Toronto Islands

Evolution of the Islands, it’s History and Development on the islands

A Research Project

By Ashna Modi 1009492817 Master of Urban Design (MUD)

Submitted to George Baird 1031H - History of Urban Toronto

John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design University of Toronto

December 13, 2022

Abstract

The following research is intended to focus on the study of the formation of Toronto on the geographical study of the creation of the Toronto Islands from the time it was first discovered until the pre-covid era. It also covers the sequences and incidents that occurred on the islands and contributed to the development of its state. Additionally, it emphasizes the value of land, the evolution of island uses over time, settlements, and their influence on the islands of today. This is meant to be a reference for individuals who want to learn more about the history of Toronto Islands, geography, people, places, traditions, and customs of the Toronto Islands as well as its influence on the present-day urban form of the islands. The geology, history, and distinctive character of the Toronto Islands are unmatched by any spit of land, sand bar, peninsula, archipelago, or island in the world.

The study is based on descriptive and illustrative information taken from well-known historical works by reputable authors available in the library. The data collection also includes data from all reliable websites that are accessible online. I contribute to some data analysis to identify the relevant facts. The study primarily focuses on the historical and geographical developments that occurred on the island and had an impact on its culture, tradition, growth, development, and way of life.

The study’s findings aid in a better understanding of the island’s formation from the bluffs, emerging vegetation, discovery, early settlements, importance, purchase, social movements, growth, destruction, development, and impact over time, which will uncover the island’s contemporary urban environment.

Based on the preceding findings, it may be inferred that the 15 islands’ present urban features have a close relationship to the past of old Toronto. It may also become apparent that the islanders are having both, positive and negative effects as a result of the changes to the island’s urban structure to date.

Keywords – Fishermen, Toronto Islands, Scarborough Bluffs, Mississauga Indians, Toronto Purchase, Lieutenant Governor John Simcoe, Gibraltar Point, Lake Ontario, Ward’s Island, Ward’s Hotel, Hanlan’s Point, Hanlan’s Hotel, Amusement Park, Centre Island, Main Drag, Royal Canadian Yacht Club, Island Airport, Island Public School, Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto, Centreville amusements, Ferries, Picnics, Festivals.

Introduction

In Lake Ontario, Canada, a small chain of islands known as the Toronto Islands can be found just offshore from the city of Toronto. Initially connected to the mainland by a peninsula, the islands gradually separated from the mainland through natural processes like wave erosion and sedimentation. The region was first occupied by Native people groups and later turned into a famous summer objective for Toronto occupants in the nineteenth and mid-twentieth hundreds of years. A bridge connecting the islands to the mainland was constructed in the 1950s, making them easily accessible to tourists. With beaches, bike paths, and attractions like the Centreville Amusement Park, the islands are now a popular park and recreation area. Separation from the mainland occurred in 1858 during a violent storm. The islands have been shaped by wind, current, dredging, and landfill activities resulting in an 8 km-long hook that is divided in half inside into tiny lagoons and islets. Centre, Muggs, Donut, Forestry, Olympic, South, Snake, and Algonquin are the eight largest islands. One million people visit Centre Island annually for its gardens, beaches, and amusement park. Hanlan’s Point’s northwest region is formed by Toronto City Centre Airport. The activities that take place on these islands are the result of numerous changes over a couple of centuries.

The formation of Islands

Toronto Island in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries might be imagined as a bank of sand slightly overgrown with trees. The waters of Lake Iroquois originally covered the area that is today known as Toronto, around 10,000 years ago near the end of the Pleistocene epoch. Around 6,000 BC, the waters of this ancient lake began to gradually retreat, forming what is now known as Lake Ontario.

The Toronto Islands were initially nothing more than a long, sandy beach. Sand and gravel deposited on a thick layer of unconsolidated clay make up the entirety of the islands. The clay was deposited on the bed of an earlier Lake Iroquois, continuing the Toronto Clay Plain. Although there are thin deposits of a fine mixture of red and black sands along the beaches that face the lake, the sand is almost entirely of the light-coloured quartz variety. The majority of this material was transported from the Canadian Shield, so it has all come directly from the glacial tills of Scarborough Heights. Some of the shale fragments found on the beach have fossils that show that they were once part of the Hudson River group, a group of rocks that were laid down east of Toronto during the Lorraine Age of the Ordovician Period. Some of this increased land is due to dredging and landfilling, but most of it is due to natural factors like littoral drift.

