St. Mark’s Church in Ortega

THE FIRST ONE HUNDRED YEARS

1922–2022

THE FIRST ONE HUNDRED YEARS

1922–2022

THE FIRST ONE HUNDRED YEARS

1922–2022

Copyright © 2022 by St. Mark’s Episcopal Church

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from St Mark’s Episcopal Church.

St Mark’s Episcopal Church

4129 Oxford Avenue

Jacksonville, Florida 32210

Book Committee

Keith Daw

Martha Hallowes

Drew Haramis

Denise Hudmon

Doug Milne

The Rev. Tom Murray

Editorial Director

Rob Levin

Author

Stacy Moser

Cover and Book Design

Amy Thomann

Index

Shoshana Hurwitz

Production

Renée Peyton

Bookhouse Group, Inc.

Covington, Georgia

www.bookhouse.net

On the ninetieth anniversary of St. Mark’s, the church dedicated the Lori Schiavone Commons, located on the Day School campus. Officiating the celebration at the 2012 event was the Right Reverend Samuel Johnson Howard (in the center wearing gold vestments and mitre, with crosier), bishop of The Episcopal Diocese of Florida.

Upper half of window of St. Mark the Evangelist. Located behind the pulpit, it was given in memory of Hardin Edward Lynch.

Upper half of window of St. Mark the Evangelist. Located behind the pulpit, it was given in memory of Hardin Edward Lynch.

FOREWORD xii

LETTERS OF CONGRATULATIONS xiii

DEDICATION xvii

PREFACE xix

CHAPTER ONE 1

The Little Brown Church ∙ 1922 – 1941

CHAPTER TWO 11

The Church Evolves ∙ 1942 – 1970

CHAPTER THREE 21

Growing a Neighborhood Church ∙ 1971 – 1994

CHAPTER FOUR 35

Embracing Change ∙ 1995 – 2005

CHAPTER FIVE 45

St. Mark’s Embraces the Next Century ∙ 2006 – Present

APPENDIX 57

Windows in the Nave Senior Wardens, Junior Wardens

INDEX 70

From the beginning, St. Mark’s has always been a neighborhood parish known for its close-knit community of generational families. In the truest sense, St. Mark’s is a Christian family, comprised of devoted members of Christ’s Body who enjoy gathering together in fellowship and celebrating their traditions. So, it should come as no surprise that a historical narrative has already been written about the church’s rich heritage on the occasions of the seventy-fifth and ninetieth anniversaries.

But with the history of St. Mark’s being documented by several prominent parishioners, including Ruby Moore and Maggie Leatherbury, it’s surprising that this story had never been officially published. While it was assumed for some time that a commemorative book would be produced for our Centennial Anniversary, the idea didn’t become a reality until the fall of 2020 when a committee was formed, a professional book publisher was retained, and the process of developing an editorial narrative began.

Thanks to the efforts of Betty Lurie and Martha Hallowes, many materials had already been categorized and preserved in the church archives. In addition to these resources, the committee obtained personal reflections and memories from parishioners who had a long time relationship with St. Mark’s. Of course, the story wouldn’t be complete without a visual history of its faithful members and the church campus. It was especially important to include the stained-glass windows in the nave, as many have been deeply affected by their beauty and the stories they depict.

One of the unique characteristics of this parish is that in the first one hundred years, there have only been seven rectors. That said, realizing the impact of those individuals given their leadership positions, intentional efforts were made to tell the story of the entire church family. We hope we’ve been successful in that endeavor.

And we hope that this collaborative effort that recalls so many images and experiences over one hundred years not only provides you with a window into the past, but also offers inspiration for future generations. The history of God’s people continues to unfold; we are all a part of it. May this book be for you a witness to the good things God has already done through this community of faith, and provide encouragement for you to join with us and be an active part of it in the years to come.

St. Mark’s Centennial Book CommitteeDear brothers and sisters of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church,

By the grace of God, I write to you as Bishop of the Diocese of Florida thanking our heavenly Father as we come together to celebrate 100 years of ministry. He has worked through St. Mark’s to do many wonderful things in this community, our city, our Diocese and throughout the larger Church. The scope, quality, and compassion of your ministries – as well as your unwavering commitment to Christian mission – are admirable, and they are a blessing to Jacksonville and to the Episcopal Church. Your ministry in the name of Jesus Christ has been an inspiration to us all for a century, and I pray that He will continue to work miracles through you.

I also wish to express my thanks for how welcoming the clergy, staff and parishioners of St. Mark’s have been to Marie and me since I became Bishop of this Diocese nearly two decades ago. We have felt at home among you and have rejoiced that in worship and in ministry, our hearts have been as one.

St. Mark’s has historically provided superb and constant leadership in the Councils of our Diocese. You have been active in leading so many of our most important missions and ministries. Even as I write this, I am reflecting on cherished friends in ministry who throughout their lives worshipped and served at St. Mark’s. I am seeing their faces in my mind’s eye and remembering their names as I give thanks to God for the marvelous things He did through them.

