REPORTAJE TERRITORIOS EN TOMA FEATURE ARTICLE TERRITORIES UNDER SEIZURE MOVIMIENTO MODERNO PERÚ Catálogo arquitectura Movimiento Moderno MODERN MOVEMENT PERÚ Modern Movement Catalog PATRIMONIO QUE SE HAGA LA LUZ Iglesia Monasterio Benedictino HERITAGE LET THE LIGHT BE MADE Chapel of the Benedictine Monastery ARQUITECTO INVITADO TOMÁS VILLALÓN ENTREVISTA INTERNACIONAL ENSAMBLE STUDIO GUEST ARCHITECT TOMÁS VILLALÓN INTERNATIONAL INTERVIEW ENSAMBLE STUDIO 46

Director

Director

Yves Besançon Prats

Comité editorial

Editorial committee

Pablo Altikes

Javiera Benavides

Yves Besançon

Gabriela de la Piedra

Francisca Pulido

Lucía Ríos

Pablo Riquelme

José Rosas

Sebastián Rozas

Alberto Texido

Edición

Editor

Sofía Arnaboldi

Dirección de arte y diseño

Art direction & graphic design

DRAFT Diseño

Traducción

Translation

WordsforWords

Correción de textos

Proofreading

Roberto Gómez

Representante legal

Legal representative

Pablo Jordán

Marisol Rojas

Mónica Álvarez de Oro

Secretaria Ejecutiva AOA

AOA Executive secretary

Lucía Ríos O’Ryan

Jefe de proyecto

Project manager

Valentina Pérez

Coordinación administrativa

Administrative coordination

Marcela Catalán

Presidente AOA

President of AOA

Pablo Jordán

Impresión

Printing

Ograma Impresores

Juan de Dios Vial Correa 1351, 1˚ piso

Providencia, Santiago, Chile

(+56 2) 2263 4117

www.aoa.cl / revista@aoa.cl

ISBN: 9770718318001

Para la composición de textos de esta publicación se utilizarón fuentes diseñadas por chilenos y comercializadas en Latinotype:

Majora & Majora Stencil

Por: Luis Bandovas

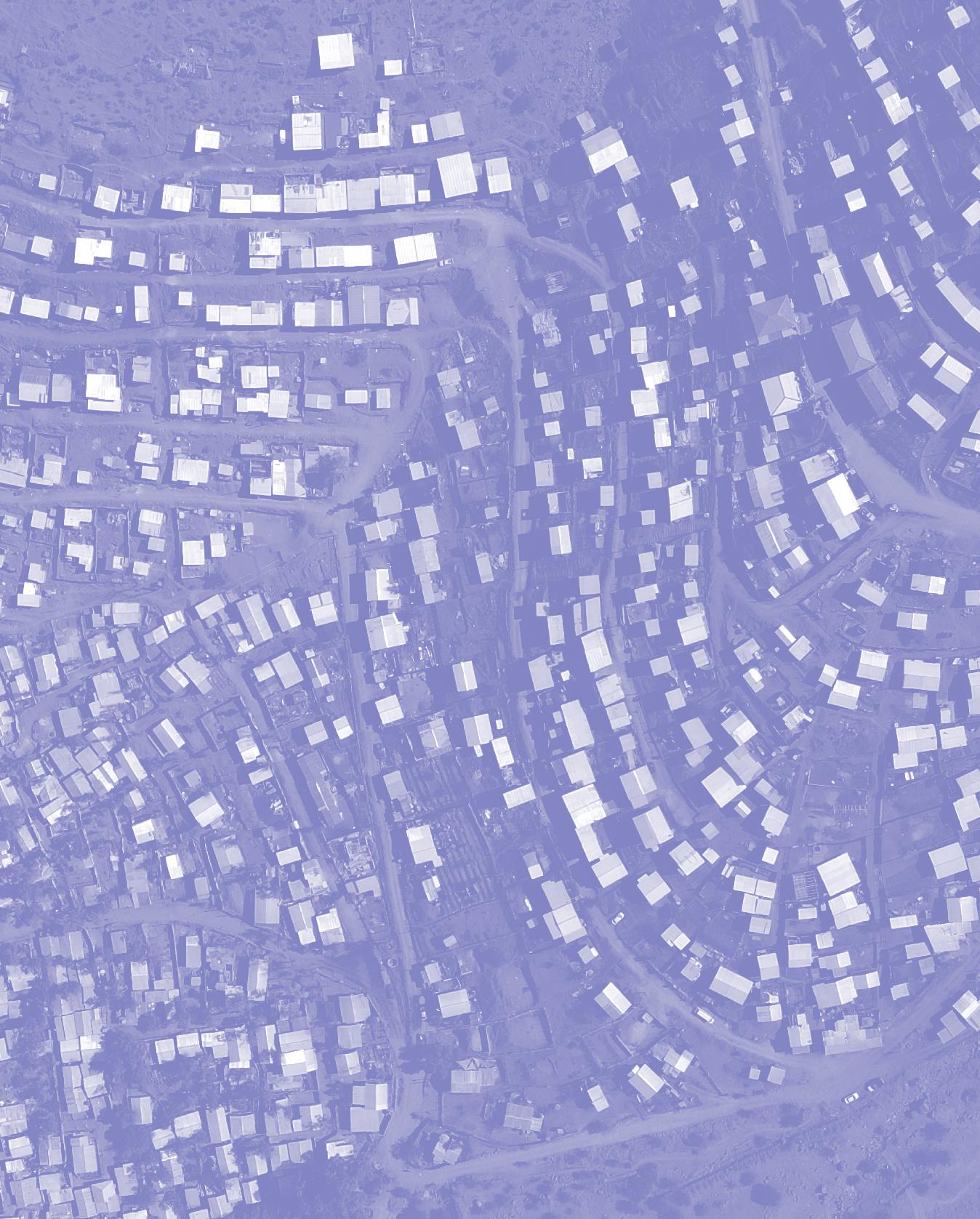

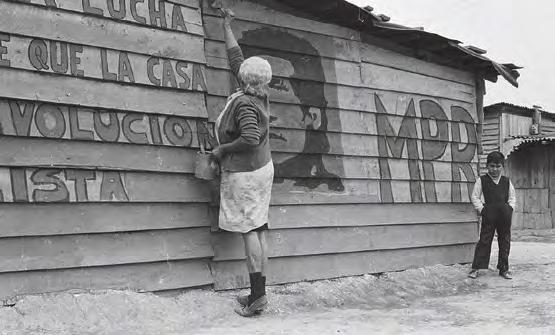

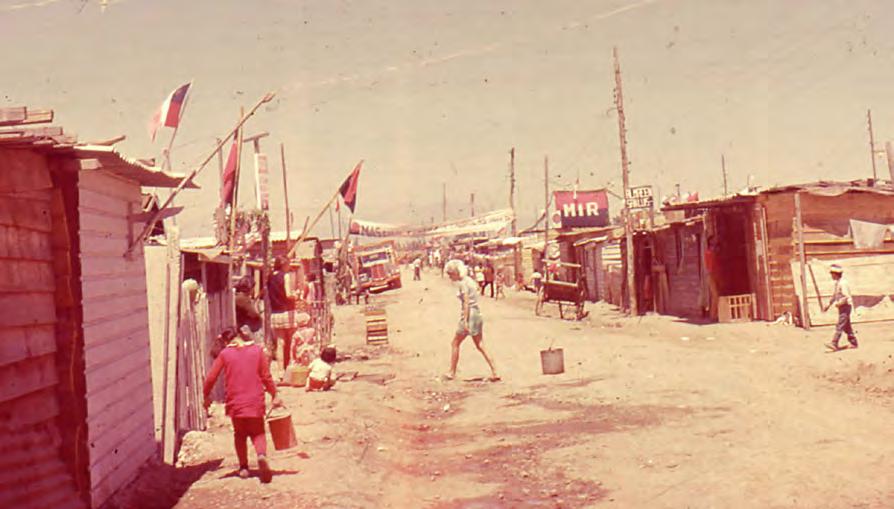

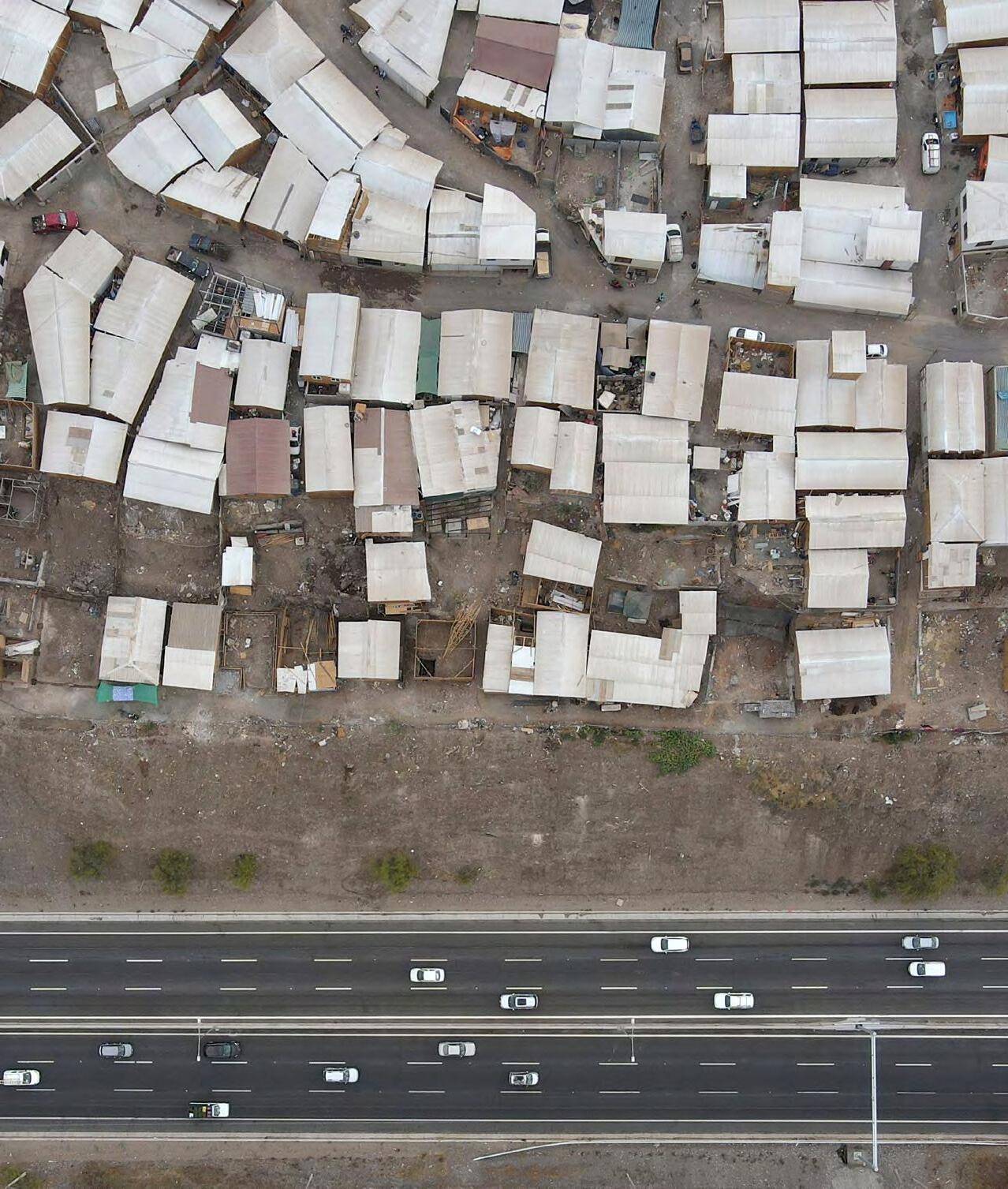

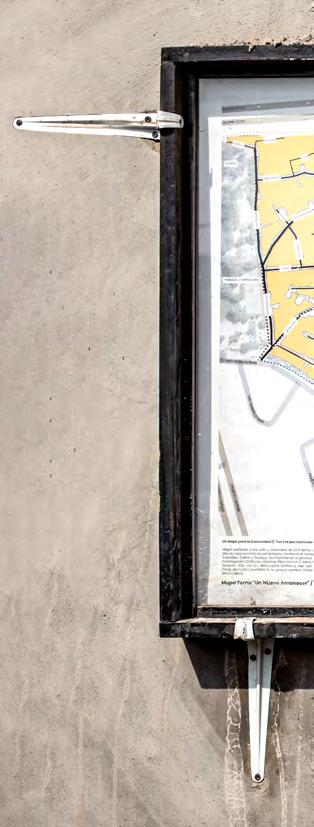

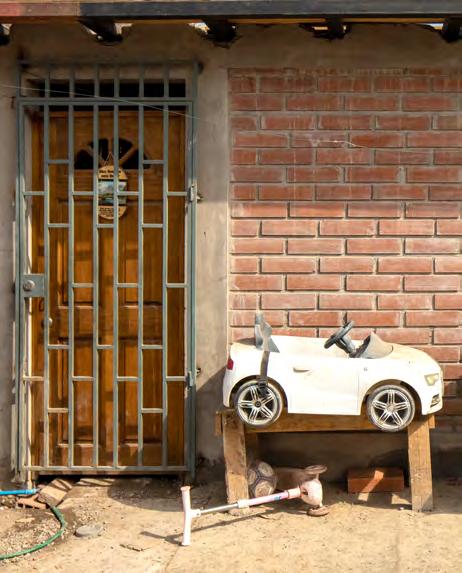

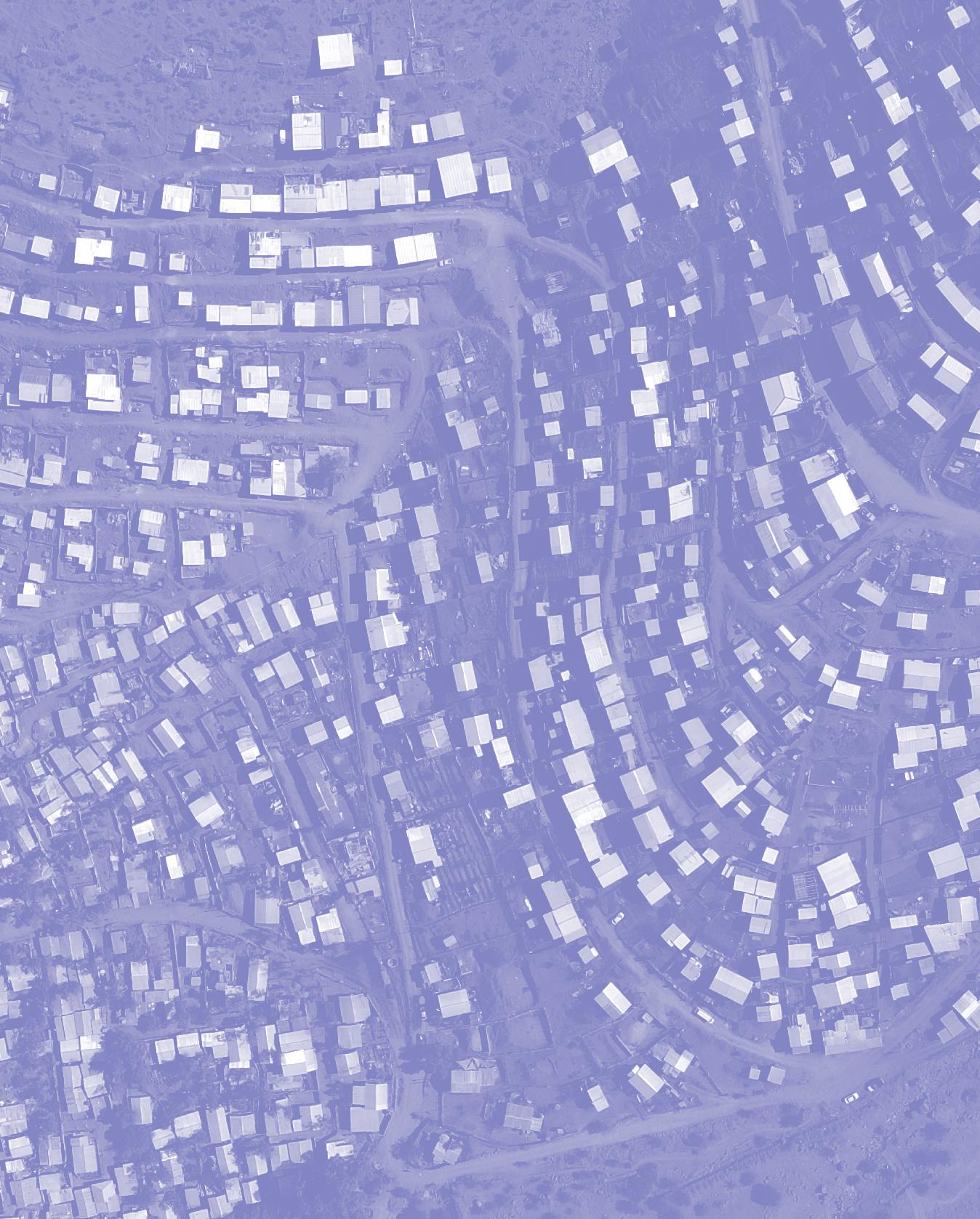

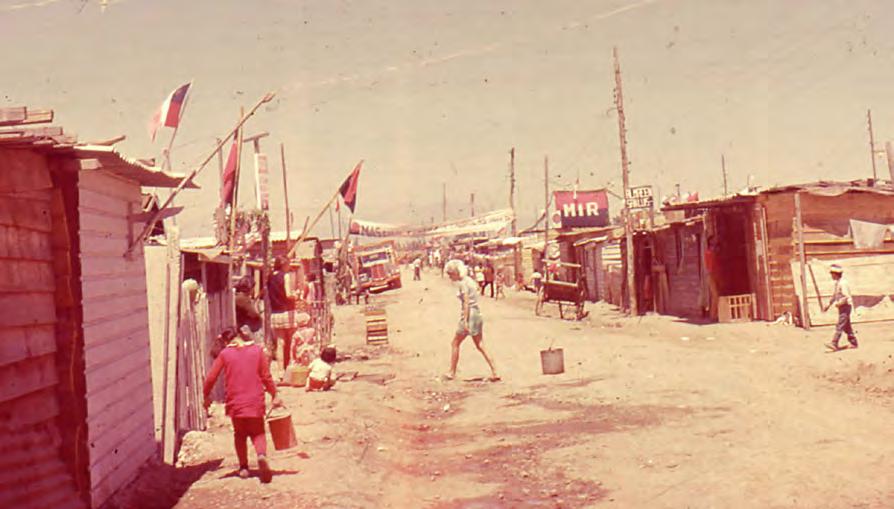

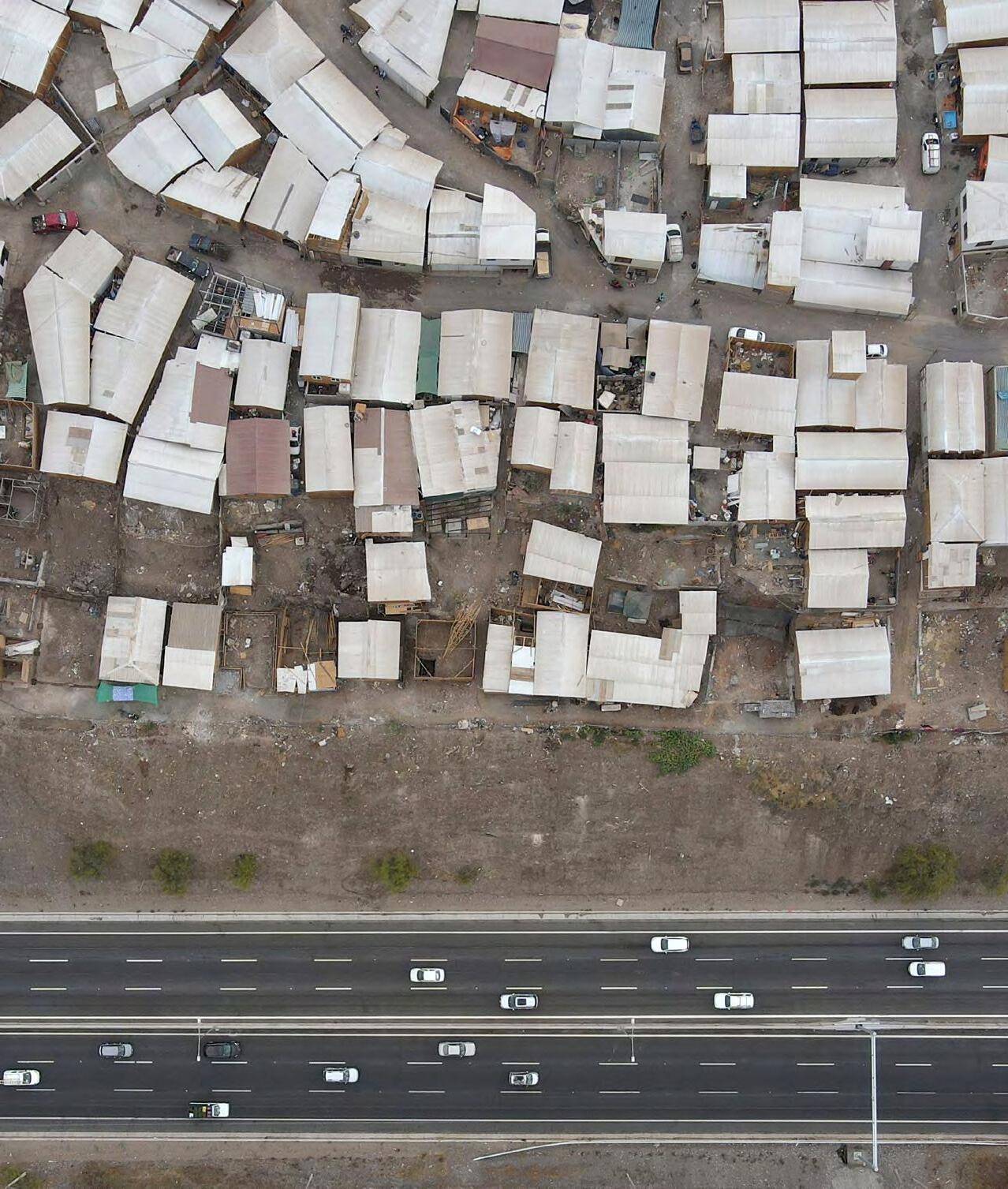

l siglo XXI llegó junto a una gran demanda por viviendas para cientos de familias en allegamiento que, junto al aumento descontrolado del arribo de migrantes americanos sumergidos en la pobreza de sus países de origen y buscando mejores horizontes, se han visto obligados a resolver su problema habitacional por sí mismos. Terrenos baldíos y abandonados han sido fuente de nuevas urbanizaciones irregulares que se han instalado organizadamente en la periferia de nuestras ciudades y campos. La problemática del justo anhelo de acceder a una vivienda, sea esta propia o arrendada, no ha sido resuelta y es por ello que los pobladores se han visto forzados a recurrir a métodos fácticos de ocupación de terrenos para proveer de un techo a sus familias. Los años de espera para pobladores sin casa que, a veces superan los nueve años, son toda una vida de inseguridad y de abandono por parte del Estado, que no ha sido capaz de resolver con dignidad y justicia los anhelos de tantos chilenos y, hoy, muchos extranjeros que no tienen dónde cobijarse.

