BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL

Imagine the excitement and anticipation after a long week of work as you load up the jon boat and head out to one of your favorite hunting or fishing spots. It’s going to be a glorious day, you think to yourself.

On the drive, you might ruminate about the grudge bass that you hooked a couple of times but couldn’t bring to the net, or the time you took your two young boys for their first waterfowl hunt or maybe the occasion when you just paddled around with your wife years before officially tying the knot. It’s a special place for you and countless others. And you probably never imagined you’d arrive there only to find the access illegally blocked by the adjoining landowner.

But that’s exactly what happened on Creslenn Lake in East Texas. Back in 2022, a private landowner made damn sure that no one could enjoy this treasured spot – except for himself – by illegally extending the land area between the road and the water using a backhoe to dredge up soil from the surrounding banks and installing an iron fence.

Down along the border of Henderson County, an oxbow lake that stretches for 12 miles parallel to the Trinity River has become a battleground for access to a public waterbody. Known locally as “The Cutoff,” Creslenn Lake has afforded generations of locals the right to hunt, fish, paddle and generally enjoy a variety of recreational opportunities available on public waters.

Access to this beloved resource has been affirmed by over a century of public use, as well as a “public waterbody” declaration by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. There is a wellestablished public right-of-way and public easement to access this navigable body of water and on two occasions the state even stocked it with Florida bass. In short, the Cutoff’s status as a public resource is not in question, even if inaction by public officials responsible for enforcing legal access is highly questionable. It might sound overly simplistic, but this really has become an issue of right vs. wrong.

The often-tenuous nature of access to public lands, waters and wildlife transcends geography. Look no further than just how much the mission of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers has resonated well beyond the region of our founding. And while there’s no qualifier or explanation needed to underscore the tremendous value of public natural resources across North America, when the right to enjoy these treasures is taken away, it might matter just a bit more in places where public resources are already limited. And in Texas, over 95% of landholdings are privately held.

So what happens when a private landowner illegally prohibits already limited access and violates a number of state and federal regulations in the process? Well, so far, nothing.

Despite three letters of formal notice by the Texas Department of Transportation regarding alteration of the transportation rightof-way and demands the fence be removed, a cease and desist order issued by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for illegal dredging and filling, and over $800,000 in damages documented by TPWD, the landowner’s underhanded action still stands. Hunters and anglers have rebuffed repeated attempts to privatize the Cutoff over the years, including passing a bill in 1931 that affirmed “[the Cutoff] shall not be sold and shall remain open to the public for hunting

and fishing,” but that doesn’t seem to matter either.

So, what’s the barrier to enforcing the law and taking decisive action? Politics, of course. Or more accurately in this case, political connections. It’s a classic case of regular, hard-working citizens getting screwed by good-ol’-boy politics and a landowner with deep pockets.

A local citizen’s group called “Save the Cutoff” was created in response to the circumstance and has filed multiple lawsuits to restore access. These efforts have garnered strong support from the Texas Rivers Protection Association and, more recently, BHA’s Texas chapter – which has contributed directly to legal fees and filed an amicus brief to the court in support of public access. It’s truly a maddening state of affairs in which citizens who have historically enjoyed recreating on the Cutoff have been draining their own financial resources to restore ownership of something that never should have been taken away in the first place. So far, close to $200,000 in legal fees have been spent taking action to restore access.

The first lawsuit filed by Save the Cutoff seeks to enforce provisions in the Clean Water Act that prohibit discharge of dredged or fill materials into waters of the United States. The second lawsuit is aimed directly at the landowner for blocking public access to a navigable waterway. This second legal action seeks to reaffirm that the Cutoff is a navigable stream, declare that the landowner violated the Texas Water Code with the placement of obstructive fill, and assert that construction of the illegal fence is a nuisance that has violated their right to fish. The third lawsuit is directed at the county and county commissioner for failure to maintain access to an adjacent roadway that has provided historic access to the Cutoff.

To date, the riprap and fill continue to pollute the water, hunters and anglers continue to be blocked by the illegal fence, and the shocking display of inaction continues to affirm that money and power matter more than clearly settled law. This is exactly why BHA exists, and knowing this could just as easily happen in your part of the world, I hope you can all find a few dollars to donate to the cause. To learn more, check out backcountryhunters.org/ save_the_cutoff

-Patrick Berry, President & CEO

“There is pleasure in the pathless woods.” - Lord Byron

Ryan Callaghan (Montana) Chairman

Dr. Christopher L. Jenkins (Georgia) Vice Chair

Jeffrey Jones (Alabama) Treasurer

Katie Morrison (Alberta) Secretary

Patrick Berry, President & CEO

Frankie McBurney Olson, Vice President of Operations

Dr. Keenan Adams (Puerto Rico)

Bill Hanlon (British Columbia)

Jim Harrington (Michigan)

Hilary Hutcheson (Montana)

Ted Koch (Idaho)

Nadia Marji, Vice President of Marketing and Communications

Katie DeLorenzo, Western Field Director

Britney Fregerio, Director of Finance

Chris Hennessey, Eastern Field Director

Dre Arman, Chapter Coordinator (ID, NV)

Brian Bird, Chapter Coordinator (NJ, NY, New England)

Chris Borgatti, Eastern Policy and Conservation Manager

Kylee Burleigh, Digital Media Coordinator

Tiffany Cimino, Membership and Community Development Manager

Trey Curtiss, Strategic Partnerships and Conservation Programs Manager

Robert DeSoto, Habitat Stewardship Coordinator (OR)

Bard Edrington V, Habitat Stewardship Coordinator (NM)

Brady Fryberger, Office Manager

Mary Glaves, Chapter Coordinator (AK)

Chris Hager, Chapter Coordinator (WA, OR)

Contributors in this Issue

On the Cover: BHA North American Board Member Hilary Hutcheson with a westslope cutthroat trout. Photo by Aaron Agosto Above Image: Samantha Lewis, 2022 Public Lands and Waters Photo Contest

Col. Mike Abell, Charlie Booher, James Brandenburg, T. Travis Brown, Jamie Cameron, Curtis Collins, Michael Drew, Luke Etchison, Heather E. Goodman, Millie Hibbs, K.C. Huxtable, Cameron J. Kirby, J.J. Laberge, Paul Lask, Jordan Lefler, David Lien, Jesse C. McEntee, Matthew Meyer, Harley McAllister, David O. Miller, Eric Nuse, Anthony Pozzi, Kurt Ratzlaff, Taylor Twisdale, Kelsey Wellington, Ben Wiley, Kelly Williams, Corey Zimmerman

Journal Submissions: williams@backcountryhunters.org

Advertising and Partnership Inquiries: mills@backcountryhunters.org

Ray Penny (Oklahoma)

Don Rank (Pennsylvania)

Peter Vandergrift (Montana)

J.R. Young (California)

Michael Beagle (Oregon) President Emeritus

Andrew Hahne, Habitat Stewardship Coordinator (MT, ID, WY)

Aaron Hebeisen, Chapter Coordinator (IA, IL, MN, MO, WI)

Jameson Hibbs, Chapter Coordinator (IN, MI, OH, OK, KY, TN, WV)

Bryan Jones, Chapter Coordinator (CO, WY)

Kaden McArthur, Goverment Relations Manager

Josh Mills, Corporate Conservation Partnerships Coordinator

Devin O’Dea, Western Policy and Conservation Manager

Brittany Parker, Habitat Stewardship Manager

Thomas Plank, Communications Manager

Kylie Schumacher, Chapter Coordinator (MT, ND, SD)

Max Siebert, Operations Coordinator

Harrison Stasik, Events Assistant

Joel Weltzien, Chapter Coordinator (CA)

Briant Wiles, Habitat Stewardship Coordinator (CO)

Zack Williams, Backcountry Journal Editor

Interns: Lars Chinburg (Backcountry Journal intern), Maisie Kroon, Sylvie Poore, Taigen Worthington

P.O. Box 9257, Missoula, MT 59807 www.backcountryhunters.org admin@backcountryhunters.org (406) 926-1908

Backcountry Journal is the quarterly membership publication of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers, a North American conservation nonprofit 501(c)(3) with chapters in 48 states and the District of Columbia, two Canadian provinces and one Canadian territory. Become part of the voice for our wild public lands, waters and wildlife. Join us at backcountryhunters.org

All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in any manner without the consent of the publisher.

