February 3 - June 28, 2025

February 3 - June 28, 2025

The Negro Negro: An Interpretation turns 100 years old this year. This anniversary presented an unique opportunity to utilize our museum gallery at the African American Research Library and Cultural Center to showcase a gem within our archival collection.

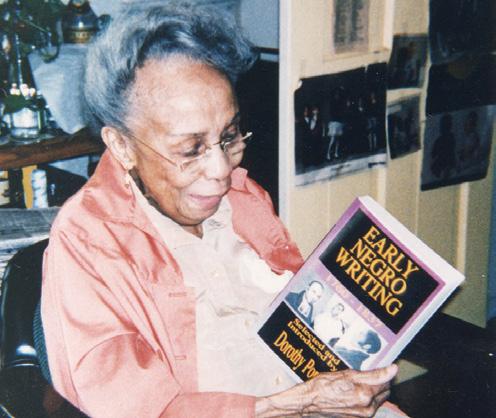

Dorothy Porter Wesley was one of the most important Black bibliophiles of the 20th century. For over 40 years as a librarian and collector, she organized the collection at the world-renowned Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University. After Wesley’s death AARLCC acquired her phenomenal personal library, with some 3,400 items including books, ephemera, and postcards. A small sampling of that material is included in this exhibition.

Reveal the Beauty: The Literature and Art of the Harlem Renaissance leverages Wesley’s collection, along with material from The Wolfsonian at Florida International University to offer a reflection on the writers, thinkers, and artists who fueled the cultural movement that we know so well. We have the additional benefit of including period art from the collection of Chris Norwood, founder of Hampton Art Lovers, who co-curated this exhibition along with Dr. Shawn Christian, chair of the Department of English for Florida International University. Together, Chris and Shawn combed the Wesley Collection to craft an exhibition that celebrates artists, poets, scholars, and writers, who helped make the Harlem Renaissance possible as well as one of the librarians who helped preserve its legacy.

AARLCC is proud to present Reveal The Beauty as a demonstration of our commitment to collect, preserve, and interpret the Black experience for our visitors.

Sincerely,

Dr. Tameka Hobbs Regional Manager, AARLCC

Featuring

Works

from

the Dorothy Porter

Inspired by Howard University philosopher Alain Locke’s essay, “The Legacy of Ancestral Arts,” in his landmark volume The New Negro: An Interpretation (1925), this exhibition celebrates the role of African American artistic expression from the 1920s to the 1940s in shaping the Harlem Renaissance. Often referred to as the cultural arts period of the New Negro movement, these dynamic years redefined Black identity and challenged stereotypes through a probing array of literature and visual arts. While closely associated with Harlem, its influence reached Black communities across the U.S., South Florida, and worldwide.

Art must discover and reveal the beauty which prejudice and caricature have overlaid. All vital art discovers beauty and opens our eyes to beauty that previously we could not see.”

– Alain Leroy Locke, “The Legacy of the Ancestral Arts,” in The New Negro: An Interpretation (1925)

Aaron Douglas, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and James Weldon Johnson, whose works captured themes of resilience and cultural pride, but also the lesser-known artists and activists who collectively shaped this vibrant cultural landscape. Platforms such as Survey Graphic, Negro History Bulletin, and The Crisis played crucial roles in disseminating their creations and fostering a new self-image rooted in authenticity and racial pride.

The Harlem Renaissance was a defining moment in American history, perhaps the nation’s greatest cultural movement. This art movement’s driving force was literature and the ability of Black writers to speak their minds and stories in their own voices. Yet, the importance of visual art during this period can’t be overstated. Alain Locke, the great philosopher and “Dean of the Harlem Renaissance,” believed that creative expression was a form of liberation and could help Black people develop their ethos. He thought that art could lead the way to a cultural and social revolution in America. In his words, “Art must discover and reveal the beauty which prejudice and caricature have overlaid.”

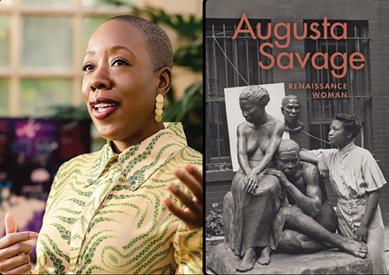

Reveal the Beauty emphasizes not only renowned artists and writers like Loïs Mailou Jones, Augusta Savage,

Highlighting the significant contributions of Dorothy Porter Wesley, an influential librarian and scholar, this exhibition honors her efforts to preserve and promote African American literature and culture during this period and after. Her collection, acquired by Broward County’s African American Research Library and Cultural Center from Wesley’s daughter, Constance Porter Uzelac, is a vital repository of 19th- and 20th-century Black authors that enriches our understanding of this impactful movement. Works from this collection are featured throughout the exhibition.

