Building a Legacy

ISBN: 978-9962-8985-2-8

©All rights reserved. The total or partial reproduction of this book by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage system, is subject to permission in writing from the City of Knowledge Foundation / Fundación Ciudad del Saber.

Photos on cover and page 6: Sergio Ochoa Photos on pages 4 and 5: Kike Calvo

First edition in Spanish: November 2010 (Print run: 2,000) English-language edition: July 2012 (Print run: 1,000)

Graphic design and prepress: Dos Productions, Inc. (Panama)

Printed in Colombia by Printer Colombiana, S.A. on PROPAL paper, internationally classifed as “environmentally friendly”. http://www.propal.com.co

BUILDING A LEGACY

Essay by Eduardo Tejeira Davis

Edited by Walo Araújo

English translation by Monica E. Kupfer

View of Omar Torrijos Avenue, in front of the City of Knowledge. Photo: S. Ochoa.

Introduction

Our purpose in publishing this book is to document the legacy of the site where the City of Knowledge is located, not only in terms of its history, but also of its architecture, urban planning, and landscaping. Thirteen years have passed since the former U.S. military base of Fort Clayton was transferred to Panama, and this is the frst publication that offers the public a Panamanian account of its historical signifcance.

During the process of research, documentation, and refection that the production of this book involved, we became aware of a great amount of previously unknown

information about this place, about the way it was planned, and the details of its 80-year history as a military base. The research led Eduardo Tejeira—the Panamanian historian and architect in charge of the essay for this book—to identify important issues about the history of this area before the construction of the canal, as well as to recognize new links between this site —which was until recently “foreign” to us—and our country’s history.

Although the guiding theme in this book’s narration is the history of the urban planning and the architectural development of this area, Tejeira establishes signifcant connections with the social, economic, environmental, political,

and cultural history of the civil and military presence of the United States in Panama.

During the past decade, the former military base has been transformed by the City of Knowledge Foundation, adapting it to the needs of a project of the Panamanian State, which was to create a fertile environment in which private companies, the academy, research centers, non-governmental organizations, and organisms for international cooperation can cohabit and collaborate, in order to put knowledge at the service of a more human and sustainable development.

We also thought it was important that this book should provide the public with information about this transformation and the criteria that have inspired it, as well as the measures that have been adopted and the projects that are carried out for the conservation and valorization of the architectural and natural legacy that we received, while always keeping in mind that what our generations are capable of developing will also provide a legacy for those who will follow.

June, 2012.

Jorge R. Arosemena R. Executive Director City of Knowledge Foundation

Aerial view of the City of Knowledge from the southeast (2010). Photo: K. Calvo.

Between the Cruces Trail and the Rio Grande

Detail of a map of the Cruces and Gorgona Trails, dated 1735, drawn by the Spanish military engineer Nicolás Rodríguez. In red, the Cruces Trail; in yellow, the Gorgona Trail. The place where these two trails meet (referred to as “apartamiento” in the language of the time) was more or less one kilometer from the current northern limit of the City of Knowledge, near a place known as Guayabal. Notice the rivers Grande, Cardenas and Caimitillo, which kept their names over the centuries. (AGI, Sevilla, code MP Panama 137).

The City of Knowledge, a large complex of buildings and natural landscapes spread out over 120 hectares, was originally established in 1919 as Fort Clayton, a U.S. military base that reverted to Panama in 1999.

During the eight decades that it was in operation, Fort Clayton—its offcial name was Fort Clayton Army Reservation— was an important link in a system of military installations meant to protect the two entrances to the Panama Canal. As such, it was part of a vast development plan that had a profound effect on the topography and landscapes of the Canal Zone. This network of meticulously planned settlements was unlike anything that had previously existed in Panama.

In Earlier Times

Before the construction of the Panama Canal, Clayton was a rural area located between the Rio Grande and the legendary Cruces and Gorgona Trails1, an area of savannas, wetlands, and rolling hills located about six kilometers from Panama’s urban center. According to British traveler John A. Lloyd, sent to Panama by Simón Bolívar in 1827 to determine the best location for a new trans-isthmian route (either a road or a canal), the old Rio Grande, which is almost forgotten today, had its source “near a mountain called Pedro Miguel: and after receiving several streams, becomes navigable for very large canoes two leagues above its mouth, which is about two miles from Panama.” Back

then, there was a large sand bank at the mouth of the river, where, “at low water, there is not more than two feet water.” 2

Today, this historical landscape of pastures and waterfront swamps is hard to imagine: both the Cruces Trail and the Gorgona Trail were abandoned a century ago, and the towns of Venta de Cruces and Gorgona both disappeared under the waters of the Chagres River and Gatun Lake. The Rio Grande, formerly a twisting and swampy river, was straightened, widened and transformed into the entrance to the Canal.

The only important geographic feature that still exists without major changes is the Cardenas River, an affuent of the Rio Grande that marks the southeast border of

the City of Knowledge. The place named Cardenas has existed for centuries: on a well known map of the Cruces and Gorgona Trails from 1735 preserved in the General Archive of the Indies in Seville, the site, which lies between the two rivers and the Caimitillo River, can be identifed at the northwest edge of Fort Clayton. The only landmark indicated in this whole area, next to the Cardenas River, is a single dwelling with the name of “Don Victoriano,” possibly its owner.

The valley of the Rio Grande went through an initial great transformation between 1850 and 1855 with the building of the Panama Railroad. Once the railway line passed through there, it was no longer a mere backyard of the Cruces and Gorgona Trails. In fact, the last station before Panama, Rio Grande, was located precisely across from the main complex of today’s City of Knowledge. Fessenden N. Otis, who crossed the Isthmus in 1857 and published his experiences under the pseudonym Oran in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in 1858 and 1859, described the landscape as follows:

“[From Paraiso, the railway continues] over ravines, and curving around the base of frequent conical mountains, gradually descending, until lowlands and swamps, with their dense growths, were around … Crossing by bridges of iron the Pedro Miguel and Caimitillo, narrow tidewater tributaries of the Rio Grande, we passed the Rio Grande station; and from thence, through alternate swamp and rolling savanna, until the muddy bed of the Cardenas River was crossed…”

There are more specifc testimonies from the same period. In 1857, two years after the railroad was completed, German geographer Moritz Wagner traveled throughout the whole trans-isthmian area and described the fora and the geological confguration of each of the route’s sections. His report, published in 18613, included a detailed map by August Petermann, one of the best known cartographers of the nineteenth century, which shows the outline of the large swampy zone between the railroad and Rio Grande that began just across from the station. The map also shows the nearby haciendas

1 The Gorgona Trail, less remembered today than the Cruces Trail, was an alternate route between Panama City and the Chagres River; it was used during the dry season.

2 Source: “Notes Respecting the Isthmus of Panama,” The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, Vol.1, 2nd edition, London, 1833.

3 “Zu einer physisch-geographischen Skizze des Isthmus von Panama,” Ergänzungsheft zu Petermanns Geographischen Mitteilungen, Gotha (Germany).

During the 1880s, the Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interocéanique, under the leadership of Ferdinand de Lesseps, began the construction of the Panama Canal. It acquired most of the railroad company’s shares and large tracts of land along the route. It was at that time that the idea of taking advantage of the Rio Grande for the excavation was proposed.

In the precise French maps from the late nineteenth century one can see the meandering course of the Rio Grande, the canal route, the Rio Grande station, and a village along the tracks that must have been located more or less where the Omar Torrijos Herrera Avenue is today except that at that time, before the landflls, the topography was more irregular.

The Canal Zone was created as a result of the signing of the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty, and its existence entailed a complete spatial reorganization as required for the

construction, management and defense of the interoceanic waterway. It is a well known fact that the U.S. Government originally wanted to build a canal through Nicaragua (not through Panama) but in the end, in 1902, Philippe Bunau-Varilla and his allies, including Oliver Nelson Cromwell and Marcus A. Hanna, convinced the Senate to approve the Panamanian route, as long as certain conditions were met. Since Bogota refused to accept them, Panama declared its independence from Colombia.

In early 1904, Panama handed over the territory of the Canal Zone to the United States for it to use at will. The frst three years were dedicated to works of sanitation and infrastructure; the fnal mammoth stretch began in 1907 with the arrival of Colonel George W. Goethals of the Army Corps of Engineers. The Canal Zone developed almost like a colony, and the plans for restructuring the territory were fne-tuned over time.

This photograph, taken between 1906 and 1907, shows canal workers lining up for a meal at the ICC Kitchen in the Rio Grande camp.

Source: ICC Annual Report, 1907, Panama Canal Authority.

