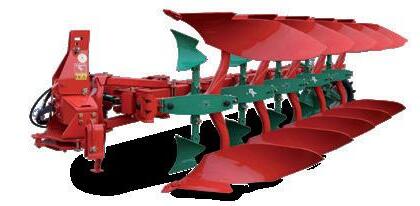

Our key reason for being in business is to help you grow. Both in respect to helping you improve the land you farm through technological and innovative techniques, also about helping you improve your bottom line and growing your business.

This is done by our people, without the experience, training and skill of our nationwide team we would be nothing. Our biggest investment in our organisation is in ensuring our people are operating at the best they can be.

Whether it is the specialists that back up our retail teams with technical product knowledge or our training for our service technicians, we believe our team makes us different from anyone else in the country. We pride ourselves on our service and we’re passionate about what we do. We have the benefit of local knowledge combined with a group knowledge that is second to none in New Zealand. We are a fully independent family owned group of companies with a three-generation 75-year history of serving the agricultural, construction, municipal and civil sector. Now with over 308 staff across 17 dealerships and

affiliated with another three independent dealers we’re proud to provide a full range of services for all your tractor, telehander, feed mixer, grass and cultivation machinery requirements.

We import the finest state of the art technology available in the world and back it through our dealership network. Our experienced national technical support team work alongside over 100 extensively trained technicians to ensure the diverse range of machinery used throughout New Zealand is consistently operating in optimum condition. With $20m worth of parts in stock, overnight

delivery available to most of New Zealand and nationwide integrated I.T. solutions, we make sure your gear continues to work as hard as you do. As a 100% kiwi owned and operated company we are committed to investing back into New Zealand throughout 2020 and into the future. Contact one of our dealerships near you to find out what it feels like to be part of the Power Farming team and enjoy the difference that we believe this will make to your business.

