VISITORS GUIDE HOUSE MUSEUM

ISBN: 978-9962-8985-9-7

CREDITS

Interpretive Center

Research and rehabilitation concept for the house: Eduardo Tejeira Davis

Realization of the rehabilitation project: City of Knowledge Foundation.

Exhibition texts:

Eduardo Tejeira Davis, Rodrigo Noriega and Walo Araújo. Museography: Reinier Rodríguez.

Additional museography: Héctor Ayarza.

Interior decoration: Sara Simpson.

Additional interior design: Sketch, Inc.

Visitors Guide

Original Spanish texts:

Eduardo Tejeira, Rodrigo Noriega and Walo Araújo.

Consulting: Wendy Tribaldos.

Design: Dos Productions, Inc. and City of Knowledge Foundation.

The purpose of interpretation is to give visitors an understanding of why and how a location and its objects are important.

Visitors Guide House Museum

Interpretive Center

Learn about the meaning and historical value of the City of Knowledge’s campus and how the transformation of the old military base has taken place.

300 acres and more than 200 buildings of the former Clayton military base have been transformed to become the City of Knowledge.

The City of Knowledge is an innovative community that drives social change through humanism, science and business. A Panamanian, private and non-profit entity is in charge of leading this project: the City of Knowledge Foundation.

From this campus, businesspersons, scientists, thinkers, artists, and community leaders, together with experts from the government, NGOs and international organizations, collaborate to develop initiatives that generate social change.

The City of Knowledge as a historical space

Where the City of Knowledge stands today, Fort Clayton operated for 80 years as part of the set of military bases that the United States of America maintained in the old Canal Zone until its transfer to Panama in December of 1999.

In the past few years the City of Knowledge has carried out much research to better understand the history around the planning and development of Fort Clayton, with the purpose of establishing criteria for the conservation of its historic buildings and spaces. Most of this research was carried out in collaboration with the architect, historian and professor Eduardo Tejeira Davis (1951 - 2016), to whom we dedicate this guide with gratitude and admiration.

Tejeira Davis designed the architectural project to rehabilitate the original house of the commander of Fort Clayton —built in 1922— to turn it into the City of Knowledge Interpretive Center.

The Center opened its doors to the public in 2018 and its mission is to inform about the historical meaning of the site as well as the legacy of its architectural, urban and landscape design.

A part of Tejeira’s studies, writings and drawings were published in the book City of Knowledge: Building a Legacy (2010), and contributed greatly to the contents of the Interpretive Center. The exhibition team also collaborated with the jurist and journalist Rodrigo Noriega, who provided an analysis and a historical account on the meaning and e ects of the prolonged US military presence on the isthmus.

In the guide that you are holding in your hands, these contents have been incorporated, as well as new resources that will lead you to discover the history of the Clayton site and the City of Knowledge, as well as the e orts being made for the conservation, value and public use of the legacy inherited. Enjoy your visit.

The original commander’s house is in itself an attraction for those interested in learning about the architecture of the Canal Zone.

Original ensemble of Fort Clayton, built between 1919 and 1922, of which 26 buildings remain. The Administration (at the center) and the four large barracks were demolished in the 1950s. Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection.

Original ensemble of Fort Clayton, built between 1919 and 1922, of which 26 buildings remain. The Administration (at the center) and the four large barracks were demolished in the 1950s. Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection.

Where are you?

A new use for the old commander’s house

The City of Knowledge Interpretive Center is located in a house built in 1922 for the commander of Fort Clayton. The original set of buildings on the base, including this house, was designed by the architect Samuel M. Hitt, the same who completed the Panama Canal Administration Building in Balboa and planned Gorgas Hospital in Ancon.

The original layout of the base was horseshoe-shaped, the commander’s residence being located in the upper and central part of the figure, in a very symbolic position. Another 18 former o cer’s houses are still preserved on the same street, which bears the name of one of the Martyrs of January 9th, 1964 (see page 55): Gonzalo Crance.

The original commander’s house is in itself an attraction for those interested in learning about the architecture of the Canal Zone.

TAKE A WALK:

The houses on Gonzalo Crance Street are connected by sidewalks that lead to their main facades, looking out onto green areas. It is the rear facades that face the street. We invite you to walk along these sidewalks and appreciate the architecture of the old houses, which today are occupied by various organizations and companies’ o ces.

The buildings of the original Fort Clayton correspond to the neoclassical period of Zonian military architecture, comparable to what was built in Forts Grant and Amador from 1913. Their current appearance di ers considerably from the original, since they underwent significant modifications over time. The porches disappeared and the openings were shortened to adapt them to new sliding panel windows, the roofs were replaced (the roof tiles were replaced by zinc sheets), and air conditioning systems were installed.

Observe the landscaping around the original commander’s house; you will notice that there are still beautiful mango, corotú and royal palm trees, all of them common species in the landscape of the old Canal Zone.

The House, on the outside

Designed for the base commander, this is the only house of its kind that was built in Clayton. The commander and his family were the only ones on the base who did not share their residence with other o cers.

It was used as the o cial residence of the Clayton commanders between the 1920s and 1940s.

Originally, it had large wooden windows covered with metal screens to keep mosquitoes out. With the introduction of air conditioning, the original windows were replaced by glass and aluminum ones.

When Fort Clayton was transferred to Panama (1999), the original architecture of the house was di cult to recognize.

In 2010, the City of Knowledge began the rehabilitation of the building. There were no original plans of the house for this project, but there were a few photographs of the exterior.

The rehabilitation returned its original appearance to the front facade of the house, even though the main door was enlarged.

Wood and glass were used to restore its original aesthetics and spaciousness to the windows, but still allowing for the use of modern air conditioning.

The house is built on 69 posts, about 90 centimeters from the ground, to protect it from moisture and vermin.

Its original roof was covered with shingles, which were replaced by sheets of zinc, possibly when it was remodeled around the sixties. Later, during the restoration in 2011, asphalt shingle sheets were installed, giving it an appearance very similar to the original roofing.