Detail of a French map (1:50,000 scale) of the proposed route for the Panama Canal, ca. 1895 showing the area between Mirafores (where Gustave Eifel proposed the construction of a set of locks) and the Bay of Panama. The Canal’s route is indicated in red and the railroad line in black. Source: Library of the Panama Canal Authority, map in exhibition.

according to the ICC Annual Report of that year. The image above is a colored postcard of the village of Rio Grande published in 1907.

Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection.

This is how the “Cardenas River Dump”, later known as the “Mirafores Dump” came into being. According to ICC data, it had a capacity for over 10 million cubic yards. Creating it had required dismantling the Rio Grande town and train station, which disappeared without a trace. Here, as in other areas, the land fll changed the topography and raised the ground. The original level of the Rio Grande station was many meters lower than the current level.

There is a large map from 1912 preserved at the Library of the Panama Canal Authority (drawn up during this transition period), in which the site of today’s City of Knowledge already appears as a possible area for military use. It coincides with a property named Cardenas, next to another area called Juan Díaz Caballero, which at one time belonged to Manuel Amador Guerrero, the Republic of Panama’s frst president. In August of that year, the U.S. Congress approved the Canal Zone Act and, on December 5th, by executive decree, the order was given to take possession of “all the land and land underwater” within its borders. The Zonian authorities evacuated the original population and created new settlements, which were different from the old riverfront villages and the temporary camps that had been established as a consequence of the excavations being carried out. there were numerous changes: places were given new names, even the topography was altered.

During the 1908 fscal year, the Isthmian Canal Commission (ICC) created a dump between the rivers Grande and Cardenas. This is how the “Cardenas River Dump”, later known as the “Mirafores Dump” came into being.

Fort Clayton

Fort Clayton, which succeeded the Mirafores Dump, was created as part of a grand plan for the canal’s defense, which started taking shape shortly before the waterway was completed. Even though the international agreements based on the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty of 1850 took for granted that, once built, the inter-oceanic canal would be strictly neutral, the United States insisted on the need for fortifying it. When Panama obtained

Detail of an Isthmian Canal Commission map (1:40,000 scale) that shows the properties that existed in the Canal Zone in 1912. Indicated in pink are the areas assigned to military use; in yellow, the land that belonged to the railroad; in green, the properties that in 1912 were still in private hands. Source: Library of the Panama Canal Authority, map in exhibition.

year later, it assigned the frst $2,000,000 for the work involved. The frst step was to protect both of the canal’s entrances with impressive gun batteries; the most powerful 16-inch guns were the largest in the world at the time. That same year, the frst permanent infantry detachments arrived and were housed in Camp Otis, not far from Camp Elliott. In 1913, plans were approved to build a large base near Balboa and two smaller ones on the Atlantic side: this was the beginning of Fort Amador, Fort Sherman and Fort Randolph, which were offcially named some time later.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914, two weeks before the canal’s opening, triggered the initiation of a truly ambitious defense plan. Within the U.S. military strategy of a century ago, when airplanes had only recently been invented and missiles did not yet exist, defense plans were based on multiple complex operations on land and at sea. In addition to protecting the entrances to the canal, the locks had to be defended, a task that

after the United States declared war on Germany, a committee under the direction of Brigadier General Adalbert Cronkhite was convened with the purpose of identifying the most convenient locations for the construction of these bases. It was suggested that one be built in Gatun (the future Fort Davis) and another one between the Mirafores Dump, Corozal, the Curundu River and Diablo that would come to be known as the Curundu Military Reservation.

This huge base, which included the Mirafores Dump, was formally created by an executive decree signed by President Woodrow Wilson on December 30th, 1919.

Just a few months later, it was decided to change the prosaic name of Mirafores Dump to Fort Clayton in honor of Colonel Bertram Tracy Clayton, who had died in combat in May of 1918 during World War I. The name Clayton didn’t mean anything to Panamanians on the other side of Ancon Hill, but it does have a place in the collective memory of the United States.

Born in Alabama in1862, in the midst of the Civil War, Clayton belonged to a distinguished Southern family. He studied at West Point military academy, where he was a classmate of the renowned General John J. Pershing. Clayton fought in the Spanish-American War of 1898, and from 1899 to 1901, he was a congressman for the state of New York. After failing in his attempt for re-election, he returned to the Army, where he held the position of Quartermaster (in charge of logistics and supplies for the troops) in several places: frst in the Philippines and later in the battlefelds of France, where he died during a German raid. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery on the outskirts of Washington D.C., and was the highest ranking West Point graduate to have died in World War I.

The enormous Curundu Military Reservation, which included Mirafores Dump, was created by President Wilson in 1919.

Aerial photo of the original Fort Clayton in the 1920s. On the right, between the Canal and the railroad line, one can still see the meandering course of the Rio Grande. Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection.

Detail of the map entitled Canal Zone and vicinity, Pacifc side, ca. 1963 (1:25,000 scale), adapted for this publication. In orange, the surface area of the former Fort Clayton (its jurisdiction included Curundu). Highlighted is the area of the City of Knowledge today. In green, the limits of the Canal Zone that existed until 1979. Fort Clayton’s surface area, with all its wooded parts, was larger than the districts of San Felipe, Santa Ana, El Chorrillo, Calidonia, Curundu and Bella Vista put together. The City of Knowledge today (120 hectares) is twice the size of Panama’s colonial quarter (Casco Antiguo). Source: Panama Canal Authority.

Fort Clayton and the other military installations in the Pacifc Division covered the southern entrance to the Canal from all sides.

Over time, Fort Clayton was separated from the original Curundu Military Reservation. It was never fully urbanized; a large part of the land was kept as a forest reserve.

Fort Clayton served as an Army base for 79 years. It was one of the military installations of the Pacifc Division—which included Howard, Kobbe, Rodman, Cocoli, Corozal, Albrook, Curundu and Quarry Heights— that covered the south entrance to the Canal from all sides. On the Atlantic side, the forts known as Sherman, Davis, De Lesseps, Gulick, Coco Solo, and Randolph formed a similar protective ring.

Until 1979, the year in which the Canal Zone ceased to exist as a political entity, U.S. military bases coexisted with the territory that was assigned to the Panama Canal itself. Once the Torrijos-Carter Treaties went into effect, the bases existed for a few more years as enclaves surrounded by land that had been returned to Panama. From 1986 to 1999, Clayton was the headquarters of the Southern Command, one of the U.S. Department of Defense’s ten Unifed Combatant Commands. Since 1963, its area of operations included all of South America and the Caribbean.

The built up areas of Fort Clayton grew in several stages until the base reached its peak and maximum population during World War II. Over time, it was separated from the original Curundu Military Reservation, which in the end was reduced to a residential area. In the 1950s, Clayton absorbed this new Curundu area. Fort Clayton was never fully urbanized; its gigantic surface area was larger than San Felipe, Santa Ana, El Chorrillo, Calidonia and Bella Vista put together. A large part of the land was kept as a forest reserve.