Over thousands of years, the Scarborough Bluffs, 300 feet high, were battered by waves, winds, and lake currents, creating the long, narrow peninsula. The powerful Niagara current carried eroded sand and gravel westward. The Don’s waters supplied the base of the peninsula. A sand ridge and a series of sandbars were formed as deposits piled up there. The land was shaped by the westerly winds into a five-mile-long hook that was divided inside into tiny lagoons and inlets.

The sandbar began to expand in size and sprout vegetation as an increasing number of sediments were transported westward from the Scarborough Bluffs through a process known as littoral drift. Reed swamps showed up. Rushes, sedges, and cattails flourished. The balm of Gilead, willows, poplars and pine trees eventually covered the area. Between the years 1755 and 1759, vines, ferns, poplars, and pines began to appear. Sand and stone carried westward by the Scarborough Bluffs’ erosion gave rise to the stunning Toronto Island. The islands, part of a progression of shoals, were once a landmass joined to the central area close to introducing day Woodbine Ave, broadening 9 km west into Lake Ontario and afterward turning north. The main part of the island was originally a peninsula formed over thousands of years by deposits from the Scarborough Bluffs (see below map of York from 1818).

Made by the Toronto Harbour Commission utilizing a shipped-in landfill, the Spit has brought about the disintegration of parts of the Toronto Islands. The volume of silt that reaches the Islands has significantly decreased as a result of the Spit. The three-mile-long Leslie Street Spit, also known as the “Outer Harbour East Headland,” has been under construction since 1958. It has harmed Centre Island, which is close to Gibraltar Point. According to the Commission of Inquiry’s report, this region of the Toronto Islands is being eroded at a rate of approximately 1.37 yards per year as a result of storms from the southwest. The Islands are protected from westward currents by the Spit, which prevents sediment from being deposited around them to make up for what winds and waves wash away. However, the low neck of land that connected it to the mainland was destroyed by a severe storm in 1858. It opened what is known as the Eastern hole, in this manner transforming the landmass into an island. The Eastern Gap was not formed until the city was battered by two massive storms in 1852 and 1858.

The Native

Indians, who saw the islands as a place of healing, were the first people to use them. Mississauga Indians came to look at this “place of trees standing out of the water,” which was used as a source of medicinal herbs. Natives who were sick were brought to the Island and cared for until they got better. The Mississaugas marvelled at the way the shoreline kept moving outward from year to year and changing with each storm because they considered the island to be sacred and a place of healing. Native council meetings were held there frequently by tribes. They frequently set up camp on its shores and fished the bay for a variety of fish, including salmon, whitefish, pickerel, bass, and sturgeon. The time’s trappers and traders knew that they camped on the island’s shores and fished at night in the bay’s waters. For centuries, the island’s sands were important to Indigenous peoples. The Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation’s ancestors gave it the name “Mnisiing,” which means “on the islands.” The landmass was viewed as a position of mending and restoration and utilized for labor, functions, and internments. It was likewise a spot for hunting and fishing. On the Island, staples like wild rice and whitefish were harvested.

In 1787 the English recorded the Toronto Buy in which the Mississaugas got arms, ammo, tobacco, and $8,500 for the land between Toronto and the Lake. The Mississaugas used the Island as a place of retreat and for tribal meetings until the middle of the 19th century. The British were successful in persuading them to accept the terms of the 1787 Toronto Purchase because they were aware that war was prohibited in this sacred region. For ten shillings, the Mississauga Indians gave up more than 250,000 acres of land, including the Islands. The Island came to be recognized for its strategic location after the 1787 Toronto Purchase.

The Evolving Life on Toronto Islands

In 1792, Lieutenant Governor John Simcoe gave Joseph Bouchette the task of surveying the harbour to build the new capital and naval base of Upper Canada. Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe was inspired to establish Fort York and the Town of York (Toronto) in 1793 by the long, curved peninsula’s natural harbour. In addition to describing this natural harbour’s military advantages, Bouchette’s survey found extensive marshlands. Water plants, grasses, weeds, and wildflowers like lilies, milkweed, and cattails thrived in abundance on these sandy, moist landforms. Elizabeth Simcoe, the wife of the Lieutenant Governor, wrote several entries in her diary about her visits to the Island, including detailed descriptions of the landscape and foliage, as well as island activities like fishing, canoeing, and horse racing. It has been well documented that Elizabeth Simcoe enjoyed her experiences in the natural meadows and marshes of the peninsula. It is believed that Lieutenant Governor John Simcoe’s decision to locate the new provincial capital in Toronto in 1793 was heavily influenced by the protected harbour and restricted entrance created by the peninsula. He gave the peninsula’s tip the name Gibraltar Point, and Simcoe built a blockhouse, a battery, and the first lighthouse in Toronto there in 1806. However, the Lieutenant Governor’s military plans for the Island and the capital were shortened due to the Island’s shifting sands, unpredictable weather, and several critics. Except for the lighthouse, which has stood for nearly 200 years, an American invasion in 1812 destroyed all military structures.

