of Architecture Annual Review 2022–2023

SMALL STEPS

At the time of writing – while the coalition formation following the Dutch provincial elections in March 2023 is progressing slowly, partly due to discussions about nitrogen deposition and whether or not the parties take nature and environment policy seriously – greenhouse gas emissions in the Netherlands (and beyond) continue unabated. One of the biggest emitters is the construction sector. In November 2022, the Dutch Council of State ruled in the case of the Porthos project that nitrogen released during the construction of projects should not be excluded from nitrogen calculations. The victory in this case, which was brought by Mobilisation for the Environment, is another small step towards the sustainability of the activities required to create buildings, cities and landscapes. The Amsterdam Academy of Architecture is making every effort to contribute to that sustainability on two fronts: in the curriculum and in its business operations. In the curriculum, our commitment is visible in the appointment of department heads. In this context, the substantiation of the (R)evolution Planet training theme is an important topic of discussion. Our department heads (including our new head of Urbanism Anna Gasco, who will join us on 1 September) ensure that attention to the climate crisis is integrated into every level of the curriculum. They refine the briefs for design and research projects and invite guest lecturers who specialize in relevant topics, including through open calls published on the Academy’s website and social media. Last academic year, for example, the open call for Ecosystems and Reflection attracted a large number of responses from guest lecturers who were not yet part of the Academy’s network, but whose backgrounds enabled them to make valuable contributions to the content of the subject. In addition, the department heads are increasingly inviting guest critics who are not active in the design disciplines, but who can make important contributions to the discussion of climate issues from their fields of expertise, including policymakers, scientists, politicians, writers, journalists and artists.

In addition to this transdisciplinary exchange, we continue to strengthen interdisciplinary collaboration among the students of the three Master’s programmes. For example, more and more design and research projects have joint initial, interim and final presentations to ensure that students and teachers are aware of each other’s projects and the knowledge generated in each other’s studios. Design and research projects are also slowly but surely becoming more closely linked to ensure that students can directly apply the results of their research to their design.

The Academy of Architecture is also making every effort to improve its business processes. The Amsterdam University of the Arts (AHK) aims to reduce its environmental impact through a sustainability

roadmap that translates the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals to the level of the institute. As part of this, we are making adjustments to the Academy of Architecture, including the forthcoming installation of a heat pump, solar panels on the roof and insulated heritage glass. Inside the Academy of Architecture, the AHK’s roadmap is further fleshed out by our Green Team, which looks for opportunities to make improvements, large and small. For example, we are currently implementing waste separation and bringing more plants into the building. The vending machine with (aluminium) cans of soft drinks will disappear. The canteen, which already serves only vegetarian meals, is adding more vegan dishes to the menu. Guests or students who previously received a bouquet of cut flowers will now receive a potted plant. The materials used in workshops are being reviewed and adapted where possible: from September, for example, Styrofoam will no longer be used to build models, and by 1 January 2024, all disposable cups will be removed from the building. ‘Bring Your Own Cup’ is in the running to become the Academy’s new slogan. These are all small steps, but each one is important and worthy of attention. Not only because together they will ensure that the Academy of Architecture contributes to a zero-emissions building sector, but also because these small steps show that working towards a cleaner world is not something for the distant future, but that the future starts today. ←

Architecture historian Hans Ibelings from Montreal, Canada, gave the Midsummer Night Lecture 2023. In this article, he explores concepts relating to the organic and inorganic world and their consequences for architecture, urbanism and landscape architecture.

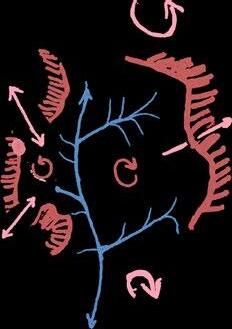

In 1968, Ray and Charles Eames made the first version of their film Powers of Ten. Even if it was a complete film, they called it A Rough Sketch for a Proposed Film Dealing with the Powers of Ten and the Relative Size of the Universe 1 I find it a great title, one that I love to apply to anything I say, or write, to underline that what I do is always just an indication of what I have in mind. Which is, in this particular case, a rough sketch of a proposed article that deals with the dire planetary circumstances we are currently in. I want to outline that this self-inflicted environmental predicament offers us an opportunity, and brings an obligation, to reconsider where we stand, as humans, as architects, landscape architects and urban planners, and to include my own field, as historians. ‘Where we stand’ means where and what we are, and how we see and position ourselves as part of the planet we inhabit. It raises the question of what our relations with the world we are in are, since, as Baptiste Morizot has argued in Ways of Being Alive, ‘the current ecological crisis . . . is a crisis in our relations with living beings’.2

For a long time, and particularly in the West, the world we are in was seen as one world, ‘ours’ to be exact, a human world, owned and occupied by ‘the Family of Man’ to use the gendered title of Edward Steichen’s famous travelling photo exhibition from the 1950s.3 If the environmental crisis has achieved anything, it is that it has made us aware that we are part of a comprehensive more-than-human world, which cannot be reduced by a binary opposition between human and non-human, or even between animals and plants (and algae, fungi, bacteria), let alone by saying that culture (or architecture) differs fundamentally from nature.

The proposed film of Powers of Ten was completed in 1977 (fittingly, it had taken roughly ten years to make it). It starts with a picnicking couple in Chicago, seen from above. Step by step the camera zooms out to the universe before rapidly zooming in again to return to the picnickers and subsequently to enter the right hand of one of them. From there it goes step by step to the subatomic level of a white blood cell.4 Ray and Charles Eames were inspired by Dutch educator Kees Boeke, who had published a book in 1957, called Cosmic View: The Universe in 40 Jumps. It did on paper what Powers of Ten later did on celluloid, zooming out and in, starting with a human, in this case a young girl.5 Albeit without going into detail, both Boeke’s book and the Eames’s film not only helped their readers and viewers to get a sense of scale, but they also underlined that there is a cosmic continuity from a proton to the universe. Two years after the 1977 version of Powers of Ten, James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis formulated their Gaia hypothesis.6 This hypothesis is an example of a rough sketch of a proposed theory, in this case for an encompassing view of the Earth, underlining the interconnectedness of everyone and everything that is part of our planet. Lovelock initially got most credit for it, but in recent years the revolutionary thinking of evolutionary biologist Margulis has gained significantly more recognition. Aside from co-developing the Gaia hypothesis, her key scientific contribution is related to symbiosis and the concept of the holobiont, which is, simply put, an acknowledgment that humans, for instance, are not just one organism, but carriers of colonies of bacterial and fungal life.7 There is the evident ‘power-of-ten’ parallel here between a human as a holobiont, and Gaia as the carrier of all lifeforms.

Both the concept of Gaia and that of the holobiont are fundamentally relational. They reflect an ecological way of thinking that goes back to Ernst Haeckel, who coined the term in 1866, to describe the encompassing entanglements between living organisms, and between organisms and their environment.8 The word ‘ecology’ is, as is commonly known, rooted in the Greek oikos, meaning home, which underscores the obvious links between ecology and architecture, and the idea of being at home in the world. The latter aligns with how the Scottish Centre of Geopoetics describes its topic of interest: ‘Geopoetics... proposes... that the various domains into which knowledge has been separated can be unified by a poetics which places the planet Earth at the centre of experience... It seeks a new or renewed sense of world, a sense of space, light and energy which is experienced both intellectually, by developing our knowledge, and sensitively, using all our senses to become attuned to the world, and requires both serious study and a certain amount of de-conditioning of ourselves by working on the body-mind.’9 With this focus on sensing and experiencing the Earth in its totality as a way of becoming attuned to the world, geopoeticians walk, at least partially, in the footsteps of the great Scottish regional planner and biologist Patrick Geddes. They ask for an understanding that is truly a worldview: to see, as Dutch architect Jaap Bakema put it in the 1950s, the totality of existence.10 Geopoetics certainly isn’t more than a rough sketch of an approach, nor is ecopoetics. As Jonathan Skinner, editor of Ecopoetics argued in the first issue of his eponymous journal: ‘“Eco” here signals – no more, no less – the house we share with several million other species, our planet Earth. “Poetics” is used as poesis, or making, not necessarily to emphasize the critical over the creative act (nor vice versa). Thus: ecopoetics, a house making.’11 The words of Skinner bring to mind a part of the title of architect Bruno Taut’s 1920 book Die Auflösung der Städte oder die Erde eine gute Wohnung: oder auch: der Weg zur alpinen Architektur. 12 With his notion of the Earth as a good dwelling, Taut expressed a sentiment that retrospectively can be considered ecopoetical. Similarly, the reference in the title of his book to the topic of his previous publication, Alpine Architektur, can be interpreted as geopoetical, as it places the Earth in the centre of experience, and implicitly proposes ‘to design like a mountain’, in analogy to what ecologist Aldo Leopold later suggested as ‘to think like a mountain’.13

