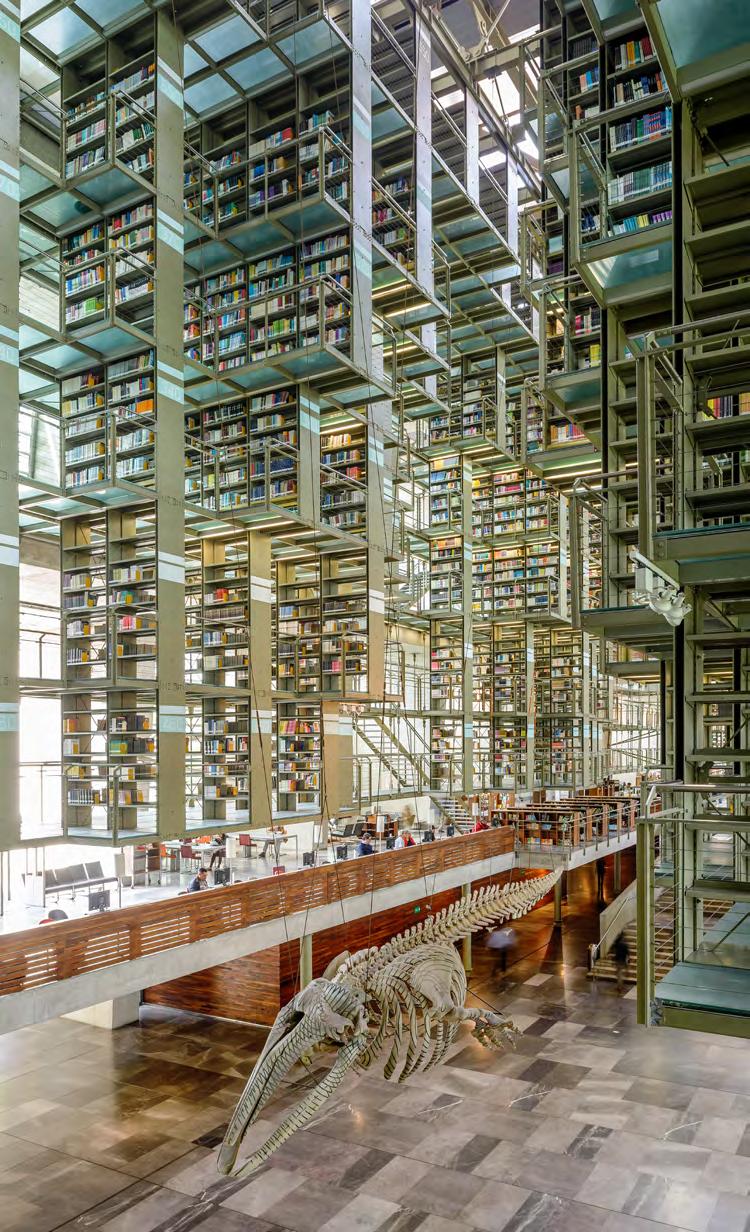

Raíces y modernidades de México Mexico's Roots & Modernities

TESIS

Thesis

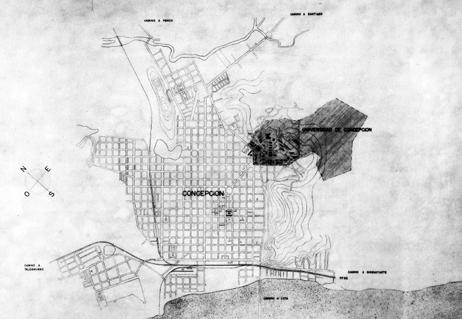

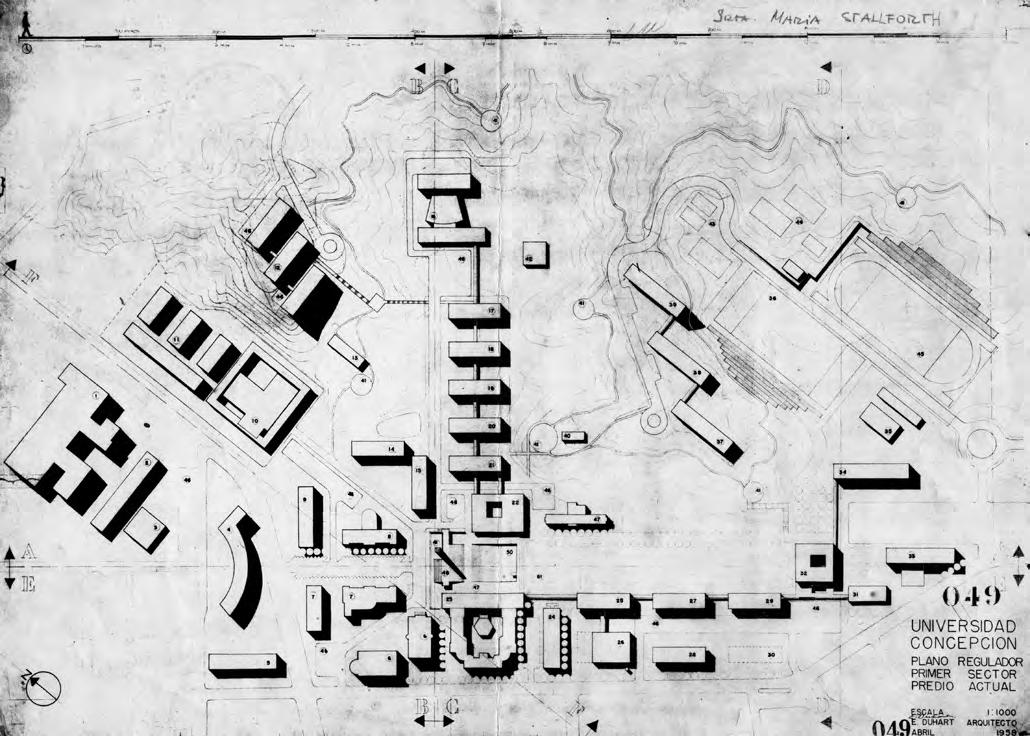

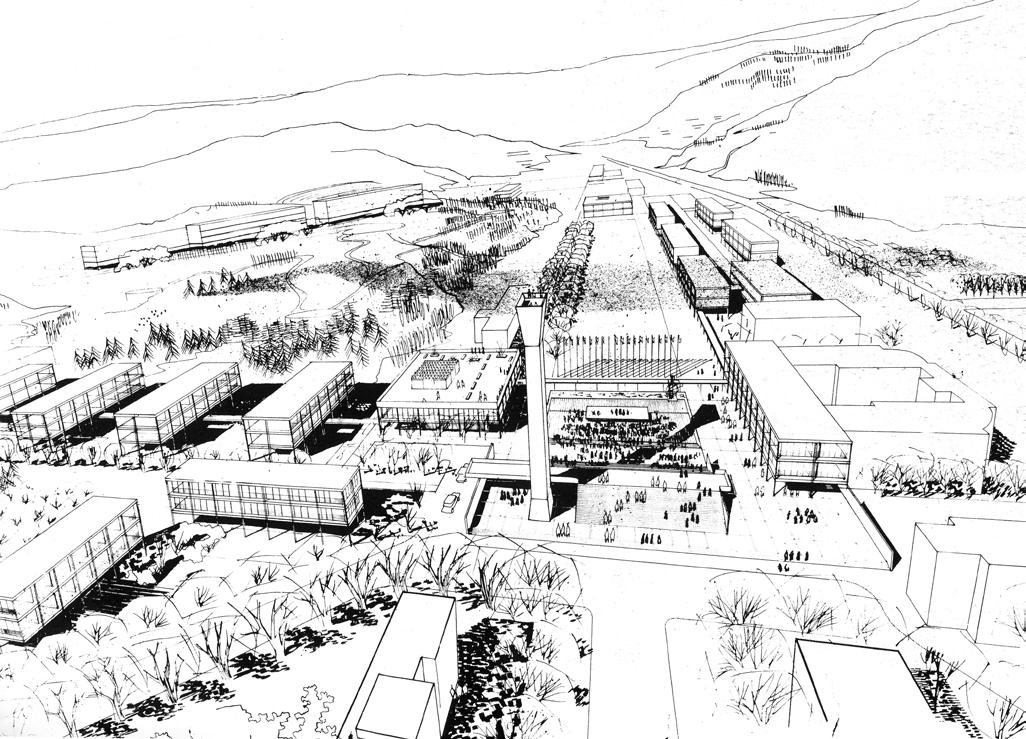

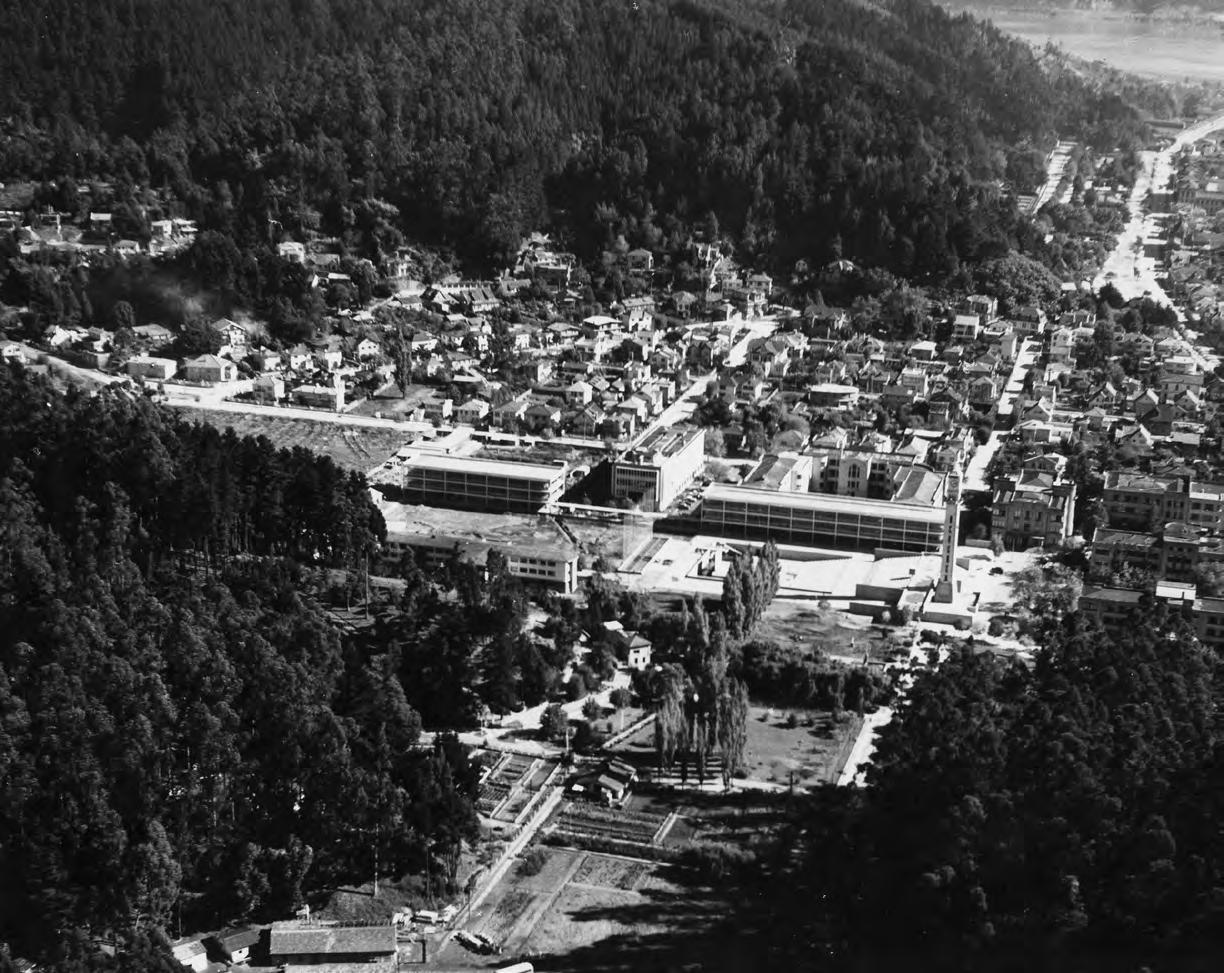

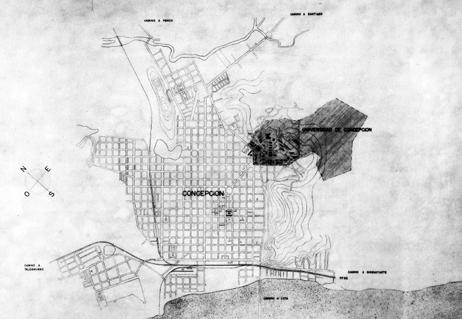

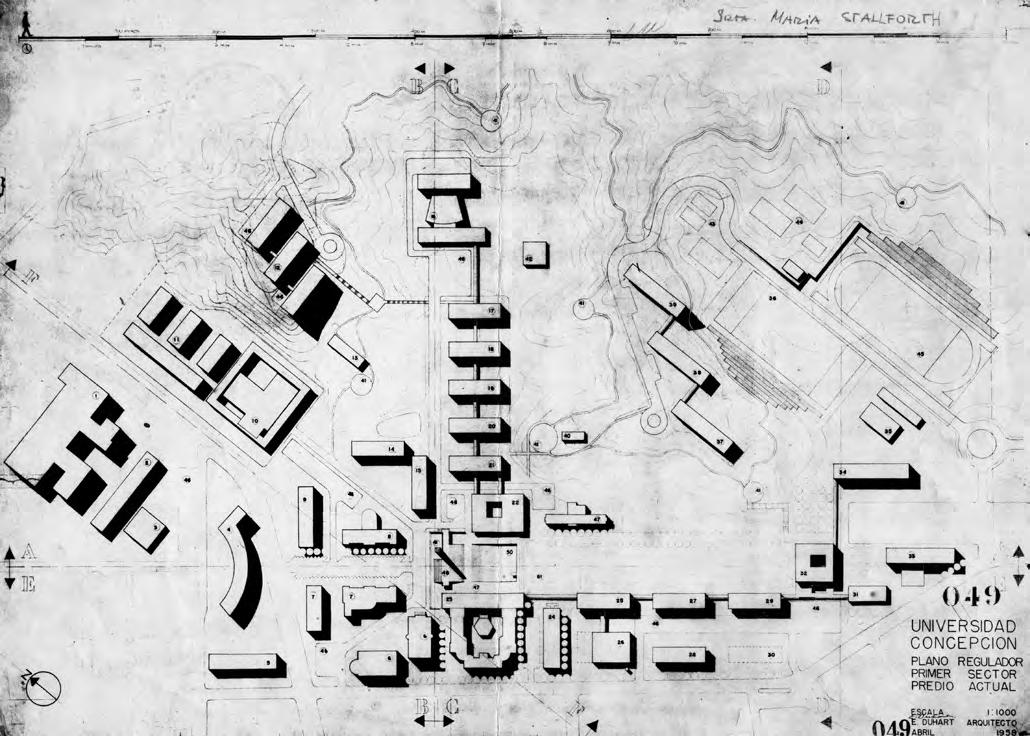

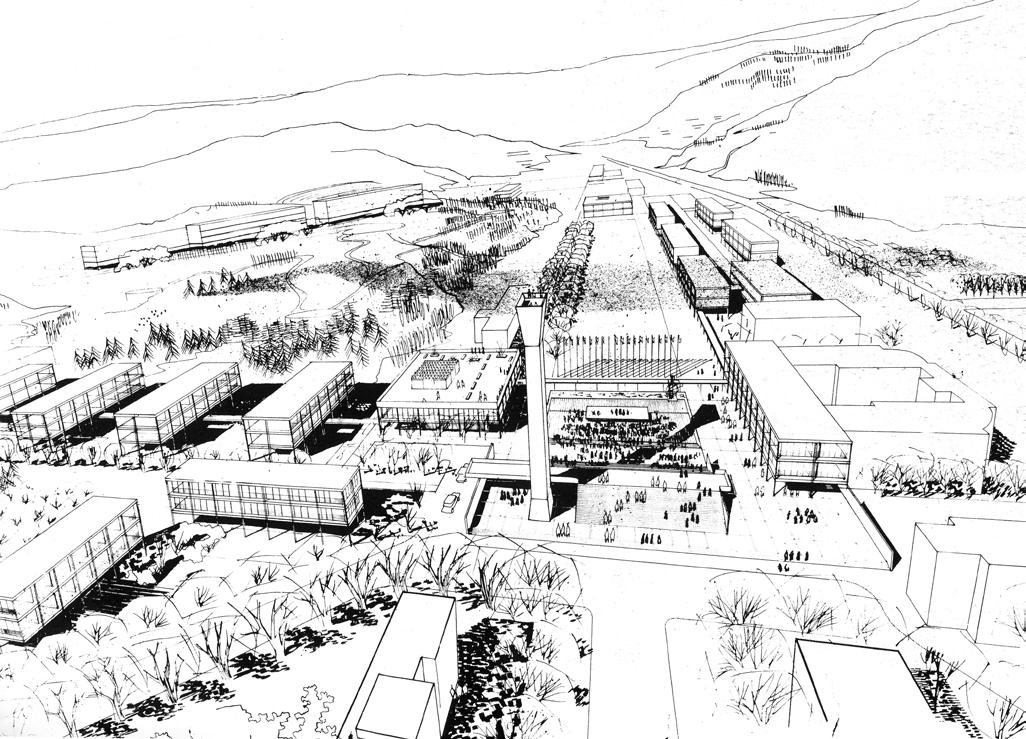

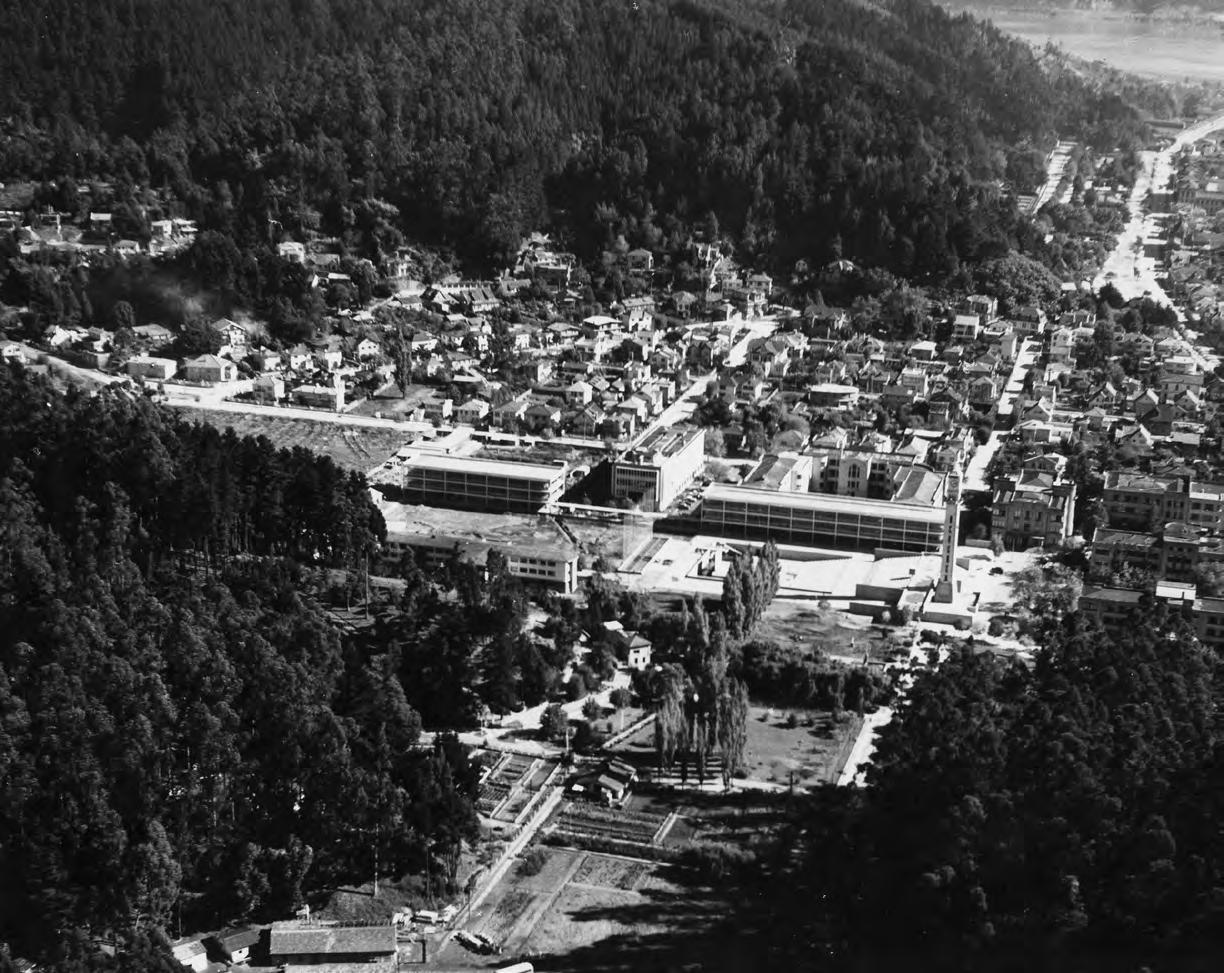

Emilio Duhart, elaboración de un espacio urbano. Ciudad Universitaria de Concepción

