A Retrospective

A Retrospective

Copyright: University of Chester. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

John Renshaw, a distinguished figure in the art world, has made significant contributions to the field of painting. His work is characterised by its profound depth, intricate detail, and emotional resonance. This retrospective will feature a diverse array of his paintings, offering visitors a unique opportunity to experience the evolution of his artistic journey.

In addition to his remarkable artistic achievements, John Renshaw has dedicated many years to nurturing the next generation of artists through his roles at the University of Chester. As a beloved educator, Renshaw has inspired countless students with his passion for art and commitment to excellence. His influence extends beyond the classroom, as he has played a pivotal role in shaping the creative landscape of the university and the broader community.

John’s dedication to his art and his students at the University of Chester is truly commendable. This exhibition not only celebrates his artistic legacy but also his profound impact on the lives of many aspiring artists.”

Bernadine Murray (Associate Professor) Head of School for the Creative Industries, University of Chester

I was interviewed by John in 1998 for my BA in Fine Art and he was a prominent voice during my early art education; having first-hand experience of the inspiration and passion that Bernadine refers to. I have also been fortunate enough to work alongside him in the Art and Design Department and latterly under his leadership as Head of Department. His selfless approach to teaching and dedication to his own practice has been inspirational to myself and many colleagues, a few of whom have kindly contributed to this catalogue. It is a privilege to help curate and organise this exhibition with John’s family, an opportunity to repay so much.

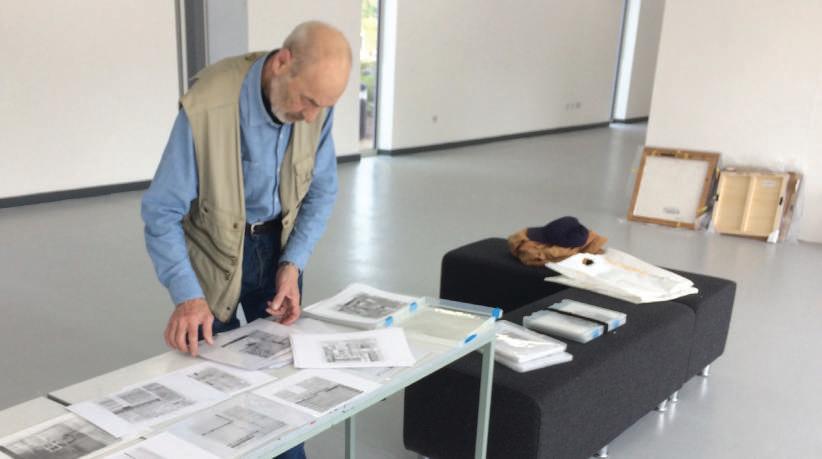

John has maintained such an active artistic career, prolific in terms of painting and drawing, and with a very impressive individual exhibition biography. It has been a difficult task to select just 115 paintings from his vast output, but the work chosen for this retrospective provides the audience with a glimpse of the styles and innovation that John has developed over the last 40+ years.

