Learn, grow, excel February

Wise WATER USE

The life force we need to collect, monitor and use wisely

CONTRACT MILKING PART II The professionals’ perspective

AGRIVOLTAICS: Harvesting the sun while farming animals

OBSERVANT OWNERS : Train your team to tell you when they are sick

THE EVOLUTION OF NEW ZEALAND’S FAVOURITE FARM BIKE

YOUNG COUNTRY

76 Honours in the dairy

78 Future’s on the farm

WELLBEING

82 Resilience: The struggle is normal

84 Smart ideas to reduce working hours

RESEARCH WRAP

85 Season impacts on 10 in 7 trial

DAIRY 101

86 All that bull

SOLUTIONS

88 Autumn transition – Why is it so easy?

89 Proven inoculants deliver maize difference

OUR STORY

90 50 years ago in the NZ Dairy Exporter

65

OUR COVER

The Mayfield Hinds Valetta Water irrigation scheme is a mix of water races and piped network from the 6.3 million cubic metres of water storage at Carew providing environmental support to 58,000ha of highly productive Mid Canterbury farmland.

DAIRY DIARY

February 22, Nelson; February 22, Amberley; February 23, Blenheim; February 23, Ashburton; February 24, Timaru; February 24, Westport; February 24, Twizel; February 25, Oamaru; February 25, Hokitika; February 28, Napier.

Taranaki; March 29, Ashburton; March 31, Winton. To find out about each event visit www.dwn.co.nz/events.

February 16 – Dairy Women’s Network is running a live webinar on Managing and Diffusing Conflict. Ideal for team managers and farm owners. The webinar runs between 12.30pm and 1.30pm. To find out more and register visit register.gotowebinar.com/ register/4613164181619839503.

February 17 – Dairy Women’s Network has an onfarm technology workshop in Taranaki. The day runs from 10.30am to 2pm and looks at onfarm reporting systems to robotics. For more visit www.dwn.co.nz/ events/on-farm-technology-taranaki.

February 16-17 – National Freshwater Conference explores the Essential Freshwater Package, Resource Management and the Three Waters Reform. Find out more at www.brightstar.co.nz/events/nationalfreshwater-conference-0.

February 17 – DairyNZ takes its Ag Emissions Pricing Feedback Roadshow

February 24 – Dairy Women’s Network runs a live webinar: Getting back on track with NAIT. Understanding NAIT’s timeframes for registration and movement recording, and why this is important for biosecurity. It runs between 12.30pm and 1.30pm. For more details and to register visit register.gotowebinar.com/ register/2787583453568014861.

March 3-5 - Northland Field Days are held near Dargaville. Visit northlandfielddays. co.nz.

March 8 – Dairy Women’s Network is running a workshop in the Far North on building resilience and managing yourself in stressful situations. To find out more and register visit www.dwn.co.nz/ events/the-challenge-of-change-far-north.

March 9-10 – The Farmax Conference is being held in Hamilton and will feature discussions about alternative ways of using

March 10 – Quorum Sense is running a bale grazing and regenerative agriculture field day near Wendonside in Southland. For details visit www.quorumsense.org.nz/ events.

March 17-19 – Central Districts Field Days in Feilding. Visit www.cdfielddays.co.nz.

March 20 – Entries close for the Fonterra Responsible Dairying Award. For more about the award and make a nomination go to www.dairyindustryawards.co.nz/responsibledairying-award.

March 30-31 – DigitalAg is the rebranded MobileTECH Ag and will take place in Rotorua for the 2022 event. It will showcase new agritech developments and provide a platform for the sector to come together, discuss the issues and encourage collaboration. The programme will be split into five sessions: technology trends post covid, ag-data digitisation, applying machine vision and Al Smarts, rethinking agritech business models and agclimate technologies. To view the two-day

Please check websites to see if events are going ahead under the Covid-19 Protection Framework or what restrictions apply.

Staying strong onfarm portrays an innovative programme run by Reporoa dairy farmer and cancer survivor Sarah Martelli, who helps other women find their balance and build strength and wellbeing to be the best they can be.

Strong Woman is an online community for women to work on their fitness with a workout to do at home, find quick and easy healthy recipes, goal planners and to connect with other women on the same journey.

Her philosophy is to help women create healthy, sustainable habits around moving and feeding their bodies and their families.

If women can prioritise their own health and fitness, they can inspire their partners, their children and their community around them, Sarah says (p82).

She is an inspirational woman creating a moment of lift for many women.

THE RIGHT DROP IN the right spot

In this issue we take a look at the regenerative agri journey some NZ farmers are already on, and that the government has signalled they want others to join in on, in our Special Report.

The regen debate has divided the farming community in a big way - many scientists are affronted that NZ would need regenerative methods from overseas countries with highly degraded soils - would that then infer that our conventional methods were degenerative?

Kiwis love water - we love to swim, surf, dive, fish, and just float around. We love to talk about it - the weather, how much rain have we had? When will it stop raining? When will it start? And farmers even more so!

Sadly, this summer has seen many drownings - a testament to how much we collectively love the water but many don’t respect it and the danger of it. A great case for renewed efforts to teach every child to swim and to respect and understand the power of wild water in our rivers and at our many beaches.

for forecasting exactly when and how much to irrigate and the strategy of the irrigation industry group. They say the best way to mitigate adverse weather is to plan for itrequiring more investment in capturing the precious drops when it falls, storing it for when it doesn’t arrive and conserving and using best irrigation practices for when we need the water the most. (pg 50)

They say the methods won't work, and that research has already shown that, and also our farmers are already following regenerative practices. Others say that the methods are not prescribed and each farmer can take out of it what they want. It has been called a social movement rather than a science and the claimed benefits of improved soil and stock health and building soil carbon through diverse species, use of biological fertilisers and laxer and less frequent grazing practices along with less nitrogen is something that resounds emotionally with many.

As I write this, the West Coast is being pummelled with up to 500mm of rain, possibly its second 100-year rainfall event in six months. I feel for those who haven’t quite finished remediating their houses and farms from the last dump and are facing a repeat.

And other parts of the country are in drought and crying out for rain.

What is this change if not climate change?

We also have part II of our contract milking feature - while it’s an excellent way to build equity, it is important to ensure the contract is set up for success at the start, and that new contractors are encouraged and educated to make the best of it.

We have taken a snapshot of thinking by scientists in MPI and DairyNZ (p46) and portrayed what farmers using the practices are finding, including ongoing coverage of the comparative trial work by Align Group in Canterbury

Well-structured contracts are a win for both parties and allow people to move through the business and put down roots, which is great for families and communities, says Dairy Holdings’ chief operating officer Blair Robinson in Canterbury. (pg 34)

(p42). We also cover the Heald family of Norsewood (p52) who have transitioned to organics, OAD philosophies and are enjoying the less intensive more resilient system they have moved to, along

There is more research to be done in the NZ system context, says MPI’s chief scientist John figure out what will and won’t work, but he encourages farmers to engage and learn more, and to embrace regenerative as a verb - saying all farmers could be more regenerative, more resilient, lowering

If you are interested in getting into farm ownership getting out but retaining an interest, read about Moss’ innovative idea for a speed-dating weekend potential partners (p11). We think it could be a

NZ Dairy

@YoungDairyED

@DairyExporterNZ

@nzdairyexporter

Sneak peek

JULY 2021 ISSUE

In the next issue:

New Zealand does not face a lack of water, but rather a lack of the right drop in the right spot, and our special report attacks that from a multitude of angles. We talk to farmers who are sharpening up the efficiency of their irrigation practice, others who are getting certainty from community and onfarm water storage, new technologies

In The Year of Yes - Phil Edmonds delves into the mood of the banking sector and finds that farmers seeking extra funding stand more chance this year. (pg14)

March 2022

• Special Report: Farming/business investment – if you are starting out or bowing out.