It has been a privilege, too, to be a friend and colleague of each rector of St. Mark’s during these past two decades. Leigh Spruill, Jon Coffey and Tom Murray have been leaders in the Councils of the Church, active in our Diocesan ministries and each of them, in his own way, a valued advisor of mine. I am especially proud to have played a role in recommending Tom Murray to you for consideration as your present Rector, and I rejoice in the power of his ministry and in the good things God is doing through his leadership.

And, of course, I shall always be grateful for the friendship, advice and prayers of Barnum McCarty, a dear friend and trusted confidante who has meant so much to each of us. He and I developed a relationship even before I became your Bishop, serving as he did on the search committee which placed my name in nomination for this position.

I cannot emphasize too much how important and valuable you are to the Diocese of Florida and what a privilege it is to be your Bishop and your friend. Marie joins me in this celebration, and we pray that God will continue to bless you as you embark on the next century in His name.

Faithfully,

The Rt. Rev. Samuel Johnson Howard Bishop of Florida

This book would not have been possible without the generous support and enthusiasm of the following members of the St. Mark’s congregation:

Norma and Hayes Basford

Lanny and Bob Dickson

Hazel and Tom Donahoo

Flavel and John Godfrey

Diane Graham

Ann Hicks

Anne and Randall Mann

Marian and Rip Poitevent

Mary Jane and Hank Wilson

Anative of Jacksonville, Barnum McCarty attended college and seminary at the University of the South and School of Theology in Sewanee, Tennessee. He returned to the Diocese of Florida, serving in several different positions before being called to be St. Mark’s third rector, a position he held for over twenty years. Upon his retirement, after serving in two parishes as interim rector, Barnum returned to Ortega and for another twenty years became a kind of ‘behind-the-scenes’ pastor in this neighborhood parish.

It’s difficult to know for sure which was more important to the life of St. Mark’s—Barnum’s leadership in growing the parish as the third rector or his humility in remaining pastorally available to parishioners throughout his retirement. I, for one, will be forever grateful for his wise counsel and support of our ministry in this place. His great love for Jesus Christ and this church family continues to inspire, and the parish will be forever influenced by his faithfulness.

Barnum went on to receive his heavenly reward as this book was being created, and it was decided at that time it would be dedicated to him in thanksgiving for his faithful witness and service to St. Mark’s Church. We join Christ in saying, “Well done, good and faithful servant.”

The Rev. Thomas P. Murray Seventh Rector of St. Mark’sEveryday life in the frontier town of Tallahassee was anything but easy at the time it became the capital of the US territory of Florida in the late 1820s. Its residents faced many challenges, both physical and spiritual, as they built their town to include six stores and a bank, making do without a doctor, effective law enforcement, or schools—all while threatened by deadly outbreaks of Yellow Fever, drought, crop failures, and constant skirmishes with the Seminole tribe.

Despite those challenges, an Episcopal missionary station took root there, consisting of a small group of families who were determined to worship. Over the years, a string of priests who attempted to help them formalize their church met with little success soliciting enough funding to construct a church building of their own. The tiny congregation’s prayers were answered, though, in 1836, when a dynamic young clergyman, the Reverend Jonathan Loring Woart, was sent by the Episcopal Church to lead them, stirring enthusiasm and hope among the worshippers as he rallied them to improve their circumstances. He energetically enlisted pledges from the growing congregation and, in 1838, they finally constructed St. John’s Church in Tallahassee—the largest church in the state—at a cost of $10,000.

The popular priest was also instrumental in the establishment of the Diocese of Florida, officially formed on January 17, 1838—made up of

The Diocese of Florida was formed on January 17, 1838, and was comprised of seven parishes: Trinity (St. Augustine); Christ Church (Pensacola); St. John’s (Jacksonville); Christ Church (now Trinity Church in Apalachicola); and St. Joseph’s (St. Joseph).

seven parishes: Trinity (St. Augustine), Christ Church (Pensacola), St. John’s (Tallahassee), St. Paul’s (Key West), St. John’s (Jacksonville), Christ Church (now Trinity Church in Apalachicola), and St. Joseph’s (St. Joseph). The new diocese operated on a meager budget, receiving assistance from the Episcopal Missionary Society to pay some expenses for its three church buildings and six clergymen. In 1851, the Reverend Francis Huger Rutledge became the diocese’s first bishop while remaining rector of St. John’s in Tallahassee. Under his leadership, the diocese grew to include fourteen congregations in his first ten years. Unfortunately, the Civil War later laid waste to many of those churches and dejected congregants abandoned efforts to rebuild them.

In 1867, two years after the war ended, the Reverend John Freeman Young became the diocese’s second bishop, shepherding all of the church congregations through a long economic depression that lasted until 1877. The hardship of those years was followed by a

period of rapid growth within the diocese as the population of Florida grew, spurred by construction of railroads crisscrossing the state. Young organized the first Episcopal church exclusively for Black worshippers in Key West and a Spanish-language parish for Cuban immigrants as well. He also traveled to Cuba, responding to a request to establish a church there.