The Queen’s Rangers constructed a blockhouse in 1793, making it the first building on the island. It was on Gibraltar Point, looking out over the harbour’s western entrance. The Crown was allowed to lease the Islands after it gave them to the City of Toronto in 1867. Realizing the Island’s strategic location, Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe ordered the construction of storehouses, a blockhouse, and a lighthouse on the peninsula across the harbour from Fort York. The blockhouse, which was finished in 1794 and had two cannons, was defended by a few soldiers. Following the War of 1812, the blockhouse was torn down. 1808 marked the completion of the Gibraltar Point Lighthouse in the southwest corner of the peninsula at the time. The oldest Toronto landmark that is still standing on its original site is the lighthouse. Coal oil was used in place of sperm oil when the tower was raised from its original 52 feet to its current height in 1832. Ships could be steered into Toronto Harbour by its bright light, which could be seen fourteen miles out into Lake Ontario. After 150 years of operation, the lighthouse is now a historic monument maintained by Metropolitan Toronto Parks. It at long last was supplanted by an electric one out of 1in 8. The construction of the lighthouse and the first homes on the peninsula occurred simultaneously, in the 1830s.

Seasonal fishermen started camping on Ward’s Island, which is on the east side of the peninsula, in the middle of the 1800s. By the turn of the 20th century, the area was known as a “tent city.” The city granted the Ward’s Islanders permission to construct year-round cottages and homes on their campsites in 1931, which are still present on Ward’s Island today. Ward’s Island is named after David Ward, an angler who settled there with his family in the mid1830s. William E. Ward built the Ward’s Hotel and other houses in the 1880s, renting tents to mainland visitors. On Ward’s Island in 1899, there was a colony of eight summer tenants. The popular “tent city” area was divided up into streets by the City of Toronto shortly before World War I. Wood-burning stoves, dressers, beds, tables, and chairs were among the campers’ initial arrivals.

To avoid having to transport their possessions back to the city, ingenious individuals constructed storage sheds. The tents were quickly set up on solid wooden floors. Flapping canvas was replaced by kitchens, porches, and rigid roofs made of wood. There were a few one-story summer cottages before 1920. Tents had completely been replaced by cottage structures by 1937. One striking feature of Ward’s Island architecture is the evidence of the transition from “canvas tent” to “year-round family cottage” in many of the structures. The City of Toronto began offering annual leases for lots on Ward’s Island by the middle of the 1930s. Island residents were encouraged to winterize their homes and use them year-round during the housing crisis of the late 1940s and 1950s. Additionally, they were requested to add rooms and lease them out to returning war veterans. By 1960, Metro Toronto Parks had made it clear that it would bulldoze the homes on Ward’s and Algonquin islands and turn them into parks.

The Hanlan family built their first house on the west side of the island in 1862. By the end of the 1870s, there were clear indications that summer cottagers were flocking to the Island. The majority of cottages were initially constructed at the island’s Hanlan’s Point end. John Hanlan built a hotel at the Point with 25 rooms for city dwellers who wanted to escape the heat of the city during the summer. The hotel had to physically move to the west as filling operations to create more land progressed. Edward Hanlan, who became known as “Ned Hanlan, champion oarsman,” was the son of John Hanlan who was a part-time bootlegger, later became an alderman of Toronto, was and the world’s single sculling champion from 1880 to 1884. This occurred at a time when sculling was as important in the sports and gambling worlds as hockey is today. Ned Hanlan took management of his father’s hotel and his hotel quickly became a distinctive landmark that drew thousands of visitors after it was built. However, several features drew people to the west end of the island. There were extraordinary games, for example, paddling matches hung on the half-mile-long regatta course at Hanlan’s. The Dominion Day Regatta was each season’s most important event. People could spend time paddling through the complex of lagoons by renting boats or canoes. He built a larger hotel in 1880, a three-story structure designed by McCaw and Lennox in a Second Empire style variation.

Picnics and baseball games were also held. However, Hanlan’s Point Amusement Park drew more visitors than any other attraction. There was a hand-carved animal merry-go-round, a switchback railway, shooting galleries, strength-testing machines, and the inevitable “freak show” with performers by 1888. At the same time, a park was built at Hanlan’s, and by 1888, there were up to one hundred tents of varying sizes, some of which were referred to as luxurious. Through the 1880s and 1990s, cottages were constructed on the western sandbar, which had previously been a tenting community as a result of the city’s building boom.