• Wildlife onfarm

• Ahuwhenua winners

• Breaking down your mating reports to plan for greater success next time

• Sheep milking conference coverage

• The latest science in pasture renewal

• Deer milking? You can milk anything with nipples…

• Dairy 101 on getting the best from casual staff

@YoungDairyED

ONLINE

New Zealand Dairy Exporter’s online presence is an added dimension to your magazine. Through digital media, we share a selection of stories and photographs from the magazine. Here we share a selection of just some of what you can enjoy. Read more at www.nzfarmlife.co.nz

IRRIGATION IMPROVEMENTS CREATING RESILIENCE

The Woodhouse family’s irrigation improvements are creating resilience. Good data and investment into spray irrigation that allows lower rates to be applied at shorter return intervals will help maintain pasture production levels as nutrient inputs reduce with regulation.

Take a look: https://youtu.be/bivsGOWbM9Q

Factum Agri is dedicated to New Zealand’s primary industry, working with the Rural Support Trust. Each week Angus Kebbell talks with farmers, industry professionals and policy makers to hear their stories and expert opinions on matters relevant to both our rural and urban communities.

Sinead Lehy

Interview with Sinead Lehy, principal agricultural science adviser at the New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre.

Emma Taylor

Interview with Emma Taylor, general manager of Vineyard Plants in the Hawke’s Bay about viticulture. The company supplies vines, predominantly sauvignon blanc, to the New Zealand wine industry.

Fiona Bush

Interview with North Canterbury sheep and beef farmer, Fiona Bush. Fiona is giving her perspective on MPI’s Primary Industry Advisory Services available to the rural sector as well as the key issues farmers face today such as the environment and the rural/urban divide.

Find these episodes and more at: buzzsprout.com/956197

Going contract milking or thinking about it? Flo and Jen Coetzee have worked their way through contract milking to equity management in an 1100 cow farm near Methven – Highveld Pastures. Take a look at our story in our February issue where they share some of the lessons they learned along the way on their journey.

Take a look: https://youtu.be/DXcvspYGA08

CONNECT WITH US ONLINE:

www.nzfarmlife.co.nz

NZ Dairy Exporter @DairyExporterNZ

NZ Dairy Exporter @nzdairyexporter

Sign up to our weekly e-newsletter: www.nzfarmlife.co.nz

NZ Dairy Exporter is published by NZ Farm Life Media PO Box 218, Feilding 4740, Toll free 0800 224 782, www.nzfarmlife.co.nz

Editor Jackie Harrigan

P: 06 280 3165, M: 027 359 7781 jackie.harrigan@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Deputy Editor

Sheryl Haitana M: 021 239 1633 sheryl.haitana@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Sub-editor:

Andy Maciver, P: 06 280 3166 andy.maciver@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Reporters

Anne Hardie, P: 027 540 3635 verbatim@xtra.co.nz

Anne Lee, P: 021 413 346 anne.lee@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Karen Trebilcock, P: 03 489 8083 ak.trebilcock@xtra.co.nz

Delwyn Dickey, P: 022 572 5270 delwyn.d@xtra.co.nz

Phil Edmonds phil.edmonds@gmail.com

Elaine Fisher, P: 021 061 0847 elainefisher@xtra.co.nz

Alex Lond lond.alexandra@gmail.com

Design and production:

Lead designer: Jo Hannam P: 06 280 3168 jo.hannam@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Emily Rees emily.rees@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Partnerships Managers: Janine Aish Auckland, Waikato, Bay of Plenty P: 027 890 0015 janine.aish@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Tony Leggett, International P: 027 474 6093 tony.leggett@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Angus Kebbell, South Island, Lower North Island, Livestock P: 022 052 3268 angus.kebbell@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Subscriptions: www.nzfarmlife.co.nz subs@nzfarmlife.co.nz

P: 0800 2AG SUB (224 782)

Printing & Distribution:

Printers: Ovato New Zealand

Single issue purchases: www.nzfarmlife.co.nz/shop

ISSN 2230-2697 (Print)

ISSN 2230-3057 (Online)

AM I walking away?

After digging a tractor out of the mud, Richard Reynold’s goes digging into the He Waka Eke Noa proposals.

Ihave been going through a grief cycle lately. No major deaths, hand-cutting or job losses this month - just coming to terms with the Zero Carbon Act and resulting agricultural emissions pricing options to be found in He Waka Eke Noa.

I, like many people, years ago was in the first stage of grief - DENIAL. I am still meeting many farmers and, more concerning, rural professionals in this stage.

The argument tends to go that the Government is not that stupid to shut down New Zealand’s economic engine, it’s all too complicated and I just don’t have time to follow it. Most commonly though is, ‘it does not affect me and what can I do about it?’

The five stages of grief do not have to follow the prescribed order. After getting a tractor stuck in a marginal block of land, failing to get it free with the second tractor and failing with the brute force of a digger, I managed to free it by showing a helper how to tie posts on to the wheels.

This all happened 17 days ago when we were wet. I look out across paddocks turning a new shade of brown every day and wish I could get a tractor stuck now.

So when DairyNZ and Beef + Lamb sent me an email about He Waka Eke Noa or emission taxing for agriculture I entered the BARGAINING stage. Here I had a block of land that was starting to cost money. I can plant it in trees, earn money and save the world, winner!

After reading through the proposal I started to feel ANGER. The more research I did the more anger I felt. My area could only be planted in natives and this can cost upwards of $13,000/hectare versus my plan for poplars homegrown approaching $700/ha. It looks to me like there is some choosing of which science we want to accept.

I am also told that for dairy the rate of tax will be about $0.05/kg milksolids (MS) in 2025. There are no predictions on what the cost would be in 2050, which is not that far away really.

When the tractor got stuck at Punakaiki and the bigger tractor and the bigger, yellow digger all failed to pull it out...thus began Richard Reynolds’ stages of grief.

The lack of information and research that I have found has led to DEPRESSION. I have asked many rural professionals, from bankers of varying colours to a senior member of the Reserve Bank, and DairyNZ and I have not found any that have done research as to what this could mean for their clients.

From the look of it for dairy farmers a bit of pain, but for sheep, beef and especially deer this could mean lots of pain. All this work at present may be of little use as the modelling shows a reduction in greenhouse gases of 1%. This has not made James Shaw the Minister of Climate Change very happy and there is still the option of the Government taking stronger action.

A pop quiz on the subject with a group of farmers over beers showed very low engagement on a topic that will have more impact on farming than clean waters.

The line that is repeated is that the less feed eaten the lower GHG emissions, a more truthful line is the less produce made the lower the GHG emissions. I have to say I am depressed about the innovation and patch protection that has happened from our industry leaders and also the level of farmer interest. A pop quiz on the subject with a group of farmers over beers showed very low engagement on a topic that will have more impact on farming than Clean Waters rules.

I am now ACCEPTING that I have to go to one of the meetings coming up and organised by Beef + Lamb, Federated Farmers and DairyNZ. I have also accepted that walking away from the land where I got stuck makes both financial and environmental sense.

The beef side hustleA REVIEW

Ihave heard that the majority of beef cattle reared and killed in New Zealand today have a dairy origin. We are contributors to this statistic by running a small, leased beef farm alongside our role as contract milkers on the family farm.

Is this a profitable addition to our dairy business?

This is yet to be determined so I thought I’d review how we run the operation and go over a snapshot of the 2020 financials.

The beef farm is 61 hectares with medium-heavy soils that hangs on to moisture well into Wairarapa summers.

The heavy soils can be challenging during winter and early spring so we limit the stocking rate over this period. This property is separated from the dairy by a country road and water is supplied from the dairy, this is a major bonus as we don’t like wasting time either driving too far afield or fixing a dodgy water supply.

My advice for any dairy-come-beef farmers, is to do your budget and due diligence before starting. Farm conservatively and build from there and if you get into trouble, you can always sell store.

We predominantly finish beef cross cattle that are bought from the dairy operation as 4/7-day-old feeder calves. We have dabbled with selling store one-year-old cattle in October-November and do like the potential returns this trade can provide.

Balage is harvested in spring and fed out in late summerautumn and winter. We renew about 10% of the farm’s pasture each year. This is done by planting a summer brassica and then returning it to new pasture in the autumn.