Published July 2024. Volume XIX, Issue III

General Inquiries: admin@backcountryhunters.org JOIN THE CONVERSATION

BY DAVID LIEN

Backcountry hunters and anglers value wild country, clean water and intact habitat. It’s a founding principal of this organization, and one that remains a priority today.

But we aren’t the only ones who know their value. Five years ago, I teamed up with rancher Bill Fales to advocate for protecting Colorado’s Thompson Divide from proposed oil and gas development. Bill and his family ranch alongside the Crystal River, south of Carbondale. The ranch has been in their family since 1924. They rely on summer grazing permits in the Thompson Divide.

“West Slope ranches rely on high-quality summer pastures and clean water from the Thompson Divide,” we wrote in an April 2019 Post Independent op-ed. “The area spans dozens of watersheds, provides domestic and agricultural water in the Crystal, Roaring Fork and Colorado River valleys, and supports 8,000 acres of cropland in the North Fork Valley, one of the most productive organic farming regions in the nation.”

“Hunters and anglers … feel the same way about protecting public lands along the Continental Divide,” we wrote. “Wildlife populations along the I-70 corridor have been in steep decline for decades due to poor land use decisions and over-development in some of the best historic habitat.”

Perry Will, a former Colorado Parks and Wildlife supervisor –now serving in the state legislature – said elk in the region just don’t have the solitude they need any longer.

For example, in a single decade approximately half of Eagle County’s elk population vanished. From Vail Pass to Glenwood Canyon, since the 2007 count by CPW, the numbers dropped by 50%. CPW previously issued about 2,000 hunting tags for the area. During 2018, just 200 were issued. “It’s not like the elk are moving somewhere else; they are just dying off,” Will said. In addition, Colorado’s statewide mule deer population plunged from 600,000 in 2006 to about 433,000 in 2018.

Big game (and other) habitat in the Thompson Divide region and across the state is being sliced and diced into ever smaller pieces by the sloppy knives of energy development, road and trail building (legal and illegal) and expanding year-round outdoor recreation, which is why the April 2024 Department of the Interior’s Thompson Divide Administrative Mineral Withdrawal announcement was welcome and long overdue.

The withdrawal protects 225,000 acres of public lands in western Colorado from future oil and gas leasing and mining for the next 20 years and is the result of a decade and a half of community collaboration – with local ranchers, hunters, anglers, businesses and numerous other concerned groups and individual citizens contributing to the long-sought victory.

“For many years, the communities surrounding the Thompson Divide have joined together to advocate for the protection of the Divide from the threat of new fossil fuel development – a use that is not compatible with the livelihoods of those that rely on this landscape today,” said Ben Bohmfalk, mayor of the town of Carbondale in an April 2024 E&E News story. “We thank the Biden administration for finalizing the process to withdraw the Thompson Divide area from new oil and gas leases.”

As mayor Bohmfalk noted, the Thompson Divide – which includes big game migration routes, spring elk and deer calving grounds and Colorado cutthroat trout habitat – is too valuable to develop; ranchers, hunters, anglers and local leaders in western Colorado all agree. Although the Federal Land Policy and Management Act authorizes the Department of Interior secretary to withdraw lands for a maximum of 20 years, our best chance to permanently protect the Thompson Divide and the Continental Divide is the Colorado Outdoor Recreation and Economy (CORE) Act.

Spearheaded by Sen. Michael Bennet (D-CO) and Rep. Joe Neguse (D-CO), the CORE Act would make the Thompson Divide withdrawal permanent, designate 71,000 acres of new wilderness areas and create nearly 80,000 acres of new recreation and conservation management areas in the region.

What Bill Fales and I emphasized in our op-ed over half a decade ago still holds true today: “Healthy, unfragmented public lands in the Continental Divide provide some of the best habitat for wildlife and the best backcountry hunting opportunities in the Central Rockies … We applaud Sen. Michael Bennet and Rep. Joe Neguse for introducing the Colorado Outdoor Recreation and Economy Act. Thank you for your bold and comprehensive vision to safeguard these revered landscapes and support our outdoor recreation economy.”

I am in favor of using our natural resources responsibly, but sometimes oil and gas companies need to take “no” for an answer; this is one of those times. As BHA members know from boots on the ground experience, we are first and foremost dedicated to protecting public lands habitat – wherever, whenever and however we can. However, only Congress can permanently protect this landscape, and we will continue to push for passage of the CORE Act to do just that.

David Lien is a former Air Force officer and co-chair of the Colorado chapter of BHA. He’s the author of Hunting for Experience: Tales of Hunting & Habitat Conservation and was the 2019 recipient of BHA’s Mike Beagle-Chairman’s Award “for outstanding effort on behalf of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers.”

As the leading voice for our wild public lands, waters, and wildlife, Backcountry Hunters & Anglers applauded the Public Lands Rule finalized in April by the Bureau of Land Management recognizing conservation in public land management as a value on par with other uses. The rule represents a long overdue acknowledgement of the tremendous value of fish and wildlife habitat and recognition that BLM land holdings are owned by all Americans.

“Hunters and anglers support the Public Lands Rule because it will prioritize important active management prescriptions to tackle invasive species, restore degraded lands and waters, and conserve intact habitats critical to wildlife corridors,” said Kaden McArthur, BHA’s government relations manager. “With less than 15% of BLM lands currently managed for conservation, this is a critical step forward to properly balancing the use of our largest public lands estate.”

The BLM stewards 245 million acres of public lands that include significant habitat and ecological resources upon which hunters and anglers rely for opportunities to pursue their outdoor passions. The rule clarifies that the management of these public lands for conservation is a valid use and should be considered as such under the multiple-use and sustained yield framework of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act.

“When implemented, the rule will provide tremendous longterm conservation and recreational benefits on land stewarded by the BLM that finally represents the interest of more Americans,” said Patrick Berry, BHA’s president and CEO.

The final rule follows an extended public comment period, including feedback from thousands of hunters and anglers to strengthen and clarify the rule. More than 90% of comments supported the rule, a testament to the importance of conservation across the United States.

The corner crossing legal fight took its next step in May as oral arguments for the legal case were held before a three-judge panel at the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver.

The case involves four Missouri hunters who used a ladder to “corner cross” from one public land parcel to another without setting foot on private land, navigating the checkerboard layout common in the West. Those legal proceedings continued to focus on key issues centered on public land access rights and private property boundaries.

Ryan Semerad, the lawyer for the hunters, argued that they were within their rights under the Unlawful Enclosures Act, which prohibits private landowners from blocking access to public lands. In contrast, the lawyers for Elk Mountain Ranch argued that the hunters trespassed into his property’s airspace, thus diminishing the value of the private land. U.S. District Judge Scott Skavdahl previously ruled in favor of the hunters, stating that corner crossing without touching private land did not constitute trespass.

BHA and other conservation groups filed amicus briefs supporting the hunters, emphasizing the importance of maintaining public access to millions of acres of federal land and arguing that a ruling against corner crossing would effectively privatize public lands, limiting access to only those wealthy enough to own adjacent properties.

The oral arguments highlighted these points, with both sides presenting their cases on the legality and implications of corner crossing. The judges on the panel peppered both lawyers with a variety of deliberate questions that indicated an interest in the greater implications of this case. The decision of the 10th Circuit will have significant ramifications for public land access across the West.

We expect that the panel will issue a ruling on this case within three months, at which point BHA will be leading the charge on the next steps for this critical issue.

20 Years of BHA with Ben Long and Patrick Berry: Ben Long is a founding board member of BHA, the author of the Hunter and Angler’s Guide to Raising Hell and a lifelong hunter-conservationist of the old breed. Ben came to Rendezvous this year to meet with new BHA President and CEO Patrick Berry of Vermont and help chart a course for the future of the most dynamic hunter and angler conservation organization in history. Join us as Hal, Patrick and Ben look back at the origins of BHA – the people, the fire and the issues – and revel in the memories of where we’ve been and celebrate where we’re headed.