In the same vein, there is biopoetics, which entails an engagement with the – living – world as well. As Andreas Weber put it: ‘“Biopoetics” pursues the idea that we can understand living beings through the aliveness we share with them. We are alive as are all organisms – and our existence follows the same principles which we know firsthand and from the inside, as it is through them we exist. These principles are alert concern, feeling, expressivity, connection-through-mutual transformation. They are the creative principles which guide poetic experience – hence the term “biopoetics”.’14

This may all sound arcane and detached from the pragmatics of architecture, urban planning and landscape design, but maybe it isn’t. Katarzyna Machtyl argued in ‘Living and Dwelling: A Biosemiotic and Anthropological View on Inhabiting, Art and Design’ that it is ‘impossible to distinguish between . . . building and dwelling, just as it is impossible to distinguish between culture and nature. . . . the very act of dwelling is actually the act of building – it is a process, it does not have an initial form – a project that is unchangeable regardless of how its realization turns out, nor a final form, because while living in a seemingly ready-made structure, we change it – whether we are human or nonhuman subjects. It is made possible by our (both human and nonhuman animals’) agency and the possibility of making choices, which . . . we make “in the moment of now”, and which “design” our future.’15

Machtyl emphasizes the connection between dwelling and building, and not coincidentally she omits the human-centric third word that Martin Heidegger added in his famous 1951 talk in Darmstadt, ‘Bauen, Wohnen, Denken’. Thinking has for too long been considered the exclusive privilege of humans. Later in the same article Machtyl dwells on (no pun intended) design for more than humans: ‘Non-anthropocentric design is nothing more than a design that is turned towards co-being, not just human well-being, and conducted from a human perspective. After all, what are nature reserves, nesting boxes for birds, clothes for pets, or gardens? They all have in common the human perspective that lies at the very beginning of the (future-oriented) design process. It is humans who decide which species to protect, which to exterminate, which to nurture and put “on display”, which to remove, which are useful (to humans, of course), which are harmful.’16

And she adds that ‘Non-human-oriented design does not mean designing birdhouses or gadgets for dogs, but is oriented towards inter-species relations, coexistence, biosemiotic dialogue.’17

This is pretty much what Andrés Jaque is trying to do with his more-than-human architecture, such as the Reggio School he recently completed in Madrid, mindful that any building will inevitably be inhabited by other organisms than humans. The analogy does not work perfectly, but his work is the architectural equivalent of a holobiont. On different scales, the same is true of Debra Solomon’s multispecies urbanism, and of Maike van Stiphout’s nature-inclusive landscape architecture. The idea of the ‘more-than-human’ goes back to David Abram, who wrote in 1996 in the concluding part of The Spell of the Sensuous: Perceptions and Language in a More-than-Human World: ‘The human mind is not some otherworldly essence that comes to house itself inside our physiology. Rather, it is instilled and provoked by the sensorial field itself, induced by the tensions and participations between the human body and the animate earth. The invisible shapes of smells, rhythms of cricketsong, and the movement of shadows all, in a sense, provide the subtle body of our thoughts. Our own reflections, we might say, are a part of the play of light and its reflections. “The inner – what is it, if not intensified sky?” By acknowledging such links between the inner, psychological world and the perceptual terrain that surrounds us, we begin to turn inside-out, loosening the psyche from its confinement within a strictly human sphere, freeing sentience to return to the sensible world that contains us. Intelligence is no longer ours alone but is a property of the earth; we are in it, of it, immersed in its depths. And indeed each terrain, each ecology, seems to have its own particular intelligence, its unique vernacular of soil and leaf and sky.’18

What does all of this have to do with architecture, landscape and urban design? Everything. Because every design intervention is on a planetary, macro scale, as well as on a micro scale connected with everything else, organic and inorganic. By not pitting architecture (or culture, or humans) against nature (or the planet), the design of buildings, cities, landscapes has the potential to become both less important, and more important. Less important if, as biosemiotician Thomas A. Sebeok – an earlier subscriber to the Gaia hypothesis – put it, we accept that we are only looking at a fraction of ‘that minuscule segment of nature some anthropologists grandly compartmentalize as culture’.19 And more important to the extent that we can understand architecture, urban design and landscape architecture as contributions to the whole of the Earth, Gaia.

IN AND FROM THE WORLD

Products of design are inseparable in the world and from the world they are in, like blood, the narrator in Italo Calvino’s short story in Ti con zero, ‘Il sangue, il mare’.20 The point of departure of this story about ‘the blood, the sea’ is the similarity in composition between blood plasma and sea water. It relates how what once surrounded humans, ocean water, has become our bodily content. The inorganic outside has become the inside of organisms. Just as we carry the ocean in our body while we swim in it, there is no categorical difference between inside and outside in architecture. If it wasn’t the title of the tear-jerking charity hit single from 1985, I would say ‘we are the world’. And simultaneously ‘the world is us’. And the same goes for architecture, which is the world, just as the world is architecture. Perhaps this is what Bakema was hinting at with his total architecture and the totality of space, which seems for architecture both humbling and gloriously liberating. ←

1 A Rough Sketch for a Proposed Film Dealing with the Powers of Ten and the Relative Size of the Universe (1968), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7f5x_ dRKIF4, accessed 23 May 2023.

2 Baptiste Morizot, Ways of Being Alive (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2022 [2020]), 4.

3 The Family of Man: The Photographic Exhibition Created by Edward Steichen for the Museum of Modern Art (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1955).

4 Powers of Ten: A Film Dealing with the Relative Size of Things in the Universe and the Effect of Adding Another Zero (1977), https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=0fKBhvDjuy0, accessed 23 May 2023.

5 Kees Boeke, Cosmic View: The Universe in 40 Jumps (New York: John Day, 1957).

6 James E. Lovelock, Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979).

7 See: Lynn Margulis and René Fester (eds.), Symbiosis as a Source of Evolutionary Innovation: Speciation and Morphogenesis (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991).

8 Ernst Haeckel, Generelle Morphologie der Organismen (Berlin: G. Reimer, 1866).

9 Scottish Centre for Geopoetics. https:// www.geopoetics.org.uk/what-is-geopoetics/, accessed

10 Bakema addressed this idea in multiple

articles. See for instance: Jaap Bakema, ‘Towards a Total Architecture’, Architectural Design (April 1959), 145-146.

11 Jonathan Skinner, ‘Editor’s Statement,’ Ecopoetics 1 (2001), 5-8: 7.

12 Bruno Taut, Die Auflösung der Städte oder die Erde eine gute Wohnung: oder auch: der Weg zur alpinen Architektur (Hagen: Folkwang Verlag, 1920).

13 Bruno Taut, Alpine Architektur (Hagen: Folkwang Verlag, 1919); Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989 [1949]), 129-133.

14 Andreas Weber, The Biology of Wonder: Aliveness, Feeling and the Metamorphosis of Science, https://biologyofwonder.org/biopoetics, accessed 22 May 2023.

15 Katarzyna Machtyl, ‘Living and Dwelling: A Biosemiotic and Anthropological View on Inhabiting, Art and Design’, Biosemiotics 15 (2022), 215-233: 226.

16 Ibid., 228.

17 Ibid., 229.

18 David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous: Perceptions and Language in a More-than-Human World (New York: Vintage, 1997 [1996]), 156.

