Protect your herd and the next generation

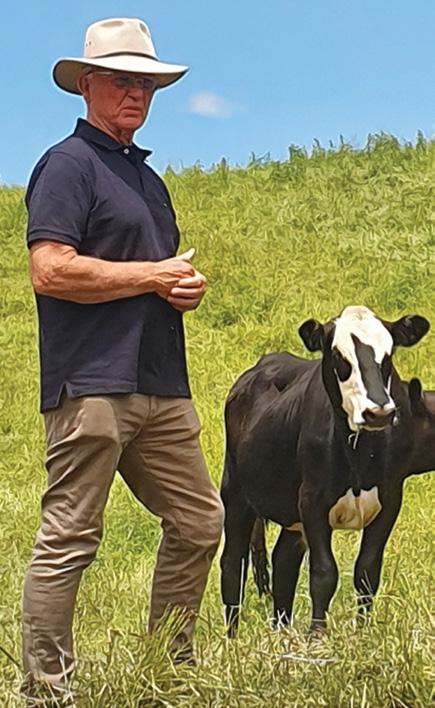

Use Bovilis BVD for 12 months of proven foetal protection1. The longest coverage available.

Exposure to BVD could mean your unborn calves become Persistently Infected (PI’s) - spreading BVD amongst your herd. It is estimated that up to 40% of dairy herds are actively infected with the BVD virus at any given time. The convenience of the longest coverage available along with flexible dosing intervals2 means you can protect this season’s calves no matter when they are conceived.

Avoid an outbreak. Ask your vet about vaccinating with Bovilis BVD or visit bovilis.co.nz

Page

SPECIAL REPORT: Cow values

44 Cashing in on cows

50 A widening quality gap

52 Eliminating bobbies: A pan-industry requirement

55 Cow value: is the dream runover?

58 Live exports: Surplus calf values set to crash

ENVIRONMENT

60 Ballance Awards: Wintering better

YOUNG COUNTRY

80 ‘I call myself a fishmonger’

RESEARCH WRAP

82 Future systems for Northland dairy

WELLBEING

84 Yarns that save lives

DAIRY 101

86 That sign at the gate

SOLUTIONS

88 MaxCare extends calf feed range

STOCK

64 Vet Voice: Prioritising colostrum

OUR STORY

90 50 years ago in the NZ

Page

66

DAIRY DIARY

August 14 – Applications close for 2023 Nuffield New Zealand Farming Scholarships. To find out more and apply, go to ruralleaders.co.nz/nuffield

August 17 – Habits for Success is a live webinar that explores practical tips and real stories to build a resilient platform for success in an environment where things constantly change. Delivered by ASB and Dairy Women’s Network, it runs between 12.30pm and 1.30pm. To register go to register.gotowebinar. com/register/1583525866467982096

August 30-31 – DairyNZ is holding two cropping field days in Northland to help farmers plan for the season ahead. Maize, summer crops, nutrients and weeds will be discussed at Waipapa on August 30 and Glenbervie on August 31. Visit the DairyNZ events page or contact Stephen Ball on 027 807 9686.

September 27-28 – DigitalAg 2022 is being held at the Distinction Hotel in Rotorua. The former MobileTECH Ag brings together technology leaders, agritech developers, early adopters and the next generation of primary industry operators. The real innovation now is in digital platforms that capture realtime data and convert it into practical information that drives productivity. To find out more about the event and to register, go to agritechnz.org.nz/event/ digitalag

September 29 – Lincoln University Dairy Farm focus day with a focus on mating, managing costs and inflation. The day begins at 10.30am. Visit www. ludf.org.nz/events

October 1 – Entries open for the 2023 Dairy Industry Awards and registrations of interest can be made at www.dairyindustryawards.co.nz

October 2-7 – World Dairy Expo 2022 is held in Madison, Wisconsin, United States. Find out more about the expo at worlddairyexpo.com

October 6-7 – The New Zealand Landcare Trust is hosting the National Catchments Forum at Te Papa Tongarewa in Wellington which brings together speakers with knowledge and experience in catchment management. It looks at water reforms, integrated farm and catchment planning, and how catchment groups are addressing the climate challenge. For more about the forum visit www.landcare.org.nz/eventitem/national-catchments-forum

October 28-30 – Waikato A and P Show is held at Claudelands Showgrounds. Visit waikatoaandp.co.nz

October 30 – Applications close for the first 2023 Kellogg Rural Leadership Programme at Lincoln which is aimed at developing leaders for the rural and agri-food sector. For more details and to apply visit ruralleaders.co.nz/kellogg

November 3 – Reprogram –Charge the Brain is a webinar run by ASB in partnership with Dairy Women’s Network. It looks at the neuroscience of attention, memory and energy to help with busy lives and increasing change. To register go to register.gotowebinar.com/ register/1687105359498338318

November 9 – The New Zealand Agricultural Show is held at Canterbury Agricultural Park in Christchurch. Livestock entries are open. For more information visit www.theshow.co.nz

November 15-17 – The NZ Grassland Association’s annual conference takes place in Invercargill. For the first time the conference will be held in conjunction with both the Agronomy Society and the NZ Society of Animal Production, enabling it to cover most research aspects of New Zealand agricultural systems. A highlight of the conference is a tour to the Southern Dairy Hub. For more information and to register, visit www.grassland.org.nz

November 30 – December 3 –Fieldays is a summer event this year at the Mystery Creek Events Centre near Hamilton. For details visit www.fieldays.co.nz

Staying strong onfarm portrays an innovative programme run by Reporoa dairy farmer and cancer survivor Sarah Martelli, who helps other women find their balance and build strength and wellbeing to be the best they can be.

Strong Woman is an online community for women to work on their fitness with a workout to do at home, find quick and easy healthy recipes, goal planners and to connect with other women on the same journey.

HURDLES ON TRADING ROUTE

Her philosophy is to help women create healthy, sustainable habits around moving and feeding their bodies and their families.

If women can prioritise their own health and fitness, they can inspire their partners, their children and their community around them, Sarah says (p82).

It’s been a well worn path for many years in the dairy industry - and one that has helped thousands of sharemilkers into their first farm - trading cows and building equity - along with what could be described as the final push for the summit - selling down half the sharemilking herd for the first farm deposit.

(p42). We also cover the Heald family of Norsewood (p52) who have transitioned to organics, OAD philosophies and are enjoying the less intensive more resilient system they have moved to, along

She is an inspirational woman creating a moment of lift for many women.

In this issue we take a look at the regenerative agri journey some NZ farmers are already on, and that the government has signalled they want others to join in on, in our Special Report.

But many factors have combined to put more obstacles in the well-worn path and in our Special Report this month we look at what’s happening to the price of cows and whether the end of live exports and shutting down of farm conversions has burst the growth in equity through cows.

some figures through the contract milker Premium Calculator to see if the reward is there. The calculations can also be used to start a conversation with the farm owner (pg 25).

The regen debate has divided the farming community in a big way - many scientists are affronted that NZ would need regenerative methods from overseas countries with highly degraded soils - would that then infer that our conventional methods were degenerative?

There is more research to be done in the NZ system context, says MPI’s chief scientist John figure out what will and won’t work, but he encourages farmers to engage and learn more, and to embrace regenerative as a verb - saying all farmers could be more regenerative, more resilient, lowering

Siobhan and Chris O’Malley have made it work this season, moving to their first farm on the West Coast after years of trading cows and scrimping and savingsomething that was certainly not fast or easy. They suffered burnout on the way, and even exited the industry for a time, but their burning passion for dairy brought them back, and fired up their dream of farm ownership. They even had their children involved in money discussions and colouring in the savings chart. Read about their journey on page 44.

Colostrum management and rotavirus are top of mind for our contributing vet Lisa Whitfield and with the latest research from Poukawa OnFarm Research team (pg 64) and Jason Archer from Beef+Lamb gives some great advice on how to select the right beef bull to breed some valuable dairy beef calves (Pg 78).

