University of La Verne Copyright © 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the University of La Verne.

1950 Third Street La Verne, California 91750

909.593.3511 www.laverne.edu

Devorah Lieberman, Ph.D. President

Myra Garcia

Vice President, University Advancement

Robert Dyer ’63, Wendy Lau ’98 125th Anniversary Co-chairs

125TH ANNIVERSARY BOOK COMMITTEE

Mary Ann Melleby ’79 Chairperson

Marlin Heckman, Ph.D. ’58

Galen Beery ’59

Jon Blickenstaff ’66

Chuck Davis

Sean Dillon ’87

Clair Hanawalt ’49

Ben Jenkins, Ph.D. ’11

Bill Lemon

Greg Asbury

Project Director

Ginger Morris

Project Assistant

BOOK DEVELOPMENT

Bookhouse Group, Inc. www.bookhouse.net

Editor Rob Levin

Author Michele Cohen Marill

Copyeditor and Indexer

Bob Land

Cover and Book Design

Richard Korab

Archivist

Renée Peyton

The University of La Verne has reached a significant milestone—125 years of transforming faculty, staff, and students’ lives and positively impacting the community. For well over a century, our core values of lifelong learning, ethical reasoning, civic and community engagement, and diversity and inclusivity have guided the university. These values provide the foundation on which we strive to fulfill the institutional mission of providing a distinctive and relevant educational experience to all traditional-age undergraduate students, adult learners, and graduate students throughout all four colleges and across all regional campuses.

The university is perfectly positioned to continue our 125-year-old mission with even greater student and community impact. The University of La Verne is recognized among national higher education leaders for accessibility, affordability, inclusivity, quality of educational experience, and lifelong learning. We are held as an exemplar for recruiting and retaining all students, including those from low-income families; fostering the success of first-generation students; and practicing significant civic and community engagement. Our signature program, the La Verne Experience, creates an interdisciplinary multiple-year experience for all students that includes both curricular and co-curricular elements, and prepares graduates to be future leaders nationally and internationally. We are also realizing our Campus Master Plan that proactively anticipates the needs of our students today, tomorrow, and decades into the future.

Higher education across the country faces many challenges, and the University of La Verne is no stranger to difficult circumstances. Over the last 125 years, the university has continually dedicated itself to accomplishing whatever is necessary to maintain academic integrity and remain focused on the success of all our students. We are most proud that the university has remained focused on its mission and connected to its values, and this anniversary is an exciting moment for the University of La Verne. As we reflect on the past 125 years of institutional progress and achievement, I also encourage us to focus on the next 125 years. I am confident they will be filled with innovation and inspiration where every member of the campus community—students, trustees, faculty, and staff—will achieve more than they ever imagined.

Congratulations on 125 years of Leo pride!

Devorah Lieberman, Ph.D. President

GENERATIONS OF TRANSFORMING LIVES

THE UNIVERSITY OF LA VERNE: FOUNDED IN 1891

With a yank of its handle, the bell resounds like a summons that echoes through the late summer breeze and through the streets of Old Town La Verne.

The heavy bronze bell, forged in 1896 just five years after the founding of the University of La Verne, carries a tone from the past, when citrus groves bloomed from the edge of town to the foothills of the slate-green San Gabriel Mountains towering to the north. CHAPTER ONE

Yet today, the sound also harkens to the future, calling the new students to their first moments of college life.

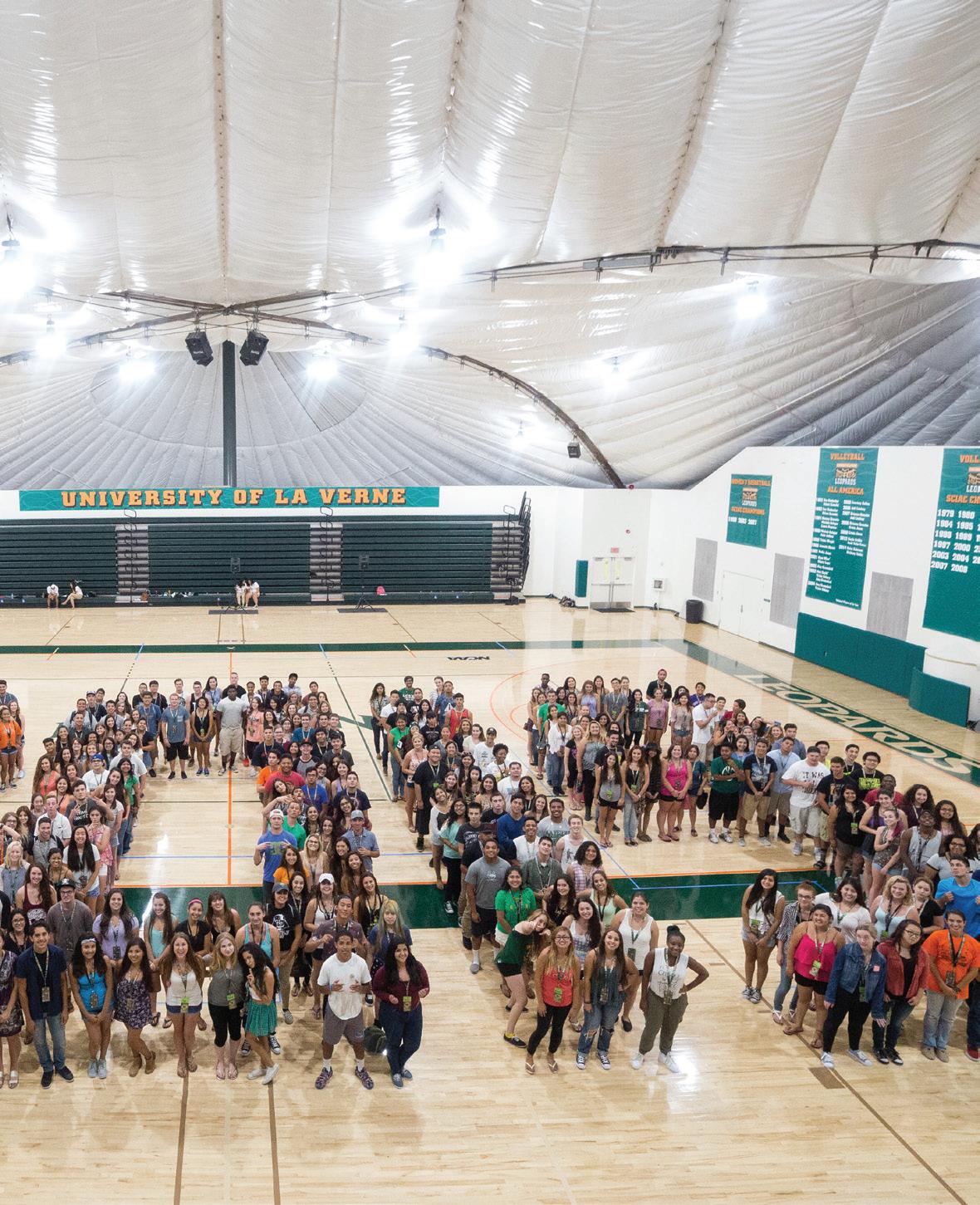

The students look up at University President Devorah Lieberman, Ph.D., who is dressed in full academic regalia, the tassel of her cap dangling near her forehead. They are standing in the Johnson Family Plaza outside the Sports Science and Athletics Pavilion where they will have their convocation. As incoming first-year students, they may not grasp the meaning of this tradition. Not yet accustomed to college, they do not know what to expect. By the conclusion of the convocation, they have a mission for this new world they are entering. Lieberman urges the students to commit themselves to their community: “This is a pivotal year for each of us: Change the world and achieve more than we ever imagined.”

For 125 years, the University of La Verne has been a place for those who want to exceed expectations. Members of the Church of the Brethren who saw promise in a failed California boomtown founded a school they called Lordsburg College. Today, the University of La Verne is a comprehensive doctoral-granting

For 125 years, the University of La Verne has been a place for those who want to exceed expectations.

university with approximately eighty-five hundred students across more than seventy graduate and undergraduate disciplines. The University of La Verne offers an avenue to the future for a student body that is diverse in age, ethnicity, culture, religion, and interests.

At a time of increasing concern about college expenses, Washington Monthly named the university as a “Best Bang for the Buck.”

Many of the University of La Verne’s students come from within Inland Southern California, a fast-growing region about thirtyfive miles east of Los Angeles. The university’s emphasis on theory-to-practice and community engagement attracts students from throughout California and well beyond. Almost 10 percent of the University of La Verne’s undergraduates are international students. Approximately twenty-five hundred alumni live in Asia, primarily in China, Taiwan, Thailand, and Singapore.

The University of La Verne is designated by the US Department of Education as a HispanicServing Institution (HSI), whose student body must be more than 25 percent Hispanic. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching recognized it as a communityengaged campus, and US News & World Report and Forbes magazines named it a top-tier national university. Its online undergraduate program ranked No. 1 among California colleges and universities for three years in a row. At a time of increasing concern about college expenses, Washington Monthly named the university as a “Best Bang for the Buck.”

Yet those and other accolades do not describe the essence of the University of La Verne. Many of the original core values of the founders remain the bedrock of the university: ethical reasoning, diversity and inclusivity, lifelong learning, and community and civic engagement.

Men of Capital, Men of Nerve, Men of Brain are investing in Lordsburg! Catch on to the BOOM!

