THE SÃO FRANCISCO RIVER BASIN COMMITTEE MAGAZINE- DECEMBER 2023

THE SÃO FRANCISCO RIVER BASIN COMMITTEE MAGAZINE- DECEMBER 2023

President: José Maciel Nunes de Oliveira

Vice President: Marcus Vinícius Polignano

Secretary: Almacks Luiz Carneiro da Silva

Produced by Communications Office

CBHSF, Tanto Expresso Comunicação e Mobilização Social

General coordination: Paulo Vilela, Pedro Vilela e Rodrigo de Angelis

Communication coordinator: Mariana Martins

Editing: Karla Monteiro

Editorial assistant: Arthur de Viveiros

Texts: Andréia Vitório, Arthur de Viveiros, Hylda Cavalcante, Karla Monteiro, Juciana Cavalcante e Mariana Martins

Graphic design: Márcio Barbalho

Layout: Albino Papa e Rafael Bergo

Photos: Agência Senado, Azael Gois, Bianca Aun, Cristiano Costa, Edson Oliveira, Fernando Piancastelli, Léo Boi, Manuela Cavadas, Marcizo Ventura e ShutterStock

Cover photo: @anandacolaa

Illustrations: Albino Papa

Review: Isis Pinto

Printing: ARW Gráfica e Editora

Print run: 3500 exemplares

FREE DISTRIBUTION

Rights Reserved. Allowed to use information provided the source is cited.

Committee Secretariat:

Rua Carijós, 166, 5º andar, Centro - Belo Horizonte - MG CEP: 30120-060 - (31) 3207-8500 secretaria@cbhsaofrancisco.org.br

Service to users of water resources in the São Francisco River Basin: 0800-031-1607

Communication Advisory: comunicacao@cbhsaofrancisco.org.br

Instagram: Instagram.com/cbhsaofrancisco

Facebook: Facebook.com/cbhsaofrancisco

On-line edition: issuu.com/cbhsaofrancisco

Vídeos: youtube.com/cbhsaofrancisco

Photos: flickr.com/cbhriosaofrancisco

Podcasts: soundclound.com/cbhsaofrancisco

It has been a challenging year, with foretold tragedies devastating landscapes and claiming lives worldwide. Perhaps 2023 will go down in history as the year when things finally became clear: global warming and its consequences in our daily lives are not in the distant future, but in the unstable present. It is no coincidence that we are all suffering from extreme heat or cold, experiencing temperatures that cause destruction everywhere.

In the report “Maximum Alert” on El Niño and the Velho Chico, you will understand what this familiar phenomenon, which periodically returns to haunt us, is all about. Growing angrier and more destructive. In response to the climate emergency, following the suggestion of CBHSF, ANA is investing in the Monitoring Room of the São Francisco River Water System. Prevention is better than cure.

Undoubtedly, many people have come to terms with reality in this year of 2023 marked by natural disasters: either we take care of the planet now or face extinction. The National Congress has just established the Parliamentary Front in Defense of the Management and Revitalization of the São Francisco River. According to engaged congressmen, if effective and comprehensive measures are not taken immediately, it will not only be the riverside populations that will pay the price, but the entire country. Without the Velho Chico, life will cease to exist in much of Brazil.

The fight continues outside the National Congress, in the Esplanade of Ministries. In the report “Onward, Margaridas,” we follow the seventh “March of the Daisies,” which, since the early 2000s, has been taking over Brasília in the name of dignity in rural work. This year, over 100,000 peasant women occupied the Federal District, demanding, among other things, the recovery of the São Francisco basin, crucial for the survival of family agriculture in the Brazilian backlands. President Lula and the first lady, Janja, were present.

In addition to discussing the weather, CHICO addresses the black struggle. In the Green Pages, quilombola Xifronese Santos tells us what it’s like to be on two battlefronts, racial and environmental. In the profile, we introduce the new commander of the Peixe Vivo Agency, economist Elba Alves, a black woman and a pioneer in water resource management. And, to end on a high note, “Itamar’s Backlands.” In this case, Itamar Vieira Jr., a Bahian author who has sold over 700,000 copies of “Torto Arado,” a book set in the Chapada Diamantina, the Velho Chico basin. “The São Francisco is life. Without it, none of this that exists here in the Brazilian interior, not even humans, would be here,” commented Xifronese. “We are very serious when we warn that the river needs help, urgent assistance. If we do not take care of it as soon as possible, not only the São Francisco, but we too will disappear.”

Happy Holidays!

Pages

By: Hylda CavalcantiXifronese Santos: the strong name resembles that of an African warrior, but even she herself does not know the origin of the curious nickname. Having been baptized like this, she ended up embodying it, carrying it with pride. At 46 years old, Xifronese, in fact, accumulates daily struggles. In the quilombola community of Caraíbas, located in the municipality of Canhoba, in Sergipe, she raised nine children working as a cook, working in the fields, and making handicrafts. However, her greatest battle lies in activism in defense of traditional peoples and the revitalization of the Velho Chico.

As a member of the São Francisco River Basin Committee (CBHSF), she does not tire. She has already managed to bring water to two indigenous communities, has proposals filed with the Committee that are under evaluation, suggests bills, and closely monitors measures adopted by municipalities and states in the region. She has been living this saga for 19 years and admits that, between victories and defeats, there is still much more to lament. “We are not issuing just any warning. The São Francisco is life. And it is important for the entire country. The situation is serious, and if degradation does not stop urgently, the Velho Chico will cease to exist,” she commented.

Xifronese is a very strong name. Is it real or a pseudonym for activism?

It is my real name. I don’t know if it’s African or what it represents. I confess that I would really like to know the origin. My father and mother were workers on a farm, and the owner suggested this name. My mother didn’t want it, but in the end, my father’s wish prevailed, as was common at that time. I won’t say that I identified with it from the beginning, but over the years, I came to identify with it, and now I know it is strong. I carry it as a name of war.

Everyone knows the warrior activist who works in defense of quilombola peoples and for the improvement of the quality of life of the population living along the São Francisco River. But what is the life of Xifronese the woman like?

I am a cook at the public school in the community, but my profession has always been handicrafts. I am still an artisan, in addition to being a farmer. I have been active in defending the quilombola people for 19 years. I got married at 15. At 46, I have been married for 32 years. We had nine children. Now the grandchildren are coming. There are already four, and we are expecting the fifth.

What is your history in activism?

Today, I represent the quilombola communities in the CBHSF. I was nominated by the National Coordination of Articulation of Rural Black Quilombola Communities (CONAQ). I am in the second year of a three-year term.

The Federal Government recently announced more resources in the 2024 Union Budget for quilombolas. In your opinion, where should this funding be prioritized?

Our main issue is the slowness of the quilombola territory demarcation processes. We need more recognition and swift demarcation of the land. I was happy, of course, to hear about these resources, and I know they will help improve life in many communities. However, unfortunately, this is not the issue that concerns us the most today. There is invisibility; the evaluation reports of quilombola areas take a long time to be completed. We defend our territory, but we know that most of these areas continue to suffer from invasions by large landowners and agribusiness at all times. It is a serious problem that involves economic power and needs to be addressed because it is our main bottleneck.

The transposition of the São Francisco River happened, but the revitalization of the river and its basins not so much. What do you see as the most serious issue in this process?

The most serious thing is the deforestation of riparian forests, the devastation of mangroves that feed the São Francisco. The way things are going, if urgent measures are not taken, we fear that the river may disappear. And this is not just a figure of speech. We suffer from drought and reduced water. The quilombola communities, for the most part, live on the riverbank but cannot use the water for drinking. Water supply is done through tanker trucks and other systems because the area has become a large cesspool. In some communities, water simply does not reach at all.

How do you assess the advancement of agribusiness in the São Francisco basin?

We have the indiscriminate use of pesticides, industrial sewage discharges, and excessive water withdrawal, mainly for agroindustrial use. All of these actions degrade a river that is national and serves the entire country. Pesticides, sewage, industrial waste, everything goes into the São Francisco. We fight, we mobilize, we work with the Committee as representatives of civil society, but this alone is not enough. We need firmer measures from municipalities, state governments, and the Federal Government.

The privatization of Eletrobras resulted in a fund of R$ 350 million for use in the revitalization and preservation of the São Francisco. How do you think these resources should be used primarily?

