Every farm is unique, even if they’re neighbours. That’s why you need a vaccination programme that fits your farm’s unique requirements.

Every farm is unique, even if they’re neighbours. That’s why you need a vaccination programme that fits your farm’s unique requirements.

The only specialised 5-in-1 pre-lamb vaccine that provides up to 4 months protection for lambs.

New Zealand’s leading 5-in-1 vaccine range with multiple options for supplementation1.

Every sheep farm is unique, so when it comes to vaccination, you need a programme that fi ts your way of getting things done.

NILVAX is the only pre-lamb vaccine that provides up to 4 months protection for lambs. This gives you the flexibility to vaccinate your ewes earlier to avoid sleepy sickness*, or vaccinate your lambs later due to the longer duration of protection provided via their mother’s colostrum.

MULTINE gives you multiple options for supplementation of Vitamin B12 or selenium in combination with New Zealand farmers favourite 5-in-1. This means you can get everything you need and nothing you don’t.

NILVAX and MULTINE. Two tried and proven pre-lamb vaccine options made right here in New Zealand, that give you flexibility and effectiveness for your farm.

Join with the team at Country-Wide to take New Zealand’s premier farming magazine up a notch.

Just like you do in your own farming businesses, we need to adapt to maintain our premium position as your trusted provider of farming information to help you learn, grow and excel.

From this issue, we’re changing the frequency of Country-Wide to two-monthly and boosting the number of pages to about 120 an issue so we can deliver more of what you want in your favourite magazine.

You will continue to see the type of content CountryWide is renowned for – on-farm excellence, cuttingedge research, coverage of new technologies and stories about the people who work on farms and agribusinesses around the country.

To complement this, we’re adding more in-depth coverage of the key issues impacting farming families and businesses. We’ll also be looking at what’s happening further down the value chain so you can get a better feel for the future and how it impacts the farmgate price for your meat, wool and crops.

0800 224 782

Six issues of the Country-Wide each year, plus our regular special Beef and Sheep publications. Regular content delivered through our email and social media channels, so you’re always up to date.

Call our subscriptions freephone on 0800 224 782 Visit country-wide.co.nz/shop and subscribe using your credit card. Farmlands or Ruralco cards are also accepted.

Or email subs@nzfarmlife.co.nz and one of our subscription team members will respond to help you through the subscription process.

12 months – $129

24 months – $252

3-* and 6-month subscription terms are available, visit our website for details.

*credit card payment only

subs@nzfarmlife.co.nz • www.country-wide.co.nz

Incomes are not matching rising costs as economic conditions deteriorate for businesses and citizens.

Companies and organisations that have been so focused on conforming to identity politics are now waking up to economic reality. They are focusing on costs and the true customer.

Auckland City Council is over staffed and Mayor Wayne Brown was elected to do a job. To help fill a $336 million budget hole, 500 jobs have to go. Will other councils, organisations and companies follow to balance their books?

The Government should be following Auckland’s lead, but won’t. If National and Act become the government after October’s election there is likely to be carnage in government departments and agencies’ back offices. Communication and middle managers should be nervous.

As inflation rises and incomes are static or fall, costs can’t easily be passed on, unless you have a monopoly.

Country-Wide’s publisher NZ Farm Life Media has had some tough decisions to make.

Most of its costs have gone up, but the worst has been NZ Post. In the past seven years magazine postage costs have doubled and now NZ Post will hike prices another 30% in July.

A campaign run by community networks and businesses is underway to keep New Zealand’s postal service open to all, especially those in rural areas. The campaign argues that the Deed of Understanding between NZ Post and the Government has been breached. All New Zealanders should have access to using post, but the price has now become a barrier.

Rather than raise the subscription price, NZ Farm Life made the decision to add value, not cost. Country-Wide has moved to a bi-monthly frequency, but we’ve added more pages. Our

writers have more time to dig deeper into issues and produce greater in-depth stories.

It’s about working with what we can control.

Farmers are handling costs by cutting back on fertiliser, shearing, etc, and being more strategic. They are using tools such as genomics or better management practices to add value, not just cost.

Adding new technologies doesn’t always end well if the cost is not supported by proven benefits. For example, buying highly fertile rams but not having the feed or management skills to profit from them.

The Government gave the Australian company Bluescope $140 million for an electric furnace at its Glenbrook steel mill in Auckland. By not burning coal it is said the plant will reduce NZ carbon emissions by 1%. Bluescope is reported to be about to build a furnace in Australia that will burn coal for 20 years.

Based on the warming effect, NZ farmers have reduced methane emission by 30% since 1990 without any subsidy.

Paying farmers to reduce emissions further rather than taxing them would be better bang for the buck.

terry.brosnahan@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Ph: 03 471 5272

CONTENTS

STATION BRED FAST FINISHED

Otairi station is a sheep and beef operation spanning three sites, which keeps manager Sam Duncan busy.