Peter Vandergrift has spent his entire career in the fly fishing industry. He cut his teeth guiding in the shadow of what would be the Pebble Mine and later guided and outfitted fly fishing in Montana and Wyoming for 18 years in total. He then worked at industry giants Simms Fishing Products and Costa. He is currently the Chief Marketing Officer of North Point Brands whose stable of brands include Cheeky Fishing, RepYourWater, RepYourWild, and Wingo Outdoors.

He lives in Missoula, Montana with his wife and two river-rat daughters. Peter is an avid bowhunter, chases upland birds with his black Lab and fishes every corner of the world he can access.

Robert was born and raised in southern Louisiana. It was during a two-month journey through the Rockies that he decided to make a career of conservation.

Robert moved to Montana in 2021 and hasn’t looked back. Splitting his time between hunting and fishing and conservation work, he feels incredibly lucky to spend most of his time in the wilds of the western U.S. As someone who has seen firsthand the impacts of poor access to and poor management of public lands, Robert is passionate about helping achieve the BHA mission.

Bard’s passion for the outdoors was instilled in him at a young age hunting the woods of Alabama. He took this passion to the University of Tennessee where he studied wildlife management and went on to work in multiple biological technician jobs. He has monitored satin bowerbirds in Australia, taught fish farming in Zambia and searched for duck nests in the praire potholes of North Dakota.

Bard is also an award winning and internationally touring singer-songwriter living in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He spends countless hours on public lands scouting and hunting solo or with his teenage son.

A graduate of Pittsburg State University in Pittsburg, Kansas, Nadia Marji worked her way up through the ranks of Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks, holding positions ranging from Publications Writer II to serving as Kansas Wildlife and Parks Magazine’s first female executive editor. After 11 years with the department, Nadia hung up her KDWP hat as Chief of Public Affairs & Engagement Officer. Nadia joined BHA as Vice President of Marketing and Communications in May 2024, bringing with her 10-plus years of progressive strategic communications, public relations, marketing and leadership experience. She is a two-time national award winner in publications and communication campaigns and remains the only Kansan to have ever achieved the internationally-recognized Communication Management Professional certification. Nadia resides in Bonner Springs, Kansas with her English bulldog, Louie.

Harrison carries on his family’s passion for the outdoors as a third generation Wisconsin hunter and angler. While attending the University of WisconsinStevens Point, Harrison was introduced to BHA and became the chair of his university’s collegiate club. The organization and the events that he attended had such impact on his life that he now finds himself living in Montana, striving to host events that inspire North America’s conservationists the same way he was inspired.

BENTONVILLE, ARKANSAS

Arkansas Chapter Chair

In 2017, I was vacationing with my family around Lake City, Colorado, and my boys asked me what all these “National Forest” signs meant. I gave them a vague answer about “public land” but I didn’t really know, and being the inquisitive minds that they are, they pressed for more. Together we looked into it. We had been recreating on public lands for most of our vacation and had no idea how or why we were allowed to be there. Later on, when I heard about efforts to divest of federal public lands, I was appalled – I had just figured out what they were, and I had so much to explore! BHA appeared on my radar, and I signed up right away. Since then, I have learned that I am part of a scrappy group of likeminded individuals who value the freedom and equality we can all find on our shared public lands and waters!

YOU WERE RECENTLY THE RECIPIENT OF BHA’S MIKE BEAGLE-CHAIRMAN’S AWARD FOR YOUR OUTSTANDING EFFORTS AS CHAIR OF THE ARKANSAS CHAPTER. FROM PROTECTING PUBLIC ACCESS AT PLACES LIKE PINETREE RESEARCH STATION TO HOSTING HUGE EVENTS LIKE THE BLACK BEAR BONANZA, YOU’RE CLEARLY DRIVEN AND DEDICATED TO BHA AND THE ORGANIZATION’S CAUSES. WHAT’S DRIVING YOU?

Protecting access to our shared resources is what I want to do. That takes on many forms. Some people are like me and my family in 2017, who didn’t even know what we had, and we need to help raise awareness about these wild places so that they remain highly valued for the experiences they can give us, just the way they are. Other people are all too aware of how precious their access is and aware of the threats to that access, and it is important to me to speak up for those people who otherwise wouldn’t. But what keeps me going is the belief that right now it is simply our turn to stand up and protect these places, and when our time passes, we should leave them better than we found them.

WHAT’S ONE ISSUE BHA IS CURRENTLY WORKING ON THAT YOU’RE PARTICULARLY PASSIONATE ABOUT? AND WHAT DO YOU SEE AS BHA’S ROLE IN ACHIEVING A POSITIVE OUTCOME?

The thing I am most concerned about right now are the attacks on our hunting and fishing heritage, especially the ones coming from inside the tent. It’s one thing to rally ourselves against a threat from outside of our ranks – like the stacking of the game commission in Washington, which the Washington chapter is fighting so valiantly. But it’s also a big concern when decision makers we think of as traditionally “for” hunting and fishing try to undermine the scientific management of our natural resources or diminish the authority of the agencies we trust to manage those resources – like what Kentucky just went through. To be successful, we need to remain vigilant, build our alliances in advance and stay engaged in the process. We must continually tell our story, or somebody else will try to tell it for us.

WHAT DO YOU LIKE TO DO IN YOUR FREE TIME ON PUBLIC LANDS AND WATERS?

I love to explore them with a rod, a bow or a gun in my hand whenever I can. I’ll never be so zealous about any one species to forsake all the others, so I’m a generalist hunter and angler at heart, and I’m always looking for the next adventure.

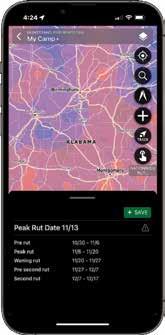

WHITETAIL RUT MAP Unlock the most extensive Rut Map in the country

WHITETAIL ACTIVITY FORECAST Plan your hunt around peak movement times

Join millions of hunters who use HuntStand to view property lines, find public hunting land, and manage their hunting property. Enjoy a powerful collection of maps and tools — including nationwide rut dates and a 7-day whitetail activity forecast with peak deer movement times.

WHITETAIL

Download and map for FREE!

BHA’s Backcountry Bounty is a celebration not of antler size but of BHA’s values: wild places, hard work, fair chase and wild-harvested food. Send your submissions to williams@backcountryhunters.org or share your photos with us by using #backcountryhuntersandanglers on social media! Emailed bounty submissions may also appear on social media.

BY MILLIE HIBBS

Find:

1. A cricket

2. A fossil

3. Pick up five pieces of trash from public lands.

4. A bald eagle

5. A blue native wildflower

6. A frog

7. A pinecone

8. A native grass

9. A cloud that looks like an animal

10. Identify a wild mushroom (with adult supervision).

11. Wildflower seeds

12. A wasp (stay clear of its backside!)

13. A piece of flint

14. A spiderweb in the outdoors

15. A nocturnal animal

Listen:

1. Listen and identify three nighttime sounds.

2. Close your eyes on a windy day and listen to the wind for three minutes.

Enjoy:

1. Wading through a stream or river (with adult supervision)

2. Rubbing your hands through moss

3. A beautiful sunset

Millie Hibbs is the 10-year-old daughter of BHA Chapter Coordinator Jameson Hibbs. Residing in Kentucky, Millie loves camping, fishing, wading through streams, collecting rocks, singing, collecting flowers, adventuring and snacking!

BHA’s Kentucky chapter successfully fights an effort to place wildlife department under the Department of Agriculture, learning valuable lessons and gaining strong partnerships along the way.

BY COL. MIKE ABELL

Science-based management of wildlife is one of the tenets of the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation – which has a long history of success. However, across North America this tenet is increasingly under threat. This year, Kentucky Senate Bill 3 became a lightning rod in the thunderstorm of attacks against our outdoor heritage and the science-based management of public lands, waters and wildlife. The bill would have moved the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources under the direct control of the Kentucky Department of Agriculture and would have given appointment authority of all nine Fish and Wildlife Commissioners to the Commissioner of Agriculture.The danger in this cannot be overstated.