19 Thomas Sebeok, ‘Vital Signs’, The American Journal of Semiotics 3/3 (1985), 1-27: 2.

20 Italo Calvino, Ti con zero (Milan: Mondadori, 2019 [1995]), 36-46.

THE ART OF ARCHITECTURE

It was a pleasure to dive into the harvest of this year’s graduation projects. Not only did it give me an insight into 44 individual plans, but it also offered me a world tour in just one morning, as so many places and continents were represented in all your plans. Let me highlight some of the interesting, surprising and disturbing aspects.

Many of the projects we found interesting share the moniker ‘Anthropocene 2.0’. This is a concept I borrowed from landscape architect and thinker Dirk Sijmons. Of course you are familiar with the term Anthropocene: the period of humanity’s extractive and abusive exploitation of the world’s natural resources. Sijmons uses the term ‘Anthropocene 2.0’ to describe the opposite position, which seeks to repair and reconstruct what humankind has destroyed by regenerating the soil, the water and the air. Quite a lot of the projects have in common that they are looking for ways to repair the destruction that has been done. In all of these plans, an emphasis on and generous attitude towards flora and fauna, in every sense of the word, is quite natural. It means that as an architect or urban planner, you need an extra skill set, that of the ecologist. If you are serious about restoring natural systems, it is not enough to draw or render nature, you need to know how it works. I don’t know about you, but speaking for myself, there is a huge knowledge gap that needs to be filled. Most spatial planners and designers don’t have this skill set yet, and even landscape designers don’t always know how to design with nature. In this day and age, we all need to broaden our interests to include ecological thinking, with its automatic long-term perspective and the inclusion of designing with nature, flora and fauna. Beyond their impressive and ingenious aspects, I was a little surprised to see that many projects lacked a direct link to the times we are living in. Do I need to mention all the crises and transitions we are experiencing? Like the pandemic, the polarization and inequality in our society, the farmers’ protests and the coming revolutions in agriculture, and the war in Ukraine. All these crises were largely absent from the projects. I didn’t see a lot of political angles in the graduation briefs; there was much more emphasis on the personal motivations for starting a project. This has its pros and cons, but sometimes it made me question the urgency. I regularly asked myself: ‘Why has this project been undertaken? What is its relevance?’ →

Michelle Provoost, partner at Crimson Historians & Urbanists and director of the International New Town Institute, was a guest critic at the graduation weekend, which drew over one thousand visitors. She gave a talk on the themes that struck her in the final projects. This is an abridged version of that talk. Text MICHELLE PROVOOST Photos JONATHAN ANDREW

This is not to say that change was not on the agenda at this graduation weekend. On the contrary, there was a clear emphasis on the need to change the way we do things, on so many levels. For more than a century, we have been accustomed to thinking about our actions in terms of progress, of doing more and doing better, in quantitative terms. However, the question inherent in some of the plans has been: ‘Can we do less but, for example, create more happiness or a better environment?’ If this is the intention, we need to change our narrative, our habits and our role as designers. In line with this, the idea of the architect as someone who designs and builds was often questioned. Other basic assumptions of the profession have also been challenged, such as ‘a building is made of concrete’ or ‘a house is made for a family’. Rightly so, I think, because in all these changes, designers can lead the way by experimenting, by showing what is possible, or by using the power of imagination to create an image of a new situation.

Another thing I saw in your projects, quite surprisingly, is a reappraisal of architecture as an autonomous field of knowledge. In contrast to the general emphasis on the social aspects of the built environment, on the collective and the community, there seems to be a renewed interest in architectural form as such, in architectural language, symbolism and aesthetics. The last time this approach to architecture was in vogue was in the 1980s. Some of the graduation designs show a similar interest in the autonomous aspects of architecture, in the history and vocabulary of architecture as a method and a body of knowledge.

In my opinion, this is just as important as the societal approach to architecture. We need both. If you’re looking for architecture as a way of imagining possible futures, you also need the formal aspects, the aesthetics, the form and the space to be convincing. I’m particularly interested in the aesthetics and the formal aspects that will come out of all these changes that you’re proposing. I’m sure that new approaches to research and construction will lead to a new architectural language, and I’m very excited to see where this will go. Thank you very much for your attention. ←

ARCHIPRIX NOMINATIONS

At the close of the Graduation Weekend 2022, director Madeleine Maaskant announced the four nominations for the Archiprix Netherlands. The four nominated graduation projects were: Exhibition for Imagination by Steven van Raan (Architecture), Exit Urbanism by Max Tuinman (Urbanism), Choreographing Resilience by Justyna Chmielewska (Landscape Architecture) and Alive Algae Architecture by Irene Wing Sum Wu (Architecture).

Additionally, both the Audience Award 2022 and the Research Award 2022 were awarded to XXX by Anna Torres (Architecture), the Engagement Award 2022 was awarded to Heelhuis by Niels Geerts (Architecture) and the [R]evolution Planet Award 2021 was awarded to The Plant by Jasmijn Rothuizen (Architecture). ←

The Amsterdam Academy of Architecture nominated two Architecture projects, one Urbanism project and one Landscape Architecture project for the annual Archiprix Netherlands competition.

FOR IMAGINATION

and materials that form interesting new spaces. The idea is to design the spaces first and then see if they will have a function, and if so, which one?

The graduation work is a study only on paper in which there are no limits, and I do not allow myself to be hindered by the reality of architecture. I was inspired by surrealistic design techniques and I want to use these to explore the extreme side of architecture. Using different design techniques gives me the opportunity to look at and design from different perspectives. I want to create a field of tension between architecture and art, but also between imagination and reality. I will take this as far as I can, to eventually design absurd spaces about which people will continuously marvel.

I began this graduation work with a return to a personal childhood drawing of a city. A city that is unknown to me and originated from my personal fantasy and memory. The drawing offers room for imagination. It triggers curiosity about what goes on behind the door of the house. Moreover, this drawing also evokes emotion. Is this a cosy part of the city or does the absence of people on the street create a disturbing feeling? As a child, you are brash, and you let go of any form of reality. This inspires me to think about how you, as an architect, can break free from the limitations you unconsciously impose on yourself. Therefore, the goal of my graduation is to (re)design a place without any form of restriction and to give back the historical experience of that place. I searched for a method with which I could create compositions I could never have imagined before. I don’t want to design a traditional building with a front door and several rooms. On the contrary, I am looking for a strategy to combine objects, spaces

real) drawings can yield a better, more exciting and more fascinating architectural design. The architect as artist versus the architect as realist. Free and intuitive creation versus deliberate and structured working. These are two completely different design approaches that intrigue me. Building on my essay, in which I argue for a more surrealist way of thinking of an architect, I would like to demonstrate in my project how these two design approaches can be brought together and how surrealism can bring innovation in architecture.

In this graduation work, you will find my design for the Frederiksplein in Amsterdam. The Frederiksplein is a place with a rich history, of which unfortunately nothing is visible in its contemporary form. I aim to restore the old historical value by means of a layered design, which is based on a lot of research, while at the same time creating space for imagination, alienation and wonder.

In the design process, I tried as an architect to disconnect from the limitations that I consciously and/ or unconsciously impose on myself –a process that I associate with drawing, a fascination of mine. I have used existing design techniques from surrealist art, another fascination of mine. This graduation work can therefore also be regarded as an investigation into the extent to which the process of making (sur -

STUDENT Steven van Raan

Architecture GRADUATION date 4 May 2022

MENTOR Rob Hootsmans COMMITTEE MEMBERS Marlies Boterman and Paul Kuipers ADDITIONAL MEMBERS Elsbeth

Falk and Gus TielensNomination

3 Three-dimensional composition of forms.

2 Two-dimensional composition of forms.

1 Selection of forms, scaled to the same size.

5 Various three-dimensional compositions tied together.

4 Various two-dimensional compositions tied together.

6 Photos of various three-dimensional compositions combined.

8 Add scale and insert in existing urban context. 9 Invert by transforming empty spaces into mass. 10 Create space by extruding mass. 11 Flat model of composition.

7 Frame and digitally enhance the composition.

Drawing on flat model.

Steven van Raan searched for a method with which he could create compositions he could never have imagined before.

