BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL

The Magazine of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers Winter 2025

The Magazine of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers Winter 2025

If you live anywhere in the country where public lands exist, be warned: Special interests have become more emboldened than ever to privatize and profit from our public lands.

As many Americans remained transfixed on the Nov. 5 election, Backcountry Hunters & Anglers has been pushing back against an ominous tidal wave of opposition and antagonism to our public lands legacy. In one of the greatest betrayals of recent times, a growing coalition of elected officials in multiple states are shamelessly pushing for the divestment of public lands owned by us all.

The most insidious of threats at our doorstep is the State of Utah’s lawsuit filed in August with the U.S. Supreme Court to seize a staggering 18.5 million acres of public lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Shockingly, elected officials in 14 states—along with a variety of self-serving trade groups and other anti-public land interests—have since jumped on board with legal support.

them, or lease them to private interests. These are our lands we’re talking about, yours and mine. These are publicly owned assets passed down by generations of Americans, and cherished by hunters, anglers, and outdoor enthusiasts in every corner of this country.

The money being funneled into Utah’s PR machine to deceive the public of their rights and to influence the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to take up the case is staggering. In addition to the $14 million burden placed on Utah taxpayers to cover the cost of the lawsuit, Utah residents will also have to pick up the tab for a marketing blitz reported to top $2.6 million. And then there’s the money being burned up by various special interests that are working overtime to back Utah’s case. Without direct financial support from people who cherish public lands, and direct engagement from leading public lands advocates like BHA, the scales will tip dangerously in favor of those seeking to exploit our public lands for profit, with consequences almost beyond comprehension.

If Utah’s lawsuit succeeds, the consequences will extend far beyond its borders. At a minimum, 211 million acres of BLM lands across the West would be at immediate risk—and potentially all federally managed lands. This includes national forests, parks, wildlife refuges, and wilderness areas. That means the repercussions would extend far beyond Utah, leaving our public lands across the country vulnerable to privatization, exploitation, or even forcing the federal land agencies to directly sell all of it rather than transfer it in the first place.

No matter how saccharine the spin from the spendy gaslighting campaign out of Utah, their true intentions starkly contradict their well-rehearsed claims that “public lands will remain in public hands.” History proves they won’t. States that forcibly attempt to seize federal public lands cannot afford the immense costs of maintaining them. Essential responsibilities like infrastructure upkeep, oversight, and wildfire response would certainly bankrupt them, leaving our public lands vulnerable to privatization and exploitation.

So, what is the real objective here? The ultimate goal for commandeering publicly owned lands is to sell them, sub-divide

Throughout our history, land barons and developers have preyed upon the inattention of hardworking Americans busy with the rest of life to swipe lands right out from underneath us. Now these longtime swindlers have a growing roster of accomplices in the form of politicians who have zero shame cutting Americans out of our own public lands legacy.

In a flurry of unknowns, one thing is certain: As nonpartisan advocates, BHA will remain unwavering in our commitment to defend our wild public lands, waters and wildlife, regardless of who holds elected office. The next generation of conservation-minded hunters and anglers is counting on all of us to stand tall in the face of incredible adversity and defend the special places where sportsmen and women pursue their passions. The question is, will you stand with us?

-Patrick Berry, President & CEO

Your support — whether through donations, advocacy, or action — is essential to ensuring these lands remain public and protected. Visit www.UtahIsNotForSale.org to join BHA in this fight..

“In the end, we conserve only what we love. We will love only what we understand. We will understand only what we are taught.”

~ Baba Dioum

Ryan Callaghan (Montana) Chairman

Dr. Christopher L. Jenkins (Georgia) Vice Chair

Jeffrey Jones (Alabama) Treasurer

Katie Morrison (Alberta) Secretary

James Brandenburg (Arkansas)

Patrick Berry, President & CEO

Frankie McBurney Olson, Vice President of Operations

Bill Hanlon (British Columbia)

Jim Harrington (Michigan)

Hilary Hutcheson (Montana)

Ted Koch (Idaho)

Ray Penny (Oklahoma)

Nadia Marji, Vice President of Marketing and Communications

Katie DeLorenzo, Western Field Director

Britney Fregerio, Director of Finance

Chris Hennessey, Eastern Field Director

Dre Arman, Chapter Coordinator (ID, NV)

Brian Bird, Chapter Coordinator (NJ, NY, New England)

Chris Borgatti, Eastern Policy and Conservation Manager

Kylee Burleigh, Digital Media Coordinator

Tiffany Cimino, Membership and Community Development Manager

Trey Curtiss, Strategic Partnerships and Conservation Programs Manager

Bard Edrington V, Habitat Stewardship Coordinator (NM)

Brady Fryberger, Office Manager

Contributors in this Issue

On the Cover: Wading through the bunchgrass and starthistle high above the Snake River. Read “Could Breaching the Lower Snake River Dams Be a Win For Hunters?” on page 7. Photo by Ben Herndon

Above Image: In the blind, Florida, Derek McNamara, 2022 Public Lands and Waters Photo Contest

Dre Arman, Arrows North, Charlie Booher, Christopher Borgatti, Mandy Carlstrom, Hugh Cummings, Caitlin Curry, Frank DeSantis Jr., Nick Fasciano, Jacob Greenslade, Ted Hansen, Leland Hart, Ben Herndon, Dalton Wayne Hoover, Henry Hughes, Dan Jordan, Cameron J. Kirby, JJ Laberge, William Lakey, Joshua Lawhorn, Jordan Lefler, Shawn McCarthy, Devin O’Dea, Don Rank, Wendi Rank, Jordan Rash, Christine Sawicki, Phil T. Seng, George Wallace, Bill Young

Journal Submissions: williams@backcountryhunters.org

Advertising and Partnership Inquiries: mills@backcountryhunters.org General Inquiries: admin@backcountryhunters.org

Don Rank (Pennsylvania)

Peter Vandergrift (Montana)

J.R. Young (California)

Michael Beagle (Oregon) President Emeritus

Mary Glaves, Chapter Coordinator (AK)

Andrew Hahne, Habitat Stewardship Coordinator (ID, MT, WY)

Aaron Hebeisen, Chapter Coordinator (IA, IL, MN, MO, WI)

Jameson Hibbs, Chapter Coordinator (IN, MI, OH, OK, KY, TN, WV)

Bryan Jones, Chapter Coordinator (CO, WY)

Kaden McArthur, Government Relations Manager

Josh Mills, Corporate Conservation Partnerships Coordinator

Devin O’Dea, Western Policy and Conservation Manager

Kylie Schumacher, Chapter Coordinator (MT, ND, SD)

Max Siebert, Operations Coordinator

Joel Weltzien, Chapter Coordinator (CA)

Briant Wiles, Habitat Stewardship Coordinator (CO)

Zack Williams, Backcountry Journal Editor

Interns: Maisie Kroon, Taigen Worthington (senior operations intern)

P.O. Box 9257, Missoula, MT 59807 www.backcountryhunters.org admin@backcountryhunters.org (406) 926-1908 BHA HEADQUARTERS

Backcountry Journal is the quarterly membership publication of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers, a North American conservation nonprofit 501(c)(3) with chapters in 48 states and the District of Columbia, two Canadian provinces and one Canadian territory. Become part of the voice for our wild public lands, waters and wildlife. Join us at backcountryhunters.org

All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in any manner without the consent of the publisher.

Published Jan. 2025. Volume XX, Issue I

BY BEN HERNDON

Two chukars zigzagged erratically across Wawawai Road along the Lower Snake River, five miles upriver from Lower Granite Dam. Experts in navigating vertical, rocky terrain, the birds seemed at a loss on the featureless asphalt near Granite Point in southeastern Washington state.

“Everyone knew and loved that place,” said lifelong outdoorsman Warren Bakes, referring to the now mostly submerged landmark. “It should have been a state park. It had these wonderful big knobs and crevices down to the river.” Bakes hunted the Lower Snake from a young age, starting around 1953. “It was seldom that you didn’t have three or four types of birds you shot in one day. Whitetail and birds—it was outstanding for both.”