Los problemas principales que generan las llamadas “tomas de terrenos” es, primero, la vulneración del derecho de propiedad que, en muchos casos, es transgredido por mafias organizadas y preparadas para hacer de la desgracia de otros un lucrativo negocio con la propiedad ajena. En segundo lugar, estas nacientes poblaciones no cuentan con las más mínimas condiciones sanitarias ni de urbanización. En tercer lugar, los costos de la vivienda y los valores de los arriendos se han multiplicado hasta llegar a niveles inalcanzables, lo que ha impedido el acceso a este bien fundamental, expulsando a cientos de familias a vivir en las calles, en plazas o en estas tomas irregulares.

Hemos llegado al límite de un problema que tiene características de una verdadera emergencia y su solución se ve lejana, a no ser de que se tomen medidas desde ahora. Generar bancos de suelos, bancos de viviendas tipo y pensar en soluciones innovadoras y creativas entre el mundo público y el mundo privado para avanzar con rapidez en disminuir el actual déficit habitacional, se convierte hoy en una necesidad urgente y creemos que las autoridades, conscientes de las consecuencias que podría generar este grave problema, deben poner toda su energía y voluntad para encaminar el futuro destino de muchas familias que ya no pueden esperar más.

Hemos querido poner este tema sobre la mesa para producir el necesario debate al respecto, y para sacar a la luz y hacer visibles a las familias que hoy viven injustamente en la precariedad y en la marginalidad social.

Yves Besançon Prats / Director

The 21st century brought with it a great demand for housing for hundreds of families living in poverty who, together with an uncontrolled increase in the arrival of American migrants submerged in poverty in their countries of origin and looking for better horizons, have been forced to solve their housing problem on their own. Vacant and abandoned land has been the source of new unregulated urbanizations that have been established in an organized manner on the outskirts of our cities and countryside. The problem of the legitimate desire to have access to housing, whether owned or rented, has not been solved and that is why the inhabitants have been forced to resort to de facto methods of land occupation to provide a roof over their families heads. The years settlers have been waiting without a home, which sometimes exceeds nine years, is a lifetime of insecurity and abandonment by the State, which has not been able to resolve the desires of so many Chileans with dignity and justice, and today many foreigners have nowhere to live.

The main problems created by the so-called "land tomas" are, first, the violation of property rights which, in many cases, are violated by organized mafias prepared to turn the misfortune of others into a lucrative business with other people's property.

Secondly, these nascent populations do not have the most basic sanitary and urbanization conditions. Thirdly, housing costs and rents have multiplied to unattainable levels, which has prevented access to this fundamental asset, forcing hundreds of families to live on the streets, in squares, or these unregulated housing projects.

We have reached the limit of a problem that represents a real emergency and its solution is very far away unless measures are taken starting now. Creating land banks, housing banks, and thinking of innovative and creative solutions between the public and private sectors to move forward quickly to reduce the current housing shortage, becomes an urgent need today and we believe that the authorities, aware of the consequences that this serious problem could cause, need to put all their energy and determination to address the future destiny of many families who can no longer wait any longer. We wanted to put this issue on the table to raise the necessary debate on the matter and to bring to light and make the families that today live unjustly in precariousness and social marginality visible.

Yves Besançon Prats / Director

E

Índice Contents

PATRIMONIO

Heritage

IGLESIA MONASTERIO BENEDICTINO

CHAPEL OF THE BENEDICTINE

MONASTERY

Patrimonio, arquitectura y oportunidades

Heritage, Architecture & Opportunities

Desde y hacia el paisaje

From and to the Landscape

ENTREVISTA INTERNACIONAL

International Interview

ENSAMBLE STUDIO

ARQUITECTO INVITADO

Guest Architect

TOMÁS VILLALÓN

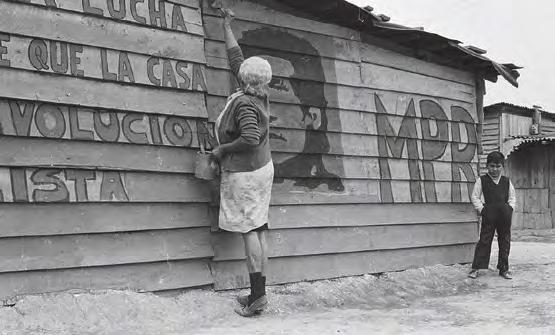

REPORTAJE

Feature Article

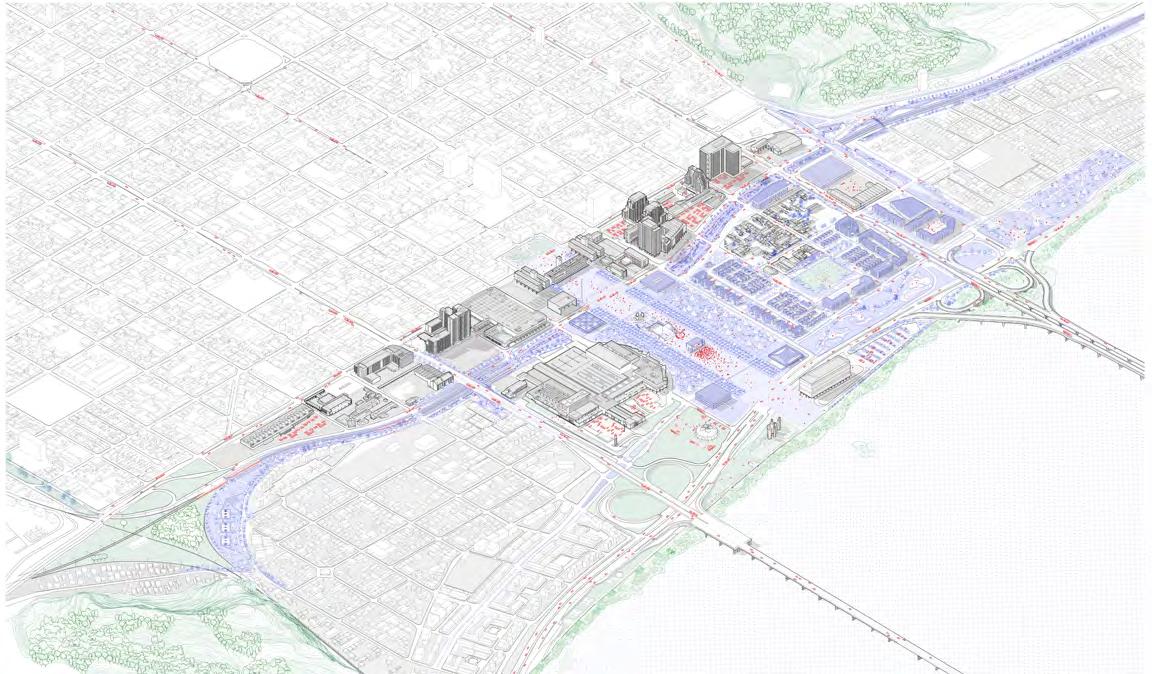

"TERRITORIOS EN TOMA"

"TERRITORIES UNDER SEIZURE"

El “nuevo campamento” y los desafíos para la cohesión social

The "New Shantytown" & the Challenges for Social Cohesion

Modelo abierto de las tomas para mejores barrios y ciudades

Open model of the tomas for better neighborhoods & cities

Campamentos: política habitacional de los pobres

Shantytowns: Housing policy for the poor

Vivir en una toma

Living in a toma

MOVIMIENTO MODERNO

Modern Movement

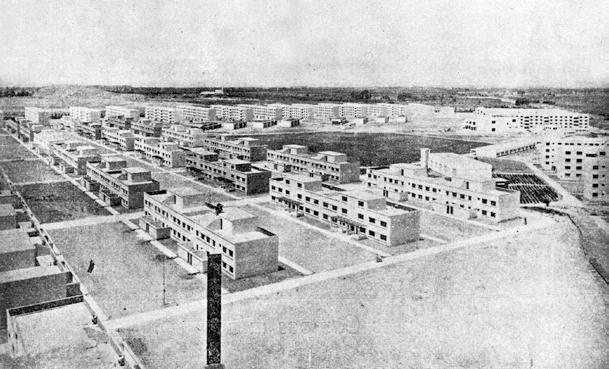

CATÁLOGO ARQUITECTURA

MOVIMIENTO MODERNO PERÚ

PERÚ MODERN MOVEMENT CATALOG

OBRAS

Works

Vivienda social La Florida

La Florida Social Housing

Vivienda social Santa Rosa

Santa Rosa Social Housing

Casa en Sao Paulo

House in Sao Paulo

Casa Almahue

Almahue House

Casa Canela

Canela House

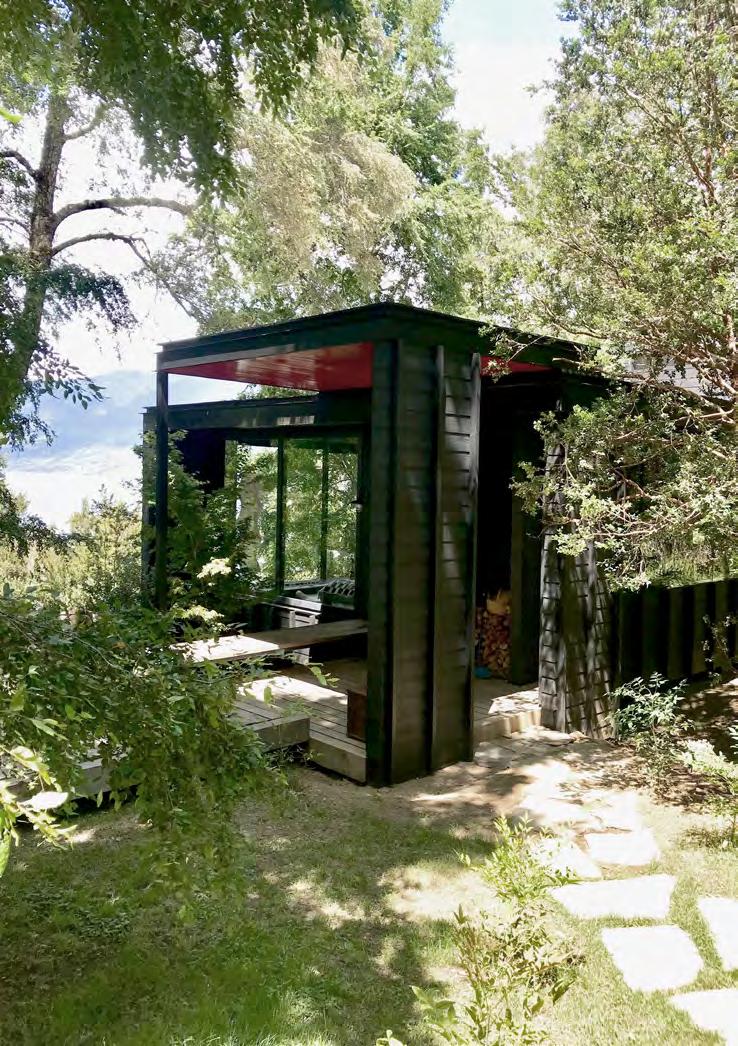

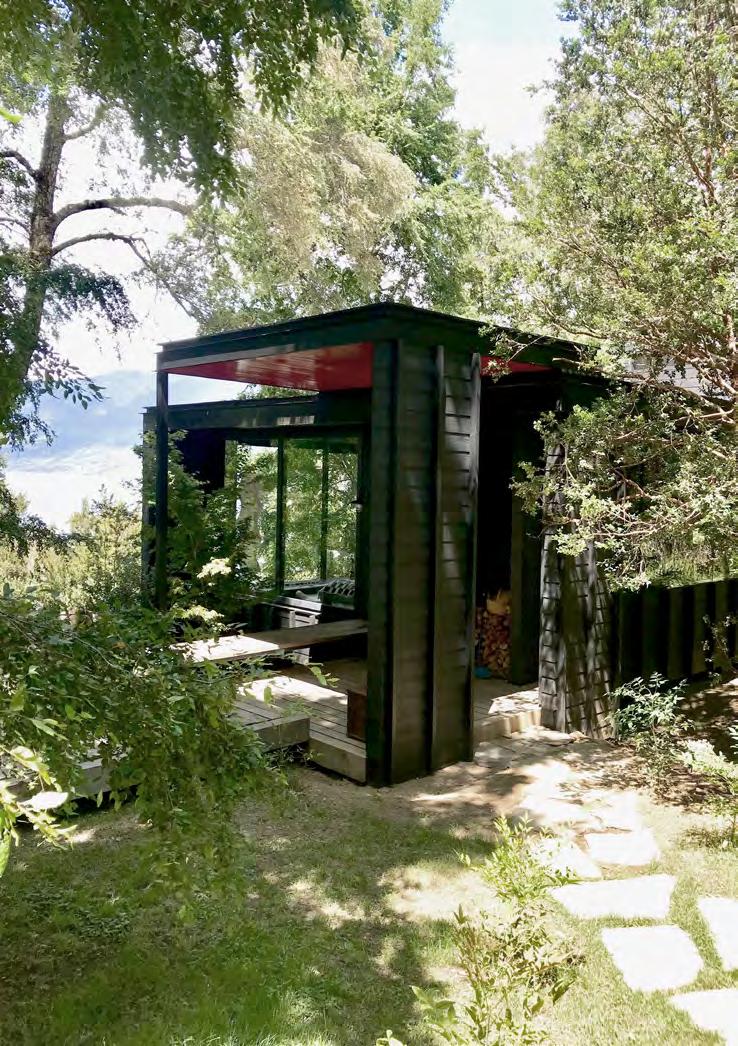

Cabaña en el bosque

Cabin in the Woods

Oficinas Unidad Coronaria Móvil y Family Office

Mobile Coronary Unit (MCU) Offices & Family Office

TESIS

Thesis

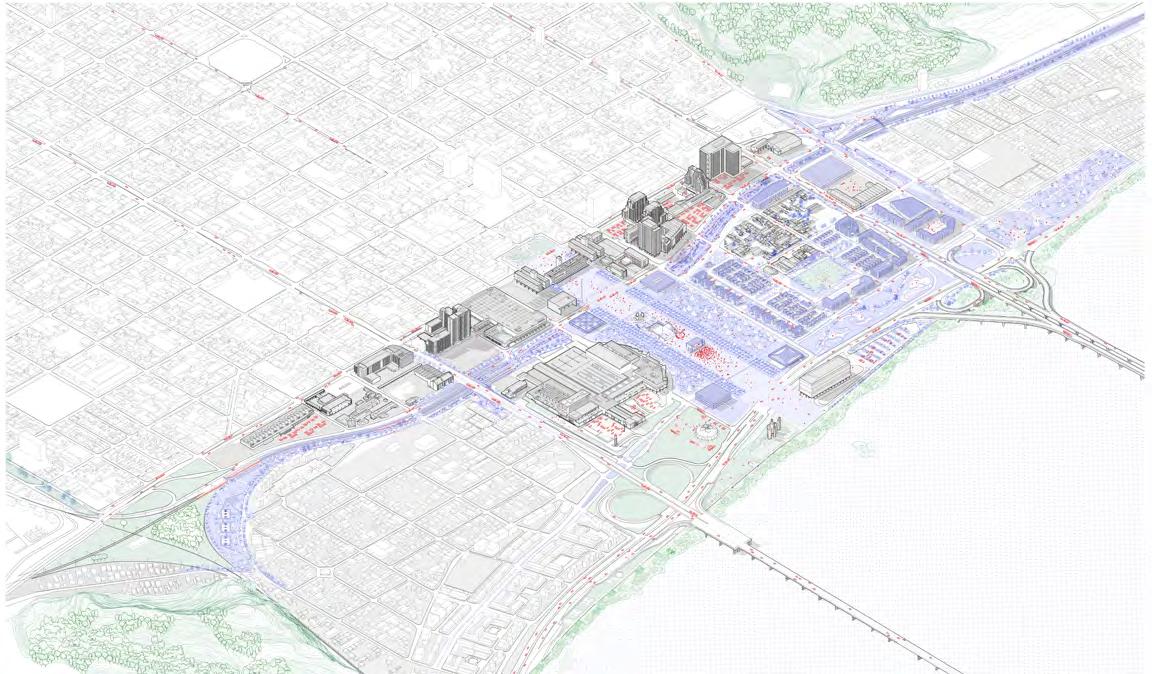

Infraestructuras habitadas: proyectando nuevas relaciones entre vías de transporte segregado y trama urbana