Emilio Duhart, elaboration of an urban space. Ciudad universitaria de Concepción

CONCURSOS

Competitions

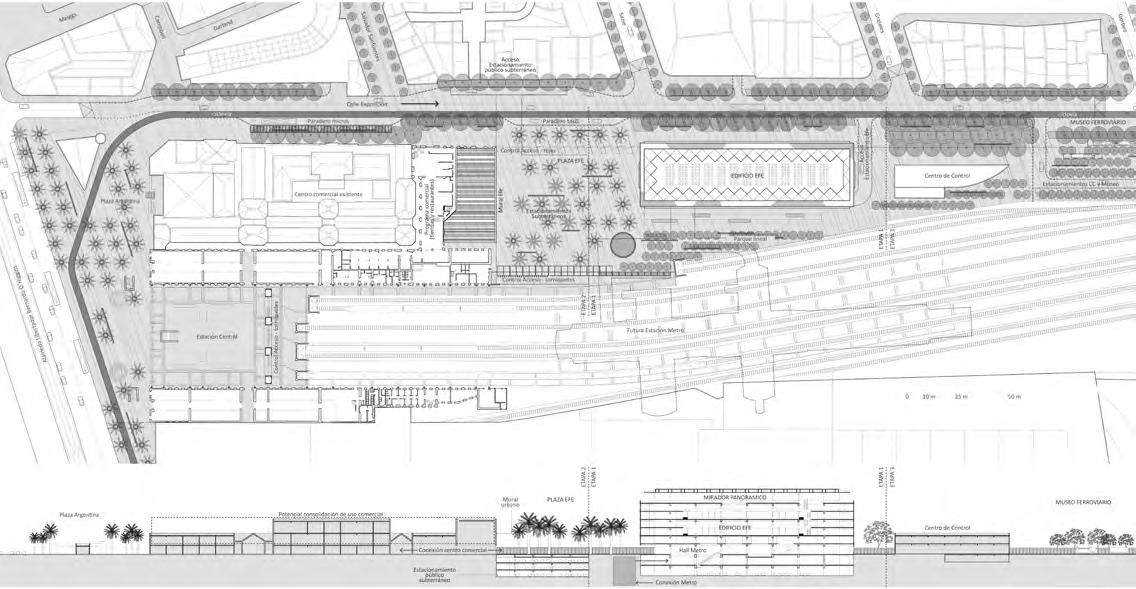

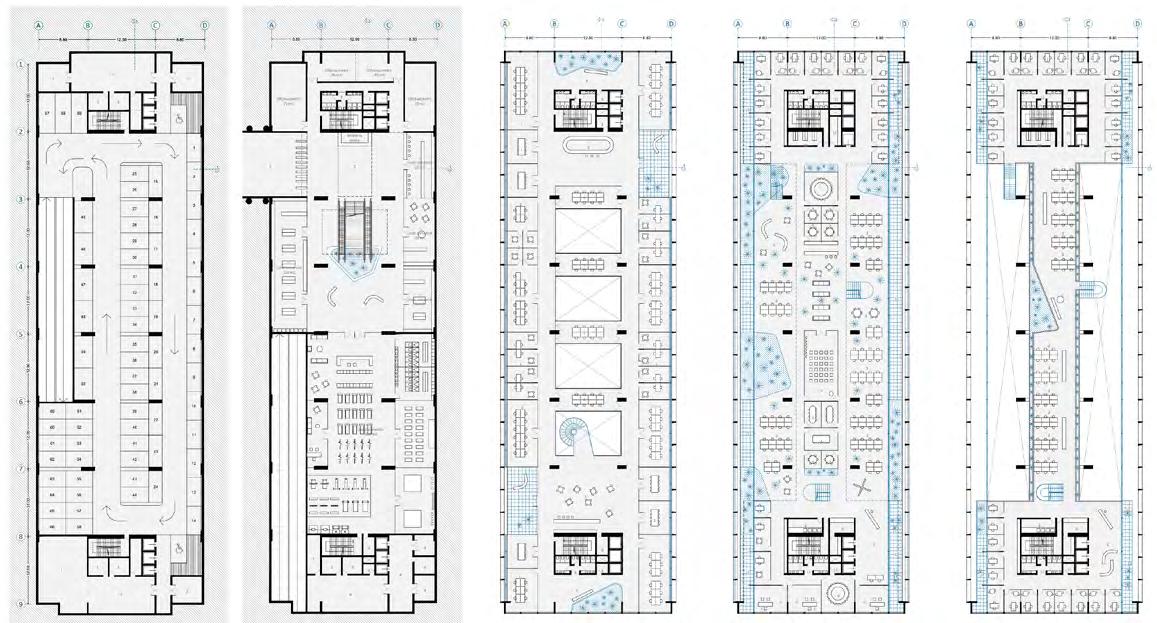

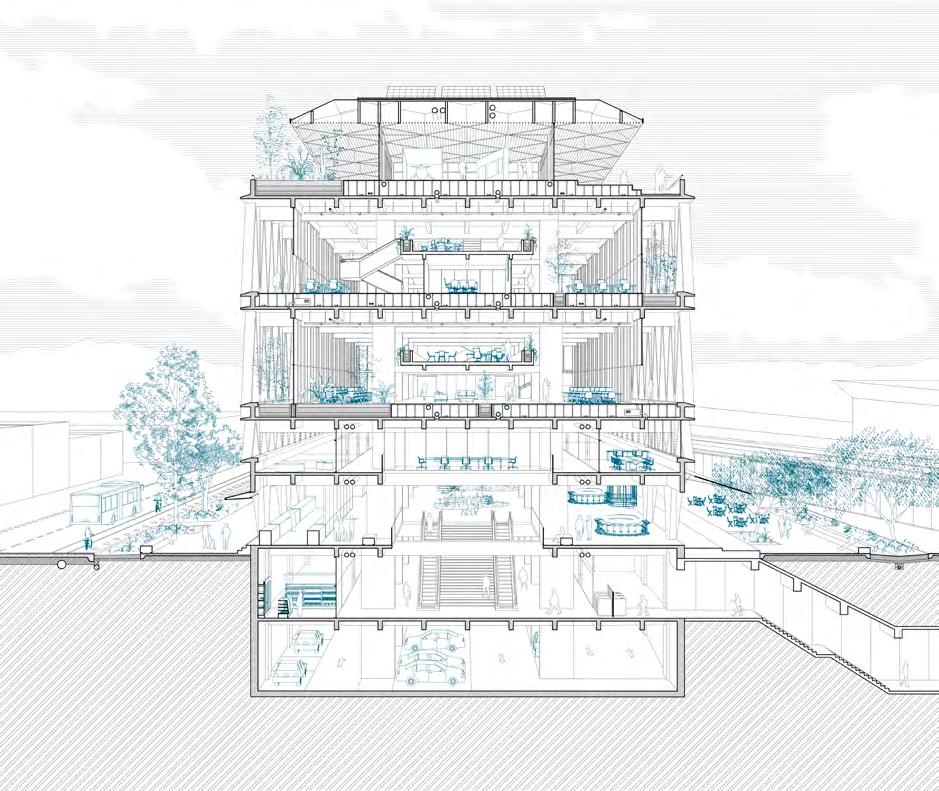

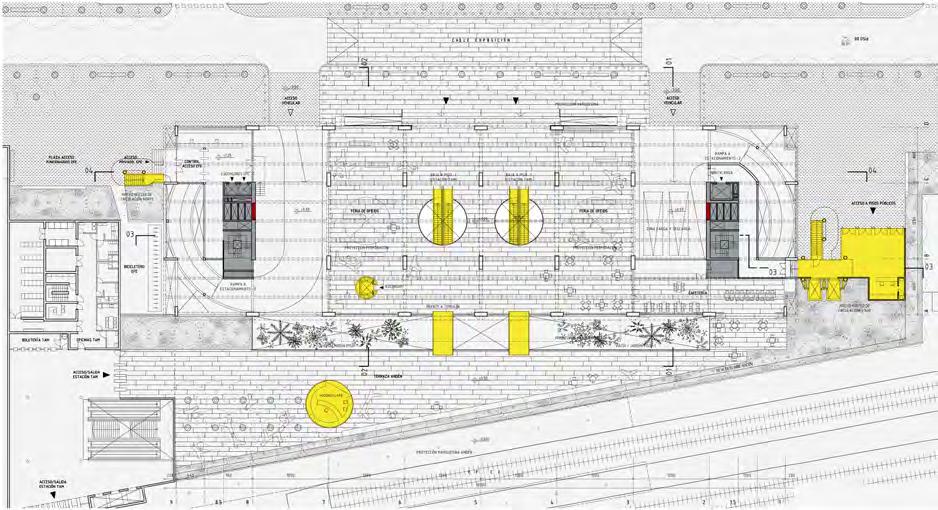

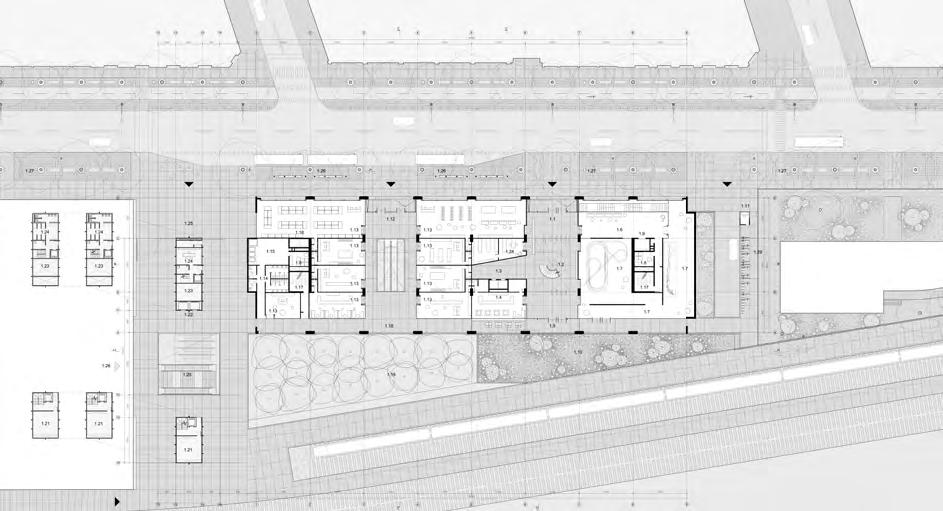

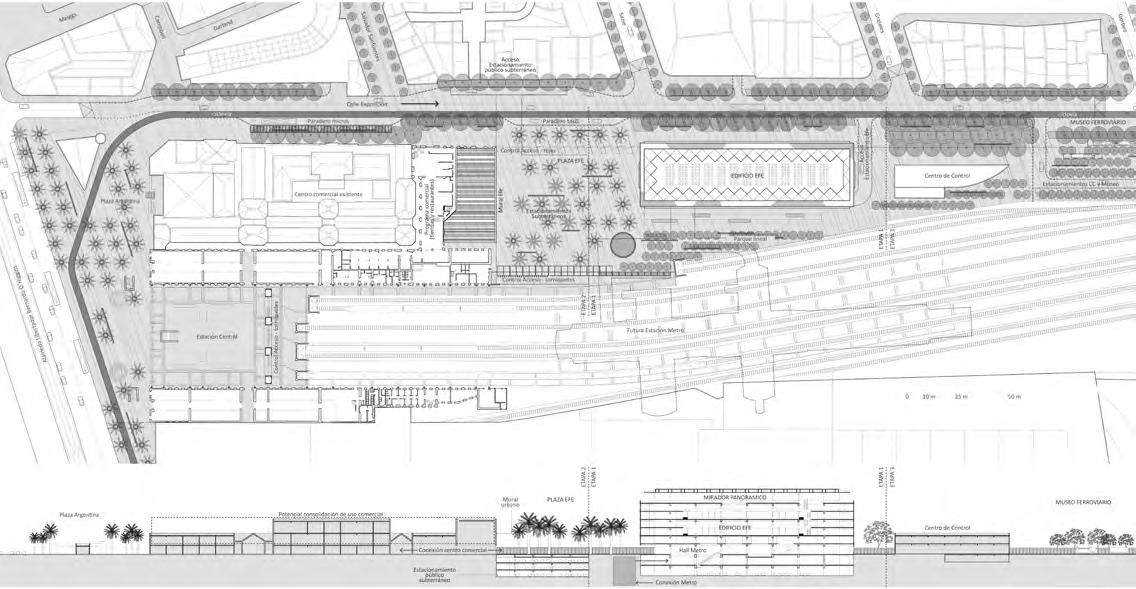

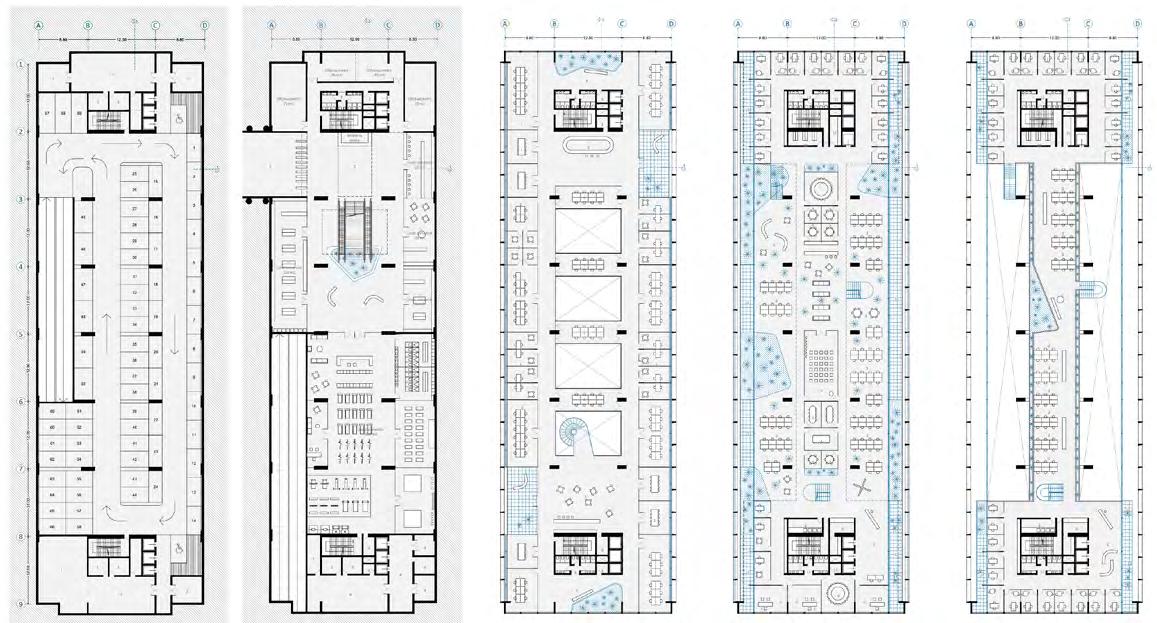

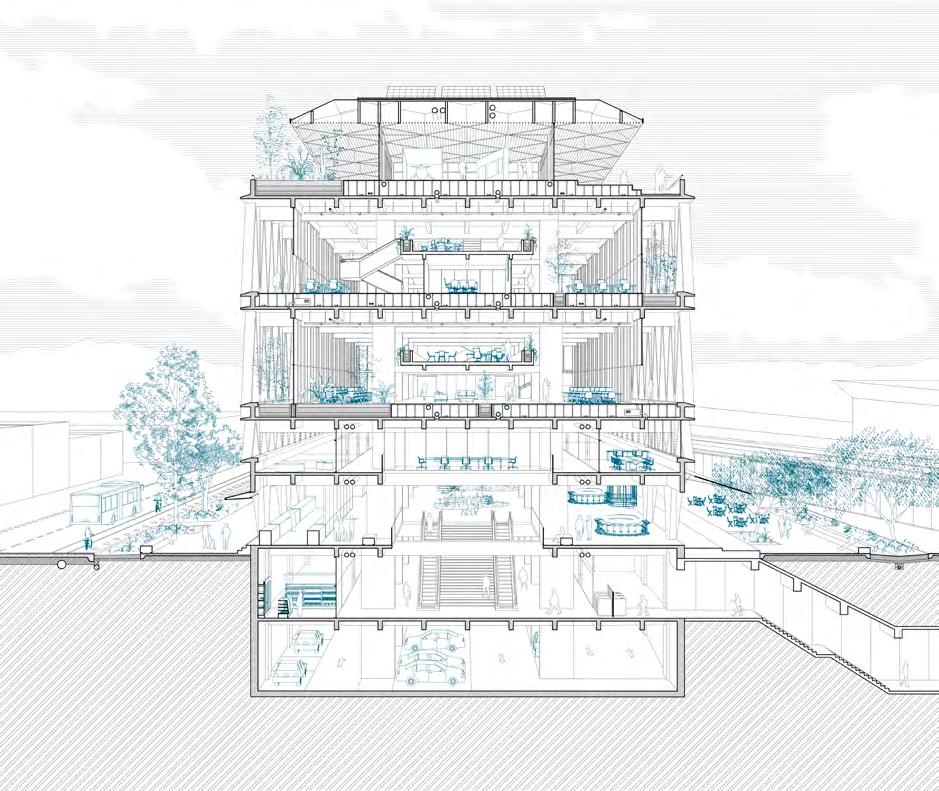

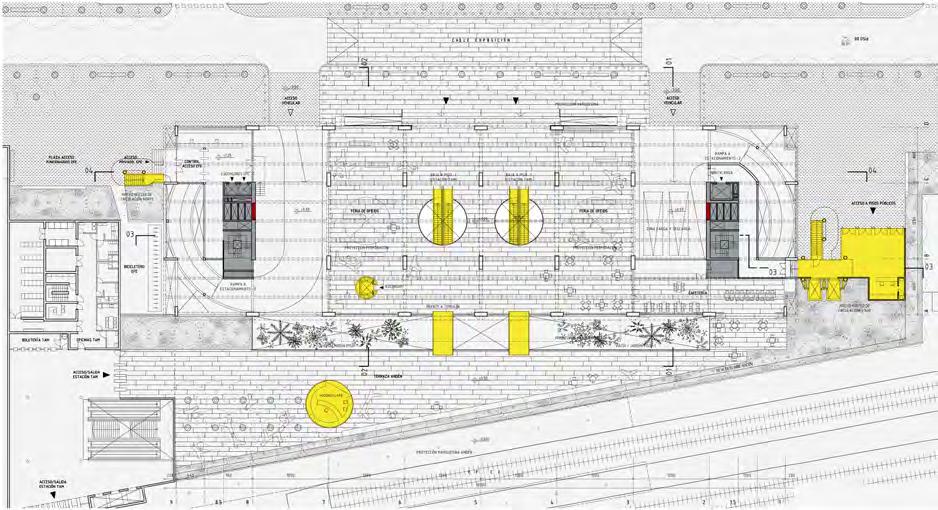

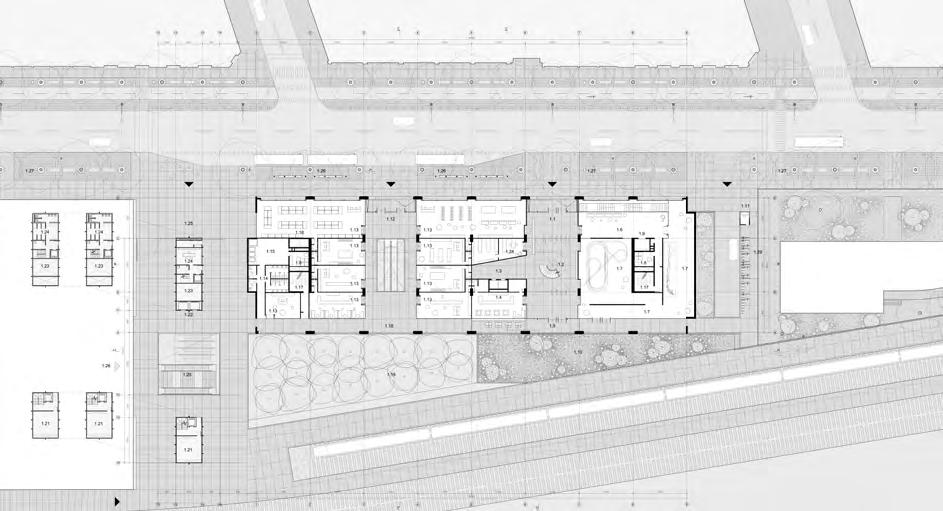

R Proyecto edificio corporativo EFE

R EFE Corporate Building Project

R Proyectar a conciencia 5.0

R Project Consciousness 5.0

R Experiencia detonante III

R Detonating Experience III

R Concurso nacional de proyectos de pregrado de Arquitectura CalienteGraphisoft Archicad

R National Competition For Undergraduate Projects Architectura Caliente-Graphisoft Archicad

40 años del Encuentro de Caburga: ideas para un debate 40 Years After the Caburga Encounter: Ideas for a Debate 04 40 94 72 130 24 48 124 152

Patrimonio / Heritage

olver a nuestros centros históricos como puntos de encuentro y recuperarlos, tanto para los habitantes, como para los visitantes fue la motivación que nos impulsó a abordar el caso de Santiago, la ciudad capital y un modelo en su momento para muchas otras del país. Esto ocurrió especialmente durante el periodo de transformaciones urbanas que siguieron a los años de la instalación de la república, en los cuales se fue forjando nuestra identidad, buscando alejarnos de la influencia colonial.

Un factor importante en esta búsqueda fue la llegada, principalmente desde Francia –dada su amplia y reconocida influencia en el ámbito de las artes y la arquitectura de la época– de personalidades como Claude Françoise Brunet de Baines, quien dejó un legado significativo durante su breve paso por Chile. Aunque no contamos con imágenes o retratos suyos, su trabajo en el país incluyó el primer curso de arquitectura, así como destacadas obras arquitectónicas, entre las que destaca el edificio del Teatro Municipal. Este edificio refleja, por un lado, que el patrimonio construido se mantiene vivo gracias a la acción de aquellos que lo habitan o interactúan con él. Por otro lado, pone de manifiesto la historia resiliente de muchos edificios similares que han tenido que enfrentar diversos desafíos a lo largo de más de 150 años de actividad cultural y presencia en la ciudad.

En los dos artículos de este número se exponen reflexiones que nos invitan a repensar en lo que se viene para las erosionadas manzanas fundacionales de nuestras ciudades y en cómo quisiéramos que los ciudadanos las habiten generando, algo así como una “ciudadanía patrimonial”, como la denomina José de Nordenflytch1, la que se reconozca y se sienta parte de estos edificios y espacios públicos, que nos precedieron y que, esperamos, nos sucedan en el tiempo.

V R

eturning to our historic centers as places to meet and restoring them for both inhabitants and visitors was the motivation that prompted us to address the case of Santiago, the capital city and a model at the time for many others in the country. This occurred especially during the period of urban transformations that followed the years after the republic was established, during which our identity was forged, attempting to distance ourselves from the colonial influence era.

An important factor in this quest was the arrival, mainly from France -given its wide and recognized influence in the field of arts and architecture of the time-, of personalities such as Claude Françoise Brunet de Baines, who left a significant legacy during his brief stay in Chile. Although we do not have images or portraits of him, his work in Chile included the first architecture course, as well as emblematic architectural works, among which the Municipal Theater building stands out. This building reflects, on the one hand, that the heritage built is kept alive by the action of those who inhabit or interact with it. On the other hand, it highlights the resilient history of many similar buildings that have had to face various challenges over more than 150 years of cultural activity and presence in the city.

The two articles in this issue present reflections that invite us to rethink what is to come for the eroded foundational blocks of our cities and how we would like citizens to inhabit them, creating something like a "heritage citizenship", as José de Nordenflytch1 calls it, which recognizes and feels a part of these buildings and public spaces that preceded us and that, we hope, will succeed us over time.

por by : javiera benavides

4 ← AOA / n°48

ARQ

&

1 José de Nordenflytch, Post Patrimonio, RIL Editores, UNAB, Viña del Mar, 2012

UITECTURA

Architecture & Republique

REPÚBLICA

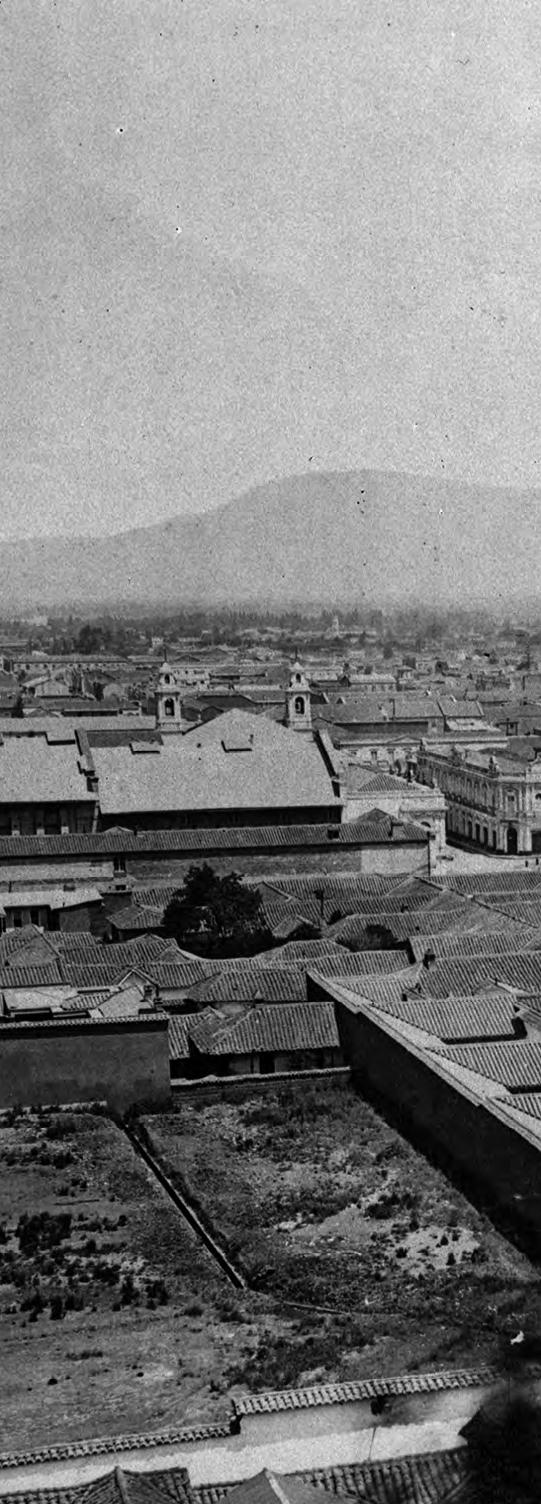

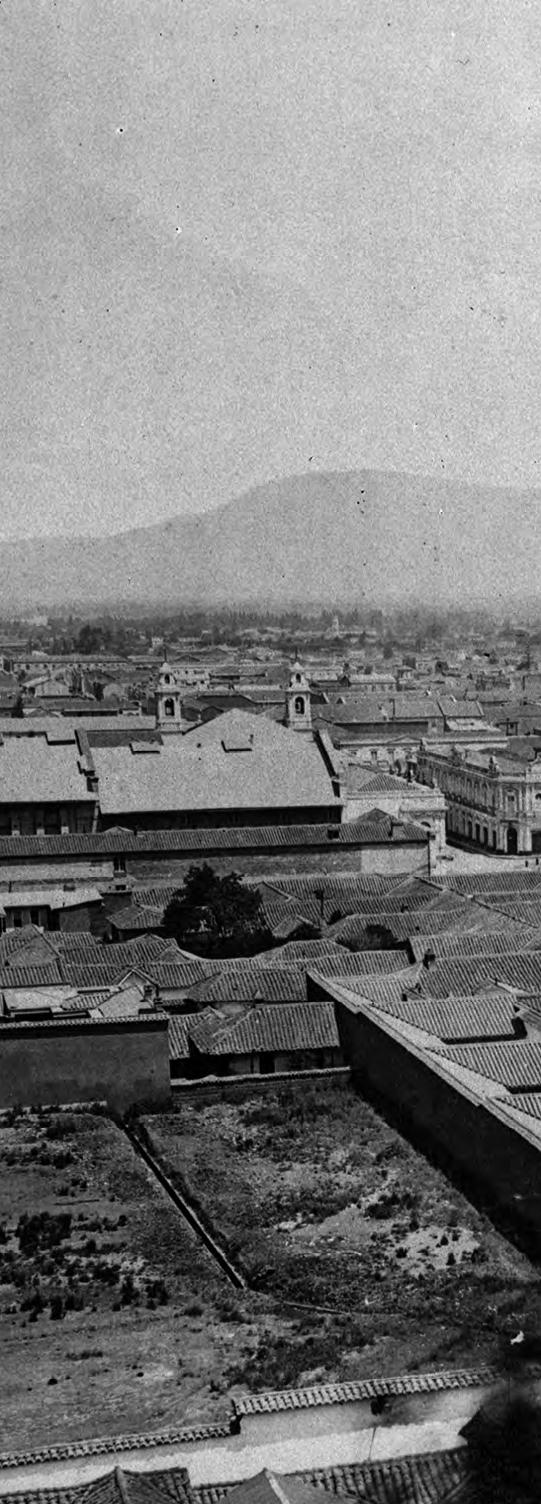

S Vista del centro de Santiago desde el cerro Santa Lucía, c. 1880. Archivo fotográfico del Museo Histórico Nacional. S View of downtown Santiago from Santa Lucia Hill, c. 1880. Source: Photographic archive from the Chilean National Historical Museum.