The question that should be asked is: how are we going to use these resources to eliminate existing bottlenecks today if we know that the entire area needs to be revitalized? The riverbanks, in particular, are in the hands of large landowners, and they are deforesting without control. We will argue that the resources should indeed be used for revitalization. But first, we need to establish control, a limit. We need to evaluate the issue of landowners who operate directly on the riverbank. What limits will they have? Will they be required to stop this work that destroys the river? Without this, we will not be able to recover anything.

The São Francisco River Basin Committee has an action plan and goals developed in collaboration with civil society. How can we effectively involve other committee members, who represent businesses and the state, in this process?

This is a significant issue because there is a general neglect from municipalities, state governments, and even federal representatives. If, like us, states and municipalities committed to the cause with dedication, we would have resolved many issues by now. In practice, public agents are either minimally active or act very slowly.

Could you provide an overview of what has been accomplished during your tenure at CBHSF for traditional communities?

We have managed to provide water to two indigenous communities and are on the verge of providing it to a third. Additionally, we have been involved in legislative projects aimed at improving the conditions of quilombolas in municipal councils and legislative assemblies and continue to highlight the delays in demarcating our territories. We are united in this struggle, which is substantial. Specifically, at CBHSF, we have presented several proposals under discussion that also aim to bring improvements to the population.

The achievements in indigenous communities and the state of Alagoas represent a collective effort from various organizations. In Sergipe, in the quilombo Resina in Brejo Grande, the quilombo Mocambo in Porto da Folha, and other traditional communities in the basin, our successes have been supported by all members of the São Francisco Committee.

What, in your view, truly captures the significance of the São Francisco River to the lives of the communities, from simple farmers to those who depend on fishing and other river-related activities? The São Francisco is life. Without it, none of this interior region of Brazil, nor even human existence here, would be possible. We are serious when we warn that the river needs urgent help. If we do not address this promptly, not only the São Francisco but we ourselves will disappear.

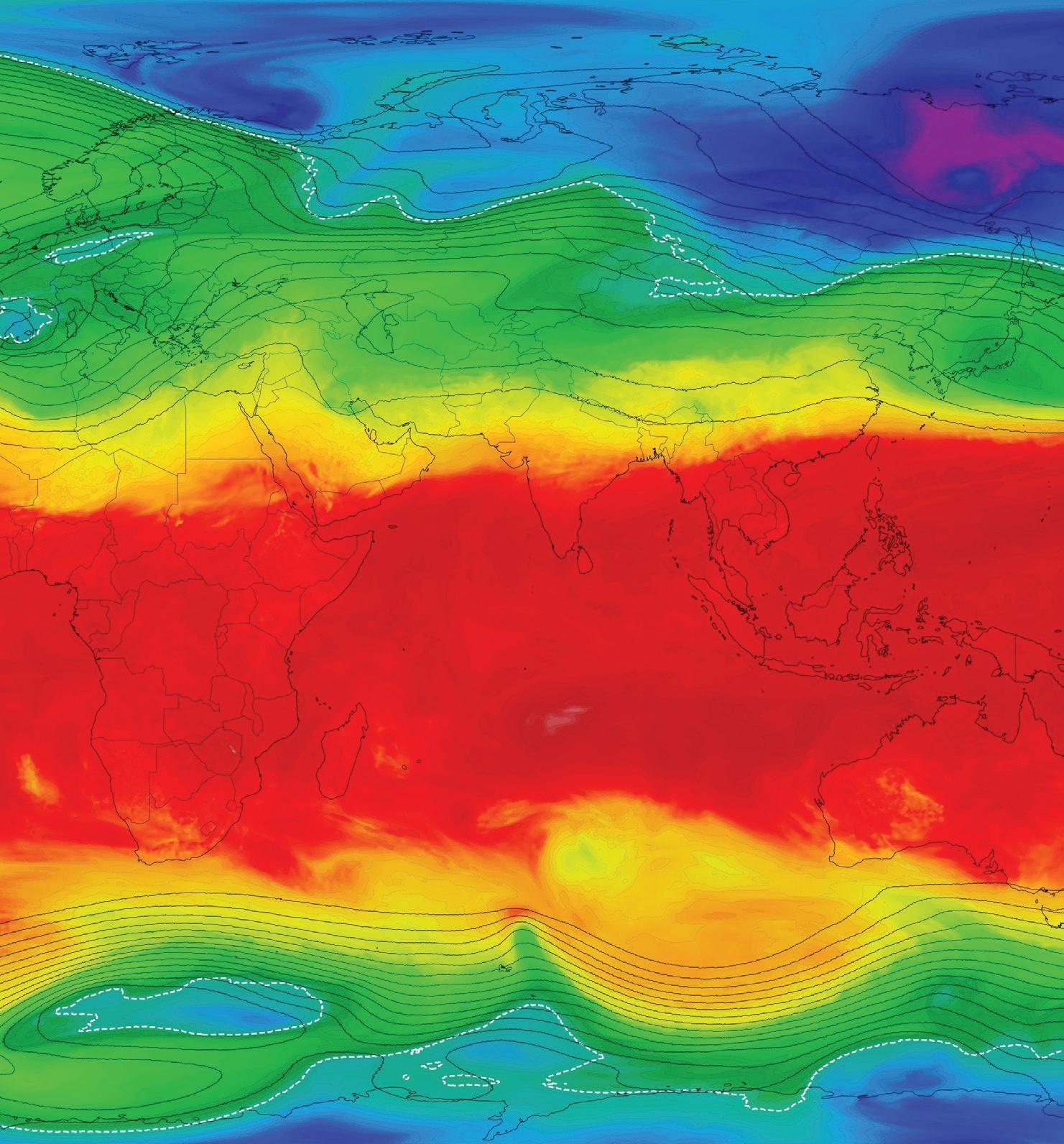

How the warming of the Pacific Ocean waters, caused by El Niño, is affecting life on the Velho Chico.

The ANA, through the São Francisco River Hydrological Monitoring Room, established in early 2022 at the suggestion of CBHSF, is closely monitoring the phenomenon.

Prolonged droughts, devastating floods: the severity of climate phenomena worldwide marked 2023. According to a joint statement from the National Institute of Meteorology (Inmet) and the National Institute for Space Research (Inpe), El Niño, which began showing signs as early as February, is to blame. Between March and April, Pacific Ocean temperatures, especially off the coasts of Ecuador and Peru, rose significantly. By June, conditions indicated the definitive establishment of El Niño. The sea temperature near the South American coast increased by over 3°C. Forecasts indicate a strong probability, over 90%, that the phenomenon will persist at least until March 2024. “The forecast indicates

By: Arthur de Viveiros Bianca Aun

that rainfall will be spatially irregular in the Central-West and Southeast regions. Meanwhile, in the central-northern part of the country, we should expect less rain than the historical average for the period. El Niño keeps temperatures above normal in much of Brazil, and the period under its influence promises to be hot, especially in the interior of the North and Northeast regions,” explained Danielle Ferreira, meteorologist and technical advisor at the National Institute of Meteorology (INMET).

Photos:

Obviously, the Velho Chico is also bearing the brunt of extreme weather. Whether in the Upper, Middle, or Lower São Francisco, climate chaos reigns, with substantial temperature increases, prolonged droughts, or excessive rainfall. For example, in São Romão, a municipality in northern Minas Gerais within the São Francisco basin, temperatures reached 43.5ºC, a record for the year. This heatwave was recorded by INMET at the end of September. In light of so much evidence of dangerous global warming, the question remains: how will these climate changes practically affect the populations along the Velho Chico basin? “Given the scenario, we can infer that the main consequence is economic. Planting requires careful planning,” commented Marília Nascimento, meteorologist at the National Institute for Space Research (INPE).

Additionally, she noted: “Besides the daily precautions people must take in terms of hydration, avoiding prolonged sun exposure, and preventing heatstroke, as we experience above-average temperatures, we may also continue to see heatwave episodes, as observed this past winter.”

Climatologist José Marengo, General Coordinator of Research and Development at the National Center for Monitoring and Early Warning of Natural Disasters (Cemaden), also issued a warning: “We may indeed face water shortages for the population, especially in the semi-arid interior, necessitating a reprogramming of agriculture and close attention to water supply, utilizing water trucks and other resources.”

According to Danielle Ferreira, another risk is the increased desertification in areas of the Velho Chico basin: “With climate models predicting the persistence of El Niño until at least the end of summer 20232024, questions arise about the impact of this event on the start of the next rainy season, which could lead to a reduction in available water volumes in the region, exacerbating environmental degradation and desertification.”