1 The cube houses / the soldier, 2 The city wall / the traveller, 3 The square / the market ladies, 4 The gate / the gatekeeper, 5 The foot walk / the touris,

8 The ruin / the firemen,

Steven van Raan used existing design techniques from surrealist art.

6 The cupola / the inventor, 7 The gallery / the violin player,

9 The grid / the modernist, 10 The artwork / the art collector, 11 The safe/ the safe keeper, 12 The tower / the bank director

Romney hut These huts are scattered over the entire are in the Baaibuurt. The Romney huts are constructed of a clamped tubular steel frame with a central entrance. The hut was used to accommodate facilities for which abnormal roof spans were required. On some airfields, two or more Romney would be erected to accommodate large stores and workshops, or occasionally used as aircraft hangars.

Niermeijer’s heritage large storage space filled to the brim with artwork of Theo Niermeijer, sculpture artist and founder of this settlement by allowing others to live around his atelier on this place.

Theo Niermeijers legacy is scattered over the area. In and out of sight are large metal sculptures being overgrown and corroding because of the weather. In the bushes, between the trees, underneath the soil, Theo’s artworks live on.

De Karavaan De Karavaan is a row of structures, cars and carts melted together into one long house. The row has been growing over the years after which it got nicknamed ‘the caravan’. Inhabited by Elya Salié and her family.

Pizza oven A place to come together, outside. A self-built pizza oven that gets used during hot summer days for providing delicious pizza for parties.

World War 2 relic one of the three out of 16 bunkers situated on Zeeburgereiland. This bunker has once been transformed into a neighborhood café and is now only in use as a workshop.

Travelerswagons

There are multiple ‘clownswagons’ scattered over the area, one of them was built in the late 19th century, others in the early 20th century. Built for living in, and still inhabited!

Sharing space Not only inside are communal spaces. but some parts outside are also being used communally. Places to play, to cook, to relax on a hot summer day. A place for kids and adults to come together. In the shade of the trees.

In nature The area is covered in green, or rather inside nature. Nature grows everywhere in the area, grasses, shrubs, under the large trees. There is a large path that runs through the area, from which the smaller paths lead to the front doors and workspaces of inhabitants.

Community building The communal building a shared place for all the inhabitants of One Peaceful World. (un-)organised gatherings, replacement of a living room, parties, band practice on stage, neighborhood council-meetings. A place to relax and sit by the fireplace or to be active together. A place well used by all of the inhabitants, inlcuding a shower and toilets.

The entrance The entrance is used by inhabitants and, when still active, used by the public as entrance to the sculpture garden and open-air museum. The area started because of Theo, and the entrances of the area still show his name on the signs: Theo NiermeijerThe iron poet “It has to be this heavy, because it can’t be any lighter.” Free entrance

The ultimate answer is not up to me; that’s not possible. Any design of what the perfect neighbourhood might be, misses the point by definition; it’s too one-sided. This is a quest, and my contribution is to stop and point in a different direction, advocating for a much slower lens. I am pleading for designers to get to know the area they work in –and question all reasons for intervening over and over. Are we still doing the right thing, or should we maybe be doing more than just design?

it? Is the greater good housing, or is it ecology, cultural values, social values, creativity or productivity? The urbanism profession and the Academy of Architecture seem to participate in the system of largescale and efficient design. I am part of that system too. But I do not believe that designing a dense car-free urban district with green roofs solves the problems we are facing. And with this graduation project, I have the possibility to question this largescale applied machinal way of developing and designing.

This project became about saving an undefined and unknown area within the city. We are eradicating entire areas without realizing the value of these anomalies for the city. We are sacrificing diverse, ecological, productive and creative but also vulnerable communities, only to build back so-called sustainable neighbourhoods hoping they become a diverse and well-working part of the city again. How do we protect and value that which, at first sight, seems worthless by current standards? Are we building in the name of people –or for people? What is the greater good, and who defines

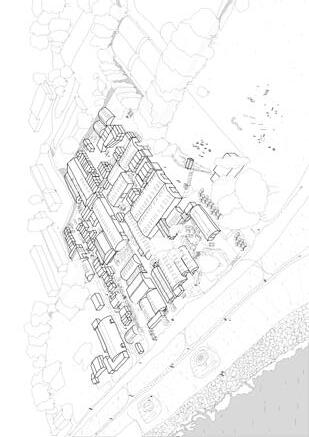

This project is not a design, this project is an approach, a changed way of thinking. The Baaibuurt-west in Amsterdam is scheduled for demolition; 900 new houses are being projected on this inhabited area. This project started with a fascination for empty and unused spaces. During the process, I managed to predict which areas in Amsterdam were going to be demolished, thanks to multiple parameters. One of those areas intrigued me; I can simply not believe that everything and everyone there is going to be flattened, cut down and evicted.

A part of the area as imagined in a possible future.

part of the area analysed by drawing.

Materials scavenged from the area, serving as base for the model. Are you willing to get your hands dirty to get to know the area?

1.200 inhabitants

(4 per house)

300 houses 33,3 house/ha

work/inhabitant

25.000+ m2 20,8+ m2

Carpenters (Car)mechanics

Sculptors Construction companies

Ateliers Storage

Second-hand stores/repairshops

Bar/dancing Intercultural organization for participation and integration

Funfair-operators

Broedplaats

Clothes store Workshops

Yogastudio Canine-training Dog daycares

Band-practice room

Self-built livingrooms

Self-built caravan café Horse meadow Recycle Lounge Gallery Club 44

Boat/Bunker Supermarket Museum beeldenpark, Zeeburg + much more!

1.620 inhabitants

(1,8 per house)

900 houses 71,4 house/ha max. 16.000m2 9,9 m2 work/inhabitant Restaurants Realtors Doctor Dentist Office Retail Gym

EXIT URBANISM

350 inhabitants (4,3 per house) 80 houses 6,3 house/ha

15.000m2 42,9 m2 work/inhabitant

Carpenters (Car)mechanics Sculptors Construction companies Ateliers Storage

Second-hand stores/repairshops Bar/dancing Intercultural organization for participation and integration Funfair-operators Broedplaats

‘GOOD’ URBANISM

Clothes store Workshops

Yogastudio Canine-training Dog daycares

Band-practice room

Self-built livingrooms Self-built caravan café Horse meadow Recycle Lounge Gallery Club 44

Boat/Bunker Supermarket Museum beeldenpark, Zeeburg

Wilkesstraat

IMAGINE SHARING WORKPLACES -

used for

working hands in the

smaller shared workshops

HornstraatLeo

HaarmslaanBob

Anthonievan Akenstraat

Keulen-DeelstrastraatAtje

AtjeKeulen-Deelstrastraat

Kamerbeekstraat

AREA self-organized festivals for the island and city

DillemastraatFoekje

Alidavanden Bosstraat

WielemapleinGeertje

EefKamerbeekstraat

EefKamerbeekstraat

DillemastraatFoekje

EefKamerbeekstraat

HOUSEa place for the

WielemapadGeertje

converted trailers

KamerbeekpadEef

KeesBroekmanstraat

KeesBroekmanstraat

HornstraatLeo SenNida straat

FARMa small animal farm for kids and elderly DIKE SHEEPmaintaining the dike with grazing animals EXPLORE VALUABLE FAÇADESconstructive artistic artworks VEGETABLE GARDENgrowing of crops and fruits LIFESTYLE living different than society demands ARTWORKS ornaments and objects BIG FIELD an important natural void TREES large adult trees WARNING CLOSED OFFpreserve open character SWAMPreed growth TRASHaccumulation of unused materials MANAGE NO MOWING TRASH COLLECTION NO PAVING MONITOR TREEShealth and size STRUCTURAL DECAYhousing and buildings ASPHALT CONDITIONuse will intensify SOUND festival noise pollution LIGHTSpublic space time sensitive lights

SECOND-HAND COMMUNITY

IMAGINE

SELF BUILT HOUSING only actually self-built allowed SECOND HAND CIRCLE stores as main supplier CRAFTING COMMUNITY inhabitants that help each other build EXPLORE

VALUABLE

SECOND HAND STORES fixing and selling TREES large Italian poplars and oaks BAR DANCING social space and country bar AVAILABLE SPACEused by postal service

WARNING STONE unnecessary paving CHARACTERfences OVERGROWTHplants overgrowing public spaces SWAMPreed growth

MANAGE TRASH COLLECTION LESS PAVING MONITOR

OCCUPATIONamount of people democratically chosen RENTAL PRICES low prices need to remain low STRUCTURAL STRENGTHhousing and buildings TREEShealth and size

Re-naturalizing rivers should serve future generations who are going to deal with even more severe floodings. This project can serve as an example for other Polish cities that have to deal with similar issues. With time people will be able to slowly accept the streams they once turned away from. Restoring the presence of the Strzyża represents the interests of other tributaries of the Vistula River, which have disappeared from the landscapes of too many Polish cities.