Today, the Lower Snake River is tame here—a wide, slack, manmade lake backed up by an aging dam and cradled by steep canyon

walls of bunchgrass and basalt. Lower Granite Dam was completed in 1975, part of a blitz of large federal hydropower projects by the Army Corps of Engineers across the Pacific Northwest in the mid1900s. It’s an impressive feat—a towering monolith of earthen fill and concrete. Two massive curving gates loom in front of the fivestory-high lock, a 674-foot-long elevator primarily used to raise and lower commercial river barge traffic navigating to and from the West Coast’s farthest inland port at Lewiston, Idaho, 465 miles from the Pacific. The dam is one of four major hydro projects on the Lower Snake River (the others are Little Goose, Lower Monumental, and Ice Harbor). Beneath the roughly 140 miles of slack water between the four dams lies 14,000-plus acres of riparian habitat inundated between the 1950s and the 1970s, drowning what many, like Bakes, recall as the best hunting on the Lower Snake. These areas—places with names like Penawawa, Almota, and Wawawai—signal their long importance to the Palus and Nez Perce tribes. Restored, the

Warren Bakes in front of the now-mostly-submerged Granite Point area of the Lower Snake River a few miles above Lower Granite Dam. “I was 10 yearsold. I cried when those dams went in.”

Beneath the roughly 140 miles of slack water between the four dams lies 14,000-plus acres of riparian habitat inundated between the 1950s and the 1970s, drowning what many, like Bakes, recall as the best hunting on the Lower Snake.

“For every industry that relied on these dams, there was another slowly dying due to the loss of a free-flowing river,” said Dre Arman, Idaho and Nevada chapter coordinator for Backcountry Hunters & Anglers.

canyons and bars could again become thriving habitats.

Alpinist, author, angler, and hunter John Roskelley recalled hunting the Lower Snake River in the 1950s and 1960s with his father, Fenton, an outdoor writer for the Spokane Chronicle and The Spokesman-Review for 63 years. “There were these wide, fertile benches where farms were located,” said Roskelley, recalling his father buying vegetables from farmers in the fall. “At that time, the farmers couldn’t farm real steep stuff like they do now, so there would be these eyebrows. That was prime habitat. There was so much cover for the birds. You almost never came across a ‘no trespassing’ sign. The pheasant hunting was just wickedly good. You couldn’t walk anywhere without busting five or 10 birds. I remember opening day one year—I couldn’t walk 20 feet without flushing a bird. I fired off a box … but that doesn’t mean I hit anything,” he said with a laugh.

“I’m still disappointed with myself decades later. It was a wild river, quite different from the big pool it is now.”

The Army Corps of Engineers knew what was at stake for hunting even as they built the dams. A 1971 Army Corps report estimated that “upland game hunting would be expected to be reduced by 28,400 hunter-days” due to the impact of the four dams.

“‘Hunter-days’ is a metric used to quantify hunting activity and the impact of environmental changes on wildlife and hunting opportunities,” said Aaron Lieberman, executive director of the Idaho Outfitters & Guides Association. “In the context of wildlife and hunting, a ‘hunter-day’ represents a single day of hunting activity by one person.”

As the riverine flats were submerged, so went prime lowland hunting. “For every industry that relied on these dams, there was

another slowly dying due to the loss of a free-flowing river,” said Dre Arman, Idaho and Nevada chapter coordinator for Backcountry Hunters and Anglers.

How much land would become public and huntable after a potential breach of the Lower Snake River dams is unknown. However, any increase in hunting access on the Lower Snake would be a win for hunters, as much of the surrounding “banana belt” canyonland is steep and privately owned, with limited access.

“In terms of hunting opportunities, there’s no question it will be beneficial,” said Lieberman. That’s partly because good hunting and healthy fish returns go hand in hand.

“Hunters are some of the most avid conservationists,” Lieberman said. “They understand ecosystems, ecosystem health, and habitat viability. And there is a very direct relationship between keystone species and overall habitat health.”

“It’s not just about 140 miles of restored river,” said Eric Crawford, Snake River campaign director for Trout Unlimited. “With renewed runs, that means increased nutrient loads,” he said,

According to a 2022 Washington state report, nearly $25 billion has been spent on salmon and steelhead restoration from 1980 to 2018 (adjusted for inflation) by the Bonneville Power Administration, which manages power from the Lower Snake River dams. “It’s the most expensive species recovery program in history,” said Maki. Regionally, a quarter to a third of utility bills go to fish restoration.

referring to the anadromous fish that spawn and die upriver, their decomposing bodies feeding riparian ecosystems downstream.

“Those fish act like 30-pound bags of fertilizer,” said Jack Hurty, salmon and steelhead coordinator for the Idaho Outfitters & Guides Association.

Not long ago, seasonal migrations numbered in the millions, but with the dams’ arrival, fish returns past the four Lower Snake River dams have plummeted.

Recent dam breaches, though smaller in scale, offer a glimpse of what a post-breach Lower Snake might look like. “We can see the Elwha [River], the Klamath [River],” said Kyle Maki, North Idaho field representative for the Idaho Wildlife Federation. “We see the recovery that happened in these systems.”

People often assume reservoir shores would take a long time to recover, but they wouldn’t remain wastelands, said Crawford. On the Elwha, whose two major dams were removed in 2012 and 2014, “It recovered almost immediately,” Crawford said. “You can’t even tell it was under hundreds of feet of water.” While the Lower Snake is drier than western Washington, shoreline habitat restoration would be measured in years, not decades.

What about heavy metals or farm runoff trapped in sediment behind the dams? “They would be systematically breached, piece by piece, ideally with controlled drawdowns allowing newly exposed sediment to stabilize,” Crawford said. Even with limited sediment release, there could be some temporary fish die-offs, particularly for non-native species. “Salmon and steelhead could be less affected, with work being conducted outside of major migration periods,” he said.

“Dam breaching gives us the best odds of getting fish started on recovery,” said Maki. “It’s going to take work. It’s going to take money. But the end result will be worth it, and we’ll be getting land back for the public and hunting.”

According to a 2022 Washington state report, nearly $25 billion

has been spent on salmon and steelhead restoration from 1980 to 2018 (adjusted for inflation) by the Bonneville Power Administration, which manages power from the Lower Snake River dams. “It’s the most expensive species recovery program in history,” said Maki. Regionally, a quarter to a third of utility bills go to fish restoration.

“That’s how much you’re paying for something that doesn’t work,” said Lieberman.

“There are certainly challenges to removing these four dams,” said Arman. “But we had the audacity and innovation to build these structures in the 20th century, and we can have the audacity and innovation to remove them in the 21st.”

“If you knew what the Lower Snake looked like before, it’d make you sick,” said Bakes. “It was marvelous.”

BHA member Ben Herndon is a freelance photographer, writer, and filmmaker based in the Inland Northwest with a focus on outdoor adventure, recreation, and conservation at the intersection of rock and river.

Delivering unmatched accuracy and weighing in at 24 ounces, the Alpine™ CT features an ultra lightweight carbon fiber Peak 44™ Bastion stock and tensioned carbon fiber BSF barrel. Built on Weatherby®’s newest bolt action platform, the Model 307 ™, and proudly manufactured in Sheridan, WY.

Make a meaningful impact on the future of our wild public lands, waters, and wildlife by giving to BHA. Every contribution, regardless of size, plays a crucial role in protecting the wild spaces that enrich our lives!

BHA’s all-new Campfire Society is an ideal way to align your passions with your charitable giving. Join to engage directly with BHA President and CEO Patrick Berry, have access to benefits and experiences distinctive to BHA, and ensure an inspiring future for the next generation of conservationminded hunters and anglers.

“As a veteran who has dedicated my life to serving this country, I am deeply troubled by an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act that would revive the Ambler Road project.” wrote BHA Armed Forces Initiative Board Member Hunter Owen in an article for the BHA website. “As a veteran, I fought to protect this nation and its values, which include a commitment to protecting our public lands. The use of national defense measures to further erode our nation’s public lands legacy feels like a betrayal of those principles.”

“We are facing an existential threat to the public lands that we and those who came before us fought to protect. In late August, Utah officials launched a multi-million dollar campaign to convince the American public that nearly 18.5 million acres of our shared public lands would be better managed in their hands. Here’s the simple truth: This land is not theirs for the taking,” wrote AFI member Garrett Robinson. “Backcountry Hunters & Anglers and the Armed Forces Initiative strongly oppose Utah’s selfish attempt to seize millions of acres of cherished wild lands owned by all Americans. We urge you to join us in standing up against this injustice by signing BHA’s petition and supporting our opposition campaign. Together, we can show Utah officials that our shared public lands are not up for grabs.”

