BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL

Hunting and fishing often provide the ultimate escape from the rest of our responsibilities. But sometimes we must step into this part of our lives from another angle, moving from gleeful participant to determined advocate. It’s a requirement of giving a damn, even when it’s inconvenient.

So, I am stepping into this message from another angle. I had fully intended to write this first column as the new president and CEO of BHA about something else entirely, perhaps an introduction of how I found my way to this inspiring role. But that will have to wait. Because the public wildlife grab of our generation is on, and Backcountry Hunters & Anglers has a key role to play.

There is a growing trend across the country to undermine over a century of successful wildlife management built on a foundation of sound, peer-reviewed science. Along with nefarious tactics of special interests to subvert – and even manipulate – the spirit and intent of the public trust doctrine that wildlife is managed for all, we are facing an unprecedented threat to our public wildlife resources. These efforts chip away at the very underpinnings and successful conservation outcomes of the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation.

These increasingly common attacks take on a variety of forms: state ballot initiatives that can sabotage effective wildlife conservation, commoditization of fish and wildlife resources, transfer of wildlife jurisdiction to other agencies, privatization of public wildlife resources by special interests, ideologically motivated changes to the composition of state wildlife boards and commissions, and appointments to these bodies of agenda-driven activists with little regard for serving the public interest.

It’s important to identify challenges where they exist – and where they don’t. Anti-hunting and animal rights activists pose the most obvious threat. On the other hand, ranchers, farmers and other private landowners often contribute to successful wildlife management, provide access for hunting and fishing and in many cases can be counted among our friends. But in certain states, however, factions of those groups are also attempting to seize power from state wildlife agencies.

Would you want elk and pronghorn in your state managed by animal rights activists?

Would you want bear hunting seasons decided by a legislature?

Would you want the deer herd managed as a commodity under the jurisdiction of an agricultural agency?

Would you want private landowners to determine how many tags the rest of the public gets to share after they’re done taking a handful?

All of these nightmare scenarios have already happened, are currently in motion or can be seen threatening on the horizon. It’s

not just the twisted and selfish view of wildlife by special interests that’s so damn galling. It’s the result. Chipping away at hunting and fishing opportunities will ultimately lead to a cascade of either unintended or ill-intended consequences.

As the readers of these pages know from education, experience or just gut instinct, hunting is conservation. Through the sustainable and scientifically guided harvest of wildlife, hunters help maintain the ecological and social carrying capacity of diverse wildlife populations at a landscape scale.

As a larger community of hunters and anglers, we contribute the vast majority of conservation funding, provide critical onthe-ground knowledge to resource managers and often rely on sustainably harvested game as an important food source. For many families, the deer in the freezer is how they get through the winter. The efforts to subvert sound fish and wildlife management not only cuts hunters out of our own conservation legacy and how we provide for our families, but it also ultimately compromises the integrity of the natural systems that support all wildlife.

It’s important to acknowledge this challenge is not new in many states. Some BHA chapters have been navigating these challenges for years, sometimes supported by the contributions of peer organizations and trade groups along the way. As BHA chapters across the country face the unprecedented elevation of attacks on the effective management of public wildlife resources, unifying our collective efforts into an organization-wide initiative is paramount. This clearly has become a national issue.

BHA has a history steeped in giving a damn, and an impressive attendance record when it matters. There’s a saying that “the world is run by people who show up,” and when it comes to taking up the mantle as the voice for public lands, waters and wildlife, the BHA faithful show up. It’s time to leverage the full strength of BHA’s distinctive community and culture to ensure the enduring health and shared value of our public wildlife resources.

-Patrick Berry, President & CEO

“Look deep into nature, and then you will understand everything better.”

- Albert Einstein

THE VOICE FOR OUR WILD PUBLIC LANDS, WATERS AND WILDLIFE

Ted Koch (Idaho) Chairman

Ryan Callaghan (Montana) Vice Chair

Jeffrey Jones (Alabama) Treasurer

Dr. Keenan Adams (Puerto Rico)

Bill Hanlon (British Columbia)

Patrick Berry, President & CEO

Frankie McBurney Olson, Vice President of Operations

Katie DeLorenzo, Western Field Director

Britney Fregerio, Director of Finance

Chris Hennessey, Eastern Field Director

Dre Arman, Idaho and Nevada Chapter Coordinator

Brian Bird, Chapter Coordinator (NJ, NY, New England)

Chris Borgatti, Eastern Policy and Conservation Manager

Kylee Burleigh, Digital Media Coordinator

Tiffany Cimino, Events and Marketing Coordinator

Trey Curtiss, R3 Coordinator

Kevin Farron, Regional Policy Manager (MT, ND, SD)

Brady Fryberger, Office Manager

Chris Hager, Washington and Oregon Chapter Coordinator

Jim Harrington (Michigan)

Hilary Hutcheson (Montana)

Dr. Christopher L. Jenkins (Georgia)

Katie Morrison (Alberta)

Ray Penny (Oklahoma)

Don Rank (Pennsylvania)

J.R. Young (California)

Michael Beagle (Oregon) President Emeritus

Jameson Hibbs, Chapter Coordinator (MI, IN, OH, KY, WV)

Trevor Hubbs, Armed Forces Initiative Coordinator

Bryan Jones, Chapter Coordinator (CO, WY)

Mary Glaves, Alaska Chapter Coordinator

Kaden McArthur, Goverment Relations Manager

Josh Mills, Conservation Partnership Coordinator

Devin O’Dea, Western Policy and Conservation Manager

Brittany Parker, Habitat Stewardship Coordinator

Thomas Plank, Communications Coordinator

Kylie Schumacher, Chapter Coordinator (MT, ND, SD)

Max Siebert, Operations Coordinator

Joel Weltzien, California Chapter Coordinator

Briant Wiles, Colorado Habitat Stewardship Coordinator

Zack Williams, Backcountry Journal Editor

Interns: Robert DeSoto, Sylvie Poore, Harrison Stasik, Taigen Worthington

Andrew Hahne, Habitat Stewardship Coordinator (MT, ID, WY)

Aaron Hebeisen, Chapter Coordinator (MN, WI, IA, IL, MO)

Josh Bent, Charlie Booher, Travis Bradford, Maya Brodkey, Mandy Carlstrom, William Dark Photography, Jan E. Dizard, Corey Ellis, Dwayne Estes, Dr. Pete Eyheralde, PhD, Jeremy French, Paul Keevan, J.J. Laberge, Jordan Lefler, Willis Mattison, Dave Quinn, B.B. Sanders, E. Donnall “Don” Thomas Jr., Lori Thomas, Geneviève Joëlle Villamizar, Chuck Way, Ned Weidner, Theo Witsell, Briant Wiles

“As you approach … from the east, there opens unexpectedly to view an extensive prairie, which contains several thousand acres, and which appears to be without a single tree, or fence, except now and then a small cluster of trees at great distances, like the little islands of a sea. Casting your eye over the prairie, you discover here and there, herds of cattle, and horses and wild deer, all grazing and happy … The grass, which soon will be 8 feet high, is now about 8 inches, and has all the freshness of spring. … The oak … with the sycamore and mulberry, borders the prairie on all sides. Flowers of red, purple, yellow and indeed of every hue, are scattered, by a bountiful God, in rich profusion.” -William Goodell, 1822, Alabama-Mississippi Border.

Close your eyes and imagine for a moment that you were one of the first explorers to step foot in the southeastern United States or one of the first long hunters to cross the Cumberland Gap in search of game. Imagine the smells, sights, sounds, animals, and ecosystems. What did you imagine? Did you imagine traipsing through oldgrowth forests of giant trees and vast expanses of forested wetlands? If so, you may have fallen victim to one of my least favorite myths.

People all across the country are taught the same old tall tale while growing up, what I affectionately refer to as “the myth of the squirrel.” The story goes something like this: Before European settlement, the entire southeastern United States was a rich, dense, old-growth forest. This forest was so vast that a motivated squirrel could theoretically go through the treetops from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi River without ever touching the ground. This tale paints visions of deep, dark forests of towering trees, big squirrels, giant tulip poplars and mosses. But this myth is exactly that – a myth! The idea that the southeastern United States was and should be one vast deciduous forest is simply incorrect, unsupported by both science and the facts of American history. In fact, it is believed that only 40% of the southeastern landscape was made up of closed canopy forests.

So, what was the other 60%? It was the Southern Serengeti.

