Celebrating 20 Years of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers Fall 2024

Celebrating 20 Years of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers Fall 2024

I didn’t grow up in a family that hunted or fished. There was no “YouTube University” or curated social media feed to cultivate my interest in outdoor adventures. Occasionally, I could find books, magazines, or a hand-me-down VHS tape, but pickin’s were slim. So, like many of us, I made it up as I went along, learned by screwing up, and prayed someone would save me from myself. It was this last strategy – by far – that was the most valuable.

Personally, I can’t imagine where I’d be as a sportsman and conservationist if it weren’t for the remarkable people who helped guide my journey. From these generous mentors I learned not only how to make a turkey call out of a straw, how to rig a drop shot, how to tie a fly and how NOT to call a duck, but I also gleaned something equally important – the intrinsic value of wild country and a desire to safeguard it.

Fly fishing luminary and noted conservation advocate Lee Wulff once said, “Every time you teach someone to fly fish, you’ve just created a new conservationist.” That truth extends to many outdoor pursuits. As the world evolves around us, acceptance of hunting by the general public is on the decline, and the sanctity of landscapes that support healthy wildlife populations are under increasing threat; mentorship matters more now than ever before.

As our primary focus, Backcountry Hunters & Anglers stands guard as the watchdog for our wild public lands, waters, and wildlife. To achieve greater mission impact, we encourage others to join the BHA community as members, advocates, and future leaders. But not all come to the table as experts with the skills needed to effectively wield a shotgun, rifle, bow, or fishing rod – or sometimes even to look through the proper end of a pair of binoculars. Others need to be encouraged to stand tall as advocates for public lands, access and opportunity, and conservation of the wild places that feed our souls.

Sometimes mentorship happens organically. Other times it happens through programs designed to cultivate a love of the outdoors and teach the skills needed to be successful in the field or on the water. Those “official” programs fall under the category of “R3,” the shorthand term for recruitment, retention and reactivation. The

goal of R3 is to increase participation in hunting, fishing, trapping, boating and shooting sports. But whether mentorship happens informally or through a pre-designed program, the value often remains the same.

At a fundamental level, aspiring newcomers to the world of hunting and fishing not only learn key skills, but they also often learn etiquette that can make for a more enjoyable outdoor experience for all – such as give other anglers plenty of space, get the cooler and gear ready before the boat is backed down the ramp, and drive past your desired hunting spot if there’s another truck already parked there. Seems like obvious stuff, right? Well, not always. That’s why we often need mentors to show the way.

There’s a little-known podcast host whose favorite pastime is to publicly bludgeon individuals and organizations who take on the selfless and laudable role of mentors to wide-eyed novice hunters eager to learn. To me, slamming the door to opportunity behind you by shaming volunteers dedicated to inspiring the next generation of outdoor enthusiasts is like kicking a puppy across the room. It also has lasting consequences. Trying to make the tent as tiny as possible while the percentage of non-hunters skyrockets into the stratosphere is a recipe for irrelevance and bad policy outcomes.

Mentors share their hunting and fishing knowledge, nurture a passion for adventure, open the door to backcountry experiences, encourage grassroots engagement, teach people how to play nice with others, and instill an enduring conservation ethic. It’s through these experiences that a community is formed – BHA – where we not only share our passions, but we unite to protect the wildlife and wild places that those passions are dependent upon.

Without someone holding the light to guide our path, we’d spend more time lost than found, and fall farther behind in the race to save the last best places. I am damn proud of the mentors across BHA who help inspire and grow the community of ethical, conservationminded hunters and anglers. You have my deepest gratitude.

-Patrick Berry, President & CEO

“I know of no restorative of heart, body, and soul more effective against hopelessness than the restoration of the Earth.”

- Barry Lopez

Ryan Callaghan (Montana) Chairman

Dr. Christopher L. Jenkins (Georgia) Vice Chair

Jeffrey Jones (Alabama) Treasurer

Katie Morrison (Alberta) Secretary

Patrick Berry, President & CEO

Frankie McBurney Olson, Vice President of Operations

Dr. Keenan Adams (Puerto Rico)

Bill Hanlon (British Columbia)

Jim Harrington (Michigan)

Hilary Hutcheson (Montana)

Ted Koch (Idaho)

Nadia Marji, Vice President of Marketing and Communications

Katie DeLorenzo, Western Field Director

Britney Fregerio, Director of Finance

Chris Hennessey, Eastern Field Director

Dre Arman, Chapter Coordinator (ID, NV)

Brian Bird, Chapter Coordinator (NJ, NY, New England)

Chris Borgatti, Eastern Policy and Conservation Manager

Kylee Burleigh, Digital Media Coordinator

Tiffany Cimino, Membership and Community Development Manager

Trey Curtiss, Strategic Partnerships and Conservation Programs Manager

Bard Edrington V, Habitat Stewardship Coordinator (NM)

Brady Fryberger, Office Manager

Mary Glaves, Chapter Coordinator (AK)

Chris Hager, Chapter Coordinator (WA, OR)

Andrew Hahne, Habitat Stewardship Coordinator (MT, ID, WY)

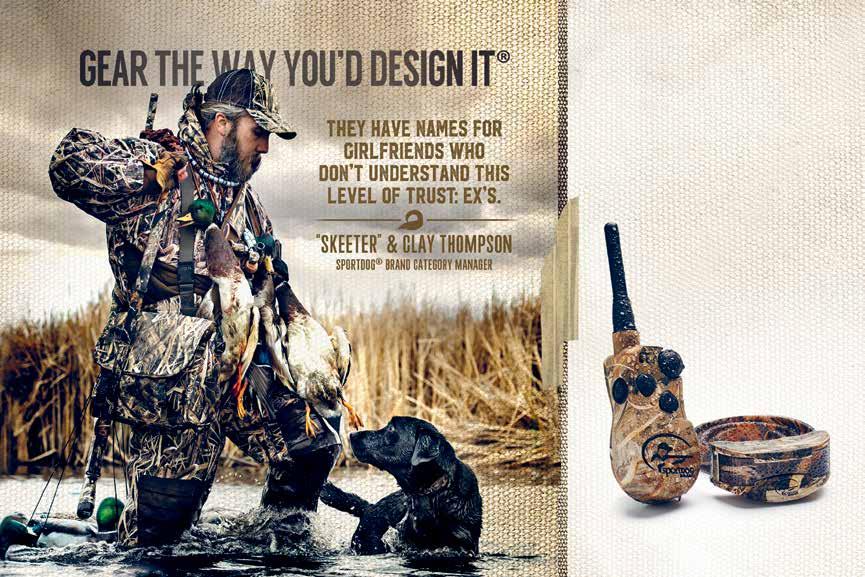

On the Cover: Celebrating 20 years of BHA with the evolution of Backcountry Journal over the years and a few of our favorite covers.

Above Image: Planting at Beer, Bands & Bitterbrush Stands. (Learn more on page 32.) Photo by Travis Bradford

Jay Beyer, Charlie Booher, Travis Bradford, Jamie Cameron, Will Caverly, Jan Dizard, Holly Endersby, Jillian Garrett, Matt Groce, Andrwe Hahne, Tony Heckard, Abby Hutcheson, Kobe Jackson, Bryan Jones, Kyle Klain, Don Klebenow, Nathan Kunze, JJ Laberge, Jake Forrest Lunsford, Kaden McArthur, Claire McAtee, Jesse C. McEntee, Devin O’Dea, Shane Oehler, Jeffrey Petersen, Cody Readinger, Ron Rohrbaugh, Sean Stiny, Josh Suggs, Jenny Nguyen-Wheatley, Kassie Yeager

Journal Submissions: williams@backcountryhunters.org

Advertising and Partnership Inquiries: mills@backcountryhunters.org

General Inquiries: admin@backcountryhunters.org

Ray Penny (Oklahoma)

Don Rank (Pennsylvania)

Peter Vandergrift (Montana)

J.R. Young (California)

Michael Beagle (Oregon) President Emeritus

Aaron Hebeisen, Chapter Coordinator (IA, IL, MN, MO, WI)

Jameson Hibbs, Chapter Coordinator (IN, MI, OH, OK, KY, TN, WV)

Bryan Jones, Chapter Coordinator (CO, WY)

Kaden McArthur, Goverment Relations Manager

Josh Mills, Corporate Conservation Partnerships Coordinator

Devin O’Dea, Western Policy and Conservation Manager

Thomas Plank, Communications Manager

Kylie Schumacher, Chapter Coordinator (MT, ND, SD)

Max Siebert, Operations Coordinator

Harrison Stasik, Events Assistant

Joel Weltzien, Chapter Coordinator (CA)

Briant Wiles, Habitat Stewardship Coordinator (CO)

Zack Williams, Backcountry Journal Editor

Interns: Lars Chinburg (Backcountry Journal intern), Maisie Kroon, Taigen Worthington (senior operations intern)

P.O. Box 9257, Missoula, MT 59807 www.backcountryhunters.org admin@backcountryhunters.org (406) 926-1908

Backcountry Journal is the quarterly membership publication of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers, a North American conservation nonprofit 501(c)(3) with chapters in 48 states and the District of Columbia, two Canadian provinces and one Canadian territory. Become part of the voice for our wild public lands, waters and wildlife. Join us at backcountryhunters.org

All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in any manner without the consent of the publisher.