In terms of workload, we figure this side of our overall business takes up about an hour a day, each day of the year. Some days we do nothing, on other days we may be drenching or feeding out for a few hours. We can spare the extra hour being a once-a-day milking farm but most likely wouldn’t have spare time if we were twice-a-day, with just three full-time staff.

Now the 2020 numbers:

• Revenue: $126k

• Farm working (including rent but not labour): $104k

• Profit: $22k

• Minus a deduction for our time: $9k (365 days *1hour*$25/ hour)

• Operating surplus: $13k

We knew from the beginning that this enterprise would not be making us millions. We had budgeted on earning an additional profit of $20K. It didn’t quite make that amount in 2020, but the beef schedule wasn’t flash and we were still working out how to operate the farm.

We are however happy with our weaner rearing costs of $220/head (including the calf) and how the property worked alongside the dairy farm. The biggest lesson learnt is that beef farmers need to focus on the market more than their dairy counterparts, and one week can make a huge difference in the schedule price.

My advice for any dairy-come-beef farmers, is to do your budget and due diligence before starting. Farm conservatively and build from there and if you get into trouble, you can always sell store.

Talk to stock agents, meat buyers and read the farming news to keep a pulse on the markets. Lastly, make sure you factor in, and cater for, the additional time and money beef farming requires to rear quality animals, don’t under budget on these. In this regard, as dairy farmers first and foremost the last thing we need is extra stress during calving, so don’t get too distracted by the beef! Cheers.

NOT ALL heroes wear capes

A couple of weeks ago, Suzanne Hanning got a phone call she never wants to be repeated.

An often overlooked group of people who work in agriculture, don’t milk the cows, feed the calves, or shift the ewes. Without them, we would be up the proverbial creek without a paddle. They have the skills, knowledge and professionalism we call on when we come across something we would otherwise put in the too-hard basket.

I’m making a feeble attempt to describe our rural veterinarians. We often talk about mental health in the rural sector and that’s great, but our vets are just as susceptible if not more so than the rest of us. We may have had one or two cows with a messy calving over the whole spring, but a rural vet could have dealt with four or five a day. Every call-out is a job that was too hard for us to deal with, but we expect them to perform miracles, sometimes in the pouring rain, in the middle of a paddock.

They listen to our descriptions of what we think is wrong with Daisy and try to decide if we’re on the right track or have taken the scenic route. They see tears in our eyes and feel the same sadness when they have to end the suffering of our beloved pets, our favourite cow or the kid’s pony. Then there is the scale of some farms where a routine task like vaccinations can become an assembly-line procedure. Again, we do it a few times a year, but our vets can spend weeks vaccinating one herd after another, day after day.

I guess what I’m trying to say is we often take vets for granted. We expect them to have all the answers, be instantly available and fix everything at a bargain price when we don’t see that they are people too, they usually have a huge geographical area and … they are human too.

I can hear some of you saying, “yeah, but they signed up for it, that’s what they’re paid for”. Yes, but one could argue the same for farmers and as with farmers, they love what they do and are emotionally invested in doing the very best job they can. They often have huge student debt and need to eat too.

We expect them to have all the answers, be instantly available and fix everything at a bargain price when we don’t see that they are people too.

A couple of weeks ago, I got a phone call I never want to get again. Our vet who had been with us nearly from the beginning of our dairying career had ended his own life. We had an inkling things had not been quite right for a while as our usually jovial, chatty, swearing (like a trooper, but it was almost a part of their personality and for some weird reason, not offensive) friend and close adviser in all things animal health had become stoic and a little distant. To me, the most heartbreaking thing was that our vet felt they were in such a dark place that the only solution was to leave this Earth, when in reality, they were well respected by those who knew them and truly loved by all who call them a friend. If only our vet had felt this when they were alive, would it have made a difference?

I’m not sure how to make this better, but maybe we all need to remember our vets are people too. Not all heroes wear capes, some wear overalls. We will miss you.

Making the most OF LOCAL…

The importance of getting a break from the farm has never been more real than now. With two Covid years behind us and ‘normal times’ seeming to be forever changed, a new normal of what getting a break from the farm looks like might need to stick around a bit longer than we thought!

Like others this summer, we have been making the most of what ‘local’ can offer with the challenges of farming meaning getting away off the farm for a break has been tricky. Whether it be staffing, farm requirements, the worries of travelling away with Covid conditions or just other ties and responsibilities, we have been determined to make the most of what ‘local’ can offer us.

The farm had great rain in December, crops were going gangbusters, cow production was steady and mating had (we hope) gone well. We went into the festive season with good grass cover and finally got some supplements made and in the bunker.

So it was time to get off-farm and find what we could do for mini-breaks off-farm that were local.

While the farm definitely needs rain, the benefit is that the beach has been a great place to go between or after milkings for a quick dip.

We haven’t been disappointed. We have mountain-biked at Mangamahoe mountain bike park, walked many times on Mt Taranaki’s numerous trails, camped in the back yard and swam regularly at the local beach.

With our two older kids as lifeguards and younger kids involved in Junior surf, there haven’t been many days where we haven’t been at the beach for some surf lifesaving club-related activity. While the farm definitely needs rain, the benefit is that the beach has been a great place to go between or after milkings for a quick dip.

Our Christmas and Boxing Days were spent milking and at the beach. Our kids were on lifeguard duty, and while Christmas day wind made it pretty miserable, Boxing Day was busy. It was so great to have a Christmas lunch of ham off-the-bone sandwiches

Getting off farm, but taking the likes of Covid-19 into account, is part of the new normal for Trish Rankin and her family.

and a box of chocolates instead of eating too much and wondering how we were going to survive milking that afternoon!

We have had best friends come to camp at ours for New Year. This has been a tradition for many years and this year’s theme was Las Vegas Pool Party! We dress up, have themed food and cocktails and dance the night away. When I got in from milking that morning, they had made brekkie and we all went and walked around Lake Rotokare reserve.

January has been a mix of milking, catching up with friends, and snatching time off farms when we could. A highlight was a community water activity day where a group of the Awatuna/Auroa Farming for the Future catchment group, funded by MPI and run with the help of Taranaki Catchment Communities, held a day where the community could come along and learn about all the different types of water testing and participate in some communityled insect investigation. The kids had a ball with a net and a white container, catching water bugs and checking out the water clarity and other water testing techniques. The adults watched on and learnt about their streams too. It was two hours well spent, and finished with a BBQ.

Our Taranaki summer theme though has been “Connect and Explore Local”. When getting ‘off-farm isn’t practical for days on end, getting off-farm in between milkings can be. Hopefully by the time you read this you have had rain, crops are going well, cows are milking consistently and you have had some time off-farm - even if for just a little bit to connect and explore local.

A NEW HERO EMERGES A NEW HERO EMERGES

LactisolTM Nucleus Z1 is armed with zinc oxide, vital in the battle to prevent facial eczema. However, only Lactisol Nucleus Z contains Hy-D®, to improve calcium adsorption, blocked as a side effect of high levels of zinc.

And of course, Lactisol Z contains the full SollusTM range of vitamins, trace minerals and antioxidants needed to make your herd healthy and robust. Ask your feed supplier for the newest hero and give yourself a fighting chance.

registered trademarks

When facial eczema threatens, you turn to a hero that has a few tricks up its sleeve.

The year of the

Farmers seeking extra finance from banks stand a better chance this year, Phil Edmonds reports.

Should I borrow? $ Can I borrow? $

$ $ $

How much is it going to cost?

$hould I borrow, can I borrow, and if I do, how much is it going to cost?

These may have been three questions farmers contemplated as the year kicked off. If this was the case, the first question was likely the easiest to answer, the last probably the hardest while the second, might well have provoked a disgruntled “who knows these days?”.

Although not specifically relevant, answering the middle question will no doubt have been influenced by hearing the daily stories of rejection being faced by borrowers following the implementation of Credit Contracts and Consumer Finance Act (CCCFA) at the end of 2021. But it will also have been prompted by the experience many farmers have now become used to when dealing with banks – the longer list of boxes to tick and criteria to meet.