Millions of acres of savannas, open woodlands, prairies, canebrakes, glades, marshes and barrens made up this complex and biodiverse mosaic of grassland and open woodland ecosystem which depended on fire, bison grazing and elk browsing. These ecosystems were also home to numerous Tribes that relied on them for foraging, hunting, fishing and agriculture. The grasslands were so vital to Indigenous life that Tribes often used prescribed fire to help maintain the grassy components of the mosaic.

It is another common misconception that these ecosystems are characterized as “early successional habitats.” Many of our southeastern grasslands have been open and evolving since the Miocene Epoch – between 23 million and 6 million years ago – to form some of the most complex and biodiverse ecosystems in the world. Many were old-growth grasslands that took millennia to assemble.

It is important to note that while savannas, woodlands and forests are all ecosystems with trees, savannas and open woodlands are very different from forests.

Forests are shaped by closed canopies and moist soils. This creates a moist, low-light environment often dominated by spring ephemeral wildflowers, shade-loving shrubs, mosses and more.

Savannas and open woodlands have fewer trees, with an open understory that is dominated by sun-loving grasses and wildflowers.

“The Southern Grassland Biome, when it is properly defined to include the longleaf pine savanna and its intermittent hardwood bottomlands, is probably the richest terrestrial biome in all of North America. To understand, cherish and preserve the great natural heritage of the Southern Grassland Biome should be a priority goal in America’s environmental movement.”

- E.O Wilson

A map of the Southeastern Grassland Institute focal region produced by NatureServe and SGI depicting areas that had a significant grassland and open grassy woodland component historically (green) and areas that were mostly forested (white).

These were likely the most common ecosystems across the Southeast, ranging from the longleaf pine-wiregrass savannas of the Atlantic Coastal Plain, to the oak-pine savannas of the Gulf Coastal Plain, to the oak-dominated savannas of the Interior Plateaus. They are also among the richest terrestrial ecosystems in North America. This assemblage of over 200 million acres of savannas and open grassy woodlands in the Southeast created a biodiversity hotspot. Every aspect of life in the Southeast was impacted by these ecosystems, whether you were an Indigenous person, early settler, long hunter or just a mussel in a creek bed.

In addition to expansive “wooded grasslands,” the Southeast had about 20 million acres of prairies – nearly treeless, rolling plains dominated by wildflowers and grasses. Some prairies had small clusters of trees here and there, along with embedded wetland marshes, ponds and seeps, which supported entirely different species of plants and animals than the drier uplands. The prairies of the Southeast were once home to roaming herds of bison, elk and deer, prairie chickens, bobwhite quail and even waterfowl like sandhill cranes, whooping cranes and all manner of ducks.

Pennyroyal Plain was one of the largest prairies east of the Mississippi – over 3 million acres in modern-day Kentucky and Tennessee. This once-vast prairie is believed to be how Kentucky got its name. (The word “Kentucky” is likely derived from the Indigenous word “kentake,” meaning “big meadows” or “meadowlands.”) The Pennyroyal was also covered in sinkhole pond marshes due to the karst limestone geology beneath it, and these wetlands undoubtedly served as magnets not only for pioneers crossing the inhospitable prairie but also for migrating waterfowl. (Sadly, of the many prairie

sinkhole ponds in the Pennyroyal Plain, we currently know of just one that still exists in an intact prairie.)

In addition to the Pennyroyal and other large grasslands in Kentucky, there were many other prairies in the Southeast: the Black Belt Prairies of Alabama and Mississippi, which formed an archipelago of prairies in a sea of savannas and woodlands; the enigmatic Piedmont Prairies east of the Appalachian Mountains, which stretched across parts of the Carolinas, Virginia, Maryland and southeastern Pennsylvania; the Cajun Prairies of southern Louisiana; the Blackland Prairies of Texas; the Grand Prairie of Arkansas, sweeping prairies of the Everglades; and even prairies on Long Island, which were once home to the now extinct heath hen.

In addition to prairies, savannas and woodlands, the Southeast had hundreds of thousands of acres of canebrakes. Canebrakes are grasslands that consist almost entirely of our native bamboo species called cane. They historically dominated many riparian zones across the Southeast. These dense groves were critical habitats for many animal species, like the extinct Carolina parakeet, black bears and bison, which also ate the cane. Cane seeds would have fed species like passenger pigeons when they produced millions of seeds at once following mass flowering. Canebrakes were and are still significant to Indigenous people, being used for everything from baskets to weapons and food. The canebrakes of the Southeast were often derided by early settlers because of how thick and tough to travel through they were, and because horses would often gorge themselves on the cane and become ill.

In addition to the landscape-scale grasslands, the Southeast is also home to a variety of glades and barrens – smaller grasslands formed on thin, rocky or chemically extreme soils. Glades are usually flat with exposed bedrock at the surface and very shallow soils. They have distinct wet and dry seasons, with wetland conditions often present in the winter and spring but very dry, desert-like conditions in the summer and early fall. This creates unique habitats with a high concentration of endemic species that occur in particular types of glades and nowhere else in the world. Barrens are similar to glades but have somewhat deeper soil and often occur on slopes. These harsh ecosystems often occur together in complexes and support desert-adapted flora like prickly-pear cactus, yucca and succulent plants like widow’s cross and rock pinks, along with animals like tarantulas, scorpions and rattlesnakes. Some of the highest concentrations of glades and barrens are in the Nashville Basin of central Tennessee and the Ozarks of Missouri and Arkansas. Sadly, the majority of glades and barrens have been degraded by littering, development, fire suppression and encroachment by woody plants like eastern red cedar. (The cedars are a natural component of the ecosystems but were much less common before the widespread grassland degradation, habitat fragmentation and fire suppression that followed settlement.)

Countless species inhabited and shaped the southeastern grasslands. Most of these species have declined or been extirpated entire-

ly from the region– species like red wolves, mountain lions, bison, beavers, elk, and prairie chickens.

Millions of bison and elk used to roam the region side by sideThese two iconic species that today bring to mind pictures of the West were once a staple of the southeastern grasslands and played a large role in the ecology of the region. In addition to these icons, beavers played an integral role by damming rivers, flooding riparian zones and creating lush wet meadows dominated by sedges and wildflowers. The Southeast also supported multiple species of prairie chickens, including the heath hen, which lived in grasslands on Long Island’s Hempstead Plains until its extinction in 1932. The greater prairie chicken was once common in the Pennyroyal Plain of central Kentucky but was eradicated around the 1810s.

I would like to say that we have learned our lesson from these losses and that grassland species are no longer declining. But even today we are watching as beloved species like bobwhite quail are rapidly declining due to habitat degradation. Grassland birds as a whole are in freefall, with estimates of a 53% decline since 1970. That’s a decline of 720 million birds in 50 years. Pollinators, likewise, are in steep decline with the American bumble bee now missing from multiple states.

The grasslands described above are some of the most endangered ecosystems in North America with 0-5% remaining, depending on the type and region.

How could the existence of such vast grasslands, so rich with history, wildlife and game, not be common knowledge?

Sadly, their decline began early, almost immediately following European contact, as early as 1700 in eastern coastal states. The wave of grassland loss from east to west across the Southeast tells a story similar to that of the American bison and passenger pigeon – even things we think are inexhaustible resources can disappear before we even realize they are disappearing.

The decline of grasslands in the East can be attributed to a few primary drivers. First, fire was removed from the landscape. Second, large grazers and browsers such as elk and bison were extirpated from the region. Third, open lands were the first areas to be converted to crops, improved for pastures and covered by towns.

These changes led to savannas changing to closed-canopied unhealthy forests dominated by mesic species. Post oaks, shortleaf pines and blackjack oaks were shaded in and, in some cases, replaced by species such as maples, sweetgums and cedars. These mesic species, which can’t tolerate fire, shaded the understory, depositing dense leaf litter that not only covers and chokes out all the wildflowers but also holds in moisture, making it harder for natural fire to return. Couple this with the removal of large mammals like elk and bison, which would have kept shrubs and saplings at bay by grazing and browsing, and by the 20th century, our once beautiful savanna-woodland communities were degraded to closed canopy second-growth forest.

The degradation and disappearance of prairies is different than that of the savanna but just as devastating. The vast majority of the prairies of the Southeast have been plowed under and turned into crop fields. The more arable lands were converted into what is now cotton, corn and soybeans, or similar crops. This is the case for places like the Pennyroyal Plain of Kentucky, the Loess Plains of Tennessee and the Black Belt Prairies of Alabama and Mississippi.