Published Oct. 2024. Volume XIX, Issue IV

JOIN THE CONVERSATION

BY HOLLY ENDERSBY

It was a sweltering September day 20 years ago when I met a guy trudging out of the Rapid River canyon in Idaho carrying a full pack with a huge elk rack attached. Heading toward him, the man looked uneasy with my approach. But when I greeted him with, “Hey, that is a great bull you have got. And I want to thank you for hunting on foot,” Barry Whitehill of Fairbanks, Alaska, relaxed. He thought for sure I was an anti-hunter lurking at the trailhead to give guys grief.

Within a couple minutes we discovered we both knew David Petersen – the author, expert elk hunter, Trout Unlimited employee and early BHA member at the time – and that Barry and I were both avid backcountry hunters. From there, it was easy to tell Barry about Mike Beagle’s dream of creating a nonprofit of hunters and anglers to advocate for the protection of backcountry public land and water.

Barry’s intuitions were right – I was lurking around the trailhead a few miles from my home, putting leaflets on windshields of trucks parked there and meeting anyone I could who was hunting on foot in the backcountry. You see, when BHA started that is all we had: chance encounters with like-minded folks at trailheads, sporting goods stores, trad-bow meets, word-of-mouth among friends and a few small outdoor shows in Oregon and Idaho. Looking back, it is astonishing that a small group of initial board members and our families and friends got the ball rolling. It was pretty much a whisper campaign.

The first BHA board meeting was held at our home in Pollock, Idaho, next to the huge Rapid River Roadless Area with a Wild and Scenic river coursing through the canyon. The weather was blisteringly hot, but after meeting for two days, we headed to the Salmon River, the longest free-flowing river in the U.S., to cool off. It was a time of hard work but also a kindling of friendships and dedication that launched BHA. From day one, Mike Beagle – the Oregonian who hatched the idea with buddies around a campfire – insisted that “boots on the ground” would be our mantra: We would know the land we wanted to protect and use that unique position to make a difference.

In Oregon, Tony Heckard in Canby and Kelly Smith in Bend reached out to fellow members of the Oregon Hunter’s Association to spread the word. Kelly was our first treasurer, and Tony took on the frustrating task of getting us nonprofit status with the IRS. In Idaho, my husband, Scott Stouder, who was also a TU employee working on the protection of roadless areas in the state, worked his large network of hunting friends. I started hanging around trailheads and meeting with Larry Fischer, the editor of Traditional Bowhunter magazine, who I had met a few years earlier. He began telling the trad-bow folks about BHA and invited us to attend their meets in Idaho. At one near Stanley, Derrick Reeves of Deary, Idaho, who volunteered to be an Idaho chapter leader, and I cooked burgers to lure people to our booth so we could share the BHA story. Word

spread in Boise due to Larry, and soon stalwarts like Sean Carrier and Jeff Barney showed up to help. Meanwhile, Barry Whitehill was talking BHA up in Alaska, and David Lyon of Homer joined him to help guide that potential chapter. Luckily, Barry hunted each September in Idaho with a cohort of friends from Washington, so quickly those seeds were planted as well. Soon, Joe Mirasole of Spokane joined BHA and worked hard to add more members. His first recruit was his dad, Bob, who also spread the word. In Utah, Dan Hines and his wife Karen Boeger led the charge that ignited that state chapter. And after Dan’s untimely passing, Karen has been a BHA mainstay for the past 20 years.

At first, telling our story was tough. With just a newsletter printed off by Mike Beagle and stapled by his kids – the first Backcountry Journals – to spread the gospel of BHA, we clearly needed money for outreach.

Making cold calls to foundations to tell the story about our unique position, Mike landed our first grant. We used the money to hire a director and one support/office person at astonishingly low salaries. Our first office was in Joseph, Oregon, a place flush with hunters but no access to airports or other forms of outreach. Mike and I continued approaching foundations, most of which were already supporting other, larger conservation groups. But we kept telling our story and assuring funders we were unique – that hunters and anglers were hungry for what BHA could offer and that their investment was a way to protect public lands and waters with a voice never heard before. Sometimes the sales pitch produced nothing, but over the first and second years, more foundations saw BHA’s potential and agreed to fund us.

The second year BHA had funding was rough. Our executive director left for other opportunities, and we only had two staff people: Rose Caslar in Joseph, Oregon, as our bookkeeper and me as conservation director and interim executive director. But with foundation money, we added our first outreach employee, hiring Tim Brass to help guide a chapter in Colorado. We were looking shaky, but the BHA board was a huge support, offering advice and

From a tiny staff in a unique but struggling organization, BHA began its amazing growth reaching far beyond what the small group of us at the beginning imagined was possible.

encouragement. We simply refused to fail. We told our funders that although we were small, we had passionate members working diligently as volunteers to engage in state and national issues to be sure our voice for conservation was heard. In Idaho, our members were showing up to provide input on the Idaho Roadless Rule, where we had a significant impact at hearings around the state.

During this time, Bill Hanlon of British Columbia contacted me and said he and others wanted to start a chapter. “Great!” I thought. “Now, how the heck do we do that?”

Bill and several friends got on the phone with me one night, and the energy to begin a BHA chapter in Canada was intense; these guys wanted to get this done! So with abundant optimism, we gave it a shot, and those Canadians made it happen. It was that same boots-on-the-ground attitude that made Bill and his buddies successful.

Then, after a year of struggle to keep BHA afloat and with new funding from foundations, the board held numerous interviews with people from national conservation groups who wanted to be a part of what BHA offered – that unique voice not for species protection but for land protection that would encompass native

species in the process. At the end of several meetings, Land Tawney interviewed in Missoula, and with his conservation experience and dedication to public land hunting and fishing, we felt there was a solid reason to hope that BHA could grow and begin to roar instead of whisper.

From a tiny staff in a unique but struggling organization, BHA began its amazing growth reaching far beyond what the small group of us at the beginning imagined was possible. It has literally been a dream come true.

Holly Endersby had a career in education as a principal before moving on to being an award-winning freelance outdoor writer for 25 years. She was BHA’s first conservation director and served as interim executive director.

Editor’s note: Enjoy a look back at 20 years of BHA on the next spread (pages 8,9).

BY JESSE C. McENTEE

For about a half dozen years prior to that winter, I had been going to a friend’s deer camp that was located adjacent to what I now appreciate is some of the best big woods hunting in Vermont. The camp is old-school: no plumbing, wood heat, holes in the floor, walls filled with tinfoil and rim joists insulated with newspaper dated circa 1975. It includes a 12-inch square of scrap plywood hanging on an interior wall that lists all the deer harvested over the years; the dates go back to the 60s and end in the mid-80s. Since then, people have hunted there, but no one’s harvested anything, and the place had acquired a reputation for being unproductive. My experience back then confirmed that sentiment, but the vastness of the big woods was irresistible; it was possible to roam for days and never worry about seeing “posted” signs or a new subdivision replacing a mature hardwood stand.

Early on my hunting approach was naïve; the interest was there, but I had no guidance other than the jumble of information and advertisements found in social media and hunting magazines. I’d head into the woods, bump a couple of deer, and inevitably come home empty-handed. Something changed in 2016 when my desire to successfully harvest a deer intensified. Gravitating toward a style

of hunting that allowed me to keep moving, I found a couple people who grew up hunting and learned from them.

Opening day of the Vermont muzzleloader season is always on a Saturday in December. With odds and ends wrapped up on the home front, I threw my hunting clothes into a cardboard box with some leaves and freshly cut spruce boughs for scent control. My Buckstalker muzzleloader, a couple armloads of firewood and a cooler filled with groceries filled the trunk of my Subaru Outback. That night at camp, big wet snowflakes were sticking to the ground and the next morning there was a thin layer of snow and relatively mild temperatures – hovering around freezing.