This house and the other 18 located on Gonzalo Crance Street are considered the Clayton “old town”.

The building was used as the o cial residence of the Clayton commanders between the 1920s and 1940s.

The House, on the inside

The house is surrounded by a large corridor, called a verandah or porch, which helped keep the interior rooms cooler and drier. It was also a social area to receive visitors informally.

Note that the verandah floor slopes slightly outward. It was designed this way to make it easier for rainwater to run o .

Much of the tongue and groove solid planks on the roof of the verandah are from the original structure.

The interior distribution of the residence was symmetrical: the design of the house was the same on one side and the other.

The living room and the dining room were in the central part; on each of its sides there were two rooms with their respective bathrooms.

The wooden furniture used for this setting in the living room and dining room is antique or was built based on period designs in the United States.

In the absence of the original house blueprints and photographs of its interior, photos of the interior of other residences in the Canal Zone were taken as a reference for the staging of the living room and dining room.

Currently, the City of Knowledge uses the living room and dining room to receive special guests.

The former four bedrooms of the residence were transformed into a library and a meeting room to accommodate the exhibition of this Interpretive Center.

The former small chamber for domestic service is used today for workshops and presentations.

Between the ceiling and the roof of the house there is a large space that at its top measures almost 2.50 meters. This helps keep the house cooler.

Somewhere in the Rio Grande Valley

Aerial view of the campus. Above: Detail of the 1735 map drawn up by the Spanish military engineer Nicolás Rodríguez.

Aerial view of the campus. Above: Detail of the 1735 map drawn up by the Spanish military engineer Nicolás Rodríguez.

Before the construction of the Panama Canal, the site where the City of Knowledge is today was a rural area in the Rio Grande Valley, located about six kilometers from the urban area of the city, near the bifurcation of the legendary colonial roads of Cruces and Gorgona.

The ancient landscape of savannas, swamps and hills began to undergo its first major alterations in the mid19th century with the construction of the inter-oceanic railroad (185055). In a place that was in front of the current main complex of the City of Knowledge, where Omar Torrijos Herrera Avenue runs today, a small train station called Rio Grande was established.

It is very likely that the site for this station was chosen because it was

near the part of the river where larger boats could dock.

In addition, the important route that linked the road to Cruces with Arraijan and La Chorrera crossed the river near there.

In 1880, the Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interocéanique de Panama began the construction of the canal. The chosen route ran very close to the train line. On the Pacific side, the canal took advantage of the course of the Rio Grande, which was straightened to facilitate navigation. When the company opted for a lock canal, it was foreseen that the first one on the Pacific side would be in Miraflores, very close to the Rio Grande station.

The cartographic records of the French canal company reflect the existence of a

hamlet in Rio Grande, which stretched on both sides of the railroad and included a company camp.

When the French canal company failed, the American government maintained the Rio Grande camp for a while, but by 1909 the site had already disappeared.

The photo on this page (on the right), taken between 1906 and 1907, shows workers lining up in the camp dining room.

The construction of the canal produced an impressive transformation in the landscape: the Rio Grande, with its previously winding course, was straightened and widened to turn it into the Pacific entrance to the waterway.

The Rio Grande emerged “near a mountain called Pedro Miguel: and after receiving several streams, becomes navigable for very large canoes two leagues above its mouth, which is about two miles from Panama.”John

Augustus Lloyd, British traveler, 1827.

May free transit not be interrupted

To fully understand the meaning of the old Clayton military base, it is necessary to look further into the more general history of PanamaUnited States relations, which began in the midnineteenth century, when the isthmus was part of the Republic of New Granada. (formerly, Gran Colombia).

The Mallarino - Bidlack treaty of 1846, between New Granada and the United States, guaranteed this rising power the right to transit through Panama, including the right to intervene militarily to guarantee it.

The first o cial landing of marines in Panama occurred after the so-called Watermelon Riot of 1856, which was caused by the deep antiAmerican sentiment that had been curdling among the local population due to the impact on local life of the thousands of passers-by who crossed the isthmus attracted by the California Gold Rush.

More than a dozen interventions had occurred before Panama was separated from Colombia (1903), especially to protect the Panama Railroad Company.

The Canal Zone was created and the territory was reorganized

After the signing of the Hay – Bunau-Varilla Treaty, Panama handed over control of the Canal Zone to the United States. This led to a total reorganization of the territory based on the construction, management and defense of the interoceanic route. In a few years it became a clean slate: they displaced the “native” settlers, changed many names, and great transformations took place in the topography and in the landscapes of the entire strip.

Little by little, the Zonian authorities evicted the local population and created new settlements, di erent from the old riverside villages and pre-existing workers camps. Finally, in 1912 the United States Congress passed the Canal Zone Act and, by executive decree, it was ordered to take possession of all the land within its limits.

LOOK IN THE EXHIBITION:

Look for the 1903 illustration of President Theodore Roosevelt heading to Panama with his “big stick”, a symbol of his foreign policy that legitimized the use of force as a means of defending the interests of the United States.

Find what the first Constitution of the Republic of Panama (1904) stated about the US military presence in the country.

Identify the image of what was called the Tenants’ Strike of 1925, and research how this led to a US military intervention.

Source: Abbot, 1914.

Panama is born, with a tutored sovereignty

The United States saw in the Panamanian separatist cause an undesirable source of instability for its interests, which is why it militarily supported the government of New Granada in its e ort to maintain its sovereignty over this territory.

Things changed when in 1903 the negotiations for the signing of the treaty that would allow the United States to build a canal across the isthmus failed. Then, the US government diplomatically and militarily supported the Panamanian separatist movement, guaranteeing the independence of the new republic.

Panama granted the United States, through the Hay –Bunau-Varilla Treaty of 1904, the use, occupation and control of the Canal Zone territory, and of others that the USA deemed necessary for the protection of the canal. The treaty also gave the United States the right “to maintain public order in the cities of Panama and Colon and the territories and harbors adjacent thereto.”