In a moment of reflection on its legacy, Reveal the Beauty invites visitors to explore the rich tapestry of the Harlem Renaissance, celebrating 100 years of artistic expression that continues to resonate today. The exhibition honors this transformative period’s creativity, resilience, and enduring spirit as we pay tribute to its lasting influence on African American and American culture.

Dorothy Porter Wesley played a transformative role in documenting and preserving Black history during her forty-three-year career at Howard University. As a key figure behind the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, she dedicated her efforts to amplifying often overlooked and marginalized voices and narratives.

In a 1995 interview, Porter stressed the importance of moving beyond the familiar: “What’s the point of rehashing the same old thing?” This commitment guided her innovative cataloging and preservation methods, fostering inclusivity in library science and ensuring that underrepresented stories gained the recognition they deserved.

Porter’s extensive network enabled her to acquire significant collections, including those of Jesse E. Moorland and Arthur B. Spingarn, expanding the library’s holdings to over 180,000 items by her retirement in 1973. Rejecting conventional categorization, she developed a system that classified materials by genre and author, aligning with the ideals of the Harlem Renaissance, which aimed to elevate Black identity through art and scholarship.

Porter laid the groundwork for Black Studies through her bibliographies and scholarship, celebrating the richness of African American contributions. Her enduring legacy inspires contemporary efforts to decolonize knowledge and recover the diverse histories of the African diaspora. The Dorothy Porter Wesley collection here at the African American Research Library and Cultural Center offers access to nearly 3,400 titles, including rare books and autographed works—several of which are on display as part of Reveal the Beauty, showcasing her impactful work in this crucial field.

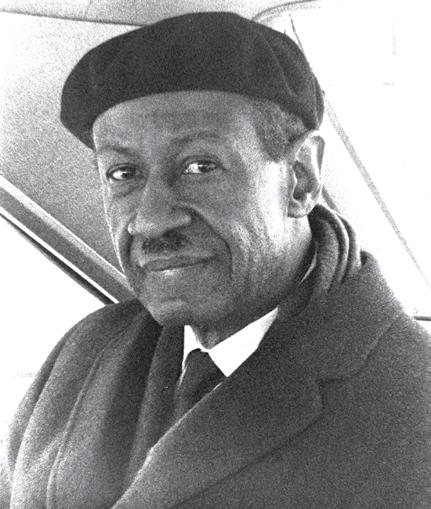

James A. Porter, a pioneering figure, was the first African American art historian and a multifaceted talent—artist, educator, mentor, and curator. His seminal 1943 publication, Modern Negro Art, represents the earliest comprehensive analysis of African American contributions to art and culture in the United States.

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, Porter graduated cum laude from Howard University in 1927. Early in his career, he joined Howard’s faculty as an art instructor, eventually becoming chair of the art department. His academic journey included graduate studies at Columbia University and the Art Students League in New York, and a fellowship at the Sorbonne in Paris, where he focused on archaeology.

Porter’s artistic output was significant; he excelled in portraiture and figure studies, capturing the essence of his subjects with sensitivity and realism. His travels inspired a shift in his work, leading him to depict cultural scenes showcasing the lives and heritage of people of African descent, particularly in Haiti and Cuba.

In 1929, Porter married Dorothy Louise Burnett, a librarian who became an invaluable partner in his scholarship, providing critical bibliographic support for his research. Together, they had one child, Constance Porter Uzelac, who became a scholar of African American history.

In 1953, Porter succeeded Professor James V. Herring as chairman of Howard University’s art department and director of its gallery. Throughout his tenure, he nurtured a generation of artists and scholars, cementing his reputation as a dedicated educator and mentor.

Through his writings and artistic endeavors, Porter laid the foundational framework for studying and appreciating African American art, leaving an indelible mark on the cultural landscape.

The Harlem Renaissance was a dynamic movement that showcased African American culture, art, and intellectual thought, aiming to reshape America’s view of its Black citizens. Its writers and artists strove to go beyond stereotypes and emphasize the valuable contributions of African Americans to literature and art. Anthologies played a crucial role in this cultural transformation by demonstrating the artistry in the works of writers, painters, and musicians while amplifying their voices to broader audiences. These volumes documented and preserved African American culture and connected past achievements with contemporary expressions.