The only way to restore the Strzyża is through various interventions: from engineered city investments on the grounds belonging to the municipality to simple community actions, which will take place in the areas owned by privatized neighbourhoods. Diverse ownerships around the river make it impossible for a single top-down plan. At this moment, the only way to fight the floods and the disappearance of the stream is by local collaborations. Only together will we be able to deal with the consequences of the lost river’s ecosystems.

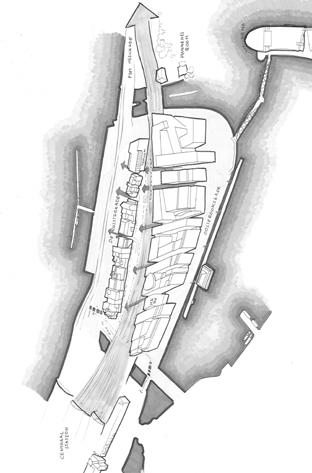

Over the past 30 years, I have observed the slow disappearance of the Strzyża Stream from the landscape of my hometown. The government sold many kilometres of the Strzyża to diverse investors. Some of her pieces belong to the national treasury, some to commercial companies, the rest is still in the ownership of Gdansk’s municipality. As a result, the river has no coherent planning, and many of her pieces have uncontrollably disappeared underground. The consequences of these money-driven actions are catastrophic: during heavy rainfall, the stream floods the city. The destroyed stream’s biotope (degraded topsoil and wiped-out riparian vegetation) is unable to absorb the rainwater, which leads to floods. Only in these moment does the Strzyża reappear, while for most of the year it remains invisible to the eye. It is necessary to act now to minimize recurring floods. In the age of climate crisis, bringing our lost rivers back to life is a necessity. The goal of my graduation project is to restore the physical presence of the Strzyża’s buried underground ecosystem and, as a result of that action, to minimize the floods. All of the designed interventions aim to improve the preparedness of citizens of Gdansk for living in a flood zone.

Each year there are fewer of them. Some have disappeared underground, from time to time reappearing in a littered ditch between the buildings, to sink into the ground again somewhere. This is the fate of the Strzyża Stream and other tributaries of the Vistula River. Almost all of the Vistula’s tributaries have disappeared from the landscape of Polish cities. In Poznań, the stream was interrupting city development, so it was moved. In Krakow, all rivers except the Vistula have disappeared. Wrocław’s streams were forgotten, they disappeared, and when they reappeared during the floods, 40 per cent of the city was underwater. Each summer the Rawa Stream dried up more until one day, it completely vanished from Katowice. In Gdansk, 2 km of the Strzyża were diverted to underground pipes.

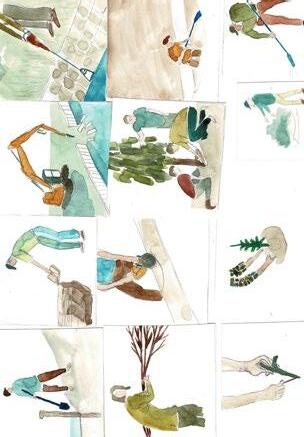

Inspired by the existing actions of placing sandbags, this project offers a choreography of resilient actions, which instead of just protecting, prepare people for upcoming floods. All of the resilient actions aim to strengthen the presence and ecological value of the Strzyża.

Every few years, the Strzyża floods the city of Gdansk. Only in these moments does the stream reappear, whereas for most of the year it remains invisible to the eye (red line).

ALIVE ALGAE ARCHITECTURE

still water and open wavy water.

I’ve created five towers (Consolidating> Growing> Dissolving> Transiting> Waving), allowing you to experience the material and landscape from different atmospheres and perspectives. The towers are connected by different bridges, which also harmoniously reflects this feature of Het Twiske: from spot to spot by bridge to bridge. This design will provide a poetic experience for the visitors towards the material and landscape: it aims to provoke the discussion about using algae as a future material or resource.

fore, this project aims to boost the market field and demand for microalgae, to encourage faster and cheaper development of the microalgae system. Or at least broaden the public’s knowledge about this new potential material.

Alive Algae Architecture demonstrates the built environment’s opportunities with microalgae. This project explores how microalgae can be integrated into the building or if they even can become construction material. The location –Het Twiske nature reserve near Amsterdam –harnesses the quality of this material in a self-sufficient ecosystem. Over time, the building will continuously change. The project boasts a rich quality of different types of landscape: forest, open grass field, reed field, inner

It focuses on a bio-based material on a microbiological scale and its application in architecture. Say ‘algae’: most people immediately think of pond scum –but what they do not realize is that we would not exist if algae didn’t exist. Microalgae are the oldest organisms on Earth; they are the beginning of the food chain. In the past few years, it has been made clear that we can no longer ignore the threats to climate change, the economy and future energy security. Microalgae can help address all these major issues. They can absorb CO2; produce oxygen, power, fuels and food; purge water during their own growing system; and produce a large amount of biomass. Despite the many advantages, the development is very small-scale and expensive. There -

It is an innovative project. It is a material-based project. It is research of microalgae. It is built from microalgae. It is built for the material. It is built for the ecosystem. It is built for the landscape. It is about nature-culture. It is about the basics of the cycle of life, also in architecture.

Alive Algae Architecture is a project that combines the knowledge of science, art and architecture: research as a scientist, craft as an artist, design as an architect. This project is a form of innovative research.

STUDENT Irene Wing Sum Wu MASTER Architecture

DATE 29 August 2022

GRADUATION

MENTOR Jeroen van Mechelen

COMMITTEE MEMBERS Laura van Santen and Marlies Boterman

ADDITIONAL MEMBERS Lada Hrsak and Milad Pallesh ARCHIPRIX Nomination

Model.

Detailed typology; a clever and sensual workspace.

unapologetically gives back the city to sex workers by inhabiting and densifying the inner roofscape of a typical Amsterdam city block –Blauwlakkenblok –which once hosted a great many sex work windows. It recognises the variety of sex workers’ needs by providing qualitative workspaces to over 70 sex workers and communal facilities. By the nature of its design, XXX alternates intimate courtyards of fresh vegetation, delicate lighting and layers of flowing veils with larger, breathing and restful public spaces for the city. The result is a project that offers sex workers and the city’s users a delightfully slow-paced, mysterious Red Light experience and honours the key role sex workers play in our society.

How can we create a more balanced solution that listens first to sex workers’ needs, all the while benefiting the city and its inhabitants? How can we learn ways to rethink a public space that has been overwhelmingly designed to cater to the heterosexual masculine fantasy?

combined with the lack of proper infrastructure results in a saturated and over-capacitated neighbourhood.

Guided by an intuitive artistic approach, a sensitive collaboration with Amsterdam’s sex work community was born. Through a series of intimate conversations with sex workers and meticulous observations of the area, precious details, stories, needs and dreams came out as the building blocks for our project. XXX playfully provides a fresh answer to the city’s current controversial questioning on how to deal with its evolving Red Light district. This intervention

The municipality of Amsterdam sees this as an opportunity to push an intensive gentrification project meant to close down windows, remove sex work and bring in a different kind of tourism, by means of an alarmist Red Light narrative. In an attempt to relocate sex workers, the municipality has been developing an ill-conceived and insensitive ‘erotic hotel’ that would push the sex work community outside the city. Conse quently, sex workers are faced with a myriad of uncertainties. With an ever-shrinking number of dedicated workspaces, room rentals are becoming increasingly unaffordable, and many sex workers see themselves working from home in unsafe conditions or simply going out of work.

view of XXX; a densifying intervention in the Red Light district.