Page 79

YOUNG COUNTRY

79 Farm workers: Filling the gap

WELLBEING

82 Grieving: Don’t forget about me…

RESEARCH WRAP

84 Nitrogen: Following the isotopes

DAIRY 101

86 Clover: Pasture’s nitrogen fixer

SOLUTIONS

88 Tech talk with cows

89 Beef farmer a winner

OUR STORY

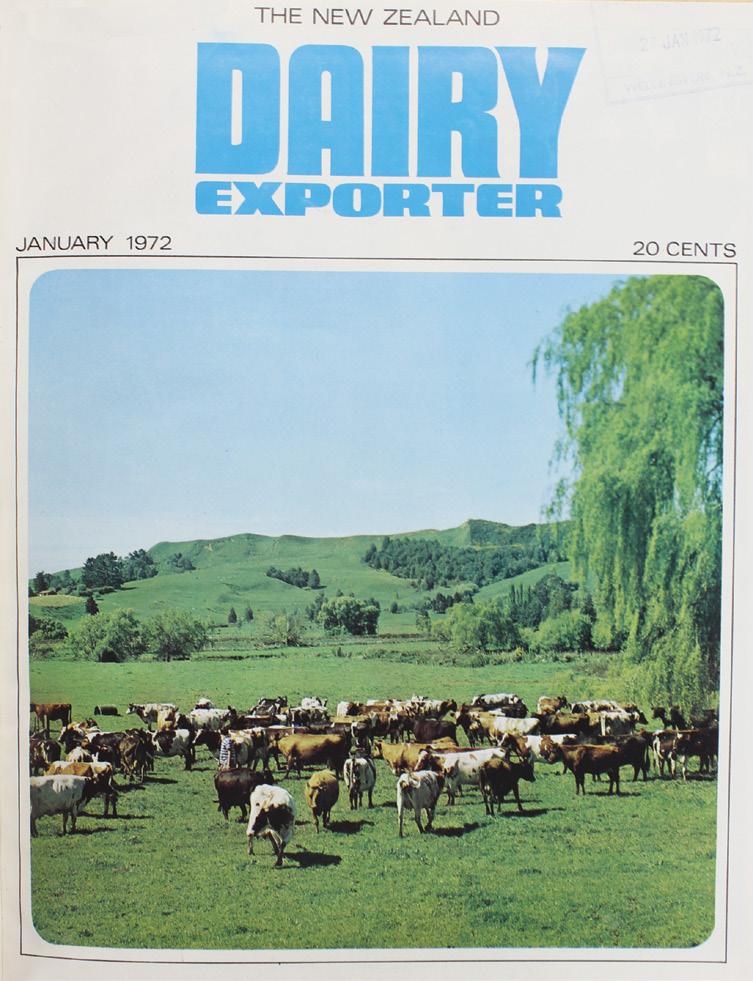

90 50 years ago in the NZ Dairy Exporter

STOCK

74 Vet Voice: A lesson in stripping

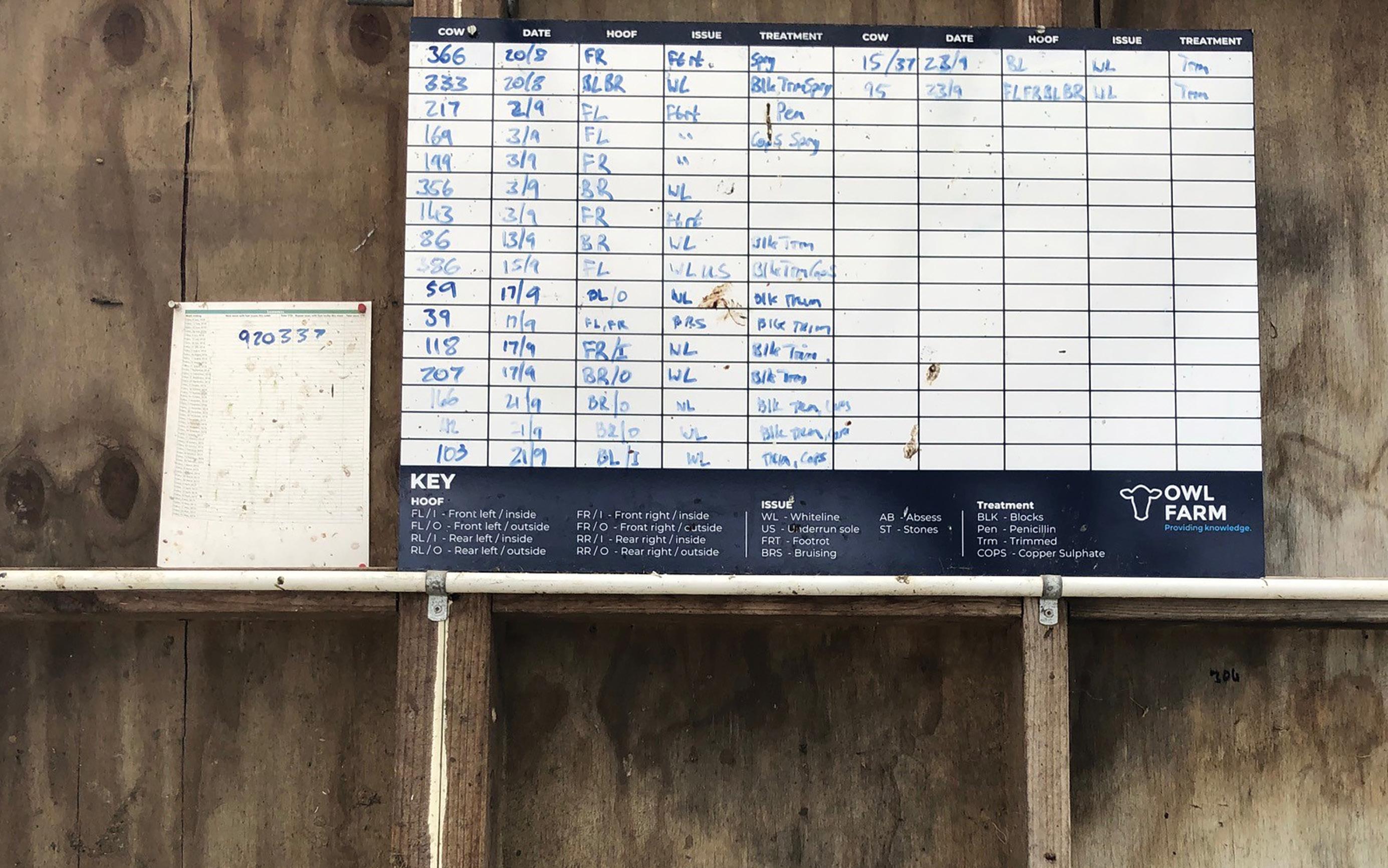

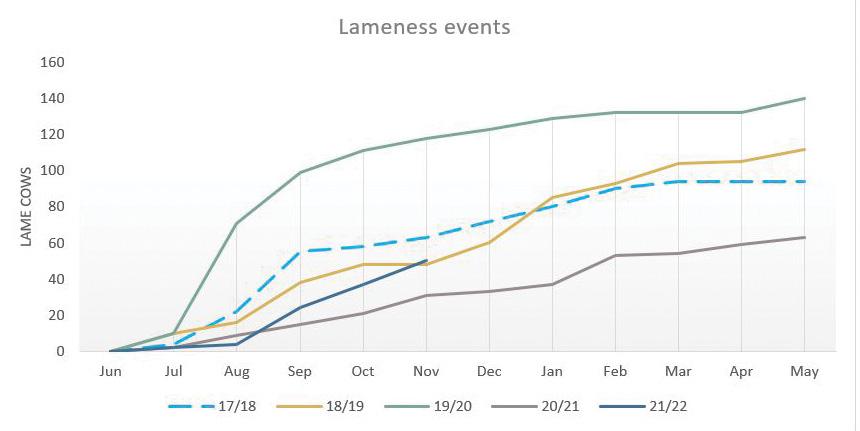

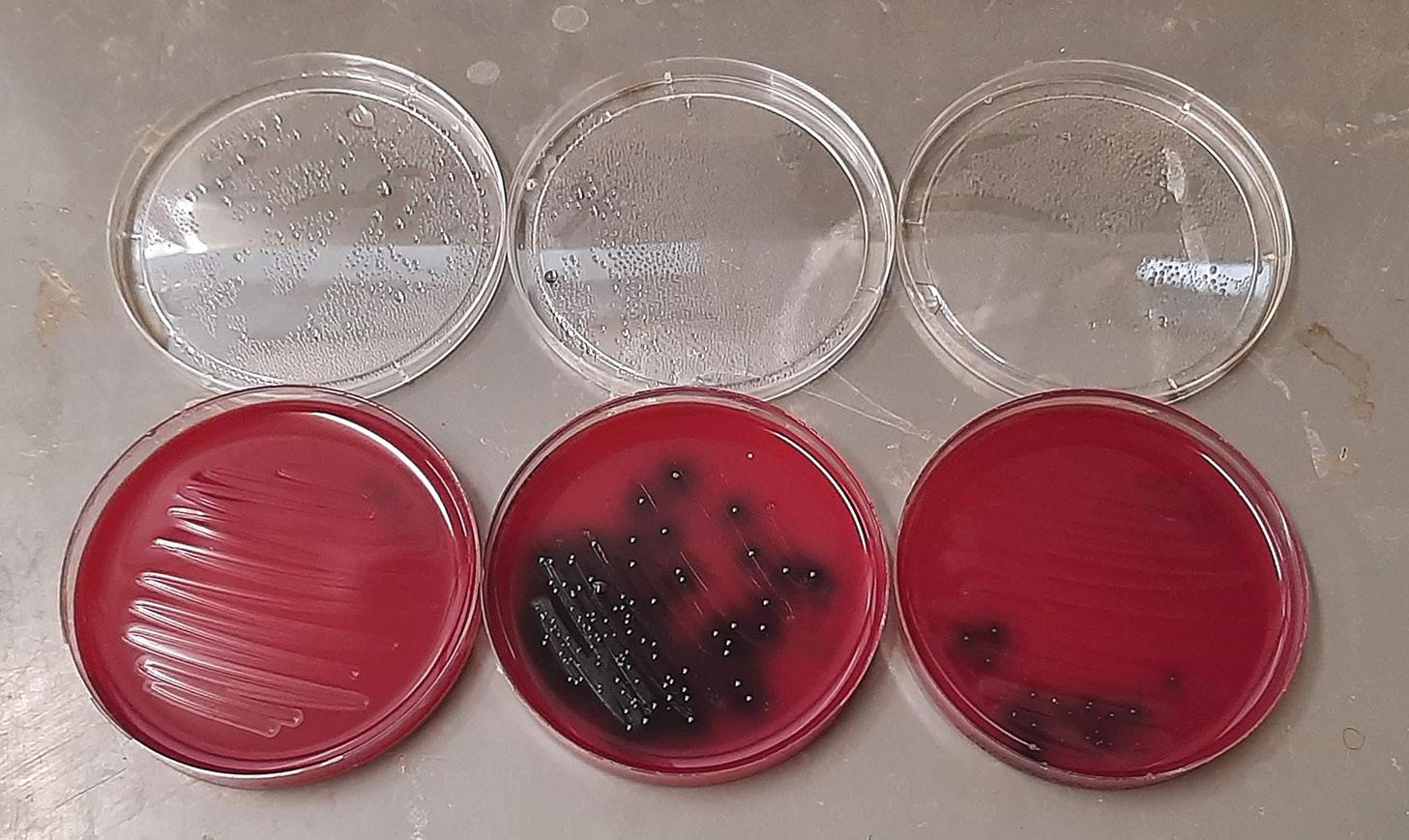

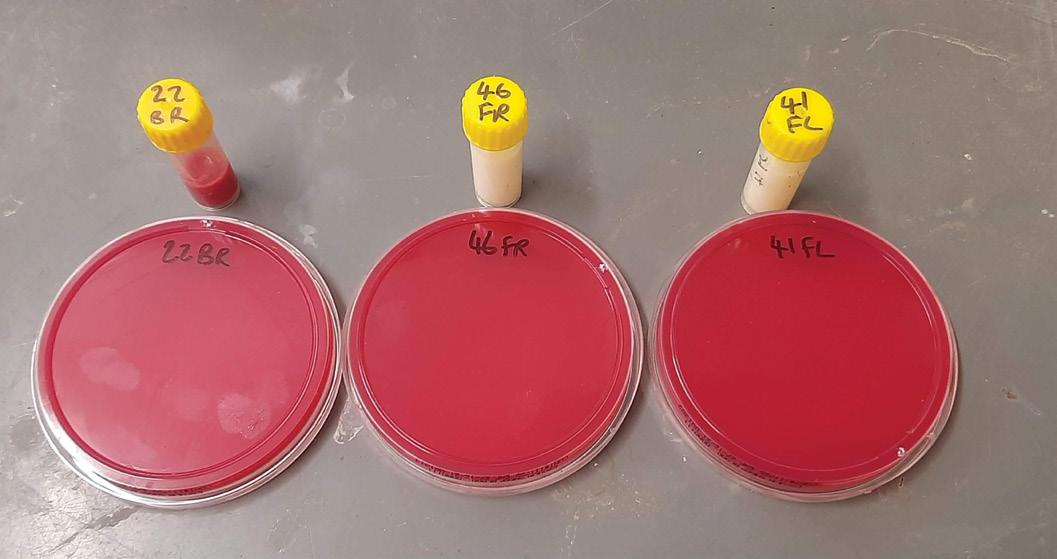

76 Tackling lameness on Owl Farm

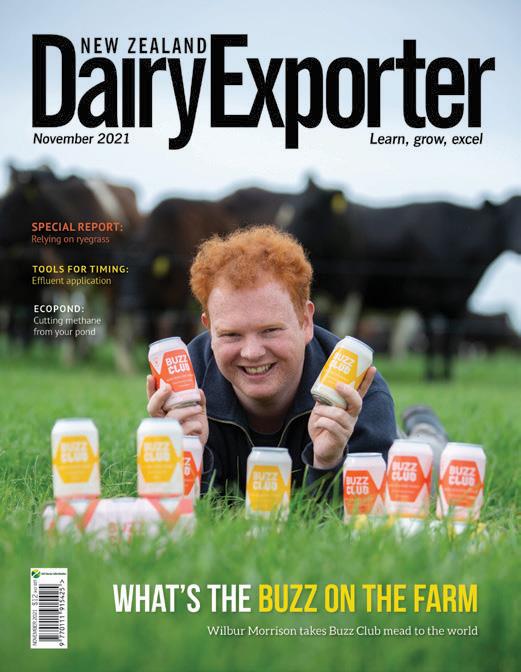

OUR COVER

Alan Gibson from Tauranga is the talented photographer who took the photos at Gavin Fisher’s organic dairy farm at Te Aroha.

Page 63

Hamilton will feature discussions about alternative ways of using Farmax to advance New Zealand farm systems. Well-known speakers and a scientist panel combine with Farmax workshops. To view the programme and to register go to www.conference2021. farmax.co.nz.

programme and to register, visit digitalag. events/digitalag-2022-programme-is-outregistrations-open. It will also be streamed online.

January 25-27 – New Zealand Dairy Event is held at Manfeild Agri-Centre, Feilding. It includes the annual sale on January 26 which will feature the pick of the herd from the famous Thurvalley Brown Swiss Stud where Tony Buehler and family offer the opportunity to pick your favourite cow, heifer or calf from the herd. Visit www.facebook. com/nzdairyevent.

February 9-11 – The 34th annual Farmed Landscapes Research Centre (FLRC) workshop at Massey University. More at www.massey.ac.nz/~flrc/workshops.html.

February 16-17 – National Freshwater Conference explores the Essential Freshwater Package, Resource Management and the Three Waters Reform. Find out more at www.brightstar.co.nz/events/nationalfreshwater-conference-0.

March 10 – Quorum Sense is running a bale grazing and regenerative agriculture field day near Wendonside in Southland. For details visit www.quorumsense.org.nz/ events.

March 17-19 – Central Districts Field Days in Feilding has been held for the past 28 years. To find out more visit www.cdfielddays.co.nz.

March 17 - Owl Farm plans a focus day on the Cambridge demonstration farm. To get more details about the farm and the latest farm data, visit www.owlfarm.nz.

March 30-31 – DigitalAg is the rebranded MobileTECH Ag and will take place in Rotorua for the 2022 event. It will showcase new agritech developments

March 31 – Entries close for the New Zealand Dairy Industry Awards including New Zealand Share Farmer of the Year, New Zealand Dairy Manager of the Year and New Zealand Trainee of the Year. Some changes have been made to the awards including an age range for trainees and no minimum time in New Zealand for the dairy manager category. The format for judging has also changed slightly. To find out more and to enter, visit www.dairyindustryawards.co.nz.

March 31 – Entries close for the Fonterra Responsible Dairying Award which recognises farmers who are demonstrating leadership in their approach to responsible dairying, have proven results and are respected by their farming peers and their community. For more about the award and to enter go to www.dairyindustryawards. co.nz/responsible-dairying-award.

Please check websites to see if events are going ahead at changing Covid Alert Levels.

Sprogramme run by Reporoa dairy farmer and cancer survivor Sarah Martelli, who helps other women find their balance and build strength and wellbeing to be the best they can be.

Strong Woman is an online community for women to work on their fitness with a workout to do at home, find quick and easy healthy recipes, goal planners and to connect with other women on the same journey.

Her philosophy is to help women create healthy, sustainable habits around moving and feeding their bodies and their families.

If women can prioritise their own health and fitness, they can inspire their partners, their children and their community around them, Sarah says (p82).

She is an inspirational woman creating a moment of lift for many women.

In this issue we take a look at the regenerative agri journey some NZ farmers are already on, and that the government has signalled they want others to join in on, in our Special Report.

(p42). We also cover the Heald family of (p52) who have transitioned to organics, philosophies and are enjoying the less intensive more resilient system they have moved to, improved profitability.

There is more research to be done in the system context, says MPI’s chief scientist figure out what will and won’t work, but farmers to engage and learn more, and to regenerative as a verb - saying all farmers be more regenerative, more resilient, lowering and building carbon storage.

So here we are at the start of another year…full of hope.

The regen debate has divided the farming community in a big way - many scientists are affronted that NZ would need regenerative methods from overseas countries with highly degraded soils - would that then infer that our conventional methods were degenerative?

Will it be another Covid-induced groundhog year? Or will this be the one where we actually come out of the other side of the pandemic and move into the new normal?

I can’t see us ever going back to the pre-pandemic days of jumping on planes and travelling the world without a mask or scanning device in sight, but it would be nice to at least carefully kick-start the tourism industry and have the odd overseas holiday.

equity growth of $97,000/year over the past three years - which they compute is equal to an annual salary of $245,000 in a town job.

If you are interested in getting into farm getting out but retaining an interest, read Moss’ innovative idea for a speed-dating potential partners (p11). We think it could

Not many couples in town jobs would have that level of combined income, nor would they be saving that much over and above their expenses, (pg 52) so we can confirm the dairy industry is still full of opportunities for growing great businesses.

They say the methods won't work, and that research has already shown that, and also our farmers are already following regenerative practices. Others say that the methods are not prescribed and each farmer can take out of it what they want. It has been called a social movement rather than a science and the claimed benefits of improved soil and stock health and building soil carbon through diverse species, use of biological fertilisers and laxer and less frequent grazing practices along with less nitrogen is something that resounds emotionally with many.

Top tips from five sharemilking couples drill down into their combined experience and wisdom which are mandatory reading for anyone embarking on the contract milking journey.

We have taken a snapshot of thinking by scientists in MPI and DairyNZ (p46) and portrayed what farmers using the practices are finding, including ongoing coverage of the comparative trial work by Align Group in Canterbury

This year 2022 will have some hard stuff for dairy farmers - the finalisation of He Waka Eke Noa or moving into the ETS will not be easy or palatable, but at least it is coming at a time when the payout for dairy solids could potentially be at an all-time high.

Because of the high payout and scarcity of good dairy workers, wages are likely to keep going up, which is a good thing for the workers, not so much for farm owners. Other costs are also under huge inflationary pressure and as always cost control and monitoring the budget are important.