→ 5 Patrimonio / Heritage

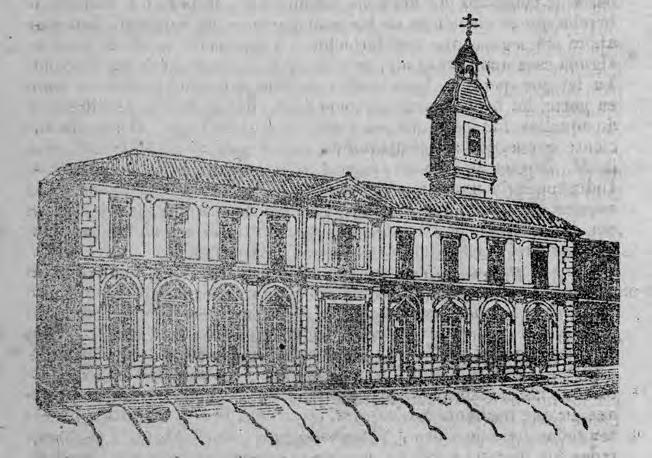

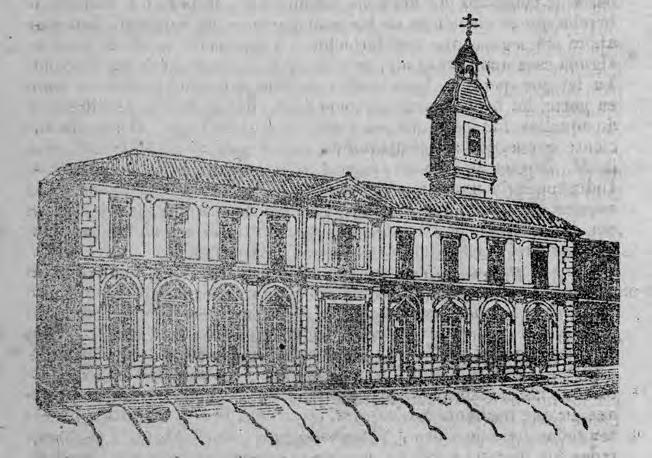

V Teatro Municipal de Santiago, c. 1860.

Fuente: Archivo fotográfico Museo Histórico Nacional de Chile. V The Santiago Municipal Theater, c. 1860.

Source: Photographic archive from the Chilean National Historical Museum.

germán hidalgo hermosilla

Arquitecto de la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (1991) y Doctor en Teoría e Historia de la Arquitectura por la ETSAB, Universidad Politécnica de Cataluña (2000). Actualmente, es profesor titular en la PUC. Es autor de varios libros entre ellos: Sobre el Croquis, Ediciones ARQ, 2015; Dibujo y Proyecto. Casos de arquitectura en Latinoamérica, Ediciones ARQ en 2018; Brunet de Baines en Santiago de Chile, 1848-1855, 2020; y El Teatro Municipal, un estudio de su planimetría histórica, 2022. Ha participado como investigador responsable en proyectos Fondecyt, Fondart, VRI y Fondedoc, donde ha examinado diversas representaciones históricas de Santiago, tanto cartográficas como iconográficas. Su trabajo también se ha centrado en la relación entre representación y proyecto de arquitectura.

Architect from the Pontificia Universidad Católica (1991) and Doctor in Theory and History of Architecture from the ETSAB, Universidad Politécnica de Cataluña (2000). Currently, he is a full professor at PUC. He is the author of several books, including Sobre el Croquis published by Ediciones ARQ in 2015; Dibujo y Proyecto. Casos de arquitectura en Latinoamérica, published by Ediciones ARQ in 2018; Brunet de Baines en Santiago de Chile, 1848-1855, in 2020; and El Teatro Municipal, un estudio de su planimetría histórica, in 2022. He has participated as a responsible researcher in projects Fondecyt, Fondart, VRI, and Fondedoc, where he has examined various historical representations of Santiago, including cartographic and iconographic materials. His work has also focused on the relationship between representation and architectural design.

6 ← AOA / n°48

Brunet de Baines en Santiago de Chile, 1848-1855

BRUNET DE BAINES IN SANTIAGO CHILE, 1848-1855

por by : germán hidalgo hermosilla

por by : germán hidalgo hermosilla

En Chile, poco se sabe del arquitecto francés Claude François Brunet de Baines, quien desarrolló su actividad profesional en Santiago entre 1848 y 1855. Prácticamente no ha quedado registro de su trabajo y los edificios que construyó han ido desapareciendo uno tras otro como producto de la desidia, la dejación y la ignorancia. Algunos de sus edificios más emblemáticos –es cierto– gozan de un reconocimiento general, como el Teatro Municipal, pero no son asociados directamente con su persona. Su participación en la creación del primer curso de arquitectura en Chile, que puede ser considerado como pionero en América Latina, tampoco ha tenido el reconocimiento que merece.1

En resumen, hasta ahora no se ha valorado suficientemente el aporte de Brunet de Baines a la cultura nacional, ni en lo profesional, ni en lo académico, pero, sobre todo, en relación a su aporte a la construcción de la identidad de Chile como Estado-nación, en un momento clave de su formación institucional. Este último aspecto es el que se quiere relevar en este artículo, mostrando cómo la contribución de Brunet de Baines fue mucho más allá de la particularidad de cada obra en la que participó, al dar una nueva imagen a Santiago como la capital de Chile la que, junto a su llegada, iniciaría un proceso de modernización irreversible.

In Chile, little is known about French architect Claude François Brunet de Baines, who developed his professional activity in Santiago between 1848 and 1855. There is practically no record of his work and the buildings he built have disappeared one after another as a result of carelessness, neglect, and ignorance. Some of his most emblematic buildings -it is true- enjoy general recognition, such as the Municipal Theater, but they are not directly associated with him. His participation in creating the first architecture course in Chile, which can be considered the pioneer in Latin America, has not been sufficiently recognized either.1

In short, Brunet de Baines' contribution to national culture has not been sufficiently recognized so far, neither professionally nor academically, but above all, in relation to his contribution to the creation of Chile's identity as a nation-state, at a key moment of its institutional formation. This last aspect is the one we want to highlight in this article, showing how the contribution of Brunet de Baines went far beyond the particularity of each project in which he participated, by giving Santiago a new image as the capital of Chile, which along with his arrival, would begin a process of irreversible modernization.

→ 7 Patrimonio / Heritage

Patrimonio / Heritage

1 Desde el año 2003, en la Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo de la Universidad de Chile, se entrega la medalla C. F. Brunet de Baines, en conmemoración de su fundación.