Upon Young’s death, the Reverend Edwin Gardner Weed was elected the diocese’s third bishop in 1886, and he was the first bishop to be consecrated in Florida at St. John’s Church in Jacksonville. He was described as a man of great energy and his gregarious personality won over the hearts of congregants during his constant travel throughout the state. By 1890, the diocese oversaw fiftyseven clergymen in nineteen parishes and eighty-one missions. As the church’s population began to migrate south, Weed realized he could not feasibly tend to the entire territory himself and, after much deliberation, at the convention that year he recommended establishing a new diocese. In 1892, the national church founded a

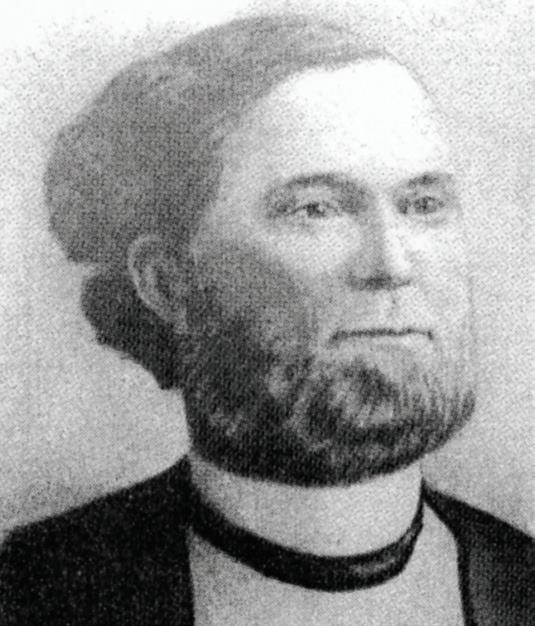

The Right Reverend Francis Huger Rutledge served as the first bishop of Florida from 1851—1856, while also serving as rector of St. John’s Church in Tallahassee. The diocese grew to include fourteen congregations under his ten years of leadership.

The Right Reverend Francis Huger Rutledge served as the first bishop of Florida from 1851—1856, while also serving as rector of St. John’s Church in Tallahassee. The diocese grew to include fourteen congregations under his ten years of leadership.

new Missionary Jurisdiction of South Florida, bounded by the southern borders of St. Johns County on Florida’s east coast and stretching to Levy County on its west coast. Thus, the Diocese of Florida now contained thirteen parishes and forty-three missions. (It wasn’t until 1922 that the southern territory was formally named the Diocese of South Florida.) At the time of this expansion, by far the greatest concentration of Episcopal churches throughout the state was in Jacksonville, with its three parishes: St. John’s, St. Andrew’s, and the Church of the Good Shepherd. St. John’s Church consisted of 397 families, the largest in the Diocese of Florida.

1892 was a busy year—an Episcopal residence was built in the growing Jacksonville neighborhood of Riverside for Bishop Weed, and the Book of Common Prayer was updated that year too. The bishop embraced the book’s modifications, saying they were “not numerous, but important.” In his travels, he met with some resistance about the new book, but he propounded its use, referring to it as “a literary gem.”