Agriculture science generally seeks to reduce wildlife in order to increase farmers’ yield with no regard for proper wildlife and fisheries management. The Kentucky Farm Bureau, “The voice of Kentucky Agriculture,” lists the following as a state priority: “Seek effective wildlife management that will reduce wildlife populations in an effort to alleviate continued crop and livestock losses.”

It could only take one full seating of fish and wildlife commissioners appointed by the Kentucky Commissioner of Agriculture to extend season dates, expand bag limits and liberalize methods of take to reduce wildlife populations to unacceptable levels.

In opposition testimony on SB3, Sen. Robin Webb (D-KY), chair of the Kentucky Sportsmen’s Caucus, said, “This bill will set us back 40 years and make us the laughingstock of North America.”

The tactics being used to push this type of legislation through are equally as terrible and undemocratic as the actual bill. It was published in the afternoon on the very last day that a senator could legally sponsor a bill, giving us the least amount of time possible to take action before the end of the session.

Unfortunately, over the last five years the KDFWR has become a political pawn in a surreal game of partisan chess. The super majority in the legislature continues to try to reduce the power of the governor, and every year that has included changes to the management and authority of the KDFWR and the appointment authority of our fish and wildlife commissioners.

The critical role that powerful and nimble grassroots organizations like BHA can play – and the coalitions our members can form – becomes fully evident in moments like these. The Kentucky chapter of BHA rallied with our partners to form a coalition to beat this year’s exigent threat.

We beat SB 3 through our grassroots advocacy. It was rumored that because we beat down the bill, the senate would not confirm any of the five fish and wildlife commissioners appointed by the governor. We rallied the troops once again, and on the very last day of the session, the senate confirmed four of the five governor’s appointments to the commission.

ORGANIZATIONS LIKE BHA CAN PLAY – AND THE COALITIONS OUR MEMBERS CAN FORM – BECOMES FULLY EVIDENT IN MOMENTS LIKE THESE.

The Kentucky chapter gained valuable knowledge and experience throughout this fight – which it and other BHA chapters and partners can lean on as we continue to confront these battles against the North American Model we hold so dear.

BHA’s 2021 Rendezvous featured a panel led by John Gale and Gaspar Perricone about building coalitions to fight the forces that seek to separate us from our public lands, waters and wildlife. Kentucky chapter leaders were present, we learned from their hard-earned lessons and went back to the Commonwealth and started working.

The coalition that beat SB3 this year included Backcountry Hunters & Anglers, Safari Club International, Sportsmen’s Alliance, the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation, the American Sportfishing Association, BASS Conservation, the Boone and Crocket Club, Delta Waterfowl, the National Wild Turkey Federation, the League of Kentucky Sportsmen, the National Deer Association, Pheasants Forever, Quail Forever, the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, the Ruffed Grouse Society, the American Woodcock Society, Trout Unlimited and associated state/local chapters. That kind of network – that kind of coalition – did not happen overnight; the effort started in 2021, so this year’s victory was four years in the making.

Here are the lessons learned:

• Lobbyists are invaluable. We cannot afford one alone. We partner with other groups, and we share our lobbyist with a medical association. The main bill payer in Kentucky is Kentuckiana Safari Club.

• Relationships are everything. You can build them at Rendezvous, in a duck blind, deer camp or at the capital. Great relationships become partnerships.

• Working on legislation, partnership building, and direct lobbying is year-round work. Form a small team who are not only good at it but enjoy it, because it can be exhausting. These are the 5% of leaders in our community who can move the 95%.

• The rest of the chapter leaders and the membership-atlarge should prepare for legislative season the way they prepare for hunting season. It is not a year-round process for them, but they must be ready when the opportunities arise.

• Partnerships must be maintained. It can be as simple as monthly emails, texts and calls to the leaders in the community. But real partners attend each other’s events and work together year-round.

• Real partners agree to disagree quietly and not in public.

• Historical leaders, past presidents and past commissioners are invaluable and should be cultivated as partners. They have wisdom and connections that can move mountains.

• Partners must play to their strengths. Our best partner is Kentuckiana Safari Club. They have more money; we have more members. We can do things they cannot and vice versa.

• Send your legislators and your commissioners copies of your blog posts about chapter activities, especially when the event is in their district. Invite them to everything.

• It is almost more important to thank legislators for their positive actions than it is to point out their shortfalls.

• To start winning and quit defending, we must connect election season with legislative season. A legislator who did good things for us during the legislative season might return to their home district and see a billboard that says, “Thank you, Senator Smith, for standing up for public lands.” The opposite is also true. When they see us taking actions that directly affect their ability to be reelected, we start winning. Sometimes, maybe it is a partner who does this instead of a BHA chapter. It is still teamwork that wins.

If you don’t know where to start, find another chapter to mentor you. We looked to the Pennsylvania chapter of BHA as an example. Their advice and counsel were instrumental in our success. I assure you that someone on our continent-wide BHA team has already solved your problem – seek them out. When you find them, you will have the advice and counsel you need to win.

After the legislative session ended, I sat down and authored dozens of emails to the senators and representatives who helped us defeat SB3.

This response from Senator Higdon sums it up: “Thanks, Mike. You can credit your members that live in my district for their passion and persistence. Perfect example of participating in the process.”

Col. (retired) Mike Abell spent most of his adult life as a U.S. Army Infantryman. He now spends his time hunting, fishing and fighting for our public lands, waters and wildlife as a BHA chapter leader and life member in Kentucky.

BHA’s Kansas chapter adapts on the fly and calls on grassroots membership to stand up for the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation against an onslaught of bad bills.

BY KURT RATZLAFF

As crazy as it sounds, deer drool on corn spewed from feeders essentially caused all of the legislative issues faced by the Kansas BHA chapter during the 2024 session.

It started when the Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks held a listening session for the Kansas Wildlife and Parks Commission to determine whether they should explore the possibility of banning the baiting of deer to slow the spread of Chronic Wasting Disease, among other reasons. A couple of the commissioners seemed to have already decided in favor of the ban, and that panicked some hunting businesses who rely on baiting deer with corn. Internet rumors and conspiracies followed.

Apparently, some political favors were called in, and every reference to the discussion of deer baiting disappeared from the KDWP website overnight and has never been seen or heard of again. Not satisfied, when the Kansas legislative session began a few weeks later, a slew of bills were immediately introduced by politicians associated with the business side of hunting. Attempts were being made to abolish the Kansas Wildlife and Parks Commission and replace it with a new commission filled with people interested in privatizing wildlife.

Additional bills were pushing different versions of transferable deer tags, which are a familiar way to privatize or commoditize wildlife. Kansas has a history of transferable tags and a couple of episodes of the Kansas BHA Podcast have been dedicated to the topic. Episode 83, “Why Landowner Transferable Big Game Tags are Bad,” featured the Montana chapter’s Thomas Baumeister describing his experiences in Europe with that hunting system, and Mike Miller, a now-retired KDWP assistant secretary. Miller was on a committee in the early 2000s that reestablished a science-based tag system to replace the transferable tag system that Kansas had at the time. That new system helped make Kansas a destination for

deer hunters from around the globe.

The two bills that set out to “reconfigure” the Kansas Wildlife and Parks Commission were initially characterized as actions taken to avoid the problems seen in wildlife commissions in Colorado and Washington. But clearly, they were attempts to replace the current commission members with new ones. The hearings on those two bills always included more arguments against banning baiting than banning anti-hunters.

Early in the session, the chapter was not prepared for how quickly the hearings were set. We thought legislative committees would value public input and set hearings accordingly. But that was not the case. Those who are politically powerful can and did set hearings with little or no notice and openly sought to suspend rules requiring public input.

In response, the Kansas BHA chapter became quicker and nimbler. With the help of BHA staff, we were able to have action alerts ready at a moment’s notice. Board members developed relationships with their respective state representatives and senators. We used our podcast to get the word out to our members. And we sent out chapter-wide emails with updates on the legislation.

In the legislature, we gave personal testimony concerning the effect of the bills on our way of life and the public’s wildlife; we provided written testimony when none of our members could attend hearings.