1 Since 2003, the C. F. Brunet de Baines medal has been awarded to the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at Universidad de Chile in commemoration of its foundation.

Q Portal Tagle. Visto desde el costado poniente de la Plaza de Armas, y aún sin concluir, c.1850. Fuente: Archivo fotográfico Museo Histórico Nacional de Chile. Q Tagle Portal. View from the west side of Plaza de Armas, still unfinished, c.1850. Source: Photographic archive from the Chilean National Historical Museum.

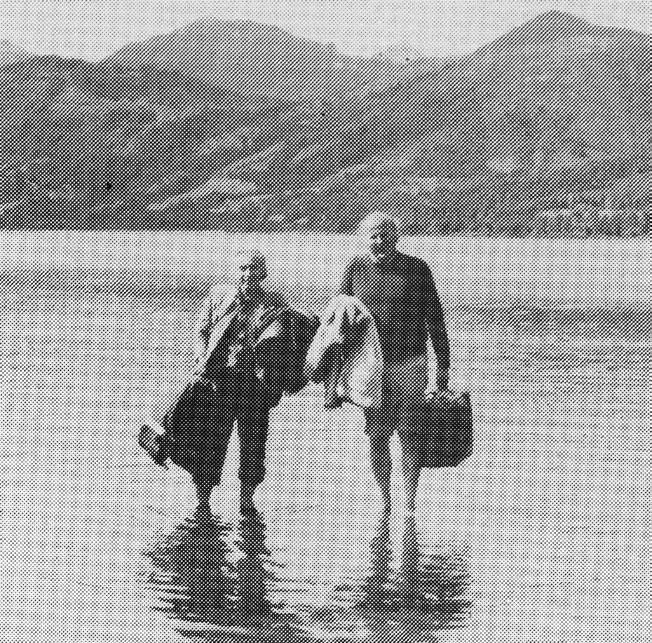

Claude François Brunet de Baines

Brunet de Baines nació el 4 de enero de 1799 en la localidad de Vannes, en el noroeste de Francia, y murió el 18 de junio de 1855 en Santiago, donde descansan sus restos. Fue hijo y hermano de arquitectos y, el menor, Charles-Fortuné-Louis (1801-1868), siguió la misma profesión, alcanzando gran éxito en Francia. A los veinte años se inscribió en la Escuela de Bellas Artes de París, donde estudió con André Chatillon (1782-1859), un brillante alumno de la misma escuela. Ejerció la profesión en el ámbito público, desempeñándose en la Comisión de Monumentos Históricos de Francia y como arquitecto inspector de Trabajos Públicos y de Catastros. Fue nombrado presidente del Consejo de la Sociedad Central de Arquitectos de Francia, institución que contribuyó a formar en 1840. En Francia, fue contactado por el encargado de negocios de Chile, el diplomático Francisco Javier Rosales, a sugerencia del director del Museo de Bellas Artes de París, M. Cailleaux. Rosales tenía la misión de reclutar a un arquitecto profesional para que se hiciera cargo de las obras que el gobierno de Chile estaba proyectando. Así, el 1 de mayo de 1848, Brunet de Baines firmó un contrato de trabajo como arquitecto oficial de la República, para ejercer entre 1848 y 1855.2 En el documento se estipulaba que debía ejecutar todo proyecto de arquitectura civil por cuenta del gobierno o de las municipalidades, pudiendo, no obstante, destinar su tiempo libre en trabajos particulares. Por último, señalaba que, si el gobierno de Chile decidía crear una escuela de arquitectura, él sería el responsable de conformarla y dirigirla.

Un arquitecto profesional en Chile

Sabemos que el 16 de noviembre de 1848 Brunet de Baines desembarcó en el puerto de Valparaíso, acompañado de su esposa e hija, e inmediatamente comenzó a trabajar en los encargos del gobierno. La gran cantidad de actividades realizada en tan breve lapso, nos hace imaginar su abultada carga de trabajos; “abrumadora”, según Pereira Salas, la cual se debió volver aún

El 1 de mayo de 1848, Brunet de Baines firmó un contrato de trabajo como arquitecto oficial de la República, para ejercer entre 1848 y 1855. En el documento se estipulaba que debía ejecutar todo proyecto de arquitectura civil por cuenta del gobierno o de las municipalidades, pudiendo, no obstante, destinar su tiempo libre en trabajos particulares. Por último, señalaba que, si el gobierno de Chile decidía crear una escuela de arquitectura, él sería el responsable de conformarla y dirigirla.

Claude François Brunet de Baines

Brunet de Baines was born on January 4, 1799 in the town of Vannes, in the northwest of France, and died on June 18, 1855 in Santiago, where his remains rest. He was the son and brother of architects, and the youngest, Charles-Fortuné-Louis (18011868), followed the same profession, achieving considerable success in France.

At the age of twenty, he enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris where he studied with André Chatillon (1782-1859), a brilliant student from the same school. He practiced his profession in the public sector, serving on the Commission of the French Historical Monuments and as an architect inspector of Public Works and Cadastres. He was appointed president of the French Council of the Central Society of Architects, an institution he helped form in 1840. In France, he was contacted by the Chilean representative, diplomat Francisco Javier Rosales, at the suggestion of the Museum director of Fine Arts in Paris, M. Cailleaux. Rosales was in charge of recruiting a professional architect to take care of the projects that the Chilean government was planning. Thus, on May 1, 1848, Brunet de Baines signed an employment contract

8 ← AOA / n°48

2 Contrato entre C.F. Brunet de Baines y Francisco Javier Rosales, París 1º de mayo de 1848. ARNAD, Fondo de la Legación de Chile en Francia y Gran Bretaña, Volumen 30.

más pesada, después que su mujer y su hija regresaran intempestivamente a Francia, al no lograr acostumbrarse a Santiago.

A comienzos de 1849, el gobierno decretó la creación de una escuela de arquitectura, de modo que, desde un principio, Brunet de Baines debió compatibilizar su actividad profesional con el trabajo docente. En estas circunstancias, preparó y dictó el primer curso de arquitectura en Chile, redactando, además, el texto docente complementario que publicó en 1853. A pesar de todos estos esfuerzos, sacrificios y de su extraordinaria productividad, Brunet de Baines recibió duras críticas. En parte debido a la incomprensión local de una disciplina desconocida y, por lo mismo, muy poco valorada, como también por las exigencias del arquitecto. A consecuencia de lo anterior, su salud se vio quebrantada, y justamente cuando ya expiraba el contrato y preparaba su regreso a Francia, la muerte lo sorprendió, repentinamente, con apenas 55 años.3

as an official architect of the Republic, in order to work between 1848 y 1855.2 The document stipulated that he would be responsible for executing all civil architecture projects on behalf of the government or municipalities, although he could spend his free time on personal projects. Finally, he stated that if the Chilean government decided to create an architecture school, he would be responsible for setting it up and directing it.

A Professional Architect in Chile

We know that on November 16, 1848, Brunet de Baines disembarked at the port of Valparaíso, accompanied by his wife and daughter, and immediately began to work on government commissions. The vast amount of activities carried out in such a short period of time, helps us imagine his heavy workload; "overwhelming", according to Pereira Salas, which must have become even heavier after his wife and daughter returned untimely to France because they could not get used to Santiago. At the beginning of 1849, the government declared the creation of an architecture school, so Brunet de Baines had to combine his professional activity with his teaching from the beginning. Under these circumstances, he prepared and taught the first architecture course in Chile, and also wrote the accompanying teaching text that he published in 1853. Despite all these efforts, sacrifices, and extraordinary productivity, Brunet de Baines received harsh criticism. Partly due to the local misunderstanding of an unknown discipline and, therefore, undervalued, as well as due to the demands of the architect. As a result of the above, his health broke down, and just as his contract was expiring and he was preparing to return to France, he was suddenly taken by surprise by his death at the age of 55.3

Santiago in 1850

When Brunet de Baines arrived in Chile, a large group of intellectuals, including foreign artists and scientists, were already in the country working for the government to consolidate its national identity. Chile at that time enjoyed social and political stability unusual among the other countries of the region, which enabled it to allocate significant resources to further the process of building the nation.

In this context, the figure of Brunet de Baines has acquired a particular significance and his work has become a fundamental reference of that process. Particularly, because he transformed the capital´s image, transforming it from a dusty village into a modern city. The nature of the commissions that he received attests to this. Although these commissions can be understood as simple isolated initiatives, when examined as a whole, we can

On May 1, 1848, Brunet de Baines signed an employment contract as an official architect of the Republic, in order to work between 1848 y 1855.2 The document stipulated that he would be responsible for executing all civil architecture projects on behalf of the government or municipalities, although he could spend his free time on personal projects. Finally, he stated that if the Chilean government decided to create an architecture school, he would be responsible for setting it up and directing it.

3 The Messenger, Santiago Chile, Monday, June 18, 1855, p. 3

→ 9 Patrimonio / Heritage

X Pasaje Bulnes. Brazo norte-sur (desde el Portal Sierra Bella a Huérfanos), c. 1870. Fuente: Archivo fotográfico Museo Histórico Nacional de Chile. X Bulnes Passageway. North-south side (from Portal Sierra Bella to Huérfanos), c. 1870. Source: Photographic archives from the Chilean National Historical Museum.

2 The contract between C.F. Brunet de Baines and Francisco Javier Rosales, Paris, May 1, 1848. ARNAD, Fund of the Chilean Legation in France and Great Britain, Volume 30.

3 El Mensajero, Santiago de Chile, lunes 18 de junio de 1855, p. 3.

Santiago en 1850

Cuando Brunet de Baines llegó a Chile, un nutrido grupo de intelectuales, entre artistas y científicos, extranjeros, ya se encontraba en el país trabajando para el gobierno, con el fin de consolidar su identidad nacional. Chile gozaba, entonces, de una estabilidad social y política inusual en aquella época entre los países de la región, lo que permitió destinar importantes recursos para profundizar el proceso de construcción de la nación.

En este contexto, la figura de Brunet de Baines adquiere una particular significación y su obra se alza como un referente fundamental de aquel proceso. Particularmente, porque transformó la imagen de la capital, haciéndola transitar de aldea polvorienta a ciudad moderna. La naturaleza de los encargos que recibió así lo avalan. Si bien estos encargos se pueden entender como simples iniciativas aisladas, al examinarlas como conjunto vemos despuntar los visos de una delicada, pero sustantiva estrategia urbana.

Su singular contribución consistió, en primer lugar, en que Brunet de Baines introdujo en Chile el lenguaje clásico académico francés, en un momento único, tanto de la historia de la arquitectura, en general, como de la de Chile, en particular. En efecto, su obra tomó cuerpo a la luz de los preceptos de un academicismo hasta entonces no visto en Chile, y la materializó través de un conjunto inédito de edificios para Santiago, tanto por la novedad de su programa arquitectónico, como por su estratégica ubicación en la ciudad. Entre estos edificios sobresale el del Teatro Municipal, así como dos edificios comerciales: el Pasaje Bulnes y el Portal Tagle; que fueron construidos simultáneamente a la capilla de la Vera Cruz, ubicado a las afueras de Santiago, en el sector que, en la actualidad, conocemos como

Su singular contribución consistió, en primer lugar, en que Brunet de Baines introdujo en Chile el lenguaje clásico académico francés, en un momento único, tanto de la historia de la arquitectura, en general, como de la de Chile, en particular.

First of all, his singular contribution consisted of the fact that Brunet de Baines introduced the classical French academic language to Chile at a unique moment in the history of architecture in general and in Chile in particular.

see the outlines of a delicate but substantial urban strategy. First of all, his singular contribution consisted of the fact that Brunet de Baines introduced the classical French academic language to Chile at a unique moment in the history of architecture in general and in Chile in particular. Indeed, his work took shape in light of the precepts of an academicism previously unseen in Chile, and he materialized it through an unprecedented set of buildings for Santiago, both for the novelty of its architectural program and for its strategic location in the city. Among these buildings, the Municipal Theater stands out, as well as two commercial buildings: Pasaje Bulnes and Portal Tagle, which were built simultaneously alongside the Vera Cruz chapel, located on the outskirts of Santiago, in the sector we know today as the Lastarria neighborhood. To these buildings, we must add those projects that were not executed, but which help us to understand the magnitude of his urban proposal and the coherence of his architectural language. Among these projects is the facade of the Archbishop's Palace, located on the western edge of Plaza de Armas, facing Portal Tagle. The other is the project for the National Congress, whose proposal is supposedly based on the current building, although -so far- we have no concrete information. These projects completed or not, demonstrate an urban strategy that operated in the most significant locations of the city, such as Plaza de Armas; the church of La Compañía block; and the Real Universidad de San Felipe. Along with these buildings, we should also consider the works he carried out for private individuals, consisting mainly of mansions for the city's most distinguished families, beginning with that of President

W Proyecto para la fachada del Palacio Arzobispal.

Fuente: Almanaque pintoresco e instructivo para el año 1852. Santiago de Chile: Imprenta de Julio Belin, 1851, p. 46. Biblioteca de la Universidad de Harvard. W Project for the Archbishop's Palace facade. Source: Picturesque and instructive almanac for 1852. Santiago Chile: Julio Belin Press, 1851, p. 46. Harvard University Library.

Q Capilla de la Vera Cruz, c.

1915. Fuente: Jorge Walton, Vistas de Chile. Santiago: Imprenta Barcelona, 1915.

Q Vera Cruz Chapel, c.

1915. Source: Jorge Walton, Views of Chile. Santiago: Barcelona Press, 1915.

10 ← AOA / n°48

U Residencia de Manuel Bulnes. Fotografía de la fachada hacia calle Compañía, c. 1950. Fuente: Archivo Bello, Universidad de Chile.

→ 11 Patrimonio / Heritage

U Manuel Bulnes' residence. Photograph of the façade facing Compañía Street, c. 1950. Source: Bello Archive, Universidad de Chile.

barrio Lastarria. A estos edificios se debe agregar aquellos proyectos que no se ejecutaron, pero que ayudan a entender la magnitud de su propuesta urbana y la coherencia de su lenguaje arquitectónico. Entre estos proyectos destaca la fachada del Palacio Arzobispal, ubicado en el borde poniente de la Plaza de Armas, enfrentando al Portal Tagle.

El otro, es el proyecto para el Congreso Nacional, cuya propuesta supuestamente está en la base del edificio actual, pero del cual –hasta ahora– no tenemos noticia cierta.

Estos proyectos, realizados o no realizados, demuestran una estrategia urbana que operó en los lugares más significativos de la ciudad, como la Plaza de Armas; la manzana de la iglesia de la Compañía, y la de la Real Universidad de San Felipe. Junto a estos edificios, se deben considerar también los trabajos que realizó para privados, consistentes principalmente en mansiones para las familias más distinguidas de la ciudad, comenzando por la del Presidente Manuel Bulnes, la mayoría de las cuales se concentró en la calle Huérfanos y en torno a la plaza.