SERIES: M BOVIS

16 More questions than answers

BUSINESS

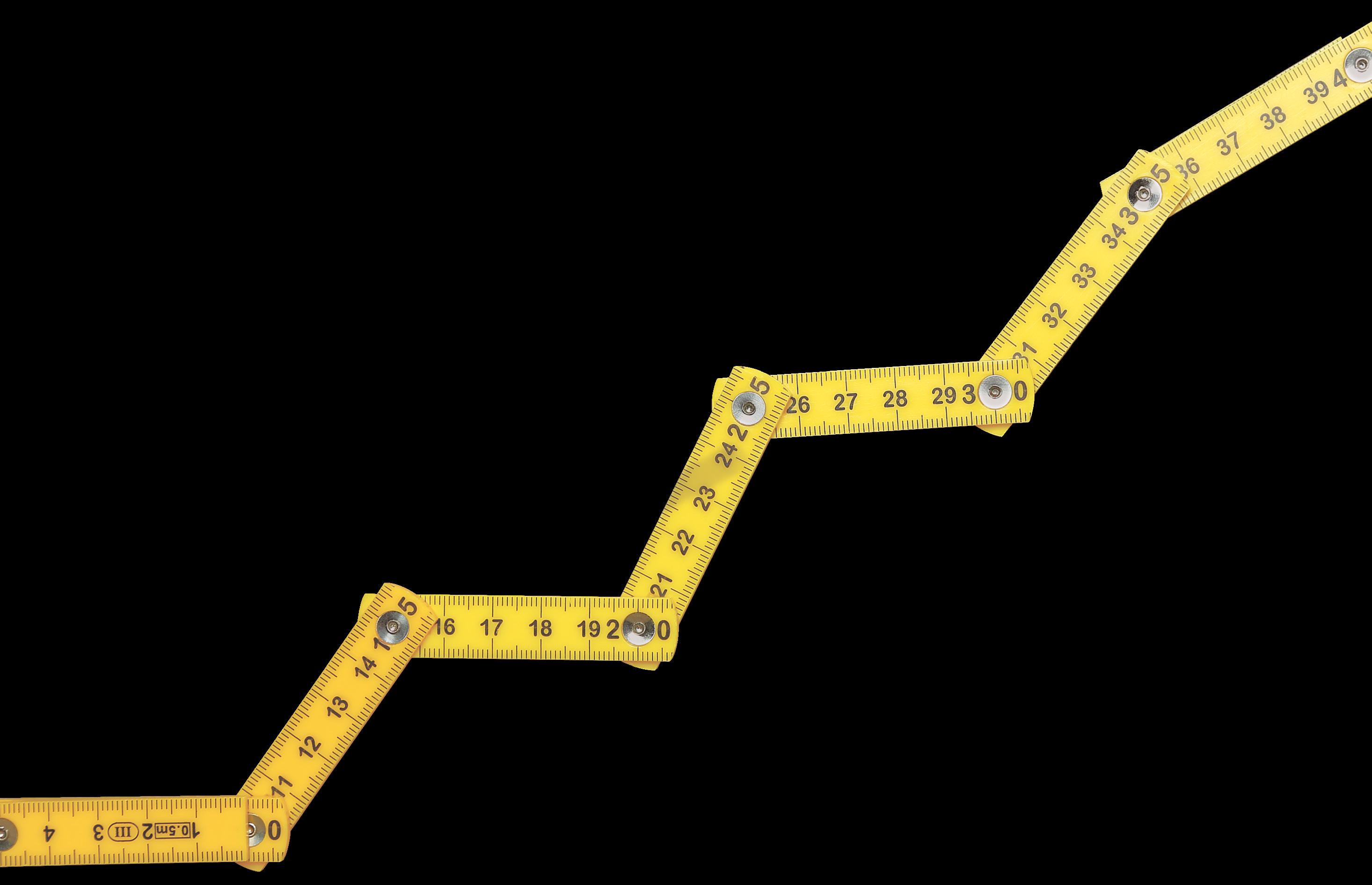

22 Look for hidden kilos and dollars

24 Measuring inflation is no easy task

27 Tim and Binds White have more in the tank

28 Jacqueline Rowarth asks: where are all the leaders?

30 Emissions: A bit of Irish biffo

32 Composite sheep advantage is not huge

ONFARM PROFILES

36 Fast-finished on Otairi

44 Crunching the numbers is second nature at Upperwood

56 West Otago’s ‘brilliant’ sheep

ANIMAL HEALTH

62 Ken Geenty: Beware subclinical FE

64 Vet Trevor Cook: The value of science

GENETICS

66 Genomic tools speed genetic gain

74 Bull sires for dairy leave their mark

SYSTEMS

82 Growth potential for Red Wagyu

90 Techno-grazing making good sense

98 Water scheme makes money flow

CROPPING

104 Fertiliser prices - Doug Edmeades asks: what to do?

108 How to achieve top maize yields

SOCIAL

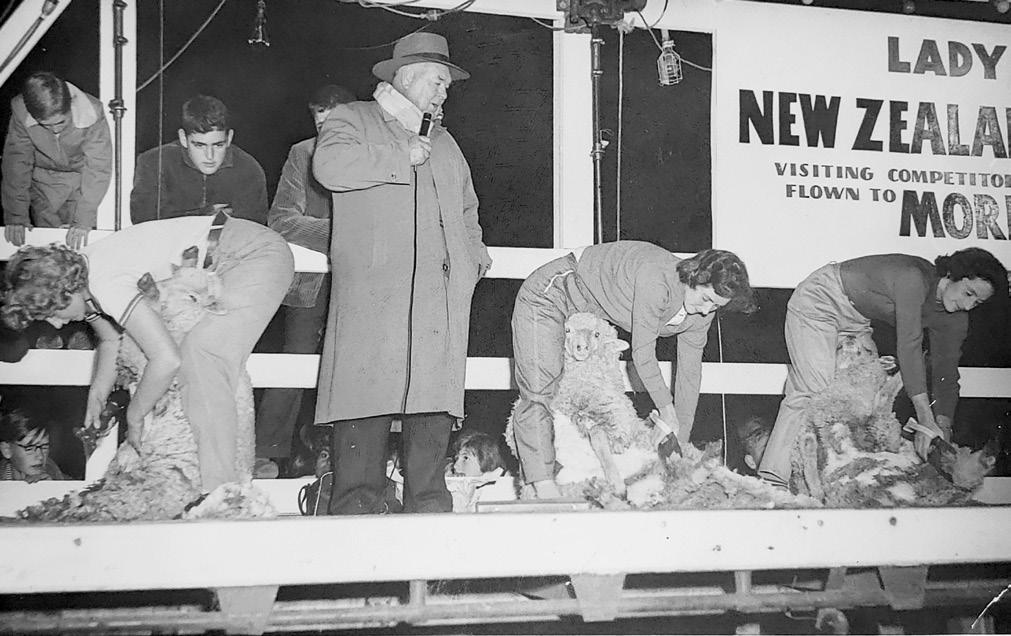

114 On the blades: A fair shear

118 Loosening the choke-hold on worry

120 Rural/urban divide exaggerated

REGULARS

9 BOUNDARIES

10 HOME BLOCK

15 AUNT THISTLEDOWN

122 FARMING IN FOCUS

Published by NZ Farm Life Media PO Box 218, Feilding 4740 Toll free 0800 224 782 www.country-wide.co.nz

Editor Terry Brosnahan 03 471 5272 | 027 249 0200 terry.brosnahan@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Publisher Tony Leggett 06 280 3162 | 0274 746 093 tony.leggett@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Sub editors Andy Maciver 06 280 3166 andy.maciver@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Alison Robertson

Designer Emily Rees 06 280 3167 emily.rees@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Production

Jo Hannam 06 280 3168

Writers

Anne Hardie 03 540 3635

Sandra Taylor 021 151 8685

James Hoban 027 251 1986

Jo Cuttance 03 976 5599

Joanna Grigg 027 275 4031

Glenys Christian 027 434 7803

Annabelle Latz 027 808 6469

Louise Savage 027 260 2750

Sarah Horrocks 027 555 7941

Partnership Managers

Janine Aish | Auckland, Waikato, BOP 027 890 0015 janine.aish@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Angus Kebbell | South Island, Lower North Island, Livestock 022 052 3268 angus.kebbell@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Tony Leggett | International 027 474 6093 tony.leggett@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Subscriptions nzfarmlife.co.nz/shop 0800 224 782 subs@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Printed by Blue Star, Petone

ISSN 1179-9854 (Print) ISSN 2253-2307 (Online)

Working dogs need powerful nutrition to help maintain vitality, energy and overall good health. Give them the fuel they need to do the job you need.

Speak to your vet clinic about ROYAL CANIN® Energy 4800

A FLATLAND AREA of Cumbrian countryside in England’s Lakes District has come on the market. It’s the largest single ring-fenced block of productive farmland the land agent has brought to the market for many years.

It’s only 116 hectares but it’s causing great excitement. While the agency mentions agriculture, the potential for solar generation and storage is the lead marketing push. For $NZ3.7 million you get some gorgeous dry-stone walls.

A study into farm sizes by the New University of Colorado Boulder has shown that globally, farm sizes are getting bigger. Small farms are being swallowed up. The researchers predict the number of farms globally will probably decline from the current 616 million in 2020 to 272 million by 2100. The average farm size is likely to double.

Smaller farms typically have more biodiversity and crop diversity. And while the world’s smallest farms might only take up 25% of the world’s agricultural land, they harvest one-third of the world’s food.

DID YOU KNOW?

The phrase ‘Daylight Robbery’ has been around for hundreds of years but its origin is far removed from the meaning of the phrase today.

The phrase came to prominence in the 1690s, when King William III was in dire need of money. He and his advisers devised the ‘Window Tax’, whereby houses with more windows would pay a greater amount of money. Because of this, people would board up their windows to avoid paying the tax. Some chose to build houses with fewer windows. This of course meant that there would be less daylight coming into their houses. Hence the phrase, ‘Daylight Robbery’.

Some of these buildings still exist in parts of England.

A young American man takes a trip out West and comes across a Native American village. He decides to stop and look around.

One of the Native women, seeing that he’s not from around there, tells the man he should visit the Chief, who she says has the longest and best memory in the world.

Intrigued, the man visits the Chief and asks: “I hear you have the

greatest memory in the world.” The Chief answers “I do. I can remember every single detail of my entire life.”

The man figures he should test this, and asks the Chief “What did you have for breakfast on April 27, 1959?”

After stopping to think for a second, the chief answers “two eggs”.

The young man isn’t convinced

so decides to carry on, he says goodbye to the Chief and leaves the village.

Twenty years later, the man takes another trip out West and visits the same village. He’s amazed when he notices the Chief, still alive after all these years. The young man stops to say hello, raises his hand and says, “How” and the Chief replies “fried”.

Jane Smith’s pleased there’s been a good autumn on her farm, but worries this year’s election might be a horror show.

to stand up for grassroots farmers and not be Wellingtonised in their approach. Post Beef + Lamb NZ’s AGM there appears to be a willingness to bring back the “by farmers, for farmers” mantra, and to scrutinise the methane myth and associated threat to one million stock units a year.

IN THE U.S, HALLOWEEN is the scariest night of the year. In New Zealand it’s election night. The election-year cup is overflowing with frothy promises, particularly for those who believe they have been marginalised, colonised or blamed for something that they actually did. Accountability has long left the building. Socialists are in a fiscal fantasy land, ignoring all signs of imminent recession while the smell of Crown money exudes out of the Wellington kremlin. Radicalists in cowboy hats do whatever the hell they like while a cacophony of hypocrisy from screeching, green feminists echoes through the corridors of misguided power.

North Otago has given us an unusually good autumn, which we feel guilty about when so many regions in the North Island are struggling to even get their fences reinstated. We have our Newhaven Perendale Stud 50th anniversary event shortly and our annual Fossil Creek Angus bull sale in mid-June. Blair looks forward to seeing each bloodline coming to fruition, while I look forward to a captive audience to talk politics with.

It’s been a challenging two years of asking agricultural representatives

A surprise came in May when the government inquiry into East Coast forestry ‘slash and run’ was completed in less than eight weeks. I’m hoping Mr Parker will finally realise that any regulation in isolation doesn’t work and communities should be able to take a “whole catchment” approach to solutions. I’m yet to see a resource consent do anything useful for the environment. All sectors should have an equal playing field, not a free pass for some and suffocation through regulation for others.

I’ve noticed the myriad of fancy primary industry conferences this year where righteous speakers with fancy job titles tell farmers what they are doing wrong. Ironically with a “special rate of only $900” to attend, there will be no real farmers in the audience anyway. I would rather spend the day and $900 at the dentist than listen to another self-proclaimed expert telling the world how NZ farmers “could” be good one day.