They say the methods won't work, and that research has already shown that, and also our farmers are already following regenerative practices. Others say that the methods are not prescribed and each farmer can take out of it what they want. It has been called a social movement rather than a science and the claimed benefits of improved soil and stock health and building soil carbon through diverse species, use of biological fertilisers and laxer and less frequent grazing practices along with less nitrogen is something that resounds emotionally with many.

Beef consultant Bob Thompson looks out to a time when it will be mandatory to make every calf a valued calf - and he puts forward a scheme to categorise non-replacement calves to give calf rearers assurance around the value and quality of those calves (Pg 52).

We have taken a snapshot of thinking by scientists in MPI and DairyNZ (p46) and portrayed what farmers using the practices are finding, including ongoing coverage of the comparative trial work by Align Group in Canterbury

Experts we talked to say it’s definitely not impossible, but you need a longer time horizon to build equity as land prices have increased faster than cow prices - whereas in 1992 you used to need to sell 14 cows to buy a hectare of land, now it takes on average 30 cows.

Dairy Exporter | www.nzfarmlife.co.nz | June 2021

Taking a step down the progression ladder we take a look at the premium contract milkers should be making over a managerial salary. They need to be rightly rewarded for the risk they are taking in setting up their own business, and they can now run

If you are interested in getting into farm ownership getting out but retaining an interest, read about Moss’ innovative idea for a speed-dating weekend potential partners (p11). We think it could be

Sneak peek

JULY 2021 ISSUE

In the next issue:

September 2022

• Special Report: Farming/business investment – if you are starting out or bowing out.

• Wildlife onfarm

• Diversification onfarm - could you go bananas? Embrace avos?

For something different, give our new podcast series a like and a listen. First up, the Young Country podcast team chat to a young Chatham Islander who built a great food business selling kai moana from the rich seas around the islands. There are lots of other great young people in the sector building businesses From The Ground Upso watch out for them too, @YoungDairyED

• Ahuwhenua winners

• Sheep milking conference coverage

Open up for accommodation?

• What’s new in the oldest professionmating?

ONLINE

New Zealand Dairy Exporter’s online presence is an added dimension to your magazine. Through digital media, we share a selection of stories and photographs from the magazine. Here we share a selection of just some of what you can enjoy. Read more at www.nzfarmlife.co.nz

PROVING THE THEORIES

PODCAST: FROM THE GROUND UP

NZ Dairy Exporter is published by NZ Farm Life Media PO Box 218, Feilding 4740, Toll free 0800 224 782, www.nzfarmlife.co.nz

Editor

Jackie Harrigan P: 06 280 3165, M: 027 359 7781 jackie.harrigan@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Deputy Editor

Sheryl Haitana M: 021 239 1633 sheryl.haitana@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Sub-editor:

Pareka farm has gone through a significant change in farm systems this season with the aim of cutting N losses and methane emissions, paving the way and creating learning opportunities for others.

Take a look:

https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=SV9t9tqB3Kc

Young Country is pleased to announce that episode one of From the Ground Up is now live on all of your favourite podcast providers. In the first episode host Rebecca Greaves catches up with Delwyn Tuanui from The Chatham Island Food Co and learns about how he chased his dreams from the ground up.

Running around Melbourne in his early 20s with a chilly bin full of Chatham Island blue cod, knocking on the doors of the city’s top chefs, Delwyn Tuanui knew he had a special product.

We love highlighting positive stories of young agri-innovators chasing their dreams and Delwyn’s story doesn’t disappoint. Listen to From the Ground Up: nzfarmlife.co.nz/podcasts-2

Check out Chatham Island Food Co on socials and learn how you can get your hands on their fresh kai moana at:

- Instagram handle @chathamisfoodco

- Facebook account @ChathamIslandFoodCo

Or via their Website www.chathamislandfood.com

Andy Maciver, P: 06 280 3166 andy.maciver@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Reporters

Anne Hardie, P: 027 540 3635 verbatim@xtra.co.nz

Anne Lee, P: 021 413 346 anne.lee@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Karen Trebilcock, P: 021 146 4512 ak.trebilcock@xtra.co.nz

Delwyn Dickey, P: 022 572 5270 delwyn.d@xtra.co.nz

Phil Edmonds phil.edmonds@gmail.com

Elaine Fisher, P: 021 061 0847 elainefisher@xtra.co.nz

Claire Ashton P: 021 263 0956 claireashton7@gmail.com

Design and production:

Lead designer: Jo Hannam P: 06 280 3168 jo.hannam@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Emily Rees emily.rees@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Partnerships Managers: Janine Aish

Auckland, Waikato, Bay of Plenty

P: 027 890 0015 janine.aish@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Welcome to the ASB Rural Insights - Succession Series podcast, where we’re talking about farm ownership transition from all sides. Thanks to the ASB Rural team for partnering NZ Farm Life Media on this four-part series. Each week Angus Kebbell will be profiling farming families, talking to experts from the advisory sector and investigating new opportunities for farmers thinking about diversifying their farming business. When it comes to ‘what’s next’ for the farm, there’s a lot to think about, so we aim to share success stories, provide useful tips and help you understand more about the many facets of succession planning in the food and fibre sector today.

To listen:

https://nzfarmlife.co.nz/podcasts-2/

CONNECT WITH US ONLINE:

www.nzfarmlife.co.nz

NZ Dairy Exporter @DairyExporterNZ

NZ Dairy Exporter @nzdairyexporter

Sign up to our weekly e-newsletter: www.nzfarmlife.co.nz

Tony Leggett, International P: 027 474 6093 tony.leggett@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Angus Kebbell, South Island, Lower North Island, Livestock

P: 022 052 3268 angus.kebbell@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Subscriptions: www.nzfarmlife.co.nz subs@nzfarmlife.co.nz

P: 0800 2AG SUB (224 782)

Printing & Distribution:

Printers: Ovato New Zealand

Single issue purchases: www.nzfarmlife.co.nz/shop

ISSN 2230-2697 (Print)

ISSN 2230-3057 (Online)

Good things TAKE TIME

Onlookers seem stuck in the mud on wintering livestock in Southland, Suzanne Hanning writes.

My older brother always used to say “patience is a virtue”. I used to counter with “You’re not very virtuous then, are you?” The word ‘virtue’ means ‘behaviour showing high moral standing’. Sadly the word ‘signalling’ gets stuck next to it from time to time and corrodes this into something dripping with sarcasm.

This is all too commonly seen on social media when it comes to the opinion of people who have nothing to do with agriculture on what farmers should or shouldn’t be doing. As I’ve mentioned in a previous column, everyone seems to have plenty of opinions on wintering livestock in Southland, but they have very little in the way of solutions.

Our fellow farmers down here in Southland have been patiently waiting for the results of our HedgehopeMakarewa Catchment Group and Southern Dairy Hub Winter Cultivation Pilot Study funded by Thriving Southland and finally, we can start to share what we’ve learned.

The key word here was “pilot study”. Wintering animals outside, on crops in situ is, to my limited knowledge, a unique method practised nowhere else in the world. Due to this uniqueness, it has never actually been studied in any great detail.

We didn’t know what we didn’t know and hence cast a huge net over a huge area and tried to have a look at what we caught. What we ended up with was a monster project with thousands of data points, pictures, and recorded observations. All this took until very recently to sift through and even now, there is still a huge amount of collected information that is being pulled out.

Our Southern Dairy Hub held a field day last month and shared some of the results of the pilot study. There is a link to the hand out on our HedgehopeMakarewa Catchment Group Facebook page if you would like a look. The study was both surprising, interesting and most certainly a lesson in patience.

My second biggest lesson from this project is that this is much bigger and more complex than anyone could have dreamed. Finding a better way to winter animals in Southland or anywhere with similar conditions to us is going to take a lot longer than any politician or activist will be comfortable with. To be fair, the real problem is the three to five rain events that happen in the 90-day winter period that seem to cause all the issues. What was obvious was the participants who paid close attention to detail, methodically followed their plans, carried out careful daily observations and acted on those observations had significantly better outcomes.

