BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL

Familiarity is something in which we all find comfort. For me, one of those binding currencies is hunting dogs. These loyal pups come in all shapes or sizes. They have different skill sets and personalities, sometimes even within the same litter. But they’re all happiest when doing what they were bred to do, and I love being part of it. Some breeds are just better than others, and that’s why I’m a Lab man, specifically a black Lab man. But I digress. …

Last spring, my wife and I traveled to Italy to celebrate our 20th anniversary. The landscape, people and food were inspiring, but at some level I was searching for familiarity – something to personally connect with.

I found that in a dog. We heard about an opportunity to tag along with a truffle hunter and jumped at the chance. From the moment Nicco jumped out of his truck with Rocket, the German shorthaired pointer, I was enthralled. We went to his private hunting ground and watched the dog do what dogs do … hunt. The quarry was different, but the rhythms were the same. The bond between handler and beast. The familiar cadence of searching and then, ultimately, the find. A beautiful symphony that anyone who has hunted with dogs knows all too well.

At lunch, conversations drifted to public land. Italy has some, but the pressure is intense. Partly this is because of the value of truffles, but mostly it’s because there just isn’t much of it. Nicco told us about carrying his dog over a mile off the road so as not to alert other hunters with dog paw prints. Even this sounded a bit familiar, as we all guard closely out best grouse, elk, huckleberry, wild rice, morel and duck spots. But carrying your dog a mile? Would you want that for anyone?

The voice for our wild public lands, waters and wildlife. Working every day to make sure you have access to public lands and waters and the quality fish and wildlife habitat when you get there.

These two simple sentences have guided Backcountry Hunters & Anglers since our inception around the founding campfire. Over the last decade I’ve had the absolute pleasure of being part of an explosive grassroots movement that has changed the proverbial conservation game.

The wins are numerous. Banning drones for hunting and scouting. Defending against the sale of public lands both at a federal level and at a state level – the latter punctuated by massive rallies. Securing permanent reauthorization of the Land and Water Conservation Fund and then the LWCF’s full and dedicated funding – $900 million annually for access and conservation in perpetuity. Defending the Antiquities Act, signed into law by Theodore Roosevelt and used since by presidents of both parties to protect the best of the best of our public lands. Securing a moratorium on mineral development in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness watershed. Defending habitat in Alberta from coal development. Defending the right to access public lands by corner crossing and the ability to access public shoreline. The list goes on. At the heart of each and every one of these victories are the

people. Without you, none of this would be possible.

Never forget about the conservation legacy you have been entrusted to uphold. Never forget that stepping into the conservation arena is inconvenient but worth it. Never forget that if you look to your left and then to your right, you are surrounded by conservation warriors just like yourself. Never forget that it’s the people – the grassroots badassery – that separates BHA from all other groups. Never forget that being bold, speaking for the land, water and wildlife that cannot, is why we have what we do today across North America. Never forget that our system of public lands and waters is the envy of the world, and it is up to us to keep it that way. Never forget that you are all storytellers. And finally, never forget to make it fun, whether in the field or testifying in Congress. Serious work always needs some levity.

Thank you for the time, talent and treasure you give our great organization. Thank you for the late nights around the campfire, phone calls, and written messages where we plotted and schemed our next moves together. Most of all, thank you for the friendships. As I step down as President and CEO and move on to a new chapter, I will cherish my time at BHA for the rest of my life. My role may have changed, but we the people will continue to carry the day to keep North America a place where no matter who your parents are, how big your bank account is, or the color of your skin … public lands, waters and wildlife are available to all … ALL!

If for no other reason, so we can watch dogs do what dogs do.

Onward and upward,

Ted Koch (Idaho) Chairman

Ryan Callaghan (Montana) Vice Chair

Jeffrey Jones (Alabama) Treasurer

T. Edward Nickens (North Carolina) Secretary

Dr. Keenan Adams (Puerto Rico) Bill Hanlon (British Columbia) Jim Harrington (Michigan) Hilary Hutcheson (Montana)

John Gale, Vice President of Policy and Government Relations, Interim CEO

Frankie McBurney Olson, Vice President of Operations, Interim CEO

Katie McKalip, Vice President of External Affairs and Communications

Dre Arman, Idaho and Nevada Chapter Coordinator

Chris Borgatti, New York and New England Chapter Coordinator

Travis Bradford, Video Production and Graphic Design Coordinator

Tiffany Cimino, Events and Marketing Coordinator

Trey Curtiss, R3 Coordinator

Katie DeLorenzo, Western Regional Manager and Southwest Chapter Coordinator

Kevin Farron, Regional Policy Manager (MT, ND, SD)

Britney Fregerio, Director of Finance

Brady Fryberger, Office Manager

Chris Hager, Washington and Oregon Chapter Coordinator

Andrew Hahne, Merchandise and Operations

Aaron Hebeisen, Chapter Coordinator (MN, WI, IA, IL, MO)

Contributors in this Issue

On the Cover: Tori Hulslander, 2022 Public Lands and Waters Photo Contest

Above Image: Lucas Standifer, 2022 Public Lands and Waters Photo Contest

Raul “Rocci” Aguirre, Charlie Booher, Lars Chinburg, Margie Crisp, Noah Davis, Phil Hayes, Sydney Howard, Kobe Jackson, J.J. Laberge, Jeff Lauze, Jake Forrest Lunsford, Harley McAllister, Jason McHenry, Jenny Nguyen-Wheatley, Russell Worth Parker, Ryan Pettigrew, Wendi Rank, Harrison Stasik, Durrell Smith, Shawn Swearingen, Land Tawney, Charlie Thorstenson, Peter Wadsworth, Dalton Wayne, Zack Weiss

Journal Submissions: williams@backcountryhunters.org

Advertising and Partnership Inquiries: mills@backcountryhunters.org

General Inquiries: admin@backcountryhunters.org

Dr. Christopher L. Jenkins (Georgia)

Katie Morrison (Alberta)

J.R. Young (California)

Michael Beagle (Oregon) President Emeritus

Chris Hennessey, Eastern Regional Manager and Chapter Coordinater (PA, Capital)

Jameson Hibbs, Chapter Coordinator (MI, IN, OH, KY, WV)

Trevor Hubbs, Armed Forces Initiative Coordinator

Bryan Jones, Chapter Coordinator (CO, WY)

Gloria Goñi Mcateer, Digital Media Coordinator

Kate Mayfield, Operations Coordinator

Kaden McArthur, Goverment Relations Manager

Josh Mills, Conservation Partnership Coordinator

Devin O’Dea, California Chapter Coordinator

Brittany Parker, Habitat Stewardship Coordinator

Thomas Plank, Communications Coordinator

Kylie Schumacher, Chapter Coordinator (MT, ND,SD)

Zack Williams, Backcountry Journal Editor

Interns: Lars Chinburg (Backcountry Journal), Sylvie Poore, Taigen Worthington

BHA HEADQUARTERS

P.O. Box 9257, Missoula, MT 59807 www.backcountryhunters.org admin@backcountryhunters.org

(406) 926-1908

Backcountry Journal is the quarterly membership publication of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers, a North American conservation nonprofit 501(c)(3) with chapters in 48 states and the District of Columbia, two Canadian provinces and one Canadian territory. Become part of the voice for our wild public lands, waters and wildlife. Join us at backcountryhunters.org

All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in any manner without the consent of the publisher.

Published Sept. 2023. Volume XVIII, Issue IV

JOIN THE CONVERSATION

“Earth provides enough to satisfy every man’s needs, but not every man’s greed”

-Mahatma Gandhi

THE VOICE FOR OUR WILD PUBLIC LANDS, WATERS AND WILDLIFE

Rolling sagebrush hills, sheer cliffs of fossil-studded rock, jet-black lava flows and river-carved canyons home to mule deer, pronghorn, bighorn sheep and upland birds: the Owyhee Canyonlands sprawl across millions of acres of southeastern Oregon, southwestern Idaho and northern Nevada. Anglers can wade into the Owyhee River, a tributary of the Snake, home to native redband trout and a world-famous brown trout fishery. Hunters can traipse across seemingly endless high desert and canyon country, glassing for the perfect muley. Backpackers and rafters can spend days or weeks exploring labyrinths of canyons, ephemeral streams and volcanic craters, or simply stargaze beneath some of the darkest night skies left in the United States.

For years, the Owyhee stood as one of the most remote and undeveloped places remaining in the American West. More recently, however, unregulated recreation, unsustainable grazing practices, wildfires and development pressure from mining, oil and gas interests threatened the area’s important and irreplaceable ecosystems.

To combat this, a diverse coalition of stakeholders joined forces to craft legislation that would protect the area for public access and recreation, healthy habitat management and sustainable ranching and resource conservation. Among others, the group included members from local ranching organizations, the Burns Paiute Tribe, and the Owyhee Sportsmen Coalition – an organization including BHA. Working with Oregon Sen. Ron Wyden, the broad stakeholder group developed a bill, the earliest versions of which were proposed in 2019.