Anivaldo Miranda, coordinator of the Regional Consultative Chamber for the Lower São Francisco, emphasized the urgency of actions to help the riverside population navigate water scarcity. “It is imperative that regulatory bodies, such as the National Water Agency (ANA) and the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA), effectively exercise their prerogatives to manage reservoir volumes optimally, preventing critical situations, enforcing essential control norms, and, if necessary, implementing usage restrictions in the event of severe scarcity.” According to Anivaldo, the past offers valuable lessons: “We know from bitter past experiences, especially the drought crisis in the São Francisco River from 2013 to 2019, that delayed action, lack of dialogue, and poor planning can cause enormous damage to ecosystems and the multiple uses of water.”

At the suggestion of the São Francisco River Basin Committee (CBHSF), the National Water Agency (ANA) established the São Francisco River Hydrological Monitoring Room at the beginning of 2022. This room focuses on monitoring potential crisis situations, particularly those related to climate change. It serves as a forum where various stakeholders interact, and this year, El Niño has been a key topic. Additionally, another group within ANA, the Northeast Region Crisis Room, is also closely examining the impacts of El Niño on the Velho Chico basin.

According to ANA, the crisis and monitoring rooms “serve as spaces for coordination and information exchange to support the adoption of measures related to water systems management or the prevention, preparation, and mitigation of impacts from critical hydrological events of any nature, such as droughts and floods.” Their monthly meetings are available on ANA’s YouTube channel and are moderated by Joaquim Gondim, the Superintendent of Operations and Critical Events at ANA.

One of the participating organizations is INMET. “INMET is monitoring oceanic and atmospheric conditions and disseminating the results in periodic bulletins, as well as participating in the monthly meetings of the São Francisco River Hydrological Monitoring Room. This initiative is led by ANA and other bodies such as government agencies, entities, and users in general, discussing the hydrological conditions of the São Francisco River basin,” commented Danielle Ferreira.

At the Federal University of Alagoas (UFAL), monitoring is conducted at the Laboratory for Satellite Image Analysis and Processing (LAPIS), which uses the Eumetcast System, hosted in northern Germany. Humberto Barbosa, the laboratory coordinator and professor at the Institute of Atmospheric Sciences (Icat), explained: “Since 2007, the laboratory has utilized this real-time data reception system, meaning all data, information, and analysis results from LAPIS researchers are based on this system.”

Furthermore, LAPIS maintains international information exchange relationships with universities worldwide, including in Slovakia. According to Barbosa: “Over the past eight years, through collaboration with Venezuelan postdoctoral professor Frank Paredes, LAPIS has focused directly on the São Francisco River, particularly in monitoring droughts, rainfall, and environmental degradation.”

Professor Humberto also highlighted a new project at LAPIS, aimed at monitoring what are known as “flash droughts,” which occur when high temperatures combine with low precipitation, a scenario anticipated for the Northeast region as the effects of El Niño persist: “Given the current climatic conditions recorded in Brazil, the trend is that these flash droughts will become increasingly prominent in various regions of the country.”

In addition to the effects on the São Francisco River basin, El Niño also impacts other parts of Brazil and the world. Here are some climate situations driven by the phenomenon.

*In Brazil*

- *Drought in the Amazon*

The severe drought recorded in the Brazilian Amazon in the last semester of this year is expected to extend until December and is linked to El Niño, according to Cemaden. Rainfall forecasts for the region have been below average in most measurements in the second half of 2023.

- *Rain and floods in southern Brazil*

The heavy rains that caused a trail of destruction and, unfortunately, deaths in the southern region of the country throughout the second half of the year are also linked to El Niño. The phenomenon causes a significant increase in rainfall for this region of Brazil.

*Worldwide*

El Niño can cause climate changes in India, Southeast Asia, and Australia, which experience prolonged droughts and increased average temperatures.

On the west coast of North America, the phenomenon leads to increased average precipitation, resulting in the formation of large storms.

New York was one of the metropolises that suffered from this increase in rainfall in September and October of this year, recording record levels of precipitation and even floods. In Central America, a hot and dry climate predominates.

In South America, as described, there are records of alternating severe droughts, increased average temperatures, and occurrences of heavy rains.

According to members of the Parliamentary Front for the Management and Revitalization of the São Francisco River, launched in September at the National Congress, the “Velho Chico” needs all of us. If effective and comprehensive measures are not taken, in ten years, it will not only be the riverside populations that will suffer the impact, but the entire country.

Photos: Cristiano CostaOn September 13, in the Chamber of Deputies, the alarm was sounded once again: the Velho Chico is in agony. With the presence of over 400 people, the launch of the Parliamentary Front for the Management and Revitalization of the São Francisco River aimed to reignite this urgent debate. Isolated actions are no longer sufficient. To save the Velho Chico, only a task force will suffice. If effective and comprehensive measures are not taken now, in ten years, it will not only be the riverside populations that will suffer, but the entire country, as the river of national integration is aptly named. Practically speaking, Brazil’s interior depends on the Velho Chico. In addition to the deputies and senators, the event was attended by representatives from Watershed Committees, authorities from various ministries, fishermen, quilombolas, mayors, councilors, and state deputies.

Will it work this time? In the Chamber of Deputies, this question lingered in the air. Over the last 30 years, throughout nine legislatures of the National Congress, from the 49th to the current 57th, seven parliamentary fronts have been created with the same goal: the recovery of the São Francisco. This time, the idea is to set objective goals, fighting on multiple fronts, from proposing legislation that benefits the environment to combating bills that move in the opposite direction. “If we do not unite, regardless of political party, ideological tendencies, or any other type of divergence, by 2040 we will place a cross in the Sobradinho reservoir with a plaque reading: ‘Here lies the São Francisco River.’ It is very sad to foresee this, but it is reality,” stated Senator Otto Alencar (PSD-BA).

Assuming the presidency of this new parliamentary front, Federal Deputy Paulo Guedes (PT-MG) highlighted the obvious. As Brazil seeks to assume global leadership on environmental issues, attention must be paid to the Velho Chico, rather than focusing solely on the Amazon. “The São Francisco must also become a priority in environmental policies aimed at water security, combining environmental preservation with economic, social, and cultural development,” he emphasized. “Every day we see pollution, domestic and industrial sewage disposal, indiscriminate use of pesticides, unregulated mining activities, deforestation of riparian forests, vegetation clearing, erosion and siltation, fires, and urbanization. All these factors contribute to increasing risks of desertification, not only due to current climatic conditions but mainly because of the lack of sustainable water resource management. A new São Francisco is possible if we revitalise the basin in an integrated manner, restoring its mission as the river of national integration.”

In Paulo Guedes’ opinion, civil society also needs to engage in the fight. Among the urgent actions, he highlighted the implementation of a system of dams to regulate flow in the São Francisco channel, combat unregulated deforestation, and a comprehensive basic sanitation program.

Members of the Direc participated in the launch of the Parliamentary Front for the Defense of the São Francisco River.

The group also proposes the creation of conservation areas and ecological corridors, the enhancement of water availability for irrigation, human consumption, industry, energy generation, flood control, aquaculture, recreation, and tourism. Naturally, the focus is on the protection and recovery of environmentally vulnerable areas, environmental adaptation of unpaved roads in riverside areas, reforestation, and restoring conditions for efficient cargo river transport, as observed in past decades. “With appropriate interventions and coordinated actions, it will be possible to promote social, environmental, and economic development for the people living in the riverside areas,” emphasized the Front’s president.

The vice-president, Deputy Pedro Campos (PSB-PE), added, “The São Francisco teaches us much along its path. One lesson is the need for unity among us. The São Francisco is composed of water, tradition, and life. We cannot speak of it and only address the water issue. We must pay attention to strategic projects, such as the resources to be allocated by the Eletrobrás management committee.” According to the legislation that permitted the privatization of Eletrobras, R$350 million per year, over a tenyear period, must be allocated for revitalization actions. In Pedro Campos’ view, the destruction of resources will require extensive debate.

Among the priorities is undoubtedly the approval of the bill proposing the protection of the Caatinga. Another project that should be monitored is the revision of the so-called Water Law. “It is part of our history, part of Brazilian culture, and of extreme environmental importance to the country as a whole. Preserving the river’s sources involves confronting economic power, setting limits to property rights in this country,” stressed Deputy Patrus Ananias (PTMG).