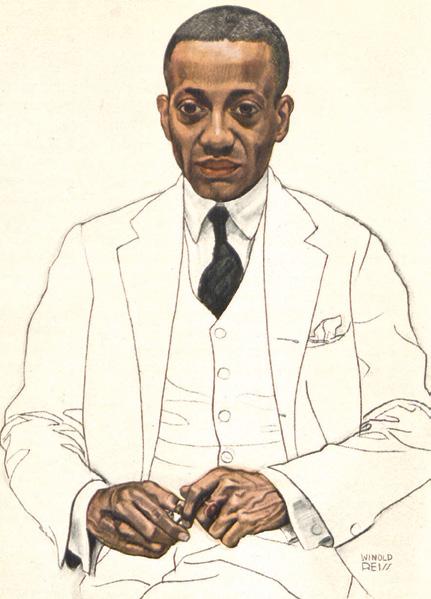

The publication in 1925 of The New Negro: An Interpretation, an illustrated collection of writings by poets, novelists, scholars, and others, was a watershed moment in African American intellectual life. Acclaimed by both Black and white readers, it connected cultural shifts to the massive social transformation of the Great Migration, in which millions of Black people moved from the South to the North seeking jobs and a more tolerant racial atmosphere. Editor Alain Locke asserted that “the Negro mind has leaped, so to speak, upon the parapets of prejudice and extended its cramped horizons.” The new manners and ways of life described in The New Negro were captured in paintings, prints, sculpture, photography, theater, and literary works from the 1920s onward.

The Harlem Renaissance is unusual among literary and artistic movements for its close relationship to civil rights and reform organizations. Crucial to the movement were magazines such as The Crisis, published by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); Opportunity, published by the National Urban League; Negro History Bulletin, published by the Association for the Study of African American Life and History; Messenger, a socialist journal eventually connected with the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, a Black labor union. Negro World, the newspaper of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association, also played a role.

Alain Locke’s comprehensive anthology, The New Negro: An Interpretation (1925), was central to the Harlem Renaissance. This collection of essays, poetry, and artwork illustrates the emergent spirit of African American identity, as Locke characterizes the “New Negro” as self-reliant, educated, and actively engaged in social change. Notable contributors like Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Claude McKay marked the diversity and richness of African American thought.

Locke’s editorial contributions extended to significant works like Negro and His Music (1936) and Negro Art: Past and Present (1940). The former chronicles the evolution of African American music by emphasizing its role as both an art form and a vehicle for cultural expression and social commentary. The latter analyzes the history of African American art and argues for its legitimacy within the broader narrative of American art history.

Poet and editor Sterling Brown also played a critical role in the Renaissance with volumes such as Negro Poetry and Drama, which examined the evolution and significance of African American poetry and theater. Additionally, historian Carter G. Woodson’s pioneering work, Negro in Our History (1921), sought to popularize African American history and correct biases in education. It helped further the recognition of African Americans’ contributions to U.S. history.

Together, these anthologies articulated and documented African American experiences during the Harlem Renaissance and offered models for future generations of artists and thinkers.

The Harlem Renaissance marked a pivotal moment in American literature, characterized by poetic expression that explored themes of universal human experience, cultural heritage, and resilience in the face of adversity. Reveal the Beauty highlights four influential texts—God’s Trombones (1927) by James Weldon Johnson, The Weary Blues (1926) by Langston Hughes, Copper Sun (1927) by Countee Cullen, and Gladiola Garden (1940) by Effie L. Newsome—alongside striking illustrations by artists Aaron Douglas, Miguel Covarrubias, Charles Cullen, and Loïs Mailou Jones.