In June of 2023, Sen. Wyden reintroduced the bill, which would permanently protect more than 1 million acres of the Owyhee Canyonlands. Known as the Malheur Community Empowerment for the Owyhee Act, it is designed to protect important ecosystems and wildlife, preserve grazing rights and further economic development in the area. In its current iteration, the bill is a robust, widely supported piece of legislation, which has the potential to be a landmark

success for public access, conservation and community empowerment in Oregon.

The bill, which in July was considered in a hearing by the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, includes two major components that BHA members and sportsmen and women in general should be excited about supporting. First, it designates about 1.1 million acres of Bureau of Land Management land as wilderness, in addition to placing almost 15 miles of the Owyhee River under Wild and Scenic River management. To facilitate ease of public access and sustainable grazing in the area, however, the million-plus acres of wilderness will be allocated across almost 30 individual areas. These proposed wilderness areas range in size from 2,911 acres (the Upper Leslie Gulch Wilderness) to over 220,000 acres (the Mary Gautreaux Owyhee River Canyon Wilderness).

While protecting over 1 million acres of habitat, the proposed legislation would maintain the ability to upgrade existing roads and establish new roads for scenic tourism and both sportsmen and rancher access. As BHA Oregon Chapter Coordinator Chris Hager put it, “This is a bill that we’re really happy with. It allows us to maintain the opportunity we have already as outdoor recreationists in the area, while creating long-lasting protections that will provide those same opportunities for future generations.”

A second major component of the proposed bill is the establishment of the Malheur Community Empowerment for the Owyhee Group (the Malheur C.E.O. Group). The C.E.O. Group will be made up of representatives from a wide-ranging set of key interest areas, including ranching, recreation and tourism, environmental protection, hunting and fishing, local Tribes and federal, state and local government agencies. According to Kaden McArthur, BHA’s government relations manager, the C.E.O. Group is a critical component of the bill because the group is “set up to make adaptive decisions for the ongoing management of the area with buy-in from different local constituencies and officials. For example, the group will have the ability to receive federal funding and then vote on how to allocate that funding to promote conservation and other import-

ant elements of the bill.”

As per the language of the bill, decisions affecting the proposed wilderness areas require unanimous support from all representatives of the C.E.O. Group with voting rights. Voting members include three representatives from livestock grazing interest groups, one member from the district irrigation group, four members who represent the interests of the hunting/fishing, recreation/tourism and environmental communities and two representatives from local Paiute Indian Tribes. There will also be eight non-voting members from federal, state and local government agencies. This ensures that all members of relevant interest groups will have a say in the ongoing management of the Owyhee, therefore maintaining access and opportunity for anyone with the gear and gumption to take on the steep trails and remote waterways of the region.

What’s next? So far, the bill has been introduced to the Senate with general support. To become law, however, it will need to pass through both the Senate and the House of Representatives before landing on the president’s desk for signing. Already, BHA members have shown incredible resolve in the early days of this bill’s creation. Chris Hager says that over 1500 members of BHA’s Oregon chapter have written directly to Sen. Wyden, expressing their support for the bill. According to him, it’s this kind of grassroots support that can really move the needle when it comes to public lands legislation, and the bill will need more of it soon if it hopes to pass both the Senate and the House.

According to both Hager and McArthur, Rep. Cliff Bentz will

moves forward. He has not yet expressed support for Sen. Wyden’s bill and has been skeptical of legislation creating wilderness areas in the past. But with support from such a diverse group of stakeholders, and with the allowances made for grazing and economic development, the bill should be considered a win for sportsmen and women, backcountry recreationists and ranchers alike.

Purple sagebrush stretching into the distance, cool streams tumbling through deep-cut canyons, rugged crags rising like fortresses painted red by the setting sun; these vast tracts of undeveloped public land shape the character of our nation and its people. The Malheur Community Empowerment for the Owyhee Act aims to protect this landscape for us and our future generations and deserves our unwavering support as stewards of public lands and waters.

Lars Chinburg is a BHA member, writer and avid outdoorsman. He lives in Missoula, Montana, and enjoys exploring the surrounding country with his partner Anna. You can find more of his writing at www.larschinburg.com.

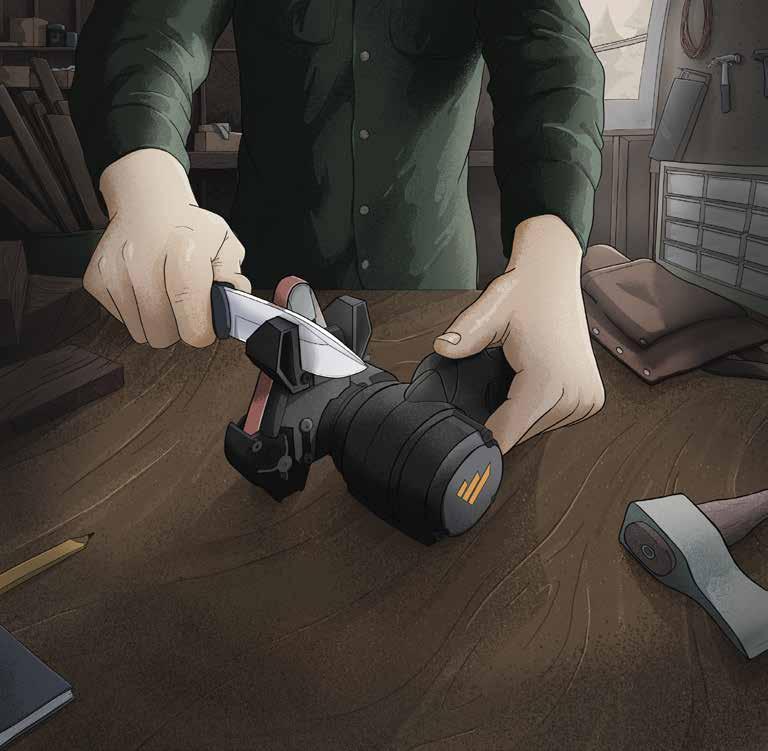

Sharper than the day you bought them.

LEARN MORE AT: WORKSHARPTOOLS.COM/WSKTS2-LEARN-MORE

Fall 2023 | VOLUME XVIII, ISSUE IV

45 ARCHER’S PARADOX by Jake Forrest Lunsford

51 BUSHYTAILS & BOOKS by Noah Davis

55 RITES OF PASSAGE by Jeff Lauze

61 HUNTING THROUGH THE TRIUNE BRAIN by Durrell Smith

65 HUMOR

The BHA Bathroom Finder by Wendi Rank

68 SHORTS

100 Fish Days by Dalton Wayne

The Search for Public Land Ducks by Shawn Swearingen

74 OPINION Habitat’s Both Public and Private by Margie Crisp

79 BEYOND FAIR CHASE

When Your Goals Conflict and Your Ethics Suffer by Harley McAllister

80 FIELD TO TABLE Venison with Chestnut Purée & Port Sauce by Jenny Nguyen-Wheatley

83 END OF THE LINE

In June, Rhode Island Gov. Dan McKee signed H5174A and S417A, completing the legislative process for the pair to become state law. The governor’s signature came less than two weeks after the Rhode Island House of Representatives and Senate passed the bills in concurrence before concluding the 2023 legislative session.

As enacted, H5174A and S417A include several provisions that will improve shoreline access in the Ocean State. Specifically, the new law:

• establishes a workable public-access boundary

• limits landowner liability

• includes educational resources

We extend our gratitude to bill sponsors, Rep. Terri Cortvriend and Sen. Mark McKenney. Both legislators were members of the 2021 Legislative Study Commission on shoreline access, chaired by Rep. Cortvriend, and have championed efforts in their respective chambers since then. Additionally, we thank House Speaker K. Joseph Shekarchi and Senate President Dominick Ruggerio. Following the introduction of differing bills early in the 2023 legislative session Speaker Shekarchi and President Ruggerio facilitated negotiations toward the unified bills that passed in concurrence. Finally, we thank Gov. McKee for signing the bills into law.

The shoreline access effort was supported by the dedication and efforts of hundreds of organizations and individuals over the last several years. While there are simply too many to list, we’d like to specifically recognize and thank our colleagues in advocacy at Save the Bay –Narragansett Bay, who have been close partners throughout the development of H5174A and S417A. From copublishing op-eds on shoreline access to being recognized on the House and Senate floors following successful votes, Save the Bay and BHA have led the organizational charge to secure access to Rhode Island’s shoreline. (Rhode Island’s shorline access issue was featured in the fall 2022 issue of Backcountry Journal.)

(letter to the editor)

Your fence removal article (summer 2023 issue) struck a chord. In the early 1990s I was in charge of the Hart Mountain National Antelope refuge (275,000 acres) in Oregon, and the Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge (575,000 acres) nearby in Nevada for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Both refuges had massive grazing programs. Data clearly showed grazing was damaging habitat in these areas. We decided to remove grazing. On Sheldon, the permits were bought out. On Hart Mountain, a long, bitter public process ended the grazing.

I transferred shortly after that for personal safety reasons. My successors were left with nearly 250 miles of interior fencing on the two refuges. Volunteers stepped in to help, removing ALL of the hundreds of miles of fence. Seeing big piles of steel posts and rolled-up wire in the refuges’ bone yards brought me to tears ... tears of joy. Now, my heart soars like a hawk when I visit these refuges and see NO fences.