Inhabited Infrastructures: Projecting

New Relationships between Segregated Transportation Routes & Urban Fabric

CONCURSOS

Competitions

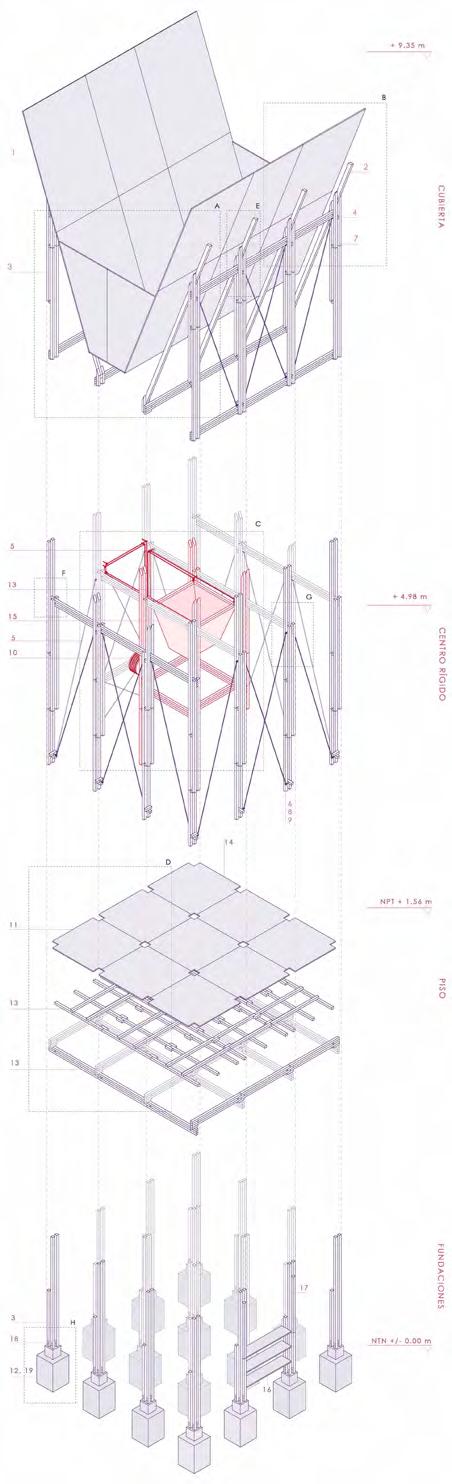

Artefactos del paisaje

Landscape Artifacts

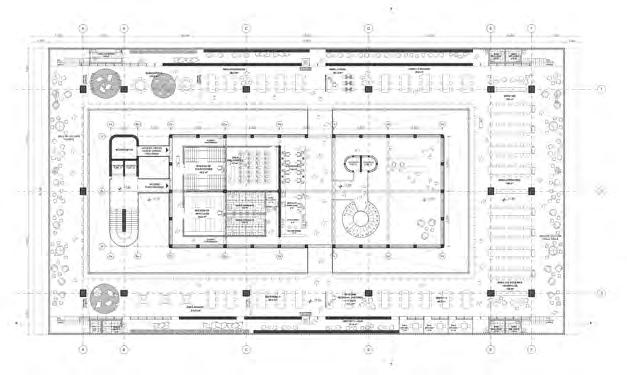

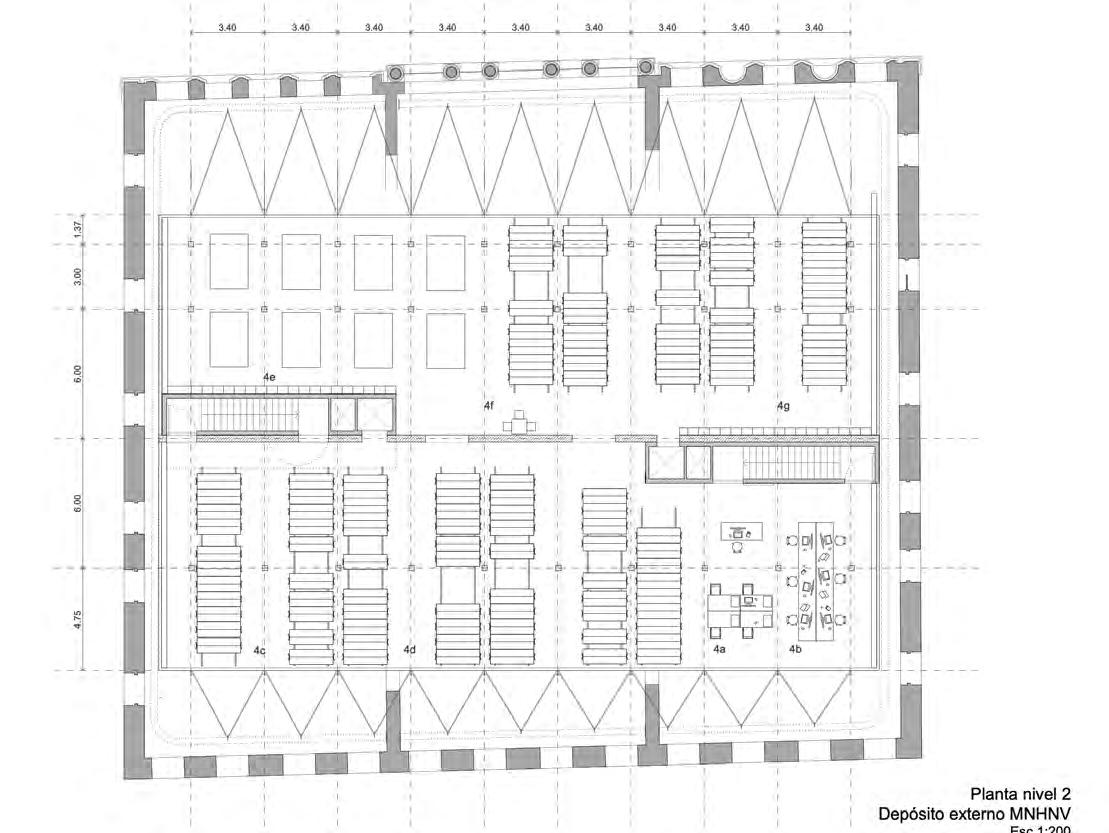

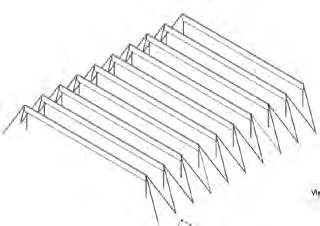

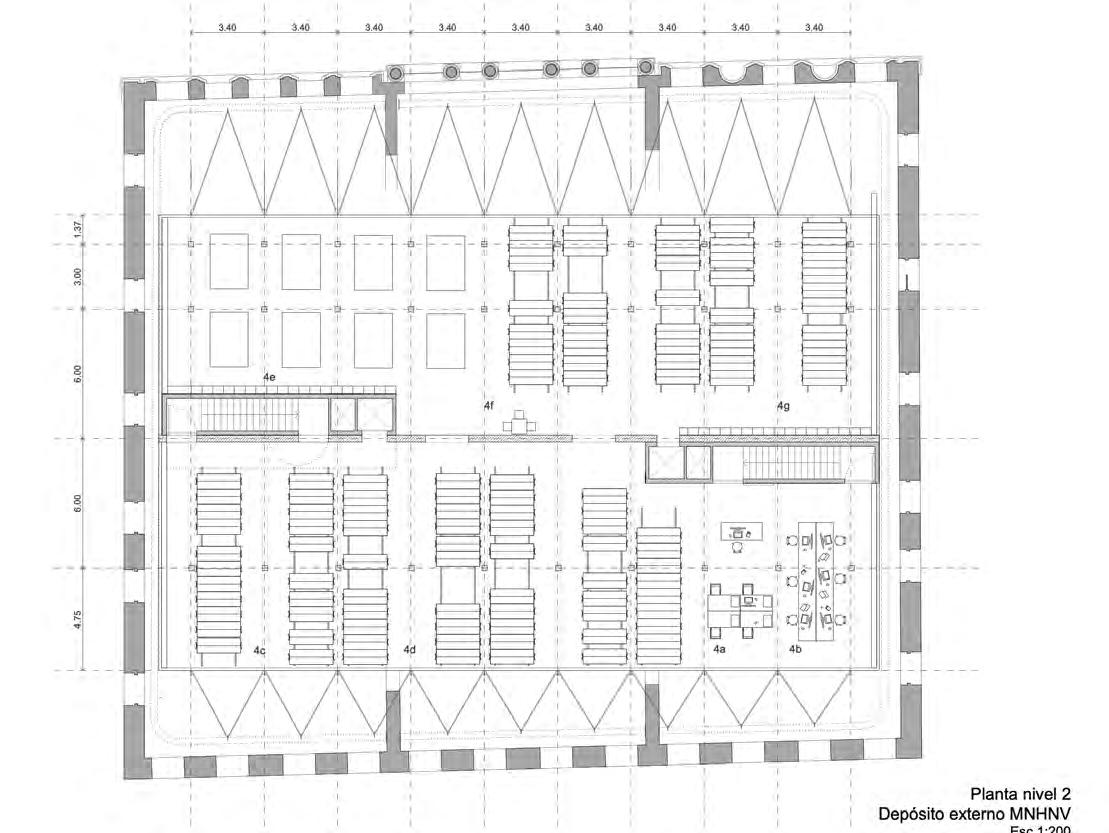

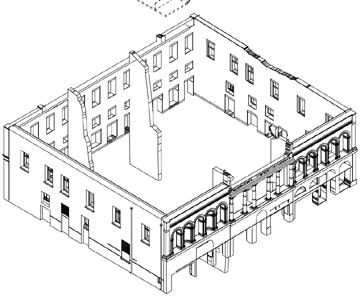

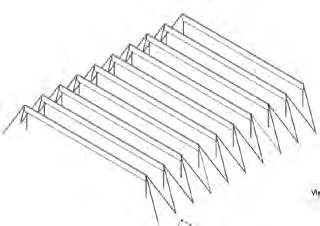

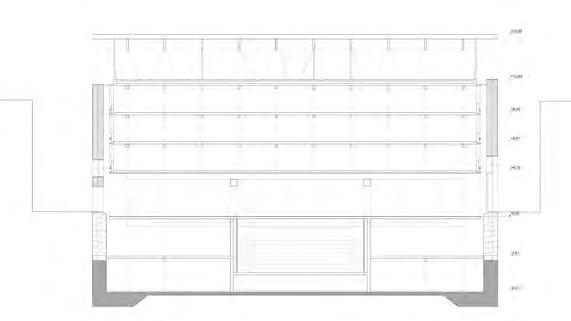

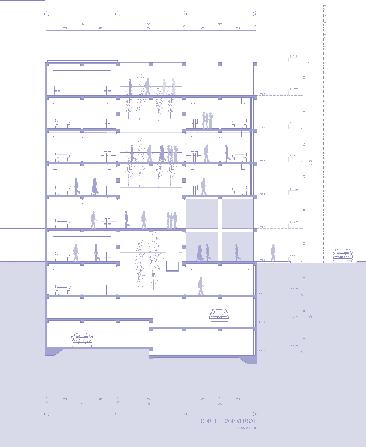

Anteproyecto diseño infraestructura regional, Biblioteca, Archivo y Depósito de colecciones, Los Ríos

Preliminary Design of Regional Infrastructure, Library, Archive & Collection Repository, Los Ríos

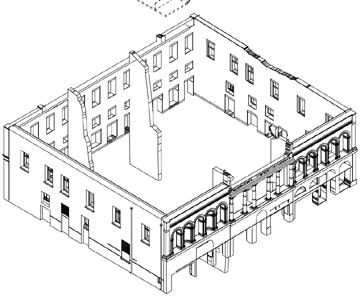

Concurso Archivo Regional de Valparaíso

Valparaíso Regional Archive Competition

04 42 110 84 146 30 54 140

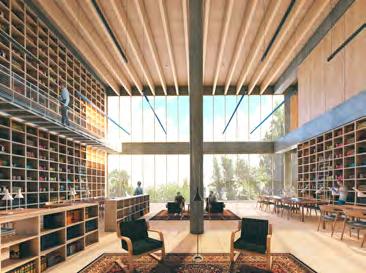

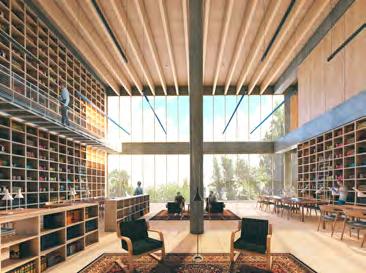

QUE SE HAGA LA LUZ

Let the light be made

4 ↤ AOA / n°46 Patrimonio / Heritage

IGLESIA MONASTERIO BENEDICTINO DE LA SANTÍSIMA TRINIDAD

Revisitamos el Monasterio Benedictino de Las Condes (publicado antes en la revista 25) presentando esta vez dos nuevos puntos de vista que contribuyen a la reflexión acerca de los valores tangibles e intangibles y la sustentabilidad en el tiempo de este Monumento Histórico de la arquitectura moderna chilena, cuyo emplazamiento en el cerro San Benito de Los Piques es protegido como Zona Típica por el Consejo de Monumentos Nacionales y que se mantiene vivo fundamentalmente gracias a la actividad diaria e ininterrumpida de los monjes que habitan en él.

Conservar preventivamente es una de las premisas consideradas por el proyecto Fiat Lux; que se haga la luz. Este proyecto de investigación aplicada, tiene por objetivo el desarrollo de un manual técnico de lineamientos para la conservación y el mantenimiento de la Capilla del Monasterio, el que mediante un inédito convenio entre la Facultad de Arquitectura de la UDD de Santiago y la Fundación Getty obtuvo el apoyo de ésta para gestionar un trabajo interdisciplinario que busca, con una visión de largo plazo, mantener en buen estado y cambiar la extendida mirada de restaurar o intervenir un bien patrimonial cuando esto ya se hace urgente, por una evaluación precisa y detallada de su estado actual en términos estructurales, materiales y de habitabilidad apoyada en un conjunto de tecnologías existentes aplicadas y no invasivas, que permita generar un plan de manejo para la conservación de la Iglesia, sentando además un precedente para posibles futuros convenios o planes de manejo similares.

Desde la arquitectura del paisaje, en una aproximación situada en el territorio donde se emplaza el Monasterio enfocada a su transformación en el tiempo, y al dialogo y la relación visual de esta obra tanto con el paisaje del valle y precordillera que la rodea como con la dinámica ciudad que lo ha ido envolviendo, Juana Zunino se basa en un estudio y propuesta realizados por encargo de los monjes entre 2003 y 2007 realizado por ella junto a Rodrigo Pérez de Arce e Iván Poduje, que buscó preservar los atributos del Monasterio mediante lineamientos de diseño urbano y actualizado a hoy a través de la experiencia del hermano Martín Correa, como arquitecto y habitante.

We revisited the Benedictine Monastery of Las Condes (previously published in magazine 25) presenting, this time, two new points of view that contribute to the reflection, both about its tangible and intangible values, as well as the sustainability over time of this historic modern Chilean architectural monument. It has been kept alive thanks to the daily and uninterrupted activity of the monks who live there, and whose location on the San Benito de Los Piques hill is protected as a typical area by the National Monuments Council.

"Preventive conservation" is one of the premises considered by the Fiat Lux project; let there be light. This applied research project aims to develop a technical guideline manual for the conservation and maintenance of the Monastery's chapel. This is thanks to an unprecedented agreement between the Faculty of Architecture at the UDD of Santiago and the Getty Foundation, which led to the latter´s support to manage an interdisciplinary project that seeks to maintain the monument in good condition with a long-term vision and to change the common view of restoring or intervening in a heritage asset when it has already become urgent. Through a precise and detailed evaluation of its current state in structural, material, and habitability terms, supported by a set of non-invasive technologies, an action plan for the conservation of the church was created, setting a precedent for possible future agreements or similar preservation plans.

From the landscape architecture, through a territorial approach where the monastery is located, Juana Zunino based her work on a study and proposal undertaken by her, along with Rodrigo Pérez de Arce and Iván Poduje, commissioned by the Benedictine monks in 2006. This research focused on transformation over time, the dialogue, and the visual relationship of this project, both with the valley´s landscape and the foothills that surround it, and with the dynamic city that surrounds it, and sought to preserve the Monastery´s attributes through urban design guidelines and updated through the experience of Brother Martin Correa as an architect and inhabitant.

por by : javiera benavides

por by : javiera benavides

↦ 5 Reportaje / Feature Article

óscar mackenney poblete

Arquitecto de la Universidad Católica de Chile, Magíster en Humanidades y Pensamiento Científico de la Universidad del Desarrollo. Vicedecano de la Facultad de Arquitectura y Arte de la Universidad del Desarrollo. Jefe de Proyecto FIAT LUX. / Architect from Universidad Católica de Chile with a Master in Humanities and Scientific Thought from Universidad del Desarrollo. Vice-Dean of the Faculty of Architecture and Art at Universidad del Desarrollo and the FIAT LUX Project Manager.

maría soledad ramos bull

Arquitecto de la Universidad del Desarrollo. Magísteren Intervención del Patrimonio Arquitectónico de la Universidad de Chile. Docente y coordinadora de la Facultad de Arquitectura y Arte de la Universidad del Desarrollo. Consultora patrimonial proyecto FIAT LUX. / Architect from Universidad del Desarrollo with a Master in Architectural Heritage Intervention from Universidad de Chile. A professor and coordinator of the Faculty of Architecture and Art at Universidad del Desarrollo and a heritage consultant for the FIAT LUX project.

maría jesús guridi rivano

Historiadora Universidad de Los Andes, Magíster en Historia y Gestión del Patrimonio Cultural de la Universidad de Los Andes. Directora ejecutiva Grupo PRAEDIO. / Historian from Universidad de Los Andes with a Master in History and Cultural Heritage Management from Universidad de Los Andes. Executive Director of the PRAEDIO Group.

santiago beckdorf solá

Arquitecto de la Universidad del Desarrollo, Magister en Arquitectura y Diseño Urbano de la Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL UK. Docente y coordinador de la Facultad de Arquitectura y Arte de la Universidad del Desarrollo. Coordinador de proyecto FIAT LUX. / Architect from Universidad del Desarrollo with a Master in Architecture and Urban Design from the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL UK. A professor and coordinator of the Faculty of Architecture and Art at Universidad del Desarrollo and the FIAT LUX project coordinator.

carlos maillet aránguiz

Arquitecto de la Universidad Mayor, Magister en Historia y Gestión del Patrimonio Cultural de la Universidad de los Andes. Director de carrera de Arte y Conservación Patrimonial Universidad San Sebastián, Miembro ICOMOS, Ex Vicepresidente ejecutivo del Consejo de Monumentos Nacionales de Chile. Experto en patrimonio proyecto FIAT LUX. / Architect from Universidad Mayor with a Master in History and Cultural Heritage Management from Universidad de los Andes. The director of Art and Heritage Conservation at San Sebastian University, a member of ICOMOS, a former Executive Vice President of the Chilean Council of National Monuments, and a heritage expert in the FIAT LUX project.

6 ↤ AOA / n°46

PATRIMONIO, ARQUITECTURA Y OPORTUNIDADES

HERITAGE, ARCHITECTURE & OPPORTUNITIES

por by : facultad de arquitectura de la universidad del desarrollo

El caso de estudio y aplicación es la Capilla del Monasterio Benedictino, primer edificio de arquitectura moderna en ser declarado Monumento Histórico en el pais, obra de los monjes Martín Correa y Gabriel Guarda

OSB, este último recientemente fallecido y Premio Nacional de Historia.

This case study and application is the Chapel of the Benedictine Monastery, the first building of modern architecture to be declared a Historic Monument in the country. The work of monks Martín Correa and Gabriel Guarda OSB, the latter recently deceased and winner of the National History Prize.

↤

Durante casi dos años se ha estado inspeccionando este edificio. Cada visita ofrece descubrimientos distintos que han ido nutriendo el nivel de conocimiento de la obra en sus distintos ámbitos

For almost two years, this building has been under inspection. Each visit offers different discoveries that have nurtured the awareness level of the work in its different areas.

El Monasterio Benedictino de la Santísima Trinidad de Las Condes, monumento nacional ubicado en la falda norte del cerro San Benito de Los Piques, es hoy una obra activa. Para conocer el estado actual de la iglesia, se obtuvo el patrocinio de la Fundación Getty1, entidad que ha dedicado importantes recursos para proteger obras señeras del patrimonio de la arquitectura moderna en el mundo.

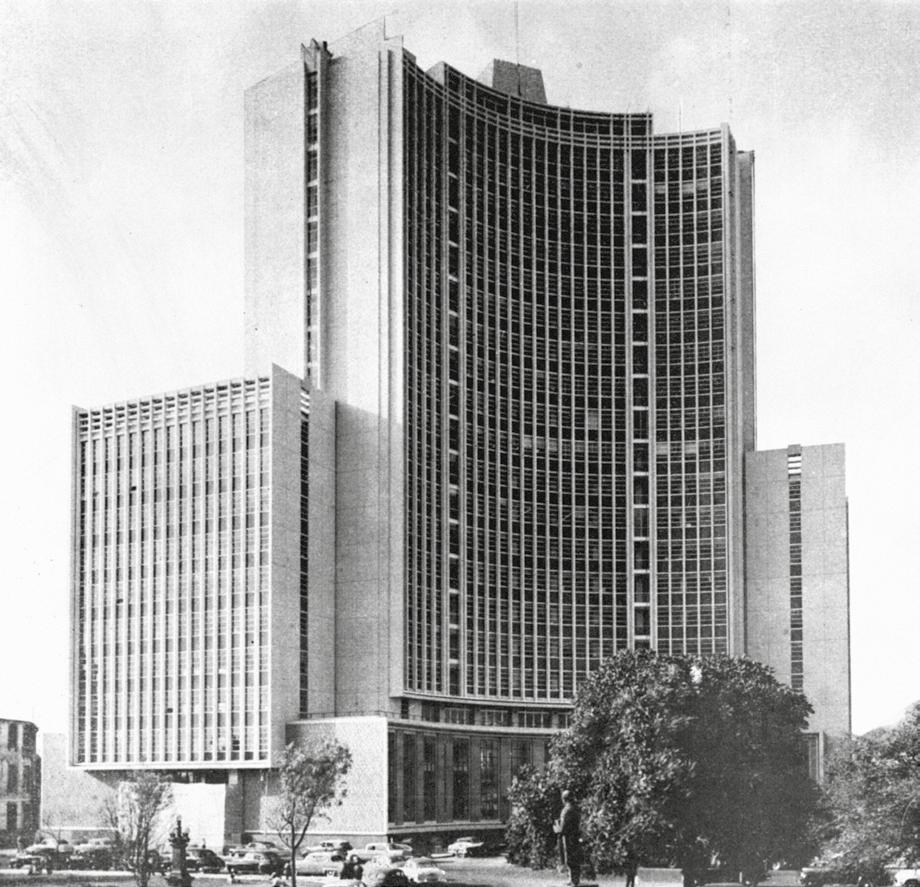

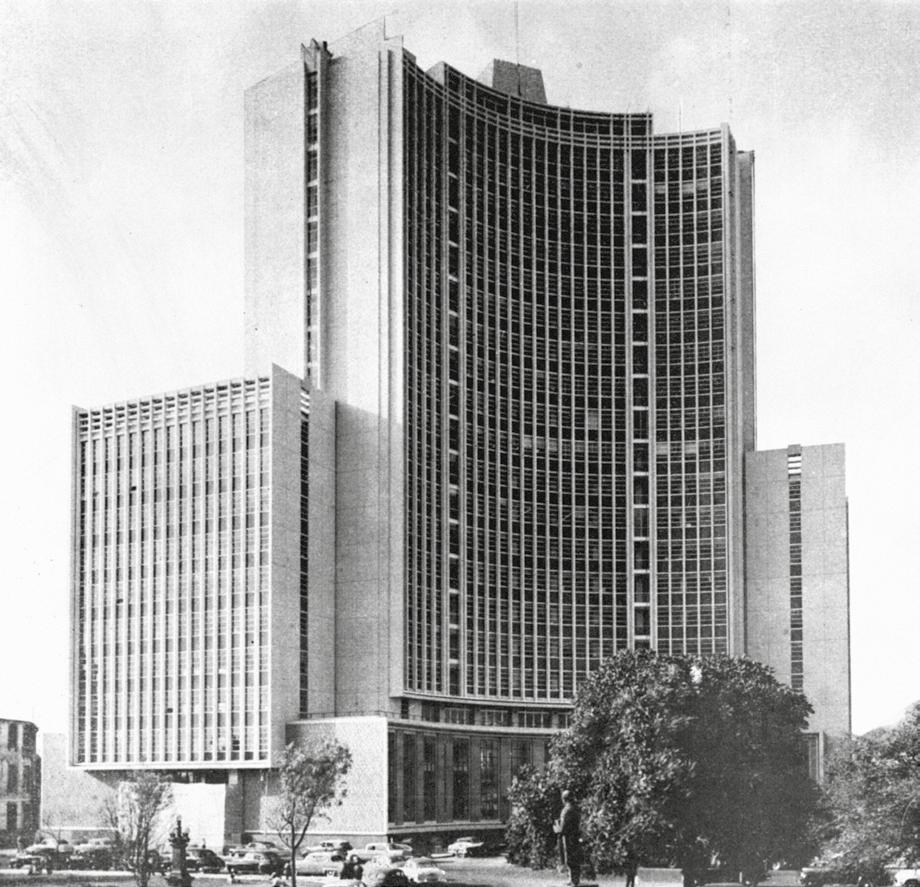

En 2018, Antoine Willmering, director de la iniciativa “Keeping it Modern”2 del Getty Conservation Institute, realizó un viaje a Chile donde, a través de Carlos Maillet, miembro del equipo de proyecto Fiat Lux3, conoció el Monasterio Benedictino y a uno de sus arquitectos, el hermano Martín Correa. A partir de esa visita, en la que se expusieron casos relevantes de la arquitectura nacional pertenecientes al Movimiento Moderno, como el edificio Biomarino de la PUCV, la Cepal y la Copelec, quedó en evidencia la falta de protección por parte del Estado hacia estos edificios, y la Fundación Getty se interesó en apoyar iniciativas que protegen el patrimonio moderno en Chile.

El proceso de análisis e investigación de la iglesia de Los Benedictinos tiene dos componentes claves. Uno se relaciona al material, concreto, técnico, físico, medible y funcional; y el segundo, a su carácter de patrimonio inmaterial. La dependencia entre uno y otro es total: forma y función están articuladas desde el origen en el orden litúrgico y ritual, puerta de entrada al patrimonio inmaterial, que se expresa nítidamente en este espacio construido con atmósferas intangibles.

Entendiendo este doble componente, el lugar se transforma, día a día, en un espacio celebrativo con los ritmos diarios de las celebraciones.

1 La Fundación Getty cumple una misión filantrópica apoyando a personas e instituciones comprometidas en una mayor comprensión y preservación de las artes visuales en el mundo. Mediante subvenciones estratégicas fortalece y promueve (entre otras) iniciativas como la práctica interdisciplinaria de la conservación.

2 Keeping It Modern: iniciativa de la Fundación Getty enfocada en la conservación de edificios del siglo XX alrededor del mundo.

3 Fiat Lux: Proyecto que tiene como objetivo la construcción de un documento que entregue lineamientos generales y específicos respecto de cómo conservar y mantener en el tiempo la Iglesia del Monasterio Benedictino de la Santísima Trinidad de Las Condes.

The Benedictine Monastery of the Holy Trinity of Las Condes, a national monument located on the northern foothills of the San Benito de Los Piques hill, is today an active construction site. In order to know the church's current state, the Getty Foundation1, an entity that has dedicated significant resources to protecting outstanding works of modern architectural heritage around the world, sponsored the project.