The two transferable deer tag bills died in the first half of the session. But the two similar bills seeking to “reconfigure” the Kansas Wildlife and Parks Commission remained stubbornly in play.

We partnered with another organization to offer a written amendment that would establish criteria for commission appointees to meet. The amendment would have addressed the issues present on the commissions in Colorado and Washington. But the amendment went nowhere, proving this effort was not aimed at anti-hunters. This was a group of people and organizations attempting to control

the commission for the purpose of privatizing wildlife.

A point our chapter expressed throughout the process was that the commission had, in fact, acted in a responsible manner and was performing actions in line with the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation.

Eventually, the two commission bills were consolidated into one. Time passed. It appeared the bill was dead. Then a shell game called “gut and go” was utilized to bring the bill back to life. We would eventually learn that a deal had been cut between key representatives and the governor. A different commissioner nominating scheme was to be put in place. In a nod to the concerns raised by the Kansas BHA chapter, our conservation partners, and resident hunters and anglers across Kansas, the final bill included language that “in no case shall a controlled shooting licensee or any employee of such licensee, or any person providing hunting outfitting services or hunting guide services, be appointed to the commission.” We requested different and more enforceable language, but the deal had been cut. The governor had agreed to sign the bill when it reached her.

While the bill had become more tolerable with the changes that had been made, the replacement of the commissioners remained a sticking point since it implied they had done something wrong, which was not the case. Our final chance was to defeat the bill in the legislature, preventing it from reaching the governor. We made more calls, we sent more emails.

Two days were left in the session when the Kansas Senate took

up the bill. Watching on YouTube, you cannot hear the votes being cast, but it felt like it was going to be close. The announced vote was a passed bill: 20-19. One senator, for some reason, then changed her vote to officially make it 21-18. The house passed it overwhelmingly. The bill has now been signed by the governor.

Our future with the effects of this bill remains a mystery. One thing we can count on is the interests who pushed this bill will continue their attacks. They will not care about the impacts to the public’s wildlife or the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation. They are businesses looking to profit off the public’s resources. And while America is the land of capitalism, that principle is not the guiding principle of American wildlife management.

To make us more effective in the future, Kansas BHA is banding together Kansas resident hunters, anglers, trappers and houndsmen to create a stronger legislative voice with the goal of providing access to quality hunting and fishing for all Kansans, regardless of means. Our group will be conducting outreach meetings with legislators over the summer and fall to help them gain a better understanding of the issues we face and the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation. We believe a better-informed legislature will better protect the outdoor heritage we all find so integral to this great nation.

BHA member Kurt Ratzlaff is an avid hunter, retired attorney and connoisseur of cheap bourbon. He is currently the legislative chair of the Kansas chapter of BHA.

BHA chapters across North America are on the frontlines, battling attacks against the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation and getting their hands dirty cleaning up public lands and waters.

• The Alaska chapter is a partner in the Alaska Copper Ammo Challenge, which aims to educate hunters about how they can reduce the occurrence of lead poisoning in wildlife by voluntarily using non-lead ammunition. The challenge has been offering Alaska hunters a rebate of up to $80 off two boxes of copper rifle ammunition.

• The chapter is holding its first annual board retreat on Kodiak Island centered around the Buskin Lake Crawfish Removal event October 16, 2024.

• The chapter has been engaging on Federal Subsistence Board wildlife proposals and special actions across the state.

• At the chapter’s first Fishing for Conservation event, attendees planted trees on the riverbank to help with erosion control at Dead Horse State Park and then enjoyed an “Intro to Fishing” overview.

• The chapter closely tracked numerous conservation bills this legislative session and had board and general member presence in multiple committee hearings in addition to distributing several action alerts.

• The chapter hosted a MeatEater Trivia Pint Night in Tempe and welcomed several new members!

• A very successful 2nd Annual Catfish Camp was held at Lake Dardanelle.

• Our work continues to identify and create access to landlocked public parcels in Arkansas, in partnership with onX and the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission.

• The chapter hosted a cleanup and OHV sign day at Dale Bumpers National White River Refuge.

• The chapter held an After Work Fish and Paddle event at Pinnacle Mountain State Park, in partnership with AGFC.

• AFI identified its priority landscapes for 2024: prairie ecosystems in Montana, the Dakotas, and northeast Wyoming.

• AFI is hosting three events focused on antelope, mule deer and various

upland species throughout September and October this year. Visit our events page for more details.

• AFI’s Memorial Day membership drive was held with a kickoff party at the First Lite headquarters with the MeatEater crew.

• AFI continues to host virtual skills classes. These are the same classes we use at our in-person events. These recordings are live on YouTube.

• The chapter became a member of the Kootenay Fishing Regulation Advisory Team, advising officials on angling regulations, fair catch and accessibility.

• Leadership was in Victoria for Provincial Hunting and Trapping Advisory Team meetings regarding regulation proposals and changes, advocating for science-based decision making.

• Members volunteered countless hours representing the chapter at trade shows across the province, successfully recruiting dozens of new members.

• The California chapter celebrated the expansions of the San Gabriel and Berryessa Snow Mountain national monuments with a spring turkey camp, which was held a few miles away from the expanded acreage of Berryessa on a ridge known as Molok Luyuk.

• The chapter has been working to garner support for restoring hunting access to the Castle Mountains National Monument. This work has paid off, with Senator Pedilla introducing the Mojave National Preserve Boundary Adjustment Act, a bill to adjust the boundary of the Mojave National Preserve to include the land within the Castle Mountains National Monument. This legislation would reauthorize hunting access to the Castle Mountains while maintaining all resource and wildlife conservation protections.

• The chapter is also celebrating the recent release of the California Department of Fish & Wildlife’s Black Bear Conservation Plan for California. In 2022, the chapter helped fund a portion of the population study to help CDFW update this plan. The newly released plan utilizes additional population estimate metrics that show the number of black bears in California to be between 50,000-80,000 bears, a significant increase from previous estimates.

• Boulder Country Assistant Regional Director Kris Hess wrote an oped, “County Closure of Sugarloaf to Hunting Harms Hunters,” for the April 28 edition of the Daily Camera.

• The Department of the Interior decision to finalize a 20-year administrative mineral withdrawal for approximately 220,000 acres of the Thompson Divide was praised by the Colorado chapter.

• The chapter supports the Dolores River Canyons National Monument proposal.

• Elliot Silbar was elected as chapter treasurer.

• The chapter hosted a Hunting 101 event at Captain Kenny’s in Jupiter in May.

• The chapter hosted a deer scouting educational event at Riverbend Park in Jupiter in June.

GEORGIA

• The Georgia chapter held a Talking Turkey hunting seminar at Sweetwater Creek State Park. We introduced new hunters to turkey hunting, which included how to use a turkey call, processing a turkey and also some wild turkey recipes.

• The chapter has been raising awareness on the potential mining of the Okefenokee Swamp.

• University of Idaho Club President Jacob Young was awarded the Rachel L. Carson Award this year at Rendezvous. This award is intended to acknowledge a young leader who goes above and beyond in their contributions to the conservation, hunting or angling communities.

• The University of Idaho Club coordinated a successful planting project at Craig Mountain Wildlife Management Area.

• The Idaho chapter will continue to hold and support projects throughout the summer. Reach out to a chapter leader for more information.

• 98% of Illinois streams remain inaccessible to the public. Illinois state law contradicts federal law meaning private landowners along the rivers own the moving water and the river bed. Since 2019, the Illinois chapter has and will continue to work to clear muddy Illinois law. Residents, get involved! Tell your legislators and the ILDNR it’s beyond time to clear Illinois stream access.

• Lake Shelbyville Archery Park is near completion. The chapter would like to thank our partners at USACE for the opportunity!

• We had a great turnout at the Wabashiki Fish & Wildlife Area grassroots workday where, in collaboration with the Indiana State University Collegiate Club and Indiana Pheasants Forever and Quail Forever, we built wood duck boxes and removed invasive plants and shrubs. This event was sponsored by a BHA Public Land Owner grant for collegiate chapters.