When I retired to Cody, Wyoming, in 2007, our Back Country Horsemen chapter teamed up with the Wyoming Wilderness Association to remove more than three miles of unneeded fence in the remote Trout Peak Roadless Area of the Shoshone National Forest. The BCH packed everybody in and out and removed the high-elevation fence in elk and wild sheep habitat. Lots of angst. Our BCH members were very suspicious of WWA members (granola crunchers, waffle stompers, liberals, etc.) After working together for three days, all of that disappeared and has not returned.

I am so pleased to see BHA focusing on fence removal in Colorado. Not only do these projects remove barriers to wildlife; these projects, I am convinced, remove barriers among wildlife, hunters and anglers and wilderness advocates. There is nothing like tearing down an old fence that makes people forget petty differences and understand what we all have in common. I would urge your state coordinators to focus on fence removal and to invite disparate groups to join together in these projects. The sum benefit of these efforts may be larger than just the fence removal.

Another great issue of Backcountry Journal. Keep up your outstanding work!

-Barry Reiswig, BHA Life MemberEpisode 161: Texas hunter and fisherman Jesse Griffiths is the author of Afield: A Chef’s Guide to Preparing and Cooking Wild Game and Fish and The Hog Book. Jesse is co-owner of the Austin, Texas, New School of Traditional Cookery and the restaurant Dai Due, whose name is drawn from the Italian proverb, Dai due regni di natura, piglia il cibo con misura: “From the two kingdoms of nature, choose food with care.”

Join us for a conversation with one of the most visionary chefs in North America, talking hogs, turkeys, panfish, hunting and fishing and foraging for food, and a life defined by the earth and her seasons. That and more on BHA’s Podcast & Blast with host Hal Herring wherever you get your podcasts.

Born and raised in Colorado with a love for the outdoors, Bryan developed a natural inclination for hunting and fly-fishing. After high school Bryan joined the United States Marine Corps. After serving 10 years, Bryan left the service and completed his bachelor’s degree in Fish and Wildlife Management. Before joining BHA, Bryan was working as the natural resource and agriculture specialist and operations supervisor for Arapahoe County Open Spaces in the front range of Colorado. Bryan currently resides in Castle Rock, Colorado, with his fiancée Christie and their dogs, Norman and Lilu.

Born and raised in New York, Tiffany embraced hunting as a natural extension of her passion for conservation and wildlife management. Her love for archery hunting and the outdoors led her to discover a welcoming community within the outdoors industry. Supporting boots-on-the-ground initiatives dedicated to preserving and managing our lands, waters and wildlife led her to BHA, where she’s excited to make meaningful contributions toward safeguarding our natural legacy for future generations.

BHA members are still buzzing after BHA’s annual Muster in the Marsh event hosted in late July by the Ohio chapter. Hundreds of folks gathered in northeast Ohio at the newly founded Covered Bridge Outfitters in Conneaut. The event hosted passionate attendees from all over, including chapter leaders and members from West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, Indiana, North Carolina, Massachusetts, Virginia and Tennessee. With a wild mix of competitions, spicy auctions, educational and interactive workshops, live music, wonderful brews and feasting, of course, money was raised for conservation causes and lifelong connections were forged.

Muster’s education and storytelling components cover a diverse array of outdoor pursuits and experiences, and we had some amazing presentations this year! The educational sessions on BHA events and policy discussions were well attended. We were in full policy swing with some solid representation from North American Board Member and MeatEater star Ryan Callaghan, BHA Government Relations Manager Kaden McArthur, Ohio chapter leaders Tony Ruffing and Dustin Lindley and Indiana Chapter Policy Chair Scott Salmon.

Events like these are essential in creating a meeting point where constituents from a vast array of policy standpoints bring distinctive perspectives and diverse opinions to the table. It’s seamlessly connected with BHA’s mission to set aside differences in philosophy or politics and say, “It’s time to shake hands. It’s time to get something done. The continuation of the very things we love – hunting, fishing, wild places, wildlife – depends upon our ability to move forward.”

After 10 years of dedicated service building an organization that has become North America’s leading voice for hunters and anglers and public lands and waters, BHA President and CEO Land Tawney announced his departure from BHA, effective the end of July.

Over the course of Land’s tenure, BHA vaulted from a small, volunteer-based, Western-centric organization with less than a thousand members to an influential powerhouse with chapters in 48 states, Washington, D.C., two Canadian provinces and one Canadian territory. With an engaged community of more than half a million members, supporters and partners and 30-plus staff, BHA is impacting policy from a local to federal level, playing an increasing role in the stewardship of the continent’s public lands and waters, winning fights for conservation and access, and creating a “big tent” gathering point for outdoorsmen and women of all stripes.

Arguably, BHA would have remained a supporting player were it not for Land. He’s skilled at building a team, and he is always quick to give credit where it’s due. But Land was the tip of the spear.

“A lot of people think their voice doesn’t count and feel disenfranchised from decisions affecting our public lands, waters and wildlife,” he noted. “Together, the dedicated volunteers, members and staff at BHA have turned that notion on its head.”

Under Tawney’s leadership, BHA established its Armed Forces Initiative, Collegiate Club and Hunting for Sustainability programs. BHA maintains a membership that is young – 63% of BHA members are 45 and younger – and is politically diverse, split almost equally among Republicans, Democrats and Independents.

“The people, the people, the people!” emphasized Tawney. “I’m in awe of the time, talent and treasure individual volunteers generously give to BHA. We are warriors in the conservation arena, and I’d bet on our kick-ass staff each and every time. I’m proud of what we have all accomplished, together.”

Land says he can’t wait to see what the next chapter will bring. Neither can we.

Go, fight, win!

BHA State Policy and Stewardship Director Tim Brass was hired as BHA’s third full-time employee during 2012 and has been on the front lines of countless conservation battles both in Colorado and across North America ever since. He was initially hired as Southern Rockies Coordinator and was BHA’s longest tenured staff member.

Tim started as the Colorado Department of Natural Resources Assistant Director of Parks, Wildlife and Lands in late July. Congratulations Tim!

“I am beyond lucky to have had the opportunity to work with you all over the years and hope to get to work more with you all in this new role!” Tim said. “Thanks for all that each of you do on behalf of our public lands, waters and wildlife!” But Tim may have best summed up his 10-plus years on BHA’s staff as, “A wild and awesome ride!”

“Like drinking from a firehouse for 10-plus years!” Colorado chapter co-chair David Lien added. “Thank you, Tim, for your decade-plus of dedication, selflessness, guidance and wise counsel to both Colorado BHA leaders and chapters/clubs across North America. We hate to see you go, but your excellent conservation work will continue with/via the Colorado DNR, and we look forward to our collaborations going forward. Wildlands and wildlife need many more like you!"

SCORE OVER $35,000 WORTH OF JAW-DROPPING PRIZES

G&H SPECIAL EDITION HOG ISLAND SKIFF & TRAILER FROM ON THE WATER MARINE

30 HP TOHATSU OUTBOARD MOTOR BOAT BLIND SYSTEM FROM POP-UP BLINDS

2 WEATHERBY 18i BOTTOMLAND 12 GAUGE SHOTGUNS

2 SETS OF GRUNDENS GORE-TEX WADERS, RAIN JACKETS & BOOTS

2 DOZEN DUCK DECOYS FROM G&H DECOYS

1 SET OF OARS FROM SAWYER

SPORTDOG DOG COLLAR

ANCHOR FROM TORNADO ANCHORS JETBOIL STOVE SYSTEM

FROM AWESOME COMPANIES LIKE ENTER NOW AT BACKCOUNTRYHUNTERS.ORG/23_FALL_SWEEPS

DAILY DRAWINGS START 9/18 - LAST DAY TO ENTER 10/17

I joined BHA because as a lifelong hunter and fisherman and a conservationist with over 28 years in the field, I liked the science-focused, data driven approach to policy and conservation issues and feel the organization best reflects my values and interests as a hunter and fisherman. Equally important, most of the people I have met through BHA are moderate, practical, genuine sportsmen and women who pursue an active outdoors lifestyle similar to mine. For me, BHA has been about community, alignment on management and conservation issues, a shared interest in putting food on the table – and doing it in an honest, hardworking and genuine manner. That many of these things come together at a pint night and fun work projects is also a big plus.

YOU WERE RECENTLY NAMED EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF THE ADIRONDACK COUNCIL (CONGRATS BY THE WAY), WORKING TO CONSERVE ADIRONDACK PARK IN NEW YORK – WHICH I JUST READ IS THREE TIMES THE SIZE OF YELLOWSTONE! WHAT ARE A FEW OF YOUR BIGGEST CONSERVATION GOALS FOR THE AREA?

The Adirondack Park is an amazing place and a public lands mecca that is the size of Vermont with large unfragmented forests, which are as wild and remote as any wilderness area I have worked in the lower 48. The park is made up of almost equal parts private and public lands, which is unlike any other state or national park in the country. For almost 50 years, the Adirondack Council has focused on protecting the ecological integrity and wild character of the park but also finding ways to support working landscapes (timber and agriculture) and fostering vibrant communities in our rural hamlets. This is not an easy balance to strike in the Adirondacks.

