Learn, grow, excel

SPECIAL REPORT: Stop the loss

Reducing N losses from the farm system

Learn, grow, excel

SPECIAL REPORT: Stop the loss

Reducing N losses from the farm system

Ed Jackson shares his tips for hitting heifer grazing targets.

THE RISE OF RURAL CRIME

SHORTER GESTATIONS

Reconsidering mating and calving dates

FROM THE GROUND

SPECIAL

Page 70

YOUNG COUNTRY

Fast track to success

An Aussie crossing the ditch for dairy

From the Ground Up: A workout for the mind

RESEARCH WRAP

Mating later, calving on time

ENVIRONMENT

54 Solar power: The power of light

Page

58 Heifers: On target with grazing.

63 Gestation: Calves arrive earlier.

64 Skin conditions: An ABC of lumps and bumps.

66 How heat Impacts your cows

Cover: Ed Jackson from Ashhurst grazes more than 300 dairy heifers each year and has some tips about how to get them up to target weights.

Page 45

December 13 – A SMASH field day at Tirau looks at inspiration for your future farm. Hosts, Adrian and Pauline Ball were the regional supreme winners of the Ballance Farm Environment Awards in 2019. They will share how they aim to be sustainable in every aspect of their business including the environment, staff and stock. Celebrity chef, Angelo Georgalli, will then demonstrate how to make the most of the game you hunt. The day runs from 10am to 1pm. For more, visit http www.smallerherds. co.nz/smash-events/field-dayinspiration-for-your-future-farm-tirauwaikato/

December 15 – DairyNZ hosts a session on feed planning for summer for its Bell Block/Lepperton summer group at Waitara in Taranaki. Former DairyNZ CO and now farm consultant, Alicia Riley, will be answering questions on the topic. The event combines with the annual Christmas barbeque and will be hosted by Tony Potroz. It runs from 11am to 1pm. For more, visit www.dairynz.co.nz/events/ taranaki/bell-blocklepperton-summergroup-december/

December 15 – Embryo transfers and Tru Test collars are the topics for the Jersey Breeders’ Christmas group get-together in Otorohanga.

Topics include embryo transfers using Vytelle, Tru-Test collars and walk-over weighing to get better herd information, plus inspection of the herd and viewing a wetland. The event is being held at Michelle and Shaun Good’s farm between 11am and 1pm. For more, visit www.dairynz. co.nz/events/waikato/jersey-breederschristmas-group-december

February 1 – The Orini Summer Group with Arjun Singh looks at the role nutrition and genetics play in maximising production and profit; the ration balancing needed to achieve 730kgMS/cow and the importance of good infrastructure in the system. The event runs between 11am and 1pm and will also look at how they set up for calving, plus heat stress through the height of summer. For more visit www.dairynz.co.nz/events/waikato/ orini-summer-group-february

February 7 – DairyNZ’s FarmTune 2023 holds a workshop in Winton. The comprehensive programme is aimed at supporting you and your team to implement Lean thinking onfarm. The workshop runs between 10am and 1.30pm. Another workshop will be held in Balclutha on February 23 and further workshops will follow in both locations. For more, contact Lynsey Stratford on 021 165 2004.

February 14 – The Te Kawa/Pokuru summer group meets to discuss mixed-species summer crops at the Wallaces’ Pokuru farm. See how the crops are growing and the herd grazing on them. For more contact Phil Irvine, DairyNZ, on 027 483 9820.

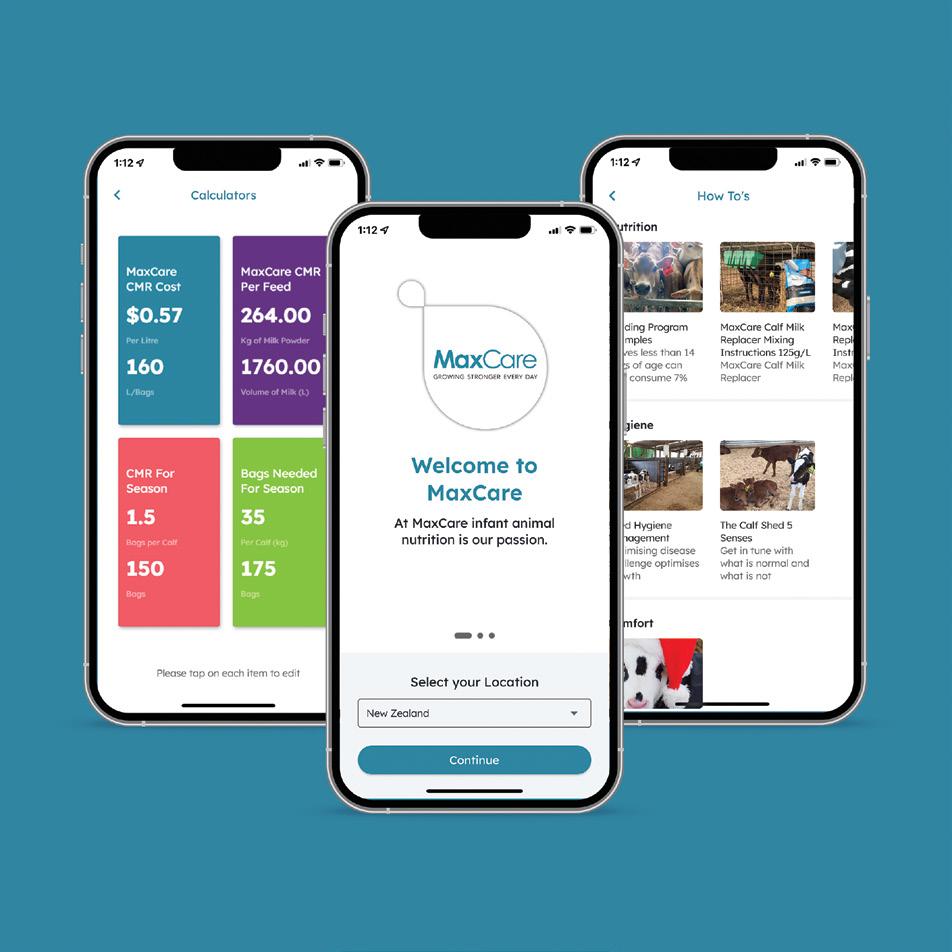

February 15 – Dairy Women’s Network in conjunction with SealesWinslow and AgriVantage is running a Today’s Calf, Tomorrow’s Cow expo in Manawatu. The event looks at proper care and nutrition for today’s calves to set them up for a lifetime of high performance. As well as stands from sector organisations, the expo will run a workshop with Natalie Hughes from SealesWinslow and Natalie Chrystal from AgriVantage on best practice to maximise calves’ potential from day one. Expo attendees have the chance to book a 10-minute slot with the speakers to discuss farm-specific challenges. Book slots at the expo which runs from 9am to 4.30pm. For more visit www.dwn. co.nz/events/todays-calf-tomorrowsmanawatu/

February 22 – A Today’s Calf, Tomorrow’s Cow expo is being held in Whangarei at the Barge Showgrounds Event Centre. See details above and visit www.dwn.co.nz/events/todayscalf-tomorrows-cow-northland

How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time… (don’t even think about how you wrangle it, chop it up, cook and tenderise it… that’s for another day.)

But for the purposes of this exercise the old mantra bears thinking about.

Farmers have always had elephants, or gnarly issues, to eat, and the trick is to not let the overwhelm get you while you think about it and decide how to go about breaking down the gnarly issue and moving forward.

Faced with a need to cut nitrogen leaching losses by 30%, mid-Canterbury farmers Tom and Sara Irving didn’t choke on the elephant, but took a multipronged approach.

Through investing in irrigation infrastructure, a slight drop in stocking rate, a big backing off the annual N application, cutting bought-in supplement and a stronger focus on pasture management they have cruised across the line, reducing N leaching to 28kg N/ ha - well under the 50kgN/ha target. And milk production is still sitting at close to the level of the last six years of 1500kg milksolids (MS)/ha or 450-470kg MS/cow.

Tom and Sara are confident advances in R&D will see more tools added to the tool

box, so are not afraid of further cuts.

Read about them in our special report on ‘stopping the loss’ of nutrients on page 40.

George Moss writes about learning from the positivity and self-belief of the conquering Black Ferns and suggests we reframe our eating an elephant problem of reducing GHG emissions to chip away at the problem and and be the “world-leading farmers that contribute to climate cooling”. (pg 10)

Here we are at the end of 2022, the December issue.

I hope you have the head space over the summer to think about how to eat your elephant - start sharpening your knife and cut it into really small pieces.