Camp borders the Green Mountain National Forest, which encompasses over 400,000 acres in central and southern Vermont, representing the largest swath of public land in the state. Typically, I’d stay close to camp, still hunting, creeping along, hoping to sneak up on (or cross paths with) a deer. That morning the snow on Route 100 was melted but the dirt roads had a fresh coat on them. It was still dark and before shooting hours when I started looking for a track crossing the road. This area is actively managed forest; it’s predominantly northern hardwoods and some softwoods (red spruce and hemlock) with a wide-variety of management techniques employed. This has resulted in everything from early

You have to clear your mind of all of that noise and worry and focus on one thing – catching up with the buck and killing him. If you’re worried about your job, your spouse, money, the newest iPhone or if your car’s going to start while in pursuit, then the buck has won.

successional habitat filled with brambles to mature maple, beech and oak stands, which provide abundant mast crops for wildlife. All of this is adjacent to the steep, rocky ridges of the Green Mountains, distinguished by subalpine krummholz. This alpine zone runs north-south throughout the entire state and is part of the northern section of the Appalachian Mountain Range, the highest peaks reaching upwards of 4,000 feet. Mountain summits are exposed and windblown, containing only vegetation that manages to grip the metamorphic rock – in this case, stunted conifers and a few other delicate alpine plant species.

There are eight congressionally designated wilderness areas contained in the Green Mountain National Forest – of 803 wilderness areas throughout all of the U.S., which total nearly 112 million acres. Established by the Wilderness Act of 1964, these areas are designated to maintain the wilderness character, allowing only human-powered activities and prohibiting the use of motorized equipment as well as mechanical transport (e.g., ATVs, bicycles, game carts, etc.). Incidentally, I would find myself in one by the end of the day.

After about 90 minutes of driving searching for tracks, legal hunting hours had started and I was antsy. This is silly. All I’m doing is driving – I’m not even in the woods. I just need to get out there. Parking at a trailhead, I walked into a hemlock stand – at the very least I’d get a nice hike in.

In discussing whitetail tracking with other hunters, I always wondered how we were supposed to ever catch up with a deer if we’re constantly just creeping along, moving so slowly as to never make a peep. It just seemed too damn slow. Sure, you may encounter another deer by chance, but catching up with the one you’re tracking

seems impossible when moving so ploddingly.

There had to be another way.

A more aggressive approach exists. Once you get on a track you’re confident is a buck, you get after it quickly, ignoring the noises you might make. A stick cracks under foot, a branch scrapes the ripstop nylon of your backpack – ignore it. Just go. You may bump the deer, but eventually he’s going to make a mistake and if you’re focused, you’ll be there for it. This is the style of whitetail hunting I adopted that morning. Influenced by Larry Benoit’s deer hunting books, I was a minimalist: a plaid green wool shirt, wool pants and sturdy leather boots. I carried all of my ammo, food, compass and map in my pockets or belt.

After about 20 minutes I spotted an old track, halfway filled with snow and headed south. Following this track was surely better than driving around all morning in my Subaru. I trailed the track uphill for about an hour until it crossed another set of large, fresh deer prints. This new track was the type of print that makes a hunter’s heart skip a beat. Even back then with less experience, I knew it was a track to follow: large hoof, wide stance, solitary. The spruce trees were becoming white, their branches heavy with snow. The walking was quiet. The pursuit was on.

Move quickly; don’t worry about the noise. My eyes scanned ahead, looking for the horizontal line of a deer’s back, a nose, set of eyes, a tail flicker, a leg. A flash 20 yards ahead caught my eye. It had been bedded. The bed itself was large, and the buck’s body heat had melted most of the snow down to leaves. Tarsal gland stains were evident in the remaining snow. It had bounded from its bed and continued to run for a couple hundred yards, eventually returning to a walk, heading steadily uphill.

While I had been after the deer for a couple of hours, fatigue had started pursuing me. I chose not to bring water on my hunts back then since it was heavy, and I thought it would slow me down. My peanut butter and jelly sandwich was long gone. Two hours-worth of melted snow on my wool shirt made the wind seem stronger and colder than it actually was. A psychological barrier emerged: doubt. How long should I follow this track? What time should I leave it to get back the car? How will I get the deer out if I shoot it? Do I feel like hiking back to my rig in the dark?

This uncertainty needed to be extinguished. It was helpful to remember the advice big-woods deer-tracking legend Larry Benoit gives in his book How to Bag the Biggest Buck of Your Life. It’s a bit of Zen philosophy where he talks about not letting these voices takeover when you’re in pursuit of a buck. You have to clear your mind of all of that noise and worry and focus on one thing –catching up with the buck and killing him. If you’re worried about your job, your spouse, money, the newest iPhone or if your car’s going to start while in pursuit, then the buck has won.

This philosophy has even more relevance today. The distractions of Larry Benoit’s time still exist, but now we have the supercomputers in our pockets where a hunter can check the map, the weather or emails. Luckily, cell service was nonexistent in the wilderness area the buck and I had just entered.

Clear mind, no distractions. No kids to pick up off the bus; no early bedtime for work the next day. Chase this buck for the next eight hours, up and down over ridges, through streams, up to the top of the mountain. Wilderness. Freedom. After a while, the deer started acting funny. Run then walk. Jump to the side. Walk back on its own track. It knew something was after it. Predator after prey.

I trudged after the deer, deeper into the wilderness area, climbing higher and higher, wind in my face. Eventually I looked up a steep incline, and there he was – only 25 yards away, standing with his head down behind a fallen tree. I switched the safety off and waited for him to lift his head so I could confirm antlers. And then I pulled the trigger.

Sprinting up through the smoke to where the deer had been, there were dark red spots on the snow. Good, there’s blood. Contact. And then there he was, laying down, looking at me from only five feet away. We locked eyes for about a second, then he got up and stumbled down the mountain crashing through hobblebush. Adrenalin pumping, I ran after the injured buck and found him sitting up, looking at me. I reloaded and finished him off with another shot into the vitals.

A classic Vermont ridge-runner, I stared at him, my hand on his body, feeling the heat escape his thick fur. Our body heat melted the snow landing on our backs. Truly alone and at peace in the moment, nothing else mattered. It was primal and raw. My mind went to a new place, a wilder place. Hyper-focused on the buck and the immediate surroundings, the noise of the modern world had disappeared. Unfinished chores and unanswered texts all faded into the background. There was plenty to figure out, but none of it mattered. It was me on the mountain, in the woods, with the buck, high from the kill. The smell of the muzzleloader shot lingered. His hair stuck to my sweaty, cold hands. The only sound was the wind. Bliss.

After gutting the deer, I tied one end of paracord to his antlers and the other to a stout stick and began to drag him out. When tired, I’d rest by sitting on his shoulders. When my hands got too

numb to grip the drag stick, I’d warm them on his ribcage.

Eventually, a couple of my buddies and I connected, and I had some help with the last bit of the drag. “Where are you?” they asked.

“I don’t know – uphill from that road.” I knew I’d get back eventually following the old philosophy of Northeast hunters: Go downhill to a stream, then follow that to a road or town.

What seemed impossible finally happened after eight years of getting skunked. I was thrilled, but it wasn’t the feeling I expected. Perhaps I had expected to be hunting with a friend when I shot my first deer, and we’d be congratulating each other, high-fiving like they do in hunting-gear advertisements. Or maybe I’d be shouting and pumping my fist in the air. Instead, the experience there deep in the backcountry started a new life chapter, seeking out experiences involving struggle, wilderness and solitude.

I hung up the deer back at camp, and we added my name to the scrap plywood piece hanging on the wall. I don’t think I took my eyes off that deer for more than a half hour that night. I would get up, turn on the spotlight and look out the window to make sure he was still there – and that it all was real.

BHA member Jesse C. McEntee is a writer from Vermont. His work explores pressing issues related to wilderness through the prism of hunting and fishing. You can learn more about his work at jessemcentee.com

Delivering unmatched accuracy and weighing in at 24 ounces, the Alpine™ CT features an ultra lightweight carbon fiber Peak 44™ Bastion stock and tensioned carbon fiber BSF barrel. Built on Weatherby®’s newest bolt action platform, the Model 307 ™, and proudly manufactured in Sheridan, WY.

A long-standing grudge against federal public lands – lands intended to be accessible by and for all Americans – has resulted in Utah officials attempting to remove from the public domain one of the crown jewels of North American conservation: our public lands. Utah officials are seeking control of “unappropriated” Bureau of Land Management territory, a profound misstep in the ideology of public land management and stewardship of natural resources in Utah. The proposed transfer of federal lands to state control also raises grave concerns about the potential for increased commercial exploitation, increased costs to state budgets, diminished conservation efforts, and restricted public access. BHA stands firmly in opposition to this political maneuver, which directly attacks the shared heritage of public lands and waters that provide hunting and angling opportunities for sportsmen and women.

