Grace Upon Grace

HOLY INNOCENTS AT 150

By Tammy Galloway

By Tammy Galloway

“And from His fulness have we all received, grace upon grace.”

—John 1:16

The historical research and writing of this book was made possible by a generous gift of Drs. Michael Stewart and Melisa Rathburn.

The editing, layout, and publication of this book was made possible by a generous gift of Susan and Dan Faulk in honor of their grandchildren: Sidney Roberts, Anna Thomas, Madeline Roberts, Will Thomas, and Chip Cummings.

Copyright © 2023 by Holy Innocents’ Episcopal Church. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from:

Holy Innocents’ Episcopal Church

805 Mount Vernon Highway Sandy Springs, Georgia 30327

Rector and Editorial Director

Rev. Bill Murray, D.Min

Author

Tammy Galloway

Proofreader

Sally Parsonson, PhD

Bookhouse Development Bookhouse Group, Inc. Covington, Georgia www.bookhouse.net

Editor

Gary S. Hauk, PhD

Book Design

Amy Thomann

Production and Archival Management

Renée Peyton

Index

Shoshana Hurwitz

HIEC offers a special note of thanks to University of Georgia Special Collections Library, Atlanta History Center Kenan Research Center, St. Philip’s Cathedral archives, and All Saints' Episcopal Church archives.

vii Dedication

xi Foreword, Rev. Bill Murray, PhD

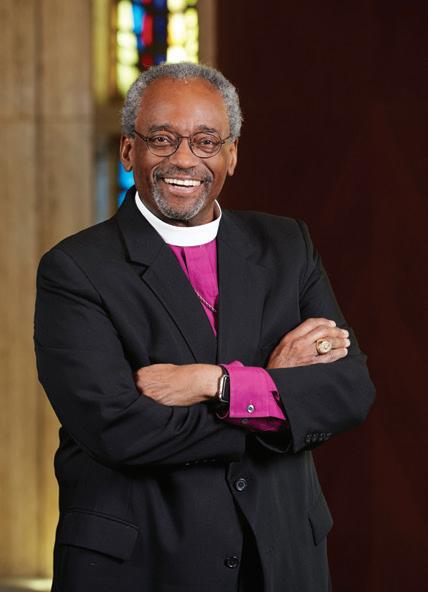

xiii Letter from the Presiding Bishop, Michael Curry

CHAPTER 1

1 Miss Nellie’s Mission (1845–1877)

CHAPTER 2

9 An Act of God (1877–1898)

CHAPTER 3

19 All Saints’ and Deaconess Wood (1900–1919)

CHAPTER 4

31 Deaconess Wood (1920–1954)

CHAPTER 5

41 Phoenix Rises and a School is Born (1955–1965)

CHAPTER 6

55 New Space, New Programs (1965–1969)

CHAPTER 7

69 A Vibrant Decade for Parish and School (1969–1977)

CHAPTER 8

81 Church and School Building a Bigger Stage (1978–1981)

CHAPTER 9

89 Expanding Space and Community Outreach (1982–1986)

CHAPTER 10

99 Difficult Challenges, Great Solutions (1987–1992)

CHAPTER 11

109 The Strange Mix of Wealth and Need (1993–2000)

CHAPTER 12

Ilove stories, good and bad, short and long, boring and interesting. I love hearing about people in all sorts and conditions. I love hearing those tales because I am addicted to stories. I believe that in sharing our lives, we begin to see patterns, share our burdens, learn from our experiences, and even find ways to be better the next time. If we do all of that with the stories of faith in hand, we begin to see God’s presence in our lives in the most unexpected places and the most heartwarming ways.

Founded by a twentyoneyearold woman, sustained by the leadership of a deaconess for forty years, and moved to no fewer than seven different locations, Holy Innocents’ Episcopal Church has a story like few others. She is a community that is worth enough to restart after a tornado, a mission worth enough to weather a move from downtown to Sandy Springs, and a church worth enough to keep going despite good and bad priests, hirings, firings, affairs, racism, sexism, homophobia, insolvency, and a thousand more stories that we may never even hear. To tell the story of Holy Innocents is to tell a tale filled with successes and failures in equal measure. It is not a hagiography of perfect people excelling in everything. It is the wonderful story of faithful lives spilled out together in a jumble of puzzle pieces that is worth repeating because we keep trying. And God tries with us.