The Santa Fe Railway created a station in this would-be town in partnership with Isaac W. Lord, a land speculator who made his fortune off the sudden popularity of Southern California. But despite this advertisement and a later pronouncement that “Lordsburg stands equal to any other place in point of productiveness and health,” it did not become the thriving destination Lord envisioned. n In 1891, the town gained a new, nobler purpose with the establishment of Lordsburg College. The Church of the Brethren founders wanted to create “a first class College or Seminary of learning for the complete education of the young in all useful learning and knowledge,” and they were undaunted when they realized that the local students were not prepared for college work. n Instead, Lordsburg College began as an academy. In a photograph soon after its opening, the first students stand in rows on the steps of the hotel-turned-college, some of them barefoot children who look as young as six or seven. Older students stand behind them. n Within a few years, the students grew tired of jibes about the name, which sounded too much like a haughty way to say “God’s town.” In 1912, they petitioned the board of trustees to change it to Palmera College. For one summer, the school moved toward this new identity—until Lord filed a complaint in court and the college backed

down. n When Lord died in 1917, demands for a name change gained new traction. The nearby La Verne Orange and Lemon Association shipped citrus around the country, and the residents of Lordsburg voted overwhelmingly to associate with that verdant image. By the fall, La Verne College opened in the town of La Verne. n The evolution from a college to a university occurred much more gradually. For many years, La Verne College was known primarily for producing teachers and missionaries. In 1963, the college began offering a master of arts in teaching. By 1975, there were six additional master’s degrees and a doctoral program in school management (EdD). The law school opened in 1970, and the College Accelerated Program for Adults began in 1971. La Verne even housed the American Armenian International College, which offered a major in Armenology (the study of Armenia). n In 1977, President Armen Sarafian asked the board to acknowledge the new reality of the school’s broad focus and change the name, setting the stage for future transformation. Eighty-six years after its first promise of spreading a values-based education, the University of La Verne offered a full array of academic programs for students of various ages and backgrounds.

Professors nurture students with as much care as they did when enrollment numbered just a few hundred.

While all colleges and universities assert that they are student-centered, “I have never been on a campus where it is more true on a daily basis than it is at the University of La Verne,” says President Lieberman. “Students graduate with the theory and knowledge of their discipline and fundamental core values, all to be applied for the rest of their lives.”

In the early 1900s, the University of La Verne evolved at the east edge of the San Gabriel Valley, blessed with leaders from the Church of the Brethren who lived their creed of simplicity, temperance, and faith. Edward Frantz, president of what was then called Lordsburg College from 1911 to 1915, believed that education would help students appreciate “the length and breadth, the height and depth of life.” Yet the early years were challenged by financial struggles, and the future of the college was often uncertain.

Today, while standing in the center of

“Education would help students appreciate the length and breadth, the height and depth of life.”

— Edward Frantz

It is hard to imagine what Church of the Brethren leader

Matthew M. Eshelman saw in 1889 when he stepped off the train platform of the Santa Fe Railway in what was then the fledgling town of Lordsburg.

campus, ensconced in a suburb that Family Circle magazine recently called one of the nation’s best places to raise a family, it is hard to imagine what Church of the Brethren leader Matthew M. Eshelman saw in 1889 when he stepped off the train platform of the Santa Fe Railway in what was then the fledgling town of Lordsburg.

Near the train station stood the massive Lordsburg Hotel, which rose like a beacon of Victorianism, the dome and spire of its ninety-foot tower visible from afar. Yet the scene was agrarian. Vacant lots surrounded the hotel, each carefully surveyed, numbered, and drafted on a town site map—all unsold. The 130-room hotel itself never hosted a paying guest.

In the early 1880s there was a land boom in Southern California, but by 1888 the real estate market had collapsed. In an unrealized dream, Eshelman saw an opportunity for education. Four Church of the Brethren colleagues agreed—providing the price was right. They offered fifteen thousand dollars for the hotel

and one hundred lots, and they may have been a bit startled when the owners accepted. The hotel alone reportedly cost about seventy-five thousand dollars to build.

By the fall of 1891 they had transformed the hotel into classrooms, offices, a chapel, library, dining hall, and dormitory for the first seventy-six students.

By the fall of 1891, about two years after that first visit, they had transformed the hotel into classrooms, offices, and a chapel, library, dining hall, and dormitory for the first seventy-six students. A sign hung on the gable proclaiming Lordsburg College, but that also was more aspiration than reality. The first students were not prepared for collegiate work, and the school served as a preparatory academy.

From the start, the college founders intended to improve their new community. Their school was inclusive, intentional, and multicultural, welcoming the children of some of the original Mexican rancheros of the area. In the first graduation photograph in 1896, students and faculty posed in front of the motto, “From Preparation into Practice,” an early expression of the school’s commitmenttoprovidingprofessionalskillsof theory-

“From Preparation into Practice,” an early expression of the school’s commitment to providing professional skills of theoryto-practice, along with a solid academic foundation.

to-practice, along with a solid academic foundation. By special arrangement, students who completed college preparatory work at Lordsburg were automatically admitted to Stanford University.

Still, tuition did not cover expenses, and the school struggled financially. In 1901–1902, with no one willing to take the helm, Lordsburg College was shuttered. W. C. Hanawalt, an educator and member of the Church of the Brethren in Pennsylvania, came west to revive it the following fall. True to the values of thrift and hard work, the Lordsburg teachers and students tended gardens, picked fruit, and milked cows. Hanawalt’s wife baked huge loaves of bread. His father kept hives of bees for honey.

Like the founders, Hanawalt believed that more prosperous times would come, and he invested in additional land for the campus. When the Church of the Brethren Annual Conference came to Los Angeles in 1907, the college advertised that “Lordsburg is an ideal city for such as may wish to withdraw from the severities of eastern climates,

and have a lovely quiet place to educate children away from the temptations and allurements of city life. There is not a saloon within twenty-five miles; no pool rooms thrive in this community.”

Eventually, Lordsburg College began to fulfill its purpose. “The [college] department has had its ups and downs but on the whole the ups have been ahead, by far,” students wrote enthusiastically in 1912 in the Orange Blossom yearbook, two years before P. J. Wiebe received the school’s first bachelor’s degree. “If in six school years such progress has been made, what fear need there be for the future?”

Take a walk around the campus today, and the future that the yearbook mentioned unveils itself. Each new building represents growth and change.

Miller Hall, named in 1926, with its neoclassical columns flanked by palm trees, was dedicated in September 1918 as a women’s dormitory and now houses the English department, photography department, and liberal arts. Founders Hall, now shaded by century-old live oak trees and partially covered in vines, arose in 1926 to replace the former Lordsburg Hotel, a wooden structure that was deemed a firetrap and torn down in 1927. A Craftsman-style gymnasium opened in 1921 and was replaced with the Campus Center, which opened in 2009. In 1917 the town and college both changed their names to La Verne.

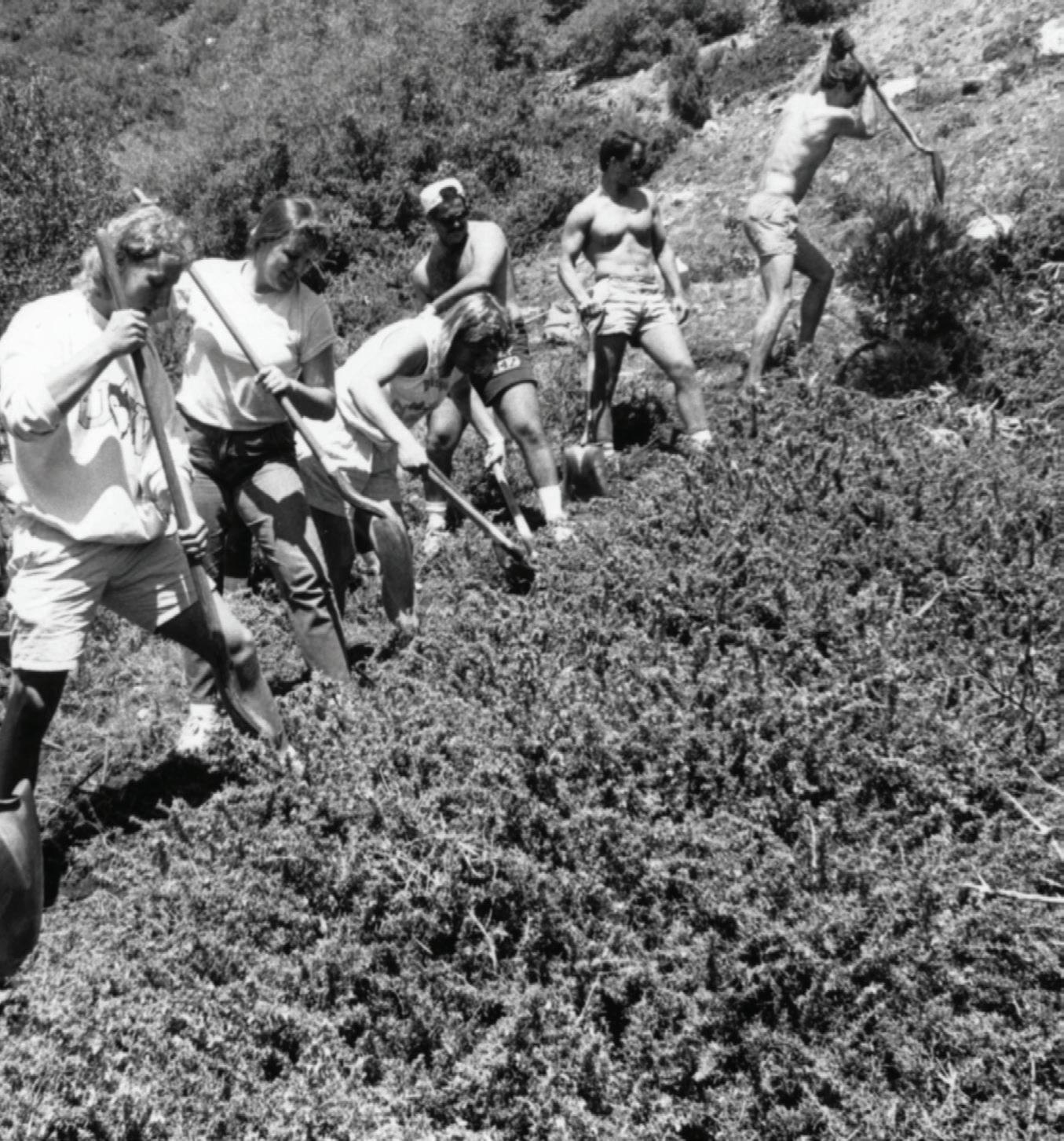

Looking north from Sneaky Park just outside Wilson Library and across the street from Miller Hall, an “L” remains visible on a mountainside. Four friends from the class of 1921 trekked

to the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains in April 1919 with bedsheets and tools to measure and then clear the brush on a ridge into the largest such emblem in the United States. One of those students, George Hollenberg ’21, later wrote the lyrics of the alma mater, imbued with nostalgia for a cherished college: “There’s a dear favored spot / that shall ne’er be forgot. . . .” This original alma mater is still sung by participants at all major university events.