“Americans who love to hunt, fish and enjoy the outdoors rely on public lands across this country as a place where they can pursue their passions and pass down our outdoor heritage from generation to generation,” said BHA President & CEO Patrick Berry. “An attempted land grab by the state of Utah of assets owned by all Americans is a shameful, short-sighted way to make political points. Public lands are the national treasure that support our way

of life, conserve wildlife and provide recreational opportunities for everyone. Allowing state control would risk the integrity of these lands, ultimately leading towards privatization and exclusion for all but those with the deepest pockets.”

This attack follows in the footsteps of Rep. Jason Chaffetz (RUT) who withdrew legislation in 2017, following an outpouring from BHA’s grassroots advocates and sportsmen and women nationwide, that would have divested public lands from the American public. BHA has long stood in staunch opposition to legislators and lobbyists who have tried to wrest control of these lands from federal hands; that’s why the Utah chapter of BHA is, once again, pushing back against this ill-advised proposal.

“While our state government claims it is committed to keeping public lands in public hands, the only guarantee that comes from such a transfer is the removal of these existing federal protections and increased exposure to privatization,” said Caitlin Curry, vice chair for the Utah chapter of BHA.

BHA has mounted a full-scale opposition campaign to ensure your voice is heard in this attack against all of OUR wild public lands, waters, and wildlife.

Learn more and get involved at www.utahisnotforsale.org

The Wilderness Act was passed by Congress in 1964, and has since protected over 109 million acres of American public lands. But the idea was born in 1924, with the vision of none other than Aldo Leopold, who was then supervisor of the Carson National Forest, and had spent almost 15 years working on and exploring the wild public lands of New Mexico. Leopold argued that among the resources the Forest Service was mandated to safeguard for the American people were open spaces for hunting, fishing and real adventure. He argued, eloquently, that these values existed in abundance on the unpeopled lands of the Gila National Forest, that they were becoming more and more rare across North America, and that the U.S. Forest Service could choose to protect them for future generations.

Celebrate Aldo Leopold, 100 years of the Gila Wilderness and 60 years of the Wildernss Act with Episode 185 of the Podcast & Blast.

And don’t miss the amazing story of Alone Winner Woniya Thibeault, and Gaspar Perricone discussing ballot box biology and Colorado’s proposed mountain lion hunting ban. Those and so much more on the Backcountry Hunters & Anglers Podcast & Blast with host Hal Herring, wherever you get your podcasts.

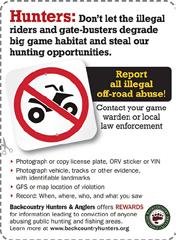

All Americans have a right to enjoy our public lands and waters – but no user group has a right to damage shared public treasures or ruin the experience of others enjoying the great outdoors. Most of us can tell stories of stalks ruined, peace and quiet shattered and wildlife spooked by illegal off-road driving.

To help encourage sportsmen and public land users to continue our longstanding tradition of policing our own ranks, BHA offers a reward of up to $500 for reports or information leading to a citation for illegal motorized use. Report illegal off-road use to your local game warden and/or land manager and help ensure that we continue to have quality habitat, hunts and access for all.

For more information on claiming a reward, visit backcountryhunters.org/ohv_and_illegal_motorized_use_program. You can still support the program, even if you don’t claim a reward: Donate to the reward fund and help safeguard our public lands habitat. And did you know: We offer a reward for those curtailing illegal dumping, too?

Taking pictures of our backcountry experiences is just one way hunters and anglers capture our most beloved memories in designated wilderness, on Bureau of Land Management tracts, U.S. Forest Service parcels, and on public waters in between. And we want to see your pics!

Backcountry Hunters & Anglers is launching our 2024 Public Lands and Waters Photo Contest with some changes to the previous format. This year we are offering three categories (Hunting on Public Lands, Fishing on Public Waters, and Backcountry Wildlife) and the winners for each category will be chosen by BHA’s marketing and communications staff. Our prize packages are also the biggest we’ve ever had, with over $4,000 in gear and credit from partners: Stone Glacier, Weston, Sitka, Sage, Seek Outside, Benchmade and Dometic!

Also new this year is a members-only category in celebration of BHA’s 20th anniversary! Share your best photos from past BHA events, including: hunting camps, fishing trips, advocacy efforts, habitat stewardship, and any other place where members have made their mark!

Along with that stellar prize package will be a photo feature in our Backcountry Journal’s summer 2025 edition and a journal cover for the overall winner of the photo contest. Enter by Nov. 30, 2024, at backcountryhunters.org/ the_2024_public_lands_and_waters_photo_contest

BHA’s one-of-a-kind annual gathering of public lands and waters enthusiasts will take place June 13-15, 2025. Join us to share stories with your community, chat with vendors and get your hands on the latest gear, and learn about the latest hunting, fishing, foraging and conservation techniques. Mark your calendars and look for a location announcement coming in November. We look forward to seeing you there!

FOR THOSE UNFAMILIAR WITH YOUR HOME REGION, WHAT DO YOU FIND SO SPECIAL ABOUT EASTERN NEVADA?

This part of Nevada has some of the best hunting in the state for both upland and big game. My first two successful mule deer hunts were in what would be lost in the Winecup Gamble exchange (see below). The diversity of the area in topography, remoteness, weather and low human population makes it desirable. It’s not difficult to venture around the northern edge of the Great Basin and have it to yourself for several days. I’ve spent the last 30-some years enjoying the history, wildlife, geology and culture that this part of Nevada has to offer.

Nevada Chapter Board Member

YOU SOUNDED THE ALARM IN NEVADA ON THE POTENTIAL WINECUP GAMBLE LAND EXCHANGE, WHICH WOULD TRANSFER 235,000 ACRES OF BLM LAND IN EXCHANGE FOR 85,000 ACRES OF PRIVATE RANCH AND COULD HAVE RESULTED IN A LARGESCALE LOSS OF PUBLIC LAND ACCESS (ALONG WITH NUMEROUS OTHER POTENTIAL ISSUES) AND THE LOSS OF SOME OF THE BEST MULE DEER HUNTING IN THE REGION. HOW DID YOU FIND OUT ABOUT THE ISSUE? AND WHAT INSPIRED YOU TO TAKE ACTION?

First of all, I was not alone in this endeavor. There were members from a slew of entities concerned about this proposal. When we first heard of the proposal, information was scarce and what was known was first thought to be rumors. The more we dug through public-records requests, talked to employees of the state and federal agencies involved and asked the right questions, the more concerned we became; what we thought first were rumors turned out to be facts. So, we sat down, researched and obtained information about those involved and compiled our information. I then volunteered to contact the NGOs who were reportedly informed by Winecup Gamble, along with what we thought were the proper NGOs to help start digging deeper into this. That led me to BHA and BHA Chapter Coordinator Dre Arman. She showed interest in this and kept in contact with me exchanging information as it came up. This issue needed to be addressed quickly, and what information we had needed to be shared with the public. We also needed to make sure that those tied to the WG land swap proposal were aware that we as public land users were not happy with their ideas. Every time there was a chance to voice our opinion, we were there, voicing it.

We got our point across, which made the WG folks backtrack for the time being. But I know this issue is not over.

WHAT IS MOTIVATING YOU IN YOUR WORK WITH BHA?

All the motivation I need is to know where I can go may someday be lost, and to also know what the country used to look like prior to poor land use and management practices.

WHAT ADVICE WOULD YOU GIVE OTHER BHA MEMBERS IN STAYING VIGILANT AND SAFEGUARDING THEIR LOCAL PUBLIC LANDS, WATERS AND WILDLIFE?

If you care, get involved.

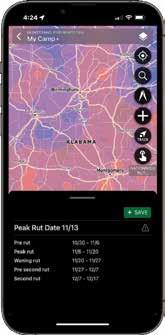

WHITETAIL RUT MAP Unlock the most extensive Rut Map in the country

WHITETAIL ACTIVITY FORECAST Plan your hunt around peak movement times

Join millions of hunters who use HuntStand to view property lines, find public hunting land, and manage their hunting property. Enjoy a powerful collection of maps and tools — including nationwide rut dates and a 7-day whitetail activity forecast with peak deer movement times.

WHITETAIL

Download and map for FREE!

BHA’s Backcountry Bounty is a celebration not of antler size but of BHA’s values: wild places, hard work, fair chase and wild-harvested food. Send your submissions to williams@backcountryhunters.org or share your photos with us by using #backcountryhuntersandanglers on social media! Emailed bounty submissions may also appear on social media.