The Island was a wonderful getaway for people who were crammed into the crowded city and had few opportunities to travel or explore the countryside. The positive effects that the Island’s sunshine and clean air have on one’s health are emphasized in numerous accounts of the day. The freedom to explore the lagoons, meadows, beaches, and wild, undiscovered locations that young people all over the world can find was especially felt by children.

The damage caused by a fire in 1909 was almost complete: Numerous buildings, including a roller coaster, amusement park, and stadium, were destroyed by fire. The merry-go-round and Durnan’s boathouse were the only attractions left. However, the amusement park and stadium were rebuilt by the Toronto Ferry Company, which was back in business the following year. Only the Bitran Hotel in Hanlan was not rebuilt. Halan is remembered for his work as a politician to construct electric lights, bicycle paths, and sidewalks on Toronto Island. The Island was given to the City of Toronto by the Federal government in 1867. Toronto Island gained popularity over time as the land was divided into lots for cottages, resort hotels, and amusement parks. The Island was dotted with homes, churches, and businesses by the late 1800s. There was a bustling amusement park and baseball stadium at Hanlan’s Point, both of which were later demolished to make way for the Island Airport.

Hanlan’s Point and Ward’s Island are separated by Centre Island. There were hotels, barbershops, grocery and hardware stores, laundry facilities, and many other establishments on and around Centre Island’s Manitou Road, which was also referred to as the “main drag.” For entertainment, there was a casino, movie theatre, and outdoor bowling alley; It was a thriving little town up until the beginning of the 1950s. Over 2,000 people lived in the year-round community, with approximately 10,000 people living there during the summer. During WWII, an extreme lodging deficiency urged many summer inhabitants to stay on the Island the whole all. Within a couple of short seasons, the small bunch of winter occupants developed into a long-lasting local area. Since only the fire department, police, and parks department could drive their vehicles there, the busy thoroughfare was lined with shops, restaurants, summer hotels, and amusement parks. Bicycles and delivery carts were everywhere. Nonetheless, just the solid spirits stayed for the colder time of year in condos, cabins, and one lodging, the Manitou, which had been winterized to endure the freezing winds which blow across Lake Ontario. Island’s Manitou Street was ‘the business and social heart of the Island’ during the 1950s. In 1956, Metro Toronto purchased 259 leasehold properties on Centre Island and completely tore down the “Main Drag,” or Manitou Road. According to authorities, the goal was to transform the entire island into a park.

Centre Island Park has long hosted a variety of large events. Company picnics were the norm up until the end of the 1940s. Three-legged races and wheelbarrow races for kids, egg-in-thespoon races for women, and tug-of-war for men are typical activities. On long tables in the park, a massive meal of ham, coleslaw, and potato salad would mark the event’s conclusion. These kinds of occasions are still cherished by many Toronto residents. Political leaders always liked to meet their current or potential supporters on Centre Island. On the Island, several more modest politicians have also held picnics or barbecues for their supporters and employees.

For numerous festivals, Centre Island has been the most popular location. Olympic Island was the location for the inaugural Mariposa Folk Festival in 1968. With dozens of stars, thousands of visitors, and lengthy ferry lines, it was a huge success. The festival was held on the island for several years, and attendance increased each year. A local radio station hosted the CHIN picnic festival, which showcased the multi-ethnic nature of Toronto better than any other event held on the Island and reached a large number of new Canadians. Politicians, too, were always present for the common political pastime of putting flesh on paper. The most popular piece of the celebration is the yearly procession through the roads of Toronto highlighting the awesome outfits commonplace in West Indian amusement parks. On Olympic Island in the evening, a massive concert featuring Caribbean music draws thousands of young people. The annual Dragon Boat Races on Centre Island’s Long Pond are the most recent addition to the festival calendar.

On ten acres of land leased from the city, the Royal Canadian Yacht Club constructed their lovely new clubhouse in 1880 at the opposite end of the Island. Islanders continued to lease the land, now from the Metro corporation, even after no one was permitted to purchase it. Steps were taken to provide summer Island residents with a place of worship as the population began to grow. The southern-plantation-style clubhouse of the Royal Canadian Yacht Club can be found close to Snug Harbour, about halfway between the ferry docks on Centre Island and Ward’s Island. The Royal Canadian Yacht Club (RCYC), which began as the Toronto Boat Club in 1852, changed its name to the Royal Canadian Yacht Club (RCYC) in 1854 and was incorporated in 1868 by a special act of the Province of Ontario. The Club was made “Royal” in 1854 after a petition to the Queen was approved. Later, in 1860, the Prince of Wales paid a visit to the RCYC and gave a prized trophy a cup as a gift.