After World War II, sentimentality gave way to an era of sturdy brick buildings, a coming of age under the steady leadership of President Harold Fasnacht that brought the W. I. T. Hoover Memorial Library, as well as Studebaker, Hanawalt, and Brandt residence halls; the Science and Education Building (now Mainiero Building);

the Davenport Dining Hall; and Dant Chapel. The alma mater sounded twice a day from speakers in the Hoover clock tower.

“There’s a dear favored spot / that shall ne’er be forgot. . . .” This original alma mater is still sung by participants at all major university events.

In 1952, when the one thousandth student graduated, La Verne College remained a small liberal arts school that specialized in teacher education. While only about half of the student body belonged to the Church of the Brethren, the foundation was set for the Brethren values to engender a broader impact. Today, the University of La Verne continues to pursue bold dreams and new opportunities for the university and all of its graduate and undergraduate students with modern facilities arising around the historic campus to meet the changing needs of students and faculty.

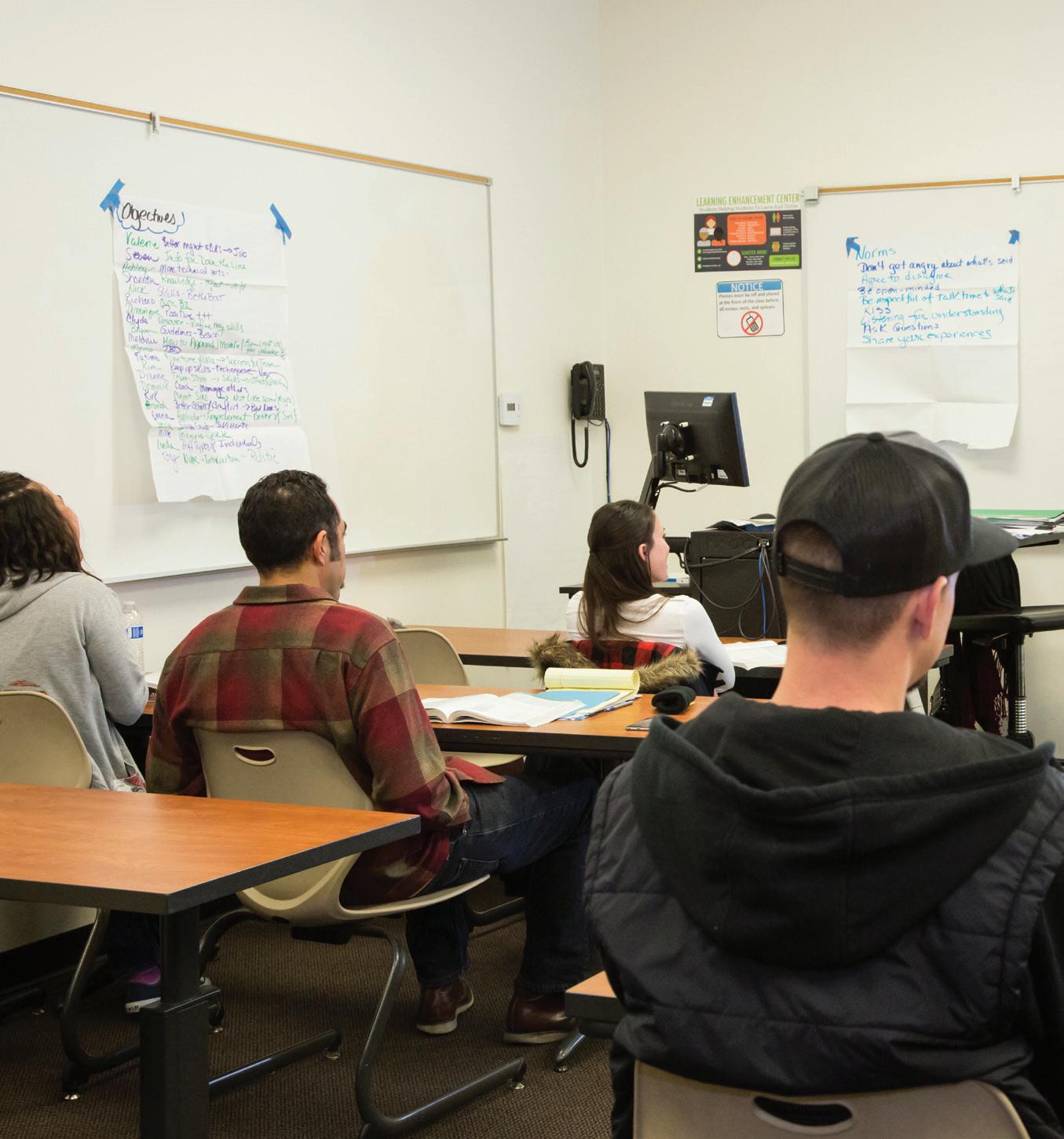

At nine o’clock on a summer morning, while their friends back home are still asleep,

The clock tower is still a prominent landmark on the University of La Verne campus. The sign announcing “Christian College Day” is testimony to the school’s deep roots in the Church of the Brethren.

fifty-seven high schoolers fill the chairs in the classroom at the University of La Verne and imagine themselves in a different sort of life. For three weeks, they experience a dream—living like college students and playing the role of top executives at a startup company. Every summer, the University of La Verne hosts the REACH

Every summer, the University of La Verne hosts the REACH

Camp to inspire local high school students to think of a greater future.

Summer Business Camp to inspire local high school students to think of a greater future. The camp, founded by longtime professor of finance Adham Chehab, is just one example of the university’s ongoing commitment to serve the diverse needs of its region.

By the end of the three-week camp, the students will devise a new business, conceive a marketing plan, and present their ideas before a group of business leaders. The winning team nets one thousand dollars, which amounts to about two hundred dollars per student. But there is a deeper purpose: In the past ten years, 96 percent of participants in the REACH camp have gone on to college, and 84 percent of them graduated. Some of them are drawn back to the University of La Verne and its mission of nurturing each student’s potential.

The REACH program is less about recruitment than it is about inspiring teenagers to believe in themselves.

“So, how are we doing on the business plan? Are you all working together?” Professor Issam Ghazzawi’s deep voice reverberates as the students nod and give their assent. “Excellent, excellent!”

Ghazzawi left a successful career as a vice president with Sigmanet, a technology company, to enter academia. Now he is distilling the principles of business management. On the whiteboard, he has written four large letters: POLC.

“What does it mean? Anytime you have a

At La Verne, Winning Is Not Everything—or the “Only Thing”

Roland Ortmayer, the University of La Verne’s storied football coach, was not known for winning games. His team only won about half the time, and that seemed about right to him. Instead, he regarded his athletes as students first, young people whose life off the field was more important than the time spent between the goalposts, and he fervently believed football should be fun. n In a sport frequently dominated by a win-at-all-costs mentality, Ortmayer was known for letting players decide their own plays, never cutting a player from the team—and occasionally turning a practice into a watermelon race. During his forty-two years as football coach, his record was 182-193-8. In a 1989 profile, Sports Illustrated called him “the most unusual football coach in the U.S.” n This Ort-ism sums up his philosophy: “Football to me is like climbing a mountain. The climbing is where it’s at.” n Today, Ortmayer’s values still resonate at the University of La Verne. Not that the coaches and players are not competitive: many of the university’s teams, including football, have been conference champions, and in the 2015–2016 season the Leopard football team was SCIAC champion. The baseball team captured national championship titles in 1972 under Coach Ben Hines ’58 and in 1995 under Coach Owen Wright. Jimmy Paschal coached the women’s volleyball team to national titles in 1981 and 1982. The University of La Verne Leopards won two other national championships (men’s volleyball in 1999 and women’s volleyball in 2001) and had individual national champions in track and field and golf. n In 2013–2014 the University of La Verne ranked 37th out of 444 schools in the Learfield Division III National

Directors’ Cup, a standing that reflects the overall success of its teams. n Every athletic office features a framed copy of the university’s vision and mission statements and its core values. Competitiveness is just one of three “standards of distinction” in the Department of Athletics Strategic Vision. The other pillars are “experiential” and “academic.” n “First and foremost, we care about our student athletes, to make sure we are helping them develop further as human beings—building leadership skills, character, all the life skills,” says Athletic Director Julie Kline, who began at La Verne as a softball and women’s volleyball coach. n About 20 percent of the University of La Verne’s traditional undergraduates are involved in athletics, and Kline cares about all of them. “We get that question all the time: What are your top sports? All twenty-one. It’s about all twenty-one programs,” she says. “We try to support each program to the level it needs to be successful.” n That sentiment influenced Ko Yajima ’16, who came to the University of La Verne from Tokyo. Attracted to the university’s tight-knit community and small classes, he walked on to the soccer team and played four years as a midfielder. “Being on the team helped me build good relationships from the start,” he says. Even though he had traveled far and to a much different environment, he says, “It felt like it was home.”