Hunter: Josh Westlund, BHA life member, and Huey (first retrieve!) | Species: mallard | State: Maryland | Method: shotgun | Distance from nearest road: two miles

Transportation: foot

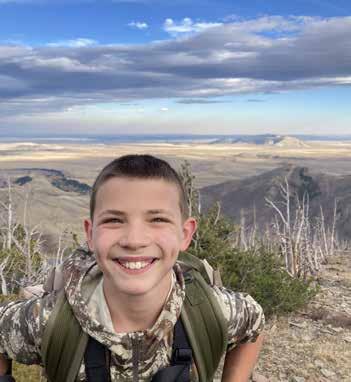

Angler: Will Barry (12), BHA life member | Species: lake trout State: New York | Method: spinning | Distance from nearest road: 7 miles | Transportation: packraft/foot

Hunter: John Perdaems | Species: bison | State: Montana Method: rifle | Distance from nearest road: 30 miles

Transportation: horseback

Hunter: Tucker Jensen, BHA member, and Tsuga | Species: blue grouse | State: Washington Method: shotgun | Distance from nearest road: one mile

Transportation: foot

Hunter: Hunter Goodwin, BHA member | Species: whitetail State: Arkansas | Method: rifle Distance from nearest road: two miles | Transportation: foot

Hunter: Jeff Lewis, BHA life member | Species: cougar State: Oregon | Method: rifle | Distance from nearest road: one mile | Transportation: foot

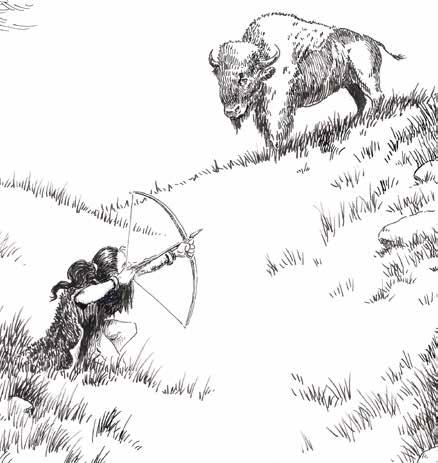

BY RON ROHRBAUGH

Before the sun had fully broken the eastern horizon, Pony could hear the bull – her bull – grunting and splashing in a wallow below her. As shafts of warm yellow light revealed the prairie’s details, Pony could see the bull’s outline. He was looking west toward a herd of cows, grazing on a hilltop ablaze with colorful wildflowers. Pony couldn’t let the bull go to the distant herd or he’d surely slip away. Her pulse quickened as she knew what had to come next.

Pony pulled a small buffalo hide over her body in hopes of tricking the old bull into thinking she was a young challenger. She paused a minute, thinking what a foolish idea this was, before getting up her nerve to crawl from the cover of the sand plums into the wide-open prairie. There was no going back now. Amazingly, the rut-crazed bull remained fixed on the herd of cows, completely unaware of Pony.

Closer and closer she crawled, her heart hammering as she closed the distance to just 50 yards, not knowing exactly what would happen but certain this was her destiny. Pony grunted in her best imitation of a young bull buffalo that was trying to horn in on the old bull’s herd of cows. There was no response from the bull. Pony waited a few seconds and grunted a second time. This time, she saw the bull’s ears swivel. He had clearly heard her but did not turn to look. Again, Pony waited.

at full draw. The arrow sped toward the bull’s chest as if it was guided by the pure will of her ancestors.

The third grunt took more courage than the first two. The bull knew she was there. What would he do if she challenged him again? She glanced at her bow to be sure an arrow was nocked and ready. She put her right hand to Echo’s neck knife and let out a long, aggressive grunt. Ooooo-ahhh!

The bull spun his 1,800-pound bulk with remarkable speed and began walking to Pony. He swung his enormous head from side to side, moving in an odd sideways walk meant to make him look even bigger. Pony moved too, pivoting to keep the bull broadside to her. She could not shoot the bull if it was facing her.

At 30 yards, the bull thrust his enormous head upward, pulling great quantities of air into his oversized nostrils. He was testing for danger. Hidden beneath her hide, Pony shook like a scared dog, waiting for what might come next. But the bull could not detect her human scent. Heated air from the rising sun pulled Pony’s smell up and away from the enraged animal.

He kept coming in his sideways walk ... 25 yards, 20 yards, 15 yards. At 10 yards, Pony could see rage in the bull’s eyes and smell the pungent urine coating his underbelly. At this range, if he charged, Pony would stand no chance of jumping out of the way. She’d be dead, and that’s all there was to it.

Eons of her people’s sorrow, guts and grit filled her hunter’s heart, giving Pony the courage for what must be done. “For those who came before,” Pony whispered to herself as she threw the hide from her back and rose to one knee with her buffalo bow already

There was a blur of brown hide and a sound like tearing canvas, as the bull spun, thundering over the prairie straight into the rising sun, where he vanished as if he had never been there.

Breathing hard, Pony dropped to her hands and knees to pull herself together. She sat on the prairie, allowing the sun to wash over her for as long as she could wait, which was not very long. She had to know. Did her shot end a 150-year-old struggle for tribal redemption or had she failed them again?

BHA member Ron Rohrbaugh is a professional conservation scientist and award-winning author. His recent works include LIVING WILD, an adventure/historical fiction series for kids and Tine to Table, a collection of essays and recipes. Ron’s book Echo was recently named Book of the Year by Children’s Book International. Ron travels the country full-time in an RV with his family, where he’s on a mission to help save wild places, share wild food and be every child’s gateway to nature. You can follow their adventures on Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram @ The Living Wild Family.

This story was excerpted from chapter 38 of The Last Prairie, which is book two in the award-winning LIVING WILD with the Orions series, appropriate for kids ages 8-14 and up. In The Last Prairie, 12-year-old woodsman Echo Orion and Pony Proudchief find themselves in the middle of a 150-year battle that began when market hunters destroyed the bison that was the Native American’s lifeblood. As Pony’s Osage Tribe seeks to recover a piece of their lost world, they must battle a new foe that threatens their modern-day Grand Bison Hunt.

the hike. the hunt. the harvest. the adventure. the journey. the spot. the story. the meal. the catch.

the fearless

Get 10% off any order with discount code BHA10

BY BRYAN JONES

This fall the public’s right to hunt will take center stage on the ballot in Colorado with a proposed ban on hunting mountain lions, bobcats and lynx (a federally protected, non-huntable species). Not only would this hunting ban define in Colorado state statute the legal hunting of multiple wildlife species as “trophy hunting,” it would also classify “trophy hunting” as a Class 1 misdemeanor.

BHA strongly opposes Propostion 127, and our concerns extend far beyond preserving hunting traditions; they are deeply rooted in the potential dangers this ban poses to wildlife management, conservation efforts and funding, and the broader ecosystem.

For more than a century, hunters and anglers have played a pivotal role in wildlife conservation across North America, guided by the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation. This model ensures that wildlife is managed for the benefit of all citizens, a success made possible largely due to the financial contributions of hunters and anglers. Through licenses, excise taxes and other direct contributions, these efforts have been critical in supporting habitat restoration, species reintroduction and the establishment of protected areas.

BHA is deeply concerned that Colorado’s proposed hunting ban could jeopardize this proven model of wildlife conservation. The initiative, driven by public opinion and emotional appeal over scientific expertise, risks dismantling the carefully structured processes that have allowed wildlife populations to thrive. Our primary objection lies in the method of pursuing this ban through

a ballot initiative – a tool that, while democratic, can oversimplify complex issues and lead to decisions that may not align with the best available science.

Wildlife management is a specialized field that requires a deep understanding of ecological dynamics, population biology and species interactions. Decisions made by popular vote, rather than by scientific evidence, carry a significant risk of unintended and potentially harmful consequences.

Moreover, banning public hunting does not eliminate the need for population control. To prevent overpopulation and its associated issues – such as increased conflicts with humans and ecological imbalances – the government will still need to intervene. This often involves employing contract hunters for hire. Unlike public hunting, which is regulated and contributes to conservation funding, contract hunting is costly for the state, diverting resources away from other crucial conservation efforts. This could lead to misunderstandings about the effectiveness and necessity of wildlife management practices, potentially undermining public trust in the science-based methods that have been successful for decades. Contract hunting is also a waste of both opportunity and resources, including the potential waste of the meat derived from the current hunting of these animals. Colorado has strict laws governing the wanton waste of big game animals, and mountain lions are no different. Not only are the harvested animals required to be inspected by Colorado Parks & Wildlife biologists, but the meat is also required to be taken and consumed. Despite what proponents of this initiative may

state, mountain lion meat is well regarded and can be utilized in a variety of recipes.

Professional wildlife managers, trained in the complexities of ecosystems, should guide decisions about wildlife populations. These experts manage predator numbers through various scientific methods, including regulated hunting, to ensure that prey species are not over-exploited, which is crucial for maintaining the health of the entire ecosystem.

Bypassing these scientific processes in favor of public opinion could undermine decades of successful wildlife management. Without the ability to manage mountain lion populations through regulated hunting, we could see a cascade of negative effects throughout the food chain, ultimately harming the very wildlife this ban aims to protect.