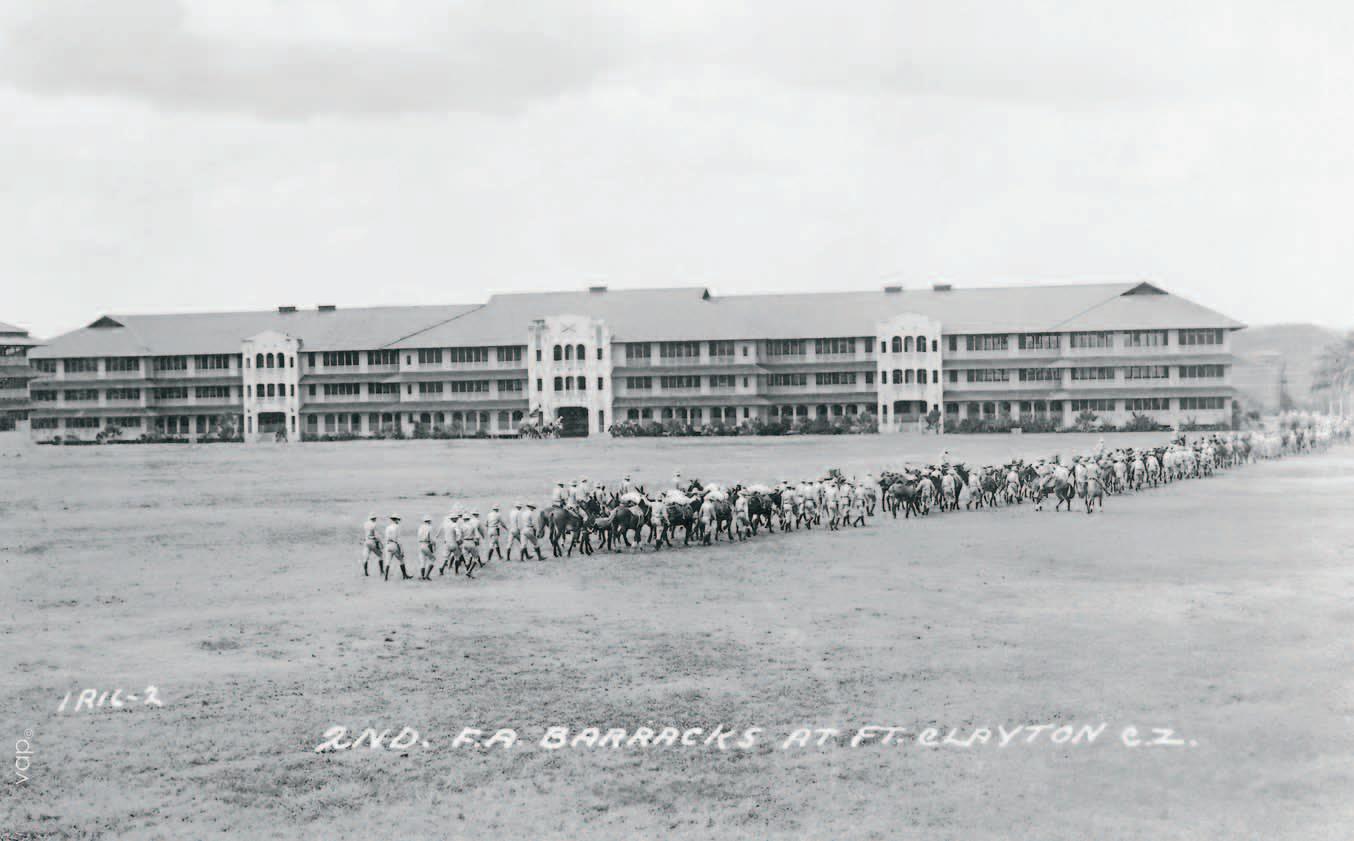

The original base outlined by the Cronkhite Committee was built on the southern end of the assigned land, between the Cardenas River and the railroad lines, precisely over the Mirafores Dump landflls. It included four large barracks for the troops, 26 houses for offcers and “NCOs” (Non-Commissioned Offcers)4, a main building for the administration, and eleven additional structures for stables and warehouses. The 33rd Infantry Detachment, which was the frst to arrive, took possession of the base on October 25th, 1920.

Although there had been a lull in the rhythm of construction in the 1920s, during the following decade the base began to grow. A regiment from the Corps of Engineers, others from the Field Artillery, the Medical Corps, the offces of the Quartermaster, and more, moved there. The population rose from 2,180 (2,117 soldiers and 63 offcers) in 1934 to 3,636 (3,543 soldiers and 93 offcers) in 1939.

The ordinal base was built between the Cardenas River and the railway tracks, exactly over the Mirafores Dump landfll. It included four large barracks for the troops and 26 houses for offcers and NCOs.

4 According to U.S. military jargon, the term “non-commissioned ofcer” refers to sergeants and certain corporals.

Music band on the parade grounds of the original base. Two of the four large barracks that were part of the base can be seen in the background. Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection.

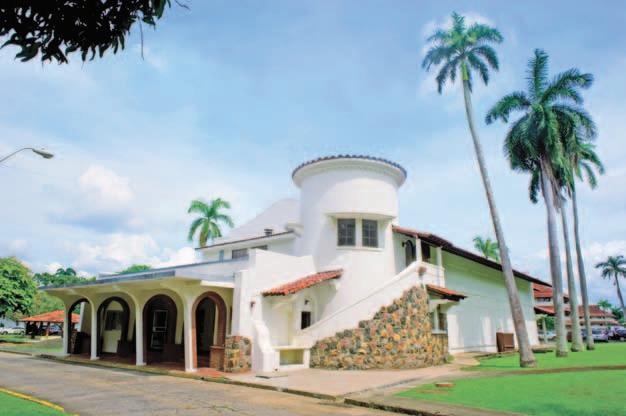

General headquarters of the original base. Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection.

Aerial view from the early 1930s, where the frst houses of Colonel’s Row (on the right side) are visible. Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection.

In 1931, the War Department created the Quartermaster Construction Division Planning Branch, which for a time employed architects and landscape designers of a certain caliber, not simple bureaucrats. As will be discussed later on, well known architects such as Rolland C. Buckley, Gustav Schay, and Harold W. Sander worked in Fort Clayton during the 1930s. Two compounds of great architectural and urban signifcance came into existence during that decade: the Offcers’ Row (or Colonels’ Row) of residential buildings that faced the vast Miller Field, part of which had initially been used as an airfeld, and the Soldiers’ Field (now known as the Central Quadrangle), where the huge Building 104 stands out.

When war broke out in Europe in 1939, Congress in Washington D.C. appropriated 50 million dollars for the improvement of the Canal’s defense system and

The architecture during Fort Clayton’s “golden age” (1930-1945) was characterized by “tropicalized” interpretations of the Mission and Art Deco styles.

President Roosevelt placed the whole Canal Zone under military orders. Fort Clayton grew even more and reached a population of 4,074 (3,927 soldiers y 147 offcers) in 1941, just before the attack on Pearl Harbor. It was at that time that the vast New Post (today’s Parque de los Lagos or Lakes Park) was created on the northwest edge of the fort.

When Clayton reverted to Panama, many of the buildings erected during the Second World War became a part of the City of Knowledge. Only the large hospital (which now belongs to the Caja del Seguro Social, Panama’s social security system), the former nurses’ residence and several sectors assigned for offcers’ residences remained outside the area. These had all been built between 1941 and 1943. After this golden age in the history of Fort Clayton, which was characterized by the widespread use of “tropicalized” Mission and Art Deco styles in its buildings, investment levels dropped.

Aerial view of the Central Quadrangle of the City of Knowledge. Photo: K. Calvo (2010).

Main façade of Building 104 (today the seat of the City of Knowledge Foundation), which was erected in 1933. The building was originally conceived as a gigantic barracks made to house four feld artillery companies. Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection.

Above: Athletic competition on the base’s track feld (see its location in the plan on page 31). In the background, one can see the ofcers’ houses built between 1932 and 1933.

Below, left: Tents on Miller Field.

Below, right: Former Clayton Hospital (1940-1943), which is today the seat of the Panama Social Security Headquarters. All three images are from the Vicente A. Pascual Collection.

Detail of

plan of Fort Clayton in 1942. Source: National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

During the Cold War, traditional defense systems based on gigantic military deployments became less important: the costs of their maintenance were too high, and they no longer offered protection against attacks from the air. In addition, relations between Panama and the United States were becoming increasingly tense. The possible loss of the Canal Zone was already being predicted in Washington D.C.’s higher circles.

In Fort Clayton (as in the rest of the “Zone”), the architectural and urban concepts took a radical turn. Although the military population of the Canal Zone was drastically reduced—from 67,000 inhabitants in 1943 to 6,600 in 1959— more and more soldiers were coming with their families. In 1961, the number of married personnel had risen to 45%. It became necessary to modify the huge old barracks, where the troops slept in large rooms with no privacy whatsoever, or to replace them with more adequate buildings with multiple

individual dwellings. Right after the Second World War, the restructuration and expansion of the fort was begun, a process that would be developed in four stages from 1947 through 1979.

The frst large housing project was developed on the so-called “Hill 2”5 on the northern edge of today’s City of Knowledge, followed by another compound located on the base’s original grounds (1958-1960). The fnal expansions, so large that they more than doubled the urban area, were carried out between 1965 and 1969, and again from 1978 to 1979, mostly toward the northeast. Several hundred housing units were built as part of the two latter expansion projects that took on a suburban character both in their layout and architectural style.

5

After the end of World War II, Fort Clayton’s architectural scheme was restructured. The frst expansion, a complex that included 36 one-story duplex houses, was carried out between 1948 and 1949.

Group of 38 housing units for corporals and sergeants fnished in 1943 (known today as buildings 301-316, 318-323, and 325-340).

Photo: K. Calvo (2010).

Source: City ok Knowledge Foundation.