We all have changes coming at us in 2023, if you can think about them with positivity and self-belief you have a much better chance of not just surviving but thriving through the changes. Wishing you a happy and healthy Christmas and all the best for 2023!

• The resurgence of equity partnerships - how to get keen young people into your business, and how to make the relationship work.

• The Brothers Green: how could converting 10% of your farm to hemp help your bottom line and GHG emissions.

• Winter bale grazing, how it works in Southland

New Zealand Dairy Exporter’s online presence is an added dimension to your magazine. Through digital media, we share a selection of stories and photographs from the magazine. Here we share a selection of just some of what you can enjoy. Read more at www.nzfarmlife.co.nz

Young Country is pleased to announce that episode nine of From the Ground Up is now live on all of your favourite podcast providers.

Episode 9: From running personal training sessions on her front lawn while her young children slept, to a thriving online health and fitness platform, Kate Ivey is inspiring people to adopt a healthier lifestyle that is sustainable long-term.

Episode 8: Merino lamb raised in the Marlborough high country and delivered direct to your door, Middlehurst Delivered is a family business with a focus on sustainability.

Episode 7: Scott Jimmieson has realised his dream of becoming a farmer, and he’s keeping it local with his new online shop business, Local Food NZ, connecting farms with consumers.

Episode 6: Standing on the sideline watching her daughter play rugby in winter, Charlotte Bell thought she’d love to have a warm wool coat to wear.

Episode 5: Edward Eaton and Wilbur Morrison talk all things Buzz Club. Launching a range of premium sparkling mead naturally brewed from native NZ honey.

Episode 4: Brad Lake from The Brothers Green talks about harnessing the potential of hemp with a range of valueadded products.

Episode 3: The Mangamaire Sunflower Field, established by farmer, photographer and mum, turned sunflower entrepreneur extraordinaire, Abbe Hoare, is turning heads for all the right reasons.

Episode 2: Amanda King founder of By The Horns. They say you should never work with children or animals, but By the Horns photographer Amanda King has carved out a niche for herself doing exactly that.

Episode 1: Delwyn Tuanui from The Chatham Island Food Co about how he chased his dreams from the ground up.

We love highlighting positive stories of young agri-innovators chasing their dreams. Listen to From the Ground Up: nzfarmlife.co.nz/podcasts-2 or scan QR code

NZ Dairy Exporter is published by NZ Farm Life Media PO Box 218, Feilding 4740, Toll free 0800 224 782, www.nzfarmlife.co.nz

Editor

Jackie Harrigan P: 06 280 3165, M: 027 359 7781 jackie.harrigan@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Deputy Editor Sheryl Haitana M: 021 239 1633 sheryl.haitana@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Sub-editor:

Andy Maciver, P: 06 280 3166 andy.maciver@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Reporters

Anne Hardie, P: 027 540 3635 verbatim@xtra.co.nz

Anne Lee, P: 021 413 346 anne.lee@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Karen Trebilcock, P: 021 146 4512 ak.trebilcock@xtra.co.nz

Delwyn Dickey, P: 022 572 5270 delwyn.d@xtra.co.nz

Phil Edmonds phil.edmonds@gmail.com

Elaine Fisher, P: 021 061 0847 elainefisher@xtra.co.nz

Claire Ashton P: 021 263 0956 claireashton7@gmail.com

Design and production:

Lead designer: Jo Hannam P: 06 280 3168 jo.hannam@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Emily Rees emily.rees@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Partnerships Managers: Janine Aish

Auckland, Waikato, Bay of Plenty P: 027 890 0015 janine.aish@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Tony Leggett, International P: 027 474 6093 tony.leggett@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Angus Kebbell, South Island, Lower North Island, Livestock

P: 022 052 3268 angus.kebbell@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Subscriptions: www.nzfarmlife.co.nz subs@nzfarmlife.co.nz

P: 0800 2AG SUB (224 782)

Printing & Distribution:

Printers: Blue Star, Petone

Single issue purchases: www.nzfarmlife.co.nz/shop

ISSN 2230-2697 (Print)

ISSN 2230-3057 (Online)

We can learn from New Zealand Women’s Rugby’s Black Ferns team’s turnaround from being almost written off to all-conquering, writes George Moss.

The Black Ferns were the tonic we all needed, not just because they won the Women’s World Rugby trophy, but for the absolute joy they brought to rugby, their personal happiness and their self belief without arrogance.

I have to confess to shedding a tear of pride when Ruby Tui led Tutira Mai Nga Iwi, a song of standing together and unity. Such is the pride and engagement engendered that there are now many young people wanting to take up rugby. Positivity and belief is infectious – we can learn from their journey from being almost written off to all-conquering.

The season continues to be challenged with significantly less silage made so far, with production being slightly behind (<1%) on one farm and slightly ahead daily on the other. Submission rates have been well in the 80%s where intervention used and low 80s without intervention.

Have looked at purchasing silage to bridge the gap. Cost of purchased silage itself is reasonable but depending on distance freight can add $60 to $70 per bale. Hence, there is going to be a rethink if serious surpluses do not arrive soon. The rise in farm costs is staggering and we only hope we can keep them under $5.50/kg MS but I’m not optimistic.

Like every other farmer, we have been closely watching the developments with He Waka Eke Noa. Now with some suggested costs for gases available, we have been able to get a good estimate on both the per hectare cost and total cost across the enterprises. We made no reduction for any carbon sequestered.

Using last year’s OverseerFM figures, the home farm (dairy plus beef operation) cost per hectare is $56.35 and the other farm cost per hectare is $69.27. Both farms are using the highest methane cost for the calculation. Absolute cost in total is just on $10,000 which equates to about 7% of the increase in our interest bill.

There are changes that need to be made to the Government’s proposal, namely pricing should be delinked from the NZ units on the ETS, we need to control how

the levy received is spent and have flexibility around that and we need to be able form collectives so that individuals can work together for mutual benefit. The fact that Iwi are disproportionately impacted needs to be addressed.

I have said it before, regardless of what we think of the He Waka proposal, the markets will be the arbiters on our progress in reducing our footprint.

Regardless of what we think of the He Waka proposal, the markets will be the arbiters on our progress in reducing our footprint.

AirNZ ‘s chief executive Greg Foran is pushing hard to have the fleet well on track to decarbonisation by 2030 potential using electric planes for very short haul, hydrogen planes for longer internal flights (aka Auckland to Wellington) and biofuels for the really big jumps. Clearly, given the huge cost involved and risks involved as a first mover they have decided that the status quo is not a long-term viable option and have chosen to lead.

Fonterra at its annual meeting forewarned of the market and financing risk if we do meet sustainability expectations. Banks are already pricing “footprints” in interest pricing. I absolutely accept this is a difficult space to operate in and manage but I do not accept the notion that it can’t be done –our own operations have weaknesses that need addressing.

The question is whether we approach the challenge with positivity and self-belief attracting others to NZ’s premier sector (and we are in desperate need of new blood and energy) or whether we talk ourselves into a negative space undermining wealth and opportunity and, worse still, affecting the “top paddock”.

Just imagine a headline, that reads “the world-leading farmers contribute to climate cooling” – surely this would appeal to the highly aware consumers wanting guilt-free nutritious food and those people wanting to be part of a winning team.

Future-proofing in the dairy is the way to go, writes Westport dairy farmer

John Milne.

John Milne.

This will be our third season using a dedicated AB facility. It came about after having an ankle reconstruction operation back in December 2019. While laid up on the couch for a solid four months, this gave the mind a chance to wander and think what changes had to be made for the upcoming season.

Unbeknown to us that this would actually be a necessity in the very near future at the time we started construction.

Before the installation there were planks hanging off a pit rail like so many other dairy farms do or did.

The AI Tech of 13 years that we have here loves the new setup, she’s confident in her footing, there are no pinch points and the cows are relaxed while they are herringboned there to be artificially inseminated.

The first comment in the first season was “Gosh your cows are relaxed.” She says she can now solely concentrate on the job in hand instead of worrying about pinch points and unsteady footing.

We can continue milking with the ‘3 in 2’ using this facility, on the one-day milking we just simply draft out the in-season cows as they come up to the cowshed and they wait there in the facility while we start milking.

Once a week over mating we draft the cows out that need a touch-up of tail paint or heat detectors. One person can do this while we are milking.

Vets love it for total herd tests i.e. pregnancy scanning, vaccines.

The TB tester just flies through them at TB testing time –no stilts needed.

We have even calved cows in there as well.

It’s just safe and bloody handy.

In the years of using the planks we only had one fall, they

Before the installation there were planks hanging off a pit rail like so many other dairy farms do or did.

just walked off the end of the plank concentrating on the job they were doing, luckily they landed on the pit mats with no injury, shrugged it off and carried on. A lucky escape I reckon.