The Lakeside Home for Children on the Island was funded by John Ross Robertson in 1883, approximately the same year that Hanlan's amusement park opened. It was one of the island's largest structures. This facility gave disabled children from Toronto a summer filled with sunshine and fresh air. From the time it opened until 1928 when the Thistledown Hospital opened northwest of the city, thousands of kids got a special summer at the home. After that, war veterans lived in the Lakeside Home structures for a long time.

Island children’s education has always been a major concern. The wife of the third lightkeeper, Mrs. Duran, opened a school for the children of the area’s fishermen by converting her own modest house. Afterward, in 1888 Toronto’s Leading body of Training opened a one-room school building at Hanlan’s Point in November 1888 until it was obliterated by fire in 1905. The following year, a school with two more rooms opened. The school has grown multiple times to accommodate a growing younger generation. In 1923, 1932, and 1948, when approximately 10,000 people were living on the Toronto Islands, additions were made to the building. This school is a vital component of Island life and serves as the focal point of numerous social occasions. A functioning Home and School Affiliation holds month-to-month gatherings and patrons’ occasions that benefit both the school and the local area. In 1948, the school needed to be expanded once more because there was a severe housing shortage during the war and an increase in Island residents as a result. At last, in June 1954, it turned into an autonomous school. Many Islanders were forced to relocate to the city when the Parks refused to renew the leases at the end of the 1950s. As a result, many classrooms were left empty, and in 1960, a portion of the school became a residential science school for children from the city.

The Island's population and size both increased significantly in the 1890s. The island's population grew to the point where it was necessary to establish an Island Residents Association to handle all island-related municipal issues. The Toronto Islands, which were 360 acres in size in 1879, have more than doubled in size, according to figures published in 1982 by the Toronto Harbour Commissioners. They represented 563 acres of land in 1912. The Toronto Islands had expanded to 820 acres by 1980.

To provide the island's residents with "high-class groceries, fancy fruits, nuts, bread, and other necessities at very reasonable rates," the Island Supply Company was established in 1895. Hanlan's Point and the former Clarke residence on Centre Island served as the business's two locations.

Three thousand summer residents formed a volunteer fire brigade on August 3, 1900, and soon there were three fire stations, each with a fire reel and hose lengths. In addition to providing the luxuries of city life, the city was busy expanding the Island by filling lagoons with excavated earth from the expanding St. Lawrence Market on the mainland and dredging from the harbour floor. By the beginning of the 1900s, the island's area had nearly doubled to 563 acres. Six years later, a more modern grandstand was built, but it was also destroyed by an even more destructive fire on August 10.

In 1911, the city's water supply system underwent significant changes. Torontonians had been given polluted bay water as a result of a break in the old water supply pipe under Toronto Bay. Although no serious illness occurred, it was evident that the city needed to improve the system. The Island's previous filtration plant, which had been in operation for more than fifty years, was decommissioned, and a ground-breaking new plant was constructed north of the old one.

While the event congregation and little summer cabins created at Hanlan's, and the Gooderhams, Nordheimers, and other well-off Torontonians constructed their palatial retreats at Centre Island, the calm isolation of Ward's Island was drawing in various kinds of guests. A tunnel under the newly constructed Western Gap, which had been relocated further south and opened in 1911, was proposed in 1913 to improve access to the Island. At that time, no actual construction was underway; however, in 1935, excavations for this tunnel were initiated. Nevertheless, work ceased almost immediately for some reason. The idea comes up again from time to time, but the 1935 excavations are still the closest the federal government has come to building the tunnel.

In 1937, the City Council made a decision that would have a significant impact on the future of Toronto Island. To use its official name, the Port George VI Airport, it was supposed to be a municipal air terminal that would also connect the city to Ottawa, Montreal, Buffalo, Cleveland, Detroit, and Chicago. It opened in 1939 as a crucial link in transcontinental commercial air service. The existing cottages had to be demolished, as well as the amusement park and ball stadium, for the airport to develop. A portion of the bungalows drifted to the far edge of the Island in an activity coordinated by a relative of David Ward.