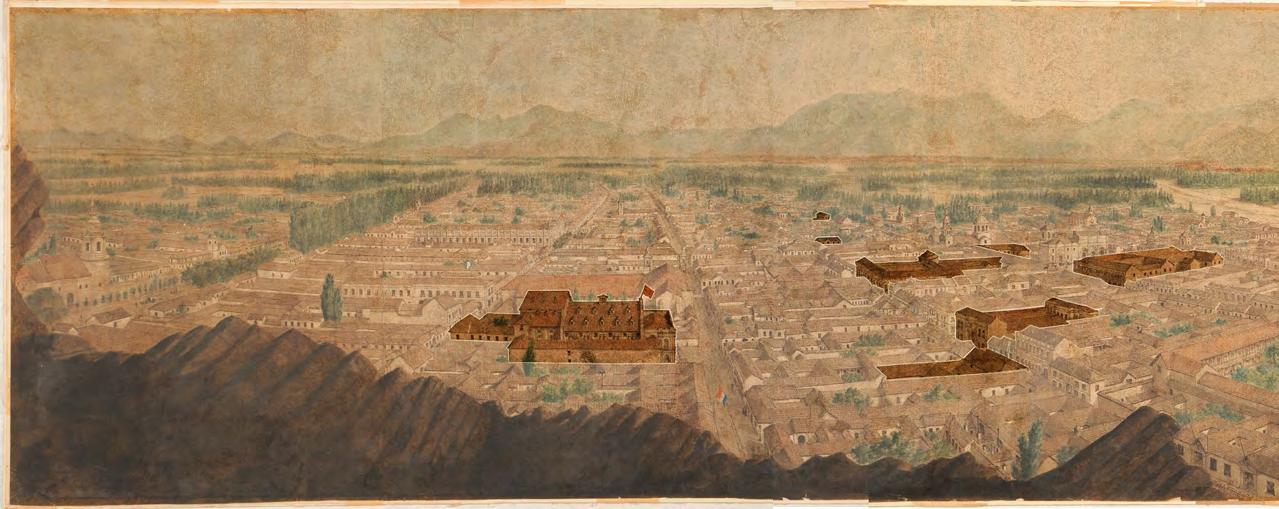

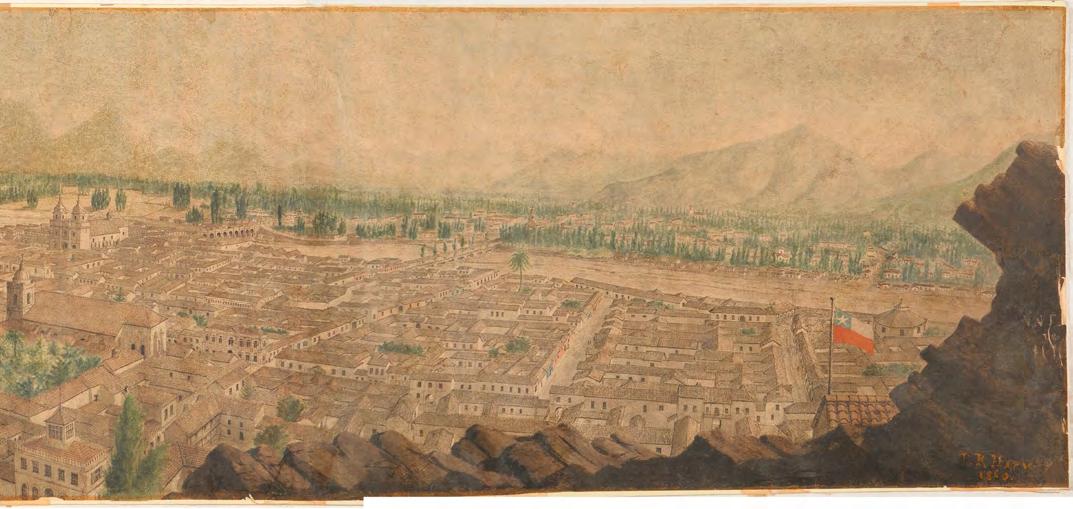

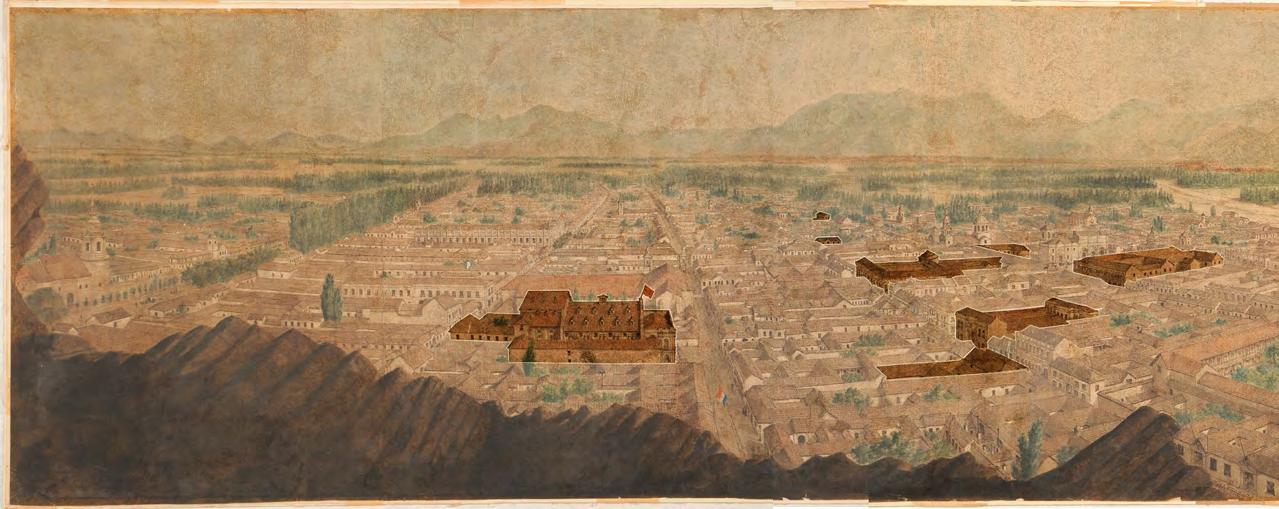

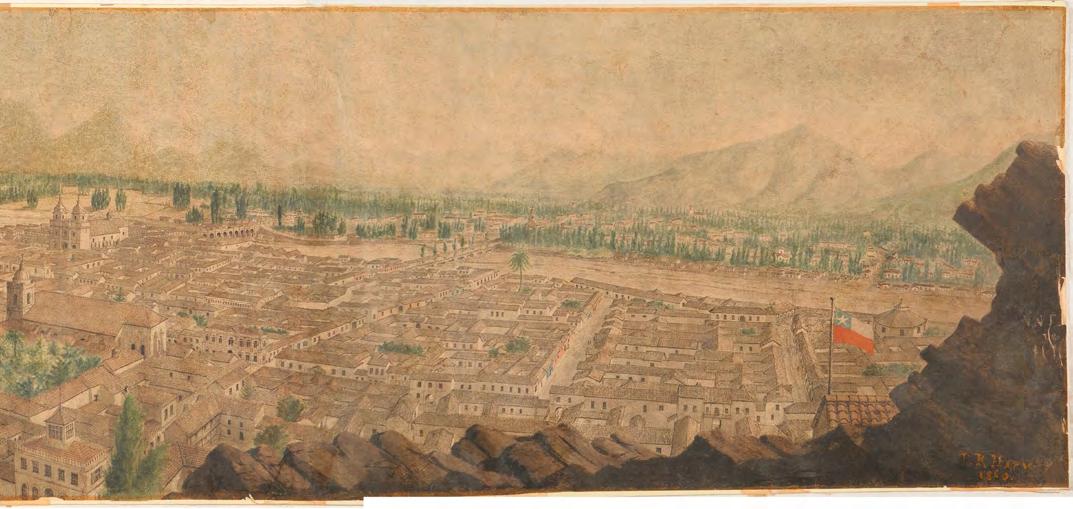

Un dibujo de la ciudad

Fortuitamente o no, hasta ahora no lo sabemos, en la vista panorámica de Santiago que T. R. Harvey dibujó desde el cerro Santa Lucía en 1860, quedó inmortalizado este especial momento: el tránsito desde una ciudad homogénea, todavía colonial, a una de orden diverso, donde se distinguen un nuevo tipo de edificaciones y un renovado orden urbano que principiaba a acentuar nuevas centralidades y recuperaba otras. Queriéndolo o no, Harvey hizo de esta representación sinóptica de Santiago un tributo a la obra de Brunet de Baines, abrochándola para siempre a ese momento inaugural de Chile como república.

A la luz de lo expuesto, se puede concluir que, en su conjunto, la obra de Brunet de Baines fue parte de un original proceso de modernización, cuyas acciones se concentraron en Santiago. Nos referimos, pues, al comienzo de un proceso de transformación que se verificó contra el telón de fondo de un momento único, casi mítico, en la historia de la nación: aquel que capitalizó el “orden portaliano” que tuvo lugar entre 1850 y 1860, en virtud de lo cual cabría denominarlo de “modernización republicana”. Significó un proceso fundamental para Chile, acaecido apenas tres décadas después de alcanzada la independencia, sin duda, un momento de apertura, el despuntar de una nación.

Manuel Bulnes, most of which were concentrated on Huérfanos Street and around Plaza de Armas.

A City Drawing

Fortuitously or not, until now we did not know that in the panoramic view that T. R. Harvey drew of Santiago from the Santa Lucía hill in 1860, that special moment was immortalized: the transition from a homogeneous city, still colonial, to one of diverse order, where new types of buildings and a renewed urban order that began to accentuate new centralities and recovered others can be distinguished. Whether he wanted it or not, Harvey made this synoptic representation of Santiago a tribute to the work of Brunet de Baines, anchoring it to that inaugural moment of Chile as a republic forever.

In light of the above, it can be concluded that, as a whole, Brunet de Baines' work was part of an original modernization process, whose actions were concentrated in Santiago. We refer, then, to the beginning of a transformation process that took place against the backdrop of a unique, almost mythical moment of the nation´s history: one that capitalized the "Portalian order" that took place between 1850 and 1860, by virtue of which it could be called "republican modernization". It meant a fundamental process for Chile, which took place barely three decades after the independence was achieved, undoubtedly, a moment that opened the emergence of a new nation.

This is a particularly notable and significant fact, but very little has been said about the role architecture had to play, and which the authorities of that time used consciously, making use of its historical representation mechanisms. Indeed, it was time to distance themselves -now definitively- from colonial references and the Hispanic cultural influence, and in this sense, one of the chapters that was justly pending was the renovation of institutional buildings, through which a new state of affairs was to be manifested. Such was the role that Brunet de Baines and his architecture had to play in the history of Chile. !

Brunet de Baines' work was part of an original modernization process, whose actions were concentrated in Santiago.

X T. R. Harvey. Vista Panorámica de Santiago, c. 1860. Destacados los proyectos de Brunet de Baines. Fuente: Museo Histórico Nacional de Chile. X T. R. Harvey. Panoramic view of Santiago, c. 1860. Brunet de Baines' projects are featured. Source: The Chilean National Historical Museum.

12 ← AOA / n°48

Este es un hecho particularmente notable y significativo, pero sobre el cual se ha dicho muy poco en relación al papel que le tocó desempeñar a la arquitectura, y que las autoridades de entonces utilizaron de modo consciente, sirviéndose de sus históricos mecanismos de representación. En efecto, era el momento de distanciarse–ya definitivamente– de los referentes coloniales y del influjo cultural hispano y, en este sentido, uno de los capítulos que justamente estaba pendiente era el de la renovación de los edificios institucionales, a través de los cuales se debía manifestar un nuevo estado de cosas. Tal fue, ni más ni menos, el papel que le tocó jugar a Brunet de Baines, y a su arquitectura, en la historia de Chile. !

REFERENCIAS

Brunet de Baines, C.F., (2008). Curso de Arquitectura [1853] Santiago: Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo, Universidad de Chile (edición facsimilar).

Delaire, Edmond A., (1907). Les architectes élèves de L’École des BeauxArts. 1793-1907. Paris: Librairie de la Construction Moderne.

Henríquez. José Manuel, (1957). Claudio Francisco Brunet de Baines y Luciano Ambrosio Hénault. Santiago: Universidad de Chile, Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo. Seminario de Historia de la Arquitectura, inédito.

Hidalgo, Germán, (2020). Brunet de Baines en Santiago de Chile, 18481855. Santiago.

Jüngersen, Francisca, (2012). De la capital poscolonial a capital republicana. Transformaciones en la arquitectura cívica de Santiago durante el proceso de consolidación de la República 1840-1879. Santiago: Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Tesis de doctorado, inédita.

Muñoz, Yolanda, (2011). El Palacio Arzobispal de Santiago de Chile (18101910): una reconstrucción crítica. Santiago: Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Tesis de Magíster inédita.

Pereira Salas, Eugenio, (1956). “La arquitectura chilena en el siglo XIX”. Anales de la Universidad de Chile, N°102.

Peliowski, Amarí, (2018). “Arquitectura, civilización y barbarie: Brunet de Baines como comentador social a mediados del siglo XIX en Chile”.

Revista 180, N°42.

Secchi, Manuel Eduardo, (1941). Arquitectura en Santiago: siglo XVII a siglo XIX. Santiago: Comisión del Cuarto Centenario de la Ciudad.

Waisberg, Myriam, (1961). “Creación y primera etapa 1849-1899. La clase de arquitectura y la sección de bellas artes”. Revista de la Facultad de Arquitectura de la Universidad de Chile, nº1.

REFERENCES

Brunet de Baines, C.F., (2008). Architecture Course [1853] Santiago: Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism, Universidad de Chile (facsimile edition).

Delaire, Edmond A., (1907). Student architects at the École des BeauxArts. 1793-1907. Paris: Modern Construction Bookstore.

Henríquez. José Manuel, (1957). Claudio Francisco Brunet de Baines & Luciano Ambrosio Hénault. Santiago: Universidad de Chile, Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism. Seminar on History of Architecture, unpublished.

Hidalgo, Germán, (2020). Brunet de Baines in Santiago Chile, 1848-1855. Santiago.

Jüngersen, Francisca, (2012). From postcolonial capital to republican capital. Transformations in Santiago's civic architecture during the process of the Republic´s consolidation. 1840-1879. Santiago: Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis.

Muñoz, Yolanda, (2011). The Archbishop's Palace in Santiago, Chile (18101910): a critical reconstruction. Santiago: Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Unpublished Master's thesis.

Pereira Salas, Eugenio, (1956). “Chilean Architecture in the 19th Century”. Universidad de Chile Annals, N°102.

Peliowski, Amarí, (2018). Architecture, Civilization and Barbarity: Brunet Debaines as a social commentator in mid-19th century Chile”. Magazine 180, N°42.

Secchi, Manuel Eduardo, (1941). Santiago Architecture: from the 17th to 19th century. Santiago: Commission of the City's 400th Anniversary. Waisberg, Myriam, (1961). “Creation and first stage 1849-1899. The architecture class and fine arts section”. Magazine from the Architecture Faculty at the Universidad de Chile, nº1.

→ 13 Patrimonio / Heritage

La obra de Brunet de Baines fue parte de un original proceso de modernización, cuyas acciones se concentraron en Santiago.