It’s just compliance, but also could be called common sense, to keep people out of harm’s way.

Here are some things that need to be considered:

• Make it long enough to hold a decent amount of cows –take a look at what your average day of AB consists of

• Make it fall into an existing water flow area to capture effluent

• Make it so it does not have to be hosed off when not in use

• Make it weatherproof for sun and rain.

We couldn’t use existing concrete so utilised an exterior garden area to keep it practical and constructed on top of this.

Look on the LIC website they have a requirement that must be met by 2025.

Think of it as future-proofing.

We don’t like the look of the industry going forward. A lot is going on outside the farm gate beyond our control that we do not agree with. Our preference is to focus on the crucial farm tasks at hand.

These are areas we enjoy doing and getting up for in the morning: mating, pasture management, feeding cows and turning grass into milk, summer crop establishment etc. These are areas we know what we need to do to be successful, we have control (mostly), and they have a direct impact on our bottom line.

But, if we want to stay in farming and influence what our future looks like, we need to be more proactive outside the farmgate.

The Government’s climate policy is shaping up to be one of our most significant policy challenges in our industry. This is happening during the running of day-to-day farm tasks, implementation of unorganised environmental legislation, coping with onfarm inflation and tripling interest rates, and seasonal climatic conditions that aren’t following typical trends (to name a few).

The stress and pressure on our farming community is evident. You only had to attend one of the many consultation sessions to observe farmers’ frustrations are at boiling point and morale is low.

So, we would be hypocritical to say we don’t like the look of the industry going forward and yet not do anything about it. Like with our onfarm tactics, we assess the situation and focus on areas that we can either have control or influence. In this case, having a voice is one option.

Our approach is to be more strategic with our time; currently it is to divide and conquer. Nic is running the dayto-day farm tasks and Kirsty is putting her time into admin that is outside the farm gate. It is important to engage in the He Waka Eke Noa consultancy process:

• attend consultation meetings and get up to speed with the details,

• give feedback.

• make our levy work for us and reflect our feedback.

• be a member of Federated Farmers.

• fill in the farmer surveys, and prepare our own submission.

• talk to our peers and get them revved up on this issue as well.

Not losing focus with happenings onfarm, over the last few months we pulled the trigger on some key management decisions. With grass failing to fire at its usual time, we decided to contract palm kernel in early September after almost a two-year hiatus. By contracting the extra feed it meant cows kept their condition into mating and have continued to milk ahead of budget this season.

After five months of drought we have changed up our summer cropping programme to target drymatter yields and trialled leafy turnip this summer on the milking platform.

So far, the decision to expand onfarm technology has been a good one. For mating we achieved a 90% threeweek submission rate, with Halter taking a huge amount of pressure off the team for heat detection.

We continue to get letters in the mail from the bank informing us of our interest rate rises. To this end, we keep revisiting our budget and refreshing it with these changes and in other areas that costs keep going up. Keeping the budget accurate allows us to be strategic in where we make key decisions – particularly when to pay down debt and how much to pay.

We always look forward to Christmas as the pressure comes off. By this time, we have done almost everything we can to set ourselves up for the rest of the season. This will be our first year experiencing ‘school holidays’ with our first-born starting school in October. It will be good to have a change of scene from the farm to the beach!

Kirstyand Nic Verhoek have taken stock of where they stand in a time of turmoil off the farm.

But, if we want to stay in farming and influence what our future looks like, we need to be more proactive outside the farmgate.Starting school.

Composting shelters have allowed the family to escape for a soak at Hanmer Springs, despite a severe weather warning, Gaye Coates writes.

Unintentionally, incorporating composting shelters into our farming system has created something of a talking point.

Building these shelters has not been a small project; there is no stepping away from them being an up-front response to improving our farm’s winter grazing practices. Unsurprisingly the direct questioning, mixed with some evasive scepticism all share the same purpose. Ultimately, people want to know if this is a solution that is going to work or, conversely, not work.

Looking for a solution to improve our winter grazing and environmental compliance, we wanted a focus on resilience. We wanted to respect not only our land and the wider environment, but also safeguard the wellbeing of our pastures, our cows and our people. Introducing our herd to the barns this winter for shelter and feeding noticeably reduced stress and fatigue across all of those three important areas – pasture, cows and people.

the barns were scheduled into the grazing plan and we escaped worry-free for some “soak and hold” in Hanmer. So, while there is a sense of realism that these are early days, the barns are absolutely working in our farming system.

Have our farming priorities changed? One of the first concerns was whether our milk could still be marketed within the framework of grass-fed? We have always been, and continue to be, a pasture-based farm with an emphasis on cow condition, production second. Our farming system has not shifted from those priorities. The barns are a resource that allows us to better use both the pasture grown onfarm and the supplements required to fill the deficits. We are in a position with the barns to balance without compromise both pasture and cow health. Have our farming practices changed? Again we were challenged by suggestions that introducing a barn into our farming system would result in us indiscriminately and excessively feeding our cows. Removing our traditional reliance on annual forage crops to meet feed demand in winter has been the major change in our farming practices.

Being precise with our feed budgeting and understanding cow feed demands remains unchanged.

Have there been challenges? The timing of a one in 100year storm just before calving saw the roofs damaged on both sheds, allowing significant rain into the barns. The success or not of the composting bed pack is reliant on a few crucial factors, one being the elimination of water from the stack.

During spring, the cows calved in the barns and following this, the barns have been “on call”, providing us with flexibility to respond to climate and weather events and to cow demands. After 12 months using the barns, cows are in good condition and definitely damage to pasture because of inclement weather has been averted.

While we haven’t achieved quite the peak milk production we had aimed for, the usual phenomenon of that high point dropping rapidly away has not happened, and production has remained stable. Lameness is significantly less, the result we believe of the extra space and kinder surface of the feed area. There has been no acceleration of mastitis and the somatic cell count remains at 100,000.

Inadvertently, there is a personal sense of security in having these dominant structures onfarm. Usually a forecast hinting at significant rain would quash any thoughts of snatching some time away. Last week a dumping of 300mm was forecast,

At the time, it was demoralising to watch a dry, warm bed transform to a less than optimal, cool quagmire. But with adversity, there is inevitably learning and we now have confidence in what it takes to reasonably quickly re-establish the composting action. We also have some assurance in knowing from experience that lack of perfection does not compromise the overall benefits.

One year in and there is still a lot to learn; 12 months really only amounts to novice experience. However, the barns definitely are feeling like the right fit for our farm. But, we are calf-length 4x4 gumboot wearers, while many others out there are ankle-high Red Band enthusiasts. And, just like any good gumboot, it’s what fits for purpose for the individual and is comfortable to wear that is most important in the consideration of whether a solution is working or not.

• First published Country-Wide December 2022

• Read more on the Coates’ barns, page 30

“Removing our traditional reliance on annual forage crops to meet feed demand in winter has been the major change in our farming practices.”

Banks are getting involved in ensuring farming meets government and market requirements on emissions compliance. Phil Edwards reports.

The prospect of being regulated and charged for greenhouse gas emissions by the government will have stolen much of farmers’ spare thinking time over the latter part of this year. The prospect of being regulated for environmental compliance by supply chain partners has however probably deserved as much attention.

In terms of compliance, the government might well hold the biggest stick, but the potential of new rules imposed by the market could be equally imposing. Don’t worry though, banks are getting ready to help.

Many farmers won’t be unaccustomed to the banks’ desire to see farms invest in environmental projects. For some time now they have promoted bespoke lending that enables farmers to borrow to make their operations more environmentally robust or bring them into line with local regulations. The emerging trend in lending is however pointing to ‘sustainable finance’ taking hold where loans are written on the condition that farms meet agreed targets that show categorical improvements. For their trouble, farmers will be eligible for discounted interest rates.

Globally, the sustainable finance category is believed to have increased by an average 20% over the past five years. Much of this is being driven by investors looking for channels to support sustainable development. This is true in New Zealand with a growing green bonds market. But there are also other pressures on banks to develop its appeal.

In 2023 The Financial Sector (Climate-related Disclosure and Other Matters) Amendment Act will come into force, which will make climate-related disclosures mandatory for banks, licensed insurers and managers of investment schemes. For banks, these disclosures will need to indicate they are acting to address climate change in order to ensure they have future access to offshore capital, where the majority of NZ funds come from. A disclosure that shows they’re funding unsustainable activities without efforts being made to change will inevitably look unappealing.

For some sectors sustainable finance is already well advanced (energy and transport for example) but agriculture has struggled to attract funds based on the sustainable finance model because investors have not had the confidence that farm-level improvements are able to be accurately measured.