Right now, we are focused on working with various state agencies to improve the overall management of the public lands and create a visitor use management framework that addresses the high levels of outdoor recreation that happen in portions of the park. We also are advocating on behalf of those agencies to make sure they have the staff and resources to be successful. The Adirondack Park is one of the few constitutionally protected public lands in the world, and we are working hard with nonprofit stakeholders, community leaders, local businesses and state agencies to make sure that this national treasure can thrive as we navigate climate change, invasive species, increased development pressure and a host of other significant challenges.

THE ADIRONDACKS ARE OBVIOUSLY

There is a quiet country road that I take on my way home from work that winds along a mountain ridge and offers fleeting views of the High Peaks through the trees. After a long day of travel and meetings, that drive helps to reset my day and remind me just how much I love these rugged mountains, the smell of pine and balsam, the people who work hard to make the most of what is offered here and the access to the type of outdoor activities and sporting life that makes living in such a remote location so worth it. It also helps that I can chase heritage-strain brook trout, backcountry bucks and high-mountain toms within a short drive from my house.

BHA has the potential to reset the conversation around access issues, game management planning, sporting related legislation and other high impact and often controversial topics that affect wild lands and large public open spaces on the East Coast. We have seen BHA’s impact on issues like that out West. The Adirondack and Catskill parks are test cases for how that Western approach could be used to effect positive change for protected lands within driving distance of major cities like New York City, Boston and Montreal. We need to become more of a legislative presence in Albany, develop and foster positive relationships with the executive leadership of our state management agencies and continue to build our state membership. This would give us a stronger voice on important issues that affect millions of acres of public lands in the Adirondacks, Catskills and across New York State.

BHA is bringing a modern approach to traditional sporting issues that offers tremendous potential for collaborations with local/place-based organizations. BHA’s emphasis on fostering community, mentoring, building relationships with non-traditional user groups, etc. is a powerful way to build support and engage new voices in the hunting/fishing space. Tapping into local knowledge and on-the-ground expertise that groups like the Adirondack Council bring to regionally relevant issues could bring much needed energy, resources and excitement to complicated and nuanced issues. Finding and cultivating these partnerships should be a priority at all levels of BHA. It provides local credibility, addresses real needs, empowers stakeholders and most of all creates the momentum necessary to achieve victories on the issues most important to BHA members. Not an easy task to build these relationships, but BHA has a unique advocacy voice that groups value and want to engage with.

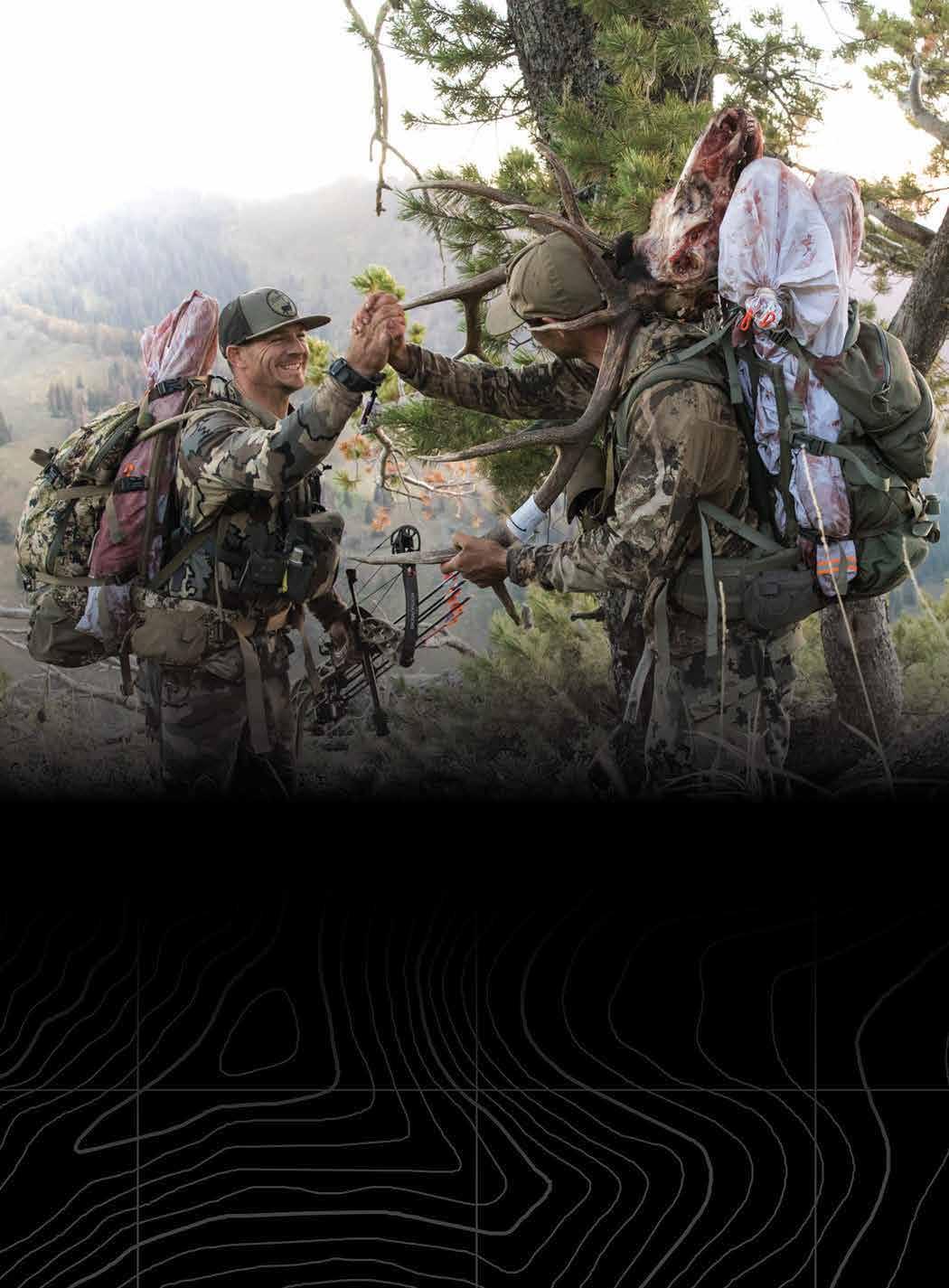

BHA’s Backcountry Bounty is a celebration not of antler size but of BHA’s values: wild places, hard work, fair chase and wild-harvested food. Send your submissions to williams@backcountryhunters.org or share your photos with us by using #backcountryhuntersandanglers on social media! Emailed bounty submissions may also appear on social media.

Hunter: Anne Jolliff, BHA Montana chapter board

Species: elk | State: Montana | Method: rifle Distance

Hunter: Zach Nordstrom, BHA member | Species: mule deer State: Idaho | Method: rifle | Distance from nearest road: four miles

Transportation: horseback

Steward: Matt Kearns, BHA member | Species: trash | State: West Virginia | Method: hand-picked | Distance from nearest road: roadside Transportation: foot

Hunter: Parker Capwell, BHA life member

Species: elk | State: Wyoming | Method: rifle

Distance from nearest road:18 miles

Transportation: horseback

Angler: Preston Mass

Species: smallmouth bass

Province: Ontario Method: spin | Distance from nearest road: 19 miles

Transportation: float plane, canoe, foot

Hunter: Jeff Swett, BHA member | Species: ruffed grouse | State: Maine | Method: shotgun | Distance from nearest road: three miles

Transportation: mountain bike, foot

Montana’s hunter education courses provide an overview of hunting-related information and skills, including Montana hunting laws, firearm safety, game ID, and fair chase ethics. Anyone born after Jan. 1, 1985, must complete hunter education in order to obtain a Montana hunting license.

The free courses are offered across Montana and are led by volunteer instructors who are experienced, knowledgeable and committed to passing on their skills to the next generation of hunters. Charlie attended two days of classroom instruction, participated in a field course and passed a final exam in order to become certified as an apprentice hunter.

Charlie is 10. Both of his parents hunt, along with many of his uncles, cousins and friends. He’s excited to head afield this fall. He talked to BHA staff about taking hunter education before, during and after it.

This week you’re taking hunter education. How do you feel?

I’m definitely excited, because I can’t wait to go hunting. Every year I help my dad hunt, but this year, if I pass the course, I’ll be able to hunt myself instead of just looking for deer.

I’m having a hard time relaxing tonight, because I’m so hyped to go to hunter education in the morning. Me and Dad are going to finish reading the study book tomorrow before we leave.

Why is hunter education important?

It teaches you about how to hunt safely and even about survival. Gun safety is important…otherwise someone could get hurt, or worse.

After Day 1:

How did the first day go?

The class was at the FWP [Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks] offices. A FWP employee told us about a bunch of important hunting laws. We went outside and learned the basic shooting stances. I’d spent a lot of time reading the book, so most of it was familiar to me already.