• We hosted a well-attended pint night at Afterburner Brewing Co. following the Wabashiki event.

• Three chapter board members represented BHA at the Sportsmen’s Luncheon at the Indiana Statehouse where they met with legislators to share BHA’s mission and discuss public lands and conservation concerns.

• The chapter board authored a letter to the editor that was published in regional newspapers, and we continue efforts to educate Hoosiers on the importance of science-based forest management.

• The chapter hosted a booth at the Iowa Deer Classic alongside BHA partner River Brothers Outfitters, where we promoted public lands, recruited new members and held a raffle.

• Board members attended the first Midwest-based BHA North American Rendezvous, where they got the opportunity to learn new innovative ideas from other chapter leaders.

• The chapter is in the process of promoting an auction for a 2024 Iowa Governor’s deer tag.

• In March, Kansas BHA members cleared hiking trails and cedar trees at the Flint Hills Nature Trail near Emporia; cleared brush at the DeSoto Wildlife Area; returned to the Chase State Fishing Lake for a trail and brush cleanup day; and held a BHA sporting clay event at Powder Creek in Lenexa where 16 shooters joined or renewed memberships.

• In April, the chapter held its first Conservation Coffee at Great Blue Heron Outdoors in Lawrence where Ned Kehde provided a history of the fishing industry in Kansas.

• Also in April, Kansas BHA hosted a sporting clay shoot at Michael Murphy and Sons Sporting Clays near Wichita.

• In February, the chapter placed the wood duck boxes we built last year at Harris-Dickerson Wildlife Management Area and also installed goose-nesting platforms at Peabody Wildlife Management Area.

• In February and March, we held two more Conservation Coffee series in Lexington with speakers including Kentucky Afield, the 6th District commissioner, conservation officers, Bluegrass Trout Unlimited, NWTF’s Double Eagle Chapter, a state senator, Canoe Kentucky and a trout fishing guide.

• In March, we went to Country Boy Brewing twice for our monthly pint nights, once for a fundraiser and again to host a turkey talk. AFI held their first-ever Fort Knox pint night. The chapter held a virtual elk talk with Kentucky Fish & Wildlife.

• In April, the chapter DEFEATED Kentucky Senate Bill 3, which would have made Kentucky Fish & Wildlife the first state fish and wildlife agency put directly under a Department of Agriculture.

• The chapter also held a virtual pre-season turkey talk and tabled at an Earth Day celebration in Winchester.

• The chapter hosted a meet and greet for new BHA President & CEO Patrick Berry at Founders Brewing in Grand Rapids.

• The chapter hosted the Grand Rapids Full Draw Film Tour on July 13.

• The chapter is looking forward to another great weekend at our 2024 Rendezvous, July 26-28.

• The chapter added Delaware to the region at the beginning of 2024; this addition included adding Patrick McMaster to the board as representation.

• To be more representative of the chapter’s footprint, the “Capital Chapter” was renamed to the Mid-Atlantic Chapter, which now includes Virginia, Maryland, Washington D.C. and Delaware.

• Events, outreach and access issues continue throughout the region. A kickoff pint night occurred in Delaware to welcome the state to the chapter. Events and networking continues with a workday scheduled at Brandywine State Park to erect new deer stands for hunters this fall.

• The chapter hosted BHA members from around the country for a chapter leader wild game potluck and a welcome party at Unmapped Brewing to kick off Rendezvous 2024.

• The chapter partnered with the U.S. Forest Service in Ely to train new sawyers and instructors for future stewardship projects on federal forest lands.

• In May, the chapter mentored 11 new hunters in a Learn to Hunt Turkey workshop in Southeastern Minnesota.

• The Missouri chapter is hosting the Full Draw Film Tour on August 10. Great films, great prizes and a great time! Get your tickets at fulldrawfilmtour.com before they sell out!

• Stop by Dive Bomb Industries Squadfest July 19 -20 in St. Louis for your chance to win a shotgun and other great prizes from the chapter. Squadfest is a free admission waterfowling event for the entire family!

• Want to see chapter events in your area? Contact Missouri@backcountryhunters.org to learn about volunteer opportunities!

• The Montana chapter raised a record amount for mule deer conservation and solidified a more equitable raffle approach as an alternative to an auction for the statewide mule deer tag.

• The chapter welcomed four new board members: Micah, Luke, John and Manning.

• The chapter supported a 17,000-acre public lands acquisition near Missoula and a 32,981-acre conservation easement in northwest Montana; discouraged the USFWS from developing waterfowl production areas; celebrated the introduction of the bipartisan Public Lands in Public Hands Act; advocated for quiet recreation, large-landscape conservation and wild lands and waters in the Lolo National Forest Plan Revision.

• The chapter has scheduled at least seven summer stewardship projects; please join us!

• The chapter continues to engage on policy issues related to energy development, public land transfers and wildlife management at various levels of government.

• The chapter is collaborating with the California chapter and other organizations to support several stewardship projects for habitat restoration across the Great Basin.

• The chapter also partnered with the California chapter to exhibit at the National Outdoor Recreation Conference, ensuring that hunters and anglers are included in recreation conversations across the U.S.

• Recent workdays have taken place around the region, including fence removal in Maine and a cleanup at Dead Creek Wildlife Management Area in Vermont.

• Connecticut members gathered for a workshop about foraging for edibles among local plants, including invasives.

• Vermont members across the state successfully raised their voices throughout the legislative session to help fight off a bill that would have radically and negatively altered how hunting, fishing and trapping are managed in the state.

• The New Jersey chapter held a trivia night in mid-June. The contest was open to current and prospective members.

• Chapter board member John Provenzale donated a custom-made sinew-backed osage longbow to the 2024 Rendezvous Online Auction. The winning bidder received a one-of-a-kind 64-inch longbow with a draw weight tailored to his or her own specifications.

• The chapter and Kirtland Air Force Base AFI volunteers joined Forest Service staff from the Lincoln National Forest to construct two beaver dam analogs in Bonito Creek in southern New Mexico to improve habitat for future native cutthroat trout reintroduction.

• For the fourth consecutive year, the chapter improved habitat permeability for pronghorn on the Kiowa National Grasslands by modifying and verifying the height of 16.8 miles of fence and completing 0.42 miles of exclosure work, which improved 6,412 acres of shortgrass prairie habitat. Less than 10 miles of interior fencing in New Mexico

remain to be modified!

• Life member and board member Mark Mattaini was appointed by the New Mexico Game Commission to a five-year term on the Habitat Stamp Citizens’ Advisory Committee.

• We partnered with Santa Fe Ducks Unlimited for a Rio Grande River cleanup near Algodones.

• Chapter volunteers gathered to help clean up Three Rivers Wildlife Management Area as part of a stewardship agreement we have with the Department of Environmental Conservation for the property. The crew of volunteers removed close to 50 bags of trash, a big screen TV and a toilet.

• The chapter collaborated with New York City Trout Unlimited and New York Hunters of Color for the Amawalk/Muscoot River Arbor Day tree planting. Over 50 trees were planted on the banks of the Muscoot River to help prevent erosion.

• The chapter was at the Western New York Sport Expo in Hamburg selling BHA merch, talking hunting and fishing and telling folks about BHA’s mission to protect our public lands and waters.

• Chapter members recently served venison smash burgers in Winston-Salem at a successful event to invite folks to try wild game, recruit new members and discuss conservation issues in the state.

• Chapter leaders are talking with members and other conservation-minded folks across the state about top wildlife and public lands issues to prioritize the rest of this year and beyond.

• The chapter will hold its second annual Conservation Banquet, to be held Aug. 17 in Charlotte.

• The chapter hosted volunteer workdays on the Sheyenne National Grasslands and Pipestem Reservoir to upgrade public facilities, pick up trash, replace signage and improve habitat.

• The chapter started the North Dakota BHA Podcast and released three episodes with special guests Hal Herring and Randy Newberg.

• Chapter leaders attended BHA’s North American Rendezvous and participated in chapter leader training.

• In March, several chapter leaders and members traveled to Bentonville, Arkansas, to partner with the Arkansas chapter to host the 3rd Annual Black Bear Bonanza. Attendance was over 1,200 people from numerous states and even Canada!