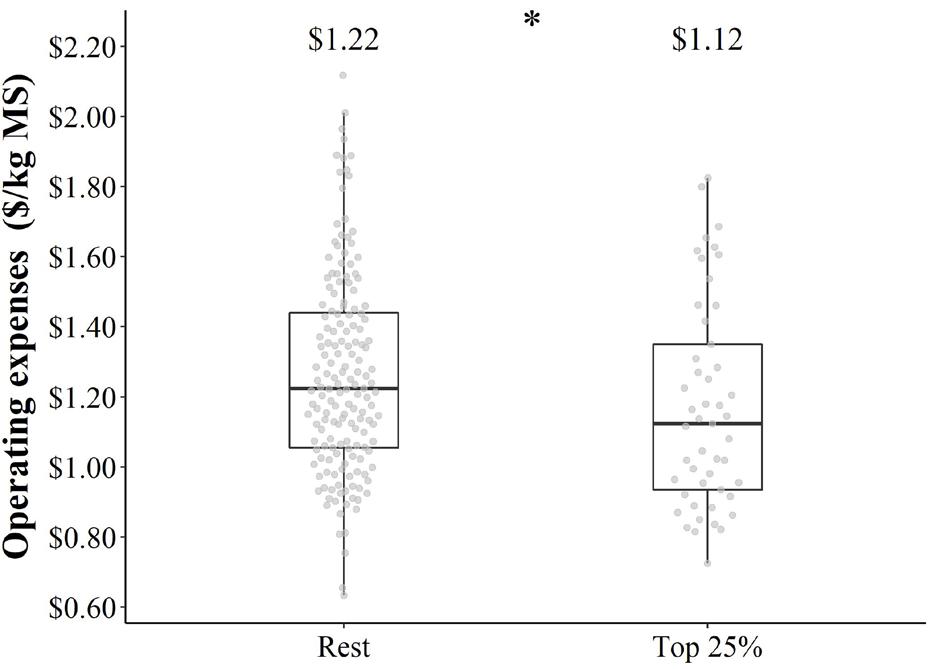

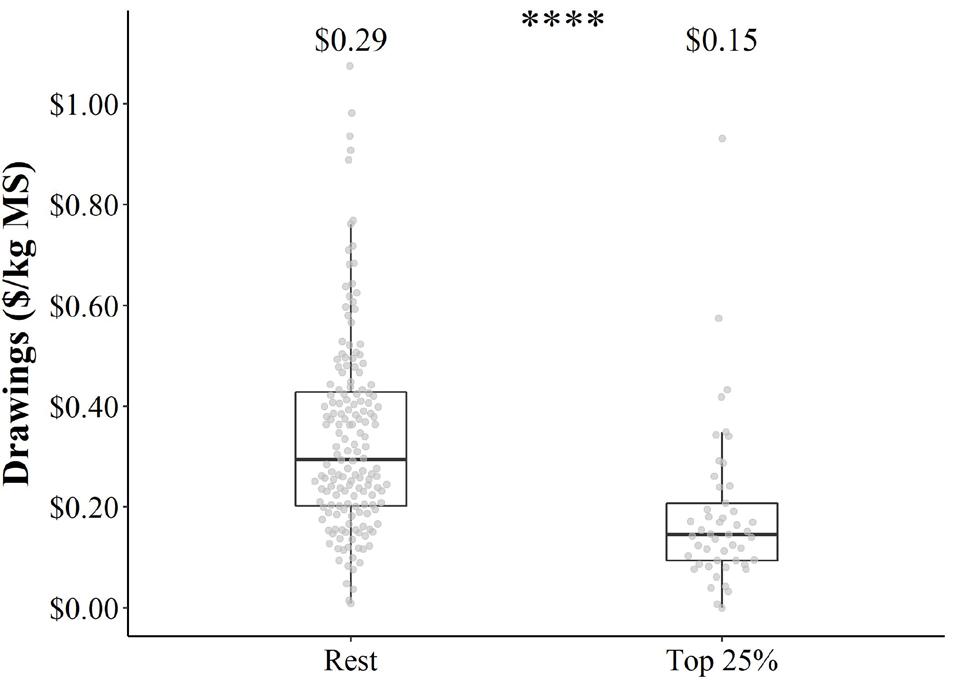

In our special report on contract milking, it’s great to read about the fantastic growth in equity some contract milkers are achieving, with a mix of good production, controlling operating costs and running a successful contract milking business.

We profile a couple of very successful contract milkers and talk to DairyNZ experts. Their recent analysis of contract milkers’ financial records show the top 25% of contract milkers can save up to 30% of their income to grow their equity, with an average

As always, communication is highlighted as a very important skill - in each contract milkers’ new role of managing staff and also for managing the relationship between themselves and their farm owner. (Pg 57)

Owl Farm in the Waikato has managed to overcome their growing lameness problem, using data, systems and new processes and results are good for the cows and the bottom line (pg 76).

And a group of young people in South Waikato have banded together to form an innovative and very diversely experienced company providing relief and casual workers for the farming industry - resulting in wellpaid, interesting and satisfying roles for them. Sounds like a lot of fun. (pg79)

JULY 2021 ISSUE

• Farming/business investment – if you are starting out or bowing out.

•

•

• Sheep milking conference coverage

In the next issue:

February 2022

• Reboot your soil, reboot your life in Rerewhakaaitu

• Contract milking part 2

• What’s really happening in the United Kingdom dairy industry?

New Zealand Dairy Exporter’s online presence is an added dimension to your magazine. Through digital media, we share a selection of stories and photographs from the magazine. Here we share a selection of just some of what you can enjoy. Read more at www.nzfarmlife.co.nz

REGEN VS. CONVENTIONAL FERTILISER

We are tracking the comparative trials at Align Farms in Canterbury, this month taking a look at the fertiliser programmes. www.youtube.com/ watch?v=zoenATHDmyk

NZ Dairy Exporter is published by NZ Farm Life Media PO Box 218, Feilding 4740, Toll free 0800 224 782, www.nzfarmlife.co.nz

Editor Jackie Harrigan P: 06 280 3165, M: 027 359 7781 jackie.harrigan@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Deputy Editor Sheryl Haitana M: 021 239 1633 sheryl.haitana@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Sub-editor:

Andy Maciver, P: 06 280 3166 andy.maciver@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Reporters

Anne Hardie, P: 027 540 3635 verbatim@xtra.co.nz

Andrew Barlass and family are committed to ryegrass on their two Canterbury diary properties - he is trying out alternative forage mixes as well, but says that ryegass is the kingpin and the other species will be grazed in a way that is not at the expense of the ryegrass.

Take a look at our story: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=fLfhOACjd-U

Factum Agri is dedicated to New Zealand’s primary industry, working with the Rural Support Trust. Each week Angus Kebbell talks with farmers, industry professionals and policy makers to hear their stories and expert opinions on matters relevant to both our rural and urban communities.

Sinead Lehy

Interview with Sinead Lehy, principal agricultural science adviser at the New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre.

Emma Taylor

Interview with Emma Taylor, general manager of Vineyard Plants in the Hawke’s Bay about viticulture. The company supplies vines, predominantly sauvignon blanc, to the New Zealand wine industry.

Fiona Bush

Interview with North Canterbury sheep and beef farmer, Fiona Bush. Fiona is giving her perspective on MPI’s Primary Industry Advisory Services available to the rural sector as well as the key issues farmers face today such as the environment and the rural/urban divide.

Find these episodes and more at: buzzsprout.com/956197

Maatua Hou. A bobby calf rearing venture with a twist - four young couples have set up an equity partnership, bought a 34ha block and created a venture where the farmers supplying the calves also pay. The farmers are guaranteed to get their money back when the calf is sold along with a share in any profit. Could this be a way to help reduce bobbies? Is there another way we could be rearing beef in this country?

Take a look at our story: ww.youtube.com/ watch?v=yLxdY5mkH8Y

MILK PAYOUT TRACKER:

2021/2022 Fonterra forecast price

Average $8.88/kg

CONNECT WITH US ONLINE:

www.nzfarmlife.co.nz

NZ Dairy Exporter @DairyExporterNZ

NZ Dairy Exporter @nzdairyexporter

Sign up to our weekly e-newsletter: www.nzfarmlife.co.nz

Anne Lee, P: 021 413 346 anne.lee@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Karen Trebilcock, P: 03 489 8083 ak.trebilcock@xtra.co.nz

Delwyn Dickey, P: 022 572 5270 delwyn.d@xtra.co.nz

Phil Edmonds phil.edmonds@gmail.com

Elaine Fisher, P: 021 061 0847 elainefisher@xtra.co.nz

Alex Lond lond.alexandra@gmail.com

Design and production:

Lead designer: Jo Hannam P: 06 280 3168 jo.hannam@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Emily Rees emily.rees@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Partnerships Managers: Janine Aish Auckland, Waikato, Bay of Plenty P: 027 890 0015 janine.aish@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Tony Leggett, International P: 027 474 6093 tony.leggett@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Angus Kebbell, South Island, Lower North Island, Livestock

P: 022 052 3268 angus.kebbell@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Subscriptions: www.nzfarmlife.co.nz subs@nzfarmlife.co.nz

P: 0800 2AG SUB (224 782)

Printing & Distribution:

Printers: Ovato New Zealand

Single issue purchases: www.nzfarmlife.co.nz/shop

ISSN 2230-2697 (Print)

ISSN 2230-3057 (Online)

You don’t know what you know.

You know you don’t know how to do something.

Consciously Competent

but still need to think.

How many of you became farmers because you wanted to be a people manager?” was one of the first questions asked at a workshop I recently attended. Out of the 20-something farmers in the room (all of whom are employing people), none could say that was the reason we became farmers.

The workshop was the first in the series of the ‘Primary Sector People and Team Leadership Programme’ and I would highly recommend the programme to any farmers who are managing or hoping to manage staff.

Funded by MPI and hosted by Great South, the programme designers recognise that progression in the farming industry often results in the need to employ and manage people, but farmers don’t usually get sent on ‘people management’ or ‘team leader’ courses the same way other industries do, and, as a result we miss out on the knowledge which makes the people management side of the job easier, legally compliant, and consequently more enjoyable (or at least less painful).

Realising an experienced person can forget to explain parts of a task – because it’s so second nature to them – and an inexperienced person doesn’t know what to ask about – because they don’t know what they don’t know – has got us rethinking our expectations.

I believe we got so much out of the course because both Duncan and I attended.

I am quite partial to a training course (particularly if it involves lunch and a free pen) but getting Duncan along to this kind of thing can be a challenge, and since it is Duncan who is working with people day in and day out, it would not have had the same impact if he hadn’t been there as well.

Our key takeaways were the different stages of learning, understanding personality differences, sharing farm goals,

and illustrating individual training and progress.

You know how to do something - it is common sense.

We learnt that few people are motivated by money or rewards, which seems hard to believe when an employee leaves for another farm offering more money. But it turns out understanding the big picture of what the business is trying to achieve, being given autonomy, and seeing their training record filling up is more likely to retain a team member than an overly large salary or gradefree bonus.

It’s no surprise that a team will be made up of different personalities, what is surprising is how little we have been taking that into account when running our farm.

An early exercise was for our farm team to complete the DOPE test (Dove, Owl, Peacock, Eagle) which identifies a person’s style and then explains the strengths, risks and how to get the best out of someone with that style. It has made us think about how to communicate, interpret, and motivate our team.

Understanding the stages of learning was a real eye opener for us. We can have someone who knows the job inside-out training someone who has never done it before. Realising an experienced person can forget to explain parts of a task –because it’s so second nature to them – and an inexperienced person doesn’t know what to ask about – because they don’t know what they don’t know – has got us rethinking our expectations.

We are far more enthusiastic about putting our learning into action on the drive home than the reality of being back on farm allows, but we are taking steps to get there. Training charts have gone up on the wall, the personality test has been added to the new starter pack, and we are working out how to best explain the big picture to our team. Interestingly, none of these initiatives cost a thing.

I’ll be the first one to say that I was a cynic as I watched alternative milking mammals rising to fame. More people than ever were milking goats and sheep, and now there are whispers of deer, and here’s me thinking what’s wrong with a cow? So, when some friends approached me about spending JulySeptember rearing lambs on a local sheep milking farm, I thought I’d better give it a go and see what all the fuss was about.

After years of rearing calves, I was optimistic about my capabilities with lambs, but I had no idea what a huge operation it would be, or indeed how much I would learn on the job! The main difference was that my main purpose, 12 hours a day, alongside a team of three other full-time lamb rearers, was to make sure every lamb remained well fed and healthy.

We fed up to 1600 lambs four times a day, first with ewes’ colostrum and then milk powder, and conducted regular health checks on every lamb to ensure no infections were getting picked up or passed on. I felt like I finally saw into the life of a full-time calf rearer, and it was a great feeling knowing that you were one of a small group of people who were producing the next generation for the farm.