According to Senator Otto Alencar, the São Francisco River has already turned into a sea. By the time it reaches Bahia, it is already salty. “We must kneel and ask the authorities to support us in this urgent fight,” he pleaded. Alencar also emphasized that every dam accumulates silt over time, but in the case of the Sobradinho and Três Marias dams, studies have found that this sedimentation is uncontrolled. For example, the Três Marias dam has 35% sedimentation, and Sobradinho has about 20%. “Given the river’s current state, R$350 million per year over 10 years is not enough to save the São Francisco,” he argued. The senator also mentioned the difficulty of securing funds in previous administrations. In the Senate’s Environment Committee in 2022, amendments totaling R$600 million for the São Francisco were proposed in the Union Budget and approved, but the funds were redirected to other environmental projects.

We want to protect the river from erosion and also focus on prevention, such as hydro-environmental processes and planting native seedlings. We will work together with the Parliamentary Front and the governors and mayors of each municipality along the river,” declared Marcelo Andrade Moreira, president of the Development Company for the São Francisco and Parnaíba Valleys (Codevasf). He highlighted that there are already projects within the organization aimed at continuing the implementation of sewage systems in riverside cities and new rural roads.

José Maciel de Oliveira, president of the São Francisco River Basin Committee (CBHSF), emphasized the importance of participation from all sectors: executive agencies, parliamentarians, leaders, indigenous peoples, quilombolas, fishermen, riverside populations, and technicians. “This is a day of great joy and celebration. We have discussed extensively with Deputy Paulo Guedes and are aware of the many problems in the São Francisco basin across various

Implementation of a dam system to regulate river flow

Actions to combat unregulated deforestation

Basic sanitation programs to contain pollution sources and provide ample, quality water for the population

Creation of conservation areas and ecological corridors

Flood control programs

Continuation or initiation of new aquaculture, recreation, and tourism projects

Protection and recovery of environmentally vulnerable areas

Environmental adaptation of unpaved roads in riverside areas

states, and we need this gesture of unity,” he stressed. Maciel noted that besides flowing through the states of Minas Gerais (where it originates), Bahia, Pernambuco, Alagoas, and Sergipe, the São Francisco now also supplies Ceará, Rio Grande do Norte, and Paraíba through transposition projects. He mentioned projects that could bring further harm to the Velho Chico, such as PL 4546, which diverts resources and effectively dismantles the current water management policy.

Deputy Delegada Catarina (PSD-SE) highlighted the challenges: “In the state of Sergipe alone, 132 municipalities are touched by the river, and some of these municipalities, incredibly, have the lowest Human Development Indexes (HDIs) in Brazil. What is only in discourse? What actions are currently being undertaken or continued? What actions need to be taken? We must evaluate this. The São Francisco passes through 505 municipalities, and only one of them has 100% treated sewage.”

Reforestation

Social, environmental, and economic development for the riverside population

Technical debate on river management and the forest system

Reassessment of the exact use of funds from the privatization of Eletrobras for river revitalization

Reevaluation of legislative projects aimed at preserving biomes in areas crossed by the river

Constant monitoring and combating of legislative measures that could harm the Velho Chico, in the National Congress, state assemblies, and municipal councils.

In the National Congress, several parliamentary fronts have been launched in defense of the Velho Chico. However, there have been few concrete results. According to common regulations, every parliamentary front lasts only one legislature, i.e., four years. It is not uncommon, however, for a parliamentary front to be recreated with each new legislature. In the case of the São Francisco, despite the constant concern of deputies and senators, the number of fronts created in the last 30 years with various names is notable.

“One cannot say that none of these fronts yielded results because various projects have been processed over the years, and many of them, focused on the environment as a whole, also pertained to the São Francisco,” commented political scientist Alexandre Ramalho, an economic analyst for the Senate. “The important takeaway is that the risk to the river is now greater, and there is a need for the group to have a strengthened role in this legislature.”

“This is a very serious situation,” she denounced. In her opinion, the São Francisco has two important characteristics: “The first is generosity, the second is resilience. But we must remember that, although the São Francisco River is very resilient—otherwise it would have died years ago—this resilience has limits.”

According to Alexandre Rezende Tofeti, coordinator of the revitalization of watersheds, water access, and multiple uses of water resources at the Ministry of the Environment, Minister Marina Silva is aware of the importance of a task force: “We advocate for management and revitalization and know there is no future without a healthy river. We are clear that urgent actions are needed for the São Francisco and we work to maintain water resource management in the country with social participation through Basin Committees. The basin plan needs to be a guiding instrument for our actions, with well-detailed diagnoses and well-designed actions.”

49th Legislature (January 1991 - January 1995) - Parliamentary Front for the Defense of the São Francisco River

50th Legislature (January 1995 - January 1999) - None

51st Legislature (January 1999 - January 2003) - Parliamentary Front for the Defense of the São Francisco

52nd Legislature (January 2003 - January 2007) - Parliamentary Front for the Revitalization of the São Francisco River

53rd Legislature (January 2007 - January 2011) - Parliamentary Front for the Revitalization of the São Francisco River 54th Legislature (January 2011 - January 2015) - None

55th Legislature (January 2015 - January 2019) - Parliamentary Front for the Defense and Development of the São Francisco River 56th Legislature (January 2019 - January 2023) - Parliamentary Front for the Defense of the São Francisco River

57th Legislature (started in January 2023)Parliamentary Front for the Management and Revitalization of the São Francisco

Opará, or Rio-mar: as the São Francisco River was initially called by indigenous peoples. It originates in Minas Gerais and flows through Bahia, Pernambuco, Alagoas, Sergipe, Goiás, and the Federal District.

Other states it supplies: Ceará, Rio Grande do Norte, and Paraíba, which have receiving basins through the transposition project.

It flows through 505 municipalities, with a combined population of over 18 million inhabitants.

The river empties into the Atlantic Ocean and spans 8% of Brazil’s territory.

Ten years ago, the CBHSF (São Francisco River Basin Committee) was among the pioneers in implementing the charging for the use of water resources in the São Francisco basin. With the resources obtained since then, fundamental projects and works of revitalization and preservation have been carried out. However, non-payment has become a significant challenge.

Nearly 10 years after the creation of the São Francisco River Basin Committee (CBHSF), in 2010, the charging for the use of water resources was approved and instituted. At that time, the São Francisco River became the third Brazilian river to implement the only effective mechanism to ensure revitalization and preservation projects. So far, the investment results amount to around R$150 million. However, there is still a long way to go to achieve the status of the “basin we can.” The Water Resources Plan (PRHSF 2016-2025) set a target for financial investments, with two budgets: strategic and executive, both containing priority activities to be carried out by the CBHSF and the delegated agency, the Agência Peixe Vivo. The strategic budget estimated the need for investments of around R$500 million over 10 years, with revenues primarily coming from the charging for the use of water resources. Initially, the amount of the charge transferred to the Committee was approximately R$24 million, and with the methodology update carried out in 2016, the amount now reaches approximately R$42 million.

“We initiated the charging for the use of water resources in the São Francisco River basin in 2010, and the operationalization of this resource came at the end of 2011 and 2012,” commented CBHSF President, Maciel Oliveira. “With these resources, we developed 116 sanitation plans, carried out many hydro-environmental projects and programs, transformed projects into programs such as rural sanitation, invested in sanitation and water supply, recovered thousands and thousands of springs, conducted fencing of permanent protection areas in indigenous areas as well, and invested in projects aimed at indigenous peoples and traditional communities. In other words, the Committee, with resources from the charge, managed to invest millions of reais in the recovery of the basin. The Committee initiated this work, and now we are reaping the rewards, seeing the improvement in the quality of life of the people living along the São Francisco.”

If revitalizing and preserving our rivers has become a matter of emergency, it is obviously essential to charge for the use of water resources. It is not a tax. Envisioned in Law No. 9,433/97 (Water Law), the charging for water use is one of the instruments established by the National Water Resources Policy, with three purposes: to ensure the budget for the recovery of watersheds, to stimulate investment in pollution control, and, above all, to promote environmental education, attributing value to water. Prioritizing water quality and environmental sanitation, the CBHSF allocated resources for the development of various studies and projects focused on basic sanitation systems in its four components: water supply, sanitation, urban solid waste, and urban drainage. Over R$16 million was invested in the development of 116 Municipal Sanitation Plans (PMSB).