The Leopards enjoyed many successes under legendary football coach Roland Ortmayer (above) and later boasted a 2015–2016 conference championship. Competitiveness is just one of the three standards established by the Department of Athletics. The other two pillars of the strategic vision are “experiential” and “academics.”

Part of a global nonprofit organization, Enactus brings together students, academics, and business leaders who are committed to using the power of entrepreneurship to transform lives, shape our society, and help sustain a better world. Professor Issam Ghazzawi established the program at the university, and since then the teams have been recognized nationally for their local and international community projects. Students have also received career job offers as a result of their participation.

business, we need to plan, right? P stands for planning, O stands for organizing, L is leading— we need to lead—and C is controlling.”

The students scribble notes on their yellow legal pads, and do their research during computer sessions in the library without distractions from cell phones.

Ghazzawi asks them to gather in their teams and create mission statements for their businesses. Soon those statements morph into nascent business ideas: customizable eyewear,

“P stands for planning, O stands for organizing, L is leading—we need to lead—and C is controlling.”

—Issam Ghazzawi

a mobile app to connect students with tutors, a food truck with Asian-Mexican fusion cuisine, and a solar-powered charging case for cellphones. All sound like viable enterprises.

In the back of the room, Jasmine Marchbanks ’17 listens and smiles. She is a REACH counselor and a member of the university’s Enactus chapter, an international network of student teams with a service focus. She, like many of these teenagers, was a little uncertain about how she would fit in

at college. “I just tell them that college is possible for everyone,” says Marchbanks, a communications major. “It’s not as hard as they think it is. I think college is attainable for anyone and everyone if you’re willing to work.”

In an era of public institutions experiencing rising costs and bulging class sizes, the University of La Verne offers a supportive and often more economical path. About half of the university’s traditional undergraduates are the first in their families to attend college. The First Generation Student Success Program provides faculty mentors and special workshops, and the First Generation Club welcomes the students like family.

The university draws about 75 percent of its entering class of traditional-age undergraduates from Inland Southern California. “One of the goals of the 2020 Strategic Vision is for the student body to reflect the demographic of the communities we serve,” says Homa Shabahang, vice president of strategic enrollment management and communications. Through outreach, the University of La Verne attracts a diverse student body while the overall academic qualifications have been rising.

For example, the university sponsors college

preparation classes at African American churches in Southern California through its Master’s Academy. The University of La Verne was also the first private university in California to become a partner of the Dream US Foundation, offering scholarships to undocumented students who have protected legal status because they came to this country as children.

The university has a history of serving those whom society often marginalizes. A prison education program spanned more than three decades, and a summer institute served children of migrant workers.

Outreach “is connected to the long history

and legacy of the Church of the Brethren—a church that from its origins believed in the full inclusion and integration of all humanity,” observes Dr. Daniel Loera ’12, director of the Office of Multicultural Services. “It all starts from that vantage point.”

Professor of biology Jerome Garcia, Ph.D., ’98 stands on the stage in the Morgan Auditorium and looks out at the rows of teenagers sitting with their parents. He once sat in those seats as a first-generation college student, and he cannot help but remember how clueless he felt—scared and confused, not sure he belonged. After his freshman year, he considered dropping out.

He tells a bit of his story to these incoming students who are beginning their journeys by meeting with faculty advisers during the Summer Opportunity for Advising and Registration (SOAR). By the time he was a senior at the University of La Verne, Garcia was doing research on a tumor-suppressor gene and had gained a prestigious place in a doctoral program at the University of Southern California.

“You’re going to develop your character, you’re going to find your passion here,” Garcia assures them. “It was service and community engagement that really helped me find my passion as a professor.”

Today, he mentors first-generation students, some of whom work in his lab,

Compared to earlier years, the clock tower today is perched amid beautiful landscaping and is a focal point on campus.

contemplating careers they could not have imagined just a year or two before. One group is studying the antioxidant properties of certain proteins in fermented milk. The work can be slow, even frustrating, but these undergraduate students practically live in the lab. They can delve as deeply as they are willing to in a research setting that at other universities is dominated by graduate students.

“We do it to learn and be a part of this,” says Sabrina Bawa ’16, a biology major from Diamond Bar, California, who dreams of becoming a physi-

The university draws about 75 percent of its entering class of traditional-age undergraduates from Inland Southern California.

cian. “It’s about being something greater than ourselves.” n

Science and other STEM programs have enjoyed tremendous growth at the University

where undergraduates can participate at a level usually reserved for graduate students at other universities.

“We do it to learn and be a part of this, it’s about being something greater than ourselves.”

Sabrina Bawa ’16

Traffic flows northward and eastward, steady as the evening tide, wave upon wave of people making their way home after a tiring day at work. The din of the freeway is audible from the parking lot of the small office building in Burbank, where students park their cars and ride the elevator to the third floor.

At five o’clock, classes are just beginning at the University of La Verne’s nine regional campuses and its Campus Accelerated Program for Adults (CAPA). Although class time may be during the day, evening, or weekend, the tradition of tying theory to practice has special relevance. The university is known for experiential learning and community engagement—projects and programs that connect the academic content to experience on the job.

“Lead people and manage things. What did you notice about that this week in your business world and your encounters?” Adjunct professor Kathleen Haworth asks one evening in the bachelor’s-level course Leadership in Organizations.

Lydia Prendiz, forty-seven, a manager at a lighting company, raises her hand immediately. Day-to-day work has become just a tactical mission, an ongoing push to get the tasks completed, she says. “It was really good to question how I can reconnect and put some leadership back into the

continued on page 38

The university is known for experiential learning and community engagement—projects and programs that connect the academic content to experience on the job.

Law schools are in crisis around the nation, with fewer applicants and anxious graduates worried about job prospects and the value of the degree.

“They are right to be concerned,” says Gilbert Holmes, dean of the University of La Verne’s College of Law. n Holmes has a clear idea of the necessary path for legal education, and it is as far from the traditional program as a faraway planet is from Earth. Holmes, a fan of sci-fi writer Isaac Asimov, thinks of the University of La Verne as the Planet Terminus of law schools—a new, more sustainable empire on a planet at the edge of the galaxy. n On the wall of his office, near the glowing blue Planet Terminus poster that reminds him of his iconoclastic mission, Holmes posted a framed copy of the core values of the College of Law: basic skills, high performance on the bar exam, ready-to-practice curriculum, a beacon of hope and inspiration. n The University of La Verne gained national attention when it set a single, affordable, and transparent annual tuition of twenty-five thousand dollars—the True Tuition model—with no discounts or scholarships to attract targeted students. While other law schools often avoid even talking about the bar exam, letting their students find their own way to prep classes or testing centers, the College of Law provides a well-staffed Center for Academic and Bar Readiness to help students prepare. n The curriculum has become increasingly experiential, with a simulation of drafting and negotiating an agreement, in addition to the litigation experience that culminates in a mock trial. Legal writing and law practice skills are embedded in the academic

program. n “We’re developing new methods of delivery of legal education while the rest of the galactic empire and legal education as a whole is slowly crumbling,” says Holmes, who came to the University of La Verne from another institution because of the unique opportunity to shape the law school. n From its inception, the University of La Verne’s College of Law grew out of a need for legal education in Inland Southern California. Superior Court Judge Paul Egly approached President Leland Newcomer ’42 in 1969 with a proposal that was quickly accepted. The La Verne College Law Center, as it was initially called, opened in 1970 with Egly as dean and an advisory committee of prominent local attorneys and judges. The law school grew quickly, merging with the San Fernando Valley College of Law in 1983. Its graduates soon made their mark as judges, prosecutors, and local attorneys. n In 2016, the law school was granted full accreditation from the American Bar Association. It was a long-sought standard, and it could not have come at a better time, as enrollment at the school continued to increase while other law schools have seen a decline. Additionally, the program is now the most affordable ABA-accredited law school in California. n A banner hangs in Holmes’s office. It proclaims, “Congratulations to our February 2014 bar exam passers! La Verne College of Law 87.5%.” That was twenty points higher than the state average for ABA-accredited programs—and a sign of the success of the University of La Verne’s relevant and experiential approach.

The University of La Verne College of Law is known for assisting students with the True Tuition model. This provides a fixed rate for all three years of fulltime students’ legal education, or all four years of part-time students’ education, with a provision for performance-based, outside-funded scholarships in the latter years. This brings financial stability to students and families knowing in advance that there will be no increases during their studies. The College opened in 1970 and soon was witnessing its students emerging in the profession as successful lawyers, judges, and prosecutors.

continued from page 34

job. Continue to manage, but remember where my focus really should be.”

Other students nod in agreement. They all know managers who lack the leadership skills they are studying, and they have all experienced days in which the main goal was just to make it until closing time. The most inspirational moments of their week come from this class.

Ruby Medina, thirty-one, mother of a child with autism and a six-month-old baby, works full-time as an administrative assistant at the Southern California Gas Company. But on Monday nights, at the University of La Verne’s regional Burbank campus, she sees herself on track for a better future.

“Once you have already had a career and you know the career life, when you learn new skills, you apply them right away.”