A major difference to calves was that these lambs stayed on mum for three days before we took them into the rearing unit. They were also all born inside, and these two factors gave them the best chance to survive and adapt. It meant keeping a keen eye on both the ewes and the lambs once they were born, making sure that no lambs were left unmothered and that ewes weren’t contracting mastitis.

There was a meticulous process involving numerous chalk colours to ensure each lamb was aged correctly, and much like cows we regularly drafted out lambed ewes to give them access to more room and tucker with their new-born lambs.

On the third day, we would complete the ‘lift’, where we moved the lambs into the lamb rearing unit and the ewes into pens ready to be milked that afternoon. Like with calves, this was a pain-free process, with mums ready to move outside on to fresh tucker and lambs already thinking about their next feed.

While I already had a lot of respect for full-time calf rearers before this job (most of all for their unwavering patience, something which certainly does not come to me naturally) this has increased a thousandfold. Furthermore, while my

After years of rearing calves, I was optimistic about my capabilities with lambs, but I had no idea what a huge operation it would be, or indeed how much I would learn on the job!

knowledge on sheep milking has grown so has my ability to understand why people are looking at alternative methods to cows.

Sheep seem to adapt naturally to the milking process, they are just as easy to feed, and you are able to milk more in a smaller space of time. The bobby calf issue faced by a lot of farmers is not a problem here; we reared both the ewe and ram lambs and the farm used their own rams during mating, while lamb rearers off farm would take on any excess to be finished or used on lifestyle blocks.

Ultimately, however, what keeps me on the side of cows is that I can absolutely, definitely, without a doubt confirm that sheep smell worse…

Normally working with cows, Alex Lond got an opportunity to experience life in the burgeoning sheep milk industry rearing lambs.Milk feeder. Ewe and three lambs.

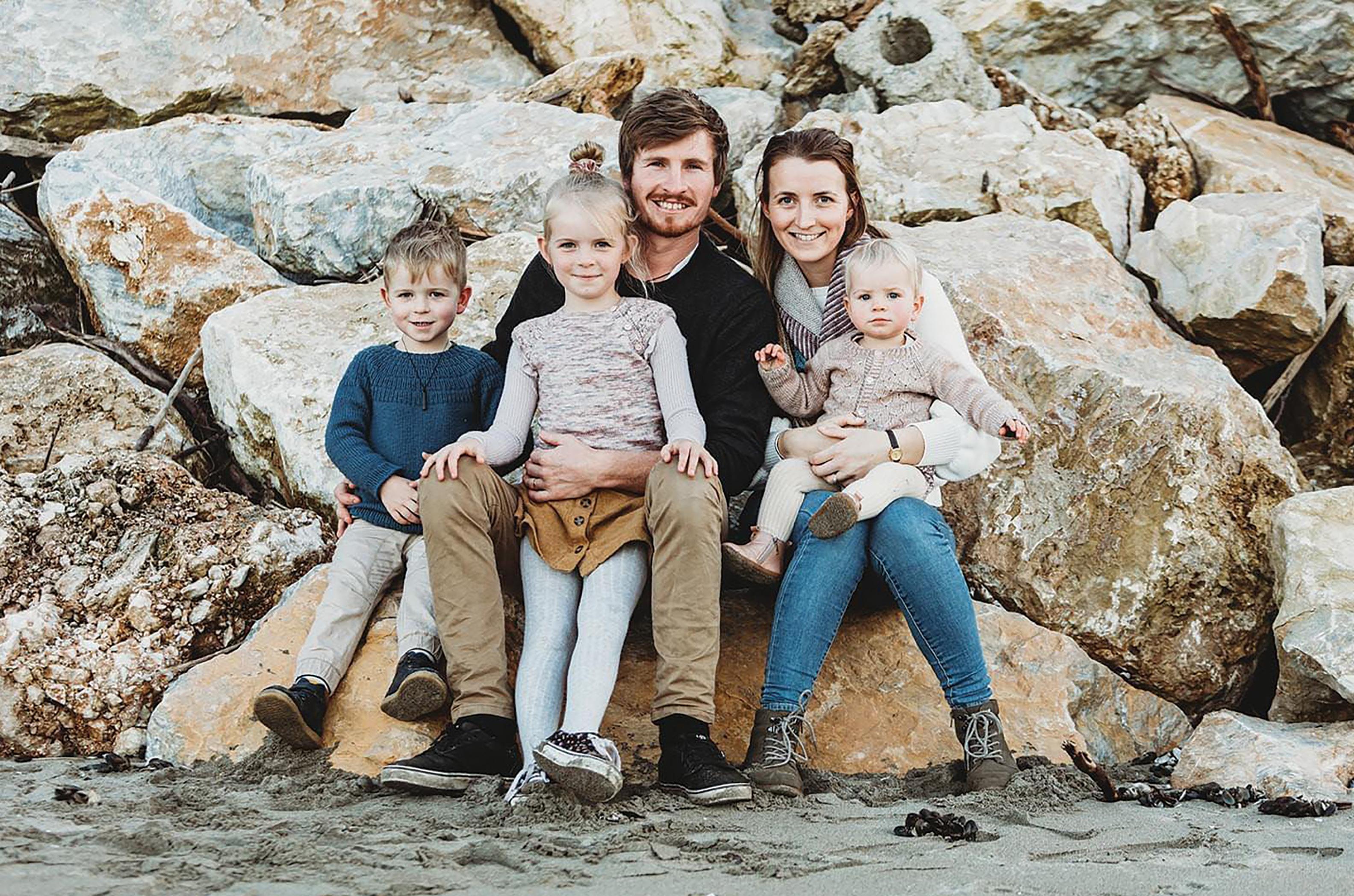

If you asked me 10 years ago what I intended to do in the future, not from a farming background, dairy farming would never have crossed my mind. Now here we are 50/50 sharemilking two neighbouring farms with kids in tow, planning to succeed in our chosen profession as well as making the most out of what our place in paradise has to offer.

It has been an incredibly interesting ride to get here, my husband Cam and I had settled down originally in Te Awamutu, Cam was agricultural contracting while I was working in retail. We started our family together and saved enough to buy our first home. We had our first daughter and not so long after our second was on the way. Cam had now been contracting for a few years and had progressed as far as he wanted to climb. With our growing family, the late nights and busy seasons had prompted him to reconsider our career path.

Cam had been raised as a farm kid and decided it was a good lifestyle to raise children. We applied for a handful of jobs and were fortunate to be selected by Andrew Clark, a farmer in my hometown of Opotiki. We sold up (unfortunately before the property boom) and moved home.

currently in the process of buying everyone out a year early. It’s been a massive learning curve, considering I had never milked a cow in my life, to be thrown into solo milkings in our 24-aside Herringbone dairy, raising calves and now three children in tow.

For a couple of years Cam worked for Andrew and Kelly, his partner, with a goal of eventually sharemilking in mind. Conversations with Andrew progressed into a shareholder partnership along with a group of farmers from our discussion group, one being our neighbour Colin.

When the right job happened to come along, I never would have imagined it would be the quaint 300 Jersey cow farm I could see from my grandmother’s house. Everyone put in a share with us being the majority shareholders and the aim was to buy everyone out within five years. We are

We bought the owner’s cows and have kept the herd predominantly Jersey. The first season was a big adjustment especially with having each other to work with. We’ve been fortunate to have a good team of people around us for advice and now we feel like we know our farm and our cows well. We know when the farm grows grass and that in summer all we have to count on is kikuyu, as the ryegrass disappears.

After four seasons here our neighbour Colin sustained an injury requiring surgery and deeming him unfit to run his farm. With six weeks before the new season we accepted the job of 50/50 sharemilking his 250 cows and promptly found someone to help us run the daily tasks.

It’s been a mammoth task and we’ve had to prioritise running the farms above having our own time out. With a foreseeable favourable payout we are hoping to be a few steps closer to our dream of farm ownership.

We applied for a handful of jobs and were fortunate to be selected by Andrew Clark, a farmer in my hometown of Opotiki.

Peter Arthur offers advice on selection, costs and care.

If you are planning to plant trees next autumn or winter, now is the time to decide what species you want, and where you are going to plant them. Then put your order in.

I get mine from Appletons Nursery, near Nelson who supply plants bare-rooted from June till August but many lines are quickly sold out so it pays to order early.

You have to order a minimum of 10 for any given tree but the price per tree is very cheap. For example, Scarlet oaks (Quercus coccinea) 1.2-1.5 metres high are $13.40 each. If you buy 50 the price is $7.90 plus gst and freight. If you get a thousand, the price is still cheaper. The same tree, a bit bigger (1.6m) and in a pot will cost about $60 at a garden centre.

Appletons grow a huge range of trees, both natives and exotics, and sell many as growing-on lines, small plants from 15-25cm high, and upwards at even cheaper prices - the Scarlet oak being $2 each.

These small plants need growing-on in a nursery bed for a year or more before planting out.

In the autumn Appletons spend several weeks roaming New Zealand to collect seed from particular trees and in some years there is a good amount of seed, in others none at all for certain species.

This means some years they will have a certain species for sale, other years they won’t. This mostly applies to the more uncommon trees like Davidia involucrata (the Handkerchief tree) and Sequoiadendron giganteum (the giant redwood or Wellingtonia).

As well as trees they supply smaller-growing native plants for riparian planting, plus of course all the major forestry species.

Prior to planting, spray the spots with Roundup and you can add Terbuthylazine for longer-term weed control. It’s best to do this at least six weeks prior to planting.

If the area is already fenced off and there is lots of really long grass I take old salt lick containers and the like and pre-dig the holes, putting the soil into the containers. This way it doesn’t get lost in the long grass, and in the recent dry years we have been having in Hawke’s Bay any rain we do get is not only going into the hole, but also into the soil in the container, a double dose of moisture. If the ground is

really dry I add about 20 litres of water when I plant. Once the tree is planted it will need to be kept weeded for the first few years. I have tried all sorts of plastic weed matting and old carpet but this year have used dag wool which is easy to apply and which to my surprise, doesn’t blow away in the wind. It is also meant to act as a bit of a hare and rabbit deterrent, but I can’t vouch for this.

Newly planted trees in very short grass seem to attract hares and rabbits. Long grass seems to deter them so long as you take long strides and try to avoid flattening it so you haven’t made a convenient track from tree to tree.

Over the past 50 years I have used all sorts of tree barricades, starting off with 44 gallon drums. Of course I couldn’t run cattle around those trees for a year or two.

I then used taller weldmesh type netting but am now on to X fence security netting 1.8m high which I cut into about 2m long lengths. This, anchored with two waratah standards, costs about $100 a tree.

Newly planted trees in very short grass seem to attract hares and rabbits. Long grass seems to deter them so long as you take long strides and try to avoid flattening it so you haven’t made a convenient track from tree to tree.

It has worked well provided there is something else in the paddock for cattle to rub on. Cattle will use the barricade as a back scratcher with unfortunate results.

I am now trying, for the first time, Cactus barricades imported from Spain by Tree Guards NZ. These come in packs of 10 and measure 1.7m high by 1m long and cost $49 plus gst per barricade. Every second horizontal wire has been cut and sticks out like a very sharp barb. It makes for a narrower barricade than I would like but I am using them to replace X fence barricades on which the cattle have been rubbing.

• First published in Country-Wide, October 2021

Towards the end of 2021 fears of a global food crisis started to ring out as fertiliser production slowed in Europe and key exporting nations turned their supplies inward to ease the risk of their own food insecurity.

New Zealand farmers may have shown little immediate concern for Europe’s problems, but they have quickly been part of the collateral damage as fertiliser prices have reached recent record highs. At the beginning of December urea was priced at about $1200/tonne. A year earlier it was under $350 and as recently as September 2021 was $590/t.