The beauty of the story we have recorded is that despite our many successes and our setbacks, the people of this community have chosen to press on and laugh and walk together. The church is not perfect and never likely will be. But this glorious group of people have learned that perfection is not the point of faith or of the church. The purpose is to lean into God’s unfailing love for us and share that hope with the world.

I hope that you enjoy the stories that we have gathered in this book. I pray that you delight in the twists and turns of our forebears in faith. I believe that you can find your life woven in these pages. That is the work of all Christians, to find our story wrapped up in tales of the bible, the narrative of God’s love for us.

May God open our eyes to see the patterns of our faith, share the burdens of our lives, and learn from the experiences of our church. May God’s presence be apparent in our lives in the most unexpected places and the most heartwarming ways. And, may God help us write new chapters in our faith and tell new, extravagant, and hopeful stories of Holy Innocents.

“We are, as a species, addicted to story. Even when the body goes to sleep, the mind stays up all night, telling itself stories.”

— Jonathan Gottschall

December 28, 2022

Feast of the Holy Innocents

TO: The Rector, Vestry, and People of Holy Innocents’ Episcopal Church Sandy Spring, Georgia

Dear sisters and brothers in Christ,

I am delighted to offer my congratualtions to you all on the sesquicentennial of the founding of your wonderful parish. 150 years is a long time, and it is a great testimony to you today, as well as all those who have preceded you there, as your ongoing faithful witness to our loving, liberating, and lifegiving God has continually been a shining example to the world around you.

The journey of Holy Innocents from a tiny mission intended to educate the poor and hungry in Atlanta after the Civil War to founding the largest parishbased Episcopal School in the United States is an amazing story! Your work in creating multiple outreach ministries while growing in numbers and faith as a community dedicated to Jesus Christ can serve as both an inspiration and challenge for the larger Church.

I give thanks to God for you, for your ongoing commitment to follow Jesus in the Way of Love, seeking to become God’s beloved community where there is plenty good room for all of God’s children. And I celebrate with you 150 years of loving God and neighbor, 150 years of turning your world upside down, like the apostle Paul and those earliest followers of Jesus did long ago. You have built upon the good work of all those who came before you, and are creating a fitting legacy for those who will follow you, and I thank God for that…and for each and every one of you.

God love you, God bless you, and keep the faith!

Your brother in Christ,

To say that Holy Innocents’ Episcopal Church had a humble beginning would be an understatement. Established as a mission for poor children on the north side of Atlanta following the Civil War, the little enterprise had a rough start and its fair share of challenges as the city of Atlanta rebuilt itself.

The Civil War had altered the city dramatically. Many of its buildings suffered shelling by Federal forces during the Battle of Atlanta in the summer of 1864. The buildings left standing were burned by Confederates while retreating or

by Union forces before they began the March to the Sea. Aside from the physical devastation, the city experienced a vast change in demographics. Many men did not return from the war, and women now found themselves opening businesses to provide for their families, while their children roamed the city streets unsupervised. Inhabitants of devastated rural areas left farms and homes to seek new life in the city. The end of the war also brought an influx of formerly enslaved African Americans looking for work and a new life. Fortune did not always come easy for any of the city’s inhabitants. Established just two decades before the war, Atlanta still had the air of a frontier town. Roads of mud and roaming livestock were common. With a booming population, the city experienced serious growing pains.

Out of this turmoil, with its increase of poor and needy people, sprung the shoot that would grow and flourish to become Holy Innocents. The seed was planted by Mary Ellen “Nellie” Peters. Nellie came to her charity work from her devout, Episcopal upbringing, and from having witnessed the horrors of war and the suffering all around her.

Nellie’s father, Richard Peters, had been born in Pennsylvania, the grandson of Judge Richard Peters, a distinguished politician and judge. The younger Richard Peters came to Georgia, in 1835 as a surveyor and civil engineer for the new Georgia Railroad Company. Peters later shared with his daughter, Nellie, “I was quite successful in keeping down expenses and was highly complimented.” He likely used the common practice of persuading plantation owners along the road to let him borrow their slaves, when not needed with the crops, in exchange for stock in the railroad. This practice, along with a free ride to the stockholders meeting each year, made the Georgia Railroad very popular. When the railroad completed its connection to the town of Marthasville eight years later, the hamlet consisted of a few log houses and a rail terminus. In this small but promising frontier, the enterprising Richard Peters soon expanded his scope and influence. In fact, as one of the pioneers of the city, he is credited as the man who, in 1845, helped initiate the change of name from Marthasville to Atlanta—a shorter name more suited to railroad freight lists.