XXX is an architectural invitation to rediscover sensuality and intimacy in the heart of Amsterdam’s historical Red Light district De Wallen.

Amsterdam’s sex work industry has always been intrinsically linked to the city’s development, dating back to its beginnings as a harbour city in the 1300s.

Over the years and through changing legislation, sex workers have seen street work evolve from exposed and unsafe into a more controlled and secure window work. This work-behind-glass typology is typical of the Dutch urban landscape. De Wallen, a central neighbourhood in the heart of Amsterdam, is notorious for its rowdy atmosphere and its confronting windows –and even more so for the women standing behind them. The Red Light district sees over 8 million visitors a year; the size of the area

2022

30

Mysterious narrow alleys

guide the entrance to the project.

guide the entrance to the project.

Cosy wooden corridors provide slow-paced circulation and lively interactions.

Warm red lights, vegetation and veils create a layered and romantic atmosphere.

A central green space and crossing walkway offer intimate public space to the city.

the environment at a given moment. This way of designing has led to a main setup: a residential building (bed house) on the Overtoom and a health clinic at the park. The exponential economic growth and political developments of the last decades have led to a privatization of healthcare. At the same time, the current pressure on the sector and the growing and aging population demand a revision of the plans for healthcare. Workshops were held in the process with relatives, care providers and care developers. Two common denominators were striking: everyone wants to provide care (‘the broad care team’) and the general call to make the building very specific, but flexible at the same time. Every patient is unique and has their own needs. We need to look at more inclusive forms of living, where prevention, inspiration and humanity are central. Heelhuis is mainly intended as an instigator to think about better care buildings, in addition to showing several concrete design solutions. After all, many care homes have been designed as efficient care machines due to the privatization of these services. In Heelhuis this is radically reversed: here, the resident, the next of kin and therefore the quality of life (and death) are central on all scale levels.

through urban life in the base and through a garden as an extension of the Vondelpark. In this way, Heelhuis is an inherent part of the city, and gives back space to the surrounding residents and visitors. Residents of Heelhuis are an inseparable and autonomous part of society. The project has been approached entirely from the resident’s point of view. During the design process, the question was constantly asked: ‘I wake up . . and then what? What do I do next? What does my day look like?’ The building has grown in this way. Step by step, spaces were added, and the scale of the design grew. Residents can determine to what extent they want to be part of the community and

Heelhuis is a proposal for a care building based entirely on the patient. The project is a response to the manifesto for the care of Boukje Bügel-Gabrëls, a fellow student who started the project. During her period of illness and rehabilitation, she experienced the limitations of the current healthcare architecture.

Laura Alvarez and Jarrik Ouburg

Boukje recorded her experiences in diaries and shared them with her loved ones. She initiated spatial proposals where hope is central to all the pieces. Heelhuis replaces the current Reade rehabilitation centre, which will move to the site of the OLVG West hospital. The current building turns away from both the city and the park behind it. Heelhuis does the opposite: it adapts to the immediate environment

van Mechelen and Stephan

The dwellings have been designed with the bed as the starting point: from intimate and quiet to open and connected.

idiom of the floor plans is then based on the room, the Vondelpark and the Overtoom.

Model showing the section of the building.

Heelhuis in different scales.

A built, sunken garden as a spa for residents and the city.

Pilgrim in the Vondelpark

Model showing the section of the building.

Heelhuis in different scales.

A built, sunken garden as a spa for residents and the city.

Pilgrim in the Vondelpark

The room.

The garden.

The community.

The recessed garden.

The health clinic.

The room.

The garden.

The community.

The recessed garden.

The health clinic.

apart to make the building permeable and accessible.

By adding public functions, which make use of the different energy flows in the building (food production, catering and various accommodation functions), it becomes a multifunctional power station. This will make the new plant a pleasant place to visit, enter and use. The Plant shows that energy facilities need not be hidden away, but can actually add value to the living environment in the neighbourhood.

ed — it is vital to see these power plants as an architectural task in their own right. This way, we prevent these new buildings from blocking the city, and the energy processes become experienceable for the resident. As an architect, I want to ensure that these power plants are given an appropriate place in the city, not only creating space for the development of renewable energies, but also enhancing urban liveability. The research for my thesis pursues a new typology of the power plant. It is important that power plants become accessible, have a recreational function and that the technology can be integrated from various perspectives –that they represent a positive change in our energy transition. The Plant is a decentralized energy supply that meets the heat demand of people living in its immediate vicinity. The new strategy transforms the large urban heat network for the city into a local network for local residents. Residents can literally experience where their heat comes from. With minor adjustments in the development plan, the power station becomes the heart of the neighbourhood, a place for all residents. Several paths for walkers and cyclists run through and around the building in the city park. As an icon, the power station gives identity to the neighbourhood. By turning the building inside out, technology is made visible. The different facets of technology are pulled

The energy transition is a huge effort to provide the Netherlands with sustainable energy. Generating energy is on the eve of a major shift. Coal and natural gas power plants are making way for wind farms and solar fields –a positive change in our energy transition. Not only the Dutch countryside, but our cities, too, are facing this inevitable change. This requires a new approach in the urban area. Where energy is now mainly generated outside the city, more and more local sustainable energy plants are popping up within the city. To prevent our cities from once again having to deal with a new generation of anonymous and meaningless utility buildings — elusive, inaccessible, unwant -

DATE 22 March 2022

Machiel Spaan

MENTOR

COMMITTEE MEMBERS Jeroen Atteveld and Kamiel Klaasse ADDITIONAL MEMBERS Dafne Wiegers and Floris Hund AMSTERDAM ACADEMY OF ARCHITECTURE (R)evolution Planet Award

Model with the heat network.

Model with the heat network.

Cold square with the cooling basins.

Heat square with the geyser bath.

Cold square with the cooling basins.

Heat square with the geyser bath.

Different routes through and around the building.

in the middle of the park and the neighbourhood.

HUMAN ZOO

Landscape architect Thijs de Zeeuw is an alumnus of the Academy of Architecture; it was in this capacity that he delivered the Kromhout lecture – named after one of the academy’s founders – during graduation weekend. The lecture, which was entitled ‘Stupid Optimism and the Power of Speculation’, explained why De Zeeuw faces the future with confidence.

De Zeeuw graduated in 2011 with a design for an urban nature garden on the site of Artis’s current car park. His design was well received by the zoo’s management, which subsequently asked him to design an elephant enclosure on a site immediately adjacent to the car park. De Zeeuw told the students present: ‘Be careful where you choose to do your graduation project!’

With this commission in his pocket, he decided to quit his job at H+N+S Landscape Architects and start his own business. He soon discovered that the other-than-human perspective was very important in this commission. ‘Designing zoos forces you to take up different perspectives,’ says De Zeeuw. ‘A zoo director will often ask: “Can you design an enclosure in which the animal performs its natural behaviour?” But it’s of course quite hard to find out if an animal likes your design. That leads to the question: What natural behaviour is relevant in a zoo?’ To answer this question, De Zeeuw cites the concept of ‘affordances’, as in: ‘A landscape that affords certain natural behaviour’. He designed a rock garden consisting of 163 unique concrete objects that all create a different kind of friction; the rough surfaces enable the elephants to scratch themselves. Another important notion is ‘agency’. How can you make sure an animal can act at will in its own environment? De Zeeuw designed the pond in which the elephants can bathe in such a way that visitors can get splashed when the elephants enter the water. The water sloshes over the edge of the pool, with startled visitors as a result. In response to the new enclosure, Dutch newspaper NRC headlined on its front page of 22 September 2022: ‘An Enclosure for Animals Should Not Be Too Perfect.’