This same story can be told across the South. The agricultural industry was built on top of prairies. In addition to the plowing of the prairies, we saw the conversion of our bison and beaver-maintained lush meadows converted to non-native Eurasian pastures dominated by detrimental grasses like fescue. The prairies, savannas and woodlands that Daniel Boone once hunted were destroyed. Only tiny fragments remain with a few people and organizations trying to restore them.

“The physical features of Washington County have undergone a very decided change in the last sixty years. When the pioneers first made it their home there were large areas of prairie which are now covered with a more or less dense growth of timber. The site of Fayetteville and several of the surrounding elevations, as well as the intervening valleys, were bare of timber, and were covered with a luxuriant growth of grasses, which afforded excellent pasturage for buffaloes and other herbivorous animals.”

-History of Washington County Arkansas, 1889

These grasslands are at the very core of what it means to be from the Southeast, yet their place in American history has largely been forgotten. Because these grasslands began disappearing before the United States ever became a country, many Americans don’t realize the impacts they had on the patterns of human migration and settlement in the region.

For example, let’s take the booming city of Nashville, Tennessee –full of giant skyscrapers, tour buses and bars. Every day thousands of people commute in and out of the city and have no idea that the reason Nashville exists is that before it was known as Nashville it was known as French Lick. Bison, elk and deer would congregate to lick the natural mineral deposits and graze the rich meadows and savannas. The highway system surrounding Nashville was built upon old bison trails leading to and from French Lick in modern-day downtown Nashville. Stories like this play out all over the Southeast.

The longleaf and shortleaf pine trees that built the South were foundational pieces of the region’s savannas and woodlands. The lumber from these trees can be found in many historic buildings and historic ships. The resinous sap of these trees was processed into turpentine, pitch and tar, which were used for waterproofing wood and many other applications of shipbuilding vital to the economy and the American Navy during the early settlement period. These trees, which require fire and open stand structure to thrive, shaped the very settlement and economy of the southeastern United States.

Whether you are a sportsman or sportswoman, a bird watcher, a researcher or just a conservationist at heart, grassland conservation in the Southeast is one of the most important fights in our lifetime. When we talk about restoring species like elk in the Southeast, declining bobwhite quail numbers or declining wild turkey numbers, we are only hinting at the true problem: the loss of grassland and open woodland species of which 99% of the grasslands are gone.

If we want our children’s children to have the opportunity to go afield and enjoy not only these wild places but the creatures that inhabit them, the first step is to acknowledge the existence of the southeastern grasslands. The second step is to decide as a community that we have seen enough loss and step in and save these special ecosystems.

Currently across the Southeast, we are watching as the last precious remnants of the grasslands, the seed sources needed to restore large areas of these habitats, are disappearing forever. We are watching as seed and rootstock banks of keystone wildflowers die under heavy leaf litter, prairies are plowed under and glades are developed. The chances to turn back the tide of grassland loss are diminishing by the day.

But we have an opportunity to have one of those rare moments in conservation history – where we decide to save something before it’s too late. Sportsmen and sportswomen saved species like whitetail deer, wild turkeys, sandhill cranes and more. Here we have an opportunity to decide to save grasslands in the Southeast. The good news is that currently, seed sources still exist, savannas can be revived by fire and selective tree removal, and the remnants that still exist can be used to replant millions of acres. If we act strategically, elk could again roam expansive savannas, deer can bound through plentiful prairies, and we can enjoy the whistle of bobs and the thunder of turkeys on a spring day. It starts with a decision to save Southeastern Grasslands.

Jeremy French is the director of stewardship at the Southeastern Grasslands Institute and an ecologist, author, historian and avid outdoorsman and wilderness explorer. He spends most of his time working but enjoys wilderness trips, hunting, fishing, botanizing, wandering and rockhounding when not working to conserve biodiversity.

If you want to learn more about saving the Southern Serengeti visit www.segrasslands.org and follow The Southeastern Grassland Institute on social media.

“The

buffaloes were more frequent than I have seen cattle in the settlements, browsing on the leaves of cane, or cropping the herbage of those extensive plains.” -Daniel Boone, 1775, Kentucky (Photo: Dr. Pete Eyheralde, PhD)

buffaloes were more frequent than I have seen cattle in the settlements, browsing on the leaves of cane, or cropping the herbage of those extensive plains.” -Daniel Boone, 1775, Kentucky (Photo: Dr. Pete Eyheralde, PhD)

As the leading voice for the protection of public lands, waters, and wildlife, Backcountry Hunters & Anglers shared its support for the Public Lands in Public Hands Act, a bill that would help protect publicly-owned land from privatization. Introduced in February in the U.S. House of Representatives by Reps. Ryan Zinke (R-MT) and Gabe Vasquez (D-NM), this bipartisan legislation recognizes the irreplaceable value that public lands have for hunters and anglers.

The Public Lands in Public Hands Act would require congressional approval for the sale or transfer of publicly accessible tracts of federal land greater than 300 acres, or greater than five acres if accessible by public waterway. This is a critical improvement from current law in which federal land management agencies have broad discretion to sell or transfer publicly owned parcels that provide valuable habitat, public access and recreational opportunities. Limiting lands previously identified for disposal by the Department of the Interior and U.S. Forest Service will greatly reduce the threat of privatization for valuable public resources owned by all Americans.

“Core to the BHA mission is the sanctity of public lands and waters, resources cherished by hunters, anglers and outdoor enthusiasts, and valued as an irreplaceable part of our natural heritage. Without publicly accessible places to recreate, many Americans who share a love for hunting and fishing would be excluded from the opportunity to pursue their passion,” said Patrick Berry, BHA’s President and CEO. “We thank Reps. Zinke and Vasquez for introducing the Public Lands in Public Hands Act, which would help to ensure our hunting and angling traditions can continue for future generations.”

The Conservation History of George Washington Carver: Join Hal Herring and Mississippi State University environmental history professor and author of My Work is that of Conservation, An Environmental Biography of George Washington Carver Mark Hersey for a fantastic American conservation story that has never been more relevant than it is right now.

Carver was also one of America’s pioneers of the science of ecology and a cutting-edge conservationist who advocated for the restoration of whitetail deer, quail and fisheries, long before such ideas became mainstream. His conservation vision was forged in the fire of his own history and in his life’s work in Alabama’s post-slavery Black Belt and along the Fall Line, known then as “the most destroyed land in all of the South,” a place where poverty, injustice and hunger were closely tied to the abuse and collapse of the systems of the earth.

Don’t miss Hal’s fascinating conversation with Mark Hersey (episode 171) and more on the BHA Podcast & Blast wherever you get your podcasts.

Brian’s first experience with the value of public land access was while earning his doctorate degree in geology from Western Michigan University. Although trapped in a small apartment, Michigan has abundant public land, and he was able to pursue deer and turkeys and expand his fishing to include Great Lakes salmon and steelhead.

Brian, along with his wife and daughter and pup, lives on a small homestead in Whitehall, New York, situated between the southeastern edge of the Adirondack Mountains and the Green Mountains of Vermont, right at southern tip of Lake Champlain with access to thousands of acres of public land and water.

Kylee was born and raised in Hells Canyon. From the second she was able, she was learning to hunt, forage and fish. She obtained her bachelor’s degree from Eastern Washington University in communications/public relations and has spent her career primarily providing communication services.

Kylee currently resides in central Washington with her husband, twin baby girls and black Lab, Bristol. When she’s not behind the computer or wrangling the twins, she’s spending as much time as possible outdoors, which includes frequent treks back to Hells Canyon and the Blue Mountains. Her passion for ancestorial living, wild places and accessibility for all led her to BHA.

As a youngster, Andrew ran wild around military installations from the desert landscapes of Camp Pendleton to the intercoastal waterways of Lejeune. Over the years, he continued to fish, became an avid shooter and hunted whitetails along the East Coast.

Andrew moved to Montana in 2021, interned with BHA and now works full time in the conservation space. He spends his fall trying to fill the freezer with big game so that he can get back to the duck blind with his chocolate Lab, Lynyrd. He strives to be a good steward of the public lands and waters he feels blessed to make use of.

Max Siebert grew up in Missoula, Montana. After working a few jobs out of state, Max missed the mountains, family and friends in Montana and moved back (to a rented room in a house where he had the good fortune to meet his future wife).

When he’s not at work, you’re sure to find Max on one of his many bicycles, hiking, studying maps and conjuring his next backcountry adventure or lounging in a canoe with a packed cooler and a fishing rod. Max hopes that working with BHA will enable him to give back to the wild places that have raised and nurtured him.