• The Oklahoma chapter hosted the International Fly Fishing Film Festival at Circle Cinema in Tulsa on March 14.

• Members of the Oklahoma chapter placed third in the Wild Game Cook-Off at the North American Rendezvous! Watch out next year!

• The Oklahoma chapter once again partnered with Quail Forever on a habitat project at Osage Rock Creek Wildlife Management Area on June 8.

• The Oregon chapter held a great event in April – their second Cut and Cook event. With a group of 50-plus, they broke down turkeys and managed to cook up some incredible table fare to share with eager participants.

• The Oregon chapter has prioritized the right to hunt and fish in its current legislation process. With the Oregon Prohibit the Injury or Killing of Animals Initiative still in play, they are working diligently in opposition across the state.

• Chapter board member Samantha Lutz has organized a series of stream restoration projects in partnership with the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

• The chapter has completed the first two installments of a three-part fly fishing course supported by a team of board members, volunteers and R3 grant funding through the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission.

• Chapter Chair Adam Eckley testified before the Pennsylvania House of Representatives Game and Fisheries Committee on April 9 in support of legislation that permits Sunday hunting.

• The chapter held a 3D archery shoot on July 13 at the Archery & Bow Club.

• The chapter is currently seeking to fill a few spots on the board to further broaden the reach within our state. Any interested people can reach out to southcarolina@backcountryhunters.org

• The chapter will continue to monitor potential changes to our turkey season regulations that could be implemented as soon as 2025, as well as a bill that could extend deer season in two of our game zones.

• The chapter will be hosting a few pint nights throughout the state later in the year. Keep up to date on new events via our social media.

• The chapter submitted a letter in opposition to the Final Environmental Assessment and Draft Decision Notice for the proposed Golden Crest Exploration Drilling Project.

• The chapter hosted a pint night tour across the state, bringing together members in Rapid City, Pierre and Sioux Falls.

• The chapter added six new members to our board. Welcome Trevor, Chris, Derek, Kevin, Tyler and Andrew!

• The Southeast chapter has teamed up with the Alabama Riverkeepers to generate support for the SHOR Act, a bill to strengthen protection of anglers’ right to know about fish consumption advisories. If you are an Alabama voter, please take a serious look at this act and express your support.

• Louisiana members need to be aware of a few changes to the 20242025 regulations, including LWCF’s notice of intent to conduct a Louisiana resident-only lottery for a black bear hunting season in Dec. 2024 and a ban on the use of drones for wounded-game recovery.

• The Southeast chapter continues to seek leaders for local, regional, state and chapter-wide roles. If you are interested in a leadership position or just want to get more involved, let us know!

• The Tennessee chapter sponsored an archery shoot at the Old Hickory Lake Bowman’s Club. This event strengthened bonds with the mid-state archery community as well as introduced shooters to BHA’s unique role in protecting Tennessee’s public lands and waters.

• The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Nashville District had a comment period last fall regarding the water control manual for Center Hill Lake Dam. The Caney Fork River flows out of the dam and was insufficiently managed to maintain enough dissolved oxygen to support the world class trout fishery. The chapter leveraged its member base to comment for the option that provided a constant flow of 250 cubic feet per second, which will support the fishery. We had many conservation partners in this effort as well.In late April, the USACE announced it was going with this option.

• Legislation was introduced in Tennessee that would allow baiting for hunting this year. BHA and our partners lobbied against this proposed legislation, and it was defeated.

• The fight continues to Save The Cutoff, with the Texas chapter supporting the group in their fight to preserve public access in east Texas.

• This spring, Texas BHA held a cleanup at Grapevine Lake, where volunteers worked with the USACE to pack out a full dump trailer of garbage from the local hunting area.

• The chapter recently held a Talking Turkey event with Chef Jesse Griffiths at Yeti in Austin.

• To engage and educate the community on conservation, the chapter hosted a MeatEater Trivia Pint Night, International Fly Fishing Film Festival, and participated in the Wasatch Fly Tying Expo.

• The chapter launched a Hunting for Sustainability initiative and conducted phragmite mitigation in Farmington Bay to support habitat health and sustainability.

• The chapter continues to work with its Conservation Coalition to identify areas of opportunity in the state legislative session. Currently, a lot of the attention is still falling on the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Commission as it has recently added new members to the governing body.

• The chapter looks forward to an eventful spring and summer starting off with their annual Methow Valley fence removal and annual archery shoot in Belfair.

• In March, the West Virginia chapter held its annual trash and trout cleanup on Dunloup Creek. With a great turnout, volunteers joined in to pick up trash along the creek and enjoy some good trout fishing.

• In May, the chapter assisted the Greenbrier River Fly Fishing Classic with their youth day for the West Virginia Children’s Home Society.

• In June, the chapter participated in the Appalachian Fly Fishing Festival and conducted some habitat work in the Snake Hill Wildlife Management Area.

• The chapter will also be hosting a round table via Teams with other sportsmen’s groups to discuss a sportsmen conservation day at the state capitol later this year.

• The Wisconsin chapter responded to recent criticism of the R3 movement by hosting not just one but two Learn To Hunt Turkey events in April – inspiring 14 new public lands and conservation advocates.

• Following the trail blazed by the Arkansas chapter, Wisconsin is kicking off a project to expand public hunting access with a specific focus on landlocked public land.

• Chapter members participated in Wisconsin Conservation Congress and Deer Advisory Council meetings to provide public input and tangibly shape local conservation policy.

• The Wyoming chapter helped defeat the proposed Columbus Peak Ranch Land Exchange after a three-year fight to prevent the swap of state-owned mountain-front acreage for a sagebrush prairie lot.

• The chapter partnered with the MeatEater Auction House of Oddities to raise over $75,000 for the Corner Crossing Legal Fund. These funds will primarily go towards the legal battle that is currently at the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver.

Find a more detailed writeup of your chapter’s news along with events and updates by regularly visiting www.backcountryhunters.org/chapters or contacting them at [your state/province/territory/region]@backcountryhunters.org (e.g. newengland@backcountryhunters.org).

BY PAUL LASK

We were stepping over and around charred deadfall in the foothill country of Glacier and Lookout mountains in Oregon’s Malheur National Forest. The mountains are the headwaters of creeks where bull trout, coveted among the angling community and federally listed as a threatened species, traditionally spawn.

The North Fork Malheur Basin is Oregon’s highest conservation priority area for the Endangered Species Act-listed bull trout. It’s thought to be home to bull trout that exhibit both resident and migratory life history strategies. Residents live in the North Fork’s cold, clear tributaries and migratory adults in the main river and Beulah Reservoir before voyaging to tributaries to spawn in autumn.

The North Fork Malheur has not been invaded by brook trout, a species that readily hybridizes with and out-competes native bull trout in many of Oregon’s watersheds.

Down here in the bottomlands, Swamp Creek was more of a stream. Unbanked, it braided the squishy ground and early seral greenery dotted with mule deer and Rocky Mountain elk scat. When the Cow Fire of 2019 and Black Butte Fire of 2021 ripped through here, they did what wildfires do, torching trees that toppled into the creeks and made their channels unstable. The loosened sediment that dumped into the water also threw off water temperature rhythms; the overload of soil nutrients heated the water, just one of the handful of threats that bull trout now faced.

The kind of country that rouses the spirits of the angling community and outdoors enthusiasts in general – pristine waterways winding through healthy wilderness – is what bull trout need for survival, summed up generally as the 4 Cs: cold, clean, complex, connected. It’s this mixture that arguably make bull trout “the poster fish for wild places in the Pacific Northwest,” according to Kirk Handley, a fish biologist with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Their habitat is currently being undermined by a warming climate, extended droughts, logging, grazing and pollutants. The young scientist I was helping was deploying an emerging scientific tool to try to maximize the likelihood that bull trout persist into the future in this quickly changing environment.