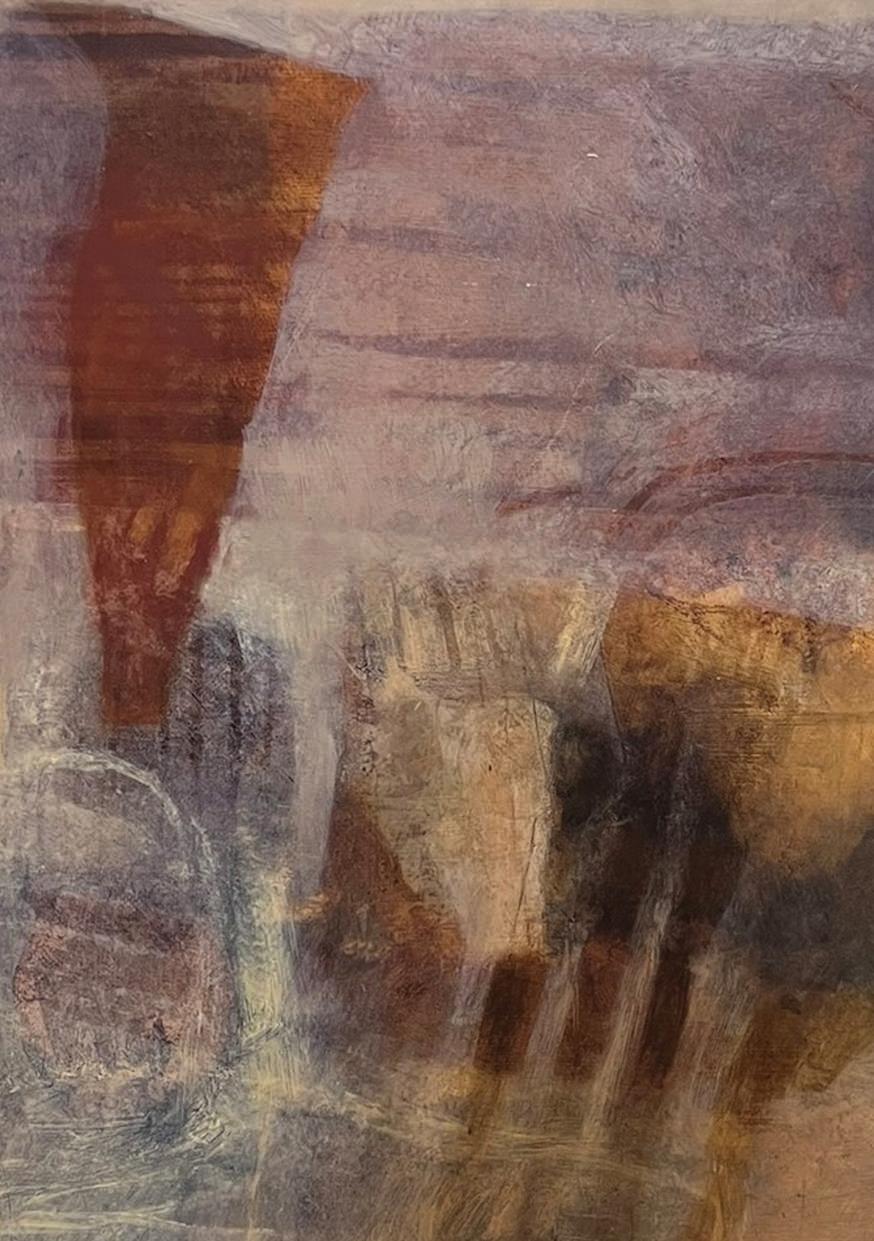

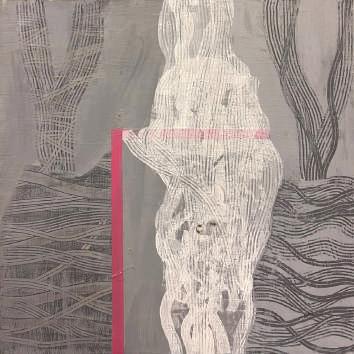

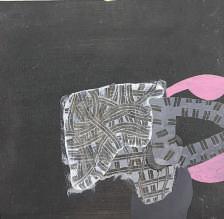

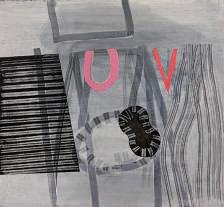

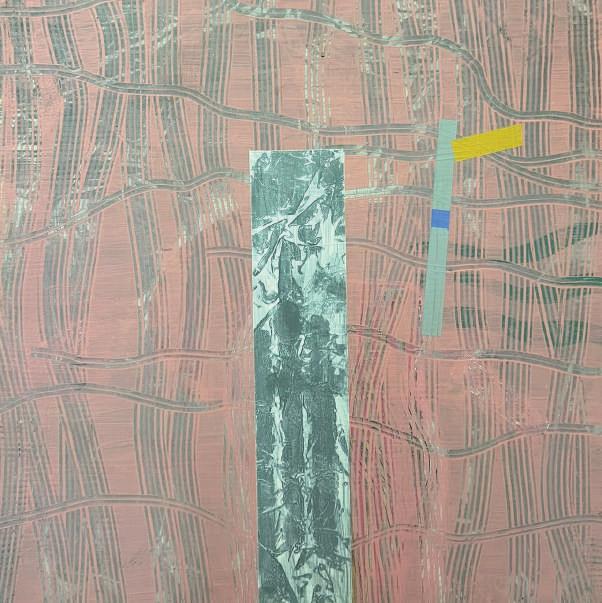

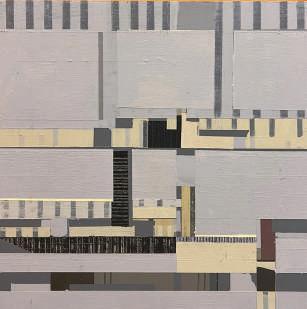

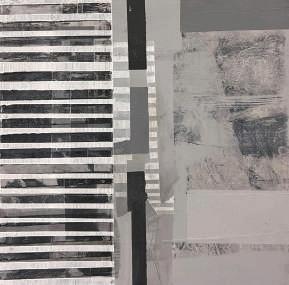

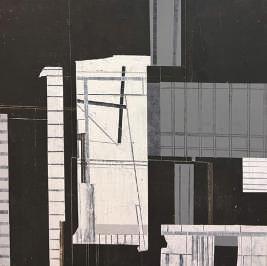

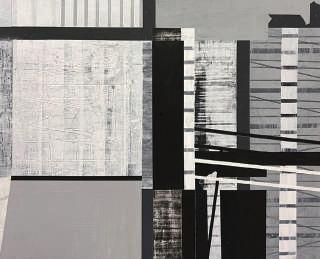

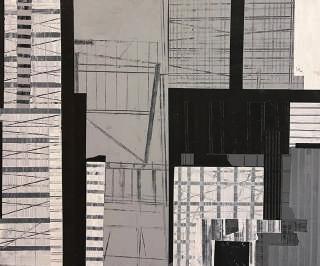

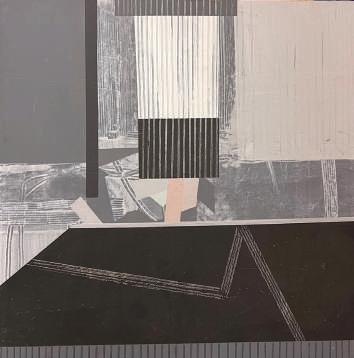

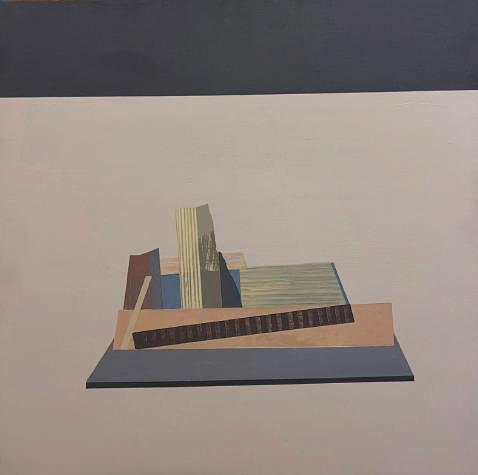

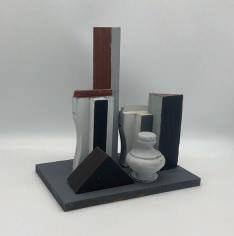

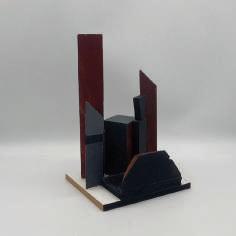

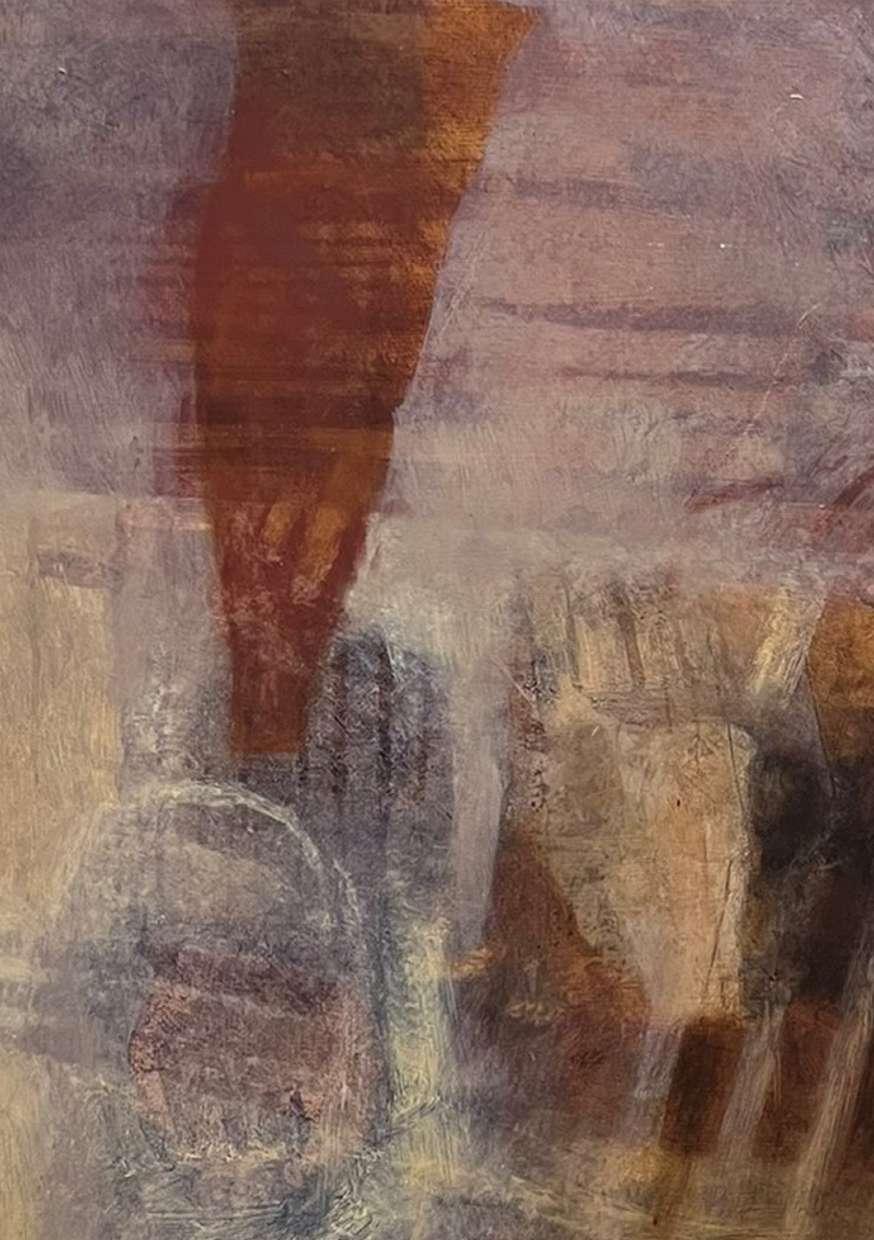

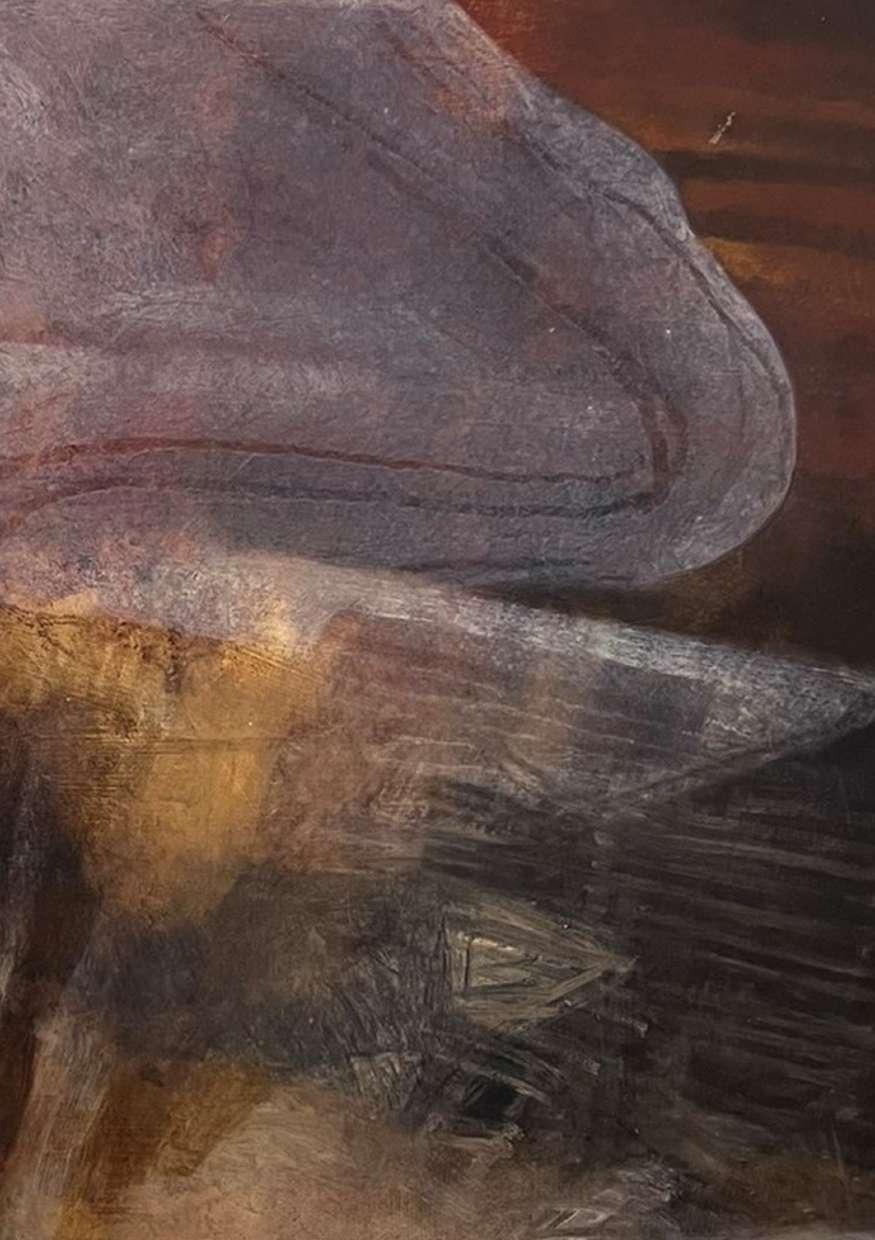

The paintings in the exhibition are informed by surface, texture and space, influenced by recollections of visual experiences - often involving shadows, the shapes and textures of buildings, their structure and interiors as well as compositions of still life objects. John refers to his paintings as “opportunities for both planned action and improvisation in response to an increasingly varied range of visual experiences – actual or recollected. They seek