As Atlanta grew, religious institutions took root and flourished as well. On May 2, 1847, the first Episcopal parish in the city was organized, with Richard Peters as one of the original vestry members. The few congregants held their first service in the parlor of Samuel G. Jones, whose twostory house stood at 99 South Forsyth Street. The services continued

in that parlor for the next year, with Bishop Stephen Elliott preaching the sermons and celebrating the Eucharist. Elliott had served since 1840 as the first bishop of the Diocese of Georgia, which in 1846 consisted of only six hundred communicants in the state, of whom about a hundred were slaves.1 At last, on May 18, 1848, Bishop Elliott consecrated St. Philip’s Church, on the corner of Washington and Hunter Streets, across from the site of the present Georgia Capitol. The small structure cost less than a thousand dollars and reflected the bishop’s pragmatic parsimony. The congregation numbered five.

Almost another decade would pass before Judge O. A. Bull of Fulton Superior Court passed an order incorporating “The Church Wardens and Vestry of St. Philip’s Church, Atlanta,” on June 7, 1857. The church received a charter for fourteen years. Richard Peters, one of the men signing the petition, had also helped raise the funds to secure the property for the church. The first rector was Rev. Richard Johnson.

Meanwhile, less than a year after the consecration of the church, a marriage took place that would lead in time to the founding of Holy Innocents. On February 18, 1848, Richard Peters married Mary Jane Thompson, the eldest daughter of Dr. Joseph Thompson, the owner of the Atlanta Hotel. The brick hotel had been built by the Georgia Railroad Company to house employees, and Peters had boarded there on his first visits to the town. It was there that he met Mary Jane, who was more than twenty years his junior. Raised as a devout Presbyterian, Mary Jane joined her husband’s Episcopal church because of the “solace and comfort” she found there.2 Together Richard and Mary Jane would raise their nine children together in the young city. This work was made easier with the assistance of nine slaves, of whom four were adults, to help care for the large family.

As the family of Richard and Mary Jane Peters grew, so did their devotion to the Episcopal Church in Atlanta. They even named two of their sons after the members of the clergy—Quintard, named for Rev. Dr. Charles T. Quintard of St. Luke’s Church, and Stephen Elliot, named for the bishop who baptized him. Among their five children, none would have so

great an impact on Episcopal life as Nellie. As the nation grew increasingly divided over the question of slavery during the 1850s, Georgia and Atlanta became caught up in debates over possible secession. About the coming Civil War, Peters afterward told Nellie that he actively opposed secession because he foresaw the failure and destruction that it would bring. He also foresaw the end of slavery, on the basis of which he had built his fortune.3 But war did come, and with it, oddly, came an expansion of the Episcopal Church in Atlanta.

St. Philip’s was Atlanta’s only Episcopal parish at the beginning of 1864, and its building was barely large enough to accommodate its worshipers. Early that year, as the rebel army of General Joseph E. Johnston wintered in Dalton, Georgia, an army chaplain took the first steps to establish another parish in Atlanta. Rev. Dr. Charles T. Quintard, a physician, surgeon, and priest serving as chaplainatlarge to the army, secured the use of a Methodist church on the corner of Garnett and Forsyth streets for Episcopal services. The congregation that gathered there would become St. Luke’s Parish. Many of its members were refugees from Kentucky and Tennessee, including members of Quintard’s old parish in Nashville. Bishop Elliott favored constructing a new building for St. Luke’s, as did Rev. Andrew F. Freeman, the rector of St. Philip’s. Richard Peters became a charter member of the new parish.

With help from men detailed from the army, construction began in February 1864. Completed at a cost of twelve thousand dollars on the corner of Walton and Broad, the building was consecrated by Bishop Elliott on April 22, 1864. Dr. Quintard described the frame structure as “a most attractive building, handsomely furnished,”4 capable of seating four hundred persons. Mary Jane Peters presented St. Luke’s with a pair of silver goblets in time for the first Sunday service in the new church, held on April 24, 1864.