When the University of La Verne developed CAPA in 1971, few options existed for people who had not completed college in the usual window of their early twenties. Typically, if you could not

“Once you have already had a career and you know the career life, when you learn new skills, you apply them right away.”

Ruby Medina

quit your job to go back to school, you could not pursue a degree.

The University of La Verne started the CAPA program with a pilot test of this new idea with just two students and then quickly expanded. Within a few years, more than one hundred students were attending weekend classes at Founders Hall. Today, about thirty-four hundred adult learners pursue undergraduate and graduate degrees, many of them through partnerships with employers who offer courses at their worksites.

“Everyone is there because they are

“Everyone is there because they are mission-driven. It is a second chance for education.”

— Dr. Steve Lesniak ’96

mission-driven,” says Dr. Steve Lesniak ’96, former dean of the regional and online campuses who retired in 2015 after thirty-nine years at the University of La Verne. “It is a second chance for education.”

The regional and online campuses reflect a broad commitment by the university to adapt education to the needs of all students. In its 125 years, the university has seen tremendous

change—and remains poised for more by pioneering new programs and teaching techniques that prepare students to succeed in an interconnected world.

For much of its history, the University of La Verne was like an extended family, a close-knit campus where everyone went to chapel once a week and enjoyed hayrides, picnics, and square dances.

For much of its history, the University of La Verne was like an extended family, a close-knit campus where everyone went to chapel once a week and enjoyed hayrides, picnics, and square dances. Beyond the usual holidays, students looked forward to Beach Day and Snow Day for annual treks to the shore and mountains. On Build La Verne Day, they helped wash windows and pull weeds. On L Day, they cleared the mountain paths of the famous L.

Lifelong learning, inclusivity, community engagement, ethical reasoning—those were natural parts of the university. “It was an extension of life as we knew it from church and home,” recalls Dr. Marlin Heckman ’58, who served as head librarian for thirty-two years and later as the university archivist.

But the tide of change that swept college campuses across the country in the 1960s also came to the University of La Verne. The change agent was Dr. Leland (Lee) Newcomer, a 1942 graduate who became the university president in 1968. A former public school superintendent, he wanted students to explore existential questions through their chosen studies: “‘Who am I? What is the meaning of my existence in the world? What is my place in it?’”

To facilitate change, Newcomer successfully pressed for the enlargement of the board of trustees, which resulted in the Church of

In the mid-1970s, La Verne College operated academic programs in Athens, Greece, and then Naples, Italy. These La Verne students enjoyed some time visiting ancient Greek ruins.

the Brethren trustees becoming a minority with decreased influence. In the next few years, under President Newcomer, the university opened its first coeducational residence hall, created the January interterm, eliminated the requirement to attend chapel, and encouraged students to devise their own majors. He developed CAPA and initiated the largest federally funded program in the United States to train bilingual educators. He even created an off-campus program for active military at the US Naval Pacific Missile Range in Point Mugu, just north of Los Angeles.

Although the Church of the Brethren

“‘Who am I? What is the meaning of my existence in the world? What is my place in it?’”

Dr.

Leland (Lee) Newcomer ’42

retained its strong historic commitment to being a peace church, the university took an all-encompassing view of its mission to serve the needs of the community. Members of the military—and their civilian support workers—were finding it hard to pursue higher education. The University of La Verne program gave them a chance to work toward a degree. Other field studies centers opened on bases in the Philippines, Greece, Italy, and Alaska.

train bilingual educators.

President Newcomer was controversial— not just because of his proposals, but also due to his brash approach. He did not shy away from controversy. He embraced it, as he explained in a yearbook comment about a “very active and exciting year”:

Some people in our community

“He was probably the most visionary person I ever worked with; he loved to stir the pot. He loved to make people uncomfortable.”

Steve Morgan ’68 former University of La Verne president

have said we created more problems this past year than we have solved.

I hope this is true and that it will continue this way, for problems create tension—tension creates dissatisfaction and dissatisfaction motivates action to change behavior or conditions. . . . So let’s get on with the identification of problems and the struggle for solutions.

“He was probably the most visionary person I ever worked with; he loved to stir

the pot. He loved to make people uncomfortable,” says Steve Morgan ’68, who worked as Newcomer’s assistant and later became the University of La Verne’s longest-serving president.

While the CAPA program became a lasting legacy, Newcomer’s last visible contribution to campus was the construction of the “Super Tents.” The world’s first permanent tensioned-membrane structure integrated a fiberglass fabric canopy coated with Teflon

Newcomer’s last visible contribution to campus was the construction of the “Super Tents.”

resin, suspended by cables and frames, to create what are now the Sports Science and Athletics Pavilion and the Dailey Theater. Opened in 1974 and renovated in 2005, the Super Tents added architecturally significant space in the most economical way, originally costing less than $3 million.

When Newcomer moved on to another post as a public school superintendent, his spirit of innovation resonated into the future.

The University of La Verne’s iconic Super Tents are suspended with cables and frames and wrapped with a Teflon-coated fiberglass fabric. Opened in 1974 and renovated in 2005, they now house the Sports Science and Athletics Pavilion and the Dailey Theater.

The University of La Verne Literacy Center is a unique learning program both for kids and the graduate students who practice teaching strategies. Since it opened in 2002, close to one thousand kids with reading challenges have benefited from the program, enabling many of them to raise their reading levels by up to two years.

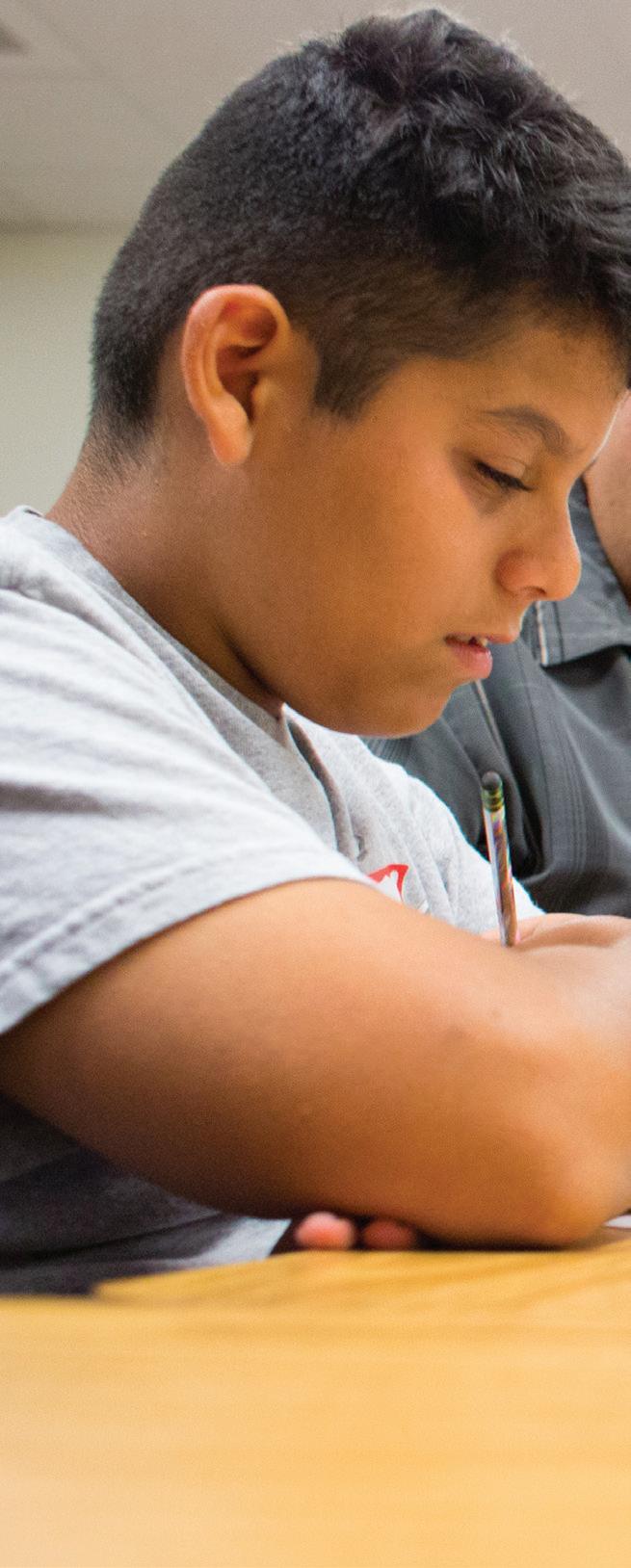

Raggedy Ann and Andy rest on a chair upholstered in an alphabet fabric, as if they are waiting for a young child to snuggle up and begin reading to them. Nearby, children sit on the floor with a board book while mothers gather toddlers on their laps. The waiting area of the University of La Verne Literacy Center feels like a mix between a cozy living room and the children’s section of a library.

It is actually the entryway to a unique learning environment, a hands-on graduate reading program that enables university students to learn teaching strategies and practice them under professional supervision. The graduate students tutor from 4 to 5:30 p.m. and then attend their own classes from 6:15 to 9 p.m.

In one classroom, Gene Simons, a high school computer applications teacher who is working toward certification as a reading specialist, pulls out a set of flashcards he has made and laminated. As he flips them over to

drill a preteen boy who has been struggling with his reading, Simons notices that the boy often tries to sound out the -tion ending of words as “tee-on.” But one word, nation , he has memorized and pronounces correctly.

“You see, this ending is the same,” Simons shows him, comparing the card with one showing “narration.” “When you see t-i-o-n at the end of word, it sounds like shun.”