I’m concerned how quiet the Three Waters debacle has gone, considering that this is step one in the great “reset”. Back in 2016, the Ministry for the Environment valued freshwater at $35 billion a year. Clipping this ticket will provide already wealthy iwi with a perpetual income stream of immense proportions every time we turn on the tap.

Speaking of co-governance, the Smith children are well versed in the fact that I run a dictatorship not a democracy and often state “money doesn’t grow on trees”. This was answered back recently

by 11-year-old George who said, “It does actually, look at carbon farmers.”

We pulled into a small provincial town car park to see a massive diesel generator powering six electric cars. I proceeded to ask each car owner if they had considered the irony. Three ignored me and one said, “Well I never actually noticed it was a diesel generator. That does seem a bit funny.”

I would rather spend the day and $900 at the dentist than listen to another selfproclaimed expert telling the world how NZ farmers “could” be good one day.

It’s been frustrating to see teachers striking over the past few months yet again. I question the strength of a union that is unable to negotiate a suitable deal in an election year under a Labour government. Blair thought he might go on strike for better working conditions but he was unable to find a contract, a union or even an HR department. However, all is not lost for middleaged white guys – Prince Charles managed to get a promotion at age 74, so Blair still has a few decades of his apprenticeship to go.

ALL GOOD THINGS MUST come to an end and, sadly, the Chambo’s time in West Otago is up. By the time you read this, we will have uprooted our possessions and memories and moved to the metropolis of Gore.

Sharemilking is never straightforward, and the wind of change is always just around the corner. There is not much I can say, other than this was not the future we had been building towards. A surprise farm sale that didn’t fall our way left us reassessing our future.

My father, being a crusty Southland sheep farmer, was by default no supporter of the dairy industry. The invasion from the north in the 1990s was akin to a modern-day gold rush. Their arguably more progressive farming practices were a shot in the arm for a conservative Southland economy. My foray into the industry, leaving behind a good trade, was met with the same negativity by my father, with his vision of my impending failure a constant reminder. Dad was, at times, a glass half-empty type of fellow.

It is not all bad news. Our

complete herd has been sold to good people just up the road; lock, (young) stock and barrel. The girls will still get to enjoy the steadfast vista that is the Blue Mountains. And more good news, I get to award myself a “gap year”. There will be, of course, a transition period – the type of transition that my tackle will survive, however. During my gap year, I intend to smell more roses. I have an opportunity that many never get – a chance to stop and think about what this next phase of my life might look like.

Mrs Chamberlain is looking forward to no more unexpected phone calls at dawn, due to another relief milker’s sudden bout of “food poisoning”, or flat tyre and/or battery. Nor will she miss their inability to commit to a Sunday morning milking as the cows’ daily routine interferes with their social calendar.

mirrors that of a six-month-old baby with colic. The dog and I will both benefit from more exercise and, as I expand my culinary repertoire beyond the humble roast, Mrs Chamberlain will be much enamored.

Will we return to dairying? Perhaps. Time will tell.

My mini break is also well timed to proffer my observant, if somewhat cynical, commentary as politicians tart themselves to the voting public. I worry that PM Chippie might buy his way back into office by printing more Monopoly play money while his government operating under a jury rig slowly drowns in a stormy sea of stupidity. Perhaps some of our politicians should take a leaf out of this humble sharemilker’s book, and they too should take a gap year, to help repair the gap between their ears. This would be incredibly beneficial and productive for our country, only returning once that cranial void has been filled.

First item on the gap year agenda – sleep. My sleep pattern

We all know that hindsight is a perfect science. Rural folk often have their backs against the wall which can act as their driver – be it finance, fear of failure (real or perceived), and more lately, compliance. That means we find ourselves continuously surfing the crest of the productivity wave to make ends meet. Farm ownership has been a goal for so long that once it appeared within reach; an honest appraisal revealed that the costs were far more than just financial. The cost to me over my years of dairying was time. Time away from family, working long hours or being so tired once home that I was mentally checked out. Special moments lost and missed. With hindsight, I was so focused on being the best farmer I could, when perhaps my focus should have been on trying to be the best father I could. Enough said.

Mark Chamberlain finds himself looking forward to a gap year he wasn’t expecting.

Regrets – I have a few

A surprise farm sale that didn’t fall our way left us reassessing our future.

Gore

May and the past few weeks have been mild, and we have grown a lot of grass, but today it’s very cold. This season was a repeat of the last two: a dry summer and grass growth well below average. We no longer know what an average year is.

All our great plans for weights we would sell lambs at and have 80% of the heifers at killable weights by May 1 were no longer achievable, so we just had to make it up week by week, trying to make the right decisions early enough so that only this season’s income is affected. We farm for damp summers and are quite highly stocked, so our farming system needs major adjustments when it is dry.

It has been one of those seasons that in hindsight management mistakes have been made; some crops not sown early enough, ewes

not condition scored as early as they could have been and EID tags not ordered on time, so lambs couldn’t be sold into a premium market when they were ready. But we have been farming long enough to know we don’t get it all right all of the time, and every year there is room for improvement.

After writing in January about my affectionate wild kitten that I tamed last winter, I now have to inform you he had a very untimely death. I was devastated.

We own more than 1000 acres behind our house, but he chose to walk 200 metres in the other direction and get killed on the road. I missed him so much that I went to the vets within a few days and adopted another kitten. Angus is a black tabby, and we are back to kitten training again. We have scratched hands and legs from sharp little claws that chase fingers and jump up on you when you least expect it.

Both Paul and I have reached ages ending in zero this year and have achieved a number of our farming goals, so where to from here? We had more than one farming couple visit this summer who have retired from farming and one of the many discussions we

had was about what we will do in the future. We have no children so there will be no family succession. Neither of us wants to lease the farm because our capital for the next stage of life is in the farm, so it will be sold one day. But where will we live, what will we do every day to fill our time?

We have been talking about these things for a few years now, and have even looked at some houses, but it is a big step to take. I would like to keep some of my pet animals and Paul says he would like to do more horse riding, so we want a few acres, but not too much or it will turn into a life-sentence block, not lifestyle, and we will still be tied to the land.

We don’t feel ready to live close to neighbours and have to shut curtains for privacy, and we don’t want to be woken by that annoying neighbour who wants to mow the lawn early on a Sunday morning. It would be good to live close to town so we can take home takeaways and not have to reheat them because we’re so far from the shop.

We both want to do some overseas travel before our bodies are too worn out to be able to do those walks in the Alps, we want to sleep in tents in Tanzania while looking for Africa’s Big 5 and have any other adventures that might come along.

Unless we have some major unfortunate event, we will be farming for a while yet and have time to make plans so that we optimise our exit from farming. Winter is fast approaching, and as usual there will be plenty to do on the farm while we plan for the future. It is never too early to think about future plans.

As Paul and Suzie Corboy hit ages ending with a zero, they’re thinking about what to do next in life’s big adventure.

Weather, cats, and the future

“...where will we live, what will we do every day to fill our time?”Meet Angus.

us around like dogs and have occasionally been welcomed into the living room to clean up cluster flies. Maybe it’s the same on most farms, as we all tend to be animal lovers. Animals certainly keep the place interesting.

I’m dreading the next six months leading up to the election. The winner of this election will need to make some hard and unpopular decisions. Those decisions will likely be expensive for the entire country.

IT’S EARLY MAY IN THE Wairarapa and lots of people are talking about duck shooting. I’m not much of a duck shooter myself. We have a Labrador called Mac who is mad keen on carrying stuff and would probably be a decent gun dog.

Pity I’m not very good at training dogs. But I’ve found a use for him that keeps his instincts happy and is very useful for us. He collects firewood. He’ll come out to the shed and happily bring a bit of wood into the house.

He’s not that keen on depositing it into the wood basket beside the fire at this stage, but I’ve got all winter to work on him. He’s a real “people pleaser” so is very keen to help and this just might be more productive than swimming in a dam chasing ducks.

We seem to attract weird pets in our house. The above-mentioned Labrador is one. Then there’s his mate Marty the foxy who’s a bit of a wimp, the half-blind retired huntaway Kell that roams the garden, and the world’s dumbest cat “Flea-taxi”. The three chooks that eat dog sausage follow

I hate to say it, but neither main party is going to help the ag sector. Just imagine if agriculture was a top priority for the government. Regional roads without potholes, new bridges planned and delivered, compliance that was straightforward and well thought out, and where you’d only have to fill out forms once. Dreams are free.

Having said that, I’m not one of those people who wants to put their hand up for public office. Good luck to all the rural-based candidates; I admire your desire to put your head above the parapet. Leadership is a minefield these days.

nearly saturated already. Might be a long winter.