There is however the potential for that to change – ironically, due to the introduction of the CCCFA –and farmers could well now be courted by banks in a way that hasn’t been the case for some time. First though the questions again.

Should I borrow? Well, right now there’s plenty to encourage a positive response. Farm revenues are manifestly higher than they have been for some time, and broadly predicted to remain that way for the next 18 months.

This should provide farmers with some confidence in their ability to service that debt (in the foreseeable future). Many farmers will also have spent the past few seasons chipping off existing debt and at a macro level the sector has continued to deleverage from unsustainable highs. With those conditions in mind, now is as good a time as any for farmers to invest in future-proofing their businesses to an extent that may not have been possible in the recent past.

Next. Can I borrow? A trickier one, which has a potential bank answer and a farm answer.

In theory, the bank answer should be increasingly yes. Because banks have been forced to curtail lending to house buyers with modest deposits and particular spending habits, they’ll be

losing business. Banks need to keep lending in order to make money, so logic suggests they will need to look to other sectors. Surely agriculture.

Andrew Laming, director of rural financial advisory firm NZAB, thinks the CCCFA should probably be a net positive for farmers with the sector’s overall debt level now more manageable and business viability (at least in the near term) looking more prosperous.

“Agriculture lending is now being repaid as fast as it is being lent out (making this unique compared with other sector lending). By default, banks need to ‘run to stand still’ which means continuing to write new loans.”

Bank lending data and a survey of credit conditions released by the Reserve Bank in the final quarter of last year also suggests farming is better placed than it has been in the recent past to encourage banks to continue capitalising the sector.

In October the Reserve Bank noted “demand for agriculture lending has proven resilient throughout Covid-19, due to strong commodity prices and low interest rates. These conditions have allowed farmers to increase their principal repayments, providing confidence in the sector and helping banks to become more comfortable pursuing quality growth in their agriculture portfolios.”

It also reported that credit availability to the agriculture sector has increased slightly over the past six months, with some easing in lending terms due to strong commodity prices, low interest rate environment and increased cashflow. As a result, it said banks were expecting around a 25% increase in demand for credit from the agri sector by March 2022, and that expectation would be broadly met by banks. In terms of the ‘easiness’ of accessing credit compared to the previous three years, banks were reporting that it had become ‘somewhat easier’ although a slight majority reported ‘about normal’.

That said, a sector lending summary released at the end of December showed that for the month of November, total agricultural lending had fallen by $187 million, and dairy lending was down for the sixth consecutive month, by $175m. In fact, agri lending ‘growth’ had not moved out of negative territory since the end of 2019.

Taken together, the ‘feel’ for the sector and the actual lending numbers perhaps reads as optimism lies ahead, but there’s no evidence of it yet.

The most recent ANZ New Zealand Business Outlook cautiously points to a near future that reflects what banks are anticipating. While overall

business confidence was reported to be falling (understandably given the Covid-19-related uncertainty), the monthly trend for agriculture showed its level of confidence to be improving.

The sector’s activity was identified as having risen sharply, as was profitability. But the sector’s own view on ‘ease of credit’ was however thought to have worsened.

This discrepancy between what appears to make sense (banks loosening their purse strings for farmers given their improved bankability) and what farmers are thinking (banking is getting harder) is what makes the question of ‘Can I borrow’ a difficult one to definitively answer.

Andrew Laming says that as ever, banks will want to make sure farmers have good financial history and good governance. They’ll also be increasingly wanting to know if farm resources are well known and certain (land use consents are in place), the production system being employed is relatively ‘normal’, and the farm is not in a naturally sensitive area. Laming says where lending can be a problem is when a farm might have a high stocking rate which the banks might view as likely to be creating lesssustainable nutrient losses and unsustainable GHG emissions.

The best answer then, maybe yes and probably yes with a capital Y – as long as you’re thinking what the banks are thinking.

How much is it going to cost?

The final question – How much is it going to cost? The hard one, but potentially solvable.

Multiple interest rate hikes are expected this year to quell inflationary pressure.

How

The Reserve Bank’s official cash rate sits at 0.75%, but economists are variously picking it could end the year more than twice as high – above 2%. The arrival of Omicron could stifle that though, if NZ’s economy mirrors what has occurred in Europe and Australia since the variant emerged.

For farmers though, it’s not just looking at OCR moves that make it difficult to determine the cost of borrowing.

Andrew Laming says that despite farm financials looking rosier, banks are pricing other sector risks beyond income into their interest rates, which are effectively pushing fixed rates higher for longer than they might otherwise be set. Banks are managing the risk they

foresee (regulatory changes having impacts on farm returns) by setting rates with a margin buffer.

“It’s noticeable that some banks are uncertain about how much additional capital they might have to hold against loans in the future, so they are making up for that by pricing the longer-dated fixed interest rates higher.”

The answer to the ‘How much is it going to cost?’ question might then instinctively be ‘Too much’.

But Laming suggests farmers might think a bit more deeply on this, which involves calculating whether that cost (albeit elevated) is still manageable, and particularly what they can do to reduce the uncertainty on what that looks like.

“If, for example, an average farmer was geared at $20/kg milksolids (MS), a 2% rise (as economists are anticipating) would just add an extra 40c/kg MS. Farmers should be in positions to manage that if their farm systems are agile (flexible enough to reduce variable costs), have supportive balance sheets, and are able to deploy product price hedging.”

The last point – hedging (beyond fixing interest rates) – is something NZ farmers are coming to see as a useful tool, and there’s plenty of scope for it to play a bigger role in de-risking financial decision making.

NZX dairy insights manager Stuart Davison says as interest rates as well as feed and other costs climb, there are more and more conversations about how farmers can create some safety buffers for their businesses.

“Most farmers that feed palm kernel or maize silage look to forward contract their required volumes, but fewer have been willing to realise fixing their milk price has the same benefits.”

That’s changing, however. There has been a massive increase in the use of NZX Milk Price Futures – up 33% on last year, with 20,868,000kg MS more milk contracted via the market. And a similar trend is holding for milk price futures for the 2023 season. Farmers see the opportunity to lock in milk price for next season at about $8.70/kg MS already. There are already 5714 lots of open interest in the September 2023 contract, 169% more than at the same time the year before.

Davison says this trend represents a change in mindset where farmers appear to be starting to lose their fear of missing out on the highs in favour of more certainty. This will inevitably appeal to banks, who like known quantities more than anyone.

2022 could be the year of the yes.

Trusted for decades and proven to perform, you can always rely on Boehringer Ingelheim products to keep your stock at their best. And to help get everything else done right, we’ll throw in these DeWalt tools.

Ensure young stock become future high producers through improved health, growth and energy at: futureproducers.co.nz

Futures forecast passes $9/kg

The start of a new year signals a fresh view of markets, and horizons being pushed further afield. Following a Christmas break of checking if I can still milk cows, mow silage and repair fences (which I can by the way) I’ve started to look to the coming season, to gauge where things may be sitting at this time next year. A very real challenge.

Please don’t take these assumptions as gospel, the following are simply thoughts at this point in the season, things in the global market move quickly! So, here we go.

First, where are we now and why? Well, the current season is well over halfway completed, and Global Dairy Trade (GDT) events have already sold some tonnage for next season, so we have a fair idea on where this season’s milk price will land.

The caveat here is that there is still enough time to see some movement, but we’re no longer talking whole dollar movements, we’re down to a 20-30 cent range potentially. So, on

current indications, the SGX-NZX Dairy Derivatives market is pricing the Milk Price Future contract for this season, the September 2022 contract, at $9.20/kg milksolids (MS).

This price is a contract high and is pricing in expectations of whole milk powder (WMP) prices appreciating at GDT events over the coming five months, along with the other reference products remaining in their current price range.

This milk price future contract price is above the top end of Fonterra’s forecast range, and leads most economists’ (and ours!) milk price forecasts by about 20 cents/kg MS.

Is it achievable? Definitely! Why? Supply and demand are out of kilter, with demand growing faster than supply over the last 18 months. China has been the big player here, growing their appetite for dairy over the last 18 months at a rate producers haven’t been able to keep up with.