The metrics for measuring climate change on farms have been slow to form, with data gaps, the inability to share farm-level data and the ‘no one-size-fits-all’ farming system making it difficult to make uniform assumptions on impacts. Those challenges are however being overcome.

NZ-based lenders have finalised a framework of measured principles through the Sustainable Finance Agriculture Initiative (SAFI) that can now be used to provide assurance on the extent to which farm-level environmental impacts are being mitigated.

“The SAFI framework is one that the New Zealand finance sector can work with to issue sustainable finance to agriculture that meets the same requirements as the European green bond,” Westpac head of agri research David Whillans says.

So far, some banks have come out with various sustainable finance products, some of which incorporate bits of SAFI. BNZ launched a sustainability-linked loan for farmers several months ago, based on adherence to three different KPIs, including greenhouse gas emissions reduction. Beyond that the loan can be otherwise tailored to focus on other goals that go over and above those that are currently regulated, including soil health, animal welfare, biodiversity, waste prevention and so on. The assurance of the BNZ offering was developed with support from AgFirst, AsureQuality and professional services firm EY.

Whillans says Westpac is trialling a sustainable finance product for agriculture based on the SAFI framework. This will include leveraging off a lot of the compliance work going on for onfarm assurance – including farm environment plans, freshwater farm plans, processor requirements, NZ Farm Assurance Programme, NZFAP Plus and so on.

“There’s a lot of different programmes that farmers are involved in or completing which capture a lot of the core components of SAFI.”

The benefits for farmers from taking on sustainable finance are not just about interest rate incentives and a lower cost of capital.

“It will mean they’ll be able to get ongoing recognition for all the work they are doing, and have the meaningful improvement to the environment they are creating through adjustments to their farm management formally acknowledged,” Whillans says.

LactisolTM Nucleus Z1 is armed with zinc oxide, vital in the battle to prevent facial eczema. However, only Lactisol Nucleus Z contains Hy-D®, to improve calcium adsorption, blocked as a side effect of high levels of zinc. And of course, Lactisol Z contains the full SollusTM range of vitamins, trace minerals and antioxidants needed to make your herd healthy and robust. Ask your feed supplier for the newest hero and give yourself a fighting chance.

‘It will mean they’ll be able to get ongoing recognition for all the work they are doing, and have the meaningful improvement to the environment they are creating through adjustments to their farm management formally acknowledged.’Dave Whillans, head of Westpac Agribusiness Research.

When facial eczema threatens, you turn to a hero that has a few tricks up its sleeve.

NZ is well placed to capitalise on the ability for banks to now offer sustainability-linked loans to the agriculture sector, he says.

“The growth in sustainable finance bonds around the world is very aggressive, and there’s a lot of investors that are wanting to place their money into investments that are verified as being sustainable. We’ve got a competitive advantage in that space because our farming models are as sustainable as any elsewhere in the world.”

There will also be opportunities to leverage the improvements formalised through this assurance by becoming more attractive supply chain partners. At a recent Institute of Financial Professionals event dedicated to sustainable finance in the primary sector, BNZ head of natural capital Dana Muir focused on this potential.

“It becomes part of a guarantee that production from a farm meets supply chain partners’ own needs.”

This latter advantage has gained significance over the past couple of months as overseas market requirements for assurance on environmental mitigation activities have started to hit NZ food manufacturers.

In November, chief executive Miles Hurrell is likely to have alarmed some attendees at the company’s AGM when he said that if Fonterra is unable to give its high value customers such as Nestle confidence that it can achieve emissions reduction targets as prescribed, they will look to other product suppliers, including those who are able to produce alternatives to milk.

Prior to this, Fonterra published its own Sustainable Finance Framework to reflect the evolving preferences of its own lenders and debt investors. Fonterra says it will do this by issuing sustainability-linked bonds and loans to mitigate environmental risks and continue to differentiate NZ milk.

It is already providing incentives for farmers to comply with its needs via the Co-Operative Difference initiative where farmers who meet specific criteria including milk quality and other onfarm improvements are eligible for a payment of up to 10c/ kg milksolids (MS).

Earlier this year Silver Fern Farms started on a similar track. In June it announced the establishment of a sustainability-linked financing facility with ANZ, tailored to addressing water use, waste management and GHG emissions reductions which implicates its farmer suppliers and their farming practices.

Like Fonterra, SFF is also mindful of being able to meet the prescriptions for environmental mitigation placed on it by its customers. At the INFINZ event in October, Silver Fern Farms chief financial officer Vicki McColl noted that in order to meet its obligations, as well as meeting the expectations of its market partners, it was possible that Silver Fern Farms won’t be able to support some of its suppliers in the future.

These barely subtle warning shots to suppliers are based on the likes of Fonterra and Silver Fern Farms and others shifting their GHG reporting to include ‘Scope 3’ emissions - those emissions the company is indirectly, as well as directly responsible for, up and down its value chain.

This means the likes of Fonterra will have to report on its own manufacturing emissions, but also those made by producers of its products and those who deliver its goods to market. As alluded to above, this directional shift is being forced on it by international customers who have their own ambitions to deliver proof of their own sustainability credentials.

If farmers are sceptical of the motivations of their co-ops and other partners, the same message is being consistently broadcast by those with exposure to wider influences on supply chains.

NZ trade negotiator Vengalis Vitalis, who stitched together the NZ European Union free trade agreement, recently made the point that he reiterated immediately after concluding the deal in June, that EU negotiators were primarily focused on sustainability and how climate change issues were being dealt with NZ.

In a sense, the message was: access to the EU market will increasingly be determined by how good our story is on sustainability. In a similar vein, Finance Minister Grant Robertson said in November that during a business delegation trip to the United States, every conversation he’d had with business people on food production was on how we could describe the impact our food exports were having on the climate.

Back to sustainable finance. There is no sense at this stage that farmers will be forced by banks into adopting it in order to qualify for new lending. For one, Whillans points out that for it to work, farmers have to want to do it. But with an ever-increasing pot of money from conscious investors wanting to make a difference, and the assurance falling into place, the advantages of at least exploring its potential benefits, particularly longer term, are stacking up.

‘We’ve got a competitive advantage in that space because our farming models are as sustainable as any elsewhere in the world.’

2022 Mystery Creek National Fieldays

Farmgate is a purpose driven company with a vision to reduce rural crime by 50% through our clever tech and partnerships.

The FarmARMr system uses license plate recognition software and high quality German cameras to detect vehicles coming and going on properties. It is solar, 4G and battery powered.

The camera and barrier arm system is specifically designed for dairy farms to help manage vehicle assess and promote visibility at the farmgate.

What makes it work?

Artificial Intelligence detects vehicle plates at the tanker entrance. Milk tankers and farm traffic pass right by the barrier arm – only unrecognised vehicles are stopped until you let them onto your farm using your mobile phone APP.

Why does this matter?

We’ve calculated that up to 60% of farm theft occurs through the tanker track in a stolen vehicle. That’s why our Stolen Vehicle Register connects NZ Police data with our community APP to notify the user and local communities when a stolen vehicle is about.

Stop crime in its tracks with Farmgate

To learn more or to request a quote via our website, visit:

www.farmgate.co.nz

Senegal, Ghana, and more recently Argentina, while still in small proportions, as none of them seem to have fit in.

While the most common complaint expressed by Brazilian dairy farmers has been the significant increase in production costs in the last two years (from NZ$4.76 to NZ$8.73/kg milksolids), their structural bottlenecks are actually labour shortage and family succession.

In farmers’ own words, “dairy farm labour is difficult to find, when we find them they’re usually no good and when they’re good they do not last”.

This will come as no surprise to Kiwi farmers, where the problem has been present for years now, but it is recent in Brazil. Mexican immigrants are known to fill a similar gap in the US, Indians in Italy, Turks in Germany, Portuguese in the United Kingdom, South Americans from various countries in New Zealand and so forth. In Brazil, we increasingly see immigrants from Venezuela, Bolivia,

Brazil has made good investments in education over the last few decades but no efforts have been made to train dairy farm operators, especially milkers. Also, Brazilian farmers are not prepared to deal with the newer generations of employees, especially in modern labour legislation.

More recently, a number of private training courses and consultancy services have specialised in helping farmers acquire the skills to better manage rural human resources, but it is far from making a difference yet.

High costs, insufficient skills, unreliable or poor performance, and high turnover are the main employers’ concerns. Employees, on the other hand, complain about low wages, long hours, not enough days off, remoteness of some farms, living and working conditions (especially housing and milking installations).

On many dairy farms, the younger generations are not interested in continuing their parents’ business. Those

who fall into this category find it takes too much effort, risk and commitment for a very limited net income. However, this perception has improved slightly with increasingly better internet access in the countryside. Parents who manage to get their children to continue their business are usually those who get them involved early in life and value their participation throughout. Also, these parents tend to be more open minded and willing to adapt and change where needed.