It is also important to recognize the broader implications of such a ban. Economic impact assessments for this initiative predict that the state could lose an estimated $410,000 annually from mountain lion hunting license sales alone, with additional losses from bobcat hunting licenses as well. More concerning, however, is the potential cascading effect on the state’s revenue from elk and mule deer hunting due to decreasing tag allocations and potential loss of licenses fees for those prey species.

As hunters and anglers, we are not just financial contributors; we are stewards of the land and wildlife. The deep connection to the natural world gained through hunting and angling fosters a profound sense of responsibility for sustainable management. This stewardship is essential to wildlife conservation and should not be sidelined by initiatives that fail to recognize its value. While BHA supports greater public involvement in wildlife management, we believe this should occur within the existing framework, which has proven effective over time. Public input is vital, and we welcome a diverse range of voices, including nonconsumptive users, in the conversation. However, this should not come at the expense of sidelining hunters and anglers or undermining science-based management practices.

In conclusion, our opposition to the proposed Colorado mountain lion hunting ban is not about excluding the nonconsumptive public from the conversation. It is about ensuring that wildlife management decisions are based on credible science and guided by professional expertise. The risks of politicizing wildlife management through ballot initiatives are significant, and we urge that proven conservation methods not be discarded in favor of processes that oversimplify complex ecological issues.

As Coloradans consider Propostion 127, it’s crucial to recognize the dangers this ban could have on wildlife management, conservation efforts and the broader ecosystem. BHA calls for a more inclusive and informed approach to wildlife management – which respects the contributions of hunters and anglers and upholds the principles of science-based management.

Bryan Jones was born and raised in Colorado with a passion for the outdoors. He served in the U.S. Marine Corps for 10 years before earning a degree in fish and wildlife management. His experience in conservation and wildlife management was developed while serving in both public and private lands management roles, and he holds a master’s degree in natural resource stewardship from Colorado State University.

Ingredients:

Mountain Lion Carnitas Servings: 6 by Bryan

Jones

• 3 pounds mountain lion meat (from the shoulder or hind quarter works well)

• ½ pound of lard or other rendered fat

• 1 cup fresh squeezed orange juice (store bought will work)

• 3 cups water

• 4 cloves of garlic

• 1 tablespoon cumin

• 2 teaspoons kosher salt

• 1 teaspoon course ground black pepper

• Tortillas, your favorite Hatch green chile salsa, cilantro and onions for serving

Instructions:

1. Cut meat into 2-inch cubes, add to a large pot with the lard, juice, water and spices. Bring to a boil and then simmer uncovered on low for 2 hours. Do not touch the meat.

2. After 2 hours, turn heat up to medium-high and continue to cook until all the liquid has evaporated, and the fat has rendered (about 45 minutes). Stir a few times, to keep meat from sticking to bottom of pan.

3. When meat has browned on both sides, it’s ready (there will be still be liquid fat in the pan). Serve either cubed or shredded (meat will be tender enough that just touching it will cause it to fall apart) with tortillas and Hatch green chile salsa. Enjoy!

BHA members in California combine boots-on-the-ground effort with policy work to improve big-game habitat

BY DEVIN O’DEA

Alpine lakes punctuated by pines slowly shift to sagebrush steppe and grasslands on the annual, arduous migration of the Loyalton-Truckee Deer Herd. The mule deer summer along the northeastern edge of the Sierra Nevada mountains and migrate approximately 26 miles to reach their winter-range habitat along the California and Nevada border, a trip with a terminus at the deadly Highway 395 – one of California’s 12 priority barriers to wildlife movement in the state.

Unfortunately for the ungulates who rely on bitterbush to survive the snowy seasons, much of their winter-range habitat has burned in recent massive fires fueled by invasive species like cheatgrass. Formerly abundant stands of bitterbrush, sagebrush and mountain mahogany at the Hallelujah Junction Wildlife Area have been replaced by pepperweed, medusa head and cheatgrass interspersed among a few native grasses and shrubs. This native flora is critical to the health of our migratory mule deer herds, pronghorn, bighorn sheep, sage grouse, pollinators and more, and their disappearance from the landscape underscores the need to invest in restoration of the sagebrush steppe habitat, native grasslands and the ecosystem integrity of our public lands – or else face the precipitous decline of our wild, iconic wildlife in the West.

Recognizing the severity of the situation, then Department of the Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke issued Secretarial Order 3362 in 2018, “Improving Habitat Quality in Western Big-Game Winter Range and Migration Corridors,’’ a landmark commitment to conservation that was lauded by BHA and partner organizations

across the board. The order called upon state, tribal and territorial wildlife agencies to “improve habitat quality and western big game winter range and migration corridors for antelope, elk and mule deer” as well as foster “improved collaboration with states and private landowners.” Pursuant to the order, select Western states developed action plans for their migratory deer, pronghorn and elk herds, which helped to inform distribution of federal funds earmarked for conservation.

The National Fish & Wildlife Foundation’s conservation grant program is one of the ways in which SO 3362 objectives were administered, and BHA was thrilled to receive $165,000 for our ongoing Hallelujah Junction Wildlife Area Post Fire Rehabilitation and Connectivity Project. BHA is leading the project in collaboration with the Department of Fish & Wildlife, the Washoe Tribe, the Sagebrush in Prisons Project and the Wildlands Network. This large-scale rehabilitation project seeks to restore critical winter range habitat for the LTH mule deer, pronghorn and elk in the region while simultaneously incorporating many plants of cultural significance to the Washoe Tribe. In addition, the project leverages the work of Wildlands Network along 395 to study wildlife movement through existing culverts and at-grade crossings to help inform priority areas for wildlife crossing infrastructure and investments – an effort that has helped to galvanize funding for a wildlife crossing structure along Highway 395 just north of the project area.

Last fall, BHA volunteers from across California and Nevada gathered to plant thousands of bitterbrush seedlings grown by inmates at the nearby Federal Correctional Institution, Herlong, through the voluntary Sagebrush in Prison Project. This program,

managed by the nonprofit Institute for Applied Ecology, has grown over 3.5 million sagebrush and bitterbrush plants used to restore sagebrush steppe ecosystems across the West. According to one formerly incarcerated participant in the program, “It’s really good giving back. I logged for a lot of years before I was incarcerated. So, it was a good feeling just to be back in the environment and knowing they’re going back out to help habitat and burned areas.”

This year, BHA is expecting 10,000 more bitterbrush plants from the Sagebrush in Prison Program, and volunteers will be gathering the weekend of October 25-27 for the annual Beer, Bands & Bitterbrush Stands event to help put them in the ground. This volunteer work party is followed by a real party in the evening, which includes on-site camping, live music, a wildgame potluck, raffles and more – all in an attempt to get more people to participate in the restoration project while building community and awareness of habitat loss across the Great Basin.

Later this year, BHA’s funding from the National Fish & Wildlife Foundation for this winter range rehabilitation project will be all but spent, with many millions more acres yet to be treated across the West. That’s why BHA has shared our enthusiastic support for the Wildlife Movement Through Partnerships Act, legislation introduced for the first time ever by Sen. Alex Padilla (D-CA) and Reps. Ryan Zinke (R-MT) and Don Beyer (D-VA).

The bill would build upon collaborative efforts to conserve big game migration corridors in conjunction with SO 3362 and the Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program passed within the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in 2021. Promoting habitat connectivity for migratory species and improving habitat quality by providing financial and technical assistance to state and tribal fish and wildlife agencies, private landowners and nongovernmental organizations. It would also direct the Department of the Interior, Department of Agriculture and Department of Transportation to coordinate efforts with those entities. Included within these directives are the establishment of the State and Tribal Migration Research Program, to collect, research and analyze data on wildlife movement corridors, and the Wildlife Movement and Movement Area Grant Program, to improve or conserve habitat through projects including habitat leases, fence modifications, and reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions. Fifty

percent of funds would also be directly allocated for conserving big game species including mule deer, elk, pronghorn, moose and wild sheep, which expands the original scope of SO 3362 while still maintaining a focus on big game.

Mega-fires, biodiversity loss, climate change and partisan politics often dominate our news feeds and can be daunting and relentless. When faced with this onslaught of cynicism, we have a choice: Stick our heads in the sand and kiss our way of life goodbye – or get to work and do something about it. This October, hunters, conservationists, vegans and volunteers from three generations will be gathering under a common banner to buck the notion that there is nothing we can do to help native wildlife and to preserve our North American heritage of hunting and fishing in a natural setting. Meanwhile, we will continue to applaud our elected leaders – on both sides of the aisle – who are fighting for legislation that bolsters our efforts on the ground.