Following its separation from Colombia, the US pressured Panama to dismantle the army. From then on, the Marines were in charge of maintaining public order and Panama would only have a small police force subordinate to the US armed forces. So, during the first decades of the Panamanian republic, the United States constantly intervened militarily in the troubled Panamanian political life and was the guarantor of public order.

Canal Zone in 1913.Miraflores Dump

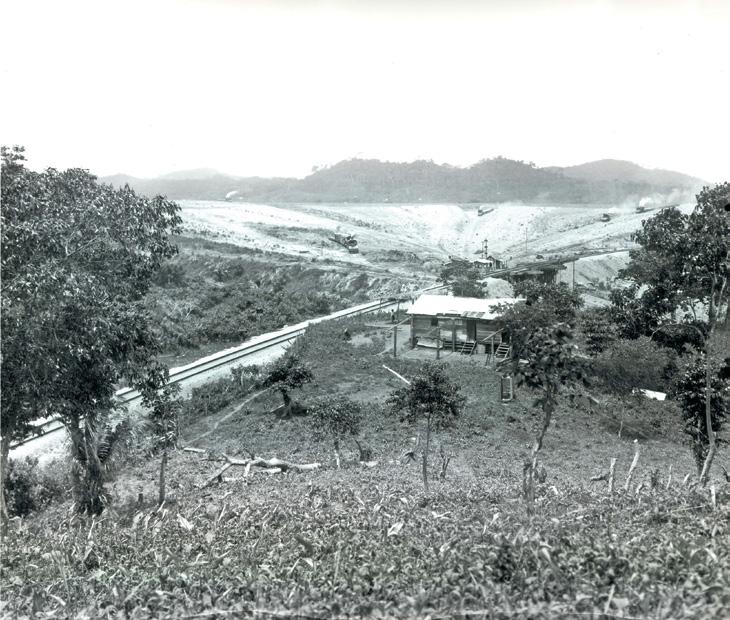

During the fiscal year of 1908, the Isthmian Canal Commission (ICC) created a new dump between the Grande and Cardenas rivers, where the City of Knowledge is located today, to deposit enormous volumes of excavated soil from the Culebra Cut. This created the Cardenas River Dump, later called the Miraflores Dump, which according to ICC data had a capacity of more than ten million cubic yards. For this, it was necessary to dismantle the town and the Rio Grande station, which disappeared without a trace. The fill changed the topography of the site and raised the ground level.

LOOK IN THE EXHIBITION:

The Rio Grande site in the 1910s, already converted into the Miraflores Dump. This photograph appears in the book America’s Triumph at Panama by Ralph E. Avery (1913). According to this publication, the landfill was over 40 feet deep. Source: ACP.

EIn 2011, during the construction of new buildings by the City of Knowledge Foundation, multiple artifacts were found in the subsoil. Observe some of them in the display case: pieces of machinery, rails, railroad ties and nails, horseshoes, bullet casings, glass and ceramic containers. Some of these objects may have been deposited on the site during the filling work carried out from 19071908, while others correspond to the years when Fort Clayton was created (1920) and its first years of operation.

Fortifying the Canal

Beginning in 1904, the U.S. Marines began to settle in old French camps located near the Culebra Cut, with the mission of protecting the canal.

The first of these camps was Camp Elliott. Nearby, Camp Otis was created, where the first military unit permanently assigned to Panama arrived in 1910. In 1914 the U.S. Army relieved the Marines of their mission.

In 1911 the United States Congress authorized the creation of military fortifications for the defense of the canal, allocating the funds for it. That same year, antiaircraft batteries began to be built in what would become Fort Amador and Fort Grant, on the Pacific; and Fort Sherman, Fort Randolph and De Lesseps on the Caribbean.

LOOK IN THE EXHIBITION:

Look for the image of the old Fort Amador during its early years. Amador was one of the first coastal fortifications on the Pacific side of the Panama Canal, built around 1913 and named after the first president of Panama.

The Creation of Fort Clayton

Image from the 1940s of the New Post barracks (currently buildings 220-225).

Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection. Above, inside the frame: Athenaeum (Ateneo) Theater, today.

Image from the 1940s of the New Post barracks (currently buildings 220-225).

Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection. Above, inside the frame: Athenaeum (Ateneo) Theater, today.

After the start of World War I in 1914, the USA launched a more ambitious defense plan. Fort Clayton (in front of the Miraflores Locks) and Fort Davis (in front of Gatun Locks) were born as part of this e ort.

Fort Clayton was created by a 1919 executive order from US President Woodrow Wilson as part of the Curundu Military Reservation. The construction of its first buildings began in 1920, on the landfill of the Miraflores Dump. The 33rd Infantry Regiment was the first to reach Clayton.

Under the American military strategy of the time, in which airplanes had only recently been invented, and missiles did not exist, defense depended on massive land or naval operations.

In addition to protecting the entrances to the canal, the locks had to be defended, a task that was assigned to the U.S. Army in Clayton and Davis.

LOOK IN THE EXHIBITION:

Observe the large aerial photograph of Clayton in the 1920s. In the image you can see the great transformation that occurred along the course and at the mouth of the old Rio Grande.

In the foreground, the original Fort Clayton. To your right, between the canal and the railway, you can still see some of the old windings of the river.

Can you locate the mouth of the Cardenas River on the map?

Where do you think Albrook is today in the image? In the background, observe the landscape of mangroves and swamps.

Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection.

About Bertram Clayton

Fort Clayton was named in honor of Colonel Bertram Tracy Clayton, born in 1862 in Alabama, at the heart of a distinguished southern family. He fought in the 1898 Spanish-American War, and he was a congressman for New York between 1899 and 1901. After failing in his reelection campaign, he returned to the army, where he was quartermaster (in charge of logistics and equipment for the troops) of the armed forces in the Canal Zone between 1914 and 1917. He also served in this position in the battlefields in France, where he was killed during a German bombardment in 1918. He was the highest-ranking graduate of the West Point military academy to die in World War I.

Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection.

Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection.

33rd Infantry Regiment during a 4th of July parade.

33rd Infantry Regiment during a 4th of July parade.

The original horseshoe

The original layout of Fort Clayton consisted of four large barracks for the troops, 26 residential buildings for o cers, sergeants and corporals, a central building for the administration and 11 more structures for stables and warehouses. It also had an airstrip (Miller Field), which was closed years later.

The City of Knowledge Interpretive Center is located in one of the base’s original buildings, in the arc of the horseshoe, along with the other 18 buildings that were intended as o cers’ residences, most of which have been adapted in recent years for use as o ces.

The six apartment buildings that were built for non-commissioned o cers also survive from the original base, and were located on the other side of the horseshoe, overlooking the canal.

The original layout of the base was horseshoeshaped. The architect in charge of the design of the entire complex was Samuel M. Hitt.

Original drawing of Fort Clayton, 1919. Source: National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

Façade of Building 161, originally built to house six single lieutenants, 1919-1920.

Original drawing by Samuel M. Hitt. Source: National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

In this book, the building numbers correspond to the current scheme, created by the City of Knowledge Foundation in 2006.

Clayton’s first expansion

EIn the 1930s Fort Clayton had to grow to accommodate several new regiments that were moved to the site. The population of the base increased from 2,180 in 1934 to 3,636 in 1939. Architects that were well known in Panama at the time, such as Rolland C. Buckley, Gustavo Schay, and Harold W. Sander, designed the new buildings.

Two of the most important ensembles of great architectural and urban value that exist in the City of Knowledge today emerged during that period: the residences on Arnoldo Cano Arosemena Street (former Colonels’ Row), and the monumental set of eight buildings that frame the City of Knowledge Central Quadrangle (former Soldiers’ Field).

O cers’ house (building 350), built in 1940.

TAKE A WALK:

Walk along the recreational trail in the City of Knowledge Park and look for the old Colonels’ Row.

Another option: Enjoy the views of the City of Knowledge Central Quadrangle.

Clayton architecture, 1934-1935.

Clayton architecture, 1934-1935.

Colonels’ Row

In order to provide lodging for o cers, a new ensemble of houses was built in the 1930s: the Colonels’ Row. They are on Arnoldo Cano Arosemena Street, in a long curved row bordering the City of Knowledge sports and recreational park.

The first 14 houses were built in 1933 according to a single style, which was also used in other bases in the Canal Zone. They were designed by the architect Rolland C. Buckley.

These residences corresponded to a new design philosophy, di erent from the neoclassicism of the first set of buildings on the base. Instead of standing on short posts, the new houses were raised several feet o the ground. This allowed the ground floor to have a larger space that

was used for the service room, garage, laundry and storage.

Between 1934 and 1935, architect Francis R. Molther built two more houses according to a di erent design. Stylistically, these houses are similar to the United States Mission Style, whose main distinguishing feature is the interesting finishes on their side facades that seem inspired by the church of Nata, one of the best-known colonial monuments in Panama.

Five more o cers’ houses were built in 1940, this time much simpler because they were temporary structures, made to fulfill a temporary demand. They belong to the type of mixed construction of concrete, wood and zinc that spread throughout the Canal Zone during the 1930s.

Clayton architecture, 1932-1933.

Clayton architecture, 1932-1933.

Iconic building 104

Architect Rolland C. Buckley designed building 104, which was completed in 1933. Today it is the headquarters of the City of Knowledge Foundation. It is the first structure to rise in the Central Quadrangle. The front part did not face the Panama Canal, instead it faced the interior field that was used for military parades. It was then called Soldiers’ Field.

Building 104 was originally a gigantic barrack that provided lodging to some 500 soldiers from four artillery companies. On the first floor of the building, separated from the ground by small posts of approximately one-meter height, there

were dining rooms, living rooms, barber shops, o ces and service areas. The top two floors were mostly occupied by bedrooms.

The building underwent major changes in 1961 when it became the Clayton Community Service Center, with a convenience store (“PX” in military slang), post o ce, library, and classrooms. When it became the headquarters of the Southern Command in 1986, it was transformed once again and remained mostly an o ce building.

Former barrack of the 11th Engineer Battalion in Soldiers’ Field, built between 1939-1940.

Former barrack of the 11th Engineer Battalion in Soldiers’ Field, built between 1939-1940.

Aerial view of the City of Knowledge Central Quadrangle.

Aerial view of the City of Knowledge Central Quadrangle.

The Central Quadrangle

The rest of the buildings in the Central Quadrangle were built as barracks, between 1936 and 1940, to lodge a regiment of engineers. The administrative o ces of the regiment were in building 100 (today a school).

The architecture of this building was distinguished from the other barracks by its two lateral wings, lower than the main body, and by the three massive Art Deco-style doorways.

At the time when these buildings reverted to Panama they looked very di erent from their original version. All had been heavily modified, mainly as a result of the installation of air conditioners.

The window bays were shortened and some were even closed completely. All the original window frames were removed, most of them in the 1960s. Given the way in which spaces were enclosed, it is di cult today to notice that the ground floors of these buildings are lifted o the ground on posts.

Spanish Colonial Revival Style in Clayton

Two buildings were designed between 1934 and 1935 by the Panamanian firm Wright & Schay: a social club (beer garden and restaurant) and a cinema, which is today the City of Knowledge Athenaeum (Ateneo) Theater.

Both were made according to the Spanish Colonial Revival trend known in Panama as “bellavistina”, a picturesque and romantic style of irregular volumes and decorative details.

The American architect James C. Wright, renowned in Panama for designing the Santo Tomás Hospital in the times of Belisario Porras, together with the Hungarian Gustavo Schay, perhaps the best designer of the time in the country, had a large clientele among the Panamanian upper class. During that same period, they created their best residential designs in Bella Vista, generally in a neocolonial style, among them the Hispania, Souza and Riviera buildings (all three still standing).