Believe it or not, NZ farmers are by no means the worst affected from what has unfolded, and despite perhaps feeling they’re being held to ransom, there are still some things farmers can do to limit the cost pressure.

The fertiliser price spike can’t simply be attributed to Covid-19 like many other inflationary cost increases. Instead, the last 12 months has seen a series of influential events that have collided at exactly the wrong time.

First, at a global level, food commodity prices started rising, prompted to some extent by displacement of labour at key seasonal timings – which was a Covid-19 derived factor. Global wheat, soy and corn prices increased to levels not seen since 2014 while meat, dairy, rice and edible oils have all followed the move.

As a direct result of this, demand quickly started rising for fertiliser to replenish soil nutrients that had been allowed to run down when commodity prices were not at levels that encouraged maximum production. This kicked in early this year, ahead of the northern hemisphere spring at exactly the same time that supply constraints started to emerge.

In the United States, several weather events stifled fertiliser production including a significant seasonal ‘freeze’ which impacted the manufacturing of nitrogen, and later there was some disruption to phosphate production due to Hurricane Ida. But the biggest handbrake was rising gas prices in Europe. The price lifted quickly to a point where producers of nitrogen simply stopped working because

Disruptions in gas supply and export bans by China have hit international fertiliser supplies. Phil Edmonds reports on thae effects on New Zealand agriculture.

they could no longer make money. Rabobank senior agricultural analyst Wes Lefroy says soaring gas prices effectively shut down 12% of Europe’s nitrogen production.

If this wasn’t enough to fuzz the market, China simultaneously slapped export restrictions on its fertiliser exports with domestic fears over food security. China itself had experienced some electricity shortages and its supply has been compromised by the introduction of environmental measures which has impacted the phosphate market.

Ballance Agri-Nutrients sales general manager Jason Minkhorst says this move can’t be underestimated in pushing up prices.

“China had previously exported 35% of the world’s DAP and this year it will be 20%, with the export ban expected to stay in place until mid-2022.”

So, what does the northern hemisphere’s woes have to do with NZ, and why are China’s actions a big deal when NZ is not particularly reliant on its fertiliser exports?

Wes Lefroy says that even though NZ imports of fertiliser may not come directly from China,

it is now facing competition in other markets from countries caught out by China’s blockade. The Middle East (particularly Morocco and Saudi Arabia) has seen demand for its nitrogen rise, and with it prices.

Finally, a further disruptor that is felt more in NZ than many others is the rise in Covid-19related transport costs. Lefroy says shipping is still congested.

“Eighteen months ago, it took between six weeks and two months to get a laden ship berthed in your own port. Now it is taking

between three and five months between procuring and landing.” Inevitably this means extra cost tied up in delays.

LactisolTM Nucleus Z1 is armed with zinc oxide, vital in the battle to prevent facial eczema. However, only Lactisol Nucleus Z contains Hy-D®, to improve calcium adsorption, blocked as a side effect of high levels of zinc. And of course, Lactisol Z contains the full SollusTM range of vitamins, trace minerals and antioxidants needed to make your herd healthy and robust. Ask your feed supplier for the newest hero and give yourself a fighting chance.

registered

When facial eczema threatens, you turn to a hero that has a few tricks up its sleeve.

‘China had previously exported 35% of the world’s DAP and this year it will be 20%, with the export ban expected to stay in place until mid-2022.’Rabobank senior agricultural analyst Wes Lefroy.

Ravensdown general manager Mike Manning says “If we’re picking up from an international port that’s been affected by a Covid outbreak, we can’t load when booked. Similarly, if large manufacturing plants have to temporarily shut for the same reason, product may not reach ports when anticipated.”

There’s no getting away from the fact NZ is heavily exposed to global fertiliser prices. But we are not necessarily as badly off as some others – which may be worth keeping in mind, even if it’s cold comfort to farmers seeing their core costs of production escalate.

In Australia for example, there has been a heightened sense of anguish over the past few months, to the extent that predictions were being made of fertiliser rationing and lower yields as a result. Both short, and long-term solutions to this have been discussed in Australia including changing crop rotations to favour crops that produce nitrogen including pulses and investigating the potential for domestic manufacturing of cheaper and greener fertiliser.

Nothing of this drastic nature has been mooted in NZ, however.

Mike Manning says Australia has a more limited window to apply fertiliser with its primary focus on arable crops. By contrast, NZ’s pasture system allows more flexibility and time to adjust to prices. For example, many farmers might plan to put fertiliser on in November, but it is not the end of the world if it is delayed a month. Rabobank’s Wes Lefroy notes that Australia typically imports 65% of its urea between April and July. In NZ it is spread throughout the year, albeit with a peak in the final third of the year.

A possibly more significant factor is that the majority of fertiliser in NZ is sourced

from the two leading co-ops, which being farmer-owned and effectively mandated to ensure supply is available when needed, means they are likely to hold more product in storage, and less likely to run out. In contrast the Australian industry is dominated by corporates, who by their nature are more likely to try and trade with less stock.

Add to that, NZ has the benefit of local production. Lefroy notes the Taranaki urea production plant certainly takes the pressure off the reliance on imported nitrogen in the North Island. It can enable imports to be more directed to the South Island, which gives another blanket of supply security.

While NZ farmers may have more confidence than their counterparts in other countries that the fertiliser cupboard won’t be bare when they need it, they are nonetheless faced with elevated prices, potentially for longer. Lefroy says if the

global price dropped

50% tomorrow, it would still take a good few months to flow through given the shipping delays spoken of above. So, what can farmers do to ease the cost pain?

Understanding potential margins and considering your appetite for risk are good starting points, suggests Lefroy.

If, for example, farmers have confidence the forecast high milk price will be realised, it probably makes sense to maintain higher soil nutrient levels albeit within regulations. But if margins were to tighten farmers could instead look to utilise the nutrients they have built up in the soil.

If farmers are more inclined to stick with

planned fertiliser applications, they should be considering at what stage to make purchases. This involves weighing up the risk of missing out on a fall in prices in the autumn or the following spring versus locking in supply albeit at higher prices.

As far as the co-ops are concerned, providing advice on precision agriculture remains a key focus.

Mike Manning says just as Ravensdown can’t do much about international fertiliser prices, nor can farmers. However, farmers can look at being more diligent and a bit more prudent about how they use it.

“One of the ways to use nitrogen more efficiently is to be really clinical about feed supply and demand, considering where the gaps are. This can involve soil testing every paddock which gives farmers the ability to be more precise about soil deficiencies.”

Manning says Ravensdown are being asked for advice more than in the past, and this reflects a desire to be more efficient.

Ballance’ Jason Minkhorst says providing expert knowledge is the co-op’s business. He says there’s no sense farmers are deliberately wasteful, and indeed they can’t afford to be with the introduction of nitrogen limits. But there is clearly a renewed focus on efficient nutrient use.

One option to reduce exposure to high prices is for farmers to decouple their use of nitrogen and phosphate by shifting away from imported DAP toward locally manufactured phosphate. This allows farmers to more precisely dial up or down their use of nitrogen as necessary.

Minkhorst suggests the price hikes present farmers with an opportunity to reassess long-term fertility plans. This is something farmers make decisions on every year – understanding how they might treat areas with naturally high levels of phosphate differently to areas they have invested in to improve the fertility, and how they might use that fertility in a year where the payout may not be as supportive.

As to fears of global food shortages with the price of, and access to fertiliser becoming prohibitive, there’s no sense that it will slow NZ’s food production, particularly as we continue to see high farmgate prices for that production.

In terms of other markets, Lefroy says there is some reason to be concerned, but at the moment Rabobank is not expecting any decreases or shortages in food.

“India, which is doing a lot of buying at the moment, recently put out a tender for 1.6m tonnes of fertiliser and were offered 2.6m t. This shows there is still supply in the market.”

As to the coming 12 months, Lefroy says we may see the price of nitrogen come off between 10 and 20% if gas prices ease. But as commodity prices remain high then fertiliser prices will likely remain elevated. The second half of next year could start to see things ease, if China comes back to the global market in June. That’s still quite a long way away.

The key message then for farmers from both a financial and productive perspective is don’t expect a material fall in price anytime soon, and given that, precision is the best form of mitigation.

In demand: Dutch dairy cows.

In the past year, various milk processors in the Netherlands have started looking for more milk. What is going on? Demand for dairy is good, stocks are low and milk supply has fallen by 4% in recent months compared to last year. Added to this is the political uncertainty about what will happen to the numbers of livestock kept. Shrinkage is very likely.

For a milk processor, there are then two options: Closing factories and disposing of the less profitable contracts is the first. This strategy is particularly obvious at FrieslandCampina, where a total of 272 million kilograms of milk will disappear next year.

Since the abolition of the milk quota, the Dutch market leader has already closed 13 factories and with the departure of the 239 farmers this year, capacity adjustment is again necessary.

The second strategy dairy processors can follow is to bring in extra milk. And that is now happening a lot. How remarkable is that and why is Dutch milk so popular? Isn’t the dairy market preeminently a market with an international playing field?

Analysts say: “The Dutch label has a

positive perception in the market that is strongly embedded. In the first place thanks to the consistent quality of Dutch milk, but also because of the positioning with grazing, clogs and windmills. That is not just marketing, it is based on 50-60 years of consistent quality and security of supply.”

There is another reason. Customers ask for ‘KKMcertified’ milk. This is milk guaranteed produced in the Netherlands under Dutch quality standards with a low environmental impact. Moreover, transporting milk is expensive, especially today. Milk is 87% water, processors cannot drive far with it. All in all, the dairy market is apparently a lot less international than

Another development is that of ‘sustainable milk projects’. Never before have they been so diverse and numerous as at present. Ten years ago there was conventional and organic milk, now there are all kinds of concepts: meadow milk, GMO-free, Planet Proof, specific supermarket-concepts, Caring Dairy and the ‘Better life quality mark’ of the Animal protection organisation. These milks are less suitable for trade between factories, which is why factories would like milk from their own dairy farmers. The question is how the battle for milk will ultimately turn out and how long it will last. In theory, if factories closed, an equilibrium would be restored, provided they were not taken over by other processors. Analysts predict the action in the milk market will continue for a while.

previously thought or imagined.

Trading via the day-to-day market also offers no solace. With continued good demand and supply drying up, this is a small market. With additional processing capacity in the Netherlands, the amount of milk from the day-to-day market will no longer increase quickly.

‘The dairy market was boring for a long time, but now there is good money to be made again, also with commodities. Apparently companies need a trigger to take action.’

‘That is not just marketing, it is based on 50-60 years of consistent quality and security of supply.’• Sjoerd Hofstee is a dairy journalist at Persbureau Langs de melkweg, Netherlands.

MAXSYN

Diploid perennial ryegrass

Setting the pace for next gen pasture

Tetraploid perennial ryegrass

Extra palatabilty and environmental benefits

@BarenbrugNZ facebook.com/BarenbrugNZ

barenbrug.co.nz

What an interesting year 2021 has been for dairy commodity prices, however, we’re at a point where lofty prices start to spook people. Some people are starting to compare this season to the last time dairy commodity prices saw these heights; the 2013-14 season.

At that time, the market was very different, and that season’s high farmgate milk price was followed by a crash in the price the following season. So, let’s look back at 2021’s dairy commodity price movements, and then discuss why it is unlikely that we will see the same boom and bust of the 2013-14 season.

At the start of 2021 dairy commodity prices hit dizzying heights, in March whole milk powder hit a magical US$4364/ tonne at the March 16 Global Dairy Trade (GDT) event. Butter was the only other key commodity offered on the GDT platform that was able to achieve a similar gain at the same auction, while the other key reference products did not manage such a dazzling price gain.