Where are we going? Well, as said above,

this is really looking into the crystal ball stuff, but let’s give it a shot.

Market fundamentals, which basically means supply and demand dynamics in the global sense, point to a slight continuation of milk supplies squeezing for some time yet. Global milk supplies are tracking below demand, which is why dairy commodity prices are above their historical averages.

There is also an odd mismatch of products being supplied by the normal dairy exporters, creating a further oddity to the market. The European Union is producing less milk, while also processing this lower volume of milk into products away from their norm, exporting larger volumes of cheese, whey and fat-filled milk powder, while exporting far less skim milk powder, whole milk powder and milkfats.

United States milk production has finally faltered, and their output is no longer growing at the extremes it was

Pasture & Forage News

Which ryegrass?

Picking the right ryegrass for renewal depends on several things, especially how long you want the new pasture to last for.

For example, if your paddock is destined for spring crop later this year, you’ll need a six to seven month pasture option. Tabu+ Italian ryegrass or Hogan annual ryegrass are the best choices here.

Don’t let dry weather rain on your pasture parade this season

For new pasture you can be proud of – even if it feels too dry to think about it right now – consider sowing seed before it rains, instead of waiting for the weather to smile on you.

Research shows ryegrass seed sown early in dry conditions germinates well after weeks with no rain. It can also grow more feed per hectare than seed sown later, and will probably persist longer too, giving you a better result all round. Plus, you’ll beat the rush for contractors when the rain does come.

Yes, you can!

We’ve been asked so many times if it’s okay to sow seed in the dry we did a trial to confirm the answer for you.

In hot Waikato peat during an autumn drought, we sowed perennial ryegrass seed with NEA2 endophyte in February, March and April.

The earliest sowing had it the hardest – the soil reached over 49 degrees C at seed depth (2 cm), with no rain for 43 days.

Even so, this February-sown seed went on to grow 2 tonnes of dry

matter per hectare more than seed sown post-rain in April, and the endophyte was fine.

Ready to grow

Seed sown before the rain comes is poised for growth as soon as conditions are right.

If seed is still in the bag when the weather breaks, it can’t grow until you drill it. By then everyone else wants to do the same thing, so contractors are flat out and delays are inevitable, especially the way things are now.

First up, best dressed

The benefits of sowing early don’t stop in the paddock. If this technique suits your farm and your soils, it will also help you get organised ahead of time.

That means no rushing around at the last minute trying to get hold of seed, and a lot more peace of mind knowing you’re as ready as you can be for one of the most important jobs of autumn.

If you’re renewing paddocks which you want to deliver great performance for the next two to three years, sow Shogun NEA hybrid ryegrass.

For longer term pastures, your best option is a perennial ryegrass - Maxsyn NEA4, Governor, 4front NEA2, or Trojan NEA4. Check out our website for details on all these cultivars.

In all cases, remember the old adage – you get what you pay for. Cheap seed can be expensive feed! Always buy certified proprietary seed. There is always a reason something sounds too good to be true, and with cheap seed it may be poor germination, high weed content, minimal endophyte, poor persistence or simply poor genetics.

earlier in 2021, however US dairy exports haven’t fallen over just yet, with more and more US skim milk powder finding its way into market holes left by the EU recently. However, this trend is expected to fall over soon enough.

Outside of these two powerhouses of milk production, the rest of the top milk-producing countries have all reported declining outputs. As you are aware, New Zealand’s milk production has been a shocker so far this season, with expectations of the entire season’s production coming in at least 1.6% behind last year’s stellar production.

Potentially, NZ’s total milk production could be much lower than this 1.6% drop forecast by the end of the season. All of this cumulatively points to a milk retraction globally of about 0.4% year on year; significantly massive, considering that population growth is far larger, and positive, than this number.

When will this dynamic reverse? Not in a hurry is the easy answer. Too much inflationary pressure is on the horizon to see milk supplies really turn around in a hurry. Basically, costs of milk production globally continue to climb faster than milk prices are increasing.

EU farmers have just spent a season losing money producing milk, though some processors have recently lifted farm gate milk prices to a point where producers are making money again. But as feed, fuel and fertiliser prices continue to lift, farmers’ profit margins are being obliterated once again.

The same can be seen in our market, with profit margins being quickly squeezed –from interest rates increasing, to feed costs remaining high, to labour costs continually increasing, not to mention everything else that gets spent on increasing over the last season due to a multitude of factors.

The same brush can be used across US dairy producers; they are fighting high feed and fuel costs too, and things don’t look likely to turn around in a hurry there either.

So, now that you’ve read through all of that, you want to know what the magic number is likely to be next season? Well, I’m not going to put a straight answer

NZX milk price futures (NZ$/kgMS)

NZX milk price fututes (NZ$/kgMS)

down in ink, as that never ages well, but I will put some ranges out there, and give some reasons.

First, let’s look to the SGX-NZX Dairy Derivatives market, which is citing next season at $8.87/kg MS, which, working off forward curves of dairy ingredient commodity prices easing into the middle of this year, makes sense. However, those futures curves assume Northern Hemisphere milk production will increase during their spring flush as a response to high commodity prices.

I’m not so sure of that assumption, as mentioned above re costs of production. So, this would lead me to think that next season’s milk price will most likely be above this price, maybe starting with $9.

On the flip side, just like dairy producers, the buyers of dairy commodities must deal with inflationary prices also, along with monetary issues as financial markets move, which always needs to be factored in when looking this far ahead. There will be a constant tension for dairy buyers, between the prices they buy and sell their goods for, and the affordability of dairy for consumers.

So following all of this, next season’s milk price forecast is for good things, but take these insights with a grain of salt, things change quickly. Remember also, as inflation increases, even a $9 payout can quickly have the shine taken off it!

Market fundamentals, which basically means supply and demand dynamics in the global sense, point to a slight continuation of milk supplies squeezing for some time yet. Global milk supplies are tracking below demand, which is why dairy commodity prices are above their historical averages.

UK farmers rue BREXIT

Britain’s dairy farmers are waking up to a new nightmare as their government turns against livestock.

By Tim Price.Some British dairy farmers thought leaving the European Union would bring freedom and prosperity; others that loss of EU markets would leave them on a limb. None expected the Conservative government to ditch its promises and adopt a radical green strategy and sign a series of trade deals that undercut their markets.

Led by Prime Minister Boris Johnson and his latest wife, new environmental campaigner Carrie, the vision for Britain’s landscape is ‘rewilding,’ creating a parklike countryside where wildlife thrives and the public can roam. Under a new support mechanism called ELMS (Environmental Land Management Schemes) farmers will be paid for a variety of activities that deliver ‘public goods’. Food production is not on the list.

As payments under the EU’s Basic Payment Scheme (BPS) are phased out over the next six years, farmers are still unsure how ELMS will work, and whether delivering them is worth the effort and masses of paperwork and inspections that goes with them.

As blame for rising methane levels continues to be laid at the livestock industry, Agriculture Minister George Eustice further alarmed farmers by suggesting a tax on meat and dairy products could be needed to curb livestock numbers.

To underline the government’s disinterest in farming a series of postBrexit trade deals have been triumphantly revealed. All offer easier access for food imports to the United Kingdom.

On January 11, the UK and New Zealand announced an agreement in principle on a free trade agreement. Widely viewed as a further indication of the UK’s desire to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for TransPacific Partnership despite being thousands of kilometres from the ocean’s shores, the deal gradually opens up the UK market to tariff-free NZ butter and cheese imports over five years.

Reacting to the announcement of the UK’s trade deal with Australia, National Farmers Union President Minette Batters summed up farmers’ bewilderment: “There appears to be extremely little in this deal to benefit British farmers. I hope that MPs will now take a good, hard look at this deal to see if it really does match up to the government’s rhetoric to support our farmers’ businesses and safeguard our high animal welfare and environmental standards. I fear they will be disappointed.”