Unfortunately, we’ve still got about 75 hectares of harvesting to go – squash pumpkin, maize grain, maize seed and some red clover still has to come in over the next month. The timing isn’t too late just yet, but the soil and weather conditions won’t make it straightforward.

Spare a thought for some of the arable farmers around the North Island this summer. Barley and pea crops have been a disaster and some northern maize crops have been hammered with disease. A nice warm dry summer is certainly on the wish list for next year.

Like a lot of the North Island, the Wairarapa has had a very wet summer. Parts of Eastern Wairarapa were hammered by the two cyclones and, like further north, are amid a major clean up. The way New Zealanders from all walks of life mobilised to help those affected was inspirational.

We had some flooding, which ruined crops, but largely the Ponatahi valley seemed to miss the worst of the weather, for which we are very grateful. We now have grass halfway up the quad bike tyres in early May and the soil is

At least the finishing cattle and lambs have done well. It’s unusual for us to be able to kill 18-month bulls at north of 550kg LW but we sent the first unit load out in early May. Lambs aren’t setting records for yields, but they’re still acceptable. We’ll scan the ewes in early June and see how our management has been over the summer. The regular heavy rains seem to have kept them fat and the facial eczema mostly under control. Let’s not talk about flystrike though.

Good luck for the winter ahead. Let’s hope the mud doesn’t get over the top of the gumboots.

Mac the Labrador is good at fetching firewood and he could make a good gun dog if Mark Guscott was a duck shooter.

“The three chooks that eat dog sausage follow us around like dogs…”Carterton

Holy hell, everything costs so much these days. Can’t hardly fart without someone sending a $1000 invoice. But still, you have to keep on keeping on, don’t you? Nothing else for it. Can you give me some pointers on how to add value onfarm without incurring extra costs?

Dear SID,

A wise person once advised me that “people go broke trying to save money”. I’m not sure how much credence to give to that, since I seem to be going broke no matter what I do. I note that top operators do splash the cash around a fair bit, but I will be damned if I know how they got it in the first place. What came first, the cash or the splash?

However, I did have a eureka moment the other day that has already saved me hours of time and many tears, for the low-low price of $20. I am happy to share it with you, but you must be warned that it is probably not the idea you are looking for. It is mainly about receiving fewer electric shocks in the crotch, which is not everyone’s priority.

The point is that I had an idea. I was able to have the idea because my head was uncharacteristically empty of chores to do and my body was not yet screaming for sleep – and out of nowhere up the damn thing popped. So that is what I recommend you do: declutter your cranium so there is room for new ideas. Adds value and doesn’t cost a thing. It might help to get off farm and mingle with other people and their ideas. I know, I know, everyone says “get off farm”. You are here to farm, but the number one piece of advice seems to be to stop doing it.

Hear me out. What do you have to do to get off farm? That’s right, you have to tidy up all the little hurdles that are “good enough” for you to struggle

through on a day-to-day basis, but “bad enough” to cause embarrassment if you had to ask anyone else to do it.

That gate that only opens three quarters and in the wrong direction.

That trough leak that has graduated to a quagmire.

Equipment that only functions when the moon is in Venus.

Maybe you could spend a little time removing the scum that builds up on the surface of life and then not even leave the farm. Just stay there and enjoy the smooth ride you were setting up for the farmsitter.

You may also want to document some of the info that lives in your head, so that you are not the only person on planet Earth who knows where your farm’s valves and switches are and what the dog is supposed to eat. That might boost some processing speed in the old brain box. Basically what I am suggesting is that you spend a bit of time greasing the

wheels so that it is quiet enough to hear yourself think.

But let me tell you about my idea, so you can judge if the payoff is even worth it. It was a smart switch for the electric-fence energiser. I can now toggle the electric fence on and off from wherever I please with my phone. Many of you with fancypants energisers can already do that, but we couldn’t because we are a family of cheap thistles.

The embarrassing thing is we had already bought a four-pack ($80) of these Kogan smart switches so that we could put a timer on the farm water pump and the child’s electric blanket… and then we got busy and stuck the other two in a drawer without ever considering the electric fence. While the switch costs $20, there needs to be internet at the shed for it to work.

Luckily for us I once dedicated a day’s frustration (and $600 of equipment) to beaming the home internet to the shed. If you have a teenager you may be able to trick them into doing this.

The beaming is done by a couple of Ubiquiti NanoStation doodackies which can talk to each other over many kilometres (line of sight) and you will need a couple of ethernet cables, an extra router and someone who knows what these words mean to sit through a YouTube tutorial. But it's a great starting point for smart gadgets and security cameras, and watching “what to do if your chainsaw isn’t working” videos in the shed.

Best of luck, Aunty Thistledown

Cali Thistledown lives on a farm where all the gates are tied together with baling twine and broken dreams. While she rarely knows what day it is, she has a rolodex of experts to call on to get the info you need. She’s Kiwi agriculture’s agony aunt. Contact our editor if you have a question for her, terry.brosnahan@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Kerry Dwyer writes about the frustration he and many other farmers experienced with the Ministry for Primary Industries as it struggled to deal with Mycoplasma bovis. He’s still wanting answers.

On August 28, 2017 MPI walked in our door chasing Mycoplasma bovis (M bovis). Since then we’ve dealt with our own problem, alongside a lot of other farmers affected to a greater or lesser extent by the response to the disease.

My wife Rosie and I depopulated all our cattle well before any other farms, because it was the best way to handle the animal welfare and financial brick wall that was ahead of us. We were aided in doing this by some very good people from the Ministry for Primary

Industries (MPI). At that stage no plans were functioning so we had to push to get cattle out, and MPI’s assistance was crucial in achieving that.

AsureQuality was given the hands-on tasks early in the response, and while we didn’t have much to do with their people, what dealings we did have were frustrating and time consuming.

Note that the Biosecurity Act states that compensation doesn’t have to be paid for “diseased organisms”, which was a situation faced by Foveaux Strait oyster farmers in 2016, and also by some North Island plant nurseries when myrtle rust appeared in 2017.

When the full primary industry response got into action in May 2018 it appeared the full budget to eliminate M bovis was $886 million; I now read it to be $870m. That was to be funded 68% by government and 32% by industry, i.e. Beef + Lamb and DairyNZ. Part of the deal was that affected businesses would be compensated for cattle and some costs incurred.

The big question is where did the money go? To date there have been 2870 claims and just under $240m has been paid as compensation to affected farmers. That is an average of just on $84,000 a claim, and note that the most affected farms will have put in multiple claims, largely because the time frame to get from initial to final compensation may be as long as three years.

It appears that all the $870m or $886m has been spent. This means $630m was spent on the response effort, being all the MPI and AsureQuality people and time, along with whatever else. I commented to Minister of Agriculture Damien O’Connor at one stage that the M bovis response was creating more jobs than the government’s Provincial Growth Fund.

While there have been various reports written on the M bovis response that have dealt largely with the effects on farmers and cattle, I question the audit process and the justification of the $630m spend.

I had a couple of AsureQuality people in for coffee in late 2017 and asked one of them how long he’d been on the project. The response was that he came from the North Island for a two-week shift then had similar time at home, because it was a “very

stressful job”. Yeah right.

One farmer I dealt with had more than 100 water troughs to be cleaned, so five people arrived with a vehicle each, a smoko portacom and toilets. On their first day they cleaned five troughs and managed to break three ball-cocks. The farmer was going to watch them but decided it would be better to empty all the troughs himself, to get rid of them earlier than the possible month or more it would have taken at that rate.

MPI might be able to justify spending $630m in their world of bureaucracy but we farmers saw a huge waste.

Transparency and bureaucracy are not natural companions, and bureaucrats have a tendency to be very defensive when questioned, let alone criticised.

To get most information from MPI you have to do an Official Information Act request (OIA), which they basically have to respond to within 20 working days. My first series of OIA requests related to

the MPI response plan for M bovis, or similar. It appeared there had been no structured plan available in 2017. What was the director of MPI doing in the years prior to that? Bugger all it seems.

My second series of OIA requests related to how compensation was assessed: i.e. what were the criteria used by their people to assess whether it should be paid or not? Again it took a series of OIA requests to get nowhere. Either they didn’t have clear assessment guidelines or wouldn’t provide them.

The third series of OIA requests I put in related to their complaints procedure. A written complaints process is basic twenty-first century governance: if you receive a complaint it outlines the process to deal with it in a fair, transparent and timely manner. MPI stuck to the pattern of asking for extensions to my OIA requests, and then basically said they didn’t have a complaints procedure. If they receive a complaint they hope you just go away when they don’t answer.

“Transparency and bureaucracy are not natural companions, and bureaucrats have a tendency to be very defensive when questioned, let alone criticised.”

My first conversation with an MPI compensation person was on August 30, 2017, who said their brief was to minimise the cost to the taxpayer. My reply was that we just wanted a fair deal. That chap did subsequently apologise to me for taking that stance, but it has been the culture we have consistently struck when dealing with compensation.