FORT CLAYTON’S BUILDING STAGES

1919-1922 (Buildings preserved from the original base)

1932-1940

1940-1941

1942-1943

1948-1949

1958-1965

1965-1979

Limits of the City of Knowledge

Drawing:

The Handover to Panama

From 1979 to 1999, the Canal Zone reverted to Panama in different ways. During these twenty years, the Canal itself was jointly administrated by the United States and Panama. The transitional administrative entity, known as the Panama Canal Commission, was later transformed into the Panama Canal Authority. In order to reorganize the territory, a master plan was drawn up and approved in 1996. The forest reserves became the responsibility of the Autoridad Nacional del Medio Ambiente (National Environmental Authority). The properties on the military bases, which had been inventoried in great detail by the Southern Command, reverted in several stages. Each one of the bases was considered as a separate entity; the main intermediary was the Autoridad de la Región Interoceánica (Authority of the Interoceanic Region), which existed until 2005 and which initiated a privatization process that is still ongoing.

Through Law Decree No. 6 of 1998, the Republic of Panama established the transfer of part of Fort Clayton for the development of the City of Knowledge project.The 120 hectares that the City of Knowledge Foundation received in November of 1999, which are governed by a Master Plan approved in 2009, match what had been the base’s “historic center.” The rest of Clayton was divided into several parts: the forested areas were annexed to the Camino de Cruces National Park, established by law in 1992. The hospital, as has already been mentioned, was assigned to Panama’s Social Security, and urbanized areas were privatized. Nowadays, these areas are subject to the same pressures that are experienced and endured by the rest of the capital city.

Joint U.S.-Panama control at a sentry box in Fort Amador during the transition period. Source: Panama Canal Authority.

On the right: General Map of the Lands and Waters of the Panama Canal Treaty. Source: Panama Canal Authority.

The U.S. Army’s presence in Panama ofcially came to a close in Fort Clayton on July 30th, 1999, with the casing of the colors during ceremonies on the parade ground (today’s Central Quadrangle). Source: Panama Canal Authority

Celebration of the countdown for the fnal transfer of the Canal to Panama, on December 31, 1999. Source: Panama Canal Authority.

Architectural

and Urban Development in the Former Canal Zone

Far from being an isolated case, Fort Clayton was an integral part of the network of civilian and military settlements built by the United States throughout the former Canal Zone.

For this reason, any analysis of the architectural and urban legacy that this former base represents for Panamanians must be based on an understanding of the “Zone” as a whole, not an easy task considering the contradictory opinions still prevalent in our society towards the Canal Zone. The return of these lands to Panama has made it possible to visualize how the present-day site of the City of Knowledge relates to its pre-Canal Zone history, connections that have never been studied.

Most of the permanent settlements in the Canal Zone were created on the basis of the aforementioned Canal Zone Act of 1912. None of the historic towns along the Cruces Trail or the Chagres River were preserved, nor hardly any of the other pre-existing settlements. Places such as Matachin, Gorgona, Buena Vista, Chagres, Rio Grande, and others were erased from the map. Cristobal, a French settlement in Colon, is one of the few surviving sites that date from before 1904, although all the original buildings, including Ferdinand de Lesseps’ mansion, were torn down. Throughout the “Zone,” many historical place names were kept, although in connection with new sites. The American townsite Gatun, for example, has nothing to do with the original Panamanian Gatun.

All townsites related with the operation of the Panama Canal—Balboa with its magnifcent suburbs, Cristobal as rebuilt after 1912, Gatun and Gamboa, among others—were planned, built and rebuilt by the Isthmian Canal Commission or its successors: the Panama Canal, which existed from 1914 to 1951, or the Canal Zone Government and the Panama Canal Company, the two entities created by law in 1950 to replace the Panama Canal. Both disappeared on September 30th, 1979, just before the Torrijos-Carter Treaties (which sealed the end of the Canal Zone) went into effect.

The Panama Canal Company was in charge of the construction and administration of houses, hotels, and commissaries, whereas the Canal Zone Government, with its impressive bureaucratic apparatus, was in charge of the administration of schools, hospitals, and other public buildings. Balboa was the center of it all; the “government palace” was the majestic Administration Building, which had been fnished in 1914.

The military bases were a different matter. These were also highly regulated settlements, although under the specifc direction of the War Department, which became the Department of Defense in 1947. Although work on the Canal had been directed by military personnel from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the administration and the defense of the Canal were two separate worlds. In fact, the Zonian government and the military authorities were in open competition with each other and did not always get along.

PANAMA CANAL COMPANY

Canal Activity Commercial Activity Housing Activity

NAVIGATION

DREDGING

LOCKS

ENGINEERING

SERVICES

TERMINAL

COAL AND OIL

RAILROAD

S. S. LINE

UTILITIES

COMMISSARY

SUPPLY AND SERVICE

HOTELS

CLUBHOUSES

INDUSTRIAL

BUREAU

EMPLOYEES QUARTERS

CANAL ZONE GOVERNMENT

CIVIL ADMINISTRATION

The administrative apparatus of the Canal Zone in action: Gold Roll ofce workers, 1929. Source: Panama Canal Authority.

Previous page: With its colonnade in the Neo-Renaissance style, the Administration Building represents the epitome of Zonian monumentalism. Photo: E. Tejeira.

Source: Panama Canal Authority.

During the frst period, when architecture was all wooden, houses were separated from the ground by small piles and had hip roofs and porches protected with metal screens, a anti-mosquito measure instituted by Gorgas in 1905.

Group of wooden houses in Balboa, built for the Gold Roll in the frst decade of the twentieth century; later demolished. In the background one sees Ancon Hill, which had been deforested due to its exploitation as a quarry. Source: Panama Canal Authority.

Group of wooden houses for executives of the Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interocéanique in Cristobal (originally Christophe-Colomb) at the time of their construction, ca.1883. Source: F. Blanc et Cie., Panama.

The Pedro Miguel camp in 1911, with its wooden houses surrounded by screened-in porches. Source: Panama Canal Authority.

Residence of the Chief Engineer of the Isthmian Canal Commission built in Culebra in 1906 and moved to Ancon in 1914. Today it is the Canal Administrator’s house. Source: Panama Canal Authority.

The Canal Zone in 1913. At the time, the Canal Zone did not yet include all of Gatun Lake. Source: Abbot, 1914.

The architecture the Canal Zone is best known for today is not that of the military facilities, but rather the one developed by the Isthmian Canal Commission and its successors. It all started with the Architect’s Offce created in 1904 to take care of the over two thousand buildings inherited from the French Canal company, and to develop new architectural types based on the demands of the climate, health concerns, and the company’s rigid hierarchies. Under its frst director, New York architect Parker O. Wright, the Architecture Offce designed twenty-four different types of houses, in addition to schools, hotels, clubhouses, and institutional buildings, which were all initially built of wood.

The idea of centralizing this Offce was maintained throughout the Canal Zone’s history, although under different names; in later years it was called the Engineering and Construction Bureau, one of six the Panama Canal Company had for its operations.

During these seventy-fve years (1904-1979), a minimum of four major periods stand out in the development of civilian architecture, all easily identifed based on their formal characteristics: the initial period of wooden camps; the monumental, historicizing architecture in the decade of 1910; the mixed (concrete and wood) construction architecture of the 1930s and 1940s; and modernist architecture from 1950 onwards.

Very little remains from the frst period, with its wooden architecture similar to that of the earlier French Canal company; its most important vestige, which is today almost a relic, is the Canal Administrator’s Residence in Balboa Heights, originally built in Culebra in 1906 and rebuilt in its current location (albeit with some changes) in 1914. The houses, which were separated from the ground by small piles, had hip roofs and porches that were protected with metal screens, an anti-mosquito measure established by Dr. William C. Gorgas in 1905.

After 1910, plans were made on a grander scale. In 1912, Austin W. Lord, the Dean of Columbia University’s School of Architecture, came to Panama to start the design of Balboa, the splendid administrative capital. The following year, the Presidency sent a Fine Arts Commission, under the leadership of sculptor Daniel C. French and landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., to make a proposal on how to “beautify” the Canal Zone. Once they were in Panama, its members insisted that such a renovation was unnecessary, but the idea became established that the Canal Zone should have beautiful and monumental public buildings, surrounded by green areas. Instead of wood, which required constant maintenance in Panama’s climate, concrete slabs and plastered block walls were to be used.

Work in Balboa was begun in 1913, initially under Lord’s direction and later—when he left due to differences with Coronel Goethals—under Mario Schiavoni and fnally, under Samuel M. Hitt. The landscape design was directed by William Lyman Phillips, who would later become one of the most prominent professionals in his feld in the United States. The architecture favored at that time, based on the experience of the City Beautiful Movement in the United States and the principles of the École des Beaux Arts in Paris, was a Neo-Renaissance style of grand and sober forms.