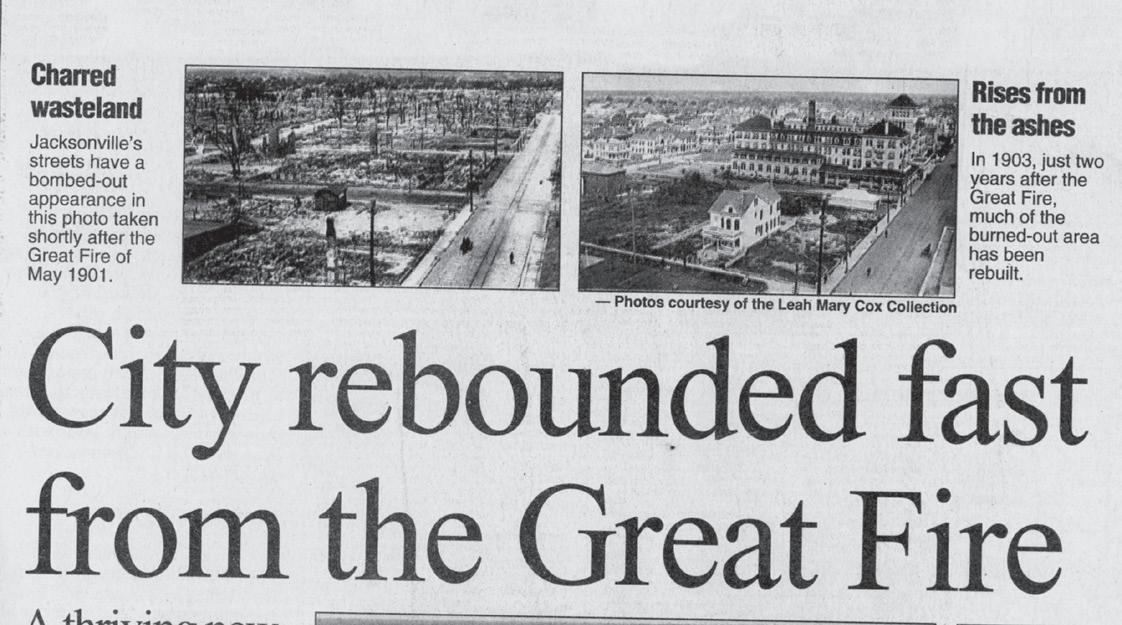

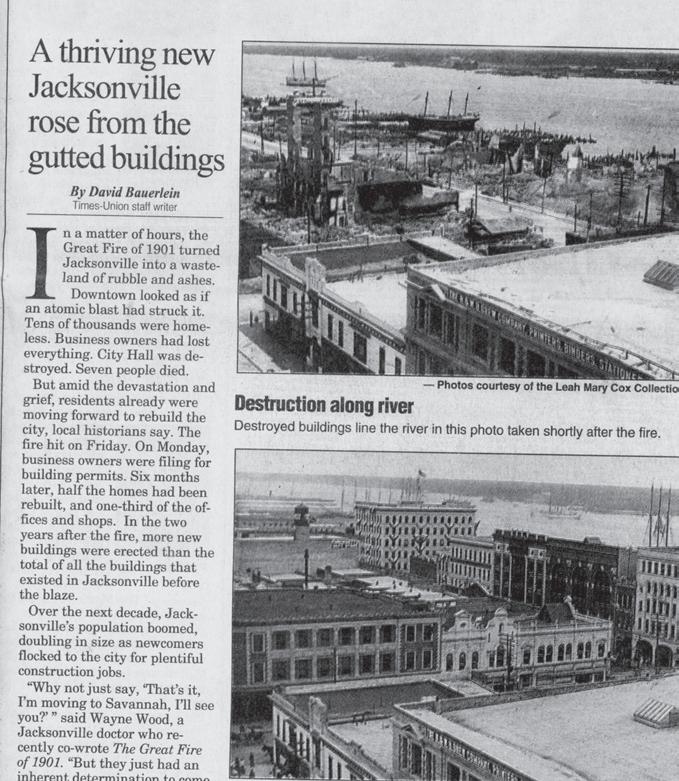

The decision to establish a new diocese weighed heavily on Bishop Weed, and he worried whether the situation was an improvement, either logistically or financially. Nine years later, on May 1, 1901, in a speech to the diocesan convention at St. Peter’s Church in Fernandina, Weed proclaimed it a success, saying the diocese was stronger than ever and delivered a message filled with hope and encouragement. On the dry, windy afternoon of May 3, Weed boarded a train to Jacksonville and, on approach to the city, was bewildered by his view from the window—giant plumes of smoke clouded the horizon as far as he could see. Jacksonville was on fire. The light from the blaze was so intense, it could be seen as far north as Savannah; the smoke as far north as Raleigh, North Carolina.

The inferno had started on Jacksonville’s northwestern edge, at the Cleveland Fiber Factory, where red-hot embers from a chimney had wafted over piles of drying moss, igniting a fire that ravaged the entire city. Over two

thousand buildings burned to the ground, leaving ten thousand homeless and, miraculously, just seven people dead. The St. John’s Church building and twenty-three other churches were gone, along with eighty percent of Jacksonville, then the largest city in Florida.

As the city’s resilient residents struggled to rebuild Jacksonville in the months after the tragedy, their sights turned to real estate on the city’s outskirts where they could establish new neighborhoods—and an island on the western bank of the St. John’s River, Ortega, was a prime candidate. Financier J. Pierpont Morgan and Florida legislator John N.C. Stockton, owner of the Ortega Company, worked together to develop home sites in Ortega. The project was connected to greater Jacksonville by one of the city’s first real bridges in 1908, a wooden swingspan bridge built by the Ortega Company. The spirit of resiliency that is characteristic of Jacksonville is often attributed to the rising from the ashes of that fire.

In 1914, on a lovely, tree-lined street overlooking the St. John’s River, strains of hymns could be heard on Sunday

afternoons emanating from the home of prominent Ortega resident Judge William Brooks Young and his wife, Margaret Rankin Young, as they hosted worship services there. Archdeacon Reverend Van Winder Shields of Jacksonville’s St. John’s Church had enlisted his protégé, the Reverend J. Hedges Webber-Thompson, to conduct services and Sunday school classes for the newly formed mission. The Journal of the 1917 Council for the Dioceses of Florida lists a $1.70 assessment that was paid by the mission to the Episcopal Church for the period between May 1, 1916, and April 30, 1917.