CALIFORNIA CHAPTER COORDINATOR

Joel grew up in a small town in southwest Montana, where his father taught him to hike, backpack and “be” in natural spaces.

After undergrad, Joel attended the University of Michigan’s School for the Environment and Sustainability, earning an M.S. in environmental policy.

After finishing his masters in the spring of 2023, Joel moved with his wife to Berkeley, where she began attending law school last autumn. While he loves to hunt and fish, he’s terrible at both activities and hopes to learn as much as possible in the coming years!

CO HABITAT STEWARDSHIP COORDINATOR

Briant’s journey began in Wyoming, where hunting and fishing were woven into the fabric of his family life. The desire to be more involved with conservation brought him to Gunnison, Colorado, where he was awarded a fellowship and completed a Master of Environmental Management. He developed a deep passion for public lands and wildlife from years spent outdoors in the mountains and high deserts. Working with BHA, Briant has poured his sweat into fence removal and modifications and knows the impact fences have on wildlife.

Here are the winners of the kid’s coloring contest from the winter issue. (We had a record number of entries and couldn’t choose just three.) Thanks to all who participated!

I am a BHA member because I truly believe it is an organization that can make a positive impact and difference toward perpetuating the health of our land and the opportunities that reside there.

YOU’VE PUT A LOT OF EFFORT INTO LEVELING UP THE WASHINGTON CHAPTER’S COMMUNICATIONS AND OUTREACH. WHAT ARE YOUR GOALS WITH THIS WORK? AND HOW ARE YOU GOING ABOUT IT?

Before I joined the board, I was getting a glimpse into what BHA was doing in Washington through a friend and now fellow board member. From the outside though, it was hard to tell what was happening and what the board was taking action on. My goal when taking the “communications lead” was to better share and highlight all that this board and chapter does in this state. From land access to conservation and policy work, to public education and so much more. In sharing all of these things with not only the BHA members in Washington but also the general population, I hope to help build a strong community of people who will continue to fight for habitat and wildlife for years to come.

WHY ARE PUBLIC LANDS AND HUNTING AND ANGLING SO IMPORTANT TO YOU?

YOU ARE PASSIONATE ABOUT HOW HUNTING IS PORTRAYED IN THE MEDIA. WHAT DO YOU SEE AS THE IMAGE PROBLEM WITH HUNTING? AND HOW CAN HUNTERS WORK TO CHANGE THAT?

Although I grew up enjoying the outdoors and fishing with my family, I had never experienced hunting more than through the Outdoor Channel, where you’d see highlight reels of people shooting large bucks, high-fiving, and then moving to the next scene.

It wasn’t until I was able to see all the dots connected between the prehunt prep, in-hunt trials and tribulations and post-hunt victories of wild game dinners or experiences and lessons learned from “unsuccessful” outings, that I cared enough to take a step toward it all.

To me, that is a big issue the hunting community is struggling with. Photos and videos are shared without any explanation, in a world where impressions are made through 10-second videos and pictures – without a story. If a hunter or angler looks at a photo of a smiling person with their “trophy,” they can imagine the story behind it and the meals in front of it. But to anyone and everyone else who now has access to that content – what will they see?

While it might not seem fair, it is quickly becoming our job to share the why and help those who don’t participate in the lifestyle of a hunter or angler understand why we care so deeply about it all, and why they should too.

When people care or have personal investment, they are exponentially more likely to engage. In a time where we need all the educated, caring advocates we can get, a simple explanation can go for miles and years.

Through hunting and fishing on public lands, I have been able to discover who I am. I’ve learned that I am capable of doing “hard things,” whether that’s hanging in a tree saddle for days on end or pushing myself past my comfort zone to stay in that prime hunting zone until shooting light is over, leaving a long solo walk back to the truck in the dark. The experiences I have in the field in pursuit of wild game have always translated to out-ofthe-field life lessons. These opportunities are there for anyone who wants to jump in and try. Better yet, these opportunities are regenerative and should be around for generations to come.

WHAT DOES YOUR PERFECT DAY LOOK LIKE ON PUBLIC LANDS AND WATERS?

My perfect day in the field takes place in the middle of each September with a bow in my hand, chasing elk through the woods. Although I have yet to harvest an elk, chasing them is where I fell in love with the opportunities and challenges our lands hold. Feeling the rumble of a bull scream in the center of my chest while in the middle of a rut frenzy and smelling that warm not-quite barnyard but close scent is what made me take the last step and dive into this world of wild game pursuit and conservation. For that reason alone, it will forever be my favorite time in the field.

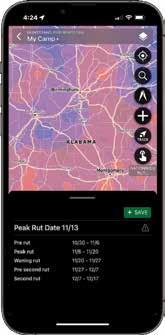

WHITETAIL RUT MAP

Unlock the most extensive Rut Map in the country

WHITETAIL ACTIVITY FORECAST

Plan your hunt around peak movement times

Join millions of hunters who use HuntStand to view property lines, find public hunting land, and manage their hunting property. Enjoy a powerful collection of maps and tools — including nationwide rut dates and a 7-day whitetail activity forecast with peak deer movement times.

NATIONWIDE PROPERTY INFO

WHITETAIL ACTIVITY FORECAST

Download and map for FREE!

WHITETAIL RUT MAP

MONTHLY SATELLITE IMAGERY

huntstand.com

WHITETAIL HABITAT MAP CROP HISTORY

NATIONAL AERIAL IMAGERY

BHA’s Backcountry Bounty is a celebration not of antler size but of BHA’s values: wild places, hard work, fair chase and wild-harvested food. Send your submissions to williams@backcountryhunters.org or share your photos with us by using #backcountryhuntersandanglers on social media! Emailed bounty submissions may also appear on social media.

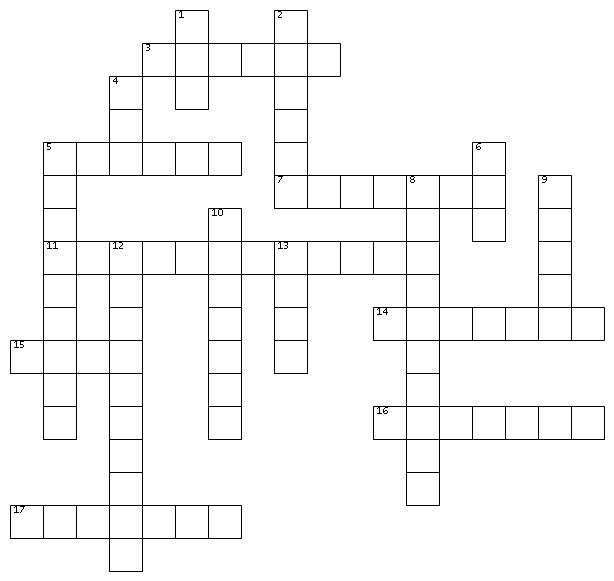

Puzzlemaker is a puzzle generation tool for teachers, students and parents. Create and print customized word sea more-using your own word lists

Crossword

ACROSS

ACROSS

3. _____ crossing – from one piece of public land to another

5. Canada’s national animal

DOWN

1. female moose or elk

3. _____ crossing – from one piece of public land to another

7. smallest Great Lake (by surface area)

11. prevention of wasteful use of a resource

5. Canada’s national animal

2. Gulf of __________

4. nickname for Backcountry Hunters & Anglers

5. deer that lives in the temperate rainforest of the West Coast

14. last name of host of the Backcountry Hunters & Anglers Podcast & Blast, also a small fish

7. smallest Great Lake (by surface area)

15. guns should always be pointed in a ______ direction

11. prevention of wasteful use of a resource

16. state where Backcountry Hunters & Anglers is headquartered

17. a warm dry wind that blows down the east side of the Rocky Mountains at the end of winter or a large North Pacific salmon

6. male turkey

8. a meeting at an agreed time and place, typically between two people

9. United States national mammal

10. animal whose paw appears in BHA logo

12. farthest east BHA chapter

14. last name of host of the Backcountry Hunters & Anglers Podcast & Blast, also a small sh

15. guns should always be pointed in a ______ direction

13. father of wildlife conservation: _________ Leopold

16. state where Backcountry Hunters & Anglers is headquar tered

*answers on page 83

17. a warm dry wind that blows down the east side of the Rocky Mountains at the end of winter or a lar