While farmers pin their hopes on politicians waking up to the reality of growing food to feed the nation and boost

trade, the combined effects of loss of EU markets, labour shortages and production cost rises are providing a massive challenge to dairy farmers.

Loss of EU markets

Brexit has reduced trade between the EU and UK by 40% in its first year. Leaving the EU saw an end of hassle-free trade between Britain and EU neighbours. Farmers exporting milk, cheese or dairy products now face a mass of form-filling and checks. The costs, including onfarm vet inspections, have forced many exporters to abandon EU countries.

Simon Spurill, of the Cheshire Cheese Company, says: “We lost £270,000 (NZ$ 542,000) in one go. Brexit is the biggest disaster that any government has ever negotiated in the history of trade negotiations”.

His online retail business was hit immediately after the UK failed to secure a frictionless trade deal with the EU.

Simon says he lost 20% of sales overnight after discovering he needed to provide a £180 (NZ$361) health certificate on each EU export order.

He is now pursuing the domestic market with greater vigour but says the cost of marketing has gone “through the roof” because all his competitors are having to do the same.

Labour shortage

Brexit brought about the end of open borders for workers from EU countries. For years farmers had relied on workers from poorer EU countries for harvesting and dairy work. The labour shortage has seen wages double in some places and has hit farming hard with truck driver shortages disrupting milk collections.

Production Costs

Farmers across the world are being hit by higher input costs, from fertiliser, feed to machinery, but Brexit is increasing the impact. The challenges of labour availability and cost, alongside higher feed, fuel and energy bills, are likely to drive structural change in the dairy sector next year, with farms looking at robotic

milking and reducing fertiliser use to cut costs.

While many have made decent profits over the past two to three years, depending on their milk contract terms, the rapid inflation of fuel and fertiliser costs is predicted to add 2p (4c)/litre to production costs in 2022.

Current labour costs for housed herds are at about 3.5p (7c)/litre and for grazing herds at about 5p (10c)/litre.

Others have swallowed the extra costs and mastered the secrets of the reams of paperwork now required to get products through to the EU.

In the north of Scotland, Connage Farm produces delicatessen cheeses for home and export markets from the farm’s 150-strong herd.

The cows, mostly Holstein Friesian with Jersey crosses and Norwegian Reds, graze clover pastures around the dairy and along the shores of the Moray Firth.

Owned by brothers Callum and Cameron Clark and their wives Jill and Eileen, Connage has expanded its direct sales through online cheese marketing and its milk and cheese sales through vending machines.

It has built up a strong social media presence to spread the word about the dairy and is growing steadily, with a team of 13 full and part-time staff.

Unlike many UK food producers, Connage has worked hard to learn how to deal with new EU paperwork – including laboriously completing hand-written forms in different coloured inks as now required, and put in place costly vet inspections to enable it to continue exporting cheese to EU countries following Brexit.

In the short term, Britain’s dairy farmers know they will need to make better use of grass and other fodder crops, control labour costs and avoid over-borrowing to stay in business longterm despite higher input costs. Despite continuing bad press and the huge impact of Covid-19, dairy product consumption has risen slightly, giving hope for the future for the industry.

Taking the big leap

Flo and Jen Coetzee are finally catching their breath after a whirlwind couple of years that saw them go from contract milking 1000 cows to variable order sharemilking for a season and then take the big leap to equity management in an 1100-cow farming operation they now call home.

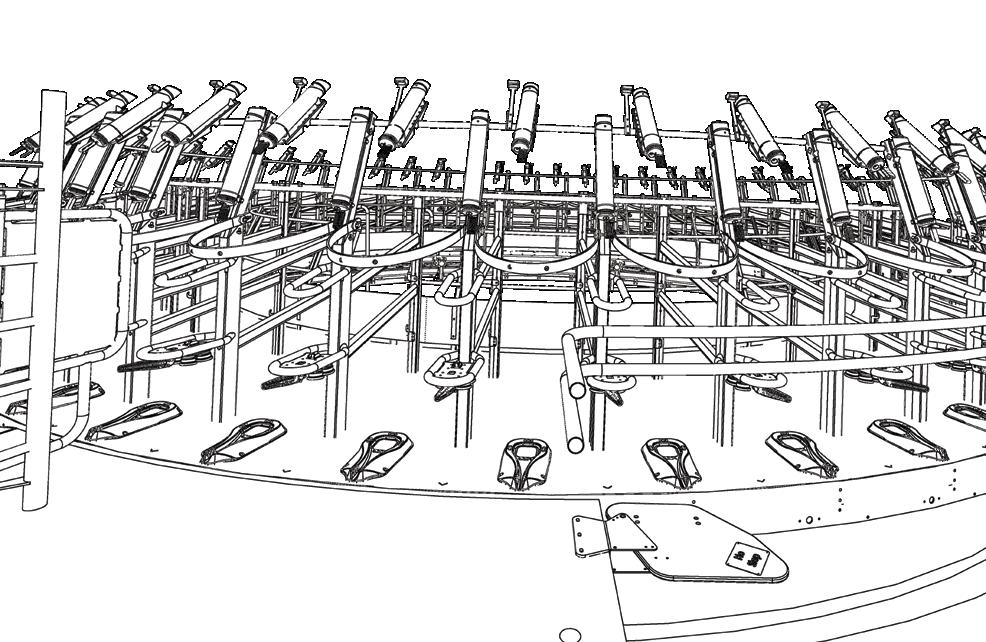

Near Methven, the irrigated 320-hectare milking platform includes 100ha of lease land, a 54-bail rotary farm dairy with Westfalia plant and automated drafting.

Eight months in and the couple say it really does feel like home.

Their equity partners in the company have made sure of that.

The farming business is called Highveld Pastures Ltd, and shareholders are Waterton Agricultural (Glenn Jones and Sarah Brett, featured in Dairy Exporter August 2021), Camden Group and personal investments from several Camden Group shareholders and staff.

“As smaller shareholders in an equity partnership you get warned by everyone when you’re going into it,” Jen says.

“But we’ve all gone into this knowing what each other wants and knowing we want to grow,” Flo says.

That’s meant an increased voice for Flo on farm operational decisions and direction and first option for the couple to purchase 50% of any shares other shareholders put up for sale.

“We actually feel very safe in this partnership, with these people around us because for years it’s been just us two, on our

Farm facts

Farmer Owner: Highveld Pastures equity partnership

Location: Methven

Area: 220ha owned and 100ha

leased

Farm dairy: 54-bail rotary Cows: 1100 Friesian cross and Kiwi

cross

Production: 430kg MS/cow

Supplement: 200kg/cow grain

Milking frequency: Three times in two days

Irrigation: centre pivots, sprinklers, linear spray

A shift to the South Island, contract milking, has led a couple to an equity management role, with the prospect of growing ownership. Anne Lee reports.Left: Flo and Jen Coetzee. Photos by Holly Lee.

own making decisions, dealing with the bank or suppliers,” Jen says.

Neither Flo nor Jen have family in farming and say they’re not really the sort of people who like to rattle anyone’s cage.

“We’re both quite passive by nature and I guess if we look back knowing what we do now we might have been more assertive when we were dealing with banks and suppliers and people like that.”

Flo is originally from South Africa and came to New Zealand in 2003 on a working holiday. He worked on dairy farms in the North Island and met Jen who is involved in medical research and sets up clinical trials. She works with district health boards and drug companies, negotiates contracts and budgets, and carries out the Medsafe and ethics approval processes.

“My Dad grew up on a dairy farm in South Taranaki but he didn’t become a dairy farmer himself,” she says.

In 2013 they decided a shift to the South Island would help move their dairying career along. Canterbury provided the larger herd sizes they were after and for Jen it meant they could be near a major airport so she could continue her work.

Their first season was managing 1000 cows for Dairy Holdings Limited (DHL) which was in itself a big jump from the 500-cow jobs Flo had been used to.

But the next step was even bigger.

“Going contract milking the next season was a massive learning curve,” Flo says.

Not only was he still coming to grips

with managing irrigation and a large herd, the shift to contract milking also meant employing staff and running their own financials.

“It was a whole new world as a contract milker – employing staff was probably the biggest learning curve,” Flo says.