Read Owen’s and Robinson’s full stories on the Armed Forces Initiative page at backcountryhunters.org/tags/afi_featured_stories

We hunt, we fish, and we Vote Public Lands & Waters. BHA celebrated several significant wins at the ballot in November:

☑️ Colorado’s Prop 127, which sought to ban mountain lion, bobcat, and lynx hunting, failed.

☑️ Florida’s Amendment 2, affirming the right to hunt and fish, passed.

☑️ Minnesota’s Amendment 1, extending the Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund through the state lottery, passed.

Thank you for advocating for BHA values with your ballot!

BHA’s family-friendly annual gathering of public lands and waters enthusiasts will return to Missoula, Montana in a new location at the University of Montana!

Join us for events like the Wild Game CookOff, seminars, demonstrations, panel discussions, games, vendors sharing the latest in gear, the one-of-a-kind Field to Table Dinner, and so much more.

See you there June 13-15, 2025! Tickets are on sale now. Visit backcountryhunters.org for more information.

During the summer of 2023, BHA’s Montana chapter successfully argued before the Fish and Wildlife Commission that there was a better, more equitable way than auctions to raise funds for conservation efforts. The chapter was granted the opportunity to instead lead a raffle of the highly coveted statewide mule deer tag.

Not only did the chapter prove that this is a viable option, but hunters helped raise the most money for mule deer conservation the Montana tag had ever generated: $56,620! This exceeded the previous Montana mule deer auction record ($41,000) by 38%.

Matt E. was the lucky raffle winner and shares his story here:

“My hunting buddies and I had an amazing experience that we will all remember for a lifetime. We did this hunt DIY and 100% on public land, making it extremely rewarding and hopefully honoring the idea that quality hunting should be available to everyone, not just the wealthy. We saw over 100 mature mule deer bucks in our six days of hunting. I finally shot my buck on the last day I had to hunt. The local biologist thought the buck is 9.5 years old, which is pretty cool.

“This wouldn’t have been possible without BHA’s efforts to convince states to move away from the auction tag format. This is important work because these opportunities mean so much more than just getting the tag itself or shooting a trophy animal. The tag is an admission ticket to an amazing experience that will become a lifelong memory.

“Everyone should have the chance to share in these experiences, celebrating our public lands, wildlife, and our hunting heritage. I am truly grateful. Keep up the great work, BHA! Cheers, Matt”

James Brandenburg joined BHA in 2018 as a volunteer after his sons introduced him to deer hunting (a reversal of the usual way of things) and the joys of wild foraged and harvested foods. Arkansas did not have its own chapter in 2018, but in 2020 Brandenburg and other like-minded individuals established the state’s thriving community. He led the Arkansas chapter until 2024, when he received the Mike Beagle-Chairman’s Award, the highest individual award BHA bestows.

A generalist hunter and angler, he is as happy throwing poppers to bream in an Ozark stream as he is pursuing black bears in the Ozark National Forest or ducks on unnamed public areas within a reasonable drive of his home in Bentonville, Arkansas.

Almost 10 years ago, career firefighter and paramedic Beau Beasley embarked on a journey to tell the true stories of America’s veterans, honestly and in their own words. He was a respected outdoor writer and flyfishing guidebook author, and was deeply affected by the friendships he’d made through his involvement with Project Healing Waters, an organization that connects veterans with fishing and other outdoor opportunities.

Beau’s book Healing Waters holds the stories of 32 American military veterans who, through flyfishing, rod building, flytying, and being part of a vibrant outdoor community, “came across from the dark side of the river to the light.”

By turns harrowing, tragic, and joyful, these stories cut to the bone, portraits of the price that some of us are willing to pay for this mighty experiment in freedom and responsibility that is the United Sates of America. Join us by listening to Episode 192 of BHA’s Podcast & Blast wherever you get your podcasts. And please, if you are a veteran, or know a veteran, who could benefit from this book or Project Healing Waters or BHA’s Armed Forces Initiative, listen and pass it on.

Why are you a BHA member and volunteer?

Public lands, public waters, and wildlife are what it’s all about for me, and there is no better organization to stand behind to ensure that these things are around and thriving for generations to come. BHA is not afraid to roll up its sleeves and get involved in challenging policy matters to defend the everyday hunter-angler, our wild places, and wildlife when it matters. The thing I find special about BHA is that it gives passionate public lands hunters and public waters anglers an avenue to be leaders in conservation. You don’t need to have a PhD in wildlife biology or a JD in public lands law. All hunters and anglers have special skillsets to contribute, and BHA has a way of effectively leveraging those diverse talents to move the needle in conservation and relevant policy issues at a grassroots level.

Utah is in the national spotlight with state officials attempting to grab 18.5 million acres of public land owned by us all, and you’ve found yourself on the frontlines of the efforts to push back against them. It’s an issue that is taking a tremendous amount of time and effort to mobilize and fight back against. What’s keeping you motivated? Why is this issue so important to you?

Public lands are the reason I live in Utah – period. Without the incredible opportunities I have nearby on federal public lands in Utah and throughout the West, I might as well move back East to be closer to family. I left everything familiar and started from scratch years ago in exchange for this everyday public land access and way of life, so I take this threat personally. I and many others have truly found purpose through public lands.

Our hunting heritage is more than just something to do on the weekends; it is a means to satisfy the natural yearning for adventure and challenge embedded deep within our DNA. It empowers us to connect with the natural world and disconnect from the stresses of modern life. It’s a way to harvest our own organic meat to nourish our bodies throughout the year. I see the risk that this land transfer attempt poses in exposing our public lands to privatization and weakening the multiple-use mandate that enables the opportunity to hunt and recreate on these lands. It’s a direct threat to that hunting heritage made possible through our public lands system, which allows all Americans, regardless of their economic status, access to these opportunities. If you value public lands, getting involved in this issue isn’t a choice; it’s just something you do.

You’ve found yourself working closely not only with your chapter but also BHA Headquarters on this issue. What has that experience been like? How do you think chapters and volunteers and BHA Headquarters staff can best work together to accomplish our shared mission?

Pairing the chapter’s on-the-ground, local policy knowledge with Headquarters’ expertise and resources has been instrumental in developing an opposition campaign to the land transfer lawsuit. One of the things I have found particularly useful throughout this process has been working together to develop a strategy and then clearly identify which parts of the strategy make sense for the chapter to execute and which are best for HQ.

BHA has a very talented and capable (but small) staff working on public lands, waters and wildlife issues across North America in the best interests of its members at large. Over the years, I have observed that chapter leaders (including myself) can sometimes get caught in this mental trap of looking at their chapter as somewhat of an independent organization reporting to HQ, but I think it’s crucial to step outside of the chapter silo mindset to recognize how the chapter fits into the bigger picture of what BHA North America is trying to accomplish and how the chapter can best collaboratively support that mission with HQ. Adopting this “one team” mindset allows us as chapter leaders to think bigger and make a more meaningful impact on a larger, continental scale rather than just within each individual state or province.

Edward Abbey once said: “Do not burn yourselves out. ... It is not enough to fight for the land; it is even more important to enjoy it.” Have you found time to hunt this fall? What type of adventures have you been enjoying on public lands?

My fall has essentially consisted of my day job, fighting the Utah land transfer lawsuit, and getting out in the mountains every chance I get. My husband and I have been fortunate to hunt big game across the West, and this fall, we drew Wyoming general elk tags. After a long, tiring, and unsuccessful 13 days of chasing bulls with our bows, we brought out the rifles in October and were able to fill our tags and freezer. Outside of that, I have been pouring my time into chasing deer and elk locally on the Wasatch Front with my bow pursuing my lifelong quest to be a halfway decent archery hunter (still working on it!). Lastly, my husband and I have developed an annual tradition of taking our red setter down to southern Arizona in pursuit of quail, other small game, wine country, and warmer temperatures between Christmas and New Years, and we’ll be headed down that way again at the end of 2024.

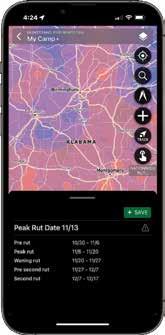

WHITETAIL RUT MAP Unlock the most extensive Rut Map in the country

WHITETAIL ACTIVITY FORECAST Plan your hunt around peak movement times

Join millions of hunters who use HuntStand to view property lines, find public hunting land, and manage their hunting property. Enjoy a powerful collection of maps and tools — including nationwide rut dates and a 7-day whitetail activity forecast with peak deer movement times.

WHITETAIL

Download and map for FREE!