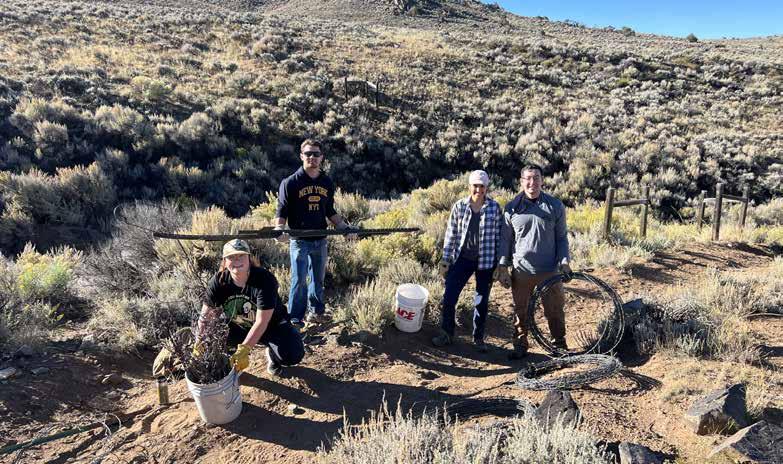

Fences continue to come down across the West thanks to BHA staff and volunteers as BHA expands its stewardship work

BY BRIANT WILESThe short, stout, sharp barbs, positioned approximately every foot on the braided wire, eagerly clutch at anything that comes their way. An iconic Western symbol, as familiar as the cowboy hat and horse, the miles of barbed wire that traverse Gunnison country are starting to come out. This welcome development is a relief for wildlife, signaling a shift in land ethic, which aims to be more inclusive of all range users — a shared cause championed by both land management agencies and conservationists.

Any given weekday during the summer and fall of 2023, my black Toyota could be seen bouncing down a dusty road, filled with fencing tools and supplies, thanks to a partnership between BHA and the Bureau of Land Management.

As a Gunnison resident and a lifelong hunter and angler, a deep connection and commitment to the conservation and enhancement of our public lands drove me to sign up for a summer of cuts and scrapes wrestling barbed wire fencing for BHA and the BLM.

The partnership between BHA and the BLM was spearheaded by BHA Habitat Stewardship Coordinator Brittany Parker, who worked closely with BLM Gunnison Wildlife Biologist Kathy Brodhead and BLM Gunnison Ecologist Rachel Miller. Both BLM staff had received project funding for fence removal, maintenance and inventory and needed help getting boots on the ground to do the work.

“Backcountry Hunters & Anglers was the perfect partner to

accept these funds and tackle the work,” Miller said of the project. “BHA has a national assistance agreement with BLM, making funding the project simple.”

The result was the removal of nearly three miles of fence, repair reconstruction of over two miles of fence and inventory of over 10 miles for potential wildlife conflicts.

Using GPS coordinates, I navigated the backcountry two-tracks. Over 18 weeks, I visited and worked on 28 different sites scattered around the Gunnison Basin. The projects were primarily focused on riparian exclosures put up decades ago, designed to fence out livestock from sensitive wet zones in otherwise dry areas. They ranged in size from a few dozen yards to over a mile in length.

Thirteen of the sites were slated for removal, put in at a time when more was expected from the wet areas. Now, in various states of disrepair, they are little more than a hazard to livestock and wildlife. Seeing those fences go offered instant satisfaction and validation that the work I was doing was impactful and important. The removal of more than 15,000 feet of fence from the landscape will prevent unnecessary wildlife deaths and contribute to healthier ecosystems.

In addition to removing the unwanted exclosures, there were a slate of projects aimed at rehabilitation. These wet meadow exclosures still serve a valuable function of protecting a sensitive area from livstock grazing and therefore prove alluring to wildlife. Upwards of 80% of terrestrial species utilize these riparian zones at one point in their life cycles. The high primary productivity of the

plants in these areas makes them desirable to migrating elk, deer and antelope. They also provide critical habitat for the threatened Gunnison sage grouse.

But fences are by design not wildlife friendly. The goal then becomes to make them, as Parker puts it, “wildlife friendlier.” By following Colorado Parks and Wildlife’s recommendations, I replaced the top and bottom wires with smooth wire, adjusted the spacing of the wires, and used wood fence stays and flagging for better visibility. The key is to make a fence stand out by replacing the old wire stays with wood and then attaching flagging, so the fence has a bigger presence making it easier for wildlife to see the wires. The wood stays also help the fence keep its shape by not bending under snow load. Removing the old riparian exclosure fences was relatively quick and straightforward compared to the much slower tasks of rebuilding old fences, where I spent upwards of four weeks on a single exclosure.

While I spent most of the summer carrying out this work alone, I was please to be joined at the tail end of the field season by Ali Aldrich, a master’s student at nearby Western State University. Together we tackled one of the bigger fence projects.

The maintenance of the exclosures was not limited to rebuilding wire fences. On a site 15 miles south of the city of Gunnison, Aldrich and I joined crews from the Upper Gunnison River Water Conservation District, BLM and Colorado Parks and Wildlife to construct an exclosure with a new type of metal fence. I had removed the old barbed-wire fence earlier in the year and was excited to see the new style in action. The new wildlife-friendlier fence, a unique freestanding metal arrangement of A-shaped posts and metal rails, went up in a single day.

At other times Aldrich and I were joined by groups of volunteers

from the local community who contributed significant time removing and repairing old fences. A particularly difficult job of carrying the cumbersome wire and heavy posts more than a quarter mile to a road demonstrated how invested this group of community volunteers is in their public lands.

Of course, the passion of BHA members and the Gunnison community is not new. This past spring BHA organized an event called Beer, Bands and Barbed Wire Strands with live music, camping and over 100 volunteers working to remove miles of fence.

In a recent Gunnison Country Times article, Colorado Parks and Wildlife Area Wildlife Manager Brandon Diamond recognized the scale of fencing on public land, the cost to wildlife and the necessity of the work BHA members across the West are undertaking: “When you have an old broken wire that’s on the ground and in a state of disrepair, it’s even less obvious than a well-maintained fence, so both of these can be hard on wildlife, everything from changing migration routes or even daily movement activities.”

The opportunity I was granted through BHA coupled with my local knowledge and tremendous support from the BLM’s Miller and Brodhead, made this collaboration a great success. Putting theory into action is, after all, the point of working on behalf of public lands and wildlife. BHA is excited and uniquely suited to build on the success of the past year.

Briant Wiles is BHA’s Colordado Habitat Stewardship Coordinatior. He lives in Gunnison, where he chases elk, grouse, waterfowl and backcountry trout – all on public lands.

Steeped in tradition, built to perform. With comfort, traction and durability that stand up to the hunt, the new Recurve boot is made for swift, confident movement through tough terrain. DANNER.COM/RECURVE

M ulti-piece trout rods that perform like one-piece rods, the new Trout Pack Series features handcrafted St. Croix quality and proven performance in two highly packable three-piece designs to support elevated o -grid angling adventures.

In California’s Silver Creek, on the east slope of the Sierra, hope comes in the form of white poly pipe and 400 volts of electricity.

Despite its rather ordinary name, Silver Creek is anything but. Its gin clear waters bubble out of springs below White Mountain and Wells Peak and then tumble downhill, picking up water from tributaries and snowmelt along the way. As it enters Bagley Meadows, it slows and snakes its way through lush grasses, pools below aspen groves and granite, and provides nutrients for lodgepole pine, willows, gooseberry and dogwoods. Eventually it meets the waters of the West Walker River in Pickle Meadows just beside the Marine Mountain Warfare Training Center.

While Silver Creek is almost storybook in its beauty, what makes it perhaps even more unique is that it is home to the federally endangered Lahontan cutthroat trout, specifically the Walker Basin LCT, which can be distinguished genetically due to its relative geographic isolation from the Pilot Peak strain famously found in Pyramid Lake. Walker Basin extends east from Sonora Junction to Walker Lake and the Gillis Range in Nevada, south to Bridgeport, California, and north past Yerington, Nevada. Its largely arid high desert climate full of brittlebrush, sage and pinyon pine represents the western edge of the Great Basin Desert.

LCT are one of two cutthroat trout native to the state of California and were a historically important food source for native Paiutes and Shoshone in the region. Thriving in the Walker Basin, LCT are “desert survivors,” says Nick Buchmaster, head fisheries supervisor for Inyo and Mono counties in California. They are also the largest non-anadromous trout in North America, sometimes

growing up to 50 pounds. Once thought to be extinct, a small population of Walker Basin LCT were found surviving in a desert creek outside Bridgeport.

“What is not to love?” Buckmaster asks rhetorically. Their green mottled backs, pale brown bodies with red bands and par stripes make them not only beautiful but an ideal gamefish because, as anyone who has picked up a fly rod east of the Mississippi knows, cutthroat are also pretty darn easy to catch.