My first, biggest lesson is we need to have more faith in humanity. The people who made this study possible at every level are not special or brilliant in any way. They are ordinary individuals who go about their days rather unremarkably, performing ordinary tasks and achieving ordinary things.

What occurred last winter was not ordinary. We had a voluntary gathering of wills to achieve something greater than the status quo. From the 17-year-old apprentice mechanic, to the agronomist, to the farmer who just tried something a little different. The culmination of their efforts resulted in a certainty that we will figure this out.

It won’t be perfect immediately, but we will get there. It will just take a little time, patience and require a bit of virtue and not of the signalling kind.

FINALLY…

a place we can call home

After a dozen moves as sharemilkers, it’s time for the family to put down roots in South Taranaki, Trish Rankin writes.

It was a big winter period for our family as we moved to a farm we have bought in an equity partnership with a couple of friends/investors. I surprised myself with how emotional I was when I told the kids late April that we had gone unconditional.

See, it has been a journey from Canterbury, Wairarapa, Hawke’s Bay, Northland to Taranaki. We have been burnt financially by not doing a good job in our diligence looking at a farm job, have had challenging farm owners or staff to manage and had some farming hard times with droughts and floods too.

But the day in April, when at 4.30pm our awesome lawyer Jax Owen phoned us to say we were sorted and we were going unconditional, I just burst into tears! We had done it. We have found a farm 9km from the kids’ high school, just out of Opunake where we spend a lot of our time, that has scope for improvement but also great infrastructure.

To get here was a battle of having a great team around us, strong resilience and goal setting. We had to exercise our right to not have to live on our sharemilking job so that we could take up this opportunity which also came with its challenges when one local farm consultant didn’t think we should be allowed to move off!

He was wrong. He was out of line actually. But, we knew if we couldn’t get into something permanent soon we weren’t going to survive another sharemilking shift in two years. We have moved 12 times in 22 years of farming and with four happy kids, loving their life here in South Taranaki, continuing the sharemilking life of moving to progress was not something we wanted to continue to do.

We still have our sharemilking job and another lease farm here for the next season, alongside our new farm so it will be a bit hectic, but we have awesome staff on the team and know we can work together to do it for just one more year.

We all know each other’s goals and that this year is a year to lift each other up and help the whole team get to their 2023 goals!

The start of the new season has been wet and wild. Lots of northerly weather patterns have brought a lot of rain and wind. Mild temperatures though and so grass continues to grow if it gets some sun and the water drains away.

Over June and July I also enjoyed getting out and about running workshops. Taranaki Catchment Communities along with Landpro hosted a Farm Pulse workshop onfarm at Warea, just under the mountain. It was a great day and learning how to identify soil qualities, healthy waterways, rules for onfarm offal holes etc was all so relevant at the moment for farmers here.

It was a pleasure to have some of our local Opunake High School year 12s come onfarm and plant our 1200 riparian plants - not many left to do on our farm and it was a bit of a novelty for us knowing that it was our block of land. The kids did an amazing job. With stony soils it wasn’t an easy task. This will find most people well into calving now. Be safe, have downtime and keep connected with others.

THE 190KG NITROGEN CAP

– a farmer’s reflection

George and Mac the dog enjoying a paddock of new grass including a mix of two new clovers ( Brace or Attribute by Agricom), a new variety of grass (Forge) and what remains of the chicory crop.

Gidday, we have just finished the first season of adhering to the 190 kilogram nitrogen cap, so how has this impacted us?

Introduced by the government, this rule states pastoral farmers can only apply a maximum of 190kg of nitrogen per hectare on to grazed land. A higher rate of nitrogen can be applied on crops so long as the extra nitrogen does not lift the overall farm average above 190.

Put succinctly, for our pasture paddocks under irrigation, we put on 23-25kg nitrogen/ha, per month, for seven to eight months (between AugustMay). We chose to skip nitrogen applications in JanuaryFebruary when clover was thriving (under irrigation) and fixing nitrogen.

On the non-irrigated and dryland run-offs we put on higher rates of nitrogen (up to 36-40kg/nitrogen/ha) as we knew we would not be able to apply nitrogen for the same seven-eight month timeframe. This would hopefully maximise our spring growth and help to increase our supplement harvested before the ground became too dry.

Chicory was used on the dairy platform as a summer crop. In theory, this herb thrives off our “little and often” approach to nitrogen.

What happened

Annual accumulated pasture grown was down on the farm by ~1tonne/ha. Overall nitrogen use was 158kg/nitrogen/ha compared to previous years of 116 (2018/19), 122 (2019/20) and 170 (2020/21). A greater amount was used on nonirrigated areas and less productive

paddocks, and at the run-offs compared to previous years –up from ~90kg/ha to 120kg/ha.

Despite more nitrogen, a poor spring resulted in less grass grown and supplements harvested. In contrast, less nitrogen was used on high-performing irrigated paddocks – down from ~230+kg/ha to 190kg/ha. These changes contributed significantly toward lower total yield.

Paddocks with healthy clover population appeared to be thriving, with less inhibition from synthetic nitrogen applications in summer months, compared to previous years. This is not surprising, but it made us reflect on the impact of previous nitrogen use on our clovers. Pasture swards with poor clover populations had lower relative growth rates and quality.

Going forward

For the most part we will stick to the same nitrogen plan. We will however switch back to turnips from chicory so we can ensure a bulk yield from our summer crop. This will be supported by one large dressing of nitrogen rather than many smaller dressings with variable response rates due to the unpredictable summers we have experienced in the last few years. We will also delay sowing our turnips by a month, so we can get more feed harvested from pasture before it’s sprayed out.

This year we will do another whole-farm soil test to ensure fertility is not limiting our clovers. These plants need to deliver more than ever! Coupled with the soil testing, we will make best use of our new ‘Clean Green’ effluent system. This will allow us to apply effluent with the same little-and-often approach as our synthetic nitrogen plan.

Most importantly, we will focus on improving the pasture production of our poorer performing paddocks, because our highest achievers are unfortunately capped! This will involve capital expenditure on drainage, subdivision, capital fertiliser and a new model of pasture species. These improvements can cost big dollars, but there is only one way to beat the evergrowing list of regulations, and that is to adapt. Something we farmers are rather good at!

There is only one way to beat the evergrowing list of regulations, and that is to adapt, writes Hamish Hammond.Left: The new clover on the block.

An obsession WITH GRAVEL

Ihave been spending a lot of time in my office lately (aka my little digger). Owning a digger has some advantages, one of which is most of the time it is pretty repetitive work requiring minimal thought. So as a result you get to think a lot.

This time my thoughts did not have to go far, they all centred on gravel and gravel management. The obsession with gravel is based on having to clean one creek out twice this winter, having to put in two new bigger culverts because the original ones blew out twice. I also have had a small creek destroy a neighbour’s culvert and cover the road before coming through my paddock. Most of the effects to me have been minor compared to other farming friends losing large amounts of land and major bridges.

My problem with gravel management in New Zealand is, well, we have just stopped doing it, we have resorted to bigger and higher stop banks at ever-increasing costs. We cart boulders around to keep rivers in their “correct place” and the removal of gravel has become an expensive and haphazard event.

sea. Our farm was made up of these gravel fans over centuries and with us having different gravel coming from each valley we can tell where the creeks have run over past history.

Naturally they are always trying to break out of their bed. Moving left or right is the aim of a waterway. Some do this with gravel, some with flax and other plants.

It is humans that have built assets like bridges that want and need waterways to keep where they are and for this to happen there has to be gravel management. This management can take the easy option of removing and using the gravel but in some cases the sheer volume of gravel is beyond any need or ability to remove and use the gravel.

Where I live we have a short and steep fall from the mountains to the sea and the production of gravel has increased over the last years due to high rainfall events and cyclones killing trees.