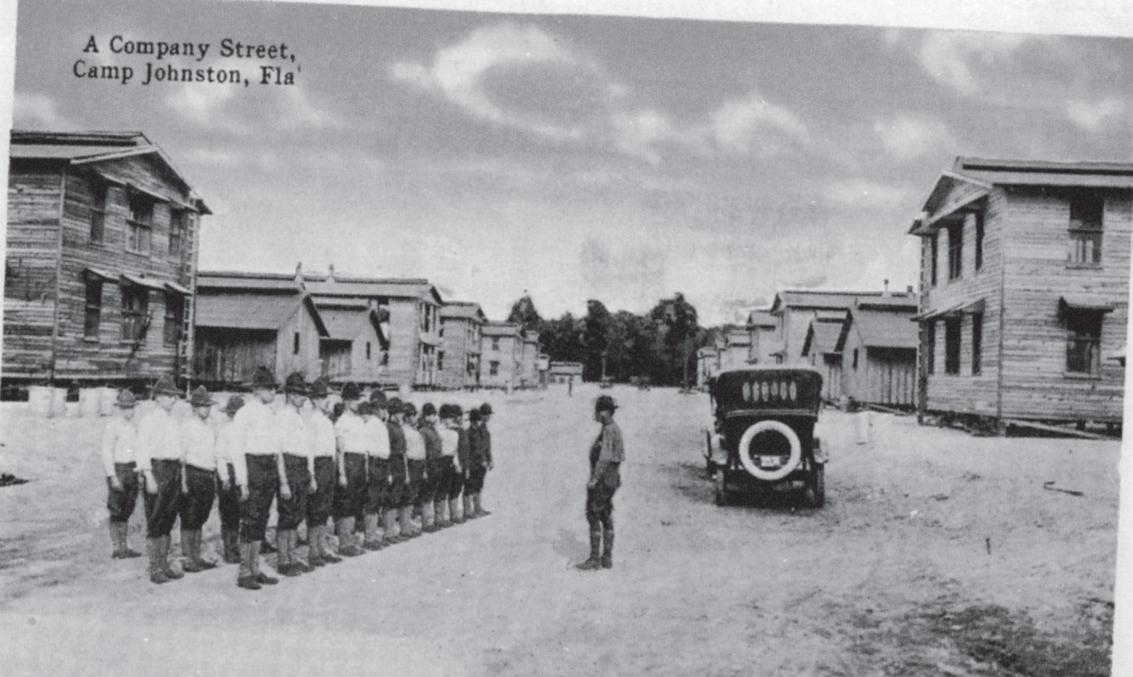

The congregation soon had more on their minds than growing their fledgling mission, as the United States entered World War I in 1917. Ortega Boulevard, a main north–south artery in the neighborhood, suddenly flowed with heavy U.S. Army traffic enroute to Camp Joseph E. Johnston at Black Point (now Naval Air Station Jacksonville). Fearing for their safety as they traversed the busy road, the congregation ceased meeting for worship services.

Webber-Thompson was appointed Camp Johnston’s chaplain and spearheaded a construction project to build

a “recreation hut” on the army post for the Brotherhood of St. Andrew (an Episcopal ministry chartered by Congress, along with the Boy Scouts of America, during Theodore Roosevelt’s administration). The Hut, as it was called, was used by service members as a hub for socialization and relaxation. At the war’s end, Camp Johnston demobilized and its buildings were either demolished or slated for removal. Fortunately for members of the Ortega mission, The Hut and its contents, including folding chairs, were saved—moved by boat in 1918 to a triangular-shaped property that had been donated to the mission. The Hut was transformed into a chapel in 1919, officially a mission of St. John’s Church, and was renamed the Chapel of St. Columba, honoring a sixth-century Celtic missionary.

In their enthusiasm to formalize their church, St. Columba members petitioned Bishop Weed for parish status. As they awaited Weed’s decision, members of the small mission gathered weekly to worship in their humble chapel, affectionately referred to as “The Little Brown Church.”

Located in the Ortega side transept, the St. Mark’s history window was given to the Glory of God by Ann and David Hicks in thanksgiving for their children, Deborah, Ann, and David.

Located in the Ortega side transept, the St. Mark’s history window was given to the Glory of God by Ann and David Hicks in thanksgiving for their children, Deborah, Ann, and David.

1922–1941

Douglas Bagwell Leatherbury slung a well-worn leather bag over his shoulder as he climbed on his bicycle outside his home in downtown Jacksonville. The lanky young clergyman braced himself against the unseasonably cold and blustery November day in 1919 as he pedaled toward the bridge spanning the St. John’s River, crossing it to make his way to a new assignment from St. John’s Church—conducting church services for the small Episcopal mission in a newly developed neighborhood in Ortega. He’d graduated from divinity school at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee, just two years prior, and he was grateful to Deacon Shields for selecting him to lead such an enthusiastic group of worshippers.

On his arrival at the Chapel of St. Columba, Leatherbury climbed the steps to the covered porch of a small wooden building, known as “The Little Brown Church.” As he pushed open the door, he felt a chilly breeze rush up through the floorboards past his ankles. He dressed the simple altar with a linen cloth and gently placed a wooden cross on it, laying his Bible alongside. He crossed the room, past rows of camp chairs that served as pews, to light the pot-bellied stove and don his vestments, waiting for members of the mission to assemble for morning services.

A current-day parishioner who attended those services when she was a child remembers the experience fondly. “It was the most modest building you could possibly imagine,” she recalls. “You’d open the door into this sweet, small church—nothing pretentious, you know, no majesty about it, just a very utilitarian building. But simplicity was definitely what the little church represented.”