I made three friends. The instructors were good. There were two pretty nice guys and one mean old man. During lunch break, my dad came to get me, and we went out to lunch at KFC!

What was really lame is that the chairs were really uncomfortable, and I had to sit still for two hours at a time. And that’s really hard for me to do!

I’m looking forward to tomorrow. If I pass the test, I get a free knife with removable blades, and my dad will take me to the shooting range!

After Day 2:

How was the second day?

We started off the day with a quiz to get us ready for the big test. Then the instructors broke us up into groups, and we learned how to cross fences while carrying a firearm. Then we practiced shooting positions and gun holds. After that we learned about shooting…where to try to hit the deer.

Lastly, we took the test. I think the questions were a little easier for me because I’d practiced ahead of time. That was the written part of the test. After that, we did animal identification. Luckily everyone in my class was able to pass. Everyone received a nice pocketknife (with removable blades), a badge and a certificate.

I was really excited when I found out I passed, because this fall I get to hunt deer, in a few weeks I’m going to go turkey hunting with my dad, and tomorrow we’re going to go to the shooting range!

Any final words of advice?

I recommend that other kids take hunter education. It prevents accidents…and it’s fun!

Editor’s Note: Although it varies by state, province or territory, many hunters in the United States and Canada are required to pass a hunter education course to legally obtain a hunting license. Most agencies require hunter education for hunters born after a certain year, and many require additional education for archery hunters. Check with your local fish and game agency to learn about the specific requirements for your area and sign up for a hunter education course. Hunter-ed (www.hunter-ed.com) is a great resource that has information on individual regulations, study guides, and online steps toward certification.

BY PHIL HAYES

BY PHIL HAYES

Iowa ranks among the lowest in the country for public lands and access – less than 2% of the landmass is publicly accessible, and even less is open to hunting and fishing, The Iowa chapter of BHA recognized the need for more and, over the last year, set a plan into motion to support land acquisitions whenever possible throughout the state. 2023 will close with new opportunities for public recreation and 478 newly added acres permanently available for all Iowans to hunt and fish.

The first of these acquisitions was in Ida County in western Iowa, spearheaded by Zach Hall, director of Ida County Conservation. The Rich Smith Wildlife Habitat Area is a 103-acre addition to public upland and bowhunting ground that will also reduce erosion in the watershed of 62-acre Crawford Creek Lake, helping to preserve this public fishing opportunity in Ida County. This was a comprehensive effort by the Iowa chapter of BHA and local NGO partners in which the chapter donated directly to the purchase and created a fundraising page to generate donations from BHA members and corporate partners in Iowa and nationwide. Funds raised locally were used to match an Iowa Habitat Stamp Grant application for nearly $350,000. A huge thanks goes out to all of our BHA members and supporters who helped promote and fundraise for this acquisition. This project helped put the Iowa chapter on the map, and inquiries for our assistance started to roll in.

After the Ida County aquisition, the chapter also supported Lyon County Conservation Director Justin Smith in the acquisition of the Nachtigal property, which adds 40 acres in northwest Iowa for public fishing and hunting. Funds from BHA memberships, dollars donated by BHA corporate partner Wilderness Lite and a letter of support from BHA for the Iowa Habitat Stamp Grant helped open this ground for public access. A 15-acre fishing pond and a halfmile section of the Little Rock River, including several oxbows, are key features that make these 40 acres a great addition to our public lands. An adjoining 130 acres also will be purchased by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, adding even more land for public hunting in Iowa.

The most recent chapter contribution to Iowa’s public lands, thanks to Chickasaw County Conservation Director Chad Humpal, was the successful acquisition of the 220th Street property. Chickasaw County Conservation has purchased 205 acres of spectacular upland hunting ground in northeast Iowa, which is expected to be open to the public for the start of the 2023 pheasant season.

All Iowans purchasing a Habitat Stamp have also supported these additional opportunities for public hunting and fishing. Each acquisition was generously funded by Habitat Stamp grants, which most notably also assure permanent access to all these acres for public hunting and fishing.

In total, efforts by BHA’s Iowa chapter helped add 478 acres for public hunting and fishing during 2022-2023. With the continuing help of our Iowa members, BHA continues to lend support to adding additional public land and access throughout the state.

Meanwhile, as the Iowa chapter of BHA was actively championing three projects to add to public lands and waters in Iowa, political powers were at work to prevent us from doing just that.

This past March, SF 516, a bill calling for only the maintenance of current public lands, blocking further public land acquisitions, passed the Iowa Senate and headed to the House for consideration. Proponents of public land, including the Iowa chapter, quickly rallied in opposition of SF 516, engaging the members of one House committee after another while supporters of the anti-public land bill sought any imaginable route to a committee approval that would lead to a vote by the entire House. If the bill became law, it would create an insurmountable barrier to future purchases of land accessible for public recreation in Iowa. Each member of the House committees considering SF516 heard our rationale, and heard it repeatedly.

They listened, and they responded to BHA and others by recognizing the importance and value that more public lands bring to Iowa, both economically and for our quality of life. SF 516 was stopped before it made it through committee. It was a gratifying victory for the chapter and like-minded Iowa public land advocates in 2023, but it is certainly a battle that will continue both to motivate our Iowa members and require our action in the years ahead.

It’s just the beginning. We have learned we cannot rest. We must monitor legislative activity each session. We must be ever vigilant to ensure laws and public policy do not block and instead facilitate acquisition of land that is open to the public for hunting and fishing. And we must doggedly rally Iowa hunters and anglers to continue their support for purchases of additional land and access.

Phil Hayes is an enthusiastic backcountry float tube fisher and owner of BHA Corporate Partner and Gold Business Member Wilderness Lite, LLC. He is a founding board member of the Iowa BHA chapter, served 4 years as chapter secretary and continues on the board, focused primarily on seeking partnerships for the Iowa chapter’s efforts to unlock more land and water for public fishing, hunting, trapping and foraging.

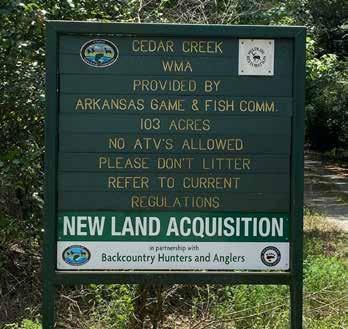

Ouachita, a French spelling of the Caddo name Washita, means “good hunting grounds.” With an abundance of black bears, whitetails, wild turkeys and all other manner of critters and flora, the Ouachita Mountains of Oklahoma and Arkansas live up to that name. Recently, BHA’s Arkansas chapter made a huge impact on access in the region with the completion of BHA’s first-ever land purchase.

The big gain in access is the result of the chapter’s closing on a small land acquisition that will improve public access to the Cedar Creek Wildlife Management Area. Upon buying the 1-acre parcel, which will provide a much-needed point of access and parking area for hunters, our chapter immediately donated it to the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission.

Currently the 103-acre Cedar Creek WMA provides walk-in access for hunting small game, turkey and deer, and a building on the site serves as a gathering area for research projects and conservation partners. Hunters who also wish to access the adjacent 150,000-acre Muddy Creek Wildlife Management Area may now legally do so by using the new parking area at Cedar Creek.

In 2022, the Arkansas chapter leaders decided to prioritize opening access to landlocked public lands. Board members Brad Green and Scott Knight began building a cooperative partnership with AGFC and onX Hunt. By December, the partnership had found its first access opportunity – the one-acre parcel available for purchase. Although the property owner had graciously allowed the public access through his property for several years, if another private owner bought the property, access could have evaporated in an instant.

“I’ve seen this property change hands a couple of times over the years,” says AGFC Region 5 wildlife biologist Jason Mitchell. “Once I learned about this project with BHA, onX and our agency, I knew we had a chance to secure it for our sportsmen and women in the area.”

Although the acreage is small, the opportunity to provide permanent legal access to such a large portion of existing public land was too great to ignore. The small scale of the purchase also had another benefit: $4,000 was an attainable price for BHA’s first ever land purchase – and a good test case for this new access partnership. It helped BHA learn how to do this type of access work and serves as a model for other chapters to follow.

Thanks to Arkansas BHA’s previous fundraising and public access work – including preventing the sale of the public Pine Tree Research Station to a private owner – the chapter had both the funds and reputation to make an offer to the seller. We always intended to donate it to the AGFC – not own land ourselves – and we did this with complete transparency. In fact, the landowner’s primary request was that the state agency owned the 1-acre parcel. So the chapter arranged a simultaneous closing – where the title could be

delivered to BHA and then to AGFC in the same filing. Thanks to the attentiveness and support of BHA staff, the transaction was completed promptly.

Why, you might wonder, did BHA get involved in the first place if the landowner wanted the property to go to the state? There are two reasons: First, the landowner wanted the funds from the sale of their property, which prevented them from donating it outright. Second, the amount of red tape required for a state agency to purchase a property, no matter how small, would have meant years in limbo for the seller and possibly a missed opportunity to secure the property for access. The Arkansas chapter was able to facilitate that transfer and spend chapter funds on what they’re meant for –furthering our mission.