This 215-section of the land air terminal, with its two 3,000-foot runways and one 4,000-foot runway, possesses the north-westerly part of Toronto Island, by and large, known as Hanlan's Point. The airport, which is open all year, is used for flight training, recreational flying, charter operations, and sightseeing. It can accommodate all kinds of light aircraft and small business jets. With an annual average of 190,000 take-offs and landings, the Island Airport ranks among the busiest in Canada. The Island Airport did not revert to civilian use until 1945. According to the Historical Board, the building's architecture is distinctive for its almost residential character, which was typical of many airport terminal buildings of the time. It is derived from the colonial style. The design of the original, now demolished Malton Airport Terminal was similar. The only intact example of an early aviation terminal building design in Ontario and probably Canada, and the only one located in the City of Toronto, it is a valuable and uncommon example.

Torontonians began to neglect the Island more and more after the airport was built and the amusement park and stadium that were there disappeared. In addition, Sunnyside Amusement Park opened on the mainland in 1922 and the automobile became more and more popular. Torontonians were only able to re-discover the Island after gas and tire rationing during the Second World War when passenger ferry boat traffic dramatically decreased. In 1946, the TTC’s entire fleet of ferries struggled to transport the two million war-weary passengers to the Island because of their overwhelming number. At the time, the island had over 8,000 summer residents, including nearly 2,000 who lived there year-round due to a housing shortage brought on by the war.

Ginn’s Casino served sodas, Bill Sutherland’s Manitou Hotel served snacks, the Islanders and their guests danced to Eddie Stroud’s band, bicycled, canoed, rode the merry-go-round, or simply strolled from Ward’s to Hanlan’s and back again for entertainment.

The Metro Parks Department began the process of converting Toronto Island into a park as directed shortly after the newly formed Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto became the new landlord. In 1909, Algonquin Island was just a useful sandbar that helped create a safe channel for small boats. Algonquin Island was once known as Sunfish Island, after an Island plane with the same name. In the late 1930s, landfill operations were used to expand the island. Thirty homes were transported from Hanlan’s Point to the new Algonquin Island when Hanlan’s Point was cleared for the Toronto Island Airport in 1937. After that, residents of Hanlan’s Point either relocated to the mainland or were re-established on the “new island.” Around the same time, a wooden bridge was built to connect the Ward’s and Algonquin islands’ residential communities. Algonquin, like Ward’s Island, has more than 100 homes and is almost entirely occupied by residents who live there all year round and their families. The massive mansions and shaky cottages were soon demolished, and the only islands with permanent residents are Ward’s and Algonquin.

Transport to the island and on the island

To attract customers to his newly opened "Hotel on the Peninsula," Michael O'Connor started the first ferry service across the bay in 1833. Two horses walked on a treadmill to power O'Connor's paddlewheel ferry. The "equine ferry," or horse boat, was moved across the bay by the horses' movement of the treadmill, which turned a paddlewheel. On the Island, liquor was readily available for those in search of it. Louis Privat and his brother purchased O'Connor's previous hotel in 1843. The Privats operated a ferry, like O'Connor; The Peninsula Packet, which they called it, was powered by five horses that trotted along a treadmill in the center of the deck.

In the 1850s, steam ferries were introduced because horses were impractical for such a long distance, and by 1857, five ferries were transporting passengers from Toronto to the attractions of the Peninsula. The John Hanlan, built in 1884 and service until 1929, is another important boat; the 1906-built Bluebell, which can accommodate up to 1,350 passengers at once; the Trillium, sent off in 1910 and once again fabricated yet in assistance today; one of the last steam tugs on the Great Lakes, the Ned Hanlan; and the Ongiara, which broke the ice and got its name from the Indian word for Niagara Falls.

According to the Toronto Transit Commission, nearly one million people travelled to Toronto Island in 1927. From 1942 to 1949, more than fourteen million people visited, or more than two million annually. Since 1927, the trip has been taken by over a million people on average every year.

When the Toronto Transportation Commission took over in 1927, the ferry service was operated by the Toronto Ferry Company. The ferry service was run by the TTC until 1962 when it was taken over by the Tommy Thompson-led Metropolitan Toronto Parks Department. The Toronto Ferry Company was established in 1890, and within a few years, all Island visitors were using vessels owned by this company.

As many as 26 nightly water taxis served the Islanders during the 1940s and 1950s when there were 10,000 summer residents. This was notwithstanding the help given by Metro's ships. The Island's decision to not allow cars on its streets was more of a practice than a deliberate political move. Distances are short, and there is no proper connection across to the central area, so it appeared to be legit to lay out the standard that main help vehicles would be permitted. Everyone used bicycles as their primary mode of transportation. Manitou Road was a thicket of bikes leaning against every tree, pole, and building in Centre Island's heyday.