Rosie and I visited MPI compensation staff in Wellington on June 1, 2018, to push the line that as citizens, we deserved communication, consultation and choice. It fell on deaf ears, or the ears changed in the constant shuffling of MPI staff.

The MPI brand is probably rated in primary industry at the same level as the Census is with Maori, maybe worse. I have had more apologies from MPI compensation than hot dinners. We just wanted them to do their job in a fair and timely manner. The audit process to achieve a compensation payment has been thorough, which seems to be lacking with the rest of the M bovis response spend.

We had all our cattle killed by a local processor, to go into the human food chain. Subsequent to that MPI realised that small cattle had a net processing cost and were better disposed of by other methods, which they called pet food. I don’t have any opinion against that, but I still cannot stomach the mis-truth that slaughtering cattle and disposing of them in landfills can then be called “processing for pet food”.

The owners of those cattle deserved to be told the truth, not blatantly and constantly lied to.

Which raises the question about what other parts of the M bovis response have been hidden under the carpet?

I attended a few MPI-arranged meetings concerning M bovis, most of which were time that I will never get back. At one I made the point that you can roll a turd in glitter, but it is still a turd.

Mfor Primary Industries (MPI). It’s taken three months for them to consider my basic questions on the Mycoplasma bovis (M bovis) eradication programme. How much did it cost? Where did the money go? Can I have some simple statistics (age and weight) of cattle slaughtered and where they went (pet or human food)? To be clear, I never meant to make any OIA requests at all. I just asked MPI for information, but they have elected to raise an OIA on my behalf. The whole process yielded very little information. But before we get into that, let’s explore what an OIA is and how it is meant to work.

The year was 1982. If I have googled correctly, then Olivia Newton-John’s “Physical” and Survivor’s “Eye of the Tiger” were battling it out in the charts. Muldoon had swept through the land

But the NZ government still found the time to create the Official Information Act of 1982 which declared that (for the most part), official information belonged to the public and should be freely shared with kiwis willing to ask for it. This was a complete change in vibe from the preceding Official Secrets Act of 1951, which threatened to prosecute any public servants who disclosed information without specific authorisation.

The OIA allows anyone in NZ to request information from a government department unless said government department has a decent reason not to. There are about 40 good reasons to choose from, mostly focused on protecting national security, the judicial system, individuals privacy and things that would unduly influence the economy.

Your snooping is not limited to

government departments. There is also a sister law called the Local Government Official Information and Meetings Act 1987, which means you can also poke around information from community boards, state education authorities, licensing trusts, airports, councils, etc. And you are allowed to violate your own privacy (or someone else’s with their permission). So, if you are in a scab-picking mood, you can also ask the Police, Oranga Tamariki, etc, for the information that they hold on you.

Ready to flex your OIA powers? The first step is to pick your department and your question. If you are stuck for inspiration, there is a website called FYI.org.nz where people can share their OIA requests. From here you can view all OIA-able authorities and look up previous requests. Want to know how many Koru club memberships Pamu/ Landcorp hold at AirNZ? Wish to view the parking receipts of the mayor of Porirua City? Heard a rumour that MPI is investigating someone’s grandmother for smuggling mooncakes through the border? FYI.org.nz has already got the official answer. You can make your own OIA requests, if you don’t mind it being on the website for the world to see.

If you want to make a private request, the Ombudsman has a helpful “Making official information requests – a guide for requesters” document on their website (ombudsman.parliament.nz) with a helpful email template to copy. Had I known I was about to OIA anyone, I would have totally read this first. They say the key is to be as specific as possible about the information requested. They also outline the timelines. From the moment the request is made, the department receiving the request has seven working days to ask for clarification, 10 working days to transfer the request if it has been made to the wrong department, 20 working days to deliver the request or issue itself an extension. The Ombudsman is where you go to complain if you are unhappy with the OIA process…if you don’t have a national magazine to vent your spleen in.

Each icon represents $1 million spent eradicating M bovis from New Zealand

$7m Cleaning infected farms (from 2020 onwards).

$54m Onfarm costs for infected farms.

$117m Replacing slaughtered cattle.

$451m Undisclosed costs.

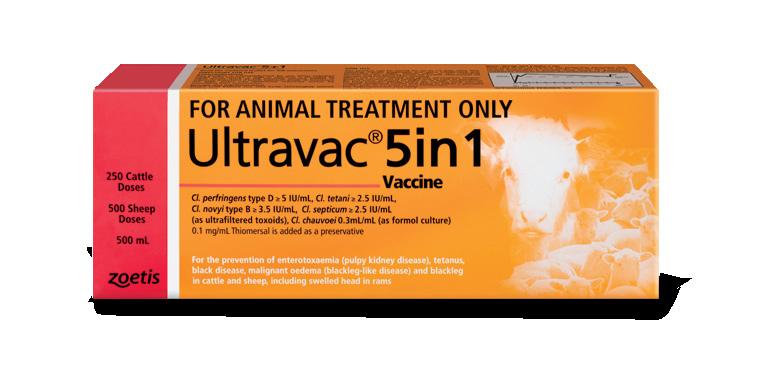

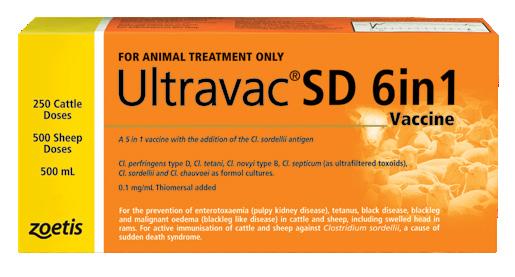

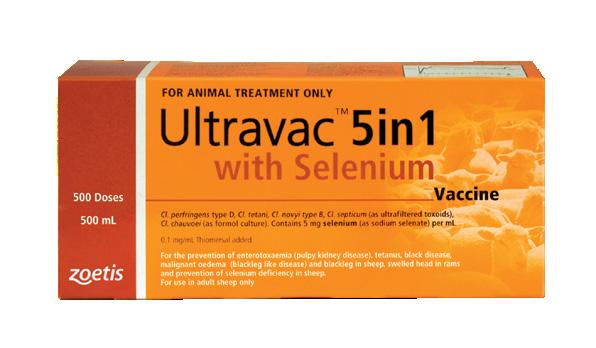

Ultravac vaccines protect ewes and lambs against the key clostridial diseases. Proven in the paddock, New Zealand trial work showed vaccination with Ultravac 5in1 reduced lamb deaths from docking to pre-lamb by 23%1. Concentrated into a 1mL dose, choose Ultravac vaccines, the proven performer in the paddock.

What did my OIA actually yield? We will start with the easiest one first, because MPI did actually give me some information on this. MPI states that as of February 2023, it had spent $629 million on the eradication of M bovis. Of this, $117.2m was compensation for slaughtered animals, $54m was other forms of on-farm compensation (feed costs, etc), $7m was for farm cleaning costs from 2020 onwards. Prior to this, cleaning costs were not separately recorded by their third party provider (presumably AsureQuality, whose annual reports attribute more than $30m/year to M bovis revenue during 2018 to 2020). That leaves $451m of other costs that I have no information about. I guess I should have asked about testing costs and salaries and research costs. My bad.

This might seem like an odd question to ask. Whatever the meat companies were paid, I am sure they were worth it. It’s not normal for quarantined animals to be funnelled towards human consumption, and the meat companies didn’t really want a bar of it. The extra cleaning and paperwork held things up, and they were being asked to kill undersized stock which didn’t exactly sweeten the deal. The thing is, the meat companies were happy to disclose that they had received payments for slaughtering stock, but MPI has tried on numerous occasions to tell me it didn’t happen. MPI has triggered a siblingreflex in me; I really only want to know because they don’t want me to know.

Anyway, the latest in this is that they didn’t tell me because I used the word “compensation” and paying processor fees is not, in their view, compensation. Or, in their words: “... as no compensation has been paid to meat processors, without knowing the exact content of your discussions with these companies, we assume they may be referring to higher processing fees

paid by MPI in the initial stages of the response. These fees were paid to cover additional costs incurred to dispose of infected animals safely.” Cool. But how much did you pay meat processors?

WHAT INFORMATION DOES THE PROGRAMME HOLD ON THE CATTLE SLAUGHTERED?

Apparently I am to be assured that information on the age-group and destination of infected animals was recorded by AsureQuality. But, the information is not centrally recorded and it is not reasonable to ask AsureQuality to manually search through 2856 compensation claims or 3000 RFID scan files to find the answer. Reasonable is in the eye of the beholder, but that wasn’t what I asked AsureQuality to do. I actually requested that they anonymise the scan files so I could compile the information myself. If you think I wouldn’t crunch through 3000 scan files, then you haven’t met me. That is a data scientist’s idea of a fun afternoon.