The acquired property will be added to the Cedar Creek WMA and will include a parking area with access to Arkansas State Highway 28. To cap off an incredible access win, Jim Taylor – the treasurer of the Arkansas Wildlife Federation, a BHA member and a great advisor and friend to the Arkansas chapter – personally donated funds for a sturdy metal gate that will assist AGFC in managing access to the new parking area.

“This represents not only the first BHA land acquisition and transfer in Arkansas; it is the first for the organization nationally,” AGFC Director Austin Booth said during a recent AGFC meeting. “This may not seem like a large piece of land, but it is a very big deal as it opens much more access to our hunters, and we hope it’s the first step in a long relationship of increasing opportunity for Arkansans.”

Although the Arkansas chapter only formed a few short years ago, the partnerships and friendships we’ve formed since then were essential to the successful completion of this access project. The chapter is elated by the success of this acquisition and is on the hunt for more parcels to add to public land throughout the Natural State.

BHA Arkansas Chapter Events Chair Ryan Pettigrew lives with his family in Prairie Grove where he works as an attorney in real estate development. He spends his free time teaching his young sons the skills he learned as a feral boy in the Arkansas backcountry.

• The Alaska chapter is completing the final planning steps on an upcoming Armed Forces Initiative Learn to Caribou Hunt event this August in the Alaska Range for 10 veterans.

• The chapter, in conjunction with the Armed Forces Initiative-Alaska, worked on a streambank restoration project on the Russian River, performing essential habitat improvement for the upcoming sockeye salmon run. More on the news page at backcountryhunters.org/alaska

• The chapter continued its engagement with the provincial government and appointed trail system managers over concerns with implementation of the Trails Act and the expansion of motorized access on public lands.

• The chapter participated in the Alberta Native Trout Collaborative’s Angling Fair, in cooperation with Trout Unlimited Canada, discussing responsible practices for angling and recreation on public land.

• The chapter hosted a series of fishing and boating events to highlight our public waters, led by our new Public Waters Chair Rick Spicer.

• The chapter continued its summer series of Bows n’ Brews 3D archery community events.

• The chapter formed a special committee to explore future public access opportunities in Arkansas.

• Volunteers spent two days cleaning up Perrin Ranch. With the help of the Arizona Game and Fish Department’s Adopt-A-Ranch program, tires,

wire fencing, trash, old camper shells and even an abandoned boat were hauled away.

• The chapter hosted a sold out gourmet wild game dinner at Greenwood Brewing. Chef Vibber prepared three courses. including smoked Coues deer and javelina Bolognese, all paired with local beer.

• Our annual Family Squirrel Camp will be held Sept. 29 through Oct. 1.

• AFI completed an access project on the Deep River near Fort Liberty, North Carolina, creating a public access point to 12 miles of river for fishing, hunting and trapping that had been inaccessible prior to this project. The new access site will be named Captain Cooper Akin Memorial Dock after Captain Cooper Akin, a U.S. Army Green Beret and board member for Fort Liberty AFI, who passed due to a service-connected cancer in early June.

• The AFI work with the interagency task force around the Accelerating Veterans Recovery Outdoors Act is ongoing. Passed in 2020, it mandates the use of federal public land for veterans’ adjunct outdoor therapy. AFI is advising the task force representatives from Department of the Interior, Veteran’s Affairs, Department of Defense and various elected officials by providing data from the field, first-hand experience and recommendations moving forward. Legislation and policy changes are anticipated by Nov. 2024.

• In June the Armed Forces Initiative reached a significant milestone, having introduced 5,000 participants to the backcountry, hunting, angling and a mission of conservation.

• Regions have been hosting events, including guest-speaker pint nights, youth range days, group hikes, a fly-fishing course, orienteering and habitat improvement projects.

• The chapter conducted a province-wide hunter survey on B.C.’s Limited Entry Hunting system to support the LEH system review by a stakeholder group.

• The chapter is taking a lead role in developing the East Kootenay Regional Wildlife and Habitat Advisory Committee. The committee will create a template for regional committees as part of the Together for Wildlife strategy.

• BHA members shut down a petition to the fish and game commission attempting to close nearshore fishing in central California.

• BHA presented the U.S. Marine Corps squadron HMLAT 303 with a plaque and ram skull to recognize their commitment to wildlife during a critical drought year.

• The chapter celebrated the reintroduction of the PUBLIC Lands Act, legislation that would have a monumental impact on rivers, forests and habitat for a number of species in the state.

• The chapter sponsored a new hunter turkey hunt through Virginia DWR’s One Shot Event.

• The chapter engaged with BHA leaders and federal lawmakers concerning the Land and Water Conservation Fund, reenforcing commitments to keep allocated funds from being redirected.

• The chapter engaged with Sen. Kaine (D-VA) in supporting the Virginia Wilderness Additions Act.

• John Chandler was recognized as BHA Member of the Month for May. John was instrumental in organizing the chapter’s biggest and most successful stewardship event, Beers, Bands & Barbed Wire Strands.

• Alex Krebs was recognized as BHA Member of the Month for June 2023. Alex helped stop a proposed mountain bike trail system impacting vital big game/elk habitat.

• Collin Hildebrand was appointed the chapter’s northwest group assistant regional director.

• Army National Guard veteran Matt Lee was named Colorado Armed Forces Initiative liaison.

• U.S. Marine Corps veteran Bryan Jones is the new BHA Colorado and Wyoming chapter coordinator.

• In July the chapter hosted its third annual scouting workshop in Jupiter, where seasoned hunters led groups on a morning scout to help identify game sign and better understand Florida habitat.

• At an FWC stakeholder meeting, the chapter successfully lobbied for an additional 30 minutes of access following afternoon waterfowl hunts on all gated stormwater treatment areas.

• The chapter provided input and participated in a public access scoping meeting for Arthur R. Marshall National Wildlife Refuge.

• The chapter is closely monitoring the proposed NOAA rule to reduce the speeds of certain boats to 10 knots off the Georgia coast.

• The Georgia chapter is busy planning its first annual sporting clays shoot.

• The chapter hosted a Salmon River cleanup near Challis and a Public Land Pack-Out day near Sandpoint.

• Classroom sessions were completed for Learn to Hunt; 20-plus stu-

dents are anticipating their fall mentored hunts.

• The chapter welcomed Melissa Hendrickson as secretary, Joshua Zifzal as the Stewardship Committee chair, Ty Thompson as a Region 2 representative, and Zach Cuddy as a Region 3 representative.

• Armed Forces Initiative-Idaho, along with 3 Heart and Lion’s Head Outfitters, hosted a successful float and fish on the Kootenai River and offered a backcountry medicine class in Coeur d’Alene.

• The Illinois chapter has had a busy summer with pint nights, work days and meetings. We want to wish everyone a successful and safe fall season on whichever public lands and waters you are on.

• Work has started on the Lake Shelbyville Archery Park. The chapter is searching for sponsors to help support the first BHA-affiliated 3-D archery trail. Email us to see how you can help!

• The Indiana chapter had three leaders attend a Train the Trainer sawyers course hosted by the U.S. Forest Service. Attendees gained firsthand experience in bucking and proper chainsaw usage and received their Level B Bucker Certifications.

• The Indiana chapter will be hosting their 3rd Annual Chapter Rendezvous Sept. 9-10 at the White River Campground. This event has great participation, and folks always leave invigorated for conservation work.

• The chapter events committee is continually looking at new event ideas and locations. Stay tuned for more great opportunities!

• In June, the chapter hosted a Learn to Fly Fish event with Dan Frasier in northwest Iowa.

• The chapter contributed funds and solicited donations for three land acquisitions in late 2022-2023 in Ida, Lyon and Chickasaw counties. The increases in public land hunting and fishing access totalled 478 acres!

• The chapter held its state rendezvous at Yellow River State Forest in July, complete with camping, a fishing contest and seminars from the Iowa DNR, Trout Unlimited and Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation.

• On May 19, volunteers with the Kansas chapter partnered with KDWP to remove Eastern red cedars on 1,000 acres of greater prairie chicken habitat in north-central Kansas.

• On June 24, Kansas BHA volunteers worked with managers at Quivira National Wildlife Refuge to remove fencing.

• On July 29, the Kansas chapter assisted the Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks in posting Walk-In-Hunting-Access signs on a large, newly enrolled property in south-central Kansas.

• On Aug. 19, the Kansas chapter attended Walton’s Brat-Fest in Wichita, where information regarding BHA was dispensed to attendees.

• We are pleased to announce state sponsor Fine Arms & Armor.

• We tabled at the Bluegrass Trout Unlimited Fly Fishing Film Tour in Lexington as a corporate sponsor in April.

• Our fourth distict director Ben Bishop led a tabling event at the first annual Kentucky Elk & Outdoor Fest in Bardstown, sponsored by KY Gun Co., with 8,000 people in attendance in May.

• Our eighth district director Samantha Lewis led the building of fish habitat structures in Buckhorn in cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and KDFWR in June.

• The chapter held a successful pint night to help educate and raise awareness of the possible Camp Grayling expansion, which would have limited access and opportunity for hunters and anglers on over 162,000 acres of public land.