Simons could almost see a light going on in the boy’s eyes. He smiles and pauses, a moment that makes the long days and late nights of work and graduate study worthwhile. “It seems like a little thing, but it’s a big deal because he learned he can do it,” Simons says.

The University of La Verne Literacy Center has worked with approximately a thousand children since it opened in 2002, helping them progress by as much as one year in their reading level in just ten weeks of free tutoring. Some children take a second session, enabling many of them to catch up by two years.

The University of La Verne Literacy Center has worked with about a thousand children since it opened in 2002, helping them progress by as much as one year in their reading level in just ten weeks of free tutoring.

“For some children, it’s a saving grace. They bond with the tutor, and something happens that couldn’t happen in the regular classroom,” says professor of education Janice Pilgreen, Ph.D., codirector of the Literacy Center and founder and chair of the Graduate Reading Program. “It becomes pretty magical. What happens at the center is amazing.”

The teachers touch lives one by one, but they also spread their successful strategies to their

colleagues in their schools. It is hard to overstate the impact the University of La Verne has had on education in Southern California. Even when it was just a small college, dozens of new teachers graduated every year. John “Skip” Mainiero ’62, who served as chair of the education department before becoming vice president for administration and finance, helped develop some of California’s rules for teacher accreditation programs.

Beginning in 1975 the doctoral program in

“For some children, it’s a saving grace. They bond with the tutor, and something happens that couldn’t happen in the regular classroom.”

Janice

school management (EdD) became a laboratory for new teaching methods that reflected the flexibility and creativity that the university sought to bring to education. Doctoral students, who were already California educators, worked in teams to improve decision-making and problem-solving.

“It was like a think tank for leadership,” says Dr. Barbara Poling ’82, professor of organizational leadership, who earned her EdD from the University of La Verne in 1981.

The bonding between student and tutor in the Literacy Center takes place over just a few weeks, but the impact and results are lifelong achievements.

The University of La Verne continues to innovate. In 2001, with a grant from the US Department of Education, the university developed a Spanish Bilingual Bicultural Counseling certificate, the first of its kind in the nation. The program gives future counselors tools and skills to help the children of native Spanish-speaking immigrants balance the culture and expectations in their homes with their need to acculturate into American society at school.

Just having academic success is not enough. That is what Dr. Rita Patel Thakur ’03, associate dean and professor of business management, remembers thinking when her business students graduated and asked for references to become a bank teller or a secretary, despite having new degrees that could open the door to professional careers. She realized that students need the practical skills and confidence to reach higher.

Thakur grew determined to reshape the College of Business and Public Management with an experiential curriculum that she calls “the most

In 2001, with a grant from the US Department of Education, the university developed a Spanish Bilingual Bicultural Counseling certificate, the first of its kind in the nation.

Cultural entertainment is under way at an annual Latino Education Access and Development (LEAD) Conference, developed by the University of

During LEAD, the school hosts several hundred Latino students from nearby school districts. The students spread across the campus, attending information sessions and listening to speakers, all in an effort to help them learn about the benefits of higher education. One recent LEAD conference offered sessions on topics such as STEM careers, Latinos in Entertainment, and Communication Career Pathways.

Thakur grew determined to reshape the College of Business and Public Management with an experiential curriculum that she calls “the most unique program in the United States.”

unique program in the United States.” Sophomores learn how to function in the business environment, from dining etiquette to resume writing. They practice interviewing and even receive feedback from area business leaders. Juniors are paired with business mentors, who take them to networking events and coach them. Seniors provide market research, financial analysis, and other consulting for local businesses, creating reports that they can later show prospective employers.

“You wouldn’t believe the confidence they build,” says Thakur, who led the application for the $2.47 million federal grant that helped establish the program.

The centerpiece of this Skills for Success program is the Integrated Business Curriculum in the junior year. Instead of listening to lectures and watching PowerPoint presentations, the University of La Verne’s business majors learn

Student housing at the University of La Verne is spread over several residential communities, each with its own style and personality. A residential life team helps coordinate all aspects of student life in housing, with special focus on respect and appreciation for diversity as well as student safety and individual academic success.

about marketing, finance, and management by actually building companies. Each team presents a business plan to a local bank and, when approved, receives a twenty-five-hundred-dollar loan to launch a product or service, to be repaid from their revenue at the end of the year. Students then select which charity will receive their net profits.

It is not just a class; it is a challenge—and the students meet it with gusto. Consider the case of ConnecTech, an enterprise that offered to solve a common problem for people who want to use their devices while they are charging. The students sold a six-foot-long charging cable to replace the typical two-foot version that does not reach very far from the outlet. The cords, offered in four colors and three models, sold for $15, or two for $25. They cost only $1.97 wholesale, netting the team a significant profit. ConnecTech raised about $10,000 for the Breast Cancer Research Foundation. Integrated Business Curriculum students have netted more than $70,000 in profits.

When business students leave the University of La Verne, they seek management and finance jobs—or start their own companies with real experience. Theory-to-practice helps build dreams. “Our students are hungry for success,” says Dr. Abe Helou, dean of the College of Business and Public Management. “When you give them a chance to demonstrate their skills, they shine.” n

“Our students are hungry for success. When you give them a chance to demonstrate their skills, they shine.”

— Dr. Abe Helou, dean of the College of Business and Public Management

Magpies screeched their wakeup call, and the dew was still fresh on the tall grass when Stephany Gonzalez ’15 stepped out into a Montana summer morning. Insects buzzed around her and a snake slithered away from her path, but she barely noticed them as she walked from the road into the ranchland. Gonzalez was peering closely at a wooden bird box where she had placed a fake cowbird egg— one that she had formed out of clay and painted to look authentic. n Would the mountain bluebird accept this intruder’s egg as its own? Or would it become aggressive and reject the egg? n For about a month, Gonzalez conducted research into brood parasitism, or what happens when one bird lays eggs in another bird’s nesting area to be raised by a different host. Her fieldwork at the University of La Verne’s Montana Research Station, also known as Magpie Ranch, yielded much more than research data. n “Coming out here has opened up my eyes to what I want to do with my life,” says Gonzalez. A biology major, she was aiming for medical school, but she discovered a new passion for field research. n The Montana Research Station is a prime example of the University of La Verne’s focus on translating theory to practice. In the 1990s, alumnus Richard Base ’61 donated 160 acres of mountainous forestland about twelve miles from Drummond, Montana, a perfect spot for naturalists. The university purchased another seven acres in the valley, which are more

accessible, and constructed two buildings that serve as laboratory and dormitory space. It even features a full laboratory for DNA molecular analysis. n Magpie Ranch is a labor of love for Dr. Robert Neher, former Natural Sciences Division chair and biology professor at the University of La Verne for fiftyfour years. Professor Neher convinced then-president Steve Morgan ’68 to develop the field station, and helped purchase the land and more recent additions. Neher and his wife, Mary, still work as managers and caretakers of the property. n “Just the experience of being up there is life changing to a lot of people,” says Neher, who notes that many students have never spent time out in nature. n Each year, University of La Verne faculty members take students on the trek northward, stopping at spectacular national parks in Arizona and Utah. In Montana, students gather data for their capstone projects at the university, which they will develop into thirtypage thesis papers. n “This gives the students some independence in their work,” says Dr. Kat Weaver, associate professor of biology and codirector of the La Verne Experience. “They run their own projects with a faculty mentor.” n Some students find the foundation for their life’s work. “It’s gotten them started in research projects that they may continue right on through to their Ph.D.s and probably after that,” Neher says.

Robert Neher coddles an old friend at the University of La Verne Montana Research Station, nestled in a valley roughly forty miles east of Missoula. Known affectionately as Magpie Ranch for the prevalent bird, the facility was Neher’s brainchild when he was a biology professor at the university. He convinced then-president Steve Morgan to pursue the concept, and Neher and his wife, Mary, now serve as its caretakers. The station is more than a rustic outpost. Serious research is conducted on its 167 acres, which includes a laboratory for DNA molecular analysis. Many field research papers that originate at Magpie lead to doctoral dissertations down the road.

The free HOLA tutoring program is yet another example of outreach that is so important to the University of La Verne’s mission. Through HOLA (Heart of Los Angeles), students who are engaged in the La Verne Experience reach into underserved neighborhoods to learn about children’s social and emotional development while assisting them with their homework, music, or athletics.

GENERATIONS OF TRANSFORMING LIVES

THE UNIVERSITY OF LA VERNE: FOUNDED IN 1891

Two days before the start of the fall semester, freshmen

at most colleges are still decorating their residence hall rooms and getting to know their roommates. They are checking out the local pizza hangout and buying textbooks and T-shirts in the campus bookstore. They are Snapchatting and

Skyping with family and friends back home. But at 8 a.m. on the Saturday before classes begin at the University of La Verne, incoming first-year students,

Community Engagement Day, a service-oriented start to their La Verne Experience, is a unique program based on the university’s values, that builds connections in the classroom and beyond.

faculty, and staff members gather behind the Sara and Michael Abraham Campus Center to get to know each other in a very different way. They form into teams based on their assigned FirstYear La Verne Experience (FLEX) classes as part of Community Engagement Day, a serviceoriented start to their La Verne Experience. A unique program based on the university’s values, that builds connections in the classroom and beyond.

For example, thirty-two of the firstyear students had signed up to take the interdisciplinary FLEX course called Markets and the Good Life, a kind of point-counterpoint experience taught by two FLEX professors: a free-market conservative and a socialistleaning liberal. Their professors appeared in khaki shorts and T-shirts, with garden gloves and sun

Community Engagement Day, which is part of the La Verne Experience, is the university’s unique way of incorporating its values into the beginning of a student’s entry into the school.

hats. Other groups of students huddled around their professors. Even the president and provost were dressed for manual labor. In all, six hundred students in thirty-three FLEX courses gathered to work in the community for the day.