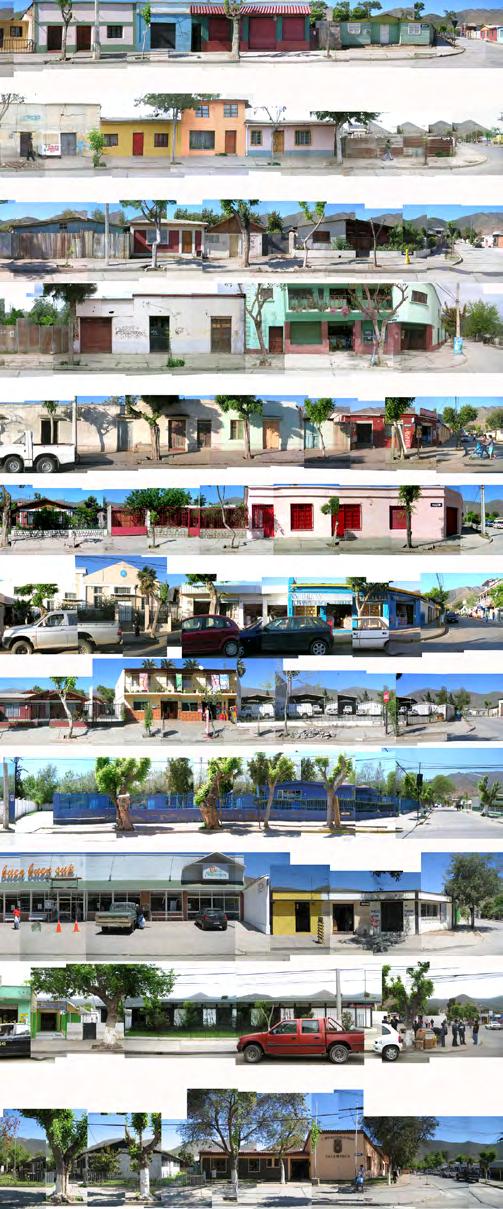

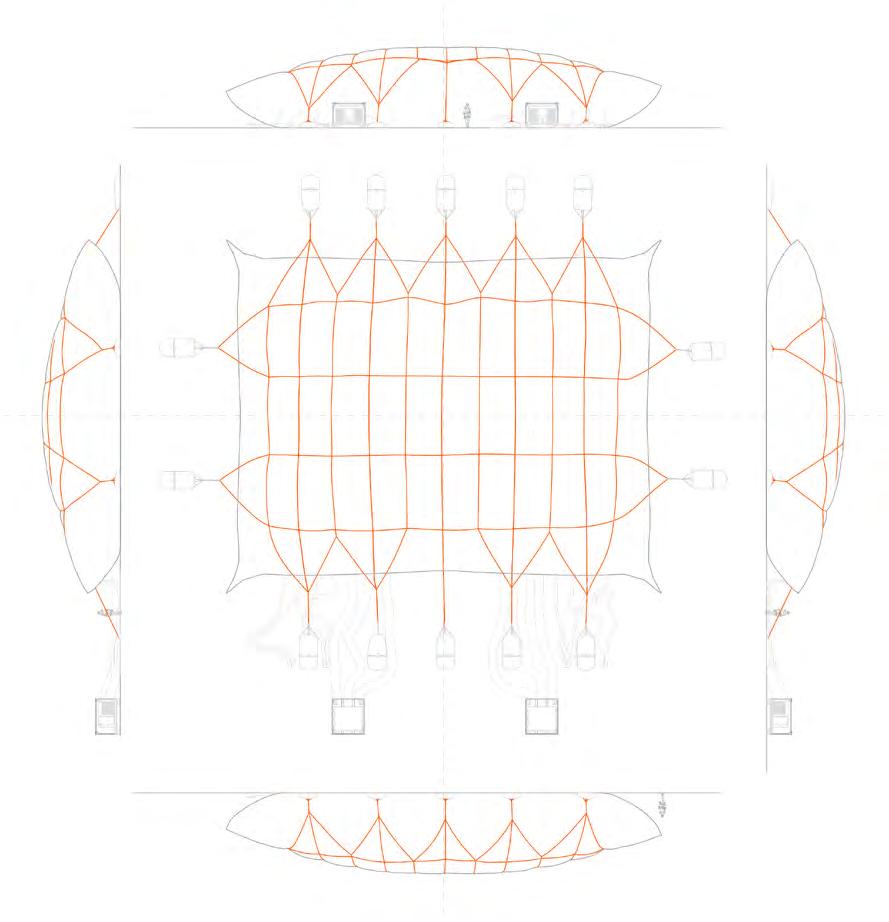

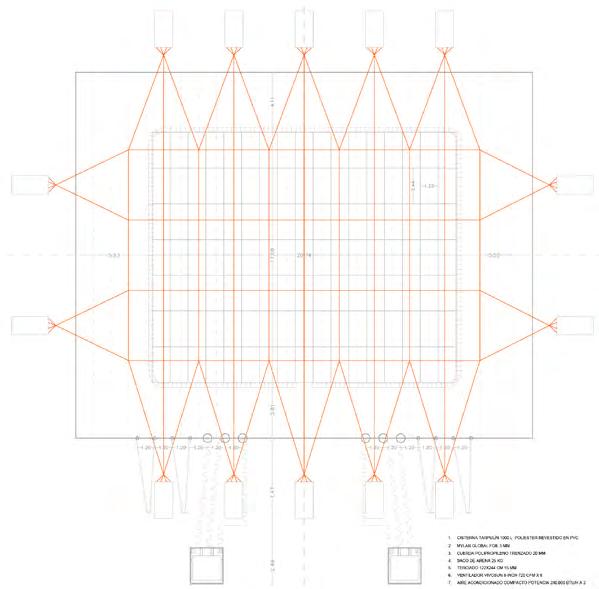

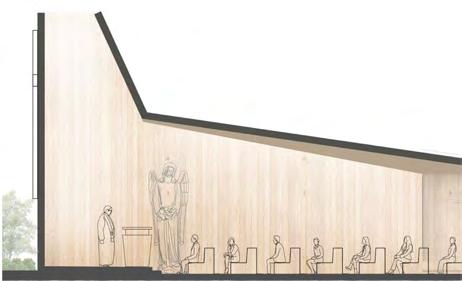

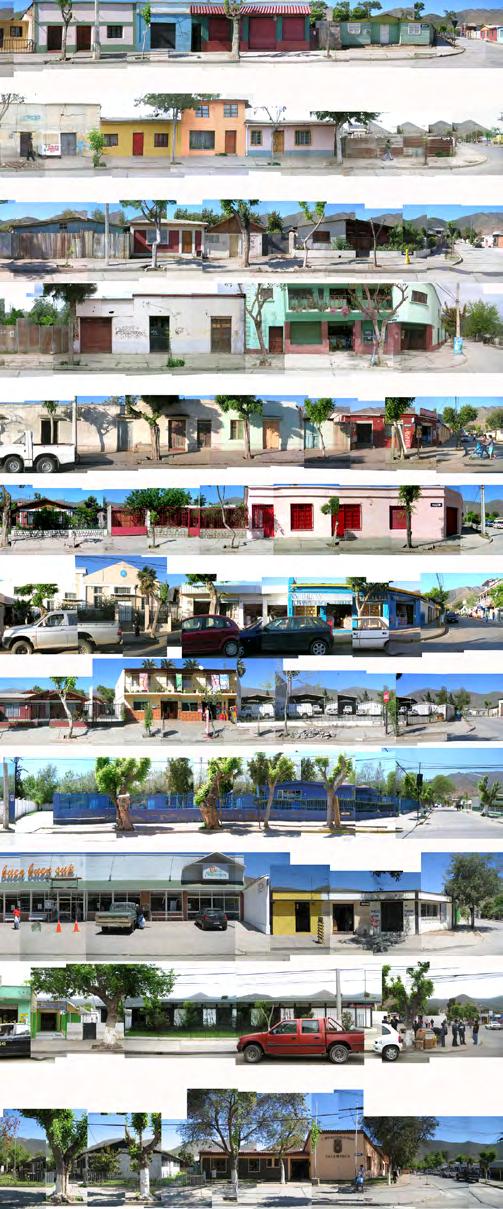

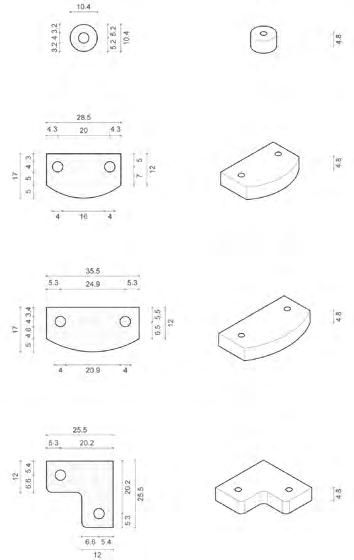

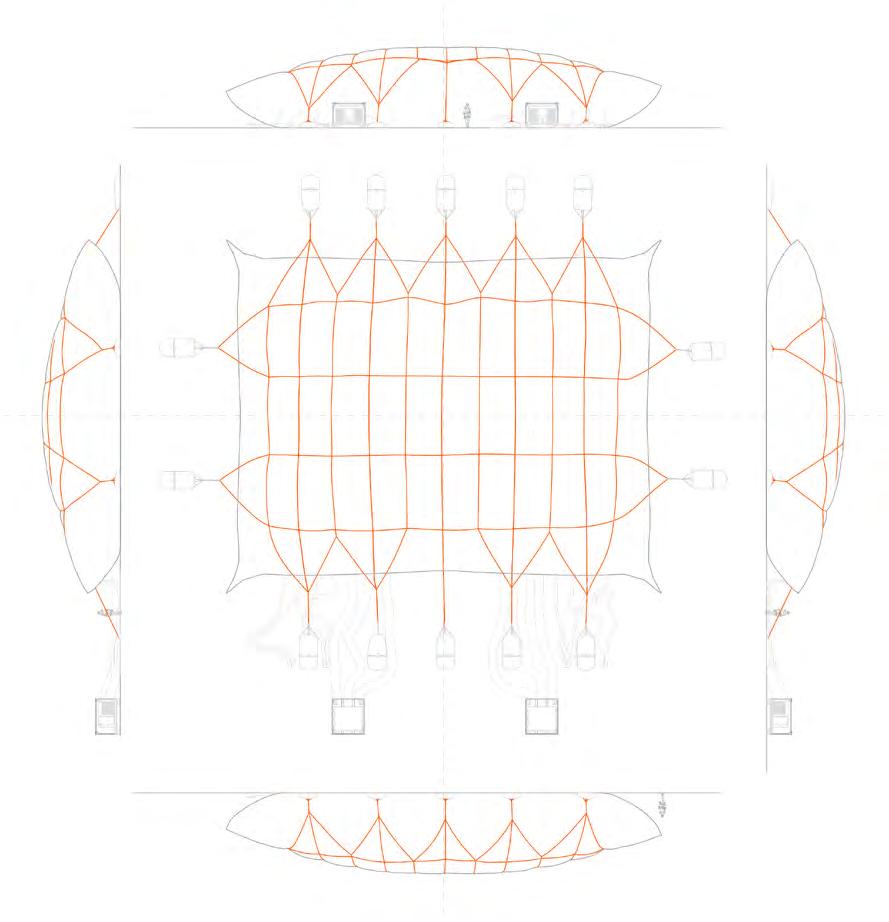

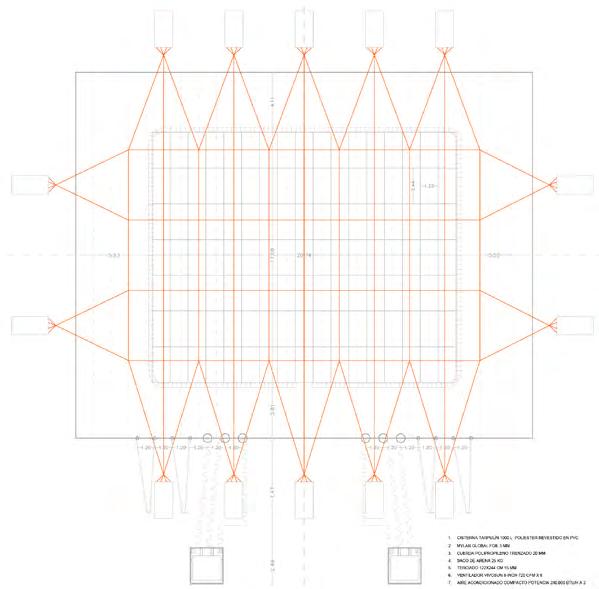

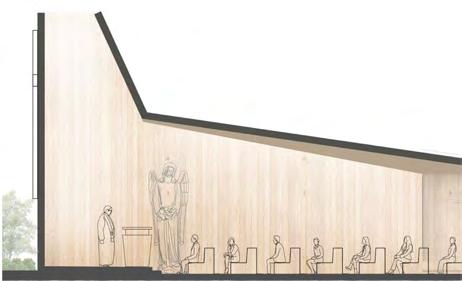

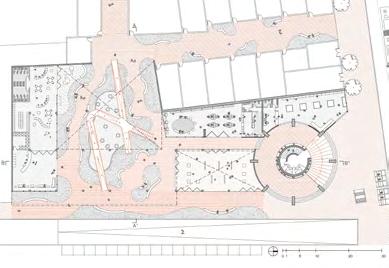

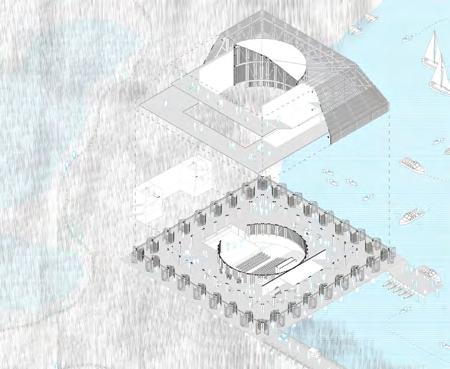

R Aproximaciones a la planimetría de fachadas de proyectos de Brunet de Baines en Santiago de Chile realizadas por el autor / R Facade Planimetry Approximations of Brunet de Baines' projects in Santiago, Chile made by the author.

Nota: Las dimensiones y proporciones de las fachadas son sólo aproximadas. Note: The facades' dimensions and proportions are only approximate.

14 ← AOA / n°48

W Pasaje Tagle / Tagle Passageway 1849-1854

W Teatro Municipal / Municipal Theater 1853-1857

W Capilla de N.S. de La Veracruz N.S. de La Veracruz Chapel 1852-1855

W Palacio Arzobispa / Archbishop's Palace 1850-1851

W Pasaje Bulnes / Bulnes Passageway 1849-1854

W Casa Matías Cousiño Jorquera Matías Cousiño Jorquera's House 1850-1854

W Residencia de Manuel Bulnes Prieto / Manuel Bulnes Prieto's Residence 1849-1854

W Residencia de Melchor de Santiago Concha y Cerda Melchor de Santiago Concha y Cerda's Residence 1849-1854

W Residencia de Ignacio Valdés Larrea / Ignacio Valdés Larrea's Residence 1849-1854

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 6 1 2 3 4 5 7 9 8

W Residencia de Carlos Mac Clure Ossandón / Carlos Mac Clure Ossandón's Residence 1849-1854

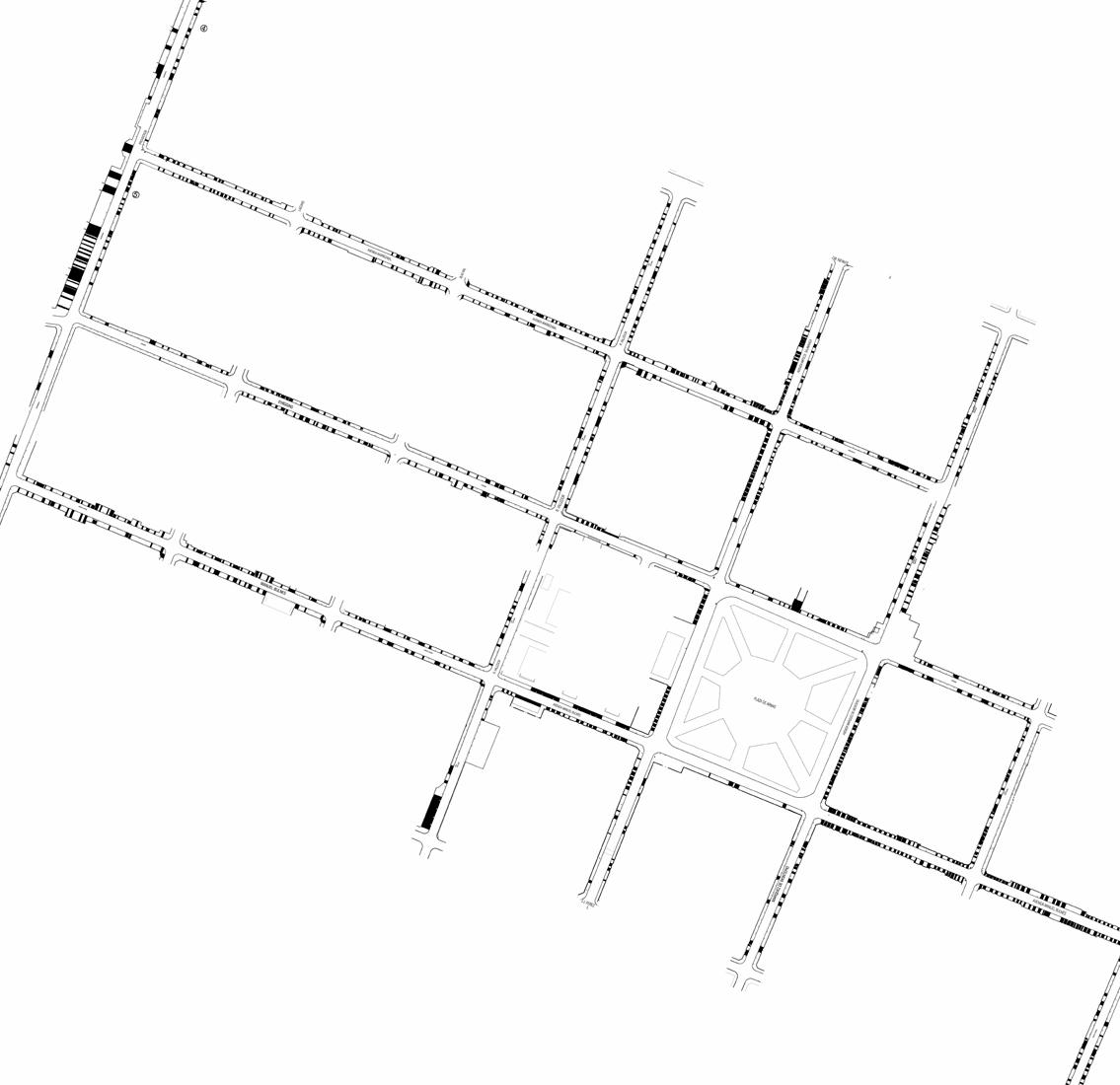

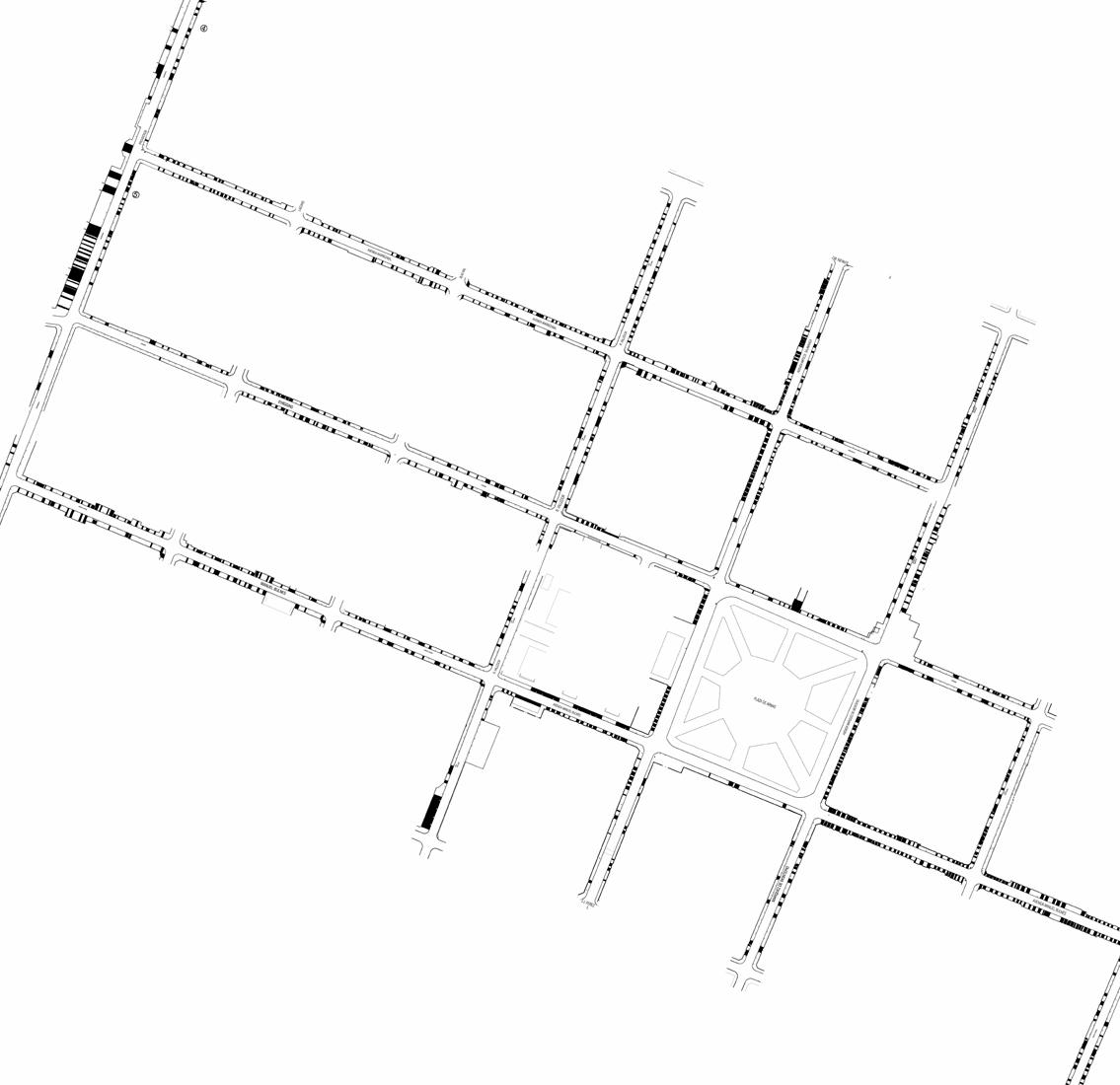

Planta de Santiago de 1850. Proyecto Fondecyt N° 1150308. Investigador responsable: Germán Hidalgo. / Plan of Santiago from 1850. Fondecyt Project N° 1150308. Principal Investigator: Germán Hidalgo.

“It was time to distance themselves -now definitively- from colonial references and the Hispanic cultural influence, and in this sense, one of the chapters that was justly pending was the renovation of institutional buildings, through which a new state of affairs was to be manifested. Such was the role that Brunet de Baines and his architecture had to play in the history of Chile. ”

Agradecimientos_Al Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Cultural y las Artes, Convocatoria 2019, que financió la investigación FONDART, Folio N°482124. A la Facultad de Arquitectura, Diseño y Estudios Urbanos de la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, por haber permitido mi dedicación a este trabajo. También a las siguientes instituciones: Museo Benjamín Vicuña Mackenna; Museo Histórico Nacional; Mapoteca de la Biblioteca Nacional de Chile; Archivo Histórico Nacional; Archivo Andrés Bello; Archivo de Arquitectura Chilena, FAU Universidad de Chile; Archivo Técnico Aguas Andinas; Archivo DOM I. Municipalidad de Santiago; Biblioteca Campus Lo Contador, UC; Flickr Santiago Nostálgico; Biblioteca Universidad de Harvard. Y a las siguientes personas: Magdalena Montalbán; Francisca Jüngersen; Yolanda Muñoz; Patricio Frez, Hernán Rodríguez Villegas; y a los entonces estudiantes de la Escuela de Arquitectura UC: Vicente Arcuch, Marjorie Barros, Gabriela Reyes y Paula González

Acknowledgments_To the Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Cultural y las Artes, Convocatoria 2019, which financed the research FONDART, Folio N°482124. To the Faculty of Architecture, Design, and Urban Studies at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, for allowing my dedication to this work. Also to the following institutions: Museo Benjamín Vicuña Mackenna; Museo Histórico Nacional; Mapoteca de la Biblioteca Nacional de Chile; Archivo Histórico Nacional; Archivo Andrés Bello; Archivo de Arquitectura Chilena, FAU Universidad de Chile; Archivo Técnico Aguas Andinas; Archivo DOM I. Municipality of Santiago; Lo Contador Campus Library, UC; Flickr Santiago Nostalgic; Harvard University Library. In addition, to the following people: Magdalena Montalbán; Francisca Jüngersen; Yolanda Muñoz; Patricio Frez, Hernán Rodríguez Villegas; and to the then students of the UC School of Architecture: Vicente Arcuch, Marjorie Barros, Gabriela Reyes, and Paula González.

→ 15 Patrimonio / Heritage

“

Era el momento de distanciarse–ya definitivamente– de los referentes coloniales y del influjo cultural hispano y, en este sentido, uno de los capítulos que justamente estaba pendiente era el de la renovación de los edificios institucionales, a través de los cuales se debía manifestar un nuevo estado de cosas. Tal fue, ni más ni menos, el papel que le tocó jugar a Brunet de Baines, y a su arquitectura, en la historia de Chile”.

mauricio sánchez

Arquitecto de la Universidad Católica, Máster en Restauración Arquitectónica de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. Es jefe del Departamento de Gestión de Proyectos de la Subsecretaría del Patrimonio Cultural. Además, es profesor adjunto de la Escuela de Arquitectura UC.

An architect from the Universidad Católica, and a Master in Architectural Restoration from Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. He is head of the Project Management Department of the Undersecretary of Cultural Heritage. He is also an Associate Professor at the Architecture School of Universidad de Católica.

santiago canales

Arquitecto y Magíster en Arquitectura de la Universidad Católica, ejerce como coordinador de Proyectos del Departamento de Gestión de Proyectos de la Subsecretaría del Patrimonio Cultural y es miembro del Cluster Patrimonio y Modernidad del Centro de Patrimonio Cultural UC desde donde ha participado en diversos proyectos de investigación.

An Architect and Master in Architecture from the Universidad Católica, he works as a Project Coordinator for the Project Management Department of the Undersecretary of Cultural Heritage and is a member of the Heritage and Modernity Cluster at the UC Cultural Heritage Center, where he has participated in several research projects.