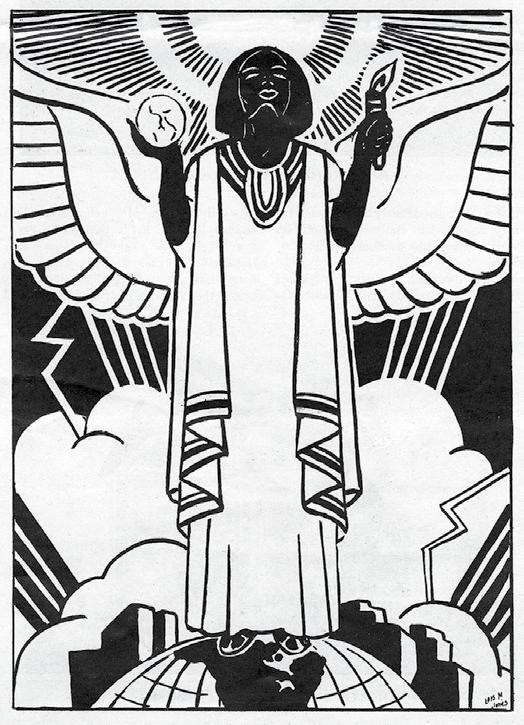

God’s Trombones, a celebration of African American spiritual life, transforms vibrant sermons into uplifting poetry. James Weldon Johnson’s resonant verses pay homage to African American preachers’ emotional depth and resilience, while Aaron Douglas’s evocative illustrations, featuring bold silhouettes and geometric shapes, visually amplify the spiritual themes explored in the text. Together, they create a dynamic interplay that honors the cultural legacy of African Americans, making the collection a hallmark of Harlem Renaissance literature.

In The Weary Blues, Langston Hughes ingeniously weaves jazz and blues rhythms into verse, creating a lyrical homage to the African American experience. His iconic poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” embodies themes of migration and roots, while Miguel Covarrubias’s cover illustration echoes the musical essence of the collection. Covarrubias’s artwork captures the spirit of Hughes’s exploration of pain and joy, symbolizing a universal human experience that resonates beyond race.

Copper Sun finds Countee Cullen reflecting on the forces that challenge African American identity and heritage. His poetry and Charles Cullen’s (no relation) illustrations evoke a longing for the lost beauty of Africa while grappling with the painful realities of life in America. Cullen’s romanticized depictions of Africa contrast sharply with the harsh truths of exile and alienation. Through his poignant verse, Cullen portrays the struggles of a people yearning for belonging, capturing the essence of the Harlem Renaissance’s quest for identity and representation. Gladiola Garden introduces readers to the wonders of nature through over 160 accessible poems, portraying the lives of animals and plants. Poet Effie L. Newsome’s scenes appeal to children and adults. Loïs Mailou Jones’s illustrations vividly capture childhood innocence, portraying African American children in nature and enriching Newsome’s poetic imagery with cultural depth. A vital introduction to children’s literature, Gladiola Garden offers comfort and assurance amidst the complexities of life.

Reveal the Beauty honors the poets of the Harlem Renaissance and their collaborations with visual artists, whose legacies complement one another. The written word and visual art interplay exemplifies the period’s creative diversity. It illustrates the power of cultural identity and artistic expression

The Harlem Renaissance was a pivotal moment for poetry and a transformative period for fiction and non-fictional narratives that explored the rich tapestry of African American life. Reveal the Beauty highlights six key works—Flight (1926) by Walter White, African Myths (1928) by Carter G. Woodson, Black Magic (1929) by Paul Morand, The Black Venus (1929) by André Salmon, and Mules and Men (1935) and Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937) by Zora Neale Hurston—alongside the powerful illustrations by artists such as Aaron Douglas and Miguel Covarrubias.

Flight tells the story of Mimi Daquin, a young Creole woman navigating her identity in the context of racial passing. White’s novel pioneeringly features a Chinese character, Wu HsehChuan, to challenge conventional narratives of race, ultimately leading Mimi to embrace her African American heritage. This complex narrative highlights the struggles and resilience of black life while critiquing societal norms around race.

In Black Magic, illustrated by Aaron Douglas, themes of exoticism and mystique are explored through the lives of Black characters, reflecting broader societal preconceptions while inviting deeper engagement with their realities. Douglas, in high demand as a book illustrator by the late 1920s, contributed his artistry to African American writers and works outside the Harlem Renaissance context. His 1929 illustrations for Paul Morand’s Black Magic and André Salmon’s Black Venus accompany narratives that intriguingly labeled Black people as objects of exotic sexuality and enigmatic rituals, often sidelining their psychological complexity as modern citizens.

African Myths gathers folktales that preserve Africa’s rich cultural heritage. It aims to educate children through narratives sharing people’s wisdom and history. The prose is accompanied by illustrations that bridge the past with contemporary understanding, providing insights into African traditions and philosophies.

The Black Venus explores race and identity within the framework of French literature, as Salmon portrayed it. Douglas’s artwork captures the allure and complexity of Black femininity in a narrative that intertwines with perceptions of beauty and otherness. This juxtaposition between visuals and text raises questions about representation and the exploitation of Black identity in art.