Bishop Edwin Weed, who’d been approached by the mission to grant it parish status, was apprehensive about permitting such a change, saying he felt it was “about ten years premature.” He responded to their request with two conditions—the members were to guarantee an enrollment of thirty-five people and promise to pay their rector a salary of twenty-five dollars per week—requirements they gladly agreed to accept. On May 15, 1922, the congregation’s thirty-two members received the happy news that their Mission of St. Columba had been granted parish status. It was decided that they would take the unusual step of renaming the church St. Mark’s Church,

in honor of St. Mark the Evangelist, author of the Gospel of Mark. Leatherbury was called to be its rector and he announced its first vestry: Austin A. Miller, senior warden; Malachi Haughton II, treasurer; R.A. Boucher, junior warden; McCoy H. Martin, secretary; and A.H. Robinson, vestryman.

Malachi Haughton III recalls, “My father told me about being on the vestry at the time. Some of its members were quite well off. Rather than each taking a turn paying the rector’s salary, they decided to have the fun of rolling dice to see who would have to come up with the twenty-five dollars!”

A string of “firsts”—first baptism, first confirmation class, and first wedding in the church—occurred that summer. Those milestones set the stage for much growth over the next year and, in July 1923, the bishop granted the parish permission to seek a larger site for their church. Parishioners contributed $3,000, $1,250 was raised by selling the old site, and a bank loan was

procured for $4,000 to purchase an entire city block at the intersection of Ionic Avenue and Ortega Boulevard, including a four-room cottage for the rector and his family. The Little Brown Church was moved to its new home and, by 1925, the congregation consisted of ninety families, ten individuals, two hundred baptized members, one hundred nine church-school students, and seventeen Sunday school teachers.

Many current-day parishioners distinctly remember Leatherbury’s powerful sermons and devotion to the formalities of worship services at St. Mark’s. One parishioner who attended the church from early childhood

reflects on the rector’s adherence to the traditional structure of services. “He was very consistent with that and his sermons were very forceful. He was not a mildmannered man at all, and he sure got his message out— loud and clear.”

In 1924, after the passing of Bishop Weed, the Reverend Frank Alexander Juhan was consecrated as the fourth bishop of the Diocese of Florida at St. John’s Church in Jacksonville. He had studied at the University of the South’s School of Theology and was the youngest

Throughout his tenure at St. Mark’s, the Reverend Leatherbury steadfastly focused on the growth of his fledgling parish and was known for his daily outreach efforts in

Ortega and beyond. Parishioner Ann Hicks recalls how Leatherbury went out of his way to personally visit families in the community: “As a child, I was never surprised to come home and find Douglas Leatherbury sitting in our living room, chatting with my parents with his coat and collar on—you know—paying ‘the proper call.’ The congregation was so small, it didn’t take him long to get around to all his parishioners.” Doug Milne recalls a similar experience: “I remember him paying a call on my parents in 1946, encouraging them, newcomers to Jacksonville, to join St. Mark’s, and they did. We had a wonderful, strong relationship with Dr. Leatherbury and St. Mark’s from that point forward.”

Leatherbury also orchestrated new missions, such as the reopening of Orange Park’s Grace Church on May 11, 1926. It was noted in the Journal of the Eighty-Second Annual Council of the Diocese of Florida: “Reverend Mr. Leatherbury, Mrs. Minnie Sims, and Ruby Trenholm spent an entire day cleaning and preparing the church for Sunday service. The church had been closed for some time.” Three members of St. Mark’s Parish took turns holding Sunday services at Grace Church after that. Leatherbury proudly described his parishioners’ missionary efforts in the Church Herald’s May 15, 1934, issue as “the crowning glory of the parish.” He encouraged his parishioners in their endeavors by saying, “The light that shines farthest, shines brightest at home.”

“The light that shines farthest, shines brightest at home.”

—The ReveRend douglas Bagwell leaTheRBuRy

bishop ever to lead the diocese. One enduring legacy of his outreach to children was the establishment of a summer camp, a place to foster their growth in the church, named Camp Weed in honor of the late third bishop of Florida.

Leatherbury shared Juhan’s devotion to the families in his parish as he worked to foster strong relationships between them and the church. His vigilance in reaching out to potential new church members was rewarded with significant growth within the church, a testament to his belief that great things could be accomplished by the enthusiastic congregation.

Parishioner Bill Schmidt recalls how Leatherbury inspired the church’s Young People’s Service League, now Episcopal Youth Community (EYC): “We would do the vespers, evening prayer, turning the lights down, and the high school kids would sing. Dr. Leatherbury would sit by himself in the back, singing. I will never forget his voice. He was a real gentleman.”

By 1925, the congregation could no longer be contained in the humble Little Brown Church—Sabine Goodman described the challenging conditions she and fellow parishioners endured during services there in the summer: “You couldn’t have been much hotter if you’d been closed in an oven.” Leatherbury encouraged his parishioners to dream of a new building for St. Mark’s and ambitious plans were made to raise $100,000 to construct a spacious church that would accommodate all of the parish’s activities. By the end of 1926, $18,000 was raised and the total value of the church’s land and possessions was appraised at $27,000. The church engaged the services of Frohman, Robb & Little Architects—a prominent Washington, DC, firm that had designed the Episcopal Church’s National Cathedral—to design a glorious new church building.