16 ← AOA / n°48

Teatro Municipal o el ideario del patrimonio propio del centro de Santiago

MUNICIPAL THEATER OR THE PROPER HERITAGE IDEOLOGY OF DOWNTOWN SANTIAGO

por by : mauricio sánchez & santiago canales

por by : mauricio sánchez & santiago canales

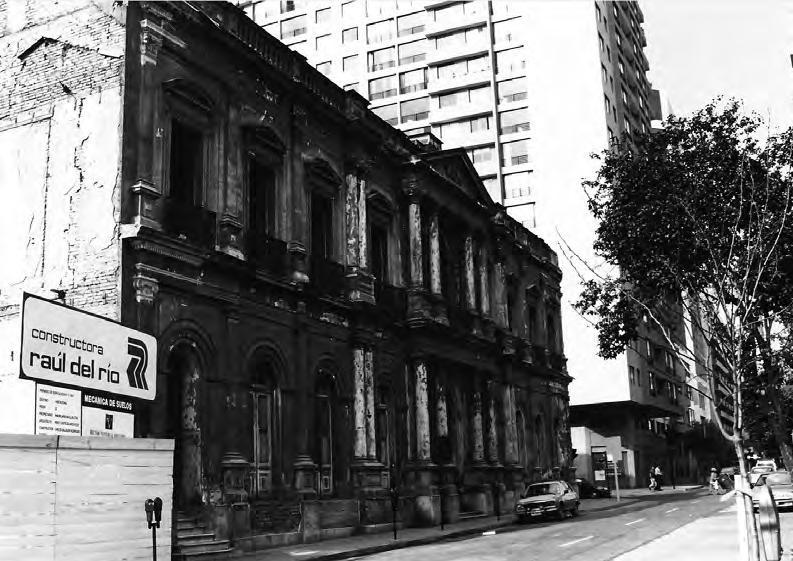

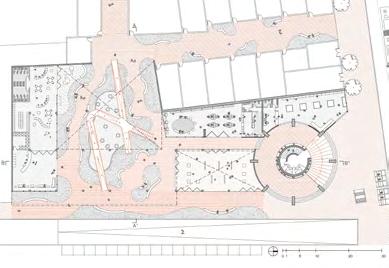

La construcción del Teatro Municipal (1857), declarado como Monumento Histórico (1974), se sitúa en los inicios de la nueva república generando, desde entonces, un espacio icónico, centro de la ópera, la danza y conciertos sinfónicos y de cámara a nivel nacional. Esta infraestructura cultural es un ejemplo de los primeros edificios del centro de Santiago que buscaron la modernización del país, para transitar desde la noción de una ciudad que disponía de un imaginario de orden colonial hacia la necesidad, a nivel nacional, de vincular todos los territorios con una sola y nueva identidad (fig. 2). En este sentido, el Municipal es parte del conjunto de decisiones estratégico-políticas que inaugura un periodo de materialización de la infraestructura pública como símbolo de la imagen nacional y, en cierto sentido, como un patrimonio nuevo para esta reciente nación.

to the need, at the national level, to link all the territories with a single new identity (fig. 2). In this sense, the Municipality is part of the strategic-political decisions that inaugurate a period of public infrastructure materialization as symbols of the national image and, in a certain sense, constituted new heritage for this recent nation.

→ 17 Patrimonio / Heritage

The construction of the Municipal Theater (1857), declared a Historic Monument (1974), was built at the beginning of the new republic, creating, since then, an iconic space, opera center, dance, symphony, and concert chamber at a national level. This cultural infrastructure is an example of the first buildings in downtown Santiago that looked to modernize the country, to move from the notion of a city that had a colonial order image

Patrimonio / Heritage

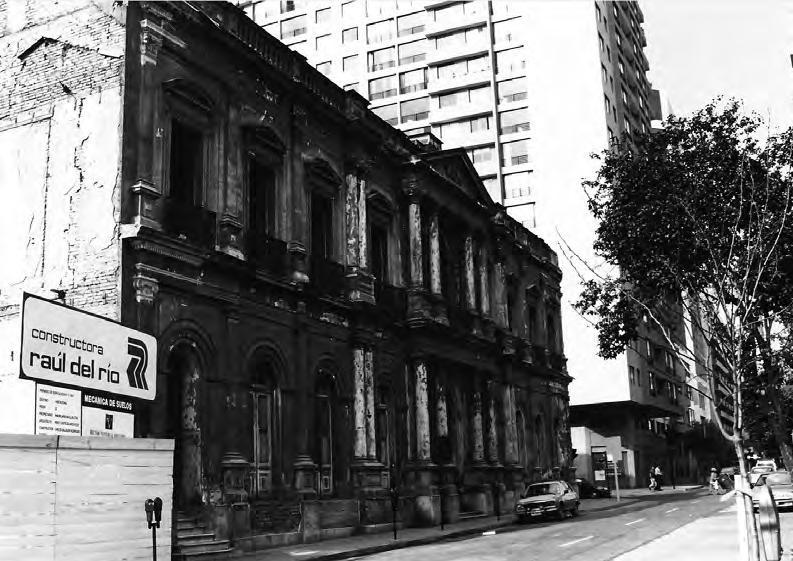

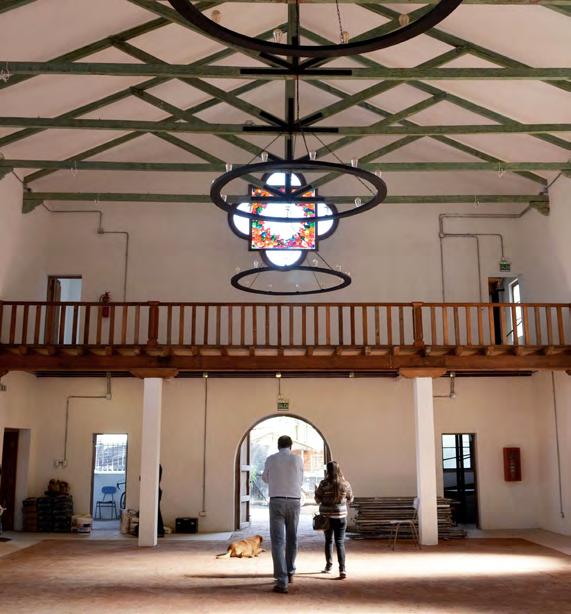

S Figura 1: Acceso principal del Teatro Municipal hacia fines del siglo XX. Fuente: Dirección de Arquitectura – MOP. S Figure 1: Main entrance of the Municipal Theater by the end of the 20th century. Source: Architecture Directorate - MOP.

Hacia fines del siglo XIX, cuando Chile se empezó a conformar territorialmente como lo conocemos hoy –con la anexión de las regiones del norte, la entrega de la Patagonia a la Argentina y la colonización del territorio al sur del río Biobío–, fue necesario desarrollar obras públicas para consolidar sus ciudades y la imagen del Estado-Nación. En este sentido, debió construir un patrimonio propio que se plasmó a través de la adquisición y materialización de bienes para el territorio referidos a la conectividad, a la productividad y, especialmente, a la consolidación de ciudades como centros geopolíticos.

La ejecución de estas obras requería de profesionales con capacidades técnicas que el país no disponía. A partir de esto, el Presidente Bulnes tomó la decisión de contratar profesionales en el extranjero, principalmente europeos, que se encargaran de desarrollar y construir estas obras. Por estos motivos, el arquitecto Claude François Brunet de Baines arribó a Chile en 1848, siendo contratado como "arquitecto de Gobierno" y con la misión de hacerse cargo de la planificación y ejecución de las nuevas edificaciones, entre ellas, el Teatro Municipal. Al mismo tiempo, asumió la labor de iniciar la formación de los primeros profesionales arquitectos, dictando un curso dentro de la Universidad de Chile. La llegada de Brunet de Baines provocó dos acciones relevantes para la arquitectura chilena: la consolidación de una arquitectura de Estado, a partir de la contratación de un "arquitecto de Gobierno" como funcionario público a cargo de la planificación y ordenamiento de nuestro territorio; y el inicio formal de la educación de la arquitectura en nuestro país –primero como cursos y luego como carrera formal en la Universidad de Chile y la Universidad Católica–.

The construction of City Hall and other buildings in the center of the capital was a radical break from the symbolic and material dimension of the building within the historical layout of the foundational center, bringing the conceptual transformation from the notion of the village to that of the historical cente.

Towards the end of the 19th century, when Chile began to take shape territorially as we know it today -with the northern regions annexation, the surrender of Patagonia to Argentina, and the territory colonization south of the Biobío River-, it was necessary to develop public works to consolidate its cities and the image of the Nation-State. In this regard, it had to build its own heritage, which took shape through the acquisition and materialization of goods for the territory related to connectivity, productivity, and, especially, the consolidation of cities as geopolitical centers.

The execution of these works required professionals with technical skills that the country did not have. As a result, President Bulnes decided to hire professionals from abroad, mainly Europeans, to develop and build these works. For these reasons, architect Claude François Brunet de Baines arrived in Chile in 1848 and was hired as a Government Architect with the responsibility of being in charge of planning and executing the new buildings, among them, the Municipal Theater. At the same time, he took charge of training the first professional architects by teaching a course at the Universidad de Chile. The arrival of Brunet de Baines brought about two relevant actions for Chilean architecture: the consolidation of State architecture, through the hiring of a Government Architect as a public official in charge of

X Figura 2: Teatro Municipal hacia fines del siglo XX. Fuente: Dirección de Arquitectura – MOP.

X Figure 2: Municipal Theater towards the end of the 20th century. Source: Architecture Directorate - MOP.

U Figura 3: Teatro Municipal en el siglo XIX. Fuente: Dirección de Arquitectura – MOP.

U Figure 3: Municipal Theater in the 19th Century. Source: Architecture Directorate - MOP.

18 ← AOA / n°48

La construcción del Municipal y de otros edificios del centro de Santiago implicó un quiebre radical a la dimensión simbólica y material del edificio dentro del trazado histórico del centro fundacional, planteando la transformación conceptual desde la noción de aldea a la de centro histórico.

Biblioteca Nacional.

Fuente: Dirección de Arquitectura – MOP.

T Figure 4: Construction of the National Library.

Source: Architecture

Directorate - MOP.

En estas circunstancias –un escenario de construcciones bajas del tipo casa-patio o edificio-patio, con fachada continua de uno o dos pisos de muros de adobe y cubiertas de tejas de arcilla o de edificios religiosos de órdenes eclesiásticas presentes hacia el siglo XIX–, el Teatro Municipal se concibió en los inicios de un momento crucial para la construcción de edificios civiles en el centro de Santiago y las grandes ciudades de Chile, dando origen a una nueva herencia construida. La construcción del Municipal y de otros edificios del centro de la capital implicó un quiebre radical a la dimensión simbólica y material del edificio dentro del trazado histórico del centro fundacional, planteando la transformación conceptual desde la noción de aldea a la de centro histórico (fig. 3).

En un Chile que no contaba con la tradición ni el desarrollo de las capitales virreinales, se importó una imagen eurocéntrica para consolidar la transformación de sus edificios. Esta nueva imagen reemplazó las casas coloniales y estructuras religiosas por palacios y edificios de mayor envergadura, especialmente a partir de la celebración del centenario, ejemplo de esto son: la construcción de la Biblioteca Nacional y sus Depósitos entre 1913 y 1915 (Gustavo García del Postigo), que reemplazaron al Monasterio e Iglesia de las Monjas Clarisas; la manzana de la Bolsa de Comercio, donde se ubica el edificio de la Bolsa (Emilio Jequier) y el Club de la Unión (Alberto Cruz Montt) levantados entre 1913 y 1925, que reemplazaron al Monasterio de las Monjas Agustinas, manteniendo solo la iglesia de la orden; o la Casa Central de la Universidad de Chile (Lucien Henault y Fermín Vivaceta) construida en la década de 1890, que reemplazó a la Iglesia de San Diego (fig. 4).

planning and organizing our territory; and the formal beginning of architectural education in our country -first as courses and then as a formal career at Universidad de Chile and Universidad Católica-, and the creation of an architecture school in Chile.

In these circumstances - a scenario of low house-courtyard or building-courtyard type construction, with a continuous facade of one or two stories of adobe walls and clay tile roofs or religious buildings of ecclesiastical orders present around the nineteenth century - the Municipal Theater was conceived at the beginning of a crucial moment for the construction of civil buildings in downtown Santiago and Chile´s large cities, giving rise to newly built heritage. The construction of City Hall and other buildings in the center of the capital was a radical break from the symbolic and material dimension of the building within the historical layout of the foundational center, bringing the conceptual transformation from the notion of the village to that of the historical center (fig. 3).

In a Chile that lacked the tradition and development of vice-royal capitals, a Eurocentric image was imported to consolidate the transformation of its buildings. This new image replaced the colonial houses and religious structures with palaces and larger buildings, especially after the centennial celebration: the construction of the National Library and its Storage between 1913 and 1915 (Gustavo García del Postigo), which replaced the Monastery and Church of the Clarisas´ Nuns; the Stock Exchange block where the Stock Exchange building is located (Emilio Jequier) and the Union Club (Alberto Cruz Montt) built between 1913 and 1925, which replaced the Augustinian Nuns´ Monastery keeping only the church of the

→ 19 Patrimonio / Heritage

T Figura 4: Construcción

La conformación de los centros históricos como un cambio de paradigma programático y de significado, el resguardo de la estructura urbana de la manzana como soporte asumiendo la pérdida de rasgos y huellas materiales existentes y la consideración de la nueva edificación como referente volumétrico para la construcción de nuevas estructuras dentro de la manzana, componen la estrategia urbana y política de esta bitácora identitaria de la segunda mitad del siglo XIX y las primeras décadas del siglo XX.

La conformación de los centros históricos como un cambio de paradigma programático y de significado, el resguardo de la estructura urbana de la manzana como soporte, asumiendo la pérdida de rasgos y huellas materiales existentes, y la consideración de la nueva edificación como referente volumétrico para la construcción de nuevas estructuras dentro de la manzana, componen la estrategia urbana y política de esta bitácora identitaria de la segunda mitad del siglo XIX y las primeras décadas del siglo XX. Su objetivo era la construcción de una nueva identidad nacional, reconociendo la responsabilidad del Estado en idear, gestionar y materializar obras que se constituirán en referentes de futuro (fig. 5).

A fines del siglo XX, la imagen del centro de Santiago osciló entre la decadencia y la densificación, siendo común las imágenes de deterioro y abandono de algunos espacios –implicando la pérdida de atributos y la integridad de áreas funcionales– y la construcción de viviendas en altura, en busca de la llegada de habitantes al centro de la ciudad. De esta forma, iniciado el siglo XXI, las demandas ciudadanas por preservar edificios y barrios

The conformation of historic centers as a change of programmatic paradigm and meaning, the safeguarding of the block´s urban structure as support, assuming the loss of existing features and material traces, and the consideration of the new building as a volumetric reference for the construction of new structures within the block, make up the urban and political strategy of this identity log of the second half of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth century.

Q Figura 5: Palacio de la Moneda – Antigua “Real Casa de Moneda” 1950.

Fuente: Colección Documental Montandón, CMN.

Q Figure 5: Palacio de la Moneda - Former "Real Casa de Moneda" 1950.

Source: Montandón Documentary Collection, CMN.

20 ← AOA / n°48

históricos convocaron a las instituciones públicas a intervenir en los suelos e inmuebles existentes para recomponer el significado del centro de Santiago (fig. 6). Estas acciones se representan en intervenciones de edificios históricos o en sitios eriazos para instalar edificación pública en sus viejas estructuras. Hechos materiales como la construcción del Centro Cultural Palacio La Moneda (Undurraga y Devés), el edificio Moneda Bicentenario (Teodoro Fernández), sede de la Subsecretaría de Desarrollo Regional que se inserta en el Barrio Cívico, los edificios del Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia (Undurraga y Devés) y del Banco del Estado (+Arquitectos/ Flaño, Núñez Tuca/ ADN Arquitectos) contiguos a la Iglesia Santa Ana, el edificio de la Fiscalía Nacional (LCV Arquitectura y Lateral Arquitectura) y la reciente restauración del Palacio Pereira (Puga, Velasco y Moletto), sede de la institucionalidad patrimonial. Estos proyectos instalan para el Estado una perspectiva respecto de los nuevos desafíos sobre la preservación, reintegración y consolidación del patrimonio construido de los centros urbanos del país. El sentido de oportunidad detrás de la intervención sobre edificios en deterioro, está en la posibilidad de instalar un nuevo discurso como política pública, desde el trabajo sobre las imágenes de una ciudad rota y su (re)interpretación. La constatación de un alto número de inmuebles con valor patrimonial en deterioro, ya sea por abandono, desastres u otros fenómenos naturales, permite al Estado de Chile vislumbrar la oportunidad de trabajar sobre esas imágenes históricas y reorientar la potencia que en ellas se almacena, como obras que consolidaron la imagen del Estado-Nación decimonónico (fig. 7). Así, entendemos que fomentar la experimentación y reinterpretación del patrimonio construido es una responsabilidad pública para la preservación efectiva de la memoria histórica que se alberga en los espacios ciudadanos. En estos últimos años, en que las experiencias de intervención y los estudios sobre los inmuebles –tanto en el centro de Santiago como en el resto de las ciudades de Chile– han sido múltiples, resulta un ejercicio pertinente revisar en retrospectiva la historia de las obras emblemáticas de la arquitectura estatal, para promover nuevas experiencias de renovación y para la proyección del próximo periodo de nuestra nación. !

order; or the Main House of Universidad de Chile (Lucien Henault and Fermín Vivaceta) built in the 1890s, which replaced the San Diego Church (fig. 4).

The conformation of historic centers as a change of programmatic paradigm and meaning, the safeguarding of the block´s urban structure as support, assuming the loss of existing features and material traces, and the consideration of the new building as a volumetric reference for the construction of new structures within the block, make up the urban and political strategy of this identity log of the second half of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth century. Its objective was the construction of a new national identity, recognizing the responsibility of the State in devising, managing, and materializing works that would become referents for the future (fig. 5).

At the end of the 20th century, the image of downtown Santiago oscillated between decadence and densification, with images of deterioration and abandonment of some spaces being common - implying the loss of attributes and the integrity of functional areas - and the construction of high-rise housing, in response to the influx of inhabitants to downtown. Thus, at the beginning of the 21st century, citizen requests for the preservation of historic buildings and neighborhoods called on public institutions to intervene in the existing land and buildings to restore the meaning of downtown Santiago (fig. 6). These actions are represented in interventions on historic buildings or on unused sites to install public buildings on their old structures. Material facts such as the construction of the Palacio de la Moneda Cultural Center (Undurraga and Devés), the Moneda Bicentenario building (Teodoro Fernández), the Undersecretary of Regional Development headquarters inserted in the Civic Quarter, the Ministry of Social Development and Family (Undurraga and Devés) and the Banco del Estado buildings (+Arquitectos/ Flaño, Núñez Tuca/ ADN Arquitectos) adjacent to the Santa Ana Church, the National Prosecutor's Office building (LCV Arquitectura and Lateral Arquitectura) and the recent restoration of the Pereira Palace (Puga, Velasco, and Moletto), headquarters of the heritage institutions. These projects provide the State with a perspective on the new challenges regarding the preservation, reintegration, and consolidation of the heritage built in the country's urban centers.