Zora Neale Hurston’s Mules and Men reflects her role as a folklorist and storyteller, capturing the essence of African American vernacular and life in Eatonville, Florida. Her intricate detailing of Black culture, rituals, and ways of thinking challenges prevailing notions of African American identity. Covarrubias’s illustrations complement Hurston’s vivid storytelling and help bring to life the spirited traditions of her all-Black community.

Hurston’s acclaimed novel Their Eyes Were Watching God is a poignant exploration of self-discovery and the dynamics of race and gender. The protagonist, Janie Crawford, embarks on a journey toward autonomy and love set against the backdrop of the South. The novel reflects several themes in Harlem Renaissance literature, including empowerment, resilience, and the search for identity.

As important genres of artistic expression, Harlem Renaissance poetry and fiction provided essential insights into African Americans’ joys and cultural identity and how they navigated modern challenges like class disparity and racism. The synergy between writers and artists during the Harlem Renaissance showcases a lively interaction of word and image, deepening our understanding of this vibrant historical period and the ongoing artistic influence it generates.

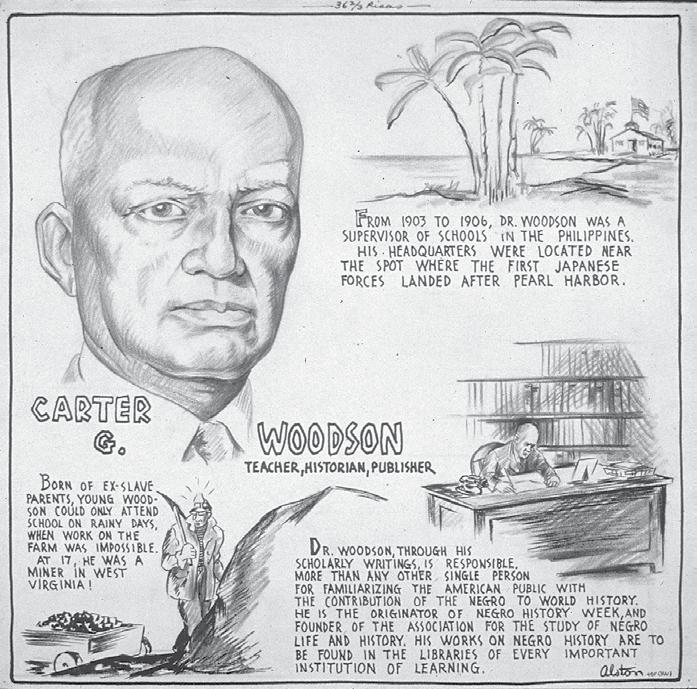

The Negro History Bulletin, founded in October 1937 by Dr. Carter G. Woodson, stands as a vital institution for African American history and art within the context of the Harlem Renaissance. Woodson, often heralded as the “Father of Black History,” addressed the lack of truthful information on the Black past by establishing the Association for the Study of Negro History (established in 1915), The Journal of Negro History (established in 1916), and Associated Publishers (established in 1920).

Woodson created the Bulletin during a period when educational resources for African American students were severely lacking due to systemic racism and segregation. With a mission to celebrate and illuminate African American contributions, the Bulletin addressed the need to counter the oftennegative portrayals of Black history.

Focused primarily on educational content, the

Carter G. Woodson – Teacher, Historian, Publisher” (1943). Charles Henry Alston (1907-1977). Office for Emergency Management. Office of War Information. Domestic Operations Branch. News Bureau. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Negro History Bulletin provided a wealth of resources for teachers and students. Its inaugural issue featured engaging articles like “The Thrilling Escape of William and Ellen Craft,” enriched with illustrations highlighting important historical narratives that affirmed resilience and ingenuity in the African American community. Each edition served as an informative tool, helping children and educators see themselves in the historical narratives, thus fostering a sense of pride and identity.

The Bulletin was notable not only for its written content but also for its illustrations. Renowned African American artists, including the prolific Loïs Mailou Jones, contributed illustrations and creative exercises that encouraged artistic expression among students. Jones introduced the “Children’s Page” in the November 1940 issue. On this activity page, schoolchildren were encouraged to color an illustration or design she had drawn or to engage in a constructive art-making project to teach Black history creatively. This integration of art and education reinforced the Bulletin’s educational objectives while celebrating Black artistry.

Under Woodson’s direction, the Bulletin aimed to dismantle the prevailing narratives that marginalized African American contributions. Centering Black voices and perspectives empowered young African Americans to view their history through the lenses of their families and communities.