Today, every Islander, young and old, own a bicycle that they use throughout the year and in all weather conditions. The rule of a car-free community has a greater impact on how Islanders interact with one another. Children are free to roam. It is a community that walks and bikes, giving everything a more human scale. Private cars are not permitted on the Island, but there are some service vehicles like the milk truck, library-on-wheels, police jeeps, and fire engines.

One of Toronto's most significant cultural landscapes in Toronto Island. The Island's natural and built forms both reflect its diverse and rich history. The Island has contributed significantly to Toronto's social, economic, and cultural development throughout its history. The nature of Toronto Island's character is rooted in its history of a variety of uses, including military service, public parklands, residences, and resorts.

The overall landform of the Island exemplifies significant cultural ties to the City of Toronto. Toronto Island, which played a significant role in establishing Toronto as the capital of Upper Canada, has continued to change and develop over time to safeguard the City's port function and improve its navigability.

One of the most enduring lands uses on the Island is the natural environment, which has always attracted visitors. The Island has continued to be a retreat for thousands of visitors annually who come to appreciate its protected environment, beginning with the Mississaugas and continuing with Elizabeth Simcoe. The Island's strong nautical traditions and car-free character maintain its status as an urban oasis and a park of regional significance. Rarely do major cities have such a significant and exceptional resource close to their downtown. The Island's geography has given it a distinct sense of place. The Island's diverse collection of park buildings, historic structures, and private residences exemplify exceptional public and private urban conditions. From Gibraltar Direct Beacon toward the mixed bungalow styles on Ward's Island, the design credits of the Island illuminate a set of experiences that is dynamic and varied.

These components now indicate a unique equilibrium in function, whereas Centreville amusement parks, private yacht clubs, and public parklands offer recreational opportunities; This urban amenity is grounded in a strong sense of community by the open residential neighbourhood.

The variety of uses, activities, and built forms found on the Island are the result of an evolutionary process that is rooted in Island customs. All eras of the Island's history and its place on Toronto's waterfront are honoured by these varying features. The Island achieves this unique equilibrium, establishing Toronto Island as a landscape deserving of recognition and protection to date. All the urban features have a close relationship to the old Toronto.

Bibliography

Books-

Sward, Robert. The Toronto Islands. Toronto : Dreadnaught, 1983.

Gibson, Sally. More than just an Island : A History of Toronto Island. Toronto : Irwin Publishing Inc., 1984.

Toronto Field Naturalists’ Club. Toronto The Green. Toronto : Toronto Field Naturalists’ Club, 1976.

Filey, Mike. Trillium and Toronto Island. Toronto : Peter Martin Associates Limited, 1976.

Clark, L. J. The formation of Toronto Island. Toronto: S.N., 1890.

Hay, G. U. (George Upham), Anderson, H. M. The history of Canada, Sketch of the history of Prince Edward Island. Toronto : Copp, Clark, 1905.

Fairburn, M. Jane. Along the shore : rediscovering Toronto’s waterfront heritage, Rediscovering Toronto’s waterfront heritage. Toronto, Ontario : ECW Press, 2013

By the students of Toronto Island Public School. A History Toronto Island. Toronto : The Coach House Press Toronto, 1972.

Freeman, Bill, The Magical Place, Toronto Islands and Its People. Toronto : James Lorimer and Company LTD., Publishers, 1938.

Websites-

Sward, R. (2015). Toronto Islands. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/toronto-islands

https://www.blogto.com/city/2011/07/a_visual_history_of_the_toronto_islands/

https://www.torontojourney416.com/toronto-island/

https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/planning-development/construction-new-facilities/ parks-facility-plans-strategies/toronto-island-park-master-plan/toronto-island-park-master-plan-overview/

https://tayloronhistory.com/2015/12/29/the-lost-hanlans-hotel-on-the-toronto-islands/

Bibliography

PDFs -

E. H. A. Architects. Toronto Island Heritage Study. August 17, 2006. https://wx.toronto.ca/inter/pmmd/callawards.nsf/fa687bbbf211bf4a8525791100515d51/8525 8049005DEA63852583F90044CD8D/$file/Addendum%204%20-%20Attachment%20-%20 Toronto%20Island%20Heritage%20Study%202006.pdf

Gibson, Sally.

http://www.sallygibson.ca/pdfs/thesis-history-pt2-sally-gibson.pdf

Figures -

Cover Page ‘Map of York’By the students of Toronto Island Public School. A History Toronto Island. Toronto : The Coach House Press Toronto, 1972.

Figure 01From a presentation by George Baird.