to explore some of the boundaries between abstraction and figuration.” He captures these moments in his own abstracted language, leaving the viewer to find meaning through a personal interpretation of the paintings. References to the visible world are to some extent, inevitable as we are invited to make the connections with visual incidents that we may encounter in our everyday lives.

Chris Millward (Cutator) Lecturer in Art & Design

University of Chester

Maggie Jackson

John has played a significant part in many of our lives for a very long time as friend, teacher, colleague, artist, comrade and mentor. His warm and affable presence has given us an anchor and a guiding point as well as inspiration and ambition in our artistic endeavours.

Ever unassuming and diffident, John’s natural warmth and charm has brought him a whole gamut of diverse friends who are attracted to his humour and his caring personality. ‘Are you alright chuck’ is one of his favourite cheering greetings.

John started his career at Stockport College, which many people here will remember with fondness, and he also made a significant contribution to the Fine Art degree course at MMU, then Manchester Polytechnic. As an Advisory teacher for Art in Cheshire, he influenced many teachers with his inspiring views on the importance of art education and constant creativity to the human spirit. In the 1990s he joined the art department of Chester College, now the University, where his dedicated and affable personality made him a much-loved member of staff for very many years and a lynchpin in a highly imaginative, creative and productive

department, full of endeavour and experimentation. Close friends from the department will remember his extraordinary office with affection, stacked with materials, papers and books. The door was always open.

John was a key figure in student trips to Italy, which were renowned throughout the County and provided unique opportunities for students and teachers alike. John has always fostered any opportunity for artists to thrive.

When Art & Design was moved from the main campus to Kingsway, John took up the mantle as Head of Department with his usual verve and commitment when morale was low and ‘improving’ the building was difficult. He, of course, came into his own, especially in building strong relationships between departments on site and delivering outstanding student satisfaction results. That fostering of camaraderie has been the hallmark of his actions. His devotion and commitment to his drawing and painting is everywhere evident, and we are delighted to be showcasing significant and fine examples of his work which span his entire career.

Cian Quayle

This essay takes its cue from a 2002 workshop and presentation by John Renshaw, which took the form of an ‘imaginary self-interview’ titled The Original Creative Principle. The conversation includes a set of annotations, which outline a constellation of artist references and resources, which establish the methodological foundation upon which Renshaw’s paintings and drawings are grounded. Renshaw sets out the strategies by which the task of painting and drawing are approached, and first and foremost, without any preconceived intentions except the prospect of their potential and possibility, and a striving for originality in what is discovered as a result of the process.