At that time, Asian buyers were keen to secure much-needed WMP and butter supplies on the way into the winter lull of production. Then, as with now, shipping disruptions were a major issue on the top of mind of all buyers, making New Zealand’s ability to get product to market very attractive.

This was the first high point of 2021, but it didn’t take long for both WMP and butter prices to settle down to land in a new price range as NZ was heading into winter, and peak milk was flowing in the Northern Hemisphere.

Over the second half of 2021, the market changed tack remarkably, with a significant shift towards protein, with less concern for WMP. As the perfect example, the NZX casein price has increased 50% from the start of 2021, currently sitting at US$12,900/t. This casein price is an

amalgamation of all casein and caseinate prices, so it is best to take with a grain of salt, but the premise remains, the market is chasing these protein products, with buyers willing to push prices ever higher to secure supply. These buyers are also not from our regular markets, with the majority of these products heading to the United States.

Cheese prices have followed similar trends to casein, but more impressively, exploding over the last two months. Cheese prices at the end of 2021 are 29% higher than where they started the year. And, in an almost unheard of trend in the world of commodity trading, the complementary product of cheese production is also in hot demand, whey. Whey prices are being pushed to levels that have some in the industry in disbelief. With two of the world’s biggest cheese producers, the US and the European Union, struggling to grow their milk production, in year-on-year terms, there seems little doubt that cheese, and therefore whey, will be in tight supply going forward. NZ cheese prices are the most expensive globally, but buyers, such as Japan, are still willing to pay these high prices to secure their much-needed supply of NZ cheese. China’s demand for whey is unlikely to diminish in the short term.

Like the proteins, the evertasty part of the dairy industry, the cream group, has been on a steady climb higher through 2021. As mentioned earlier, butter prices exploded higher in March, but trended lower through winter, before shifting steadily higher.

Anhydrous milk fat (AMF) prices didn’t peak in March quite like butter prices, but did trend slightly lower in winter, before marching ever higher over the second half of 2021. Together, butter and AMF prices are now at seven-year highs. Demand for both products is very steady and is being helped by the real lack of exports coming out of the EU and US. During the 2013-14 season, the cream group didn’t see any real value gains, compared to the

boom WMP and SMP prices managed. So, how is this different to the 2013-14 season? Well, in 2013-14 there was a major shortage of WMP in China, so the Chinese government encouraged importers to reinstate their inventories, and thus the rush of demand for WMP… This time around, as mentioned above, the dynamics are very different.

Proteins are in the driving seat, with strong global demand for an array of milk protein products. The cream group has formed a solid price base, due to demand for protein products. Processing of these products moves milk away from production of cream derived products; tightening milkfat supply globally. Adding to these factors, the outlook for WMP looks very solid, with stream return calculations also likely seeing excess milk flowing away from WMP driers, into other processes, further tightening the global supply of milk for WMP.

Looking forward, we’re seeing a global market that is unlikely to fulfill its requirements in the short term, as milk production remains tight, and is likely to get tighter over the short term.

Shipping remains another key issue buyers are willing to pay a premium for, as global shipping remains very disrupted. Only when these two market factors return to balance, will it be likely to see downward pressures return for the NZ farmgate milk price. However, from what we’ve seen over the last year, it’s not going to be a fast turnaround.

“Changing ballcock arms was a daily routine job for me during the summer months, taking up time and causing stress and frustrations when water was scarce. Since inventing the Springarm and using them on our farm, over the past 18 months, we have not had a single broken ballcock arm.”

Ric

Ric

Awburn,

Dairy Farmer, Waikato, Inventor of Springarm

Dairy Farmer, Waikato, Inventor of Springarm

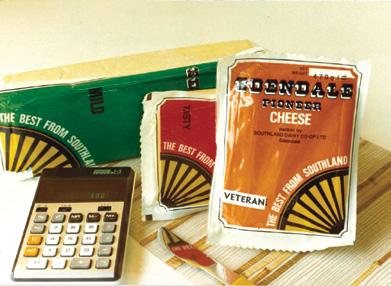

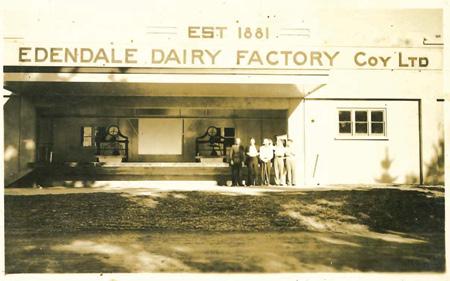

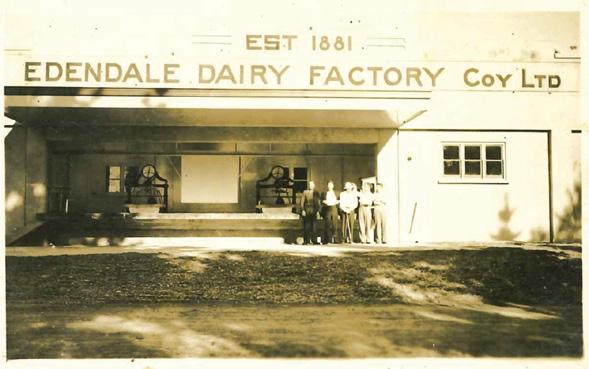

Cheesemaking at Fonterra’s Edendale site in Southland celebrates 150 years this month.

After celebrating 150 years of New Zealand’s first dairy cooperative in spring last year, Fonterra has another milestone this month.

On January 18, 1882, 140 years ago, the first batch of cheese was produced and placed on the press at 3pm at the Edendale dairy factory.

The milk for the cheese came from the factory’s own herd of 300 cows.

Sheep had proved unprofitable on the new pastures at Edendale owned by the New Zealand and Australian Land Company so in 1881, the company’s superintendent, Thomas Brydone from Scotland, thought dairying would be better.

Brydone made sure lime and fertiliser was added to the young grasses and they soon flourished. The Edendale Dairy Factory Company Ltd was born.

The same year, 1882, the SS Dunedin began sailing to England loaded with refrigerated mutton and lamb. Brydone made sure Edendale butter and cheese was onboard too.

By the early 1900s, Edendale was processing 3000 litres of milk and, in 1920, milk pasteurisation was added, a first for the country.

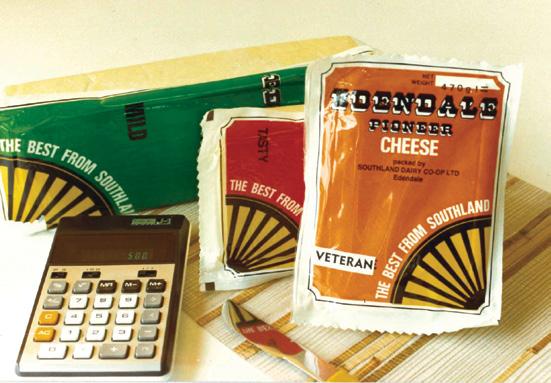

Its cheese was sold under the Pioneer label.

In 1914 all the whey from Edendale was processed into lactose milk sugar (1387 lbs), a first for the Southern Hemisphere, and sold under the brand name Wyndale.

Lactose is still produced under the Wyndale brand at Fonterra Kapuni in Taranaki.

A contractor’s tip truck was fitted with a removable 7000 litre tank in 1958 and

By Karen Trebilcock.became Edendale’s first milk collection tanker for farm pickups. Before this, farmers delivered their own milk to the plant.

In 1987, the first of what are now three Anhydrous Milk Fat (AMF) plants was commissioned (0.5 t/hr) to process whey cream and the first night collection of milk started.

In 1994, Drier 1 commenced production, processing 900 cubic metres/day of Whole Milk Powder (WMP) and Skim Milk Powder (SMP).

Drier 2 powder plant was commissioned

Still proud of its history.

in 2002 (2500 cu m/day WMP and SMP), Drier 3 the following year (2500 cu m/day, WMP and SMP, 11 M litre site capacity) and in 2009 Drier 4 (4000 cu m/day WMP 15 M litre site capacity) making Edendale the largest raw milk processing site in the world at the time.

Edendale’s 2015 expansion project involved building four new plants on site –a milk protein concentrate plant, a reverse osmosis plant, a milk treatment plant, and an anhydrous milk fat plant. It now has 13 plants making it one of Fonterra’s largest processing sites.

Cheese Plant manager, good things do take time just like in the TV ad. But it’s not the cheese he’s talking about, because at Edendale they can turn liquid milk into a 20kg block of cheddar in about five and a half hours. Instead, he’s talking about his career.

He started at the Edendale factory from his family’s Southland sheep and beef farm at 18, in September 1975, as a cheese hand and is now the plant’s longest serving employee.

Of the 140 years of history of the plant, he’s been there for a third of them.

“I was due to finish up school and I didn’t know what I wanted to do next. I got offered the job at Edendale, my dad knew the plant manager, and I started the very next day.

• Collects milk from more than 800 southern farmers with a fleet of 65 tankers

• Processes up to 15 million litres of milk per day at peak

• Exports products to more than 70 markets throughout the world

• Employs more than 670 people

• Produces 14 million bags of milk powder annually which if laid end-to-end would reach from Invercargill to Dubai

• Milk powders include whole, skim, butter, fat filled and milk protein concentrate, each specialised for customer needs

“It was daunting at first, with all of the white lab coats, boots and hats and you had to be fit with all of the manual handling.

“Some people didn’t last their first day. We worked seven days on and one day off and our wages were split between us so when we were short staffed we made a lot of money. One year I worked three months without a day off.

“In those days you worked hard and then you played hard. There were plenty of events – we were one big family and you just enjoyed each other’s company.

“It was a lot of fun, making cheese, there was also a cheese bar on site, so you got to see locals loving the product as well.”

When he started, the changeover was happening from farmers bringing their own milk to the factory to milk tankers only. From a cheese hand, he worked at CIP (clean in place), then as a pasteuriser,

Edendale Cheese Plant manager David Thwaites.

a starter, a salter operator, supervisor and finally, for the past 25 years in management. Although Pioneer branded cheese from Edendale could be bought in New Zealand until about 15 years ago, now all of the cheese produced at the site is sold on the Global Dairy Auction.

“We’re a peak milk plant so we run from September until the start of December each year and all of the product is exported. It can go anywhere in the world.”

A 12-hour shift produces 47,000kg of cheese.

“It hasn’t really changed since 1882. It’s still the same cheese, made the same way. It’s just more automated now and we make a more consistent product.

“The cheddar is made using microbial rennet starter cultures which comes from Fonterra Palmerston North, and then it’s pH controlled through the process and salt is added.”

Mild cheddar is about two months old, tasty is six to nine months and veteran is nine months to a year and a half.

“It’s all about the temperature as well. We keep our cheese at 4C but if it’s at say 10C it ages a lot faster.”

David says the great taste of Edendale cheese comes from Southland’s cows and the grass they eat and he’s a fan of veteran cheddar – “something with a bit of bite”.

“The milk from our cows down here brings out the best flavour. It’s a very exportable cheese. We have a wall of awards from New Zealand and Australia, and from all over the world including Europe.

“It’s something we’re very proud of.”

Grazing principles include vertical grazing on Gavin Fisher’s organic dairy farm at Te Aroha. Gavin is farmer ambassador for the Organic Dairy Hub Coop NZ Ltd. He talked to Sheryl Haitana about how he’s creating a future-proof farming business.

Any tree planted on Gavin Fisher’s farm during the past 41 years has had to tick as many boxes as possible: shade, shelter, habitat, nutrient cycling, produce, dietary and health benefits for the cows to name just a few.

Gavin associates all the trees, shrubs and plants grown on the milking platform as part of his grazing rotation, utilising every vertical inch of growth as well.