BHA’s Backcountry Bounty is a celebration not of antler size but of BHA’s values: wild places, hard work, fair chase and wild-harvested food. Send your submissions to williams@backcountryhunters.org or share your photos with us by using #backcountryhuntersandanglers on social media! Emailed bounty submissions may also appear on social media.

Forager: George Fischer, BHA member | Species: blackberry and chokecherry wine | State: Idaho | Method: hand-picked |

Distance from nearest road: five to ten miles

Transportation: foot

Trapper: Paul F Noel, BHA member | Species: fisher State: Vermont | Method: body grip trap | Distance from nearest road: two miles | Transportation: foot

Hunter: Cody Vavra, BHA member | Species: cougar | State: Oregon | Method: bow | Distance from nearest road: two miles

Transportation: foot

Hunter: James Fey, BHA life member | Species: blacktail | State: California | Method:bow Distance from nearest road: two miles

Transportation: kayak, foot

Hunter: Cole Chelmo (11), BHA member

Species: mountain goat | State: Alaska | Method: rifle | Distance from nearest road: three miles

Transportation: foot

Hunter: Dave Iverson, BHA member

Species: ruffed grouse | State: Wisconsin | Method: shotgun

Distance from nearest road: one mile

Transportation: foot

Kids, ask your parent or guardian to email a photo of your coloring entry, along with your name and age, to williams@backcountryhunters.org by Mar. 1, 2025. We’ll choose three winners to receive a BHA hat or shirt of your choice! Winners will be announced in the spring 2025 Backcountry Journal.

About the artist: BHA memberTed Hansen is an artist and a middle school art teacher in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He is an avid angler, hunter, and distance hiker and those pursuits inspire most of his artwork. His work can be found on his website (tedhansenfineart.com), on instagram (@tedhansen_art), or through his etsy shop (etsy.com/shop/TedHansenFineArt).

DESTINATION: ALBERTA, CANADA

I F IT’S HARD GETTING TO, IT’S WORTH GETTING TO.

Let the extra mile be your starting line. From rugged trails to remote waters, we design, develop, and build for what’s beyond. You get one life. Fish it Well.

INTRODUCING OUR FULLY REENGINEERED WHITETAIL SYSTEM.

We invited arguably the most dedicated whitetail hunters in the country to share their ideas and provide detailed product feedback. Taking that potent knowledge, we developed a line that breaks the mold of the common seasonal system. We then turned the gear over to our pro team to give it their worst. After extensive testing and tuning, we now offer you an all-new whitetail system that truly makes a difference.

ONE

SCAN THE QR CODE TO FIND YOURS

BY JORDAN RASH

In the fall of 2021, the Washington State Fish and Wildlife Commission met via Zoom to discuss several items related to managing the state’s wildlife resources. Their agenda was broad, ranging from coastal steelhead fishing regulations and rulemaking for the state’s hydraulic code to planning future commission meetings and setting the season for the spring 2022 black bear hunt. Historically, these season-setting items provided little in the form of entertainment; commissioners typically supported the scientific analysis completed by Department of Fish and Wildlife biologists and set seasons based on their recommendations as well as the tenets of the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation.

But the months leading up to this vote were different. The tenor of the commission’s deliberations had been strained. Commissioners were finding it difficult to see eye-to-eye, and a majority faction was pushing policies that eroded hunter and angler opportunities as well as the principles of the North American Model. But it was this meeting, just before Thanksgiving, that kicked the metaphorical hornet’s nest.

When the commission took up a motion to set a special permit season for the spring bear hunt, there was extensive discussion on both the science used to establish the season and the ethics of such a hunt. While commission meetings had been heated, it was the anti-science rhetoric espoused by half of the policymaking body that made this particular meeting noteworthy. Several commissioners made inaccurate comments and uninformed assumptions about bear biology, hunting practices, and ethics

that poisoned the debate. Ultimately, the commission was split evenly, which prevented agency staff from moving forward with a spring hunt.

The commission’s decision has wide-ranging ramifications for hunters and anglers. First, while the state had recently closed the harvest of some game species due to diminishing populations— such as steelhead on the Olympic Peninsula or harlequin duck because of depleted numbers—the black bear population has been on the rise for decades. Thus, losing a harvest opportunity when there is a strong and growing population of a game animal is both confusing and concerning. Second, the mischaracterization of hunting ethics and practices by those in the commission majority demonstrates that hunters and anglers had ceded the narrative to anti-hunters.

Finally, the commission’s shift from the North American Model to a colonialist and anti-harvest regime represents a tangible threat to the sustainability of Washington’s public lands as well as the fish and wildlife that inhabit them. When a fish and wildlife commission takes away harvest opportunities, it is likely that fewer hunters and anglers will purchase licenses, tags, and hunt applications that generate revenue to support stewardship of wildlife areas. This is detrimental not only to harvestable game species but also to the many fish and wildlife species that utilize habitats protected and stewarded with revenue generated by hunters and anglers. While a state could backfill that lost revenue with money from the general fund (i.e., your regular tax dollars), those funds are closely protected by legislatures for other purposes. Losing this critical, dedicated source of revenue for fish and wildlife management is akin to shooting oneself in the foot.

The actions of the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission and other fish and wildlife commissions around the country do not happen in a vacuum. Rather, the actions they take are a reflection of the people they hear from—both good and bad— as well as the fish and wildlife policy direction provided by state legislatures.

With respect to actions taken by the commission, we as hunters and anglers became complacent. We were not organized to engage with the commission, our messaging was scattershot, and our presence in legislative halls has been largely ineffective at managing the public perception of hunting and angling. Long story short, our voice was not relevant, which was reflected in policymakers’ decisions.

The Washington chapter of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers, along with several other groups and individual contributors in the state, has been working to change that. Mandy Carlstrom is the communications lead for the Washington chapter and has served on the chapter board for the past several years while the chapter has organized its members to testify before the Fish and Wildlife Commission. “Knowing is the first battle; knowing what to do is the second,” Carlstrom said. “Our goal is to not only educate BHA members here, but all hunters and anglers, and provide the tools and encouragement to easily and effectively engage in these conversations to create one unified voice that neither the commission nor the legislators can dismiss. We can no longer assume someone else will speak for us or do so in an impactful way. It’s time for each person to step up. Collectively, we can make a difference.”

To change the narrative before the commission, the chapter provided talking points to its members, organized testimony, and used its email list and social media accounts to engage and encourage people to contact commissioners and elected officials on fish and wildlife topics. The chapter also began engaging with legislators who are responsible for everything from setting budgets and passing bills to holding hearings on gubernatorial appointments to the Fish and Wildlife Commission.

These efforts have shown promise. When the legislature introduced a bill to ban the sale of fur from wild animals, they

did not account for the negative impacts the bill would have on the state’s fly anglers. Hard to tie flies without elk or deer hackle, right? BHA, among other hunter and angler organizations, mobilized to oppose the bill as written and offered amendments to clarify its intent. Thanks to these efforts, the bill died before the “cutoff,” and now the chapter is ready to engage again on this issue should it arise in future legislative sessions. This example demonstrates our ability to effect change if we’re mobilized, provide clear, concise, and effective messaging, and offer that messaging forcefully but respectfully.

But this is an example from one year and one bill. State legislatures will be convening again soon, with new bills introduced and budgets to pass. How can BHA chapters and their members engage effectively with legislators as well as with other elected and appointed officials?

First, as an individual member, not just as a chapter, you can build a relationship with your state representatives and senators. You want them to know who you are, what your interests are, and what drives you to vote. Take them on a fishing trip, extend an offer to go scouting for deer, invite them to meet with the state chapter board, or any other way to show them what you care about. Personal relationships in politics are the basis for getting things done, and BHA would benefit tremendously from its members and chapter leaders being able to pick up the phone to directly engage their elected officials.

Second, work with your state chapter to get tuned in to what your fish and wildlife commission is working on, and then provide input on your commission’s agenda topics. Whether it’s season setting, harvest quotas, land acquisition, or any other topic, they need to hear from hunters and anglers when considering policy. Don’t take your commission for granted. If they’re not hearing from you, they’re going to set policy in your absence.

Third, in addition to engaging with your fish and wildlife commission, don’t be shy about contacting your state legislators, governor, or congressional delegation. An email or a phone call can be tremendously effective, particularly if it’s part of a coordinated campaign. You’d be surprised how few people actually contact their legislators, and thus how notable it is when a legislative office receives even four or five phone calls on a topic. And for the purposes of engagement with elected officials, ignore the political party. It doesn’t matter what their political affiliation is; they need to hear from you and what you care about.