Devin O’Dea grew up abalone diving, spearfishing and backpacking in California before discovering a love for bowhunting and wing shooting. He worked for an environmental consulting firm and as a marketing manager for an archery division of Mitsubishi, but the allure of adventure, wild food and wild places led him to his current role as the western policy and conservation manager for BHA.

BY JAMIE CAMERON

Raise your hand if you’re a get-your-hands-dirty, give-up-yourweekend-to-volunteer, shout-from-the-mountaintop member of BHA. Keep ’em up if you scour your state chapter’s social media accounts for the next river cleanup, hunting-skills camp, pint night trivia or group campout to drive halfway across the state so you can show your support.

There’s no shortage of willing donors of blood, sweat, time and tears in this organization. It’s the bedrock of our commitment to the mission “to ensure North America’s outdoor heritage of hunting and fishing in a natural setting, through education and work on behalf of wild public lands, waters and wildlife.”

But there comes a moment in every state chapter’s vision for the future where the question needs to be answered, “How much money do we have for all this?” And for just about everyone here the answer is, “Not much.” And our work could use more; money is a valuable resource to a nonprofit organization, and the effects of every little bit more of it the organization has can be felt in both the quantity and the quality of the conservation work we do.

The North Carolina chapter has been grappling with getting the most it can with limited funding since its inception in 2018. Year after year, its dedicated members have done more with less. But there comes a time where folks start to wonder what they might accomplish if there was more in the bank account, whether it’s the chapters or BHA Headquarters.

Enter North Carolina board members Jordan Linger and Zach Brady. During the past year they’ve seemingly unlocked the secret to reliable income for their chapter’s coffers, in amounts of $300-500, on any given evening, with limited resources, anywhere in the state. Linger and Brady have tapped into the burgeoning craft brewery and distillery industry, and they’re doing it with the inescapable allure of sizzling meat and smoke. They’re flipping wild-game burgers for donations at pop-up “Smashburger” events, and they believe the model they’ve created can be adopted by BHA members anywhere in the nation.

What made you think you could do this?

Jordan: I have a background in the restaurant industry. More than that, though, I grew up in the South, and food was everything to my family. I learned to cook in my grandmother’s kitchen, fixing fried chicken on Sundays after church.

Zach: I grew up with great food and cooks in my family. My first job was washing dishes in a pizza place. When I got older, I helped my father cater events. We entered barbecue competitions with a giant smoker we trailered across North Carolina. Feeding lots of people isn’t a daunting prospect for me.

How do you avoid crossing laws against selling and trading wild fish and game meat?

Jordan: Every state is a little different I’d imagine, but in North Carolina you can stay legal if you ask for a suggested donation (we recommend $8 per burger, $12 for a double) that goes directly to a 501(c)(3) organization. Each state has a health department website that will have the particular regulations that must be followed.

How do you find your locations to host these events?

Jordan: It’s common for breweries to partner with food trucks that take care of that side of serving the customers. But it’s also common for food trucks to cancel: The truck breaks down; staff doesn’t show up; a festival comes to town and draws them elsewhere. Those cancellations put a lot of stress on breweries. You can call places and ask if they have any open dates where you can fill in. You can ask to be put on standby. Just start a relationship with the management and see where it leads.

What does food, specifically wild food, mean to you?

Zach: It’s not just sustenance. Even the simplest meals have someone behind that food. It’s showing appreciation and love for the people you’re serving. When you add wild food to the equation, it adds another layer to the story you’re trying to tell. When someone orders a venison burger at one of our events it’s often the first time they’ve ever thought about eating wild game. From the time they

place an order to the time I’m handing it to them on a plate, we’ve had four or five minutes to connect. During that interaction I can tell them about BHA and the overarching mission. People are generally curious, especially when it comes to food, and almost everyone is using public land in some form or fashion. Cooking a deer burger or a squirrel taco or ladling a bowl of Brunswick stew and handing it to someone is an open and honest invitation to have a conversation about all the things public lands provide to every American and how BHA is working to protect and enhance these places for all of us.

What You Need

• A portable flattop griddle (preferably two, one for burgers, one for buns)

• A burger press

• A dome (or two) for melting cheese

• Seasonings (salt, pepper, garlic powder)

Mise En Place

• Weigh and roll ground meat into balls (we do 1.5 ounces)

• Buns, softened butter and sliced cheese easily accessible

• Cardboard serving trays, napkins and condiments

BHA life member Jamie Cameron is a North Carolina State Parks ranger. As such, his duties include natural resources management, law enforcement, search and rescue and wildland firefighting. His passion lies in opportunities to educate young people about the outdoors and teach them to become stewards of the land.

New air chamber sleeping pads made with recycled ripstop nylon.

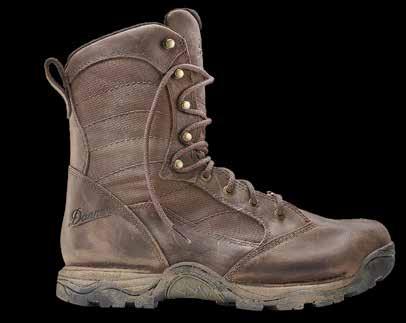

The fifth generation Pronghorn boot is everything you would expect from a legend and more. Featuring our Terra Force® Next™ platform, it’s lighter, faster and built to meet the demands of the hunt. Available online or at your local hunting boot retailer. DANNER.COM/PRONGHORN

BHA chapters across North America are on the frontlines, battling attacks against our public lands and the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation and getting their hands dirty cleaning up public lands and waters.

• The Alaska chapter had a Pop-Up Pint Night in Anchorage on July 24 with a meet and greet with chapter board members and staff. Southcentral was excited for a BHA resurgence in the region.

• This year, the Alaska chapter, along with the Armed Forces Initiative and service members from Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, installed the final fencing along the Russian River ahead of the salmon opener. They worked alongside Forest Service and StreamWatch volunteers to place barriers and fencing protecting sensitive sites and archaeological digs. As they worked, they were regaled with stories and photos from the past, which showed the level of destruction before organizations stepped in to help.

• The chapter is planning its first annual board retreat on Kodiak Island around an invasive species removal of crayfish from Buskin Lake, a collaboration with the Sun’aq Tribe.

• The Arizona chapter completed volunteer improvement work on Perrin Ranch, which participates in the Adopt-A-Ranch program through the Arizona Game and Fish Department.

• Three separate showings of the Full Draw Film Tour were held throughout the state. The participation from the hunting community in Arizona was outstanding.

• A variety of events were held this fall for supporters of BHA, including a sporting clay shoot, mushroom hunt, family squirrel camp, volunteer work at Diablo Trust and pint nights.

• Arkansas Game and Fish Commission Large Carnivore Biologist Myron Means reports that remote cameras purchased with a donation from the Black Bear Bonanza are being used with great success. The cameras allow biologists to target specific bears for collaring or other research and also ensure safe capture when cubs are involved.

• The chapter has recently joined as a founding member the Arkansas Conservation Coalition – a group of conservation organizations that will unite to form a strong voice at the state and federal levels.

• The chapter held a Public Land Pale Ale release party at Flyway Brewery

on Sept. 12. BHA partnered with breweries across the nation to celebrate Public Lands Month.

• The Arkansas Public Waters Committee hosted the Lake Bob Kidd cleanup on Sept. 7.

• The Arkansas chapter is currently seeking volunteers to help with projects and events across the state. If you would like to get more involved, please reach out to arkansas @backcountryhunters.org

• AFI has been busy with many stewardship projects over the last quarter, giving veterans an opportunity to find a new mission in conservation, post-service. Events included fence pulls in Colorado and Montana, a range cleanup on Kirtland Air Force Base and a cleanup/goose-banding event in Nebraska.

• Reach out to your local chapter’s AFI liaison for ways to get involved next quarter!

• Our Annual General Meeting was held in June. The chapter welcomed Andrew Van Vliet as Provincial Chair and Steve Nikirk as Co-Chair. We thank Alan Duffy for his passion and dedication as past chair, as he continues on as the chapter’s conservation director.

• The chapter is participating in the provincial CWD working group, advocating for appropriate management of the disease by the province.

• Regional tables held several events: range and firearm safety day, trap shooting and learn-to-butcher, along with hosting educational speakers.

• The chapter held a Beer & Deer Pint Night presented by onX with North American board member J.R. Young.

• The chapter continued work protecting public access to the Truckee River, including engaging with state law enforcement agencies.

• The chapter continues to monitor the ongoing draft Black Bear Management Plan, identifying potential areas for expansion of hunting opportunities.

• Jerod Swanson volunteered to be the chapter’s Central Rockies assistant regional director, and Jarret Childers volunteered to be the chapter’s Southwest Colorado assistant regional director.