Access to new technological solutions, especially in the last decade or so, has helped improve quality of life and to some extent the perception that the young ones had about dairy farming as “slaves’ work”, as it was often uttered.

The table illustrates recorded and expected changes in number of farms and cows, as well as in cow and farm annual production, all relative to 2015 (set to 100), for the state of Rio Grande do Sul in South Brazil, one of the most important dairy regions in the country. From 2015 to 2021 there was a staggering 52% reduction in the number of dairy farms, 26% reduction in cow numbers but only a 3% reduction in milk production. This was thanks to a 31% increase in milk production per cow.

The trend is forecast to continue to 2030, when only 14% of the farmers will be milking 44% of the cows, which will have more than doubled their production to yield a similar amount of milk per farm, as of 2015 figures.

Numbers of dairy farms and cows have plummeted in Brazil, but milk production has largely held up. By Wagner Beskow.

Few things are more relaxing than the sight and sound of calm, happy cows tucking into a good paddock of grass. But look closer – your girls aren’t actually relaxing! Each one is working hard to get the thousands of mouthfuls she needs to sustain herself for the day.

What if you could take some of the effort out of that process for them? From next autumn, you can, simply by sowing a new ryegrass that has been purpose-built for easier eating. Just what the doctor ordered Cows can’t tell us in words what makes a pasture able to be consumed more efficiently. So when we started breeding Array NEA2 ryegrass for high intake and easier grazing, we sought the next best source of advice.

Working with an animal scientist, the research tells us grass that stands up tall and erect – closer to those busy mouths – takes less time and effort to graze than grass that flops on the ground.

Twenty years of research and development later, the erect, dense pasture produced by Array NEA2 is now standing by to help your cows eat their fill more easily every day, and give them more time to relax,

ruminate and produce milk. That’s better for them, and for you, too.

In research trials, Array NEA2 has grown significantly more feed under low nitrogen conditions than other ryegrass cultivars.

What does this mean for your farm? More even pasture growth at times when soil nitrogen is deficient, something that happens on virtually every farm at some stage during the year; and a win for the environment, because you’re utilising nitrogen more efficiently.

This new diploid also has the best cool season growth of any perennial ryegrass we’ve bred, to help fill the gap when feed is short, and make your farm more resilient in shifting climatic patterns.

Seed for Array NEA2 is available for autumn sowing. Find out more from your retailer.

If you like hard data to support your pasture renewal decisions, check out the latest results from the National Forage Variety Trials – they’re available now.

Independent, industry-run and audited, these trials provide a forum for pasture companies to test their breeding material, and rank its performance compared with others.

We’re involved because want you to be confident about buying our seed. That’s why we’re pleased to see new Array NEA2 diploid perennial ryegrass at the top of the national summaries, unbeaten for total yield.

That lifts your supply of farm grown feed, and keeps animals well-fed.

Because National Forage Variety Trials trials are run under very good management, they give a good snapshot of optimal yield. So we also test new cultivars under real-world conditions on farms with known persistence issues, to give us a better picture of pasture resilience.

We need to know how new ryegrasses perform in dry summers and wet winters, for example. Like our low nitrogen breeding trials, this multi-faceted approach helps us create pastures that meet the wide-ranging goals of New Zealand dairy, both today and tomorrow.

Visit www.barenbrug.co.nz for more information.

John Maynard Keynes presented The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money in 1936, profoundly changing economic theory at the time. It still drives the basis of most economic theory today.

One of the key theories outlined in this revolutionary work was “The Propensity to Consume”, which states that as interest rates increase, all else being equal, then the propensity to consume must reduce. See where I’m going?

So, we find ourselves in the middle of another period economics students will study for years to come: a pandemic, the fallout from the resultant monetary response by governments and then the bubbling global economy that is the result, let alone what Tsar Vladimir’s imperial war has done to oil, fertiliser and grain markets. Not to mention the pain as interest rates are pumped higher to cool raging inflation, before it burns through the value of any currency in front of our eyes and reduces us to mediaeval squalor. A stretch maybe, but a rough comparative for the basis for monetary policy responses to inflation. I’m sure you’ve made the link. Interest rates are going up, so consumption will fall. Now, the tricky part is zooming into one commodity within an entire global economy. Economic forecasts are relatively simple when you’re looking at the entire system. When looking at a diverse product like dairy, and how the consumption of the 100+ products that are derived from milk will shift, it gets difficult. Thus why most analysts stick to the big-ticket items, and use them as a proxy for the rest of the market; I’m not going to be any different, I’m just outlining why I can’t tell you the rate of change of cream cheese lollipop sales in China for Q2 2024.

So, the global consumer is faced with rising interest rates,

along with the expectation that most developed economies will be in a recession at some point during 2023. As explained, we know the increases in interest rates will cannibalise overall consumption in some way, but the question is: where on the chain of value do consumers place dairy products today?

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) resulted in dairy being consumed less by most consumers as dairy was viewed as a luxury, especially in Asian markets where it is not a cornerstone of the historical diet. This definition of luxury meant dairy was one of the first products left out of the shopping trolley.

But something is very different with this economic speed bump, post-pandemic is a very different position to post-GFC. Throughout history, pandemics change how humans behave around health and self-care, while financial crises just ruin the population’s trust in capital markets.

The easiest example here is the change in communication around the health or immunity benefits of consuming more protein, especially dairy protein, from the Chinese government during early stages of the pandemic. This change in association of products from “luxury” to “health product” is one of the key indicators that

consumption levels of dairy are likely to be very different to those post-GFC. But it’s harder to pinpoint the scale of the change. This is partly due to the unknown impact of interest rate increases or the depth and length of the likely recessions.

Notably, the significant change to Chinese consumption is the normality with which younger generations consume dairy. This wave of generational change is helping to cushion consumption, with the benefits of including a great source of calcium and protein into children’s diets not lost on parents in China. As a generalisation, we expect overall product lines like cheese, caseins and liquid milk consumption to have a much higher consumption baseline than 14 years ago, which is less likely to be influenced by inflation than other dairy products. The entire cheese category is growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 22.6% since 2008 in China, with yoghurt and sour milk products coming in second best, only managing a CAGR of 12.0% over the same period. So, we know interest and inflation are going to impact consumption over the coming year, without doubt. We are seeing these metrics change in markets already. However, we estimate that due to changes in consumer habits over the last 14 years, we expect baseline demand to be significantly higher than during the 2008 GFC, a small cushion for what could be a hard landing.