Additionally, the Negro History Bulletin demonstrated the communal spirit of Harlem Renaissance print culture, which was characterized by a robust exchange of ideas and a commitment to uplifting African American narratives. The

Bulletin’s circulation grew rapidly, reflecting its importance within the African American community; by February 1938, it had increased to 25,000 copies, indicating its broad reach and significant impact.

Though distinct from other publications of the time, such as The Crisis, Opportunity Magazine, and the Messenger, The Negro History Bulletin shared a commitment to promoting African American culture and history. Each publication, however, had its unique focus and editorial style. The Crisis, edited by W.E.B. Du Bois, featured a blend of literature, art, and social commentary, advocating for civil rights. Opportunity Magazine, published by the National Urban League and initially edited by Charles Johnson, emphasized economic empowerment and professional development for African Americans. At the same time, Messenger, founded by A. Philip Randolph, focused more explicitly on labor rights and socialist perspectives.

The Negro History Bulletin was not just a publication; it was a vital educational resource that empowered African Americans through history and art and influenced the cultural landscape of the Harlem Renaissance. Its enduring legacy continues as it has evolved into the Black History Bulletin, still published by the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. It maintains its mission to feature and elevate African American perspectives and lives. As an essential feature of Harlem Renaissance print culture, it inspired generations to embrace their history and identity. The Negro History Bulletin was a tangible and sharable resource for reflection, celebration, and education for African Americans and readers of all backgrounds.

Dr. Shawn Anthony Christian is Associate Professor and Chairperson of the Department of English at Florida International University. He is also an affiliate faculty member in FIU’s African and African Diaspora and Women’s and Gender Studies programs. Dr. Christian specializes in twentieth-century African American literary and print culture and is the author of The Harlem Renaissance and the Idea of a New Negro Reader (Massachusetts, 2016). He has published articles in related journals, including American Periodicals, Ethnic Studies Review, and Legacy: A Journal of American Women Writers. He also has contributed chapters to the volumes Reading African American Experiences in the Obama Era, The Harlem Renaissance Revisited, Editing the Harlem Renaissance, and African American Literature in Transition: 1930–1940. He served as curatorial consultant for Silhouettes: Image and Word in the Harlem Renaissance, which exhibited at The Wolfsonian-FIU and co-curated the Google Arts and Culture webpage “The Harlem Renaissance: Origins, Influences, and Currents.” Dr. Christian is also a former actor and occasional director, having performed in a production of James Baldwin’s The Amen Corner and co-directed a production of Ntozake Shange’s for colored girls who have considered suicide when the rainbow is enuf. Dr. Christian grew up in Miami and received his education in Dade County Public Schools.

Christopher Norwood, J.D., serves on the editorial board of The International Review of African American Art and is the Principal of Norwood Consulting. With 25 years of experience spanning consulting, board leadership, employment, and volunteerism in human services, Mr. Norwood has cultivated an extensive network and a strong commitment to community engagement. A proud alumnus of Hampton University in Hampton, Virginia, he earned his degree in Social Work and Community Organization in 1995. He further pursued a Master of Public Administration at Cornell University’s Institute for Public Affairs (1995–1997) and obtained his Juris Doctorate from St. Thomas University School of Law in 2002. Mr. Norwood is a passionate and strategic community organizer whose work emphasizes children’s issues and development. He is a founding board member of Florida Memorial University’s Social Work Program and a past chair of the Council on the Social Status of Black Men and Boys, an appointment he received in 2007 from then-Speaker Marco Rubio of the Florida House of Representatives. His dedication to education and governance is reflected in his roles on the Miami-Dade Public Schools Audit and Budget Committee and the City of Miami’s Education Advisory Board. As the founder of the Florida Association of Independent Public Schools and the Governance Institute for School Accountability, Mr. Norwood continues to advocate for equity and accountability in education and social services.

Established in 2002 by the Board County Board of Commissioners as a part of Broward County Libraries Division, the African American Research Library and Cultural Center (AARLCC) is a flagship library. At the time of its opening, it was only the third institution of its kind in the nation. AARLCC is firmly rooted in the community as an anchor institution providing a stabilizing and educational presence within the Sistrunk Corridor in Northwest Fort Lauderdale, Florida. The mission of AARLCC is to collect, preserve, and provide access to resources focusing on the history and culture of people of African, African American, and Caribbean descent.

CURATORIAL TEAM:

Dr. Tameka Bradley Hobbs, Regional Manager, AARLCC

Rochelle Pienn, Curator

Emily Calderon, Special Collections Librarian

Erin Purdy, Senior Archivist

Jermaine Thompson, Facilities Manager

Sabrina Alexander, Graphic Design