The first step to a University of La Verne education is to get your hands dirty, work hard alongside people who may be very different from you, and make the surrounding community better.

For Marvin Tapia ’17, that entry to college feels a lot like the dynamic in his extended Latino family in Anaheim. “That’s one of the reasons I came to this school,” says Tapia, a first-generation college student. “They create community here.”

The La Verne Experience involves more than service. It extends the personal touch of professors and the support of peers beyond the classroom. It links the university’s core values with academic disciplines. It builds critical thinking and communications skills by requiring students to reflect on their experiences. And it connects the theory from class to the greater community:

The first step to a University of La Verne education is to get your hands dirty, work hard alongside people who may be very different from you, and make the surrounding community better.

theory-to-practice.

Thoroughly connecting disciplines and coursework with community building, “It is the current incarnation of our 125-year history.”

Provost Jonathan Reed, Ph.D.

The La Verne Experience extends throughout the four years: the first-year FLEX program, second-year SoLVE (Sophomore La Verne Experience), junior-year experiential education, and senior-year capstone courses. The La Verne Experience enhances the CAPA (College Accelerated Program for Adults) and graduate programs.

Thoroughly connecting disciplines and coursework with community building, “It is the current incarnation of our 125-year history,” explains Provost Jonathan Reed, Ph.D.

At first, students may not fully appreciate why the La Verne Experience is special. But then, one day, it clicks. Tapia was working with the Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice in Los Angeles as part of the University of La Verne’s Summer Service, a program that dates

back to 1957.

Some Summer Service students travel to work with summer camps in Washington and Oregon or at a sustainable living center in Virginia. Others mentor local teenagers, lead activities in a nursing home, or run a peace camp for the La Verne Church of the Brethren.

Tapia helped promote workers’ rights, and during his first week he served as a marshal at a protest march helping guide people along the designated route. That is when he realized something that will shape his future: “Alone you can’t really do much, but if you come together and create one big voice, you can actually make a difference,” he says.

Some Summer Service students . . . mentor local teenagers, lead activities in a nursing home, or run a peace camp for the La Verne Church of the Brethren.

The drive to make a difference also describes the motivation of many professors who came as young faculty members to the University of La Verne and stayed for their entire academic careers.

“We take people with potential and we really develop that potential. We give them new opportunities.”

Dr. Steve Morgan ’68

One of those who came early and happily stayed late was Dr. Steve Morgan ’68, who was just thirty-nine when he became one of the nation’s youngest college presidents. His life had been shaped by the University of La Verne, the alma mater of his grandmother, Grace Hileman Miller in the class of 1914; his mother, Ruth Miller Morgan ’36; and numerous cousins, aunts, and uncles. He graduated in 1968 with an aspiration to become a city manager, but he lingered at La Verne, working for President Leland Newcomer ’42, who convinced him to stay in the academic world after he completed his doctorate at the University of Northern Colorado.

As with so many other students and faculty, he discovered that the legacy of contributing to the surrounding community appealed greatly to him, well before it had a formal name as the La Verne Experience. The University of La Verne, he realized, was the place to shape future leaders and to build a better world. “We take people with potential and we really develop that potential. We give them new opportunities,” says Morgan, who spent nine years as executive director of the Independent Colleges of Northern California Consortium before returning to the University of La Verne as president in 1985.

The university has stayed true to its core values throughout its history. It remains an intimate campus, a place where professors get to

One could call the rock that sits solidly in front of Founders Hall a sort of campus instant messaging service as its hard surface endures paint job after paint job as students overlay each layer with everything from club names to inspirational slogans. Whether what is painted is art—however short-lived—is best left to the beholder. But, if nothing else, it’s one of the most enduring traditions at the university, which has given voice to issues, thoughts, and passionate debate over the decades.

know their students and offer them guidance and encouragement. Skipping class is not an option; wayward students are likely to run into their professor, who will pepper them with questions and may leave them with a stern lecture.

The university has stayed true to its core values throughout its history. It remains an intimate campus, a place where professors get to know their students and offer them guidance and encouragement.

The university also needed to adapt to changing times in practical ways. Morgan discovered that while the university continued to inspire a new generation, behind the scenes, the finances were in disrepair. In fact, budget deficits and accumulated debt placed its future in peril. Morgan rolled up his sleeves and took a scalpel to the budget, while rallying the university community around its longtime strengths and emphasizing its core mission. “I had confidence that if all of us moved in the same direction, we could achieve new levels of excellence for the university,” he

continued on page 82

Ahmed Ispahani, Ph.D., landed at the University of La Verne in 1964, though his journey began in his native Pakistan. As a business professor, he has taught generations of students, through different economies and political landscapes. Through it all, he has remained eternally optimistic and takes pride in the accomplishments of his students, including former university president Steve Morgan.

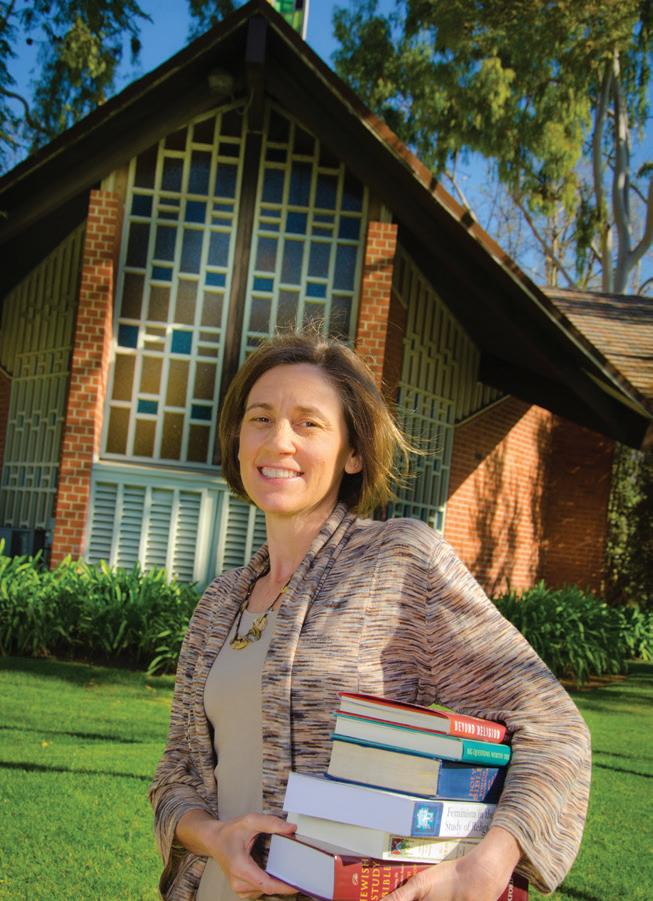

Being at the University of La Verne has been a soul journey for Roxana Bautista ’16—figuratively and literally. n As president of Common Ground, an interfaith organization on campus, she takes part in “Souljourns,” or visits to different houses of worship. But the Mormon from Ontario, California, also has deepened her own spirituality as she reaches out to others of different faiths. n “We’re building friendships across very vast differences, but showing that those drastic differences do not have to separate us,” says Bautista. n The University of La Verne’s diverse student body includes people of many faiths—Christian, Muslim, Jewish, Buddhist, Sikh, and Hindu. The largest group may be “nones”—young people with a sense of spirituality but no organized religion, humanists, agnostics, or atheists. The university has a large Secular Student Alliance. n “It becomes very important for them to develop language to ask the big questions in life,” says Dr. Zandra Wagoner ’89, university chaplain and a Church of the Brethren ordained pastor. “With core values that emphasize inclusivity and no coercion in religion, the University of La Verne is a supportive place for them to explore issues of faith and spirituality,” she says. n Interfaith work played a role in the university’s recognition as part of the 2014 President’s Higher Education Community Service Honor Roll. The university recently created a minor in interfaith studies, which includes courses in conflict resolution and the history of pacifism. It is one of the first such academic

programs in the country. n But this is not a new direction for the University of La Verne. It is an extension of years of interfaith work, spearheaded by Dr. Richard Rose, professor of religion and philosophy, who is also assistant pastor at an African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church in Irvine. n Every week, students gather downstairs at the Interfaith Chapel for guided meditation, and the interfaith student group, Common Ground, tends a community garden at the Church of the Brethren. They participate in a community peace walk and other interfaith activities. n “I feel like there’s nothing better I can leave in the world than an understanding among these different faith traditions,” says Bautista, who is a psychology major. ”It helps break down walls of prejudice.”

Friendships forged at the University of La Verne Interfaith Chapel cross genders, cultures, and religions—sometimes all on the same day.

continued from page 78

says.

Morgan also knew that appearance matters. His wife, Ann, spearheaded a beautification effort, planting flowers and shrubs and greening the lawns. Morgan added new space that enabled the university to expand its programs—first in the most economical way, by repurposing buildings. The Alpha Beta Market became the new library; the automatic doors remained in place for many years, until it underwent major expansion and remodeling in 1993. The Tastee Freez was painted and renovated into a music building; it retains the iconic A-frame style. The Office

Morgan added new space that enabled the university to expand its programs.

of University Advancement took over the office donated by Dr. Marvin Snell, former director of Student Health Services, on Bonita Avenue.

Upgrading the campus also enabled the university to project a new public image. “The overwhelming modesty of the Brethren culture made it uncomfortable for La Verne to brag about itself, to promote its successes, to market, to advertise,” says Phil Hawkey, the university’s

Vista La Verne is home to 378 students who live in suite-style apartments consisting of bedrooms, bathrooms, and a living room. The LEED-certified facility was the largest building on campus when it was completed in 2012. Vista is one of several residence halls on campus, including the Oaks Residence Hall. Studebaker-Hanawalt (“Stu-Han”), and Brandt Hall. The university also offers themed living and learning communities, such as the Women’s Experience community located in Oaks.