• The chapter hosted an engaging pint night to increase knowledge and awareness of the Cornwall Dam issues.

• The chapter hosted our annual state rendezvous at the Looking Glass River Sportsman Club in Laingsburg from July 28-30. This event allows numerous people an opportunity to engage with like-minded conservationists and walk away feeling charged and ready to make a positive impact around our state. A huge thanks to all involved and those who attended this wonderful weekend!

• The Minnesota chapter participated in the first planning meeting as a partner member for the Minnesota Governor’s Deer Opener.

• The chapter enjoyed hosting its first Cocktails for Conservation trivia night with Minnesota Deer Hunters Association. This event was hosted at the brand new Obbink Distilling Company in St. Joseph.

• At the close of the state legislative session, chapter leaders totaled 12 in-person testimonies on behalf of BHA members in regard to multiple legislative topics. The chapter was also an active participant in the conference committee process.

• The Missouri chapter recently hosted a pint night in Kansas City.

• The chapter attended Dive Bomb Industries’ 3rd Annual Squadfest in St. Louis. We were able to raise a lot of money and talk to waterfowl hunters from all over the region about BHA’s mission.

• The chapter hosted Mark Kenyon on his Working for Wildlife tour near St. Louis for a public habitat improvement project and fundraiser afterwards.

• The chapter helped introduce, pass and see legislation signed into law that increases the fine 1,000% for illegally blocking public roads.

• The chapter cheered the reintroduction of the Blackfoot-Clearwater Stewardship Act and supported multiple proposed conservation easements; engaged in season-setting and FWP’s elk-management planning process; published op-eds in support of the BLM Public Lands Rule.

• The chapter hosted pint nights in Billings and Helena, pulled problematic fences in pronghorn country, and lined up a summer of stewardship projects yet to come!

• The chapter held its third annual backpacking clinic, with live demos of field dressing, quartering and deboning and pack dumps for various hunts.

• The chapter submitted comments on the Nevada Solar PEIS, the new BLM Public Lands Rule and the Greenlink Energy Development Plan.

• Summer pint nights were held with Nevada Wildlife Federation and Nevada Division of Wildlife.

• The chapter completed several apple-tree release projects on Vermont state lands, as well as an AFI Grouse Camp, with hunting on the nearby Green Mountain National Forest.

• New Hampshire members weighed in on the fish and game commission’s five-year strategic plan.

• In Rhode Island, shoreline access has been protected and restored in a big legislative win!

• On Aug. 26 the New Jersey chapter participated in the Public Lands Pack-Out presented by onX. The chapter board organized three separate pack-outs at wildlife management areas, including Whittingham WMA in the north, Colliers Mill WMA in central Jersey and Makepeace WMA in the south. Each pack-out was attended by BHA members from across the state, as well as officials from the NJ Fish and Game.

• The chapter and Kirtland AFI rebuilt two beaver dam analogs in the Lincoln National Forest, contributing to a long-term goal of native Rio Grande cutthroat trout reintroduction. The crew also removed hundreds of feet of hose that was left in a riparian bottom following a revegetation project.

• The New Mexico and Texas chapters were awarded the U.S. Forest Service’s 2023 Prairie Partner Award in recognition of our Kiowa and Rita Blanca national grasslands work, demonstration of resource stewardship, a willingness to provide funding and other resources to grassland projects and producing innovative practices and results.

• The chapter’s Hike to Hunt event at Ellicottville Brewing was a great time, including hiking, a fitness challenge and archery.

• The chapter collaborated with Hunters of Color, New York Nature Conservancy and NY DEC on an Introduction to Archery day. Over 70 new hunter-conservationists came out for this event where they learned archery, treestand safety and basic deer scouting skills.

• The chapter rendezvous will be at the Hungry Trout Resort in September on the banks of the Ausable River, surrounded by mountains and public land. Top speakers, seminars, great food, conservation and campfires are in the works!

• The chapter expanded its board to add a social media manager and East Grand Forks and Minot representatives.

• The chapter partnered with Roughriders Archers to host the 2023 Badlands Classic Archery Shoot, which took place 100% on public land at the Little Missouri National Grasslands.

• The Ohio chapter hosted the party of the summer, Muster in the Marsh, at Covered Bridge Outfitters in beautiful and fishy Conneaut, Ohio. The event featured entertainment including live music, crazy raffle prizes, games for the kids and even a turtle butchering demonstration. The Cleveland Field Kitchen made magic with ingredients from the marsh and woods for our Conservation Dinner, and we were joined by the always-engaging Ryan Callaghan and Kevin Murphy.

• It’s not all parties, however, and the Ohio chapter board continues to keep an eye on developments to public land hydraulic fracturing. We continue to push for greater transparency in the leasing process for fracking under our state parks. Of particular concern are some proposed well pads very near huntable public land and those uphill from important waterways. Read more on the Ohio chapter page of the BHA website.

• On June 17, volunteers with both the Oklahoma chapter and Quail Forever joined up to perform hack and squirt conservation efforts at Osage WMA, Rock Creek Unit. Thousands of trees were killed off in order to establish habitat back to a savanna-type landscape for quail, turkey and other species.

• On July 21-23, the Oklahoma chapter, along with members of the Arkansas chapter, hosted its Stateline Rendezvous at the Illinois River in northeast Oklahoma, which included a river float, fishing and conservation work.

• The chapter helped pass HB 3086, which reforms the ODFW commission to have members represented by the five river basins in the state, instead of by population.

• The third annual Cut and Cook event was completed, where 40-plus participants learned how to shuck oysters and filet/prepare salmon.

• The chapter held its inaugural Clam Jam, where participants of all ages gathered at Seaside to learn how to harvest razor clams along Oregon’s coastline.

• The chapter was awarded a Certificate of Recognition from the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission for its work on the Adopt an Access program, where BHA members adopt boat access sites for regular cleanups. The chapter was the pilot group for the new program.

• Board Member Adam Eckley held the third annual Learn to Trout Fish program. Participants camped out and received hands on training on the fundamentals of fly fishing for trout.

• BHA members completed the chapter’s annual Pennsylvania Wilds Trail Challenge. This year the group covered 28 miles in the Hammersley Wild Area.

• The chapter joined local partners in three water cleanups this past summer: Missouri River at Yankton, Enemy Swim Lake and Missouri River at Pierre/Fort Pierre.

• The chapter rallied members to send over 30 letters in two days to oppose the Golden Crest Mining Project in the Black Hills.

• The chapter submitted testimony to the BLM and USFS to support a 20-year mining withdrawal within the Pactola-Rapid Creek watershed, which provides access and clean water to the Rapid City area and nearby Ellsworth Air Base.

• The chapter will be hosting a family fishing get-together at Mississippi’s Percy Quinn State Park on Sept. 9. Details will be announced soon, but please reach out if you would like more information.

• With the discovery of CWD in a deer in northwest Florida, Alabama’s DCNR has implemented their CWD response protocols to assess and hopefully contain the situation. Hunters in the southwest portion of Alabama should be sure to read and understand any guidelines and rules implemented for the upcoming season.

• Please share your adventures and experiences with us this fall on the chapter’s Facebook and Instagram pages!

• The chapter recently participated in stakeholder meetings at the invitation of the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency. The purpose of the meetings were to identify problems and solutions in regards to TWRA’s management of deer and turkey resources. It was an honor to represent Tennessee’s public land hunters and anglers within a diverse group of stakeholders.

• The West Fork of the Red River is a heavily used section of river. The chapter recently floated it and hauled out 20 bags of garbage, old tires and even an old, abandoned grill.

• The chapter held the 2nd Annual Rita Blanca Fence Project, a habitat restoration effort to help improve habitat connectivity for Texas pronghorns.

• The chapter was awarded the National Grassland Prairie Partner award for 2023 for their work conserving the Rita Blanca Grasslands.

• The chapter partnered with Save the Cutoff in Henderson County on the first annual Save the Cutoff Crappie Tournament in April. The funds from this tournament went to litigation costs in the case of protecting this piece of public water.

UTAH

• With the help of Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, SITLA, onX and Sportsmen for Fish and Wildlife, the Utah chapter successfully restored the southern trailhead access to the Book Cliffs in Sego Canyon and is preparing next steps on a restoration project for the northern trailhead.

• This fall Utah BHA members will join our friends at Fishing for Garbage on a Weber River cleanup project.

• In collaboration with the Wildlands Network, the chapter is in preparation mode on a large-scale migration corridor improvement fencing project on the Paunsaugunt Plateau. This will be a multi-phase endeavor that will make herd crossing safer for the Paunsaugunt deer herd and other wildlife, reducing crossing injuries and fatalities, as well as collect migration route data for the Utah DWR.

WASHINGTON

• April through July, the chapter accomplished six stewardship projects ranging from fence pulls to public land cleanups.

• Alongside WDFW and the Rocky Mountain Goat Alliance, the chapter will participate in mountain goat surveys in the Lake Chelan area this summer.

• The chapter held its 5th Annual Access Freedom Archery Shoot at KBH Archers with over 80 competitors in attendance. Congratulations to Clarence Rushing for leading and organizing the event for the fifth consecutive year.