LCT were federally listed on the Endangered Species Act in 1977, and for the past 50 years, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife has been working to help the species recover. The problem, as is the problem with many cutthroat recovery programs, is invasive trout. In this case, the highly fecund brook trout. No one really knows how brook trout got in the stream in the first place. Possibly sheepherders hoping to “improve” on nature or some other attempt to fix a system that wasn’t broken. But the reality is that as long as brook trout remain, LCT will struggle to survive.

CDFW tried poisoning the stream in the mid-1990s, but that did not prove effective, and until five years ago, they were trying to remove as many brook trout as possible in the hopes LCTs could outcompete the brookies. The problem? Unless you remove all the brook trout, life will find a way, as Jeff Goldblum famously said in Jurassic Park. Kill off the bigger brook trout and the young of the year multiply even more. In fishery terms, they call it the hydra effect.

Until somewhat recently, CDFW had been fighting the hydra effect without much luck. That is until Buckmaster and his team decided to try something novel – dewater 11 miles of stream on Silver Creek, segment by segment, and remove every single brook

trout – a monumental task, and one that had not been done before.

So for the past five years, Buckmaster and his interdisciplinary CDFW and CalTrout team have been hauling miles of poly pipe (an irrigation material used in arid climates), water pumps, generators, sandbags and electrofishing equipment up into the backcountry and removing brook trout from the Silver Creek system. It is a massive operation full of sandbag dams and white poly pipe stretching as far as the eye can see. But their plan is working.

After they pump out the water and remove all brook trout via electroshock fishing from a given section, they move on to the next section. Year after year Buckmaster and his team are seeing a 99.1% decrease in brook trout populations in Silver Creek. To put that in perspective, in 2022 they removed 6,000 brook trout from the stream. This past year they only found 47 invasive fish to remove. Most of the brook trout that are removed are relocated to a nearby lake.

This past year, California BHA members chipped in to help Buckmaster and his team by hauling poly pipe, assisting in electrofishing, and moving pumping equipment. CDFW hopes to finish up operations on Silver Creek by next year, and BHA will be there to assist again. The goal is to open the creek to the public for fishing within the next three years, and I for one couldn’t be more excited.

The thought of taking a tent, a three-weight and a cooler of beer up to Silver Creek and casting a size 14 Adams to hungry 16-inch Lahontans should get the blood of any angler pumping.

What happened and what is happening on Silver Creek is representative of the larger battle surrounding Lahontans, specifically, and the Endangered Species Act more broadly. Lahontans are becoming a success story. Not only do they thrive in places like Pyramid Lake and a few other Walker Basin streams, but if Buckmaster and his team have their way, soon LCTs will be restored fully to their native range and hopefully be found in places like Walker Lake in Nevada. This will be good for anglers and the ecosystem – a rare win-win.

Last year, 21 species were removed from the Endangered Species List due to extinction. Of the 1,732 different species that have been listed, only 57, including the gray wolf and bald eagle, have been delisted because of recovery. The Lahontan cutthroat trout looks to be the next.

Usually to organizations like BHA, CalTrout, and CDFW, conservation and restoration feels like a Sisyphean task. But sometimes, with a little ingenuity and collaboration and a lot of grit, hope can prevail.

Ned Weidner is a BHA member who, when he is not drifting BWOs or stalking black bear near his home in California’s Eastern Sierra, works as an English professor at Mt. San Antonio College. His writing can be found in Still: The Journal, The Write Launch, Medium and various other journals.

Last year, 21 species were removed from the endangered species list due to extinction. Historically of the 1,732 different species that have been listed, only 57, including the gray wolf and bald eagle, have been delisted because of recovery. The Lahontan cutthroat trout looks to be the next.

Meant to complement the historic Mark V® and Vanguard® lineups, the Model 307 is a 2-Lug, fully cylindrical action compatible with many aftermarket accessories. Proudly built in Sheridan, WY, the Model 307 will be available in a wide range of Weatherby and nonWeatherby calibers. Nothing shoots flatter, hits harder or is more accurate than a Weatherby. Learn more at Weatherby.com

• The chapter held a Brooks Range story contest to amplify the proposed Ambler Road project and BHA’s opposition. (Read the winning story on page 69 of this issue!)

• Chapter board members testified at multiple BLM public hearings and commented in favor of the “No Action” alternative for the Alaska D-1 land withdrawals.

• In February, chapter leaders held pint nights celebrating drawn tags in Fairbanks, Anchorage, Juneau and Kodiak.

• The chapter is excited to welcome many new board members this spring, growing the chapter’s strengths and skills to do more in the vast state.

• Volunteers removed spent shells and trash from the popular waterfowl hunting area Ed Gordon Point Remove Wildlife Management Area in early February.

• The third annual Black Bear Bonanza was held March 9, attracting hundreds of families for a fun-filled day and raising thousands of dollars for conservation.

• Chapter leaders met with other conservation partners in early March, forming the Arkansas Conservation Coalition, to work for sound conservation policy and laws within the state.

• The chapter’s 4th Annual Hunting for Sustainability workshop was a huge success. New hunters learned about small game hunting near Tucson, with support from mentors and first harvests.

• Welcome to new chapter board members and new roles: Eric Kowal (social media), Alex Young (legislative), Brad Butterfield (stewardship chair), and Kyle Short (secretary).

• The Arizona and Utah chapters will meet near Kanab, Utah for the Paunsaugunt Fencing Project and Southwest BHA Rendezvous on May 16-19, 2024. Join us!

• AFI has elected five new board members, expanding our leadership team to help support the 2,800 participants we are introducing to conservation at over 180 events in 2024. See our recent blog post for more information and the events page for more details.

• AFI’s 2023 Year in Review is live on the BHA website; we hosted 146 events introducing over 2,300 participants to hunting, trapping and angling in 49 States and two Canadian provinces.

• AFI introduced military waterfowl season creation bills in New Hampshire and Nebraska in 2023 and a similar bill in Wisconsin in March 2024. Read more on our blog.

• The Fish, Wildlife and Habitat Coalition hosted ministers and elected officials in Victoria to discuss improving management of fish, wildlife and habitat and promote biodiversity through protection of intact landscapes and dedicated funding. Shamus Stone attended to represent the chapter.

• The chapter submitted comment letters for draft policy changes in British Columbia: biodiversity and ecosystem health framework, Wildlife Act review, and supporting wildlife protective order proposals.

• CWD has unfortunately been detected in BC, and the chapter will be monitoring the province’s response closely.

• The California chapter, in conjunction with the Armed Forces Initiative, partnered with the U.S. Marine Corps and volunteers from other NGOs and state agencies to install new guzzlers supporting bighorn sheep and other wildlife in the southern California desert. Volunteers from BHA and other groups hiked out to the guzzler sites in the dark to prepare for the Marine helicopters, pump water between tanks and plumb the systems once the tanks were in place.

• As part of the second phase of a grant award to restore critical winter range habitat for mule deer and other animals lost to wildfire, volunteers from the California chapter organized the Beer, Bands and Bitterbrush Stands event to plant more than 4,000 bitterbrush plants in northeast California.

• Chapter board member Reina Seraaj organized a women’s backcountry rifle clinic in conjunction with BHA AFI to teach women rifle shooting skills that will help them succeed on their next hunt.

• Legislative Liaison Ivan James was appointed to the Colorado Wildlife Habitat Stamp Committee by Gov. Jared Polis.

• Steve Witte was appointed to serve as our indemnity land liason.

• Our 15th Annual Colorado BHA Rendezvous will be held June 21-23 at the Soap Creek Corral Dispersed Camping Area (the same locale as last year), west of Gunnison.

• Our 2nd Annual Colorado Public Lands Day Bash will be held in Gunnison, May 17-18.

• In December, the chapter hosted our 4th Annual Small Game Hunt at Dinner Island Ranch. In February, we also hosted our first small game hunt in Apalachicola National Forest.

• The chapter partnered with FL Camo to host a turkey hunting workshop on February 22 for hunters trying to learn the ropes of hunting high-pressured birds on public land.

• In March, the chapter partnered with BHA HQ and Minority Outdoor Alliance to present Backcountry in Your Backyard, an all-inclusive workshop for those wanting to learn about hunting, wild food and the conservation community.

• Members were busy at events across the state, including the inaugural University of Idaho Banquet, the Western Idaho Fly Fishing Expo, the Idaho Sportsman Show, several International Fly Fishing Film Festivals, the Idaho Sporting and Wildlife Partnership Legislative Reception, the Idaho Chapter of the Wildlife Society and various pint nights.