In 2018, Antoine Willmering, director of the Getty Conservation Institute's "Keeping it Modern"2 initiative, made a trip to Chile where, through Carlos Maillet, a member of the Fiat Lux3 project team, he visited the Benedictine Monastery and one of its architects, Brother Martín Correa. From that visit, in which relevant national architectural cases belonging to the Modern Movement were presented, such as the Biomarine building of the PUCV, the Cepal, and the Copelec, the lack of protection by the State for these buildings became evident, and the Getty Foundation became interested in supporting initiatives that protect modern heritage in Chile.

The analysis and research process of the Benedictine church has two key components. One is related to the material, concrete, technical, physical, measurable, and functional; and the second is to its intangible heritage character. The dependence between one and the other is absolute: form and function are articulated from the origin in the liturgical and ritual order, the gateway to the intangible heritage, which is clearly expressed in this place built with intangible atmospheres.

Understanding this double feature, the place is transformed, day by day, into a celebratory space with daily rhythms of celebrations.

1 The Getty Foundation fulfills the Getty Trust's philanthropic mission by supporting individuals and institutions committed to advancing greater understanding and preservation of the visual arts in Los Angeles and around the world. Through strategic grant making initiatives, it strengthens art history as a global discipline, promotes interdisciplinary conservation practice.

2 Keeping It Modern: iniciativa de la Fundación Getty enfocada en la conservación de edificios del siglo XX alrededor del mundo.

3 Fiat Lux: The project's objective is to develop a document that provides general and specific guidelines on how to conserve and maintain the Benedictine Monastery Church of the Holy Trinity in Las Condes over time.

↦ 7 Reportaje / Feature Article

Patrimonio / Heritage

El Monasterio Benedictino, un patrimonio inmaterial

THE BENEDICTINE MONASTERY, AN INTANGIBLE HERITAGE

por by : carlos maillet

La reflexión más inmediata en torno a lo que significa la arquitectura del Monasterio Benedictino, en especial de su iglesia, radica en dos aspectos principales: fue proyectada por dos monjes y, corresponde a un patrimonio inmaterial (litúrgico). Destaca en el edificio el valor de “lo moderno” y la maestría del encofrado que hace deslizar la luz cenital por sus muros de una manera quirúrgica que se traduce en juegos de luz y oscuridad.

Otros de sus atributos son su simpleza, su dualidad, el uso del blanco y el asomo que tiene el emplazamiento de este monumento sobre el valle del Mapocho. La evolución de este concepto “inmaterial y litúrgico,” es lo que ordena todas las ideas y priorizaciones, tanto tectónicas como académicas e, inclusive, espirituales.

En Chile, del total de monumentos declarados expresamente mediante decreto en algunas de las categorías que contempla la legislación, existen 143 que, expresamente, son conjuntos de iglesias, capillas, conventos y catedrales; cinco sitios que corresponden a lugares sagrados del pueblo mapuche; y un caso excepcional vinculado a la fiesta del Cuasimodo, que se declaró a comienzos de 2006, y que se relaciona a los bienes materiales que ocupa esta tradición.

El proceso metodológico para sostener la conservación patrimonial de un espacio espiritual como la Iglesia de los Benedictinos, no solo radica en los principios modernos o en valores atingentes a los definidos por la tectónica o tecnología, sino esencialmente, en el valor inmaterial del conjunto.

The most immediate reflection on the Benedictine Monastery's architectural significance, and especially that of its church, lies in two main aspects: it was designed by two monks and it is part of an immaterial heritage (liturgical). The building stands out for its "modern" value and the mastery of the formwork that makes the zenithal light slide through its walls in a surgical way that translates into a game of light and darkness. Another one of its attributes is its simplicity, the duality, the white, and the view that this monument has over the Mapocho valley.

However, the most radical research and approach to this space is about its immaterial heritage character. The evolution of this "immaterial and liturgical" concept is what brings together all the ideas and prioritizations, both tectonic and academic, and even spiritual.

In Chile, from the total number of monuments expressly declared by decree in some of the legislative categories, there are 143 that are expressly declared as collections of churches, chapels, convents, and cathedrals; five sites that represent sacred places of the Mapuche people; and an exceptional case linked to the Quasimodo festival, which was declared at the beginning of 2006, and which is related to the material properties occupied by this tradition.

The methodological process to sustain the heritage conservation of a spiritual space such as the Benedictine Church is not only based on modern principles or values related to those defined by tectonics or technology but essentially, on the immaterial value of the complex.

Un aspecto crucial dentro del camino hacia el conocimiento de esta obra y su estado real de conservación ha sido el contacto cercano y generoso con la comunidad de monjes Benedictinos.

A crucial aspect in the path towards understanding this work and its actual state of conservation has been the close and generous contact with the community of Benedictine monks.

The methodological process to sustain the heritage conservation of a spiritual space such as the Benedictine Church is not only based on modern principles or values related to those defined by tectonics or technology but essentially, on the immaterial value of the complex.

↧

El proceso metodológico para sostener la conservación patrimonial de un espacio espiritual como la Iglesia de los Benedictinos, no solo radica en los principios modernos o en valores atingentes a los definidos por la tectónica o tecnología, sino esencialmente, en el valor inmaterial del conjunto.

El Monasterio Benedictino, un patrimonio material

THE BENEDICTINE MONASTERY, A MATERIAL HERITAGE

por by : facultad de arquitectura de la universidad del desarrollo

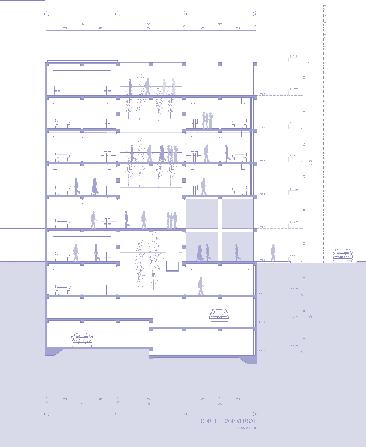

Considering the importance of early conservation, technology has been at the service of heritage since ancient times. When we talk about past times, we face both the Modern Movement conservation, as well as new references of contemporary architecture that, as the years go by, we will consider as heritage.

Keeping it Modern

Hubo que recurrir a técnicas de inspección no intrusivas para analizar el estado de los elementos estructurales no visibles, como las barras de refuerzos de los muros.

Non-intrusive inspection techniques had to be used to assess the condition of non-visible structural elements, such as the wall´s reinforcement bars.

Con el patrocinio de la Fundación Getty, a través de su iniciativa Keeping it Modern, se está llevando a cabo un plan de trabajo enfocado a la conservación preventiva de la Iglesia de los Benedictinos. A través de tecnología de punta, y un equipo multidisciplinario, se ha implementado una estrategia de estudio que profundiza el análisis del edificio, desde su estructura, hasta los elementos que se consideran de alta significancia. Son 90 las obras de arquitectura moderna que han sido analizadas alrededor del mundo bajo esta metodología, implementando planes de manejo para la protección de bienes que, por su importancia histórica, cultural, compositiva o espacial, son considerados para su puesta en valor por medio de una respuesta técnica.

Metodología de intervención para edificios en uso

Para auscultar este edificio de arquitectura moderna, que se encuentra vigente, se planteó consensuar la investigación con los tiempos propios del usuario. El diseño del plan de manejo, conllevó, de esta manera, una simbiosis correlativa entre los requerimientos del usuario y los lineamientos metodológicos.

Keeping it Modern

With the Getty Foundation's sponsorship, through its "Keeping it Modern" initiative, a work plan is being carried out focused on the Benedictine Church's preventive conservation. Through state-of-the-art technology and a multidisciplinary team, a study strategy has been implemented that deepens the building's analysis, from its structure to the elements that are considered to be highly significant. There are 90 works of modern architecture that have been analyzed around the world under this methodology, implementing management plans for the protection of properties that, due to their historical, cultural, compositional, or spatial importance, are considered for their value through a technical response.

Intervention Methodology for Buildings in Use

In order to study this modern architectural building, which is still in use today, the research had to be carried out following the user's own time frame. The management plan design thus involved a correlative symbiosis between the user's requirements and the methodological guidelines.

Considerando la importancia de conservar de manera temprana, la tecnología se pone al servicio del patrimonio desde tiempos pretéritos. Cuando hablamos de tiempo pretérito, nos enfrentamos tanto a la conservación del Movimiento Moderno, así como a nuevos referentes de arquitectura contemporánea que, con el pasar de los años, consideraremos patrimonio.

↧

Se tomó en cuenta la temporalidad de los usos litúrgicos de los monjes y su Ora et labora4 para determinar los lineamientos de mantenimiento y conservación, prevaleciendo la situación temporal y estacionaria. Más de 18 meses de seguimiento fueron necesarios para una detallada evaluación, y observar distintos escenarios vinculados a fenómenos climáticos y temperatura, siempre asociados a los ritos y al carácter de protección que ofrece el monumento.

Los monjes utilizan la iglesia cerca de cinco horas diarias. En época invernal, cuatro de las siete celebraciones transcurren de noche, sin luz natural. Esta rutina tiene implicancias en la dinámica ascética reflejada en la componente térmica y lumínica del templo y, directamente, en sus usuarios.

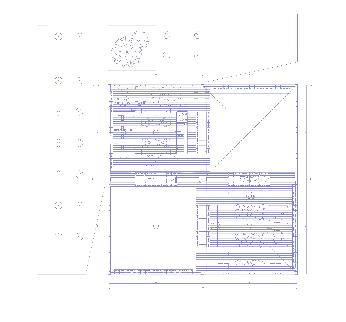

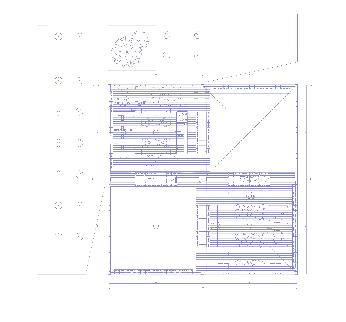

A partir del levantamiento crítico como diagnóstico fundacional, se definieron las especialidades que convergen en el estudio. Por medio de la observación de la temperatura interior, así como de humedades, filtraciones, desprendimientos, y oxidación, entre otras alteraciones, se estableció lo que constituye prioridad.

La iglesia del Monasterio Benedictino requiere, fundamentalmente, mantenimiento y el eventual reemplazo de elementos que no son significativos a nivel estructural y que tienen una alta tolerancia al cambio. Se detectó una contraposición entre el estilo de vida ascético de los monjes y la habitabilidad de la iglesia en los meses de junio y julio debido a las bajas temperaturas que no solo implican corrientes de aire, sino que, además, dificultan el canto característico de las celebraciones religiosas. Los requerimientos son prácticos: templar el lugar en invierno, ventilar en verano, sellar filtraciones, mejorar la acústica y aislar para mantener una temperatura mínima que permita su habitabilidad.

Por otra parte, la calidad de la iluminación artificial constituye un desafío importante que requiere compatibilizar elementos estéticos, definidos como de alto valor patrimonial y ascético, y las necesidades lumínicas que permitan una correcta lectura.

The liturgical seasonality of the monks and their Ora et Labora4 was taken into account to determine the guidelines for maintenance and conservation, emphasizing the temporary and stationary situation. More than 18 months of evaluation were necessary for a detailed assessment, and to observe different scenarios linked to climatic phenomena and temperature, always associated with the rites and the protective character offered by the monument.

The monks use the church for about five hours a day. During the winter season, four of the seven celebrations take place at night, without natural light. This routine has implications on the ascetic dynamics reflected in the church's thermal and lighting components and, directly, on its users.

From the critical survey as a foundational diagnosis, the specialties that converge on the study were defined. Priorities were established by observing the interior temperature, as well as humidity, leaks, peeling, and corrosion, among other alterations.

The Benedictine Monastery church requires, fundamentally, maintenance and the eventual replacement of elements that are not structurally significant and that have a high probability of change. A conflict was detected between the monks' ascetic lifestyle and the church's habitability in the months of June and July due to the low temperatures, which not only imply drafts but also hinder the characteristic chanting of religious celebrations. The requirements are practical: temper the place in winter, ventilate in summer, seal leaks, improve acoustics, and insulate to maintain a minimum temperature that allows its habitability.

On the other hand, artificial lighting quality is an important challenge that requires the compatibility of aesthetic elements, defined as having a high heritage and ascetic value, and the lighting needs that enable suitable reading.

Se llevó a cabo una acuciosa revisión de las instalaciones del edificio (agua, luz y calefacción), de manera de identificar posibles riesgos y establecer recomendaciones para un correcto mantenimiento.

A thorough review of the building's installations (water, electricity, and heating) was carried out in order to identify possible risks and establish recommendations to maintain it properly.

The Benedictine Monastery church requires, fundamentally, maintenance and the eventual replacement of elements that are not structurally significant and that have a high probability of change.

4 El lema Ora et labora, ora y trabaja, es de tradicióse le atribuye a la Orden de San Benito. Pretende plasmar el equilibrio de la jornada monstica benedictina definida en la regla de san Benito.

↧

4 The motto Ora et labora, to pray and work, is a medieval tradition attributed to the Order of St. Benedict. It is intended to embody the balance of the Benedictine monastic day as defined by the Rule of St. Benedict.

La iglesia del Monasterio Benedictino requiere, fundamentalmente, mantenimiento y el eventual reemplazo de elementos que no son significativos a nivel estructural y que tienen una alta tolerancia al cambio.

Lineamientos de intervención

La definición de niveles de intervención, según elementos muebles e inmuebles, y su clasificación como elementos de valor, son vitales para la determinación de las acciones a seguir. Cada recomendación técnica específica responde a un nivel de significancia cultural5 y, por tanto, a la tolerancia al cambio permitido6

El monasterio, después de 64 años de existencia, conserva sus características originales. No ha variado ni su función ni su destino ni sus usuarios ni sus habitantes. Sus autores, ancianos en un pacífico silencio monástico, estaban vivos cuando comenzó la investigación.

Siguiendo esta línea, se sugiere mantener la imagen prístina del edificio como principal valor patrimonial, y los elementos singulares por medio de una adecuada conservación. Un ejemplo son algunos marcos de fierro afectados por oxidación como consecuencia de la falta de mantenimiento. Para elementos que puedan tener afecciones mayores, se propone la compatibilidad matérica guardando un prudente principio de diferenciación que no altere la imagen ascética y prístina del conjunto. La eliminación de elementos desconfigurantes se realiza principalmente en intervenciones como el retiro de equipos de iluminación o cableado eléctrico en desuso.

Tecnología al servicio ascético

El manual de lineamientos contempla la profundizacion del trabajo multidisciplinar para las dimensiones de valor patrimonial que se busca conservar y promover. Estas son: ingeniería estructural y comportamiento sísmico; acondicionamiento ambiental para detección de la calidad del aire, temperatura, humedad y luz; sellos e impermeabilización; iluminación y lampistería; redes eléctricas; redes sanitarias; patologías bióticas; ingeniería acústica; prevención de riesgos; paisajismo; levantamiento modelo as built mediante escaner LiDar7; riesgo de incendios; y normativa y permisos. Se trata de una primera aproximación investigativa al primer edificio declarado en su tipología en nuestro país. Una experiencia de conservación patrimonial y técnica para la arquitectura moderna. Un proceso metodológico que guarda relación con una contundente bibliografía, glosario y levantamientos críticos capaces de ser referentes argumentativos para otros inmuebles históricos y, principalmente, para aquellos que actualmente están en uso y serán patrimonio futuro. /

Intervention Guidelines

The definition of intervention levels, according to movable and immovable elements, and their classification as elements of value, are vital to determine the actions to be taken. Each specific technical recommendation reflects a level of cultural significance5 and, therefore, the tolerance of permitted change.6

The monastery, after 64 years of existence, retains its original characteristics. Neither its function, its destination, its users, nor its inhabitants have changed. Its authors, elderly in peaceful monastic silence, were still alive when the research began.

Following this approach, it is recommended to maintain the building's pristine image as the main heritage value, and the unique elements through adequate conservation. An example is some of the iron frames affected by corrosion as a consequence of insufficient maintenance. For elements that may be more seriously affected, material compatibility is proposed while maintaining a prudent principle of differentiation that does not alter the complex's ascetic and pristine image. The elimination of misconfigured elements is mainly performed in interventions such as lighting equipment or electrical wiring in disuse.

Technology at the Service of Asceticism

The guidelines manual contemplates the multidisciplinary depth of the heritage value dimensions to be preserved and promoted. These are, structural engineering and seismic performance; environmental conditioning to detect air quality, temperature, humidity, and light; seals and waterproofing; lighting and plumbing; electrical wiring; sanitary networks; biotic pathologies; acoustic engineering; risk prevention; landscaping; an as-built model survey using LiDar scanners7; fire risk; and regulations and permits.

This is an initial investigative approach for the first building declared in its typology in our country. An experience in heritage and technical conservation for modern architecture. A methodological process that is related to a strong bibliography, glossary, and critical surveys capable of being argumentative references for other historic buildings and, mainly, for those that are currently in use and will be future heritage. /

5 En la documentación de la Getty Foundation se cita “significancia cultural” a lo que denominamos en nuestra legislación nacional como “valores y atributos”

6 Niveles de significancia cultural consideran la graduación desde A alta, B moderada, C baja y D discordante. Se asigna a valores y atributos del sitio. Los niveles de tolerancia al cambio se establecen para indicar el alcance de la intervención. A mayor nivel de significancia del elemento más estrictas, por tanto más conservativas, las acciones. Se establecen 4 grados de intervención donde el primer grado es el más conservativo y responde a elementos de alto valor patrimonial y, por el contrario, el cuarto grado es el definido como discordante, donde la modificación o eliminación se permite dado que el componente se considera perjudicial para el inmueble o elemento.

7 Un LiDar es un dispositivo que permite determinar la distancia desde un emisor láser a un objeto o superficie utilizando un haz láser pulsado. La distancia al objeto se determina midiendo el tiempo de retraso entre la emisión del pulso y su detección a través de la señal reflejada.

5 The Getty Foundation's documentation cites "cultural significance" to what we refer to in our national legislation as "values and attributes".

6 Cultural significance levels are graded from A high, B moderate, C low and D discordant. It is assigned to the site's values and attributes. Change tolerance levels are established to indicate the extent of intervention. The higher the level of element significance, the stricter and therefore more conservative the actions. Four degrees of intervention are established, where the first degree is the most conservative and responds to elements of high heritage value, while the fourth degree is defined as discordant, where modification or elimination is permitted because the component is considered detrimental to the property or element.

7 A LiDar is a device that helps determine the distance from a laser emitter to an object or surface using a pulsed laser beam. The distance to the object is determined by measuring the time delay between the pulse emission and its detection from the reflected signal.