But, I think it is worth pausing to wonder why AsureQuality hasn’t recorded this data in a central location. How on earth did this information not find its way into the NAIT database?

or Progressive which does not always record weights) and deducting any meat payment received in sending the animal to the abattoir.”

OK, I understand this to a degree. They would not have the carcaseweights of every single animal. Especially not the ones that allegedly went into landfill. And I can understand that the compensation (and therefore the main focus) was based on the difference between the replacement value and the salvage value of the stock. Maybe it is not strictly necessary to record all the raw numbers that led to the compensation value. But I would have thought that one would hold on to kill sheets for auditing purposes. And if you didn’t, you can be damn sure that the major meat processors did. So why then is there not any kill information at hand?

Is it all done and dusted and I am raking over old coals? Should we just sit back and assume the money was well spent? I vote no. The OIA was designed so that Jo Public could hold authorities accountable. So I guess I fire up the email and ask them very specific questions. How many animals do you know for

Does NAIT not exist to centrally record the movements of infected animals? How on earth can nobody pull the data on where 186,000 confiscated cattle went? Or how old they were when they went there? Surely to goodness someone was tracking these animals and making sure they got to where they were supposed to be, right?

Even more curiously, AsureQuality ”were unable to find any information regarding the carcaseweights or meat values of the culled cattle”, and “Compensation is assessed for destroyed stock by taking the market value of the animal at the point of cull (based on a valuation by either PGG, Alliance

sure went to meat processors? How much money (money – money not “compensation”) was paid to meat processors for the purposes of disposing of infected stock? What was the total cost spent on testing? Staff remuneration (assuming the word “remuneration” is specific enough)? Research costs?

Yours sincerely, Nicola.

“MPI has triggered a sibling-reflex in me; I really only want to know because they don’t want me to know.”Nicola Dennis is a scientist, farmer and data wrangler.

rates combined with the huge cost of feeding. All the feedlots we saw would not accept animals unless they had been yard weaned as calves.

On return to NZ, yard weaning was adopted by many of the group and it is now a well-established practice by many farmers to build a positive relationship between young cattle and humans.

To say our beef farming world is under some pressure at present would be the understatement of the century.

Our beef market lacks enthusiasm and New Zealand farming has an invasion of high interest rates and production costs, and now the odd cyclone thrown in just to keep us all standing on our absolute tippy toes.

It is important to not only survive the ride, but land squarely on your feet and learn from every sniff of the experience.

Only from learning will we be able to build more resilient beef farming systems and farming policies.

I think it was Pita Alexander who said, “No, money is not the most important thing in the world, but it comes a close second to oxygen.”

Resilience can mean earning lots of money from hot policies such as bull beef in the good times so you have a strong cash position when tough times call.

We must remember that our main job with hill country farming is to cost effectively turn grass into as much saleable beef as is possible.

So where are some of the opportunities and where is some of slippage in our beef systems?

Are high nitrogen prices trying to tell us a lesson? We need to continue to try to maximise the amount of clover in our pastures to drive the amount of natural nitrogen that is fixed.

Creating and maintaining low-cost healthy pastures are key drivers going into or out of troubled times.

Are high trucking costs trying to teach us all a lesson?

Shifting young surplus dairy animals around NZ at 120kg liveweight, it is conceptually important for many of the country’s beef finishing policies. However, conceptually from then on, as much beef as possible should be finished within a farm and within a region. An animal only has so much value, so why not try to capture as much of it as possible before it leaves?

If you are spending $40 a head trucking 18-month-old cattle, it is going to take the first two to three weeks of growth to recover that cost. This is before you consider the stress associated with loading, unloading, and trucking over our hilly back-country roads. Stress is so hard to measure in this situation and may present itself as subtlety as increased vulnerability to health issues such as parasitism.

A few years back I went to Australia with a group of local beef farmers as part of the Beef Profit Partnership programme. It was a great opportunity to relieve some personal stress. It was also an opportunity to understand the huge impact of stress in growing beef.

Australia has long had some wild beef breeds and plenty of wide-open spaces to miss out on human interaction.

Problems arose when many of the steers and heifers headed towards feedlots to be finished.

Stress was seen as a constant issue that had the potential to erode growth and profits. The feedlots visited were a great opportunity to look at relative growth

Further emphasis on the removal of stress in Australia was demonstrated by their focus on using flight time in stud genetic selection. Flight time is a measurement of a beef animal’s natural nervousness whilst in the yards and around people.

Now our top operators are trying to take reduced stress management practices out into the paddock.

Over the past 20 years our stud breeders in NZ have made huge progress in creating quieter genetics.

On most farms I visit there is opportunity for a 5% increase in the calf crop. This could simply be achieved by moving the heifer-mate date later to coincide with the cows.

To take out some risk, the heifers could be mated for three cycles, then foetal age the calves at pregnancy diagnosis to potentially take out the last cycle.

There is also a 5% opportunity to increase calf survival by selecting the right calving paddock or calving behind a wire.

This is also a good time to get into some monitoring and weighing of your growing cattle. It starts the discussion about how we can make all of them as heavy as the best.

In good times we tend to drift into lazy practices and beef policies that often suit us rather than suiting optimised cattle production.

Now is a good time to look for the hidden kilograms and the hidden dollars inside your beef policy to build a more resilient business for the future.

Hill country farmers need to remember their main job is to cost effectively turn grass into saleable beef.

Peter Andrew.Peter Andrew is an AgFirst agribusiness consultant based in Gisborne.

Dr Dennis Wesselbaum outlines how inflation is measured, its value, its flaws and ideas for better accuracy.

German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe is believed to be the originator of the saying “God is in the details”. The saying means that while something appears to be simple, the underlying details can be complicated. The same applies to measuring inflation.

In general terms, inflation is a positive change in prices between two periods. I guess this is intuitive. However, how we arrive at one number, the inflation rate, is more complicated than most will appreciate and involves a high degree of mathematical theory. At its core, the inflation rate reflects the change in the amount of money needed to maintain a certain standard of living.

Computing the overall change in prices in an economy is a difficult task. Not only do consumers buy thousands of different goods and services, the characteristics of these goods

and services are changing with consumer preferences varying, quality changes, new goods being introduced and some goods being taken off the market. Therefore, it is a challenge to combine all these prices into an index that gives one number that we can track over time.

To do so, we rely on a price index. A price index is a measure that summarises the change in prices of many goods and services from one period to another. In fact, it is better to think about a representative basket of goods and services. This implies that the change in prices of the goods and services that I consume will be different to the price change you will experience by buying your basket of goods and services. However, if we aggregate across all consumers in an economy, we arrive at an index that represents the representative (or average)

consumer. These prices are obtained through postal surveys, store visits (>2,800 in 12 cities), and the internet by StatsNZ.

Furthermore, the price index is usually a weighted average of a given basket of goods and services; i.e. not all goods and services count equally. For example, in the current price index for New Zealand, housing and household utilities is the largest group with a weight of 28% and food is the second largest group with a weight of about 19%. This also implies that some prices in the economy can fall while the overall inflation rate is positive.

To be precise, when we talk about inflation, we talk about the change in prices based upon the CPI, the Consumer Price Index. It measures the change in prices of a fixed basket of goods and services (649 for NZ, to be precise).

It applies the so-called Laspeyres price index formula, which relates the costs of buying a fixed basket of goods and services in a base period with the cost of purchasing the same basket in the next period. An alternative is the so-called Paasche index, which computes the costs of buying a fixed basket today and compares it with the costs of purchasing this basket in a previous period. Of course, hybrid indices exist, which

combine these two (and other definitions).

The Laspeyres index is subject to several biases and generally overstates price changes (while the Paasche index understates them). These include the substitution bias, where the index does not take into account that consumer preferences (and therefore demand) changes. Also, the quality bias, where the index fails to incorporate quality changes and the new good bias, new goods are typically not included until they achieve some market position. It assumes one price for a good, whereas in reality, prices are likely to vary across outlets and even locations.

To limit these biases, the basket is updated regularly. In New Zealand this happens every three years. Updating the basket in every period is called “chaining” (the New Zealand CPI is therefore chain-linked every three years). The US central bank focuses on the so-called “Personal Consumption Expenditure” price index (PCE), which is an example of a chained index. While the CPI and the PCE show a similar trend over time, the CPI tends to increase more than the PCE. This relates directly to the frequency at which the price index and, hence inflation, is computed. In New Zealand, inflation is measured quarterly, but monthly in other countries, for example the US. Generally speaking, having more information should allow one to make better decisions. However, I think this ignores a political economy story and behavioural factors (e.g. “action bias”, where people prefer to do

something over doing nothing and “optimism bias”, where we overestimate the success chance).