The “Spanish” touch, above all in residential architecture, was achieved through the use of white walls, red roof tiles, and ornate brackets of colonial inspiration. The urban plan emerges from a grand central avenue enhanced by royal palms: the Prado.

On the other side of Ancon Hill, the hospital complex originally created by the French in 1881 was made more monumental. This brought about the creation of Ancon Hospital, which was renamed Gorgas Hospital in 1928. Architect Samuel M. Hitt projected a series of spacious neoclassical and neo-Renaissance buildings, all constructed between 1915 and 1919. Unlike the Prado, with its Versailles-like urban rigor, the hospital complex follows the lines of the sinuous topography.

Based on the experience of the City Beautiful Movement in the United States and the principles of the École des BeauxArts in Paris, the preferred architectural standard during the second decade of the 20th century was a Neo-Renaissance style of grand and sober forms.

Audience watching a match on the Ancon Baseball Field, as part of the Fourth of July celebrations in 1912. Source: Panama Canal Authority.

View of Gorgas Hospital, ca. 1920. Today it houses the Ministry of Health. Source: LOC/HABS.

View of Balboa from Sosa Hill, ca. 1920. In the background, the Prado and the Canal’s Administration Building, erected between 1913 and 1914. Source: Panama Canal Authority.

Along with the abandonment of the frst camps, the conclusion of the Canal and the massive reduction of the permanent population, the Zonian government drastically reduced its architectural programs. The most important urban project carried out in inter-war period by the canal company was Gamboa, which developed into a proper town when the Dredging Division was set up there in 1936. A new kind of mixed-construction architecture was used in Gamboa, one which allowed for the use of wood in the buildings’ upper foors. The ground foors, which were most susceptible to damage from termites and humidity, were built in concrete. The buildings continued to be made with hip roofs and wide eaves. Something similar was done in Margarita, a town established near Gatun in 1940, when the construction of the third set of locks was begun, but which was abandoned after Pearl Harbor.

Another important example from that period is New Cristobal in Colon. In 1912, the Canal Zone had received from the Republic of Panama the northeastern quarter of Manzanillo Island. The new settlement was planned with the same rigor as the other towns in the “Zone” (at the time, Colon only reached as far as Central Avenue). Houses and schools were built for the white population that did not ft in the original area of Cristobal, which had become too small once the port facilities were enlarged.

Between the two World Wars, the Canal Company’s most important project was Gamboa, where a new kind of mixedconstruction architecture of both wood and concrete was used.

Mixed-construction houses in New Cristobal, Colon, built in 1929.

Photo: E. Tejeira.

Aerial view of Gamboa, beautifully integrated into the landscape at the spot where the Chagres River meets the Panama Canal. Photo: E. Tejeira.

Mixed construction houses in Gamboa. (1941; Architect: Meade Bolton). Photo: E. Tejeira.

Colon, Boxed In by the “Zone”

For a long time, the city of Colon lived in the shadow of the United States. It was founded in 1850 by the Panama Railroad Company, a U.S. corporation, and in 1904, when the Canal Zone was created, most of its land came under Zonian control.

Cristobal, originally a suburb founded by the French in 1883, became an actual part of the “Zone,”and in 1912 Panama also handed over the northeastern part of Manzanillo Island so that New Cristobal could be established. During the construction of the Canal, the historic center of Colon, which was boxed in between Cristobal and New Cristobal, became a sort of bedroom-city for immigrant laborers, most of whom lived huddled in large wooden tenement houses. After numerous fres, wooden construction was prohibited and a neoclassical Colon came into being, with building rules that were based on Zonian regulations. It was not until 1943 that the control over Colon’s lands reverted to Panama.

Colon’s wooden architecture is now practically nonexistent. The photograph was taken in 1908, not long after the streets had been paved. Source: Underwood & Underwood.

Roosevelt Avenue in Cristobal, 1933. In the background one can see Front Street in downtown Colon.

Recent photograph of the Panama Railroad Company building. Photo: E. Tejeira.

The Canal Zone’s modernist architecture from the time after World War II, which was the product of a complete reorganization begun in 1950, envisaged replacing the remaining wooden buildings with more functionally designed structures: bungalows, semi-detached houses, schools, shopping centers, and hospitals, all of light construction, with no decoration whatsoever, and painted in pastel colors. Some important architects from the United States, above all the Chicago frm of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, were hired as consultants. This frm was responsible, for example, for the well known archetype of the “breezeway house,” a onefamily home designed to take maximum advantage of the breeze. The model urban project, with its network of roads based on several loops, was that of Los Rios (1952-1954) located between Albrook Field and Fort Clayton, which was followed by Cardenas (1961). Initially, the Zonian community showed no enthusiasm for this new type of architecture: according to some inhabitants, the houses were too plain and looked like “chicken coops”.

The Canal Zone’s post- World War II modernist architecture, which was the product of a complete reorganization begun in 1950, proposed the replacement of the remaining wooden buildings with more functionally designed structures.

Expansion carried out in the Ancon area in 1952. Source: Panama Canal Authority.

Aerial photo of Los Rios, 1955, with its semi-circular roads and dead-end streets, which were considered innovative at the time.

Source: Panama Canal Review, December 2, 1955.

Detail of one of the “breezeway houses” in Diablo Heights, the model for which was designed by the Chicago frm of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill in 1950. The two symmetric wings on the left and right generate a breezeway through the central section, which was used as the dining room. Photo: E. Tejeira

Civilian settlements had open plans, that is, they had neither fences nor sentry boxes. They were really like company towns for the Canal’s employees, and included movie halls, stores, clubhouses, bowling alleys, and other recreational facilities.

The settlements established by the Isthmian Canal Commission and its successors had open plans, that is, they had neither fences nor sentry boxes. They were really like company towns for the Canal’s employees, and included movie halls, stores, club houses, bowling alleys, and other recreational facilities. They had much in common with United Fruit Company’s banana plantations and other American company towns overseas, except that the scale was much grander, more imperial. There was no private ownership of land (which is why some people make reference to “Zonian socialism”), and no one had property rights over their living quarters. Living in the Canal Zone was directly dependent on working there. Every now and then, the Canal Company would rebuild, reorganize, or abandon complete communities, which meant the population had to be relocated. The term “permanence” had limited meaning; nevertheless, there was a strong sense of community, anchored in a surprising number of charity organizations, civic clubs, and religious associations.

Institutionalized racism was one of the most unpleasant features of Zonian society. As early as the time of the building of the canal, the camps were strictly segregated by race and salary ranking—the famous Gold Roll and Silver Roll— a fact that directly infuenced the architecture; non-whites always had worse houses, worse schools and worse community centers than the whites. After World War II, cracks started to appear in the system.

The terms Gold Roll and Silver Roll were replaced by US Rate and Local Rate, which people considered less humiliating. One by one, the segregationist measures in jobs, housing, schools, hospitals, restaurants, movies, and sports facilities were eliminated. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 gave the system its fnal coup de grâce, although discrimination persisted in less obvious ways for a long time.

According to the offcial hierarchy, Balboa and its suburbs—Balboa Heights, Ancon, Los Rios, Cardenas, and Diablo Heights on the Pacifc side—were for employees on US Rate salaries, whereas the more peripheral neighborhoods of La Boca, Paraiso and Pedro Miguel, were for Local Rate employees. At the other end of the “Zone,” Cristobal, New Cristobal and Margarita were the privileged areas, and Rainbow City was their black counterpart.6 Gatun and Gamboa were mixed, albeit segregated. The most exclusive area in the Zonian urban hierarchy was Balboa Heights, which was reserved for the governor and the highest-ranking employees of the Canal Company. Local Rate townsites were gray and impersonal.

Above left: Canal Zone Police. Above right: Curundu Elementary School. Center: a Canal Zone commissary. Bottom left: cayuco races. Bottom right: Balboa Union Church. Source: Panama Canal Authority.

Outstanding within the military landscape were the barracks: huge three or four story dormitories. This type of building did not exist in Balboa, Cristobal or Gamboa.

The military bases, intertwined in a complicated territorial puzzle within the Panama Canal’s system of civilian settlements, were more subordinated to Washington D.C.’s guidelines and had a different structure, a much more hierarchical one, due to the very nature of the chain of command. They were fenced in for security reasons—all had sentry boxes at their entrance gates— and the urban schemes were also more rigid; the buildings (above all the houses) refected their inhabitants’ rank. On the other hand, racial segregation was eliminated in the U.S. Armed Forces long before it was in the Panama Canal.