↦ 11 Reportaje / Feature Article

12 ↤ AOA / n°46

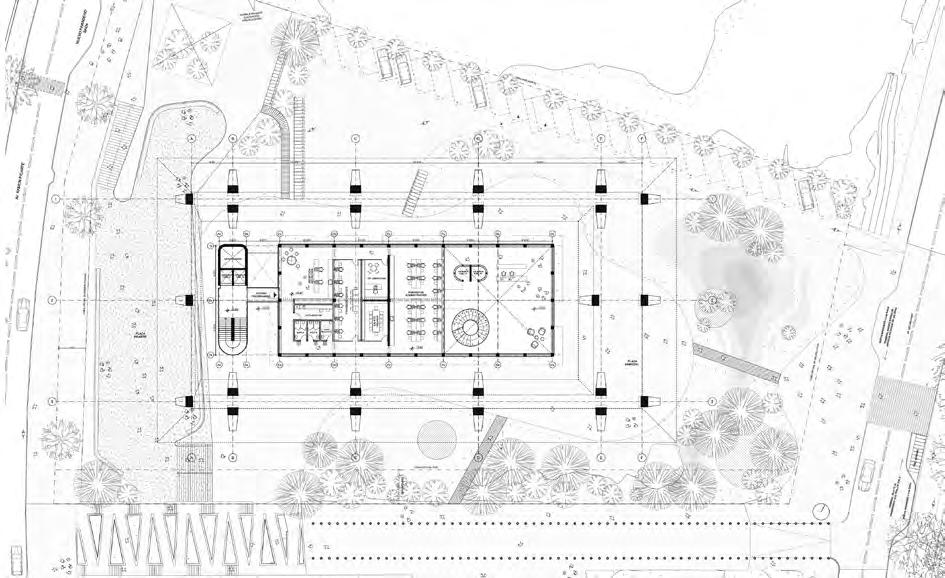

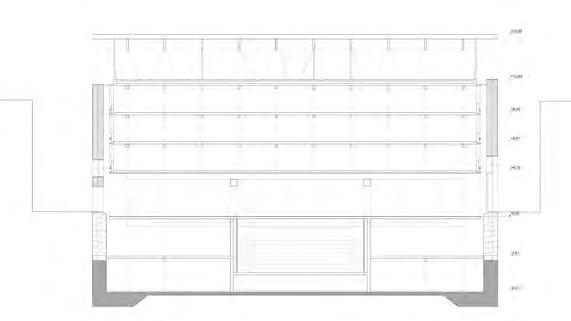

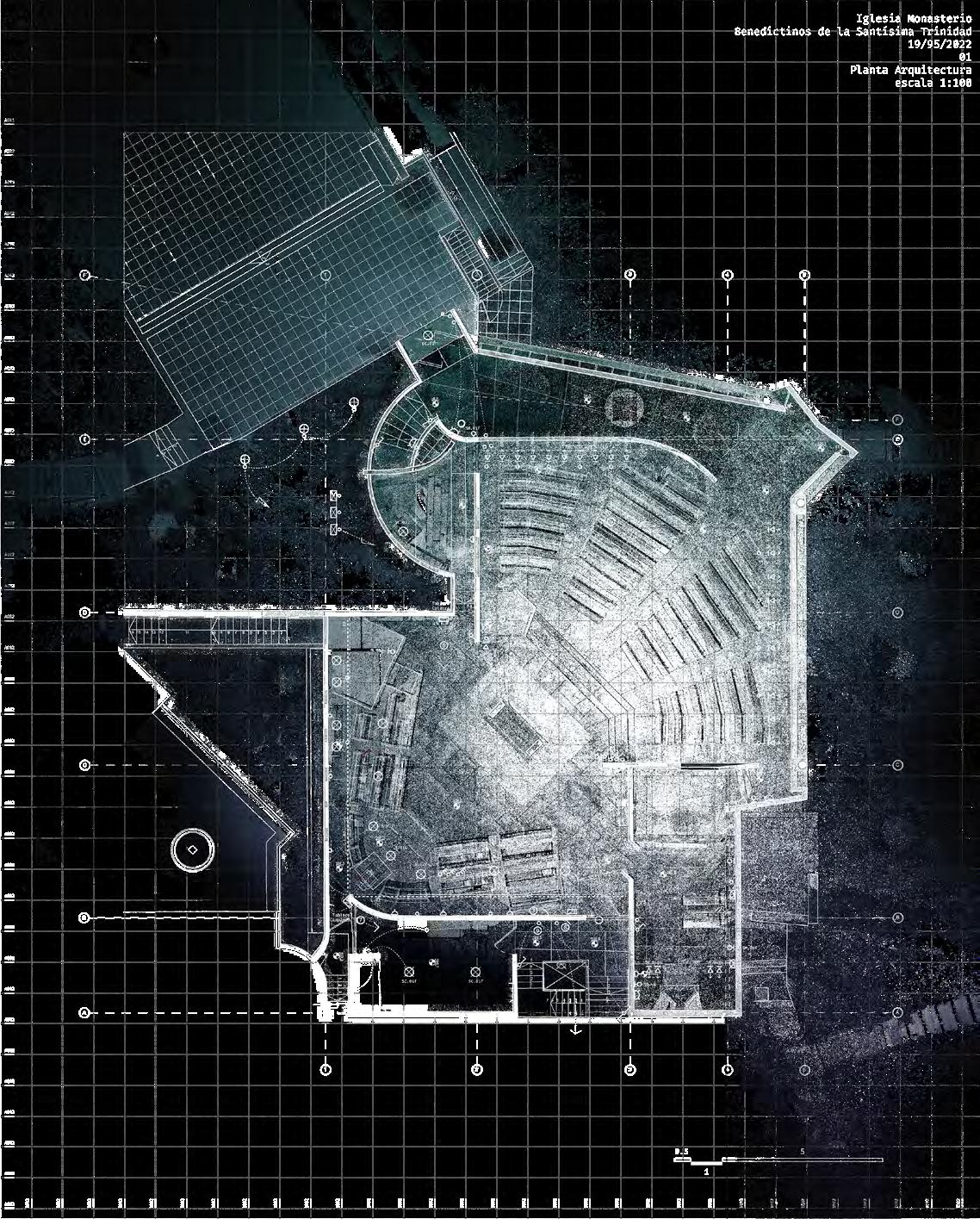

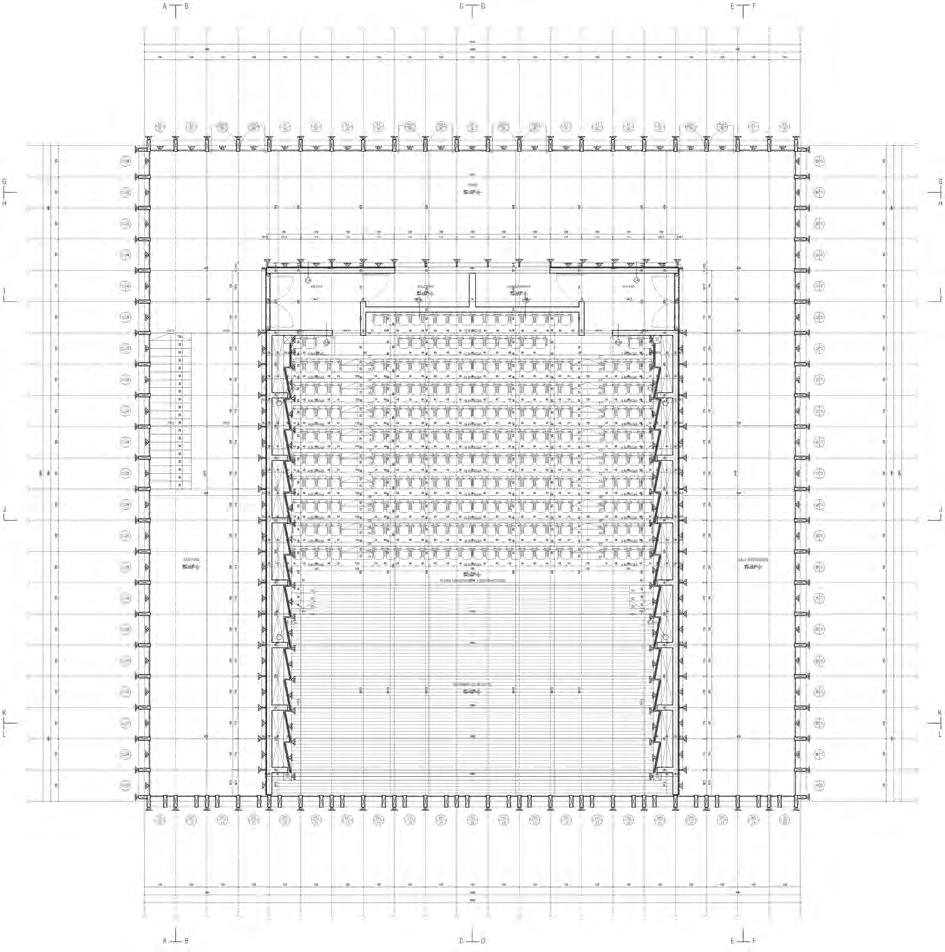

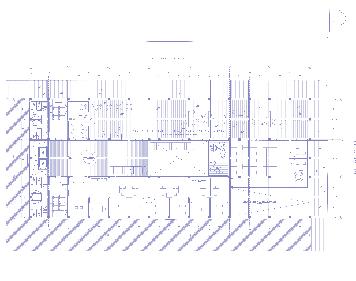

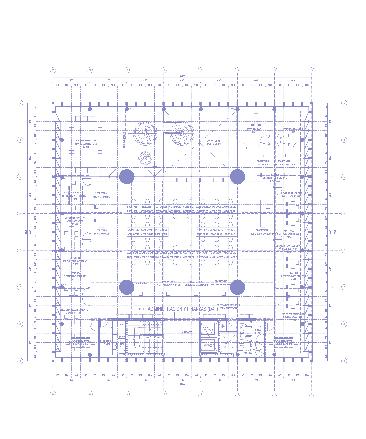

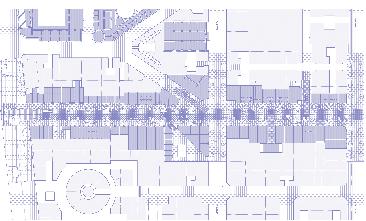

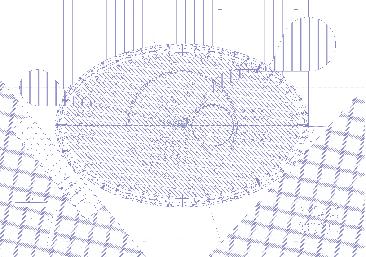

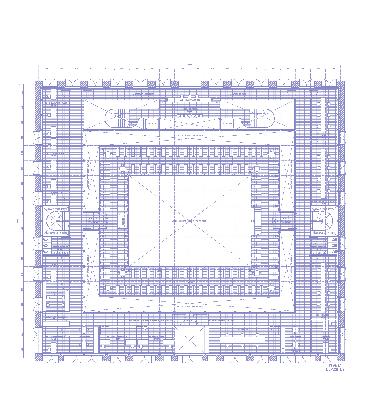

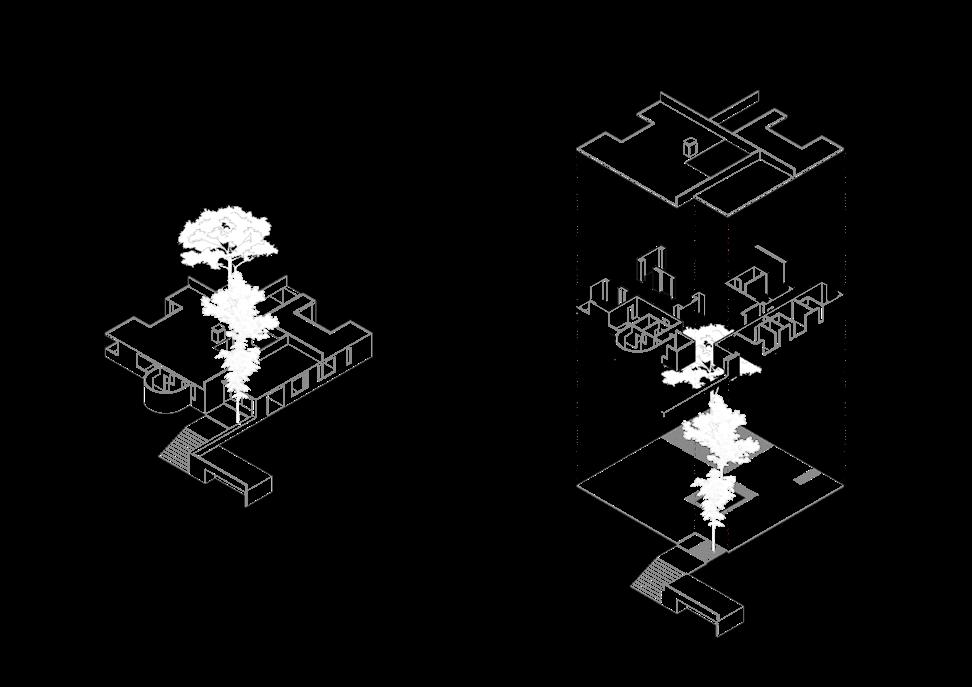

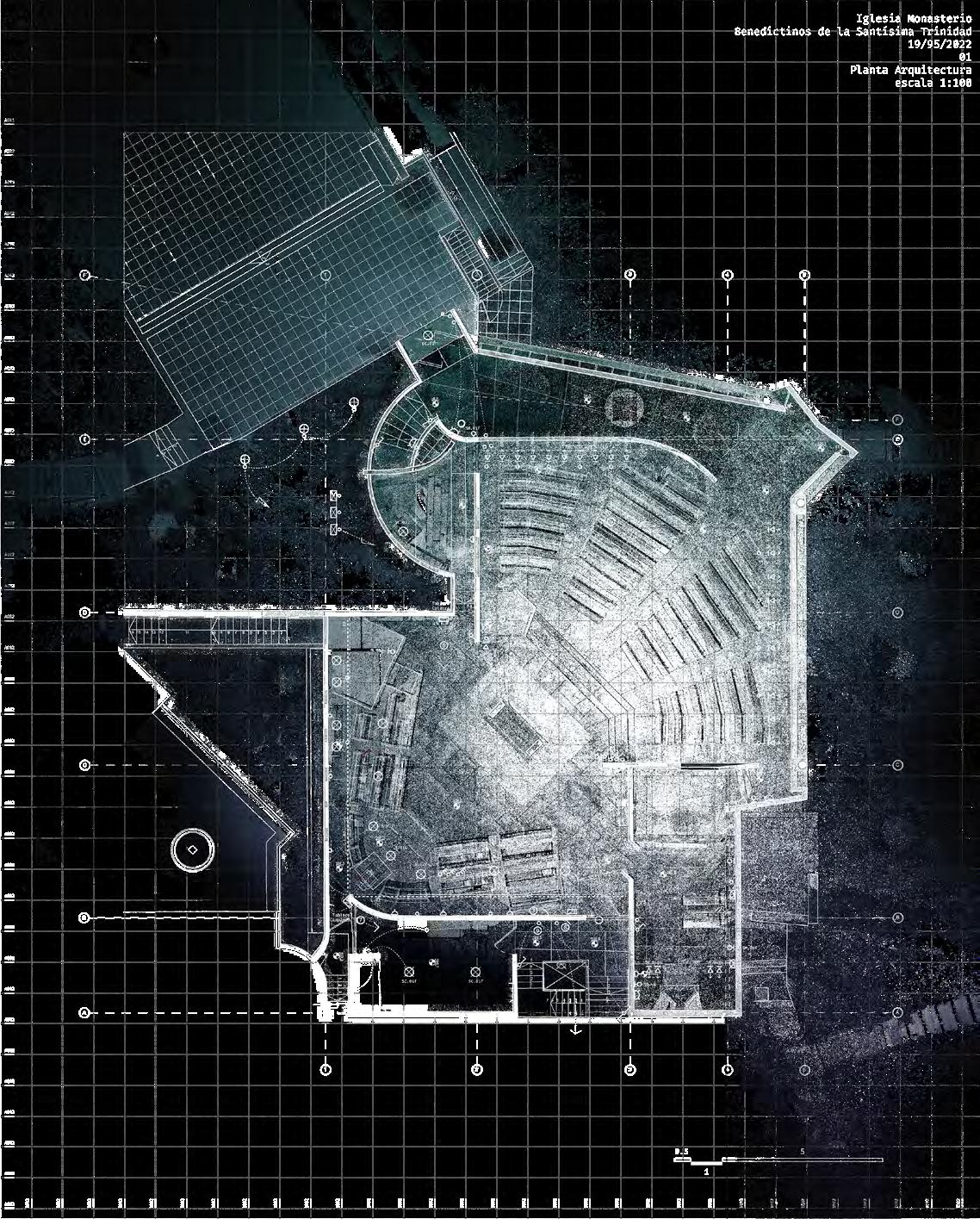

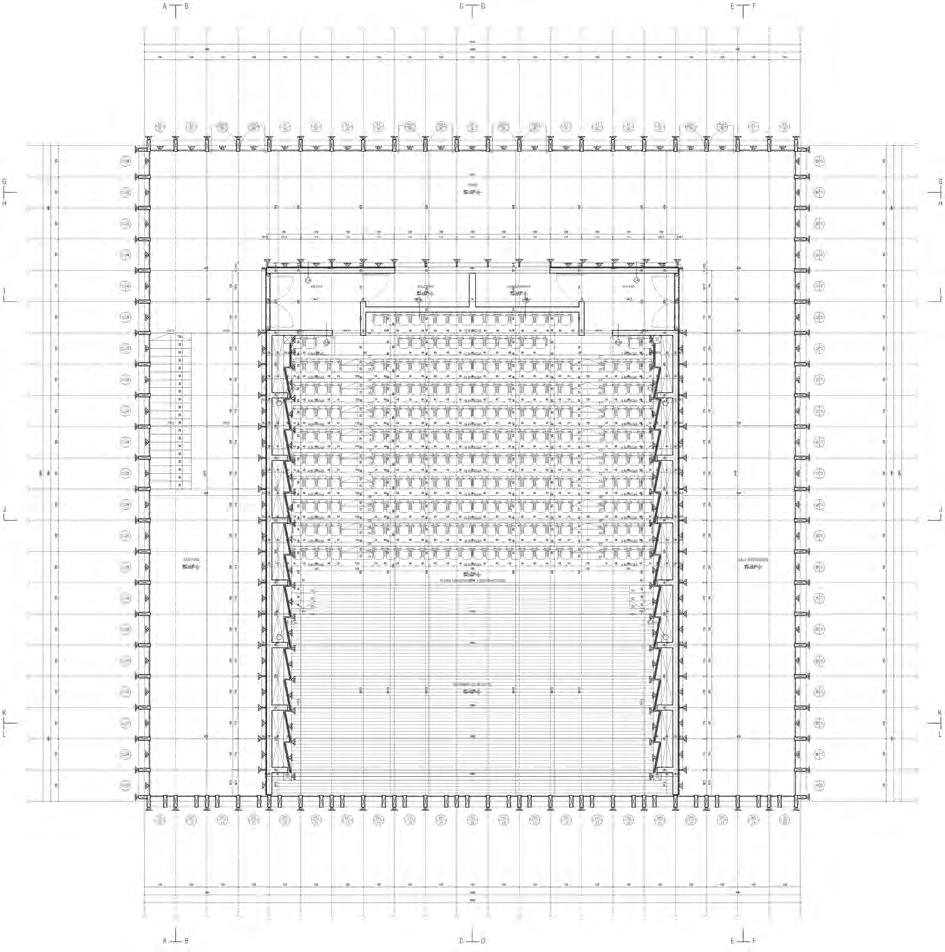

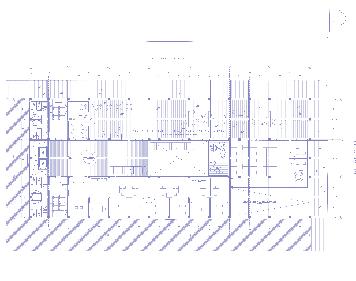

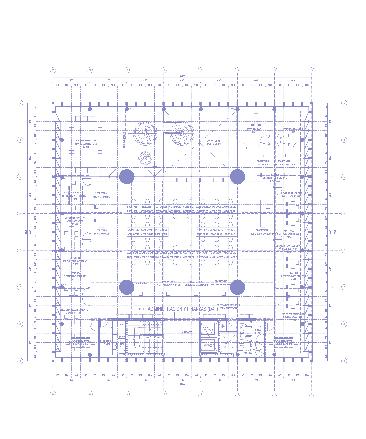

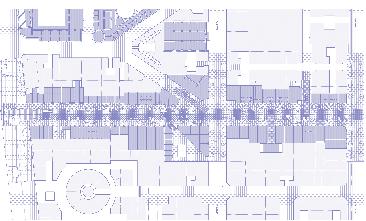

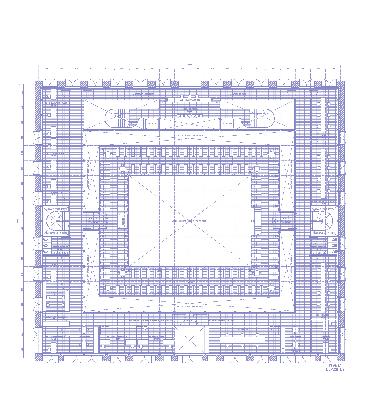

Iglesia Monasterio Benedictino de la Santísima Trinidad Planta arquitectura_Architecture plan

Fachada poniente_West facade

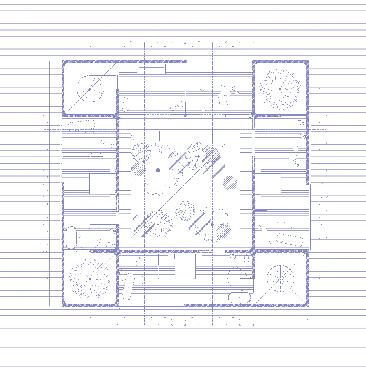

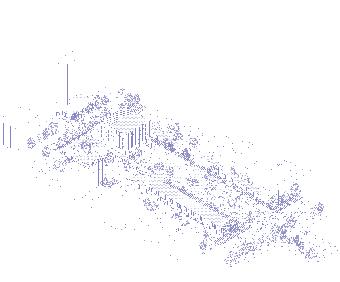

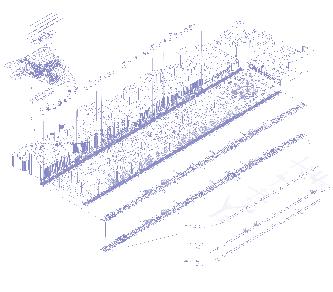

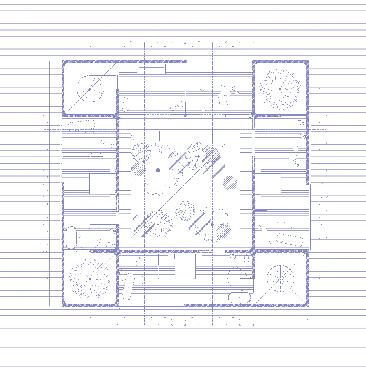

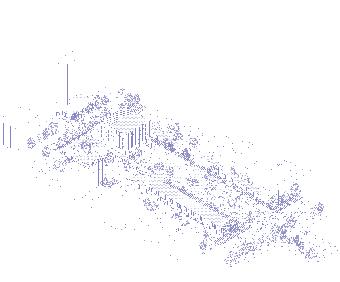

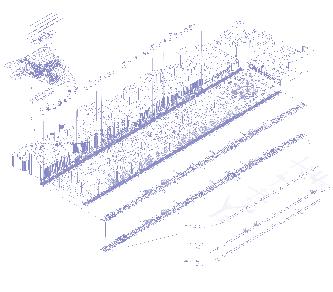

Proceso de escaneo LiDar para modelo de nube de puntos, desarrollado por empresa GetArq.

LiDar scanning process for a point cloud model, developed by GetArq.

Fachada norte_North facade

↦ 13

Reportaje / Feature Article

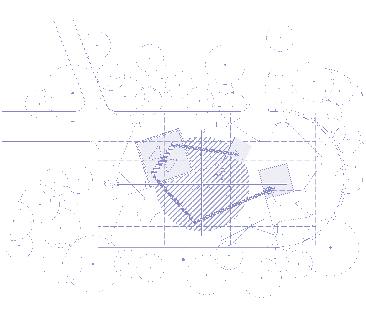

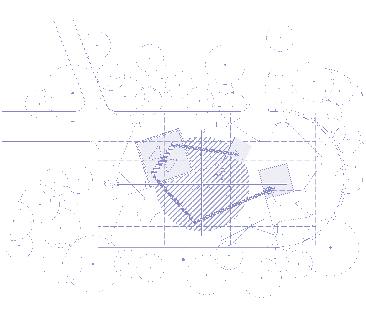

Pérdida de sección de muros_Loss of wall sections

Humedad interna_Internal humidity

Humedad por riego_Moisture from irrigation

Suciedad superficial_Surface dirt

Fisuras_Fissures

Grietas_Cracks

Intervenciones con estucos_Stucco interventions

Musgos y líquenes_Moss and lichens

Excremento de aves_Bird droppings

Corrosión estructuras metálicas_Metal structure corrosion

Suciedad por escurrimiento_Dirt due to runoff

Desprendimiento de pintura_Peeling paint

Iglesia Monasterio Benedictino de la Santísima Trinidad Levantamiento crítico fachada sur_Critical survey south facade

AOA / n°46 14 ↤

A partir de tecnologías como el escaneo LiDar, es posible contar con un modelo as built del edificio que permita entender, con absoluta exactitud, el comportamiento que ha tenido durante más de 60 años desde su fecha de construcción

Using technologies such as LiDar scanning, it is possible to have an as-built model of the building that provides an absolute accurate understanding of the way it has behaved for more than 60 years since it was built.

↦ 15 Reportaje / Feature Article

“Heritage preservation is essential for two reasons: first, because of its universal value in aesthetic and historical terms; and second, because of its importance for the societies and cultures that are entrusted with its safekeeping. By establishing a link between the past and the present, cultural heritage enhances the sense of identity and social cohesion among both individuals and communities, thus laying the foundations on which societies build their future”.