Renderings of those plans were reproduced by the Architectural Building Book Company in American Church Building of Today: A Selection of Photographs of

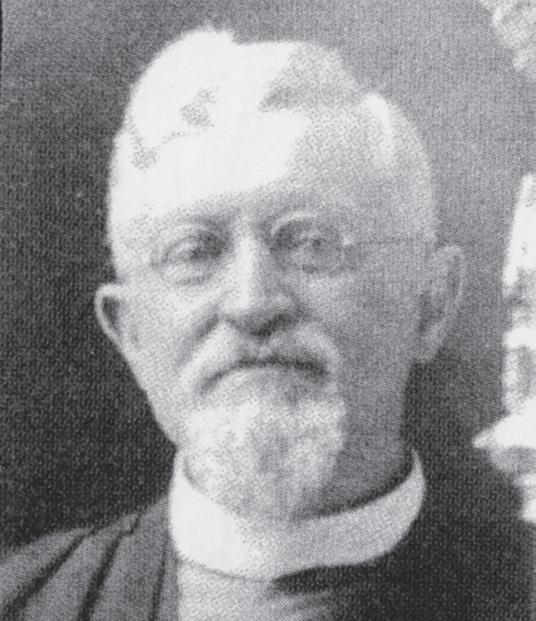

The Right Reverend Edwin Gardner Weed, the third bishop of the diocese, served from 1886—1924. Weed was at first apprehensive about granting church status to the Mission of St. Columba, but ultimately agreed after conditions regarding a minimum congregation size and the rector’s salary were met.

The Right Reverend Edwin Gardner Weed, the third bishop of the diocese, served from 1886—1924. Weed was at first apprehensive about granting church status to the Mission of St. Columba, but ultimately agreed after conditions regarding a minimum congregation size and the rector’s salary were met.

Though humble and beloved, the Little Brown Church was not without its challenges. During summer services parishioner Sabine Goodman once exclaimed, “You couldn’t have been much hotter if you’d been closed in an oven.” The Reverend Douglas Leatherbury encouraged a proposal to raise funds for construction of a new church building that would accommodate the growing congregation.

Exteriors, Interiors, Details and Plans of Churches Recently Erected, which lauded the plan’s striking architectural features. The book went to press on January 1, 1929.

Sadly, just ten months later, in October 1929, the US stock market crashed, dashing the church’s hopes of beginning construction on their new building as the nation’s economy fell into disarray. The closely knit congregation—one of sixteen parishes and fifty-one missions in the diocese—did their best to cope with the financial disaster and mourned their exciting plans for a new building. They waited patiently through the uncertain years of the Great Depression, offering services for parishioners in need, providing them with fellowship and support. Organized groups, like the Women’s Auxiliary and Layman’s League, laid the foundation for what would become important ministries of St. Mark’s, such as the Episcopal Church Women (ECW), Marksmen, Altar Guild, Intercessory Prayer Group, and Saturday Workers, among many others. The Order of the Daughters of the King

was established in 1930, meeting monthly for prayer and to perform home services for the elderly. The women of St. Mark’s rallied parishioners’ spirits by holding a bazaar to repair The Little Brown Church, raising money for a railing to surround the building’s foundation—meant to discourage the neighborhood’s wandering feral pigs and goats from disrupting church services. Another community outreach effort was undertaken that year when St. Mark’s hosted the growing Boy Scout Troop 26, which moved its activities from Ortega Methodist Church to St. Mark’s, where it is still active today—one of the oldest in Jacksonville.

As the diocese struggled to maintain its churches during the economic unrest, St. Alban’s Church in Murray Hill was disbanded. When the question arose as to where to send its wooden church pews, Leatherbury volunteered to take them—happy to find a replacement for the old camp chairs currently used in The Little Brown Church. A truck was secured and the heavy pews were piled so high in its bed that the unwieldy contraption was forced to stop on its path through town every time

Matthew Scott Morgan at his baptism in January 1959, with the Reverend Henry Babbit (left) and the Reverend Douglas Leatherbury (right). Morgan is still a parishioner of St. Mark’s in 2022.

Matthew Scott Morgan at his baptism in January 1959, with the Reverend Henry Babbit (left) and the Reverend Douglas Leatherbury (right). Morgan is still a parishioner of St. Mark’s in 2022.