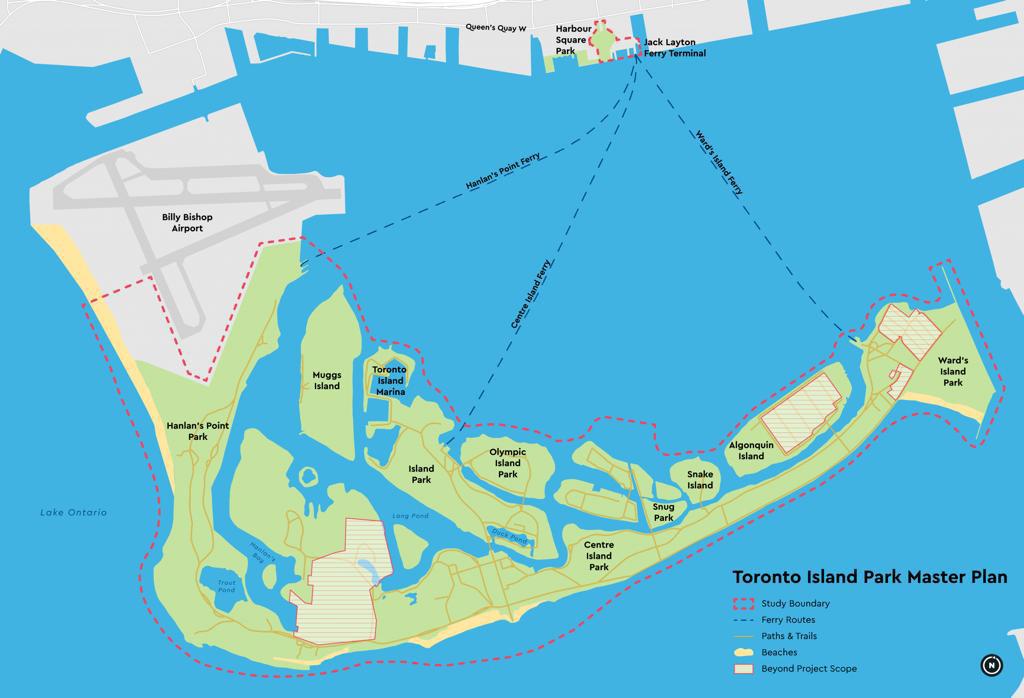

Figure 02Government Website

https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/planning-development/construction-new-facilities/ parks-facility-plans-strategies/toronto-island-park-master-plan/toronto-island-park-master-plan-overview/

Figure 03Toronto Field Naturalists’ Club. Toronto The Green. Toronto : Toronto Field Naturalists’ Club, 1976.

Figure 04Book in Eberhard Zeidler Library | Daniels - University of Toronto

Figure 05Sward, Robert. The Toronto Islands. Toronto : Dreadnaught, 1983.

Figure 06Gibson, Sally. More than just an Island : A History of Toronto Island. Toronto : Irwin Publishing Inc., 1984.

Figure 07 -

https://www.torontojourney416.com/toronto-island/

Figures -

Figure 08 -

Freeman, Bill, The Magical Place, Toronto Islands and Its People. Toronto : James Lorimer and Company LTD., Publishers, 1938.

Figure 09 -

https://www.torontojourney416.com/toronto-island/

Figure 10 -

https://www.torontojourney416.com/toronto-island/

Figure 11 -

https://www.torontojourney416.com/toronto-island/

Figure 12 -

https://www.torontojourney416.com/toronto-island/

Figure 13 -

Freeman, Bill, The Magical Place, Toronto Islands and Its People. Toronto : James Lorimer and Company LTD., Publishers, 1938.

Figure14 -

By the students of Toronto Island Public School. A History Toronto Island. Toronto : The Coach House Press Toronto, 1972.

Figure15 -

By the students of Toronto Island Public School. A History Toronto Island. Toronto : The Coach House Press Toronto, 1972.

Figure16 -

Google Archieves- Island Public School

https://photos.google.com/share/AF1QipNkkhJZGUg4QBgFAnaUbzOOL-k8fkZNI9ZNt8fLibAZveq-adAGhGbZq4icI0Marg?pli=1&key=Z1NDTExMbjF1cDFPMExZOWNOODI3d3NDZ2Q4TnNn

Figure 17 -

https://www.torontojourney416.com/toronto-island/

Figure 18 -

By the students of Toronto Island Public School. A History Toronto Island. Toronto : The Coach House Press Toronto, 1972.

Figure 19 -

https://www.torontojourney416.com/toronto-island/