Fourth, if you have the ability, the time, and the interest, provide testimony on a bill, budget proviso, gubernatorial appointment, or other policy proposal. As with the above, when we show up, elected officials take notice. Many legislatures now allow for remote engagement through Zoom or a similar program, so if you can’t drive to your state capitol to provide testimony, you can do so from the comfort of your home.

Finally, if you connect with those elected or appointed officials, be mindful, direct, and honest in your engagement. Avoid namecalling or characterizing their thinking; instead, articulate what it is you want to happen and why it’s important to you personally. Be direct—don’t go off on a tangent that has little or nothing to do with why you’re there to speak. Be honest; tell them what it is you want them to do, whether it is to introduce or vote for a bill, offer an amendment to existing legislation, support a budget request

(a “proviso”), or support or oppose a gubernatorial appointment. And when you connect with an elected official, unless you are doing a field visit or attending an event like a rally, skip the camo and hunter orange. Opportunities to hunt and fish are ours to defend and maintain. They won’t be taken away if we can keep the non-hunting public on our side. For if we do, when we go to engage with elected and appointed officials, we can remind them we are watching, and so are all of their constituents.

BHA member Jordan Rash is a freelance writer, podcaster, outdoorsman, and conservation advocate in Washington state. He’s spent his career on and around the forests, mountains, wetlands, and rivers of the Pacific Northwest fighting wildfires, developing public policy, passing legislation, and leading conservation real estate efforts. He can be reached via Instagram at @jordan_ rash1.

BHA’s New York Chapter advocates for wildlife crossing research and funding

BY CHRISTOPHER BORGATTI

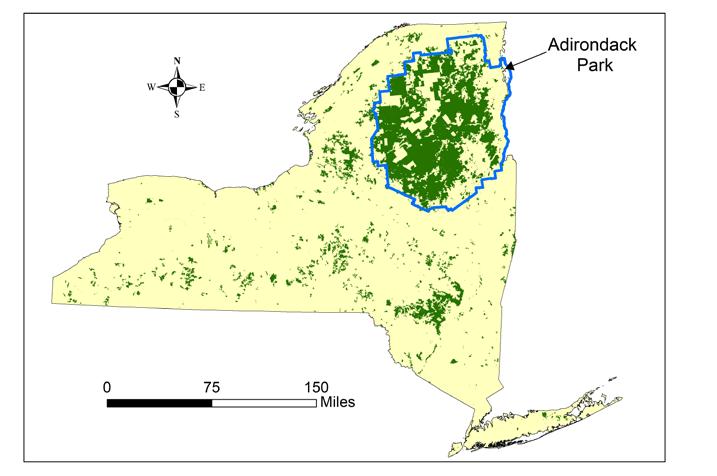

The New York chapter of BHA, along with a coalition of organizations, is on the brink of a successful campaign to pass New York’s Wildlife Crossing Act (A4243B/S4198B). As it awaits Gov. Kathy Hochul’s signature, the bill could transform road safety for both people and wildlife by directing the New York Department of Transportation to identify locations for wildlife crossings that reduce collisions and connect habitats.

Roads do more than just transport people. According to awardwinning environmental journalist and New York native Ben Goldfarb, roads dramatically alter ecosystems, creating “a moving fence of traffic” that prevents animals from reaching essential resources like habitat, mates, and food. Goldfarb, author of Crossings: How Road Ecology is Shaping the Future of Our Planet, notes that while roadkill is often visible, the unseen consequences can be even more devastating. In many cases, animals may face genetic isolation, reduced access to food, and even starvation because they are blocked from traditional migratory routes.

This issue affects species from mountain lions in California to pronghorn and mule deer across the West—and it’s no different in New York. Here, animals like black bears, bobcats, and turtles struggle to navigate the road networks that intersect their habitats. In northern New York, for example, a study led by Dr. Kate Cleary, an environmental studies professor at SUNY Potsdam, found nearly 800 dead animals along a 12-mile stretch of Route 37 over seven weeks, highlighting the impact of roads on local wildlife.

Wildlife crossings—whether overpasses, underpasses, or even simple fencing—help mitigate these impacts by providing safe passageways and reducing collisions with vehicles. These crossings are more common in Western states like Wyoming and Colorado, where they serve predictable migration routes for large animals such as elk and mule deer. Studies show these crossings have reduced roadkill and helped maintain the genetic health of wildlife populations.

Eastern states like New York have traditionally hesitated to adopt such measures, citing a lack of clear migratory paths for wildlife. But recent studies in Virginia and Connecticut demonstrate that with proper planning, crossings can be equally effective on the East Coast. Simple directional fencing and culvert retrofits have dramatically reduced vehicle-animal collisions, saving lives and cutting costs for drivers and the government alike.

Beyond their environmental benefits, wildlife crossings make financial sense. New York reports more than 65,000 vehicle-deer collisions annually, most causing $20,000 to $40,000 in damages. Surprisingly, the cost of effective crossings in the East is much lower than many projects in the West. New York Chapter Coordinator Brian Bird worked in the Capitol to dispel misconceptions about the financial feasibility of crossings. “Cost is the most common concern,” Bird explained. “Directional fences are inexpensive and effective; they steer animals toward existing culverts.”

The Wildlife Crossing Act aims to identify key crossing sites and prioritize projects that improve public safety and wildlife movement. If signed into law, it would empower agencies to

“It’s incredible how wildlife crossings bridge political lines, just as they bridge habitats and cross freeways.”

collaborate on projects that consider environmental and safety needs, while also pursuing federal funding from programs, some of which are supported by the recent infrastructure bill. New York, as the largest state in the Northeast, has the potential to significantly impact regional ecology and safety for both drivers and wildlife.

One of the bill’s unique strengths is its broad appeal. It received overwhelming bipartisan support in both the New York Assembly and Senate. This widespread backing reflects the bill’s practical scope, laying the groundwork for New York to tap into federal funding for wildlife crossings—many of which could pay for themselves within a few years by significantly reducing insurance claims from wildlifevehicle collisions.

Goldfarb noted that an issue like this is rare in today’s polarized climate: “It’s incredible how wildlife crossings bridge political lines, just as they bridge habitats and cross freeways.”

As the New York chapter awaits the governor’s decision, it will continue to apply pressure and encourage the New York

conservation community to do the same. The goal is to raise broader awareness about the impact of roads on wildlife and the tangible benefits of wildlife crossings.

Christopher Borgatti resides in Massachusetts and works as BHA’s Eastern Policy & Conservation Manager

Note: This story and associated quotes are compiled from interviews conducted for the New England and New York BHA chapters’ podcast, “Conservation Cooperative.” The topic was featured in “Episode 3 –Road Ecology & Wildlife Crossings.” Conservation Cooperative is available wherever you listen to podcasts.

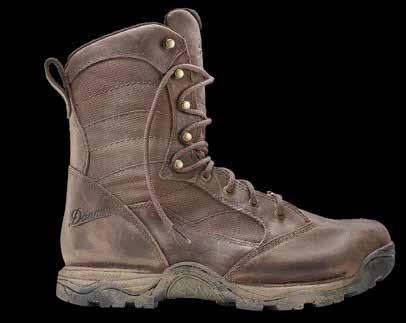

The fifth generation Pronghorn boot is everything you would expect from a legend and more. Featuring our Terra Force® Next™ platform, it’s lighter, faster and built to meet the demands of the hunt. Available online or at your local hunting boot retailer. DANNER.COM/PRONGHORN

Ever had a pizza delivered by helicopter several miles into the wilderness? In a critical effort to support Peninsular bighorn sheep and other native wildlife in California’s Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, the California Chapter of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers and the California Chapter of the Wild Sheep Foundation completed a major guzzler tank replacement project. This effort was made possible through tremendous helicopter support provided by the U.S. Marines from Camp Pendleton.

BHA chapters across North America spent the fall cleaning up public lands and waters, advocating for positive policy outcomes, and uniting a community around the BHA ethos.

• The Alaska chapter hosted a successful crayfish removal event at Buskin Lake in Kodiak, followed by its first annual board retreat and chapter planning meeting.

• On Oct. 26, the chapter held its first BHA Beer Dinner Fundraiser in Juneau, featuring Darren Bruning, deputy director of Wildlife Conservation with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, who presented on wood bison restoration.

• In November, the chapter partnered with Midnight Sun Fly Casters to host a Trout Fusion Film Festival screening in Fairbanks.

• Board member Paul Forward’s Sitka film series, “The Hard Way,” was released this fall.