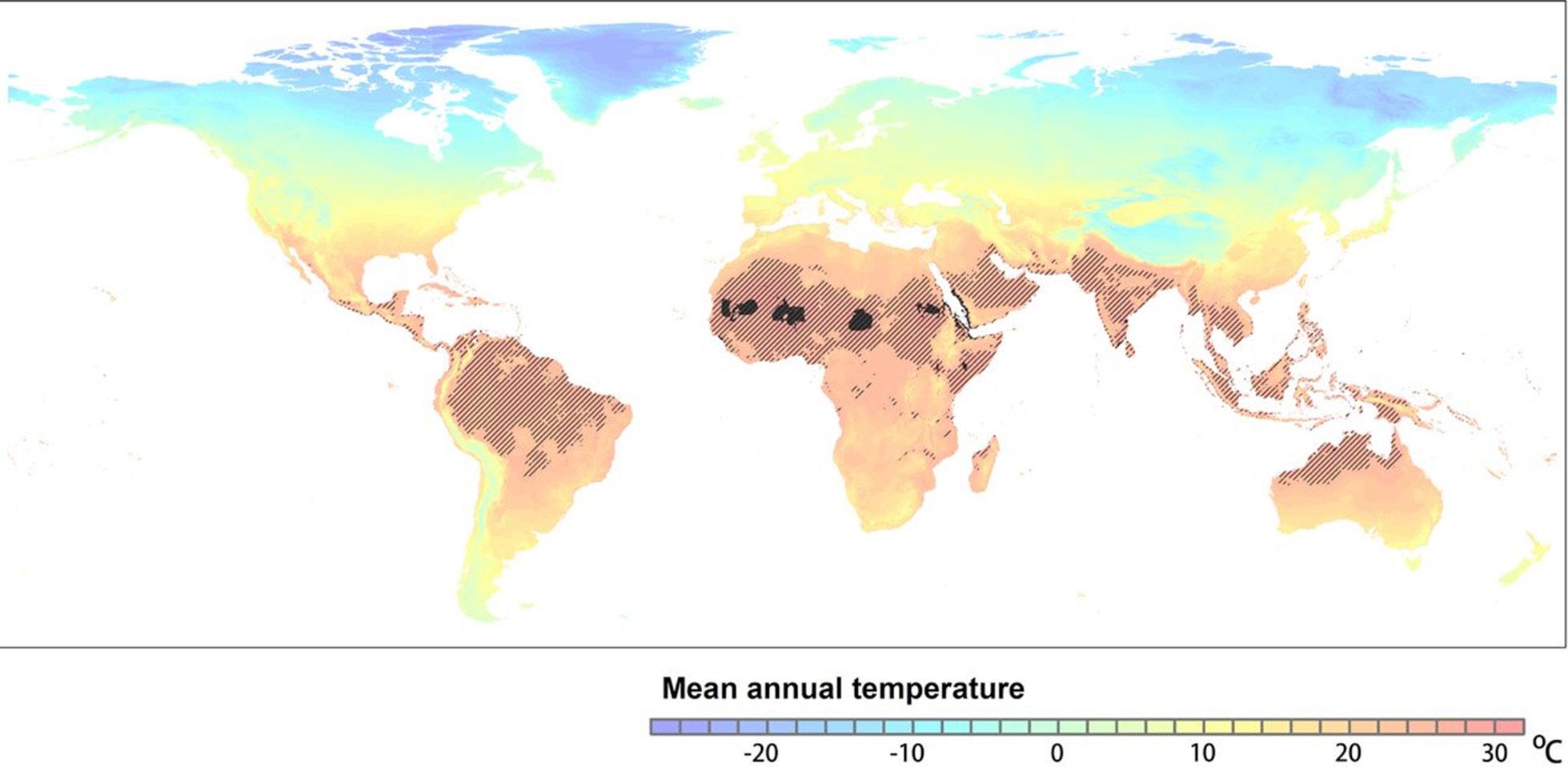

Robust evidence shows the Earth’s temperature is rising at a pace not seen before in its history and New Zealand farmers must take steps now to avoid the worst impacts.

That was the message delivered to those who attended the NZ Institute of Primary Industry Management (NZIPIM) Climate Change Seminar for Rural Professionals in November.

“Some say climate change doesn’t matter to New Zealand but that’s not true. It will have implications globally and for us. It will cost us to mitigate but cost us a lot more if we don’t,” Sinead Leahy, Principal Science Advisor New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre (NZAGRC) said during the seminar.

“There is still a wide spectrum of opinion about climate change including that the climate isn’t warming and we shouldn’t worry.

“However, it is very difficult to argue against the data which shows temperatures rising from the 1950s onward and increasing at a rate never experienced in our planet’s history. It is indisputable now that humans are causing climate change and Earth’s inhabitants need to be incredibly concerned about it,” Sinead said.

Fellow presenter Phil Journeaux, agriculture economist with AgFirst said as NZ’s climate changes, it might not be possible to farm in the same way as we do now.

“A couple of degrees of warming might not seem much, but it can have a big effect on pasture

The world, and New Zealand, is getting hotter and weather patterns are changing as the heat goes up.

and crop growth and on pests, diseases and animal welfare. Ryegrass won’t grow at temperatures above 25 degrees.

“The upper North Island could go from a subtropical to a semi-monsoon climate with wet winters and hot dry summers. Friesian, Hereford and Angus cattle would be long gone in this scenario.

“Farming will be very different, and we need to sort out water policies because irrigation will be crucial in many areas.”

Designed to expand rural professionals’ understanding of climate change, why agricultural greenhouse gas emissions are important in NZ, how they can be estimated within the farm system, and how they can be reduced on different farms, the allday seminar, was attended by 25 rural professionals from around the country. Nearly 40 of these seminars have been held since mid-2019, attracting more than 670 people.

The seminar sought to answer some of the questions rural professionals most often heard from farmers including around animal emissions, methane and carbon sequestration.

A frequently heard comment was that there had always been large numbers of ruminant animals on the planet emitting greenhouse gases.

“The number of ruminant animals in the world has never been greater than today. In North America it’s estimated there were once 70 million bison but today

there are more than 200 million cattle in the USA,” Phil said.

“In New Zealand if you go back a few hundred years there were no ruminant animals here. Today we have around 40 million in NZ and those growth trends have happened all around the globe.”

Another argument was that methane doesn’t matter or that methane and nitrous oxide make an insignificant contribution and should not be targeted in any national framework for reducing emissions.

Sinead said although methane (CH4) is a shortlived gas, it does matter when it comes to limiting global warming.

“Methane can have a very important role to play in reducing climate change. New Zealand is the first country in the world to acknowledge that not all greenhouse gases are the same. There are different targets for different gases in New Zealand, recognising the different warming effect of methane in the atmosphere.”

The Government has legislated long-term targets to reduce NZ’s greenhouse gas emissions, including that carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide (the ‘long-lived’ gases) need to reduce to net zero by 2050. Methane emissions are to reduce to 10% below 2017 levels by 2030, and 24-47% below 2017 levels by 2050.

However, in the scenarios for achieving the goal of limiting warming to well below 2°C, in contrast to carbon dioxide emissions, methane emissions do

‘A COUPLE OF DEGREES OF WARMING MIGHT NOT SEEM MUCH, BUT IT CAN HAVE A BIG EFFECT ON PASTURE AND CROP GROWTH AND ON PESTS, DISEASES AND ANIMAL WELFARE.’This map shows average temperatures, highlighting in black the areas that are too hot for human habitation today. In cross-hatched black are the areas that will be too hot for humans by the year 2070. Such areas include some of the most populated regions of the globe. Source: “Future of the human climate niche”, Xu et al, PNAS 2020.

not need to go to zero. Methane has several sources, including wetlands, landfills, forest fires, agriculture and fossil fuel extraction. In NZ, the largest proportion (about 95% of total methane) is belched out by livestock. This is known as ‘enteric methane’.

The average dairy cattle beast produces about 98kg of methane a year, the average beef cattle beast produces 61kg a year, the average deer about 25kg and the average sheep about 13kg a year.

who live here. We export close to 90% of the food we produce and as a result we are dependent on what our customers want. Our big clients like McDonalds, Nestle, Danone and Tesco are all facing regulations in regards to climate.”

For many of NZ’s customers, a significant proportion of their greenhouse gas emissions will come from their farmer suppliers so it is likely they will impose emission reduction targets for them to meet.

Many places will see more than 80 days a year above 25C by 2100, which will have a significant impact on ryegrass growth (it prefers temperatures of 5-18C) and animal performance

Winter and spring are very likely to have increased rainfall in the west of the North and South Islands and be drier in the east.

Summer is likely to be wetter in the east of both islands, while the west and central North Island will be drier.

All areas are likely to get more very extreme rainfall, especially shorter, more intense events.

Increased drought frequency in many regions of New Zealand and farmers in dry areas can expect up to 10% more drought days by 2040.

Nitrous oxide is emitted into the atmosphere when naturally occurring microbes act on nitrogen introduced to the soil via dung, urine and fertiliser. Nitrous oxide accounted for 11% of NZ’s total greenhouse gas emissions in 2020, the largest source of which came from livestock urine and dung.

NZ dairy farmers had become very efficient in increasing milksolids per cow through means including better genetics and pasture management, Sinead said.

“We do know if farmers farmed the same way now as in 1990, instead of 17%, our total agricultural emissions would have increased by about 40%. Farmers have made a lot of efficiency gains which have nothing to do with climate change but with their bottom line. Efficiency gains still have a role to play in reducing absolute emissions,” she said.

Overall, NZ’s emissions are small at just 0.17% of global gross emissions (22nd among developed countries). However, per capita our emissions are the sixth highest in the world.

Sinead said some people argue that reducing NZ’s emissions is perverse.

“They say that if we reduce production here with a price on agricultural greenhouse gas emissions, other, less-efficient, producers will increase their production and total global emissions will go up. But it’s not quite as simple as that.”

Many of NZ’s competitors produce similar emissions per unit of product and have national mitigation targets to meet. If they expand their agricultural production, emissions must reduce somewhere else in their economy. Competitors in the developed world also face constraints on production. There is scope to maintain production and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

“We are a trading nation and produce more food than required by the five million people

Phil said some farmers asked why they could not claim carbon credits for the grass they grew.

“Grass removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as it grows but returns it to the atmosphere when it is harvested and utilised,” he said.

Trees do exactly the same. However, the interval between growing/harvesting grass is weeks, whereas trees are harvested after decades or centuries – or not at all. The same quantity of carbon is stored in grass at the start and end of each year. The quantity of carbon in a tree increases year on year, while the tree grows.

The seminar spelled out clearly that NZ’s gross emissions are increasing and why action to reduce them is crucial.