There were over 50 hydro-environmental projects, with an estimated investment of over R$20 million: formatting and monitoring the implementation of hydro-environmental projects aimed at the protection and conservation of water sources, adaptation of rural roads, fencing of springs and recharge areas, erosion control processes, as well as activities to sensitize and mobilize communities. The hydro-environmental projects, distributed in the four physiographic regions of the São Francisco River Basin, served, for example, the basins of the Rio das Pedras and Córrego Buritis, the Córrego da Onça, Rio Jatobá, Surroundings of the Três Marias Reservoir, in the Upper SF; Rio Itaguari, a tributary of the Rio Carinhanha, Rio das Fêmeas, Rio Pituba in the Middle; the Salitre River basin, Rio Mocambo, Córrego Onça Basin, in the Submedium; Rio Jacaré, Rio Boacica, Rio Piauí, in the Lower SF, among others.

In addition, large-scale actions were carried out to ensure water security, such as: feasibility studies for the implementation of the S.O.S. Lagoa de Itaparica Action Plan (Gentio do Ouro and Xique-Xique, Bahia); engineering executive project for the implementation of gates in the irrigated perimeter of the Vale do Paramirim; environmental diagnosis, prognosis, and definition of environmental and urban requalification projects for waste lagoon in the municipality of Felixlândia/ MG; execution of works and services for environmental requalification in the Riacho das Pedras Watershed, in the municipality of Bonfinópolis de Minas/MG; execution of works and services for the implementation of the Water Supply System for the Serrote dos Campos Village in Itacuruba, Pernambuco; implementation of a raw water collection and conveyance system in the municipality of Pirapora/MG; implementation of lung tanks in Piaçabuçu, Alagoas; preparation of feasibility study and basic and executive projects for the water supply system for the population of the Kariri-Xocó Village (Porto Real do Colégio, Alagoas); in addition to the construction of native seedling nurseries in the municipalities of Lapão, in the Middle São Francisco, Patos de Minas, in the Upper São Francisco, Santana do Ipanema and Piaçabuçu, in the Lower, and Jaguarari, in the Submedium, actions that, altogether, required investments of around R$30 million.

In 2018, the default rate in the São Francisco basin reached 15%, and with the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, the estimate was that this number would double, reaching around 30%. This year, the National Water Agency (ANA) pointed out an outstanding amount of R$ 65,308,003.71 million in default related to the charge for the use of water resources. An overview based on this report showed that the 100 largest defaulters are responsible for 70.64% of the debt, equivalent to R$ 46,128,846.90, a value that represents the loss of more than a year of revenue, considering the collection in the order of R$ 42 million. In 2022, R$ 55,337,224 were invested, almost double the amount invested in 2021, when R$ 28,557,227 were invested throughout the basin.

“There are important sectors, especially in the economy, with a mentality that dates back to the last century. They don’t want to pay, still believing that water is infinite and there is no responsibility in management. This creates serious problems. Those who don’t pay tend to make inappropriate or excessive use, without contributing anything to maintain ecosystem health. As we use something and don’t pay for it, not only do we set a bad example, but we also deprive resources to maintain ecosystem health. The problem we face today is: what price will we pay until we acquire this awareness? We are seeing increasingly destructive and burdensome environmental disasters. The day will come when there will be no more public money to face the recovery of what is being destroyed every year due to climate tragedies,” evaluated Anivaldo Miranda, environmentalist and coordinator of the Regional Advisory Chamber of the Lower São Francisco. “This demands time, persistence, that people don’t lose faith in the future and in the effectiveness of the path we are building. I believe that all factors will show sooner or later that we are on the right path and that we need to accelerate the pace to transform life on the planet into a more sustainable one, which we have not done so far.”

Recently, according to Anivaldo Miranda, the country has been experiencing an attempt to dismantle the National Water and Basic Sanitation Agency (ANA), with the possibility of withdrawing the transfer of 0.7% of the Financial Compensation for the Use of Water Resources (CFURH) in the energy sector. In process at the National Congress, the proposal is included in the bill of Senator Luís Carlos Heinze (PP/RS). “Bill 2918/2021 intends to end the transfer of 0.75% of CFURH to ANA and Basic Sanitation, resources in the order of R$ 217 million per year (2022), with application linked to the National Policy of Water Resources (PNRH) and noncontingent. This resource with which ANA has been fulfilling its mission,” said Ângelo Lima, executive secretary of the Water Governance Observatory. “Let’s imagine a country that experiences drought and floods at the same time, without being able to plan based on the data from this network? We will have more catastrophes. The proposal would marginally allocate what has so far been allocated to the PNRH and the SINGREH to benefit a small set of 727 municipalities already benefiting from the majority of the CFURH.”

An in-depth look at the program that is transforming water management in Brazil

Until very recently, it seemed that water would never run out, an endless resource that could be continuously wasted. However, it is now known that it is not quite like that. According to the United Nations (UN), by 2050, at least one in four people will live in a country facing a shortage of clean water. Today, more than 2 billion people in the world no longer have access to water for their own consumption. Faced with this bleak future if the world continues on the same path, the National Water Agency (ANA) decided to take action. The Water Producer Program has come to revolutionize water management in Brazil.

Currently, there are 60 projects supported by the program, covering 72 Brazilian municipalities. Of these projects, 31 have active arrangements for Payment for Environmental Services (PES). The payments made in PES currently amount to approximately R$ 5.25 million, benefiting about 1,000 rural producers. According to ANA’s Superintendent of Plans, Programs, and Projects, Henrique Veiga, so far, 2,500 rural properties have been benefited, totaling approximately 86,000 hectares, distributed across nine metropolitan regions, in 13 states and the Federal District, directly or indirectly affecting over 1.6 million Brazilians.

“Based on reports presented by local project management structures regarding the impacts of conservation practices on improving the quality of water bodies, we highlight the emergence or restoration of springs, increased agricultural productivity, regularization of the flow of the worked watercourse, and improvement in water quality,” emphasized Veiga.

The Water Producer Program is an innovative approach that acknowledges the role of rural producers in the conservation and sustainable management of water resources. It offers financial incentives, training, and support for these actors to adopt practices that help protect and restore springs, rivers, and water reservoirs. The program’s underlying principle is straightforward: rural producers who implement water-preserving measures on their properties are financially rewarded. These measures include protecting and reforesting permanent preservation areas, building small reservoirs, constructing terraces, fencing off areas, creating firebreaks, installing biodigester pits, and other practices that reduce erosion and water contamination.

In the Alto São Francisco region, the program is led and executed by Dirceu Costa, a member of the São Francisco River Basin Committee and president of the Alto São Francisco Basin Committee. According to him, “Initially, a survey of potential areas for action is conducted. Then, a socio-environmental diagnosis of the micro-basin is made, and an economic valuation of environmental services is performed. A project for the rural unit belonging to the program is then developed, and the rural producer, the owner of the unit, signs a contract committing to invest in actions that benefit water quality and quantity. Consequently, payment for environmental services (PES) is made to producers based on the results achieved.”

Several rural producers in Alto São Francisco have already benefited from PES, including residents of Piumhi, Doresópolis, Pará de Minas, Pimenta, Capitólio, Passos, Formiga, Luz, Bom Despacho, and Carmo do Cajuru. “We conduct technical visits from time to time, meet with producers, evaluate, and monitor the program’s progress,” explained Dirceu.

Day-by-Day

Hélio Francisco de Camargos, a rural producer in Doresópolis, known locally as Tio Gordo, has benefited from the Water Producer Program. On his property, which previously suffered from flooding, small reservoirs were built. Simultaneously, the springs were fenced off to prevent animal entry. According to him, the PES money is used for maintaining the improvements. “We use the funds to repair damaged fences and for tree planting,” he commented. For Hélio, the key now is to expand access to the program for more rural producers. “Especially my neighbors, so they can help me. If they helped, we could produce much more water.”

The adherence of rural producers to the project has been organic, mainly through positive recommendations. In Piumhi, rural producer Xênia Almada notes that the Water Producer Program arrived at the right time for her property, which focuses on dairy cattle. “We had cesspools on the property, and we didn’t like that. The program installed two biodigesters instead of the cesspools,” she said. “We also had small reservoirs built on the property, as the roads were in poor condition during the rainy season. With the fencing, our reserve (Permanent Preservation Area - APP) is fully protected. So, we are very pleased to participate in this work, and I think more people should join because it is good for nature and everyone.”