Being the boss was probably the hardest step for him. It took him a while before he was confident in dealing with tricky people situations at work.

“It’s something I’ve got a lot better at over the years. I don’t like conflict but I’ve got a bit firmer and it’s about good communication really,” he says.

A lot of issues could be headed off right at the recruitment stage, the couple says.

“Unless I’m looking for someone to fill a role like 2IC, I’m going to employ people on their attitude and their fit with the team.

“I can teach them what they need to know but you can’t teach them how to get on with people or attitude – not easily.

“We often recruit people through our existing staff,” he says.

“At the start it was harder because we didn’t really know what our rights were as employers or the processes you should go through when people weren’t working out.

“We’re more confident in that now,” Jen says.

Having employment contracts for staff, deciding what payroll system to use, what accountancy package - they were all new too.

“From a business perspective the

paperwork was overwhelming to start with when you didn’t really know what you were doing – there was payroll every two weeks, monthly bill payments, coding invoices and paying GST.

“When we first started there wasn’t a system that imported your bank transactions, it was all a lot more manual.

“But the more you did it the easier all of that got,” Jen says.

Their advice to anyone starting out is to get help to start with.

Most online systems now have help desks where they can log into your computer and see your screen and that’s an enormous help, she says.

“We’ve used four different payroll systems over the years – I really loved PaySauce because it worked well with a dairy farm business where it’s not Monday to Friday.

“We’re using Smartly now because we run our payroll through Camden and that works well too. We’re also using Figured and Xero now with Camden, running our accounts through their office so I don’t have to spend as much time on the admin side anymore.”

Jen says they used Farm Focus – formerly Cash Manager, when they were doing their own accounts because it worked well for their farming business and quickly helped them see how they were tracking to budget.

Your accountant and other rural professionals can log into it to make sharing information easier too.

‘Unless I’ m looking for someone to fill a role like 2IC, I’ m going to employ people on their attitude and their fit with the team.’Right: Flo Coetzee, left and Gill - Satveer Singh. Left: Tarun Bagga, left and Prabesh Thapa.

“I think that’s something you don’t realise at the start – just how important a good accountant can be.

“They see hundreds of accounts and they can quickly see if a cost area is a bit high or pick up on something you haven’t noticed.

“When you’re looking at jobs and going through a budget for a contract, they’re really valuable,” Flo says.

The couple say they use their accountant for advice not just to process their accounts each year.

They say it’s important you have an accountant you feel comfortable doing that with, someone who makes themselves available and is prepared to take a good look at your situation and give you advice.

Bankers, too, should be part of the team but they’ve often found that without family connections and movement of bank staff it wasn’t easy to build that relationship.

When they started out contract milking they were able to get a loan of $150,000 to get the gear they needed.

They paid that back quickly and then each year took out another loan to buy stock – again each year paying debt right down.

They were disciplined with spending but also took a friend’s advice when they started out - “Don’t let it run you into the ground.

“So, we always made sure we had a break each year and we saved up and took holidays,” Jen says.

After six years they had 320 cows leased back into the herd and they decided it was time to have a crack at 50/50 sharemilking.

“That had always been our goal – we’d had a go at it a little earlier but we couldn’t get the finance and, in the end, it was lucky because that next season the payout crashed to $3.90/kg milksolids (MS).”

Flo says they gave notice in October 2019 they were leaving their contract milking job but then it was much tougher than they thought to find a 50/50 sharemilking job.

“We kept getting down to the last two or three at interviews or they’d want us to buy the cows on the farm so we’d have to sell ours to get the finance sorted and we were struggling to find buyers at the right price because it was getting late.

“It was pretty stressful and, in the end, we took a job variable order sharemilking and leased the cows out but then we went into lockdown so it made getting things sorted a bit harder.”

The pair say that while they had goals, they hadn’t written them down in a formal way and when they couldn’t make the 50/50 sharemilking step that probably contributed to them feeling a bit lost in where they were heading.

But then, their friends Glenn and Sarah started talking with them about equity management as part of plans they were trying to pull together.

“In the end that all came together really quickly and here we are,” she says.

“We did our due diligence and we were

sure that if we were going to do this, these were the right people to be doing it with.”

The equity partnership has brought a whole new level of learning in terms of business structure and governance.

“We never really had a mentor as such but this feels like that now,” Flo says.

They’ve been watching and learning with farm business and board meetings structured with agendas and notes taken.

“We have the same mindset and values,” he says.

It’s been a tricky season to start the venture on but they’ve been realistic with budgets.

They’ve used a three in two milking schedule, due in part to long walks for cows and for the people side of the business.

It’s worked well and cows are on track to produce about 430kg MS/cow with about 200kg/cow of grain.

“We’ve made a fair bit of silage so we’ll look at our stocking rate for next season.

“We treat it like it’s our own but we’re not alone – we’ve got a great team to be in business with and that’s a good feeling.”

Get it all in writing

No matter how well you know them or how great you think it is that someone’s giving you an opportunity – never go into a contract milking agreement on a handshake, warns Jon Jarman, chartered accountant and director of Leech and Partners in Christchurch.

“For some there’s a temptation to think - well this person is giving me an opportunity so I won’t push them too much on the detail. They get caught up and think it’ll be okay in the end – well, often it’s not.

“You can get burned badly.

“You must have a legal agreement and have the detail down on paper in a formal contract.

“You can use your accountant or rural professional as the bad cop if you like – tell your farm owner that they won’t sign anything off unless there’s a proper contract with all the details.”

In setting up your budget to calculate what the contract rate will provide, he says wages are likely to be the biggest cost “by a country mile”.

“So, understand the staffing requirements – the number needed and the salary bands.

“Then sit down and do a draft roster, will you have a 2IC, how many dairy assistants will you need?”

Do a draft roster for each seasonal period and work out what the wages bill is likely to be for each pay period over those different seasonal times so you can work out what your cash flow needs will be.

Unless the agreement offers contract payments through the winter months, you’ll have to meet the wages bill from savings or overdraft.

Ask for records for shed running costs and production history and get right into the detail of other costs.

Understand the policy on supplementary feed and the effect of lower nitrogen inputs on production and seasonal production variability. Have good insurance cover - look at income/profit protection, key man insurance, talk with a broker who understands the risks in farming.

It’s easy to get burned with a handshake arrangement. Set up a formal contract, Anne Lee writes.

If it’s your first year it will be difficult to prove income.

“Look into using ACC’s CoverPlus Extra (CPX) – you can nominate the amount of income you want to be covered for if you can’t work so it’s a set amount and doesn’t fluctuate with your annual income.”

Tax is the cost people forget about.

It can be almost two years before the tax from your first season contract milking has to be paid given you don’t have to file a return until 12 months from the end of the season and you then have until April 7 the following year to pay the tax owing.

“The problem is people think great, I have all this money in the bank but they’ll also have to start paying provisional tax for the coming year as well as their tax from the previous season.

“Talk to your accountant early on about tax and how much it might be and think about setting up a tax account so you can start putting money into it.

“You’ll pay roughly 30% of your profit as tax and in a good year that can be a significant amount.

“If you’re not a good saver and know you’ll be tempted to dip into that tax account, then make voluntary payments to the IRD monthly as you go.”

Some accounting software will include a tax calculation so you can see your tax position as you go.

“Do your budgeting and financial work in the morning, not late at night after everything else. The best budgets are done at 10am not 10pm.

“If you’re doing them the night before you go and see the bank, there will be holes in it – you won’t have had time to think about it.

“Your accountant should be someone you feel comfortable to pick up the phone and ask questions, not just someone you see once a year when you pick up your accounts.

“Likewise, it doesn’t work only telling the bank manager as much as you have to – put them on your team and make sure they understand what you’re doing and what you’re trying to achieve.

“Work with them early on and keep them in the loop.”

Business structures for contract milkers

There are three main business structures –partnership, sole trader and company.

Each has its own benefits depending on your situation and each has its pitfalls. A company structure is the most common.