Until the 1950s, most of the population consisted of troops of single men; the army did not look favorably upon (and for a long time actually prohibited) common soldiers being married. For this reason, the military landscape was dominated by barracks, gigantic three or four story dormitories which did not exist in areas such as Balboa, Cristobal or Gamboa.

The military bases went through architectural stages that were similar, but not identical. There was also an initial phase of wooden camps, of which some houses in Quarry Heights have survived; a monumentalhistoricizing phase with barracks inspired in the plantations of the Old South; and a modernist phase. The most impressive growth, however, took place between the two World Wars, when the building activity in the civilian areas such as Balboa was minimal. The most important compounds in Fort Clayton (the Central Quadrangle and the Lakes Park that will be described in greater detail below) were built precisely during that period.

Postcards from 1960’s published by Dexter Press, Inc., N.Y. Left page, above: US Army Fort Clayton; below: Albrook Air Force Base. This page, above: Howard Air Force Base; below left: Fort Amador; right: U.S. Army School of the Americas at Fort Gulick.

Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection.

All of Zonian architecture, both military and civilian, had certain common characteristics. To begin with, it all had a very low density in comparison to Panama and Colon. In 1969, the population of Balboa and its suburbs did not reach 6,000 inhabitants, whereas San Felipe, Santa Ana and Chorrillo, with less than half the surface area, were home to twelve times more people. Zonian constructions were also necessarily “tropical,” because air conditioning was not introduced until the 1950s. Cross-ventilation was essential, and the architects in charge would combine closed spaces with semi-open areas—porches or verandas—which offered a transition to the outside. Later on, this “tropicality,” this special character defned by houses with large hip roofs that were surrounded by vegetation, would disappear; and although the residential architecture of the 1950s and 1960s was also based on coping with the rigors of the tropics, it was no longer “unique” nor immediately recognizable as “Zonian” in its style. In the sixties, the use of air conditioning became widespread, and the civilian and military authorities began to close porches and windows. In the process, the older buildings began to lose their charm.

In describing this urban system, Panamanians often portray it as a “garden-city” due to the low density, the curving streets, and the prominence of the vegetation in this unique environment of rain forests and lakes. However, the term is not really precise. The original garden city in England, which Ebenezer Howard dreamed of, was altogether different. The Canal Zone was more similar to the “greenbelt towns” of the 1930s in the United States, which specifcally promoted the public ownership of the land, as well as “the use of forested greenbelts as buffers between urban areas”7 as Kurt Dillon and Roger Trancik have described it.

It is also true that the original decision to reduce the urban areas to a minimum and allow everything else to remain wooded forested was taken very early on, possibly based on a direct recommendation by Goethals himself, who alleged reasons of security; the existence of this thick jungle complicated any invasion by land. The dramatic contrast between the buildings and the natural areas must also be understood cum grano salis: the “natural” is not really all that natural, because the landscapes and vegetation of today are very different from those which existed before the Americans arrived in Panama; some species were even imported from other tropical zones, including Africa and Asia. There were radical interventions in the topography everywhere: landflls, artifcial lakes and hills, channeled rivers. Drainage systems were perfected to such an extent that there were never any puddles of water.

Gatun Dam, possibly the best example of how engineering, architecture and natural landscape were integrated during the building of the Canal. The dam includes not only the spillway, but also all the fat, grass-covered grounds. It is so large that it can only be properly appreciated from the air. Photo: E. Tejeira.

7 Garden City: Progressive Planning and the Panama Canal, exhibition, Manuel E. Amador Hall, University of Panama, 8th Panama Art Biennial, September 2008.

The Buildings and Landscapes of the City of Knowledge

The previous chapter makes it clear that Fort Clayton’s legacy has much in common with that of other bases and the Canal Zone in general. Few buildings are unique, however, due to the fact that a more or less standardized architectural style was employed in all the forts, with certain variations depending on the historical period.

This history is very well documented. Most of the information, including a large collection of architectural plans, is preserved in the United States, mainly at the headquarters of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in College Park, Maryland.

In 2000, immediately after the end of the handover of the Canal Zone, the Southern Command sponsored the publication of a comprehensive monograph entitled Guarding the Gates: The Story of Fort Clayton - Its Setting, its Architecture, and its Role in the History of the Panama Canal, written by Susan I. Enscore, Suzanne P. Johnson, Julie L. Webster and Gordon L. Cohen.8 In this book, each building is described in meticulous detail, albeit strictly within the context of military history.

It is worthwhile to reconsider this heritage from the perspective of Panama’s civil society. Most important within this interpretation are the values that have transcended the political changes over the years, especially those related to architecture, urban planning, and landscape design. These are the values that we hope to understand and preserve for the future.

The Oldest Buildings in the City of Knowledge

Twenty-six houses for offcers and NCOs built from 1919 to 1922 survive from the time of the original Fort Clayton – the base proposed by the Cronkhite Committee in 1919 – all of which have been adapted for offce use.

The original layout of the base was horseshoe-shaped and strictly axial. An almost identical scheme was employed in Fort Davis, built at the same time on the Atlantic side across from the Gatun Locks. Instead of being assigned to the Armed Forces, the responsibility for the design and development of the plans went to the Panama Canal’s Building Division, which had all the necessary technical personnel. The architect was none other than Samuel M. Hitt, who had been in charge of completing the Administration Building in Balboa and of the project for the impressive Gorgas Hospital in Ancon (now the offces of Panama’s Ministry of Health).

Three enormous barracks measuring 146 x 13 meters were built around a large trapezoidal open space, known as the Parade Ground. Each one had enough

space for four infantry companies. There was a fourth, “special” barrack that had three foors rather than two. As mentioned previously, these barracks were all demolished in 1957, when they were replaced by a group of simple duplex houses. (Today, former Fort Davis still has barracks similar to those built in Clayton between 1919 and 1920).

The offcers lived in a different section, separated from the troops by a street and the headquarters building, which no longer exist. Their houses (Buildings 161, 162 and 164-181)9 clearly refect military hierarchy: there was one for single lieutenants, six for married lieutenants, seven for captains, fve for feld offcers, and one for the commander. The captains, feld offcers and commanders were expected to be married and to move to Panama with their families. The only offcer entitled to live with his family in a private, unshared space was the commander, a colonel. His house, located right on the symmetrical axis, was the last one to be built (in 1922), and the most traditional in design. With a wide veranda on three sides and an ample roof, originally shingled, the house resembles the bungalow of a grand 19th century colonial landowner in Africa or Asia. The inside layout is symmetrical: the living room and dining room are located in the middle and there are two bedrooms on each side, one in each corner of the house.

8 This chapter is based in great part on the information in that book.

9 In this book, the numbers correspond to the current scheme, created by the City of Knowledge Foundation in 2006 (see the plan on page 144). The original numeration used by the Americans appears in the 1942 plan on pages 30 and 31.

Original plan of Fort Clayton, 1919. The buildings located along Gonzalo Crance Street and Vicente Bonilla Street that still stand today are marked in green. Source: National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

Building 171 on Gonzalo Crance Street, while it was being refurbished in 2010. Photo: K. Clavo.

Previous page: Aerial photograph taken from the southeast end of the City of Knowledge in 2010. In the foreground on the right, in the shape of an arch, are the buildings on the Gonzalo Crance Street, which were part of the original Clayton complex.

The main façades of the original offcers’ houses look out on large green areas: nine towards the open space formerly known as Miller Field and eleven towards the opposite side.

Perspective view of Buildings 178, 176, 174, 172 and 170 (from left to right), built between 1919 and 1920. Photo: S. Ochoa (2010).

The nineteen houses for other offcers, fnished in 1920, are quite similar to each other and have a design that refects architect Hitt’s academic background. There were six units for single lieutenants; the married lieutenants were housed in buildings with four apartments, and the offcers of higher rank lived in buildings with two apartments each. Every apartment had a kitchen, a laundry area and a bathroom. The commander was entitled to four household servants, the feld offcers had two, and the lieutenants had one.

These houses belong to the neoclassical stage in Zonian military architecture, comparable to what was built in Fort Grant and Fort Amador in the 1910’s. Their strictly symmetrical main facades were decorated with neoclassical pillars. The lieutenants’ houses were statelier: they had double-height pillars in front of large verandas protected with mosquito netting. The buildings for feld offcers and captains, which were smaller because they only contained two apartments each, had a more intimate scale, with pillars placed in a more irregular rhythm.

The main façades of these twenty houses face large green areas: nine look out on the open space formerly known as Miller Field and the other eleven houses face the opposite side. The green areas create a view that gives the whole complex a dignifed and peaceful impression. The current access road (now called Gonzalo Crance Street) originally led to the back doors where the servants’ quarters were located. The back façades, which are relatively unattractive, have no decorative details whatsoever.