Unfortunately, St. Luke’s had a short life. Shelling of the church during the Battle of Atlanta in July 1864 rendered the building unusable, and several months later the church went down in flames during the burning of Atlanta in November 1864. During its ninemonth existence, however, it was the site of two memorable funerals. The first was that of General Leonidas Polk, an Episcopal bishop and Confederate general best remembered as the leading founder of the University of the South, Sewanee. Killed in battle at Pine Mountain on June 14, 1864, Polk lay in state in front of the altar at St. Luke’s before his burial. Less than two weeks later, parishioners gathered for the funeral of oneyearold Stephen Elliott Peters, son of Richard and Mary Jane Peters. St. Luke’s was struck by artillery shells the next day.5

Atlanta during the summer of 1864 was a scene of chaos and anguish. Nellie Peters later recalled sick soldiers brought to Atlanta by the thousands, and makeshift

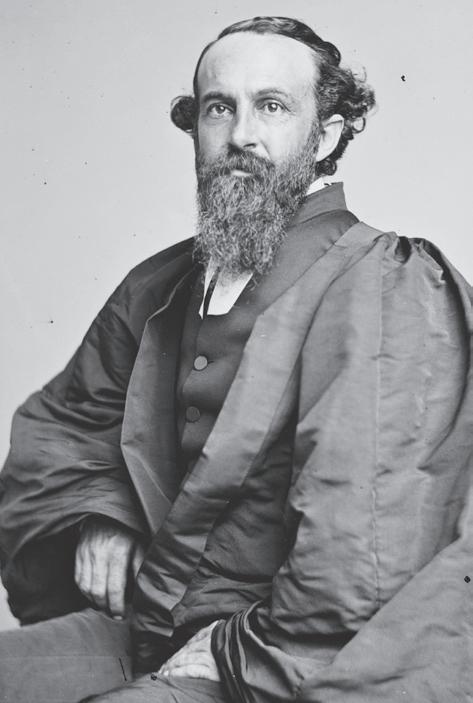

Rt. Rev Charles Quintard, the second Bishop of Tennessee, started as a medical doctor before becoming a priest. As close friends with the Peters family, he would draw on their support to restart the University of the South.

hospitals springing up to meet the demands. She and an enslaved man named Mose accompanied her mother and other women of the St. Philip’s Hospital Aid Society in volunteering to help with the injured and carry food to soldiers. Nellie witnessed the horrors of war firsthand as a teenage girl, and the experience shaped her commitments in later years. As Federal forces advanced on Atlanta, the family fled to Augusta. Union troops crossed the Chattahoochee on July 8 around the area of Heard’s Ferry—near where Holy Innocents would make its home ninety years in the future.

The Peters family returned to Atlanta after Federal forces had left on their March to the Sea. Nellie wrote in her unpublished autobiography that the “Ruin and destruction left small semblance of the happy little village.”6 Her father soon resumed his leading role in the city, and after the war he became a member of the city council, serving as chairman of the council. The city government, of which he was a key member, struggled to provide relief for the growing poor population. The 1867 local census counted 155 widows of soldiers and 294 orphans.7 Thousands of other poor included an estimated 2,200 whites and 1,200 blacks left “utterly destitute.”8 Private relief helped meet the need. Mary Jane and Nellie did their part by organizing events to gather coal, wood, and clothing, and from these endeavors the Ladies Relief Society was founded.

Richard Peters had weathered the war nicely thanks to a blockade running business and was 3 million dollars richer than before it began. He thus was in a position to give his children the best education. Nellie, having finished her primary schooling,9 was sent north in 1867 to continue her education at Miss Maria Eastman’s Brooke Hall in Media, Pennsylvania, where Nellie had family ties. After completing her coursework, she returned to Atlanta in 1870, and now the progress toward founding Holy Innocents picked up speed.

After Nellie finished school, her father gave her cash to buy a diamond, which he saw as a sound investment. Instead, Nellie bought a large, black horse with a diamondshaped white spot on its forehead. She named it Diamond, and the two became celebrities of a sort, particularly among the poor, as Nellie would ride through the poorer sections of town and the countryside, checking on people and offering help where she could. This exposure to what was going on in Atlanta prompted Nellie to approach her father with the idea of donating land for a small mission north of town—the first formal mission to the poor in Atlanta.