Partnership

“Jointly and severally liable” - so if one partner runs up a debt the other is liable for the full amount, not just their own share of it.

It’s quick and easy to set up but the downside is the liability. There are also tax advantages in the ability to split the profit between the partners.

Sole trader

If you’re a sole operator this is a good structure because it’s quick and easy to set up with minimal paperwork required.

The downside is you’re the only person liable for the debt rather than any other entity – so if you have debts all of your assets are up for grabs. Tax is calculated on your personal tax rate, so the tax rate could be high with good earnings.

Company

The most common structure, a company is a separate legal entity to you personally so if things don’t go well the debt is limited to the company assets and not your personal assets. However, a bank may want a personal guarantee which would override this.

This limited liability also doesn’t extend to health and safety or wages – you personally must pay if the company can’t.

The company pays tax rather than the individual which gives you more flexibility –profits can stay in the company or be allocated out to shareholders in recognition of the work they undertake for the company.

It costs approximately $500 to set it up and there are increased compliance costs due to a few extra hoops for preparing accounts, so ongoing costs will be higher.

Also, be aware that directors of a company have serious responsibilities, particularly in terms of health and safety so if you’re a director make sure you’re aware of how the business is being run. If you aren’t actively involved in the business – for instance working off-farm and don’t have an influence on policies or actions relating to health and safety, don’t be a director.

Chartered accountant Jon Jarman, Leech and Partners in Christchurch.

Chartered accountant Jon Jarman, Leech and Partners in Christchurch.

‘Do your budgeting and financial work in the morning, not late at night after everything else. The best budgets are done at 10am, not 10pm.’

both parties

Words by: Anne LeeIf washing your hands of staffing issues is your key motivation for taking on a contract milker then you probably shouldn’t do it, FARMit Accountants director Brett Bennett warns.

Employing a contract milker requires effort and care in setting up the system so it works for both parties.

It’s not simply a farm manager minus the staff employment, Brett says.

“It will cost you more to run your farm business because the contract milker is taking on a level of risk and additional responsibilities and they need to be rewarded for that.

“So, it can be financially more expensive but it comes down to how you value your own time – the time you get back as a result, what does it allow you to do?

“A good contract milker may also add more value so shouldn’t always be looked at as being more expensive.”

While it may mean many of the responsibilities of employing staff are handed over, there are some responsibilities you can’t contract out of.

“Health and safety for one – as the farm owner there’s still a legal responsibility to ensure the farm is safe for people to work on, that any hazards are identified and any infrastructure issues are dealt with.”

Minimum staff numbers should be stipulated in the contract – not only to

ensure the farm is run well but to ensure hours worked or burnout don’t become a health and safety issue in themselves.

“That’s a minimum requirement and really you have to remember that even though the staff are being employed by someone else they’re still there working on your farm, milking your cows.

“You want to be supporting your contract milker, especially if they’re in their first season and being an employer is new to them.”

Wages and fuel have had the biggest cost increases over the last year and are both costs born by contract milkers so it’s important the budgets drawn up to calculate contract rates are adjusted accordingly.

Brett says when working with potential contract milkers it’s important to give them accurate and up-to-date budgets.

“You want to give them evidence of real costs – we’ve had to go back to a couple of farmers and say actually we need to review the contract rate because specific costs have gone up over time and the farm owner hasn’t looked at that detail for a while.

“I think farm owners understand there has to be something in it for the contract milker, in terms of margin over costs and what they could earn as a farm manager – to reward them for the additional risk they’re taking.

“I have seen contract milkers with contract rates that mean it’s just a wasted season –they’ve pretty much made nothing.”

“So, you need to give them evidence of those real costs and evidence of production and a realistic expectation of budgeted production.”

Contracts must work for

‘A contractgood milker may also add more value so shouldn’t always be looked at as being more expensive. ’

Work through the what if scenarios when discussing the contract so everyone’s clear on what will happen given different situations such as drought.

A well-documented, formal farm plan is a must so the contract milker is clear on the owner’s expectations on how the farm should be run and what the targets are for the season.

They need to understand your health and safety plan and how their plan dovetails into yours and they need to understand their responsibilities within your farm environment plan.

Brett says contract milkers should never sign the contract until it’s been reviewed –preferably by a rural professional who has a good understanding of farm budgets and contracts.

“There have been a lot of changes to legislation and compliance and that has to be factored into the contract.

“We’d want to see the costs are realistic

Ripcord

Insecticide

and go through the detail to make sure there’s enough money dropping out of it to be worth it.”

Brett says his company has put together a booklet for farm managers who are looking at moving to contract milking.

“There are plenty of managers out there breaking their necks to become contract milkers but they’re not fully aware of all that entails and what they need to know.

“One of the biggest things is improving their financial literacy and ensuring they have financial acumen.

“They’ve got to understand PAYE, GST and ACC for instance.”

He uses a three-stage process to bring people up to speed so they aren’t overwhelmed at the outset.

Having good online systems for accounting and paying staff that their rural professionals can have visibility into means they can get help quickly.

“The aim is to help them grow their own

Don’t let flies take away all your hard work

Rip into nuisance ies, lice and ticks with the proven power of Ripcord®. Just one easy application provides long lasting protection from nasties around the herd and in the milking shed. And because Ripcord is MPI approved for use in dairy sheds, there is no milk withholding period. Ripcord is the perfect product to use. Don’t settle for fly-by-night treatments. Insist on Ripcord. Visit pest-control.basf.co.nz for more details or visit your local distributor.

financial acumen and build those skills quickly because that enables a better understanding of their business, helps cost control and empowers them,” he says.

“We help them get their heads around using a cashflow planning tool so they can see where costs come in and how to manage that with their income flow.

“We also want them to have a personal spending budget and a cashflow for that too.”

It’s important at the outset to ensure expectations are understood between contract milker and farm owner, he says.

• “Be clear about the farm plan.

• “Be clear about the contract.

• “Be clear about what’s on offer.

• “Be clear about your vision.” Communicate well throughout the season both with the farm owner and with rural professionals – make them part of your team, he says.

Be clear about the farm plan. Be clear about the contract. Be clear about what’s on offer. Be clear about your vision.

surethere’s enough money dropping out of it to be worth it.”

Staying in the business

Having accurate data on what it costs to run the farm is a must for contract milking agreements, Dairy Holdings Ltd (DHL) chief operating officer Blair Robinson says.

The company runs 75% of its 60 dairy farms under contract milking agreements which offer higher contract milking rates and opportunities to rear stock, along with a bonus if payout surpasses a set threshold and a guaranteed minimum return in the contract but also include a share of a wider range of costs than typical.

“Contract milking provides a pathway for progression – we have a small number of farms with a farm manager and contract milking allows managers and good 2ICs across any of our farms a step up.

“It means we can keep people in our business longer as they develop.

“We have sharemilked farms that range from sharemilkers owning 51% of cows right up to 100%.

“Structuring the contract milking agreement the way we do gives people an opportunity to stay in the business and go all the way from dairy assistant to 2IC or farm manager to contract milker and on to sharemilker without having to leave.”

In some cases that progression can happen all on the same farm.

“People get to put down roots and stay in a community which is great for families – people with kids at school.

“But it’s also good for us because over that time they build their skills and know the farm well and that’s good for farm performance too.”

DHL’s contract milking agreement sees contract milkers pay the usual farm dairy running costs such as electricity, chemical and rubberware along with supplying motorbikes and feedout gear including the tractor and paying for fuel. They also pay 20% of bought-in supplement cost, 20% of mixed-age cow wintering, 20% of irrigation electricity and up until next season

Well-structured contracts allow people to progress through the business and put down roots. Anne Lee reports.

‘We base our expectations of those costs on a lot of data so we have a high degree of confidence that what we pay them will cover it.’

20% of urea and spreading costs. Blair says the contract rate is set so it covers those costs but it’s not just a matter of giving with one hand and taking with the other.

“It’s aimed at driving behaviours and efficiency.

“We base our expectations of those costs on a lot of data so we have a high degree of confidence that what we pay them will cover it.

“If they can come in under that then that’s a win for them.