On the other side of the horseshoe (and with a view of the Canal), six more houses for NCOs were built, each one for four families (Buildings 112, 113, 114, 116, 124 y 125). These sergeants and corporals were not supposed to live near the offcers but rather near the troops, which is why they were housed on both sides of the “special” barracks. The houses are similar to the lieutenants’ residences, except that they are simpler: the design is of neoclassical inspiration, but without any ornamentation.

The later history of this complex has much in common with what happened elsewhere on the base until its handover to Panama in 1999. In the ffties, the kitchens and bathrooms were redone and louvered windows were installed. Between 1976 and 1978, all the window frames were reduced in order to adapt them to new, smaller, sliding windows. In 1986, the roofs were changed as tiles were replaced with metal sheathing, and air conditioning systems were installed. As of 1981, these houses were occupied by NCOs, rather than by lieutenants or captains.

The commander’s house, located on the base’s axis of symmetry, was the last to be built and the most traditional in its design:

century colonial landowner in Africa or Asia.

The architect in charge of the design and development of plans for the original base was Samuel M. Hitt, the same architect who fnished the Administration Building in Balboa and designed the Gorgas Hospital in Ancon.

The two façades of Building 161, originally built to house six single lieutenants, 1919-1920. Original plan by Samuel M. Hitt. Source: National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

One of the four-family housing units meant for sergeants and corporals. Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection.

The original commander’s house in Fort Clayton (Building 173), built in 1922. Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection.

Main façade of Building 112, which faces towards Omar Torrijos Avenue. Photo: S. Ochoa (2010).

Offcers’ Housing in the 1930s

In 1930, it was decided to move the 2nd Field Artillery Battalion from Fort Davis to Fort Clayton, and the housing needs of the troops and its offcers made it necessary to construct new buildings. Residences for offcers were built in a long curved line bordering Miller Field that became known as Offcers’ Row or Colonels’ Row, located exactly on the opposite side from the neoclassical houses built between 1919 and 1922.

The frst fourteen units (Buildings 355-368) were designed according to a single type, which was also used on other bases in the Canal Zone. The construction, for which the Winston Brothers Company of Minneapolis, Minnesota was hired, started in 1932 and fnished in 1933. All materials (with the exception of the sand and stone) were imported from the United States. The architect in charge of the design was Rolland C. Buckley, an American who had arrived a few years earlier and who was also successful as an architect in Panama’s capital city. It should be noted that there are two important projects of his in the city center: the original headquarters of the Compañía Panameña de Fuerza y Luz (Panama’s electric company) on Central Avenue (1932) and the old Century Club (1928-1929), today the Biblioteca Eusebio A. Morales, located across from the Palacio Justo Arosemena, Panama’s Legislative Palace. The latter especially refects the architect’s eclectic taste

In comparison with the offcers’ residences of the previous period, this group shows a better visual integration to the oval shape of Miller Field. There is a wide green strip between the sports feld and the houses around it that serves as a transitional element between the public and private areas. It is separated from the feld by a path and from the houses by another path and a backdrop of palms, trees and shrubs which add to the sense of privacy. Fences were not necessary.

The houses themselves corresponded to a new design philosophy, far removed from the rigors of Neoclassicism. The irregular character of the forms was accentuated by the asymmetry and geometric complexity of the roofs. The lack of monumentality went well with the picturesque quality of the landscaping, which is reminiscent of an English garden. In the Zonian collective memory, this type of house was considered truly “tropical.”

The structure is a concrete skeleton; between the pillars and the beams are small decorative brackets. Instead of raising the whole house above the ground—a solution

that produces dead spaces diffcult to keep clean– the architect placed it directly on the ground and left the frst foor to serve as a service area (maid’s room, garage, laundry, and storage space). The house itself, with its living-dining room in the middle plus its three bedrooms, kitchen, and bathrooms on either side, was on the upper foor, far from any pests. Facing Miller’s Field, each house originally had a wide porch, closed in with broad lengths of mosquito screens and shutters. This was the main façade; the one facing Arnoldo Cano Arosemena Street was the service entrance.

The main prototype for these new houses was designed by Rolland C. Buckley, an architect who also worked successfully in Panama City.

Page on the left: One of the frst fourteen houses on Ofcers’ Row, built between 1932 and 1933, seen from the sports feld of the City of Knowledge. Photo: E. Tejeira (2010).

Above: A house on Ofcers’ Row that shows Rolland C. Buckley’s original design. Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection.

The former Century Club (1928-1929), located across from the Legislative Palace, was one of Rolland C. Buckley’s well-known projects in Panama City. Photo: E. Tejeira.

Between 1934 and 1935, two more houses were built (Buildings 353 and 354) according to a different design by architect Francis R. Molther, a Cornell graduate who also worked in Panama. They were built by the Panamanian construction company Grebien & Martinz, which was authorized to work in the Canal Zone. This company had a long tradition and was very well known both in Panama and Colon. This time, the tiles were bought in Panama, rather than imported from the United States.

The foor plans are very similar to the earlier houses, except for the fact that these were designed for offcers of higher rank; for this reason, they had more bathrooms and better fnishes. In terms of style, they closely resemble the Mission Style in the United States, characterized mainly by the use of elaborately curved gables. The Mission Style is commonly inspired in California’s colonial baroque style. Nevertheless, in Panama the point of reference for this detail may have been the main façade of the church of Nata, one of the country’s best known monuments.

Five more houses for offcers were built in 1940. This time, they were much simpler because they were meant to be provisional structures, made to fll a temporary need. They are not architecturally pretentious and belong to the type of construction that combines concrete, wood and zinc that went up all over the Canal Zone during the 1930s. Four of these structures (Buildings 349-352) still exist today.

After 1950, houses were modernized in the usual manner. The most signifcant change was the closing in –with conventional doors and windows– of the porches that faced the green areas, eliminating the houses’ original feeling of transparency. In 1988, central air conditioning systems were installed, making natural ventilation unnecessary.

Aerial photograph that shows (in the foreground) the houses on Arnoldo Cano Arosemena Street, formerly known as Ofcers’ Row or Colonels’ Row. Note the ample green spaces in the sports area (the former Miller Field). Photo: K. Calvo (2010).

An image that shows House 353 (the same one that appears in the photograph on the left), shortly after its construction.

Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection.

A house for ofcers (Building 350) built in 1940. Photo: K. Calvo.

The Church of Nata (18th century) with its curved gable. Photo: E. Tejeira.

House 353 on Arnoldo Cano Arosemena Street, constructed in 1934-1935 by the Panamanian frm of Grebien & Martinz. The architect in charge of the design was Francis R. Molther. Photo: E. Tejeira.

Building 104, the largest and most emblematic structure in Fort Clayton, was originally a huge barracks. Like the frst houses on Colonels’ Row, it was designed by Rolland C. Buckley.

The Central Quadrangle

Today, the central core of the City of Knowledge is the monumental, rectangular complex that was known during the American period as Soldier’s Field.

This complex developed in stages. The frst building to be erected was No.104, the largest and most emblematic structure in all of Fort Clayton. The architect in charge of its design was Rolland C. Buckley, the same one who had been responsible for the project of the frst houses on Offcers’ Row, who drew the corresponding plans in 1932. The contractor was also the same one: Winston Brothers Co. The construction was fnished in 1933.

The huge building (it measures 156 x 22 meters) is remembered today as the last of the Southern 10

Command’s headquarters in Panama, but originally it was no more than a gigantic barracks that housed four feld artillery companies; approximately fve hundred soldiers lived there. On the ground foor, there were dining rooms, day rooms, barber shops, a few offces and the service areas—kitchens, storerooms and refrigeration rooms. The two upper stories were occupied mainly by large dormitories, each of which had sixty beds. The main façade was the one facing the feld; the one towards the canal was originally the rear façade.

Thus it remained until 1961, when it was transformed into the base’s Community Services Center, with a “PX,”10 a post offce, a library, and classrooms. When it was designated as the headquarters for the Southern Command in 1986, it was again transformed, becoming mainly an offce building.

The large dimensions make the building seem almost palatial. Its composition is based on the canons of academic European design, with a division of the main volume into fve sections, following an A-B-C-B-A rhythm that was common in monumental architecture during the 18th and 19th centuries. The original proportions were carefully thought out. The visual rhythms, fnely calculated based on the modulation of the concrete structure (with sections that measured 20 x 20 feet or 6.1 x 6.1 meters), required the distribution of the voids in uneven numbers and the highlighting of the symmetrical axis. Although there are three portals in each longitudinal façade, the one in the center is slightly larger than the other two. The roofs are more prominent in the center and the corners, and the eaves on each foor emphasize the sense of horizontality. Architect Buckley included some details derived from the Art Deco movement and the Mission Style, above all in the portals. The shaded corridor that faces the plaza is an evident reminder of the Hispanic urban tradition.