Ben Wiley is an Oregon State University graduate student who as an undergraduate was the first to detect an invasive crayfish in a tributary of the Tennessee River using eDNA. The “e” in eDNA stands for environmental. Organisms continually shed cells containing their DNA into a given environment. A scientist collects samples from the environment, returns the gathered water or soil to a laboratory to extract and analyze its DNA. Wiley’s creek water, for example, may start to tell the story, through the language of DNA particles, of which segments of habitat in the North Fork Malheur and its tributaries bull trout use the most.

Wiley lugged a thirty-plus pound briefcase housing a pump and filter to our various off-trail locales. Every 500 meters, he and I and an undergraduate from Texas A&M, Sam Scharck, would bushwhack to a waypoint along the creek. Once there, Scharck opened the briefcase and began assembling the pump. Wiley put on latex gloves and waded into the creek. He scooped water into a small cup attached to a hose that shimmied as it pumped water to its other end, a bucket marked with a line inside at five liters. Meanwhile, I took readings of the shade cover and water temperature.

Once the water hit the five-liter mark, Sam flipped off the pump, and Ben got a fresh pair of tweezers out of a plastic bag. He carefully removed the filter inside the cup and placed it in another bag with silica desiccant. We then assembled the top-setting wading rod, a long metal pole with wires attached to a battery-operated computer. With this we would read creek depth and speed, noted with pencil in a Rite in the Rain notebook.

Toss all this data into a pot, and you’ve begun assembling ingredients for your eDNA soup.

From a non-scientific perspective, I felt the three of us – with the clunky briefcase resembling 1950s spy gear, the staff-like

wading rod, the glass-domed shade reading tool in its cloth satchel – were in a vintage science fiction movie surveying a charred but potentially beautiful planet. The kicker was, our efforts were likely more scientifically efficient than traditional methods used to study the watershed.

One commonly practiced surveying method is electrofishing. The day before I joined Wiley, U.S. Forest Service and Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife biologists had dipped an electric wand into the water so as to temporarily stun and capture its inhabitants. According to Dr. Kellie Carim, a USFS research ecologist, electrofishing for a delicate species like bull trout can be “stressful by the bare fact that you’re handling organisms.” In contrast, eDNA collection requires little training for its practitioners, is highly efficient and can gather information it would take field scientists multiple seasons and crews to collect using traditional methods.

Another surveying technique is redd surveys. Biologists from the Burns Paiute Tribe and USFS have for decades completed trout spawning surveys by walking every inch of the sandy cobbly creeks looking for redds – depressions on creek floors scoured by the tails of female fish to lay eggs in.

While redd surveys are noninvasive, they are also laborious and only allow biologists to make “rough inferences about population size because they only estimate the number of adult spawning fish,” according to Wiley.

“We know that even if fish are present at extremely low abundance (think 1 or 2 fish in a 500-meter stretch of stream), eDNA analysis is very likely to detect those fish,” he told me.

This all relates to the issue of management.

Here in the Malheur National Forest – deemed the “Land of Many Uses” – cattle, whose grazing erodes stream banks, were currently compounding the habitat damage done by wildfires. I was surprised to see cow patties dotting the ground near these remote creeks.

If scientists “missed” trout counts with traditional methods, wrong inferences could be made; if bull trout weren’t detected, for example, decisions regarding grazing could be made that were not ideal for the protection of the fish.

Beyond aiding a fish significant to Pacific Northwest Tribes and the outdoors community, what we do for bull trout can proliferate into healthier habitats for riparian systems as a whole. Bull trout are both indicator and umbrella species. The former means they indicate “overall ecological integrity” of a watershed, according to Dr. Kathleen O’Malley, Wiley’s graduate advisor. And the protections in place for bull trout habitat act as an umbrella for many other species of flora and fauna.

eDNA’s accuracy, efficiency, low cost, and relatively easy fieldwork may lead to more robust datasets for management to make better decisions around these issues.

It’s the science that aligns with the thoughts of Taylor McCroskey, a Eastern Oregon chapter leader for BHA: “As bull trout populations in Oregon have continued to decline, the essential work to better understand habitat utilization, movement and overall population dynamics is imperative to protect these species into the future.”

We spent the day working our way up the creek using a faint hunting trail, which wove through the warm pine forest. Grouse thumped from their hiding spots. Deer appeared and vanished. Life was returning to the burn, and as we left the trail to make our way down to one of our last stations, Wiley pointed out a nice calm pool.

“Good bull trout habitat,” he said.

This was some ideal real estate. It was partially shaded, cool, riffling. When migratory bull trout make their annual spawning migration, they almost always return to the same tributary in which they hatched. This homing to their natal streams is accomplished with remarkable precision. And yet here in the Land of Many Uses, the question over how the land would be used, of whether bull trout were even being given the chance to make it up this far, was being posed.

It’s an issue that transcends species and landscape – does the modern world have room for apex predators like bull trout? Do we value wild places for their own sake?

Science is working to help answer the ecological aspects of such questions. Joined with the voices and votes of the people who love wilderness, we have a shot at giving future generations the gift of this culturally, ecologically and spiritually vital species.

BHA member Paul Lask is a freelance journalist specializing in the outdoors, environment and science. He teaches community college writing and literature.

BY CHARLIE BOOHER

Much of our National Wildlife Refuge System is crumbling around us. The landscapes encompassed by the system are changing rapidly, but our collective capacity to manage wildlife habitat, address visitor concerns, provide necessary infrastructure and enforce rules and regulations in these places continues to decline.

System-wide, the NWRS is down at least 800 classified staff from fiscal year 2010 to fiscal year 2024. Discretionary appropriations have remained largely the same since then, as well, and inflation has continued to rise. Between FY23 and FY24, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service budget decreased by 4%. It’s not unlikely that the NWRS budget decreases by another 4% in FY25. And without necessary funding, workplans can’t be executed, visitor centers will continue to close, invasive species will continue to spread, and the mission of the NWRS will suffer. There’s no doubt that efficiencies can be improved, which will solve some problems; however, it is equally clear that more funding is needed.

First established by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1903, the NWRS was constructed “to conserve, manage and restore fish, wildlife, plants and their habitats, as well as provide quality wildlife-dependent recreational opportunities that foster wildlife conservation for the enjoyment of future generations.” The USFWS, the agency charged with managing the NWRS, is the oldest federal bureau dedicated to wildlife research and conservation. Further, USFWS is the only agency in the federal government that is primarily responsible for the management of biological resources on behalf of the American public.

Today, the NWRS includes 571 refuge units, which cover more than 95 million land acres in all 50 states and receive in excess of 67 million annual visits. Nearly three million of those visits include hunting and more than 8.6 million include fishing. Most

metropolitan areas are within an hour’s drive of a national wildlife refuge, each of which provide outdoor recreation opportunities that range from fishing, hunting and boating to bird watching, photography and environmental education. According to the latest economic surveys, NWRS lands support 41,000 jobs and $3.2 billion of economic activity every year.

According to USFWS, the NWRS “network protects some of the country’s most iconic ecosystems and the fish and wildlife that rely on them: prairies of the heartland, teeming with native pollinators and bison; hardwood forests of the Southeast, a source of regional and cultural pride; desert Southwest landscapes, home to vibrant and rare plant communities that draw new life during the summer monsoon season. The refuge system also conserves waterways that give life to all of them – critical ecosystems along rivers, streams, wetlands, coasts and marine areas.”

However, without adequate funding and resource management planning, none of this can happen, and the results of chronic underfunding and understaffing are already evident.

Michigan’s Shiawassee National Wildlife Refuge is operating at FY10 funding levels, which means that regular refuge operations, including invasive species control and habitat management, are significantly hampered. The list of deferred maintenance and upgrades to infrastructure and equipment continues to grow. North Carolina’s Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge and Red Wolf Education & Health Care Facility have both been forced to close to the public in the past five years due to a chronic lack of staff, which fails to serve the public or the mission of the refuge system. Tennessee’s Hatchie National Wildlife Refuge no longer has any personnel, and private philanthropic dollars are having to be turned away due to insufficient internal staff capacity. And equally concerning, Maryland’s Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge is threatened by rising sea levels and infrastructure adaptation is

hamstrung by a lack of baseline staff resources. The list continues to grow, and is likely impacting your hometown refuge, as well.