This is no different to other waterways, it just happens quicker here because of the slope. The basic fact is gravel and water all want to go to a lower area on their journey to the

I think the only option is to let the waterway do what it wants to do and change course and dump its gravel in a lower-lying area. It would take a brave council to have this as a management plan with all the work it would involve of land swaps and taking on the people that believe rivers are sacred and should stay where they are. In the long term it would be a much cheaper and more natural approach to gravel management than what we have at the moment.

I think the only option is to let the waterway do what it wants to do and change course and dump its gravel in a lower-lying area.Spending time remediating culverts and creeks after winter rains has given Richard Reynolds lots of time to think about the grave issues - like gravel management.

REALPOLITIK IN WORLD DAIRY MARKETS

While industry advocates have bemoaned the limits of the free trade agreement with the European Union - one of the world’s most protected markets, Phil Edmonds looks at the positives.

With the dust settling in the wake of New Zealand and the European Union revealing a free trade agreement had been landed after years of deliberation, the opportunities for dairy export growth need to be reimagined.

In the lead up to the EU deal being finalised, some industry advocates were arguing a favourable deal was essential for NZ to ensure the value of our dairy exports could keep growing. What was negotiated, however, was widely acknowledged to be ‘unfavourable’. Does this mean all hopes for growing the value of what we produce have been dealt a fatal blow? The answer is likely no, but it might mean we’ll have to work harder to achieve it.

Recently back from the bargaining table, New Zealand’s chief negotiator for the FTA with Europe, Vengalis Vitalis spoke at the Primary Industries Summit in Auckland, and called for those upset by the paucity of sweeteners for dairy to take stock of the wider market reality. Vitalis openly accepted the gains from the deal were miserly and expressed frustration at that. But the context was also important. He noted that NZ is the only market other than the United Kingdom that has preferential access on dairy.

While quotas will still limit the extent that dairy exports can grow, the near elimination of tariffs over seven years will mean some butter (36,000 tonnes) will be able to enter with a tariff of 95 euros per tonne, down from 770 euros.

The fact that this has been afforded to other markets beyond the UK sounds like cold comfort, but the reality is NZ will have an edge on others. For example, Mercosur (the South American bloc of countries including Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay) had negotiated 30,000t of cheese quota in its deal (which is currently floundering and won’t be ratified anytime soon) but with tariffs phased out over 10 years. NZ secured 31,000 tonnes of quota that goes to zero tariff on day one.

Among the other reality checks we need to consider are how European dairy producers felt about the deal.

Vitalis noted the European Fed Farmers equivalent, Copa-Cogeca responded by saying EU dairy farmers had been sacrificial lambs and they had paid a very high price. Almost comically, they argued the new access NZ dairy products had obtained will increase market pressure on European production. If the prospect of the very occasional baguette being slathered with NZ butter does induce sleepless nights,

it’s hard not to conclude they’re still on a reasonable wicket.

All that said, everything is relative.

We might wish to ignore it, but recent legislative changes in Europe have compelled farmers to make radical adjustments to their operations, which will undoubtedly impact on their productive capacity. Over the past couple of years, the Netherlands, for example, has introduced a 13-year plan to significantly reduce livestock numbers to address nitrogen problems. This plan also involves initiatives to prompt farmers to leave the industry. Any further imposition, however minor in impact is likely to add fuel to EU farmers’ sense of struggle.

It’s possible to say that European farmers’ blight in this regard is no different to that being experienced by their NZ counterparts. But again, that won’t have forced them to think of us as comrades in arms.

Interestingly though, the deal implies just that, via the joint commitment to the principles of sustainability. Both the EU President Ursula von der Leyen and NZ trade minister Damien O’Connor made a point of highlighting a clause that states neither party will deviate from the Paris Accord for climate change for trade advantage.

The EU President said it was a first for a trade deal to include sanctionable commitments to the Paris Climate Agreement, while O’Connor made the unsubtle point that NZ would be taken to task if it strayed off its stated climate obligations. For Vitalis, this represents a reassuring outcome in that NZ would be able to raise concerns about the impact on prices of European environmental subsidies in a legally binding way. Furthermore, one of the reasons the Mercosur FTA with the EU has run into problems in the pre-ratification process is that a commitment to reducing its environmental footprint is out of alignment with the EU’s. With NZ sharing the EU’s goal, our goods should have more appeal. Equally though, there’s justification to be cynical about the EU’s apparent respect for the efforts NZ is making to de-carbonise its economy. Proper respect would have meant NZ dairy products being afforded fairer access. As DCANZ said in its assessment, “The EU has largely rejected the opportunity to provide its own consumers with access to NZ dairy products that have considerably lower carbon footprint. New Zealand dairy farmers will be disappointed that their considerable efforts in adopting onfarm sustainability practices are not able to gain the extent of market recognition they deserve under this outcome.”

It would be nice to think European consumers would have the ability to reward NZ farmers for this, but with the quotas set for cheese and butter, there’s very few consumers who will have an opportunity to do so. DCANZ added a stark reminder of the market imbalance where the EU has about 15% share of the NZ domestic dairy market, but NZ would only have about 0.14 percent of the EU market.

With that sobering reality in mind, what now are the opportunities for NZ to achieve export growth?

With the EU deal concluded, suggestions have been made that for the time being at least, there’s not much more we should expect to see in free market access. The government has pointed to opportunities that will arise if NZ was to gain associate membership of the Pacific Alliance (Mexico, Peru, Colombia and Chile). Colombia is said to be a noteworthy importer of dairy products. Elsewhere access could be improved by advancing the FTA with the Gulf Cooperation Council, which would create a level playing field for exporters.

On the face of it, this suggests there are now limited

prospects for the NZ dairy industry to grow its exports. Not only that, but the charge also to transition from ‘volume to value’ (which is fundamentally where NZ must go with milk production having peaked) is challenged with the highest value markets (EU, together with the United States) either marginally accessible or inaccessible. However, that presumes accessing high value markets is simply based on increasing rules-based free access on a country-bycountry basis. Obviously, those conditions enable growth by the easiest means. What we probably need to come to terms with is there remains plenty of opportunity to capitalise on high value markets within countries that NZ has existing free trade deals with –but they are niche and will require more effort.

It’s also worth reflecting on NZ’s existing competitive advantage in the trade of dairy products, where we are closer to the world’s key growth markets than our rivals. The EU has tended to push its surplus output down into the Middle East and Africa, and excess production in South American markets has tended to fill gaps within the region itself. But those markets have not been high growth or high value, unlike Asia, and specifically China where NZ still commands a head start with an existing trusted relationship.

Yes, you never want all your eggs in one basket. To some extent that has been the reason many felt the EU deal has been a particularly sore loss, with government regularly nudging exporters to diversify away from a reliance on China. But you also need to focus on where the growth is, and despite potential geopolitical tension, China and Asia is where growth opportunities remain. There’s no point ignoring that – other market producers will be more than happy to fill the void. ANZ agricultural economist Susan Kilsby says this will require a turnaround in our thinking, which means identifying niche groups of premium consumers within existing markets and responding to their needs.

“To some extent we do that anyway. Fonterra has long supplied Nestle with ingredients that give consumers what they want. But there will be more demand for products to be produced in a way that will command more value. At the moment there is an information gap, where market information doesn’t necessarily flow back to the farmgate. But some suppliers are being linked in through processors to give consumers something extra.

“Synlait and Miraka have identified this and are meeting specific market needs on a smaller scale. Fonterra will eventually do this on a much bigger scale.”

The hurt over the missed EU opportunity won’t disappear overnight, but to move forward we can’t afford to dwell on being locked out of a geographical market. Rather we need to dwell on what it takes to be locked into high-value markets within markets, wherever they may be.

ECLIPSE® and EPRINEX® have formed the backbone to New Zealand farms over the generations for animal health. So together with these Merino Icebreaker Thermals, we’ve created the ultimate legends of the land for you and your stock this season.

Purchase qualifying cattle drench products this season and you’ll receive either an ICEBREAKER short sleeve merino tee or a long sleeve merino jersey absolutely FREE *

*Promo runs from 1st August - 30th September 2022. Ask in clinic for qualifying products.