16 ↤ AOA / n°46

La conservación del patrimonio es fundamental por dos motivos: primero, por su valor universal en el plano estético e histórico; y segundo, por la importancia que reviste para las sociedades y culturas a quienes incumbe su custodia. Al establecer un vínculo entre el pasado y el presente, el patrimonio cultural potencia el sentimiento de identidad y la cohesión social, tanto entre los individuos, como entre las comunidades, estableciendo así los cimientos sobre los que las sociedades edifican su futuro”.

Kōichirō Matsuura, 2005

“

El

registro fotográfico y planimétrico corresponde al material recolectado por el equipo de proyecto Fiat Lux de la Facultad de Arquitectura de la Universidad del Desarrollo, Grupo PRAEDIO y la oficina de diseñadores SimpleLab. / The photographic and planimetric record reflects the material collected by the Fiat Lux project team from the Faculty of Architecture at Universidad del Desarrollo, Grupo PRAEDIO, and the SimpleLab design office.

La relación, siempre cercana y constructiva, que se ha logrado tener con quién no solo fue uno de los arquitectos de la obra, sino uno de sus usuarios, ha sido clave para poder llevar a cabo un rescate de la tradición oral en cuanto al cuidado y preservación de este edificio.

The relationship, always close and constructive, that has been achieved with the person who was not only one of the work´s architects but also one of its users, has been key to rescue of the oral tradition regarding this building´s care and preservation.

↦ 17 Reportaje / Feature Article

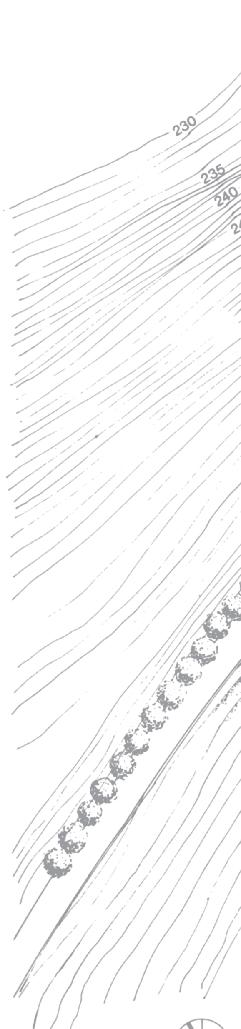

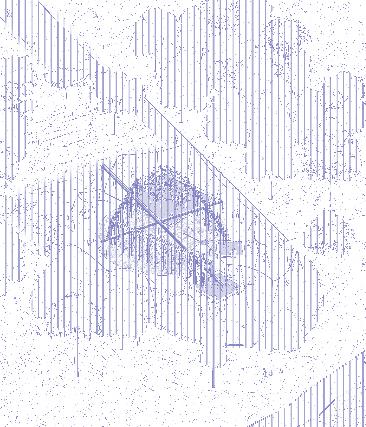

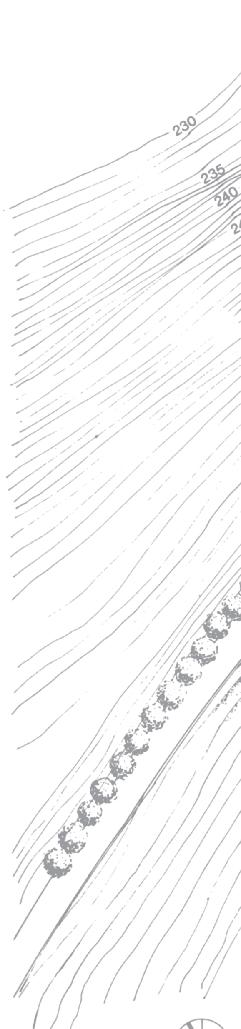

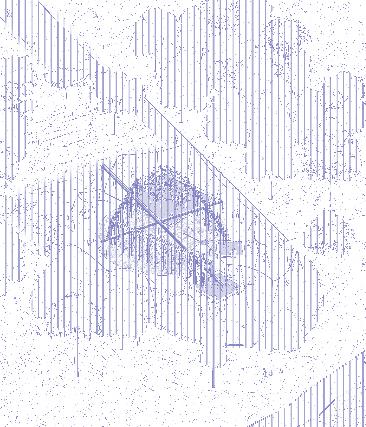

El monasterio en el paisaje de la proximidad: un espacio de interrelaciones entre caminos, senderos, canales, un tranque, cultivos frutales en línea y el lomaje natural. The monastery in the surrounding landscape: a space of interrelationships between roads, trails, canals, a dam, fruit orchards, and the natural hillside.

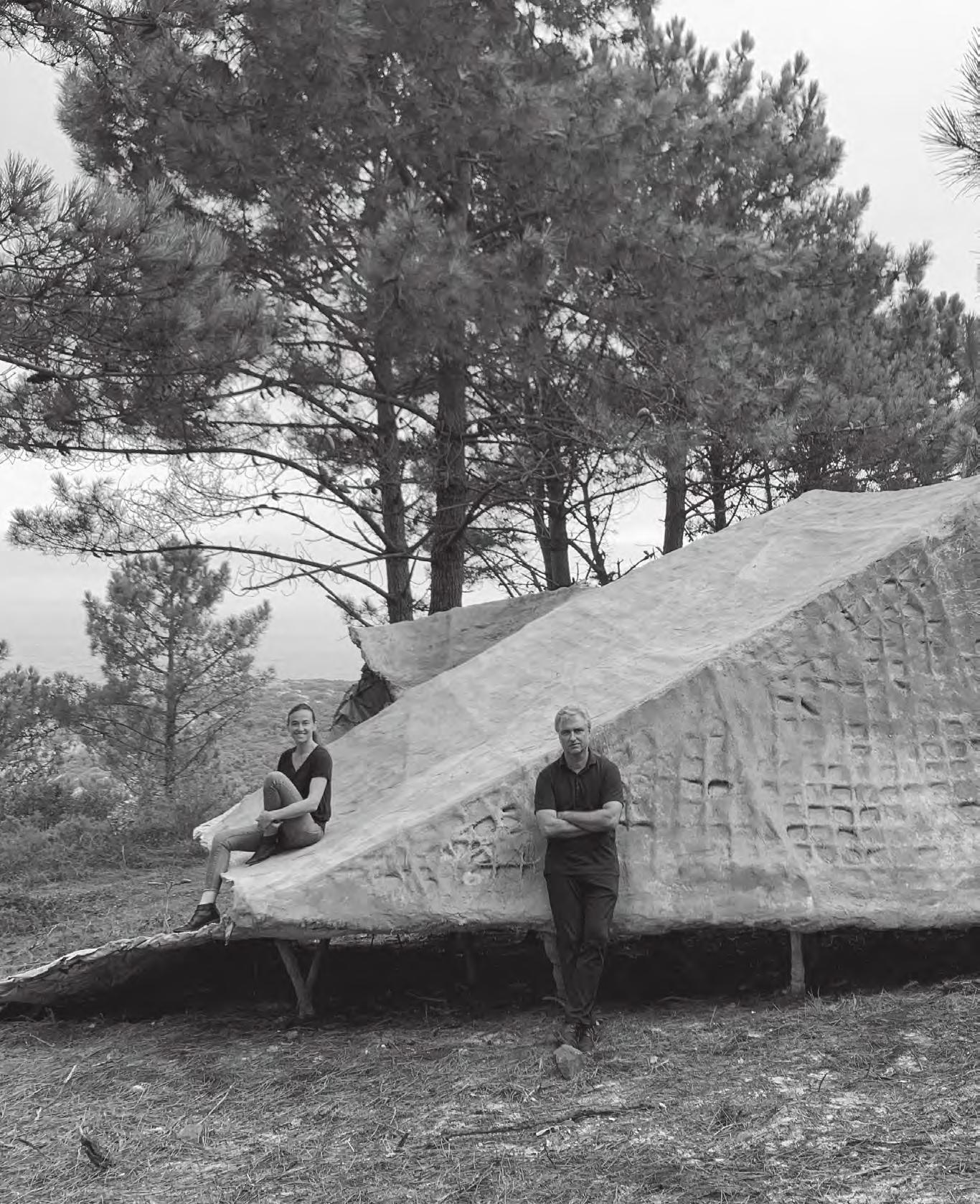

Arquitecta de la Universidad Católica de Valparaíso con postítulo en Arquitectura del Paisaje FADEU, PUC. Editora de la Revista CA, 1978-1992. Jefe de programa en postítulos en Arquitectura y Manejo del Paisaje y Diplomado en Diseño de Paisaje PUC, 2000-2016. Fundadora de la oficina Geopaisaje de Juana Zunino y Paz Carreño dedicada a proyectos de arquitectura del paisaje en espacios públicos y privados.

Architect from Universidad Católica de Valparaíso with postgraduate degree in Landscape Architecture FADEU, PUC. Editor of CA Magazine, 1978-1992. The head of the program for postgraduate degrees in Landscape Architecture and Management and Certified course in Landscape Design PUC, 2000-2016. The Founder of Geopaisaje, Juana Zunino and Paz Carreño office that is dedicated to landscape architecture projects in public and private spaces.

juana zunino muratori © Pablo

Altikes

DESDE Y HACIA EL PAISAJE

FROM AND TO THE LANDSCAPE

por by : juana zunino muratori

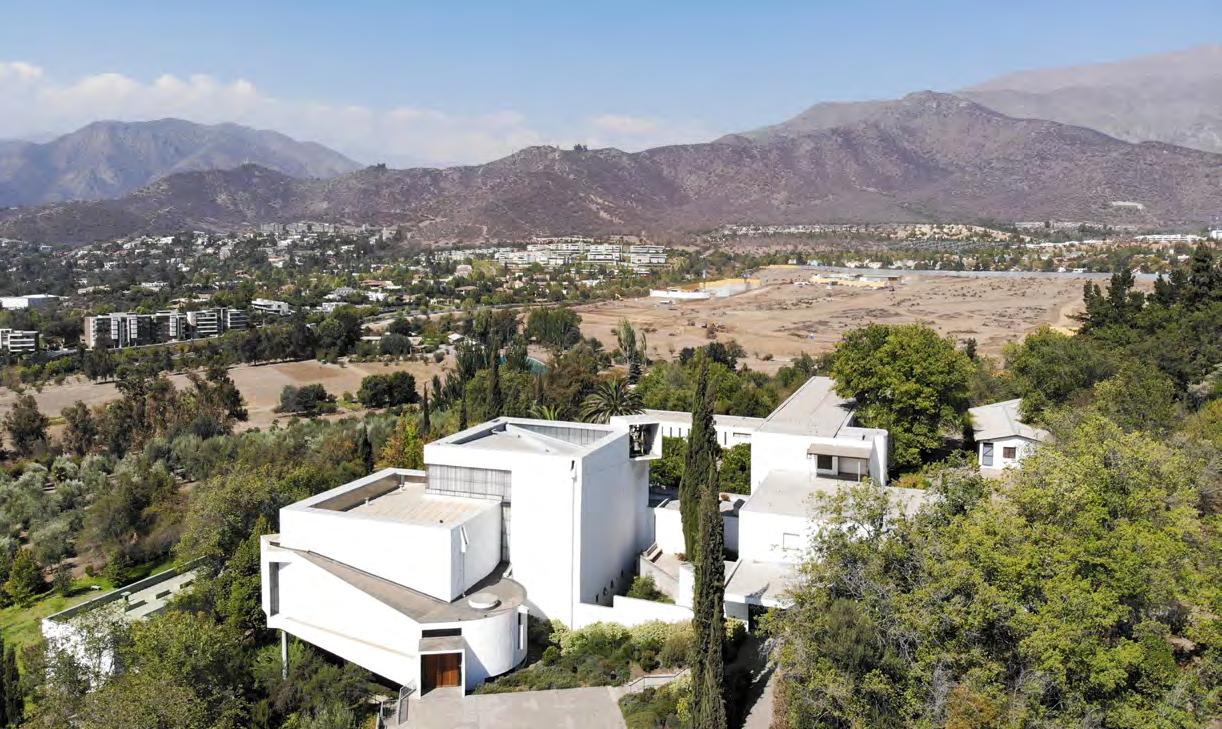

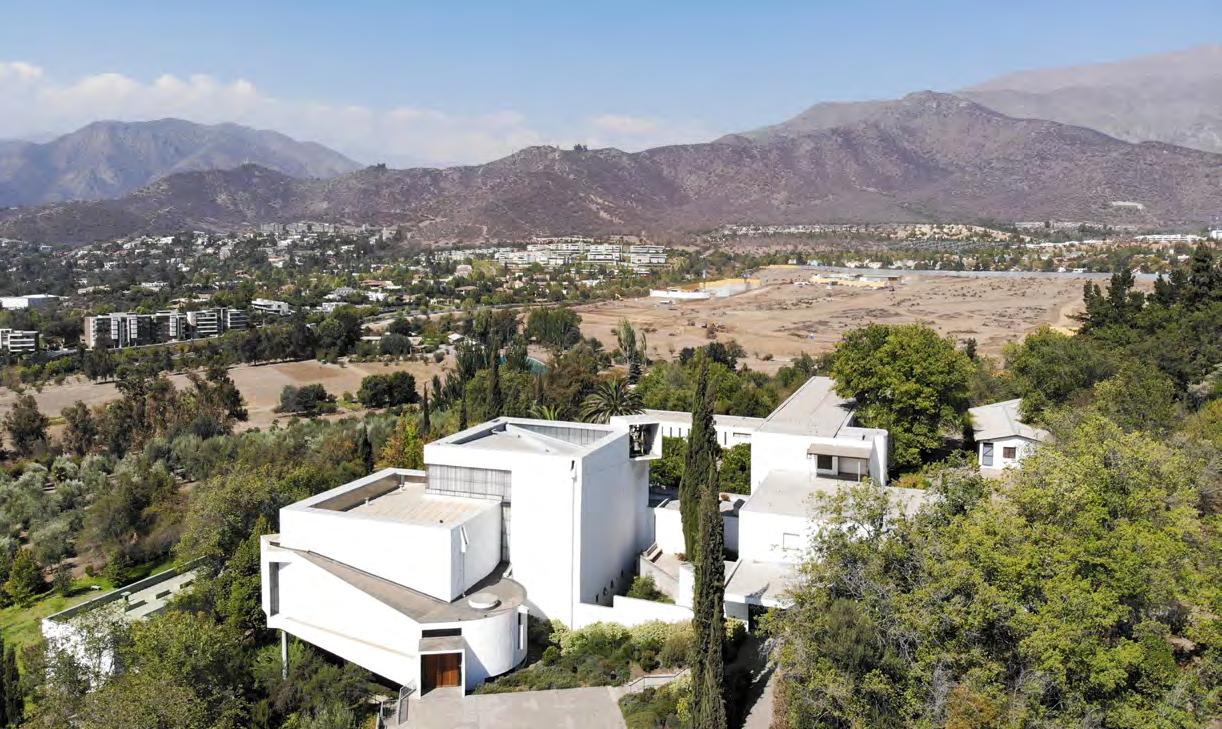

El Monasterio Benedictino, emplazado armoniosamente en la frontera precordillerana, al oriente de la ciudad de Santiago, es un lugar de peregrinación, tanto por su carácter religioso como por su belleza arquitectónica.

Jaime Bellalta, arquitecto de la primera obra construida allí, la que entregó las bases para el conjunto final, comentaba «Es una obra de arquitectura contemporánea. Solo responde al destino del lugar. ¿Acaso la arquitectura no es la habitación del hombre? ¿No es el habituarse a su medio, a sus posibilidades, a su destino? Si la arquitectura muestra eso, se hace obra del lugar, del espacio, del viento, del sol, del hombre». (1.Pag 70)

Para describir el monasterio hoy, en su relación con el paisaje, ha sido necesario seguir una trayectoria buscando la aproximación, tanto de personas que han intervenido en las obras y que han experimentado su presencia en la vida diaria, como en publicaciones sobre el tema. El paisaje es una síntesis virtuosa de atributos naturales, geográficos y culturales, que fue impregnada en el origen del proyecto y cuidadosamente respetada por todos los actores.

architecture shows that, it becomes the work of the location, of the space, of the wind, of the sun, of man». (1. Page 70)

Jaime Bellalta, the architect responsible for the first project built there, which provided the foundations for the final complex, commented, «It is a work of contemporary architecture. It only responds to the location´s destiny. Isn't architecture man´s habitat? Isn't it the habit of getting used to his environment, to his possibilities, to his destiny? If

To describe the monastery today, in its relationship with the landscape, it has been necessary to follow a trajectory searching for an approach, both from people who have been involved in the projects and who have experienced its presence in daily life, as well as in publications on the subject. The landscape is a virtuous synthesis of natural, geographical, and cultural attributes, which were impregnated in the project´s origin and carefully respected by all the actors.

The Benedictine Monastery, harmoniously located in the foothills of the Andes, east of Santiago, is a place of pilgrimage, both for its religious character and its architectural beauty.

Patrimonio / Heritage ↦ 19 Reportaje / Feature Article

Elección del lugar

El hermano Martín Correa1 explica: «La vida monástica benedictina está centrada en la búsqueda de Dios a través de la oración, el estudio y el trabajo. De aquí nuestra máxima: Ora et Labora. Tal tipo de vida requiere un ambiente de silencio. Silencio exterior que favorezca el silencio interior que es lo importante para la escucha.

Las colinas, los cerros, tienen una vinculación especial con la vida espiritual. Jesucristo gustaba de orar frecuentemente en la montaña. San Benito amaba los montes y en el año 529 funda el primer monasterio de Occidente en Montecassino, una colina estratégica entre Roma y Nápoles. (3)

El monasterio está conectado con la ciudad a la vez que resguarda la clausura. Este modelo se replica en lugares con una geografía montañosa, como es nuestro país.

En 1938, el padre Pedro Subercaseaux fundó el Monasterio Benedictino en Santiago, en un lugar apartado de la capital, hoy el Hospital Fach de Las Condes. La cercanía de un estadio obligó a los monjes a buscar un lugar más lejano. El cerro Los Piques garantizaba una permanencia efectiva.

Según el padre Gabriel Guarda, cuando realizaron la visita de inspección para evaluar la conveniencia del terreno, entraron por el cerro Los Piques, caminando a media ladera, de poniente a oriente. A mitad de camino, con el asomo de la cordillera y la vista del valle de La Dehesa, sus expresiones de satisfacción eran ‘gritos de júbilo'». (1. Pag 35)

The monastery is connected to the city while protecting the enclosure. This model is replicated in locations with a mountainous geography, as is our country.

Site location

Brother Martin Correa1 explains: «Benedictine monastic life is centered on the search for God through prayer, study, and work. Hence our maxim: Ora et Labora ´´Pray and work´´. Such a life requires an atmosphere of silence. Exterior silence fosters interior silence, which is important for listening. The hills have a special connection with spiritual life. Jesus Christ liked to pray frequently in the mountains. St. Benedict loved the mountains and in 529 founded the first monastery in the West at Montecassino, a strategic hill between Rome and Naples. (3)

Vista hacia el norte. El valle con los nuevos barrios y el perfil de los cerros circundantes.

View to the north. The valley with the new neighborhoods and the outline of the surrounding hills.

20 ↤ AOA / n°46

↧

El monasterio está conectado con la ciudad a la vez que resguarda la clausura. Este modelo se replica en lugares con una geografía montañosa, como es nuestro país.

1 Martín Correa, arquitecto y monje benedictino, uno de los autores del proyecto junto al padre Gabriel Guarda.

©

1 Martin Correa, architect and Benedictine monk, one of the project´s authors along with Father Gabriel Guarda.

Pablo Altikes

Hacia el oriente, el macizo cordillerano, las altas cumbres y los grandes hitos orientadores del valle de Santiago.

To the east, the massif of the Andes, the high peaks, and the great guiding landmarks of the Santiago valley.

El lugar geográfico

El cerro Los Piques es un promontorio que se ubica en el centro del primer valle que se abre desde el cajón del río Mapocho, por el nororiente, en el inicio de la planicie inclinada de Santiago, en el borde del pie andino.

Se sitúa en una posición equidistante de los cerros circundantes, que otorgan la medida espacial de este pequeño valle, tanto la distancia horizontal como la dimensión vertical dada por las cumbres que la conforman. Ellos articulan el espacio aéreo, definiendo la extensión visual del lugar geográfico orientado por las cumbres que son hitos significantes.

En sus laderas y en el perfil de las cumbres se refleja el recorrido de la luz durante el día y a través de las estaciones, mostrando, tanto el relieve y las formas de lomajes, como las hendiduras del terreno reforzadas por la vegetación natural.

Entre los cerros se abre la perspectiva hacia otros valles, como La Dehesa por el norte, el valle de Santiago hacia el surponiente y la quebrada de Apoquindo hacia el suroriente.

Hacia el oriente, los montes se suceden uno tras otro formando el macizo cordillerano y, hacia el poniente, aparecen pequeños cerros islas que sobresalen en el valle de Santiago.

El cerro Los Piques no es un cerro simétrico y ofrece características paisajísticas diferenciadas en sus laderas. Se eleva a media altura, unos 15 a 20 m desde el nivel intermedio de las edificaciones, hacia el sur oriente, formando la cumbre, dejando el espacio para el acceso, desde el sur, por la calle Otoñal y desde el oriente, por la calle Bulnes Correa.

- Hacia el norte y poniente, forma una atalaya natural, una situación de mirador a una altura de 50 a 55 m. hacia el espacio circundante, que conforma una franja de pendiente abrupta hacia el plano inferior, donde limita con la calle Charles Hamilton, un zócalo natural.

- Hacia el nororiente, se encuentra la quebrada San Francisco, desahogo natural de las aguas de deshielo, invernales y ocasionales desde la cordillera, y figura geográfica que se repite en ritmos que identifican la precordillera del valle de Santiago.

The monastery is connected to the city while protecting the enclosure. This model is replicated in locations with a mountainous geography, as is our country.

In 1938, Father Pedro Subercaseaux founded the Benedictine Monastery in Santiago, in a remote part of the capital, today it is the Fach Hospital in Las Condes. The proximity of a stadium forced the monks to look for a more distant location. The Los Piques hill guaranteed an effective permanence.

In a quote, Father Gabriel Guarda, says that when they made the inspection visit, to evaluate the land´s suitability, they entered through the Los Piques hill, walking halfway up the slope, from west to east. Halfway, with the view of the mountain range and the view of the La Dehesa valley, their expressions of satisfaction were 'shouts of joy» (1. Page 35).

The geographical location

Los Piques Hill is a promontory located in the center of the first valley that opens up from the Mapocho River to the northeast, at the beginning of Santiago´s sloping plain, on the edge of the Andean foothills.