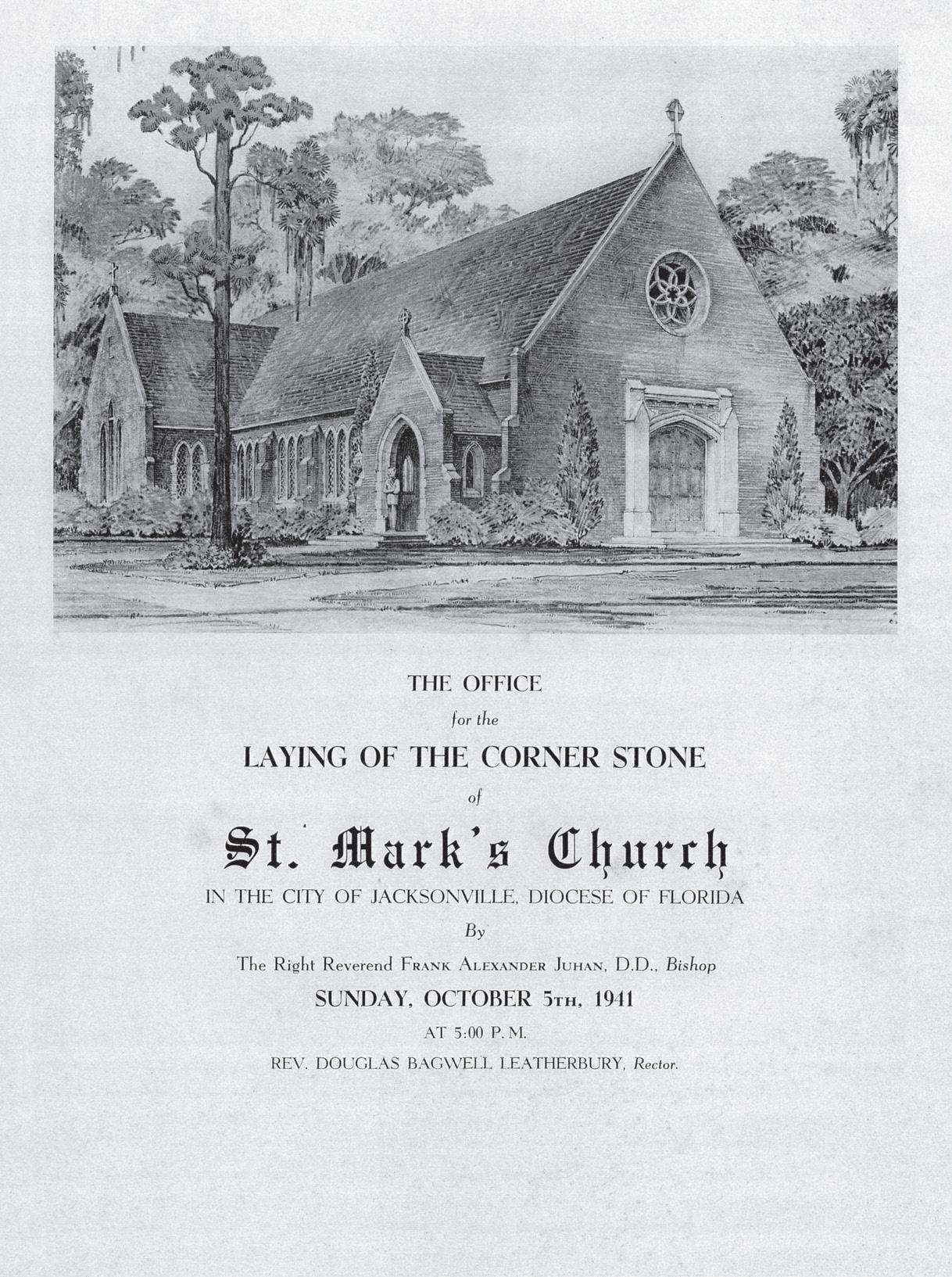

As announced in this special church bulletin, the Little Brown Church would officially be replaced with a new church building, beginning with the laying of the cornerstone at a ceremony on October 5, 1941. By the end of the year, the country would be embroiled in a second world war.

overhead electric and trolley wires crossed the street. The endeavor eventually met with success, as the determined crew toiled throughout the day to bring the pews to their new home at St. Mark’s.

By 1937, the St. Mark’s community regained its financial equilibrium and renewed its determination to construct a new church building. In a report to the Council of the Diocese of Florida, it was written: “This Parish is in good financial condition and its property is unencumbered. They have a beautiful site, on a high bluff, overlooking the St. John’s River . . . in one of the most attractive suburbs of this metropolitan city. They are surrounded by homes of cultured and refined people; they have a neat, well-arranged rectory, conveniently located, adjoining the church. [Their] rector is a man they are very much attached to. . . . [H]opes are again being entertained that . . . means may be devised [to] enable the building of a fitting church edifice on the space long reserved for it.

“ This Parish is in good financial condition. They have a beautiful site, on a high bluff, overlooking the St. John’s River in one of the most attractive suburbs of this metropolitan city. ”

Today the future of St. Mark’s appears very bright and promising for a further career of much good and benefit to the community.”

On October 5, 1941, just weeks before the country would find itself in a world war, the congregation gathered as a cornerstone was laid for the new church by Leatherbury and Juhan. Parishioner Fred Mohle recalled waiting in his car prior to the ceremony with Juhan, an avid baseball fan, as they listened to the final game of the World Series. The parishioners joyfully left the ceremony that day, certain that their beautiful new church building would at last become a reality.

1937 diocese of floR ida siTe RepoRT

1937 diocese of floR ida siTe RepoRT