• In August we teamed up with the WVDNR for a turkey-brood habitat restoration workday at Stonewall WMA.

• We hosted a virtual summer wild edibles workshop in July led by foraging experts from the West Virginia Mushroom Club.

• Stay tuned to our e-newsletter and social channels for upcoming chapter events.

• The chapter has been participating in quarterly roundtables with Wisconsin DNR Secretary Adam Payne, his executive staff and various conservation leaders from across the state. These roundtables catalyze ideas with other groups, reiterate the needs of our hunters and anglers and ensure the chapter’s voice is heard by the ultimate decision makers.

• The chapter is gearing up for another year of R3 events, mentoring another 50-plus students to navigate public lands and waters in the pursuit of deer, turkeys, pheasants and waterfowl – thereby creating a new generation of conservation and public-access advocates!

Find a more detailed writeup of your chapter’s news along with events and updates by regularly visiting www.backcountryhunters.org/chapters or contacting them at [your state/province/territory/region]@backcountryhunters.org (e.g. newengland@backcountryhunters.org)

BY HARRISON STASIK

BY HARRISON STASIK

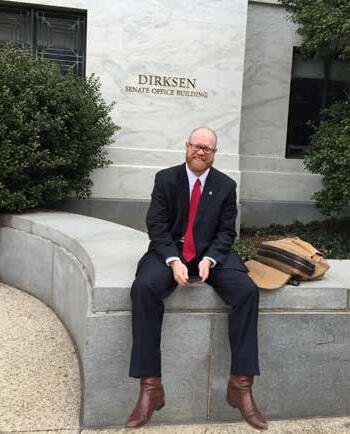

I’ve been fortunate enough to visit our nation’s capital twice in my life. Once was the typical eighth grade field trip to D.C. that many students partake in, but this second time I had the pleasure to stay on Capitol Hill with Land Tawney. We were there to advocate for our wild public lands, waters and wildlife, and the rights of all Americans to experience them. This experience did not mirror that of my eighth grade trip many years ago.

It began with a Wildlife and Hunting Conservation Council meeting at the Department of Interior, overseen by the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of Agriculture. Tawney is one of several conservation leaders who sit on the council to provide recommendations to the federal government that encourage partnerships among conservation organizations and the public, advocate for wildlife and natural resources and support fair chase and recreational hunting. It was remarkable to see the wide array of perspectives that provide input on how our nation can better manage, preserve and conserve various regions and wildlife across the United States.

On a more local level of advocacy, I was able to meet with the staff of Sen. Baldwin, Sen. Johnson and Rep. Van Orden from Wisconsin. During these meetings we had the opportunity to discuss several important outdoor and wildlife issues that our state currently faces. Although brief, these conversations reminded me of the importance and our duty as public land stewards to reach out to our representatives and to convey our thoughts on outdoor issues impacting our nation and the states we come from.

There was little downtime, but I could not think of a more appropriate way to spend a few free hours than by enjoying the

public lands and waters around D.C. The most memorable of these experiences was when we had the opportunity to navigate the Potomac River in pursuit of catfish and striped bass. Although the striped bass eluded us, we did tie into several catfish before a scenic ride back to the boat launch past the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial at dusk.

My admiration of our nation’s history of recreational hunting and fishing didn’t stop there: At the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, I was astonished to gaze upon the African lion and white rhino that President Theodore Roosevelt collected on behalf of the Smithsonian from 1909-1910. This historical hunting expedition led to a better understanding of thousands of plants and animals.

Whether it was time spent advocating to representatives in Congress or appreciating the past and present of the outdoors world, I can confidently reiterate that my school trip many years ago did not compare to this experience in the slightest. I never saw myself being in a position in life to advocate for and represent our environment, wildlife and outdoor rights, but I am humbled and grateful for this tremendous experience.

I want to extend my gratitude and thanks to Land Tawney and Backcountry Hunters & Anglers for such an awe-inspiring trip! After my return home, I was able to conclude this overall experience by reflecting on it while in the turkey woods of Wisconsin.

Harrison Stasik is an avid outdoorsman and previously led the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point BHA collegiate club. Post graduation, he is pursuing a career in nonprofit conservation while continuing to volunteer for BHA in the Midwest. He was the 2023 recipient of BHA’s Rachel L. Carson Award for emerging conservation leaders.

On the night in 2004 that Backcountry Hunters & Anglers came to life, at least two of the faces glowing orange and red in the flickering light of a campfire belonged to veterans of military service. Almost 20 years later, 20% of BHA’s members are active duty or veterans of military service, a rate more than twice that found amongst the remainder of our citizenry. It’s not a surprise people drawn to protect national security are also drawn to protect the lands held in common by all North Americans. It’s also not a surprise that most people who serve in the military move on to something else after their initial term of service.

Fortunately, service ethos is not something one takes off and hangs in the closet like a uniform. It’s more akin to a campfire’s ember, waiting for oxygen and a little fuel to bring it roaring back to life. For many veterans, the BHA Armed Forces Initiative offers the ability to answer that call through R3, public land cleanups and the power of their ballots. Still, some veterans feel the mission to serve the land, and the wildlife upon it, as a professional calling. Jason McHenry and Zack Weis are two of them. Both men grew up in the outdoors. Both served as United States Marines. Both felt called to law enforcement. And both recognize that our public lands are a right and a responsibility worth protecting as game wardens.

years, the son and brother of Alabama Highway Patrol Troopers has served his nation, his state and his community in dangerous ways, demanding the deepest commitment. Over those decades, McHenry saw close-quarters combat in Iraq as a United States Marine, made solo drug busts in the dark woods as a highway patrol trooper and protected legislators as a member of the Alabama Capitol Police. Now, as a lieutenant in the Alabama Department of Conservation of Natural Resources, McHenry leads conservation enforcement officers enforcing the state’s wildlife laws in seven counties.

As a conservation enforcement officer, McHenry says, “I feel like I am making a difference. I like helping people. As a trooper I could help folks in crisis, maybe find someone at a low point in their life and help them move forward. As a warden I’m not often encountering folks at their lowest point, but I do get a chance to educate the public about conservation and hopefully give someone a positive experience with law enforcement. It’s not just lawenforcement – it’s hopefully altering behavior to help people be better down the road.”

Service is in Jason McHenry’s blood. For more than half of his 42

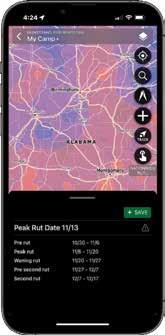

McHenry’s idea of helping people be “better down the road” is a notion completely in keeping with BHA’s mission to “ensure North America’s outdoor heritage of hunting and fishing in a natural setting, through education and work on behalf of wild public lands, waters, and wildlife.” The work to make it happen appeals to the longtime deer and turkey hunter because most of it happens on the public lands he considers “a huge asset. … I have a wildlife management area 15 minutes from my house on which to hunt deer, turkey, waterfowl and small game. For $47 a year I have

thousands of acres. Additionally, I like the challenge of hunting on public lands, as the laws mean it’s a natural hunt.” Of course, as the father of six, it doesn’t hurt that his passion for hunting public land also puts healthy, sustainable meat on the table.

His love of the hunt carries over to the job. The same skills the bowhunter uses to track an arrowed deer are useful in finding law breakers. “I’m a trained canine officer and have a beagle that I use to track poachers,” McHenry says. “But people get creative on public land! They will park and move a long way away. It’s illegal to hunt over bait on public land in Alabama, so sometimes I will find a bait pile and track the hunter from there. Once I found a guy’s bait pile and was able to get his name from his license plate.” He laughs as he says, “We knew he was hiding from us, but then he answered when I called his name.”

McHenry finds the work of a conservation enforcement officer appealing because he can be out in the woods or on the waters pursuing particularly egregious violators – commercial fishers violating catch regulations, people hunting at night from a roadway, out-of-season hunters or those exceeding their bag limit. But it’s the softer sides of his job that he truly loves – search and rescue, conservation education, and the extension of grace to people needing education more than sanction.

McHenry smiles as he tells of finding a car with a “help” sign in the window and clothes spread on the ground nearby, often a sign of panic. He tracked the man until he lost the sign. His beagle found the man, missing for three days. For McHenry, the positive feelings from those kinds of experiences last longer than the adrenaline blast of armed combat or a roadside drug bust. That’s a reflection of the positive person that he is. He’d just rather help, an ethos illustrated when he tells a story of catching, “some kids mud riding on public land. They had done several thousand dollars’ worth of damage. I could’ve written them a ticket and made a big issue out of it. Instead, I explained to them that hunters pay for the land they wrecked, that hunters are the only ones paying for it through Pittman-Robertson, and that by doing thousands of dollars’ worth of damage in an environment in which license revenues are declining, they are making it harder and harder to take care of our public asset.” It could have ended there but, “[t]hose kids went home and told their parents what they had done and what I had said. Their parents sent them back to me and they ended up doing a lot more work than required to repair the damage they caused. That kind of lesson lasts a whole lot longer than a ticket.”