If more frequent inflation data were to be available, this could create an incentive for a central bank to micro-manage and overcorrect the economy. I think this risk is particularly strong for the case of the RBNZ with a weak leadership without credible expertise in monetary policy.

I would like to close with some final remarks. CPI Inflation only applies to households. There are also various producer price indices that measure the changes in prices (input or output) for producers. Furthermore, it is very difficult to put prices on goods and services that are not produced or sold on markets. For example, household production (e.g. care of children, sick, or older adults, or growing vegetables) is difficult to measure accurately.

A solution for biases in the index could be to use electronic scanner data, which includes detailed information that can be used to limit these biases. Efforts are already underway, for example, in Australia, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland. NZ has introduced scanner data for consumer electronics and plans to extend the usage of scanner data in the future. Overall, measuring inflation is a difficult task in theory and in practice. This requires a careful interpretation considering the strength and weakness of a given measure of inflation. Furthermore, it also requires considering not just one measure of inflation but a range of measures that, hopefully, paint a picture of the underlying inflationary pressures.

"If more frequent inflation data were to be available, this could create an incentive for a central bank to micro-manage and overcorrect the economy."

Remember, not all milk replacers are formulated the same or made from the same ingredients. In some cases, the same brand will differ from batch to batch.

High digestibility is key; it ensures the animal gets maximum value from the feed, providing them with the protein and energy they need to grow.

Here are some basic guidelines:

1.Choose a milk replacer with balanced amino acids. Proteins play an important role in many bodily functions, including formation of muscle and structural tissues and hormones. Each of these proteins are made from a different combination of amino acids.

Having a whole lot of one amino acid is not useful if you do not have enough of the others - the young animal is limited in the amount of protein it can produce and any excess amino acids must be excreted. Not only is this expensive, but it also contributes to nitrogen loading and can lead to elevated ammonia levels in the shed.

2.Choose a milk replacer that contains highly digestible fat sources.

The source of ingredients and the manufacturing processes both play significant roles in milk replacer digestibility.

Butter fat, palm fat and coconut oil are all highly digestible while homogenisation of fat also helps to increase fat digestibility, as the very small particles are more easily absorbed from the digestive tract.

3.Ask about vitamins and minerals.

A good quality milk replacer will contain added vitamins, micro minerals (like selenium, zinc and copper) and macro minerals (like calcium and phosphorus) with any added vitamins and minerals specifically formulated to complement the nutrients provided by the other ingredients in the milk replacer.

The source of ingredients used in a milk replacer can dramatically affect digestibility. Some processing methods can damage the proteins in milk powders, affecting digestibility. Often, ingredients that cannot be used for human food, because digestibility has been negatively affected during processing, are diverted for use in milk replacer.

Ask your milk replacer supplier about how they source their ingredients and what manufacturing technologies are used to help ensure high digestibility.

From easy-to-follow instructions on the bag right through to easy mixing and feeding, a milk replacer should be easy to use, no matter what your system. Find out from other farmers how a product has worked for them.

It’s tempting to buy a product with a wide range of different additives in the hopes that this will improve the nutritive value of the product. Make sure any additives included in the product are there for a reason, and not to hide the use of poor quality ingredients.

Ask your reseller for Sprayfo lamb milk replacers this season –the science-based brand with proven performance in New Zealand lamb rearing systems.

Tim and Binds White have knocked over a big prize by winning this year’s Keinzley Ag Wairarapa Sheep & Beef Farm Business of the Year Award, but they aren’t ready to take their foot off the accelerator just yet.

Both in their early fifties and with two daughters in their early twenties (Maggie and Grace), the pair only started fulltime farming a decade ago.

They see plenty of upside in farming their 420ha (effective) property Upperwood, at Matahiwi just northwest of Masterton, and feel it still has potential to produce 30% more meat

and wool over its already impressive 300kg/ha in their 2021/22 financial year.

“This property has potential to get to 400kg/ha, but we would need to change our system to do that.

“How hard we chase it will come down to how much we invest in more man hours, more intensification and more use of things like Farmax to help us manage the feed budget.”

Tim says they would have to go back to bulls and shifting hot wires, fewer ewes, more trading stock and more nitrogen used strategically. Also more cropping so they could lift their stocking rate over the summer months.

“We’ve got soil fertility about okay in the mid-twenties but we’d need to lift pH, do more drainage and subdivision to get to that level of performance.”

He’s confident of producing 400kg/ ha of product off the easier country, but says the challenge would be the medium hill third of the farm that’s producing 250kg/ha of product.

At $6/kg, 400kg/ha of meat and wool would generate a gross farm revenue (GFR) from stock of $2400/ha, 50% higher than Upperwood’s class-topping 2021/22 GFR of $1748/ha.

Tim says the downsides from higher performance included more internal worm burden, pugging issues, with more older cattle and more environmental challenges.

“It would be a roller coaster ride for sure, and we’re enjoying what we’re doing now.”

Tim says the performance and system is in a good “spot”.

“But we’ll ponder how hard we chase the next production lift.”

For the next five years, Tim wants to stay actively farming Upperwood before slowly exiting the day-to-day labour contribution he makes now.

Upperwood is their biggest single investment. It has multiple titles, plenty of road frontage and lots of new planting. Being so close to town, selling off some land is always a backstop.

The Whites have stuck with the primary sector with other investments, including shares in kiwifruit and Rockit apple orchards, a coolstore and two poultry sheds. They also have a shareholding in a commercial building and have developed a large portfolio of shares and fixed-rate bonds.

However it is not all work. Time for travelling and enjoying the outdoors, particularly ski-ing, remains a priority for them both.

New Zealand lacks good leaders, and while leadership courses are plentiful, Jacqueline Rowarth finds they are not created equal.

New Zealand agricultural businesses, from farms through to levy bodies, co-operatives, banks and other rural professional groups, invest money in upskilling staff. Upskilling in nutrient management, finances or animal health might seem a more obvious investment than leadership – but leadership is needed for the future success of the country. And there are many people champing at the bit to assist. Picking the right

course and the right person has become an art.

A Google search on “leadership lacking in NZ” produces more than 11 million hits in less than half a second. Add “agriculture” and the hits are more than three million in the same time frame.

Across the ditch, the search produces more than eight million hits for agriculture. Change NZ to Ireland and 3.7 million hits appear.

In the complaint about

leadership, NZ is not alone. Blaming lack of leadership is a common response to ‘things’ not progressing in the way anticipated or desired. The complaints often come from people who feel they have not been heard or included in the decision-making process. The big question is whether or not they have the ability to do a better job. What do they think is lacking? And do they have the skills to fill what they perceive as the void?

Responding to this apparent need, leadership courses have proliferated globally. Google produces 99 million hits for NZ alone. Some are directed at minorities (women and ethnic backgrounds, for instance), others at particular ages and stages, and some at agriculture. Most offer challenge, development and

skills. Some are also linked to a certificate which may or may not be accredited by a recognising body (e.g. a professional organisation).

Increasingly, analysts are wondering if the global initiative to upskill people for leadership is working. It has been estimated that global organisations spend more than US$60 billion (NZ$98b) on leadership development but only 10% of corporate spending achieves positive results.

For NZ agriculture, a 10:1 ratio doesn’t seem like a good return on investment. However, improving the outcome is possible.

Researchers from Fordham University and the Harvard Kennedy School of Government have identified the factors that create lasting positive change. Their article in Harvard Business Review in February reported that successful programmes have a focus on whole-person growth

with opportunities for selfreflection and meaning-making (making sense of real-life events), followed by stress reduction. The value of short, intensive courses was emphasised, rather than those that cover a semester, year or longer.

Another factor for success was the candidate. Though this isn’t surprising, the type of candidate was.

The research found that people who had the most clarity in their sense of self and who were highly conscientious exhibited the least positive change in response to development programmes. This means those with drive, who one might pick as natural leaders, are not going to benefit as much as those without.

For the people with a track record of leadership, it might be the networking that becomes the value of a leadership course. This is difficult to achieve online – it is shared experiences and concerns

that build relationships and trust. Networks also allow exchange of information. With information and imagination, it becomes possible to create a vision that is credible and identify the steps to create that vision. Leaders then need the energy to get going and energise others. The latter requires an emotional quotient to understand the perspectives and position of those around them –the people who might follow to make the team.

The right person in the right course will add to the team, and with knowledge might also turn into the leader that is right for the time.

In her Kellogg report in 2016, Agmardt leadership scholarship recipient Sarah Bell wrote, “There is no doubt the agricultural sector needs strong, courageous, brave, skilled leaders with good judgement. Some of this currently exists, but a larger cross section of leaders with diverse perspectives need to display these attributes.”

NZ is a work in progress – as is the rest of the world. By homing in on what we are trying to achieve with the next generation, we can become the leaders in leadership in agriculture. Some might argue we already are – but maintaining the position will take careful investment.