The next project was an enclosure for two crocodiles (or, more precisely, false gharials) named Harry and Layla. ‘The challenge was: make an environment in which they might breed, so they produce offspring,’ says De Zeeuw. ‘Can you design an enclose that gets crocodiles in the mood for sex? That’s quite difficult to imagine, because I feel closer to elephants than to alligators.’ There was little information about the crocodiles’ requirements. Given were the water depth (it had to be deep enough for them to float, without their belly hitting the floor) and the temperature. That was all. ‘What is similar to the sexual life of crocodiles?’ De Zeeuw asked himself. ‘I thought of the seasons. They’re from south-east Asia. They have a wet and a dry season there. For the wet season, we designed a rain machine with a nice, fat tropical raindrop. When we first introduced the rain machine, it turned out that Harry and I are more alike than I thought, because neither of us like rain. He swam around the rain showers. That made me wonder if I’d done something wrong. Then I realized: being able to avoid rain is actually a good thing: it gives him agency over his wellbeing.’ In terms of offspring production, his design was less successful. ‘Eventually Harry and Layla were very affectionate, but unfortunately no young crocodiles were born.’ →

After studying Landscape Architecture at the Academy of Architecture, Thijs de Zeeuw designed several animal enclosures at Artis Amsterdam Royal Zoo. In his Kromhout lecture, he talked about this fascinating challenge involving numerous ethical questions.

Text DAVID KEUNING Photo GREG JENNIE

One assignment led to another, and De Zeeuw subsequently designed an aviary for snowy owls and cranes, an enclosure for prairie dogs and, together with Anna Fink, a habitat for oryx, which are extinct in the natural environment. Gradually, however, he began to have reservations. Already during the design of the elephant enclosure, De Zeeuw had second thoughts about locking up animals. Today, the elephants are doing better than they did in their previous enclosure, but still it’s a system that takes away freedom from animals. De Zeeuw started to speculate about other futures for the zoo. He received 5,000 euros from the Creative Industries Fund NL and organized a symposium at Sexyland. Inside the venue, an auditorium was built in the shape of a monkey enclosure for humans, with wooden rafters, car tires, bananas and nuts. The main questions at the symposium were: Can we design a zoo for the future? What should that zoo be about? What is nature? Can the zoo serve as an urban model? Would it be possible to design a city more like a zoo?

Together with Ira Koers, Bart de Hartog and David Habets, De Zeeuw built an impressive model, loosely based on the Swiss city of Zurich. ‘In the model we opened 10 per cent of the streets of Zurich to animals such as elephants and giraffes,’ said De Zeeuw. ‘The zoo has a lot of colonial associations. It’s a very Western concept to lock up wild animals and put them in a position where they can always be seen.’ The model gave rise to many subsequent questions: What is wildness? How wild are humans? Many zoos have a vulture. Can humans organize sky burials, where the body of a deceased person is given to the vultures? What place does sex have in a zoo? Shouldn’t every animal have a free choice of partner? De Zeeuw calls this project ‘an ongoing speculative laboratory. For me, this project is essential to keep working on zoos’.

Discussing the last project, De Zeeuw went one step further. The idea that nature has rights has become increasingly common in the last few years. But how do you know what nature wants? How do you give a voice to the non-human, or – more specifically – to an animal? Together with the Embassy of the North Sea, De Zeeuw started a project titled ‘A Voice for the Eel’. The aim of this project was to investigate to what extent it is possible to start a conversation with an eel. ‘First, I ate my last eel ever,’ said De Zeeuw, ‘which already changed my relation to it.’ He found out that eels can travel huge distances. A young, still transparent glass eel swims 6,000 km from the Sargasso Sea to the Netherlands, chooses a ditch to grow up in and then swims back to the Sargasso Sea. They only reproduce once, so they can’t be bred. Knowing there are eels in the water of the IJ, behind architecture centre Arcam, De Zeeuw went diving there and tried to make sound recordings of eels that were swimming around. It turned out that it’s very noisy under water, because sounds travel much faster in water than in air. Based on the data, he made a design for an underwater eel park, consisting of, among other things, cubical housing elements that he placed in the water.

Earlier in the process, he’d made a model of his design, in a basin with real water in it. After a week, there was a layer of algae floating on the water surface. ‘I had to come to terms with the fact that my model, which represented the living environment, actually became a living environment itself,’ said De Zeeuw. ‘I was tempted to kill the algae, but didn’t. Eventually, a tiny larva of a small black fly inhabited the water in my model. It was quite ugly, but also the perfect 1:100 scale eel. That larva became my hero.’ ←

zooofthefuture.com

T KNOW EVERY’THING

So the climate crisis will become a major issue in education?

WE DON

MARKUS ‘Can we exchange the word crisis for something else please? Portraying it as a perpetual emergency has the opposite effect. It’s like a fire alarm: if it’s gone off 20 times, no-one responds to it anymore. This alarmism is getting us nowhere. We need to accept that this is our new reality and work towards operating in it as spatial designers.’

JANNA ‘All of the projects that students are working on are situated in the transition, and each time in a different way. As designers we have the possibility to positively contribute to the transition, but it’s also important that we take this as our starting point.’

JOOST ‘The current generation of students grew up with the fact that they are in this crisis. They get a bit tired of people showing them pictures of floods or fires, it doesn’t trigger anything anymore. But they are very enthusiastic and positive to bring this change about. So it’s the context in which we operate, and we make them aware of that, even if they’re designing a chair.’

Do they need that?

JO ‘I think that differs per discipline. In landscape architecture it’s part of the profession to relate yourself to everything around you.’

JA ‘I think the differences are more on an individual level. Everyone’s an expert, developing their own unique path.’

MA ‘As spatial designers we work on a better future. Designing dystopia is not something you can sensibly do. Students get fed everyday with news stories of crises. On the one hand they’re afraid, and on the other hand paralysed. Cynicism can emerge from that, the feeling that nothing matters anyway. We want to overcome this and get them back to the belief that they can work on a better future. It’s not too late, and doing nothing certainly is not the better option.’

JO ‘I also try to make them aware that it’s always in collaboration. We need to step away from the idea that one designer can fix everything – a God-like person that draws the future. We’re all operating in a system together and need to collaborate on all levels, not just our disciplines but all kinds of expertise.’

JA ‘There is an absolute richness in students working together on projects within their discipline, but we’re also very much aware that the engagement with other disciplines and other forms of knowledge is necessary. We’re coming from a period where the role of the designer had more focus on the creative process, materiality and form. Now the questions are: How do you engage with growing volumes of knowledge? How do you build on the knowledge from other fields? As a design profession, we relate to and build on this knowledge from other fields, but it requires other skills in communication, exchange of information, hosting interviews and conversation, writing and being able to work in the context of and with other forms of knowledge as well.’

Is this interdisciplinary approach new?

JO ‘I was just reading the applications for next year and 75 per cent of them mention the interdisciplinary approach as one of the reasons they want to study in Amsterdam. You don’t master the other disciplines, but you know your position and role and you are aware of the field that you’re operating in.’

JA ‘And of the strength of the other fields and collaborations.’ Markus: ‘A long time ago one person did everything. Constructing buildings came out of craftsmanship. In the twentieth century everything got specialized. As an urbanist you used to design the whole city, including the infrastructure. Now everything is situated in ‘silos’ – separated fields of expertise, with project managers connecting everything. Luckily, in the Netherlands it’s relatively better than in other parts of the world. But things are getting more complex by the day. With all the global and local agendas, like climate change, you don’t come to satisfying conclusions or solutions with this specialist approach. Often, a lack of knowledge is not the problem. It’s the interface between the people in these silos – and with many others – that needs attention. This is where we need to engage.’ →

The three heads of the Master’s programmes at the Amsterdam Academy of Architecture meet in Rotterdam, to discuss the new climate curriculum over a coffee in the café of Het Nieuwe Instituut.

Janna Bystrykh (Architecture), Markus Appenzeller (Urbanism) and Joost Emmerik (Landscape Architecture) talk about chaos, bad ideas and the need for a hook to hang your towel on.

Text TARA LEWIS Photos MARJOLEIN ROELEVELD

That’s also a skill.

JA ‘Absolutely, a skill of reading, writing and communicating. Hosting and moderating conversations. Within our professions drawing is often our main way of communicating among the three disciplines and related fields. But we’re coming into an age where we need to rely on conversations and input from other disciplines. We’re entering a world where other species and forms of knowledge are also taken into account in designing, which requires a different understanding.’