The original details, recorded in the 1932 plans, had much in common with the houses Buckley had designed for the Offcers’ Row; the panels that originally flled the concrete skeleton, with metal screening and louvers in the windows, were practically identical, granting the building a certain feeling of lightness in spite of its immense size. Unlike the houses on Offcers’ Row, however, the frst foor was separated from the ground by small piles, approximately one meter in height, in keeping with the traditional solution in Zonian architecture.

The Central Quadrangle today. In the background, Building 104, fnished in 1933. To the right, Buildings 102 and 103 (1940). Photo: M. Chapman (2012).

Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection

Building 100, headquarters for the main offce of the 11th Engineer Regiment, was a unique project in Clayton and in the entire Canal Zone.

The Central Quadrangle came into being when the decision was made to bring the 11th Engineer Regiment to Clayton. In order to have enough housing, it was necessary to build seven new barracks. These were grouped together around the new parade ground, which had an area of 2.3 hectares and was therefore somewhat larger than the original one from 1919.

The frst to be built, in 1936-1937, were Buildings 105 and 106, located on the southern side; the contractor was the Panamanian frm of Novey & Luttrell. The architectural style repeated the guidelines established by Rolland C. Buckley in Building 104: the screened windows with louvers, the modulation based on sections that measured 20 x 20 feet, the eaves on every foor, and the construction on pilings. Each barracks housed between 130 and 150 men. On the ground foor, there were common areas; the dormitories and bathrooms were located on the upper foors.

The fve remaining barracks (Buildings 100-103 and 107) were built between 1939 and 1940; the contractor was Robert E. McKee from El Paso, Texas. Four were made just like the frst two barracks; but the ffth, Building 100, was a special project that is unique in Clayton and in all of the Canal Zone. In addition to the dormitories for 180 men, the building housed the main offces of the 11th Engineer Regiment. From an architectural point of view, it stood out from the other barracks because of its two side wings, which were lower than the main body, and because of the three massive Art Deco portals, probably inspired by the Pueblo style of New Mexico or the famous “Puerta del Sol” in Tiahuanaco, Bolivia. The windows were also different: they no longer had louvers.

Building 100 was converted into the Clayton Elementary School in 1962. Since then, it has housed several schools. The eight buildings around the Central Quadrangle have been greatly modifed since the time they were built, due above all to the installation of air conditioning. In addition, all of the original fenestration was removed, mostly during the 1960s.

Recent photograph of one of Building 100’s Art Deco portals.

Source: City of Knowledge Foundation.

Building 100, administrative headquarters of the 11th Engineer Regiment, shortly after its construction.

Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection.

The Buildings of the New Post

With the breakout of World War II in 1939, the Canal Zone’s military population increased exponentially and it became necessary to enlarge some of the bases, including Clayton. New housing needed to be built for the troops and the offcer corps.

For the US Army Coast Artillery, a vast expansion was made on the northwest side of the fort, beyond an area that had been used until then for warehouses, parking lots, the fre station and other utilitarian structures; it was known as the New Post. Built between 1940 and 1941, it included seventeen barracks of three different types that were designed to house 100, 150 or 200 men (Buildings 221-225, 227-228, 230-235 and 237-240), all grouped around a large empty polygonal space with a surface area of over seven hectares. The standard barracks prototypes developed in 1939 by the American architect Harold W. Sander were employed. A much smaller building, to be used as the detachment’s main offce, was built on a hill (Building 220, fnished in 1942). The contractor was the U.S. frm of Tucker, McClure, Thompson & Markham, with headquarters in Los Angeles.

On the opposite end of the base, next to the original complex of 1919-1920, three more barracks in the style developed by Sander were constructed (Buildings 128, 129 and 130 on Arnoldo Cano Arosemena Street). These types of barracks, which were also built in Albrook, Corozal, Howard, Davis, and Sherman, were slightly different from the earlier versions on the Central Quadrangle: the windows no longer had louvers and, instead of the Dutch-hip roofs (a combination of gable and hip roofs), the barracks had hip roofs without the two gables, which had been used in traditional Zonian architecture to improve the ventilation inside the roofs. In this case, ventilation was achieved through the installation of ridge ventilators on the rooftops. The

New Post’s barracks also had a very low (2.30 meters) additional foor in replacement of the dead space that previously separated the buildings from the ground; in the fve barracks on the north side, these spaces formed a kind of basement against a sloping ground, but the rest had windows on all four sides.

The frst foor was planned for the common areas (living rooms, dining rooms, kitchens, etc.) and the two upper foors were for the dormitories. There were sleeping quarters for 16 and 32 men, and in the larger barracks they had some for 64 men. The NCOs had separate bedrooms.

The fact that these barracks were designed by Harold W. Sander now has practically been forgotten. Sander has gone down in history as one of the founders of the Modern Movement in Panama, above all because of his association with Octavio Méndez Guardia, with whom he developed well-known projects such as the Caja de Ahorros (a savings bank) on Central Avenue (1948), which was recently demolished; and the Hotel El Panama (1947-1951), which he designed in collaboration with Edward D. Stone. In fact, Sander worked successfully in both territories. When he came to the Isthmus in 1931, he worked in the Canal Zone, but later he expanded his area of activity to include Panama. Before working with Méndez Guardia, he designed Carlos Eleta’s residence in La Cresta (19401941), an eclectic project with an Art Deco undertone. Like no other architect, Sander managed to remain important to two clienteles: one Zonian and the other Panamanian. In the 1950s, when he separated from Méndez Guardia, Sander again worked in the Canal Zone; there he created schools in a modernist style for the Panama Canal Company. The best known is that in Diablo (1960), now occupied by the Policía Nacional (Panama’s National Police).

The New Post’s barracks became practically obsolete by the 1950s, when Fort Clayton’s population diminished and living concepts changed. In most cases, the large sleeping quarters were subdivided or recycled for other purposes. The introduction of air conditioning also led to the closing in of many of the open spaces, a process through which Sander’s buildings lost their character. At the time of the handover to Panama, the only barrack that was still in a state similar to its original form was number 230.

Harold W. Sander has gone down in history as one of the founders of the Modern Movement in Panamanian architecture, above all because of his association with Octavio Méndez Guardia, with whom he carried out several of his most acclaimed projects.

Building 220, which housed the New Post’s main ofces, was built in 1942. Photo: E. Tejeira.

Elevation drawings of standard barracks for 200 men, 1939. Buildings 221, 238 and 240, fnished in 1941, follow this model. Architect: Harold W. Sander. Source: National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

Photograph from the 1940s showing fve of the New Post barracks (current Buildings 221-225, from right to left).

Source: Vicente A. Pascual Collection.

Harold Sander’s Legacy

The fgure of U.S. architect Harold W. Sander, known in the Canal Zone for his designs of barracks and schools, proves that there was some degree of interchange between the closed Zonian world and the Republic of Panama. The famous Hotel El Panama, for example, was a design produced jointly by Sander, Edward D. Stone and Panamanian architect Octavio Méndez Guardia. This interchange explains certain similarities between Panamanian and Zonian architecture during the 1950s and 1960s. It is not coincidental that the very tropical residence designed by Méndez & Sander for Leroy Watson in Altos del Golf (1951) shows a certain similarity with the Breezeway House proposed by the Chicago frm of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill of Chicago for the modernization of Zonian architecture (see page 54); both have H-shaped foor plans, created in order to channel the breeze. This case was not unique; ten, twenty years before, the style for all of Bella Vista was infuenced by the Canal Zone Mission Style. Here and there, there are still apartment buildings directly inspired by Canal Zone barracks.

Above: Hotel El Panama (1947-1951). Architects: Edward D. Stone, Octavio Méndez Guardia and Harold W. Sander. Campo Alegre, an extension of Bella Vista developed in the 1940s, appears in the background. Flatau postcard, ca. 1951.

Bellow: Residence of Leroy Watson in Altos del Golf, Panama City (1951). Architects: Méndez & Sander. Photo: courtesy of Octavio Méndez Guardia.

Apartment building that belonged to David Montefore Toledano (1930), 50th Street, Bella Vista, demolished in the 1980s. Zonian infuence is clearly visible. Photo: E. Tejeira (1977).

Other Housing Complexes