• The chapter’s fifth annual Dove Cook-off took place in Yuma over the season opener. The gathering included a group hunt, Pint Night, and dove dish competition.

• The eighth annual Family Squirrel Camp was a success, with more than 40 attendees hunting squirrels, band-tailed pigeons, and enjoying time with family and friends.

• The Arizona chapter honored founding member Kurt Bahti, who recently passed away. His dedication to conservation and ecosystem protection inspired many.

• The Arkansas chapter completed a pollinator project on Nov. 2, collecting wild seeds for a pollinator garden at Lake Winona Wildlife Management Area.

• On Nov. 22, the chapter toured the Cedar Creek property to plan a trash removal event. A parking area and gate were completed at Cedar Creek WMA on land purchased by Arkansas BHA and donated to the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission.

• The chapter partnered with the commission to remove cedar trees from sensitive glade habitats and sank them in Beaver Lake to create fish habitat.

• Volunteers are needed for projects and events statewide. Contact arkansas@backcountryhunters.org to get involved.

• With hunting seasons in full swing across the country, the Armed Forces Initiative has been hosting dual-skills camps to equip veterans with conservation skills for post-service life. In October, the AFI national board organized an antelope and mule deer hunting camp in southeastern Wyoming. Nine veterans, representing every branch of the armed forces, participated, focusing on conservation challenges in this National Priority Landscape. Contact your local chapter leadership to get involved in upcoming events.

• The B.C. chapter concluded its third annual alpine lakes citizen science survey in West Kootenay. Data were submitted to provincial biologists, and participants were entered into a prize draw.

• Advocacy and education for hunter-led CWD testing continued, including a live demonstration of sample submission.

• Stay connected for upcoming events across the province and visit BHA booths at outdoor shows this spring.

• The California chapter hosted its annual Beer, Bands & Bitterbrush event, planting bitterbrush at Hallelujah Junction Wildlife Area.

• Members assisted with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s Lahontan cutthroat trout restoration project while holding a bear hunting camp in the same area.

• The chapter hosted a Range Day at the Sacramento Valley Shooting Center in Sloughhouse.

• The Colorado chapter welcomed Britt Parker and Janet George to its board.

• Co-Chair Don Holmstrom leads efforts to overturn restrictive public stream access laws, which are among the most limiting in the West.

• The chapter joined Sportsmen for the Dolores to advocate for a Dolores River Canyons National Monument proposal.

• Mark your calendars: The 2025 Colorado Public Lands Day Bash is set for May 16-18 at the I Bar Ranch in Gunnison.

• The chapter opposed a proposed ban on mountain lion hunting in the state.

• The Florida chapter hosted its annual small game hunt at Dinner Island Ranch Wildlife Management Area on Dec. 14.

• The chapter celebrated the passage of Amendment 2, adding the right to fish and hunt to the Florida Constitution.

• A Pint Night was held on Nov. 21 at Old Kinderhook in Sanford.

• Public Lands Month was a success, with events held in North Idaho, Bogus Basin, Summit Creek, Boise, Moscow, and the Boise River Wildlife Management Area.

• Nate Collins rejoined the chapter board as policy chair.

• Learn-to-Hunt classes were successfully held in North Idaho and Treasure Valley this year, with mentors guiding students through fall hunting seasons.

• The Muddy Waters Tour continued to educate the public about Illinois’ limited stream access laws and the need for updates. Online and in-person events highlighted that only about 2% of Illinois waterways are public.

• Lake Shelbyville Archery Park is nearing completion, with a grand opening scheduled for spring 2025.

• The chapter has continued to grow and become a known steward of public lands in Illinois. Support the chapter by gifting memberships or sponsoring Illinois BHA today.

• The Indiana chapter worked on two stewardship projects in one day: a trout habitat improvement day on the Little Elkhart River in partnership with Trout Unlimited, and a river cleanup with Friends of the White River near Indianapolis.

• Educational efforts included a virtual session with the Indiana Natural Resources Commission on the rulemaking process, and a successful “Learn to Butcher Your Own Deer” workshop in Indianapolis, which sold out. The Indiana State University Collegiate Club hosted a table

at the “Explore Wabashiki” event, which included diverse conservation partners introducing kids to conservation, fishing, and hunting.

• The chapter hosted its annual Indiana Rendezvous, featuring a trapping workshop, stewardship events, and raffles supported by state sponsors.

• In September, the Iowa chapter completed a public lands cleanup at Wicks Wildlife Area in Story County, removing old fencing.

• In October, with support from national sponsor Wilderness Lite Float Tubes, the chapter donated $1,000 toward purchasing 61 acres of public hunting land and 4,000 feet of stream access in Mitchell County.

• A tailgate fundraiser was held on Nov. 29 at the Iowa vs. Nebraska football game.

• On Aug. 15, Kansas BHA helped sink 220 cedar trees into Kirwin Reservoir to improve fish habitat.

• In September, the chapter participated in multiple river cleanups, including the One KC River Cleanup and a Manhattan Battery Cleanup Day on the Kansas River.

• Other fall efforts included brush clearing with The Nature Conservancy to enhance access to public lands at the Flint Hills Tallgrass Prairie Preserve and a cleanup at Wellington Walk-in Hunting Access Area on Nov. 2.

• The chapter’s second annual clay shoot, held in conjunction with the Kentucky chapter of Safari Club International, honored Herbert Mackey. Other summer activities included a fishing day at Falls of the Ohio, archery workshops, and habitat improvements at Otter Creek Outdoor Recreation Area.

• In September, the chapter celebrated its first Public Lands Pilsner Release in partnership with Country Boy Brewing.

• October highlights included the annual trout stocking in Red River Gorge and a Clay WMA cleanup and squirrel hunt.

• The Michigan chapter hosted an event with Chad Stewart, ungulate wildlife specialist for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, discussing whitetail antler point restrictions.

• In partnership with Lansing Brewing Company, the chapter released a Public Lands Pale Ale to celebrate Public Lands Month.

• The chapter engaged in conservation advocacy on the Boyne River Dam issue and ATV use in the Jordan River area.

• The chapter engaged U.S. senators about the Maryland Piedmont Reliability project and its potential impact on easements, farmland, wildlife habitat, and Chesapeake Bay watershed restoration efforts.

• The chapter officially supported Virginia’s Great Outdoors Act, which allocates $200 million from recordation tax revenue without increasing taxes or reducing local funding.

• The board is expanding, adding new members from Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware.

•

• The Minnesota chapter will host its third annual Icebreaker on Jan. 25, 2025, featuring demonstrations in spearing, winter camping, ice fishing, and a wild game cook-off.

• This fall, the chapter held a Learn-to-Hunt Grouse event for new hunters in partnership with the Trust for Public Land.

• Minnesota BHA also celebrated the successful renewal of the Environment & Natural Resources Trust Fund initiative, which passed with 77% voter support.

• The Missouri chapter relaunched its Springfield branch, highlighted by a Full Draw Film Tour screening and a Pint Night at 4by4 Brewing.

• With over 15 events statewide in 2024, the chapter engaged in stewardship projects, Pint Nights, archery shoots, and Full Draw Film Tour screenings.

• The board has begun planning an even bigger 2025, with more stewardship and community events.

• The Montana chapter supported the protection of over 30,000 acres of publicly accessible land through the Montana Great Outdoors Conservation Easement project.

• Members wrote letters of support for wildlife crossing projects on U.S. Highways 93 and 191, and provided comments on the state’s mule deer management plan.

• Public Lands Day was celebrated with a river cleanup on the upper Missouri River, wrapping up the chapter’s 2024 stewardship efforts.

• The chapter sponsored the Montana Stream Access Rally and organized the General Season Send Off at the Sitka Depot in Bozeman.

• The chapter welcomed two new board members: Josh Liljedahl and Collin Peterson.

• The Rhode Island team sponsored a youth mentored waterfowl hunt, which was a resounding success.

• In New Hampshire, chapter members joined the University of New Hampshire and New Hampshire Fish & Game in checking more than 20 trail cameras as part of a moose and mesocarnivore study.

• The Vermont team hosted a Pint Night with local author Ethan Tapper, discussing his book, How to Love a Forest, at Bear Naked Growler in Montpelier.

• In September, the New Jersey chapter held a virtual meet-and-greet where board members shared stories of memorable hunting and fishing experiences.

• In October and November, the chapter launched a virtual mentor series, giving members of all experience levels a chance to ask questions about hunting various game species.