Yve-Alain Bois’s Painting as Model – a review of Hubert Damisch’s ‘Fenêtre jaune cadmium, ou, Le dessous de la peinture’ – opens with the following provocation from Damisch: “What does it mean for a Painter to think?’ An ekphrasis is the verbal representation of visual imagery and this essay attempts to rationalise in writing and words a process, which is the outcome of ‘visual thought’. A ‘visual proposition’ related to the daily practice of painting which in its simultaneous planning and improvisation also acknowledges Robert Motherwell’s ‘automatism’. What I have written here is a kind of stream of consciousness evocation, which like Renshaw’s work is intuitive, personal and subjective, and which I hope captures the essence of the work.

Relative to ‘visual thought’ Renshaw cites the significance of reflection when considering the open proposition posed by one work, upon its completion, and the hiatus before beginning the next. Then, what it leads to in how the next painting continues an open dialogue with what has preceded it in what has been found or discovered, and carried over into the next: ‘Paintings and drawings may stand as metaphors or analogies for experience but also function as catalysts, stimulating memories or

unexpected associations. Such issues arise not only during the process of creating the work, but also during periods of reflection following its completion.’ (Renshaw 2002). In The Original Creative Principle Renshaw (2011) goes on to explain the way that this reflection might also be written: ‘testing the function of language in relation to visual experience. Written lists or sentences may be constructed, finding words that help to trap essential characteristics.’

In their abstraction this experience is not retinal or one defined by the opticality of Clement Greenberg and the pre-Damascene conversion of Michael Fried’s ideas. To return to Yve-Alain Bois (1986) and the theoretical mode of painting, Damisch’s analysis, and here Renshaw’s paintings:

[…] the formulation of a question raised by the work of art within a historically determined framework, and the search for a theoretical model to which one might compare the work’s operations and with which one might engage them. This approach simultaneously presupposes a rejection of the stylistic categories (and indirectly an interest in new groupings or transverse categories), a fresh start of the inquiry in the face of each new work, and a permanent awareness of the opening rule of painting in relation to discourse.

In the paintings which date from 2015 - 2016 there is a sense of space which is opened up in the way that they give rise to an architectonic matrix in their structure and equilibrium. Other paintings open up a glimpse or suggestion of an apparition or intimation of something seen, recalled and lost, forgotten and refound. The production of relations with other forms of visual experience found in drawing or photography are also analogous with other visual structures with which the paintings are synonymous. There is also an unfathomable depth in the exchange of position between

surface and what lies beneath it. The works are drawn into existence through the iterative and additive rendering of marks and forms in an epistemological moment of technique where thought and invention are located in the detail of the signifier of their constituent elements. Renshaw made the following observation on this basis:

For example, a certain configuration of shapes in the drawing [or painting] might raise comparisons with a shell, or scaffolding, or a brick wall. The search for comparable visual phenomena in the real world is thus prompted by the marks, and these initially aimless marks help to endorse a connection with related visual experiences. The marks help their maker to claim an aspect of visual experience as their own. A connection or correspondence not made on the basis of what things are, but through how they appear or how they look.

The paintings arise from what is seen on the ground, from overhead, and raised onto the vertical plane of studio wall at which they are worked. Again, Damisch, provides the means by which Renshaw’s paintings might be understood in this respect: ‘the projection onto a vertical plane of the canvas of the horizontal plane of the floor, which no longer functions as a neutral and indifferent background but as an essential factor in the vision of things, and can—almost—constitute the very subject of the painting.’

The paintings and drawings here are febrile and agitated in the intensity and the ambiguity of their ‘doodling’, attaining to a spatial formation in their sometime striated patchwork of linear mark-making, and the oscillation of figure and ground. The significance of which are enmeshed and interwoven within the work and what lies underneath in the texture and facture of a surface that collapses the privileging of this opposition. In other paintings the space is subsumed in a translucent, scrim-like, overlay in an ethereal suspension between transparency and opacity.