North America’s dairy dispute

Lawyers and lobbyists appear to be the winners in a tussle between United States and Canadian dairy industries. By Anne Cote.

The United States, Canada and Mexico signed a new trade deal in 2020 after three years of tough negotiations. Part of the deal, known in Canada as CUSMA and in the US as USMCA, focused on Canada’s supply-managed dairy industry. US dairy producers and processors wanted Canada to drop the supply-managed system and allow full access to the Canadian market for US dairy products. Canadian dairy producers and processors dug in their heels and fought to keep the system.

The Canadian dairy industry won, sort of. In return for keeping their supply-managed system they agreed to allow the US to increase dairy exports to Canada but set out specific TRQs to be managed by the Canadian dairy industry and government trade personnel.

The elusive TRQ, an acronym that pops up over and over in dairy conversations on both sides of the border, is “tariff-ratio quota”. It allows a set amount of product to enter a country at a lower rate than the regular tariff.

It didn’t take long before the US launched several claims against Canada’s trade practices. The only complaint the US won was the one pertaining to the dairy TRQ allotment mechanism.

They said it hindered the flow of dairy products from the US to Canada by assigning a portion of the TRQ to Canadian processors. The CUSMA dispute resolution panel ruled Canada should revisit its method of allotting TRQs to processors and distributors. Canada complied and announced a new allocation mechanism on May 16, 2022. Mary Ng, Canada’s minister of international trade, export promotion, small business and economic development, said in reference to the result of recent US challenges to CUMSA, “The dispute settlement panel’s report ruled in favour of Canada in a majority of the claims. The new policies address the sole finding of a CUSMA dispute panel that Canada’s practice of reserving TRQ pools exclusively for the use of dairy processors is inconsistent with the agreement. The new policies end the use of processor-specific TRQ pools.”

According to a Dairy Farmers of Canada statement the same day, “The new allocation mechanism, which

is based on market share, does not reserve any portion of the CUSMA TRQs specifically to Canadian dairy processors and is therefore fully compliant with the CUSMA dispute settlement panel decision.” (2022).

So, the U.S. won its argument on TRQs but they didn’t stop there. They launched a second complaint, again about the allocation and management of dairy TRQs.

The US Dairy Export Council (USDEC) and the National Milk Producers Federation (NMPF) continue to push for more access to the Canadian market and issued a joint

statement on May 25, 2022. In it, Jim Mulhern, president and CEO of NMPF states, “Dairy farmers appreciate USTR’s (United States Trade Representative) continued dedication to aggressively pursuing the full market access expansion into the Canadian market that USMCA was intended to deliver.”

This type of back and forth rhetoric over trade deals is not new to US and Canada trade relationships. The greatest winners always seem to be the lawyers and lobbyists as years grind by with little or no progress on a myriad of claims presented to dispute panels.

Minister Ng supports Canada’s stand on dairy TRQs saying, “Canada has met its obligations under CUSMA to ensure that our TRQ system is compliant. We respect the right of the United States to initiate the dispute resolution mechanism as part of the agreement. Canada will actively participate in CUSMA’s consultation process and stand by our position to administer our TRQs in a manner that supports our dairy supply management system.”

• Anne Cote is a Canadian dairy journalist.

Make more green this summer with 501 Chicory

Extra value $450/ha*

501 Chicory is very fast establishing and out-yields some other varieties. This could mean an extra 50kg MS/ha worth $450/ha*.

*Based on 550kg DM/ha extra yield and $9/kg MS milk price. Yield data based on yield info from combined trial analysis of Cambridge 11-12, and Canterbury 12-13.

Peeking over the farm gate

An intricacy of the New Zealand dairy industry is the extreme isolation from our consumersunless you’re selling dairy products at the end of the driveway or in a local shop, you have very little to do with the end consumer of your beautiful white gold.

This intricacy is both a positive and negative result of how our industry took on the world markets; that is, combining resources into a cooperative, and separating the skill set between farmers and processors to optimise the outcome of smaller farms at the time.

It has made the world of difference over the last 100 years. However, at our current scale, and comfortability, I feel as farmers in the day-to-day grind onfarm, we often forget that our product requirements are still determined by the consumer at the end of the day. I think of end consumers as the largest risk outside the farm gate, that will undoubtedly influence any farm business.

These consumers exclusively determine the market outcomes via their wallets. This is hard to argue with. However, where and how deep the wallet is opened and pillaged is determined by the consumer making an informed decision around the product they’re buying.

Using the word “informed” in the last line is often the first point of arguments, but let’s face it, everyone thinks they’re right, it’s called an opinion...

With its distance from most consumers, the New Zealand dairy industry sometimes has difficulty making the connections. By

This is the changing face of consumers’ buying habits - tightly held opinions. The entire primary production system globally is facing the same predicament. Consumers have rapidly shifted their buying decisions over the last two years, both as a result of Covid and digitalisation of our lives increasing.

These changes have led to including key decisions now involving such things as environmental factors, health and wellbeing impacts, immunebuilding abilities of a product, associated status induced from the purchase and oddly enough, taste is still somewhat important. The underlying product has not changed - it is still cow’s milk. However, to differentiate in a competitive environment, products must seem better than the competitor’s product next in line on the shelf, which leads to the list of now important factors to consumers. All of this leads me to my favourite saying; treat your farm like a restaurant. If you walk into any establishment for food that doesn’t please your eyes, you will most likely turn and leave. It’s human nature most likely established from not eating food covered in muck. The old saying “we eat with our eyes” comes in nicely here. Our consumers are the same, but from a massive distance. They want the same assurance of a clean restaurant, but from anywhere in the world while they enjoy their room temperature drinking yoghurt or buttersoaked croissant.

Stu Davison.

Unfortunately, the array of global consumers and their differing demands have shifted so quickly over the last 1015 years, that it is very hard to keep up with what they actually want, and let’s be honest, I don’t actually think they really know what they want, but some very slick marketing is helping to convince them of this thinking. Unfortunately, that is the power of good marketing; it works for and against every producer, an everperpetuating problem.

So, as we look forward to what else will impact farm businesses from this everchanging array of consumers, expect more product differentiation to come down the pipeline, in one form or another.

Unfortunately, the wheels of change are spinning quickly in all parts of the value chain, such as Miraka’s geothermalpowered powder drier, Synlait’s electrode boilers and Fonterra’s woodchip/biomass boiler in Te Awamutu. All the start of ongoing changes to help NZ dairy stand out from our competition, as we try to keep our place in changing world markets. However, making changes to consumers’ buying decisions starts with those at the coal face, ironic statement in this context, I know. Unfortunately, we have two options: give the consumer what they demand and be rewarded with top dollar or keep the status quo and slide to the bottom of the demand pile.

GETTING IN, GETTING OUT

Whether you’re moving into the industry, or on your way out, it pays to be well prepared. Anne Lee reports.

Whether you are putting the first tentative step on the progression ladder or looking to ease out in terms of time or equity, being “best dressed” for the job will carry you a long way.

“Getting in or getting out” was the title of a SIDE workshop run by Compass Agribusiness in Oamaru in June.

Regardless of where you are at – getting in or getting out – being investible either as a business or more personally will help set you apart from others and make you someone others want to align with.

Take stock

• Understand where you are now – in terms of skills and financially.

• Understand what the other party wants and build towards that if you’re not there already. Use a third party to help with that assessment – someone who has the skills to do so.

• Know your strengths and weaknesses – if you are stepping up to be a sharemilker or contract milker, are you a good manager of people, do you understand PAYE, rosters and the regulations?

If you are a farm owner taking on a sharemilker or looking to reduce your input through equity partnership or succession, can

you actually let go and allow someone else to do it?

• What’s your reputation or brand?

• Know your values – do they align with the other party? That’s crucially important if you’re moving into any kind of business relationship.

• What’s the quality of the asset? What are its strengths and weaknesses? Is there contingent liability – upgrades needed to effluent systems, irrigation, farm dairy?