• The New Mexico chapter donated 100 care packages to support the Village of Pecos Kids Fishing Derby in late September.

• For the fourth consecutive year, the chapter held a drawing for a donated cow elk tag, gifted by the Soules family in honor of the late New Mexico Game Commissioner David Soules. The chapter is thrilled to put another coveted tag back in public hands. This year’s winner was military-affiliated member Austin Hannum. Thank you to the Soules family for their continued generosity.

• Several Pint Nights throughout the state provided opportunities for members and the public to connect, share hunting stories, and plan for the upcoming seasons.

• The New York chapter partnered with The Nature Conservancy and NY Hunters of Color to host a mentored early season doe hunt. Six mentees hunted solo for the first time, and two harvested their first deer.

• The chapter packed out two full pickup trucks of trash from East Otto State Forest in Western New York.

• New York BHA is promoting the state’s Wildlife Crossing Act, which has passed the Senate and Assembly and is awaiting the governor’s signature.

• Following Tropical Storm Helene, North Carolina chapter members organized a two-day relief mission to assist victims in remote mountain areas.

• The Armed Forces Initiative’s Whitetail Archery Dual Skills Camp at Uwharrie National Forest was a success, teaching participants new skills despite unfilled tags.

• Visit the North Carolina BHA/AFI booth at the Dixie Deer Classic in Raleigh, Feb. 8-Mar. 2, 2025.

• The North Dakota chapter attended early engagement meetings for the Dakota Prairie Grasslands Travel Management Plan, with scoping to begin in 2025.

• The chapter donated $5,000 to the North Dakota Wildlife Federation’s Fire Relief Fund to support grazing communities affected by wildfires.

• Planning is underway for the 2025 legislative session.

• The Ohio chapter welcomed new board members James Morton, Sarah Medziuch, Leslie Gair, and Jared Hostetler, while saying goodbye to several leaders who moved out of state.

• In September, 13 volunteers packed out 123 tires from Wayne National Forest.

• In August, the Oklahoma chapter hosted a Full Draw Film Tour event in Oklahoma City at Rodeo Cinema.

• The chapter held a public land pack-out event on the Lower Illinois River, cleaning trash from the streambed and surrounding areas.

• Board members met with state officials to discuss conservation concerns.

• The Oregon chapter hosted its fourth annual Adult Hunter Workshop, combining online classes with an in-person field day.

• In September, the chapter held a volunteer appreciation work party in partnership with the BLM, ODFW, and USFS, repairing and modifying a quarter mile of fencing.

• The Pennsylvania chapter hosted its third annual Bustin’ Clays fundraising event on Oct. 6, which continues to grow and supports legislative work in Harrisburg.

• Chapter leaders celebrated successful public land hunts from Maine to Alaska, while reflecting and relaxing after a busy year of policy, outreach, and advocacy.

• The South Dakota chapter submitted comments on the Pactola-Rapid Creek Watershed Mineral Withdrawal proposal.

• The chapter celebrated the dedication of the Stengle Tract, a 560-acre addition to the Frozen Man Creek Game Production Area, in partnership with Pheasants Forever and South Dakota Game, Fish & Parks.

• A lake cleanup was held at Thompson Lake as part of the Adopt-ALake program.

• Chapter members collaborated with Black Hills Fly Fishers and Pheasants Forever for a creek cleanup.

• The Southeast chapter, in collaboration with Mobile Baykeeper, hosted a public lands pack-out at Mobile Tensaw Wildlife Management Area on Oct. 12, removing 450 cubic feet of debris around the historic Ghost Fleet site.

• The chapter is organizing regional wilderness first aid certification events. Contact southeast@backcountryhunters.org for more information.

• Alabama’s Attorney General has joined other AGs in several states in filing an Amicus Brief in support ofUtah’s federal land transfer efforts. BHA Headquarters sent out an email containing an action alert. Please express your opinion on this matter to Alabama’s leadership!

• The chapter enjoyed a leisurely float and campout on the Perdido River in September, and plans are underway for more group activities, including the annual squirrel hunt.

• The Texas chapter met its $2,000 fundraising goal for the “Save the Cutoff” campaign, unlocking matching funds to support the initiative.

• The chapter’s R3 Chair, with BHA volunteers, hosted a whitetail deer hunt for new hunters on over 20,000 acres in southwest Texas.

• Preparations are underway for statewide public land workdays in February and March.

• Utah BHA board members fielded media requests and published articles discussing their opposition to public land transfer lawsuits.

• The chapter participated in the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources’ proposal cycle, supporting efforts to grow mule deer populations while maintaining hunting opportunities.

• Utah BHA hosted “Stewards on Stage Presents: Taking Back or Just Taking? A Conversation About the Law and Public Lands in Utah,” fostering conversations about public land laws and their implications.

• The Washington chapter, in partnership with the Department of Natural Resources, organized a Capitol Forest clean-up, where 30 volunteers removed over two tons of trash.

• In October, the chapter hosted Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife biologists to discuss elk hoof disease, which is impacting herds across the coastal range.

• Chronic wasting disease was detected in Washington for the first time, and the chapter is working with WDFW to encourage hunters to test their harvests.

• The chapter hosted a Backcountry Skills Camp at Sleepy Creek Wildlife Management Area on Oct. 12.

• A Public Lands Pint Night was held in Parkersburg to celebrate the deer season opener on Nov. 22.

• West Virginia BHA will participate in the WV Hunting and Fishing Show in Charleston from Jan. 19–21, with another Public Lands Pint Night planned for Jan. 19.

• The chapter is spearheading the first annual WV Sportsmen’s Capitol Conservation Day on Feb. 21.

• Wisconsin BHA called for a sustainable hunting season for Sandhill Cranes, advocating science-based management through public hunting opportunities of the state’s population of over 90,000 birds.

• The chapter’s R3 team hosted Learn-to-Hunt events for raccoons, white-tailed deer, and pheasants, teaching conservation, ethics, and public land advocacy to participants.

• Quarterly habitat clean-up days were launched in partnership with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, restoring critical habitats and improving trail access.

• In October, Wyoming Chapter leaders supported the rifle sight-in for the Wyoming Women’s Foundation Antelope Hunt.

• The chapter collaborated with six wildlife conservation groups to produce the Hunt-Fish-Vote Resource website, providing information for conservation-minded voters.

• Wyoming BHA submitted comments to Bridger-Teton National Forest about proposed trail enhancements in the Kemmerer Ranger District, focusing on impacts to mule deer and elk summer range habitat in the Wyoming Range.

Find a more detailed writeup of your chapter’s news along with events and updates by regularly visiting www.backcountryhunters.org/chapters or contacting them at [your state/province/territory/region]@backcountryhunters.org (e.g. newengland@backcountryhunters.org).

NRS Approach Rafts give you the flexibility to fish anywhere, anytime, anyhow. They’re designed to fit between the wheel wells of a full-size truck or on the roof of an SUV—no trailer or boat ramp required. Every detail has been examined for angler comfort and convenience. The NRS Slot Rail frame system lets users easily adjust the placement of the seats, oar mounts, and foot bar to optimize the rower’s position and weight distribution. You can also dial in your setup for the coming adventure, from full-luxury fishing to an ultralight format for light-and-fast missions. We include dry box seats, integrated angler trays and rod holders, a quick release anchor system, and motor mount. 16-inch side tubes and a 6-inch drop-stitch floor insert enhance buoyancy, and welded PVC construction resists abrasion on shallow and overgrown streams. No boats give you more options for exploring different ways, and places, to fish.

Scan to see all Approach packages and learn more.

BY DALTON WAYNE HOOVER

I was the last person to arrive that day at the Old Post Duck Lodge in Gillett, Arkansas. I had driven five hours from Louisiana to participate in a Train-the-Trainer event for the Armed Forces Initiative (AFI) of BHA. I had only met a few of these veterans in person and only a few more on a Zoom call, but when I walked through the door, a crowd of people greeted me who you would have thought I had known my whole life.

There were members from all over the country taking part in this event, from Texas and Louisiana to Virginia and Michigan, all either active-duty military or veterans of some sort. We were here to gain knowledge and guidance on how to return to our respective homes and start a local AFI chapter of BHA, to complement our state-level chapters, which a number of us were already active participants in.

After we had eaten, we started the intros. The first thing I noticed was that each one of the members who sat before me and spoke was as enthusiastic about habitat conservation as I was, and we all possessed the same sense of dark humor that the military had instilled in us as a by-product of stressful employment.