“Our grazing is tiered, we have vertical and canopy grazing. A cow can reach at least 1.5m high.”

Every paddock fence line is planted out, with the tree trunks protected behind fencing and it’s clearly visible where the trees have been grazed.

Farmer: Gavin & Sheryn Fisher

Location: Te Aroha, Waikato

Area: 74ha (50ha milking platform)

Runoff: 16ha

Cows: 150 Ayrshires, polled, A2

Empty rate: 4%, AI and bulls

Farm dairy: 20-aside

herringbone

Effluent irrigation: 20ha with travelling irrigator.

“If you fold that out, it’s a huge grazable area that you wouldn’t have ever had. So it’s utilisation of the land.”

Not surprisingly, it’s brought a whole lot of bird life into the property and they’ve got native birds that have never been seen on the farm before.

Gavin has a vast array of plantings across the farm, from hedges of feijoas, olives and rosemary to nut trees, fruit trees and native trees.

There is a mix of deciduous and evergreen trees and a lot of shrubs which are cow height to protect the cows in winter from southerly winds.

The species selected are also chosen for what is good for the cows’ diet, such as flax which the cows love grazing on and helps to prevent worm burden.

“When I look at what I’m planting, in the summer you want shade and filtered light. In the winter you want warmth.”

The bigger trees lose their leaves in autumn, which is part of the nutrient recycling system, and it lets light in for the winter months to avoid the farm becoming too cold and damp.

Gavin has planted using angles, so in summer there is only sunlight penetrating half the paddock at a time.

This helps with giving cows ample shade while also keeping moisture on the ground for longer to help with grass growth during the hotter months.

A lot of the trees and plant roots go down many metres further than the shallow rooting grasses, so they are able to pull up more nutrients. It’s adding a diversity of minerals and nutrients to the cows’ diets that the animals wouldn’t otherwise be getting, Gavin says.

“At the same time it’s creating the ecology and habitat I need in my system.

“I try to nurture and foster ecologies and just farm them in a sustainable way. I think that’s a really good food production system.”

The cow is a bovine biological harvester and giving them access to a larger variety of food groups which lets the cows be selective of what they want and need to browse on.

The paddocks contain multiple grass and herb species mixtures. The grass growth curve is more continuous rather than boom and bust and the cows graze

the pasture at a higher residual level, which allows the plants to continue to regenerate and for the cows to benefit from the oils in the soft seed heads.

“I’ve been doing this for over 20 years, these days industry is calling some of what I do Regenerative Ag. Most of the practices I’ve done on this property I got told wouldn’t work but I stuck to my guns and it’s paid off.

“A lot of the stuff I did was to futureproof the family business. It’s working out well and will continue to do so in the future. This farm has fed two families and put the children through their education.”

Gavin grows summer crops and prepares paddocks by using a tine rototiller to create just enough soil-to-seed contact for seed germination. The objective is to stunt the growth of the existing pasture so the crop can establish itself. Gavin does not want to kill off the existing pasture which has been there for 40 odd years surviving adverse weather conditions as the pasture has proven its resilience.

He usually plants a multi-seed summer crop which when established looks more like a food forest for the cows. The plants include sunflowers, buckwheat, rye corn, oats, radish,vetch and plantain to name a few. The crop is designed by layering, the taller species are usually grazed on first, then as the cows make their way through, they graze down to the lower species such as the plantain, so I can get four or so feeds off one crop easily, Gavin says.

“If you want diverse plants to grow you have to have diverse conditions. Trees really help you out there with changes in moisture, shade and heat conditions.”

Gavin’s advice to any farmer wanting to go down the organic or regenerative route is to ensure they do their own research. Talk to farmers who have been doing this a while and check out their land.

“Go and look at someone’s farm and see if their farm matches their talk. Seeing is believing.”

In the back of all farmers’ minds is how they will navigate incoming regulation and how they will stay profitable, so more farmers are looking at organic or regenerative principles.

Farmers seem to be looking at it in increments which feels comfortable for them and introducing some parts to see

what works on their farm, which is a good way to do it, Gavin says.

“I respect people who do their own research or experiments on their farms. I think it’s important for farmers to go see farms where they can see it working. Farmers are really good at looking at pastures and animals and seeing what works.”

Gavin started working on the family farm near Te Aroha 41 years ago and has been planting trees ever since.

“I took a more ecological and biological approach and then I looked at how I could add value by tapping into the market premium.”

The farm has been certified organic for 21 years and was one of Fonterra’s first organic suppliers.

Gavin switched to Organic Dairy Hub Co-op Ltd when the co-operative formed in 2015 and is enjoying the fact that organic farming is the sole focus of the business.

After coming from Fonterra, where the organic programme makes up only a tiny percentage of the wheel, it’s nice to be able to feel more connected to the business and its products, he says.

“There is more of a sense of belonging, when you see your products on the shelf.

“You know all of the Hub farmers and can ring anyone on the board of directors and right up to the CEO. The farmer

directors are also organic dairy farmers so they understand the business.”

Gavin sees the future of organics continuing to get stronger because more people are looking at a reason when they are purchasing food, whether that’s the nutritional benefit, the welfare of the animals or the environmental impact of the farming system.

Gavin has his own brand ‘Off the Planet Organics’ and sells fruit and free range eggs from his 90 chickens, which helps him stay connected to the local community.

as farmers aware of the customers’ needs. A lot of the decisions Gavin made around going organic and planting trees was around being future oriented to prepare for future regulation and changing markets.

“NZ and Overseas Organic regulations will always change or expand. One of my roles as the Organic Dairy Hub Farmers Ambassador is putting some systems in place, driving innovation on farms and looking at making sure we are in front of compliance for new stuff coming out.”

“There is a lens on supporting local at the moment. We are lucky in NZ, we can export but still supply to ensure some produce is held back for the local community as well.”

The spinoff for farmers supplying produce locally is that it builds a good connection with the community. They then have a good understanding of the farm systems used and can trust and trace the produce from that farm, it also keeps us

A lot of organic farmers will probably have a headstart when it comes to meeting some environmental regulation changes. However, the challenge will be how organic farming is modelled with the tools that are developed to measure and set overall national targets.

“It’s going to get tricky, do we fit in the same box as the non-organic farmers? Will the regulations capture some of the things we are doing and how organic farming

“I try to nurture and foster ecologies and just farm them in a sustainable way. I think that’s a really good food production system.’

mitigates some of the environmental impacts? That’s going to be the challenge.”

Leaching is a good example and whether models will take into account trees or topsoil quality on a property.

“If you 3D this place you would see all these roots going down capturing nutrients.

“Soils can be a sponge if they’re functioning properly, When I get rain, it doesn’t run off with the nutrients, the soil is absorbing it and holding on to it.”

Gavin has faded most fertilisers out now and relies on the natural nutrient recycling within his own farming system.

“I’ve never thought it was a good idea to rely on a nutrient coming on a ship from the other side of the world so we can grow food in NZ. Is that really a sustainable system going forward?”

The disruption of Covid-19 and the resulting supply issues, rising prices has brought it more to the fore how exposed NZ farmers can be.

“If I got told tomorrow there would be no fertiliser coming into the country for the next five-10 years, it wouldn’t impact my food production system.”

The way Gavin farms now is different to how he used to. He has gradually eased fertiliser use out and was told he would be mining his soil fertility, however after more than 20 years that argument doesn’t stand up, he says.

As an organic farmer, he doesn’t claim to have all the silver bullets, or that he is not affected by droughts or has no animal health issues, but says “we are less impacted and more resilient from adverse

weather conditions”. Organic farmers are more proactive than reactive. He always has a barn full of organic-certified hay for the feed pinch that could occur, especially in the winter.

If any health issue arises he is always looking at the reason behind it.

“When it comes to issues such as mastitis or bloat, I always look at what has caused that issue in the first place, then I can find the right solution as opposed to just using a remedy to move past it.

“If you had a rock next to your bed and kicked every morning, would you continue to kick it and put an organic Bandaid on your foot, or would you get rid of the rock and save yourself a sore foot, it’s about root causes not Bandaids.”

Gavin explained an example that on a ‘Financial ledger’, doing things like planting your farm with trees didn’t make financial sense at the time. Regardless Gavin went ahead and did it anyway as he saw it as an investment for the future. Now, he hardly has to spend any money on animal health, he has a cash crop off the fruit trees and grows more grass because of the shade provided.

“It wasn’t a waste of money but if you got me to show the figures at the time I was planting them it wouldn’t have convinced people to spend money on planting trees.

“Historically, it has always been about looking at production figures first and foremost. I just think we need a different way of looking at things, setting yourself up for tomorrow and for the generations to come on the land after you’ve gone is just as important.”

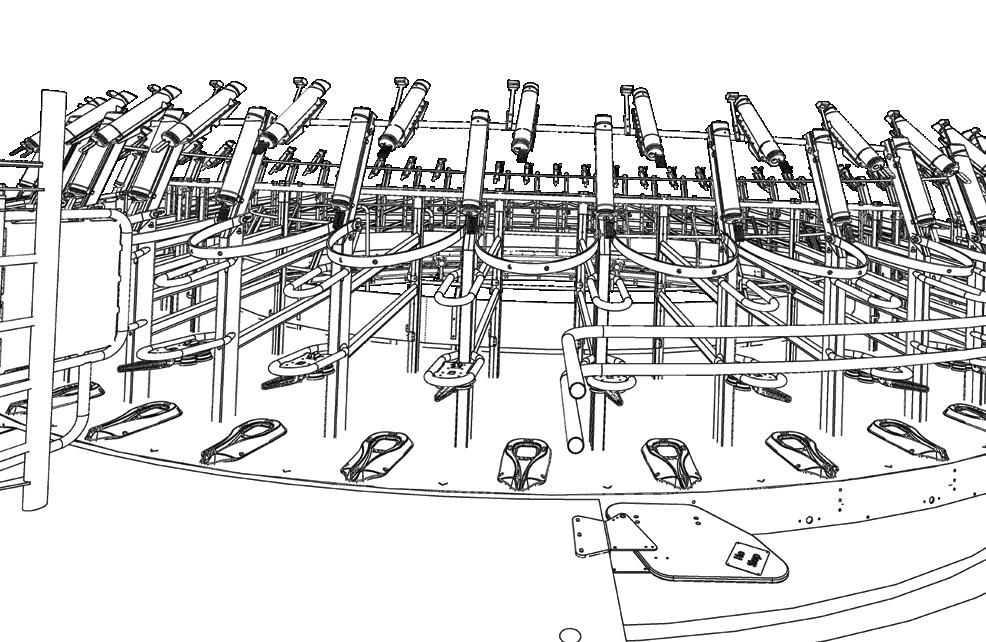

With a custom-built iFLOW Rotary Refit.

Frustrated with your old underperforming rotary? Take the pressure off yourself, your staff and your bottom line with an iFLOW Rotary Refit.

Refitting a new rotary into your existing building is by far the most cost-effective option to upgrading your parlour. Plus, the iFLOW is proven for its trouble free-operation and offers the lowest running costs on the market!

Don’t build new. Refit your old rotary with us. Call us today –0800 GEA FARM.

gea.com

Drive dairy efficiencies? We can help.

Organic Dairy Hub (ODH) is now in a position to recruit new suppliers next year with strong interest growing in their new A3 milk powder products.

The co-operative wanted to first maximise the value of existing milk supply before taking on new supply, ODH chief executive Clay Fulcher says.

“We are now at the point where customers are wanting more and we can pull the trigger.”

ODH launched its A3 trademark brand early in 2021; A3 is A2 Beta-casein cow’s milk certified under the United States’ USDA organic standard.

Later in the year the cooperative introduced A3 whole milk and skim milk powders, including lactose-free whole and skim milk powder.