The sense of opportunity behind the intervention in deteriorating buildings lies in the possibility of installing a new discourse as public policy, from the work on the images of a broken city and its (re)interpretation. The finding of a high number of buildings with heritage value in deterioration, either by abandonment, disasters, or other natural phenomena, allows the Chilean State to glimpse the opportunity to work on these historical images and reorient the power stored in them, as works that consolidated the image of the nineteenth-century nation-state (fig. 7). Hence, we understand that encouraging experimentation and reinterpretation of the heritage built is a public responsibility for the effective preservation of the historical memory housed in citizen spaces. In recent years, in which the experiences of intervention and studies on buildings in downtown Santiago and in the rest of the cities of Chile have been numerous, it is a pertinent exercise to review the history of the emblematic works of state architecture in retrospect, to promote new experiences of renovation, and to project the next period of our nation. !

→ 21 Patrimonio / Heritage

X Figura 6: Palacio Pereira en ruinas hacia fines del siglo XX. Fuente: Centro de Extensión Palacio Pereira

X Figure 6: Pereira Palace in ruins towards the end of the 20th century.

Source: Pereira Palace Extension Center

22 ← AOA / n°48

T Figura 7: Calle Bandera, manzana Club de la Unión y Bolsa de Comercio.

Fuente: Dirección de Arquitectura – MOP

T Figure 7: Bandera Street, Union Club, and Stock Exchange block.

Source: Architecture Directorate - MOP

“In recent years, in which the experiences of intervention and studies on buildings in downtown Santiago and in the rest of the cities of Chile have been numerous, it is a pertinent exercise to review the history of the emblematic works of state architecture in retrospect, to promote new experiences of renovation, and to project the next period of our nation. ”

→ 23 Patrimonio / Heritage

En estos últimos años, en que las experiencias de intervención y los estudios sobre los inmuebles tanto en el centro de Santiago como en el resto de las ciudades de Chile han sido múltiples, resulta un ejercicio pertinente revisar en retrospectiva la historia de las obras emblemáticas de la arquitectura estatal, para promover nuevas experiencias de renovación y para la proyección del próximo período de nuestra nación”.

“

© Aryeh Kornfeld

R Fernando Pérez es reconocido como uno de los teóricos, intelectuales y arquitectos más influyentes en Chile. Su aporte desde la investigación, la teoría y la docencia, así como sus obras construidas, lo hacen un referente para varias generaciones de arquitectos. A pocos días de terminar su cargo como director del Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Santiago, cargo que ejerció desde 2019, conversó con nosotros sobre su trayectoria, obra y visión de la arquitectura. R Fernando Pérez is recognized as one of the most influential theorists, intellectuals, and architects in Chile. His contribution from research, theory, and teaching, as well as his built works, make him a reference for several generations of architects. A few days before the end of his tenure as director of the National Museum of Fine Arts, a position he held since 2019, he spoke with us about his career, work, and vision of architecture.

por_by:Sofía Arnaboldi

PÉREZ FERNANDO

→ 25 ENTREVISTA INTERVIEW

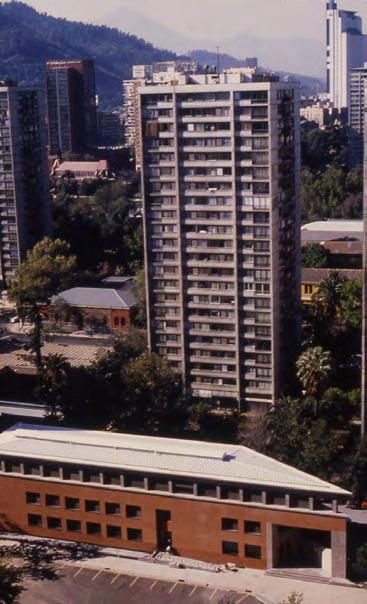

Dentro del panorama arquitectónico chileno, Fernando Pérez es reconocido por su capacidad de adentrarse y profundizar en las incontables posibilidades que ofrece la disciplina. A lo largo de su carrera, ha sabido unir la teoría, la historia y los proyectos, con la docencia, la investigación y las publicaciones, dejando un legado que ha marcado a la arquitectura chilena e hispanoamericana, así como también, a varias generaciones de estudiantes. Su producción teórica constituye un referente que combina la perspectiva local con la internacional, con libros como Le Corbusier y Sud América (Ediciones ARQ, 1991), y sus publicaciones sobre la Escuela de Valparaíso o acerca de Juan Borchers, han contribuido a mostrar internacionalmente las vanguardias chilenas. Actualmente se encuentra trabajando en el tercero de cuatro tomos de Arquitectura en el Chile del siglo XX. Además de su contribución como investigador, Fernando Pérez ha ejercido como profesor en la Universidad Católica desde 1974, misma institución de la que fue director de la Escuela de Arquitectura entre 1987 y 1990, y decano de la Facultad de Arquitectura y Bellas Artes entre 1990 y 2000. Pérez Oyarzún ha llevado su labor docente más allá de las fronteras como profesor invitado en universidades como Harvard, Rio Grande do Sul, Roma Tre y Cambridge, entre otras.

Entre sus proyectos construidos destacan obras como la Escuela de Medicina y la Biblioteca de Biomédica, en el Campus Central de la Universidad Católica, en colaboración con Alejandro Aravena; el Centro de Cáncer Nuestra Señora de la Esperanza con Tomás dalla Porta, Osvaldo Muñoz y Equipo DPI; y el Centro de Extensión Oriente con José Quintanilla y Juan Eduardo Ojeda.

En 2022, el gran aporte a la disciplina de Fernando Pérez fue reconocido con el Premio Nacional de Arquitectura que otorga el Colegio de Arquitectos, el que manifestó: “Pocas figuras en Chile han explorado como el arquitecto Fernando Pérez Oyarzún de manera tan consistente las incontables posibilidades que abre la arquitectura como campo de acción de todo tipo (…) La claridad de su planteo y el cuidado de los detalles reflejan el mismo espíritu que puede observarse en sus ensayos y en su obra escrita. De ahí, esa inusual convergencia entre palabra escrita y construcción, que ya había sido señalada por Alberti como característica de la «arquitectura culta» y que nada cuesta encontrar en la creación de Pérez Oyarzún”.

Within the Chilean architectural panorama, Fernando Pérez is recognized for his ability to delve into and deepen the countless possibilities offered by the discipline. Throughout his career, he has been able to unite theory, history, and projects with teaching, research, and publications, leaving a legacy that has marked Chilean and Latin American architecture, as well as several generations of students. His theoretical production constitutes a reference that combines local and international perspectives, with books such as Le Corbusier y Sud América (Ediciones ARQ, 1991), and his publications on the School of Valparaíso or about Juan Borchers, have contributed to showing the Chilean avant-garde internationally. He is currently working on the last of four volumes of Architecture in 20th Century Chile. In addition to his contribution as a researcher, Fernando Pérez has been a tenured professor at Universidad Católica since 1974, the same institution where he was the School of Architecture director between 1987 and 1990, and Faculty of Architecture and Fine Arts dean between 1990 and 2000. Pérez Oyarzún has taken his teaching work beyond the borders as a visiting professor at universities such as Harvard, Rio Grande do Sul, Roma Tre, and Cambridge, among others. Among its construction projects are the School of Medicine and the Biomedical Library at the Central Campus of Universidad Católica, in collaboration with Alejandro Aravena; the Nuestra Señora de la Esperanza Cancer Center with Tomás dalla Porta, Osvaldo Muñoz and Equipo DPI; and the Oriente Extension Center with José Quintanilla, Juan Eduardo Ojeda, Juan Eduardo Ojeda, and José Quintanilla.

In 2022, Fernando Pérez's great contribution to the discipline was recognized with the National Architecture Prize awarded by the College of Architects, which stated "Few figures in Chile have explored as consistently as architect Fernando Pérez Oyarzún the countless possibilities that architecture opens up as a field of action of all kinds (...) The clarity of his approach and his attention to detail reflect the same spirit that can be seen in his essays and his written work. Hence, that unusual convergence between the written word and construction, which had already been pointed out by Alberti as a characteristic of "cultured architecture" and which is easy to find in Pérez Oyarzún's creation".

26 ← AOA / n°48

Entrevista / Interview

R “Few figures in Chile have explored as consistently as architect Fernando Pérez Oyarzún the countless possibilities that architecture opens up as a field of action of all kinds.”

R COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTS, 2022

R COLEGIO DE ARQUITECTOS, 2022

R “Pocas figuras en Chile han explorado como el arquitecto Fernando Pérez Oyarzún de manera tan consistente las incontables posibilidades que abre la arquitectura como campo de acción de todo tipo”.

En Chile, son pocos los arquitectos que se han dedicado a rescatar el patrimonio, a estudiarlo y difundirlo, y su trabajo ha sido clave en esto. ¿En qué momento conecta con la historia de la arquitectura?

Al inicio de mi carrera sentía que existía una polarización en la que, quienes se interesaban por los proyectos, no querían saber nada de historia de la arquitectura, y quienes se dedicaban a estudiar la historia, buscaban enfrentar otro tipo de problemas: políticos, sociales, culturales y no se ponían en la perspectiva de los proyectos. Como estudiante en la Universidad Católica recibí muy tempranamente una oferta del del profesor Claude Ferrari Peña para participar en el área de teoría e historia. En ese momento, prácticamente no había docentes jóvenes en la escuela y él, además de regalarme la oportunidad de enseñar, me dio una formación como de posgrado: me hacía leer, me tomaba las lecciones, me presentó a grandes referentes… Nos juntábamos todos los miércoles y conversábamos sobre lo que había leído. Otro periodo importante fue el doctorado que cursé en Barcelona a comienzo de los 80, en un momento glorioso de la arquitectura española, donde tuve la suerte de cruzar puntos de vista con personajes como Rafael Moneo o Helio Piñón. Cuando volví del doctorado, traía una nueva perspectiva, me interesaba hacer ese cruce entre teoría, historia y proyecto, y comencé a abordar esos temas a nivel local.

In Chile, few architects have dedicated themselves to rescuing heritage, studying it, and disseminating it, and your work has been key in this. At what point do you connect with the history of architecture?

A At the beginning of my career, I felt that there was a polarization in which those who were interested in projects did not want to know anything about the history of architecture, and those who were dedicated to the study of history sought to face other types of problems: political, social, cultural and did not put themselves in the projects' perspective. As a student at Universidad Católica, I received an early offer from Professor Claude Ferrari Peña to participate in the area of theory and history. At that time, there were practically no young teachers in the school and he, besides allowing me to teach, gave me postgraduate training: he made me read, he taught me lessons, he introduced me to great references... We met every Wednesday and talked about what I had read. Another important period was the doctorate I did in Barcelona at the beginning of the 80s, in a glorious moment of Spanish architecture, where I

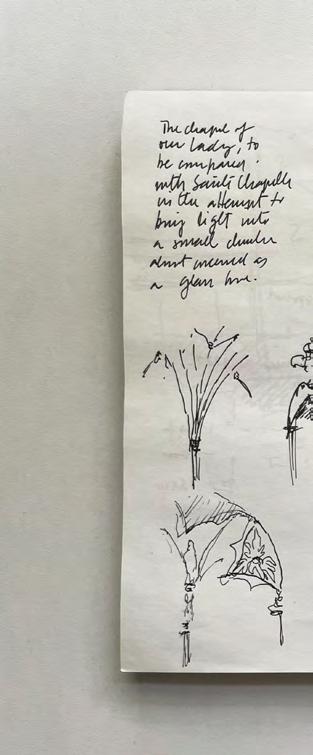

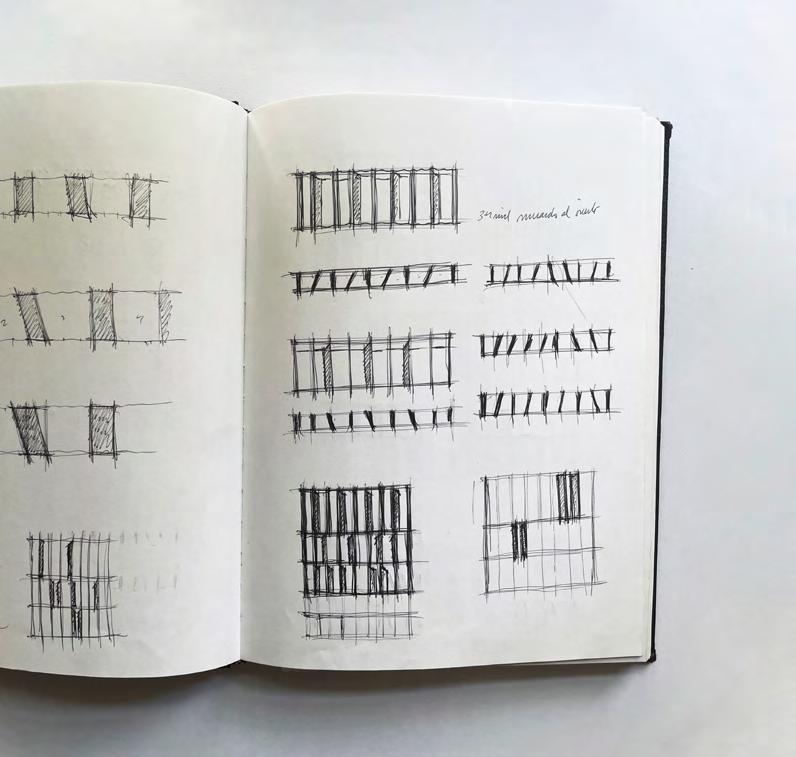

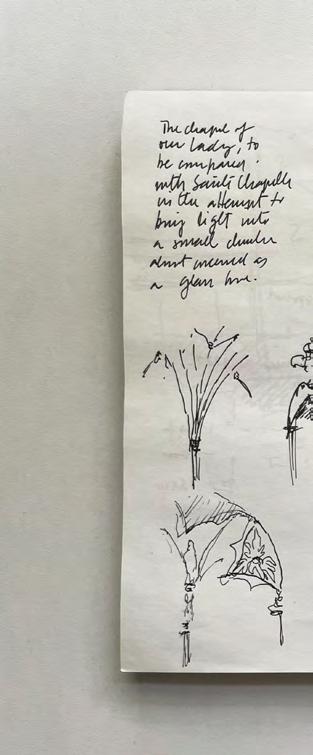

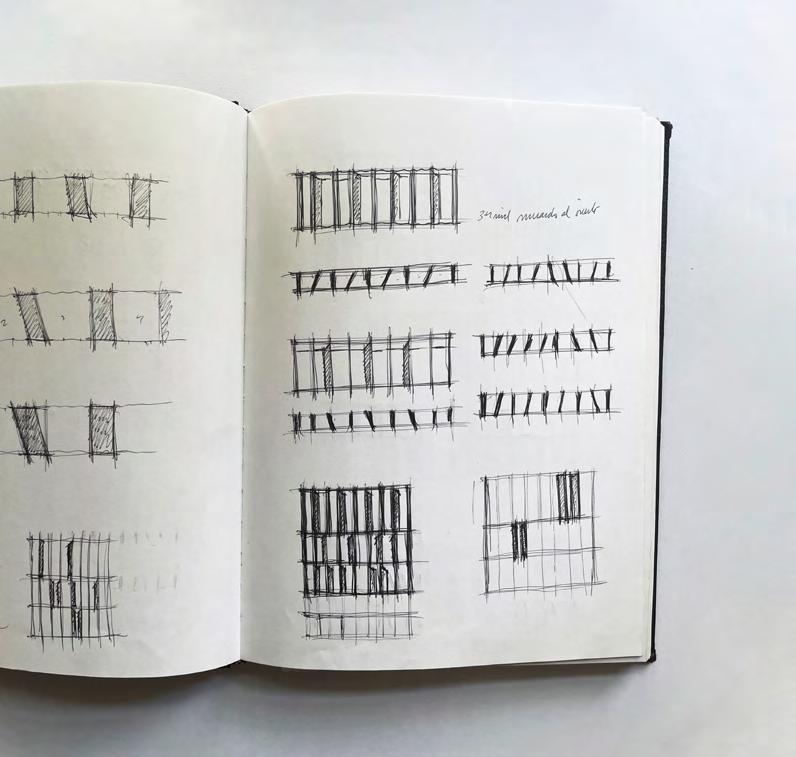

S Q Bocetos Cambridge - Ely, UK. Cuaderno de Fernando Pérez, 2000.

Bocetos de la fachada de la Escuela de Medicina PUC. Cuaderno de Fernando Pérez, 2001.

S Q Cambridge Sketches - Ely, UK. Notebook by Fernando Pérez, 2000.

Sketches of the PUC School of Medicine facade. Notebook by Fernando Pérez, 2001.

→ 27 Entrevista / Interview

© Catalina Pérez

© Catalina Pérez

Ha sido un personaje muy importante en la Universidad Católica, fue protagonista de una relación directa entre las Escuela de Arquitectura de la Universidad de Chile y de la Universidad Católica, y creó el programa de intercambio entre estas dos instituciones. ¿Cómo fue esa experiencia para usted? Primero, me gustaría ponerlo en perspectiva. Yo no fui el primero en tener esa idea. Cuando Sergio Larraín era decano de la Católica ya tenía una relación muy fluida con algunas personas de la Universidad de Chile. Por otro lado, en el año 90, estando en Harvard, me enteré de que existía un convenio con el MIT, donde los cursos de una institución eran válidos para la otra, y me pareció que era una idea que se podía replicar en Chile.

Cuando fui decano, teníamos una relación muy cercana con Manuel Fernández, mi contraparte en la Universidad de Chile, una persona con un background cultural y profesional importantes. En muchas ocasiones nos juntábamos a conversar, almorzábamos en Lastarria y compartíamos aspectos de nuestra experiencia como decanos. Ese ambiente de amistad, de dos autoridades que quieren a sus instituciones y que las quieren sacar adelante, fue un factor a favor de hacer estos intercambios. Esto fue en 1999 y nos anticipamos, porque, si no me equivoco, después ambas universidades hicieron un convenio de ese tipo, a nivel general. Creo que fue una experiencia estupenda, y lo único que me extraña es que no hubiera sido mucho más aprovechada, porque uno siempre se queda con la sensación de que hay algo que tienen en la otra escuela que no tiene la propia. Y esto permitía un tránsito y una formación tanto más más civilizada y desarrollada, aprovechando las capacidades que tienen las instituciones.

was lucky enough to cross points of view with people like Rafael Moneo, or with Helio Piñol. When I returned from my doctorate, I brought a new perspective, I was interested in making that cross between theory, history, and project, and I began to address these issues at the local level and create content.

You have been a very important figure at Universidad Católica, you were the protagonist of a direct relationship between the Architecture School at Universidad de Chile and Universidad Católica, and you created the exchange program between these two institutions. What was that experience like for you? First, I would like to put it in perspective. I was not the first one to have that idea. When Sergio Larraín was dean of Universidad Católica, he already had a very fluid relationship with some people from Universidad de Chile. On the other hand, in 1990, when I was at Harvard, I found out that there was an agreement with MIT, where the courses of one institution were valid for the other, and I thought it was an idea that could be duplicated in Chile.