It is located in an equidistant position from the surrounding hills, which gives spatial measure to this small valley, both the horizontal distance and the vertical dimension given by the peaks that form it. They articulate the aerial space, defining the visual extension of the geographic location oriented by the summits that are significant landmarks.

The slopes and the profile of the peaks reflect the path of light during the day and through the seasons, showing both the relief and the shapes of the hills, as well as the land´s crevices reinforced by the natural vegetation.

Between the hills, the perspective opens up to other valleys, such as La Dehesa to the north, the Santiago valley to the southwest, and the Apoquindo ravine to the southeast.

To the east, the mountains come one after the other forming the Cordillera massif and, to the west, small island hills appear, jutting out into the Santiago valley.

Los Piques Hill is not a symmetrical hill and offers differentiated landscape characteristics on its slopes. It rises to a medium height, about 15 to 20 m from the buildings´ intermediate level, towards the southeast, forming the summit, leaving space for access from the south, along Otoñal Street, and from the east, along Bulnes Correa Street.

- To the north and west, it forms a natural watchtower, a lookout at a height of 50 to 55 m. towards the surrounding area, which forms a strip of steep slopes towards the lower plane, where it borders Charles Hamilton Street, a natural plinth.

- To the northeast is the San Francisco ravine, a natural outlet for winter and occasional snowmelt from the mountains, and a geographic figure that is repeated in rhythms that identify the foothills of the Santiago valley.

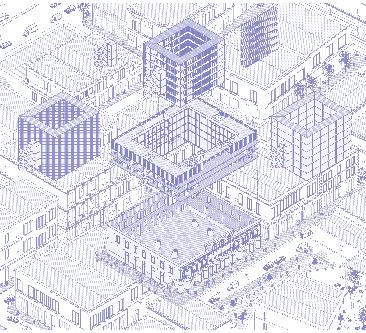

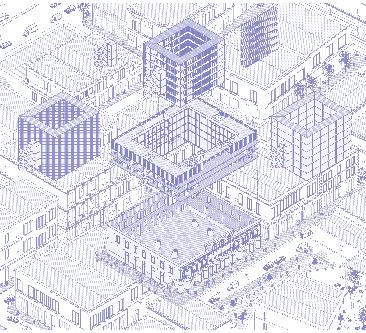

The neighborhood. Stages of urban development

In the area´s occupation, four historical stages can be recognized. They originated the creation of the current urbanization with its arborization.

In the first stage, the avenues with large trees, the old houses of the Lo Fontecilla hacienda, and the surrounding park - remodeled by Prager in the 1930s - made up a complex whose presence enhanced the value of the area. It was in the center of large crops, natural meadows for animals, hawthorn trees on sunny slopes, and evergreen trees in the ravines.

↦ 21 Reportaje / Feature Article ↥

© Guy Wenborne

El barrio. Etapas de desarrollo urbano

En la ocupación del sector, se pueden reconocer cuatro etapas históricas. Ellas originaron la conformación de la actual urbanización con su arborización.

En la primera etapa, las avenidas con grandes árboles, las antiguas casas de la hacienda Lo Fontecilla y el parque que la rodea –remodelado por Prager en los años 30–componían un conjunto cuya presencia valorizó el sector. Era el centro de cultivos de grandes extensiones, praderas naturales para los animales, espinos en laderas asoleadas y árboles siempreverdes en las quebradas.

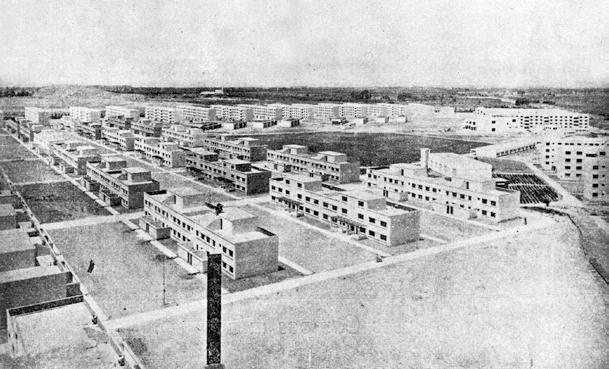

En los años 50 en el valle, cuyo límite superior es el canal de regadío El Bollo, se distribuyeron parcelas que se transformaron en quintas con frutales y casas de fin de semana. Las construcciones estaban distanciadas entre los cultivos y convivían las casas patronales y las de los inquilinos. La imagen del valle era la de huertos plantados en forma ordenada, de propiedades agrícolas medianas y pequeñas, con cortinas rectas de álamos en divisiones o canales. Se levantaban, también, avenidas de acceso de árboles caducos, de gran envergadura y de fácil reproducción, como olmos, acacios y plátanos orientales. Se apreciaba un colorido amarillo-beige en otoño y verde claro en la primavera. Lo complementaban espinos, litres y arbustos nativos, en lomajes asoleados sobre el canal y la vegetación esclerófila en las quebradas.

En los años 60, se subdividieron las parcelas en sitios de 3 mil a 5 mil m2. Se inició un nuevo proceso de transformación en la densidad y calidad de la arborización. Aparecieron nuevas calles arboladas con especies homogéneas o diversas y los sitios cambiaron el huerto por el jardín ornamental, con piscinas y árboles con variedad de colorido, altura, volumen y procedencia.

In the valley in the 50s, whose upper limit is the El Bollo irrigation canal, plots of land were distributed and transformed into farms with fruit trees and weekend houses. The buildings were spaced between the crops, and the owners´ houses and tenants coexisted. The valley´s image was that of orchards planted in an orderly way, with medium and small agricultural properties, with straight curtains of poplars in divisions or channels. There were also access avenues of deciduous trees, large in size and easy to reproduce, such as elms, acacias, and oriental plane trees. The coloring was yellow-beige in autumn and light green in spring. It was complemented by hawthorns, litres, and native shrubs on sunny hillsides above the canal and sclerophyll vegetation in the ravines.

In the 1960s, the plots were subdivided into 3000 to 5000 m2 sites. A new transformation process began in the density and quality of tree planting. New tree-lined streets appeared with homogeneous or diverse species and the sites changed from orchards to ornamental gardens, with pools and trees with a variety of color, height, volume, and origin.

On the plateau between the hill and Las Condes Avenue, a homogeneous park was created, with a visual blending of species developed on private properties and transformed into a mass of trees that is a collective landscape asset and the buildings can be seen through it.

In the 80s and 90's San Carlos de Apoquindo was urbanized, with structuring avenues, incorporating palm trees in the center median, and houses with small plots of land where there was no room for large trees. It is a neighborhood dominated by buildings.

The former working-class neighborhood, which had been established to the east of the El Bollo canal, was eliminated in 1982.

Between Las Condes Avenue and Charles Hamilton, residential buildings appeared in the wooded areas. In the streets, the trees from the previous era were replaced by pyramid-shaped species smaller in size and with brighter colors, such as liquidambar and tulipero, which were planted in single or double rows.

Monastery site

Brother Martin recalls that «in 1950 when we moved in, only hawthorn trees covered the hill. The surrounding area consisted of agricultural plots with a few trees: poplars and eucalyptus. There were a few tenant houses, animals grazing, and little collective movement. In short, a rural environment». (3)

Elm trees were planted on the access road, on the hillsides, and on sunny slopes, fruit orchards, olive, almond, apricot trees, and vines were planted in rows, combined with a shady forest of insigne pines to the southeast, and the untamed vegetation was reserved on the hillsides near the summit or those with steeper slopes. The existing hawthorn grove is considered a bastion of the original situation.

On the hillside between the monastery buildings and the neighborhood park located on the Las Condes Avenue plane, there is a strip of hill cliff and ravines with areas of native vegetation, hawthorns, and birches, which separate the two areas and preserve the site´s viewpoint and silent intimacy.

The agricultural-artisanal sector is located on the lateral plains, to the north, bordering the San Francisco ravine and, to the east, the canal and Bulnes Correa Street, in a north-south direction

El cerro Manquehue, siempre presente hacia el poniente, desde las terrazas en altura y desde la planicie norte del predio, al borde de la quebrada.

The Manquehue hill is always present to the west, from high terraces and the property's northern plain, at the edge of the ravine.

22 ↤ AOA / n°46

↙

©Juana Zunino

«En 1950, fecha de nuestra instalación, solo espinos cubrían el cerro. El entorno estaba constituido por parcelas cultivadas con pocos árboles: álamos y eucaliptus. Había algunas casas de inquilinos, animales pastando y escasa movilización colectiva.

En resumen, un ambiente rural».

«In 1950 when we moved in, only hawthorn trees covered the hill. The surrounding area consisted of agricultural plots with a few trees: poplars and eucalyptus. There were a few tenant houses, animals grazing, and little collective movement. In short, a rural environment».

las calles se reemplazaron los árboles de la época anterior por especies de forma piramidal, de menor tamaño y de coloridos más fuertes, como liquidámbar y tulipero, los que se plantaban en hileras simples o dobles. La trama actual de calles y avenidas alcanzó la complejidad de la ciudad central.

Sitio del monasterio

El hermano Martín recuerda que «en 1950, fecha de nuestra instalación, solo espinos cubrían el cerro. El entorno estaba constituido por parcelas cultivadas con pocos árboles: álamos y eucaliptus. Había algunas casas de inquilinos, animales pastando y escasa movilización colectiva. En resumen, un ambiente rural». (3)

los cerros aledaños que se ven desde las terrazas y desde el interior de las celdas.

En la planicie entre el cerro y la avenida Las Condes, se constituyó un parque homogéneo, con la fusión visual de especies desarrolladas en propiedades particulares y se transformó en una masa arbórea, que es un bien colectivo como paisaje, y las construcciones se vislumbran a través de ella.

En los años 80-90 se urbanizó San Carlos de Apoquindo con avenidas estructurantes, incorporando palmeras en el bandejón central y casas con pequeños terrenos donde no caben árboles de envergadura. Es un barrio donde predominan las construcciones.

La antigua población popular, que se había establecido al oriente del canal El Bollo, fue erradicada el año 1982.

Entre la avenida Las Condes y Charles Hamilton, aparecieron edificios residenciales en los sitios arbolados. En

En la calle de acceso se plantaron olmos y, en las laderas con menor pendiente y asoleadas, se cultivan, en líneas, huertos frutales, olivos, almendros, damascos y vid que se combinan con un bosque sombrío de pino insigne hacia el suroriente y se reserva la naturaleza agreste, en los lomajes próximos a la cumbre o en aquellos con mayor pendiente. El renoval de espinos existente se considera un reducto de la situación original.

En la ladera entre los edificios del monasterio y el barrio parque ubicado en el plano de la avenida Las Condes, se conserva una franja de cerro-acantilado y quebradillas con sectores de vegetación nativa, espinos y litres, que separan ambas situaciones y preservan la condición de mirador y de intimidad silenciosa del recinto.

El sector agrícola-artesanal se desarrolla en las planicies laterales, hacia el norte, limitando con la quebrada San Francisco y, hacia el oriente, con el canal y la calle Bulnes Correa, en dirección norte-sur.

↦ 23 Reportaje / Feature Article

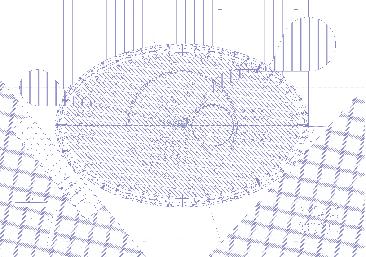

↥ Dibujo del hermano Martín Correa, identificando

LA PALOMA EL ALTAR EL PLOMO EL PROVINCIA LOS PIQUES LA DEHESA ALVARADO 18

A drawing by Brother Martín Correa identifies the surrounding hills that can be seen from the terraces and from inside the cells.

Desde la planicie de cultivo, al borde de la quebrada San Francisco, mirando el cerro Manquehue, el Monasterio emerge silencioso, a media ladera, en el centro de las distancias de lugares habitados.

From the cultivated plain, on the edge of the San Francisco Ravine, overlooking the Manquehue hill, the Monastery emerges silently, halfway up the slope, in the distant center of inhabited areas.

El agua

El canal de riego El Bollo, corre paralelo al pie del monte y dio el trazado a la calle Bulnes Correa, que se prolonga hasta la calle de la quebrada San Francisco, completando un circuito continuo.

El canal relaciona las diferencias de alturas del valle y entra por el contorno del cerro para regar el predio de los Benedictinos. Era el límite superior de las parcelas regadas.

Los tranques de agua de la empresa de agua potable vecina temperan el clima y atraen aves al sector. Son parte significante del paisaje que se observa desde el sur del cerro Los Piques, desde el cementerio y la cumbre.