• Where are the risks and opportunities for the business? Understand where it sits with environmental compliance, what regulations and rules will impact it. Has the production and analysis of profit been done with those rules in mind?

• What are your non-negotiables? What’s so important to you that you’d decline an opportunity with a person or business?

Set goals and plan

Goals can be long, medium and short range. They should be SMART

It may not be linear to get there – sometimes you may have to move sideways or even back down and then back up again to make it to your goals.

What do you need to learn, what skills and competencies do you need?

If you are looking to take on a sharemilker, equity partner or carry out succession what skills or attributes are you looking for to get you to your goals. Understand what the other person’s goals are – are they compatible with yours.

Being best dressed

Build a strong reputation.

Build a strong, credible CV. Build your skills.

Build strong relationships - make sure the people you work for and alongside become your backers.

Take opportunities to learn and educate yourself.

Avail yourself of courses and programmes within the dairy sector such as Mark and Measure and the NZ Dairy Industry Awards.

Work closely with trusted, capable advisers.

Understand your accounts and finances.

If you’re getting in – limit your debts, have a personal budget and understand where your money is going. Have a savings history. All of that will give a banker more confidence in you.

Assessing the opportunity, due diligence

Does the opportunity align with your goals?

What will your position be if you take the opportunity, full financial analysis, stress test it?

Treat every opportunity like a partnership and assess the people involved – are your values aligned, do your farming styles align, do they have someone who can act as a referee?

What will life look like day to day?

Use a third party to do the assessment or to check your assessment.

Keep the emotion out of it to start with and do the clinical assessments but at the end when that’s completed ask – what does your gut tell you?

Family situations have more emotion –bring in the skilled, trusted third parties.

Goals will give you direction and give you boundaries when making decisions – will this help me get closer to my goal or push me away from it?

Write them down – that makes you more accountable, reminds you what they are, clarifies your goals, helps you review progress.

A Harvard business study found people who write their goals down are more likely to achieve them, if they share their goals with someone else and let them know how they’re going along the way to achieving them they become even more likely to achieve them.

You can change your goals.

Once you have set the destination, plan – how will you get there? Understand what’s needed to achieve them.

Planning allows you to break down the goals into more manageable pieces.

If you’re getting out- have a farm business that’s investible not just a farm that’s saleable.

Know your business inside and out.

Is your system repeatable?

Be happy to share information – it gives investors comfort, helps them understand the operation and the full proposition.

Information should include – production history, operating costs, key inputs, staff structures, assets, impacts of changing rules, stress test it all.

You can get out to varying degrees by bringing in a manager, contract milker, sharemilker, equity partner, succession or selling up.

KEY QUESTIONS:

If you’re looking to become less involved consider smaller steps first – could bringing in an officer manager free you up, can you handle stepping away and giving up a small amount of control?

For a sharemilker looking at an opportunity – understand the labour requirements and how production is achieved. Stress test and ask the what if scenarios – milk price drop, cost increases, climatic stress, infrastructure failure. Check for robustness. Understand the farm infrastructure, cup removers, irrigation, effluent, is the farm up to scratch for rules and coming rule changes?

Is the financial reward commensurate with the risk?

Check out the farm owners – their values, reputation.

Remember just because it’s a step up in terms of the normal historic pathway it may not be a step up in terms of profit or a move towards your goals.

Have a pros and cons list.

A good outcome is where each party is moving towards their goals.

Eprinex is not only the 1 and only drench to have worldwide NIL milk withholding when treating lactating cows - it is also the No.1 drench for return on investment by far. For example, based on an average herd size of 500 cows and a $9.00 payout, farmers can expect a return of $67.44 per cow. Eprinex makes a lot of sense… and cents.

Contract milkers miss out on premium

Dairy NZ hopes ist new calculator will make contract milker premiums transparent, Anne Lee writes.

Almost a third of the contract milkers included in a DairyNZ analysis made close to no premium over managers’ wages, sparking a call for contract milkers and their farm owners to carefully run their numbers through a new DairyNZ contract milker premium calculator.

DairyNZ systems specialists Paul Bird and Phillipa Hedley have analysed financial data from DairyBase for 80 contract milkers over four consecutive financial years looking at the returns made over and above a farm management wage.

Because contract milkers employ the staff to operate the farm and take on additional risks and responsibilities compared with a farm manager their contract rate is expected to be set to recognise and compensate them for those additional risks and responsibilities.

“But what we’ve found is that 27% of contract milkers would actually be better off financially if they were managing.

“Most of that 27% were in fact worse off – their premium was negative and, in a few cases, substantially negative.

“If we lift the cut-off point to $10,000/ year (premium over wages) then we’re talking about a third of the contract milkers we looked at who were no better off than if they were managing the farm.

“There’s no return to them to cover

things like taking on the responsibility of employing labour or production and other risks,” Paul says.

Receiving a fair return for contract milking helps provide stability from year to year so good people remain onfarm and, in the longer term allows them to grow their wealth so they can become the farm owners of the future, he says.

DairyNZ has been working with Federated Farmers in developing the contract milker premium calculator and are promoting it with rural professionals.

Paul says the analysis using the calculator was carried out on budgets from 2018 to 2021 and while the premium has fluctuated from year to year this season it’s likely to come under particular pressure from the rapid rise of onfarm cost inflation.

“This season we’ve seen very big lifts in some costs, especially labour, so it’s

‘WHAT WE’VE FOUND IS THAT 27% OF CONTRACT MILKERS WOULD ACTUALLY BE BETTER OFF FINANCIALLY IF THEY WERE MANAGING.’

Contractor milker premium per season 2018-2021

CHECK LIST

To help ensure that contract milking rates are set fairly when developing contracts, contract milkers and farmers should:

• Carefully review the contract expectations and figures and get independent advice if required –this is particularly important for contract milkers who are new to the role or who aren’t strong on financial management.

• With inflationary costs changing quickly check that the contract is based on current figures and not out of date numbers.

important for all contract milkers and farm owners to review their budgets to ensure the premium is there.”

While the median contract milker premium has been $26,000/year the results of the analysis show a wide variation with some contract milkers earning a premium of more than $80,000/year and a small number more than $140,000.

Larger contract milking jobs do tend to have higher contract milker premiums but the data analysis found some largescale jobs with small premiums and some average size jobs (of about 500 cows) with larger premiums.

“It’s not our job to set a specific premium level – what we want to do with the calculator is shine a light for contract milkers and farm owners on the real return premium the operator of the farm is receiving.

“By making the contract milker premium transparent both the contract milker and farm owner can then make their own judgements on whether it’s at the right level.”

The calculator, while simple to use in terms of inputting data, has complex calculations sitting behind it to account for factors such as the tax benefits of being a business owner. It also allows for the contract milker’s full budget with all associated costs to be inputted.

“The terms of contracts can vary quite significantly – some will include costs others don’t, and farms can have situations specific to them.

“The calculator creates a kind of agenda for a discussion between farm owner and contract milker and possibly a third party, rural professional, so nothing gets missed –benefits or costs.”

Paul says there’s usually two main reasons why a contract milker isn’t receiving a premium over farm management wages.

“One is that the contract rate is set too low to cover the costs the contract milker is expected to cover.

“The other is that the contract milker isn’t achieving the production expected in the contract.

“That could be because the contract milker doesn’t have the farming skills and they would in fact be better off going back to managing and sharpening their pasture management skills for example.”

Paul also advises both contract milkers and farm owners to take a careful look at the numbers going into the budget.

“Look at it line by line and get updated costs for everything.

“We do see costs rising over time so it’s always a good idea to review the budget carefully every year but this year – even

• Ensure that the contract makes allowances for further cost increases and is set up to ensure that contract milkers aren’t penalised for this – for example many contracts provide an opportunity for contract variations. Some contracts also provide additional rewards to contract milkers in high payout years.

• Use DairyNZ’s contract milker premium calculator to assess the contract milker return based on current costs.