• The chapter submitted a comment letter in support of HB404.

• We look forward to stewardship projects this spring, check the events page on the website for projects in your area.

• The Illinois chapter board met at the Lake Shelbyville Army Corp of Engineers office to work on strategic planning for 2024 and beyond. Thank you to the Corp for their partnership and use of the facilities.

• Be on the lookout for the upcoming grand opening of the BHA ar-

chery park at Lake Shelbyville. More news to come.

• State legislators have proposed a new stream access bill. Reach out to your local officials and everyone you know to voice your support.

• We had a successful turnout at the wood duck box build at J.E. Roush Fish and Wildlife. Twenty wood duck boxes were built and provided through donations from our state sponsors.

• The chapter had a booth at the Deer and Turkey Expo. Members gathered at Half-Liter BBQ for a pint night in conjunction with Pheasants Forever.

• A virtual event Turkey Talk was hosted featuring Tom “Doc” Weddle, who is a four-time U.S. super slam holder.

• The chapter helped kill HF2104, an anti-public land bill that would prohibit the DNR from purchasing land at auction.

• The chapter held our annual chapter planning meeting, where we laid out our plans for success in 2024.

• Chapter board members held the annual strategic planning meeting on January 21. In review of 2023 Kansas chapter activity, they noted that the chapter had completed 11 workdays and 12 events, all centered on improving and promoting public lands in the state.

• Kansas chapter board members helped organize and participated in the first Kansans for Conservation Day at the state capitol on January 22. NGOs and other conservation groups, along with the Kansas chapter, teamed up to discuss current legislation for this session with Kansas legislators.

• In January, the chapter helped with brush removal at Butler State Fishing Lake.

• February 24, the chapter worked with KDWP to construct fish habitat at Olathe Lake.

• In October we held our first ever Louisville Bird Dog Pint Night.

• In November the chapter tabled at the Gun Show and Preparedness Expo in Hindman and The Wildlife Society Annual Conference in Louisville.

• The chapter held its annual Maysville Public Land Film Fest, along with its first-ever Walton (northern Kentucky) Pint Night.

• In January the chapter resumed its annual Conservation Coffee series, with speakers from Ducks Unlimited and Daniel Boone National Forest and a DIY western hunting presentation.

• The chapter also tabled for the first time at the Louisville Boat, RV & Sport Show and held informal monthly Lexington pint nights.

• The chapter changed its name from the Capital chapter to Mid-Atlantic chapter to now include the state of Delaware. The chapter held an inaugural pint night in Delaware to kick off the new relationship, which was attended by state officials and BHA members.

• Board members organized and held a mentored deer hunt in Virginia. Participants were selected via application and received instruction on scouting, firearms practice and in-field techniques.

• The chapter attended the Virginia Fly and Wine Festival again in Doswell. The two-day festival had attendees from around the country.

• The chapter held two incredible MeatEater Trivia pint nights in conjunction with the MeatEater Live podcast events.

• The chapter took a strong stance against a commercial fishing bill that would have lasting effects on the conservation of the Great Lakes.

• The chapter supported two youths with full tuition to a summer camp held by MUCC.

• The Minnesota chapter was busy gearing up in preparation for the North American Rendezvous, held at the Minneapolis Convention Center April 18-20.

• Members should expect a survey for our member campout this summer/fall.

• The chapter participated in a public lands day at the Capital in March.

• The chapter has released its upcoming schedule of events for 2024, which includes pint nights, archery shoots, conservation work days, Dive Bomb’s Squadfest 2024 and more. Please check out backcountryhunters.org/missouri for more info.

• Chapter board members recently attended the North American Rendezvous in Minnesota. Go to Instagram.com/missouri_bha to see content from the event.

• The Missouri board has a few committee vacancies. If you would like to get involved, come say “hi” at an event or email Missouri@backcountryhunters.org

• The chapter launched a raffle for a statewide mule deer license to raise money for mule deer conservation.

• The chapter said thanks and farewell to outgoing board members Scott Desena and Corey Ellis and welcomed new board members Caleb Teigen, Sunni Heikes-Knapton and Dan Tracey.

• The chapter championed the Lost Creek proposed land acquisition, weighed in on the new elk management plan and season-setting regulations, sounded the alarm on a deceiving ballot initiative, asked for deeper analysis on a proposal to drastically increase commercial use on the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest, supported the Montana Headwaters Legacy Act and advocated for strong protections in the Great Burn Proposed Wilderness.

• The chapter tabled at the Nebraska Bowhunter Association Banquet; good to see everyone at the BHA booth!

• Thank you to those who came out for the fence removal project at Wapiti WMA in March.

• The Trashy Cat Event is on again this year in May at Medicine Creek WMA. It’s a weekend of camping, fishing and a little clean-up of the WMA. Keep an eye out for dates and additional information.

• The chapter would like to welcome Dallas B. Hatch, Don Klebenow and Jeremy Mitchell to the Nevada board.

• The Nevada chapter doubled membership in 2023!

• It was great to see our members at the annual meeting and welcome all the new members we met at Sheep Show.

• The Rhode Island team opposed an aquaculture permitting application that would negatively affect shellfish and sea duck wintering habitat.

• The Massachusetts team held a small game hunting workshop with MassWildlife in January and hosted a small game hunt in February.

• In Maine, a long-term public land project to remove several hundred feet of fencing continues to evolve in partnership with Maine IF&W and BPL. Contact maine@backcountryhunters.org to receive updates and get involved.

• The New Hampshire team submitted a statement of support to the NH Fish & Game Department during the biennial comment period.

• Volunteers from southern New England made their way to Rhode Island to assist the DEM with duck banding.

• This past fall the the chapter joined the New Jersey State Federation of Sportsman’s Clubs.

• The chapter was invited to host a seminar covering E-scouting, backcountry hunting logistics and the gear required for backpack hunting at the annual Garden State Deer Classic. The two-day show also included one-hour seminars hosted by the various sportsman’s clubs in the state of New Jersey.

• For the third consecutive year, the chapter teamed up with the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish for the Sandia Mountains bowhunting outreach event. During a youth-only bowhunt in November, and a second bowhunt in January, over 500 contacts were made with members of the public at highly trafficked trailheads near Albuquerque. Information regarding safety, hunting area boundaries and regulations were shared to mitigate potential conflicts with the public and ensure future hunting access to the Sandia Mountains.

• Volunteers represented the New York chapter at the Syracuse Outdoor Expo. We met current members, added some new ones and spread the word about protecting public lands.

• The chapter collaborated with Artemis Sportswomen and WildHERness at the Ice Fishing 101 event. It was a day full of smiles, laughs, good food and fish.

• The chapter collaborated with Hunters of Color and The Nature Conservancy of New York on the 3rd Annual Mentored Bow Hunt on Long Island. Eight new bowhunters built the skills to continue on their hunting journey, and all went home with delicious venison and plenty of practice butchering wild game.

• The chapter board met with Dakota Prairie Grasslands and North Dakota Game & Fish Department staff as a part of their annual chapter planning meeting where they discussed work and goals for 2024.

• The chapter worked with the Department of Trust Lands to reduce the number of acres closed during portions of the 2023 hunting season by half.

• The chapter celebrated the end of hunting season with the 6th Annual Trashy Squirrel Hunt. Regional BHA member teams prowled public lands over three weeks in late January and February for bushytails and litter, with points awarded for total poundage, squirrels bagged, new hunters and new BHA members registered.

• March saw the first chapter-organized camping trip, with members from across the state meeting up in the Uwharrie National Forest to reconnect with friends, refocus on the mission and reload with positive energy for the year to come.

• The Camp Lejeune AFI Club is hosting an inshore fishing camp, June 14-16, in New Bern. If you are or know a servicemember who’d like to participate, contact ncafi@backcountryhunters.org.

• The Ohio chapter board met to reflect on 2023 and eagerly planned ahead for 2024. In 2023, we held a big ol’ party, Muster in the Marsh, which was successful in many ways, tangible and intangible. It was also a significant fundraising year even with the high price tag of running such a large event.

• Our focus for 2024 is more boots-on-the-ground work, volunteer engagement, policy talks and of course public events – including a booth and pint night at the Sportsmans Expo in Columbus, multiple fly-tying events, river cleanups and more. The summer won’t pass without an Ohio BHA party, and we’re looking to fill up some dumpsters too. It’s gonna be a good year!