JO ‘I like this metaphor of professional expertise being situated in different silos, which were created to make everything more efficient. That brought us great wealth at the cost of others. We try to tell our students that this focus on efficiency got us in the current situation, so we need other values.’

How do you implement this in the curriculum?

JA ‘The role of education is very important. In the past architecture studio briefs that were shared with students were written in an abstract way: to design a school, or a complex building, focusing on the object. Today much of what we discuss is how do we make sure that we provide enough context to the design question we are posing. If a building typology is suggested at all, the question is how it fits into that context.’

JO ‘One recent graduation project is a good example of this. After doing extensive research, the student decided that not designing anything was the answer. But he wasn’t allowed to graduate without a design. Our system clashed with what we believe in.’

JA ‘In some ways we still have a lot of catching up to do, and our students have an important role in that as well, to show us where bridges are missing and provide us with homework. It’s an exciting process.’

JO ‘The three of us also work that way: deciding together on what’s important, taking into account what students come up with. In my field, for example, plant knowledge was completely eradicated from the curriculum. But students tell me all the time: we want to learn about that. So we include that. And if there are any other pressing matters five years from now, we’ll change it again. We’re under no illusions of knowing everything.’

JA ‘That’s a very good example. They’re not being educated to be botanists or ecologists, but they’re learning the vocabulary of the discipline in order to be able have meaningful conversations with those experts. And that is an important shift in design education.’

Why is vocabulary important?

MA ‘The vocabulary of all the disciplines has grown smaller over time. Fifty years ago urbanists knew everything about sewage systems, now they know what a sewer is. Our work is to thicken the dictionary of each discipline again. Not just with professional knowledge from within the field, but also with terminology from sociology, economy and environmental studies and many other fields. If you don’t know what term to search for, you won’t find anything. I had a teacher in secondary school who taught me: you don’t have to know everything. But it’s like a towel, you need a hook to hang your towel on. If you don’t have that hook the towel cannot hang on the wall. Without a basic understanding of key terminology, a whole field of expertise becomes non-existent to you.’

Does this also require certain skills from students?

MA ‘The idea is that there’s not one solution. The problems are big and complex and the important thing is the critical path you take and the strategy you choose. That requires openness, sensitivity and curiosity. And also the analytical ability to dissect a problem into subproblems you can understand.’

JO ‘In most of students’ work assignments it actually works in the classical way. They get a very clear goal to work towards. Therefore it’s extra important that at the Academy we create the freedom to look at assignments differently.’

JA ‘The scale of the school allows us to be flexible and have personal conversations with the tutors and have a close connection to the students. So that helps.’

Do students enjoy this new way of educating? Flexible, comprehensive, no clear paths from A to B. I imagine that some students just want to become architects and learn how to design buildings.

JA ‘That’s an important question. When we have interviews with incoming students this is part of the conversation: be aware that this is how we work. It’s a climate-focused curriculum, which means that it might include addressing certain topics, collaborations or forms of knowledge that you wouldn’t necessarily expect in an architectural curriculum, but which hopefully will become common practice in the future. At the same time, it’s important that the students also question us and are critical of what we’re doing.’

MA ‘But let’s face it, we also have students that come in with a rather traditional definition of what the profession is. It’s interesting to see how they develop within that context. I sometimes find the transition they go through in four years unbelievable. With others, less so. That’s also part of education.’

So there’s still space for the one-dimensional student?

MA ‘No, there isn’t.’

JA ‘The transition is here. We all need to contribute to it. From the architectural perspective, there’s a lot of room for discussion about and active exploration of the architect of today and tomorrow. That doesn’t mean that there’s no room for students and professionals who want to focus on designing and building. On the contrary, there are some very important questions to be answered from an architectural perspective. How should we build? With what materials? Under which circumstances? And what does that mean globally?’

JO ‘When we started our studies, it was very clear what you had to become. Today, that’s less clear. Some students really relate to this interconnectedness and the interdisciplinary approach, while for others it’s just: “I want to do landscape architecture.” It’s already valuable that they learn a bit about other professions and maybe later in their careers make use of that. There’s a nice quote by artist and gardener Ian Hamilton Finlay: “There are many levels of understanding and none is to be despised.” When I studied architecture in Delft, it felt like the course very much catered to the 1 per cent who were going to be Rem Koolhaas or Le Corbusier. Everybody else was considered of lesser importance. That was horrible because I was not an exceptional student and it felt like there was probably no place for me in this world.’

MA ‘That’s why you became a landscape architect.’

Joost laughs and continues: ‘With the transition we’re in we need a wide range of perspectives. It’s all hands on deck and I’m happy with every landscape architect that we can get out there.’

Will they be able to bring about the necessary change?

MA ‘There’s a very long road ahead. For now I see a lot of business as usual, and a lot of good work in the periphery. But the system is hard to change.

JA ‘And that’s why I think it’s important that not only design but also writing, speculative thinking, public engagement and other forms are all part of design education. Even within our profession, the needed change is not defined by the discipline, but across the many political levels and professional fields that shape it. It’s a conversation that needs to develop gradually and collectively across fields, and designers are in a good position to have an important role and support that transition in different ways.’

JO ‘That’s also why we ask people from other fields of expertise as guest lectures. If you only have designers, you limit the discussion. If you want to define our current profession, you need to have a conversation about society and culture as well. Maybe it sounds ambitious, but change requires a certain chaos. Perhaps in five years we’ll think: bringing in the anthropologist was a very bad idea.’

JA ‘We won’t.’

MA ‘That’s why we encourage students to take risks. To experiment. The history of mankind is a history of successfully failing.’ ←

LET’S START

On Thursday morning 25 August, more than 70 firstyear students drew each other’s portraits, in a kind of ‘panic design approach’, in rows of two. Participants each had 30 seconds per portrait and then moved on. Education manager Henri Snel argued that offering both physical and cognitive activities simultaneously is a good combination to promote learning. ‘Research has shown that people who read a book while cycling on an exercise bike remember what they have read better than people who read a book while sitting on a sofa,’ he said. ‘So that also means you observe better if you draw while being physically active.’ The next assignment was to draw two things you’d put in your suitcase if you were emigrating. ‘That’s a great starting point for a conversation,’ Snel said.

In the afternoon the students, guided by artists, carried out sensory assignments at various locations around the city. First up was a homemade lunch (sense of taste). Students had put them together beforehand and brought them to the academy to give to another student they didn’t yet know, the idea being that ‘you give something away from your own cultural background and you also get something back’, a special way to get to know each other and start a conversation. After lunch, there were assignments at four other locations.

Led by alumni Jacopo Grilli and Laurens van Zuidam, a new group of students started their studies at the Amsterdam Academy of Architecture.

Text DAVID KEUNING Photo MARLISE STEEMAN

‘There was a lot of interaction between students,’ said Grilli. In Bethaniënstraat, they created a performance: passers-by could cycle or walk between a double row of students, who gave them a huge round of applause. In the Zuiderkerk, the students depicted what they believed, using their bodies rather than sounds. This was quite touching. To experience sight deprivation, they walked through the city in a long line with face masks in front of their eyes, holding hands. Grilli: ‘The students were thrilled. One student said: “I did expect something weird. But this was really, really weird.” Mission accomplished.’

Friday started relaxed, with a yoga session on the helicopter pad of the Marineterrein, near the MakerSpace. This was followed by three lectures by the heads of the Academy’s three Master’s programmes: Janna Bystrykh (Architecture) at the MakerSpace; Markus Appenzeller (Urbanism) and Joost Emmerik (Landscape Architecture) at the Academy. The afternoon programme took place in the courtyard, where participants executed three performances at the end of the day, in three groups of over 20 students each. They had two and a half hours to prepare their performances. During the conclusion, with food and drinks, the freshmen had the opportunity to get to know the one or two students they hadn’t talked to during the previous two days. ←

ABOVE AND BELOW

Artist-in-residence Mari Bastashevski looks back on the Winter School 2023.

Text MARI BASTASHEVSKI Photos GREG JENNIE

Text MARI BASTASHEVSKI Photos GREG JENNIE