In 2020, NZ gross emissions were 78,778 kilotonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (Mt CO2-e), comprising 44% carbon dioxide, 44% methane, 11% nitrous oxide and 2% fluorinated gases. This represents a 21% increase in emissions since 1990 (which is when international reporting obligations for greenhouse gas emissions began).

In 2020, 73.1% of NZ’s reported agricultural emissions was enteric methane from ruminant animals. A further 20% of agricultural emissions was nitrous oxide, largely from the nitrogen in animal urine and dung, with a smaller amount from the use of synthetic fertilisers. The remainder of agricultural emissions in 2020 were mostly methane from manure management (4.4%) and carbon dioxide from fertiliser, lime and dolomite.

For more information on the topics covered in this seminar, please see www.agmatters.nz

CRIME SCENE – CRIME SCENE – CRIME SCENE – CRIME SCENE – CRIME SCENE – CRIME SCENE – CRIME

CRIME SCENE – CRIME SCENE – CRIME SCENE – CRIME SCENE – CRIME SCENE – CRIME SCENE – CR

The increase in the incidence and frequency of known and suspected rural crime is borne out by last year’s Federated Farmers survey. The 2021 survey answered by 1200 Feds members showed more than half (52%) of the respondents had experienced or suspected they had been the target of rural crime.

That’s a 10% increase from the previous survey in 2016. Over the same period the frequency of rural crime increased with 37% reporting two or more incidents compared to 22% in 2016.

The stats will come as no surprise but raises the questions of what’s driving it, and what steps farmers can take to keep livestock, property and themselves safe from criminal harm.

Federated Farmers rural crime spokesperson Colin Hurst believes the trend is reflective of what’s happening across society as more people struggle financially and illicit drug dealing becomes more widespread.

“I think that generally rural people are honest so there’s naivety about how criminals work and what they get up to, especially when it’s based around drugs. What we do know is that once the drug element is present it tends to turn a rural community upside down.”

The Feds are doing their bit to raise crime and security awareness by running rural crime prevention workshops, in conjunction with the police, throughout the country. They’re not intended as a precursor to a Neighbourhood Watch type of group but rather a starting point for discussions and awareness around rural crime, and to encourage farmers to report suspected thefts.

Hurst says the under-reporting of actual or suspected rural crime is a big problem. Farmers often flag the reporting of burglary, vandalism and other acts of crime because they don’t have sufficient evidence or assume police won’t be interested enough to follow-up. But he says the reporting of suspicious activity is a crucial step in prevention because it can uncover patterns and waves of crime which over time can lead to the apprehending of offenders.

But the tardiness of the police in responding to crime in rural areas is a huge frustration which is covered off in just over three pages of an 80-page report by the Independent Police Conduct Authority Review.

The 2018 report followed several complaints about policing in small communities. Discussion around the question of ‘are members of small communities easily

Rural crime is an increasing problem as more people struggle financially and illicit drug dealing becomes more widespread, Lynda Gray reports.

Are farmers doing enough to keep their stuff and property safe?

No, judging by responses to the 2021 survey with just over half improving their security in the wake of a rural crime incident.

Lock and key are no longer enough to keep property safe. Experienced criminals armed with easy-to-use cutting tools can make short work of padlocks and chains on gates to paddocks, implement sheds and woolsheds.

However, criminals are more likely to bypass farms that have padlocked access along with other deterrents such as sensor lights, dogs near sheds, and security cameras.

The NZ Police security checklist is a good starting point to gauge the status of your farm security.

https://www.police. govt.nz/aboutus/publication/ security-checklistnew-zealand-ruralproperties

able to contact their local officers’ highlighted the difficulty people had in getting hold of help. Police took too long to answer calls or respond to messages, which discouraged them from trying and this is why crime was underreported.

If you see something, do something, that’s the message from Inspector Paul Carpenter who is leading the New Zealand rural police model.

The finger is often pointed at police for not following up on reported rural crime due to the perception of scant resources but that’s not the case, he says.

“We understand that farmers are interested in what’s happening due to perceived resource constraints and we want to change that.”

The answer is not through the employment of more rural police but rather improved communication links and promotion of them, he says.

There are 165 police staff distributed among 104 one-to-three police officer rural community stations which cover about 60% of the country’s geographical area. It’s a huge expense and satisfying everyone is not easy, but Carpenter says feedback from rural police is that the fundamental model is working although it needs to be updated to deal with the increasing volume of calls.

“The police are there and contactable, our job is to raise awareness of how best to share information.”

A combination of online means and better resourcing of the 105 Police nonemergency number is being worked on, he says.

The 2021 rural crime survey is the second undertaken by Federated Farmers.

The first in 2016 gave a snapshot of where rural crime was occurring and what the focus of those crimes was.

Respondents in both surveys were quizzed on property stolen, livestock stolen, livestock killed, poaching or foraging, property damaged or vandalised, and the clandestine onfarm growing of drugs.

Of those surveyed last year more than half had been victims of crimes during the past two years.

Smaller farm equipment (other than machinery) accounted for 46% of items stolen followed by fuel at 45%. The theft of motorbikes, quadbikes or other farm vehicles accounted for 27% of reported thefts.

Survey feedback noted very new bikes and vehicles were targeted, probably by the same criminals who stole the old vehicle. Respondents reported several occasions of quadbike theft despite removing keys and locking sheds.

Some were now using specialist quadbike locking systems to prevent further thefts. About 14% of respondents had had or suspected stock had been stolen from their farm.

About 8% of total respondents had had or suspected that drugs, mostly cannabis with some suspecting methamphetamine, were grown or manufactured on their farm. Many of the respondents who knew cannabis was being grown on their farm avoided the area and didn’t report the activity to avoid repercussions.

The grouping of respondents according to their location revealed Bay of Plenty, Hawke’s Bay, Gisborne-Wairoa and North Otago as crime hot-spots, recording significantly above the average for having had or suspecting an incident in the last two years.

Rural Outlook is a new-release police app for logging suspicious activity. It was launched in early May and is being trialled in the Waimakariri and Hurunui districts of North Canterbury.

Federated Farmers is backing the trial by encouraging farmers to upload the app. By mid-June about 2000 had uploaded it and 40 incidents had been reported. The app can be used outside of cellphone range and farmers can tag their location, upload photos, and other relevant details. It is intended particularly for incidents which might otherwise go unreported such as illegal hunting, trespassing, illegal use of drones, deliberate damage, theft of fuel and stock.

“We know that under-reporting of crime is a big problem in rural areas and we hope this will encourage people to report these incidents,” Federated Farmers North Canterbury president, Caroline Amyes. She has her own story of not bothering to report suspected crime. Gates went missing from her lifestyle block at Whitecliffs. “It was

a pain and rather than report it we just went and replaced them. We later found out it was happening around the community so if we had reported it the police may have got on to it sooner.”

Feedback from users of the trial app has been positive. It’s easy to use and people say they’ve had good follow-up from the police, Amyes says.

A couple of recent examples was the reporting of illegal street racing. The logging and photograph with clear identification of number plates was the evidence police needed to follow up. In another situation police were able to get the exact location of a dumped car in an isolated area from a photo sent on the app.

“It’s giving the police more data of where incidents are happening so that they can target their resources.”

The app is being trialled for two years after which a decision will be made about further rollout.

• First published in Country-Wide magazine, August 2022.

The installation of sensor lights about six months ago on Colin Hurst’s cropping farm at Makihiki, South Canterbury, was a simple $1700 investment. He bought two Eufy Cam Security kits from Noel Leeming. The system, ready-to-go out of the box, is wire-free with a 365-day battery which keeps working if and when there’s a power outage.

The system has facial recognition to reduce false alerts, stores video without the need for cloud storage and is weatherproof. The high-resolution camera picks up clearly the number plates and defining features of unwanted guests. The cameras overlook the fuel tanks, workshop, house and driveway.

"Generally rural people are honest so there’s naivety about how criminals work and what they get up to..."

Dairy Holdings is selling nearly 3000 hectares of dairy farms near the top of the South Island which were all converted by entrepreneur Avon Gillespie, who changed the face of the Maruia Valley to dairying.

In the late 1990s, Gillespie was a star in the dairy industry – a champion sharemilker - on a farm in the Tutaki Valley near Murchison. In just a few years he converted six large-scale dairy farms between the Tutaki and Springs Junction that each milked between 1000 and 1700 cows.

More farms were owned or leased around Murchison and Westport in his farming enterprises that milked about 10,000 cows before it all went sour. By the end of 2006, eight farming companies that he co-directed were in receivership, owing the Bank of New Zealand about $37.5 million.

He was on a downhill spiral that went beyond financial woes, with crimes involving drugs, violence and weapons sending him to prison and also fraud after he created a fictitious herd to gain more funding.