• At the end of 2023, we said goodbye to three long-serving members of the board: Gabe Karns, Brandon Skiver and Levi Arnold. The loss of these serious and thoughtful conservationists is not easy, but the structures and friendships they built will continue. We love all of them dearly, and all are forever welcome around our campfires.

• In December, the Oklahoma chapter hosted its 2nd Annual Duck Camp at G&H Decoys Headquarters in Henryetta.

• The International Fly Fishing Film Festival was successfully held March 14 at Circle Cinema in Tulsa. Thanks to everyone who attended!

• Stay tuned to the OK chapter social channels for updates on all events, policy news and other conservation topics!

• The Oregon chapter supported a wildlife omnibus bill (HB4148) that would address and expand resources – to combat zoonotic diseases including CWD, migration corridor crossing, wildlife coexistence and invasive species on the landscape.

• The chapter held its annual meeting to reflect on wins from 2023 and we look forward to what is to come in 2024.

• The chapter hosted two MeatEater Trivia pint nights in November in support of the live tour. At the show, member Kyle Collins bested the crew and donated his winnings back to the chapter. Thank you, Kyle!

• Chapter leaders Bob Smith and Mike Strollo organized three work days on State Game Lands 52, removing invasive plant species. This is the third year of the project.

• The annual in-person board meeting was held by chapter leaders in State College on January 13.

• The chapter submitted a letter in objection to the final Environmental Impact Assessment and Draft Decision Notice for the proposed Golden Crest Exploration Drilling Project.

• The chapter board hosted a series of virtual planning sessions for 2024.

• Chapter leaders hosted a Backcountry Bird Hunt experience in partnership with Weatherby. Two lucky Rendezvous Auction winners chased prairie grouse and pheasants in the backcountry prairies of northwest South Dakota.

• The Tennessee chapter spent a day in January at Percy Priest WMA near Nashville building wood duck houses with the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency. It was a great day of conservation work and education for all the volunteers. Our volunteers learned why boxes are needed for wood ducks in the breeding season. They learned the importance of proper spacing, so that each box was not inundated with too many egg-laying females. This event further solidifies the chapter’s work with TWRA. It was a great hands-on event.

• The chapter kicked off its 2024 Hunting for Sustainability program for new adult big game hunters.

• Members stayed informed on relevant bills related to public lands, waters and wildlife throughout the 2024 Utah Legislative Session through advocacy articles published by the chapter board on the chapter’s web page.

• Preparation for the chapter’s flagship fence surveying project on the Paunsaugunt unit, Miles For Muleys, has been in full swing and members are gearing up for the overnight stewardship opportunity in southern Utah on May 17-18.

• The chapter successfully combated a fur ban bill and garnered over 400 messages in opposition through an action alert aimed at the committee hearing the bill.

• The chapter held its annual meeting where it looked at wins from 2023 and planned for what is to come in 2024.

• The chapter hosted several great events in Q1, including a Bugs & Brew fly-tying pint night in Rivesville and a pint night in Charleston, coinciding with a great presence at the Charleston Trophy Hunters Expo.

• The chapter will be part of the Greenbriar Fly-Fishing Classic, May 18, and the Appalachian Fly-Fishing Festival, May 31-June 2. Be sure to stop by our booth space and chat all things conservation and public lands!

• The chapter continues staying engaged on West Virginia public lands issues while planning events around the state. So be sure to follow oursocial channels on both Instagram and Facebook for the latest updates!

• The Wyoming chapter hosted an IF4 Film Showing in Cheyenne at the Kiwanis Community House on March 7.

• The chapter joined other sportsmen’s organizations to ask the Wyoming Legislature to conserve the Kelly Parcel by supporting conveyance to Grand Teton National Park.

Find a more detailed writeup of your chapter’s news along with events and updates by regularly visiting www.backcountryhunters.org/chapters or contacting them at [your state/province/territory/region]@backcountryhunters.org (e.g. newengland@backcountryhunters.org).

As the last American-made decoy company, we will support and preserve American waterfowling for the next generation.

Will you join us?

On the opening day of the Montana turkey season, BHA’s Armed Forces Initiative, in partnership with Patrol Base Abbate, a nonprofit focused on providing veterans an oasis to the chaos of life after service, came together for a few days to talk public lands and hunt turkeys. The wall tents, cold food, and Copenhagen-lined conversation formed a familiar and welcoming atmosphere for those accustomed to patrol bases on the tattered fringe of American influence. The mission and decreased danger level presented the only real changes, and those drying gear over the wood stoves after a long day’s hunt appreciated both.

“Your sector of fire lies from that big tree to that pile of scrub brush,” Casey instructed with the customary knife hand as I scanned my sector of the wind-beaten Montanan landscape. Finding myself assigned a field of fire that interlocked with teammates perfectly to maximize coverage of the engagement zone does not present me with a new experience. However, the novelty of hunting with those as fluent in the military way of life and just as passionate about the outdoors infected me. The three of us sat, spread out so that interlocking fields of fire covered all avenues of approach to the roosting trees we guarded. With our ambush set, we waited for an incoming gobbler.

Our fire team worked diligently in the places assigned to us to hunt, calling, waiting and stalking the gobblers we located with determination and zeal. Finally, on the third day, in the pouring rain, Ryan Phillips low-crawled 60 yards over an hour to get within shotgun range of a lone tom feeding in a field. With his chest and legs soaked in cow pie-infused mud, he raised his 20 gauge and took the first bearded tom he ever aimed at.

Though Ryan got to pull the trigger and take the fan home, the thrill of victory pulsed through our small fire team. We endured hours of punishment from the austere Montana weather, emptyhanded returns and brutally long days. Hearing Ryan’s shot, I felt I had killed one myself. I will never forget the fist pumps and cheers while he held his first-ever turkey up for the world to admire.

My few days in Montana formed me. Sitting around the fire making fun of one another, pouring over maps and wargaming what strategy to employ the next day felt like two chapters in my life had merged. The technical practices of the Army had married

the spirit of every hunting camp I have experienced, producing a unique offspring not found elsewhere.

Nowhere else have I found people who think, plan, work and execute at that level of intensity and passion outside the military. The military machine transforms young kids into modern warfighters capable of solving any problem placed before them. As a result, a unique population forms with its own highs and lows, culture and counterculture, skillsets and vices.

While the military took undisciplined high school students and made them into a part of the most deadly force this world has ever known, it completely fails to teach them how to deploy, engage and destroy problems once they come back home. Though durable and veracious, many have problems when they depart one of the branches of the armed forces. They don’t anticipate that they will give up more than just a paycheck. Many don’t realize that as they turn in more than just rucksacks as they out-process, they also surrender their purpose and identity.

Nonprofits rush to their aid, retreats and group therapies try to bandage the wounded heroes, and sometimes they produce results worthy of celebration. Many times they don’t. No matter what, none of that will fill the gaping hole left in the chest of every service member. Nothing can replace the seductive, addictive and exhilarating feeling of executing a mission with your closest friends. Replicating that sort of environment nears impossible.

Yet, hope remains. The Armed Forces Initiative, led by veterans for the cause of public lands advocacy, creates that environment and provides a mission for those missing a disciplined life of purpose.

Previous generations figured this out. After World War II, many returning veterans came home to build the outdoors industry and the conservation landscape. They helped set hunting seasons, established the ski industry and worked in outdoor advocacy for the rest of their lives. The few years they had fought the enemies of the United States of America served as the formative period for the next centuries worth of hunters, anglers and public land advocates.

However, a narrative of victimhood remains undeniably strong in today’s veteran community. They suckle on lies of their marginalized, lost and forgotten victimhood. A time and place exist to remedy elements of that reality, but aid stations have no mailbox. The purpose of any type of physical, mental or spiritual care lies in dusting off trauma victims and getting them back into the fight.

As Gen James Mattis put it, “While victimhood in America is exalted, I don’t think our veterans should join those ranks.” Veterans do not linger about broken; they rise to become a force to contend with.

As Gen James Mattis put it, “While victimhood in America is exalted, I don’t think our veterans should join those ranks.” Veterans do not linger about broken; they rise to become a force to contend with. They shape outcomes and do not embrace victimhood. Far from the ramshackle relics of a war misunderstood, today’s veterans will evolve into the foundation on which we build tomorrow.

A mission lies before the veterans of today – the American way of life lies besieged by those who don’t understand it. Errant government policies, greed and ideologues seek to siphon off public lands, destroy the world’s best conservation system and end a way of life that built the greatest nation the world has ever seen.