Interior scene in the old Clayton Social Club, built in 1934.

Interior scene in the old Clayton Social Club, built in 1934.

The good neighbor

In the early 1930s, US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt launched his “good neighbor policy” toward Latin American countries, which would allow the US to strengthen its influence in the region with a less military-focused interventionist approach.

In this context, the idea of a Panamanian police force, less dependent on the military forces of “the Zone” was gaining ground in Panama. The presidential term of Harmodio Arias (1932 - 36) was witness to the beginnings of the process of

institutionally reorganizing and professionalizing the National Police.

The Treaty signed in 1936 between Presidents Harmodio Arias and Franklin Delano Roosevelt represented a fundamental legal change in the relations between Panama and the United States. The treaty eliminated the right of the latter to intervene militarily and suppressed the concept of a protected country. The Treaty was not ratified by the United States Senate until 1939, the year in which World War II began.

Presidents Franklin Roosevelt (United States) and Harmodio Arias (Panama), during a visit to Fort Clayton, 1935.

Second World War Military bases all over the isthmus

During WWII the Panama Canal was probably the most strategic location in the world, providing the US with a crucial passageway between the oceans that facilitated the safe movement of warships, troops, and supplies.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt placed the Canal and the entire “Zone” under military orders in 1939. The US Congress allocated $50 million to improve the canal’s defenses, a sum equivalent to 10% of the entire US military budget.

The sympathy of Panamanian President Arnulfo Arias for Nazi Germany and his refusal to collaborate with the US on defense matters, made the US government consider the convenience of a Panamanian military apparatus aligned with its strategic interests.

A coup by the National Police ended Arnulfo Arias Madrid’s first term (1940 - 1941) and placed Ricardo de la Guardia Arango (1941 -1945) in the Presidency. He declared war on the Axis Powers in December 1941, making Panama the first Latin American country to do so.

In 1941, President de la Guardia promoted Jose Antonio Remón Cantera to Second Commander of the National Police, position from which he undertook the process of militarizing this entity, whose interventionism in the political life of the country intensified thereafter.

De la Guardia also signed the Lease of Defense Sites Agreement of 1942, whereby Panama leased to the United States 134 defense sites scattered across the country, including 77 airstrips, the most relevant being that of Rio Hato.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, American analysts assumed that the next target would be the Panama Canal, so an air patrol system that covered the entire isthmus was immediately launched. Later it acquired regional scope.

Howard Air Force Base (opened in 1941) played a major role in this scheme. The Canal defense also included an extensive network of naval reconnaissance.

The total number of U.S. troops in Panama reached its all-time high in 1943: close to 67,000 o cers and soldiers, which represented at that time one American soldier for every five Panamanian men.

Building in Clayton during World War II

During WWII, the military population of “the Zone” increased exponentially. It was necessary to expand some bases, including Clayton, and to build more housing for troops and the o cer corps. On the eve of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 Clayton already had a population of 4,074.

It was at that time that the so-called New Post was created, a vast expanse at the northwest end of the base, which today in the City of Knowledge is known as Lakes Park. This complex, created between 1940 and 1941, had 17 barracks, all grouped around a huge empty polygonal space of just over 17 acres. The standard barracks models developed by the American architect Harold W. Sander were used (also

seen in Albrook, Corozal, Howard, Davis and Sherman).

This type of barracks became practically obsolete in the 1950s, when Clayton’s population declined and housing concepts changed. In most cases, the large sleeping rooms were subdivided or recycled for other purposes. The introduction of air conditioning also led to the closing of large windows, so that the character of Sander’s architecture was lost.

Current aerial view of Lakes Park (formerly known as the New Post)

Current aerial view of Lakes Park (formerly known as the New Post)

TAKE A WALK:

Walk through Lakes Park in the City of Knowledge.

Discover “Los Fundadores” Square, where you will see the sculptures of Panamanian artist Brooke Alfaro in homage to Gabriel Galindo and to Fernando Eleta, who at the end of the 20th century envisioned transforming Fort Clayton into a Socratic plaza, seeking to replace “soldiers with students and weapons with books.”

Postwar and Cold War in Clayton

In Fort Clayton, as in the rest of “the Zone”, architectural and urban concepts took a radical turn. While the military population of the Canal Zone dropped dramatically (from around 67,000 in 1943, to 6,600 in 1959), soldiers increasingly came with their families.

The designs, much more standardized and inexpensive than those of the pre-war era, were developed in the United States. Between 1948 and 1949 a set of 36 single-story simple and modern duplex houses were built for sergeants and corporals. These houses were located at the far north of the current City of Knowledge. Despite being designed with the tropical climate in mind, they were the first buildings in Clayton to break away from the traditional image of Canal Zone architecture.

Stages of construction of Fort Clayton between 1922 and 1979.

STAGES OF CONSTRUCTION IN FORT CLAYTON BUILDINGS CONSERVED FROM THE ORIGINAL BASE, 1919-1922

EXPANSION, 1932-1940

EXPANSION, 1940-1941

EXPANSION, 1942-1943

EXPANSION, 1948-1949

RESIDENTIAL AREAS, 1958-1969

RESIDENTIAL AREAS, 1978-1979

BORDERS OF THE CITY OF KNOWLEDGE

The traditional defense systems, based on enormous military presences, lost their validity during the Cold War, because their maintenance was very expensive and they no longer offered any protection against air attacks.

In 1957 the large infantry barracks built in 1920 and the old stables at the southern end of the base, near the Cardenas River, were demolished. They were replaced by new duplex houses, almost all single-story and inexpensive.

By 1961, the number of married personnel had risen to 45%. It

was necessary to modify the old massive barracks, where the troops slept in large rooms without any privacy; or to replace them with more comfortable buildings with individual dwellings.

The last expansions in Clayton were carried out between 1965-1969 and 1978-1979. These expansions more than doubled the urbanized area, mostly towards the northeast, outside the area occupied today by the City of Knowledge. Several hundred housing units of a suburban character due to their layout and architecture, were built in these last two expansions.