“The products are getting a lot of attention.”

The cooperative’s Ours Truly brand has multiple certification labels on it that make it a premium choice for customers domestically and globally, including food service; A3, (organic certified and A2), nonGMO and grass-fed.

Premium products like this are only growing with people around the world taking more interest in the nutritional benefits of their food and how it is produced, Clay says.

While the jury may still be out on the nutritional benefits of A2 milk, it’s a trend that is highly in demand and where Clay sees all dairy herds in NZ ending up.

ODH currently has 28 farmer suppliers in the North Island producing about 20 million litres of milk.

About half of the suppliers are already supplying A2 milk, with the remaining farmers breeding their herds in that direction. ODH is helping its suppliers transition to A2 milk, and is also interested in helping new suppliers with their transition to becoming certified, Clay says.

For farmers interested in switching suppliers, or becoming organic, ODH has a very accessible share structure and great knowledge and experience within the Hub to assist anyone new to organics to get them on the journey and support them through that process. The farms are also working on a collective A2 breeding programme, Clay says.

ODH processes about a quarter of its suppliers’ milk into their own branded products under the Ours Truly range and sells the rest to partnerships they have with companies including Waiu Dairy Company, Lewis Road Creamery and the

Wellington Chocolate Factory. They also fly fresh milk to China weekly.

The recent launch of Ours Truly Organic Lactose Free powder products has seen huge enquiry domestically and offshore that is driving demand for ODH milk and the need to increase its milk pool.

Ours Truly milk, cheese and other dairy products are also available for New Zealanders to buy online and get delivered to their door in certain areas within NZ, and are carried by a growing list of retailers and cafes.

“One of the huge things for our farmers is having their product in a bottle that their family or friends can buy.”

Being able to offer the brand doorto-door has been a great way to launch and get their name out there, especially during Covid 19, and being able to make it more accessible in retail stores is the next stepping stone, Clay says.

Clay Fulcher - Organic Dairy Hub is ready for new suppliers.

‘One of the huge things for our farmers is having their product in a bottle that their family or friends can buy.’

Trust Alliance New Zealand provides tools and protocols for sharing data, to prove provenance, authentication and food safety as well as biosecurity tracking and tracing.

By Elaine FisherIn a world of emerging distrust fuelled by claims and counterclaims, especially around food products, trust is becoming a key issue, says Chris Claridge, chair of Trust Alliance New Zealand.

“That’s the reason ‘trust’ is part of our name,” Chris says. He is among the speakers at the Primary Sector Marketers Forum in Wellington in February 2022.

“Trading and the exchange of goods is based on trust. Without it, transactions cannot occur. New Zealand as a trading nation must operate at the highest levels of trust possible.”

Launched in 2020, Trust Alliance, NZ’s first national blockchain consortium focused on the primary sector, is described as a change agent for primary industries, connecting participants and providers across the entire primary sector value chain.

“In the 20th century, a brand promise was a shared set of values and principles which underlined a brand. That was communicated by words and imagery.

TANZ goes one step further to brand proof and transparency in order that the brand story is underpinned by evidence, facts and data not just rhetoric.”

The alliance began when a group of like-minded organisations came together to establish a trusted digital infrastructure for NZ producers, growers, exporters, retailers and consumers to easily share verified and trusted data. By late 2021 it had 30 members and was growing monthly.

Chris, who is also chief executive of Potatoes New Zealand, says it provides tools and protocols for sharing data, to prove provenance, authentication and food safety as well as biosecurity tracking and tracing.

“Those who came together two years ago to form an unincorporated joint venture, were interested to see if new technologies could provide answers to key issues facing our primary sector around traceability, data accumulated in silos and the increasing compliance costs in time and money for farmers.

Main

• Simple installation, operation and service

• Designed and made in Israel

• No power or water meter required

• No filter required unless water is very dirty

• High pressure option up to 14bar

• Fully warranted

“Many farmers and growers are providing the same data, increasingly required by the marketplace and importing countries, to several different departments and companies. It’s estimated that farmers and growers can spend between 500 and 1000 hours a year meeting compliance requirements.

“Compliance costs have gone through the roof as each organisation, including government departments, local bodies, marketers and export companies, demand the use of separate information systems.

“Our economic analysis shows that up to one third of the costs of getting produce to port is chewed up in compliance costs at the farm gate. Many of those costs, removed in the 1990s through deregulation, have now been transferred to bureaucratic information interfaces surrounding farm operations.”

Through a series of workshops TANZ identified issues around data integrity, data sharing and data interoperability that, if solved, would significantly reduce cost and friction in the marketplace for all participants. TANZ was established to connect data silos and allow the sharing of data in a secure, trusted and permissioned manner.

Among TANZ’s agri-sector members are SilverFern Farms, LIC, Federated Farmers, Farm IQ, Norwood, ANZCO Foods, EcoDetection and MyEnviro.

Chris says it hasn’t been hard to encourage companies and organisations to share data for the benefit of all. “It’s very much in line with the co-operative model, beyond the farm gate, that NZ farmers are used to.

“Farmers are already digitally connected through websites, apps or other forms of collecting data. Now through our current membership we digitally touch each farm four to five times to create a network of linked organisations.”

The Trust Alliance digital tools and protocols have been built by TrackBack Ltd, a decentralised technology provider which is providing the blockchain technology that underscores the data sharing and interoperability of the TANZ consortium.

TANZ members are able to validate critical data elements including compliance,

provenance, traceability and engage with customers. “Connecting growers with consumers will allow them to tell their grower story and get useful direct feedback to improve customer satisfaction and loyalty.”

Chris says TANZ is not a platform. “It is an enabler. It is like the wiring or plumbing in a building. It works in the background but enables others to operate efficiently. It is just another tool to use and so long as the why and what are clear, how you do it is quite secondary.

“The tech we use now is 30 to 40 years old and emerging technologies like blockchain are the forerunners of what happens next which will include automation of systems allowing computers to talk to each other.”

Chris predicts that in future systems will become decentralised, and individuals will have autonomy while still interacting in data sharing.

The dairy industry is well placed to take advantage of the new world of wider data sharing.

“Dairy farmers share data on a daily basis and measure just about everything. In New Zealand we also have unbelievable talent in the agri-tech space but what we didn’t have was the mechanisms to work in concert together. Now we have the choice to be the architects of our own digital systems, rather than have them designed for us.”

The subject of the presentation TANZ will make to the Primary Sector Marketers Forum in February is “Connecting growers with consumers to tell the “farmer, grower, fisherman” story.

• To find out more about the forum go to: www.brightstar.co.nz/events/primarymkt

• To find out more about TANZ go to trustalliance.co.nz

‘Many farmers and growers are providing the same data, increasingly required by the marketplace and importing countries, to several different departments and companies.’

The New Zealand Story offers a tool kit containing thousands of high-quality images.

By Elaine Fisher.

By Elaine Fisher.

Humans understand stories better than anything else which is why a well-told, intriguing story is a powerful way to engage consumers, The New Zealand Story chief executive David Downs says.

And NZ has some of the best stories to tell.

“New Zealand’s tourism proposition is around our beautiful landscapes but that’s only part of our story,” David says. He is among the speakers at the Primary Sector Marketers Forum in Wellington in February 2022.

“Internationally people regard New Zealanders as reliable, trustworthy and friendly and during the Covid pandemic, we have seen that globally, the positive perception of New Zealand has gone up.”

Marketers who leverage brand New Zealand as part of their marketing strategy achieve a premium for their products, because of the positive perceptions and emotional responses consumers have to anything associated with the country.

This is borne out by research The New Zealand Story conducts into international perceptions every three months. Research conducted by One Picture in August and September 2021, showed NZ continued to be perceived as progressive, inclusive and decisive by the majority of key international markets including Australia, China and the United States.

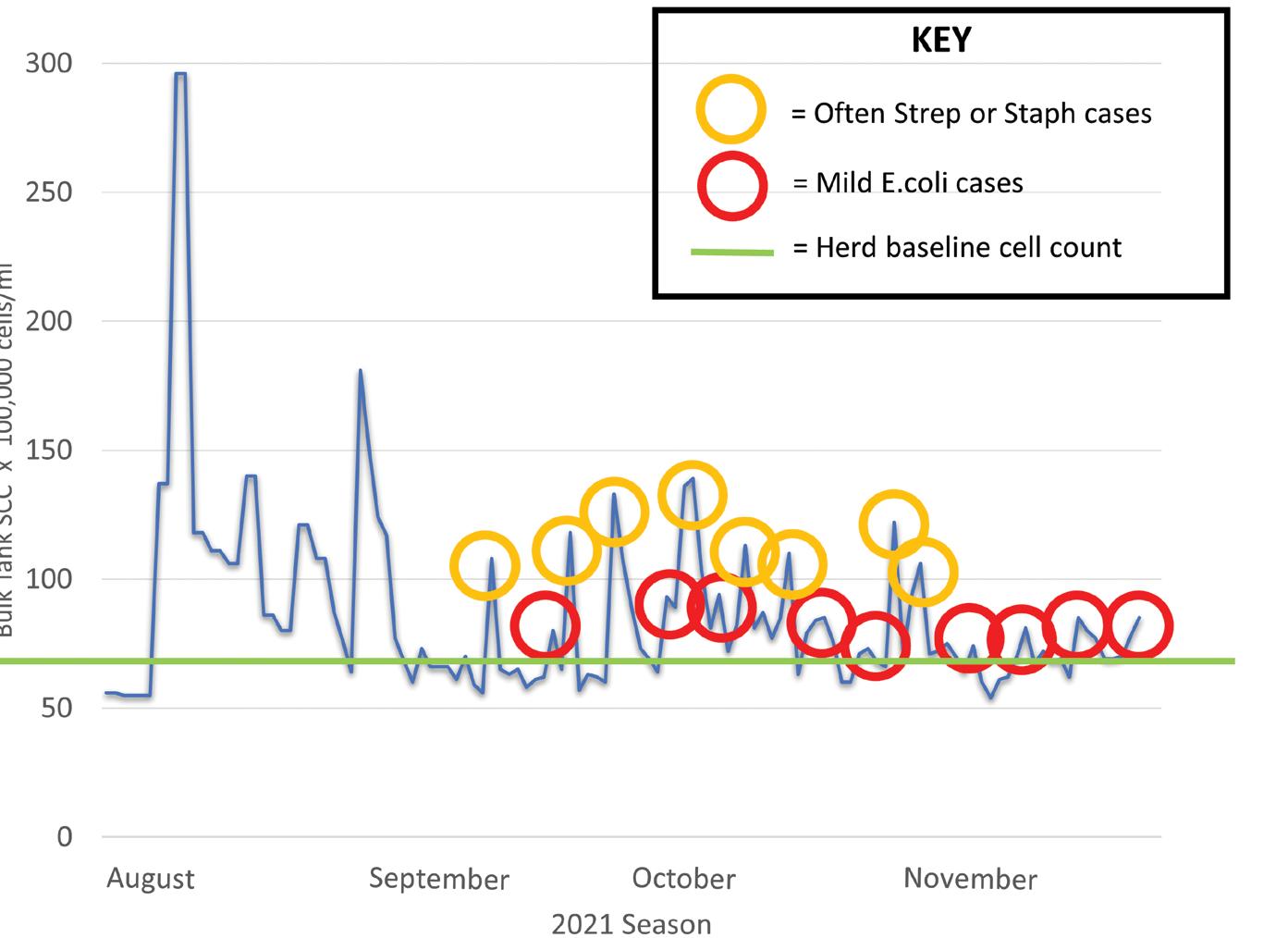

However, some markets including Germany, Dubai and Japan were forming perceptions that NZ was isolated, unfamiliar, unprepared, and closed.