For the past ten years, the Public Ministry has been a partner of the Water Producer Program in the Alto São Francisco region. Convinced by the National Water Agency (ANA) to join, the ministry has been fostering projects, lending its institutional credibility to the organization of financial transfers. Prosecutor André Vasconcelos highlights that the program’s benefits go beyond environmental improvements. “The environmental protection proposed by the program facilitates and enhances the agronomic aspects of properties. The techniques implemented by the project not only promote water production but also substantially improve traditional production, whether in cattle raising, coffee cultivation, or other activities present on the properties.”

Another significant partner in the implementation of the program in Alto São Francisco is the Minas Gerais Water Management Institute (IGAM), which is part of the State System of Environment and Water Resources (Sisema) and the State Water Resources System (SEGRH) in Minas Gerais. “IGAM’s partnership with producers occurs through Project Management Units (UGPs). These units are created to manage the project and be closer to the involved communities, especially the rural producers who play a fundamental role, as it is on their properties that actions to improve water quality and quantity will be developed,” explained IGAM’s director-general, Marcelo da Fonseca.

The São Francisco River Basin Committee is also a partner in the program. According to Altino Rodrigues, coordinator of the Alto São Francisco Regional Consultative Chamber, the committee plans to allocate resources to the Water Producer Program. The idea is to expand the program to other regions of the basin. There are two areas with potential for the application of Payment for Environmental Services: Alto São Francisco and Médio São Francisco. “The strategic choice is based on these regions’ capacity to produce water, foreseeing greater efficiency of the program in these specific territories. Thus, the initial intention is to expand the program to Médio São Francisco, aiming to enhance its positive impacts on water resource conservation and quality,” he said.

The program’s success is directly related to projects that follow its operational model, with management through partnerships, voluntary and equitable adherence of rural producers, consensual and agreed environmental adaptation of rural properties, the use of the best and most suitable environmental intervention techniques, measurement and monitoring of results over time, and, when applicable, payment for environmental services.

Henrique Veiga, Superintendent of Plans, Programs, and Projects at ANA, states, “the next steps involve recognizing other existing initiatives, validating project management, and disseminating their results to partners interested in investing in or studying this watershed revitalization model. Additionally, there will be full support for managing bodies and Basin Committees in utilizing the model and seeking funding for such projects. The understanding is that the sustainability or continuity of the Program over time is increasingly tied to the leadership and empowerment of local and regional governance structures of the projects. These should become sources of coordination, capacity building, knowledge creation, and result dissemination to society.”

Payment for Environmental Services (PES):

Rural landowners receive financial incentives to adopt soil and water conservation practices, such as restoring degraded areas and preserving riparian forests. This payment is based on the environmental services provided, like improved water quality and aquifer recharge.

Technical Assistance:

Program participants receive specialized technical guidance to implement sustainable practices on their properties. This includes proper use of agrochemicals, conservation agriculture techniques, and integrated watershed management.

Environmental Monitoring:

Water quality is continuously monitored, assessing the outcomes of the adopted practices. This ensures that conservation actions are generating tangible benefits for the aquatic ecosystem.

Investment in Works:

Construction of small dams, terraces, fences, planting seedlings, and installing septic systems aim to improve water quality and increase water production, the primary objective of the Water Producer Program.

Watch the video about the Water Producer Program (ANA) in the Upper São Francisco region: Acesse: bit.ly/ppa-alto-sf

A native of Teófilo Otoni, Minas Gerais, but residing in Bahia for the past 16 years, Elba Alves, an economist with a master’s degree in Water Resources and Environmental Sanitation, has taken over as the General Director of the Peixe Vivo Agency.

In 1997, while studying economics at PUC-MG, Elba Alves was suddenly compelled to move to Porto Alegre. She didn’t know the city, had no friends there, and had to wait for her transfer between universities to be completed. With nothing to do, she decided to follow the advice of her older sister, Eraly, who had been living in the capital of Rio Grande do Sul for a while, pursuing a master’s degree at the Hydraulic Research Institute (IPH) of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul. Why not take a technical course in hydrology? Initially, she found the idea strange and distant from her field. After all, she was an economics student and couldn’t see the connection between the two. Nevertheless, she took the admission exams. From then on, her life took an entirely unexpected turn.

Two decades later, in late October 2023, Elba assumed the role of General Director at Peixe Vivo, the basin agency that serves, among other committees, the São Francisco River Basin Committee (CBHSF). For her, in addition to representing a new challenge, Peixe Vivo is the culmination of a career that began by chance and turned into a vocation. “I have always greatly admired the work of Peixe Vivo, and being the general director of the agency is both very challenging and a tremendous achievement. The selection process included highly qualified candidates,” commented Elba, who, at the time of the interview for CHICO magazine, was still packing her bags to move to Belo Horizonte after living in Salvador for 16 years. “My training is closely tied to the implementation of charging processes. In Bahia, where the charging process is being implemented, we have made significant progress in this regard.”

Born in Teófilo Otoni, in the Mucuri Valley of Minas Gerais, Elba

arrived in Salvador in 2007. Before that, however, her life took many twists and turns.

First, she completed her technical course in hydrology in Porto Alegre with one certainty: she would return to Minas Gerais, finish her economics degree, and then go back to IPH for her master’s. “I am very determined,” she remarked, noting that she had even chosen her advisor, Professor Eduardo Lanna, one of the leading figures in water resources in Latin America. The plan worked out. With a master’s degree in Water Resources and Environmental Sanitation, she decided to spend her vacation in Bahia: “I came to visit my sister who had moved to Salvador. Life is full of surprises!”

In Bahia’s capital, Elba built her career. Between 2007 and 2011, she worked at the Institute for Water and Climate Management of the State of Bahia (INGÁ), and from 2011 onwards, she held key positions in the State of Bahia’s Department of Environment (SEMA/BA), ultimately becoming the Superintendent of Innovation and Environmental

Development. In her opinion, the recent tragic extreme weather events, such as the floods in New York and Rio Grande do Sul, make it undeniable that climate change is real. Therefore, it is more critical than ever to focus on and invest in water resource management. “I am very hopeful. The challenge is global. But decision-makers have already understood that we need to unite to mitigate the scenario ahead. It is not an easy scenario,” she commented. “But I am always very positive. Economic instruments, such as water usage fees, are meant precisely to instigate a change in mentality and behavior. One of the goals of charging is to rationalize use.”

“While working at SEMA, I was the institutional representative on Basin Committees. And in the CBHSF, in 2007, I began working in the Technical Chamber of Permitting and Charging (CTOC). I was the secretary of this Technical Chamber until recently,” she recounted. “I joined the CTOC when the implementation of charging models was taking off. I followed this work closely through the CTOC.”

At 50, Elba seemed pleased with the changes. “I am going back home,” she said, not losing her accent and remaining a supporter of Galo, as the Atlético Mineiro Football Club is known. In her spare time, she enjoys cooking and proudly claims her feijão tropeiro, a traditional dish from Minas Gerais, is highly praised. “I like to make feijão tropeiro and stewed fish. Miners don’t like dendê, so it’s not Bahian moqueca. Cooking is my therapy,” she commented. An optimist by nature, she believes better days are ahead. “I bet we are moving towards a change in mentality. I place a lot of hope in environmental education,” she said, adding, “In 1997, when I went to Porto Alegre, I was startled by my sister’s proposal for me to take a technical course in hydrology. Today, combining a background in economics with water resource management is perfectly normal. Undoubtedly, environmental awareness continues to evolve.”

Created in 2006 in response to the need for efficient water management in the Rio das Velhas Basin, the Peixe Vivo Agency now serves two state committees in Minas Gerais, CBH Velhas (SF5) and CBH Pará (SF2), as well as the Federal Committee of the São Francisco River Basin (CBHSF).

The Agency’s purpose is to provide technical and operational support for the management of water resources in the watersheds under its jurisdiction. This is achieved through the planning, execution, and monitoring of various initiatives, such as actions, programs, projects, research, and other procedures, all aligned with the guidelines and resolutions of the Basin Committees as well as State and Federal Water Resources Councils.

Its reach extends across six states and the Federal District, including Minas Gerais, Goiás, Bahia, Pernambuco, Alagoas, and Sergipe. Among the numerous secretarial and technical support actions that the Peixe Vivo

Agency performs are the execution of Hydro-environmental Recovery Projects, the development of Municipal Basic Sanitation Plans (PMSB), Environmental Education Programs (PEA), Communication and Social Mobilization Campaigns, as well as studies and works aimed at improving the quality and quantity of water in the basins under its jurisdiction. All projects are funded with resources derived from water use fees.