The Sara and Michael Abraham Campus Center hosts programs for student leadership, personal growth, and community development. Opened in 2009, the Center is essentially La Verne’s family room, a gathering place and campus hub. Its 40,200 LEED-certified square feet contain recreational facilities, lounges, dining areas, a rooftop garden, and meeting spaces. The Abrahams—Mr. Abraham serves on La Verne’s board—provided $4 million in matching funding to make the Center possible.

executive vice president. The university began to look outward.

The university’s centennial in 1991 was truly a cause for celebration. As the university began to thrive, more ambitious projects became possible, exemplified by the sleek, glass-walled Abraham Campus Center, the Oaks Residence Hall, and the purchase of the fifty-five-acre Campus West for athletic fields and future expansion. When Morgan retired in 2011, the university had grown dramatically, from about four thousand

“The overwhelming modesty of the Brethren culture made it uncomfortable for La Verne to brag about itself, to promote its successes, to market, to advertise.”

Phil Hawkey

full-time-equivalent undergraduate and graduate students to almost seven thousand. The endowment, virtually nonexistent when he arrived due to debt obligations, approached $30 million.

Morgan’s twenty-six-year tenure made him the longest-serving president in the university’s history. “My intention was to stay for ten [years],

but like many people at the University of La Verne, I got hooked in,” he says. “At La Verne, you realize you can make a difference.”

How do you describe the La Verne Experience?

For Peggy Redman, who received her bachelor’s (’60), master’s (’87), and doctoral (’91) degrees at the University of La Verne, and whose parents, siblings, aunts, uncles, and cousins came to the College beginning in the 1920s, it was a feeling as natural and comfortable as breathing. La Verne was a place that truly became a lifelong home.

“My intention was to stay for ten [years], but like many people at the University of La Verne, I got hooked in. At La Verne, you realize you can make a difference.”

Dr. Steve Morgan ’68

Redman was a student at La Verne College during a time of innocence, the post–World War II years when American culture celebrated the sort of wholesome life found on campus. The continued on page 90

Picture these scenes: Dr. Felicia Beardsley, professor of anthropology, forges a path through a jungle on a remote Pacific island, clearing vines away from a cliffside cave and discovering an ancient carving of a giant face. Dr. Ahmed Ispahani, professor of business administration and economics, who was an economic adviser to the Shah of Iran and to his own cousin, then–Pakistan prime minister Benazir Bhutto, describes a secret meeting between the US secretary of state Henry Kissinger and Chairman Mao Zedong of China. n Dr. Jonathan Reed, provost and archaeologist, digs for artifacts of early Christians in the Galilee of Israel. Dr. Juli MinovesTriquell, professor of comparative politics, teaches from his perspective as the former minister of foreign affairs, permanent representative to the United Nations, and ambassador to the United States and Canada from the tiny country of Andorra, tucked between Spain and France. Dr. Abe Helou, dean of the College of Business and Public Management, developed a partnership with the International Business School of Sao Paulo in Brazil, bringing hundreds of South American students to the university each year. n The world comes alive in classrooms at the University of La Verne, thanks in part to the extensive international work by these and other professors. n Beardsley, a consulting archaeologist for Micronesia, collaborated on the World Heritage nomination for massive stone cities found on manmade islands in the lagoons on two islands. She collects oral histories from people of the islands and uses their stories to guide her work. During a January trip in 2013, she discovered a painted cave and a giant face carved onto a cliff—then headed back to her classroom at La Verne, where she showed her students the photographs. n It might seem a bit anticlimactic to return to the Southern California

expanse of suburbia after navigating through remote jungles, but Beardsley feels grounded in the open and flexible academic environment of La Verne. “We are creating global citizens and students who can think rationally—reasonably, be creative and imaginative thinkers—and who really can adapt to just about anything the world is likely

to throw at them,” she says. n Ispahani came to La Verne when he was finishing his dissertation and needed to make a little extra money. He ended up staying for more than fifty years. “What really attracted me were the people—incredible people,” he says. “They went out of their way to accommodate me. They treated everyone like a

family.” n Ispahani took a few leaves of absence over the years, including a five-year stint as the economic adviser of the Central Bank of Iran. But he always came back to the university. Today he coteaches a course in international economics with University President Devorah Lieberman, whose scholarly work focuses on intercultural communication. n In the story about Henry Kissinger’s meeting, a precursor to President Richard Nixon’s historic trip to China, Ispahani notes that Kissinger had first traveled to Pakistan, where newspapers reported he was absent from his scheduled local events because he was ill. He was actually attending the secret meetings in China. n “What you hear officially and what is unofficial are two different things,” Ispahani tells his students. “Do not trust everything you read in the newspaper.” n In the College of Business and Public Management, Helou prepares students to enter a marketplace that is constantly changing. The course work blends practical skills and decision-making with management theory. By recruiting international students, Helou has infused the program with a global perspective. Indeed, as a native of Lebanon (he migrated to the United States in 1985) with an undergraduate degree from Lebanese University, a worldwide perspective is important to him. Since his appointment as dean, he has worked to dramatically increase the enrollment of international MBA students and boost recruitment contacts on the Pacific Rim.

n When Helou first came to the University of La Verne in 1993, after earning a Ph.D. in finance from Arizona State University, he was like many of the students today—full of youthful ambition. He stayed at the university because he had the freedom to flourish.

“After a few months here, I found out this is the place you can really make the biggest difference in students’ lives,” he says.

continued from page 86

Krankers were a campus club of hot-rodders who fixed and raced cars. GATs—or Girls About Town—sponsored the school’s Christmas Tea and made decorations for the May Daze celebration.

The University of La Verne was also a place where you could find your passion—which, in Redman’s case, was teaching. She worked as a math teacher and later became director of teacher education and finally the director of the La Verne Experience.

In 2011 President Devorah Lieberman arrived to succeed Morgan, bringing fresh ideas about strengthening student engagement. A native of Covina, California, she had spent over

How do you describe the La Verne Experience? For Peggy Redman it was a feeling as natural and comfortable as breathing. La Verne was a place that truly became a lifelong home.

thirty years in higher education as a professor, a vice provost, a special assistant to the president, and, during the seven and a half years

before taking over as director of the La Verne Experience.

prior to coming to the University of La Verne, the provost at Wagner College on Staten Island, New York. On her first visit to the University of La Verne campus, she fell in love with the open and inclusive atmosphere. She had a keen sense of the school’s legacy and a deep appreciation for the school’s core values. Lieberman challenged Peggy Redman and others to define what makes the University of La Verne distinctive and relevant and to give it permanence and structure in the curriculum and cocurriculum.

“For me, the La Verne Experience is all about connection. That is at its core,” says Lieberman.

In 2011 President Devorah Lieberman arrived to succeed Morgan, bringing fresh ideas about strengthening student engagement.

“It is connecting students with students, students with faculty, students across disciplines, students with the greater community, and students with their futures.”

In Peggy Redman’s day, such interactions needed no special recognition. Her class of 1960 was the first to have one hundred graduates. It was easy to know everyone, and with so many siblings and cousins attending, the University of

La Verne resembled a large family.

“For me, the La Verne Experience is all about connection. That is at its core.”

— President Devorah Lieberman

Today, the University of La Verne enrolls approximately eighty-five hundred students— almost twenty-seven hundred traditional undergraduates and two thousand graduate students on the main campus, and about thirty-four hundred graduate, online, CAPA, and regional campus students—yet the university still places a priority on creating community. About two-thirds of the undergraduate classes have fewer than twenty students, allowing for close relationships to develop between them and the faculty.

From 11:30 a.m. to 1 p.m. on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays—community hours when no classes are scheduled—the Campus Center is abuzz with friends connecting or student organizations meeting. Just outside in Sneaky Park, students offer an impromptu concert, set up booths to raise money for charity, or hold outreach events for campus organizations.

One visible sign of togetherness occurs on the third Tuesday of every month, when throngs

Homecoming festivities are a chance to reconnect with old friends and make new ones—as well as catch an errant football bobbling through the stands. Other somewhat more organized activities spread over a three-day weekend in October typically include receptions, an alumni awards dinner, a street fair, Fun Run, a parade, soccer and football games, and a service at the Church of the Brethren.

From 11:30 a.m. to 1 p.m. on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays—community hours when no classes are scheduled—the Campus Center is abuzz with friends connecting or student organizations meeting.

Catching up with classmates and grabbing a bite to eat at the patio outside of Davenport Dining Hall is all part of the day. Several restaurants operate within Davenport, and they each source their food locally as much as possible. Indeed, the menus are often written based on seasonality and availability of farm-fresh items, and occasionally there are themed food events such as Oktoberfest and French food days. But food is not the only item on the menu at Davenport’s restaurants, as sometimes live entertainment is offered.

of students walk from campus to the La Verne Church of the Brethren a few blocks away to attend an evening of fellowship and homecooked food, dubbed the Food Network. A host and organizer is Corlan Ortmayer Harrison ’79, daughter of longtime football coach Roland Ortmayer and parent of first-year student Rayna Harrison ’19.

That enduring sense of connection inspired the La Verne Experience, a unique program of learning communities that weaves together interdisciplinary academic study, co-curricular activities, self-reflection, and community engagement. When Lieberman received the 2015 President of the Year award from the Association of College Unions International, the association cited the novel program as a way of successfully engaging students, alumni, and the community.