• The chapter joined our partners at Trout Unlimited in establishing Sportsmen for the Dolores, a coalition of hunters and anglers aimed at conserving fish and wildlife habitat and sporting opportunities in the Dolores River watershed of southwest Colorado.

• The chapter supported the Thompson Divide Mineral Withdrawal, protecting the region from proposed oil and gas development.

• Amendment 2, “The Right to Fish and Hunt,” will be on the ballot in Florida this November. Vote Yes!

• In June, the chapter hosted a deer-scouting educational event at Riverbend Park in Jupiter.

• This December the chapter will host a small game hunt at Dinner Island Ranch.

• The Georgia chapter has been monitoring new saltwater fishing regulations and the proposed mine at the Okefenokee Swamp.

• Idaho chapter members floated from Challis to Salmon for the 6th Annual Cleanup and Invasive Weed Pull along the world-renowned Salmon River.

• In North Idaho, members gathered for a foraging and forest health hike, where they learned about silviculture, as well as how to make syrup from foraged spruce tips.

• Members near Irwin spent a Saturday removing three dump trailers of barbed wire and other debris from the BLM’s newly acquired Irwin Recreation Site.

• The chapter spent the summer traveling the state with the Muddy Waters Tour. The tour is a compilation of several opportunities and events across Illinois designed to increase awareness, education and involvement in the conservation of Illinois waterways. If interested in hosting an event this fall, reach out to the chapter.

• The chapter hosted the Full Draw Film Tour at the historic Artcraft Theater in Franklin. The event was a wild success and our largest fundraiser of the year.

• The chapter has continued its work opposing the Benjamin Harrison National Recreation and Wilderness Establishment Act legislation (S. 4402, previously S. 2990), which seeks to halt USFS management projects that would diversify forest age class, improve oak-hickory systems and address the rapid decline in Indiana’s grouse population.

• With the Indiana DNR, the chapter hosted a frog giggin’ event at Goose Pond Fish and Wildlife Area, with over 50 attendees learning how to gig for frogs.

• In July, the chapter worked with the property manager at the 10,000acre Willow Slough FWA to remove old waterfowl resting area signs and install new ones. This project opened up some previously restricted areas to hunting and helped to improve the quality of the resting area, which will benefit all migratory birds.

• In June, the chapter completed its inaugural Bluegill Bash. Participants spent Father’s Day catching lots of panfish.

• The chapter auctioned off an Iowa Governor’s deer tag. $30,000 was raised with half of the proceeds going to the Iowa DNR and the other half to BHA.

• In August, the chapter held a gear swap at the VFW in Des Moines.

• In May, Kansas chapter members worked on clearing a new 40-acre tract of land at Sandhills State Park in Hutchinson. This area has hiking and equine trails and is open to limited public hunting access.

• In June, members hosted a Public Lands Appreciation Sporting Clays Shoot for Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks public-land workers and their families. Walton’s provided bratwursts for lunch for all who attended.

• Also in June, BHA members worked to clean up the iWIHA area by Overbrook and partnered with the Pass It On program to help youth work on cleaning up a public shooting range by Jetmore.

• In May, the chapter held a 5th Anniversary Pint Night with TU, a Derby City Fly Fishers Pint Night, tabled at the Kentucky Elk & Outdoor Fest and held a Post-Season Turkey Talk and USCE Fish Habitat Build.

• In June, the chapter held a statewide event called Small Game Boot Camp, along with a How-To-Hunt Fort Knox Pint Night and an archery practice event.

• In July, the chapter held the Fire, Grasses and Beers Pint Night, a LearnTo-Fish Pint Night, a 7th District Pint Night, archery practice and a Higginson-Henry WMA Workday.

• The chapter board was asked to offer advice on whitetail management by the DNR, allowing us to weigh in on public land conservation in the state.

• The chapter held its annual Michigan Rendezvous with educational presentations, fun events, amazing raffle items and some delicious food as the focus of the weekend.

• Once again, the chapter partnered with the USFS to pull old cattle fencing on public land, helping both wildlife movement and hunter access.

• The chapter kicked off the summer with a great 3D archery event at Maryland’s famed Big Truck Brewery. They have a great 3D trail course, and the chapter is grateful to have been hosted by them. We’re looking forward to next year’s event!

• The chapter’s second annual Richmond Lowcountry Boil was held in early August with continued success. This event serves as a great outreach opportunity for the region, and we look forward to growing this event in the years to come.

• The chapter will host our Public Lands Pack-Out in partnership with the Virginia DWR at the C.F. Phelps Wildlife Management Area again this September for Public Lands Month.

• The chapter partnered with federal agencies USFS and USACE to clear trails and install waterfowl houses on public lands.

• The chapter kicked off deer season hosting several CWD-focused pint nights and sponsoring the Minnesota Governor’s Deer Opener.

• The chapter played a vital role in advocating for clarification on dog leash rules for Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness hunters.

• The Missouri chapter relaunched operations in Springfield thanks to new chapter leaders Casey Callison and Aaron Samek! Please check out the chapter website or Instagram to learn more.

• The chapter had a busy summer with several pint nights, archery shoots, Full Draw Film Tour dates and public-land stewardship events.

• The chapter is looking to expand into the Columbia area for 2025. Please send us an email (Missouri@backcountryhunters.org) and let us know if you are interested in seeing BHA events in Mid-Missouri!

• The chapter celebrated a major legal victory in the UPOM case; a District Court judge denied UPOM’s motion for summary judgment, reaffirming the Public Trust Doctrine and ensuring wildlife remains public and not a private commodity.

• The chapter completed seven public land stewardship projects, ranging from fence removals to trail maintenance, with over 50 volunteers. Thank you to Timberline Ace, Gastro Gnome, Black Coffee Roasting Co. and RightOnTrek for supporting these projects!

• The chapter joined partners for the Ducks Unlimited duck-calling competition at the Sitka Depot, brought together members at a Missoula Paddleheads Game, raised awareness with Willie’s Distillery and joined the Gallatin Forest Partnership’s Wildlife Backyard Bash.

• Chapter leaders and members continued a fence removal project started last year in Halsey National Forest.

• Thank you to the Nebraska Bowhunters Association for allowing us to set up a BHA information tent and share in the festivities at the Jamboree.

• Chapter members helped rebuild fence at Hickory Ridge WMA back in August. A big thank you to all who attended.

• The Nevada chapter hosted a range day in Carson City and helped 20plus hunters get sighted in for the season ahead.

• Chapter board members volunteered with the Nevada Department of Wildlife to host hunter education.

• Monthly pint nights continue on the third Wednesday of the month at IMBIB Reno.

• Nevada Chapter Policy Co-Chair Molly Beaupre attended the BLM Nevada Recreation Summit in Reno to provide input on the challenges and opportunities we face in outdoor recreation on Nevada public lands.

• The chapter continued investing in Atlantic striped bass release mortality research being conducted by the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries.

• The chapter assisted with camera trap placement, checking and maintenance for the University of New Hampshire’s Wildlife Management and Modeling Lab.

• The chapter sponsored the Rhode Island Youth Waterfowl Training & Mentored Hunt, organized by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management Fish & Wildlife Division.

• Chapter members worked with Forest Service staff to repair and replace fencing around the Sargent KV trick tank in the San Mateo Mountains in order to exclude cattle from the area but still allow wildlife access.

• Over the course of three stewardship events, chapter members have improved wildlife connectivity on over 10 square miles of habitat on the Rio Grande Del Norte National Monument. In June, they removed 1.5 miles of old fencing, which was replaced with wildlife-friendly fencing by the BLM. In July, they modified one mile of fencing to meet the wildlife-friendly fencing guidelines. In August, chapter members removed almost two miles of netwire fencing, reducing the chance of wildlife entanglement.

• The chapter hosted a Full Draw Film Tour event in Albuquerque and had a great turnout.

• Chapter volunteers worked alongside the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish biologists and volunteers from RMEF on the Marquez/L-Bar WMA to remove fencing, which will improve habitat permeability for crucial elk calving areas.

• The chapter worked to push a bill granting more flexibility on licensing and tagging methods (including electronic) and to remove the requirement to wear a back tag. The bill was passed and signed into law just before session closed.

• The chapter partnered with Hunters of Color and Columbia Land Conservancy to host a weekend turkey camp for 10 new hunters of color. Hunters were on birds both days, and one hunter even tagged out!

• The chapter hosted an event at Filson NYC with Melanie Sawyer, a New York-based contestant from Alone Season 10. Melanie put on an amazing presentation, showing the gear and skills she used to survive 43 days in the wild.

• The chapter partnered with the Armed Forces Initiative to reconstruct a long-ago decommissioned fishing pier at Hammocks Beach State Park. The renovated pier will provide public access to fishing in Bogue Sound.