• If contract rates have been set too low for the current season – then both parties should discuss the situation as a first step. Involving professional advisors can also be useful. You may be able to identify opportunities to review contract conditions or to agree on how cost increases can be managed.

over the last few months, we’ve seen costs really take off.”

It’s possible that a contract signed early this year could now leave a contract milker with little to no premium over farm manager wages by the end of the season.

While farm owners may be looking at a high payout, contract milkers’ rates are fixed but contracts can include additional payments during high payout years.

Farmers must be in the driver’s seat

Words by: Anne LeeSri Lanka’s disastrous organic farming experience should serve as a warning to New Zealand farmers that they must have a strong voice when it comes to regulation and primary sector strategies, Ngai Tahu farming and forestry general manager Will Burrett says.

While an extreme example, he says it shows what can happen with uninformed change.

Will was speaking at a future focused forum Dairy 2032 hosted by agritech company Halter at Ngai Tahu’s 6757-hectare Te Whenua Hou farming operation at Eyrewell, north of Christchurch.

Will told about 100 farmers that watching events unfold in Sri Lanka had been an “aha” moment. The economic and social impacts of a poorly informed and sudden move by the government to stop importing fertiliser and ban the use of pesticides has been swift and brutal, he says.

The decreed, whole-of-country shift to organic agriculture was reportedly carried out with little input from mainstream farmers and the country’s agricultural science sector.

Its aim, in part, was to improve Sri Lanka’s balance of payments by increasing the value of food exports and cutting fertiliser imports at a time when the country was already suffering the Covid-19 related collapse of the tourism sector.

Instead, yields of tea and rice rapidly slumped and the country has quickly swung from being a net exporter of products such as rice to becoming a net importer as it fights to feed the population.

While it’s not the only factor in the country’s spiralling economic collapse and social unrest it has arguably played

a significant role. The decree has since been abandoned. Will says any change for the agricultural sector in NZ, particularly when it comes to government or local body regulatory change, must be based on a well-informed strategy and driven by farmers from behind the farm gate.

Farmers know the realities of farming and those realities need to be considered to inform change within a solid strategy that then leads to better value.

“We can’t forget our first principles of agriculture. We are marginal-cost farmers. We need to maintain our cost structures.

“We are in a really inflated commodities market at the moment which is really exciting but we have to stay true to our core.”

As to where the world is headed in the next 10 years Will pointed to indications for shifts in consumer preferences.

The somewhat controversial EATLancet report in 2019 suggested that to improve human health and environmental outcomes by 2050 people in many developed countries in particular needed to move to eating a lot less red meat (up to 50% reduction) and dairy while doubling the consumption of wholegrains, vegetables, nuts and legumes.

But what does that kind of shift mean for those behind the farm gate?

There’s more talk of a farm mosaic compared with the current situation where 90% of total income is derived through one product or channel such as milk.

“What could that look like by 2032?

“Do we have the same number of cows on our farms? Are we ascribing more areas to crop and a different protein revenue?”

Technology such as Halter with its ability to direct cows to different areas of the farm or areas within paddocks may make such mosaics easier to manage.

Consumer preferences around diet, animal health and welfare and environmental concerns all needed to be considered when challenging thinking on farm system design.

“If we have a bucket of capital in our business – how are we going to allocate that capital to get a return?

“Granted some of the money we are going to spend will be on our licence to operate our current systems but there are certainly going to be other things that will provide channels of new revenue.

“We all need to be on the same page as to what that looks like and be confident the consumer will be willing to pay.”

Farmers must also be the drivers of the strategies on how to get there.

REPORTS AND FURTHER READING

The EAT-Lancet report:

• eatforum.org/content/ uploads/2019/07/EATLancet_Commission_ Summary_Report.pdf

Not everyone was happy with the report:

• italiarappginevra.esteri. it/rappginevra/en/ ambasciata/news/dallambasciata/2019/03/ comunicato-stampa-sullancio-del.html

Sri Lanka:

• www.nytimes. com/2021/12/07/world/ asia/sri-lanka-organicfarming-fertilizer.html

WHEN THE WORLD MAKES SENSE

Technology and data will be an integral part of dairying in the next decade with the insights they provide used to design farm systems, to tell our farming stories to consumers and to certify our our quality assurance. That’s the view from a three-person panel at Dairy 2032 – an event hosted in Canterbury recently by agritech company Halter.

Veterinarian and animal health researcher Scott McDougall, Canterbury environmental consultant Charlotte Glass and Waikato dairy farmer Peter Morgan joined a panel discussion led by host Scotty Stephenson.

Charlotte told the audience of about 100 farmers the sector must move its thinking beyond compliance

Welcome to continuous transparency

Think of yourself as a Formula One driver with a crew chief in your ear, explaining what’s going on and a whole team of engineers, probably working remotely, monitoring and evaluating data and the environment you’re working in and the performance of your operation.

That’s the analogy Lincoln University Professor Hamish Gow uses to explain farming into the next decade where data and insights from it will inform and certify the business. He says the sector is about to undergo a series of “flips.”

“We’re moving from a world that was

regulated and compliance-based to a world that’s certified and going to be driven by the conscious consumer.

“We’re moving from a world that’s ‘tick the boxes,’ to one which has continuous transparency driven by digital passports.”

Farmers will go from jack of all trades to running high-performance teams, moving from tacit knowledge to having codified, digitised and artificial intelligence (AI) enabled data so all the players in the high-performance team can engage.

alone, shifting towards customised strategies for individual farms that deal with both the current and foreseeable environmental issues.

“The nice thing is that when you get 10 years ahead of compliance and you look back, you’re considering emissions and sequestration, changed climate and water quality and then you start to realise the mitigations you should be doing work for all of those things and the world starts to make sense.”

Canterbury had a head start on most regions and has been working in an audited environment for almost 10 years. While the goal posts – in terms of rules - aren’t shifting, necessarily, they can be confusing and there are a lot of them, she says.

“What we do to cope with that – we try and get it ahead of it by 10 years – build a strategy and then you can choose the bits you want to fight and the bits you don’t want to.

“The more you have to provide

“Telling the story isn’t enough anymoreit has to be validated.”

Conscious, high-value consumers in Europe were already demanding products with digital passports for items such as textiles and electric cars and it was just a matter of time before that included food.

“We are at the point of systems change. “We don’t know exactly what it will look like but we know it’s coming.

“The government has already put its flag in the sand with its Fit for a Better World strategy.”

It’s not something to fear though. New

Ten years of working in an audited environment is paying off for Canterbury farmers, Anne Lee writes.MC Scotty Stevenson and the panel – from left Charlotte Glass, Scott McDougall and Peter Morgan.

evidence the more you question the logic and the more you do that the more you ask questions of research and you get on to the front foot.

“There’s a big change in direction towards understanding environmental aspects, and rightly so – we probably overpushed things a wee bit and whilst we turn the big old Thames truck around - which is the strategy for the country - it takes us a bit of time to inform the logic.

“But NZ farmers are the best in the world at innovating and that’s because they like to understand things from first principles.”

The rules at present relate to water quality but the rules in terms of greenhouse gas emissions are coming and it will take a different kind of thinking to find farm systems solutions for them.

“We’ll have to think about biogenic emissions differently - we can’t produce our way out of this one.

“Even if we get mitigations, they won’t be free, they’ll come at a cost.”

Peter says 10 years isn’t very long in a farming time horizon.

“It’s the day after tomorrow.”

“We’re going to have to be better connected – connecting staff with pastures, with animal management and our farm system so staff not only understand how the farm works but also how they contribute to it. “Farmers must stay in control, contributing as reasonable people to the discussions with government and regional councils, taking our consumers along with us so they understand we’re

human and they understand our story.”

He and wife Ann own a 265-hectare farm running 630 cows all fitted with Halter technology. Two of their farm team are career changers who aren’t that driven by technology, he says.

“But that can be ideal because they don’t want to ‘play’ with toys.

“They want to create outcomes - how do I optimise my time, my animal movements, my grazing management?”