The impacts of the Agency’s work potentially reach over 20 million people in the covered areas. In 2022, more than 66 million reais from water use fees were invested in actions and programs focused on the watersheds served by the Agency.

It was considered the largest women’s mobilization in Latin America. Among the demands of the 100,000 women who took to Brasília in August was the crucial recovery of the São Francisco River Basin.

“Better to die fighting than to die of hunger”: the cry of Margarida Maria Alves, the union leader from Paraíba assassinated on August 12, 1983, has never been silenced. From August 15 to 18, forty years after her brutal murder, the March of the Margaridas reached its seventh edition, this time with an expanded agenda. In addition to the historic demand for improved working conditions in the countryside, women from all parts of Brazil and 34 other countries joined the struggle for the revitalization of river basins, especially the São Francisco Basin. With the presence of President Lula and First Lady Janja, the event gathered over 100,000 women in Brasília. The first edition took place in August 2000, when around 20,000 women marched on the federal capital, carrying the voice of the union leader who was shot dead at her home in Alagoa Grande by a gunman hired by local landowners.

Held every four years, the 2023 March of the Margaridas dominated Brasília for four days. Practically all state ministers attended at some point during the mobilizations. The program included marches, debates, meetings with authorities, and even tributes in the National Congress. “This year’s march was marked as the largest women’s action in Latin America. I am here alongside women from the countryside, forests, and waters of all Brazil, to listen to social movements and, together, rebuild the country,” Lula said at the opening.

In the same vein, the event coordinator, Mazé Morais, emphasized that this edition would “yield historic results.” On behalf of the Ministry of Women, Cida Gonçalves summarized: “When women march, it is not just for themselves. It is for Brazil, for their children, for life, for dignity, citizenship, and democracy.”

Encouraged by public support, the march also represented the revival of social movements that lost ground during the Bolsonaro administration. As Mazé explained, “Our goal is to resume the dialogue that was interrupted.” After all, according to Cícera Costa, Secretary of Women of the Federation of Rural Workers of Ceará (Fetraece), “About 70% of the food produced today in Brazil that reaches the tables of Brazilians comes from family farming. However, despite these numbers, many rural women still face difficulties accessing public policies and technical assistance that would aid their production.”

Cícera emphasized: “We monitor various programs, projects, and actions, creating agendas and meeting with women to work on female empowerment, say no to violence, and address social issues and parity issues. These are our banners of struggle so that we can develop.”

Participatory Democracy and Popular Sovereignty

Power and Political Participation of Women

Self-Determination of Peoples, with Food, Water, and Energy Sovereignty

Democratization of Land

Access and Guarantee of Territorial and Maritime Rights (spaces constituted from mangroves and the sea)

According to Mazé Morais, the Margaridas are not just 100,000 or 200,000 women: “We are millions. We brought only a part of the vast numbers outside here to present an important agenda that helps us rebuild Brazil and achieve well-being. This means we want to establish a non-exploitative relationship with nature, enjoy the right to live in our lands and territories, and propose new ways of food production based on agroecology.”

Indigenous leader Gracilda Pereira, from the Aticum-Jurema tribe of Petrolina (PE), also spoke. According to her, many indigenous women living in the São Francisco Basin were there for the same reason: to demand the demarcation of their territories. After all, traditional communities are essential for the preservation of the São Francisco River. “Our indigenous health area is uncovered. We have no health agents or doctors. The nearest facility, for emergencies only, is far away. Education is also an issue. Students attend schools in the municipality, outside the village. There are many shortages, especially in the São Francisco Valley,” Gracilda highlighted. Rural worker Suzana da Silva Pimentel from Monte Santo, Bahia, added: “Just leaving the interior of Bahia and coming to this gathering with women from other regions shows strength. It demonstrates how much we need to organize. And it is us, the women in the Caatinga, who must organize and fight.”

Healthy Life with Agroecology, Food Security, and Nutrition

Right to Access and Use

Biodiversity, Defense of Common Goods, and Protection of Nature with Environmental and Climate Justice

Economic Autonomy, Productive Inclusion, Employment, and Income

Non-Sexist and Anti-Racist Public Education, and the Right to Education of and in the Countryside

Public, Universal, and Solidary Health, Social Security, and Social Assistance

Universal Access to the Internet and Digital Inclusion

Life Free from All Forms of Violence, Without Racism and Sexism

Autonomy and Freedom of Women Over Their Bodies and Sexuality

Source: Contag

Productive Gardens for Rural Women

To promote food and nutritional security, as well as economic autonomy. By 2026, 90,000 gardens will be established across Brazil.

Resumption of Agrarian Reform with Priority for Rural Women*

Eight new settlements, 5,711 new families settled, and 40,000 families regularized.

National Program for Citizenship and Well-Being for Rural Women

Ensure access to documentation, joint land titling, and territory.

Collective Laundries

A pilot project with the installation of nine units in settlements across three states in the Northeast (Piauí, Rio Grande do Norte, and Ceará).

Creation of the National Commission for Combating Violence in the Countryside (CNEVC)

To mediate conflicts in rural areas.

National Pact for the Prevention of Femicide

To prevent all forms of discrimination, misogyny, and gender violence against women through intersectoral actions with a gender perspective.

Actions include the delivery of 270 mobile units for direct support and guidance to women, plus 10 vehicles for team mobility and transporting equipment for user support. Boats and launches will also be provided for regions needing riverine services for women in forests, waters, and the Pantanal.

Green Grant

Environmental Conservation Support Program, which provides payments to families in protected areas to encourage conservation. Previously, the payment per family was R$300. Now, it is increased to R$600.

Source: Secom/Presidency of the Republic

Thanks to the Integrated Preventive Inspection of the São Francisco River Basin (FPI), cheese dairies in the Sergipe hinterland are professionalizing and diversifying their production.

The Sergipe hinterland is no longer limited to producing only coalho cheese. With the impetus provided by the Integrated Preventive Inspection of the São Francisco River Basin in Sergipe (FPI/SE), during the edition held from July 23 to August 4, local cheese dairies have significantly improved in quality and variety. “We decided to become regularized and sought all the legal means to do so,” commented Bruna Letícia Santos Aragão, production manager and partner at Laticínio LagGlória, located in Nossa Senhora da Glória. “We achieved the SIE (State Inspection Seal) and then the SISBI seal (Brazilian System for the Inspection of Animal-Origin Products), which allows the company to sell throughout Brazil.”

According to Bruna, the latest FPI/SE was the starting point for a revolution in the way dairy products are produced and marketed in the Sergipe interior. Fourteen municipalities in the mid-region of the São Francisco were covered, involving around 200 professionals and nine inspection groups, including the Abate Group, responsible for inspecting the regularity of slaughterhouses, dairies, and municipal markets.

Maciel Oliveira, President of CBHSF, noted that the FPI serves as an inducer of public policies, going beyond mere inspection: “Following the FPI, many cheese dairies became regularized. And what do these cheese dairies have to do with the São Francisco? First, it’s a matter of public health, as people consumed cheeses produced in inadequate conditions. Beyond food safety, all these dairies generated effluents due to pigsties, releasing highly impactful waste into water bodies, tributaries of the São Francisco.”

This time, 21 cheese dairies and dairy plants were inspected by FPI/SE. Seven companies presented remediable irregularities and did not have their operations interrupted; another seven, detected with severe and irreparable irregularities, were shut down until they comply with regulations, while the remaining seven operated under regular conditions. Among the latter were LacGlória, Ouro Bom, and Fazenda Nova, which were revisited and found to be exemplary in adhering to all rules for cheese and dairy production, as highlighted by Sandro Luiz da Costa, Director of the Operational Support Center for the São Francisco and Springs of the Public Ministry of Sergipe, who was part of the Abate Group.

“Beyond the environmental issues of effluents, waste, and air pollution, there’s also the matter of health and consumer rights, which are violated when a company supposed to produce high-hygiene and high-quality products sells them without ensuring these standards,” Costa emphasized. “Comparing the two FPIs in the region, the one in 2016 and this one in 2023, the revisited companies showed substantial improvement.”

Laticínio LacGlória, one of the revisited cheese dairies, is a family business that started operations 25 years ago. It produces mozzarella, coalho cheese, and butter, employs 18 people, and uses about 22,000 liters of milk per day for production, up from the previous 10,000-15,000 liters/day. According to Bruna Letícia Santos Aragão, the inspection prompted positive changes: alongside the rush to regularize factory documentation, new equipment was purchased to meet required standards. With these improvements, sales increased, reaching the capital Aracaju and states like Paraíba and Alagoas. Two new employees were hired, one for product quality control and another for cleaning, now a core value at LacGlória.