Richard Peters agreed, and in 1872 a Sunday School mission named the Chapel of the Holy Innocents was established on land donated by Peters. The chapel was nicknamed “Miss Nellie’s Mission.”10 Deacon A. J. Drysdale, assisted by a “few earnest women of the church”—including Nellie, Julia Force, Rosa Wright, and Misses Edwards11—aimed to “gather the uncaredfor children of the neighborhood” on Sunday afternoons.12

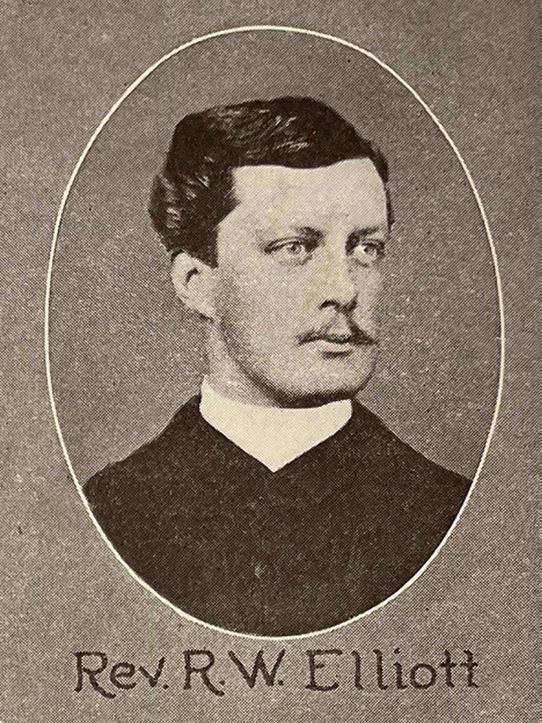

Rev. Robert W. B. Elliott, the rector of St. Philip’s Church, pledged the church’s Easter offering that year (totaling $1,200) to the cause. On June 4, 1872, Dr. W. S. Townsend, the superintendent of the Sunday School at St. Philip’s, presented a plan for the mission, and construction began.

The land donated by Richard Peters occupied the southeast corner of Second Street (now Ponce de Leon Avenue) at Juniper Street, fronting one hundred feet on each street in what is now Midtown Atlanta. Conveyed to the wardens and vestry of St. Philip’s, the tract was worth about twelve hundred dollars and consisted of a hillside of broomsedge with a few scattered trees and dirt roads. A building committee, chaired by Dr. Townsend, was appointed to oversee the construction of the chapel.

The name, Holy Innocents, recalled the infants slaughtered by King Herod in a jealous attempt to kill the infant Jesus: “Then Herod, when he saw he had been tricked by the wise men, was in a furious rage, and he sent and killed all the male children in Bethlehem and in all that region that were two years old and under according to the time he had ascertained from the wise men” (Matthew 2:16). During the fifth century, the Feast of the Holy Innocents (also called Childermas or Innocents’ Day, December 28) was first celebrated as a reminder of the Christian’s responsibility to defend the oppressed.

On July 25, 1872, eight years after the Battle of Atlanta, Dr. Townsend reported to the vestry of St. Philip’s that the Chapel of the Holy Innocents, with funding from Mrs. George Walker, combined with the St. Philip’s Easter offering and a donation from Nellie Peters, had been completed and was paid for in full. In this report the name of Nellie was

mentioned officially in connection with establishing Holy Innocents. She had donated six hundred dollars.

By Easter of 1874, St. Philip’s had two missions. Encouraged by the success of the Chapel of the Holy Innocents, the women of the parish established the Mission School of the Redeemer in a rented hall in a southwestern suburb of the city, hoping for similar success. Nellie Peters was one of the women who made this possible, because the church had “the means of reaching a large proportion of our population that the mother Parish would have been unable to care for.”13 Both missions were placed under the guidance of Rev. Douglas C. Peabody, a deacon and assistant to the rector. By 1877, there were thirtyeight communicants in Holy Innocents’ Chapel, fortynine in the Chapel of the Redeemer, and 489 in the parish proper, for a total of 576. About this time, Rev. Drysdale accepted a call to a church in Chattanooga, and he was replaced by Rev. Reverdy Estill.14

The Chapel of the Holy Innocents is mentioned just a few times over the next six years in the vestry minutes of St. Philip’s. The diocese reported that “the Mission of the Holy Innocents, under the direction of its exceedingly able Superintendent, Dr. W. S. Townsend, has been thoroughly accomplishing the work for which it was organized—giving the children belonging to it definite views of religion, besides improving them steadily by the example and refining influences of their teachers.”15 For a brief time, Rev. Thomas Boone was in

Nellie Peters donated much of her time to the cause, leading and teaching at the mission. She would attend services at St. Philip’s on Sunday morning with her family and then hold services at Holy Innocents in the afternoon, followed by teaching Sunday School to little children from poor families. Sometimes as many as 130 children enrolled. They came from all over the city because they liked the teachers, did not have to dress up, and enjoyed the school.