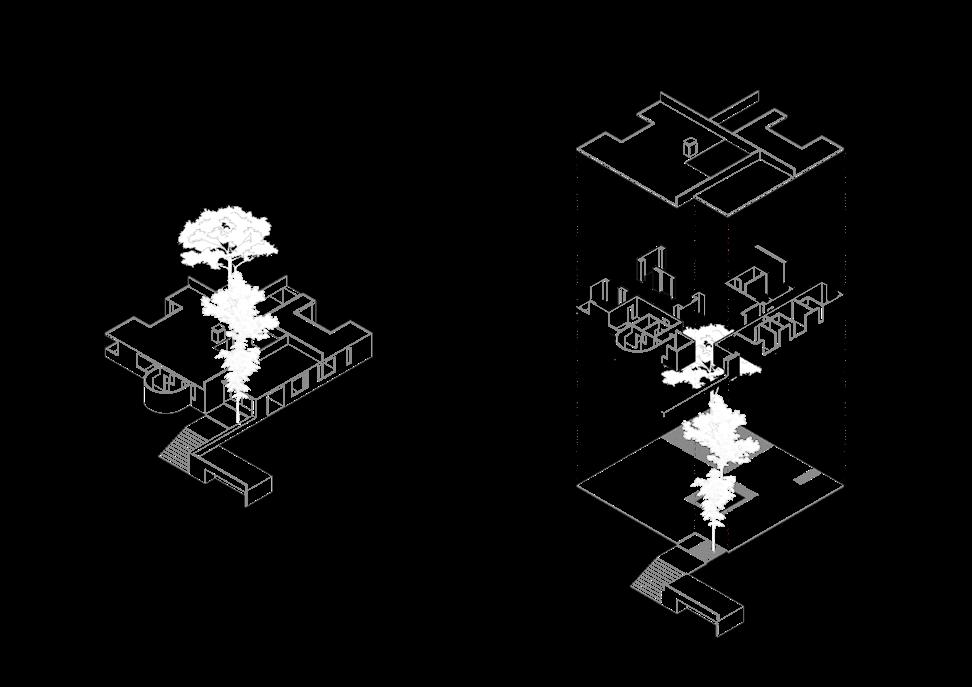

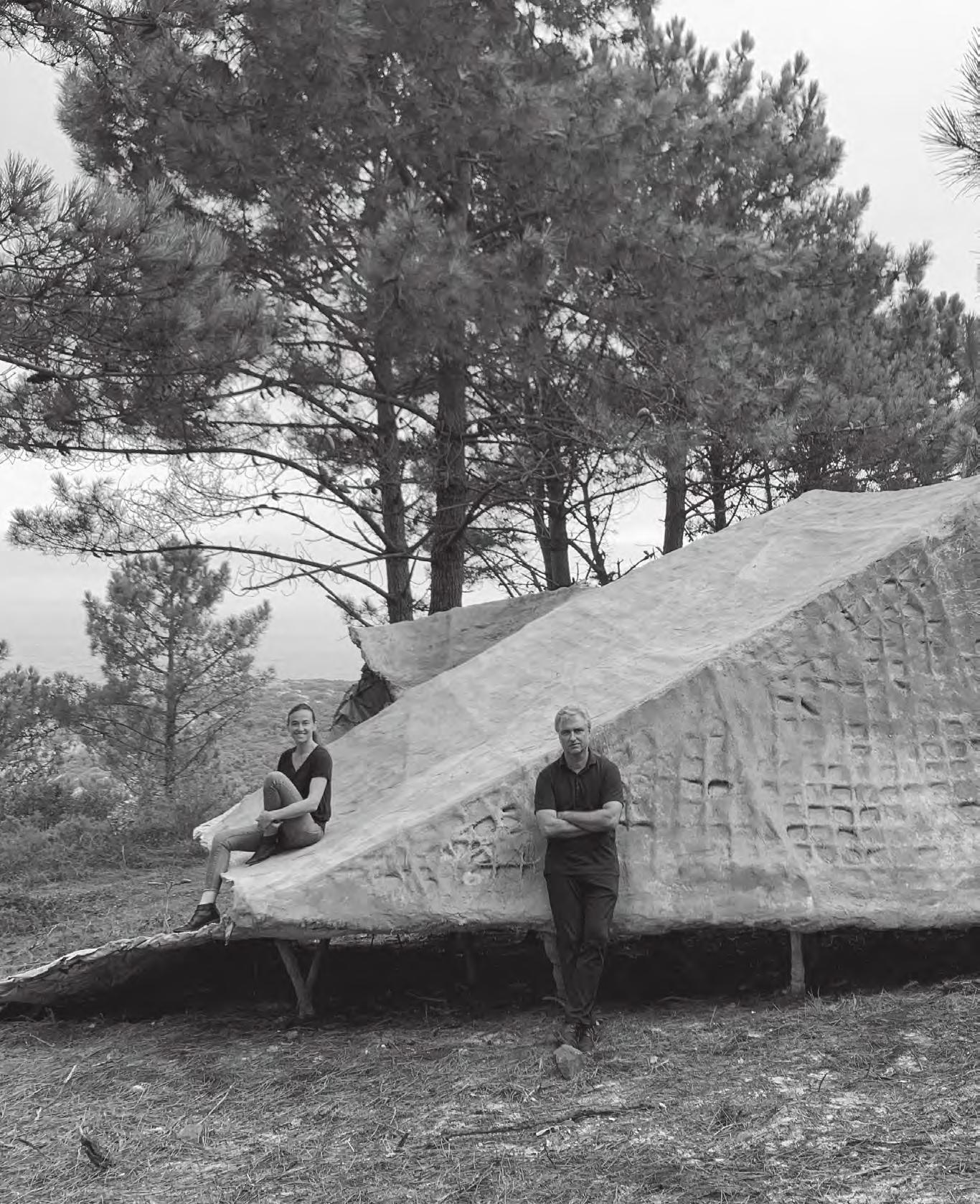

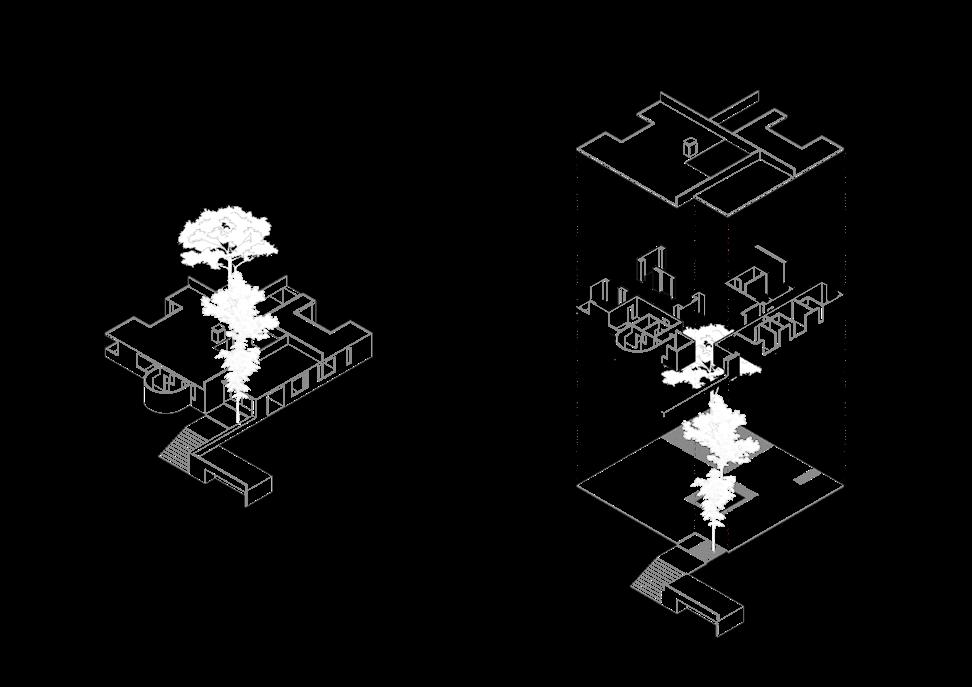

Emplazamiento del monasterio

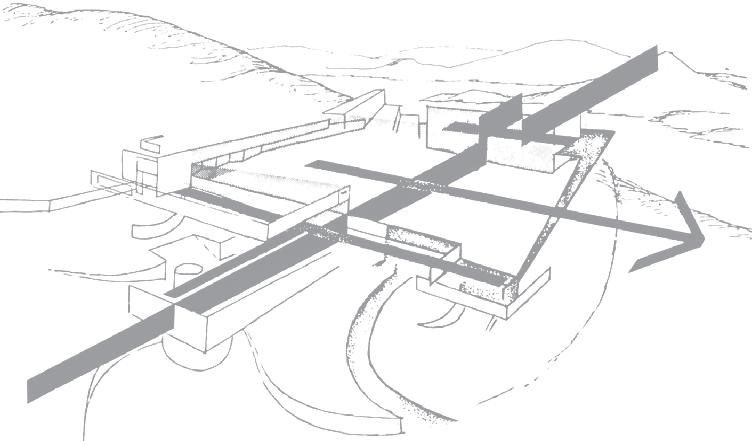

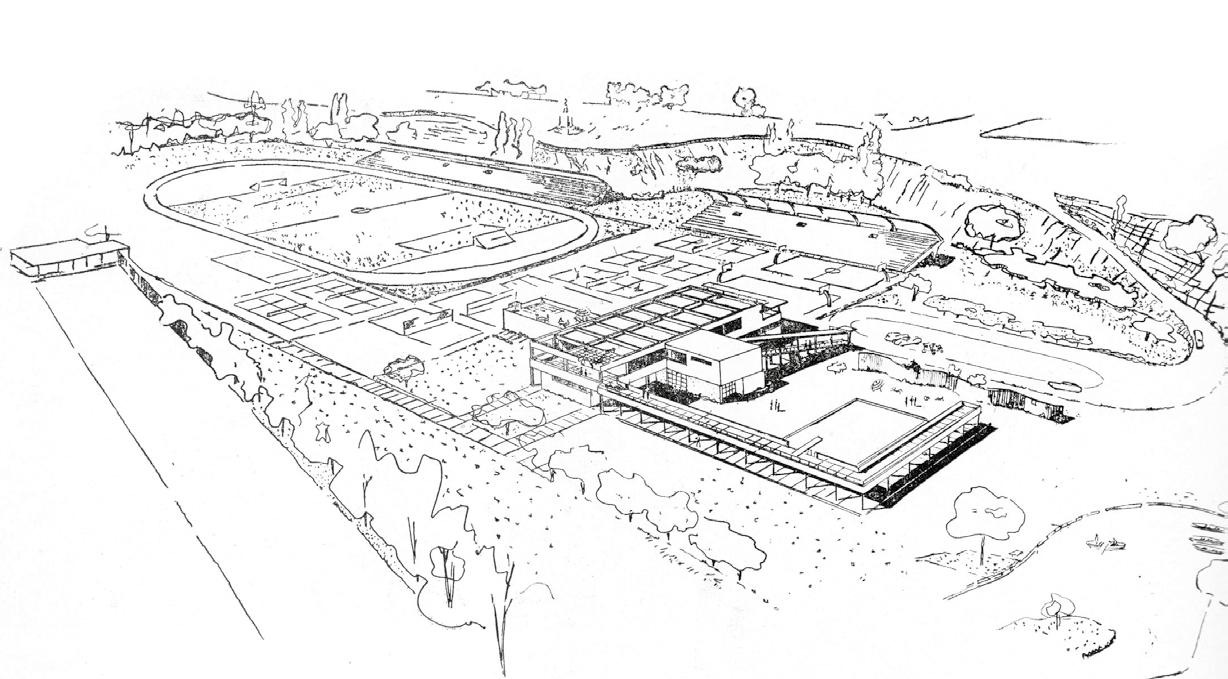

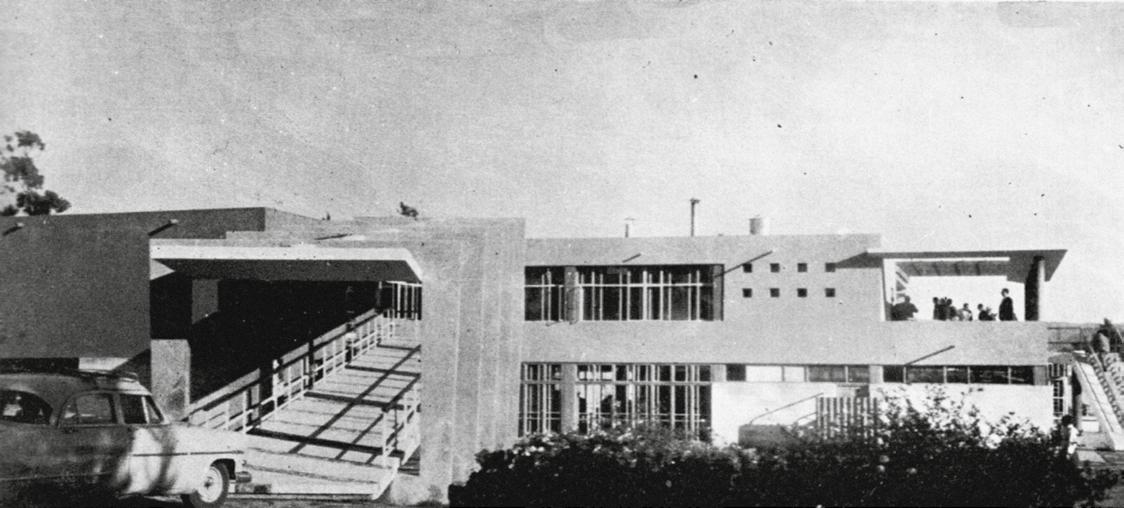

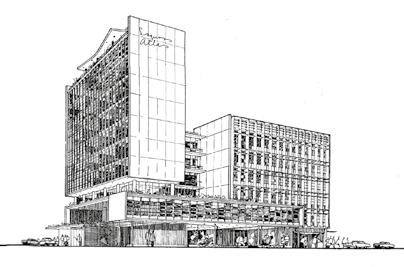

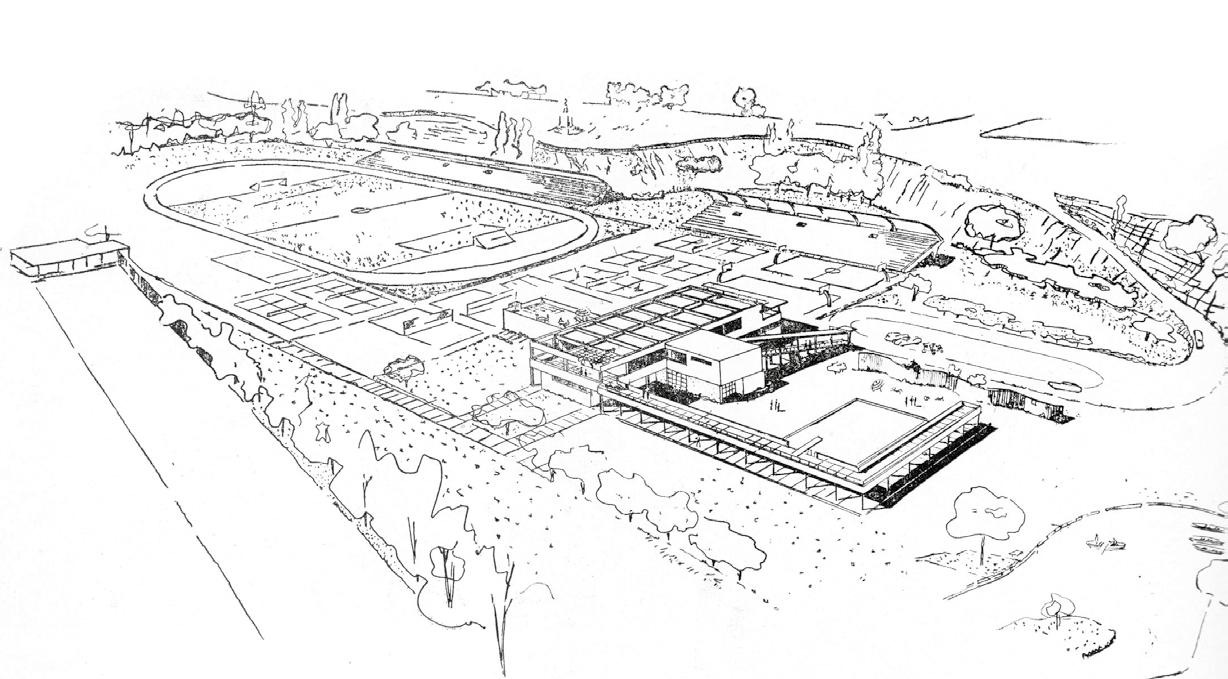

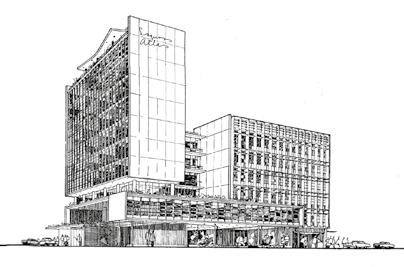

El año 1953 se realizó un concurso privado de anteproyectos de arquitectura, eligiéndose la propuesta que había dirigido Jaime Bellalta y el equipo del Instituto de Arquitectura de la UCV, incluyendo a su mujer, Esmée Cromie, como paisajista.

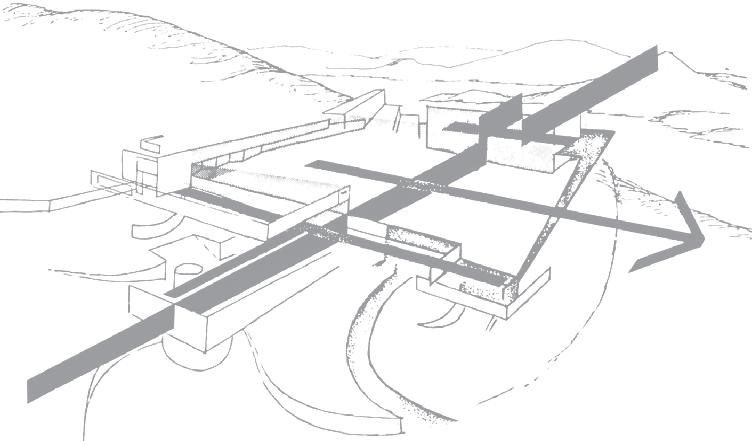

El emplazamiento es a media ladera del cerro y en un punto preciso que orienta la disposición de los edificios de acuerdo a referentes geográficos próximos y lejanos. (1. Pag 36 y 38)

Water

The El Bollo irrigation canal runs parallel to the foothill and formed the path of Bulnes Correa Street, which extends to San Francisco Creek Street, forming a continuous circuit. The canal links the valley's height differences and enters along the hill´s contour to irrigate the Benedictine estate. It was the upper limit of the irrigated plots.

The water reservoirs of the neighboring potable water company temper the climate and attract birds to the area. They are a significant part of the landscape that can be seen from the south of Los Piques hill, from the cemetery and the summit.

The monastery site

In 1953, a private competition was held for preliminary architectural projects, and the proposal directed by Jaime Bellalta and the team from the UCV Architecture Institute, including his wife, Esmée Cromie, as the landscape designer, was chosen.

The location is halfway up the hillside and at a precise point that orients the buildings´ layout according to nearby

↤

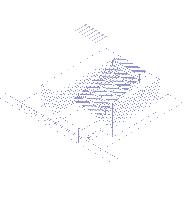

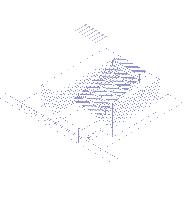

Dibujo original de Jaime Bellalta con las direcciones espaciales del proyecto inicial. (Libro 1. Pág. 35). El cerro Manquehue es un referente.

The original drawing by Jaime Bellalta with the spatial directions of the initial project (Book 1. Page 35). The Manquehue hill is a reference.

24 ↤

↤

©Juana Zunino

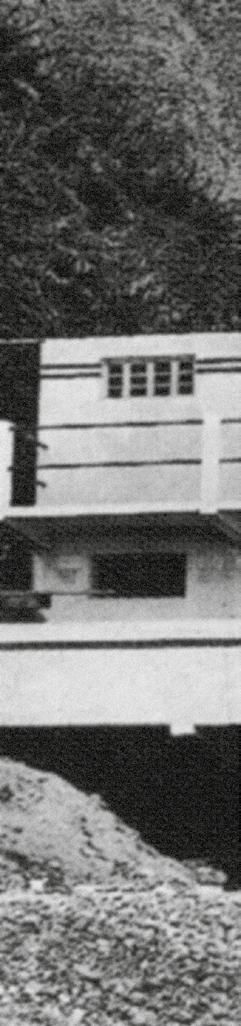

Foto de Jaime Bellalta del primer edificio de las celdas, que muestra su emplazamiento en el paisaje y su relación con las montañas.

(Libro 1. Pág. 43).

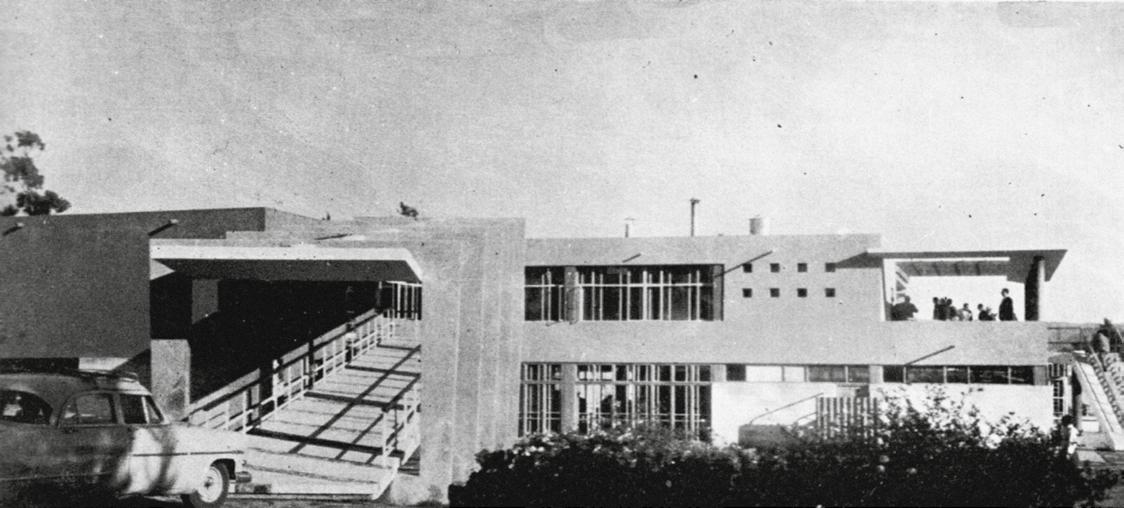

En 1956, se construyó el block de celdas y un block provisorio en que había una pequeña capilla, el comedor y la cocina. El lugar de emplazamiento era menos inclinado que el resto, pero exigía varios niveles de la construcción, lo cual posibilitaba un enriquecimiento espacial. (3)

El conjunto de edificios conserva un distanciamiento con los bordes del terreno que permite mantener un aislamiento para el ritmo propio de la vida contemplativa.

El emplazamiento a media altura está respaldado por la cumbre del cerro que protege del viento, del frío cordillerano y del acontecer cotidiano de las nuevas urbanizaciones.

La posición en altura entrega la posibilidad de una vista hacia la contemplación, hacia el horizonte lejano y, también, hacia las urbanizaciones cercanas.

Desde lejos, el conjunto es una unidad que se destaca entre el verde que lo rodea. La iglesia sobresale levemente, marcando un punto de atracción para las personas que deseen concurrir al lugar.

and distant geographic references. (1. Page 36 and 38)

In 1956, the cell block and a temporary block containing a small chapel, dining room, and kitchen were built. The site was less inclined than the rest but required several levels of construction, which made a spatial enrichment possible. (3)

The group of buildings maintains a distance from the land´s edges that allows it to remain isolated from the rhythm of the contemplative life.

The medium-height location is supported by the hilltop that protects it from the wind, the cold of the mountain range, and the everyday life of the new housing developments.

The elevated position provides the chance for a view towards contemplation, towards the distant horizon, and, also, towards the nearby residential areas.

From a distance, the complex is a unit that stands out among the surrounding greenery. The church stands out slightly, making it a point of attraction for people who wish to visit the place.

↘

© Archivo

A photo by Jaime Bellalta from the first building´s cells shows its location within the landscape and its relationship with the mountains. (Book 1. P. 43).

histórico José Vial Universidad Católica de Valparaíso

El claustro, corazón del Monasterio, lugar del caminar rezando, circundado por tres lados por los edificios principales, queda abierto al valle. (3)

La condición del patio central, donde convergen todos los edificios: comedor, capítulo y biblioteca, es un lugar protegido para estar, caminar y encontrarse bajo la sombra de los naranjos que, junto a la vegetación mediterránea aromática, rememora los antiguos patios coloniales.

Acceso y recorridos

Empezando a subir hacia el Monasterio, desde la calle Montecassino, todo apunta hacia la iglesia recortada contra la cordillera. (3)

El camino a la iglesia y a las actividades públicas, de libre acceso, es un mirador hacia el valle y un recorrido de preparación para el silencio.

El camino por detrás del cerro, es el del barrio, de las actividades de trabajo y de servicio a la comunidad.

La geografía del lugar favoreció esta doble manera de acceder al recinto, diferenciando las funciones, a la vez que se establecieron circuitos que recorren el terreno por diversos niveles, siempre orientados por los elementos naturales y culturales del paisaje.

La arquitectura y el lugar

Jaime Bellalta expone:

El proyecto se fundamentó en tres ideas principales:

1. Comprensión de la vida cotidiana benedictina contemporánea.

2. Decisión del emplazamiento, frente al espacio existente del cerro Los Piques. Se estableció a media falda, para no tocar la cumbre, dejándola libre para la clausura monástica y ubicándolo de manera que el acceso desde Santiago permitiera reconocer la ciudad al llegar (reconocer el origen) y, por otra parte, la obra se viera como un signo desde la zona habitada.

3. Todo el entorno se graduó cuidadosamente midiendo la relación monasterio-lugar, sea como paisaje, vista, ámbito de trabajo, paseo o como material-mineral-piedra en sus muros.

The cloister

The cloister, the heart of the monastery, the place to walk and pray, surrounded on three sides by the main buildings, is open to the valley. (3)

The central courtyard, where all the buildings converge: dining room, chapter, and library, is a protected place to be, to walk, and to meet under the shade of the orange trees along with the aromatic Mediterranean vegetation, reminding one of the old colonial courtyards.

Access and paths

Starting to climb towards the Monastery, from Montecassino street, everything points towards the church silhouetted against the mountain range. (3)

The path to the church and the public activities, freely accessible, is a lookout over the valley and a path of preparation for silence.

The site's geography facilitated this double access to the site, differentiating the functions, while establishing circuits that run through the terrain at different levels, always guided by the natural and cultural features of the landscape.

Architecture and location

Jaime Bellalta exhibits:

The project was based on three main ideas:

1. Understanding Benedictine contemporary daily life.

2. Location decision, in front of the existing Los Piques hill area. It was established halfway up the slope, so that it would not touch the summit, leaving it open for the monastic cloister and positioning it in such a way that the access from Santiago would make it possible to recognize the city upon arrival (recognizing the origin) and, on the other hand, the project would be seen as a sign from the inhabited area.

3. The entire surroundings were carefully classified by measuring the relationship between monasteries and place, whether as landscape, view, working environment, walkway, or as material-mineral-stone in its walls.

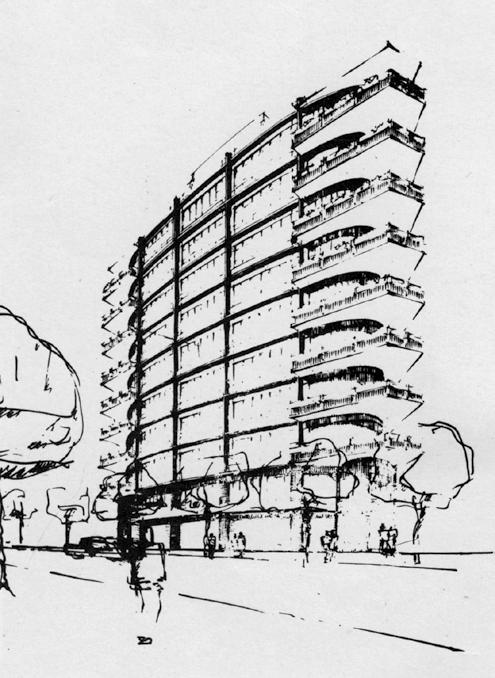

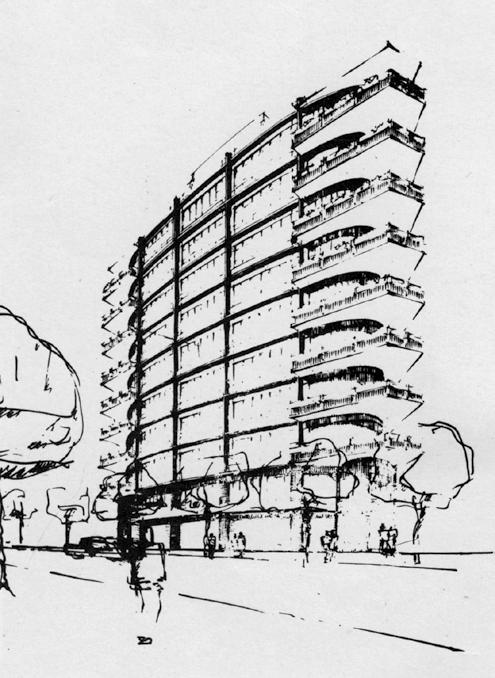

↤ Estudios para la iglesia definitiva. Alberto Cruz y el equipo del Instituto de Arquitectura de la Universidad Católica de Valparaíso.

Studies for the definitive church. Alberto Cruz and the team from the Institute of Architecture at Universidad Católica de Valparaíso.

26 ↤ AOA / n°46

El claustro

© Archivo

Histórico José Vial Armstrong

El convento en 1988.

Plano de Ubicación:

1. Acceso

El cuerpo de las celdas, se estableció libremente y en correspondencia con el ámbito circundante, conformando una relación de contraste entre lo construido, asentadamente geométrico, rectilíneo y cúbico, y lo paisajístico que se intentó mantener y acentuar en su condición natural. (1. Pag 76)

The cells´ body was established freely and according to the surrounding environment, forming a contrasting relationship between the built, geometrically set, rectilinear, and cubic, and the landscape that was intended to be maintained and emphasized in its natural state. (1. Page 76)

The convent in 1988.

Location Plan:

1. Access

La iglesia

El hermano Martín se pregunta, ¿qué es lo que haría que tales espacios convocara a monjes y fieles, a celebrar? La respuesta la dio la experiencia en un bosque de pinos en la costa, en que la luz se filtraba desde el cielo. Esa era la clave, porque allí, se daba un espacio casi etéreo, simple, silencioso, que movía hacia la oración, a dar las gracias a Dios por su belleza.

Entonces, el desafío era crear en esos volúmenes funcionales de la arquitectura, esa misma atmósfera, ese mismo clima luminoso experimentado.

La influencia determinante de la arquitectura de Jaime Bellalta confirmaba. Entonces quedó claro que la atmósfera buscada, la daría la luz en esos muros y espacios. (3)

The church

Brother Martin wondered what would make such places bring monks and the faithful together to celebrate? The answer was given by the experience in a coastal pine forest, where the light filtered down from the sky. That was the key because there, there was an almost ethereal, simple, silent space, which moved towards prayer, to give thanks to God for its beauty.

Therefore, the challenge was to create those functional architectural volumes, that same atmosphere, and that same luminous climate experience.

The decisive influence of Jaime Bellalta's architecture was confirmed. It was then clear that the desired atmosphere would be provided by the light in those walls and spaces (3).

↦ 27

↥

2. Monasterio

3. Cementerio

4. Servicios

5. Mueblería

6. Gallineros.

(Libro 1. Pág. 65).

2. Monastery

3. Cemetery

4. Services

5. Furniture Workshop

6. Henhouse.

(Book 1. P. 65).

0 10

Conversación con el hermano Martín Correa en abril de 2022

En el Monasterio Benedictino de Las Condes, el hermano Martín Correa nos recibió para contarnos sobre su experiencia como habitante del lugar, más allá de su rol de arquitecto del edificio.

¿Cómo se concibe el espacio interior de la Iglesia en este lugar?