The data collected by the solar-powered collars is also giving the team an extra layer of insight into the “secret lives of cows”, he says.

Cows can be so staunch sometimes they don’t show signs they’re unwell early on, he says. The data will be imperative to prove to consumers that cows are happy and healthy, Scott says.

“If we don’t have social license, we ain’t got an industry.”

Having the swathe of data collar technology such as Halter can provide is one thing, but it will be vital that smart algorithms then monitor and analyse that data to create dashboards and management options for farmers.

We also need robust science on how that data tells us cows are happy - what defines a happy cow?

“What does good rumination actually look like, for instance?”

Then we’ll be able to tell overseas consumers, hand-on-heart, that our cows are happy and healthy and we have the data to prove it, he says.

SETTING THE BENCHMARK

Welcome to the next generation of in-bail automatic teat sprayers. Fully automated and ready to integrate into any rotary system, the iSPRAY4 makes milking easier and hits its target each and every time. Ensuring full coverage of teat spray to each milking quarter, it’s your herds’ best asset in the fight against mastitis.

Automate your milking routine: GEA.com/new-zealand

Zealand farmers have done it before, he says.

Halter chief executive Craig Piggott agrees.

“Change can be really exciting and building a better business is super exciting.

“We’ve got to lean into this.

“You won’t be in the machine running it all the time, you’ll be working on it.

“You, as the farmer, become the decision maker, critical thinker you’re strategising about how to make trade-offs.”

Farmers will become the pilots in their business and insights from data will provide them with information to make the best decisions as well as tools to help them execute their management decisions.

WATCH VIDEO: www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ct1EbjnT0bY

Two terms later…

A governance development programme saw Donna Smit climb the ranks in boardrooms.

By Claire AshtonDonna Smit’s governance resume reads like a who’s who of the primary industry sector; Dairy Women’s’ Network trustee, and directorships of EastPack, Ballance Agri-Nutrients, Primary ITO, Eastern Bay Energy Trust, and until November 2022, farmer-elected board director at Fonterra.

Her path to such a pivotal governance role began when she saw an advertisement in a rural magazine for the Governance Development Programme with Fonterra which was established in 2006 to help address dairy industry and rural sector succession needs, and boost regional governance.

She had been a company administrator at Eastpack for 24 years, where they took it from a small co-op to the largest supplier of Gold Kiwifruit to Zespri.

Eastpack was close to home, family, and thier Bay of Plenty farms. However, Donna had a bit of a wake-up call driving home, yet again late for dinner, and decided it was time for a change and applied successfully to the governance development programme.

Donna took part in the Fonterra governance programme for two years while wrapping up work at EastPack. The programme was intensive at times, and involved week-long training sessions, book reviews, personality tests and coaching.

Persistence and her stellar resume saw Donna’s applications to director positions on Fonterra and Ballance boards be accepted simultaneously, however, with a clash of meeting times, Donna opted for the Fonterra role in August 2017. She had previously applied and been ‘first loser’, however, perseverance pays. She wanted to be on the team to take the co-op back to its core values.

“You could see there were issues at Fonterra, and you could see that the place could be so much

better when you see how other boards operate. There was a dominant leadership culture in that board at the time, and that’s not how highly effective boards run - you need to run the full skills of the whole team. Alongside that, Fonterra’s strategy to be globally relevant wasn’t working.

“The whole strategy was at odds with our competitive advantage, quality, highly nutritious pasture-based milk,” Donna says, and the strategy to focus on New Zealand milk resonates well with farmers.

“To me, no matter what board you are on, you have to work out; how does this business create value and then how do you go after that value?”

The Fonterra Board, during Donna’s time, has had three different chairmen; John Wilson, John Monaghan and now, Peter McBride, two chief executives, and two chief financial officers. The previous 12-member board was reduced to 11, with nine out of the 11 having a tenure of six years or less, only Leonie Guiney and Clinton Dines have been on the board longer.

This relatively new board has seen major changes in strategy, purpose, risk settings, culture and capital structure. Donna would also like to compliment the openness and transparency CFO Marc Rivers has brought to both the reported financials and the board packs.

“It’s really important we understand what creates value in a global business of this scale and transparent financials go a long way in understanding the drivers. “

Now, after six years as an elected director on the Fonterra board, Donna steps down come

‘THERE WAS A DOMINANT LEADERSHIP CULTURE IN THAT BOARD AT THE TIME, AND THAT’S NOT HOW HIGHLY EFFECTIVE BOARDS RUN - YOU NEED TO RUN THE FULL SKILLS OF THE WHOLE TEAM.’

November from her two terms, a period over which the co-op has has seen a see-saw in prices from the highest forecast farm gate milk price (2021-22 forecast midpoint $9.30/kgms ) to in 2019, the worst reported net loss after tax in Fonterra’s history (a $605 million loss, due to a $826m write down and one-off accounting adjustments to DPA Brazil, Fonterra Brands NZ and China Farms.)

“It feels good what we as a board achieved. I really encourage farmers to stay engaged, this is the strength of the co-op. A lot has been done but there is still a lot to do.”

Peter McBride is chairman and on behalf of the co-operative’s farmers, thanked Donna for her contribution.

“Donna has been a valued member of our board at a critical juncture for the co-op as we have overseen the reset of the co-op’s culture, long-term strategy, governance and risk settings, and our capital structure.”

At the time of the business reset it was incredibly challenging, and Donna reflects that, “It was a very necessary thing, a very cleansing thing, sometimes there is nothing like a crisis to create change. I remember thinking; ‘We are going out to talk to farmers with the worst financial results in Fonterra’s history, but as we were coming out with openness and transparency, farmers were very appreciative of this.’

“A big challenge of being on the Fonterra board is the enormity of the decisions and how it affects the livelihoods of 9500 farmers. I mean you just cannot please everyone. The decision to change to a flexible capital structure is the right decision but was highly impactful - we have affected our shareholders’ balance sheets with the strategy to improve them for the future.”

Donna lists examples of what she perceives is the value of a company. For example, with Primary ITO its assets are people and their ability to train and teach a curriculum. EastPack is a post-harvest provider in a highly competitive market, so they need to pack efficiently at a low cost and ensure any investment in automation and technology not only gives a return on investment but also looks after the grower’s fruit. That is how they create value.

“At Fonterra we have many competitive advantages:

• We are world leaders at efficiently producing whole milk powder through scale dryers that operate to the grass curve (ie: produce milk when the grass is there).

• Our scale allows us to produce the right product and to sell to the best customer as market dynamics change, an example of this was during the China Covid lockdown, we changed the

product mix from food service to ingredients and maintained profit.

• We have over 150 years of investment in dairy innovation, and we are very good at meeting our customers needs with the right formulation.

• Our scale allows us to load whole ships, and this was useful during the Covid supply chain disruptions.

• NZ is the best place in the world to keep a cowfrom a sustainability lens it will take investment to ensure we stay ahead.

Donna sees we can add value with our sustainability credentials and meet the demands of the most discerning consumer, and governors must ensure farmers get a premium for this.

“When I arrived on the board six years ago, sustainability was about fencing waterways and riparian planting. It is so much more today. Climate change has become a major focus for governments, producers and supply chains globally. The need for sustainable products is now customer led.”

Every business is considering how it can be more sustainable and farming is no different.

“I know it is unpalatable to many, but we only have to look to the Netherlands to see the demands being placed on Dutch farmers in the south to cut nitrous oxide and GHGs to understand the power of the consumer.”

Onfarm with Donna

Donna is chartered accountant for Corona Farms: the family owns two dairy farms in the North Island and two in the South, another two have been sold, one to each of the Smits’ sons as they work through a succession plan. They also have support blocks, kiwifruit orchards, a beef farm, and forestry.

Corona farms have never used a lot of nitrogen and it is easy to come in under the 190kg N/ha limit, particularly in the North Island, but also achievable on the South Island farms.

A way they looked at practising sustainability on the South Island farms was to switch from border dyke irrigation to pivots.