Canal, militarism, sovereignty …

General protests by the Panamanian people against the US military presence, succeeded in canceling the Filós-Hines Agreement in 1947, which would have given permanence to the military bases located outside the Panama Canal Zone.

The broad set of relationships established during WWII between the US and the Latin American and Caribbean armies subsequently served as a platform for war e orts against communism. To that end, the School of the Americas was established at Gulick, as well as the Inter-American Air Force Academy at Howard and the School of Military Cartography at Fort Clayton.

Jose Antonio Remón Cantera was in charge of Panama’s National Police between 1947 and 1951. He maintained close relations with Washington and directly benefitted from its growing economic and political support for militarism in Latin America, in response to the growing insurrection and social rebellion in the region, within the framework of the Cold War.

1952: An important moment for the advancement of militarism in Panama was the arrival of Remón Cantera to the Presidency of the Republic, from where he turned the National Police into a National Guard, a body already fully militarized. With Remón moving into the Presidency, Bolívar Vallarino became head of the National Guard, a position that he held for 16 years (until 1968).

In January 1955, a few days after the assassination of President Remón, Panama and the United States signed the treaty known as Remón-Eisenhower, in which Washington made important economic concessions and returned some land and properties to Panamanian jurisdiction in Colon, Panama and Taboga. In exchange, the US received authorization to carry out military exercises in Rio Hato for 15 years (until 1970).

Between 1951 and 1999, Fort Sherman in the Caribbean hosted the jungle operations training center, through which thousands of US soldiers passed and which contributed to the testing of equipment, materials and armaments for tropical warfare.

US military bases in Panama were used to train soldiers who would go to the Vietnam War (1955-1975), and in the 1960s for the so-called “space race” with the Soviet Union.

For 13 years, between 1968 and 1981, General Omar Torrijos was head of State. In the photo, in December 1969, Torrijos is speaking to the country, after blocking an attempted coup against him.

In January 1964, an incident initiated by students from both countries led to serious clashes in the cities of Panama and Colon between the US armed forces and the Panamanian civilian population, causing 23 deaths and more than 500 wounded on the Panamanian side.

Those events gave rise to a significant change in Panamanian public opinion and favored the negotiation of a treaty that would transfer to Panama the operation of the canal and all jurisdiction over the Canal Zone, as well as assuring the departure of US troops from Panamanian territory.

The growing role of the National Guard in political life and in the conduct of state a airs as a parallel power, led to a coup d’état in 1968, starring its middle commanders.

The regime that emerged from the 1968 coup suspended the political party system, freedom of the press, and other civil and democratic rights. In spite of this, Torrijos’ charismatic leadership achieved growing popular support for the cause of Panamanian sovereignty over the Canal and “the Zone”.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Latin American Southern Cone intelligence agencies worked together under “Operation Condor” to eliminate all political dissent to dictatorial regimes. From the bases in the Canal Zone, this operation received support logistically and through advanced communications.

LOOK IN THE EXHIBITION:

Watch a five-minute video on the screen explaining the US military base system in the Canal Zone as it operated around 1963. Look for the photograph in which President Remón appears carrying a weapon.

Do you know what the School of the Americas was and where it was located?

Incident between students and Canal Zone police in Balboa, January 9th, 1964. Postcard of the old School of the Americas at Fort Gulick, Colon.

TO DISCUSS:

Why do you think General Torrijos said that the Canal Neutrality Treaty placed the isthmus “under the Pentagon’s umbrella”?

Torrijos-Carter Treaties The eighties

In 1977, the Torrijos - Carter Treaties were signed, eliminating the Canal Zone as the territorial jurisdiction of the United States in Panama, and establishing the calendar for the transfer of the canal and the military bases over to Panamanian control. A simultaneous treaty established the permanent neutrality of the Panama Canal and put it “under the Pentagon’s umbrella” (to quote Torrijos). The implementation of the Treaties took place over 20 years, between 1979 and 1999.

At the beginning of the 1980s, the proliferation of revolutionary movements in Central America led the US Southern Command to play a logistical, military intelligence and counterinsurgency supporting role in the region.

In 1981, Torrijos died in a plane crash. After various maneuvers, in 1983 Manuel Antonio Noriega assumed command of Panama’s National Guard. Noriega transformed the National Guard into the Defense Forces, a highly specialized military body that included command and special forces trained in Israel and in the United States.

Signing the Torrijos - Carter Treaties in Washington D.C., September 7, 1977.

Members of the National Guard march down Central Avenue during the 1968 coup d’état.

North American soldiers practice maneuvers on the eve of the invasion of Panama in 1989.

Signing the Torrijos - Carter Treaties in Washington D.C., September 7, 1977.

Members of the National Guard march down Central Avenue during the 1968 coup d’état.

North American soldiers practice maneuvers on the eve of the invasion of Panama in 1989.

LOOK IN THE EXHIBITION:

Observe on the screen the historical account presented in the film “The Last Soldier” (2010) by Panamanian filmmaker Luis Romero. As you will see in the selected testimonies, the historical significance the US military enclave in Panama has been understood in a contradictory way by the di erent layers and sectors of Panamanian society.

Noriega’s close collaboration with the United States in Central America and the Caribbean, as well as his duties as a bridge and mediator with Colombian drug cartels, made him extremely valuable to President Reagan’s regional policy.

Triggered by the assassination of Hugo Spadafora (1987), human rights violations in Panama would lead to an escalation of mobilization against Noriega and repression at the end of the 1980s.

The general’s growing involvement in drug tra cking, as well as scandals linked to the Iran-Contra a air, weakened Noriega’s politics in Washington. In 1988 he was indicted by a

Miami prosecutor’s o ce for his role in drug tra cking.

In December 1989, Noriega was overthrown and captured by the US armed forces during an invasion of Panama that caused (according to the Panamanian Catholic Church) more than 600 deaths among the Panamanian population, ending 21 years of military rule in Panama. There is still no o cial death count. The 1989 invasion of Panama involved more than 27,000 soldiers, making it perhaps the most important US military operation at the time since the Vietnam War.