I haven’t always been accepted with open arms by the veteran community. I only served for about two years before I severely injured my lower back during a training mission and received a medical discharge at only 21 years old. Though I attended many training schools in my short time, I never saw combat. Many fellow infantrymen with whom I didn’t serve treated me as if I wasn’t a veteran at all.

As soon as I was discharged, I vowed never to go outside again, to run and hide from my military past—many had made it perfectly clear I didn’t have one anyway. I no longer looked to nature for solace; instead, I turned to alcohol and drugs. This lasted for a few years until I made the decision to get sober. And then I got bored. I discovered public lands and decided to start hiking again for exercise, which turned into camping, which turned into light backpacking, which led to rekindling the fire inside me for fishing, a sport I had been absent from for years.

After a year or so on the wagon, just as I was beginning to falter during the summer of COVID, I met AFI member D.J. Zor at a gas station in Idaho where I was trying to obtain a fishing license. He invited me to share a meal with him and another friend who had just spent over a week in the wilderness bowhunting black bears

with traditional archery equipment.

I thought that was the coolest thing I ever heard, and when he noticed that I was intrigued, he introduced me to the organization which I now proudly call home. I bought a BHA membership and ran with it. I started fishing in the saltwater flats of southern Louisiana for redfish and speckled trout. I bought a cheap pump shotgun and began hunting squirrels and turkeys. Transformation was complete the first time I harvested a duck. Hunting and fishing had given me a purpose in life again, filling a hole that had been empty for so long. I can honestly say that it saved my life, as cliché as it sounds.

Once I found out that our public lands were constantly under attack, I found a new mission in life—one that I could use all of my military skills and training to pursue. Former AFI Coordinator Trevor Hubbs put it best in his Armed Forces Initiative’s Commander’s Intent: “To instill within the military community a knowledge of conservation practices and theories, a love of wild places, and a desire to elevate America’s public wildlands as fundamental components of American freedom.” As profound as that quote may be, my favorite quote by Mr. Hubbs is much simpler, and one that resonates through every fiber of my being: “We want to give the military community a new mission, and that mission is conservation.” I do not have PTSD, but once I realized that nature and conservation saved my life, I thought of the millions of fellow veterans out there suffering from the silent killer, and I wanted to help them.

A 3:00 a.m. wake-up call is jarring to anyone, even a dozen veterans. I don’t know about all the other participants, but this time my eyes were wide open and ready to go at 2:50. Many of us had never hunted snow geese before, and even more of us had never hunted in layout blinds, so in the waning hours of darkness we practiced rais-

ing up out of the blind and taking aim. Then many of us took naps, waiting on the daylight and the birds. Most of us ribbed each other in the dying darkness like we had known each other for years—like we had all served together in the past. The guide looked over and asked me how long we had all known each other, to which I replied, “We all just met last night.” I don’t think he believed me one bit.

That night, over a steaming plate of snow goose dirty rice, we sat around a large dining table and learned how to run an AFI event of our own. Members of the AFI board went over the checklist for events and gave us the necessary materials to get local funding for our individual AFI chapters. We went over proper medical procedures and emergency plans, which is when many of us realized just how serious this entire event was. That’s the moment when I realized the responsibility that we had to the members of our respective chapters as well as the veterans we choose to bring out in the future.

Later, each person told us the best part of their day, the worst part of their day, and who they thought the best hunter of the day was. It was easy as can be for each of us to pick who the best hunter was, and even easier for each person to describe the best part of their day. But every single person in the room struggled when it came to choosing the worst part of their day.

When it finally came to me, I grappled with the question just as much as anyone, if not more, because I didn’t have a flock of children to miss or a long drive home the next day. I decided to be honest, and I told the group the worst part of my day was the off-brand Pop-Tart I had for breakfast. While I do have an affinity for namebrand breakfast pastries, it was really more of a way to express that I could not find a single thing wrong with the previous 24 hours. On that day, I finally felt like the veteran community accepted me for

who I was and not what I had done, and that this newfound passion of mine wouldn’t just be a hobby on the weekends anymore. I felt like I was a part of something bigger than myself, an emotion I hadn’t felt since I was discharged from the Army.

We all went to bed that night floating just above the ground. The next morning did not pan out for us like the day before. The weather didn’t cooperate, nor did the wind, and the birds began feeding—teasing us—in fields just 500 yards away. The geese unlikely to move anytime soon, we all thought of long drives home with ice chests full of yesterday’s birds and made the decision to pack up and call it a day. We ribbed each other while we picked up the decoy spread—700 shells and stakes to match 700 jokes and jabs. The dry, military humor hovered through the air, like ducks cupping into decoys at daybreak. The guide looked over at me again and asked, “Are you sure you guys just met only two days ago?”

BY LELAND HART

Silent, scarce, and ghostly, the desert tree squirrels of the Southwest present challenges to even the most skilled small-game hunters. Before the military brought me to Arizona, I grew up hunting and fishing in Michigan. Now, I am the Backcountry Hunters & Anglers Armed Forces Initiative Fort Huachuca chapter leader, and I have become an avid public land hunter and angler. I’ve learned some harsh lessons about pursuing “Old Bushytail” in the desert Southwest. Squirrels in the “Sky Island” region of southeastern Arizona act wildly different from squirrels anywhere else in the country. They are difficult to reach, hard to find, and often scarcer than their cousins in wetter climates. However, the rewards are well worth the effort.

The Arizona gray squirrel (Sciurus arizonensis)—despite its name—is more closely related to, and behaves more like, a fox squirrel. These squirrels typically live in the “Sky Islands” of isolated mountains surrounded by arid deserts. Within these small mountains, they are most easily hunted in the valleys and river bottoms. The best hunting is often found in areas with open-canopy forest and sparse ground cover; squirrels may live elsewhere, but hunters have the best visibility in these areas. Still-hunting is the technique of choice for Arizona gray squirrels. Choose a creek or river bottom in the mountains. Plan to park and hunt the entire river bottom, out and back. Walk slowly, pausing frequently to look for movement or squirrel bodies. When desired, turn around and hunt the same bottom again, moving with similar caution and awareness. Once your party spots a squirrel, keep your eyes on it and move into position for a shot. A varmint-caliber rifle or shot-loaded shotgun is sufficient to bring the squirrel down. Although this may sound similar to squirrel hunting elsewhere, the

Southwest presents challenges unique to the species and environment.

The mountainous habitat of these squirrels is often at a high elevation. Oxygen deprivation is a well-known challenge for elk and mountain mule deer hunters but is rarely faced by Midwestern small-game hunters. Moreover, the riparian bottoms of mountain valleys are often rocky, steep, and unforgiving of careless hiking. Cacti and thorned brush abound, presenting obstacles not found in more temperate regions. Weather in these river bottoms is often windier and colder than in lower areas, and can be surprisingly chilly to those accustomed to desert climates. A sturdy pair of boots, physical fitness, and strong situational awareness are essential to overcoming these challenges. Utilizing public land with maintained trails and access points will aid hunters and help prevent mishaps.

One key challenge these squirrels present is a rare silence. Squirrels in other areas often chatter with one another, scold intruders, and screech challenges to rivals, accompanied by noisy movement along the ground. But the Arizona gray squirrel is almost ninja-like in comparison. To compensate, hunters must rely heavily on their eyes, focusing on movement and shape instead of noise. Fuzzy tails often betray their location, even when they are standing still. Hunters will often spook squirrels into moving, which can be the only clue to their presence.

Scarcity also presents a challenge not typically faced by smallgame hunters. Midwest whitetail hunters are often overrun by squirrels—sometimes by handfuls or even dozens. The Arizona gray squirrel, however, seems to be less gregarious than squirrels elsewhere. This may be due to the desert environment, the number of predators, or other unknown factors. This scarcity certainly impacts a planned hunt, but hunters can compensate by covering as much of a river bottom as possible. Dedicate as much time as you can, and

pass through an area multiple times.

Good shooting is a must. Using supported shooting positions pays dividends, and silence is more productive than noise. Teamwork is often the key to success, as more sets of eyes increases your chances. A shotgun hunter in the group can often bring down a moving squirrel that eludes a varmint-rifle hunter.

The challenges aside, Southwest squirrels are a rewarding quarry. Their meat is similar to that of other squirrels—flavorful and tasty. Moreover, the terrain may offer additional small-game opportunities, depending on the exact region, with some areas having game species like coatimundi or quail not found in many other hunting spots.