Despite his spectacular fall from grace, Dairy Holdings’ chief executive, Colin Glass, says Gillespie was generally remembered as a likeable rogue who wasn’t

scared to push the boundaries.

Dairy Holdings, the largest milk supplier and shareholder of Fonterra, bought six of Gillespie’s dairy farms in 2005 when the companies had gone into receivership and he was still in charge of the farms.

The company’s initial contact with Gillespie was in his helicopter, perusing the farms from the air. Alongside a multitude of farms, Gillespie owned the helicopter business, a farm machinery business in Richmond, a limeworks and a Murchison hotel. The businesses were operated through various companies, partnerships and trusts known collectively as the Gillespie Group.

“When we first looked at the farms, he flew us over by chopper and we very quickly realised he had a finger in a lot of pies. He was a very clever man and it all ran away with him a bit. But it was amazing what he put together in a short period of time and when we see what we have, we are very grateful.”

Glass says Gillespie managed to curry favour with the bank and he was very aggressive with buying land to create larger parcels that he then converted to largescale dairy units. A few small dairy farms with walk-through dairies became part of the larger units. Each unit was converted

to a high standard with rotary dairies, good laneways and drainage. Some blocks were leased around freehold land to create larger milking platforms.

“It hadn’t happened on that scale in that area – he was a pioneer.”

The conversions in the Maruia Valley took on the names of Morecow1, Morecow2, Morecow 3, as well as Shingle Creek and one based around Gillespie’s original family farm, Frog Flat. Those names continue under Dairy Holdings’ ownership.

Glass says the numerous pieces of leased land made it difficult to know what was freehold and what was leased, which was part of the enigma of Gillespie’s growth in dairying. Likewise, there was stock leased from various farmers which added to the confusion.

He says the local story was Gillespie had a “run-in” with the bank, which led to the companies going into receivership. However, receivership was the least of his problems. Drugs, violence and

firearms were involved including possession of pseudoephedrine with intent to make the drug P. Gillespie was sentenced to four-and-a-half years in prison on those charges, with fraud charges adding another two-and-a-half years. At the time the Serious Fraud Office’s case was that Gillespie had applied funds for his own personal expenses and to pay creditors not approved by the BNZ.

Glass says there were stories of machinery hidden in the bush from Gillespie’s Richmond machinery business that had also gone into receivership. Even after Gillespie was convicted, the farms had people calling in to see if they could find items that had disappeared.

Meanwhile, Dairy Holdings took over ownership of the six large-scale dairy units, adding more houses, calf-rearing facilities, upgrading drainage and putting irrigation on four of the farms.

The Tutaki Valley farm was sold about a decade ago because of its isolated location, whereas the remaining five lie relatively close together along the valley between Maruia and Springs Junction.

Today, the farms milk a similar number of cows to Gillespie’s time on the farms. The total land area of the five farms is nearly 3000ha and 1713ha is effective. In the 2022 season, the farms milked 3570 cows and the average total production for the past 16 years is 1,006,283kg milksolids.

Glass says cow numbers haven’t changed much over the years, but instead of wintering them elsewhere as Gillespie did in the past, they are now wintered on the farms which removes winter-grazing costs. Dairy Holdings has focused on running the farms as low-cost, fully selfcontained seasonal supply operations.

The remote location of the valley, distant from the company’s other farming enterprises, has prompted Dairy Holdings to put the properties on the market and concentrate on its other properties around the South Island. Glass says there has been interest in the farms which could be bought together – though he admits that is a big ask – or as individual farms.

He says Gillespie never really recovered from his fall from grace and time in prison. Gillespie died in Reefton in 2020 at the age of 57.

‘When we first looked at the farms, he flew us over by chopper and we very quickly realised he had a finger in a lot of pies.’

Composting barns allowed Murray and Gaye Coates to quit winter crops and reduce soil damage, potential phosphate loss from mud and nitrogen leaching on their West Coast farm. By Anne Hardie.

Murray and Gaye Coates are learning how to make compost and are discovering the process is far more forgiving than they feared. Their key message to other farmers new to composting barns, is don’t panic when there are hiccups in the system.

The couple farm 805 crossbred cows in the Haupiri Valley at the base of the West Coast’s mountain backdrop where 3.2-metres of rain falls annually on their 320-hectare milking platform. In the past they had a 400-cow feedpad with

the necessary consent, but they were not satisfied. They needed more space for their 805-cow herd and wet springs could result in significant pasture damage which was stressful.

Environmentally, the composting barns ticked the boxes by quitting winter crops and reducing soil damage, reducing potential phosphate loss from mud and less nitrogen leaching.

They saw how successful composting barns were working in Taranaki which also had high rainfall and after a couple of

years of talking with farmers, consultants and anyone with any knowledge on the barns, they took the plunge. They now have two composting ‘mootels’ that each cater for 400 cows.

Aztec Buildings built the barns along a design created by Headlands Consultancy specifically for the climate and needs of the Haupiri Valley farm. Each shed is 80m in length by 45m wide which includes two 5m-wide feed lanes inside, under cover. That gives each cow 6.5 square metres of space which works well, though the cows are getting bigger because they have better utilisation of feed.

The sheds were built in time for the cows to winter in them and they remained in them until they had calved. The final touches to the project have continued

through to spring and tweaks are ongoing. It is all part of the continuing improvements on the farm to try and future-proof it, environmentally and economically.

Taking a step back, Murray and Gaye bought half of his family’s farm at the end of the 1990s and ran sheep, beef and deer for years. Then, they joined the movement to dairying by converting the farm in 2008.

“Cows got expensive to buy, but by that stage we were at the point of no return,” Murray says. “The first year we started milking we had the clawback from Westland.”

They borrowed more money to clear more land and increased cow numbers to 590 on a 270ha milking platform. Today the farm has a total area of 420ha and uses 320ha as a milking platform, with the remainder in bush. The bulk of the farm is river silt and the high rainfall is delivered in often big events. This spring they had 130mm of rain one night, but the cows were in the shed on their wood chips which will slowly turn to compost, while the pasture and soils were protected.

“It’s the relief,” Murray says. “It’s hard to put a figure on that.”

Their barns are a steel and pole design because the wind can really rip down the valley from the nearby mountain pass. Between wind and high rainfall, they added a few extras to try and keep them intact and keep the rain out.

The strengthened ventilation running the length of the roof ridges is open permanently but is built with a good overlap so rain cannot get inside. As Murray points out, rain can run uphill with wind behind it and the overlap needed to cater for that.

On a hot day, the ventilation is designed to create a draft to cool the barns, as do the dimensions. The barns’ height begins at 4.5m and climbs to 11.8m at their apex, with an 18-degree pitch roof.

Airflow is crucial for successful compost and likewise, keeping excess moisture out. Through winter, the barns did not have the gables attached at each end which let rain drive about 10m inside and wet compost. Murray says water “is the killer of compost” and soil probes showed some of the woodchip was sitting about 20C in the wet areas and 40C in other areas.

“We were panicking because we thought it had to be 60 degrees,” Murray says. “We learnt the biggest thing is don’t panic. Compost is more forgiving than people believe.”

Gaye says they overcame the wet problem by tilling, tilling and more tilling to keep the composting process working.

“I think you have to go into this with the realisation of learning through experimentation and perfection won’t always be attained first up,” she says.

All going well, they hope they will not have to replace the compost bedding for several years. One of the farmers they

Farm Owners: Murray and Gaye Coates

Location: Haupiri Valley West Coast

Herd: 805 cows

Milking platform: 320ha

Annual rainfall: About 3.2m

Barns: Two composting for 800 cows

Production: 450kg MS/cow before barns

spoke to in Taranaki has not replaced their compost in seven years. Eventually, the Coates plan to spread the composted bedding over the farm.

Murray and Gaye are keen to point out that the options they have chosen are to suit their own farm and system and other farmers may do their research and choose different options.

Their farm consultant at the time,

George Reveley, challenged them every step of the way to think about how they could create a multi-purpose and flexible space for their farm and weather conditions. He stressed it needed to be safe, practical and pleasant for cows and people.

“He wanted us to think about how a shelter could work in with our existing farming system, rather than change our system to fit a barn,” Gaye says.

That meant thinking about how the space could and would be used at different times, like mating and calving. Also, the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of various shelter options for seasonal and climatic variances.

“For us, composting barns seemed to be weighted more to the strengths and opportunities presented by our existing farming system within the context of our climate and environment.”

Work on their barns continued through to spring and they now have the gables in place and mesh on the sides to stop rain driving inside. The eight water troughs are inside the barns, so cows do not walk out into rain for a drink and bring that moisture back on to the compost.