Former Vice President Guillermo Ford in the documentary, “The Last Soldier”.

Guillermo Endara, Ricardo Arias Calderón and Guillermo Ford sworn in as President and Vice-Presidents of Panama, in a photo probably taken in Fort Clayton during the US invasion in December 1989.

Former Vice President Guillermo Ford in the documentary, “The Last Soldier”.

Guillermo Endara, Ricardo Arias Calderón and Guillermo Ford sworn in as President and Vice-Presidents of Panama, in a photo probably taken in Fort Clayton during the US invasion in December 1989.

Panama reorganizes its security forces

With democracy restored and the Defense Forces having been dismantled, Guillermo Endara’s government (1989-1994) was responsible for creating a new institution, for which it had American help. The new National Police was subordinated to the executive power and attached to the so-called Public Force. A reform to the constitution in 1991 established that “Panama will not have an army.”

The National Police (established in the Law of 1997) is today an armed body of a civil nature, attached to the Ministry of Public Security, in charge of maintaining and guaranteeing public order at the national level.

In 1998, the United States and Panama failed in an attempt to reach an agreement to continue US military presence in Panama to combat drug tra cking; and in the case of natural disasters, to continue providing humanitarian assistance.

On December 31, 1999, the Panama Canal and the entire contiguous territory of civil and military use passed over to Panama. For the first time in its republican history, there were no permanent US troops in Panama.

When the Southern Command left Panama, its new headquarters were established in the city of Miami, Florida. The bulk of drug tra cking violence in the region has passed in recent decades from Colombia to Mexico, and to the northern triangle of Central America.

Currently, “Panamax” military maneuvers are periodically carried out with the participation of naval forces from Latin American countries and the United States, with the purpose of maintaining military response capacity in the face of possible threats to Panama Canal operations.

The National Police, together with the National Aeronaval Service (SENAN), the National Border Service (SENAFRONT) and the Institutional Protection Service (SPI) currently constitute what is known as the Public Force.

El fin de una era

The land that made up the former Canal Zone reverted to Panama in various ways, through a gradual process that lasted 20 years. During the reversion process, the US defense sites subsisted as enclaves surrounded by territories that had already been returned to Panama. The handover of these sites was carried out on a schedule that ran from 1979 to 1999.

The U.S. Army presence in Panama was o cially terminated at Fort Clayton, on July 30, 1999, with the Casing of the Colors. Nine decades of continuous US Army presence in Panama culminated with this ceremony. The first permanent troops had arrived in 1910.

LOOK IN THE EXHIBITION:

On July 1, 1999, the Southern Command Network - SCN (better known by Panamanians as Channel 8) television channel transmitted its newscast from Clayton for the last time: “SCN Evening News”, a fragment of which can be seen on the monitor. The closing ceremony held that day culminated 58 years of operation, which had begun as a radio station in 1941 and also as a television channel in 1954. The first Panamanian television station (RPC-TV Canal 4) began operating in 1960.

US soldiers in a change of command ceremony at the old Soldiers’ Field, today the Central Quadrangle of the City of Knowledge. May 1997. Source: National Archives and Records Administration.

US soldiers in a change of command ceremony at the old Soldiers’ Field, today the Central Quadrangle of the City of Knowledge. May 1997. Source: National Archives and Records Administration.

From Military Base to Socratic Plaza

View of building 104, currently the headquarters of the City of Knowledge Foundation.

View of building 104, currently the headquarters of the City of Knowledge Foundation.

General planning for the Reverted Areas

An unprecedented urban-regional planning process was launched in Panama to manage the use of the former Canal Zone land and facilities and their connection to the country’s development. This process was led by the Authority of the Interoceanic Region - ARI (1993-2005) and included the participation of a wide range of sectors from Panamanian society.

As part of this process, the Regional Plan for the Development of the Interoceanic Region and the General Plan for the Use, Conservation and Development of the Canal Area, o cially approved as a law in July 1997, were drafted. It was this conceptual framework that favored the emergence of a strategic project such as the City of Knowledge.

“In this reversion process, the great challenge is undoubtedly the development of the national capacity to maintain and increase the e ciency of the Canal and the use of the reverted assets for the social and economic development of the country. That development of national capacity cannot take place e ectively without the participation of all members of Panamanian society.”

Federico Mayor Zaragoza, Director of UNESCO, at the presentation of the book City of Knowledge: A possible utopia (1996).

In 1993 a group of Panamanian businessmen conceived the idea of creating a “Socratic plaza” in Reverted Areas facilities, receiving the support from the national government the following year. In order to execute the initiative, the City of Knowledge Foundation, a private non-profit entity, was created in July 1995.

The conceptual development of the project was enriched by a process of contributions and consultations with broad social participation, which included advice from UNESCO. The results of this process were synthesized in the document City of Knowledge: A possible utopia (1996). Through Decree Law No. 6 of 1998, the Panamanian State established the transfer of 300 acres of old Fort Clayton to the City of Knowledge Foundation.

The formal transfer of the base to Panama took place on November 30, 1999. The ensemble was received by the National Government, and in the same ceremony it was handed over to the City of Knowledge Foundation, including the land and facilities that conformed it. Two days later, on December 2, 1999, the 11 persons who at that time made up the Foundation’s team entered the premises.

The rest of Clayton was divided into several parts. The forest areas were annexed to the Camino de Cruces National Park, created by law in 1992. The hospital passed over to the Social Security Fund and the rest of the built areas were privatized.

A new purpose

The City of Knowledge Foundation is responsible for the transformation of the former military base so that it can fulfill its new purpose.

The process of transforming the old military base has required the design and implementation of architectural, urban and landscape interventions inspired by guidelines that the City of Knowledge Foundation has been developing and perfecting since its creation.