These paintings are about abstraction with no purpose other than the refinement of a process, which is built layer-upon-layer, until the totality of their visual and material presence is resolved at any one time, and in this the paintings have been worked on in serial form. In their seriality, they activate an open dialogue through the emotional wrangling of the material from which they are made. There is no closure, from one work

to the next, as what is discovered and revealed in one work, is carried over and reinvestigated within the space of the next. An imperceptible knowledge base is thus established where the sustained engagement with the act of painting is key to their validation and interpretation. Ultimately, Renshaw’s paintings produce a body of evidence upon which to reflect upon ‘recurrent characteristics’ and their condition as objects of visual thought and new forms of visual experience.

References:

Bois, Y.A. & Shepley, J. (Trans) Painting as Model. Book Review: Fenêtre jaune cadmium, ou, Les dessous de la peinture by Hubert Damisch. In: October, Vol. 37 (Summer, 1986), pp. 125 - 137.

Fried, M. (2008) Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Renshaw, J. (2002) The Original Creative Principle. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 21: 303 - 310. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5949.00327

Renshaw, J. (2011) John Renshaw (Statement) In: Art & Design Staff Portfolio Edition (250). Cian Quayle & Mireille Fauchon eds., Chester: University of Chester.

Jeremy Turner

John Renshaw is a prolific artist, his output in terms of both drawing and painting is consummate. To visit John’s studio, to have been taught by him or indeed, to have worked alongside him within academia would be to recognise the centrality Fine Art practice has to his very existence.

What is the root of this sustained, consistent and serious production of work? What causes it to occur? Generous with his time, lengthy, detailed and infinitely knowledgeable in his discussion, committed to the student experience well before such a thing was considered worth measuring statistically, it must be noted that practice has not been the only call on his time.

In his 2005 introductory essay for the exhibition Drawing: Looking + Thinking: Marks + Meaning at the Grosvenor Museum, Chester, John’s context for the relevance of drawing, (and arguably, by extension, painting), is clear. He states, “…drawing appears to be enjoying something of a renaissance. It remains a valuable means through which we are able to engage with the world in both visual and conceptual terms. Drawing practice in the twenty-first century continues to provide unique opportunities to record, represent and interpret our experiences, offering a means by which we can visualise and interrogate ideas. Through drawing, we are able to reflect on the past and speculate about the future, tell stories and explore the depths of our imagination. Making drawings is not only about recording the visible world, but can also stimulate us to think and engage in the process of constructing meaning for ourselves or for others.”

Engagement with the world, processes of recording, representing, interpreting, visualising, interrogating, reflecting, speculating…these are vital activities for human beings to undertake so as to make some sense out of the world we inhabit. This is the same for our forebears as ourselves, irrespective of the century in question; the world after all has never had cause (or chance) to slow down. Thus John’s practice, and its proliferation is

in part a response to an omnipresent imperative to navigate, consider and engage with successive waves of change, chance, experience and stimuli. It is worth here making the distinction between repetition of means and repetition of outcome. Whilst John’s means may have a familiarity borne of long experience and experimentation, whilst his activity may be repetitive the individual outcomes are by no so. There is a visual (and conceptual) lineage in his practice but also a constant invention. To use one of his phrases oft repeated, ‘if you know what you’re doing, you’ve been there before.’ His practice, and the drive to maintain it is such that he constantly and incrementally edges into new territory.

More than that though, there is something egalitarian in his practice, drawing in particular, that indicates a belief that Fine Art activity has the potential to be received, engaged with and ultimately embarked upon, thus removing any perception of boundary in that transition from viewer to maker, from interested bystander to active participant.

It’s a generous view, but a wise one. Anyone can potentially do this, and probably most of us should.

Since our earliest memories, Dad has been passionate about art; painting and drawing in particular. We have been surrounded by it for decades, but it is incredibly important to us that his work is seen and shared with the public.

We are so grateful for the support, advice and enthusiasm of Chris Millward from University of Chester, and Katherine from Stockport War Memorial Art Gallery for accommodating this retrospective exhibition.

John, Leigh and Anna would like to thank:

Stockport War Memorial Art Gallery

Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council

The University of Chester and the Division of Art, Design & Innovation CASC Gallery

Frames Didsbury

Wilmslow Manor Care Centre

Avanti signs ltd

Chris Millward

Robert Lomas

Greg Fuller

Maxine Bristow

Sarah Connor

Simon Owen

Jeremy Turner

Cian Quayle

Maggie Jackson

Chris Bebbington

Bernadine Murray

Alan Summers

James Kington

Peter Ashworth

Katherine Rosati