Maria Joseane, the owner of Queijaria Fazenda Nova, also decided to change her business direction with the inspection’s encouragement, “which showed the paths to obtaining the State Inspection Seal,” allowing statewide sales. The dairy was founded eight years ago, but regularization came later, in February 2023. Today, it has four employees and produces mozzarella, requeijão, frescal, seasoned cheeses, and butter, using about 2,000 liters of milk daily.

“We are going through an adaptation process, seeking new markets, more qualifications, and credit to continue improving and growing,” Maria Joseane noted. “This achievement is a childhood dream. My husband’s family are cheesemakers, and we are in the third generation of cheesemaking, so seeing what we’ve built so far is gratifying and gives us the courage to aim higher.”

With 70 employees, Laticínio Ouro Bom advanced towards qualification and became a regional reference by producing mozzarella, prato, and coalho cheeses, as well as butter, adhering to legal standards. For production, 50,000 liters of milk are used daily. “The first FPI encouraged us to leave illegality,” said Alan Diego Barros Silveira, general director of the company founded in 1993 and only recently regularized after obtaining state and federal inspection seals, SIE and SISBI, which certify product origin and allow market expansion.

Improvements continue. Ouro Bom, also located in Nossa Senhora da Glória, keeps investing in machinery, infrastructure, tanks for producer collection, and quality. “It was a dream of my parents that today my brother and I are able to put into practice. Our company is 30 years old, and seeing it regularized, growing, and helping to develop the community by generating jobs and income is very emotional,” he concluded.

According to the account provided by veterinarian Salete Dezen Vieira, who has been participating in all actions of FPI/SE since 2016, the cheese factories in the region covered by FPI in Sergipe were operating irregularly, lacking hygiene both in the premises and among the handlers. It was common to find pigsties near the processing area to facilitate pig feeding, and many flies were present in the manufacturing space - none of them had environmental licensing. Starting from the first FPI in 2016, basic criteria were established for the operation and regularization of the industry: immediate removal of the pigsty, ensuring compliance with legal distance regulations; high-resistance flooring; screens on doors and windows; ceiling; uniformed handlers, stainless steel equipment, with wooden artifacts not permitted in the manufacturing process. Currently, many cheese factories have environmental licensing and are adapting to sanitary regulations to obtain inspection services. The facilities of the enterprises have improved, as well as the awareness of owners and consumers regarding the importance of producing and consuming a product made under adequate conditions. “Of the five editions held in the region, more than 100 cheese factories were inspected, many of which were revisited and found to have a completely different structure from the initial one,” Salete commented.

In the hinterland of Sergipe, there are over 300 cheese factories receiving an average of 3000 liters per day from local producers. The closure of a large industry in the region in the 1990s explains the exponential growth of small cheese factories, as producers found themselves with nowhere to place their production and had to start over. The tradition of artisanal cheese production gained strength with the diversification and introduction of new products such as mozzarella cheese and butter cheese. The region of the Alto Sertão Sergipano is characterized by small rural properties that experience a long period of drought during the year and have a strong inclination for dairy cattle farming. Dairy production accounts for a significant portion of employment in a productive chain that begins long before, with planting and production of corn for silage or feed, and continues with cultivation and care of forage palm, animal management, and of course, industry.

The Integrated Preventive Inspection of the São Francisco River Basin in Sergipe (FPI/SE) was conducted from July 23 to August 4, 2023, and involved a multidisciplinary team of 200 professionals and 30 partner institutions, including security teams from the Federal Highway Police and the Military Police. Coordination was carried out by the State and Federal Public Ministries, the Labor Ministry, and the São Francisco River Basin Committee (CBHSF).

Visited Municipalities

Alto Sertão Sergipano: Canindé do São Francisco, Poço Redondo, Porto da Folha, Monte Alegre de Sergipe, Nossa Senhora da Glória, Gararu, Nossa Senhora de Lourdes.

Middle Sertão Sergipano: Aquidabã, Graccho Cardoso, Itabi, and Feira Nova. Lower São Francisco Sergipano: Canhoba, Malhada dos Bois, and Amparo de São Francisco.

The Integrated Preventive Inspection (FPI) is a continuous program, mainly educational in nature, focused on protecting the environment and people’s lives in the São Francisco River Basin.

By: Karla Monteiro

By: Karla Monteiro

Illustration: Albino Papa

Set in the Chapada Diamantina, the backlands of Bahia, “Torto Arado” has already reached the historic milestone of 700 thousand copies sold. In the work, Itamar Vieira Jr. revisits the regionalist novel, embracing issues that are both ancestral and contemporary, that permeate the struggle for land.

When the twins Bibiana and Belonísia emerged in the infinite imagination of Itamar Vieira Jr., he was only 16 years old. Then, unpretentiously, he began to write the book that would make him an author of 700 thousand copies sold: “Torto Arado.” While reading the unavoidable work, released in 2019, by Todavia, it is inevitable to let the mind wander back to the genre that has given us the best of our literature: the regionalist novel. Recollections of Graciliano Ramos, Érico Veríssimo, Guimarães Rosa, Jorge Amado come to mind. Obviously, this is not a comparison of authors. But rather that powerful feeling that invades us when encountering a great writer. Born in Salvador in 1979, Itamar is already on his second bestseller: “Salvar o fogo” (Save the Fire). Before arriving in bookstores, the new book had already sold 35 thousand copies in pre-sale.

What does the Bahiano have?

Undoubtedly, one of the achievements of “Torto Arado” is to transport us back to the interior of the country. It’s like looking in the mirror, recognizing ourselves in the formation of Brazilian social fabric. The story revolves around the sisters Belonísia and Bibiana, born and raised on the Água Negra farm in the Chapada Diamantina. The entire plot that surrounds them is irrevocably connected to that land - and its ancestries. In fact, the backlands penetrate everything, reflecting in the characters’ hardened souls. Still children, the twins, daughters of Zeca Chapéu Grande, the spiritual leader of the community and practitioner of Jarê, an exclusive religion of the Chapada Diamantina, find a knife in their grandmother Donana’s suitcase. Everyone had left, and they found themselves alone. In the middle of the play, one of them has her tongue severed. From then on, one becomes the voice of the other, and the reader doesn’t know who was mutilated until almost the end of the novel.

“Torto Arado” is a place where knowledge of the land and knowledge of the world fraternize,” wrote critic Rodrigo Soares de Cerqueira in the Piauí magazine. Born in Salvador in 1979, Itamar delved deep to construct this masterful work. At 16, he began writing, producing about 80 pages. However, with changes in the family, the original manuscript was lost. Many years later, already a geography graduate, he decided to revisit the idea. By this time, he had accumulated extensive knowledge of rural life. Working for INCRA for 15 years, he traversed the diverse Brazil, the Brazil that fights for land and survival in the countryside. It is the lives of these people, who do not yield despite being rendered invisible by the power of agribusiness, that he brought to the pages.

“We talk about the backlands, the semiarid region, it seems like it’s all the same thing, but the backlands of the Chapada have a regularity of rain, a diversity of landscape, of bush, that leaps to the eyes,” said Itamar when launching “Torto Arado.”

On the “Água Negra” farm, where the daily lives of Bibiana and Belonísia unfold, workers do not have salaries. In exchange for their sweat, they only earn the right to plant for subsistence and also to build clay huts. Not brick ones. Of course, almost all are black, descendants of recently freed slaves. The individualization of the sisters will only happen when their cousin Silvério enters the plot. Between the love of the two, the young man chooses Bibianaand together, the couple flees, meeting the political formation in the social movements for land rights, returning to Água Negra changed. Meanwhile, Belonísia remains. Upon finishing “Torto Arado,” it is impossible not to be completely involved with these twins, who, at one moment, divide, only to later merge again.

“I am a Brazilian author who writes from Bahia. And Bahia brings together many of the references that mirror what this country is, so my next novel will continue to focus on land issues,” Itamar declared to El País newspaper, already announcing “Salvar o Fogo” (Save the Fire), which takes place in the Recôncavo: “I always conceived ‘Torto Arado’ as a larger project to speak about this relationship between man and his territory.”

In 2022, there were over a million visitors. With breathtaking landscapes, the São Francisco River Natural Monument is now among the top ten most visited places in Brazil.