In 2004, the City of Knowledge Foundation launched the process of preparing the Urban Development Master Plan for the site. The process took several years, and was o cially approved in January 2009. Its general objective was to organize the growth of the City of Knowledge, enabling the development of new structures and spaces on campus, within a comprehensive vision and with an adequate provision of infrastructures.

The Master Plan

The Master Plan is a living document. Its last update was made in 2019.

It identifies areas and establishes heritage conservation criteria.

It establishes the permanence of more than 60% of the campus as green areas. It determines expansion and densification areas for the development of new activities related to the institution’s mission.

It defines land uses.

It establishes urban regulations, and includes a road plan, pedestrian circulation and new parking areas.

It foresees interventions in the landscape to improve the quality of the surroundings.

The enhancement of a legacy

Old Fort Clayton is an important testimony of the US military presence in Panama and of the history of transits through the isthmus. The heritage value as a cultural landscape of its historic center stands out due to the urban concept that led to the four large complexes created between 1919 and 1941. The City of Knowledge Master Plan provides for the preservation of these and other values, establishing the mandatory conservation of the main complexes.

During the two decades since its inception, the City of Knowledge Foundation has managed to transform and make productive use of the 300 acres and more than 200 buildings that it received from the former Clayton military base to execute a national project: the creation of a space that favors the generation of knowledge, innovation and collaboration between the business, scientific, academic, cultural and humanistic communities, for the benefit of the development of Panama and the region.

The first 20 years of the City of Knowledge

Unlike other scientific and technological parks, the City of Knowledge focused from the beginning on integrating many elements of a true community into the project, with residential areas, schools, commercial services, recreational and sports areas, as well as a varied program of activities of knowledge dissemination and cultural and community activities, open to the general public. This has greatly favored the process of collective appropriation of this place by Panamanian society, that scarcely two decades ago was foreign and inaccessible.

As a result of this long e ort, the City of Knowledge Foundation has managed to bring together on campus an open and unique community in which scientists, thinkers, artists, businesspersons, entrepreneurs, experts from the government, NGOs and international organizations coexist, along with community representatives, who have all collaborated in the search for innovative solutions that generate social change.

A major challenge for the organization has been the transformation of historic buildings and spaces of former military use into a suitable environment for the development of the City of Knowledge project and its community of clients, users and visitors. The Foundation has made a constant institutional e ort to guarantee the necessary provision of services and infrastructure on campus, and achieve an e ective, sustainable and competitive management of spaces and buildings, as well as urban planning.

The Foundation has also managed to develop a specialized human team, experienced and committed to its mission. It has the leadership of a competent executive team, as well as the guidance of an active Board of Directors and a Board of Trustees in which prominent representatives of multiple sectors of the country participate: academic, scientific, business and governmental. An important community of allied persons and entities collaborates with the Foundation in the

development of impactful initiatives in multiple sectors.

Throughout the years the Foundation has ensured an e cient and transparent administration of its operations and finances, aligned with the priorities of the City of Knowledge project and ensuring its long-term sustainability. The organization is financially self-su cient since 2005, not receiving any government subsidy for its operations since then.

Its autonomy and stability have allowed the organization to develop a vision of what its role and contribution should be in a country in constant transformation. There have been many people who along the way have enriched the vision of the City of Knowledge project with their ideas, helping it to remain aligned with the needs of a changing environment, growing with the country and with the world.

The former Fort Clayton Post Chapel today houses coworking spaces for entrepeneurs.

The former Fort Clayton Post Chapel today houses coworking spaces for entrepeneurs.

“… A society where the vital logic of the majority governs over an exclusionary logic. Economy, democracy and society at the service of human beings. A country and a canal for peace. A country no longer bristling with weapons but strewn with justice and freedom. I believe that the City of Knowledge helps to achieve this .”

Activities and events with the community.

Mural at the Urban Market in the City of Knowledge.

Raúl Leis, 2010.

The public enjoys a music festival on campus.

Activities and events with the community.

Mural at the Urban Market in the City of Knowledge.

Raúl Leis, 2010.

The public enjoys a music festival on campus.

PREVIOUS NAME:

Dw ye r Stre et Steven s Stre et Coine r Stre et G e rra rd Stre et Winth rop Stre et M orse Ave n u e

Craig Ave n u e

C a ples Stre et M uir Ave n u e

G ailla rd Ave n u e

H awkin s Ave n u e

H a milton Pla ce

L a n d rich Pla ce

Stewa r t Loop

S a ltzm a n Pla ce

B oyles Pla ce

J oh n son Loop

Rom e ro Pla ce

Davis Loop

Pulle n Stre et An de rson Stre et H e n r y Pla ce

Wells Pla ce

Rich e Loop

names were not changed.

CURRENT NAME:

C a lle Ros a Elen a L a n d echo

C a lle Ric a rdo M u rg a s Villa m onte

C a lle J a cinto Pa la cios Cob os

C a lle Ovidio S a lda ñ a

C alle Víc tor Iglesia s

C a lle Albe r to O riol Teja d a

C a lle J osé E . G il

C a lle Víc tor M a n u el G a riba ldo

C a lle Et a nisla o O robio Willia m

C a lle Arn oldo C a no Arose m en a

C alle Vice nte B onilla

C a lle C a rlos Ren ato L a ra

C a lle G u st avo L a ra

C a lle Evelio L a ra

C a lle G onza lo Cra nce

C a lle Albe r to N ichols Con st a nce

C a lle Teófi lo B elis a rio d e la Torre

C a lle J osé d el Cid Cob os

C alle Celestino Villa rret a

C a lle Eze q uiel G onzá lez M en eses

Pulle n Stre et An de rson Stre et

H e n r y Pla ce

Wells Pla ce

Rich e Loop

9th,

TAKE A WALK:

The streets of the City of Knowledge bear the names of Panamanians who died during the events of January 9th, 1964. That day, a group of students from the National Institute school marched to Balboa High School in the Canal Zone to enforce the decree to raise the Panamanian flag next to the United States flag, according to the agreement that had been reached.

The