Choose with care.

“The right person in the right course will add to the team, and with knowledge might also turn into the leader that is right for the time.”Dr Jacqueline Rowarth, Adjunct Professor Lincoln University, has a PhD in Soil Science (nutrient cycling) and is a director of Ravensdown, DairyNZ, Deer Industry NZ and NZAEL. The analysis and conclusions above are her own. jsrowarth@gmail.com

Billboards in the Republic of Ireland are highlighting a big boxing match coming to town that is set to be quite controversial for the country’s livestock industry.

By Chris McCullough.In the red corner are the suckler farmers, the historical stalwarts of the Irish beef industry, who are battling the dairy farmers, seen as the wealthy, in the blue corner.

This is really a fight for emissions and which sector gets the upper hand to be safeguarded against harsh-hitting environmental regulations sweeping European Union countries.

At the last count in 2022, Ireland is home to 7.4 million cattle, 2.4m more than there are people. Within the livestock count, the number of dairy cows rose by 1.4% (22,800 head) to 1.6m, while the number of beef cows fell by 2.9% (27,100 head) to 913,000.

And this is where it gets interesting, as the trend of the dairy herd expanding and the suckler herd contracting continues. Since 2017, the Irish dairy herd has increased by 14% (194,600 head), while the suckler herd has shrunk by 16% (167,800 head).

Since the EU milk quota system ended in 2015, Irish dairy farmers have continued to expand and have recently

enjoyed higher milk prices and incomes. Suckler farmers, however, have been squeezed harder financially over the years, forcing some to switch to dairying in hope of a better return. As more farmers took the bold step to give up their suckler cows and replace them with dairy equivalents, this created the sway in overall livestock sector numbers.

Ireland’s 135,000 farms produce 37.5% of the country’s emissions, the highest in all the EU’s 27 member states.

The Irish government has found itself under incredible pressure from the EU to reduce these GHG emissions – in the past promising a reduction of 25% by the year 2030.

Methane, largely produced by livestock, makes up 65% of Irish emissions, therefore the dairy and beef sectors are high up the pecking order to be targeted for major reform.

With such pressure on the government, all kinds of whacky solutions to reduce these emissions have been barked by various officials and groups.

Farmers know emissions must be reduced, which ultimately means cattle numbers must be cut, but they are somewhat at loggerheads when it comes to which animals must go.

Ireland’s Minister for Agriculture

Charlie McConalogue has got the hairs on the backs of suckler farmers raised after suggesting a voluntary reduction scheme would be offered to dairy farmers. In absence of a similar scheme, where the dairy farmers are offered “cash to cull”, being considered for suckler farmers, let’s just say tempers are high.

There are fears that in order to achieve these targets to reduce emissions from farms, Ireland could lose 20% of its beef output, costing the industry €700 million (NZ$1.2b) a year and effectively seeing 14,500 beef farmers walk away from the sector.

Using better breeding and genetics can help produce cows that are more efficient and more carbon neutral, which could help Ireland’s farmers’ dilemma.

One breed being hyped as “the most efficient and profitable animals available in the marketplace” is the Stabiliser breed, first developed in the United States.

In the late 1970s, the USDA Meat Animal Research Centre in Nebraska started looking at the benefits of composite breeding techniques for cattle efficiencies, using crosses between breeds such as the Hereford and Angus, and the continental breeds, in particular the Simmental and Gelbvieh.

After extensive trials, it emerged the best-performing mix consisted of 25% genetics from the Hereford, Angus, Simmental and Gelbvieh, therefore the renaissance of the Stabiliser breed.

Over the years the breed has become popular with beef farmers in the United Kingdom and Ireland due to its docility, early maturing, easy calving, high-feed efficiency, high-milk production and good fertility.

With these traits the breed claims it is in a good position to be more carbon efficient, therefore reducing the

emissions they produce. In fact, with a combination of management techniques and genetic changes, Stabiliser farmers say they can reduce the carbon footprint of their suckler unit by up to 40%, while at the same time realising significant production efficiencies.

During trials on the breed, changes to management systems, such as male calves finished as bulls, reducing cow size, calving heifers at two years old and improving feed efficiency, were practised.

Breed researchers found significant carbon savings were easily and quickly achievable by improving many things incrementally rather than one thing outright.

The new system with all forage-fed cows included improved fertility, growth rate and feed efficiency, reducing cow

size, and calving at two years old. It produced a carbon saving of 31% under the full steer finishing system and a saving of 40% under the bull finishing system.

Northern Ireland beef farmer and former vet Billy O’Kane was the first to bring the Stabiliser breed into north and south Ireland back in 2002 when he bought 200 cattle for his Ballymena farm.

“I bought them because they are more profitable. They are a scientifically developed hybrid animal that eats less, grows faster and is sent to the factory younger.”

By using this breed and its traits, combined with new management procedures, Billy has reduced the farm’s GHG emissions. Cutting his nitrogen fertiliser usage in half by introducing more clover to his grassland and by using low-emission slurry spreading techniques were some of those new management decisions.

“There is more carbon loss from ploughing than any other type of farming. The key is not to expose the carbon in the organic matter of the soil to oxygen by direct drilling. That way, the soil will regain its embedded carbon through photosynthesis into the leaves and roots of plants.

“As a beef farmer working with the Stabiliser system, my part of the jigsaw is to demonstrate that the proven 40% carbon saving per kilogram of meat in our system would allow our sector of farming to produce the same amount of human food with a 40% reduction in carbon with no added costs,” O’Kane said.

His Stabiliser heifers normally calve at two years old and he finishes male calves as bulls on 1.5 tonnes of meal, averaging 380kg deadweight at 14 months old.

With such pressure on the government, all kinds of whacky solutions to reduce these emissions have been barked by various officials and groups.

Tom Ward looks at the advantages and disadvantages of composite sheep.

In recent years, the term composites has been used to describe a sheep containing a mix of high performance breeds, each providing a different trait. For example, Texel for muscle development, the Finn for fecundity and East Friesian for milking ability. The composite may or may not be a first cross or a stabilised breed. These are essentially bigger sheep than the standard 65kg crossbred, leading to the question of whether or not the greater productivity outweighs the greater appetite and whether or not composites

are superior to other breeds of the same size.

It is difficult to gauge the interest in composites. The concept appears less popular than 15 to 20 years ago. Some large South Island farms are developing a strong composite programme. Other farmers are staying with conventional breeds and growing a 75–80kg ewe anyway. Complicating the picture is not all composites are huge sheep, and not all high-producing ewes weigh more than 65kg. Wairere Romney’s Derek Daniels said he used to sell 1000

composite rams a year, but now very few. Buyers decided the benefit was in the hybrid vigour (first cross).

Some South Island sheep and beef farms are changing to Headwaters sheep, a composite of Romney, Perendale, Texel and Finn as a breed. The ewes weigh 72kg, manage a 155% docking, and wean on average a 28kg liveweight (LW) lamb. Headwaters is regarded as a stabilised breed, with 15 years’ selection, so there is no hybrid vigour effect.

Management regards it as a tough sheep, not one that needs pampering.

The Headwaters business incorporates Lumina lamb, a brand which, through the genetic makeup of the Headwaters sheep, claims to improve lamb quality by putting the fat back into sheep. The meat is evidently higher in polyunsaturated fats and intramuscular fat (IMF), leading to improved tenderness and taste. To further enhance these fats, the animals are grazed on chicory for at least 30 days. The $25/head premium for lamb fitting the criterion is expected to increase to $35 and $45/head in 2024 and 2025 respectively.

Another example is a South Canterbury farm running 4600 Texel/ Romney stabilised composite ewes weighing 75–80kg (empty) on hill country blocks. The ewes scan 205%, and survival to sale is 163%. Triplet rearing is assisted with two calfaterias so that every lamb gets a chance. Typically, 60–70% of the terminal lambs are sold pre-wean or off mum at 19.5–21.0kg

carcaseweight (41–46.5kg LW). These are very large well-fed ewes, probably with a body condition score of 3.5+. The average daily pre-wean lamb growth rate is 450gm/day.

A North Island hill country unit runs 1500 five- and six-year-old Romney ewes, and 2000 composite (first cross) ewes with 750 dry beef cattle. The Romneys are mated with a Romney/Texel/East Friesian cross ram to produce a first-cross composite ewe. Hybrid vigour is a driver in the performance of these first-cross composite ewes. This 900ha, 8000 stock unit farm is run by one man.

A North Canterbury, dryland, droughtprone farm, runs a predominantly sheep operation wintering 3200 Romney ewes and replacements. On a stock unit wintered basis the cattle are only 17% total stock units, and all lambs are sold by Dec 25, 70% fat at an average 38kg LW. The ewes are normally lambed on 2000kg DM/ha grass covers, saved from the autumn, as most of the ewes are wintered on a crop.